Title: Jack Hinton: The Guardsman

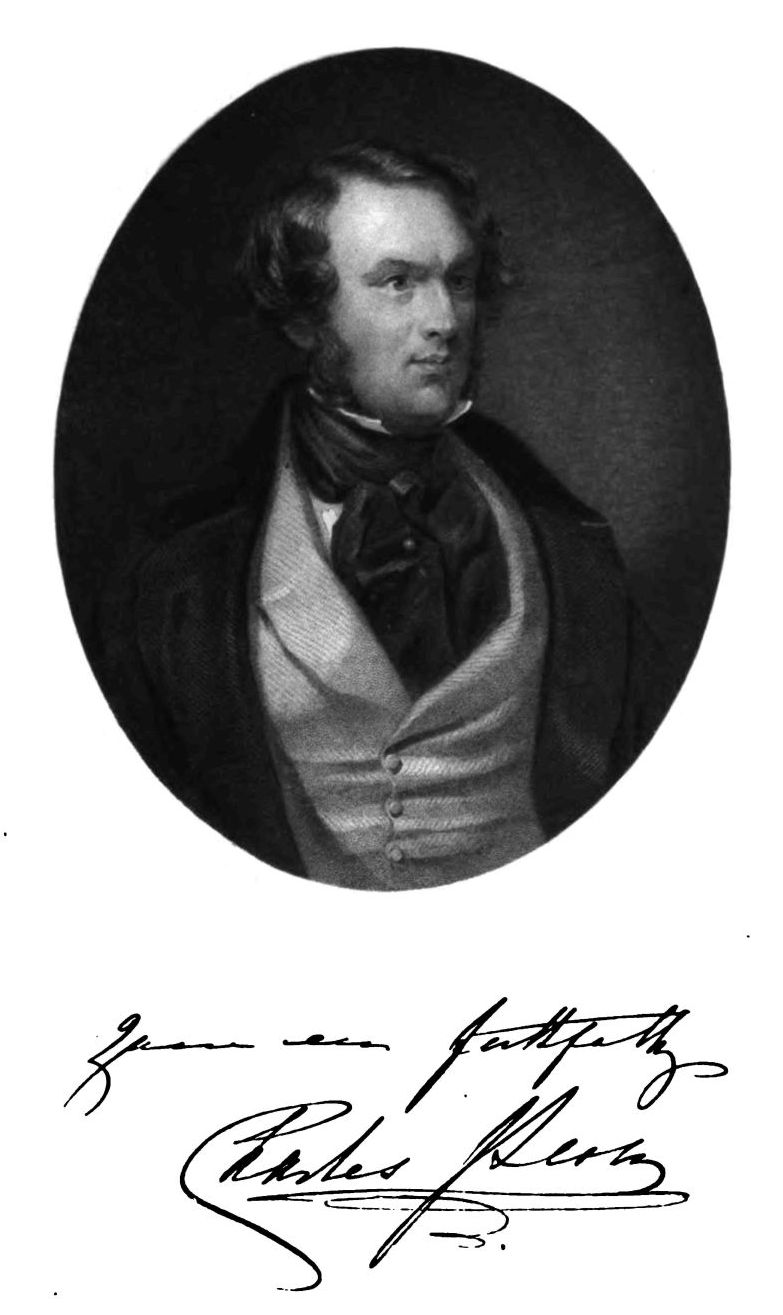

Author: Charles James Lever

Illustrator: Hablot Knight Browne

Release date: July 5, 2010 [eBook #33082]

Most recently updated: February 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

PREFACE.

JACK HINTON, THE GUARDSMAN

CHAPTER I. A FAMILY PARTY

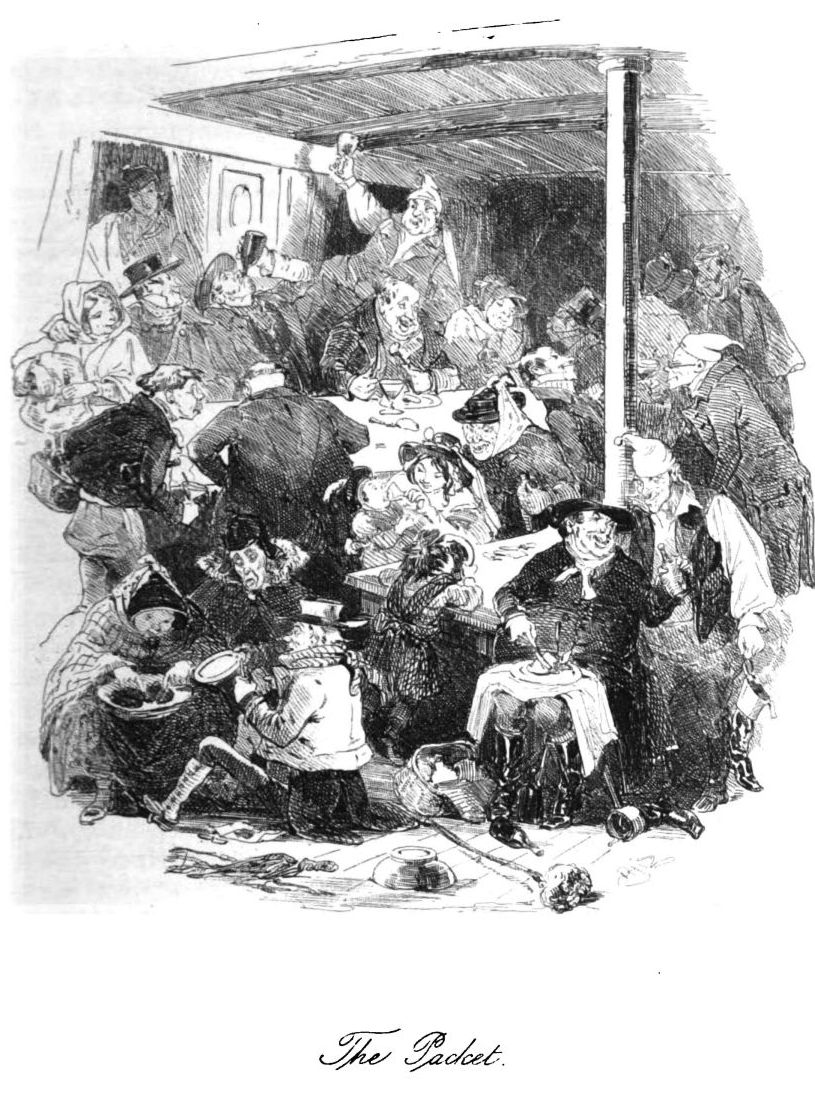

CHAPTER II. THE IRISH PACKET

CHAPTER III. THE CASTLE

CHAPTER IV. THE BREAKFAST

CHAPTER V. THE REVIEW IN THE PHOENIX

CHAPTER VI. THE SHAM BATTLE

CHAPTER VII. THE ROONEYS

CHAPTER VIII. THE VISIT

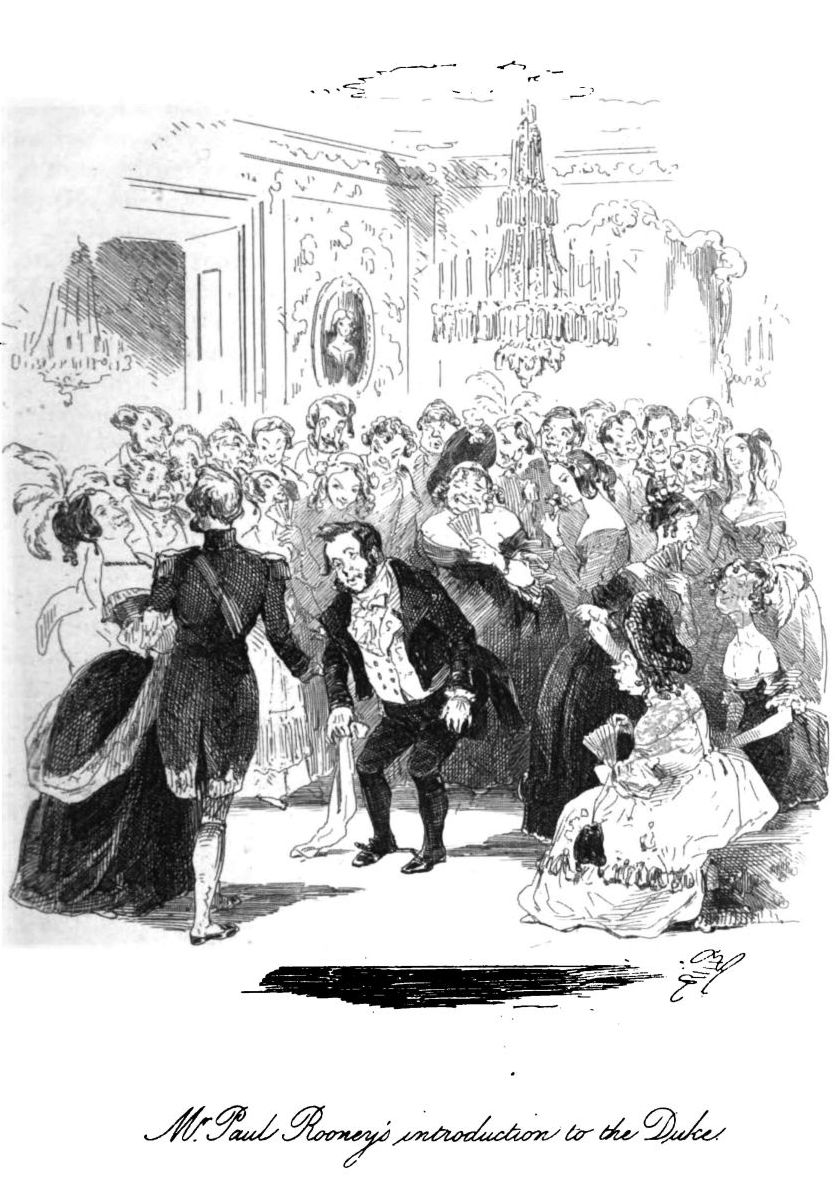

CHAPTER IX. THE BALL

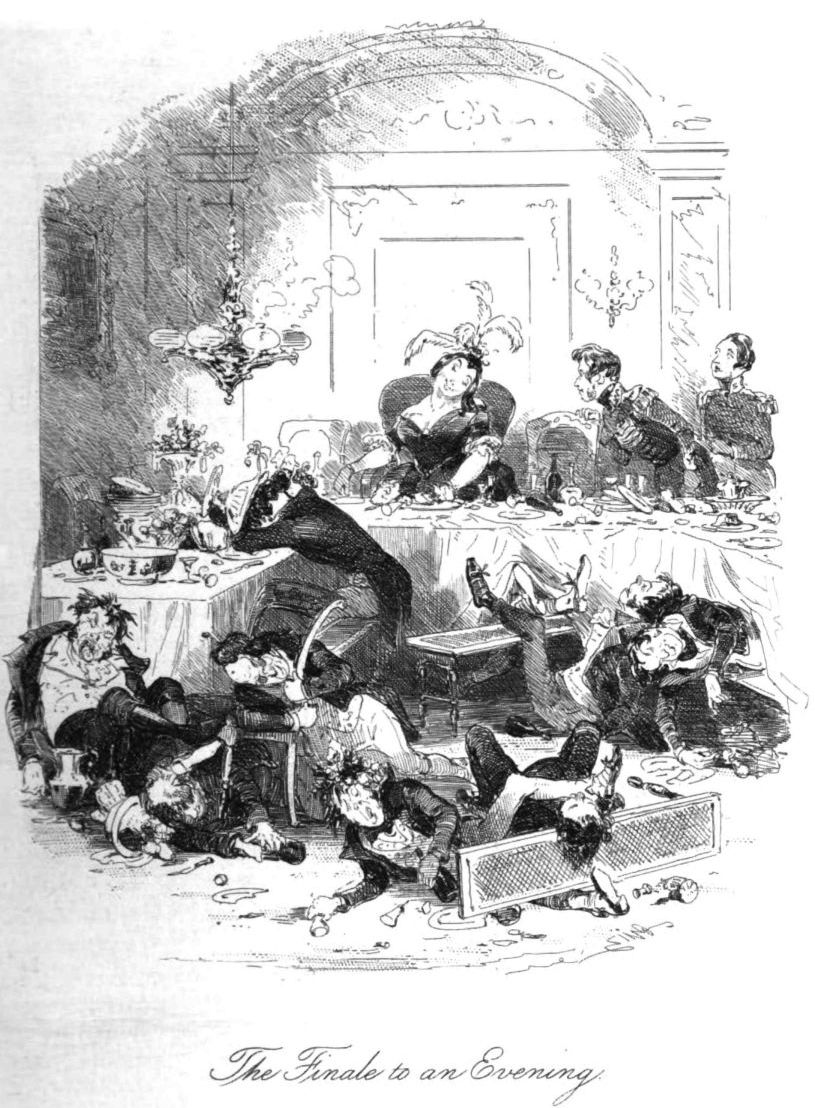

CHAPTER X. A FINALE TO AN EVENING

CHAPTER XI. A NEGOTIATION

CHAPTER XII. A WAGER

CHAPTER XIII. A NIGHT OF TROUBLE

CHAPTER XIV. THE PARTING

CHAPTER XV. THE LETTER FROM HOME

CHAPTER XVI. A MORNING IN TOWN

CHAPTER XVII. AN EVENING IN TOWN

CHAPTER XVIII. A CONFIDENCE

CHAPTER XIX. THE CANAL-BOAT

CHAPTER XX. SHANNON HARBOUR

CHAPTER XXI. LOUGHREA

CHAPTER XXII. A MOONLIGHT CANTER

CHAPTER XXIII. MAJOR MAHON AND HIS QUARTERS

CHAPTER XXIV. THE DEVIL'S GRIP

CHAPTER XXV. THE STEEPLECHASE

CHAPTER XXVI. THE DINNER-PARTY AT MOUNT BROWN

CHAPTER XXVII. THE RACE BALL

CHAPTER XXVIII. THE INN FIRE

CHAPTER XXIX. THE DUEL

CHAPTER XXX. A COUNTRY DOCTOR

CHAPTER XXXI. THE LETTER-BAG

CHAPTER XXXII. BOB MAHON AND THE WIDOW

CHAPTER XXXIII. THE PRIEST'S GIG

CHAPTER XXXIV. THE MOUNTAIN PASS

CHAPTER XXXV. THE JOURNEY

CHAPTER XXXVI. MURRANAKILTY

CHAPTER XXXVII. SIR SIMON

CHAPTER XXXVIII. ST. SENAN'S WELL

CHAPTER XXXIX. AN UNLOOKED-FOR MEETING

CHAPTER XL. THE PRIEST'S KITCHEN

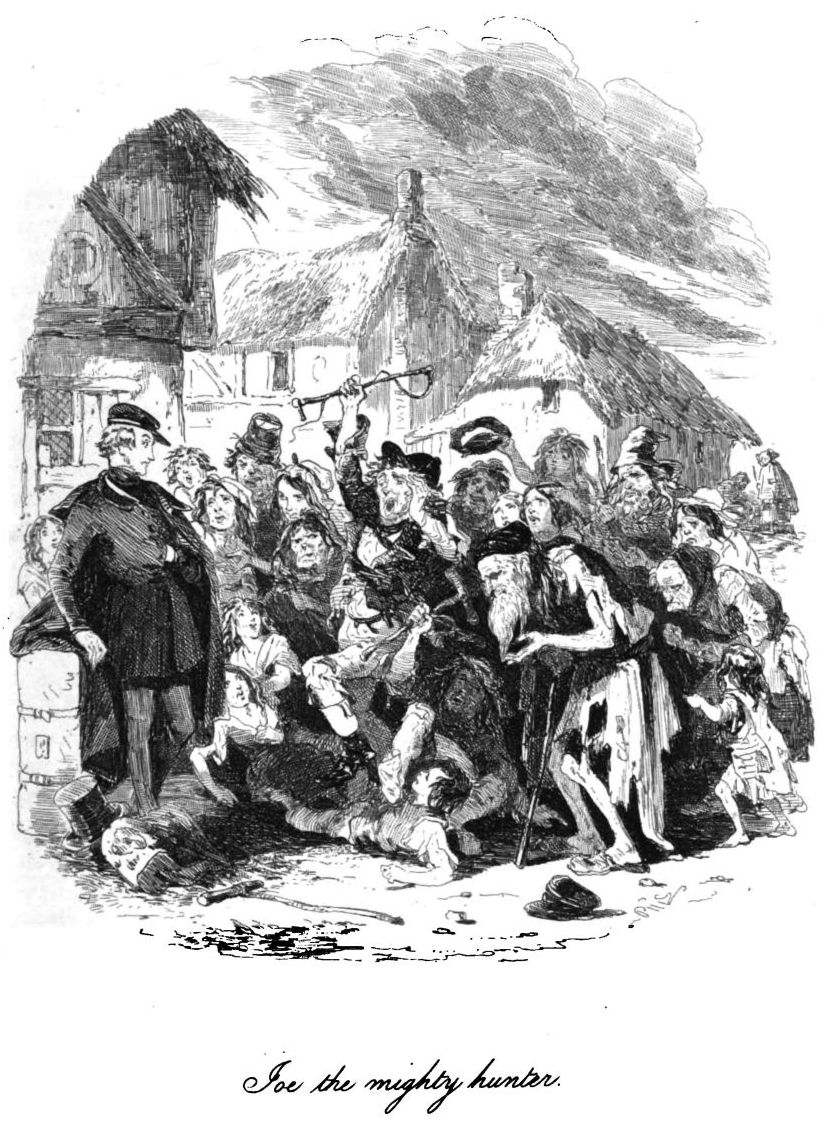

CHAPTER XLI. TIPPERARY JOE

CHAPTER XLII. THE HIGHROAD

CHAPTER XLIII. THE ASSIZE TOWN

CHAPTER XLIV. THE BAD DINNER

CHAPTER XLV. THE RETURN

CHAPTER XLVI. FAREWELL TO IRELAND

CHAPTER XLVII. LONDON

CHAPTER XLVIII. AN UNHAPPY DISCLOSURE

CHAPTER XLIX. THE HORSE GUARDS

CHAPTER L. THE RETREAT FROM BURGOS

CHAPTER LI. A MISHAP

CHAPTER LII. THE MARCH

CHAPTER LIII. VITTORIA

CHAPTER LIV. THE RETREAT

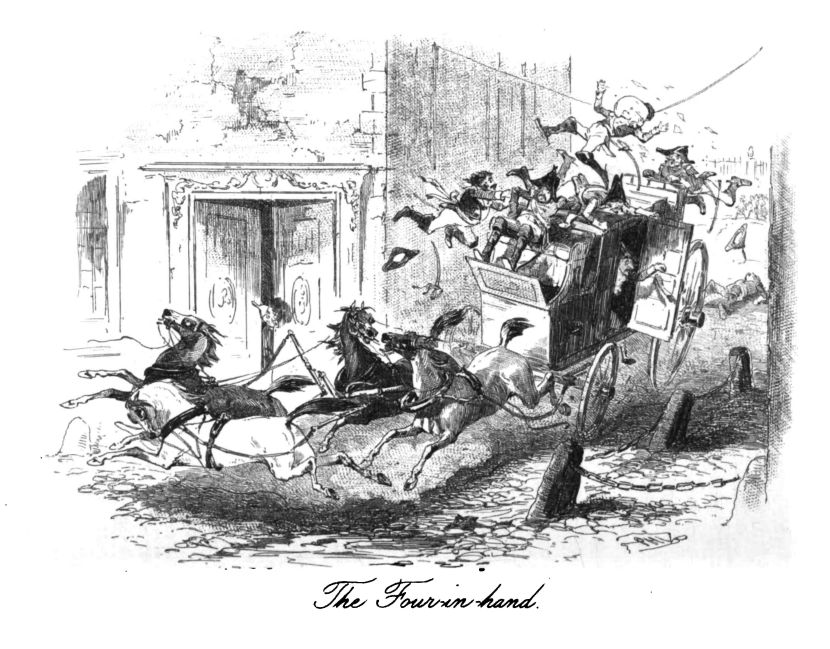

CHAPTER LV. THE FOUR-IN-HAND

CHAPTER LVI. ST. DENIS

CHAPTER LVII. PARIS IN 1814

CHAPTER LVIII. THE RONI FÊTE

CHAPTER LIX. FRESCATI'S

CHAPTER LX. DISCLOSURES

CHAPTER LXI. NEW ARRIVALS

CHAPTER LXII. CONCLUSION

Very few words of preface will suffice to the volume now presented to my readers. My intention was to depict, in the early experiences of a young Englishman in Ireland, some of the almost inevitable mistakes incidental to such a character. I had so often myself listened to so many absurd and exaggerated opinions on Irish character, formed on the very slightest acquaintance with the country, and by persons, too, who, with all the advantages long intimacy might confer, would still have been totally inadequate to the task of a rightful appreciation, that I deemed the subject one where a little “reprisal” might be justifiable.

Scarcely, however, had I entered upon my story, than I strayed from the path I had determined on, and, with very little reference to my original intention, suffered Jack Hinton to “take his chance amongst the natives,” and with far too much occupation on his hands to give time for reflecting over their peculiarities, or recording their singular traits, I threw him into the society of the capital, under the vice-royalty of a celebrated Duke, all whose wayward eccentricities were less marked than the manly generosity and genuine honesty of his character. I introduced him into a set where, whatever purely English readers may opine, I have wonderfully little exaggerated; and I led him down to the West to meet adventures which every newspaper, some twenty-five years ago, would show were by no means extravagant or strange.

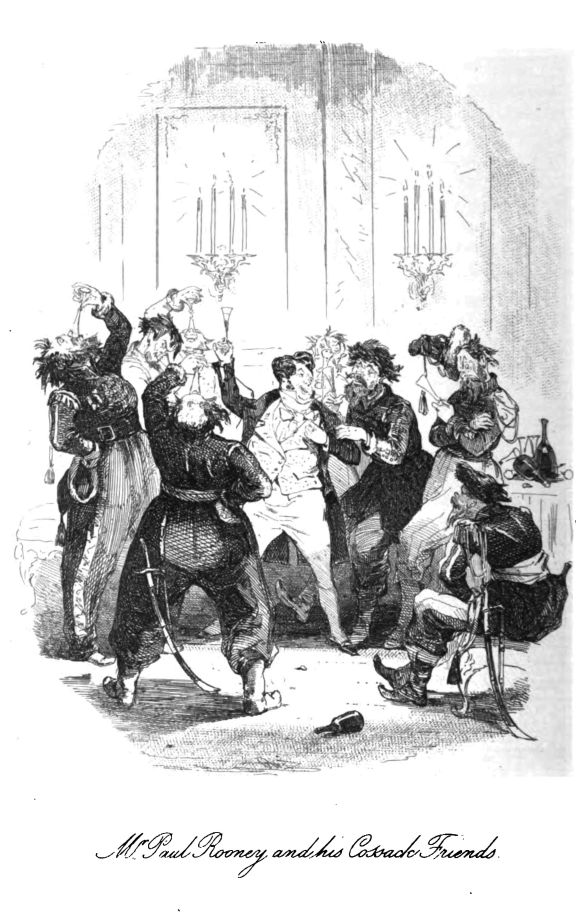

As for the characters of the story, there is not one for which I did not take a “real sitter;” at the same time, I have never heard one single correct guess as to the types that afforded them. To Mrs. Paul Rooney, Father Tom Loftus, Bob Mahon, O'Grady, Tipperary Joe, and even Corny himself, I have scarcely added a touch which nature has not given them, while assuredly I have failed to impart many a fine and delicate tint far above the “reach of—'my—art,” and which might have presented them in stronger light and shadow than I have dared to attempt. Had I desired to caricature English ignorance as to Ireland in the person of my Guardsman, nothing would have been easier; but I preferred merely exposing him to such errors as might throw into stronger relief the peculiarities of Irishmen, and, while offering something to laugh at, give no offence to either. The volume amused me while I was writing it,—less, perhaps, by what I recorded, than what I abstained from inditing; at all events, it was the work of some of the pleasantest hours of my life, and if it can ever impart to any of my readers a portion of the amusement some of the real characters afforded myself, it will not be all a failure. That it may succeed so far is the hope of the reader's

Very devoted servant,

CHARLES LEVER.

Casa Capponi, Florence, March, 1857.

It was on a dark and starless night in February, 181—, as the last carriage of a dinner-party had driven from the door of a large house in St. James's-square, when a party drew closer around the drawing-room fire, apparently bent upon that easy and familiar chit-chat the presence of company interdicts.

One of these was a large and fine-looking man of about five-and-forty, who, dressed in the full uniform of a general officer, wore besides the ribbon of the Bath; he leaned negligently upon the chimney-piece, and, with his back towards the fire, seemed to follow the current of his own reflections: this was my Father.

Beside him, but almost concealed in the deep recess of a well-cushioned arm-chair, sat, or rather lay, a graceful figure, who with an air of languid repose was shading her fine complexion as well from the glare of the fire as from the trying brilliancy of an Argand lamp upon the mantelpiece. Her rich dress, resplendent with jewels, while it strangely contrasted with the careless ease of her attitude, also showed that she had bestowed a more than common attention that day upon her toilette: this, fair reader, was my Mother.

Opposite to her, and disposed in a position of rather studied gracefulness, lounged a tall, thin, fashionable-looking man, with a dark olive complexion, and a short black moustache. He wore in the button-hole of his blue coat the ribbon of St. Louis. The Count de Grammont, for such he was, was an émigré noble, who, attached to the fortunes of the Bourbons, had resided for some years in London, and who, in the double capacity of adviser of my father and admirer of my lady-mother, obtained a considerable share of influence in the family and a seat at its councils.

At a little distance from the rest, and apparently engaged with her embroidery, sat a very beautiful girl, whose dark hair and long lashes deepened the seeming paleness of features a Greek sculptor might have copied. While nothing could be more perfect than the calm loveliness of her face and the delicate pencilling of her slightly-arched eyebrows, an accurate observer could detect that her tremulous lip occasionally curled with a passing expression of half scorn, as from time to time she turned her eyes towards each speaker in turn, while she herself maintained a perfect silence. My cousin, Lady Julia Egerton, had indeed but that one fault: shall I venture to call by so harsh a name that spirit of gentle malice which loved to look for the ludicrous features of everything around her, and inclined her to indulge what the French call the “esprit moqueur” even on occasions where her own feelings were interested?

The last figure of the group was a stripling of some nineteen years, who, in the uniform of the Guards, was endeavouring to seem perfectly easy and unconcerned, while it was evident that his sword-knot divided his attention with some secret thoughts that rendered him anxious and excited: this was Myself!

A silence of some moments was at length broken by my mother, who, with a kind of sigh Miss O'Neill was fond of, turned towards the Count, and said,

“Do confess, Count, we were all most stupid to-day. Never did a dinner go off so heavily. But it's always the penalty one pays for a royal Duke. A propos, General, what did he say of Jack's appointment?”

“Nothing could be more kind, nothing more generous than his Royal Highness. The very first thing he did in the room was to place this despatch in my hands. This, Jack,” said my father, turning to me, “this is your appointment as an extra aide-de-camp.”

“Very proper indeed,” interposed my mother; “I am very happy to think you'll be about the Court. Windsor, to be sure, is stupid.”

“He is not likely to see much of it,” said my father, dryly.

“Oh, you think he'll be in town then?”

“Why, not exactly that either.”

“Then what can you mean?” said she, with more of animation than before.

“Simply, that his appointment is on the staff in Ireland.”

“In Ireland!” repeated my mother, with a tragic start. “In Ireland!”

“In Ireland!” said Lady Julia, in a low, soft voice.

“En Irlande!” echoed the Count, with a look of well got up horror, as he elevated his eyebrows to the very top of his forehead; while I myself, to whom the communication was as sudden and as unexpected, assumed a kind of soldier-like indifference, as though to say, “What matters it to me? what do I care for the rigours of climate? the snows of the Caucasus, or the suns of Bengal, are quite alike; even Ireland, if his Majesty's service require it.”

“Ireland!” repeated my mother once more; “I really never heard anything so very shocking. But, my dear Jack, you can't think of it. Surely, General, you had presence of mind to decline.”

“To accept, and to thank most gratefully his Royal Highness for such a mark of his favour, for this I had quite presence of mind,” said my father, somewhat haughtily.

“And you really will go, Jack?”

“Most decidedly,” said I, as I put on a kind of Godefroy de Bouillon look, and strutted about the room.

“And pray what can induce you to such a step?”

“Oui, que diable allait-il faire dans cette galère?'” said the Count.

“By Jove!” cried my father, hastily, “you are intolerable; you wished your boy to be a Guardsman in opposition to my desire for a regiment on service. You would have him an aide-de-camp: now he is both one and the other. In Heaven's name, what think ye of getting him made a lady of the bedchamber? for it's the only appointment I am aware of——”

“You are too absurd, General,” said my mother, pettishly. “Count, pray touch the bell; that fire is so very hot, and I really was quite unprepared for this piece of news.”

“And you, Julia,” said I, leaning over the back of my cousin's chair, “what do you say to all this?”

“I've just been thinking what a pity it is I should have wasted all my skill and my worsted on this foolish rug, while I could have been embroidering a gay banner for our young knight bound for the wars. 'Partant pour la Syrie,'” hummed she, half pensively, while I could see a struggling effort to suppress a laugh. I turned indignantly away, and walked towards the fire, where the Count was expending his consolations on my mother.

“After all, Miladi, it is not so bad as you think in the provinces; I once spent three weeks in Brittany, very pleasantly indeed: oui, pardieu, it's quite true. To be sure, we had Perlet, and Mademoiselle Mars, and got up the Précieuse Ridicules as well as in Paris.”

The application of this very apposite fact to Ireland was clearly satisfactory to my mother, who smiled benignly at the speaker, while my father turned upon him a look of the most indescribable import.

“Jack, my boy!” said he, taking me by the arm, “were I your age, and had no immediate prospect of active service, I should prefer Ireland to any country in the world. I have plenty of old friends on the staff there. The Duke himself was my schoolfellow——”

“I hope he will be properly attentive,” interrupted my mother. “Dear Jack, remind me to-morrow to write to Lady Mary.”

“Don't mistake the country you are going to,” continued my father; “you will find many things very different from what you are leaving; and, above all, be not over ready to resent, as an injury, what may merely be intended as a joke: your brother officers will always guide you on these points.”

“And above all things,” said my mother, with great earnestness, “do not adopt that odious fashion of wearing their hair. I've seen members of both Houses, and particularly that little man they talk so much of, Mr. Grattan, I believe they call him——”

“Make your mind perfectly easy on that head, my lady,” said my father, dryly, “your son is not particularly likely to resemble Henry Grattan.”

My cousin Julia alone seemed to relish the tone of sarcasm he spoke in, for she actually bestowed on him a look of almost grateful acknowledgment.

“The carriage, my lady,” said the servant. And at the same moment my mother, possibly not sorry to cut short the discussion, rose from her chair.

“Do you intend to look in at the Duchess's, General?”

“For half an hour,” replied my father; “after that I have my letters to write. Jack, you know, leaves us to-morrow.”

“'Tis really very provoking,” said my mother, turning at the same time a look towards the Count.

“A vos ordres, Madame,” said he, bowing with an air of most deferential politeness, while he presented his arm for her acceptance.

“Good night, then,” cried I, as the party left the room; “I have so much to do and to think of, I shan't join you.” I turned to look for Lady Julia, but she was gone, when and how I knew not; so I sat down at the fire to ruminate alone over my present position, and my prospects for the future.

These few and imperfect passages may put the reader in possession of some, at least, of the circumstances which accompanied my outset in life; and if they be not sufficiently explicit, I can only say, that he knows fully as much of me as at the period in question I did of myself.

At Eton, I had been what is called rather a smart boy, but incorrigibly idle; at Sandhurst, I showed more ability, and more disinclination to learn. By the favour of a royal Duke (who had been my godfather), my commission in a marching regiment was exchanged for a lieutenancy in the Guards; and at the time I write of I had been some six months in the service, which I spent in all the whirl and excitement of London society. My father, who, besides being a distinguished officer, was one of the most popular men among the clubs, my mother, a London beauty of some twenty years' standing, were claims sufficient to ensure me no common share of attention, while I added to the number what, in my own estimation at least were, certain very decided advantages of a purely personal nature.

To obviate, as far as might be, the evil results of such a career, my father secretly asked for the appointment on the staff of the noble Duke then Viceroy of Ireland, in preference to what my mother contemplated—my being attached to the royal household. To remove me alike from the enervating influence of a mother's vanity, and the extravagant profusion and voluptuous abandonment of London habits, this was his object. He calculated, too, that by new ties, new associations, and new objects of ambition, I should be better prepared, and more desirous of that career of real service to which in his heart he destined me. These were his notions, at least; the result must be gleaned from my story.

A few nights after the conversation I have briefly alluded to, and pretty much about the same hour, I aroused myself from the depression of nearly thirty hours' sea-sickness, on hearing that at length we were in the bay of Dublin. Hitherto I had never left the precincts of the narrow den denominated my berth; but now I made my way eagerly on deck, anxious to catch a glimpse, however faint, of that bold coast I had more than once heard compared with, or even preferred to, Naples. The night, however, was falling fast, and, worse still, a perfect down-pour of rain was falling with it; the sea ran high, and swept the little craft from stem to stern; the spars bent like whips, and our single topsail strained and stretched as though at every fresh plunge it would part company with us altogether. No trace or outline of the coast could I detect on any side; a deep red light appearing and disappearing at intervals, as we rode upon or sank beneath the trough of the sea, was all that my eye could perceive: this the dripping helmsman briefly informed me was the “Kish,” but, as he seemed little disposed for conversation, I was left to my unassisted ingenuity to make out whether it represented any point of the capital we were approaching or not.

The storm of wind and rain increasing at each moment, drove me once more back to the cabin, where, short as had been the period of my absence, the scene had undergone a most important change. Up to this moment my sufferings and my seclusion gave me little leisure or opportunity to observe my fellow travellers. The stray and scattered fragments of conversation that reached me, rather puzzled than enlightened me. Of the topics which I innocently supposed occupied all human attention, not a word was dropped; Carlton House was not once mentioned; the St. Leger and the Oaks not even alluded to; whether the Prince's breakfast was to come off at Knights-bridge or Progmore, no one seemed to know, or even care; nor was a hint dropped as to the fashion of the new bearskins the Guards were to sport at the review on Hounslow. The price of pigs, however, in Ballinasloe, they were perfect in. Of a late row in Kil—something, where one half of the population had massacred the other, they knew everything, even to the names of the defunct. A few of the better dressed chatted over country matters, from which I could glean that game and gentry were growing gradually scarcer; but a red-nosed, fat old gentleman, in rusty black and high boots, talked down the others by an eloquent account of the mawling that he, a certain Father Tom Loftus, had given the Reverend Paul Strong, at a late controversial meeting in the Rotunda.

Through all this “bald, disjointed chat,” unceasing demands were made for bottled porter, “matarials,” or spirits and wather, of which, were I to judge from the frequency of the requests, the consumption must have been awful.

There would seem something in the very attitude of lying down that induces reflection, and, thus stretched at full length in my berth, I could not help ruminating upon the land I was approaching, in a spirit which, I confess, accorded much more with my mother's prejudices than my father's convictions. From the few chance phrases dropped around me, it appeared that even the peaceful pursuits of a country market, or the cheerful sports of the field, were followed up in a spirit of recklessness and devilment; so that many a head that left home without a care, went back with a crack in it. But to return once more to the cabin. It must be borne in mind that some thirty odd years ago the passage between Liverpool and Dublin was not, as at present, the rapid flight of a dozen hours, from shore to shore; where, on one evening, you left the thundering din of waggons, and the iron crank of cranes and windlasses, to wake the next morning with the rich brogue of Paddy floating softly around you. Far from it! the thing was then a voyage. You took a solemn leave of your friends, you tore yourself from the embraces of your family, and, with a tear in your eye and a hamper on your arm, you betook yourself to the pier to watch, with an anxious and a beating heart, every step of the three hours' proceeding that heralded your departure. In those days there was some honour in being a traveller, and the man who had crossed the Channel a couple of times became a kind of Captain Cook among his acquaintances.

The most singular feature of the whole, however, and the one to which I am now about to allude, proceeded from the fact that the steward in those days, instead of the extensive resources of the present period, had little to offer you, save some bad brandy and a biscuit, and each traveller had to look to his various wants with an accuracy and foresight that required both tact and habit. The mere demands of hunger and thirst were not only to be considered in the abstract, but a point of far greater difficulty, the probable length of the voyage, was to be taken into consideration; so that you bought your beefsteaks with your eye upon the barometer, and laid in your mutton by the age of the moon. While thus the agency of the season was made to react upon your stomach, in a manner doubtless highly conducive to the interests of science, your part became one of the most critical nicety.

Scarcely were you afloat, and on the high seas, when your appetite was made to depend on the aspect of the weather. Did the wind blow fresh and fair, you eat away with a careless ease and a happy conscience, highly beneficial to your digestion. With a glance through the skylight at the blue heaven, with a sly look at the prosperous dog-vane, you helped yourself to the liver wing, and took an extra glass of your sherry. Let the breeze fall, however, let a calm come on, or, worse still, a trampling noise on deck, and a certain rickety motion of the craft betoken a change of wind, the knife and fork fell listlessly from your hand, the unlifted cutlet was consigned to your plate, the very spoonful of gravy you had devoured in imagination was dropped upon the dish, and you replaced the cork in your bottle, with the sad sigh of a man who felt that, instead of his income, he has been living on the principal of his fortune.

Happily, there is a reverse to the medal, and this it was to which now my attention was directed. The trip as occasionally happened, was a rapid one; and while under the miserable impression that a fourth part of the journey had not been accomplished, we were blessed with the tidings of land. Scarcely was the word uttered, when it flew from mouth to mouth; and I thought I could trace the elated look of proud and happy hearts, as home drew near. What was my surprise, however, to see the enthusiasm take another and very different channel. With one accord a general rush was made upon the hampers of prog. Baskets were burst open on every side. Sandwiches and sausages, porter bottles, cold punch, chickens, and hard eggs, were strewn about with a careless and reckless profusion; none semed too sick or too sore for this general epidemic of feasting. Old gentlemen sat up in their beds and bawled for beef; children of tender years brandished a drumstick. Individuals who but a short half-hour before seemed to have made a hearty meal, testified by the ravenous exploits of their appetites to their former forbearance and abstemiousness. Even the cautious little man in the brown spencer, who wrapped up the remnant of his breakfast in the Times, now opened his whole store, and seemed bent upon a day of rejoicing. Never was such a scene of riotous noise and tumultuous mirth. Those who scowled at each other till now, hob-nobbed across the table; and simpering old maids cracked merry thoughts with gay bachelors, without even a passing fear for the result. “Thank Heaven,” said I, aloud, “that I see all this with my sense and my intellects clear about me.” Had I suddenly awoke to such a prospect from the disturbed slumber of sickness» the chances were ten to one I had jumped overboard, and swam for my life. In fact, it could convey but one image to the mind, such as we read of, when some infuriated and reckless men, despairing of safety, without a hope left, resolve upon closing life in the mad orgies of drunken abandonment.

Here were the meek, the tranquil, the humble-minded, the solitary, the seasick, all suddenly converted into riotous and roystering feasters. The lips that scarcely moved, now blew the froth from a porter cup with the blast of a Boreas: and even the small urchin in the green face and nankeen jacket, bolted hard eggs with the dexterity of a clown in a pantomime. The end of all things (eatable) had certainly come. Chickens were dismembered like felons, and even jokes and witticisms were bandied upon the victuals. “What, if even yet,” thought I, “the wind should change!” The idea was a malicious one, too horrible to indulge in. At this moment the noise and turmoil on deck apprised me that our voyage was near its termination.

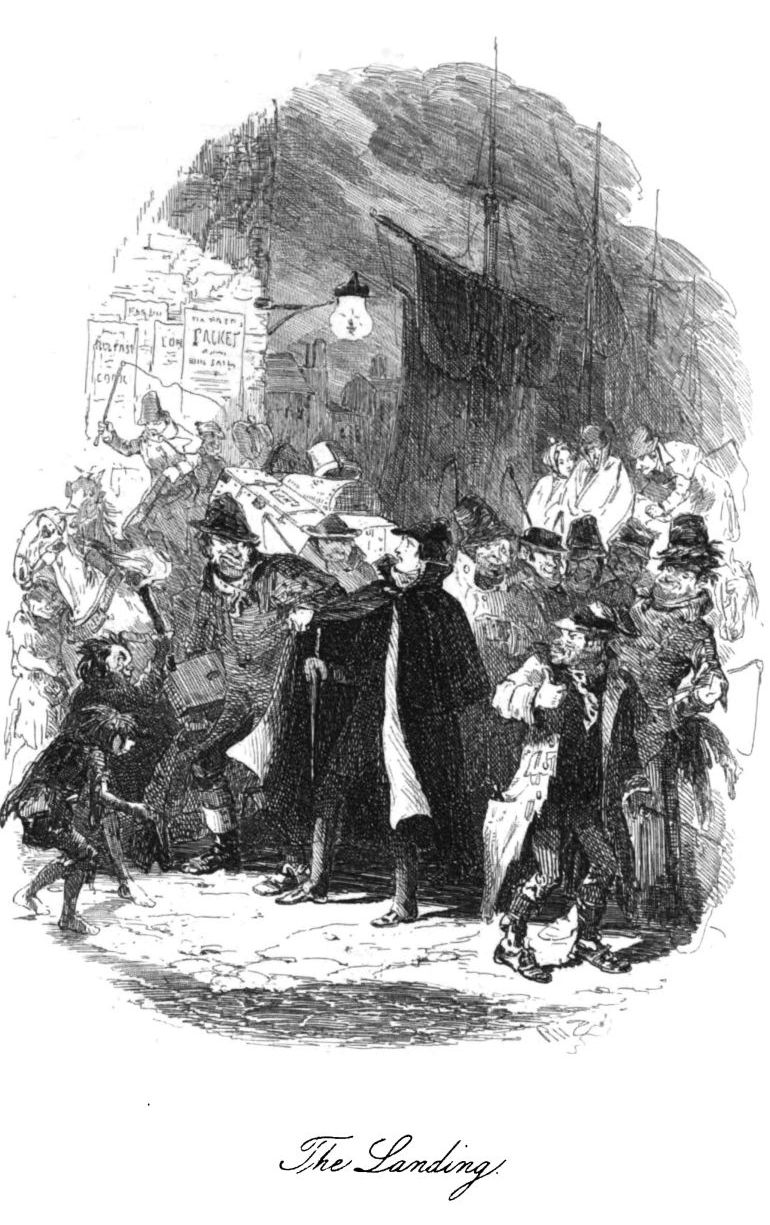

The night, as I have said, was dark and stormy. It rained too—as it knows only how to rain in Ireland. There was that steady persistence, that persevering monotony of down-pour, which, not satisfied with wetting you to the skin, seems bent upon converting your very blood into water. The wind swept in long and moaning gusts along the bleak pier, which, late and inclement as it was, seemed crowded with people. Scarcely was a rope thrown ashore, when we were boarded on every side, by the rigging, on the shrouds, over the bulwarks, from the anchor to the taffrail; the whole population of the island seemed to flock in upon us; while sounds of welcome and recognition resounded on all sides—

“How are you, Mister Maguire?” “Is the mistress with you?” “Is that you, Mr. Tierney?” “How are you, ma'am?” “And yourself, Tim?” “Beautiful, glory be to God!” “A great passage, entirely, ma'am.” “Nothing but rain since I seen you.” “Take the trunks up to Mrs. Tun-stall; and, Tim, darling, oysters and punch for four.”

“Great mercy!” said I, “eating again!”

“Morrisson, your honour,” said a ragged ruffian, nudging me by the elbow.

“Reilly, sir; isn't it? It's me, sir—the Club. I'm the man always drives your honour.”

“Arrah, howld your prate,” said a deep voice, “the gentleman hasn't time to bless himself.”

“It's me, sir; Owen Daly, that has the black horse.”

“More by token, with a spavin,” whispered another; while a roar of laughter followed the joke.

“A car, sir—take you up in five minutes.”

“A chaise, your honour—do the thing dacently.”

Now, whether my hesitation at this moment was set down by the crowd of my solicitors to some doubt of my solvency or not, I cannot say; but true it is, their tone of obsequious entreaty gradually changed into one of rather caustic criticism.

“Maybe it's a gossoon you'd like to carry the little trunk.”

“Let him alone; it's only a carpet-bag; he'll carry it himself.”

“Don't you see the gentleman would rather walk; and as the night is fine, 'tis pleasanter—and—cheaper.”

“Take you for a fipp'ny bit and a glass of sparits,” said a gruff voice in my ear.

By this time I had collected my luggage together, whose imposing appearance seemed once more to testify in my favour, particularly the case of my cocked-hat, which to my ready-witted acquaintances proclaimed me a military man. A general rush was accordingly made upon my luggage; and while one man armed himself with a portmanteau, another laid hands on a trunk, a third a carpet-bag, a fourth a gun-case, and so on until I found myself keeping watch and ward over my epaulet-case and my umbrella, the sole remnant of my effects. At the same moment a burst of laughter and a half shout broke from the crowd, and a huge, powerful fellow jumped on the deck, and, seizing me by the arm, cried out,

“Come along now, Captain, it's all right. This way—this way, sir.”

“But why am I to go with you?” said I, vainly struggling to escape his grasp.

“Why is it?” said he, with a chuckling laugh; “reason enough—didn't we toss up for ye, and didn't I win ye.”

“Win me!”

“Ay; just that same.”

By this time I found myself beside a car, upon which all my luggage was already placed.

“Get up, now,” said he.

“It's a beautiful car, and a dhry cushion,” added a voice near, to the manifest mirth of the bystanders.

Delighted to escape my tormentors, I sprang up opposite to him, while a cheer, mad and wild enough for a tribe of Iroquois, yelled behind us. Away We rattled over the pavement, without lamp or lantern to guide our path, while the sea dashed its foam across our faces, and the rain beat in torrents upon our backs.

“Where to, Captain?” inquired my companion, as he plied his whip without ceasing.

“The Castle; you know where that is?”

“Faix I ought,” was the reply. “Ain't I there at the levees. But howld fast, your honour; the road isn't good; and there is a hole somewhere hereabouts.”

“A hole! For Heaven's sake, take care. Do you know where it is?”

“Begorra! you're in it,” was the answer; and, as he spoke, the horse went down head foremost, the car after him; away flew the driver on one side, while I myself was shot some half-dozen yards on the other, a perfect avalanche of trunks, boxes, and portmanteaus rattling about my doomed head. A crashing shower of kicks, the noise of the flying splinters, and the imprecations of the carman, were the last sounds I heard, as a heavy imperial full of books struck me on the head, and laid me prostrate.

Through my half-consciousness, I could still feel the rain as it fell in sheets; the heavy plash of the sea sounded in my ears; but, somehow, a feeling like sleepiness crept over me, and I became insensible.

When I next came to my senses, I found myself lying upon a sofa in a large room, of which I appeared the only occupant. A confused and misty recollection of my accident, some scattered fragments of my voyage, and a rather aching sensation in my head, were the only impressions of which I was well conscious. The last evening I spent at home was full in my memory, and I could not help thinking over my poor mother's direful anticipations in my vain endeavours to penetrate what I felt had been a misfortune of some kind or other. The mystery was, however, too deep for my faculties; and so, in despair of unravelling the past, I set myself to work to decipher the present. The room, I have already said, was large; and the ceiling, richly stuccoed and ornamented, spoke of a day whose architecture was of a grand and massive character. The furniture, now old and time-worn, had once been handsome, even magnificent—rich curtains of heavy brocaded silk, with deep gold fringes, gorgeously carved and gilded chairs, in the taste of Louis XV.; marble consoles stood between the windows, and a mirror of gigantic proportions occupied the chimney-breast. Years and neglect had not only done their worst, but it was evident that the hand of devastation had also been at work. The marbles were cracked; few of the chairs were available for use; the massive lustre, intended to shine with a resplendent glare of fifty wax-lights, was now made a resting-place for chakos, bearskins, and foraging caps; an ominous-looking star in the looking-glass bore witness to the bullet of a pistol; and the very Cupids carved upon the frame, who once were wont to smile blandly at each other, were now disfigured with cork moustaches, and one of them even carried a short pipe in his mouth. Swords, sashes, and sabretasches, spurs and shot-belts, with guns, fishing-tackle, and tandem whips, were hung here and there upon the walls, which themselves presented the strangest spectacle of all, there not being a portion of them unoccupied by caricature sketches, executed in every imaginable species of taste, style, and colouring. Here was a field-day in the Park, in which it was easy to see the prominent figures were portraits: there an enormous nose, surmounted by a grenadier cap, was passing in review some trembling and terrified soldiers. In another, a commander of the forces was seen galloping down the lines, holding on by the pommel of the saddle. Over the sofa I occupied, a levee at the Castle was displayed, in which, if the company were not villanously libelled, the Viceroy had little reason to be proud of his guests. There were also dinners at the Lodge; guards relieved by wine puncheons dressed up like field-officers; the whole accompanied by doggrel verses explanatory of the views.

The owner of this singular chamber had, however, not merely devoted his walls to the purposes of an album, but he had also made them perform the part of a memorandum-book. Here were the “meets” of the Kildare and the Dubber for the month of March; there, the turn of duty for the garrison of Dublin, interspersed with such fragments as the following:—“Mem. To dine at Mat Kean's on Tuesday, 4th.—Not to pay Hennesy till he settles about the handicap.—To ask Courtenay—for Fanny Burke's fan; the same Fanny has pretty legs of her own.—To tell Holmes to have nothing to do with Lanty Moore's niece, in regard to a reason!—Five to two on Giles's two-year-old, if Tom likes. N.B. The mare is a roarer.—A heavenly day; what fun they must have!—may the devil fire Tom O'Flaherty, or I would not be here now.” These and a hundred other similar passages figured on every side, leaving me in a state of considerable mystification, not as to the character of my host, of which I could guess something, but as to the nature of his abode, which I could not imagine to be a barrack-room.

As I lay thus pondering, the door cautiously opened, and a figure appeared, which, as I had abundant leisure to examine it, and as the individual is one who occasionally turns up in the course of my history, I may as well take the present opportunity of presenting to my reader. The man who entered, scarcely more than four feet and a half high, might be about sixty years of age. His head, enormously disproportioned to the rest of his figure, presented a number of flat surfaces, as though nature had originally destined it for a crystal. Upon one of these planes the eyes were set; and although as far apart as possible, yet upon such terms of distance were they, that they never, even by an accident, looked in the same direction. The nose was short and snubby; the nostrils wide and expanded, as if the feature had been pitched against the face in a moment of ill-temper, and flattened by the force. As for the mouth, it looked like the malicious gash of a blunt instrument, jagged, ragged, and uneven. It had not even the common-place advantage of being parallel to the horizon, but ran in an oblique direction from right to left, enclosed between a parenthesis of the crankiest wrinkles that ever human cheek were creased by. The head would have been bald but for a scanty wig, technically called a “jasy,” which, shrunk by time, now merely occupied the apex of the scalp, where it moved about with every action of the forehead and eyebrows, and was thus made to minister to the expression of a hundred emotions that other men's wigs know nothing about. Truly, it was the strangest peruke that ever covered a human cranium. I do not believe that another like it ever existed. It had nothing in common with other wigs. It was like its owner, perfectly sui generis. It had not the easy flow and wavy curl of the old beau. It had not the methodical precision and rectilinear propriety of the elderly gentleman. It was not full, like a lawyer's, nor horse-shoed, like a bishop's. No. It was a cross-grained, ill-tempered, ill-conditioned old scratch, that looked like nothing under heaven save the husk of a hedgehog.

The dress of this strange figure was a suit of very gorgeous light brown livery, with orange facings, a green plush waistcoat and shorts, frogged, flapped, and embroidered most lavishly with gold lace, silk stockings, with shoes, whose enormous buckles covered nearly the entire foot, and rivalled, in their paste brilliancy, the piercing brightness of the wearer's eye. Having closed the door carefully behind him, he walked towards the chimney, with a certain air of solemn and imposing dignity that very nearly overcame all my efforts at seriousness; his outstretched and expanded hands, his averted toes and waddling gait, giving him a most distressing resemblance to the spread eagle of Prussia, had that respectable bird been pleased to take a promenade in a showy livery. Having snuffed the candles, and helped himself to a pinch of snuff from a gold box on the mantelpiece, he stuck his arms, nearly to the elbows, in the ample pockets of his coat, and with his head a little elevated, and his under-lip slightly protruded, seemed to meditate upon the mutability of human affairs, and the vanity of all worldly pursuits.

I coughed a couple of times to attract his attention, and, having succeeded in catching his eye, I begged, in my blandest imaginable voice, to know where I was.

“Where are ye, is it?” said he, repeating my question in a tone of the most sharp and querulous intonation, to which not even his brogue could lend one touch of softness,—“where are ye? and where would you like to be? or where would any one be that was disgracing himself, or blackguarding about the streets till he got his head cut and his clothes torn, but in Master Phil's room: devil other company it's used to. Well, well! It is more like a watchhouse nor a gentleman's parlour, this same room. It's little his father, the Jidge”—here he crossed himself piously—“it is little he thought the company his son would be keeping; but it is no matter. I gave him warning last Tuesday, and with the blessin' o' God——”

The remainder of this speech was lost in a low muttering grumble, which I afterwards learnt was his usual manner of closing an oration. A few broken and indistinct phrases being only audible, such as—“Sarve you right”—“Fifty years in the family”—“Slaving like a negur”—“Oh, the Turks! the haythins!”

Having waited what I deemed a reasonable time for his honest indignation to evaporate, I made another effort to ascertain who my host might be.

“Would you favour me,” said I, in a tone still more insinuating, “with the name of——”

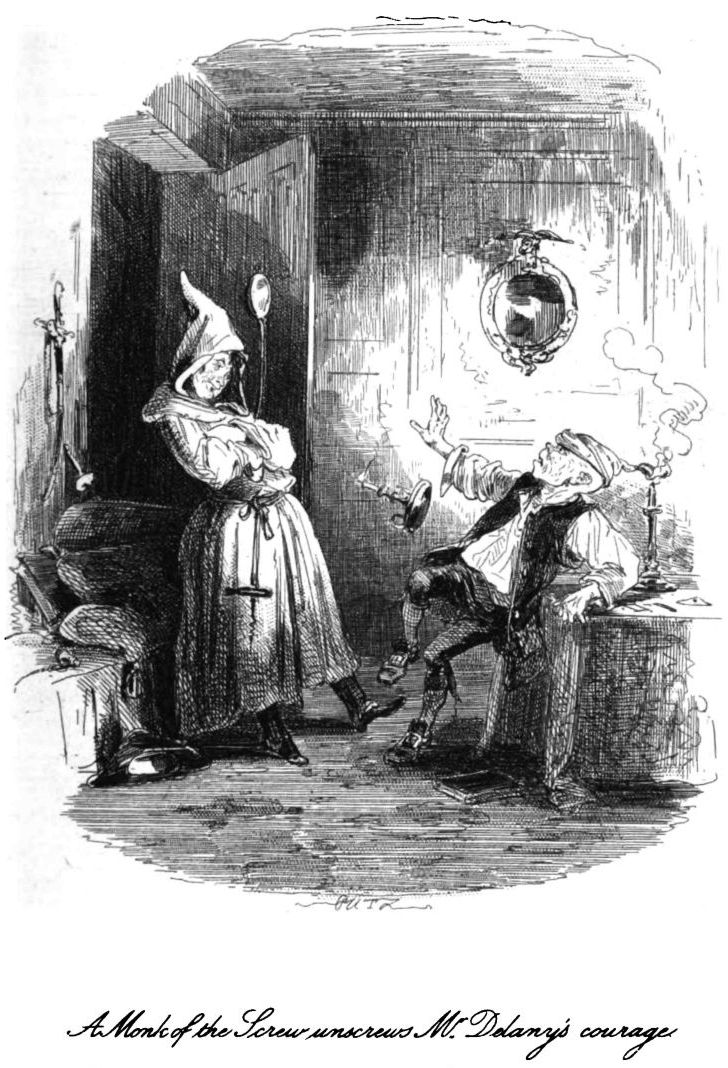

“It's my name, ye want? Oh, sorrow bit I am ashamed of it! Little as you think of me, Cornelius Delany is as good a warrant for family as many a one of the dirty spalpeens about the Coort, that haven't a civiler word in their mouth than Cross Corny! Bad luck to them for that same.”

This honest admission as to the world's opinion of Mister Delany's character was so far satisfactory as it enabled me to see with whom I had to deal; and, although for a moment or two it was a severe struggle to prevent myself bursting into laughter, I fortunately obtained the mastery, and once more returned to the charge.

“And now, Mister Delany, can you inform me how I came here? I remember something of an accident on my landing; but when, where, and how, I am totally ignorant.”

“An accident!” said he, turning up his eyes; “an accident, indeed! that's what they always call it when they wring off the rappers, or bate the watch: ye came here in a hackney-coach, with the police, as many a one came before you.”

“But where am I?” said I, impatiently.

“In Dublin Castle; bad luck to it for a riotous, disorderly place.”

“Well, well,” said I, half angrily, “I want to know whose room is this?”

“Captain O'Grady's. What have you to say agin the room? Maybe you're used to worse. There now, that's what you got for that. I'm laving the place next week, but that's no rayson——”

Here he went off, diminuendo, again, with a few flying imprecations upon several things and persons unknown.

Mr. Delany now dived for a few seconds into a small pantry at the end of the room, from which he emerged with a tray between his hands, and two decanters under his arms.

“Draw the little table this way,” he cried, “more towards the fire, for, av coorse, you're fresh and fastin'; there now, take the sherry from under my arm—the other's port: that was a ham, till Captain Mills cut it away, as ye see—there's a veal pie, and here's a cold grouse—and, maybe, you've eat worse before now—and will again, plaze God.”

I assured him of the truth of his observation in a most conciliating tone.

“Oh, the devil fear ye,” was the reply, while he murmured somewhat lower, “the half of yees isn't used to meat twice in the week.”

“Capital fare this, Mr. Delany,” said I, as, half famished with long fasting, I helped myself a second time.

“You're eating as if you liked it,” said he, with a shrug of his shoulders.

“Upon my word,” said I, after throwing down a bumper of sherry, “that's a very pleasant glass of wine; and, on the whole, I should say, there are worse places than this in the world.”

A look of unutterable contempt—whether at me for my discovery, or at the opinion itself, I can't say—was the sole reply of my friend; who, at the same moment, presuming I had sufficient opportunities for the judgment I pronounced, replaced the decanters upon the tray, and disappeared with the whole in the most grave and solemn manner.

Repressing a very great inclination to laughter, I sat still; and a silence of a few moments ensued, when Mr. Delany walked towards the window, and, drawing aside the curtains, looked out. All was in darkness save on the opposite side of the court-yard, where a blaze of light fell upon the pavement from over the half shutters of an apparently spacious apartment. “Ay, ay, there you go; hip, hip, hurrah! you waste more liquor every night than would float a lighter; that's all you're good for. Bad luck to your Grace—making fun of the people, laughing and singing as if the potatoes wasn't two shillings a stone.”

“What's going on there?” said I.

“The ould work, nather more nor less. The Lord-Liftinnant, and the bishops, and the jidges, and all the privy councillors roaring drunk. Listen to them. May I never, if it isn't the Dean's voice I hear—the ould beast; he is singing 'The Night before Larry was stretched.'”

“That's a good fellow, Corny—Mr. Delany I mean—do open the window for a little, and let's hear them.”

“It's a blessed night you'd have the window open to listen to a set of drunken devils: but here's Master Phil; I know his step well It's long before his father that's gone would come tearing up the stairs that way as if the bailiffs was after him; rack and ruin, sorrow else, av I never got a place—the haythins! the Turks!”

Mr. Delany, who, probably from motives of delicacy, wished to spare his master the pain of an interview, made his exit by one door as he came in at the other. I had barely time to see that the person before me was in every respect the very opposite of his follower, when he called out in a rich, mellow voice,

“All right again, I hope, Mr. Hinton; it's the first moment I could get away; we had a dinner of the Privy Council, and some of them are rather late sitters; you're not hurt, I trust?”

“A little bruised or so, nothing more; but pray, how did I fall into such kind hands?”

“Oh! the watchmen, it seems, could read, and, as your trunks were addressed to the Castle, they concluded you ought to go there also. You have despatches, haven't you?”

“Yes,” said I, producing the packet; “when must they be delivered?”

“Oh, at once. Do you think you could make a little change in your dress, and manage to come over? his Grace always likes it better; there's no stiffness, no formality whatever; most of the dinner-party have gone home; there are only a few of the government people, the Duke's friends, remaining, and, besides, he's always kind and good-natured.”

“I'll see what I can do,” replied I, as I rose from the sofa; “I put myself into your hands altogether.”

“Well, come along,” said he; “you'll find everything ready in this room. I hope that old villain has left hot water. Corny! Corny, I say! Confound him, he's gone to bed, I suppose.”

Having no particular desire for Mr. Delany's attentions, I prevailed on his master not to disturb him, and proceeded to make my toilette as well as I was able.

“Didn't that stupid scoundrel come near you at all?” cried O'Grady.

“Oh yes, we have had a long interview; but, somehow, I fear I did not succeed in gaining his good graces.”

“The worst-tempered old villain in Europe.”

“Somewhat of a character, I take it.”

“A crab-tree planted in a lime-kiln, cranky and cross-grained; but he is a legacy, almost the only one my father left me. I've done my best to part with him every day for the last twelve years, but he sticks to me like a poor relation, giving me warning every night of his life, and every morning kicking up such a row in the house that every one is persuaded I am beating him to a jelly before turning him out to starve in the streets.”

“Oh, the haythins! the Turks!” said I, slyly.

“Confound it!” cried he, “the old devil has been opening upon you already; and Jet, with all that, I don't know how I should get on without Corny; his gibes, his jeers, his everlasting ill-temper, his crankiness that never sleeps, seem to agree with me: the fact is, one enjoys the world from all its contrasts. The olive is a poor thing in itself, but it certainly improves the smack of your Burgundy. In this way Corny Delany does me good service. Come, by Jove, you have not been long dressing. This way: now follow' me.” So saying, Captain O'Grady led the way down the stairs to the colonnade, following which to the opposite side of the quadrangle we arrived at a brilliantly lighted hall, where several servants in full-dress liveries were in waiting. Passing hastily through this, we mounted a handsome staircase, and, traversing several ante-chambers, at length arrived at one whose contiguity to the dinner-room I could guess at from the loud sound of many voices. “Wait one moment here,” said my companion, “until I speak to his Grace.” He disappeared as he spoke, but before a minute had elapsed he was again beside me. “Come this way; it's all right,” said he. The next moment I found myself in the dinner-room.

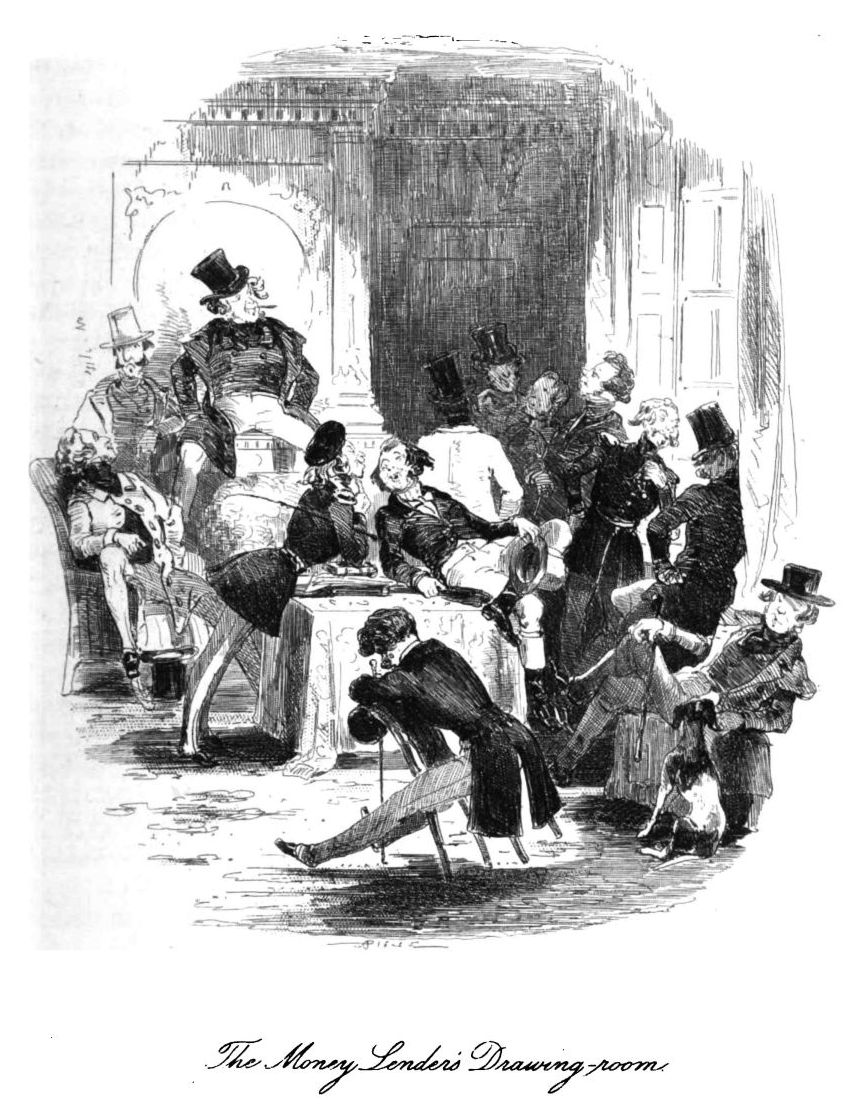

The scene before me was altogether so different from what I had expected, that for a moment or two I could scarce do aught else than stand still to survey it. At a table which had been laid for about forty persons, scarcely more than a dozen were now present. Collected together at one end of the board, the whole party were roaring with laughter at some story of a strange, melancholy-looking man, whose whining voice added indescribable ridicule to the drollery of his narrative. Grey-headed general officers, grave-looking divines, lynx-eyed lawyers, had all given way under the irresistible impulse, and the very table shook with laughter.

“Mr. Hinton, your Excellency,” said O'Grady for the third time, while the Duke wiped his eye with his napkin, and, pushing his chair a little back from the table, motioned me to approach.

“Ah, Hinton, glad to see you; how is your father?—a very old friend of mine, indeed; and Lady Charlotte—well, I hope? O'Grady tells me you've had an accident—something slight, I trust. So these are the despatches.” Here he broke the seal of the envelope, and ran his eye over the contents. “There, that's your concern.” So saying, he pitched a letter across the table to a shrewd-looking personage in a horse-shoe wig. “They won't do it, Dean, and we must wait. Ah!—so they don't like my new commissioners; but, Hinton, my boy, sit down. O'Grady, have you room there? A glass of wine with you.”

“Nothing the worse of your mishap, sir?” said the melancholy-looking man who sat opposite to me.

I replied by briefly relating my accident.

“Strange enough,” said he, in a compassionate tone, “your head should have suffered; your countrymen generally fall upon their legs in Ireland.” This was said with a sly look at the Viceroy, who, deep in his despatches, paid no attention to the allusion.

“A very singular thing, I must confess,” said the Duke, laying down the paper. “This is the fourth time the bearer of despatches has met with an accident. If they don't run foul of a rock in the Channel, they are sure to have a delay on the pier.”

“It is so natural, my Lord,” said the gloomy man, “that the carriers should stop at the Pigeon-house.”

“Do be quiet, Curran,” cried the Duke, “and pass round the decanter. They'll not take the duty off claret, it seems.”

“And Day, my Lord, won't put the claret on duty; he has kept the wine at his elbow for the last half-hour. Upon my soul, your Grace ought to knight him.”

“Not even his Excellency's habits,” said a sharp, clever-looking man, “would excuse his converting Day into Knight.”

Amid a shower of smart, caustic, and witty sayings, droll stories, retort and repartee, the wine circulated freely from hand to hand; the presence of the Duke adding fresh impulse to the sallies of fun and merriment around him. Anecdotes of the army, the bench, and the bar, poured in unceasingly, accompanied by running commentaries of the hearers, who never let slip an opportunity for a jest or a rejoinder. To me, the most singular feature of all this was, that no one seemed too old or too dignified, too high in station, or too venerable from office, to join in this headlong current of conviviality. Austere churchmen, erudite chief-justices, profound politicians, privy councillors, military officers of high rank and standing, were here all mixed up together into one strange medley, apparently bent on throwing an air of ridicule over the graver business of life, and laughing alike at themselves and the world. Nothing was too grave for a jest, nothing too solemn for a sarcasm. All the soldier's experience of men and manners, all the lawyer's acuteness of perception and readiness of wit, all the politician's practised tact and habitual subtlety, were brought to bear upon the common topics of the day with such promptitude, and such power, that one knew not whether to be more struck by the mass of information they possessed, or by that strange fatality which could make men, so great and so gifted, satisfied to jest where they might be called on to judge.

Play and politics, wine and women, debts and duels, were discussed, not only with an absence of all restraint, but with a deep knowledge of the world and a profound insight into the heart, which often imparted to the careless and random speech the sharpness of the most cutting sarcasm. Personalities, too, were rife; no one spared his neighbour, for he did not expect mercy for himself; and the luckless wight who tripped in his narrative, or stumbled in his story, was assailed on every side, until some happy expedient of his own, or some new victim being discovered, the attack would take another direction, and leave him once more at liberty. I feel how sadly inadequate I am to render even the faintest testimony to the talents of those, any one of whom, in after life, would have been considered to have made the fortune of a dinner-party, and who now were met together, not in the careless ease and lounging indifference of relaxation, but in the open arena where wit met wit, and where even the most brilliant talker, the happiest relater, the quickest in sarcasm, and the readiest in reply, felt he had need of all his weapons to defend and protect him. This was a mêlée tournament, where each man rode down his neighbour, with no other reason for attack than detecting a rent in his armour. Even the Viceroy himself, who, as judge of the lists, might be supposed to enjoy an immunity, was not safe here, and many an arrow, apparently shot at an adversary, was sent quivering into his corslet.

As I watched, with all the intense excitement of one to whom such a display was perfectly new, I could not help feeling how fortunate it was that the grave avocations and the venerable pursuits of the greater number of the party should prevent this firework of wit from bursting into the blaze of open animosity. I hinted as much to my neighbour, O'Grady, who at once broke into a fit of laughter at my ignorance; and I now learnt to my amazement that the Common Pleas had winged the Exchequer, that the Attorney-General had pinked the Bolls, and, stranger than all, that the Provost of the University himself had planted his man in the Phoenix.

“It is just as well for us,” continued he, in a whisper, “that the churchmen can't go out; for the Dean, yonder, can snuff a candle at twenty paces, and is rather a hot-tempered fellow to boot. But come, now, his Grace is about to rise. We have a field-day to-morrow in the Park, and break up somewhat earlier in consequence.”

As it was now near two o'clock, I could see nothing to cavil at as to the earliness of the hour, although, I freely confess, tired and exhausted as I felt, I could not contemplate the moment of separation without a sad foreboding that I ne'er should look upon the like again. The party rose at this moment, and the Duke, shaking hands cordially with each person as he passed down, wished us all a good night. I followed with O'Grady and some others of the household, but when I reached the ante-chamber, mv new friend volunteered his services to see me to my quarters.

On traversing the lower castle-yard, we mounted an old-fashioned and rickety stair, which conducted to a gloomy, ill-lighted corridor. I was too much fatigued, however, to be critical at the moment, and so, having thanked O'Grady for all his kindness, I threw off my clothes hastily, and, before my head was well upon the pillow, was sound asleep.

There are few persons so unreflective as not to give way to a little self-examination on waking for the first time in a strange place. The very objects about are so many appeals to your ingenuity or to your memory, that you cannot fail asking yourself how you became acquainted with them: the present is thus made the herald of the past, and it is difficult, when unravelling the tangled web of doubt that assails you, not to think over the path by which you have been travelling.

As for me, scarcely were my eyes opened to the light, I had barely thrown one glance around my cold and comfortless chamber, when thoughts of home came rushing to my mind. The warm earnestness of my father, the timid dreads of my poor mother, rose up before me, as I felt myself, for the first time, alone in the world. The elevating sense of heroism, that more or less blends with every young man's dreams of life, gilds our first journey from our father's roof. There is a feeling of freedom in being the arbiter of one's actions, to go where you will and when you will. Till that moment the world has been a comparative blank; the trammels of school or the ties of tutorship have bound and restrained you. You have been living, as it were, within the rules of court—certain petty privileges permitted, certain small liberties allowed; but now you come forth disenchanted, disenthralled, emancipated, free to come as to go—a man in all the plenitude of his volition; and, better still, a man without the heavy, depressing weight of responsibility that makes manhood less a blessing than a burden. The first burst of life is indeed a glorious thing; youth, health, hope, and confidence have each a force and vigour they lose in after years: life is then a splendid river, and we are swimming with the stream—no adverse waves to weary, no billows to buffet us, we hold on our course rejoicing.

The sun was peering between the curtains of my window, and playing in fitful flashes on the old oak floor, as I lay thus ruminating and dreaming over the fature. How many a resolve did I then make for my guidance—how many an intention did I form—how many a groundwork of principle did I lay down, with all the confidence of youth! I fashioned to myself a world after my own notions; in which I conjured up certain imaginary difficulties, all of which were surmounted by my admirable tact and consummate cleverness. I remembered how, at both Eton and Sandhurst, the Irish boy was generally made the subject of some jest or quiz, at one time for his accent, at another for his blunders. As a Guardsman, short as had been my experience of the service, I could plainly see that a certain indefinable tone of superiority was ever asserted towards our friends across the sea. A wide-sweeping prejudice, whose limits were neither founded in reason, justice, or common sense, had thrown a certain air of undervaluing import over every one and every thing from that country. Not only were its faults and its follies heavily visited, but those accidental and trifling blemishes—those slight and scarce perceptible deviations from the arbitrary standard of fashion—were deemed the strong characteristics of the nation, and condemned accordingly; while the slightest use of any exaggeration in speech—the commonest employment of a figure or a metaphor—the casual introduction of an anecdote or a repartee, were all heavily censured, and pronounced “so very Irish!” Let some fortune-hunter carry off an heiress—let a lady trip over her train at the drawing-room—let a minister blunder in his mission—let a powder-magazine explode and blow up one-half of the surrounding population, there was but one expression to qualify all—“How Irish! how very Irish!” The adjective had become one of depreciation; and an Irish lord, an Irish member, an Irish estate, and an Irish diamond, were held pretty much in the same estimation.

Reared in the very hot-bed, the forcing-house, of such exaggerated prejudice, while imbibing a very sufficient contempt for everything in that country, I obtained proportionably absurd notions of all that was Irish. Our principles may come from our fathers; our prejudices certainly descend from the female branch. Now, my mother, notwithstanding the example of the Prince Regent himself, whose chosen associates were Irish, was most thoroughly exclusive on this point. She would admit that a native of that country could be invited to an evening party under extreme and urgent circumstances—that some brilliant orator, whose eloquence was at once the dread and the delight of the House—that some gifted poet, whose verses came home to the heart alike of prince and peasant—that the painter, whose canvas might stand unblushingly amid the greatest triumphs of art—could be asked to lionise for those cold and callous votaries of fashion, across the lake of whose stagnant nature no breath of feeling stirred, esteeming it the while, that in her card of invitation he was reaping the proudest proof of his success; but that such could be made acquaintances or companions, could be regarded in the light of equals or intimates, the thing never entered into her imagination, and she would as soon have made a confidant of the King of Kongo as a gentleman from Connaught.

Less for the purposes of dwelling upon my lady-mother's “Hibernian horrors,” than of showing the school in which I was trained, I have made this somewhat lengthened exposé. It may, however, convey to my reader some faint impression of the feelings which animated me at the outset of my career in Ireland.

I have already mentioned the delight I experienced with the society at the Viceroy's table. So much brilliancy, so much wit, so much of conversational power, until that moment I had no conception of. Now, however, while reflecting on it, I was actually astonished to find how far the whole scene contributed to the support of my ancient prejudices. I well knew that a party of the highest functionaries—bishops and law-officers of the crown—would not have conducted themselves in the same manner in England. I stopped not to inquire whether it was more the wit or the will that was wanting; I did not dwell upon the fact that the meeting was a purely convivial one, to which I was admitted by the kindness and condescension of the Duke; but, so easily will a warped and bigoted impression find food for its indulgence, I only saw in the meeting an additional evidence of my early convictions. How far my theorising on this point might have led me—whether eventually I should have come to the conclusion that the Irish nation were lying in the darkest blindness of barbarism, while, by a special intervention of Providence, I, was about to be erected into a species of double revolving light—it is difficult to say, when a tap at the door suddenly aroused me from my musings.

“Are ye awake, yet?” said a harsh, husky voice, like a bear in bronchitis, which I had no difficulty in pronouncing to be Corny's.

“Yes, come in,” cried I; “what hour is it?”

“Somewhere after ten,” replied he, sulkily; “you're the first I ever heerd ask the clock, in the eight years I have lived here. Are ye ready for your morning?”

“My what?” said I, with some surprise.

“Didn't I say it, plain enough? Is it the brogue that bothers you?”

As he said this with a most sarcastic grin he poured, from a large jug he held in one hand, a brimming goblet full of some white compound, and handed it over to me. Preferring at once to explore, rather than to question the intractable Corny, I put it to my lips, and found it to be capital milk punch, concocted with great skill, and seasoned with what O'Grady afterwards called “a notion of nutmeg.”

“Oh! devil fear you, that he'll like it. Sorrow one of you ever left as much in the jug as 'ud make a foot-bath for a flea.”

“They don't treat you over well, then, Corny,” said I, purposely opening the sorest wound of his nature.

“Trate me well! faix, them that 'ud come here for good tratement, would go to the devil for divarsion. There's Master Phil himself, that I used to bate, when he was a child, many's the time, when his father, rest his sowl, was up at the coorts—ay, strapped him, till he hadn't a spot that wasn't sore an him—and look at him now; oh, wirra! you'd think I never took a ha'porth of pains with him. Ugh!—the haythins!—the Turks!”

“This is all very bad, Corny; hand me those boots.”

“And thim's boots!” said he, with a contemptuous expression on his face that would have struck horror to the heart of Hoby. “Well, well.” Here he looked up as though the profligacy and degeneracy of the age were transgressing all bounds. “When you're ready, come over to the master's, for he's waiting breakfast for you. A beautiful hour for breakfast, it is! Many's the day his father sintenced a whole dockful before the same time!”

With the comforting reflection that the world went better in his youth, Corny drained the few remaining drops of the jug, and, muttering the while something that did not sound exactly like a blessing, waddled out of the room with a gait of the most imposing gravity.

I had very little difficulty in finding my friend's quarters; for, as his door lay open, and as he himself was carolling away, at the very top of his lungs, some popular melody of the day, I speedily found myself beyond the threshold.

“Ah! Hinton, my hearty, how goes it? your headpiece nothing the worse, I hope, for either the car or the claret? By-the-by, capital claret that is! you've nothing like it in England.”

I could scarce help a smile at the remark, as he proceeded,

“But come, my boy, sit down; help yourself to a cutlet, and make yourself quite at home in Mount O'Grady.”

“Mount O'Grady!” repeated I. “Ha! in allusion, I suppose, to these confounded two flights one has to climb up to you.”

“Nothing of the kind; the name has a very different origin. Tea or coffee? there's the tap! Now, my boy, the fact is, we O'Gradys were once upon a time very great folk in our way; lived in an uncouth old barrack, with battlements and a keep, upon the Shannon, where we ravaged the country for miles round, and did as much mischief, and committed as much pillage upon the peaceable inhabitants, as any respectable old family in the province. Time, however, wagged on; luck changed; your countrymen came pouring in upon us with new-fangled notions of reading, writing, and road-making; police and petty sessions, and a thousand other vexatious contrivances followed, to worry and puzzle the heads of simple country gentlemen; so that, at last, instead of taking to the hill-side for our mutton, we were reduced to keep a market-cart, and employ a thieving rogue in Dublin to supply us with poor claret, instead of making a trip over to Galway, where a smuggling craft brought us our liquor, with a bouquet fresh from Bordeaux. But the worst wasn't come; for you see, a litigious spirit grew up in the country, and a kind of vindictive habit of pursuing you for your debts. Now, we always contrived, somehow or other, to have rather a confused way of managing our exchequer. No tenant on the property ever precisely knew what he owed; and, as we possessed no record of what he paid, our income was rather obtained after the maimer of levying a tribute, than receiving a legal debt. Meanwhile, we pushed our credit like a new colony: whenever a loan was to be, obtained, it was little we cared for ten, twelve, or even fifteen per cent.; and as we kept a jolly house, a good cook, good claret, and had the best pack of beagles in the country, he'd have been a hardy creditor who'd have ventured to push us to extremities. Even sheep, however, they say, get courage when they flock together, and so this contemptible herd of tailors, tithe-proctors, butchers, barristers, and bootmakers, took heart of grace, and laid siege to us in all form. My grandfather, Phil,—for I was called after him,—who always spent his money like a gentleman, had no notion of figuring in the Four Courts; but he sent Tom Darcy, his cousin, up to town, to call out as many of the plaintiffs as would fight, and to threaten the remainder that, if they did not withdraw their suits, they'd have more need of the surgeon than the attorney-general; for they shouldn't have a whole bone in their body by Michaelmas-day. Another cutlet, Hinton? But I am tiring you with all these family matters.”

“Not at all; go on, I beg of you. I want to hear how your grandfather got out of his difficulties.”

“Faith, I wish you could! it would be equally pleasant news to myself; but, unfortunately, his beautiful plan only made bad worse, for they began fresh actions. Some, for provocation to fight a duel; others, for threats of assault and battery; and the short of it was, as my grandfather wouldn't enter a defence, they obtained their verdicts, and got judgment, with all the costs.”

“The devil they did! That must have pushed him hard.”

“So it did; indeed it got the better of his temper, and he that was one of the heartiest, pleasantest fellows in the province, became, in a manner, morose and silent; and, instead of surrendering possession, peaceably and quietly, he went down to the gate, and took a sitting shot at the sub-sheriff, who was there in a tax-cart.”

“Bless my soul! Did he kill him?”

“No; he only ruffled his feathers, and broke his thigh; but it was bad enough, for he had to go over to France till it blew over. Well, it was either vexation or the climate, or, maybe, the weak wines, or, perhaps, all three, undermined his constitution, but he died at eighty-four—the only one of the family ever cut off early, except such as were shot, or the like.”

“Well, but your father—”

“I am coming to him. My grandfather sent for him from school when he was dying, and he made him swear he would be a lawyer. 'Morris will be a thorn in their flesh, yet,' said he; 'and look to it, my boy,' he cried, 'I leave you a Chancery suit that has nearly broke eight families and the hearts of two chancellors;—see that you keep it goings—sell every stick on the estate—put all the beggars in the barony on the property—beg, borrow, and steal them—plough up all the grazing-land; and I'll tell you a better trick than all——' Here a fit of coughing interrupted the pious old gentleman, and, when it was over, so was he!”

“Dead!” said I.

“As a door-nail! Well, my father was dutiful; he kept the suit moving till he got called to the Bar! Once there, he gave it all his spare moments; and when there was nothing doing in the Common Pleas or King's Bench, he was sure to come down with a new bill, or a declaration, before the Master, or a writ of error, or a point of law for a jury, till at last, when no case was ready to come on, the sitting judge would call out, 'Let us hear O'Grady/ in appeal, or in error, or whatever it was. But, to make my story short, my father became a first-rate lawyer, by the practice of his own suit—rose to a silk-gown—was made solicitor and attorney-general—afterwards, chief-justice——”

“And the suit?”

“Oh! the suit survived him, and became my property; but, somehow, I didn't succeed in the management quite as well as my father; and I found that my estate cost me somewhere about fifteen hundred a year—not to mention more oaths than fifty years of purgatory could pay off. This was a high premium to pay for figuring every term on the list of trials, so I raised a thousand pounds on my commission, gave it to Nick M'Namara, to take the property off my hands, and as my father's last injunction was, 'Never rest till you sleep in Mount O'Grady,'—why, I just baptised my present abode by that name, and here I live with the easy conscience of a dutiful and affectionate child that took the shortest and speediest way of fulfilling his father's testament.”

“By Jove! a most singular narrative. I shouldn't like to have parted with the old place, however.”

“Faith, I don't know! I never was much there. It was a rackety, tumble-down old concern, with rattling windows, rooks, and rats, pretty much like this; and, what between my duns and Corny Delany, I very often think I am back there again. There wasn't as good a room as this in the whole house, not to speak of the pictures. Isn't that likeness of Darcy capital? You saw him last night. He sat next Curran. Come, I've no curaçoa to offer you, but try this usquebaugh.”

“By-the-by, that Corny is a strange character. I rather think, if I were you, I should have let him go with the property.”

“Let him go! Egad, that's not so easy as you think. Nothing but death will ever part us.”

“I really cannot comprehend how you endure him; he'd drive me mad.”

“Well, he very often pushes me a little hard or so; and, if it wasn't that, by deep study and minute attention, I have at length got some insight into the weak parts of his nature, I frankly confess I couldn't endure it much longer.”

“And, pray, what may these amiable traits be?”

“You will scarcely guess”

“Love of money, perhaps?”

“No.”

“Attachment to your family, then?”

“Not that either.”

“I give it up.”

“Well, the truth is, Corny is a most pious Catholic. The Church has unbounded influence and control over all his actions. Secondly, he is a devout believer in ghosts, particularly my grandfather's, which, I must confess, I have personated two or three times myself, when his temper had nearly tortured me into a brain fever; so that between purgatory and apparitions, fears here and hereafter, I keep him pretty busy. There's a friend of mine, a priest, one Father Tom Loftus——”

“I've heard that name before, somewhere.”

“Scarcely, I think; I'm not aware that he was ever in England; but he's a glorious fellow; I'll make you known to him, one of these days; and when you have seen a little more of Ireland, I am certain you'll like him. But I'm forgetting; it must be late; we have a field-day, you know, in the Park.”

“What am I to do for a mount? I've brought no horses with me.”

“Oh, I've arranged all that. See, there are the nags already. That dark chesnut I destine for you; and, come along, we have no time to lose; there go the carriages, and here comes our worthy colleague and fellow aide-de-camp. Do you know him?”

“Who is it, pray?”

“Lord Dudley de Vere, the most confounded puppy, and the emptiest ass— But here he is.”

“De Vere, my friend Mr. Hinton—one of ours.”

His Lordship raised his delicate-looking eyebrows as high as he was able, letting fall his glass at the same moment from the corner of his eye; and while he adjusted his stock at the glass, lisped out,

“Ah—yes—very happy. In the Guards, I think. Know Douglas, don't you?”

“Yes, very slightly.”

“When did you come—to-day?”

“No; last night.”

“Must have got a buffeting; blew very fresh. You don't happen to know the odds on the Oaks?”

“Hecate, they say, is falling. I rather heard a good account of the mare.”

“Indeed,” said he, while his cold, inanimate features brightened up with a momentary flush of excitement. “Take you five to two, or give you the odds, you don't name the winner on the double event.”

A look from O'Grady decided me at once on declining the proffered wager; and his Lordship once more returned to the mirror and his self-admiration.

“I say, O'Grady, do come here for a minute. What the deuce can that be?”

Here an immoderate fit of laughter from his Lordship brought us both to the window. The figure to which his attention was directed was certainly not a little remarkable. Mounted upon an animal of the smallest possible dimensions, sat, or rather stood, the figure of a tall, gaunt, raw-boned looking man, in a livery of the gaudiest blue and yellow, his hat garnished with silver lace, while long tags of the same material were festooned gracefully from his shoulder to his breast; his feet nearly touched the ground, and gave him rather the appearance of one progressing with a pony between his legs, than of a figure on horseback; he carried under one arm a leather pocket, like a despatch bag; and, as he sauntered slowly about, with his eyes directed hither and thither, seemed like some one in search of an unknown locality.

The roar of laughter which issued from our window drew his attention to that quarter, and he immediately touched his hat, while a look of pleased recognition played across his countenance. “Holloa, Tim!” cried O'Grady, “what's in the wind now?”

Tim's answer was inaudible, but inserting his hand into the leathern con-veniency already mentioned, he drew forth a card of most portentous dimensions. By this time Corny's voice could be heard joining the conversation.

“Arrah, give it here, and don't be making a baste of yourself. Isn't the very battle-axe Guards laughing at you? I'm sure I wonder how a Christian would make a merry-andrew of himself by wearing such clothes; you're more like a play-actor nor a respectable servant.”

With these words he snatched rather than accepted the proffered card; and Tim, with another flourish of his hat, and a singularly droll grin, meant to convey his appreciation of Cross Corny, plunged the spurs till his legs met under the belly of the little animal, and cantered out of the court-yard amid the laughter of the bystanders, in which even the sentinels on duty could not refrain from participating.

“What the devil can it be?” cried Lord Dudley; “he evidently knows you, O'Grady.”

“And you, too, my Lord; his master has helped you to a cool hundred or two more than once before now.”

“Eh—what—you don't say so! Not our worthy friend Paul—eh? Why, confound it, I never should have known Timothy in that dress.”

“No,” said O'Grady, slyly; “I acknowledge it is not exactly his costume when he serves a latitat.”

“Ha, ha!” cried the other, trying to laugh at the joke, which he felt too deeply; “I thought I knew the pony, though. Old three-and-fourpence; his infernal canter always sounds in my ears like the jargon of a bill of costs.”

“Here comes Corny,” said O'Grady. “What have you got there?”

“There, 'tis for you,” replied he, throwing, with an air of the most profound disdain, a large card upon the table; while, as he left the room, he muttered some very sagacious reflections about the horrors of low company—his father the Jidge—the best in the land—riotous, disorderly life; the whole concluding with an imprecation upon heathens and Turks, with which he managed to accomplish his exit.

“Capital, by Jove!” said Lord Dudley, as he surveyed the card with his glass.

“'Mr. and Mrs. Paul Rooney presents'—the devil they does—'presents their compliments, and requests the honour of Captain O'Grady's company at dinner on Friday, the 8th, at half-past seven o'clock.'”

“How good! glorious, by Jove! eh, O'Grady? You are a sure ticket there—l'ami de la maison!”

O'Grady's cheek became red at these words; and a flashing expression in his eyes told how deeply he felt them. He turned sharply round, his lip quivering with passion; then, checking himself suddenly, he burst into an affected laugh,

“You'll go too, wont you?”

“I? No, faith, they caught me once; but then the fact was, a protest and an invitation were both served on me together. I couldn't accept one, so I did the other.”

“Well, I must confess,” said O'Grady, in a firm, resolute tone, “there may be many more fashionable people than our friends; but I, for one, scruple not to say I have received many kindnesses from them, and am deeply, sincerely grateful.”

“As far as doing a bit of paper now and then, when one is hard up,” said Lord Dudley, “why, perhaps, I'm somewhat of your mind; but if one must take the discount out in dinners, it's an infernal bore.”

“And yet,” said O'Grady, maliciously, “I've seen your Lordship tax your powers to play the agreeable at these same dinners; and I think your memory betrays you in supposing you have only been there once. I myself have met you at least four times.”

“Only shows how devilish hard up I must have been,” was the cool reply; “but now, as the governor begins to behave better, I think I'll cut Paul.”

“I'm certain you will,” said O'Grady, with an emphasis that could not be mistaken. “But come, Hinton, we had better be moving; there's some stir at the portico yonder, I suppose they're coming.”

At this moment the tramp of cavalry announced the arrival of the guard of honour; the drums beat, the troops stood to arms, and we had barely time to mount our horses, when the viceregal party took their places in the carriages, and we all set out for the Phoenix.