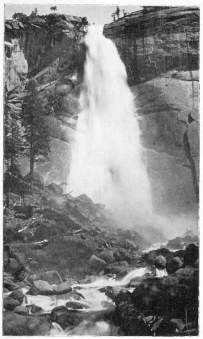

Nevada Falls (Height 617 Feet). Yosemite Valley.

Click Thumbnail for full-size Illustration

Title: Stories of California

Author: Ella M. Sexton

Release date: August 20, 2004 [eBook #13232]

Most recently updated: December 18, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ronald Holder and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

To recount in simple, accurate narratives the early conditions and subsequent development of California is the purpose of this book. In attempting to picture the romantic events embodied in the wonderful history of the state, and to make each sketch clear and concise as well as interesting, the author has avoided many dry details and dates.

Several of the stories endeavor to explain the remarkable physical characteristics of California. The work to this end was rendered lighter by the hope that the reader might find the book merely an introduction to that larger knowledge of personal observation and inquiry.

But the writer's chief aim has been to interest the children of California in the beautiful land of their birth, to unfold to them the life and occurrences of bygone days, and to lead them to note and to enjoy their fortunate surroundings.

Among the many authorities consulted for the work, special acknowledgment is due to the historians, Theodore H. Hittell and H.H. Bancroft.

CALIFORNIA'S NAME AND EARLY HISTORY

THE STORY OF THE MISSIONS AND OF FATHER SERRA

THE AMERICANS AND THE BEAR-FLAG REPUBLIC

THE DAYS OF GOLD AND THE ARGONAUTS OF '49

HOW POLLY ELLIOTT CAME ACROSS THE PLAINS

THE BUILDING OF THE OVERLAND RAILROAD

1. NEVADA FALLS (height 617 feet), YOSEMITE VALLEY

4. OLD SAN DIEGO MISSION. Founded 1769

5. MISSION SAN LUIS REY. Founded 1798

6. MISSION DOLORES. Established 1776

7. SANTA BARBARA MISSION. Founded 1786

9. PLACER GOLD MINING. Washing with Cradle

10. AN ORANGE TREE WITH FRUIT AND BLOSSOMS

11. PALMS OVER 100 YEARS OLD AT LOS ANGELES

12. HOP VINES [1]

13. AMONG THE HOP VINES[1]

14. WHITE SANTA BARBARA POPPY[1]

15. WILD CALIFORNIA POPPY[1]

18. "WAWONA" (28 feet in diameter)

19. THE GRIZZLY GIANT (33 feet in diameter)

20. BIG TREES AT FELTON, SANTA CRUZ CO.

21. YOUNG TOWHEE

22. BABY YELLOW WARBLERS. From photographs by Elizabeth Grinnell

23. CALIFORNIA RED DEER. From a photograph by George V. Robinson

24. LEAPING TUNA

25. BLACK SEA BASS

26. HUMPBACK WHALE (57 feet long)

28. INDIAN WOMAN WITH PAPPOOSE

30. INDIAN BASKETS

32. THE NEW CLIFF HOUSE, SAN FRANCISCO

33. ENTRANCE TO JAPANESE TEA GARDEN, SAN FRANCISCO

34. FALLEN LEAF LAKE

35. MOUNT SHASTA FROM STRAWBERRY VALLEY

36. "EL CAPITAN" (3300 feet in height)

37. YOSEMITE FALLS

38. NATURAL BRIDGE, SANTA CRUZ

[Compiler's note 1: Four illustrations were omitted from the published book, but were listed in the Illustrations pages.]

A Spanish story written four hundred years ago speaks of California as an island rich in pearls and gold. Only black women lived there, the story says, and they had golden spears, and collars and harness of gold for the wild beasts which they had tamed to ride upon. This island was said to be at a ten days' journey from Mexico, and was supposed to lie near Asia and the East Indies.

Among those who believed such fairy tales about this wonderful island of California was Cortes, a Spanish soldier and traveller. He had conquered Mexico in 1521 and had made Montezuma, the Mexican emperor, give him a fortune in gold and precious stones. Then Cortes wished to find another rich country to capture, and California, he thought, would be the very place. He wrote home to Spain promising to bring back gold from the island, and also silks, spices, and diamonds from Asia. For he was sure that the two countries were near together, and that both might be found in the Pacific Ocean, or South Sea, as he called it, by sailing northwest.

So for years Cortes built ships in New Spain (or Mexico), and sent out men to hunt for this golden island. They found the Gulf of California, and at last Cortes himself sailed up and down its waters. He explored the land on both sides, and saw only poor, naked Indians who had a few pearls but no gold. Cortes never found the golden island. We should remember, however, that his ships first sailed on the North Pacific and explored Lower California, and that he first used the name California for the peninsula.

It was left for a Portuguese ship-captain called Cabrillo to find the port of San Diego in 1542. He was the first white man to land upon the shores of California, as we know it. Afterwards he sailed north to Monterey. Many Indians living along the coast came out to his ship in canoes with fish and game for the white men. Then Cabrillo sailed north past Monterey Bay, and almost in sight of the Golden Gate. But the weather was rough and stormy, and without knowing of the fine harbor so near him, he turned his ship round and sailed south again. He reached the Santa Barbara Islands, intending to spend the winter there, but he died soon after his arrival. The people of San Diego now honor Cabrillo with a festival every year. He was the sea-king who found their bay and first set foot on California ground.

About this time Magellan had discovered the Philippine Islands, and Spain began to send ships from Mexico to those islands to buy silks, spices, and other rich treasures. The Spanish galleons, or vessels, loaded with their costly freight, used to come home by crossing the Pacific to Cape Mendocino, and then sailing down the coast of California to Mexico. Before long the English, who hated Spain and were at war with her, sent out brave sea-captains to capture the Spanish galleons and their cargoes. Sir Francis Drake, one of the boldest Englishmen, knew this South Sea very well, and on a ship called the Golden Hind (which meant the Golden Deer), he came to the New World and captured every Spanish vessel he sighted. He loaded his ship with their treasures, gold and silver bars, chests of silver money, velvets and silks, and wished to take his cargo back to England. He tried to find a northern, or shorter way home, and at last got so far north that his sailors suffered from cold, and his ship was nearly lost. Obliged to sail south, he found a sheltered harbor near Point Reyes, and landed there in 1579. Drake claimed the new country for the English Queen, Elizabeth, and named it New Albion. A great many friendly Indians in the neighborhood brought presents of feather and bead work to the commander and his men. These Indians killed small game and deer with bows and arrows, and had coats or mantles of squirrel skins.

|

NATURAL BRIDGE, SANTA CRUZ. Click photo to see full-sized. |

Drake and his sailors repaired and refitted their vessel during the month they stayed at Drake's Bay. They made several trips inland also and saw the pine and redwood forests with many deer feeding on the hills; but they did not discover San Francisco Bay. On leaving New Albion, Drake sailed the Golden Hind across the Pacific to the East Indies and the Indian Ocean, and round the Cape of Good Hope home to England, with all the treasure he had taken. The queen received him with great honors and his ship was kept a hundred years in memory of the brave admiral, who had commanded it on this voyage.

During the next century several English commanders of vessels sailed the South Sea while hunting Spanish galleons to capture, and these ships often touched at Lower California for fresh water. Some of the captains explored the coast and traded with the Indians, but no settlements were made.

Then the Spanish tried to find and settle the country they had heard so many reports of, thinking to provide stations where their trading ships might anchor for supplies and protection. Viscaino, on his second voyage for this purpose, landed at San Diego in 1602. Sailing on to the island he named Santa Catalina, Viscaino found there a tribe of fine-looking Indians who had large houses and canoes. They were good hunters and fishermen and clothed themselves in sealskins. Viscaino went on to Monterey and finally as far north as Oregon, but owing to severe storms, and to sickness among his sailors, he was obliged to return to Mexico.

For a long time after this failure to settle upon the coast, the Spanish came to Lower California for the pearl-fisheries. Along the Gulf of California were many oyster-beds where the Indians secured the shells by diving for them. Large and valuable pearls were found in many of the oysters, and the Spanish collected them in great quantities from the Indians who did not know their real value.

In this peninsula of Lower California fifteen Missions, or settlements, each having a church, were founded by Padres of the Jesuits. But later the Jesuits were ordered out of the country, and their Missions turned over to the Franciscan order of Mexico.

With the coming of the Franciscans a new period of California's history began. Spain wished to settle Alta California, or that region north of the peninsula, and Father Serra, the head and leader of these Franciscans, was chosen to begin this work.

How he did this, and how he and his followers founded the California Missions you will read in the story of that time.

The old Missions of California are landmarks that remind us of Father Serra and his band of faithful workers. There were twenty-one of their beautiful churches, and though some are ruined and neglected, others like the Mission Dolores of San Francisco and the Santa Barbara and Monterey buildings are still in excellent condition. From San Diego to San Francisco these Missions were located, about thirty miles apart, and so well were the sites chosen that the finest cities of the state have grown round the old churches.

|

FATHER JUNIPERO SERRA

Click photo to see full-sized. |

Father Junipero Serra was the president and leader of the Franciscan missionaries and the founder of the Missions. He had been brought up in Spain, and had dreamed from his boyhood of going to the New World, as the Spanish called America, to tell the savages how to be Christians. He began his work as a missionary in Mexico and there labored faithfully among the Indians for nearly twenty years. But as his greatest wish was to preach to those in unknown places he was glad to be chosen to explore Alta or Upper California.

Marching by land from Loreto, a Mission of Lower California, Father Serra, with Governor Portola and his soldiers, reached San Diego in 1769. Here he planted the first Mission on California ground. The church was a rude arbor of boughs, and the bells were hung in an oak tree. Father Serra rang the bells himself, and called loudly to the wondering Indians to come to the Holy Church and hear about Christ. But the natives were suspicious and not ready to listen to the good man's teachings, and several times they attacked the newcomers. Finally, after six years, they burnt the church and killed one of the missionaries. But later on there was peace, and the priests, or Padres as they were called, taught the Indians to raise corn and wheat, and to plant olive orchards and fig trees, and grapes for wine. They built a new church and round it the huts, or cabins, of the Indians, the storehouses, and the Padre's dwelling. In the early morning the bells called every member of the Mission family to a church service. After a breakfast of corn and beans they spent the morning in outdoor work or in building. At noon either mutton or beef was served with corn and beans, and at two o'clock work began again, to last till evening service. A supper of corn-meal mush was the Indians' favorite meal. They had many holidays, when their amusements were dancing, bull-fighting, or cock-fighting.

San Diego, called the Mother Mission, because it is the oldest church, is now also most in ruins. But its friends hope to put new foundations under the old walls, and to recap firm ones with cement, and preserve this monument of early California history.

|

MISSION CHURCH, MONTEREY. Click photo to see full-sized. |

After Father Serra had started the San Diego settlement he set sail for Monterey. Landing at Monterey Bay, he built an altar under a large oak tree, hung the Mission bells upon the boughs, and held the usual services. The Spanish soldiers fired off their guns in honor of the day and put up a great cross. The Indians had never heard the sound of guns and were so frightened that they ran away to the mountains. The second Mission was built on the Carmel River, a little distance from the site of the first altar. This was called San Carlos of Monterey, and the settlement was the capital of Alta California for many years. It was also the Mission that Father Serra loved the best, and after every trip to other and newer settlements he returned to San Carlos as his home. This Monterey Mission is well preserved, and books, carved church furniture, and embroidered robes used in the old services are still shown.

At both San Diego and Monterey a presidio, or fort, was built for the soldiers. These forts had one or two cannon brought from Spain, and had around them high walls, or stockades, to protect, if it should be necessary, the Mission people from the Indians. The cannon were fired on holidays, or to frighten troublesome Indians.

All the Mission buildings were of brown clay made into large bricks about a foot and a half long and broad, and three or four inches thick. These bricks, dried in the sun, were called adobes, and were plastered together and made smooth by a mortar of the same clay. Then the walls were coated outside and inside with a lime stucco and whitewashed. The roof timbers were covered with hollow red tiles, each like the half of a sewer pipe, and these were laid to overlap each other so that they kept the rain out. The floors were of earth beaten hard, and the windows had bars or latticework, but no glass. The large church was snowy white within and without and had pictures brought from Spain and much carved furniture, such as chairs, benches, and the pulpit made by the Indians. One or two round-topped towers and five or six belfries, each holding a large bell, were on the church roof, and a great iron cross at the very top.

|

OLD SAN DIEGO MISSION. Founded 1769. Click photo to see full-sized. |

Night and morning the Mission bells rang to call the Indians to mass or service, and chimes or tunes were rung on holidays or for weddings. These Mission bells were brought from Spain, and it was thought a blessing rested on the ship which carried them, and that shipwreck could not come to such a vessel. We read of one captain joyfully receiving the Mission bells to take to San Diego. When nearing the coast his vessel struck a rock, yet passed on in safety because, as he said, no harm could happen with the bells on board. On his journeys every missionary carried a bell with him for the new church he was to build. Father Serra's first act on reaching a stopping-place was to hang the bell in a tree and ring it to gather the Indians and people for service.

San Antonio, a very successful Mission, was the third one established, and it was in a beautiful little valley of the Santa Lucia Mountains. Every kind of fruit grew in its orchards, and the Indians there were very happy and contented, and in large workshops made cloth, saddles, and other things. San Gabriel, not far from Los Angeles and sometimes called the finest church of all, was the next to be built. This was the richest of the Missions and had great stores of wool, wheat, and fruit, which the hard-working Indians earned and gave to the church. The Indians, indeed, were almost slaves, and worked all their lives for the Padres without rest or pay. At San Gabriel the first California flour-mill worked by a stream of water turning the wheel, was put up. Some of the old palms and olive trees are still growing there.

San Juan Capistrano, founded in 1776, was one of the best-known Missions, for it had a seaport of its own at San Juan. Vessels came to its port for the hides and tallow of thousands of cattle herded round the Mission. The first fine church of this Mission was destroyed by an earthquake, and many people were killed by its falling roof. It was rebuilt, however, and still shows its fine front, and long corridors or porches round a hollow square where a garden and fountain used to be.

|

MISSION DOLORES. Established 1776. Click photo to see full-sized. |

Old records tell us that Father Serra felt that there should be a church named in honor of Francis, who was the founder and patron saint of the Franciscan brotherhood of monks to which these missionaries belonged. When Father Serra spoke of this to Galvez, that priest replied, "If our good Saint Francis wants a Mission, let him show us that fine harbor up above Monterey and we will build him one there." Several explorers had failed to find this port about which Indians had spoken to the Spanish. At last Ortega discovered it, and Father Palou, in 1776, consecrated the Mission of San Francisco. Near the spot was a small lake called the "Laguna de los Dolores," and from this the church was at last known as the Mission Dolores. But the great city bears the Spanish name of Saint Francis, or San Francisco. A fort was erected where the present Presidio stands, and later a battery of cannon was placed at Black Point. It is told that the Indians were very quarrelsome here and fought so among themselves that the Padres could get no church built for a year. In that part of San Francisco called the Mission, the old building with its odd roof and three of the ancient bells is a very interesting place to visit. There are pictures, and other relics of the past to see, and in the graveyard many of San Francisco's early settlers were buried. This was the sixth Mission of Alta California.

|

SANTA BARBARA MISSION. Founded 1786. Click photo to see full-sized. |

The Santa Barbara Mission, where Franciscan fathers still live, has a fine church with double towers and a long row of two-story adobe buildings enclosing a hollow square where a beautiful garden is kept. One of the brotherhood, wearing a long brown robe just as Father Serra did, takes visitors into the church, and also shows them the garden and a large carved stone fountain. This church is built of sandstone with two large towers and a chime of six bells, and was finished in 1820.

The Santa Ynez Mission was much damaged by the heavy earthquake that in 1812 ruined other Missions. Here the Indians raised large crops of wheat and herded many cattle. Over a thousand Indians, it is said, attacked this church in 1822, but the priest in charge frightened them away by firing guns. This warlike conduct so displeased the Padres, who wished the natives ruled by kindness, that the poor priest was sent away from the Mission.

One of the early Missions was San Luis Obispo, where services are still held. It was specially noted for a fine blue cloth woven by the Indians from the wool of the Mission flocks of sheep. The Indians there also wove blankets, and cloth from cotton raised upon their own lands.

|

MISSION SAN LUIS REY. Founded 1798. Click photo to see full-sized. |

San Juan Bautista, or St. John the Baptist, north of Monterey, had a splendid chime of nine bells said to have been brought from Peru and to have very rich, mellow tones. San Miguel had a bell hung up on a platform in front of the church, and now at Santa Ysabel, sixty miles from San Diego, where the Mission itself is only a heap of adobe ruins, two bells hang on a rude framework of logs. The Indian bell-ringer rings them by a rope fastened to each clapper. The bells were cast in Spain and much silver jewellery and household plate were melted with the bell-metal. Near them the Diegueño Indians worship in a rude arbor of green boughs with their priest, Father Antonio, who has worked for thirty years among the tribe. They live on a rancheria near by and are making adobe bricks, hoping soon to build a church like the old Mission long since crumbled away.

The last of the Missions was built in 1823 at Sonoma, and proved very active in church work, some fifteen hundred Indians having been there baptized.

Father Junipero Serra died at more than seventy years of age, at San Carlos. During all his life in America he endured great hardships and suffering to bring the gospel to the heathen as he had dreamed of doing in his boyish days. A monument to his memory has been erected at Monterey by Mrs. Stanford, but the Missions he founded are his best and most lasting remembrances.

This is the story Señora Sanchez told us children as we sat on the sunny, rose-covered porch of her old adobe house at Monterey one summer afternoon. And as she talked of those early times she worked at her fine linen "drawn-work" with bright, dark eyes that needed no glasses for all her eighty years and snow-white hair.

"When I was a girl, California was a Mexican republic," said the Señora, "and Los Gringos, as we called the Americans, came in ships from Boston. They brought us our shoes and dresses, our blankets and groceries; all kinds of goods, indeed, to trade for hides and tallow, which was all our people had to sell in those days. For no one raised anything but cattle then, and all summer long cows cropped the rich clover and wild oats till they were fat and ready to kill. In the fall the Indians and vaqueros, or cowboys as you children call them, drove great herds of cattle to the Missions near the ocean where the Gringos came with their ship-loads of fine things and waited for trading-days.

"For weeks every one worked hard, killing the cattle, stripping off their skins and hanging the green or fresh hides over poles to dry in the sun. When dried hard and stiff as a board the skins were folded hair-side in, and were then worth about two dollars apiece. The beef-suet, or fat, from these cattle was put into large iron kettles and melted. While still hot it was dipped out with wooden dippers into rawhide bags, each made from an animal's skin. When cold and hard these bags of tallow were sewed up with leather strings, and thus they were taken to Boston.

"So much beef was on hand at such times that not even the hungry Indians could eat it all while it was fresh. The nicest pieces were cut into long strips, dipped into a boiling salt brine full of hot red peppers and hung up to dry where the sunshine soon turned the meat into carne seca, or dried beef. We put it away in sacks, and very good it was all the year for stews, and to eat with the frijoles, or red beans, and tortillas, which were corn-cakes.

"All we bought from the Gringos was paid for with hides and tallow, so it was well, you see, children, that my father owned ten thousand cattle; for counting relatives and Indian servants, we always had more than thirty people on our ranch to feed and clothe. We raised grain and corn and beans enough for the family, but had to buy sugar, coffee, and such things.

"Did we have many horses, you say? Yes, droves of them, and we almost lived on horseback, for no one walked if he could help it, and there were almost no carriages or roads. Neither were there any barns or stables, for the mustangs, or tough little ponies, fed on the wild grass and took care of themselves. Every morning a horse was caught, saddled and bridled, and tied by the door ready to use. All the ladies rode, too, and I often used to ride twenty miles to a dance with Juan, my young husband, and back again in a day or so.

"Sometimes we went to the rodeo, where once a year the great herds of cattle were driven into corrals, and each ranchero or farmer picked out his own stock. Then those young calves or yearlings not already marked were branded with their owner's stamp by a red-hot iron that burnt the mark into the skin. After that the bellowing, frightened animals were turned out to roam the grassy plains for another year. We had plenty of feasting and merry-making at these rodeos, and a whole ox was roasted every day for the hungry crowds, so no one went fasting to bed.

"Those were gay times, my children," and Señora Sanchez sighed and sewed quietly for a while till Harry asked her if they kept Christmas before the Gringos came.

|

A CHRISTMAS GARDEN.

Click photo to see full-sized. |

"Yes, indeed," she said, laughing, "we kept Christmas for a week, and all our friends and relatives were welcome, so that our big ranch-house was full of company. Indeed, some of the visitors slept in hammocks or rolled up in blankets on the verandas. Our house was built round the four sides of a square garden, with wide porches, where we sat on pleasant days. There was a fountain in this garden, and orange trees, which at Christmas-time hung full of golden fruit and sweet white flowers. On 'the holy night,' as we called Christmas Eve, we hung lanterns in the porches, and everybody crowded there or in the garden for their gifts.

"No, we had no Santa Claus nor Christmas tree, but my father gave presents to all, even to the Indian servants and their children. A fan or a string of pearls, perhaps, for my sisters, the young Señoritas; a fine saddle or a velvet jacket for my brother; and red blankets or gay handkerchiefs for the Indians, with sacks of beans or sweet potatoes to eat with their Christmas feast of roast ox or a fat sheep. Afterwards we danced till morning came, or sang to the sweet tinkle of the guitars. Well do I remember, children, when the good Padres, or priests, at the Mission forbade us to waltz, that new dance the Gringos had taught us to like. I recall, also, that the governor only laughed and said that the young folks could waltz if they wished. So at my wedding, soon after, when we danced from Tuesday noon till Thursday morning, you may be sure we had many a waltz.

"Pretty dresses, Edith? Yes, gay, bright silk or satin ones, with many ruffles on the skirts and wide collars and sleeves of lace, or yellow satin slippers and always a high comb of silver or tortoise-shell and a spangled fan. And we had long gold and coral earrings and strings of pearls from the Gulf, and, see!" as she pulled aside her neck-scarf, "here is the necklace of gold beads that was my wedding gift. We had no hats or bonnets, but wore black lace shawls, or mantillas, to church, or twisted long silk scarfs over our heads to go riding.

"You will think the gentlemen were fine dandies in those Mexican days, when I tell you that they often wore crimson velvet knee trousers trimmed with gold lace, embroidered white shirts, bright green cloth or velvet jackets with rows and rows of silver buttons, and red sashes with long, streaming ends. Their wide-brimmed sombrero hats were trimmed with silver or gold braid and tassels. They dressed up their horses with beautiful saddles and bridles of carved leather worked all over with gold or silver thread and gay with silver rosettes or buttons. Each gentleman wore a large Spanish cloak of rich velvet or embroidered cloth, and if it rained, he threw over his fine clothes a serape, or square woollen blanket with a slit cut in the middle for the head.

"Los Gringos used to laugh at the Mexican and his cloak, and not long after they came the 'Greasers,' as the Americans called the young men born here in California, began to wear the ugly clothes the Gringos brought out from Boston. And so the times changed, children, and our people learned to do everything as the Americans did it and to work hard and save money instead of dancing and idling away the time.

"And the bull-fights, Harry? Oh, yes, there was a bull-fight every Sunday afternoon, and everybody went, as you do to the football games. The ladies clapped their hands if the sport was good, or if the bull was killed by the brave swordsman. And if the men got hurt or the horses,—well, we only thought that was part of the game, you see. El toro, as we called the bull, always tried to save himself; and if he was savage and cruel, that was his nature, to try to kill his enemies. The gay dresses and the music was what I cared for, and then all my friends were there, also.

"But you must be tired of my old stories; is it not so, my children? No, you want to hear about the dances, you say? Well, every party was a dance; a fandango or ball, if it was given in a hall where everybody could come, but at houses where just the people came who were invited we called it only a dance. Every old grandfather or little girl, even, danced all night long, and the rooms were hung with flags and wreaths. All the Spanish dances were pretty, and the ladies with their gay dresses and mantillas, and the gentlemen in velvet suits trimmed with gold, made a fine picture. At the cascarone, or egg-shell dance, baskets of egg-shells filled with cologne or finely cut tinsel or colored papers were brought into the room, and the game was to crush these shells over the dancers' heads. If your hair got wet with cologne or full of gilt paper, everybody laughed, and you laughed too, for that was the game, you know. Ah, there was plenty of merry-making and feasting in those days, children," and Señora Sanchez sighed again and went on with her "drawn-work," while the bell in the old Mission church near by rang five o'clock, and we children ran home talking of those old times before the Gringos came to California.

While Spain owned Mexico and the two Californias, the Missions were at their best and grew rich in stores of grain and in cattle and horses. Almost all the people were Spanish or Indians, and they lived at the Missions or in ranches near by. But when Mexico in 1822 refused to be ruled by Spain, Alta or Upper California became a Mexican territory, and, later on, a republic with governors sent from Mexico. The Mission Padres did not like the change, and thought that Spain should still own the New World. Before long it was ordered that the Missions should be turned into pueblos, or towns, and that the Padres were no longer to make slaves of the Indians. The missionaries were to stay as priests, and to teach the Indians in schools, but the Mission lands were to be divided so that each Indian family might have a small farm to cultivate. From that time the Missions began to decay and were finally given up to ruin.

Then Americans began to come in, the first party of hunters and trappers travelling from Salt Lake City to the San Gabriel Mission. All kept talking of the rich country where farming was so easy, and they wished to have land. But the Mexicans and the native Californians did not believe in allowing the Americans, as they called all the people from the Eastern states, to take up their farming lands and hunt and trap the wild animals. So there was much quarrelling. But the Americans still poured in, got land grants, and built houses.

In 1836, though Alta California declared itself a free state, and no longer looked to Mexico for support, Mexican rule still continued. The United States had wanted California for a long time, and had tried to buy it from Mexico. The fine bay and harbor of San Francisco, known to be the best along the coast, was especially needed by the United States as a place to shelter or repair ships on their way to the Oregon settlements. England also wanted this bay, but the Californians tried to keep every one out of their country.

Among the Americans who came overland and across the Rocky Mountains about this time was John C. Fremont, a surveyor and engineer, who was called the "Pathfinder." On his third trip to the Pacific Coast in '46 he wished to spend the winter near Monterey, with his sixty hunters and mountaineers. Castro, the Mexican general, ordered him to leave the country at once, but Fremont answered by raising the American flag over his camp. As Castro had more men, Fremont did not think it wise to fight, but marched away, intending to go north to Oregon. He turned back in the Klamath country on account of snow and Indians, as he said, and camped where the Feather River joins the Sacramento. It is almost certain that Fremont wished to provoke Castro and the Californians into war, and so to capture the country for the United States.

A party of Fremont's men rode down to Sonoma, where there was a Mission, and also a presidio with a few cannon in charge of General Vallejo. These men captured the place and sent Vallejo and three other prisoners back to Fremont's camp. Then the independent Americans concluded to have a new republic of their own, and a flag also. So they made the famous "Bear-flag" of white cloth, with a strip of red flannel sewed on the lower edge, and on the white they painted in red a large star and a grizzly bear, and also the words "California Republic." They then raised the flag over the Bear-flag Republic. Many Americans joined their party, but when the American flag went up at Monterey, the stars and stripes replaced the bear-flag.

At this time the United States and Mexico were at war on account of Texas, and Commodore Sloat was in charge of the warships on the Pacific Coast. The commodore had been told to take Alta California, if possible; so, sailing to Monterey, he raised the stars and stripes there in July, 1846, and ended Mexican power forever. The American flag flew at the San Francisco Presidio two days later, and also at Sonoma, Sutter's Fort, or wherever there were Americans. The flag was greeted with cheers and delight. Then Commodore Sloat turned the naval force over to Stockton and returned home, leaving all quiet north of Santa Barbara.

Commodore Stockton sent Fremont and his men to San Diego and, taking four hundred soldiers, went himself to Los Angeles, where the native Californians and Mexicans were determined to fight against the rule of the United States. General Castro and his men and Governor Pico, the last of the Mexican governors, were driven out of the country. Stockton then declared that Upper and Lower California were to be known as the "Territory of California."

In less than a month, however, the Californians in the south gathered their forces again and took Los Angeles. General Kearny was sent out with what was called the "army of the west," to assist Fremont and Stockton in settling the trouble. Peace was declared after several battles, and Kearny acted as governor of the new territory, displacing Fremont. At last, by the treaty which closed the Mexican war in 1848 Alta California became the property of the United States, and Lower California was left to Mexico.

From that time there was peace and quiet, and before long the discovery of gold brought the new territory into great importance. The rush to the gold mines brought thousands of men, and as no government had been provided for the territory, Governor Riley in '49 called a convention to form a plan of government.

This Constitutional Convention of delegates from each of California's towns met in Monterey. The constitution there drawn up lasted for thirty years, and under it our great state was built up. It declared that no slavery should ever be allowed here, and settled the present eastern boundary line.

The first Thanksgiving Day for the territory was set by Governor Riley, in '49. The first governor elected by California voters was Burnett, and in the first legislature Fremont and Gwin were chosen as senators. Congress at last admitted California into the Union by passing the California bill. On September 9, 1850, President Fillmore signed the bill.

Every year on the 9th of September, or "Admission Day," we therefore keep our state's birthday. At San Jose, in '99, a Jubilee Day was held in remembrance of the beginning of state government fifty years before.

California has well earned her name of "Golden State," for from her rich mines gold to the value of thirteen hundred millions has been taken. Yet every year she adds seventeen millions more to the world's stock of gold. No country has produced more of this precious yellow metal that men work and fight and die for. The "gold belt" of the state still holds great wealth for miners to find in years to come.

Long, long ago people knew that gold was here, for in 1510 a Spanish novel speaks of "that island of California where a great abundance of gold and precious stones is found." In 1841 the Indians near San Fernando Mission washed out gold from the river-sands, and other mines were found not far from Los Angeles.

But James W. Marshall was the man who started the great excitement of '48 and '49 by finding small pieces of gold at a place now called Coloma, on the American River. Marshall, who was born in New Jersey, came to this state in 1847, and being a builder wished to put up houses, sawmills, and flour-mills. Finding that lumber was very dear, he decided to build a sawmill to exit up the great trees on the river-bank. He had no money, but John A. Sutter, knowing a mill was needed there, gave Marshall enough to start with.

So the mill was built, and when it was ready to run Marshall found that the mill-race, or ditch for carrying the water to his mill-wheel, was not deep enough. He turned a strong current of water into it, and this ran all night. Then it was shut off, and next day the ditch showed where the stream had washed it deeper and had left a heap of sand and gravel at the end of it. Here Marshall saw some shining little stones, and picking them up he laid one on a rock and hammered it with another till he saw how quickly it changed its shape. He was sure that these bright, heavy, easily hammered pebbles were gold, but the men working about the mill would not believe it. So he went to Sutter, who lived near at a place called Sutter's Fort, because his stores, house, and other buildings were built around a hollow square with high walls outside to keep off the Indians. Sutter weighed the little yellow lumps and said they certainly were gold.

The flood-gates between the mill-race and the river were opened again, and water ran through the ditch, washing more gold in sight. Sutter picked up enough of this to make a ring and had these words marked on it:—

"The first gold found in California, January, 1848."

Both Sutter and Marshall tried to keep what they had found a secret, but that was impossible, and soon people were flocking to the gold-fields. Then began a wild excitement known as the "gold-fever," and men left their stores and houses, gave up business, and left crops ungathered in a wild chase after nuggets of gold.

By December of 1848, thousands of miners were washing for gold all along the foot-hills from the Tuolumne River to the Feather, a distance of 150 miles. A hundred thousand men came to California during 1849, these Argonauts, or gold-hunters, taking ship or steamer for the long trip from New York by the Isthmus of Panama. Some went round Cape Horn, or else made a weary journey overland across the plains. "To the land of gold" was their motto, and these pioneers endured every hardship to reach this "Golden State."

|

PLACER GOLD MINING. Washing with Cradle. Click photo to see full-sized. |

Then the miners, with pick, shovel, and pan for washing out gold from the gravel it was found in, started out "prospecting" for "pay-dirt." The gold-diggings were usually along the rivers, and this surface, or "placer," mining was done by shovelling the "pay-dirt" into a pan or a wooden box called a cradle, and rocking or shaking this box from side to side while pouring water over the earth. The heavy gold, either in fine scales or dust, or in lumps called nuggets, dropped to the bottom, while the loose earth ran out in a muddy stream. The rich sand left in pan or cradle was carefully washed again and again till only precious, shining gold remained.

So rich were some of the sand bars along the American and Feather rivers that the first miners made a thousand dollars a day even by this careless way of washing gold where much of it was lost. Then again for days or weeks the miner found nothing at all. He would wander up and down the cañons and gulches, prospecting for another claim, and dreaming day and night of finding a stream with golden sands, or of picking up rich nuggets. If he found good "diggings" he would build a rough shanty under the pines, and dig and wash till the gold-bearing sand or gravel gave out again. Sometimes he had a partner and a donkey, or burro, to carry tools and pack supplies. More often the Argonaut cooked his own bacon and slapjacks and simmered his beans over a lonely camp-fire, and slept wrapped in a blanket under the trees. If he had much gold, he would go to the nearest town, buy food enough for another prospecting tramp, and often spend all the rest of his money in foolish waste.

Sometimes a company of miners would build a dam across a river or stream, and turn it from its course, so they could dig out and wash the rich gravel in the river-bed. A flume, or ditch, would often carry all the water to a lower part of the river, leaving the bed of the upper stream dry for miles. In this kind of mining the "pay-dirt" was shovelled into long wooden boxes called sluices, and a constant stream of water kept the gravel and earth moving on out to a dumping-place. The gold dropped down or settled into riffles, or spaces between bars placed across the bottom of the sluices, and once a week the water was turned off and a "clean-up" made of the gold.

It was not long before the rivers, creeks, and gulches had all been worked over and most of the gold taken out. The miners knew that this loose gold had been washed out of the hills by the rains and storms of countless years. So some one thought of using a heavy stream of water to break down the foot-hills themselves and to carry the gold-bearing gravel to sluice boxes. This is called hydraulic mining and is the cheapest way of handling earth, as water does all the work and very little shovelling is needed. But since a strong water-power is necessary, a large reservoir and miles of ditches or wooden flumes must be built, so the first expense is large. The water usually comes from higher up in the mountains, and is forced under great pressure through iron pipes, the nozzle or "giant" being directed at the hillside, which has already been shattered by heavy blasts of powder. The water tears thousands of tons of earth and gravel apart, and the muddy stream flows through sluices, where the gold is left. In this kind of mining a great quantity of débris, or "tailings," must be disposed of.

For years this débris was washed into the rivers or on farming lands, filling up and ruining both, and leading to endless quarrels between farmers and miners. But at last the courts stopped hydraulic mining except in northern counties, where débris went into the Klamath River, upon which no boats could run and near which was little farming. But all the mines in the Sacramento and San Joaquin river-basins were idle till, in 1893, Congress appointed a débris Commission. These mining engineers issue licenses to work the mines when satisfied that the débris will be kept out of the rivers. There are in the state many hundred thousand acres of gold-bearing gravel lands yet untouched, that could be worked by hydraulic mining.

In drift-mining the rich gravel is covered by hard lava rock thrown up by some old volcanic outburst. Tunnels are driven by blasting with dynamite, or by drilling under the rock to reach the gravel which usually lies in the buried channel of an old river. The long drifts, or tunnels, needed are very expensive and only mine owners with capital can work these claims.

Richest of all are the quartz mines, where beautiful white rock, rich with sparkling gold, is found in veins, or "lodes," cropping out of hillsides or dipping down under the earth. The great "Mother-lode" of our state runs like an underground wall across Amador, Calaveras, Tuolumne, and Mariposa counties and has been traced for eighty miles.

Some poor miner usually finds a ledge of quartz-rock and digs down the way the ledge goes. He puts up a windlass, worked by hand, over the well-like hole he has dug out, and hoists the ore out in buckets. But he soon finds, as the hole or shaft goes deeper, that he must timber the sides to keep them from caving in, that he must have an engine to raise the ore and a mill to crush the hard rock. So he sells out to a company of men, who put in costly machinery, deepen the shaft, and by heavy expenditure get large returns.

The quartz ledges dip and turn, so tunnels and cross-cuts are run to follow the golden vein, and all these are timbered with heavy wooden supports to keep the earth and rock from falling in on the men. The miners work in day and night gangs, using dynamite to break up the hard rock, and sending ore up in great iron buckets, or in cars if the tunnel ends in daylight, on the hillside. Sometimes the miners strike water, and that must be pumped out to keep the mine from being flooded.

The ore is crushed by heavy stamps, or hammers, and then mixed with water and quicksilver. This curious metal, quicksilver, or mercury, is fond of gold and hunts out every little bit, the two metals mixing together and making what is called an amalgam. This is heated in an iron vessel, and the quicksilver goes off in steam or vapor, leaving the gold free. The quicksilver, being valuable, is saved and used again, while the gold, now called bullion, is sent to the mint to be coined into bright twenties, or tens, or five-dollar pieces.

Some of the gold in the crushed ore will not mix with the quicksilver, and this is treated to a bath of cyanide, a peculiar acid that melts the gold as water does a lump of sugar. So all of value is saved, and the worthless "tailings" go to the dump. Even the black sands on the ocean beach have gold in them. In the desert also there is gold, which is "dry-washed" by putting the sand into a machine and with a strong blast of air blowing away all but the heavy scales of gold.

Though the Argonauts of '49 found much wealth in yellow gold, our "Golden State," on hillsides, in river-beds, or deep down in hidden quartz ledges, still holds great fortunes waiting to be found.

A large book might be filled with the stories told by the men who found gold in the early days. Their "lucky strikes" in the "dry-diggings" sound like fairy tales. Imagine turning over a big rock and then picking up pieces of gold enough to half fill a man's hat from the little nest that rock had been lying in for years and years!

And think of finding forty-three thousand dollars in a yellow lump over a foot long, six inches wide and four inches thick! This was the biggest nugget on record and actually weighed one hundred and ninety-five pounds. The next one, too, you might have been glad to pick up, as it held a hundred and thirty-three pounds of solid gold. Little seventy-five and fifty-pound treasures were common, and a soldier stopping to drink at a roadside stream found a nugget weighing over twenty pounds lying close to his hand.

It paid to get up early those days, also for a man in Sonora, while taking his morning walk, struck his foot against a large stone, and forgot the pain when he saw the stone was nearly all gold. Another man, with good eyes, got a fifty-pound nugget on a trail many people used all the time. One day, after a heavy rain, a man who was leading a mule and cart through a street in Sonora, noticed that the wheel struck a big stone; he stooped to lift it out of the way, and found the stone to be a lump of gold weighing thirty-five pounds. In less than an hour all that part of the town and the street was staked off into mining-claims, but no more was found. One of the largest of these nuggets was found by three or four men, who took it to San Francisco and the Eastern states, and exhibited it for money. They guarded the precious thing day and night, but at last quarrelled so that it had to be broken up and divided between them.

The first piece Marshall found was said to be worth about fifty cents, and the second over five dollars. Almost all, though, that was found was like beans or small seeds or in fine dust. No one tried to weigh or measure such gold more correctly than to call a pinch between the finger and thumb a dollar's worth, while a teaspoonful was an ounce, or sixteen dollars' worth. A wineglassful meant a hundred dollars, and a tumblerful a thousand. Miners carried their "dust" in a buckskin bag, and this was put on the counter, and the storekeeper took out what he thought enough to pay for the things the miner bought. A large thumb to take a large pinch of the gold-dust meant a good many extra dollars to the storekeeper in '48 and '49. Yet nearly every one was honest, and gold might be left in an open tent untouched, for there was plenty more to be had for the picking up. Those who would rather steal than work were driven out of camp.

Some of the "sand bars," or banks of gravel and earth, washed down by the Yuba River were so rich that the men could pick out a tin cupful of gold day after day for weeks. One place was called Tin-cup Bar for this reason. Spanish Bar, on the American River, yielded a million dollars' worth of dust, and at Ford's Bar, a miner, named Ford, took out seven hundred dollars a day for three weeks. At Rich Bar, on the Feather River, a panful of earth gave fifteen hundred dollars.

Yet the miners were seldom satisfied, but were always prospecting for richer claims. A man would shoulder his roll of blankets, his pick and shovel, with a few cooking things, and start off hoping to find some rich nugget, leaving a fairly good claim untouched.

The most extravagant prices were charged the miner for everything he had to buy. Ten dollars apiece for pick and shovel, fifty more for a pair of long boots, with bacon and potatoes at a dollar and a half a pound, soon took all his gold-dust to pay for. A dozen fresh eggs cost ten dollars, and a box of sardines half an ounce of gold-dust, which was eight dollars. There was no butter to buy, for any milk was quickly sold at a dollar a pint. The hotels charged three dollars a meal, or a dollar for a dish of pork and beans, and a dollar for two potatoes.

Lumber cost a dollar and a half a foot, but carpenters would not build houses when they could make fifty dollars a day by mining. As there was no lumber for the cabin floors, the ground was beaten hard and really made a good floor. In Placerville the houses were built along the bed of a ravine, and in sweeping these earthen floors some one saw gold-dust glittering, and found that rich diggings were under foot. Thereupon many of the miners dug up their cabin floors, and one man took about twenty thousand dollars in nuggets and gold-dust from the small space his cabin covered.

Very few women and children came to the mines in early days, and the first white woman to arrive in a camp had all sorts of attentions. Sometimes the town was named for the woman first in the place as Sarahsville and Marietta. If a lady visited a mining-camp, the men far and near would drop work and come in just to look at the visitor. One lady, who sang for the miners on her arrival in their town, was given about five hundred dollars' worth of gold-dust.

A child was a great curiosity, and any pretty little girl was sure to have a collection of nuggets or a quantity of gold-dust presented to her. The theatre and circus companies who visited mining-camps soon found out that a little child who could sing or dance was a great attraction. The miners used to throw a shower of money or nuggets at the feet of such little favorites as we throw flowers now.

As there were no women living here for some time, the men having left their families at home in the Eastern states, miners had to wash and cook and make bread for themselves. Men who had been lawyers or ministers at home, when there was no one else to do such things, washed their dishes or their red flannel shirts. On Sunday no one worked at mining, and the men baked bread and cleaned house, and Sunday afternoons they dried, patched, and mended their clothes. If a minister was in town, he held services on a hillside, or in the dining room of some shanty called a hotel, and all the camp came to hear him speak, or sang the hymns with him.

So the miners lived and worked and wandered along rivers and rough mountain trails on the west side of the Sierras, gathering up gold washed down by mountain streams. These Argonauts, or gold-seekers of fifty years ago, are almost all dead now, but the treasures they found made California known throughout the world. Their golden harvest has made the state richer than they found it, for they used the wealth to build cities, to cultivate farming-lands, and to plant orchards and vineyards where the mining-camps used to be.

This is the story of a little girl who in 1849 rode all the way from Ohio to California in an emigrant wagon. Polly Elliott has grandchildren of her own now, but she remembers very well the spring morning when her father came home and said to her mother, "Lizzie, can you get ready to start for the land of gold next week?" She hears again her mother saying, "Oh, John, with all these little children?" She says her father answered by swinging her, the eleven-year-old Polly, up to his shoulder and calling out, "Here's papa's little woman; she'll help you take care of them," as he carried her round the room, laughing.

This was "back East," as Polly Elliott, now Mrs. Davis, says,—in Ohio, where they had a pretty white house set round with apple and peach orchards all white and pink that May day. Her mother cried because they must leave the house, and because they had to sell all their furniture and the stock except Daisy, the pet cow, and Buck and Bright, the oxen, who were to draw the wagon. A round-topped cover of white cloth was fixed on the big farm-wagon. Then they piled into it their bedding in calico covers, a chest or two holding clothes and household goods, a few dishes and cooking things, and plenty of flour, corn meal, beans, bacon, dried apples and peaches, tied up in sacks.

Polly says she supposed the trip would just be one long picnic, while the four children thought it fine fun to "sit on mother's featherbed and go riding," as they said. So they started off for California. A long, long ride these emigrants had before them; a weary trip, plodding along day after day with the patient oxen walking slowly and the burning sun or pelting rain beating down on the wagon cover. There was a train of other wagons with them, some pulled by horses but more by yoked oxen, and the men walked beside the animals and cracked long whips. A few men were on horseback, but all kept together, for Indians were plenty and were often hiding near the road, watching for a chance to cut off and capture any wagons lagging behind the party.

Day after day, Polly told me, they travelled westward to the setting sun. They left the orchards and shady woods of Ohio and Indiana far behind them, and crossed the wide prairies of Illinois and Missouri also. When they came to rivers they drove through shallow fording-places, where Polly and the children used to laugh to see the little fishes swimming round the wagon wheels. Sometimes the rivers were deep, and the wagons were ferried over on a flatboat that was fastened to a wire rope, while oxen and horses swam through the water behind them. If it did not rain, the children and all were happy, and it did seem like a picnic. But Polly says she never hears the rain pouring nowadays as it did then, and that there were many times when they were wet and cold and miserable, and because the wood and ground were wet they could not even have a fire.

At night the teams were unhitched and the wagons left in a circle round a big camp-fire, where supper was cooked. Polly says her mother used to bake biscuits in an iron spider with red-hot coals heaped on its iron cover, and these biscuits with fried bacon and tea made their meal. They always cooked a big potful of corn-meal mush for the children, and this, with Daisy's milk and a little maple sugar or molasses, was supper and breakfast too. Then the women and children cuddled up in the wagons for the night, while men slept, wrapped in blankets, around the camp-fire or under the wagons, with one always on guard against danger from prowling Indians or wolves.

Every man or boy carried a rifle or shotgun, and killed plenty of game. Deer and antelope were always in sight after they crossed the Missouri River, and the meat was broiled or roasted over the coals of their campfire. Wild turkeys and prairie-chicken tasted much better than bacon, Polly said, and she learned to cook them herself.

When the emigrants reached Nebraska, they were in the "buffalo country," and great herds of big, shaggy, brown or black buffaloes were feeding on the grassy plains. The animals were larger than oxen, and the Indians depended upon the flesh for food and the thick, warm skins for robes or blankets. The emigrants shot thousands of buffalo cows and calves, and what meat could not be eaten at once was cut into long strips and hung in the sun or over the fire to dry. This was called "jerking" the meat. On jerked buffalo or venison and flour pancakes many emigrants lived all the way across. Game was so plenty and so easy to shoot, that by stopping a few days, a good stock of meat could be laid in while the oxen were resting. So they travelled through Nebraska, and for weeks and weeks saw nothing but long grass waving in the summer winds, and yellow sunflowers—miles and miles of sunflowers. Polly grew very tired of the hot sun blazing down on the close-covered wagon, and of the dust raised by the long wagon-train.

About this time she remembers that her father bought her a little Indian pony, and from that happy day the child rode beside the wagon, and could keep out of the dusty trail, or ride a little way off on the prairie, if she liked. The pony carried double very well, so a small sister or brother was often lifted on behind for a ride. One night the Indians, who were always prowling round and coming as near the wagon-train as they dared, frightened the horses and got away with ten of them. All the women and children cried, Polly says, for they were afraid the redskins would come back and kill them. In the morning Polly's father and some of the men found the Indians' trail and tracked them to a wooded cañon. The hungry thieves had killed one horse and were so busy feasting on it that the white men surprised them and shot all the Indians but two or three. The lost horses and Polly's pony whinnied to their masters from a thicket, where they were tied, and were taken back to camp.

On and on over the great plains of Wyoming the wagons carried these emigrants. Many found the trip grow tiresome, while the oxen and mules would often lie down in their traces and refuse to go any farther. A few days' rest, and the rich bunch-grass to crop soon set the stock all right, and the white-topped wagons crawled ahead again. Soon the emigrants saw blue, hazy mountains, far off at first, then nearer and nearer, till at last their road led through a pass between the peaks.

Then Polly remembers riding through Utah, with its queer red cliffs and high rocks carved in strange shapes by winds and weather; the stretches of sandy desert; and beyond those, grassy meadows and streams fringed with green willows. After a while Great Salt Lake lay sparkling in the sun and looking cool and blue. All around it were alkali deserts or wide plains, hot and dusty and white with salt or soda. The "prairie schooners," with their covers faded and burnt by the sun, went very slowly over these desert wastes, Polly thought, and Nevada, with its dusty gray sage-brush land on either side of the road, seemed not much better.

"Papa's little woman" had her hands full now; for her mother was so ill she seldom left the wagon. All the cooking fell to Polly's share, and then she would ride along for hours with a little sister on her lap and fat brother "Bub" behind her on the saddle-blanket, so that her mother might rest and be quiet.

But soon the clear green Truckee River ran foaming and fretting beside the road, and off in the west rose the snowy peaks of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Then the people began to laugh and to sing, for they knew that California, the land of gold, was almost in sight and that their weary journey was nearly ended.

|

UPPER SACRAMENTO RIVER.

Click photo to see full-sized. |

And one day they said joyfully to each other, "We are in California at last;" and it was a happy company that travelled down through the pines of the mountain sides and the oak trees of the foot-hills. Many emigrants left the train when they got to the great Sacramento River valley, and settled here and there to farming. Polly's father with others kept on to the gold-diggings and camped there. He built a log-cabin soon, for it was almost winter and time for the rains, and Polly says she was glad to have a house at last. They finally took up farming land near what is now Stockton, as gold-mining did not pay.

Mrs. Davis, who is straight and strong, and still a hard worker, says her five months' trip across the plains was almost like a long picnic after all, for she has forgotten many of the trying and disagreeable things.

The army of emigrants and gold-hunters who crossed the plains to California found it was a long and tiresome trip by wagon-train or on horseback. The oxen or mules would sometimes get so tired that they could go no farther; and because the food often ran short, there was much suffering from hunger.

The longest way of all to California was by sailing vessel from New York round Cape Horn, nearly nineteen thousand miles to San Francisco. The passengers paid high prices and were six months on the way. Those who came by the Panama route had trouble crossing the isthmus, where it was so hot and unhealthy that many died of fevers and cholera. The Pacific mail steamers connecting with a railroad across the isthmus at last shortened the time of this trip of six thousand miles to twenty-five days. For ten years all the Eastern mail came this way twice a month.

It was thought a wonderful thing when the "pony express" carried mail twice a week between St. Joseph, Missouri, where the Eastern railroads ended, and Sacramento. To do this a rider, with the mail-bag slung over his shoulder, rode a horse twenty-four miles to the next station, where a fresh pony was ready. Hardly waiting to eat or sleep, the rider galloped on again. Five dollars was often charged at that time to bring the letter railroads carry now for two cents.

So you will see that a railroad to join California to the Eastern states was a great necessity and had often been talked of. Several ways to bring the iron horse puffing across the plains and up the mountains with his long train of cars had been laid out on paper. The emigrants had found that the best highway from the Missouri River to California was to keep along the Platte River in Nebraska to Fort Laramie and the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains, then by Salt Lake, and along the Humboldt and Truckee rivers, crossing the Sierras at Donner Pass. Other roads were talked of, and Senator Benton of Missouri favored a nearly straight line between St. Louis and San Francisco. Some one, in objecting to this, said that only engineers could lay out a railroad, and such men did not believe a straight line possible. The senator answered: "There are engineers who never learned in school the shortest and straightest way to go, and those are the buffalo, deer, bear, and antelope, the wild animals who always find the right path to the lowest passes in the mountains, to rich pastures and salt springs, and to the shallow fords in the rivers. The Indians follow the buffalo's path, and so does the white man for game to shoot. Then the white man builds a wagon-road and at last his railroad, on the trail the buffalo first laid out."

For two or three years surveyors and explorers tried to find the easiest way to build this great overland road. Several railroad acts or bills were passed by Congress, and the California Legislature gave the United States the right of way for a road to join the two oceans.

The first railway in the state was opened in '56 from Sacramento to Folsom, a distance of twenty-two miles. This was built by T.D. Judah, an engineer who had thought and studied a great deal about the overland road so much needed to bring mail and passengers quickly from East to West.

A railroad convention, made up of men from the Pacific states and territories, was held in San Francisco in '59, with General John Bidwell, a pathfinder of early days, as the chairman. Here Mr. Judah gave such a clear and full account of the central way he had planned, that the convention sent him to Washington, D.C., to see the President, and to try to get Congress to pass a Pacific Railroad Bill. He had very little help in the East, but at last four men of Sacramento, Leland Stanford, C.P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker, took an interest in Judah's plans, and in '61 the Central Pacific Railroad Company was formed. Mr. Judah went back to the mountains and studied the pines in summer and the winter snowbanks, to make sure of the easiest grades and the shortest and best way for the track-layers. He found that to follow the Truckee River from near Lake Donner to the Humboldt Desert, would mean the least work. The tunnels would be through rock, and he believed that snow might easily be kept off the track with a snow-plough.

His report pleased the company, and they sent him again to present the case at Washington. In '62 President Lincoln signed an act or bill to allow the Union and Central Pacific companies to build a railroad and a telegraph line from the Missouri River to the Pacific. In California the land for fifteen miles on each side of the way laid out was given to the railroad company, and two years was allowed them to build the first hundred miles of track.

Ground was broken for the Central Pacific the next year in Sacramento, and Governor Stanford dug up the first shovelful of earth. Then the work went steadily on, but it was hard to raise money. Stanford and his company carried the line forward as fast as possible. More land-grants were given, which doubled the company's holdings, and in '65 the road was fifty-five miles past Sacramento and had climbed over much difficult work.

The steamship owners, the express and stage companies were all against the railroad, and tried in every way to make people think that an engine could never cross the Sierras. Yet the grading went on, while an army of five thousand men and six hundred horses was at work cutting down trees and hills and filling up the low places. A bridge was built over the American River, and slowly but surely the track climbed the steep mountain-sides. Most of the laborers were Chinese, as white men found mining or farming paid them better.

In '67 the iron horse had not only climbed the mountains but had reached the state line, and the Union Pacific, which had been laying its tracks over the plains of the Platte River, began to hasten westward. The two railroads were racing to meet each other, and the Central sometimes laid ten miles of rails in one day.

Ogden was made the meeting-point, though at Promontory, fifty miles west of Ogden, the last spike was driven. A thousand people met at that place in May, '69, to see the short space of track closed and the road finished. A Central train and locomotive from the Pacific came steaming up, and an engine and cars from the Atlantic pulled in on the other side. Both engines whistled till the snow-capped mountains echoed. The last tie was of polished California laurel wood, with a silver plate on which the names of the two companies and their officers were engraved. It was put under the last two rails, and all was fastened together with the last spike. This spike, made of solid gold, Governor Stanford hammered into place with a silver hammer. East and west the news was flashed over the long telegraph line, that the overland railroad had been finished and that two oceans were joined by iron rails.

Now, while flying along in the cars so fast that the trip from Chicago to San Francisco takes but three days, it is hard to believe that little more than thirty years ago travellers in the slow-moving "prairie-schooner" took over five months to cover this same distance.

The Spanish Padres, as the Mission priests were called, taught the Indians to plough and seed with wheat the lands belonging to the church or Mission. They used a simple wooden plough, which oxen pulled. When the warm brown earth was turned up, the Indians broke the clods by dragging great tree branches over them. After the fall rains they scattered tiny wheat kernels and covered them snugly for their nap in the dark ground.

More rain fell, and soon the soaked seeds waked, and started in slender green shoots to find the sunshine, and day by day the stalks grew stronger and the fields greener. Higher and ever higher sprang the wheat, till summer winds set the tall grain waving in a sea of green billows. Have you ever watched the wind blow across a wheat-field? Over and over the long rollers bend the tops of the grain, that rise as the breeze goes on and bend low again at the next breath of wind.

When the hot sun had ripened the grain, and all round the white-walled, red-roofed Mission the fields stretched golden and ready for harvest, the Indians cut the wheat, and scattering the bundles over a spot of hard ground, drove oxen round and round on the sheaves till the wheat was threshed out from the straw. Then Indian women winnowed out the chaff and dirt by tossing the grain up in the wind, or from basket to basket, till in this slow way the yellow kernels were made clean and ready to grind.

A curious mill, called an arrastra, ground the grain between two heavy stones. A wooden beam was fastened to the upper stone, and oxen or a mule hitched to this beam turned the stone as they walked round. The first flour-mill worked by water was put up at San Gabriel Mission, and it was thought a wonderful thing indeed.

Even in those early days California wheat was known to be excellent, and many ships came on the South Sea, as they then called the Pacific Ocean, to load with grain for Mexico or Boston or England. Since that time our state has fed countless people, and over a million acres of valley and hill lands are green and golden every year with food for the world. To Europe, to the swarming people of China, Japan, and India, to South Africa and Australia, our grain is carried in great ships and steamers, and hungry nations in many lands look to us for bread.

For a long time after the Mission days, all the grain had to be hauled to the rivers or sea-coast for shipping. Then the overland railroad was finished, and within the next fifteen years an additional two thousand miles of railways were built in California, and nearly every mile opened up rich wheat land that had never been cultivated. Soon great wheat ranches stretched far over the dry, hot valley plains.

The ground is ploughed and seeded after November rains, and all winter the tender blades of grain grow greener and stronger day by day March and April rains strengthen the crop wonderfully, and June and July bring the harvest-time. As no rain falls then, the ripe wheat stands in the field till cut, and afterward in sacks without harm. All the work except ploughing is done by machinery, and this makes the wheat cost less to raise, since a machine does the work of many men and the expense of running it is small.

Some of the ranches have three or four thousand acres in wheat, and it may interest you to know how such large farms are managed. The ploughing is done by a gang-plough, as it is called, which has four steel ploughshares that turn up the ground ten inches deep. Eight horses draw this, and as a seeder is fastened to the plough, and back of the plough a harrow, the horses plough, seed, harrow, and cover up the grain at one time. There the seed-wheat lies tucked up in its warm brown bed till rain and sunshine call out the tiny green spears, and coax them higher and stronger, and the hot sun of June and July ripens the precious grain.

Then a great machine called a "header and thresher" is driven into the field and sweeps through miles and miles of bending grain, cutting swaths as wide as a street, and harvesting, threshing, and leaving a long trail of sacked wheat ready to ship on the cars. Thirty-six horses draw the header, and five or six men are needed to attend to this giant, who bites off the grain, shakes out the kernels, throws them into sacks and sews them up, all in one breath, as you might say. The harvesters work from daylight to dusk, and three-fourths of our wheat crop is gathered in this way.

Much golden straw is left, besides that which the "headers" burn as fuel, and farmers stack this straw for cattle to nibble at. The stock feed in the stubble fields, too, and strange visitors also come to these ranches to pick up the scattered grains of wheat. These strangers are wild white geese, in such large flocks that when feeding they look like snow patches on the ground. They eat so much that often they cannot fly and may be knocked over with clubs. In the spring these geese must be driven away by watchmen with shot-guns to keep them from pulling up the young grain.

The largest single wheat-field in California is on the banks of the San Joaquin River, in Madera County. This covers twenty-five thousand acres and is almost as flat as a floor. It is nearly a perfect square in shape, and each side of the square is a little over six miles long. There are no roads through this solid stretch of grain. Two hundred men, a thousand horses, and many big machines are needed to work this wheat-field.

Some of the big harvesters that cut and thresh the wheat are drawn by a traction-engine instead of horses. In running a fifty-horse-power engine high-priced coal had to be burnt but now the coal grates are replaced by petroleum burners, and crude coal-oil is the cheap fuel. This does not make sparks to set the fields on fire like burning coal or straw and so is safer to use.

On large ranches wheat can be grown for less than a cent a pound, while it has brought two cents or double the money when sold. But there are not always good crops, as the grain needs plenty of moisture in the spring when rains are uncertain.

The wheat crop of the state has fallen off of late to less than half the yield of earlier years, but the deep, rich valley soil still grows grain enough to feed hungry people in Europe, Asia, and Africa, as well as in our own Union. Great quantities are taken in large four-masted ships to Liverpool, England, and there made into American flour. Our own flour-mills turn out thousands of barrels of flour, and this travels far, too. The first thing picked up in Manila after Admiral Dewey's victory was a flour sack with a California mill mark.

It would need a long, long story to tell how far from home and into what strange places the yellow kernels of California wheat sometimes travel, or to picture the odd people who depend upon us for food.

Long ago the Mission Fathers taught the Indians to plant and to take care of vines and fruit-trees. They built water-works to bring life to the thirsty trees in the dry summers, and to grow oranges, limes, and figs, as well as peaches, apricots, and apples. They trained grape-vines over arbors and trellises round the Mission buildings, and from the small, black grapes made wine. Olive trees and date-palms did well at the southern settlements. But most of these orchards died when the Mission Fathers were no longer allowed to make the Indians work for the church property, though a few old palms and olive trees are still standing.

During Mexican days each ranch owner raised enough grain or corn and beans for his own family but planted no fruit, or but little, while the Americans who came to seek gold thought farming a slow way of making a living. People soon found out, however, that our fine climate and rich soil made good crops almost certain, and there was such demand for fruit and farm products that more and more acres were cultivated each year.

Our leading industry now is farming and fruit-growing, and California's delicious fresh or cured fruit is sent all over the world. Large amounts of barley and hops are shipped from here to Europe, and our state produces almost all the Lima beans used in the country.

The citrus fruits, as oranges, lemons, and pomelos, or "grape-fruit," are called, grow in the seven southern counties, or in the foothills on the western slope of the Sierras. The trees cannot endure frost and must be irrigated in the summer. Orange trees are a pretty sight, with their shining green leaves, white, sweet-smelling flowers, and the green or golden fruit. About Christmas-time, when oranges ripen, both blossoms and fruit may be picked from the same tree. Los Angeles and Orange County grow most oranges, but San Diego is first in lemon culture. Half a million trees in that county show the bright yellow fruit and fragrant blossoms every month in the year. The other southern counties also raise lemons by the car-load to send east, or for your lemonade and lemon pies at home.

There, too, the olive grows well, that little plum-shaped fruit you usually see as a green, salt pickle on the table. The Mission Fathers brought this tree first from Spain, where the poor people live upon black bread and olives. Olives are picked while green and put in a strong brine of salt and water to preserve them for eating. Dark purple ripe olives are also very good prepared the same way. Did you know that olive-oil is pressed out of ripe olives? The best oil comes from the first crushing, and the pulp is afterwards heated, when a second quality of oil is obtained. Olive trees grow very slowly, and do not fruit for seven years after they are planted. But they live a hundred years, and bear more olives every season.

The black or purple fig which grew in the old Mission gardens bears fruit everywhere in the state. Either fresh and ripe, or pressed flat and dried, it is delicious and healthful. White figs like those from abroad have been raised the last few years, and it is hoped in time to produce Smyrna figs equal to the imported.

While peach orchards blossom and bear fruit six months of the year in the south, most of this pretty pink-cheeked fruit grows in the great valleys, or along the Sacramento River. Pears also show their snowy blossoms and yellow fruit in the valleys and farther north. The Bartlett pear is sent to all the Eastern states in cold storage cars kept cool by ice, and also to Europe.