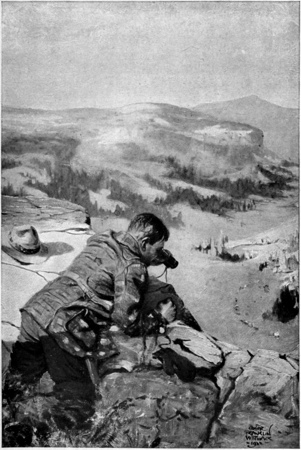

He saw the trail across the cañon alive with moving men and beasts.

(Frontispiece—Page 261)

Title: Louisiana Lou

Author: William West Winter

Release date: June 3, 2009 [eBook #29028]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Dan Horwood, Michael and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Louisiana Lou

A Western Story

BY

WILLIAM WEST WINTER

AUTHOR OF

“The Count of Ten”

CHELSEA HOUSE

79 Seventh Avenue New York City

Copyright, 1922

By CHELSEA HOUSE

Louisiana Lou

(Printed in the United States of America)

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandinavian.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Prologue | 11 | |

| I. | A General Demoted | 32 |

| II. | Morgan la Fee | 42 |

| III. | A Sporting Proposition | 54 |

| IV. | Heads! I Win! | 66 |

| V. | A Marriage of Convenience | 78 |

| VI. | Where the Desert Had Been | 94 |

| VII. | Maid Marian Grown Up | 103 |

| VIII. | Getting Down to Business | 112 |

| IX. | Behind Prison Bars | 123 |

| X. | The Get-away | 140 |

| XI. | Jim Banker Hits the Trail | 153 |

| XII. | A Reminder of Old Times | 162 |

| XIII. | At Wallace’s Ranch | 174 |

| XIV. | Ready for Action | 182 |

| XV. | The Sheriff Finds a Clew | 189 |

| XVI. | In the Solitudes of the Canyon | 203 |

| XVII. | The Secret of the Lost Mine | 217 |

| XVIII. | Telltale Bullets | 236 |

| XIX. | The Finding of Sucatash | 247 |

| XX. | Louisiana! | 259 |

| XXI. | Gold Seekers | 271 |

| XXII. | Vengeance! | 283 |

| XXIII. | To the Vale of Avalon | 298 |

The sun was westering over Ike Brandon’s ranch at Twin Forks. It was the first year of a new century when the old order was giving place to the new. Yet there was little to show the change that had already begun to take place in the old West. The desert still stretched away drearily to the south where it ended against the faint, dim line of the Esmeralda Mountains. To the north it stretched again, unpopulated and unmarked until it merged into prairie grass and again into mountains. To west and east it stretched, brown and dusty. To the south was the State of Nevada and to the north the State of Idaho. But it was all alike; bare, brown rolling plain, with naught of greenness except at the ranch where the creek watered the fields and, stretching back to the north, the thread of bushy willows and cottonwoods that lined it from its source in the mountains.

Ike Brandon was, himself, a sign of change and of new conditions, though he did not know it. A sheepman, grazing large herds of woolly pests in a country which, until recently, had been the habitat of cattlemen exclusively, he was a symbol of conquest. He remembered the petty warfare that had 12 marked the coming of his kind, a warfare that he had survived and which had ended in a sort of sullen tolerance of his presence. A few years ago he had gone armed with rifle and pistol, and his herders had been weaponed against attack. Now he strode his acres unafraid and unthreatened, and his employees carried rifle or six-shooter only for protection against prowling coyotes or “loafer” wolves. Although the cow hands of his erstwhile enemies still belted themselves with death, they no longer made war. The sheep had come to stay.

The worst that he and his had to expect was a certain coldness toward himself on the part of the cattle aristocracy, and a measure of contempt and dislike toward his “Basco” herders on the part of the rough-riding and gentle-speaking cow hands.

These things troubled him little. He had no near neighbors. To the north, across the Idaho border, there was none nearer than Sulphur Falls, where the Serpentine, rushing tumultuously from the mountains, twisted in its cañon bed and squirmed away to westward and northward after making a gigantic loop that took it almost to the Line. To the south, a ranch at Willow Spring, where a stubborn cattleman hung on in spite of growing barrenness due to the hated sheep, was forty miles away. To east and west was no one within calling distance.

At Sulphur Falls were two or three “nesters,” irrigating land from the river, a store or two and a 13 road house run by an unsavory holdover of the old days named “Snake” Murphy. For a hundred and twenty-five miles to southward was unbroken land. The cattle were mostly gone—though in days to come they were to return again in some measure. Even the Esmeralda Mountains were no longer roamed by populous herds. They were bare and forbidding, except where the timber was heavy, for the sheep of Brandon and others, rushing in behind the melting snow in the spring, had cropped the tender young grass before it had a chance to grow strong.

Brandon’s ranch was an idyllic spot, however. His dead wife and, after her, her daughter, also dead, had given it the touch of feminine hands. Vines and creepers half hid the dingy house behind a festoon of green and blossoms. Around it the lush fields of clover were brilliant and cool in the expanse of brown sultriness. And here, Ike, now growing old, lived in content with his idolized granddaughter, Marian, who was about six years old.

Brandon, at peace with the world, awaited the return from the summer range of “French Pete,” his herder, who was to bring in one of the largest flocks for an experiment in winter feeding at and in the vicinity of the ranch. The other flocks and herders would, as usual, feed down from the mountains out into the desert, where they would winter.

Little Marian hung on the swinging gate which 14 opened onto the apology for a wagon road. She liked quaint French Pete and looked forward to his return with eagerness. Like her grandfather, he always spoiled her, slavishly submitting to her every whim because she reminded him of his own p’tit bébé, in his far-away, Pyrenean home. Marian was used to being spoiled. She was as beautiful as a flower and, already, a veritable tyrant over men.

But now she saw no sign of French Pete and, being too young for concentration, she let her glance rove to other points of the compass. So she was first to become aware that a rider came from the north, the direction of Sulphur Falls, and she called her grandfather to come and see.

The horseman loped easily into sight through the brown dust that rose about him. His horse was slim and clean limbed and ran steadily, but Brandon noted that it was showing signs of a long journey made too fast. It was a good horse, but it would not go much farther at the pace it was keeping.

And then he frowned as he recognized the rider. It was a young man, or rather, boy, about nineteen or twenty years old, rather dandified after the cow-puncher fashion, sporting goatskin chaps and silver-mounted bridle and spurs, silk neckerchief, and flat-brimmed hat of the style now made common by the Boy Scouts. His shirt was flannel, and his heavy roping saddle studded with silver conchas. He was belted with heavy cartridges, and a holster strapped 15 down to his leg showed the butt of a six-shooter polished by constant handling.

“It’s that damned Louisiana!” said Brandon, with disgust.

The rider trotted through the gate which he swung open and dropped to the ground before the little veranda. Marian had run back behind the vines whence she peered at him half curiously and half afraid. The young fellow, teetering on his high heels, reached for her and, smiling from pleasant eyes, swung her into the air and lifted her high, bringing her down to his face and kissing her.

“Howdy, little Lily Bud!” he said, in a voice which was a soft blend of accents, the slurred Southern, the drawled Southwestern, and something subtly foreign.

He was a handsome, slender, dashing figure, and Marian’s gleeful echo to his laughter claimed him as her own. Even Ike Brandon relaxed and grinned. If the little lady of his heart adopted the stranger, Ike would put aside his prejudice. True, the man was that vanishing rarity, a reputed gunman, uncannily skilled with six-shooter and frowned on by a Western sentiment, new grown, for law and order, which had determined to have peace if it had to wage war to accomplish it.

After all, reflected Ike, the boy, though noted for skill and a certain arrogance which accompanied it, was not yet a killer. The younger element among 16 the cowmen, reckless enough though it was, boasted no such skill as had been common with its fathers. They carried weapons, but they recognized their limitations and there were few of them who would care to test the skill that this young man was supposed to possess. He might, and probably would, go through life peaceably enough, though he was, potentially, as dangerous as a rattlesnake.

“I reckon you could eat,” he remarked, and Louisiana agreed.

“I reckon I can,” he said. “And my old hoss can wrastle a bag of oats, too. He’s got a ride in front of him and he’d appreciate a chance to rest and limber up.”

“You’ll stay the night?”

“No, thanks, seh! An hour or two’s all I can spare. Got business somewhere else.”

Brandon did not urge nor show curiosity. That was not etiquette. But little Marian, taken with the new acquaintance, broke into a wail.

“I want you should stay while I show you my dolly that Pete made me!” she cried, imperiously. Louisiana laughed and ruffled her curls.

“You show me while I eat,” he said. Then he followed Ike into the cabin, debonair and apparently unconcerned. The little girl came too, and, as the Mexican servant set the table, the stranger talked and laughed with her, telling her stories which he made up as he went along, tying his neckerchief into 17 strange shapes of dolls and animals for her, fascinating her with a ready charm that won, not only her, but Ike himself.

He had seen that his horse was fed, and, after he had eaten, he sat unconcerned on the veranda and played with the little girl who, by now, was fairly doting on him. But at last he rose to go and she voiced her sorrow by wails and commands to stay, which he sorrowfully defied.

“I’ve got to ramble, little Lily Bud,” he told her as he led his resaddled and refreshed horse from the stable. “But don’t you fret. I’ll come roamin’ back hereaways some o’ these days when you’ve done married you a prince.”

“Don’t want to marry a prince!” screamed Marian. “Don’t want to marry no one but you-ou! You got to stay!”

“When I come back I sure will stay a whole lot, sweetheart. See here, now, you-all don’t cry no more and when I come back I’ll sure come a-ridin’ like this Lochinvar sport and marry you-all a whole lot. That’s whatever! How’d you like that!”

“When will you come?” demanded Marian.

“Oh, right soon, honey! And you’ll sure have a tame and dotin’ husband, I can tell you. But now, good-by!”

“You’ll come back?”

“You’re shoutin’, I will! With a preacher and a license and all the trimmin’s. We’ll certainly have 18 one all-whoopin’ weddin’ when I come rackin’ in, Petty! Kiss me good-by, like a nice sweetheart and just dream once in a while of Louisiana, won’t you?”

“I’ll say your name in my prayers,” she assured him, watching him doubtfully and hopefully as he wheeled his horse, striving to keep back the tears.

And then he was gone, riding at a mile-eating pace toward the south and the Esmeralda Mountains.

Two hours later a tired group of men and horses loped in and wanted to know where he had gone. They were on his trail for, it seemed, he had shot “Snake” Murphy in his own road house in a quarrel over some drab of the place who was known as Lizzie Lewis.

Ike was cautious. It was not a regularly deputized posse and the members were rather tough friends of Murphy. Between the two, he preferred Louisiana. He remembered how unconcernedly that young man had waited until he and his horse were fed and rested, though he must have known that Death was on his trail. And how he had laughed and petted Marian. There was good in the boy, he decided, though, now he had started on his career as a killer, his end would probably be tragic. Ike had no desire at any rate to hasten it.

Nor, as a matter of fact, had the posse. Their courage had cooled during the long ride from Sulphur Falls as the whisky had evaporated from their systems. They were by no means exceedingly anxious 19 to catch up with and encounter what was reputed to be the fastest gun in southern Idaho.

“Whatever starts this hostile play?” asked Ike of the leader of the posse.

“This here Louisiana, I gather, gets in a mix-up with Snake,” the officer explained rather languidly. “I ain’t there and I don’t know the rights of it myself. As near as I can figure it Lizzie takes a shine to him which he don’t reciprocate none. There is some words between them and Liz sets up a holler to Snake about this hombre insultin’ of her.”

“Insultin’ Lizzie Lewis?” said Ike, mildly surprised. “I’d sure admire to hear how he done it.”

“Well, Liz is a female, nohow, and in any case Snake allows it’s his play to horn in. Which he does with a derringer. He’s just givin’ it a preliminary wave or two and preparin’ his war song according to Hoyle when Louisiana smokes him up a plenty.”

“I reckon Snake starts it, then,” remarked Ike.

“You might say so. But rightfully speakin’ he don’t never actually get started, Snake don’t. He is just informin’ the assembly what his war plans are when Louisiana cracks down on him and busts his shootin’ arm. But this Louisiana has done frightened a lady a whole lot and that’s as good an excuse to get him as any.”

“Well,” said Ike, dryly, “the gent went by here maybe two hours gone headin’ south. He was 20 goin’ steady but he don’t seem worried none as I noticed. If you want him right bad I reckon you can run him down. As for me I’m plumb neutral in this combat. I ain’t lost no Louisiana.”

Members of the posse looked at each other, glanced to the south where the gray expanse of sage presented an uninviting vista, fidgeted a little and, one by one, swung down from their saddles. The officer observed his deputies and finally followed them in dismounting.

“I reckon you’re about right,” he said. “This here buckaroo has got a good start and we ain’t none too fresh. You got a bunk house here where we can hole up for the night?”

Ike nodded his assent, noting that the posse seemed relieved at the prospect of abandoning the chase. In the morning they headed back the way they had come.

French Pete had not appeared on the following day, although he was due, and Brandon decided that he would ride south and meet him. Leaving Marian in charge of the Mexican woman, he took a pack horse and rode away, making the Wallace Ranch at Willow Spring that evening. Although Wallace was a cattleman with an enmity toward Brandon’s fraternity, it did not extend to Ike himself, and he was made welcome by the rancher and his wife. Wallace’s freckle-faced son, a lad of five years, who was known among his vaqueros as “Sucatash,” was 21 the other member of the family. Ike, who was fond of children, entertained this youngster and made a rather strong impression on him.

On the following morning the sheepman saddled up and packed and got away at a fairly early hour. He headed toward the Esmeraldas, pointing at the break in the mountain wall where Shoestring Cañon flared out on the plains, affording an entry to the range. This was the logical path that the sheep-herders followed in crossing the range and, indeed, the only feasible one for many miles in either direction, though there was a fair wagon road that ran eastward and flanked that end of the range, leading to Maryville on the other side of the mountains, where the county seat was located.

But Ike rode until noon without seeing a sign of his missing herder and his sheep. French Pete should have entered the plains long before this, but, as yet, Ike was not alarmed. Many things might occur to delay the flock, and it was impossible to herd sheep on hard and fast schedules.

As he rode Ike looked at the trail for signs of passing horsemen, but he noted no tracks that resembled those of Louisiana, which he had observed for some distance after he had left the ranch at Twin Forks. Just where they had left the trail and disappeared he had not noted, having but an idle interest in them after all. He had not seen them for many miles before reaching Willow Spring, he 22 remembered. This fact gave no clew to the direction the man had taken, of course, since, being pursued, he would naturally leave the trail at some point and endeavor to cover his sign. He might have continued south as he had started or he might have doubled back.

At about one o’clock in the afternoon, as he was approaching the gap that opened into Shoestring, Ike saw, far ahead, a group on the trail. There seemed to be a wagon around which several men were standing. The wagon resembled one of his own camp equipages, and he spurred up his horse and hastened forward with some idea that the cow-punchers might be attacking it.

As he came nearer, however, one of the men swung into his saddle and headed back toward him at a gallop. Ike drew the rifle from its scabbard under his knee and went more cautiously. The man came on at a hard run, but made no hostile move, and when he was near enough Ike saw that he was not armed. He shoved the rifle back beneath his knee, as the rider set his horse on its haunches beside him.

“Ike Brandon?” the man asked, excitedly, as he reined in. “Say, Ike, that Basco ewe-whacker o’ yours is back there a ways and plumb perforated. Some one shore up and busted him a plenty with a soft-nose thirty. We’re ridin’ for Wallace, and we found him driftin’ along in the wagon a while back. 23 I’m ridin’ for a medicine man, but I reckon we don’t get one in time.”

“Who done it?” asked Ike, grimly. The cow-puncher shook his head.

“None of us,” he said, soberly. “We ain’t any too lovin’ with sheep-herders, but we ain’t aimin’ to butcher ’em with soft-nose slugs from behind a rock, neither. We picks him up a mile or two out of Shoestring and his hoss is just driftin’ along no’th with him while he’s slumped up on the seat. There ain’t no sheep with him.”

Ike nodded thoughtfully. “None o’ you-all seen anythin’ of Louisiana driftin’ up this a way?” he asked.

“Gosh, no!” said the rider. “You pickin’ Louisiana? He’s a bad hombre, but this here don’t look like his work.”

“Pete’s rifle with him?” asked Ike.

The man nodded. “It ain’t been fouled. Looks like he was bushwacked and didn’t have no chance to shoot.”

Ike picked up his reins, and the man spurred his horse off on his errand. The sheepman rode on and soon met the wagon being escorted by two more cowboys while a third rode at the side of the horses, leading them. They stopped as Ike rode up, eying him uncomfortably. But he merely nodded, with grim, set face, swung out of his saddle as they pulled 24 up, and strode to the covered vehicle, drawing the canvas door open at the back.

On the side bunk of the wagon where the cowboys had stretched him, wrapped in one of his blankets, lay the wounded man, his face, under the black beard, pale and writhen, the eyes staring glassily and the lips moving in the mutterings of what seemed to be delirium. Ike climbed into the wagon and bent over his employee, whose mutterings, as his glazing eyes fell on his master’s face, became more rapid. But he talked in a language that neither Ike nor any of the men could understand.

With a soothing word or two, Ike drew the blanket down from Pete’s chest and looked at the great stain about the rude bandage which had been applied by the men who had found him. One glance was enough to show that Pete was in a bad way.

“Lie still!” said Ike, kindly. “Keep your shirt on, Pete, and we’ll git you outa this pretty soon.”

But Pete was excited about something and insisted on trying to talk, though the froth of blood on his lips indicated the folly of it. In vain Ike soothed him and implored him to rest. His black eyes snapped and his right hand made feeble motions toward the floor of the wagon where, on a pile of supplies and camp equipment, lay a burlap sack containing something lumpy and rough.

“Zose sheep—and zose r-rock!” he whispered, shifting to English mixed with accented French. 25 “Pour vous—et le bébé! Le p’tit bébé an’ she’s mère—France—or——”

“Never mind the sheep,” said Ike. “You rough-lock your jaw, Pete, an’ we’ll take care o’ the sheep. Lie still, now!”

But Pete moaned and turned his head from side to side with his last strength.

“Mais—mais oui! ze sheep!” He again stuttered words meaningless to his hearers who, of course, had no Basque at command. But here and there were words of English and French, and even some Spanish, which most of them understood a little.

“Ze r-rock—pierre—or! Eet eez to you et le bébé one half. Ze res’ you send—you send heem—France—pour ma femme—mi esposa an’ ze leet-leetla one? Mi padron—you do heem?”

“What’s he drivin’ at?” muttered one of the cowboys. But Ike motioned them to proceed and drive as fast as possible toward Willow Spring. He bent toward the agitated herder again.

“I’ll take care of it, Pete,” he assured him. “Don’t worry none.”

But Pete had more on his mind. He groped feebly about and whined a request which Ike finally understood to be for paper and a pencil. He looked about but found nothing except a paper bag in which were some candles. These he dumped out and, to pacify the man, handed the paper to him with his own pencil. It was evident that Pete would not rest until 26 he had had his way, and if he was crossed further his excitement was bound to kill him almost at once. In obedience to Pete’s wishes Ike lifted him slightly and held him up while he wrote a few scrawling, ragged characters on the sack. Almost illegible, they were written in some language which Ike knew nothing about but, at the bottom of the bag Pete laboriously wrote a name and address which Ike guessed was that of his wife, in the far-off Basse Pyrenean province of France.

“I’ll see it gits to her,” said Ike, reassuringly. But Pete was not satisfied.

“Zose or,” he repeated, chokingly. “I find heem—on ze Lunch R-rock, where I step. Eet ees half to you an’ lettl’ Marian—half to ma femme an’ ze bébé. You weel find heem?”

“Ore?” repeated Ike, doubtingly. “You talking French or English?”

“Or! Oui! Een Englees eet ees gol’, you say! I find heem—back zere by ze Lunch R-rock. Zen some one shoot—I no see heem! I not know w’y. One ‘bang!’ I hear an’ zat ees all. Ze wagon run away, ze sheep are los’, an’ I lose ze head!”

“Ore!” repeated Ike, blankly. “You found gold, is that what you’re telling me? Where?”

“Back—back zere—by ze Lunch Rock where I eat! Much or—gold! I find heem an’ half is yours!”

“That’s all right,” soothed Ike, thinking the man 27 was crazy. “You found a lot of gold and half is mine and Marian’s, while the rest goes to your folks? That’s it, ain’t it?”

Pete nodded as well as he could and even tried to grin his satisfaction at being understood, waving a feeble hand again in the direction of the burlap sack. But his strength was gone and he could not articulate any more. Pretty soon, as the wagon jolted onward, he relapsed into a coma, broken only by mutterings in his native and incomprehensible tongue. By his side Ike sat, vainly wondering who had shot the man and why. But Pete, if he knew, was past telling. To the story of gold, Ike paid hardly any heed, not even taking the trouble to look into the sack.

After a while the mutterings ceased, while his breathing grew more labored and uneven. Then, while Willow Spring was still miles away, he suddenly gasped, choked, and writhed beneath the blanket. The blood welled up to his lips, and he fell back and lay still.

Ike, with face twisted into lines of sorrow, drew the blanket over the man’s head and sat beside his body with bowed face.

As they rode he pondered, endeavoring to search out a clew to the perpetrator of the murder, certainly a cold-blooded one, without any provocation. Pete’s rifle, the cowboys had said, was clean and therefore had not been fired. Furthermore, the wound was in 28 the back. It had been made by a mushrooming bullet, and the wonder was that the man had lived at all after receiving it.

He questioned the cowboys. They knew nothing except that Pete had been found about two miles down on the plain from Shoestring and that his sheep were, presumably, somewhere up the cañon. When Ike sought to know who was in the Esmeraldas, they told him that they had been riding the range for a week and had encountered no one but Pete himself, who, about five days back, had driven into the cañon on his way through the mountains. They had seen nothing of Louisiana, nor had they cut his trail at any time.

The wound showed that it had been recently made; within twelve hours, certainly. But the horses had traveled far in the time given them. One of Wallace’s riders had ridden back up the cañon to search for possible clews and would, perhaps, have something to say when he returned.

They finally arrived at Wallace’s ranch, and found there a doctor who had come from a little hamlet situated to the east. His services were no longer of avail, but Ike asked him to extract the bullet, which he did, finding it to be an ordinary mushroomed ball, to all appearance such as was shot from half the rifles used in that country. There was no clew there, and yet Ike kept it, with a grim idea in the back of his mind suggested by tales which Pete had 29 often told of smuggling and vendettas among the Basques of the border between Spain and France.

It was when the sack was opened, however, that the real sensation appeared to dwarf the excitement over the murder of the sheep-herder. It was found to contain a number of samples of rock in which appeared speckles and nuggets of free gold, or what certainly looked like it. On that point the doubt was settled by sending the samples to an assayer, and his report left nothing to be desired. He estimated the gold content of the ore to be worth from fifty to eighty thousand dollars a ton.

The coroner’s inquest, at Maryville, was attended by swarms, who hoped to get from the testimony some clew to the whereabouts of the mine. But many did not wait for that. Before the assayer’s report had been received there were prospectors hurrying into the Esmeraldas and raking Shoestring Cañon and the environs. It was generally thought that the Bonanza lay on the southern side of the range, however, and on that side there were many places to search. Pete might have taken almost any route to the top of the divide, and there were very few clews as to just where he had entered the mountains and how he had reached the cañon.

Nor did the inquest develop anything further except the fact that Wallace’s cow-puncher, who had ridden back up the cañon after finding Pete, had found the spot where he had been shot, about five 30 miles from the exit on the plain, but had failed to discover anything indicating who had done it. Other searchers also reported failure. There had been burro tracks of some prospector seen at a point about six miles from the cañon, but nothing to show that the owner of them had been in that direction.

The verdict was characteristic. Louisiana’s exploit had been noised about; it was known that he was heading for the Esmeraldas when last seen, and the fact that he was a gunman, or reputed to be one, furnished the last bit of evidence to the jurors. No one else had done it, and therefore Louisiana, who had quit the country, must have been the culprit. In any event, he was a bad man and, even if innocent of this, was probably guilty of things just as bad. Therefore a verdict was returned against Louisiana, as the only available suspect.

Ike Brandon, after all, was the only person who cared much about the fate of a sheep-herder, who was also a foreigner. Every one else was chiefly interested in the gold mine. Ike offered a reward of five hundred dollars, and the obliging sheriff of the county had handbills printed in which, with characteristic directness, Louisiana was named as the suspect.

The mountains swarmed for a time with searchers who sought the gold Pete had found. It remained hidden, however, and, as time passed, interest died out and the “Lunch Rock” was added to the long list 31 of “lost mines,” taking its place by the side of the Peg Leg and others.

Ike wrote to Pete’s wife in France and sent her his last message. With it went a sample of the ore and the bullet that had killed Pete. Ike reasoned that some of his relatives might wish to take up the hunt and would be fortified by the smashed and distorted bullet. 32

The general of division, De Launay, late of the French army operating in the Balkans and, before that, of considerable distinction on the western front, leaned forward in his chair as he sat in the Franco-American banking house of Doolittle, Rambaud & Cie. in Paris. His booted and spurred heels were hooked over the rung of the chair, and his elbows, propped on his knees, supported his drooping back. His clean-cut, youthful features were morose and heavy with depression and listlessness, and his eyes were somewhat red and glassy. Under his ruddy tan his skin was no longer fresh, but dull and sallow.

Opposite him, the precise and dapper Mr. Doolittle, expatriated American, waved a carefully manicured hand in acquired Gallic gestures as he expatiated on the circumstances which had summoned the soldier to his office. As he discoursed of these extraordinary matters his sharp eyes took in his client and noted the signs upon him, while he speculated on their occasion.

The steel-blue uniform, which should have been immaculate and dashing, as became a famous cavalry 33 leader, showed signs of wear without the ameliorating attention of a valet. The leather accouterments were scratched and dull. The boots had not been polished for more than a day or two and Paris mud had left stains upon them. The gold-banded képi was tarnished, and it sat on the warrior’s hair at an angle more becoming to a recruit of the class of ’19 than to the man who had burst his way through the Bulgarian army in that wild ride to Nish which marked the beginning of the end of Armageddon.

The banker, though he knew something of the man’s history, found himself wondering at his youthfulness. Most generals, even after nearly five years of warfare, were elderly men, but this fellow looked as much like a petulant boy as anything. It was only when one noted that the hair just above the ears was graying and that there were lines about the eyes that one recalled that he must be close to forty years of age. His features failed to betray it and his small mustache was brown and soft.

Yet the man had served nearly twenty years and had risen from that unbelievable depth, a private in the Foreign Legion, to the rank of general of division. That meant that he had served five years in hell, and, in spite of that, had survived to be sous-lieutenant, lieutenant, capitaine, and commandant during the grueling experience of nine more 34 years of study and fighting in Africa, Madagascar, and Cochin China.

A man who has won his commission from the ranks of the Foreign Legion is a rarity almost unheard of, yet this one had done it. And he had been no garrison soldier in the years that had followed. To keep the spurs he had won, to force recognition of his right to command, even in the democratic army of France, the erstwhile outcast had had to show extraordinary metal and to waste no time in idleness. He was, in a peculiar sense, the professional soldier par excellence, the man who lived in and for warfare.

He had had his fill of that in the last four years, yet he did not seem satisfied. Of course, Mr. Doolittle had heard rumors, as had many others, but they seemed hardly enough to account for De Launay’s depression and general seediness. The man had been reduced in rank, following the armistice, but so had many others; and he reverted no lower than lieutenant colonel, whereas he might well have gone back another stage to his rank when the war broke out. To be sure, his record for courage and ability was almost as extraordinary as his career, culminating in the wild and decisive cavalry dash that had destroyed the Bulgarian army and, in any war less anonymous than this, would have caused his name to ring in every ear on the boulevards. Still, there were too many generals in the army to 35 find place in a peace establishment, and many a distinguished soldier had been demoted when the emergency was over.

Moreover, not one that Mr. Doolittle had ever heard of had been presented with such compensation as had this adventurer. High rank, in the French army, means a struggle to keep up appearances, unless one is wealthy, for the pay is low. A lower rank, when one has been unexpectedly raised to unlimited riches, would be far from insupportable, what with the social advantages attendant upon it.

This was what Doolittle, with a kindly impulse of sympathy, was endeavoring tactfully to convey to the military gentleman. But he found him unresponsive.

“There’s one thing you overlook, Doolittle,” De Launay retorted to his well-meant suggestions. The banker, more used to French than English, felt vaguely startled to find him talking in accents as unmistakably American as had been his own many years ago, though there was something unfamiliar about it, too—a drawl that was Southern and yet different. “Money’s no use to me, none whatever! I might have enjoyed it—or enjoyed the getting of it—if I could have made it myself—taken it away from some one else. But to have it left to me like this after getting along without it for twenty years and more; to get it through a streak of tinhorn 36 luck; to turn over night from a land-poor Louisiana nester to a reeking oil millionaire—well, it leaves me plumb cold. Anyway, I don’t need it. What’ll I do with it? I can’t hope to spend it all on liquor—that’s about all that’s left for me to spend it on.”

“But, my dear general!” Doolittle found his native tongue rusty in his mouth, although the twenty-year expatriate, who had originally been of French descent, had used it with the ease of one who had never dropped it. “My dear general! Even as a lieutenant colonel, the social advantages open to a man of such wealth are boundless—absolutely boundless, sir! And if you are ambitious, think where a man as young as you, endowed with these millions, can rise in the army! You have ability; you have shown that in abundance, and, with ability coupled to wealth, a marshal’s baton is none too much to hope for.”

De Launay chuckled mirthlessly. “Tell it to the ministry of war!” he sneered. “I’ll say that much for them: in France, to-day, money doesn’t buy commands. Besides, I wouldn’t give a lead two-bit piece for all the rank I could come by that way. I fought for my gold braid—and if they’ve taken it away from me, I’ll not buy it back.”

“There will be other opportunities for distinction,” said Mr. Doolittle, rather feebly.

“For diplomats and such cattle. Not for soldiers. There was a time when I had ambition—there are 37 those who say I had too much—but I’ve seen the light. War, to-day, isn’t what it used to be. It’s too big for any Napoleon. It’s too big for any individual. It’s too big for any ambition. It’s too damn big to be worth while—for a man like me.”

Mr. Doolittle was puzzled and said so.

“Well, I’ll try to make it clear to you. When I started soldiering, it was with the idea that I’d make it a life work. I had my dreams, even when I was a degraded outcast in the Legion. I pursued ’em. They were high dreams, too. They are right in suspecting me of that.

“For a good many years it looked as though they might be dreams that I could realize. I’m a good soldier, if I do say it myself. I was coming along nicely, in spite of the handicap of having come from the dregs of Sidi-bel-Abbes up among the gold stripes. And I came along faster when the war gave me an opportunity to show what I could do. But, unfortunately for me, it also presented to me certain things neither I nor any other man could do.

“You can’t wield armies like a personal weapon when the armies are nations and counted in millions. You can’t build empires out of the levy en masse. You can’t, above all, seize the imagination of armies and nations by victories, sway the opinions of a race, rise to Napoleonic heights, unless you can get advertising—and nowadays a kid aviator who downs his fifth enemy plane gets columns of it while nobody 38 knows who commands an army corps outside the general staff—and nobody cares!

“Where do you get off under those circumstances? I’ll tell you. You get a decoration or two, temporary rank, mention in the Gazette—and regretful demotion to your previous rank when the war is over.

“War, Mr. Doolittle, isn’t half the hell that peace is—to a fellow like me. Peace means the chance to eat my heart out in idleness; to grow fat and gray and stupid; to—oh! what’s the use! It means I’m through—through at forty, when I ought to be rounding into the dash for the final heights of success.

“That’s what’s the trouble with me. I’m through, Mr. Doolittle; and I know it. That’s why I look like this. That’s why money means nothing to me. I don’t need it. Once I was a cow-puncher, and then I became a soldier and finally a general. Those are the things I know, and the things I am fit for, and money is not necessary to any of them.

“So I’m through as a soldier, and I have nothing to turn back to—except punching cows. It’s a comedown, Mr. Doolittle, that you’d find it hard to realize. But I realize it, you bet—and that’s why I prefer to feel sort of low-down, and reckless and don’t-give-a-damnish—like any other cow hand that’s approaching middle age with no future in front of him. That’s why I’m taking to drink after twenty years 39 of French temperance. The Yankees say a man may be down but he’s never out. They’re wrong. I’m down—and I’m out! Out of humor, out of employment, out of ambition, out of everything.”

“That, if you will pardon me, general, is ridiculous in your case,” remonstrated the banker. “What if you have decided to leave the army—which is your intention, I take it? There is much that a man of wealth may accomplish; much that you may interest yourself in.”

De Launay shook a weary head.

“You don’t get me,” he asserted. “I’m burned out. I’ve given the best of me to this business—and I’ve realized that I gave it for nothing. I’ve spent myself—put my very soul into it—lived for it—and now I find that I couldn’t ever have accomplished my ambition, even if I’d been generalissimo itself, because such ambitions aren’t realized to-day. I was born fifty years too late.”

Mr. Doolittle clung to his theme. “Still, you owe something to society,” he said. “You might marry.”

De Launay laughed loudly. “Owe!” he cried. “Such men as I am don’t owe anything to any one. We’re buccaneers; plunderers. We levy on society; we don’t owe it anything.

“As for marrying!” he laughed again. “I’d look pretty tying myself to a petticoat! Any woman would have a fit if she could look into my nature. 40 And I hate women, anyway. I’ve not looked sideways at one for twenty years. Too much water has run under the bridge for that, old-timer. If I was a youngster, back again under the Esmeraldas——”

He smiled reminiscently, and his rather hard features softened.

“There was one then that I threatened to marry,” he chuckled. “If they made ’em like her——”

“Why don’t you go back and find her?”

De Launay stared at him. “After twenty years? Lord, man! D’you think she’d wait and remember me that long? Especially as she was about six years old when I left there! She’s grown up and married now, I reckon, and she’d sick the dogs on me if I came back with any such intentions.”

He chuckled again, but his mirth was curiously soft and gentle. Doolittle had little trouble in guessing that this memory was a tender one.

But De Launay rose, picked up a bundle of notes that lay on the table in front of him, stuffed them carelessly into the side pocket of his tunic and pushed the képi still more recklessly back and sideways.

“No, old son!” he grinned. “I’m not the housebroke kind. The only reason I’d ever marry would be to win a bet or something like that. Make it a sporting proposition and I might consider it. Meantime, I’ll stick to drink and gambling for the remaining days of my existence.” 41

Doolittle shook his head as he rose. “At any rate,” he said, regretfully, “you may draw to whatever extent you wish and whenever you wish. And, if America should call you again, our house in New York, Doolittle, Morton & Co., will be happy to afford you every banking facility, general.”

De Launay waved his hand. “I’ll make a will and leave it in trust for charity,” he said, “with your firm as trustee. And forget the titles. I’m nobody, now, but ex-cow hand, ex-gunman, once known as Louisiana, and soon to be known no more except as a drunken souse. So long!”

He strode out of the door, swaggering a little. His képi was cocked defiantly. His legs, in the cavalry boots, showed a faint bend. He unconsciously fell into a sort of indefinable, flat, stumping gait, barely noticeable to one who had never seen it before, but recognizable, instantly, to any one who had ridden the Western range in high-heeled boots.

In some indefinable manner, with the putting off of his soldierly character, the man had instantly reverted twenty years to his youth in a roping saddle. 42

In the hands of Doolittle, Rambaud & Cie., was a rather small deposit, as deposits went with that distinguished international banking house. It had originally amounted to about twenty thousand francs when placed with them about the beginning of the war and was in the name of Mademoiselle Solange d’Albret, whose place of nativity, as her dossier showed, was at a small hamlet not far from Biarritz, in the Basse Pyrenees, and her age some twenty-two years at the present time. Her occupation was given as gentlewoman and nurse, and her present residence an obscure street near one of the big war hospitals. The personality of Mademoiselle d’Albret was quite unknown to her bankers, as she had appeared to them very seldom and then only to add small sums to her deposit, which now amounted to about twenty-five thousand francs in all. She never drew against it.

Such a sum, in the hands of an ordinary Frenchwoman would never have remained on deposit for that length of time untouched, but, if not needed, would have been promptly invested in rentes. The unusualness of this fact, however, had not disturbed the bankers and had, in fact, been of so little importance 43 that they had failed to notice it at all. When, therefore, a young woman dressed in a nurse’s uniform appeared at the bank and rather timidly asked to see Mr. Doolittle, giving the name of Mademoiselle d’Albret, there was some hesitancy in granting her request until a hasty glance at the state of her account confirmed the statement that she was a considerable depositor.

Mr. Doolittle, informed of her request, sighed a little, under the impression that he was about to be called upon for detailed advice and fatherly counsel in the investment of twenty-five thousand francs. He pictured to himself some thrifty, suspicious Frenchwoman with a small fortune who would give him far more trouble than any millionaire who used his bank, and whose business could and would actually be handled by one of his clerks, whom she might as well see in the first place without bothering him. As well, however, he knew that she would never consent to see anybody but himself. Somewhat wearily, but with all courtliness of manner, he had her shown into his consultation room.

Mademoiselle d’Albret entered, her nurse’s cloak draped gracefully from her shoulders, the little, nunlike cap and wimple hiding her hair, while a veil concealed her face to some extent. Through its meshes one could make out a face that seemed young and pretty, and a pair of great, dark eyes. Her figure also left nothing to be desired, and she 44 carried herself with grace and easy dignity. Mr. Doolittle, who had an eye for female pulchritude, ceased to regret the necessity of catering to a customer’s whim and settled himself to a pleasant interview after rising to bow and offer her a chair.

“Mademoiselle has called, I presume, about an investment,” he began, ingratiatingly. “Anything that the bank can do in the way of advice——”

“Of advice, yes, monsieur,” broke in mademoiselle, speaking in a clear, bell-like voice. “But it is not of an investment that I have need. On the contrary, the money which you have so faithfully guarded for me during the years of the war is reserved for a purpose which I fear you would fail to approve. I have come to arrange with you to transfer the account to America and to seek your assistance in getting there myself.”

The account had been profitable to the bank in the years it had lain idle there, the lady was good to look upon and, even if the account was to be lost, he felt benevolent toward her. Besides, her voice and manner were those of a lady, and natural courtesy bade him extend to her all the aid he could. Therefore he smiled acquiescence.

“The transfer of the money is a simple matter,” he stated. “A draft on our house in New York, or a letter of credit—it is all one. They will gladly serve you there as we have served you here. But 45 if you wish to follow your money—that, I fear, is a different matter.”

“It is because it is different—and difficult—that I have ventured to intrude upon you, monsieur, and not for an idle formality. It is necessary that I get to America, to a place called Eo-dah-o—is it not? I do not know how to say it?”

“Spell it,” suggested the tactful Doolittle.

Mademoiselle spelled it, and Doolittle gave her the correct pronunciation with a charming smile which she answered.

“Ah, yes! Idaho! It is, I believe, at some distance from New York, perhaps a night and a day even on the railroad.”

“Or even more,” said Doolittle. “Mademoiselle speaks of America, and that is a large country. From New York to Idaho is as far as from Paris to Constantinople—or even farther. But I interrupt. Mademoiselle would go to Idaho, and for what purpose?”

“It is there, I fear, that the difficulty lies,” said mademoiselle with frankness. “It is necessary, I presume, that one have a purpose and make it known?”

“It is not, so far as permission to go is concerned, although the matter of a passport may be difficult to arrange. But there is the further question of passage.” 46

“And it is precisely there that I seek monsieur’s advice. How am I to secure passage to America?”

Doolittle was on the point of insinuating that a proper use of her charms might accomplish much in certain quarters, but there was something so calmly virginal and pure about the girl as she sat there in her half-sacred costume that instinct conquered cynicism and he refrained. Unattached and unchaperoned as she was, or appeared to be, the girl commanded respect even in Paris. Instead of answering at once he reflected.

“Do you know any one in America?” he asked.

“No one,” she replied. “I am going to find some one, but I do not even know who it is that I seek. Furthermore, I am going to bring that some one to his death if I can do so.”

She was quite calm and matter-of-fact about this statement, and therefore Mr. Doolittle was not quite so astounded as he might otherwise have been. He essayed a laugh that betrayed little real mirth.

“Mademoiselle jests, of course?”

“Mademoiselle is quite serious, I assure you, and not at all mad. I will be brief. Twenty years ago, nearly, my father was murdered in America after discovering something that would have made him wealthy. His murderer was never brought to justice, and the thing he found was lost again. We are Basques, we d’Albrets, and Basques do not forget an injury, as you may know. I am the last of his 47 family, and it is my duty, therefore, to take measures to avenge him. After twenty years it may be difficult, and yet I shall try. I should have gone before, but the war interrupted me.”

“And your fortune, which is on deposit here?” asked the curious Mr. Doolittle.

“Has been saved and devoted to that purpose. My mother left it to me after providing for my education—which included the learning of English that I might be prepared for the adventure. The war is over—and I am ready to go.”

“Hum!” said Doolittle, a little dazed. “It is an extraordinary affair, indeed. After twenty years—to find a murderer and to kill him. It is not done in America.”

“Then I will be the first to do it,” said the young woman, coolly.

“But there is no possibility—there is no possible way in which you could secure passage with such a story, mademoiselle. Accommodations are scarce, and one must have the most urgent reasons before one can secure them. Every liner is a troopship, filled with returning soldiers, and the staterooms are crowded with officers and diplomats. Private errands must yield to public necessities and, above all, such exceedingly private and personal errands as you have described. Instead of allowing you to sail, if you told this story, they would put you under surveillance.” 48

“Exactly,” said mademoiselle. “Therefore I shall not tell it. It remains, therefore, that I shall get advice from you to solve my dilemma.”

“From me!” gasped the helpless Doolittle; “how can I help solve it?”

Yet, even as he said this, he recalled his client of the previous day and his strange story and personality. Here, indeed, were a pair of lunatics, male and female, who would undoubtedly be well mated. And why not? The soldier needed something to jolt him out of his despondency, to occupy his energy—and he was American. A reckless adventurer, no matter how distinguished, was just the sort of mate for this wild woman who was bent on crossing half the earth to conduct a private assassination. Mr. Doolittle, in a long residence in France, had acquired a Gallic sense of humor, a deep appreciation of the extravagant. It pleased him to speculate on the probable consequences of such a partnership, the ex-légionnaire shepherding the Pyrenean wild cat who was yet an aristocrat, as his eyes plainly told him. He had an idea that the American West was as wild and lawless as it had ever been, and it pleased him to speculate on what might happen to these two in such a region. And, come to think about it, De Launay had referred to himself as having been a cowboy at one time, before becoming a soldier. That made it even more deliciously suitable. He also recalled having made a suggestion to the general 49 which had been met with scorn. And yet, the man had said that he would gamble on anything. If it were made what he called a “sporting proposition” he might consider it.

“How can I help solve it?” And even as he said it again, he knew that here was a possible solution.

“I see no way except that you should marry a returning American soldier,” he said, at last, while she stared at him through her veil, her deep eyes making him vaguely uncomfortable.

“Marry a soldier—an American! Me, Morgan la fée, espouse one of these roistering, cursing foreigners? Monsieur, you speak with foolishness!”

“Morgan la fée!” Doolittle gasped. “Mademoiselle is——”

“Morgan la fée in the hospitals,” answered Solange d’Albret icily. “Monsieur has heard the name?”

“I have heard it,” said Doolittle feebly. He had, in common with a great many other people. He had heard that the poilus had given her the name in some fanatic belief that she was a sort of fairy ministering to them and bringing them good luck. They gave her a devout worship and affection that had guarded her like a halo through all the years of the war. But she had not needed their protection. It was said that a convalescent soldier had once offered her an insult, a man she herself had nursed. She had knifed him as neatly as an apache could have done and other soldiers had finished the 50 job before they could be interfered with. French law had, for once, overlooked the matter, rather than have a mutiny in the army. Doolittle began to doubt the complete humor in his idea, but its dramatic possibilities were enhanced by this revelation. Of course this spitfire would never marry a common soldier, either American or of any other race. He did not doubt that she claimed descent from the Navarrese royal family and the Bourbons, to judge from her name. But then De Launay was certainly not an ordinary soldier. His very extraordinariness was what qualified him in Doolittle’s mind. The affair, indeed, began to interest him as a beautiful problem in humanity. De Launay was rich, of course, but he did not believe that mademoiselle was mercenary. If she had been she would not have saved her inheritance for the purpose of squandering it on a wild-goose chase worthy of the “Arabian Nights.” Anyway De Launay had no use for money, and mademoiselle probably had. However, he had no intention of telling her of De Launay’s situation. He had a notion that Morgan la fée would be driven off by that knowledge.

“But, mademoiselle, it is not necessary that you marry a rough and common soldier. Surely there are officers, gentlemen, distinguished, whom one of your charms might win?”

“We will not bring my charms into the discussion, monsieur,” said Solange. “I reject the idea that I 51 should marry in order to get to America. I have serious business before me, and not such business as I could bring into a husband’s family—unless, indeed, he were a Basque. But, then, there are no Basques whom I could marry.”

“I wouldn’t suggest a Basque,” said Doolittle. “But I believe there is one whom you could wed without compromising your intentions. Indeed, I believe the only chance you would have to marry him would be by telling him all about them. He is, or was, an American, it is true, but he has been French for many years and he is not a common soldier. I refer to General de Launay.”

“General de Launay!” repeated Solange wonderingly. “Why, he is a distinguished man, monsieur!”

“It would be more correct to say that he was a distinguished man,” said Doolittle, smiling at the recollection of the general as he had last seen him. “He has been demoted, as many others have been, or will be, but he has not taken it in good part. He is a reckless adventurer, who has risen from the ranks of the Legion, and yet—I believe that he is a gentleman. He has, I regret to say, taken to—er—drink, to some extent, out of disappointment, but no doubt the prospect of excitement would restore him to sobriety. And he has told me that he might marry—if it were made a sporting proposition.”

“A sporting proposition! Mon Dieu! And is such 52 a thing their idea of sport? These Americans are mad!”

“They might say the same of you, it seems to me,” said the banker dryly. “At any rate there it stands. The general might agree as a sporting proposition. Married to the general there should be no difficulty in securing passage to America. After you get to America the matter is in your hands.”

“But I should be married to the general,” exclaimed Solange in protest. Doolittle waved this aside.

“The general would, I believe, regard the marriage merely as an adventure. He does not like women. As for the rest, marriage, in America, is not a serious matter. A decree of divorce can be obtained very easily. If this be regarded as a veritable mariage de convenance, it should suit you admirably and the general as well.”

“He would expect to be paid?”

“Well, I can’t say as to that,” said Doolittle, smiling as he thought of De Launay’s oil wells. “He might accept pay. But he is as likely to take it on for the chance of adventure. In any event, I imagine that you are prepared to employ assistance from time to time.”

“That is what the money is for,” said Solange candidly. “I have even considered at times employing an assassin. It is a regrettable fact that I hesitate to kill any one in cold blood. It causes me to 53 shudder, the thought of it. When I am angry, that is a different matter, but when I am cold, ah, no! I am a great coward! This General de Launay, would he consider such employment, do you think?”

“Judging from his reputation,” said Doolittle, “I don’t believe he would stop at anything.”

Solange knew something of De Launay and Doolittle now told her more. Before he had finished she was satisfied. She rose with thanks to him and then requested the general’s address.

“I think you’ll find him,” he referred to a memorandum on his desk, “at the café of the Pink Kitten, which is in Montmartre. It is there that he seems to make his headquarters since he resigned from the army.”

“Monsieur,” said Solange, gratefully, “I am indeed indebted to you.”

“Not at all,” said Doolittle as he bowed her out. “The pleasure has been all mine.” 54

Louis de Launay, once known as “Louisiana” and later, as a general of cavalry, but now a broken man suffering from soul and mind sickness, was too far gone to give a thought to his condition. Thwarted ambition and gnawing disappointment had merely been the last straw which had broken him. His real trouble was that strange neurosis of mind and body which has attacked so many that served in the war. Jangled nerves, fibers drawn for years to too high a tension, had sagged and grown flabby under the sudden relaxation for which they were not prepared.

His case was worse than others as his career was unique. Where others had met the war’s shocks for four years, he had striven titanically for nearly a score, his efforts, beginning with the terrible five-year service in the Légion des Etrangers, culminating in ever-mounting strain to his last achievement and then—sudden, stark failure! He was, as he had said, burned out, although he was barely thirty-nine years old. He was a man still young in body but with mind and nerves like overstrained rubber from which all resilience has gone. 55

His uniform was gone. Careless of dress or ornamentation, he had sunk into roughly fitting civilian garb of which he took no care. Of all his decorations he clung only to the little red rosette of the Legion of Honor. Half drunk, he lolled at a table in a second-class café. He was in possession of his faculties; indeed, he seldom lost them, but he was dully indifferent to most of what went on around him. Before him was stacked a respectable pile of the saucers that marked his indebtedness for liquor.

When the cheerful murmur of his neighbors suddenly died away, he looked around, half resentfully, to note the entrance of a woman.

“What is it?” he asked, irritably, of a French soldier near him.

The Frenchman was smiling and answered without taking his eyes from the woman, who was now moving down the room toward them.

“Morgan la fée,” he answered, briefly.

“Morgan—what the deuce are you talking about?”

“It is Morgan la fée,” reiterated the soldier, simply, as though no other explanation were necessary.

De Launay stared at him and then shifted his uncertain gaze to the figure approaching him. He was able to focus her more clearly as she stopped to reply to the proprietor of the place, who had hastened to meet her with every mark of respect. Men at the tables she passed smiled at her and murmured 56 respectful greetings, to which she replied with little nods of the head. Evidently she was a figure of some note in the life of the place, although it also seemed that as much surprise at her coming was felt as gratification.

She presented rather an extraordinary appearance. Her costume was the familiar one of a French Red Cross nurse, with the jaunty, close-fitting cap and wimple in white hiding her hair except for a few strands. Her figure was slender, lithe and graceful, and such of her features as were visible were delicate and shapely; her mouth, especially, being ripe and inviting.

But over her eyes and the upper part of her face stretched a strip of veiling that effectually concealed them. The mask gave her an air of mystery which challenged curiosity.

De Launay vaguely recalled occasional mention of a young woman favorably known in the hospitals as Morgan la fée. He also was familiar with the old French legend of Morgan and the Vale of Avalon, where Ogier, the Paladin of Charlemagne, lived in perpetual felicity with the Queen of the Fairies, forgetful of earth and its problems except at such times as France in peril might need his services, when he returned to succor her. He surmised that this was the nurse of whom he had heard, setting her down as probably some attractive, sympathetic girl whom the soldiers, sentimental and wounded, endowed with 57 imaginary virtues. He was not sentimental and, beholding her in this café, although evidently held in respect, he was inclined to be skeptical regarding her virtue.

The young woman seemed to have an object and it was surprising to him. She exchanged a brief word with the maître, declined a proffered seat at a table, and turned to come directly to that at which De Launay was seated. He had hardly time to overcome his stupid surprise and rise before she was standing before him. Awkwardly enough, he bowed and waited.

Her glance took in the table, sweeping over the stacked saucers, but, behind the veil, her expression remained an enigma.

She spoke in a voice that was sweet, with a clear, bell-like note.

“Le Général de Launay, is it not? I have been seeking monsieur.”

“Colonel, if mademoiselle pleases,” he answered. Then suspicion crept into his dulled brain. “Mademoiselle seeks me? Pardon, but I am hardly a likely object——”

She interrupted him with an impatient wave of a well-kept hand. “Monsieur need not be afraid. It is true that I have been seeking him, but my motive is harmless. If Monsieur Doolittle, the banker, has told me the truth——”

De Launay’s suspicions grew rapidly. “If Doolittle 58 has been talking, I can tell you right now, mademoiselle, that it is useless. What you desire I am not disposed to grant.”

Mademoiselle caught the meaning of the intonation rather than any in the words. Her inviting mouth curled scornfully. Her answer was still bell-like but it was also metallic and commanding.

“Sit down!” she said, curtly.

De Launay, who, for many years had been more used to giving orders than receiving them, at least in that manner, sat down. He could not have explained why he did. He did not try to. She sat down opposite him and he looked helplessly for a waiter, feeling the need of stimulation.

“You have doubtless had enough to drink,” said the girl, and De Launay meekly turned back to her. “You wonder, perhaps, why I am here,” she went on. “I have said that Monsieur Doolittle has told me that you are an American, that you contemplate returning to your own country——”

“Mademoiselle forgets or does not know,” interrupted De Launay, “that I am not American for nearly twenty years.”

“I know all that,” was the impatient reply. She hurried on. “I know monsieur le général’s history since he was a légionnaire. But it is of your present plans I wish to speak, not of your past. Is it not true that you intend to return to America?”

“I’d thought of it,” he admitted, “but, since they 59 have adopted prohibition——” He shrugged his shoulders and looked with raised eyebrows at the stack of saucers bearing damning witness to his habits.

She stopped him with an equally expressive gesture, implying distaste for him and his habits or any discussion of them.

“But Monsieur Doolittle has also told me that monsieur is reckless, that he has the temperament of the gamester, that he is bored; in a word, that he would, as the Americans say, ‘take a chance.’ Is he wrong in that, also?”

“No,” said De Launay, “but there is a choice among the chances which might be presented to me. I have no interest in the hazards incidental to——”

Then, for the life of him, he could not finish the sentence. He halfway believed the woman to be merely a demimondaine who had heard that he might be a profitable customer for venal love, but, facing that blank mask above the red lips and firm chin, sensing the frozen anger that lay behind it, he felt his convictions melting in something like panic and shame.

“Monsieur was about to say?” The voice was soft, dangerously soft.

“Whatever it was, I shall not say it,” he muttered. “I beg mademoiselle’s pardon.” He was relieved to see the lips curve in laughter and he recovered his 60 own self-possession at once, though he had definitely dismissed his suspicion.

“I am, then a gambler,” he prompted her. “I will take risks and I am bored. Well, what is the answer?”

Mademoiselle’s hands were on the table and she now was twisting the slender fingers together in apparent embarrassment.

“It is a strange thing I have to propose, perhaps. But it is a hazard game that monsieur may be interested in playing, an adventure that he may find relaxing. And, as monsieur is poor, the chance that it may be profitable will, no doubt, be worthy of consideration.”

De Launay had to revise his ideas again. “You say that Doolittle gave you your information?” She agreed with a nod of the head.

“Just what did he tell you?”

Mademoiselle briefly related how Doolittle, coming from his interview with De Launay to hear her own plea for help, had laughed at her crazy idea, had said that it was impossible to aid her, and had finally, in exasperation at both of them, told her that the only way she could accomplish her designs was by the help of another fool like herself, and that De Launay was the only one he knew who could qualify for that description. He—De Launay—was reckless enough, gambler enough, ass enough, to do the thing necessary to aid her, but no one else was. 61

“And what,” said De Launay, “is this thing that one must do to help you?” It seemed evident that Doolittle, while he had told something, had not told all.

She hesitated and finally blurted it out at once while De Launay saw the flush creep down under the mask to the cheeks and chin below it. “It is to marry me,” she said.

Then, observing his stupefaction and the return of doubt to his mind, she hurried on. “Not to marry me in seriousness,” she said. “Merely a marriage of a temporary nature—one that the American courts will end as soon as the need is over. I must get to America, monsieur, and I cannot go alone. Nor can I get a passport and passage unaided. If one tries, one is told that the boats are jammed with returning troops and diplomats, and that it is out of the question to secure passage for months even though one would pay liberally for it.

“But monsieur still has prestige—influence—in spite of that.” Her nod indicated the stack of saucers. “He is still the general of France, and he is also an American. It is undoubtedly true that he will have no difficulty in securing passage, nor will it be denied him to take his wife with him. Therefore it is that I suggest the marriage to monsieur. It was Monsieur Doolittle that gave me the idea.”

De Launay was swept with a desire to laugh. “What on earth did he tell you?” he asked. 62

“That the only way I could go was to go as the wife of an American soldier,” said mademoiselle. “He added that he knew of none I could marry—unless, he said, I tried Monsieur de Launay. You, he informed me, had just told him that the only marriage you would consider would be one entered into in the spirit of the gambler. Now, that is the kind of marriage I have to offer.”

De Launay laughed, recalling his unfortunate words with the banker to the effect that the only reason he’d ever marry would be as a result of a bet. Mademoiselle’s ascendency was vanishing rapidly. Her naïve assumption swept away the last vestiges of his awe.

“Why do you wear that veil?” he asked abruptly.

She raised her hand to it doubtfully. “Why?” she echoed.

“If I am to marry you, is it to be sight unseen?”

“It is merely because—it is because there is something that causes comment and makes it embarrassing to me. It is nothing—nothing repulsive, monsieur,” she was pleading, now. “At least, I think not. But it makes the soldiers call me——”

“Morgan la fée?”

“Yes. Then you must know?” There was relief in her words.

“No. I have merely wondered why they called you that.”

“It is on account of my eyes. They are—queer, 63 perhaps. And my hair, which I also hide under the cap. The poor soldiers ascribe all sorts of—of virtues to them. Magic qualities, which, of course, is silly. And others—are not so kind.”

In De Launay’s mind was running a verse from William Morris’ “Earthly Paradise.” He quoted it, in English:

|

“The fairest of all creatures did she seem; |

“Is that it?” he murmured to himself. To his surprise, for he had not thought that she spoke English, she answered him.

“It is not. It is my eyes; yes, but they are not to be described so flatteringly.” Yet she was smiling and the blush had spread again to cheeks and chin, flushing them delightfully. “It is a superstition of these ignorant poilus. And of others, also. In fact, there are some who are afraid.”

“Well,” said De Launay, “I have never had the reputation of being either ignorant or afraid. Also—there is Ogier?”

“What?”

“Who plays the rôle of the Danish Paladin?”

Mademoiselle blushed again. “He is not in the story this time,” she said. 64

“I hardly qualify, you would say. Perhaps not. But there is more. Where is Avalon and what other names have you? You remember

|

“Know thou, that thou art come to Avalon, |

“What are they?”

“I am Solange d’Albret, monsieur. I am from the Basses Pyrenees. A Basque, if you please. If my name is distinguished, I am not. On the contrary, I am very poor, having but enough to finance this trip to America and the search that is to follow.”

“And Avalon—where is that? Where is the place that you go to in America?”

She opened a small hand bag and took from it a notebook which she consulted.

“America is a big place. It is not likely that you would know it, or the man that I must look for. Here it is. The place is called ‘Twin Forks,’ and it is near the town of Sulphur Falls, in the State of Idaho. The man is Monsieur Isaac Brandon.”

In the silence, she looked up, alarmed to see De Launay, who was clutching the edge of the table and staring at her as though she had struck him.

“Why, what is the matter?” she cried.

De Launay laughed out loud. “Twin Forks! Ike 65 Brandon! Mademoiselle, what do you seek in Twin Forks and from old Ike Brandon?”

Mademoiselle, puzzled and alarmed, answered slowly.

“I seek a mine that my father found—a gold mine that will make us rich. And I seek also the name of the man that shot my father down like a dog. I wish to kill that man!” 66

De Launay turned and called the waiter, ordering cognac for himself and light wine for mademoiselle.

“You have rendered it necessary, mademoiselle,” he explained. Mademoiselle’s astounding revelation and the metallic earnestness of murder in her voice alike took him aback. He saw that her sweet mouth was set in a cruel line and her cameo chin was firm as a rock. But her homicidal intentions had not affected him as sharply as the rest of it.

Mademoiselle took her wine and sipped it, but her mouth again relaxed to scornful contempt as she saw him toss off the fiery liquor. She was somewhat astonished at the effect her words had had on the man, but she gathered that he was now considering her bizarre proposal with real interest.

The alcohol temporarily enlivened De Launay.

“So,” he said, “Avalon is at Twin Forks and I am to marry you in order that you may seek out an enemy and kill him. There was also word of a gold mine. And your father—d’Albret! I do not recall the name.”

“My father,” explained Solange, “went to America 67 when I was a babe in arms. He was very poor—few of the Basques are rich—and he was in danger because of the smuggling. He worked for this Monsieur Brandon as a herder of sheep. He found a mine of gold—and he was killed when he was coming to tell about it.”

“His Christian name?”

“Pedro—Pierre.”

“H’m-m! That must have been French Pete. I remember him. He was more than a cut above the ordinary Basco.” He spoke in English, again forgetting that mademoiselle spoke the language. She reminded him of it.

“You knew my father? But that is incredible!”

“The whole affair is incredible. No wonder you have the name of being a fairy! But I knew your father—slightly. I knew Ike Brandon. I know Twin Forks. If I had made up my mind to return to America, it is to that place that I would go.”

It was mademoiselle’s turn to be astonished.

“To Twin Forks?”

“To Ike Brandon’s ranch, where your father worked. It must have been after my time that he was killed. I left there in nineteen hundred, and came to France shortly afterward. I was a cow hand—a cowboy—and we did not hold friendship with sheepmen. But I knew Ike Brandon and his granddaughter. Now, tell me about this mine and your father’s death.” 68

Mademoiselle d’Albret again had recourse to her hand bag, drawing from it a small fragment of rock, a crumpled and smashed piece of metal about the size of one’s thumb nail and two pieces of paper. The latter seemed to be quite old, barely holding together along the lines where they had been creased. These she spread on the table. De Launay first picked up the rock and the bit of metal.

He was something of a geologist. France’s soldiers are trained in many sciences. Turning over the tiny bit of mineral between his fingers, he readily recognized the bits of gold speckling its crumbling crystals. If there was much ore of that quality where French Pete had found his mine, that mine would rank with the richest bonanzas of history.

The bit of metal also interested him. It had been washed but there were still oxydized spots which might have been made by blood. It was a soft-nosed bullet, probably of thirty caliber, which had mushroomed after striking something. His mouth was grim as he saw the jagged edges of metal. It had made a terrible wound in whatever flesh had stopped it.

He laid the two objects down and took the paper that mademoiselle handed to him. It seemed to be a piece torn from a paper sack, and on it was scrawled in painful characters a few words in some language utterly unknown to him.

“It is Basque,” said mademoiselle, and translated: 69 “‘My love, I am assassinated! Farewell, and avenge me! There is much gold. The good Monsieur Brandon will——’”

It trailed off into a meaningless, trembling line.

The other was a letter written on ruled paper. The cramped, schoolboyish characters were those of a man unused to much composition and the words were the vernacular of the ranges.

“Dear madam,” it began, “I take my pen in hand to write you something that I sure regrets a whole lot. Which I hope you all bears up under the blow like a game woman, which your late respected husband sure was game that a way. There ain’t much I can say to break the news, ma’am, and I can’t do nothing, being so far away, to show my sympathy. Your husband has done passed over. He was killed by some ornery hound who bushwhacked him somewheres in the hills, and who must have been a bloody killer because Pete, your husband, sure didn’t have no enemies, and there wasn’t no one that had any reason to kill him. He was coming home from the Esmeraldas with his sheep which we was allowing to winter close to the ranch instead of in the desert to see if feeding them would pay and some murdering gunman done up and shot him with a thirty-thirty soft nose, which makes it worse. I’m sending the slug that done it.

“Pete was sure a true-hearted gent, ma’am, and we was all fond of him spite of his being a Basco. 70 If we could have found the murderer we would sure have stretched him a plenty but there wasn’t no clew.

“Pete had found a gold mine, ma’am, and the specimens he had in his war bags was plenty rich as per the sample I am sending you herewith. He tried to tell me where it was but he was too weak when we found him. He said he wanted us to give you half of it if we found it and we sure would do that though it don’t look like we got much chance because he couldn’t tell where it was. The boys have been looking but they haven’t found it yet. If they do you can gamble your last chip they will split it with you or else there will be some more funerals around hereaways. But it ain’t likely they will find it, I got to tell you that so’s you won’t put your hopes on it and be disappointed.

“I am all broke up about Pete, and if there is anything I can do to help don’t you hesitate to let me know. I was fond of Pete, ma’am, and so was my granddaughter, which he made things for her and she sure doted on him. He was a good hombre.”

The letter was signed “I. Brandon.”

De Launay mused a moment. “Is that all?” he asked finally.

“It is all,” said mademoiselle. “But there is a mine, and, especially, there is the man who killed him.”

De Launay looked at the date on the letter. It was October, 1900. 71

“After nineteen years,” he reminded her, “the chances of finding either the mine or the man are very remote. Perhaps the mine has been found long ago.”

“Monsieur,” replied the girl, and her voice was again metallic and hard, “my mother received that letter. She put it away and treasured it. She hoped that I would grow up and marry a Basque, who would avenge her husband. She sent me to a convent so that I might be a good mate for a man. When she died she left me money for a dot. She had saved and she had inherited, and all was put aside for the man who should avenge her husband.

“But the war came before I was married, and afterward there was little chance that any Basque would take the quarrel on himself. It is too easy for the men to marry now that they are so scarce, and it is very difficult for one like me to find a husband. Besides, I have lived in the world, monsieur, and, like many others, I do not like to marry as though that were all that a woman might do. I do not see why I cannot go to America, find this mine and kill this man. The money that was to be my portion will serve to take me there and pay those who will assist me.”

“You desire to find the mine—or to kill the man?”