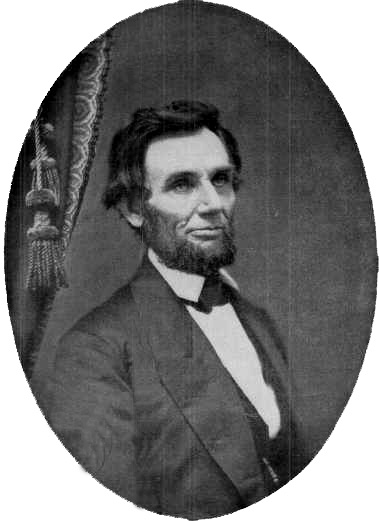

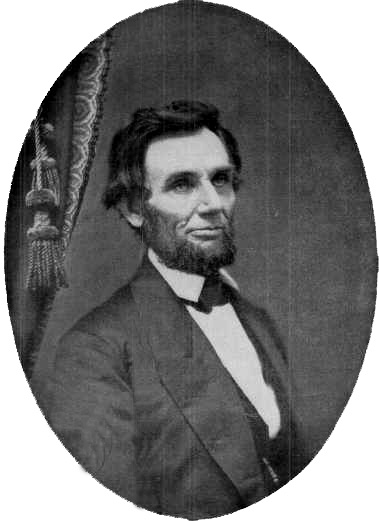

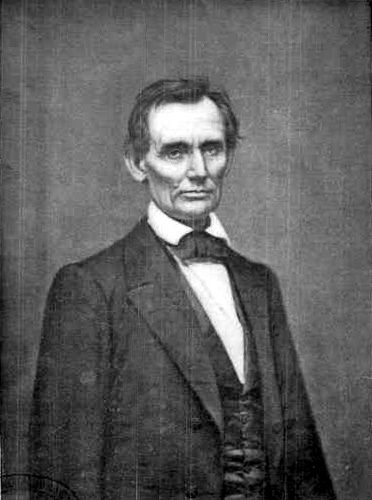

ABRAHAM LINCOLN IN 1861.—NOW FIRST PUBLISHED.

From a photograph owned by Allen Jasper Conant, to whose courtesy we owe the right to reproduce it here. This photograph was taken in Springfield in the spring of 1861, by C.S. German.

Title: McClure's Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 2, January, 1896

Author: Various

Release date: October 5, 2004 [eBook #13637]

Most recently updated: December 18, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Richard J. Shiffer and the PG Online

Distributed Proofreading Team

ABRAHAM LINCOLN. Edited by Ida M. Tarbell.115

Lincoln's First Experiences in Illinois. 115

In Charge of Denton Offutt's Store. 115

The Clary's Grove Boys. 117

Lincoln Studies Grammar. 119

A Candidate for the General Assembly. 122

The Black Hawk War. 127

Lincoln a Captain. 129

The Black Hawk Campaign. 132

Electioneering for the General Assembly. 135

EUGENE FIELD AND HIS CHILD FRIENDS. By Cleveland Moffett.137

POEMS OF CHILDHOOD. By Eugene Field. 140

With Trumpet and Drum. 140

The Delectable Ballad of the Waller Lot. 140

The Rock-a-by Lady. 142

"Booh!" 142

The Duel. 143

The Ride to Bumpville. 143

So, So, Rock-a-by So! 144

Seein' Things. 144

A CENTURY OF PAINTING. By Will H. Low.145

THE DEFEAT OF BLAINE FOR THE PRESIDENCY. By Murat Halstead.159

THE NEW STATUE OF WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON. By Frank B. Gessner.172

THE SILENT WITNESS. By Herbert D. Ward.175

THE SUN'S LIGHT. By Sir Robert Ball.187

CHAPTERS FROM A LIFE. By Elizabeth Stuart Phelps.191

Life in Andover before the War. 191

THE WAGER OF THE MARQUIS DE MÉROSAILLES. By Anthony Hope.198

MISS TARBELL'S LIFE OF LINCOLN. 206

THE KIRKHAM'S GRAMMAR USED BY LINCOLN AT NEW SALEM.

SITE OF DENTON OFFUTT'S STORE.

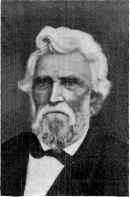

JOHN REYNOLDS, GOVERNOR OF ILLINOIS 1831-1834.

A DISCHARGE FROM SERVICE IN BLACK HAWK WAR SIGNED BY ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

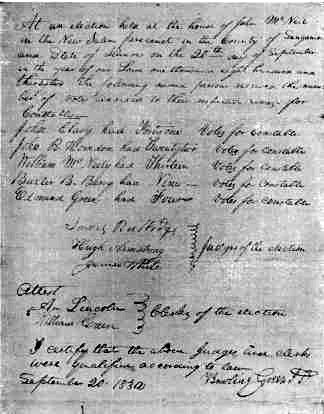

A FACSIMILE OF AN ELECTION RETURN WRITTEN BY LINCOLN.

VIEW OF THE SANGAMON RIVER NEAR NEW SALEM.

THE LAST PORTRAIT OF EUGENE FIELD.

JAMES BRECKINRIDGE WALLER, JR..

ROSWELL FRANCIS FIELD, EUGENE FIELD'S YOUNGEST SON.

JACQUES LOUIS DAVID AS A YOUNG MAN.

JUSTICE AND DIVINE VENGEANCE PURSUING CRIME.

THE COUNTESS REGNAULT DE SAINT-JEAN-D'ANGELY.

BRUTUS CONDEMNING HIS SONS TO DEATH.

MADAME LEBRUN AND HER DAUGHTER.

FRANCIS I., KING OF FRANCE, AND CHARLES V., EMPEROR OF THE HOLY ROME EMPIRE.

MR. BLAINE AT HIS DESK IN THE STATE DEPARTMENT.

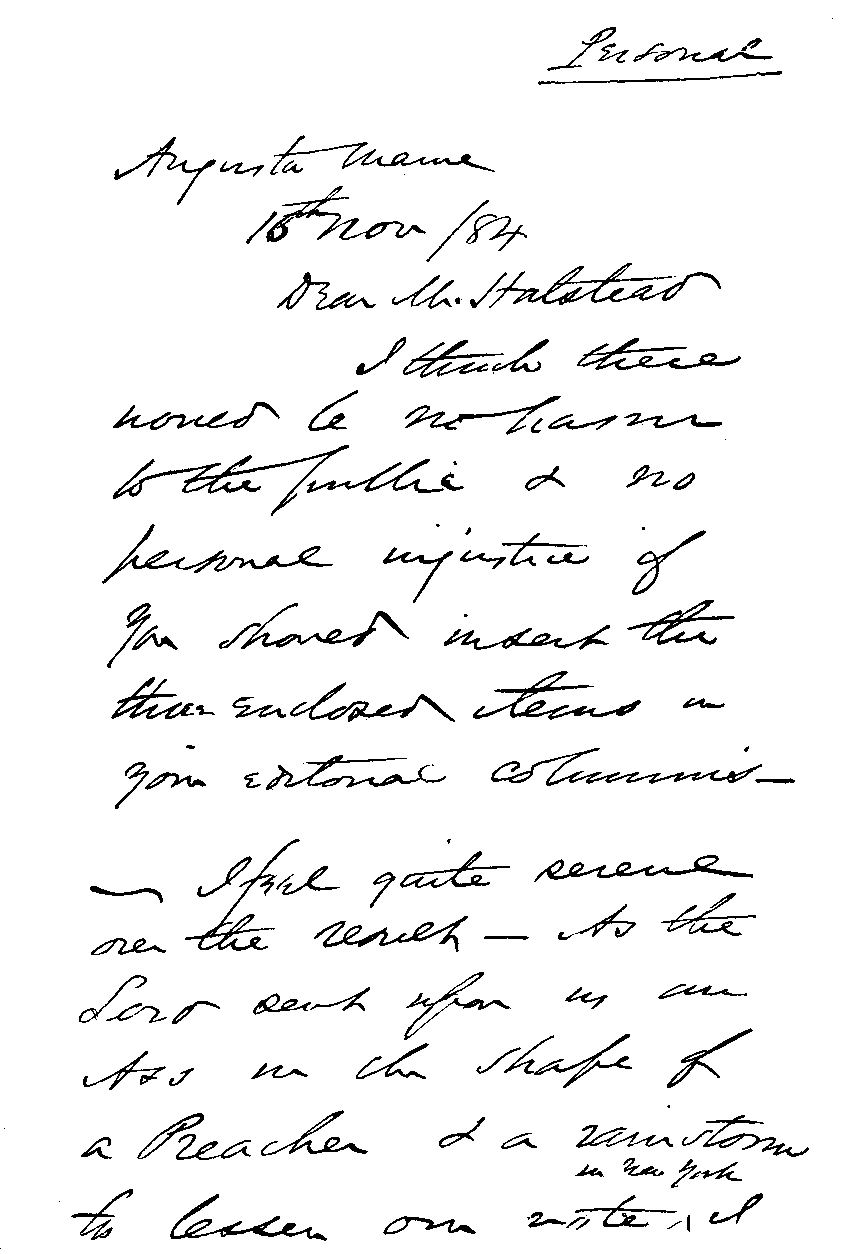

FACSIMILE OF THE LETTER WRITTEN BY MR. BLAINE TO MR. HALSTEAD

BLAINE'S GRAVE AT WASHINGTON, D.C..

STATUE OF WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON.

"AM--I--IMPRISONED BECAUSE I AM FRIENDLESS AND POOR? IS THIS YOUR LAW?"

"OH, MY GOD!" HE SOBBED. "MY GOD! MY GOD!"

ERUPTIVE PROMINENCE AT 10.34 A.M.

ERUPTIVE PROMINENCE AT 10.40 A.M.

ERUPTIVE PROMINENCE AT 10.58 A.M.

THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY BUILDINGS, ANDOVER, MASSACHUSETTS.

PROFESSOR AUSTIN PHELPS'S STUDY.

VIEW LOOKING FROM THE FRONT OF ELIZABETH STUART PHELPS'S HOME.

THE PHYSICIAN RECEIVING THE PRINCESS IN THE MARQUIS'S SICKROOM.

SHE STOLE UP AND SAW MONSIEUR DE MÉROSAILLES SITTING ON THE GROUND.

From a photograph owned by Allen Jasper Conant, to whose courtesy we owe the right to reproduce it here. This photograph was taken in Springfield in the spring of 1861, by C.S. German.

This article embodies special studies of Lincoln's life in New Salem made for this Magazine by J. McCan Davis.

T was in March, 1830, when Abraham Lincoln was twenty-one years of age, that he moved from Indiana to Macon County, Illinois. He spent his first spring in the new country helping his father settle. In the summer of that year he started out for himself, doing various kinds of rough farm work in the neighborhood until March of 1831, when he went to Sangamon town, near Springfield, to build a flatboat. In April he started on this flatboat for New Orleans, which he reached in May. After a month in that city, he returned, in June, to Illinois, where he made a short visit at his parents' home, now in Coles County, and in July went to New Salem, to take charge of a store and mill owned by Denton Offutt, who had employed him on the flatboat1. The goods for the new store had not arrived when Lincoln reached New Salem. Obliged to turn his hand to something, he piloted down the Sangamon and Illinois rivers, as far as Beardstown, a flatboat bearing the family and goods of a pioneer bound for Texas. At Beardstown he found Offutt's goods waiting to be taken to New Salem. As he footed his way home he met two men with a wagon and ox-team going for the goods. Offutt had expected Lincoln to wait at Beardstown until the ox-team arrived, and the teamsters, not having any credentials, asked Lincoln to give them an order for the goods. This, sitting down by the roadside, he wrote out; and one of the men used to relate that it contained a misspelled word, which he corrected.

The precise date of the opening of Denton Offutt's store is not known. We only know that on July 8, 1831, the County Commissioners' Court of Sangamon County granted Offutt a license to retail merchandise at New Salem; for which he paid five dollars, a fee which supposed him to have one thousand dollars' worth of goods in stock. When the oxen and their drivers returned with the goods, the store was opened in a little log house on the brink of the hill, almost over the river.

The copy of Kirkham's Grammar studied by Lincoln belonged to a man named Vaner. Some of the biographers say Lincoln borrowed [it,] but it appears that he became the owner of the book, either by purchase or through the generosity of Vaner, for it was never returned to the latter. It is said that Lincoln learned this grammar practically by heart. "Sometimes," says Herndon, "he would stretch out at full length on the counter, his head propped up on a stack of calico prints, studying it; or he would steal away to the shade of some inviting tree, and there spend hours at a time in a determined effort to fix in his mind the arbitrary rule that 'adverbs qualify verbs, adjectives and other adverbs.'" He presented the book to Ann Rutledge [the story of Ann Rutledge will appear in a future number of the Magazine], and it has since been one of the treasures of the Rutledge family. After the death of Ann it was studied by her brother, Robert, and is now owned by his widow, who resides at Casselton, North Dakota. The title page of the book appears above. The words, "Ann M. Rutledge is now learning grammar," were written by Lincoln. The order on James Rutledge to pay David P. Nelson thirty dollars and signed "A. Lincoln, for D. Offutt," which is shown above, was pasted upon the front cover of the book by Robert Rutledge. From a photograph made especially for MCCLURE'S MAGAZINE.—J. McCan Davis.

The frontier store filled a unique place. Usually it was a "general store," and on its shelves were found most of the articles needed in a community of pioneers. But to be a place for the sale of dry goods and groceries was not its only function; it was a kind of intellectual and social centre. It was the common meeting-place of the farmers, the happy refuge of the village loungers. No subject was unknown there. The habitués of the place were equally at home in talking politics, religion, or sport. Stories were told, jokes were cracked and laughed at, and the news contained in the latest newspaper finding its way into the wilderness was discussed. Such a store was that of Denton Offutt. Lincoln could hardly have chosen surroundings more favorable to the highest development of the art of story-telling, and he had not been there long before his reputation for drollery was established.

But he gained popularity and respect in other ways. There was near the village a settlement called Clary's Grove. The most conspicuous part of the population was an organization known as the "Clary's Grove Boys." They exercised a veritable terror over the neighborhood, and yet they were not a bad set of fellows. Mr. Herndon, who had a cousin living in New Salem at the time, and who knew personally many of the "boys," says:

"They were friendly and good-natured; they could trench a pond, dig a bog, build a house; they could pray and fight, make a village or create a state. They would do almost anything for sport or fun, love or necessity. Though rude and rough, though life's forces ran over the edge of the bowl, foaming and sparkling in pure deviltry for deviltry's sake, yet place before them a poor man who needed their aid, a lame or sick man, a defenceless woman, a widow, or an orphaned child, they melted into sympathy and charity at once. They gave all they had, and willingly toiled or played cards for more. Though there never was under the sun a more generous parcel of rowdies, a stranger's introduction was likely to be the most unpleasant part of his acquaintance with them."

From a water-color by Miss Etta Ackermann, Springfield, Illinois. "Clary's Grove" was the name of a settlement five miles southwest of New Salem, deriving its name from a grove on the land of the Clarys. It was the headquarters of a daring and reckless set of young men living in the neighborhood and known as the "Clary's Grove Boys." This cabin was the residence of George Davis, one of the "Clary's Grove Boys," and grandfather of Miss Ackermann. It was built seventy-one years ago—in 1824—and is the only one left of the cluster of cabins which constituted the little community.

Denton Offutt, Lincoln's employer, was just the man to love to boast before such a crowd. He seemed to feel that Lincoln's physical prowess shed glory on himself, and he declared the country over that his clerk could lift more, throw farther, run faster, jump higher, and wrestle better than any man in Sangamon County. The Clary's Grove Boys, of course, felt in honor bound to prove this false, and they appointed their best man, one Jack Armstrong, to "throw Abe." Jack Armstrong was, according to the testimony of all who remember him, a "powerful twister," "square built and strong as an ox," "the best-made man that ever lived;" and everybody knew the contest would be close. Lincoln did not like to "tussle and scuffle," he objected to "woolling and pulling;" but Offutt had gone so far that it became necessary to yield. The match was held on the ground near the grocery. Clary's Grove and New Salem turned out generally to witness the bout, and betting on the result ran high, the community as a whole staking their jack-knives, tobacco plugs, and "treats" on Armstrong. The two men had scarcely taken hold of each other before [pg 118] it was evident that the Clary's Grove champion had met a match. The two men wrestled long and hard, but both kept their feet. Neither could throw the other, and Armstrong, convinced of this, tried a "foul." Lincoln no sooner realized the game of his antagonist than, furious with indignation, he caught him by the throat, and holding him out at arm's length, he "shook him like a child." Armstrong's friends rushed to his aid, and for a moment it looked as if Lincoln would be routed by sheer force of numbers; but he held his own so bravely that the "boys," in spite of their sympathies, were filled with admiration. What bid fair to be a general fight ended in a general hand-shake, even Jack Armstrong declaring that Lincoln was the "best fellow who ever broke into the camp." From that day, at the cock-fights and horse-races, which were their common sports, he became the chosen umpire; and when the entertainment broke up in a row—a not uncommon occurrence—he acted the peacemaker without suffering the peacemaker's usual fate. Such was his reputation with the "Clary's Grove Boys," after three months in New Salem, that when the fall muster came off he was elected captain.

Nancy Green was the wife of "Squire" Bowling Green. Her maiden name was Nancy Potter. She was born in North Carolina in 1797, and married Bowling Green in 1818. She removed with him to New Salem in 1820, and lived in that vicinity until her death in 1864. Lincoln was a constant visitor in Nancy Green's home.

Lincoln showed soon that if he was unwilling to indulge in "woolling and pulling" for amusement, he did not object to it in a case of honor. A man came into the store one day who used profane language in the presence of ladies. Lincoln asked him to stop; but the man persisted, swearing that nobody should prevent his saying what he wanted to. The women gone, the man began to abuse Lincoln so hotly that the latter finally said, coolly: "Well, if you must be whipped, I suppose I might as well whip you as any other man;" and going outdoors with the fellow, he threw him on the ground, and rubbed smartweed in his eyes until he bellowed for mercy. New Salem's sense of chivalry was touched, and enthusiasm over Lincoln increased.

From a photograph made for this Magazine.

Owned by Mrs. Ott, of Petersburg, Illinois. These Dutch ovens were in many cases the only cooking utensils used by the early settlers. The meat, vegetable, or bread was put into the pot, which was then placed in a bed of coals, and coals heaped on the lid.

His honesty excited no less admiration. Two incidents seem to have particularly impressed the community. Having discovered on one occasion that he had taken six and one-quarter cents too much from a customer, he walked three miles that evening, after his store was closed, to return the money. Again, he weighed out a half-pound of tea, as he supposed. It was night, and this was the last thing he did before [pg 119] closing up. On entering in the morning he discovered a four-ounce weight on the scales. He saw his mistake, and closing up shop, hurried off to deliver the remainder of the tea.

After a photograph owned by Mrs. Harriet Chapman of Charleston, Illinois. Mrs. Chapman is a grand-daughter of Sarah Bush Lincoln, Lincoln's step-mother. Her son, Mr. R.N. Chapman of Charleston, Illinois, writes us: "In 1858 Lincoln and Douglas had a series of joint debates in this State, and this city was one place of meeting. Mr. Lincoln's step-mother was making her home with my father and mother at that time. Mr. Lincoln stopped at our house, and as he was going away my mother said to him: 'Uncle Abe, I want a picture of you.' He replied, 'Well, Harriet, when I get home I will have one taken for you and send it to you.' Soon after, mother received the photograph she still has, already framed, from Springfield, Illinois, with a letter from Mr. Lincoln, in which he said, 'This is not a very good-looking picture, but it's the best that could be produced from the poor subject.' He also said that he had it taken solely for my mother. The photograph is still in its original frame, and I am sure is the most perfect and best picture of Lincoln in existence. We suppose it must have been taken in Springfield, Illinois."

From a recent photograph. John Potter, born November 10, 1808, was a few months older than Lincoln. He is now living at Petersburg, Illinois. He settled in the country one and one-half miles from New Salem in 1820. Mr. Potter remembers Lincoln's first appearance in New Salem in July, 1831. He corroborates the stories told of his store, and of his popularity in the community, and of the general impression that he was an unusually promising young man.

As soon as the store was fairly under way Lincoln began to look about for books. Since leaving Indiana, in March, 1830, he had had, in his drifting life, little leisure or opportunity for study—though he had had a great deal for observation. Nevertheless his desire to learn had increased, and his ambition to be somebody had been encouraged. In that time he had found that he really was superior to many of those who were called the "great" men of the country. Soon after entering Macon County, in March, 1830, when he was only twenty-one years old, he had found he could make a better speech than at least one man who was before the public. A candidate had come along where John Hanks and he were at work, and, as John Hanks tells the story, the man made a speech. "It was a bad one, and I said Abe could beat it. I turned down a box, and Abe made his speech. The other man was a candidate—Abe wasn't. Abe beat him to death, his subject being the navigation of the Sangamon River. The man, after Abe's speech was through, took him aside, and asked him where he had learned so much and how he could do so well. Abe replied, stating his manner and method of reading, what he had read. The man encouraged him to persevere."

He had found that people listened to him, that they quoted his opinions, and that his friends were already saying that he was able to fill any position. Offutt even declared the country over that "Abe knew more than any man in the United States," and "some day he would be President."

John A. Clary was one of the "Clary's Grove Boys." He was a son of John Clary, the head of the numerous Clary family which settled in the vicinity of New Salem in 1818. He was born in Tennessee in 1815 and died in 1880. He was an intimate associate of Lincoln during the latter's New Salem days.

Under this stimulus Lincoln's ambition increased. "I have talked with great men," he told his fellow-clerk and friend, Greene, "and I do not see how they differ from others." He made up his mind to put himself before the public, and talked of his plans to his friends. In order to keep in practice in speaking he walked seven or eight miles to debating clubs. "Practising polemics" was what he called the exercise. He seems now for the first time to have begun to study subjects. Grammar was what he chose. He sought Mentor Graham, the schoolmaster, and asked his advice. "If you are going before the public," Mr. Graham told him, "you ought to do it." But where could he get [pg 121] a grammar? There was but one, said Mr. Graham, in the neighborhood, and that was six miles away. Without waiting further information the young man rose from the breakfast-table, walked immediately to the place, borrowed this rare copy of Kirkham's Grammar, and before night was deep into its mysteries. From that time on for weeks he gave every moment of his leisure to mastering the contents of the book. Frequently he asked his friend Greene to "hold the book" while he recited, and, when puzzled by a point, he would consult Mr. Graham.

Lincoln's eagerness to learn was such that the whole neighborhood became interested. The Greenes lent him books, the schoolmaster kept him in mind and helped him as he could, and even the village cooper let him come into his shop and keep up a fire of shavings sufficiently bright to read by at night. It was not long before the grammar was mastered. "Well," Lincoln said to his fellow-clerk, Greene, "if that's what they call a science, I think I'll go at another." He had made another discovery—that he could conquer subjects.

From a photograph taken for this Magazine.

The building in which Lincoln clerked for Denton Offutt was standing as late as 1836, and presumably stood until it rotted down. A slight depression in the earth, evidently once a cellar, is all that remains of Offutt's store. Out of this hole in the ground have grown three trees, a locust, an elm, and a sycamore, seeming to spring from the same roots, and curiously twined together; and high up on the sycamore some genius has chiselled the face of Lincoln.

Before the winter was ended he had become the most popular man in New Salem. Although in February, 1832, he was but twenty-two years of age, had never been at school an entire year in his life, had never made a speech except in debating clubs and by the roadside, had read only the books he could pick up, and known only the men who made up the poor, out-of-the-way [pg 122] towns in which he had lived, "encouraged by his great popularity among his immediate neighbors," as he says himself, he decided to announce himself, in March, 1832, as a candidate for the General Assembly of the State.

At the breaking out of the Black Hawk war, Zachary Taylor, afterwards general in the Mexican War, and finally President of the United States, was colonel of the First Infantry. He joined Atkinson at the beginning of the war, and was in active service until the end of the campaign.

The only preliminary expected of a candidate for the legislature of Illinois at that date was an announcement stating his "sentiments with regard to local affairs." The circular in which Lincoln complied with this custom was a document of about two thousand words, in which he plunged at once into the subject he believed most interesting to his constituents—"the public utility of internal improvements."

From a photograph taken for this Magazine.

Bowling Green's log cabin, half a mile north of New Salem, just under the bluff, still stands, but long since ceased to be a dwelling-house, and is now a tumble-down old stable. Here Lincoln was a frequent boarder, especially during the period of his closest application to the study of the law. Stretched out on the cellar door of his cabin, reading a book, he met for the first time "Dick" Yates, then a college student at Jacksonville, and destined to become the great "War Governor" of the State. Yates had come home with William G. Greene to spend his vacation, and Greene took him around to Bowling Green's house to introduce him to "his friend, Abe Lincoln." Unhappily there is nowhere in existence a picture of the original occupant of this humble cabin. Bowling Green was one of the leading citizens of the county. He was County Commissioner from 1826 to 1828; he was for many years a justice of the peace; he was a prominent member of the Masonic fraternity, and a very active and uncompromising Whig. The friendship between him and Lincoln, beginning at a very early day, continued until his death in 1842.—J. McCan Davis.

At that time the State of Illinois—as, indeed, the whole United States—was convinced that the future of the country depended on the opening of canals and railroads, and the clearing out of the rivers. In the Sangamon country the population felt that a quick way of getting to Beardstown on the Illinois River, to which point the steamer came from the Mississippi, was, as Lincoln puts it in his circular, "indispensably necessary." Of course a railroad was the dream of the settlers; but when it was considered seriously there was always, as Lincoln says, "a heart-appalling [pg 123] shock accompanying the amount of its cost, which forces us to shrink from our pleasing anticipations." Improvement of the Sangamon River he declared the most feasible plan. That it was possible, he argued from his experience on the river in April of the year before (1831), when he made his flatboat trip, and from his observations as manager of Offutt's saw-mill. He could not have advocated a measure more popular. At that moment the whole population of Sangamon was in a state of wild expectation. Some six weeks before Lincoln's circular appeared, a citizen of Springfield had advertised that as soon as the ice went off the river he would bring up a steamer, the "Talisman," from Cincinnati, and prove the Sangamon navigable. The announcement had aroused the entire country, speeches were made, and subscriptions taken. The merchants announced goods direct per steamship "Talisman" the country over, and every village from Beardstown to Springfield was laid off in town lots. When the circular appeared the excitement was at its height.

From a photograph made for this Magazine.

After a portrait by George Catlin, in the National Museum at Washington, D.C., and here reproduced by the courtesy of the director, Mr. G. Brown Goode. Makataimeshekiakiak, the Black Hawk Sparrow, was born in 1767 on the Rock River. He was not a chief by birth, but through the valor of his deeds became the leader of his village. He was imaginative and discontented, and bred endless trouble in the Northwest by his complaints and his visionary schemes. He was completely under the influence of the British agents, and in 1812 joined Tecumseh in the war against the United States. After the close of that war, the Hawk was peaceable until driven to resistance by the encroachments of the squatters. After the battle of Bad Axe he escaped, and was not captured until betrayed by two Winnebagoes. He was taken to Fort Armstrong, where he signed a treaty of peace, and then was transferred as a prisoner of war to Jefferson Barracks, now St. Louis, where Catlin painted him. Catlin, in his "Eight Years," says: "When I painted this chief, he was dressed in a plain suit of buckskin, with a string of wampum in his ears and on his neck, and held in his hand his medicine-bag, which was the skin of a black hawk, from which he had taken his name, and the tail of which made him a fan, which he was almost constantly using." In April, 1833, Black Hawk and the other prisoners of war were transferred to Fortress Monroe. They were released in June, and made a trip through the Atlantic cities before returning West. Black Hawk settled in Iowa, where he and his followers were given a small reservation in Davis County. He died in 1838.

From a photograph made for this Magazine.

After a painting by R.M. Sully in the collection of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, and here reproduced through the courtesy of the secretary, Mr. Reuben G. Thwaites. Black Hawk had two sons; the elder was the Whirling Thunder, the younger the Roaring Thunder; both were in the war, and both were taken prisoners with their father, and were with him at Jefferson Barracks and at Fortress Monroe and on the trip through the Atlantic cities. At Jefferson Barracks Catlin painted them, and the pictures are in the National Museum. While at Fortress Monroe the above picture of Whirling Thunder was painted. A pretty anecdote is told of the Whirling Thunder. While on their tour through the East the Indians were invited to various gatherings and much done for their entertainment. On one of these occasions a young lady sang a ballad. Whirling Thunder listened intently, and when she ended he plucked an eagle's feather from his head-dress, and giving it to a white friend, said: "Take that to your mocking-bird squaw." Black Hawk's sons remained with him until his death in 1838, and then removed with the Sacs and Foxes to Kansas.

Lincoln's comments in his circular on two other subjects on which all candidates of the day expressed themselves are amusing in their simplicity. The practice of loaning money at exorbitant rates was then a great evil in the West. Lincoln proposed a law fixing the limits of usury, and he closed his paragraph on the subject with these words, which sound strange enough from a man who in later life showed so profound a reverence for law:

"In cases of extreme necessity, there could always be means found to cheat the law; while in all other cases it would have its intended effect. I would favor the passage of a law on this subject which might not be very easily evaded. Let it be such that the labor and difficulty of evading it could only be justified in cases of greatest necessity."

A change in the laws of the State was also a topic which he felt required a word. "Considering the great probability," he said, "that the framers of those laws were wiser than myself, I should prefer not meddling with them, unless they were attacked by others; in which case I should feel it both a privilege and a duty to take that stand which, in my view, might tend most to the advancement of justice."

From a photograph made for this Magazine.

After a painting in the collection of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, and here reproduced through the courtesy of the secretary, Mr. Reuben G. Thwaites. The chief of an Indian village on the Rock River, White Cloud was half Winnebago, half Sac. He was false and crafty, and it was largely his counsels which induced Black Hawk to recross the Mississippi in 1832. He was captured with Black Hawk, was a prisoner at both Jefferson Barracks and Fortress Monroe, and made the tour of the Atlantic cities with his friends. The above portrait was made at Fortress Monroe by R.M. Sully. Catlin also painted White Cloud at Jefferson Barracks in 1832. He describes him as about forty years old at that time, "nearly six feet high, stout and athletic." He said he let his hair grow out to please the whites. Catlin's picture shows him with a very heavy head of hair. The prophet, after his return from the East, remained among his people until his death in 1840 or 1841.

From a photograph made for this Magazine.

After an improved replica of the original portrait painted by R.M. Sully at Fortress Monroe in 1833, and now in the museum of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, at Madison. It is reproduced through the courtesy of the secretary of the society, Mr. Reuben G. Thwaites.

From a photograph loaned by H.W. Fay of DeKalb, Illinois. After Lincoln's nomination for the presidency, Alex Hesler of Chicago published a portrait he had made of Lincoln in 1857. (See McCLURE'S MAGAZINE for December, p. 13.) At the same time he put out a portrait of Douglas. The contrast was so great between the two, and in the opinion of the politicians so much in Douglas's favor, that they told Hesler he must suppress Lincoln's picture; accordingly the photographer wrote to Springfield requesting Lincoln to call and sit again. Lincoln replied that his friends had decided that he remain in Springfield during the canvass, but that if Hesler would come to Springfield he would be "dressed up" and give him all the time he wanted. Hesler went to Springfield and made at least four negatives, three of which are supposed to have been destroyed in the Chicago fire. The fourth is owned by Mr. George Ayers of Philadelphia. The above photograph is a print from one of the lost negatives.

The audacity of a young man in his position presenting himself as a candidate for the legislature is fully equalled by the humility of the closing paragraphs of his announcement:

"But, fellow-citizens, I shall conclude. Considering the great degree of modesty which should always attend youth, it is probable I have already been more presuming than becomes me. However, upon the subjects of which I have treated, I have spoken as I have thought. I may be wrong in regard to any or all of them; but, holding it a sound maxim that it is better only sometimes to be right than at all times to be wrong, so soon as I discover my opinions to be erroneous, I shall be ready to renounce them.

"Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say, for one, that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow-men by rendering myself worthy of their esteem. How far I shall succeed in gratifying this ambition is yet to be developed. I am young, and unknown to many of you. I was born, and have ever remained, in the most humble walks of life. I have no wealthy or popular relations or friends to recommend me. My case is thrown exclusively upon the independent voters of the county; and, if elected, they will have conferred a favor upon me for which I shall be unremitting in my labors to compensate. But, if the good people in their wisdom shall see fit to keep me in the background, I have been too familiar with disappointments to be very much chagrined."

Tomahawk. Indian Pipe. Powder-horn. Flintlock Rifle. Indian Flute. Indian Knife.

From a photograph made for this Magazine.

This group of relics of the Black Hawk War was selected for us from the collection in the museum of the Wisconsin Historical Society by the Secretary, Mr. Reuben G. Thwaites. The coat and chapeau belonged to General Dodge, an important leader in the war. The Indian relics are a tomahawk, a Winnebago pipe, a Winnebago flute, and a knife. The powder-horn and the flintlock rifle are the only volunteer articles. One of the survivors of the war, Mr. Elijah Herring of Stockton, Illinois, says of the flintlock rifles used by the Illinois volunteers: "They were constructed like the old-fashioned rifle, only in place of a nipple for a cap they had a pan in which was fixed an oil flint which the hammer struck when it came down, instead of the modern cap. The pan was filled with powder grains, enough to catch the spark and communicate it to the load in the gun. These guns were all right, and rarely missed fire on a dry, clear day; but unless they were covered well, the dews of evening would dampen the powder, and very often we were compelled to withdraw the charge and load them over again. We had a gunsmith with us, whose business it was to look after the guns for the whole regiment; and when a gun was found to be damp, it was his duty to get his tools and 'draw' the load. At that time the Cramer lock and triggers had just been put on the market, and my rifle was equipped with these improvements, a fact of which I was very proud. Instead of one trigger my rifle had two, one set behind the other—the hind one to cock the gun, and the front one to shoot it. The man Cramer sold his lock and triggers in St. Louis, and I was one of the first to use them."

Very soon after Lincoln had distributed his handbills, enthusiasm on the subject of the opening of the Sangamon rose to a fever. The "Talisman" actually came up the river; scores of men went to Beardstown to meet her, among them Lincoln, of course; and to him was given the honor of piloting her—an honor which made him remembered by many a man who saw him that day for the first time. The trip was made with all the wild demonstrations which always attended the first steamboat. On either bank a long procession of men and boys on foot or horse accompanied the boat. Cannons and volleys of musketry were fired as settlements were passed. At every stop speeches were made, congratulations offered, toasts drunk, flowers presented. It was one long hurrah from Beardstown to Springfield, and foremost in the jubilation was Lincoln, the pilot. The "Talisman" went as near Springfield as the river did, and there tied up for a week. When she went back Lincoln again had a conspicuous position as pilot. The notoriety this gave him was quite as valuable politically, probably, as was the forty dollars he received for his service financially.

From a photograph in the war collection of Robert A. Coster.

Born in Kentucky in 1805. In 1825 graduated at West Point. Anderson was on duty at the St. Louis Arsenal when the Black Hawk war broke out. He asked permission to join General Atkinson, who commanded the expedition against the Indians; was placed on his staff as Assistant Inspector General, and was with him until the end of the war. Anderson twice mustered Lincoln out of the service and in again. When General Scott was sent to take Atkinson's place, Anderson was ordered to report to the former for duty, and was sent by him to take charge of the Indians captured at Bad Axe. It was Anderson who conducted Black Hawk to Jefferson Barracks. His adjutant in this task was Lieutenant Jefferson Davis. From 1835-37 Anderson was an instructor at West Point. He served in the Florida War in 1837-38, and was wounded at Molino del Rey in the Mexican War. In 1857 he was appointed Major of the First Artillery. On November 20, 1860, Anderson assumed command of the troops in Charleston Harbor. On April 14 he surrendered Fort Sumter, marching out with the honors of war. He was made brigadier-general by Lincoln for his service. On account of failing health he was relieved from duty in October, 1861. In 1865 he was brevetted major-general. He died in France in 1871.

While the country had been dreaming of wealth through the opening of the Sangamon, and Lincoln had been doing his best to prove that the dream was possible, the store in which he clerked was "petering out"—to use his own expression. The owner, Denton Offutt, had proved more ambitious than wise, and Lincoln saw that an early closing by the sheriff was probable. But before the store was fairly closed, and while the "Talisman" was yet exciting the country, an event occurred which interrupted all of Lincoln's plans.

One morning in April a messenger from the governor of the State rode into New Salem scattering a circular. It was an address from Governor Reynolds to the militia of the northwest section of the State, announcing that the British band of Sacs and other hostile Indians, headed by Black Hawk, had invaded the Rock River country, to the great terror of the frontier inhabitants; and calling on the citizens who were willing to aid in repelling them, to rendezvous at Beardstown within a week.

On June 24, 1832, Black Hawk attacked Apple River Fort, fourteen miles east of Galena, Illinois, but was unable to drive out the inmates. The next day he attacked a spy battalion of one hundred and fifty men at Kellogg's Grove, sixteen miles further east. A detachment of volunteers relieved the battalion, and drove off the savages, about fifteen of whom were killed. The whites lost five men, who were buried at various points in the grove. During the summer of 1886 the remains of these men were collected and, with those of five or six other victims of the war, were placed together under the monument here represented.—See "The Black Hawk War," by Reuben G. Thwaites, Vol. XII. in Wisconsin Historical Collections. This account of the Black Hawk War is the most trustworthy, complete, and interesting which has been made.

The name of Black Hawk was familiar to the people of Illinois. He was an old enemy of the settlers, and had been a tried friend of the British. The land his people had once owned in the northwest of the present State of Illinois had been sold in 1804 to the government of the United States, but with the provision that the Indians should hunt and raise corn there until it was surveyed and sold to settlers.

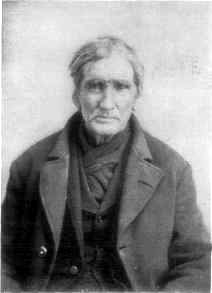

After a steel engraving in the Governor's office, Springfield, Illinois. John Reynolds, Governor of Illinois from 1831 to 1834, was born in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, February 26, 1788. He was of Irish parentage. When he was six months old his parents moved to Tennessee. In 1800 they removed to Illinois. When twenty years old, John Reynolds went to Knoxville, Tennessee, to college, where he spent two years. He was admitted to the bar at Kaskaskia in 1812. In the war of 1812 he rendered distinguished service, earning the title of "the Old Ranger." He began the practice of law in the spring of 1814. In 1818 he was made an associate justice of the Supreme Court; in 1826 he was elected a member of the legislature; and in 1830, after a stirring campaign, he was chosen Governor of Illinois. The most important event of his administration was the Black Hawk War. He was prompt in calling out the militia to subdue the Black Hawk, and went upon the field in person. In November, 1834, just before the close of his term as Governor, he resigned to become a member of Congress. In 1837, aided by others, he built the first railroad in the State—a short line of six miles from his coal mine in the Mississippi bluff to the bank of the river opposite St. Louis. It was operated by horse power. He again became a member of the legislature in 1846 and 1852, during the latter term being Speaker of the House. In 1860, in his seventy-third year, he was an anti-Douglas delegate to the Charleston convention, and received the most distinguished attentions from the Southern delegates. After the October elections, when it became apparent that Lincoln would be elected, he issued an address advising the support of Douglas. His sympathies were with the South, though in 1832 he strongly supported President Jackson in the suppression of the South Carolina nullifiers. He died in Belleville in May, 1865. Governor Reynolds was a quaint and forceful character. He was a man of much learning; but in conversation (and he talked much) he rarely rose above the odd Western vernacular, of which he was so complete a master. He was the author of two books—one an autobiography, and the other "The Pioneer History of Illinois."

Long before the land was surveyed, however, squatters had invaded the country, and tried to force the Indians west of the Mississippi. Particularly envious were these whites of the lands at the mouth of the Rock River, where the ancient village and burial place of the Sacs stood, and where they came each year to raise corn. Black Hawk had resisted their encroachments, and many violent acts had been committed on both sides.

Finally, however, the squatters, in spite of the fact that the line of settlement was still fifty miles away, succeeded in evading the real meaning of the treaty and in securing a survey of the desired land at the mouth of the river. Black Hawk, exasperated and broken-hearted at seeing his village violated, persuaded himself that the village had never been sold—indeed, that land could not be sold:

"My reason teaches me," he wrote, "that land cannot be sold. The Great Spirit gave it to his children to live upon, and cultivate, as far as is necessary for their subsistence; and so long as they occupy and cultivate it, they have the right to the soil, but if they voluntarily leave it, then any other people have a right to settle upon it. Nothing can be sold but such things as can be carried away."

Supported by this theory, conscious that in some way he did not understand he had been wronged, and urged on by White Cloud, the prophet, who ruled a Winnebago village on the Rock River, Black Hawk crossed the Mississippi in 1831, determined to evict the settlers. A military demonstration drove him back, and he was persuaded to sign a treaty never to return east of the Mississippi. "I touched the goose quill to the treaty, and was determined to live in peace," he wrote afterward; but hardly had he [pg 129] "touched the goose quill" before his heart smote him. Longing for his home; resentment at the whites; obstinacy; brooding over the bad counsels of White Cloud and his disciple Neapope, an agitating Indian who had recently been East to visit the British and their Indian allies, and who assured Black Hawk that the Winnebagoes, Ottawas, Chippewas, and Pottawottomies would join him in a struggle for his land, and that the British would send him "guns, ammunition, provisions, and clothing early in the spring"—all persuaded the Hawk that he would be successful if he made an effort to drive out the whites. In spite of the persuasion of many of his friends and of the Indian agent in the country, he crossed the river on April 6, 1832, and with some five hundred braves, his squaws and children, marched to the Prophet's town, thirty-five miles up the Rock River.

As soon as they heard of Black Hawk's invasion, the settlers fled in a panic to the forts in the vicinity, and they rained petitions for protection on Governor Reynolds. General Atkinson, who commanded a company at Fort Armstrong, wrote the governor he must have help; and accordingly on the 16th of April Governor Reynolds sent out "influential messengers" with a sonorous summons. It was one of these messengers riding into New Salem who put an end to Lincoln's canvassing for the legislature, freed him from Offutt's expiring grocery, and led him to enlist.

From a photograph made for this Magazine.

After a painting by the late Mrs. Obed Lewis, niece of Major Iles, and owned by Mr. Obed Lewis, Springfield, Illinois. Elijah Iles was born in Kentucky, March 28, 1796, and when young went to Missouri. There he heard marvellous stories about the Sangamon Valley, and he resolved to go thither. Springfield had just been staked out in the wilderness, and he reached the place in time to erect the first building—a rude hut in which he kept a store. This was in 1821. "In the early days in Illinois," he wrote in 1883, "it was hard to find good material for law-makers. I was elected a State Senator in 1826, and again for a second term. The Senate then comprised thirteen members, and the House twenty-five." In 1827 he was elected major in the command of Colonel T. McNeal, intending to fight the Winnebagoes, but no fighting occurred. In the Black Hawk War of 1832, after his term as a private in Captain Dawson's company had expired, he was elected captain of a new company of independent rangers. In this company Lincoln reenlisted as a private. Major Iles lived at Springfield all his life. He died September 4, 1883.

There was no time to waste. The volunteers were ordered to be at Beardstown, nearly forty miles from New Salem, on April 22d. Horses, rifles, saddles, blankets were to be secured, a company formed. It was work of which the settlers were not ignorant. Under the laws of the State every able-bodied male inhabitant between eighteen and forty-five was obliged to drill twice a year or pay a fine of one dollar. "As a dollar was hard to raise," says one of the old settlers, "everybody drilled."

Preparations were quickly made, and by April 22d the men were at Beardstown. Here each company elected its own officers, and Lincoln became a candidate for the captaincy of the company from Sangamon to which he belonged.

His friend Greene gave another reason than ambition to explain his desire for the captaincy. One of the "odd jobs" which Lincoln had taken since coming into Illinois was working in a saw-mill for a man named Kirkpatrick. In hiring Lincoln, Kirkpatrick had promised to buy him a cant-hook to move heavy logs. Lincoln had proposed, if Kirkpatrick would give him two dollars, to move the logs with a common hand-spike. This the proprietor had agreed to, but when pay day came he refused to keep his word. When the Sangamon company of volunteers was formed, Kirkpatrick aspired to the captaincy; and Lincoln, knowing it, said to Greene: "Bill, I believe I can now pay Kirkpatrick for that two dollars he owes me on the cant-hook. I'll run against him for captain;" and he became a candidate. The vote was taken in a field, by directing the men at the command "march" to assemble around the man they wanted for captain. When the order was given, three-fourths of the men gathered around [pg 130] Lincoln2. In Lincoln's curious third-person autobiography he says he was elected "to his own surprise;" and adds, "He says he has not since had any success in life which gave him so much satisfaction."

The company was a motley crowd of men. Each had secured for his outfit what he could get, and no two were equipped alike. Buckskin breeches prevailed. There was a sprinkling of coon-skin caps, and the blankets were of the coarsest texture. Flintlock rifles were the usual arm, though here and there a man had a Cramer. Over the shoulder of each was slung a powder-horn. The men had, as a rule, as little regard for discipline as for appearances, and when the new captain gave an order were as likely to jeer at it as to obey it. To drive the Indians out was their mission, and any orders which did not bear directly on that point were little respected. Lincoln himself was not familiar with military tactics, and made many blunders of which he used to tell afterwards with relish. One of these was an early experience in drilling. He was marching with a front of over twenty men across a field, when he desired to pass through a gateway into the next inclosure.

"I could not for the life of me," said he, "remember the proper word of command for getting my company endwise, so that it could get through the gate; so, as we came near the gate, I shouted, 'This company is dismissed for two minutes, when it will fall in again on the other side of the gate!'"

Nor was it only his ignorance of the manual which caused him trouble. He was so unfamiliar with camp discipline that he once had his sword taken from him for shooting within limits. Another disgrace he suffered was on account of his disorderly company. The men, unknown to him, stole a quantity of liquor one night, and the next morning were too drunk to fall in when the order was given to march. For their lawlessness Lincoln wore a wooden sword two days.

But none of these small difficulties injured his standing with the company. Lincoln was tactful, and he joined his men in sports as well as duties. They soon grew so proud of his quick wit and great strength that they obeyed him because they admired him. No amount of military tactics could have secured from the volunteers the cheerful following he won by his personal qualities.

The men soon learned, too, that he meant what he said, and would permit no dishonorable performances. A helpless Indian took refuge in the camp one day; and the men, who were inspired by what Governor Reynolds calls Indian ill-will—that wanton mixture of selfishness, unreason, and cruelty which seems to seize a frontiersman as soon as he scents a red man—were determined to kill the refugee. He had a safe conduct from General Cass; but the men, having come out to kill Indians and not having succeeded, threatened to take revenge on the helpless savage. Lincoln boldly took the man's part, and though he risked his life in doing it, he cowed the company, and saved the Indian.

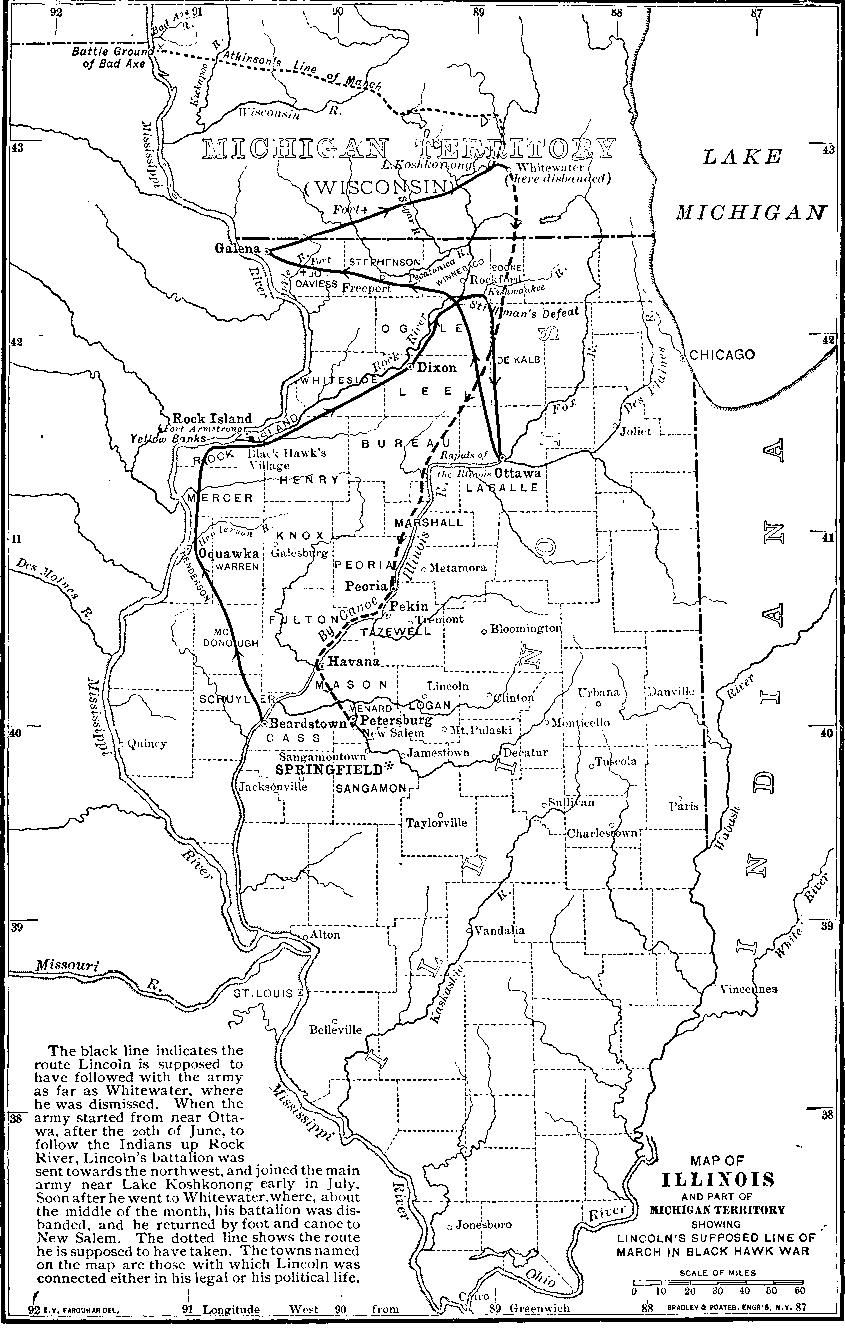

[Transcriber's note: The map includes the following legend: The black line indicates the route Lincoln is supposed to have followed with the army as far as Whitewater, where he was dismissed. When the army started from near Ottawa, after the 20th of June, to follow the Indians up Rock River, Lincoln's battalion was sent towards the northwest, and joined the main army near Lake Koshkonong early in July. Soon after he went to Whitewater, where, about the middle of the month, his battalion was disbanded, and he returned by foot and canoe to New Salem. The dotted line shows the route he is supposed to have taken. The towns named on the map are those with which Lincoln was connected either in his legal or his political life.]

It was on the 27th of April that the force of sixteen hundred men organized at Beardstown started out. The spring was cold, the roads heavy, the streams turbulent. The army marched first to Yellow Banks on the Mississippi, then to Dixon on the Rock River, which they reached on May 12th. None but hardened pioneers could have endured what Lincoln and his followers did in this march. They had insufficient supplies; they waded in black mud for miles; they swam rivers; they were almost never dry or warm; but, hardened as they were, they made the march gayly. At Dixon they camped, and near here occurred the first bloodshed of the war.

A body of about three hundred and forty rangers, not of the regular army, under Major Stillman, asked to go ahead as scouts, to look for a body of Indians under Black Hawk, rumored to be about twelve miles away. The permission was given, and on the night of the 14th of May Stillman and his men went into camp. Black Hawk heard of their presence. By this time the poor old chief had discovered that the promises of aid from the Indian tribes and the British were false, and, dismayed, he had resolved to recross the Mississippi. When he heard of the whites near he sent three braves with a white flag to ask for a parley and permission to descend the river. Behind them he sent five men to watch proceedings. Stillman's rangers were in camp when the bearers of the flag of truce appeared. The men were many of them half drunk, and when they saw the Indian truce-bearers, they rushed out in a wild mob, and ran them into camp. Then catching sight of the five spies, they started after them, killing two. The three who reached Black Hawk reported that the truce-bearers had been killed as well as their two companions. Furious at this violation of faith, Black Hawk "raised a yell," and declared to the forty braves, all he had with him, that they must have revenge. The Indians immediately sallied forth, and met Stillman's band of over three hundred men, who by this time were out in search of the Indians. Black Hawk, too maddened to think of the difference of numbers, attacked the whites. To his surprise the enemy turned, and fled in a wild riot. Nor did they stop at their camp, which from its position was almost impregnable; they fled in complete panic, sauve qui peut, through their camp, across prairie and rivers and swamps, to Dixon, twelve miles away, where by midnight they began to arrive. The first arrival reported that two thousand savages had swept down on Stillman's camp and slaughtered all but himself. Before the next night all but eleven of the band had arrived.

Stillman's defeat, as this disgraceful affair is called, put all notion of peace out of Black Hawk's mind, and he started out in earnest on the warpath. Governor Reynolds, excited by the reports of the first arrivals from the Stillman stampede, made out that night, "by candle-light," a call for more volunteers, and by the morning of the 15th had messengers out and his army in pursuit of Black Hawk. But it was like pursuing a shadow. The Indians purposely confused their trail. Sometimes it was a broad path, then it suddenly radiated to all points. The whites broke their bands, and pursued the savages here and there, never overtaking them, though now and then coming suddenly on some terrible evidences of their presence—a frontier home deserted and burned, slaughtered cattle, scalps suspended where the army could not fail to see them.

This fruitless warfare exasperated the volunteers; they threatened to leave, and their officers had great difficulty in making them obey orders. On reaching a point in the Rock River, beyond which lay the Indian country, a company under Colonel Zachary Taylor refused to cross, and held a public indignation meeting, urging that they had volunteered to defend the State, and had the right, as independent American citizens, to refuse to go out of its borders. Taylor heard them to the end, and then said: "I feel that all gentlemen here are my equals; in reality, I am persuaded that many of them will, in a few years, be my superiors, and perhaps, in the capacity of members of Congress, arbiters of the fortunes and reputation of humble servants of the republic, like myself. I expect then to obey them as interpreters of the will of the people; and the best proof that I will obey them is now to observe the orders of those whom the people have already put in the place of authority to which many gentlemen around me justly aspire. In plain English, gentlemen and fellow-citizens, the word has been passed on to me from Washington to follow Black Hawk and to take you with me as soldiers. I mean to do both. There are the flatboats drawn up on the shore, and here are Uncle Sam's men drawn up behind you on the prairie." The volunteers were quick-witted men, and knew true grit when they met it. They dissolved their meeting and crossed the river without Uncle Sam's men being called into action.

From the original now on file in the County Clerk's office, Springfield, Illinois. The first civil office Lincoln ever held was that of election clerk, and the return made by him, of which a facsimile is here presented, was his first official document. The New Salem election of September 20, 1832, has the added interest of having been held at "the house of John McNeil," the young merchant who was then already in love with Ann Rutledge, the young girl to whom Lincoln afterwards became engaged. All the men whose names appear on this election return are now dead except William McNeely, now residing at Petersburg. John Clary lived at Clary's Grove; John R. Herndon was "Row" Herndon, whose store Berry and Lincoln purchased, and at whose house Lincoln for a time boarded; Baxter Berry was a relative of Lincoln's partner in the grocery business, and Edmund Greer was a school-teacher, and afterward a justice of the peace and a surveyor. James Rutledge was the keeper of the Rutledge tavern and the father of Ann Rutledge; Hugh Armstrong was the head of the numerous Armstrong family; "Uncle Jimmy" White lived on a farm five miles from New Salem, and died about thirty years ago in the eightieth year of his age; William Green (spelled by the later members of the family with a final "e") was the father of William G. Greene, Lincoln's associate in Offutt's store; and as to Bowling Green, more is said elsewhere. In the following three or four years, very few elections were held at which Lincoln was not a clerk. It is a somewhat singular fact that Lincoln, though clerk of this election, is not recorded as voting.—J. McCan Davis.

The march in pursuit of the Indians led the army to Ottawa, where the volunteers became so dissatisfied that on May 27th and 28th Governor Reynolds mustered them out. But a force in the field was essential until a new levy was raised; and a few of the men were patriotic enough to offer their services, among them Lincoln, who on May 29th was mustered in at the mouth of the Fox River by a man in whom, thirty years later, he was to have a keen interest—General Robert Anderson, commander at Fort Sumter in 1861. Lincoln became a private in Captain Elijah Iles's company of Independent Rangers, not brigaded—a company made up, says Captain Iles in his "Footsteps and Wanderings," of "generals, colonels, captains, and distinguished men from the disbanded army." General Anderson says that at this muster Lincoln's arms were valued at forty dollars, his horse and equipment at one hundred and twenty dollars. The Independent Rangers were a favored body, used to carry messages and to spy on the enemy. They had no camp duties, and "drew rations as often as they pleased." So that as a private Lincoln was really better off than as a captain.3

With the exception of a scouting trip to Galena and back, fruitful of nothing more than Indian scares, Major Iles's company remained quietly in the neighborhood of the Rapids of the Illinois until June 16th, when Major Anderson mustered it out. Four days later, June 20th, at the same place, he mustered Lincoln in again as a member of an independent company under Captain Jacob M. Early. His arms were valued this time at only fifteen dollars, his horse and equipment at eighty-five dollars.4 The army moved up Rock River soon after the middle of June. Black Hawk was overrunning the country, and scattering death wherever he went. The settlers were wild with fear, and most of the settlements were abandoned. At a sudden sound, at the merest rumor, men, women, and children fled. "I well remember these troublesome times," says one old Illinois woman. "We often left our bread dough unbaked to rush to the Indian fort near by." When Mr. John Bryant, a brother of William Cullen Bryant, visited the colony in Princeton in 1832, he found it nearly broken up on account of the war. Everywhere the crops were neglected, for the able-bodied men were volunteering. William Cullen Bryant, who travelled on horseback in June from Petersburg to near Pekin and back, wrote home: "Every few miles on our way we fell in with bodies of Illinois militia proceeding to the American camp, or saw where they had encamped for the night. They generally stationed themselves near a stream or a spring in the edge of a wood, and turned their horses to graze on the prairie. Their way was barked or girdled, and the roads through the uninhabited country were as much beaten and as dusty as the highways on New York Island. Some of the settlers complained that they made war upon the pigs and chickens. They were a hard-looking set of men, unkempt and unshaved, wearing shirts of dark calico and sometimes calico capotes."

Soon after the army moved up the Rock River, the independent spy company, of which Lincoln was a member, was sent with a brigade to the northwest, near Galena, in pursuit of the Hawk. The nearest Lincoln came to an actual engagement in the war was here. The skirmish of Kellogg's Grove took place on June 25th; Lincoln's company came up soon after it was over, and helped bury the five men killed. It was probably to this experience that he referred when he told a friend once of coming on a camp of white scouts one morning just as the sun was rising. The Indians had surprised the camp, and had killed and scalped every man.

"I remember just how those men looked," said Lincoln, "as we rode up the little hill where their camp was. The red light of the morning sun was streaming upon them as they lay heads towards us on the ground. And every man had a round red spot on the top of his head about as big as a dollar, where the redskins had taken his scalp. It was frightful, but it [pg 135] was grotesque; and the red sunlight seemed to paint everything all over." Lincoln paused, as if recalling the vivid picture, and added, somewhat irrelevantly, "I remember that one man had buckskin breeches on."5

By the end of the month the troops crossed into Michigan Territory—what is now Wisconsin—and July was spent in floundering through swamps and stumbling through forests, in pursuit of the now nearly exhausted Black Hawk. A few days before the last battle of the war, that of Bad Axe on August 2d, in which the whites finally massacred most of the Indian band, Lincoln's company was disbanded at Whitewater, Wisconsin, and he and his friends started for home. The volunteers in returning, in almost every case, suffered much from hunger. Mr. Durly, of Hennepin, Illinois, who walked home from Rock Island, says all he had to eat on the journey was meal and water baked in rolls of bark laid by the fire. Lincoln was little better off. The night before his company started from Whitewater he and one of his mess-mates had their horses stolen; and, excepting when their more fortunate companions gave them a lift, they walked as far as Peoria, Illinois, where they bought a canoe, and paddled down the Illinois River to Havana. Here they sold the canoe, and walked across the country to New Salem.

Lincoln arrived only a few days before the election, and at once plunged into [pg 136] "electioneering." He ran as "an avowed Clay man," and the county was stiffly Democratic. However, in those days political contests were almost purely personal. If the candidate was liked he was voted for irrespective of principles. Around New Salem the population turned in and helped Lincoln almost to a man. "The Democrats of New Salem worked for Lincoln out of their personal regard for him," said Stephen T. Logan, a young lawyer of Springfield, who made Lincoln's acquaintance in the campaign. "He was as stiff as a man could be in his Whig doctrines. They did this for him simply because he was popular—because he was Lincoln."

It was the custom for the candidates to appear at every gathering which brought the people out, and, if they had a chance, to make speeches. Then, as now, the farmers gathered at the county-seat or at the largest town within their reach on Saturday afternoons, to dispose of produce, buy supplies, see their neighbors, and get the news. During "election times" candidates were always present, and a regular feature of the day was listening to their speeches. Public sales also were gatherings which they never missed, it being expected that after the "vandoo" the candidates would take the auctioneer's place.

Lincoln let none of these chances to be heard slip. Accompanied by his friends, generally including a few Clary's Grove Boys, he always was present. The first speech he made was after a sale at Pappsville. What he said there is not remembered; but an illustration of the kind of man he was, interpolated into his discourse, made a lasting impression. A fight broke out in his audience while he was on the stand, and observing that one of his friends was being worsted, he bounded into the group of contestants, seized the fellow who had his supporter down, threw him "ten or twelve feet," mounted the platform, and finished the speech. Sangamon County could appreciate such a performance; and the crowd that day at Pappsville never forgot Lincoln.

His appearance at Springfield at this time was of great importance to him. Springfield was not at that time a very attractive place. Bryant, visiting it in June, 1832, said that the houses were not as good as at Jacksonville, "a considerable proportion of them being log cabins, and the whole town having an appearance of dirt and discomfort." Nevertheless it was the largest town in the county, and among its inhabitants were many young men of education, birth, and energy. One of these men Lincoln had become well acquainted with in the Black Hawk War—Major John T. Stewart,6 at that time a lawyer, and, like Lincoln, a candidate for the General Assembly. He met others at this time who were to be associated with him more or less closely in the future in both law and politics, such as Judge Logan and William Butler. With these men the manners which had won him the day at Pappsville were of no value; what impressed them was his "very sensible speech," and his decided individuality and originality.

The election came off on August 6th. The first civil office Lincoln ever held was that of clerk of this election. The report in his hand still exists; as far as we know, it is his first official document.

Lincoln was defeated. "This was the only time Abraham was ever defeated on a direct vote of the people," say his autobiographical notes. He had a consolation in his defeat, however, for in spite of the pronounced Democratic sentiments of his precinct, he received two hundred and seventy-seven votes out of three hundred cast.7

(Begun in the November number, 1895; to be continued.)

Footnote 1: (return)The story of Lincoln's first seventeen months in Illinois, outlined in this paragraph, is told in MCCLURE'S MAGAZINE for December.>

Footnote 2: (return)This story of Kirkpatrick's unfair treatment of Lincoln we owe to the courtesy of Colonel Clark E. Carr of Galesburg, Illinois, to whom it was told several times by Greene himself.

Footnote 3: (return)William Cullen Bryant, who was in Illinois in 1832 at the time of the Black Hawk War, used to tell of meeting in his travels in the State a company of Illinois volunteers, commanded by a "raw youth" of "quaint and pleasant" speech, and of learning afterwards that this captain was Abraham Lincoln. As Lincoln's captaincy ended on May 27th, and Mr. Bryant did not reach Jacksonville, Illinois, until June 12th, and as the nearest point he came to the army was Pleasant Grove, eight miles from Pekin on the Illinois River, and that was at a time when the body of Rangers to which Lincoln belonged was fifty miles away on the rapids of the Illinois, it is evident that the "raw youth" could not have been Lincoln, much as one would like to believe that it was. See "Life of William Cullen Bryant," by Parke Godwin, vol. i. page 283. Also Prose of William Cullen Bryant, edited by Parke Godwin, vol. ii. page 20.

Footnote 4: (return)See Wisconsin Historical Collections, vol. x., for Major Anderson's reminiscences of the Black Hawk War.

Footnote 6: (return)There were many prominent Americans in the Black Hawk War, with some of whom Lincoln became acquainted. Among the best known were General Robert Anderson; Colonel Zachary Taylor; General Scott, afterwards candidate for President, and Lieut.-General; Henry Dodge, Governor of the Territory of Wisconsin and United States Senator; Hon. William L.D. Ewing and Hon. Sidney Breese, both United States Senators from Illinois; William S. Hamilton, a son of Alexander Hamilton; Colonel Nathan Boone, son of Daniel Boone; Lieutenant Albert Sydney Johnston, afterwards a Confederate general. Jefferson Davis was not in the war, as has been so often stated.]

Footnote 7: (return)In the New Salem precinct, at the August election of 1832, exactly three hundred votes were cast. Of these Lincoln received 277. The facts upon this point are here stated for the first time. The biographers as a rule have agreed that Lincoln received all of the votes cast in the New Salem precinct except three. Mr. Herndon places the total vote at 208; Nicolay and Hay, at 277; and Mr. Lincoln himself, in his autobiography, has said that he received all but seven of a total of 277 votes, basing his statement, no doubt, upon memory. An examination of the official poll-book in the County Clerk's office at Springfield shows that all of these figures are erroneous. The fact remains, however—and it is a fact which has been commented upon by several of the biographers as showing his phenomenal popularity—that the vote for Lincoln was far in excess of that given any other candidate. The twelve candidates, with the number of votes of each were: Abraham Lincoln, 277; John T. Stewart, 182; William Carpenter, 136; John Dawson, 105; E.D. Taylor, 88; Archer G. Herndon, 84; Peter Cartwright, 62; Achilles Morris, 27; Thomas M. Neal, 21; Edward Robeson, 15; Zachariah Peters, 4; Richard Dunston, 4.

Of the twenty-three who did not vote for Lincoln, ten refrained from voting for Representative at all, thus leaving only thirteen votes actually cast against Lincoln. Lincoln is not recorded as voting. The judges were Bowling Green, Pollard Simmons, and William Clary, and the clerks were John Ritter and Mentor Graham.—J. McCan Davis.

The form of the expressions of regard and regret called out on all sides by the untimely death of Eugene Field, at his home in Chicago, on November 4, 1895, makes clear that the character in which the public at large knew and loved Mr. Field best was that of the poet of child life. What gives his child-poems their unequalled hold on the popular heart is their simplicity, warmth, and genuineness; and these qualities they owe to the fact that Field himself lived in the closest and fondest intimacy with children, had troops of them for his friends, and wrote his poems directly under their suggestion and inspiration. Mr. T.A. Van Laun of Chicago, who was one of Mr. Field's closest friends, has kindly given me many reminiscences, and helped me to much material, illustrating all sides of Mr. Field's life, among others this fine relation with the children. A characteristic incident occurred on Field's marriage day. The hour of the ceremony was all but at hand, and the bridal party was waiting at the church for the bridegroom to appear. But he did not come; and, after an anxious delay, some of his friends went in search of him. They found him a short distance away, engaged in settling a dispute that had arisen among some street gamins over a game of marbles. There he was, down on his knees in the mud, listening to the various accounts of the origin of the quarrel; and it was only on the arrival of his friends that he suddenly recollected his more pressing and more pleasant duties.

One day, as was often happening, Field received a letter written in the scrawling hand of a child, which told him how the writer, a little girl, had read most of his poems, spoke of the pleasure they had given her, and said that when she grew up she intended to be just such a writer as he was. Following his usual kindly custom, Field answered this letter, telling the child [pg 138] of the beauties of nature that surrounded him, of the twittering birds, and the lovely flowers he had in sight from his window, and concluding: "Now I must go out and shoot a buffalo for breakfast."

Dr. Gunsaulus of Chicago, who was one of Mr. Field's most intimate friends, tells a story of Field's first visit to his house that shows how quick the poet was to make himself at home with children. For years the little ones in the Doctor's household had heard of Eugene Field as a wonderful person; and when they were told that he had come to see them their delight knew no bounds, and they ran into the library to pay him homage. It was in the evening, and, presumably, Field had already dined; but he told the children with his first breath that he wanted to know where the cookery was. They, overjoyed at being asked a service they were able to render, trooped out into the kitchen with Field following. The store of eatables was duly exposed, and Field seized upon a turkey, or what remained of one from dinner, and carried it into the dining-room. There he seated himself at table, with the children on his knees and about him, and fell to with a good appetite, talking to the little ones all the time, telling them quaint stories, and making them listen with all their eyes and ears. Having thus become good friends and put them quite at their ease, he spent the rest of the evening singing lullabies to them, and reciting his verses. Naturally, before he went away the children had given him their whole hearts. And this was his way with all the children with whom he came in contact.

One day on the cars Mr. Field chanced to sit near a workingman who had with him his wife and baby. The father, it seemed, had heard Field lecture the night before, and had been deeply impressed. With great deference he brought his child up to Field, and said: "Now, little one, I want you to look at this gentleman. He is Mr. Field, and when you grow up you'll be glad to know that once upon a time he spoke to you." At this Field took the baby in his arms, and played with it for an hour, to the surprise and, of course, to the delight of the parents.

Of recent years Mr. Field rarely went to the office of the Chicago "News," the paper for which during the last ten years he had written a daily column under the title of "Sharps and Flats," but did most of his work at his home in Buena Park, which he called the Sabine Farm. Here he began his day about nine o'clock, by having breakfast served to him in bed, after which he glanced through the papers, and then settled himself to his writing, with feet high on the table, and his pages before him laid neatly on a piece of plate glass. He wrote with a fine-pointed pen, and had by him several different colored inks, with which he would illuminate his capitals and embellish his manuscript. The first thing he did was his "Sharps and Flats" column, which occupied three or four hours, the task being usually finished by one o'clock. His other work he did in the afternoons and evenings, writing at odd hours, sometimes in the garden if the weather was pleasant. He was much interrupted by friends dropping in to see him; but, however busy, he welcomed whoever came, and would turn aside good-naturedly from his manuscript to entertain a visitor or to hear a story of misfortune. After dinner he retired to his "den" to read; for he read constantly, whatever the distractions about him, and was much given to reading in bed.

And of all his visitors the most constant and appreciative were children. These he never sent away without some bright word, and he rarely sent them away at all. Nowhere could they find such an entertaining playmate as he—one who would tell them such wonderful stories and make up such funny rhymes for them on the spur of the moment, and romp with them like one of themselves. It was in the homely incidents of these visits, and the like intimacy with his own children, that he found the subjects for his poems. He could voice the feelings of a child, because he knew child life from always living it.

On his own children he bestowed pet names—"Pinney," "Daisy," "Googhy," "Posey," and "Trotty;" and they almost forgot that they had others. His eldest daughter, for instance, now a lovely girl of nineteen, has remained "Trotty" from her babyhood, and "Trotty" she will always be. At her christening Field had an argument with his wife about the name they should give her. Mrs. Field wished her to be called Frances, to which Field objected on the ground that it would be shortened into Frankie, which he disliked. Then other names were suggested, and, after listening to this one and that one, Field finally said: "You can christen her whatever you please, but I shall call her Trotty." "Pinney" was named from the comic opera "Pinafore," which was in vogue at the time he was born; and "Daisy" got his name from the song, popular when [pg 139] he was born: "Oh My! A'int He a Daisy?"

A devotion so unfailing in his relations with children would, naturally, show itself in other relations. His devotion to his wife, for example, was of the completest. In all the world she was the one woman he loved, and he never wished to be away from her. In one of his scrap-books, under her picture, are written these lines:

You are as fair and sweet and tender,

Dear brown-eyed little sweetheart mine!

As when, a callow youth and slender,

I asked to be your valentine.

Often she accompanied him on his readings. Last summer it happened that they went together to St. Joe, Missouri, the home of Mrs. Field's girlhood. On their arrival, Mrs. Field's friends took possession of her and carried her off to a lunch-party, where it was arranged that Mr. Field should join her later. But he, left alone, was swept by his thoughts back to the time when, a youth of twenty-one, he had here paid court to the woman now his wife, then a girl of sixteen; and so affected was he by these memories that, instead of going to the lunch-party, he took a carriage, and all alone drove to the places which he and she had been wont to visit in the happy time of their love-making, especially to a certain lover's lane where they had taken many a walk together.

From a copyrighted photograph by Place & Coover, Chicago; reproduced by permission of the Etching Publishing Co., Chicago.

The day before Field's death the mail brought a hundred dollars in payment for a magazine article he had written. It was in small bills, and there was quite a quantity of them. As he lay in bed, Field spread them out on the covers, and then called Mrs. Field. As she came in she said: "Why, what are you doing with all that money?"

Field, laughing, snatched the bills up and tucked them under the pillow, saying: "You shan't have it, this is my money." After his death, the bills, all crumpled up, were found still under his pillow.

It was a common happening in the "News" office, while Mr. Field still did his work there, for some ragged, unwashed, woe-begone creature, too much abashed to take the elevator, to come toiling up the stairs and down the long passage into one of the editorial rooms, where he would blurt out fearfully, sometimes half defiantly, but always as if confident in the power of the name he spoke: "Is 'Gene Field here?" Sometimes an overzealous office-boy would try to drive one of these poor fellows away, and woe to that boy if Field found it out. "I knew 'Gene Field in Denver," or, "I worked with Field on the 'Kansas City Times,'"—these were sufficient pass-words, and never failed to call forth the cheery voice from Field's room: "That's all right, show him in here; he's a friend of mine." And then, after a grip of the hand and some talk over former experiences—which Field may or may not have remembered, but always pretended to—the inevitable half dollar or dollar was forthcoming, and another unfortunate went out into the world blessing the name of a man who, whether he was orthodox or not in his religious views, always acted up to the principle that it is more blessed to give than to receive.