THE

PLATTSBURG MANUAL

A HANDBOOK FOR MILITARY TRAINING

BY

O. O. ELLIS MAJOR, UNITED STATES INFANTRY

AND

E. B. GAREY MAJOR, UNITED STATES INFANTRY

(INSTRUCTORS, PLATTSBURG TRAINING CAMP, 1916) (INSTRUCTORS, OFFICERS'

TRAINING CAMP, FT. MCPHERSON, GA., 1917) (INSTRUCTORS, OFFICERS'

TRAINING CAMP, FT. OGLETHORPE, GA., 1917)

WITH MORE THAN 220 ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK THE CENTURY CO. 1918

Copyright, 1917, by

The Century Co.

Published, March, 1917

Second Edition, March, 1917

Third Edition, April, 1917

Fourth Edition, April, 1917

Fifth Edition, May, 1917

Sixth Edition, May, 1917

Seventh Edition, August, 1917

Eighth Edition. September, 1917

Ninth Edition, January, 1918

Tenth Edition, May, 1918

TO

THOSE FAR-SEEING MEN

WHO INAUGURATED AND ATTENDED THE

FIRST FEDERAL TRAINING CAMP

THIS TEXT IS RESPECTFULLY

DEDICATED

FOREWORD

The Plattsburg Manual, written by Majors Ellis and Garey, will prove

very useful to men who are contemplating military training. It will also

be of great value to those who are undergoing training.

It is full of practical information presented in a simple and direct

manner and gives in detail much data not easily found elsewhere. It is a

useful book, easily understandable by those who have had little or no

military experience.

It will be useful not only at training camps but it will be of very

great value at schools and colleges where military instruction is being

given.

The authors of this book have performed a valuable service, one which

will tend to facilitate and aid very much the development of military

training in this country. In addition to the purely mechanical details

of training the book presents in a very effective and simple manner the

tactical use of troops under various conditions.

In a word it is a useful and sound work and one which can be commended

to those who contemplate a course in military training.

(Signed) Leonard Wood,

Major General U. S. A.

February 27, 1917.

PREFACE

This book is intended to serve as a foundation upon which the military

beginner may build so that he may in time be able to study the technical

service manuals intelligently. It has been written as an elementary

textbook for those who desire to become Reserve Officers, for schools

and colleges, and for those who may be called to the colors.

The authors have commanded companies at Plattsburg, New York, and,

noting the need of such a text, compiled their observations while there.

The average man undergoing military training wants to know as much as

possible about the art and science of war. He wants to acquire a good

knowledge of the principles involved. He is interested in the technique

of movements. He is willing to work for these things, but he often

becomes lost in confusion when he attempts to study the technical

service manuals. He does not know how to select the most important and

omit the less important. The authors have selected from the standard

texts some of the vitally important subjects and principles and have

presented them to the civilian in a simple and plain way.

The first part of the text is for the beginner. It tells him how to

prepare physically for strenuous military work. After assisting him

through the elementary part of his instruction, it presents for his

consideration and study the Officers' Reserve Corps.

The second part, or supplement, is a more technical discussion of those

subjects introduced in the first. It is intended principally for those

who have made excellent progress.

CONTENTS

- General Advice 3

- Physical Exercise 21

- School of the Soldier 28

- School of the Squad 63

- School of the Company 86

- Fire Superiority 130

- The Service of Security 136

- Attack and Defense 144

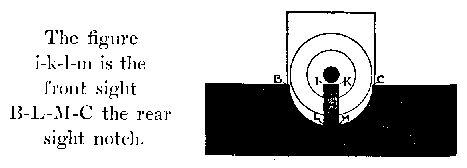

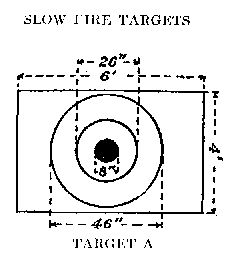

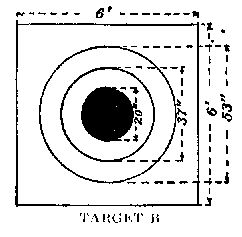

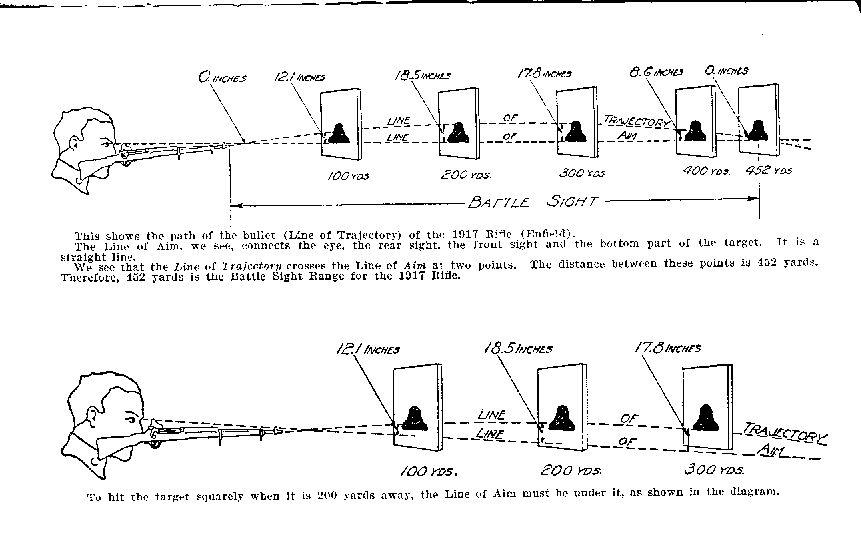

- General Principles of Target Practice 153

- Practice March or "Hike" 159

- Officers' Reserve Corps 169

SUPPLEMENT

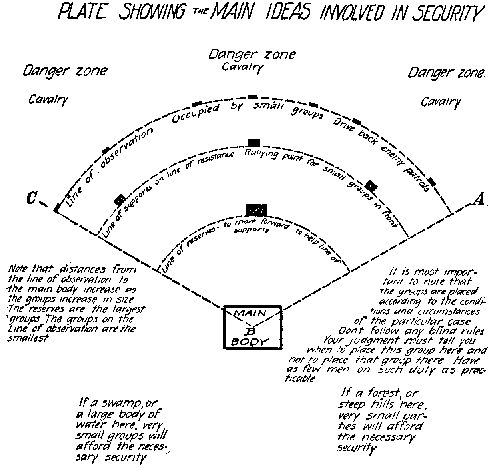

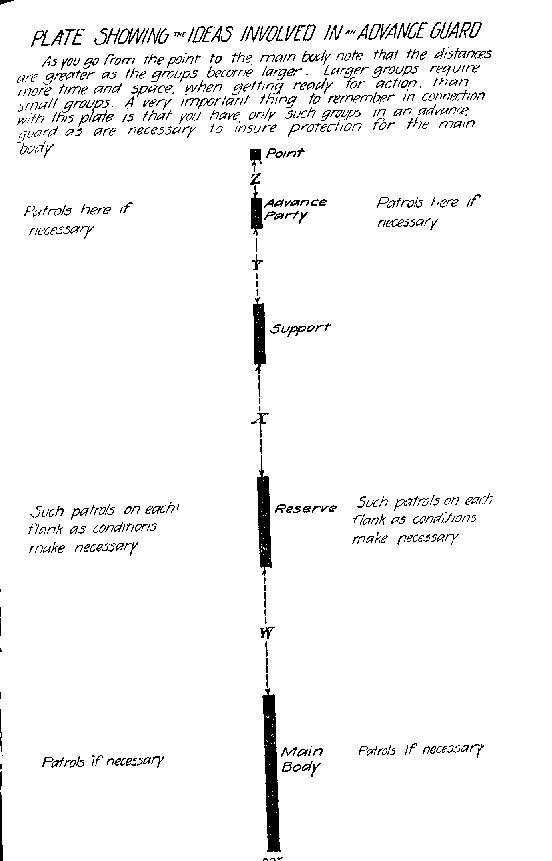

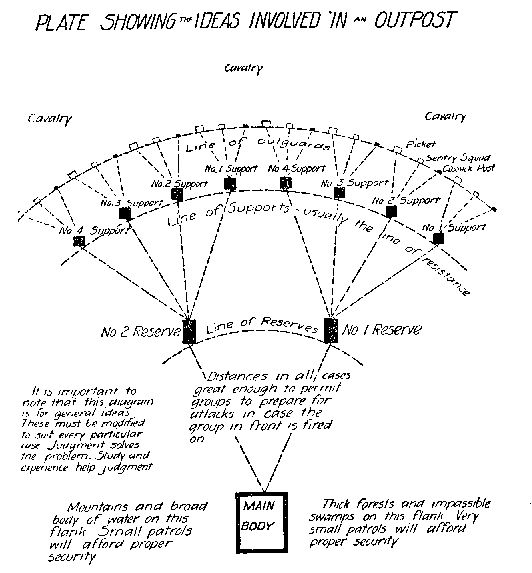

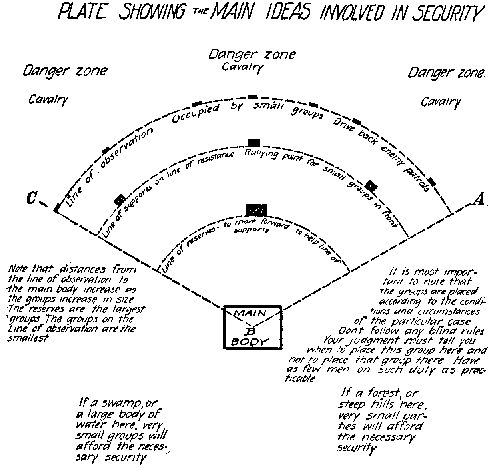

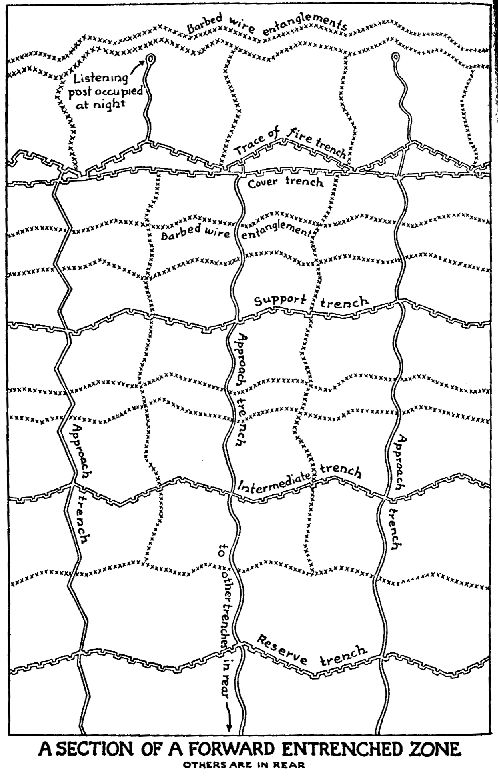

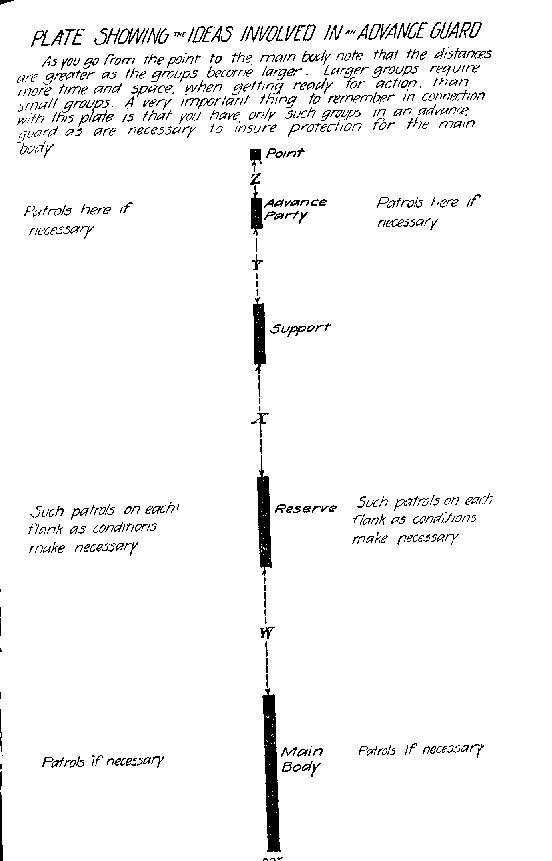

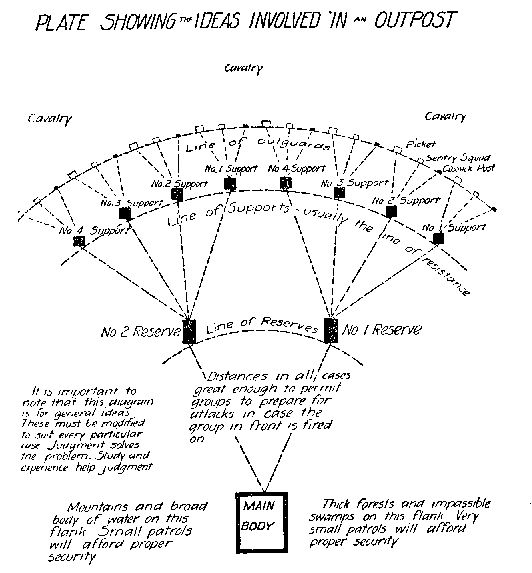

- The Theory of Security 221

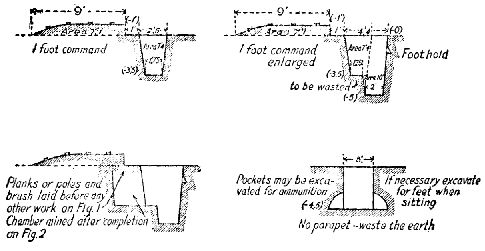

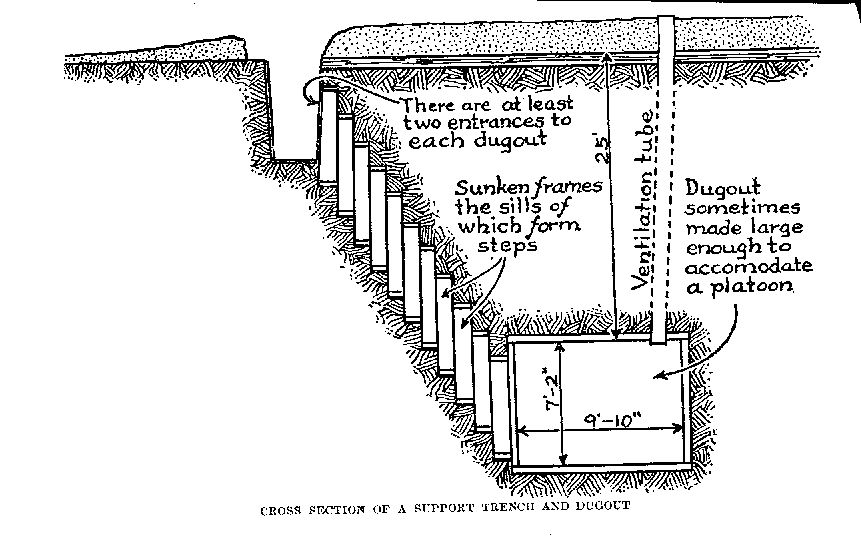

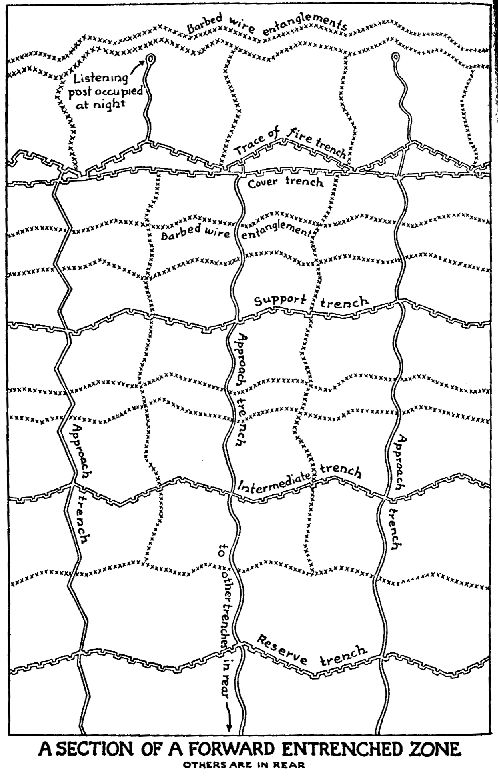

- Attack and Defense 242

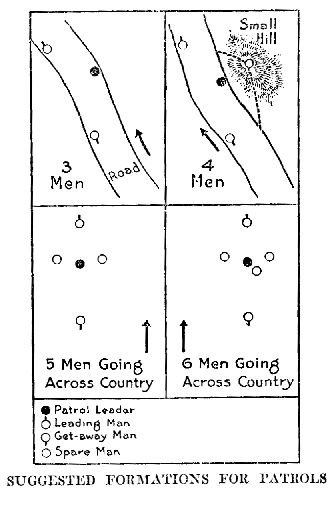

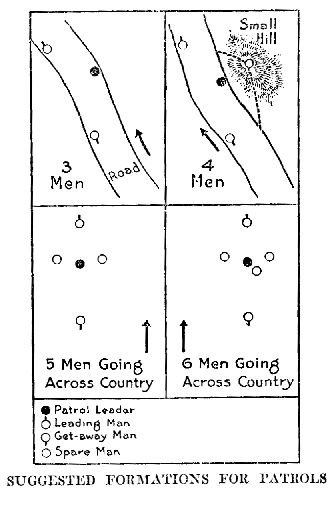

- Patrolling 254

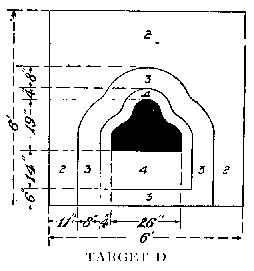

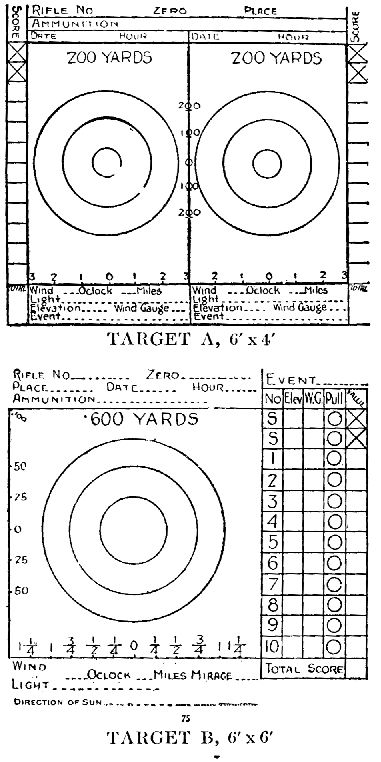

- Target Practice 260

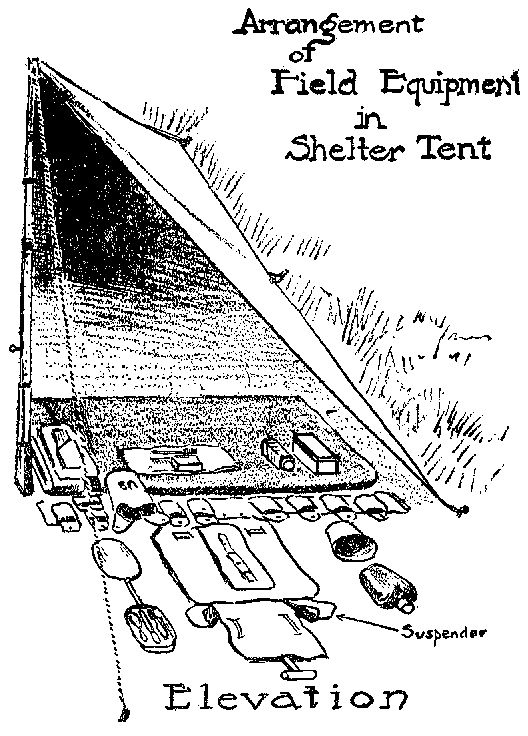

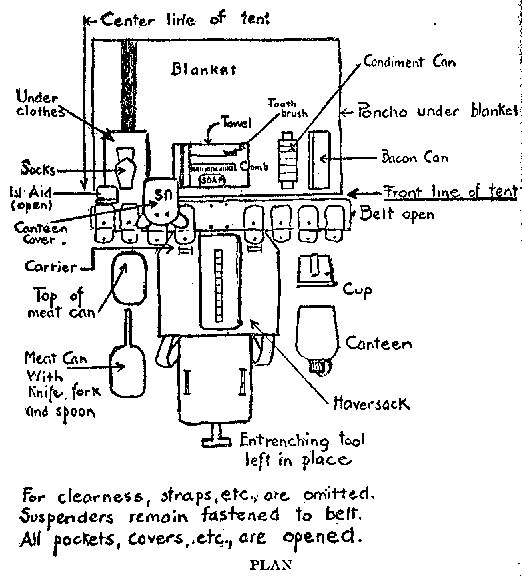

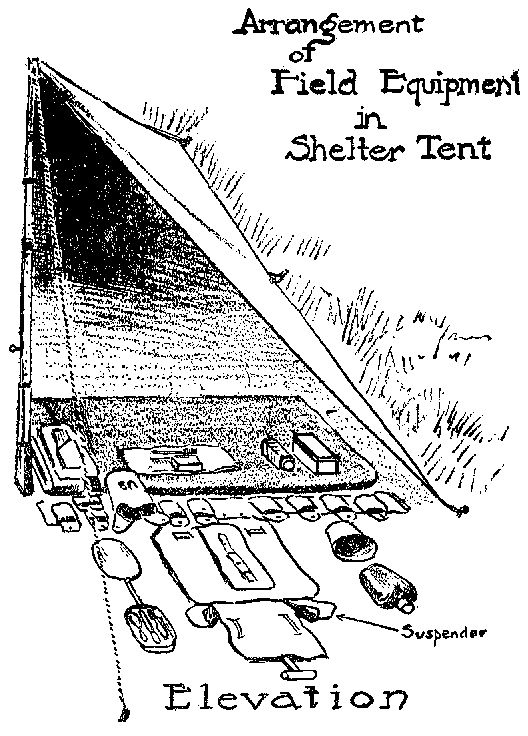

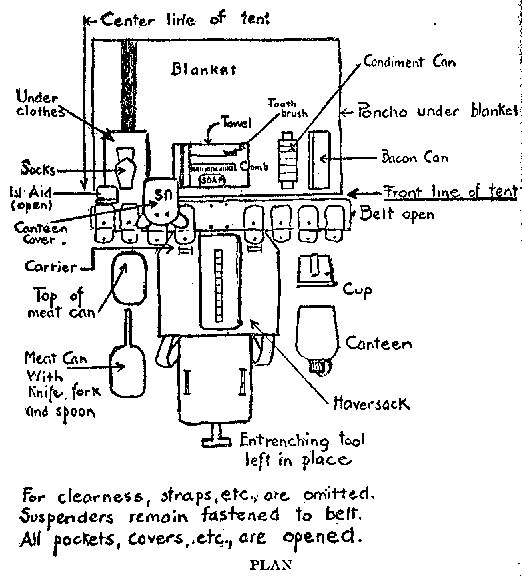

- Tent Pitching 292

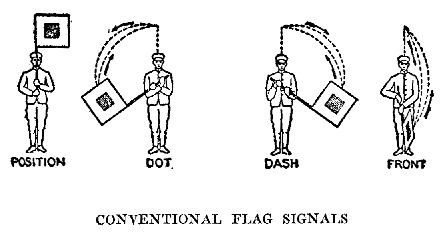

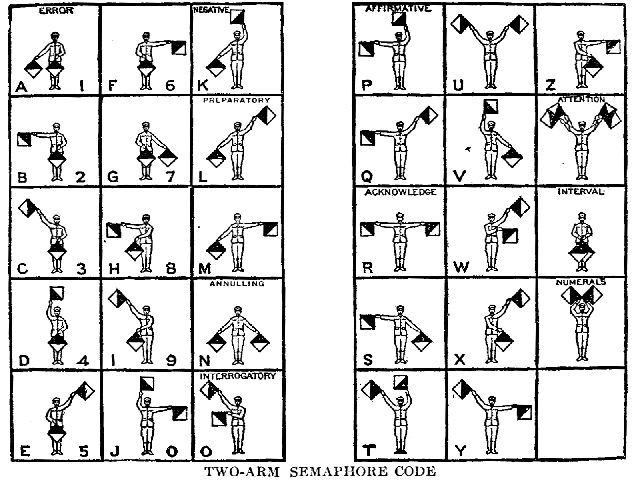

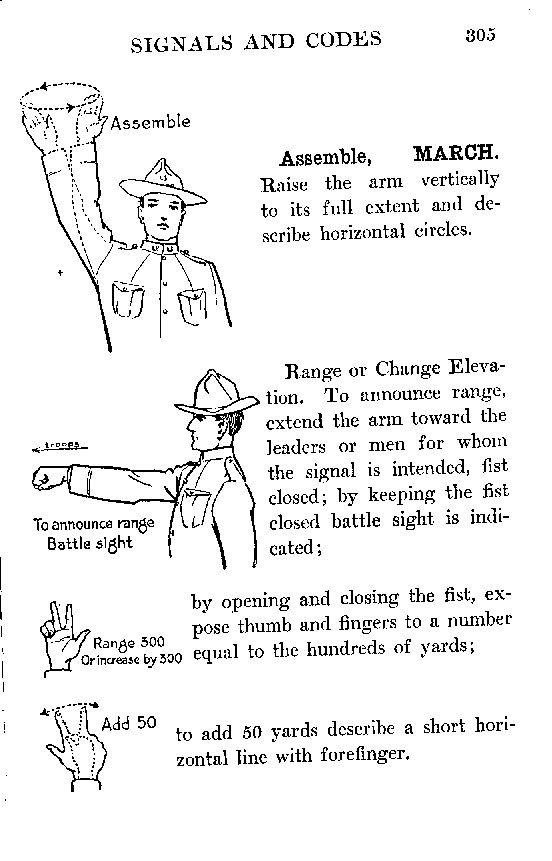

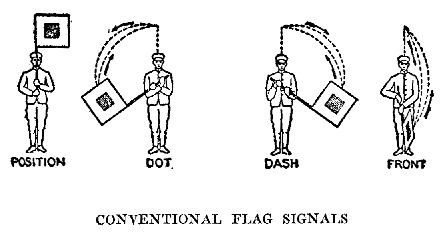

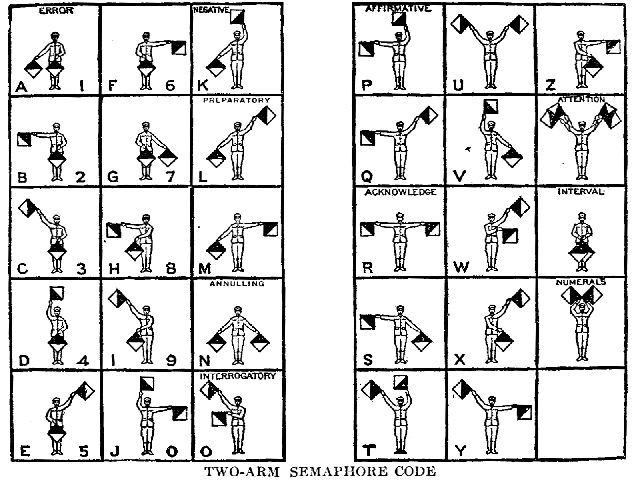

- Signals and Codes 297

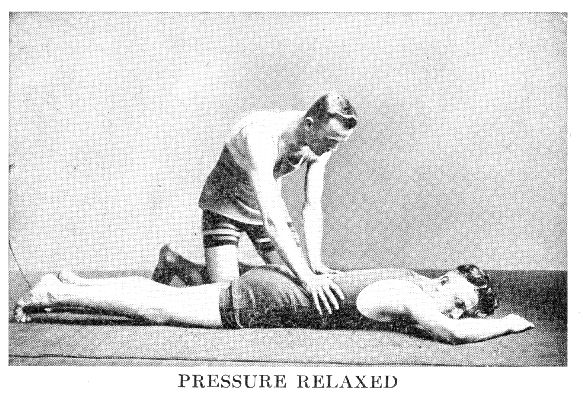

- First Aid to the Injured 309

Appendixes 321

Index 331

THE PLATTSBURG MANUAL

CHAPTER I

GENERAL ADVICE

The United States is divided geographically into military departments

with a general officer commanding each department. The departments and

their headquarters are as follows:

(1) The Northeastern Department, with headquarters at Boston,

Massachusetts.

(2) The Eastern Department, with headquarters at Governors Island,

New York.

(3) The Southeastern Department, with Headquarters at Charleston,

South Carolina.

(4) The Central Department, with Headquarters at Chicago, Illinois.

(5) The Southern Department, with Headquarters at Fort Sam Houston,

Texas.

(6) The Western Department, with Headquarters at San Francisco,

California.

Overseas Departments

(7) The Philippine Department, with Headquarters at

Manila.

(8) The Hawaiian Department, Departments with

Headquarters at Honolulu, Hawaii.

(For States comprising each department, see Appendix)

If you are a civilian and desire any information in regard to the army,

any training camps, the officers' reserve corps, or any military

legislation or orders affecting you, write to the "Commanding General"

of the Department in which you live. Address your letter to him at his

headquarters.

MAIL

Mail is most often delayed because there is not sufficient information

for the Postmaster on the envelope. The delivery of your mail will be

delayed unless your letters are sent to the company and the regiment to

which you belong. Therefore, prepare, before you reach camp, several

stamped postal cards, addressed to your family and business associates,

containing directions to address all communications to you care of

Company----, Regiment----. As soon as you are assigned to a company and

regiment, fill in these data and mail these postal cards at once. This

should be done by wire in case important mail is expected during the

first week of camp. Mail is delivered to each company as soon as a

complete roll of the organizations can be made out and sent to the

post-office.

INOCULATIONS AND VACCINATION

As soon as you become a member of the army, whether as a private or as

an officer, you will receive the typhoid prophylaxis inoculation and be

vaccinated against smallpox.

WHAT TO BRING

1. Travel light. Bring only the bare necessities of life with you.

Don't bring a trunk. Enlisted men (not officers) will be supplied

with all necessary uniforms and underwear. This includes shoes.

2. Bring a pair of sneakers, or slippers. They will add greatly to

your comfort after a long march or hard day's work. A complete

bathing suit often comes in handy.

3. Report in uniform if you have one.

4. The Government will provide you with the necessary shoes.

However, if you can afford it, buy before you report for duty, a

pair of regulation tan shoes, larger than you ordinarily wear, and

break them in well before arrival. Rubber heels are recommended.

5. Bring your toilet articles (comb, brush, mirror shaving

equipment, etc.), and a good supply of handkerchiefs, and towels.

WHAT TO DO ON YOUR ARRIVAL

There is a general rule of procedure to follow in reporting for duty at

any post or training camp.

1. If you receive an order directing you to report for duty at a

camp or post at a certain specified time, read it carefully, put it

in a secure place, and, on the day that you are to report for duty

at the camp or post, present yourself in uniform, if you have one,

with your order. Be careful not to lose your order or leave it at

home. Have it in your pocket book.

2. Upon being assigned to a company, unless you receive orders to

the contrary, report at once with your baggage to your company

commander (captain), whom you can easily find when you reach your

barracks or company street. If you cannot locate your company

commander, report to the first sergeant.

3. It is a custom of the service to have an experienced soldier

explain to a new man exactly where he is to go and what he is to do.

Feel no embarrassment at being ignorant of your new duties and

surroundings. The Government does not expect anything of you except

eagerness to learn and willingness to obey.

4. After reporting to your company commander or first sergeant, you

will have a bed assigned to you and you will be issued the property

and uniforms necessary to your comfort and duties. Check your

property carefully as it is issued to you. You will have to sign for

all of it. Look after your property at all times.

5. After checking your property, make up your bed and arrange neatly

your personal and issued property on or under your bed or cot.

6. Spend all your spare time cleaning your rifle and bayonet until

they satisfy your company commander. Then keep them clean.

7. Don't leave the company street or barracks on the first day,

except with the permission of your company commander. Don't ask for

this permission unless you have a valid reason.

RULES OF CONDUCT FOR CAMP LIFE

The first few days will be easy and profitable if you will read

carefully and adhere to the following plan of procedure:

1. Get up at the first note of reveille and get quickly into proper

uniform.

2. Get within two or three feet of your place in ranks and await the

sounding of assembly for reveille and then step into ranks.

3. Stand at attention after the first sergeant commands "Fall In."

Remember that this command is equivalent to "Company, Attention."

4. After reveille, make up your bed, arrange neatly your equipment,

and clean up the ground under and around your cot. The company

commander will require the beds made up and the equipment arranged

in a prescribed way.

5. Wash for breakfast.

6. Upon returning from breakfast, go at once to the toilet. Next,

prepare the equipment prescribed to be worn to drill. This is

especially important when the full pack is prescribed. Assist your

tent mates in policing the ground in and around your tent.

7. If you need medical attention give your name to the first

sergeant at reveille and report to him at his tent upon your return

from breakfast. Don't wait until you are sick to report to the

hospital, but go as soon as you feel in the least unwell.

8. When the first call for drill is blown, put on your equipment,

inspect your bed and property to see that everything is in order,

and then go to your place in ranks.

9. After the morning drill, get ready for dinner. Get a little rest

at this time if possible.

10. After dinner a short rest is usually allowed before the

afternoon drill. Take advantage of this opportunity; get off your

feet and rest. Be quiet so that your tent mates may rest.

11. Following the afternoon drill there is a short intermission

before the ceremony of retreat. During this time take a quick bath,

shave, get into the proper uniform for retreat, shine your shoes and

brush your clothes and hat. Be the neatest man in the company.

12. Supper usually follows retreat.

13. After supper, you usually have some spare time until taps. The

Y. M. C. A. generally provides a place supplied with Bibles,

newspapers, good magazines, and writing material. Don't be ashamed

to read the Bible. Don't forget to write to the folks back home.

14. Be in bed with lights out at taps. After taps and before

reveille, remain silent, thus showing consideration for those who

are sleeping or trying to sleep.

15. Consult the company bulletin board at least twice daily. On this

bulletin board is usually found the following information:

- A list of calls.

- The proper uniform for each formation.

- Schedule of drills.

- Special orders and instructions.

16. Get all your orders from (a) the bulletin board, (b) the first

sergeant, (c) the acting noncommissioned officers, (d) the company

commander. Don't put much faith in rumors.

ADVICE REGARDING HABITS

Your life in camp in regard to food, exercise, hours of sleep,

surroundings, and comforts, will differ greatly from that you lead as a

civilian. You will submit your body to a sudden, severe, physical test.

In order to prepare your body for this change in manner of living and

work, we recommend that for a short time prior to your arrival in camp,

and thereafter, you observe the following suggestions:

1. Use no alcohol of any kind.

2. Stop smoking, or at least be temperate in the use of tobacco.

3. Eat and drink moderately. Chew your food well. It is advisable,

however, to drink a great deal of cool (not cold) water between

meals.

4. Don't eat between meals.

5. Accustom yourself to regular hours as to sleeping, eating, and

the morning functions.

6. Keep away from all soda fountains and soft drink stands.

7. For at least two weeks prior to your arrival at camp, take

regularly the exercises described in this book.

Most men are troubled with their feet during the first week of each

camp, usually because they do not observe the following precautions:

1. If you have ever had trouble with the arches of your feet, wear

braces for them.

2. Lace your shoe as tightly as comfort will permit.

3. Wash the feet daily.

4. Every morning shake a little talcum powder or "Foot Ease" in

each shoe.

5. Each morning put on a fresh pair of socks. Your socks should fit

the feet so neatly that no wrinkles remain in them and yet not be

so tight that they bind the foot. Do not wear a sock with a hole in

it or one that has been darned.

6. Some men cannot wear light wool socks with comfort. Do not wear

silk or cotton socks until you have given light wool socks a fair

trial.

7. In case of a blister, treat it as directed in Chapter X.

8. Most of the foot troubles are caused by wearing shoes that do

not fit properly. If the shoe is too large it rubs blisters, if too

small it cramps the foot and causes severe pain. Marching several

hours while carrying about thirty pounds of equipment causes each

foot to expand at least one half a size in length and

correspondingly in breadth; hence the size of the shoe you wear in

the office will be too small for training camp use. If you have

been living a sedentary life, ask for a pair of shoes larger than

you ordinarily wear.

9. In case the tendon in your heel becomes tender, report at once

to the hospital tent and get it strapped.

A DISCIPLINED SOLDIER

You will be expected to become quickly amenable both mentally and

physically to discipline. A clear conception on your part of what drills

are disciplinary in character and what discipline really is, will help

you to become a disciplined soldier. Drills executed at attention are

disciplinary exercises and are designed to teach precise and soldierly

movements and to inculcate that prompt and subconscious obedience which

is essential to proper military control. Hence, all corrections should

be given and received in an impersonal manner. Never forget that you

lose your identity as an individual when you step into ranks; you then

become merely a unit of a mass. As soon as you obey properly, promptly,

and, at times, unconsciously, the commands of your officers, as soon as

you can cheerfully give up pleasures and personal privileges that

conflict with the new order of life to which you have submitted, you

will then have become a disciplined man.

DRESS

The uniform you will wear stands for Duty, Honor, and Country. You

should not disgrace it by the way you wear it or by your conduct any

more than you would trample the flag of the United States of America

under foot. You must constantly bear in mind that in our country a

military organization is too often judged by the acts of a few of its

members. When one or two soldiers in uniform conduct themselves in an

ungentlemanly or unmilitary manner to the disgrace of the uniform, the

layman shakes his head and condemns all men wearing that uniform. Hence,

show by the way in which you wear your uniform that you are proud of it;

this can be best accomplished by observing the following rules:

1. Carry yourself at all times as though you were proud of

yourself, your uniform, and your country.

2. Wear your hat so that the brim is parallel to the ground.

3. Have all buttons fastened.

4. Never have sleeves rolled up.

5. Never wear sleeve holders.

6. Never leave shirt or coat unbuttoned at the throat.

7. Have leggins and trousers properly laced.

8. Keep shoes shined.

9. Always be clean shaved.

10. Keep head up and shoulders square.

11. Camp life has a tendency to make one careless as to personal

cleanliness. Bear this in mind.

SALUTING

The military salute is universal. It is at foundation but a courteous

recognition between two individuals of their common fellowship in the

same honorable profession, the profession of arms. Regulations require

that it be rendered by both the senior and the junior, as bare courtesy

requires between gentlemen in civil life. It is the military equivalent

of the laymen's expressions "Good Morning," or "How do you do?"

Therefore be punctilious about saluting; be proud of the manner in which

you execute your salute, and make it indicative of discipline and good

breeding. Always look at the officer you are saluting. The junior

salutes first. It is very unmilitary to salute with the left hand in a

pocket, or with a cigarette, cigar, or pipe in the mouth. Observe the

following general rules:

1. Never salute an officer when you are in ranks.

2. Indoors (in your tent) unarmed, do not salute but stand at

attention, uncovered, on the entrance of an officer. If he speaks

to you, then salute.

3. Indoors, armed, render the prescribed salute, i.e., the rifle

salute at order arms or at trail.

4. Outdoors, armed, render the prescribed salute, i.e., the rifle

salute at right shoulder arms.

5. Outdoors, unarmed, or armed with side arms, salute with the

right hand.

ARMY SLANG

The following army slang is universally employed:

"Bunkie"--the soldier who shares the shelter half or tent of a

comrade in the field. A bunkie looks after his comrade's property

in the event the latter is absent.

"Doughboy"--the infantryman.

"French leave"--unauthorized absence.

"Holy Joe"--the chaplain.

"K.O."--the commanding officer.

"On the carpet"--a call before the commanding officer for

admonition.

"Q.M."--quartermaster.

"Rookie"--a new recruit.

"Sand rat"--a soldier on duty in the rifle pit during target

practice.

"Top sergeant"--the first sergeant.

"Come and get it"--the meal is ready to be served.

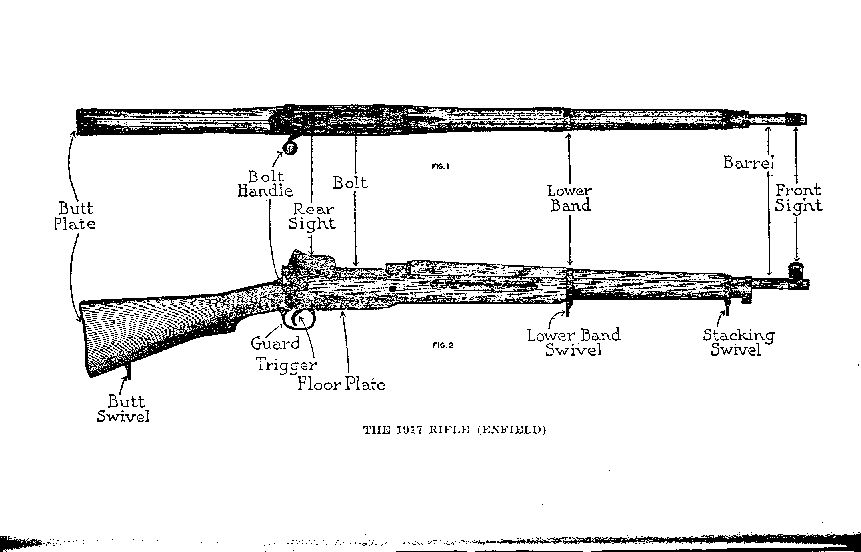

HOW TO CLEAN A RIFLE AND BAYONET

Get a rag and rub the heavy grease off; then get a soft pine stick,

pointed at one end, and with this point remove the grease from the

cracks, crevices and corners. Clean the bore from the breech. When the

heavy grease has been removed, the metal part of the gun, bore included,

should be covered with a light coating of "3-in-1" oil. Heavy grease can

be removed from the rifle by rubbing it with a rag which has been

saturated with gasoline or coal oil.

FRIENDS

There are a few men in all companies who play, loaf, and who are

constantly in trouble. As the good men in each company will not become

friendly with them, they seek their acquaintances among the new men on

whom they have a baneful influence. We wish to warn you about making

friends too quickly.

FINAL SUGGESTIONS

Don't be profane or tell questionable stories to your bunkies or around

the company. There is a much greater number of silent and unprotesting

men in camp than is generally supposed, to whom this is offensive. Keep

everything on a high plane.

CHAPTER II1

Read this chapter as soon as you decide to attend a Camp.

PHYSICAL EXERCISE

The greatest problem you will have to solve will be that of making your

body do the work required. Every one else will be doing exactly what you

are doing, and you have too much pride to want to take even a shorter

step than the man by your side. Some men have to leave the training

camps because they are not in the proper physical condition to go on

with the work. If this chapter is taken as seriously as it should be, it

will be of great help to you.

If you have not a pair of sensible marching shoes (tan, high-tops, no

hooks on them) get a pair. These shoes should be considerably larger

than a pair of office shoes.

Walk to and from your business. Take every opportunity to get out in the

country where the air is pure. Fill your lungs full. Get into the habit

of taking deep breaths now and then. Don't make this a task, but

surround it with pleasantries. Get some delightful companion to walk

with you. Walk vigorously.

Let down on your smoking. Better to leave it alone for a while. You will

enjoy the air. Deep breathing seems to be more natural.

Make it a work for your country. View it in that light. If you are not

going to be called upon to undergo the cruel hardships and physical

strain of some campaigns, your son will be, and you can be of great help

to him by being fit yourself. You and your sons will form the backbone

of America's strength in her next peril.

You will have a great deal of walking after you arrive in camp, possibly

a great deal more than you have ever had, and probably a great deal more

than you expect, even with this word of warning. If you have failed to

provide yourself with proper shoes and socks, great will be the price of

your lack of forethought. You will wince at your own blisters. You will

get no sympathy from any one else. It is the spirit of the camp for each

man to bear his own burdens. So arrive at camp with hardened legs and

broken in shoes. Don't buy shoes with pointed or narrow toes. They

should be broad and airy.

Immediately after you arise in the morning and just before you retire at

night, go through the following exercises for two or three minutes. In a

short time you may want to make it more. No objection. Give it a fair

trial. Be brisk and energetic. Forget, for the time being, what you are

going to get out of it. Give and then give more. The result will take

care of itself.

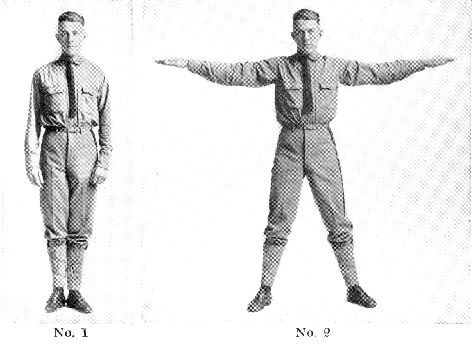

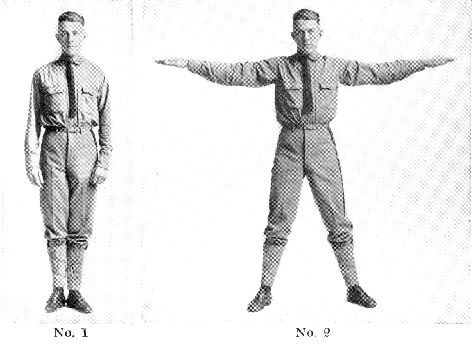

1st Exercise

Involving practically every important muscle in the body.

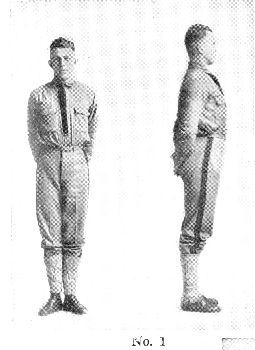

No. 1 No. 2

From first position spring to second position; instantly return to first

position and continue.

Be light on your feet. Alight on your toes. Begin with a limited number

of times. Day by day increase it a little until you reach a fair number.

Be most moderate at first. Never allow yourself in any exercise to

become greatly fatigued.

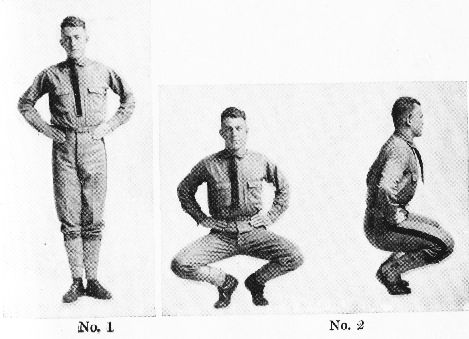

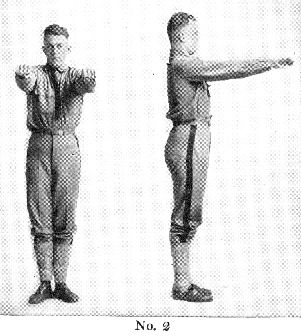

2d Exercise

To reduce waist, strengthen back muscles, and become limber.

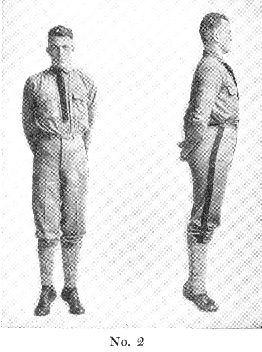

No. 1 No. 2

Assume position No. 1.

Swing to position (No. 2), return at once to No. 1, and continue.

Shoot your head and arms as far through your legs as your conformation

permits.

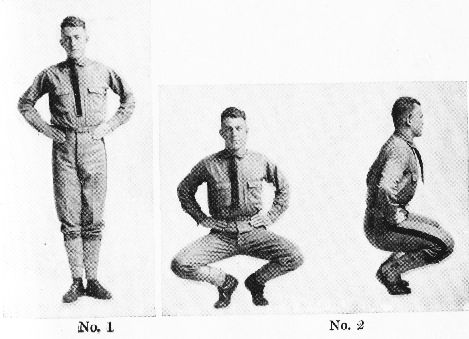

3rd Exercise

To harden leg muscles and exercise joints.

No. 1 No. 2

From position No. 1 come to position No. 2. Return at once to No. 1 and

continue.

Toes turned well out. Body and head erect. Up with a slight spring.

After a little practice, you will have no difficulty with this exercise

in balancing yourself.

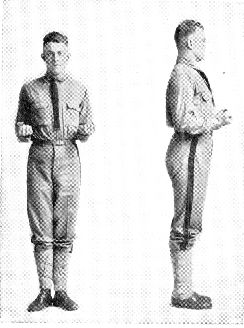

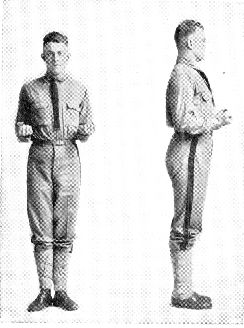

4th Exercise

To exercise arms and shoulders and organs of chest and shoulder muscles.

No. 1

From position No. 1 thrust arms forward to position No. 2, and return at

once to position No. 1.

No. 2

Vary by thrusting arms downward, sideward and upward. Be moderate at

first. Grow more vigorous with practice.

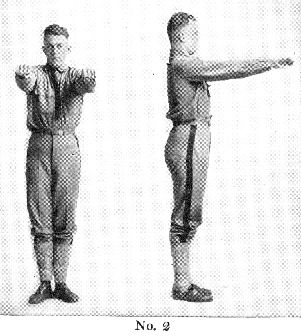

5th Exercise

No. 1

To strengthen ankles and insteps.

From position No. 1 rise on the toes to position No. 2, return at once

to position No. 1, and continue.

Go up on your toes as high as you can.

No. 2

CHAPTER III

SCHOOL OF THE SOLDIER

Based on the Infantry Drill Regulations

Success in battle is the ultimate object of all military training; hence

the excellence of an organization is judged by its field efficiency.

Your instruction will be progressive in character, and will have as its

ultimate purpose the creation of a company measuring up to a high

standard of field efficiency.

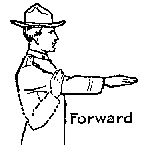

The Preparatory Command, such as Forward, indicates the movement that is

to be executed.

The Command of Execution, such as MARCH, HALT, or ARMS, commences the

execution of the movement.

Preparatory Commands are distinguished by bold face, those of execution

by capitals. As, 1. Forward, 2. MARCH.

The average man understands better and learns faster when you show him

how a thing is done. Don't be content with telling him how. Bear this in

mind when you become an instructor.

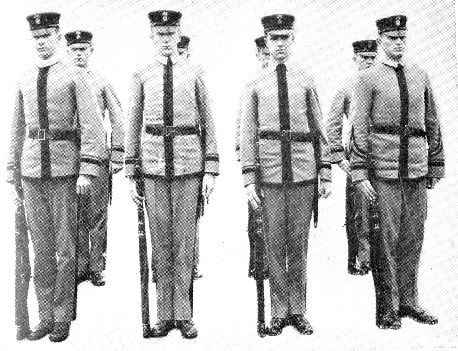

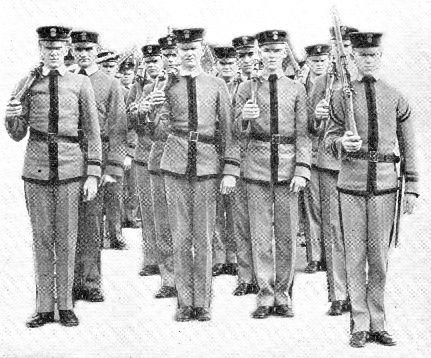

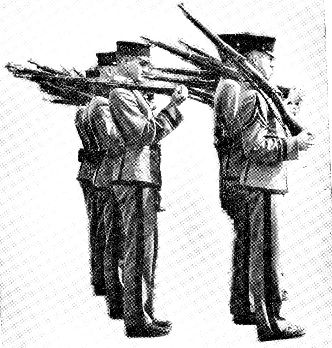

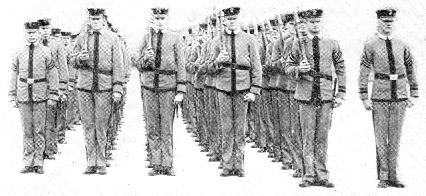

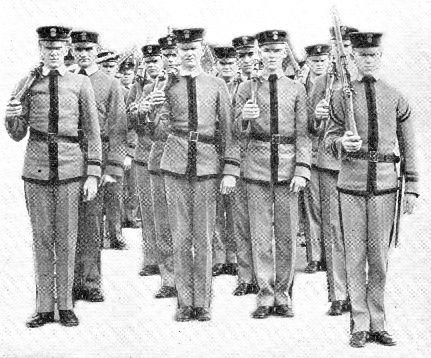

On account of the absence of the Regular Army on the border, it was not

practical to obtain photographs of regular troops with which to

illustrate this book. The photographs used were taken under the direct

supervision of the authors.

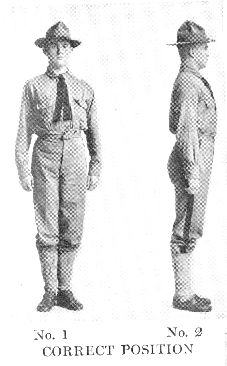

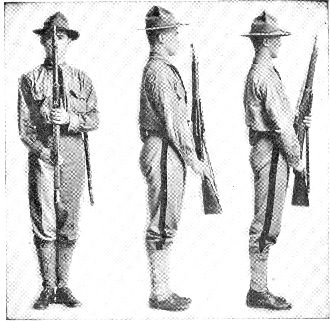

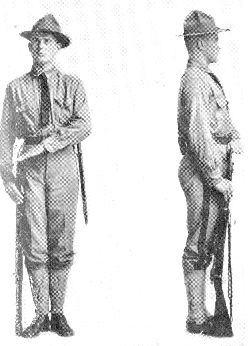

POSITION OF A SOLDIER AT ATTENTION

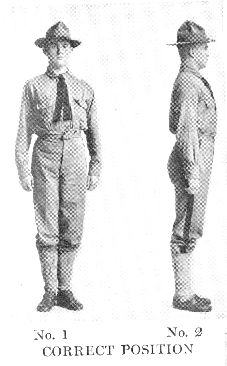

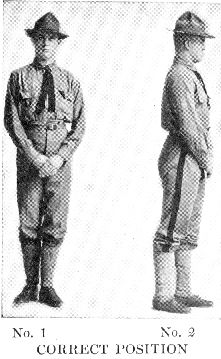

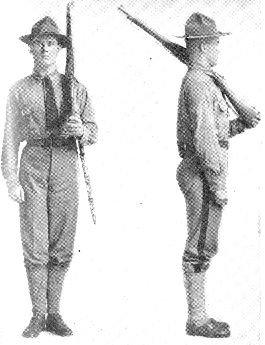

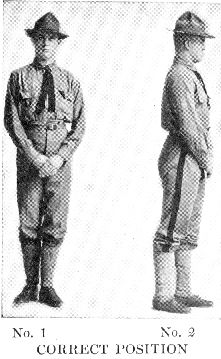

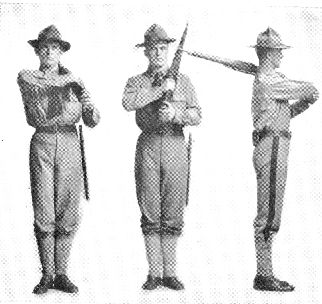

No. 1 No. 2 CORRECT POSITION

No. 1. Eyes to the front. Hands hang naturally. Rest weight of the body

equally on feet. Feet turned out making angles of 45°.

No. 2. Head erect. Shoulders down and back. Chest out. Stomach up. Thumb

along the seams of trousers. Knees straight, not stiff. Heels on line

and together. Do not stiffen the fingers: The mind ought also to be at

attention.

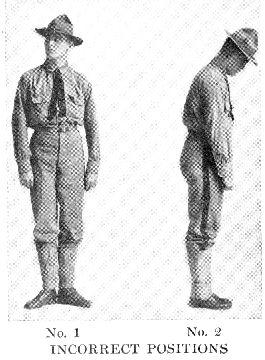

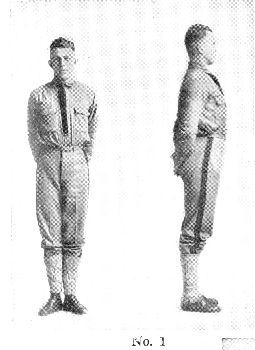

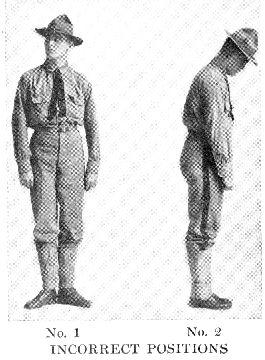

No. 1 No. 2 INCORRECT POSITIONS

No. 1. Don't gaze about. That's not playing the game. Don't turn your

feet out making an angle of 100°.

No. 2. Don't slouch. Hold yourself up. Keep your eyes off the ground.

These are the common errors of beginners.

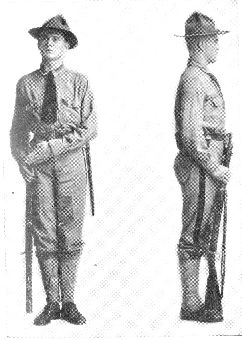

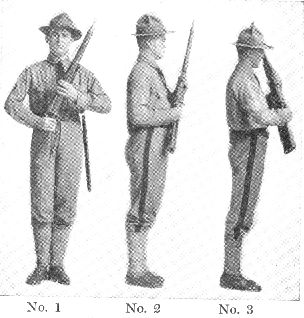

1. Parade, 2. REST.

No. 1 No. 2 CORRECT POSITION

No. 1. Clasp hands without constraint in front of center of body. Left

hand uppermost. Fingers joined. Thumb and fore finger right hand clasps

the left thumb.

No. 2. Bend left knee slightly. Right foot is carried 6 inches straight

to the rear.

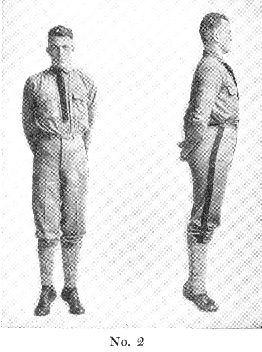

No. 1 No. 2 INCORRECT POSITIONS

No. 1. Not looking straight to the front. Right foot not carried

straight to the rear.

No. 2. Leaning back too far. Right foot carried back too far.

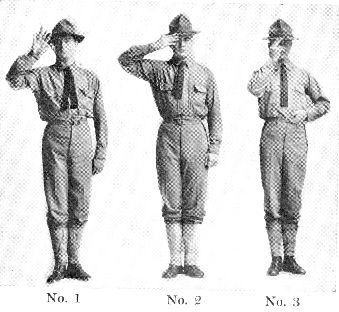

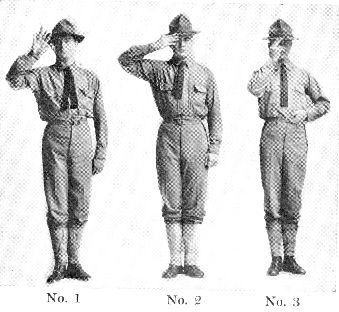

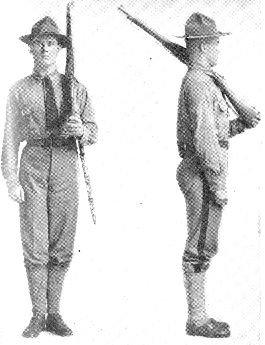

1. Hand, 2. SALUTE.

No. 1 No. 2 CORRECT POSITION

No. 1. Look toward the person saluted.

No. 2. Tip of forefinger right hand touches cap or hat above right eye.

Thumb and forefingers extended and joined. Hand and wrist straight. Palm

to the left.

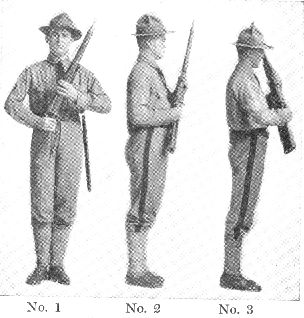

No. 1 No. 2 No. 3 INCORRECT POSITIONS OR COMMON ERRORS

No. 1. Palm of the hand to the front and fingers not joined.

No. 2. Arm held too high. Fingers not perfectly joined.

No. 3. Fingers not extended and joined. Left hand not by side while

salute is being made.

Some beginners forget, while saluting, to remove their pipes,

cigarettes, or cigars from their mouths. This proves clearly that they

are beginners, for trained and experienced men are careful about

military honors and salutes.

THE RESTS

Being at a halt, the commands are: FALL OUT; REST; AT EASE; and 1.

Parade, 2. REST.

At the command fall out, the men may leave the ranks, but are required

to remain in the immediate vicinity. They resume their former places, at

attention, at the command fall in.

At the command rest, each man keeps one foot in place, but is not

required to preserve silence or immobility.

At the command at ease, each man keeps one foot in place and is required

to preserve silence, but not immobility.

1. Parade, 2. REST. Previously explained.

To resume the attention: 1. Squad, 2. ATTENTION. The men take the

position of the soldier.

EYES RIGHT OR LEFT

1. Eyes, 2. RIGHT (LEFT), 3. FRONT.

At the command right, turn the head to the right oblique, eyes fixed on

the line of eyes of the men in, or supposed to be in, the same rank. At

the command front, turn the head and eyes to the front. Notice the right

file does not turn the eyes to the right.

FACINGS

To the flank: 1. Right (left), 2. FACE.

Raise slightly the left heel and right toe; face to the right, turning

on the right heel, assisted by a slight pressure on the ball of the left

foot; place the left foot by the side of the right. Left face is

executed on the left heel in the corresponding manner.

Right (left) Half Face is executed similarly, facing 45°.

To the rear: 1. About, 2. FACE.

Carry the toe of the right foot about a half foot-length to the rear and

slightly to the left of the left heel without changing the position of

the left foot; face to the rear, turning to the right on the left heel

and right toe; place the right heel by the side of the left. There is no

left about face.

STEPS AND MARCHINGS

All steps and marchings executed from a halt, except right step, begin

with the left foot.

The length of the full step in quick time is 30 inches, measured from

heel to heel, and the cadence is at the rate of 120 steps per minute.

The length of the full step in double time is 36 inches; the cadence is

at the rate of 180 steps per minute.

The instructor, when necessary, indicates the cadence of the step by

calling one, two, three, four, or left, right, the instant the left and

right foot, respectively, should be planted.

All steps and marchings and movements involving march are executed in

quick time unless the squad be marching in double time, or double

time be added to the command; in the latter case double time is added

to the preparatory command. Example: 1. Squad right, double time, 2.

MARCH (School of the Squad).

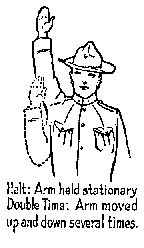

QUICK TIME

Being at a halt, to march forward in quick time: 1. Forward, 2. MARCH.

At the command forward, shift the weight of the body to the right leg,

left knee straight.

At the command march, move the left foot smartly straight forward 30

inches from the right, sole near the ground, and plant it without shock;

next, in like manner, advance the right foot and plant it as above;

continue the march. The arms swing naturally.

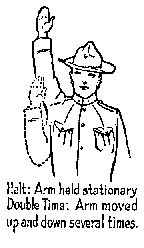

Being at a halt, or in march in quick time, to march in double time: 1.

Double time, 2. MARCH.

If at a halt, at the first command shift the weight of the body to the

right leg. At the command march, raise the forearms, fingers closed, to

a horizontal position along the waist line; take up an easy run with the

step and cadence of double time, allowing a natural swinging motion to

the arms.

If marching in quick time, at the command march, given as either foot

strikes the ground, take one step in quick time, and then step off in

double time.

To resume the quick time: 1. Quick time, 2. MARCH.

At the command march, given as either foot strikes the ground, advance

and plant the other foot in double time; resume the quick time, dropping

the hands by the sides.

TO MARK TIME

Being in march: 1. Mark time, 2. MARCH. At the command march, given as

either foot strikes the ground, advance and plant the other foot; bring

up the foot in rear and continue the cadence by" alternately raising each

foot about 2 inches and planting it on line with the other.

Being at a halt, at the command march, raise and plant the feet as

prescribed above. Common errors are to raise the feet several inches and

to run up the cadence, i.e., go too fast.

1. Half step, 2. MARCH.

Take steps of 15 inches in quick time, 18 inches in double time.

Forward, half step, halt, and mark time may be executed one from the

other in quick or double time. Any step less than the full step (i.e.,

half step, right step, or backward) is apt to be too fast, i.e., greater

than 120 steps a minute.

To resume the full step from half step or mark time: 1. Forward, 2.

MARCH.

SIDE STEP

Being at a halt or mark time: 1. Right (left) step, 2. MARCH.

Carry and plant the right foot 15 inches to the right; bring the left

foot beside it and continue the movement in the cadence of quick time.

The side step is used for short distances only and is not executed in

double time.

If at order arms, the side step is executed at trail without command.

BACK STEP

Being at a halt or mark time: 1. Backward, 2. MARCH.

Take steps of 15 inches straight to the rear.

The back step is used for short distances only and is not executed in

double time.

If at order arms, the back step is executed at trail without command.

TO HALT

To arrest the march in quick or double time: 1. Squad, 2. HALT.

At the command halt, given as either foot strikes the ground, plant the

other foot as in marching; raise and place the first foot by the side of

the other. If in double time, drop the hands by the sides.

TO MARCH BY THE FLANK

Being in march: 1. By the right (left) flank, 2. MARCH.

No. 1 No. 2

The command march must be given when the right foot is on the ground as

shown in No. 1. Then advance and plant the left foot and turn on the

toes to right as shown in No. 2, and step off with the right foot.

TO MARCH TO THE REAR

Being in march: 1. To the rear, 2. MARCH.

No. 1 No. 2

At the command march, given as the right foot strikes the ground,

advance and plant the left foot; turn to the right about on the balls of

both feet and immediately step off with the left foot.

The turn is made on the toes as shown.

The command march must be given when the right foot is on the ground.

The left foot is then advanced to the position shown.

If marching in double time, turn to the right about, taking four steps

in place, keeping the cadence, and then step off with the left foot.

CHANGE STEP

Being in march; 1. Change step, 2. MARCH.

At the command march, given as the right foot strikes the ground,

advance and plant the left foot; plant the toe of the right foot near

the heel of the left and step off with the left foot.

The change on the right foot is similarly executed, the command march

being given as the left foot strikes the ground.

MANUAL OF ARMS

To acquire proficiency in the Manual of Arms, you should practice,

practice, and practice.

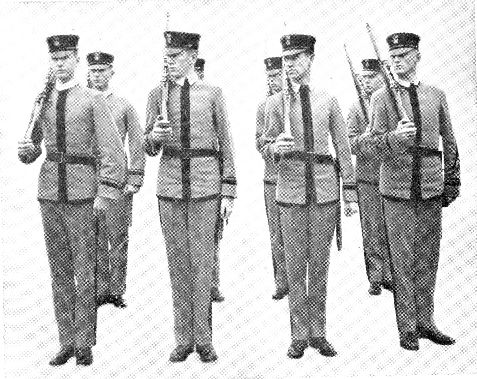

Position of order arms standing, i.e., the position of attention under

arms.

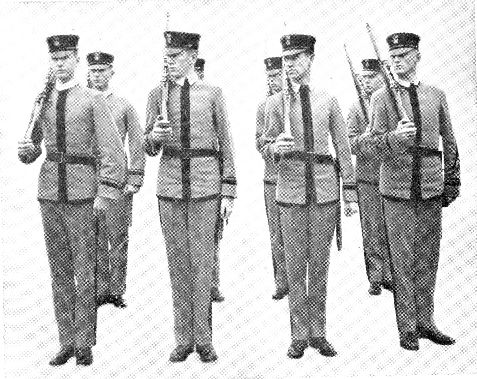

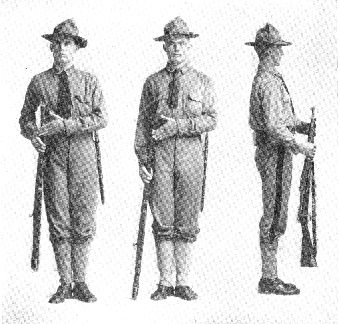

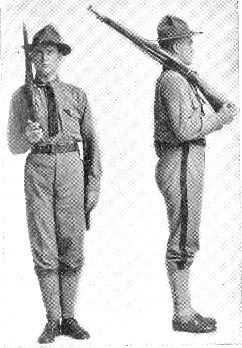

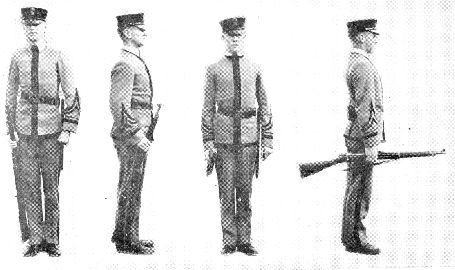

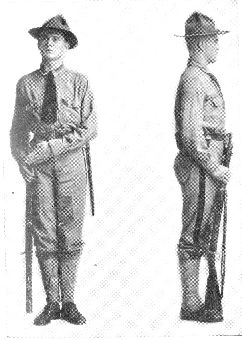

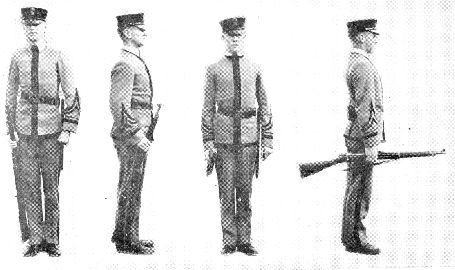

No. 1 No. 2 CORRECT POSITION

No. 1. Arm and hands hang naturally. Right hand holding piece between

thumb and fingers. Butt rests evenly on ground. Barrel to the rear.

No. 2. Toe of the butt on a line with toe of and touching the right

shoe.

To execute the movements in detail, the instructor first cautions: "By

the Numbers"; all movements divided into motions, are then executed

singly. That is to say, make one motion and then wait until a further

command for another. This is for the purpose of correcting erroneous

positions and giving detailed instructions. We are explaining the manual

by the numbers.

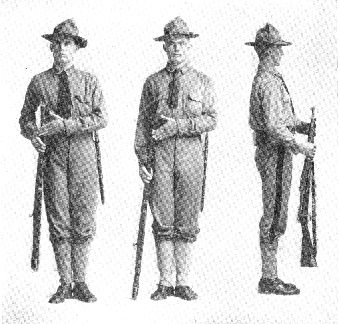

FIRST POSITION OF PRESENT ARMS FROM ORDER ARMS

Being at order arms: 1. Present, 2. ARMS. It takes two counts.

At command arms, with the right hand carry the piece in front of the

center of the body. Barrel to the rear and vertical. Grasp it with left

hand at the balance. Left forearm is horizontal and rests against body.

The balance of the piece is approximately the position of the rear

sight.

CORRECT POSITION OF PRESENT ARMS

At command two, grasp the small of the stock with the right hand.

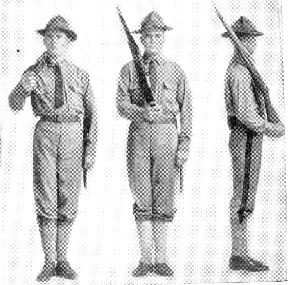

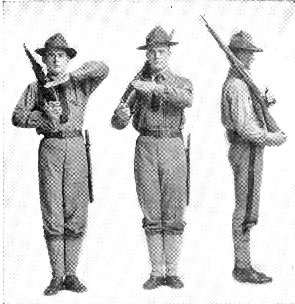

No. 1 No. 2 No. 3

INCORRECT POSITION OF PRESENT ARMS

These are the common errors made by beginners." />

No. 1 No. 2 No. 3

INCORRECT POSITION OF PRESENT ARMS

These are the common errors made by beginners.

No. 1. Thumb along barrel.

No. 2. Piece held too low. The front sight will be a little above the

eyes when the left fore arm is horizontal.

No. 3. Piece not vertical; too close to body.

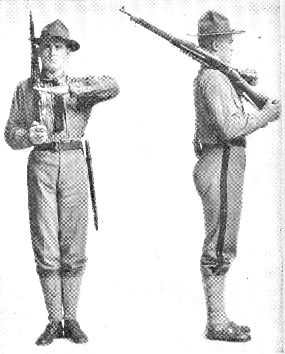

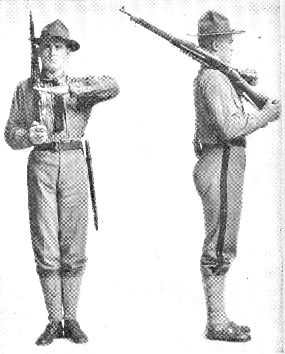

Being at order arms: 1. Port, 2. ARMS. It takes one count.

CORRECT POSITION OF PORT ARMS

At the command ARMS, with the right hand raise and throw the piece

diagonally across the body, grasp it smartly with both hands; the right;

palm down, at the small of stock; the left, palm up, at the balance;

barrel up, sloping to the left and crossing opposite the junction of the

neck with the left shoulder; right forearm horizontal; left forearm

resting against the body. The rifle is held in a vertical plane parallel

to the front.

In executing this movement, it is a common error with beginners to raise

the piece as though it weighed much more than it does. No part of the

body should move except the arms, in coming to "port arms" from "order

arms."

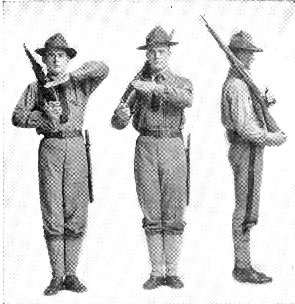

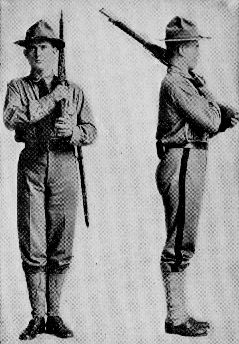

No. 1 No. 2 No. 3 INCORRECT POSITIONS OF PORT ARMS

No. 1. Arms held away from side.

No. 2. Piece held too low and too close to body.

No. 3. Piece held too high and not in a vertical plane parallel to the

body.

Being at present arms: 1. Port, 2. ARMS. It is executed in one count. At

the command arms, carry the piece diagonally across the body and take

the position of "port arms."

Being at port arms: 1. Present, 2. ARMS. It is executed in one count. At

the command arms, carry the piece to a vertical position in front of the

center of the body and take the position of present arms.

Being at present or port arms: 1. Order, 2. ARMS. It is executed in two

counts.

NEXT TO THE LAST POSITION OF ORDER ARMS

At the command arms, let go with the right hand; lower and carry the

piece to the right with the left hand; regrasp it with the right hand

just above the lower band; let go with the left hand and take the

position shown here, which is the next to the last position in coming to

the order. The left hand should be above and near the right, steadying

the gun, fingers extended and joined, forearm and wrist straight and

inclined downward. Barrel to the rear. All the fingers of the right hand

grasp the gun. Butt about 3 inches from the ground.

Being in the above position, at the command Two, lower the piece gently

to the ground with the right hand, drop the left hand quickly by the

side, and take the position of order arms.

The common errors are to slam the gun down on the ground and to drop the

left hand by the side in a slow and indifferent manner.

No. 1 No. 2 No. 3 INCORRECT POSITIONS

Common errors in the next to the last positions of order arms.

No. 1. Thumb is up. Gun too far from the ground.

No. 2. Gun too near to ground. Thumb is up. Butt of gun too far to the

right.

No. 3. Gun held too high and too far away from body.

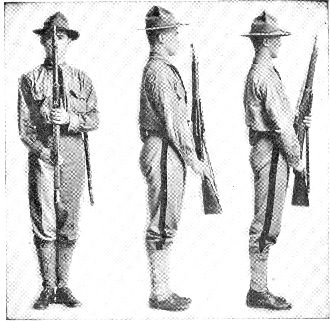

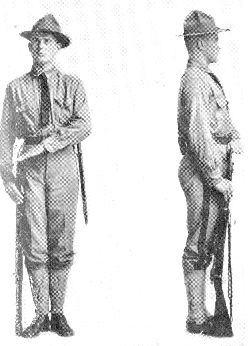

Being at order arms: 1. Right shoulder, 2. ARMS. It is executed in three

counts.

At the command arms, with the right hand raise and throw the piece

diagonally across the body; carry the right hand quickly to the butt,

and at the same time grasp the heel between the first two fingers as

shown. Note the position of the first two fingers of right hand.

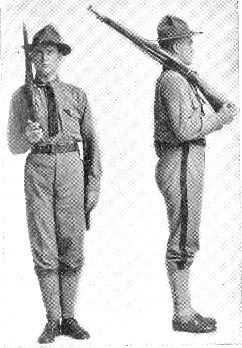

THE FIRST POSITION OF RIGHT SHOULDER ARMS FROM THE ORDER

At the command two, without changing the grasp of the right hand, place

the piece on the right shoulder, right elbow near the side, the piece in

a vertical plane perpendicular to the front; carry the left hand, thumb

and fingers extended and joined, to the small of the stock, wrist

straight and elbow down. Barrel up, and inclined at an angle of about

45° from the horizontal. Trigger guard in the hollow of the shoulder,

tip of forefinger touching the cocking piece. Right fore arm horizontal.

NEXT TO THE LAST POSITION OF RIGHT SHOULDER ARMS

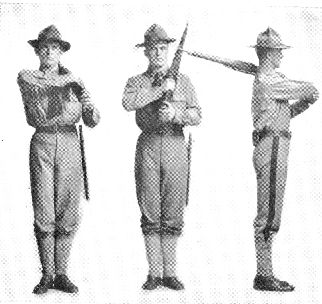

No. 1 No. 2 No. 3 COMMON ERRORS IN THE NEXT TO THE LAST

POSITION OF RIGHT SHOULDER ARMS

No. 1. Right arms not by side. Left arm too high. Remember that the left

arm rests on the chest. This is very commonly confused with the rifle

salute.

No. 2. Thumb is up. Butt of rifle carried to the right.

No. 3. Trigger guard not against shoulder. Butt held too low. Hand not

straight.

CORRECT POSITION OF RIGHT SHOULDER ARMS

At the command three, drop the left hand by the side.

No. 1 No. 2 No. 3

INCORRECT POSITION OF RIGHT SHOULDER ARMS

No. 1. Right arm not by side. Right forearm not horizontal.

No. 2. Heel of gun too far to left.

No. 3. Trigger guard not against shoulder. Butt held too low.

Being at right shoulder Arms: 1. Order, 2. ARMS. It is executed in 3

counts.

Press the butt down quickly and throw the gun diagonally across the

body, to the position shown here.

At the command two, lower the gun and assume the next to the last

position of order arms. At the command three, come to the order arms.

The common errors in this movement are to move the head to the left and

to throw the gun too far to the front.

Being at port arms: 1. Right shoulder, 2. ARMS. It is executed in three

counts.

At the command arms, change the right hand to the butt.

At the command two and three, come to the right shoulder as from order

arms.

Being at right shoulder arms: 1. Port, 2. ARMS. It is executed in two

counts.

At the command arms, press the butt down quickly and throw the piece to

the diagonal position across the body with the left hand grasping it at

the balance; the right hand retaining its grasp of the butt.

At the command two, change the right hand to the small of the stock.

Being at right shoulder arms: 1. Present, 2. ARMS. It is executed in

three counts.

At the command arms, execute port arms. (This requires two counts.) At

the command three, execute present arms.

Being at present arms: 1. Right shoulder, 2. ARMS. It is executed in

four counts.

At the command arms, execute port arms. At the command two, three, four,

execute right shoulder arms as from port arms.

Being at port arms: 1. Left shoulder, 2. ARMS. It is executed in two

counts.

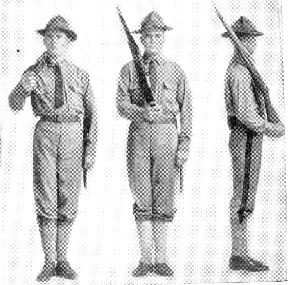

THE NEXT TO THE LAST POSITION OF THE LEFT SHOULDER ARMS

At the command ARMS, carry the piece with the right hand and place it on

the left shoulder; at the same time grasp the butt with the left hand,

heel between first and second fingers. Thumb and fingers of right hand

closed on the stock. Barrel up, trigger guard in the hollow of the

shoulder.

No. 1 No. 2 No.3

COMMON ERRORS IN THE NEXT TO THE LAST POSITION OF LEFT SHOULDER ARMS

No. 1. Right arm too high. Butt too high.

No. 2. Butt too close to center of body. Not grasping gun correctly with

fingers of left hand.

No. 3. Right arm too high. Butt too high.

At the command two, drop the right hand by the side.

THE CORRECT POSITION OF LEFT SHOULDER ARMS

The incorrect positions are usually the same as are found in the right

shoulder arms, and as illustrated here.

Being at left shoulder arms: 1. Port, 2. ARMS. It is executed in two

counts.

At the command arms, grasp the piece with the right hand at the small of

the stock.

At the command two, carry the piece, with the right hand to the position

of port arms, regrasp it with the left.

Left shoulder arms may be ordered from the order, right shoulder or

present, or the reverse. At the command arms, execute port arms and

continue to the position ordered.

Being at order arms: 1. Parade, 2. REST. It is executed in one count.

At the command rest, carry muzzle in front of the center of the body,

barrel to the left. Grasp piece with the left hand just below the

stacking swivel, and with the right hand below and against the left.

Left knee slightly bent. Carry the right foot 6 inches straight to the

rear.

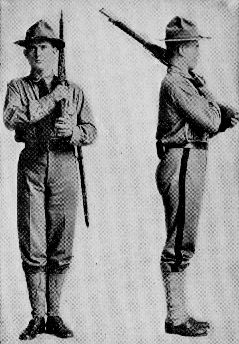

CORRECT POSITION OF PARADE REST

Being at parade rest: 1. Squad, 2. ATTENTION. Executed in one count.

At the command attention (it is a custom of the service to execute the

movement at the last syllable of the command), resume the order, the

left hand quitting the piece opposite the right hip.

Being at order arms: 1. Trail, 2. ARMS.

At the command arms, raise the piece, right arm slightly bent, and

incline the muzzle forward so that the barrel makes an angle of about

30° with the vertical.

When it can be done without danger or inconvenience to others, the piece

may be grasped at the balance and the muzzle lowered until the piece is

horizontal; a similar position in the left hand may be used.

CORRECT POSITION OF TRAIL ARMS

Being at trail arms: 1. Order, 2. ARMS.

At the command arms, lower the gun with the right hand and resume the

order.

Being at right shoulder arms: 1. Rifle, 2. SALUTE. It is executed in two

counts.

At the command salute, carry the left hand smartly to the small of the

stock, forearm horizontal, palm of hand down, thumb and fingers joined,

forefinger touching end of cocking piece. Look toward the person

saluted. At the command two, drop the hand by the side; turn the head

and eyes to the front.

THE CORRECT POSITION OF RIFLE SALUTE, BEING AT RIGHT

SHOULDER ARMS.

COMMON ERRORS IN RIFLE SALUTE AT RIGHT SHOULDER ARMS.

No. 1. Left elbow too low. Forearm should be horizontal.

No. 2. Left elbow too high. Fingers not extended and joined.

Being at order or trail arms: 1. Rifle, 2. SALUTE.

At the command salute, carry the left hand smartly to the right side,

palm of the hand down, thumb and fingers extended and joined, forefinger

against piece near the muzzle; look toward the person saluted. At the

command two, drop the left hand by the side; turn the head and eyes to

the front.

RIFLE SALUTE BEING AT ORDER ARMS

COMMON ERRORS IN RIFLE SALUTE AT ORDER OR TRAIL ARMS

No. 1. Fingers not extended and joined.

No. 2. Fingers not joined. Gun held too high.

Being at order arms: 1. Fix, 2. BAYONET.

If the bayonet scabbard is carried on the belt: execute parade rest;

grasp the bayonet with the right hand, back of hand toward the body;

draw the bayonet from the scabbard and fix it on the barrel, glancing at

the muzzle; resume the order.

If the bayonet is carried on the haversack: draw the bayonet with the

left hand and fix it in the most convenient manner.

Being at order arms: 1. Unfix, 2. BAYONET.

If the bayonet scabbard is carried on the belt: Execute parade rest;

grasp the handle of the bayonet firmly with the right hand, pressing the

spring with the forefinger of the right hand; raise the bayonet until

the handle is about 12 inches above the muzzle of the piece; drop the

point to the left, back of the hand toward the body, and, glancing at

the scabbard, return the bayonet, the blade passing between the left arm

and the body; regrasp the piece with the right hand and resume the

order.

If the bayonet scabbard is carried on the haversack: Take the bayonet

from the rifle with the left hand and return it to the scabbard in the

most convenient manner.

If marching or laying down, the bayonet is fixed and unfixed in the most

expeditious and convenient manner and the piece returned to the original

position.

Fix and unfix bayonet are executed with promptness and regularity but

not in cadence.

Exercises for instruction in bayonet combat are prescribed in the Manual

for Bayonet Exercise.

Being at order arms: 1. Inspection, 2. ARMS.

At the command arms, take the position of port arms; at the command two,

seize the bolt handle with the thumb and forefinger of the right hand,

turn the handle up, draw the bolt back, and glance at the chamber.

Having found the chamber empty, or having emptied it, raise the head and

eyes to the front. Keep your right hand on the bolt.

INSPECTION ARMS

It is a very common error to change the position of the piece while

drawing the bolt back. Guard against this.

Being at inspection arms: 1. Order (or right shoulder, or port), 2.

ARMS.

At the preparatory command (i.e., at the command order), push the bolt

forward, turn the handle down, pull the trigger, and resume port arms.

At the command arms, complete the movement ordered.

TO DISMISS THE SQUAD

Being at a halt: 1. Inspection, 2. ARMS, 3. Port, 4. ARMS, 5.

DISMISSED.

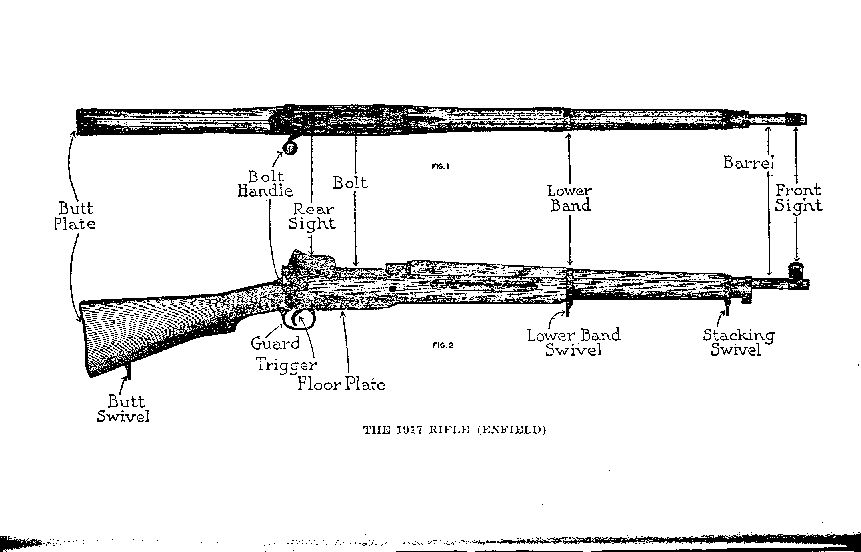

Make a point of becoming sufficiently familiar with the different parts

of the rifle to obey the following general rules governing the manual.

The following rules govern the carrying of the piece:

First. the piece is not carried with cartridges in either the chamber or

the magazine except when specifically ordered. When so loaded, or

supposed to be loaded, it is habitually carried locked; that is, with

the safety lock turned to the "safe." At all other times it is carried

unlocked with the trigger pulled.

Second. Whenever troops are formed under arms, pieces are immediately

inspected at the commands: 1. Inspection, 2. ARMS, 3. Order (right

shoulder, port), 4. ARMS.

A similar inspection is made immediately before dismissal.

If cartridges are found in the chamber or magazine they are removed and

placed in the belt.

Third. The cut-off is kept turned "off" except when cartridges are

actually used.

Fourth. The bayonet is not fixed except in bayonet exercise, on guard,

or for combat.

Fifth. Fall in is executed with the piece at the order arms. Fall

out, rest, and at ease are executed as without arms. On resuming

attention the position of order arms is taken.

Sixth. If at the order, unless otherwise prescribed, the piece is

brought to the right shoulder at the command march, the three motions

corresponding with the first three steps. Movements may be executed at

the trail by prefacing the preparatory command with the words at

trail; as, 1. At trail, forward, 2. MARCH; the trail is taken at the

command march.

When the facings, alignments, open and close ranks, taking interval or

distance, and assemblings are executed from the order, raise the piece

to the trail while in motion and resume the order on halting.

Seventh. The piece is brought to the order on halting. The execution of

the order begins when the halt is completed.

Eighth. A disengaged hand in double time is held as when without arms.

The following rules govern the execution of the manual of arms:

First. In all positions of the left hand at the balance (center of

gravity, bayonet unfixed) the thumb clasps the piece; the sling is

included in the grasp of the hand.

Second. In all positions of the piece, "diagonally across the body" the

position of the piece, left arm and hand are the same as in port arms.

Third. In resuming the order from any position in the manual, the motion

next to the last concludes with the butt of the piece about 3 inches

from the ground, barrel to the rear, the left hand above and near the

right, steadying the piece, fingers extended and joined, forearm and

wrist straight and inclining downward, all fingers of the right hand

grasping the piece. To complete the order, lower the piece gently to the

ground with the right hand, drop the left quickly by the side, and take

the position of order arms.

Allowing the piece to drop through the right hand to the ground, or

other similar abuse of the rifle to produce effect in executing the

manual, is prohibited.

Fourth. The cadence of the motions is that of quick time; the recruits

are first required to give their whole attention to the details of the

motions, the cadence being gradually acquired as they become accustomed

to handling their pieces. The instructor may require them to count aloud

in cadence with the motions.

Fifth. The manual is taught at a halt and the movements are, for the

purpose of instruction, divided into motions and executed in detail; in

this case the command of execution determines the prompt execution of

the first motion, and the commands, two, three, four, that of the

other motions.

To execute the movements in detail, the instructor first cautions: By

the numbers; all movements divided into motions are then executed as

above explained until he cautions: Without the numbers; or commands

movements other than those in the manual of arms.

Sixth. Whenever circumstances require, the regular positions of the

manual of arms and the firings may be ordered without regard to the

previous position of the piece.

Under exceptional conditions of weather or fatigue the rifle may be

carried in any manner directed.

CHAPTER IV

SCHOOL OF THE SQUAD

Based on the Infantry Drill Regulations

CLOSE ORDER DRILLS

For several days after reporting you will undergo many hours of close

order drill. You will ask yourself, "Why is all this mental and physical

strain necessary when these exercises are not used in battle?" The

answer is: they are disciplinary exercises and are designed to inculcate

that prompt and subconscious obedience which is essential to proper

military control and to teach you precise and soldierly movements;

hence, they are executed at attention.

DEFINITIONS

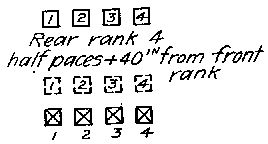

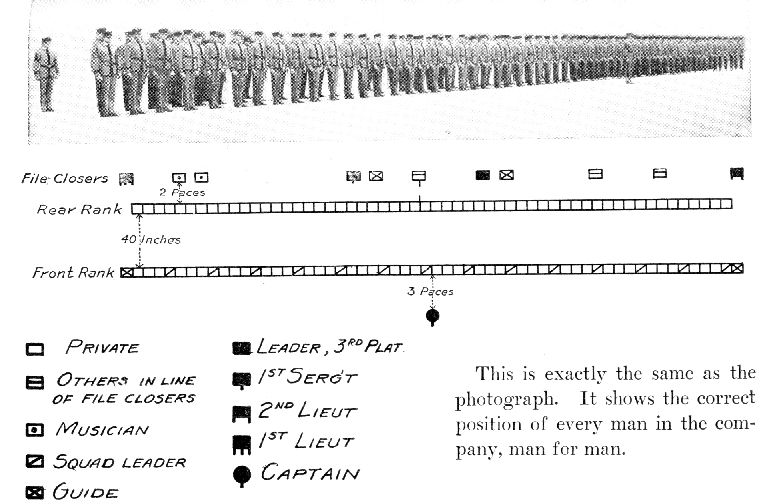

Deploy. To extend the front. A squad deploys when it goes "As

skirmishers." A company likewise deploys when it goes from column into

line.

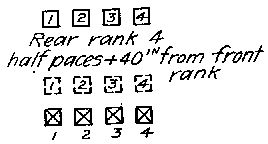

File. Two men, the front rank man and the corresponding man in the

rear rank. The front rank man is the file leader. A file which has no

rear rank man is a blank file.

Interval. Space between elements of the same line. The interval

between men in ranks is 4 inches and is measured from elbow to elbow. It

is to get this interval that each man is required to raise his arm when

the company is formed.

Distance. Space between elements in the direction of depth. It is

measured from the back of the man in front to the breast of the man in

rear. The rear rank when in line or column is 40 inches from the front

rank.

The guide of a squad in line is right unless otherwise announced.

The guide of a squad deployed, (i.e., skirmishers) is center unless

otherwise announced.

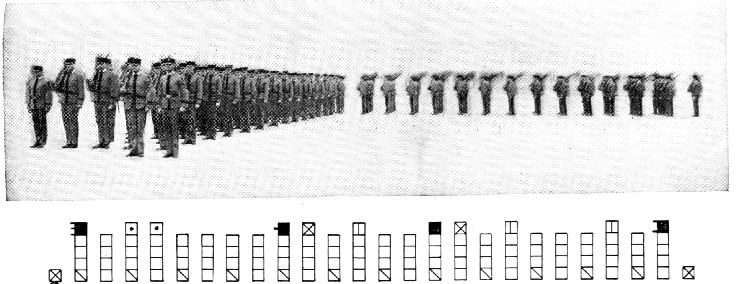

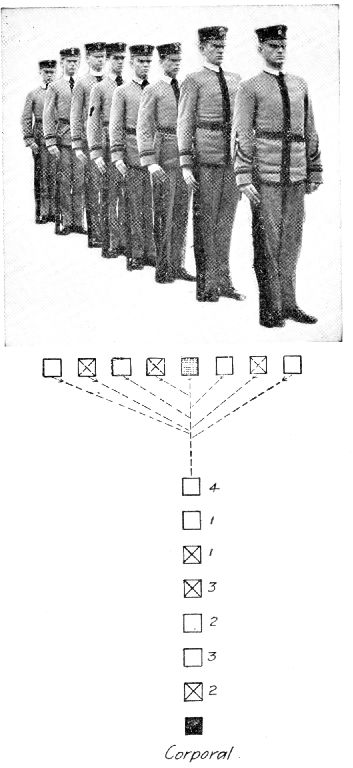

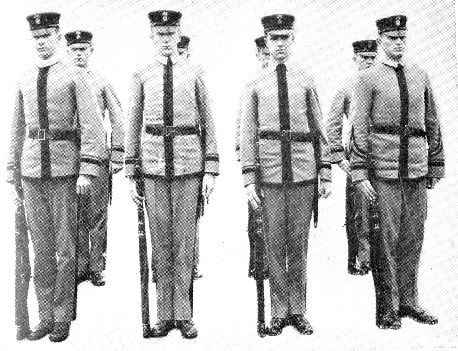

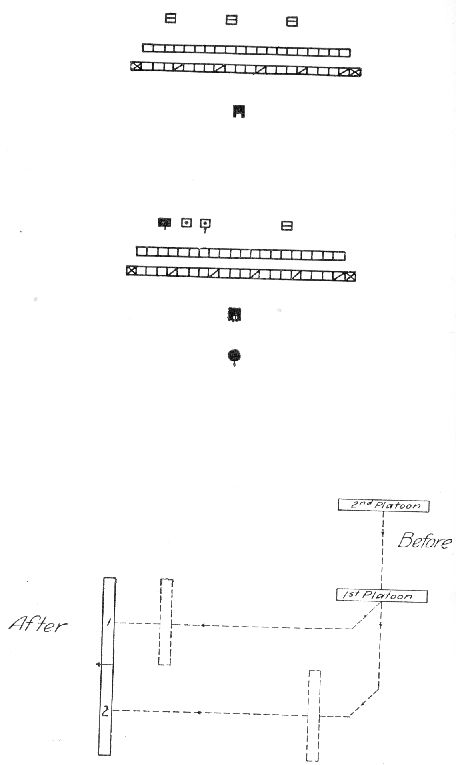

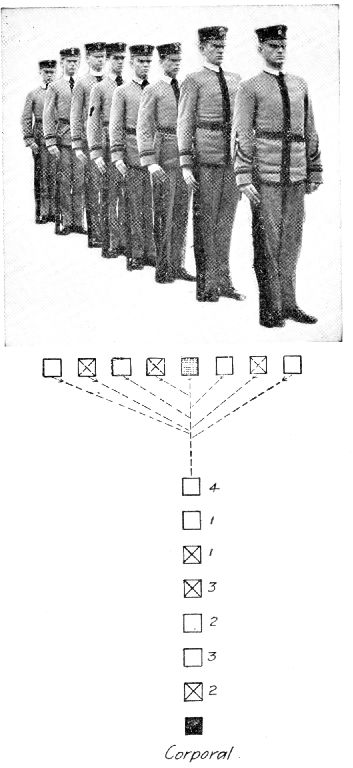

TO FORM THE SQUAD

To form the squad the instructor places himself 3 paces in front of

where the center is to be and commands: Fall in.

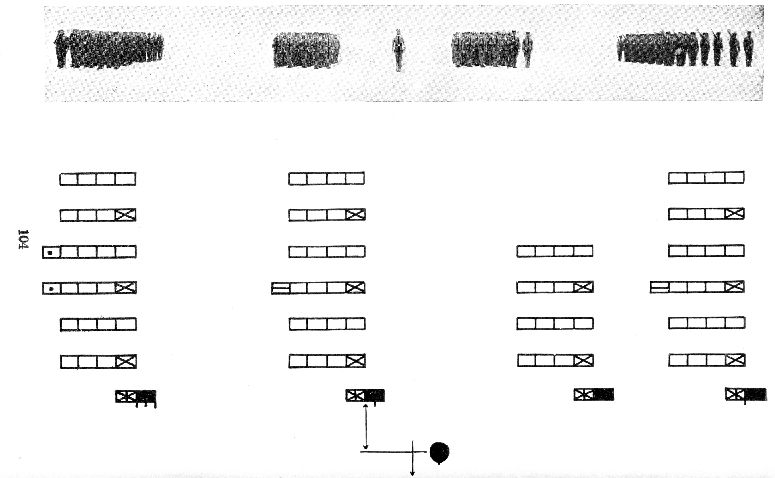

The men assemble at attention, pieces at the order, and are arranged by

the corporal in double rank, as nearly as practicable in order of height

from right to left, each man dropping his left hand as soon as the man

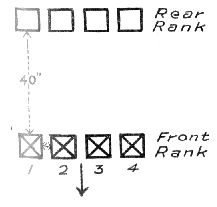

on his left has his interval. The rear rank forms with distance of 40

inches.

The instructor then commands: Count off.

At this command all except the right file execute eyes right, and

beginning on the right, the men in each rank count one, two, three,

four--one, two, three, four; each man turns his head and eyes to the

front as he counts.

Pieces are then inspected.

The purpose of putting the left hand on the hip is to get enough elbow

room. A man should have sufficient space to operate his piece. These

four-inch intervals give it to him.

Note the space between elbows (interval) is 4 inches. The space between

the front and rear rank (distance) is 40 inches, and is measured from

the back of the man in front to the breast of the man in the rear.

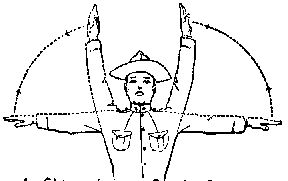

ALIGNMENTS

To align the squad, the base file or files having been established: 1.

Right (left), 2. DRESS, 3. FRONT.

At the command dress, all men place the left hand upon the hip (whether

dressing to the right or left); each man, except the base file, when on

or near the new lines executes eyes right, and, taking steps of 2 or 3

inches, places himself so that his right arm rests lightly against the

elbow of the man on his right (vice versa in left dressing), and so that

his eyes and shoulders are in line with those of the men on his right,

and also that each man can see the eyes of at least two men on his

right.

The instructor verifies the alignment of both ranks from the right flank

and orders up or back such men as may be in the rear, or in advance, of

the line; only the men designated move.

At the command front, given when the ranks are aligned, each man turns

his head and eyes to the front and drops his left hand by his side.

There are in dressing a number of common errors that we should try to

avoid. Don't jab the man on your left with your elbow. If you are not on

the line, move your feet. Don't lean forward or backward. Be sure to

touch gently the man on your right with your right arm. Be certain to

keep your left elbow forced well to the front. This is a little

uncomfortable at first, but unless we do this our arms will not measure

the 4 inches correctly. Don't hump up the left shoulder, and don't turn

the shoulders to the right. Keep fingers of left hand extended and

joined.

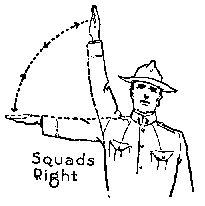

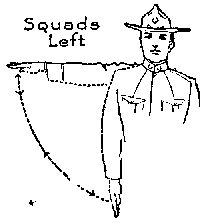

We want to place especial stress on the importance of three movements

in the school of the squad. When you have thoroughly mastered these

three, you will have a splendid basis for the remainder of the School of

the Squad, the full value of which you will later appreciate. These are:

Squad right, Squad right about, and Right turn.

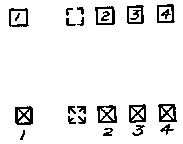

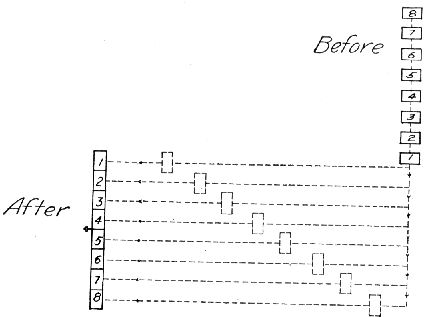

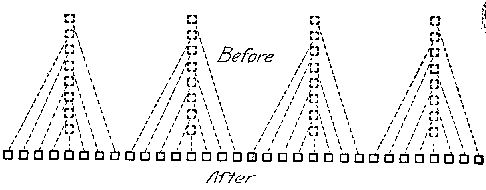

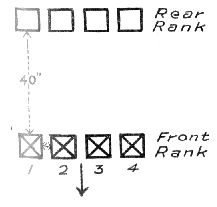

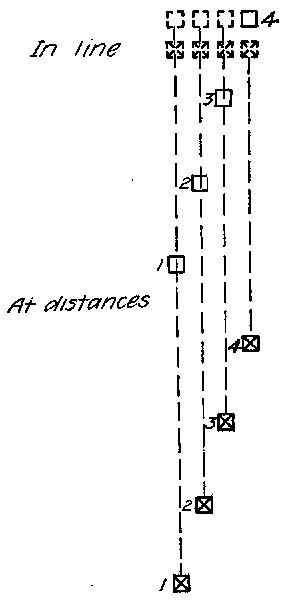

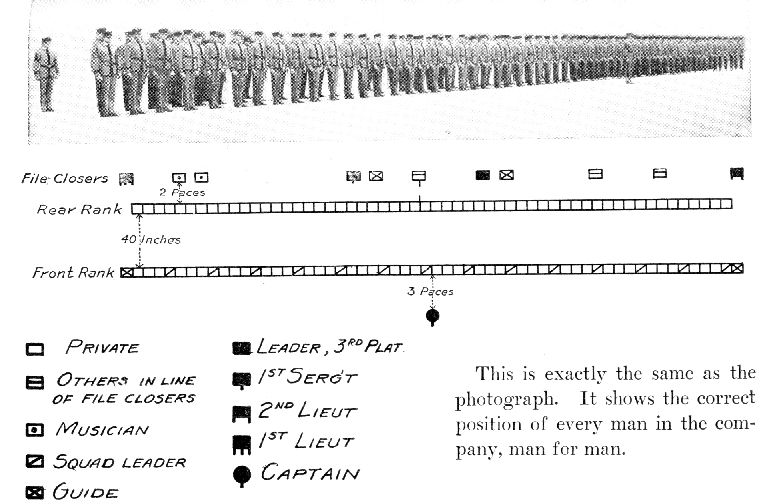

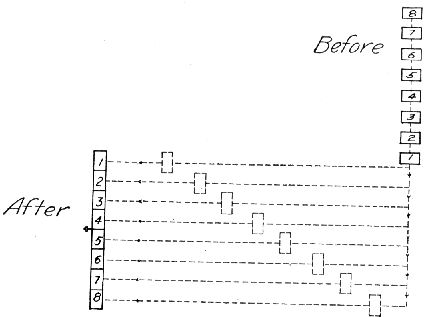

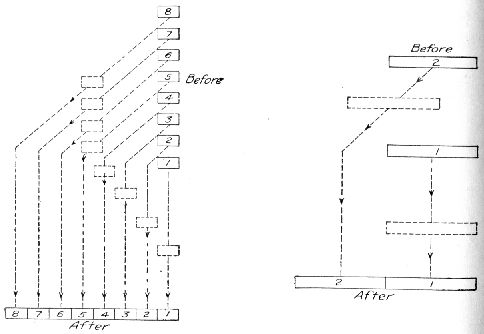

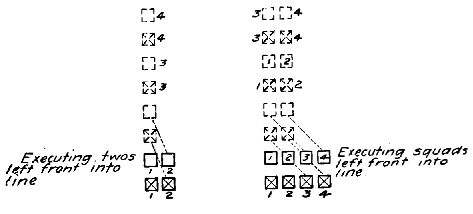

The first line drawing in this chapter shows correct proportions of

interval and distance. To save space and for convenience, the drawings

hereafter are made without regard to proportions (intervals and

distances).

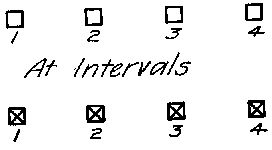

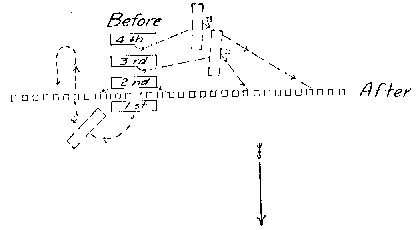

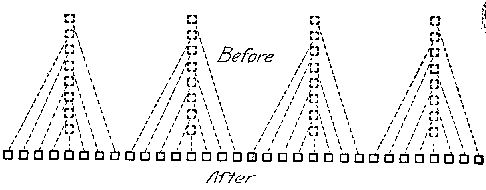

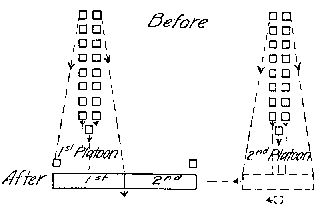

First Movement

SQUAD RIGHT

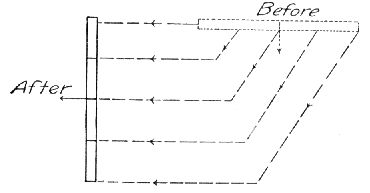

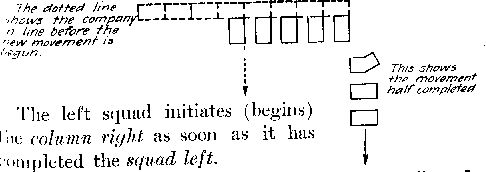

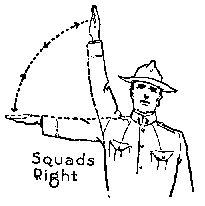

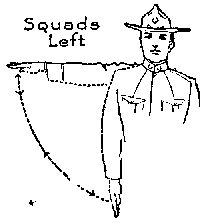

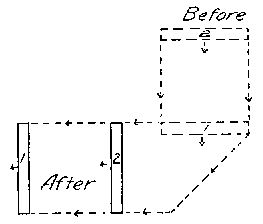

Being in line, to turn and march: 1. Squad right (left), 2. MARCH.

In this movement many instructors have recruit squads step off on the

7th count. When the drill progresses the squad should step off on the

5th count.

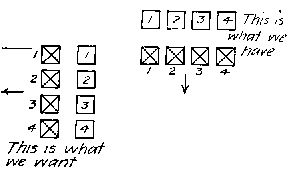

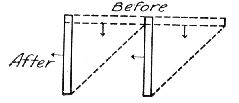

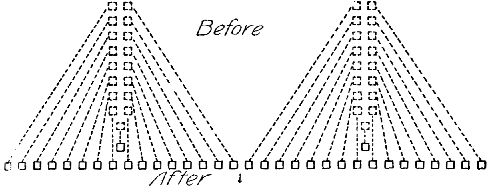

This is what we have

This is what we want" />

This is what we have

This is what we want

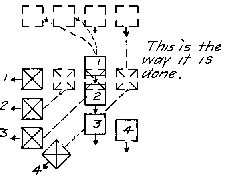

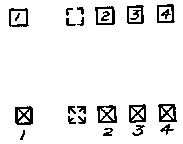

At the command march, No. 1 in the front rank faces to the right in

marching and marks time; Nos. 2, 3, and 4 of the front rank turn 45

degrees to the right (right oblique), place themselves abreast (on the

same line) of No. 1 and mark time.

Now it is difficult quickly to understand the movements of the rear

rank. Give them a lot of study and don't go on until you are certain

that you understand.

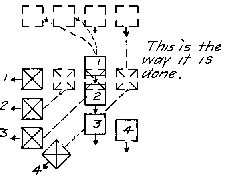

This is the way it is done.

No. 3 moves straight to the front.

No. 2 follows No. 3.

No. 1 follows No. 2.

When they (Nos. 3, 2 and 1) arrive in rear of their file leaders, (Nos.

3, 2 and 1, front rank) they face to the right in marching and mark

time.

No. 4 of the rear rank moves straight to the front four paces, and

places himself abreast of No. 3, rear rank.

When No. 4, front rank, and No. 4, rear rank, are on the line, (and the

remainder of the squad must glance toward them to see when that is

true), the whole squad moves forward without further command.

Note that we have said that No. 1 front rank marks time. We see that he

becomes, temporarily, an immovable pivot for his squad. We, therefore,

call him a fixed pivot.

Had the command been squad left, instead of squad right, No. 4 would

have been the fixed pivot instead of No. 1.

Being in line, to turn and halt: 1. Squad right (left), 2. MARCH, 3.

Squad, 4. HALT.

The turn is executed as prescribed in the preceding case except that all

men, on arriving on the new line, mark time until the command halt is

given, when all halt.

Whenever the third command (i.e., squad) is given means that the command

halt is to follow. This is caution to the squad to prepare to halt. The

command halt should be given as No. 4 arrives on the line.

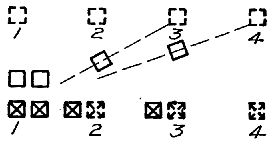

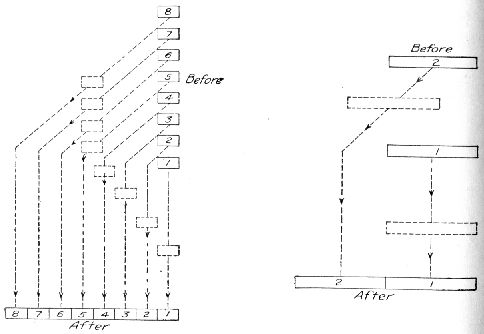

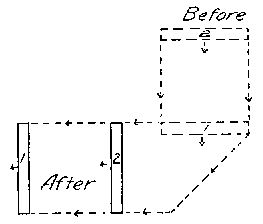

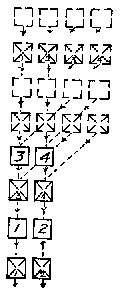

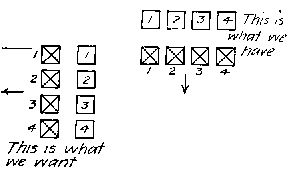

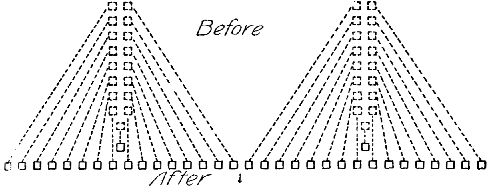

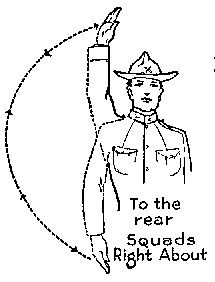

Second Movement

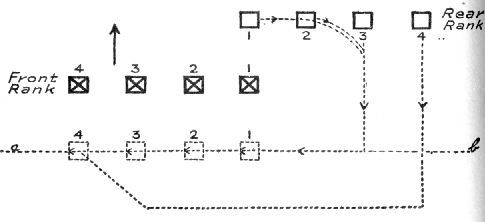

SQUAD RIGHT ABOUT

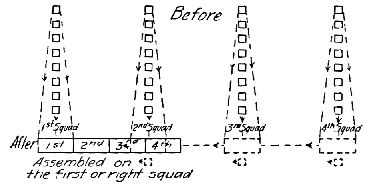

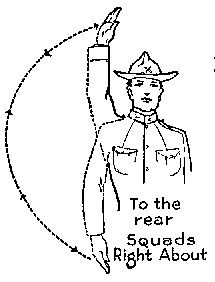

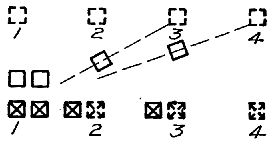

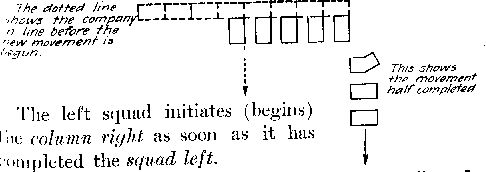

Being in line, to turn about and march: 1. Squad right (left) about, 2.

MARCH.

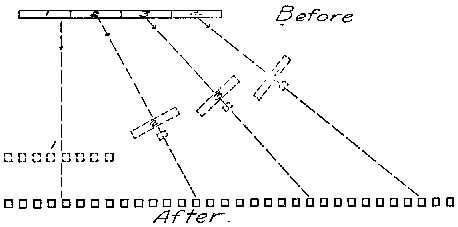

[Illustration pos32:

This is what we have

This is what we want]

At the command march, the front rank twice executes Squad right,

initiating (starting) the second Squad right when No. 4 has arrived on

the line. That much is very simple.

The rear rank has a harder task. Let us have the front and rear rank

execute the movement separately:

The rear rank is to take its place on the dotted line a b.

No. 3 rear rank moves straight to the front until in prolongation of

the line to be occupied by the rear rank.

No. 2 follows No. 3.

No. 1 follows No. 2.

When No. 3 arrives on the line to be occupied by the rear rank he

changes direction to the right; he moves in the new direction until in

rear of No. 3, front rank, when Nos. 3, 2, and 1, rear rank, are in rear

of Nos. 3, 2, and 1, front rank, (i.e., when they are in rear of their

front rank men), they face to the right in marching and mark time. No. 4

marches on the left of No. 3 to his new position. As he arrives on the

line, both ranks execute forward march without command, For the

remainder of the squad to know when No. 4 front and rear rank have

arrived on the line, they glance to see. The squad should step off on

the 9th count.

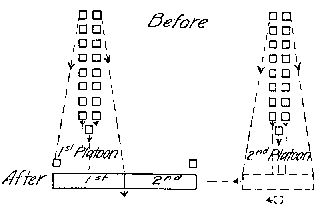

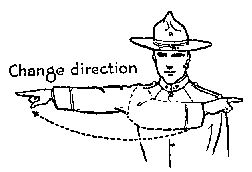

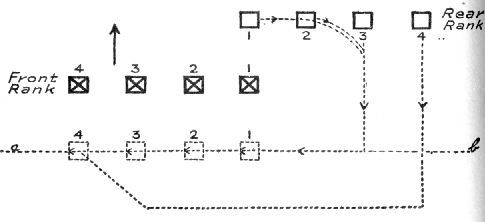

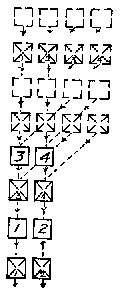

Third Movement

RIGHT TURN

Being in line: 1. Right (left) turn, 2. MARCH.

THIS IS THE WAY IT IS DONE

At the command march, No. 1 front rank faces to the right in marching

and takes the half step. Nos. 2, 3, and 4 front rank right oblique

(turn 45 degrees to the right) until opposite their places in line, then

execute a second right oblique and take the half step on arriving

abreast of the pivot man. When No. 4 arrives on the line Nos. 1, 2, 3,

and 4 take the full step without further command. (To know when No. 4

arrives on the line it is necessary to glance in his direction.) Full

step on the 7th count.

The rear rank executes the movement in the same way and turns on the

same ground as the front rank. The rear rank, therefore, moves forward

at the command march, or continues to move forward, if already marching,

until it arrives at the place where the front turned, when it turns.

Note that the squad turns on No. 1 front rank but that he does not

remain in his position even temporarily, as in squad right; he is,

therefore, called the moving pivot. No. 4 is called the marching flank.

Had the command been left turn, No. 4 would have been the moving pivot,

and No. 1 the marching flank.

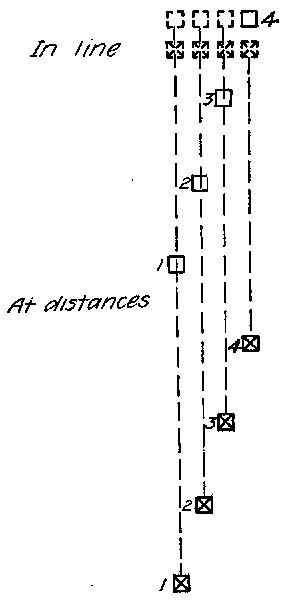

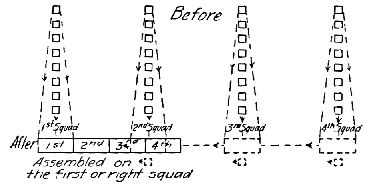

Knowing the three above movements, we are prepared for the following:

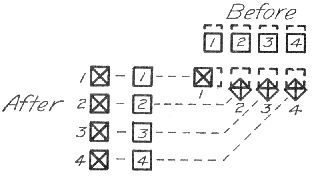

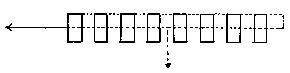

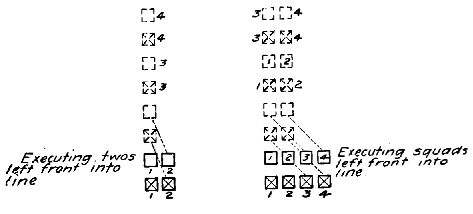

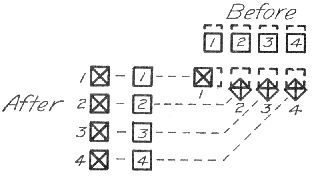

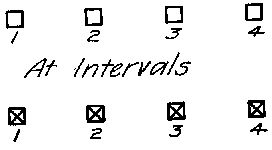

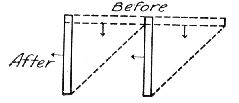

Being in line at a halt: 1. Take interval, 2. To the right (left), 3.

MARCH, 4. Squad, 5. HALT.

BEING IN THIS FORMATION

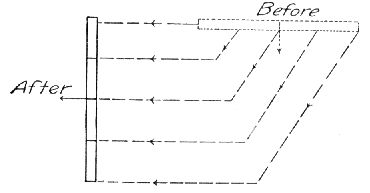

At the command to the right (left), the rear rank men march backward

four steps (15 inches each step) and halt.

LIKE THIS

Note that the actual distance from the front rank to the rear rank is

now 40 plus 4x15 inches, i.e., 100 inches." />

LIKE THIS

Note that the actual distance from the front rank to the rear rank is

now 40 plus 4x15 inches, i.e., 100 inches.

At the command march, all face to the right and No. 1 front and rear

rank step off. No. 2, front and rear rank, follow No. 1, front and rear

rank, at a distance of four paces. Likewise with the other numbers.

Like this, when No. 1 front and rear rank have gained

four paces distance.

At the command halt, given when No. 3 is three paces distant from No. 4,

all halt and face to the front.

The squad looks like this when the movement is

completed.

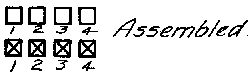

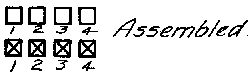

Being at intervals: 1. Assemble, to the right, (left), 2. MARCH.

At the command march, No. 1 front rank stands fast. No. 1 rear rank

closes to 40 inches. The other men face to the right, close by the

shortest line, and face to the front.

Being in line at a halt: 1. Take distance, 2. MARCH, 3. Squad, 4. HALT.

At the command march, No. 1 of the front rank moves straight to the

front; Nos. 2, 3, and 4 of the front rank and Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the

rear rank, in the order named, move straight to the front, each stepping

off so as to follow the preceding man at four paces. The command halt is

given when all have their distances.

In case more than one squad is in line, each squad executes the movement

as above. The guide of each rank of numbers is right.

The front rank men should walk straight to the front and their rear rank

men should cover them accurately.

Being at distances, to assemble the squad: 1. Assemble, 2. MARCH.

No. 1 of the front rank stands fast; the other numbers move forward to

their proper places in line.

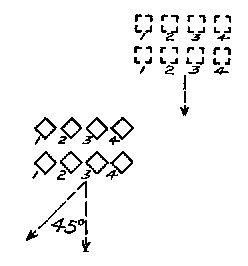

THE OBLIQUE MARCH

For the instruction of recruits, the squad being in column or correctly

aligned, the instructor causes the squad to face half right (or half

left), points out to the men their relative positions, and explains that

these are to be maintained in the oblique march.

1. Right (left) oblique, 2. MARCH.

Each man steps off in a direction 45 degrees to the right of his

original front. He preserves his relative position, keeping his

shoulders parallel to those of the guide (the man on the right front of

the line or column), and so regulates his steps that the ranks remain

parallel to their original front.

At the command halt, the men halt faced to the front.

To resume the original direction: 1. Forward, 2. MARCH.

The men half face to the left in marching and then move straight to the

front.

If at half step or mark time while obliquing, the oblique march is

resumed by the commands: 1. Oblique, 2. MARCH.

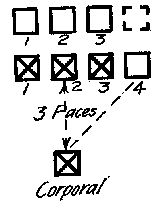

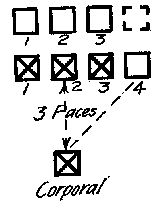

TO FOLLOW THE CORPORAL

Being assembled or deployed, to march the squad without unnecessary

commands, the corporal places himself in front of it and commands:

FOLLOW ME.

If in line or skirmish line, No. 2 of the front rank follows in the

track of the corporal at about 3 paces; the other men conform to the

movements of No. 2, guiding on him and maintaining their relative

positions.

If in column, the head of the column follows the corporal.

Note that No. 4 rear rank takes the place of the corporal when the

corporal is in front of the squad. This a general rule. When any front

rank man is absent his rear rank man steps up in the front rank. When

the squad is following the corporal No. 4 rear rank remains blank (i.e.,

No. 3 does not step to the left and cover No. 4).

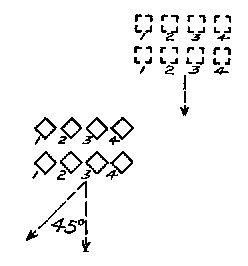

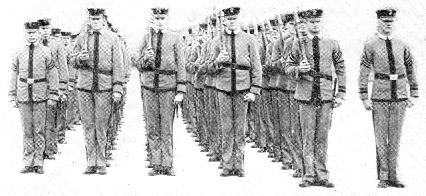

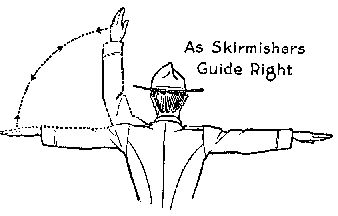

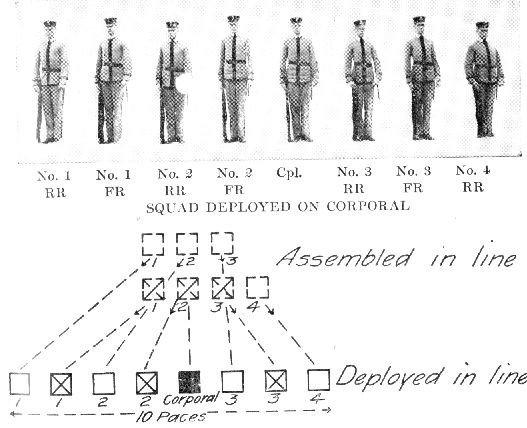

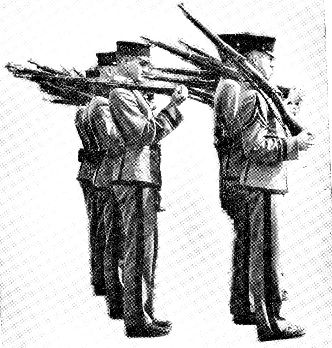

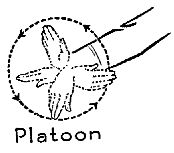

TO DEPLOY AS SKIRMISHERS

Being in any formation, assembled: 1. As skirmishers, 2. MARCH.

The corporal places himself in front of the squad, if not already there.

Moving at a run, the men place themselves abreast of the corporal at

half-pace intervals. Nos. 1 and 2 on his right, Nos. 3 and 4 on his

left, rear-rank men on the right of their file leaders, extra men on the

left of No. 4; all then conform to the corporal's gait.

There is a rule of thumb that must be remembered. The rear-rank man is

always on the right of his file leader.

A common error is for beginners to execute the movement at a slow trot

which a run is required.

When the squad is acting alone, skirmish line is similarly formed on No.

2 of the front rank, who stands fast or continues the march, as the case

may be; the corporal places himself in front of the squad when advancing

and in rear when halted.

When deployed as skirmishers, the men march at ease, pieces at the trail

unless otherwise ordered.

The corporal is the guide when in the line; otherwise No. 2 front rank

is the guide. The guide is center.

The normal interval between skirmishers is one-half pace, resulting

practically in one man per yard of front. The front of a squad thus

deployed as skirmishers is about 10 paces.

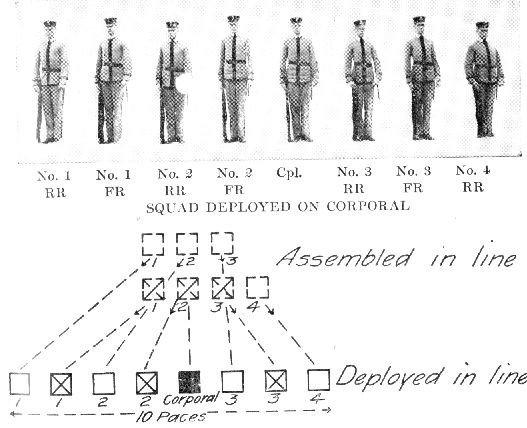

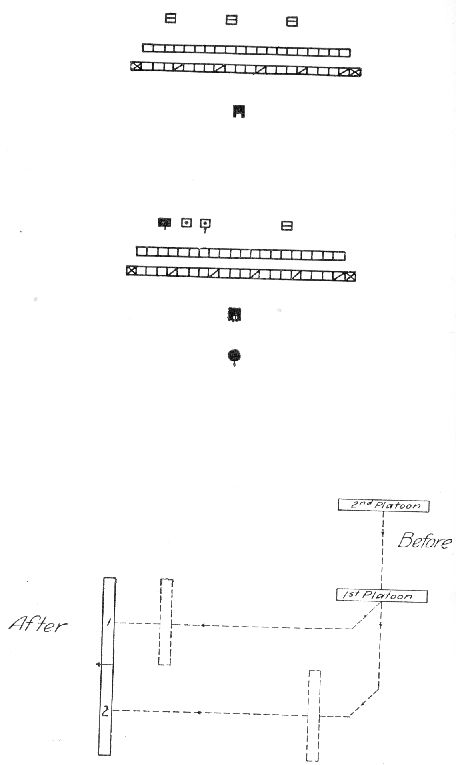

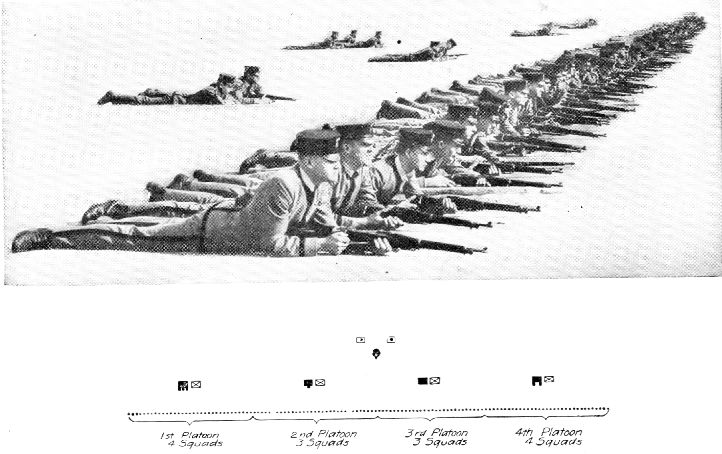

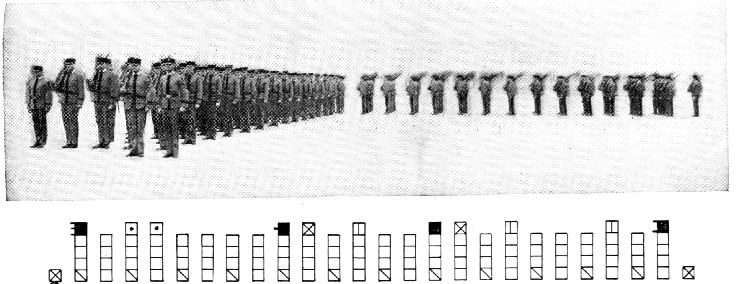

SQUAD DEPLOYED ON CORPORAL

THIS IS THE WAY IT IS DONE" />

SQUAD DEPLOYED ON CORPORAL

THIS IS THE WAY IT IS DONE

The common error is to keep an interval of a very few inches when 15

inches are required.

TO INCREASE OR DIMINISH INTERVALS

If assembled, and it is desired to deploy at greater than the normal

interval; or if deployed, and it is desired to increase or decrease the

interval: 1. As skirmishers, (so many) paces, 2. MARCH.

Intervals are taken at the indicated number of paces. If already

deployed, the men move by the flank or away from the guide.

The above command is used but very little.

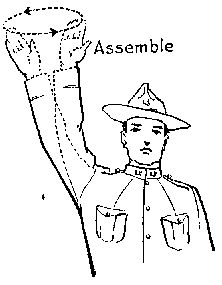

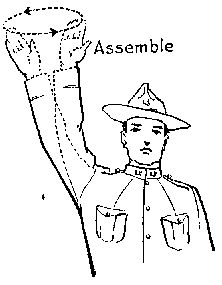

THE ASSEMBLY

Being deployed: 1. Assemble, 2. MARCH.

The men move toward the corporal and form in their proper places.

If the corporal continues to advance, the men move in double time, form,

and follow him.

The assembly while marching to the rear is not executed.

Note. It will be better for the beginner to let the remainder of

this chapter go for awhile. Your instructor will explain all of the

following points in a way that will be easier for you than for you

to try to work them out alone. They will come up in the first

month's work and will be explained and shown as you go along. As

you become more proficient we advise you, then, to take up the

remainder of the chapter.

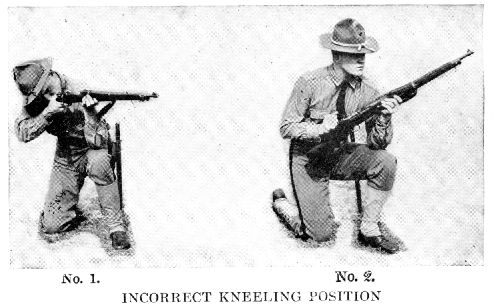

If standing: KNEEL.

Half face to the right; carry the right toe about 1 foot to the left

rear of the left heel; kneel on the right knee, sitting as nearly as

possible on the right heel; left forearm across left thigh; piece

remains in position of order arms, right hand grasping it above the

lower hand.

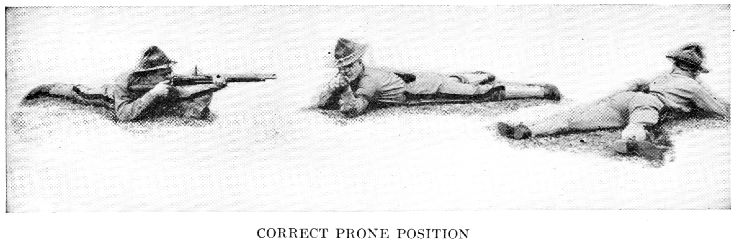

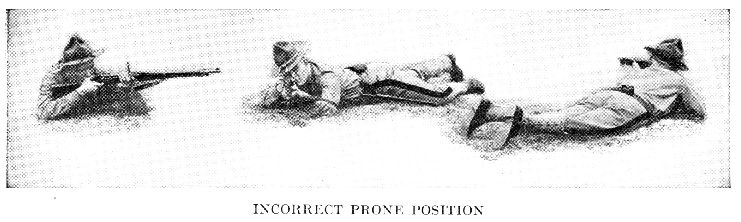

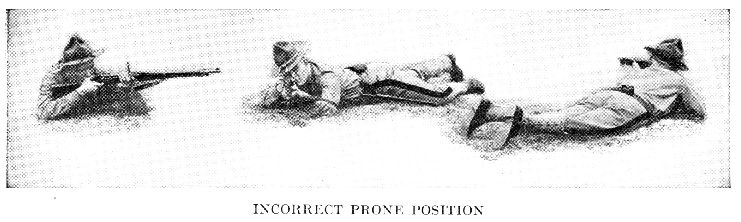

If standing or kneeling: LIE DOWN.

Kneel, but with right knee against left heel; carry back the left foot

and lie flat on the belly, inclining body about 35 degrees to the

right; piece horizontal, barrel up, muzzle off the ground and pointed to

the front; elbows on the ground; left hand at the balance, right hand

grasping the small of the stock opposite the neck. This is the position

of order arms, lying down.

If kneeling or lying down: RISE.

If kneeling, stand up, faced to the front, on the ground marked by the

left heel.

If lying down, raise body on both knees; stand up, faced to the front,

on the ground marked by the knees.

If lying down: KNEEL.

Raise the body on both knees; take the position of kneel.

In double rank, the positions of kneeling and lying down are ordinarily

used only for the better utilization of cover.

When deployed as skirmishers, a sitting position may be taken in lieu of

the kneeling position.

LOADINGS AND FIRINGS

The commands for loading and firing are the same whether standing,

kneeling, or lying down. The firings are always executed at a halt.

When kneeling or lying down in double rank, the rear rank does not load,

aim, or fire.

The instruction in firing will be preceded by a command for loading.

Loadings are executed in line and skirmish line only.

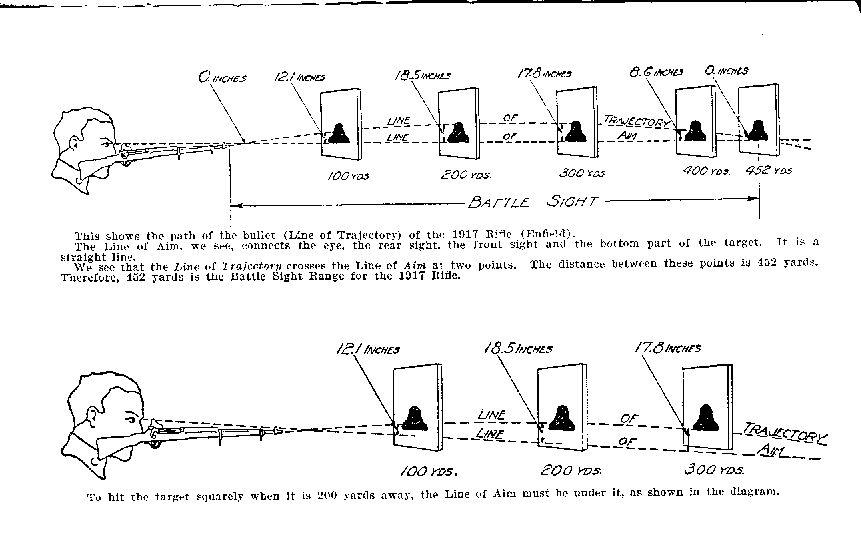

Pieces, having been ordered loaded, are kept loaded without command

until the command unload, or inspection arms, fresh clips being

inserted when the magazine is exhausted.

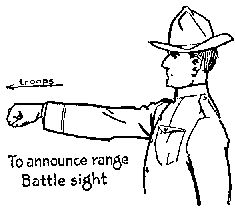

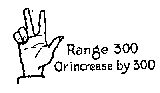

The aiming point or target is carefully pointed out. This may be done

before or after announcing the sight setting. Both are indicated before

giving the command for firing, but may be omitted when the target

appears suddenly and is unmistakable; in such case battle sight is used

if no sight setting is announced.

The target or aiming point having been designated and the sight setting

announced, such designation or announcement need not be repeated until a

change of either or both is necessary.

Troops are trained to continue their fire upon the aiming point or

target designated, and at the sight setting announced, until a change is

ordered.

If the men are not already in the position of load, that position is

taken at the announcement of the sight setting; if the announcement is

omitted, the position is taken at the first command for firing.

When deployed, the use of the sling as an aid to accurate firing is

discretionary with each man.

TO LOAD

Being in line or skirmish line at halt: 1. With dummy (blank or ball)

cartridges, 2. LOAD.

At the command load each front-rank man or skirmisher faces half right

and carries the right foot to the right, about 1 foot, to such position

as will insure the greatest firmness and steadiness of the body;

raises, or lowers, the piece and drops it into the left hand at the

balance, left thumb extended along the stock, muzzle at the height of

the breast, and turns the cut-off up. With the right hand, he turns and

draws the bolt back, takes a loaded clip and inserts the end in the clip

slots, places the thumb on the powder space of the top cartridge, the

fingers extending around the piece and tips resting on the magazine

floor plate; forces the cartridges into the magazine by pressing down

with the thumb; without removing the clip, thrusts the bolt home,

turning down the handle; turns the safety lock to the "safe" and carries

the hand to the small of the stock. Each rear rank man moves to the

right front, takes a similar position opposite the interval to the right

of his front rank man, muzzle of the piece extending beyond the front

rank, and loads.

A skirmish line may load while moving, the pieces being held as neatly

as practicable in the position of load.

If kneeling or sitting, the position of the piece is similar; if

kneeling, the left forearm rests on the left thigh; if sitting the

elbows are supported by the knees; if lying down, the left hand steadies

and supports the piece at the balance, the toe of the butt resting on

the ground, the muzzle off the ground.

STACK AND TAKE ARMS

The subject of stack and take arms is less important than the rest of

this chapter. It is difficult to be learned from a book. Your company

commander will explain it to you. It is given here to serve as a

reference.

Being in line at a halt: STACK ARMS.

Each even number of the front rank grasps his piece with the left hand

at the upper band and rests the butt between his feet, barrel to the

front, muzzle inclined slightly to the front and opposite the center of

the interval on his right, the thumb and forefinger raising the stacking

swivel; each even number of the rear rank then passes his piece, barrel

to the rear, to his file leader, who grasps it between the bands with

his right hand and throws the butt about two feet in advance of that of

his own piece and opposite the right of the interval, the right hand

slipping to the upper band, the thumb and forefinger raising the

stacking swivel, which he engages with that of his own piece; each odd

number of the front rank raises his piece with the right hand, carries

it well forward, barrel to the front; the left hand, guiding the

stacking swivel, engages the lower hook of the swivel of his own piece

with the free hook of that of the even number of the rear rank; he then

turns the barrel outward into the angle formed by the other two pieces

and lowers the butt to the ground, to the right of and against the toe

of his right shoe.

The stacks made, the loose pieces are laid on them by the even numbers

of the front rank.

When each man has finished handling pieces, he takes the position of the

soldier.