Title: The Camp Fire Girls in the Mountains; Or, Bessie King's Strange Adventure

Author: Jane L. Stewart

Release date: July 27, 2009 [eBook #29528]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

1. THE CAMP FIRE GIRLS IN THE WOODS

2. THE CAMP FIRE GIRLS ON THE FARM

3. THE CAMP FIRE GIRLS AT LONG LAKE

4. THE CAMP FIRE GIRLS IN THE MOUNTAINS

5. THE CAMP FIRE GIRLS ON THE MARCH

6. THE CAMP FIRE GIRLS AT THE SEASHORE

| I. | PEACEFUL DAYS |

| II. | FOREBODINGS OF TROUBLE |

| III. | A NEW PLAN |

| IV. | A FRIEND IN TROUBLE |

| V. | A TANGLED NET |

| VI. | BESSIE KING'S PLUCK |

| VII. | BACK AT LONG LAKE |

| VIII. | A NOVEL RACE |

| IX. | THE PATHFINDERS |

| X. | THE SIGNAL SMOKES |

| XI. | OFF TO THE MOUNTAINS |

| XII. | ENEMIES WITHOUT CAUSE |

| XIII. | A PLAN OF REVENGE |

| XIV. | THE SPIRIT OF WO-HE-LO |

| XV. | COALS OF FIRE |

On the shores of Long Lake the dozen girls who made up the Manasquan Camp Fire of the Camp Fire Girls of America were busily engaged in preparing for a friendly contest and matching of skill that had caused the greatest excitement among the girls ever since they had learned that it was to take place.

For the first time since the organization of the Camp Fire under the guardianship of Miss Eleanor Mercer, the girls were living with no aid but their own. They did all the work of the camp; even the rough work, which, in any previous camping expedition of more than one or two days, men had done for them. For Miss Mercer, the Guardian, felt that one of the great purposes of the Camp Fire movement was to prove that girls and women could be independent of men when the need came.

It was her idea that before the coming of the Camp Fire idea girls had been too willing to look to their brothers and their other men folks for services which they should be able, in case of need, to perform for themselves, and that, as a consequence, when suddenly deprived of the support of their natural helpers and protectors, many girls were in a particularly helpless and unfortunate position. So the Camp Fire movement, designed to give girls self-reliance and the ability to do without outside help, struck her as an ideal means of correcting what she regarded as faults in the modern methods of educating women.

Before the camp on Long Lake was broken up they hoped to have a ceremonial camp fire, but there were gatherings almost every night around the big fire that was not a luxury and an ornament at Long Lake, but a sheer necessity, since the nights were cool, and at times chilly. This fire was never allowed to go out, but burned night and day, although, of course, it reached its full height and beauty after dark, when the flames shot up high and sent grotesque shadows dancing under and among the trees, and on the sandy beach which had been selected as the ideal location for the camp.

At these meetings everyone had a chance to speak. Miss Eleanor, or Wanaka, as she was called in the ceremonial meetings, did not attempt to control the talk on these occasions. She only led it and tried, at times, to guide it into some particular channel. It would have been easy for her to impress her own personality on the girls in her charge, since they not only admired, but loved her, but she preferred the expression of their own thoughts, and she knew, also, that to accomplish her own purpose and that of the founders of the Camp Fire, it was necessary for the girls to develop along their own lines, so that when they reached maturity they would have formed the habit of thinking things out for themselves and knowing the reason for things, as well as the facts concerned.

"I think we're too likely to forget the old days when this country was being explored and opened up," Eleanor said one night. "Out west that isn't so, and out there, if you notice, women play a much bigger part than they do here. Those states in the far west, across the Mississippi, give women the right to vote as soon as women show that they want it. They are more ready to do that than the states in the east."

"Why is that, Wanaka?" asked Margery Burton, one of the Fire-Makers of the Camp Fire.

"In the west," said Eleanor, answering the question, "men and women both find it easier to remember the old days of the pioneers, when the women did so much to make the building of our new country possible. They faced the hardships with the men. They did their share of the work. They travelled across the desert with them, and, often, when the Indians made attacks, the women used guns with the men."

"But there isn't any chance for women to do that sort of thing now," said Dolly Ransom, or Kiama, as she was known in the ceremonial meetings. "The Indians don't fight, and the pioneer days are all over."

"They'll never be over until this country is a perfect place to live in, Dolly, and it isn't—not yet. Some people are rich, and some are poor, and I'm afraid it will always be that way, because it has always been so. But everyone ought to have a chance to rise, no matter how poor his or her parents are. That was the idea this country was built on. You know the words of the Declaration of Independence, don't you? That all men are created free and equal? This was the first country to proclaim that."

"But what is there to do about that?"

"Ever so many things, Dolly. Some men who have money use it to get power they shouldn't have, to make people work without proper conditions, and for too little money. Oh, there are all sorts of things to be made right! And one reason that some of them have gone wrong is that women who have plenty of comforts, and people to look after them, have forgotten about the others. There is as much work for women to do now as there ever was in the pioneer days—more, I think."

"The Camp Fire Girls are going to try to make things better, aren't they, Wanaka?" asked Margery Burton. For once she wasn't laughing, so that her ceremonial name of Minnehaha might not have seemed appropriate. But as a rule she was always happy and smiling, and the name was really the best she could have chosen for herself.

"Yes, indeed," said Eleanor. "So far we've been pretty busy thinking about ourselves, and doing things for ourselves, but there has been a reason for that."

"What reason, Miss Eleanor?" asked Dolly.

"Well, it's hard to get much done unless you're in the right condition to do it. You know when an athlete is going to run in a long race, he doesn't just go out and run. He trains for it a long time before he is to run, and gets his body in fine condition. And it's the same with a man who has some mental task. If he has to pass an examination, for instance, he studies and prepares his mind. That's what we have to do; prepare our minds and bodies. In the city, in the winter, we will take up a lot of these things. I'm just mentioning them to you now so that you can think about them and won't be surprised when we start to go into them seriously."

"I know something I've thought about myself," said Dolly, eagerly. "In some of the stores at home they have seats so that the girls can sit down when they don't have to wait on people. And in some they don't. But in the stores where they do have them, the girls get more done, and one of them told me once that she felt ever so much stronger and better when the rush came in the afternoon, if she'd been able to sit down instead of standing up all day."

"Of course. And that's a splendid idea, Dolly. Some of the stores make the girls stand up all day long, because they think it pleases the women who come in to shop. But if you could make those store keepers see that they'd really get more work done by the girls if they let them rest when the stores are empty, they'd soon provide the chairs, even if the law didn't make them do it."

"This place looks as if pioneers might have lived here, Wanaka," said Margery Burton.

"They passed along here once, Margery, years and years ago, but they were going on, and they didn't stop. You see, the reason this country has stayed so wild is that it's hard to get at. The trees haven't been cleared away, and roads haven't been built."

"Isn't it good land? Wouldn't it pay to plough it, after the trees were cut down?" asked Bessie King.

"It would, and it wouldn't, Bessie. It's just about the same sort of land as in the valleys below, where there are some of the best farms in the whole state. But we need the forests, too. You know why, don't you?"

"No, I don't," said Bessie, after a moment's thought. "I know they're beautiful, and that it's splendid for people to be able to come up here and live, and camp out. But that isn't the only reason, is it?"

"No, it isn't even anywhere near the most important, Bessie. You know what a dry summer means, don't you? You lived long enough on Paw Hoover's farm at Hedgeville to know that?"

"Yes, indeed! It's bad for the crops; they all get burned up. We had a drought two or three years ago. It never rained at all, except for little showers that didn't do any good, all through July and August, and for most of June, as well. Paw Hoover was all broken up about it. He said one or two more summers like that would put him in the poor-house."

"Well, if there weren't any forests, all our summers would be like that. The woods are great storehouses of moisture, and they have a lot to do with the rain. Countries where they don't have forests, like Australia, are very dry. And that's the reason."

"They have something to do with floods, too, don't they, Wanaka?" asked Dolly. "I think I read something like that, or heard someone say so."

"They certainly have. In winter it rains a good deal, and snows, and if there are great stretches of woods, the trees store up all that moisture. But if there are no trees, it all comes down at once, in the spring, and that's one of the chief reasons for those terrible floods and freshets that do so much damage, and kill so many people."

"But if that's so, why are the trees cut down so often?"

"That's just one of the things I was talking about. Some men are selfish, you see. They buy the land and the trees, and they never think, or seem to care, how other people are affected when they start cutting. They say it's their land, and their timber; that they paid for it."

"Well, I suppose it is—"

"Yes, but like most selfish people, they are short-sighted. It is very easy to cut timber so that no harm is done, and in some countries that really are as free and progressive as ours, things are managed much better. We waste a whole forest and leave the land bare and full of stumps. Then, you see, it isn't any use as a storehouse for moisture, which nature intended it to be, and neither is it any use to the timber cutters, so that they have to move on somewhere else."

"Could they manage that differently?"

"Yes, if they would only cut a certain number of trees in any particular part of the woods in any one year, and would always plant new ones for every one that is taken out, there wouldn't be such a dreadful waste, and the forests would keep on growing. That's the way it is usually done abroad—in Germany, and in Russia, and places like that. Over there they make ever so much more money than we do out of forests, because they have studied them, and know just how everything ought to be done."

"Don't we do anything like that at all?"

"Yes, we're beginning to now. The United States government, and a good many of the states, have seemed to wake up in the last few years to the need of looking after the woods better, and so I really believe that in the future things will be managed much better. But there has been a terrible lot of waste, here and in Canada, that it will take years to repair."

"They don't spoil the woods about here that way, do they?"

"No; but then, you see, this is a private preserve, and one of the reasons it is so well looked after is that some of the men who own it like to come here for the shooting."

"I know," said Margery. "I thought that was why the guides were kept here."

"It is, but it's only one reason. A few miles away, if we go that way, I can show you acres and acres of woods that were burned two years ago, and you never saw such a desolate spot in all your life. It's beginning to look a little better now, because, if you give nature a chance, she will always repair the damage that men do from carelessness, and from not knowing any better."

"Oh, I think it would be dreadful for all these lovely woods to be burned up! And that wouldn't do anyone any good, would it?"

"Of course not! That's the pitiful part of it. But a terrible lot of fires do start in the woods almost every year. You see, after a hot, dry summer, when there hasn't been much rain, the woods catch fire easily, and a small fire, if it isn't stamped out at once, grows and spreads very fast, so that it soon gets to be almost impossible to put out at all."

"I saw a forest fire once, in the distance," said Dolly. "It was when I was out west, and it looked as if the whole world was burning up."

"I expect it did, Dolly. And if you'd been closer, you'd have seen how hard the rangers and everyone in the neighboring towns had to fight to get control of that fire. It doesn't seem as if they could burn as fast as they do, but they're terrible. It's the hardest fire of all to put out, if it once gets away. That's why we have such strict rules about never leaving a camping place without putting out a fire."

"Would one of the little fires we make when we stop on the trail for lunch start a great big blaze?"

"It certainly would. It's happened just that way lots and lots of times. Many campers are careless, and don't seem to realize that a very few sparks will be enough to start the dry leaves burning. Sometimes people see that their fire is just going out, as they think, and they don't feel that it's necessary to pour water on it and make sure that it's really dead. You see, the fire stays in the embers of a wood fire a long, long time, smouldering, after it seems to be out, and then—well, can't you guess what might happen?"

"I suppose the wind might come up, and start sparks flying?"

"That's exactly what does happen. Why, in the big forest preserves out west they have men in little watch-towers on the high spots in the hills, who don't do anything but look for smoke and signs of a fire. They have big telescopes, and when they see anything suspicious they make signals from one tower to the next, and tell where the fire is. Then all the rangers and watchers run for the fire, and sometimes, if it's been seen soon enough, they can put it out before it gets to be really dangerous."

"Well, I know now why I've got to be careful," said Dolly. "I wouldn't start a fire for anything!"

"Good! And I think it's time to sing the good-night song!"

"I think we'll beat those old Boy Scouts easily when we have that field day, Bessie," said Dolly Ransom to her chum, Bessie King. "Look at the way we beat them in the swimming match the other day."

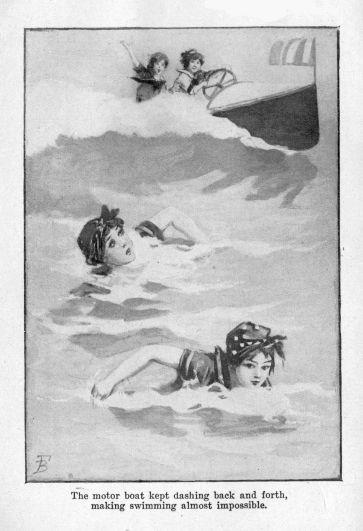

A friendly rivalry between the Camp Fire Girls and the Boy Scouts of a troop that was camping at a lake some miles away had led, a short time before, to a swimming contest in which skill, and not speed and strength, had been the determining factors, and, vastly to the surprise and disgust of the boys, the girls had had the best of them.

"We don't want to be over-confident," said Bessie. "You know they thought we were easy, and I don't believe they tried as hard as they might have done. After all, girls and boys aren't the same, and if boys are any good, they're stronger and better at games than girls, no matter how good the girls are."

"Oh, they tried right enough," said Dolly. "They just couldn't do it, that's all."

"Another thing, Dolly, we've got to remember, is that those weren't races. If they had been we'd have been beaten, because those boys could really swim a lot faster than we could. It was just a case of doing certain things and doing them just the right way. Anyone can learn that if they're patient enough, and it's not really very important. I'm glad we won, because I think boys sometimes get the idea that girls can't do anything, and it's just as well for them to find out that we can."

"You're getting on, Bessie. When you first came from Hedgeville you wouldn't have believed that, or, if you had, you wouldn't have said it."

"Oh, I think I would have, Dolly. You know about the only boy I had much to do with in those days was Jake Hoover, and you saw him when he tried to help get me back where I'd be bound over to that Farmer Weeks until I was grown up."

"That's so, Bessie. You wouldn't have much use for boys if you thought they were all like him, would you?"

"I know they're not, though, Dolly. So I never got any such foolish ideas."

"What sort of things will we do in this field day, Bessie? Do you know?"

"Not exactly. Miss Mercer hasn't arranged everything yet with their Scoutmaster, Mr. Hastings. You know the reason we're going to have it is that Mr. Hastings used to tease Miss Mercer about the Camp Fire Girls."

"That's what I thought. He said we really couldn't manage by ourselves, didn't he, if we were caught out in the woods without a man to do a lot of things for us?"

"I think he did. They say a lot of the Boy Scouts think the Camp Fire Girls are just imitating them, and that isn't so at all, because I got Miss Eleanor to tell me all about it. The Camp Fire Girls are more serious. They want to prepare girls to make good homes, and look after them properly, and to help them to make things better in their own homes.

"The Boy Scouts were organized partly to give boys something to do, and to keep them out in the open air as much as possible, to make the boys stronger, and healthier, and keep them from being idle and getting into mischief."

"Well, that's what we're for, too, isn't it?"

"Yes, but not so much. Girls don't get into just the same sort of mischief that boys do, so it's a different thing altogether. But, anyhow, Miss Eleanor says it's silly for one to laugh and jeer at the other; that all the Camp Fire people, the ones who are at the head of the movement, approve of the Boy Scouts and think it's a fine thing, and that most of the men who started the Boy Scout movement are interested in the Camp Fire, too."

"Then she's going to try to prove that we really can manage by ourselves?"

"Yes. And I think the idea is for their troop of Boy Scouts and our Camp Fire to make a march on the same day, going about the same distance, and doing everything without any help at all; cooking meals, finding water, making camp, getting firewood, and everything of that sort. A certain time is to be allowed for eating, and we are to make smoke signals when we reach the camping place, and again when we leave. There aren't to be any matches; all fires are to be made by rubbing sticks together. We're to cook just the same sort of meals, and the party that gets back to the starting point first wins."

"We're not to go together, then?"

"No. Won't it be much more exciting? You see, we won't know how nearly finished they are. And they won't be able to see how fast we are working. So each side ought to work just as fast as it can. It's a new sort of a race, and I think it will be great sport."

"Oh, so do I! We're each to spend the same amount of time eating?"

"Yes, because if we didn't, one side could hurry through its meal, or eat almost nothing at all, and get a start that way. And there's no object in eating fast. It's to see how quietly we can march and prepare our food and clean up afterward that we're having the test. It isn't to be exactly like a race. The idea is to get as much fun and good exercise out of it as anything else."

"Still it really will be a race, because each side will want to win. Don't the Boy Scouts have contests like that among themselves, sometimes?"

"Oh, yes. That's where the idea came from, of course."

"My, Bessie, but I'm glad everything is so quiet around here now! It doesn't seem possible that we've had such exciting times since we've been here, does it?"

"You mean about the gypsy who mistook you for me and tried to kidnap you?"

"Yes. I think he's safe for a time now. Did you see Andrew, the guide, when he came in to tell Miss Eleanor about how they'd taken those gypsies down to the town, where the sheriff took hold of them?"

"No. What did he say?"

"Why, it seems that on the way down, John—he's the one who actually carried me off, you know—tried to bribe them and get them to let him go free. He said he had a friend who would pay a whole lot of money if they would let him escape, and they could pretend that he just got away, so that no one would ever know that they had had anything to do with it."

"I suppose they just laughed at him?"

"They certainly did, and tied him up a little tighter, so that there wouldn't be any chance of his managing to get away."

"Did he want them to let Lolla and Peter go, too?"

"No, that's the funny part of it. He didn't seem to care at all what happened to them, so long as he didn't have to go to jail. He's just as mean as a snake, Bessie. I've got no use for him at all."

"He was glad enough to have them help him when he wanted to get hold of us, Dolly. But when he saw a chance to desert them he didn't remember that, I suppose. What did Andrew think they would do to them?"

"Well, he didn't know. He said that when the people in the town heard what the gypsies had done they were pretty mad, but, of course, they didn't really start to do anything to hurt them. The sheriff said he'd see that they were kept tight until they could be tried, and Andrew guessed they wouldn't have much chance of getting off when the people around the town would be on the jury. The men in those parts haven't any use for gypsies, you see, and they'd be pretty sure to see to it that they were properly punished."

"I wouldn't mind seeing Lolla get off, Dolly. I don't think she's as bad as the others."

"Oh, I do, Bessie. I think she's worse. Why, she did her best to get you into the same trap I was in! She was treacherous and lied to you."

"I know all that, too, Dolly. But it was because John made her do it. He frightened her, I think, and besides that she's going to be married to him, and among the gypsies a woman isn't supposed to do any thinking when her husband tells her to do something. She just has to do it, whether she thinks it's right or not. It isn't as if she had planned the whole thing out."

"Well, she hurt you more than she did me. If you don't want her to be punished, I don't see why I should."

"I don't think I want anyone to be punished, Dolly. But it isn't just what I want that counts, and I suppose that if that man John got off so easily it would be a bad thing, because if he's punished it may frighten some others who'd be ready to do the same thing, and make them understand that they'd better be careful before they do things that are against the law."

"Well, I'd like to see him in jail, just to get even for the fright he gave me when he snatched me up and carried me off through the woods. And he left me there in that place he found, too, with a handkerchief in my mouth, and tied up so that I couldn't move, so I don't see why I shouldn't be glad to see him suffering himself. It was awful, Bessie, and if you hadn't followed me and had a chance to sneak in there and cheer me up, I don't know what I would have done."

"We'll have to tell what we know about what happened to us, I suppose," said Bessie. "I don't like the idea of that, but Miss Eleanor says we can't help it; that the law will make us do it."

"Oh, I think it will be good fun. We'll get our names in the newspapers, Bessie, and maybe there will be pictures of us. I won't have any trouble telling them, either. I don't believe I'll ever forget the things that happened to us that day, if I live to be a hundred years old."

"No, neither shall I."

They had no more chance to discuss the matter, for just then they heard the voice of Eleanor Mercer, the Guardian of their Camp Fire, calling them. When they answered her call, finding her in the opening of her own tent, her face was very grave.

"I've just had a letter from Charlie Jamieson, my cousin, the lawyer," she said. "I wrote to him about the extraordinary attempt that this gypsy made to kidnap Dolly, and of how certain we were that Mr. Holmes was back of it."

"I wish we knew why Mr. Holmes is so anxious to get hold of me, or to get me into the same state I came from, so that Farmer Weeks can keep me there until I'm twenty-one," said Bessie, looking worried.

"I wish so, too, Bessie," said Eleanor, anxiously. "I don't know how much Dolly knows about this business, but I'm very much afraid that she may be drawn into it from now on. And Mr. Jamieson agrees with me."

"Why, how is that possible?" asked Bessie. "You don't mean that they may try to take her away?"

"I don't know, Bessie. That's the worst part of it. You see, they may think she knows too much for it to be safe to leave her out of any plans they are making now. We don't know what those plans are. This last time, you see, Mr. Holmes evidently thought he had a splendid chance to get hold of you through this gypsy, without being suspected himself."

"He thought everyone would just blame the gypsy and never think about him at all, you mean?"

"You see, the gypsy misunderstood—or rather Mr. Holmes misled him by accident. He thought Dolly was Bessie, and the other way around. So Dolly really suffered in your place that time, Bessie."

"I'm very glad I did!" said Dolly, stoutly.

"I know that, Dolly. You're not selfish, no matter what your other faults may be. But I think you've got to understand just what we know about the reasons for all this, though it isn't very much. Bessie doesn't know much about her parents. They left her—because they had to—when she was a very small girl, in charge of Mr. and Mrs. Hoover, farmers, in Hedgeville."

"I know about that, Miss Eleanor. The place where we first met Bessie and Zara, you mean."

"Yes. And Mrs. Hoover and her son Jake didn't treat Bessie well. In fact, they treated her so badly that finally she ran away. You know that the Camp Fire thinks people ought to stay at home, even if things aren't very pleasant, but Bessie was quite right, I believe, to run away then, because they had no real claim to her."

"I should say she was!"

"Well, you know about Bessie's chum, Zara, too. Her father was in trouble, and was to be arrested. And when Zara and Bessie found out that Zara was to be taken by this Mr. Weeks, a miser and a money lender, Zara ran away, too, and we Camp Fire Girls helped them to get away from that state and have been looking after them since."

"And then they stole Zara away!"

"No, not exactly. They lied to Zara, and told her things that made her willing to go with them. Mr. Holmes seems to have been responsible for that. You remember yourself how Mr. Holmes tricked you and Bessie into going for a ride with him in his automobile, when we were all at the farm?"

"I certainly do! I ought to, because all the trouble we had then was my own fault."

"Well, never mind that, because, as it turned out, it was owing to that ride that we got Zara back. She's with us now, and we are going to try to keep her, and get her father out of prison, because Mr. Jamieson is sure he is innocent. But we've got to be mighty careful, because we don't know how Mr. Holmes happens to be mixed up with Farmer Weeks, and why either of them should care anything about Bessie and Zara and Zara's father. That's why I wanted to be sure that you understood as much as we do ourselves."

"I see, and I'll promise to be as careful as I can, Miss Eleanor. I wouldn't get Bessie or Zara into any more trouble for the world."

"I know you wouldn't, Dolly, and I hope it won't be very long before the whole thing is straightened out. Mr. Jamieson is working hard to try to find out what it is all about, and I think he's sure to find out soon. This letter I had from him today is a new warning, really. He says Mr. Holmes has hired lawyers to try to get that gypsy off."

"That proves that he hired him, too, I should think," said Bessie.

"It seems to, certainly, but I'm afraid it isn't legal proof, even though it satisfies us. But the chief point is that Mr. Jamieson is worried about you two when you have to testify."

"Why, there couldn't be anything they could do to us then, I should think!" exclaimed Dolly.

"I hope not," said Miss Mercer. "But, well, we've had reason to learn to be careful when we're dealing with these people. And Mr. Jamieson seems to think that the thing to fear most is the other gypsies."

"I thought of that, too," said Bessie, gravely. "They stick to one another, don't they?"

"Yes, they certainly do. They're very clannish. And Mr. Holmes, I'm afraid, is clever enough and unscrupulous enough to be willing to use them for his own purposes. He wouldn't tell them directly what he wanted, you see. He'd just hire someone who was clever enough to get them inflamed and worked up to the point of being willing to hurt you two, and, if they could get at her, Zara, too, by way of revenge."

"We can't help going down there if they send for us, I suppose, Miss Eleanor?"

"No. There's no way out of it. You see, if someone does you an injury—borrows money from you and doesn't pay it back, say—the law will help you get it, if you want to be helped. You can decide whether you want to do anything or not. But if a crime is committed, then it's a different matter, and you've got to get the law's help, whether you want to or not.

"For instance, if someone robs your house, you might be willing to forgive the robber, but the law has to be satisfied, because that's the sort of crime that affects everyone, and not just you alone."

"I see. And I suppose that this time the law feels that if they are not punished, those gypsies might try to kidnap someone else?"

"Yes. The idea isn't just punishment. It's the way people who live together in towns and countries have to protect themselves. In the early days there wasn't any law. If a man was robbed, and he was strong enough, he protected himself by going out and fighting the robber. But that wouldn't work very well, because if a man was very strong, and wicked as well, he could rob his neighbors, and no one of them was strong enough to protect himself.

"So it wasn't very long before people began to find out that, while no one of them was strong enough to stop such robbers, a whole lot of them banded together were stronger than any one man. And so they made the first laws."

"Oh, I see," said Dolly. "Bessie isn't strong enough by herself to do anything to Mr. Holmes, or to stop him from doing what he likes to her, because he's rich. But if all the other people who live in the state take her side he can't fight against them. That's it, isn't it?"

For a day or two after that peace reigned over the camp by Long Lake. The girls looked forward eagerly to the field day that had been planned, but they looked forward to it, too, with a certain degree of regret, for it would mark the climax and the end, as well, of their stay at the lake, which, though it had been so exciting, had also been so delightful that all the girls wished for nothing better than to stay there indefinitely. But they could not do that, as Miss Mercer explained to them.

"We've got to make way for others," she said, in telling them of the new plans. "You see, my father is only one of the owners of this preserve, and we take it in turns to use this lake for a camping site. Now Mr. Spurgeon, one of the other owners, is going to bring up a party of his friends, and we must make room for them."

"Are we going home?" asked Margery Burton, disappointedly.

"Why, don't you want to go home?" asked Eleanor, with a laugh, which was echoed by the other girls, who heard the note of sorrow in the question.

"Oh, I suppose so," said Margery. "But one is home quite a good deal, after all, in the winter, and we do have such a good time when we're out in the woods this way. I love to get right close to nature."

"Well, you needn't be frightened, Margery, because I've got a plan that will keep us as close to nature as anyone could want to be."

A chorus of excited voices was raised at that.

"Where are we going next, Miss Mercer?"

"What are we going to do?"

"Shall we get to the seashore this summer?"

"Later on, I expect," she answered, to the last question. "You do love the beach and the surf, don't you? Well, so do I, and I expect we shall want to spend a little time there. But first I've a plan I think some of you will like even better."

"We're sure to like anything you plan, Miss Eleanor," said Dolly, with enthusiasm. "I don't believe any Camp Fire has as nice a Guardian as you. It seems to me you spend all your time thinking up ways of giving us a good time."

"What is the new plan?" asked Margery. "I wonder if I can guess?"

"I don't know. You might all try, and see how near you come to it."

"I think we're going to go home by walking!" said Margery.

"I believe we'll go through the chain of lakes that begins at Little Bear in a boat, or in boats!" said Dolly.

But, though they all took turns in guessing, Eleanor only smiled wisely when the last guess had been made.

"You were very nearly right, Margery," she said. "We are going to tramp home, but not the way we came. We're going to take the long way round. We're going straight up and through the mountains and down the other side, and then we'll have a long trip on fairly level ground, but we won't go straight home."

"Where, then?" asked Dolly.

"Why, we'll combine everything on the one trip, Dolly, and we'll wind up at the seashore. By the time we've had a little swimming and sailing there it'll be time to think about what we're going to do in the autumn—school, and, work, and all the other things."

"Oh, that's splendid!" cried Margery, her eyes shining. "I've always wanted to go up in the real mountains, where you were so high that you could see all around the country. We'll do that, won't we? Here we're in the mountains, really, but it doesn't seem like it. Everything's so high, you can't see over."

Eleanor pointed to the distant hills, blue in the haze that hung over them.

"Do you see Mount Grant, the big one in the center, there?" she said. "And do you see that other mountain that seems to be right next to it? That's Mount Sherman. And right between them there's a little gap. Really, it's quite wide, though you can't tell that from here. Well, that's Indian Notch, and we get through the mountain range by going through it. It's a fine, wild country, but there's a good road through the notch now, and sometimes one meets quite a lot of automobiles going through. I think it will be a glorious trip, don't you, girls?"

"I certainly do!" said Bessie King. "I'm like Margery. I've always wanted to see the real mountains. I used to dream about them, and sometimes I'd think I'd really been there. But I guess it was just because I dreamed so much that I got to thinking so."

Eleanor looked at her curiously.

"Maybe your people came from the mountains, Bessie," she said. "It's very strange that some natural things seem to get into the blood of peoples and races. Like the mountains, and the sea, and great rivers. Sometimes all the men in a family, for generations, will be sailors, even if their parents have planned something else for them. The sea is in their blood, and it calls them."

"Sometimes I think the mountains are calling me just that way," said Bessie. "But I never really understood that before."

"It's the same way with mountaineers. The Swiss are never really happy except among their mountains. And that's true of every mountainous race. The people who live along the Mississippi, here, and along the Don and the Vistula, and the other great rivers in Russia, never seem to be able to live happily unless they can see the great river rolling by their homes every day. If they go far away they get homesick."

"I'm not a bit like that!" exclaimed Dolly. "One place is just as good as another for me, if I like the people. I like to travel and see new places. I'd like to be on the move all the time."

"I think a great many Americans are getting to be that way," said Eleanor, reflectively. "It's natural, in a way, you see. For generations the young men and women have been moving on, from settled parts of the country to new land, where there were greater opportunities to make a fortune."

"I've read about that," said Dolly. "You mean like the people from New England, who went west to Oregon and Washington?"

"Yes. But that can't go on forever, you see, because about all the new land is taken up and settled now. Of course, out in the far west, there's still room for people; lots and lots of room. But this whole country is settled now. Law and order have been established about everywhere. And we'll begin to settle down soon, and our people will love their homes, and the places where they were born, just as the Virginians and the other Southerners do now."

"Oh, it isn't that I don't like my own home!" said Dolly. "If I were away from it very long I know I'd get dreadfully homesick, and want to go back. But I don't want to stay there or anywhere else all the time."

"You're a wanderer," laughed Eleanor. "That's what's the matter with you, Dolly. You want to see everything that's to be seen. Well, I'm a little that way myself. When I was a little bit of a kiddie I always got tremendously excited if we were going on a journey. I guess it's a pretty good thing, really, that we are that way. It's the reason this country has grown so wonderfully, that spirit of enterprise and adventure. That's what made the pioneers."

"It isn't just Americans who do it, either, is it?" said Margery. "The Italians and the other foreigners who come here seem to be just as anxious to find new places—"

"Oh, but that's different," said Zara, the silent one, quickly. "I know, because my father and I are foreigners. And do you know why we came here? It was because we couldn't live happily in our own country!"

The girls looked at her curiously, so fiery was her speech, and so much in earnest was she.

"We come from Poland," she said. "Over there, a man can't call his soul his own. Soldiers and policemen used to come to our house, and wake us up in the middle of the night to look for papers. And often and often they would steal anything we had that they liked. Oh, how I hate the Russians!"

Eleanor sighed. Gradually, slowly but surely, she felt that she was finding her way into the secret of Zara and her father.

"Then you came here because you had heard that this was a free country and a refuge for those who were oppressed?" she ventured, gently.

"Yes," said Zara. "And it's not true! There are kind people here, like you, and Bessie, and Mr. Jamieson. But haven't they put my father in prison, just the way they did in Poland and in Sicily, when we tried to live there quietly? And didn't all the people in Hedgeville persecute him, and tell lies about both of us? We haven't been happy here."

"I'm afraid that's true, Zara. But you are going to be, remember that. You have good friends working for you now, you and your father both. And it isn't the fault of this country that there are bad and wicked men in it, who are willing to do wrong if they see a chance to make money by doing so."

"But if this country is all that people say about it, they shouldn't be allowed to do it. The law is helping them. In Poland, it was just the same. The law was against my father there—"

"Listen, Zara! The law may seem to help them at first, but you may be very sure of one thing. If your father has done nothing wrong, and his enemies have lied and deceived the people in authority in order to get the law on their side, they will pay bitterly, for it in the end."

"But the law ought to know that my father is right—"

"The law works slowly, Zara, but in the end it is sure to be right. You see, your father's case is a very exceptional one. The people who made the law in the beginning couldn't have expected it to come. But the wonderful thing about the law is that, while it is often very hard, it will always find out the truth sooner or later.

"Sometimes, for a little while, people who are innocent have to suffer because they are unjustly accused. But the law will free them if they have really done no wrong, and, what is more, it will punish those who swear falsely against them. Be patient, and you will find that you and your father made no mistake when you believed that this was the land of the free and the home of those who are oppressed in their own countries."

Zara's eyes, dark and sombre, seemed to be full of fire.

"Oh, I hope so," she cried, passionately. "For my father's sake! He has been disappointed and deceived so often."

"We'll have a good long talk sometime, Zara," she said, finally. "Then maybe I'll be able to explain some things to you better, and make you understand the real difference between this country and the ones you have known."

Then she brightened, and turned to the other girls, who had all been rather sobered by the sudden revelation, through Zara, of a side of life hidden from them as a rule.

"We're not going to take that trip just for ourselves and our own fun," she said. "We're going to be missionaries, in a way; we want to spread the light of the Camp Fire, and see if we can't get a lot of new Camp Fires organized in the places we pass through. It's just in such lonely, country places that the girls need the Camp Fire most, I believe."

"That will be splendid," said Margery Burton. "We could stay and teach them all the ceremonies, and the songs, and how to organize new Camp Fires, couldn't we?"

"Yes. We want to make them see how much it has done for us. When they know that they'll do the rest for themselves, I think. I shall expect all you girls to help, because you can do ever so much more than I. It's the girls who really count—not the Guardians, you know."

The next morning Eleanor Mercer, summoned from the group of girls with whom she was discussing some details of the coming contest with the Boy Scouts by the appearance of a man who had rowed up to the little landing stage, accompanied by one of the guides, old Andrew, called Bessie King and Dolly Ransom to her with a grave face.

"This is Deputy Sheriff Rogers, from Hamilton," she explained. "He says that you must go there today to testify against those gypsies."

"Sorry, ma'am, if it's awkward jest now," said the officer. "But law's law, and orders is orders."

"Oh, we understand that perfectly, Mr. Rogers," said Eleanor. "You have to do your duty, and of course we are anxious to see that the law is properly enforced. Don't think we're complaining. But I will admit I am nervous."

"Nervous, ma'am? Why, there ain't nothin' to be nervous about!"

"I hope you're right, Mr. Rogers. But there are things back of this attempt to kidnap my two girls here that haven't come out at all yet. I don't suppose you've heard of them. And it's been suggested to me that it might not be quite safe for them at Hamilton."

The deputy sheriff laughed heartily at that.

"Safe?" he said. "Well, I should some guess they'll be safe down there! Sheriff Blaine—he's my boss, ma'am, you see—would jest about rip the hide off of anyone who tried to tech them young ladies while they was there obeyin' the orders of the court. Don't you worry none. We'll look after them all right enough."

"As long as you know that there may be some danger, I shall be relieved, and feel that everything is all right," said Eleanor, pleasantly. "It's when we're not expecting their blows that the people we are afraid of have been able to strike at us successfully. There is a Mr. Holmes—"

"I know him well, if it's Mr. Holmes, the big storekeeper from the city you mean, ma'am," interrupted Rogers. "Say, if he's a friend of yours, you can be sure you'll be looked after all right down to Hamilton. We think a sight of him down there. He's a fine man, m'am; yes, indeed, a fine man!"

Eleanor looked startled, and only Bessie's quick pinch of her arm prevented Dolly from crying out in surprise and disgust. Knowing what they did of the treachery and meanness of Holmes, this praise of him was disturbing to a degree. But Eleanor never changed countenance. She understood, as if by some instinct, that this was a time for keeping her own counsel.

"I shall go to Hamilton with you," said Eleanor, decidedly. "Will you be able to wait a little while, Mr. Rogers, while we get ready?"

"Surely, ma'am," said Rogers. "We want to get the train that goes down from the station here at noon, and that gives us lots of time. If we start two hours from now we'll catch it, with time to spare."

"Then if you'll sit down and make yourself comfortable," she said, "we'll be ready when it's time to start."

As soon as Rogers had taken himself off, Eleanor called the girls together in her own tent.

"I feel that it is my duty to be with Bessie and Dolly at Hamilton," she explained. "And, because I rather foresaw this, I have arranged for a friend of mine to come over here and take my place as Guardian at short notice. She is Miss Drew—Miss Anna Drew—and some of you must have met her in the city. She has had plenty of experience as a Camp Fire Guardian, and you'll all like her, I know.

"Please make it as easy for her as possible. Do just as she tells you, even if she doesn't have the same way of doing everything that I have. I'll get back as soon as I can, and I want you to have a good time while we're gone."

"We'll see that she doesn't have any trouble, Wanaka," said Margery Burton loyally. "She'll find that this Camp Fire can behave itself, all right!"

"Thanks! I knew I could count on all of you," said Eleanor. "Now I'm going to send her a note by Andrew. Her people own some of this land, and she happens to be in their camp at one of the other lakes, so that she'll be able to get here before we go if she starts at once."

Andrew was quite ready to carry the note, and went off while Eleanor and the two girls made the simple preparations that were necessary for their trip.

"I'm so glad you didn't say anything when the deputy sheriff spoke that way of Mr. Holmes," she said to Bessie and Dolly. "I was afraid one of you would cry out and I really couldn't have blamed you if you had."

"I would have—I was just going to," said Dolly honestly, "but Bessie pinched me, so I shut up, though I couldn't see why. I still think he ought to know that this man he seems to think so much of is the very one they ought to watch most carefully if they really want to make sure that we don't get into any trouble while we're going down there."

"The trouble is that he wouldn't believe it, Dolly, and it would simply discredit us with him and all the other authorities at Hamilton, so that they wouldn't believe us when we had something to tell them that we were sure was true."

"But we're sure that Mr. Holmes was behind this gypsy. We've got the letter he wrote to him to prove it!"

"Yes, but Mr. Jamieson doesn't want anyone to know we have that letter until the proper time comes. He wants to catch Mr. Holmes in a trap if he possibly can, so that he'll be harmless after this. You can see what a good thing that would be."

"Oh, yes. I never thought of that! He doesn't want to put him on his guard, you mean?"

"Just exactly that, Dolly. You see, if Mr. Holmes thinks we don't suspect him, it's possible that he may betray himself in some fashion. He'll feel sure that this man John hasn't betrayed him, and if he thinks we don't know anything about the part he had in this kidnapping plan, he may try to do something, else that will get him into serious trouble.

"And we've got to move very slowly and very carefully, because it's quite plain that he has a lot of friends at Hamilton and that they won't believe anything against him, no matter how serious it may be, unless they get absolute proof."

"Oh, I do hope Mr. Jamieson will be able to catch him this time! I'd feel ever so much better about Bessie and Zara if I knew that they didn't need to be afraid of him any longer."

"So would I, Dolly, and so would Mr. Jamieson. It's this man who is worrying us more than all the other enemies Bessie and Zara have, put together."

"Because he's so rich?"

"Partly that, and because he's so clever, too. And if all I hear about him is true, the more he is beaten, the more dangerous he becomes. He doesn't like to be beaten, and it makes him so angry that he takes all sorts of chances, and does the wildest, most desperate things to get even. They say he was very unfair to a lot of small shopkeepers in the city when he was building up his big store."

"How do you mean, Miss Eleanor?"

"Why, he did everything he could to make them sell out to him for a small price, and, if they wouldn't do it, he did his best to ruin their business. He would circulate false stories about them, and he used his influence with the police and the city authorities to make all sorts of trouble for them.

"Then he would open a store next door to them, sometimes, and sell everything they did cheaper, at a loss, so that people would stop buying from them. You see, he could afford to lose money doing that, because he knew that if he once got them out of the way, he could put prices up again, and get his money back."

"You didn't know all that the day after Zara was taken away, did you, Miss Eleanor?" asked Bessie. "Don't you remember how you laughed at me then for saying I didn't like him, and that I thought he might be mixed up in Zara's disappearance?"

"Yes, I do remember it very well, Bessie. I've often thought what a good thing it was that your eyes were so sharp, and that you suspected him even when all the rest of us thought he was all right. If it hadn't been for that, Mr. Jamieson would never have looked up the records that gave him the clue to where Mr. Holmes had hidden Zara."

"I think Bessie would make a pretty good detective," said Dolly. "They do have women detectives now, don't they? And she seems to be able to tell from looking at people whether they can be trusted or not."

Bessie laughed heartily at that suggestion.

"I can't do anything of the sort," she said. "And, even if I could, I wouldn't be a detective, Dolly. The trouble with you is that you read too many novels. You think people behave in real life just the way the people in the books you read do, and they don't."

The return of old Andrew, the guide, who had rowed across the lake on his return from carrying Eleanor's note to Miss Drew, was the signal to complete the preparations for departure.

"I caught her, all right, Miss Eleanor," said Andrew. "Says she won't be able to come over here till after lunch, but she'll be right over then with a bundle of sticks to keep the young ladies in order till you get back yourself."

"Good!" laughed Eleanor. "That's all right, then, and I can leave here with a clear conscience. Andrew, you'll sort of keep an eye on things till I get back, won't you?"

"Leave it to me, ma'am," said Andrew. "Say, me and some of the boys was thinking maybe you'd like to have some of us turn up, sort of casual like, down at Hamilton?"

"Why, it's very good of you, Andrew, but I don't believe we'll need any help from you, thanks."

"You can't always sometimes tell," said Andrew, sagely. "Now, this here Rogers is a good fellow enough, but obstinate as a mule, and the sheriff might be his twin brother for that. They're birds of a feather, see? And onct they get it into their heads that a thing's so, there ain't nothin' I know of, short of a stick of dynamite, will make them change their minds. So we thought that mebbe it wouldn't be a bad idea to have some of us within call."

"I'll let you know if we need any help, Andrew," promised Eleanor. "And it's very good of you to offer to come. But Mr. Jamieson will be there—you know him, don't you?"

"Mister Charlie? Indeed I do, ma'am, and a fine young chap he is, too. I've often hunted with him through these woods up here. If he's goin' to look after the law part of this for you, you'll have a good chance to beat them sharks down there. Some pretty smart lawyers there at Hamilton, they tell me, ma'am. I ain't never been to law myself. Any time I get into a fight I can't settle with my tongue, I use my hands. Cheaper, and better, too, in the long run."

"It's the old-fashioned way, Andrew. Most people can't settle their troubles so easily. Well, you'll row us to the end of the lake, I suppose?"

"Get right in, ma'am! Might as well start, so's you can take it easy on the trail. Not a bit of use hurryin' when there ain't no need of it, I say. There's lots of times when it can't be helped, without lookin' for a chance."

So, with the strains of the Wo-he-lo cheer rising from the girls who were left behind, they started in the boat for the first stage of the short journey to Hamilton.

Andrew insisted on going with them as far as the station, and as the train pulled out, they heard his cheery voice.

"Now, remember if you need me or any of the boys, all you've got to do is to send us word, and we'll find a way to get there a bit quicker than we're expected," he cried. "Ain't nothin' we wouldn't do for you and the young ladies, Miss Eleanor!"

"You leave them to us, old timer," Rogers called back from the car window. "We'll guarantee to return them, safe and sound. And it won't take any long time, neither. There's a good case against that sneaking gypsy, and we'll have him on his way to the penitentiary in two shakes of a lamb's tail."

"If you don't, I'll vote for another sheriff next election," vowed Andrew, "if I have to vote a Demmycratic ticket to do it, and that's somethin' I ain't done—not since I was old enough to vote."

Rogers was reassuring enough in his speech and manner, but Eleanor had a presentiment of evil; a foreboding that something was wrong.

The railroad trip to Hamilton was not a long one, and within two hours of the time they had left Long Lake the brakeman called out the name of the county seat. Eleanor and the two girls, with Rogers carrying their bags, moved to the door, and, as they reached the ground, looked about eagerly for Jamieson.

He was nowhere to be seen. But Holmes was there, avoiding their eyes, but with a grin of malicious triumph that worried Eleanor. And Rogers, a moment after he had left them to speak to a friend, returned, his face grave.

"I hear your friend Mr. Jamieson is arrested," he said.

"Arrested?" cried Eleanor, startled. "Why, what do you mean? How can that be?"

"That's all I know, ma'am," said Rogers, soberly. "Even if I did know anything more, I guess maybe I oughtn't to be saying anything about it. I'm an officer, you see. But here's the district attorney. Maybe he'll be able to tell you what you want."

He pointed to a tall, thin man who was talking earnestly to Holmes, and who came over when Rogers beckoned to him.

"This is Mr. Niles, Miss Mercer," said Rogers. "I'll leave you with him."

"Glad to meet you, Miss Mercer," said Niles, heartily, "though I'm sorry to have dragged you away from your good times at Long Lake. These, I suppose, are the young ladies who were kidnapped?"

"Yes, though of course they weren't really kidnapped, because they got away before any real harm was done," Eleanor replied. "But, Mr. Niles, what is this absurd story about my cousin, Mr. Jamieson? Mr. Rogers said something about his having been arrested."

Niles grew grave.

"I hope you're right—I hope it is absurd, my dear young lady," he said. "Your cousin, you say? Dear me, that's most distressing—most distressing, upon my word! However, you will understand I had nothing to do with the matter.

"I have to take cognizance, in my official capacity, of any charges that are made, but I am allowed to have my own opinion as to the guilt or innocence of those accused—yes, indeed! And I am quite sure that Mr. Jamieson had nothing to do with this attempted kidnapping!"

"What?" gasped Eleanor. "Do you mean to say that it is on such a charge as that that he has been arrested?"

She laughed, in sheer relief. The absurdity of such an accusation, she was sure, would carry proof in itself that Charlie was innocent. No matter who was trying to spoil his reputation, they could not possibly succeed with such a flimsy and silly charge.

"I'm glad it seems so funny to you, Miss Mercer," said Niles, stiffly. "I'll confess that it looked serious to me, although, as I say, I do not believe in Mr. Jamieson's guilt. However, he will have to clear himself, of course, just as anyone else accused of a crime must do. Where I have jurisdiction, no favors are shown.

"The poor are on a basis of equality with the rich; I would send a guilty millionaire to prison with a light heart, and on the same day I would move heaven and earth to secure the freedom of an innocent beggar, though men of wealth were trying to railroad him to jail!"

He finished that peroration with a sweeping and dignified bow. And then he stopped, thunder-struck, as a clear, girlish laugh rose on the air. It was Dolly who laughed.

"I couldn't help it," she said, afterward. "He was so funny, and he didn't know it! As if anyone would take a man who talked such rot as that seriously!"

But the trouble was that, vain and pompous as Niles plainly was, his official position made it necessary to take him seriously. Though at first she was disposed to agree with Dolly, and had, indeed, had difficulty in keeping a straight face herself while he was boasting of his own incorruptibility, Eleanor discovered that fact as soon as she had a chance to talk with Charlie Jamieson.

"I shall be glad to arrange for you to have an interview with your cousin, Miss Mercer," Niles informed her. "Theoretically, he is a prisoner, although of course he will be able to arrange for his own release on bail as soon as he finds some friend who owns property in this county. But I have given orders that he is not to be confined in a cell. I trust he is making himself very much at home in the parlor of Sheriff Blaine. If you will honor me, I will take you there."

"I should like to see him at once," said Eleanor. "Come, girls! Mr. Niles, I am sure, will find a place where you can wait for me while I talk with Mr. Jamieson."

Charlie greeted her with a sour grin when she was taken to the room where, a prisoner, he was sitting near a window and smoking some of the sheriff's excellent tobacco.

"Hello, Nell!" he said. "First blood for our friend Holmes on this scrap, all right. First time I've ever been in jail. It's intended as a little object lesson of what he can do when he once starts out to be unpleasant, I fancy. He must know that he hasn't any sort of chance of keeping me here."

"Why, Charlie, I never heard anything so absurd!" said Eleanor, hotly. "As if you, who have done everything possible for those girls, would do such an insane thing as hire that gypsy to kidnap them. And especially when we know who did do it!"

"That's just the rub! We know, but can we prove it? You see, it's my idea that Holmes is starting this as a sort of backfire. He thinks we're going to accuse him, and he wants to strike the first blow. He's clever, all right."

"I don't see what good it can do him, Charlie."

"A lot of good, and this is why. He puts me on the defensive, right away. He wants time as much as anything else. And if he can keep me busy proving my own innocence, he figures that I'll have less time to get after him. It's a good move. The more chance he has to work on those gypsies, the less likely they are to say anything that will make trouble for him. He can show them his power and scare them, even if he can't buy them.

"And I think the chances are that he won't find it very hard to buy them. They pinched me as soon as I got off the train this morning. I've sent out a lot of telegrams, asking fellows to come up here and bail me out, but of course I can't really expect to get an answer today—an answer in person, at least."

"Mr. Niles seems friendly. He said that he doesn't believe you're guilty, Charlie."

"That's kind of him, I'm sure. Niles is an ass—a pompous, self-satisfied ass! Holmes is using him just as he likes, and Niles hasn't got sense enough to see it. He's honest enough, I think, but he hasn't got the brains of a well-developed jellyfish."

Eleanor laughed at the comparison.

"Well, if he's honest, you don't have anything to fear, I suppose," she said. "I'm glad of that, Charlie. I was afraid at first that he might be just a tool of Mr. Holmes, and that he would do what Mr. Holmes told him."

"I'd feel easier in my mind if he were a regular out-and-out crook, Nell. That sort always has a weakness. Your crook is afraid of his own skin, and when he knows he's doing things for pay, he'll always stop just short of a certain danger point. He won't risk more than so much for anyone. But with this chap it's different. He's probably let Holmes, or Holmes's gang, fill him up with a lot of false ideas, and they're clever enough to get him to wanting to do just what they want him to do."

"And you mean that he'll think he's doing the right thing?"

"Yes, and not only that, but he'll persuade himself that he figured the whole thing out, thought it out for himself, when really he'll just be carrying out their own suggestions. We've got to find some way to spike his guns, or else Holmes will work things so that his gypsy will get off, and there'll be no sort of chance to pin the guilt down to him, where it belongs."

"Then the first thing to do is to get you out, isn't it?"

"Yes, but I've done all that can be done on that. There's really nothing to be done now but just wait—and I'd rather do pretty nearly anything I can think of but that."

"I don't know, Charlie. Why can't I give bail for you? You know, Dad made over all that land up in the woods around Long Lake that he owns to me. So I'm a property holder in this county—and that's what is needed, isn't it?"

"By Jove! You're right, Nell! Here, I'll make out an application. You send for Niles, and we'll get him to approve this right now. Then we'll get the judge to sign the bail bond, and I'll get out. I never thought of that—good thing you've got a good head on your shoulders!"

Eleanor, pleased and excited, went out to find Niles, and returned to Charlie with him at once.

"H'm, bail has been fixed at a nominal figure—five thousand dollars," said Niles. "I may mention that I suggested it, knowing that you would not try to evade the issue, Mr. Jamieson. We have heard of you, sir, even up here. If the young lady will come to the judge's office with me, I have no doubt we can arrange the matter."

Before long it was evident there was a hitch.

"I am sorry, Miss Mercer," said Niles, with a long face, "but there seems to be some doubt as to this. You have not the deed with you—the deed giving title to this property?"

"No," said Eleanor. "But the records are here, are they not? Certainly you can make sure that I own it?"

Niles shook his head.

"I'm afraid we must have the deed," he said.

For the moment it looked as if Charlie would have to stay in confinement over night, at least. But suddenly Eleanor remembered old Andrew and his offer to help. And twenty minutes later she was explaining matters to him over the telephone.

"Why, sure," he said. "I can fix you up, Miss Eleanor. I've saved money since I've been working here, and I've put it all into land. I know these woods, you see, and I know that when I get ready to sell I'll get my profit. I'll be down as soon as I can come."

"Don't say a word," said Charlie. "It wouldn't be past them to fake some way of clouding the old man's title if they knew he was coming. We'll spring that on them as a surprise. Evidently they figure on being able to keep me here until to-morrow, at least. They've got some scheme on foot—they've got a card up their sleeves that they want to be able to play while I'm not watching them. I don't just get on to their game—it's hard to figure it out from here. But if I once get out I won't be afraid of them. We'll be able to beat them, all right, thanks to you. You're a brick, Nell!"

Andrew was as good as his word. He reached the town in time to go to the judge with the deeds of his property, and though Holmes, who was evidently watching every move of the other side closely, scowled and looked as if he would like to make some protest, there was nothing to be done. He and his lawyers had no official standing in the case—they could only consult with and advise Niles in an unofficial fashion. And, though Niles held a long conference with Holmes and his party before the bail bond was signed, it proved to be impossible for the court to decline to accept it. Some things the law made imperative, and, much as Niles might feel that he was being tricked, he could not help himself.

Once he was free, as he was when the bail bond was signed, Jamieson wasted no time. He saw Eleanor and the two girls settled in the one good hotel of Hamilton, and then rushed back to the court house. And there he found a strange state of affairs. Holmes had brought with him from the city two lawyers, though Isaac Brack, the shyster, was not one of them. And the leader, a man well known to Jamieson, John Curtin by name, now appeared boldly as the lawyer for the accused gypsies. Moreover, he refused absolutely to allow Charlie to see his clients.

In answer to Charlie's protests he merely looked wise, and refused to say anything more than was required to reiterate his refusal. But Charlie had other sources of information, and an hour after his release, meeting Eleanor, who had walked down to look around the town, leaving the girls behind at the hotel, he gave her some startling news.

"They're trying to get those gypsies out right now," he said. "They were indicted, you know, for kidnapping. Now Curtin has got a writ of habeas corpus, and he's kept it so quiet that it was only by accident I found it was to be argued."

"What does that mean?" asked Eleanor. "I don't know as much about the law as you do, you know."

"It means that a judge will decide whether they are being legally held or not, Nell. And it looks very much to me as if Holmes had managed to fix things so that they'll get off without ever going before a jury at all! Niles isn't handling the case right. He's allowed Holmes and his crowd to pull the wool over his eyes completely. If we had some definite proof I could force him to hold them. But—"

Eleanor laughed suddenly.

"I didn't suppose it was necessary to give this to you until the trial," she said. "But look here, Charlie—isn't this proof?" And she handed him the letter found on John, the gypsy—a letter from Holmes, giving him the orders that led to the kidnapping of Dolly.

Charlie shouted excitedly when he read it.

"By Jove!" he said. "This puts them in our power. You were quite right—we don't want to produce this yet. But I think I can use it to scare our friend Niles. If I'm right, and he's only a fool, and not a knave, I'll be able to do the trick. Here he is now! Watch me give him the shock of his young life!"

Niles approached, with a sweeping bow for Eleanor, and a cold nod for Jamieson. But the city lawyer approached him at once.

"How about this habeas corpus hearing, Mr. District Attorney?" he asked. "Are you going to let them get those gypsies out of jail?"

"The case against them appears to be hopelessly defective, sir," returned Niles, stiffly. "I am informed by counsel for the defense that there are a number of witnesses to prove an alibi for the man John, and I feel that it is useless to try to have them held for trial."

"Suppose I tell you that I have absolute evidence—evidence connecting them with the plot, and bringing in another conspirator who has not yet been named? Hold on, Mr. Niles, you have been tricked in this case. I don't hold it against you, but I warn you that if you don't make a fight in this case, papers charging you with incompetence will go to the governor at once, with a petition for your removal!"

"I—I don't know why I should allow one of the prisoners in this case to address me in such a fashion!" stuttered Niles.

"I don't care what you know! I'm telling you the truth, and, for your own sake, you'd better listen to me," said Jamieson, grimly. "I mean just what I say. And unless you want to be lined up with your friend Curtin in disbarment proceedings, you'd better cut loose from him. I suppose Holmes has told you he'll back your ambitions to go to Congress, hasn't he?"

Niles seemed to be staggered.

"How—how did you know that?" he gasped.

As a matter of fact, Charlie had not known it; he had only made a shrewd guess. But the shot had gone home.

"There's more to this than you can guess, Mr. Niles," he said, more kindly. "It's a plot that is bigger than even I can understand and they have simply tried to use you as a tool. I knew that once you had a hint of the truth, your native shrewdness would make you work to defeat it. You understand, don't you?"

Coming on top of the bullying, this sop to the love of Niles for flattery was thoroughly effective. Charlie was using the same sort of weapons that the other side had employed. And Niles held out his hand.

"I'll take the chance," he said. "I'll see that those fellows stay in jail, Mr. Jamieson. As I told Miss Mercer, I was sure from the beginning that you were all right. May I count on you for aid when the case comes up for trial?"

"You may—and I'll give you a bigger prisoner than you ever thought of catching," said Charlie.

"We've got them, I think," Jamieson said to Eleanor Mercer and the two girls after his talk with District Attorney Niles. "There's just one thing; I don't understand how Holmes can be so reckless as to take a chance when he must remember that he hasn't got a leg left to stand on."

"He probably doesn't know that we know anything about it," said Bessie. "And I guess he thinks that if we had had that note all this time we'd have produced it before, so that he thought it was safe to act."

"You're probably right, Bessie," said Eleanor. "I thought that letter would be useful, Charlie, when we took it from that gypsy. I don't suppose I really had any right to keep it, but just then, you see, Andrew and the other guides were the only people around, and they would never question anything I did—they'd just be sure I was right."

"Good thing they do, for you usually are," laughed Charlie. "I've given up expecting to catch you, Nell. You guess right too often. And this time you've certainly called the turn. Niles is convinced. All I'm afraid of now is that he won't be able to hold his tongue."

"You want to surprise Mr. Holmes, then?"

"I certainly do. I'd give a hundred dollars right now to see his face when I spring that letter and ask for a warrant for his arrest. Mind you, I don't suppose for a minute we'll be able to do him any real harm. He's got too much influence, altogether, with bigger people than Niles and this judge here."

"You know I'm not very vindictive, Charlie, but I would like to see him get the punishment he deserves. I'd much rather have them let those poor gypsies off, if only they would put him in prison in their place. I feel sorry for them—really, I do. It seems to me that they were just led astray by a man who certainly should know better."

"That part of it's all right enough, Eleanor. But if one accepted the excuse from every criminal that he was led astray by a stronger character, no one would ever be punished. Pretty nearly everyone who ever gets arrested can frame up that excuse."

"You don't think it's a good one?"

"It is, to a certain extent. But if our way of punishing people for doing wrong is any good at all, and if it is really to have any good effect, it's got to teach the weaklings that every man is responsible himself for what he does, that he can't shift the blame to someone else and get out of it that way.

"You remember the poem Kipling wrote about that? I mean that line that goes: 'The sins that we sin by two and two we must pay for one by one.' It seems pretty hard sometimes, but it's got to be done. However, even if Holmes gets out of this, it's a thundering good thing that we've got as much as we have against him."

"I don't see why, if you say he's going to get off without punishment."

"Well, I think it's apt to make him more careful, for one thing. And for another, some people will believe the evidence against him, and he'll have the punishment of being partly discredited at least. That's better than nothing, you know. One reason he's in a position to do these rotten things without fear of being caught is that he's supposed to be so respectable. Let people once begin to think he isn't any better than he should be, and he'll have to mind his p's and q's just like anyone else, I can tell you."

"That's so! I didn't think of that."

"The thing to do now is to make sure that the trial comes off at once. I've got an idea that they'll try to get a delay, now that they've had to give up their hope of rushing it through while I was tied up and couldn't tell whatever I happened to know. They'll figure that the more time they have, the more chance there is that they can work out some new scheme, or that something will turn up in their favor—some piece of luck. And it's just as likely to happen as not to happen, too, if we give them a chance to hold things up for a few weeks. You want to get away, too, don't you?"

"We certainly do, Charlie. The girls would be dreadfully disappointed if we didn't get back in time to make the tramp through the mountains with them."

"Well, I guess we'll manage it all right. Leave that to me. You've had bothers and troubles enough already since you got here. I ought to have a nurse! Here I come to look after your interests, and see that nothing goes wrong with you and your affairs, and the first thing you have to do is to get me out of jail!"

Eleanor returned his laugh.

"We really enjoyed it, though you've got Andrew to thank, not me," she said. "Do you really think they'll manage to get it postponed after to-morrow?"

"Not if I have to sit up with Niles and hold his hand all night, to keep him in line," vowed Jamieson.

And, indeed, the morning proved that there was no cause for worry. Niles, stiffened by Jamieson, refused even to see the men from the other side, who were employed by Holmes, when they came to his office to beg for an adjournment, or to ask him to consent to it, at least, since only the judge had the power to grant it. And the trial began at the appointed time.

Charlie, not being actively engaged as a lawyer in the case, could not spring his sensation himself. But he sat near Niles, waiting for the opportune moment, and, before the morning session was over, since he saw that the time was drawing near, he wrote a note to Niles, explaining his plan to surprise Holmes fully, which he handed to him in the quiet courtroom.

"That's great—great!" said Niles. "It's immense, Jamieson! I never dreamed of anything like that. Heavens! How I have been deceived in this man Holmes! You have the original letter, you say?"

Jamieson tapped his breast pocket significantly.

"You bet I've got it!" he said. "And it doesn't leave my possession, either, until it's been read into the records of this court. You'll have to call me as a witness, Niles. That's the only way we can get this over, since I can't very well act as counsel for either side of the case."

"All right. First thing after lunch," said Niles.

Holmes was in the courtroom, and Jamieson, happening to look up just as Niles spoke to him, caught the merchant pointing to him, the while he bent over and talked earnestly with a sinister, scowling man who was unknown to the lawyer, but who seemed to be on the most intimate terms with Holmes. However, he thought nothing of the incident. He had understood from the first that in opposing Holmes, and doing all he could to spoil his plans regarding Bessie and Zara, he was incurring the millionaire's enmity, and he did not greatly care.

"You know," he had said to Eleanor, "this chap Holmes thinks—or he did think, at least—that I'd be scared by his ability to help or hurt a man in my profession in the city. But I think a whole lot of that is bluff on his part. I don't believe he can do as much as he thinks he can. And I don't know that I care a whole lot, anyhow. He hasn't gone out of his way to help me so far, and I've managed to get along pretty well. I guess I can do without him to the end of the chapter."

Just after the court adjourned for lunch, Niles was called away by Curtin, the leader of the lawyers Holmes had hired to defend the gypsy prisoners, and Jamieson saw them talking earnestly together for several minutes. Naturally, he did not try to overhear the conversation, but he could not have done so in any case, for Curtin kept looking about him, so that it was evident that he, at least, regarded what he had to say as both important and confidential. But Charlie waited patiently, sure that Niles would tell him all he wanted to know, unless he should again go over to the other side.

"They're wise to us," said Niles, when he returned. "Curtin knows we've got something up our sleeves, and maybe he wasn't anxious to find out what it was!"

"You didn't tell him, I hope?"

"Not I! Trust me to know better than that! But I think he's got an inkling."

"Lord, why shouldn't he?" said Charlie to himself, bitterly. "Of course, there's no reason why that gypsy shouldn't tell him! He probably doesn't realize what the letter means, but we do, and if the rascal has told them that it was taken away from him they would realize at once that they were up against it, and hard!"

"Well, you haven't told me the whole story," he said, with a suggestion of being offended in his tone. "So I can't give you my advice as I would be glad to do if you had taken me into your confidence."