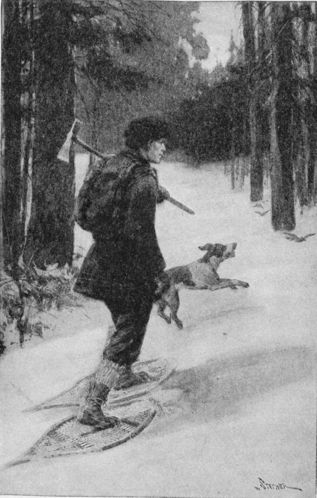

THE HERMIT AND PAL TOOK MANY A TRIP INTO THE FOREST.

Title: Followers of the Trail

Author: Zoe Meyer

Illustrator: William F. Stecher

Release date: August 13, 2007 [eBook #22311]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

FOLLOWERS OF THE TRAIL BY ZOE MEYER Illustrated by WILLIAM F. STECHER  BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY 1926 |

Copyright, 1926,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Published May, 1926

Printed in the United States of America

| Pal | 1 |

| The Call of the Spring | 19 |

| The Adventures of Kagh, the Porcupine | 35 |

| The Trail of the Moose | 48 |

| In the Beavers' Lodge | 65 |

| Silver Spot | 81 |

| When the Moon is Full | 96 |

| The Further Adventures of Ringtail, the Raccoon | 109 |

| The Haunter of the Trail | 126 |

| Where Winter Holds No Terrors | 140 |

| Brown Brother | 154 |

| In the Wake of the Thaw | 171 |

| The Twins | 184 |

| The White Wolf | 202 |

| The Hermit And Pal Took Many a Trip Into the Forest. | Frontispiece |

| Slowly it advanced, its body almost brushing the snow | 15 |

| And then occurred a memorable battle | 33 |

| Pal stopped, clearly astonished | 45 |

| As if carved from the rock the big moose stood | 49 |

| The Hermit took the one chance that presented itself | 59 |

| The dam, when finished, was a work worthy of a trained engineer | 67 |

| A full grown fox stood motionless in the sunlight, a rabbit hanging limply from her jaws | 83 |

| The big frog was flipped out upon the bank | 97 |

| Ringtail had heard the agonized cry of his playmate | 119 |

| He crouched upon a branch, glaring down at the animated leaf-pile | 131 |

| The hawk dropped like a thunderbolt and caught him in its talons | 143 |

| Instantly the fawn thrust out his delicate muzzle and licked the outstretched hand | 154 |

| Both glared but refused to let go | 175 |

| The Other Cub Forgot Her Fear And Demanded Her Sugar Lump. | 188 |

| High on his rocky ledge he lifted his muzzle to the moon | 205 |

In the depths of the green wilderness, where dark spruce and hemlock guard the secrets of the trail, are still to be found wild creatures who know little of man and who regard him with more of curiosity than of fear. Woodland ponds, whose placid waters have never reflected the dark lines of a canoe, lie like jewels in their setting of green hills; ponds where soft-eyed deer come down to drink at twilight, and where the weird laughter of the loon floats through the morning mists. Toward the south, however, man is fast penetrating the secrets of the forest, blazing dim trails and leaving fear and destruction in the wake of his guns and traps.

Occasionally a hunter, unarmed save perhaps for a camera, enters the wilderness to study its inhabitants, not that he may destroy them, but that he may the better understand them, and through them draw closer to nature. Such a man was the Hermit, who dwelt alone in a log cabin where the southern border of the wilderness terminated abruptly at an old snake fence. Tall forest trees leaned toward the clearing and many a follower of dim forest trails approached the fence during the hours of darkness to peer curiously, though somewhat fearfully, at the lonely cabin.

Perhaps the visitor might be a black bear in search of the berries which were sure to be found at the edges of the cleared ground; perhaps a lynx, staring with pale, savage eyes upon the cabin, hating the man who occupied it, yet fearing his power. Again it might be an antlered deer who paused a moment, one dainty hoof uplifted, brown eyes, wholly curious, fixed upon the silent dwelling. Only the smaller woodfolk such as rabbits, squirrels, raccoons, porcupines, and now and then a fox, dared make a closer investigation of the clearing.

As for the man himself, he would, if possible, have made a friend of every wild creature who came near his dwelling. Broken in health, he had turned wearily from the rush and clamor of the city to the clear, balsam-scented air of the woods, where he was fast gaining a health and vigor that he had not believed possible. Out of a lean face, tanned by exposure and wrinkled with kindly humor, a pair of keen gray eyes looked with never-flagging interest upon the busy world about him.

The Hermit, in spite of his comparative isolation from those of his kind, was far from leading a life of uselessness. Having been from boyhood an enthusiastic student of botany, he had located in the big woods many a leaf, bark and root which, when sent back into the busy world, proved a blessing to ailing humanity.

He knew where to find the aromatic spice-bush to cool the burning of fever, and where in the spring grew the tenderest willow twigs whose bark went into cures for rheumatism. Sassafras yielded its savory roots for tea and tonics, and the purplish red pokeberry supplied a valuable blood purifier. So he harvested the woods for others, at the same time finding for himself health and contentment.

Twice yearly he took his harvest to the nearest shipping center, setting forth as the first streaks of dawn appeared in the east, and returning when the serrated wall of the wilderness was etched sharply against the sunset sky, and the songs of the robin and the hermit thrush gave voice to the twilight.

Since his arrival at the cabin the Hermit had been much alone, his only visitors being occasional hunters or trappers who passed his home by chance, or asked shelter when overtaken by the night. At infrequent intervals one of his distant neighbors would drop in to chat or to ask aid in case of illness or accident, for many had found the Hermit a help at such a time. They were, for the most part, busy farmers wresting a home from the wilderness, a task which left them little idle time.

One summer evening, as the fiery ball of the sun was sinking out of sight behind the forest wall, leaving the world bathed in the hush of twilight, the Hermit heard a scratching upon his doorstep. Looking up from the fire over which he was cooking his supper, he saw in the open doorway a small black and white dog, its forefeet upon the sill, its great brown eyes fixed in mute appeal upon the face of the man. A moment they looked into each other's eyes; then, without a word, the Hermit held out his hand.

It was a simple gesture, yet it heralded a change in the lives of both. Into the eyes of the homeless dog sprang a glad light, followed by such a look of adoration that the man experienced a warm glow of pleasure. Out of their loneliness each had found a friend.

From that day the two were never far apart. When the Hermit went into the forest for his harvesting, Pal, as the wanderer had been named, accompanied him, his proud protector. While the man worked, Pal often ranged the near-by woods, his sensitive nose eagerly seeking out the latest news of the wild; yet he was never out of sound of the Hermit's call. To the dog, as to the man, the woods were a never-ending source of interest, and he seldom offered to molest the wild creatures unless they seemed unfriendly toward his master. Pal would have attacked the biggest beast of the wilderness unhesitatingly in defense of the one who had befriended him.

In going about his work the Hermit, as a rule, saw few of the forest inhabitants, but from tree or thicket bright eyes were sure to be following his every movement with keen interest. Fear, when once instilled into the wild creatures, is not easily banished, but little by little they came to regard this quiet man as a friend.

An instance of their trust was shown one day when, as the Hermit worked in his herb garden at the rear of the cabin, a rabbit slipped through the fence. With great bounds the little animal crossed the garden toward him, its ears lying along its back and its gentle eyes wide with terror. The Hermit glanced up in surprise; then his face set and he raised his hoe threateningly. Close behind the fleeing bunny came a weasel, its savage red eyes seeing nothing but its expected prey. In another bound the rabbit would have been overtaken and have suffered a terrible death had not the Hermit stepped between with his uplifted hoe.

With a snarl the weasel paused, its eyes flaming with hatred. For a moment it seemed inclined to attack the man. At that point Pal rounded the corner of the cabin to see the savage little beast confronting his adored master. The sight aroused all the ferocity in the dog's nature. The light of battle flared in his usually mild eyes and the hair rose stiffly along his back. With a sharp bark, he charged. The weasel, seeing itself outnumbered, turned and sped toward the forest, where it vanished with the dog in hot pursuit. The Hermit returned to his hoeing, glad that he and Pal had been the means of saving one life from the cruel fangs which kill purely for the lust of killing.

On another day the Hermit owed his own life to the faithful dog. He had gone some distance into the woods to visit a bed of ginseng which he had discovered a fortnight before. In the rich leaf-mold the plants grew lustily, covering the forest floor for some distance with their spreading green umbrellas. With delighted eyes the Hermit stood gazing upon his rich find, but when he stooped to ascertain whether or not the roots were ready for drying, his outstretched hand was quickly arrested by Pal's frenzied barking. He quickly withdrew his hand and moved slightly until he could follow the dog's gaze. There, scarcely a foot away, lay a coiled rattler, the ugly head raised. Even as the man looked, the tail sent out its deadly warning.

The Hermit was surprised but not alarmed, for he had dealt with rattlers before. With one blow of the mattock, which he always carried for digging, the head of the big snake was crushed and its poisoned fangs buried in the earth.

"Good old Pal! You probably saved my life. I would never have seen the reptile in time," the Hermit said feelingly, as he patted the head of the gratified dog. The rattles were carried home as trophies and the love between man and dog was deepened, if such a thing were possible.

Thus, with long rambles in the forest and with hours of harvesting and drying roots and berries, the days sped by, lengthening into weeks and the weeks into months. Birch and maple dropped their leaves, a rustling carpet about their feet. Wedges of wild geese winged their way southward through the trackless sky, making the nights vocal with their honking. The bear, woodchuck, skunk, raccoon and chipmunk, fat from their summer feeding, had retired to den or hollow tree where they were to sleep snugly through the cold months.

Then one night the Storm King swept down from the North, locking the forest in a frozen grip which only the spring could break. A thick mantle of snow covered the wilderness over which a deep silence brooded, broken now and then by a sharp report from some great pine or spruce as the frost penetrated its fibers. The sun, which now shone but a few hours of the day, could make no headway against the intense cold, but those creatures of the wilderness which were still abroad were prepared to meet it with warm coats of fur, through which the frost could not penetrate.

The Hermit and Pal enjoyed the short crisp days and took many a trip into the forest, the man upon snowshoes, the dog with his light weight easily upborne by the crust. Then there were long, quiet evenings by the fire, when the Hermit studied and Pal drowsed beside him, one eye on the man, ready to respond to the least sign of attention.

At this season of hunger many wild creatures, which in the days of abundance were too shy to approach the cabin, overcame their timidity, to feast upon the good things spread for them about the clearing. The birds, especially, grew so tame that they would fly to meet the Hermit the moment he stepped forth. The bolder ones even found a perch on his shoulders or head, chatting sociably or scolding at each other. Occasionally one of the larger animals visited the banquet, and though these were regarded somewhat askance by the regular frequenters, a truce which was never violated held about the food supply.

One clear, crisp day in the late winter when the snow crust sparkled under the sun's rays as if strewn with diamond dust, and the cold was intense, Pal frolicked away by himself into the woods as the Hermit was feeding his wild friends. That was nothing unusual but, as the afternoon wore on and he did not return, his master began to feel a slight uneasiness. Pal had never before stayed away so long. Occasionally the Hermit went to the window which looked out upon the dark wall of the wilderness, but there was no movement in its borders and the cold soon drove him back to his warm fireside.

At length, when the sun was well down in the western sky, there came a familiar scratching on the door of the cabin. The Hermit sprang to open it, giving a relieved laugh at sight of Pal upon the doorstep. But, strange to say, the dog would not enter. With a sharp bark he trotted a short distance down the path, looking back at his master.

"No, no, Pal, I don't want to take a walk to-day. Come in and get warm, you rascal, and give an account of yourself," the Hermit called, still holding the door open though the air was chilling.

The dog wagged his tail, but made no move toward the house. Instead, he whined, trotted a few steps farther and looked eagerly back into his master's face. It was clear to the Hermit that Pal wished him to follow, but for a moment he hesitated, contrasting the warmth within the cabin with the bitter cold and loneliness of the forest. Then he looked again at the dog, who had not taken his pleading eyes from his master's face.

"All right, Pal, just come in until I bundle up. This cold would freeze a man in no time if he were not well protected."

The Hermit turned back into the cabin and the dog, apparently understanding, no longer hung back. His adored master had not failed him. A few minutes later both issued from the house with the dog in the lead, soon disappearing from sight in the shadows of the forest.

In the morning of that same day Dave Lansing, a young hunter and trapper, had left his rude cabin some miles to the north of the Hermit's clearing to visit his trap line. Ill luck seemed to be with him. In the first place he had been delayed long after his accustomed time for starting. Then, one after another, he had found his traps rifled, until he had turned away from the last one angry and disgusted. Still a perverse fate seemed to be following him. Several miles from his cabin, he stumbled upon something buried in the snow; there was a sharp click, and with a sudden grunt of pain he sank to the ground, his axe flying from his hand and skimming for some distance over the smooth snow crust.

Dave sat up, dazed. The pain which he suffered, however, soon cleared his brain and he found that he was caught in the steel jaws of a trap. The trap was not of his own setting, but this made him no less a captive. He tried to press open the jaws but they held stubbornly. Then he remembered his axe. Crawling as far as the trap would permit, he stretched himself at full length upon the snow and reached desperately. The instrument which would have been his salvation was six inches out of reach. Moreover, the strain upon his foot was so unbearable that he was obliged to draw back in order to ease it.

Now, as the full significance of his plight dawned upon him, even Dave's stout heart quailed. He was helpless to free himself without the axe, and so far as he knew there was no human being within ten miles of the spot. Moreover the intense cold was beginning to penetrate his warm clothing. He no longer felt the pain of his imprisoned foot. Circulation had slowed down and numbness was fast creeping up his limb. He swung his arms and beat his hands upon his breast, but in spite of all he could do the chill penetrated more deeply into his bones. He realized that if he were not rescued within a few hours he would freeze to death, for no one could long remain inactive in that biting cold. Dave smiled somewhat grimly as he reflected that he was now in the predicament of the helpless creatures which every day perished in his traps.

Suddenly his unpleasant thoughts were interrupted by a scratching in the snow behind him, and turning quickly he saw a small black and white dog regarding him in a friendly manner. Dave's heart leaped. Surely, where there was a dog there must be a man. He held out his hand to the dog while he shouted again and again with all his might, waiting breathlessly each time for the answer which did not come.

At length he gave up the attempt and turned his attention to his small companion. It was evident that the dog was alone, but perhaps if he could be made to understand, he might bring help. With this thought new hope returned. Pointing in the direction from which the dog had appeared and looking intently into the great brown eyes, Dave commanded, "Go, sir! Go get your master."

Several times the words were repeated while Pal stood undecided. Then suddenly he seemed to understand and with a joyous bark trotted swiftly away and soon disappeared down a white corridor of the woods. It was not until he had gone that Dave remembered the axe which the dog might have brought to him had he not, in his eagerness, forgotten it. He groaned and buried his face in his hands, but the opportunity was gone and he resolutely fixed his thoughts upon the hope of the dog's return.

The woods were very still. As the coppery sun sank lower, it cast long blue shadows upon the snow, while the cold grew more intense. Dave shivered and huddled down as far as possible into his coat.

Gradually there grew upon him the feeling that he was not alone; that he was being watched by hostile eyes. A strange prickling of his scalp under his fur cap caused him to turn his head slightly and so meet the unwinking gaze of a pair of pale yellow orbs. Involuntarily Dave stiffened. The creature's round, moon-like face, gray-brown fur and tufted ears proclaimed it a Canada lynx, one of the most savage of the cat tribe.

As a rule, the lynx, in common with other wilderness inhabitants, is shy of man; still he is not to be trusted. The winter had been a hard one, game was scarce and the animal was emboldened by hunger. Moreover it seemed to know that the man was crippled. Slowly it advanced, its body almost brushing the snow, its huge furry pads making no sound upon the smooth crust, its unwinking eyes fixed upon those of the man.

The perspiration stood out upon Dave's forehead as he stared back into the brilliant, cruel eyes of the lynx. He was unarmed save for his hunting knife, a poor weapon against so savage a beast, yet he drew it, determined to die fighting.

A few paces away the lynx paused and the trapper could see the muscles of its powerful hind legs gather for the spring. His own muscles braced instinctively to meet it. But strangely the animal's attention wavered. It sniffed the air uncertainly. An instant later there came a furious barking and a yell which seemed to shatter the silence as a delicate vase is shattered by a blow. The lynx shrank back and with one bound melted into the shadows of the forest. At the same moment Pal, closely followed by his master, rushed up and with a friendly red tongue licked the trapper's face.

"I didn't know I could yell so," chuckled the Hermit. "Like to scared the beast to death. It is a good thing Pal found you when he did, though. You look about frozen."

He had picked up the trapper's axe, which he now used to good effect. In another moment the cruel jaws of the trap had been loosened and the foot was free, though Dave was unable to stand. Good woodsmen as they were, they were equal to the emergency. The axe again came into play, and on a rude sledge made of thick spruce boughs, the wounded man began the trip to the Hermit's cabin which was nearer than his own. Pal frisked joyously about, now at the head of the little procession, again bringing up the rear, growling deep in his throat at some imaginary enemy of the wonderful beings whom it was his duty to protect. It was some distance through the heavy forest, fast growing shadowy with the coming of night. Before the old rail fence came into view, the Hermit was spent with fatigue, while Dave Lansing was all but fainting from the pain of his rough ride.

At length, however, the cabin was reached. The almost frozen trapper was gradually thawed out and his wound dressed, the Hermit showing himself wonderfully skillful in the process. This done, the host set about the preparation of supper while Dave lay comfortably in the bunk watching him, with a warm glow of thankfulness for his rescue and a determination to be more humane in his dealings with the creatures of the wild. As for Pal, he dozed contentedly before the fire, his eyes occasionally turning to the man whom he had rescued from death, but for the most part following every movement of his adored master.

As the days began to lengthen and the sun climbed higher, the forest country of the north stirred under the icy fetters that had bound it for long, weary months, during which the snow had drifted deep and famine had stalked the trails. Under the influence of a warm south wind the sunlit hours became musical with the steady drip, drip of melting snow, while new life seemed to flow in the veins of the forest creatures grown gaunt under the pinch of hunger. Only Kagh, the porcupine, had remained full fed, but Kagh had been unusually blessed by a kind Providence, in that every tree held a meal for him in its soft inner fibers.

It was yet too early to expect the final breaking up of winter. There would still be days when the cold would be intense and snow would drift in the trails. Nevertheless spring had called, and even the sluggish blood of the porcupine responded. Every day the earth's white mantle grew more frayed about the edges, leaving a faint tinge of green on warm southward slopes.

It was on one of these mild days that Mokwa, the black bear, shouldered aside the underbrush which concealed the mouth of the snug cave where he had hibernated, and stepped forth into the awakening world. Half blinded by the glare of sunlight upon the snow, he stood blinking in the doorway before he shambled down the slope to a great oak tree where a vigorous scratching among the snow and leaves brought to light a number of acorns. These he devoured greedily and, having crunched the last sweet morsel, sniffed eagerly about for more. Mokwa had fasted long, and now his appetite demanded more hearty fare than nuts and acorns.

The nights were chill, but each day brought a perceptible shrinking of the snowy mantle, leaving bare patches of wet, brown earth. One day Mokwa, breaking through a thick clump of juniper bushes, came out upon the bank of the Little Vermilion, its glassy surface as yet apparently unaffected by the thaw. For a moment the bear hesitated, his little near-sighted eyes searching the opposite bank and his nose sniffing the wind inquiringly; then, as if reassured, he stepped out upon the ice and made for the opposite shore.

On the surface the ice appeared solid enough, but in reality it was so honeycombed by the thaw that it threatened to break up at any moment and go out with a rush. Mokwa was in mid-stream when a slight tremor beneath his feet warned him of danger. He broke into a shuffling trot, but had gone only a few steps when, with a groaning and cracking which made the hair rise upon his back, the entire surface of the river seemed to heave. A great crack appeared just before him. With a frantic leap he cleared it, only to be confronted the next moment by a lane of rushing black water too wide for even his powerful muscles to bridge. Mokwa crouched down in the center of his ice cake, which was now being swept along in mid-stream with a rapidity which made him giddy. The weight of the bear helped to steady his queer craft, and unless it should strike another floating cake, Mokwa was in no immediate danger.

Thus he drifted for miles, while the banks seemed to glide swiftly to the rear and the stream grew gradually wider. At length a faint roar, growing louder every moment, caused Mokwa to stir uneasily as he peered ahead across the seething mass of black water and tumbling ice cakes. Suddenly his body stiffened and his eyes took on new hope. His cake had entered a side current which carried him near shore. Closer and closer drifted the great cakes all about him until at length, with a hoarse grinding, they met, piling one upon the other, but making a solid bridge from shore to shore. The jam lasted but a moment, but in that moment the bear leaped, as if on steel springs, and as the ice again drifted apart and swept on to the falls not far below, he scrambled ashore, panting but safe. Here, with tongue hanging out, he stood a moment watching the heaving waters which seemed maddened at the loss of their prey. Then he turned and vanished into the forest.

Mokwa now found himself in unknown territory, but, as he managed to find food to supply his needs, he accepted the situation philosophically and was far from being unhappy.

One day his wanderings brought him to the edge of the wilderness where, inclosed by a zigzag fence of rails, he caught his first glimpse of human habitation. Concealed in a clump of young poplars, he gazed curiously at the Hermit who was chopping wood at the rear of his cabin, and at Pal who ran about, sniffing eagerly here and there, but never far from his adored master.

At length one of his excursions into the border of the forest brought to Pal's keen nostrils the scent of the bear. Pal hated bears. The hair stiffened along his back while a growl grew in his throat, rumbled threateningly and broke forth into a volley of shrill barks.

"Bear! Bear! Bear!" he called in plain dog language; but the ears of the Hermit seemed to be strangely dull and, thinking that the dog had taken up the trail of a rabbit or at the most that of a fox, he whistled Pal back to the clearing. Pal obeyed reluctantly, stopping every few steps to look back and voice his opinion of the intruder; but, by the time he had joined his master, the bear had slipped into the forest.

Late that same afternoon, as Mokwa stood at the top of a small hill, a bright glitter from a grove of straight, smooth trees below, caught his eye. The glitter was alluring and, with no thought save to gratify his curiosity, the bear shambled quickly down the slope and brought up before a tree on the trunk of which hung a small, shining bucket. The sunlight reflected from the tin dazzled his little eyes, while to his ears came a curious, musical "plop, plop."

Without even taking the precaution to glance around him, Mokwa reared upon his haunches and examined the pail into which a clear fluid splashed, drop by drop, from a little trough inserted in the tree. A faint but delectable odour drifted to the sniffing black nose of the bear. It was Mokwa's first experience with maple sap and he proceeded to make the most of it.

Though unable to reach the liquid, owing to the smallness of the pail, he could easily lick the spile which conveyed the sap from the tree, and this Mokwa did with evident relish. His tongue sought out every crevice and even greedily lapped the tree about the gash; then, growing impatient at the slowness with which the wonderful fluid appeared, he turned his attention to the pail. Mokwa wished, no doubt, that several inches might have been added to the length of his tongue, but, though that useful member failed him, necessity found a way. He soon discovered that it was possible to dip in one paw from which the sweetness could easily be licked. However, the pressure of his other paw upon the rim of the pail caused it to tip, and sliding from the spile, it rolled upon the ground.

The accident did not dismay the bear. On the contrary it filled him with joy, for it served to bring the contents of the pail within reach, and he lapped up every drop before it could soak into the earth. The pail, too, was cleansed of sap as far as the eager tongue could reach, though, during the process, it rolled about in a way which sorely tried the bear's patience. At length it came to rest against the trunk of a tree, with which solid backing Mokwa was enabled to thrust in his muzzle far enough to lap up the last sweet drops.

But alas! when he attempted to withdraw his head, Mokwa found himself a prisoner. With the pressure against the tree the sap-bucket had become wedged so tightly upon his head that it refused to come off. Though the bear twisted and turned, banging the tin upon the ground and against trunks of trees, the endeavor to rid himself of this uncomfortable and unwelcome headdress was in vain. Mokwa grew more and more frantic and the din was so terrific that a horrified cottontail, with eyes bulging until they seemed in danger of rolling down his nose, sat frozen in his tracks at the edge of a spruce thicket. The Hermit, on his way to inspect his sap-buckets, broke into a run.

Mokwa, in his mad scramble, had paused a moment for breath. He heard the man's footfalls and the sound filled him with fresh alarm. With a last despairing effort he rose upon his haunches and tugged at the battered pail. This time his efforts were rewarded. A peculiar twist sent it flying, and the bear, free at last, made quick time to the friendly shelter of the spruce thicket, sped by the loud laughter of the Hermit.

"Guess that bear will never bother my sap-buckets again," the man chuckled, as he picked up his bright new pail, battered now past all recognition.

On the day following his harrowing experience in the sugar-maple grove Mokwa was a much chastened bear, but the incident soon faded from his memory and he once more trod the forest trails as if they had been presented to him for his sole use by Dame Nature herself. In the swamp the pointed hoods of skunk cabbage were appearing, the heat generated by their growth producing an open place in the snow about them. The odour from which the name is derived was not at all offensive to the bear who eagerly devoured many of the plants, varying the diet with roots and small twigs swelling with sap.

In the damp hollows the coarse grass was turning green, and before long the swamps were noisy with the shrill voice of the hylas, while the streams once more teemed with fish.

As the season advanced Mokwa grew fat and contented, exerting himself only enough to shuffle from one good feeding ground to another. He would grunt complainingly at any extra exertion, as, for instance, that which was required to reach the small wild sweet apples which he dearly loved, and which were clustered thickly on their small trees at the edge of the forest. At this season Mokwa's diet was almost strictly vegetarian and the smaller creatures of the wilderness, upon which he sometimes preyed, had little to fear from him.

The long summer days drifted by and autumn was not far away. Mokwa grew restless; both his food and surroundings palled upon him. At length, following a vague though persistent inner impulse, he turned his face northward toward the hills which had been his birthplace and from which he had been so strangely carried.

Long before daylight he had taken the trail and, in spite of the protests of his overfed body, had pushed steadily on, pausing at the edge of the tamarack swamp long enough to open with his sharp claws a rotting log that lay in his path, a log which yielded him a meal of fat grubs. Then he shambled on, drawn by some irresistible force. The mist which hung like a white veil over the low ground bordering the swamp was fast dissolving in curling wisps of vapor under the ardent rays of the sun. The forest was alive with bird song; squirrels chattered to him from the trees and the rattle of the kingfisher was in his ears, but Mokwa held a steady course northward, his little eyes fixed on some unseen goal.

About noon he came out upon the bank of the Little Vermilion, not far from the place where he had so narrowly escaped death on the floating ice. The roar of the falls came to him clearly on the still air and the big bear shivered. If he remembered his wild ride, however, the memory was quickly effaced by the discovery of a blueberry thicket, a luscious storehouse that apparently had never been rifled. Mokwa feasted greedily, at first stripping the branches of fruit and leaves alike; but at length, the keen edge of his appetite dulled, he sought only the finest berries, crushing many and ruthlessly tearing down whole bushes in his greed to get a branch of especially choice fruit. Then, his face and paws stained with the juice and his sides uncomfortably distended, he sought a secluded nook in which to sleep off his feast.

Toward evening, when the shadows grew long and the hills were touched with the red and gold of the setting sun, Mokwa again took up the northward trail, to which he held steadily most of the night. Morning found him emerging from a thicket of juniper upon the banks of the river at a place that he instantly recognized as the one from which he had begun his unwilling travels.

Turning sharply to the right, the bear's eager eyes discovered the trunk of a hemlock which had been blasted by lightning. Rearing himself upon his haunches against it, and reaching to his utmost, he prepared to leave his signature where he had so often left it, always above all rivals. Ere his unsheathed claws could leave their mark, however, he paused, gazing at another mark several inches above his own.

The hair rose along his back and his little eyes gleamed red while he growled deep in his chest; yet, stretch as he would, he could not quite reach the signature of the other bear. Mokwa dropped to all fours, rage filling his breast at this indication of a rival in what he considered his own domain. He hurried on, keenly alert, growing more and more incensed at every fresh trace of the interloper. Here he came upon evidences of a meal which the rival had made upon wake-robin roots. Satisfied before he had devoured all he had dug, some of the roots still lay scattered about, but, though Mokwa was hungry, he disdained the crumbs from the other's table. He dined, instead, upon a fat field mouse which he caught napping beside its runway. Again he pressed on, his anger steadily fanned by fresh evidences of the hated rival who seemed always just ahead.

Mokwa slept that night in his old den, but the next morning found him once more on the trail of the enemy, a trail which was still fresh. He had not gone far when his rival was, for the time being, forgotten, while he sniffed eagerly at a new odour which drifted to his sensitive nostrils. It was the scent of honey, a delicacy which a bear prizes above all else. At that moment, as if to confirm the evidence of his nose, a bee flew by, followed by another and another, all winging their way back to the hive. The red gleam faded from Mokwa's eyes as he followed their flight; then he broke into a shuffling run as he came within sight of the tree to which the bees were converging from all directions.

About half way up the great trunk Mokwa's eyes discovered a hole which he knew at once to be the mouth of the hive. He quickly climbed the tree on the side opposite the hole, peering cautiously around until he had reached a point directly opposite the hive. Then, craftily reaching one paw around the tree, with his claws he ripped off a great section of bark, disclosing a mass of bees and reeking comb.

At once the bees seemed to go mad. Their angry buzzing filled the air, but failed to strike terror to the heart of the robber. His thick fur rendered him immune to their fiery darts, though he was careful to protect his one vulnerable spot, the tender tip of his nose. In another moment he would have been enjoying the feast had he not discovered something which caused the hair to rise along his back and his eyes to glow with hate.

Advancing from the opposite direction was another bear, a bear larger than Mokwa and scarred with the evidences of many battles, a bear who trod the forest with a calm air of ownership. Across Mokwa's mind flashed the memory of a certain tree with his own signature the highest save one. The owner of that one was now approaching with the evident intention of claiming the sweet prize.

Mokwa's anger rose. He scrambled from the tree and, with a savage roar, was upon his rival almost before the latter had become aware of his presence. And then occurred a memorable battle, a battle for sovereignty and the freedom of the trails. Mokwa's rival was the larger of the two, but Mokwa had the advantage of youth. Sounds of the fray penetrated far into the woods. Delicate flowers and vigorous young saplings were trampled underfoot; timid little wild creatures watched with fast beating hearts, ready for instant retreat should they be observed, while above their heads the bees were busy carrying the exposed honey to a safer hiding-place.

Back and forth the combatants surged. For a time it was impossible to judge to whom the victory would go; but at length youth began to tell. The older bear was pushed steadily back. At last, torn and bleeding, his breath coming in laboring gasps, he turned and beat a retreat, far from the domain of the bear whose claim he had preëmpted.

Mokwa, too exhausted to follow, glared after him until he had vanished among the trees; then, much the worse for his fight, he turned again to the spoils, now doubly his by the right of conquest as well as of discovery. The owners of the hive, too busy to molest him, went on about their work of salvaging the contents and Mokwa made a wonderful meal, although he licked up a number of bees in his eagerness for the honey. Then, glutted with the feast, he crept away to lick his bruises and recover from the fray.

Mokwa fell asleep with the pleasant assurance that no more would the hated signature appear above his own on the hemlock trunk. The spring had called him to great adventure, but the summer had led him home and left him master of the forest.

As the moon swung clear of the pointed fir tops and shone full upon a tall spruce tree in the wilderness, a dark object, looking not unlike a great bird's nest upon one of the branches, suddenly came to life. Kagh, the porcupine, had awakened from his dreamless slumber and, though scarce two hours had elapsed since his last satisfying meal upon tender poplar shoots, he decided that it was time to eat. With a dry rustling of quills and scratching of sharp claws upon the bark, he scrambled clumsily down the tree. Then, with an air of calm fearlessness which few of the wilderness folk can assume, he set off toward the east, his short legs moving slowly and awkwardly as if unaccustomed to travel upon the ground.

Now, when Kagh left the spruce tree, it seemed he had in mind a definite goal; yet he had not gone far when his movements took on the aimlessness characteristic of most of a porcupine's wanderings. Here and there he paused to browse upon a young willow shoot or to sniff inquiringly at the base of some great tree. Once he turned sharply aside to poke an inquisitive nose into a prostrate, hollow log, where a meal of fat white grubs rewarded his search.

Kagh emerged from the thick, tangled underbrush upon a faint trail, invisible to all save the keen eyes of the forest folk. Here travel was easier and he made better time, though it could not be said that he hurried. He had not gone far upon the trail when he heard behind him a soft pad, pad. At the sound he paused a moment to stare indifferently, expecting to be given a wide berth, for, though Kagh seldom takes the offensive, even the savage lynx, unless crazed by winter hunger, will let him severely alone. This time, however, Kagh was disappointed, for the newcomer was a furry bear cub who had never had experience with a porcupine to teach him wisdom.

The cub stopped and sat upon his haunches to stare curiously at the strange creature in his path, while Kagh, incensed by the delay, tucked his nose under him until he resembled nothing so much as a huge bristling pincushion. He lay still, his small eyes shining dully among his quills. The cub regarded him for a moment; then he advanced and reached out an inquisitive paw toward the queer-looking ball. For this Kagh had been waiting. There was a lightning swing of his armed tail which, if it had reached its mark, would have filled the paw with deadly quills. Fortunately, however, the cruel barbs failed to reach their mark, for, an instant before the swing, the small bear received a cuff which sent him sprawling into the bushes, and Mother Bruin stood in the trail confronting the porcupine.

Kagh, like most of the wilderness folk, knows that there is a vast difference between a full-grown bear and a furry, inquisitive cub. Though he was not afraid, the appearance of the mother bear was more than he had bargained for, and he immediately rolled himself into a ball again, every quill bristling defiantly. The old bear, however, wise in the lore of the dim trails, paid no more attention to him. Calling her cub, she shambled off through the bushes, the youngster casting many a backward glance at this little, but seemingly very dangerous creature. Kagh went on his way well satisfied with himself. As before, he traveled leisurely, pausing often to browse or to stare at some larger animal upon whose path he chanced.

Of all the creatures of the wilderness the porcupine seems the most slow and stupid, yet he bears a charmed life. In the woods, where few may cross the path of the hunter and live, the porcupine is usually allowed to go unhurt. Because he can easily be killed without a gun, his flesh has more than once, it is said, been the means of saving a lost hunter from starvation. As a rule, the creatures of the wilderness, too, let him strictly alone, knowing well the deadly work of his quills, which, when embedded in the flesh, sink deeper and deeper with every frantic effort toward dislodgment.

Only under the stress of winter hunger will an animal sometimes throw caution to the winds and attack this living pincushion. And then his dinner is usually the price of his life, for there is no escaping the lightning-like swing of the barbed tail.

In the course of time Kagh came to the edge of a tamarack swamp. Here the ground was soft and spongy. The prostrate trunks of a number of great trees lay half submerged in lily-choked pools, beside which stalks of the brilliant cardinal flower flamed by day in the green dimness. Scrambling upon one of these decaying logs the porcupine made his way, almost eagerly for him, far out among the lily-pads. Kagh reveled in succulent lily stems and buds, and as he feasted he uttered little grunts of satisfaction.

Here he would probably have been content to spend the remainder of the night had not an interruption occurred. Another porcupine crawled out upon the same log and proceeded confidently toward the choice position at its farther end. At sight of Kagh he paused a moment; then he went on, his quills raised. Kagh looked up from his feasting, astonished that any one should thus intrude upon his hunting-ground.

And then on the end of the old log in the tamarack swamp was fought a bloodless battle, a conflict mainly of pushing and shoving. Much to his disgust, Kagh was hustled to the very end of the log and was at length pushed off, splashing into the cool water beneath. For a moment the victor peered down at him with indifferent eyes, then deliberately turned his back and began to feed upon the lilies, leaving Kagh either to sink or swim. The latter, however, was in no danger. Buoyed up by his hollow quills he soon reached the shore, none the worse for his sudden bath, save for his sorely ruffled feelings. For the time being his hunger for lily-pads had been satisfied but, as he shambled out of the swamp toward the dryer woods, he grunted complainingly.

A dim light among the trees warned him of the approach of day, and Kagh looked about for a place to take a nap. Immediately in his path a prostrate pine trunk with a snug hollow at the center offered an inviting shelter, but when the porcupine poked in his blunt black nose, he found the retreat occupied. A red fox lay curled in a furry ball, fast asleep. Even in slumber, however, a fox is alert. At the sound of Kagh's heavy breathing the occupant of the log was instantly wide awake.

By right of discovery and occupation the hollow trunk belonged to the fox, but Kagh's moral sense was either lacking or undeveloped. He wanted the hollow. Therefore he set about securing it in the easiest and most effective way. By pressing his quills close to his body and backing into the log, the sharp points presented a formidable front against which the fox had no protection. So, as Kagh backed in, the fox backed out, incensed but helpless. In a very few moments the porcupine was fast asleep, his conscience quite untroubled. As the sun rose higher, a bloodthirsty weasel thrust its pointed nose into the log and glared with red eyes of hate upon the sleeping porcupine, then went his way, spreading terror and destruction among the smaller wood folk.

About noon Kagh awoke and, crawling to the opening of the log, looked about him. As a rule the porcupine travels and feeds by night, but Kagh was a creature of whims and he decided that he had been fasting quite long enough. Accordingly he set out in a leisurely search for food, loafing along the base of a sunny ledge of rock. A meal of grubs and peppery wake-robin roots left him happy, but still he rambled on, following his nose and alert for any new adventure.

Suddenly he lifted his head and sniffed the air. To his nostrils drifted the faint scent of smoke, and smoke in Kagh's mind was associated with campfires and delectable bits of bacon rind or salty wood. For the first time since leaving his spruce tree the evening before, Kagh hurried. He blundered along the trail in a way which would have scandalized the other forest inhabitants, among whom silence is the first law of preservation.

Near the camp a rabbit had crept timidly from the forest and was sitting erect upon its haunches, its quivering nose testing the wind, its bulging eyes missing nothing that went on around it. Kagh paid no more attention to the rabbit than to the bush under which it sat. He blundered into the camp, from which the hunter was absent in search of game, but the next moment he backed off, squeaking with pain and surprise. He had walked straight into the warm ashes of the campfire.

His discomfort was soon forgotten, however, as he came upon a board saturated with bacon grease. Kagh's teeth were sharp as chisels and the sound of his gnawing could be heard far in the still air. He ate all he could hold of the toothsome wood, then started upon a tour of inspection of the camp.

An open tent-flap drew his attention. Forthwith he walked inside, knocking down as he went, an axe which had been propped close beside the entrance. Kagh sampled the axe-helve and, finding to his liking the faint taste of salt from the hand of the man who had wielded it, he succeeded in rendering it almost useless before his interest flagged. His inquisitive nose now drew him to a small bag of tobacco beside which lay a much blackened cob pipe. Whether Kagh did not care for tobacco, or whether some new fancy at that moment took possession of him, no one can tell. At any rate he nosed the pipe from its place, scattered the tobacco to the four winds, and then shambled from the tent and disappeared among the trees.

Ten minutes later he was sound asleep in a poplar sapling. What the hunter said when he returned to camp and beheld the work of his visitor is not recorded.

Kagh's was a restless spirit. Moonrise again found him abroad in search of food and adventure. This time he traveled far for a slow old fellow. At length he came to the zigzag fence of split rails which prevented the wilderness from encroaching upon the clearing of the Hermit.

From the top rail of the fence he could see the gray roof of the Hermit's cabin, silvered with the radiance of the full moon. At no time was Kagh troubled with bashfulness and now, under the influence of that flooding radiance, he decided to investigate the cabin and the clearing. The fence, ending in a rough wall of field stone, made a capital highway along which he shuffled happily until brought to an abrupt halt by the appearance of another fence traveler. The white quills with their dark points erected themselves from his blackish-brown fur until he looked twice his normal size. This time, however, his armor failed to strike terror to the heart of the enemy.

Kagh, the porcupine, was scornful of man and feared but one beast, the one who now advanced toward him along the wall. That long, silky fur, jet black save for two broad white stripes running down the back, and that plumy tail, could belong to but one creature. The skunk, returning from a neighborly visit to the Hermit's cabin, probably with a view to a meal of fat chicken, advanced with its usual air of owning the earth. This time the porcupine did not dispute the passage. Instead, he curled up and dropped to the ground, whence he proceeded on his way, complaining peevishly to himself.

All was still about the cabin. Kagh circled it until he came to the lean-to at the back that served the Hermit as a storehouse. Here the animal's useful nose caught an alluring scent. The logs of the building were thick, but patient search was at length rewarded by the discovery of a large chink. His keen cutting-teeth at once came into play and the sound of his gnawing, which carried clearly in the still night air, awakened the Hermit.

"Only a porcy," he said to himself, after listening a moment, and he went peacefully to sleep, little dreaming of the havoc which that same "porcy" was to make.

In a very short time Kagh had succeeded in gnawing a hole large enough to permit his entrance into the storehouse. Then indeed he found himself in rich pasturage. The first thing he came to was a small basket of eggs, a delicacy which he prized highly. When these were neatly reduced to shells, he gnawed a hole in a barrel near by and sampled the little stream of flour which ran out. This was not to be compared with eggs, however, and after scattering a goodly quantity about the floor, he finished his meal on a side of fat bacon. When at last he turned his face toward the forest, he found that the hole, which had been a tight squeeze when he entered, was now out of the question, and he must do some further gnawing before he could squeeze his fat sides through.

Once in the open he set a leisurely course toward the borders of the forest, only to be interrupted by a series of staccato barks as Pal rounded the cabin and glimpsed the night prowler. Like the bear cub, Pal had had no experience with a porcupine to teach him prudence. He felt that the beast had no business in the clearing and accordingly charged, barking furiously, only to be met by a round ball of bristling quills. Pal stopped, clearly astonished. Then, as the ball lay deceivingly still, he rashly tried closer investigation, and was met with a smashing blow from the barbed tail.

Several quills fastened themselves in the dog's soft and tender nose and there they stayed, paining him unbearably. The aggressive challenge changed to yelps of pain and, as swiftly as he had charged, Pal retreated to the cabin, vainly trying to free his muzzle of the fiery barbs. With his efforts they but sank the deeper. He suffered agony until his master, aroused by the outcry, came to his relief. Holding the struggling dog firmly with both hands, the Hermit extracted the quills with his teeth. It was a painful process and both were glad when the last quill was out.

Meanwhile, Kagh continued on his placid way toward the black forest wall, just beyond the rail fence. He had fed well and had quickly routed his enemy. Altogether he considered the world a happy place for porcupines. In the darkness which precedes the dawn he took his way to a slender poplar sapling standing near the border of the woods. This he climbed as far as his weight would permit and, seated comfortably on one branch, with his hand-like paws tightly clasping another, he went peacefully to sleep, lulled by every passing breeze.

On a bare, rocky promontory far up in the north country, where the turbulent waters of the Little Vermilion cut through lanes of pointed fir and dark spruce, a gigantic moose stood, his ungainly body and huge antlers silhouetted against the sky of sunset. Below him the noisy, hurrying waters were churned into foam over innumerable hidden rocks; to the rear lay the wilderness, green, shadowy and mysterious.

The moose was a magnificent beast, the ridge of his shoulders rising to a height of little less than seven feet. His great antlers, the admiration and desire of every hunter in the Little Vermilion country, showed a spread of almost six feet from tip to tip. As if carved from the rock the big moose stood, his eyes on the distant waters, only his ears moving slightly to test the wind. Then, as some vagrant whiff from the gently moving air assailed the sensitive nostrils, or some faint sound reached his ears, the great beast turned and vanished into the forest, as light and soundless as thistledown for all his twelve hundred pounds of bulk. Not even a twig snapped under his feet.

As night shrouded the dim trails, the moose turned southward through the darkness. In spite of the dense wilderness he advanced rapidly, his huge antlers laid along his back that they might impede his progress as little as possible, his nose thrust upward, sifting the wind. In about an hour he came out upon the shore of a lonely pond among the hills. A faint breeze ruffled the mirror-like surface upon which the delicate white cups of water-lilies seemed to hold a light of their own among the dark green pads.

With a sigh of satisfaction the moose waded in and plunged his muzzle into the clear water, breaking the star reflections into innumerable points of light as the ripples widened over the pond. For some time he fed greedily, moving slowly along the shore. At times his great head was wholly submerged as his long, flexible upper lip sought out the succulent roots and buds; again it was raised, while from the gently moving jaws the water dripped with a musical plash into the pond.

Suddenly the wilderness was startled from its calm by the appearance of a dazzling finger of light which crept across the pond and came to rest upon the dark bulk of the moose at his feeding. The great beast raised his head to stare into the strange, blinding radiance. He could not see the dark form crouched in the boat behind the light, nor the long sinister object leveled upon him. He could only stare, fascinated, an easy mark for the hunter behind the jack-light.

From the forest in the rear of the moose came a faint sound. It was only the crackling of a twig, yet it served to break the spell under which the beast stood, for in the wilderness the snap of a twig is one of the most ominous of sounds. The animal wheeled sharply just as the hunter pulled the trigger. There was the sharp crack of a rifle which woke the echoes and startled the wilderness into an added alertness, while the ball sped across the water, barely missing the form of the moose. Before the disappointed hunter could again pull the trigger the great beast had reached the shore with a bound and was crashing through the forest, over windfalls and through thickets with the speed of an express train. Lesser wilderness folk watched his flight with startled eyes, keeping well out of his path. Even the fierce Canada lynx knew better than to attack that living whirlwind, though his pale eyes gleamed maliciously and his claws dug deep into the bark as the moose passed directly beneath the branch on which the big cat crouched. The fleeing animal did not see him.

That night, far from the pond, the moose made his bed on a wooded knoll, lying, as is the custom of his kind, with his back to the wind. Should danger approach from the rear his keen nose would give him warning, while eyes and ears would protect him from anything approaching against the wind.

With the first light of day he was on his feet, enjoying a breakfast of birch twigs, obtained by breasting down a sapling and holding it beneath his body while he fed upon the tender tips. His meal finished, he backed off, leaving the sapling to spring up again unharmed. His fear of the night before had vanished and once more he was lord of the wilderness, a beast to be admired but let severely alone.

Again he turned southward, stepping daintily, the "bell," or tuft of coarse hair beneath his chin, swinging to his pace. Occasionally a cottontail leaped from his path and paused to stare, big ears alert and nose twitching sensitively; or a red squirrel, that saucy mischief-maker of the woods, chattered derisively at him from the safe side of a spruce trunk. But the moose paid no more heed to them than to the lofty trees which arched above his path.

Gradually the shadows lengthened and again dusk swathed the forest aisles in gray mystery. As the darkness deepened, the moose moved more cautiously, testing each step for crackling twigs. His great head swung much lower than the ridge of his shoulders as he paused occasionally to listen, his gray-brown form melting into the shadows as if he wore a cloak of invisibility.

Thus he came again to the wilderness pond where he had so nearly met fate in the form of the hunter's bullet. The glare was gone and peace once more brooded over the placid water. For a long moment he stood upon the bank, listening and looking; then a vagrant puff of air brought to his nostrils a strange odor. His great muscles tightened, but, as no sound broke the stillness, he moved cautiously in the direction of the scent.

At the edge of a small natural clearing among the trees he paused to reconnoiter. In the center of the clearing glowed the embers of a campfire, the smoke of which had reached him at the pond. A small tongue of flame occasionally leaped up, illuminating a circle of darkness. On the side opposite the moose lay a still, dark form wrapped in a blanket.

For some time the animal stood, the pupils of his eyes contracting or expanding as the glow of the embers waxed or waned. Then a brand in the campfire burned through and broke with a snap, sending up a shower of sparks. Whether the sound reminded him of the rifle report of the previous night or whether the man-smell at that moment startled him, is uncertain. At any rate his eyes suddenly grew red with anger and, with a roar, he charged straight toward the sleeping form beside the fire.

Immediately the hunter awoke to action. In order to free himself of the entangling blanket he rolled over, a fortunate move which accomplished a double purpose in that it took him just out of reach of the charging animal. Before the moose could stay his mad rush and turn, the man had scrambled up a tree. From that safe perch he watched helplessly the destruction of his camp. The hunter being out of reach, the big moose charged upon his camp supplies, and the night was made hideous with the crashing of pots and pans.

The noise seemed to drive the brute to a frenzy. With a wild bellow he crashed away through the forest, the remains of a frying pan impaled upon the sharp point of an antler. As he rushed, it banged against trees and drove him to greater speed until it was left behind on a branch. As for the hunter, he could only gaze wrathfully upon his wrecked camp and bemoan the fate which had twice brought to him the coveted game, only to snatch it away again unharmed.

The night tumult had aroused the Hermit in his cabin, a mile distant at the edge of the forest. With the coming of daylight he set out to ascertain what had happened. By good fortune he stumbled upon the camp just as the disgusted hunter was leaving and he heard the story of the charging moose, the evidence of whose mad flight was apparent for some distance. He invited the hunter to spend a few days in his cabin, an invitation which the man thankfully accepted. Though each morning found him abroad, armed and eager, he caught no further glimpse of the big moose.

Meanwhile, the wilderness was becoming an uncomfortable place for the hunter. The myriad swarms of insects gave him no peace by day or night, while the big moose was spending long peaceful hours far away at the edge of a tiny, wood-girt lake. During the day the moose dozed on a cool mud bed in the shallows, his body submerged save for the tip of his nose. This, too, disappeared from sight occasionally as the flies became too persistent. At night he wandered abroad, searching out the best feeding-grounds.

Late summer gave place to autumn with its warm mellow days and its nights tinged with frost. The sun shone through a faint haze, touching to glowing color the maples in the swamp and the golden birches on the knolls. Now and then a leaf drifted to the ground with a faint rustle.

At the edge of the wilderness where stood the cabin of the Hermit and those of his widely scattered neighbors, the aromatic smell of burning leaves hung all day in the still air, while the early stars looked down on bright heaps of burning rubbish. It was the outdoor cleaning time.

On several occasions, as the Hermit stood dreamily watching the thin wisps of smoke curl upward from the burning heap, he heard the call of a moose to its mate or its challenge to a rival. The sound thrilled him as no sound had for years. He longed to answer the summons. Accordingly, one day he made a trip into the borders of the wilderness where a group of slender birch trees huddled. Like Hiawatha he stripped one of a section of its bark.

The next evening found him seated comfortably on the top rail of the snake fence which separated his upland pasture from the closely pressing forest. The sun had set, and a mellow twilight with a tang of frost in the air was fast obscuring the black stumps and welding together the clumps of blueberries and wild raspberries.

The man sat so still that gradually the small inhabitants of the wilderness went fearlessly about their hunting or playing. If they noticed him at all, perhaps they mistook him for a stake of the fence upon which he sat. As he watched dreamily, the dusk grew deeper and the first stars came out, one by one. Then the harvest moon appeared, peeping over the tops of the firs and finally riding clear in the dark sky, throwing a mysterious radiance over the clumps of juniper in the pasture and trying vainly to penetrate the thick stand of second-growth fir, spruce and maple at the edge of the forest.

Now the Hermit slowly raised to his lips the birch-bark trumpet which he had fashioned. The next moment the brooding silence of the night was startled by a harsh roar. The Hermit chuckled softly. "If there is a moose within a mile he can't help hearing that," he thought.

He waited, his heart beating fast with excitement. The echoes rolled for a moment among the hills, then died away, leaving the silence unbroken.

Again he raised the trumpet to his lips and sent out a call into the night. This time the sound had scarcely died away when an answering challenge rolled from a pair of great lungs back in the wilderness. In his excitement the man almost lost his perch upon the fence. "That's an old bull, sure enough. Probably the same one that broke up the hunter's camp," he said, speaking aloud, as is often the custom of those living alone.

He listened a moment. Hearing no further sound, once more he raised his trumpet, this time giving a low, seductive call. The effect was immediate and unexpected. A short distance back in the forest there came the crash of trampled undergrowth and, the next moment, a huge black bulk detached itself from the dark background and stood forth in the moonlight, alarmingly close.

The Hermit caught his breath. It was without doubt the big moose, and that he was in no gentle mood was soon apparent. He listened a moment, motionless as the trees at his back; then he brought forth a harsh roar that sent a chill to the heart of the unprotected man. When he had come to the pasture to try his trumpet, the Hermit had little expected an answer, or at best had hoped merely to call up a cow moose. Instead, he found himself confronted by the biggest bull moose he had ever seen. Though his heart thrilled at sight of the great head and antlers, he wished ardently that there might have been some stronger protection than the frail fence between them.

Absolute immovability was his only hope and, like Molly Cottontail, he "froze." Incensed at the silence where he had expected to find either a mate or a rival, the big moose began to grumble deep in his throat and to shake his antlers threateningly. Then he advanced a few steps. Perspiration stood out upon the face of the Hermit, but he made no movement. The moonlight was deceptive and the beast did not see the man until he was uncomfortably close. Then a great bellow of rage burst from him. At the same moment the Hermit took the one chance that presented itself and dropped on the opposite side of the fence. The charge of the big moose smashed the slight barrier as if it had been straw, but it gave the man the chance he desired. He sprinted as he never had sprinted before to a wild cherry tree which stood in an angle of the fence. With an agility which he would not have believed possible, he drew himself into its branches just as the moose reached the spot. There the Hermit sat panting while the animal raged underneath, trying vainly to spear his enemy with the bayonet-sharp points of his antlers.

Finding the man out of reach, the moose turned his attention to the fence which he quickly reduced to kindling wood. The Hermit could only watch the destruction of that which had taken days of labor. He used vigorously the only weapon which he possessed, his tongue, but the big moose cared nothing for the sound of the human voice raised in protestation. Having vented his rage upon the hapless fence, he took up his position beneath the tree, rumbling threateningly and tearing up the ground with his sharp hoofs, one blow of which would have instantly killed the man.

Occasionally he stepped into the fringe of the forest but at the least movement of his prisoner in the tree he was back on guard, shaking his huge antlers threateningly. Thus the time wore on. As the air grew frostier, the Hermit shivered and huddled closer to the trunk of his tree. "Wish I had your hide!" he muttered, looking wrathfully down at his jailer.

Now and then the Hermit could hear Pal howling lonesomely. Fortunately, he had shut the dog up in the house when he set forth upon his rash adventure. "Never mind, Pal," he said aloud, "you may be glad you are alone. I only wish I were." He aimed a vicious kick at the antlers, which were not far below, but was forced to draw up his foot quickly.

At last, when the Hermit's cramped position had grown distressingly painful, there came a welcome interruption. Suddenly the big moose ceased his pawing and listened intently, his great ears strained to some sound which had been inaudible to the Hermit. Both waited expectantly. Far off, but unmistakable, came the call of a cow moose. Instantly the bull sent out his rumbling reply, though he did not desert his post. Again came the call, this time much nearer. The Hermit in his interest forgot that he was a prisoner, that his feet had gone to sleep, and that he was chilled through and through.

Now a crackling sounded from among the trees and a moment later a shadowy bulk, followed by a smaller one which the Hermit rightly judged to be a yearling calf, emerged from the dark forest. The bull, with a low bleat ridiculous in so large a beast, sprang to meet them. The man in the tree was forgotten as the two big animals followed by the calf, vanished, three shadows among the darker shadows of the woods. The Hermit was glad enough to lower himself from the tree and make his way painfully to the cabin and the comfort of his fire and his dog. He had had enough of moose-calling for a season.

The big moose reigned supreme in all the northland. When the snows of winter began to whiten the wilderness, he led his herd to a sheltered nook deep among the hemlocks. There the yard was formed, a labyrinth of intersecting paths, kept free from deep snow and leading to the best places for food and shelter. The herd lived in comparative comfort until spring returned to the wilderness, and the bull moose, having shed his great antlers, sought seclusion until a new pair should once more clothe him with strength and courage.

Ahmeek, the beaver, swimming slowly with only his eyes and the tip of his nose above the water, came to a stop at a spot where the shores of the stream were low and flat. He was soon joined by his mate and the two clambered out upon the bank where they looked about with satisfaction.

It was an ideal location for a beaver settlement. Poplars, yellow birches and willows on the banks offered material for a dam and assured an abundance of winter food; the low banks would enable the stream to spread out, making a pond deep enough to prevent freezing to the bottom in winter; best of all, it was a lonely spot where there was no evidence of man.

Dusk had fallen like a gray mantle upon the wilderness when the beavers began their work. Ahmeek selected a poplar to his liking, not far from the bank of the stream. Grasping the trunk with his hand-like paws and turning his head to one side in order to bring his great cutting teeth into play, he bit out a huge chunk, following it with another and another until the tree swayed and crashed to the ground. Then both beavers set to work to strip it of branches and lay the foundations for the dam.

The dam, when finished, was a work worthy of a trained engineer. The twigs and trunks of trees Ahmeek and his mate laid lengthwise with the current. On the upper face, where the force of the water would but drive it the more tightly, the mass was plastered and bound together with a cement of mud and stones, which in the freezing days of winter would become impenetrable. Here again the beavers showed their wisdom by leaving several low places over which the water could trickle, thus relieving the pressure that otherwise would have broken the dam. Now the stream overflowed its low banks, making a deep pond, soon to become the home of pickerel and trout and of a great colony of water-lilies, a delicacy for the beaver larder.

The next work was the construction of the lodge, a hollow mound of mud, sticks and stones twelve feet in width and four in height, within which was a dry room, its floor safely above the high-water mark. Two passages led to this room, one straight, for carrying food, the other winding. The main entrance was cleverly concealed beneath the roots of a great tree which had fallen across the stream.

Ahmeek and his mate were soon joined by other beavers, pioneers from farther south, who, finding the spot to their liking, decided to establish a colony. As with the human pioneers, there was a great felling of trees and hours of heavy labor before the dwellings were finished and the various families ensconced in their snug homes.

That first winter in the new colony was uneventful and when the ice broke up in the spring the beaver city was swarming with sleek brown youngsters who, while learning the serious business of life, found time to indulge in play just as do the children of their human neighbors. At twilight one after another would appear upon the bank, where he would make his toilet, combing his thick, chestnut brown fur until it shone like satin. No beaver is untidy about his dress.

Among the young beavers there was one who from the first took the lead. Born in the lodge of old Ahmeek, king of the beavers, he showed every indication of following in the footsteps of his father. He it was who led the others in their frolic in the pond and upon the banks, and when the sharp slap of a tail upon the water told of danger, none was more quick to obey its warning.

The young beavers did not spend all their time in play. The dam constantly needed repair; wood must be cut and stored at the bottom of the pond, so that the colony might have food through the winter. At this work Flat Tail, son of Ahmeek, laboured manfully. His teeth were not yet long and sharp enough for felling trees, but they could cut off the smaller branches. Flat Tail was very proud when he could swim back to the lodge with one of these branches over his shoulder, kept in place by his fore-paws held close to his body.

One day toward the end of the summer Flat Tail had a narrow escape. He was sitting on the bank, combing his glossy brown fur, of which he was very proud, when a prowling panther discovered him. The big cat's mouth watered, for beaver at all times is a delicate morsel for the flesh-eating animals. The green eyes narrowed to mere slits as, silent as a shadow, the panther climbed a tree and made its way out to a point from which a straight drop would land it upon its unsuspecting quarry. In another moment Flat Tail, intent upon his toilet and oblivious of his danger, would undoubtedly have furnished a meal for the panther had not old Ahmeek appeared, swimming upward from the lodge. Immediately his keen eyes discovered the crouching animal and, with a sound like the crack of a rifle, his flat, horny tail descended upon the water.

It was a sound which all beavers are taught to obey instantly and without question. Even as the big cat dropped, Flat Tail dived backward into the stream. The panther, with a scream of rage, dug its claws into the earth where its prey had been sitting a moment before. The beaver was out of reach, however, and there was nothing for the panther to do but continue on his hungry way, his scream having warned every animal for miles around to hide. As for Flat Tail, he swam directly to the lodge where he crouched trembling.

The summer passed, and autumn with its flaming colors and hint of frost came to the wilderness. On a warm Indian summer day the Hermit, in his search for healing roots, came out upon the shore of the stream which sheltered the beaver colony. As he approached he heard a resounding slap and saw a number of sleek brown forms dive into the water. Thus, when he stepped out upon the shore, there was not a beaver in sight, though evidences of their work were all about. The Hermit's eyes had grown keen and his brain wise in the lore of the wilderness, so that now he knew beyond a doubt that the colony was busy building the dam higher and raising the lodges farther above the stream.

"Must be expecting a freshet," he mused.

For some time he waited, concealed in a clump of bushes, hoping to catch sight of the inhabitants of the pond or perhaps even watch them at work. His waiting was vain, however, for the bright eyes of the wily little beasts had penetrated his hiding place and not one ventured forth until the Hermit gave up in despair and went on his way. Then immediately the shining face of Ahmeek appeared at the surface and the pond once more swarmed with activity.

Under Ahmeek's direction the dam was made much higher and the floors of the lodges were raised above the highest mark which the stream had ever reached. Then the whole colony turned its attention to providing food for the winter. Aspen, poplar and willow branches were carried to the pond where, as they became waterlogged, they sank to the bottom, there to remain until needed. Lily-pads floating lightly upon the surface of the pond gave promise of white succulent roots which penetrated the ooze beneath. Sweet flag was abundant, and close by grew a clump of dark green, spicy mint.

The warm, hazy days of Indian summer passed. The leaves drifted to the ground where they spread a rustling carpet, hiding the sweet three-cornered beechnuts upon which squirrels and raccoons waxed fat and contented. The activities of the beavers continued until, one morning after a clear cold night, when the stars seemed to twinkle immeasurably far above the wilderness, a film of ice covered the surface of the pond.

Then, in a night, winter descended upon the forest. The ice grew thick and solid. The domes of the lodges froze as hard as stone and only a thin, almost imperceptible wisp of steam, arising from the ventilating holes, gave indication of the life within. This was the beavers' season of rest and they made the most of it. Snow covered land and water alike. Icy gales swept over the wilderness, sending the inhabitants to cover and lashing the great trees until it seemed as if they could not stand. For most of the wilderness folk it was the hunger time, when game is scarce and exceedingly wary.

For the beavers, however, it was a time of plenty. On their warm beds of leaves under the frozen domes where never a cold breeze touched them, they dreamed away the hours or, waking, nibbled a bit of aspen bark thoughtfully provided on the floor of the lodge. The sticks were then carried out and used in strengthening the dam. Occasionally a black, whiskered face would appear beneath the ice where the snow had been blown away, and stare out for a moment at the wintry world, but it would be quickly withdrawn as the beaver returned to his comfortable lodge.

One day in midwinter, when the sun shone upon a world of sparkling white, the Hermit, this time upon snowshoes, again visited the beaver pond. The white domes of the lodges dotted the snowy surface but there was no sign of life. The man stepped out upon the dam and hacked at it with an axe which he had brought to provide himself with firewood. There was no penetrating its stony surface, and, as he looked out across the hard, rounded domes, he smiled to himself, picturing the beavers in their snug retreats. He knew that beneath the ice was a fortune in valuable furs, but the thought brought with it no desire for possession. In the Hermit's opinion the skins were of far greater value to the beavers than to himself.

Knowing that the forest folk, after having been storm-bound for days, would now be driven abroad by hunger, the Hermit concealed himself in a fir thicket not far from the pond and waited to see what of interest chance would bring to him. He had waited scarcely ten minutes when a lithe, tawny form appeared, sniffing at his trail and pausing often to look suspiciously about. "Panther," thought the Hermit, with a thrill of pleasure that his watching had so soon yielded results.