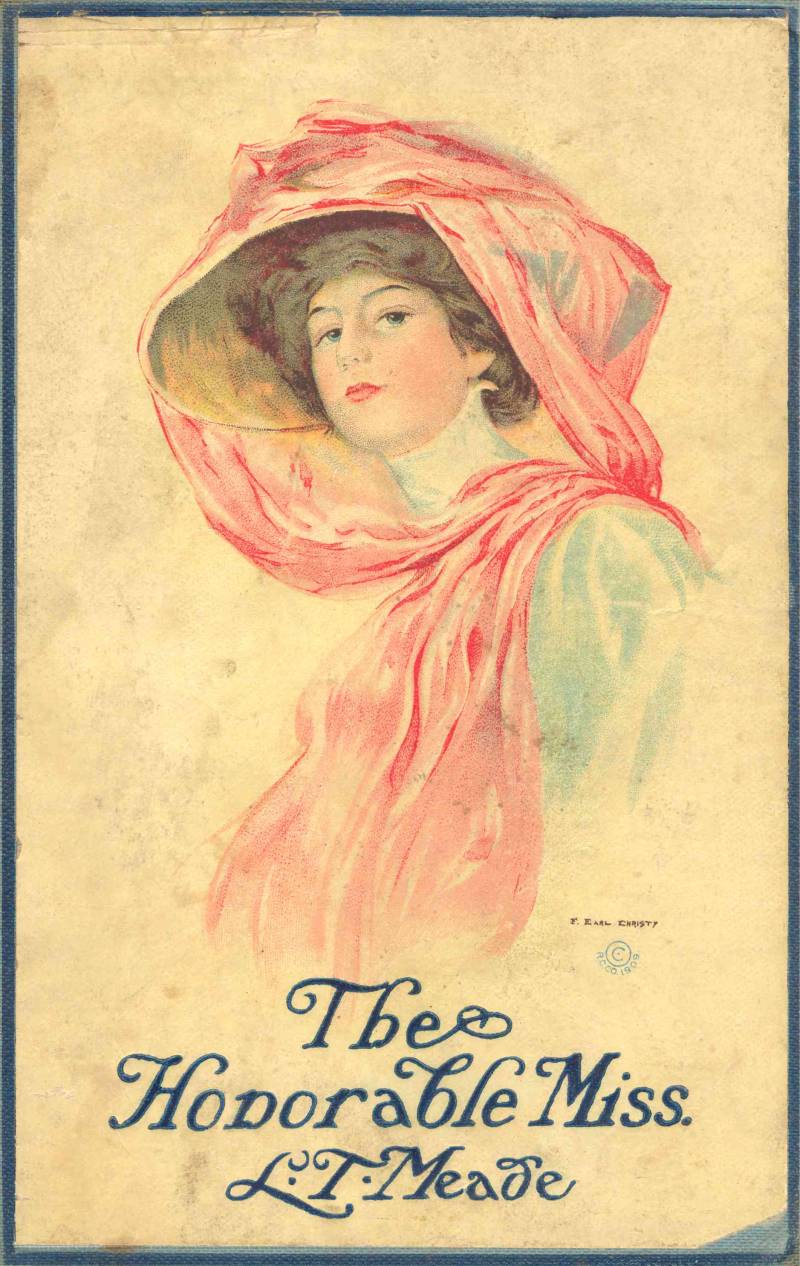

Title: The Honorable Miss: A Story of an Old-Fashioned Town

Author: L. T. Meade

Illustrator: F. Earl Christy

Release date: May 7, 2005 [eBook #15778]

Most recently updated: December 14, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Garcia and the Online Distributed Proofreader Team.

AUTHOR OF "THE YOUNG MUTINEER," "WORLD OF GIRLS,"

"A VERY NAUGHTY GIRL," "SWEET GIRL GRADUATE," ETC.

NEW YORK

HURST & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME

Bunch of Cherries, A.

Daddy's Girl.

Dr. Rumsey's Patient.

Francis Kane's Fortune.

Gay Charmer, A.

Girl in Ten Thousand, A.

Girls of St. Wodes, The.

Girl of the People, A.

Girls of the True Blue.

Heart of Gold, The.

Honorable Miss, The.

How It All Came About.

Little Princess of Tower Hill.

Merry Girls of England.

Miss Nonentity.

Palace Beautiful.

Polly, a New-Fashioned Girl.

Rebels of the School.

Sweet Girl Graduate, A.

Their Little Mother.

Time of Roses, The.

Very Naughty Girl, A.

Wild Kitty.

World of Girls.

Young Mutineers, The.

Price, postpaid, 50¢ each, or any three books for $1.25

HURST & COMPANY PUBLISHERS, NEW YORK

CHAPTER I. BEATRICE WILL FIT.

CHAPTER II. MRS. BERTRAM'S WILL.

CHAPTER III. A GENTLEMAN, MADAM.

CHAPTER IV. TWO LETTERS.

CHAPTER V. THE USUAL SORT OF SCRAPE.

CHAPTER VI. FOR MY PART, I AM NOT GOING TO TAKE ANY NOTICE OF THE BERTRAMS.

CHAPTER VII. REPLY FOR US, KATE.

CHAPTER VIII. NOBODY ELSE LOOKED THE LEAST LIKE THE BERTRAMS.

CHAPTER IX. THE GHOST IN THE AVENUE.

CHAPTER X. THE REASON OF THE VISIT.

CHAPTER XI. SOMEBODY ADMIRED SOMEBODY.

CHAPTER XII. NINA, YOU ARE SO PERSISTENT.

CHAPTER XIII. THE WHITE BOAT AND THE GREEN.

CHAPTER XIV. AT HER GATES.

CHAPTER XV. JOSEPHINE LOOKED DANGEROUS.

CHAPTER XVI. A BRITISH MERCHANT.

CHAPTER XVII. THE WITCH WITH THE YELLOW HAIR.

CHAPTER XVIII. "WHEN DUNCAN GRAY CAME HOME TO WOO."

CHAPTER XIX. THE RECTOR'S GARDEN PARTY.

CHAPTER XX. YOU CAN TAKE ANY RANK.

CHAPTER XXI. WITH CATHERINE IN THE ROSE BOWER.

CHAPTER XXII. SPARE THE POOR CHILD'S BLUSHES.

CHAPTER XXIII. THAT FICKLE MATTY.

CHAPTER XXIV. EVENTS MOVE APACE.

CHAPTER XXV. WEDDING PRESENTS.

CHAPTER XXVI. WE WILL RETURN TO OUR SECLUSION.

CHAPTER XXVII. THE LIGHTS WERE DIM.

CHAPTER XXVIII. RIVALS.

CHAPTER XXIX. THE FEELINGS OF A CRUSHED MOTH.

CHAPTER XXX. GUARDIANS ARE NOT ALWAYS TO BE ENVIED.

CHAPTER XXXI. CIVIL WAR AT NORTHBURY.

CHAPTER XXXII. THE NIGHT BEFORE THE WEDDING.

CHAPTER XXXIII. THE MORNING OF THE WEDDING.

CHAPTER XXXIV. THE BRIDE!

CHAPTER XXXV. BEATRICITES—EVERY ONE.

"So," continued Mrs. Meadowsweet, settling herself in a lazy, fat sort of a way in her easy chair, and looking full at her visitor with a complacent smile, "so I called her Beatrice. I thought under the circumstances it was the best name I could give—it seemed to fit all round, you know, and as he had no objection, being very easy-going, poor man, I gave her the name."

"Yes?" interrogated Mrs. Bertram, in a softly surprised, and but slightly interested voice; "you called your daughter Beatrice? I don't quite understand your remark about the name fitting all round."

Mrs. Meadowsweet raised one dimpled hand slowly and laid it on top of the other. Her smile grew broader.

"A name is a solemn thing, Mrs. Bertram," she continued. "A name is, so to speak, to fit the person to whom it is given, for life. Will you tell me how any mother, even the shrewdest, is to prophecy how an infant of a few weeks old is to turn out? I thought over that point a good deal when I gave the name, and said I to myself however matters turn 'Beatrice' will fit. If she grows up cozy and soft and petting and small, why she's Bee, and if she's sharp and saucy, and a bit too independent, as many lasses are in these days, what can suit her better than Trixie? And again if she's inclined to be stately, and to hold herself erect, and to think a little more of herself than her mother ever did—only not more than she deserves—bless her—why then she's Beatrice in full. Oh! and there you are, Beatrice! Mrs. Bertram has been good enough to call to see me. Mrs. Bertram, this is my daughter Beatrice."

A very tall girl came quietly into the room, bowed an acknowledgment of her mother's introduction, and sat down on the edge of the sofa. She was a dignified girl from the crown of her head to her finger-tips, and Mrs. Bertram, who had been listening languidly to the mother, favored the newcomer with a bright, quick, inquisitive stare, then rose to her feet.

"I am afraid I must say good-bye, Mrs. Meadowsweet. I am glad to have made your daughter's acquaintance, and another day I hope I shall see more of her. I have of course heard of you from Catherine, my dear," she added, holding out her hand frankly to the young girl.

"Yes. Is Catherine well?" asked Beatrice, in a sweet high-bred voice.

"She is well, my dear. Good-bye, Mrs. Meadowsweet. I quite understand the all-roundness and suitability of your choice in the matter of names."

Then the great lady sailed out of the room, and Beatrice flew to the window, placed herself behind the curtain and watched her down the street.

"What were you saying about me, mother?" she asked, when Mrs. Bertram had turned the corner.

"I was only telling about your name, my dearie girl. He always gave me my way, poor man, so I fixed on Beatrice. I said it would fit all round, and it did. Shut that window, will you, Bee?—the wind is very sharp for the time of year. You don't mind my calling you Bee now and then—even if it doesn't seem quite to fit?" continued Mrs. Meadowsweet.

"No, mother, of course not. Call me anything in the world you fancy. What's in a name?"

"Don't say that, Trixie, there's a great deal in a name."

"Well, I get confused with mine now and then. Mother, I just came in to kiss you and run away again. Alice Bell and I are going to the lecture at the Town Hall. It begins at five, and it's half-past four now. Good-bye, I shall be home to supper."

"One moment, Bee, I am really pleased that your fine friend's mother has chosen to call at last."

Beatrice frowned.

"Catherine is not my fine friend," she said.

"Well, your friend, then, dearie. I am glad your friend's mother has called."

"I am not—that is, I am absolutely indifferent. Now, I really must run away. Good-bye until you see me again."

She tripped out of the room as lightly and carelessly as she had entered it, and Mrs. Meadowsweet sat on by the window which looked into the garden.

Mrs. Meadowsweet had the smoothest and most tranquil of faces. She had taken as her favorite motto in life, that somehow, if you only allowed them, things did fit all round. Each event in her own career, to use her special phraseology "fitted." As her husband had to die, he passed away from this life at the most fitting moment. As Providence had blessed her with only one child, a daughter was surely the most fitting companion for a widowed mother. The house Mrs. Meadowsweet lived in fitted her requirements to perfection. In short, she was fat and comfortable, both in mind and body; she never fretted, she never worried; she was not rasping and disagreeable; she was not fault-finding. If her nature lacked depth, it certainly did not lack affection, generosity, and a true spirit of kindliness. If she were a little too well pleased with herself, she was also well pleased with her neighbors. She was not especially appreciated, for she was considered prosy and commonplace. Prosy she undoubtedly was, but not commonplace, for invariable contentment and unbounded good-nature are more and more difficult to find in this censorious world.

Mrs. Meadowsweet now smiled gently to herself.

"However Beatrice may take it, I am glad Mrs. Bertram called," she murmured. "He'd have liked it, poor man! he never put himself out, and he never interfered with me, no, never, poor dear. But he liked people to show due respect—it's a respect to Beatrice for Mrs. Bertram to call. It shows that she appreciates Beatrice as her daughter's friend. Mrs. Bertram, notwithstanding her pride, is likely to be very much respected in Northbury, and no wonder. She's a little above most of us, but we like her all the better for that. We are going to be proud of her. It's nice to have some one to be proud of. And she has no airs when you come to know her, no, she hasn't airs; she's as pleasant as possible, and seems interested too, that is, as interested as people like us can expect from people like her. She didn't even condescend to Beatrice. I wonder how my little girl would have taken it, if she had condescended to her. Yes, Jane, do you want me?"

An elderly servant opened the drawing-room door.

"If you please, ma'am, Mrs. Morris has called, and she wants to know if it would disturb you very much to see her?"

"Disturb me? She knows it won't disturb me. Show her in at once. And Jane, you can get tea ready half-an-hour earlier than usual. I daresay, as Mrs. Morris has called she'd like a cup. How do you do, Mrs. Morris? I'm right glad to see you, right glad. Sit here, in this chair—or perhaps you'd rather sit in this one; this isn't too near the window. And you'll like a screen, I know;—not that there's any draught—for these windows fit as tight as tight when shut."

Mrs. Morris was a thin, tall woman. She always spoke in a whisper, for she was possessed of the belief that she had lost her voice in bronchitis. She had not, for when she scolded any one she found it again. She was not scolding now, however, and her tones were very low and smothered.

"I saw her coming in, my dear; I was standing at the back of the wire blind, and I saw her going up your steps, so I thought I'd come across quickly and hear the news. You'll tell me the news as soon as possible, won't you? Mrs. Butler and Miss Peters are coming to call in a few minutes. I met them and they told me so. They saw her, too. You'll tell me the news quickly, Lucy, for I'd like to be first, and it seems as if I had a right to that much consideration, being an old friend."

"So you have, Jessie."

Mrs. Meadowsweet looked immensely flattered.

"I suppose you allude to Mrs. Bertram having favored me with a call," she continued, in a would-be-humble tone, which, in spite of all her efforts, could not help swelling a little.

"Yes, dear, that's what I allude to; I saw her from behind the wire screen blind. We were having steak and onions for dinner, and the doctor didn't like me jumping up just when I had a hot bit on my plate. But I said, it's Mrs. Bertram, Sam, and she's standing on Mrs. Meadowsweet's steps! There wasn't a remonstrance out of him after that, and the only other remark he made was, 'You'll call round presently, Jessie, and inquire after Mrs. Meadowsweet's cold.' So here I am, my dear. And how is your cold, by the way?"

"It's getting on nicely, Jessie. Wasn't that a ring I heard at the door bell?"

"Well, I never!" Mrs. Morris suddenly found her voice. "If it isn't that tiresome Mrs. Butler and Miss Peters. And now I won't be first with the news after all!"

Mrs. Meadowsweet smiled again.

"There really isn't so much to tell, Jessie. Mrs. Bertram was just affable like every one else. Ah, and how are you, Mrs. Butler? Now, I do call this kind and neighborly. Miss Peters, I trust your cough is better?"

"I'm glad to see you, Mrs. Meadowsweet," said Mrs. Butler, in a slightly out-of-breath tone.

"My cough is no better," snapped Miss Peters. "Although it's summer, the wind is due east; east wind always catches me in the throat."

Miss Peters was very small and slim. She wore little iron-gray, corkscrew curls, and had bright, beady black eyes. Miss Peters was Mrs. Butler's sister. She was a snappy little body, but rather afraid of Mrs. Butler, who was more snappy. This fear gave her an unpleasant habit of rolling her eyes in the direction of Mrs. Butler whenever she spoke. She rolled them now as she described the way the east wind had treated her throat.

Mrs. Butler seated herself in an aggressive manner on the edge of the sofa, and Miss Peters took a chair as close as possible to Mrs. Morris, who pushed hers away from her.

Each lady was anxious to engross the whole attention of Mrs. Meadowsweet, and it was scarcely possible for the good-natured woman not to feel flattered.

"Now, you'll all have a cup of tea with me," she said. "I know Jane's getting it, but I'll ring the bell to hasten her. Ah, thank you, Miss Peters."

Miss Peters had sprung to her feet, seized the bell-rope before any one could hinder her, and sounded a vigorous peal. Then she rolled her eyes at Mrs. Butler and sat down.

Mrs. Morris said that when Miss Peters rolled her eyes she invariably shivered. She shivered now in such a marked and open way that poor Mrs. Meadowsweet feared her friend had taken cold.

"Dear, dear—I only wish I had a fire lighted," she said. "Your bronchitis will be getting worse, if you aren't careful, Jessie. Miss Peters, a cup of tea will do your throat good. It always does mine when I get nipped."

"Don't encourage Maria in her fancies," snapped Mrs. Butler. "There's nothing ails her throat, only she will wrap herself in so much wool that she makes herself quite delicate. I tell her she fancies she is a hothouse plant."

"Oh, nothing of the kind," whispered Mrs. Morris.

"That's what I say," nodded back Mrs. Butler. "More of the nature of the hardy broom. But now we haven't come to discuss Maria and her fads. You have had a visitor to-day, Mrs. Meadowsweet."

"Ah, here comes the tea," exclaimed Mrs. Meadowsweet. "Bring the table over here, Jane. Now this is what I call cozy. Jane, you might ask cook to send up some buttered toast, and a little more cream. Yes, Mrs. Butler, I beg your pardon."

"I was remarking that you had a visitor," repeated Mrs. Butler.

"Ah, so I had. Mrs. Bertram called on me."

"And why shouldn't she call on you, dear?" suddenly whispered Mrs. Morris. "Aren't you quite as good as she is when all's said and done? Yes, dear, I'll have some of your delicious tea. Such a treat! Some more cream? Thank you, yes; I'll help myself. Why shouldn't Mrs. Bertram call on Mrs. Meadowsweet? That's what I say, ladies," continued Mrs. Morris, looking over the top of her cup of tea in a decidedly fight-me-if-you-dare manner.

"Nobody said she shouldn't call," answered Mrs. Butler. "Maria, you'll oblige me by going into the hall and fetching my wrap. There's rather a chill from this window—and the weather is very inclement for the time of year. No, thank you, Mrs. Morris, I wouldn't take your seat for the world. As you justly remark, why shouldn't Mrs Bertram call on our good friend here? And, for that matter, why shouldn't she cross the road, and leave her card on you, Mrs. Morris?"

Mrs. Morris was here taken with such a fit of bronchial coughing and choking that she could make no response. Miss Peters rolled her eyes at her sister in a manner which plainly said, "You had her there, Martha," and poor Mrs. Meadowsweet began nervously to wish that she had not been the honored recipient of Mrs. Bertram's favors.

"She came to see me on account of Beatrice," remarked the hostess. "At least I think that was why she came. I beg your pardon, did you say anything, ladies?"

"Oh! fie, fie! Mrs. Meadowsweet," said Miss Peters, "you are too modest. In my sister's name and my own, I say you are too modest."

"And in my name too," interrupted Mrs. Morris. "You are too humble, my dear friend. She called to see you for your own dear sake and for no other."

"And now let us all be friendly," continued Miss Peters, "and learn the news. I think we are all of one mind in wishing to learn the news."

Mrs. Meadowsweet smoothed down the front of her black satin dress. She knew, and her friends knew, that she would have much preferred the honor of Mrs. Bertram's call to be due to Beatrice's charms than her own. She smiled, however, with her usual gentleness, and plunged into the conversation which the three other ladies were so eager to commence.

Before they departed they had literally taken Mrs. Bertram to pieces. They had fallen upon her tooth and nail, and dissected her morally, and socially, and with the closest scrutiny of all, from a religious point of view.

Mrs. Meadowsweet, who never spoke against any one, was amazed at the ingenuity with which the character of her friend (she felt she must call Mrs. Bertram her friend) was blackened. Before the ladies left Mrs. Meadowsweet's house they had proved, in the ablest and most thorough manner, that Mrs. Bertram was worldly and vain, that she lived beyond her means, that she trained her daughters to think of themselves far more highly than they ought to think, that in all probability she was not what she pretended to be, and, finally, that poor Mrs. Meadowsweet, dear Mrs. Meadowsweet, was in great danger on account of her friendship.

"I don't agree with you, ladies," said the good woman, as they were leaving the house, but they neither heeded nor heard her remark.

The explanation of their conduct was simple enough. They were devoured with jealousy. Had Mrs. Bertram called on any one of them, she would have been in that person's estimation the most fascinating woman in Northbury.

And Mrs. Bertram did not care in the least what anybody thought of her. She was in no sense of the word a sham. She was well-born, well-educated, respectably married, and fairly well-off. The people in Northbury considered her rich. She always spoke of herself as poor. In reality she was neither rich nor poor. She had an income of something like twelve hundred a year, and on that she lived comfortably, educated her children well, and certainly managed to present a nice appearance wherever she went.

There never was a woman more full of common sense than Mrs. Bertram. She had quite an appalling amount of this virtue; no one ever heard her say a silly thing; each step she took in life was a wise one, carefully considered, carefully planned out. She had been a widow now for sis years. Her husband had nearly come into the family estate, but not quite. He was the second son, and his eldest brother had died when his heir was a month old. This heir had cut out Mrs. Bertram's husband from the family place, with its riches and honors. He himself had died soon after, and had left his widow with three children and twelve hundred a year.

The children were a son and two daughters. The son's name was Loftus, the girls were called Catherine and Mabel. Loftus was handsome in person, and very every-day in mind. He was good-natured, but not remarkable for any peculiar strength of character. His mother had managed to send him to Rugby and Sandhurst, and he had passed into the army with tolerable credit. He was very fond of his mother, devotedly fond of her, but since he entered the army he certainly contrived to cost her a good deal.

She spoke to him on the subject, believed as much as she chose of his earnest promises to amend, took her own counsel and no one else's, gave up her neat little house in Kensington, and came to live at Northbury.

Catherine and Mabel did not like this change, but as their mother never dreamt of consulting them, they had to keep their grumbles to themselves.

Mrs. Bertram considered she had taken a wise step, and she told the girls so frankly. Their house in Kensington was small and expensive. In the country they had secured a delightful old Manor—Rosendale Manor was its pretty name—for a small rent.

Mrs. Bertram found herself comparatively rich in the country, and she cheered the girls by telling them that if they would study economical habits, and try to do with very little dress for the present, she would save some money year by year, so that by the time Catherine was twenty they might have the advantage of a couple of seasons in town.

"Catherine will look very young at twenty," remarked the mother. "By that time I shall have saved quite a fair sum out of my income. Catherine looked younger at twenty than Mabel at eighteen. They can both come out together, and have their chances like other girls."

Catherine did not want to wait for the dear delights of society until she had reached so mature an age. But there was no murmuring against her mother's decree, and as she was a healthy-minded, handsome, good-humored girl, she soon accommodated herself to the ways and manners of country folk, and was happy enough.

"I shall live on five hundred a year at Rosen dale Manor," determined Mrs. Bertram. "And I have made up my mind that Loftie shall not cost me more than three. Thus I shall save four hundred a year. Catherine is only seventeen now. By the time she is twenty I shall have a trifle over and above my income to fall back upon. Twelve hundred pounds is a bagatelle with most people, but I feel I shall effect wonders with it. Catherine and Mabel will be out of the common, very out of the common. Unique people have an advantage over those who resemble the herd. Catherine and Mabel are to be strongly individual. In any room they are to be noticeable. Little hermits, now, some day they shall shine. They are both clever, just clever enough for my purpose. Catherine might with advantage be a shade less beautiful, but Mabel will, I am convinced, fulfil all my expectations. Then, if only Loftie," but here Mrs. Bertram sighed. She was returning from her visit to Mrs. Meadowsweet, walking slowly down the long avenue which led to the Manor. This avenue was kept in no order; its edges were not neatly cut, and weeds appeared here and there through its scantily gravelled roadway. The grass parterre round the house, however, was smooth as velvet, and interspersed with gay flower-beds. It looked like a little agreeable oasis in the middle of a woodland, for the avenue was shaded by forest trees, and the house itself had a background of two or three acres of an old wood.

Mrs. Bertram was tired, and walked slowly. She did not consider herself a proud woman, but in this she was mistaken. Every line of her upright figure, each glance of her full, dark eyes, each word that dropped from her lips spoke of pride both of birth and position. She often said to herself, "I am thankful that I don't belong to the common folk; it would grate on my nerves to witness their vulgarities,—their bad taste would torture me; their want of refinement would act upon my nature like a blister. But I am not proud, I uphold my dignity, I respect myself and my family, but with sinful, unholy pride I have no part."

This was by no means the opinion held of her, however, by the Northbury folk. They had hailed her advent with delight; they had witnessed her arrival with the keenest, most absorbing interest, and, to the horror of the good lady herself, had one and all called on her. She was petrified when this very natural event happened. She had bargained for a life of retirement for herself and her girls. She had never imagined that society of a distinctly lower strata than that into which she had been born would be forced on her. Forced! Whoever yet had forced Mrs. Bertram into any path she did not care to walk in?

She was taken unawares by the first visitors, and they absolutely had the privilege of sitting on her sofas, and responding to a few icy remarks which dropped from her lips.

But the next day she was armed for the combat. The little parlor-maid, in her neat black dress, clean muslin apron, large frilled, picturesque collar, and high mob-cap, was instructed to say "Not at home" to all comers. She was a country girl, not from Northbury, but from some still more rusticated spot, and she thought she was telling a frightful lie, and blushed and trembled while she uttered it. So apparent was her confusion that Miss Peters, when she and her sister, Mrs. Butler, appeared on the scene, rolled her eyes at the taller lady and asked her in a pronounced manner if it would not be well to drop a tract on the heinousness of lying in the avenue.

This speech was repeated by Clara to the cook, who told it again to the young ladies' maid, who told it to the young ladies, who narrated it to their mother.

Mrs. Bertram smiled grimly.

"Don't repeat gossip, my dears," she said, Then after a pause she remarked aloud: "The difficulty will be about returning the calls."

Mabel, the youngest and most subservient of the girls, ventured to ask her mother what she intended to do, but Mrs. Bertram was too wise to disclose her plans, that is, if she had made any.

The Rector of Northbury was one of the first to visit the new inhabitants of the Manor. To him Mrs. Bertram opened her doors gladly. He was old, unmarried, and of good family. She was glad there was at least one gentleman in the place with whom she might occasionally exchange a word.

About a fortnight after his visit the Rector inclosed some tickets for a bazaar to Mrs. Bertram. The tickets were accompanied by a note, in which he said that it would gratify the good Northbury folk very much if Mrs. Bertram and the young ladies would honor the bazaar with their presence.

"Every soul in the place will be there," said Mr. Ingram. "This bazaar is a great event to us, and its object is, I think, a worthy one. We badly want a new organ for our church."

"Eureka!" exclaimed Mrs. Bertram when she had read this note.

"What is the matter, mother?" exclaimed Mabel.

"Only that I have found a way out of my grand difficulty," responded their mother, tossing Mr. Ingram's note and the tickets for the bazaar into Catherine's lap.

"Are you so delighted to go to this country bazaar, mother?" asked the eldest daughter.

"Delighted! No, it will be a bore."

"Then why did you say Eureka! and look so pleased?"

"Because on that day I shall leave cards on the Northbury folk—not one of them will be at home."

"Shabby," muttered Catherine. Her dark cheek flushed, she turned away.

Mabel put out her little foot and pressed it against her sister's. The pressure signified warning.

"Then you are not going to the bazaar, mother?" she questioned.

"I don't know. I may drop in for a moment or two, quite at the close. It would not do to offend Mr. Ingram."

"No," replied Mabel. "He is a dear, gentlemanly old man."

"Don't use that expression, my love. It is my object in life that all your acquaintances in the world of men should be gentlemen. It is unnecessary therefore to specify any one by a term which must apply to all."

Mrs. Bertram then asked Mabel to reply to Mr. Ingram's note. The reply was a warm acceptance, and Mr. Ingram cheered those of his parishioners who pined for the acquaintance of the great lady, with the information that they would certainly meet her at the bazaar.

Accordingly when the fateful day arrived the town was empty, and the Fisherman's Hall (Northbury was a seaport), in which the bazaar was held was packed to overflowing. Accordingly Mrs. Bertram in a neat little brougham, which she had hired for the occasion, dropped her cards from house to house in peace; accordingly, too, she caught the maids-of-all-work in their undress toilets, and the humble homes looking their least pretentious.

The bazaar was nearly at an end, when at last, accompanied by her two plainly-dressed, but dainty looking girls, she appeared on the scene.

The Northbury folk had all been watching for her. Those who had been fortunate enough to enter the sacred precincts of the Manor watched with interest, mingled with approval. (Her icy style was quite comme-il-faut, they said.) Those who had been met by the frightened handmaid's "not at home" watched with interest, mixed with disapproval, but all, all waited for Mrs. Bertram with interest.

"How late these fashionable people are," quote Miss Peters. "It's absolutely five o'clock. My dear Martha, do sit down and rest yourself. You look fit to drop. I'll keep an eye on the door and tell you the very moment Mrs. Bertram comes in. Mrs. Gorman Stanley has promised to introduce us. Mrs. Gorman Stanley was fortunate enough to find Mrs. Bertram in. It was she who told us about the drawing-room at the Manor. Fancy! Mrs. Bertram has only a felt carpet on her drawing-room. Not even a red felt, which looks warm and wears. But a sickly green! Mrs. Gorman Stanley told me as a fact that the carpet was quite a worn-out shade between a green and a brown; and the curtains—she said the drawing room curtains were only cretonne. You needn't stare at me, Martha. Mrs. Gorman Stanley never makes mistakes. All the same, though she couldn't tell why, she owned that the room had a distingué effect. En règle, that was it; she said the room was en règle."

"Maria, if you could stop talking for a moment and fetch me an ice, I'd be obliged," answered Mrs. Butler. "Oh!" standing up, "there's Mrs. Gorman Stanley. How do you do, Mrs. Gorman Stanley? Our great lady hasn't chosen to put in her appearance yet. For my part I don't suppose she's any better than the rest of us, and so I say to Maria. Well, Maria, what's the matter now?"

"Here's your ice," said Miss Peters; "take it. Don't forget that you promised to introduce us to Mrs. Bertram, Mrs. Gorman Stanley."

Mrs. Gorman Stanley was the wealthy widow of a retired fish-buyer. She liked to condescend; also to show off her wealth. It pleased her to assume an acquaintance with Mrs. Bertram, although she thoroughly despised that good lady's style of furnishing a house.

"I'll introduce you with pleasure, my dear," she said to Mrs. Butler. "Yes, I like Mrs. Bertram very much. Did you say she was out when you called? Oh! she was in to me. Yes, I saw the house. I don't think she had finished furnishing it. The drawing-room looked quite bare. A made-up sort of look, you understand. Lots of flowers on the tables, and that nasty, cold, cheap felt under your feet. Not that I mind how a house is furnished." (She did very much. Her one and only object in life seemed to be to lade her own mansion with ugly and expensive upholstery.) "Now, what's the matter, Miss Peters? Why, you are all on wires. Where are you off to now?"

"I see the Rector," responded Miss Peters. "I'll run and ask him when he expects Mrs. Bertram. I'll be back presently with the news."

The little lady tripped away, forcing her slim form through the ever-increasing crowd. The rector was walking about with a very favorite small parishioner seated on his shoulder.

"Mr. Ingram," piped Miss Peters. "Don't you think Mrs. Bertram might favor us with her presence by now? We have all been looking for her. It's past five o'clock, and—"

There was a hush, a pause. At that moment Mrs. Bertram was sailing into the room. Miss Peters' exalted tones reached her ears. She shuddered, turned pale, and also turned her back on the eager little spinster.

Nobody quite knew how it was managed, but Mrs. Bertram was introduced to very few of the Northbury folk. They all wanted to know her; they talked about her, and came in her way, and stared at her whenever they could. There was an expectant hush when she and the Rector were seen approaching any special group.

"I do declare it's the Grays she's going to patronize," one jealous matron said.

But the Grays were passed over just as sedulously as the Joneses and the Smiths. Excitement, again and again on the tenter-hooks, invariably came to nothing. Even Mrs. Gorman Stanley, who had sat on Mrs. Bertram's sofa, and condemned her felt carpet was only acknowledged by the most passing and stately recognition. Little chance had the poor lady of effecting other introductions; she realized for the first time that she was only a quarter introduced to the great woman herself.

The fact was this: There was not a soul in Northbury, at least there was not an acknowledged soul who could combat Mrs. Bertram's will. She had made up her mind to talk to no one but Mr. Ingram at the bazaar. She carried out her resolve, and that though the Rector had formed such pleasant visions of making every one cheerful and happy all round, for he knew the simple weaknesses and desires of his flock, and saw not the smallest harm in gratifying them. Why should not the Manor and the town be friendly?

Mrs. Bertram saw a very good reason why they should not. Therefore the Rector's dreams came apparently to nothing.

Only apparently. Every one knows how small the little rift within the lute is. So are most beginnings.

Mrs. Bertram felt, that in her way, she had effected quite a victory. She stepped into her brougham to return to Rosendale Manor with a pleasing sense of triumph.

"I am thankful to say that ordeal is over," she remarked. "And I think," she continued, with a smile, "that when the Northbury people see my cards, awaiting them on their humble hall-tables, they will have learnt their lesson."

Neither of the girls made any response to this speech. Mabel was leaning back in the carriage looking bored and cross, but Catherine's expression was unusually bright.

"Mother," she exclaimed suddenly, "I met such a nice girl at the bazaar."

"You made an acquaintance at the bazaar, my dear Catherine," answered Mrs. Bertram with alacrity. "You made an acquaintance? The acquaintance of a girl? Who?"

"Her name is Beatrice Meadowsweet. She is a dear, delightful, fresh girl, and exactly my own age."

Catherine's dark face was all aglow. Her handsome brown eyes shone with interest and pleasure.

"Catherine, how often, how very often have I told you that expressions of rapture such as you have just given way to are underbred."

"Why are they underbred, mother?" Catherine's tone was aggressive, and Mabel again kicked her sister's foot.

The kick was returned with vigor, and Catherine said in an earnest though deliberate voice:

"Why are expressions of rapture underbred? Can enthusiasm, that fire of the gods, be vulgar?"

"Kate, you are cavilling. Expressions of rapture generally show a lack of breeding because as a rule they are exaggerated, therefore untrue. In this case they are manifestly untrue, for how is it possible for you to tell that the girl you have just been speaking to is dear, delightful, and fresh?"

"Her face is fresh, her manners are fresh, her expression is delightful. There is no use, mother, you can't crush me. I am in love with Beatrice Meadowsweet."

Mrs. Bertram's brow became clouded. It was one of the bitter defeats which she had ever and anon to acknowledge to herself that, in the midst of her otherwise victorious career, she could never get the better of her eldest daughter Catherine.

"Who introduced you to this girl?" she asked, after a pause.

"The Rector. He saw me standing by one of the stalls, looking what I felt—awfully bored. He came up in his kind way and took my hand, and said: 'My dear, you don't know any one, I am afraid. You would like to make some acquaintances, would you not?' I replied: 'I am most anxious to know some of the nice people all around me.'"

"My dear Catherine! The nice people! And when you knew my express wishes!"

"Yes, mother, but they weren't mine. And I had to be truthful, at any cost. Beatrice was standing not far off, and when I said this my eye met hers, and we both smiled. Then the rector introduced me to her, and we mutually voted the bazaar close and hot, and went out to watch the tennis players in the garden. We had a jolly time. I have not laughed so much since I came to this slow, poky corner of the world."

"And what were you doing, Mabel?" questioned her mother. "Did you, too, pick up an undesirable acquaintance and march away into the gardens with her? Was your new friend also fresh, delightful and dear?"

"I wish she had been, mother," answered Mabel, her tone still very petulant. "But I hadn't Kate's luck. I was introduced to no one, although lots of people stared at me, and whispered about me as I passed."

"And you saw this paragon of Catherine's?"

"Yes, I saw her."

"What did you think of her, May? I like to get your opinion, my love. You have a good deal of penetration. Tell me frankly what you thought of this low-born miss, whom Catherine degraded herself by talking to."

Mabel looked at her sister. Catherine's eyes flashed. Mabel replied demurely:

"I thought Miss Meadowsweet quiet-looking and graceful."

Catherine took Mabel's hand unnoticed by their mother and squeezed it, and Mrs. Bertram, who was not wholly devoid of tact, thought it wisest to let the conversation drop.

The next day the Rector called, and Mrs. Bertram asked him, in an incidental way what kind of people the Meadowsweets were.

"Excellent people," he replied, rubbing his hands softly together. "Excellent, worthy, honorable. I have few parishioners whom I think more highly of than Beatrice and her mother."

Mrs. Bertram's brow began to clear.

"A mother and daughter," she remarked. "Only a mother and a daughter, Mr. Ingram?"

"Only a mother and a daughter, my dear madam. Poor Meadowsweet left us six years ago. He was one of my churchwardens, a capital fellow, so thoroughgoing and reliable. A sound churchman, too. In short, everything that one could desire. He died rather suddenly, and I was afraid Mrs. Meadowsweet would leave Northbury, but Bee did not wish it. Bee has a will of her own, and I fancy she's attached to us all."

"I am very glad that you can give us such a pleasant account of these parishioners of yours, dear Mr. Ingram," responded Mrs. Bertram. "The fact is, I am in a difficult position here. No, the girls won't overhear us; they are busy at their embroidery in that distant corner. Well, perhaps, to make sure. Kate," Mrs. Bertram raised her voice, "I know the Rector is going to give us the pleasure of his company to tea. Mr. Ingram, I shall not allow you to say no. Kate, will you and Mabel go into the garden, and bring in a leaf of fresh strawberries. Now, Mr. Ingram I want you to see our strawberries, and to taste them. The gardener tells us that the Manor strawberries are celebrated. Run, dears, don't be long."

The girls stepped out through the open French window, interlaced their arms round one another and disappeared.

"They are good girls," said the mother, "but Kate has a will of her own. Mr. Ingram, you will allow me to take you into my confidence. I am often puzzled to know how to act towards Catherine. She is a good girl, but I can't lead her. She is only seventeen, only just seventeen. Surely that is too young an age to walk quite without leading strings."

Mr. Ingram was an old bachelor, but he was one of those mellow, gentle, affectionate men who make the most delightful companions, whose sympathy is always ready, and tact always to the fore. Mr. Ingram was full of both sympathy and tact, but he had also a little gentle vanity to be tickled, and when a handsome woman, still young, appealed to him with pathos in her eyes and voice, he laid himself, metaphorically, at her feet.

"My dear madam," he responded, "it is most gratifying to me to feel that I can be of the least use to you. Command me at all times, I beg. As to Miss Catherine, who can guide her better than her excellent mother? I don't know much about you, Mrs. Bertram, but I feel—forgive me, I am a man of intuition—I feel that you are one to look up to. Miss Catherine is a fortunate girl. You are right. She is far too young to walk alone. Seventeen, did you say—pooh—a mere child, a baby. An immature creature, ignorant, innocent, fresh, but undeveloped; just the age, Mrs. Bertram, when she needs the aid and counsel of a mother like you."

Mrs. Bertram's dark eyes glowed with pleasure.

"I am glad you agree with me," she said. "The fact is, Mr. Ingram, we have come to the Manor to retrench a little, to economize, to live in retirement. By-and-bye, I shall take Catherine and Mabel to London. As a mother, I have duties to perform to them. These, when the time comes, shall not be neglected. Mr. Ingram, I must be very frank, I don't want to know the good folk of Northbury."

Mr. Ingram started at this very plain speaking. He had lived for thirty years with the Northbury people. They had not vulgarized him; their troubles and their pleasures alike were his. His heart and soul, his life and strength were given up to them. He did not feel himself any the less a gentleman because those whom he served were, many of them, lowly born. He started, therefore, both inwardly and outwardly at Mrs. Bertram's plain speech, and instantly, for he was a man of very nice penetration, saw that the arrival of this lady, this brilliant sun of society, in the little world of Northbury, would not add to the smoothness of his lot.

Before he could get in a word, however, Mrs. Bertram quickly continued:

"And Catherine is determined to make a friend of Beatrice Meadowsweet."

"She is quite right, Mrs. Bertram. I introduced Miss Catherine to Beatrice yesterday. They will make delightful companions; they are about the same age—I can vouch for the life and spirit possessed by my friend Bee, and if I mistake not Miss Catherine will be her worthy companion."

Mrs. Bertram laughed.

"I wish I could tell you what an imp of mischief Kate is," she said. "She is the most daring creature that ever drew the breath of life. Dear Mr. Ingram, forgive me for even doubting you for a moment. I might have known that you would only introduce my daughter to a lady."

The Rector drew himself up a very little.

"Certainly, Beatrice Meadowsweet is a lady," he replied. "If a noble heart, and frank and fearless ways, and an educated mind, and a refined nature can make a lady, then she is one—no better in the land."

"I am charmed, charmed to hear it. It is such a relief. For, really Mr. Ingram, some people from Northbury came and sat on that very sofa which you are occupying, who were quite too—oh, well, they were absolutely dreadful. I wonder if Mrs. Meadowsweet has called. I don't remember the name, but I suppose she has. I must look amongst the cards which have absolutely been showered on us and see. I must certainly return her visit and at once. Poor Mr. Meadowsweet—he was in the army perhaps! I am quite glad to know there are people of our position here. Did you say the army? Or perhaps a retired gentleman,—ah, I see Catherine and Mabel coming back. Which was Mr. Meadowsweet's regiment?"

Poor Mr. Ingram's face grew absolutely pink.

"At some time in his life poor Meadowsweet may have served in the local volunteers," he replied. "He was however, a—ah, Miss Catherine, what tempting strawberries!"

The rector approached the open French window. Mrs. Bertram followed him quickly.

"A—what?" she repeated. "The girls needn't know whom we are talking about. A gentleman who lived on his private means?"

"A gentleman, madam, yes, a gentleman,—and he lived on his means,—and he was wealthy. He kept a shop, a draper's shop, in the High Street. Now, young ladies, young ladies—I call this wrong. Such strawberries! Strawberries are my special weakness. Oh, it is cruel of you to tempt me. I ought to be two miles from here now."

"You ought not," said Catherine in a gay voice. "You must sit with us on the lawn, and drink our tea, and eat our strawberries."

Catherine had given a quick, lightning glance at her mother's face. She saw a cloud there, she guessed the cause. She felt certain that her mother would consult Mr. Ingram on the subject of Beatrice. Mr. Ingram's report was not satisfactory. Delightful! She felt the imp of mischief taking possession of her. She was a girl of many moods and tenses. At times she could even be sombre. But when she chose to be gay and fascinating she was irresistible. She was only seventeen, and in several ways she was unconventional, even unworldly. In others, however, she was a perfect woman of the world, and a match for her mother.

Northbury was so completely out of the world that it only had a postal delivery twice a day. The early post was delivered at eight o'clock, so that the good people of the place could discuss their little items of outside news over their breakfast-tables. The postman went round with his evening delivery at seven. He was not overwhelmed by the aristocracy of Rosendale Manor, and, notwithstanding Mrs. Bertram's open annoyance, insisted on calling there last. He said it suited him best to do so, and what suited Sammy Benjafield he was just as determined to do, as Mrs. Bertram was to carry out her own schemes.

Consequently, the evening letters never reached the Manor until between eight and half-past. Mrs. Bertram and her daughters dined at seven. They were the only people in Northbury who ate their dinner at that aristocratic hour; tea between four and five, and hot, substantial and unwholesome suppers were the order of the day with the Northbury folk. Very substantial these suppers were, and even the Rector was not proof against the hot lobster and rich decoctions of crab with which his flock favored him at these hours.

For the very reason, however, that heavy suppers were in vogue at Northbury, Mrs. Bertram determined to adhere to the refinement of a seven-o'clock dinner. Very refined and very simple this dinner generally was. The fare often consisting of soup made out of vegetables from the garden, with a very slight suspicion of what housekeepers call stock to start it; fish, which meant as often as not three simple but fresh herrings; a morsel of meat curried or hashed would generally follow; and dessert and sweets would in the summer be blended into one; strawberries, raspberries or gooseberries from the garden forming the necessary materials. Cream did not accompany the strawberries, and the rich wine in the beautiful and curiously-cut decanters was placed on the table for show, not for use.

But then the dinners at the Manor were so exquisitely served. Such napery, such china, such sparkling and elegant glass, and such highly-polished plate. Poor little Clara, the serving-maid, who had not yet acquired the knack of telling a lie with sang froid absolutely trembled, as she spread out her snowy table-cloths, and laid her delicate china and glass and silver on the board.

"It don't seem worth while," she often remarked to the cook. "For what's an' erring? It seems wicked to eat an' erring off sech plates as them."

"It's a way the quality have," retorted Mrs. Masters, who had come from London with the Bertrams and did not mean to stay. "They heats nothing, and they lives on sham. Call this soup! There, Clara, you'll be a sham yourself before you has done with them."

Clara thought this highly probable, but she was still young and romantic, and could do a great deal of living on make-beliefs, like many other girls all the world over.

As the Bertrams were eating their strawberries off delicate Sevres plates on the evening of the day when Mr. Ingram had disclosed the parentage of poor Beatrice Meadowsweet, the postman was seen passing the window.

Benjafield had a very slow and aggravating gait. The more impatient people were for their letters, the more tedious was he in his delivery. Benjafield had been a fisherman in his day, and had a very sharp, withered old face. He had a blind eye, too, and walked by the aid of a crutch but it was his boast that, notwithstanding his one eye and his lameness, no one had ever yet got the better of him.

"There's Benjafield!" exclaimed Mabel. "Shall I run and fetch the letters, mother?"

Mrs. Bertram rose slowly from her seat at the head of the board.

"The post is later than ever," she remarked; "it is past the half-hour. I shall go myself and speak to Benjafield."

She walked slowly out through the open window. She wore an evening dress of rusty black velvet with a long train. It gave her a very imposing appearance, and the effect of her evening dress and her handsome face and imperious manners were so overpowering that the old postman, as he hobbled toward her, had to mutter under his breath:

"Don't forget your game leg, Benjafield, nor your wall eye, and don't you be tooken down nor beholden to nobody."

"Why is the post so late?" inquired Mrs. Bertram. "It is more than half-past eight."

"Eh!" exclaimed Benjafleld.

"I asked why the post was so late."

"Eh? I'm hard of hearing, your ladyship."

He came a little nearer, and leered up in the most familiar way into the aristocratic face of Mrs. Bertram.

"Intolerable old man," she muttered, aloud: "Take the letters from him, Catherine, and bring them here."

Then raising her voice to a thin scream, she continued:

"I shall write to the general post-office on this subject; it is quite intolerable that in any part of England Her Majesty's Post should be entrusted to incapable hands."

Old Benjafield, fumbling in his bag, produced two letters which he presented to Catherine. He did so with a dubious, inquiring glance at her mother, again informed the company generally that he was hard of hearing, and hobbled away.

One of the letters, addressed in a manly and dashing hand, was for Catherine. The other, also in manly but decidedly cramped writing, was addressed to Mrs. Bertram.

She started when she saw the handwriting, instantly forgot old Benjafield, and disappeared into the house.

When she was gone Mabel danced up to her sister's side, and looked over her shoulder at the thick envelope addressed in the manly hand.

"Kate, it's from Loftie!" she exclaimed.

"Yes, it's from Loftie," responded Catherine. "Let us come and sit under the elm-tree and read what he says, May."

The girls seated themselves together on a rustic bench, tore open the thick letter, and acquainted themselves with its contents.

"Dearest,—I'm coming home to-morrow night. Must see the mater. Have got into a fresh scrape. Don't tell anyone but May—I mean about the scrape.

"Your devoted brother,

"Loftus."

Catherine read this letter twice, once to herself, then aloud for Mabel's benefit.

"Now, what's up?" exclaimed Mabel. "It must be very bad. He never calls you 'dearest;' unless it's awfully bad. Does he, Kitty?"

"No," said Catherine. "Poor mother," she added then, and she gave a profound and most ungirlish sigh.

"Why, Catherine, you have been grumbling at mother all day! You have been feeling so cross about her."

"You never will understand, Mabel! I grumble at mother for her frettiness, but I love her, I pity her for her sorrows."

Mabel looked full into her sister's face.

"I confess I don't understand you," she said. "I can't love one side of a person, and hate the other side; I don't know that I love or hate anybody very much. It's more comfortable not to do things very much, isn't it, Kitty?"

"I suppose so," replied Catherine, "but I can't say. That isn't my fashion. I do everything very much. I love, I hate, I joy or sorrow, all in extremes. Perhaps it isn't a good way, but it's the only way I've got. Now let us talk about Loftus. I wonder if he is going to stay long, and if he will make himself pleasant."

"No fear of that," responded Mabel. "He'll be as selfish and exacting as ever he can be. He'll keep mother in a state of fret, and you in a state of excitement, and he'll insist on smoking a cigarette close to the new cretonne curtains in the drawing-room, and he'll make me go out in the hot part of the day to gather fresh strawberries for him. Oh, I do think brothers are worries! I wish he wasn't coming. We are very peaceful and snug here. And mother's face doesn't looked harassed as it often did when we were in town. I do wish Loftus wasn't coming to upset everything. It was he turned us away from our nice, sprightly, jolly London, and now, surely he need not follow us into the country. Yes, Catherine, what words of wisdom or reproof are going to drop from your lips?"

"Not any," replied Catherine. "I can't make blind people see, and I can't bring love when there is no love to bring. Of course, it is different for me."

"How is it different for you?"

"I love Loftus. He gives me pain, but that can be borne, for I love him."

At this moment Mrs. Bertram's tall figure was seen standing on the steps of the house. It was getting dark; a heavy dew was falling, and the air was slightly, pleasantly chill after the intense heat of the day. Mrs. Bertram had wrapped a white fleecy cloud over her head. She descended the steps, stood on the broad gravel sweep, and looked around her.

"We are here, mother," said May, jumping up. "Do you want us?"

"I want Catherine. Don't you come, Mabel. I want Catherine alone."

"Keep Loftus's letter," said Catherine, tossing it into her sister's lap. "I know by mother's tone she is troubled. Don't let us show her the letter to-night. Put it in your pocket, May."

Aloud she said,—

"Yes, mother, I'm coming. I'll be with you directly." She ran across the grass, looking slim and pale in her white muslin dress, her face full of intense feeling, her manner so hurried and eager that her mother felt irritated by it.

"You need not dash at me as if you meant to knock me down, Kate," she said.

"You said you wanted me, mother."

"So I did, Catherine. I do want you. Come into the house with me."

Mrs. Bertram turned and walked up the steps. She entered the wide hall which was lit by a ghostly, and not too carefully-trimmed, paraffin lamp. Catherine followed her. They went into the drawing-room. Here also a paraffin lamp gave an uncertain light; very feeble, yellow, and uncertain it was, but even by it Catherine could catch a glimpse of her mother's face. It was drawn and white, it was not only changed from the prosperous, handsome face which the girl had last looked at, but it had lost its likeness to the haughty, the proud, the satisfied Mrs. Bertram of Catherine's knowledge. Its expression now betokened a kind of inward scare or fright.

"Mother, you have something to worry you," said Kate, "I see that by your face. I am sorry. I am truly sorry. Sit down, mother. What can I do for you?"

"Nothing, my dear, except to be an attentive daughter—attentive and affectionate and obedient. Sometimes, Catherine, you are not that."

"Oh, never mind now, when you are in trouble, I'd do anything in the world for you when you are in trouble. You know that."

Mrs. Bertram had seated herself. Catherine knelt now, and took one of her mother's hands between her own. Insensibly the cold hand was comforted by the warm steadfast clasp.

"You are a good child, Kate," said her mother in an unwonted and gentle voice. "You are full of whims and fancies; but when you like you can be a great support to one. Do you remember long ago when your father died how only little Kitty's hand could cure mother's headaches?"

"I would cure your heartache now."

"You can't, child, you can't. And besides, who said anything about a heartache? We have no time, Kate, to talk any more sentimentalities. I have had a letter, my dear, and it obliges me to go to town to-night."

"To-night? Surely there is no train?"

"There is. One stops at Northbury to take up the mails at a quarter to twelve. I shall go by it."

"Do you want me to go with you?"

"By no means. Of what use would you be?"

"I don't know. Perhaps not of any use, and yet long ago when you had headaches, Kitty could cure them."

There was something so pathetic and so unwonted in Catherine's tone that Mrs. Bertram was quite touched. She bent forward, placed her hand under the young chin, raised the handsome face, and printed a kiss on the brow.

"Kitty shall help her mother best by staying at home," she said. "Seriously, my love. I must leave you in charge here. Not only in charge of the house, of the servants, of Mabel—but—of my secret."

"What secret, mother?"

"I don't want any one here to know that I have gone to London."

Catherine thought a moment.

"I know you are not going to give me your reasons," she said, after a pause. "But why do you tell me there is a secret?"

"Because you are trustworthy."

"Why do tell me that you are going to London?"

"Because you must be prepared to act in an emergency."

"Mother, what do you mean?"

"I will tell you enough of my meaning to guide you, my love. I have had some news that troubles me. I am going to London to try and put some wrong things right. You need not look so horrified, Kate; I shall certainly put them right. It might complicate matters in certain quarters if it were known that I had gone to London, therefore I do it secretly. It is necessary, however, that one person should know where to write to me. I choose you to be that person, Catherine, but you are only to send me a letter in case of need."

"If we are ill, or anything of that sort, mother?"

"Nothing of that sort. You and Mabel are in superb health. I am not going to prepare for any such unlikely contingency as your sudden illness. Catherine, these are the only circumstances under which you are to communicate with your mother. Listen, my dear daughter. Listen attentively. A good deal depends on your discretion. A stranger may call. The stranger may be either a man or a woman. He or she will ask to see me. Finding I am away this person, whether man or woman, will try to have an interview with either you or Mabel, and will endeavor by every means to get my address. Mabel, knowing nothing, can reveal nothing, and you, Kate, you are to put the stranger on the wrong scent, to get rid of the stranger by some means, and immediately to telegraph to me. My address is in this closed-up envelope. Lock the envelope in your desk; open it if the contingency to which I have alluded occurs, not otherwise. And now, my dear child, I must go upstairs and pack."

Catherine roused herself from her kneeling position with difficulty. She felt cold and stiff, queer and old.

"Shall I help you, mother," she asked.

"No, my dear, I shall ring for Clara. I shall tell Clara that I am going to Manchester. A train to Manchester can be taken from Fleet-hill Junction, so it will all sound quite natural. Go out to Mabel, dear. Tell her any story you like."

"I don't tell stories, mother. I shall have nothing to say to Mabel."

"Tell her nothing, then; only run away. What is the matter now?"

"One thing before you go, mother. I too had a letter to-night."

"Had you, my dear? I cannot be worried about your correspondence now."

"My letter was from Loftie."

"Loftus! What did he write about?"

"He is coming here to-morrow night."

Catherine glanced eagerly into her mother's face as she spoke. It did not grow any whiter or any more careworn.

She stood still for a moment in the middle of the drawing-room, evidently thinking deeply. When she spoke her brow had cleared and her voice was cheerful.

"This may be for the best," she said.

Catherine stamped her foot impatiently.

"Mother," she said, "you quite frighten me with your innuendoes and your half-confidences. I don't understand you. It is very difficult to act when one only half understands."

"I cannot make things plainer for you, my dear. I am glad Loftie is coming. You girls must entertain him as well as you can. This is Wednesday evening. I hope to be back at the latest on Monday. It is possible even that I may transact my business sooner. Keep Loftus in a good temper, Kate. Don't let him quarrel with Mabel, and, above all things, do not breathe to a soul that your mother has gone to London. Now, kiss me, dear. It is a comfort to have a grown-up daughter to lean on."

On the following evening Loftus Bertram made his appearance at Rosendale Manor. Catherine and Mabel were both waiting for him under the shade of the great oak tree which commanded a view of the gate. His train was due at Northbury at seven o'clock. He was to come by express from London, and the girls concluded that the express would not be more than five minutes late. Allowing for this, and allowing also for the probability that Loftus would be extremely discontented with the style of hackney coach which alone would await him at the little station and might in consequence prefer to walk to the Manor, the girls calculated he might put in an appearance on the scene at about twenty minutes past seven. They had arranged to have dinner at a quarter to eight, and sat side by side now, looking a little forlorn in the frocks they had grown out of, and a little lonely, like half-fledged chicks, without their mother's august protection.

"Loftie will wonder," said Mabel, "at mother going off to Manchester in such a hurry."

It was the cook who had told Mabel about Manchester, Clara having informed her.

"There's Loftus!" suddenly exclaimed Catherine. "I knew he'd walk. I said so. There's the old shandrydan crawling after him with the luggage. Come, Mabel. Let's fly to meet the dear old boy."

She was off and away herself before Mabel had time to scramble to her feet. Her running was swift as a fawn's—in an instant she had reached her brother—threw herself panting with laughter and joy against him, and flung one arm round his neck.

"Here you are!" she said, her words coming out in gasps. "Isn't it jolly? Such a fresh old place! Lots of strawberries—glad you'll see it in the long days—give me a kiss, Loftie—I'm hungry for a kiss!"

"You're as wild an imp as ever," said Loftus, pinching her cheek, but stooping and kissing her, nevertheless, with decided affection. "Why did you put yourself out of breath, Kitty? Catch May setting her precious little heart a-beating too fast for any fellow! Ah, here you come, lazy Mabel. Where is the mater? In the house, I suppose? I say, Kate, what a hole you have pitched upon for living in? I positively couldn't ride down upon the thing they offered me at the station. It wasn't even clean. Look at it, my dear girls! It holds my respectable belongings, and not me. It's the scarecrow or ghost of the ordinary station-fly. Could you have imagined the station-fly could have a ghost?"

"No," retorted Mabel, "being so scarecrowy and ghost-like already. Please, driver, take Captain Bertram's things up to the house. He heard you speak, Loftie. These Northbury people are as touchy as if they were somebodies. Oh, Loftus, you will be disappointed. Mother has gone to Manchester."

"To Manchester?" retorted Loftus. "My mother away from home! Did she know that I was coming?"

"Yes," answered Kate, "I told her about your letter last night."

"Did you show her my letter?"

"No."

"Why didn't you? If she had read it she wouldn't have gone. I said I was in a scrape. I was coming down on purpose to see the mater. You might have sent me a wire to say she would not be at home, or you might have kept her at home by showing her my letter. You certainly did not act with discretion."

"I said you'd begin to scold the minute you came here, Loftie," remarked Mabel. "It's a way you have. I told Kitty so. See, you have made poor Kitty quite grave."

Loftus Bertram was a tall, slim, young fellow. He was well-made, athletic, and neat in appearance, and had that upright carriage and bearing which is most approved of in her Majesty's army. His face was thin and dark; he had a look of Kate, but his eyes were neither so large nor so full; his mouth was weak, not firm, and his expression wanted the openness which characterized Catherine's features.

He was a selfish man, but he was not unkind or ill-natured. The news which the girls gave him of their mother's absence undoubtedly worried and annoyed him a good deal, but like most people who are popular, and Loftus Bertram was undoubtedly very popular, he had the power of instantly adapting himself to the exigencies of the moment.

He laughed lightly, therefore, at Mabel's words, put his arm round his younger sister's unformed waist, and said, in a gay voice:

"I won't scold either of you any more until I have had something to eat."

"We live very quietly at the Manor," remarked Mabel, "Mother wants to save, you know. She says we must keep up our refinement at any cost, but our meals are very—" she glanced with a gay laugh at Catherine.

"Oh, by Jove! I hope you don't stint in the matter of food," exclaimed the brother. "You'll have to drop it while I'm here, I can tell you. I thought the mater would be up to some little game of this kind when she buried you alive in such an out-of-the-way corner. She makes a great mistake though, and so I shall tell her. Young girls of your age ought to be fed up. You'll develop properly then, you won't otherwise. That's the new dodge. All the doctors go upon it. Feed up the young to any extent, and they'll pay for it by-and-bye. Plenty of good English beef and mutton. What's the matter, Kate? What are you laughing in that immoderate manner for?"

"Oh, nothing, Loftie. I may laugh, I suppose, without saying why. I wish you would not put on that killing air, though. And you know perfectly there is no use in laying down the law in mother's house."

The three young people were now standing in the hall, and Clara tripped timidly forward.

"We want dinner as quickly as possible, Clara," said Mabel. "Come, Loftus, let us take you to your room."

That night the choicely served repast was less meagre than usual. Caller herring graced the board in abundance, and even Loftus did not despise these, when really fresh and cooked to perfection. The hash of New Zealand mutton, however, which followed, was not so much to this fastidious young officer's taste, but quantities of fine strawberries, supplemented by a jug of rich cream, put him once more into a good humor. He did not know that Kate had spent one of her very scarce sixpences on the cream, and that the girls had walked a mile-and-a-half through the hot sun that morning to fetch it.

The decanters of wine did not only do duty as ornaments that evening, and as the black coffee which followed was quite to Loftus' taste, he forgot the New Zealand mutton, or, at least, determined not to speak on the subject before the next morning.

After Mabel went to bed that night Kate asked her brother what the fresh scrape was about. He was really in an excellent humor then; the seclusion and almost romance of the old place soothed his nerves, which were somewhat jaded with the rush and tear of a life not lived too worthily. He and Kitty were strolling up and down in the moonlight, and when she asked her question and looked up at him with her fine, intelligent, sympathetic face, he pulled her little ear affectionately, and pushed back the tendrils of soft, dark hair from her brow.

"The usual thing, Kitty," he responded. "I'm in the usual sort of scrape."

"Money?" asked Catherine.

"Confound the thing, yes. Why was money invented? It's the plague of one's life, Catherine. If there was no money there'd be no crime."

"Nonsense," answered Catherine, with shrewdness. "If there wasn't money there would be its equivalent in some form or other. Are you in debt again, Loftie?"

"How can I help it? I can't live on my pittance."

"But mother gives you three hundred a year."

"Yes—such a lot! You girls think that a fine sum, I suppose! That's all you know. Three hundred! It's a pittance. No fellow has a right to go into the army with such small private means."

"But, Loftie, you would not accept Uncle Roderick Macleod's offer. He wrote so often, and said he could help you if you joined him in India."

"Yes, I knew what that meant. Now, look here, Kate. We needn't rake up the past. My lot in life is fixed. I like my profession, but I can't be expected to care for the beggary which accompanies it. I'm in a scrape, and I want to see the mater."

"Poor mother! I wish you weren't going to worry her, Loftie."

"It doesn't worry a mother to help her only son."

"But she has helped you so often. You know it was on account of you that we came down here, because mother had given you so much, and it was the only way left to us to save. It wasn't at all a good thing for Mabel and me, for we had to leave our education unfinished. But mother thought it best. What's the matter, Loftie?"

"Only if you're going on in this strain I'm off to bed. It is hard on a fellow when he comes once in a while to see his sisters to be called over the coals by them. You know I'm awfully fond of you, Kitty, and somehow I thought you'd be a comfort to me. You know very little indeed of the real worries of life."

Loftus spoke in a tone of such feeling that Catherine's warm heart was instantly touched.

"I won't say any more," she answered. "I know it isn't right of me. I always wished and longed to be a help to you, Loftie."

"So you can. You are a dear little sis when you like. You're worth twenty of May. I think you are going to be a very handsome girl, Kate, and if you are only fed up properly, and dressed properly, so that the best points of your figure can be seen—well—now what's the matter?"

"Only I won't have you talking of me as if I were going to be put up to auction."

"So you will be when you go to London. All girls are. The mothers are the auctioneers, and the young fellows come round and bid. Good gracious, what a thunder-cloud! What flashing eyes! You'll see what a famous auctioneer mother will make! What is the matter, Kitty?"

"Nothing. Good-night. I'm going to bed."

"Come back and kiss me first. Poor little Kit! Dear, handsome, fiery-spirited little Kit! I say though, what a shabby frock you've got on!"

"Oh, don't worry me, Loftie! Any dress will do in the country."

"Right, most prudent Catherine. By the way, when did you say mother would come back?"

"Perhaps on Monday."

"What did she go to Manchester for?"

"I can't tell you."

"Well, I trust she will be back on Monday evening, for I am due at the Depot on Tuesday. Lucky for me I got a week's leave, but I didn't mean to see it out. It will be uncommonly awkward if I cannot get hold of the mater between now and Tuesday, Kate."

"Loftus—are you going to ask her to give you much money?"

"My dear child, you would think the sum I want enormous, but it isn't really. Most fellows would consider it a trifle. And I don't want her really to give it, Kate, only to lend it. That's altogether a different matter, isn't it? Of course I could borrow it elsewhere, but it seems a pity to pay a lot of interest when one's mother can put one straight."

"I don't know how you are to pay the money back, Loftus."

Loftus laughed.

"There are ways and means," he said. "Am I going to take all the bloom off that young cheek by letting its owner into the secrets of Vanity Fair? Come Kitty, go to bed, and don't fret about me, I'll manage somehow."

"Loftus, how much money do you want mother to lend you?"

"What a persistent child you are. You positively look frightened. Well, three fifty will do for the present. That oughtn't to stump anyone, ought it?"

"I suppose not," answered Kate, in a bewildered way.

She put her hand to her forehead, bade her brother good-night, and sought her room.

"Three hundred and fifty pounds!" she murmured. "And mother won't buy herrings more than eightpence a dozen! And we scarcely eat any meat, and lately we have begun even to save the bread. Three hundred and fifty pounds! Well, I won't tell Mabel. Does Mabel really know the world better than I do, and is it wrong of me in spite of everything to love Loftus?"

But notwithstanding all worries, the world in midsummer, when the days are longest and the birds sing their loudest, is a gay place for the young. Catherine Bertram stayed awake for quite an hour that night. An hour was a long time for such young and bright eyes to remain wide open, and she fancied with a wave of self-pity how wrinkled and old she would look in the morning. Not a bit of it! She arose with the complexion of a Hebe, and the buoyant and gladsome spirit of a lark.

As she dressed she sang, and when she ran downstairs she whistled a plantation melody with such precision and clearness that Loftus exclaimed, "Oh, how shocking!" and Mabel rolled up her eyes, and said sagely, that no one ever could turn Kate into anything but a tom-boy.

"Girls, what are we to do after breakfast?" asked the brother.

"Have you any money at all in your pocket, Loftie?" demurely asked Mabel, "for if so, if so—" her eyes danced, "I can undertake to provide a pleasant day for us all."

"Well, puss, I don't suppose an officer in her Majesty's Royal Artillery—is quite without some petty cash. How much do you want?"

"A few shillings will do. Let us pack up a picnic basket. Kate, you needn't look at me. I have taken Mrs. Masters into confidence, and there's a cold roast fowl downstairs—and—and—but I won't reveal anything further. We can have a picnic—we can go away an hour after breakfast, and saunter to that place known as the Long Quay, and hire the very best boat to be had for money, and we can float about on this lovely harbor, and land presently on the shore over there where the ruins of the old Port are; and we can eat our dinners there and be jolly. Remember that we have never but once been on the water since we came. Think how we have pined for this simple pleasure, Loftie, and fork out the tin."

"My dear Mabel, I must place my interdict on slang."

"Nonsense. When the cat's away. Oh, don't look shocked! Are we to go?"

"Go! of course we'll go. Is there no pretty girl who'll come with us? It's rather slow to have only one's sisters."

"Very well, Loftus. We'll pay you out presently," said Kate.

"And there is a very pretty girl," continued Mabel, "At least Catherine considers her very pretty—only—" her eyes danced with mischief.

"Only what?"

"The mother doesn't like her. There's a dear old Rector here, and he introduced the girl to Kitty, and mother was wild. Mother sounded the Rector the next day and heard something which made her wilder still, but we are not in the secret. Kate fell in love with the girl."

"Did you, Kate? When a woman falls in love with another woman the phenomenon is so uncommon that a certain amount of interest must be roused. Describe the object of your adoration, Kitty."

"Her name," responded Kate, "is Beatrice Meadowsweet. I won't say any more about her. If ever you meet her, which isn't likely, you can judge for yourself of her merits."

"Kitty is rather cross about Beatrice," said Mabel; then she continued, "Loftie, what do you think? Mother has cut all the Northbury folk."

"Mabel, you talk very wild nonsense."

It was Kate who spoke. She rose from the breakfast-table with an annoyed expression.

"Wild or not—it is true," replied Mabel. "Mother has cut the Northbury people, cut them dead. They came to see us, they came in troops. Such funny folk! The first lot were let in. Mother was like a poker. She astonished her visitors, and the whole scene was so queer and uncomfortable, although mother was freezingly polite, that Kate and I got out of the room. The next day more people came—and more, and more every day, but Clara had her orders, and we weren't 'at home.' Kitty and I used to watch the poor Northburians from behind the summer-house. One day Kitty laughed. It was awful, and I am sure they heard.

"Another day a dreadful little woman with rolling eyes said she would leave a tract on Lying in the avenue—I wish she had. But I suppose she thought better of it.

"Then there came a bazaar, a great bazaar, and the Rector invited us, and said all the Northburians would be there. What do you think mother did? She returned their calls on that day. She knew they'd be out, and they were. Wasn't that a dead cut, Loftie?"

"Rather," responded Loftus.

He rose slowly, looked deliberately at Kate, and then closed his lips.

"Mother is away, so we won't discuss her," said Kate. "Run and pack the picnic basket, Mabel, and then we'll be off."

The picturesque little town of Northbury was built on the slope of a hill. This hill gently descended to the sea. Nowhere was there to be found a more charming, landlocked harbor than at Northbury. It was a famous harbor for boating. Even at low tide people could get on the water, and in the summer time this gay sheet of dark blue sparkling waves had many small yachts, fishing smacks, and row-boats of all sizes and descriptions skimming about on its surface. In the spring a large fishing trade was done here, and then the steamers whistle? and shrieked, and disturbed the primitive harmony of the place. But by midsummer the great shoals of mackerel went away, and with them the dark picturesque hookers, and the ugly steamers, and the inhabitants were once more left to their sleepy, old-fashioned, but withal pleasant life.

Rosendale Manor was situated on high ground. It was surrounded by a wall, and the wide avenue was entered by ponderous iron gates. It was about eleven o'clock when the girls and their brother started gayly off for their day on the water. Loftus carried a couple of rugs, so that the fact of Mabel lugging a heavy picnic basket on her sturdy left arm did not look specially remarkable. They went down a steep and straggling hill, passed through an old-fashioned green, with the local club at one side, and a wall at the other which seemed to hang right over the sea.

They soon reached the Long Quay, and made their bargain for the best boat to be had. A man of the name of Driver kept many boats for hire, and he offered now to accompany the young party and show off the beauties of the place.

This, however, Mabel would not hear of. They must go alone or not at all. Loftus did not like to own to his very small nautical experience; the sea was smooth and shining, and apparently free from all danger, and the little party embarked gayly, and put out on their first cruise in high spirits.

Miss Peters and Mrs. Butler watched them with intense interest from their bay window. Miss Peters had possession of the spy-glass. With this held steadily before her eyes, she shouted observations to her sister.

"There they go! No, Dan Driver is not going with them! Any one can see by the way that young man handles the oar that he doesn't know a great deal about the water. Good gracious, Martha, they're taking a sail with them! Now I do call that tempting Providence. That young man has a very elegant figure, Martha, but mark my words he knows nothing at all about the management of a boat. The girls know still less."