Title: The Colonel of the Red Huzzars

Author: John Reed Scott

Illustrator: Clarence F. Underwood

Release date: November 22, 2005 [eBook #17131]

Most recently updated: December 13, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Al Haines

E-text prepared by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | A PICTURE AND A WAGER |

| II. | CONCERNING ANCESTORS |

| III. | IN DORNLITZ AGAIN |

| IV. | THE SALUTE OF A COUSIN |

| V. | THE SALUTE OR A FRIEND |

| VI. | THE SIXTH DANCE |

| VII. | AN EARLY MORNING RIDE |

| VIII. | THE LAWS OF THE DALBERGS |

| IX. | THE DECISION |

| X. | THE COLONEL OF THE RED HUZZARS |

| XI. | THE FATALITY OF MOONLIGHT |

| XII. | LEARNING MY TRADE |

| XIII. | IN THE ROYAL BOX |

| XIV. | THE WOMAN IN BLACK |

| XV. | HER WORD AND HER CERTIFICATE |

| XVI. | THE PRINCESS ROYAL SITS AS JUDGE |

| XVII. | PITCH AND TOSS |

| XVIII. | ANOTHER ACT IN THE PLAY |

| XIX. | MY COUSIN, THE DUKE |

| XX. | A TRICK OF FENCE |

| XXI. | THE BAL MASQUE |

| XXII. | BLACK KNAVE AND WHITE |

| XXIII. | AT THE INN OF THE TWISTED PINES |

| XXIV. | THE END OF THE PLAY |

It was raining heavily and I fastened my overcoat to the neck as I came down the steps of the Government Building. Pushing through the crowds and clanging electric cars, at the Smithfield Street corner, I turned toward Penn Avenue and the Club, whose home is in a big, old-fashioned, grey-stone building—sole remnant of aristocracy in that section where, once, naught else had been.

For three years I had been the engineer officer in charge of the Pittsburgh Harbor, and "the navigable rivers thereunto belonging"—as my friend, the District Judge, across the hall, would say—and my relief was due next week. Nor was I sorry. I was tired of dams and bridges and jobs, of levels and blue prints and mathematics. I wanted my sword and pistols—a horse between my legs—the smell of gunpowder in the air. I craved action—something more stirring than dirty banks and filthy water and coal-barges bound for Southern markets.

Five years ago my detail would have been the envy of half the Corps. But times were changed. The Spanish War had done more than give straps to a lot of civilians with pulls; it had eradicated the dry-rot from the Army. The officer with the soft berth was no longer deemed lucky; promotion passed him by and seized upon his fellow in the field. I had missed the war in China and the fighting in the Philippines and, as a consequence, had seen juniors lifted over me. Yet, possibly, I had small cause to grumble; for my own gold leaves had dropped upon me in Cuba, to the disadvantage of many who were my elders, and, doubtless, my betters as well. I had applied for active service, but evidently it had not met with approval, for my original orders to report to the Chief of Engineers were still unchanged.

The half dozen "regulars," lounging on the big leather chairs before the fireplace in the Club reception-room, waiting for the dinner hour, gave me the usual familiar yet half indifferent greeting, as I took my place among them and lit a cigar.

"Mighty sorry we're to lose you, Major," said Marmont. "Dinner won't seem quite right with your chair vacant."

"I'll come back occasionally to fill it," I answered. "Meanwhile there are cards awaiting all of you at the Metropolitan or the Army and Navy."

"Then you don't look for an early assignment to the White Elephant across the Pacific?" inquired Courtney.

"Good Lord!" exclaimed Hastings, "did you apply for the Philippines?"

"What ails them?" I asked.

"Everything—particularly Chaffee's notion that white uniforms don't suit the climate?"

I shrugged my shoulders.

"Is that a criticism of your superior officer?" Marmont demanded.

"That is never done in the Army," I answered.

"Which being the case let us take a drink," said Westlake, and led the way to the café.

"Looks rather squally in Europe," Courtney observed, as the dice were deciding the privilege of signing the check.

"It will blow over, I fancy," I answered.

"Have you seen the afternoon papers?"

"No."

"Then you don't know the Titian Ambassador has been recalled."

"Indeed! Well, I still doubt if it means fight."

Courtney stroked his grey imperial. "Getting rather near one, don't you think?" he said.

"No closer than France and Turkey were only a short while ago," I answered. "Moreover, in this case, the Powers would have a word to say."

"Yes, they are rather ready to speak out on such occasions; but, unless I'm much mistaken, if the Titians and the Valerians get their armies moving it will take more than talk from the Powers to stop them."

"And it's all over a woman," I observed carelessly.

Courtney gave me a sharp glance. "I thought that was rather a secret," he replied.

I laughed. "It's one, at least, that the newspapers have not discovered—yet. But, where did you get it?"

"From a friend; same as yourself," he said, with the suggestion of a smile.

"My dear fellow," I said. "I know more about the Kingdom of Valeria than—well, than your friend and all his assistants of the State Department."

"I don't recall mentioning the State Department," Courtney replied.

"You didn't. I was honoring your friend by rating him among the diplomats."

He ignored my thrust. "Ever been to Valeria?" he asked.

I nodded.

"Recently?"

"About six years ago."

"Is that the last time?"

"What are you driving at?" I asked.

He answered with another question: "Seen the last number of the London Illustrated News?"

"No," I answered.

He struck the bell. "Bring me the London News," he said to the boy. Opening it at the frontispiece he pushed it across to me.

"Has she changed much since you saw her?" he asked, and smiled.

It was a woman's face that looked at me from the page; and, though it was six years since I had seen it last, I recognized it instantly. There was, however, a certain coldness in the eyes and a firm set of the lip and jaw that were new to me. But, as I looked, they seemed to soften, and I could have sworn that for an instant the Princess Dehra of Valeria smiled at me most sweetly—even as once she herself had done.

"You seem uncommonly well pleased with the lady," Courtney observed.

I handed back the News.

"You have not answered my question," he insisted.

"Look here, Courtney," I said, "it seems to me you are infernally inquisitive to-night."

"Maybe I am—only, I wanted to know something," and he laughed softly.

"Well?"

"I think I know it now," he said.

"Do you?" I retorted.

"Want to make a bet?" he asked.

"I never bet on a certainty," said I.

Courtney laughed. "Neither do I, so here's the wager:—a dinner for twenty that you and I are in Valeria thirty days from to-night and have dined with the King and danced with the Princess."

"Done!" said I.

"All I stipulate is that you do nothing to avoid King Frederick's invitation."

"And the Princess?" I asked.

"I'm counting on her to win me the bet," he laughed.

I picked up the picture and studied it again. The longer I looked the more willing I was to give Courtney a chance to eat my dinner.

"If the opportunity comes I'll dance with her," I said.

"Of course you will—but will you stop there, I wonder?"

I tapped my grey-besprinkled hair.

"They are no protection," he said. "I don't trust even my own to keep me steady against a handsome woman."

"They are playing us false even now," said I. "I'm not going to Valeria to decide a dinner bet."

"You're not. You're going as the representative of our Army to observe the Valerian-Titian War."

"You're as good as a gypsy or a medium. When do I start?"

"Don't be rude, my dear chap, and forget that, under the wager, I'm to be in the King's invitation—also the dance. We sail one week from to-day."

"A bit late to secure accommodations, isn't it?"

"They are booked—on the Wilhelm der Grosse."

"You are playing a long shot—several long shots," I laughed:—"War—Washington—me."

"Wrong," said Courtney. "I'm playing only War. I have the Secretary and the Princess has you."

"You have the Secretary!"

"Days ago."

"The Devil!" I exclaimed, lifting my glass abstractedly.

"The Princess! you mean," said Courtney quickly, lifting his own and clicking mine.

I looked at the picture again—and again it seemed to smile at me.

"The Princess!" I echoed; and we drank the toast. "We're a pair of old fools," said I, when the glasses were emptied.

Courtney picked up the News and held the picture before me.

"Say that to her," he challenged.

"I can't be rude to her very face," I answered lamely.

Just then one of the "buttons" handed me a telegram. I tore open the yellow envelope and read the sheet, still damp from the copy-press. It ran:—

"Titia declares war. Detail as attaché open. If desired report at

headquarters immediately. Hennecker relieves you in morning. Answer."

"(signed) HENDERSON, A. A. G."

I tossed it over to Courtney. "You're that much nearer the dinner," I said.

"And the Princess also," he added.

"Then you're actually going?" I asked.

"My dear Major, did you ever doubt it?"

"Your vagaries are past doubting," I answered.

"And yours?"

"I am going under orders of the War Department."

"Of course," he answered, "of course. And, that being so, you won't mind my confessing that I'm going largely on account of—a woman."

"I won't mind anything that gives me your companionship."

"So, it's settled," he said. "Let us have some dinner, and then cut in for a farewell turn in the game of hearts upstairs."

"It will be another sort of game over the water," I observed.

"Yes—with a different sort of hearts," he said thoughtfully.

"Is it possible, Courtney, you are growing sentimental?" I demanded.

He shrugged his shoulders. "There's no fool like an old fool, you know," he answered.

"Unless it be one that is just old enough to be neither old nor young," said I.

Then we went in to dinner.

Courtney is a good fellow; one of the best friends a man can have; well born, rich, with powerful political connections in both Parties, and having no profession nor necessary occupation to tie him down. His tastes ran to diplomacy, and Secretaries of State—knowing this fact, and being further advised of it at various times by certain prominent Senators—had given him numerous secret missions to both Europe and South America. Legations had been offered to him but these he had always declined; for, as he told me, he preferred the quiet, independent work, that carried no responsible social duties with it.

It happened that General Russell, our representative at the Court of Valeria, was home on vacation. Naturally, he would now return in all haste. Here, I imagined, was an explanation of my sudden orders. He was an intimate of our family; had known me since childhood, and, doubtless, had asked for my detail to his household, and also for Courtney's. And Courtney, naturally, having been early consulted in the matter, knew all the facts and so was able to bluff at me with them. It would be just as well to call him.

"Is General Russell crossing with us?" I asked carelessly.

Courtney shook his head. "He is not going back to Valeria."

"Oh!" said I, realizing suddenly my mistake, "I didn't appreciate I was dining with an Ambassador."

"It's not yet announced. However, I'm glad it does not change me," he laughed.

"I can tell that better after we reach Valeria—and you have danced with the Princess."

He sipped his coffee meditatively. "Yes, there may be changes in Valeria in us both," he said presently.

"Don't do the heavy reproof if I chance to forget the difference in our rank," I answered. "But you must manage one turn for me with Her Royal Highness, if you're to eat my dinner, you know."

"How many times have you been to Valeria?" he asked suddenly.

"Some half dozen," I replied, surprised.

"Ever been in the private apartments of the Palace of Dornlitz?"

"No—I think not."

"I mean, particularly, the corridor where hang the portraits of the Kings?"

"I don't recall them."

He laughed shortly. "Believe me, you would recall them well," he said.

"What the devil are you driving at?" I asked.

"I'll show you the night you dance with the Princess."

"A poor army officer doesn't usually have such honors."

"No—not if he be only a poor army officer. But, if he chance to be——-"

"Well," I said, "be what?"

"I'll tell you in the picture gallery," he answered.

And not another word would he say in the matter.

However, I did not need to wait so long for my answer. I knew it quite as well as Courtney—maybe a trifle better. Nevertheless, it is a bit jolting to realize, suddenly, that some one has been prying into your family history.

On the west wall of the Corridor of Kings, in the Palace of Dornlitz, hung the full-length portrait of Henry, third of the name and tenth of the Line. A hundred and more years had passed since he went to his uncertain reward; and now, in me, his great-great-grandson, were his face and figure come back to earth.

I had said, truly enough, that I had never been in the Gallery of Kings. But it was not necessary for me to go there to learn of this resemblance to my famous ancestor. For, handed down from eldest son to eldest son, since the first Dalberg came to American shores, and, so, in my possession now, was an ivory miniature of the very portrait which Courtney had in mind.

And the way of it, and how I chanced to be of the blood royal of Valeria, was thus:

Henry the Third—he of the portrait—had two sons, Frederick and Hugo, and one daughter, Adela. Frederick, the elder son, in due time came to the throne and, dying, passed the title to his only child, Henry; who, in turn, was succeeded by his only child, Frederick, the present monarch.

Adela, the daughter, married Casimir, King of Titia,—and of her descendants more anon.

Hugo, the younger son, was born some ten years after his brother,—to be accurate, in 1756,—and after the old King had laid aside his sword and retired into the quiet of his later years. With an honestly inherited love of fighting, and the inborn hostility to England that, even then, had existed in the Valerians for a hundred years, Hugo watched with quickening interest the struggle between the North American Colonies and Great Britain which began in 1775. When the Marquis de Lafayette threw in his fortunes with the Americans, Hugo had begged permission to follow the same course. This the old King had sternly refused; pointing out its impropriety from both a political and a family aspect.

But Hugo was far from satisfied, and his desire to have a chance at England waxing in proportion as the Colonies' fortunes waned, he at last determined to brave his fierce old father and join the struggling American army whether his sire willed it or no. His mind once formed, he would have been no true son of Henry had he hesitated.

The King heard him quietly to the end,—too quietly, indeed, to presage well for Hugo. Then he answered:

"I take it sir, your decision is made beyond words of mine to change. Of course, I could clap you into prison and cool your hot blood with scant diet and chill stones, but, such would be scarce fitting for a Dalberg. Neither is it fitting that a Prince of Valeria should fight against a country with which I am at peace. Therefore, the day you leave for America will see your name stricken from the rolls of our House, your title revoked, and your return here prohibited by royal decree. Do I make myself understood?"

So far as I have been able to learn, no one ever accused my great-grandfather of an inability to understand plain speech, and old Henry's was not obscure. Indeed, Hugo remembered it so well that he made it a sort of preface in the Journal which he began some months thereafter, and kept most carefully to the very last day of his life. The Journal says he made no answer to his father save a low bow.

Two days later, as plain Hugo Dalberg, he departed for America. For some time he was a volunteer Aide to General Washington. Later, Congress commissioned him colonel of a regiment of horse; and, as such, he served to the close of the war. When the Continental Army was disbanded, he purchased a place upon the eastern shore of Maryland; and, marrying into one of the aristocratic families of the neighborhood, settled down to the life of a simple country gentleman.

He never went back to the land of his birth, nor, indeed, even to Europe. And this, though, one day, there came to his mansion on the Chesapeake the Valerian Minister to America and, with many bows and genuflections, presented a letter from his brother Frederick, announcing the death of their royal father and his own accession, and offering to restore to Hugo his rank and estates if he would return to court.

And this letter, like his sword, his Order of the Cincinnati, his commissions and the miniature, has been the heritage of the eldest son. In his soldier days his nearest comrade had been Armand, Marquis de la Rouerie, and for him his first-born was christened; and hence my own queer name—for an American: Armand Dalberg.

There was one of the traditions of our House that had been scrupulously honored: there was always a Dalberg on the rolls of the Army; though not always was it the head of the family, as in my case. For the rest, we buried our royal descent. And though it was, naturally, well known to my great-grandsire's friends and neighbors, yet, in the succeeding generations, it has been forgotten and never had I heard it referred to by a stranger.

Therefore, I was surprised and a trifle annoyed at Courtney's discovery. Of course, it was possible that he had been attracted only by my physical resemblance to the Third Henry and was not aware of the relationship; but this was absurdly unlikely, Courtney was not one to stop at half a truth and Dalberg was no common name. Doubtless the picture had first put him on the track and after that the rest was easy. What he did not know, however, but had been manoeuvring to discover, was how far I was known at the Court of Valeria. Well, he was welcome to what he had got.

Now, as a matter of fact, it was quite likely that the Dalbergs of Dornlitz had totally forgotten the Dalbergs of America. Since Frederick's minister had rumbled away from that mansion on the Chesapeake, a century and more ago, there had been no word passed between us. Why should there be? We had been disinherited and banished. They had had their offer of reinstatement courteously refused. We were quits.

I think I was the first of the family to set foot within Valeria since Hugo left it. Ten years ago, during a summer's idling in Europe, I had been seized with the desire to see the land of my people. It was a breaking of our most solemn canon, yet I broke it none the less. Nor was that the only time. However, I had the grace,—and, possibly, the precaution,—to change my name on such occasions. In the Kingdom of Valeria I was that well-known American, Mr. John Smith.

I did the ordinary tourist; visited the places of interest, and put up at the regular hotels. Occasionally, I was stared at rather impertinently by some officer of the Guards and I knew he had noted my resemblance to the national hero. I never made any effort to be presented to His Majesty nor to establish my relationship. I should have been much annoyed had anything led to it being discovered.

Once, in the park of the palace, I had passed the King walking with a single aide-de-camp, and his surprise was such he clean forgot to return my salute; and a glance back showed him at a stand and gazing after me. I knew he was thinking of the portrait in the Corridor of Kings. That was the last time I had seen my royal cousin.

The next day, while riding along a secluded bridle path some miles from Dornlitz, I came upon a woman leading a badly-limping horse. She was alone,—no groom in sight,—and drawing rein I dismounted and asked if I could be of service. Then I saw her face, and stepped back in surprise. Her pictures were too plentiful in the capital for me to make mistake. It was the Princess Dehra.

I bowed low. "Your Royal Highness's pardon," I said. "I did not mean to presume."

She measured me in a glance. "Indeed, you are most opportune," she said, with a frank smile. "I have lost the groom,—his horse was too slow,—and I've been punished by Lotta picking a stone I cannot remove."

CONCERNING ANCESTORS 25

"By your leave," I said, and lifted the mare's hoof. Pressing back the frog I drew out the lump of sharp gravel.

"It looks so easy," she said.

"It was paining her exceedingly, but she is all right now."

"Then I may mount?"

I bowed.

"Without hurting Lotta?" she asked.

I turned the mare about and dropped my hand into position. For a moment she hesitated. Then there was the swish of a riding skirt, the glint of a patent-leather boot, an arched foot in my palm, and without an ounce of lift from me she was in the saddle.

I stepped back and raised my hat.

She gathered the reins slowly; then bent and patted the mare's neck.

I made no move.

"I am waiting," she said presently, with a quick glance my way.

"I do not see the groom," said I, looking back along the road.

She gave a little laugh. "You won't," she said. "He thinks I went another way."

"Then Your Highness means——"

"You do not look so stupid," she remarked.

"Sometimes men's looks are deceiving."

"Then, sir, Her Highness means she is waiting for you to mount," she said, very graciously.

"As her groom?" I asked.

"As anything you choose, so long as you ride beside me to the hill above the Park."

I took saddle at the vault and we trotted away.

"Why did you make me ask for your attendance?" she demanded.

"Because I dared not offer it."

"Another deception in your looks," she replied.

I laughed. She had evened up.

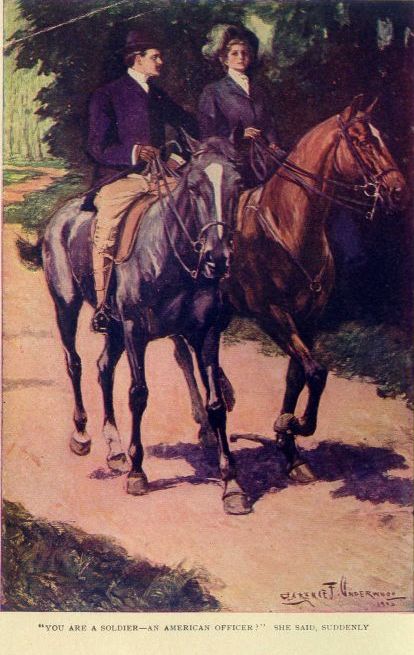

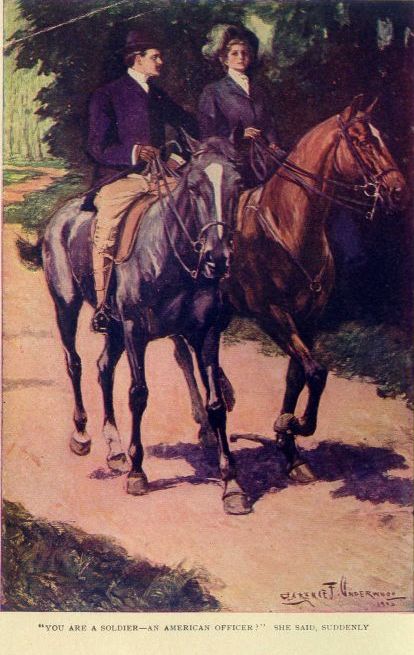

"You are a soldier—an American officer?" she said suddenly.

"Your Highness has guessed most shrewdly," I answered, in surprise.

"Are you staying at the Embassy?" she asked.

"No," said I. "I am not on the staff. I am only a bird of passage."

"Do you know General Russell?"

"My father knew him, I believe," I answered, evasively, and turned the talk into less personal matters.

When we reached the hill I drew rein. Down in the valley lay the Summer Palace and the gates of the Park were but a few hundred yards below us. I dismounted to say good-bye.

"I am very grateful for your courtesy," she said.

"It is for the stranger to be grateful for your trust," I answered.

She smiled,—that smile was getting into my poor brain—"A woman usually knows a gentleman," she said.

I bowed.

"And under certain circumstances she likes to know his name," she added.

For a moment I was undecided. Should I tell her and claim my cousinship? I was sorely tempted. Then I saw what a mistake it would be,—she would not believe it,—and answered:

"John Smith, Your Royal Highness, and your most obedient servant."

She must have noticed my hesitation, for she studied my face an instant, then said, with a pause between each word and a peculiar stress on the name:

"General—Smith?"

"Simple Captain," I answered. "We do not climb so rapidly in our Army."

Just then, from the barracks three miles away, came the boom of the evening gun.

"Oh!" she exclaimed, "I am late. I must hasten. Good-bye, mon Capitaine; you have been very kind."

She drew off her gauntlet and extended her hand. I bent and kissed,—possibly too lingeringly,—the little fingers.

"Farewell, Princess," I said. And then, half under my breath, I added: "Till we meet again."

She heard, and again that smile. "'Auf Wiedersehen' be it," she answered.

Then she rode away.

I leaned against my horse's shoulder and watched her as she went slowly down the hill, the full glory of the sinking sun upon her, and the shadows of the great trees close on either side. Presently there came a bend in the road and, turning in the saddle, she waved her hand.

I answered with my hat. Then she was gone. That was how I met the Princess Royal of Valeria. And, unless she has told it (which, somehow, I doubt), none knows it but ourselves. I had never seen her since. Perhaps that is why I was quite content for Courtney to win his bet. Truly, a man's heart does not age with his hair.

The declaration of war by Titia had come so suddenly that when Courtney and I sailed for Europe, the Powers were still in the air and watching one another. No battle had been fought; but the armies were frowning at each other on the frontier, and several skirmishes had occurred.

Ostensibly, the trouble was over a slice of territory which Henry the Third had taken from Titia as an indemnity for some real or fancied wrongs done him. Valeria, with its great general and powerful army, was too strong in those days for Titia to do more than protest—and, then, to take its punishment, which, for some reason that was doubtless sufficient to him. Henry had seen fit to make as easy as it might be, by giving his daughter, Adela, to Casimir for wife.

Whether the lady went voluntarily or not I cannot say. Yet it was, doubtless, the same with both Kings: The one got an unwilling province; the other, an unwilling bride. Only, Titia's trouble was soonest over.

This ravished Murdol had always been a standing menace to the peace of the two countries; Titia had never forgiven its seizure, and Valeria was afflicted with the plague of disaffected subjects on its very border. Here, as I have said, was the real casus belli,—a constant irritation that had at length got past bearing.

But, in truth, the actual breach was due to a woman. The Crown Prince of Titia had come a wooing of the Princess Royal of Valeria, and had been twice refused by her. King Frederick had left the question entirely in her hands. Her choice was her own, to marry or to decline. As a matter of state policy the match was greatly desired by him and his Ministers. They were becoming very weary of Murdol and the turmoil it maintained on the border, and the great force of troops required there to preserve order. Then, too, Titia had grown vastly in wealth and population since old Henry's time, and, now, was likely more than a match for its ancient enemy. Frederick was aging and desired peace in his closing years. He had long wished for a diplomatic way to rid himself of the troublesome province, and the marriage of Casimir and Dehra would afford it. Murdol could be settled upon the Princess as her dower.

It was an admirable solution of the whole vexing question. Yet, unlike old Henry, Frederick was the father before he was the King; and, beyond telling the Princess frankly the policy which moved him in the matter, he did nothing to coerce her. But the Ministers had no scruples of affection nor of kinship to control them and they brought all sorts of persuasive pressure upon her to obtain her consent to the match. All this was known to the Kingdom, and the vast majority of the people were with the Princess. The Army was with her to a man.

The first proposal Dehra had declined promptly to the Prince in person. He had made it lover-like, and not through the diplomatic channels. After that the Titian Foreign Office took a hand, and the poor girl's troubles began.

For six months the matter pended,—and still Dehra held firm. Then Titia mobilized its army and demanded a decision within two days:—either the Princess or Murdol. It got a "No" in two hours. The declaration of war followed straight-way.

Most of these facts were already known to me. Those of latest happening came to Courtney from the State Department on the eve of our sailing.

"It looks like a one-battle war," he had observed.

"Add a letter to your sentence and you will be nearer right," I answered.

He laughed. "A none-battle war, you mean."

And so it proved. When we landed it was to find that Germany had offered to mediate, and that, while the two Kingdoms were thinking it over, a truce had been declared. Consequently, instead of hurrying straight to the Valerian army, I journeyed leisurely with Courtney to the capital. There the first news that met us was that Germany's mediation had been accepted and that the war was at an end—for the present, at least.

So, once again, had the Powers, in the interest of European peace, struck up the swords.

As we drove from the station to the Embassy we observed flags flying from almost every house, and that the public buildings were lavishly decorated.

"Peace seems to be well received," I remarked.

"It's the King's birthday," Courtney answered.

"And a very happy one, I fancy."

Courtney stared at me. "How so?" he said.

"He can now both keep his daughter and be rid of Murdol."

"The Princess is saved, of course, but in deference to the national self-respect, he dare give up Murdol only in one contingency:—if Titia can be persuaded to pay a money value for it. Which I doubt."

I said nothing. I, too, doubted.

"However, it's not important to us," said he. "Whatever the outcome the lady will be here long enough for you to lose the wager."

"Damn the wager," I exclaimed.

"Damn everything you have a mind to, my dear fellow," he encouraged.

"And you in particular," I said.

"Wherefore, my dear Major?" he laughed.

"For suggesting this fool thing."

"Poor boy! I should have regarded your youthful impetuosity."

I shrugged my shoulders.

"And grey hairs," he added.

"I've a mind to toss you out of the carriage," said I.

"Do it,—and save me the trouble of getting myself out," he answered; and then we drew under the porte cochère at the Embassy.

The matter of a residence had not bothered Courtney. He simply took General Russell's lease off his hands, and twenty thousand a year rent with it. I was to live at the Legation, there being no Ambassadorial women folks to make the staff de trop. Naturally, I was quite satisfied. It was a bit preferable to hotel hospitality. And, then, the assistants were good fellows.

Cosgrove, who had been First Secretary for ten years, was from the estate next my own on the Eastern Shore. It was through him I had been able to preserve my incog. so securely during my former visits to Valeria. And if he had any curiosity as to my motives, he was courteous enough never to show it. "The best assistant in Europe," Courtney had once pronounced him.

Then there was Pryor, the Naval Attaché. He had been off "cruising with the Army," as Cosgrove put it, pending my arrival and was not yet returned to Dornlitz. The others of the office force were young fellows,—rich boys, either in presente or futuro,—who, likely, could only be depended upon to do the wrong thing. Being fit for nothing at home, therefore, they had been considered to be particularly well qualified for the American diplomatic service.

My room overlooked the Avenue, and the writing-desk was near the window. I was drawing the formal report to the War Department of my arrival at Dornlitz and the status political and military, when the clatter of hoofs on the driveway drew my attention. It was a tall officer in the green-and-gold of the Royal Guards, and pulling up sharply he tossed his rein to his orderly. I heard the door open and voices in the hall; and, then, in a few minutes, he came out and rode away, with the stiff, hard seat of the European cavalryman. I was still watching him when Courtney entered.

"What do you think of him?" he asked.

"I haven't seen enough of him to think," said I.

"Not even enough to wonder who he is?"

I yawned. "His uniform tells me he is a colonel of the Guard."

"But nothing else?"

"I can read a bit more."

"From the uniform?" he asked.

I nodded.

"You're a veritable Daniel," Courtney laughed. "What saith the writing—or rather, what saith the uniform?"

"It's very simple to those who read uniforms."

"So!" said he. "I await the interpretation."

"It's too easy," I retorted. "A Point Plebe could do it. Your visitor was one of His Majesty's Aides-de-Camp bearing an invitation to the ball at the Palace to-night."

For once I saw Courtney's face show surprise.

"How did you guess it?" he said, after a pause.

"A diplomat should watch the newspapers," said I, and pointed to this item in the Court News of that morning's issue:

"His Excellency the Honorable Richard Courtney, the newly accredited American Ambassador, is expected to arrive to-day. He is accompanied by Major Dalberg, the Military Attaché. His Majesty has ordered his Aide-de-Camp, Colonel Bernheim, to invite them to the Birthday Ball to-night; where they will be honored by a special presentation."

Courtney read it carefully. "At last I see the simple truth in a daily paper," he commented. "But, as for you, my friend, button your coat well over your heart for it's in for a hard thump tonight."

"So?" said I.

"There won't be so much indifference after you've met Her and—seen a certain picture in the Corridor of Kings," he retorted, with a superior smile.

"Think not?" said I, with another yawn. "What if I've done both years ago?"

He eyed me sharply. "It's foolish to bluff when a show-down is certain," he said.

"So one learns in the army."

"Of course not every hand needs to bluff," he said slowly.

"No—not every hand," I agreed.

He went over to the door. On the threshold he turned.

"I wonder if this is my laugh, or yours, to-night," he said.

"We will laugh together," I answered.

Then he went out.

I would have been rather a wooden sort of individual had I felt no stir in my heart as, for the first time, I entered the Castle of my ancestors and stood in the ante-chamber waiting to be presented to the Head of my House. I believe I am as phlegmatic as most men, but I would give very little for one who, under like conditions, would not feel a press of emotion. I know it came to me with sharp intensity,—and I see no shame in the admission; nor will any one else whose heart is the heart of an honest man. I have no patience with those creatures who deride sentiment. They are either liars or idiots. Religion, itself, is sentimental; and so is every refined instinct of our lives. Destroy the sentimental in man and the brute alone remains.

We waited but a moment and then were ushered into the royal presence. The greeting was entirely informal. Courtney was no stranger to Valeria, and had met the King frequently during the last ten years. Frederick came forward and shook his hand most cordially and welcomed him to Court. It was like the meeting of two friends. During it I had time to observe the King.

He wore the green uniform of a General, with the Jewel of the Order of the Lion around his neck. His sixty odd years sat very lightly and left no mark save in the facial wrinkles and grey hair. He was a true Dalberg in height and general appearance, and with the strong, straight nose that was as distinctive to our family as was the beak to the Bourbons.

I had remained in the background during Courtney's greeting, but, when he turned and presented me, I advanced and bowed. As I straightened, the King extended his hand saying:

"We are glad to———"

Then he caught a full view of my face and stopped, staring. I dropped his hand and stepped back; and, for a space, no one moved. Only, I shot a side glance at Courtney and caught a half smile on his lips. Then Frederick recovered himself.

"Your pardon, sir, but I did not catch the name," he said.

Courtney's finesse saved me the embarrassment of a self-introduction.

"Major Dalberg, of the United States Army, Your Majesty," he said quickly. "The representative of our War Department with your army."

"Dalberg—Dalberg," he muttered; then added, perfunctorily: "Our army is at your service, sir, though I fear we shall be unable to give you the war."

"The army is quite enough, Sire," I began; but it was plain he did not hear me. He was studying my face again and thinking. Courtney, I could see, was having the finest sort of sport. I could have throttled him.

"You have our name, Major," said the King. "May I ask if it is a common one in America?"

"I know of no family but my own that bears it, there," I answered.

He sat down and motioned for us to do likewise.

"I am interested," said he. "Has your family been long in America?"

"Since the year 1777."

He leaned a bit forward. "That was during your Revolutionary War."

"Yes, Your Majesty. It was that year Lafayette joined Washington's Army." That will give him a surprise, I thought.

It did.

"Do you know the name of the Dalberg of 1777?" he asked quickly.

I saw no profit in evasion. "He was Hugo, second son of Henry the Third of Valeria," I replied.

"I knew it," he exclaimed, jumping up and coming over to me. "And you are?"

"His great-grandson and eldest male heir."

"Then, as such, I salute you, cousin," he said, and suddenly kissed me on the cheek.

Were you ever kissed by a man? If so, and you are a woman, it doubtless was pleasant enough, and, maybe, not unusual; but if you are a man, it will surprise you mightily the first time.

Of course, I understood all the significance of Frederick's action. Royalty on the Continent so greets only royalty or relatives. It meant I was accepted as one of the Blood and a Prince of my House. I admit my pride was stirred.

"Your Majesty overwhelms me," I said, bowing again. "I expected no recognition. I am entitled to none. Our name was stricken from the Family Roll."

He made a deprecating gesture. "Don't let that disturb you, cousin."

"And believe me, also, I had no intention to disclose my relationship," I protested.

The King laughed. "You could not hide it with that face," he said.

I must have flushed, for he exclaimed: "Ha! You know that, do you?"

For answer I drew out the miniature of old Henry, which I had brought hoping for an opportunity to compare it with the original, and handed it to him.

He gave it a quick glance and nodded. "Yes, that went with Hugo," he said.

I was surprised and looked it.

"Oh, the family records are very complete as to the affair of your headstrong ancestor," he explained. "Old Henry himself set it all out in his journal; and he speaks of this very miniature as having been given to Hugo by his mother, the day he left Dornlitz. There were two of them, copied from the portrait in the Corridor." He crossed to a cabinet. "And here is the other one," he said.

I glanced at Courtney. He threw up his hands in defeat; at the same time, however, signifying that I should press my advantage while the King was so well disposed.

But I shook my head. My descent had been acknowledged, and that was quite enough—more than enough, indeed. I had come to Valeria as a Major in the American Army. I sought no favors from the Dalbergs here. From which it would seem that a bit of Hugo's stubborn independence had come down to me. As for Courtney, the shrug of his shoulders was very eloquent of what he thought of such independence.

"Perchance you never heard of a certain letter dispatched to Hugo by his brother, Frederick, after Henry's death?" the King asked.

"And delivered by his Ambassador," I supplemented.

"The same. Hugo, too, seems to have kept a journal."

"He kept the letter itself, and a copy of his answer," I added.

The King laughed. "Altogether, Hugo must have been a rare fine fellow, with a mind of his own."

"He was a son of Henry the Third," I answered.

The King nodded. "Yet 'twas a pity he did not accept Frederick's offer."

"I fancy the new life was more to his mind."

"Doubtless,—but, had he returned, it would be you and not Ferdinand of Lotzen who would be the Heir Presumptive of Valeria."

I smiled. "Had he returned I would not be I."

"True enough," said he. "But think of the crown of your ancestors that might be yours."

"It is enough to be a Dalberg. I have never thought of the crown," I answered.

"There spoke the son of Hugo," he said.

Then, suddenly, he seemed to remember that we were not alone, and, springing up, he sought out Courtney, who, though unable to get out of ear-shot, had courteously retired to the remotest corner of the room.

"My dear Courtney," he exclaimed. "I have been unpardonably rude. I forgot you completely. Yet, you brought it on yourself; you should have prepared me for my cousin."

But Courtney had his part to play. He must keep the American Ambassador free from fault.

"Major Dalberg never disclosed his relationship to your Majesty," he said, formally; "else, as you are well aware, he could not have been given the detail without your express permission. As it is, I shall be obliged to report the matter to my Government and——"

"Do so, by all means, if it will keep your records clear," the King cut in, in the same formal tone; "but be careful, at the same time, to say to your State Department that we shall deem it a personal affront if our Kinsman be recalled. And, now, sir," he went on with an amused smile and dropping the conventional air, "confess it. Didn't you suspect the relationship?"

"I have been a guest at the Court of Valeria too often not to have noted a certain resemblance," Courtney admitted readily. Then, like a good fellow, he set me right. "But, be assured, Your Majesty, not I nor I believe anyone, has ever heard Major Dalberg speak of his royal descent; though I admit I have tried hard to draw him to it."

The King looked at me and nodded in approval.

"It is a law of the family, laid down by Hugo himself," I explained. "Though, of course, our silence does not prevent anyone from proving the fact who investigates our genealogy," and I glanced significantly at Courtney.

This time it was he who doubled his fist at me.

Then a door behind me opened and I heard the trail of a gown—whose, it was easy to guess. Only one woman could have the privilege of entering the King's presence unbidden.

As Courtney and I arose and stepped back, the Princess halted uncertainly.

"Come, Dehra," said the King. "You know the American Ambassador."

Courtney bowed, but the Princess held out her hand, saying cordially:

"We are glad to welcome Mr. Courtney here as a resident."

Courtney made some fitting reply,—there was always one on the end of his tongue. And then the King turned to me.

"Major Dalberg," he said, "salute your cousin."

I do not know which cousin was the more startled, but I am quite sure which was the more embarrassed. In truth, for a moment, I was too confused to move. The one thought that kept pounding through my brain was: "What am I expected to do?" Frederick had saluted me with a kiss; was it possible he meant me to kiss Dehra! I glanced across at Courtney,—he was struggling to suppress his merriment,—then back at the Princess; and caught what I was fool enough to imagine was a look of glad surprise. She had recognized and remembered me.

That settled it. I stepped forward and deliberately kissed her on the cheek.

The next instant my mouth stung with the blow of an open hand, and I was looking down into the flashing eyes and flaming face of the Princess.

It was quite evident I had not been expected to kiss her.

"Sir!" she exclaimed. "Sir!" And with each word she seemed to strike me afresh. Then words failed her, and with another gesture of disdain she gave me her back.

"Your Majesty, who is this——?" she began.

Then she stopped and I heard her catch her breath. The next moment, with high-held head she swept by me and from the room. And with her going crumbled all the bright castles I had builded on the memories of that ride in the forest, six years before.

Of course I had been a silly fool. The fiend himself must have possessed me. But I had kissed her, and that was something to remember,—though, doubtless, that itself but proved me the greater idiot. All this and much more whirled through my mind in the moment of the Princess's leaving; then I turned, expecting to face the scorn of the King,—and found him wiping the tears from his eyes and shaking with laughter.

So this was what had seat Dehra from the room in anger. And, straightway, the skies brightened. Plainly, if her father were not offended, I might yet make my peace with her.

Then I, too, began to smile. Doubtless there was a funny side to it; though it seemed to be more evident to the spectators than to me. At any rate, the King still laughed, and so did Courtney; though quietly and discreetly. His, I admit, I did not relish; so I spoke.

"I am very sorry, Your Majesty; I meant no offence——" I began.

"Nonsense, Major," the King interrupted. "You gave none."

"Indeed!" I said, and rubbed my mouth.

"Oh, don't hold that against the Princess," he chuckled.

"She didn't hit half hard enough." I said. "She should have knocked me down."

He shook his head. "She misunderstood the whole matter. I forgot she, doubtless, knows nothing of the American branch of the House; so, my calling you cousin conveyed no meaning, if indeed she even heard it. She simply thought you a presumptuous stranger."

"And so I am."

He waved the idea aside. "You are her nearest male relative after myself."

"That may mitigate my presumption—but, none the less, I'm a stranger."

"No Dalberg is stranger to a Dalberg, and least of all in the presence of the Dalberg King," he said. Then the smile came again. "But, by the Lord, sir, I admire your pluck—to kiss the Princess Royal of Valeria before her father's very face."

"It wasn't pluck," I protested. "It was rank ignorance. I was at a loss what greeting was proper;" and I explained my perplexity.

"Of course," he said kindly, but with a shrewd twinkle in his blue eyes, "I understand. Only, I fancy it would be wiser that I make your excuses to your cousin. For, believe me, my dear Major, for one in such doubt you kissed her with amazing promptness."

This time Courtney laughed aloud and the King and I joined him.

"Then you think I may venture, sometime, to speak to her without renewed offence?" I asked presently, as we were about to retire.

"Assuredly," said the King. "When you meet her again to-night act as though you had known her always. I'll answer for it, she will not respond with a blow."

Just at the door he called to me.

"Major," he said, "which would be your preference: to be introduced to-night as one of the Blood, or to hold off a while and continue your duties as American Attaché?"

I had had this very matter in my mind a moment before. "With Your Majesty's permission I will execute my orders—at least, for the present," I said.

"I think that were the proper course under the circumstances. Meanwhile, we will provide that you have the entrée, and as many prerogatives of your birth as are properly consistent with conditions."

Without, a chamberlain awaited to conduct us to the Hall of the Kings, where the birthday ball was to be held.

One Court function is pretty much like another, Europe over. There is the same sparkle of jewels and shimmer of silk on aristocratic woman; the same clank of spur and rattle of sword and brilliancy of uniform on official man.

Courtney had long ago become familiar with it all, and I in my details and travels had seen enough to make me indifferently easy, at least. We had tarried overtime with the King, and, so, were the last to reach the Hall. At the door Cosgrove joined us and under his guidance we made our way to the diplomatic line. Scarcely were we there when His Majesty and the Princess Royal were announced and between the ranks of bowing guests they passed to the throne. As Frederick stepped upon the dais there arose spontaneously the shout, thrice repeated:

"Long live the King!"

And then someone cried:—

"Long live Dalberg!" And the throng joined in it twice again.

How the King acknowledged it I do not know. My whole attention was given to the Princess. It was my first good view of her since the day I had acted as substitute groom. For the bad few minutes lately passed had been given over to labial and mental sensations to the exclusion of the ocular. Now I had more leisure while those ranking and senior to Courtney made their felicitations upon the royal birthday.

She was little changed from my lady of the forest; only a bit more roundness to the figure and maturity in the face, particularly about the set of the mouth when in repose. Otherwise, she was the same charming woman who had smiled me into subjection six years before. Beautiful? Of course; but do not ask me for description, other than that she was medium in height, willowy in figure and dark blonde in type. With that outline your imagination must fill in the rest. Words only caricature a glorious woman.

When it came our turn, the King seemed to make it a point to greet me with marked cordiality; not waiting for my name to be announced, but stepping over to the edge of the dais to meet me and holding me in conversation an unusual time. It was noticed to the Court that I had the royal favor.

Then, with the quiet aside: "It's all explained," he passed me over to the Princess.

She was talking with Courtney, and turned and met me with a smile.

"Let us shake hands and be friends, cousin," she said.

The graciousness of the gesture, was plain enough to the whole room, but the words reached only Courtney and me.

"I don't deserve it—cousin," I said; but I took her hand, none the less.

Then, after a word more, we gave place to those that followed us. But, as I bowed away, she said low: "The sixth dance, cousin."

And so I knew my peace was made.

I looked for some banter from Courtney, but there was none; only a bit of a smile under the grey moustache. What he said was:

"Come, let us circle the room and see whom we know."

"We know none, if I'm to do the knowing," I said.

"Queer state of affairs," he reflected; "the true Heir Presumptive, yet a stranger in the Court."

"Oh! drop that nonsense," I said.

His hand went up to his imperial. "Nonsense? Well, maybe so,—and there's the pity of it."

I laughed. "My dear fellow," I said, "you are becoming sentimental, and without even the excuse of a pretty woman in the case."

He faced toward the throne. "You don't act like a blind man," he said.

"I can see the Princess very clearly, but only with Major Dalberg's eyes," I replied.

"But if you were proclaimed the——"

I cut him short. "I am too old for rainbow-chasing, and Spanish Castles don't become an ambassador."

"There you are wrong, my dear Major; diplomacy deals in chateaux en Espagne. It has builded many upon weaker foundations than this one, that have, in time, become substantial and lasting."

"Then, it's a good thing that we army fellows are called upon, occasionally, to tumble a few of them about your diplomatic ears."

He laughed. "You poor military men don't know it's only the phantom castles you tumble. We never give you a chance at any others."

"So I've been a Don Quixote all these years and didn't know it?"

"About that!"

"And that warrants you in sending me to tilt against this foolish heir-presumptive windmill."

"But if it were to prove no windmill?"

"Surely," I said—"Surely, you are not serious?"

He gave me one of his quick glances and his hand went back to his chin.

"'Quién sabe?' as the Spaniard would say, Major; 'Quién sabe?'" he replied.

"Don't be an ass, Courtney," I exclaimed. "And don't play me for one, either."

A lift of the eyebrows was his answer—but Courtney could say much that way.

"It's not a bad sort of occupation—being a King," he reflected.

I ignored him.

"And you could fill the place quite as well as Ferdinand of Lotzen," he went on.

"You will be offering presently to wager that I'll be the next King of Valeria," I scoffed.

"With the proper odds, I'd risk it."

"Name them."

"No—not yet," he said; "but I'll go you five thousand even, now, that you marry the Princess Royal."

"This court atmosphere seems to go to your head."

"That has nothing to do with the wager," he insisted.

"I'll not take you," I said. "The last fool bet is enough for me."

"I thought I heard someone say: 'The sixth dance, cousin.'"

"You did."

"And you call that a 'fool bet'?"

"I do,—and the more so that we were sober when we made it."

"You're a bit hard to please, lately," he mocked.

"I'm a bit easily led astray, lately, you mean," I retorted.

All this talk, as we made our way through the crowd, was interrupted at intervals while Courtney greeted those he knew and presented me. They were mainly of the diplomatic corps and, if they noted the coincidence of my name and Dalberg features, they were adepts enough not to show it. Not so, however, with some of the elderly Valerian dignitaries and army officers; they were very evidently surprised and curious,—and, very shortly, it was plain I was the object of their discussion and careful observation.

"How do you enjoy it?" Courtney inquired.

"You forget that this is not my first visit to Dornlitz," I answered.

"Some day I'd like to know of those other visits."

"There's nothing to know; they were like any other tourist's."

"Really, Major, you throw your opportunities away," he said, and I saw he did not believe me.

"What opportunities?" I asked.

He smiled. "Well, not those for prevarication, certainly."

"Isn't that a necessary qualification of a diplomatic attaché?" I said.

"Quite the most important,—and I don't doubt you will find it useful before you leave Valeria."

Then the band blared out into a waltz and the crowd drew away from the centre of the floor. I expected the real Heir Presumptive to lead out the Princess. I admit I was curious to see him. Report made him a very able young fellow, and his pictures showed a goodly figure. Instead, however, someone in a Colonel's uniform was her partner to open the dance. I turned to Courtney interrogatingly.

"It is Prince Charles, Lotzen's brother," he explained.

"And the Duke?" I asked.

"Still with the Army, I suppose."

Then the Princess swung by and, catching my eye, gave me a quick smile.

"Sort of a relief, isn't it?" Courtney remarked.

I nodded mechanically.

"Only I wouldn't tell her so," he said.

"Wouldn't tell her what?" I demanded.

"That you were relieved to know she could dance."

"I never doubted it," I said shortly.

He looked surprised. "Oh!" he remarked; "Oh!"—and fell to stroking his imperial.

"Courtney," said I, "you're a great fool—and I'm another."

"True, Major, quite true; I found that out long ago."

My irritation went down before his unfailing good nature. It was always so.

"Since we are unanimous on that point," I said, "I have no ground for quarrel."

I danced the next number with Lady Helen, the youngest daughter of Lord Radnor, the British Ambassador. We were old friends, after the modern fashion. I had met her in Washington some four or five years before, while on staff duty, and we had danced and dined ourselves into each other's regard. Then, Lord Radnor was transferred to Dornlitz and I went back into active service. So I had been altogether well pleased to find her with the Radnors when we chanced upon them during the stroll around the room, and I had engaged a pair of dances to give us a chance for a quiet little chat.

"Do you know, Major, for a stranger you are arousing extraordinary curiosity?" she remarked, as we sat on the terrace.

I smiled. "Yes, I believe I am."

She looked surprised. "So you have heard of it?"

"I knew it years ago."

"Oh, how stupid!" she exclaimed. "Of course, this is not your first visit to Dornlitz. Yet, it's a queer coincidence that you should have both the family name and the great Henry's features."

"Oh, no," said I; "not particularly queer, since I am his great-great-grandson."

She closed her fan with a snap. "His great-great-grandson!" she echoed.

I nodded.

"But I thought yours an old American family. Didn't you tell me, one day at Mount Vernon, that a Dalberg fought with Washington?"

It was my turn to be surprised. I had long forgotten both the circumstance and the remark. "And I told you truly enough," I answered.

She frowned a bit; then shook her head. "I cannot understand," she said.

Doubtless I was foolish—Courtney would have called it something stronger—but, nevertheless, I told her the story of Hugo. For the benefit of the scoffer let me say that the Lady Helen could be very fetching when she was so minded, and this was our first meeting in four years.

"How romantic!" she exclaimed, when I had finished my tale. "Father will be so interested."

I almost tumbled out of the chair. "Lord Radnor will not have the opportunity to be interested," I said sharply. "You may not tell him, nor anyone."

"Certainly not, if you wish it," she said instantly.

I thought she could be trusted; but it would do no harm to give her a bit of warning as to the situation.

"None but the King, the Princess and Courtney knows of this relationship," I said.

She regarded me with an amused smile. "Which means, if it become known, I alone could be the tattler."

There was no need to press the point further.

"It is His Majesty's secret as well as mine," I said, as if in explanation.

She shrugged her pretty shoulders. "I shall keep it because it's—yours," she answered.

There was no doubt Lady Helen could be fetching when she was so minded.

I took her hand and kissed it. Then I glanced around for onlookers.

Lady Helen laughed softly. "You men always do that," she said.

"Oh!" said I.

"You look only after it's all over."

"Oh!" said I, again.

"At least, so I have observed," she admitted, frankly.

"You mean such has been your experience?"

"Well," said she, with a mischievous gleam in her grey eyes, "wasn't it so just now?"

I got up and looked carefully around. No one was very near and we were in the shadow. I leaned over and quickly kissed her on the cheek.

"It wasn't so that time," I said.

She sat perfectly quiet for a bit.

"Let us hope," she said, at length; "let us hope that your eyes were trustworthy. Otherwise——"

"Yes?" I questioned.

"Otherwise our engagement must be announced or——"

"Yes?"

"You must give me the chance to cut you publicly, after which you must leave Dornlitz."

Here was a mess, sure enough. Yet, I was in for it—as most fools usually are.

"Which shall it be?" I said gayly.

She leaned close and looked me in the eyes. And beside her winsome face I saw, in my mind's eye, the Princess's, too—but only for an instant. Then I took her hand again. She smiled sweetly, almost as sweetly as Dehra herself could do.

"Let us wait until we know if we were seen," she said.

I made a move to kiss her again, but she drew away.

"Not so, sir; that time you did not look," she said, and stepped out into the light. Then I took her back to Lady Radnor.

"Don't be disconsolate, Major," she said, as we parted. "No one saw you—on the terrace."

I looked down at her gravely. "I am beginning to hope someone did," I said.

She shot a quick glance at me over her fan. "Are you tired of Dornlitz so soon?" she asked.

"I think I want to stay in Dornlitz," I answered.

"But the alternative, Major, the alternative."

"That is why I want to stay."

She smiled. "You did that very prettily," she said. "I shall forgive you the—the kiss."

"But if someone saw it?" I protested.

"You great stupid," she exclaimed, "no one did. Do you think I didn't look?"

"Oh!" said I. "Oh!"

"Sometimes you men are very foolish," she sympathized.

I looked at her a bit in silence. "You have changed since America," I remarked.

"For the better?"

I shrugged my shoulders.

"That's not nice of you," she said.

Then Courtney came up.

"Run along, Major," he ordered; "you've kept the Lady Helen over time."

She took his arm. "Please take me out on the terrace," she said. Then she smiled at me aggravatingly.

"Maybe our chairs are still vacant; better take Courtney to them," I said maliciously.

It was not quite fair, possibly; and she told me so with her eyes, though her lips smiled. I knew I had given her another score to settle.

It was Colonel Bernheim who brought me the Princess's commands for the dance; and the courteous way he did his office made me like him on the instant. And this, though there was a certain deference of manner that was rather suggestive.

The Princess was in the small room behind the throne and, when I was announced, beckoned me to her.

"Major Dalberg," said she, when I had made my bow, "I have ordered the band to play an American quickstep; will you dance it with me as it is done at your great school—West Point, is it not?"

It was done very neatly, indeed. No one of those present could have imagined there was any prior arrangement as to that particular dance. I saw the King smile approvingly.

"Your Royal Highness honors my country and its army, but through a very unworthy representative, I fear," I said, as I gave her my arm. Then the music began.

I have very little recollection of that dance; but I do know that Dehra needed no instruction in our way of doing the two-step; she glided through it as naturally as a Point-girl herself. And, when I told her so, she shrugged her pretty shoulders and answered:

"You are not the first American attaché, you know."

"Nor the last, either," I replied, and then held my peace, though I saw her hide a smile behind her roses.

"But you are the first that has been my cousin," she said sweetly,—and I succumbed, of course. Yet I was punished promptly, nevertheless, for at the throne she stopped and I led her back to the King.

"May I not have another dance later?" I asked.

She shook her head. "Don't you think you have been already favored more than you deserve, cousin?"

"Yes," said I, "I do; that's why I am encouraged to ask for more."

"What a paragon of modesty!" she mocked.

I passed it by. "And the dance?" I asked.

"I shall dance no more to-night," she said. Then we reached the door and found the small room crowded with officials and dignitaries. The Princess halted sharply. "But you may take me for a turn on the terrace," she concluded.

As we crossed the wide floor the crowd fell back,—but Dehra gave no greeting to anyone, though she must have known all eyes were upon us. Yet, to give her due credit, she seemed as unconscious of it as if we were alone in the room. As for me, I admit I was acutely conscious of it, and the walk to the door seemed endless. I must have shown my relief when it was over, for the Princess looked up with a smile.

"That's your first trial as one of the Blood," she said.

"There are compensations," I answered.

She ignored the point. "They are very few."

"Sometimes, one would be ample."

Again she evaded. "Yes, the privilege to be as free as the lowest subject," she answered, instantly.

"Pure theory," I said. "The lowest subject would think you mad."

"I would gladly exchange places," she said.

"Don't make any of them the offer."

"No—out of regard for my Father I won't."

"It's a great thing to be a Princess Royal," I ventured.

"Oh, I dare say—to those who care for great things."

"Who do not?"

"I don't. At least I think I don't."

"You would think so only until you were not the Princess Royal."

"That may be; but, as I am the Princess Royal and cannot well change my birthright, I don't see how I am to get the chance to think otherwise."

"It's better to think you do not like great things when you have them, than to like them and not have them."

"You make it only a choice of unhappinesses," she said.

"I make it only life."

"You are too young to be pessimistic," she said.

"And you are too fortunate in life to be unhappy," I answered.

"But you said life was but a choice of unhappinesses."

"Only to the discontented."

"Oh!" said she. "Instead of a pessimist you are a philosopher."

"I sincerely trust I'm neither."

"So do I, cousin," she laughed, "if we are to be friends. I don't like philosophers; which is natural, doubtless; and as a pessimist I prefer no rival."

"Which is also natural," I added. "And I promise not to interfere with your prerogative nor do the Socrates act again."

"Entre nous, I think you're wise; neither becomes you particularly."

I laughed. "You're frank."

"It's the privilege of cousins," she replied.

"Oh!" said I. "I'm glad you think so."

"That is—in matters strictly cousinly," she added quickly.

"I shall remember," I said.

She gave me a quick glance. "Can you remember several years back?" she said.

(So, she had recognized me.)

"That depends," said I. "I have a bad memory except for pleasant things."

"Then I am quite sure you will remember," she laughed, and fell to picking a rose apart, petal by petal.

"I am ready to remember anything," I said, catching one of the petals.

"Oh! But maybe I don't want you to remember."

"Then I'm ready——"

She looked at me quickly. "To forget?" she interrupted.

"To remember only what you wish," I ended.

"That means you will remember nothing until I wish it?"

I caught the half-plucked rose as she let it fall.

"It means my memory is at your command," I said.

She drew out another rose and dropped it deliberately.

"I am very awkward," she said, as I bent for it.

"On the contrary, I thought you did it very prettily," I answered.

She laughed. "Then you may keep it instead of the torn one."

"I shall keep both."

"Always?" she mocked.

"At least until I leave you."

"Thank Heaven, cousin, for once in my life I have had an honest answer!" she exclaimed, holding out her hand.

I took it. I did not kiss it, though that may seem strange. Sometimes, I do have the proper sense of the fitness of things.

"It's the privilege of cousins to be frank," I quoted.

"Have you always been frank with me?" she asked.

"Rather too much so, I fear."

She gave me a sharp look. "Do you know a Captain Smith of your Army?"

"Smith is a very common name in America. I know at least a dozen who are officers."

"John Smith is his name. He was a Captain, six years ago."

I appeared to think a moment. "I know two such—one in the Cavalry, the other in the Engineers."

"Describe them, please."

I showed surprise. "Does Your Royal Highness——?"

She cut in. "That is just what she is trying to find out."

"Yes?"

"Whether either of them is the Captain Smith I have in mind."

"Both would be much honored."

"I am not so sure as to the one I mean. He was a very conceited fellow."

I gritted back a smile. "It must have been the Engineer," I said. "He's a good deal of a prig."

She bent over the roses. "Oh, I wouldn't call him just that."

"It's no more than I've heard him call himself," I said.

"You must know him rather intimately."

"On the contrary, I know him very slightly, though I've been thrown with him considerably."

"Are you not friendly?" she asked.

"We have had differences."

Again the roses did duty. "I fear you are prejudiced," she said, and I thought I caught a smothered laugh.

"Not at all," I insisted. "I am disposed in his favor."

"So I should judge."

I could not decide which way she meant it. "Oh, he is not all bad," I condescended. "In many ways he is a good sort of chap."

"Now, that's better." she rejoined; "to say for him what he could not, of course, say for himself."

I forced back another laugh. "Oh, I don't know why he should not have said that to a friend," said I.

"It would depend much on the friend."

I did not know if she had given the opening, deliberately, but I took it.

"Of course, he would say that only to one he felt could understand him."

"You are painting him rather better than you did at first," she observed.

"I'm warming up to the subject."

"Then suppose you tell me what he looks like."

"That," said I, "is to tell his greatest fault."

"I do not understand."

"He looks like me," I explained.

"How horrible," she laughed.

"He has never ceased to deplore it," I said humbly.

"Surely, he never told you."

"To my face, many times."

"You had good cause for differences, then."

"Thank you, cousin," I said.

"And, may I ask," she went on, "what you did to him at such times?"

I shook my head. "It would not tell well."

"No, possibly not; but tell me, anyway," she said.

"Sometimes, I put him to bed—-and, sometimes, I bought him a superabundance of red liquor."

"Don't tell me the other times," she interposed.

"No," said I, "I won't."

She fell to plucking the roses again.

"This Captain Smith," she said presently; "was he in Valeria six years ago?"

"That would be in 189—?" I reflected a moment. "Yes he was here that year."

She thought a bit. "Was he given to reminiscing?"

"No one in America but myself knew he had been to Valeria."

She smiled.

I saw the blunder. "It happened he knew of my Dalberg descent," I hastened to add.

"Has he ever mentioned an adventure in the forest near the Summer Palace?"

"I am quite sure he has not," I said, but without looking at her.

Then I felt a touch on my arm—and I took her gloved fingers in my own and held them.

"You are very good, cousin," she said, then loosed her hand.

"When did you recognize me?" I asked.

"When you kissed me. That was why I was so angry."

"I noticed you were annoyed."

"Yet, I was more disappointed."

"Yes?" I inflected.

"To have my ideal Captain Smith shattered so completely."

"But when you learned it was your cousin?"

"That saved the ideal."

"But I cannot live up to the Captain."

She shook her head. "There is no need. The Captain is dead. It is my cousin Armand now."

"But every woman has her ideal," I ventured.

"Yes, I shall have to find a new one."

"Then it's only exit the Captain to enter a stranger," I said.

"Not necessarily a stranger," she returned.

"To be sure," I agreed; "there is His Royal Highness, the Duke of Lotzen."

"Or Casimir of Titia," she added, drawing down her mouth. "Or even my new-found cousin Armand."

"He died with the Captain," I laughed.

"No, the Captain died with him."

"I think, as a matter of proper precaution, it would be well to go in," I said.

"Are you tired of me, so soon?"

"You know very well it's because I'm fearful of disgracing the Captain again."

"Please don't," she said smilingly, "here comes a friend of yours."

It was Courtney with Lady Helen on his arm.

"Two friends of mine," I said, as they passed.

"You know Lady Helen Radnor?"

"After a fashion. I was stationed in Washington while Lord Radnor was Ambassador there."

"You two would suit each other."

"Yes?"

"You both are—shall I say it—flirts."

I began to disclaim.

"Nonsense!" she cut in. "Don't you think a woman knows another woman—and also a man?"

"By your leave, cousin, I'll not think," I said.

"It's a bit unnecessary sometimes," she laughed.

I made no reply. In truth, I knew none. But the Princess did not seem to notice it. She was plucking at the roses again.

"I wish I might flirt," she broke out suddenly.

I grasped the marble rail for support.

"Don't look so surprised," she laughed, "I'll not try it—I know what is permitted me."

"Then you never flirted?" I asked with assumed seriousness.

"No; that's another penalty of birth. With whom may the Princess Royal flirt?"

I waved my hand toward the ball room.

"I hope I am neither cruel nor indiscreet," she said, rather curtly.

"But there are many royal guests come to Dornlitz," I ventured.

She shrugged her shoulders. "They all bore me."

"Which only makes them the better material to practice on."

"Surely, I am very innocent," she said. "I thought at least a bit of sentiment was required."

"Sentiment only endangers the game," I explained.

"But suppose the sentiment were to come suddenly—in the midst of the 'game,' as you call it?"

"Then," said I, "there is rare trouble ahead for the other party."

"But if that one also were to become—you know," she went on.

"There's an end to the flirtation; it's a different kind of game then."

"Are you quite sure there can be flirtation without sentiment?" she persisted.

"It's the only artistic sort; and the only safe sort, too," I answered sagely.

"And is it a pleasant game to play for a while in that fashion?" she asked.

"Doubtless," I answered evasively; "only it is rarely done."

She went back to the roses again. "I think, cousin, I shall flirt with you," she said suddenly.

I took a fresh hold on the railing. I was surprised.

But I was more troubled; for I was quite sure she meant it.

"Don't you think, Princess, you are putting me to a heavy test?" I objected. "I may cease to be artistic."

"You said it could be done."

"Yes, as a general———"

"Then your test is no heavier than mine," she interrupted.

I bowed. So, this was her punishment for the kiss of salutation.

"But if I were to fail to carry the game through properly?" I said.

She hesitated. "I may fail, too," she said.

"And then?" I asked.

She looked away. "It would make no difference in the ending. You would go away; and I—would make some crazy marriage of political expediency."

I straightened up. Maybe she had not been maliciously leading me out. Maybe she was simply unhappy and wanting a new sensation. Then, suddenly, she put her hand on my arm.

"Come, Armand," she said; "take me back to the King. We have flirted enough for one evening."

"We?" I said wonderingly.

She took a rose from her gown—and drew it through my sword belt.

"Yes," she said; and gave me one of those bewildering smiles. "Wouldn't you call it that? At least, you have taught me to-night all I know of the game."

"And how about six years ago, cousin?" I said, securing her hand.

She looked down demurely. "Well, maybe I did learn a little that day," she admitted.

The second morning after the ball I arose early—in fact, just as the bugles of the garrison were sounding reveille—and went for a horseback ride into the country. Though I knew about all the roads in the vicinity, I confess it never occurred to me to take any but that which led toward the Summer Palace and the place where I had first met the Princess.

It may be some will scoff at this, but I venture that by far the majority will deem it only natural. For myself I may further admit that I ordered my horse the night before for no other purpose; and I have no excuse to offer. From all of which it may be inferred that I, at least, was scarcely likely to be artistic long in a certain flirtation.

I had thought it all over during the last thirty-six hours, and, as I jogged through the streets, I went over with it again—and always with the same result: I would enjoy it while it lasted. Afterward—well, afterward would be time enough when it came. So I shrugged my shoulders and returned the salute of the officer at the gate and rode out into the open country.

I had gone, possibly, a mile when there came the beat of running hoofs behind me and rapidly nearing. Thinking it might be a messenger from the Embassy I swung around in saddle—only to find the front horse was ridden by a woman and the other by a groom.

My first thought was: "The Princess!" my next: "By Jove, she rides well!" Then something familiar in seat and figure struck me and I recognized Lady Helen Radnor. Evidently she had already made me out, for she waved her crop and pulled down to a canter. Here was an end to my solitary ride; I turned back to meet her.

"Why, Major Dalberg, what luck!" she cried. "One might imagine we were in Washington again."

"What need for Washington," said I, "since we are here?"

"True! It's always the people that make the place," she laughed.

"Then you like Dornlitz as well as Washington?"

"Yes, lately."

"If I were at all conceited I would guess that 'lately' meant——"

"Yes?" she asked.

"But as I'm not conceited I won't guess."

"I'm afraid it's not quite the same, then, as in Washington!"

I made no reply.

"There, you would have been ready to believe I followed you intentionally."

"Did you ever do that?" I asked.

She laughed. "We are quits now."

"Then I may ride with you?"

"Surely—why do you think I overtook you?"

I bowed to my horse's neck. "I am flattered," I said.

"You ought to be, sir."

I looked at her quickly. It was said, it seemed to me, a bit sharply; but she gave me only the usual mocking smile.

"Where shall we go?" I asked.

"You have no choice?"

"None—all roads are alike delightful now. Besides, you forget I came here only two days ago; this is my first ride since then."

"Then, suppose we go out by the Forge and around by the hill road above the Palace?"

"You must be the guide," I replied.

"Come along, then; we turn to the right here."

"Only"——I began.

"Oh! I'll have you back in time for breakfast," she cut in. "That was what you meant?"

"Your Ladyship is a mind reader."