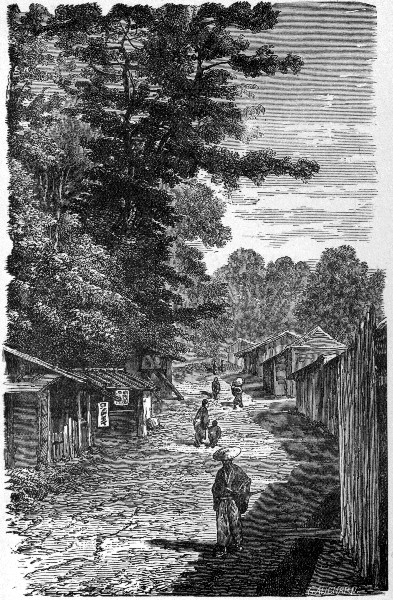

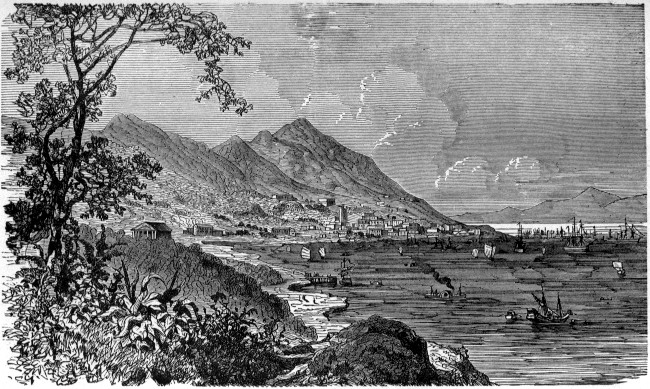

YOKOHAMA.

YOKOHAMA.

Title: Celebrated Women Travellers of the Nineteenth Century

Author: W. H. Davenport Adams

Release date: March 3, 2010 [eBook #31479]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell, Josephine Paolucci and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net.

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

YOKOHAMA.

YOKOHAMA.

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & CO.

1903

PAGE

Countess Dora D'Istria 17

The Princess of Belgiojoso 48

Madame Hommaire de Hell 66

Madame Léonie D'Aunet 126

Miss Frederika Bremer 134

Mademoiselle Alexina Tinné 184

Madame Ida Pfeiffer 215

Madame de Bourboulon 270

Lady Hester Stanhope 302

Lady Brassey 340

Lady Morgan 379

Mrs. Trollope 385

Miss Harriet Martineau 404

Miss Isabella Bird 418

Lady Florence Dixie 437

Miss Gordon Cumming 443

Florence and Rosamond Hill 452

Lady Barker 456

"Magyarland" 458

The Princess Helena Koltzoff-Massalsky, better known by her pseudonym of Dora d'Istria,[1] came of the family of the Ghikas, formerly princes of Wallachia, and was born at Bucharest, on the 22nd of January, 1829. Through the care and conscientiousness of her instructor, Mons. Papadopoulos, and her own remarkable capacity, she acquired a very complete and comprehensive education. When but eleven years old, she composed a charming little story, and before she had reached womanhood, undertook a translation of the Iliad. She showed no inclination for the frivolous amusements of a frivolous society. Her view of life and its responsibilities was a serious one, and she addressed all her energies to[Pg 18] the work of self-improvement and self-culture. She read and re-read the literary masterpieces of England, France and Germany. As a linguist she earned special distinction.

"Her intellectual faculties," says her master, M. Papadopoulos, "expanded with so much rapidity, that the professors charged with her instruction could not keep any other pupil abreast of her in the same studies. Not only did she make a wholly unexpected and unhoped-for progress, but it became necessary for her teachers to employ with her a particular method: her genius could not submit to the restraint of ordinary rules."

She was still in the springtime and flush of youth, when she went on a tour to Germany, and visited several German courts, where she excited the same sentiments of admiration as in her own country; it was impossible to see her without being attracted by so much intellect, grace and amiability. Travelling enlarged her horizon: she was able to survey, as from a watch-tower, the course of great political events, and she found herself mixing continually with the most celebrated savants and statesmen of the age. Her friendly relations with persons of very diverse opinions, while enabling her to compare and contrast a great variety of theories, did but strengthen in her "the idea and sentiment of liberty, which can alone conduct society to its true aim." Finally, from the Italian revolution of 1848, which awoke her warmest[Pg 19] sympathies, she learned to understand the fatal consequences of despotic government, as well as the inevitable mistakes of freedom, when first unfettered and allowed to walk alone.

At the age of twenty she was married (February, 1849), and soon afterwards she set out for St. Petersburg, where she was recognised as the ornament of the higher society. In the midst of her numerous engagements, in the midst of the homage rendered to her wit and grace, she found time to collect a mass of valuable notes on the condition and inner life of the great Russian Empire, several provinces of which she knew from personal observation. From St. Petersburg to Moscow, from Odessa to Revel, her untiring activity carried her. Most social questions are at work under an apparent calm, and offer, therefore, subjects well worthy of careful study, especially to so grave and clear an intellect as that of Princess Dora d'Istria, who possessed, in the highest degree, the faculty of steady meditation amidst the movement and the world-stir that surrounded her. The world, charmed by her personal attractions, had no suspicion of the restlessness and activity of her inquiring mind.

Her departure to the South brought her inquiries and investigations to an end. She had suffered so much from the terrible winters of the great Northern capital, and her health was so seriously shaken, that her doctors presented to her the grave alternative of departure or death (1855).[Pg 20]

The Princess Dora d'Istria, as we have hinted, was a fine linguist. She made herself mistress of nine languages. Her historical erudition was profound; her mind was continually in search of new knowledge. She seemed to have inherited from one of her illustrious friends, M. von Humboldt, that "fever of study," that insatiable ardour, which, if not genius, is closely akin to it.

The great Berlin philosopher and the young Wallachian writer lived for some time in an intellectual confraternity, which, no doubt, is to this day one of the most valuable souvenirs of the brilliant author of "La Vie Monastique dans l'Eglise Orientale." In reference to this subject, we take leave to quote a passage from the graceful pen of M. Charles Yriarte:—

"The scene lies at Sans-Souci, in one of the celebrated saloons where the great Frederick supped with Voltaire, d'Alembert and Maupertuis. 'Old Fritz' has been dead a hundred years; but the court of Prussia, under the rule of Frederick William, is still the asylum of beaux esprits. The time is the first and brilliant period of his reign, when the king gathers around him artists and men of science, and writes to Humboldt invitations to dinner in verse, which he seals with the great Seal of State, in order that the philosopher may have no excuse for absenting himself. A few years later, and, alas, artists and poets give place to soldiers!

"The whole of the royal family are collected at a[Pg 21] summer fête, and with them the most famous names in art and science, and some strangers of distinction.

"The prince has recently received a consignment of ancient sculptures and works of art, and while the royal family saunter among the groves of Charlottenhof, M. von Humboldt and the aged Rauch, the Prussian sculptor, examine them, and investigate their secrets. Rauch is a grand type of a man. This senior or doyen of the German artists, who died overwhelmed with glory and honours, had been a valet de chambre in the Princess Louisa's household. He had followed the princess to Rome, where, among the masterpieces of antiquity and of the Renaissance, she had divined the budding genius of him who was to carve in everlasting marble the monumental figure of the great Frederick.

"These two illustrious men are bending over a basso-relievo with a Greek inscription, when the king enters; he is accompanied by a gentleman, who has on either arm a fair young girl in the spring of her youth and beauty. The king invites M. von Humboldt to explain the inscription, and the gallant old man goes straight to one of the young girls, excusing himself for not attempting to translate it in the presence of one of the greatest Hellenists of the time.

"'Come, your Highness,' he says, 'make the oracle speak.'

"And the young princess reads off the inscription fluently, setting down M. von Humboldt's ignorance to the account of his politeness.[Pg 22]

"The king compliments the handsome stranger, and Rauch, struck by her great beauty, inquires of his friend who may be this fair, sweet Muse, who gives to the marbles the tongue of eloquence, who, young and lovely as an antique Venus, seems already as wise and prudent as Minerva.

"You see that it is a pretty tableau de genre, worthy of the brush of Mentzel, the German painter, or of the French Meissonier. For background the canvas will have the picturesque Louis Quatorze interiors of Sans-Souci; in the foreground, the king and the great Humboldt, who inclines towards the young girl; farther off, her sister leaning on their father's arm, and the aged Rauch, who closes up the scene and holds in his hand the bas-relief.

"That young girl, who has just given a proof of her erudition is Helena Ghika, now famous under the literary pseudonym of Dora d'Istria. The old man is the Prince Michael, her father, whose family, originally of Epirus, has for the last two centuries been established in the Danubian Principalities, and has supplied Wallachia with Hospodars. The other young lady is Helena's sister."

Dora d'Istria was one of those fine, quick intelligences which look upon the world—that is, upon humanity—as, in the poet's words, "The proper study of mankind."

"It has always seemed to me," she one day observed,[Pg 23] "that women, in travelling, might complete the task of the most scientific travellers; for, as a fact, woman carries certain special aptitudes into literature. She perceives more quickly than man everything connected with national life and the manners of the people. A wide field, much too neglected, lies open, therefore, to her observation. But, in order that she may fitly explore it, she needs, what she too often fails to possess, a knowledge of languages and of history, as well as the capability of conforming herself to the different habitudes of nations, and the faculty of enduring great fatigues.

"Happily for myself, I was not deficient in linguistic knowledge. In my family the only language made use of was French. M. Papadopoulos at an early age taught me Greek, which in the East is as important as French in the West. The Germanic tongues terrified me at first, the peoples of Pelasgic origin having no taste for those idioms. But I was industrious enough and patient enough to triumph over all such difficulties, and though the study of languages is far from being popular in the Latin countries, I did not cease to pursue it until the epoch of my marriage.

"M. Papadopoulos has often referred to my passionate love of history even in my early childhood. This passion has constantly developed. The more I have travelled, the more clearly I have perceived that one cannot know a people unless one knows thoroughly its antecedents; that is, if one be not fully acquainted[Pg 24] with its annals and its chief writers. In studying a nation only in its contemporary manifestations, one is exposed to the error into which one would assuredly fall if one attempted to estimate the character of an individual after living only a few hours in his company.

"Besides, to understand nations thoroughly, it is necessary to examine, without any aristocratic prejudice, all the classes of which they are composed. In Switzerland, I lived among the mountains, that I might gain an exact idea of the Alpine life. In Greece, I traversed on horseback the solitudes of the Peloponnesus. In Italy, I have established relations with people of all faiths and conditions, and whenever the opportunity has occurred, have questioned with equal curiosity the merchant and the savant, the fisherman and the politician. When I appear to be resting myself, I am really making those patient investigations, indispensable to all who would conscientiously study a country."

After residing for some years in Russia, she felt the need of living thenceforward in a freer atmosphere, and betook herself to Switzerland. Her sojourn in that country—a kind of Promised Land for all those who in their own country have never enjoyed the realisation of their aspirations—was very advantageous to her. She learned in Switzerland to love and appreciate liberty, as in Italy the fine arts, and in England industry.

The work of Dora d'Istria upon German Switzerland is less descriptive than philosophical. The plan she has[Pg 25] adopted is open perhaps to criticism: such mixture of poetry and erudition may offend severer tastes; we grow indulgent, however, when we perceive that the writer preserves her individuality while passing from enthusiastic dithyrambs to the most abstract historical dissertations.

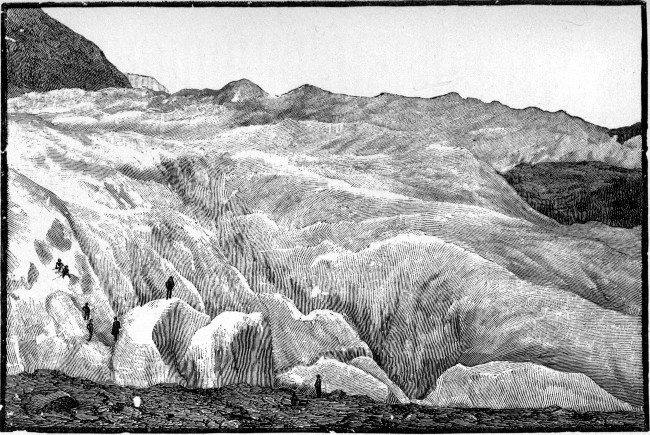

It is not, however, the woman of letters so much as the patient untiring female traveller whom we seek to introduce to our readers in these pages. We attempt therefore, no analysis of her works,[2] but proceed to speak of her mountaineering experiences: the most important is the ascent of the Mönch, a summit of the Jungfrau system—one of the lofty snow-clad peaks which enclose the ice-rivers of the Oberaar and the Unteraar. We shall allow Madame Dora d'Istria to conduct us in person through the difficulties of so arduous an enterprise.

"When I announced my project of scaling the highest summits of the Alps, the astonishment was general. Some imagined that it was a mere whim which would be fully satisfied by the noise it caused. Others exclaimed against a hardihood willing to encounter so many perils. None were inclined to regard my words as dictated by an intimate conviction. None[Pg 26] could accustom themselves to the idea of so extraordinary a scheme. The excitement was redoubled at the departure of the different telegraphic despatches summoning from their village homes the guides spoken of as the most resolute in the district. One hope, however, remained: that these guides themselves would dissuade me from my enterprise. Pierre was encouraged to dilate upon the dangers which I should incur among the glaciers. Through the telescope I was shown the precipices of the Jungfrau. All the manuals of travellers of Switzerland lay upon my tables. Everybody insisted on reading to me the most frightful passages—those most likely, as they thought, to unnerve me. But, on the contrary, these stirring stories did but sharpen my curiosity, did but quicken my impatience to set out. I ceased to think of anything but the snowy wildernesses which crown the lofty mountain summits.

"I summoned Pierre to my private apartment, and spoke to him with firmness, so as to strengthen his resolutions. My words reassured him. 'Whatever happens,' he said, 'do you take the responsibility?' 'Assuredly,' I answered; and I gave him my hand, engaging him at the same time to remain unmoved by any remonstrance, to encourage the guides on their arrival, before they could be exposed to any foreign influence. He promised, and his face brightened at the sight of my tranquil smile. He went away to superintend the preparations for the expedition, and arrange my masculine costume, which consisted of woollen pantaloons striped with black and[Pg 27] white, of a closely buttoned coat descending to my knees, of a round felt hat like that of a mountaineer, and a pair of large strong boots. Oh, how slow the hours seemed to me! I dreaded so keenly any occurrence which might thwart my wishes, that I could scarcely listen to the questions put to me respecting the necessary arrangements. Everything wearied me, except the sight of the Jungfrau and of Pierre, who seemed to me a friend into whose hands I had entrusted my dearest hope.

"The first to arrive were the guides of Grindelwald. I uttered a cry of joy when Pierre Bohren appeared, a man of low stature but thickset limbs, and Jean Almer, who was tall and robust. Both were chamois hunters, renowned for their intrepidity. They looked at me with curious attentiveness. They confessed, with the frank cordiality peculiar to these brave mountaineers, that their experience would be of no service in the expedition I was undertaking, as they had never attempted any one like it. They knew, however, the perils of the glaciers, for every day they risked their lives among them. But Bohren, who had ventured the farthest, had not passed beyond the grotto of the Eiger.

"Before coming to a definite decision, we waited the arrival of Hans Jaun of Meyringen, who had accompanied M. Agassiz in his ascent of the Jungfrau (in 1841). He arrived towards morning, and called upon me in company with Ulrich Lauerer, of Lauterbrunnen. The latter was as tall as Almer, but did not seem so ready. I learned afterwards that he was still suffering from a fall which he[Pg 28] had but recently met with while hunting. Hans Jaun was the oldest of all and the least robust. His hair was growing grey, his eyelids were rimmed with a blood-coloured border. However, he presided over the gathering. I had closed the door, so that no one should disturb our solemn conference. The guides appeared meditative, and sought to read in my eyes if my firmness were real or assumed.

"It was decided that we should take with us four porters loaded with provisions, ladders, ropes, and pick-axes; that towards evening I should start for Interlachen with Pierre and Jaun, and that the other guides should await me at Grindelwald. Then we separated with the friendly greeting, 'Au revoir.'

"Scarcely had the sun dropped below the horizon, streaked with long bars of fire, when I took my solitary seat in an open carriage. Peter occupied the box. We traversed the walnut-tree avenues of Interlachen and its smiling gardens. We followed the banks of the pale Lütschina, which bounds through the midst of abrupt rocks. Clouds accumulated on the sky. Soon we heard the distant roar of thunder. We passed into the presence of colossal mountains, whose rugged peaks rose like inaccessible fortresses. On turning round, I could see nothing in the direction of Interlachen but gloomy vaporous depths, impenetrable to the eye. Nearer and nearer drew the thunder, filling space with its sonorous voice. The wind whistled, the Lütschina rolled its groaning waters. The spectacle was sublime. Night[Pg 29] gathered in all around, and the vicinity of Grindelwald I could make out only by the lights in the châlets scattered upon the hill.

"I had scarcely entered beneath the hospitable roof of the hotel of the Eagle, before the rain fell in torrents, like a waterspout. I elevated my soul to God. At this moment the thunder burst, the avalanches resounded among the mountains, and the echoes a thousand times repeated the noise of their fall.

"The stars were paling in the firmament when I opened my window. Mists clothed the horizon. The rushing wind soon tore them aside, and drove them into the gorges, whence descend, in the shape of a fan, the unformed masses of the lower glacier, soiled with a blackish dust.

"The storm of the preceding evening, those dense clouds which gave to the Alps a more formidable aspect than ever, the well-meant remonstrances of the herdsmen of the valley, all awakened in the heart of my guides a hesitation not difficult to understand on the part of men who feared the burden of a great responsibility. They made another effort to shake my resolution. They showed me a black tablet attached to the wall of the church which crowns the heights:—

"I said to Pierre, after glancing at this pathetic inscription, 'The soul of this young man rests in peace in the bosom of the Everlasting. As for us, we shall soon return here to give thanks to God.'

"'Good!' replied Pierre; 'that is to say, nothing will make you draw back.'

"He rejoined his companions, and I went to shut myself up in my chamber.

"The deep solitude around me had in it something of solemnity. Before my eyes the Wetterhorn raised its scarped acclivities; to the right, the masses of the Eiger, to the left, the huge Scheideck and the Faulhorn. Those gloomy mountains which surrounded me, that tranquillity troubled only by the rash of the torrent in the valley and by an occasional avalanche, all this was truly majestic, and I felt as if transported into a world where all things were unlike what I had seen before. My mind had seldom enjoyed a calm so complete.

"I had not the patience to wait for morning. Before it appeared, I was on foot. I breakfasted in haste, and assumed my masculine dress, to which I found it difficult to grow accustomed. I was conscious of my awkwardness, and it embarrassed all my movements. I summoned Pierre, and asked him if I could by any means be conveyed as far as the valley. He sent, to my great satisfaction, for a sedan-chair. Meanwhile, I exercised myself by walking up and down my room, for I feared the guides would despair of me if they saw me[Pg 31] stumble at every step. I was profoundly humiliated, and only weighty reasons prevented me from resuming my woman's dress. At last I bethought myself of an expedient. I made a parcel of my silk petticoat and my boots (brodequins), and gave it to a porter, so that I might resort to them if I should be completely paralyzed by those accursed garments which I found so inconvenient.

"We had to wait until eight o'clock before taking our departure. The sun then made its appearance, and the mountains gradually threw off their canopy of mist. Having wrapped myself in a great plaid, I took my seat in the sedan-chair and started, accompanied by four guides, four porters, and a crowd of peasants, among whom was a Tyrolean. All sang merrily as they marched forth, but those who remained looked sadly after us. It was the 10th of June, 1855.

"We marched without any attempt at order, and the people of Grindelwald carried our baggage as a relief to our porters. The sun was burning. The peasants took leave of us as soon as we struck the path which creeps up the Mettenberg, skirting the 'sea of ice.' Only the Tyrolean, accompanied by his young guide, remained with us. He said that curiosity impelled him to follow us as long as he could, that he might form some idea of the way in which we were going to get out of the affair. He sang like the rest of the caravan, his strong voice rising above all.

"It was the first time I had seen the immense glacier popularly called 'La Mer de Glace.' Through the[Pg 32] green curtains of the pinewoods, I gazed upon the masses rising from the gulf, the depths of which are azure-tinted, while the surface is covered with dirt and blocks of snow. The spectacle, however, did not impress me greatly, whether because I was absorbed in the thought of gaining the very summit of the Alps, or because my imagination felt some disappointment in finding the reality far beneath what it had figured.

"I descended from my sedan-chair when we arrived at an imprint in the marble rock known as 'Martinsdruck.' The gigantic peaks of the Schreckhorn, the Eiger, the Kischhorn, rose around us, almost overwhelming us with their grandeur. To the right, the Mittelegi, a spur of the Eiger, elevated its bare and polished sides. Suddenly the songs ceased, and my travelling companions uttered those exclamations, familiar to Alpine populations, which re-echoed from rock to rock. They had caught sight of a hunter, gliding phantom-like along the steep ascent of the Mittelegi, like a swallow lost in space. But in vain they pursued him with cries and questions; he continued to move silently along the black rock.

"At length we descended upon the glacier. They had abandoned me to my own resources, probably to judge of my address. I was more at ease in my clothes, and with a sure step I advanced upon the snow, striding across the crevasses which separated the different strata of ice. By accident, rather than by reflection, I looked out for the spots of snow and there planted my feet. Later I learned that this is always the safest route, and never leads one into danger. The Tyrolean took leave of us, convinced at last that I should get out of the affair. As for the guides, they gave vent to their feelings in shouts of joy. They said that, in recognition of my self-reliance, they would entrust to me the direction of the enterprise. After crossing the Mer de Glace, we began to climb the steep slopes of the Ziegenberg.

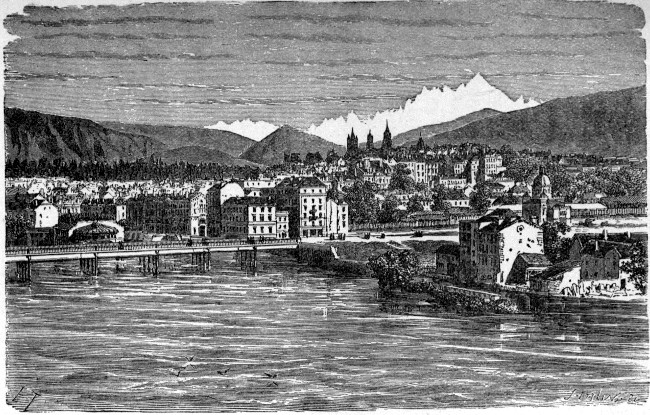

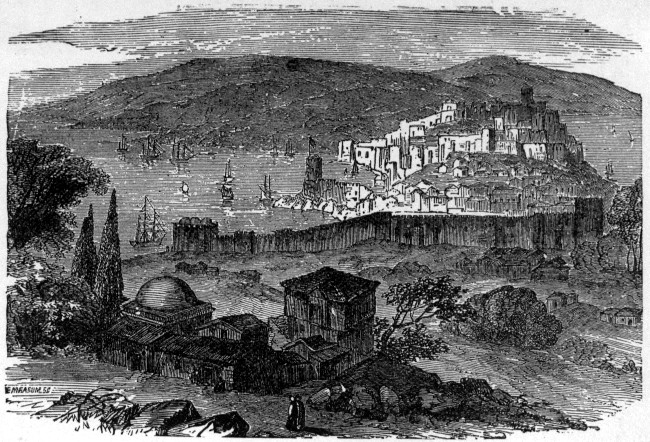

GENEVA AND MONT BLANC.

GENEVA AND MONT BLANC.

"For a long time the songs, a thousand times repeated, continued to answer each other from side to side of the glacier. Then we could hear no longer the voice of men, nor the bell of the church of Grindelwald, whose melancholy notes the wind had hitherto wafted to us. We were in the bosom of an immense wilderness, face to face with Heaven and the wonders of Nature. We scaled precipitous blocks of stone, and left behind us the snowy summits. The march became more and more painful. We crawled on hands and feet, we glided like cats, leaped from one rock to another like squirrels. Frequently, a handful of moss or a clump of brushwood was our sole support, where we found no cracks or crevices. Drops of blood often tinted, like purple flowers, the verdure we crushed under foot. When this was wanting we contrived to balance ourselves on the rock by the help of our alpenstocks, having recourse as seldom as possible to one another's arms, for fear of dragging the whole company into the abyss. Hundreds of feet below us glittered the deep crevasses of the glacier, in which the rays of the sun disported. The cold winds,[Pg 34] blowing from the frozen heights, scarcely cooled our foreheads. We were streaming with perspiration, but our gaiety increased, instead of diminishing, with the dangers. When we came to a stretch of granite, our speed was doubled, and whoever first set foot upon it would announce the fact to the others. There we slipped but seldom, and by assisting one another, we could walk erect and more quickly. Bohren the younger, who was one of our porters and the youngest of the company, continued his merry song. In moments of peril his voice acquired a decided quaver, but he never paused in his march or in his cadences, and never fell back a step.

"The prospect, which embraced the whole valley, was magnificent. We could perceive the châlets of Grindelwald, like miniatures sprinkled over the greensward. My guides exclaimed, 'Ah, it is from the height of the heavens that we behold our wives!' And we continued our ascent, leaving beneath us the clouds floating everywhere like grey scarves. At eleven o'clock we halted on a promontory where we contrived to find room by sitting one behind the other.

"The fatigue and heat had exhausted us, and no one stirred, except the two Bohrens, who climbed a little higher in search of wood, so that we might light a fire, and prepare some refreshment. A crystalline spring, filtering through the marble and the brushwood, murmured close beside us. But all vigorous vegetation had disappeared. Nothing was to be seen but the grasses and mosses; the juniper, the wild thymes, which[Pg 35] perfumed the air, and fields of purple rhododendron, the metallic leaves of which mingled with the black lichens. At intervals, a few stunted larches were outlined against the everlasting snows. The Bohrens arrived with some brushwood, and soon a fire crackled and sparkled cheerily, the water boiled, and, to my great satisfaction, rhododendron flowers and fragments of juniper were put into it—my companions assuring me that this kind of tea was excellent and very wholesome.

"My thirst was keen, and I drank with avidity the odoriferous beverage, which seemed to me excellent.

"The guides had brought me a large posy of beautiful Alpine roses, and I made them into a wreath, which I twined around my hat.

"After an hour's halt, we resumed our march, and soon could see only the cold white snow around us, without the least sign of vegetation or life. The acclivity we were climbing was very steep, but having quitted the bare rocks, we no longer ran any risk of sliding. We endeavoured to quicken our steps, in order to reach, before nightfall, an immense cavern known only to two of our chamois hunters, who made use of it as a hiding-place when their unconquerable passion for heroic adventures tempted them to disregard the cantonal regulations. Joyous shouts broke forth when the yawning mouth of the grotto opened wide under thick layers of snow. Our songs recommenced, and, as night was coming on, we pressed forward rapidly. For some hours I had been unconscious of fatigue, and I could[Pg 36] have marched for a considerably longer period without feeling any need of rest.

"But the guides were impatient to gain a shelter where we should not be exposed to the avalanches which rumbled in every direction.

"A mysterious twilight partly illumined the extensive cavern, its farthest recesses, however, remaining in deep shadow. We could hear rivulets trickling and drops of water falling with monotonous slowness. Never had I penetrated into a place of such savage beauty. In the middle of the cavern, opposite the entrance, was a great pillar of ice, resembling a cataract suddenly frozen. Beyond this marvellous block, glittering like crystal, spread a stream of delicious freshness. When we had kindled a large fire with branches of juniper, accumulated by the hunter who most frequented the retreat, the ice shone with a myriad diamond tints; everything seemed to assume an extraordinary form and life. The fantastically carved walls of rock sparkled with capricious gleams. From the sides of black granite hung pendent icicles, sometimes slender and isolated, sometimes grouped in fanciful clusters. In the hollows, where damp and darkness for ever reign, climbed a bluish-grey moss, a melancholy and incomplete manifestation of life in the bosom of this death-like solitude. Within, the whole scene impressed the imagination strongly, while without, but close beside us, resounded, like thunder, the avalanches which scattered their ruins over our heads, or plunged headlong into fathomless gulfs.[Pg 37]

"Some white heifer-skins were laid down under a block which formed a kind of recess at the farther end of the grotto. I wrapped myself in my coverings and shawls, for the cold increased in severity, but I was protected from it by the assiduous care of my good guides, who heaped upon me all their furs and cloaks. Then, seated around the fire, they prepared the coffee which was to serve us the whole night. None of them thought of sleeping, nor felt inclined to repress their natural but modest gaiety. If one complained that his limbs were stiff, the others immediately cried out that he was as delicate as a woman, and that we had no cause of complaint while sojourning in a palace grander than kings' palaces. They inscribed my name upon the roof near to the entrance.

"Two of the guides had sallied forth to clear a pathway and cut steps in the snow, for there would be some difficulty in getting out of the grotto. On their return they informed us that we might rely on a fine day—words which were welcomed with loud applause. After undergoing so much fatigue, it was natural we should desire a complete success. I rejoiced to see so near me the immense glaciers and lofty peaks of the Alps, the image of which had often haunted my happiest dreams. Yet I felt somewhat uneasy at the symptoms of indisposition which would not be concealed. I experienced slight attacks of nausea, and a depression which I sought to conquer by rising abruptly and giving the signal of departure. I was forced to change[Pg 38] my boots, for those I had worn the day before were in shreds.

"About three o'clock in the morning we took leave of the hospitable cavern, but it was not without difficulty we crossed the precipices which frowned before us, and for the first time had to employ our long ladder. We supported it against the side of a chasm, the opposite brink of which lay several hundred feet below. We descended backwards the close and narrow steps, strictly forbidden to cast a downward glance. Day advanced rapidly. The masses of snow which rose around us resembled so many mountains piled upon other mountains. We were in the heart of the vast solitudes of the Eiger, which seemed astonished by the echoes of our steps. We often made use of the ladder. By the third time I had recovered my liberty of action, and no longer descended backward, but contemplating with an undefinable charm the gaping gulfs which vanished in the obscure recesses of the glacier, bluer than the skies of the East.

"The troop soon divided into two sections. We wore blue glasses to protect our eyes from the dazzling brilliancy of the snow, which every moment became less compact. Almer had even covered his face with a green veil, but mine I found inconvenient, and resolutely exposed my skin to the burning rays of the sun, which were reflected from the glittering frozen surfaces, though the sun itself was hidden by clouds. The fissures in the glacier were few and very narrow, and we employed[Pg 39] the ladder but once or twice in the immense plain of powdery snow which, towards eight o'clock, opened before us. It was then that our real sufferings began. The heat was excessive; walking, slow and very difficult, for at each step we sank almost to our knees. Sometimes the foot could find no bottom, and when we withdrew it we found a yawning azure-tinted crevasse. The guides called such places mines, and feared them greatly. The air every instant grew more rarefied; my mouth was dry; I suffered from thirst, and to quench it swallowed morsels of snow and kirsch-wasser, the very odour of which became at last insupportable, though I was sometimes compelled to drink it by the imperative orders of the guides.

"It had taken us long to cross the region of springs and torrents; not so long to traverse that in which the fissures of the glacier were hidden under the snow; and now at last we trod the eternal and spotless shroud of the frozen desert. I breathed with difficulty, my weakness increased, so that it was with no small pleasure I arrived at the halting-place marked out by our foremost party. I threw myself, exhausted, but enchanted, on the bed of snow which had been prepared for me. Avalanches were frequent. Sometimes they rolled in immense blocks with a sullen roar; sometimes whirlwinds of snow fell upon us like showers of heavy hail. To our great alarm the mist rose on all sides so that we often lost sight of those of our party who were acting as pioneers. After leaving the plain of snow[Pg 40] we ascended a steep and difficult incline. The guides had hardly strength enough to clear a path, so rude was the acclivity and so dense the snow.

"At length, about ten o'clock, we halted on a platform which stretched to the base of the Mönch, whose ridge or backbone rose before our eyes. Here a small grotto had been excavated in the ice in which I was bidden to rest myself, thoroughly well wrapped up. We were literally on the brink of a complete collapse, respiration failed us, and for some minutes I expectorated blood. However, I regretted neither my fatigues, nor the resolution which had carried me to this point. All that I feared was that I should not be able to go farther. The very air which I endured so badly was an object of interest and study on account of its extraordinary purity. One of the guides, having brought from the grotto a few juniper branches, kindled a fire and melted some snow, which we drank with eagerness. I then remarked that they had collected in a group at some distance apart, and were conversing in a low tone and with anxious faces. The Jungfrau had been indicated as the goal of our enterprise, and their apprehensive glances were turned towards that mountain, which rose on our left, shrouded in dense fogs. I felt a vague fear that they wished to interpose some obstacle to the complete realization of my projects; and, in fact, they soon came to tell me that it would not be possible to climb the Jungfrau that day; that there was still a long march to be made before we could reach its base, which, by an[Pg 41] optical illusion, seemed so near to us; and that from thence to the summit would be at least another three hours' climb.

"It seemed scarcely practicable to pass the night on the snow at so great an elevation, where the effort of breathing was a pain, and the icy cold threatened to freeze our aching limbs, and, besides, the guides were unanimous in predicting a violent storm in the evening. 'And then,' said they, 'what shall we do without shelter, without coverings, without fire, without any hot drink (for our supply of coffee was exhausted), in the midst of this ice?' I knew in my heart they were right, but I was keenly disappointed at failing to reach the goal when it seemed so near. As I could not make up my mind to adopt their opinion, Almer rose, and laying the ladder at my feet, said, with much energy, 'Adieu, I leave you, for my conscience as an honest man forbids me to lend a hand to a peril which I know to be inevitable.'

"I called him back, and rising in my turn, exclaimed: 'Will the difficulties be as great in the way of an ascent of the Mönch? There it is, only a few paces from us. It is free from mist, why should we not reach its summit?' At these words the astonishment was general, and everybody turned towards the peak I had named. The snow upon it seemed quite solid, and I thought it would be impossible to find there anything more dangerous than we had already experienced. Their hesitation surprised me. 'Are you aware,' said they,[Pg 42] 'that yonder mountain has never been ascended?' 'So much the better,' said I, 'we will baptize it!' And, forgetting in a moment my weariness, I started off with a firm step. Pierre Jaun and Pierre Bohren, seeing me so resolved, seized our flag, set out in advance, and never rested till they had planted it on the loftiest summit of the Mönch, before the rest of us could get up. The flag was of three colours, white, yellow, and blue, and bore the beloved name of 'Wallachia,' embroidered in large letters. As if Heaven favoured our wishes, while clouds rolled upon all the surrounding mountains, they left free and clear the peak of the Mönch.

"Though the acclivity was much steeper than that of the Eiger, we did not find the difficulties much greater. The snow was hard, and as we did not sink far into it, our march was less fatiguing. We held to one another so as to form a chain, and advanced zigzag, fired with impatience to reach the summit. All around us I saw deep beds of snow, but nowhere such blocks of ice as M. Deser found upon the crest of the Jungfrau. It is probable that, owing to the season, the Mönch was still buried under the accumulated snows of winter, and this circumstance greatly contributed to our success.

"The image of the Infinite presented itself to my mind in all its formidable grandeur. My heart, oppressed, felt its influence, as my gaze rested upon the Swiss plain half hidden in the mists of the surrounding mountains, which were bathed in golden vapours. I was filled with such a sense of God that my heart—so it seemed to[Pg 43] me—was not large enough to contain it. I belonged wholly to Him. From that moment my soul was lost in the thought of His incomprehensible power.

"But the time had come for our departure, and I must take leave of the mountain where I was so far from men! I embraced the flag, and at three o'clock we began our homeward march. With much toil and trouble we descended the declivities of the Mönch. We were obliged to lend each other more assistance than in ascending, and more than once we nearly fell into the abysses. But as soon as we regained the Eiger, we swept forward as rapidly as the avalanche which knows no obstacles, as the torrent which carves out its own channel, as the bird which on mighty pinions cleaves space. Seated on the snow, we allowed ourselves to slide easily down those steeps which we had so painfully climbed, even to the very brink of the precipices, which we had crossed on a ladder instead of bridge. We observed that the gulfs yawned wide which in the morning we had crossed upon the snow that covered them; for the aspect of these mountains changes with a truly extraordinary rapidity. Song and laughter soon broke forth again, provoked by our strange fashion of travelling. Great was our joy when we found ourselves once more in an atmosphere favourable to the life of vegetation, and all of us rushed headlong to the first brook, whose murmur sounded as sweet to us as the voice of a friend.

"But as soon as we reached the rocks free from snow,[Pg 44] our troubles recommenced; difficulties reappeared, and were even more serious than those we had met with in our ascent. The peril was extreme; and but for the courageous Pierre Bohren, who carried me rather than supported me, I could never have descended the bare rocks that skirt the edge of the glacier. When we struck the Mer de Glace, we fell in with so many gaping fissures that we could cross them only by hazardous leaps and bounds. We had not reached the other side before we were met by our porters with the sedan-chair; and we arrived singing and cheering at Grindelwald, where everybody eyed us with as much wonder as if we had risen from the dead. I asked for some citrons, which I devoured while changing my clothes. Though completely knocked up, I set out immediately for Interlachen, to reassure those who were awaiting me there. At the foot of the Grindelwald hill, I stopped at Pierre Bohren's châlet to pay a visit to his wife, who held in her arms an infant only a few days old. I embraced it and promised to be its godmother.

"About midway between Grindelwald and Interlachen, we were overtaken by a storm as violent as that which had heralded our departure.

"The guides, therefore, had made no mistake. We should have experienced this tempest among the loftiest summits of the Alps, if we had continued our excursion.

"When I rose next morning, my face was one great wound, and for a long time I endured the keenest sufferings. Not less fatigued than myself, the guides at[Pg 45] length arrived singing, and brought me a superb diploma upon official paper."[3]

The princess afterwards travelled in Greece, where she received an enthusiastic welcome, and ovations were offered to her as to a sovereign. Everybody did homage to the bright and generous author of "La Nationalité Hellénique,"—the liberal and zealous advocate of the rights, the manners, the character, and the future of Greece. But of nationalities she was always the defender, and her wide sympathies embraced not only the Greeks, but the Albanians and the Slavs.

After having studied the antiquities of Athens, undertaken sundry scientific and archæological excursions into Attica, and enjoyed a delightful intercourse at Athens with kindred spirits—such as Frederika Bremer—she traversed the nomarchies, or provinces, of the kingdom of Greece, with the view of obtaining an exact and comprehensive account of the moral and material condition of the rural population.

As M. Pommier remarks, this long excursion in a country which offers no facilities to travellers, and where one must always be on horseback, could not be accomplished without displaying a courage unexampled, an heroic perseverance, and a physical and moral strength equal to every trial. She had to undergo the strain of[Pg 46] daily fatigue and the heat of a scorching sun; to fear neither barren rocks, nor precipices, nor dangerous pathways, nor brigands. In spite of the counsels of prudence and of a timorous affection, the intrepid traveller would not omit any portion of her itinerary; she traversed successively into Bœotia, Phocis, Ætolia, and the Peloponnesus. When the mountaineers of Laconia saw her passing on horseback through the savage gorges, they cried out in their enthusiasm, "Here is a Spartan woman!" And they invited her to put herself at their head and lead them to Constantinople.

From Greece she went into Italy, in 1861, and took up her residence, where she has ever since remained, at Florence. Garibaldi has saluted as his sister this ardent champion of the rights of nationalities, who, to this day, has continued her philanthropic exertions. In 1867, she published "La Nazionalità Albanese secondo i Canti popolari;" in 1869, "Discours sur Marco Polo;" in 1870, "Venise en 1867;" in 1871-1873, "Gli Albanesi in Rumenia," a history of the princely family of the Ghikas from the 17th century; in 1871, a couple of novels, "Eleanora de Hallingen," and "Ghizlaine;" in 1877, "La Poésie des Ottomans;" and in 1878, "The Condition of Women among the Southern Slavs."

The princess, besides plunging into historical labours, sedulously cultivates the Fine Arts, and is moreover a first-rate pistol-shot. A true Albanian, she loves arms, and handles them skilfully.[Pg 47]

It cannot be denied, that she deserves her splendid reputation. Any one of her works, says a French critic, would make a man famous; and they are unquestionably marked by all the characteristics of an independent and observant mind. But it is her life that best justifies her renown—her life with its purity, its enthusiasm, its zeal for the oppressed, its intense love of knowledge, its vivid sympathies and broad charities, and its constant striving after truth and freedom, and the highest beauty.

[1] A pseudonym derived from the ancient name of the Danube—Ister.

[2] The chief of which are: "La Vie Monastique dans l'Eglise Orientale," 1855; "La Suisse Allemande," 1856; "Les Héros de la Roumanie;" "Les Roumains et la Papauté" (in Italian); "Excursions en Roumélie et en Morée," 1863; "Les Femmes de l'Orient," 1858; "Les Femmes d'Occident;" "Les Femmes, par une Femme," 1865.

[3] See the princess's "La Suisse Allemande et l'Ascension du Mönch." 4 vols., 1856.

A French writer observes, that in an age like ours, when firm convictions and settled beliefs are rare, it is no small satisfaction to have to record a career like that of the Princess of Belgiojoso—a career specially illustrious, because, above all things, honourable. But truly great minds, to paraphrase some words of Georges Sand, are always good minds.

The princess's chief titles to distinction are as a vigorous writer and a liberal thinker; she did not qualify herself for a place among great female travellers until unhappy events exiled her from her country.

Christina Trivulzia, Princess of Belgiojoso, was born on the 28th of June, 1808. At the early age of sixteen she was married to the Prince Emile de Barbian de Belgiojoso. She died in 1871.

Passionately devoted to the cause of a "free Italy," she was unable to live under the heavy yoke of the Austrian supremacy, and hastened to establish herself at Paris, where her rank, her fortune, her love of letters[Pg 49] and the arts, and the boldness of her political opinions, made her the attraction of the highest society. She formed an intimate acquaintance with numerous great writers and celebrated statesmen, particularly of Mignet and Augustin Thierry, whose daily diminishing liberalism she rapidly and boldly outstripped. In 1848 she plunged with all the ardour of an enthusiastic nature—a child of the warm South—into that wild revolutionary movement which swept over almost every country in Europe, rolling from the Alps to the Carpathians, from Paris to Berlin. She hastened to Milan, which had expelled its Austrian garrison, and at her own expense equipped two hundred horse, whom she led against the enemy. But Italy was not then united; she was not strong enough to encounter her oppressor; the bayonets of Radetzky re-imposed the Austrian domination; the princess was compelled to fly, and her estates were confiscated.

During the insurrectionary fever at Rome, in 1849, she fearlessly made her way into the very midst of the fighting-men, and in her own person directed the ambulances. Her love of freedom and her humanity were rewarded by banishment from the territories of the Church. As she could nowhere in Italy hope for a secure resting-place, she resolved to reside for the future in the East, and, repairing to Constantinople, she founded there a benevolent institution for the daughters of emigrants.

But in a short time she withdrew from European Turkey,[Pg 50] and at Osmandjik, near Sinope, laid the foundations of a model farm. In 1850 she published in a French journal, the National, her memorials of Veile; and as a relief to the stir and unrest of politics, she wrote, in the following year, her "Notions d'Histoire à l'usage des Enfants" (1851). The narrative of her journey in Asia Minor appeared at a later date in the well-known pages of the Revue des deux Mondes.

Having recovered possession of her estates, thanks to the amnesty proclaimed by the Emperor Francis Joseph, she sought in literary labour a field for the activity of her restless intellect. Balzac points to that great female artist and republican, the Duchess of San-Severins, in Stendhal's "La Chartreuse de Parme," as a portrait of the princess. Whether this be so or not, she was assuredly one of the most conspicuous and original figures of the time.

Her chief title to literary reputation rests upon her "Études sur l'Asie-Mineure et sur les Turcs." In reference to these luminous and eloquent sketches, a critic says: "I have read many works descriptive of Mussulman manners, but have never met with one which gave so exact and full an idea of Oriental life." But in the princess's writings we must not seek for those richly coloured pictures, those highly decorative paintings in which style plays the principal part—pictures composed for effect, and entirely indifferent to accuracy of detail or truth of composition. She never seeks to dazzle or beguile the reader; her language is direct and vigorous[Pg 51] and full of vitality because it always embodies the truth.

No one has shown a juster appreciation of that strange Eastern institution, the harem, though it is no easy thing to form a clear and impartial judgment upon a system so alien to Western ideas and revolting to Christian morality. A vast amount of unprofitable rhetoric has been expended upon this subject. Let us turn to the princess's discriminative statement of facts.

After explaining the many points of contrast between the people of the East and the people of the West, she continues:—

"Of all the virtues held in repute by Christian society, hospitality is the only one which the Mussulmans think themselves bound to practise. Where duties are few, it is natural they should be greatly respected. The Orientals, therefore, have recognized in its highest form this sole and unique virtue, this solitary constraint which they have agreed to impose upon themselves.

"Unfortunately, every virtue which is content with appearances is subject to sudden changes. This is what has happened—is happening to-day—in respect of Oriental hospitality. A Mussulman will never be consoled for having failed to observe the laws of hospitality. Take possession of his house; turn him out of it; leave him to stand in the rain or sun at his own door; plunder his store-rooms; use up his supplies of coffee and brandy; upset and pile one upon another his carpets, his mattresses, his cushions; break his crystal; ride his horses, and even[Pg 52] founder them if it seems good to you—he will not utter a word of reproach, for you are a monzapi, a guest,—it is Allah himself who has sent you, and whatever you do, you are and will ever be welcome. All this is admirable; but if a Mussulman finds the means of appearing as hospitable as laws and customs require, without sacrificing an obolus, or even while gaining a large sum of money, fie upon virtue, and long live hypocrisy! And such is the case ninety-nine times out of a hundred. Your host overwhelms you while you sojourn beneath his roof; but if at your departure you do not pay him twenty times the value of what he has given you, he will wait until you have crossed his threshold, and consequently doffed your sacred title of monzapi, to throw stones at you.

"It goes without saying that I speak of the rude multitude, and not of the simple honest hearts who love the good because they find it pleasant, and practise it because in practising it they taste a secret enjoyment. My old mufti of a Tcherkess is one of these. His house, like all good houses in Eastern countries, consists of an inner division reserved for women and children, and an outer pavilion, containing a summer-saloon, and a winter-saloon, with one or two rooms for servants. The winter-saloon is a pretty apartment heated by a good stove, covered with thick carpets, and passably furnished with silken and woollen divans arranged all round the apartment.

"As for the furniture of the summer-saloon, it consists of a leaping, shining fountain in the centre, to which[Pg 53] are added, when circumstances require it, cushions and mattresses on which to sit or recline. There are neither windows, nor doors, nor any kind of barrier, between the exterior and the interior. My old mufti, who, at the age of ninety, possesses numerous wives, the oldest of whom is only thirty, and children of all ages, from the baby of six months, up to the sexagenarian, professes the repugnance of good taste for the noise, disorder, and uncleanness of the harem. He repairs there every day, as he goes to his stable to see and admire his horses; but he dwells and he sleeps, according to the season, in one or other of the saloons. The good fellow understood that if long habit had not rendered the inconveniences of the harem tolerable to himself, it would be still worse for me, freshly disembarked from that land of enchantments and refinements which men here call 'Franguistan.' So at the outset he informed me that he would not relegate me to that region of obscurity and confusion, smoke and infection, named the harem, but would give up to me his own apartment. I accepted it with gratitude. As for himself, he took up his abode in the summer-saloon. Though it was the end of January, and snow was deep on the ground, both in town and country, he preferred his frozen fountain, his damp pavement and draughts of air, to the hot, but unwholesome, atmosphere of the harem.

"Perhaps I destroy a few illusions, in speaking of the harem with so little respect. We have all read of it in 'The Thousand and One Nights,' and other Oriental[Pg 54] stories; we have been told that it is the dwelling-place of Love and Beauty; we are authorized to believe that the written descriptions, though exaggerated and embellished, are nevertheless founded upon reality, and that in this mysterious retreat are to be found all the marvels of luxury, art, magnificence and pleasure. How far from the truth! Picture to yourself walls black and full of chinks, wooden ceilings, split in many places and dark with dust and spiders' webs, sofas torn and greasy, door-hangings in tatters, traces of oil and candle-grease everywhere. When for the first time I set foot in one of these supposed charming nooks, I was shocked; but the mistresses of the house detected nothing. Their persons are in harmony with the surroundings. Mirrors being very rare, the women bedizen themselves with tinsel, the bizarre effect of which they have no means of appreciating.

"They stick a number of diamond pins and other precious stones in the handkerchiefs of printed cotton which they twist around their head. To their hair they pay no attention, and none but the great ladies who have resided in the capital have any combs. As for the many-coloured ointment which they use so immoderately, they can regulate its application only by consulting one another, and as the women occupying the same house are all rivals, they willingly encourage one another in the most grotesque daubs of colouring. They put vermilion on the lips, rouge on the cheeks, nose, forehead and chin, white anywhere to fill up,[Pg 55] blue round the eyes and under the nose. But strangest of all is the manner in which they tint the eyebrows. They have undoubtedly been told that, to be beautiful, the eyebrow should form a well-defined arch, and hence they have concluded that the greater the arch the greater will be the beauty, without asking if the place of that arch were not irrevocably fixed by nature. Such being the case, they give up to their eyebrows the whole space between the temples, and paint the forehead with two wide arches, which, starting from the origin of the nose, extend, one on each side, as far as the temple. Some eccentric beauties prefer the straight line to the curve, and describe a great streak of black all across the forehead; but they are few in number.

"Most deplorable is the influence of this painting when combined with the sloth and uncleanness natural to the women of the East. Each feminine countenance is a work of high art that cannot be reconstructed every morning. It is the same with the hands and feet, which, variegated with orange, fear the action of water as injurious to their beauty. The multitude of children and servants, especially of negresses, who people the harems, and the footing of equality on which mistresses and attendants live, are also aggravating causes of the general uncleanliness. I shall not speak of the children—everybody knows their manners and customs—but consider for a moment what would become of our pretty European furniture if our cooks and maids-of-all-work rested from their labours on our settees and fauteuils,[Pg 56] with their feet on our carpets, and their back against our hangings. Remember, too, that glass windows in Asia are still but curiosities; that most of the windows are filled up with oiled paper, and that where corn-paper is scarce the windows are blocked up, and light enters only by the chimney—light more than sufficient for the inmates to drink and smoke by and to apply the whip to refractory children—the only occupations during the day of the mortal houris of faithful Mussulmans. Let not the reader suppose, however, that an Egyptian darkness prevails in these windowless apartments. The houses being all of one story, the chimneys being very wide and not rising above the level of the roof, it often happens that by stooping a little in front of the chimney-place you see the sky through the opening. What these apartments are really deficient in is air; but the ladies are far from making any complaint. Naturally chilly, and having no means of warming themselves by exercise, they remain for hours at a time huddled on the ground before the fire, and cannot understand that a visitor is almost choked by the atmosphere. If anything recalls to my mind these artificial caverns, crowded with tattered women and noisy children, I feel ready to faint."

The princess does not, on the whole, speak unfavourably of the Turkish character. Perhaps the reader would judge it more severely; but still the consensus of the best authorities supports the view[Pg 57] taken by the princess, and it is the governing-class, rather than the masses, that seems to justify the general dislike. Of Turkish officials it would be difficult, perhaps, to say anything too severe; the ordinary Turk, however, has many good qualities, which need only the stimulus of good government for their happy development. As to the governing-class, their vices are the natural result of the corruption of the harems, and until these are reformed, it is useless to expect any elevation of the low moral standard which now unfortunately prevails among the pashas.

The Turkish people, if less enlightened than other European nations, are not without qualities that demand recognition. They are temperate, hospitable, and orderly. They are faithful husbands and good wives.

The Turkish peasant is at once father, husband, and lover to his wife, whom he never contradicts willingly and knowingly, and there is little to which he will not submit in the depth of his affection for her.

In these climates, and under the influence of coarse and unwholesome food, the woman ages early; whereas the man, better constituted to endure fatigue and privation, preserves his vigour almost to the last unimpaired. Nothing is more common here than to see an old man of eighty and odd surrounded by little children who are his flesh and bone. In spite of this disproportion between man and woman, the union, contracted almost in childhood, is only dissolved by death. The Princess de Belgiojoso tells us that she has[Pg 58] seen hideous, decrepit, and infirm women tenderly cared for and adored by handsome old men, straight as the mountain pine, with beard silvered but long and thick, and eyes bright, clear, and serene.

One day, our traveller met an old woman, blind and paralytic, whom her husband brought to her in the hope that the princess would restore her sight and power of movement.

The woman was seated astride an ass, which her husband led by the bridle. On arriving, he took her in his arms, deposited her on a bench near the door, and installed her on a heap of cushions with all the solicitude of a mother for her child.

"You ought to be very fond of your husband," said the princess to the blind woman.

"I should like to be able to see clearly," answered she. The princess looked at the husband, he smiled sadly, but without any shadow of ill-will.

"Poor woman," he remarked, passing the back of his hand over his eyes, "her blindness renders her very unhappy. She cannot accustom herself to it But you will give her back her sight, will you not, Bessadée?"

As the Princess Christina shook her head, and began to protest her powerlessness, he plucked the skirt of her robe and made her a sign to be silent.

"Have you any children?"

"Alas! I had one, but he died a long time ago."

"And how is it you have not taken another wife, as[Pg 59] your law allows—a strong and healthy woman who might have brought you children?"

"Ah, that is easily said; but this poor creature would have been sadly vexed, and then I could not have been happy with another, not even if she had brought me children. You see, Bessadée, we cannot have everything in this world. I have a wife whom I have loved for nearly forty years, and I shall make no second choice."

The man who spoke thus was a Turk. His wife was as much his property as a piece of furniture; none of his neighbours would have blamed, no law would have punished him, if he had got rid by any violent means of his useless burden. Happily, the character of the Turkish people neutralizes much of what is pernicious and odious in their customs and creed. They possess at bottom a wonderful quality of goodness, of gentleness, of simplicity, a remarkable instinct of reverence for that which is good and beautiful, of respect for that which is weak. This instinct has resisted, and will, let us hope, continue to resist, the influence of injurious institutions founded exclusively upon individual selfishness and the right of the strong hand. If you would understand the mildness and the serenity which are natural to the Turk, you must observe the peasant among his fields, or at the market, or on the threshold of a café. Seedtime and harvest, the price of grain, the condition of his family—these are the invariable topics of his simple childlike conversation. He never raises his voice in anger, never lets drop a pleasantry which might wound or even fatigue[Pg 60] his companions, never indulges in those profanities and indecencies unhappily too common in the speech of the lower orders in European countries. This admirable reticence, this nobility and simplicity of manner, do they owe it to education? Not at all; it is the gift of nature. In some respects nature has been very liberal to the Turkish people; but all the gifts she has bestowed upon them, their institutions tend to debase and invalidate. And in proportion as we carry our observations above the classes which so happily preserve their primitive characteristics, to the bourgeoisie, or into regions higher still, so shall we find the growth and development of vice; it extends, predominates, and finally reigns alone.

The peculiar interest and permanent value of the writings of the Princess de Belgiojoso are due to the fact that they owe nothing to received ideas. Moreover, she indulges in no conjectures regarding the subjects she takes up, she has investigated them carefully, and understands them thoroughly. In each page of her work upon Turkey we meet with calm statements of established facts which overthrow the speculations and fancies too often found in works of great popularity from the pen of distinguished writers. It is the truth she speaks; and her influence is all the greater because she makes no effort to convince or impose upon her readers; she writes gravely and deliberately, without passion and without imagination.[Pg 61]

A few facts from the princess's pages will not be without interest for the reader, at a time when "the unspeakable Turk" is the object of so much public discussion.

"Passing through one of the streets of Pera (the European suburb), I was arrested by a score of persons grouped round a gavas (a kind of civic guard) who was endeavouring to persuade a negress to be conducted to the palace where she was expected, and where, he told her, she would meet with all the pleasures imaginable. The negress answered only with sobs, and the cry, 'Kill me rather!' The gavas resumed his enthusiastic and fanciful descriptions of the good bed, the good cheer, the fine clothes, the pipe always alight, the floods of coffee, all the delights which would convert this prison into a complete paradise. For half-an-hour I listened to the discussion, and when I went on my way no decision had been arrived at. I asked a kind of valet de place who accompanied me, why the gavas lost his time in attempting to convince the negress, instead of forcibly conveying her to her destination. 'A woman!' was his answer, completely scandalized by my question, and I began to suspect that the Turks were not such brutes as they are popularly supposed to be in Europe."

"The following anecdote also relates to my residence at Constantinople. A woman, a Marseillaise by birth[Pg 62] but married to a Mussulman, was engaged in a law-suit on some matter which I have forgotten; but I know that her adversaries grounded their hopes and pretensions on a document which they had placed in the judge's hands. Informed of this circumstance, the Marseillaise repaired to the Cadi, and begged him to acquaint her with its contents. Nothing could be more reasonable. The Cadi took the paper, and prepared to read it to her; but he had scarcely perched his glasses on his nose when the lady leaped forward, sprang at his throat, seized the paper, put it in her pocket, made her obeisance, and calmly passed out through the vestibule, which was filled with slaves and servants. The Marseillaise defied her opponents to produce any written document in their favour, and she won her cause. When this story was told to me, I remarked that the judge must have been bribed by the Marseillaise, since nothing could have been easier for him than, if he wished it, to have her arrested by his guards, and deprived of the paper which she had carried off with so much audacity. Again I received the answer: 'But she was a woman!'"

Among female travellers the Princess of Belgiojoso must hold an honourable place, in virtue of the accuracy of her observation and the clearness of her judgment. Moreover, she is always impartial: she has no preconceived theories to support, and consequently she is at liberty neither to extenuate nor set down aught in malice. In picturesqueness of description she has been excelled[Pg 63] by many, in soberness and correctness of statement by none; and, after all, it is more important that our travellers should tell us what they have really seen, than what they would have wished to see; should trust to their intelligence as observers rather than to their fancy as poets.

Note on the Harem, or Harum.—It is curious to compare with the princess's disillusionizing account of a harem, such a poetical and romantic description as the following, in which it becomes a bower of beauty, tenanted by an Oriental Venus:—

"The lady of the harum—couched gracefully on a rich Persian carpet strewn with soft billowy cushions—is as rich a picture as admiration ever gazed on. Her eyes, if not as dangerous to the heart as those of our country, where the sunshine of intellect gleams through a heaven of blue, are, nevertheless, perfect in their kind, and at least as dangerous to the senses. Languid, yet full, brimful of life; dark, yet very lustrous; liquid, yet clear as stars; they are compared by their poets to the shape of the almond and the bright timidness of the gazelle. The face is delicately oval, and its shape is set off by the gold-fringed turban, the most becoming head-dress in the world; the long, black, silken tresses are braided from the forehead, and hang wavily on each side of the face, falling behind in a glossy cataract, that[Pg 64] sparkles with such golden drops as might have glittered upon Danaë, after the Olympian shower. A light tunic of pink or pale blue crape is covered with a long silk robe, open at the bosom, and buttoned thence downward to the delicately slippered little feet, that peep daintily from beneath the full silken trousers. Round the loins, rather than the waist, a cashmere shawl is loosely wrapt as a girdle, and an embroidered jacket, or a large silk robe with loose open sleeves, completes the costume. Nor is the fragrant water-pipe, with its long variegated serpent, and its jewelled mouth-piece, any detraction from the portrait.

"Picture to yourself one of Eve's brightest daughters, in Eve's own loving land. The woman-dealer has found among the mountains that perfection in a living form which Praxiteles scarcely realized, when inspired fancy wrought out its ideal in marble. Silken scarfs, as richly coloured and as airy as the rainbow, wreathe her round, from the snowy breast to the finely rounded limbs half buried in billowy cushions; the attitude is the very poetry of repose, languid it may be, but glowing life thrills beneath that flower-soft exterior, from the varying cheek and flashing eye, to the henna-dyed taper fingers, that capriciously play with her rosary of beads. The blaze of sunshine is round her kiosk, but she sits in the softened shadow so dear to the painter's eye. And so she dreams away the warm hours in such a calm of thought within, and sight or sound without, that she starts when the gold-fish gleam in[Pg 65] the fountain, or the breeze-ruffled roses shed a leaf upon her bosom."—Eliot Warburton, "The Crescent and the Cross," etc. etc.

As European gentlemen are never admitted to the harem, it is hardly credible that Major Warburton could have had an opportunity of seeing the beauty which he paints in such glowing colours.

Not only as a persevering and enlightened traveller, but as a poet, Madame Hommaire de Hell has gained distinction. It is in the former capacity that she claims a place in these pages.

She was born at Artois, in 1819. While she was still an infant, her mother died; but it was her good fortune to find in the love of an only sister no inadequate substitute for maternal affection. Her father seems to have been one of those individuals whom Fortune tosses to and fro with pertinacious ill-humour; moreover, he had something of the nomad in his temperament, and without any real or sufficient motive, moved from place to place, entailing upon his young family sudden and burdensome journeys. Before Adela was seven years old, she had been carried from Franche-Comté into the Bourbonnais, thence into Auvergne, and thence to Paris. She was afterwards placed in a boarding-school at Saint-Maudé,[Pg 67] but her father's death restored her to her sister's guardianship at Saint-Etienne.

A short time after her arrival in this town, she attracted the attention of Xavier Hommaire de Hell, since so justly celebrated as a traveller and a scientist. He fell passionately in love with her, and though she was but fifteen years of age, and had no fortune, he rested not until his family gave their consent to his marriage.

To provide for his child-wife he obtained an office in the railway administration, but only temporarily, for already he had made up his mind to seek fortune and reputation in some foreign country. He pushed his solicitations with so much energy that, in the first year of his wedded life, he secured an appointment under the Turkish Government. His wife, to whom a child had just been given, was unable to accompany him. The pain of separation was very great, but both knew that in France there was no present opening for his talents, and both were agreed that their separation should not be for long. And, indeed, before the end of the year, Madame de Hell clasped her babe to her bosom, and set out to join her husband.

Her poetical faculties were first stimulated by her voyage to the East. Previously she had cherished a deep love for nature, for the music of verse, for nobility of thought, but had made no attempt to define and record her impressions. The isles and shores of the Mediterranean,[Pg 68] with their myriad charms and grand historic associations:—

loosened her genius, so to speak, and stimulated her to clothe her feelings and sentiments in a metrical form. It is not difficult to understand the effect which, on a warm imagination and sensitive temperament, that richly-coloured panorama of "the isles of Greece," and that exquisite prospect of Constantinople and the Golden Horn, would necessarily produce. For some time, as she herself tells us, she lived in a kind of moral and intellectual intoxication; she was absorbed in an ideal world, which bewildered while it delighted her.

The plague was then dealing heavily with the unfortunate Mussulman populations, but it did not terrify our enthusiastic travellers; as if they bore a charmed life, they went to and fro, seeing whatever was fine or memorable, and yet all unable to satisfy that thirst for beauty which the beautiful around them had excited. Madame de Hell was under the influence of a subtle spell; her quick fancy was profoundly impressed by the picturesque aspects of Oriental life, by its glow of colour and grace of form, so different from the commonplace and monotonous realities of the West. She seemed to be living in the old days of the Khalifs—those days which the authors of the "Thousand and One Stories"[Pg 69] have immortalized—to be living, for example, in the "golden prime of good Haroun Al-Raschid"—as she saw before her the motley procession of veiled women, Persians with their pointed bonnets, Hindu jugglers with lithe lissom figures, negro slaves, grey-bearded beggars looking like princes in disguise, and Armenians wrapped in their long furred cloaks. She delighted, accompanied by her husband, to explore the silent recesses of the hilly and almost solitary streets in the less frequented quarters of Stamboul, where a latticed window or a half-open door would suggest a romance of love and mystery, or a vision of some gorgeous palace interior, of

When Madame de Hell visited the East, it was considered dangerous for Franks to venture into the streets of Constantinople, and they occupied only the suburbs of Pera and Galata, which were exclusively made over to the Christian population, and separated from the Mussulman city by the arm of the sea known as the Golden Horn. And as in those days, which were long before the introduction of Mr. Cook's "personally conducted tours," tourists were few, the presence of a "giaour" in the Mohammedan quarter was an extraordinary event. Those who should have fallen in with our two young adventurers, their eager gaze roving everywhere in quest[Pg 70] of new discoveries, strolling hither and thither like two children out for a holiday, would never for one moment have supposed that a terrible pestilence was raging through the city, and nowhere more fatally than in the very districts they had chosen for their explorations. But perhaps the danger from disease was not so imminent as the peril they incurred in penetrating into the chosen territory of Islam. Fortune favoured them, however, or their frank bearing disarmed fanaticism, and they escaped without molestation or even insult.

As Monsieur and Madame de Hell resided for a year in Constantinople, it is needless to say they remained long enough for the glamour to disappear, in which at first their lively imaginations had invested everything around them. The gorgeous visions vanished, and their eyes were opened to the hard realities of Mohammedan ignorance, bigotry and misgovernment. They learned, perhaps, that the order and freedom of Western civilization are infinitely more valuable than the picturesqueness of Oriental society. In 1838 they set out for Odessa, where Monsieur de Hell hoped to obtain a position worthy of his talents. The future of the young couple rested wholly on a letter of recommendation to General Potier, by whom they were warmly welcomed. The general, who owned a large estate in the neighbourhood, where he cultivated a famous breed of Merino sheep, had formed a project for erecting mills upon the Dnieper. To carry it out he needed an engineer, and in M. Hommaire de Hell he found one. Straightway they[Pg 71] proceeded to his estate at Kherson, and M. de Hell set to work on the necessary plans. While thus engaged, he conceived the idea of a scientific expedition to the Caspian Sea—a basin of which little was then known to our geographers—and this idea held him so firmly that, a few months later, he gave up his employment in order to realize it. In one of his excursions to the cataracts of the Dnieper, where the mills were to be erected, his geological knowledge led him to the discovery of the rich veins of an iron mine, which has since been profitably worked.

"This period of my life," wrote Madame de Hell, afterwards, "spent in the midst of the steppes, remote from any town, appears to me now in so calm, tender, and serene a light, that the slightest memorial of it moves me profoundly. Only to see the shore where we passed whole days in seeking for shells, only to hear the sound of the great waves rolling on the sandbanks and among the seaweed, only to recall a single one of the impressions of that happy epoch, I would willingly repeat the voyage."

For his great scientific expedition, M. de Hell made vigorous preparations during the winter of 1838, and having obtained from Count Vorontzov, the governor of New Russia, strong letters of recommendation to the governors and officials of the provinces he would have to traverse, he and his wife started in the middle of May, 1839, accompanied by a Cossack, and an excellent[Pg 72] dragoman, who spoke all the dialects current in Southern Russia.

Their journey through the country of the Don Cossacks we shall pass over, as offering nothing of special novelty or interest, and take up Madame de Hell's narrative at the point of her arrival on the banks of the Volga.