She truly did well in this performance.

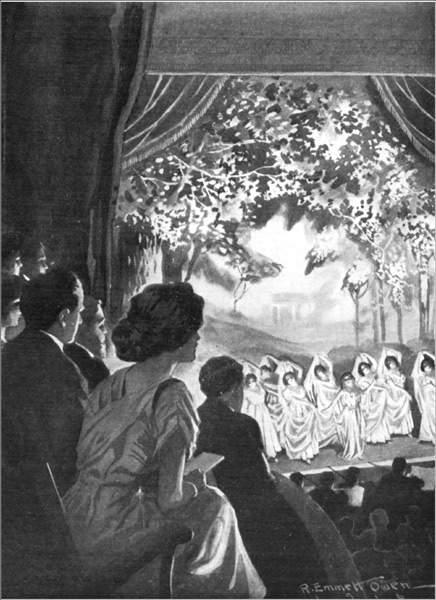

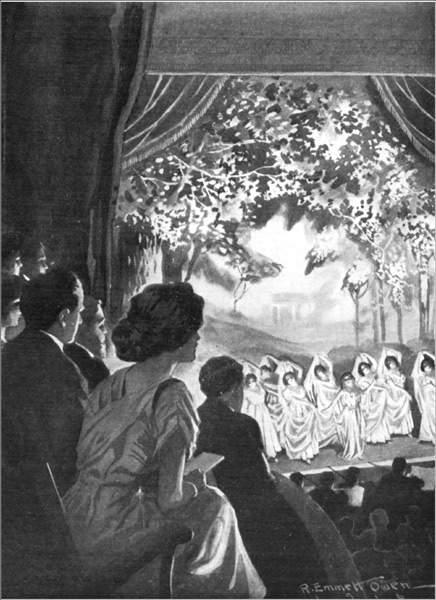

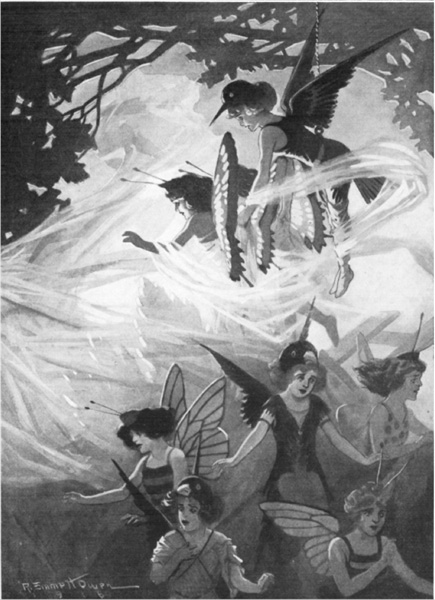

She truly did well in this performance.(Page 252) Frontispiece

Title: The Corner House Girls in a Play

Author: Grace Brooks Hill

Illustrator: Robert Emmett Owen

Release date: March 21, 2010 [eBook #31722]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

She truly did well in this performance.

She truly did well in this performance.THE

CORNER HOUSE GIRLS

IN A PLAY

HOW THEY REHEARSED

HOW THEY ACTED

AND WHAT THE PLAY BROUGHT IN

BY

Author of "The Corner House Girls," "The Corner

House Girls at School," etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

R. EMMETT OWEN

NEW YORK

BARSE & HOPKINS

PUBLISHERS

BOOKS FOR GIRLS

The Corner House Girls Series

By Grace Brooks Hill

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume,

75 cents, postpaid.

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS AT SCHOOL

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS UNDER CANVAS

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS IN A PLAY

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS' ODD FIND

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS ON A TOUR

(Other volumes in preparation)

BARSE & HOPKINS

PublishersNew York

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Sovereigns of England | 9 |

| II | The Lady in the Gray Cloak | 18 |

| III | Billy Bumps' Banquet | 27 |

| IV | The Basket Ball Team in Trouble | 42 |

| V | The Stone in the Pool | 57 |

| VI | Just Out of Reach | 66 |

| VII | The Core of the Apple | 75 |

| VIII | Lycurgus Billet's Eagle Bait | 84 |

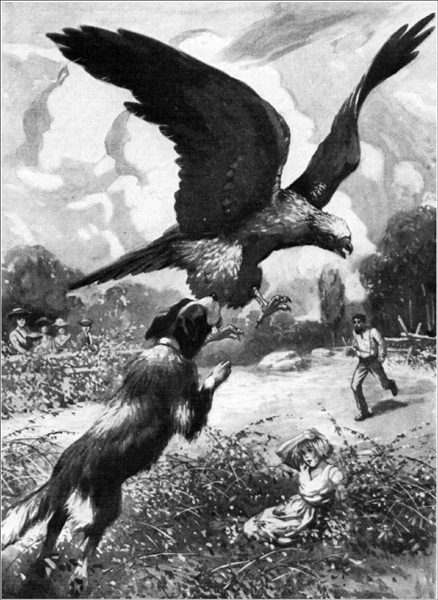

| IX | Bob Buckham Takes a Hand | 101 |

| X | Something About Old Times | 112 |

| XI | The Strawberry Mark | 122 |

| XII | Tea With Mrs. Eland | 134 |

| XIII | Neale Suffers a Shortening Process | 145 |

| XIV | The First Rehearsal | 156 |

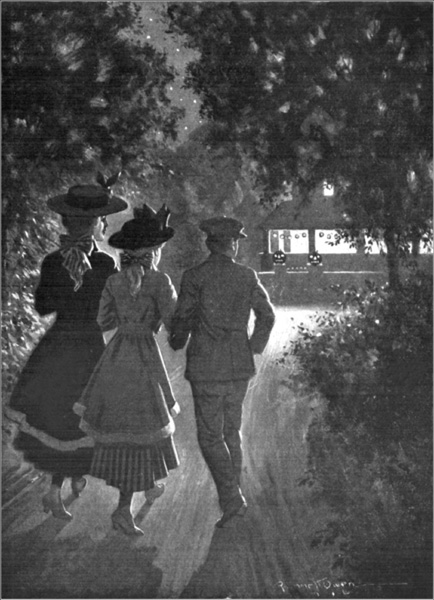

| XV | The Hallowe'en Party | 167 |

| XVI | The Five-dollar Gold Piece | 175 |

| XVII | The Mysterious Letter | 184 |

| XVIII | Miss Pepperill and the Gray Lady | 193 |

| XIX | A Thanksgiving Skating Party | 198 |

| XX | Neale's Endless Chain | 206 |

| XXI | The Corner House Thanksgiving | 212 |

| XXII | Clouds and Sunshine | 217 |

| XXIII | Swiftwing, the Hummingbird | 228 |

| XXIV | The Final Rehearsal | 240 |

| XXV | A Great Success | 247 |

| PAGE | |

| She truly did well in this performance | Frontispiece |

| At the moment the eagle dropped with spread talons, the big dog leaped | 103 |

| They saw two huge pumpkin lanterns grinning a welcome from the gateposts | 173 |

| The scaffolding pulled apart slowly, falling forward through the drop | 238 |

"I never can learn them in the wide, wide world! I just know I never can, Dot!"

"Dear me! I'm dreadfully sorry for you, Tess," responded Dorothy Kenway—only nobody ever called her by her full name, for she really was too small to achieve the dignity of anything longer than "Dot."

"I'm dreadfully sorry for you, Tess," she repeated, hugging the Alice-doll a little closer and wrapping the lace "throw" carefully about the shoulders of her favorite child. The Alice-doll had never enjoyed robust health since her awful experience of more than a year before, when she had been buried alive.

Of course, Dot had not got as far in school as the sovereigns of England. She had not as yet heard very much about the history of her own country. She knew, of course, that Columbus discovered it, the Pilgrims settled it, that George10 Washington was the father of it, and Abraham Lincoln saved it.

Tess Kenway was usually very quick in her books, and she was now prepared to enter a class in the lower grammar grade of the Milton school in which she would have easy lessons in English history. She had just purchased the history on High Street, for school would open for the autumn term in a few days.

Mr. Englehart, one of the School Board and an influential citizen of Milton, had a penchant for beginning at the beginning of things. As he put it: "How can our children be grounded well in the history of our own country if they are not informed upon the salient points of English history—the Mother Country, from whom we obtained our first laws, and from whom came our early leaders?"

As the two youngest Kenway girls came out of the stationery and book store, Miss Pepperill was entering. Tess and Dot had met Miss Pepperill at church the Sunday previous, and Tess knew that the rather sharp-featured, bespectacled lady was to be her new teacher.

The girls whom Tess knew, who had already had experience with Miss Pepperill called her "Pepperpot." She was supposed to be very irritable, and she did have red hair. She shot questions out at one in a most disconcerting way, and Dot was quite amazed and startled by the way Miss Pepperill pounced on Tess.

11 "Let's see your book, child," Miss Pepperill said, seizing Tess' recent purchase. "Ah—yes. So you are to be in my room, are you?"

"Yes, ma'am," admitted Tess, timidly.

"Ah—yes! What is the succession of the sovereigns of England? Name them!"

Now, if Miss Pepperill had demanded that Tess Kenway name the Pleiades, the latter would have been no more startled—or no less able to reply intelligently.

"Ah—yes!" snapped Miss Pepperill, seeing Tess' vacuous expression. "I shall ask you that the first day you are in my room. Be prepared to answer it. The succession of the sovereigns of England," and she swept on into the store, leaving the children on the sidewalk, wonderfully impressed.

They had walked over into the Parade Ground, and seated themselves on one of the park benches in sight of the old Corner House, as Milton people had called the Stower homestead, on the corner of Willow Street, from time immemorial. Tess' hopeless announcement followed their sitting on the bench for at least half an hour.

"Why, I can't never!" she sighed, making it positive by at least two negatives. "I never had an idea England had such an awful long string of kings. It's worse than the list of Presidents of the United States."

"Is it?" Dot observed, curiously. "It must be awful annoyable to have to learn 'em."

12 "Goodness, Dot! There you go again with one of your big words," exclaimed Tess, in vexation. "Who ever heard of 'annoyable' before? You must have invented that."

Dot calmly ignored the criticism. It must be confessed that she loved the sound of long words, and sometimes, as Agnes said, "made an awful mess of polysyllables." Agnes was the Kenway next older than Tess, while Ruth was seventeen, the oldest of all, and had for more than three years been the house-mother of the Kenway family.

Ruth and Agnes were at home in the old Corner House at this very hour. There lived in the big dwelling, with the four Corner House Girls, Aunt Sarah Maltby (who really was no relative of the girls, but a partial charge upon their charity), Mrs. MacCall, their housekeeper, and old Uncle Rufus, Uncle Peter Stower's black butler and general factotum, who had been left to the care of the old man's heirs when he died.

The first volume of this series, called "The Corner House Girls," told the story of the coming of the four sisters and Aunt Sarah Maltby to the Stower homestead, and of their first adventures in Milton—getting settled in their new home and making friends among their neighbors.

In "The Corner House Girls at School," the second volume, the four Kenway sisters extended the field of their acquaintance in Milton and thereabout, entered the local schools in the several13 grades to which they were assigned, made more friends and found some few rivals. They began to feel, too, that responsibility which comes with improved fortunes, for Uncle Peter Stower had left a considerable estate to the four girls, of which Mr. Howbridge, the lawyer, was administrator as well as the girls' guardian.

Now the second summer of their sojourn at the old Corner House was just ending, and the girls had but recently returned from a most delightful outing at Pleasant Cove, on the Atlantic Coast, some distance away from Milton, which was an inland town.

All the fun and adventure of that vacation are related in "The Corner House Girls Under Canvas," the third volume of the series, and the one immediately preceding the present story.

Tess was seldom vindictive; but after she had puzzled her poor brain for this half hour, trying to pick out and to get straight the Williams and Stephens and Henrys and Johns and Edwards and Richards, to say nothing of the Georges, who had reigned over England, she was quite flushed and excited.

"I know I'm just going to de-test that Miss Pepperpot!" she exclaimed. "I—I could throw this old history at her—I just could!"

"But you couldn't hit her, Tess," Dot observed placidly. "You know you couldn't."

"Why not?"

"Because you can't throw anything straight14—no straighter than Sammy Pinkney's ma. I heard her scolding Sammy the other day for throwing stones. She says, 'Sammy, don't you let me catch you throwing any more stones.'"

"And did he mind her?" asked Tess.

"I don't know," Dot replied reflectively. "But he says to her: 'What'll I do if the other fellers throw 'em at me?' 'Just you come and tell me, Sammy, if they do,' says Mrs. Pinkney."

"Well?" queried Tess, as her sister seemed inclined to stop.

"I didn't see what good that would do, myself," confessed Dot. "Telling Mrs. Pinkney, I mean. And Sammy says to her: 'What's the use of telling you, Ma? You couldn't hit the broad side of a barn!' I don't think you could fling that hist'ry straight at Miss Pepperpot, Tess."

"Huh!" said Tess, not altogether pleased. "I feel I could hit her, anyway."

"Maybe Aggie could learn you the names of those sov-runs——"

"'Sovereigns'!" exclaimed Tess. "For pity's sake, get the word right, child!"

Dot pouted and Tess, being in a somewhat nagging mood—which was entirely strange for her—continued:

"And don't say 'learn' for 'teach.' How many times has Ruthie told you that?"

"I don't care," retorted Dorothy Kenway. "I don't think so much of the English language—or15 the English sov-er-reigns—so now! If folks can talk, and make themselves understood, isn't that enough?"

"It doesn't seem so," sighed Tess, despondent again as she glanced at the open history.

"Oh, I tell you what!" cried Dot, suddenly eager. "You ask Neale O'Neil. I'm sure he can help you. He teached me how to play jack-stones."

Tess ignored this flagrant lapse from school English, and said, rather haughtily:

"I wouldn't ask a boy."

"Oh, my! I would," Dot replied, her eyes big and round. "I'd ask anybody if I wanted to know anything very bad. And Neale O'Neil's quite the nicest boy that ever was. Aggie says so."

"Ruth and I don't approve of boys," Tess said loftily. "And I don't believe Neale knows the sovereigns of England. Oh! look at those men, Dot!"

Dot squirmed about on the bench to look out on Parade Street. An erecting gang of the telegraph company was putting up a pole. The deep hole had been dug for it beside the old pole, and the men, with spikes in their hands, were beginning to raise the new pole from the ground.

Two men at either side had hold of ropes to steady the big pine stick. Up it went, higher and higher, while the overseer stood at the butt to guide it into the hole dug in the sidewalk.

16 Just as the pole was about half raised into its place, and a lineman had gone quickly up a neighboring pole to fasten a guy-wire to hold it, the interested children on the park bench saw a woman crossing the street near the scene of the telegraph company men's activities.

"Oh, Tess!" Dot exclaimed. "What a funny dress she wears!"

"Yes," said the older Kenway girl, eying the woman quite as curiously as her sister.

The strange woman wore a long, gray cloak, and a little gray, close bonnet, with a stiff, white frill framing her face. That face was very sweet, but rather sad of expression. The children could not see her hair and had no means of guessing her age, for her cheeks were healthily pink and her gray eyes bright.

These facts Tess and Dot observed and digested in their small minds before the woman reached the curb.

"Isn't she pretty?" whispered Tess.

Before Dot could reply there sounded a wild cry from the man on the pole. The guy-wire had slipped.

"'Ware below!" he shouted.

The woman did not notice. Perhaps the close cap she wore kept her from hearing distinctly. The writhing wire flew through the air like a great snake.

Tess dropped her history and sprang up; but Dot did not loose her hold upon the rather battered17 "Alice-doll" which was her dearest possession. She clung, indeed, to the doll all the closer, but she screamed to the woman quite as loudly as Tess did, and her little blue-stockinged legs twinkled across the grass to the point of danger, quite as rapidly as did Tess' brown ones.

"Oh, lady! lady!" shrieked Tess. "You'll be killed!"

"Please come away from there—please!" cried Dot.

Their voices pierced to the strange lady's ears. Just as the pole began to waver and sink sidewise, despite the efforts of the men with the spikes, she looked up, saw the gesticulating children, observed the shadow of the pole and the writhing wire, and sprang upon the walk, and across it in time to escape the peril.

The wire's weight brought the pole down with a crash, in spite of all the men could do. But the woman in the gray cloak was safe with Tess and Dot on the greensward.

"My dear girls!" the woman in the gray cloak said, with a hand on a shoulder of each of the younger Corner House girls, "how providential it was that you saw my danger. I am very much obliged to you. And how brave you both were!"

"Thank you, ma'am," said Tess, who seldom forgot her manners.

But Dot was greatly excited. "Oh, my!" she gasped, clinging tightly to the Alice-doll, and quite breathless. "My—my pulse did jump so!"

"Did it? You funny little thing," said the woman, half laughing and half crying. "What do you know about a pulse?"

"Oh, I know it's a muscle that bumps up and down, and the doctor feels it to see if you're better next time he comes," blurted out Dot, nothing loath to show what knowledge she thought she possessed.

"Oh, my dear!" cried the lady, laughing heartily now. And, dropping down upon the very bench where Tess and Dot had been sitting, she drew the two children to seats beside her. "Oh, my dear! I shall have to tell that to Dr. Forsyth."

19 "Oh!" ejaculated Tess, who was looking at the pink-cheeked lady with admiring eyes. "Oh! we know Dr. Forsyth. He is our doctor."

"Is he, indeed? And who are you?" responded the lady, the sad look on her face quite disappearing now that she talked so animatedly with the little Kenways.

"We are Dot and Tess Kenway," said Tess. "I'm Tess. We live just over there," and she pointed to the big, old-fashioned mansion across the Parade Ground.

"Ah, then," said the woman in the gray cloak, "you are the Corner House girls. I have heard of you."

"We are only two of them," said Dot, quickly. "There's four."

"Ah! then you are only half the quartette."

"I don't believe we are half—do you, Tess?" said Dot, seriously. "You see," she added to the lady, "Ruthie and Aggie are so much bigger than we are."

The lady in the gray cloak laughed again. "You are all four of equal importance, I have no doubt. And you must be very happy together—you sisters." The sad look returned to her face. "It must be lovely to have three sisters."

"Didn't you ever have any at all?" asked Dot, sympathetically.

"I had a sister once—one very dear sister," said the lady, thoughtfully, and looking away across the Parade Ground.

20 Tess and Dot gazed at each other questioningly; then Tess ventured to ask:

"Did she die?"

"I don't know," was the sad reply. "We were separated when we were very young. I can just remember my sister, for we were both little girls in pinafores. I loved my sister very much, and I am sure she loved me, and, if she is alive, misses me quite as much as I do her."

"Oh, how sad that is!" murmured Tess. "I hope you will find her, ma'am."

"Not to be thought of in this big world—not to be thought of now," repeated the lady, more briskly. She picked up the history that Tess had dropped. "And which of you little tots studies this? Isn't English history rather far advanced for you?"

"Tess is nawful smart," Dot hastened to say. "Miss Andrews says so, though she's a nawful strict teacher, too. Isn't she, Tess?"

Her sister nodded soberly. Her mind reverted at once to the sovereigns of England and Miss Pepperill. "I—I'm afraid I'm not very quick to learn, after all. Miss Pepperill will think me an awful dunce when I can't learn the sovereigns."

"The sovereigns?" repeated the woman in gray, with interest. "What sovereigns?"

So Tess (of course, with Dot's valuable help) explained her difficulty, and all about the new teacher Tess expected to have.

"And she'll think I'm awfully dull," repeated21 Tess, sadly. "I just can't make my mind remember the succession of those kings and queens. It's the hardest thing I ever tried to learn. Do you s'pose all English children have to learn it?"

"I know they have an easy way of committing to memory the succession of their sovereigns, from William the Conqueror, down to the present time," said the lady, thoughtfully. "Or, they used to have."

"Oh, dear me!" wailed Tess. "I wish I knew how to remember the old things. But I don't."

"Suppose I teach you the rhyme I learned when I was a very little girl at school?"

"Oh, would you?" cried Tess, her pretty face lighting up as she gazed admiringly again at the woman in the gray cloak.

"Yes. And we will add a couplet or two at the end to bring the list down to date—for there have been two more sovereigns since the good Queen Victoria passed away. Now attend! Here is the rhyme. I will recite it for you, and then I will write it down and you may learn it at your leisure."

Both Tess and Dot—and of course the Alice-doll—were very attentive as the lady recited:

There you have it—with an original four lines at the end to complete the list," laughed the lady.

Dot's eyes were big; she had lost the sense of the rhyme long before; but Tess was very earnest. "I—I believe I could learn 'em that way," she confessed. "I can remember poetry quite well. Can't I, Dot?"

"You recite 'Little Drops of Water, Little Grains of Sand' beautifully," said the smallest Corner House girl, loyally.

"Of course you can learn it," said the lady, confidently.23 "Now, Tess—is that your name—Theresa?"

"Yes, ma'am—only almost nobody ever calls me by it all. Miss Andrews used to when she was very, very angry. But I hope my new teacher, Miss Pepperill, won't be angry with me at all—if I can only learn these sovereigns."

"You shall," declared the lady in gray. "I have a pencil here in my bag. And here is a piece of paper. I will write it all out for you and you can study it from now until the day school opens. Then, when this Miss Pepperill demands it, you will have it pat—right on the end of your tongue."

"I hope so," said Tess, with dawning cheerfulness.

I believe I can learn to recite it all if you are kind enough to write it down."

The lady did so, writing the lines in a beautiful, round hand, and so plain that even Dot, who was a trifle "weak" in reading anything but print, could quite easily spell out the words.

"Weren't there any more names for kings when those lived?" the youngest Kenway asked seriously.

"Why, what makes you ask that?" asked the smiling lady.

"Maybe there weren't enough to go 'round," continued the puzzled Dot. "There are so many24 of 'em of one name——Williams, and Georges, and Edwardses. Don't English people have any more names to give to their sov-runs?"

"Sov-er-eigns," whispered Tess, sharply.

"That's what I mean," said the placid Dot. "The lady knows what I mean."

"Of course I do, dear," agreed the woman in the gray cloak. "But I expect the mothers of kings, like the mothers of other little boys, like to name their sons after their fathers.

"Now, children, I must go," she added briskly, getting up off the bench and handing Tess the written paper. "Good-bye. I hope I shall meet you both again very soon. Let me kiss you, Tess—and you, Dorothy Kenway. It has done me good to know you."

She kissed both children quickly, and then set off along the Parade Ground walk. Tess and Dot bade her good-bye shrilly, turning themselves toward the old Corner House.

"Oh, Dot!" exclaimed Tess, suddenly.

"What's the matter now?" asked Dot.

"We never asked the lady her name—or who she was."

"We-ell——would that be perlite?" asked Dot, doubtfully.

"Yes. She asked our names. We don't know anything about her—and I do think she is so nice!"

"So do I," agreed Dot. "And that gray cloak——"

25 "With the pretty little bonnet and ruche," added Tess.

"She isn't the Salvation Army," said Dot, remembering that that order was uniformed from seeing them on the streets of Bloomingsburg, where the Kenways had lived before they had fallen heir to Uncle Peter Stower's estate.

"Of course not!" Tess cried. "And she don't look like one o' those deaconesses that came to see Ethel Mumford's mother when she was sick—do you remember?"

"Of course I remember—everything!" said the positive Dot. "Wasn't I a great, big girl when we came to Milton to live?"

"Why—why," stammered her sister, not wishing to displease Dot, but bound to be honest. "You aren't a very big girl, even now, Dot Kenway."

"Humph!" exclaimed Dot, quite vexed. "I wear bigger shoes and stockings, and Ruth is having Miss Ann Titus let down the hems of all my old dresses a full inch—so now!"

"I expect you have grown some, Dot," admitted Tess, reflectively. "But you aren't big enough even now to brag about."

The youngest Kenway might have been deeply offended by this—and shown that she had taken offence, too—had something new not taken her attention at the very moment she and Tess were entering the side gate of the old Corner House premises.

26 The house was a three story and attic mansion which was set well back from Main Street, but the side of which was separated from Willow Street by only a narrow strip of sward. The kitchen was in the wing nearest this last-named street, and there was a big, half-enclosed side porch, to which the woodshed was attached, and beyond which was the long grape arbor.

The length of the old Corner House yard, running parallel with Willow Street, was much greater than its width. The garden, summer house, henhouses, and other outbuildings were at the back. The lawn in front was well shaded, and there were plenty of fruit trees around the house. Not many dwellings in Milton had as much yard-room as the Stower homestead.

"Oh my, Tess!" gasped Dot, with deep interest, staring at the porch stoop. "Who is that—and what's he doing?"

"Dear me!" returned Tess, hesitating at the gate. "That's Seneca Sprague—the man who wears a linen duster and straw hat all the year round, and 'most always goes barefooted. He—he isn't just right, they say, Dot."

"Just right about what?" asked Dot.

"Mercy me, Dot!" exclaimed Tess, exasperated.

"Well, what is he?" asked Dot, with vigor.

"Well—I guess," said Tess, "that he thinks he is a minister. And, I do declare, I believe he's preaching to Sandyface and her kittens! Listen, Dot!"

Almost the first thing that would have caught the attention of the visitor to the old Corner House at almost any time, was the number of pets that hovered about that kitchen porch. Ruth, with a sigh, sometimes admitted that she was afraid she supported a menagerie.

Just at this hour—it was approaching noon—Mrs. MacCall, or the girl who helped her in the kitchen, might be expected to appear at the door with a plate of scraps or vegetable peelings or a little spare milk or other delicacy to tempt the appetites of the dumb creatures that subsisted upon the kindness of the Corner House family.

The birds, of course, got their share. In the winter the old Corner House was the rendezvous of a chattering throng of snow-buntings and sparrows and starlings, for the children tied suet and meat-bones to the branches of the fruit trees, as well as scattered crumbs upon the snow-crust. In summer the feathered beggars took toll as they pleased of the cherries and small fruits in the garden.

In the garden, too, was the only martin house in town, set upon a tall pole. There every spring28 a battle royal went on between the coming martins and the impudent sparrows, as the latter horde always appropriated the martin house during the absence of its proper owners in the South. Each cherry tree had its robin's nest—sometimes two. Mr. Robin likes to be near the supply of his favorite fruit. The wrens built under the eaves of the porch, and above the windows, in sheltered places. All the pigeons in the neighborhood flew here to strut and coo, and help eat any grain that might be thrown out.

What one saw now, waiting at the porch steps, was principally a family of cats. There were no less than nine posing expectantly before the queer looking character known to Milton folks as Seneca Sprague.

First of all, Sandyface, the speckled tabby-cat, sat placidly washing her face on the lower step. Close at her back, on the ground—one was even playing with its mother's steadily waving tail—was Sandyface's latest family, the four kittens bearing the remarkable names of Starboard, Port, Hard-a-lee and Mainsheet.

Grouped farther away from the mother cat were the four well-grown young cats, Spotty, Almira, Popocatepetl and Bungle.

Much farther in the background, and in the attitude of sleep, with his head on his forepaws, but with a blinking eye that lost nothing of what went on at the porch (for Mrs. MacCall might appear at any moment with his own particular29 dish) lay a big Newfoundland dog, with a noble head, intelligent brown eyes, and a muzzle now graying with age. This was the Corner House girls' newest and most valued pet, Tom Jonah.

In addition, on the clothes-drying green, was Billy Bumps. This suggestively named individual was a sturdy, wise-looking goat, with a face and chin-whisker which Mrs. MacCall declared was "as long as the moral law," and whose proclivity to eat anything that could be masticated was well-known to the Kenway children.

This collection of dumb pets the tall, lank, barefooted man in the broken straw hat and linen duster, now faced with a serious mien as though he were a real preacher and addressed a human congregation.

Seneca Sprague was a harmless person, considered "not quite right," as Tess had said, by his fellow-townsmen. Whether his oddities arose from a distraught mind, or an indulgence in a love of publicity, it would be hard to say.

His sharp-featured face and long, luxurious iron-gray hair, which he sometimes wore knotted up like a woman's, marked him wherever he went. Even those who thought him the possessor of a mind diseased agreed that he was quite harmless.

He came and went as he pleased, often preaching on street corners a doctrine which included a belief in George Washington as a supernatural being; and he was patriotic to the core.

Sometimes bad boys made fun of him, and followed30 and pelted him in the street; but, of course, the Corner House girls, who were kind to everybody and everything, would not have thought of harrying the queer old man, or ridiculing him.

Occasionally Seneca Sprague wrote and had printed a tract in which he ramblingly expressed his religious and patriotic beliefs, and an edition of this tract he was now selling from house to house in Milton. Ruth had, of course, purchased one and as Tess and Dot came into the old Corner House yard, Mr. Sprague was just turning away from the door, and had caught sight of the expectant congregation of pets gathered below him.

"Lo, and behold! lo, and behold!" ejaculated Seneca Sprague, in a solemn and resonant voice. "What saith the Scriptures? Him that hath ears to hear, let him hear."

Every cat's ears were pricked forward expectantly and even Tom Jonah lifted his glossy ears—probably hearing Mrs. MacCall's step at the kitchen door. Billy Bumps lifted a ruminant head and blatted softly.

"Thus saith the prophet," went on Seneca Sprague, in his sing-song tone. "There is yet a little time in which man may repent. Then cometh the Crack o' Doom! Beware! beware! beware!"

Here Dot whispered to Tess: "How did Mr. Seneca Sprague come to know so much about prophets, and what's going to happen, and all that? And what is the Crack o' Doom?"

31 "Mercy, I don't know, child!" exclaimed Tess. "I'm sure I didn't crack it."

The queer old man was interrupted just here, too, by Ruth Kenway's reappearance upon the porch. Ruth was a very intelligent looking girl, if not exactly a pretty one. She was dark and her hair was black; she had warm, brown eyes and a sweet, steady smile that pleased most people.

"Oh, Mr. Sprague!" she said, attracting that queer individual's attention. He actually swept off his torn straw hat and bowed before her.

Ruth's voice was low and pleasant. Mrs. MacCall said she had an old head upon young shoulders. But there had been good reason for the oldest of the Corner House girls to show in her look and manner the effect of responsibility and burden of forethought beyond her years.

Before the fortune had come to them the little Kenways had had only a small pension to exist upon, and they had had to share that with Aunt Sarah Maltby. For nearly two years Ruth had taken her mother's place and looked after the family.

It had made her seem old beyond her real age; but it had likewise given her a confidence in herself which she otherwise would not have had. People deferred to Ruth Kenway; even Mr. Howbridge thought she was quite a wonderful girl.

"Oh, Mr. Sprague," she said again. "I meant to tell you that you are welcome to some of those32 fall pippins, down there by the hen-run—if you care to pick them up. Just help yourself. I know you don't use meat, and that you live on fruit and vegetables; and apples are hard to get at the store."

"Thank you—thank you," said the strange, old man, politely. "I will avail myself of the privilege you so kindly offer. It is true I live on the fruits of the earth wholly, for are we not commanded to shed no blood—no, not at all? Yea, verily, he who lives by the sword shall die by the sword——"

"And I hope you will like the pippins, Mr. Sprague," broke in Ruth, knowing how long-winded the old fellow was, and being cumbered by many cares herself just then.

"Ah! there you are, children," she added, addressing Tess and Dot. "Come right in and make ready for lunch. Don't let us keep Mrs. MacCall waiting. She and Linda are preserving to-day and they want to get the lunch over and out of the way."

The smaller girls hastened into the house, thus admonished, and up to the dressing room connected with the two, big, double bedrooms in the other wing, which the four sisters had occupied ever since coming to the old Corner House. Ruth went with them to superintend the washing of hands and face, smoothing of hair and freshening of frocks and ribbons. Ruth had to act as inspector after the youngest Kenway's ablutions,33 Tess declaring: "Dot doesn't always wash into all the corners."

"I do, too, Tess Kenway!" cried the smaller girl. "Ruthie has to watch us 'cause you button your apron crooked. You know you do!"

"I don't mean to," said Tess, "but I can't see behind me. I'd like to be as neat looking all the time as that lady in the gray cloak. Oh, Ruthie! who was she?"

"I have no idea whom you are talking about," said the elder sister, curiously. "'The lady in the gray cloak'? What lady in a gray cloak?"

At once Tess and Dot began to explain. They were both eager, they were both vociferous; and the particulars of the morning's adventure, including the meeting with Miss Pepperill, the falling of the telegraph pole, the woman in the gray cloak, and the sovereigns of England, became most remarkably mixed in the general relation of facts.

"Mercy! Mercy, children!" cried Ruth, in despair. "Let us go at the matter in something like order. Why did the lady in the gray cloak want you to learn the succession of the sovereigns of England? And did the telegraph pole hit poor Miss Pepperill, or was she merely scared by its fall?"

Tess stared at her older sister wonderingly. "Well, I do despair!" she breathed at last, repeating one of good Mrs. MacCall's odd exclamations. "I never did suppose you could misunderstand a body so, Ruthie Kenway."

34 Ruth threw back her head at that and laughed heartily. Then she endeavored to get at the meat in the nut by asking questions. Soon—by the time her little sisters were ready to descend to the dining room—Ruth had a fair idea of the happening and the reason for the interest Tess and Dot displayed in the identity of the woman in the gray cloak.

But Ruth could not help the little ones to discover the name of the stranger. They all went down to dinner when Uncle Rufus rang the gong at the hall door.

That front hall of the old Corner House was a vast place, with a gallery all around it at the level of the second story, out of which opened the "grand" bedrooms (only one of which had ever been occupied during the girls' occupancy of the house, and that by Aunt Sarah) and it had a broad staircase with beautifully carved balustrades.

Uncle Rufus was a tall (though stooped), lean and brown negro, with a fringe of snow-white wool around his brown, bald crown. He always appeared to serve at table in a long, claw-hammer coat, a white vest and trousers, and gray spats. He was the type of old Southern house servant one reads about, seldom finds in the North; and he had lived in the old Corner House and served Uncle Peter Stower "endurin' of twenty-four year," as he often boasted.

Uncle Rufus did much more than serve the table, care for the silver and linen, and perform35 the other duties of a butler. He was Ruth's chief assistant in and out of the house. Despite his age, and occasional attacks of rheumatism, he was "purty spry yit," according to his own statement. And since the Kenway girls had come to the old house, Uncle Rufus seemed to have taken a new lease on life.

Aunt Sarah Maltby was already in her place at the table when Ruth and the two smaller girls entered the dining room. She was a withered wisp of a woman, with bright brown eyes under rather heavy brows. There were three deep wrinkles between her eyes; otherwise Aunt Sarah did not show in her countenance many of the ravages of time.

Her hair was only a little frosted; she wore it crimped on the sides, doing it up carefully in little "pigtails" every night before she retired. She was scrupulous in the care of her hands, being one of those old ladies who almost never are seen bare-handed—wearing mits or gloves on all occasions.

Her plainly made dresses were starched and prim in every particular. She was a spinster who never told her age, and defied the public to guess it! Living a sort of detached life in the Kenway family, nothing went on in domestic affairs of which she was not aware; yet she was seldom helpful in any emergency. Usually, if she interfered at all, it was at a time when Ruth could have well excused her assistance.

36 Aunt Sarah had chosen the best bedroom in the house when first they had come to Milton to live; and, as well, she had the best there was to be had of everything else. She had, all her life, lived selfishly, been waited upon, and considered her own comfort first. It was too late now for Aunt Sarah to change in many particulars.

Mrs. MacCall bustled in from the kitchen, her face rather red and a burned stripe on her forearm which she had floured over to take out the smart. "Always get burned when I am driv' like I be to-day," declared the housekeeper, whom Ruth insisted should always eat at their table. Mrs. MacCall was much more than an ordinary houseworker; she was the friend and confidant of the Kenway sisters, and was nearer to all their hearts than was stiff and almost wordless Aunt Sarah.

"Do you know who the lady in the gray cloak is?" asked Tess, of Mrs. MacCall, having put the question fruitlessly to both Uncle Rufus and Aunt Sarah.

"What's that—a conundrum?" asked the housekeeper. "Don't bother me, child, with questions to-day. I've got too much on my mind."

"I guess," sighed Tess to Dot, "we never shall find out who she is."

"Don't mind," said the comforting Dorothy. "She gave you the list of sov-runs. You've got them, anyhow."

"But I do mind!" declared Tess. "She is just37 one of the nicest ladies I ever met. Of course I want——"

But who is this bursting into the dining room like a young cyclone, and late to lunch? "Oh, Agnes! you are late again," said Ruth, admonishingly. Aunt Sarah glared at the newcomer, while Mrs. MacCall said:

"You come pretty near not getting anything more than cold pieces, child."

All their wrath was turned, however, by Agnes' smile—and her beauty. Nobody—not even Aunt Sarah Maltby—could retain a scowl and still look at Agnes Kenway, plump and pretty, and brown from the sea air and sun. Naturally she was light, blue-eyed and with golden-yellow hair. The hair was sunburned now and her round cheeks were as brown as fall leaves in the woods.

"Oh, dear! I couldn't really help being late," she said, dropping into the seat Uncle Rufus pulled out for her. The old darkey began at once heaping her plate with tidbits. He all but worshipped Ruth; but Agnes he petted and spoiled.

"I couldn't help being late," she repeated. "What do you think, Ruth? Eva Larry was just telling me at the front gate that Mr. Marks has threatened to forfeit all the basket ball games our team won in the half-series last spring against the other teams of the Milton County League, and will refuse to let us play the series out this fall. Isn't that awful?"

"I don't know," said Ruth, placidly; she was38 not a basket ball enthusiast herself. But Agnes had secured a place on the first team of the Milton Schools a few weeks before the June closing. She was athletic, and, although only in the grammar grade then, was big and strong for her age.

"I don't know just how awful it is," repeated the oldest sister. "What have you all done that the principal should make that ruling?"

"Goodness knows!" wailed Agnes. "I'm sure I haven't done anything."

"Of course you haven't, Aggie," put in Dot, warmly. "You never do!"

This made the family laugh. Dot's loyalty to Agnes was really phenomenal. No matter what Agnes did, it must be all right in the little one's eyes.

"Well, I don't care," repeated Dot, sturdily, "Agnes is awful good! 'Course, not the same goodness as Ruthie; but I know she doesn't break any school rules. And she knows a lot!"

"I wish she knew who my gray lady is," put in Tess, rather complainingly.

"What gray lady?" demanded Agnes, quickly.

Dot, the voluble, got ahead of her sister in this explanation. "She isn't the Salvation Army, nor she isn't a deaconess like Mrs. Mumford had come to see her; but she's something awfully religious, I know."

Tess managed to tell again about the sovereigns of England, too.

"Oh, I know whom you mean," Agnes said39 briskly. "I saw her with you up on the Parade. Eva Larry told me she was the matron of the Women's and Children's Hospital—and they're going to shut it up."

"The child means Mrs. Eland," said Mrs. MacCall, interestedly. "She is a splendid woman and that hospital is doing a great work. You don't mean they are really going to close it, Agnes?"

"So Eva says. They have to. There are no funds, and two or three rich people who used to help them every year have died without leaving the hospital any legacy. Mrs. Eland doesn't know what will become of her now. She's been matron and acting superintendent ever since the hospital was opened, five years ago. Dr. Forsyth is the head visiting physician."

"Mercy, child!" gasped Ruth. "Where do you pick up so much gossip?"

"Eva Larry has been here," said Tess, soberly. "And, you know, she's a fluid talker. You said so yourself, Ruthie."

"Fluent! fluent!" gasped Agnes. "And Eva always does have the news."

"She is growing up to be a second Miss Ann Titus," said Ruth drily. "And I think Tess got it about right. She is a fluid speaker. When Eva talks it is just like opening the spigot and letting the water run."

It was later, after lunch was over, and Tess and Dot had wandered into the garden with their dolls. Tess said, reflectively:

40 "I wish awfully we might help that Mrs. Eland. She's such a lovely lady. And I know the sovereigns of England half by heart already."

Dot was usually practical. "Let's gather her some apples and take them to her," she suggested.

"We-ell," said Tess, slowly. "That won't keep the hospital going, but maybe she likes apples."

"Who doesn't?" demanded Dot, stoutly. "Come on."

When they reached the fall pippin tree which, that year, was loaded with golden fruit, the two little girls were quite startled at what they saw.

"O-o-oh!" gasped Dot. "See Billy Bumps!"

"For pity's sake! what's he doing?" rejoined Tess, in amazement.

The old goat had the freedom of the yard, as the garden was shut away from him by a strong wire fence. He liked apples himself, did Billy Bumps, and perhaps he considered the bagful that Mr. Seneca Sprague had picked up and prepared to carry away, a direct poaching upon his preserves.

Mr. Sprague had reclined on the soft grass under the wide-spreading tree and filled his own stomach to repletion, as could be seen by the cores thrown out in a circle about him. Billy Bumps had approached, eyed the long hair of the "prophet" askance, and finally began to nibble.

The luxuriant growth of hair that the odd, old man had allowed to grow for years, seemed to attract Billy Bumps' palate. Mr. Seneca Sprague41 slept and Billy gently nibbled at the hair on one side of Seneca's head.

It was just at this moment that Tess and Dot spied the tableau. Billy Bumps browsing on Seneca Sprague's hair was a sight to startle and amaze anybody.

"O-o-oh!" gasped Dot again.

"Billy! you mustn't!" shrieked Tess, realizing that all of the "prophet's" hair was in danger, and fearing, perhaps, that, snake-like, Billy might be about gradually to draw the whole of Mr. Seneca Sprague within his capacious maw.

"Billy! stop!" cried both girls together.

At this moment Mr. Sprague awoke. Between the shrieking of the little girls and the activities of Mr. Sprague when he learned what was going on, Billy Bumps' banquet was quite spoiled.

"Get out, you beast!" shouted the "prophet," but using most unprophetical language. "Ow! ow! ouch!"

For Billy had no idea of losing what he had already masticated. He pulled so hard that he drew Mr. Sprague over on his back, where he lay with his legs kicking in the air, wild yells of surprise and pain issuing from him.

Over the fence at the rear of the Corner House premises bobbed a flaxen head, and a boyish voice shouted: "What's the matter, girls?"

"Oh, Neale O'Neil!" shrieked Dot. "Do come! Quick! Billy Bumps is eating up Mr. Sneaker Sp'ague—and he's beginning at his hair."

Billy Bumps backed away in time to escape the vigorous blow Neale O'Neil aimed at him with the stick he had picked up. But the old goat had managed to tear loose some of the hair on one side of the odd, old fellow's head, and now stood contemplating the angry and excited Sprague, with the hair hanging out of his mouth and mingling with his own long beard.

"Shorn of my locks! shorn of my locks! Samson has lost his glory and strength—yea, verily!" cried the owner of the hair, mournfully. "Yea, how hath the mighty fallen and the people imagined a vain thing! And if there were anything here hard enough to throw at that old goat!"

Thus getting down to a more practical and modern form of language, Seneca Sprague looked wrathfully around for a club or a rock, nothing less being sufficiently hard to suit him.

"Oh, you mustn't!" cried Dot. "Poor Billy Bumps doesn't know any better. Why, once he chewed up my Alice-doll's best dress. And I didn't hit him for it!"

A comparison of a doll's dress with his own hair did not please Mr. Sprague much. He shook43 his now ragged head, from which the lock of hair had been torn so roughly. Billy Bumps considered this a challenge and, lowering his horns, suddenly charged the despoiled prophet.

"Drat the beast!" yelled Seneca, forgetting his Scriptural language entirely; and leaped into the air just in time to make a passage for Billy Bumps between his long legs.

Neale, for laughter, could not help.

Slam! went Billy's horns against the end of the hen-house. Mr. Sprague was not there to catch the goat on the rebound, for, leaving his bag of apples, he rushed for the side gate and got out upon Willow Street without much regard for the order of his going, voicing prophecies this time that had only to do with Billy Bumps' immediate future.

The disturbance brought Ruth and Agnes running from the house, but only in time to see the wrathful Seneca Sprague, his linen duster flapping behind him, as he disappeared along Willow Street. When Ruth heard about Billy Bumps' banquet, she sent the bag of apples to Seneca Sprague's little shanty which he occupied, down on the river dock.

"Of all the ridiculous things a goat ever did, that is the most ridiculous!" exclaimed Agnes.

"There's more than one hair in the butter this time," repeated Neale O'Neil, with laughter.

"I can't laugh, even at that stale joke," sighed Agnes.

44 "What's the matter, Aggie?" demanded Neale. "Have you soured on the world completely?"

"I feel as though I had," confessed Agnes, her sweet eyes vastly troubled and her red lips in a pout. "What do you think, Neale?"

"A whole lot of things," returned the boy. "What do you want me to think?"

"Mr. Smartie! But tell me: Have you heard anything about our basket ball team being set back? Eva told me she'd heard Mr. Marks was dreadfully displeased at something we'd done and that he said we shouldn't win the pennant."

"Not win the pennant?" cried Neale, aghast. "Why, you girls have got it cinched!"

"Not if Mr. Marks declares all the games we won last spring forfeited. I think he's too, too mean!" cried Agnes.

"Oh, he wouldn't do that!" urged Neale.

"She says he is going to."

"Eva Larry doesn't always get things straight," said Neale, comfortingly. "But what does he do it for?"

"I don't know. I'm sure I haven't done anything."

"Of course not!" chuckled her boy friend, looking at her rather roguishly. "Who was it proposed that raid on old Buckham's strawberry patch that time, coming home from Fleeting?"

"Oh! he couldn't know about that," cried Agnes, actually turning pale at the suggestion.

"I don't know," Neale said slowly. "Trix45 Severn was in your crowd then, and she'd tell anything if she got mad."

"And she's mad all right," groaned Agnes.

"I believe she is—with you Corner House girls," added Neale O'Neil.

"She'd be telling on herself—the mean thing!" snapped Agnes.

"But she is not on the team. She was along only as a rooter. The electric car broke down alongside of Buckham's strawberry patch. Wasn't that it?"

"Uh-huh," admitted Agnes. "And the berries did look so tempting."

"You girls got into Buckham's best berries," chuckled Neale. "I heard he was quite wild about it."

"We didn't take many. And I really didn't think about it's being stealing," Agnes said slowly. "We just did it for a lark."

"Of course. 'Didn't mean to' is an old excuse," retorted the boy.

"Well, Mr. Buckham couldn't have known about it then," cried Agnes. "I don't believe Mr. Marks heard of it through him. If he had, why not before this time, after months have gone by?"

"I know. It's all blown over and forgotten, when up it pops again. 'Murder will out,' they say. But you girls only murdered a few strawberries. It looks to me," added Neale O'Neil, "as though somebody was trying to get square."

"Get square with whom?" demanded Agnes.

46 "Well—you were all in it, weren't you?"

"All the team?"

"Yes."

"I suppose so. But Trix and some of the others picked and ate quite as many berries as we did. The girls that went over to Fleeting to root for us were all in it, too."

"I know," Neale said. "If the farmer had been sure who you were, or any of the electric car men had told—— Had the car all to yourselves, didn't you?"

"We girls were the only passengers," said Agnes.

"Then make up your mind to it," the wise Neale rejoined, "that if Mr. Marks has only recently been told of the raid, some girl has been blabbing. The farmer or the conductor or the motorman would have told at once. They wouldn't have waited until three months and more had passed."

"Oh dear, Neale! do you think that?"

"It looks just like a mean girl's trick. Some telltale," returned the boy, in disgust.

"Trix Severn might do it, I s'pose, because she doesn't like me any more."

"You remember what Mr. Marks told us all last spring when we grammar grade fellows were let into the high school athletics? He said that one's conduct outside of school would govern the amount of latitude he would allow us in school athletics. I guess he meant you girls, too."

47 "He's an awfully strict old thing!" complained Agnes.

"They tell me," pursued Neale O'Neil, "that once a part of the baseball nine played hookey to go swimming at Ryer's Ford, and Mr. Marks immediately forfeited all the games in the Inter-scholastic League for that year, and so punished the whole school."

"That's not fair!" exploded Agnes.

"I don't know whether it is or not. But I know the baseball captain this year was mighty strict with us fellows."

The topic of the promised punishment of the basket ball team for an old offense was discussed almost as much at the Corner House that evening as was the "lady in gray" and the sovereigns of England.

Tess kept these last subjects alive, for she was studying the rhyme and would try to recite it to everybody that would listen—including Linda, who scarcely understood ten words of English, and Sandyface and her family, gathered for their supper in the woodshed. Tess was troubled about the closing of the Women's and Children's Hospital, because of its effect upon Mrs. Eland, too.

I do hope," ruminated Tess, "that that poor Mrs. Eland won't be turned out of her place. Don't you hope so, Ruthie?"

48 "I am sure it would be a calamity if the hospital were closed," agreed the older sister. "And the matron must be a very lovely lady, as you say, Tess."

"She is awfully nice—isn't she, Dot?" pursued Tess, who usually expected the support of Dorothy.

"Just as nice as she can be," agreed the smallest Corner House girl. "Couldn't she come to live in our house if she can't stay in the horsepistol any longer?"

"At the what, child?" gasped Agnes. "What is it you said?"

"Well—where she lives now," Dot responded, dodging the doubtful word.

"Goodness, dear!" laughed Ruth, "we can't make the old Corner House a refuge for destitute females."

"I don't care!" spoke up Dot, quickly. "Didn't they make the Toomey-Smith house, on High Street into a home for indignant old maids?"

At that the older girls shouted with laughter. "'In-di-gent'—'in-di-gent'! child," corrected Agnes, at last. "That means without means—poor—unable to care for themselves. 'Indignant old maids,' indeed!"

"Maybe they were indignant," suggested Tess, too tender hearted to see Dot's ignorance exposed in public, despite her own private criticism of the little one's misuse of the English language. "See49 how indignant Aunt Sarah is—and she's an old maid."

This amused Ruth and Agnes even more than Dot's observation. It was true that Aunt Sarah Maltby was frequently "an indignant old maid."

But Tess endured the laughter calmly. She was deeply interested in the problem of Mrs. Eland's future, and she said:

"Maybe Uncle Peter ought to have left the hospital some of his money when he died, instead of leaving it all to us and to Aunt Sarah."

"Do you want to give up some of your monthly allowance to help support the hospital, Tess?" demanded Ruth, briskly.

"I—I—— Well, I couldn't give much," said the smaller girl, seriously, "for a part of it goes to missions and the Sunday School money box, and part to Sadie Goronofsky's cousin who has a nawful bad felon, and can't work on the paper flowers just now——"

"Why, child!" the oldest Kenway said, with a tender smile, and putting her hand lightly on Tess' head, "I didn't know about that. How much of your pin money goes each month to charity already? You only have a dollar and a half."

"I—I keep half a dollar for myself," confessed Tess. "I could give part of that to the hospital."

"I'll give some of my pin money, too," announced Dot, gravely, "if it will keep Mrs. Eland from being turned out of the horsepistol."

Ruth and Agnes did not chide the little one for50 her mispronunciation of the hard word this time, but they looked at each other seriously. "I wonder if Uncle Peter was one of those rich people who should have remembered the institution in his will?" Ruth said.

"Goodness!" exclaimed Agnes. "If we go around hunting for duties Uncle Peter Stower left undone, and do them for him, where will we be? There will be no money left for ourselves."

"You need not be afraid," Ruth said, with a smile. "Mr. Howbridge will not let us use our money foolishly. He is answerable for every penny of it to the Court. But maybe he will approve of our giving a proper sum towards a fund for keeping the Women's and Children's Hospital open."

"Is there such a fund?" demanded Agnes.

"There will be, I think. If everybody is interested——"

"And how you going to interest 'em?" asked the skeptical Agnes.

"Talk about it! Publicity! That is what is needed," declared Ruth, vigorously. "Why! we might all do something."

"Who—all? I want to know!" responded her sister. "I don't have a cent more than I need for myself. Only two dollars and a half." Agnes' allowance had been recently increased half a dollar by the observant lawyer.

"All of us can help," said Ruth. "Boys and girls alike, as well as grown people. The schools51 ought to do something to raise money for the hospital's support."

"Like a fair, maybe—or a bazaar," cried Agnes, eagerly. "That ought to be fun."

"You are always looking for fun," said Ruth.

"I don't care. If we can combine business with pleasure, so much the better," laughed Agnes. "It's easier to do things that are amusing than those that are dead serious."

"There you go!" sighed Ruth. "You are becoming the slangiest girl. I believe you get it all from Neale O'Neil."

"Poor Neale!" sniffed Agnes, regretfully. "He gets blamed for all my sins and his own, too. If I had a wooden arm, Ruth, you'd say I caught it of him, you detest boys so."

Part of this conversation between her older sisters must have made a deep impression on Tess Kenway's mind. She went forth as an apostle for the Women's and Children's Hospital, and for Mrs. Eland in particular. She said to Mr. Stetson, their groceryman, the next morning, with profound gravity:

"Do you know, Mr. Stetson, that the Women's and Children's Hospital has got to be closed?"

"Why, no, Tess—is that so?" he said, staring at her. "What for?"

"Because there is no money to pay Mrs. Eland. And now she won't have any home."

"Mrs. Eland?"

"The matron, you know. And she's such a nice52 lady," pursued Tess. "She taught me the sovereigns of England."

Mr. Stetson might have laughed. He was frequently vastly amused by the queer sayings and doings of the two youngest Corner House girls, as he often told his wife and Myra. But on this occasion Tess was so serious that to laugh at her would have hurt her feelings. Mr. Stetson expressed his regret regarding the calamity which had overtaken Mrs. Eland and the hospital. He had never thought of the institution before, and said to his wife that he supposed they "might spare a trifle toward such a good cause."

Tess carried her tale of woe into another part of the town when she and Dot went with their dolls to call on Mrs. Kranz and Maria Maroni, on Meadow Street, where the Stower tenement property was located.

"Did you know about the Women's and Children's Hospital being shut up, Mrs. Kranz?" Tess asked that huge woman, who kept the neatest and cleanest of delicatessen and grocery stores possible. "And Mrs. Eland can't stay there."

"Ach! you dond't tell me!" exclaimed the German woman. "Ist dodt so? And vor vy do dey close de hospital yedt? Aind't it a goot vun?"

"I think it must be a very good one," Tess said soberly, "for Mrs. Eland is an awfully nice lady, and she is the matron. She taught me the sovereigns of England. I'll recite them for you." This she proceeded to do.

53 "Very goot! very goot!" announced Mrs. Kranz. "Maria can't say that yedt."

Maria Maroni, the very pretty Italian girl (she was about Agnes' age) who helped Mrs. Kranz in the store, laughed good-naturedly. "I guess I knew them once," she said. "But I have forgotten. I never like any history but 'Merican history, and that of Italy."

"Ach! you foreigners are all alike," Mrs. Kranz protested, considering herself a bred-in-the-bone American, having lived in the country so long.

Although she was scolding her brisk and pretty little assistant most of the time, she really loved Maria Maroni very dearly. Maria's mother and father—with their fast growing family—lived in the cellar of the same building in which was Mrs. Kranz's shop. Joe Maroni, as was shown by the home-made sign at the cellar door, sold

ISE COLE WOOD VGERTABLS

and was a smiling, voluble Italian, in a velveteen suit and cap, with gold rings in his ears, who never set his bright, black eyes upon one of the Corner House girls but he immediately filled a basket with his choicest fruit as a gift for "da leetla padrona," as he called Ruth Kenway. He had an offering ready for Tess and Dot to take home when they reappeared from Mrs. Kranz's back parlor.

"Oh, thank you, Mr. Maroni," Tess said, while54 Dot allowed one of the smaller Maronis to hold the Alice-doll for a blissful minute. "I know Ruthie will be delighted."

"Si! si! dee-lighted!" exclaimed Joe, showing all his very white teeth under his brigand's mustache. "The leetla T'eressa ees seek?"

"Oh, no, Mr. Maroni!" denied Tess, with a sigh. "I am very well. But I feel very bad in my mind. They are going to close the Women's and Children's Hospital and my friend, Mrs. Eland, who is the matron, will have no place to go."

Joe looked a little puzzled, for although Maria and some of her brothers and sisters went to school, their father did not understand or speak English very well. Tess patiently explained about the good work the hospital did and why Mrs. Eland was in danger of losing her position.

"Too bad-a! si! si!" ejaculated the sympathetic Italian. "We mak-a da good mon' now. We geev somet'ing to da hospital for da poor leetla children—si! si!"

"Oh, will you, Mr. Maroni?" cried Tess. "Ruth says there ought to be a fund started for the hospital. I'll tell her you'll give to it."

"Sure! you tell-a leetla padrona. Joe geeve—sure!"

"Oh, Dot! we can int'rest lots of folks—just as Ruth said," Tess declared, as the two little girls wended their way homeward. "We'll talk to everybody we know about the hospital and Mrs. Eland."

55 To this end Tess even opened the subject with Uncle Rufus' daughter, Petunia Blossom, who chanced to be at the old Corner House when Tess and Dot arrived, delivering the clothes which she washed each week for the Kenways.

Petunia Blossom was an immensely fat negress—and most awfully black. Uncle Rufus often said: "How come Pechunia so brack is de mysteriest mystery dat evah was. She done favah none o' ma folkses, nor her mammy's. She harks back t' some ol' antsistah dat was suttenly mighty brack—yaas'm!"

"I dunno as I kin spar' anyt'ing fo' dis hospital, honey," Petunia said, seriously, when Tess broached the subject. "It's a-costin' me a lot t' keep up ma dues wid de Daughters of Miriam."

"What's the Daughters of Miriam, Petunia?" asked Agnes, who chanced to overhear this conversation on the back porch. "Is it a lodge?"

"Hit's mo' dan a lodge, Miss Aggie," proclaimed Petunia, with pride. "It's a beneficial ordah—yaas'm!"

"And what benefit do you derive from it?" queried Agnes.

"Why, I doesn't git nottin' f'om it yet awhile, honey," said Petunia, unctiously. "But w'en I's daid, I gits one hunderd an' fifty dollahs. Same time, dey's 'bleeged t' tend ma funeral."

"Dat brack woman suah is a flickaty female," grumbled Uncle Rufus, when he heard Agnes repeating the story of Petunia's "benefit" to the56 family at dinner that night. When nobody but the immediate family was present at table, Uncle Rufus assumed the privilege of discussing matters with the girls. "She's allus wastin' her money on sech things. Dere, she has got t' die t' git her benefit out'n dem Daughters of Miriam. She's mighty flickaty."

"What does 'flickaty' mean, Uncle Rufus, if you please?" asked Dot, hearing a new word, and rather liking the sound of it.

"Why, chile, dat jes' mean flickaty—das all," returned the old butler, chuckling. "Dah ain't nottin' in de langwidge what kin explanify dat wo'd. Nor dah ain't no woman, brack or w'ite, mo' flickaty dan dat same Pechunia Blossom."

"Great oaks from little acorns grow." Tess Kenway, with her little, serious effort, had no idea what she was starting for the benefit of Mrs. Eland, and incidentally for the neglected Women's and Children's Hospital. And this benefit was not of the unpractical character for which Petunia Blossom was paying premiums into the treasury of the Daughters of Miriam!

Tess' advertisement, wherever she went, of the hospital's need, called the attention of many heretofore thoughtless people to it. Through Mr. Stetson and Mrs. Kranz many people were reminded of the institution that had already done such good work. They said, "It would be a shame to close that hospital. Something ought to be done about it."

Tess Kenway's word was like a stone dropped into a placid pool. The water stirred by the plunge of the stone spreads in wavelets in an ever widening circle till it compasses the entire pool. So with the little Corner House girl's earnest speech regarding the hospital's need of funds.

Tess and Dot did not see the woman in the gray cloak again—not just then, at least; but they58 thought about her a great deal, and talked about her, too. A bag of the pippins went to the hospital by Neale O'Neil's friendly hand, addressed to Mrs. Eland, and with the names of the two youngest Corner House girls inside.

"I do hope she likes apples," Tess said. "I'm so much obliged to her for the sovereigns of England."

Tess wondered, too, if she should take some of the apples to school that first day of the fall term to present to Miss Pepperill. Dot took her teacher some. Dot was to have the same teacher this term that she had had the last. Tess finally decided that the sharp and red-haired Miss Pepperill might think that she, Tess, was trying to bribe her to forget the sovereigns of England.

"And I am quite sure I know them perfectly. That is, if she doesn't fuss me too much when she asks the question," Tess said to Ruth, with whom she discussed the point. "I won't take her the apples, I guess, until after I have recited the sovereigns."

Despite the declaration that she had learned perfectly the rhyme Mrs. Eland had written out for her, Tess Kenway went into school that first day of the term feeling very sober indeed. Many of the girls in her class looked sober, too. Pupils who had graduated from Miss Pepperill's class had reported the red-haired lady as being "awfully strict."

Indeed, before the scholars were quite settled59 at their desks, they had a proof of Miss Pepperill's discipline. Some of the boys in Tess' class had reputations to maintain (or thought they had) for "not bein' scart of teacher." Sammy Pinkney often boasted to wondering and wide-eyed little girls that "no old teacher could make him a fraid cat."

"What's your name—you with the black hair and warts on your hands?" demanded the new teacher, sharply and suddenly.

She pointed directly at the grinning and inattentive Sammy. There was no mistaking Miss Pepperill's meaning and some of the other boys giggled, for Sammy did have warts on his grimy little paws.

"What's your name?" repeated the teacher, with rising inflection.

"Sam—Sam Pinkney," replied Sammy, just a little startled, but trying to appear brave.

"Stand up when you reply to a question!" snapped Miss Pepperill.

Sammy stumbled to his feet.

"Now! What is your name? Again."

"Sam Pinkney."

"Sam-u-e-l?"

"Well—that's 'Sam,' ain't it?" drawled the boy, gaining courage.

But he never spoke so again when Miss Pepperill addressed him. That woman strode down the aisle to Sammy's seat, seized the cringing boy by the lobe of his right ear, and marched him up60 to her desk. There she sat him down "in the seat of penitence" beside her own chair, saying:

"I'll attend to your case later, young man. Evidently the long vacation has done you no good. You have forgotten how to speak to your teacher."

The girls were much disturbed by this manifestation of the new teacher's sternness. Sadie Goronofsky whispered to Tess:

"Oh! don't she get excited easy?"

The whites of Alfredia Blossom's eyes were fairly enlarged by her surprise and terror at this proceeding on the new teacher's part. After that, Alfredia jumped every time Miss Pepperill spoke.

Miss Pepperill noted none of this cringing terror on the part of her new pupils. Or else she was used to it. She marched up and down the aisles, seating and reseating the pupils until she had them arranged to her satisfaction, and suddenly she pounced on Tess.

"Ah!" she said, stopping before the Corner House girl's desk. "You are Theresa Kenway?"

Tess arose before replying. "Yes, ma'am," she said.

"Ah! Didn't I give you a question to answer this first day?"

"Yes, ma'am," replied Tess, trying to speak calmly.

Miss Pepperill evidently expected to find Tess at fault. "What was the question, Theresa?" she asked.

61 "You told me to be prepared to recite for you the succession of the sovereigns of England."

"Well, are you prepared?" snapped Miss Pepperill.

"Yes, ma'am," Tess said waveringly. "I learned them in a rhyme, Miss Pepperill. It was the only way I could remember them all—and in the proper succession. May I recite them that way?"

"Let me hear the rhyme," commanded the teacher.

Tess began in a shaking voice, but as she progressed she gained confidence in the sound of her own voice, and, knowing the rhyme perfectly, she came through the ordeal well.

"Who taught you that, Theresa?" demanded Miss Pepperill, not unkindly.

"Mrs. Eland wrote it down for me. She said she learned it so when she was a little girl. At least, all but the last four lines. She said they were 'riginal."

"Ah! I should say they were," said Miss Pepperill. "And who is Mrs. Eland?"

"Mrs. Eland is an awfully nice lady," Tess said eagerly, accepting the opening the teacher unwittingly gave her. "She is matron of the Women's and Children's Hospital, and do you know, they say they are going to close the hospital because there aren't enough funds, and poor Mrs. Eland won't have any place to go. We think it's dreadful and, Miss Pepperill,——"

62 "Well, well!" interposed Miss Pepperill, with a grim smile, "that will do now, Theresa. I have heard all about that. I fancy you must be the little girl who is going around telling everybody about it. I heard Mr. Marks speak this morning about the needs of the Women's and Children's Hospital.

"We'll excuse your further remarks on that subject, Theresa. But you recited the succession of the English sovereigns very well indeed. I, too, learned that rhyme when I was a little girl."

Tess thought the bespectacled teacher said this last rather more sympathetically. She felt rebuked, however, and tried to keep a watch on her tongue thereafter in Miss Pepperill's presence.

At least, she felt that she had comported herself well with the rhyme, and settled back into her seat with a feeling of thankfulness.

Miss Pepperill's mention of Mr. Marks' observation before the teachers regarding the little girl who was preaching the gospel of help for the hospital, made no impression at all on Tess Kenway's mind. She had no idea that she had made so many grown people think of the institution's needs.

Before the high school classes early in that first week of school, the principal incorporated in his welcoming remarks something of importance regarding this very thing.

"We open school this term with quite a novel proposal before us. It has not yet been sanctioned63 by the Board of Education, although I understand that that body is soon to have it under advisement. In several towns of Milton's size and importance, there were last winter presented spectacles and musical plays, mainly by the pupils of the public schools of the several towns, and always for worthy charitable objects.

"The benefit to be gained by the schools in general and by the pupils that took part in the plays in particular, looked very doubtful to me at a distance; but this summer I made it my business to examine into the results of such appearances in musical pieces by pupils of other schools. I find it develops their dramatic instinct and an appreciation of music and acting. It gives vent, too, to the natural desire of young people to dance and sing, and to 'act out' a pleasant story, while they are really helping a worthy work of charity.

"One of the most successful of these school plays is called The Carnation Countess. It is a play with music which lends itself to brilliant costuming, spectacular scenery, and offers many minor parts which can easily be filled by you young people. A small company of professional players and singers carry the principal parts in The Carnation Countess; but if we are allowed to take up the production of this play—say in holiday week—I promise you that every one who feels the desire to do so, may have a part in it.

"The matter is all unsettled at present. But it is something to think of. Besides, a very small64 girl, I understand, a pupil in our grammar grade, is preaching a crusade for Milton's Women's and Children's Hospital. Inspired or not, that child has, during the past few days, awakened many people of this town to their duty towards that very estimable institution.

"The Women's and Children's Hospital is poor. It needs funds. Indeed, it is about to be closed for lack of sufficient means to pay salaries and buy supplies. The Post has several times tried to awaken public interest in the institution, but to no avail.

"Now, this child, as I have said, has done more than the public press. And quite unconsciously, I have no doubt.

"This is the way great things are often done. The seed timidly sown often brings forth the abundant crop. The stone thrown into the middle of the pool starts a wave that reaches the very shore.

"However, if we act the play for the charity proposed or not, there is a matter somewhat connected with it," continued the principal, his face clouding for a moment, "that I am obliged to bring to your attention. Of course, it is understood that only the pupils who do their work satisfactorily to their immediate instructors, will have any share in the production of the play.

"This rule, I am sorry to say, will affect certain members of our athletic teams who, I find, have been anything but correct in their behavior. I shall take this serious matter up in a few days65 with the culprits in question. At present I will only say that the basket ball match set for next Saturday with the team from the Kenyon school, will be forfeited. All the members, I understand, of our first basket ball team are equally guilty of misbehavior at a time when they were on honor.

"I will see the members of the team in my office after the second session to-day. You are dismissed to your classes, young ladies and gentlemen."

The blow had fallen! Agnes was so amazed and troubled that she failed to connect Mr. Marks' observations about the child who was arousing Milton to its duty towards the Women's and Children's Hospital, with her own little sister, Tess.

Ruth Kenway, however, realized that it was Tess who was the instrument which was being used in arousing public interest in the Women's and Children's Hospital—and likewise in Mrs. Eland, who had given five years of faithful work to the institution.

She was particularly impressed on this very afternoon, when poor Agnes was journeying toward Mr. Marks' office with her fellow-culprits of the basket ball team, with Tess' preachment of the need of money for the hospital. Ruth came home from school to find Mr. Howbridge waiting for her in the sitting room with Tess, who had arrived some time before, entertaining him.

As the door was open into the hall, Ruth heard the murmur of their voices while she was still upstairs at her toilet-table; so when she tripped lightly down the broad front stairs it was not eavesdropping if she continued to listen to her very earnest little sister and the lawyer.

"But just supposing Uncle Peter had been 'approached,' as you say, for money for that hospital—and s'pose he knew just how nice Mrs. Eland67 was—don't you think he would have left them some in his will, Mr. Howbridge?"

"Can't say I do, my dear—considering what I know about Mr. Peter Stower," said the lawyer, drily.

"Well," sighed Tess, "I do wish he had met my Mrs. Eland! I am sure he would have been int'rested in her."

"Do you think so?"

"Oh, yes! For she is the very nicest lady you ever saw, Mr. Howbridge. And I do think you might let us give some of the money to the hospital that Uncle Peter forgot to give—if he had been reminded, of course."

"That child should enter my profession when she grows up," said Mr. Howbridge to Ruth, when Tess had been excused. "She'll split hairs in argument even now. What's started her off on this hospital business?"

Ruth told him. She told, too, what Tess did each month with her own pin money, and the next allowance day Tess was surprised to find an extra half dollar in her envelope.

"Oh—ee!" she cried. "Now I can give something to the hospital fund, can't I, Ruthie?"

Meanwhile, Agnes, with Eva Larry, Myra Stetson, and others of her closest friends (Agnes had a number of bosom chums) waited solemnly in Mr. Marks' office. More than the basket ball team was present in anxious waiting for the principal's appearance.

68 "Where's Trix Severn?" demanded Eva in a whisper of the other girls. "She ought to be in this."

"In what?" demanded another girl, trying to play the part of innocence.

"Ah-yah!" sneered Eva, very inelegantly. "As though you didn't know what it is all about!"

"Well, I'm sure I don't," snapped this girl. "Mr. Marks sent for me. I don't belong to your old basket ball team."

"No. But you were with us on that car last May," said Agnes, sharply, "You know what we're all called here for."

"No, I don't."

"If you weren't told so publicly as we were to come here, you'll find that he knows all about your being in it," said Eva.

"And that will amount to the same thing in the end, Mary Breeze," groaned Agnes.

"I don't know at all what you are talking about," cried Miss Breeze, tossing her head, and trying to bolster up her own waning courage.

"If you don't know now, you'll never learn, Mary," laughed Myra Stetson. "We are all in the same boat."

"You bet we are!" added the slangy Eva.

"Every girl here was on that car that day coming from Fleeting," announced Agnes, after a moment, having counted noses. "You were in the crowd, Mary."

"What day coming from Fleeting?" snapped69 the girl, who tried to "bluff," as Neale O'Neil would have termed it.

"The time the car broke down," cried another. "Oh, I remember!"

"Of course you do. So does Mary," Eva said. "We were all in it."

"And, oh, weren't those berries good!" whispered Myra, ecstatically.

"Well, I don't care!" said Mary Breeze, "you started it, Aggie Kenway."

"I know it," admitted Agnes, hopelessly.

"But nobody tied you hand and foot and dragged you into that farmer's strawberry patch—so now, Mary!" cried Eva Larry. "You needn't try to creep out of it."

"Say! Trix seems to be creeping out of it," drawled Myra. "Don't you s'pose Mr. Marks has heard that she was in the party?"

"Sh!" said Agnes, suddenly. "Here he comes."

The principal came in, stepping in his usual quick, nervous way. He was a small, plump man, with rosy cheeks, eyeglasses, and an ever present smile which sometimes masked a series of very sharp and biting remarks. On this occasion the smile covered but briefly the bitter words he had to say.

"Young ladies! Your attention, please! My attention has been called to the fact that, on the twenty-third of last May—a Saturday—when our basket ball team played that of the Fleeting70 schools, you girls—all of you—on the way back from the game, were guilty of entering Mr. Robert Buckham's field at Ipswitch Curve, and appropriated to your own use, and without permission, a quantity—whether it be small or large—of strawberries growing in that field. The farmer himself furnishes me with the list of your names. I have not seen him personally as yet; but as Mr. Buckham has taken the pains to trace the culprits after all this time has elapsed he must consider the matter serious.