Title: The Story of the 2/4th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

Author: Geoffrey Keith Rose

Release date: January 18, 2007 [eBook #20395]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Geetu Melwani, Christine P. Travers, Carl Hudkins, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net/c/) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries (http://www.archive.org/details/toronto)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/24thoxfordshire00roseuoft |

A Soldier of the Battalion

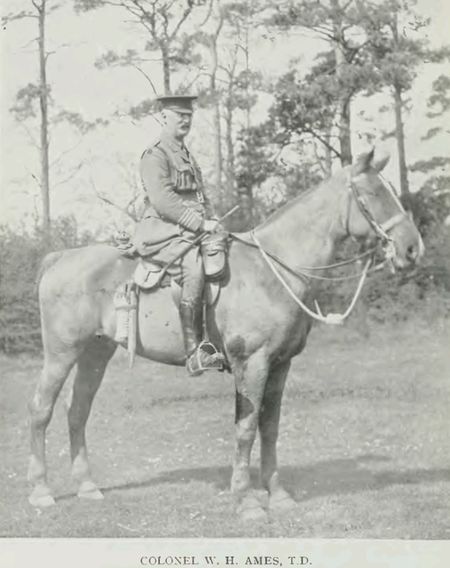

Colonel W. H. Ames, T.D.

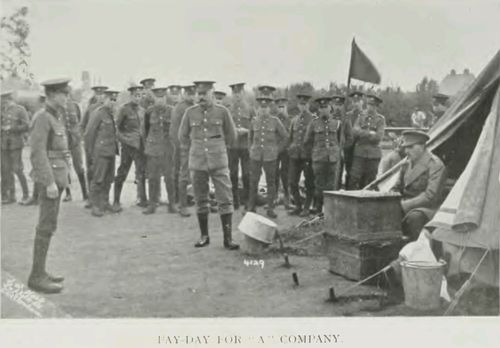

Pay-day for 'A' Company

Robecq from the South

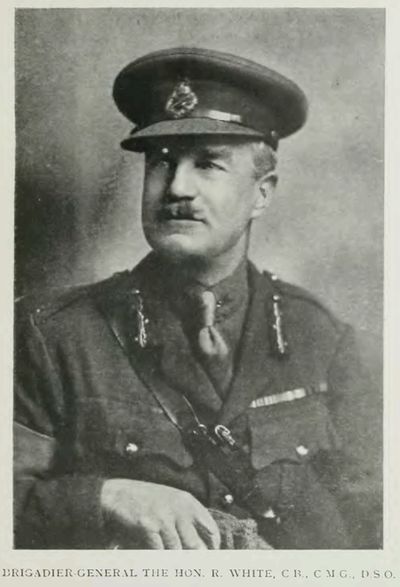

Brigadier-General the Hon. R. White, C.B.

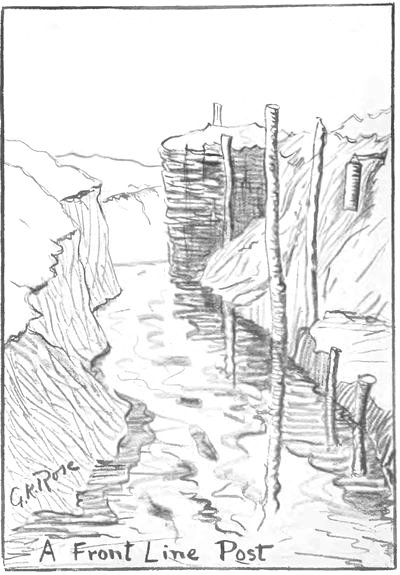

A Front-line Post

Company Sergeant-Major E. Brooks, V.C.

Vlamertinghe—The Road to Ypres

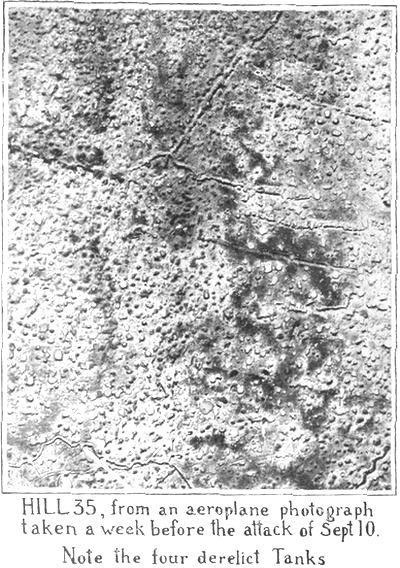

Hill 35, from an aeroplane photograph

A Street in Arras

'Tank Dump'

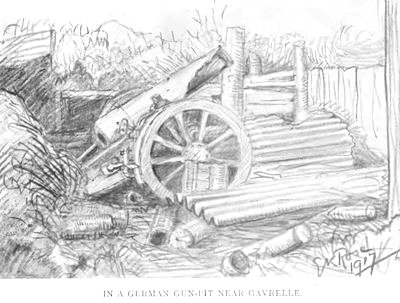

In a German gun-pit near Gavrelle

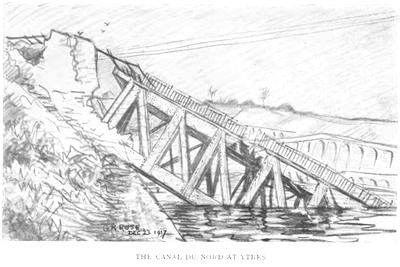

The Canal du Nord at Ypres

Lieut.-Colonel H. E. de R. Wetherall, D.S.O., M.C.

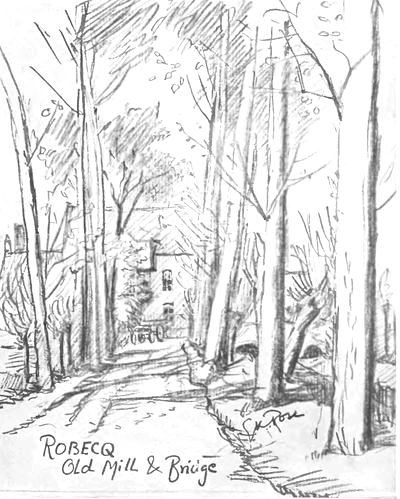

Robecq. Old Mill and Bridge

The Headquarters Runners, July, 1918

Corporal A. Wilcox, V.C.

Officers of the Battalion, December, 1918

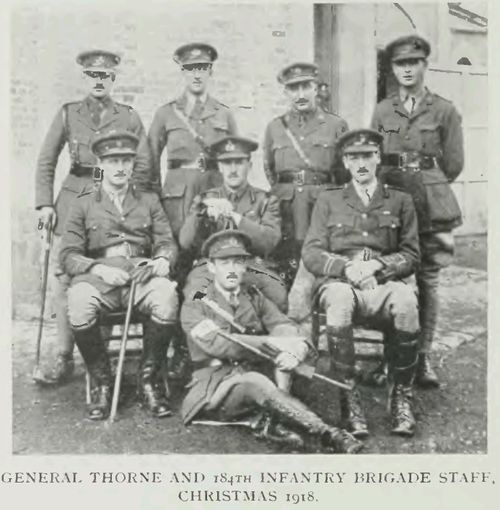

184th Infantry Brigade Staff

The Adjutant. Cambrai. The Battalion Cooks

Lieut.-Colonel E. M. Woulfe-Flanagan, C.M.G., D.S.O.

R.S.M. W. Hedley, D.C.M.

R.Q.M.S. Hedges

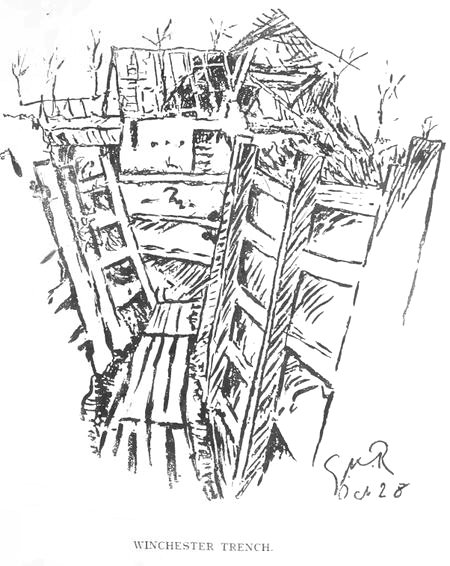

Winchester Trench

The March to the Somme

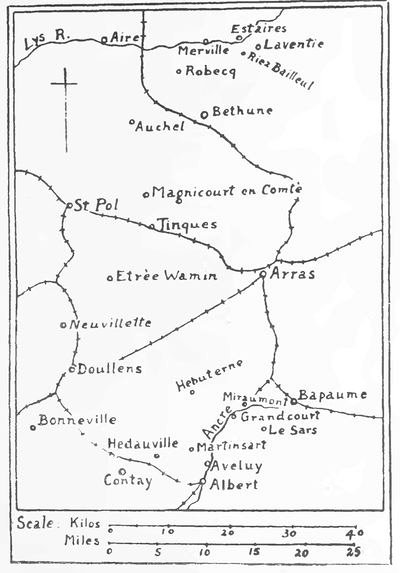

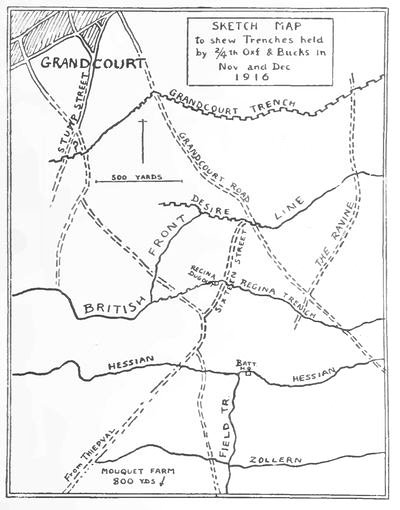

Somme Trench Map

Maison Ponthieu

Harbonnières

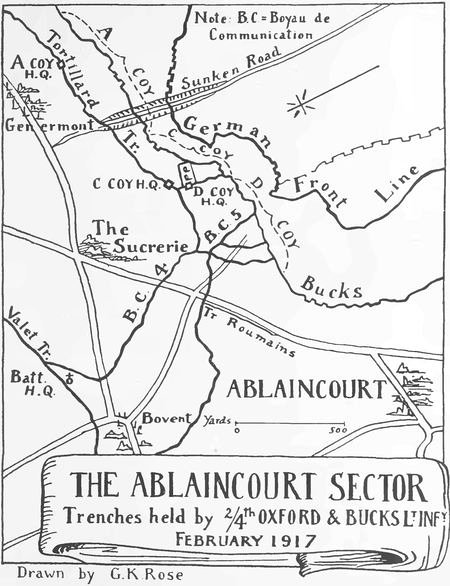

The Ablaincourt Sector

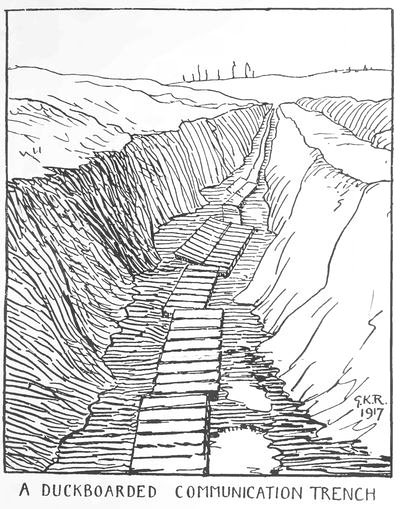

A Duckboarded Communication Trench

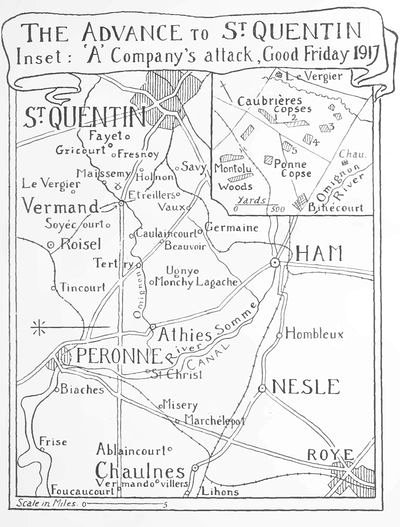

The Advance to St. Quentin

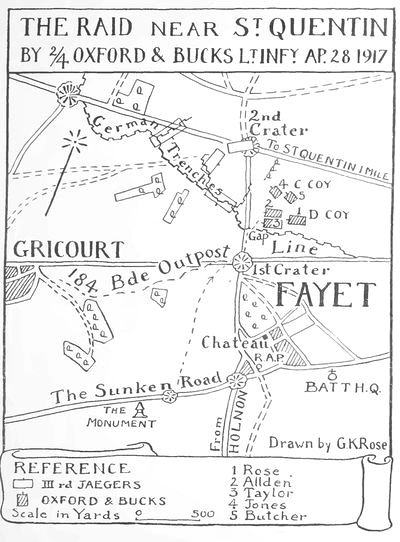

The Raid near St. Quentin

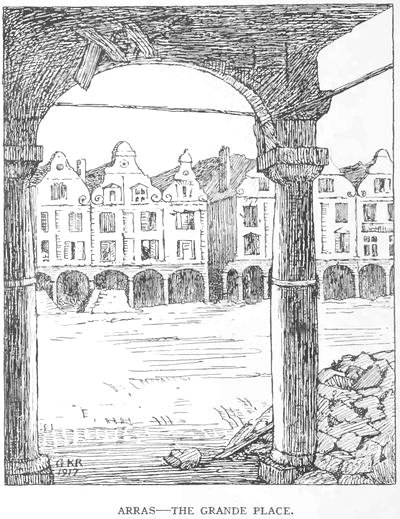

Arras: The Grande Place

Noeux Village

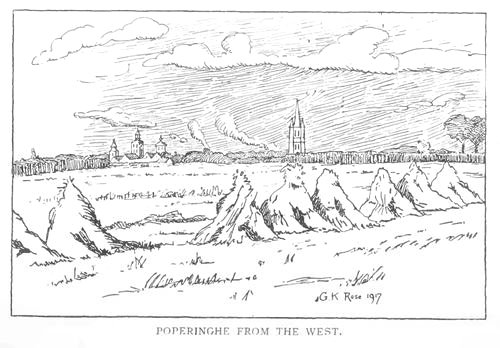

Poperinghe from the West

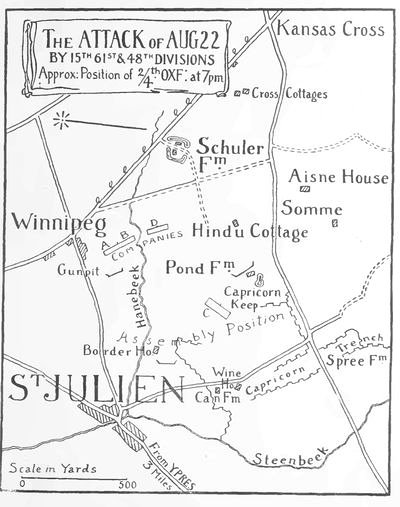

The Attack of August 22, 1917

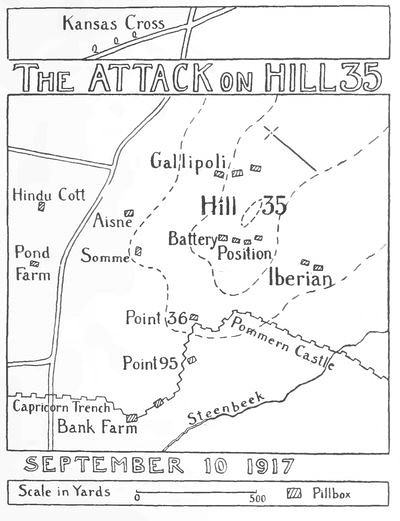

The Attack on Hill 35

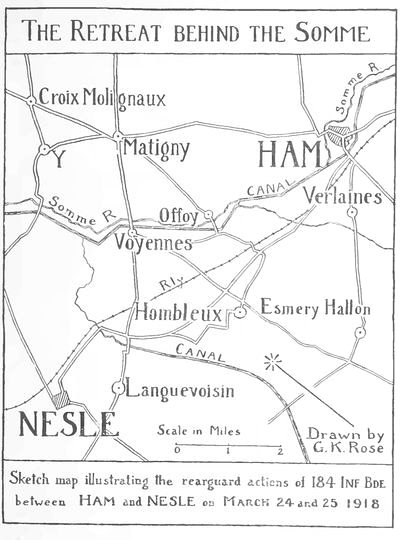

The Retreat behind the Somme

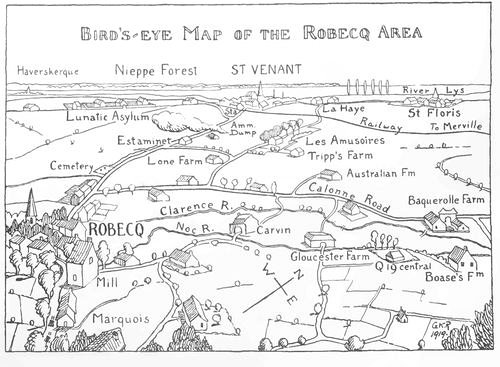

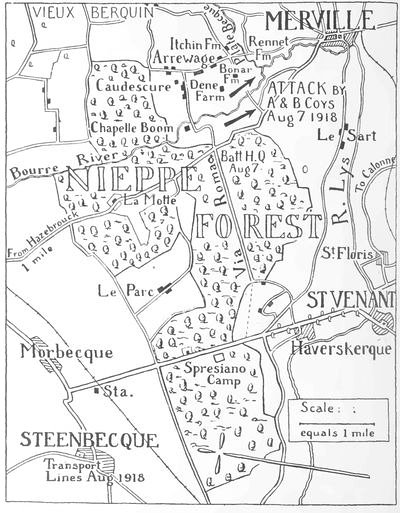

Bird's-eye Map of the Robecq Area

The Nieppe Forest

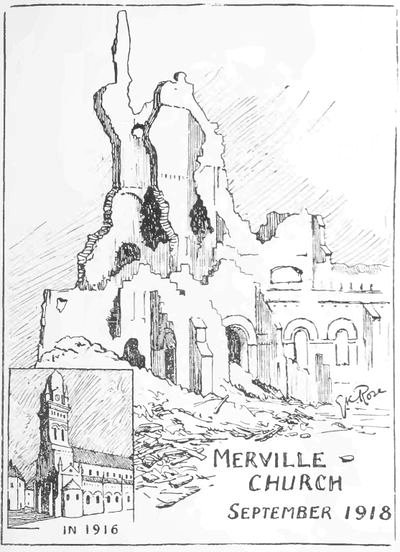

Merville Church

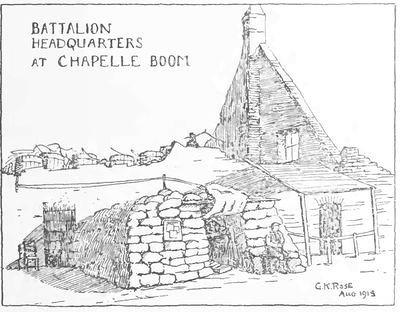

Battalion H.Q. at Chapelle Boom

Chapter I. LAVENTIE, May to October, 1916

The 61st Division lands in France. — Instruction. — The Laventie sector. — Trench warfare at its height. — Moberly wounded. — B Company's raid. — Front and back areas. — July 19. — Changes in the Battalion. — A Company's raid. — A projected attack. — Laventie days. — Departure for the Somme.

Chapter II. THE SOMME BATTLEFIELD, November, 1916

Departure from Laventie. — At Robecq. — The march southwards. — Rest at Neuvillette. — Contay Wood. — Albert. — New trenches. — Battle conditions. — Relieving the front line. — Desire Trench. — Regina dug-out. — Mud and darkness. — A heavy barrage. — Fortunes of Headquarters. — A painful relief. — Martinsart Wood.

Chapter III. CHRISTMAS ON THE SOMME, December, 1916

The move from Martinsart to Hedauville. — Back to Martinsart. — Working parties. — Dug-outs at Mouquet Farm. — Field Trench. — Return to the front line. — Getting touch. — Guides. — An historic patrol. — Christmas in the trenches.

Chapter IV. AT MAISON PONTHIEU, January-February, 1917

Visitors to the Battalion. — The New Year. — A wintry march. — Arrival at Maison Ponthieu. — Severe weather. — At war with the cold. — Training for offensive action. — By rail to Marcelçave. — Billets at Rainecourt. — Reconnoitring the French line near Deniécourt.

(p. vi) Chapter V. IN THE ABLAINCOURT SECTOR, February, 1917

German retreat foreshadowed. — The Battalion takes over the Ablaincourt Sector. — Issues in the making. — Lieutenant Fry mortally wounded. — The raid by German storm-troops on February 28. — The raid explained.

Chapter VI. LIFE IN THE FRONT LINE, Winter, 1916-1917

Ignorance of civilians and non-combatants. — The front line posts. — Hardships and dangers. — Support platoons. — The Company Officers. — The Battalion relieved by the 182nd Brigade.

Chapter VII. THE ADVANCE TO ST. QUENTIN, March to April, 1917

The enemy's retirement. — Road-mending in No-Man's-Land. — The devastated area. — Open warfare. — The Montolu campaign. — Operations on the Omignon river. — The 61st Division relieved before St. Quentin. — End of trench-warfare.

Chapter VIII. THE RAID AT FAYET, April, 1917

A German vantage-point. — Shell-ridden Holnon. — A night of confusion. — Preparing for the raid of April 28. — The enemy taken by surprise. — The Battalion's first V.C. — The affair at Cepy Farm.

Chapter IX. ARRAS AND AFTERWARDS, May, June, July, 1917

Relief by the French at St. Quentin. — A new Commanding Officer. — At the Battle of Arras. — Useful work by A Company. — Harassing fire. — A cave-dwelling. — At Bernaville and Noeux. — In G.H.Q. reserve. — A gas alarm by General Hunter Weston. — The Ypres arena.

Chapter X. THE THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES, August, 1917

A Battalion landmark. — Poperinghe and Ypres. — At Goldfish Château. — The attack near St. Julien on August 22. — Its results. — A mud-locked battle. — The back-area. — Mustard gas. — Pill-box warfare.

(p. vii) Chapter XI. THE ATTACK ON HILL 35, September, 1917

Iberian, Hill 35, and Gallipoli. — The Battalion ordered to make the seventh attempt against Hill 35. — The task. — A and D Companies selected. — The assembly position. — Gassed by our own side. — Waiting for zero. — The attack. — Considerations governing its failure. — The Battalion quits the Ypres battlefield.

Chapter XII. AUTUMN AT ARRAS AND THE MOVE TO CAMBRAI, October, November, December, 1917

The Battalion's return to Arras. — A quiet front. — The Brigadier and his staff. — A novelty in tactics. — B Company's raid. — A sudden move. — The Cambrai front. — Havrincourt Wood. — Christmas at Suzanne.

Chapter XIII. THE GREAT GERMAN ATTACK OF MARCH 21, January-March, 1918

(p. viii) The French relieved on the St. Quentin front. — The calm before the storm. — A golden age. — The Warwick raid. — The German attack launched. — Defence of Enghien Redoubt. — Counter-attack by the Royal Berks. — Holnon Wood lost. — The battle for the Beauvoir line. — The enemy breaks through.

Chapter XIV. THE BRITISH RETREAT, March, 1918

Rear-guard actions. — The Somme crossings. — Bennett relieved by the 20th Division at Voyennes. — Davenport with mixed troops ordered to counter-attack at Ham. — Davenport killed. — The enemy crosses the Somme. — The stand by the 184th Infantry Brigade at Nesle. — Colonel Wetherall wounded. — Counter-attack against La Motte. — Bennett captured. — The Battalion's sacrifice in the great battle.

Chapter XV. THE BATTLE OF THE LYS, April-May, 1918

Effects of the German offensive. — The Battalion amalgamated with the Bucks. — Entrainment for the Merville area. — A dramatic journey. — The enemy break-through on the (p. ix) Lys. — The Battalion marches into action. — The defence of Robecq. — Operations of April 12, 13, 14. — The fight for Baquerolle Farm. — A troublesome flank. — Billeted in St. Venant. — The lunatic asylum. — La Pierrière. — The Robecq sector.

Chapter XVI. THE TURNING OF THE TIDE, May, June, July, August, 1918

Rations and the Battalion Transport. — At La Lacque. — The bombing of Aire. — General Mackenzie obliged by his wound to leave the Division. — Return of Colonel Wetherall. — Tripp's Farm on fire. — A mysterious epidemic. — A period of wandering. — The march from Pont Asquin to St. Hilaire. — Nieppe Forest. — Attack by A and B Companies on August 7. — Headquarters gassed. — A new Colonel. — The Battalion goes a-reaping.

Chapter XVII. LAST BATTLES, August to December, 1918

German retreat from the Lys. — Orderly Room and its staff. — The new devastated area. — Itchin Farm, Merville and Neuf Berquin. — Mines and booby-traps. — Advance to the Lys. — Estaires destroyed. — Laventie revisited. — The attack on Junction Post. — Lance-Corporal Wilcox, V.C. — Scavenging at the XI Corps school. — On the Aubers ridge. — The end in sight. — Move to Cambrai. — In action near Bermerain and Maresches. — A fine success. — Domart and Demobilisation. — Work at Etaples. — Off to Egypt.

Composition of the Battalion on going Overseas

Composition of the Battalion at the Armistice

My cordial thanks are due to my old Brigadier for his kindness and trouble in writing the Preface, and also to Colonel Ames for contributing the Introduction.

From many friends in the Regiment I have received information and assistance.

This book is based on a series of articles, which appeared in the Oxford Times during the summer of 1919. The project, of which this volume is the outcome, was assisted by that newspaper and by the courtesy of its staff.

G. K. ROSE.

Oxford, November 1919.

My friend, Major G. K. Rose, has set out to describe the doings of the 2/4th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry during the Great War.

If I judge his purpose rightly, he designs to paint without exaggeration and without depreciation a picture which shall recall not only now, but more especially in the days to come, the wonderful years during which we ceased to be individuals pursuing the ordinary avocations of life and became indeed a band of brothers, linked together in a common cause and inspired, however subconsciously, by one common hope and interest. If I am correct in my surmise, then I think that Major Rose has written particularly for his comrades of the 2/4th Oxfords and, in a wider sense, of the 184th Infantry Brigade and the 61st Division. And in doing this he seems to me to be performing a great service.

Unfettered by the necessity of drawing an attractive picture and of appealing to the natural desire of the general reader for dramatic and sensational episode, he can rely on his readers to fill in for themselves the emotional and psychological aspects of the narrative. We, his comrades, have but to turn the pages of his story to live again those marvellous days and to feel the hopes and fears, the pathos and the fun, the excitement and the weariness, and the hundred other emotions which gave to life in the Great War a sense of adventure which we can hardly hope to savour again.

It (p. xii) is perhaps right that those who through poor health, age, bad luck or other causes, were unable to leave home and take an active part in the life of the front line, should generously speak of their more fortunate compatriots as 'heroes.' The term is somewhat freely used in these days. I am, however, happy to think that the British officer and soldier is not apt to consider himself in that light and has, indeed, a distinct aversion from being so described. Rather does he pride himself, in his quiet way, on his light-hearted and stoical indifference to danger and discomfort and his power to see the comical and cheery side of even the most appalling incidents in war. Long may this be so.

Viewed in this light, Major Rose's book will in after years give a true picture of the experiences of an English Territorial Battalion in the 'Great Adventure.' Shorn of fictitious glamour, events are narrated as they presented themselves to the regimental officers, non-commissioned officers, and men who bore the heat and burden of the day.

Having said so much, I may be allowed to think that Major Rose is almost too reticent and modest as regards the splendid record of his Battalion.

After the 'big push' of July, 1916, on the Somme, I had the honour to be promoted to the command of the 184th Infantry Brigade, 61st Division. In September I found the Brigade occupying a portion of the line in front of Laventie, just north of Neuve Chapelle. The 61st Division, recently landed from England and before it had had time to 'feel its feet,' had to be pushed into an attack against the enemy's position in front of the Aubers ridge. (p. xiii) In this attack it suffered severe losses. The Division, naturally, was burning to 'get its own back.' Unfortunately it had for some weeks to content itself with routine work in the Flanders trenches.

In this connection I may remark that the 61st Division had an unduly large share of the 'dirty work' of demonstrations, secondary operations, and taking over and holding nasty parts of the line. Those who have been through this mill will sympathise, knowing how credit was apt to go to those who took part in the first 'big push' rather than to the luckless ones who had to relieve attacking divisions and take over the so-called trenches which had been won from the enemy. Those trenches had to be consolidated under a constant and accurate bombardment. However, grumbling was not the order of the day, and during the last year of the war the 61st Division came into its own. It received in frequent mentions and thanks from the Commander-in-Chief and the higher command the just reward for its loyal spade work and splendid fighting qualities.

In November, 1916, the 184th Infantry Brigade and the 2/4th Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry found themselves, as the narrative shows, on classic ground near Mouquet Farm. Here I was first thrown into close contact with the Battalion and learned to know and value it. The work was, if you like, mere routine, mere holding the line. But what a line! Shall we ever forget Regina and Desire trenches, with their phenomenal mud and filth; or Rifle Dump and Sixteen Street and Zollern Redoubt—and (p. xiv) Martinsart Wood and the 'rest' there? Names, names! but with what memories!

I am tempted to follow the fortunes of the Battalion through the varied scenes of its experience. I should like to talk of happy mornings 'round the line' with Colonel or Adjutant, or cheery lunches with good comrades in impossibly damp and filthy dug-outs, of midnight assemblies before, and early-morning greetings after, successful raids, and of how we inspected Boche prisoners, machine-guns and other 'loot.'

I should like to recall memories of such comrades as Bellamy and Wetherall, Cuthbert, Bennett, Davenport, 'Slugs' Brown, Rose, 'Bob' Abraham, Regimental Sergeant-Major Douglas, Company Sergeant-Major Brooks, V.C., and a host of other friends of all ranks.

I look back with pride on many stirring incidents.

Among these I recall the raid near St. Quentin on April 28, 1917, admirably planned and carried out by Captain Rose and his company, and resulting in the capture of two machine-guns and prisoners of the 3rd Prussian Jaeger regiment, three companies of which were completely surprised and outflanked by the dashing Oxford assault. On this occasion Company Sergeant-Major Brooks deservedly won the V.C. and added lustre to the grand records of his regiment.

Equally gallant was the fine stand made by the Oxfords on August 22 and 23, 1917, in front of Ypres. Captain Moberly and his brave comrades, surrounded by the enemy and completely isolated, stuck (p. xv) doggedly for 48 hours to the trench which marked the furthest point of the Brigade's objective.

Few battalions of the British Army could boast a finer feat of arms than the holding of the Enghien Redoubt by Captain Rowbotham, 2nd Lieutenant Cunningham, Regimental Sergeant-Major Douglas and some 150 men of D Company and Battalion Headquarters. From 10.30 a.m. till 4.30 p.m. on March 21, 1918, these brave soldiers, enormously outnumbered and completely surrounded, stemmed the great tide of the German attack and by their devoted self-sacrifice enabled their comrades to withdraw in good order. 2nd Lieutenant Cunningham, the sole surviving officer for many hours, remained in touch with Brigade Headquarters by buried cable until the last moment. Further resistance being hopeless, he received my instructions, after a truly magnificent defence, to destroy the telephone instruments and cut his way out.

But I must not encroach on the domain of our author, a real front line officer, who lived with his men throughout the war under real front line conditions.

It fell to my lot for 18 months to have the Battalion amongst those under my command. Attacking, resting, raiding, marching, the 2/4th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry not only upheld but enhanced the glory of the old 43rd and 52nd Regiments of the Line.

ROBERT WHITE,

Brigadier General.

The raising of the Second Line of the Territorial Force became necessary when it was decided to send the First Line overseas. The Territorial Force was originally intended for home defence, a duty for which its pre-war formations soon ceased to be available. The early purpose, therefore, of the Second Line was to defend this country.

On September 8, 1914, I was privileged to begin to raise the 2/4th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, the Battalion whose history is set out in the following pages. I opened Orderly Room in Exeter College, Oxford, and enrolled recruits. The first was Sergeant-Major T. V. Wood. By the end of the day we had sworn in and billeted over 130 men.

The Battalion was created out of untrained elements, but what the recruits lacked in experience they made up in keenness. The Secretary of the County Association had an excellent list of prospective officers, but these had to learn their work from the beginning. We were lucky to secure the services of several non-commissioned officers with Regular experience; Colour-Sergeants Moore, Williams, Bassett and Waldon, and Sergeant Howland worked untiringly, whilst the keenness of the officers to qualify themselves to instruct their men was beyond praise.

At (p. 002) the end of ten days sufficient recruits had been enrolled to allow the formation of eight companies, which exactly reproduced those of the First Line, men being allotted to the companies according to the locality whence they came. A pleasant feature was the number of Culham students, who came from all parts of England to re-enlist in their old Corps. Well do I remember my feelings when I sat down to post the officers to the companies. It was a sort of 'Blind Hookey,' but seemed to pan out all right in the end. Company officers had to use the same process in the selection of their non-commissioned officers. Of these original appointments all, or nearly all, were amply justified—a fact which said much for the good judgment displayed.

With the approach of the Oxford Michaelmas Term the Battalion had to move out of the colleges (New College, Magdalen, Keble, Exeter, Brasenose and Oriel had hitherto kindly provided accommodation) and into billets. Training was naturally hurried. As soon as the companies could move correctly a series of battalion drills was carried out upon Port Meadow. This drill did a great deal to weld the Battalion together. The elements of digging were imparted by Colonel Waller behind the Headquarters at St. Cross Road, open order was practised on Denman's Farm, whilst exercises in the neighbourhood of Elsfield gave the officers some instruction in outpost duties and in the principles of attack and defence.

The important rudiments of march discipline were soon acquired. Weekly route marches took place almost from the first. Few roads within a radius (p. 003) of 9 miles from Oxford but saw the Battalion some time or other. The Light Infantry step caused discomfort at first, but the Battalion soon learned to take a pride in it. The men did some remarkable marches. Once they marched from the third milestone at the top of Cumnor Hill to the seventh milestone by Tubney Church in 57 minutes. Just before Christmas, 1914, they marched through Nuneham to Culham Station and on to Abingdon, and then back to Oxford through Bagley Wood, without a casualty.

At the end of 1914 Second Line Divisions and Brigades were being formed, and the 2/4th Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry became a unit of the 184th Infantry Brigade under Colonel Ludlow, and of the 61st Division under Lord Salisbury. Those officers inspected the Battalion at Oxford before it left, at the end of January, 1915, for Northampton.

The move from Oxford terminated the first phase in the Battalion's history. At Northampton fresh conditions were in store. Smaller billets and army rations replaced the former system of billets 'with subsistence.' Elementary training was reverted to. The Battalion was armed with Japanese rifles, a handy weapon, if somewhat weak in the stock, and range work commenced. The seven weeks at Northampton, if not exactly relished at the time, greatly helped to pull the Battalion together. The period was marked by a visit of General Sir Ian Hamilton, who inspected and warmly complimented the men on their turn-out.

A minor incident is worthy of record. One Saturday night a surprise alarm took place about midnight. (p. 004) The Battalion was young, and the alarm was taken very seriously. Even the sick turned out rather than be left behind, and marched the prescribed five miles without ill effects.

Just before Easter, 1915, the 61st Division moved into Essex in order to occupy the area vacated by the 48th. The Battalion's destination was Writtle, where the amicable relations already established with the inhabitants by Oxfordshire Territorials were continued. Though our stay was a short one, we received a hearty welcome, when, on our return from Epping, we again marched through the village.

After a fortnight at Writtle, the Battalion moved to Hoddesdon, to take part in digging the London defences. We left Writtle 653 strong at 8 a.m., and completed the march of 25 miles at 5 p.m., with every man in the ranks who started. Three weeks later we were ordered to Broomfield, a village east of Writtle and near Chelmsford. There was keen competition to take part in the return march from Hoddesdon; 685 men started on the 29 mile march, which lasted 11 hours; only 3 fell out. The band marched the whole way and played the Battalion in on its arrival at Broomfield.

In the spring of 1915 it was decided to prepare the Territorial Second Line for foreign service. Considerable improvement resulted in the issue of training equipment. Boreham range occupied much of our time. A musketry course was begun but never finished; indeed, the bad condition of the rifles made shooting futile. Six weeks were also spent at Epping in useful training, at the conclusion of (p. 005) which we returned to Broomfield. The Battalion was billeted over an area about six miles long by one wide, until leave was obtained for a camp. For nearly three months the men were together under canvas, with the very best results. Strenuous training ensued. I am reminded of a little incident which occurred during some night digging at Chignal Smealy. The object of the practice was to enure the men to work, not only when fresh, but when tired. Operations opened with digging with the entrenching tool—each man to make cover for himself. By 8 p.m. this stage had been reached, so tea and shovels were issued. At 9 p.m. serious digging began, the shelters being converted into trenches, and this continued till 1.30 a.m. Coffee was then served, and work went on till dawn, which provided an opportunity to practise standing-to. A rest followed, but after breakfast work was again resumed. About 10 a.m. an officer found a man sitting down in the trenches and ordered him to renew his efforts. The man obeyed the order at once, but was heard to remark to his neighbour, 'Well! If six months ago a bloke had told me that I was a-going to work the 'ole ruddy night and the 'ole ruddy day for one ruddy bob, I'd never 'ave believed him!'

At the end of October, 1915, I consider that the Battalion reached the zenith of its efficiency during its home service. It was a great pity that the Division could not have been sent abroad then. Instead, each battalion was reduced in November to a strength of 17 officers and 600 men. Individual training recommenced, until specialists of every kind flourished (p. 006) and multiplied. At a General's inspection during the winter a most varied display took place. Scouts were in every tree, a filter party was drawing water from the village pond, cold shoeing was being practised at the Transport, cooking classes were busy making field ovens, wire entanglements sprang up on every side, nor was it possible to turn a corner without encountering some fresh form of activity. I fancy the authorities were much impressed on this occasion, for nothing was more difficult than to show the men, as they normally would be, to an inspecting officer.

In January, 1916, the Battalion, having been recently made up with untrained recruits, moved to Parkhouse Camp on Salisbury Plain to complete its training with the rest of the Division. We arrived in frost and snow and left, three months later, in almost tropical heat—remarkable contrasts within so short a period. The Division was speedily completed for foreign service; new rifles were issued, with which a musketry course was successfully fired, though snow showers did not favour high scoring. We were made up to strength with drafts from the Liverpool, Welsh, Dorset, Cambridge, and Hertfordshire Regiments, were inspected by the King, and embarked as a unit of the first Second Line Division to go abroad.

Thus at the end of 18 months' hard work the preparatory stage in the Battalion's history was concluded. Its subsequent life is traced in the chapters of this volume.

The period of home service is wrapped in pleasant memory. It was not always plain sailing, but (p. 007) difficulties were lightened by the wonderful spirit that animated all ranks and the pride which all felt in the Battalion. I recall especially the work of some who have not returned; Davenport, Scott, Stockton, Zeder, and Tiddy among the officers, and among the non-commissioned officers and men a host of good comrades. Nor do I forget those who came safely through. No commanding officer was ever better supported, and my gratitude to them all is unending. I think the Battalion was truly animated by the spirit of the famous standing order, 'A Light Infantry Regiment being expected to approach nearer to perfection than any other, more zeal and attention is required from all ranks in it.' Equally truly was it said that not by the partial exertions of a few, but by the united and steady efforts of all, was the Battalion formed and its discipline created and preserved.

W. H. AMES, Colonel.

The 61st Division lands in France. — Instruction. — The Laventie sector. — Trench warfare at its height. — Moberly wounded. — B Company's raid. — Front and back areas. — July 19th. — Changes in the Battalion. — A Company's raid. — A projected attack. — Laventie days. — Departure for the Somme.

On May 24, 1916, the 2/4th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry landed in France. Members of the Battalion within a day or two were addressing their first field postcards to England. Active service, of which the prospect had swung, now close, now far, for 18 months, had begun.

The 61st Division, to which the Battalion belonged, concentrated in the Merville area. The usual period of 'instruction' followed. The 2/4th Oxfords went to the Fauquissart sector, east of Laventie. Soon the 61st relieved the Welsh Division, to which it had been temporarily apprenticed, and settled down to hold the line.

It (p. 009) was not long before the Battalion received what is usually termed its 'baptism of fire.' Things were waking up along the front in anticipation of the Franco-British attack on the Somme. Raids took place frequently. Fighting patrols scoured No-Man's-Land each night. In many places at once the enemy's wire was bombarded to shreds. By the end of June an intense feeling of expectancy had developed; activity on both sides reached the highest pitch. The Battalion was not slow in playing its part. One of the early casualties was Lieutenant Moberly, who performed a daring daylight reconnaissance up to the German wire. He was wounded and with great difficulty and only through remarkable pluck regained our lines.

That same night the Battalion did its first raid, by B Company under Hugh Davenport. The raid was ordered at short notice and was a partial success. If the tangible results were few, B Company was very properly thanked for its bravery on this enterprise, which had to be carried out against uncut wire and unsubdued machine-guns. Zeder, a lieutenant with a South African D.C.M., was mortally wounded on the German wire and taken prisoner. The casualties were numerous. Davenport himself was wounded, but unselfishly refused treatment until his men had been fetched in. It was a night of battle and excitement. To the most hardened troops a barrage directed against crowded breastworks was never pleasant. The Battalion bore itself well and earned recital, albeit with some misdescription, in the English press a few days later.

During (p. 010) July 1916 the Battalion was in and out of the breastworks between Fauquissart and Neuve Chapelle. When the 184th Infantry Brigade went back to rest the Battalion had billets on the outskirts of Merville, a friendly little town, since levelled in ruins; and, when reserve to the Brigade, in Laventie. Brigade Headquarters were at the latter and also the quartermasters' stores and transport of battalions in the line.

Some favourite spots were the defensive 'posts,' placed a mile behind the front line and known as Tilleloy, Winchester, Dead End, Picantin. Reserve companies garrisoned these posts. No arduous duties spoilt the days; night work consisted chiefly in pushing trolley-loads of rations to the front line. Of these posts the best remembered would be Winchester, where existed a board bearing the names of Wykhamists, whom chance had led that way. Battalion Headquarters were there for a long time and were comfortable enough with many 'elephant' dug-outs and half a farmhouse for a mess—the latter ludicrously decorated by some predecessors with cuttings from La Vie Parisienne and other picture papers.

Though conditions were never quiet in the front line, during the summer of 1916 back area shelling was infrequent. Shells fell near Laventie cross-roads on most days and, when a 12 inch howitzer established itself behind the village, the Germans retaliated upon it with 5.9s, but otherwise shops and estaminets flourished with national nonchalance. The railway, which ran from La Gorgue to Armentières, was used by night as far as Bac St. Maur—an (p. 012) instance of unenterprise on the part of German gunners. Despite official repudiation, on our side the principle of 'live and let live' was still applied to back areas. Trench warfare, which in the words of a 1915 pamphlet 'could and must cease' had managed to survive that pamphlet and the abortive strategy of the battle of Loos. Until trench warfare ended divisional headquarters were not shelled.

Meanwhile the comparative deadlock in the Somme fighting rendered necessary vigorous measures against the enemy elsewhere on the front. A gas attack from the Fauquissart sector was planned but never carried out. Trench mortars and rifle grenades were continuously employed to make life as unpleasant as possible for the enemy, whose trenches soon became, to all appearances, a rubbish heap. All day and much of the night the 'mediums' fell in and about the German trenches and, it must be confessed, occasionally in our own as well. Whilst endeavouring to annihilate the Wick salient or some such target, one of our heaviest of heavy trench mortars dropped short (perhaps that is too much of a compliment to the particular shot) in our trenches near a company headquarters and almost upon a new concrete refuge, which the R.E. had just completed and not yet shown to the Brigadier. Though sometimes supplied, the co-operation of this arm was never asked for.

This harassing warfare had a crisis in July. The operations of July 19, which were shared with the 61st Division by the 5th Australian holding trenches further north, were designed as a demonstration to assist our attack upon the Somme and to (p. 013) hold opposite to the XI Corps certain German reserves, which, it was feared, would entrain at Lille and be sent south. That object was achieved, but at the cost of severe casualties to the divisions engaged, which were launched in daylight after artillery preparation, which results proved to have been inadequate, against a trench-system strongly manned and garrisoned by very numerous machine-guns. The objectives assigned to the 61st Division were not captured, while the Australians further north, after entering the German trenches and taking prisoners, though they held on tenaciously under heavy counter-attacks, were eventually forced to withdraw. 'The staff work,' said the farewell message from the XI Corps to the 61st Division three months later, 'for these operations was excellent.' Men and officers alike did their utmost to make the attack of July 19 a success, and it behoves all to remember the sacrifice of those who fell with appropriate gratitude. It was probably the last occasion on which large parties of storming infantry were sent forward through 'sally ports.' The Battalion was in reserve for the attack. C Company, which formed a carrying party during the fighting, lost rather heavily, but the rest of the Battalion, though moved hither and thither under heavy shelling, suffered few casualties. When the battle was over, companies relieved part of the line and held the trenches until normal conditions returned.

Soon after these events the Battalion was unlucky to be deprived of Colonel Ames, a leader whose energy and common sense could ill be spared. (p. 014) This was the first change which the Battalion had in its Commanding Officer, and it was much regretted. A change in Adjutant had occurred likewise, Major D. M. Rose having been invalided to England early in July and his place taken by R. F. Cuthbert, formerly commander of D Company. Orderly Room work passed from safe hands into hands equally safe. Soon afterwards I joined the Battalion, having been transferred from the 1/4th, and received command of D Company. The new Commanding Officer, Major R. Bellamy, D.S.O., came from the Royal Sussex Regiment and assumed command early in August. Robinson, an officer from the Middlesex and one of the best the Battalion ever had, Callender and Barton also joined about this time. Brucker, of C Company, became Adjutant of the 61st Divisional School, and command of his company passed to Kenneth Brown, a great fighter and best of comrades, the first member of this Battalion to win the Military Cross. Major Beaman was still Second in Command. Two original officers of the 2/4th, Jack Bennett and Hugh Davenport, commanded A and B Companies respectively. W. A. Hobbs, well known as Mayor of Henley, was Quartermaster, and 'Bob' Abraham the Transport Officer. Regimental Sergeant-Major Douglas and Regimental Quartermaster-Sergeant Hedges were the senior warrant officers.

Higher up a new Brigadier in the person of General Dugan arrived and held command for a short while. The General, I regret to say, did not stay long enough for the full benefit of his experience and (p. 015) geniality to accrue, a fragment of a Stokes' mortar shell wounding him at a demonstration near Merville and causing his retirement to hospital. The new Brigadier, the Hon. R. White, C.M.G., joined us at the beginning of September, 1916, from action on the Somme, and soon made his cheery criticisms felt.

After the operations of July 19 the former methods of trench warfare were resumed. The Division's casualties in the attack had been over 2,000, and time was required to reorganise and make up these losses.

Early in August an unlucky shell deprived the Battalion of one of its best officers. Lieutenant Tiddy had joined the Infantry in a spirit of duty and self-sacrifice, which his service as an officer had proved but to which his death more amply testified. The regrets of friends and comrades measured the Battalion's loss.

At 10 p.m. on August 19 a raid upon the German trenches near the 'Sugar Loaf' was carried out by A Company. The raid was part of an elaborate scheme in which the Australians upon the left and the 2/5th Gloucesters on our own front co-operated. The leading bombing party, which Bennett sent forward under Sergeant Hinton, quickly succeeded in reaching the German parapet and was doing well, when a Mills bomb, dropped or inaccurately thrown, fell amongst the men. The plan was spoilt. A miniature panic ensued, which Bennett and his Sergeant-Major found it difficult to check. As in many raids, a message to retire was passed. The wounded were safely brought in by Bennett, whose control (p. 016) and leadership were worthy of a luckier enterprise.[1]

The Battalion was not called upon for much fighting activity in September, 1916. Raids and rumours of raids kept many of us busy. An attack by the 184th Brigade upon the Wick salient was planned, but somewhat too openly discussed and practised to deceive, I fancy, even the participating infantry into the belief that it was really to take place. Upon the demolished German trenches many raids were made. In the course of these raids, the honour of which was generously shared between all battalions in the Brigade, sometimes by means of the Bangalore Torpedo, sometimes by the easier and more subtle method of just walking into them, the enemy's front line was usually entered; and rarely did a raiding party return without the capture of at least an old bomb, an entrenching tool or even a live German. These 'identification' raids possibly did as much to identify ourselves to the enemy as to identify him to us, but they proved useful occasions on which to send parties 'over the top' (always an enjoyable treat!) and gave practice to our trench mortars, which fired remarkably well and drew down little retaliation—always the bug-bear of the trench mortar.

The mention of these things may make dull reading (p. 017) to the blasé warrior of later battlefields, but, as there are some whose last experience abroad was during Laventie days and who may read these lines, I feel bound to recall our old friend (or enemy) the trench mortar, the rent-free (but not rat-free) dug-out among the sandbags, the smelly cookhouses, whose improvident fires were the scandal of many a red-hatted visitor to the trenches, the mines, with their population of Colonial miners doing mysterious work in their basements of clay and flinging up a welter of slimy blue sandbags—all these deserve mention, if no more, lest they be too soon forgotten.

Days, too, in Riez Bailleul, Estaires and Merville will be remembered, days rendered vaguely precious by the subsequent destruction of those villages and by lost comrades. Those of the Battalion who fell in 1916 were mostly buried in Laventie and outside Merville. Though both were being fought over in 1918 and many shells fell among the graves, the crosses were not much damaged; inscriptions, if nearly obliterated, were then renewed when, by the opportunity of chance, the Battalion found itself once more crossing the familiar area, before it helped to establish a line upon the redoubtable Aubers ridge, to gain which so many lives at the old 1915 battles of Neuve Chapelle and Festubert had been expended.

It was a fine autumn. The French civilians were getting in their crops within a mile or two of the trenches, while we did a series of tours in the Moated Grange sector, with rest billets at the little village of Riez Bailleul.

And (p. 018) then box respirators were issued.

Laventie days are remembered with affection by old members of the Battalion. In October, 1916, however, there were some not sorry to quit an area, which in winter became one of the wettest and most dismal in France. The Somme battle, which for three months had rumbled in the distance like a huge thunderstorm, was a magnet to attract all divisions in turn. The predictions of the French billet-keepers were realised at the end of October, when the 2/4th Oxfords were relieved in the trenches by a battalion of the Middlesex Regiment and prepared to march southwards to the Somme.

Departure from Laventie. — At Robecq. — The march southwards. — Rest at Neuvillette. — Contay Wood. — Albert. — New trenches. — Battle conditions. — Relieving the front line. — Desire Trench. — Regina dug-out. — Mud and darkness. — A heavy barrage. — Fortunes of Headquarters. — A painful relief. — Martinsart Wood.

At the end of October, 1916, the 61st Division left the XI Corps and commenced its march southwards to join the British forces on the Somme. We were among the last battalions to quit the old sector. Our relief was completed during quite a sharp outburst of shelling and trench-mortaring by the enemy, whose observers had doubtless spotted the troops moving up to take over.

After one night in the old billets at Riez Bailleul the Battalion marched on October 29 to Robecq, where the rest of the Brigade had already assembled, and took up its quarters in farms and houses along the Robecq-Calonne road. Battalion Headquarters were established at a large farmstead subsequently known as Gloucester Farm, while to reach the billets allotted to them the companies marched through the farmyard and across the two small bridges, since so familiar to some, which (p. 020) spanned the streams Noc and Clarence. My company was furthest south and almost in Robecq itself; my headquarters were in a comfortable house with an artesian well bubbling up in its front garden. When fighting was taking place at Robecq in April, 1918, and I found myself, under very different circumstances, in command of the Battalion, knowledge of the ground obtained eighteen months before, even to the position of garden gates and the width of ditches, proved most useful. I am afraid the Battalion's old billets were soon knocked down, the favourite estaminet in D Company area being among the first houses to go.

On November 2, 1916, the Battalion left Robecq, where it had been well-housed and happy for a week, for Auchel, a populous village in the mining district, and marched the next day to Magnicourt en Comté, an especially dirty village, and thence again through Tinques and Etrée-Wamin to Neuvillette. The civilians in some of the villages passed were not friendly, the billets crowded and often not yet allotted when the Battalion arrived, having covered its 14 kilometres with full pack and perhaps through rain. Nobody grumbled, for the conditions experienced were normal, but this march with its daily moves involved toil and much footsoreness on the part of the men, and for the officers much hard work after the men were in, and many wakings-up in the night to receive belated orders for the morrow.

After reaching Neuvillette, a pretty village four miles north by west of Doullens, a ten days' rest was (p. 021) made. Boots had become very worn in consequence of the march, and great efforts were now made by Hobbs to procure mending leather; unfortunately the motor car seemed to have forgotten its poor relation, the boot, and no leather was forthcoming. During the stay at Neuvillette a (p. 022) demonstration in improvised pack saddlery was arranged at Battalion Headquarters, the latest and most disputed methods of wiring and trench-digging were rehearsed, and two really valuable Brigade field days took place. More than a year afterwards the Battalion was again billeted at Neuvillette, whose inhabitants remembered and warmly welcomed the Red Circle.

On November 16 we marched away to Bonneville and the next day reached Contay, where we climbed up to some unfloored huts in a wood. The weather on this march had been bitterly cold, but fine and sunny. A dusky screen of clouds drifted up from the west the evening of our arrival and the same night snow fell heavily. The cookers were not near the huts and neither stores nor proper fuel existed. There was the usual scramble for the few braziers our generous predecessors had left behind. With snow and wind the Battalion tasted its first hardship.

As in all such situations, things soon took a cheerful turn. When the General came up next morning, the camp was reeking with smoke from braziers and the smell of cookers and the wood alive with sounds of woodchopping and cries of foragers. This change from a bad look-out to a vigorous optimism and will to make the best of things was characteristic of the British 'Tommy', who, exhausted and 'fed-up' at night, was heard singing and wood chopping the next morning, as if wherever he was were the best place in the world. I shall always remember Contay Woods, the huts with their floors of hard mud reinforced by harder tree-stumps, (p. 023) and the slimy path down to parade when we left.

On November 19 we reached Albert, whose familiar church needs no description. What struck me principally on arrival was the battered sordidness of the place and the filthy state of the roads, on which the mud was well up to the ankles. Some civilians were living in the town and doing a brisk trade in souvenir postcards of the overhanging Virgin. Traffic, as always through a main artery supplying the prevalent battlefield, was positively continuous. The first rain of autumn had already fallen and men, horses and vehicles all bore mud stains significant of winters approach. Our arrival—we went into empty, rather shell-damaged houses near the station—coincided with the later stages of the Beaumont Hamel offensive, and German prisoners and, of course, British casualties were passing through the town.

At Albert, Bennett was taken from A Company to act as Second in Command of the Berks. Brown assumed command of his company and Robinson about this time of C Company, Brucker having returned to the 61st Divisional School, which was set up at St. Riquier. Just now much sickness occurred among the officers, John Stockton, Moorat and several others being obliged to go away by attacks of trench fever. From Albert C and D Companies moved forward to some Nissen huts near Ovillers to be employed on working parties. For the same duties A and B Companies soon afterwards were sent to Mouquet Farm, while Battalion Headquarters went to Fabick Trench.

After (p. 024) some rain had fallen, fine autumn weather returned and our guns and aeroplanes were shewing the activity typical of the late stages of a great battle, when future movements were uncertain. A string of 30 balloons stretching across the sky in a wide circumference (whose centre, as in all 'pushes,' would have been somewhere behind our old front) industriously watched the enemy's back area. There was probably little comfort for the Germans west of Bapaume, or even in it, for our reluctance to shell towns, villages and (formerly most privileged of targets) churches was rapidly diminishing.

On November 21 the Brigade took over its new sector of the line and with it a somewhat different régime to what it had known before. It was heard said of the 61st Division that it stayed too long in quiet trenches (to be sure, trenches were only really 'quiet' to those who could afford to visit them at quiet periods). Still the Somme 'craterfield' presented a complete contrast to the old breastworks with their familiar landmarks and daylight reliefs. Battle conditions remained though the advance had stopped. Our recent capture of Beaumont-Hamel and St. Pierre Divion left local situations, which required clearing up. The fragments of newly-won trenches above Grandcourt, trenches without wire and facing a No-Man's-Land of indeterminate extent, gave their occupants their first genuine tactical problems and altogether more responsibility than before. In some respects the Germans were quicker than ourselves to adapt themselves to conditions approximating to open warfare. (p. 025) The principle of an outpost line and the system of holding our front in depth had been pronounced often as maxims on paper, but had resulted rarely in practice. Subordinate staffs, on whom the blame for local reverses was apt to fall rather heavily, were perhaps reluctant to jeopardise the actual front line by holding it too thinly, while from the nature of the case, the front line was something far more sacred to us than to the enemy. Since the commencement of trench warfare the Germans had held their line on the 'depth' principle, keeping only a minimum of troops, tritely referred to as 'caretakers,' in their front trench of all, while we for long afterwards crammed entire companies, with their headquarters, into the most forward positions.

On the evening of November 25, 1916, Robinson of C Company and myself, taking Hunt and Timms (my runner) and one signaller, left for the front line. This was being held along Desire—my fondness for this trench never warranted that name—with a line of resistance in Regina, a very famous German trench, for which there had recently been heavy fighting. Our reconnaissance, which was completed at dawn, was lucky and satisfactory; moreover—I do not refer to any lack of refreshment by the Berks company commander—I was still dry at its conclusion, having declined all the communication trenches, which were already threatening to become impassable owing to mud.

The next night the Battalion moved up to relieve the Berks, but was conducted, or conducted itself, along the very communication trench which I (p. 026) had studiously avoided using and which was in a shocking state from water and mud. As the result of the journey, D Company reached the front line practically wet-through to a man, and in a very exhausted condition. A proportion of their impedimenta had become future salvage on the way up, while several men and, I fancy, some officers, had compromised themselves for some hours with the mud, which exacted their gumboots as the price of their future progress. I regret that my own faithful servant, Longford, was as exhausted as anybody and suffered a nasty fall at the very gates of paradise (an hyperbole I use to justify the end of such a mud-journey), namely Company Headquarters in Regina, where, like a sort of host, I had been waiting long.

Desire Trench, the name by which the front line was known, was a shallow disconnected trough upholstered in mud and possessing four or five unfinished dug-out shafts. These shafts, as was natural, faced the wrong way, but provided all the front line shelter in this sector. At one end, its left, the trench ran into chalk (as well as some chalk and plenty of mud into it!) and its flank disappeared, by a military conjuring trick, into the air. About 600 yards away the Germans were supposed to be consolidating, which meant that they were feverishly scraping, digging and fitting timbers in their next lot of dug-outs. To get below earth was their first consideration.

Regina dug-out deserves a paragraph to itself. This unsavoury residence housed two platoons of D Company, Company Headquarters, and Stobie, our (p. 027) doctor, with the Regimental Aid Post. In construction the dug-out, which indeed was typical of many, was a corridor with wings opening off, about 40 feet deep and some 30 yards long, with 4 entrances, on each of which stood double sentries day and night. Garbage and all the putrefying matter which had accumulated underfoot during German occupation and which it did not repay to disturb for fear of a worse thing, rendered vile the atmosphere within. Old German socks and shirts, used and half-used beer bottles, sacks of sprouting and rotting onions, vied with mud to cover the floor. A suspicion of other remains was not absent. The four shafts provided a species of ventilation, reminiscent of that encountered in London Tubes, but perpetual smoking, the fumes from the paraffin lamps that did duty for insufficient candles, and our mere breathing more than counterbalanced even the draughts and combined impressions, fit background for post-war nightmares, that time will hardly efface. Regina Trench itself, being on a forward slope and exposed to full view from Loupart Wood, was shelled almost continuously by day and also frequently at night. 'Out and away,' 'In and down' became mottoes for runners and all who inhabited the dug-out or were obliged to make repeated visits to it. Below, one was immune under 40 feet of chalk, and except when an entrance was hit the 5.9s rained down harmlessly and without comment.

During the day I occasionally ploughed my way along Regina Trench to some unshelled vantage point to watch the British shells falling on the yet grassy (p. 028) slopes above Miraumont and south of Puisieux. Baillescourt Farm was a very common target. At this time Miraumont village was comparatively intact and its church, until thrown down by our guns, a conspicuous object. Grandcourt lay hidden in the hollow.

Such landscape belonged to the days; real business, when one's orbit was confined to a few hundred yards of cratered surface, claimed the nights. A peculiar degree of darkness characterised these closing days of November, and with rain and mud put an end to active operations. Wiring, the chief labour of which was carrying the coils up to the front and afterwards settling the report to Brigade, occupied the energies of the Battalion after rations had been carried up. In this last respect much foresight and experience were required and arrangements were less good than they soon afterwards became; food that was intended to arrive hot arrived cold, and, having once been hot, received precedence over things originally cold but ultimately more essential. Hot-food containers proved too unwieldy for the forward area.[2]

Although quite a normal circumstance in itself, the extreme darkness at this period was a real obstacle to patrols and to all whose ability to find the (p. 029) way was their passport. Amid these difficulties there was an element of humour. To make one false turn, or to turn without noticing the fact, by night threw the best map-reader or scout off his path and bewildered his calculations. One night about this time a party of us, including Hunt and 'Doctor' Rockall, the medical corporal, who had accompanied me round the front posts, lost its way hopelessly in the dark. Shapes looming up in the distance, I enquired of Hunt as to his readiness for hostile encounter, whereupon the reassuring answer was given that 'his revolver was loaded, but not cocked.' I leave the point (if any) of this story to the mercy of those whose fate it has been to lose their way on a foggy night among shell-holes, broken-down wire and traps of all descriptions. Temporary bewilderment of the calculation destroyed reliance on any putative guides such as 'Verey' lights, shells, rifle fire, &c., which on these occasions appeared to come from all directions, and English and German seemed all alike.

Hunt, who at this time, being my only officer not partially sick, has called for somewhat repeated reference, usually devoted the hours after midnight to taking a patrol to locate a track shown on the map and called Stump Road, his object being to meet another patrol from a neighbouring unit. Success did not crown the work. Stump Road remained undiscovered and passed into the apocrypha of trench warfare.

At 5 p.m. on November 29, 1916, the Germans opened a heavy barrage with howitzers on the front line, giving every indication of impending attack. Regina (p. 030) Trench, where were the headquarters of C and D, the companies then holding the line, was also heavily shelled, and telephonic communication with the rear was soon cut. On such occasions it was always difficult to decide whether or not to send up the S.O.S—on the one hand unnecessary appeal to our artillery to fire on S.O.S. lines was deprecated, on the other, no forward commander could afford to guess that a mere demonstration was on foot; for the appearance of attacking infantry followed immediately on a lifting of the barrage, a symptom in itself often difficult to recognise. On this occasion I intended and attempted to send up a coloured rocket, but its stick became stuck between the sides of the dug-out shaft and, by the time the efforts of Sergeant Collett had prepared the rocket for firing, the barrage died down as suddenly as it had started. This very commonplace episode illustrates the routine of this phase of warfare. The trenches were, of course, blown in and some Lewis guns damaged, but, as frequently, few casualties occurred.

While speaking of the life furthest forward I do not forget the very similar conditions, allowing for the absence of enemy machine-guns and snipers, which prevailed at Battalion Headquarters. Confined to a dug-out (a smaller replica of Regina) in Hessian Trench, with a continual stream of reports to receive and instructions to send out, and being continually rung up on the telephone, Colonel Bellamy and Cuthbert had their hands full, and opportunities for rest, if not for refreshment, were very limited. Nor do I omit our runners from the fullest (p. 031) share in the dangers and activities of this time.

Under battle-conditions life at one remove from the front line was rarely much more agreeable than in the line itself, and was less provided with those compensations which existed for the Infantryman near the enemy. It was necessary to go back to Divisional Headquarters to find any substantial difference or to live an ordered life on a civilised footing; and there, too, responsibility had increased by an even ratio.

The Battalion Transport during this time was stationed at Martinsart and its task, along bad roads, in bringing up rations each day was not a light one.

On the night of November 30 the Battalion was relieved by the 2/4th Gloucesters and marched back to huts in Martinsart Wood. This march of eight miles, coming after a four days' tour in wet trenches under conditions of open warfare, proved a trying experience. For four miles the path lay along a single duckboard track, capsized or slanting in many places, and the newly-made Nab Road, to which it led, was hardly better. A number of men fell from exhaustion, while others, their boots having worn completely through before entering the trenches, were in no state to compete with such a distance. After passing Wellington Huts and through Aveluy the going became easier, until at last the area of our big guns was reached and, adjoining it, the 'rest billets.' The latter consisted of unfloored huts built of tarred felt and surrounded by mud only less bad than in the trenches. Our lights (p. 032) and noise scared the rats, which infested the camp.

The relief and march occupied until 4 a.m., and were succeeded by mist and frost. The concussion of our neighbours, the 6-inch naval guns, echoed among the trees, heralding the first of December, 1916.

The move from Martinsart to Hedauville. — Back to Martinsart. — Working parties. — Dug-outs at Mouquet Farm. — Field Trench. — Return to the front line. — Getting touch. — Guides. — An historic patrol. — Christmas in the trenches.

On December 2, 1916, the Battalion moved from Martinsart to Hedauville, on its way passing through Englebelmer, the home of one of our 15-inch howitzers, but no longer of its civilian inhabitants. The march was regulated by Pym, the new Brigade Major, who had replaced Gepp a few days before. The latter had proved himself a most efficient staff officer, and his departure to take up a higher appointment was regretted by everybody.

Hedauville was an indifferent village, but our billets were not bad. Brigade Headquarters were at the château. One heard much about the habitual occupation of the French châteaux by our staffs during the war. On this particular occasion the Brigade had only two or three rooms at its disposal, and on many others would be licencees of only a small portion of such buildings. The 184th Infantry Brigade Staff was always most solicitous about the (p. 034) comfort of battalions, and its efforts secured deserved appreciation from all ranks. During the winter Harling retired from the office of Staff Captain, and after a brief interregnum Bicknell, a Gloucester officer, who already had been attached to the Brigade for some time, received the appointment. For the ensuing three years Bicknell proved himself both an excellent staff officer and a consistent friend to the Infantry.

After scraping off the remains of the mud it had carried from the trenches, the Battalion settled down at Hedauville to a normal programme for ten days. The weather was bad, and a good deal of sickness now occurred among the troops, until so many officers were sick that leave for the others was stopped. Of general interest little occurred to mark this first fortnight of December. At its close the Battalion marched back to Martinsart and reoccupied its former huts. Battalion and Brigade were now in support, and our energies were daily devoted to working parties in the forward area. As these were some of the most arduous ever experienced by the Battalion I will describe an example.

I take December 16—a Saturday. My company was warned for working party last night, so at 6 a.m. we get up, dress, and, after a hurried breakfast, parade in semi-darkness. As the outing is not a popular one and reduction in numbers is resented by the R.E., the roll is called by Sergeant-Major Brooks (recently back from leave and in the best of early morning tempers) amid much coughing and scuffling about in the ranks. At 7 a.m. we (p. 035) start our journey towards the scene of labour, some 80 strong (passing for 100). We go first along a broad-gauge railway line (forbidden to be used for foot traffic) and afterwards through Aveluy and past Crucifix Corner to near Mouquet Farm.

After a trivial delay of perhaps 40 minutes, the D.C.L.I. or 479 have observed our arrival and tools are counted out and issued, the homely pick and shovel. The task is pleasantly situated about 150 yards in front of several batteries of our field guns (which open fire directly we are in position) and consists in relaxing duckboards, excavating the submerged sleepers of a light railway or digging the trench for a buried cable.

Perhaps the work only requires 50, not 100 (nor even 80) men. Very well! It is a pity those others came, but here are a thousand sandbags to fill, and there a pile of logs dumped in the wrong place last night, so let them get on with it!

For six hours we remain steadily winning the war in this manner and mildly wondering at the sense of things and whether the Germans will shell the batteries just behind our work—until, without hooter or whistle, the time to break off has arrived. By 3 p.m. the party is threading its way back, and as darkness falls once more reaches the camp. Cries of 'Dinner up' and 'Tea up' resound through the huts, and all is eating and shouting.

By December 20 it was once more the Brigade's turn to relieve the front line. Berks and Gloucesters again took first innings in the trenches, while the Bucks and ourselves stayed in support. Battalion Headquarters with A and B Companies were in (p. 036) Wellington Huts, near Ovillers; C and D went two miles further forward to some scattered dug-outs between Thiepval and Mouquet Farm. My own headquarters were at the farm, to whose site a ruined cellar and a crumbling heap of bricks served to testify. The Germans had left a system of elaborate dug-outs, some of which now housed Brigade Headquarters, but others, owing to shelling and rain, had collapsed or were flooded. On each of the four nights spent at Mouquet Farm my company supplied parties to carry wire and stakes up to the front line. These journeys were made through heavy shelling, and we were always thankful to return safely. My policy was never to allow the pace to become that of the slowest man, for there was no limit to such slowness. I myself set a pace, which I knew to be reasonable, and men who straggled interviewed me next day. By this policy the evening's work was completed in two-thirds of the time it would otherwise have taken, and my disregard of proverbial maxims probably saved the Battalion many casualties.

Since our last tour in the line real winter conditions had set in. Shell-holes and trenches everywhere filled with water till choice of movement was confined to a few duckboard tracks. Those in our area led past Tullock's Corner and from the Gravel Pit to Mouquet Farm, and thence to the head of Field Trench, with a branch sideways to Zollern Redoubt. Field Trench, an old German switch, led over the Pozières ridge, whose crest was well 'taped' by the German guns. The British advance having reached a standstill, the enemy's artillery was (p. 037) now firing from more forward positions and paid much attention to places like Mouquet Farm, Tullock's Corner, Zollern Redoubt and Field Trench. Parties of D.C.L.I. were daily at work upon the latter, duckboarding and revetting, and completed a fine pioneers' job right up to Hessian. Field Trench ranked among the best performances of the Cornwalls, whose work altogether at this time deserved high praise.

On (p. 038) Christmas eve, 1916, the Battalion relieved the front line. Brown and Davenport took their companies to Desire and Regina. Battalion Headquarters had an improved position at Zollern Redoubt, and their old dug-out in Hessian was left to D Company Headquarters. Robinson with C Company was also in Hessian, to the left of D. His headquarters possessed plenty of depth but neither height nor breadth. The dug-out entrance was the size of a large letter-box and nearly level with the trench floor.

After the march up, the remainder of the night was devoted to the trying process of 'getting touch.' This meant finding the neighbouring sentry-posts on each flank—an important duty, for the Germans usually knew the date and sometimes the hour of our reliefs and the limits of frontage held by different units (we naturally were similarly informed about the enemy). For reasons of security no relief could be held complete before not only our own men were safely in but our flanks were established by touch with neighbouring posts.

In the course of the very relief I have mentioned, a platoon of one battalion reached the front line but remained lost for more than a day. It could neither get touch with others nor others with it. 'Getting touch' seemed easy on a map and was often done in statements over the telephone. Tangible relations were more difficult and efforts to obtain them often involved most exasperating situations, for whole nights could be spent meandering in search of positions, which in reality were only a few hundred yards distant. Total absence of guiding landmarks (p. 039) was freely remarked as the most striking characteristic of this part of the Somme area. I refer only to night movement, for by day there were always distant objects to steer by, and the foreground, seemingly a cratered wilderness of mud, to the trained eye wore a multitude of significant objects.

My last topic introduces the regimental guide. Guides performed some of the hardest and most responsible work of the war. Staff work could at time be botched or boggled without ill-effects; for mistakes by guides some heavy penalty was paid. Whenever a relief took place, men to lead up the incoming unit into the positions it was to occupy were sent back, usually one per platoon, or, in cases of difficult relief and when platoon strengths were different, one per sentry-post. Guides rarely received much credit when reliefs went well, but always the blame when they went ill. The private soldiers, who guided our troops into trench and battle, played a greater part in winning the war than any record has ever confessed.

I have already spoken of patrols, their difficulties and dangers. Than General White no man in the Brigade was better acquainted with its front or a more punctual visitor to the most forward positions. What 'Bobbie' could not himself see by day he was resolved to have discovered for him by night, and thus a high measure of activity by our patrols was required. About Christmas the question whether the eastern portion of a trench, known as Grandcourt Trench, was held by the enemy, was set to the Battalion to answer. Vowed to accomplish this (p. 040) task or die, a picked patrol started one dark night. Striking in a bee line from our trenches, the patrol passed several strands of wire and presently discovered fragments of unoccupied trench. On further procedure, sounds were heard and, after the necessary stalking and listening, proof was obtained that a large hostile wiring party, talking and laughing together, was only a few yards distant. With this information the patrol veered to a flank, again passing through wire and crossing several trenches which bore signs of occupation. A line for home was then taken, but much groping and long search failed to reveal the faithful landmarks of our front line. At length, as dawn was breaking, the situation became clear. The patrol was outside D Company Headquarters in Hessian, more than 800 yards behind the front line. The report of German wiring parties laughing and talking did not gratify, and on reconstruction of its movements it was found that the patrol had spent the entire night reconnoitring not the German but our own defensive system. The wire so easily passed through, the noise and laughter, and the final dénouement at Hessian allowed for no other conclusion. A few nights later Brown, with a small party and on a clear frosty night, solved the riddle by boldly walking up to Grandcourt Trench and finding the Germans not at home.

I mention the story of this first patrol for the benefit, perhaps, of some who took part in it and who will now, I feel sure, enjoy the humour of its recollection. I mention it more to show of what unrequited labour Infantry was capable. The most wholehearted (p. 041) efforts were not always successful. One had this confidence on patrol, that one's mistakes only affected a handful. It was otherwise for artillery commanders who arranged a barrage, commanders of Field Companies who guaranteed destruction of a bridgehead, or of Special Companies undertaking a gas projection. Such was the meaning of responsibility.

The Battalion spent December 25, 1916, in the trenches under some of the worst conditions that even a war Christmas could bring. Christmas dinners were promised and afterwards held when we were in rest.

As in previous years, our army circulars had forbidden any fraternisation with the enemy. Though laughed at, these were resented by the Infantry in the line, who at this stage lacked either wish or intention to join hands with the German or lapse into a truce with him. On the other hand, a day's holiday from the interminable sounds of shelling would have been appreciated, and casualties on Christmas Day struck a note of tragedy. This want of sagacity on the part of our higher staff, as if our soldiers could not be trusted to fight or keep their end up as well on Christmas as any other day, was a reminder of those differences on which it is no object of this history to touch.

Visitors to the Battalion. — The New Year. — A wintry march. — Arrival at Maison Ponthieu. — Severe weather. — At war with the cold. — Training for offensive action. — By rail to Marcelçave. — Billets at Rainecourt. — Reconnoitring the French line near Deniécourt.

I cannot often treat my readers to a ride by motor car. Jump into this staff car that is waiting—it will not take you to the trenches! You will have distinguished company. Colonel A. and Major Q. have decided to pay a visit to the Battalion. It is at Maison Ponthieu, nearly 50 miles behind the line, whither it marched two days since to undergo a period of rest.

Arrived there, you learn that the Commanding Officer is out, placating with the assistance of the Brigade interpreter the wrath of the village hunchback, a portion of whose wood-stack was reported missing last night. This is not the first time that A. and Q. have visited the village (their lives are martyred to the study of regimental comfort), so our journey opens with an inspection of the two Nissen huts on the village 'green.'

'Disgraceful! At least two planks, which helped to line the roof of this hut, have been burnt. (p. 043) Stoves? One was sent to each battalion only yesterday, and ten more have been promised by Corps. Fuel? I am astounded to hear that the supply is inadequate. Quartermaster! How many pounds of dripping did you send to the Base last week? The A.S.C. sent twice that quantity. Who is cooking on that field kitchen? It will be impossible to make the war last if things are abused in this way. Your men have no rifle racks, more ablution benches must be provided and the sanitary arrangements made up to date....'

This little parable has made me outstrip my narrative. You must come another day and see what Sergeant Parsons is doing with the vast quantities of timber, corrugated iron, and other stores supplied to make the billets staff-proof for the future.

The end of the last chapter left the Battalion complaining of our guns and otherwise merrymaking in the front line. A day or two before the New Year, companies marched back to huts near Pioneer Station and the next morning reached Hedauville. Here, shortly afterwards, Christmas dinners, consisting of pigs and plum-pudding, were consumed. It was believed that we had left Regina and Desire for good, were leaving the Corps and likely to do training in a back area for several weeks. Colonel Bellamy went on leave, and Bennett, amid many offers to accompany him as batman, departed for three months' instruction at Aldershot as a senior officer. A new Major, W. L. Ruthven, arrived in January and temporarily was in command. Loewe and John Stockton returned from (p. 044) hospital and Jones from a Divisional working party, which had been engaged for a month on the wholesale manufacture of duckboards. Lyon, an officer equally popular in and out of the line, had found egress from the Somme dug-outs troublesome and withdrew for a time to easier spheres. Men's leave was now going well and frequent parties left Acheux Station for 'Blighty.'

This list of changes is, of course, incomplete, and I only give it to show how constantly the wheel of alteration was turning. Comparatively few officers or men stayed very long with one battalion. 'Average lives' used to be quoted for all cases, ranging from a few weeks for a platoon officer to the duration for R.T.O's and quartermaster-sergeants! Old soldiers may never die, but I think our new soldiers 'faded away,' not the old, who grew fat and crafty!

The Battalion marched away from Pioneer Huts—whither it had returned after its rest at Hedauville—on January 15. The first stage on the rearward journey carried us to Puchevillers, a village full of shell dumps and now bisected by a new R.O.D. line from Candas to Colincamps. Snow, which had fallen heavily before we left Puchevillers, made the ensuing march through Beauval and Gézaincourt to Longuevillette a trying one. The going was quite slippery and the Transport experienced difficulty in keeping up with the Battalion, especially for the last two miles. The road marked on the map had by that time degenerated, in characteristic fashion, to a mere farm track across country. The Battalion was (p. 045) in its billets at Longuevillette by 6 o'clock, but blankets arrived so late that it was midnight before Hobbs could issue them. On the next day, January 18, the march was continued through Bernaville to Domqueur, a distance of 11 miles, on frost bound roads. No man fell out. The 2/4th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry was one of the best marching battalions in France. On January 19 we reached the promised destination, Maison Ponthieu, of whose billets glowing accounts had been received; which, as often, were hardly realised.

At Maison Ponthieu the Battalion remained for nearly three weeks. Brigade Headquarters, the Machine-gun Company, and some A.S.C. were already (p. 046) in the village—ominous news for a billeting party.

Now much snow had already fallen throughout the countryside, and the weather since the New Year had been growing steadily more cold. In the middle of January, 1917, an iron frost seized Northern France till ponds were solid and the fields hard as steel. This spell, which lasted a month, was proclaimed by the villagers to be the coldest since 1890. As day succeeded day the sun still rose from a clear horizon upon a landscape sparkling with snow and icicles, and each evening sank in a veil of purple haze. Similar frost was experienced in England, but the wind swept keener across the flat plains of Ponthieu than over our own Midlands. This turn of the weather was a military surprise. It produced conditions novel in trench warfare. Severe cold was a commonplace, but now for three weeks and more the ground everywhere had been hard as concrete, digging and wiring were quite impossible, and movement in our front area easier than ever before. It almost seemed as if our opportunity for open warfare had arrived. Certainly at this moment in the military situation the enemy could not have availed himself of his old tactics as guarantee against a break through, nor could he, as formerly during the Somme Battle, have protected himself from gradual defeat by digging fresh trenches and switch lines and putting out new wire in rear wherever his front line was threatened. No doubt there were reasons prohibiting an attempt to rush the enemy on a grand scale from his precarious salient between Arras and Péronne (p. 047) other than fear of being 'let down' by the weather; though perhaps the latter consideration alone, from a Supply standpoint, constituted sufficient veto.

At all events the tactics of the Battalion were in quite another order. How to shave, how to wash, how to put on boots frozen hard during the night, above all, how to keep warm—these were the problems presented. I doubt if there was much washing in cold water before parade, and, as for shaving, I know a portion of the breakfast tea was often used for this purpose. Sponge and shaving brush froze stiff as matters of habit. To secure fuel provided constant occupation and frequent stumbling-blocks. On our arrival most rigid orders had been issued not to burn our neighbours' fences and I am able to say that the fences survived our stay. Temptation grew, nevertheless, in orchards and rows of small pollards (usually of ash), which formed the hedges in this part of France, not to mention a wood at the lower end of the village. That ancient trick of covering tree stumps with earth needed little learning. Each night for such as had ears, if not official ones, wood and thicket rang with the blows of entrenching tool on bole and sapling, till past the very door of Sergeant-Major sipping his rum, or company officers seated around sirloin and baked potatoes would be dragged trunk and branches of a voting tree, that in peace time and warmer weather might have lived to grace an avenue. There should be variety in story telling; here was one told very much out of school.