Title: The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 10

Editor: Charles F. Horne

Rossiter Johnson

LL. D. John Rudd

Release date: November 21, 2006 [eBook #19893]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

A COMPREHENSIVE AND READABLE ACCOUNT OF THE WORLD'S

HISTORY, EMPHASIZING THE MORE IMPORTANT EVENTS, AND

PRESENTING THESE AS COMPLETE NARRATIVES IN THE

MASTER-WORDS OF THE MOST EMINENT HISTORIANS

ON THE PLAN EVOLVED FROM A CONSENSUS OF OPINIONS GATHERED

FROM THE MOST DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARS OF AMERICA

AND EUROPE, INCLUDING BRIEF INTRODUCTIONS BY SPECIALISTS

TO CONNECT AND EXPLAIN THE CELEBRATED NARRATIVES.

ARRANGED CHRONOLOGICALLY, WITH THOROUGH INDICES,

BIBLIOGRAPHIES, CHRONOLOGIES, AND COURSES OF READING

TRACING BRIEFLY THE CAUSES, CONNECTIONS, AND

CONSEQUENCES OF THE GREAT EVENTS

(AGE OF ELIZABETH AND PHILIP II)

Philip II succeeded his father Charles V on the throne of Spain. The vast extent of his domains, the absoluteness of his authority, and, above all, the enormous wealth that poured into his coffers from the Spanish conquests in America, made him the most powerful monarch of his time, the central figure of the age. It was largely because of Philip's personal character that the great religious struggle of the Reformation entered upon a new phase, became far more sinister, more black and deadly, extended over all Europe, and bathed the civilized world in blood. England stood forth as the centre of opposition against Philip, and under the unwilling leadership of Elizabeth entered on its epic period of heroism, was stimulated to that remarkable outburst of energy and intellect and power which we call the Elizabethan age.

Philip, with a tenacity of purpose from which no fortune good or bad could lure him for a moment, pursued two objects throughout his reign (1555-1598), the reëstablishment of Catholicism over all Europe, and the extension so far as might be of his own personal authority. If we consider his personal ambition, we must count his reign a failure; for at his death his country had already fallen from its foremost rank in Europe and started on that process of decay which in later centuries has become so marked. If, however, we look to Philip's religious purpose, it is undeniable that during his reign Catholicism revived. Philip II, the Jesuits, the Council of Trent—these three were the powers by means of which the Roman Church beat back its foes, saved itself from what for a time had seemed a threatened extinction, and so far reëstablished its power that for over a century it appeared not improbable that Philip's purpose of reuniting Europe might be accomplished.

Before the beginning of this reactionary wave, the North had become wholly Protestant. It has been estimated that nine-tenths of the people of Germany were of the new faith; half the population of France had adopted it; even in Italy protest and disbelief were widespread and active. Only in Spain did the Inquisition with firmest cruelty trample down each vestige of revolt.

The Inquisition was established in Italy, which, as we have seen, was really a Spanish possession. It was introduced into the Netherlands by Charles V (1550), but remained feebly merciful there until Philip, to whom we must at least give the credit of having been a sincere fanatic, insisted on its rigorous enforcement. Over England also Philip sought to extend his hand. There the eagerly Protestant Edward VI had died in 1553, and his Catholic sister Mary succeeded to the throne. Philip was wedded to her in 1554, even before he became King of Spain, and both he and she did their utmost to restore the kingdom to the Roman faith. So many Protestants were burned at the stake that England remembers the queen as "bloody Mary"; and so recklessly did she antagonize the spirit of her people that even her husband counselled her to a caution which she despised. He had no love for his cold, pale, embittered English wife, except as an instrument in his policy; and when he found that it was impossible for him, as her husband, to become King of England, he practically abandoned her, and returned to Spain.

When his father's abdication gave him power in 1555, Philip's first active movement was against France. He sought to avenge his father's loss of Metz, and persuaded his English wife to join him in war against young Henry II. With his splendid Spanish troops Philip won a great victory at St. Quentin.[1] "Has he yet taken Paris?" cried his father eagerly when the news reached his secluded monastery. But Philip had not, he had erred from over-caution and given France time to recover. Two able generals, the great Protestant leader Coligny, and the dashing Catholic hero of Metz, Francis of Guise, held the Spaniards in check. Guise even seized Calais, and so snatched from England her last territory in France (1558). Its loss filled full the measure of poor Mary's unpopularity with her subjects and also of her own unhappiness. She had sacrificed everything for love of a husband who had no love for her. She died the same year. "They will find 'Calais,'" she said, "engraven on my heart."[2]

Her Protestant sister, Elizabeth, daughter of Anne Boleyn, succeeded to the throne, and England with a cry of relief threw off the hated Spanish alliance. She was free again. Free, but in infinite danger. The Catholic Pope and Catholic Philip, remembering that the divorce under which Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn had never been admitted by the Church, declared Elizabeth illegitimate, and pointed to her cousin Mary Stuart of Scotland as the lawful ruler of England. Mary had been married to the French prince Francis II, who at this moment succeeded his father Henry II as king of France. Here was a chance indeed for Spain and France and Scotland all three to unite against Elizabeth and place a second Catholic Mary on England's throne. Many Englishmen themselves were still Catholic, and might easily have been persuaded to approve the change. That Elizabeth, by her cool and cunning diplomacy, managed to evade the threatened danger, has ever been held as little short of providential by the Protestants of the world.[3] In truth, however, each of the powers which might have assailed Elizabeth, had religious difficulties of its own to encounter.

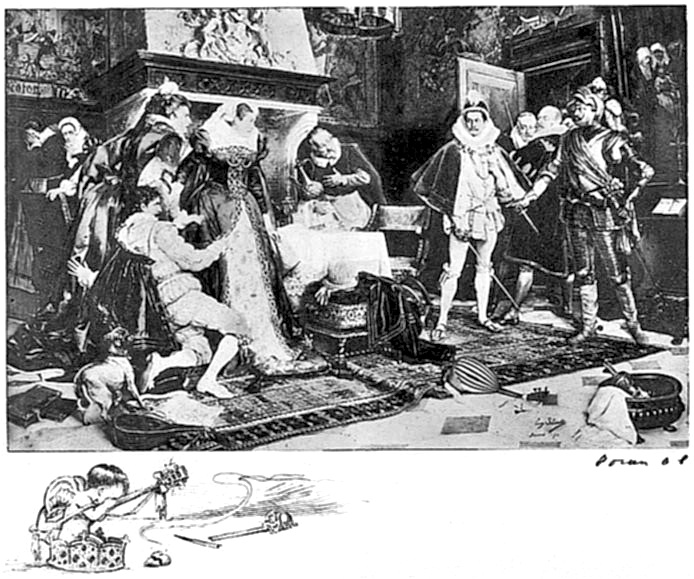

In Scotland there was civil war. The Protestant faith had been slow of introduction there, but under the leadership of John Knox it had become at length supreme.[4] The Regent, mother of the young queen, Mary Stuart, had French troops to aid her against the reformers, but had been compelled to yield to their demands. When Queen Mary herself returned to rule Scotland after the death of her French husband, King Francis, she found her path anything but easy. A sovereign of one faith and a nation of another had not yet learned to endure each other, and there were queer doings in Scotland, wild nobles running off with the Queen, wilder fanatics lecturing at her in her own court, her French favorite assassinated, a new husband, a Scotch one, sent the same dark road, more civil war, imprisonments, romantic escapes. It ended in Mary's secret flight to England. She who had so nearly marched into the land a conqueror, entered it a fugitive supplicating Elizabeth's protection. The remainder of her life she passed in an English prison, and eighteen years later was executed on an only half-proven charge of conspiring against the rival who had kept her in such dreary durance.[5]

Let us not, however, judge Elizabeth too harshly. In reading only English history we are apt to do so, to fail in realizing the atmosphere that surrounded her, the spirit of the age throughout Europe. Statecraft, which had been grasping under Charles V and false under Francis I, seemed now to have adopted fully the maxims of Machiavelli, and pursued its ends by means wholly base, by subtle treacheries, secret murders and open massacre. The gloomy spirit of Philip II hung like blackest night over all the world. He hesitated at no crime which should advance his purposes. Where he might next strike, no man knew, until the blow had fallen. His dark secrecy and enormous power weighed as a nightmare upon the imaginations of men. We enter an age of plots. Elizabeth was unquestionably surrounded by them; and where so many existed, a thousand more were naturally suspected—leading on all sides to counterplots. Scotland had seen several assassinations. England guarded herself desperately against them. France, nearest to Spain's borders, suffered worst of all. Five times in succession did the chief leader of the state fall by sudden murder. In some of these crimes Philip had no part; in others he was plainly implicated.

The early and unexpected death of Henry II of France (1559) had left the throne to one after another of his young and feeble sons. The first of these, Francis II, the husband of Mary Stuart, ruled only a year. He was completely under the control of the great Catholic family, the Guises, who began a vigorous attempt to suppress the Protestants of France, the Huguenots as they were called. But these Huguenots included many of the highest and ablest of the French nobility and did not yield easily to suppression. Francis II died, and the Queen-mother, Catherine de' Medici, became regent for her second son, Charles IX. At first Catherine feared the power of the Guises and encouraged the Huguenots; but Philip of Spain interfered here as everywhere in the Catholic behalf. A civil war broke out in 1562; and for over a generation France, divided against herself, became the theatre of repeated conflicts and savage massacres. She had no thought to give to other lands.

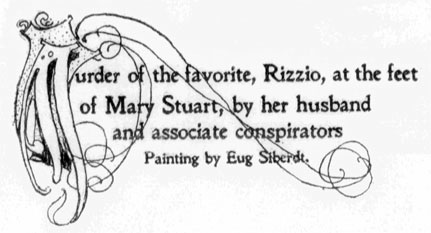

The first of her chiefs to be assassinated was Francis of Guise, the great Catholic leader and general, shot by a Huguenot. Next the Catholics attempted the murder of Coligny. They failed at first, and Catherine de' Medici, who by this time had embraced fully the Catholic cause, planned the awful massacre of St. Bartholomew (1572). A marriage was arranged between the highest Huguenot in rank, the young prince Henry of Navarre, and a royal princess. This was supposed to mark the amicable ending of all disputes, and the chief Huguenots gathered gladly to Paris for the ceremony. Suddenly an army of assassins were let loose on them. Young Henry was spared, but Coligny and more than twenty thousand Huguenots were slain.[6]

The massacre spread over all France. The Protestants rallied, stern and desperate, for defence and for revenge. The civil war was resumed again and again, with false peaces patched in between. Philip might well triumph at the utter anarchy into which he had helped to throw the kingdom which had been his father's rival.

The feeble French king, Charles IX, died, in remorse and madness it is said, for having permitted the great massacre. Henry III, last of the sons of Catherine, ascended the throne, and was also guided by the dark genius of his Italian mother. He found the new Duke of Guise, head of the Catholic party, far more powerful than he, so caused his assassination. That roused the Catholics to war on the King; the Huguenots were also in arms under Henry of Navarre; there were now three parties to the strife. Queen Catherine died, worn out and despairing. King Henry was murdered in his turn, and with him perished the direct line of the royal house. Henry of Navarre was the nearest heir to the throne.

Of course the Catholics would not consent to be ruled by this champion of the Huguenots; so again the strife went on. Henry proved himself a dashing and heroic leader, winning splendid battles. Spanish forces invaded the country, and he beat them, too. Though Protestant, he was recognized even by his foes as the national hero. At last he took that much-debated resolve, than which was never act more statesmanly. He became a Catholic. His opponents gladly laid down their arms; even fanatic Paris hailed him with extravagant delight. In 1598 he proclaimed the Edict of Nantes, granting safety and religious freedom to his former comrades, the Huguenots. The religious wars of France ended; the wisdom and power of one man had healed what seemed a hopeless confusion.[7]

Under this great monarch, Henry IV, France resumed her former place of power in Europe. Her chief began planning grim revenge on Spain for all her injuries. And then he, too, fell by the assassin's knife (1610).

We have traced the French tumults to the end of the present period; let us go back to see why, with his chief foe so helpless, Philip II accomplished no more in extending his own power. It is one of the most amazing tales in history. Where he had thought himself most secure, there he failed. The foe which had seemed most helpless, proved his undoing. He had insisted on the enforcement of the Inquisition in the Netherlands. It is said that thirty thousand people perished there in its flames. Yet even with thirty thousand of their bravest gone, the Protestants refused submission. Gradually the temper of the oppressed people grew more and more bitter, till in 1566 they flared into open revolt. "The beggars," they were contemptuously called by the Spaniards, and they adopted the name as a badge of honor. Penniless, helpless they might be, yet they would fight.[8]

The cruel Alva was sent by Philip to suppress them, and for six years (1567-1573) his savagery and that of his brutal Spanish soldiers made the Netherlands a theatre of horror—and of heroism. The revolt in the southern provinces, now Belgium, was finally put down. The inhabitants there were mostly Catholics, and their strife was only against the general despotism and cruelty of Spain. But the North would never yield. The terrific siege of Leyden, with its accompanying horrors of starvation and defiance, is world-famed.[9] In 1581 Holland finally proclaimed its complete independence of Spain.

At enormous expense and waste of his American treasure, Philip II continued to pour troops and troops into the rebellious provinces. Their leader throughout had been the highest of their nobles, William of Orange, called "the silent." Philip openly proclaimed an enormous reward to the man who could reach and assassinate this obstacle in his path; and at last after repeated attempts the reward was earned (1584).[10] The fall of William ended all chance of the union of the northern and southern provinces; he had been the only man all trusted. But Holland under his son Maurice continued the strife even more bitterly. No sacrifice was too great for the heroic Dutch. Spain was exhausted at last; Philip II died a disappointed man. His son, Philip III, in 1609 consented sullenly to a truce—peace he would not call it—and it was many years before Spain formally acknowledged the independence of her defiant provinces.

Philip II had met also an even heavier defeat from Protestant England. But before speaking of this, let us look to his few successes. In 1580 he added Portugal to his dominions and so, temporarily at least, united the entire Spanish peninsula as one state. This gave him control over the vast Portuguese colonial possessions and over the rich trade with India and the isles beyond. Australia was probably touched more than once by his ships, though not definitely discovered until 1606.[11]

It was under Philip that in 1564 the Spaniards extended their American settlements northward and founded St. Augustine, the first town within the present mainland of the United States. The French had attempted to plant a colony even earlier. At the first outbreak of their civil wars, some Huguenots had fled from persecution to the coast of Florida (1562). The Spaniards regarded this as an encroachment on their territories. Moreover, the intruders were heretics. They were attacked and massacred. It was partly to keep further Frenchmen off the coast that St. Augustine was founded.[12]

An even more important triumph came to Philip in 1571, when his ships, united with those of Venice and other states, gained a great naval victory over the Turks. This battle of Lepanto stands among the turning-points of history. It marks the checking of the Turkish power which for over two centuries had been rising steadily against Europe. Lepanto crushed the naval supremacy which the followers of Mahomet had more than once asserted over the Mediterranean. For another century and more they remained formidable on land, but at sea they never recovered their ascendency.[13]

At Lepanto as a common soldier, fought Miguel de Cervantes, a Spaniard, who, toward the close of a roving life, settled down to literature in his native land, and after Philip's death wrote what was in many ways a satire upon that monarch's rule in Spain. Cervantes' Don Quixote altered the taste of the whole literary world. Its influence spread from Spain to France and over all Europe. It was the death-song of ancient chivalry, the first book since the days of Dante to alter markedly the literary thought of man.[14]

Of the world farther eastward during this period we need say little. The fortunes of Germany, luckily for herself, had been separated from those of Spain at the abdication of Charles V. The Hapsburg possessions in Austria had been bequeathed to his brother Ferdinand; and both Ferdinand and his next successor as emperor of Germany abided by the conditions of that remarkable religious peace of Augsburg which had allowed every prince to settle the religion of his own domains. Although themselves Catholic, the Emperors were not strict in enforcing Catholicism even in their own Austrian domains. They reserved all their effort for the struggle against the Turks. Disputes between the leaders of the differing faiths did of course occur, but none reached an active stage until a later generation.

Sweden rose greatly in importance. Poland declined. Russia was almost conquered by one or the other, a prey, like France, to civil wars. Yet some Cossacks in her service, wandering plunderers really, invaded Siberia, defeated the few scattered Tartar tribes, and annexed the entire waste of Northern Asia to the Russian crown. Never again was this to be a secretly growing, unknown world from which vast hordes might suddenly burst forth on Europe.[15]

Turn now to England, emerging at last from the exhaustion of the Wars of the Roses to assert her place among the great powers of the world. Philip and Elizabeth, restrained by other anxieties, might maintain a hollow peace at home: they could not control the rising spirits of the English nation. English sailors, the most daring in the world, penetrated all seas. Spanish and Portuguese ships had been almost everywhere before them. The North was still half a century behind the South in progress. Yet the difference is worth noting. On the southern ships a few gallant, aristocratic leaders headed a crowd of trembling peasants, ever begging to be taken home, sometimes mutinying through very frenzy of fear. On England's ships each sailor was as stubborn and dauntless as his chief, differing from him only in the intellect to command.

Such men as these were little like to accept Spanish claims to all the wealth of all the new lands of the world. They cruised at will, and fought the Spaniards successfully wherever found. Frobisher began the long and dreary search for the "northwest passage," by which the northern countries of Europe might send ships to round America and reach Asia as Magellan had done to southward.[16] Gilbert raised his country's standard over Newfoundland, England's first clearly established possession beyond seas.[17] The memory of the Cabots' voyages was revived, and in their name England claimed the North American coast. Sir Walter Raleigh attempted to plant a colony, and called the new land Virginia in honor of the Virgin Queen.[18]

To Drake, greatest of all these wild adventurers, was it left to embroil his country utterly with Spain. He followed Magellan in circumnavigating the globe, and wherever he went he left a track of plundered Spanish settlements behind. Elizabeth was in despair; she alternately knighted him and threatened to hang him as a pirate. The Spaniards, re-reading his name, called him the Dragon. He was the terror of their seas.

At last the long accumulating quarrel of religious and commercial motives reached a head. Philip began gathering in all his ports that vast "Invincible Armada," which was to assert his supremacy on sea as upon land, to crush England and Protestantism forever. This was the supreme effort of his life. There was no question as to where the blow would fall. Elizabeth knew it coming, not to be evaded by any policy or concessions. Drake knew it coming, and, taking time by the forelock, sailed boldly into the harbor of Cadiz to "singe the King of Spain's beard," destroyed all the ships and stores accumulated there.[19] But Cadiz was only one port among several where preparations were being hurried forward; there were others the hardy Dragon could not penetrate. The next year (1588) the "Invincible Armada" sailed for England.

The story of its destruction is too well known for repetition. This was England's proudest achievement. Philip accepted the terrific downfall of all his scheming and ambitions with a gallant calm. He had truly believed that Heaven wished him to reassert Catholicism. He accepted the storms which partly destroyed his fleet as the divine refusal of his aid. "You could not strive against the will of Heaven," he said kindly to his defeated admiral.[20]

In England, the repeated plunderings of Spanish ships, and now this final victory, flooded the land with wealth and triumph. The internal improvement, the intellectual advance of the people, were prodigious. The "Elizabethan Age" is the most famed in English literature. The first English theatre was built in 1570, a crude and queer affair for cruder, queerer plays.[21] Yet, in perhaps that very armada year of 1588, Shakespeare began writing his remarkable plays. In 1601 the drama rose to its perfection in his Hamlet, the flower of English literary genius, accredited by some as the grandest new creation that ever came from the hand of man.[22]

Elizabeth died in 1603. Her reign had seen also the final suppression of the Irish Catholics and their subjugation to the English crown. In the year of her death came the "Flight of the Earls," the mournful abandonment of Ireland by the last of the great lords who had fought for and now despaired of her independence.[23]

The age of Elizabeth can scarcely, however, be said to cease at her death. The English people had grown greater than their sovereign, and upon them the influences of their Spanish victory continued. Shakespeare is even more the Elizabethan age than Elizabeth, and his writings continued until 1611. Drake had died in 1596; Raleigh lived till 1618.

Since Elizabeth was childless, she was succeeded on the throne by the Scotch king James VI (James I of England), son of the Mary Stuart whose claims had caused such trouble. James, removed from his mother's care, had been educated by his subjects as a Protestant, so he was welcome to England. The first step toward uniting the two halves of the island was made when they thus came under a common sovereign. The same atmosphere of plot and treachery which had surrounded Elizabeth reached also to her successor. In 1605 was unearthed the "Gunpowder Plot," a scheme to blow up James with all his chief ministers and subjects in the House of Parliament. The date of its discovery is still kept as a national holiday in England.[24]

Then in 1607 came the fruition of Raleigh's efforts and those of Drake, the beginning surely of a new era. Spain being no longer able to oppose, a new colony was sent out from England to Virginia. It settled at Jamestown, and began the successful colonization of the United States.[25] The next year, the French, supported by their great king Henry IV, made a similar beginning. Quebec was founded by them on the St. Lawrence.[26] The era of American discovery was over, and that of American settlement was come.

[FOR THE NEXT SECTION OF THIS GENERAL SURVEY SEE VOLUME XI]

ENGLAND LOSES HER LAST FRENCH TERRITORY

BATTLE OF ST. QUENTIN

A.D. 1558

From 1347, when it was taken by Edward III, Calais remained a stronghold of England until it was retaken for France by the Duke of Guise (François de Lorraine), in 1558. With the surrender of Calais the English lost their last foothold in French territory.

Weary with the long tumults and wars of his reign, Charles V in 1555 resigned all his crowns to his son, Philip II of Spain, and his brother Ferdinand, King of Bohemia and Hungary. Pope Paul IV, wishing to subvert the Spanish power, entered into a league with Henry II of France against Philip. Guise, who had warred successfully with Charles V, against whom he defended Metz when it was won for France (1553), now espoused the papal cause. His main object was to recover Naples to his own family. Thus he became a leading actor in the events culminating in the capture of Calais.

Throughout the reign of Philip II his chief aim was to restore the Roman Catholic religion in Protestant countries and to establish a uniform despotism over his dominions. In 1554 he had married Queen Mary of England, and after a short sojourn in that country, whose crown he vainly tried to obtain, and to whose people he was obnoxious, he returned to the Continent. Soon after "he was called to a destiny more suited to his proud and ambitious nature than to be the unequal partaker of sovereign power over a jealous insular people."

In March, 1557, Philip returned to England. He came, not out of affection for his wife or of regard for his turbulent insular subjects, but to stir up the old English hatred of France and to drag the nation into a war for his personal advantage. The fiery Pope, Paul IV, panted for the freedom of Italy as it existed in the fifteenth century; he wanted to accomplish his wishes by an alliance with France; he would place French princes on the thrones of Milan and Naples. The Spaniards he pronounced as the spawn of Jews and Moors, the dregs of the earth.

When there was a question of temporal dominion to be fought out, the Pope did not hesitate to wage war against that faithful son of the Church, King Philip; nor did King Philip hesitate to send the Duke of Alva, the exterminator of Protestants, to enter the Roman states and lay waste the territories of the Pope. Frane and Spain were upon the brank of open war when Philip arrived in England. He urged a declaration of war against France. There were grievances in the alleged encouragement which had been given in Wyat's rebellion, and in the lukewarmness with which Henry II met Queen Mary's desire that he should afford her the means of vengeance upon the exiles for religion who took shelter in France.

The most recent complaint was that France had connived at the equipment of a force by Thomas Stafford, a refugee, who had invaded England with thirty-two followers and had surprised Scarborough castle. This adventurer claimed to be the house and blood of the Duke of Buckingham, who was beheaded in the times of Henry VIII. The proclamation which he issued from his castle of Scarborough, which he held only two days, was addressed to the English hatred of the Spaniards, rather than directed against the ecclesiastical persecution under which the country was suffering: "As the duke of Buckingham, our forefathers and predecessors, have always been defenders of the poor commonalty against the tyranny of princes, so should you have us at this juncture, most dearly beloved friends, your protector, governor, and defender against all your adversaries and enemies; minding earnestly to die rather, presently, and personally before you in the field, than to suffer you to be overrun so miserably with strangers, and made most sorrowful slaves and careful captives to such a naughty nation as Spaniards." Stafford and his band were soon made prisoners; and he was beheaded on Tower Hill, and three of his followers hanged, on May 25th. Seizing upon this absurd attempt as a ground of quarrel, war was declared against France on June 7th; and Philip quitted the country on July 6th, never to return.

An English force of four thousand infantry, a thousand cavalry, and two thousand pioneers joined the Spanish army on the Flemish frontier. The army was partly composed of German mercenaries; the lanzknechts and reiters, the pikemen and cavalry, who, at the command of the best paymaster, were the most formidable soldiers of the time. But the Spanish cavaliers were there, leading their native infantry; and there were the Burgundian lances. The army was commanded by Emanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, who had aspired to the hand of Elizabeth. Philip earnestly seconded his suit, but Mary, wisely and kindly, would not put a constraint upon her sister's inclinations. The wary Princess saw that the crown would probably be hers at no distant day; and she would not risk the loss of the people's affection by marrying a foreign Catholic. She had sensible advisers about her, who seconded her own prudence; and thus she kept safe amid the manifold dangers by which she was surrounded.

The Duke of Savoy, though young, was an experienced soldier, and he determined to commence the campaign by investing St. Quentin, a frontier town of Picardy. The defence of this fortress was undertaken by Coligny, the Admiral of France, afterward so famous for his mournful death. Montmorency, the Constable, had the command of the French army. The garrison was almost reduced to extremity—when Montmorency, on August 10th, arrived with his whole force, and halted on the bank of the Somme. On the opposite bank lay the Spanish, the English, the Flemish, and the German host. The arrival of the French was a surprise, and the Duke of Savoy had to take up a new position. He determined on battle. The issue was the most unfortunate for France since the fatal day of Agincourt. The French slain amounted, according to some accounts, to six thousand; and the prisoners were equally numerous. Among them was the veteran Montmorency.

On August 10th Philip came to the camp. Bold advisers counselled a march to Paris. The cautious King was satisfied to press on the siege of St. Quentin. The defence which Coligny made was such as might have been expected from his firmness and bravery. The place was taken by storm, amid horrors which belong to such scenes at all times, but which were doubled by the rapacity of troops who fought even with each other for the greatest share of the pillage. After a few trifling successes, the army of Philip was broken up. The German mercenaries; the lanzknechts and reiters, the pikemen and cavalry, who, at the command of the best paymaster, were the most formidable soldiers of the time. But the Spanish cavaliers were there, leading their native infantry; and there were the Burgundian lances. The army was commanded by Emanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, who had aspired to the hand of Elizabeth. Philip earnestly seconded his suit, but Mary, wisely and kindly, would not put a constraint upon her sister's inclinations. The wary Princess saw that the crown would probably be hers at no distant day; and she would not risk the loss of the people's affection by marrying a foreign Catholic. She had sensible advisers about her, who seconded her own prudence; and thus she kept safe amid the manifold dangers by which she was surrounded.

The Duke of Savoy, though young, was an experienced soldier, and he determined to commence the campaign by investing St. Quentin, a frontier town of Picardy. The defence of this fortress was undertaken by Coligny, the Admiral of France, afterward so famous for his mournful death. Montmorency, the Constable, had the command of the French army. The garrison was almost reduced to extremity—when Montmorency, on August 10th, arrived with his whole force, and halted on the bank of the Somme. On the opposite bank lay the Spanish, the English, the Flemish, and the German host. The arrival of the French was a surprise, and the Duke of Savoy had to take up a new position. He determined on battle. The issue was the most unfortunate for France since the fatal day of Agincourt. The French slain amounted, according to some accounts, to six thousand; and the prisoners were equally numerous. Among them was the veteran Montmorency.

On August 10th Philip came to the camp. Bold advisers counselled a march to Paris. The cautious King was satisfied to press on the siege of St. Quentin. The defence which Coligny made was such as might have been expected from his firmness and bravery. The place was taken by storm, amid horrors which belong to such scenes at all times, but which were doubled by the rapacity of troops who fought even with each other for the greatest share of the pillage. After a few trifling successes, the army of Philip was broken up. The English and Germans were indignant at the insolence of the Spaniards; and the Germans were more indignant that their pay was not forthcoming. Philip was glad to permit his English subjects to take their discontents home. They had found out that they were not fighting the battle of England.

The war between England and France produced hostilities between England and Scotland. Mary of Guise, the Queen Dowager and Regent of Scotland, was incited by the French king to invade England. The disposition to hostilities was accompanied by a furious outbreak of the Scottish borderers. They were driven back. But the desire of the Queen Dowager that England should be invaded was resisted by the chief nobles, who declared themselves ready to act on the defensive, but who would not plunge into war during their sovereign's minority. The alliance of France and Scotland was, however, completed, in the autumn of 1558, by the marriage between the Dauphin and the young Queen Mary, which was solemnized at Paris, in the Cathedral of Notre Dame.

The Duke of Guise, the uncle of the Queen of Scots, at the beginning of 1558, was at the head of a powerful army to avenge the misfortune of St. Quentin. The project committed to his execution was a bold and patriotic one—to drive the English from their last stronghold in France. Calais, over whose walls a foreign flag had been waving for two centuries, was to France an opprobrium and to England a trophy. But it was considered by the English government as an indispensable key to the Continent—a possession that it would not only be a disgrace to lose, but a national calamity. The importance of Calais was thus described by Micheli, the Venetian ambassador, only one year before it finally passed from the English power:

"Another frontier, besides that of Scotland, and of no less importance for the security of the kingdom, though it be separated, is that which the English occupy on the other side of the sea, by means of two fortresses, Calais and Guines, guarded by them (and justly) with jealousy, especially Calais, for this is the key and principal entrance to their dominions, without which the English would have no outlet from their own, nor access to other countries, at least none so easy, so short, and so secure; so much so that if they were deprived of it they would not only be shut out from the Continent, but also from the commerce and intercourse of the world. They would consequently lose what is essentially necessary for the existence of a country, and become dependent upon the will and pleasure of other sovereigns, in availing themselves of their ports, besides having to encounter a more distant, more hazardous, and more expensive passage; whereas, by way of Calais, which is directly opposite to the harbor of Dover, distant only about thirty miles, they can, at any time, without hinderance, even in spite of contrary winds, at their pleasure, enter or leave the harbor—such is the experience and boldness of their sailors—and carry over either troops or anything else for warfare, offensive and defensive, without giving rise to jealousy and suspicion; and thus they are enabled, as Calais is not more than ten miles from Ardres, the frontier of the French, nor farther from Gravelines, the frontier of the imperialists, to join either the one or the other, as they please, and to add their strength to him with whom they are at amity, in prejudice of an enemy.

"For these reasons, therefore, it is not to be wondered at that, besides the inhabitants of the place, who are esteemed men of most unshaken fidelity, being the descendants of an English colony settled there shortly after the first conquest, it should also be guarded by one of the most trusty barons which the King has, bearing the title of deputy, with a force of five hundred of the best soldiers, besides a troop of fifty horsemen. It is considered by everyone as an impregnable fortress, on account of the inundation with which it may be surrounded, although there are persons skilled in the art of fortification who doubt that it would prove so if put to the test. For the same reason Guines is also reckoned impregnable, situated about three miles more inland, on the French frontier, and guarded with the same degree of care, though, being a smaller place, only by a hundred fifty men, under a chief governor. The same is done with regard to a third place, called Hammes, situated between the two former, and thought to be of equal importance, the waters which inundate the country being collected around."

Ninety years later Calais was regarded in a very different light: "Now it is gone, let it go. It was but a beggarly town, which cost England ten times yearly more than it was worth in keeping thereof, as by the accounts in the exchequer doth plainly appear."

The expedition against Calais was undertaken upon a report of the dilapidated condition of the works and the smallness of its garrison. It was not "an impregnable fortress," as Micheli says it was considered. The Duke of Guise commenced his attack on January 2d, when he stormed and took the castle of Ruysbank, which commanded the approach by water. On the 3d he carried the castle of Newenham bridge, which commanded the approach by land. He then commenced a cannonade of the citadel, which surrendered on the 6th. On the 7th the town capitulated. Lord Wentworth, the Governor, and fifty others remained as prisoners. The English inhabitants, about four thousand, were ejected from the home which they had so long colonized, but without any exercise of cruelty. "The Frenchmen," say the chroniclers, "entered and possessed the town; and forthwith all the men, women, and children were commanded to leave their houses and to go to certain places appointed for them to remain in, till order might be taken for their sending away.

"The places thus appointed for them to remain in were chiefly four, the two churches of Our Lady and St. Nicholas, the deputy's house, and the stable, where they rested a great part of that day and one whole night and the next day till three o'clock at afternoon, without either meat or drink. And while they were thus in the churches and those other places the Duke of Guise, in the name of the French King, in their hearing made a proclamation charging all and every person that were inhabitants of the town of Calais, having about them any money, plate, or jewels to the value of one groat, to bring the same forthwith, and lay it down upon the high altars of the said churches, upon pain of death; bearing them in hand also that they should be searched. By reason of which proclamation there was made a great and sorrowful offertory.

"While they were at this offertory within the churches, the Frenchmen entered into their houses and rifled the same, where were found inestimable riches and treasures; but especially of ordnance, armor, and other munitions. Thus dealt the French with the English in lieu and recompense of the like usage to the French when the forces of King Philip prevailed at St. Quentin; where, not content with the honor of victory, the English in sacking the town sought nothing more than the satisfying of their greedy vein of covetousness, with an extreme neglect of all moderation."

Within the marches of Calais the English held the two small fortresses of Guines and Hammes. Guines was defended with obstinate courage by Lord Grey, and did not surrender till January 20th. His loss amounted to eight hundred men. From Hammes the English garrison made their escape by night.

A.D. 1558-1603

Elizabeth's reign has been regarded by many writers as the most glorious period of England's career. There were no great land battles fought by English troops; but at sea those famous rovers, half pirates, Drake, Raleigh, and their like, definitely established that maritime supremacy which has ever since been their country's proudest boast. Moreover, the intellectual awakening of England which had taken place in the time of Henry VII and Henry VIII now bore fruit in a glorious literary outburst, which has made the Elizabethan Age the envy and despair of more recent literary periods.

There were clearly marked causes for this brilliant and patriotic era. The indiscriminate marriages of Henry VIII had thrown more than a shadow of doubt upon the legitimacy of every one of his children. On his death he was succeeded, without serious dispute, by his only son, Edward VI. Edward did not live to manhood, but during his short reign his guardians pushed the land far in the direction of Protestantism. Unfortunately they plundered the common people cruelly and persecuted, though only in two cases to the point of burning, both Catholics and the more extreme Protestants.

The early death of Edward left no male heir to the royal house. For the first time in English history there were none but women to claim the crown. Moreover, of these at least four had some show of right. They were Mary, the Catholic daughter of King Henry's first wife, and Elizabeth, his Protestant daughter by Anne Boleyn. Or, if both these were to be considered illegitimate, then came their cousins, Mary Stuart, descended from one of Henry's sisters, and Lady Jane Grey, from another. The friends of Lady Jane tried to raise her to the throne, but only succeeded in bringing her to the scaffold. The Catholic, Mary, was declared the rightful queen and ruled England for five years, during most of which she kept her half-sister Elizabeth in prison.

Queen Mary was devoted to her religion. The fires which had burned in Henry's time were kindled again, but now for the torture of Protestants, bishops, and men of mark. Mary wedded the Catholic king and cruel fanatic Philip II of Spain, the most powerful monarch of Europe; so that only to her death and the reign of the persecuted Elizabeth could Protestant Englishmen look for relief. Thus the accession of the learned and coquettish Elizabeth brought far more than a mere promise of youth and pleasure; it was a bursting of the fetters of fear.

The age of Elizabeth was preëminently distinguished by the operation of just principles, of generous sentiments, of elevated objects, and of profound piety. Elizabeth, it is true, was vindictive, arbitrary, and cruel. Two prevailing sentiments filled her mind and chiefly influenced her conduct throughout life. The first of these was the idea of prerogative. Any assumption of rights, any freedom of debate, any theological discussion or profession of sentiments which seemed to infringe on the sacred limits of royalty was sure to be visited with her severest wrath. She detested the Puritans, from whom she had suffered nothing, but whose republican spirit appeared to her at war with royalty in the abstract, far more than the papists, by whom her life had been made a life of danger and suffering, but who respected forms and ceremonies, and whose system encouraged reverence for the powers that be and loyal sentiment toward the person whom they regarded as the lawful sovereign. Nothing but the earnest entreaties of Cecil and the imminent danger of a French invasion could induce her to give assistance to the Scottish Protestants when they were persecuted by the Queen Regent. And even her hatred of Mary could not prevent her taking sides with that ill-fated Princess when the "Congregation" claimed the right of trying their sovereign for alleged crimes, after having deposed and imprisoned her.

The other sentiment which in no small degree influenced the conduct of the great Queen was her excessive fondness for admiration as a woman. She filled her solitary throne with a dignity and a majesty which could not be surpassed; and it is difficult, if not impossible, to conceive of a character which should have strength and impetuosity enough, even if marriage could have given the right, to overawe her lion-like spirit and assume the reins of government in defiance of her will. Certain it is that no such prince then lived. But while the queen resolutely excluded all human participation in the lonely eminence on which she stood, the woman was constantly claiming the tribute of sympathy and admiration. Her eager desire was to be a heroine, a beauty, the queen of hearts, cynosure of gallants' eyes; to reign supreme in the court of love and chivalry; to be the watchword and war-cry of the knight and the theme of the troubadour.

Here was the source of the unbounded flattery which was lavished upon her by courtiers, even to the latest years of her life, and which appears to have at times actually deceived her, in spite of her extraordinary penetration. To this sentiment are owing nearly all of the few instances of disaster and disappointment which occurred during her splendid reign. She preferred to risk the safety of her allies, and the cause of Protestantism on the Continent, rather than to refuse the command of her troops to her favorite, who had entreated it. To gratify another favorite and insure his glory she forgot her habitual economy, levied an army larger than she had ever supported, except at the time of the invasion, and sent it to Ireland under the command of a man who was utterly unfit for the place. And when, beset by enemies, harassed by defeat, and overwhelmed with shame, the impetuous and noble-hearted Essex rushed into the presence of majesty as a lover would have sought his mistress, her woman's heart forgave him all. Had this frame of mind continued, had not the resumed majesty of the queen condemned what the woman forgave, the world would have been spared the consummation of one of the most mournful tragedies in history, and the last days of Elizabeth might have been serene and happy, instead of being tortured with anguish and despair.

The former of these sentiments made her an object of dread, the latter of ridicule; and both conspired to render her tyrannical. But she was not a tyrant in the full sense of the word. She never acted upon the nation with that degrading influence which is always the attendant of selfish, cold-hearted, and perfidious tyranny; she never had the power, and we doubt if she ever had the wish, to make slaves of her people. She understood the English character; she comprehended, appreciated, and admired its nobleness; and she had sagacity enough to see that this very character constituted her chief glory. A thorough and hearty affection subsisted between her and her people; an affection Which was increased and cemented by many circumstances of a nature not to be forgotten. As a nation, England had been persecuted, distressed, and trampled upon during the reign of Mary. The party which triumphed in the ascendency of the Roman Catholic religion was small; the great majority of the people were not very zealous in favor of one side or the other; they had been ready to welcome Protestantism under Edward VI, and they were not disposed to fight against the Church of Rome under Mary. The number of zealous papists, they who were in favor of the rack and the stake, was not more than a thirtieth part of the nation. The other twenty-nine parts, though perhaps nearly equally divided on the question of religion, condemned alike the bigotry of their melancholy sovereign and looked on with sorrowful indignation while the bloody Mary, assisted by a few narrow-minded bigots, was carrying on the infernal work of persecution. It was a sorrow and a shame to all true Englishmen, whether Catholic or Protestant; and the hated Philip felt the effects of their vengeance till the day of his death.

In these times of tribulation there was one who shared in the common danger, suffering, and humiliation, and who, from the exalted rank which she occupied, and the station to which she seemed destined, was peculiarly an object of distrust and alarm to the bigots, who were exulting in their day of power. The gloom which overhung the whole country equally surrounded her; the fires of Smithfield and Oxford were kindled for her terror as for the terror of the people. She had been made to pass through that sorrowful passage from which few ever returned alive, the Traitor's Gate in the Tower of London.

Her course was one and the same with that of the entire English nation; and the only light which shone upon the darkness, the only hope that cheered the universal despondency, the dependence of all real patriots, the trust of all friends of truth, and the pride of all free and honorable men were centred in the prison of Elizabeth.

There is no bond so strong as the bond of common perils and sufferings; and, when the young Princess ascended the throne, it was amid the thankful acclamations of a liberated and happy people, who loved her for the dangers she had shared with them, and for whom she entertained the interest and affection due to fellow-sufferers. This feeling was prolonged in an uncommon manner throughout her reign; for it so happened that there was no danger which threatened the Queen during her whole life that was not equally formidable to the people. So difficult was the question of succession that the prudent Burleigh never ventured to express his mind upon the subject, and carried down to the grave the secret of his opinion. Any change would have been for the worse; as it would either have plunged the nation into a civil war or have placed a Roman Catholic prince on the throne. The dangers which menaced the crown of Elizabeth were alike formidable to the cause of freedom in England and of the Protestant religion in Europe. The invasion of England, which was attempted by the French under the Queen Regent of Scotland, and afterward the gigantic preparations of Philip, foreboded more than the ordinary horrors of an offensive warfare. These enemies came with the stake and the fagot in their hands; they came not merely to invade, but to convert; not merely to conquer, but to persecute; they were stimulated not merely by ambition, but by bigotry; they were prepared not merely to enslave, but to torture. It was therefore not a matter of indifference to the English nation whether Elizabeth were to be their queen or whether some other prince should ascend the throne. In her reign, and hers alone, they saw the hope of peace, freedom, and prosperity. Never, therefore, were nation and ruler more closely and firmly knit together.

The sentiment of loyalty, consequently, was never more sincere and enthusiastic in the hearts of Englishmen than at that period. To the nation at large the Queen really appeared what the flattery of her courtiers and poets represented her. She was to them, in truth, the Gloriana of Fairyland; the magnificent, the undaunted, the proud descendant of a thousand years of royalty, and the "Imperial Votress." She was only a tyrant within the precincts of the court. There she reigned, it is true, with more than oriental despotism; and she seems to have delighted occasionally in torturing mean spirits by employing them upon such thankless offices as their hearts revolted from, though they had not the courage to refuse them. But beyond the immediate circle of the palace she was the queen and the mother of her people. To the nation at large, too, she was equally a heroine, a beautiful idol enshrined in their hearts. Living on "in maiden meditation fancy-free," rejecting the proposals of every prince, disregarding the remonstrances of her subjects, where marriage was spoken of, there was something in the very unapproachableness of her state which both commanded the respect and excited the imagination of her people. As a woman, they regarded her just as she wished them to regard her, as the throned Vestal, the watery Moon, whose chaste beams could quench the fiery darts of Cupid. She was to them, in fact, the Belphœbe of Spenser, "with womanly graces, but not womanly affections—passionless, pure, self-sustained, and self-dependent"; shining "with a cold lunar light and not the warm glow of day." This feeling was increased by the spirit of chivalry which still lingered in English society, and, like the setting sun, poured a flood of golden light over the court.

The incense, then, that was offered to the Queen by such men as Spenser, Raleigh, Essex, Shakespeare, and Sidney, the most noble, chivalrous, and gifted spirits that ever gathered round a throne, is not to be judged of as the flattery which cringing courtiers pay to a dreaded tyrant; but rather as the outpouring of a general enthusiasm, the echo of the stirring voice of chivalry, and the expression of the feelings of a devoted yet free people.

An age of tyranny is always an age of frivolity, of heartless levity, of dwarfish objects and pursuits, of dreadful contrasts—laughter amid mourning, rioting and wantonness amid judgments and executions; dancing and music at the hour of death. Such was the frivolity of the days of Nero; such was the mirth of the "death-dance" in the days of Robespierre. Nothing like this sickly and appalling joy could be seen in the times of Elizabeth. There were masques and balls and tournaments at the court, and gay revels as the stately Queen went from castle to castle, and palace to palace, in her visits to her princely subjects. But such amusements did not form the chief object or occupation of the court of Elizabeth. The Queen, and those who had grown up with her, had passed through too many dangers and witnessed too much suffering to allow them to become frivolous or very light-hearted. They had lived among scenes of cruelty, persecution, and death. Their childhood had witnessed the successive horrors of the reign of Henry VIII, and their youth had suffered from the bloody fanaticism of Mary. Sorrow and tribulation had overspread the morning of their life like a cloud.

Miss Aikin, in the beginning of her charming work upon the court of Queen Elizabeth, has described the gorgeous procession which filed along the streets of London at the baptism of the infant princess. The same picture also forms the closing scene of Shakespeare's Henry VIII. As we look upon the gay and splendid train, marching in their robes of state, beneath silken canopies, and then glance our eye along the map of history till we trace almost every actor in the pageant to a bloody grave, we can scarcely believe that it is a scene of joy and festivity that we are witnessing. The angel of death seems to hover over them; there is something dreadful in their rejoicing; their gaudy robes, their mantles, their vases, their fringes of gold, assume the sable hue of the grave; and, instead of a baptismal train, it seems like a funeral procession descending to the tomb.

The mournful scenes which the generation which grew up with Elizabeth had been compelled to witness, and the terror in which most of the leading characters in her reign had passed their youth, had undoubtedly tended to sober their minds and induce them to reflect much upon the great and solemn duties of life. The character of the age was stamped with the dignity which hallows tribulation, and with the force and nerve which the habitual contemplation of danger rarely fails to confer. The same causes undoubtedly promoted the religious spirit which prevailed. While bigotry and fanaticism appeared in a small portion of the nation, it is certain that the age of Elizabeth was marked by the general diffusion of a spirit of deep devotion. There was enough of chivalry left to keep alive the fervor which prevailed at an earlier period, and enough of intelligence to temper this fervor into rational religion. The feeling of shame at professing faith and devoutness was the growth of a later day; it was unknown in those times. The gayest courtier that chanted his love-song in the ear of the high-born maiden, and the gravest statesman who debated at the table of the privy council, were alike penetrated with devotional sentiment, and alike ready to offer up prayers and thanksgiving to the Most High. We are perfectly aware that the outward signs of piety displayed by a few principal characters are not a faithful index of the state of religion at any period. It is not fair to infer, because Elizabeth devoutly commended herself to the care of the Almighty when forsaken, friendless, an orphan, alone, and helpless, she was landed at the foot of the Traitor's Stairs in the Tower of London, or because she returned to the same gloomy fortress when a triumphant queen, to offer up her praise and gratitude to God for his marvellous mercies, that she lived in a pious age. Neither are we to regard it as a sure indication of the prevailing spirit, when Burleigh solemnly commends his son to the Almighty in his letter of advice; when the chivalrous Sidney is found composing a prayer, which, for solemnity, grandeur, and devotion, is scarcely surpassed in the English liturgy; when the adventurous Raleigh displays an amount of knowledge on sacred subjects that might be the envy of an Oxford professor of theology, or when the city of London presents to the young Queen, on the day of her coronation and in the midst of her glittering pageantry, the Bible, as the most appropriate and acceptable offering.

These are not certain signs of a religious age; but they would pass for something at any period, even if they were mere hypocrisy. They would show that religion was held in such respect and by so numerous a class somewhere, as to make it worth while for the Queen and her court to assume at least the outward badges of piety. But they have additional force when we reflect at the same time that, at the period when they were manifested, the Reformation was making a gradual but sure progress in England; that the question of religion occupied every intelligent mind and affected the interests of every family; that the lives and fortunes of millions, the fate of kingdoms, and the progress of intellectual freedom throughout the civilized world were inseparably connected with the cause of Protestantism.

If bigotry and fanaticism had been prevalent in England, and the opposing party of Romanist and Reformer nearly equal, there would have been witnessed in that country during the sixteenth century a succession of atrocities and horrors compared with which the wars of the white and red roses were bloodless. If; on the other hand, the great mass of the nation had been indifferent, with regard not merely to forms, but to religion itself, we should not have seen the outward show of piety in the highest ranks; we should not have seen a house of commons legislating in favor of Edward's liturgy, and a nation turning to worship in their vernacular tongue. Nothing but a widely diffused spirit of piety can account for the character of those miracles of literature which made the days of Elizabeth glorious, and which are stamped with nothing more strongly than their deep and wise religion.

Moreover, in the age of Elizabeth, England was more distinguished for patriotism than any nation in civilized Europe. On the Continent the feeling of nationality was absorbed, and the distinction of language, laws, and country absolutely lost, in the zeal for religious belief. Nations, which for centuries had been enemies, were found leagued against their natural allies; inhabitants of the same state were divided, and at war with each other; the prophecy was literally fulfilled that "the brother shall betray the brother to death, and the father the son, and children shall rise up against their parents, and shall cause them to be put to death." "The Palatine," says Schiller, "now forsakes his home to go and fight on the side of his fellow-believer of France, against the common enemy of their religion. The subject of the King of France draws his sword against his native land, which had persecuted him, and goes forth to bleed for the freedom of Holland. Swiss is now seen armed for battle against Swiss, and German against German, that they may decide the succession of the French throne on the banks of the Loire or the Seine. The Dane passes the Eider, the Swede crosses the Baltic, to burst the fetters which are forged for Germany."

Nothing of this kind was seen in England. The number of Catholics who preferred the triumph of their party to the welfare of their country was too small to be of any consideration. A few fanatics in the college at Rheims, and a few romantic champions of the unhappy Queen of Scots, were the only domestic enemies whom Elizabeth had to fear. With a great majority of the Romanists, the love of country prevailed over all religious distinctions; and, when the invasion was threatened by Philip, they united cordially with the Protestants in the defence of their native land; they enlisted as volunteers in the army and navy; they equipped vessels at their own charge, armed their tenants and vassals, encouraged their neighbors and prepared, heart and hand, for a desperate resistance of the common foe.

The energies of the nation were naturally brought into vigorous action by the great objects, interests, and enterprises which the times presented. The effects of the Reformation were felt just enough to produce a bold and free exercise of thought, without kindling the passions to fierce excitement. The storm which burst with all its fury on the Continent, wrapping nations in the flames of civil war, prostrating, withering, and overwhelming civil institutions, and marking its path with desolation did but exert a salutary influence in England. The lightning was seen flashing in the distant horizon, the rolling thunder could be heard afar off, but the fury of the storm fell at a distance; the atmosphere was purified and the soil refreshed, and the rainbow was glittering in the heavens.

Never in the history of England had there been a time when energy and wisdom were more needed than that period. The nation was compelled, by irresistible force of circumstances, to stand forth as the champion of Protestantism. The eyes of all civilized countries were fixed upon her; some, with imploring looks; some, glaring upon her with jealousy, fierceness, and settled hatred. Enemies were springing up, with whom peace was hopeless. A popish princess was heir to the throne of Scotland, with a powerful ally ready to support her pretensions to the English crown. On the Continent were allies, whom England was compelled to support at the risk of a war with the mightiest empire that had risen since the fall of Rome. And an armament was preparing for the invasion of Britain, of an extent that seemed to render resistance hopeless, by a monarch whose resources appeared inexhaustible, while Ireland was in open rebellion and ready to receive the Spanish fleets into her ports.

From all these difficulties and impending calamities, the nation gathered a harvest of glory that alone would make her name famous forever. It is with a feeling of joy and exultation that we trace the history of England during these years of terror and of triumph. We behold her extricating herself from embarrassments that seemed endless, and turning them into the means of safety; encouraging and supporting her allies without exhausting her own resources, and finally crushing the vast engines which were put into operation for her destruction.

The blood quickens in our veins, as we read of the wisdom and the sublime moral courage, of the daring adventure, the romantic enterprise, the chivalrous bravery, and the brilliant triumphs of that age of great men. We see Cecil and Wotton negotiating with Scotland so wisely as to win the confidence and affection of that nation, and to destroy the influence of France in that country forever; Walsingham, fathoming the secrets of the French court, or watching in silence, but certainty, the progress of conspiracies at home, and crushing them on the eve of maturity; the Queen, with a prudence which seems almost sublime, rejecting a second time the proffer of the sovereignty of Holland; Drake, circumnavigating the earth, and returning laden with the spoils of conquered fleets and provinces; Cavendish, coming up the Thames to London, with sails of damask and cloth of gold, and his men arrayed in costly silks; Lancaster, dashing his boats to pieces on the strand of Pernambuco, that he might leave his men no alternative but death or victory; Raleigh, plunging into the fire of the Spanish galleots, and fighting his way through overwhelming numbers, with a courage that rivalled the incredible tales of chivalry, planting colonies in the pleasantest vales of the New World, or ascending the Orinoco in search of the fabled Dorado; Sidney, gallantly returning from battle on his war-horse, though struggling with the agony of his death-wound, and giving the cup of cold water to the wounded soldier, with those noble words which would alone be enough to preserve his memory forever; Essex, tossing his cap into the sea for very joy when the command is given, in compliance with his earliest entreaties, for the assault on Cadiz, and with that failing of memory so becoming to a brave man, forgetting the cautions of his sovereign, and rushing into the thickest of the fight; the naval supremacy of England completely established by the defeat of the Armada, and the great deep itself made a monument of the nation's glory.

The boast of the age of Elizabeth was the splendid specimens of humanity which it produced. "There were giants in those days." Individuals seemed to condense in themselves the attainments of hosts. The accomplishments and prowess of the men of those times inspire us with something like the feeling of wonder with which the soldier of the present day handles the sword of Robert Bruce, or the gigantic armor of Guy of Warwick. When we read the beautiful verses "addressed to the author of the Faerie Queene," by Raleigh, it is difficult to believe that they were penned by the same person whose system of tactics was adopted so triumphantly at the Spanish invasion; who was equally eminent as a general, a seaman, an explorer, and a historian; and who shone unsurpassed for knightly graces and accomplishments amid the stars of the court. Such instances were not rare and prodigious. Raleigh was not the Crichton of his age; if the compliment belongs to anyone peculiarly, it is Sidney; but as we read over the list of distinguished persons to whom Spenser addressed dedicatory stanzas to be "sent with the Faerie Queene," we become more and more at a loss to distinguish the greatest among them; and we could believe that many ages had been searched for so noble a catalogue.

The principles which formed society were precisely such as were best calculated for the finest developments of character. The old high, fervid spirit of chivalry was not lost; there were the same sense of honor, the same knightly bearing, the same passion for glory, and the same admiration for courage and prowess that had prevailed in the earlier days of its sway. But these were tempered by milder and more attractive virtues and accomplishments; the clerkly learning, which had held so humble a rank in the days when nobles could scarcely sign their names, had now risen into far higher estimation. Great warriors were now no longer ashamed to know how to read and write; on the contrary, the possession of learning and literature, the delicate arts of poetry and music, the graces of conversation and manners, were now as requisite to the full accomplishment of the knight, as his horsemanship, or his skill in the management of his lance. In a word, the sterner characteristics of the ancient knight were softened down, in the age of Elizabeth, into the more perfect and graceful attributes of the gentleman. The perfect gentleman was more completely exhibited in the days of Elizabeth than at any time before; for the chivalry and the accomplishments which were then united in the same individual, had been formerly divided between the noble and the churchman or the clerk.

Were we called upon to characterize the age in which Spenser lived, by a single word, we could find none that would better express its combined attributes, than the word which the poet uses in describing his principal hero: "In the person of Prince Arthure," says he in his letter to Raleigh, "I set forth magnificence." The age of Elizabeth was distinguished by magnificence, in the highest sense of the word, by the most brilliant display of great qualities of all kinds; and the hero of the Faerie Queene seems to be the personification of the splendid attributes of the age. A prevailing sentiment, in the mind of Spenser, was the perfectness of character to which the gentlemen of his time aspired, and on this model he fashioned his hero. He observes that "the general end, therefore, of all the books is to fashion a gentleman or noble person in gentle and virtuous discipline." And again, "I labor to pourtraict in Arthure, before he was King, the image of a brave knight, perfected in the twelve moral virtues." And as we read the gorgeous description of the prince, when he first meets the forsaken Una, we could fancy that the magnificent characteristics of the golden age of England had blended together, and blazed forth in one dazzling form before us.

JOHN KNOX HEADS THE SCOTTISH REFORMERS

A.D. 1559

In the year of Martin Luther's death (1546) Protestant doctrines were preached in Scotland by George Wishart. This reformer was burned at St. Andrew's, in the same year (March 12th), at the instigation of Cardinal Beaton. Two months later the Cardinal himself, who practically controlled the Scottish government, was murdered in the castle of St. Andrew's. Beaton's death was "fatal to the Catholic religion and to the French interest in Scotland." The interest of France was represented by the Queen Regent, Mary of Lorraine, also called Mary of Guise, daughter of Claude, Duke of Guise. She was the widow of James V of Scotland, and mother of Mary Stuart, now four years old and living in France.

During his brief season of Protestant preaching, Wishart had deeply impressed a scholar, then forty years of age, who gave up his calling as teacher, and in 1547 began to preach the reformed religion at St. Andrew's. This was John Knox.

From this moment dates the birth of the Protestant Reformation in Scotland. Knox was imprisoned by the French (1547-1549), was released, and for two years preached at Berwick. For several years now he lived a life of many vicissitudes, partly in Great Britain and partly on the Continent, and by his sermons and writings powerfully influenced the growth of the Protestant faith. While at Geneva, where he was much influenced by Calvin, in 1558, he published his First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, a denouncement which brought him into bitter antagonism with the Queen Regent and with other Catholic authorities in England and France.

In 1559 the Queen Regent took active steps for repressing the Congregation, as the whole body of Scotch Protestants were called, and in the same year Knox returned once more to Scotland, there to perform a work which made his name perhaps second only to that of Luther among the personal forces of the Reformation.

The first of the following accounts shows Knox and his followers in the midst of their warfare against the Regent's repressive policy. In the second we have one of Carlyle's most fervent eulogies, for to him Knox is the priestly hero enacting a glorious part.

The year 1559 began ominously for the success of the Queen Regent's policy of suppression. To this point national feeling and religious conviction had been the driving-forces of the coming revolution. But, as is the case in all national upheavals, there were likewise economic forces at work which were none the less potent because they were obscured behind the dramatic development of sensational events. A remarkable document, the author of which is unknown, gave striking expression to this aspect of the Scottish Reformation. It was entitled the Beggars' Summons, and purported to come from "all cities, towns, and villages of Scotland."

On January 1, 1559, this terrible manifesto, breathing the very spirit of revolution, was found placarded on the gates of every religious establishment in Scotland. The Summons begins as follows: "The blind, crooked, lame, widows, orphans, and all other poor visited by the hand of God as may not work, to the flocks of all friars within this realm, we wish restitution of wrongs past, and reformation in times coming, for salutation." It may be sufficient to quote the concluding passage of this extraordinary effusion, and it is a passage which should never be out of mind in any estimate of the forces that were about to effect the great cataclysm in the national life: "Wherefore, seeing our number is so great, so indigent, and so heavily oppressed by your false means that none taketh care of our misery, and that it is better to provide for these our impotent members which God hath given us, to oppose to you in plain controversy, than to see you hereafter, as ye have done before, steal from us our lodging, and ourselves in the mean time to perish and die for want of the same; we have thought good, therefore, ere we enter in conflict with you, to warn you in the name of the great God by this public writing, affixed on your gates where ye now dwell, that ye remove forth of our said hospitals betwixt this and the feast of Whitsunday next, so that we, the only lawful proprietors thereof, may enter thereto, and afterward enjoy the commodities of the Church which ye have heretofore wrongfully holden from us; certifying that if ye fail, we will at the said term, in whole number and with the help of God and assistance of his saints on earth, of whose ready support we doubt not, enter and take possession of our said patrimony, and eject you utterly forth of the same. Let him, therefore, that before hath stolen, steal no more; but rather let him work with his hands, that he may be helpful to the poor."

The inflammatory statements of revolutionaries must be taken for what they are worth; but there is abundant evidence to prove that the above indictment of the national Church was not without foundation in fact. It has been computed that one-half of the wealth of the country was in possession of the clergy; and we have the testimony of unimpeachable witnesses to the unworthy uses to which it was put. Hector Boece, John Major, and Ninian Winzet were all three faithful sons of the Church, and all three cried aloud at the venality, avarice, and luxurious living of the higher clergy. "But now, for many years," wrote Major, "we have been shepherds whose only care it is to find pasture for themselves, men neglectful of the duties of religion. By open flattery do the worthless sons of our nobility get the governance of convents in commendam, and they covet these ample revenues, not for the good help that they thence might render to their brethren, but solely for the high position that these places offer." To the same effect Ninian Winzet wrote after the judgment had come. "The special roots of all mischief," he says, "be the two infernal monsters, pride and avarice, of the which unhappily has up-sprung the election of unqualified bishops and other pastors in Scotland."

This spectacle of the national Church, with its disproportionate wealth and its selfish, incompetent, and often degraded officials, could not but be a growing offence to the developing intelligence of the nation; and to quicken this feeling there were minor grievances which were an ancient ground of complaint on the part of the laity against their spiritual advisers. On every important event of his life the poor man was harassed by exactions which Sir David Lyndsay has so keenly touched in his Satire of the Three Estates. Says the Pauper in the interlude:

"Quhair will ye find that law, tell gif ye can,

To tak thine ky, fra ane pure husbandman?

Ane for my father, and for my wyfe ane uther,

And the third cow, he tuke fra Mald my mother."

And Diligence replies:

"It is thair law, all that they have in use,

Tocht it be cow, sow, ganer, gryse, or guse."

If the poor had these grounds of discontent, the rich likewise had theirs; and they made bitter complaint against the protracted processes in the consistorial courts, and the frequent appeals to the Roman Curia, by which both their means and their patience were exhausted.

It was in the face of feelings such as these that, in the spring of 1559, the Queen Regent entered on her new line of policy toward her refractory subjects. Her first steps were taken with her usual prudence. A provincial council of the clergy was summoned to meet on March 1st for the express purpose of dealing with the religious difficulty. It was the last provincial council of the ancient Church that was to meet in Scotland; and, if the expression of its good intentions could have availed, the Church might yet have been saved. All that its worst enemies had said of its shortcomings was frankly admitted, and admirable decrees were passed with a view to a speedy and effective reform. But the hour had passed when the mere reform of life and doctrine would have sufficed to meet the desires of the new spiritual teachers. As was speedily to be seen, it was revolution and not reform on which these new teachers were now bent with an ever-growing confidence that their triumph was not far off. A double order issued by the Regent toward the end of March brought her face to face with the consequences of her changed policy. Unauthorized persons were forbidden to preach, and the lieges were commanded to observe the festival of Easter after the manner ordained by the Church. The preachers disregarded both edicts and were summoned to answer for their disobedience.