Title: Anecdotes & Incidents of the Deaf and Dumb

Author: W. R. Roe

Release date: August 29, 2009 [eBook #29841]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, Rose Acquavella and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

W. R. ROE, M. C. T. D. & D.,

Head Master Midland Deaf and Dumb Institution, Derby,

Author Of "Alice Gray: a True Story;" &c.

DERBY:

FRANCIS CARTER, IRON GATE.

1886.

The Deaf and Dumb cannot help themselves as others can. From the cradle they are cut off from their fellow creatures. They can only cry, like the dumb brute, to make their pains and wishes known. God only can know the bitterness of heart, the desolation of the deaf and dumb child of the poor, as it grows up in a world without speech or sound—a lifelong silence! A mother's smile it may understand, but her soothing voice never comforts or delights it. While others grow in love, and life, and intelligence, its heart is chilled and its mind enfeebled. Only under suitable instruction, given at an early age, can the deaf mute become anything but a burden to others and to himself.

The anecdotes in the following pages will doubtless be read with considerable curiosity, and it is hoped that the Midland Institution for the Deaf and Dumb at Derby will receive some pecuniary assistance by the publication of this little book.

There are 1119 Deaf and Dumb in the Institution's district, which comprises six of the Midland Counties.

The Institution is supported by voluntary contributions.

W. R. R.

Midland Deaf and Dumb Institution,

Friar Gate, Derby.

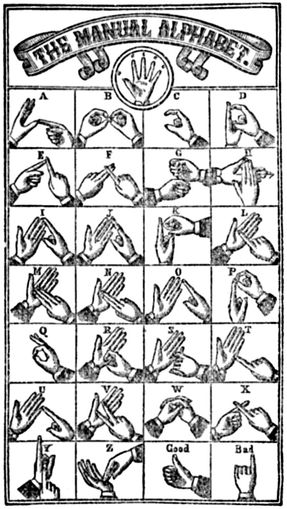

little boy was admitted as a pupil into the

Institution for the Deaf and Dumb at Derby.

Previous to his admission he had given his

parents and friends a great deal of trouble, and

fears were entertained that he would be none

the less troublesome to those in charge of him at

the Institution. Happily however, owing to the firmness and

kindness of his teachers, he very soon yielded to the rules and

became a good, obedient boy. At length the time came for

the vacation, and, amongst others, this little fellow went home

for his holiday. The dinner hour arrived, and sitting down

with his parents, he looked up at his father and put his hands

[Pg 6]together. He wanted his father to ask a blessing. The father

made the boy understand he did not know what to say, then

the poor little fellow began to cry. At last he thought of a

plan, he would ask the blessing himself; and so he spelt on

his fingers the blessing he had learnt at the Institution, and

got his friends to spell on their fingers after him letter by letter

and word by word, and thus overcame the difficulty in which

he was placed.

In America there are four deaf and dumb clergymen working in connection with the Church Missions to the Deaf and Dumb. There are also in connection with the same mission eight lay readers, all of whom are deaf and dumb.—Deaf Mute World.

n a vast majority of cases where the deaf and dumb

are allowed to grow up uneducated and uncared

for they become inmates of Workhouses or Lunatic

Asylums. Many years ago L—— K—— was taken

from a workhouse in Derbyshire where he had been

for a number of years, and educated and apprenticed

to a suitable trade; he is now a steady, industrious man, married,

and himself a ratepayer. This is only one of many similar

instances that have come within our experience. In some

other cases they are struggling to support widowed mothers

and sisters.

The following is taken from the Manchester Mercury and Harrop's General Advertiser, June 10, 1800:—"On the 12th ult., in the Island of Anglesea, Mr. Henry Ceclar, a gentleman well known for his pedestrian feats, to Miss Lucy Pencoch (the rich heiress of the late Mr. John Hughes, Bawgyddanhall), a lady of much beauty, but entirely deaf and dumb. This circumstance drew together an amazing concourse of people to witness the ceremony, which, on the bride's part, was literally performed by proxy. A splendid entertainment was given on the occasion by the bridegroom; but a dreadful catastrophe closed the scene, for the bride, in coming down stairs, made a false step, and fell with so much violence against a chair that she immediately expired."

This gentleman, who is now senior professor in the Paris Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, is described as a man of rare merit, probably superior in literary abilities and acquirements to any other deaf mute from birth that any country can produce. He is the author of several works that would do credit to a well-educated man whose knowledge of language had been acquired through the ear. On a recent occasion of a public exercise at the Institution he was decorated by the President of the Republic with the Cross of the Legion of Honour, the first time such a distinction had ever been conferred on a deaf and dumb person.

In a letter received by the head master at the Deaf and Dumb Institution at Derby, a lady writes about a little boy she had assisted in obtaining admission into the Institution, and said that "During the little time (18 months) that William has been in the Institution he has improved wonderfully." She writes—"You know he used to be so wild, dirty, and careless; he was always interfering with everybody, in fact he went in the village by the name of Troublesome Dummy. All is changed; he is a nice clean, well behaved boy, and people are beginning to call him by his right name, William. We shall never forget what you have done for him."

We were lately shown a curiosity in the shape of a sewing machine entirely of wood. It was whittled out of ordinary pine with an ordinary jack-knife by an ordinary boy—no, not an ordinary boy; it was the handiwork of a deaf and dumb boy who resides at Massachusetts. A machine was left at the house of the boy by an agent, and the lad, with considerable ingenuity, made a counterpart of the machine, and did it wholly with a jack-knife.

At a meeting held in a country village in aid of the Deaf

and Dumb Institution, Derby, a number of the pupils

were present on the platform. One of the speakers called attention

to a bright looking little fellow, and asked the audience if

they knew him? and amidst general laughter spoke of the

boy's earlier

years, how

he had seen

him running

about barefooted

and

dirty, playing

with the

worst boys in

the streets;

but now

completely

changed in

his habits

and character.

He went

on to relate

a little incident

he had

himself observed

a few

weeks previous,

when

the boy was

home from the Institution for his holiday. The little deaf and

dumb boy was coming along the road, looking clean and bright,

and carrying a book in his hand, when four of his old gutter

companions, all in dirt, and who ought to have been at school,

saw him, and one of them shouted out, "Hello, here's owd

dummy comin;" and all four went to meet him, and tried to

make friends with him, but he thought they were scarcely clean

enough for his company, and quietly passed on his way towards

home. The boys were surprised, and stared at each other for

some time; at last one of them said, "Oh, ain't he got mighty

proud?"

A deaf and dumb sculptor named Van Louy de Canter has recently obtained two prizes, one a silver medal with a ribbon of Belgian colours, and a second class award for his best work in marble; the other a bronze medal; he has also an honourable certificate from the Belgian Exhibition of 1880. It is encouraging to hear of his success, and to know that from his devotion to the art, he will persevere in the right way to be a credit to his country and to his numerous friends among the deaf and dumb.

By Sir John Lubbock, Bart, M.P., &c.

This work is one of the many magnificent contributions to the literature of natural history issued by the Royal Society. It treats of curious animals which the author considers as more nearly allied to the Insecta than to the Crustacea or Arachnidæ. It is magnificently illustrated with 78 plates (31 being coloured), and the whole of the illustrations were executed by a painstaking deaf and dumb artist, Mr. Hollick. It will mark an era in the study of those neglected, but intensely curious animals, and we doubt not will repay both author, and artist, and the Society for the labour bestowed upon it.—Daily Paper.

The following curious

anecdote is related

of Mary, Countess

of Orkney. She was deaf

and dumb, and was married

in 1753, by signs.

She lived with her husband,

who was also her

first cousin, at his seat,

Rostellan, on the harbour

of Cork. Shortly

after the birth of her first

child, the nurse, with considerable

astonishment,

saw the mother cautiously approach the cradle in which the

infant was sleeping, evidently full of some deep design. The

Countess having perfectly assured herself that the child really

slept, took a large stone, which she had concealed under her

shawl, and to the horror of the nurse—who, like all persons of

the lower order in her country, indeed in most countries, was

fully impressed with an idea of the peculiar cunning and malignity

of "dumbies"—raised it with an intent to fling it down

vehemently. Before the nurse could interpose the Countess

had flung the stone—not, however, as the servant had apprehended

at the child, but on the floor, where of course it made

a great noise. The child immediately awoke, and cried. The

Countess, who had looked with maternal eagerness to the

result of her experiment, fell on her knees in a transport of

joy. She had discovered that her child possessed the sense

which was wanting in herself.

In St. Modwen's Churchyard at Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, the following inscription has been copied from the tombstone of a deaf and dumb man:—

This Stone

Was raised by Subscription

To the Memory of

Thomas Stokes,

An eccentric and much-respected deaf and dumb man,

Better known by the name of

Dumb Tom,

Who departed this life Feb. 25th, 1837,

Aged 57 years.

ot long ago there died in the county Wexford, in

Ireland, a deaf and dumb shoemaker named Henry

Plunkett. He had for many years been a true

and sincere christian, and therefore when he came

to die he was not afraid, but rejoiced at the thought

of meeting his Saviour. During the last few hours

of his life on earth he suffered much pain; but he was quite

sensible, and made signs that if the house was piled up with

gold he would not take it all and live, for, he said, pointing his

hand upwards, "I wish to go up." To the woman who attended

him he signed, "Do not fret, not never; I am going to

Jesus." "The contrast between the white face—white as marble—and

the long jet black hair and beard is striking," wrote

the clergyman who sent this account, shortly after his death.

But beautiful as he looked in death, he looks far more beautiful

in heaven, where he now is, clothed in the white robe of

Christ's righteousness, which he has provided for all who truly

love and serve him.

The state coach for the Lord Mayor elect will be furnished by Mr. J. Offord, of Wells Street and Brook Street, who has also supplied the chariot for Mr. Sheriff Johnson. The coach for the new Lord Mayor is quite in harmony with modern ideas and taste. The side windows, instead of being rounded off in the corners as formerly, are cut nearly square, to follow the outlines of the body. This novelty renders the body of the carriage much lighter than usual, and more elegant in appearance. Another 'innovation' is the painting. It has hitherto been usual to paint the under part of the carriage white or drab, relieved by the same colour as the body, but in the present case the whole vehicle has been painted a dark green, the family colour of the Lord Mayor elect, relieved by large lines of gold upon the body, and gold and red upon the under carriage. The natural elegance of this arrangement of colouring is heightened by the beautiful heraldic paintings of the City arms and those of the Fishmongers' and Spectacle Makers' Companies, of which Mr. Alderman Lusk is a member. These have been executed by Mr. D. T. Baker, the celebrated deaf and dumb artist.—The Times, 1883.

Deaf and Dumb men have a poor chance in Texas. One of them went to a farmhouse, and, when asked what he wanted, put his hand in his pocket to get a pencil, and he was at once shot down by the farmer, who thought his visitor was feeling for a pistol.

e are quite sure the Indians were

delighted by the reception tendered

them by the children of the public

schools and the inmates of the Institutions

for the Blind and Deaf and

Dumb last Friday, in the Academy

of Music, but their happiness was made

complete, on Sunday evening, at the La

Pierre house, by a visit which they received

from six of the pupils, all girls, of the Deaf

and Dumb Institute, accompanied by the

Principal, Mr. Foster, and one of the teachers.

On their arrival at the hotel they were

received by Mr. Welsh, the humane commissioner, and shown

into a well furnished private parlour, when they were introduced,

one by one, to General Smith and his Indians, whose

faces plainly showed the delight which their hearts felt. They

at once singled out the two girls who had taken part in the

reception at the Academy, and bestowed upon them special

marks of friendship.

Tea being announced in a few minutes, the whole party proceeded to the dining room, where they were seated at well spread tables, three Indians and one mute at each. Here the striking similarity between the signs used by the Indians of the West and our deaf mutes was plainly observable in the spirited conversation which ensued. The merry laughter which broke forth from these usually quiet stolid men was sufficient to mark their keen appreciation of what was said. One old chief, slightly confused, sought to excuse his awkwardness with the knife and fork to one of the young ladies, by stating that at [Pg 16]home he never used them, but ate with his fingers. They exchanged signs for butter, coffee, milk, meat, bread, salt, sugar, knife, fork, &c., which were remarkably similar.

After tea the whole party assembled in the parlour, and then began a scene indescribable. The Indians, wild with delight, talked away to the mutes, who, equally happy, seemed to catch and understand everything they said. They described their homes, their hunting expeditions, their wives and children; how they lived and how they buried their dead. One of them gave a very graphic account of the great snowstorms which frequently occur among the mountains. One told about the wars he had engaged in, and the number of scalps he had taken, and then asked the teacher if he had ever killed a man, and on receiving a reply in the negative, seemed quite disgusted. Another, a great rider, said that with them the horses had plenty of grass to eat, and were fat, but here, in the city, they had none, and were consequently very poor. Another old chief, a very fine looking man, stated that he had a large family of children at home, and then asked the smallest of the girls if she wouldn't go home with him, promising to bring her back as soon as she had taught his little boys and girls how to make signs like the mutes.

These wild men seemed thoroughly at home in the presence of the children, their habitual restlessness and reserve disappeared; they had met for once white persons with whom they could converse without the tedious process of interpreting, and the conversation, as Mr. Welsh expressed it, went directly to their hearts. In parting with their young visitors, the Indians freely expressed the pleasure which their visit had afforded them, then sorrow at the separation, and promised to relate all that had occurred to their friends and kindred in the West.

When it is remembered that all this and much more took place between a delegation of wild Indians and six mute girls attending the Institution in our city, it certainly will be considered remarkable, and probably never before in the history of civilization has such a meeting occurred. As a means of communication with the wild tribes roaming over our western plains, the capacity of the sign-language of mutes can hardly be over estimated, and a few well-trained mute missionaries could, without doubt, be made the instruments for accomplishing much good among this down-trodden despised race.—New York Herald.

At the great Exhibition in 1851 there was exhibited a set of oak tables and cabinet of Stanton oak, combined with glass and ormolu, etc., made and carved by three deaf and dumb persons; the castings by Marsh, of Dudley.

etty Hutson lives in the

city of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania,

a girl seventeen

years old, who has been

deaf and dumb and blind

from birth. She is active in her

nature, and has a remarkably intelligent

mind. Through the one

medium of gestures, as perceived

by the touch, she understands

wonderfully well, and in turn

makes herself understood. She

will wipe dishes and put them

away with scrupulous care and exactness; will go down the

cellar alone at her mother's bidding and get apples; then,

running up with astonishing rapidity, will give them to anyone

she is bid, and put her own into her pocket. At a motion from

her father she will go upstairs and get his best hat, deciding

by touching his broadcloth suit which hat he wants. She knits

and sews in a very creditable style, and manifests a desire to

learn to do other kinds of work. She is neat and orderly in

her habits, and ever acts in a ladylike manner, while in disposition

she is cheerful as a sunbeam, and as playful as a kitten.

For about one year, at irregular intervals, a young minister of

the name of J. B. Howell, devoted one hour each week to her

instruction, and she made some advancement, novel as his

method was; but in June last he went to Brazil as a missionary,

since which time she has been without instruction until

[Pg 19]recently. She is now receiving daily instruction by means of

the manual alphabet. It is, however, to be regretted that her

present teacher is an entire novice in the work she has undertaken,

but as she has large sympathy for her, and individual

experience as to the needs of her pupil, it seems safe to hope

that she may lay a substantial foundation, upon which some

more accomplished person may build an education which will

make this greatly afflicted being equal to Laura Bridgman, of

world wide fame.

Among some of the islands of the South Sea the compound word for "hope" is beautifully expressive; it is "manaolona" or "swimming thought"—"faith" floating and keeping its head aloft above water, when all the waves and billows are going over it—a strikingly beautiful definition of "hope," worthy to be set down along with the answer which a deaf and dumb person wrote with his pencil, in reply to the question "What is your idea of forgiveness?" "It is the odour which flowers yield when trampled on."

avid Simons, of Boston, is deaf and dumb; he is

also blind; likewise he is lame. Penniless he is,

and houseless. Finally, he is black, which may or

may not be considered a misfortune. No,—finally

he was run over by a team and dreadfully bruised.

Yet we suppose that John Simons still desires to live, for he

consented to be carried to a hospital.—Deaf Mute Advance.

(From The Graphic, May, 1874.)

Messrs. Doulton and Co., who have done so well with stoneware, dignifying the simplest material by giving even to the most ordinary and cheapest articles shapes of real beauty, exhibit in Room 9 a most praiseworthy set of examples (3719) of very remarkable art and character, demonstrating principally possibilities of wall decoration. On the floor at the base of the division are some noble pieces of graphite stoneware contributed by Mr. Frank A. Butler, who is deaf and dumb.

(From the Journal of the Society of Arts, May 1, 1874.)

Another artist who has made his mark on the ware by the originality of his forms is Frank A. Butler. He is quite deaf and almost dumb. He is one of many thus heavily afflicted who have passed through the school. He began his artistic life as a designer of stained glass, but his invention was not needed, nor, I dare say, discovered in the practice of an art which is almost traditional. I introduced him to the new work, and in a few months he brought out many new thoughts from the silent seclusion of his mind. A bold originality of treatment, and the gift of invention, are characteristic of his work. He has struck out many new paths. A certain massing together of floral forms, and ingenious treatment of discs, dots, and interlacing lines indicate his hand.

A little coloured

deaf and dumb girl in

Demerara came to Mrs.

H——'s school, and wished

to learn to read. It was

thought impossible to teach

her; the missionary's wife

therefore shook her head,

and made signs for her to

go home. But she would

take no denial; so Mrs.

H—— sent to England for

the "Deaf and Dumb Alphabet."

It was astonishing

how quickly the child

was taught to read the New Testament, from which she learned

to know Jesus as her Saviour. One day she signed to her kind

teacher, "Missie, me too happy. You would think when me

walk out that there were two people in the road; but it is

Jesus and me. He talk and me talk, and we two so happy

together."

Mr. James Wyllie (the Herd Laddie), the greatest living draught player, has been in Aberdeen for a whole week, playing in public against all comers. He played altogether 98 games, of which he won 79, lost 3, and 6 drawn. It is worthy of notice that three of the draws were secured by Mr. Benjamin Price, a deaf mute, and a well known local player.—Scotsman.

sabella Green was a young woman

who was completely blind and deaf, and

she was brought before a number of

eminent surgeons to see if anything

could be done for her. Her sad condition

had been produced by violent

pain in the head. The only method

of communicating with her was by tapping

her hand, which signified no, and

squeezing it, which signified yes. The

surgeons concluded that her case was

incurable, and in reply to her earnest

inquiries she received the unwelcome

tap. She immediately burst into tears,

in all the bitterness of anguish. "What!" said she, "shall I

never see the light of day, or hear a human voice? Must I

remain shut up in darkness and silence as long as I live?" A

friend who was present took up a Bible and placed it to her

breast. She put her hands on it, and asked "Is this the

Bible?" Her hand was squeezed in reply. She immediately

clasped it in her hands, and held it to her bosom, and exclaimed,

"This is the only comfort I have left. I shall never

be able to look upon its blessed pages, but I can think of the

promises I have learned from it." And she then began to

repeat some of the promises—"Cast thy burden upon the

Lord, and He will sustain thee;" "Call upon me in the day

of trouble, and I will deliver thee;" "My grace is sufficient

for thee," &c. She dried her tears, and became peacefully

submissive to the will of God.

orot the Artist had a deaf and dumb pupil. The

young fellow was employed in copying one of his

master's beautiful pencil drawings, when he even

tried to imitate a stain of glue which was on the

paper. Corot, when he saw it, smiled, and said, or

at least wrote, "Très bien, mon ami; mais quand vous serez

devant la nature; vous ne verrez pas de taches." "(Very well,

my friend; but when you are before nature you will not see

any stains.)"

M. Jean Baptist Corot, the great French landscape painter, died February 23rd, 1875, aged 79.

Two years ago, says the Auburn Advertizer, George Scott, one of a gang of desperadoes in New York City, committed a robbery, for which he ought to have received ten years in prison. When he was arrested he feigned to be deaf and dumb. Upon his trial he made much of his infirmity, and the result was that he succeeded in escaping with a sentence of two years. Being transferred from Sing Sing to Auburn prison, he still kept up appearances, by means of which he escaped from doing heavy work, but was assigned to duty in shoe shop No. 1 as waiter, being supposed to be fit for no more valuable service. He was sharp, ready and intelligent, and generally well [Pg 24]behaved, though hot tempered. Keeper Bacon, under whom he was placed, had him always under strict surveillance, but never was led to suspect by anything in his conduct that he was not deaf and dumb. Indeed, he says that he once saw Scott, who always went in the shop by the name of "Dummy," so roused up and maddened by something that had occurred, that he thought he would go crazy, yet he gave no sign that he was otherwise in respect to hearing and speaking than he seemed. About two months ago Dummy's time was up, and he was discharged. To give him a start in life again, keeper Bacon hired him to do some gardening. Principal keeper Gallup did the same thing. He worked in this way for two or three weeks. While at his work children would talk to him and play round him, yet he was always apparently oblivious to their presence. But Dummy had a tongue and could use it, and his hearing was as keen as anybody's. One day he fell in with a fellow convict who had just been discharged from prison, and they went off up the street together, talking gaily. Captain Russell, foreman in one of the departments of the prison shoe shop, who was in the street, overheard their conversation; and on another occasion it happened that one of the keepers met Dummy at Louis Schuch's and talked with him for a long time.

A fact without precedent has just happened at the Sorbonne. A young deaf mute, M. Dusuzeau, underwent recently with success the examinations for the degree of [Pg 25]"Bachelor of Science." This distinguished pupil has answered by writing all the questions which have been put to him. This success, unexpected a few years ago, greatly honours the Imperial Institution in Paris, and is due to the high standard which its learned director, M. Vaisse, maintains in the studies, and to the devotedness of the censor, M. Valade Reoni, head master of the instruction, and who has been the affectionate master of M. Dusuzeau.

M. Dusuzeau was married on the third of March last, at the church of St. Germain, l'Auxerrois, Paris, to Miss Matilda Freeman, daughter of James B. Freeman, Esq., of Philadelphia, in the presence of a distinguished circle of friends. Miss Freeman stayed in England some months in 1882, and is therefore well known to many of our deaf and dumb friends.

lorence B——, a little girl in the Deaf and

Dumb Institution at Derby, was painting in water

colours during her leisure hours. She had been

told to be very careful with the card she was

painting, and do it exactly the same as the copy,

and to these instructions she strictly adhered.

When the card was finished she took it to the head master,

who at once noticed a black spot painted on a bright flower.

On being told she had spoilt the card with doing this, she

replied "But it's like the copy," and at once produced it, when

it was found that by some means an ink spot had got on the

copy.

poor deaf and dumb man,

who might be said to be entirely

friendless in the world

until the Institution of the

Deaf and Dumb was formed

at Derby, was continually in

trouble, owing to his intemperate

habits. "Drunken

Billy," as he was called by

some, had however a tender

place in his heart, and we frequently visited him at his lodgings

and assisted him in various ways. After a time Billy was persuaded

to sign the temperance pledge, and began to attend the

lectures and services for the adult deaf and dumb. For a time

all went well, but one hot summer day one of his fellow workmen,

who ought to have known better, knowing that Billy had

signed the temperance pledge, offered him a shilling if he would

drink a glass of ale he held in his hand. The temptation was

too strong for Billy to resist, and having taken one, it was

not easy for him to resist a second, and in the end poor Billy

got taken up by the police. The head master of the Institution

at Derby appeared, by request, to interpret the evidence,

and it transpired that Billy had been sent to prison in the

same month, June, each year, for the seven previous years.

The magistrates however expressed their reluctance at sending

Billy to prison, and asked him, through the interpreter, if he

would try and keep sober, and if he would again sign the pledge;

this he promised to do, and the magistrates on the bench not

only dismissed the case, but each became subscribers of one

guinea annually to the Deaf and Dumb Institution. Billy,

[Pg 27]true to his promise kept sober, and again attended the services

for the deaf and dumb, and when nearly 70 years of age gave a

brief lecture of his "Life's Experiences" to the deaf and dumb,

which caused considerable amusement, especially his remarks

about Derby fifty years ago. Billy was always thankful for

the help rendered him by the Institution, and frequently said

"If he might have his way he would be glad to die and get to

heaven where he could hear." Poor Billy's life was a hard

one, for death took a good wife and four little ones during the

first ten years of his wedded life, and one by one the whole of

his relations passed away. Billy has now done with temptation,

and recently passed away to the majority, his last remarks

bearing testimony to the value of the Institution for the Deaf

and Dumb.

esterday week a young man named Sydney

Cornwall, of Coventry, started at six o'clock in

the morning for Salisbury (a distance of 128

miles) on a bicycle. On the morning following

his friends received a letter from him, posted at

Taunton, stating that he had reached that place

and had yet fourteen miles to go that evening; and a subsequent

letter on Wednesday morning informed them that he

had arrived at his destination at six o'clock on Tuesday evening,

having stopped the previous night at a hostelry some miles

beyond Taunton. This young man is deaf and dumb, and

his enquiries for the right road must have cost him some considerable

time. The driving wheel of his machine is only forty

inches in diameter.—Bicycle News.

On Tuesday last an inquest was held by Mr. Michael Fullam, Coroner, at Aughaward, near Ballinale in this County, on the body of a respectable middle class farmer named James Prunty. It appears the deceased, a feeble old man of 76 years of age, went into an out-house occupied by his own bull for the purpose of cleaning it out, and while in the act of doing so, the bull broke its chain and turned on him. By the interposition of providence, his daughter, a deaf mute, happened to come that way, and looked into the bull-house, her attention having been attracted by seeing the door lying open; [Pg 29]and there, at the instant her eyes rested on the interior, she saw her aged father tossed high in the air above the bull's head; when he fell on the ground the bull gored him with his horns, pawed him with his feet, and raged with fury. The daring girl—the poor deaf mute—did not hesitate for an instant, but with most surprising presence of mind rushed to the rescue. She caught up the old man's stick which she saw on the floor as she entered, and seizing the bull by a copper ring in his nose, she thrashed him soundly on the head. The struggle was terrific—it was one of life and death, both for herself and the old man who now lay helpless at her feet. The bull did not tamely submit to his chastisement, but directed his assault on the lone girl; he tore her from her ankle to her armpit, struck her on the breast, and dashed her against the wall: but still she clung with a death grasp to his nose, and belaboured him with the stick, until she finally conquered and forced the infuriated animal to yield to her command. She then threw away the stick, and changing the ring into her right hand, raised the disabled old man from the ground and carried him on her left arm outside the door, forced back the bull, and closed the door in his face. Such heroic conduct as this has seldom been manifested by the bravest of men, but it is almost beyond credence that the deaf mute who was examined before the jury through an interpreter could have performed such an extraordinary feat. Yet so it was, and the jurors one and all were thoroughly satisfied with the clear and intelligible description of the most minute particulars of the occurrence exhibited by this most wonderful girl. It is sad to say that after all her exertions, the poor old man died in an hour after his release from the bull-house. The jury handed to the coroner the following memorandum at the close of the proceedings:—

"We cannot separate without putting on record our entire admiration of the heroic conduct of Bridget Prunty (an orphan and deaf mute), who, at the risk of her life, relieved her aged father, James Prunty, from the furious assault of his own bull, (from the effects of which he died yesterday), by catching him by a ring in his nose, and while holding him back, carried the old man on her left arm out of the house in which he was attacked: and we urgently recommend her to the notice of those benevolent gentlemen who appreciate and reward such an act of noble daring for the preservation of human life."

"Given at Aughaward, 22nd Jan., 1878,

Bartholomew Quinn, Foreman."

(For self and fellows),

"M. Fullam, Coroner."

Longford Journal.

We are glad to say that on hearing of the bravery of this little deaf and dumb girl, Mr. Harman, M.P., at once sent £5, and many other friends also shewed their appreciation of the girl's conduct in a practical way.

The following touching lines were composed by a Deaf friend after seeing the account in the "Longford Journal":—

THE BRAVE DEAF MUTE.

The tale of bravery I tell,

Will your attention hold,

Though not performed on battle field,

Nor by a warrior bold.

[Pg 31]

An Irish girl, to whom the Lord

Nor speech nor hearing gave,

Tho' but a poor deaf mute was she,

Her heart was stout and brave.

Deaf, dumb, yes, poor and motherless,

Friendless and obscure;

Only her father left to her,

And he was old and poor.

A farmer he, and owned a bull,

That in a shed was chained,

For it was savage, but one day

Its liberty obtained.

The poor old man was unaware

The bull had broke its chain,

Until the beast upon him turned

Ere he the door could gain.

The dumb girl neared the open shed,

As she the threshold crossed;

Oh! dreadful sight, her father high

By savage bull was tossed.

She could not hear if help was nigh,

She could not call for aid;

So quick to rescue him she ran,

Too brave to feel afraid.

One hand she slipped within a ring,

That through its nose was placed;

And with her father's stick upraised,

The angry bull she faced.

[Pg 32]

Oh! then ensued a struggle, fit

To fill her heart with dread;

While at her feet her father lay,

To all appearance dead.

Long and fierce the battle raged

Between the bull and maid;

Nor would she yield, tho' by its horns

Her side was open laid.

Blow after blow upon its head,

With heavy stick she rained,

Until the savage beast was cowed,

And she the victory gained.

And then the stick away she threw,

(But held on as before,)

Her father with one arm she raised,

And slowly neared the door.

Then back into the shed she forced

The bull, and slammed the door,

While in her aching, bleeding arms,

Her father's form she bore.

But, sad to say, her father dear,

Whom thus to save she tried,

Had been so injured by the bull,

In one short hour he died.

An orphan now, alone and poor,

Homeless, and deaf and dumb;

Oh, who will help some christian friends,

To make for her a home?

[Pg 33]

If you who read these simple lines,

With speech and hearing blest,

And have it in your power to aid

And comfort the distressed,

Oh! think of this brave-hearted girl,

And help her in her need;—

With voice and pen on her behalf

For timely help I plead.

eter Sims, a deaf and dumb boy, was walking past

a large shop one day in winter, when he saw a

beautiful pair of skates in the window. He had

often wished for skates that he might skate upon

the ice, and when he saw these he desired to have

them. He looked; no one was watching; he

thought, "I can take these skates easily, and no one will

know."

Before he had been sent to school this boy had been a very bad boy; he had often stolen little articles, but now he was learning about God, and he knew that God had said "Thou shalt not steal." As he stood looking at the skates this commandment came into his mind, and there was a struggle in his heart. His old bad nature said, "Take the skates;" his conscience answered, "No, for it is wrong to steal." At last he [Pg 34]made the signs, "steal, bad, not" (he was seen, though he did not know it), and went on without taking them. He had gained a great victory over the temptation of the devil, and the next time he was so tempted the fight was not so severe, as sin had less power over him.

Not far from Osborne House, Isle of Wight, there lives a poor man in a small cottage, who a few years ago had a deaf and dumb daughter, who used to do a great deal of knitting for the Queen. Her Majesty frequently visited this woman, and used to talk to her on her fingers. The deaf and dumb woman is now dead, and during her illness the Queen visited her and talked to her for her comfort. Her Majesty apologised that she could not now talk so fast as when she was young.

auncey, a little deaf and dumb boy, was admitted

to the Institution, at Derby, and night and morning

he would watch with keen interest the other

boys kneeling at the bed-side, and spelling on their

fingers their prayers. In a few days the little boy

learnt the alphabet, and the head master on going

upstairs to look round, was surprised to see him kneeling reverently

by his bed-side, eyes closed, and spelling on his fingers

the alphabet right through. A strange prayer, the reader will

think; but not so to our Heavenly Father, who doubtless

would accept it as the poor boy's best offering.

uring a revival of religion in one of the New

England villages, a son of the clergyman returned

home for a brief visit. The lad was a deaf mute,

and had spent his first term in the Deaf and Dumb

Institution, just then commencing its history.

His parents having no knowledge of the language of signs, and

the boy being an imperfect writer, it was almost impossible to

interchange with him any but the most familiar ideas. He,

therefore, heard nothing of the revival. But before he had

been at home many days, he began to manifest signs of

anxiety, and at length wrote with much labour upon his slate,

"Father, what must I do to be saved?" His father wrote in

reply, "My son, you must repent of sin, and believe in the

Lord Jesus Christ." "How must I do this?" asked the boy

again upon his slate. His father explained to him as well as

he could, but the poor untaught boy could not understand.

He became more than ever distressed; would leave the house

in the morning for some retired place, and would be seen no

more until his father went in search of him. One evening, at

sunset, he was found upon the top of the hay, under the roof

[Pg 36]of the barn, on his knees, his hands uplifted and praying to

God in the signs of the mutes. The distress of the parents

was so intense, that they sent for one of the teachers of the

Asylum, and then for another; but it seemed that the boy

could not be guided to the Saviour of sinners. One afternoon

the father was on his way to fulfil an engagement in a

neighbouring town, and as he drove leisurely over the hills, the

poor inquiring and helpless son was continually in his thoughts.

In the midst of his supplications his heart became calm, and

his long distracted spirit was serene in the one thought that

God was able to do his own work. The speechless boy at

length began to tell how he loved his Saviour, and that he first

found peace on the very afternoon when the spirit of his father

on the mountains was calmed and supported by the thought

that what God had promised he was able to perform.

n entering the school room one morning, one of the

little deaf and dumb girls quickly turned over her

slate, and colouring in the face. The teacher asked,

"What have you been doing?" The girl signed,

in reply, "Nothing bad, sir." On turning over the

slate we found the girl had written "Drunkenness

clothes a man with rags."

—— L—— lived near

Derby. Hers was a sad

case—deaf, dumb, and so

nearly blind that she had

to be led about; moreover,

she suffered from

extreme weakness in the

legs, and was delicate on

the chest. Her father

being dead, it was difficult for her

to obtain the necessaries of life, and

it was thought the workhouse must

be her future home. The case was

brought under the notice of the

Committee of the Deaf and Dumb

Institution at Derby, who decided

not to let her go into the workhouse

without trying what could be done for her. Accordingly she

came under their care, and gradually became stronger; but

the difficulties in the way of her education, owing to her sight,

were not easily overcome, in fact she had to be taught as one

perfectly deaf, dumb, and blind. She however made good progress,

and is now a good tempered, hard working girl, actually

earning her own living. She can wash and scour and knit and

sew quite as well as many persons blessed with the senses of

sight and hearing. She frequently attends the meetings for the

adult deaf and dumb, and always has something interesting to

say, especially on religious subjects.

Among those who were ordained deacons on Trinity Sunday last year by the Bishop of Winchester was Mr. R. A. Pearce, who is deaf and dumb, and who is to devote himself specially to Missionary work among the deaf mutes in the diocese of Winchester. The Rev. C. M. Owen, Secretary to the Mission, believes that this is the first instance of a deaf and dumb man being ordained in the Church of England.—Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette.

The Rev. R. A. Pearce has had the honour of being presented to the Queen. Mr. Pearce has visited the Institution for the Deaf and Dumb at Derby.

The Rev. R. Stewart says: "I knew of a gentleman who went to a Deaf and Dumb Asylum to make known to the inmates the way of salvation through Jesus Christ. He asked questions by means of writing them on a blackboard. One day he wrote the question, 'What does God do with the sins of the people who believe in Him?' One of the lads wrote below the question, 'All our sins were written in God's book, but Jesus came and drew His bleeding hand across the pages where the sins of the people were entered who believe in Him; thus covering over with His own blood the transgressions of His people.' Was this poor deaf and dumb lad right? Yes, indeed, for 'The blood of Jesus Christ, God's Son, cleanseth us from all sin.'"

he following little incident

will show how interested

the deaf and dumb are

in trying to help Institutions

struggling to obtain

monetary support in order

to admit the numerous

cases pressing for admission.

A number of the

pupils from the Institution

at Derby were present

at a meeting, when

the head master was advocating

its claims for

support. At the close of the meeting a deaf and dumb young

man came up and said, "I have been very pleased with what

I saw the children do, they will soon be very clever. I hope

the people will all help you; other people helped me to get a

good education, now I must help others who are deaf and

dumb to go to school. I will try and collect £5 for you."

True to his promise he did collect £5, and sent it saying,

"Next year I must try and collect £10." A little time since

he called at the Institution with the handsome sum of £10,

which he had collected in pence from 371 persons. Several

other deaf mutes have shown their interest by collecting

£1 to £3 from time to time.

The Washington Post gives an account of Canon Farrar's visit to that city. He was interviewed by one of their reporters as to what he thought of the place, and he replied that he was greatly pleased, but what interested him most was the Deaf Mute College. He was of opinion there was nothing of its kind in the world. The Canon was conducted through the College by Dr. Gallaudet, the president, who explained to him the various arrangements, after which Mr. Olof Hanson, a Swede, who has mastered English since the loss of his hearing, delivered orally the following address:—Two and a half centuries ago the Pilgrim Fathers laid the foundation of the nation. America may in a sense be called the child of England—and a well-grown child, of which she need not be ashamed. In visiting this country, therefore, you do not, we trust, feel like a stranger, but, as it were, among relatives and friends. Archdeacon Farrar is no stranger to us; his beautiful "Life of Christ" is a well-known volume in many a public and private American library, and there are few who have not read his noble eulogy on our departed hero, General Grant. As a friend then, we bid him welcome. Permit me now to say a few words about the instruction of the deaf in this country. In 1817 the first deaf mute school in America was founded at Hartford, Connecticut; there are now upwards of sixty schools for the deaf and dumb in the United States, and to day more than 7000 pupils receiving instruction. The minds of the deaf are just like those of other people, and only need to be developed. Although the avenue [Pg 41]of the ear is closed, through the other senses information is imparted, and sight, being the most convenient, is chiefly made use of in instructing the deaf; but to teach them persons of experience and intelligence are required, and to obtain such teachers money is necessary. Our Government has wisely recognised this, and it accordingly makes liberal provision for educating the deaf, as well as the hearing, all our institutions being supported mainly by the Government. It was long doubted that the deaf could master the higher branches of study, and it has been reserved for this college to see if they can. In this country we have the deaf as teachers, lawyers, chemists, artists, clergymen, editors, &c. Many take a most creditable rank among the hearing persons in their professions. Among the graduates of this college will be found some of the most intelligent and best educated deaf mutes in the world. The college is the only one of its kind in existence. Two young men from the old world have come all the way here to obtain an education which they could not get at home. They are cordially welcomed, and we hope many more will come until the time arrives when they have a college of their own, where they may acquire the advantages of a high and liberal education. Mr. Francis Maginn, son of the Rev. C. A. Maginn, county Cork, was then introduced to Canon Farrar, and his address read by Dr. Gallaudet. "As one of the two students from Europe just alluded to by my friend, I have the pleasure of welcoming my distinguished countryman, Archdeacon Farrar, to Washington. Having acquired the rudiments of my education in the metropolis of Great Britain, where you from Sunday to Sunday expound the unsearchable riches of Christ, and being a native of Ireland, where my father ministers in the Church of Ireland, it is but natural I should express my deep gratifica[Pg 42]tion that you should have come amongst my American brethren in affliction. I am sure, sir, that you have felt as I have done when coming to the great and prosperous United States, that the American people is one of which we may well be proud—a great and highly civilised people, with whom we are connected by every tie of blood, and every relation of business—they are a people who bear our civilisation, in many things improved, our language, literature, laws, and religion. In an educational point of view the nation is prominent, and her silent children have the advantages of spacious institutions, supported by her revenues. It is greatly to be regretted that our brethren in Great Britain enjoy none of these elaborate advantages of intellectual culture. Whilst Mr. Foster's Act benefits thousands, and while $15,000,000 are annually voted for the masses, one third of the mutes of right school age are being left uneducated. What that means, the English have no conception, or they would not be apathetic or unconcerned; no class when uneducated is more entirely cut off from all human intercourse than the deaf and dumb." The Canon, in reply, expressed his thanks for the cordial reception given him, and concluded with a short prayer, which was interpreted by Dr. Gallaudet, President of the Deaf and Dumb College.

![]() uring the Franco-German War, an army corps of

400 deaf and dumb Frances-Tireurs were led to battle

against the Germans.—Paris Journal.

uring the Franco-German War, an army corps of

400 deaf and dumb Frances-Tireurs were led to battle

against the Germans.—Paris Journal.

![]() obert S. Lyons went about Ireland last summer visiting

the deaf and dumb, and talking to them about

Jesus. He was then home for vacation from America, where he

had gone to study, in order to fit himself to be a missionary to

the deaf and dumb. We all hoped that he would have entered

on his duties as such this summer, and that many of his deaf

country men and women would have been helped by him on

the way to heaven. But God has ordered it otherwise. He

died at his father's residence, near Newtownstewart, after a

long and painful illness, on the evening of Friday, the 5th of

June last.

obert S. Lyons went about Ireland last summer visiting

the deaf and dumb, and talking to them about

Jesus. He was then home for vacation from America, where he

had gone to study, in order to fit himself to be a missionary to

the deaf and dumb. We all hoped that he would have entered

on his duties as such this summer, and that many of his deaf

country men and women would have been helped by him on

the way to heaven. But God has ordered it otherwise. He

died at his father's residence, near Newtownstewart, after a

long and painful illness, on the evening of Friday, the 5th of

June last.

Mr. Francis Maginn, who is also deaf and dumb, went with Robert Lyons to America last autumn, and left his studies in the College that he might take care of him on the journey home, has written some reminiscences of his friend, of which the following is a part:—

"It was my privilege to be his companion on his return to Washington, and to share the same rooms. He spent much time in Bible reading and prayer. He was attacked in February last with a serious illness, which he bore with wonderful patience. At one time his death was expected. We sat up one night watching for his last breath, but life was lengthened.

He seemed to improve for a while, and was able to go out for a drive in the President's carriage. Every comfort was his, supplied by the kind ladies of Dr. Gallaudet's family. Flowers, books, pictures; every delicacy possible constantly sent to tempt the appetite; but his strength scarcely increased. Prayers were daily offered on his behalf. Even a little girl prayed daily for him, and said, 'I know God will hear my prayers, and he will recover.' But such was not the will of God. He was sent home, and given up to my care. The voyage was fine four days, when a gale arose which lasted five [Pg 44]days, and tried his strength terribly. He seemed sinking, and said, 'I will not live to see my parents again.' I said, 'You will, if you trust in God, and if it is His will.' When we came to see lights of the Irish coast we felt joy and comfort. Arrived in Londonderry he had scarcely any strength to stand. When Newtownstewart was reached his relations and I knew each other by our troubled and anxious faces."

His sister wrote that on the last two occasions that his mother talked to him of his sufferings his reply each time was, "If we suffer with Him (Jesus), we shall reign with Him." Again, he said he left himself in the hands of his Lord, to take him or leave him as He pleased. He breathed his last in the arms of his brother John, on Friday, the 5th of June, at 10.30 p.m. The end was so peaceful that they could not tell when the last breath was drawn.

The funeral took place on Monday, the 8th, when the long procession of vehicles, some forty or fifty in number, bore testimony to the love and respect with which he was regarded in his own neighbourhood. Next after the chief mourners walked Samuel Carrigan and young M'Causland, two deaf mutes who loved and honoured him. Many others would have been present also, had it been in their power, for Robert had the love and regard of all the deaf and dumb who knew him.

Copy of a letter given to R. S. Lyons on leaving America, by Dr. Gallaudet, President of the College:—

National Deaf Mute College, Kendal Green,

Near Washington.

My dear Robert,—I want to give you more than a mere "good-bye" in words, as you take your leave of us. I want to tell you how much I have been pleased with your course here as a student, how gratified I have been to see your pleasantness in your work, and how thoroughly you have won my respect and esteem; and then want to add that your patience and cheerfulness under the heavy cross of extreme illness has made you seem a real hero. It is an added pleasure to think that this heroism is of that sort which those sons of men alone exhibit who are filled with the spirit of our good and glorious leader, Christ. I believe, dear Robert, that you have [Pg 45]that spirit, truly and fully, and I am sure it will sustain you in all future work. As you go far away over the ocean to your home, to your loved ones, and to that work which God will give you to do, my prayers will follow you daily that God will give you health and strength to do His will, and, above all, that the "peace of God" which passeth knowledge may fill your soul. Wishing you every blessing that earth and heaven can bestow,—I am, yours in loving friendship,

E. M. Gallaudet.

Helen Silvie was a Scotch

girl. She was born in the

village of Dunblane, situated

on the beautiful banks of the

river Allan.

She lost her hearing by fever when about five years of age, and two years after she was sent to the Edinburgh Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb.

She was a very shy child, and would not speak any words after she became deaf, so she soon forgot how to do so, and when her education was begun, she was nearly like a child born deaf.

For a time she was peevish and discontented; her mind was dark. But so soon as she began to understand, it was as if light shone into her mind, and she became cheerful and happy like her companions.

At first she did not seem very clever. But after two years she began to improve fast, and soon was one of the best pupils in the Institution. She was very amiable and affectionate, and a great favourite with her companions.

When she grew up she became an assistant in the school, she taught one of the junior classes in the early part of the day, and instructed the girls in sewing in the evenings. For some years she was thus usefully employed. But her brother wished her to go and live with him, and keep house for him at Bannockburn, and she consented and left the Institution.

After a time Helen wished to return to the Institution. So she wrote a letter to a friend and asked her to find out if she would be allowed to become a teacher again. But the Superintendent of the Institution was ill, and no answer was sent to her letter. Then Helen thought she would go herself to the Institution and see if they would employ her. It was winter. She set out from Stirling in a steamer on the last day of the year 1845, and arrived at Granton Pier at night. It was dark. A gentleman offered to conduct her up the pier, but he did not know the way. He should have turned to go towards the town, but he led her straight on. They came to the edge of the pier, and in an instant both were plunged into the sea. They were soon picked up, and carried to the hotel. Helen soon seemed quite well, and she was sent on to the Institution. She felt so happy at being again among her old friends that she did not soon go to bed. She thought herself much better than she was. She caught a very bad cold. In a few days inflammation of the lungs came on. Her sufferings were very great, but, she bore them patiently; and on Sabbath morning, the 18th of January, 1846, her spirit took its flight to her Saviour's bosom.

Her pastor, who visited her on her death-bed, was much pleased to see how fully she trusted in Jesus. He said of her after she died "I think of her as one of the spirits of the just made perfect."

The chill wind was moaning, the rain falling drearily, and day darkening rapidly, when a lady might have been seen walking along quickly through Eccles Street. She was thinking of home, with its bright warm fire, and how soon she could get in out of the cold and wet.

Suddenly she stopped, as a feeble cry arrested her footsteps, and looking round, she perceived a cat crouched against some steps. The storm was beating on the poor harmless creature, and night coming on.

The lady did not turn away and hurry on, as some selfish people would have done, but pitied and called the poor cat. It looked so forlorn, and gave a frightened glance in her face. Gaining courage from what it saw there, it trusted her, and jumped up, curled its tail over its back, and trotted contentedly after her. The lady went on. When she looked back now and then, there was pussy trotting steadily behind.

Presently the lady knocked at a hall door, and when it was opened they passed into a bright room, and pussy sat down to dry before a warm fire, where two other cats, sleek and well fed, kept her company. Well, our puss, whose name was "Gipsy," very soon was lapping a saucer of warm milk. After [Pg 48]that she looked at the fire, and winked her eyes until she fell asleep.

Sarah Darby, who is deaf and dumb, was at that time living in this house. Pussy became very fond of Sarah, and liked to sit in her lap because she was kind to it. Now Sarah did not think a cat could help her, but she knew that God commands us to be kind to helpless creatures, and He always rewards us when we obey Him.

You will wonder how a cat could help anyone, so I will tell you. Sometimes Sarah was alone in the house, and when a knock came to the hall door there was no one to tell her but puss, and puss did so. How? She jumped down off Sarah's lap, and looked up in her face every time a knock came, and after the door had been opened got on her lap again, and waited for the next one. So this is how the cat helped the deaf and dumb woman.

![]() t a meeting in aid of the deaf and dumb held in Dundee,

at which Lord Panmure presided, a number of deaf and

dumb children were present and put through an examination.

The question was put on the blackboard, "Who is the greatest

living statesman of Great Britain?" One of the boys instantly

wrote, "The Earl of Shaftesbury." The chairman patted the

boy on the head, and asked, "Why do you think the Earl of

Shaftesbury is the greatest living statesman?" The boy answered,

"Because he cares a great deal for the like of us deaf

mutes."

t a meeting in aid of the deaf and dumb held in Dundee,

at which Lord Panmure presided, a number of deaf and

dumb children were present and put through an examination.

The question was put on the blackboard, "Who is the greatest

living statesman of Great Britain?" One of the boys instantly

wrote, "The Earl of Shaftesbury." The chairman patted the

boy on the head, and asked, "Why do you think the Earl of

Shaftesbury is the greatest living statesman?" The boy answered,

"Because he cares a great deal for the like of us deaf

mutes."

![]() lady who graduated from

the Institution at New

York some years ago, was questioned

as to the capacity of the

deaf to enjoy music; she wrote:

"I think all deaf persons have an

idea more or less vague of musical

sounds. It comes to all who

cannot hear through the sense of

touch. The vibrations of the

chords of a piano, when strongly

played, are sufficient to produce

real enjoyment by means of feeling to one who can touch the

case merely. The soft, tremulous notes, even convey an impression

through the nerves, similar, I fancy, to that which

others obtain through the ear. But the real music for us

comes through the eye. The rippling of waves, the tremulous

vibration of leaf and blossom and twig, all these sights make

for us a harmony perhaps as perfect as the most finished

orchestra."

lady who graduated from

the Institution at New

York some years ago, was questioned

as to the capacity of the

deaf to enjoy music; she wrote:

"I think all deaf persons have an

idea more or less vague of musical

sounds. It comes to all who

cannot hear through the sense of

touch. The vibrations of the

chords of a piano, when strongly

played, are sufficient to produce

real enjoyment by means of feeling to one who can touch the

case merely. The soft, tremulous notes, even convey an impression

through the nerves, similar, I fancy, to that which

others obtain through the ear. But the real music for us

comes through the eye. The rippling of waves, the tremulous

vibration of leaf and blossom and twig, all these sights make

for us a harmony perhaps as perfect as the most finished

orchestra."

![]() n Tuesday evening last the Stamford Corn Exchange was

crowded with people eager to see half a score little deaf

mutes from the Institution at Derby. The children—six boys

and four girls—caused considerable amusement, and also pain

to think they should be so afflicted. The youngsters can draw,

read, and write in a way that is surprising, and some of the

faces were marked by unusual brightness and intelligence.—Stamford

Mercury, Sep. 18th, 1884.

n Tuesday evening last the Stamford Corn Exchange was

crowded with people eager to see half a score little deaf

mutes from the Institution at Derby. The children—six boys

and four girls—caused considerable amusement, and also pain

to think they should be so afflicted. The youngsters can draw,

read, and write in a way that is surprising, and some of the

faces were marked by unusual brightness and intelligence.—Stamford

Mercury, Sep. 18th, 1884.

![]() deaf and dumb lady living in a German city, had,

as a companion, a younger woman, who was also

deaf and dumb. They lived in a small set of rooms opening

on the public corridor of the house. Somebody gave the elder

lady a dog as a present. For some time, whenever anybody

rang the bell at the door, the dog barked to call the attention

of his mistress. The dog soon discovered, however, that

neither the bell nor the barking made any impression on the

women, and he took to the practice of merely pulling one of

them by the dress with his teeth, in order to explain that some

one was at the door. Gradually the dog ceased to bark altogether,

and for more than seven years before his death he

remained as mute as his two companions.

deaf and dumb lady living in a German city, had,

as a companion, a younger woman, who was also

deaf and dumb. They lived in a small set of rooms opening

on the public corridor of the house. Somebody gave the elder

lady a dog as a present. For some time, whenever anybody

rang the bell at the door, the dog barked to call the attention

of his mistress. The dog soon discovered, however, that

neither the bell nor the barking made any impression on the

women, and he took to the practice of merely pulling one of

them by the dress with his teeth, in order to explain that some

one was at the door. Gradually the dog ceased to bark altogether,

and for more than seven years before his death he

remained as mute as his two companions.

atthew Jones, a poor deaf and dumb boy,

once wrote the meaning of Jesus Christ's blood

washing away sin. Being asked if he was afraid

God would punish him for his sins, he wrote

this answer, "No, for when God sees my name

down in His book, and all the things I have done wrong, and

all that I have left undone, there will be a long account; but

He won't be able to read it, because Jesus Christ's bleeding

hand will have blotted all the account out, and He would see

nothing on that page but the Saviour's blood, for I have asked

Him to wash all my sins away."

![]() he following is taken from the British and Foreign

Bible Society's Report for 1885, being an extract from

one of their agents in Belgium named Gazan:—"For the last

fourteen years Gazan has been in the habit of getting shaved by

a barber who also keeps a drinking saloon. Though not a member

of a temperance society Gazan is an abstainer, and is none

the less welcome, and he occasionally is able to sell to persons

who frequent the place. One day last year when the barber's

shop was full, a man was there who had often prevented people

buying, and when Gazan left began to say all the harm he could

of him. This he heard from the barber's wife, who expressed

great annoyance at it. Some time after a young man, deaf and

dumb, called upon Gazan and gave him to understand he

wanted a Bible. With the aid of a pencil they carried on a

[Pg 52]conversation, in the course of which Gazan showed him several

passages marked in the Bible. This was on a Sunday morning,

and in the afternoon the deaf and dumb young man came

back to attend the service, for which Gazan lends his room;

and he continued to come Sunday after Sunday, when by signs

and giving him passages to read he was interested in the service.

He was introduced to the deaf and dumb evangelist in

Brussels, and having found work as a printer, is living there

now, lodging at the house of M. Crispells, who holds the

service at Louvain. On Christmas Day he went to Louvain

to see Gazan, and showed him a number of texts which had

been pointed out to him during his former visits, and showed

remarkable familiarity with the Scriptures. This deaf and

dumb young man is no other than the son of the man above

referred to, who had spoken against him in the barber's shop.

The conversion of his son has had a remarkable effect upon

him; he is now quite a changed man, and does all he can to

assist Gazan and to induce people to buy his books."

he following is taken from the British and Foreign

Bible Society's Report for 1885, being an extract from

one of their agents in Belgium named Gazan:—"For the last

fourteen years Gazan has been in the habit of getting shaved by

a barber who also keeps a drinking saloon. Though not a member

of a temperance society Gazan is an abstainer, and is none

the less welcome, and he occasionally is able to sell to persons

who frequent the place. One day last year when the barber's

shop was full, a man was there who had often prevented people

buying, and when Gazan left began to say all the harm he could

of him. This he heard from the barber's wife, who expressed

great annoyance at it. Some time after a young man, deaf and

dumb, called upon Gazan and gave him to understand he

wanted a Bible. With the aid of a pencil they carried on a

[Pg 52]conversation, in the course of which Gazan showed him several

passages marked in the Bible. This was on a Sunday morning,

and in the afternoon the deaf and dumb young man came

back to attend the service, for which Gazan lends his room;

and he continued to come Sunday after Sunday, when by signs

and giving him passages to read he was interested in the service.

He was introduced to the deaf and dumb evangelist in

Brussels, and having found work as a printer, is living there

now, lodging at the house of M. Crispells, who holds the

service at Louvain. On Christmas Day he went to Louvain

to see Gazan, and showed him a number of texts which had

been pointed out to him during his former visits, and showed

remarkable familiarity with the Scriptures. This deaf and

dumb young man is no other than the son of the man above

referred to, who had spoken against him in the barber's shop.

The conversion of his son has had a remarkable effect upon

him; he is now quite a changed man, and does all he can to

assist Gazan and to induce people to buy his books."

![]() he following were won by deaf mutes:—Both certificate

and prize, E. Morgan, for painted album; A. Corkey,

doll's dress; B. Henderson, same; J. Giveen, stitching;

J. O'Sullivan, knitting; G. Seabury, laundry work. Also,

prizes were won by J. Armstrong, handwriting; L. Corkey,

texts in Bible album; E. Phibbs, doll's suit; E. Gray, knitting.

A Bible album made by deaf mutes at Cork was much

admired. Each page has a picture with a great many texts

written round it.

he following were won by deaf mutes:—Both certificate

and prize, E. Morgan, for painted album; A. Corkey,

doll's dress; B. Henderson, same; J. Giveen, stitching;

J. O'Sullivan, knitting; G. Seabury, laundry work. Also,

prizes were won by J. Armstrong, handwriting; L. Corkey,

texts in Bible album; E. Phibbs, doll's suit; E. Gray, knitting.

A Bible album made by deaf mutes at Cork was much

admired. Each page has a picture with a great many texts

written round it.

![]() few years since

an aged man,

who had long been a

sincere and devoted

christian, was placed in

the same ward in the

Infirmary of N——

with a deaf and dumb

youth. The former received

and enjoyed the

visits of the chaplain,

whilst the latter was

considered inaccessible

to instruction. An arrangement

was at length

made for the good old man to

partake of the sacrament of the

Lord's Supper, when he made,

as it appeared to the chaplain and

matron, the singular request that

the young mute might partake of

it with him. A secret was then

divulged which had been known only to

the two patients themselves. Having

spent a long period of time together, the

old man had improved the opportunity

thus afforded to effect intercourse with the

youth by signs, and had been enabled, by the

Divine blessing, to convey to him a knowledge

of salvation through a crucified Redeemer.

[Pg 54]There appeared every reason to believe that the poor fellow

possessed an enlightened understanding and a renewed mind,

and he was allowed to participate in the desired privilege.

few years since

an aged man,

who had long been a

sincere and devoted

christian, was placed in

the same ward in the

Infirmary of N——

with a deaf and dumb

youth. The former received

and enjoyed the

visits of the chaplain,

whilst the latter was

considered inaccessible

to instruction. An arrangement

was at length

made for the good old man to

partake of the sacrament of the

Lord's Supper, when he made,

as it appeared to the chaplain and

matron, the singular request that

the young mute might partake of

it with him. A secret was then

divulged which had been known only to

the two patients themselves. Having

spent a long period of time together, the

old man had improved the opportunity

thus afforded to effect intercourse with the

youth by signs, and had been enabled, by the

Divine blessing, to convey to him a knowledge

of salvation through a crucified Redeemer.

[Pg 54]There appeared every reason to believe that the poor fellow

possessed an enlightened understanding and a renewed mind,

and he was allowed to participate in the desired privilege.

Shortly after this the old man died, and when the youth was made sensible of the event, his countenance brightened with joy; he waved his hand and pointed up to the sky to intimate that he was gone into heaven. After a time the mute followed his kind friend and instructor. When he felt himself dying, he first put his fingers in his ears and took them out again, to show that his ears would be unstopped; he then put out his tongue and pointed to heaven, to show that that would be unloosed.

These facts were communicated to a friend by the matron of the Infirmary—herself an eminent christian, who has since died, and who did not doubt that the youth had obtained a correct and experimental knowledge of the gospel of salvation.

![]() n Thursday afternoon a singular scene was witnessed

during the proceedings of the Revision Court, at

Ashton-under-Lyne. A man named James Booth, of 3, Dog

Dungeon, Hurst polling district, was objected to by the Conservatives,

and Mr. Booth, their solicitor, announced that the

man was deaf and dumb, but just able to utter a monosyllable

now and then. Mr. Chorlton, the Liberal solicitor: What can

I do (laughter)? Mr. Booth first by writing asked what the

man's name was, and then began to talk to him with his

fingers, but being an indifferent chirologist he made very poor

progress. He had merely elicited that the man was the owner

[Pg 55]when Mr. Chorlton began to grow impatient, and inquired,

Why don't they both go to the Isle of Man for a week (laughter)?

Nothing more could be got out of the man except a

"yes" or "no" after questions had been patiently propounded

by Mr. Booth in the dactyologic alphabet. At length the

Barrister spied a rent book, and this was pounced upon and

the vote allowed very joyfully, to save further trouble. The

dumb man then spake, stuttering, and with great effort, I claim

my expenses. Mr. Chorlton: He's got those words all right,

at any rate (laughter.) Mr. Booth: He can talk a little but

hear nothing. Recourse was again had by Mr. Booth to his

digits, and he interpreted to the court that the man was a hat

body maker, and wanted 5s. 6d. The Barrister: I will allow

5s. The money was handed to the man, and he went away

smiling.—Newcastle Journal.

n Thursday afternoon a singular scene was witnessed

during the proceedings of the Revision Court, at

Ashton-under-Lyne. A man named James Booth, of 3, Dog

Dungeon, Hurst polling district, was objected to by the Conservatives,

and Mr. Booth, their solicitor, announced that the

man was deaf and dumb, but just able to utter a monosyllable

now and then. Mr. Chorlton, the Liberal solicitor: What can

I do (laughter)? Mr. Booth first by writing asked what the

man's name was, and then began to talk to him with his

fingers, but being an indifferent chirologist he made very poor

progress. He had merely elicited that the man was the owner

[Pg 55]when Mr. Chorlton began to grow impatient, and inquired,

Why don't they both go to the Isle of Man for a week (laughter)?

Nothing more could be got out of the man except a

"yes" or "no" after questions had been patiently propounded

by Mr. Booth in the dactyologic alphabet. At length the

Barrister spied a rent book, and this was pounced upon and

the vote allowed very joyfully, to save further trouble. The

dumb man then spake, stuttering, and with great effort, I claim

my expenses. Mr. Chorlton: He's got those words all right,

at any rate (laughter.) Mr. Booth: He can talk a little but

hear nothing. Recourse was again had by Mr. Booth to his