Title: Foch the Man: A Life of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Armies

Author: Clara E. Laughlin

Release date: January 14, 2006 [eBook #17511]

Most recently updated: August 22, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Al Haines

[Transcriber's note: The letter in the second and third illustrations is shown translated on the following page.]

Dear MADEMOISELLE LAUGHLIN:

I have read with the keenest interest your sketch of the life of Marshal Foch. It is not yet history: we are too close to events to write it now, but it is the story of a great leader of men on which I felicitate you because of your real understanding of his character.

Christian, Frenchman, soldier, Foch will be held up as an example for future generations as much for his high moral standard as for his military genius.

It seems that in writing about him the style rises with the noble sentiments which inspire him.

Thus in form of presentation as well as in substance you convey admirably the great lesson which applies to each one of us from the life of Marshal Foch.

Please accept, Mademoiselle, this expression of my respectful regards.

LT.-COLONEL E. RÉQUIN.

Three Spirits stood on the mountain peak

And

gazed on a world of red,--

Red with the blood of heroes,

The

living and the dead;

A mighty force of Evil strove

With

freemen, mass on mass.

Three Spirits stood on the mountain peak

And cried: "They shall not

pass!"

The Spirits of Love and Sacrifice,

The

Spirit of Freedom, too,--

They called to the men they had dwelt among

Of the Old World and the

New!

And the men came forth at the trumpet call,

Yea,

every creed and class;

And they stood with the Spirits who called to

them,

And cried:

"They shall not pass!"

Far down the road of the Future Day

I

see the world of Tomorrow;

Men and women at work and play,

In the midst of their joy

and sorrow.

And every night by the red firelight,

When

the children gather 'round

They tell the tale of the men of old.

These noble ancestors, grim and bold,

Who

bravely held their ground.

In thrilling accents they often speak

Of the Spirits Three on the mountain peak.

O

Freedom, Love and Sacrifice

You

claimed our men, alas!

Yet

everlasting peace is theirs

Who

cried, "They shall not pass!"

ARTHUR A. PENN.

Stirring traditions and historic scenes which surrounded him in childhood.

The horsemarkets at Tarbes. The school. Foch at twelve a student of Napoleon.

What Foch suffered in the defeat of France by the Prussians.

Foch begins his military studies, determined to be ready when France should again need defense.

Begins to specialize in cavalry training. The school at Saumur.

Seven years at Rennes as artillery captain and always student of war. Called to Paris for further training.

Parallels in their careers since their school days together.

Where Foch's great work as teacher prepared hundreds of officers for the superb parts they have played in this war.

Some of the principles Foch taught. Why he is not only the greatest strategist and tactician of all time, but the ideal leader and coordinator of democracy.

Clemenceau's part in giving Foch his opportunity.

How the Superior War Council prepared for the inevitable invasion of France. Foch put in command at Nancy.

True to his belief that "the way to make war is to attack" Foch promptly invaded Germany, but was obliged to retire and defend his own soil.

How the brilliant generalship there thwarted the German plan; and how Joffre recognized it in reorganizing his army.

"The Miracle of the Marne" was Foch. How he turned defeat to victory.

Foch's skill and diplomacy in that crisis show him a great coordinator.

How Foch stopped the German drive that nearly separated the French and English armies.

The completest humiliation ever inflicted on a proud nation.

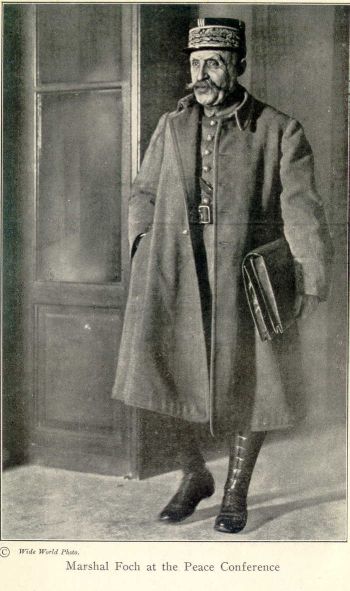

How Foch carries himself as victor.

When the Great War broke out, one military name "led all the rest" in world-prominence: Kitchener. Millions of us were confident that the hero of Kartoum would save the world. It was not so decreed. Almost immediately another name flashed into the ken of every one, until even lisping children said Joffre with reverence second only to that wherewith they named Omnipotence. Then the weary years dragged on, and so many men were incredibly brave and good that it seemed hard for anyone to become pre-eminent. We began to say that in a war so vast, so far-flung, no one man could dominate the scene.

But, after nearly four years of conflict, a name we had heard and seen from the first, among many others, began to differentiate itself from the rest; and presently the whole wide world was ringing with it: Foch!

He was commanding all the armies of civilization. Who was he?

Hardly anyone knew.

Up to the very moment when he had compassed the most momentous victory in the history of mankind, little was known about him, outside of France, beyond the fact that he had been a professor in the Superior School of War.

Now and then, as the achievements of his generalship rocked the world, someone essayed an account of him. They said he was a Lorrainer, born at Metz; they said his birthday was August 4; they said he was too young to serve in the Franco-Prussian war; and they said a great many other things of which few happened to be true.

Then, as the summer of 1918 waned, there came to me from France, from Intelligence officers of General Foch's staff, authoritative information about him.

And also there came those, representing France and her interests in this country, who said:

"Won't you put the facts about Foch before your people?"

If I could have fought for France with a sword (or gun) I should have been at her service from the first of August, 1914, when I heard her tocsin ring, saw her sons march away to fight and die on battlefields as familiar to me as my home neighborhood.

Not being permitted that, I have yielded her such service as I could with my pen.

And when asked to write, for my countrymen, about General Foch, I felt honored in a supreme degree.

In due course we shall have many volumes about him: his life, his teachings, his writings, his great deeds will be studied in minutest details as long as that civilization endures which he did so much to preserve to mankind.

But just now, while all hearts are overflowing with gratefulness to him, it may be—I cannot help thinking—as valuable to us to know a little about him as it will be for us to know a great deal about him later on.

My sources of information are mainly French; and notable among them is a work recently published in Paris: "Foch, His Life, His Principles, His Work, as a Basis for Faith in Victory," by René Puaux, a French soldier-author who has served under the supreme commander in a capacity which enabled him to study the man as well as the General.

French, English and some few American periodicals have given me bits of impression and some information. French military and other writers have also helped. And noted war correspondents have contributed graphic fragments. The happy fortune which permitted me to know France, her history and her people, enabled me to "read into" these brief accounts much which does not appear to the reader without that acquaintance. And distinguished Frenchmen, scholars and soldiers, including several members of the French High Commission to the United States, have helped me greatly; most of them have not only close acquaintance with General Foch, having served as staff officers under him, but are eminent writers as well, with the highest powers of analysis and of expression.

Lieutenant-Colonel Édouard Réquin of the French General Staff, who was at General Foch's side from the day Foch was made commander of an army, has been especially kind to me in this undertaking; I am indebted to him, not only for many anecdotes and suggestions, but also for his patience in reading my manuscript for verification (or correction) of its details and its essential truthfulness.

And I want especially to record my gratefulness to M. Antonin Barthélemy, French Consul at Chicago, the extent and quality of whose helpfulness, not alone on this but on many occasions, I shall never be able to describe. Through him the Spirit of France has been potent in our community.

Thus aided and encouraged, I have done what I could to set before my countrymen a sketch of the great, dominant figure of the World War.

The thing about Foch that most impresses us as we come to know him is not primarily his greatness as a military genius, but his greatness as a spiritual force.

Those identical qualities in him which saved the world in war, will serve it no less in peace—if we study them to good purpose.

As a leader of men, his principles need little, if any, adaptation to meet the requirements of the re-born world from which, we hope, he has banished the sword.

Not to those only who would or who must captain their fellows, but to every individual soul fighting alone against weakness and despair and other foes, his life-story brings a rising tide of new courage, new strength, new faith.

For the young man or woman struggling with the principles of success; for the man or woman of middle life, fearful that the time for great service has gone by; to the preacher and the teacher and other moulders of ideals—to these, and to many more, he speaks at least as thrillingly as to the soldier.

This is what I have tried to make clear in my simple sketch here offered.

Ferdinand Foch was born at Tarbes on October 2, 1851.

His father, of good old Pyrenean stock and modest fortune, was a provincial official whose office corresponded to that of secretary of state for one of our commonwealths. So the family lived in Tarbes, the capital of the department called the Upper Pyrénées.

The mother of Ferdinand was Sophie Dupré, born at Argèles, twenty miles south of Tarbes, nearer the Spanish border. Her father had been made a chevalier of the empire by Napoleon I for services in the war with Spain, and the great Emperor's memory was piously venerated in Sophie Dupré's new home as it had been in her old one. So her first-born son may be said to have inherited that passion for Napoleon which has characterized his life and played so great a part in making him what he is.

There was a little sister in the family which welcomed Ferdinand. And in course of time two other boys came.

These four children led the ordinary life of happy young folks in France. But there was much in their surroundings that was richly colorful, romantic. Probably they took it all for granted, the way children (and many who are not children) take their near and intimate world. But even if they did, it must have had its deep effect upon them.

To begin with, there was Tarbes.

Tarbes is a very ancient city. It is twenty-five miles southeast of Pau, where Henry of Navarre made his dramatic entry upon a highly dramatic career, and just half that distance northeast of Lourdes, whose famous pilgrimages began when Ferdinand Foch was a little boy of seven.

He must have heard many soul-stirring tales about little Bernadette, the peasant girl to whom the grotto's miraculous qualities were revealed by the Virgin, and whose stories were weighed by the Bishop of Tarbes before the Catholic Church sponsored them. The procession of sufferers through Tarbes on their way to Lourdes, and the joyful return of many, must have been part of the background of Ferdinand Foch's young days.

Many important highways converge at Tarbes, which lies in a rich, elevated plain on the left bank of the River Adour.

The town now has some 30,000 inhabitants, but when Ferdinand Foch was a little boy it had fewer than half that many.

For many centuries of eventful history it has consisted principally of one very long street, running east and west over so wide a stretch of territory that the town was called Tarbes-the-Long. Here and there this "main street" is crossed by little streets running north and south and giving glimpses of mountains, green fields and orchards; and many of these are threaded by tiny waterways—small, meandering children of the Adour, which take themselves where they will, like the chickens in France, and nobody minds having to step over or around them, or building his house to humor their vagaries.

Tarbes was a prominent city of Gaul under the Romans. They, who could always be trusted to make the most of anything of the nature of baths, seem to have been duly appreciative of the hot springs in which that region abounds.

But nothing of stirring importance happened at or near Tarbes until after the battle of Poitiers (732), when the Saracens were falling back after the terrible defeat dealt them by Charles Martel.

Sullen and vengeful, they were pillaging and destroying as they went, and probably none of the communities through which they passed felt able to offer resistance to their depredations—until they got to Tarbes. And there a valiant priest named Missolin hastily assembled some of the men of the vicinity and gave the infidels a good drubbing—killing many and hastening the flight, over the mountains, of the rest.

This encounter took place on a plain a little to the south of Tarbes which is still called the Heath of the Moors.

When Ferdinand Foch was a little boy, more than eleven hundred years after that battle, it was not uncommon for the spade or plowshare of some husbandman on the heath to uncover bones of Christian or infidel slain in what was probably the last conflict fought on French soil to preserve France against the Saracens. And there may still have been living some old, old men or women who could tell Ferdinand stories of the 24th of May (anniversary of the battle) as it was observed each year until the Revolution of 1789. At the southern extremity of the battlefield there stood for many generations a gigantic equestrian statue, of wood, representing the holy warrior, Missolin, rallying his flock to rout the unbelievers. And in the presence of a great concourse singing songs of grateful praise to Missolin, his statue was crowned with garlands by young maidens wearing the picturesque gala dress of that vicinity.

Some forty-odd years after Missolin's victory, Charlemagne went with his twelve knights and his great army through Tarbes on his way to Spain to fight the Moors. And when that ill-starred expedition was defeated and its warriors bold were fleeing back to France, Roland—so the story goes—finding no pass in the Pyrénées where he needed one desperately, cleaved one with his sword Durandal.

High up among the clouds (almost 10,000 feet) is that Breach of Roland—200 feet wide, 330 feet deep, and 165 feet long. A good slice-out for a single stroke! And when Roland had cut it, he dashed through it and across the chasm, his horse making a clean jump to the French side of the mountains. That no one might ever doubt this, the horse thoughtfully left the mark of one iron-shod hoof clearly imprinted in the rock just where he cleared it, and where it is still shown to the curious and the stout of wind.

It is a pity to remember that, in spite of such prowess of knight and devotion of beast. Roland perished on his flight from Spain.

But, like all brave warriors, he became mightier in death even than he had been in life, and furnished an ideal of valor which animated the most chivalrous youth of all Europe, throughout many centuries.

With such traditions is the country round about Tarbes impregnated.

It has been suggested that the name Foch (which, by the way, is pronounced as if it rhymed with "hush") is derived from Foix—a town some sixty miles east of St. Gaudens, near which was the ancestral home of the Foch family.

Whatever the relatives of Ferdinand may have thought of this as a probability, it is certain that Ferdinand was well nurtured in the history of Foix and especially in those phases of it that Froissart relates.

Froissart, the genial gossip who first courted the favor of kings and princes and then was gently entreated by them so that his writing of them might be to their renown, was on his way to Blois when he heard of the magnificence of Gaston Phoebus, Count of Foix. Whereupon the chronicler turned him about and jogged on his way to Foix. Gaston Phoebus was not there, but at Orthez—150 miles west and north—and, nothing daunted, to Orthez went Froissart, by way of Tarbes, traveling in company with a knight named Espaing de Lyon, who was a graphic and charmful raconteur thoroughly acquainted with the country through which they were journeying. A fine, "that-reminds-me" gentleman was Espaing, and every turn of the road brought to his mind some stirring tale or doughty legend.

"Sainte Marie!" Froissart cried. "How pleasant are your tales, and how much do they profit me while you relate them. They shall all be set down in the history I am writing."

So they were! And of all Froissart's incomparable recitals, none are more fascinating than those of the countryside Ferdinand Foch grew up in.

The country round about Tarbes has long been famed for its horses of an Arabian breed especially suitable for cavalry.

Practically all the farmers of the region raised these fine, fleet animals. There was a great stud-farm on the outskirts of town, and the business of breeding mounts for France's soldiers was one of the first that little Ferdinand Foch heard a great deal about.

He learned to ride, as a matter of course, when he was very young. And all his life he has been an ardent and intrepid horseman.

A community devoted to the raising of fine saddle horses is all but certain to be a community devotedly fond of horse racing.

Love of racing is almost a universal trait in France; and in Tarbes it was a feature of the town life in which business went hand-in-hand with pleasure.

In an old French book published before Ferdinand Foch was born, I have found the following description of the crowds which flocked into Tarbes on the days of the horse markets and races:

"On these days all the streets and public squares are flooded with streams of curious people come from all corners of the Pyrénées and exhibiting in their infinite variety of type and costume all the races of the southern provinces and the mountains.

"There one sees the folk of Provence, irascible, hot-headed, of vigorous proportions and lusty voice, passionately declaiming about something or other, in the midst of small groups of listeners.

"There are men of the Basque province—small, muscular and proud, agile of movement and with bodies beautifully trained; plain of speech and childlike in deed.

"There are the men of the Béarnais, mostly from towns of size and circumstance—educated men, of self-command, tempering the southern warmth which burns in their eyes by the calm intelligence born of experience in life and also by a natural languor like that of their Spanish neighbors.

"There are the old Catalonians, whose features are of savage strength under the thick brush of white hair falling about their leather-colored faces; the men of Navarre, with braided hair and other evidences of primitiveness—vigorous of build and handsome of feature, but withal a little subnormal in expression.

"Then, in the midst of all these characteristic types, moving about in a pell-mell fashion, making a constantly changing mosaic of vivid hues, there are the inhabitants of the innumerable valleys around Tarbes itself, each of them with its own peculiarities of costume, manners, speech, which make them easily distinguishable one from another."

It was a remarkable crowd for a little boy to wander in.

If Ferdinand Foch had been destined to be a painter or a writer, the impressions made upon his childish mind by that medley of strange folk might have been passed on to us long ago on brilliant canvas or on glowing page.

But that was not the way it served him.

I want you who are interested to comprehend Ferdinand Foch, to think of those old horsefairs and race meets of his Gascony childhood, and the crowds of strange types they brought to Tarbes, when we come to the great days of his life that began in 1914—the days when his comprehension of many types of men, his ability to "get on with" them and harmonize them with one another, meant almost as much to the world as his military genius.

Tarbes had suffered so much in civil and religious wars, for many centuries, that not many of her ancient buildings were left. The old castle, with its associations with the Black Prince and other renowned warriors, was a ramshackle prison in Ferdinand Foch's youth. The old palace of the bishops was used as the prefecture, where Ferdinand's father had his office.

There were two old churches, much restored and of no great beauty, but very dear to the people of Tarbes nevertheless.

Ferdinand and his brothers and sister were very piously reared, and at an early age learned to love the church and to seek it for exaltation and consolation.

Later on in these chapters we shall see that phase of a little French boy's training in its due relation to a maréchal of France, directing the greatest army the world has ever seen.

The college of Tarbes, where Ferdinand began his school days, was in a venerable building over whose portal there was, in Latin, an inscription recording the builder's prayer:

"May this house remain standing until the ant has drunk all the waves of the sea and the tortoise has crawled round the world."

Ferdinand was a hard student, serious beyond his years, but not conspicuous except for his earnestness and diligence.

When he was twelve years old, his fervor for Napoleon led him to read Thiers' "History of the Consulate and the Empire." And about this time his professor of mathematics remarked of him that "he has the stuff of a polytechnician."

The vacations of the Foch children were passed at the home of their paternal grandparents in Valentine, a large village about two miles from the town of St. Gaudens in the foothills of the Pyrénées. There they had the country pleasures of children of good circumstances, in a big, substantial house and a vicinity rich in tranquil beauty and outdoor opportunities. And there, as in the children's own home at Tarbes, one was ashamed not to be a very excellent child, and, so, worthy to be descended from a chevalier of the great Napoleon.

In the mid-sixties the family moved from Tarbes to Rodez—almost two hundred miles northeast of their old locality in which both parents had been born and where their ancestors had long lived.

It was quite an uprooting—due to the father's appointment as paymaster of the treasury at Rodez—and took the Foch family into an atmosphere very different from that of their old Gascon home, but one which also helped to vivify that history which was Ferdinand's passion.

There Ferdinand continued his studies, as also at Saint-Étienne, near Lyons, whither the family moved in 1867 when the father was appointed tax collector there.

And in 1869 he was sent to Metz, to the Jesuit College of Saint Clément, to which students flocked from all parts of Europe.

He had been there a year and had been given, by unanimous vote of his fellow students, the grand prize for scholarly qualities, when the Franco-Prussian war began.

Immediately Ferdinand Foch enlisted for the duration of the war.

There is nothing to record of Ferdinand Foch's first soldiering except that from the dépôt of the Fourth Regiment of Infantry, in his home city of Saint-Étienne, he was sent to Chalon-sur-Saône, and there was discharged in January, 1871, after the capitulation of Paris.

He did not distinguish himself in any way. He was just one of a multitude of youths who rushed to the colors when France called, and did what they could in a time of sad confusion, when a weak government had paralyzed the effectiveness of the army—of the nation!

Whatever blows Ferdinand Foch struck in 1870 were without weight in helping to avert France's catastrophe. But he was like hundreds of thousands of other young Frenchmen similarly powerless in this: In the anguish he suffered because of what he could not do to save France from humiliation were laid the foundations of all that he has contributed to the glory of new France.

At the time when his Fall term should have been beginning at Saint Clément's College, Metz was under siege by the German army, and its garrison and inhabitants were suffering horribly from hunger and disease; Paris was surrounded; the German headquarters were at Versailles; and the imperial standards so dear to young Foch because of the great Napoleon were forever lowered when the white flag was hoisted at Sedan and an Emperor with a whole army passed into captivity.

How much the young soldier-student of the Saône comprehended then of the needlessness of the shame and surrender of those inglorious days we do not know. He cannot have been sufficiently versed in military understanding to realize how much of the defeat France suffered was due to her failure to fight on, at this juncture and that, when a stiffer resistance would have turned the course of events.

But if he did not know then, he certainly knew later. And as soon as he got where he could impress his convictions upon other soldiers of the new France he began training them in his great maxim: "A battle is lost when you admit defeat."

What his devotion to Saint Clément's College was we may know from the fact of his return there to resume his interrupted studies under the same teachers, but in sadly different circumstances.

He found German troops quartered in parts of the college, and as he went to and from his classes the young man who had just laid off the uniform of a French soldier was obliged to pass and repass men of the victorious army of occupation.

The memory of his shame and suffering on those occasions has never faded. How much France and her allies owe to it we shall never be able to estimate.

For the effect on Foch was one of the first acid tests in which were revealed the quality of his mind and soul. Instead of offering himself a prey to sullen anger and resentment, or of flaring into fury when one time for fury was past and another had not yet come, he used his sorrow as a goad to study, and bent his energies to the discovery of why France had failed and why Prussia had won. His analysis of those reasons, and his application of what that analysis taught him, is what has put him where he is to-day—and us where we are!

From Metz, Foch went to Nancy to take his examination for the Polytechnic at Paris.

Just why this should have been deemed necessary I have not seen explained. But it was, like a good many other things of apparent inconsequence in this young man's life, destined to leave in him an impress which had much to do with what he was to perform.

I have seldom, if ever, studied a life in which events "link up" so marvelously and the present is so remarkably an extension of the past.

Nancy had been chosen by General Manteuffel, commander of the First German Army Corps, as headquarters, pending the withdrawal of the victors on the payment of the last sou in the billion-dollar indemnity they exacted of France along with the ceding of Alsace-Lorraine. (For three years France had to endure the insolent victors upon her soil.)

And with the fine feeling and magnanimity in which the German was then as now peculiarly gifted General Manteuffel delighted in ordering his military bands to play the "Retreat"—to taunt the sad inhabitants with this reminder of their army's shame.

Ferdinand Foch listened and thought and wrote his examinations for the school of war.

Forty-two years later—in August, 1913—a new commandant came to Nancy to take control of the Twentieth Army Corps, whose position there, guarding France's Eastern frontier, was considered one of the most important—if not the most important—to the safety of the nation.

The first order he gave was one that brought out the full band strength of six regiments quartered in the town. They were to play the "March Lorraine" and the "Sambre and Meuse." They were to fill Nancy with these stirring sounds. The clarion notes carrying these martial airs were to reach every cranny of the old town. It was a veritable tidal wave of triumphant sound that he wanted—for it had much to efface.

Nancy will never forget that night! It was Saturday, the 23d of August, 1913. And the new commandant's name was Ferdinand Foch!

Less than a year later he was fighting to save Nancy, and what lay beyond, from the Germans.

And this time there was to be a different story! Ferdinand Foch was foremost of those who assured it.

Ferdinand Foch entered the Polytechnic School at Paris on the 1st of November, 1871, just after he had completed his twentieth year.

This school, founded in 1794, is for the technical education of military and naval engineers, artillery officers, civil engineers in government employ, and telegraphists—not mere operators, of course, but telegraph engineers and other specialists in electric communication. It is conducted by a general, on military principles, and its students are soldiers on their way to becoming officers.

Its buildings cover a considerable space in the heart of the great school quarter of Parts. The Sorbonne, with its traditions harking back to St. Louis (more than six centuries) and its swarming thousands of students, is hard by the Polytechnic. So is the College de France, founded by Francis I. And, indeed, whichever way one turns, there are schools, schools, schools—of fine arts and applied arts; of medicine in all its branches; of mining and engineering; of war; of theology; of languages; of commerce in its higher developments; of pedagogy; and what-not.

Nowhere else in the world is there possible to the young student, come to advance himself in his chosen field of knowledge, quite such a thrill as that which must be his when he matriculates at one of the scores of educational institutions in that quarter of Paris to which the ardent, aspiring youth of all the western world have been directing their eager feet from time immemorial.

Cloistral, scholastic atmosphere, with its grave beauty, as at Oxford and Cambridge, he will not find in the Paris Latin Quarter.

Paris does not segregate her students. Conceiving them to be studying for life, she aids them to do it in the midst of life marvelously abundant. They do not go out of the world—so to speak—to learn to live and work in the world. They go, rather, into a life of extraordinary variety and fullness, out of which—it is expected—they will discover how to choose whatever is most needful to their success and well-being.

There is no feeling of being shut in to a term of study. There is, rather, the feeling of being "turned loose" in a place of vast opportunity of which one may make as much use as he is able.

To a young man of Ferdinand Foch's naturally serious mind, deeply impressed by his country's tragedy, the Latin Quarter of Paris in those Fall days of 1871 was a sober place indeed.

Beautiful Paris, that Napoleon III had done so much to make splendid, was scarred and seared on every hand by the German bombardment and the fury of the communards, who had destroyed nearly two hundred and fifty public and other buildings. The government of France had deserted the capital and moved to Versailles—just evacuated by the Germans.

The blight of defeat lay on everything.

In May, preceding Foch's advent, the communards—led by a miserable little shoemaker who talked about shooting all the world—took possession of the buildings belonging to the Polytechnic, and were dislodged only after severe fighting by Marshal MacMahon's Versailles troops.

The cannon of the communards, set on the heights of Pére-Lachaise (the great city of the dead where the slumber of so many of earth's most illustrious imposed no respect upon the "Bolsheviki" of that cataclysm) aimed at the Pantheon, shot short and struck the Polytechnic. One shell burst in the midst of an improvised hospital there, gravely wounding a nurse.

At last, on May 24, the Polytechnic was taken from the revolutionists by assault, and many of the communards were seized.

In the days following, the great recreation court of the school was the scene of innumerable executions, as the wretched revolutionists paid the penalty of their crimes before the firing squad. And the students' billiard room was turned into a temporary morgue, filled with bodies of those who had sought to destroy Paris from within.

The number of Parisians slain in those days after the second siege of Paris has been variously estimated at from twenty thousand to thirty-six thousand. And all the while, encamped upon the heights round about Paris, were victorious German troops squatting like Semitic creditors in Russia, refusing to budge till their account was settled to the last farthing of extortion.

The most sacred spot in Paris to young Foch, in all the depression he found there, was undoubtedly the great Dôme des Invalides, where, bathed in an unearthly radiance and surrounded by faded battle flags, lies the great porphyry sarcophagus of Napoleon I.

With what bitter reflections must the young man who had been nurtured in the adoration of Bonaparte have returned from that majestic tomb to the Polytechnic School for Warriors—to which, on the day after his coronation as Emperor, Napoleon had given the following motto:

"Science and glory—all for country."

But, also, what must have been the young southerner's thought as he lifted his gaze on entering the Polytechnic and read there that self-same wish which was inscribed over the door of his first school in Tarbes:

"May this house remain standing until the ant has drunk all the waves of the sea and the tortoise has crawled round the world."

The edifice in which part of the Polytechnic was housed was the ancient College of Navarre, and a Navarrias poet of lang syne had given to the Paris school for his countrymen this quaint wish, repeated from the inscription he knew at Tarbes.

France had had twelve different governments in fourscore years when Ferdinand Foch came to study in that old building which had once been the college of Navarre. Houses of cards rather than houses of permanence seemed to characterize her.

Yet she has always had her quota—a larger one, too, than that of any other country—of those who look toward far to-morrows and seek to build substantially and beautifully for them.

That forward-looking prayer of old Navarre, and recollection of the centuries during which it had prevailed against destroying forces, was undoubtedly an aid and comfort to the heavy-hearted youth who then and there set himself to the study of that art of war wherewith he was to serve France.

Among the two hundred and odd fellow-students of Foch at the Polytechnic was another young man from the south—almost a neighbor of his and his junior by just three months—Jacques Joseph Césaire Joffre, who had entered the school in 1869, interrupted his studies to go to war, and resumed them shortly before Ferdinand Foch entered the Polytechnic.

Joffre graduated from the Polytechnic on September 21, 1872, and went thence to the School of Applied Artillery at Fontainebleau.

Foch left the Polytechnic about six months later, and also went to Fontainebleau for the same special training that Joffre was taking.

Both young men were hard students and tremendously in earnest. Both were heavy-hearted for France. Both hoped the day would come when they might serve her and help to restore to her that of which she had been despoiled.

But if any one, indulging in the fantastic extravagancies of youth, had ventured to forecast, then, even a tithe of what they have been called to do for France, he would have been set down as madder than March hares know how to be.

When Ferdinand Foch graduated, third in his class, from the artillery school at Fontainebleau, instead of seeking to use what influence he might have commanded to get an appointment in some garrison where the town life or social life was gay for young officers, he asked to be sent back to Tarbes.

No one, to my knowledge, has advanced an explanation for this move.

To so earnest and ambitious a student of military art (Foch will not permit us to speak of it as "military science") sentimental reasons alone would never have been allowed to control so important a choice.

That he always ardently loved the Pyrenean country, we know. But to a young officer of such indomitable purpose as his was, even then, it would have been inconceivable that he should elect to spend his first years out of school in any other place than that one where he saw the maximum opportunity for development.

"Development," mind you—not just "advancement." For Foch is, and ever has been, the kind of man who would most abhor being advanced faster than he developed.

He would infinitely rather be prepared for a promotion and fail to get it than get a promotion for which he was not thoroughly prepared.

Nor is he the sort of individual who can comfortably deceive himself about his fitness. He sustains himself by no illusions of the variety: "If I had so-and-so to do, I'd probably get through as well as nine-tenths of commanders would."

He is much more concerned to satisfy himself that his thoroughness is as complete as he could possibly have made it, than he is to "get by" and satisfy the powers that be!

So we know that it wasn't any mere longing for the scenes of his happy childhood which directed his choice of Tarbes garrison when he left the enchanting region of Fontainebleau, with its fairy forest, its delightful old town, and its many memories of Napoleon.

His mind seems to have been fixed upon a course involving more cavalry skill than was his on graduating. And after two years at Tarbes, with much riding of the fine horses of Arabian breed which are the specialty of that region, he went to the Cavalry School at Saumur, on the Loire.

King René of Anjou, whose chronic poverty does not seem to have interfered with his taste for having innumerable castles, had one at Saumur, and it still dominates the town and lends it an air of medievalism.

Toward the end of the sixteenth century Saumur was one of the chief strongholds of Protestantism in France and the seat of a Protestant university.

But the revocation of the Edict of Nantes granting tolerance to the Huguenots, brought great reverses upon Saumur, whose inhabitants were driven into exile. And thereupon (1685) the town fell into a decline which was not arrested until Louis XV, in the latter part of his reign, caused this cavalry school to be established there.

It is a large school, with about four hundred soldiers always in training as cavalry officers and army riding masters. And the riding exhibitions which used to be given there in the latter part of August were brilliant affairs, worth going many miles to see.

There Ferdinand Foch studied cavalry tactics, practiced "rough riding" and—by no means least important—learned to know another type of Frenchman, the men of old Anjou.

In our own country of magnificent distances and myriad racial strains we are apt to think of French people as a single race: "French is French."

This is very wide of the truth. French they all are, in sooth, with an intense national unity surpassed nowhere on earth if, indeed, it is anywhere equaled. But almost every one of them is intensely a provincial, too, and very "set" in the ways of his own section of country—which, usually, has been that of his forbears from time immemorial.

In the description I quoted in the second chapter, showing some of the types from the vicinity of Tarbes which frequent its horse market, one may get some idea of the extraordinary differences in the men of a single small region which is bordered by many little "pockets" wherein people go on and on, age after age, perpetuating their special traits without much admixture of other strains.

Not every part of France has so much variety in such small compass. But every province has its distinctive human qualities. And between the Norman and the Gascon, the Breton and the Provençal, the man of Picardy and the man of Languedoc, there are greater temperamental differences than one can find anywhere else on earth in an equal number of square miles—except in some of our American cities.

To the commander of General Foch's type (and as we begin to study his principles we shall, I believe, see that they apply to command in civil no less than in military life) knowledge of different men's minds and the way they work is absolutely fundamental to success.

And his preparation for this mastery was remarkably thorough.

At Saumur he learned not only to direct cavalry operations, but to know the Angevin characteristics.

In each school he attended, beginning with Metz, he had close class association with men from many provinces, men of many types. And this was valuable to him in preparing him to command under-officers in whom a rigorous uniformity of training could not obliterate bred-in-the-bone differences.

Many another young officer bent on "getting on" in the army would have felt that what he learned among his fellow officers of the provincial characteristics was enough.

But not so Ferdinand Foch.

Almost his entire comprehension of war is based upon men and the way they act under certain stress—not the way they might be expected to act, but the way they actually do act, and the way they can be led to act under certain stimulus of soul.

For Ferdinand Foch wins victories with men's souls—not just with their flesh and blood, nor even with their brains.

And to command men's souls it is necessary to understand them.

Upon leaving the cavalry school at Saumur, in 1878, Ferdinand Foch went, with the rank of captain of the Tenth Regiment of Artillery, to Rennes, the ancient capital of Brittany and the headquarters of France's tenth army corps.

He stayed at Rennes, as an artillery captain, for seven years.

It is not a particularly interesting city from some points of view, but it is a very "livable" one, and for a student like Foch it had many advantages. The library is one of the best in provincial France and has many valuable manuscripts. There is also an archaeological museum of antiquities found in that vicinity, many of them relating to prehistoric warfare. Some good scientific collections are also treasured there.

What is now known as the University of Rennes was styled merely the "college" in the days of Foch's residence there. But it did substantially the same work then as now, and among its faculty Foch undoubtedly found many who could give him able aid in his perpetual study of the past.

Rennes especially cherishes the memory of Bertrand du Guesclin, the great constable of France under King Charles V and the victorious adversary of Edward III. This brilliant warrior, who drove the English, with their claims on French sovereignty, out of France, was a native of that vicinity. And we may be sure that whatever special opportunity Rennes afforded of studying documents relating to his campaigns was fully improved by Captain Foch.

In that time, also, Foch had ample occasion to know the Bretons, who are, in some respects, the least French of all French provincials—being much more Celtic still than Gallic, although it is a matter of some fifteen hundred years since their ancestors, driven out of Britain by the Teutonic invasions, came over and settled "Little Britain," or Brittany.

The Bretons maintained their independence of France for a thousand years, and only became united with it through the marriage of their last sovereign, Duchess Anne, with Charles VIII, in 1491 and—after his death—with his successor, Louis XII.

And even to-day, after more than four centuries of political union, the people of Brittany are French in name and in spirit rather than in speech, customs, or temperament. Many of them do not speak or understand the French language. Few of them, outside of the cities, have conformed appreciably to French customs. Quaint, sturdy, picturesque folk they are—simple, for the most part, superstitious, tenacious of the old, suspicious of the new, and governable only by those who understand them.

Foch must have learned, in those seven years, not only to know the Bretons, but to like them and their rugged country very well. For he has had, these many years past, his summer home near Morlaix on the north coast of Brittany. It was from there that he was summoned into the great war on July 26, 1914.

In 1885 Captain Foch was called to Paris and entered the Superior School of War.

This institution, wherein he was destined to play in after years a part that profoundly affected the world's destiny, was founded only in 1878 as a training school for officers, connected with the military school which Louis XV established in 1751 to "educate five hundred young gentlemen in all the sciences necessary and useful to an officer."

One of the "young gentlemen" who profited by this instruction was the little Corsican whom Ferdinand Foch so ardently venerated.

The building covers an area of twenty-six acres and faces the vast Champ-de-Mars, which was laid out about 1770 for the military school's use as a field for maneuvers.

This field is eleven hundred yards long and just half that wide. It occupies all the ground between the school buildings and the river.

Across the river is the height called the Trocadéro, on which Napoleon hoped to build a great palace for the little King of Rome; but whereon, many years after he and his son had ceased to need mansions made by hands, the French republic built a magnificent palace for the French people. This vast building, with its majestic gardens, was the principal feature of the French national exhibition of 1878, which, like its predecessor of 1867 and its successors of 1889 and 1900, was held on the Champ-de-Mars.

Facing the Trocadéro Palace, on the Champ-de-Mars, is the Eiffel Tower (nearly a thousand feet high) which was erected for the exposition of 1889, and has served, since, then-unimaginable purposes during the stress and strain of war as a wireless station. The "Ferris" wheel put up for the exposition of 1900 is close by. And a stone's throw from the military school are the Hôtel des Invalides, Napoleon's tomb, and the magnificent Esplanade des Invalides down which one looks straightway to the glinting Seine and over the superb Alexander III bridge toward the tree-embowered palaces of arts on the Champs-Élysées.

On the other side of the Hôtel des Invalides from that occupied by the military school and Champ-de-Mars is the principal diplomatic and departmental district of Paris, with many embassies (not ours, however, nor the British—which are across the river) and many administrative offices of the French nation.

Soldiers and government officials and foreign diplomats dominate the quarter—and homes of the old French aristocracy.

The Hotel des Invalides, founded by Louis XIV and designed to accommodate, as an old soldiers' home, some seven thousand veterans of his unending wars, has latterly served as headquarters for the military governor of Paris, and also—principally—as a war museum.

Here are housed collections of priceless worth and transcendent interest. The museum of artillery contains ten thousand specimens of weapons and armor of all kinds, ancient and modern. The historical museum, across the court of honor, was—in the years when I spent many fascinating hours there—extraordinarily rich in personal souvenirs of scores of illustrious personages.

What it must be now, after the tragic years of a world war, and what it will become as a treasure house for the years to come, is beyond my imagination.

It was into this enormously rich atmosphere, pregnant with everything that conserves France's most glorious military traditions, that Captain Ferdinand Foch was called in 1885 for two years of intensive training and study.

After quitting the School of War in 1887 (he graduated fourth in his class, as he had at Saumur; he was third at Fontainebleau), Ferdinand Foch was sent to Montpellier as a probationer for the position of staff officer.

He remained at Montpellier for four years—first as a probationer and later as a staff officer in the Sixteenth Army Corps, whose headquarters are there.

It is a coincidence—without special significance, but interesting—that Captain Joseph Joffre had spent several years at the School of Engineering in Montpellier; he left there in 1884, after the death of his young wife, to bury himself and his grief in Indo-China; so the two men did not meet in the southern city.[1]

Joffre returned from Indo-China in 1888, while Foch was at Montpellier, and after some time in the military railway service, and a promotion in rank (he was captain for thirteen years), received an appointment as professor of fortifications at Fontainebleau.

Some persons who claim to have known Joffre at Montpellier have manifested surprise at the greatness to which he attained thirty years later; he did not impress them as a man of destiny. That is quite as likely to be their fault as his. And also it is possible that Captain Joseph Joffre had not then begun to develop in himself those qualities which made him ready for greatness when the opportunity came.

If, however, any one has ever expressed surprise at Ferdinand Foch's attainment, I have not heard of it. He seems always to have impressed people with whom he came in contact as a man of tremendous energy, application, and thoroughness.

The opportunities for study at Montpellier are excellent, and the region is one of extraordinary richness for the lover of history. The splendor of the cities of Transalpine Gaul in this vicinity is attested by remains more numerous and in better preservation than Italy affords save in a very few places. And awe-inspiring evidences of medievalism's power flank one at every step and turn. Without doubt, Foch made the most of them.

Needless to remark, the commander-in-chief of the allied armies has not confided to me what were his favorite excursions during these four years at Montpellier. But I am quite sure that Aigues-Mortes was one of them. And I like to think of him, as we know he looked then, pacing those battlements and pondering the warfare of those militant ages when this vast fortress in the wide salt marshes was one of the most formidable in the world. What fullness of detail there must have been in the mental pictures he was able to conjure of St. Louis embarking here on his two crusades? What particularity in his appreciation of those defenses!

The place is, to-day, the very epitome of desolation—much more so than if the fortifications were not so perfectly preserved. For they look as if yesterday they might have been bristling with men-at-arms—whereas not in centuries has their melancholy majesty served any other purpose than that of raising reflections in those to whom the past speaks through her monuments.

From Montpellier, Ferdinand Foch returned to Paris, in February, 1891, as major on the general army staff.

He and Joffre had now the same rank. Joffre became lieutenant colonel in 1894 and colonel in 1897; similar promotions came to Foch in 1896 and 1903. He was six years later than Joffre in attaining a colonelcy, and exactly that much later in becoming a general.

Neither man had a quick rise but Foch's was (as measurable in grades and pay) specially slow.

About the time that Major Joffre went to the Soudan, to superintend the building of a railway in the Sahara desert, Major Foch went to Vincennes as commander of the mounted group of the Thirteenth Artillery.

Vincennes is on the southeastern skirts of Paris, close by the confluence of the Seine and the Marne; about four miles or so from the Bastille, which was the city's southeastern gate for three hundred years or thereabouts, until the fortified inclosure on that side of the city was enlarged under Louis XIV.

The fort of Vincennes was founded in the twelfth century to guard the approach to Paris from the Marne valley. And on account of its pleasant situation—close to good hunting and also to their capital—the castle of Vincennes was a favorite residence of many early French kings.

It was there that St. Louis is said to have held his famous open-air court of justice, which he established so that his subjects might come direct to him with their troubles and he, besides settling them, might learn at first hand what reforms were needed.

Five Kings of France died there (among them Charles VI, the mad king, and Charles IX, haunted by the horrors of the massacre on St. Bartholomew's eve), and one King of England, Harry Hotspur. King Charles V was born there.

From the days of Louis XI the castle has been used as a state prison. Henry of Navarre was once a prisoner there, and so was the Grand Condé, and Diderot, and Mirabeau, and it was there that the young Duc d'Enghien was shot by Napoleon's orders and to Napoleon's everlasting regret.

The castle is now (and has been for many years) an arsenal and school of musketry, artillery, and other military services. Before its firing squad perish many traitors to France, whose last glimpse of the country they have betrayed is in the courtyard of this ancient castle.

The vicinity is very lovely. The Bois de Vincennes, on the edge of which the castle stands, is scarcely inferior to the Bois de Boulogne in charm. We used to go out there, not infrequently, for luncheon, which we ate in a rustic summerhouse close to the edge of the lake, with many sociable ducks and swans bearing us company and clamoring for bits of bread.

It would be hard to imagine anything more idyllic, more sylvan, on the edge of a great city—anything more peaceful, restful, anywhere.

Yet the whole locality was, even then, a veritable camp of Mars—forts, barracks, fields for maneuvers and for artillery practice, infantry butts, rifle ranges, school of explosives; and what not.

France knew her need of protection—and none of us can ever be sufficiently grateful that she did!

But she did not obtrude her defensive measures. She seldom made one conscious of her military affairs.

In Germany, for many years before this war, remembrance of the army and reverence to the army was exacted of everyone almost at every breath. Forever and forever and forever you were being made to bow down before the God of War.

In France, on the contrary, it was difficult to think about war—even in the very midst of a place like Vincennes—unless you were actually engaged in organizing and preparing the country's defenses.

After three years at Vincennes, Ferdinand Foch was recalled to the army staff in Paris. And on the 31st of October, 1895, he was made associate professor of military history, strategy, and applied tactics, at the Superior School of War.

He had then just entered upon his forty-fifth year; and the thoroughness of his training was beginning to make itself felt at military headquarters.

[1] I have found it interesting to compare the careers of Joffre and Foch from the time they were at school together, and I daresay that others will like to know what steps forward he was taking who is not the subject of these chapters but inseparably bound up with him in many events and forever linked with him in glory.

After a year's service as associate professor of military history, strategy, and applied tactics at the Superior School of War in Paris, Ferdinand Foch was advanced to head professorship in those branches and at the same time he was made lieutenant-colonel. This was in 1896. He was forty-five years old and had been for exactly a quarter of a century a student of the art of warfare.

His old schoolfellow, Joseph Joffre, was then building fortifications in northern Madagascar; and his army rank was the same as that of Foch.

It was just twenty years after Foch entered upon his full-fledged professorship at the Superior School of War that Marshal Joffre, speaking at a dinner assembling the principal leaders of the government and of the army, declared that without the Superior School of War the victory of the Marne would have been impossible.

All the world knows this now, almost as well as Marshal Joffre knew it then. And all the world knows now as not even Marshal Joffre could have known then, how enormous far, far beyond the check of barbarism at the first battle of the Marne—is our debt and that of all posterity to the Superior School of War and, chiefly, to Ferdinand Foch.

It cannot have been prescience that called him there. It was just Providence, nothing less!

For that was a time when men like Ferdinand Foch (whose whole heart was in the army, making it such that nothing like the downfall of 1870 could ever again happen to France), were laboring under extreme difficulties. The army was unpopular in France.

This was due, partly to the disclosures of the Dreyfus case; partly to a wave of internationalism and pacifism; partly to jealousy of the army among civil officials.

An unwarranted sense of security was also to blame. France had worked so hard to recoup her fortunes after the disaster of 1870 that her people—delighted with their ability as money makers, blinded by the glitter of great prosperity—grudged the expanse of keeping up a large army, grudged the time that compulsory military training took out of a young man's life. And this preoccupation with success and the arts and pleasures of prosperous peace made them incline their ears to the apostles of "Brotherhood" and "Federation" and "Arbitration instead of Armament."

Little by little legislation went against the army. The period of compulsory service was reduced from three years to two; that cut down the size of the army by one-third. The supreme command of the army was vested not in a general, but in a politician—the Minister of War. The generals in the highest commands not only had to yield precedence to the prefects of the provinces (like our governors of states), but were subject to removal if the prefects did not like their politics and the Minister of War wished the support of the prefects.

Even the superior war council of the nation might be politically made up, to pay the War Minister's scores rather than to protect the country.

All this can happen to a people lulled by a false sense of security—even to a people which has had to defend itself against the savage rapacity of its neighbors across the Rhine for two thousand years!

It was against these currents of popular opinion and of government opposition that Ferdinand Foch took up his work in the Superior School of War—that work which was to make possible the first victory of the Marne, to save England from invasion by holding Calais, and to do various other things vital to civilization, including the prodigious achievements of the days that have since followed.

Foch foresaw that these things would have to be done and, with absolute consecration to his task, he set himself not only to train officers for France when she should need them, but to inspire them with a unity of action which has saved the world.

I have various word-pictures of him as he then appeared to, and impressed, his students.

One is by a military writer who uses the pseudonym of "Miles."

"The officers who succeeded one another at the school of war between 1896 and 1901," he says, referring to the first term of Foch as instructor there, "will never forget the impressions made upon them by their professor of strategy and of general tactics. It was this course that was looked forward to with the keenest curiosity as the foundational instruction given by the school. It enjoyed the prestige given it by the eminent authorities who had held it; and the eighty officers who came to the school at each promotion, intensely desirous of developing their skill and judgment, were always impatient to see and hear the man who was to instruct them in these branches.

"Lieutenant-Colonel Foch did not disappoint their expectations. Thin, elegant, of distinguished bearing, he at once struck the beholder with his expression—full of energy, of calm, of rectitude.

"His forehead was high, his nose straight and prominent, his gray-blue eyes looked one full in the face. He spoke without gestures, with an air of authority and conviction; his voice serious, harsh, a little monotonous; amplifying his phrases to press home in every possible way a rigorous reasoning; provoking discussion; always appealing to the logic of his hearers; sometimes difficult to follow, because his discourse was so rich in ideas; but always holding attention by the penetration of his surveys as well as by his tone of sincerity.

"The most profound and the most original of the professors at the school of war, which at that time counted in its teaching corps many very distinguished minds and brilliant lecturers: such Lieutenant-Colonel Foch seemed to his students, all eager from the first to give themselves up to the enjoyment of his lessons and the acceptance of his inspiration."

Colonel E. Réquin of the French general staff, who has fought under Foch in some of the latter's greatest engagements, says:

"Foch has been for forty years the incarnation of the French military spirit." For forty years! That means ever since he left the cavalry school at Saumur and went, as captain of the Tenth regiment of artillery, to Rennes. "Through his teachings and his example," Colonel Réquin goes on to say, in a 1918 number of the World's Work, "he was the moral director of the French general staff before becoming the supreme chief of the allied armies. Upon each one of us he has imprinted his strong mark. We owe to him in time of peace that unity of doctrine which was our strength. Since the war we owe to him the highest lessons of intellectual discipline and moral energy.

"As a professor he applied the method which consists in taking as the base of all strategical and tactical instruction the study of history completed by the study of military history—that is to say, field operations, orders given, actions, results, and criticisms to be made and the instructions to be drawn from them. He also used concrete cases—that is to say, problems laid by the director on the map or on the actual ground.

"By this intellectual training he accustomed the officers to solving all problems, not by giving them ready-made solutions, but by making them find the logical solution to each individual case.

"His mind was trained through so many years of study that no war situation could disturb him. In the most difficult ones, he quickly pointed out the goal to be reached and the means to employ, and each one of us felt that it must be right."

But best of all the things said about Foch in that period of his life, I like this, by Charles Dawbarn, in the Fortnightly Review:

"Such was"—in spite of many disappointments—"his fine confidence in life, that he communicated to others not his grievances, but his secret satisfactions."

Foch made the men who sat under him love their work for the work's sake and not for its rewards. He fired them with an ardor for military art which made them feel that in all the world there is nothing so fascinating, so worth while, as knowing how to defend one's country when she needs defense.

He was able, in peace times when the military spirit was little applauded and much decried, to give his students an enthusiasm for "preparedness" which flamed as high and burned as pure as that which ordinarily is lighted only by a great national rush to arms to save the country from ravage.

It was tremendously, incalculably important for France and for all of us that Ferdinand Foch was eager and able to impart this enthusiasm for military skill.

But also it is immensely important, to-day, when the war is won, and in all days and all walks of life, that there be those who can kindle and keep alight the enthusiasm of their fellows; who can overlook the failure of their own ardor and faithfulness to win its fair reward, and convey to others only the alluring glow of their "secret satisfactions."

In the five years, 1895-1901 (his work at the school was interrupted by politics in 1901), "many hundreds of officers," as René Puaux says, "the very elite of the general staffs of our army, followed his teaching and were imbued with it; and as they practically all, at the beginning of the war, occupied high positions of command, one may estimate as he can the profound and far reaching influence of this one grand spirit."

Let us try to get some idea of the sort of thing that Foch taught those hundreds of French army officers, not only about war but about life.

From all his study, he repeatedly declared, one dominant conviction has evolved: Force that is not dominated by spirit is vain force.

Victory, in his belief, goes to those who merit it by the greatest strength of will and intelligence.

It was his endeavor, always, to develop in the hundreds of officers who were his students, that dual strength in which it seemed to him that victory could only lie: moral and intellectual ability to perceive what ought to be done, and intellectual and moral ability to do it.

In his mind, it is impossible to be intelligent with the brain alone. The Germans do not comprehend this, and therein, to Ferdinand Foch, lies the key to all their failures.

He believes that each of us must think with our soul's aid—that is to say, with our imagination, our emotions, our aspiration—and employ our intelligence to direct our feeling.

And he asks this combination not from higher officers alone, but from all their men down to the humblest in the ranks.

He believes in the invincibility of men fighting for a principle dearer to them than life—but he knows that ardor without leadership means a lost cause; that men must know how to fight for their ideals, their principles; but that their officers are charged with the sacred responsibility of making the men's ardor and valor count.

At the beginning of his celebrated course of lectures on tactics he always admonished his students thus:

"You will be called on later to be the brain of an army. So I say to you to-day: Learn to think."

By this he was far from meaning that officers were to confine thinking to themselves, but that they were to teach themselves to think so that they might the better hand on intelligence and stimulate their men to obey not blindly but comprehendingly.

It was a maxim of Napoleon's, of which Foch is very fond, that "as a general rule, the commander-in-chief ought only to indicate the direction, determine the ends to be attained; the means of getting there ought to be left to the free choice of the mediums of execution, without whom success is impossible."

This leaves a great responsibility to officers, but it is the secret of that flexibility which makes the French army so effective.

For Foch carries his belief in individual judgment far beyond the officers commanding units; he carries it to the privates in the ranks.

An able officer, in Foch's opinion, is one who can take a general command to get his men such-and-such a place and accomplish such-and-such a thing, and so interpret that command to his men that each and every one of them will, while acting in strict obedience to orders, use the largest possible amount of personal intelligence in accomplishing the thing he was told to do.

It is said that there was probably never before in history a battle fought in which every man was a general—so to speak—as at the battle of Château Thierry, in July, 1918. That is to say, there was probably never before a battle in which so many men comprehended as clearly as if they had been generals what it was all about, and acted as if they had been generals to attain their objectives.

It was an intelligent democracy, acting under superb leadership that vanquished the forces of autocracy.

Foch has worked with a free hand to test the worth of his lifelong principles. And the hundreds of men he trained in those principles were ready to carry them out for him.

No wonder his first injunction was: Learn to think!

To him, the leadership of units is not a simple question of organization, of careful plans, of strategic and tactical intelligence, but a problem involving enormous adaptability.

Battles are not won at headquarters, he contends; they are won in the field; and the conditions that may arise in the field cannot be foreseen or forestalled—they must be met when they present themselves. In large part they are made by the behavior of men in unexpected circumstances; therefore, the more a commander knows about human nature and its spiritual depressions and exaltations, the better able he is to change his plans as new conditions arise.

German power in war, Foch taught his students, lay in the great masses of their effective troops and their perfect organization for moving men and supplies. German weakness was in the absolute autocracy of great headquarters, building its plans as an architect builds a house and unable to modify them if something happens to make a change necessary.

This he deduced from his study of their methods in previous wars, especially in that of 1870.

And with this in mind he labored so that when Germany made her next assault upon France, France might be equipped with hundreds of officers cognizant of Germany's weakness and prepared to turn it to her defeat.

"It was not," Napoleon wrote, "the Roman legions which conquered Gaul, but Caesar. It was not the Carthaginian soldiers who made Rome tremble, but Hannibal. It was not the Macedonian phalanx which penetrated India, but Alexander. It was not the French army which reached the Weser and the Inn, but Turenne. It was not the Prussian soldiers who defended their country for seven years against the three most formidable powers in Europe; it was Frederick the Great."

And already it has been suggested that historians will write of this war: "It was not the allied armies, struggling hopelessly for four years, that finally drove the Germans across the Rhine, but Ferdinand Foch."

But I am sure that Foch would not wish this said of him in the same sense that Napoleon said it of earlier generals.

For Foch has a greater vision of generalship than was possible to any commander of long ago.

His strategy is based upon a close study of theirs; for he says that though the forms of making war evolve, the directing principles do not change, and there is need for every officer to make analyses of Xenophon and Caesar and Hannibal as close as those he makes of Frederick and Napoleon.

But his conception of military leadership is permeated with the ideals of democracy and justice for which he fights.

One of his great lectures to student-officers was that in which he made them realize what, besides the route of the Prussians, happened at Valmy in September, 1792.

On his big military map of that region (it is on the western edge of the Argonne) Foch would show his students how the Prussians, Hessians and some Austrian troops; under the Duke of Brunswick, crossed the French frontier on August 19 and came swaggering toward Paris, braggartly announcing their intentions of "celebrating" in Paris in September.

Brunswick and his fellow generals were to banquet with the King of Prussia at the Tuileries. And the soldiers were bent upon the cafés of the Palais Royal.

Foch showed his classes how Dumouriez, who had been training his raw troops of disorganized France at Valenciennes, dashed with them into the Argonne to intercept Brunswick; how this and that happened which I will not repeat here because it is merely technical; and then how the soldiers of the republic, rallied by the cry, "The country is in danger," and thrilled by "The Marseillaise" (written only five months before, but already it had changed the beat of nearly every heart in France), made such a stand that it not only halted Prussia and her allies, but so completely broke their conquering spirit that without firing another shot they took themselves off beyond the Rhine.

"We," Foch used to tell his students, "are the successors of the revolution and the empire, the inheritors of the art, new-born upon the field of Valmy to astonish the old Europe, to surprise in particular the Duke of Brunswick, the pupil of Frederick the Great, and to tear from Goethe, before the immensity of a fresh horizon, this profound cry: 'I tell you, from this place and this day comes a new era in the history of the world!'"

It is that new era which Foch typifies—that new era which his adversaries, deaf to Goethe's cry and blind to Goethe's vision, have not yet realized.

It was "the old Europe" against which Foch fought—the old Europe which learned nothing at Valmy and had learned nothing since; the old Europe that fought as Frederick the Great fought and that had not yet seen the dawn of that new day which our nation and the French nation greeted with glad hails much more than a century ago.

In 1792 Prussia measured her military skill and her masses of trained men against France's disorganization—and overlooked "The Marseillaise."

In 1914 she weighed her might against what she knew of the might of France—and omitted to weigh certain spiritual differences which she could not comprehend, but which she felt at the first battle of the Marne, has been feeling ever since, and before which she had to retire, beaten but still blind.

In 1918 she estimated the probable force of those "raw recruits" whom we were sending overseas—and laughed. She based her calculations on our lack of military tradition, our hastily trained officers, our "soft," ease-loving men uneducated in those ideals of blood and iron wherein she has reared her youth always. She overlooked that spiritual force which the "new era" develops and which made our men so responsive to the command of Foch at Château Thierry and later.

"The immensity of a fresh horizon" whereon Goethe saw the new era dawning, is still veiled from the vision of his countrymen. But across its roseate reaches unending columns of marching men passed, under the leadership of Ferdinand Foch, to liberate the captives the blind brute has made and to strike down the strongholds of "old Europe" forever.

For nearly six years Foch taught such principles as these and others which I shall recall in connection with great events which they made possible later on.

Then came the anti-clerical wave in French politics, and on its crest a new commandant to the School of War—a man elevated by the anti-clericals and eager to keep his elevation by pleasing those who put him there.

Foch adheres devoutly to the religious practices in which he was reared, and one of his brothers belongs to the Jesuit order.

These conditions made his continuance at the school under its new head impossible. Whether he resigned because he realized this, or was superseded, I do not know. But he left his post and went as lieutenant-colonel to the Twenty-ninth artillery, at Laon.

He was there two years and undoubtedly made a thorough study of the country round Laon—which was for more than four years to be the key to the German tenure in that part of France.

Ferdinand Foch, with his brilliant knowledge and high ideals of soldiering, was now past fifty and not yet a colonel.

Strong though his spirit was, sustained by faith in God and rewarded by those "secret satisfactions" which come to the man who loves his work and is conscious of having given it his best, he must have had hours, days, when he drank deep of the cup of bitterness. There are, though, bitters that shrivel and bitters that tone and invigorate. Or perhaps they are the same and the difference is in us.

At any rate, Foch was not poisoned at the cup of disappointment.

And when the armies under his command encircled the great rock whereon Laon is perched high above the surrounding plains I hope Foch was with them—in memory of the days when he was "dumped" there, so to speak, far away from his sphere of influence at the School of War.

In 1903 he was made colonel and sent to the Thirty-fifth artillery at Vannes, in Brittany.

Only two years later he was called to Orleans as chief of staff of the Fifth army corps.

On June 20, 1907, he was made Brigadier General and passed to the general staff of the French army at Paris. Soon afterwards, Georges Clemenceau became Minister of War, and was seeking a new head for the Staff College. Everyone whose advice he sought said: Foch. So the redoubtable old radical and anti-clerical summoned General Foch.

"I offer you command of the School of War."

"I thank you," Foch replied, "but you are doubtless unaware that one of my brothers is a Jesuit."

"I know it very well," was Clemenceau's answer. "But you make good officers, and that is the only thing which counts."

Thus was foreshadowed, in these two great men, that spirit of "all for France" which, under the civil leadership of one and the military leadership of the other, was to save the country and the world.

In 1911 Foch, at 60, was given command of the Thirteenth division at Chaumont, just above the source of the Marne. On December 17, 1912, he was placed at the head of the Eighth Army Corps, at Bourges. And on August 23, 1913, he took command of the Twentieth corps at Nancy.

"When," says Marcel Knecht, "we in Nancy heard that Foch had been chosen to command the best troops in France, the Twentieth Army Corps, pride of our capital, everybody went wild with enthusiasm."