Title: Northern Nut Growers Association Thirty-Fourth Annual Report 1943

Editor: Northern Nut Growers Association

Release date: September 12, 2007 [eBook #22587]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe, Janet Blenkinship,

Barbara Kosker and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

DISCLAIMER

The articles published in the Annual Reports of the Northern Nut Growers Association are the findings and thoughts solely of the authors and are not to be construed as an endorsement by the Northern Nut Growers Association, its board of directors, or its members. No endorsement is intended for products mentioned, nor is criticism meant for products not mentioned. The laws and recommendations for pesticide application may have changed since the articles were written. It is always the pesticide applicator's responsibility, by law, to read and follow all current label directions for the specific pesticide being used. The discussion of specific nut tree cultivars and of specific techniques to grow nut trees that might have been successful in one area and at a particular time is not a guarantee that similar results will occur elsewhere.

| Officers and committees | 3 |

| State Vice-Presidents | 4 |

| List of members | 5 |

| Constitution | 18 |

| By-Laws | 19 |

| Foreword—W. C. Deming | 20 |

| Report of the Secretary for 1942-43 | 20 |

| Report of the Treasurer for 1942-43 | 21 |

| The Status of Nut Growing in 1943. Survey Report—John Davidson, Chairman of Committee. | 22 |

| Side-lights on the 1943-44 Survey | 47 |

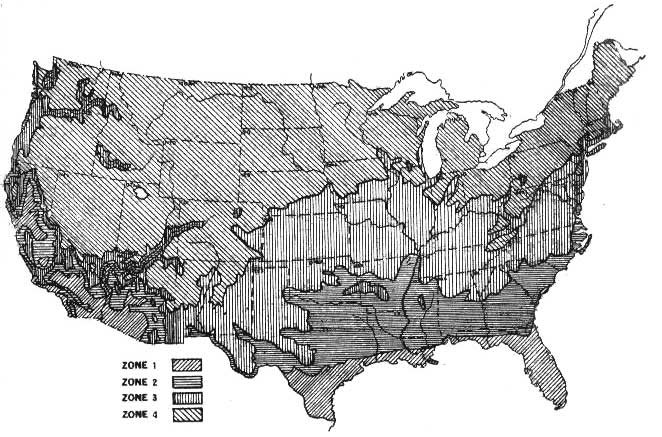

| Seasonal Zone Map of United States | 51 |

| Juglone: The active Agent in Walnut Toxicity—George A. Gries | 52 |

| Possible Black Walnut Toxicity on Tomato and Cabbage—Otto Reinking | 56 |

| Preliminary Studies on Catkin Forcing and Pollen Storage of Corylus and Juglans—L. G. Cox | 58 |

| Storage and Germination of Nuts of Several Species of Juglans—W. C. Muenscher and Babette I. Brown | 61 |

| A Key to Some Seedlings of Walnuts (Juglans)—W. C. Muenscher and Babette I. Brown | 62 |

| Further Tests with Black Walnut Varieties—L. H. MacDaniels and J. E. Wilde | 64 |

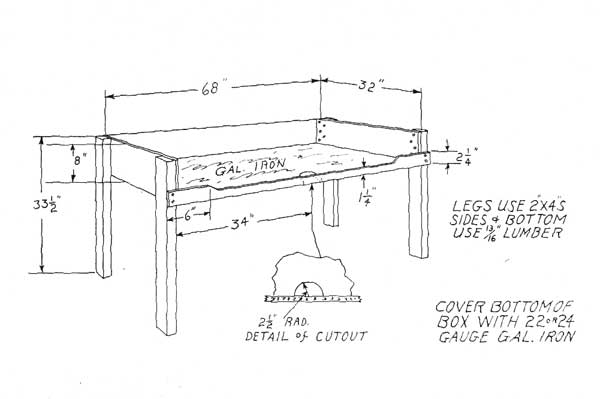

| Shelling Black Walnuts—G. J. Korn | 83 |

| Better Butternuts, Please—S. H. Graham | 85 |

| The Use of Fertilizer in a Walnut Orchard—L. K. Hostetter | 88 |

| Lime and Fertilizers for our Black Walnut Trees—Seward Berhow | 89 |

| The Propagation of Black Walnuts through Budding—Sterling Smith | 89 |

| Northern Nut Growing—Joseph Gerardi | 91 |

| Nut Puttering in an Off Year—W. C. Deming | 94 |

| Nut Nursery Notes—H. F. Stoke | 96 |

| Report from the Tennessee Valley—Thomas G. Zarger | 98 |

| Report from Minnesota—Carl Weschcke | 99 |

| Be Thrifty with Nut Trees—Carl Weschcke | 104 |

| Report of Season 1943—George Hebden Corsan | 105 |

| American Walnut Manufacturers Association Carries out Industrial Forestry Program—W. C. Finley | 106 |

| The Crath Carpathian Walnut in Illinois—A. S. Colby | 107 |

| Ohio Nut Growers' Meeting—G. J. Korn | 110 |

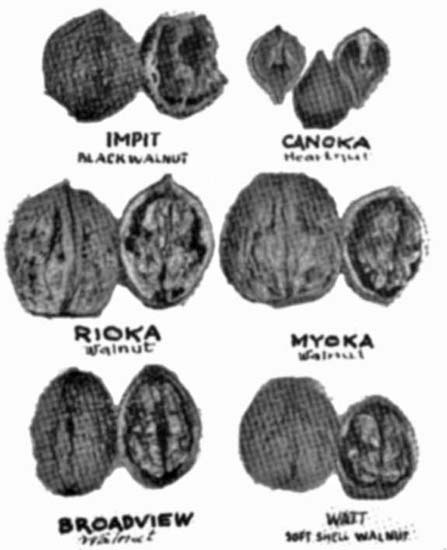

| Walnut and Heartnut Varieties; Notes and Remarks—J. U. Gellatly | 112 |

| Letters | 116 |

| Experiment Station Investigates Tree Believed to be the Oldest Chestnut in Connecticut | 120 |

| Report of Committee of Ohio Nut Growers—A. A. Bungart | 122 |

| Dr. John Harvey Kellogg—Obituary | 126 |

Transcriber's note:

The illustrations are not as good as hoped, but have been placed.

| President | Carl Weschcke, | 96 South Wabasha St., St. Paul, MINN. |

| Vice-President | Dr. L. H. MacDaniels, | Cornell University, Ithaca, N. Y. |

| Secretary | George L. Slate, | Experiment Station, Geneva, N. Y. |

| Treasurer | D. C. Snyder, | Center Point, Iowa. |

The Officers—and J. F. Wilkinson, Rockport, Indiana, and Dr. A. S. Colby, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois.

| Auditing—Dr. William Rohrbacher, Chairman. |

| Finance—Carl F. Walker, Chairman, Zenas H. Ellis, Harry R. Weber. |

| Press and Publication—Dr. W. C. Deming, Chairman, Mrs. Alan Buckwalter, Clarence A. Reed, George L. Slate, Dr. L. E. Theiss. |

| Varieties and Contest—Alan R. Buckwalter, Chairman, John W. Hershey, C. A. Reed, D. C. Snyder, H. F. Stoke. |

| Survey—John Davidson, Chairman. |

| Exhibits—G. H. Corsan, Chairman, Gilbert Becker, Paul C. Crath, S. H. Graham, Homer L. Jacobs, G. J. Korn, O. C. Lounsberry, Sargent H. Wellman. |

| Program—Gilbert Becker, Chairman, John Bregger, Spencer B. Chase, Dr. H. L. Crane, G. J. Korn, J. W. McKay, Clarence Reed, G. H. Corsan, Prof. R. B. Thomson, W. J. Strong, Dr. Conelly, Prof. White, Prof. Dwight. |

| Membership—Dr. J. Russell Smith, Chairman, L. V. Kline, Spencer B. Chase, Miss Mildred Jones, J. F. Wilkinson, Miss Amelia Riehl, H. F. Stoke, S. H. Graham, D. C. Snyder, Carl Weschcke, John W. Hershey, Gilbert Becker, Harry R. Weber. |

Dr. Robert T. Morris, Stamford, Connecticut.

Zenas H. Ellis, Fairhaven, Vermont.

Dr. W. C. Deming, Litchfield, Conn.

American Fruit Grower, 1770 Ontario Street, Cleveland, Ohio.[Pg 4]

| Arkansas | Prof. N. F. Drake |

| Alberta, Canada | A. L. Young |

| British Columbia, Canada | J. U. Gellatly |

| California | Will J. Thorpe |

| Canal Zone | L. C. Leighton |

| Connecticut | George D. Pratt, Jr. |

| District of Columbia | L. H. Mitchell |

| Georgia | Walter P. Pike |

| Illinois | Dr. A. S. Colby |

| Indiana | Hon. Hugh D. Wickens |

| Iowa | D. C. Snyder |

| Kansas | Frank E. Borst |

| Kentucky | E. C. Rice |

| Maine | Herman G. Perkins |

| Maryland | Dr. H. L. Crane |

| Massachusetts | Sargent H. Wellman |

| Mexico | Julio Grandjean |

| Michigan | Harry Burgart |

| Minnesota | Carl Weschcke |

| Missouri | Victor H. Schmidt |

| Nebraska | William Caha |

| New Hampshire | Prof. L. P. Latimer |

| New Jersey | A. R. Buckwalter |

| New York | Dr. L. H. MacDaniels |

| North Carolina | D. R. Dunstan |

| Ohio | Harry R. Weber |

| Ontario, Canada | Rev. Paul C. Crath |

| Oregon | C. E. Schuster |

| Pennsylvania | John Rick |

| Quebec, Canada | Dr. R. H. McKibben |

| Rhode Island | Phillip Allen |

| South America | Celedonio V. Pereda |

| South Carolina | John T. Bregger |

| Tennessee | L. V. Kline |

| Texas | Y. D. Carroll |

| Vermont | Zenas H. Ellis |

| Virginia | Dr. J. Russell Smith |

| Washington | Major H. B. Ferris |

| West Virginia | Dr. John E. Cannaday |

| Wisconsin | Marvin Dopkins |

| ALABAMA |

| McDaniel, John, McDaniel Nursery Specialties Co., Hartselle |

| Orr, Lovie, Penn-Orr-McDaniel Orchards, R. No. 1, Danville |

| Richards, Paul N., R. No. 1, Box 308, Birmingham |

| ARKANSAS |

| *Drake, Prof. N. F., Fayetteville. |

| Johnson, Searles, Japton |

| Williams, Jerry F., R. No. 1, Viola |

| CALIFORNIA |

| Armstrong Nurseries, 408 No. Euclid Ave., Ontario |

| Gray, G. A., 1507 11th St., Santa Monica |

| Haig, Dr. Thomas R., 3344 H. St., Sacramento |

| Kemple, W. H., 222 West Ralston St., Ontario |

| Meyer, James R., Guayale Research Project, Box 1708, Salinas |

| Parsons, Chas. E., Felix Gillet Nursery, Nevada City |

| Thorpe, William J., 3203 Anna St., San Francisco |

| Welby, Harry S., 500 Buchanan St., Taft |

| CANADA |

| Cook, C., 6226 Vine St., Vancouver, B. C. |

| Corsan, George H., Echo Valley, Islington, Ontario |

| Crath, Rev. Paul C., R. No. 2, Connington, Ontario |

| Creed, Fred H., 276 Sandwich St. W., Windsor, Ontario |

| Filman, O., Aldershot, Ontario |

| Gellatly, J. U., Westbank, B. C. |

| Giegerich, H. C., Con-Mine, Yellow Knife, N W T |

| Housser, Levi, Beamsville, Ontario |

| * Neilson, Mrs. Ellen, Box 852, Guelph, Ontario |

| Papple, Elton E., R. No. 3, Gainesville, Ontario |

| Porter, Gordon, Y.M.C.A., Windsor, Ontario |

| Somers, Gordon L., 37 London St., Sherbrooke, Quebec |

| Stephenson, Mrs. J. H., North Bend, B. C. |

| Trayling, E. J., 509 Richards St., Vancouver, B. C. |

| Troup, Alex, R. No. 1, Jordon Station, Ontario |

| Wagner, A. S., Delhi, Ontario |

| Wood, C. F., c/o Hobbs Glass Limited, 689 Notre Dame St., West Montreal, P. Q. |

| Yates, J., 2150 E. 65th Ave., Vancouver, B. C. |

| Young, A. L., Brooks, Alta. |

| CANAL ZONE |

| Leighton, L. C., Box 1452, Cristobal |

| COLORADO |

| Colt, W. A., Lyons |

| Wilder, W. E., 915 West 4th, La Junta |

| Williams, Erasmus W., P. O. Box 966, Durango |

| CONNECTICUT |

| Biology Department, Avon Old Farms, Avon |

| Coote, Albert W., 1104 Farmington Ave., West Hartford. |

| David, Alexander M., 480 So. Main St., West Hartford |

| Dawley, Arthur E., R. No. 1, Norwich |

| Deming, Dr. W. C., Litchfield |

| Frueh, Alfred J., West Cornwall or (34 Perry St., N. Y., N. Y.) |

| * Huntington, A. M., Stanerigg Farms, Bethel |

| Jennings, Clyde, 30 West Main St., Waterbury |

| Lehr, Frederick L., 45 Elihu St., Hamden |

| Lobdell, Mrs. Frank C., 225 Verna Hill Rd., Fairfield |

| Milde, Karl F., Town Farm Rd., Litchfield |

| * Morris, Dr. Robert T., RFD., Stamford |

| * Newmaker, Adolph, R. No. 1, Rockville |

| Page, Donald T., Box 228, R. No. 1, Danielson |

| Pratt, George D., Jr., Bridgewater |

| Rourke, Robert U., R. 1, Pomfret Center, Conn. |

| Senior, Sam P., R. No. 1, Bridgeport |

| Walsh, James A., c/o Armstrong Rubber Co., West Haven |

| White, Heath E., Box 630, Westport |

| White, George E., R. No. 2, Andover |

| DELAWARE |

| Lake, Edward C., Sharpless Rd., Hockessin |

| DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA |

| American Potash Inst., Inc., Librarian, 1155 16th St., N. W., Washington |

| Bush, Dr. Vannevar, 4901 Hillbrook Lane, Washington |

| Littlepage, Thomas P., Union Trust Bldg., Washington |

| Mitchell, Col. Lennard H., 2657 Woodley Rd. N. W., Washington |

| FLORIDA |

| Cook, Dr. Ernest A., c/o County Health Dept., Quincy |

| McDaniel, J. C., Box 1111, Haines City |

| GEORGIA |

| Eidson, G. Clyde, 1700 Westwood Ave. S. W., Atlanta |

| Hunter, H. Reid, 561 Lakeshore Dr. N. E., Atlanta |

| Skyland Farms, S. C. Noland & C. H. Crawford, Prop., 161 Spring St. N. W., Atlanta |

| IDAHO |

| Dryden, Lynn, Peck |

| Swayne, Samuel F., Orofino |

| ILLINOIS |

| Achenbach, W. N., 410 N. Michigan Ave., Chicago |

| Adams, James S., R. 1, Hinsdale |

| Allen, Theodore R., Delavan |

| Anthony, A. B., R. No. 3, Sterling |

| Baber, Adin, Kansas |

| Best, R. B., Eldred |

| Bolle, Dr. A. C., 324 E. State St., Jacksonville |

| Bontz, Mrs. Lillian, 161 W. Mass. Ave., Peoria |

| Bronson, Earl A., 800 Simpson St., Evanston |

| Churchill, Woodford M., 4250 Drexel Blvd., Chicago |

| Colby, Dr. Arthur S., University of Illinois, Urbana |

| Colehour, Francis H., 411 Brown Bldg., Rockford |

| Dintelman, L. F., Belleville |

| Duis, J. G., Shattuc |

| Edmunds, Mrs. Palmer D., La Hogue |

| Frey, Mrs. Frank H., 2315 West 108th Place, Chicago |

| Frey, Frank H., 2315 West 108th Place, Chicago |

| Frierdich, Fred, 3907 W. Main St., Belleville |

| Gerardi, Joseph, O'Fallon |

| Gott, Lawrence E., P. O. Box No. 104, Enfield |

| Gusler, Carl, 213 N. Taylor Ave., Oak Park |

| Haeseler, L. M., 1959 W. Madison St., Chicago |

| Helmle, Herman C., 123 N. Walnut St., Springfield |

| Jungk, Adolph, 817 Washington Ave., Alton |

| Kilner, F. R., c/o American Nurseryman, 508 So. Dearborn St., Chicago |

| Kinsel, Dr. O. A., Box 53, Morrison |

| Knobloch, Miss Margaret, Arthur |

| Kreider, Ralph, Jr., Hammond |

| Livermore, Ogden, 801 Forest Ave., Evanston |

| Logan, George F., Dallas City |

| Love, W. Wray, 601 E. Boone St., Salem |

| Maxwell, Leroy O., 312 W. Avondale St., Champaign |

| Oakes, Royal, Bluffs |

| Peterson, Dr. Joel A., 602 University Ave., Urbana |

| Powell, Charles A., Hickory St., Jerseyville |

| Remaly, Howard A., 1120 E. Maple St., Kankakee |

| Riehl, Miss Amelia, Evergreen Heights, Godfrey |

| Trobaugh, Frank E., West Frankfort |

| Valley Landscape Co., Box 688, Elgin |

| Van Cleave, Bruce, 1049 Chatfield Rd., Winnetka |

| Walantas, John, 3464 Lituanica Ave., Chicago |

| Werner, Edward H., 282 Ridgeland Ave., Elmhurst |

| Whitford, A. M., Farina |

| INDIANA |

| Behr, J. E., Laconia |

| Boyer, Clyde C., Nabb |

| Gentry, Herbert M., R. No. 2, Noblesville |

| Minton, Charles F., R. No. 5, Huntington |

| Morey, B. F., 453 S. 5th St., Clinton |

| Olson, Albert L., 1230 Nuttman Ave., Fort Wayne |

| Prell, Carl F., 803 West Colfax Ave., South Bend |

| Skinner, Dr. Chas. H., Indiana University, Bloomington |

| Sly, Donald R., R. No. 3, Rockport |

| Tormohlen, Willard, 321 Cleveland St., Gary |

| Wallick, Ford, R. No. 4, Peru |

| Warren, E. L., New Richmond |

| Wilkinson, J. F., Indiana Nut Nursery, Rockport |

| IOWA |

| Andrew, Dr. Earl V., Maquoketa |

| Beeghly, Dale, Pierson |

| Berhow, S., Berhow Nurseries, Huxley |

| Boice, R. H., R. 1, Nashua |

| Cerveny, Frank L., R. No. 4, Cedar Rapids |

| Christensen, Everett G., Gilmore City |

| Crumley, Joe F., 221 Park Rd., Iowa City |

| Ferris, Wayne, Hampton |

| Gardner, Clark, c/o Gardner Nurseries, Osage |

| Harrison, L. E., Nashua |

| Hill, Clarence S., Hilburn Stock Farm, Minburn |

| Huen, E. F., Eldora |

| Iowa State Horticultural Society, State House, Des Moines |

| Kivell, Ivan E., R. No. 3, Greene |

| Lehmann, F. W., Jr., 3220 John Lynde Rd., Des Moines |

| Lounsberry, C. C., 209 Howard Ave., Ames |

| Mahon, Milton, Blakesburg |

| McLeran, Harold F., Mt. Pleasant |

| Rohrbacher, Dr. Wm., 811 East College St., Iowa City |

| Schlagenbusch Bros., R. No. 3, Ft. Madison |

| Schlanbusch, Dr. O. E., 350 Magowan Ave., Iowa City |

| Snyder, D. C., Center Point |

| Steffen, R. F., Box 62, Sioux City |

| Van Meter, W. L., Adel |

| Wade, Miss Ida May, 1410 Avalon Ave., Waterloo |

| Wingert, John O., Dallas Center |

| Wood, Roy A., Castana |

| KANSAS |

| Borst, Frank E., 1704 Shawnee St., Leavenworth |

| Boyd, Elmer, R. No. 1, Box 95, Oskaloosa |

| Funk, M. D., 1501 N. Tyler St., Topeka |

| Hofman, Rayburn, R. No. 5, Manhattan |

| Leavenworth Nurseries, R. No. 3, Leavenworth |

| Schroeder, Emmett H., 800 W. 17th, Hutchinson |

| Wise, H. S., 579 W. Douglas Ave., Wichita |

| KENTUCKY |

| Alves, Robert H., c/o Nehi Bottling Co., Henderson |

| Baughn, Cullie, R. No. 6, Box 1, Franklin |

| Bureau of School Service, University of Kentucky, Lexington |

| Cornett, Lester, Box 566, Lynch |

| Gooch, Perry, R. No. 1, Oakville |

| Moss, Dr. C. A., Williamsburg |

| Rice, E. C., Absher |

| Tatum, W. G., No. R. 4, Lebanon |

| Watt, R. M., R. No. 1, Lexington |

| Whittinghill, Lonnie M., Box 10, Love |

| LOUISIANA |

| Fullilove, J. Hill., Box 157, Shreveport |

| Louisiana State University and A. & M. College, General Library, University |

| MAINE |

| Pike, Radcliffe B., Lubec |

| MARYLAND |

| Crane, Dr. H. L., Bureau of Plant Industry Station, Beltsville |

| Gravatt, Dr. G. F., Forest Pathology, Plant Industry, USDA, Beltsville |

| Hodgson, Wm. C., R. No. 1, White Hall |

| Hoopes, Wilmer, Forest Hill |

| Kemp, Homer S., Bountiful Ridge Nurseries, Princess Anne |

| Kingsville Nurseries, Kingsville |

| Lewis, Dean, Bel Air |

| McCollum, Blaine, White Hall |

| McKay, J. W., Bureau of Plant Industry Station, Beltsville |

| Nogus, Mrs. Herbert, 4514 32nd St., Mt. Rainier |

| Porter, John J., 1199 The Terrace, Hagerstown |

| Purnell, J. Edgar, Spring Hill Rd., Salisbury |

| Reed, C. A., Bureau of Plant Industry Station, Beltsville |

| Shamer, Dr. Maurice E., 3300 W. North Ave., Baltimore |

| MASSACHUSETTS |

| Allen, Edward E., Hotel Ambassador, Cambridge |

| Beauchamp, A. A., 603 Boylston St., Boston |

| Booson, Campbell, 30 State St., Boston |

| Brown, Daniel L., 60 State St., Boston |

| Chatterton, R. M., 44 Cedar St., Malden |

| Fitts, Walter H., 39 Baker St., Foxboro |

| Fritze, E., Osterville |

| Garlock, Mott A., 17 Arlington Rd., Longmeadow |

| Gauthier, Louis R., Wood Hill Rd., Monson |

| Groff, George H., 46 Chestnut St., Brookline |

| Kaan, Dr. Helen W., Wellesley College, Wellesley |

| Kendall, Henry P., Moose Hill Farm, Sharon |

| Kibrick, I. S., 106 Main St., Brockton |

| LaBeau, Henry A., 1556 Massachusetts Ave., North Adams |

| McTavish, W. C., 50 Congress St., Boston |

| Perells, Walter J., North-Falmouth |

| Rice, Horace J., 5 Elm St., Springfield |

| *Russell, Mrs. Newton H., 12 Burnett Ave., South Hadley |

| Swartz, H. P., 206 Checopee St., Checopee |

| Short, I. W., 299 Washington St., Taunton |

| Stewart, O. W., 75 Milton Ave., Hyde Park |

| Trudeau, Dr. A. E., 14 Railroad St., Holyoke |

| Van Meter, Dr. R. A., French Hall, M. S. C., Amherst |

| Wellman, Sargent H., Windridge, Topsfield |

| Westcott, Samuel K., 79 Richview Ave., North Adams |

| Weston Nurseries, Inc., Brown & Winter Sts., Weston |

| Weymouth, Paul W., 183 Plymouth St., Holbrook |

| MEXICO |

| Grandjean, Julio, P. O. Box 748, Mexico, D. F. |

| MICHIGAN |

| Andersen, Charles, Andersen Evergreen Nurseries, Scottville |

| Aylesworth, C. F., 920 Pinecrest Dr., Ferndale |

| Barlow, Alfred L., 13079 Flanders Ave., Detroit, 5 |

| Becker, Gilbert, Climax |

| Binder, Charles, 34 E. Michigan Ave., Battle Creek |

| Boylan, P. B., Cloverdale |

| Bradley, L. J., R. No. 1, Springport |

| Buell, Dr. M. F., Dept. of Health & Recreation, Dearborn |

| Bumler, Malcolm R., 1089 Lakeview, Detroit |

| Burgart, Harry, Michigan Nut Nursery, R. No. 2, Union City |

| Burgess, E. H., Burgess Seed & Plant Co., Galesburg |

| Cardinell, H. A., Michigan State College, E. Lansing |

| Corsan, H. H., R. No. 1, Hillsdale |

| Daubenmeyer, H., 7647 Sylvester, Detroit |

| Emerson, Ralph, 161 Cortland Ave., Highland Park, 3 |

| Farrington, Robert A., Chittenden Nursery, U. S. F. A., Wellston |

| Gage, Nina M., 6440 Kensington Rd., Wixom |

| Hay, Francis H., Ivanhoe Place, Lawrence |

| Healey, Scott, R. No. 2, Otsego |

| Hewetson, Prof. F. N., Michigan State College, East Lansing |

| **Kellogg, W. K., Battle Creek |

| Korn, G. J., R. No. 1, Richland |

| Lee, Michael, Lapeer |

| Lemke, Edwin W., 2432 Townsend Ave., Detroit, 14 |

| Lewis, Clayton A., 1219 Pine St., Port Huron |

| Mann, Charles W., 221 Cutler St., Allegan |

| Mason, Harold E., 1580 Montie, Lincoln Park |

| McShane, Gerald, 1320 Franklin St. S. E., Grand Rapids |

| McMillan, Vincent U., 17926 Woodward Ave., Detroit, 3 |

| Miller, Louis, 1300 O'Keefe, Cassopolis |

| Ricker, John E., 14642 Marlowe Ave., Detroit |

| Scofield, Mr. and Mrs., Box 215, Woodland |

| Stocking, Frederick N., Harrisville |

| Stotz, Raleigh R., 1546 Franklin S. E., Grand Rapids, 6 |

| Tate, D. L., 959 Westchester Way, Birmingham |

| Wise, C. E., R. No. 3, Milford |

| MINNESOTA |

| Andrews, Miss Frances E., 48 Park View Terrace, Minneapolis |

| Cothran, John C., 512 N. 19th Ave. E., Duluth |

| Grosch, Robert H., 2732 Drew Ave. S., Minneapolis |

| Hodgson, R. E., Dept. of Agriculture, S. E. Exp. Station, Waseca |

| Skrukrud, Baldwin, Sacred Heart |

| Vaux, Harold C., R. No. 4, Faribault |

| Weschcke, Carl, 96 So. Wabasha St., St. Paul |

| MISSOURI |

| Barnes, Dr. F. M., Jr., 4952 Maryland Ave., St. Louis |

| Bucksath, Charles E., Dalton |

| Fisher, J. B., R. R. H. 1, Pacific |

| Hay, Leander, Gilliam |

| Johns, Jeannette F., R. No. 1, Festus |

| Ochs, C. T., Box 291, Salem |

| Owen, Dr. Lyle, Branson |

| Richterkessing, Ralph, R. No. 1, St. Charles |

| Schmidt, Victor H., 5821 Virginia, Kansas City |

| Stevenson, Hugh, Elsberry |

| Thompson, J. D., 600 West 3rd St., Kansas City |

| NEBRASKA |

| Brand, George, R. No. 5, Box 60, Lincoln |

| Caha, William, Wahoo |

| Clark, Ivan E., Concord |

| DeLong, F. S., 1510 2nd Corso, Nebraska City |

| Ferguson, Albert B., Dunbar |

| Hess, Harvey W., The Arrowhead Garden, Box 209, Hebron |

| Hoyer, L. B., 7554 Maple St., Omaha |

| Lydick, J. J., Craig |

| Wever, Francis E., Box 312, Sutherland |

| White, Bertha G., 7615 Leighton Ave., Lincoln |

| NEW HAMPSHIRE |

| Lahti, Matthew, Locust Lane Farm, Wolfeboro |

| Latimer, Prof. L. P., Department of Horticulture, Durham |

| Ryan, Miss Agnes, Mill Rd., Durham |

| Vannevar, Dr. Bush, E. Jaffrey or (4901 Hillbrook Lane, Washington, D. C.) |

| NEW JERSEY |

| Blake, Harold, Box 93, Saddle River |

| Brewer, J. L., 10 Allen Place, Fair Lawn |

| Bottom, R. J., 41 Robertson Rd., West Orange |

| Buch, Philip O., 106 Rockaway Ave., Rockaway |

| Buckwalter, Alan R., Flemington |

| Buckwalter, Mrs. Alan R., Flemington |

| Case, Lynn B., Mountain Ave. & Piedmont Dr., Bound Brook |

| Collins, Joseph N., 769 First St., Westfield |

| Cumberland Nursery, R. No. 1, Millville |

| Donnelly, John H., Mountain Ice Co., 51 Newark St., Hoboken |

| Dougherty, Wm. H., Broadacres-on-Bedens, Box 425, Princeton |

| Fuhlbruegge, Edward, R. No. 1, Box 21, Pittstown |

| Gardenier, Dr. Harold C., Westwood |

| Gottein, Louis, 1081 So. Clinton Ave., Trenton |

| *Jacques, Lee W., 74 Waverly Place, Jersey City |

| Jewett, Edmund Gale, R. No. 1, Port Murray |

| McCulloch, J. D., 73 George St., Freehold |

| Mueller, R., R. 1, Box 81, Westwood |

| Ritchie, Walter M., 402 St. George St., Rahway |

| Rocker, Louis P., The Rocker Farm, Andover |

| Szalay, Dr. S., 931 Garrison Ave., Teaneck |

| Terhune, Gilbert V. P., Apple Acres, Newfoundland |

| Todd, E. Murray, R. No. 2, Matawan |

| Tolley, Fred C., 223 Berkeley Ave., Bloomfield |

| Van Doren, Durand H., 310 Redmond Rd., South Orange |

| White, Co. J. H., Jr., Picatinny Arsenal, Dover |

| Williams, Harold G., Box 344, Ramsey |

| Youngberg, Harry W., 304 Hillside Ave., Nutley |

| NEW MEXICO |

| Bryan, Lawrence, P. O. Box 1053, Artesia |

| Williams, Erasmus D., Box No. 6, Wagon Mound |

| NEW YORK |

| Benton, William A., Wassaic |

| Bernath's Nursery, R. No. 1, Poughkeepsie |

| Bixby, Henry D., East Drive, Halesite, L. I. |

| Bixby, Mrs. Willard G., 32 Grand Ave., Baldwin |

| Black, Mrs. William A., 450 W. 24th St., New York |

| Brinckeroff, John H., 150-09 Hillside Ave., Jamaica |

| Brook, Victor, 171 Rockingham St., Rochester |

| Brooks, William G., Monroe |

| Collins, James F., Cold Spring Rd., Stanfordville |

| Cowan, Harold, 643 Southern Bldg., The Bronx, New York |

| Davis, Clair, 140 Broadway, Lynbrook |

| De Schauensee, Mrs. A. M., Easterhill Farm, Chester |

| Dutton, Walter, 264 Terrace Park, Rochester |

| Ellwanger, Mrs. William D., 510 East Ave., Rochester |

| Fagley, Richard M., 29 Perry St., New York, 14 |

| Feil, Harry, 1270 Hilton-Spencerport Rd., Hilton |

| Flanigen, Charles F., 16 Greenfield St., Buffalo |

| Freer, H. J., 20 Midvale Rd., Fairport |

| Garcia, M., 62 Rugby Rd., Brooklyn |

| Graham, S. H., R. No. 5, Ithaca |

| Graves, Dr. Arthur H., Botanic Garden, Brooklyn |

| Gressel, Henry, R. No. 2, Mohawk |

| Guillaume, Ronald P., 5210 Maine St., Wmsville |

| Gwinn, Ralph W., 522 5th Ave., New York |

| Hasbrouck, Walter, Jr., New Paltz |

| Heckelman, Edward, 245 S. Franklin St., Hempstead |

| Hubbell, James F., Mayro Bldg., Utica |

| Iddings, William, 165 Ludlow St., New York |

| Kelly, Mortimer B., 17 Battery Place, New York |

| Kirstein, Edward K., 89 Westminster Rd., Rochester |

| *Lewis, Clarence, 1000 Park Ave., New York |

| Little, George, Ripley |

| *MacDaniels, Dr. L. H., Cornell University, Ithaca |

| Maloney Bros. Nursery Co., Inc., Danville |

| Mevius, William E., East Church St., Eden |

| Miller, J. E., R. No. 1, Naples |

| *Montgomery, Robert H., 1 E. 44th St., New York |

| Newell, P. F., 53 Elm St., Nassau |

| Oeder, Dr. Lambert R., 551 Fifth Ave., New York |

| Ohligor, Louis H., R. No. 2, New City |

| Phillips, Clyde F., 11 Olive Ave., Batavia |

| Pickhardt, Dr. Otto C., 117 East 80th St., New York |

| Pomeroy, Robert Watson, Wassaic |

| Potter, Wilson, Jr., Pomona Country Club, Suffern |

| Price, J., 385 Arbuckle Ave., Cedarhurst, L. I. |

| Rebillard, Frederick, 164 Lark St., Albany |

| Salzer, George, 169 Garford Rd., Rochester |

| Schlegel, Charles P., 990 South Ave., Rochester |

| Schmidt, Carl W., 180 Linwood Ave., Buffalo |

| Schwartz, Mortimer L., 1243 Boynton Ave., Bronx, New York |

| Slate, Prof. George L., State Agricultural Experiment Sta., Geneva |

| Smith, Gilbert L., State School, Wassaic |

| Smith, Jay L., Chester |

| Steiger, Harwood, Red Hook |

| Stern-Montegny, Hubert, Erbonia Farm, Gardiner |

| Sucsy, Emil J., West Nyack |

| Warren, Herbert E., P. O. Box 109, Norwich |

| Wilson, Mrs. Ida J., Candor, New York |

| Windisch, Richard P., W. E. Burnet & Co., 11 Wall St., New York |

| *Wissman, Mrs. F. de R., 9 W. 54th St., New York |

| NORTH CAROLINA |

| Dunstan, R. T., Greenboro College, Greenboro |

| Malcolm, Van R., Celo P. O., Yancey County |

| Parks, C. H., R. No. 2, Asheville |

| OKLAHOMA |

| Billups, Richard A., Hales Bldg., Oklahoma City |

| Clifton, Edward C., 1325 East 66th St., R. No. 2, Tulsa |

| Hirschi's Nursery, 414 N. Robinson, Oklahoma City |

| Hughes, C. V., 5600 N. W. 16, R. No. 5, Oklahoma City |

| Jarrett, C. F., 2208 W. 40th St., Tulsa |

| Meek, E. B., R. No. 2, Wynnewood |

| Swan, Oscar E., Jr., 1431 E. 35th St., Tulsa |

| OHIO |

| Bungart, A. A., Avon |

| Cinadr, Mrs. Katherine, 13514 Coath Ave., Cleveland, 20 |

| Cole, Mrs. J. R., 163 Woodland Ave., Columbus |

| Cook, H. C., R. No. 1, Box 125, Leetonia |

| Cranz, Eugene F., Mount Tom Farm, Ira |

| Crooks, John L., 4600 Chester, Cleveland |

| Davidson, John, 234 E. 2nd St., Xenia |

| Diller, Oliver D., Dept. of Forestry, Experiment Sta., Wooster |

| Dubois, Wilber, & Son, Madisonville, Cincinnati, 27 |

| Emeh, Frank, Genoa |

| Fickes, W. R., R. No. 1, Wooster |

| Franks, M. L., R. No. 1, Montpelier |

| Garden Center of Greater Cleveland, 1190 East Blvd., Cleveland |

| Gauly, Dr. Edward, 1110 Euclid Ave., Cleveland |

| Gerber, E. P., Kidron |

| Gerhardt, Gustave A., 13125 Jefferson Ave., Cincinnati |

| Gerstenmafer, John A., 18 Pond S. W., Massillon |

| Hoch, Gordon F., 6292 Glade Ave., Cincinnati |

| Hill, Dr. Albert A., 4187 Pearl Rd., Cleveland |

| Irish, Charles F., 418 105th St., Cleveland |

| Jacobs, Homer L., c/o Davey Tree Expert Co., Kent |

| Jacobs, Mason, 3003 Jacobs Rd., Youngstown |

| Kappel, Owen, Bolivar |

| Kintzel, Frank M., 2506 Briarcliffe Ave., Cincinnati, 13 |

| Kirby, R. L., Box 131, R. No. 1, Sharonville |

| Kratzer, George, Kidron |

| Lacknett, G. S., 510 E. Main St., Newark |

| Lehmann, Carl, Union Trust Bldg., Cincinnati |

| Madison, Arthur E., 13608 5th Ave. E., Cleveland |

| McBride, William B., 2398 Brandon Rd., Columbus, 8 |

| Meikle, William J., 730 Thornhill Dr., Cleveland |

| Metzger, A. J., 724 Euclid Ave., Toledo |

| Ochs, C. T., Box 291, Salem |

| Ochs, Norman M., R. No. 2, Brunswick |

| Osborn, Frank C., 4040 W. 160th St., Cleveland |

| Ransbottom, Earl A., 1057 W. Market St., Lima |

| Scarff's Sons, W. N., New Carlisle |

| Shelton, E. M., 1468 W. Clifton Blvd., Lakewood, 7 |

| Shessler, Sylvester M., Genoa |

| Silvis, Raymond E., 1725 Lindberg Ave. N. E., Massillon |

| Smith, Sterling A., 630 W. South St., Vermillion |

| Spring Hill Nurseries Co., Tipp City |

| Toops, Herbert A., 1430 Cambridge Blvd., Columbus |

| Van Voorhis, J. F., 215 Hudson Ave., Apt. B-1, Newark |

| Walker, Carl F., 2351 E. Overlook Rd., Cleveland |

| *Weber, Harry R., 123 East 6th St., Cincinnati |

| Weber, Martha R., R. No. 1, Morgan Rd., Cloves |

| Willett, Dr. G. P., Elmore |

| Wischhusen, J. F., 15031 Shore Acres Dr. N. E., Cleveland |

| OREGON |

| Carlton Nursery Co., Carlton |

| Doharian, S. H., P. O. Box 346, Eugene |

| Flanagan, George C., 909 Terminal Sales Bldg., Portland |

| Miller, John E., R. No. 1, Box 312-A, Oswego |

| Russ, E., R. No. 1, Halsey |

| Schuster, C. E., Horticulturist, Corvallis |

| PENNSYLVANIA |

| Allaman, R. P., R. No. 1, Harrisburg |

| Allen, Lt. Col. Thomas H., St. Thomas |

| Banks, H. C., R. No. 1, Hollortown |

| Barnhart, Emmert M., R. No. 4, Waynesboro |

| Baum, Dr. F. L., Boyertown |

| Beard, H. K., R. No. 1, Sheridan |

| Blair, Dr. G. D., 702 N. Homewood Ave., Pittsburgh |

| Bowen, John C., R. No. 1, Macungie |

| Brenneman, John E., R. No. 6, Lancaster |

| Brown, Morrison, Carson Long Military Academy, New Bloomfleld |

| Creasy, Luther P., Catawissa |

| Dewey, Richard, Box 41, Peckville |

| Driver, Warren M., R. No. 4, Bethlehem |

| Diefenderfer, C. E., 918 3rd St., Fullerton |

| Duckham, William C., R. No. 2, Allison Park |

| Ebling, Aaron L., R. No. 2, Reading |

| Ellenberger, Herman A., 333 S. Burrows St., State College |

| Etter, Fayette, P. O. Box 57, Lemasters |

| Gebhardt, F. C., 140 East 29th St., Erie |

| Heckler, George Snyder, Hatfield |

| Heilman, R. H., 2303 Beechwood Blvd., Pittsburgh |

| Hershey, John W., Nut Tree Nurseries, Downingtown |

| High Tor Nursery, R. No. 6, Pittsburgh |

| Hostetter, C. F., Bird-In-Hand |

| Hostetter, L. K., R. No. 3, Lancaster |

| Jackson, Schuyler, New Hope |

| Johnson, Robert F., R. No. 5, Box 56, Crafton |

| Jones, Dr. Truman W., Coatesville |

| Jones, Miss Mildred, P. O. Box 356, Lancaster |

| Kaufman, M. M., Clarion |

| Kirk, DeNard B., Forest Grove |

| Kline, Dr. Florence M., 909 Arlington Apts., Corner Acken and Center Aves., Pittsburgh |

| Leach, Will, Court House, Scranton |

| Long, Carleton C., 141 Walnut St., Beaver |

| Losch, Walter, 133 E. High St., Topston |

| Lutz, Stanley W., Egypt |

| Mattoon, H. Gleason, 1008 Commercial Trust Bldg., Philadelphia |

| McCartney, T. Lupton, Room 1, Horticultural Bldg., State College |

| Miller, Robert O., 3rd and Ridge St., Emmaus |

| Moyer, Philip S., Union Trust Bldg., Harrisburg |

| Owens, G. F., 700 E. Line Ave., Ellwood City |

| Reidler, Paul G., Ashland |

| Rial, John, 528 Harrison Ave., Greensburg |

| *Rick, John, 439 Pennsylvania Sq., Reading |

| Ruch, George, Huntingdon Valley |

| Rupp, Edward E., Jr., 57 W. Pomfret St., Carlisle |

| Sameth, Sigmund, Grandeval Farm, R. No. 3, Kutztown |

| Schaible, Percy, Upper Black Eddy |

| Schmidt, Albert J., 534 Smithfield St., Pittsburgh |

| Siebley, J. W., Star Route, Landisburg |

| Shelly, David B., R. No. 2, Elizabethtown |

| Silin, I. J., Echo Mountain, Fairview |

| Smith, Dr. J. Russell, 550 Elm Ave., Swarthmore |

| Southampton Nurseries, Southampton |

| Stoebener, Harry W., 6227 Penn. Ave., Pittsburgh |

| Theiss, Dr. Lewis E., Bucknell University, Lewisburg |

| Waggoner, Charles W., 432 Harmony Ave., Rochester |

| *Wister, John C., Clarkson Ave. and Wister St., Germantown |

| Wood, Wayne, R. No. 1, Newville |

| Wright, Ross Pier, 235 West 6th St., Eric |

| RHODE ISLAND |

| **Allen, Philip, 178 Dorance St., Providence |

| R. I. State College, Library Dept., Green Hall, Kingston |

| SOUTH AMERICA |

| Pereda, Celedonia V., Arroyo 1142, Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| SOUTH CAROLINA |

| Bregger, John T., Clemson |

| SOUTH DAKOTA |

| Bradley, Homer L., Lacreek National Wildlife Refuge, Martin |

| TENNESSEE |

| Chase, Capt. Spencer B., Hqs. Det. Sta. Camp, Camp Tyson |

| Kirk, Charles H., Oak Ridge |

| Howell Nurseries, Sweetwater |

| McDaniel, J. C., P. O. Box 331, Brownsville |

| Rhodes, G. B., R. 2, Covington |

| Zarger, Thomas G., Norris |

| TEXAS |

| Carroll, Y. D., 2093 McFadden St., Beaumont |

| Florida, Kaufman, Box 154, Rotan |

| Price, W. S., Jr., Gustine |

| UTAH |

| Oleson, Granville, 1210 Laird Ave., Salt Lake City, 5 |

| Petterson, Harlan D., 2164 Jefferson Ave., Ogden |

| VERMONT |

| Aldrich, A. W., R. No. 3, Springfield |

| *Ellis, Zenas H., Fair Haven |

| Foster, Forest K., West Topsham |

| VIRGINIA |

| Acker, E. D., Co., Broadway |

| Brewster, Stanley II., "Cerro Cordo," Gainesville |

| Burton, Geo. L., 728 College St., Bedford |

| Carey, Graham, Fair Haven |

| Dickerson, T. C., 316 56th St., Newport News |

| Gibbs, H. R., McLean |

| Johnson, Dr. Walt R., 2602 B. Monument Ave., Richmond |

| Landess, S. S., 2103 N. Quantico St., Arlington |

| Lewis, Pvt. Hewlett W., H. & H. Co., 938 Engr. Avn. Cam. Bn., A. A. B., Richmond |

| Morse, Chandler, Valross, R. No. 5, Alexandria |

| Nix, Robert W., Jr., Lucketts |

| Peters, John Rogers, P. O. Box 37, McLean |

| Pertzoff, Dr. V. A., Carter's Bridge |

| Stoke, H. F., 1420 Watts Ave., Roanoke |

| Stoke, Dr. John H., 408-10 Boxley Bldg., Roanoke |

| Varcity Products Co., 5 Middlebrook Ave., Staunton |

| Webb, John, Hillsville |

| Zimmerman, Ruth, Bridgewater |

| WASHINGTON |

| Altman, Mrs. H. E., Cedarbrook Nut Farm, Nooksack |

| Barth, J. H., Box 1827, R. No. 3, Spokane |

| Carey, Joseph E., 4219 Letona Ave., Seattle |

| Clark, R. W., 4221 Phinney Ave., Seattle |

| Denman, George L., 1319 East Nina Ave., Spokane |

| Ferris, Major Hiram B., P. O. Box 74, Spokane |

| Kling, William L., R. No. 2, Box 230, Clarkston |

| Linkletter, F. D., 8034 35th Ave. N. E., Seattle |

| Lynn Tuttle Nursery, The Heights, Clarkston |

| Martin, Fred A., Star Route, Chelan |

| Naderman, G. W., R. No. 1, Box 370, Olympia |

| Shane Bros., Vashon |

| Wilson, John A., East 1517 16th Ave., Spokane |

| WEST VIRGINIA |

| Cannaday, Dr. John E., Charleston General Hospital, Charleston |

| Hoover, Wendell W., Webster Springs |

| Slotkin, Meyer S., 1671 6th Ave., Huntington, 1 |

| WISCONSIN |

| Aoppler, C W., Box 239, Oconomowoc |

| Bassett, W. S., 1522 Main St., La Crosse |

| Dopkins, Marvin, R. No. 1, River Falls |

| Downs, M. L., 1024 N. Leminwah St., Appleton |

| Koelsch, Norman, Jackson |

| Zinn, Walter G., P. O. Box 747, Milwaukee |

*Life Member

**Contributing Member[Pg 18]

Article I

Name—This Society shall be known as the Northern Nut Growers Association, Incorporated.

Article II

Object—Its object shall be the promotion of interest in nut-bearing plants, their products and their culture.

Article III

Membership—Membership in this society shall be open to all persons who desire to further nut culture, without reference to place of residence or nationality, subject to the rules and regulations of the committee on membership.

Article IV

Officers—There shall be a president, a vice-president, a secretary and a treasurer, who shall be elected by ballot at the annual meeting; and a board of directors consisting of six persons, of which the president, the two last retiring presidents, the vice-president, the secretary and the treasurer shall be members. There shall be a state vice-president from each state, dependency, or country represented in the membership of the association, who shall be appointed by the president.

Article V

Election of Officers—A committee of five members shall be elected at the annual meeting for the purpose of nominating officers for the following year.

Article VI

Meetings—The place and time of the annual meeting shall be selected by the membership in session or, in the event of no selection being made at this time, the board of directors shall choose the place and time for the holding of the annual convention. Such other meetings as may seem desirable may be called by the president and board of directors.

Article VII

Quorum—Ten members of the Association shall constitute a quorum but must include two of the four elected officers.

Article VIII

Amendments—This constitution may be amended by a two-thirds vote of the members present at any annual meeting, notice of such amendment having been read at the previous annual meeting, or copy of the proposed amendment having been mailed by any member to each member thirty days before the date of the annual meeting.[Pg 19]

Article I

Committees—The Association shall appoint standing committees as follows: On membership, on finance, on programme, on press and publication, on exhibits, on varieties and contests, on survey, and an auditing committee. The committee on membership may make recommendations to the Association as to the discipline or expulsion of any member.

Article II

Fees—Annual members shall pay two dollars annually. Contributing members shall pay ten dollars annually. Life members shall make one payment of fifty dollars and shall be exempt from further dues and shall be entitled to the same benefits as annual members. Honorary members shall be exempt from dues. "Perpetual" membership is eligible to any one who leaves at least five hundred dollars to the Association and such membership on payment of said sum to the Association shall entitle the name of the deceased to be forever enrolled in the list of members as "Perpetual" with the words "In Memoriam" added thereto. Funds received therefor shall be invested by the Treasurer in interest bearing securities legal for trust funds in the District of Columbia. Only the interest shall be expended by the Association. When such funds are in the treasury the Treasurer shall be bonded. Provided that in the event the Association becomes defunct or dissolves then, in that event, the Treasurer shall turn over any funds held in his hands for this purpose for such uses, individuals or companies that the donor may designate at the time he makes the bequest or the donation.

Article III

Membership—All annual memberships shall begin October 1st. Annual dues received from new members after April first shall entitle the new member to full membership until October first of that year and a credit of one-half annual dues for the following year.

Article IV

Amendments—By-laws may be amended by a two-thirds vote of members present at any meeting.

Article V

Members shall be sent a notification of annual dues at the time they are due and, if not paid within two months, they shall be sent a second notice, telling them that they are not in good standing on account of non-payment of dues and are not entitled to receive the annual report.

At the end of thirty days from the sending of the second notice, a third notice shall be sent notifying such members that, unless dues are paid within ten days from the receipt of this notice, their names will be dropped from the rolls for non-payment of dues.[Pg 20]

For the third time in the forty-four years of our existence our annual convention has been omitted. Each time this has been due to war conditions. The first was in 1918, the others in 1942 and 1943. No report was issued for 1918 but one was compiled for last year, and this present little volume will show that your members and officers are still functioning. We have great hope for the future.

An important part of this report is the result of the work of the Chairman of the Survey Committee, Mr. John Davidson, a good job well done. Considering the still elementary state of nut growing it is remarkable—a really immense undertaking. The responses to this survey show enthusiasm that is encouraging. The war and its emphasis on food seems to have increased interest in nut culture.

The Association has had a successful year in spite of the war and the cessation of our annual meetings because of the restrictions on wartime travel. Interest in the Association and nut culture appears to be well-maintained. The program committee assembled a report for 1942 and is already working on one for 1943.

During the past year the membership increased from 400 as of August 10, 1942 to 466 as of July 1, 1943. If this rate of increase continues, we shall pass the 500 mark before the end of 1944. In the 1932 report 134 members were listed and each year since then has shown a substantial increase.

Accompanying this letter is a questionnaire from the survey committee which is designed to extract as much information as possible from the members. The secretary is especially interested in the section on personal information as it should give some idea as to the interests of the members and indicate how they may best be served by the officers and committees. The program committee can also use this information in preparing programs.

President Weschcke announces that the committees and state vice-presidents for 1942 will continue for another year.

The membership circulars which contain the list of nut nurseries and a list of publications on nut culture may be had from the secretary by all who wish to distribute it.

The sets of reports as now sold lack the report for 1935. The few remaining copies are being reserved for agricultural libraries. If members have copies of this report for which they no longer have any use their return to the secretary's office will be appreciated as it may make possible the supplying of complete sets to libraries.[Pg 21]

| Receipts: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Memberships | $774.15 | |

| (Philip Allen $10.00) | ||

| (Exchange .15) | ||

| Sale of Reports | 102.85 | |

| Sale of Index | .75 | |

| Sale of Advertising (1941 Report) | 5.00 | |

| Carl Weschcke Contribution | 50.00 | |

| ——— | ||

| $932.75 | $932.75 | |

| Disbursements: | ||

| Fruit Grower Subscriptions | 71.20 | |

| Printing and Mailing 1942 Report | 328.37 | |

| Reporting 1941 Convention | 32.50 | |

| Expense of President | None | |

| Expense of Secretary | 74.02 | |

| Expense of Treasurer | 26.38 | |

| Supplies and Miscellaneous | 26.71 | |

| ——— | ||

| $559.18 | $559.18 | |

| ——— | ———- | |

| Excess of Receipts over Expenditures | 373.57 | |

| Balance on Hand Aug. 15, 1942 | 216.05 | |

| ———- | ||

| Balance on Hand Sept. 1, 1943 in North Linn Savings Bank | $589.62 | |

This survey of nut tree growing in the United States and Canada is a cross section of the industry and has been conducted through the membership of our Association. Questionnaires were submitted to all members, of whom a very satisfactory percentage responded with reports which usually were as complete as the age of the planted trees made possible. Our thanks are due to all who had the patience to reply to so searching a questionnaire. Their reward, we hope, will be increased by nuggets of information from others. The survey committee is indebted to the officers of the Association, to Mr. Slate particularly, who took care of the multigraphing and mailing drudgery, and to the experienced men who lent invaluable aid in formulating and revising the exhaustive and detailed questions.

The results are here set forth in three sections: Northern United States, Southern United States and Canadian. It is evident that trees which do well in the south may act very differently in the north; yet, to a certain and very important extent, the experience of the south has a bearing upon conditions in the north. For example, the pawpaw, though not a nut tree, has seemed to edge itself into the affections and interest of many nut tree men. It is in reality a tropical fruit which has adapted itself to northern latitudes. The pecan seems to be trying to do the same thing. Both illustrate a way of working that nature practices more or less with all species. By cross pollination and selection, human hands are having a part in speeding up this process of adaptation in pecans, Persian walnuts and other tender species. In fact, this is one of the jobs to which the Association is dedicated.

We wish here to pay tribute to the nurserymen of this Association. Most nurserymen are intelligent and honest but sometimes they have a tough time of it. Their worst competitor is a nurseryman who sells seedlings for named varieties, who advertises widely and prospers upon the work of others. When we think of the painstaking care of the honest nurseryman, of his days of drudgery, of the thousands of failed experimental trees and plants that he destroys, of the service he renders his fellows, we know that we should make slow progress without his help.

The conscientious worker in the experiment stations is in the same category. He does his best work largely for love of it.

In addition to many letters and other valuable sources of information this survey covers reports from more than 150 planters of named varieties of nut trees. Many are also planters of seedlings from selected and named varieties with which they are experimenting and from which they are making selections for future tests. Some are experimenting with cross pollination. As one example of careful work, we have now on file blue prints from the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Development, from Gerald A. Miller, of Trenton, showing exact locations by name and number of one of the largest variety collections of hybrid walnut trees in the world. From the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens, Arthur H. Graves, Cura[Pg 23]tor, we have valuable records of the breeding of chestnut trees, with selections made primarily for tree growth and timber production. There is also hope for some good nuts from the trees. The timber, in money value, is of course more important than the nuts. If successful, we shall again have both.

It is difficult to interest "hurry-up" Americans in planting trees for future generations. They want results now. But the sooner we develop reliable and adaptable fruiting trees for general planting, the sooner will thousands of people begin to plant trees. The late rapid growth of membership in this Association shows an awakened interest that could be swollen into a mighty flood of tree planters if good trees were available. If there were more agencies like the Tennessee Valley Authority, more trees of the better sort would be developed. Its tree crop activities have now been transferred to a "Forest Resources Division" under the supervision of Mr. W. H. Cummings, and its testing and selection work is going ahead steadily. Thomas G. Zarger, Jr., Botanist, is handling the black walnut work in connection with other investigations of "Minor Forest Products." The headquarters is at Norris, Tennessee. Charles V. Kline, now Assistant Chief of the Watershed Protection Division, still keeps his old interest in the black walnut and tree crop program. Definite and important results are bound to follow from so sustained and well organized a project. Most state agencies complain of lack of appropriations and help. The real trouble lies in lack of vision and knowledge upon the part of legislators. The President has proposed an immense program of communications and highway development as a post-war project. We suggest that fruitful land is still more important, and that highways through desert countries are almost unknown except as means for getting from one fruitful land to another. Perhaps this Association could do more than it has done toward spreading the gospel among legislatures.

The largest source of contribution to the survey is, of course, from the Northern United States. For purposes of tabulation, we have included everything north of Central Tennessee in this class. Nearly one hundred planters of nut trees contribute their experiences in this section. Of the lot, only fourteen of them plant trees for sale as nurserymen. Today we could keep more of them with stocks sold out. Seventy-six are interested in planting primarily for the production of nuts; fifty-seven, in grafting and budding trees from named varieties; forty-five in planting seed from the better varieties, either for production of stocks upon which to graft or, in large quantities, for observation and selection. As many as twenty-six are doing important work in hybridizing. Fifty-one are top-working young trees to better varieties. Only twenty-one count upon the growth of timber for a part of their profit. But certainly the growth of timber, especially black walnut, is not an item to be left out of consideration. Much, here, depends upon the manner of planting, whether in orchard or forest formation. However, even in orchard plantings, the stumps alone are valuable for beautifully patterned veneers.

Fifty-seven correspondents tell us that they are testing standard varieties, while forty-two are interested in discovering and developing new varieties, certainly an index to the pioneering and creative urge which dominates many of our members. As is to be expected, most of our newer members are thus far feeling their way by growing a few of the better[Pg 24] varieties for home use. Only nine of the whole number say that they are working with nut trees at an experiment station.

As to the species of trees being planted, black walnut heads the list with eighty-nine planters. Persian walnuts are next with seventy-three, including five who specify Carpathians or Circassians. Sixty-eight are planting Chinese chestnuts, and sixty-four hickories. Filberts and pecans are tied with fifty planters each; forty-eight say they are planting hazels; forty-three heartnuts; and forty-two persimmons—if we may include these trees for the time being among the nuts. Thirty-eight are planting butternuts; thirty-two, Japanese Walnuts; twenty-eight, pawpaws; twenty-seven, mulberries; twenty-four, Japanese chestnuts. After these, in order, come almonds along the southern borders, beech toward the north, hicans, tree hazels, oaks, Japanese persimmons, honey-locust, jujube, black locust (the correspondent explains, "for bees and chickens"), Manchurian walnuts, and finally, coral and service berries.

As an indication of the adaptation of species and varieties to the climates in which these men, and several women, are working, they listed at out request the following native trees found most plentifully in their sections. Black walnuts and hickories stand at the head of the list, as reported by seventy-five correspondents each. Then follow in order, butternuts, hazel, beech, oaks (probably overlooked by many), pecans and chestnuts.

Of nut trees found sparingly in these sections, butternut trees, surprisingly, take first place, indicating broad adaptation but a certain weakness, perhaps a slow susceptibility to blight or fungi, which prevents this tree from being found plentifully. It is significant that it is found most plentifully in the more rigorous areas of New England where fungous ravages are discouraged by cold. Add chinquapins to the number of scarce trees, and the list is complete.

As a further gauge of climatic conditions, fifty reported that peaches are reliably hardy in their sections, while fifty said they are not. This, according to the late Thomas P. Littlepage, is a fairly reliable index to the climatic adaptability of present varieties of northern grown pecans. Ninety-two planters reported that their seasons are long enough to mature Concord grapes. Only four said "no." For Catawba grapes? "Yes," said forty-two; "No," fourteen. For field corn? "Yes," ninety-three; "No," four. This question was improperly asked. Field corn varies too widely in length of maturity for accuracy in this respect.

Lowest temperatures expected range from 8°F above to 30°F below zero, with the usual lower range in the greater portion of the northern states, from zero to 12° below. Lowest known temperatures range all the way from 10° to 52° below, but in most portions from 15° to 35° below.

Returns indicate that winter injury is not always, nor even usually, the result of low temperatures but, rather, to the condition in which the trees enter the winter. If late excessive growth leaves them with wood not wholly dormant, they suffer. If not, they will stand extraordinary low temperatures with little or no damage. One way to guard against this damage is by preventing late growth. A means of doing this will be found in an important contribution by Mr. H. P. Burgart, of Union City, Michigan. Mr. Burgart says:[Pg 25]

"After 21 years of experience with growing, selling and planting nut trees, I have had to have a neighbor show me the best way to care successfully for them. I have studied and practiced Mr. Baad's methods, and in comparing them with my former practice, and with the practice of others who have failed with their trees, I will suggest the following cultural procedure to be given all plantings when possible, and to be continued for at least three years, or even longer for best nut production.

"Nut trees should be given clean cultivation right after being planted (in the spring) and until August 1st. This encourages root growth and conserves moisture. Then sow a cover crop of rye, cow peas or soy beans to take up moisture, slow up growth and prevent the late sappy condition that is often responsible for winter injury. Leave the cover crop over winter and turn it under in the spring for humus. Before turning under, a light application of some kind of manure, along with some superphosphate and potash, should be sprinkled around each tree. Then thorough cultivation again until August, and repeat.

"Soil for nut trees should be tested for acidity, nitrogen, phosphate and potash. It has been determined that most nut trees prefer a pH range of 6.0 to 8.0; but I have frequently found people planting trees on soils of 4.0 and 5.0, where nothing but sickly growth could be expected.

"Where it is not possible to work all of the ground between nut trees, cultivation should begin with a three or four foot circle around each tree, annually increasing this space with the growth of the branches. Cultivation, with attention to humus and fertility, are necessary to proper tree growth and nut production. Sod culture will never do."

Mr. Burgart's method has the advantage not only of guarding the trees from excessive winter injury but at the same time adds an almost immediately available source of humus and nutrients to the soil for spring growth. If followed, it should greatly reduce the number of reports of winter injury, failure to start, and of weak growth afterward.

Excessive summer heat is not so great a problem in most portions of the northern states. The highest expected temperatures range, in our reports, from 86° to 110°; mostly from 90° to 100°. The highest known are reported to be all the way from 95° to 120°, but mostly from 100° to 110°. A method of guarding against heat damage will be found in a communication from Mr. H. F. Stoke, of Roanoke, Va., which appears later in this report.

Drouth and hot, dry winds are more dangerous enemies than either cold or heat. It is somewhat ominous that, out of eighty-three reports, forty-two, originating all the way from Maine to Oregon and from Canada to Tennessee, report the occurrence today of frequent drouths, while forty report hot, dry winds. Surely the need for tree planting is immediate and urgent. Mulching, and the protection of recently planted trees by wrapping their trunks, are preventives of some damage, but can not stand up forever against the longer and longer periods of drouth now being reported, during which the water table is gradually being lowered beyond the reach of tree roots.

The length of the frost-free season has an important bearing upon the production of nuts after the trees are matured. This is true in the south as well as in the north. One of the most frequently reported causes of loss[Pg 26] of nut production in southern sections is an early spring, inducing growth of buds and blossoms, followed by a frost. No protection seems to have been found against this damage except by use of heavy smudges. Large orchardists protect themselves, but planters of small groves rarely do so. This explains the autumn scramble, reported by many members, in search of early fallen nuts. We should continue our search for trees which produce nuts of early maturity. Thus far the search has not been too successful among most species, but some progress has been made and the future is more encouraging in this respect than it was a decade or two ago. Some early maturing nuts have been found and pollen from the trees is being used for cross-pollination with better known nut producers. In the northern states, dates of the latest spring frosts range from April 1 to June 1, with the average around May 15. The earliest fall frosts come from Sept. 5 to Oct. 15, with the average about Sept. 15 to 20. Where the frosts fall much outside these limits—too late in the spring or too early in the fall—protective measures will help but will not always prevent damage.

Soil Conditions. There is a slight preponderance of clay soils over loam among the returns from planters. Loams and sandy loams are tied for second place. A smaller number report that these top soils lie shallow over hard-pan or rock. Fewer still report a soil underlaid with sand or gravel.

By far the best growth for most kinds of nut trees, as well as the best production of nuts, is to be found where trees are planted in deep loam. Next come the trees in clay loam; then come trees in sandy loam and in clay over sand or gravel. Numerous complaints of poor growth come from members who have trees set in a soil which is shallow over rock or hard-pan. Some of the hazels and butternuts are reported as able, for a time at least, to establish themselves in such soils, but their fight for survival seems precarious and is apparently short-lived. Black walnuts, particularly, require deep, rich soils into which their long taproots can easily penetrate. This is one of the few nut tree facts so definitely established that there can no longer be any doubt about it. The reports show that the planting of black walnuts in any but good deep soil should be discouraged. It leads only to disappointment and often to loss of interest.

A somewhat sandy soil, particularly if loamy, seems adapted to the planting of chestnuts and to such trees as do well on ground that will successfully grow peach trees. If such soil is found upon a hillside or hill top, so much the better. All such soils, of course, require more attention to fertility maintenance, for they leach out more quickly than soils with more of a clay constituent.

Do any of the nut tree species prefer an acid to an alkaline soil? This is a question our questionnaire does not answer. Thirty correspondents say their trees are set in a lime soil, fourteen in an alkaline soil (which may or may not, in the commonly accepted usage of that term, have lime as a source of alkalinity). Sixty-one report an acid soil. Only eight of this group report the use of lime, two the use of bone meal, and one of wood ash as acid correctives. Unfortunately, we did not ask definitely about the reaction of trees to the use or non-use of lime. Puzzled by this comparative neglect of lime as a corrective on acid soils, we asked Mr. H. F. Stoke, of Roanoke, Va., a very accurate and acute observer, who had reported plantings in both kinds of soils, what his experience had been. Also we asked[Pg 27] Miss Mildred Jones, whose experience with nut trees is second to none, the same question. Their replies follow:

Mr. Stoke says: "In response to your inquiry, 'What nut trees, if any, do best in acid soils?' I should reply that the chestnut leads the list, followed closely by the mockernut hickory.

"Throughout its native habitat the heaviest stands of the native chestnuts are to be found on acid soils over granitic and sandstone formations, rather than on limestone ridges. The best stands are on granite ridges, partly due, no doubt, to the poverty of sandstone soils.

"The mockernut hickory occurs about anywhere on the poor, acid, clay soils of the south, its vigor depending on fertility. Shagbark does not occur on the acid (granitic) Blue Ridge mountains, but is found on the limestone Alleghanies running parallel only a few miles away. I have never seen a shagbark hickory between Roanoke and the coast, more than 200 miles away, but it occurs freely to within two or three miles on the west. The difference is not in elevation or rainfall, but in the soil.

"On the other hand, black walnut occurs on both acid and limestone soils, but seems to prefer the latter. Part of its preference may be due to the generally greater fertility and better drainage to be found in limestone soil. Persian walnut, I believe, when on its own roots, is more or less allergic to acid soil. Wild hazels grow here on both limestone and granite soils.

"Frankly, I believe the matter of soil acidity, as such, is rather over-emphasized. There are other factors entering into the problem that are of as great or greater importance. I doubt if there was actually any really alkaline soil, in its native state, in the humid region lying east of the Mississippi River. In the glaciated region lying to the north, the soil seems to have been more nearly neutral (pH 7). Such was the case in Iowa and in Minnesota where I homesteaded many years ago.

"Throughout the south the soil averages much more acid, even much limestone soil being greatly benefitted by liming. North or south, soil acidity is greatly affected by drainage and by the resulting native vegetation.

"Peat or muck soils are notably acid; also they are notably deficient in potash. The addition of wood ashes greatly benefits such soils in two ways. On the other hand, the addition of wood ashes to a soil already alkaline might be harmful even though in need of potash.

"In the last several years I have been making some soil experiments that I may write up when I am sure I know what I am talking about. In general, I may say I should prefer a soil slightly on the acid side for any and all tree and farm crops if I had an eye to future fertility. Lime breaks down vegetable matter and makes its constituent plant foods quickly available, but prevents a build-up of humus in the soil. The effect is very pronounced in times of drought, the alkaline soil crops drying up much more quickly than do those on acid soil. On the other hand, such soil elements as phosphorus seem to require the lime as a flux to prevent the phosphates from becoming fixed and unavailable to crops.

"In regard to peat moss, it is undoubtedly acid, but it is beneficial in its water-holding properties and in the comparatively slow release of its nutritive elements. Lime added to the peat will break it down rapidly and make it more available as a fertilizer, but until the decomposition reaches[Pg 28] a certain point; its effect is to impoverish rather than to enrich the mixture. This seeming paradox can perhaps best be explained by some experiments I have been making with sawdust. A number of plots were prepared and given various treatments, including mixing one surface-inch of sawdust with the soil, and wheat was sown on the area.

"Wheat sown on the test plot without any treatment or fertilizer was normal for the poor clay soil on which the experiments were made. Where sawdust, only, was added, the wheat came up but sickened and produced no filled heads. The same was true where lime was added to the sawdust. Where heavy applications of nitrate of soda were added to the sawdust treated plots, both with and without lime, the 'sickness' disappeared and wheat was matured.

"My analysis of this, coupled with experiments in composting, leads to the following conclusion: During the period of decomposition of the sawdust (hastened, no doubt, by the lime), the bacteria of decomposition fed so heavily on the nitrates in the soil that the plants were starved. When the material had reached the condition of humus, the bacterial activity decreased to the point where fertility was restored.

"The above analysis accounts for the fact that coarse vegetable material, injures crops, when plowed under, for the current season. Fresh succulent material decays so quickly that it becomes almost immediately available, releasing its constituent plant food.

"With proper conditions of moisture and aeration, sawdust, when mixed with quickly decaying material like kitchen garbage, can be reduced to an excellent, usable humus in three summer months. In fact, it is then better material than if permitted to lie out in the weather for fifteen years.

"There is another factor I think important in tree growth, especially where summers are hot, and that is soil temperature.

"For any of our nut trees I should say that an acidity test of pH 6 to 7 would be entirely satisfactory. If the soil is infertile, some form of humus should be worked in at the time of planting. If much such material is used, some lime may be added. Better yet, wood ashes and bone meal will furnish potash, phosphorus, and the lime necessary to correct acidity and maintain the phosphorus in an available condition. Add to this, proper drainage and cool soil achieved by, first, cultivation, and later by heavy mulching, artificial shading, or shrubby undergrowth extended outside the root area, and your tree should 'go to town.' When the tree is large enough to shade its own root area it will take care of its own soil refrigeration. Nature knew what she was about when she planted trees in forests. Trees require warm heads (sunshine) and cool feet (shade), just the opposite from us humans."

Mr. Stoke's letter recalls a very ancient Arabian proverb connected with the date palm. "The date palm tree must have his head in hell and his feet in water." We are indebted both to Mr. Stoke and to the Arab scientists for many things.

Miss Mildred Jones' reply, fortunately, goes into other and equally important phases of the same subject. She says: "Anyone who is going to lime and fertilize nut trees should take at least a five year period for his work, using lime and fertilizer each year, and not dump it all in one year, then wait for results. He should study the return on a five year basis. One[Pg 29] year is too short a term. Weather conditions can upset a program to the extent that both lime and fertilizer may not have their effect until the following year. Let those who really want to know, make graphs of growth in young trees and of nut production from older trees, in pounds, for five years, as against five of the same years during which trees similarly situated received no fertilizer or lime.

"I shouldn't be at all surprised if those who state in reports to you that they have an acid soil, merely have a top acid soil. They may be growing their trees in basic limestone soils. Walnut trees grow in this environment very well, because they are found growing wild in woods where laurel and other types of plants loving an acid condition grow. This is true here in our county, but these soils are not seriously acid. They grow good garden crops.

"Ground, or pulverized, limestone is the safest type of lime to apply to trees or crops, in my estimation. Some of it is ground so fine that it looks like hydrated lime and is used for medicinal purposes. I am inclined to think that any reports you received that noted injury from the use of lime may have been due to the use of burned lime (calcium oxide) which is caustic when wet. This type of lime may be used in winter, but during the growing season, or too close to the growing season, may injure trees. I believe such injury depends entirely upon weather conditions, but it is a good thing to be on the safe side and use a lime which will not have the hot reaction that burned lime has.

"Your reports will serve an excellent purpose if they lead to getting a yearly record by planters on bearing and tree growth of their varieties. Few people know enough to go into the matter of soils and treatments intelligently. One can hardly blame them. It is a baffling subject. An unbalance in one element will lock up another element until one has quite a time unlocking them again. It seems that a conservative middle course is about the best to advise."

Upon reflection, it seems likely that if our questionnaire had asked specifically about the use of lime, many more reports would have been received of its use.

In response to an inquiry as to how weed competition near young trees is controlled, the replies are encouraging. Forty-seven practiced mulching; forty-five, mowing; thirty-four, occasional cultivation; twenty, regular cultivation, and a few others, slag or cinders around the trees. As is evident, some used several of the above methods. A few used none and suffered losses. Their honesty is admired, and their experience, disappointing as it is, is useful information.

As to fertilizing, forty-three reported the use of manure in some form as the principal material; twenty-eight used nitrogenous fertilizer; twenty-one, a complete fertilizer. Other materials were, in order, lime, compost, bone meal, ammonium sulphate, wood ash, tankage. One used a mixture of muck and manure and got results in excellent growth where the use of muck alone produced unsatisfactory growth. Several reported injury from too much fertilizer or from too late an application. Tree growth was thus pushed on into late fall; the trees were too sappy to stand the winter freezes and suffered from winter killing. The same result was reported from "over-cultivation." In this connection, we refer back to the letter[Pg 30] from Mr. H. P. Burgart, of Michigan, whose suggestions on cultivation and fertilizing are well worth careful study and practice by all who have had this trouble. It is possible that some planters, especially those whose trees are set on hillsides, where erosion is a robber of fertility, would modify Mr. Burgart's practice of turning under the green crop in the spring. They might prefer, as indeed might others who would like to see their green manure nearer the top of the soil, to disk in the green crop rather than bury it deeply with mouldboard plows. They would of course follow it up with repeated diskings until the time came for sowing another cover crop. This is, however, entirely in line with Mr. Burgart's recommendations.

Pursuing this subject to its conclusion, we next asked: "When young trees failed to grow with you, what percentage of these failures was due to ..." (various causes enumerated below)? The question was misunderstood. Many evidently gave percentages of all trees planted. Others, correctly, gave percentages merely of the trees which failed to grow. As nearly as could be arrived at, about 30 percent of losses were among trees that failed even to start; 40 percent failed from weak growth the first year or two; 10 percent from failure to maintain later growth; 16 percent were winter killed, and 3 or 4 percent died from rodent or similar (mole, gopher, deer, bear) injury. It is evident that by far the greatest losses were suffered within the first two years—not less than seventy percent. Probably more. It would seem that two years of intensive care should not be too burdensome a stint for a reward which lasts a lifetime.

Rodent and similar injuries were no doubt kept low because of extra protective care. Hardware cloth (galvanized wire ¼" mesh, 24" high, preferred) around each tree proved the most common and effective preventive. Following this, in order of use, were: wrapping the trunks (including wrappings of tar paper); mounding with earth or ashes; poison bait, dogs and cats, clean cultivation; resinous paint; spray (with Purdue formula mentioned); and, finally, hogs, against mice.

Anti-rodent treatments which proved injurious to trees were reported to be; tar paper wrappings; coal tar washes; close-set creosoted posts; oil sprays; "any paint"; any chemical to smear on trunks; rooting cement. For those who are located in regions where deer are a source of injury, Mr. J. U. Gellatly, of West Bank, B. C., reports the successful use of an old and heroic Russian formula. Spray or paint all branches with manure water, using hog or human offal. Deer will stay away. Naturally.

Next come answers to some personal questions as to experiences from which the reader may glean a wide variety of suggestions. The first of these questions is:

"What is your ONE greatest source of success?" The answers seem to show many royal roads, each of which was the one road for someone. The answers: Mulching young trees; watering care; planting seeds; planting one-year seedlings; wrapping-with paper; 50% moist peat mixed with earth in transplanting; manure; sod in bottom of planting hole and use of nitrogen later; setting trees at bottom of slopes; clean cultivation until August then sowing rye, soy beans or cow peas as cover crops to turn under in spring; topworking hickories; grafting in cool, moist spring weather; pigs in orchard; chickens in orchard; planting 12-14-foot trees severely cut back, burlap wrapped, heavily mulched.[Pg 31]

It seems a pity that limitations of space do not permit the telling of the various stories connected with the above glimpses of successful solutions. Each represents a little or a big success story connected with an individual problem. It is sufficient, perhaps, to know that someone somewhere found that each was the answer to his own difficulties.

The next question brings out the reverse side of the planters' work: "What is your chief source of failure?" The answer most often given was the honest one, lack of attention. We can all convict ourselves here, either involuntarily or otherwise. Especially during this period of warfare, when so many have been taken away from their plantings and have been unable to get help, there is no question but that our trees have suffered. The next in frequency is "unsuitable soil." Following this come: lack of water; poor planting; planting too big a tree; spring planting of nut trees; buying 5 to 7 year-old trees; climate; transplanting failures; grafting; grafting in dry, hot, springs; top-working old trees; stink bugs on filberts (nuts); lack of drainage; forcing with nitrogenous fertilizer; fertilizing young trees too much; birds breaking off top growth. It had been the intention to confine this question to young trees, but it was not so phrased, so we shall let the answers stand as they are. It is a bit ironical that some found their chief source of failure exactly where others had made their best success. The explanation must lie in differences in technique, in soil or in some other local condition. Skill, knowledge, and persistence must always play a great part in any success.

We next asked, "What have been your chief difficulties with established, bearing trees?" The difficulties here shift from matters of soil, rodent protection and the like to other types; caterpillars, neglect, winter injury, limited crops, failure of nuts to fill, disappointing quality of nuts, bag and tent worms, blight, "blight" due to drought, too early leaf fall, insects in early spring, trees drowned out in flooded bottom lands. It is probable that this last disaster happened to younger trees.

As to the species of trees chiefly damaged by these causes, black walnut comes first (possibly because more of these trees have been planted), then hickories, Persian walnuts, chestnuts (blight), heartnuts, pecans, filberts, butternuts, and finally butternuts in the south areas from fungus troubles.

Trees reported to have been least damaged were, first, butternuts, then hazels and filberts, black walnuts, hickories, Manchurian walnuts, Jap. walnuts, heartnuts, chestnuts, pecans, Persian walnuts.

In response to the specific question, "What insects damaged the trees?", we found that walnut caterpillars were more common than any others, followed closely by web or "tent" worms. The Japanese beetle is a close second and is broadening its entrenched positions steadily. Others are flat-headed apple borers, lace-wing fly, aphis, leaf hoppers. To this list two reporters added sapsuckers among the insects. These birds would almost girdle some of the branches with punctures.

Insect damage was reported as serious by eight reporters, as slight or occasional by six, and of yearly occurrence by nearly all. Others reported damage as serious if not controlled.