Title: The Modern Scottish Minstrel, Volume 4.

Editor: Charles Rogers

Release date: October 11, 2006 [eBook #19525]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Susan Skinner, Ted Garvin and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Lithographed for the Modern Scottish Minstrel, by Schenck & McFarlane.

Lithographed for the Modern Scottish Minstrel, by Schenck & McFarlane.

IN SIX VOLUMES;

VOL. IV.

EDINBURGH:

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK, NORTH BRIDGE,

BOOKSELLERS AND PUBLISHERS TO HER MAJESTY.

M.DCCC.LVI.

EDINBURGH:

PRINTED BY BALLANTYNE AND COMPANY,

PAUL'S WORK.

TO

FRANCIS BENNOCH, ESQ., F.S.A.,

ONE OF THE MOST ACCOMPLISHED OF LIVING SCOTTISH SONG-WRITERS,

AND THE MUNIFICENT PATRON OF MEN OF LETTERS,

THIS FOURTH VOLUME

OF

The Modern Scottish Minstrel

IS DEDICATED,

WITH SINCERE REGARD AND ESTEEM,

BY

HIS VERY FAITHFUL SERVANT,

CHARLES ROGERS.

It is exceedingly difficult to settle the exact place of, as well as to compute the varied influences wielded by, a great original genius. Every such mind borrows so much from his age and from the past, as well as communicates so much from his own native stores, that it is difficult to determine whether he be more the creature or the creator of his period. But, ere determining the influence exerted by Burns on Scottish song and poetry, it is necessary first to inquire what he owed to his predecessors in the art, as well as to the general Scottish atmosphere of thought, feeling, scenery and manners.

First of all, Burns felt, in common with his forbears in the genealogy of Scottish song, the inspiring influences breathing from our mountain-land, and from the peculiar habits and customs of a "people dwelling[Pg vi] alone, and not reckoned among the nations." He was not born in a district peculiarly distinguished for romantic beauty—we mean, in comparison with some other regions of Scotland. The whole course of the Ayr, as Currie remarks, is beautiful; and beautiful exceedingly the Brig of Doon, especially as it now shines through the magic of the Master's poetry. But it yields to many other parts of Scotland, some of which Burns indeed afterwards saw, although his matured genius was not much profited by the sight. Ayrshire—even with the peaks of Arran bounding the view seaward—cannot vie with the scenery around Edinburgh; with Stirling—its links and blue mountains; with "Gowrie's Carse, beloved of Ceres, and Clydesdale to Pomona dear;" with Straths Tay and Earn, with their two fine rivers flowing from finer lakes, through corn-fields, woods, and rocks, to melt into each other's arms in music, near the fair city of Perth; with the wilder and stormier courses of the Spey, the Findhorn, and the Dee; with the romantic and song-consecrated precincts of the Border; with the "bonnie hills o' Gallowa" and Dumfriesshire; or with that transcendent mountain region stretching up along Lochs Linnhe, Etive, and Leven—between the wild, torn ridges of Morven and Appin—uniting Ben Cruachan to Ben Nevis, and including in its sweep the lonely and magnificent Glencoe—a region unparalleled in wide Britain for its quantity and variety of desolate grandeur, where every shape is bold, every shape blasted, but all blasted at such different angles as to produce endless diversity, and yet where the whole seems twisted into a certain terrible harmony; not to speak of the glorious isles

Iona, which, being interpreted, means the "Island of[Pg vii] the Waves," the rocky cradle of Scotland's Christianity; Staffa with grass growing above the unspeakable grandeur which lurks in the cathedral-cave below, and cows peacefully feeding over the tumultuous surge which forms the organ of the eternal service; and Skye, with its Loch Coriskin, piercing like a bright arrow the black breast of the shaggy hills of Cuchullin. Burns had around him only the features of ordinary Scottish scenery, but from these he drank in no common draught of inspiration; and how admirably has he reproduced such simple objects as the "burn stealing under the lang yellow broom," and the "milk-white thorn that scents the evening gale," the "burnie wimplin' in its glen," and the

These objects constituted the poetry of his own fields; they were linked with his own joys, loves, memories, and sorrows, and these he felt impelled to enshrine in song. It may, indeed, be doubted if his cast of mind would have led him to sympathise with bold and savage scenery. In proof of this, we remember that, although he often had seen the gigantic ridges of Arran looming through the purple evening air, or with the "morning suddenly spread" upon their summer summits, or with premature snow tinging their autumnal tops, he never once alludes to them, so far as we remember, either in his poetry or prose; and that although he spent a part of his youth on the wild smuggling coast of Carrick, he has borrowed little of his imagery from the sea—none, we think, except the two lines in the "Vision"—

His descriptions are almost all of inland scenery. Yet, that there was a strong sense of the sublime in his mind is manifest from the lines succeeding the above—

as well as from the delight he expresses in walking beside a planting in a windy day, and listening to the blast howling through the trees and raving over the plain. Perhaps his mind was most alive to the sublimity of motion, of agitation, of tumultuous energy, as exhibited in a snow-storm, or in the "torrent rapture" of winds and waters, because they seemed to sympathise with his own tempestuous passions, even as the fierce Zanga, in the "Revenge," during a storm, exclaims—-

Probably Burns felt little admiration of the calm, colossal grandeur of mountain-scenery, where there are indeed vestiges of convulsion and agony, but where age has softened the storm into stillness, and where the memory of former strife and upheaving only serves to deepen the feeling of repose—vestiges which, like the wrinkles on the stern brow of the Corsair,

With these records of bygone "majestic pains," on the other hand, the genius of Milton and Wordsworth seemed made to sympathise; and the former is never greater than standing on Niphates Mount with Satan,[Pg ix] or upon the "hill of Paradise the highest" with Michael, or upon the "Specular Mount" with the Tempter and the Saviour; and the latter is always most himself beside Skiddaw or Helvellyn. Byron professes vast admiration for Lochnagar and the Alps; but the former is seen through the enchanting medium of distance and childish memory; and among the latter, his rhapsodies on Mont Blanc, and the cold "thrones of eternity" around him, are nothing to his pictures of torrents, cataracts, thunderstorms; in short, of all objects where unrest—the leading feeling in his bosom—constitutes the principal element in their grandeur. It is curious, by the way, how few good descriptions there exist in poetry of views from mountains. Milton has, indeed, some incomparable ones, but all imaginary—such, at least, as no actual mountain on earth can command; but, in other poets, we at this moment remember no good one. They seem always looking up to, not down from, mountains. Wordsworth has given us, for example, no description of the view from Skiddaw; and there does not exist, in any Scottish poetical author, a first-rate picture of the view either from Ben Lomond, Schehallion, Ben Cruachan, or Ben Nevis.

After all, Burns was more influenced by some other characteristics of Scotland than he was by its scenery. There was, first, its romantic history. That had not then been separated, as it has since been, from the mists of fable, but lay exactly in that twilight point of view best adapted for arousing the imagination. To the eye of Burns, as it glared back into the past, the history of his country seemed intensely poetical—including the line of early kings who pass over the stage of Boece' and Buchanan's story as their brethren over the magic glass of Macbeth's witches—equally fantastic and equally[Pg x] false—the dark tragedy of that terrible thane of Glammis and Cawdor—the deeds of Wallace and Bruce—the battle of Flodden—and the sad fate of Queen Mary; and from most of these themes he drew an inspiration which could scarcely have been conceived to reside even in them. On Wallace, Bruce, and Queen Mary, his mind seems to have brooded with peculiar intensity—on the two former, because they were patriots; and on the latter, because she was a beautiful woman; and his allusions to them rank with the finest parts in his or any poetry. He seemed especially adapted to be the poet-laureate of Wallace—a modern edition, somewhat improved, of the broad, brawny, ragged bard who actually, it is probable, attended in the train of Scotland's patriot hero, and whose constant occupation it was to change the gold of his achievements into the silver of song. Scottish manners, too, as well as history, exerted a powerful influence on Scotland's peasant-poet. They were then far more peculiar than now, and had only been faintly or partially represented by previous poets. Thus, the christening of the wean, with all its ceremony and all its mirth—Hallowe'en, with its "rude awe and laughter"—the "Rockin'"—the "Brooze"—the Bridal—and a hundred other intensely Scottish and very old customs, were all ripe and ready for the poet, and many of them he has treated, accordingly, with consummate felicity and genius. It seems almost as if the final cause of their long-continued existence were connected with the appearance, in due time, of one who was to extract their finest essence, and to embalm them for ever in his own form of ideal representation.

Burns, too, doubtless derived much from previous poets. This is a common case, as we have before[Pg xi] hinted, with even the most original. Had not Shakspeare and Milton been "celestial thieves," their writings would have been far less rich and brilliant than they are; although, had they not possessed true originality, they would not have taken their present lofty position in the world of letters. So, to say that Burns was much indebted to his predecessors, and that he often imitated Ramsay and Fergusson, and borrowed liberally from the old ballads, is by no means to derogate from his genius. If he took, he gave with interest. The most commonplace songs, after they had, as he said, "got a brushing" from his hands, assumed a totally different aspect. Each ballad was merely a piece of canvas, on which he inscribed his inimitable paintings. Sometimes even by a single word he proclaimed the presence of the master-poet, and by a single stroke exalted a daub into a picture. His imitations of Ramsay and Fergusson far surpass the originals, and remind you of Landseer's dogs, which seem better than the models from which he drew. When a king accepts a fashion from a subject, he glorifies it, and renders it the rage. It was in this royal style that Burns treated the inferior writers who had gone before him; and although he highly admired and warmly praised them, he must have felt a secret sense of his own vast superiority.

We come now shortly to speak of the influence he has exerted on Scottish poetry. This was manifold. In the first place, a number were encouraged by his success to collect and publish their poems, although few of them possessed much merit; and he complained that some were a wretched "spawn" of mediocrity, which the sunshine of his fame had warmed and brought forth prematurely. Lapraik, for instance, was induced by the praise of Burns to print an edition of his poems,[Pg xii] which turned out a total failure. There was only one good piece in it all, and that was pilfered from an old magazine. Secondly, Burns exerted an inspiring influence on some men of real genius, who, we verily believe, would, but for Burns, have never written, or, at least, written so well—such as Alexander Wilson, Tannahill, Macneil, Hogg, and the numerous members of the "Whistle-Binkie" school. In all these writers we trace the influence of the large "lingering star" of the genius of Burns. "Wattie and Meg," by Wilson, when it first appeared anonymously, was attributed to Burns. Tannahill is, in much of his poetry, an echo of Burns, although in song-writing he is a real original. Macneil was roused by Burns' praises of whisky to give a per contra, in his "Scotland's Scaith; or, the History of Will and Jean." And although the most of Hogg's poetry is entirely original, we find the influence of Burns distinctly marked in some of his songs—such as the "Kye come Hame."

But there is a wider and more important light in which to regard the influence of our great national Bard. He first fully revealed the interest and the beauty which lie in the simpler forms of Scottish scenery, he darted light upon the peculiarities of Scottish manners, and he opened the warm heart of his native land. Scotland, previous to Burns' poetry, was a spring shut up and a fountain sealed.

The glories of her lakes, her glens, her streams, her mountains, the hardy courage, the burning patriotism, the trusty attachments, the loves, the games, the superstitions, and the devotion of her inhabitants, were all[Pg xiii] unknown and unsuspected as themes for song till Burns took them up, and less added glory than shewed the glory that was in them, and shewed also that they opened up a field nearly inexhaustible. Writers of a very high order were thus attracted to Scotland, not merely as their native country, but as a theme for poetry; and, while disdaining to imitate Burns' poetry slavishly, and some of them not writing in verse at all, they found in Scottish subjects ample scope for the exercise of their genius; and in some measure to his influence we may attribute the fictions of Mrs Hamilton and Miss Ferrier, Scott's poems and novels, Galt's, Lockhart's, Wilson's, Delta's, and Aird's tales and poetry, and much of the poetry of Campbell, who, although he never writes in Scotch, has embalmed, in his "Lochiel's Warning," "Glenara," "Lord Ullin's Daughter," some interesting subjects connected with Scotland, and has, in "Gertrude of Wyoming," and in the "Pilgrim of Glencoe," made striking allusions to Scottish scenery. That the progress of civilisation, apart from Burns, would have ultimately directed the attention of cultivated men to a country so peculiar and poetical as Scotland cannot be doubted; but the rise of Burns hastened the result, as being itself a main element in propelling civilisation and diffusing genuine taste. His dazzling success, too, excited emulation in the breasts of our men of genius, as well as tended to exalt in their eyes a country which had produced such a stalwart and gifted son. We may, indeed, apply to the feeling of pride which animates Scotchmen, and particularly Scotchmen in other lands, at the thought of Burns being their countryman, the famous lines of Dryden[Pg xiv]—

The poor man, says Wilson, as he speaks of Burns, always holds up his head and regards you with an elated look. Scotland has become more venerable, more beautiful, more glorious in the eyes of her children, and a fitter theme for poetry, since the feet of Burns rested on her fields, and since his ardent eyes glowed with enthusiasm as he saw her scenery, and as he sung her praise; while to many in foreign parts she is chiefly interesting as being (what a portion of her has long been called) the Land of Burns.

The real successors of Burns, it is thus manifest, were not Tannahill or Macneil, but Sir Walter Scott, Campbell, Aird, Delta, Galt, Allan Cunningham, and Professor Wilson. To all of these, Burns, along with Nature, united in teaching the lessons of simplicity, of brawny strength, of clear common sense, and of the propriety of staying at home instead of gadding abroad in search of inspiration. All of these have been, like Burns, more or less intensely Scottish in their subjects and in their spirit.

That Burns' errors as a man have exerted a pernicious influence on many since, is, we fear, undeniable. He had been taught, by the lives of the "wits," to consider aberration, eccentricity, and "devil-may-careism" as prime badges of genius, and he proceeded accordingly to astonish the natives, many of whom, in their turn, set themselves to copy his faults. But when we subtract some half-dozen pieces, either coarse in language or equivocal in purpose, the influence of his poetry may be[Pg xv] considered good. (We of course say nothing here of the volume called the "Merry Muses," still extant to disgrace his memory.) It is doubtful if his "Willie brew'd a peck o' Maut" ever made a drunkard, but it is certain that his "Cottar's Saturday Night" has converted sinners, edified the godly, and made some erect family altars. It has been worth a thousand homilies. And, taking his songs as a whole, they have done much to stir the flames of pure love, of patriotism, of genuine sentiment, and of a taste for the beauties of nature. And it is remarkable that all his followers and imitators have, almost without exception, avoided his faults while emulating his beauties; and there is not a sentence in Scott, or Campbell, or Aird, or Delta, and not many in Wilson or Galt, that can be charged with indelicacy, or even coarseness. So that, on the whole, we may assert that, whatever evil he did by the example of his life, he has done very little—but, on the contrary, much good, both artistically and morally, by the influence of his poetry.

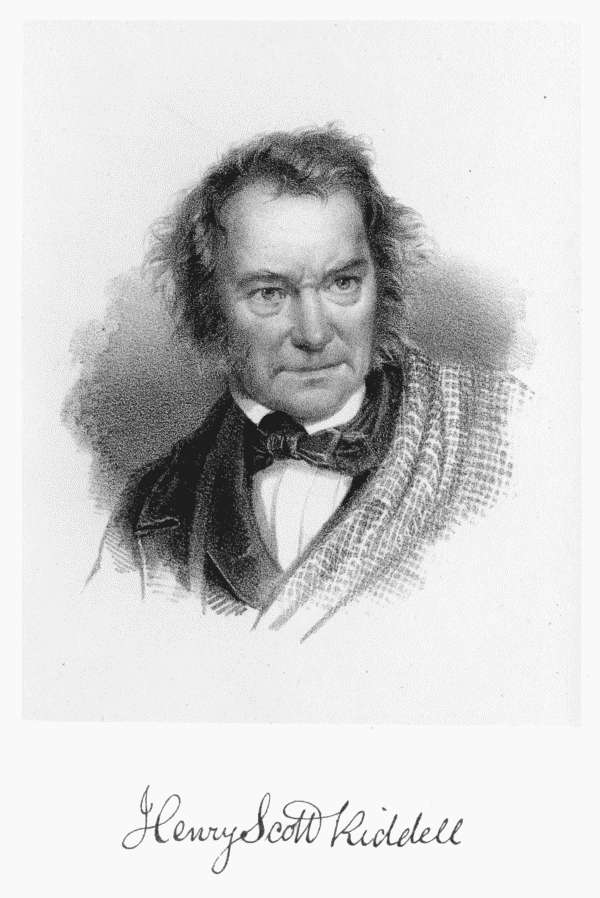

Henry Scott Riddell, one of the most powerful and pleasing of the living national song-writers, was born on the 23d September 1798, at Sorbie, in the Vale of Ewes—a valley remarkable for its pastoral beauty, lying in the south-east of Dumfriesshire. His father was a shepherd, well acquainted with the duties of his profession, and a man of strong though uneducated mind. "My father, while I was yet a child," writes Mr Riddell, in a MS. autobiography, "left Sorbie; but when I had become able to traverse both burn and brae, hill and glen, I frequently returned to, and spent many weeks together in, the vale of my nativity. We had gone, under the same employer, to what pastoral phraseology terms 'an out-bye herding,' in the wilds of Eskdalemuir, called Langshawburn. Here we continued for a number of years, and had, in this remote, but most friendly and hospitable district, many visitors, ranging from Sir Pulteney Malcolm down to Jock Gray, whom Sir Walter Scott, through one of his strange mistakes, called Davy Gellatly....[Pg 2] Among others who constituted a part of the company of these days, was one whom I have good reason to remember—the Ettrick Shepherd. Nor can I forbear observing that his seemed one of those hearts that do not become older in proportion as the head grows gray. Cheerful as the splendour of heaven, he carried the feelings, and, it may be said, the simplicity and pursuits of youth, into his maturer years; and if few of the sons of men naturally possessed such generous influence in promoting, so likewise few enjoyed so much pleasure in participating in the expedients of recreation, and the harmless glee of those who meet under the rural roof—the shepherd's bien and happy home. This was about the time when Hogg began to write, or at least to publish: as I can remember from the circumstance of my being able to repeat the most part of the pieces in his first publication by hearing them read by others before I could read them myself. It may, perhaps, be worth while to state that at these meetings the sons of farmers, and even of lairds, did not disdain to make their appearance, and mingle delightedly with the lads that wore the crook and plaid. Where pride does not come to chill nor foppery to deform homely and open-hearted kindness, yet where native modesty and self-respect induce propriety of conduct, society possesses its own attractions, and can subsist on its own resources.

"At these happy meetings I treasured up a goodly store of old Border ballads, as well as modern songs; for in those years of unencumbered and careless existence, I could, on hearing a song, or even a ballad, sung twice, have fixed it on my mind word for word. My father, with his family, leaving Langshawburn, went to Capplefoot, on the Water of Milk, and there for one year occupied a farm belonging to Thomas Beattie, Esq. of[Pg 3] Muckledale, and who, when my father was in Ewes, had been his friend. My employment here was, along with a younger brother, to tend the cows. In the winter season we entered the Corrie school, but had only attended a short while when we both took fever, and our attendance was not resumed. At Langshawburn, my father for several winters hired a person into his house, who taught his family and that of a neighbouring shepherd. In consequence of our distance from any place of regular education, I had also been boarded at several schools—at Devington in Eskdale, Roberton on Borthwick Water, and Newmill on the Teviot, at each of which, however, I only remained a short time, making, I suppose, such progress as do other boys who love the football better than the spelling-book.

"At the Whitsunday term my father relinquished his farm, and returned to his former employment in the Forest of Ettrick, under Mr Scott of Deloraine, to whom he had been a shepherd in his younger days. With this family, indeed, and that of Mr Borthwick, then of Sorbie, and late of Hopesrigg, all his years since he could wear the plaid were passed, with the exception of the one just mentioned. It was at Deloraine that I commenced the shepherd's life in good earnest. Through the friendly partiality of our employer, I was made principal shepherd at an age considerably younger than it is usual for most others to be intrusted with so extensive a hirsel[1] as was committed to my care. I had by this time, however, served what might be regarded as a regular apprenticeship to the employment, which almost all sons of shepherds do, whether they adhere to herding sheep in after-life or not. Seasons and emergencies not seldom occur when the aid which the little[Pg 4] boy can lend often proves not much less availing than that of the grown-up man. Education in this line consequently commences early. A knowledge of the habits, together with the proper treatment of sheep, and therefore of pastoral affairs in general, 'grows with the growth' of the individual, and becomes, as it were, a portion of his nature. I had thus assisted my father more or less all along; and when a little older, though still a mere boy, I went for a year to a friend at Glencotha, in Holmswater, as assistant shepherd or lamb-herd. Another year in the same capacity I was with a shepherd in Wester Buccleuch. It was at Glencotha that I first made a sustained attempt to compose in rhyme. When in Wester Buccleuch my life was much more lonely, and became more tinged with thoughts and feelings of a romantic cast. Owing to the nature of the stock kept on the farm, it was my destiny day after day to be out among the mountains during the whole summer season from early morn till the fall of even. But the long summer days, whether clear or cloudy, never seemed long to me—I never wearied among the wilds. My flocks being hirsled, as it is expressed, required vigilance: but, if this was judiciously maintained, the task was for the most part an easy and pleasant one. I know not if it be worth while to mention that the hills and glens on which my charge pastured at this period formed a portion of what in ancient times was termed the Forest of Rankleburn. The names of places in the district, though there were no other more intelligible traditions, might serve to shew that it is a range of country to which both kings and nobles had resorted. If from morning to night I was away far from the homes of living men, I was not so in regard to those of the dead. Where a lesser stream from the wild uplands[Pg 5] comes down and meets the Rankleburn, a church or chapel once stood, surrounded, like most other consecrated places of the kind, by a burial-ground. There tradition says that five dukes, some say kings, lie buried under a marble stone. I had heard that Sir Walter, then Mr Scott, had, a number of years previously, made a pilgrimage to this place, for the purpose of discovering the sepulchres of the great and nearly forgotten dead, but without success. This, however, tended, in my estimation, to confirm the truth of the tradition; and having enough of time and opportunity, I made many a toilsome effort of a similar nature, with the same result. With hills around, wild and rarely trodden, and the ceaseless yet ever-varying tinkling of its streams, together with the mysterious echoes which the least stir seemed to awaken, the place was not only lonely, but also creative of strange apprehensions, even in the hours of open day. It is strange that the heart will fear the dead, which, perhaps, never feared the living. Though I could muster and maintain courage to dig perseveringly among the dust of the long-departed when the sun shone in the sky, yet when the shadow of night was coming, or had come down upon the earth, the scene was sacredly secure from all inroad on my part: and to make the matter sufficiently intelligible, I may further mention that, some years afterwards, when I took a fancy one evening to travel eight miles to meet some friends in a shepherd's lone muirland dwelling, I made the way somewhat longer for the sake of evading the impressive loneliness of this locality. I had no belief that I should meet accusing spirits of the dead; but I disliked to be troubled in waging war with those eery feelings which are the offspring of superstitious associations.

"While a lamb-herd at Buccleuch, I read when I could[Pg 6] get a book which was not already threadbare. I had a few chisels, and files, and other tools, with which I took pleasure in constructing, of wood or bone, pieces of mechanism; and I kept a diary in which I wrote many minute and trivial matters, as well, no doubt as I then thought, many a sage observation. In this, likewise, I wrote rude rhymes on local occurrences. But I have anticipated a little. On returning home from Glencotha, and two years before I went to Buccleuch, a younger brother and I had still another round at herding cattle, which pastured in a park near by my father's cottage. Our part was to protect a meadow which formed a portion of it; and the task being easy to protect that for which the cattle did not much care, nor yet could skaithe greatly though they should trespass upon it, we were far too idle not to enter upon and prosecute many a wayward and unprofitable ploy. Our predilections for taming wild birds—the wilder by nature the better—seemed boundless; and our family of hawks, and owls, and ravens was too large not to cost us much toil, anxiety, and even sorrow. We fished in the Ettrick and the lesser streams. These last suited our way of it best, since we generally fished with staves and plough-spades—thus far, at least, honourably giving the objects of our pursuit a fair chance of escape. When the hay had been won, we went to Ettrick school, at which we continued throughout the winter, travelling to and from it daily, though it lay at the distance of five miles. This we, in good weather, accomplished conveniently enough; but it proved occasionally a serious and toilsome task through wind and rain, or keen frost and deep snow, when winter days and the mountain blasts came on.

"My father after being three years in Stanhopefoot, on the banks of the Ettrick, went to Deloraineshiels, an[Pg 7] out-bye herding, under the same employer. In the winter season either I or some other of the family assisted him; but so often as the weather was fine, we went to a school instituted by a farmer in the neighbourhood for behoof of his own family. When by and by I went to herd the hirsel which my father formerly tended, like most other regular shepherds I delighted in and was proud of the employment. A considerable portion of another hirsel lying contiguous, and which my elder brother herded, was for the summer season of the year added to mine, so that this already large was made larger; but exempted as I was from attending to aught else but my flock, I had pleasant days, for I loved the wilds among which it had become alike my destiny and duty to walk at will, and 'view the sheep thrive bonnie.' The hills of Ettrick are generally wild and green, and those of them on which I daily wandered, musing much and writing often, were as high, green, and wild, as any of them all.... It may be the partiality arising from early habit which induces me to think that a man gets the most comprehensive and distinct view of any subject which may occupy thought when he is walking, provided fatigue has not overtaken him. Mental confidence awake amid the stir seems increased by the exercise of bodily power, and becomes free and fearless as the step rejoicing in the ample scope afforded by the broad green earth and circumambient sky. On the same grounds, I have sometimes marvelled if it might not be the majesty of motion, as one may say, reigning around the seaman's soul, that made his heart so frank in communication, and in action his arm so vigorously energetic. At all events, there was in these days always enough around one to keep interest more or less ardent awake[Pg 8]—

"According to my ability I studied while wandering among the mountains, and at intervals, adopting my knee for my desk, wrote down the results of my musing. Let not the shepherd ever forget his dog—his constant companion and best friend, and without which all his efforts would little avail! Mine knew well the places where in my rounds I was wont to pause, and especially the majestic seat which I occupied so often on the loftiest peak of Stanhopelaw. It had also an adopted spot of rest the while, and, confident of my habits, would fold itself down upon it ere I came forward; and would linger still, look wistful, and marvel why if at any time I passed on without making my wonted delay. I did not follow these practices only 'when summer days were fine.' The lines of an epistle written subsequently will convey some idea of my habits:—

"The ancients had a maxim—'Revenge is sweet.' In rural, as well as in other life, there are things said and done which are more or less ungenerous. These, if at any time they came my way, I repelled as best I might. But I did not stop here; whether such matters, when occurring, might concern myself as an individual or not, I took it upon me, as if I had been a 'learned judge,' to write satires upon such persons as I knew or conceived to have spoken or acted in aught contrary to good manners. These squibs were written through the impulse of offended feeling, or the stirrings of that injudicious spirit which sometimes prompts a man to exercise a power merely because he possesses it. They were still, after all, only as things of private experiment, and not intended ever to go forth to the world—though it happened otherwise. I usually carried a lot of these writings in my hat, and by and by, unlike most other young authors, I got a publisher unsought for. This was the wind, which, on a wild day, swept my hat from my head, and tattering its contents asunder from their fold, sent them away over hill and dale like a flock of wild fowl. I recovered some where they had halted in bieldy places; others of them went further, and fell into other hands, and particularly into those of a neighbour, who, a short while previously, had played an unmanly part relating to a sheep and the march which ran between[Pg 10] us. He found his unworthy proceeding boldly discussed, in an epistle which, I daresay, no other carrier would ever have conveyed to him but the unblushing mountain blast. He complained to others, whom he found more or less involved in his own predicament, and the thing went disagreeably abroad. My master, through good taste and feeling, was vexed, as I understood, that I should have done anything that gave ground for accusation, though he did not mention the subject to myself; but my father, some days after the mischief had commenced, came to me upon the hill, and not in very good humour, disapproved of my imprudent conduct. As for the consequences of this untoward event, it proved the mean of revealing what I had hitherto concealed—procuring for me a sort of local popularity little to be envied. I made the best improvement of it, as I then thought, that lay in my power—by writing a satire upon myself.

"I continued shepherd at Deloraine two years, and then went in the same capacity to the late Mr Knox of Todrigg; and if at the former place I had been well and happy, here I was still more so. His son William, the poet of 'The Lonely Hearth,' paid me much friendly attention. He commended my verses, and augured my success as one of the song-writers of my native land. In those days, I did not write with the most remote view to publication. My aim did not extend beyond the gratification of hearing my mountain strains sung by lad or lass, as time and place might favour. And when, in the dewy gloaming of a summer eve, returning home from the hill, and 'the kye were in the loan,' I did hear this much, I thought, no doubt, that

"William Crozier, author of 'The Cottage Muse,' was also my neighbour and friend at Todrigg, during the summer part of the year; and even at this hour I feel delight in recalling to memory the happy harmony of thought and feeling that blended with and enhanced the genial sunshine of those departed days. I rejoice to dwell upon those remote and rarely-trodden pastoral solitudes, among which my lot in the early years of life was so continually cast; few may well conceive how distinctly I can recall them. Memory, which seems often to constitute the mind itself, more, perhaps, than any other faculty, can set them so brightly before me, as if they were painted on a dark midnight sky with brushes dipped in the essence of living light. To appreciate thoroughly the grandeur of the mountain solitudes, it is necessary to have dwelt among the scenes, and to have looked upon them at every season of the ever-changing year. They are fresh with solemn beauty, when bathed in the deep dews of a summer morning; or in autumn, if you have attained to the border of the mystery which has overhung your path, and therefore to a station high enough for the survey, all that meets the eye shall be as a dream of poetry itself. The deep folds of white vapour fill up glen and hollow, till the summit of the mountains, near and far away—far as sight itself can penetrate—are only seen tinged with the early radiance of the sun, the whole so combined as to appear a limitless plain of variegated marble, peaceful as heaven, and solemnly serene as eternity. What Winter writes with his frozen finger I need not state. When the venerable old man, Gladstanes, perished among the stormy blasts of these wilds, I was one of about threescore of men who for three days traversed them in search of the dead. Then was the scenery of the mountains impressive, much[Pg 12] beyond what can well be spoken. The bridal that loses the bride through some wayward freak of the fair may be sad enough; so also the train, in its dark array, that conveys the familiar friend to the chamber where the light of nature cannot come. But in this latter case, the hearts that still beat, necessarily know that their part is resignation, and suspense and anxiety mingle not in the mood of the living, as it relates to the dead; but otherwise is it with those who seem already constituting the funeral train of one who should have been—yet who is not there to be buried.

These are a few out of many more lines written on this subject, which at the time was so deeply interesting to mind and heart."

Mr Riddell here states that his poetical style of composition about this period underwent a considerable change. He laid aside his wayward wit for serious sentiment, an improvement which he ascribes to his admiration of the elegant strains of his friend, young Knox.

"My fortune in life," he proceeds, "had not placed me within the reach of a library, and I had read almost none; and although I had attempted to write, I merely followed the course which instinct pointed out. Need I state further, that if in these days I employed my mind and pen among the mountains as much as possible, my thoughts also often continued to pursue the same practice, even when among others, by the 'farmer's ingle.' I retired to rest when others retired, but if not outworn by matters of extra toil, the ardour of thought, through love of the poet's undying art, would, night after night for many hours, debar the inroads of sleep. The number of schools which I have particularised as having attended may occasion some surprise at the deficiency of my scholarship. For this, various reasons are assignable, all of which, however, hinge upon these two formidable obstacles—the inconveniency of local position, and the thoughtless inattention of youth. In remote country places, long and rough ways, conjoined not unfrequently with wild weather, require that children, before they[Pg 14] can enter school, be pretty well grown up; consequently, they quit it the sooner. They are often useful at home in the summer season, or circumstances may destine them to hire away. Among these inconveniences, one serious drawback is, that the little education they do get is rarely obtained continuously, and regular progress is interrupted. Much of what has been gained is lost during the intervals of non-attendance, and every new return to the book is little else than a new beginning. So was it with me. At the time when my father hired a teacher into his house, it was for what is termed the winter quarter, and I was then somewhat too young to be tied down to the regular routine of school discipline; and if older when boarded away, the other obstruction to salutary progress began to operate grievously against me. I acquired bit by bit the common education—reading, writing, and arithmetic. So far as I remember, grammar was not much taught at any of these schools, and the spelling of words was very nearly as little attended to as the meaning which they are appointed to convey was explained or sought after.

"But the non-understanding of words is less to be marvelled at than that a man should not understand himself. At this hour I cannot conceive how I should have been so recklessly careless about learning and books when at school, and yet so soon after leaving it seriously inclined towards them. I see little else for it than to suppose that boys who are bred where they have no companions are prone to make the most of companionship when once attained to. And then, in regard to books, as of these I rarely got more than what might serve as a whet to the appetite, I might have the desire of those whose longings after what they would obtain are increased by the difficulties which interpose between[Pg 15] them and the possession. One book which in school I sometimes got a glance of, I would have given anything to possess: this was a small volume entitled, 'The Three Hundred Animals.'

"I cannot forbear mentioning that, when at Deloraine, I was greatly advantaged by an old woman, called Mary Hogg, whose cottage stood on an isolated corner of the lands on which my flock pastured. Her husband had been a shepherd, who, many years previous to this period, perished in a snow-storm. In her youth she had opportunities of reading history, and other literature, and she did not only remember well what she had read, but could give a distinct and interesting account of it. In going my wonted rounds, few days there were on which I did not call and listen to her intelligent conversation. She was a singularly good woman—a sincere Christian; and the books which she lent me were generally of a religious kind, such as the 'Pilgrim's Progress,' and the 'Holy War;' but here I also discovered a romance, the first which I had ever seen. It was printed in the Gothic letter, and entitled 'Prissimus, the Renowned Prince of Bohemia.' Particular scenes and characters in 'Ivanhoe' reminded me strikingly of those which I had formerly met with in this old book of black print. And I must mention that few books interested me more than 'Bailey's Dictionary.' Day after day I bore it to the mountains, and I have an impression that it was a more comprehensive edition of the work than I have ever since been able to meet with.

"At Todrigg my reading was extended; and having begun more correctly to appreciate what I did read, the intention which I had sometimes entertained gathered strength: this was to make an effort to obtain a regular education. The consideration of the inadequacy of my[Pg 16] means had hitherto bridled my ambition; but having herded as a regular shepherd nearly three years, during which I had no occasion to spend much of my income, my prospects behoved to be a little more favourable. It was in this year that the severest trial which had yet crossed my path had to be sustained. The death of my father overthrew my happier mood; at the same time, instead of subduing my secret aim, the event rather strengthened my determination. My portion of my father's worldly effects added something considerable to my own gainings; and, resigning my situation, I bade farewell to the crook and plaid. I went to Biggar, in Clydesdale, where I knew the schoolmaster was an approved classical scholar. Besides, my Glencotha reminiscences tended to render me partial to this part of the world, and in the village I had friends with whom I could suitably reside. The better to insure attention to what I was undertaking, I judged it best to attend school during the usual hours. A learner was already there as old in years, and nearly as stout in form, as myself, so that I escaped from the wonderment which usually attaches to singularity much more comfortably than I anticipated. There were also two others in the school, who had formerly gone a considerable way in the path of classic lore, and had turned aside, but who, now repenting of their apostasy, returned to their former faith. These were likewise well grown up, and I may state that they are now both eminent as scholars and public men. The individual first mentioned and I sat in the master's desk, which he rarely, if ever, occupied himself; and although we were diligent upon the whole, yet occasionally our industry and conduct as learners were far from deserving approbation. To me the confinement was frequently irksome and[Pg 17] oppressive, especially when the days were bright with the beauty of sunshine. There were ways, woods, and even wilds, not far apart from the village, which seemed eternally wooing the step to retirement, and the mind to solitary contemplation. Some verses written in this school have been preserved, which will convey an idea of the cast of feeling which produced them:—

"My teacher, the late Richard Scott, was an accurate[Pg 19] classical scholar, which perhaps accounts for his being, unlike some others of his profession, free from pedantry. He was kind-hearted and somewhat disposed to indolence, loving more to converse with one of my years than to instruct him in languages. He had seen a good deal of the world and its ways, and I learned much from him besides Greek and Latin. We were great friends and companions, and rarely separate when both of us were unengaged otherwise.

"I bore aloof from making many acquaintances; yet, ere long, I became pretty extensively acquainted with the people of the place. It went abroad that I was a bard from the mountains, and the rumour affixed to me a popularity which I did not enjoy. A party of young men in the village had prepared themselves to act 'the Douglas Tragedy,' and wished a song, which was to be sung between this and the farce. The air was of their own fixing, and which, in itself, was wild and beautiful; but, unfortunately, like many others of our national airs possessed of these qualities, it was of a measure such as rendered it difficult to write words for. Since precluded from introducing poetic sentiment, I substituted a dramatic plot, and being well sung by alternate voices, the song was well received, and so my fame was enhanced.

"It was about this time that I wrote 'The Crook and Plaid'—not by request, but with the intention of supplanting a song, I think of English origin, called 'The Plough-boy,' and of a somewhat questionable character. 'The Crook and Plaid' accomplished the end intended, and soon became popular throughout the land. So soon as I got a glimpse of the Roman language, I began to make satisfactory progress in its acquisition. But I daily wrote more or less in my old way—now also embracing in my attempts[Pg 20] prose as well as verse. I wrote a Border Romance. This was more strongly than correctly expressed. Hogg, who took the trouble of reading it, gave me his opinion, by saying that there were more rawness and more genius in it than in any work he had seen. It, sometime afterwards, had also the honour of being read—for I never offered it for publication—by one who felt much interest in the characters and plot—Professor Wilson's lady—who, alas! went too early to where he himself also now is; lost, though not to fond recollection, yet to love and life below. I contributed some papers to the Clydesdale Magazine, and I sent a sort of poetic tale to the editor, telling him to do with it whatever he might think proper. He published it anonymously, and it was sold about Clydesdale.

"My intention had been to qualify myself for the University, and, perhaps in regard to Latin and Greek acquirements, I might have proceeded thither earlier than I ventured to do; but having now made myself master of my more immediate tasks, I took more liberty. A gentleman, who, on coming home after having made his fortune abroad, took up his residence at Biggar. I had, in these days, an aversion to coming into contact with rich strangers, and although he lived with a family which I was accustomed to visit, I bore aloof from being introduced to him. But he came to me one day on the hill of Bizzie-berry, and frankly told me that he wished to be acquainted with me, and therefore had taken the liberty of introducing himself. I found excuse for not dining with him on that day, but not so the next, nor for many days afterwards. He was intellectual—and his intelligence was only surpassed by his generosity. He gave me to understand that his horse was as much at my service as his own; and one learned, by and by,[Pg 21] to keep all wishes and wants as much out of view as possible, in case that they should be attended to when you yourself had forgotten them. When he began to rally me about my limited knowledge of the world, I knew that some excursion was in contemplation. We, on one occasion, rode down the Clyde, finding out, so far as we might, all things, both natural and artificial, worthy of being seen; and when at Greenock, he was anxious that we should have gone into the Highlands, but I resisted; for although not so much as a shade of the expenses was allowed to fall on me, I felt only the more ashamed of the extent of them.

"I had become acquainted with a number of people whom I delighted to visit occasionally; one family in particular, who lived amid the beauty of 'the wild glen sae green.' The song now widely known by this name I wrote for a member of this delightful family, who at that time herded one of the hirsels of his father's flocks on 'the heathy hill.' With the greater number of persons in the district possessing literary tastes I became more or less intimate. The schoolmasters I found friendly and obliging; one of these, in particular (now holding a higher office in the same locality), I often visited. His high poetic taste convinced me more and more of the value of mental culture, and tended to subdue me from those more rugged modes of expression in which I took a pride in conveying my conceptions. With this interesting friend I sometimes took excursions into rural regions more or less remote, and once we journeyed to the south, when I had the pleasure of introducing him to the Ettrick Shepherd. But of my acquaintances, I valued few more than my modest and poetic friend, the late James Brown of Symington.[2] Though humble in[Pg 22] station, he was high in virtuous worth. His mind, imbued with and regulated by sound religious and moral principle, was as ingenious and powerful as his heart was 'leal, warm, and kind.'

"Entering the University of Edinburgh, I took for the first session the Greek and Latin classes. Attending them regularly, I performed the incumbent exercises much after the manner that others did—only, as I have always understood it to be a rare thing with the late Mr Dunbar, the Greek Professor, to give much praise to anything in the shape of poetry, I may mention that marked merit was ascribed to me in his class for a poetical translation of one of the odes of Anacreon. I had laid the translation on his desk, in an anonymous state, one day before the assembling of the class. He read it and praised it, expressing at the same time his anxiety to know who was the translator; but the translator having intended not to acknowledge it, kept quiet. He returned to it, and praising it anew, expressed still more earnestly his desire to know the author; and so I made myself known, as all great unknowns I think, with the exception of Junius, are sooner or later destined to do.

"Of the philosophical classes, those that I liked best were the Logic and Moral Philosophy—particularly the latter. I have often thought that it is desirable, could it be possibly found practicable, to have all the teachers of the higher departments of education not merely of high scholastic acquirements, but of acknowledged genius. Youth reveres genius, and delights to be influenced by it; heart and spirit are kept awake and refreshed by it, and everything connected with its forthgivings is rendered doubly memorable. It fixes, in a certain sense, the limit of expectation, and the prevailing sentiment is—we are under the tuition of the highest among those[Pg 23] on earth who teach; if we do not profit here, we may not hope to do so elsewhere. These remarks I make with a particular reference to the late Professor Wilson, under the influence of whose genius and generous warmth of heart many have felt as I was wont to feel. If it brings hope and gladness to love and esteem the living, it also yields a satisfaction, though mingled with regret, to venerate the dead; and now that he is no more, I cannot forbear recording how he treated a man from the mountains who possessed no previous claim upon his attention. I had no introduction to him, but he said that he had heard of me, and would accept of no fee for his class when I joined it; at least he would not do so, he said, till I should be able to inform him whether or not I had been pleased with his lectures. But it proved all the same in this respect at the close as it was at the commencement of the session. He invited me frequently to his house as a friend, when other friends were to meet him there, besides requesting me to come and see him and his family whenever I could make it convenient. He said that his servant John was very perverse, and would be sure to drive me by like all others, if he possibly could; so he gave me a watchword, which he thought John, perverse as he was, would not venture to resist. I thus became possessed of a privilege of which I did not fail to avail myself frequently—a privilege which might well have been gratifying to such as were much less enthusiastic with regard to literary men and things than I was. To share in the conversation of those possessed of high literary taste and talent, and, above all, of poetic genius, is the highest enjoyment afforded by society; and if it be thus gratifying, it is almost unnecessary to add that it is also advantageous in no ordinary degree, if, indeed, properly appreciated and[Pg 24] improved. Any one who ever met the late Professor in the midst of his own happy family, constituted as it was when I had this pleasure, was not likely soon to forget a scene wherein so much genius, kindness, loveliness, and worth were blended. If the world does not think with a deep and undying regret of what once adorned it, and it has now lost, through the intervention of those shadows which no morning but the eternal one can remove, I am one, at least, who in this respect cannot follow its example.

"Edinburgh, with its 'palaces and towers,' and its many crowded ways, was at first strangely new to me, being as different, in almost all respects, to what I had been accustomed as it might seem possible for contrariety to make earthly things. Though I had friends in it, and therefore was not solitary, yet its tendency, like that of the noisy and restless sea, was to render me melancholy. Some features which the congregated condition of mankind exhibited penetrated my heart with something like actual dismay. I had seen nothing of the sort, nor yet even so much as a semblance of it, and therefore I had no idea that there existed such a miserable shred of degradation, for example, as a cinder-woman—desolate and dirty as her employment—bowed down—a shadow among shadows—busily prone, beneath the sheety night sky, to find out and fasten upon the crumb, whose pilgrimage certainly had not improved it since falling from the rich man's table. Compassion, though not naturally so, becomes painful when entertained towards those whom we believe labouring under suffering which we fain would but cannot alleviate.

"I had enough of curiosity for wishing to see all those things which others spoke of, and characterised as worthy of being seen; but I contented myself meanwhile with a[Pg 25] survey of the city's external attributes. In a week or two, however, my friend A. F. Harrower, formerly mentioned, having come into town from Clydesdale, took pleasure in finding out whatever could interest or gratify me, and of conveying me thither. With very few exceptions, every forenoon he called at my lodgings, leaving a note requesting me to meet him at some specified time and place. I sometimes sent apologies, and at other times went personally to apologise; but neither of these methods answered well. Through his persevering attentions towards me, I met with much agreeable society, and saw much above as well as somewhat below the earth, which I might never otherwise have seen. In illustration of the latter fact, I may state that, having gone to London, he returned with two Englishmen, when he invited me to assist them in exploring the battle-field of Pinkie. We terminated our excursion by descending one of Sir John Hope's coal-pits. These humorous and frank English associates amused themselves by bantering my friend and myself about the chastisement which Scotland received from the sister kingdom at Pinkie. As did the young rustic countryman—or, at least, was admonished to do—so did I. When going away to reside in England, he asked his father if he had any advice to give him. 'Nane, Jock, nane but this,' he said; 'dinna forget to avenge the battle o' Pinkie on them.' Ere I slept I wrote, in support of our native land, the song—'Ours is the land of gallant hearts;' and thus, in my own way, 'avenged the battle of Pinkie.'

"One of two other friends with whom I delighted to associate was R. B., an early school companion, who, having left the mountains earlier than I did, had now been a number of years in Edinburgh. Of excellent[Pg 26] head and generous heart, he loved the wild, green, and deep solitudes of nature. The other—G. M'D.—was of powerful and bold intellect, and remarkable for a retentive memory. Each of us, partial to those regions where nature strives to maintain her own undisturbed dominion, on all holidays hied away from the city, to the woodland and mountainous haunts, or the loneliness of the least frequented shores of the sea. The spirit of our philosophy varied much—sometimes profound and solemn, and sometimes humorous; but still we philosophised, wandering on. They were members of a literary society which met once a week, and which I joined. My propensity to study character and note its varieties was here afforded a field opening close upon me; but I was also much profited by performing my part in carrying forward the business of the institution. During all the sessions that I attended the University, but especially as these advanced toward their termination, I entered into society beyond that which might be regarded as professionally literary. I had an idea then, as I still have, that, in every process of improvement, care should be taken that one department of our nature is not cultivated to the neglect of another. There are two departments—the intellectual and the moral;—the one implying all that is rational, the other comprising whatever pertains to feeling and passion, or, more simply, there are the head and the heart; and if the intellect is to be cultivated, the heart is not to be allowed to run into wild waste, nor to sink into systematic apathy. Lore-lighted pages and unremitting abstract studies will make a man learned; but knowledge is not wisdom; and to know much is not so desirable, because it is not so beneficial, either to ourselves or others, as to understand, through the more generous and active sympathies of our nature, how the[Pg 27] information which we possess may be best applied to useful purposes. This we shall not well know, if the head be allowed or encouraged to leave the heart behind. If we forget society it will forget us, and, through this estrangement, a sympathetic knowledge of human nature may be lost. Thus, in the haunts of seclusion and solitary thought our acquirements may only prove availing to ourselves as matters of self-gratification. The benevolent affections, which ought not merely to be allowed, but taught to expand, may thus not only be permitted but encouraged to contract, and the exercise of that studious ingenuity, which perhaps leads the world to admire the achievements of learning, thus deceive us into a state of existence little better than cold selfishness itself. Sir Isaac Newton, who soared so high and travelled so far on the wing of abstract thought, gathering light from the stars that he might convey it in intelligible shape to the world, seems to have thought, high as the employment was, that it was not good, either for the heart or mind of man, to be always away from that intercourse with humanity and its affairs which is calculated to awaken and sustain the sympathies of life; and therefore turned to the contemplation of Him who was meek and lowly. And no countenance has been afforded to monks and hermits who retired from the world, though it even was to spend their lives in meditation and prayer; for Heaven had warned man, at an early date, not to withhold the compassionate feelings of the heart, and the helping-hand, from any in whom he recognised the attributes of a common nature, saying to him, 'See that thou hide not thyself from thine own flesh.'

"My last year's attendance at the College Philosophical Classes was at St Andrews. I had a craving to acquaint[Pg 28] myself with a city noted in story, and I could not, under the canopy of my native sky, have planted the step among scenes more closely interwoven with past national transactions, or fraught with more interesting associations. In attending the Natural Philosophy Class, not being proficient in mathematic lore, I derived less advantage than had otherwise been the case with me. Yet I did not sit wholly in the shade, notwithstanding that the light which shone upon me did not come from that which Campbell says yielded 'the lyre of Heaven another string.' A man almost always finds some excuse for deficiency; and I have one involving a philosophy which I think few will be disposed to do otherwise than acquiesce in—namely, that it is a happy arrangement in the creation and history of man, that all minds are not so constituted as to have the same predilections, or to follow the same bent. Considering that I had started at a rather late hour of life to travel in the paths of learning, and having so many things, interesting and important, to attend to by the way, it was perhaps less remarkable that I should be one who 'neither kenn'd nor cared' much about lines that had no breadth, and points which were without either breadth or length, than that I should have felt gratified to find on my arrival some of my simple strains sung in a city famed for its scientific acquirements.

"The ruins which intermingle with the scenery and happy homes of St Andrews, like gray hairs among those of another hue, rendered venerable the general aspect of the place. But I did not feel only the city interesting, but the whole of Fifeshire. By excursions made on the monthly holidays then as well as subsequently, when in after-years I returned to visit friends in the royal realm, I acquainted myself with a goodly number of those haunts and scenes which history and tradition have ren[Pg 29]dered attractive. A land, however, or any department of it, whatever may be its other advantages, is most to be valued in respect of the intelligence or worth of its inhabitants. And if so, then I am proud to aver that in Fife I came to possess many intelligent and excellent friends. Many of these have gone to another land—'the land o' the leal,' leaving the places which now know them no more, the more regretfully endeared to recollection. Of those friends who survive, I cannot forbear an especial mention of one, who is now a professor in the college in which he was then only a student. A man cannot be truly great unless he also be good, and I do not alone value him on the colder and statelier eminence of high intellectual powers and scientific acquirements, but also, if not much rather, for his generous worth and his benevolent feeling. My friend is one in whom these qualities are combined, and as I sincerely think, I will likewise freely say, that those will assuredly find a time, sooner or later, greatly to rejoice, whose fate has been so favourable as to place them under the range and influence of his tuition.

"I studied at St Andrews College under the late Dr Jackson, who was an eminent philosopher and friendly man; also under Mr Duncan, of the Mathematical Chair, whom I regarded as a personification of unworldly simplicity, clothed in high and pure thought; and I regularly attended, though not enrolled as a regular student, the Moral Philosophy Class of Dr Chalmers. Returning to Edinburgh and its university, I became acquainted, through my friend and countryman, Robert Hogg, with R. A. Smith, who was desirous that I should assist him with the works in which he was engaged, particularly 'The Irish Minstrel,' and 'Select Melodies.' Smith was a man of modest worth and superior intelligence;[Pg 30] peculiarly delicate in his taste and feeling in everything pertaining to lyric poetry as well as music; his criticisms were strict, and, as some thought, unnecessarily minute. Diffident and retiring, he was not got acquainted with at once, but when he gave his confidence, he was found a pleasant companion and warm-hearted friend. If, as he had sought my acquaintance, I might have expected more frankness on our meeting, I soon became convinced that his shyer cast arose alone from excess of modesty, combined with a remarkable sensitiveness of feeling. Proudly honourable, he seemed more susceptible of the influences of all sorts that affect life than any man I ever knew; and, indeed, a little acquaintance with him was only required to shew that his harp was strung too delicately for standing long the tear and wear of this world. He had done much for Scottish melody, both by fixing the old airs in as pure a state as possible, and by adding to the vast number of these national treasures some exquisite airs of his own. For a number of the airs in the works just mentioned, but particularly in the 'Select Melodies,' he had experienced difficulty in procuring suitable words, owing chiefly to the crampness of the measures—a serious drawback which appears to pervade, more or less, the sweetest melodies of other nations as well as those of our own. A number of these I supplied as well as I could.

"About this time the native taste for Scottish song in city society seemed nearly, if not altogether lost, and a kind of songs, such as 'I've been roaming,' 'I'd be a butterfly,' 'Buy a broom,' 'Cherry-ripe,' &c. (in which if the head contrived to find a meaning, it was still such as the heart could understand nothing about), seemed alone to be popular, and to prevail. R. A. Smith disliked this state of things, but, perhaps, few[Pg 31] more so than Mr P. M'Leod, who gave a most splendid evidence of his taste in his 'Original National Melodies.' Both Smith and M'Leod were very particular about the quality of the poetry which they honoured with their music. M'Leod was especially careful in this respect. He loved the lay of lofty and undaunted feeling as well as of love and friendship; for his genius is of a manly tone, and has a bold and liberal flow. And popular as some of the effusions in his work have become, such as 'Oh! why left I my hame?' and 'Scotland yet!' many others of them, I am convinced, will yet be popular likewise. When the intelligence of due appreciation draws towards them, it will take them up and delight to fling them upon the breezes that blow over the hills and glens, and among the haunts and homes of the isle of unconquerable men. To Mr M'Leod's 'National Melodies' I contributed a number of songs. In the composition of these I found it desirable to lay aside, in some considerable degree, my pastoral phraseology, for, as conveyed in such productions, I observed that city society cared little about rural scenery and sentiment. It was different with my kind and gifted friend Professor Wilson. He was wont to say that he would not have given the education, as he was pleased to term it, which I had received afar in the green bosom of mountain solitude, and among the haunts and homes of the shepherd—meaning the thing as applicable to poetry—for all that he had received at colleges. Wilson had introduced my song, 'When the glen all is still,' into the Noctes, and La Sapio composed music for it; and not only was it sung in Drury-lane, but published in a sheet as the production of a real shepherd; yet it did not become popular in city life. In the country it had been popular previous to this, where it is so still,[Pg 32] and where no effort whatever had been made to introduce it.

"About the time when I had concluded the whole of my college course, the 'Songs of the Ark,'[3] were published by Blackwood. These, as published, are not what they were at first, and were intended only to be short songs of a sacred nature, unconnected by intervening narrative, for which R. A. Smith wished to compose music. Unfortunately, his other manifold engagements never permitted him to carry his intention into practice; and seeing no likelihood of any decrease of these engagements, I gave scope to my thoughts on the subject, and the work became what it now is. But I ought to mention that this was not my first poetic publication in palpable shape. Some years previously I published stanzas, or a monody, on the death of Lord Byron. I had all along thought much, and with something like mysterious awe, upon the eccentric temperament, character and history of that great poet, and the tidings which told the event of his demise impressed me deeply. Being in the country, and remote from those who could exchange thoughts with me on the occurrence, I resorted to writing. That which I advanced was much mixed up with the result, if I may not say of former experience, yet of former reflection, for I had entertained many conjectures concerning what this powerful personage would or might yet do; and, indeed, his wilful waywardness, together with the misery which he represented as continually haunting him, constituted an impressive advertisement to the world, and served to keep human attention awake towards him.

"Those who write because it brings a relief to feeling, will write rapidly: likely, too, they will write with[Pg 33] energy, because not only the head but also the heart is engaged. 'The Monody,' which is of a goodly length, I finished in a few days; and though I felt a desire of having it published, yet it lay over for a time, till, being in Edinburgh, a friend shewed it to Dr Robert Anderson. I had been well satisfied with the result, had the production accomplished nothing more than procured me, as it did, the friendly acquaintance of this excellent, venerable man. He knew more of the minutiæ of literature, together with the character and habits of the literary men of his day, and of other days also, than any I had then or have since met with; and he seemed to take great pleasure in communicating his knowledge to others. He thought well of 'The Monody,' and warmly advised me to publish it. It was published accordingly by Mr John Anderson, bookseller, North Bridge, Edinburgh.

"Some of the reviewers, in regard to the 'Songs of the Ark,' seemed to think that a sufficiency of eastern scenery did not obtain in them. Doubtless this was correct; but I remark, that if my object in the undertaking had been to delineate scenery, I would not have turned my attention to the East, the scenes of which I never saw. Human nature being radically the same everywhere, a man, through the sympathies of that nature, can know to a certain extent what are likely to be the thoughts and feelings of his fellow-kind in any particular circumstances—therefore he has data upon which he can venture to give a representation of them; but it is very different from this in regard to topographical phenomena. It was therefore not the natural, but, if I may so call it, the moral scenery in which I was interested, more particularly since the whole scene of nature here below was, shortly after the period at[Pg 34] which the poem commences, to become a blank of desolate uniformity, as overwhelmed beneath a waste of waters.

"At the risk of incurring the charge of vanity, I would venture to adduce one or two of the favourable opinions entertained in regard to some of the miscellaneous pieces which went to make up the volume of the 'Songs of the Ark.' Of the piece entitled 'Apathy,' Allan Cunningham thus wrote:—'Although sufficiently distressful, it is a very bold and original poem, such as few men, except Byron, would have conceived or could have written.' Motherwell said of the 'Sea-gray Man,' that it was 'the best of all modern ballads.' This ballad, shortly after I had composed it, I repeated to the Ettrick Shepherd walking on the banks of the Yarrow, and he was fully more pleased with it than with anything of mine I had made him acquainted with. He was wont to call me his 'assistant and successor;' and although this was done humorously, it yet seemed to furnish him with a privilege on which he proceeded to approve or disapprove very frankly, that in either case I might profit by his remarks. He was pleased especially with the half mysterious way in which I contrived to get quit of the poor old man at last. This, indeed, was a contrivance; but the idea of the rest of the ballad was taken from an old man, who had once been a sailor, and who was wont to come to my mother's, in the rounds which he took in pursuit of charity at regular periods of the year, so that we called him her pensioner.

"The summer vacations of college years I passed in the country, sometimes residing with my mother, and eldest brother, at a small farm which he had taken at the foot of the Lammermuir hills, in East-Lothian, called Brookside, and sometimes, when I wished a variety,[Pg 35] with another brother, at Dryden, in Selkirkshire. At both places I had enough of time, not only for study, but also for what I may call amusement. The latter consisted in various literary projects which I entered upon, but particularly those of a poetic kind, and the writing of letters to friends with whom I regularly, and I may say also copiously corresponded; for in these we did not merely express immediate thoughts and feelings of a more personal nature, but remarked with vigorous frankness upon many standard affairs of this scene of things. To this general rule of the manner of my life at this time, however, I must mention an exception. A college companion and I, thinking to advantage ourselves, and perhaps others, took a school at Fisherrow. The speculation in the end, as to money matters, served us nothing. It was easier to get scholars than to get much if anything for teaching them. Yet neither was the former, in some respects, so easy as might have been expected. The offspring of man, in that locality, may be regarded as in some measure amphibious. Boys and girls equally, if not already in the sea, were, like young turtles, sure to be pointing towards it with an instinct too intense to err. I never met, indeed, with a race of beings believed, or even suspected to be rational, that, provided immediate impulses and inclinations could be gratified, cared so thoroughly little for consequences. On warm summer days, when we caused the school door to stand open, it is not easy to say how much of intense interest this simple circumstance drew towards it. The squint of the unsettled eye was on the door, out at which the heart and all its inheritance was off and away long previously, and the more than ordinarily propitious moment for the limbs following was only as yet not arrived. When that moment came, off went one, fol[Pg 36]lowed by another; and down the narrow and dark lanes of sooty houses. As well might the steps have proposed to pursue meteors playing at hide-and-seek among the clouds of a midnight sky that the tempest was troubling. Nevertheless, Colin Bell, who by virtue of his ceaseless stir in the exercise of his heathen-god-like abilities, had constituted himself captain of the detective band, would be up and at hand immediately, and would say 'Master—sir, Young an' me will bring them, sir, if ye'll let's.' It was just as good to 'let' as to hinder, for, for others to be out thus, and he in, seemed to be an advantage gained over Colin to which he could never be rightly reconciled. He was bold and frank, and full of expedients in cases of emergency; especially he appeared capable of rendering more reasons for an error in his conduct than one could well have imagined could have been rendered for anything done in life below. Another drawback in the case was, that one could never be very seriously angry with him. If more real than pretended at any time, his broad bright eye and bluff face, magnificently lifted up, like the sun on frost-work, melted down displeasure and threatened to betray all the policy depending on it; for in the main never a bit of ill heart had Colin, though doubtlessly he had in him, deeply established, a trim of rebellion against education that seemed ever on the alert, and which repulsed even its portended approach with a vigour resembling the electric energy of the torpedo.

"As we did not much like this place, we did not remain long in it. I had meanwhile, however, resources which brought relief. Those friends whose society I most enjoyed occasionally paid us a visit from Edinburgh; and in leisure hours I haunted the banks of the Esk, which, with wood, and especially with wild-roses,[Pg 37] are very beautiful around the church of Inveresk. This beauty was heightened by contrast—for I have ever hated the scenery of, and the effect produced by, sunny days and dirty streets. Nor do the scenes where mankind congregate to create bustle, 'dirdum and deray,' often fail of making me more or less melancholy. In the week of the Musselburgh Races, I only went out one day to toss about for a few hours in the complicated and unmeaning crowd. I insert the protest which I entered against it on my return:—

"I have dwelt at the greater length on these matters, trivial though they be, in consequence of my non-intention of tracing minutely the steps and stages of my probationary career. These, with me, I suppose, were much like what they are and have been with others. My acquaintance was a little extended with those that inhabit the land, and in some cases a closer intimacy than mere acquaintance took place, and more lasting friendships were formed.

"My brother having taken a farm near Teviothead, I left Brookside, and as all the members of the family were wont to account that in which my mother lived their home, it of course was mine. But, notwithstanding that the change brought me almost to the very border of[Pg 39] the vale of my nativity, I regretted to leave Brookside. It was a beautiful and interesting place, and the remembrance of it is like what Ossian says of joys that are past—'sweet and mournful to the soul.' I loved the place, was partial to the peacefulness of its retirement, its solitude, and the intelligence of its society. I was near the laird's library, and I had a garden in the glen. The latter was formed that I might gather home to it, when in musing moods among the mountains, the wild-flowers, in order to their cultivation, and my having something more of a possessory right over them. It formed a contrast to the scenery around, and lured to relaxation. Occasionally 'the lovely of the land' brought, with industrious delight, plants and flowers, that they might have a share in adorning it. Even when I was from home it was, upon the whole, well attended to; for although, according to taste or caprice, changes were made, yet I readily forgave the annoyances that might attend alteration, and especially those by the hands that sometimes printed me pleasing compliments on the clay with the little stones lifted from the walks. If the things which I have written and given to the world, or may yet give, continue to be cared for, these details may not be wholly without use, inasmuch as they will serve to explain frequent allusions which might otherwise seem introduced at capricious random, or made without a meaning.