Title: The Nursery, October 1873, Vol. XIV. No. 4

Author: Various

Release date: March 29, 2008 [eBook #24941]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net Music

by Linda Cantoni.

| IN PROSE. | |

| PAGE. | |

| Threading the Needle | 97 |

| The Butter Song | 100 |

| Our Pony | 103 |

| Nelly's Kitten | 105 |

| A Morning Ride | 108 |

| Perils of the Sea | 112 |

| In Honor of Rosa's Birthday | 114 |

| Walter's Disappointment | 116 |

| The Tide coming in | 119 |

| Letter to George | 122 |

| Peepy's Pet | 124 |

IN VERSE. | |

| PAGE. | |

| The Singing Mouse | 101 |

| A Funny Little Grandma | 107 |

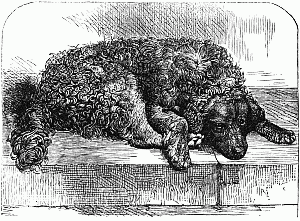

| Old Trim | 110 |

| Our One-Year-Old | 115 |

| The Boasting Boy | 117 |

| Cakes and Pies | 118 |

| Sunrise | 121 |

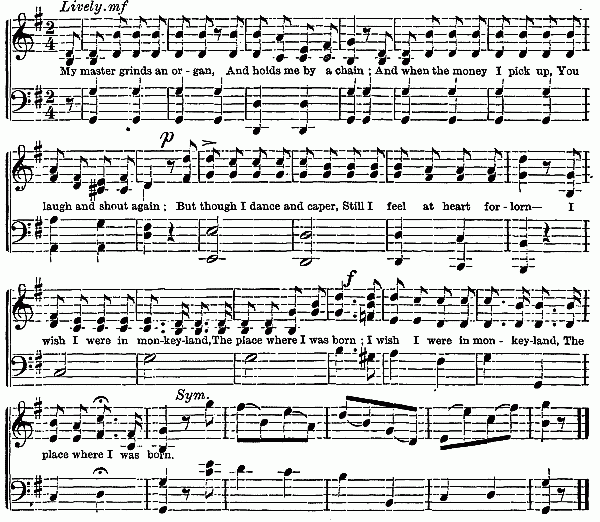

| Song of the Monkey (with music) | 128 |

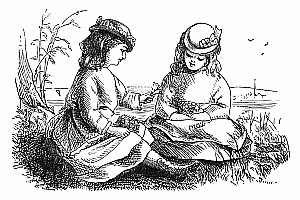

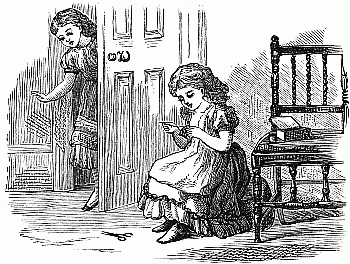

THREADING THE NEEDLE.

THREADING THE NEEDLE.

"I left her five minutes ago, trying to thread a needle," replied Anna.

"She is a long while about it," said Mrs. Ludlow. "Send her to me."

When Lucy entered the room, her mother asked her what she had been about; and Lucy replied, "I have been teaching myself to thread a needle."

"But you have been a long time about it," said mother.

"I will tell you why," continued Lucy. "When I went to walk with papa yesterday, he saw me get over a stone-wall, which I did rather clumsily: so he said, 'A thing that is worth doing at all is worth doing well. Let me teach you how to get over a wall quickly and gracefully.'"

"So he gave you a lesson in getting over walls, did he?"

"Yes, mother: he kept me at it at least half an hour; and now I can get over a wall as quickly and well as any boy."

"But what has getting over walls to do with threading a needle?"

"Only this: I thought I would apply papa's rule, and learn to do well what I was trying to do. So I have been threading and unthreading the needle, till now I can thread it easily."

"You have done well to heed your father's advice," said Mrs. Ludlow. "If you do not see the importance of it now, you will see it often in your life as you grow older."

It was not many months before Lucy comprehended how wise her father had been in training his little girl. She was gathering violets in a field one day, when she heard a[99] trampling sound, and, looking round, saw a fierce bull plunging and twisting himself about, and all the time drawing nearer and nearer to her. Suddenly he made a rush towards her in a straight line.

Not far off was a high stone-wall. It would once have seemed to Lucy a hopeless attempt to try to get over it before the bull could reach her; but now she felt confident she could do it: and she did it bravely. Confidence in her ability to do it kept off all fear; and she did not even tremble.

The bull came up, and roared lustily when he found she had escaped, and was on the other side of the wall. But Lucy turned to him, and said, "Keep your temper, old fellow! This child's father taught her how to get over a stone-wall in double-quick time. You must learn to scale a wall yourself, if you hope to catch her."

"Boo-oo-oo!" roared the bull, prancing up and down, but not knowing how to get over.

"Why, what a sweet humor you are in to-day, sir!" said Lucy, walking away, and arranging her bunch of violets for Cousin Susan as she went.

When I was a little boy, I often helped my mother when she was making butter.

I liked to stand in the cool spring-house, and churn for a little while; but I liked better to look out of the window, and watch the ducks swimming in the creek, or the little shiners and sunfish darting back and forth through the clear bright water.

Sometimes I would forget all about my work, and stand watching the insects, ducks, and fishes, until some one would call me, and tell me to go to work again.

One day I wanted to churn very fast; for my mother had told me that I might take a swim in the creek when my work was done.

So I sang a little song that our German girl Bertha had taught me. She called it the "Butter Song;" and here it is:—

I thought then, as Bertha told me, that if I sang that song a hundred and eleven times, and didn't stop churning once while singing it, the butter would soon be made. I believe so yet; but I think now, that the steady work had more to do with it than the song had.

Have you ever heard of singing mice? There are such creatures, you must know, or you will not believe what my verses will tell you. Yes, indeed: it was only the other day that I heard of one that was kept in a little cage, like those used for squirrels, and sang so delightfully that her owner used to have her by his bedside to charm him to sleep. She was a wood-mouse. Wood-mice are the best singers. Whether the one about which you shall hear came from the woods or not, I cannot say; nor how she happened to be in my friend C.'s house: but there she certainly was; and this is the story of what she did there. I call it,

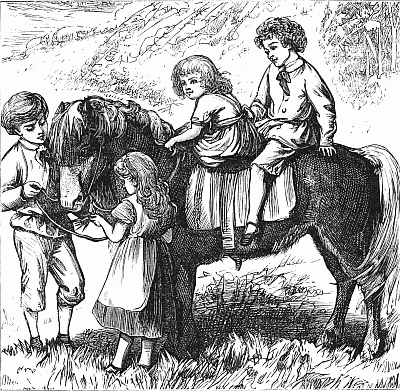

We have a pony whose name is Duke. He was very skittish when we first had him. There are four of us children who ride him,—Mamie, Winnie, Arthur, and myself. We have another little sister, Florence; but she is not old enough to ride, being only five years old.

Winnie is a nice little rider. Duke was Mamie's birthday present. We were all very much pleased when he came. We danced round him, and clapped our hands. Mamma wanted to surprise us: so, while we were at dinner, she had the pony brought up and put in the barn.[104]

After dinner we went out to play; and Winnie saw the whip and the saddles, and then she suspected something. So she began looking around in the stalls. There she found the pony, and then came running in to mamma to ask if it was really ours. Mamma said, Yes.

Then we were very much pleased, and said we would ride him. Winnie rode him up to the house first; then Mamie wanted to ride, so she got on the boys' saddle. Duke would not stand still for her; and, when she got on, he went galloping down to the barn. Her hat flew off, and she was very much frightened. She kept calling out, "Stop him!" but he would not stop until he reached the barn. Duke was frightened too, because we shouted at him.

Mamie is thirteen, but is more afraid to ride than Winnie, who is only seven. Mamie asks if boys always ride better than girls. I say, "No! Look at Winnie." Once we tied Duke to the swing; and then he got his nose pulled by getting the rope twisted round it. Sometimes we have a good frolic with him in the pasture. He never kicks us.

Mamie loves to feed Duke; but she wants Arthur to hold him carefully by the bridle while she does it. As for Winnie, she loves to gallop over the hills and far away. Sometimes she lets me ride behind her. Duke seems to love the bold Winnie, and will do whatever she tells him to.

Nelly's kitten was the handsomest kitten that ever was. So her little mistress thought. Nelly made a great pet of her, and brought her up with great care; and, when she had become a well-grown cat, Nelly gave her the name of "Pussy Gray."

One morning while Nelly was being dressed, her sister told her there was something nice down stairs, and asked her to guess what it was. "I guess it's pickled limes," said Nelly; for she dearly loved pickled limes. But her sister said "No."—"Then I guess it's kittens," said Nelly; and so it was.[106]

Out in the back-room, in a barrel of shavings, were two little bunches of fur; and, when Nelly took them out and put them on the floor, they looked as though they were all legs and mouths. Their eyes were shut tight, and their little pink mouths were wide open.

But, in a week or two, the eyes came open, and the little kitties saw their feet and tails for the first time. Then they stood upon their feet, and played with their tails till they found their mother had one that was bigger and longer; and then they played with their mother's tail whenever she forgot to tuck it away and put her paw on it.

The kittens were always in somebody's way. When Nelly's mamma sat down in the big rocking-chair for a little rest, the first time she rocked back, "Mew, mew, mew!" would be heard, and away would scamper a little kit.

When Nelly's sister walked across the room in the dark, she was sure to hit her foot against a little soft ball, and "Oh, dear! there's one of the kittens," she would say.

If mamma went out to work in the kitchen, there would be a scampering from under her feet; and the kittens would be right before her. If she went to the closet to get any thing, she was sure to knock one of the kits over as she came out. When she was making pies, something would come up her dress; and, before she could stop it, there would be a kitten on her shoulder ready to fall into the pie.

One day, after mamma had stepped on kittens, and fallen over kittens, till her patience was all gone, she said she believed she must have the kittens drowned, they were so much in the way. Pussy Gray, their mother, was in the room, and heard what was said. She at once went out of the door, calling the kittens after her.

That night they didn't come back, nor the next day, nor the next; and, now that they were really gone, mamma[107] began to feel badly. So she searched all through the garden, calling "Kitty, kitty;" but though she looked down the cellar-stairs, and under the back-doorsteps, and everywhere she could think of, no kitten came.

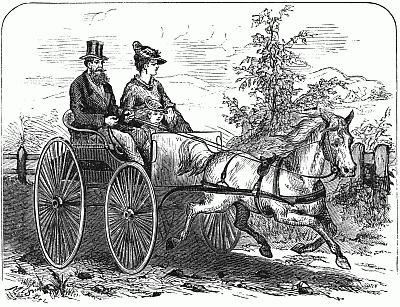

Maud is spending her vacation among the woods and mountains of Maine, where she went with her father and mother about two weeks ago.

One very pleasant morning papa said, "I think we had better take a ride this morning." So Maud was called in to get ready; and Hannah, the good white horse, was harnessed into the buggy.

The buggy had but one seat: so mamma found a nice box, and folded her shawl and put on it; and that made a good place for the little girl, between her father and mother; and they all started on their ride.

They went along a shady road near the river, and soon they saw some geese. Several of them were swimming in the water, and one or two were on the bank. One of these[109] had a sort of frame around its neck, and was standing on one leg.

Maud said, "Why, see that poor goose! It has only one leg; and they have put that frame on so it can walk better." But a few minutes after she looked again, and the goose was standing very comfortably on both feet. So it really had two, but had been curling up one of them quite out of sight.

After riding some time, they came to a ferry,—a place for crossing the Androscoggin River; and papa drove through a pleasant field down to the bank of the river. Here they saw a man cutting grass, and asked him about the ferry-boat. He came up and took a horn that hung on a post, and blew a blast, which the ferry-boy on the other side of the river heard.

When the boy heard it, he began to unfasten his boat, and pull it over; and Maud and her father and mother waited, sitting in the buggy, until the boy brought his boat close to the shore, so that they could drive on to it easily.

Then papa said, "Are you all ready?" and the boy answered, "Yes, sir;" and Hannah walked on the boat and stood perfectly still, while the boy kept pulling a strong rope, until he drew the boat, with the horse and buggy and people, safely over to the other side. Then they drove up the bank of the river, and came to a gate, which a little girl opened.

Next they came to a very pleasant wood,—so pleasant that papa stopped Hannah in the shade, and said she might rest a little; and[110] mamma and Maud got out of the buggy, and picked the young boxberry-leaves, and the red berries, and pulled long vines of evergreen, and gathered moss.

When papa thought it was time to go, he said, "All aboard!" and they got in, and he drove on. They had not gone far when Maud asked if she might drive. So papa handed her the reins; and Hannah seemed to go on just as well as ever.

After Maud had been driving a little while, her father said he thought she had better give the reins to him. This she did, and they went to the village, stopped at the post-office, and then drove swiftly home in season for dinner.

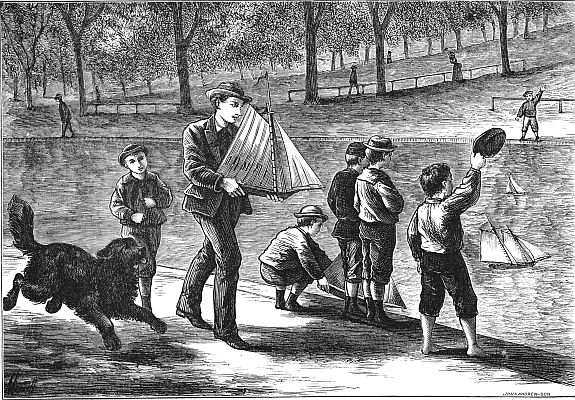

Edwin had a present of a ship, sent to him from England; and he named it, after the giver, "The Uncle George." It was a splendid ship. It had three masts, as a ship ought to have, and was rigged in complete style.

One fine day last month, Edwin took his ship down to the Frog Pond on Boston Common, and set her afloat. On the opposite side of the pond he saw four boys sailing their boats, and a tall boy carrying a sloop, and followed by his small brother.

A sloop, you know, has but one mast. None of these boys had a ship with three masts, like "The Uncle George." Edwin felt a little proud when he saw his good ship catch the wind in her sails, and go plunging up and down over the pond.

But, dear me, think of the risks of ship-owners! Consider, too, that Edwin's ship was not insured. What, then, was his dismay, when, as she got into the middle of the Atlantic Ocean (for so Edwin called the pond), a flaw of wind threw her on her beam-ends, and sent her masts down under water till she foundered, sank, and disappeared.

There was a shout from the owners of vessels on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. "What a pity!" exclaimed the boy with a dog.

"What's her name?" asked the tall boy.

"The Uncle George!" shouted back Edwin.

"Any insurance on her?" inquired a boy waving his hat.

"What do you mean by insurance?" asked Edwin.

"Go and look in your dictionary," said the boy with his hat off.

Then the tall boy repeated these lines:—

PERILS OF THE SEA.

PERILS OF THE SEA.

Edwin was half disposed to cry; but then he thought that crying was no way to get out of trouble. He took a survey of the Atlantic Ocean, and wondered how deep it was where his ship wend down.

Then taking off his shoes and stockings, and rolling up his pantaloons, he waded in, and succeeded, with the aid of a long stick, in saving "The Uncle George."

"Hurrah! Well done, little one!" shouted a boy on the other side. The tall boy again launched into poetry, and cried out,—

Charles.—Am I right madam? is not this Miss Rosa's birthday?

Mary.—Yes, sir. My little girl is two years old to-day.

Charles.—So I understood; and I have brought her a birthday present. Here it is,—the largest rose I could find in all the land. Do me the honor to accept it.

Mary.—With pleasure, sir, I accept it for Rosa; but, if I may trust my eyes, this is a sunflower, not a rose.

Charles.—Excuse me madam, in Doll-land they told me it was a rose.

Mary.—Ah! they sometimes forget names in Doll-land.[115] I am obliged to you, sir, all the same. You are very polite.

Charles.—I ought to be polite, madam; for my sister Helen goes to dancing-school. I will bid you good-morning, madam.

Mary.—Good-morning, sir. Call again some fine day.

Charles.—I shall call without waiting for a fine day, madam. It is always a fine day when I am with you.

"Here is the last white rose in my garden," said Laura to her brother Walter; "and you shall have it if you will be a good boy."

"I don't want a white rose," said Walter; "and, if I can't go with Jim Bacon and the other fellows on the pond, I'll not be a good boy: I'll make myself as disagreeable as I can."

"Why, Walter, what a threat!" said Laura, laughing; "but you are a good deal like the minister's dog Bunkum, who barks terribly, but never bites."[117]

"See what I get for being a good boy!" replied Walter. "The first time a chance for a little fun comes along, then it's, 'O Walter! you and the other boys are too young to be trusted alone on the water.'"

Hardly had Walter given utterance to these words, when there were cries from the roadside near by; and men and women were seen running towards the pond. What could be the matter?

It soon was made known what the matter was. The little fellows in the boat had upset it; and five of them were floundering about in the water. Fortunately no life was lost. All were saved, but not until all were wet through to the skin.

"Now, Walter," said Laura, "are you going to fret, and make yourself disagreeable, because you did not get a ducking with the other boys?"

"Sister," said Walter, with a smile, "I think I will accept that beautiful white rose you offered me just now."

Julia and Rose were on a visit to their uncle, who lived near the seaside. They came from Ohio, and did not know about the ebb and flow of the tide of the ocean. They ran down on the sandy beach, and seated themselves on a rock.

Their cousin Rodney was not far off, engaged in fishing for perch. All at once there was a loud cry from Julia, the[120] elder of the two sisters. The water had crept up all round the rock on which they sat, thus forming an island of it; and they did not know what to make of it.

"The water has changed its place," shouted Rose.

Rodney was alarmed, and began to blame himself for neglecting, in his eagerness to catch a few fish, the little girls under his charge.

He took off his shoes and stockings, rolled up his pantaloons, and ran into the water over the sandy bottom to the rock. Taking Rose in his arms, he told Julia to follow.

"But I shall wet my nice boots," said Julia.

"Then, wait on the rock," said Rodney, "while I carry Rose, and set her down on dry land. I will then come for you, and carry you pickback to the shore."

"No, Cousin Rodney," said Julia: "I think I will not ride pickback. I should be too heavy a load. I must not mind wetting my boots and stockings."

"Then, place your hand on my shoulder, and come along," said Rodney. "The tide is gaming on us very fast."

"I don't know what you mean by the tide," said Julia.

"Why, cousin," said Rodney, "you must know that the tides are the rise and fall of the waters of the ocean. It will be high tide an hour from now; then the water will cover all these rocks you see around us. After that, the water will sink and go back till we can see the rocks again, and walk a long way on the sand; then it will be low tide. But we must not stay here talking: the water will soon be too deep for us."

So Rodney took Rose in his arms, and Julia placed her left hand on his right shoulder; and in this way they went through the water to the dry part of the beach.

"We must look out for this sly tide the next time," said little Rose as she ran to tell papa of their adventure.

SUNRISE.

Come and see the sunrise,

Emily Carter.Children, come and see; Wake from slumber early, Wake, and come with me. Where the high rock towers, We will take our stand, And behold the sunshine Kindling all the land. You shall hear the birdies Sing their morning lay; You shall feel the freshness Of the new-born day; You shall see the flowers Opening to the beams, Flooding all the tree-tops, Flashing on the streams. |

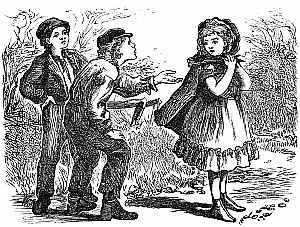

There was a little girl who was called Peepy; but why she was called so I do not know: perhaps it was because, when a baby, she used to peep from behind a curtain or a door, and cry, "Peep-O!"

She was a good little girl; but, when she was five years old, her mother had to go to Europe for her health, and Peepy was sent to board in the family of a farmer whose name was Miller.

One day Mr. Miller made her a present of a bright silver quarter of a dollar. Peepy had been taught to sew by Susan Miller; and so Peepy put her work-box on a chair in her little room, and sat down and made a little bag in which to keep the bright silver coin.

Then she took a walk near the grove, and saw two boys who had caught a robin, and were playing with it. They had tied a string to its legs; and, when the poor bird tried to[125] fly away, they pulled it back again, and laughed at its struggles.

At last the little robin was so tired and frightened, that it lay on the ground, panting, with its feathers ruffled, and its beak wide open, and its eyes half closed. It seemed ready to die. Then the rude, cruel boys pulled the string to make it fly again.

"Please don't be so cruel," said little Peepy. "How can you be so cruel?" And she ran to the poor bird, and took it up very gently.

"You let our bird alone!" one of the boys cried out. But Peepy still held it, and was ready to cry when she felt its little heart beating with fear.

"Do give it to me, please," said Peepy. "I will thank you for it very much." But the boys laughed at her, and told her roughly to let the bird alone. "We caught the bird, and the bird is ours," said one of them.

"Will you sell me the bird?" asked Peepy, taking her bright quarter of a dollar out of its bag, and offering it.[126]

"Ah! now you talk sensibly," said the larger of the boys. "Yes: we'll sell it."

So Peepy parted with her money, but kept the precious bird. The boys ran off, knowing they had done a mean thing, and fearing some man might come along, and inquire into it.

Peepy took the bird home; and Mrs. Miller told her she had done right, and helped her to mend an old cage into which they could put the poor little bruised bird. Soon it took food from their hands, and grew quite tame.

Peepy named it Bella, and kept it in her chamber where she could hear it sing. Bella loved Peepy, and would fly about the room, and light on her head, and play with her curls.

But as summer came on, and the weather grew warm and pleasant, Peepy thought to herself, "Bella loves me, and is grateful for all my care; but liberty is as sweet to birds as to little girls. I will not selfishly keep this bird in prison. I will take it into the grove, and set it free."[127]

So Peepy took it into the grove, and set it free; and Bella lighted on a bough, and sang the sweetest song you ever heard. It then flew singing round Peepy's head, as if to say, "Thank you! thank you a thousand times, you dear little girl!" If Bella's song could have been translated into words, I think they would have been these:—

Peepy went home rather sad with her empty cage. But what was her joy the next day, to see Bella on the window-sill! She opened the window, Bella flew in, and they had a nice frolic. Then, when the dinner-bell rang, the little bird flew off. Peepy was happy to think it had not forgotten her.

| 2 There cocoanuts are growing Around the palm-tree's crown: I used to climb and pick them off, And hear them—crack!—come down. There all day long the purple figs Are falling, I declare: How pleasant 'tis in monkey-land! Oh, would that I were there! | 3 On some tall tree's top branches The fleecy clouds would sail Just over me: I wish that I Were swinging by my tail! I'd swing and swing so merrily, How happy I would be! But oh! a travelling monkey's life Is very hard for me. |

Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

This issue was part of an omnibus. The original text for this issue did not include a title page or table of contents. This was taken from the July issue with the "No." added. The original table of contents covered the second half of 1873. The remaining text of the table of contents can be found in the rest of the year's issues.