Title: Uncle Sam's Boys in the Philippines; or, Following the Flag against the Moros

Author: H. Irving Hancock

Release date: November 11, 2007 [eBook #23447]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

Author of Uncle Sam's Boys in the Ranks, Uncle Sam's Boys on Field Duty, Uncle Sam's Boys as Sergeants, The Motor Boat Club Series, The Grammar School Boys Series, The High School Boys Series, The West Point Series, The Annapolis Series, The Young Engineers Series, etc., etc.

Illustrated

PHILADELPHIA

HENRY ALTEMUS COMPANY

Copyright, 1912, by Howard E. Altemus

Uncle Sam's Boys in the Philippines

The Filipino Dandy

A Meeting at the Nipa Barracks

Plotters Travel With the Flag

Cerverra's Innocent Shop

Enough to "Rattle" the Victim

Life Hangs on a Word

The Kind of Man Who Masters Others

The Right Man in the Guard House

News Comes of the Uprising

The Insult to the Flag

In the First Brush With Moros

The Brown Men at Bay—For How Long?

A Tale of Moro Blackmail

The Call for Midnight Courage

In a Cinch With Cold Steel

Datto Hakkut Makes a New Move

"Long" Green and Kelly Have Innings

Sentry Miggs Makes a Gruesome Find

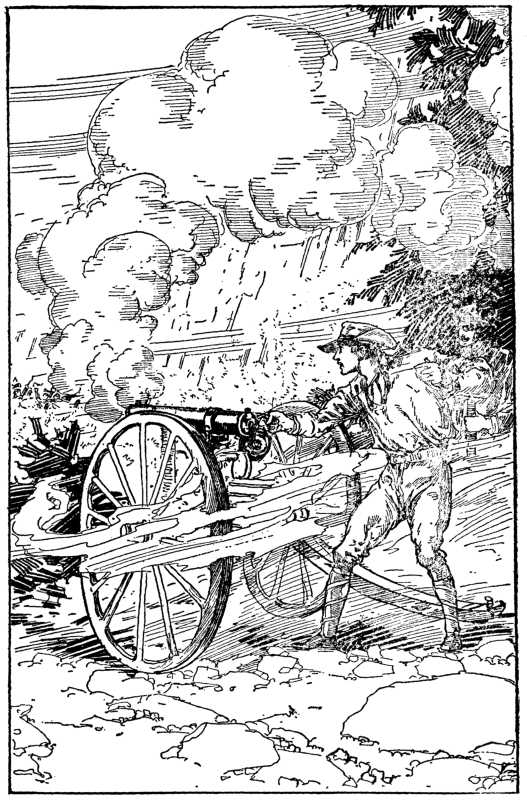

Hal Turns the Gatling Gun Loose

Corporal Duxbridge's Mistake

Scouting in Deadly Earnest

Playing Goo-Goo in a Grim Game

Dooming the Datto

Conclusion

"We've solved one problem at last, Noll," declared Sergeant Hal Overton seriously.

"Only one?" demanded young Sergeant Terry quizzically.

But Hal, becoming only the more serious, went on earnestly:

"At last we begin to understand just what the 'lure of the Orient' means! For years I've been reading about the Orient, and the way that this part of the world charms men and holds them. Now, that we are here on the spot, I begin to understand it all. Noll, my boy, the East is a great and wonderful place! I wonder if I shall ever tire of it?"

"I believe I could tire of it in time," remarked Sergeant Terry, of the Thirty-fourth United States Infantry.

"But you haven't yet," insisted Sergeant Hal.

"What, when we've been here only three days? Naturally I haven't. And, besides, all we've seen is Manila, and certainly Manila can't be more than one little jumping-off corner of the Orient that you're so enthusiastic about."

"You're wild about the Far East, too—even the one little corner of it that we've seen," retorted Sergeant Hal. "Don't be a grouch or a knocker, Noll. Own up that you wouldn't start for the United States to-morrow if you were offered double pay back in the home country."

"No; I wouldn't," confessed Sergeant Terry. "I want to see a lot more of these Philippine Islands before I go back to our own land."

"Just halt where you are and look about you," went on enthusiastic Sergeant Hal. "Try to picture this scene as Broadway, in New York."

"Or Main Street in our own little home city," laughed Sergeant Terry quietly.

Certainly the scene was entirely different from anything that the two young Army boys had ever seen before.

They stood on the Escolta, which is the main business thoroughfare of New Manila, as that portion of the Philippine capital north of the little river is called. South of the river is Old Manila, the walled city of the old days of the Spanish conquerors. South of the walled city lie two rather fashionable residence suburbs, Ermita and Malate.

But the Thirty-fourth was temporarily stationed in big nipa barracks at Malate. It was in the newer Manila that the two boyish young sergeants found their greatest interest.

It was a busy, bustling scene. There is nothing exactly like the Escolta in any other part of the world. The whole of this crooked, winding thoroughfare seemed alive with horses and people—with the horses in more than goodly proportion.

Along the Escolta are the principal wholesale and retail houses of the city. Here is the post office, there the "Botanica" or principal drug store, operating under English capital and a Spanish name; down near the water front is the Hotel de Paris, a place famous for the good dinners of the East. Further up the Escolta, just around a slight bend, is the Oriente Hotel, the stopping place of Army officers and their families, of passing travelers and of civil employees of the government.

At this point along the Escolta are the busiest marts of local trade. The sidewalks are crowded with hurrying throngs; the streets jammed with traffic, for in Manila few of the whites or the wealthier natives ever think of walking more than a block or two. The quilez, the little two-wheeled car drawn by a six-hundred-pound pony, is the common means of getting about. A dollar in American money will charter one of these quilez for hours, and the heat renders it an advisable investment for one who has far to go.

Automobiles were scarce, though they had penetrated even this congested Escolta. Here and there an Army officer or orderly appeared on horseback in the crush of the street. If he attempted to ride at a canter the horseman seemed to be taking his life in his own hands, with the chances all against him.

Save for the lazy calls of drivers—cocheros—to their horses, the hum of human voices was subdued. In the heat of the Escolta the people of all colors seem to have reached a tacit understanding that it requires less exertion to talk in low tones.

White people of both sexes appeared, clad usually in the white attire so customary in the tropics. Filipino dandies affected the same garbing, with the exception of here and there a natty, nervous, little brown man who appeared in the more formal black frock coat. But few, even of these, had the courage to come out in sun-up hours wearing the silk hat that is the usual accompaniment of the long-tailed frock coat.

Despite the heat, the faces of most of the people in the crowded streets appeared cheerful, even happy. Life is not taken too seriously in the Orient. The natives always find plenty of time for laughter; the stranger soon acquires the trick.

Banks, stores, restaurants, mineral water kiosks—all the places of resort along the Escolta—were abundantly patronized, yet none save the cocheros perched up on the little seats of the quilez appeared to be at all in a hurry.

Yet one man in particular appeared to be devoid of hurry. In fact, he paused or halted whenever the two boyish young sergeants did. He invariably kept about a hundred feet behind them in this queerly bustling yet ever leisurely crowd that thronged the sidewalks of the Escolta.

While Hal and Noll were curiously noting the fact—that the Escolta seems always so busy, but the individuals who make up the life there seem never in a hurry—the man who was plainly following them never glanced at them directly, yet never once lost sight of them.

Neither Hal nor Noll had yet noted the man, about whom there were some points that would have been amusing to the American youngsters.

This man was a Filipino. At first glance one would have believed him to be a Tagalo, or member of the most warlike and ambitious of all the eighty-odd tribes that make up the peoples of these islands. The Tagalos are the tribe most frequently found in and around Manila, and in the provinces nearest to that city. In appearance the Tagalos look a good deal like underfed Japanese. It was to the Tagalos that the insurrecto leader, Aguinaldo, belonged.

These Tagalos, however, consider themselves in every way the equals and match for any white man. The Tagalos have absorbed much of the Spanish civilization. Many of them are wealthy and the sons of such families generally hold degrees from Philippine colleges. Well-to-do Tagalos, despite their undersized stature and dark-brown skins, affect all the culture—and the vices—of well-to-do white people. They conduct banks, engage in commerce, mingle with white society, and consider themselves as bright lights of civilization. Above all, every Tagalo takes keen interest in politics. Yet these Tagalos, up to date, are only veneered Malays.

This Filipino who was so patiently following Sergeants Hal and Noll appeared to belong to the well-to-do class. Certainly he was an immaculate dandy. He was about five feet two inches in height, and wore neat-fitting, well-tailored white duck garments. The blouse was buttoned down in front, a military, braided white collar standing up stiffly, rendering the wearing of a shirt unnecessary. On his feet were highly polished tan shoes of American make. On his head he wore a jaunty, straight-brimmed straw hat of the best native manufacture. In his right hand this irreproachable Filipino dandy lightly swung a feather-weight bamboo cane.

His eyes were dark, gleaming, intense—fitted either to reflect laughter or sharp anger. But what rendered this man, who appeared to be close to thirty-five years of age, ridiculous to American eyes was his mustache. This was blue-black in color, waxed to two fine, bristling, upturned points—a fashion that this dandy had undoubtedly caught from some former Spanish military officer.

"They are boys—they will suit my purpose excellently," murmured the Filipino to himself, as he halted before a window where tropical outfittings for men were attractively displayed. Yet, though he gazed in at the window, he saw Sergeants Hal and Noll out of the corners of his eyes. "They are young, ambitious; they are enlisted men, therefore poor. Even in this short time these boys must have learned the craving for the things that money alone will buy. No man, in the Orient, can escape that knowledge and that longing for money. That is why it is so easy to buy men's souls here in the East. Shall I go up and speak to them? But no! There they go into a curio store where they will find much that they may wish to buy. I will follow my young sergentes inside in five minutes—or ten. Then they will be ripe for the man who talks money."

Hal and Noll had entered one of the most attractive little shops to be found anywhere along the Escolta. This store is kept by a Chinaman, who sells the more costly curios of the Far East. China's choicest silks are here displayed; also her finest teakwoods and curious boxes and cabinets of sandal and other valued woods, inlaid with pearl, or studded with rare jades. Here are wonderful creations carved out of ivory, idols of all kinds and sizes, of the highest grades of artistic workmanship. Here are wonderful beaded portieres and the most costly of curious Chinese garments for women. In a word, the bazaars of China are nobly represented on the Escolta. But there is much more besides. The most attractive curios from India, from Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula and of native Filipino workmanship are all to be found here. It is not the place to enter when one has not much money.

No wonder Sergeant Overton and Sergeant Terry moved from counter to counter, pricing and sighing. Each young Army boy wanted to send home something worth while to his mother. Yet how small a sergeant's pay seems in such a bazaar!

Hal Overton and Noll Terry need no introduction to the reader of the earlier volumes in this series. "Uncle Sam's Boys in the Ranks," as our readers are aware, details how Hal and Noll, reared in love of the Flag and respect for the military, determined, at the age of eighteen, to enlist in the Regular Army. Our readers followed the new recruits to the recruit rendezvous, where the young men received their first drillings in the art of being a soldier. From there they followed Hal and Noll westward, to Fort Clowdry, in the Colorado mountains, where the young soldiers went through their first thrilling experiences of the strenuous side of Army life, proving themselves, whether in barracks, on drill ground or under fire on a lonely sentry post, to be the sort of American youths of whom the best soldiers are made.

Readers of "Uncle Sam's Boys on Field Duty" already know how Hal and Noll went several steps further in learning the work of the soldier; of their surprisingly good and highly adventurous work in practical problems of field life. In this volume was described field life and outpost duty, and scouting duty as well, as they are actually taught in the Army. In this volume is told also how Hal and Noll while out with a scouting party supplied their company with unexpected bear meat. Our readers, too, will remember the thrilling work of Hal and Noll, under Lieutenant Prescott, in capturing a desperate character badly wanted by the state authorities. These young soldiers were heroes of other absorbing adventures; their fine work eventually leading to their appointments as corporals.

In "Uncle Sam's Boys As Sergeants" our readers will recall a host of happenings that belong to military life, among them the stirring military tournament in which a battalion of "Ours" took part at Denver, and the all but tragic results of that tournament; the soldier hunting-party up in the Rockies, in which Hal and Noll thoroughly distinguished themselves both as hunters and as soldiers and commanders.

And now we find the entire Thirty-fourth Infantry in Manila, stationed there briefly pending details at other points in the islands.

As we look in upon Sergeants Overton and Terry to-day we find them two years older than when they first enlisted—but many years older in all the fine qualities that go to make up the best manhood.

Either young sergeant's word was as good as his bond in the Thirty-fourth. Truthful, ambitious, manly, thoroughly trained and capable of commanding; in a word, men in character and abilities, while yet boys in years.

This much had two years of life in the United States Army done for Hal Overton and Noll Terry. Could other training have done more?

And these were the young Americans whom the alert-eyed, trailing Filipino dandy had already singled out and had planned to corrupt to his own purposes.

Yet the astute man of the world knows more than one way of ruining and disgracing simple-hearted, true-souled young fellows. Not even Satan is credited with appearing often in evil guise at first.

Perhaps this Filipino, a wicked fellow of long training, knew how to go about his work.

"Going to buy anything, Noll?" asked Hal at last, after the two young sergeants had made the round of the bewildering, attractive store.

"I would, if I could find anything worth while that didn't take a sergeant's whole year's pay," sighed Terry.

"Things are fearfully dear here, aren't they?" murmured Overton. "Yet I want to send something home as a remembrance to mother."

"What do you fancy most?" asked Noll.

"If you haven't anything else on your mind, come around and I'll show you," Hal proposed.

Nodding, Noll accompanied his chum. Hal stopped to rest one hand lightly on a very wonderful little chest, made out of teak and sandal woods. It was richly, wonderfully carved, the darker teakwood being also inlaid with pearl. Inside were compartments and drawers, including two little secret drawers that the smiling Chinese salesman artfully opened and exposed to view.

"One all same fo' dinero (money), other fo' plecious stones, jewels, you sabe," cooed the yellow attendant.

"It's a beauty and a wonder," murmured Hal. "Mother'd be the proudest woman in town if I could send it home to her. How much did you say it cost?"

"Him tloo hundled pesos," stated the Chinaman gravely.

A peso is the Spanish name for a Mexican dollar, worth about forty-seven cents; but two pesos and an American dollar are reckoned as of the same value in Manila.

"A hundred dollars gold! Why, that's the same price you asked me before," cried Hal in good-natured protest.

"Yep, allee same; him plenty cheap."

"It's too much," sighed Sergeant Hal. But the Chinaman, as though he had not heard, asked:

"You likee? You buy?"

"I can't afford it at that price."

"All light; come in some other day," invited the Chinaman politely, and glided over to where another possible customer was examining some handsome jade jewelry.

"My soldado (soldier) friend has not been long in Manila?" inquired a low, pleasant, courteous voice behind the two young soldiers.

Hal wheeled. It was the Filipino dandy whom he confronted. That smiling, prosperous-looking native was employing his left hand to twist one end of the upturned moustache to a finer point.

"No; we haven't been here long," Hal smiled. "Three days, in fact."

"And you do not yet know how to bargain with these sharp-witted Chinos (Chinese)?"

"I'm afraid not," said Sergeant Overton.

"May I ask, señor, what you wished to buy?"

"This box," Hal answered.

"And how much did the Chino want for it, if I may make bold enough to ask so much of the señor's business?"

"Why, he wants a hundred dollars in gold," Hal responded.

The Filipino dandy inspected the box critically.

"You are right, señor; the price is too high. It is muy caro (very dear), in fact. It could be bought for less, if you knew better how to deal with these smiling yellow heathen."

"I'd be greatly obliged, then, if you would tell me how to put the bargain through."

"You should get this rare and handsome box, señor, for ninety dollars, gold—even, perhaps, for not much more than eighty."

"Even that would be a fearful price for me to pay," murmured Hal, shaking his head regretfully. "I shall have to give up the idea, I guess."

"Ah, but no!" cried the Filipino, as though struck suddenly by an idea. "Not if the señor will do me one very great favor!"

"What favor can I possibly do you?" asked Sergeant Hal, regarding the little brown man with considerable astonishment.

"Why, it is all very simple, señor. Simply let me feel that I have been permitted to do a courtesy to an Americano to one of the race to which I owe so much. In a word, señor, I am not—as you may perhaps guess"—here the Filipino swelled slightly with a pride that was plain—"I am not exactly a poor man, not since the Americanos came to these islands and gave us the blessings of liberty and just government. I have many business ventures, and one of them lies in my being a secret—no, what you Americanos call a silent partner of the Chino who conducts this store. Now the favor that I ask—señor, I beg you to let me present you with this handsome little box, that you may send it over the waters to your sweetheart."

"Make me a present of it?" demanded Sergeant Hal in amazement.

"Ah, yes, exactly so, señor; and I shall be greatly honored by your very kind acceptance. And your friend—he shall select anything—valuable and handsome—that he would like for his sweetheart."

Neither young sergeant had a sweetheart outside of his mother. It was for their mothers that they sought suitable-priced curios. In their amazement, however, neither Hal nor Noll took the trouble to correct this smiling, polite stranger.

"Thank you," said Overton promptly. "We can't accept, of course, though it is very kind of you to make the offer—so very kind that it almost takes our breath away."

"And why can you not accept?" insisted the Filipino. He was still smiling, but there was now something so insistent in his voice that Noll answered quickly:

"Because we cannot accept gifts from strangers."

"Ah, but you do not yet know the Orient. You must have things here; you must have money to spend, and feel the pleasure of spending it, or you will die."

"Thank you," laughed Sergeant Hal, "but at present my health is excellent. As for dying, that has no terror for the soldier."

"Ah, yes, to die like a soldier!" protested the Filipino, with a shrug of his shoulders. "But would you die of sheer weariness and envy? There are pleasures in this country which only money will buy. Without the money, without these pleasures, life soon becomes bitter. You do not know, but I do, for I have watched thousands of your Americano soldiers here. Now, I have money—too much! It is my whim to see that the soldados enjoy themselves. I have begged many a soldier to honor me by letting me purchase him a little pleasure. Come, I will show you now! Wait! I will send for a carriage—not a quilez, but a victoria. Say the word, give the consent, and I will show you at once what is called pleasure here in the East—in Manila."

Though he spoke in low tones, the Filipino made almost extravagant gestures. As he kept on he warmed up to his subject.

"Shall I call a victoria?" he asked.

"If you wish," replied Sergeant Hal dryly.

"Ah, that is the way I like to hear you say it!" cried the little Filipino, and hastened toward the door.

He went away so rapidly, in fact, that he did not have time to note young Sergeant Overton's altered manner. From a feeling of embarrassment over having to repulse a stranger's ill-advised offer of generosity, Hal, his eyes watching the man's face, speedily took a dislike to the Filipino.

"Come along, Noll," Overton whispered. "We'll get out of this. I don't like the fellow."

"You like him as well as I do," muttered Sergeant Terry.

At the door of the store they again caught sight of the dandy, who, with hand extended, was at that moment signaling a cochero to drive his victoria in to the curb.

"It could not have been better," cried the little brown tempter. "Just as I came out I saw an empty victoria."

"I congratulate you," smiled Sergeant Hal.

"No, but this is the carriage, here," cried the Filipino, as Hal and Noll turned to walk down the Escolta.

"Get in, then, and enjoy yourself," called back Hal.

In an instant the Filipino was in front of them, barring their way.

"But you permitted me to stop a carriage," he protested, bewildered.

"Exactly," nodded Hal, "and we hope you will enjoy yourself. Step aside, please, for we want to pass on."

"But you are not going with me, after——"

"Nothing was said about that," Hal answered, "and we have other plans. Good-bye."

As the Filipino dandy once more tried to place himself in front of the young sergeant, Hal gently but firmly thrust the insistent fellow aside.

The Filipino stood glaring after them until the two Army boys were out of sight. The glint in his eyes was far from pleasant.

"Now, what on earth did that fellow want of us?" demanded Noll wonderingly.

"Nothing good, anyway," returned Hal Overton. "Intending benefactors don't act in that fashion. He may represent a bad phase of life out here. Let's forget him. Say, here's a store we must have overlooked on our way up here. Let's go in."

Half an hour later the Army boys came out of the store, each carrying a small parcel. For his first present home each young soldier had bought for his mother a small assortment of the wonderfully filmy pina lace handkerchiefs made by the native women.

"No quilez around here for hire," said Hal, after looking up and down the Escolta. "Let's walk across the bridge over the Pasig. We'll be more likely to find an idle cochero on the other side of the river."

As they started the sky was darkening, and the lightning beginning to flash, for this was in early July, at the height of the rainy season.

"I hope we find a cochero soon," muttered Noll, looking up at the dark sky. "I don't fancy the idea of walking all the way out to Malate in a downpour."

They were not quite over the bridge when the storm broke in all its force. Tropical thunder crashed with a fury that made artillery fire seem trifling. Great sheets of lightning flashed on all sides.

"Hustle, before we get drowned," laughed Sergeant Hal, breaking into a fast run. "There's shelter just beyond the end of the bridge."

The shelter for which both soldiers headed was a kiosk, barely larger than a sentry-box, that had once been erected for the convenience of the native boys who stood there with relief horses for the service of the old street car line.

The door stood open. Eager to make any port in a storm, Hal and Noll bolted inside just in time to hear an angry voice declare:

"I had them picked out—two young sergentes, mere boys. At first they were very polite—a minute later they made fun of me to my face—me, Vicente Tomba! But I shall know them again, I shall see them, and I shall make them wish they had never been born. I——"

The Filipino dandy stopped short as the two Army boys stepped briskly inside. He gave a gasp as he recognized them.

"We meet again," remarked Hal dryly.

The dandy's companion, a big, florid-faced man of forty, in the usual immaculate white duck of the white man, eyed the boys keenly.

It was only for a moment.

Then, without answering Hal's remark, the Filipino clutched at the white man's arm, shoving him out into the rain. The native followed.

Just then a cochero with an empty quilez drove up. With instant presence of mind Vicente Tomba, as the dandy had called himself, held up his hand.

It was all done in an instant, and native and white friend were driving away through the gusts of rain.

"Wonder who our friends are?" Noll remarked curiously.

"We know that one of them calls himself Vicente Tomba," replied Sergeant Hal.

"But he spoke of having us picked out for something, and he seemed almost peevish because we didn't suit him," smiled Noll.

"I can't imagine what it is," replied Hal, undisturbed. "It couldn't be anything in the high treason line, anyway."

"Why not even that?" demanded Sergeant Noll.

"Why, look here, old fellow, we're just two plain, kid, doughboy sergeants of the line. If that fellow had wanted anything in the treasonable variety, what sort of goods could we deliver him, anyway? Nothing, much, beyond our own arms and a copy of the company's roll."

"Then what on earth was the fellow up to, anyway?"

"I don't know, Noll, and I don't much care. I've heard that there are sharks of all sorts here in Manila, ready to put up all sorts of games to get the easy-mark soldier's pay away from him. Probably Tomba and his friend belong in that class."

"Pooh! Tomba has plenty of money," snorted Noll Terry. "He wouldn't have to be out for a poor, buck-foot soldier's pay."

"Swindlers sometimes do have plenty of money, for a while, until the law rounds them up and puts them where they ought to be," observed Sergeant Hal sagely. "Let's forget the fellow, Noll, unless we see him again. Tomba is evidently up to something crooked, and we're not, so we haven't any real interest in him, have we?"

"Except to be on our guard," said Noll.

"You speak as though you had some forebodings regarding Tomba, or Tomba and his friend," smiled Hal quizzically.

"Well, then, I have," returned Noll Terry.

"Not scared, are you?"

"That's a fine question to ask a soldier," sniffed Noll.

"Well, I'm not going to waste any more thoughts on Tomba, or on his white-man companion, either. Whee! Look at that rain. It——"

But a fearfully vivid flash of tropical lightning caused Sergeant Hal Overton to step further back into the little shed and close his eyes for an instant. Right after the flash came a prolonged, heavy roll of thunder that made the earth shake.

"Cochero, para!" shouted Noll right after that, and a fareless quilez stopped near the door of the shed.

"Occupado (occupied)?" called Noll.

"No, señor."

Hal and Noll bolted through the rain, darted into the quilez through the door at the rear, and plumped themselves down on the seats.

"Sigue directio, Malate, cuartel nipa," ordered Hal, thus instructing the driver to go straight ahead to Malate and to take them to the nipa barracks.

The Filipino driver himself was drenched. In his thin cotton clothing the little brown man perched on the box outside, shivered until his teeth chattered. He did not propose, however, to let personal discomfort stop him from earning a fare.

Around the Walled City (Old Manila) the quilez carried the young soldiers. These massive walls, centuries old, enclose perhaps a square mile of city. Once past the Walled City the little vehicle glided on through pretty Ermita. Here, passing along Calle Real (Royal Street), the driver turned into the straight stretch for the next suburb, Malate.

For months before sailing for the Philippines both young sergeants had devoted a good deal of their spare time to the study of Spanish. They had, however, learned the best Spanish of old Castile. First Sergeant Gray, who had put in three terms of service in the Philippines, had taken pains to teach them much of the local Spanish dialect as it is spoken in this far-away colony of Uncle Sam's.

To-day the Filipino children speak English rather well and musically, for English is the language of the public schools of the islands. Many of the older natives, however, even those with English-speaking children, know only a few words at most of the tongue of the Americanos.

By the time that the little cab turned in at the barracks grounds much of the fury of the storm had passed. The rain, however, continued at a steady downpour, and seemed good for the night.

"We may have to be campaigning in this kind of weather in another fortnight," remarked Hal.

"Fine business," commented Noll dryly.

"Well, it all goes in the life of a soldier. It can't hurt the soldier much, either, for somehow he's healthier than fellows who clerk or work in machine shops."

"Clerking? Shops?" repeated Noll, with a smile of mild disgust. "Did we ever stand that sort of life, Hal?"

"Once upon a time, Noll."

"Thank goodness that day has gone by."

"Here we are," announced Sergeant Hal, reaching for the rear door and opening it. "I'll pay the cochero this time, Noll; you paid for our last ride."

On the broad veranda of the barracks, well out of the rain, lounged half a hundred of the men of the Thirty-fourth. A few of them were at tables writing home letters.

"Did you give my regards to the Escolta, Sergeant?" called Private Kelly, from one of the groups.

"I didn't forget you, Kelly," laughed Hal.

"Get those picture post cards for me?" called Corporal Hyman.

"Here you are, Hyman," responded Noll, opening his blouse and exploring an inner pocket. "I hope I haven't got them too wet, and that the views will suit."

"Any views will suit," retorted Hyman. "My kid brothers and cousins have never been out here and one view will please them as well as another."

A few more soldiers came forward to ask about errands that the young sergeants had undertaken. No one's commissions had been forgotten.

"Your leave didn't do you two so much good this afternoon," grinned Corporal Hyman.

"Why not?" Sergeant Overton wanted to know.

"On account of the weather we didn't have parade, anyway."

"I'm no parade shirker," retorted Hal. "On the busiest day we're not being overworked here. We may strike something hard in the tropics yet, but so far, since reaching Manila, the men of this regiment haven't been worked more than a quarter as hard as in barracks at home. But I wonder when we go south?"

"Haven't you heard?" asked Corporal Hyman.

"Not a word," Hal declared.

"I haven't, either. But we heard that the 'Warren' came in this afternoon."

The "Warren" was the United States Army transport vessel that was much used in carrying troops between the different islands.

"We ought to be under way soon, then," Hal replied thoughtfully. "I suppose we're still slated to go down among the Moros."

"That's the talk in the regiment, anyway," replied Corporal Hyman.

"I hope it's true."

"You're one of the few that does, then," retorted Hyman, with a grimace. "In these islands the real fine place for a regiment to be stationed is right here on the outskirts of Manila. Plenty of grub, kitchen-cooked; little work to do, and no danger of anything except guard duty to call us out of our bunks."

"That's altogether too lazy for a soldier," objected Hal, with spirit. "I don't want to see any trouble start in these islands, but if there's going to be any campaigning, I want to see the Thirty-fourth right in the thick of it."

"You'll get over that, by and by, Sergeant," responded Corporal Hyman. "More than half of the fellows in the Thirty-fourth have been out here in other years, and have seen plenty of fighting. Now, getting shot at by a lot of strangers is all right enough for a soldier when it has to be done; but you'll find that the older men in this regiment are not doing any praying that 'Ours' will get more than its share of fighting."

"Perhaps I won't, when I've seen as much fighting as some of you fellows have," Hal nodded. "I've never been in a real battle yet."

"You've been under stiff enough fire, right back in the good old Rocky Mountains," retorted Corporal Hyman. "You don't need any more by way of training."

"Perhaps not; but I want it, just the same. I'm a hog, ain't I?" laughed the boyish young sergeant.

"No; you're simply a kid soldier," grumbled Hyman. "All the kids want a heap of fighting—until after they've had it. When you've been with the colors a few years longer you'll be ready to agree that three 'squares' a day and a soft bed at night are miles and miles ahead of desperate charges or last-ditch business."

"So the 'Warren' is in port from her last trip south," Hal went on. "Oh, I wonder when we start."

"So do a lot of us," retorted Private Kelly. "But we hope it won't be soon, Sarge."

"Oh, you coffee-coolers!" taunted Hal good-naturedly.

The Army "coffee-cooler" is the man who is left behind in stirring times. Uncle Sam's soldiers explain that a coffee-cooler is a man who won't go forward, in the morning, until his coffee is cool enough for him to drink it with comfort. Hence a coffee-cooler is a man who is detailed on work at the rear of the fighting line simply because he is of no earthly use at the front.

It is not as bad, however, to be a coffee-cooler as a cold-foot. A "cold-foot" is a soldier paralyzed with terror; he is worse than useless anywhere in the Army. The cold-foot is ironically asked why he didn't bring his woolen socks along. If a cold-foot gets into deadly action it is said that the cold chills chase each other down his spine and all settle in his feet, so that he is frozen in his tracks. However, a soldier who betrays cowardice in the face of the enemy may be shot for his cowardice, for which reason "cold feet" sometimes become cold for all time to come.

Soldiers there have been who have shown "cold feet" in their first battle or two, and yet have been among the best of soldiers later on. But the cold-foot is a rarity, anyway, among the regulars.

"Hello," broke in Kelly, peering out through the rain, "there goes some good fellow to the rainmakers."

Many of the other soldiers looked. Two hospital-corps men were carrying a stretcher in the direction of the post hospital. None could make out, however, who was on the stretcher, as, owing to the downpour of rain, the unfortunate one was covered with three or four rubber ponchos.

"I hope none of our good fellows is badly hurt," broke in Sergeant Noll Terry.

"Rheumatism, most likely," grunted Corporal Hyman. "Did you ever see a country where the rain fell as steadily when it got started?"

"Well, this is the rainy season, isn't it?" inquired Noll.

"Yes."

"But half of the year we have a dry season, don't we?"

"We do," admitted Hyman. "Yet, of the two, you'll prefer the wet season a whole lot. In the dry season the dust is blowing in your face day and night."

An orderly stepped briskly out on the veranda.

"Sergeant Overton is directed to report immediately to Lieutenant Prescott at the latter's quarters."

"I'll be there before the words are out of your mouth, Driggs," laughed Hal, rising and starting.

"Hold on, Sarge," called Private Kelly. "Look at the sheets of dew coming down, and you haven't your poncho. Here, put mine on."

"Thank you; I will," Hal assented, halting.

The poncho is a thin rubber, blanket-like affair. In the field the men usually spread the poncho on the ground, under their blankets. But in the middle of the poncho is a hole through which the head may be thrust, the poncho then falling over the trunk of the body like a rain coat.

Getting this on and replacing his campaign hat, Hal started briskly toward officers' quarters.

Lieutenant Prescott was in his room when Hal knocked, and promptly called, "Come in."

Hal entered, saluting his lieutenant, who was writing at a table. He looked up long enough to receive and return Hal's soldierly salute.

"With you in a moment, Sergeant," stated Lieutenant Prescott, who then turned back to his writing.

"Very good, sir."

Hal did not stir, but merely changed from his position of attention to one of greater ease.

Lieutenant Prescott is no stranger to our readers. He was second lieutenant of Captain Cortland's B Company of the Thirty-fourth. Readers of our "High School Boys Series" recall Dick Prescott as a schoolboy athlete, and readers of the "West Point Series" have followed the same Dick Prescott through his four years of cadetship at the United States Military Academy.

After finishing a page and signing it, Lieutenant Prescott wiped his pen, laid it down and wheeled about in his chair.

"You heard about Sergeant Gray?" asked the young West Pointer.

"Nothing in especial, sir."

"He was badly hurt ten minutes ago in stopping the runaway horses of Colonel Thorpe, of the Thirty-seventh Infantry. Colonel Thorpe was visiting our colonel, and only the two little Thorpe youngsters were in the carriage when the horses bolted, pitching the native driver from the seat."

"Badly hurt, sir?" cried Hal Overton in a tone of genuine distress. "That will be bad news in the company, sir. I don't think any of them know it yet, or I would have heard it before. Sergeant Gray is a man we swear by, sir, in the squad rooms."

"Sergeant Gray is a splendid soldier," observed Lieutenant Prescott warmly. "It is not believed that he will have to be retired, but he may have to put in two or three months on sick report before he can come back to duty. But that is not what I sent for you to tell you, Sergeant Overton. As Sergeant Hupner was left behind on detailed duty in the United States, the accident to Gray now leaves you the ranking sergeant in the company. Until further orders you will take over the duties of acting first sergeant, by Captain Cortland's direction."

"Very good, sir."

"This is Tuesday, Sergeant. Thursday, at eleven in the morning, the Thirty-fourth is due before the office of the captain of the port, to take boats for the transport 'Warren.' This regiment sails for Iloilo and other ports."

"May I repeat that to the men, sir?"

"It is going to be necessary, for you will have to see to it that all the personal and company baggage is ready for the teamsters at four to-morrow afternoon."

"Very good, sir."

"And, Sergeant, this is not official, but I believe it to be reliable; some of the Moro dattos (chieftains) are said to be preparing to stir up trouble in some of the southern islands. In that case the Thirty-fourth will bear the brunt of it all."

"I am really very glad to hear that, sir," cried Sergeant Hal eagerly.

"So am I, Sergeant," admitted the lieutenant, who, like most of the younger officers, hungered for active service against an enemy. "You understand your instructions, Sergeant?"

"Yes, sir."

"Very good; that is all, Sergeant."

Hal Overton saluted his officer with even more snap than usual, then hastened back to barracks.

Supper soon followed, and before the meal was over the rain had stopped. After supper several of B Company's men went out into the near-by street to stroll in the somewhat cooler air of the tropical evening.

A little later Hal and Noll followed. Presently, in the shadow under a densely foliaged yllang-yllang tree, they came upon two figures standing there, just in time to hear Corporal Hyman's voice saying heartily:

"That sounds like just as good a time as you make it out to be. And it won't take us over three hours? This is a hard night to get off, as the packing-up order has been given. I'll see our first sergeant, however, and find out whether there's any chance of my getting leave for the evening. If he says so, I can put it by the captain all right. Wait here, and——"

"I guess it won't be necessary, Corporal Hyman," broke in Hal's voice, sounding rather cool, for Hal had recognized Hyman's companion—none other than Vicente Tomba.

"Hello! There you are, Sarge," cried Hyman, while the little Filipino dandy started, peered at the young sergeants and then scowled.

"I'll try to fix it for you to get a pass to-night, Corporal," Hal went on, "if you really want one. But I don't exactly believe that you do. This native gentleman tried to butt in with us this afternoon, and at first we took it in good part. But he was too eager. Then, a little later in the afternoon, we heard him denouncing us to a white man because we weren't eager enough. Corporal, unless you know a lot about this man, I don't believe you want anything to do with him."

Tomba's face was blazing hotly, while his eyes gleamed angrily at Sergeant Overton's words.

"If that's the kind of fellow he is, then I don't want a pass to-night," Hyman replied. "This little man has just been telling me how much he loves American soldados, and he proposed to get a quilez and take me over into the city for the time of my life."

"From what happened this afternoon I'm a little shaky on Señor Tomba," Hal continued.

"You never saw me before!" cried Tomba, wheeling about on Hal. "Liar! Thief!"

Hal's reply was prompt, sufficient, military. He delivered a short-arm, right-hand blow that struck the native in the neck, felling him to the sidewalk.

But Tomba was up in an instant, and a knife flashed in his hands.

Hal did not flinch. He leaped upon the little brown man, getting a clinch that held the rascal powerless. Then Noll coolly took away the knife, striking the blade into the tree trunk and snapping the steel in two.

"Shall I call the guard, Sergeant, to take this little brown rat?" demanded Corporal Hyman.

"No; he isn't big enough, or man enough to bother the guard with," replied young Sergeant Overton. "I'll take care of him myself."

Whirling the Filipino around, Hal gave him a vigorous start, emphasized by a kick, and Vicente Tomba slid off into the darkness.

Malay blood is not forgiving. There were other reasons, too, why it would have been far better had Sergeant Hal turned Tomba over to the guard.

From the deck of the "Warren" only distant glimpses of land, on the horizon line, were visible.

The sea to-day was without a ripple, yet, as it was not raining, the sun beat down with a heat that would have wilted most of the passengers, had it not been for the awnings stretched over every deck.

Up on the saloon deck was a mixture of the field uniforms of Army officers, the white duck or cotton of male civilian passengers, and the white dresses of the women. Most of the married officers of the Thirty-fourth had brought their families along with them, and so children played along the saloon deck, or ran down among the friendly soldiers on the spar deck. Here and there, among the women, was a Yankee schoolma'am, going to some new charge in the islands.

A number of the male cabin passengers were not Army people. Some belonged to the postals service, the islands civil service, or were planters or merchants of wealth and influence in the islands, who had been permitted to take passage on the troop ship.

Between decks the enlisted men of "Ours" were quartered and berthed by companies. Each enlisted man, by way of a bed, had a bunk whose frame was of gas pipe, to which frame was swung the canvas berth. These berths were in tiers, three high.

Away forward, in special quarters by themselves, as a sort of steerage passengers, were some two score natives of the islands who were making the journey for one reason or another. These natives, however, kept to themselves, and the soldiers saw little of them.

Altogether, the "Warren" carried something more than fourteen hundred passengers, which meant that quarters were at least sufficiently crowded. Yet the soldiers, with the cheerful good nature of their kind, took this crowded condition as one of the incidents of the life.

Noll was up on deck enjoying himself; Hal, as acting first sergeant, was otherwise occupied during the greater part of the forenoon. At the head of B Company's quarters, two decks below, young Overton sat at a little table, busily working over a set of papers that he had to make up. This "paper work" is one of the banes of first sergeants and of company commanders.

It was after eleven o'clock when Sergeant Hal finished his last sheet. The papers he folded neatly and thrust them into a long, official envelope, which he endorsed and blotted. Rising, he thrust the envelope into the breast of his blouse and started for the nearest companionway.

"I'm glad, old fellow, that you are the acting first sergeant," grinned comfortable Noll Terry, as his chum came upon deck with forehead, face and neck beaded with perspiration.

"Oh, it doesn't hurt a fellow to have a little work to do," replied Overton, smiling. "You see, you've just been loafing this morning, almost ever since inspection, while I have a consciousness of work well performed."

"Keep your consciousness and enjoy it," retorted Noll, as the two boyish sergeants stepped along the deck.

"I wonder if Captain Cortland is on deck at this moment?" remarked Sergeant Hal.

"I saw him five minutes ago," Noll answered.

Almost at that moment B Company's commander came to the forward rail of the saloon deck and looked down. Then his glance rested on Hal.

"Are the papers ready, Sergeant?" the captain called down.

"Yes, sir; I have them with me," replied Hal. Pressing through the throng of soldiers, he ascended the steps to the saloon deck, saluting and passing over the envelope.

"Thank you, Sergeant."

"I think you'll find them all right, sir. I'm somewhat new at the work, but I've taken a lot of pains."

"There's always a lot of pains taken with any work that you do, Sergeant."

"Thank you, sir."

Hal saluted and was about to turn away when he heard a voice saying:

"What we need, in dealing with the Moros in these southern islands, is to show them that——"

Just then the speaker happened to turn, and stopped talking for a moment.

The voice was new, but Sergeant Overton started at sight of the speaker's face.

"Why, that's the same big, florid-faced fellow that I saw in the shed with Tomba, that time it rained so hard," flashed through the young sergeant's astonished mind. "What can he be doing here—a cabin passenger on a United States troop ship?"

Unconsciously Hal was staring hard at the stranger. It appeared to annoy the florid-faced man.

"Well, my man," he cried impatiently, looking keenly at Hal, "are you waiting to say something to me?"

"No, sir," Sergeant Hal replied quickly.

"Perhaps you thought you knew me?"

"No, sir; I merely remembered having once seen you."

"You've seen me before? Then your memory is better than mine, Sergeant. Where have you ever seen me before?"

"The other afternoon, sir, on the south side of the Pasig River at Manila. You were in a shed, out of the rain, with a native calling himself Vicente Tomba."

The florid-faced man betrayed neither uneasiness nor resentment. Instead, he smiled pleasantly as he replied:

"I thought you were in error, Sergeant, and now I'm certain of it, for I don't know any Vicente Tomba."

"Then I beg your pardon for the mistake, sir," Hal replied quickly.

"No need to apologize, Sergeant, for you have done no harm," replied the florid-faced man.

Here Captain Cortland's voice broke in, cool and steady:

"Yet I know, Mr. Draney, that Sergeant Overton feels embarrassed by the mere fact of his having made a mistake. Sergeant Overton is one of our best and most capable soldiers, and he rarely makes a mistake of any kind."

"I'm glad to hear that he's one of your best soldiers," replied Draney pleasantly. "It seems odd, doesn't it, Captain, to see so boyish a chap wearing sergeant's chevrons?"

"Sergeant Overton, Mr. Draney, is more than merely a sergeant. He is acting first sergeant of B Company, and is likely to continue as such for some months to come."

"He has risen so high?" cried Draney. "I certainly congratulate the young man."

There appeared to be no further call for Hal to remain on the saloon deck. After flashing an inquiring look at his company commander, and saluting that officer, Hal next raised his uniform cap to Draney, then turned and made his way down to the spar deck.

"Your sergeant looks like a very upright young man, Captain," observed Mr. Draney.

"Overton?" rejoined Captain Cortland. "I am certain that he is the soul of honor."

"His loyalty has often been tested, I presume?" persisted the florid-faced fellow.

"He's a very thoroughly trustworthy young man, if that's what you mean."

Captain Cortland was beginning to feel somewhat annoyed, for, truth to tell, he did not like Draney very well.

"Is your sergeant," asked Draney, "a young man much interested in the joys of life, or is he of the quiet, studious sort who seldom care for good times?"

"You seem to be uncommonly interested in Sergeant Overton, Mr. Draney," remarked the captain almost testily.

"Only as a type of American soldier," replied Draney blandly. "I was wondering if my estimate of the young man were borne out by your experience with him."

"Sergeant Overton is fond of the joys of life, if you mean the quiet and decent pleasures. He is a good deal of a student, and that type is never interested in drinking or gambling, or any of the vices and dissipations, if that is what you mean."

Then, noting that Colonel North had just stepped out on deck from his stateroom, Captain Cortland added hastily:

"Pardon me; I wish to speak with the commanding officer."

As colonel and captain met they exchanged salutes.

"I told Draney, sir, that I wished to speak with you," Captain Cortland reported, in a low voice. "I did not tell him, however, that I wished to speak with you mainly as a pretext for getting away from his society."

"You don't like Draney?" smiled Colonel North, eying his captain shrewdly.

"I certainly do not," Cortland confessed.

"And I'm almost as certain that I don't, either," replied the regimental commander. "However, Cortland, we shall have to treat him with a fair amount of courtesy, for Draney is an influential man down in the part of the world for which we are headed. He is influential with the Moros, I mean. Often he is in a position to give the military authorities useful information of intended native mischief. Draney is a very big planter, you know, and white planters are somewhat scarce in the Moro country. It is one of the great disappointments of our government that more American capital is not invested in establishing great plantations in the extremely rich Moro country. But, as you know, Cortland, some of the Moro dattos are given to heading sudden, unexpected and very desperate raids on white planters, and that fact has discouraged Americans, Englishmen and Germans from investing millions and millions of capital in the Moro country."

"Yet the fellow Draney is a planter there, sir?"

"Draney owns half a dozen very successful plantations."

"And is he never molested by the Moros, sir?" inquired Captain Cortland.

"Never enough to discourage him in his investments. Rather odd, isn't it, Cortland?"

"Very odd, indeed, sir," replied Captain Cortland dryly.

That same afternoon Captain Cortland, after finishing a promenade on the saloon deck, went forward, descending to the spar deck. There, under the awning, he came upon Sergeants Hal and Noll, who saluted as he addressed them.

"Sergeant Overton," began the captain in a low tone, "you seemed, this forenoon, to feel a good deal of surprise at seeing Mr. Draney on board."

"I was surprised, sir."

"Tell me what you know about the man."

Sergeant Hal briefly related the adventure that he and Noll had had with Vicente Tomba on the Escolta, and their subsequent meeting with Tomba and Draney on the south side of the Pasig. Hal also repeated what they had overheard Tomba saying to Draney. Hal then described the flight of the pair in the quilez.

"Yet Draney declares that he never heard of Tomba," said the captain musingly. "Sergeant Overton, do you think it possible that you have mistaken Mr. Draney for someone else?"

"It may be, of course, sir," Hal admitted. "But I hardly believe it possible. Besides, I have pointed out Mr. Draney to Sergeant Terry and he also is positive that it is the same man."

At that moment all three turned to look forward. There was some sort of commotion going on there. It proved, however, to be nothing but the herding of the Filipino passengers on deck near the bow, while one of the regiment's officers was inspecting their quarters below.

The three officers returned to their conversation, but presently Hal murmured:

"Don't look immediately, Noll, but presently take a passing glance at the Filipino standing away up in the bow. Tell Captain Cortland who the fellow is."

"It's Vicente Tomba, although I'd hardly know him in that costume of the peon (laborer)," Noll answered.

"You are both certain that the man is Tomba?" inquired Captain Cortland keenly.

"Yes, sir," both young sergeants declared, and Hal added:

"There's Corporal Hyman up forward, sir. If you'll go up and speak to the corporal, and allow us to accompany you, sir, you can see whether Hyman knows the fellow. He, too, was approached by Tomba, at the nipa barracks."

Accordingly the test was made.

"Why, certainly, the fellow is Tomba," replied Hyman, "though he looks a lot different, sir, from the dandy who was talking to me last Tuesday night."

Captain Cortland asked all three of the non-commissioned officers some further questions as they stood there. None of the quartette discovered the fact that, close to them, crouching under the canvas cover of a life boat as it swung at davits, lay one of the keen-eyed Filipino passengers. This swarthy little fellow was only about half versed in English, but he understood enough of the talk to realize what was in the wind.

In some mysterious manner what this swarthy little spy overheard traveled, less than an hour later, to Mr. Draney, planter, and that gentleman, as he sat in his stateroom and thought it all over, was greatly disturbed.

Still later that afternoon—not long before sundown—while the "Warren" was still ploughing her way through the sea, the little brown spy drew Vicente Tomba to one side in the native steerage.

To make assurance doubly sure, both Filipinos spoke in their own Malay dialect, the Tagalos.

"Tomba!"

"Luis?"

"Tomba, the Señor Draney is greatly disturbed. Sergeant Overton and Sergeant Terry have recognized him as one whom they saw with you in Manila."

"Bah! That amounts to little. Señor Draney can deny."

"But they have recognized you also, my Tomba, and so has Corporal Hyman. More, they have told Captain Cortland all they know, and all they can guess."

"The dogs!" growled Vicente Tomba, his snarl showing his fine, white teeth.

"You do well to call them dogs," grinned Luis. "Señor Draney bids me to remind you what becomes of dogs that are troublesome. You have others here with you who can help. At the first chance, then, Overton, Terry and Hyman are to bite the bone that kills—and Captain Cortland, too, if you can manage it!"

"D'ye know what I'm thinking about?" demanded Private Kelly, as he turned to look out southward from Fort Benjamin Franklin.

"Not being a mind reader—no," replied Hal.

"I'm thinking this country is a fine place to dream about."

"It's worth it," declared Sergeant Overton, with unsullied boyish enthusiasm.

"Worth it—huh!" retorted Kelly, who had served longer in the Army. "Mind ye, I said this was a good country to dream about. But to live in—give me 'God's country.'"

The United States soldier on foreign service, invariably alludes to home in this way.

Send him to the fairest spot on which the human eye ever rested, and the soldier will still longingly speak of home as "God's country."

"Then I'll be polite," retorted Sergeant Hal, "and say that I wish, Kelly, that you could be at home. But as for me, I'm glad I'm here."

"Wait until you are in your third enlistment, and have put in another two years in the islands, after this time," growled Kelly.

"Why, where can you find a more beautiful spot than this?" demanded Hal Overton, gazing across the fields toward the town of Bantoc. "I never saw a more beautiful spot. I wonder if there are many like it in the tropics?"

"Beautiful?" rumbled Kelly. "Sure! But ye can't eat beauty. 'Tis a long way from anywhere, this spot, and that's what I've got against it."

"Grumbling again, Kelly?" asked Sergeant Noll Terry, joining them.

"Not grumbling," retorted Kelly. "Just giving my opinion. But this boy sergeant is trying to make me think this swamp on northern Mindanao is an earthly paradise."

"Well, isn't it?" challenged Noll. "I know what ails you, Kelly. When all is peace and comfort, with three 'squares' a day, and not a heap to do, your old soldier is always kicking. But just send you and the rest, Kelly, hiking up through those mountains yonder, give you twenty miles a day of rough climbing, drown you out with rain and let you use up your shoes chasing a lot of ugly brown men, and never a kick will we hear coming from you."

"Sure, no," replied Kelly philosophically. "'Tis then we'd be doing a soldier's work, and a kicker on a hike is as useless as a coffee-cooler at an afternoon tea."

"In other words," laughed Hal, "a real soldier of the Regular Army is as patient as a camel when things are all going wrong. The only time when your real soldier kicks is when he's having it easy and is too comfortable to be patient. Curious, isn't it?"

"Oh, well, 'tis no use talking to you two," retorted Private Kelly, shaking his head and strolling away. "Ye've not seen much of service yet."

"That's another joke," laughed Hal in a low voice, as soon as Kelly had stepped out of hearing. "Here's a man like Kelly, with fairly long service to his credit, but he's a private still, and probably always will be. If the colonel made him a corporal, Kelly wouldn't rest until he had the chevrons taken from his sleeve so that he could be a private soldier again. Now you and I, Noll, work like blazes all the time, and win our promotion, yet Kelly considers us only boys, and boys who don't know much, either. Either one of us can take Kelly out in a squad and work him until he runs rivers of perspiration, and he can't talk back without danger of being disciplined. Yet all the time, Kelly, under our orders, is thinking of us, half contemptuously, as boys who don't really know anything about soldiering."

"That's because we're young," laughed Noll.

"And because we're also boyish enough to have a little enthusiasm left in our make-ups. Noll, how do you really like our new station?"

"I wouldn't be anywhere else," retorted Sergeant Terry, "except some where else in the Philippines, possibly. One of the prospects that caught me for the service was the chance of seeing some of our foreign possessions."

"It's what catches half the young fellows who enlist to-day," went on Hal. "I've been looking forward to the Philippines from the day I first took the oath in the recruiting station."

"Well, we're here," replied Noll, breathing in the warm air with lazy satisfaction. "And I'm mighty glad that we're in for two years of it."

The Thirty-fourth had come out to the islands as a complete regiment. They had reëmbarked at Manila also as a regiment, but now the time had come when "Ours" was well scattered through the southern islands of the archipelago.

The second battalion and headquarters, with the band, had disembarked at Iloilo; two companies had been left on the island of Negros, and two more on Cebu. B and C Companies had been left at Fort Franklin, in the Misamis district on northern Mindanao, and the remaining two companies had been carried on to Zamboanga.

On its return trip the "Warren" had picked up the scattered military commands which the Thirty-fourth had relieved. Two companies of the Thirty-second infantry had gone from Bantoc the day before.

Mindanao is the second largest and the most fertile island in the Philippine group. The natural beauty is as great as the fertility. If it were not for the occasional ferocity of some of the tribes this island could be turned into one vast net-work of plantations as rich as any that the world can show.

Bantoc was a sleepy, sunlit little town, half Spanish and half Moro. Thanks to American rule, the streets were clean and order reigned. There were about forty stores and other mercantile establishments in Bantoc, for this town was headquarters for a large country district. The people of Bantoc, outside of the small white population, were more than half Moros, the other islanders belonging to the Tagalo and other allied tribes. Almost without exception these people were lazy and good-natured. A newcomer would have difficulty in believing that such men as he met in Bantoc could ever give the soldiers trouble. It was to this town that the few planters and many small native farmers sent rich stores of rice, cocoa, hemp, cotton, indigo and costly woods.

There was also the port of Bantoc, through which these products were sent out to do their part in the world's commerce.

The native leaders of the population of Bantoc were wealthy little brown men. There was much money in circulation, the leading Moros and Tagalos having handsome homes and entertaining lavishly. There was a native fashionable set, just as exclusive and autocratic as any that exists in a white man's country.

Fort Franklin overlooked the bay at the opposite end from the port. Yet it was a "fort" only in being a military station. There was no artillery here, and the only fortifications were semi-permanent earthworks, fronted by ditches, thrown up around the officers' quarters and the barracks and other buildings. The parade ground and recreation spaces were outside these very ordinary fortifications.

"The whole scene looks too peacefully lazy to match with the yarns we hear of trouble breeding among the Moros in those mountains yonder," remarked Hal musingly.

"If trouble is coming, I hope it will come soon," returned Sergeant Noll. "The only one thing that I have against our life out here is that it threatens to become too lazy an existence. If there's going to be any active service for us, I want to see it happen soon, for active service is what I came to the Philippines for, anyway, as far as I had any interest in the trip."

"From the gossip of the town and barracks, I think we'll have our trouble soon enough," Hal replied. "You have fatigue duty this afternoon, haven't you, Noll?"

"Yes; thanks to your detail," replied Noll.

"But I couldn't help the detail, old fellow. Fatigue was for you in your turn. I'm sorry it came to you to-day, though, for I've a pass and I'm going to run over into Bantoc. I want to see more of that queer little town."

"Going to be back for parade?"

"Yes; my pass extends only to parade. I never want to miss that when I can help it."

Hal glanced at his watch, then back at barracks, where hardly a soldier showed himself, for all had caught the spirit of indolence in this hot, moist climate of Mindanao.

"Well, I must be going, Noll. Don't work your fatigue party too hard until the men get used to this heat."

"Small danger of my working 'em too hard," laughed Noll. "It's only as a sort of special favor that the fellows will work at all."

Hal, with a nod to his chum, stepped out on to the hard, level, white road that led from Fort Franklin to Bantoc.

It was a pretty road, shaded at points by beautiful palms; yet the shade was not sufficient to protect the young soldier all the way into town. Ere he had gone far he found it necessary to carry his damp handkerchief in one hand, prepared to mop his steaming face.

"Mindanao is certainly some hot," he muttered. "It keeps a fellow steaming all the time."

Yet there was plenty to divert one's thoughts from himself, for along this road lay some of the prettiest small farms to be found on northern Mindanao. Instead of farms they really looked more like well-kept gardens.

"It's the finest spot in the world to be lazy in," thought the young sergeant, as he glanced here and there over the charming scene. "If I settled down here for life I'd want money enough to pay other fellows to do all the work for me."

Though Hal did not know it, from the window of one room in a house that he passed a pair of unusually bright, keen eyes glared out at him.

"That is he, the sergente, Overton," growled Vicente Tomba to himself. "Since we have Señor Draney's orders that the sergente is to leave this life as soon as possible, why not to-day? He is going to Bantoc, where it will be easy to snare him. And his friend Terry is not with him. That pair, back to back, might put up a hard fight—but one alone should be easy for our bravos. Then, another day, we can plan to get the Sergente Terry."

Hal was not quite in Bantoc when a Tagalo on a pony rode by him at a gallop. Hal glanced at the fellow indolently, but did not recognize him, as it was not Tomba, but one of that worthy's messengers.

Up and down the principal street Sergeant Overton wandered. He glanced into shops, though only idly, for to-day he was not on a buying mission.

At last the cool-looking interior of a little restaurant attracted him. He entered, ordering an ice cream. When this was finished he ate another. It was so restful, sitting here, that when he had disposed of the second order, he paid his account but did not rise at once.

"The sergente is newly arrived here?" asked a white-clad Filipino, rising from another table and joining Overton.

"Yes."

"Then you have not seen much of Bantoc?" asked the Filipino, speaking in Spanish.

"Not as much as I mean to see of the town," Hal answered in the same tongue.

"Then possibly, Señor Sergente, you have not yet seen the collection of ancient Moro weapons in the shop of Juan Cerverra."

"I haven't," Hal admitted.

"Then you have missed much, señor, but you will no doubt go to see the collection one of these days."

"I'd like to. Where is the shop?"

"Four doors below here. If you have time, Señor Sergente, I am walking that way and will show you the place."

"Thank you; I'll be glad to go," answered Hal, rising promptly. His was the profession of arms, and a display of any unfamiliar weapons was sure to attract the young sergeant.

Juan Cerverra, despite his Spanish-sounding name, proved to be a full-blooded Moro. He wore his Moro costume, with its tight-fitting trousers and short, embroidered blouse. There were no customers in the shop when Hal and his Tagalo acquaintance entered.

In another moment Sergeant Hal was deeply absorbed in several wall cases of swords and knives, all of them of old-time patterns. It was a sight that would have bewildered a lover and collector of curios of past ages.

One case was filled entirely with fine specimens of that once-dreaded weapon, the Moro "campilan." This is a straight sword, usually, with a very heavy blade, which gradually widens towards the end. This is a heavy cutting sword, and one that was placed in Sergeant Hal's hands, though Cerverra claimed that it was two hundred years old, had an edge like a razor.

"How much is such a sword as this?" Hal inquired.

"Forty dollars," replied Cerverra.

"Gold!"

"No; Mex."

Hal felt almost staggered with the cheapness of things here, as compared with the curio stores in Manila. Forty dollars "Mex" meant but about twenty dollars in United States currency.

"I have some cheaper ones," went on Cerverra. "Here is one at eighteen dollars."

"I'm going to have one of these campilan," Hal told himself.

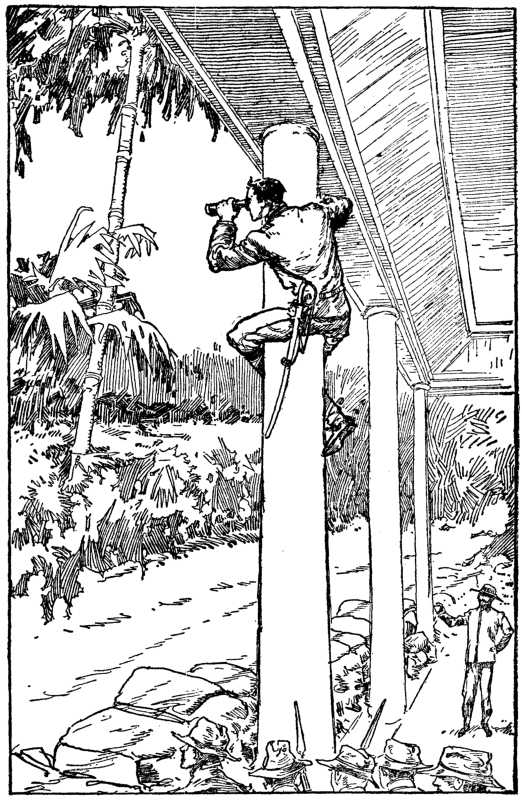

In his interest he did not note that the Tagalo who had brought him to the shop had left him and was standing on the sidewalk outside.

"Are you interested in these creeses?" inquired Cerverra, passing down the shop and pointing to another wall case.

The creese is an ancient Malay knife, with a waved, snaky blade—a weapon with which the Malay pirates of the past used to do fearful execution.

Hal stepped before the wall case. "They are very interesting looking," he replied. "What does a good creese cost?"

The young sergeant did not wait for an answer.

Click! A spring bolt on the under side of a trap door on which he was standing shot out of place.

Down dropped the trap door with such suddenness that Hal Overton did not have even time to clutch at anything.

Then the trap door, relieved of his weight, flew back into place.

Sergeant Hal shot down a steep incline, too smooth for him to be able to stay his downward progress.

Bump!

Sergeant Hal landed at least twenty feet below with a suddenness that jarred all the breath out of him for a moment.

Ere he could recover his half-scattered senses he felt himself seized. Nor had the Army boy fallen into one pair of hands. Four or five men, as nearly as he could judge, seized hold of different parts of his body.

There was little use in a prostrate youth fighting against such odds. Hal was swiftly rolled over on to his face, in the dark, and two of his captors threw themselves upon him, holding him down.

At the same time another thrust an armful of hemp under his face, holding it close against his mouth.

Then the light of a dark lantern was flashed on the scene. With the speed of skilled hands at the game these brown-skinned captors bound the young sergeant hand and foot.

"Quit this!" Sergeant Overton tried to shout angrily, but the wad of hemp was forced between his teeth and only a faint sound came forth.

"Help!" he tried to shout, but the sound came hardly louder than a sigh.

Now he was whirled over on his back, helpless, and two of the brown rascals finished their work by thrusting the hemp far enough into his mouth to shut off all speech. Then the gag was bound into place.

Hal could form little idea of his prison, save that it was an oblong, cellar-like place, perhaps a dozen feet wide by twenty feet long.

As nearly as the Army boy could guess, this cellar must be located under the street itself.

"They've got me for fair," thought the young soldier in a rage that included himself as well as his captors. "What's their game, I wonder? Robbery? If it is, they'll feel sold when they find how little money they are going to get."

By the light of the dark lantern, as he lay on his back on the damp ground, Hal made out the fact that his captors numbered eight. Five men had the look and wore the costumes of Moros; the other three rascals looked as though they might be Tagalos.

One after another the wretches looked down at the young soldier and grinned, though not one of them spoke.

Of a sudden the light went out. Hal, his ears unusually acute now, heard their moving footsteps. Then all became intensely still.

"I wonder whether I'm a tremendously big fool, or whether I'm merely unfortunate?" thought Hal bitterly. "However, how was I to guess? In this Moro country must it be considered unsafe even to step into a store and look at the merchandise?"

There was no answer to this. By degrees Hal began to feel decidedly uncomfortable as to the fate that he might expect.

"If they meant only to rob me," he reflected, "then why didn't they proceed at once? But not a single brown rascal of the lot took the trouble to thrust an exploring hand into my pockets. What, then? Do they want an Army prisoner, and if so, for what?"

The longer the young soldier thought it over, the greater the puzzle became. Nor did it escape his imagination that possibly he was not to be allowed ever to see his comrades again. That thought, of course, sent a chill of horror chasing up and down young Overton's spine. He was not afraid to die in battle, if need be—but to be treated like a rat in a trap—that was different.

"Well, they've got me, and I don't see any likelihood of getting away," decided Hal at last, after fully an hour devoted largely to futile efforts to wriggle out of the bonds that held his wrists secure behind his back. "These knots have been tied by masters. I don't believe I could get out of them in hours. If they had only tied my hands in front of me, so that I could work them loose. Confound the pirates!"

After what seemed like the passage of hours, the boy heard a slight sound. Listening intently, he heard it repeated.

Next a light was turned on—from the same dark lantern.

Behind the light Hal's dazzled eyes could make out the figure of a man.

Toward him the light came, Hal blinking in the glare until the newcomer halted beside him.

"Ah, Señor Sergente!" cried a mocking voice.

Then the new comer bent over the Army boy, and Overton knew him in an instant—Vicente Tomba.

"That hemp in your mouth looks as though it might give you discomfort—a thousand pardons," observed Tomba mockingly, as he removed the cord that held the hemp in place.

Tomba now squatted on the ground beside the young soldier's head and drew out the wad of hemp.

"So you are in this, Tomba?" inquired the Army boy coldly. "What's the game, anyway?"

"Possibly," sneered the Filipino, "when you know more, you'll feel like making a noise. Let me assure you that no friend will hear if you do call. But any great amount of noise on your part might provoke me, and that would not be wise under the circumstances."

Showing his white, even teeth in an evil smile, Tomba took out of the breast of his blouse a small, bright-bladed creese that might have been borrowed from one of the wall cases in Cerverra's shop.

"Why has this trick been played on me?" demanded Sergeant Hal angrily.

"A trick?" laughed Tomba softly. "Is that what you think it is? My friend, you will find that it is much more than a trick—it is a decree!"

"A decree?" raged Sergeant Overton. "What do you mean?"

"It is a decree from Señor Draney," went on Tomba coldly, maliciously. "It can do no harm to mention that name since you can never repeat it to anyone but me, for Señor Draney's decree is that, when you go forth from here—to-night—you will know nothing afterwards, for you will be past knowing."

"You are talking like a madman," sneered Hal.

"And next you will be begging like one," returned Tomba, with that same easy but deadly laugh.

Hal, despite his grit, felt a start of terror. Cold sweat was now gathering on his forehead.

"You refused my friendship some days ago," continued Tomba. "You did not know how valuable it might be."

"Can the friendship of a scoundrel like you ever be valuable?" asked Overton.

"In the present case it would be worth a little to you—your life!"

"What did you want of me, when you sought my acquaintance?" demanded Hal.

He had suddenly become seized with a desire to prolong the talk with this little brown monster—to gain time!

"There was something that you could have done for me," replied Vicente Tomba.

The Tagalo, like others of his race, was not averse to talking, either. The little Filipino knew that he had the whole situation in his hands. With the cruelty of a cat, Tomba delighted in the feline pastime of playing with a victim that could not escape him.

"What did you want me to do?" Hal asked almost blandly.

"I wanted your services."

"Yes, but what kind of services?"

"What is the use of telling you—now?"

"Tell me one thing, though, Tomba."

"Why?"

"Just to gratify my curiosity," explained Sergeant Hal, and he spoke slowly while his eyes watched those of the Filipino. "Did you want me to betray my Flag?"

"Not the Flag itself."

"But, in some way, you wanted me to turn against my comrades—to serve you and your friends at the expense of the United States Government."

"Yes," assented Tomba. "But do not think to deceive me. It is too late now to save yourself by promising what I would have wanted of you."

"I don't intend to serve you and your rascal friends at any price—at least, I haven't yet come to that decision," Hal added, in a more conciliatory tone. "However, I am curious."

"Curiosity can do you no good now," retorted Tomba softly, with a shrug of his shoulders.

"What part is Draney playing with you brown-skinned men?"

Tomba again shrugged his shoulders, this time more mockingly.

"Señor Draney serves the same cause that I do," laughed the Filipino.

"And what cause is that?"

"His purse."

"Then, in other words, Tomba, you are not even a Filipino patriot. You are merely a twentieth-century type of pirate."

"If you like the word," replied Tomba, in a tone of indifference.

Then he yawned—next placed the creese on the ground beside him, while his right hand explored his pockets. He soon brought to light a package of Manila cigarettes. Tomba's left hand produced a box of matches.

"Do you care for one last smoke, Señor Sergente?" inquired the Filipino with mocking politeness, as he held out the package.

"Thank you; I never picked up the vice," Sergeant Hal answered, but he said it good-naturedly, for he had an object now in not provoking the enemy.

"So? You call smoking a vice?"

"The vice of pigs," declared Hal, but again he laughed good-humoredly.

"Oh, I do not mind your insolence," replied Tomba, striking a match and holding it to the end of the cigarette in his mouth. "Abuse me all you please, Señor Sergente."

"Thank you!"