Title: Marie Antoinette and the Downfall of Royalty

Author: Imbert de Saint-Amand

Translator: Elizabeth Gilbert Martin

Release date: May 18, 2010 [eBook #32408]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | PARIS AT THE BEGINNING OF 1792 | 1 |

| II. | COUNT DE FERSON'S LAST JOURNEY TO PARIS | 14 |

| III. | THE DEATH OF THE EMPEROR LEOPOLD | 23 |

| IV. | THE DEATH OF GUSTAVUS III | 32 |

| V. | THE BEGINNINGS OF MADAME ROLAND | 46 |

| VI. | MADAME ROLAND'S ENTRANCE ON THE SCENE | 60 |

| VII. | MARIE ANTOINETTE AND MADAME ROLAND | 73 |

| VIII. | MADAME ROLAND AT THE MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR | 85 |

| IX. | DUMOURIEZ, MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS | 94 |

| X. | THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS | 103 |

| XI. | THE FÊTE OF THE SWISS OF CHATEAUVIEUX | 110 |

| XII. | THE DECLARATION OF WAR | 126 |

| XIII. | THE DISBANDING OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL GUARD | 137 |

| XIV. | THE SUFFERINGS OF LOUIS XVI | 148 |

| XV. | ROLAND'S DISMISSAL FROM OFFICE | 158 |

| XVI. | A THREE DAYS' MINISTRY | 166 |

| XVII. | THE PROLOGUE TO JUNE TWENTIETH | 176 |

| XVIII. | THE MORNING OF JUNE TWENTIETH | 186 |

| XIX. | THE INVASION OF THE TUILERIES | 198 |

| XX. | MARIE ANTOINETTE ON JUNE TWENTIETH | 210 |

| XXI. | THE MORROW OF JUNE TWENTIETH | 219 |

| XXII. | LAFAYETTE IN PARIS | 229 |

| XXIII. | THE LAMOURETTE KISS | 239 |

| XXIV. | THE FÊTE OF THE FEDERATION IN 1792 | 248 |

| XXV. | THE LAST DAYS AT THE TUILERIES | 259 |

| XXVI. | THE PROLOGUE TO THE TENTH OF AUGUST | 267 |

| XXVII. | THE NIGHT OF AUGUST NINTH TO TENTH | 275 |

| XXVIII. | THE MORNING OF AUGUST TENTH | 284 |

| XXIX. | THE BOX OF THE LOGOGRAPH | 299 |

| XXX. | THE COMBAT | 306 |

| XXXI. | THE RESULTS OF THE COMBAT | 316 |

| XXXII. | THE ROYAL FAMILY IN THE CONVENT OF THE FEUILLANTS | 329 |

| XXXIII. | THE TEMPLE | 337 |

| XXXIV. | THE PRINCESS DE LAMBALLE'S MURDER | 350 |

| XXXV. | THE SEPTEMBER MASSACRES | 359 |

| XXXVI. | MADAME ROLAND DURING THE MASSACRES | 372 |

| XXXVII. | THE PROCLAMATION OF THE REPUBLIC | 384 |

| INDEX | 395 |

Paris in 1792 is no longer what it was in 1789. In 1789, the old French society was still brilliant. The past endured beside the present. Neither names nor escutcheons, neither liveries nor places at court, had been suppressed. The aristocracy and the Revolution lived face to face. In 1792, the scene has changed. The Paris of the nobility is no longer in Paris, but at Coblentz. The Faubourg Saint-Germain is like a desert. Since June, 1790, armorial bearings have been taken down. The blazons of ancient houses have been broken and thrown into the gutters. No more display, no more liveries, no more carriages with coats-of-arms on their panels. Titles and manorial names are done away with. The Duke de Brissac is called M. Cossé; the Duke de Caraman, M. Riquet; the Duke d'Aiguillon, M. Vignerot. The Almanach royal of 1792 mentions not a single court appointment.

In 1789, it was still an exceptional thing for the nobility to emigrate. In 1792, it is the rule. Those among the nobles who have had the courage to remain at Paris in the midst of the furnace, so as to make a rampart for the King of their bodies, seem half ashamed of their generous conduct. The illusions of worldliness have been dispelled. Nearly every salon was open in 1789. In 1792, they are nearly all closed; those of the magistrates and the great capitalists as well as those of the aristocracy. Etiquette is still observed at the Tuileries, but there is no question of fêtes; no balls, no concerts, none of that elegance and animation which once made the court a rendezvous of pleasures. In 1789, illusions, dreams, a naïve expectation of the age of gold, were to be found everywhere. In 1792, eclogues and pastoral poetry are beginning to go out of fashion. The diapason of hatred is pitched higher. Already there is powder and a smell of blood in the air. A general instinct forebodes that France and Europe are on the verge of a terrible duel. On both sides passions have touched their culminating point. Distrust and uneasiness are universal. Every day the despotism of the clubs becomes more threatening. The Jacobins do not reign yet, but they govern. Deputies who, if left to their own impulses, would vote on the conservative side, pronounce for the Revolution solely through fear of the demagogues. In 1789, the religious sentiment still retained power among the {3} masses. In 1792, irreligion and atheism have wrought their havoc. In 1789, the most ardent revolutionists, Marat, Danton, Robespierre, were all royalists. At the beginning of 1792, the republic begins to show its face beneath the monarchical mask.

The Tuileries, menaced by the neighboring lanes of the Carrousel and the Palais Royal, resembles a besieged fortress. The Revolution daily augments its trenches and parallels around the sanctuary of the monarchy. Its barracks are the faubourgs; its soldiers, red-bonneted pikemen. Louis XVI. in his palace is like a general-in-chief in a stronghold, who should have voluntarily dampened his powder, spiked his cannon, and torn his flags. He no longer inspires his troops with confidence. A capitulation seems imminent. The unfortunate monarch still hopes vaguely for assistance from abroad, for the arrival of some liberating army. Vain hope! He is blockaded in his castle, and the moment is at hand when he will be compelled to play the buffoon in a red bonnet.

Glance at the palace and see how closely it is hemmed in by the earthworks of the Revolution. The abode of luxury and display, intended for fêtes rather than for war, Philibert Delorme's chef-d'oeuvre has in its architecture none of those means of defence by which the military and feudal sovereignties of old times fortified their dwellings. On the side of the courtyards a multitude of little {4} streets contain a hostile population ready to swell every riot. Near the Pavilion of Marsan is the Palais Royal, that headquarters of insurrection, with its cafés, its gambling-dens, its houses of ill-fame, its wooden galleries which are known as the camp of the Tartars. It is the Duke of Orleans who has democratized the Palais Royal. In spite of the sarcasms of the aristocracy and the lawsuits of neighboring proprietors, he has destroyed the fine gardens bounded by the rue de Richelieu, the rue des Petit-Champs, and the rue des Bons-Enfants. In the place it occupied he has caused the rue de Valois, the rue de Beaujolais, and the rue de Montpensier to be opened, all of them inhabited by a revolutionary population. The remaining space he has surrounded on three sides with constructions pierced by galleries, where he has built the shops that form the finest bazaar in Europe. The fourth side of these new constructions was originally intended to form part of the Prince's palace, and to be composed of an open colonnade supporting suites of apartments. But this side has not been erected. In place of it the Duke of Orleans has run up some temporary wooden sheds, containing three rows of shops separated by two large passage-ways, the ground of which has not even been made level.

The privileges pertaining to the Orleans family prevent the police from entering the enclosure of the Palais Royal. Hence it becomes the rendezvous of all conspirators. The taking of the Bastille was {5} plotted there, and there the 20th of June and the 10th of August will yet be organized.

A little further off is the National Assembly. Its sessions are held in the riding-school built when the little Louis XV. was to be taught horsemanship. It adjoins the terrace of the Feuillants. One of its courtyards which looks towards the front of the edifice, is at the upper end of the rue de Dauphin. The other extremity occupies the site where the rue Castiglione will be opened later on. There, close beside the Tuileries, sits the National Assembly, the rival and victorious power that will overcome the monarchy.

The Assembly terrorizes the Tuileries. The Jacobin Club terrorizes the Assembly. Close beside the Hall of the Manège, on the site to be occupied afterward by the market of Saint-Honoré, the revolutionary club holds its tumultuous sessions in the former convent founded in 1611 by the Jacobin, or Dominican, friars. The club meets three times a week, at seven in the evening. The hall is a long rectangle with a vaulted roof. Four rows of stalls occupy the longer sides, while the two ends serve as public galleries. Nearly in the middle of the hall, the speaker's platform and the president's writing-table stand opposite each other. Hither come all ambitious revolutionists who desire to talk, to agitate, to make themselves conspicuous. Here Robespierre lords it, not being a deputy in consequence of the law forbidding members of the {6} Constituent Assembly to belong to the legislative body. Those who love disorder come here to seek emotions. Some find lucrative employment, applause being paid for, and the different parties having each its claque in the galleries. Since April, 1791, the Jacobin Club has affiliations in two thousand French towns and villages. At its orders and in its pay is an army of agents whose business it is to make stump speeches, to sing in the streets, to make propositions in cafés, to applaud or to hiss in the galleries of the National Assembly. These hirelings usually receive about five francs a day, but as the number of the chevaliers of the revolutionary lustrum increases, the pay diminishes, until it is finally reduced to forty sous. Deserters and soldiers dismissed from their regiments for misconduct are admitted by preference.

For some days past, the Club of Moderate Revolutionists, friends of Lafayette, who might have closed the old clubs after the sanguinary repression of the riot in the Champ-de-Mars, and who contented themselves with opening a new one, have been meeting in the convent of the Feuillants, rue Saint-Honoré. But this new club has not been a great success; moderation is not the order of the day; the Jacobins have regained their empire, and on December 26, 1791, seals are placed on the door of the Club of the Feuillants.

At the other extremity of Paris there is a club still more inflammatory than that of the Jacobins: {7} that of the Cordeliers. "The Jacobins," said Barbaroux, "have no common aim, although they act in concert. The Cordeliers are bent on blood, gold, and offices." Speaking as a rule, the Cordeliers belong to the Jacobin Club, while hardly a single Jacobin is a Cordelier. The Cordeliers are the advance-guard of the Revolution. They are, as Camille Desmoulins has said, Jacobins of the Jacobins. The chiefs are Danton, Marat, Hébert, Chaumette. They take their names from those religious democrats, the Minorite friars of Saint Francis, who wear a girdle of rope over their coarse gray habit. They meet in the Place of the School of Medicine, in a monastery whose church was built in the reign of Saint Louis, in 1259, with the fine paid as indemnity for a murder. In 1590, it became the resort of the most famous Leaguers. Chateaubriand says: "There are places which seem to be the laboratory of seditions." How well this expression of the author of the Mémoires d'Outre-tombe describes the club-room of the Cordeliers! The pictures, the sculptured or painted images, the veils and curtains of the convent, have been torn down. The basilica displays nothing but its bare bones to the eyes of the spectator. At the apse, where wind and rain enter through the unglazed rose-window, joiners' work-benches serve as a desk for the president and as places on which to deposit the red caps. Do you see the fallen beams, the wooden benches, the dismantled stalls, the relics of saints pushed or rolled against the walls {8} to serve as benches for "dirty, dusty, drunken, sweaty spectators in torn jackets, pikes on their shoulders, or with their bare arms crossed"? Do you hear the orators who "call each other beggars, pickpockets, robbers, assassins, to the discordant noise of hisses and those proper to their different groups of devils? They find the material of their metaphors in murder, they borrow them from the filthiest of sewers and dungheaps, and from places set apart for the prostitution of men and women. Gestures render their figures of speech more comprehensible; with the cynicism of dogs, they call everything by its own name, in an impious and obscene parade of oaths and curses. To destroy and to produce, death and generation, nothing else can be disentangled from the savage jargon which deafens one's ear." And what is it that interrupts the speakers? "The little black owls of the cloister without monks and the steeple without bells, making themselves merry in the broken windows in expectation of their prey. At first they are called to order by the tinkling of an ineffectual bell; but as their cries do not cease, they are shot at to make them keep silence. They fall, palpitating, bleeding, and ominous, into the midst of the pandemonium."

So, then, clubs take the place of convents. Since the Constituent Assembly had decreed the abolition of monastic vows by its vote of February 13, 1790, many persons, rudely detached from their usual way of life and its duties, had abandoned their vocation. {9} The nun became a working-woman; the shaved Capuchin read his journal in suburban taverns; and grinning crowds visited the profaned and open convents "as, in Grenada, travellers pass through the abandoned halls of the Alhambra, or as they pause, at Tivoli, under the columns of the Sibyl's temple."

The Jacobin Club and the Club of the Cordeliers will destroy the monarchy. In the Memoirs of Lafayette it is remarked that "it is hard to understand how the Jacobin minority and a handful of pretended Marseillais made themselves masters of Paris when nearly all the forty thousand citizens composing the National Guard desired the Constitution; but the clubs had succeeded in scattering the true patriots and in creating a dread of vigorous measures. Experience had not yet taught what this feebleness and disorganization must needs cost."

The dark side of the picture is plainly far more evident than it was in 1789. But how vivid it is still! Those who hunger after sensations are in their element. When has there been more noise, more tumult, more movement, more unexpected or more varied scenes? Listen once more to Chateaubriand who, on his return from America, passed through Paris at this epoch: "When I read the Histoire des troubles publics ches divers peuples before the Revolution, I could not conceive how it was possible to live in those times. I was surprised that Montaigne wrote so cheerfully in a castle which he could not walk around without risk of being abducted by bands {10} of Leaguers or Protestants. The Revolution has enabled me to comprehend this possibility of existence. With us men, critical moments produce an increase of life. In a society which is dissolving and forming itself anew, the strife between the two tendencies, the collision of the past and the future, the medley of ancient and modern manners, form a transitory combination which does not admit a moment of ennui. Passions and characters, freed from restraint, display themselves with an energy they do not possess in well-regulated cities. The infraction of laws, the emancipation from duties, usages, and the rules of decorum, even perils themselves, increase the interest of this disorder."

Yes, people complain, grow angry, suffer, but they are not bored. How many incidents, episodes, emotions, there are in this strange tragi-comedy! Everywhere there is something to be seen; in the Assembly, the clubs, the public places, the promenades, streets, cafés, and theatres. Brawls and discussions are heard on every side. If by chance a salon is still open, disputes go on there as they would at a club. What quarrels take place in the cafés! Men stand on chairs and tables to spout. And what dissensions in the theatres! The actors meddle with politics as well as the spectators. In the greenroom of the Comédie-Française there is a right side, whose chief is the royalist Naudet, and a left side led by the republican Talma. Neither actor goes out except well armed. There are pistols {11} underneath their togas. The kings of tragedy, threatened by their political adversaries, have real poniards wherewith to defend themselves. Les Horaces, Brutus, La Mort de César, Barnevelt, Guillaume Tell, Charles IX., are plays containing in each tirade allusions which inflame the boxes and the pit. The theatre is a tilting-ground. If the royalists are there in force, they cause the orchestra to play their favorite airs: Charmante Gabrielle, Vive Henri Quatre! O! Richard, O! mon roi! The revolutionists protest, and sing their own chosen melody, the Ça ira. Sometimes they come to blows, swords are drawn, and, the play over, elegant women are dragged through the gutters. There is a general outbreak of insults and violence. The journals play the chief part in this universal madness. Sometimes the press is eloquent, but it is oftener ribald or atrocious. To borrow an expression from Montaigne, "it lowers itself even to the worthless esteem of extreme inferiority." The beautiful French tongue, once so correct and pure, is no longer recognizable. Vulgar words fall thick as hail. To the language of the Academy has succeeded the jargon of the markets.

What a swarm! what a swirl! How noisy, how restless, is this revolutionary Paris! What excited crowds fill the clubs, the Assembly, the Palais Royal, the gambling-houses, and the tumultuous faubourgs! Riotous gatherings, popular deputations, detachments of cavalry, companies of {12} foot-soldiers; gentlemen in French coats, powdered hair, swords at their sides, hats under their arms, silk stockings and low shoes; democrats close-cropped and unpowdered, with English frock coats and American cravats; ragged sans-culottes in red caps, weave in and out in ceaseless motion.

Do you know what was the chief distraction of this crowd in April, 1792? The debut of that new and fashionable machine, the guillotine. It was used for the first time on the 25th, for a criminal guilty of rape. Sensitive people congratulated each other on the mitigated torment, which they were pleased to consider a humanitarian improvement. The excellent philanthropist, Doctor Guillotin, was lauded to the skies. His machine was named guillotine in his honor, just as the stage-coaches established by Turgot had been called turgotines.

What enthusiasm, what infatuation, for this guillotine, already so famous and destined to be so much more so! The editors of the Moniteur declare in a lyric outburst that it is worthy of the approaching century. The truth is that it accelerates and makes less difficult the executioner's task. In the end the crowd would become disgusted with massacres. The delays of the gibbet would weary their patience. The sans-culottes, who doubtless have a presentiment of all that is going to happen, welcome the guillotine, then, with acclamations. At the Ambigu theatre a ballet-pantomime, called Les Quatre Fils Aymon, is given, and all Paris runs to {13} see the heads of all four fall at once, in the midst of loud applause, under the blade of the good doctor's machine. People amuse themselves with their future instrument of torture as if it were a toy. In a Girondin salon they play at guillotine with a moveable screen that is lifted and let fall again. At elegant dinners a little guillotine is brought in with the dessert and takes the place of a sweet dish. A pretty woman places a doll representing some political adversary under the knife; it is decapitated in the neatest possible style, and out of it runs something red that smells good, a liqueur perfumed with ambergris, into which every lady hastens to dip her lace handkerchief. French gaiety would make a vaudeville out of the day of judgment. Poor society, which passes so quick from gay to grave, from lively to severe, and which, like the Figaro of Beaumarchais, laughs at everything so that it may not weep!

It has been supposed until lately that after the day when he bade farewell to the royal family at the beginning of the Varennes journey, Count de Fersen never again saw Marie Antoinette. A new publication of very great importance proves that this is an error, and that the Swedish nobleman came to Paris for the last time in 1792, and had several interviews with the King and Queen. This publication is entitled: Extraits des papiers du grand maréchal de Suède, Comte Jean Axel de Fersen, and is published by his great-nephew, Baron de Kinckowstrom, a Swedish colonel. There is something romantic in this episode of the mysterious journey made by Marie Antoinette's loyal chevalier, which merits to leave a trace in history.

Fersen was one of those men whose sentiments are all the more profound because they know how to veil them under an apparently imperturbable calm. A soul of fire under an exterior of ice, as the Baroness de Korff describes him, courageous to temerity, devoted to heroism, he had conceived for Marie Antoinette one of those disinterested and ardent {15} friendships which lie midway between love and religion. Almost as much a Frenchman as he was a Swede, he did not forget that he had fought in America under the standard of the Most Christian King, and had been colonel of a regiment in the service of France. Having been the courtier of the happy and brilliant Queen, he remained the courtier of the Queen overcome by anguish. He had enkindled in the soul of his sovereign, Gustavus III., the same chivalrous sentiment which animated his own, and was impatiently awaiting the time when he could hasten to the aid of Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette under the Swedish flag. His dearest ambition was to draw his sword in the Queen's defence. From the Varennes journey up to the day of Marie Antoinette's execution, he had but one thought: to rescue the woman for whom he would willingly have shed the last drop of his blood. This fixed idea has left its trace on every line of his journal. The sad and melancholy countenance of Fersen, the courtier of misfortune, the friend of unhappy days, is assuredly one of the celebrated types in the drama of Versailles and the Tuileries. This man, who would have made no mark in history but for the martyr Queen, is certain, thanks to her, not to be forgotten by posterity. Marie Antoinette was to return him in glory what he gave her in devotion.

On her return to the Tuileries after the disastrous journey to Varennes, the Queen wrote to {16} Fersen, June 27, 1791: "Be at ease about us; we are living," and Fersen replied: "I am well, and live only to serve you." June 29, she wrote him another letter in which she said: "Do not write to me; it would endanger us; and, above all, do not return here under any pretext; all would be lost if you should make your appearance. They never lose sight of us by night or day; which is a matter of indifference to me. Be tranquil; nothing will happen to me. The Assembly desires to treat us with gentleness. Adieu. I shall not be able to write to you again."

Marie Antoinette was in error when she supposed she would not write again. She was in error, likewise, when she imagined that Fersen, in spite of all dangers and difficulties, would not find means to see her again. Their correspondence was not interrupted. After the acceptance of the Constitution, Marie Antoinette wrote to him: "Can you understand my position and the part I am continually obliged to play? Sometimes I do not understand myself, and am obliged to consider whether it is really I who am speaking; but what is to be done? It is all necessary, and be sure our position would be still worse than it is if I had not at once assumed this attitude; we at least gain time by it, and that is all that is required. I keep up better than could be expected, seeing that I go out so little and endure constantly such immense fatigue of mind. What with the persons whom I must see, my {17} writing, and the time I spend with my children, I have not a moment to myself. The last occupation, which is not the least, gives me my sole happiness. When I am very sad, I take my little boy in my arms, embrace him with my whole heart, and for a moment am consoled."

Fersen, touched and pitying, was constantly thinking of that fatal palace of the Tuileries where the Queen was so much to be compassionated. An invincible attraction drew him thither. There, he thought, was the post of devotion and of honor. November 26, he wrote: "Tell me whether there is any possibility of going to see you entirely alone, without a servant, in case I receive the order to do so from the King (Gustavus III.); he has already spoken to me of his desire to bring this about." Of all the sovereigns who interested themselves in the fate of Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette, Gustavus was the most active, brave, and resolute; he was also the only one in whom Marie Antoinette placed absolute confidence. She expected less from her own brother, the Emperor Leopold, and it was to Stockholm above all that she turned her eyes. Gustavus ordered Fersen to go secretly to Paris, and on December 22, 1791, he sent him a memoir and certain letters, commissioning him to deliver them to Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette. He recommended, as forcibly as he could, a new attempt at flight, but with precautions suggested by the lesson of Varennes. He thought the members of the royal {18} family should depart separately and in disguise, and that, once outside of his kingdom, Louis XVI. should call for the intervention of a congress. The following passage occurs in the letter of the Swedish King to Marie Antoinette: "I beg Your Majesty to consider seriously that violent disorders can only be cured by violent remedies, and that if moderation is a virtue in the course of ordinary life, it often becomes a vice when there is question of public matters. The King of France can re-establish his dominion only by resuming his former rights; every other remedy is illusory; anything except this would merely open the way to endless discussions which would augment the confusion instead of ending it. The King's rights were torn from him by the sword; it is by the sword that they must be reconquered. But I refrain; I should remember that I am addressing a princess who, in the most terrible moments of her life, has shown the most intrepid courage."

Fersen obtained permission from Louis XVI. to accomplish the mission confided to him by Gustavus III. He left Stockholm under an assumed name and with the passport of a Swedish courier, and reached Paris without accident, February 13, 1792. He was so adroit and prudent that no one suspected his presence. On the very evening of his arrival he wrote in his journal: "Went to the Queen by my usual road; very few National Guards; did not see the King." Fersen, therefore, only reappeared at the Tuileries in the darkness, like a fugitive or {19} an outlaw. He found the Queen pale with grief and with hair whitened by sorrow and emotion. It was a solemn moment. The storm was raging within France and beyond it. Terrible omens, snares, and dangers lay on every side. One might have said that the Tuileries were about to be swallowed up in a gulf of fire and blood.

The next day Fersen saw the King. He wrote in his journal: "Tuesday, 14. Saw the King at six in the evening. He will not go and can not, on account of the extreme vigilance. In fact, he scruples at it, having so often promised to remain, for he is an honest man.... He sees that force is the only resource; but, being weak, he thinks it impossible to resume all his authority.... Unless he were constantly encouraged, I am not sure he would not be tempted to negotiate with the rebels. He said to me afterwards: 'That's all very well! We are by ourselves and we can talk; but nobody ever found himself in my position. I know I missed the right moment; it was the 14th of July; we ought to have gone then, and I wanted to, but how could I when Monsieur himself begged me to stay, and Marshal de Broglie, who was in command, said to me: "Yes, we can go to Metz. But what shall we do when we get there?" I lost the opportunity and never found it again. I have been abandoned by everybody.'" Louis XVI. desired Fersen to warn the Powers that they must not be surprised at anything he might be forced to do; that he was {20} obliged, that it was the effect of constraint. "They must put me out of the question," he added, "and let me do what I can."

Fersen had a long talk with Marie Antoinette the same day. She entered into full details about the present and especially about the past. She explained why the flight to Varennes, in which Fersen had taken such a prominent part, and which had succeeded so well so long as he directed it, had ended in failure. The Queen described the anguish of the arrest and the return. To the project of a new effort to escape, she replied by pointing out the implacable surveillance of which she was the object, and the effervescence of popular passions, which this time would overleap all restraint if the fugitives were taken. It would be better for the royal family to suffer together than to expose themselves to die separately. It would be better to die like princes, who abdicate majesty only with life, than as vagabonds, under a vulgar disguise. "The Queen," adds Fersen, "told me that she saw Alexander Lameth and Duport; that they always tell her that there is no remedy but foreign troops; failing that, all is lost, that this cannot last, that they have gone farther than they wished to. In spite of all this, she thinks them malicious, does not trust them, but uses them as best she can. All the ministers are traitors who betray the King." Fersen had a final interview with Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette on February 21, 1792. By February 24, {21} he had returned to Brussels. He was profoundly moved on quitting the Tuileries, but, dismal and lugubrious as his forebodings may have been, how much more sombre was the reality to prove!

What a terrible fate was reserved for the chief actors in this drama! Yet a few days, and the chivalrous Gustavus was to be assassinated. The hour of execution was approaching for Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette. Fersen, likewise, was to have a most tragic end. From the moment when he bade his last adieu to the unhappy Queen, his life was but one long torment. His disposition, already inclined to melancholy, became incurably sad. His loyal and devoted soul could not accustom itself to the thought of the calamities weighing so cruelly upon that good and beautiful sovereign of whom he said in 1778: "The Queen is the prettiest and most amiable princess that I know." On October 14, 1793, he will still be endeavoring, with the aid of Baron de Breteuil, to bring to completion a thousandth plot to extricate the august captive from her fate. He will learn the fatal tidings on the 20th. "I can think of nothing but my loss," he will write in his journal. "It is frightful to have no positive details. It is horrible that she should have been alone in her last moments, with no one to speak to, or to receive her last wishes. No; without vengeance, my heart will never be content." Covered with honors under the reign of Gustavus IV., senator, chancellor of the Academy of {22} Upsal, member of the Seraphim Order, grand marshal of the kingdom of Sweden, there will remain in the depths of his heart a wound which nothing can heal. An inveterate fatality will pursue him as it had done the unfortunate sovereign of whom he had been the chevalier. He will perish in a riot at Stockholm, June 20, 1810, at the time of the obsequies of the Prince Royal. Struck down by fists and walking-sticks, his hair pulled out, his clothes torn to rags, he will be dragged about half-naked, rolled underfoot, assassinated by a maddened populace. Before rendering his last sigh, he will succeed in rising to his knees, and, joining his hands, he will utter these words from the stoning of Saint Stephen: "O my God, who callest me to Thee, I implore Thee for my tormentors, whom I pardon." If not the same words, they are at least the same thoughts as those of Marie Antoinette on the platform of the scaffold.

One after another, Marie Antoinette lost her last chances of safety; blows as unforeseen as terrible beat down the combinations on which she had built her hopes. Within a fortnight she was to see the two sovereigns disappear from whom she had expected succor: her brother, the Emperor Leopold, and Gustavus III., the King of Sweden. Leopold had not been equal to all the illusions which his sister had cherished with regard to him, but, nevertheless, he showed great interest in French affairs, and a lively desire to be useful to Louis XVI. Pacific by disposition, he had temporized at first, and adopted a conciliatory policy. He desired a reconciliation with the new principles, and, moreover, he was not blind to the inexperience and levity of the émigrés. But the obligation, to which he was bound by treaties, to defend the rights of princes holding property in Alsace, his fear of the propaganda of sedition, the aggressive language of the National Assembly and the Parisian press, had ended by determining him to take a more resolute attitude, and it was at the moment when he was {24} seriously intending to come to his sister's aid that he was carried off by sudden death. Though she did not desire a war between Austria and France, the Queen had persisted in wishing for an armed congress, which would have been a compromise between peace and war, but which the National Assembly would have regarded as an intolerable humiliation. It must not be denied, the situation was a false one. Between the true sentiments of Louis XVI. and his new rôle as a constitutional sovereign, there was a real incompatibility. As to the Queen, she was on good terms neither with the émigrés nor with the Assembly.

In order to get a just idea of the sentiments shown by the émigrés, it is necessary to read a letter written from Trèves, October 16, 1791, by Madame de Raigecourt, the friend of Madame Elisabeth, to another friend of the Princess, the Marquise de Bombelles: "I see with pain that Paris and Coblentz are not on good terms. The Emperor treats the Princes like children.... The Princes cannot avoid suspecting that it is the influence of the Queen and her agents which thwarts their plans and causes the Emperor to behave so strangely.... Some trickery on the part of the Tuileries is still suspected in this country. They ought to explain themselves to each other once for all. Is the Queen afraid lest the Count d'Artois should arrogate an authority in the realm which would diminish her own? Let her be at ease on that score; she will {25} always be the King's wife and always dominant. What is she afraid of, then? She complains that she is not sufficiently respected. But you know the good heart and the uprightness of our Prince; he is incapable of the remarks attributed to him, and which have certainly been reported to the Queen with the intention of estranging them entirely." Madame de Raigecourt ends her letter with this complaint against Louis XVI.: "Our wretched King lowers himself more and more every day; for he is doing too much, even if he still intends to escape.... The emigration, meanwhile, increases daily, and presently there will be more Frenchmen than Germans in this region." At this very time, the Queen was having recourse to her brother Leopold as to a saviour. She wrote to him, October 4, 1791: "My only consolation is in writing to you, my dear brother; I am surrounded by so many atrocities that I need all your friendship to tranquillize my mind.... A point of primary importance is to regulate the conduct of the émigrés. If they re-enter France in arms, all is lost, and it will be impossible to make it believed that we are not in connivance with them. Even the existence of an army of émigrés on the frontier would be enough to keep up the irritation and afford ground for accusations against us; it appears to me that a congress would make the task of restraining them less difficult.... This idea of a congress pleases me greatly; it would second the efforts we are {26} making to maintain confidence. In the first place, I repeat, it would put a check on the émigrés, and, moreover, it would make an impression here from which I hope much. I submit that to your better judgment.... Adieu, my dear brother; we love you, and my daughter has particularly charged me to embrace her good uncle."

While Marie Antoinette was thus turning towards Austria for assistance, the National Assembly at Paris repelled with energy all thought of any intervention whatsoever on the part of foreign powers. January 1, 1792, it issued a decree of impeachment against the King's brothers, the Prince de Conde, and Calonne. The confiscation of the property of the émigrés and the taxation of their revenues for the benefit of the State had been prescribed by another decree to which Louis XVI. had offered no opposition. January 14, Guadet said in the tribune, while speaking of the congress: "If it is true that by delays and discouragement they wish to bring us to accept this shameful mediation, ought the National Assembly to close its eyes to such a danger? Let us all swear to die here rather than—" He was not allowed to finish. The whole assembly rose to their feet, crying: "Yes, yes; we swear it!" And in a burst of enthusiasm, every Frenchman who would take part in a congress having for its object the modification of the Constitution, was declared an infamous traitor. January 17, it was decreed that the King should require the {27} Emperor Leopold to explain himself definitely before March 1.

By a curious coincidence, this date of March 1 was precisely that on which the Emperor Leopold was to die of a dreadful malady. He was in perfect health on February 27, when he gave audience to the Turkish envoy; he was in his agony, February 28, and on March 1, he died. His usual physician asserted that he had been poisoned. The idea that a crime had been committed spread among the people. Vague rumors got about concerning a woman who had caused remark at the last masked ball at court. This unknown person, under shelter of her disguise, might have presented the sovereign with poisoned bonbons. The Jacobins, who might have desired to get rid of the armed chief of the empire, and the émigrés, who might have reproached him as too luke-warm in his opposition to the principles of the French Revolution, were alternately suspected. The last hypothesis was hardly probable, nor does anything prove that the Jacobins had any hand in the possibly natural death of the Emperor Leopold. But minds were so overexcited at the time that the parties mutually accused each other, on all occasions, of the most execrable crimes. For that matter, there were Jacobins who, out of mere bravado, would willingly have gloried in crimes of which they were not guilty, provided that these crimes had been committed against kings.

What is certain is, that Marie Antoinette believed {28} in poison. "The death of the Emperor Leopold," says Madame Campan, "occurred on March 1, 1792. The Queen was out when the news arrived at the Tuileries. On her return, I gave her the letter announcing it. She cried out that the Emperor had been poisoned; that she had remarked and preserved a gazette in which, in an article on the session of the Jacobin Club at the time when Leopold had declared for the Coalition, it was said, in speaking of him, that a bit of piecrust could settle that affair. From that moment the Queen had regarded this phrase as an inadvertence of the propagandists."

On the very day when Marie Antoinette's brother died, Louis XVI.'s Minister of Foreign Affairs, De Lessart, had enraged the National Assembly by reading them extracts from his diplomatic correspondence, which they found not sufficiently firm. They were indignant at a despatch in which Prince de Kaunitz said: "The latest events give us hopes; it appears that the majority of the French nation, impressed with the evils they have prepared, are returning to more moderate principles, and incline to render to the throne the dignity and authority which are the essence of monarchical government." When De Lessart came down from the tribune, the whispering changed into cries of rage and threats against the minister and the court, which, it was said, was planning a counter-revolution at the Tuileries, and dictating to the cabinet of Vienna the language by which it hoped to intimidate France. {29} At the evening session of the same day, Rouyer, a deputy, proposed to impeach the Minister of Foreign Affairs. "Is it possible," cried he, "that a perfidious minister should come here to make a parade of his work and lay the responsibility of it on a foreign power? Will the time never arrive when ministers shall cease to betray us? Were my head to be the price of the denunciation I am making, I would none the less go on with it." At the session of March 6, Guadet said: "It is time to know whether the ministers wish to make Louis XVI. King of the French, or the King of Coblentz."

On the 10th the storm broke. The day before, Narbonne had received his dismission. Brissot accused De Lessart of having compromised the safety of France, withheld from the Assembly the documents establishing the alliance between the Emperor and the King of Prussia, discredited the assignats, depreciated the credit, lowered the rate of exchange, and encouraged interior disorder. Vergniaud followed him, exclaiming: "From the tribune where I am speaking may be seen the palace where perverse counsellors lead astray and deceive the King given to you by the Constitution; where they forge chains for the nation, and arrange the manoeuvres which are to deliver us up to Austria, after having caused us to pass through the horrors of civil war. Terror and dismay have often issued from that famous palace. Let them re-enter it to-day in the name of the law, let them penetrate all hearts, and {30} teach all who dwell there, that our Constitution accords inviolability to the King alone. Let them know that the law will overtake all the guilty without exception, and that there will not be a single head convicted of crime which can escape its sword." The decree of impeachment against the ministers was voted by a very large majority. De Lessart was advised to take flight, but he refused. "I owe it to my country," said he, "I owe it to my King and to myself to make my innocence and the regularity of my conduct plain before the tribunal of the high court, and I have decided to give myself up at Orleans." He was conducted by gendarmes to that city, where he was imprisoned. Louis XVI. dared not do anything to save his favorite minister. On March 11, Pétion, the mayor of Paris, came to the bar of the Assembly, and read, in the name of the Commune, an address in which it was said: "When the atmosphere surrounding us is heavy with noisome vapors, Nature can relieve herself only by a thunder-storm. So, too, society can purge itself from the abuses which disturb it only by a formidable explosion.... It is true, then, that responsibility is not an idle word; that all men, whatever may be their stations, are equal before the law; that the sword of justice is poised over all heads without distinction." Was not this language like a prognostic of the 21st of January and the 16th of October? Encompassed by a thousand snares, hated by each of the extreme parties, by the {31} émigrés as well as by the Jacobins, Marie Antoinette no longer beheld anything but aspects of sorrow. Abroad, as in France, her gaze fell on dismal spectacles only. Her imagination was affected. She hardly dared taste the dishes served at her table. All had conspired to betray her. She had experienced so many deceptions and so much anguish; fate had pursued her with so much bitterness, that her heart, exhausted with emotions, and overwhelmed with sadness, was weary of all things, even of hope.

The drama of the Revolution is not French alone; it is European. It has its afterclap in every empire, in every kingdom, even to the most distant lands. It excites minds in Stockholm almost as much as in Paris. Among the Swedes there are people whose greatest desire would be to parody the October Days, and to carry about on pikes the bleeding heads of their adversaries. The new ideas take fire and spread like a train of gunpowder. It is the fashion to go to extremes; a nameless frenzy and fatality seem let loose upon this epoch of agitations and catastrophes. All those who, at one time or another, have been guests at the palace of Versailles, are condemned, as by a mysterious sentence, either to exile or to death.

How will terminate the career of that brilliant King of Sweden, who had received from Versailles and from Paris, from the court and from the city, such an enthusiastic reception? Gustavus, the idol of the great lords, the philosophers, and the fashionable beauties, who, after being the hero of the encyclopædists, came to hold his court at {33} Aix-la-Chapelle amid the French émigrés, and who, on his return to Stockholm, prepared there the great crusade for authority, announcing himself as the avenger of divine right, the saviour of all thrones? The last days of his life, his presentiments, which recall those of Cæsar, his superstitions, his belief in prophecies, his magic incantations, that warning which he scorns, as the Duke de Guise did at the castle of Blois, that masked ball where the costumes, the music, the flowers, the lights, offer a painfully strange contrast to the horror of the attack; all is sinister, lugubrious, in these fantastic and fatal scenes which have already tempted more than one dramatist, more than one musician, and whose phases a Shakespeare only could retrace. The crime of Stockholm is linked closely to the death-struggle of French royalty. The funeral knell which tolled at this extremity of the North had echoes in Paris. The Swedish regicides set the example to the regicides of France.

M. Geffroy has remarked very justly in his work, Gustave III. et la cour de France, that the bloody deed which put an end to the reign and the life of Gustavus is not an isolated fact: "The faults committed by this Prince would not have sufficed to arm his assassins. The true source whence Ankarstroem and his accomplices drew their first inspiration was that vertigo caused during the last years of the century by the annihilation of all religious and even all philosophical faith.... No moment of {34} modern history has presented an intellectual and moral anarchy comparable to that which accompanied the revolutionary period in Europe."

The eighteenth century was punished for incredulity by superstition. Having refused to believe the most holy truths, it lent credence to the most fantastic chimeras. For priests it substituted sorcerers; for Christian ceremonies, the rites of freemasonry. The time was coming when, because it had rejected the Sacred Heart of Jesus, it was going to bow before the sacred heart of Marat. The adepts of Mesmer and of De Puysegur, the seekers after the philosopher's stone, the Nicolaites of Berlin, the illuminati of Bavaria, enlarged the boundaries of human credulity, and the men who succumbed in the most naïve and foolish manner to these wretched weaknesses of mind, were precisely the haughtiest philosophers, those who had prided themselves the most on their distinction as free-thinkers. Such a one was Gustavus III.

This Voltairean Prince, who had held the Christian verities so cheap, was superstitious even to puerility. He did not believe in the Gospels, but he believed in books of magic. In a corner of his palace he had arranged a cupboard with a censer and a pair of candlesticks, before which he performed cabalistic operations in nothing but his shirt. Throughout his entire reign he consulted a fortune-teller named Madame Arfwedsson, who read the future for him in coffee-grounds. Around his neck {35} he wore a gold box containing a sachet in which there was a powder that, according to his belief, would drive away evil spirits. All this apparatus of incantation and sorcery was one of the causes of Gustavus's fall. It multiplied the snares around the unfortunate monarch, and served to mask his enemies. Prophecies announced his approaching end, and conspirators took care to fulfil the prophecies.

The Duke of Sudermania, the King's brother, without being an accomplice in the project of crime, encouraged underhand practices. Sectarians approached Gustavus to reproach him for his luxury, his prodigalities, his entertainments, or addressed him anonymous warnings which, in Biblical language, declared him accursed and rejected by the Lord. Their insolence knew no bounds. Madame Arfwedsson had counselled the King to beware if he should meet a man dressed in red. Count de Ribbing, one of the future conspirators, having heard of this, ordered a red costume out of bravado, and presented himself in it before his sovereign, whom such an apparition caused to reflect if not to tremble.

Gustavus, like Cæsar, was to see his Ides of March. It had been predicted to him that the month of March would be fatal to him. This month approached, and the monarch diverted himself by fêtes and boisterous entertainments in order to banish the presentiments which never ceased to assail {36} him. He said to himself that all this phantasmagoria would probably soon vanish; that the funereal images would of themselves depart; and that the spectres would disappear at the sound of arms. The monarchical crusade of which he proposed to be the leader grew upon him as the best means by which to escape the incessant obsessions haunting his spirit. In vain was he reminded that Sweden was in need of money, and that a war of intervention in the affairs of France was not popular. His resolution remained unshaken. He counted the days and hours which still separated him from the moment of action: his sole idea was to chastise the Jacobins and avenge the majesty of thrones.

Returned to Stockholm from Aix-la-Chapelle, at the beginning of August, 1791, the impetuous monarch began to be very active in his warlike preparations. The Marquis de Bouillé, who had been obliged to quit France at the time of the unsuccessful journey to Varennes, had entered his service and was to counsel him and fight at his side under the Swedish flag. At the same time Gustavus officially renewed his promises of aid to the King of France. Louis XVI. replied:—

"MONSIEUR MY BROTHER AND COUSIN: I have just received the lines with which you have honored me on the occasion of your return. It is always a great consolation to have such proofs of a friendly sentiment as are given me by this letter. The concern, Sire, which you take in all that relates to {37} my interest touches me more and more, and I recognize in each word the august soul of a king whom the world admires as much for his magnanimous heart as for his wisdom."

Meanwhile the conspirators, animated either by personal rancor or the passions common to nobles hostile to their king, were secretly preparing for an attack. The five leaders were Captain Ankarstroem, Count de Ribbing, Count de Horn, Count de Lilienhorn, major of the Blue Guards, and Baron Pechlin, an old man of seventy-two, who had been distinguished in the civil wars, and was the soul of the plot. The conspirators had doubts before committing the crime. During the Diet, which met at Gefle, January 25, 1792, they refrained at the very moment when they were about to strike.

Gustavus was in his castle of Haga, about a league from Stockholm, without guards or attendants. Three of the conspirators approached the castle at five in the evening. They were armed with carbines, and, having placed themselves in ambush near the King's apartment on the ground-floor, were awaiting an opportunity to kill their sovereign. Gustavus coming in from a long walk, went in his dressing-gown to sit in the library, the windows of which opened like doors into the garden. He fell asleep in his armchair. Whether they were alarmed by the sound of footsteps, or whether the contrast between the slumber of the unsuspicious King and the death poising above his head awakened {38} some remorse, the assassins once more abandoned their meditated crime.

Weary of the attempts they had been planning for six months, and which never came to anything, the conspirators might possibly have given them up altogether if a circumstance which they considered providential had not come to rekindle their regicidal zeal. The last masked ball of the season was to be given in the Opera-house on the night of March 16-17, and it was known that Gustavus would be present. To strike the monarch in the midst of the festival, in order to chastise him for his love of pleasure, was an idea which charmed the assassins. Moreover, the mask alone could embolden them; they thought that if the august victim were enveloped in a domino they need no longer dread that royal prestige which had more than once caused them to recoil.

Gustavus was counselled to be on his guard. The young Count Louis de Bouillé, who was then at Stockholm, and who had been informed by a letter from Germany that the King was about to be assassinated, begged him to profit by the warnings reaching him from every quarter. Gustavus replied that he would rather go blindly to meet his fate than torment himself with the numberless precautions which such suspicions would demand. "If I listened," added he, "to all the advice I receive, I could not even drink a glass of water; besides, I am far from believing in the execution of such a plot. {39} My subjects, although very brave in war, are extremely timid in politics. The successes I expect to gain in France, the trophies of which I shall bring back to Stockholm, will speedily augment my power by the confidence and general respect which will be their result."

Meantime the fatal hour was approaching. The masked ball of March 16 was about to open. Before going there, Gustavus took supper with a few of the persons belonging to his household. While he was at table he received a note, written in French and unsigned, in which he was entreated not to enter the playhouse, where he was about to be stricken to death. The author of the note urgently recommended the King not to make his appearance at the ball, and, if he persisted in going, to suspect the crowd which would press around him, because this gathering was to be the prelude and signal of the blow aimed at him. The really bizarre thing about this was that the man who wrote these lines was himself one of the conspirators, Count de Lilienhorn.

"It is impossible to tell," says the Marquis de Bouillé in his Memoirs, "whether his conscience wished to acquit itself in this manner towards the King, to whom he owed everything, without forfeiting his word to his party, or whether, knowing the fearless character of this prince, he did not offer his anonymous advice as a bait to his courage. It certainly produced the latter effect." Gustavus made no {40} reflections on reading this note, and went fearlessly to the ball.

The orchestra is playing wildly. The dances are animated. The hall, adorned with flowers, sparkles under the glow of the chandeliers. Gustavus appears for a moment in his box. It is only then that he shows to Baron d'Essen, his first equerry, the anonymous note he had received while at supper. That faithful servant begs him not to go down into the hall. Gustavus disregards the prudent counsel. He says that hereafter he will wear a coat of mail, but that, for this time, he is perfectly determined to be reckless about danger. The King and his equerry go into the saloon in front of the royal box, where each puts on a domino. Then they enter the hall by way of the stage. There are men essentially courageous, who love danger for its own sake. Gustavus is one of them. Hence he takes pleasure in braving all his assassins. As he is crossing the greenroom with Baron d'Essen on his arm, "Let us see," says he, "whether they will really dare to kill me." Yes, they will dare it. The moment that the King enters he is recognized in spite of his mask and his domino. He walks slowly around the hall, and then goes into the pit, where he strolls about during several minutes. He is about to retrace his steps, when he finds himself surrounded, as had been predicted, by a group of maskers who get between him and the officers of his suite. Several black dominos approach. They are the assassins. One of them, {41} Count de Horn, lays a hand on his shoulder: "Good day, fine masker!" he says. This Judas salute, this ironical welcome given by the murderers to their victim, is the signal for the attack. On the instant, Ankarstroem fires on the King with a pistol loaded with old iron.

Gustavus, struck in the left hip, cries, "I am wounded!" The pistol, which had been wrapped in wool, made only a muffled report, and the smoke spreading throughout the room, the crowd does not think of a murder, but a fire. Cries of "Fire! fire!" augment the confusion. Baron d'Essen, all covered with his master's blood, helps him to gain a little box called the OEil-de-Boeuf, and from there a salon, where he is laid upon a sofa. Baron d'Armfelt orders the doors of the theatre to be closed, and every one to unmask. A man, brazening it out, lifts his mask before the officer of police, and says to him with assurance, "As for me, sir, I hope that you will not suspect me." It is Ankarstroem, the assassin. He goes out quietly. But, after the crime was committed, his weapons, a pistol and a knife like that of Ravaillac, had fallen on the floor. A gunsmith of Stockholm will recognize the pistol and declare that he had sold it a few days before to a former officer of the guards, Captain Ankarstroem. It is the token which will cause the arrest of the assassin, and his punishment by the penalty of parricides,—decapitation and the cutting off of his right hand.

The King showed admirable calm and resignation during the thirteen days he had still to live. He asked with anxiety if the murderer had been arrested, and being answered that his name was not yet known: "Ah! God grant," said he, "that he may not be discovered!" As soon as the first bandages were put on, the wounded man was taken to his apartments at the castle. There he received his courtiers and the foreign ministers. When he saw the Duke d'Escars, who represented the brothers of Louis XVI. at Stockholm: "This is a blow," said he, "which is going to rejoice your Parisian Jacobins; but write to the Princes that if I recover from it, it will change neither my sentiments nor my zeal for their just cause." In the midst of his sufferings he preserved a dignity above all praise. Neither recriminations nor murmurs issued from his lips. He summoned to his death-bed both his friends and those who had been among the number of his enemies, but would have been horrified to have been accomplices in a crime. When the old Count de Brahé, leader of the nobles of the opposition, presented himself, Gustavus said, as he pressed him in his arms: "I bless my wound, since it has brought back an old friend who had withdrawn from me. Embrace me, my dear count, and let all be forgotten between us."

The fate of his son, who was about to ascend the throne at the age of thirteen, was the chief preoccupation of the King. "Let them put me on a litter," cried he; "I will go to the public square and speak to {43} the people." And he said to Baron d'Armfelt: "Go, and like another Antony, show the bloody vestments of Cæsar." It was also to D'Armfelt that he said as he was signing with his dying hand his commission as Governor of Stockholm: "Give me your knightly word that you will serve my son as faithfully as you have served me." He made his confession to his grand-almoner: "I fear," he said to him, "that I have no great merit before God, but at least I am sure that I have never done harm to any one intentionally." He meant to receive the sacraments according to the Lutheran form, and to have the Queen brought to him, as he had not seen her since his illness. But while seeking sleep in order to tranquillize his mind before this emotion, he found the slumber of death, March 29, 1792, at eleven in the morning. He was forty-six years old.

Thus terminated the brilliant and stormy career of the prince on whom the Marquis de Bouillé has pronounced the following judgment: "His manners and his politeness rendered him the most amiable and attractive man in his country, although the Swedes are naturally intelligent. He had a vivid imagination, a mind enlightened and adorned by a taste for letters, a masculine and persuasive eloquence, and an easy elocution even when speaking French; useful and agreeable acquirements, a prodigious memory, polite and affable manners, accompanied by a certain oddity which did not displease. His strong and ardent soul was enkindled with an inordinate love of glory; but a {44} chivalrous spirit and loyalty dominated there. His sensitive heart rendered him clement, when he ought, perhaps, to have been severe; he was even susceptible of friendship, and this prince has had and has preserved friends whom I have known, and who were worthy to be such. He had a firm and decided character, and, above all, that resolution so necessary to statesmen, without which wit, prudence, talents, experience, are not only useless, but often injurious."

According to the Marquis de Bouillé, Gustavus should have been the King of France, and Louis XVI. King of Sweden. "As the sovereign of France, Gustavus would have been, beyond all doubt, one of its greatest kings. He would have preserved that beautiful realm from a revolution; he would have governed with glory and with splendor.... Louis XVI., on the other hand, placed on the throne of Sweden, would have obtained the respect and esteem of that simple people by his moral and religious virtues, his economy, his spirit of justice, and his good and benevolent sentiments. He would have contributed to the happiness of the Swedes, who would have wept above his tomb; whereas both these monarchs perished at the hands of their subjects. But the designs of Providence are impenetrable, and we ought, in respect and silence, to obey its unalterable decrees."

The Jacobins of Paris, who affected to despise the projects of Gustavus III., showed how much they had feared him by the mad joy they displayed on {45} learning of his death. They lavished praises on "Brutus Ankarstroem." Although it had been committed by the nobles, there was a certain reminiscence of the French Revolution about the assault. In their secret meetings the conspirators had agreed to carry around on pikes the heads of Gustavus's principal friends, "in the French style," as was said in those days. Count de Lilienhorn, brought up, nourished, and drawn from poverty and obscurity by Gustavus, and overwhelmed to the last moment by the benefits of the generous monarch, explained his monstrous ingratitude and the part he had taken in the attack, by saying he had been led astray by the idea of commanding the National Guards of Stockholm after the Revolution, and playing the same part as Lafayette. The Girondin ministry attained to power in France a few days after Gustavus had been struck down in Sweden. There was no connecting link between the two facts; but at Paris, as at Stockholm, the cause of kings sustained a terrible repulse. The tragic death of their faithful friend must have caused Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette some painful forebodings concerning their own fate. The murder of Gustavus was the first of a series of great catastrophes. The pistol of the Swedish regicide heralded the blade of the Parisian guillotine. The 16th of March was the prelude of the 21st of January.

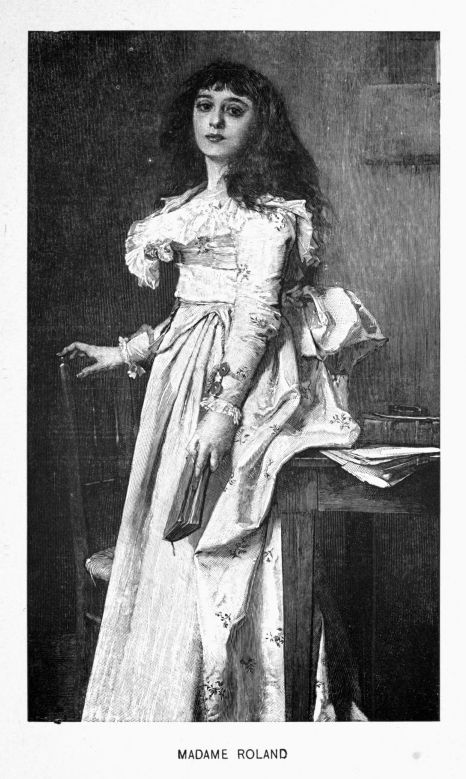

The moment is at hand when a woman of the middle class, born in humble circumstances, is about to make her appearance on the scene of politics; a woman who, after living in obscurity during thirty-eight years, was to become famous in a few days, and attract the attention of all France first and afterwards that of Europe entire. No figure is more curious to study than hers, and it is not surprising that of late years it has tempted men of great merit, such as MM. Daubant and Faugère, whose publications have shed great light on the Egeria of the Girondins.

At every epoch of history there are certain women who become as it were living symbols, and sum up in their own persons the passions, prejudices, and illusions of their time. They reflect at once its vices and its virtues, its qualities and its defects. Such was Madame Roland. All the distinctive characteristics of the close of the eighteenth century are resumed in her: ardent enthusiasm, generous ideals, aspiration towards progress, passion for liberty, heroic courage in view of persecution, captivity, and death; an absence of religious faith, an implacable vanity, a {47} thirst for emotions, plagiarism of antiquity, declamatory language and sentiments, and childish imitation of Greece and Rome. Nothing is more interesting than to analyze the conceptions of this mind, count the pulsations of this heart, and surprise the inmost secrets of a woman whose psychological importance is as considerable as her place in history. Intellectually as well as morally, Madame Roland is the daughter of Jean-Jacques Rousseau; socially she is the personification of that third estate which, having been nothing, wished at first to be something and afterwards to be all; politically, she is by turns the heroine and the victim of the Revolution, which, under pretext of liberty, engendered tyranny, which used the guillotine and perished by the guillotine, and which after dreaming of light expired in mire and blood.

How was it that this little bourgeoise, the daughter of Philipon the engraver, a man midway between an artisan and an artist, whose very origin seemed to remove her so far from any political rôle, attained to high renown? What influences formed this woman whose qualities were masculine? Whence was drawn the inspiration of this siren, destined to be taken in her own snares and die the victim of her own incantations? A rapid glance at the earliest years of Marie-Jeanne Philipon, the future Madame Roland, is enough to explain her passions and her hopes, her errors and her talents, her rages and her enthusiasms.

She was born in Paris, March 18, 1754, of an intelligent but frivolous father, and a simple, devoted, {48} honestly commonplace mother. From infancy she felt herself superior to those by whom she was surrounded. Thence sprang an unmeasured pride and a continual hunger to produce an impression. The infant prodigy preluded the female politician. Speaking of herself in her Memoirs, she becomes ecstatic over the child who "read serious works, explained very well the circles of the celestial globe, used crayons and the burin, found at eight years that she was the best dancer in an assembly of young persons older than herself," and who, nevertheless, "was often summoned to the kitchen to make an omelette, clean the vegetables, or skim the pot." She admires her own willingness to descend to domestic cares: "I was never out of my element," she says; "I could make soup as skilfully as Philopoemen could chop wood; but no one, observing me, could imagine that this was suitable employment." Still speaking of herself, she celebrates "the little person who on Sundays went to church or out walking in a spick-and-span costume whose appearance was fully sustained by her demeanor and her language." She calls attention to the contrast by which, on week-days, the same child went out alone, in a little cloth frock, to buy parsley and salad at a short distance from home. "It must be owned," she adds, "that I did not like this very well; but I did not show it, and I had the art of doing my errands in such a way as to find some pleasure in it. I united such great politeness to a certain dignity, that the fruit-seller or other person {49} of the sort, took pleasure in serving me first, and even those who came before me thought this proper."

So the little Philipon wanted to take the chief place in the fruiterer's shop, just as, later on, she desired it on the political stage or the Ministry of the Interior. This enemy of privileges will admit them only for herself. In everything she made pretentions: pretentions to elegance, beauty, distinction, talent, knowledge, eloquence, genius, and, when she wanted to be simple, to simplicity. In her style as in her conversation, in her public as in her private life, what she sought before all things was effect. It was absolutely essential that people should talk about her, that she should be playing a part, or standing on a pedestal. Assuredly, if she had a fault, it was not excess of modesty. She regarded herself as the flower of her sex, a superior woman, made to be loved, flattered, and adored. She speaks of her charms with the precision of a doctor and the enthusiasm of a poet. Not one of her perfections escapes her. It is through a magnifying-glass and before a mirror that she studies and admires herself. She discovers that a society in which a woman so remarkable and so attractive is not thoroughly well known, must be badly organized. Middle-class by birth, and aristocratic by instinct, she represents what one might then have called the new social strata. A secret voice told her that the day was to come when she would make herself feared by the powerful of the earth, those giants with feet of clay who, at the beginning of her {50} career, were still looked at kneeling. Banished by fate from the theatre where the human tragi-comedy is played, she said to herself: "I too will have a part one of these days." In the earliest stage of her existence there was in her a confused medley of uneasiness and ambition, of spite and anger. She had a horror of the slightly disdainful protection of people of quality. She conceived an aversion for persons like that Demoiselle d'Hannaches, "big, awkward, dry, and yellow," infatuated with her nobility, annoying everybody with her titles, and yet, in spite of her ignorance, her stiff manners, her old-fashioned dress and her follies, well received everywhere on account of her birth.

Slowly, but steadily, the future amazon of the Revolution prepared herself for the combat. The books which she read and re-read incessantly were the arsenal whence she drew her weapons. One of those presentiments which do not deceive, promised her a stormy but illustrious destiny. More Roman than French, more pagan than Christian, she longed for glory like that of the heroines of Plutarch, her favorite author. In the humble dwelling of her father, situated at the corner of the Pont-Neuf and the Quai des Orfévres, she caught a glimpse of horizons as wide as her thoughts. "From the upper part of our house," she says, "a great expanse offered itself to my dreamy and romantic imagination. How often from my north window have I contemplated with emotion the deserts of the sky, its superb azure {51} vault splendidly outlined from the bluish dawn far behind the Pont du Change, to the sunset gilded with a faint purplish lustre behind the trees of the Champs Elysées and the houses of Chaillot."

Irritated with the obscurity to which she was condemned by fate, there was but one resource which could have consoled her for the social inequalities which bruised her vanity and her pride. That resource would have been religion. Nothing but an ideal of humility could have appeased the interior revolts of this soul of fire. To such a woman, what is lacking is heaven. Earth, no matter what happens, can give her nothing but deceptions. The only moment of her life when she felt herself really happy was that when she enjoyed the supreme good, peace of heart. Of all parts of her Memoirs, the most pure and touching are those she devotes to her recollections of the convent. One might think that the author of Rolla had remembered them when he described in such penetrating terms the mystic poetry of the cloister, and the regrets often engendered by the loss of faith in the minds and hearts of people who have become unbelievers.

The little Philipon, being in her twelfth year, asked to be sent to a convent, in order to prepare better for her first communion. She was placed with the Ladies of the Congregation, rue Neuve-Saint-Étienne, in the Faubourg Saint-Marcel, near Sainte-Pélagie, her future prison: "How I pressed my dear mamma in my arms at the moment of parting {52} from her for the first time! I was stifled, overwhelmed; but I obeyed the voice of God, and crossed the threshold of the cloister, offering Him with tears the greatest sacrifice that I could make. The first night I spent at the convent was agitated: I was no longer under the paternal roof. I felt that I was far from that good mother who was surely thinking of me with tenderness. There was a feeble light in the room where I had been put to bed, with four other children of my own age; I rose quietly and went to the window. The moonlight permitted me to see the garden upon which it looked. The most profound silence reigned; I listened to it, so to say, with a sort of respect; great trees cast their gigantic shadows here and there, and promised a safe refuge for tranquil meditation. I lifted my eyes to the pure and serene sky, and thought I felt the presence of the Divinity, who smiled at my sacrifice and already offered me its recompense in the peace of a celestial abode. Delicious tears flowed slowly down my cheeks; I reiterated my vows with a holy transport, and I enjoyed the slumber of the elect."

As if in these silent cloisters, which she crossed slowly so as to enjoy their solitude more fully, she had a presentiment of the storms in her destiny and her heart, she sometimes stopped beside a tomb on which was engraven the eulogy of a holy maiden. "She is happy!" she said to herself with a sigh. While she was in prison she remembered with emotion a novice's taking the veil: "I experience yet the {53} thrill caused by her faintly tremulous voice when she chanted melodiously the customary versicle: 'Elegi: Here I have chosen my abode, and I will not depart from it forever.' I have not forgotten the notes of this little air; I can repeat them as exactly as if I had heard them yesterday."

Unhappily, religious ideas were soon to undergo a change in the mind of the future Madame Roland. Returning to the paternal dwelling, she was badly brought up there; her mother let her read everything, even Candide. Voltaire, Helvétius, Diderot, had no secrets for this young girl. Extreme disorder and confusion in mind and heart were the result. When she had the misfortune to lose her mother at the age of twenty-one, the book in which she sought consolation was the Nouvelle Héloise. Jean-Jacques became her god. "It seems," she says, "as if he were my natural aliment and the interpreter of the sentiment I had already, and which he alone knew how to explain to me.... To have the whole of Jean-Jacques," she says again, "to be able to consult him incessantly, to enlighten and elevate one's self with him at all times of life, is a felicity which can only be tasted by adoring him as I did." Such reading robbed her of faith. It made her a free-thinker and a bluestocking. It inspired her with an unhealthy ambition, sullied her imagination, and troubled the peace of her heart. It deprived her of that moral delicacy, lacking which, even virtue itself loses its charms. She was no longer anything but a young {54} girl, well-conducted but not pure, honest but shameless.

Was not a day coming when, a prisoner and on the point of getting into the fatal cart, she would throw off the terrible anxieties of her situation in order to imitate the impurities of the Confessions of Jean-Jacques, and retrace indecent details with complacency? Do not seek in her that flower of innocence which is the young girl's grace. The charming puritan does not commit great faults, but she has astonishing licenses of thought and speech. For her, Louvet's Faublas is "one of those charming romances known to persons of taste, in which the graces of imagination ally themselves to the tone of philosophy." Is not this woman, who begins her life like a saint and ends it as a pupil of Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the symbol of that troubled eighteenth century which opened in fidelity to religious faith and closed in the depths of the abyss of incredulity? The ravages caused by bad reading in the soul of this young girl explain the catastrophes of the entire century.

From the time when she replaced the Gospels by the Contrat Social and the Imitation of Jesus Christ by the Nouvelle Héloise, there was no longer anything simple or natural remaining in the young philosopher. All her thoughts and actions became declamatory. There was something theatrical in her attitudes and gestures, and even in the sound of her voice. Her speech was rhythmical, cadenced, marked {55} by a special accent. Even her private letters often resemble the amplifications of rhetoric rather than the effusions of friendship. One might say that their author had a presentiment that they would be printed. She wrote to Mademoiselle Sophie Cannet, January 3, 1776: "In any case, burn nothing. Though my letters were one day to be read by all the world, I would not hide the only monuments of my weakness, and my sentiments." Monuments of weakness—is not the expression worthy of the bombast of the time?

Not finding love, Mademoiselle Philipon married philosophically. Her union bears a striking imitation to that of Héloise with M. de Volmar. "Looking her destiny peacefully and tenderly in the face, greatly moved but not infatuated," she united herself to a man whom she esteemed but did not love. This was Roland de la Platière, who was descended from an ancient and very honorable middle class family. Though not rich, he was at least comfortably well off. "Well educated, honest, simple in his tastes and manners, he fulfilled his duties as inspector of manufactures in a notable way. The marriage was celebrated on February 4, 1780. Roland was forty-six years old, while his wife was not yet twenty-six. Thin, bald, careless in his dress, the husband was not at all an ideal person. It had taken him five years to declare his passion, and this hesitation, as his wife was to write thirteen years later, "left not a vestige of illusion in his sentiments." "I have often felt," {56} says she, "that there was no similarity between us. If we lived in retirement, I spent many painful hours; if we mingled in society, I was loved by persons among whom I perceived there were some who might affect me too much; I plunged into labor with my husband.... It was a long time before I gained courage to contradict him."