Title: The Young Emigrants; Madelaine Tube; the Boy and the Book; and Crystal Palace

Author: Susan Anne Livingston Ridley Sedgwick

Release date: March 1, 2004 [eBook #11585]

Most recently updated: December 25, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by The Internet Archive Children's Library; The University of Florida; and David Cortesi and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

| Note: |

Images of the original pages are available through the Florida

Board of Education, Division of Colleges and Universities,

PALMM Project, 2001. (Preservation and Access for American and

British Children's Literature, 1850-1869.) See http://purl.fcla.edu/fcla/tc/juv/UF00001868.jpg or http://purl.fcla.edu/fcla/tc/juv/UF00001868.pdf |

"Could he make such a fearful leap?"

Chapter I. Sights at Sea.

Chapter II. The New World.

Chapter III. A New Home, and A Narrow Escape.

Chapter IV. An Intruder.

Chapter V. Striving and Thriving.

Frontispiece: "Could he make such a fearful leap?"

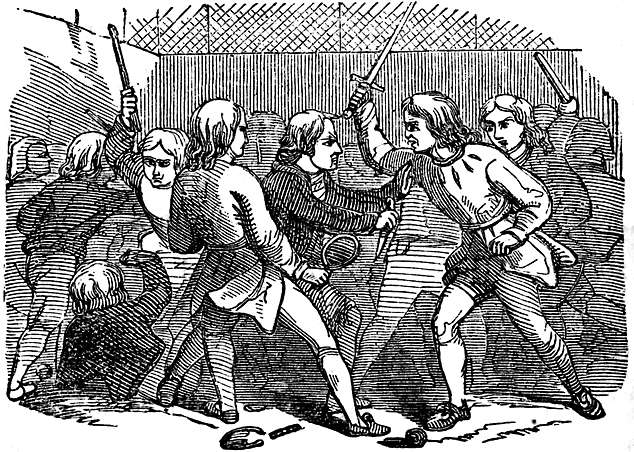

"Camping for the night."

"Fishes with wings."

"The bear prepared to give battle."

It was a lovely morning towards the end of April, and the blue waves of the Atlantic Ocean danced merrily in the bright sunlight, as the good ship Columbia, with all her canvass spread, scudded swiftly before the fresh breeze. She was on her way to the great western world, and on her deck stood many pale-faced emigrants, whom the mild pleasant day had brought up from their close dark berths, and who cast mournful looks in the direction of the land they had left a thousand miles behind them.

But though fathers and mothers were sad, not so the children—the ship's motion was so steady that they were able to run and play about almost as well as on land; and the sails, filled full by the favorable wind, needed so little change that the second mate, whose turn it was to keep watch, permitted many a scamper, and even a game at hide-and-seek among the coils of cable, and under the folds of the great sail, which some of the crew were mending on the deck. Tom and Annie Lee, however, stood quietly by the bulwarks, holding fast on, as they had promised their mother that they would, and though longing to join in the fun, they tried to amuse themselves with watching the foaming waves the swift vessel left behind, and the awkward porpoises which seemed to be rolling themselves with delight in the sunny waters.

"For shame, Tom," said his more patient sister, "you know what mother means? Suppose you should fall overboard!"

"I should be downright glad, I can tell you! I'd have a good swim before they pulled me out,—aye, and a ride on one of those broad-backed black gentlemen tumbling about yonder!"

"Oh, Tom!" sighed the gentle little girl, quite shocked at her brother's bold words, and she turned from him to watch for her father. To her great content, his head presently appeared above the hatchway.

"You look very dull, Tom," said he as he joined them; "what are you thinking of?"

"Why, father," replied Tom, "I don't want to be standing about, holding on always, like a baby. I wish mother wouldn't be so afraid of me. She won't let me run up the rigging, or do anything I like."

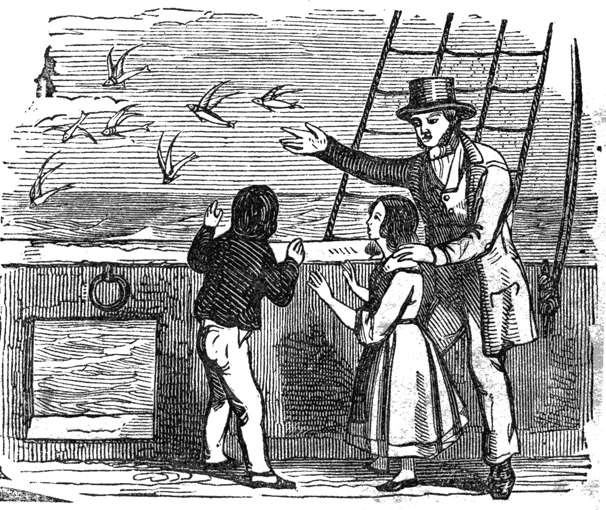

"You mean she will not let you break your neck, foolish boy. You know well, Tom, your mother refuses you no reasonable amusement. Hey, look there!" As Mr. Lee spoke, a dozen or so of flying fishes rose from the sea, and fell again within a yard of the ship's side. As the sun shone on their wet glittering scales, you might have fancied them the broken bits of a rainbow. Annie clapped her hands and screamed with delight, and even Tom's sulky face brightened.

"Why, father," cried he, "I never knew before that there were fishes with wings!"

"These have not exactly wings, though they resemble them," answered Mr. Lee, "but long fins, with which they raise themselves from the water, when too closely pursued by their enemies. But I came to call you to dinner—your mother is waiting. Should it be pleasant to-night, we will bring her on deck, when George and Willie are in bed, and show her the sights."

"What sights, what sights?" cried both the children at once, but their father was already on the ladder, and did not reply.

The night was mild and clear, and the bright full moon shone high in the heavens, when the little Lees came up again with their father and mother. Tom was no longer the discontented grumbling boy he seemed in the morning, for though he often spoke thoughtlessly, and murmured sometimes at his parents' commands, he knew in his heart that all they wished was for his good, and soon returned to his duty, and recovered his temper. He was just turned twelve, and considered himself the man of the family in his father's absence, often frightening poor Annie, who was a year younger, and of a quiet, timid disposition, by his declarations of what he "wouldn't mind doing." Little George, who was seven, admired and respected him exceedingly.

"I promised to show you some sights, this evening," said Mr. Lee, as they walked slowly up and down the deck, "and is not this ship bounding over the heaving ocean, with its white sails spread, and its tall masts bending to the wind, a most striking one? Is it not a great specimen of man's skill and power? And look above at that starry sky, and that bright lamp of night which shines so softly down on us,—look at the dashing waters, whose white crested waves sparkle as they break against our vessel—are they not wonderful in their beauty?"

"They are indeed beautiful," replied his wife, "and man's work shrinks into nothing when compared with them! And how fully the sense of our weakness comes upon us while thus tossing about upon the broad sea. What a consolation it is to remember, that He who neither slumbereth nor sleepeth, protects us ever."

"Father," cried Annie, after a short silence, "I do not understand at all how the captain finds out the way to America. It is so many miles from any other land! Tom knows all about it, but he says he can't exactly explain."

"Come, come, Tom," said his father, "try; nothing can be done without a trial; tell us now what you know on the subject."

"Well, father," answered Tom, "the man at the wheel has a compass before him, and he looks at that, and so knows how to point the ship's head. As America is in the west, he keeps it pointed to the west."

"Quite right, so far," said his father, "but tell us what a compass is."

"Oh! a compass is a round box, and the bottom is marked with four great points, called North, South, East, and West; then smaller points between them; and in the middle is a long needle, balanced, so that it turns round very easily, and as this needle always points to the North, we can easily find the South, and East, and West."

"But, father," cried Annie, "why does that needle always point to the North? my needle only points the way I make it when I sew."

"Your needle, dear Annie, has never been touched by the wonderful stone! You must know that some few hundred years ago, people discovered that a mineral called the loadstone, found in iron mines, had the quality of always pointing to the North, and they found, too, that any iron rubbed with it would possess the same quality. The needle Tom tells us of has undergone this operation. Before the invention of the compass, it was only by watching the stars that sailors could direct their course by night. Their chief guide was one which always points towards the North pole, and is therefore called the Pole star. But on a cloudy night, and in stormy weather, when they could not read their course in the sky, think what danger they were in! Such a voyage as ours, they could never have ventured on."

"Listen!" cried Mrs. Lee, "do you know, I fancy I hear the twittering of birds."

"Yes, ma'am, and no mistake," said the mate, who was pacing the deck, near them, wrapped up in a great dreadnaught coat, and occasionally stopping to look up at the sails, or at the compass, or over the ship's side; "Mother Carey's chickens are out in good numbers to-night."

"Are they not a sign of rather rough weather, Mr. James?" asked Mr. Lee.

"Why, so some say, sir; but I have heard them night after night in as smooth a sea and light a wind as you would wish for."

"What a funny name they have," said Annie. "I wonder it they are pretty."

"Can we catch them?" asked Tom, eagerly.

"I have caught them," said Mr. James, "but it was many years ago, and perhaps they have grown wiser; but we can try if you like. Only remember, no killing; we sailors think it very unlucky!"

"It would be very cruel, because very useless," said Mrs. Lee; "but are they not also called Stormy Petrels?"

"Yes, ma'am, in books, I believe; but come, Tom, fetch some good strong cotton, such as your mother sews with, and I will show you how to catch some of Old Mother Carey's brood."

Off ran Tom, and soon returned with a reel from Annie's work-box; Mr. James fastened together at one end a number of very long needlefulls, which he tied to the stern of the vessel, where they were blown about by the wind in all directions. Tom and Annie were very curious to know how these flying strands could possibly catch birds, but their father and mother could not explain, and Mr. James seemed determined to keep the secret. So they had no alternative but to await the event. As they leaned over the stern to fasten their threads, they were surprised to see the frothy waves which the vessel left behind shine with a bright clear light, and yet the moon cast the great black shadow of the ship over that part of the sea. Their astonishment was increased, when their father told them that this luminous appearance was produced by a countless number of insects, whose bodies gave forth the same kind of lustre as that of the glow-worm, and Mr. James assured them that he had seen the whole surface of the ocean, as far as the eye could reach, glittering with this beautiful light.

"And now, children," said Mrs. Lee, "I think it is bed-time—say good night to Mr. James."

"And kiss father!" cried Annie, as she jumped at his neck, and was caught in his ever-ready arms.

The children were beginning to doubt Mr. James's power of catching Stormy Petrels, when early one morning, as they were dressing, they heard the three knocks he always gave on the deck when he wanted to show them something. They hurried up, and to their delight found him-untwisting the cotton strands from the wings of a brownish-black bird, which had entangled itself in them during the night.

"Oh! what a funny little thing!" cried Annie; "what black eyes! and what black legs it has!"

"Is that one of Mother Carey's chickens?" asked Tom; "I thought they were much larger."

"Yes," replied Mr. James, "this is one of the old lady's fowls, and a fine one, too; her's are the smallest web-footed birds known. Just feel how plump it is—almost fat enough for a lamp."

"For a lamp!" cried Tom. "What do you mean, Mr. James?"

"Just what I say. Master Tom. I once touched at the Faroe Islands, and saw Petrels often used as lamps there. The people draw a wick through their bodies, which is lighted at the mouth; they are then fixed upright, and burn beautifully."

"How curious they must look!" said Annie.

"Rather so; but now watch this one running on the deck; it can't fly unless we help it by a little toss up such as the waves would give it."

The odd-looking little thing, whose eyes, beak, and legs were as black and bright as jet, ran nimbly but awkwardly up and down, to the great amusement of the children. Annie made haste to fetch her mother and father, George, and even Willie, who laughed and clapped his hands, and cried, "Pretty, pretty!" At length Mr. James thought the stranger had shown himself quite long enough, so taking it up, he threw it into the air, and it disappeared over the ship's side. Every one ran to get a look at it on its restless home, but in vain—it could be seen nowhere.

Mrs. Lee, however, was surprised by the color of the water in which they were then sailing; it was of a beautiful blue, instead of the dark, almost black hue it had hitherto appeared: immense quantities of sea-weed were also floating in it. Mr. James informed her that this water was called the Gulf Stream; a great current flowing from the Gulf of Mexico northwards along the coast of America. "In the sea-weed," added he, "are many kinds of animals and insects; I will try what I can find for Georgy." So saying, he seized a boat-hook, and soon succeeded in hauling up a great piece, from which he picked a crab not much bigger than a good-sized spider. Georgy nursed it very tenderly until he went to bed, and, even then, could with difficulty be persuaded to part with it till morning.

A few days after this, a cry of "Land!" was heard from the mast-head, and when just before tea the Lee family came on deck it was to watch the sun set amid clouds of purple and gold, behind the still distant but distinctly seen shores of the land which was to be their future home. By the same hour on the following day, the good ship Columbia had borne them safely across the deep, and was anchored in the beautiful bay of New York.

Mr. Lee was a religious, kind-hearted, sensible man, and his wife as truly estimable as himself. They both loved their children dearly, and were unceasing in their efforts to secure their happiness and prosperity. Still it is possible they would never have thought of seeking fortune in the wild back-woods of the United States, had it not been for the repeated entreaties of Mrs. Lee's only brother, John Gale, an industrious, enterprising young man, who had gone there some four years before this tale commences. John soon perceived that all his brother-in-law's exertions in England would never enable him to provide as well for his children, nor for the old age of himself and wife, as he could in America. Privations at the outset, and very hard work, would have, it is true, to be endured; but John believed him and his wife to be endowed with courage and patience to sustain any trial. He therefore spared no pains to prevail on them to cross the Atlantic, and settle on some small farm in one of the western States. He promised his help until they felt able to do without him, if they would only come. After some hesitation and deliberation, Mr. Lee determined to follow John's advice. He therefore gave up his situation as foreman in a large furniture manufactory in London, sold off all his household goods, and only adding somewhat to the family stock of clothes, which are cheaper in England than any where else, he left his native country for the strangers' land, with but a hundred pounds in his pocket; but with a stout heart, a willing hand, and a firm reliance on the never-failing protection of Divine Providence.

John Gale had made the purchase of two eighty-acre lots for them before they sailed, and was to meet them at the town nearest to their destination. They made as short a stay, consequently, as possible, in New York; and by railways, canal-boat, and steamer, in about a week arrived at the beautiful city of Cincinnati. As the vessel neared the wharf, they were gladdened by the sight of a well-known face, which smiled a heartfelt welcome on them from among the busy crowd which awaited the landing of the passengers.

"Hurrah!" cried Uncle John, for the face belonged to him, waving his hat, and quite red with the excitement, and pushing his way; "Hurrah! here you are! Hurrah!"

Then jumping on board, even before the vessel was safely moored, he caught his sister in his arms, kissing her most heartily; and when he at last released her, it was to shake Mr. Lee's hand as if he meant it to come off.

"And where are the children?" cried he. "This Tom! how he is grown! Give me your hand, my boy! Here is quiet little Annie, I'm sure. Kiss me, dear! Ah! Master Georgy, that's you, I know, though you did wear petticoats when I last saw you! Is that the young one? Don't look so cross, sir! But come along. Where's your baggage? This way, sister—this way. I'm so glad to see you all again!"

"Uncle John," said Tom, as he and George were walking with their uncle the day after their arrival, "I never saw so many pigs running about a town before. I wonder the people let them wallow in the streets so! Just look at those dirty creatures there."

"Don't insult our free-born, independent swine," cried Uncle John, laughing. "Those dirty creatures, as you call them, are our scavengers while alive, and our food, candles, brushes, and I don't know what besides, when dead! But look, Georgy! what say you to a ride?"

They turned a corner as he spoke, and beheld half a dozen boys mounted on pigs, which squealed miserably as they trotted along, now in the gutter, and now on the sidewalk, to the great discomfort of the pedestrians. George was so moved by the fun, and encouraged by his uncle's good-natured looks, that letting go his hand, he rushed after a broad-backed old hog, which, loudly grunting, permitted himself to be chased some short distance, and then, just as George thought he had caught him, flopped over in a dirty hole in the gutter, bringing his pursuer down upon him. The poor little fellow was in a sad condition when Tom helped him up—his face and clothes covered with mud, and his nose bleeding.

"You're strangers here, I guess," said a man who had witnessed the whole affair, "or you would know that old fellow never lets a boy get on his back. He's well known all over the city for that trick of his."

George did not recover his spirits during the remainder of the walk, and was very glad to get home to his mother again, and have his poor swelled nose tenderly bathed, and his stained clothes changed.

The next few days were busily employed in buying and packing the things necessary for their future comfort; and Mr. Lee had reason to rejoice that he had so good a counsellor and assistant as Uncle John. Flour, Indian meal, molasses, pickled pork, sugar and tea, a couple of rifles, powder and shot, axes saws, etc., a plough, spades and hoes, a churn, etc., were the principal items of their purchases; and to convey these, and the boxes they had brought from England, it was necessary to hire one of the long, covered wagons of the country. Uncle John had already bought, at a great bargain, a pair of fine oxen, and a strong ox-cart. These were a great acquisition. Mrs. Lee was anxious to get a cow and some poultry; but her brother advised her to wait, as they would be so great a trouble on the journey, and it was, besides, most probable that they could be procured from their nearest neighbor—a settler about ten miles from their place.

Early one bright morning, they started for their new home, the wagon taking the lead. It was drawn by four strong horses, driven by Mr. Jones, from whom it had been hired, and contained the best of the goods: the beds were arranged on the boxes within, so as to form comfortable seats for Mrs. Lee, Annie, and the two little ones. The ox-cart followed, guided by Uncle John, assisted by Mr. Lee and Tom, both of whom were desirous to learn the art of ox-driving, of which they were to have so much by-and-by. The journey was long and wearisome; and it was not until the evening of the fifth day after leaving Cincinnati, that they arrived at Painted Posts—a village about twenty miles distant from their destination. From this place the road became almost impassible, and the toil of travelling very disheartening. They were frequently obliged to make a long circuit to avoid some monster tree which had fallen just across the track, and to ford streams whose stony beds and swift-flowing waters presented a fearful aspect. Mr Jones the wagoner walked nearly all day at the head of the foremost pair of horses, with his axe in his hand, every now and then taking off a slice of the bark of the trees as he passed. Annie watched him for some time with great curiosity.

"What can he do it for?" said she to her mother. "Please ask him, mother?"

"We call it blazing the track, Marm," replied Mr. Jones to Mrs. Lee's inquiry. "You see, in this new country, where there's no sartain road, we're obliged to mark the trees as we go, if we want to come back the same way. Now, these 'ere blazed trees will guide me to Painted Posts without any trouble, when I've left you at your place."

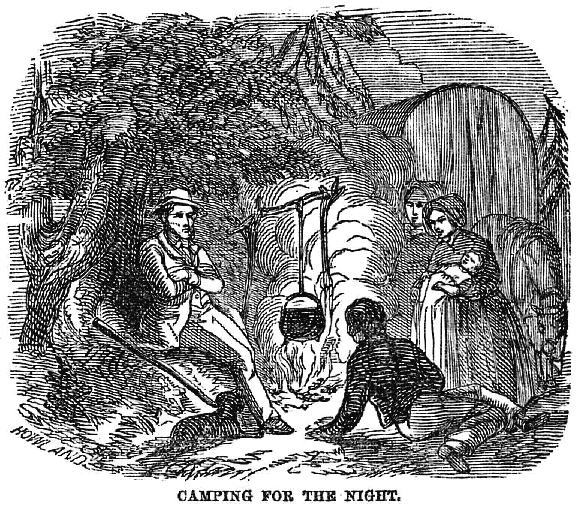

At sunset on the sixth day, they found themselves within five miles of the end of the journey, happily without having experienced worse than a good deal of jolting and some occasional frights. As it was impossible to travel after dark, they camped for the night near a spring on the road side. A good fire was kindled at the foot of a large tree, the kettle slung over it by the help of three crossed sticks; and while Mrs. Lee and Annie got out the provisions for supper, the men and Tom fed and tethered the horses and oxen close by. When Mr. Jones had done his part in these duties, he brought from his private stores in the wagon a large bag and a saucepan.

"I reckon I'll have a mess of hominy to-night," said he. "It's going on five days since I've had any."

"A mess of hominy," cried Tom; "that does not sound very nice."

"I guess if you tasted it you'd find it nice," answered the wagoner. "You British don't know anything of the vartues of our corn."

He poured into the saucepan as he spoke a quantity of the Indian corn grains, coarsely broken, and covering it with water, put it on the fire. It was soon swelled to twice its former bulk, and looked and smelt very good. With the addition of a little butter and salt, it made such a "mess of hominy," as Mr. Jones called it, that few persons would not have relished. Tom certainly did, as he proved at supper, when the good-natured wagoner invited all to try it.

The meal was a merry one, notwithstanding the fatigue they had all experienced during the hard travel of that day—the merrier because of their anticipated arrival on the morrow at their future home. They all talked of it, wondering where they should build their house—by the river (for Uncle John had told them there was one near) or by the wood? Tom wished for the first, as he thought what fine fishing he might have at any hour; but Annie preferred the shade of the trees.

"Oh! father," cried she, "I hope there will be as many flowers as I saw to-day on the road. Such beautiful Rhododendrons! a whole hill covered with them, all in blossom! And did you see the yellow butterflies? Mother and I first noticed them when they were resting on a green bank, and we thought they were primroses until they rose and fluttered off."

"I tell you what, Annie," said Tom, "you'll have to keep a good look-out after your chickens. There are plenty of hawks about here. I saw one this afternoon pounce down on a squirrel, and he was carrying it off, when I shouted with all my might, and he let it drop."

"Oh, Tom! was it hurt?"

"Not it! but hopped away as if nothing had happened."

"You must learn to use your rifle, Tom," remarked Uncle John; "you'll find it very necessary, as well as useful, in the woods."

"Well, uncle, I'll promise you a dish of broiled squirrels before October of my own shooting! I intend to practice constantly, if father will let me."

"If, by 'constantly,' you mean at fitting times," replied Mr. Lee, "I certainly shall not object. I, too, must endeavor to become somewhat expert, for in this wild country, where bears and wolves are still known, it is absolutely necessary to be able to defend oneself and others."

"I never think of savage animals," said Mrs. Lee, "but of snakes, I must confess I am very much afraid of them, particularly of rattlesnakes."

"You needn't mind them a bit, Marm," answered Mr. Jones; "they none of them will strike you, if you don't meddle with them; and as for the rattlesnake, why, as folks call the lion the king of beasts, I say the rattlesnake is king of creeping things; he don't come slyly twisting and crawling, but if you get in his way, gives you sorter warning before he bites."

"Indeed, sister," said Uncle John, "Mr. Jones is right when he tells you you need not be afraid of them—they are more afraid of us, and besides are wonderfully easy to kill; a blow with a stick, in the hand of a child, on or about the head, will render them powerless to do hurt."

"And if you should get a bite, Marm," added Mr. Jones, "the very best thing you can do is to take a live chicken, split it in two, and lay it on to the wound: it's a sartain sure cure."

"Why, Annie, if there are many rattlesnakes," cried Tom, laughing, "it will be worse for your chickens than the hawks!"

"Annie will dream to-night of you, and snakes, and chickens, all in a jumble, Mr. Jones; but don't you think it is time to prepare our sleeping-place? It is past eight o'clock, and we must be stirring early."

After packing up the remains of the supper, Mrs. Lee and the children retired to their mattresses in the wagon, and the men having put together a kind of wigwam of branches for themselves, and piled up the fire, were soon resting from the labors of the day.

The sun had scarcely risen the next morning when our travellers were prepared for their last day's journey. All was bustle and excitement with Uncle John and Tom; and Mr. and Mrs. Lee, though quiet, felt an eager impatience for a sight of their future dwelling-place. And fast and hard was the beating of their hearts, when after a few hours they beheld before them their own little possession! Some thirty acres of rich pasture-land, sloped gently to the margin of a broad stream, which flowed with a smooth and rapid current, and whose opposite shore gave a view of a lovely undulating country, bounded by distant mountains, robed in misty blue. The grand primeval forest nearly enclosed the other three sides of this vast meadow. It was a beautiful scene, and to Mr. Lee it almost seemed that he must be dreaming, to look upon it as his own. Deep and heartfelt was the thanksgiving he silently breathed to the Giver of all good, that He had brought him to this land of plenty, and given him such a heritage in the wilderness.

But more than gazing and admiring had to be done that day, so after a hasty dinner, a sheltered spot was sought for the erection of the shanties, which were to serve them as sleeping-rooms until the house should be built. This was soon found, and in a couple of hours two good-sized ones were made; the walls were formed of interwoven branches, and the roofs of bark; the fourth side of the men's was to be left open, as a fire was kept up every night in front of it, to scare away the wolves, and other wild beasts, should there be any in the neighborhood.

The next morning a council was held as to their future proceedings; to prepare a house was, of course, a work to be commenced immediately, but it required some deliberation as to how they should set about it. Mr. Jones had taken a great liking to the family, and he now proved his goodwill by declaring that he would "stay awhile, and help them a bit." But first of all, the goods must be unpacked, and a shed of some kind made to receive them. This was set about at once, and by dinner time it was completed, the wagon and cart unloaded, and their contents arranged as most convenient to Mrs. Lee. The rest of the day was occupied in chopping down trees for the principal building, and very hard work it was, especially to Tom, whose young arms and back ached sadly when he went to bed that night. By the end of a week of this toil, a good number of logs had been prepared, and Uncle John proposed that he and Tom should make their way to the settler's, about ten miles distant, and see if there were any men he could ask to help put up the house, as the raising of the great logs would prove a slow and laborious task to so few workmen as they now numbered. He was provided with a pocket-compass, a rifle, and a good map of the country, and there was no real danger to be feared, so Mrs. and Mr. Lee readily consented, and accordingly Uncle John mounted on one of Mr. Jones's horses, and Tom on his father's, which was one of the four that had drawn the wagon, with a bag of provisions slung behind him, and an axe to blaze the track, started the next morning by day-break. Although they were not expected to return until the next day, the night passed anxiously with the little family, and it was a joyful relief to them when about three in the afternoon they heard Tom's well-known halloo from the western wood, and presently saw him appear, followed by two strangers, and his uncle driving a fine cow.

"Here we are, mother, safe and sound!" exclaimed the boy, as he jumped from his horse, and ran to kiss her, "and a fine time we've had!"

"We've been successful you see, sister," said Uncle John, who had also dismounted, and came up with the cow; "Mr. Watson and his son have very kindly consented to help us; and isn't this a beauty?"

"Indeed, ma'am," said Mr. Watson, shaking her hand heartily, "it's but a trifling way of showing how well pleased we are to get neighbors. We have been living some six years out here, and never had a house nearer than Painted Posts, a good thirty miles off. My wife says she hopes to be good friends with you, and when you are fairly settled she will come over. She's English, too, and longs sadly to talk about the old country with some one just from it."

"It will give me a great deal of pleasure to see her, Mr. Watson," replied Mrs. Lee, looking as she felt, very happy at this prospect of not being quite alone in the wilderness; "and as we shall both meet with the wish to be good friends, I think there is no fear of our not being so."

"You'll soon have some chickens, and turkeys, and pigs, mother," said Tom; "Mrs. Watson has such a number, and she says you shall have some of the best. And mother, just look what Jem Watson gave me!"

Tom opened the bag which the day before had carried the provisions for the journey, and to Annie and Georgy's great delight, pulled out a very pretty little puppy.

"Now, Annie, you shall name him; he's got no name yet. What shall it be?"

The children went away to consult on this important matter, and Mr. Lee, who had been chopping in the wood, now arriving, welcomed his friendly neighbor, and thanked him warmly for so readily coming to help them.

"Nonsense," rejoined Mr. Watson; "no need of thanks; you would do the same for me, or you don't deserve the blessings I see around you. My maxim, Mr. Gale, is a helping hand and a cheering word for every one who needs them."

Six weeks afterwards, our young emigrants felt themselves once more at home. The log-house was finished, and consisted of one large room, which served as kitchen and parlor, and of three smaller ones for sleeping. The roof was covered with large pieces of bark; the chinks of the wall were stopped up with clay; and the chimney and floor were of the same material, beaten hard and smooth. The windows were as yet but square openings with shutters, but before winter came, and it is very severe in Ohio, Mr. Lee meant to put in glazed frames, as glass could be procured at Painted Posts. The building stood upon the highest rise of the prairie, and in front flowed the beautiful river, while the thick forest screened it behind from the cold winds of the north. No trees, however, were near it, except three fine sycamores, which gave a grateful shade when the noon-day sun shone bright and hot. Tom had already contrived seats of twisted branches beneath them, and it was very pleasant to sit there in the evening and watch the glorious colors of the western sky, which Annie compared to the changing hues of a pigeon's neck, or the glancing of the brilliant fire-flies that night brought forth from their hiding-places under the leaves. A well-fenced yard was at the back of the dwelling, and enclosed the wood-pile, stable, and hen and storehouses. A garden had also been commenced around the other three sides of the house, in which Tom worked, assisted by his sister and brother, whenever he could be spared from more important labors. He was indeed an active, industrious boy, and by his example made even little George useful. Mr. Jones, who had departed as soon as the walls of the house were raised, used often to say of him, and it was intended as great praise, "That Tom is a riglar Yankee—a rael go-a-head!"

In doors things also began to look comfortable; it is true they had only three chairs and one table, but Mr. Lee had knocked together some stools and a dresser, which the children thought superior to any they had ever seen; a rack over it held their small stock of crockery, and a few hanging shelves on the wall were their book-case: cleanliness and neatness made up for the want of more and better furniture, and cheerfulness and content were at home in the humble cottage. Annie was a great help to her mother, and fast learning to be a good housewife. The poultry was her particular care, and she had already received from Mrs. Watson a cock, half a dozen hens, and two pairs of fine turkeys, with many useful directions concerning their management. She would soon perhaps have lost them all, however, if it had not been for an adventure which happened to George, and which made her very watchful of them.

He came running home one day smelling so horribly that he was perfectly intolerable, and the whole house was scented by his clothes.

"Oh, mother!" he cried, "I was playing in the wood, when I saw such a pretty animal; I thought it was a squirrel at first, or a young fox, and it seemed so tame that I ran to catch it, but it ran a little way off, and then stopped and looked back at me—at last, just when I thought I should get hold of it, it squirted all over me. Oh! it smells so nasty!"

"You may well say that, Georgy," said his uncle; "but it was lucky it did not squirt into your eyes, or you might have been blinded for life. That was a skunk, and very likely thinking of paying a visit to the chickens when you disturbed it. It makes great havoc in a hen-roost, Annie; and I would advise you to get Tom to make yours safe."

"That I will, this very day," cried Tom; "but, uncle, I never heard of a skunk before; what kind of a looking thing is it?"

"Rather a pretty animal, Tom, about eighteen inches in length, with a fine bushy tail as long as its body. Its fur is dark, with a white stripe down each side. It can be easily tamed, and would serve very well as a cat in a house, were it not for the disgusting way in which it shows its anger. The fluid it squirts from under its tail will scent the whole country round. Even dogs can't bear it."

"I feel quite uncomfortable now from the smell of George's clothes," said Annie.

"The worst of it too, is, that you can't get rid of it; no washing will take it away."

And so it proved; for notwithstanding repeated washing and airings, that suit of George's was so offensive that he could no longer wear it; and as everything placed near it was infected, it was at last burnt.

Tom stopped up every cranny of the hen-house which looked in the least dangerous, with such neatness and skill that his father and uncle were quite pleased.

Annie and George were watching him finish his job, when Uncle John came up with what looked like a large, green grasshopper, which he had caught on a sycamore.

"Here, Annie," cried he, "is one of the fellows that make such a grating, knife-grinding sort of noise every night."

"I thought you said the little tree-toads made it, uncle."

"The tree-toads and the katydids too. This is a katydid, or, perhaps, a katydidn't; for people say they are divided in opinion, and that as soon as one party begins to cry 'katydid,' the other shrieks louder still 'katydidn't,' which accounts for the noise they make."

"Oh, uncle! do they really?" cried George.

"You must listen, Georgy," replied his uncle, laughing.

"When we first came here" remarked Tom, "mother could not sleep for the noise they and the tree-toads made."

"The voice of the tree-toad is very loud for so small a creature, but the katydid has really no voice at all."

"No voice, uncle?"

"No, Annie; the chirp of all kinds of grasshoppers is produced by their thighs rubbing against their wing-cases."

"How very curious!" exclaimed the children, and the katydid was examined with still greater interest before it was released to rejoin its companions on the sycamore.

"What do you think of our building a boat, Tom?" said his uncle to him, a few days after he had finished the hen-house. "It seems to me that you and I could manage it. What do you say?"

"Oh! capital!" cried Tom, with delight; "I'm sure we could! let's begin to-day!"

"Well, we'll try at any rate. When you have driven out the cows, come to me at the fences."

"Where there's a will there's a way," was Uncle John's favorite maxim, and certainly he had reason to believe in the truth of it, for he succeeded in everything he undertook. The boat was no exception: it was built in a wonderfully short time, and launched one fine day in the presence of the assembled family. It was not large enough to hold more than two persons safely, but as Uncle John said, if it did well, it would be an encouragement to build another capable of containing the whole household, and then, what pleasant trips they might take!

The two boat-builders rowed several times a couple of miles up and down the river in the course of the week, bringing home, after each excursion, a tolerable supply of cat-fish. This was an acceptable change in their diet, for, except when Uncle John killed some venison, which had as yet only happened once, or Tom shot squirrels enough to broil a dishfull, their usual dinner was salt pork and hominy.

But a couple of miles up and down did not at all satisfy Tom's desire of exploration; he wanted to see more of the river, and especially to discover a short cut by water to Mr. Watson's mill. Uncle John hesitated to give his consent to going any distance until something more was known of the currents and difficulties of the stream, so the boy determined to go alone. One day, therefore, when his father and uncle were chopping fences in the woods, he unmoored the little boat, and rowed off. The weather was very fine, and the current rippled gently on between the beautiful banks, which were now darkly wooded, now smiling with green prairies and sunny flowers. The sweet clear song of the robin, or the monotonous tapping of the brilliant crimson-headed woodpecker, alone broke the stillness of the scene; and after a time, Tom, somewhat wearied and heated by the exertion of rowing, felt inclined to yield to the spirit of rest which breathed around. So he laid aside his oars, and let the boat drift idly on while he refreshed himself with the cold meat and bread he had provided for the occasion. The current gradually became stronger, the banks grew rocky and steep—soon large masses of stone appeared scattered in the river's bed, and the waters dashed noisily past. Tom roused up at length, and began to wish that he had not ventured so far; he seized the oars to return, but too late—his single strength could no longer direct the laboring boat, now hurried along by the rushing stream. The banks rose steeper—the river narrowed—the hoarse sound of falling waters was heard, and Tom saw with despair that he was approaching a terrific cataract. There seemed no escape from destruction—there was no hope of help from human hand. The boy looked around with a pale cheek, but brave heart—one chance yet remained to save him from certain death—one chance alone! A black and rugged rock, around which the waters madly leaped and broke, parted the current some feet from the direction in which his little vessel was impelled;—if he could reach it, he would be saved! As he approached it he stood up;—could he make such a fearful leap?—he sat down again, and tried to calculate calmly the distance and his powers. He drew near the rock—still nearer—one moment more, and his only chance of life would be gone forever! He sprang upon the edge of the boat, and, leaping from it with all the strength of despair, fell, clinging with a death-grasp, to the projections of the wet and slippery stone, while the boat, whirling round and round by the impulse, dashed onwards and disappeared!

For some time Tom dared not raise his head; he felt too bewildered, too terrified by the danger he had escaped, to comprehend perfectly his present situation. At length he sat up, and endeavored to collect his thoughts, and determine what next he should do. The river-bank rose almost perpendicularly full twenty feet; no straggling vine, by whose help he might have clambered up, fell from it, and the foaming torrent rushing between it and him, rendered any attempt to scale it, without some aid from above, utterly impossible. He must, then, call for help; but who was there to hear him in this wild place—.and how could he make himself heard above the din of the raging waters which surrounded him? He was nigh despairing again, when he remembered the whistle with which he used to call the pigs, and which he always carried about him; he took it from his pocket, and blew a long, shrill cry—it rose high above all the roar and tumult of the cataract, and his failing hope and courage revived.

"Dick," said Jem Watson to his elder brother, as they were shooting squirrels that afternoon in the woods, about three miles from home, "did you hear that whistle just now?"

"A whistle! No; whereabouts?"

"It seemed to come from the Fall; but who should be there! father's at home, isn't he?"

"Yes, father's at home. But, hark! I hear it now! Who can it be?—let's go see!"

The young man ran off, followed by Jem, and they were soon on the cliff above poor Tom, who sat wearily looking upwards. "Tom Lee!" they both cried in a breath, as his pale face met their eyes.

"Why, Tom! how came you there?" called Jem.

"Don't stand bawling, Jem," said his brother; "he'd rather tell you up here than where he is, I'll be bound! Cut off home as fast as you can, and tell father to come and bring a rope—that one hanging over my tool chest. Now be off—that poor fellow looks almost at death's door already."

Jem needed no second telling, but was out of sight in a moment, while Dick stayed near the cliff, that Tom might be encouraged by the sight of a friend. He had not to wait long; in little more than an hour Mr. Watson and Jem arrived with the rope, and after some trouble they contrived to pull the wet and shivering boy up in safety. They hastened with him to the farm, where Mrs. Watson made him change his dripping clothes for a suit of Jem's, and take some very welcome refreshment, after which she hurried his return home, knowing from her own mother's heart how dreadful must be the anxiety of Mr. and Mrs. Lee, ignorant as they were as to what had become of their son.

It was near sunset when Dick started on horseback, with Tom behind him, for the ten mile journey through the forest. They had proceeded about two-thirds of the distance, and had lighted one of the splinters of turpentine pine they had brought for torches, when they heard a shot. Dick answered it by another, and a loud halloo! and presently a light appeared through the trees approaching them. As it came near, Tom recognised his father and uncle, who had scoured the woods around the log-house in search of him, and were now on their way to Mr. Watson's, hoping almost against hope to find him there.

It would be vain to attempt to describe the tenderness lavished on the truant that night by the happy family, or repeat the many grateful words spoken to Dick. All the pain that the thoughtless boy had caused was forgotten in joy for his safety. "You should have remembered, Tom, how unhappy your absence without our permission would make your mother and me. How often, my son, have I said to you that—

These were the only reproving words his father's full heart could utter, but Tom felt them; and when all knelt together before retiring to rest, to give humble and hearty thanks for the blessings of the past day—while each heart poured forth its gratitude for the especial mercy that had been granted—his prayed also for power to resist temptation.

"I wonder what is the matter with Snap," cried George one evening about a week after, as the family were at tea; "he sits there looking at that corner as if he was quite frightened; I've watched him such a time, father!"

"Oh yes, father, do look!" cried Annie; "he sees something between that box and the wall, I'm sure!"

"Hi! hi! good dog! at him!" shouted Tom, trying to incite the dog to seize the object, whatever it might be. Snap's eyes sparkled and he ran forwards, but as quickly drew back again, with every sign of intense fear. At the same moment a mingled sound, as of the rattling of dried peas and hissing, was heard from the spot. "A snake!" cried Uncle John, jumping up from the table, and seizing a stout stick which was at hand, while Mrs. Lee, at the word, catching Willie in her arms, and dragging George, retreated to the farthest part of the room, followed by Annie. As the box was carefully drawn away, the hissing and rattling became louder, and presently a large rattlesnake glided out with raised head and threatening jaws, and made for the door. Snap stood near the entrance, as if transfixed by fear, his tail between his legs, and trembling in every limb. Uncle John aimed a blow, but the irritated reptile darting forwards bit the poor dog in the throat. Before, however, Snap's yelp of agony had died away, the stick fell on the creature's head, and it lay there lifeless.

"He's done for!" cried Tom, triumphantly.

"Yes, and so I fear is Snap, too," said his father; "poor fellow!"

"Can't we do anything for him, Uncle?" asked Tom, anxiously.

"Nothing that I know of—there is but one antidote, it is said, and that is the rattlesnake weed,—the Indians believe it to be a certain cure for the bite, but I don't know it by sight."

Mrs. Lee now ventured forward to look for a moment at the still writhing snake, and Tom then dragged it out of the house; but before throwing it away, he cut off the rattle, which was very curious. It consisted of thin, hard, hollow bones, linked together, somewhat resembling the curb-chain of a bridle, and rattling at the slightest motion. Uncle John showed him how to ascertain the age of the reptile. The extreme end, called the button, is all it has until three years old; after that age a link is added every year. As the snake they had just killed had thirteen links, besides the button, it must have been sixteen years old; it measured four feet in length, and was about as thick as a man's arm.

The unfortunate dog died after three or four hours' great suffering, and was buried the next day at the foot of a tree in the forest. His loss was especially felt by George, who busied himself for some hours in raising a little mound over the grave, and then fencing it round, as a mark of esteem, he said, for a friend.

Meanwhile the summer was slipping fast away, and October came, bringing with it cool weather and changing leaves. The woods soon looked like great gardens, filled with giant flowers. The maple became a vivid scarlet, the chestnut orange, the oak a rich red brown, and the hickory and tall locust were variegated with a deep green and delicate yellow. Luxuriant vines, laden with clusters of ripe grapes, twined around and festooned the trees to their summits, while the ground beneath was strewn with the hard-shelled hickory-nut and sweet mealy chestnut, which pattered down in thousands with the falling leaves.

It was at day-break on one of the brightest and mildest mornings of this delightful season, that the family were awakened by the shouts of Tom, who was already up and out of doors, setting the pigs, which were his particular charge, free for their daily rambles in the forest.

"Oh, Uncle John!" he cried, running in for his gun, "do get up: there are such lots of pigeons about! Flock upon flock! you can hardly see the sun!"

Every one hastily dressed and rushed out—it was indeed a wonderful sight which presented itself. The heavens seemed alive with pigeons on their way from the cold north to more temperate climates; they flew, too, so low, that by standing on the log-house roof one might have struck them to the earth with a pole. Millions must have passed already, when there approached a dense cloud of the birds, which seemed to stretch in length and breadth as far as eye could reach. It formed a regular even column—a dark solid living mass, following in a straight undeviating flight the guidance of its leader. The sight was so exciting that Mr. Lee and Uncle John ran for their rifles as Tom had done, and opened a destructive fire as it passed over.

The ground was soon covered with the victims, and the sportsmen still seemed intent on killing, as if they thought only of destroying as many as possible of the crowded birds, when Mrs. Lee called to them to desist.

"There are more of the pretty creatures already slain," she said, "than we can eat,—it is a shocking waste of life!"

"And see, Tom," cried his sister, "the poor things are not dead, only wounded and in pain!"

They all instantly ceased firing, and Mr. Lee looked on the bleeding birds scattered around, with the regretful feeling that he had bought a few minutes' amusement at a great expense of suffering. Uncle John and Tom, however, only thought of pigeon-pies, and went to work to put the sufferers out of their misery, and prepare them for cooking.

A few days after this memorable morning, the children and Uncle John set out for a regular nutting excursion; Annie had made great bags for their gatherings, and Mrs. Lee provided a fine pigeon-pie for their dinner; Tom took charge of it, his sister of Georgy, and Uncle John carried his constant companion on a ramble—his good rifle. By noon they had gone more than three miles into the depths of the forest; their bags were nearly filled, and Tom began to grumble at the weight of the pie, so that when they reached a pleasant open spot near a spring, it was at once decided that they should dine there. They spread their little store on the ground, adding to it some bunches of grapes from the vines around, and then sat down with excellent appetites and the merriest of tempers.

"I am never tired of watching the squirrels!" cried Annie, who had been looking for some time at the lively little animals scampering in the trees; "just look what funny little things those are!"

"The young ones are just old enough now to eat the nuts and berries," replied Uncle John; "see how they are feasting!"

"Where do they live, uncle; in a hole?" asked George.

"Oh, George! where are your eyes!" cried his brother; "look up there; don't you see the little mud and twig cabins at the very top of the tree! those are their nests!"

"I once read an interesting story," remarked Uncle John, "of a squirrel that tried to kill himself; would you like to hear it?"

"Oh yes, uncle!" they all cried in a breath.

"Well, this squirrel was very ill-treated by his companions; they used to scratch and bite him, and jump on him till they were tired, while he never offered to resist, but cried in the most heart-rending manner. One young squirrel, however, was his secret friend, and whenever an opportunity offered of doing it without being seen, would bring him nuts and fruits. This friend was detected one day by the others, who rushed in dozens to punish him, but he succeeded in escaping from them by jumping to the highest perch of the tree, where none could follow him. The poor outcast, meanwhile, seemingly heart-broken by this last misfortune, went slowly to the river's side, ascended a tree which stood by, and with a wild scream jumped from it into the rushing waters!"

"Oh, uncle! what a melancholy story," cried Anne, quite touched by the squirrel's sorrows.

"But wait, dear; our wretched squirrel did not perish this time, he was saved by a gentleman who had seen the whole affair, and who took him home and tamed him. He was an affectionate little creature, and never attempted to return to the woods, although left quite free. His end was a sad one at last; he was killed by a rattlesnake!"

"Oh, horrid!" cried George, "that was worse than drowning."

"So I think, Georgy. But isn't it time for us to move homewards? Wash the dish, Annie, at the spring, and Tom shall bag it again."

It was nearly dark when they reached the log-house, tired with their long walk, and the weight of their full bags, but in great spirits nevertheless, for they brought back a prize in an immense wild turkey, which Uncle John had shot on the return march. They had seen a great many of these beautiful birds during the day, but none near enough to shoot; at last a gang of some twenty ran across the path close to them, and the ready rifle secured the finest. Uncle John carried it by the neck, slung over his shoulder, and so stretched, it measured full six feet from the tip of the beak to the claws. The plumage of its wings and spreading tail was of a rich, glossy brown, barred with black, and its head and neck shone with a brilliant metallic lustre.

The nutting party were very glad to get to bed that night, especially George, who was more foot-sore than he liked to confess. Before saying good-night, they agreed to rise very early the next morning, to spread their chestnuts in the sun, as Uncle John had told them it would improve their sweetness exceedingly, besides making them better for storing during the winter. A great change in the weather took place, however, during the night; a cutting north-easterly wind and rain set in, and continued with little intermission for nearly a week. When bright, clear days returned, the country showed that winter was approaching rapidly. Uncle John took advantage of a call Dick Watson made at the log-house with his team, to accompany him to Painted Posts to buy glass for the windows. On their return, Dick stayed a couple of days to help with the job, which was not finished before it was needed, for they had begun to feel the cold very sensibly, notwithstanding the great wood fire they kept up.

The Indian summer—a delightful week in the beginning of November, when the air is mild and still, and a beautiful blueish mist floats in the atmosphere, through which the landscape is seen as through a veil of gossamer—had come and gone, and a slight flurry of snow had covered the ground with a white mantle, when one morning a great squealing was heard from the pen in which the pigs were now kept.

"What can be the matter there?" said Mrs. Lee, "they are not fighting, I hope."

"I'll go and see, mother," said Tom, running out. A moment after his voice was heard shouting, "a bear! a bear!" and he was seen running towards the prairie, armed with a rail which he had picked up in the yard. When Mr. Lee and Uncle John rushed after him with their rifles, he was gaining fast on a huge black bear, which had just paid a visit to the hog-pen, and was now trotting off to the woods with a squalling victim. "Stop, stop, Tom!" cried his father; but Tom was too excited to hear or see anything but the object of his pursuit; he ran on, and soon got near enough to make his rail sound on the bear's hard head. But though Tom was a strong, big fellow for his years, he was no match for an American bear, which is not so easily settled, and so Bruin seemed determined to let him know; he immediately dropped the pig with a growl, and erecting himself on his hind legs, prepared to give battle. Tom tried to keep him off with the rail, but a bear is a good fencer, and a few strokes of his great paws soon left the boy without defence. The deadly hug of the angry animal seemed unavoidable, when a shot from Uncle John, which sent a bullet through the left eye into the very brain, stretched the bear lifeless on the snow.

"If it hadn't been for you I should have had a squeeze, uncle!" cried Tom, laughing.

"You're a thoughtless, foolish boy, Tom!" said his uncle; "who but you, I wonder, would have run after a bear with nothing but a rail!"

"He is indeed a thoughtless boy," said his father, "but I hope a grateful one; you have most probably saved his life!"

"Uncle knows I am grateful, I'm sure," said Tom, "I needn't tell him!"

"It's a fine beast, and fat as butter," remarked Uncle John, feeling its sides as he spoke, "yet he must have been hungry, fond as a bear is of pork, to venture so near a house by daylight!"

"What a warm fur!" observed Mr. Lee, "just feel how thick the hair is!"

"But what can we do with such a mountain of flesh and fat?" asked Tom. "We can't eat it, and we've no dogs."

"O, we'll eat it fast enough!" replied his uncle; "a bear ham is a delicacy, I assure you."

"I think we may as well set about skinning and cutting it up for curing at once, as we have little to do to-day. What say you, John?"

"Yes, we had better; but we must do the business here, for the skin would be quite spoiled were we to attempt to drag the carcase into the yard, though it would be more convenient to have it there. We can take the hams and fur, and leave the rest."

"What a busy day this has been," said Tom, that evening, when he and his sister had finished the reading and writing lessons their father gave them every night; "what with helping to catch the bear, and then to skin and cut him up, and dinner and tea, and reading and writing, I've not had a spare moment."

"As to helping to catch the bear," said his father, laughing, "you may leave that out of the catalogue of your occupations."

"Not at all, father; for, if I hadn't gone to see what was the matter, he would have walked off with the pig, and no one the wiser."

"Oh, certainly, Tom helped!" cried his uncle; "and his mother helped, too, for, you remember, she wondered what was the matter in the hog-pen!"

"I don't mind your fun, uncle," said Tom; "I shall shoot a bear myself some day."

"I'm glad that, if the poor bear was to come, it came to-day rather than to-morrow, for to-morrow will be Sunday," remarked Annie; "the week has seemed so short to me!"

"So it has to me," said her brother; "the weeks seem to fly fast."

"Because you are always occupied," observed Mr. Lee; "time is long and tedious only with the idle. What a blessing work is; it adds in every way to the happiness of life!--it is good for the mind, and good for the body!"

"I used to think it very disagreeable, I remember!"

"You have grown wiser as well as older, Tom, during the past year," said his mother.

"If I only do so every year, mother!"

"If you do, Tom, you will indeed be a happy man, for the ways of wisdom are ways of pleasantness;—but it must be time for your usual wash."

"Aye, so it is! I believe I like the Saturday night wash almost as well as the Sunday rest. One seems to feel better, as well as cleaner, after it!"

Sunday, in the family of the emigrants, was generally happy; even the very youngest seemed to be influenced by the spirit of peace that breathed around on that holy day. No loud boisterous voice, no jeering laugh was ever heard; a subdued, composed, yet cheerful manner, marked the enjoyment of rest from the fatigues of the past well-spent six days of labor, while the earnest remembrance of their Maker, the eager desire and striving to learn and to do their duty to Him and to each other, made the commencement of each new week as profitable as it was welcome. The recollection, too, of the land they had left was more tender on this quiet day, and past joys and trials were often recalled with a kind of melancholy pleasure, sometimes with an almost regretful feeling that the scenes in which they had laughed and toiled should know them no longer. The green fields—the hawthorn hedges—the cottages and the little gardens, gay with the rose and the hollyhock—the ivy-grown village church—all were remembered and talked of in love—seeming ever more beautiful as memory dwelt on them. They acknowledged with thankfulness the blessings of their present lot—they looked forward hopefully to the future—but, oh! how deeply they felt that the far-off island, the land of their birth, could never be forgotten!

Here in the woods, where no church was near, when the never-omitted morning prayer was ended, Mr. Lee read aloud some good plain discourse, and explained those passages the children had not perfectly understood; the evening was spent in listening to interesting portions of the sacred history, and in instructive and pleasant conversation. Before retiring to rest, all voices joined in some sweet hymn of praise, and then, with hearts softened by the touching sounds, and purified by the blessed influences of a day so passed, they slept the calm, untroubled sleep of innocence, to awaken on the morrow strengthened and refreshed, to obey once more the Divine command—"Six days shalt thou labor."

Ten years after the settlement and incidents related in the preceding chapters, it would have been difficult to recognise the log-cabin in the substantial farm-house that occupied its place. The forest which once so nearly enclosed it was gone, or only to be traced here and there in a few decaying stumps, or the gray ruins of girdled trees which yet resisted wind and weather. The meadow land was covered with grazing sheep and cattle, the yard filled with stacks of hay and fodder, and large convenient barns and stables stood where the little out-houses, which once sufficed to accommodate all the emigrants' gear, had formerly been; corn fields, and orchards of peaches and apples surrounded the dwelling, which, with its flowergrown piazza and gay garden, presented a pretty picture of peace and plenty.

But these changes had only been wrought by slow degrees and hard work, nor had they been unaccompanied by many trials and disappointments. Crops had failed, or been destroyed, when promising a bountiful harvest, by fierce storms of rain and wind; and once the woods had caught fire, and spread desolation over the country. Prompt exertions saved the house, but the labors of the year had been lost, and the corn-fields ready for the harvest, and the rich pastures left black and smoking.

Nor was the neighboring country less changed and improved: the narrow blazed tracks which had formerly led to Mr. Watson's and to Painted Posts had widened into well-travelled roads; and clearings visible on hill-sides in the distance, and frequent columns of curling smoke rising above the far-off tree-tops, gave evidence of the habitations of men, and that our emigrants were no longer alone in the wilderness.

Change had also been busy with the family, as well as with their home and its surroundings. Mr. and Mrs. Lee showed least its power; for though ten years older, the time had passed too prosperously on the whole to leave many wrinkles on their cheerful, contented faces. But some of the children were children no longer. Tom, now a fine young man of twenty-two, had married Jem Watson's sister Katie, and settled on a small lot which lay on the banks of the river just below the Fall that had once been so nearly fatal to him. Taking advantage of the facilities offered by the situation for a mill, he had raised one near the rapids, and as the neighborhood became more populous, he found increasing profit, as well as employment, and was quickly becoming a thriving miller. Uncle John, still good-natured and light-hearted, had established himself near him on a comfortable farm, with a wife he had brought from Cincinnati, and who was as cheerful as himself, and the cleverest housewife of the whole country round. They had a little son and daughter, one four, the other two years old, who were the delight and pride of their parents. "Bub," or "Bubby," as boys are familiarly called in the United States, could already mount a horse, call in the pigs, and sing Yankee Doodle as well, his father declared, as he could himself; while "Sissy" nursed her rag-doll, and lulled it to sleep, in her tiny rocking-chair, with as much tenderness and patience as a larger woman. They were wonderful children! Uncle John said.

The kind and gentle Annie had grown up, beloved by all who knew her, and Jem Watson had often thought what a good wife she would make, and what a happy house that would be of which she was mistress, before he summoned courage to ask her to be his. When she consented, he believed himself the most fortunate man in Ohio. But she would not leave her mother quite alone, with her many household cares, and therefore it was determined that though the marriage should take place in the autumn, she should not move to Jem's house until George, who had taken his elder brother's place in helping his father, should be old enough to bring home a wife to undertake his sister's duties. Jem, meanwhile was to cultivate and improve the eighty-acre lot his father had purchased for him within six miles of Painted Posts, a place which was rapidly increasing, and already offered a profitable market to the neighboring farmers, more especially as a railway now passed within two miles.

We shall have mentioned all our old friends when we add that the baby Willy had become just such another thoughtless daring boy as Tom had been at his age, and that Dick Watson was established in Cincinnati, now called the "Queen of the West," as a pork merchant, and was getting rich very fast.

The maize, or Indian corn, had attained its ripest hue, and been plucked from the dry stems, which had been deprived of their leaves as soon as the ear was fully formed, that nothing might screen the sun's hottest rays from the grain, and the golden-colored pumpkins which had been planted between the rows, that no land might be wasted, even left to ripen alone amid the withering corn-stalks. The neighbors from far and near had visited each other's houses in turn, for the "Husking frolic," when all joined to strip from the ear the long leaves in which it was wrapped, and which were to be stacked as fodder for the sheep and cattle. The apples had been sliced and dried in the sun, and then strung and suspended in festoons from the kitchen ceiling, the pumpkins had at last been gathered in and stored in great piles in the barn—all provision for winter pies,—and the fall, as the Americans call the autumn, from the falling of the leaf, was drawing to a close when Annie's wedding-day arrived.

The Watson and the Lee families were so much respected by their neighbors, that when Tom was married, a year before, and now, also, all seemed to think that they could not sufficiently show their good will, unless they overwhelmed them with whatever might be thought most likely to please in the way of dainties. For a day or two before, the bearer of some present might have been seen each hour at the Lees' door.

"Please, Mrs. Lee, mother sends her compliments, and a pot of first-rate quince preserves," said one.

"I've just run over with some real sweet maple, Mr. Lee," cried another. "I reckon it's better sugar than you've tasted yet!"

Annie and her mother began to wonder how such an abundance of good things as poured in upon them could ever be disposed of.

Breakfast had scarcely been cleared away on the morning of the appointed day, when Tom and Katie came trotting to the door in their light wagon. They had scarcely alighted when Uncle John arrived, driving up with his wife and children. "Only just ahead of us, Tom!" he cried, as he jumped out, and ran up the steps to kiss Annie. "Bless you, my girl!"

"I am so glad you are all come," said Annie, with a smiling, blushing face. "Mother is so busy, and wishing so for Aunt Abby and Katie!"

"Aye, they're two good ones for setting things to rights!" cried Uncle John; "but I say, Annie, we met a party of red ladies and gentlemen coming here."

"What do you mean, uncle?"

"Why, half a dozen Indians, with their squaws and papooses are on the road, and I told them to stop here, and I would trade with them—so get something for them to eat, will you?"

The travellers soon made their appearance; a strange-looking set of red-skinned, black-eyed Indians, wrapped in dirty, many-colored blankets. The men were hard-featured, and degraded in their bearing, not at all resembling the description we have received of their warlike ancestors, before the fatal "fire water," as they call rum, had become known to them; but some of the women had a soft, melancholy expression of countenance, which was very pleasing. They carried their babies, which were bandaged from head to foot, so that they could not move a limb, in a kind of pouch behind; the little dark faces peeped over the mothers' shoulders, and looked contented and happy.

The party stopped at the gate, and all the family went out to inspect the articles of their own manufacture, which the Indians humbly offered for sale. These consisted of baskets ornamented with porcupine quills, moccasins of deer-skin, and boxes of birch bark. Mrs. Lee's and Aunt Abby's heart bled for the way-worn looking mothers and their patient babes; they relieved their feelings, however, by making them eat as much as they would. Uncle John and Tom were glad to buy some of the pretty toys for wedding presents, and after an hour's stay the party resumed their march.

"Those Indians always make me feel sad," remarked Uncle John when they were gone; "a poor disinherited race they are,—homeless in the broad land which once belonged to their fathers!"

"It is a melancholy thought at first, certainly," replied Mr. Lee; "but if you reflect awhile you will find consolation. There are many towns which were founded by persons still living, whose inhabitants already outnumber all the hunter tribes which once possessed the forest; and surely the industry of civilization is to be preferred to the wild rule of the savage!"

"You are right," said Uncle John, with a sigh; "but still I must be sorry for the Indians!"

The Watsons arrived shortly after, and every one was busy, though, as Mrs. Lee often said laughingly, no one did anything but Aunt Abby, and she was indefatigable. Soon after dinner the neighbors began to assemble, and when the minister from Painted Posts arrived, the ceremony which united the young couple was performed in the neat little parlor of the farm-house. At six o'clock an immense tea-table was spread with all the luxuries of the American back-woods;—there were huge dishes of hot butter-milk rolls, and heaps of sweet cake (so called from its being in great part composed of molasses)—and plum cakes, and curiously twisted nut-cakes—and plates of thin shaven smoked beef, of new made cheese and butter—and there were pies of pumpkin, peach, and apple, with dishes of preserves and pickles. The snow-white table-cloth was scarcely visible, so abundant was the entertainment which covered it. After this feast, the evening passed in merry games among the young people, while the elders looked on and laughed, or formed little groups for conversation, of which, indeed, the remembrance of former weddings was the principal subject.

Mr. Watson and Mr. Lee, now doubly connected through their children, sat together a little apart, recalling, as they talked, the various trials of their first experience of the wilderness, and comparing the present with the past.

"Who would have anticipated such a scene as this," remarked the latter, "when you and Dick came to help us build the log-house?"

"And yet it has come to pass by most simple means," replied Mr. Watson,—"industry and perseverance. These qualities, as we are now old enough to know, will gain a home and its comforts in any part of the world,—in our native land as well as here, although too many doubt the fact. Yet there are times when a man in the crowded communities of Europe sees no refuge but in emigration. When such is the case, he must make up his mind to leave behind the faults and the follies which have there hindered his well-being. If he cannot do this he will be as poor and discontented here as in England. You and I have reason, my friend, to be grateful that the Providence which guided us hither, gave us courage to bear patiently the dangers and privations which must be conquered before a home and prosperity can be won by the Emigrant."

Chapter I. The Broken Cup.

Chapter II. A Picture of Poverty.

Chapter III. Uneasiness.

Chapter IV. Christmas Gifts.

Chapter V. Happiness Destroyed.

Chapter VI. New Misfortunes.

Chapter VII. Trouble Increases.

Chapter VIII. The Sale.

Chapter IX. "When Distress Is Greatest, Help Is Nearest."

Chapter X. The Wonders of the Eye.

Chapter XI. The Journey and the Baths.

Chapter XII. The Operation.

Chapter XIII. The Enjoyment of Sight.

Chapter XIV. Conclusion.

"May God give you a happy Christmas."

"Come! boys," said Master Teuzer, a potter of Dresden, to his work people, who had just finished their breakfast, consisting of coffee and black bread, "Come! to work."

He stood up; the work people did the same, and went into the adjoining work-shop, where each of them placed himself at a bench.

"Who is knocking at the door?" said the Master, interrupting the silence which reigned. "Come in there!" he added in a rough tone. The door opened, and a little girl entered, saluted him timidly, and remained standing on the threshold. The clock had not yet struck five, nevertheless the fair hair of the little girl, who was about ten years old, had already been nicely combed, and every part of her dress, although poor, was neat and in order, her cheeks and hands were of that rosy color which is produced by the habit of washing in cold water.

Master Teuzer observed all this with secret satisfaction, he looked kindly at the timid child. "Ah, my little one, so early, and already up, are you then of opinion that the morning is best for work? It is well, my child, and appears to agree with you—you are as fresh as a rose of the morning. Well; what have you brought me?"

The little girl took from her apron, which she held up, a china cup, broken into two pieces—"I only wished to ask you," said she, in a sad voice, "if you can mend this cup so that the crack will not be seen."

Teuzer examined the pieces attentively, they were of fine china, and ornamented with painted flowers. "So that one must not see the crack," he repeated, "it will be difficult—but we will try." So saying, he laid the pieces on one side, and returned to his work. But the little girl, looking much disappointed, said, "Ah, sir, have the kindness to mend the cup immediately, I will wait until it is done."

The potter and his workmen began to laugh; "then," said the former, "you will have long enough to wait, for after being cemented, the cup must be baked. It will be three days before I heat the furnace again, and it will be five before you can have your cup."

The child looked disappointed, and Teuzer continued, "Ah, I see why you are up so early—your mother does not know that you have broken the cup, and you wanted to have it mended before she is awake. I am right I see—go then and tell your mother the exact truth—that will be best, will it not?"

The little girl said "Yes," in a low voice, and went away.

Very early on the following morning the child returned.

"I told you," said Teuzer, frowning, "that you could not have your cup for five days."

"It is not for that I have come," replied the child, "but I have brought you something else to mend,"—and she took from her apron the pieces of a brown jar.

Teuzer laughed again, and said, "We can do nothing with this—you think it is china because it is glazed, but it is from the Waldenburg pottery, and quite a different clay from ours. It would be a fine thing indeed if we could mend all the broken jars in Dresden, we should then be soon obliged to shut up shop, and eat dry bread—throw away the pieces, child."

The little girl turned pale, "The jar is not ours," she said, crying, "it belongs to Mrs. Abendroth, who sent us some broth."

"I am sorry for it," replied Teuzer, "but you must be more careful in using other people's things."

"It was not my fault," said the child—"my poor mother has the rheumatism in her hands, and cannot hold anything firmly—and she let it fall. Have you jars of this kind, and how much would one of this size cost?"

Teuzer felt moved with compassion, "I have a few in the warehouse," he answered, "but they are three times as dear as the common ones."

He went to look for one to make a present to the little girl, but on his return, chancing to glance into her apron, he saw a little paper parcel. "What have you there," he asked, "coffee or sugar?"

The little girl hesitated a moment. She was almost afraid to tell him what she had in her apron. She thought he might possibly suspect that she had been taking something which did not belong to her. Still, she hesitated but a moment. She felt that she was honest, and she saw no good reason why he should doubt her honesty. So she said,

"It is seed for our canary, our pretty Jacot. He is a dear little creature, and he has had nothing to eat for a long time. How glad he will be to get it."

"Oh, seed for a bird," said Teuzer, slowly; and putting down the jar he was about to give her, he returned to his work, saying to himself, "if you can afford to keep a bird you can pay me for my goods. Yes, yes, people are often so poor, so poor, and when one comes to inquire, they keep dogs, cats, or birds; and yet they will ask for alms."

So the little girl had to go away without the jar; however, she returned at the end of four days for her cup. The crack could scarcely be perceived, and Teuzer asked sixpence for mending it. The little girl searched in her pocket, without being able to find more than four-pence.

"It wants two-pence," said she, timidly, and looking beseechingly at the potter, who replied, dryly, "I see: well, you will bring it to me on the first opportunity," he then gave her the cup, and she slipped away quite humbled.

"Now I have got rid of her," said Teuzer, to his men, "we shall see no more of her here."

But to his surprise, she returned in two days bringing the two-pence.

"It is well," said he to her, "it is well to be so honest, had you not returned, I knew neither where you lived, nor your name. Who are your parents?"

"My father is dead, he was a painter, we live at No. 47 South Lane, and my name is Madelaine Tube."

"Your father was a painter, and perhaps you can paint also, and better too, than my apprentice that you see there with his great mouth open, instead of painting his plates?"