Title: Practical Grammar and Composition

Author: Thomas Wood

Release date: September 11, 2007 [eBook #22577]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Robert J. Hall

BY

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

NEW YORK CHICAGO

This book was begun as a result of the author's experience in teaching some classes in English in the night preparatory department of the Carnegie Technical Schools of Pittsburg. The pupils in those classes were all adults, and needed only such a course as would enable them to express themselves in clear and correct English. English Grammar, with them, was not to be preliminary to the grammar of another language, and composition was not to be studied beyond the everyday needs of the practical man.

Great difficulty was experienced because of inability to secure a text that was suited to the needs of the class. A book was needed that would be simple, direct and dignified; that would cover grammar, and the essential principles of sentence structure, choice of words, and general composition; that would deal particularly with the sources of frequent error, and would omit the non-essential points; and, finally that would contain an abundance of exercises and practical work.

It is with these ends in view that this book has been prepared. The parts devoted to grammar have followed a plan varying widely from that of most grammars, and an effort has been made to secure a more sensible and effective treatment. The parts devoted to composition contain brief expositions of only the essential principles of ordinary composition. Especial stress has been laid upon letter-writing, since this is believed to be one of the most practical fields for actual composition work. Because such a style seemed best suited to the general scheme and purpose of the book, the method of treatment has at times been intentionally rather formal.

Page vi Abundant and varied exercises have been incorporated at frequent intervals throughout the text. So far as was practicable the exercises have been kept constructive in their nature, and upon critical points have been made very extensive.

The author claims little credit except for the plan of the book and for the labor that he has expended in developing the details of that plan and in devising the various exercises. In the statement of principles and in the working out of details great originality would have been as undesirable as it was impossible. Therefore, for these details the author has drawn from the great common stores of learning upon the subjects discussed. No doubt many traces of the books that he has used in study and in teaching may be found in this volume. He has, at times, consciously adapted matter from other texts; but, for the most part, such slight borrowings as may be discovered have been made wholly unconsciously. Among the books to which he is aware of heavy literary obligations are the following excellent texts: Lockwood and Emerson's Composition and Rhetoric, Sherwin Cody's Errors in Composition, A. H. Espenshade's Composition and Rhetoric, Edwin C. Woolley's Handbook of Composition, McLean, Blaisdell and Morrow's Steps in English, Huber Gray Buehler's Practical Exercises in English, and Carl C. Marshall's Business English.

To Messrs. Ginn and Company, publishers of Lockwood and Emerson's Composition and Rhetoric, and to the Goodyear-Marshall Publishing Company, publishers of Marshall's Business English, the author is indebted for their kind permission to make a rather free adaptation of certain parts of their texts.

Not a little gratitude does the author owe to those of his friends who have encouraged and aided him in the preparation of his manuscript, and to the careful criticisms and suggestions made by those persons who examined the completed manuscript in behalf of his publishers. Above all, a great debt of Page vii gratitude is owed to Mr. Grant Norris, Superintendent of Schools, Braddock, Pennsylvania, for the encouragement and painstaking aid he has given both in preparation of the manuscript and in reading the proof of the book.

T.W.

Braddock, Pennsylvania.

| CHAPTER | ||

| I.— | Sentences—Parts of Speech—Elements of Sentence—Phrases and Clauses | |

| II.— | Nouns | |

|

Common and Proper Inflection Defined Number The Formation of Plurals Compound Nouns Case The Formation of the Possessive Case Gender | ||

| III.— | Pronouns | |

|

Agreement with Antecedents Person Gender Rules Governing Gender Number Compound Antecedents Relative Interrogative Case Forms Rules Governing Use of Cases Compound Personal Compound Relative Adjective Miscellaneous Cautions | ||

| IV.— | Adjectives and Adverbs | |

|

Comparison Confusion of Adjectives and Adverbs Page x Improper Forms of Adjectives Errors in Comparison Singular and Plural Adjectives Placing of Adverbs and Adjectives Double Negatives The Articles | ||

| V.— | Verbs | |

|

Principal Parts Name-form Past Tense Past Participle Transitive and Intransitive Verbs Active and Passive Voice Mode Forms of the Subjunctive Use of Indicative and Subjunctive Agreement of Verb with its Subject Rules Governing Agreement of the Verb Miscellaneous Cautions Use of Shall and Will Use of Should and Would Use of May and Might, Can and Could Participles and Gerunds Misuses of Participles and Gerunds Infinitives Sequence of Infinitive Tenses Split Infinitives Agreement of Verb in Clauses Omission of Verb or Parts of Verb Model Conjugations To Be To See | ||

| VI.— | Connectives: Relative Pronouns, Relative Adverbs, Conjunctions, and Prepositions | |

|

Independent and Dependent Clauses Page xi Case and Number of Relative and Interrogative Pronouns Conjunctive or Relative Adverbs Conjunctions Placing of Correlatives Prepositions | ||

| Questions for the Review of Grammar | ||

| A General Exercise on Grammar | ||

| VII.— | Sentences | |

|

Loose Periodic Balanced Sentence Length The Essential Qualities of a Sentence Unity Coherence Emphasis Euphony | ||

| VIII.— | Capitalization and Punctuation | |

|

Rules for Capitalization Rules for Punctuation | ||

| IX.— | The Paragraph | |

|

Length Paragraphing of Speech Indentation of the Paragraph Essential Qualities of the Paragraph Unity Coherence Emphasis | ||

| X.— | Letter-Writing | |

|

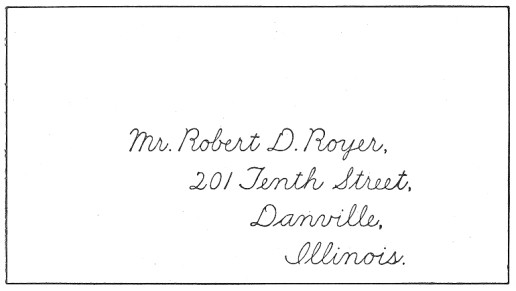

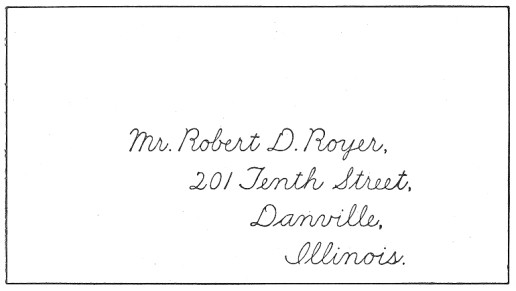

Heading Inside Address Salutation Body of the Letter Page xii Close Miscellaneous Directions Outside Address Correctly Written Letters Notes in the Third Person | ||

| XI.— | The Whole Composition | |

|

Statement of Subject The Outline The Beginning Essential Qualities of the Whole Composition Unity Coherence The Ending Illustrative Examples Lincoln's Gettysburgx Speech Selection from Cranford List of Books for Reading | ||

| XII.— | Words—Spelling—Pronunciation | |

|

Words Good Use Offenses Against Good Use Solecisms Barbarisms Improprieties Idioms Choice of Words How to Improve One's Vocabulary Spelling Pronunciation | ||

| Glossary of Miscellaneous Errors | ||

Page 1 PRACTICAL GRAMMAR AND COMPOSITION

SENTENCES.—PARTS OF SPEECH.—ELEMENTS OF THE SENTENCE.—PHRASES AND CLAUSES

1. In thinking we arrange and associate ideas and objects together. Words are the symbols of ideas or objects. A Sentence is a group of words that expresses a single complete thought.

2. Sentences are of four kinds:

1. Declarative; a sentence that tells or declares something; as, That book is mine.

2. Imperative; a sentence that expresses a command; as, Bring me that book.

3. Interrogative; a sentence that asks a question; as, Is that book mine?

4. Exclamatory; a declarative, imperative, or interrogative sentence that expresses violent emotion, such as terror, surprise, or anger; as, You shall take that book! or, Can that book be mine?

3. Parts of Speech. Words have different uses in sentences. According to their uses, words are divided into classes called Parts of Speech. The parts of speech are as follows:

1. Noun; a word used as the name of something; as, man, box, Pittsburgh, Harry, silence, justice.

Page 2 2. Pronoun; a word used instead of a noun; as, I, he, it, that.

Nouns, pronouns, or groups of words that are used as nouns or pronouns, are called by the general term, Substantives.

3. Adjective; a word used to limit or qualify the meaning of a noun or a pronoun; as, good, five, tall, many.

The words a, an, and the are words used to modify nouns or pronouns. They are adjectives, but are usually called Articles.

4. Verb; a word used to state something about some person or thing; as, do, see, think, make.

5. Adverb; a word used to modify the meaning of a verb, an adjective, or another adverb; as, very, slowly, clearly, often.

6. Preposition; a word used to join a substantive, as a modifier, to some other preceding word, and to show the relation of the substantive to that word; as, by, in, between, beyond.

7. Conjunction; a word used to connect words, phrases, clauses, and sentences; as, and, but, if, although, or.

8. Interjection; a word used to express surprise or emotion; as, Oh! Alas! Hurrah! Bah!

Sometimes a word adds nothing to the meaning of the sentence, but helps to fill out its form or sound, and serves as a device to alter its natural order. Such a word is called an Expletive. In the following sentence there is an expletive: There are no such books in print.

4. A sentence is made up of distinct parts or elements. The essential or Principal Elements are the Subject and the Predicate.

The Subject of a sentence is the part which mentions that about which something is said. The Predicate is the part which states that which is said about the subject. Man walks. In this sentence, man is the subject, and walks is the predicate.

Page 3 The subject may be simple or modified; that is, may consist of the subject alone, or of the subject with its modifiers. The same is true of the predicate. Thus, in the sentence, Man walks, there is a simple subject and a simple predicate. In the sentence, The good man walks very rapidly, there is a modified subject and a modified predicate.

There may be, also, more than one subject connected with the same predicate; as, The man and the woman walk. This is called a Compound Subject. A Compound Predicate consists of more than one predicate used with the same subject; as, The man both walks and runs.

5. Besides the principal elements in a sentence, there are Subordinate Elements. These are the Attribute Complement, the Object Complement, the Adjective Modifier, and the Adverbial Modifier.

Some verbs, to complete their sense, need to be followed by some other word or group of words. These words which "complement," or complete the meanings of verbs are called Complements.

The Attribute Complement completes the meaning of the verb by stating some class, condition, or attribute of the subject; as, My friend is a student, I am well, The man is good Student, well, and good complete the meanings of their respective verbs, by stating some class, condition, or attribute of the subjects of the verbs.

The attribute complement usually follows the verb be or its forms, is, are, was, will be, etc. The attribute complement is usually a noun, pronoun, or adjective, although it may be a phrase or clause fulfilling the function of any of these parts of speech. It must not be confused with an adverb or an adverbial modifier. In the sentence, He is there, there is an adverb, not an attribute complement.

The verb used with an attribute complement, because such verb joins the subject to its attribute, is called the Copula ("to couple") or Copulative Verb.

Page 4 Some verbs require an object to complete their meaning. This object is called the Object Complement. In the sentence, I carry a book, the object, book, is required to complete the meaning of the transitive verb carry; so, also in the sentences, I hold the horse, and I touch a desk, the objects horse and desk are necessary to complete the meanings of their respective verbs. These verbs that require objects to complete their meaning are called Transitive Verbs.

Adjective and Adverbial Modifiers may consist simply of adjectives and adverbs, or of phrases and clauses used as adjectives or adverbs.

6. A Phrase is a group of words that is used as a single part of speech and that does not contain a subject and a predicate.

A Prepositional Phrase, always used as either an adjective or an adverbial modifier, consists of a preposition with its object and the modifiers of the object; as, He lives in Pittsburg, Mr. Smith of this place is the manager of the mill, The letter is in the nearest desk.

There are also Verb-phrases. A Verb-phrase is a phrase that serves as a verb; as, I am coming, He shall be told, He ought to have been told.

7. A Clause is a group of words containing a subject and a predicate; as, The man that I saw was tall. The clause, that I saw, contains both a subject, I, and a predicate, saw. This clause, since it merely states something of minor importance in the sentence, is called the Subordinate Clause. The Principal Clause, the one making the most important assertion, is, The man was tall. Clauses may be used as adjectives, as adverbs, and as nouns. A clause used as a noun is called a Substantive Clause. Examine the following examples:

Adjective Clause: The book that I want is a history.

Adverbial Clause: He came when he had finished with the

work.

Noun Clause as subject: That I am here is true.

Noun Clause as object: He said that I was mistaken.

Page 5 8. Sentences, as to their composition, are classified as follows:

Simple; a sentence consisting of a single statement; as, The man walks.

Complex; a sentence consisting of one principal clause and one or more subordinate clauses; as, The man that I saw is tall.

Compound; a sentence consisting of two or more clauses of equal importance connected by conjunctions expressed or understood; as, The man is tall and walks rapidly, and Watch the little things; they are important.

Exercise 1

In this and in all following exercises, be able to give the reason for everything you do and for every conclusion you reach. Only intelligent and reasoning work is worth while.

In the following list of sentences:

(1) Determine the part of speech of every word.

(2) Determine the unmodified subject and the unmodified predicate; and the modified subject and the modified predicate.

(3) Pick out every attribute complement and every object complement.

(4) Pick out every phrase and determine whether it is a prepositional phrase or a verb-phrase. If it is a prepositional phrase, determine whether it is used as an adjective or as an adverb.

(5) Determine the principal and the subordinate clauses. If they are subordinate clauses, determine whether they are used as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs.

(6) Classify every sentence as simple, complex, or compound.

Exercise 2

(1) Write a list of six examples of every part of speech.

(2) Write eight sentences, each containing an attribute complement. Use adjectives, nouns, and pronouns.

(3) Write eight sentences, each containing an object complement.

(4) Write five sentences, in each using some form of the verb to be, followed by an adverbial modifier.

NOUNS

9. A noun has been defined as a word used as the name of something. It may be the name of a person, a place, a thing, or of some abstract quality, such as, justice or truth.

10. Common and Proper Nouns. A Proper Noun is a noun that names some particular or special place, person, people, or thing. A proper noun should always begin with a capital letter; as, English, Rome, Jews, John. A Common Noun is a general or class name.

11. Inflection Defined. The variation in the forms of the different parts of speech to show grammatical relation, is called Inflection. Though there is some inflection in English, grammatical relation is usually shown by position rather than by inflection.

The noun is inflected to show number, case, and gender.

12. Number is that quality of a word which shows whether it refers to one or to more than one. Singular Number refers to one. Plural Number refers to more than one.

13. Plurals of singular nouns are formed according to the following rules:

1. Most nouns add s to the singular; as, boy, boys; stove, stoves.

2. Nouns ending in s, ch, sh, or x, add es to the singular; as, fox, foxes; wish, wishes; glass, glasses; coach, coaches.

3. Nouns ending in y preceded by a vowel (a, e, i, o, u) add s; as, valley, valleys, (soliloquy, soliloquies and colloquy, colloquies are exceptions). When y is preceded by a consonant (any letter other than a vowel), y is changed to i and es is added; as, army, armies; pony, ponies; sty, sties.

4. Most nouns ending in f or fe add s, as, scarf, scarfs; safe, safes. Page 8 A few change f or fe to v and add es; as, wife, wives; self, selves. The others are: beef, calf, elf, half, leaf, loaf, sheaf, shelf, staff, thief, wharf, wolf, life. (Wharf has also a plural, wharfs.)

5. Most nouns ending in o add s; as, cameo, cameos. A number of nouns ending in o preceded by a consonant add es; as, volcano, volcanoes. The most important of the latter class are: buffalo, cargo, calico, echo, embargo, flamingo, hero, motto, mulatto, negro, potato, tomato, tornado, torpedo, veto.

6. Letters, figures, characters, etc., add the apostrophe and s ('s); as, 6's, c's, t's, that's.

7. The following common words always form their plurals in an irregular way; as, man, men; ox, oxen; goose, geese; woman, women; foot, feet; mouse, mice; child, children; tooth, teeth; louse, lice.

Compound Nouns are those formed by the union of two words, either two nouns or a noun joined to some descriptive word or phrase.

8. The principal noun of a compound noun, whether it precedes or follows the descriptive part, is in most cases the noun that changes in forming the plural; as, mothers-in-law, knights-errant, mouse-traps. In a few compound words, both parts take a plural form; as, man-servant, men-servants; knight-templar, knights-templars.

9. Proper names and titles generally form plurals in the same way as do other nouns; as, Senators Webster and Clay, the three Henrys. Abbreviations of titles are little used in the plural, except Messrs. (Mr.), and Drs. (Dr.).

10. In forming the plurals of proper names where a title is used, either the title or the name may be put in the plural form. Sometimes both are made plural; as, Miss Brown, the Misses Brown, the Miss Browns, the two Mrs. Browns.

11. Some nouns are the same in both the singular and the plural; as, deer, series, means, gross, etc.

12. Some nouns used in two senses have two plural forms. The most important are the following:

| brother | brothers (by blood) | brethren (by association) |

| cloth | cloths (kinds of cloth) | clothes (garments) |

| die | dies (for coinage) | dice (for games) |

| fish | fishes (separately) | fish (collectively) Page 9 |

| genius | geniuses (men of genius) | genii (imaginary beings) |

| head | heads (of the body) | head (of cattle) |

| index | indexes (of books) | indices (in algebra) |

| pea | peas (separately) | pease (collectively) |

| penny | pennies (separately) | pence (collectively) |

| sail | sails (pieces of canvas) | sail (number of vessels) |

| shot | shots (number of discharges) | shot (number of balls) |

13. Nouns from foreign languages frequently retain in the plural the form that they have in the language from which they are taken; as, focus, foci; terminus, termini; alumnus, alumni; datum, data; stratum, strata; formula, formulœ; vortex, vortices; appendix, appendices; crisis, crises; oasis, oases; axis, axes; phenomenon, phenomena; automaton, automata; analysis, analyses; hypothesis, hypotheses; medium, media; vertebra, vertebrœ; ellipsis, ellipses; genus, genera; fungus, fungi; minimum, minima; thesis, theses.

Exercise 3

Write the plural, if any, of every singular noun in the following list; and the singular, if any, of every plural noun. Note those having no singular and those having no plural.

News, goods, thanks, scissors, proceeds, puppy, studio, survey, attorney, arch, belief, chief, charity, half, hero, negro, majority, Mary, vortex, memento, joy, lily, knight-templar, knight-errant, why, 4, x, son-in-law, Miss Smith, Mr. Anderson, country-man, hanger-on, major-general, oxen, geese, man-servant, brethren, strata, sheep, mathematics, pride, money, pea, head, piano, veto, knives, ratios, alumni, feet, wolves, president, sailor-boy, spoonful, rope-ladder, grandmother, attorney-general, cupful, go-between.

When in doubt respecting the form of any of the above, consult an unabridged dictionary.

14. Case. There are three cases in English: the Nominative, the Possessive, and the Objective.

The Nominative Case; the form used in address and as the subject of a verb.

The Objective Case; the form used as the object of a verb or a preposition. It is always the same in form as is the nominative.

Page 10 Since no error in grammar can arise in the use of the nominative or the objective cases of nouns, no further discussion of these cases is here needed.

The Possessive Case; the form used to show ownership. In the forming of this case we have inflection.

15. The following are the rules for the forming of the possessive case:

1. Most nouns form the possessive by adding the apostrophe and s ('s); as, man, man's; men, men's; pupil, pupil's; John, John's.

2. Plural nouns ending in s form the possessive by adding only the apostrophe ('); as, persons, persons'; writers, writers'. In stating possession in the plural, then one should say: Carpenters' tools sharpened here, Odd Fellows' wives are invited, etc.

3. Some singular nouns ending in an s sound form the possessive by adding the apostrophe alone; as, for appearance' sake, for goodness' sake. But usage inclines to the adding of the apostrophe and s ('s) even if the singular noun does end in an s sound; as, Charles's book, Frances's dress, the mistress's dress.

4. When a compound noun, or a group of words treated as one name, is used to denote possession, the sign of the possessive is added to the last word only; as, Charles and John's mother (the mother of both Charles and John), Brown and Smith's store (the store of the firm Brown & Smith).

5. Where the succession of possessives is unpleasant or confusing, the substitution of a prepositional phrase should be made; as, the house of the mother of Charles's partner, instead of, Charles's partner's mother's house.

6. The sign of the possessive should be used with the word immediately preceding the word naming the thing possessed; as, Father and mother's house, Smith, the lawyer's, office, The Senator from Utah's seat.

7. Generally, nouns representing inanimate objects should not be used in the possessive case. It is better to say the hands of the clock than the clock's hands.

Note.—One should say somebody else's, not somebody's else. The expression somebody else always occurs in the one form, and in such cases the sign of the possessive should be added to the last word. Similarly, say, no one else's, everybody else's, etc.

Page 11 Exercise 4

Write the possessives of the following:

Oxen, ox, brother-in-law, Miss Jones, goose, man, men, men-servants, man-servant, Maine, dogs, attorneys-at-law, Jackson & Jones, John the student, my friend John, coat, shoe, boy, boys, Mayor of Cleveland.

Exercise 5

Write sentences illustrating the use of the possessives you have formed for the first ten words under Exercise 4.

Exercise 6

Change the following expressions from the prepositional phrase form to the possessive:

Exercise 7

Correct such of the following expressions as need correction. If apostrophes are omitted, insert them in the proper places:

16. Gender. Gender in grammar is the quality of nouns or pronouns that denotes the sex of the person or thing represented. Those nouns or pronouns meaning males are in the Masculine Gender. Those meaning females are in the Feminine Gender. Those referring to things without sex are in the Neuter Gender.

In nouns gender is of little consequence. The only regular inflection is the addition of the syllable-ess to certain masculine nouns to denote the change to the feminine gender; as, author, authoress; poet, poetess. -Ix is also sometimes added for the same purpose; as, administrator, administratrix.

The feminine forms were formerly much used, but their use is now being discontinued, and the noun of masculine gender used to designate both sexes.

PRONOUNS

17. Pronoun and Antecedent. A Pronoun is a word used instead of a noun. The noun in whose stead it stands is called its Antecedent. John took Mary's book and gave it to his friend. In this sentence book is the antecedent of the pronoun it, and John is the antecedent of his.

18. Pronouns should agree with their antecedents in person, gender, and number.

19. Personal Pronouns are those that by their form indicate the speaker, the person spoken to, or the person or thing spoken about.

Pronouns of the First Person indicate the speaker; they are: I, me, my, mine, we, us, our, ours.

Pronouns of the Second Person indicate the person or thing spoken to; they are: you, your, yours. There are also the grave or solemn forms in the second person, which are now little used; these are: thou, thee, thy, thine, and ye.

Pronouns of the Third Person indicate the person or thing spoken of; they are: he, his, him, she, her, hers, they, their, theirs, them, it, its.

Few errors are made in the use of the proper person of the pronoun.

20. Gender of Pronouns. The following pronouns indicate sex or gender; Masculine: he, his, him. Feminine: she, her, hers. Neuter: it, its.

In order to secure agreement in gender it is necessary to know the gender of the noun, expressed or understood, to which the pronoun refers. Gender of nouns is important only so far as it concerns the use of pronouns. Study carefully the Page 14 following rules in regard to gender. These rules apply to the singular number only, since all plurals of whatever gender are referred to by they, their, theirs, etc.

The following rules govern the gender of pronouns:

Masculine; referred to by he, his, and him:

1. Nouns denoting males are always masculine.

2. Nouns denoting things remarkable for strength, power, sublimity, or size, when those things are regarded as if they were persons, are masculine; as, Winter, with his chilly army, destroyed them all.

3. Singular nouns denoting persons of both sexes are masculine; as, Every one brought his umbrella.

Feminine; referred to by she, her, or hers:

1. Nouns denoting females are always feminine.

2. Nouns denoting objects remarkable for beauty, gentleness, and peace, when spoken of as if they were persons, are feminine; as, Sleep healed him with her fostering care.

Neuter; referred to by it and its:

1. Nouns denoting objects without sex are neuter.

2. Nouns denoting objects whose sex is disregarded are neuter; as, It is a pretty child, The wolf is the most savage of its race.

3. Collective nouns referring to a group of individuals as a unit are neuter; as, The jury gives its verdict, The committee makes its report.

An animal named may be regarded as masculine; feminine, or neuter, according to the characteristics the writer fancies it to possess; as, The wolf seeks his prey, The mouse nibbled her way into the box, The bird seeks its nest.

Certain nouns may be applied to persons of either sex. They are then said to be of Common Gender. There are no pronouns of common gender; hence those nouns are referred to as follows:

1. By masculine pronouns when known to denote males; as, My class-mate (known to be Harry) is taking his examinations.

2. By feminine pronouns when known to denote females; as, Each of the pupils of the Girls High School brought her book.

Page 15 3. By masculine pronouns when there is nothing in the connection of the thought to show the sex of the object; as, Let every person bring his book.

21. Number of Pronouns. A more common source of error than disagreement in gender is disagreement in number. They, their, theirs, and them are plural, but are often improperly used when only singular pronouns should be used. The cause of the error is failure to realize the true antecedent.

If anybody makes that statement, they are misinformed. This sentence is wrong. Anybody refers to only one person; both any and body, the parts of the word, denote the singular. The sentence should read, If anybody makes that statement, he is misinformed. Similarly, Let everybody keep their peace, should read, Let everybody keep his peace.

22. Compound Antecedents. Two or more antecedents connected by or or nor are frequently referred to by the plural when the singular should be used. Neither John nor James brought their books, should read, Neither John nor James brought his books. When a pronoun has two or more singular antecedents connected by or or nor, the pronoun must be in the singular number; but if one of the antecedents is plural, the pronoun must, also, be in the plural; as, Neither the Mormon nor his wives denied their religion.

When a pronoun has two or more antecedents connected by and, the pronoun must be in the plural number; as, John and James brought their books.

Further treatment of number will be given under verbs.

Exercise 8

Fill in the blanks in the following sentences with the proper pronouns. See that there is agreement in person, gender, and number:

Exercise 9

By what gender of the pronouns would you refer to the following nouns?

Snake, death, care, mercy, fox, bear, walrus, child, baby, friend (uncertain sex), friend (known to be Mary), everybody, someone, artist, flower, moon, sun, sorrow, fate, student, foreigner, Harvard University, earth, Germany?

23. Relative Pronouns. Relative Pronouns are pronouns used to introduce adjective or noun clauses that are not interrogative. In the sentence, The man that I mentioned has come, the relative clause, that I mentioned, is an adjective clause modifying man. In the sentence, Whom she means, I do not know, the relative clause is, whom she means, and is a noun clause forming the object of the verb know.

Page 18 The relative pronouns are who (whose, whom), which, that and what. But and as are sometimes relative pronouns. There are, also, compound relative pronouns, which will be mentioned later.

24. Who (with its possessive and objective forms, whose and whom) should be used when the antecedent denotes persons. When the antecedent denotes things or animals, which should be used. That may be used with antecedents denoting persons, animals or things, and is the proper relative to use when the antecedent includes both persons and things. What, when used as a relative, seldom properly refers to persons. It always introduces a substantive clause, and is equivalent to that which; as, It is what (that which) he wants.

25. That is known as the Restrictive Relative, because it should be used whenever the relative clause limits the substantive, unless who or which is of more pleasing sound in the sentence. In the sentence, He is the man that did the act, the relative clause, that did the act, defines what is meant by man; without the relative clause the sentence clearly would be incomplete. Similarly, in the sentence, The book that I want is that red-backed history, the restrictive relative clause is, that I want, and limits the application of book.

26. Who and which are known as the Explanatory or Non-Restrictive Relatives, and should be used ordinarily only to introduce relative clauses which add some new thought to the author's principal thought. Spanish, which is the least complex language, is the easiest to learn. In this sentence the principal thought is, Spanish is the easiest language to learn. The relative clause, which is the least complex language, is a thought, which, though not fully so important as the principal thought, is more nearly coördinate than subordinate in its value. It adds an additional thought of the speaker explaining the character of the Spanish language. When who and which are thus used as explanatory relatives, we see Page 19 that the relative clause may be omitted without making the sentence incomplete.

Compare the following sentences:

Explanatory relative clause: That book, which is about history, has a red cover.

Restrictive relative clause: The book that is about history has a red cover.

Explanatory relative clause: Lincoln, who was one of the world's greatest men, was killed by Booth.

Restrictive relative clause: The Lincoln that was killed by Booth was one of the world's greatest men.

Note.—See §111, for rule as to the punctuation of relative clauses.

27. Interrogative Pronouns. An Interrogative Pronoun is a pronoun used to ask a question. The interrogative pronouns are, who (whose, whom), which, and what. In respect to antecedents, who should be used only in reference to persons; which and what may be used with any antecedent, persons, animals, or things.

Exercise 10

Choose the proper relative or interrogative pronoun to be inserted in each of the following sentences. Insert commas where they are needed. (See §111):

28. Case Forms of Pronouns. Some personal, relative, and interrogative pronouns have distinctive forms for the different cases, and the failure to use the proper case forms in the sentence is one of the most frequent sources of error. The case to be used is to be determined by the use which the pronoun, not its antecedent, has in the sentence. In the sentence, I name him, note that him is the object of the verb name. In the sentence, Whom do you seek, although coming at the Page 21 first of the sentence, whom is grammatically the object of the verb seek. In the use of pronouns comes the most important need for a knowledge of when to use the different cases.

Note the following different case forms of pronouns:

Nominative: I, we, you, thou, ye, he, she, they, it, who.

Objective: me, us, you, thee, ye, him, her, it, them, whom.

Possessive: my, mine, our, ours, thy, thine, your, yours, his, her, hers, its, their, theirs, whose.

It will be noted that, while some forms are the same in both the nominative and objective cases, I, we, he, she, they, thou, and who are only proper where the nominative case should be used. Me, us, him, them, thee, whom, and her, except when her is possessive, are only proper when the objective case is demanded. These forms must be remembered. It is only with these pronouns that mistakes are made in the use of the nominative and objective cases.

29. The following outline explains the use of the different case forms of the pronouns. The outline should be mastered.

The Nominative Case should be used:

1. When the noun or pronoun is the subject of a finite verb; that is, a verb other than an infinitive. See 3 under Objective Case.

2. When it is an attribute complement. An attribute complement, as explained in Chapter I, is a word used in the predicate explaining or stating something about the subject. Examples: It is I, The man was he, The people were they of whom we spoke.

3. When it is used without relation to any other part of speech, as in direct address or exclamation.

The Objective Case should be used:

1. When the noun or pronoun is the object of a verb; as, He named me, She deceived them, They watch us.

2. When it is the object of a preposition, expressed or understood: as, He spoke of me, For whom do you take me, He told (to) me a story.

3. When it is the subject of an infinitive; as, I told him to go, I desire her to hope. The infinitives are the parts of the verb preceded by to; as, to go, to see, to be, to have been seen, etc. The sign Page 22 of the infinitive, to, is not always expressed. The objective case is, nevertheless, used; as, Let him (to) go, Have her (to be) told about it.

4. When it is an attribute complement of an expressed subject of the infinitive to be; as, They believed her to be me, He denied it to have been him. (See Note 2 below.)

The Possessive Case should be used:

When the word is used as a possessive modifier; as, They spoke of her being present, The book is his (book), It is their fault.

Note 1.—When a substantive is placed by the side of another substantive and is used to explain it, it is said to be in Apposition with that other substantive and takes the case of that word; as, It was given to John Smith, him whom you see there.

Note 2.—The attribute complement should always have the case of that subject of the verb which is expressed in the sentence. Thus, in the sentence, I could not wish John to be him, him is properly in the objective case, since there is an expressed subject of the infinitive, John, which is in the objective case. But in the sentence, I should hate to be he, he is properly in the nominative case, since the only subject that is expressed in the sentence is I, in the nominative case.

Note 3.—Where the relative pronoun who (whom) is the subject of a clause that itself is the object clause of a verb or a preposition, it is always in the nominative case. Thus the following sentences are both correct: I delivered it to who owned it, Bring home whoever will come with you.

Exercise 11

Write sentences illustrating the correct use of each of the following pronouns:

I, whom, who, we, me, us, they, whose, theirs, them, she, him, he, its, mine, our, thee, thou.

Exercise 12

In the following sentences choose the proper form from the words in italics:

30. The Compound Personal Pronouns are formed by adding self or selves to certain of the objective and possessive personal pronouns; as, herself, myself, itself, themselves, etc. They are used to add emphasis to an expression; as, I, myself, did it, He, himself, said so. They are also used reflexively after verbs and prepositions; as, He mentioned himself, He did it for himself.

The compound personal pronouns should generally be confined to their emphatic and reflexive use. Do not say, Myself and John will come, but, John and I will come. Do not say, They invited John and myself, but, They invited John and me.

The compound personal pronouns have no possessive forms; but for the sake of emphasis own with the ordinary possessive form is used; as, I have my own book, Bring your own work, He has a home of his own.

31. There are no such forms as hisself, your'n, his'n, her'n, theirself, theirselves, their'n. In place of these use simply his, her, their, or your.

Exercise 13

Write sentences illustrating the correct use of the following simple and compound personal pronouns:

Myself, me, I, them, themselves, him, himself, her, herself, itself, our, ourselves.

Exercise 14

Choose the correct form in the following sentences. Punctuate properly. (See §108):

Exercise 15

Fill the blanks in the following sentences with the proper emphatic or reflexive forms. Punctuate properly. (See §108):

32. The Compound Relative Pronouns are formed by adding ever, so, or soever to the relative pronouns, who, which, and what; as, whoever, whatever, whomever, whosoever, whoso, whosoever, etc. It will be noted that whoever, whosoever, and whoso have objective forms, whomever, whomsoever, and whomso; and possessive forms, whosoever, whosesoever, and Page 28 whoseso. These forms must be used whenever the objective or possessive case is demanded. Thus, one should say, I will give it to whomever I find there. (See §29 and Note 3.)

Exercise 16

Fill the following blanks with the proper forms of the compound relatives:

33. There are certain words, called Adjective Pronouns, which are regarded as pronouns, because, although they are properly adjective in their meaning, the nouns which they modify are never expressed; as, One (there is a possessive form, Page 29 one's, and a plural form, ones), none, this, that, these, those, other, former, some, few, many, etc.

34. Some miscellaneous cautions in the use of pronouns:

1. The pronoun I should always be capitalized, and should, when used as part of a compound subject, be placed second; as, James and I were present, not I and James were present.

2. Do not use the common and grave forms of the personal pronouns in the same sentence; as, Thou wilt do this whether you wish or not.

3. Avoid the use of personal pronouns where they are unnecessary; as, John, he did it, or Mary, she said. This is a frequent error in speech.

4. Let the antecedent of each pronoun be clearly apparent. Note the uncertainty in the following sentence; He sent a box of cheese, and it was made of wood. The antecedent of it is not clear. Again, A man told his son to take his coat home. The antecedent of his is very uncertain. Such errors are frequent.

In relative clauses this error may sometimes be avoided by placing the relative clause as near as possible to the noun it limits. Note the following sentence: A cat was found in the yard which wore a blue ribbon. The grammatical inference would be that the yard wore the blue ribbon. The sentence might be changed to, A cat, which wore a blue ribbon, was found in the yard.

5. Relative clauses referring to the same thing require the same relative pronoun to introduce them; as, The book that we found and the book that he lost are the same.

6. Use but that when but is a conjunction and that introduces a noun clause; as, There is no doubt but that he will go. Use but what when but is a preposition in the sense of except; as, He has no money but (except) what I gave him.

7. Them is a pronoun and should never be used as an adjective. Those is the adjective which should be used in its place; as, Those people, not, Them people.

8. Avoid using you and they indefinitely; as, You seldom hear of such things, They make chairs there. Instead, say, One seldom hears of such things, Chairs are made there.

9. Which should not be used with a clause or phrase as its antecedent. Both the following sentences are wrong: He sent me to see Page 30 John, which I did. Their whispering became very loud, which annoyed the preacher.

10. Never use an apostrophe with the possessive pronouns, its, yours, theirs, ours and hers.

Exercise 17

Correct the following sentences so that they do not violate the cautions above stated:

ADJECTIVES AND ADVERBS

35. An Adjective is a word used to modify a noun or a pronoun. An Adverb is a word used to modify a verb, an adjective, or another adverb. Adjectives and adverbs are very closely related in both their forms and their use.

36. Comparison. The variation of adjectives and adverbs to indicate the degree of modification they express is called Comparison. There are three degrees of comparison.

The Positive Degree indicates the mere possession of a quality; as, true, good, sweet, fast, lovely.

The Comparative Degree indicates a stronger degree of the quality than the positive; as, truer, sweeter, better, faster, lovelier.

The Superlative Degree indicates the highest degree of quality; as, truest, sweetest, best, fastest, loveliest.

Where the adjectives and adverbs are compared by inflection they are said to be compared regularly. In regular comparison the comparative is formed by adding er, and the superlative by adding est. If the word ends in y, the y is changed to i before adding the ending; as, pretty, prettier, prettiest.

Where the adjectives and adverbs have two or more syllables, most of them are compared by the use of the adverbs more and most, or, if the comparison be a descending one, by the use of less and least; as, beautiful, more beautiful, most beautiful, and less beautiful, least beautiful.

37. Some adjectives and adverbs are compared by changing to entirely different words in the comparative and superlative. Note the following: Page 33

| POSITIVE | COMPARATIVE | SUPERLATIVE |

| bad, ill, evil, badly | worse | worst |

| far | farther, further | farthest, furthest |

| forth | further | furthest |

| fore | former | foremost, first |

| good, well | better | best |

| hind | hinder | hindmost |

| late | later, latter | latest, last |

| little | less | least |

| much, many | more | most |

| old | older, elder | oldest, eldest |

Note.—Badly and forth may be used only as adverbs. Well is usually an adverb; as, He talks well, but may be used as an adjective; as, He seems well.

38. Confusion of Adjectives and Adverbs. An adjective is often used where an adverb is required, and vice versa. The sentence, She talks foolish, is wrong, because here the word to be modified is talks, and since talks is a verb, the adverb foolishly should be used. The sentence, She looks charmingly, means, as it stands, that her manner of looking at a thing is charming. What is intended to be said is that she appears as if she was a charming woman. To convey that meaning, the adjective, charming, should have been used, and the sentence should read, She looks charming. Wherever the word modifies a verb or an adjective or another adverb, an adverb should be used, and wherever the word, whatever its location in the sentence, modifies a noun or pronoun, an adjective should be used.

39. The adjective and the adverb are sometimes alike in form. Thus, both the following sentences are correct: He works hard (adverb), and His work is hard (adjective). But, usually, where the adjective and the adverb correspond at all, the adverb has the additional ending ly; as, The track is smooth, (adjective), and The train runs smoothly, (adverb).

Page 34 Exercise 18

In the following sentences choose from the italicized words the proper word to be used:

Exercise 19

The adjectives and adverbs in the following sentences are correctly used. In every case show what they modify:

Page 36 Exercise 20

Write sentences containing the following words correctly used:

Thoughtful, thoughtfully, masterful, masterfully, hard, hardly, cool, coolly, rapid, rapidly, ungainly, careful, carefully, eager, eagerly, sweet, sweetly, gracious, graciously.

40. Improper Forms of Adjectives. The wrong forms in the following list of adjectives are frequently used in place of the right forms:

| RIGHT | WRONG |

| everywhere | everywheres |

| not nearly | nowhere near |

| not at all | not much or not muchly |

| ill | illy |

| first | firstly |

| thus | thusly |

| much | muchly |

| unknown | unbeknown |

| complexioned | complected |

Exercise 21

Correct the errors in the following sentences:

41. Errors in comparison are frequently made. Observe carefully the following rules:

Page 37 1. The superlative should not be used in comparing only two things. One should say, He is the larger of the two, not He is the largest of the two. But, He is the largest of the three, is right.

2. A comparison should not be attempted by adjectives that express absolute quality—adjectives that cannot be compared; as, round, perfect, equally, universal. A thing may be round or perfect, but it cannot be more round or most round, more perfect or most perfect.

3. When two objects are used in the comparative, one must not be included in the other; but, when two objects are used in the superlative, one must be included in the other. It is wrong to say, The discovery of America was more important than any geographical discovery, for that is saying that the discovery of America was more important than itself—an absurdity. But it would be right to say, The discovery of America was more important than any other geographical discovery. One should not say, He is the most honest of his fellow-workmen, for he is not one of his fellow-workmen. One should say, He is more honest than any of his fellow-workmen, or, He is the most honest of all the workmen. To say, This machine is better than any machine, is incorrect, but to say, This machine is better than any other machine, is correct. To say, This machine is the best of any machine (or any other machine), is wrong, because all machines are meant, not one machine or some machines. To say, This machine is the best of machines (or the best of all machines), is correct.

Note the following rules in regard to the use of other in comparisons:

a. After comparatives followed by than the words any and all should be followed by other.

b. After superlatives followed by of, any and other should not be used.

4. Avoid mixed comparisons. John is as good, if not better than she. If the clause, if not better, were left out, this Page 38 sentence would read, John is as good than she. It could be corrected to read, John is as good as, if not better than she. Similarly, it is wrong to say, He is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, man in history.

Exercise 22

Choose the correct word from those italicized:

Exercise 23

Correct any of the following sentences that may be wrong. Give a valid reason for each correction:

42. Singular and Plural Adjectives. Some adjectives can be used only with singular nouns and some only with plural nouns. Such adjectives as one, each, every, etc., can be used only with singular nouns. Such adjectives as several, various, many, sundry, two, etc., can be used only with plural nouns. In many cases, the noun which the adjective modifies is omitted, and the adjective thus acquires the force of a pronoun; as, Few are seen, Several have come.

Page 40 The adjective pronouns this and that have plural forms, these and those. The plurals must be used with plural nouns. To say those kind is then incorrect. It should be those kinds. Those sort of men should be that sort of men or those sorts of men.

43. Either and neither are used to designate one of two objects only. If more than two are referred to, use any, none, any one, no one. Note the following correct sentences:

Neither John nor Henry may go.

Any one of the three boys may go.

44. Each other should be used when referring to two; one another when referring to more than two. Note the following correct sentences:

The two brothers love each other.

The four brothers love one another.

Exercise 24

Correct such of the following sentences as are incorrect. Be able to give reasons:

45. Placing of Adverbs and Adjectives. In the placing of adjective elements and adverbial elements in the sentence, one should so arrange them as to leave no doubt as to what they are intended to modify.

| Wrong: A man was riding on a horse wearing gray trousers. |

| Right: A man wearing gray trousers was riding on a horse. |

The adverb only requires especial attention. Generally only should come before the word it is intended to modify. Compare the following correct sentences, and note the differences in meaning.

Only he found the book.

He only found the book.

He found only the book.

He found the book only.

The placing of the words, almost, ever, hardly, scarcely, merely, and quite, also requires care and thought.

Exercise 25

Correct the errors in the location of adjectives and adverbs in the following sentences:

46. Double Negatives. I am here is called an affirmative statement. A denial of that, I am not here, is called a negative statement. The words, not, neither, never, none, nothing, etc., are all negative words; that is, they serve to make denials of statements.

Two negatives should never be used in the same sentence, since the effect is then to deny the negative you wish to assert, and an affirmative is made where a negative is intended. We haven't no books, means that we have some books. The proper negative form would be, We have no books, or We haven't any books. The mistake occurs usually where such forms as isn't, don't, haven't, etc., are used. Examine the following sentences:

| Wrong: It isn't no use. |

| Wrong: There don't none of them believe it. |

| Wrong: We didn't do nothing. |

Hardly, scarcely, only, and but (in the sense of only) are often incorrectly used with a negative. Compare the following right and wrong forms:

| Wrong: It was so dark that we couldn't hardly see. |

| Right: It was so dark that we could hardly see. |

| Wrong: There wasn't only one person present. |

| Right: There was only one person present. |

Page 43 Exercise 26

Correct the following sentences:

47. The Articles. A, an, and the, are called Articles. A and an are called the Indefinite Articles, because they are used to limit the noun to any one thing of a class; as, a book, a chair. But a or an is not used to denote the whole of that Page 44 class; as, Silence is golden, or, He was elected to the office of President.

The is called the Definite Article because it picks out some one definite individual from a class.

In the sentence, On the street are a brick and a stone house, the article is repeated before each adjective; the effect of this repetition is to make the sentence mean two houses. But, in the sentence, On the street is a brick and stone house, since the article is used only before the first of the two adjectives, the sentence means that there is only one house and that it is constructed of brick and stone.

Where two nouns refer to the same object, the article need appear only before the first of the two; as, God, the author and creator of the universe. But where the nouns refer to two different objects, regarded as distinct from each other, the article should appear before each; as, He bought a horse and a cow.

A is used before all words except those beginning with a vowel sound. Before those beginning with a vowel sound an is used. If, in a succession of words, one of these forms could not be used before all of the words, then the article must be repeated before each. Thus, one should say, An ax, a saw, and an adze (not An ax, saw and adze), made up his outfit. Generally it is better to repeat the article in each case, whether or not it be the same.

Do not say, kind of a house. Since a house is singular, it can have but one kind. Say instead, a kind of house, a sort of man, etc.

Exercise 27

Correct the following where you think correction is needed:

48. No adverb necessary to the sense should be omitted from the sentence. Such improper omission is frequently made when very or too are used with past participles that are not also recognized as adjectives; as,

Poor: I am very insulted. He was too wrapped in thought to notice the mistake.

Right: I am very much insulted. He was too much wrapped in thought to notice the mistake.

Exercise 28

Write sentences containing the following adjectives and adverbs. Be sure that they are used correctly.

Both, each, every, only, evidently, hard, latest, awful, terribly, charming, charmingly, lovely, brave, perfect, straight, extreme, very, either, neither, larger, oldest, one, none, hardly, scarcely, only, but, finally, almost, ever, never, new, newly, very.

VERBS

49. A Verb has already been defined as a word stating something about the subject. Verbs are inflected or changed to indicate the time of the action as past, present, or future; as, I talk, I talked, I shall talk, etc. Verbs also vary to indicate completed or incompleted action; as, I have talked, I shall have talked, etc. To these variations, which indicate the time of the action, the name Tense is given.

The full verbal statement may consist of several words; as, He may have gone home. Here the verb is may have gone. The last word of such a verb phrase is called the Principal Verb, and the other words the Auxiliaries. In the sentence above, go (gone) is the principal verb, and may and have are the auxiliaries.

50. In constructing the full form of the verb or verb phrase there are three distinct parts from which all other forms are made. These are called the Principal Parts.

The First Principal Part, since it is the part by which the verb is referred to as a word, may be called the Name-Form. The following are name-forms: do, see, come, walk, pass.

The Second Principal Part is called the Past Tense. It is formed by adding ed to the name-form; as, walked, pushed, passed. These verbs that add ed are called Regular Verbs. The verb form is often entirely changed; as, done (do), saw (see), came (come). These verbs are called Irregular Verbs.

The Third Principal Part is called the Past Participle. It is used mainly in expressing completed action or in the passive voice. In regular verbs the past participle is the same in Page 47 form as the past tense. In irregular verbs it may differ entirely from both the name-form and the past tense, or it may resemble one or both of them. Examples: done (do, did), seen (see, saw), come (come, came), set (set, set).

51. The name-form, when unaccompanied by auxiliaries, is used with all subjects, except those in the third person singular, to assert action in the present time or present tense; as, I go, We come, You see, Horses run.

The name-form is also used with various auxiliaries (may, might, can, must, will, should, shall, etc.) to assert futurity, determination, possibility, possession, etc. Examples: I may go, We shall come, You can see, Horses should run.

By preceding it with the word to, the name-form is used to form what is called the Present Infinitive; as, I wish to go, I hope to see.

What may be called the s-form of the verb, or the singular form, is usually constructed by adding s or es to the name-form. The s-form is used with singular subjects in the third person; as, He goes, She comes, It runs, The dog trots.

The s-form is found in the third personal singular of the present tense. In other tenses, if present at all, the s-form is in the auxiliary, where the present tense of the auxiliary is used to form some other tense of the principal verb. Examples: He has (present tense), He has gone (perfect tense), He has been seen.

Some verbs have no s-form; as, will, shall, may. The verb be has two irregular s-forms: Is, in the present tense, and was in the past tense. The s-form of have is has.

52. The past tense always stands alone in the predicate; i. e., it should never be used with any auxiliaries. To use it so, however, is one of the most frequent errors in grammar. The following are past tense forms: went, saw, wore, tore. To say, therefore, I have saw, I have went, It was tore, They were wore, would be grossly incorrect.

53. The third principal part, the past participle, on the Page 48 other hand, can never be used as a predicate verb without an auxiliary. The following are distinctly past participle forms: done, seen, sung, etc. One could not then properly say, I seen, I done, I sung, etc.

The distinction as to use with and without auxiliaries applies, of course, only to irregular verbs. In regular verbs, the past tense and past participle are always the same, and so no error could result from their confusion.

The past participle is used to form the Perfect Infinitives; as, to have gone, to have seen, to have been seen.

54. The following is a list of the principal parts of the most important irregular verbs. The list should be mastered thoroughly. The student should bear in mind always that, the past tense form should never be used with an auxiliary, and that the past participle form should never be used as a predicate verb without an auxiliary.

In some instances verbs have been included in the list below which are always regular in their forms, or which have both regular and irregular forms. These are verbs for whose principal parts incorrect forms are often used.

PRINCIPAL PARTS OF VERBS

| Name-form | Past Tense | Past Participle |

| awake | awoke or awaked | awaked |

| begin | began | begun |

| beseech | besought | besought |

| bid (to order or to greet) | bade | bidden or bid |

| bid (at auction) | bid | bidden or bid |

| blow | blew | blown |

| break | broke | broken |

| burst | burst | burst |

| choose | chose | chosen |

| chide | chid | chidden or chid |

| come | came | come |

| deal | dealt | dealt |

| dive | dived | dived |

| Name-form | Past Tense | Past Participle Page 49 |

| do | did | done |

| draw | drew | drawn |

| drink | drank | drunk or drank |

| drive | drove | driven |

| eat | ate | eaten |

| fall | fell | fallen |

| flee | fled | fled |

| fly | flew | flown |

| forsake | forsook | forsaken |

| forget | forgot | forgot or forgotten |

| freeze | froze | frozen |

| get | got | got (gotten) |

| give | gave | given |

| go | went | gone |

| hang (clothes) | hung | hung |

| hang (a man) | hanged | hanged |

| know | knew | known |

| lay | laid | laid |

| lie | lay | lain |

| mean | meant | meant |

| plead | pleaded | pleaded |

| prove | proved | proved |

| ride | rode | ridden |

| raise | raised | raised |

| rise | rose | risen |

| run | ran | run |

| see | saw | seen |

| seek | sought | sought |

| set | set | set |

| shake | shook | shaken |

| shed | shed | shed |

| shoe | shod | shod |

| sing | sang | sung |

| sit | sat | sat |

| slay | slew | slain |

| sink | sank | sunk |

| speak | spoke | spoken |

| Name-form | Past Tense | Past Participle Page 50 |

| steal | stole | stolen |

| swim | swam | swum |

| take | took | taken |

| teach | taught | taught |

| tear | tore | torn |

| throw | threw | thrown |

| tread | trod | trod or trodden |

| wake | woke or waked | woke or waked |

| wear | wore | worn |

| weave | wove | woven |

| write | wrote | written |

Notes.—Ought has no past participle. It may then never be used with an auxiliary. I had ought to go is incorrect. The idea would be amply expressed by I ought to go.

Model conjugations of the verbs to be and to see in all forms are given under §77 at the end of this chapter.

Exercise 29

In the following sentences change the italicized verb so as to use the past tense, and then so as to use the past participle:

| Example: | (Original sentence), | The guests begin to go home. |

| (Changed to past tense), | The guests began to go home. | |

| (Changed to past participle), | The guests have begun to go home. |

Exercise 30

Write original sentences containing the following verbs, correctly used:

Begun, blew, bidden, bad, chose, broke, come, dealt, dived, drew, driven, flew, forsook, froze, given, give, gave, went, hanged, knew, rode, pleaded, ran, seen, saw, shook, shod, sung, slew, spoke, swum, taken, torn, wore, threw, woven, wrote, written.

Exercise 31

Insert the proper form of the verb in the following sentences. The verb to be used is in black-faced type at the beginning of each group:

Page 55 Exercise 32

Correct the errors in the use of verbs in the following sentences:

Exercise 33

Write sentences in which the following verb forms are properly used:

begun, blew, broke, chose, come, came, done, did, drew, drunk, drove, ate, flew, forsook, froze, forgot, gave, give, went, hang, hung, knew, rode, run, shook, sung, slew, spoke, stole, took, tore, threw, wore, wrote.

55. Transitive and Intransitive Verbs. A Transitive Verb is one in which the action of the verb goes over to a receiver; Page 56 as, He killed the horse, I keep my word. In both these sentences, the verb serves to transfer the action from the subject to the object or receiver of the action. The verbs in these sentences, and all similar verbs, are transitive verbs. All others, in which the action does not go to a receiver, are called Intransitive Verbs.

56. Active and Passive Voice. The Active Voice represents the subject as the doer of the action; as, I tell, I see, He makes chairs. The Passive Voice represents the subject as the receiver of the action; as, I am told, I am seen, I have been seen, Chairs are made by me. Since only transitive verbs can have a receiver of the action, only transitive verbs can have both active and passive voice.

57. There are a few special verbs in which the failure to distinguish between the transitive and the intransitive verbs leads to frequent error. The most important of these verbs are the following: sit, set, awake, wake, lie, lay, rise, arise, raise, fell, and fall. Note again the principal parts of these verbs:

| wake (to rouse another) | woke, waked | woke, waked |

| awake (to cease to sleep) | awoke, awaked | awaked |

| fell (to strike down) | felled | felled |

| fall (to topple over) | fell | fallen |

| lay (to place) | laid | laid |

| lie (to recline) | lay | lain |

| raise (to cause to ascend) | raised | raised |

| (a)rise (to ascend) | (a)rose | (a)risen |

| set (to place) | set | set |

| sit (to rest) | sat | sat |

The first of each pair of the above verbs is transitive, and the second is intransitive. Only the first, then, of each pair can have an object or can be used in the passive voice.

Page 57 NOTES.—The following exceptions in the use of sit and set are, by reason of usage, regarded as correct: The sun sets, The moon sets, They sat themselves down to rest, and He set out for Chicago.

Lie, meaning to deceive, has for its principal parts, lie, lied, lied. Lie, however, with this meaning is seldom confused with lie meaning to recline. The present participle of lie is lying.

Compare the following sentences, and note the reasons why the second form in each case is the correct form.

| WRONG | RIGHT |

| Awake me early to-morrow. | Wake me early to-morrow. |

| He was awoke by the noise. | He was woke (waked) by the noise. |

| He has fallen a tree. | He has felled a tree. |

| I have laid down. | I have lain down. |

| I lay the book down (past tense). | I laid the book down. |

| The river has raised. | The river has risen. |

| He raised in bed. | He rose in bed. |

| I set there. | I sat there. |

| I sat the chair there. | I set the chair there. |

Exercise 34

Form an original sentence showing the proper use of each of the following words:

Lie, lay (to place), sit, set, sat, sitting, setting, lie (to recline), lie (to deceive), lying, laying, rise, arose, raised, raise, fell (to topple over), fallen, felled, awake, wake, awaked, woke, falling, felling, rising, raising, waking, awaking, lain, laid, lied.

Exercise 35

Correct such of the following sentences as are wrong:

Exercise 36

In the following sentences fill the blanks with the proper forms of the verbs indicated:

SIT AND SET

LAY AND LIE

RAISE AND RISE (ARISE)

FELL AND FALL

AWAKE AND WAKE

58. Mode. Mode is that form of the verb which indicates the manner in which the action or state is to be regarded. There are several modes in English, but only between the indicative and subjunctive modes is the distinction important. Generally speaking, the Indicative Mode is used when the statement is regarded as a fact or as truth, and the Subjunctive Mode is used when the statement expresses uncertainty or implies some degree of doubt.

59. Forms of the Subjunctive. The places in which the subjunctive differs from the indicative are in the present and past tenses of the verb be, and in the present tense of active verbs. The following outline will show the difference between the indicative and the subjunctive of be:

| INDICATIVE PRESENT OF BE | INDICATIVE PAST OF BE | ||

| I am | we are | I was | we were |

| thou art | you are | thou wert or wast | you were |

| he (she, it) is | they are | he (she, it) was | they were |

| SUBJUNCTIVE PRESENT OF BE | SUBJUNCTIVE PAST OF BE | ||

| If I be | If we be | If I were | If we were |

| If thou be | If you be | If thou were | If you were |

| If he (she, it) be | If they be | If he (she, it) were | If they were |

Page 62 If is used only as an example of the conjunctions on which the subjunctive depends. Other conjunctions may be used, or the verb may precede the subject.

Note.—It will be noticed that thou art and thou wast, etc., have been used in the second person singular. Strictly speaking, these are the proper forms to be used here, even though you are and you were, etc., are customarily used in addressing a single person.

In the subjunctive of be, it will be noted that the form be is used throughout the present tense; and the form were throughout the past tense.

In other verbs the subjunctive, instead of having the s-form in the third person singular of the present tense, has the name-form, or the same form as all the other forms of the present tense; as, indicative, he runs, she sees, it seems, he has; subjunctive, if he run, though she see, lest it seem, if he have.

Note.—An examination of the model conjugations under §77 will give a further understanding of the forms of the subjunctive.

60. Use of Indicative and Subjunctive. The indicative mode would be properly used in the following sentence, when the statement is regarded as true: If that evidence is true, then he is a criminal. Similarly: If he is rich, he ought to be charitable. Most directly declarative statements are put in the indicative mode.

But when the sense of the statement shows uncertainty in the speaker's mind, or shows that the condition stated is regarded as contrary to fact or as untrue, the subjunctive is used. Note the two sentences following, in which the conditions are properly in the subjunctive: If those statements be true, then all statements are true, Were I rich, I might be charitable.

The subjunctive is usually preceded by the conjunctions, if, though, lest, although, or the verb precedes the subject. But it must be borne in mind that these do not always indicate the subjunctive mode. The use of the subjunctive depends on Page 63 whether the condition is regarded as a fact or as contrary to fact, certain or uncertain.

It should be added that the subjunctive is perhaps going out of use; some of the best writers no longer use its forms. This passing of the subjunctive is to be regretted and to be discouraged, since its forms give opportunity for many fine shades of meaning.

Exercise 37

Write five sentences which illustrate the correct use of be in the third person singular without an auxiliary, and five which illustrate the correct use of were in the third person singular.

Exercise 38

Choose the preferable form in the following sentences, and be able to give a definite reason for your choice. In some of the sentences either form may be used correctly:

61. Agreement of Verb with its Subject. The verb should agree with its subject in person and number. The most frequent error is the failure of the verb to agree in number with its subject. Singular subjects are used with plural verbs, and plural subjects with singular verbs. These errors arise chiefly from a misapprehension of the true number of the subject.

The s-form of the verb is the only distinct singular form, and occurs only in the third person, singular, present indicative; as, He runs, she goes, it moves. Is, was, and has are the singular forms of the auxiliaries. Am is used only with a subject in the first person, and is not a source of confusion. The other auxiliaries have no singular forms.

Failure of the verb and its subject to agree in person seldom occurs, and so can cause little confusion.

Examine the following correct forms of agreement of verb and subject:

A barrel of clothes was shipped (not were shipped).

A man and a woman have been here (not has been here).

Boxes are scarce (not is scarce).

When were the brothers here (not when was)?

Page 65 62. Agreement of Subject and Verb in Number. The general rule to be borne in mind in regard to number, is that it is the meaning and not the form of the subject that determines whether to use the singular or the plural form of the verb. This rule also applies to the use of singular or plural pronouns.

Many nouns plural in form are singular in meaning; as, politics, measles, news, etc.

Many, also, are treated as plurals, though in meaning they are singular; as, forceps, tongs, trousers.

Some nouns, singular in form, are, according to the sense in which, they are used, either singular or plural in meaning; as, committee, family, pair, jury, assembly, means. The following sentences are all correct: The assembly has closed its meeting, The assembly are all total abstainers, The whole family is a famous one, The whole family are sick.

In the use of the adjective pronouns, some, each, etc., the noun is often omitted. When this is done, error is often made by using the wrong number of the verb. Each, either, neither, this, that, and one, when used alone as subjects, require singular verbs. All, those, these, few, many, always require plural verbs. Any, none, and some may take either singular or plural verbs. In most of these cases, as is true throughout the subject of agreement in number, reason will determine the form to be used.

Some nouns in a plural form express quantity rather than number. When quantity is plainly intended the singular verb should be used. Examine the following sentences; each is correct: Three drops of medicine is a dose, Ten thousand tons of coal was purchased by the firm, Two hundred dollars was the amount of the collection, Two hundred silver dollars were in the collection.

Page 66 Exercise 39

In each of the following sentences, by giving a reason, justify the correctness of the agreement in number of the verb and the noun:

Exercise 40

Construct sentences in which each of the words named below is used correctly as the subject of some one of the verbs, is, was, has, have, are, was, have, go, goes, run, runs, come, comes:

One, none, nobody, everybody, this, that, these, those, former, latter, few, some, many, other, any, all, such, news, pains, measles, gallows, ashes, dregs, goods, pincers, thanks, victuals, vitals, mumps, Page 67 flock, crowd, fleet, group, choir, class, army, mob, tribe, herd, committee, tons, dollars, bushels, carloads, gallons, days, months.

Exercise 41

Go over each of the above sentences and determine whether it or they should be used in referring to the subject.

63. The following rules govern the agreement of the verb with a compound subject:

1. When a singular noun is modified by two adjectives so as to mean two distinct things, the verb should be in the plural; as, French and German literature are studied.

2. When the verb applies to the different parts of the compound subject, the plural form of the verb should be used; as, John and Harry are still to come.

3. When the verb applies to one subject and not to the others, it should agree with that subject to which it applies; as, The employee, and not the employers, was to blame, The employers, and not the employee, were to blame, The boy, as well as his sisters, deserves praise.

4. When the verb applies separately to several subjects, each in the singular, the verb should be singular; as, Each book and each paper was in its place, No help and no hope is found for him, Either one or the other is he, Neither one nor the other is he.

5. When the verb applies separately to several subjects, some of which are singular and some plural, it should agree with the subject nearest to it; as, Neither the boy, nor his sisters deserve praise, Neither the sisters nor the boy deserves praise.

6. When a verb separates its subjects, it should agree with the first; as, The leader was slain and all his men, The men were slain, and also the leader.

Exercise 42

Choose the proper form of the verb in the following sentences:

64. Some miscellaneous cautions in regard to agreement in number:

1. Do not use a plural verb after a singular subject modified by an adjective phrase; as, The thief, with all his booty, was captured.

2. Do not use a singular form of the verb after you and they. Say: You were, they are, they were, etc., not, you was, they was, etc.

3. Do not mistake a noun modifier for the noun subject. In the sentence, The sale of boxes was increased, sale, not boxes, is the subject of the verb.

4. When the subject is a relative pronoun, the number and the person of the antecedent determine the number and the person of the verb. Both of the following sentences are correct: He is the only one of the men that is to be trusted, He is one of those men that are to be trusted. It is to be remembered that the singulars and the plurals of the relative pronouns are alike in form; that, who, etc., may refer to one or more than one.

5. Do not use incorrect contractions of the verb with not. Don't cannot be used with he or she or it, or with any other singular subject in the third person. One should say, He doesn't, not he don't; it doesn't, not it don't; man doesn't, not man don't. The proper form of the verb that is being contracted in these instances is does, not do. Ain't and hain't are always wrong; no such contractions are recognized. Such colloquial contractions as don't, can't, etc., should not be used at all in formal composition.

Exercise 43

Correct such of the following sentences as are wrong:

Exercise 44

In the following sentences correct such as are wrong:

65. Use of Shall and Will. The use of the auxiliaries, shall and will, with their past tenses, is a source of very many Page 72 errors. The following outline will show the correct use of shall and will, except in dependent clauses and questions:

To indicate simple futurity or probability:

Use shall with I and we; use will with all other subjects.

To indicate promise, determination, threat, or command on the part of the speaker; i. e., action which the speaker means to control;

Use will with I and we; use shall with all other subjects.