Title: The Grocery Man And Peck's Bad Boy

Author: George W. Peck

Release date: May 16, 2008 [eBook #25488]

Most recently updated: February 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

|

Great God, Hanner, We Are Blowed Up The Old Man, the Hired Girl and The Goat The Minister and Deacons Salted |

CHAPTER I.

VARIEGATED DOGS—THE BAD BOY SLEEPS ON THE ROOF—A MAN DOESN'T

KNOW EVERYTHING AT FORTY-EIGHT—THE OLD MAN WANTS SOME POLLYNURIOUS

WATER—THE DYER'S DOGS—PROCESSION OF THE DOGS—PINK, BLUE, GREEN AND

WHITE—“WELL, I'M DEM'd”—HIS PA DON'T APPRECIATE.

CHAPTER II.

HIS PA PLAYS JOKES—A MAN SHOULDN'T GET MAD AT A JOKE—THE MAGIC

BOUQUET—THE GROCERY MAN TAKES A TURN—HIS PA TRIES THE BOUQUET AT

CHURCH—ONE FOR THE OLD MAID—A FIGHT ENSUES—THE BAD BOY THREATENS THE

GROCERY man—A COMPROMISE.

CHAPTER III.

HIS PA STABBED—THE GROCERY MAN SETS A TRAP IN VAIN—A BOOM IN

LINIMENT—HIS PA GOES TO THE LANGTRY SHOW—THE BAD BOY TURNS

BURGLAR—THE OLD MAN STABBED—HIS ACCOUNT OF THE FRAY—A GOOD SINGLE

HANDED LIAR.

CHAPTER IV.

HIS PA BUSTED—THE CRAZE FOR MINING STOCK—WHAT'S A BILK?—THE PIOUS

BILK—THE OLD MAN INVESTS—THE DEACONS AND EVEN THE HIRED GIRLS

INVEST—HOT MAPLE SYRUP FOR ONE—GETTING A MAN'S MIND OFF HIS TROUBLES.

CHAPTER V.

HIS PA AND DYNAMITE—THE OLD MAN SELLING SILVER STOCK—FENIAN

SCARE—“DYNAMITE” IN MILWAUKEE—THE FENIAN BOOM—“GREAT GOD, MANNER!

WE ARE BLOWED UP!”—HIS MA HAS LOTS OF SAND—THE OLD MAN USELESS IN

TROUBLE—THE DOG AND THE FALSE TEETH

CHAPTER VI.

HIS PA AN ORANGEMAN—THE GROCERY MAN SHAMEFULLY ABUSED—HE GETS

HOT—BUTTER, OLEOMARGARINE AND AXLE GREASE—THE OLD MAN WEARS ORANGE

ON ST. PATRICK'S DAY—HE HAS TO RUN FOR HIS LIFE—THE BAD BOY AT SUNDAY

SCHOOL—INGERSOLL AND BEECHER VOTED OUT—MARY HAD A LAMB

CHAPTER VII.

HIS MA DECEIVES HIM—THE BAD BOY IN SEARCH OF SAFFRON—“WELL, IT'S A

GIRL, IF YOU MUST KNOW”—THE BAD BOY IS GRIEVED AT HIS MA'S DECEPTION—

“SH-H-H TOOTSY GO TO SLEEP”—“BY LOW, BABY”—THAT SETTLED IT WITH

THE CAT—A BABY! BAH! IT MAKES ME TIRED

CHAPTER VIII.

THE BABY AND THE GOAT. THE BAD BOY THINKS HIS SISTER WILL BE A FIRE

ENGINE—“OLD NUMBER TWO”—BABY REQUIRES GOAT MILK—? THE GOAT IS

FRISKY—TAKES TO EATING ROMAN CANDLES—THE OLD MAN, THE HIRED GIRL, AND

THE GOAT—THE BAD BOY BECOMES TELLER IN A LIVERY STABLE

CHAPTER IX.

A FUNERAL PROCESSION—THE BAD BOY ON CRUTCHES—“YOU OUGHT TO SEE THE

MINISTER”—AN ELEVEN DOLLAR FUNERAL—THE MINISTER TAKES THE LINES—AN

EARTHQUAKE—AFTER THE EARTHQUAKE WAS OVER—THE POLICEMAN FANS THE

MINISTER—A MINISTER SHOULD HAVE SENSE

CHAPTER X.

THE OLD MAN MAKES A SPEECH. THE GROCERY MAN AND THE BAD BOY HAVE

A FUSS—THE BOHEMIAN BAND—THE BAD BOY ORGANIZES A SERENADE—“BABY

MINE”—THE OLD MAN ELOQUENT—THE BOHEMIANS CREATE A FAMINE—THE Y. M. C.

A. ANNOUNCEMENT

CHAPTER XI.

GARDENING UNDER DIFFICULTIES—THE GROCERY MAN IS DECEIVED—THE BAD

BOY DON'T LIKE MOVING—GOES INTO THE COLORING BUSINESS—THE OLD MAN

THOROUGHLY DISGUSTED—UNCLE TOM AND TOPSY—THE OLD MAN ARRESTED—WHAT

THE GROCERY MAN THINKS—THE BAD BOY MORALIZES ON HIS FATE—RESOLVES TO

BE GOOD

CHAPTER XII.

THE OLD MAN SHOOTS THE MINISTER—THE BAD BOY TRIES TO LEAD A DIFFERENT

LIFE—MURDER IN THE AIR—THE OLD MAN AND HIS FRIENDS GIVE THEMSELVES

AWAY—DREADFUL STORIES OF THEIR WICKED YOUTH—THE CHICKEN COOP

INVADED—THE OLD MAN TO THE RESCUE—THE MINISTER AND THE DEACONS SALTED

CHAPTER XIII.

THE BAD BOY A THOROUGHBRED. THE BAD BOY WITH A BLACK EYE—A POOR

FRIENDLESS GIRL EXCITES HIS PITY—PROVES HIMSELF A GALLANT

KNIGHT—THE OLD MAN IS CHARMED AT HIS SON'S COURAGE—THE GROCERY MAN

MORALIZES—FIFTEEN CHRISTS IN MILWAUKEE—THE TABLES TURNED—THE OLD MAN

WEARS THE BOY'S OLD CLOTHES

CHAPTER XIV.

ENTERTAINING Y. M. C. A. DELEGATES—THE BAD BOY MINISTERS AT THE Y.

M. C. A. WATER FOUNTAIN—THE DELEGATES FLOOD THEMSELVES WITH SODA

WATER—TWO DELEGATES DEALT TO HIS MA—THE NIGHT KEY—THE FALL OF THE

FLOWER STAND—DELEGATES IN THE CELLAR ALL NIGHT—THE BAD BOY'S GIRL IS

WORKING HIS REFORMATION

CHAPTER XV.

HE TURNS SUPE. THE BAD BOY QUITS JERKING SODA—ENTERS THE DRAMATIC

PROFESSION—“WHAT'S A SUPER”—THE PRIVILEGES OF A SUPE'S FATHER—BEHIND

THE SCENES—THE BAD BOY HAS PLAYED WITH MC'CULLOUGH—“IWAS THE

POPULACE.”—PLAYS IT ON HIS SUNDAY SCHOOL TEACHER—“I PRITHEE, AU

RESERVOIR, I GO HENS!”

CHAPTER XVI.

UNCLE EZRA PAYS A VISIT. UNCLE EZRA CAUSES THE BAD BOY TO

BACKSLIDE—UNCLE EZRA AND THE OLD MAN WERE BAD PILLS—THEIR RECORD IS

AWFUL—KEEPING UNCLE EZRA ON THE RAGGED EDGE—THE BED SLATS FIXED—THE

OLD MAN TANGLED UP—THIS WORLD IS NOT RUN RIGHT—UNCLE EZRA MAKES HIM

TIRED

CHAPTER XVII.

HE DISCUSSES THEOLOGY. MEDITATIONS ON NOAH'S ARK—THE GARDEN OF

EDEN—THE ANCIENT DUDE—ADAM WITH A PLUG HAT ON—“I'M A THINKER FROM

THINKERSVILLE”—THE APOSTLES IN A PATROL WAGON—ELIJAH AND ELISHA—THE

PRODIGAL SON—A VEAL POT PIE FOR DINNER

CHAPTER XVIII.

THE DEPARTED ROOSTER. THE GROCERY MAN DISCOURSES ON DEATH—THE DEAD

ROOSTER—A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH—THE TENDERNESS BETWEEN THE ROOSTER

AND HIS FAITHFUL HEN—THE HEN RETIRES TO SET—THE CHICKENS—THE PROUD

ROOSTER DIES—THE FICKLE HEN FLIRTING IN INDECENT HASTE

CHAPTER XIX.

ONE MORE JOKE ON THE OLD MAN—UNCLE EZRA RETURNS—THE BASKET ON THE

STEPS—THE ANONYMOUS LETTER—“O, BROTHER THAT I SHOULD LIVE TO SEE THIS

DAY!”—AN UGLY DUTCH BABY—THE OLD MAN WHEELS THE BABY NOW—A FROG IN

THE OLD MAN'S BED

CHAPTER XX.

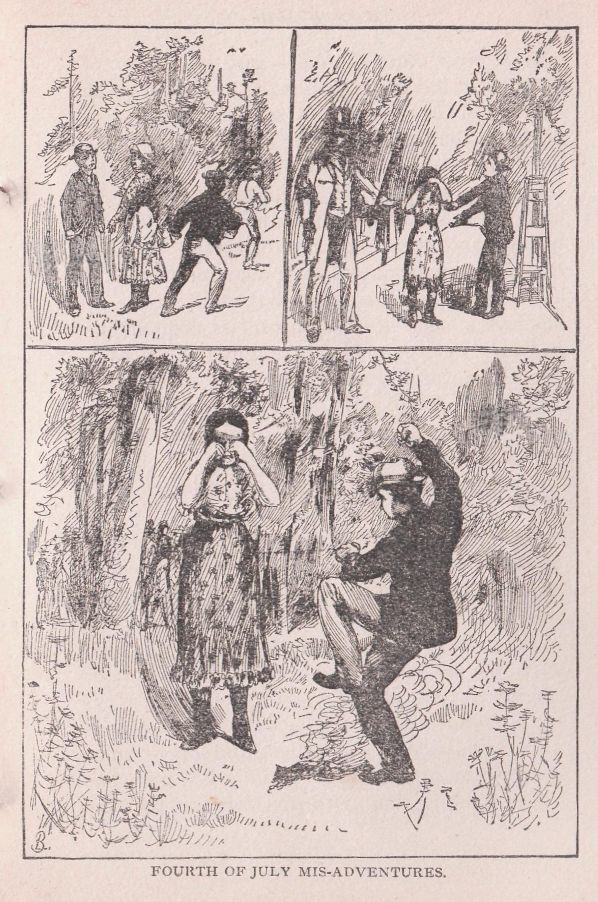

FOURTH OF JULY MISADVENTURES. TROUBLE IN THE PISTOL POCKET—THE GROCERY

MAN'S CAT THE BAD BOY A MINISTERING ANGEL—ASLEEP ON THE FOURTH OF

JULY—GOES WITH HIS GIRL TO THE SOLDIER'S HOME—TERRIBLE. FOURTH OF JULY

MISADVENTURES—THE GIRL WHO WENT OUT COMES BACK A BURNT OFFERING

CHAPTER XXI.

WORKING ON SUNDAY. TURNING A GRINDSTONE IS HEALTHY—“NOT ANY GRINDSTONE

FOR HENNERY!”—THIS HYPOCRISY IS PLAYED OUT—ANOTHER JOB ON THE OLD

MAN—HOW THE DAYS OF THE WEEK GOT MIXED—THE NUMEROUS FUNERALS—THE

MINISTER APPEARS—THE BAD BOY GOES OVER THE BACK FENCE

CHAPTER XXII.

THE OLD MAN AWFULLY BLOATED. THE OLD MAN BEGINS DRINKING AGAIN—THINKS

BETTING IS HARMLESS—HAD TO WALK HOME FROM CHICAGO—THE SPECTACLES

CHANGED—A SMALL SUIT OF CLOTHES—THE OLD MAN AWFULLY BLOATED—“HENNERY,

YOUR PA IS A MIGHTY SICK MAN”—THE SWELLING SUDDENLY GOES DOWN

CHAPTER XXIII.

THE GROCERY MAN AND THE GHOST. GHOSTS DON'T STEAL WORMY FIGS—A GRAND

REHEARSAL—THE MINISTER MURDERS HAMLET—THE WATER MELON KNIFE—THE OLD

MAN WANTED TO REHEARSE THE DRUNKEN SCENE IN RIP VAN WINKLE—NO HUGGING

ALLOWED—HAMLET WOULDN'T HAVE TWO GHOSTS—“HOW WOULD YOU LIKE TO BE AN

IDIOT?”

CHAPTER XXIV.

THE CRUEL WOMAN AND THE LUCKLESS DOG—THE BAD BOY WITH A DOG AND A BLACK

EYE—WHERE DID YOU STEAL HIM?—ANGELS DON'T BREAK DOGS' LEGS—A WOMAN

WHO BREAKS DOGS' LEGS HAS NO SHOW WITH ST. PETER—ANOTHER BURGLAR

SCARE—THE GROCERY DELIVERY MAN SCARED

CHAPTER XXV.

THE BAD BOY GROWS THOUGHTFUL—WHY IS LETTUCE LIKE A GIRL?—KING SOLOMON

A FOOL—THINK OF ANY SANE MAN HAVING A THOUSAND WIVES—HE WOULD HAVE

TO HAVE TWO HOTELS DURING VACATION—300 BLONDES—600 BRUNETTES, ETC.—A

THOUSAND WIVES TAKING ICE CREAM—“I DON'T ENVY SOLOMON HIS THOUSAND”

CHAPTER XXVI.

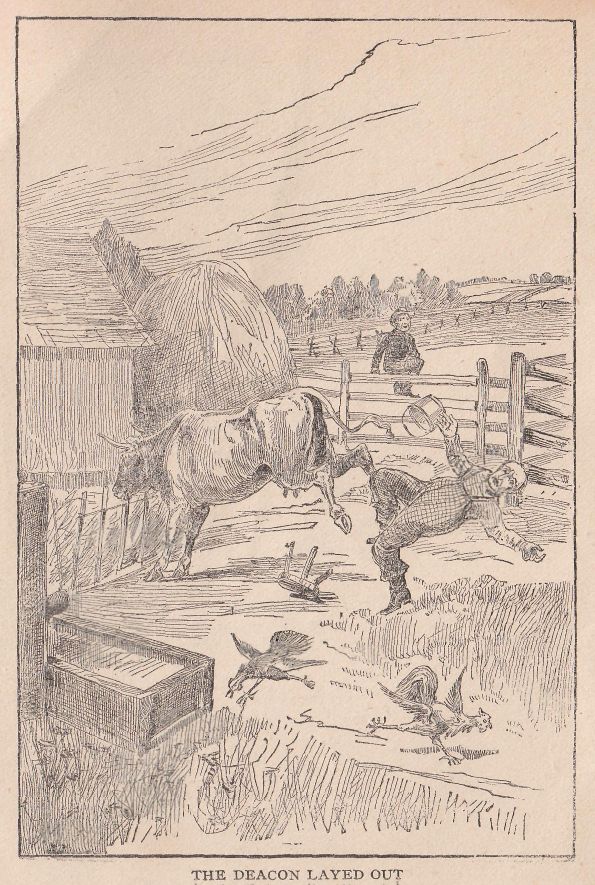

FARM EXPERIENCES. THE BAD BOY WORKS ON A FARM FOR A DEACON—HE KNOWS

WHEN HE HAS GOT ENOUGH—HOW THE DEACON MADE HIM FLAX AROUND—AND HOW HE

MADE IT WARM FOR THE DEACON

DRINKING CIDER IN THE CELLAR—THE DEACON WILL NOT ACCEPT HENNERY'S

RESIGNATION—HE WANTS BUTTER ON HIS PANCAKES—HIS CHUM JOINS HIM—THE

SKUNK IN THE CELLAR—THE POOR BOY GETS THE “AGER.”

VARIEGATED DOGS—THE BAD BOY SLEEPS ON THE KOOP—A MAN

DOESN'T KNOW EVERYTHING AT FORTY-EIGHT—THE OLD MAN WANTS

SOME POLLYNURIOUS WATER—THE DYER'S DOGS—PROCESSION OP THE

DOGS—PINK, BLUE, GREEN AND WHITE—“WELL I'M DEM'D—HIS PA

DON'T APPRECIATE.

“How do you and your Pa get along now,” asked the grocery-man of the bad boy, as he leaned against the counter instead of sitting down on a stool while he bought a bottle of liniment.

“O, I don't know. He don't seem to appreciate me. What he ought to have is a deaf and dumb boy, with only one leg, and both arms broke—then he could enjoy a quiet life. But I am too gay for Pa, and you needn't be surprised if you never see me again. I talk of going off with a circus. Since I played the variegated dogs on Pa, there seems to have been a coldness in the family, and I sleep on the roof.

“Variegated dogs,” said the store keeper, “what kind of a game is that? You have not played another Daisy trick on your Pa, have you?”

“Oh, no, it was nothing of that kind. You know Pa thinks he is smart. He thinks because he is forty-eight years old he knows it all; but it don't seem to me as though a man of his age, that had sense, would let a tailor palm off on him a pair of pants so tight that he would have to use a button-hook to button them; but they can catch him on everything, just as though he was a kid smoking cigarettes. Well, you know Pa drinks some. That night the new club opened he came home pretty fruitful, and next morning his head ached so he said he would buy me a dog if I would go down town and get a bottle of pollynurious water for him. You know that dye house on Grand avenue, where they have got the four white spitz dogs. When I went after the penurious water, I noticed they had been coloring their dogs with the dye stuff, and I put up a job with the dye man's little boy to help me play it on Pa. They had one dog dyed pink, another blue, another red, and another green, and I told the boy I would treat him to ice cream if he would let one out at a time, when I came down with Pa, and call him in and let another out, and when we started to go away, to let them all out. What I wanted to do was to paralyze Pa, and make him think he had got 'em, got dogs the worst way. So, about ten o'clock when his head got cleared off, and his stomach got settled, he changed ends with his cuffs, and we came down town, and I told him I knew where he could get a splendid white spitz dog for me, for five dollars; and if he would get it, I would never do anything disrespectful again, and would just sit up nights to please him, and help him up stairs and get seltzer for him. So we went by the dye house, and just as I told him I didn't want anything but a white dog, the door opened, and the pink dog came out and barked at us, and I said 'that's him' and the boy called him back. Pa looked as though he had the colic, and his eyes stuck out, and he said 'Hennery, that is a pink dog?' and I said 'no, it is a white dog, Pa,' and just then the green dog came out, and I asked Pa if it wasn't a pretty white dog, and and he turned pale and said 'hell, boy, that is a green dog—what's got into the dogs?' I told him he must be color blind, and was feeling in my pocket for a strap to tie the dog, and telling him he must be careful of his health or he would see something worse than green dogs, when the green dog went in, and the blue dog came rushing out and barked at Pa. Well, Pa leaned against a tree box, and his eyes stuck out like stops on an organ, and the sweat was all over his face in drops as big as kernels of hominy.

“I think a boy ought to do everything he can to make it pleasant for his Pa, don't you. And yet some parents don't realize what a comfort a boy is. The blue dog was called in, and just as Pa wiped the perspiration off his forehead, and rubbed his eyes and put on his specks, the red maroon dog came out. Pa acted as if he was tired, and sat down on a horse block. Dogs do make some people tired, don't they? He took hold of my hand, and his hand trembled just as though he was putting a gun wad in the collection plate at church, and he said, 'My son, tell me truly, is that a red dog?'”

“A fellow has got to lie a little if he is going to have any fun with his Pa, and I told him it was a white dog, and I could get it for five dol-dars. He straightened up just as the dog went into the house, and said 'Well, I'm dem'd;' and just then the boy let all the dogs out and sicked them on a cat, which ran up a shade tree right near Pa, and they rushed all around us—the blue dog going between his legs, and the green dog trying to climb the tree, and the pink dog barking, and the red dog standing on his hind feet.

“Pa was weak as a cat, and told me to go right home with him, and he would buy me a bicycle. He asked me how many dogs there were, and what was the color of them. I s'pose I did awful wrong, but I told him there was only one dog, and a cat, and the dog was white.

“Well, sir, Pa acted just as he did the night Hancock was beat, and he had to have the doctor to give him something to quiet him (the time he wanted me to go right down town and buy a hundred rat traps, but the doctor said never mind, I needn't go). I took him home and Ma soaked his feet, and give him some ginger tea, and while I was gone after the doctor he asked Ma if she ever saw a green dog.

“That was what made all the trouble. If Ma had kept her mouth shut I would have been all right, but she up and told him that they had a green dog, and a blue dog, and all colors of spitz dogs down at the dyers. They dyed them just for an advertisement, and for him to be quiet and he would feel better when he got over it. Pa was all right when I got back and told him the doctor had gone to Wauwatosa, and I had left an order on his slate. Pa said he would leave an order on my slate. He took a harness tug and used it for breeching on me. I don't think a boy's Pa ought to wear a harness on his son, do you? He said he would learn me to play rainbow dogs on him. He said I was a liar, and he expected to see me wind up in Congress. Say, is Congress anything like Waupun or Sing Sing? No, I can't stay, thank you, I must go down to the office and tell Pa I have reformed, and freeze him out of a circus ticket. He is a a good enough man, only he don't appreciate a a boy that has got all the modern improvements. Pa and Ma are going to enter me in the Sunday school. I guess I'll take first money, don't you?”

And the bad boy went out with a visible limp, and a look of genius cramped for want of opportunity.

HIS PA PLAYS JOKES—A MAN SHOULDN'T GET MAD AT A JOKE—THE

MAGIC BOUQUET—THE GROCERY MAN TAKES A TURN—HIS PA TRIES

THE BOUQUET AT CHURCH—ONE FOR THE OLD MAID—A FIGHT ENSUES—

THE BAD BOY THREATENS THE GROCERY MAN—A COMPROMISE.

“Say, do you think a little practical joke does any hurt,” asked the bad boy of the grocery man, as he came in with his Sunday suit on, and a bouquet in his button-hole, and pried off a couple of figs from a new box that had been just opened.

“No sir,” said the groceryman, as he licked off the syrup that dripped from a quart measure, from which he had been filling a jug. “I hold that a man who gets mad at a practical joke, that is, one that does not injure him, is a fool, and he ought to be shunned by all decent people. That's a nice bouquet you have in your coat. What is it, pansies? Let me smell of it,” and the grocery man bent over in front of the boy to take a whiff at the bouquet. As he did so a stream of water shot out of the innocent looking bouquet and struck him full in the face, and run down over his shirt, and the grocery man yelled murder, and fell over a barrel of axe helves and scythe snaths, and then groped around for a towel to wipe his face.

“You condemn skunk,” said the grocery man to the boy, as he took up an axe-helve and started for him, “what kind of a golblasted squirt gun have you got there. I will maul you, by thunder,” and he rolled up his shirt sleeves.

“There, keep your temper. I took a test vote of you on the subject of practical jokes, before the machine began to play upon the conflagration that was raging on your whiskey nose, and you said a man that would get mad at a joke was a fool, and now I know it. Here, let me show it to you. There is a rubber hose runs from the bouquet, inside my coat to my pants pocket, and there is a bulb of rubber, that holds about half a pint, and when a feller smells of the posey, I squeeze the bulb, and you see the result. It's fun, where you don't squirt it on a person that gets mad.”

The grocery man said he would give the boy half a pound of figs if he would lend the bouquet to him for half an hour, to play it on a customer, and the boy fixed it on the grocery man, and turned the nozzle so it would squirt right back into the grocery man's face. He tried it on the first customer that come in, and got it right in his own face, and then the bulb in his pants pocket got to leaking, and the rest of the water ran down the grocery man's trouser's leg, and he gave it up in disgust, and handed it back to the boy.

“How was it your Pa had to be carried home from the sociable in a hack the other night?” asked the grocery man, as he stood close to the stove so his pants leg would dry. “He has not got to drinking again, has he?”

“O, no,” said the boy, as he filled the bulb with vinegar, to practice on his chum, “It was this bouquet that got Pa into the trouble. You see I got Pa to smell of it, and I just filled him chuck full of water. He got mad and called me all kinds of names, and said I was no good on earth, and I would fetch up in state's prison, and then he wanted to borrow it to wear to the sociable. He said he would have more fun than you could shake a stick at, and I asked him if he didn't think he would fetch up in state's prison, and he said it was different with a man. He said when a man played a joke there was a certain dignity about it that was lacking in a boy. So I lent it to him, and we all went to the sociable in the basement of the church. I never see Pa more kitteny than he was that night. He filled the bulb with ice water, and the first one he got to smell of his button-hole bouquet was an old maid who thinks Pa is a heathen, but she likes to be made something of by anybody that wears pants, and when Pa sidled up to her and began talking about what a great work the christian wimmen of the land were doing in educating the heathen, she felt real good, and then she noticed Pa's posey in his button-hole and she touched it, and then she reached over her beak to smell of it. Pa he squeezed the bulb, and about half a teacupful of water struck her right in the nose, and some went into her strangle place, and O, my, didn't she yell.”

“The sisters gathered around her, and they said her face was all covered with perspiration, and the paint was coming off, and they took her in the kitchen, and she told them Pa had slapped her with a dish of ice cream, and the wimmin told the minister and the deacons, and they went to Pa for a nexplanation, and Pa told them it was not so, and the minister got interested and got near Pa, and Pa let the water go at him, and hit him on the eye, and then a deacon got a dose, and Pa laughed; and then the minister who used to go to college, and be a hazer, and box, he got mad and squared off and hit Pa three times right by the eye, and one of the deacons kicked Pa, and Pa got mad and said he could clean out the whole shebang, and began to pull off his coat, when they bundled him out doors, and Ma got mad to see Pa abused, and she left the sociable, and I had to stay and eat ice cream and things for the whole family. Pa says that settles it with him. He says they haven't got any more christian charity in that church than they have in a tannery. His eyes are just getting over being black from the sparring lessons, and now he has got to go through oysters and beef-steak cure again. He says it is all owing to me.”

“Well, what has all this got to do with your putting up signs in front of my store, 'Rotten Eggs,' and 'Frowy Butter a specialty,' said the grocery man as he took the boy by the ear and pulled him around. You have got an idea you are smart, and I want you to keep away from here. The next time I catch you in here I shall call the police and have you pulled. Now git!”

The boy pulled his ear back on the side of his head where it belonged, took out a cigarette and lit it, and after puffing smoke in the face of the grocery cat that was sleeping on the cover to the sugar barrel he said:

“If I was a provision pirate that never sold anything but what was spoiled so it couldn't be sold in a first class store, who cheated in weights and measures, who bought only wormy figs and decayed cod-fish, who got his butter from a fat rendering establishment, his cider from a vinegar factory, and his sugar from a glucose factory, I would not insult the son of one of the finest families. Why, sir, I could go out on the corner, and when I saw customers coming here, I could tell a story that would turn their stomachs, and send them to the grocery on the next corner. Suppose I should tell them that the cat sleeps in the dried apple barrel, that the mice made nests in the prune box, and rats run riot through the raisins, and that you never wash your hands except on Decoration day and Christmas, that you wipe your nose on your shirt sleeves, and that you have the itch, do you think your business would be improved? Suppose I should tell the customers that you buy sour kraut of a wood-en-shoed Polacker, who makes it of pieces of cabbage that he gets by gathering swill, and sell that stuff to respectable people, could you pay your rent? If I should tell them that you put lozengers in the collection plate at church, and charge the minister forty cents a pound for oleomargarine, you would have to close up. Old man, I am onto you, and now you apologize for pulling my ear.”

The grocery man turned pale during the recital, and finally said the bad boy was one of the best little fellows in this town, and the boy went out and hung up a sign in front:—

GIRL WANTED

TO COOK

HIS PA STABBED—THE GROCERY MAN SETS A TRAP IN VAIN—A BOOM

IN LINIMENT—HIS PA GOES TO THE LANGTRY SHOW—THE BAD BOY

TURNS BURGLAR—THE OLD MAN STABBED—HIS ACCOUNT OF THE FRAY—

A GOOD SINGLE HANDED LIAR.

“I hear you had burglars over to your house last night,” said the grocery man to the bad boy, as he came in and sat on the counter right over a little gimlet hole, where the grocery man had fixed a darning needle so that by pulling a string the needle would fly up through the hole and run into the boy about an inch. The grocery man had been laying for the boy about two days, and now that he had got him right over the hole the first time, it made him laugh to think how he would make him jump and yell, and as he edged off and got hold of the string the boy looked unconscious of impending danger. The grocery man pulled, and the boy sat still. He pulled again, and again, and finally the boy said:

“Yes, it is reported that we had burglars over there. O, you needn't pull that string any more. I heard you was setting a trap for me, and I put a piece of board inside my pants, and thought I would let you exercise yourself. Go ahead if it amuses you. It don't hurt me.”

The grocery man looked sad, and then smiled a sickly sort of a smile, at the failure of his plan to puncture the boy, and then he said, “Well, how was it? The policeman didn't seem to know much about the particulars. He said there was so much deviltry going on at your house that nobody could tell when anything was serious, and he was inclined to think it was a put up job.”

“Now let's have an understanding,” says the boy. “Whatever I say, you are not to give me away. It's a go, is it? I have always been afraid of you, because you have a sort of decayed egg look about you. You are like a peck of potatoes with the big ones on top, a sort of a strawberry box, with the bottom raised up, so I have thought you would go back on a fellow. But if you won't give this away, here goes. You see, I heard Ma tell Pa to bring up another bottle of liniment last night. When Ma corks herself, or has a pain anywhere, she just uses liniment for all that is out, and a pint bottle don't last more than a week. Well, I told my chum, and we laid for Pa. This liniment Ma uses is offul hot, and almost blisters. Pa went to the Langtry show, and did not get home till eleven o'clock, and me and my chum decided to teach Pa a lesson. I don't think it is right for a man to go to the theaters and not take his wife or his little boy.

“So we concluded to burgle Pa. We agreed to lay on the stairs, and when he came up my chum was to hit him on the head with a dried bladder, and I was to stab him on his breast pocket with a stick, and break the liniment bottle, and make him think he was killed.

“It couldn't have worked better if we had rehearsed it. We had talked about burglars at supper time, and got Pa nervous, so when he came up stairs and was hit on the head with the bladder, the first thing he said was 'Burglars, by mighty,' and he started to go back, and I hit him on the breast pocket, where the bottle was, and then we rushed by him, down stairs, and I said in a stage whisper, 'I guess he's a dead man,' and we went down cellar and up the back stairs to my room and undressed.”

“Pa hollered to Ma that he was murdered, and Ma called me, and I came down in my night-shirt, and the hired girl she came down, and Pa was on the lounge, and he said his life-blood was fast ebbing away. He held his hand on the wound, and said he could feel the warm blood trickling clear down to his boots. I told Pa to stuff some tar into the wound, such as he told me to put on my lip to make my mustache grow, and Pa said, 'My boy, this is no time for trifling. Your Pa is on his last legs. When I came up stairs I met six burglars, and I attacked them, and forced four of them down, and was going to hold them and send for the police, when two more, that I did not know about, jumped on me, and I was getting the best of them when one of them struck me over the head with a crowbar, and the other stabbed me to the heart with a butcher knife. I have received my death wound, my boy, and my hot southern blood, that I offered up so freely for my country in her time of need, is passing from my body, and soon your Pa will be only a piece of poor clay. Get some ice and put on my stomach, and all the way down, for I am burning up.' I went to the-water pitcher and got a chunk of ice and put inside Pa's shirt, and while Ma was tearing up an old skirt to stop the flow of blood, I asked Pa if he felt better, and if he could describe the villains who had murdered him. Pa gasped and moved his legs to get them cool from the clotted blood, he said, and he went on, 'One of them was about six foot high, and had a sandy mustache. I got him down and hit him on the nose, and if the police find him, his nose will be broke. The second one was thick set, and weighed about two hundred. I had him down, and my boot was on his neck, and I was knocking two more down when I was hit. The thick set one will have the mark of boot heels on his throat. Tell the police when I'm gone, about the boot heel marks.'

“By this time Ma had got the skirt tore up, and she stuffed it under Pa's shirt, right where he said he was hit, and Pa was telling us what to do to settle his estate, when Ma began to smell the liniment, and she found the broken bottle in his pocket, and searched Pa for the place where he was stabbed, and then she began to laugh, and Pa got mad and said he didn't see as a death-bed scene was such an almighty funny affair; and then she told him he was not hurt, but that he had fallen on the stairs and broke his bottle, and that there was no blood on him, and he said, 'do you mean to tell me my body and legs are not bathed in human gore?' and then Pa got up and found it was only the liniment. He got mad and asked Ma why she didn't fly around and get something to take that liniment off his legs, as it was eating them right through to the bone; and then he saw my chum put his head in the door, with one gallus hanging down, and Pa looked at me, and then he said, 'Lookahere, if I find out it was you boys that put up this job on me, I'll make it so hot for you that you will think liniment is ice cream in comparison.' I told Pa it didn't look reasonable that me and my chum could be six burglars, six feet high, with our noses broke, and boot-heel marks on our neck, and Pa, he said for us to go to bed alfired quick, and give him a chance to rinse of that liniment, and we retired. Say, how does my Pa strike you as a good, single-handed liar?” and the boy went up to the counter, while the grocery man went after a scuttle of coal.

In the meantime, one of the grocery man's best customers—a deacon in the church—had come in and sat down on the counter, over the darning needle, and as the grocery man came in with the coal, the boy pulled the string, and went out door and tipped over a basket of rutabagas, while the deacon got down off the counter with his hand clasped, and anger in every feature, and told the grocery man he could whip him in two minutes. The grocery man asked what was the matter, and the deacon hunted up the source from whence the darning needle came through the counter, and as the boy went across the street, the deacon and the grocery man were rolling on the floor, the grocery man trying to hold the deacon's fists while he explained about the darning needle, and that it was intended for the boy. How it came out the boy did not wait to see.

HIS PA BUSTED—THE CRAZE FOR MINING STOCK—WHAT'S A BILK?—

THE PIOUS BILK—THE OLD MAN INVESTS—THE DEACONS AND EVEN

THE HIRED GIRLS INVEST—HOT MAPLE SYRUP FOR ONE—GETTING A

MAN'S MIND OFF HIS TROUBLES.

“Say, can't I sell you some stock in a silver mine,” asked the bad boy of the grocery man, as he came in the store and pulled from his breast pocket a document printed on parchment paper, and representing several thousand dollars stock in a silver mine.

“Lookahere,” says the grocery man, as he turned pale, and thought of telephoning to the police station for a detective, “you haven't been stealing your father's mining stock, have you? Great heavens, it has come at last! I have known, all the time that you would turn out to be a burglar, or a defaulter or robber of some kind. Your father has the reputation of having a bonanza in a silver mine, but if you go lugging his silver stock around he will soon be ruined. Now you go right back home and put that stock in your Pa's safe, like a good boy.”

“Put it in the safe! O, no, we keep it in a box stall now, in the barn. I will trade you this thousand dollars in stock for two heads of lettuce, and get Pa to sign it over to you, if you say so. Pa told me I could have the whole trunk full if I wanted it, and the hired girls are using the silver stock to clean the windows, and to kindle fires, and Pa has quit the church, and says he won't belong to any concern that harbors bilks. What's a bilk?” said the boy, as he opened a candy jar and took out four sticks of hoarhound candy.

“A bilk,” said the grocery man, as he watched the boy, “is a fellow that plays a man for candy, or money, or anything, and don't intend to return an equivalent. You are a small sized bilk. But what's the matter with your Pa and the church, and what has the silver mine stock got to do with it?”

“Well, you remember that exhorter that was here last fall, that used to board around with the church people all the week, and talk about Zion and laying up treasures where the moths wouldn't gnaw them, and they wouldn't get rusty, and where thieves wouldn't pry off the hinges. He was the one that used to go home with Ma from prayer meetings, when Pa was down town, and who wanted to pay off the church debt in solid silver bricks. He's the bilk. I guess if Pa should get him by the neck he would jerk nine kinds of revealed religion out of him. O, Pa is hotter than he was when the hornets took the lunch off of him. When you strike a pious man on the pocket-book it hurts him. That fellow prayed and sang like an angel, and boarded around like a tramp. He stopped at our house over a week, and he had specimens of rock that were chuck full of silver and gold, and he and Pa used to sit up nights and look at it. You could pick pieces of silver out of the rock as big as buck shot, and he had some silver bricks that were beautiful. He had been out in Colorado and found a hill full of the silver rock, and he wanted to form a stock company and dig out millions of dollars. He didn't want anybody but pious men that belonged to the church, in the company, and I think that was one thing that caused Pa to unite with the church so suddenly. I know he was as wicked as could be a few days before he joined the church; but this revivalist, with his words about the beautiful beyond where all shall dwell together in peace, and sing praises; and his description of that Colorado mountain where the silver stuck out so you could hang your hat on it, converted Pa. That man's scheme was to let all the church people who were in good standing, and who had plenty of money, into the company, and when the mine begun to return dividends by the car load, they could give largely to the church and pay the debts of all the churches, and put down carpets and fresco the ceiling. The man said he felt that he had been steered on to that silver mine by a higher power, and his idea was to work it for the glory of the cause. He said he liked Pa, and would make him vice president of the company. Pa, he bit like a bass, and I guess he invested five thousand dollars in stock, and Ma, she wanted to come in, and she put in a thousand dollars that she had laid up to buy some diamond ear-rings, and the man gave Pa a lot of stock to sell to other members of the church. They all went into it, even the minister. He drew his salary ahead, and all of the deacons they come in, and the man went back to Colorado with about thirty thousand dollars of good, pious money. Yesterday Pa got a paper from Colorado, giving the whole snap away, and the pious man has been spending the money in Denver, and whooping it up. Pa suspected something was wrong two weeks ago, when he heard that the pious man had been on a toot in Chicago, and he wrote to a man in Denver, who used to get full with Pa years ago when they were both on the turf; and Pa's friend said the man that sold the stock was a fraud, and that he didn't own no mine, and that he borrowed the samples of ore and silver bricks from a pawnbroker in Denver. I guess it will break Pa up for a while, though he is well enough fixed with mortgages and things; but it hurts him to be took in. He lays it all to Ma—he says if she hadn't let that exhorter for the silver mine go home with her this would not have occurred, and Ma says she believes Pa was in partnership with the man to beat her out of her thousand dollars that she was going to buy a pair of diamond ear-rings with. O, it is a terror over to the house now. Both the hired girls put in all the money they had, and took stock, and they threaten to sue Pa for arson, and they are going to leave to-night, and Ma will have to do the work. Don't you never try to get rich quick,” said the boy as he peeled a herring, and took a couple of crackers.

“Never you mind me,” said the grocery man, “they don't catch me on any of their silver mines; but I hope this will have some influence on you, and teach you to respect your Pa's feelings, and not play jokes on him while he is feeling so bad over his being swindled.”

“O, I don't know about that, I think when a man is in trouble, if he has a good little boy to take his mind from his troubles and get him mad at something else, it rests him. Last night we had hot maple syrup and biscuit for supper, and Pa had a saucer full in front of him, just a steaming. I could see he was thinking too much about his mining stock, and I thought if there was anything I could do to take his mind off of it and place it on something else, I would be doing a kindness that would be appreciated. I sat on the right of Pa, and when he wasn't looking I pulled the table cloth so the saucer of red hot maple syrup dropped off in his lap.”

“Well, you'd a dide to see how quick his thoughts turned from his financial troubles to his physical misfortunes. There was about a pint of hot syrup, and it went all over his lap, and you know how hot melted maple sugar is, and how it sort of clings to anything. Pa jumped up and grabbed hold of his pants legs to pull them away from hisself, and he danced around and told Ma to turn the hose on him, and then he took a pitcher of ice water and poured it down his pants, and he said the condemned old table was getting so ricketty that a saucer wouldn't stay on it, and I told Pa if he would put some tar on his legs, the same kind that he told me to put on my lip to make my moustache grow, the syrup wouldn't burn so; and then he cuffed me, and I think he felt better It is a great thing to get a man's mind off of his troubles, but where a man hasn't got any mind like you, for instance—”

At this point the grocery man picked up a fire poker, and the boy went out in a hurry and hung up a sign in front of the grocery:

CASH PAID

FOR FAT DOGS.

HIS PA AND DYNAMITE—THE OLD MAN SELLING SILVER STOCK—

FENIAN SCARE—“DYNAMITE” IN MILWAUKEE—THE FENIAN BOOM—

“GREAT GOD HANNER WE ARE BLOWED UP!”—HIS MA HAS LOTS OF

SAND—THE OLD MAN USELESS IN TROUBLE. THE DOG AND THE FALSE

TEETH.

“I guess your Pa's losses in the silver mine have made him crazy, haven't they?” said the grocery man to the bad boy, as he came in the store with his eye winkers singed off, and powder marks on his face, and began to play on the harmonica, as he sat down on the end of a stick of stove wood, and balanced himself.

“O, I guess not. He has hedged. He got in with a deacon of another church, and sold some of his stock to him, and Pa says if I will keep my condemn mouth shut he will unload the whole of it, if the churches hold out. He goes to a new church every night there is prayer meeting or anything, and makes Ma go with him, to give him tone; and after meeting she talks with the sisters about how to piece a silk bed quilt, while Pa gets in his work selling silver stock. I don't know but he will order some more stock from the factory, if he sells all he has got,” and the boy went on playing “There's a land that is fairer than Day.”

“But what was he skipping up street for the other night with his hat off, grabbing at his coat tails as though they were on fire? I thought I never saw a pussy man run any faster. And what was the celebration down on your street about that time? I thought the world was coming to an end,” and the grocery man kept away from the boy, for fear he would explode.

“O, that was only a Fenian scare. Nothin' serious. You see Pa is a sort of half Englishman. He claims to be an American citizen, when he wants office, but when they talk about a draft he claims to be a subject of Great Brit-tain, and he says they can't touch him. Pa is a darn smart man, and don't you forget it. There don't any of them get ahead of Pa much. Well, Pa has said a good deal about the wicked Fenians, and that they ought to be pulled, and all that, and when I read the story in the papers about the explosion in the British Parliament Pa was hot. He said the damnirish was ruining the whole world. He didn't dare say it at the table or our hired girl would have knocked him silly with a spoonful of mashed potatoes, 'cause she is a nirish girl, and she can lick any Englishman in this town. Pa said there ought to have been somebody thereto have taken that bomb up and throwed it in the sewer before it exploded. He said that if he ever should see a bomb he would grab it right up and throw it away where it wouldn't hurt anybody. Pa has me read the papers to him nights, cause his eyes have got splinters in 'em, and after I had read all there was in the paper I made up a lot more and pretended to read it, about how it was rumored that the Fenians here in Milwaukee were going to place dynamite bombs at every house where an Englishman lived, and at a given signal blow them all up. Pa looked pale around the gills, but he said he wasn't scared.

“Pa and Ma were going to call on a she deacon that night, that has lots of money in the bank, to see if she didn't want to invest in a dead sure paying silver mine, and me and my chum concluded to give them a send off. We got my big black injy rubber foot-ball, and painted 'Dinymight' in big white letters on it, and tied a piece of tarred rope to it for a fuse, and got a big fire cracker, one of those old fourth of July horse scarers, and a basket full of broken glass. We put the foot-ball in front of the step and lit the tarred rope, and got under the step with the firecrackers and basket, where they go down into the basement. Pa and Ma came out the front door, and down the steps, and Pa saw the football, and the burning fuse, and he said 'Great God, Hanner, we are blowed up!' and he started to run, and Ma she stopped to look at it. Just as Pa started to run I touched off the fire cracker, and my chum arranged it to pour out the broken glass on the brick pavement just as the fire cracker went off.”

“Well, everything went just as we expected, except Ma. She had examined the foot-ball, and concluded it was not dangerous, and was just giving it a kick as the firecracker went off, and the glass fell, and the firecracker was so near her that it scared her, and when Pa looked around Ma was flying across the sidewalk, and Pa heard the noise and he thought the house was blown to atoms. O, you'd a died to see him go around the corner. You could play crokay on his coat-tail, and his face was as pale as Ma's when she goes to a party. But Ma didn't scare much. As quick as she stopped against the hitching post she knew it was us boys, and she came down there, and maybe she didn't maul me. I cried and tried to gain her sympathy by telling her the firecracker went off before it was due, and burned my eyebrows off, but she didn't let up until I promised to go and find Pa.

“I tell you, my Ma ought to be engaged by the British government to hunt out the dynamite fiends. She would corral them in two minutes. If Pa had as much sand as Ma has got, it would be warm weather for me. Well, me and my chum went and headed Pa off or I guess he would be running yet. We got him up by the lake shore, and he wanted to know if the house fell down. He said he would leave it to me if he ever said anything against the Fenians, and I told him he had always claimed that the Fenians were the nicest men in the world, and it seemed to relieve him very much. When he got home and found the house there he was tickled, and when Ma called him an old bald-headed coward, and said it was only a joke of the boys with a foot ball, he laughed right out, and said he knew it all the time, and he ran to see if Ma would be scared. And then he wanted to hug me, but it wasn't my night to hug and I went down to the theater. Pa don't amount to much when there is trouble. The time Ma had them cramps, you remember, when you got your cucumbers first last season, Pa came near fainting away, and Ma said ever since they had been married when anything ailed her, Pa has had pains just the same as she has, only he grunted more, and thought he was going to die. Gosh, if I was a man I wouldn't be sick every time one of the neighbors had a back ache, would you?

“Well you can't tell. When you have been married twenty or thirty years you will know a good deal more than you do now. You think you know it all, now, and you are pretty intelligent for a boy that has been brought up carelessly, but there are things that you will learn after a while that will astonish you. But what ails your Pa's teeth? The hired girl was over here to get some corn meal for gruel, and she said your Pa was gumming it, since he lost his teeth.”

“O, about the teeth. That was too bad. You see my chum has got a dog that is old, and his teeth have all come out in front, and this morning I borried Pa's teeth before he got up, to see if we couldn't fix them in the dog's mouth, so he could eat better. Pa says it is an evidence of a kind heart for a boy to be good to dumb animals, but it is a darn mean dog that will go back on a friend. We tied the teeth in the dog's mouth with a string that went around his upper jaw, and another around his under jaw, and you'd a dide to see how funny he looked when he laffed.

“He looked just like Pa when he tried to smile so as to get me to come up to him so he can lick me. The dog pawed his mouth a spell to get the teeth out, and then we gave him a bone with some meat on, and he began to gnaw the bone, and the teeth come off the plate, and he thought it was pieces of the bone, and he swallowed the teeth. My chum noticed it first, and he said we had got to get in our work pretty quick to save the plates, and I think we were in luck to save them. I held the dog, and my chum, who was better acquainted with him, untied the strings and got the gold plates out, but there were only two teeth left, and the dog was happy. He woggled his tail for more teeth, but we hadn't any more. I am going to give him Ma's teeth some day. My chum says when a dog gets an appetite for anything you have got to keep giving it to him or he goes back on you. But I think my chum played dirt on me. We sold the gold plates to a jewelry man, and my chum kept the money. I think, as long as I furnished the goods, he ought to have given me something besides the experience, don't you? After this I don't have no more partners, you bet.” All this time the boy was marking on a piece of paper, and soon after he went out the grocery man noticed a crowd outside, and on he found a sign hanging up which read:

WORMY FIGS

FOR PARTIES.

HIS PA AN ORANGEMAN—THE GROCERY MAN SHAMEFULLY ABUSED—-HE

GETS HOT—BUTTER, OLEOMARGARINE AND AXLE GREASE—THE OLD MAN

WEARS ORANGE ON ST. PATRICK'S DAY—HE HAS TO RUN FOR HIS

LIFE—THE BAD BOY AT SUNDAY SCHOOL—INGERSOLL AND BEECHER

VOTED OUT—“MARY HAD A LITTLE LAM.”

“Say, will you do me a favor,” asked the bad boy of the grocery man, as he sat down on the soap box and put his wet boots on the stove.

“Well, y-e-s,” said the grocery man hesitatingly, with a feeling that he was liable to be sold. “If you will help me to catch the villain who hangs up those disreputable signs in front of my store, I will. What is it?”

“I want you to lick this stamp and put it on this letter. It is to my girl, and I want to fool her,” and the boy handed over the letter and stamp, and while the grocery man was licking it and putting it on, the boy filled his pockets with dried peaches out of a box.

“There, that's a small job,” said the grocery man, as he pressed the stamp on the letter with his thumb and handed it back. “But how are you going to fool her?”

“That's just business,” said the boy, as he held the letter to his nose and smelled of the stamp. “That will make her tired. You see, every time she gets a letter from me she kisses the stamp, because she thinks I licked it. When she kisses this stamp and gets the fumes of plug tobacco, and stale beer, and limburg cheese, and mouldy potatoes, it will knock her down, and then she will ask me what ailed the stamp, and I will tell her I got you to lick it, and then it will make her sick, and her parents will stop trading here. O, it will paralize her. Do you know, you smell like a glue factory. Gosh I can smell you all over the store, Don't you smell anything that smells spoiled?” The grocery man thought he did smell something that was rancid, and he looked around the stove and finally kicked the boy's boot off the stove and said, “It's your boots burning. Gracious, open the door. It smells like a hot box on a caboose. Whew! And there comes a couple of my best lady customers.” The ladies came in and held their handkerchiefs to their noses, and while they were trading the boy said, as though continuing the conversation:

“Yes, Pa says that last oleomargarine I got here is nothing but axle grease. Why don't you put your axle grease in a different kind of a package? The only way you can tell axle grease from oleomargarine is in spreading it on pancakes. Pa says axle grease will spread, but your alleged butter just rolls right up and acts like lip salve, or ointment, and is only fit to use on a sore—”

At this point the ladies went out of the store in disgust, without buying anything, and the grocery man took a dried codfish by the tail and went up to the boy and took him by the neck. “Golblast you, I have a notion to kill you. You have driven away more custom from this store than your neck is worth. Now you git,” and he struck the boy across the back with the codfish.

“That's just the way with you all,” says the boy, as he put his sleeve up to his eyes and pretended to cry, “when a fellow is up in the world, there is nothing too good for him, but when he gets down, you maul him with a codfish. Since Pa drove me out of the house, and told me to go shirk for my living, I haven't had a kind word from anybody. My chum's dog won't even follow me, and when a fellow gets so low down that a dog goes back on him there is nothing left for him to do but to loaf around a grocery, or sit on a jury, and I am too young to sit on a jury, though I know more than some of the beats that lay around the court to get on a jury. I am going to drown myself, and my death will be laid to you. They will find evidences of codfish on my clothing, and you will be arrested for driving me to a suicide's grave. Good-bye. I forgive you,” and the boy started for the door.

“Hold on here,” says the grocery man, feeling that he had been too harsh, “Come back here and have some maple sugar. What did your Pa drive you away from home for?”

“O, it was on account of St. Patrick's Day,” said the bad boy as he bit off half a pound of maple sugar, and dried his tears. “You see, Pa never sees Ma buy a new silk handkerchief, but he wants it. Tother day Ma got one of these orange-colored handkerchiefs, and Pa immediately had a sore throat and wanted to wear it, and Ma let him put it on. I thought I would break him of taking everything nice that Ma got, so when he went down town with the orange handkerchief on his neck, I told some of the St. Patrick boys in the Third ward, who had green ribbons on, that the old duffer that was putting on style was an orange-man, and he said he could whip any St. Patrick's Day man in town. The fellers laid for Pa, and when he came along one of them threw a barrel at Pa, and another pulled the yellow handkerchief off his neck, and they all yelled 'hang him,' and one grabbed a rope that was on the sidewalk where they were moving a building, and Pa got up and dusted. You'd a dide to see Pa run. He met a policeman and said more'n a hundred men had tried to murder him, and they had mauled him and stolen his yellow handkerchief. The policeman told Pa his life was not safe, and he better go home and lock himself in, and he did, and I was telling Ma about how I got the boys to scare Pa, and he heard it, and he told me that settled it. He said I had caused him to run more foot races than any champion pedestrian, and had made his life unbearable, and now I must go it alone. Now I want you to send a couple of pounds of crackers over to the house, and have your boy tell the hired girl that I have gone down to the river to drown myself, and she will tell Ma, and Ma will tell Pa, and pretty soon you will see a bald headed pussy man whooping it up towards the river with a rope. They may think at times that I am a little tough, but when it comes to parting forever, they weaken.

“Well, the teacher at school says you are a hardened infidel,” said the grocery man, as he charged the crackers to the boy's Pa. “He says he had to turn you out to keep you from ruining the morals of the other scholars. How was that?”

“It was about speaking a piece. When I asked him what I should speak, he told me to learn some speech of some great man, some lawyer or statesman, so I learned one of Bob Ingersoll's speeches. Well, you'd a dide to see the teacher and the school committee, when I started in on Bob Ingersoll's lecture, the one that was in the papers when Bob was here. You see I thought if a newspaper that all the pious folks takes in their families, could publish Ingersoll's speech, it wouldn't do any hurt for a poor little boy, who ain't knee high to a giraffe, to speak it in school, but they made me dry up. The teacher is a republican, and when Ingersoll was speaking around here on politix, the time of the election, the teacher said Bob was the smartest man this country ever produced. I heard him say that in a corcus, when he went bumming around the ward settin' 'em up nights specting to be superintendent of schools. He said Bob Ingersoll just took the cake, and I think it was darn mean in him to go back on Bob and me too, just cause there was no 'lection. The school committee made the teacher stop me, and they asked me if I didn't know any other piece to speak, and I told them I knew one of Beecher's, and they let me go ahead, but it was one of Beecher's new ones where he said he didn't believe in any hell, and afore I got warmed up they said that was enough of that, and I had to wind up on “Mary had a Little Lam.” None of them didn't kick on Mary's Lam and I went through it, and they let me go home. That's about the safest thing a boy can speak in school, now days, either “Mary had a Little Lam,” or “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.” That's about up to the average intelleck of the committee. But if a boy tries to branch out as a statesman, they choke him off. Well, I am going down to the river, and I will leave my coat and hat by the wood yard, and get behind the wood, and you steer Pa down there and you will see some tall weeping over them clothes, and maybe Pa will jump in after me, and then I will come out from behind the wood and throw in a board for him to swim ashore on. Good bye. Give my pocket comb to my chum,” and the boy went out and hung up a sign in front of the grocery, as follows:

POP CORN THAT THE CAT

HAS SLEPT IN, CHEAP FOR

POP CORN BALLS FOR SOCIABLES.

HIS MA DECEIVES HIM—THE BAD BOY IN SEARCH OF SAFFRON—

“WELL, IT'S A GIRL IF YOU MUST KNOW”—THE BAD BOY IS GRIEVED

AT HIS MA'S DECEPTION—“S-H-H TOOTSY GO TO SLEEP”—“BY LOW,

BABY”—THAT SETTLED IT WITH THE CAT—A BABY! BAH! IT MAKES

ME TIRED.

“Give me ten cents worth of saffron, quick,” said the bad boy to the grocery man, as he came in the grocery on a gallop, early one morning, with no collar on and no vest. He looked as though he had been routed out of bed in a hurry and had jumped into his pants and boots, and put on his coat and hat on the run.

“I don't keep saffron,” said the grocery man as he picked up a barrel of ax-handles the boy had tipped over in his hurry. “You want to go over to the drug store on the corner, if you want saffron. But what on earth is the mat—”

At this point the boy shot out of the door, tipping over a basket of white beans, and disappeared in the drug store. The grocery man got down on his knees on the sidewalk, and scooped up the beans, occasionally looking over to the drug store, and just as he got them picked up, the boy came out of the drug store and walked deliberately towards his home as though there was no particular hurry. The grocery man looked after him, took up an ax-handle, spit on his hands, and shouted to the boy to come over pretty soon, as he wanted to talk with him. The boy did not come to the grocery till towards night; but the grocery man had seen him running down town a dozen times during the day and once he rode up to the house with the doctor, and the grocer surmised what was the trouble. Along towards night the boy came in in a dejected sort of a tired way, sat down on a barrel of sugar, and never spoke.

“What is it, a boy or girl,” said the grocery man, winking at an old lady with a shawl over her head, who was trying to hold a paper over a pitcher of yeast with her thumb.

“How in blazes did you know anything about it?” said the boy, as he looked around in astonishment, and with some indignation. “Well, it's a girl, if you must know, and that's enough,” and he looked down at the cat playing on the floor with a potato, his face a picture of dejection.

“O, don't feel bad about it,” said the grocery man, as he opened the door for the old lady. “Such things are bound to occur; but you take my word for it, that young one is going to have a hard life unless you mend your ways. You will be using it for a cork to a jug, or to wad a gun with, the first thing your Ma knows.”

“I wouldn't touch the darn thing with the tongs,” said the boy, as he rallied enough to eat some crackers and cheese. “Gosh, this cheese tastes good. I hain't had noth-to eat since morning. I have been all over this town trolling for nurses. They think a boy hasn't got any feelings. But I wouldn't care a goldarn, if Ma hadn't been sending me for neuralgia medicine, and hay fever stuff all winter, when she wanted to get rid of me. I have come into the room lots of times when Ma and the sewing girl were at work on some flannel things, and Ma would hide them in a basket and send me off after medicine. I was deceived up to about four o clock this morning, when Pa come to my room and pulled me out of bed to go over on the West Side after some old woman that knew Ma, and they have kept me whooping ever since. What does a boy want of a sister, unless it is a big sister. I don't want no sister that I have got to hold, and rock, and hold a bottle for. This affair breaks me all up,” and the boy picked the cheese out of his teeth with a sliver he cut from the counter.

“Well, how does your Pa take it?” asked the grocery man, as he charged the boy's Pa with cheese, and saffron, and a number of such things.

“O, Pa will pull through. He wanted to boss the whole concern until Ma's chum, an old woman that takes snuff, fired him out into the hall. Pa sat there on my hand-sled, a perfect picture of dispair, and I thought it would be a kindness to play in on him. I found the cat asleep in the bath-room, and I rolled the cat up in a shawl and brought it out to Pa and told him the nurse wanted him to hold the baby. It seemed to do Pa good to feel that he was indispensible around the house, and he took the cat on his lap as tenderly as you ever saw a mother hold her infant. Well, I got in the back hall, where he couldn't see me, and pretty soon the cat began to wake up and stretch himself, and Pa said 's-h-h-tootsy, go to sleep now, and let its Pa hold it,' and Pa he rocked back and forth on the hand sled and began to sing 'by, low, baby.' That settled it with the cat.”

“Well, some cats can't stand music, anyway, and the more the cat wanted to get out of the shawl, the louder Pa sung, and bimeby I heard something-rip, and Pa yelled, 'scat you brute,' and when I looked around the corner of the hall the cat was bracing hisself against Pa's vest with his toe nails, and yowling, and Pa fell over the sled and began to talk about the hereafter like the minister does when he gets excited in church, and then Pa picked up the sled and seemed to be looking for me or the cat, but both of us was offul scarce. Don't you think there are times when boys and cats are kind of few around their accustomed haunts? Pa don't look as though he was very smart, but he can hold a cat about as well as the next man. But I am sorry for Ma. She was just getting ready to go to Florida for her neuralgia, and this will put a stop to it, cause she has to stay and take care of that young one. Pa says I will have a nice time this summer pushing the baby wagon. By the great horn spoons, there has got to be a dividing line somewhere, between business and pleasure, and I strike the line at wheeling a baby. I had rather catch a string of perch than to wheel all the babies ever was. They needn't procure no baby on my account, if it is to amuse me. I don't see why babies can't be sawed off onto people that need them in their business. Our folks don't need a baby any more than you need a safe, and there are people just suffering for babies. Say, how would it be to take the baby some night and leave it on some old batchelor's door step. If it had been a bicycle, or a breech loading shot-gun, I wouldn't have cared, but a baby! Bah! It makes me tired. I'd druther have a prize package. Well, I am sorry Pa allowed me to come home, after he drove me away last week. I guess all he wanted me to come back for was to humiliate me, and send me on errands. Well, I must go and see if he and the cat have made up.”

And the boy went out and put a paper sign in front of the store:

LEAVE YOUR MEASURE

FOR SAFFRON TEA.

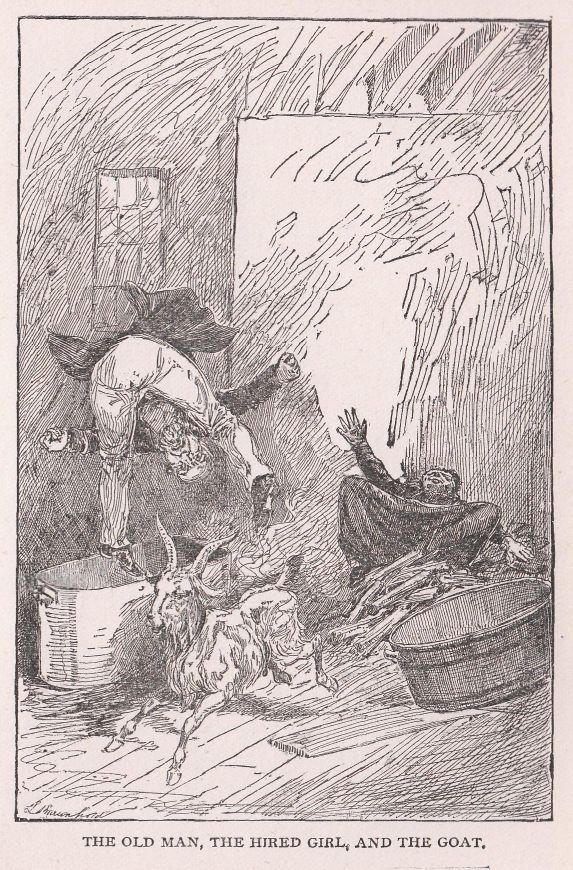

THE BABY AND THE GOAT—THE BAD BOY THINKS HIS SISTER WILL BE

A FIRE ENGINE—“OLD NUMBER TWO “—BABY REQUIRES GOAT MILK—

THE GOAT IS FRISKY—TAKES TO EATING ROMAN CANDLES—THE OLD

MAN, THE HIRED GIRL AND THE GOAT—THE BAD BOY BECOMES TELLER

IN A LIVERY STABLE.

“Well, how is the baby?” asked the grocery man of the bad boy, as he came into the grocery smelling very “horsey,” and sat down on the chair with the back gone, and looked very tired.

“O, darn the baby. Everybody asks me about the baby as though it was mine. I don't pay no attention to the darn thing, except to notice the foolishness going on around the house. Say, I guess that baby will grow up to be a fire engine. The nurse coupled the baby onto a section of rubber hose that runs down into a bottle of milk, and it began to get up steam and pretty soon the milk began to disappear, just like the water does when a fire engine couples on to a hydrant. Pa calls the baby “Old Number Two.” I am “Number One,” and if Pa had a hook and ladder truck and a hose cart, and a fire gong he would imagine he was chief engineer of the fire department. But the baby kicks on this milk wagon milk, and howls like a dog that's got lost. The doctor told Pa the best thing he could do was to get a goat, but Pa said since we 'nishiated him into the Masons with the goat he wouldn't have a goat around no how. The doc told Pa the other kind of a goat, I think it was a Samantha goat he said, wouldn't kick with its head, and Pa sent me up into the Polack settlement to see if I couldn't borrow a milk goat for a few weeks. I got a woman to lend us her goat till the baby got big enough to chew beef, for a dollar a week, and paid a dollar in advance, and Pa went up in the evening to help me get the goat. Well it was the darndest mistake you ever see. There was two goats so near alike you could not tell which was the goat we leased, and the other goat was the chum of our goat, but it belonged to a Nirish woman. We got a bed cord hitched around the Irish goat, and that goat didn't recognize the lease, and when we tried to jerk it along it rared right up, and made things real quick for Pa. I don't know what there is about a goat that makes it get so spunky, but that goat seemed to have a grudge against Pa from the first. If there were any places on Pa's manly form that the goat did not explore, with his head, Pa don't know where the places are. O, it lammed him, and when I laffed Pa got mad. I told him every man ought to furnish his own goats, when he had a baby, and I let go the rope and started off, and Pa said he knew how it was, I wanted him to get killed. It wasn't that, but I saw the Irish woman that owned the goat coming around the corner of the house with a cistern pole. Just as Pa was getting the goat out of the gate the goat got cross ways of the gate, and Pa yanked, and doubled the goat right up, and I thought he had broke the goats neck, and the woman thought so too, for she jabbed Pa with the cistern pole just below the belt, and she tried to get a hold on Pa's hair, but he had her there. No woman can get the advantage of Pa that way 'cause Ma has tried it. Well, Pa explained it to the woman, and she let Pa off if he would pay her two dollars for damages to her goat, and he paid it, and then we took the nanny goat, and it went right along with us. But I have got my opinion of a baby that will drink goat's milk. Gosh, it is like this stuff that comes in a spoiled cocoanut. The baby hasn't done anything but blat since the nurse coupled it onto the goat hydrant. I had to take all my playthings out of the basement to keep the goat from eating them. I guess the milk will taste of powder and singed hair now. The goat got to eating some Roman candles me and my chum had laid away in the coal bin, and chewed them around the furnace, and the powder leaked out and a coal fell out of the furnace on the hearth, and you'd a dide to see Pa and the hired girl and the goat. You see Pa can't milk nothing but a milk wagon, and he got the hired girl to milk the goat, and they were just hunting around the basement for the goat, with a tin cup, when the fireworks went off.”

“Well, there was balls of green, and red and blue fire, and spilled powder blazed up, and the goat just looked astonished, and looked on as though it was sorry so much good fodder was spoiled, but when its hair began to burn, the goat gave one snort and went between Pa and the hired girl like it was shot out of a cannon, and it knocked Pa over a wash boiler into the coal bin, and the hired girl in amongst the kindling wood, and she crossed herself and repeated the catekism, and the goat jumped up on the brick furnace, and they couldn't get it down. I heard the celebration and went down and took Pa by the pants and pulled him out of the coal bin, and he said he would surrender, and plead guilty of being the biggest fool in Milwaukee. I pulled the kindling wood off the hired girl, and then she got mad, and said she would milk the goat or die. O, that girl has got sand. She used to work in the glass factory. Well, sir, it was a sight worth two shillings admission, to see that hired girl get upon a step ladder to milk that goat on top of the furnace, with Pa sitting on a barrel of potatoes, bossing the job. They are going to fix a gang plank to get the goat down off the furnace. The baby kicked on the milk last night. I guess besides tasting of powder and burnt hair, the milk was too warm on account of the furnace. Pa has got to grow a new lot of hair on that goat, or the woman won't take it back. She don't want no bald goat. Well, they can run the baby and goat to suit themselves, 'cause I have resigned. I have gone into business. Don't you smell anything that would lead you to surmise that I had gone into business? No drugstore this time,” and the boy got up and put his thumbs in the armholes of his vest, and looked proud.

“O, I don't know as I smell anything except the faint odor of a horse blanket. What you gone into anyway?” and the grocery man put the wrapping paper under the counter, and put the red chalk in his pocket, so the boy couldn't write any sign to hang up outside.

“You hit it the first time I have accepted a situation of teller in a livery stable,” said the boy, as he searched around for the barrel of cut sugar, which had been removed.

“Teller in a livery stable! Well that is a new one on me. What is a teller in a livery stable?” and the grocery man looked pleased, and pointed the boy to a barrel of seven cent sugar.

“Don't you know what a teller is in a livery stable? It is the same as a teller in a bank. I have to grease the harness, oil the buggies, and curry off the horses, and when a man comes in to hire a horse I have to go down to the saloon and tell the livery man. That's what a teller is. I like the teller part of it; but greasing harness is a little too rich for my blood, but the livery man says if I stick to it I will be governor some day, 'cause most all the great men have begun life taking care of horses. It all depends on my girl whether I stick or not. If she likes the smell of horses I shall be a statesman, but if she objects to it and sticks up her nose, I shall not yearn to be governor, at the expense of my girl. It beats all, don't it, that wimmen settle every great question. Everybody does everything to please wimmen, and if they kick on anything that settles it. But I must go and umpire that game between Pa, and the hired girl, and the goat. Say, can't you come over and see the baby? 'Taint bigger than a small satchel,” and the boy waited till the grocery man went to draw some vinegar, when he slipped out and put up a sign written on a shingle with white chalk:

YELLOW SAND WANTED

FOR MAPLE SUGAR.

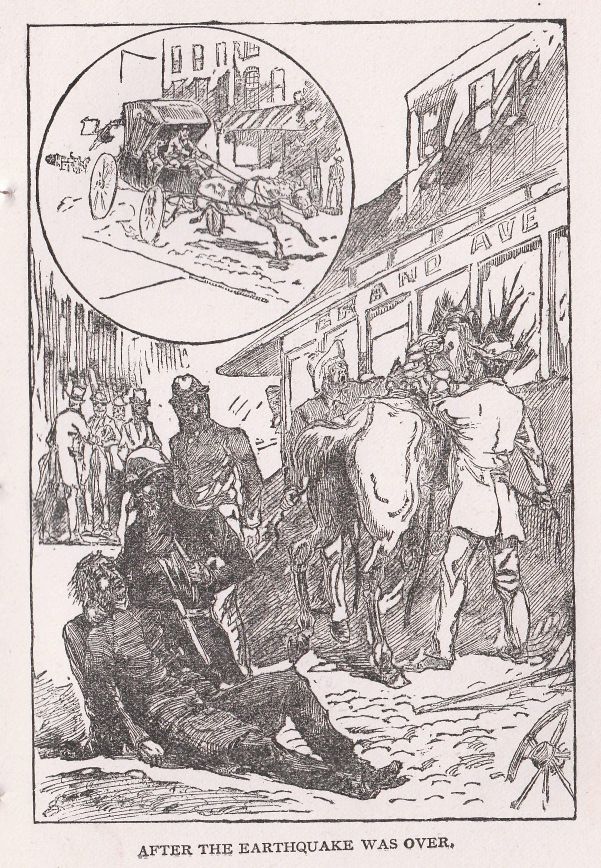

A FUNERAL PROCESSION—THE BAD BOY ON CRUTCHES—“YOU OUGHT TO

SEE THE MINISTER!”—AN ELEVEN DOLLAR FUNERAL—THE MINISTER

TAKES THE LINES—AN EARTHQUAKE—AFTER THE EARTHQUAKE WAS

OVER—THE POLICEMAN FANS THE MINISTER—A MINISTER SHOULD

HAVE SENSE.

“Well, great Julius Cæsar's bald-headed ghost, what's the matter with you?” said the grocery man to the bad boy, as he came into the grocery on crutches, with one arm in a sling, one eye blackened, and a strip of court plaster across his face “Where was the explosion, or have you been in a fight, or has your Pa been giving you what you deserve, with a club? Here, let me help you; there, sit down on that keg of apple-jack. Well, by the great guns, you look as though you had called somebody a liar. What's the matter?” and the grocery man took the crutches and stood them up against the show case.

“O, there's not much the matter with me,” said the boy, in a voice that sounded all broke up, as he took a big apple off a basket, and began peeling it with his upper front teeth. “If you think I am a wreck, you ought to see the minister. They had to carry him home in installments, the way they buy sewing machines. I am all right; but they have got to stop him up with oakum and tar, before he will hold water again!”

“Good gracious, you have not had a fight with the minister, have you? Well, I have said all the time, and I stick to it, that you would commit a crime yet, and go to state prison. What was the fuss about?” and the grocery man laid the hatchet out of the boy's reach for fear he would get excited and kill him.

“O, I want no fuss, it was in the way of business. You see the livery man that I was working for promoted me. He let me drive a horse to haul sawdust for bedding, first, and when he found I was real careful he let me drive an express wagon to haul trunks. Day before yesterday, I think it was—yes, I was in bed all day yesterday—day before yesterday there was a funeral, and our stable furnished the outfit. It was only a common, eleven dollar funeral, so they let me go to drive the horse for the minister—you know, the buggy that goes ahead of the hearse. They gave me an old horse that is thirty years old, that has not been off of a walk since nine years ago, and they told me to give him a loose rein, and he would go along all right. It's the same old horse that used to pace so fast on the avenue, years ago, but I didn't know it. Well, I wan't to blame. I just let him walk along as though he was hauling sawdust, and gave him a loose rein. When we got off of the pavement, the fellow that drives the hearse, he was in a hurry, 'cause his folks was going to have ducks for dinner, and he wanted to get back, so he kept driving along side of my buggy, and telling me to hurry up. I wouldn't do it, 'cause the livery man told me to walk the horse. Then the minister, he got nervous, and said he didn't know as there was any use of going so slow, because he wanted to get back in time to get his lunch and go to a minister's meeting in the afternoon, but I told him we would all get to the cemetery soon enough if we took it cool, and as for me I wasn't in no sweat. Then one of the drivers that was driving the mourners, he came up and said he had to get back in time to run a wedding down to the one o'clock train, and for me to pull out a little. I have seen enough of disobeying orders, and I told him a funeral in the hand was worth two weddings in the bush, and as far as I was concerned, this funeral was going to be conducted in a decorous manner, if we didn't get back till the next day. Well, the minister said, in his regular Sunday school way, 'My little man, let me take hold of the lines,' and like a darn fool I gave them to him. He slapped the old horse on the crupper with the lines, and then jerked up, and the old horse stuck up his off ear, and then the hearse driver told the minister to pull hard and saw on the bit a little, and the old horse would wake up. The hearse driver used to drive the old pacer on the track, and he knew what he wanted. The minister took off his black kid gloves and put his umbrella down between us, and pulled his hat down tight on his head, and began to pull and saw on the bit. The old cripple began to move along sort of sideways, like a hog going to war, and the minister pulled some more, and the hearse driver, who was right behind, he said, so you could hear him clear to Waukesha, 'Ye-e-up,' and the old horse kept going faster, then the minister thought the procession was getting too quick, and he pulled harder, and yelled 'who-a' and that made the old horse worse, and I looked through the little window in the buggy top. behind, and the hearse was about two blocks behind, and the driver was laughing, and the minister he got pale and said, 'My little man I guess you better drive,' and I said 'Not much Mary Ann, you wouldn't let me run this funeral the way I wanted to, and now you can boss it, if you will let me get out,' but there was a street car ahead and all of a sudden there was an earthquake, and when I come to there were about six hundred people pouring water down my neck, and the hearse was hitched to the fence, and the hearse driver was asking if my leg was broke, and a policeman was fanning the minister with a plug hat that looked as though it had been struck by a pile driver, and some people were hauling our buggy into the gutter, and some men were trying to take old pacer out of the windows of the street-car, and then I guess I fainted away agin. O, it was worse than telescoping a train loaded with cattle.”

“Well, I swan,” said the grocery man, as he put some eggs in a funnel shaped brown paper for a servant girl. “What did the minister say when he come to?”

“Say! What could he say? He just yelled 'whoa,' and kept sawing with his hands, as though he was driving. I heard that the policeman was going to pull him for fast driving, till he found it was an accident. They told me, when they carried me home in a hack, that it was a wonder everybody was not killed, and when I got home Pa was going to sass me, until the hearse driver told him it was the minister that was to blame. I want to find out if they got the minister's umbrella back. The last I see of it the umbrella was running up his trouser's leg, and the point come out by the small of his back. But I am all right, only my shoulder sprained, and my legs bruised, and my eye black. I will be all right, and shall go to work to-morrow, 'cause the livery man says I was the only one in the crowd that had any sense. I understand the minister is going to take a vacation on account of his liver and nervous prostration. I would if I was him. I never saw a man that had nervous prostration any more than he did when they fished him out of the barbed wire fence, after we struck the street car. But that settles the minister business with me. I don't drive for no more preachers. What I want is a quiet party that wants to go on a walk,” and the boy got up and hopped on one foot towards his crutcher, filling his pistol pocket with fig he hobbled along.

“Well, sir,” said the grocery man, as he took a chew of tobacco out of a pail, and offered some to the boy, knowing that was the only thing in the store the boy would not take, “Do you know I think some of these ministers have about as little sense on worldly matters, as anybody? Now, the idea of that man jerking on an old pacer. It don't make any difference if the pacer was hundred years old, he would pace if he was jerked on.”

“You bet,” said the boy, as he put his crutches under his arms, and started for the door. “A minister may be sound on the Atonement, but he don't want to saw on an old pacer. He may have the subject of infant baptism down finer than a cambric needle, but if he has ever been to college, he ought to have learned enough not to say 'ye up' to an old pacer that has been the boss of the road in his time. A minister may be endowed with sublime power to draw sinners to repentance, and make them feel like getting up and dusting for the beautiful beyond, and cause them, by his eloquence, to see angles bright and fair in their dreams, and chariots of fire flying through the pearly gates and down the golden streets of New Jerusalem, but he wants to turn out for a street car all the same, when he is driving a 2:20 pacer. The next time I drive a minister to a funeral, he will walk,” and the boy hobbled out and hung out a sign in front of the grocery:

SMOKED DOG FISH AT HALIBUT PRICES,

GOOD ENOUGH

FOR COMPANY.

THE OLD MAN MAKES A SPEECH—THE GROCERYMAN AND THE BAD BOY

HAVE A FUSS—THE BOHEMIAN BAND—THE BAD BOY ORGANIZES A

SERENADE—“BABY MINE”—THE OLD MAN ELOQUENT—THE BOHEMIANS

CREATE A FAMINE—THE Y. M. C. A. ANNOUNCEMENT.

“There, you drop that,” said the groceryman to the bad boy, as he came limping into the store, and began to fumble around a box of strawberries. “I have never kicked at your eating my codfish, and crackers and cheese, and herring, and apples, but there has got to be a dividing line somewhere, and I make it at strawberries at six shillings a box, and only two layers in a box. I only bought one box, hoping some plumber, or gas man would come along and buy it, and by gum, everybody that has been in the store has sampled a strawberry out of that box. shivered as though it was sour, and gone off without asking the price,” and the grocery man looked mad, took a hatchet and knocked in the head of a barrel of apples, and said, “There, help yourself to dried apples.”

“O, I don't want your strawberries or dried apples,” said the boy, as he leaned against a show case and looked at a bar of red, transparent soap. “I was only trying to fool you. Say, that bar of soap is old enough to vote. I remember seeing it in your show case when I was about a year old, and Pa came in here with me and held me up to the show case to look at that tin tobacco box, and that round zinc looking-glass, and the yellow wooden pocket comb, and the soap looks just the same, only a little faded. If you would wash yourself once in a while your soap wouldn't dry up on your hands,” and the boy sat down on the chair without any back, feeling that he was even with the grocery man.