SPECIAL EDITION

WITH THE WORLD’S

GREAT TRAVELLERS

EDITED BY CHARLES MORRIS

AND OLIVER H. G. LEIGH

Vol. II

Title: With the World's Great Travellers, Volume 2

Editor: Charles Morris

Oliver Herbrand Gordon Leigh

Release date: August 20, 2010 [eBook #33472]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D Alexander and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Copyright 1896 and 1897

by

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

Copyright 1901

E. R. DuMONT

BOSTON COMMON, BOSTON, MASS.

BOSTON COMMON, BOSTON, MASS.

| SUBJECT. | AUTHOR. | PAGE |

| New York, Washington, Chicago | Oliver H. G. Leigh | 5 |

| Winnipeg Lake and River | W. F. Butler | 21 |

| A Fine Scenic Route | Henry T. Finck | 31 |

| South Pass and Fremont’s Park | John C. Fremont | 42 |

| In the Yellowstone Park | Ferdinand V. Hayden | 49 |

| The Country of the Cliff-Dwellers | Alfred Terry Bacon | 58 |

| Lake Tahoe and the Big Trees | A. H. Tevis | 68 |

| The Chinese Quarter in San Francisco | Helen Hunt Jackson | 78 |

| Mariposa Grove and Yosemite Valley | Charles Loring Brace | 88 |

| A Sportsman’s Experience in Mexico | Sir Rose Lambert Price | 99 |

| The Scenery of the Mexican Lowlands | Felix L. Oswald | 108 |

| Among the Ruins of Yucatan | John L. Stephens | 119 |

| The Route of the Nicaragua Canal | Julius Froebel | 130 |

| The Destruction of San Salvador | Carl Scherzer | 137 |

| Scenes in Trinidad and Jamaica | James Anthony Froude | 145 |

| The High Woods of Trinidad | Charles Kingsley | 157 |

| Animals of British Guiana | C. Barrington Brown | 169 |

| Life and Scenery in Venezuela | Alexander von Humboldt | 179 |

| The Llaneros of Venezuela | Ramon Paez | 190 |

The Forests of the Amazon and Madeira Rivers |

Franz Keller | 200 |

| Canoe- and Camp-Life on the Madeira | Franz Keller | 212 |

| Besieged by Peccaries | James W. Wells | 219 |

| The Perils of Travel | Ida Pfeiffer | 232 |

| Brazilian Ants and Monkeys | Henry W. Bates | 240 |

| The Monarchs of the Andes | James Orton | 251 |

| Inca High-Roads and Bridges | E. George Squier | 261 |

| Boston Common, Boston, Mass. | Frontispiece |

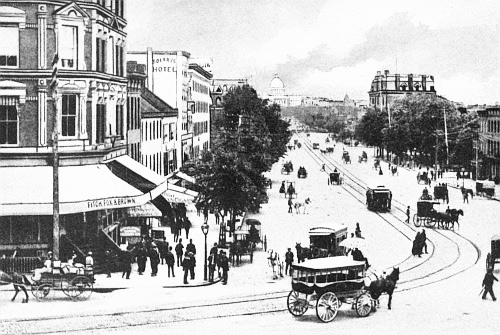

| Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington | 14 |

Memorial Monument to Samuel de Champlain, Founder of Quebec |

34 |

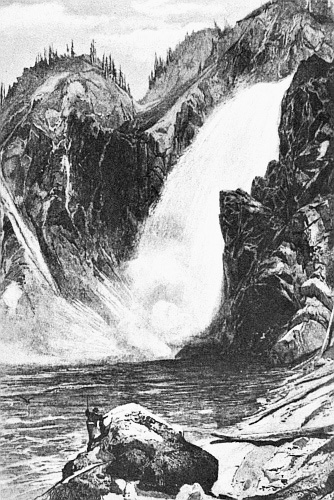

| The Upper Yellowstone Falls | 50 |

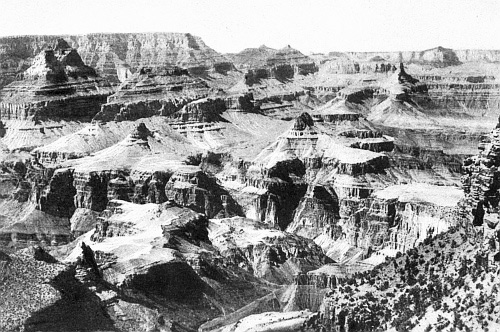

| Grand Cañon, Arizona | 66 |

| Red Wood Tree, California | 96 |

| Regina Angelorum (Queen of the Angels) | 116 |

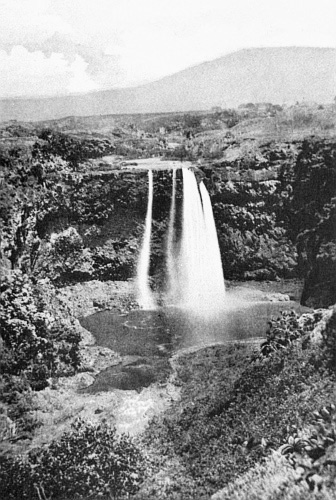

| A Waterfall in the Tropics | 146 |

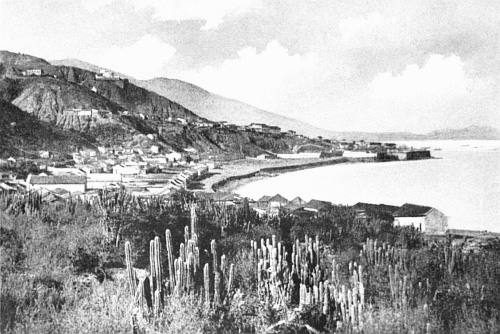

| La Guayra, Venezuela | 180 |

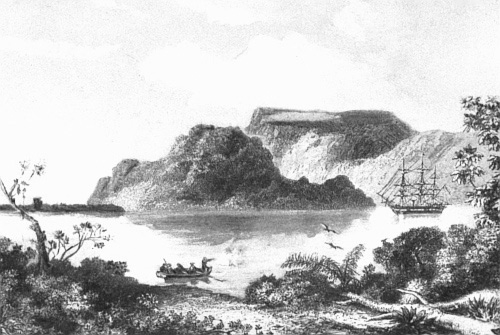

| A South Sea Island | 214 |

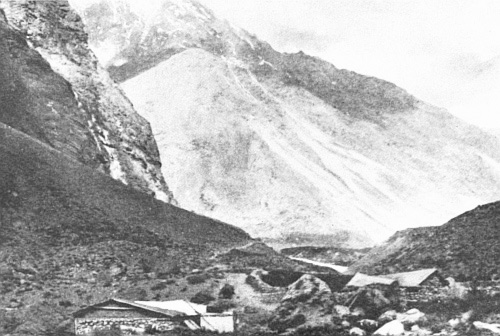

| The Monarchs of the Andes | 252 |

The reflective voyager, on his first sight of New York, is baffled when he attempts to catalogue his sensations. All is so completely in contrast with the capitals of Europe. The gloriously bright sky, air that drinks like champagne, the resultant springiness of life and movement, that overdoes itself in excitement and premature exhaustion, and the obtrusively visible defects of this surface enthusiasm, monotonous streets, unfinished or unbegun city improvements, and the conspicuous lack of play-spaces for children—this is the rough portrait sketch New York draws of itself for the newcomer. It does not disguise the fact that money-making was for many years the dominant consideration. The city was laid out for business, and public comfort had to look out for itself. The workers, the poor, and the helpless were apparently overlooked.

But there are at least three New Yorks to explore. Old New York stretches from the bay up to once aristocratic Madison Square, and this is the section that first leaves its mark on the aforesaid visitor. Then comes new New York, the splendid modern metropolis that spreads from Central Park along the Hudson to the northern [Pg 6]heights where the stately mausoleum of Grant, the transplanted Columbia University, and the great Cathedral-to-be add majestic dignity to the grandly picturesque panorama by the river. The antiquated brownstone wilderness of fashionable houses blossoms into white and gray and red clusters of mansions, richly varied in form and treatment, with the welcome grassy settings so pitifully missing in the older quarter. From a neglected span of prairie ground, pimpled with bare rocks and goat-sheltering shanties also shared by dago families, this section has in a few years qualified itself to rival the famous features of old-world cities. A nobler prospect than Riverside Drive alongside the mighty Hudson cannot be desired nor found. At last the city has discovered and worthily utilized its splendid opportunities. Then, thirdly, there is Greater New York. For the simplification of local government it is doubtless excellent policy for London and New York to lasso their humbler neighbor towns that the big cities may pose as suddenly greater than ever. The thing is done with a stroke of the pen and does not wound the pride of the newly scooped-in citizens, because the individuality of the suburban districts remains unchanged, but in our infantile capacity as mere sightseers the side-shows do not affect the glories of the ring proper. If this fashion of acquiring greatness continues, being inclusion rather than expansion, there need be no limit to the ciphers periodically tacked on to the population of the world’s swarming hives. Now that New York is growing, it might drop its insignificant borrowed name and assume its rightful one of dignity and historic import, Manhattan. It fills the twenty-two square miles between Harlem river, the Hudson, the East River, and the bay, which area is Manhattan Island. North of the Harlem it includes the district of [Pg 7]the Bronx, a little stream which for half a mile or so affords as exquisite a picture of nature’s beauty as can be found anywhere. The drift from town to country homes is a sign of the times and an augury of great good to the coming generation, physical and patriotic. After all, bricks and mortar are not the making of a city. New York is at its best beyond the borders. Its rich citizens overflow into these northern suburbs and lordly estates, and across the East River into Brooklyn and Long Island’s garden villages, and across the Hudson into New Jersey’s charming towns, and down the bay to Staten Island. In no great metropolis this side of Constantinople is it so easy and inexpensive to slip quickly from the office or home and enjoy the bracing delights of a sail down the salt water (the upper bay has fourteen square miles and the lower over eighty) or up a stately river with all the charms of the Hudson. Everything is on the grand scale, once the city’s square blocks of barracky houses are left behind.

Old-world quietists are surprised to discover one cosy quarter, perhaps two, in the grimy section of New York. Stuyvesant Square and its immediate belongings around St. George’s Church still survive as an oasis of sweetness and light in a wilderness of dismal commonplace. Washington Square carries somewhat of the old aristocratic flavor to the borders of Bohemia, and the Theological College in Chelsea used to give a solemnizing leaven to that changing district. The social transformation is still in progress. It may, perhaps, be a token of the rise to metropolitanism that the distinctively American hotels of the old-fashioned type have virtually disappeared. European models have the preference for the time being in the in- and outdoor life of New Yorkers. English sports have apparently taken firm root, as seen in the [Pg 8]popularity of golf, football, horse-racing, rowing, and some less desirable practices incident to one or two of these erstwhile sports that have developed into business undertakings, to the regret of true sportsmen. In this connection it is worth while to notice the striking disparity in the sizes of the audiences and outdoor crowds of New York and London. If fifteen thousand people pay to see the Harvard-Yale football game, or other such sport, it is considered worthy of special headlines in the papers. Madison Square Garden holds that number, seated, but the occasions when it has been filled at meetings have been few. Football crowds in England range from thirty up to seventy thousand, by turnstile record. The Crystal Palace accommodates over one hundred thousand holiday-makers without being crowded, in its central nave, sixteen hundred feet by eighty, besides transepts, and its famous grounds. The late Rev. C. H. Spurgeon had congregations of six thousand, seated, twice each Sunday for twenty-eight years. Mr. Gladstone and others have addressed twenty-five thousand in the Agricultural Hall, which covers over three acres, and St. Paul’s Cathedral has occasional congregations of over twenty thousand. These facts are the more curious as applying to a small country.

One explanation of this contrast lies in the fact that New York is not a homogeneous community. In a more marked degree than other capitals it is a congeries of towns and colonies, largely alien in sympathies. You can wander in turn through Judea, China, Italy, Ireland, France, Russia, Poland, Germany, Holland, and colored colonies. Local color is strong in each. The English speech is not used, not known, by many of these people. The picturesqueness of tenement life and its Babel sounds does not atone for the want of the deep-rooted Americanism [Pg 9]which must sooner or later be the test of welcome immigration.

Broadway is one of the great streets of the world though really a Narrow-way for so important a thoroughfare. Running north and south and having no rival for its most used section it has more than its natural share of traffic. From the historic Bowling Green and Trinity Church—two fine monuments of pre-Revolution days—up to Fourteenth Street, Broadway is mainly a wholesale market. Then it changes to a retail bazaar, and its trading features disappear as it nears the park. There used to be a well-defined sky-line in the lower city, but this has been sadly damaged by the towering office Babels that make the older quarter of the city a cave of the winds. If some day an earthquake were to shake the lower end of Manhattan Island, mighty would be the fall of these presumptuous files and woe betide their inhabitants. Fifth Avenue up to Thirty-fourth Street has given up its fashionable prestige in exchange for the profits of business. The Stock and Produce Exchanges are far down-town, among the multitude of banks that crowd around the spot made sacred ground to future generations of patriots as the scene of Washington’s inauguration as President. The city and its environs are rich in historic sites and monuments of the Revolutionary struggle. These, happily for the country’s future, are every year being sought and studied by the young, also by bands of teachers from states near and far, and by visitors from abroad. The devotion of one or more societies of private individuals has of late years conferred a boon upon the public which can hardly be too highly appreciated, in causing durable memorial tablets to be placed on buildings of historic interest. In this and kindred ways New York is fast removing all [Pg 10]justification for the stale reproach that it cared not for shrines and took small interest in its own history.

A mere suggestion, yet a very helpful one, toward realizing somewhat of the enormous shipping business done for the country by New York can be got by a tour of the main wharves. There is a water-front of twenty-five miles around the island, without reckoning the shores of Brooklyn and Hoboken. The bird’s-eye view from the wonderful and graceful Suspension Bridge enlarges one’s conception of what such a metropolis is and can do. Alpine grain elevators circle the city on the opposite shore of the rivers and upper bay. Two thousand ships sail out each year laden with the grain that feeds the nations on the other hemisphere. Three thousand steamships enter these wharves yearly with human and commercial freight from foreign ports. Nearly ten thousand steerage immigrants land each week the year round, besides an immense passenger contingent. These are the sights that fascinate the thoughtful: the comings and goings of the peoples of the earth and its products. Old Castle Garden and the Battery have greatly changed in recent years, but their memories linger. If it had been possible to keep the triangle south of Fourteenth Street as the select residential quarter, what an unrivalled site it would now be! A water panorama worth crossing the Atlantic to see, for its immensity, its picturesque bordering, and the magnificent view of the foreground of an embowered city by the sea.

Human needs shaped these water avenues to other destinies. They draw from the great ocean beyond the Narrows the sources of all that has gone to the building of national greatness. In turn they have borne to other lands the seeds of a larger liberty, patterned after and stimulated by the unparalleled success that has so splendidly [Pg 11]rewarded self-achieved freedom to grow, to think, to speak out, and to speed the commerce of the world.

The wealth thus created has of recent years done much to beautify the city with palatial residences. In the northern districts detached mansions in grass-plots supersede the monotonous brownstone rows. Many of these vie with each other in the extent and delicacy of decorative carvings outside. Others are fashioned after the castellated structures of Europe. The general impression left by a town of the newer fashion quarter is that Jeffersonian simplicity, in architecture at least, is no longer to be understood as synonymous with severe plainness. Probably no other city can point to an equally rapid transition from conventional taste, excellent for its period, to the present enthusiasm for the best in artistic construction, whatever its cost.

The bicycle proved a revolutionizer of dress as well as a stimulus to outdoor exercise. Each nation learns from the others and so we progress, though there is possible weakness in the tendency toward rigid uniformity. The picturesque and the primitive are disappearing in every land. National individuality should not lightly be allowed to lapse, even in minor matters of costume and recreation.

Experienced travellers know that a country is not to be judged by its metropolis. There is a sturdier back-bone of conservatism in the provinces than in the great cities, so largely made up of aliens and sojourners. A goodly proportion of the business men whose genius has made New York what it is, and who are admittedly qualifying it soon to become the financial centre of the world, are country-born and raised. Great as New York is, and mightier as it will become by reason of its situation, the true and abiding greatness of the nation is spread over [Pg 12]the thousand cities and towns that equally represent American pluck and stability. In the farming districts and the scattered rural communities, in vast agricultural areas of which city people take too little note, and in the steady, plodding, smaller towns, there abides a calm but potent force that throbs with high patriotism, and will prove an all-sufficient strength in time of peril.

Washington! Its very name an inspiration, its every feature a fascination to the lover of his country who makes his first pilgrimage to the national shrine. Other great cities bear the glorious marks of the tribulations and triumphs they suffered and enjoyed as they passed through their historic experiences. Here is a capital created as the consummation of a people’s release from thralldom. A new city, invented as the proclamation of a new nation’s advent, the symbol and promise of a mightier world-power than its proudest founders ever conceived possible in their highest enthusiasms. The youngest of famous capitals, it already holds its own with the best of its kind for grandeur and the rus in urbe charm. Its spacious avenues, one hundred and sixty feet wide, are lined with trees and grassy walks. Their stately sweep gives chances for fine landscape effects, which are finely used. The vistas of the grand avenues are bounded by some piece of memorial statuary or an imposing structure in the distance, as is Pennsylvania avenue by the incomparable Capitol. No national monument is better known throughout the world than this noble edifice. Its majestic stateliness is enhanced by its snowy whiteness.

The Capitol is the greatest building for its purposes in the United States. It covers three acres and a half, and has a frontage of seven hundred and fifty feet. The great dome, with its figure of Liberty, reaches a height [Pg 13]of over three hundred and seven feet. Standing on the rising ground among the rich foliage it has an aspect of quiet strength, an impressive assurance of dignity and permanence peculiar to itself among massive buildings in the great cities. Everyone goes, or should go, to see Congress at work, and to explore the corridors trod by generations of the nation’s legislators, soldiers, jurists, orators, in short, by all the great makers of the nation since Washington laid its foundation stone. A singular instance of fate thwarting intention is found in the situation of the Capitol. It was planned to face eastward, the White House was to be in the rear, and the city was expected to spread away from the river, eastwardly. But it perversely grew to the northwest, with the result that the Capitol turns its back on the capital. No one would suppose this is so unless told, so splendidly balanced in architectural dignity are both fronts of the edifice. Another peculiarity is that the head city of the republic is monarchically governed, and governed better than any other city in the Union. Three commissioners are appointed by the President, and the citizens have no political franchise. The city was planned as a grand example of what a capital should be. Impressed by the lessons of the revolutions in Paris the designer dotted the area with circular grass-plots or miniature parks, from which avenues and streets radiate like wheel-spokes. In case of need a gun in each of the circles could command an enemy approaching from any quarter. The peaceful use of these charming sites is more befitting the spirit of the republic. Statues of its soldier-heroes who saved the Union adorn each circle and give historic interest to the vistas. There are two hundred miles of streets. In summer-time they are groves of rich foliage. They and the park spaces [Pg 14]take up half the area of the city. It is wisely intended to re-name the principal streets after famous American patriots instead of alphabetically.

Washington is pre-eminently a city of “sights.” The great government buildings are distributed over the city with excellent effect. They are noble edifices, worthy of the Capitol and the capital. The Treasury, with its never-to-be-forgotten scenes inside, the Army and Navy offices, the Smithsonian Institution, and the rest of the head-quarters of national business need no further mention here. The Corcoran Art Gallery, the Patent Office, and the new Library of Congress demand a special word. The latter is one of the most exquisite buildings in the world, with interior decorative treatment quite beyond anything hitherto known in the country. Its brilliant dome does not suffer by proximity to the Capitol. An inspection of the Patent Office is a revelation of genius peculiarly American, and its display throws the clearest light on the secret of the country’s amazing material prosperity. A visit to Washington ought to be the finishing touch to the schooling of every girl and boy. Historic sites and shrines appeal to the mature mind, but the show places of the capital peculiarly suit the youthful instinct for the novel and striking in matters of fact.

PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE, WASHINGTON

PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE, WASHINGTON

To see the Senate and House of Representatives in session is a high privilege for any citizen, yet it is hampered by few, if any, such restrictions as are imposed in other national legislatures. The chambers are spacious and handsome, so are the classified galleries for spectators, and the sessions are held in daylight. Equally impressive is the Supreme Court of the United States—a temple of equity in all its features, wherein the instinctive reverence for the highest embodiment of justice and legal authority is encouraged by the surroundings. The robes worn by [Pg 15]the justices invest the bench and court with a dignity which various state courts wisely emulate by adopting the same rule. Isolated in striking grandeur, the lofty Washington obelisk lifts the contemplative mind to heights above the level of material evidences of prosperity. Like the Stuart portrait, this memorial of Washington leaves the meaner measurements of a man’s stature for other seasons and moods, and by a touch of sublimity gives the nobler cue to patriotic devotion and whole-hearted enthusiasm for him who, though human indeed, in his life-work neared the divine.

Summer is not the best time to appreciate the social life of the capital. It lies low, the Potomac’s swampy margin is near and the street forests of trees aid humidity. The White House snugly reposes in beautiful grounds, with the great obelisk as a perpetual reminder of the first President’s example and reward. Another white portico gleams in the distance, Arlington, the resting-place of the nation’s hero-martyrs. In the winter season Washington blooms into cosmopolitan grandeur. It becomes the focus of the nation’s lights in statesmanship, art, literature, and social pleasures. The foreign embassies supply the grace of brilliant color so lacking in the gatherings of men in the sombre attire of the period. A continuous round of social festivities gladdens the mild winter days and nights. Here, as in royal capitals, society has its greater and lesser constellations. There are the senatorial, judicial, diplomatic, military, and naval groups, too sharply divided, to judge from audible criticisms in New York circles. Still literature, art, and commerce have as free a welcome in Washington salons as anywhere else, despite the plaints of overlooked suppliants. The White House knows nothing of artificial shibboleths. It happily dispenses its hospitalities—which are coveted honors—impartially [Pg 16]upon all whom it is an honor to honor, and so sustains the true American principle of equal courtesy to citizens and sojourners of every degree. Washington is an inexhaustible field for the student of men, manners and movements, a theatre on whose stage the comedy of life plays itself, with all-potent moulders of opinion and legislation as the actors, backed by a supernumerary army of minor aids. Among its most eager auditors are outsiders, reporting every byplay to profoundly interested critics across the seas. The drama cannot be too deeply watched and pondered, for it is fraught with issues vital to the well-being of coming generations.

Chicago is usually figured as a conventionally insipid beauty, in flowing garments which would obstruct her progress and could never be kept white. This is a mistake. Most masculine of cities, most American of America’s great centres, its shield should portray a strong youth in the flush of adolescence, conscious power in his proud curled lip, fire in his eye, springing to the foreground in the first ray of dawn, in his right hand the sceptre of genius and his left grasping the key of destiny. The good people of Chicago are not conspicuously lacking in civic self-appreciation. They are accustomed to being twitted by rivals in the rear on their boundless faith in their city’s future greatness. They can afford to listen smilingly. If the child is father of the man, full-grown Chicago must some day tower above the up-stretched heads of its envious seniors like a giant among, say, a committee of venerable municipal Solons. Ordinary cities develop as babies do, slow growth to maturity, but this extraordinary late-comer into the family attained mental and muscular precocity in shorter time than its sisters required to cut their wisdom-teeth. Considered in relation to its geographical position [Pg 17]and its express-speed rate of progress, Chicago has the promise and potency of an imperial greatness no easier to exaggerate than to limit. It was tried by fire in the day of small things, but quickly rose to a new life and it still carries the memorial glow in its heart as an inspiration to great things.

The word Chicago is a simpler form of the Indian name, Chacaqua, given to the river in honor of their deity, the Thunderer. The position of Chicago makes it the greatest lake port in the world. It is already the second city in the United States, though only born in 1830, and has hopes of becoming the first, by growth, and not by annexation policy. True, the newest city inherits the wealth and experience which the older ones had to gain for themselves, yet Chicago has done some fine original things. It hitched up an inland sea as its beast of burden and made a vast lake its pleasure pond. Finding itself only seven feet above the level of Lake Michigan it lifted itself bodily another seven feet, churches, warehouses, dwellings and all, with jack-screws, and shovelled a new foundation of dry earth beneath. Fifteen years later the great fire laid it lower than ever. On Oct. 8, 1871, began the disaster that made nearly a hundred thousand people homeless, destroyed seventeen thousand buildings and two hundred lives, and caused the loss of two hundred millions of dollars. Within a year or so the wooden town was transformed into a city of massive palaces built of stone and brick. It is now fast changing itself into a maze of towering Babels, whose tops support the pall of smoke that tells of manufacturing activity. It drove tunnels beneath its river for street-cars. Its thirty-five bridges were not enough for the constant rush. On its lake first swam the novel whale-back boats. One sin will rise up against the city on the day of doom: the twenty-mile line [Pg 18]of lake shore has been largely prostituted to railway interests instead of being conserved as an unrivalled pleasure park for the people and an adornment to the city. It can plead in mitigation of sentence that its six public parks cover more than three square miles, besides some sixty linear miles of park-like boulevards of which Paris might be proud. Of these Michigan Avenue has a well-won fame. No business traffic is permitted on its wide and well-sprinkled roadway, the morning and afternoon procession of carriages taking its wealthy residents to and from business at times recalls the Queen’s Drive in the London season. If the Chicago man of affairs works hard at his calling, he takes his pleasure zestfully and plenty of it. On the grand occasion of the American Derby (for Chicago has its Epsom and Ascot in one) it is a revelation to see the gay caravan en route to the race-course, as impressive a display of metropolitan luxury as any capital can present. And on this day the West can match the big crowds of England with this sixty thousand throng, each person paying two dollars for bare admission to the ground.

In a city primarily devoted to business it takes time for the development of the beautiful. Chicago has its “sights” for seekers after the merely outlandish, who often miss the real greatnesses that are less catchy to the eye. One of its achievements which impresses both the trained and untrained observer is the undertaking which has the uninviting name of Drainage Canal. The pure water of Lake Michigan used to be polluted by the inflow of the Chicago River. To prevent this the city has made an immense waterway by which the lake water is carried to the Illinois River and the tide of the Chicago River is diverted from its former course. The new canal is navigable and opens a route between the great lakes and the [Pg 19]Gulf of Mexico. The territory involved embraces the city and forty-three square miles of Cook County. The main channel is twenty-eight miles long and the cost was about thirty millions.

In their commercial aspect the famous Stock-yards have greater interest than as a show place. They cover four hundred acres, the plant is valued at four million dollars, and about twenty millions of animals are killed and packed in a year. Similarly imposing are the statistics of most of Chicago’s enterprises. The Board of Trade is one of the most remarkable sights in the country. Its public galleries are usually filled with spectators of the feverish bidding of the grain operators, whose slightest nod affects the markets of the world. The Stock Exchange is yearly taking a more important share in the money market. The financial institutions of Chicago and the West have more than once saved the East from impending panic, and immense loans are constantly being renewed, insuring the speedy recognition of the city as a force in the money markets of the nations.

More interesting is the honor-roll of Chicago’s intellectual enterprise. The Columbian World’s Fair of 1893 astonished the world with its beauty, its perfection of artistic skill and taste. It gave an impetus to the pursuit of the beautiful and refining which has borne substantial results. Near the site of the Fair is a cluster of buildings constituting the University of Chicago, dating from 1891, to which a single donor has given nine million dollars, and loyal citizens are continually adding to its possessions. The heads of the University count on an endowment fund of fifty millions. Nowhere is Chicago enthusiasm for progress more finely manifested than here. The great public libraries of the city are envied by foreign visitors. The central Public Library is a splendid triumph of architecture, [Pg 20]next in interior elegance to the Library of Congress. It is valued at three millions, exclusive of its books. The Newberry and Crerar libraries form special branches of the system. The city’s churches and charities are doing nobly in ameliorating the condition of the toilers and the handicapped in life’s race. The name and fame of Miss Jane Addams and the Hull House settlement are world-wide. How difficult the task is may be conceived from the fact that out of a million and seven hundred thousand people in the city, nine hundred thousand are Americans, German, and Irish; the remainder represent twenty-four nationalities, exclusive of negroes. A report issued by an investigating committee of Hull House states that “the density of population in the Polish quarter in Chicago is three times that of the most crowded portions of Tokio, Calcutta, and many other Asiatic cities.”

As in New York there is a marked tendency among the richer people to set up country homes. New suburban towns and villages of great attractiveness are drawing an increasing number away from the smoky city. On the other hand the far-famed hospitality of its people to prophets of every school of thought, and the spirit of enterprise which welcomes every new idea, attracts eccentrics and adventurers whose trumpetings are loud enough to mislead superficial observers into the notion that Chicago is the crank’s paradise. If a fault at all, this amiable toleration leans to virtue’s side. Rightly to appreciate the depth and breadth of Chicago’s influence we must follow its trade to the remotest corners of the earth. We must trace the influences of its seats of learning and refinement. We must count, if we can, the tremendous results of its world-renowned enterprises that have stimulated nations to follow the successful lead. Be its faults what they may, Chicago has the heart, the will, and the muscle [Pg 21]to mend them, as the world will see, and then will the true greatness of the Western metropolis be discerned, and its full influence be felt.

[Colonel W. F. Butler, in “The Great Lone Land,” gives us some very interesting information about the life and scenery of the great American Northwest, from which we select the following description of a picturesque lake and river. His journey was made during the Riel rebellion, and the traveller was on his way to the Lake of the Woods, where he expected to meet an expedition sent for the suppression of the rebellion. The Red River Indians gave him a hearty send-off.]

The chief gave a signal, and a hundred trading guns were held aloft, and a hundred shots rang out on the morning air. Again and again the salutes were repeated, the whole tribe moving down to the water’s edge to see me off. Putting out to the middle of the river, I discharged my fourteen-shooter into the air in rapid succession; a prolonged war-whoop answered my salute, and, paddling their very best, for the eyes of the finest canoers were upon them, my men drove the little craft flying over the water until the Indian village and its still firing braves were hidden behind a river bend. Through many marsh-lined channels, and amidst a vast sea of reeds and rushes, the Red River of the North seeks the water of Lake Winnipeg. A mixture of land and water, of mud, and of the varied vegetation which grows thereon, this delta of the Red River is, like other spots of a similar description, inexplicably lonely.

The wind sighs over it, bending the tall weeds with mournful rustle, and the wild bird passes and repasses with plaintive cry over the rushes which form his summer home.

Emerging from the sedges of the Red River, we shot out into the waters of an immense lake,—a lake which stretched away into unseen spaces, and over whose waters the fervid July sun was playing strange freaks of mirage and inverted shore-land.

This was Lake Winnipeg,—a great lake, even on a continent where lakes are inland seas. But vast as it is now, it is only a tithe of what it must have been in the earlier ages of the earth.

The capes and headlands of what once was a vast inland sea now stand far away from the shores of Winnipeg. Hundreds of miles from its present limits these great landmarks still look down on the ocean, but it is an ocean of grass. The waters of Winnipeg have retired from their feet, and they are now mountain-ridges, rising over seas of verdure. At the bottom of this by-gone lake lay the whole valley of the Red River, the present Lakes Winnepegoos and Manitoba, and the prairie islands of the Lower Assiniboine,—one hundred thousand square miles of water. The water has long since been drained off by the lowering of the rocky channels leading to Hudson Bay, and the bed of the extinct lake now forms the richest prairie-land in the world.

But although Winnipeg has shrunken to a tenth of its original size, its rivers still remain worthy of the great basin into which they once flowed. The Saskatchewan is longer than the Danube, the Winnipeg has twice the volume of the Rhine. Four hundred thousand square miles of continent shed their waters into Lake Winnipeg; a lake as changeful as the ocean, but, fortunately for us, in [Pg 23]its very calmest mood to-day. Not a wave, not a ripple on its surface, not a breath of breeze to aid the untiring paddles. The little canoe, weighed down by men and provisions, had scarcely three inches of its gunwale over the water, and yet the steersman held his course far out into the glassy waste, leaving behind the marshy headlands which marked the river’s mouth.

A long low point stretching from the south shore of the lake was faintly visible on the horizon. It was past mid-day when we reached it; so, putting in among the rocky boulders which lined the shore, we lighted our fire and cooked our dinner. Then, resuming our way, the Grand Traverse was entered upon. Far away over the lake arose the point of the Big Stone, a lonely cape whose perpendicular front was raised high above the water. The sun began to sink towards the west; but still not a breath rippled the surface of the lake, not a sail moved over the wide expanse, all was as lonely as though our tiny craft had been the sole speck of life on the waters of the world. The red sun sank into the lake, warning us that it was time to seek the shore and make our beds for the night. A deep sandy bay, with a high backing of woods and rocks, seemed to invite us to its solitudes. Steering in with great caution among the rocks, we landed in this sheltered spot, and drew our boat upon the sandy beach. The shore yielded large store of drift-wood, the relics of many a northern gale. Behind us lay a trackless forest, in front the golden glory of the western sky. As the night shades deepened around us and the red glare of our drift-wood fire cast its light upon the woods and rocks, the scene became one of rare beauty.

As I sat watching from a little distance this picture so full of all the charms of the wild life of the voyageur and the Indian, I little marvelled that the red child of the lakes [Pg 24]and the woods should be loath to quit such scenes for all the luxuries of our civilization. Almost as I thought with pity over his fate, seeing here the treasures of nature which were his, there suddenly emerged from the forest two dusky forms. They were Ojibbeways, who came to share our fire and our evening meal. The land was still their own. When I lay down to rest that night on the dry sandy shore, I long watched the stars above me. As children sleep after a day of toil and play, so slept the dusky men who lay around me. It was my first night with these poor wild sons of the lone spaces; it was strange and weird, and the lapping of the mimic wave against the rocks close by failed to bring sleep to my thinking eyes.

[The next day an early start was made]

We entered the mouth of the Winnipeg River at mid-day and paddled up to Fort Alexander, which stands about a mile from the river’s entrance. Here I made my final preparations for the ascent of the Winnipeg, getting a fresh canoe better adapted for forcing the rapids, and at five o’clock in the evening started on my journey up the river. Eight miles above the fort the roar of a great fall of water sounded through the twilight. In the surge and spray and foaming torrent the enormous volume of the Winnipeg was making its last grand leap on its way to mingle its waters with the lake. On the flat surface of an enormous rock which stood well out into the boiling water we made our fire and our camp.

The pine-trees which gave the fall its name stood round us dark and solemn, waving their long arms to and fro in the gusty winds that swept the valley. It was a wild picture. The pine-trees standing in inky blackness; the rushing water, white with foam; above, the rifted thunder-clouds. Soon the lightning began to flash and the voice of [Pg 25]the thunder to sound above the roar of the cataract. My Indians made me a rough shelter with cross poles and a sail-cloth, and, huddling themselves together under the upturned canoe, we slept regardless of the storm....

A man may journey very far through the lone spaces of the earth without meeting with another Winnipeg River. In it nature has contrived to place her two great units of earth and water in strange and wild combinations. To say that the Winnipeg River has an immense volume of water, that it descends three hundred and sixty feet in a distance of one hundred and sixty miles, that it is full of eddies and whirlpools, of every variation of waterfall from chutes to cataracts, that it expands into lonely pine-cliffed lakes and far-reaching island-studded bays, that its bed is cumbered with immense wave-polished rocks, that its vast solitudes are silent and its cascades ceaselessly active,—to say all this is but to tell in bare items of fact the narrative of its beauty. For the Winnipeg, by the multiplicity of its perils and the ever-changing beauty of its character, defies the description of civilized men as it defies the puny efforts of civilized travel. It seems part of the savage,—fitted alone for him and for his ways, useless to carry the burdens of man’s labor, but useful to shelter the wild things of wood and water which dwell in its waves and along its shores. And the red man who steers his little birch-bark canoe through the foaming rapids of the Winnipeg, how well he knows its various ways! To him it seems to possess life and instinct, he speaks of it as one would of a high-mettled charger which will do anything if he be rightly handled. It gives him his test of superiority, his proof of courage. To shoot the Otter Falls or the Rapids of Barrière, to carry his canoe down the whirling of Portage-de-l’Isle, to lift her from the rush of water at the Seven Portages, or launch her by the edge of the whirlpool below the Chute-à-Jocko, [Pg 26]all this is to be a brave and a skilful Indian, for the man who can do all this must possess a power in the sweep of his paddle, a quickness of glance, and a quiet consciousness of skill, not to be found except after generations of practice. For hundreds of years the Indian has lived amidst these rapids, they have been the playthings of his boyhood, the realities of his life, the instinctive habit of his old age. What the horse is to the Arab, what the dog is to the Esquimaux, what the camel is to those who journey across Arabian deserts, so is the canoe to the Ojibbeway. Yonder wooded shore yields him from first to last the materials he requires for its construction: cedar for the slender ribs, birch bark to cover them, juniper to stitch together the separate pieces, red pine to give resin for the seams and crevices. By the lake or river shore, close to his wigwam, the boat is built;

“And the forest life is in it,—

All its mystery and its magic,

All the tightness of the birch-tree,

All the toughness of the cedar,

All the larch’s supple sinews.

And it floated on the river

Like a yellow leaf in autumn,

Like a yellow water-lily.”

It is not a boat, it is a house; it can be carried long distances overland from lake to lake. It is frail beyond words, yet you can load it down to the water’s edge; it carries the Indian by day, it shelters him by night; in it he will steer boldly out into a vast lake where land is unseen, or paddle through mud and swamp or reedy shallows; sitting in it, he gathers his harvest of wild rice, or catches his fish or shoots his game; it will dash down a foaming rapid, brave a fiercely running torrent, or lie like a sea bird on the placid water.

For six months the canoe is the home of the Ojibbeway. [Pg 27]While the trees are green, while the waters dance and sparkle, while the wild rice bends its graceful head in the lake, and the wild duck dwells amidst the rush-covered mere, the Ojibbeway’s home is the birch-bark canoe. When the winter comes and the lake and rivers harden beneath the icy breath of the north wind, the canoe is put carefully away; covered with branches and with snow, it lies through the long dreary winter until the wild swan and the wavey, passing northward to the polar seas, call it again from its long icy sleep.

Such is the life of the canoe, and such the river along which it rushes like an arrow.

The days that now commenced to pass were filled from dawn to dark with moments of keenest enjoyment, everything was new and strange, and each hour brought with it some fresh surprise of Indian skill or Indian scenery.

The sun would be just tipping the western shores with his first rays when the canoe would be lifted from its ledge of rock and laid gently on the water; then the blankets and kettles, the provisions and the guns, would be placed in it, and four Indians would take their seats, while one remained on the shore to steady the bark upon the water and keep its sides from contact with the rock; then when I had taken my place in the centre, the outside man would spring gently in, and we would glide away from the rocky resting-place. To tell the mere work of each day is no difficult matter: start at five o’clock a.m., halt for breakfast at seven o’clock, off again at eight, halt at one o’clock for dinner, away at two o’clock, paddle until sunset at seven-thirty; that was the work of each day. But how shall I attempt to fill in the details of scene and circumstance between these rough outlines of time and toil, for almost every hour of the long summer day the great Winnipeg revealed some new phase of beauty and of peril, [Pg 28]some changing scene of lonely grandeur? I have already stated that the river in its course from the Lake of the Woods to Lake Winnipeg, one hundred and sixty miles, makes a descent of three hundred and sixty feet.

This descent is effected not by a continuous decline, but by a series of terraces at various distances from each other; in other words, the river forms innumerable lakes and wide expanding reaches bound together by rapids and perpendicular falls of varying altitude; thus when the voyageur has lifted his canoe from the foot of the Silver Falls and launched it again above the head of that rapid, he will have surmounted two-and-twenty feet of the ascent; again, the dreaded Seven Portages will give him a total rise of sixty feet in a distance of three miles. (How cold does the bare narration of these facts appear beside their actual realization in a small canoe manned by Indians!) Let us see if we can picture one of these many scenes. There sounds ahead a roar of falling water, and we see, upon rounding some pine-clad island or ledge of rock, a tumbling mass of foam and spray studded with projecting rocks and flanked by dark wooded shores; above we can see nothing, but below, the waters, maddened by their wild rush amidst the rocks, surge and leap in angry whirlpools. It is as wild a scene of crag and wood and water as the eye can gaze upon, but we look upon it not for its beauty, because there is no time for that, but because it is an enemy that must be conquered.

Now mark how these Indians steal upon this enemy before he is aware of it. The immense volume of water, escaping from the eddies and whirlpools at the foot of the fall, rushes on in a majestic sweep into calmer water; this rush produces along the shores of the river a counter- or back-current which flows up sometimes close to the foot of the fall; along this back-water the canoe is carefully [Pg 29]steered, being often not six feet from the opposing rush in the central river; but the back-current in turn ends in a whirlpool, and the canoe, if it followed this back-current, would inevitably end in the same place. For a minute there is no paddling, the bow-paddle and the steersman alone keeping the boat in her proper direction as she drifts rapidly up the current. Among the crew not a word is spoken, but every man knows what he has to do, and will be ready when the moment comes; and now the moment has come, for on one side there foams along a mad surge of water, and on the other the angry whirlpool twists and turns in smooth hollowing curves round an axis of air, whirling round it with a strength that would snap our birch bark into fragments, and suck us down into the great depths below. All that can be gained by the back-current has been gained, and now it is time to quit it; but where? for there is often only the choice of the whirlpool or the central river. Just on the very edge of the eddy there is one loud shout given by the bow-paddle, and the canoe shoots full into the centre of the boiling flood, driven by the united strength of the entire crew; the men work for their very lives, and the boat breasts across the river, with her head turned full towards the falls; the waters foam and dash about her, the waves leap high over the gunwale, the Indians shout as they dip their paddles like lightning into the foam, and the stranger to such a scene holds his breath amidst this war of man against nature. Ha! the struggle is useless; they cannot force her against such a torrent; we are close to the rocks and foam; but see, she is driven down by the current, in spite of those wild fast strokes. The dead strength of such a rushing flood must prevail. Yes, it is true, the canoe has been driven back; but behold, almost in a second the whole thing is done,—we float suddenly beneath a little rocky isle on the foot of the [Pg 30]cataract. We have crossed the river in the face of the fall, and the portage landing is over this rock, while three yards out on either side the torrent foams its headlong course.

Of the skill necessary to perform such things it is useless to speak. A single false stroke and the whole thing would have failed; driven headlong down the torrent, another attempt would have to be made to gain this rock-protected spot, but now we lie secure here; spray all around us, for the rush of the river is on either side, and you can touch it with an outstretched paddle. The Indians rest on their paddles and laugh; their long hair has escaped from its fastening through their exertion, and they retie it while they rest. One is already standing upon the wet, slippery rock, holding the canoe in its place; then the others get out. The freight is carried up, piece by piece, and deposited on the flat surface some ten feet above; that done, the canoe is lifted out very gently, for a single blow against this hard granite boulder would shiver and splinter the frail birch-bark covering; they raise her very carefully up the steep face of the cliff and rest again on the top. What a view there is from coigne of vantage! We are on the lip of the fall; on each side it makes its plunge, and below we mark at leisure the torrent we have just braved; above, it is smooth water, and away ahead we see the foam of another rapid. The rock on which we stand has been worn smooth by the washing of the water during countless ages, and from a cleft or fissure there springs a pine-tree or a rustling aspen. We have crossed the Petit Roches, and our course is onward still.

Through many scenes like this we held our way during the last days of July. The weather was beautiful; now and then a thunder-storm would roll along during the night, but the morning sun, rising clear and bright, would almost tempt one to believe that it had been a dream, if [Pg 31]the pools of water in the hollows of the rocks and the dampness of blanket or oil-cloth had not proved the sun a humbug. Our general distance each day would be about thirty-two miles, with an average of six portages. At sunset we made our camp on some rocky isle or shelving shore: one or two cut wood, another got the cooking things ready, a fourth gummed the seams of the canoe, a fifth cut shavings from a dry stick for the fire; for myself, I generally took a plunge in the cool, delicious water; and soon the supper hissed in the pans, the kettle steamed from its suspending stick, and the evening meal was eaten with appetites such as only the voyageur can understand.

Then when the shadows of the night had fallen around and all was silent, save the river’s tide against the rocks, we would stretch our blankets on the springy moss of the crag, and lie down to sleep with only the stars for a roof.

Happy, happy days were these,—days the memory of which goes very far into the future, growing brighter as we journey farther away from them; for the scenes through which our course was laid were such as speak in whispers, only when we have left them,—the whispers of the pine-tree, the music of running water, the stillness of great lonely lakes.

[From Henry T. Finck’s “The Pacific Coast Scenic Tour” we select the following description of the Canadian Pacific Railway route, which is acknowledged to possess a long succession of grand and beautiful scenery, unequalled by any other railroad route in America. The description is too long a one to be given in full, and for further acquaintance with it the reader must be referred to the book itself.]

After leaving Vancouver, and before reaching Westminster, the train for some time runs along Burrard Inlet, on which is situated Fort Moody, another town which had hoped to be chosen as terminus, and actually did enjoy that privilege for a short time. The shores of the inlet are beautifully wooded, and some of the trees are of enormous size. At the crossing of Stave River a fine view is obtained of Mount Baker, looking forward to the right; and the bridge over the Harrison River, where it meets the Frazer, also affords a picturesque view. For the next fifteen or sixteen hours the train follows the banks of the Frazer River and its tributaries, and this is one of the grandest sections of the route.

At the first the Frazer is a muddy, yellow river, about the size of the Willamette above Oregon City, but more rapid and winding, and an occasional steamer may be seen floating along with the current, or slowly making headway against it. In some places the railway runs so close to the precipitous bank of the river that a handkerchief might be dropped from a car window into the swirling eddies, fifty feet below. At other places it leaves room—and just room enough—for the old wagon-road between the track and the river; but it would take a cool driver, with much confidence in his horses, to remain on his wagon here when a train passes. At last the road itself becomes frightened and crosses the river on a bridge, whereupon it winds along the hill-side above the opposite bank, at a safe distance.

This road was made during the Frazer River gold excitement in 1858, when twenty-five thousand miners flocked into this region, and wages for any kind of work were ten to eighteen dollars a day. To-day the metal no longer exists in what white men consider paying quantity; but Chinamen may still be seen along the river, washing for remnants, their earnings being about fifty cents a day. [Pg 33]There is also a “Ruby Creek” in this neighborhood, and some Indian habitations and salmon-fishing places. Shortly before reaching Yale, which for a long time was the western end of the road, there is a slight intermission in the scenic drama, represented by some rich, level, agricultural lands, as if to give the passengers a moment’s rest before the wonders of the Frazer Cañon begin to monopolize their bewildered attention, till darkness sets in and drops the curtain on the superb panorama.

Yale, which is so completely shut in by high, frowning mountain walls on every side that the sun touches the village only during part of the day, has lost its importance since it ceased to be a terminus, and seems at present to be inhabited chiefly by Indians and half-breeds. The train is invaded by a bevy of half-breed girls with baskets of splendid apples and pears, which could not be beaten for size and flavor in any of our States, and indicate a possible use for these mountain regions in the future. And now the train plunges into the midst of the series of terrific gorges which constitute the Frazer Cañon, and which make this railway literally the most gorge-ous in the world. Here were appalling engineering difficulties to overcome, which no private corporation without the most liberal government support could have undertaken. Yet the builders had to be thankful even for this wild and rugged cañon dug out by the Frazer River, without which the Cascade range would have been impassable.

The palace cars of the Canadian Pacific, which contain all the best features of the Pullman cars, with home improvements, have a special observatory, with large windows, at the end of the train, whence the cañon should be viewed; but to see it at its best one must sit on the rear platform, so as to see at the same time both of the wild and precipitous cañon walls, between which the river [Pg 34]rushes along as if pursued by demons. At every curve you think the gorge must come to an end, but it only grows more stupendous, and the river, lashed into foam and fury, dashes blindly against the rocks which try to arrest its course. These rocks, ten to thirty feet wide and sometimes twice as long, form many pretty little stone islands in the middle of the torrent, and are a characteristic feature of the cañon scenery. Numerous tunnels, resembling those on the Columbia River, are built through arches seemingly projecting over the river. The train plunges into them recklessly, but always comes out fresh and smiling on the other side, although it seems that if the bottom of the tunnel should by any chance drop out, the train would be precipitated into the river below.

Once in a while the river takes a short rest, and in these comparatively calm stretches hundreds of beautiful large red fish can be seen from the train, in the clear water, struggling up-stream. With their dark backs and bright red sides they form a sight which is none the less interesting when you are told that they are “only dog salmon,” which are not relished by whites, though the Indians eat them.

[A night now passes, during which much fine scenery is missed. But the best is reserved for the next day.]

Scenic wonders now succeed one another with bewildering rapidity throughout the day. This second day, in fact, represents the climax of the trip, and the attention is not allowed to flag for a second. However much such a confession may go against the grain of patriotism, every candid traveller must admit that there is nothing in the United States in the way of massive mountain scenery (except, perhaps, in Alaska) to compare with the glorious panorama which is unfolded on this route. Within thirty-six hours after leaving Vancouver we traverse three of the [Pg 35]grandest mountain ranges in America,—the Cascades, Selkirks, and Rockies,—all of them the abode of eternal snow and glaciers, and all of them traversed through by cañons which vie with each other in terrific grandeur.

MEMORIAL MONUMENT TO SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN, FOUNDER OF

QUEBEC

MEMORIAL MONUMENT TO SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN, FOUNDER OF

QUEBEC

Before the Selkirks are reached the train passes the Columbia or Gold range, through the Eagle Pass, so called because it was discovered by watching an eagle’s flight. Eagle’s Pass is a poetic and appropriate name, and yet I think it would be well to re-name this mountain pass and call it Mirror Lake Cañon, because that would call the attention of tourists to what is its most characteristic feature, which may otherwise be overlooked. There are four lakes and many smaller bodies of water in this valley, in whose placid surface the finely-sloped mountain ridges and summits of the pass are reflected with marvellous distinctness, so that here, as in the Yosemite Mirror Lake, the copy is more lovely than the original. Some of the mountain-sides reflected in these mirrors are naked rocks, others are covered with living evergreen trees, and others still with dead trees. In the mirror these dead forests look hardly less beautiful than the living ones; but in the original the eye dwells with more pleasure on the green forests which here, and almost everywhere in British Columbia, grow with the rank luxuriance of a Ceylon jungle. The soil under these dense tree-masses, consisting of decayed pine- and fir-needles, a foot deep, and always moist, makes a paradise for lovely mosses and ferns. Here, also, is the home of the bear, and one would not have to walk far in this thicket to encounter a grizzly, black, or cinnamon bruin.

On emerging from the Mirror Lake Cañon, a great surprise awaits the passengers. The Columbia River—to which they had fancied they had said a final farewell when they were ferried across it on the way from Portland to Tacoma—suddenly comes upon the scene again, as clear [Pg 36]and as picturesque as ever; and even at this immense distance from its mouth still large enough to require a bridge half a mile long to cross it. A few hours later the train again crosses the Columbia, at Donald, where the river has become much smaller than it seems that it should in such a short distance.

To get an explanation of this circumstance, it is interesting to glance at the map and notice what an immense curve northward the Columbia has made in this interval in order to find a passage through the Selkirk range; and in thus encircling the snowy Selkirks it has, of course, added to its volume the contents of innumerable glacier streams and mountain brooks. Its real sources are southeast of Donald, on the summit of the Rockies, separated by but a short distance from springs which run down on the eastern side and find their way through the Mississippi into the Gulf of Mexico. Thus do extremes meet. It would be difficult to find anything so curious in the course of any other river as this immense, irregular parallelogram which the Columbia here describes from its sources to Arrow Lake....

The snow-peaks of the Selkirks are now looming up on all sides, and the atmosphere becomes more bracing and Alpine as the train slowly creeps up the mountain-side, doubling up on itself in a loop. The Glacier House is reached before long, and here every tourist who has time to spare should get off and spend a day or two, since next to Banff, in the National Park, this is the finest point along the whole route, scenically speaking, while the air is even more salubrious, cool, and intoxicating than at Banff, owing to the nearness of the glacier. It would be difficult, even in Switzerland, to find a more romantic spot for a hotel than the location of the Glacier House. High peaks rise up on every side, so finely moulded, so deeply mantled [Pg 37]with snow, and presenting such various aspects from different points of view, that we forget our disgust at the fact that, as usual in the West, these grand eternal peaks have been named after ephemeral mortals,—Browns, Smiths, and Joneses. The Grizzly and Cougar Mountains are more aptly named, as these animals will long continue to abound in the impenetrable forests which adorn these peaks below the snow-line. Looking from the hotel towards the glacier, to the left is a peak which looks like the Matterhorn, the most unique mountain in Switzerland, and, what is still more striking, at its side is another smaller peak, which is an exact copy of the Little Matterhorn....

The principal difference between the Swiss Alps and the Selkirk range lies in the aspect of the mountain-sides below the snow-line. These, in Switzerland, are green meadows dotted with browsing cows, and presenting one unbroken mass of dark green, except where an avalanche has tobogganed down and opened what seems at a distance like a roadway, but is found to be a battle-field strewn with the corpses of cedars three and four feet in diameter.

The most imposing view of such a mountain forest unbroken by a single avalanche path is obtained from the snow-sheds just above the hotel. Sitting outside these sheds and looking towards the left, you see a vast mountain slope covered with literally millions of dark-green trees. Why has none of the world’s greatest poets ever been permitted to gaze on such a Selkirk forest, that he might have aroused in his unfortunate readers who are not privileged to see one emotions similar to those inspired by it? But I fear that neither verse nor photographs, nor even the painter’s brush, can ever more than suggest the real grandeur of such a forest scene. This mountain is not snow-crowned in September, but its wooded summit makes a sharp green line against the snow-peaks beyond [Pg 38]and above. From this summit down to the foot stand the giant cedars, as crowded as the yellow stalks in a Minnesota wheatfield. But in place of the flat monochrome of a wheatfield, our sloping forest presents a most fascinating color spectacle. The slanting rays of the sun tinge the waving tree-tops with a deeply saturated yellowish-green, curiously interspersed with a mosaic of dark, almost black streaks and patches of shade, due to clouds and other causes, and the whole edged by the dazzling snow.

If we descend and enter this forest, a cathedral-like awe thrills the nerves. Daylight has not the power to penetrate to the ground hidden by this dense mass of tree-tops rising two hundred to three hundred feet into the air,—except that an occasional ray of sunlight may steal in for a second, like a flash of lightning. And the carpet on which this forest stands! In America we rarely see a house, even of a day-laborer, without a carpet; why, then, should these royal trees do without one? The carpet is itself a miniature forest of ferns and mosses, luxuriating in riotous profusion on an ever-moist soil, the product of thousands of generations of pine-needles. Nor is this carpet a monochrome, for the green is varied by numerous berries of various kinds, most of which are red, as they should be,—the complementary color of green. But there are also acres of blueberries as large as cherries; and if you will tear off a few branches of these and bring them to the young bear chained up near the Glacier Hotel, he will be very grateful, and you will find it amusing to watch him eating them.

There is music, too, in this Forest Cathedral, which is heard to best advantage from the elevated gallery occupied by the snow-sheds. It takes a trained ear to distinguish the steady, rippling staccato sound of a snow-fed mountain brook from the prolonged legato sigh of a pine [Pg 39]forest, swelling to fortissimo, and dying away by turns. In the romantic spot we have chosen these sounds are blended, the music of the torrents being caught up by the sloping forest as by a huge sounding-board, and increased in loudness by being mingled with the mournful strains of the tree-tops, as orchestral colors are blended by modern masters. Those err who say there is no music in nature. It is not in “Siegfried” alone that the Waldweben is musical, that leaves sing as well as birds, while the thunder occasionally adds its loud basso profundo. The æsthetic exhilaration which we owe to these poetic sights and sounds is intensified by the salubrious breezes which waft this music to our ears. Born among the clouds and glaciers, they are perfumed in passing across the forests, warmed by the sun’s rays in passing over the valley; and every breath of this elixir adds a day to one’s life. It is not surprising that mountains should make the best health-resorts; for do they not themselves understand and obey the laws of health? They keep their heads cool under a snow-cap, their feet warm in a mossy blanket, and their sides covered with a dense fir overcoat....

For the greater part of the two hours which the train requires to go from Donald to Golden City it passes along the bank of the Columbia River; and there is, perhaps, no part of the whole route where grandeur and beauty are so admirably united as here, especially in the autumn. The grandeur lies in the snowy summits which frame in this Columbia valley—the Selkirks on one side, the Rockies on the other. The beauty lies in the river itself and in the young trees and bushes along its banks, dressed in fall styles and colors, some as richly yellow as a golden-rod, others as deeply purple or crimson as fuchsias or begonias, the yellow predominating. These colored trees occur in groups and streaks along the river, and in isolated patches [Pg 40]on the mountain-sides, where they might be mistaken for brown mosses or lichen-colored rocks. There may be as beautifully colored trees in our Eastern forests, but they are not mixed, as here, with young evergreen pines, nor have they a framework of snow mountains, like these, to enhance their beauty.

High up on the ridges there is another variety of trees of a beautiful russet color set off by a deep-blue sky. Talk of color symphonies. Here they are—miles of them—long as a Wagner trilogy, and as richly orchestrated. Even the masses of blackened logs and stumps—if one can set aside for the moment all thought of pity for the poor charred trees, so happy before the fire in their green luxuriance, and of the sad waste of useful timber—enhance the charm of this scene by contrast.

I have said that the time-table of the Canadian Pacific Railway is so arranged that the finest scenery is passed in daylight, in both directions; but of course there must be exceptions, and, as a matter of fact, as long as the road crosses the three great mountain ranges of the Cascades, Selkirks, and Rockies, there is hardly a mile that does not offer something worth seeing. Consequently, as darkness again closes in soon after leaving Golden, east-bound passengers must resign themselves to lose sight of the Kicking Horse Cañon, the Beaverfoot and Ottertail Mountains, the large glacier on Mount Stephen, etc.,—which is all the more provoking as they have to sit up anyway till midnight, when Banff is reached; for, of course, every tourist who is in his right senses and not a slave to duty gets off here to spend a few days in the Canadian National Park.

[The description of this park we can give only in summary.]

Summing up on the Canadian National Park, we may say it has not so many natural wonders as the Yellowstone [Pg 41]Park,—no geysers, steam-holes, gold-bottomed rivulets, paint-pots, nor anything to place beside the Yellowstone Cañon and Falls. But the Minnewonka Lake may fairly challenge comparison with the Yellowstone Lake, and the mountain scenery is grander in the Canadian Park, and the snow and glaciers are nearer, though not so near as at the Glacier House, where the air is in consequence cooler and more bracing in summer than even at Banff. As the Canadian Park is only twenty-six miles long and ten wide, while the Yellowstone Park is about sixty-two by fifty-four miles, the former can be seen in much less time than it takes to do justice to the latter.

When we get ready to leave Banff we have to take the midnight train, so there is no chance to say good-by to the mountains. But we have seen so much of them since leaving Vancouver, that we have felt almost tempted to cry out to Nature, “Hold, enough; less would be more!” Now we get ample opportunity to ruminate in peace over our crowded impressions. When we get up we are on the prairie; we go to bed on the prairie, after traversing a territory larger than a European kingdom; again we rise on the prairie, and again go to bed on it; and not till Lake Superior is approached does the scenery once more become interesting....

As a general thing, it is no doubt wiser to take the Canadian Pacific Railway westward than eastward, as the scenic climax is on the western side. However, it is quite possible to avoid the feeling of anti-climax on going east, if we conclude the trip with the Thousand Islands and the Rapids of the St. Lawrence, together with Montreal; or with Niagara Falls and the Hudson River. The Pacific slope, no doubt, is scenically far more attractive than the Atlantic; still, there are some things in the East which even California would be proud to add to her attractions.

[Captain John Charles Fremont, one of the earliest government explorers of the Rocky Mountain region and the Pacific slope, was born at Savannah, Georgia, in 1813. Becoming a civil engineer in the government service, in 1842 he explored the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains, ascending in August the highest peak in the Wind River range. This has since been known as Fremont’s Peak. In the following year he explored Great Salt Lake. In 1845 he led a third expedition to the Pacific, and during the Mexican war was instrumental in securing California for the United States. He led subsequent expeditions westward, was Republican candidate for the Presidency in 1856, served during the war, and in 1878-82 was governor of Arizona. He died in 1890. We subjoin his account of the crossing of the South Pass and discovery and ascent of Fremont’s Peak.]

The view [of the Wind River Mountains] dissipated in a moment the pictures which had been created in our minds by many travellers who have compared these mountains with the Alps in Switzerland, and speak of the glittering peaks which rise in icy majesty amidst the eternal glaciers nine or ten thousand feet into the region of eternal snows.

[Continuing their course, they encamped on August 7 near the South Pass, and the next morning set out for the dividing ridge.]

About six miles from our encampment brought us to the summit. The ascent had been so gradual that, with all the intimate knowledge possessed by Carson, who had made the country his home for seventeen years, we were obliged to watch very closely to find the place at which we reached the culminating point. This was between two low [Pg 43]hills, rising on either hand fifty or sixty feet. When I looked back at them, from the foot of the immediate slope on the western plain, their summits appeared to be about one hundred and twenty feet above. From the impression on my mind at this time, and subsequently on our return, I should compare the elevation which we mounted immediately at the Pass to the ascent of the Capitol hill from the avenue at Washington. It is difficult for me to fix positively the breadth of this pass. From the broken ground where it commences, at the foot of the White River chain, the view to the southeast is over a champaign country, broken, at the distance of nineteen miles, by the Table Rock, which, with the other isolated hills in its vicinity, seem to stand in a comparative plain. This I judged to be its termination, the ridge recovering its rugged character with the Table Rock.

It will be seen that it in no manner resembles the places to which the term is commonly applied,—nothing of the gorge-like character and winding ascents of the Alleghany passes in America; nothing of the Great St. Bernard and Simplon passes in Europe. Approaching it from the mouth of the Sweet Water, a sandy plain, one hundred and twenty miles long, conducts, by a gradual and regular ascent, to the summit, about seven thousand feet above the sea; and the traveller, without being reminded of any change by toilsome ascents, suddenly finds himself on the waters which flow to the Pacific Ocean. By the route we had travelled, the distance from Fort Laramie is three hundred and twenty miles, or nine hundred and fifty from the mouth of the Kansas.

[They continued their course westward, crossing several tributaries of the Colorado River, and on the 10th reached unexpectedly a beautiful lake.]

Here a view of the intensest magnificence and grandeur burst upon our eyes. With nothing between us and their feet to lessen the effect of the whole height, a grand bed of snow-capped mountains rose before us, pile upon pile, glowing in the bright light of an August day. Immediately below them lay the lake, between two ridges, covered with dark pines, which swept down from the main chain to the spot where we stood. “Never before,” said Mr. Preuss, “in this country or in Europe, have I seen such grand, magnificent rocks.” I was so much pleased with the beauty of the place that I determined to make the main camp here, where our animals would find good pasturage, and explore the mountains with a small party of men.

[On the 12th this party set out, crossing intervening hills, and ascending through dense forests to the summit of the ridge.]

We had reached a very elevated point, and in the valley below, and among the hills, were a number of lakes of different levels, some two or three hundred feet above others, with which they communicated by foaming torrents. Even to our great height the roar of the cataracts came up, and we could see them leaping down in lines of snowy foam. From this scene of busy waters we turned abruptly into the stillness of a forest, where we rode among the open bolls of the pines, over a lawn of verdant grass, having strikingly the air of cultivated grounds. This led us, after a time, among masses of rock, which had no vegetable earth but in hollows and crevices, though still the pine-forest continued. Towards evening we reached a defile, or rather a hole in the mountains, entirely shut in by dark pine-covered rocks.

[In the morning they ascended a mountain stream, to its source in a small lake surrounded by a lawn-like expanse.]

Here I determined to leave our animals, and make the rest of our way on foot. The peak appeared so near that [Pg 45]there was no doubt of our returning before night; and a few men were left in charge of the mules, with our provisions and blankets. We took with us nothing but our arms and instruments, and, as the day had become warm, the greater part left our coats. Having made an early dinner, we started again. We were soon involved in the most rugged precipices, nearing the central chain very slowly, and rising but little. The first ridge hid a succession of others; and when, with great fatigue and difficulty, we had climbed up five hundred feet, it was but to make an equal descent on the other side; all these intervening places were filled with small deep lakes, which met the eye in every direction, descending from one level to another, sometimes under bridges formed by huge fragments of granite, beneath which was heard the roar of the water. These constantly obstructed our path, forcing us to make long détours; frequently obliged to retrace our steps, and frequently falling among the rocks. Maxwell was precipitated towards the face of a precipice, and saved himself from going over by throwing himself flat on the ground. We clambered on, always expecting, with every ridge that we crossed, to reach the foot of the peaks, and always disappointed, until about four o’clock, when, pretty well worn out, we reached the shore of a little lake, in which was a rocky island.

By the time we had reached the farther side of the lake we found ourselves all exceedingly fatigued, and, much to the satisfaction of the whole party, we encamped. The spot we had chosen was a broad, flat rock, in some measure protected from the winds by the surrounding crags, and the trunks of fallen pines afforded us bright fires. Near by was a foaming torrent, which tumbled into the little lake about one hundred and fifty feet below us, and which, by way of distinction, we have called Island Lake. [Pg 46]We had reached the upper limit of the piney region; as, above this point, no tree was to be seen, and patches of snow lay everywhere around us, on the cold sides of the rock. From barometrical observations made during our three days’ sojourn at this place, its elevation above the Gulf of Mexico is ten thousand feet....

[They set out early the next morning.]

On every side, as we advanced, was heard the roar of waters, and of a torrent, which we followed up a short distance, until it expanded into a lake about one mile in length. On the northern side of the lake was a bank of ice, or rather of snow covered with a crust of ice. Carson had been our guide into the mountains, and, agreeably to his advice, we left this little valley and took to the ridges again, which we found extremely broken, and where we were again involved among precipices. Here were ice-fields, among which we were all dispersed, seeking each the best way to ascend the peak. Mr. Preuss attempted to walk along the upper edge of one of these fields, which sloped away at an angle of about twenty degrees; but his feet slipped from under him, and he went plunging down the plain. A few hundred feet below, at the bottom, were some fragments of sharp rock, on which he landed; and, though he turned a couple of somersets, fortunately received no injury beyond a few bruises.