Title: The Three Eyes

Author: Maurice Leblanc

Illustrator: George W. Gage

Translator: Alexander Teixeira de Mattos

Release date: December 16, 2010 [eBook #34653]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Steven desJardins and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Print project.)

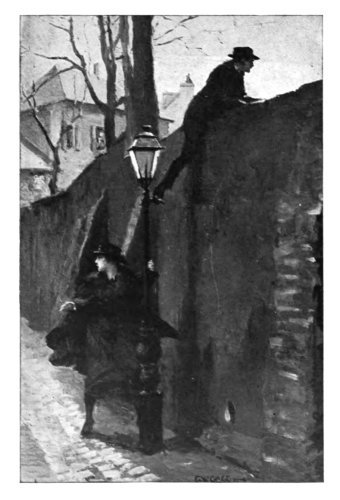

Bérangère stopped. . . .

(The Three Eyes) Frontispiece

By

MAURICE LEBLANC

Translated by

Alexander Teixeira de Mattos

Author of

"The Secret of Sarek."

Frontispiece by

G. W. GAGE

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Published by arrangement with The Macaulay Company

Copyright, 1921, by

THE MACAULAY COMPANY

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Bergeronnette | 9 |

| II | The "Triangular Circles" | 23 |

| III | An Execution | 39 |

| IV | Noël Dorgeroux's Son | 51 |

| V | The Kiss | 66 |

| VI | Anxieties | 86 |

| VII | The Fierce-Eyed Man | 99 |

| VIII | "Some One Will Emerge from the Darkness" | 113 |

| IX | The Man Who Emerged From the Darkness | 132 |

| X | The Crowd Sees | 148 |

| XI | The Cathedral | 161 |

| XII | The "Shapes" | 174 |

| XIII | The Veil is Lifted | 192 |

| XIV | Massignac and Velmot | 214 |

| XV | The Splendid Theory | 227 |

| XVI | Where Lips Unite | 247 |

| XVII | Supreme Visions | 262 |

| XVIII | The Château de Pré-Bony | 275 |

| XIX | The Formula | 293 |

For me the strange story dates back to that autumn day when my uncle Dorgeroux appeared, staggering and unhinged, in the doorway of the room which I occupied in his house, Haut-Meudon Lodge.

None of us had set eyes on him for a week. A prey to that nervous exasperation into which the final test of any of his inventions invariably threw him, he was living among his furnaces and retorts, keeping every door shut, sleeping on a sofa, eating nothing but fruit and bread. And suddenly he stood before me, livid, wild-eyed, stammering, emaciated, as though he had lately recovered from a long and dangerous illness.

He was really altered beyond recognition! For the first time I saw him wear unbuttoned the long, threadbare, stained frock-coat which fitted [Pg 10]his figure closely and which he never discarded even when making his experiments or arranging on the shelves of his laboratories the innumerable chemicals which he was in the habit of employing. His white tie, which, by way of contrast, was always clean, had become unfastened; and his shirt-front was protruding from his waistcoat. As for his good, kind face, usually so grave and placid and still so young beneath the white curls that crowned his head, its features seemed unfamiliar, ravaged by conflicting expressions, no one of which obtained the upper hand over the others: violent expressions of terror and anguish in which I was surprised, at moments, to observe gleams of the maddest and most extravagant delight.

I could not get over my astonishment. What had happened during those few days? What tragedy could have caused the quiet, gentle Noël Dorgeroux to be so utterly beside himself?

"Are you ill, uncle?" I asked, anxiously, for I was exceedingly fond of him.

"No," he murmured, "no, I'm not ill."

"Then what is it? Please, what's the matter?"

"Nothing's the matter . . . nothing, I tell you."

I drew up a chair. He dropped into it and, at my entreaty, took a glass of water; but his[Pg 11] hand trembled so that he was unable to lift it to his lips.

"Uncle, speak, for goodness' sake!" I cried. "I have never seen you in such a state. You must have gone through some great excitement."

"The greatest excitement of my life," he said, in a very low and lifeless voice. "Such excitement as nobody can have ever experienced before . . . nobody . . . nobody. . . ."

"Then do explain yourself."

"No, you wouldn't understand. . . . I don't understand either. It's so incredible! It is taking place in the darkness, in a world of darkness! . . ."

There was a pencil and paper on the table. His hand seized the pencil; and mechanically he began to trace one of those vague sketches to which the action of an overmastering idea gradually imparts a clearer definition. And his sketch, as it assumed a more distinct form, ended by representing on the sheet of white paper three geometrical figures which might equally well have been badly-described circles or triangles with curved lines. In the centre of these figures, however, he drew a regular circle which he blackened entirely and which he marked in the middle with a still blacker point, as the iris is marked with the pupil:

[Pg 12]"There, there!" he cried, suddenly, starting up in his agitation. "Look, that's what is throbbing and quivering in the darkness. Isn't it enough to drive one mad? Look! . . ."

He had seized another pencil, a red one, and, rushing to the wall, he scored the white plaster with the same three incomprehensible figures, the three "triangular circles," in the centre of which he took the pains to draw irises furnished with pupils:

"Look! They're alive, aren't they? You see they're moving, you can see that they're afraid. You can see, can't you? They're alive! They're alive!"

I thought that he was going to explain. But, if so, he did not carry out his intention. His eyes, which were generally full of life, frank and open as a child's, now bore an expression of distrust. He began to walk up and down and continued to do so for a few minutes. Then, at last, opening the door and turning to me again, he said, in the same breathless tone as before:

"You will see them, Vivien; you will have to see them too and tell me that they are alive, as I have seen them alive. Come to the Yard in an hour's time, or rather when you hear a whistle, and you shall see them, the three eyes,[Pg 13] and plenty of other things besides. You'll see."

He left the room.

The house in which we lived, the Lodge, as it was called, turned its back upon the street and faced an old, steep, ill-kept garden, at the top of which was the big yard in which my uncle had now for many years been squandering the remnants of his capital on useless inventions.

As far back as I could remember, I had always seen that old garden ill-tended and the long, low house in a constant state of dilapidation, with its yellow plaster front cracked and peeling. I used to live there in the old days with my mother, who was my aunt Dorgeroux's sister. Afterwards, when both the sisters were dead, I used to come from Paris, where I was going through a course of study, to spend my holidays with my uncle. He was then mourning the death of his poor son Dominique, who was treacherously murdered by a German airman whom he had brought to the ground after a terrific fight in the clouds. My visits to some extent diverted my uncle's thoughts from his grief. But I had had to go abroad; and it was not until after a very long absence that I returned to Haut-Meudon Lodge, where I had now[Pg 14] been some weeks, waiting for the end of the vacation and for my appointment as a professor at Grenoble.

And at each of my visits I had found the same habits, the same regular hours devoted to meals and walks, the same monotonous life, interrupted, at the time of the great experiments, by the same hopes and the same disappointments. It was a healthy, vigorous life, which suited the tastes and the extravagant dreams of Noël Dorgeroux, whose courage and confidence no trial was able to defeat or diminish.

I opened my window. The sun shone down upon the walls and buildings of the Yard. Not a cloud tempered the blazing sky. A scent of late roses quivered on the windless air.

"Victorien!" whispered a voice below me, from a hornbeam overgrown with red creeper.

I knew that it must be Bérangère, my uncle's god-daughter, reading, as usual, on a stone bench, her favourite seat.

"Have you seen your god-father?" I asked.

"Yes," she replied. "He was going through the garden and back to his Yard. He looked so queer!"

Bérangère pushed aside the leafy curtain at a place where the trelliswork which closed the[Pg 15] arbour was broken; and her pretty face, crowned with rebellious golden curls, came into view.

"This is pleasant!" she said laughing. "My hair's caught. And there are spiders' webs too. Ugh! Help!"

These are childish recollections, insignificant details. Yet why did they remain engraved on my memory with such precision? It is as though all our being becomes charged with emotion at the approach of the great events which we are fated to encounter and our senses thrilled beforehand by the impalpable breath of a distant storm.

I hastened down the garden and ran to the hornbeam. Bérangère was gone. I called her. I received a merry laugh in reply and saw her farther away, swinging on a rope which she had stretched between two trees, under an arch of leaves.

She was delicious like that, graceful and light as a bird perched on some swaying bough. At each swoop, all her curls flew now in this direction, now in that, giving her a sort of moving halo, with which mingled the leaves that fell from the shaken trees, red leaves, yellow leaves, leaves of every shade of autumn gold.

Notwithstanding the anxiety with which my uncle's excessive agitation had filled my mind, I[Pg 16] lingered before the sight of this incomparable light-heartedness and, giving the girl the pet name formed years ago from her Christian name of Bérangère, I said, under my voice and almost unconsciously:

"Bergeronnette!"

She jumped out of her swing and, planting herself in front of me, said:

"You're not to call me that any longer, Mr. Professor!"

"Why not?"

"It was all right once, when I was a little mischief of a tomboy, hopping and skipping all over the place. But now . . ."

"Well, your god-father still calls you that."

"My god-father has every right to."

"And I?"

"No right at all."

This is not a love-story; and I did not mean to speak of Bérangère before coming to the momentous part which, as everybody knows, she played in the adventure of the Three Eyes. But this part was so closely interwoven, from the beginning and during all the early period of the adventure, with certain episodes of our intimate life that the clearness of my narrative would suffer if it were not mentioned, however briefly.

Well, twelve years before the time of which[Pg 17] I am speaking, there arrived at the Lodge a little girl to whom my uncle was god-father and from whom he used to receive a letter regularly on each 1st of January, bringing him her good wishes for the new year. She lived at Toulouse with her father and mother, who had formerly been in business at Meudon, near my uncle's place. Now the mother had died; and the father, without further ceremony, sent the daughter to Noël Dorgeroux with a short letter of which I remember a few sentences:

"The child is dull here, in the town. . . . My business"—Massignac was a wine-agent—"takes me all over the country . . . and Bérangère is left behind alone. . . . I was thinking that, in memory of our friendly relations, you might be willing to keep her with you for a few weeks. . . . The country air will restore the colour to her cheeks. . . ."

My uncle was a very kindly, good-hearted man. The few weeks were followed by several months and then by several years, during which the worthy Massignac at intervals announced his intention of coming to Meudon to fetch the child. So it came about that Bérangère did not leave the Lodge at all and that she surrounded my[Pg 18] uncle with so much gay and boisterous affection that, in spite of his apparent indifference, Noël Dorgeroux had felt unable to part with his god-daughter. She enlivened the silent old house with her laughter and her charm. She was the element of disorder and delightful irresponsibility which gives a value to order, discipline and austerity.

Returning this year after a long absence, I had found, instead of the child whom I had known, a girl of twenty, just as much a child and just as boisterous as ever, but exquisitely pretty, graceful in form and movement and possessed of the mystery which marks those who have led solitary lives within the shadow of an old and habitually silent man. From the first I felt that my presence interfered with her habits of freedom and isolation. At once audacious and shy, timid and provocative, bold and shrinking, she seemed to shun me in particular; and, during two months of a life lived in common, when I saw her at every meal and met her at every turn, I had failed to tame her. She remained remote and wild, suddenly breaking off our talks and displaying, where I was concerned, the most capricious and inexplicable moods.

Perhaps she had an intuition of the profound disturbance that was awaking within me; per[Pg 19]haps her confusion was due to my own embarrassment. She had often caught my eyes fixed on her red lips or observed the change that came over my voice at certain times. And she did not like it. Man's admiration disconcerted her.

"Look here," I said, adopting a roundabout method so as not to startle her, "your god-father maintains that human beings, some of them more than others, give forth a kind of emanation. Remember that Noël Dorgeroux is first and foremost a chemist and that he sees and feels things from the chemist's point of view. Well, to his mind, this emanation is manifested by the emission of certain corpuscles, of invisible sparks which form a sort of cloud. This is what happens, for instance, in the case of a woman. Her charm surrounds you . . ."

My heart was beating so violently as I spoke these words that I had to break off. Still, she did not seem to grasp their meaning; and she said, with a proud little air:

"Your uncle tells me all about his theories. It's true, I don't understand them a bit. However, as regards this one, he has spoken to me of a special ray, which he presupposed to explain that discharge of invisible particles. And he calls this ray after the first letter of my name, the B-ray."

[Pg 20]"Well done, Bérangère; that makes you the god-mother of a ray, the ray of seductiveness and charm."

"Not at all," she cried, impatiently. "It's not a question of seductiveness but of a material incarnation, a fluid which is even able to become visible and to assume a form, like the apparitions produced by the mediums. For instance, the other day . . ."

She stopped and hesitated; her face betrayed anxiety; and I had to press her before she continued:

"No, no," she said, "I oughtn't to speak of that. It's not that your uncle forbade me to. But it has left such a painful impression. . . ."

"What do you mean, Bérangère?"

"I mean, an impression of fear and suffering. I saw, with your uncle, on a wall in the Yard, the most frightful things: images which represented three—sort of eyes. Were they eyes? I don't know. The things moved and looked at us. Oh, I shall never forget it as long as I live."

"And my uncle?"

"Your uncle was absolutely taken aback. I had to hold him up and bring him round, for he fainted. When he came to himself, the images had vanished."

"And did he say nothing?"

[Pg 21]"He stood silent, gazing at the wall. Then I asked him, 'What is it, god-father?' Presently he answered, 'I don't know, I don't know: it may be the rays of which I spoke to you, the B-rays. If so, it must be a phenomenon of materialization.' That was all he said. Very soon after, he saw me to the door of the garden; and he has shut himself up in the Yard ever since. I did not see him again until just now."

She ceased. I felt anxious and greatly puzzled by this revelation:

"Then, according to you, Bérangère," I said, "my uncle's discovery is connected with those three figures? They were geometrical figures, weren't they? Triangles?"

She formed a triangle with her two fore-fingers and her two thumbs:

"There, the shape was like that. . . . As for their arrangement . . ."

She picked up a twig that had fallen from a tree and was beginning to draw lines in the sand of the path when a whistle sounded.

"That's god-father's signal when he wants me in the Yard," she cried.

"No," I said, "to-day it's for me. We fixed it."

"Does he want you?"

"Yes, to tell me about his discovery."

[Pg 22]"Then I'll come too."

"He doesn't expect you, Bérangère."

"Yes, he does; yes, he does."

I caught hold of her arm, but she escaped me and ran to the top of the garden, where I came up with her outside a small, massive door in a fence of thick planks which connected a shed and a very high wall.

She opened the door an inch or two. I insisted:

"Don't do it, Bérangère! It will only vex him."

"Do you really think so?" she said, wavering a little.

"I'm positive of it, because he asked me and no one else. Come, Bérangère, be sensible."

She hesitated. I went through and closed the door upon her.

What was known at Meudon as Noël Dorgeroux's Yard was a piece of waste-land in which the paths were lost amid the withered grass, nettles and stones, amid stacks of empty barrels, scrap-iron, rabbit-hutches and every kind of disused lumber that rusts and rots or tumbles into dust.

Against the walls and outer fences stood the workshops, joined together by driving-belts and shafts, and the laboratories filled with furnaces, pneumatic receivers, innumerable retorts, phials and jars containing the most delicate products of organic chemistry.

The view embraced the loop of the Seine, which lay some three hundred feet below, and the hills of Versailles and Sèvres, which formed a wide circle on the horizon towards which a bright autumnal sun was sinking in a pale blue sky.

"Victorien!"

My uncle was beckoning to me from the doorway of the workshop which he used most often. I crossed the Yard.

[Pg 24]"Come in," he said. "We must have a talk first. Only for a little while: just a few words."

The room was lofty and spacious and one corner of it was reserved for writing and resting, with a desk littered with papers and drawings, a couch and some old, upholstered easy-chairs. My uncle drew one of the chairs up for me. He seemed calmer, but his glance retained an unaccustomed brilliance.

"Yes," he said, "a few words of explanation beforehand will do no harm, a few words on the past, the wretched past which is that of every inventor who sees fortune slipping away from him. I have pursued it for so long! I have always pursued it. My brain had always seemed to me a vat in which a thousand incoherent ideas were fermenting, all contradicting one another and mutually destructive. . . . And then there was one that gained strength. And thenceforward I lived for that one only and sacrificed everything for it. It was like a sink that swallowed up all my money and that of others . . . and their happiness and peace of mind as well. Think of my poor wife, Victorien. You remember how unhappy she was and how anxious about the future of her son, of my poor Dominique! And yet I loved her so devotedly. . . ."

[Pg 25]He stopped at this recollection. And I seemed to see my aunt's face again and to hear her telling my mother of her fears and her forebodings:

"He will ruin us," she used to say. "He keeps on making me sell out. He considers nothing."

"She did not trust me," Noël Dorgeroux continued. "Oh, I had so many disappointments, so many lamentable failures! Do you remember, Victorien, do you remember my experiment on intensive germination by means of electric currents, my experiments with oxygen and all the rest, all the rest, not one of which succeeded? The pluck it called for! But I never lost faith for a minute! . . . One idea in particular buoyed me up and I came back to it incessantly, as though I were able to penetrate the future. You know to what I refer, Victorien: it appeared and reappeared a score of times under different forms, but the principle remained the same. It was the idea of utilizing the solar heat. It's all there, you know, in the sun, in its action upon us, upon cells, organisms, atoms, upon all the more or less mysterious substances that nature has placed at our disposal. And I attacked the problem from every side. Plants, fertilizers, diseases of men and animals, photographs: for all these I wanted the collaboration of the solar[Pg 26] rays, utilized by the aid of special processes which were mine alone, my secret and nobody else's."

My uncle Dorgeroux was talking with renewed eagerness; and his eyes shone feverishly. He now held forth without interrupting himself:

"I will not deny that there was an element of chance about my discovery. Chance plays its part in everything. There never was a discovery that did not exceed our inventive effort; and I can confess to you, Victorien, that I do not even now understand what has happened. No, I can't explain it by a long way; and I can only just believe it. But, all the same, if I had not sought in that direction, the thing would not have occurred. It was due to me that the incomprehensible miracle took place. The picture is outlined in the very frame which I constructed, on the very canvas which I prepared; and, as you will perceive, Victorien, it is my will that makes the phantom which you are about to see emerge from the darkness."

He expressed himself in a tone of pride with which was mingled a certain uneasiness, as though he doubted himself and as though his words overstepped the actual limits of truth.

"You're referring to those three—sort of eyes, aren't you?" I asked.

[Pg 27]"What's that?" he exclaimed, with a start. "Who told you? Bérangère, I suppose! She shouldn't have. That's what we must avoid at all costs: indiscretions. One word too much and I am undone; my discovery is stolen. Only think, the first man that comes along . . ."

I had risen from my chair. He pushed me towards his desk:

"Sit down here, Victorien," he said, "and write. You mustn't mind my taking this precaution. It is essential. You must realize what you are pledging yourself to do if you share in my work. Write, Victorien."

"What, uncle?"

"A declaration in which you acknowledge that . . . But I'll dictate it to you. That'll be better."

I interrupted him:

"Uncle, you distrust me."

"I don't distrust you, my boy. I fear an imprudence, an indiscretion. And, generally speaking, I have plenty of reasons for being suspicious."

"What reasons, uncle?"

"Reasons," he replied, in a more serious voice, "which make me think that I am being spied upon and that somebody is trying to discover what my invention is. Yes, somebody came in[Pg 28] here, the other night, and rummaged among my papers."

"Did they find anything?"

"No. I always carry the most important notes and formulae on me. Still, you can imagine what would happen if they succeeded. So you do admit, don't you, that I am obliged to be cautious? Write down that I have told you of my investigations and that you have seen what I obtain on the wall in the Yard, at the place covered by a black-serge curtain."

I took a sheet of paper and a pen. But he stopped me quickly:

"No, no," he said, "it's absurd. It wouldn't prevent . . . Besides, you won't talk, I'm sure of that. Forgive me, Victorien. I am so horribly worried!"

"You needn't fear any indiscretion on my part," I declared. "But I must remind you that Bérangère also has seen what there was to see."

"Oh," he said, "she wouldn't understand!"

"She wanted to come with me just now."

"On no account, on no account! She's still a child and not fit to be trusted with a secret of this importance. . . . Now come along."

But it so happened that, as we were leaving the workshop, we both of us at the same time saw Bérangère stealing along one of the walls[Pg 29] of the Yard and stopping in front of a black curtain, which she suddenly pulled aside.

"Bérangère!" shouted my uncle, angrily.

The girl turned round and laughed.

"I won't have it! I will not have it!" cried Noël Dorgeroux, rushing in her direction. "I won't have it, I tell you! Get out, you mischief!"

Bérangère ran away, without, however, displaying any great perturbation. She leapt on a stack of bricks, scrambled on to a long plank which formed a bridge between two barrels and began to dance as she was wont to do, with her arms outstretched like a balancing-pole and her bust thrown slightly backwards.

"You'll lose your balance," I said, while my uncle drew the curtain.

"Never!" she replied, jumping up and down on her spring-board.

She did not lose her balance. But the plank shifted and the pretty dancer came tumbling down among a heap of old packing-cases.

I ran to her assistance and found her lying on the ground, looking very white.

"Have you hurt yourself, Bérangère?"

"No . . . hardly . . . just my ankle . . . perhaps I've sprained it."

I lifted her, almost fainting, in my arms and[Pg 30] carried her to a wooden bench a little farther away.

She let me have my way and even put one arm round my neck. Her eyes were closed. Her red lips opened and I inhaled the cool fragrance of her breath.

"Bérangère!" I whispered, trembling with emotion.

When I laid her on the bench, her arm held me more tightly, so that I had to bend my head with my face almost touching hers. I meant to draw back. But the temptation was too much for me and I kissed her on the lips, gently at first and then with a brutal violence which brought her to her senses.

She repelled me with an indignant movement and stammered, in a despairing, rebellious tone:

"Oh, it's abominable of you! . . . It's shameful!"

In spite of the suffering caused by her sprain, she had managed to stand up, while I, stupefied by my thoughtless conduct, stood bowed before her, without daring to raise my head.

We remained for some seconds in this attitude, in an embarrassed silence through which I could catch the hurried rhythm of her breathing. I tried gently to take her hands. But she released them at once and said:

[Pg 31]"Let me be. I shall never forgive you, never."

"Come, Bérangère, you will forget that."

"Leave me alone. I want to go indoors."

"But you can't, Bérangère."

"Here's god-father. He'll take me back."

My reasons for relating this incident will appear in the sequel. For the moment, notwithstanding the profound commotion produced by the kiss which I had stolen from Bérangère, my thoughts were so to speak absorbed by the mysterious drama in which I was about to play a part with my uncle Dorgeroux. I heard my uncle asking Bérangère if she was not hurt. I saw her leaning on his arm and, with him, making for the door of the garden. But, while I remained bewildered, trembling, dazed by the adorable image of the girl whom I loved, it was my uncle whom I awaited and whom I was impatient to see returning. The great riddle already held me captive.

"Let's make haste," cried Noël Dorgeroux, when he came back. "Else it will be too late and we shall have to wait until to-morrow."

He led the way to the high wall where he had caught Bérangère in the act of yielding to her curiosity. This wall, which divided the Yard from the garden and which I had not remarked[Pg 32] particularly on my rare visits to the Yard, was now daubed with a motley mixture of colours, like a painter's palette. Red ochre, indigo, purple and saffron were spread over it in thick and uneven layers, which whirled around a more thickly-coated centre. But, at the far end, a wide curtain of black serge, like a photographer's cloth, running on an iron rod supported by brackets, hid a rectangular space some three or four yards in width.

"What's that?" I asked my uncle. "Is this the place?"

"Yes," he answered, in a husky voice, "it's behind there."

"There's still time to change your mind," I suggested.

"What makes you say that?"

"I feel that you are afraid of letting me know. You are so upset."

"I am upset for a very different reason."

"Why?"

"Because I too am going to see."

"But you have done so already."

"One always sees new things, Victorien; that's the terrifying part of it."

I took hold of the curtain.

"Don't touch it, don't touch it!" he cried. "No one has the right, except myself. Who[Pg 33] knows what would happen if any one except me were to open the closed door! Stand back, Victorien. Take up your position at two paces from the wall, a little to one side. . . . And now look!"

His voice was vibrant with energy and implacable determination. His expression was that of a man facing death; and, suddenly, with a single movement, he drew the black-serge curtain.

My emotion, I am certain, was just as great as Noël Dorgeroux's and my heart beat no less violently. My curiosity had reached its utmost bounds; moreover, I had a formidable intuition that I was about to enter into a region of mystery of which nothing, not even my uncle's disconcerting words, was able to give me the remotest idea. I was experiencing the contagion of what seemed to me in him to be a diseased condition; and I vainly strove to subject it in myself to the control of my reason. I was taking the impossible and the incredible for granted beforehand.

And yet I saw nothing at first; and there was, in fact, nothing. This part of the wall was bare. The only detail worthy of remark was that it was not vertical and that the whole base of the[Pg 34] wall had been thickened so as to form a slightly inclined plane which sloped upwards to a height of nine feet. What was the reason for this work, when the wall did not need strengthening?

A coating of dark grey plaster, about half an inch thick, covered the whole panel. When closely examined, however, it was not painted over, but was rather a layer of some substance uniformly spread and showing no trace of a brush. Certain gleams proved that this layer was quite recent, like a varnish newly applied. I observed nothing else; and Heaven knows that I did my utmost to discover any peculiarity!

"Well, uncle?" I asked.

"Wait," he said, in an agonized voice, "wait! . . . The first indication is beginning."

"What indication?"

"In the middle . . . like a diffused light. Do you see it?"

"Yes, yes, I think I do."

It was as when a little daylight is striving to mingle with the waning darkness. A lighter disk became marked in the middle of the panel; and this lighter shade spread towards the edges, while remaining more intense at its centre. So far there was no very decided manifestation of anything out of the way; the chemical reaction of a substance lately hidden by the curtain and[Pg 35] now exposed to the daylight and the sun was quite enough to explain this sort of inner illumination. Yet something gave one the haunting though perhaps unreasonable impression that an extraordinary phenomenon was about to take place. For that was what I expected, as did my uncle Dorgeroux.

And all at once he, who knew the premonitory symptoms and the course of the phenomenon, started, as though he had received a shock.

At the same moment, the thing happened.

It was sudden, instantaneous. It leapt in a flash from the depths of the wall. Yes, I know, a spectacle cannot flash out of a wall, any more than it can out of a layer of dark-grey substance only half an inch thick. But I am setting down the sensation which I experienced, which is the same that hundreds and hundreds of people experienced afterwards, with a like clearness and a like certainty. It is no use carping at the undeniable fact: the thing shot out of the depths of the ocean of matter and it appeared violently, like the rays of a lighthouse flashing from the very womb of the darkness. After all, when we step towards a mirror, does our image not appear to us from the depth of that horizon suddenly unveiled?

Only, you see, it was not our image, my uncle[Pg 36] Dorgeroux's or mine. Nothing was reflected, because there was nothing to reflect and no reflecting screen. What I saw was . . .

On the panel were "three geometrical figures which might equally well have been badly described circles or triangles composed of curved circles. In the centre of these figures was drawn a regular circle, marked in the middle with a blacker point, as the iris is marked by the pupil."

I am deliberately using the terminology which I employed to describe the images which my uncle had drawn in red chalk on the plaster of my room, for I had no doubt that he was then trying to reproduce those same figures, the appearance of which had already upset him.

"That's what you saw, isn't it, uncle?" I asked.

"Oh," he replied, in a low voice, "I saw much more than that, very much more! . . . Wait and look right into them."

I stared wildly at the three "triangular circles," as I have called them. One of them was set above the two others; and these two, which were smaller and less regular but exactly alike, seemed, instead of looking straight before them, to turn a little to the right and to the left. Where did they come from? And what did they mean?

[Pg 37]"Look," repeated my uncle. "Do you see?"

"Yes, yes," I replied, with a shudder. "The thing's moving."

It was in fact moving. Or rather, no, it was not: the outlines of the geometrical figures remained stationary; and not a line shifted its place within. And yet from all this immobility something emerged which was nothing else than motion.

I now remembered my uncle's words:

"They're alive, aren't they? You can see them opening and showing alarm! They're alive!"

They were alive! The three triangles were alive! And, as soon as I experienced this precise and undeniable feeling that they were alive, I ceased to regard them as an assemblage of lifeless lines and began to see in them things which were like a sort of eyes, misshapen eyes, eyes different from ours, but eyes furnished with irises and pupils and throbbing in an abysmal darkness.

"They are looking at us!" I cried, quite beside myself and as feverish and unnerved as my uncle.

He nodded his head and whispered:

"Yes, that's what they're doing."

The three eyes were looking at us. We were conscious of the scrutiny of those three eyes,[Pg 38] without lids or lashes, but full of an intense life which was due to the expression that animated them, a changing expression, by turns serious, proud, noble, enthusiastic and, above all, sad, grievously sad.

I feel how improbable these observations must appear. Nevertheless they correspond most strictly with the reality as it was beheld at a later date by the crowds that thronged to Haut-Meudon Lodge. Like my uncle, like myself, those crowds shuddered before three combinations of motionless lines which had the most heart-rending expression, just as at other moments they laughed at the comical or gayer expression which they were compelled to read into those same lines.

And on each occasion the spectacle which I am now describing was repeated in exactly the same order. A brief pause, followed by a series of vibrations. Then, suddenly, three eclipses, after which the combination of three triangles began to turn upon itself, as a whole, slowly at first and then with increasing rapidity, which gradually became transformed into so swift a rotation that one distinguished nothing but a motionless rose-pattern.

After that, nothing. The panel was empty.

It must be understood that, notwithstanding the explanations which I must needs offer, the development of all these events took but very little time: exactly eighteen seconds, as I had the opportunity of calculating afterwards. But, during these eighteen seconds—and this again I observed on many an occasion—the spectator received the illusion of watching a complete drama, with its preliminary expositions, its plot and its culmination. And when this obscure, illogical drama was over, you questioned what you had seen, just as you question the nightmare which wakes you from your sleep.

Nevertheless it must be said that none of all this partook in any way of those absurd optical illusions which are so easily contrived or of those arbitrary ideas on which a whole pseudo-scientific novel is sometimes built up. There is no question of a novel, but of a physical phenomenon, an absolutely natural phenomenon, the explanation of which, when it comes to be known, is also absolutely natural.

[Pg 40]And I beg those who are not acquainted with this explanation not to try to guess it. Let them not worry themselves with suppositions and interpretations. Let them forget, one by one, the theories over which I myself am lingering: all that has to do with B-rays, materializations, or the effect of solar heat. These are so many roads that lead nowhere. The best plan is to be guided by events, to have faith and to wait.

"It's finished, uncle, isn't it?" I asked.

"It's the beginning," he replied.

"How do you mean? The beginning of what? What's going to happen?"

"I don't know."

I was astounded:

"You don't know? But you knew just now, about this, about those strange eyes! . . ."

"It all starts with that. But other things come afterwards, things which vary and which I know nothing about!"

"But how can that be possible?" I asked. "Do you mean to say that you don't know anything about them, you who prepared everything for them?"

"I prepared them, but I do not control them. As I told you, I have opened a door which leads into the darkness; and from that darkness unforeseen images emerge."

[Pg 41]"But is the thing that's coming of the same nature as those eyes?"

"No."

"Then what is it, uncle?"

"The thing that's coming will be a representation of images in conformity with what we are accustomed to see."

"Things which we shall understand, therefore?"

"Yes, we shall understand them; and yet they will be all the more incomprehensible."

I often wondered, during the weeks that followed, if my uncle's words were to be fully relied upon and if he had not uttered them in order to mislead me as to the origin and meaning of his discoveries. How indeed was it possible to think that the key to the riddle remained unknown to him? But at that moment I was wholly under his influence, steeped in the great mystery that surrounded us; and, with a constricted feeling at my heart, with all my overstimulated senses, I thought of nothing but gazing into the miraculous panel.

A movement on my uncle's part warned me. I gave a start. The dawn was rising over the grey surface.

I saw, first of all, a cloudy radiance whirling around a central point, towards which all the[Pg 42] luminous spirals rushed and in which they were swallowed up while whirling upon themselves. Next, this point expanded into an ever wider circle, covered with a light, hazy veil which gradually dispersed, revealing a vague, floating image, like the apparitions raised by spiritualists and mediums at their sittings.

Then followed as it were a certain hesitation. The phantom image was striving with the diffuse shadow and seeking to attain life and light. Certain features became more pronounced. Outlines and separate planes took shape; and at last a flood of light issued from the phantom image and turned it into a dazzling picture, which seemed to be bathed in sunlight.

It was a woman's face.

I remember that at that moment my mental confusion was such that I felt like darting forward to feel the marvellous wall and lay my hands upon the living material in which the incredible phenomenon was vibrating. But my uncle dug his fingers into my arm:

"I won't have you move!" he growled. "If you budge an inch, the whole thing will fade away. Look!"

I did not move; indeed, I doubt whether I could have done so. My legs were giving way beneath me. Both of us, my uncle and I,[Pg 43] dropped into a sitting posture on the fallen trunk of a tree.

"Look, look!" he commanded.

The woman's face had approached in our direction until it was twice the size of life. The first thing that struck us was the cap, which was that of a nurse, with the head-band tightly drawn over the forehead and the veil around the head. The features, handsome and regular and still young, wore that look of almost divine dignity which the primitive painters used to give to the saints who are suffering or about to suffer martyrdom, a nobility compounded of pain and ecstasy, of resignation and hope, of smiles and tears. Bathed in that light which really seemed to be an inward flame, the woman opened, upon a scene invisible to us, a pair of large dark eyes which, though filled with nameless terror, nevertheless were not afraid. The contrast was remarkable: her resignation was defiant; her fear was full of pride.

"Oh," stammered my uncle, "I seem to observe the same expression as in the Three Eyes which were there just now. Do you see: the same dignity, the same gentleness . . . and also the same dread?"

"Yes," I replied, "it's the same expression, the same sequence of expressions."

[Pg 44]And, while I spoke and while the woman still remained in the foreground, outside the frame of the picture, I felt certain recollections arise within me, as at the sight of the portrait of a person whose features are not entirely unfamiliar. My uncle received the same impression, for he said:

"I seem to remember . . ."

But at that moment the strange face withdrew to the plane which it occupied at first. The mists that created a halo round it, drifted away. The shoulders came into view, followed by the whole body. We now saw a woman standing, fastened by bonds that gripped her bust and waist to a post the upper end of which rose a trifle above her head.

Then all this, which hitherto had given the impression of fixed outlines, like the outlines of a photograph, for instance, suddenly became alive, like a picture developing into a reality, a statue stepping straight into life. The bust moved. The arms, tied behind, and the imprisoned shoulders were struggling against the cords that were hurting them. The head turned slightly. The lips spoke. It was no longer an image presented for us to gaze at: it was life, moving and living life. It was a scene taking place in space and time. A whole background[Pg 45] came into being, filled with people moving to and fro. Other figures were writhing, bound to posts. I counted eight of them. A squad of soldiers marched up, with shouldered rifles. They wore spiked helmets.

My uncle observed:

"Edith Cavell."

"Yes," I said, with a start, "I recognize her: Edith Cavell; the execution of Edith Cavell."

Once more and not for the last time, in setting down such phrases as these, I realize how ridiculous they must sound to any one who does not know to begin with what they signify and what is the exact truth that lies hidden in them. Nevertheless, I declare that this idea of something absurd and impossible did not occur to the mind when it was confronted with the phenomenon. Even when no theory had as yet suggested the smallest element of a logical explanation, people accepted as irrefutable the evidence of their own eyes. All those who saw the thing and whom I questioned gave me the same answer. Afterwards, they would correct themselves and protest. Afterwards, they would plead the excuse of hallucinations or visions received by suggestion. But, at the time, even though their reason was up in arms and though they, so to speak, "kicked" against facts which[Pg 46] had no visible cause, they were compelled to bow before them and to follow their development as they would the representation of a succession of real events.

A theatrical representation, if you like, or rather a cinematographic representation, for, on the whole, this was the impression that emerged most clearly from all the impressions received. The moment Miss Cavell's image had assumed the animation of life, I turned round to look for the apparatus, standing in some corner of the Yard, which was projecting that animated picture; and, though I saw nothing, though I at once understood that in any case no projection could be effected in broad daylight and without omitting shafts of light, yet I received and retained that justifiable impression. There was no projector, no, but there was a screen: an astonishing screen which received nothing from without, since nothing was transmitted, but which received everything from within. And that was really the sensation experienced. The images did not come from the outside. They sprang to the surface from within. The horizon opened out on the farther side of a solid material. The darkness gave forth light.

Words, words, I know! Words which I heap upon words before I venture to write those which[Pg 47] express what I saw issuing from the abyss in which Miss Cavell was about to undergo the death-penalty. The execution of Miss Cavell! Of course I said to myself, if it was a cinematographic representation, if it was a film—and how could one doubt it?—at any rate it was a film like ever so many others, faked, fictitious, based upon tradition, in a conventional setting, with paid performers and a heroine who had thoroughly studied the part. I knew that. But, all the same, I watched as though I did not know it. The miracle of the spectacle was so great that one was constrained to believe in the whole miracle, that is to say, in the reality of the representation. No fake was here. No make-believe. No part learned by heart. No performers and no setting. It was the actual scene. The actual victims. The horror which thrilled me during those few minutes was that which I should have felt had I beheld the murderous dawn of the 8th of October, 1915, rise across the thrice-accursed drill-ground.

It was soon over. The firing-platoon was drawn up in double file, on the right and a little aslant, so that we saw the men's faces between the rifle-barrels. There were a good many of them: thirty, forty perhaps, forty butchers, booted, belted, helmeted, with their straps under[Pg 48] their chins. Above them hung a pale sky, streaked with thin red clouds. Opposite them . . . opposite them were the eight doomed victims.

There were six men and two women, all belonging to the people or the lower middle-class. They were now standing erect, throwing forward their chests as they tugged at their bonds.

An officer advanced, followed by four Feldwebel carrying unfurled handkerchiefs. Not any of the people condemned to death consented to have their eyes bandaged. Nevertheless, their faces were wrung with anguish; and all, with an impulse of their whole being, seemed to rush forward to their doom.

The officer raised his sword. The soldiers took aim.

A supreme effort of emotion seemed to add to the stature of the victims: and a cry issued from their lips. Oh, I saw and heard that cry, a fanatical and desperate cry in which the martyrs shouted forth their triumphant faith.

The officer's arm fell smartly. The intervening space appeared to tremble as with the rumbling of thunder. I had not the courage to look; and my eyes fixed themselves on the distracted countenance of Edith Cavell.

[Pg 49]She also was not looking. Her eyelids were closed. But how she was listening! How her features contracted under the clash of the atrocious sounds, words of command, detonations, cries of the victims, death-rattles, moans of agony. By what refinement of cruelty had her own end been delayed? Why was she condemned to that double torture of seeing others die before dying herself?

Still, everything must be over yonder. One party of the butchers attended to the corpses, while the others formed into line and, pivoting upon the officer, marched towards Miss Cavell. They thus stepped out of the frame within which we were able to follow their movements; but I was able to perceive, by the gestures of the officer, that they were forming up opposite Nurse Cavell, between her and us.

The officer stepped towards her, accompanied by a military chaplain, who placed a crucifix to her lips. She kissed it fervently and tenderly. The chaplain then gave her his blessing; and she was left alone. A mist once more shrouded the scene, leaving her whole figure full in the light. Her eyelids were still closed, her head erect and her body rigid.

She was at that moment wearing a very sweet[Pg 50] and very tranquil expression. Not a trace of fear distorted her noble countenance. She stood awaiting death with saintly serenity.

And this death, as it was revealed to us, was neither very cruel nor very odious. The upper part of the body fell forward. The head drooped a little to one side. But the shame of it lay in what followed. The officer stood close to the victim, revolver in hand. And he was pressing the barrel to his victim's temple, when, suddenly, the mist broke into dense waves and the whole picture disappeared. . . .

The spectator who has just been watching the most tragic of films finds it easy to escape from the sort of dark prison-house in which he was suffocating and, with the return of the light, recovers his equilibrium and his self-possession. I, on the other hand, remained for a long time numb and speechless, with my eyes riveted to the empty panel, as though I expected something else to emerge from it. Even when it was over, the tragedy terrified me, like a nightmare prolonged after waking, and, even more than the tragedy, the absolutely extraordinary manner in which it had been unfolded before my eyes. I did not understand. My disordered brain vouchsafed me none but the most grotesque and incoherent ideas.

A movement on the part of Noël Dorgeroux drew me from my stupor: he had drawn the curtain across the screen.

At this I vehemently seized my uncle by his two hands and cried:

[Pg 52]"What does all this mean? It's maddening! What explanation are you able to give?"

"None," he said, simply.

"But still . . . you brought me here."

"Yes, that you might also see and to make sure that my eyes had not deceived me."

"Therefore you have already witnessed other scenes in that same setting?"

"Yes, other sights . . . three times before."

"What, uncle? Can you specify them?"

"Certainly: what I saw yesterday, for instance."

"What was that, uncle?"

He pushed me a little and gazed at me, at first without replying. Then, speaking in a very low tone, with deliberate conviction, he said:

"The battle of Trafalgar."

I wondered if he was making fun of me. But Noël Dorgeroux was little addicted to banter at any time; and he would not have selected such a moment as this to depart from his customary gravity. No, he was speaking seriously; and what he said suddenly struck me as so humorous that I burst out laughing:

"Trafalgar! Don't be offended, uncle; but it's really too quaint! The battle of Trafalgar, which was fought in 1805?"

[Pg 53]He once more looked at me attentively:

"Why do you laugh?" he asked.

"Good heavens, I laugh, I laugh . . . because . . . well, confess . . ."

He interrupted me:

"You're laughing for very simple reasons, Victorien, which I will explain to you in a few words. To begin with, you are nervous and ill at ease; and your merriment is first and foremost a reaction. But, in addition, the spectacle of that horrible scene was so—what shall I say?—so convincing that you looked upon it, in spite of yourself, not as a reconstruction of the murder, but as the actual murder of Miss Cavell. Is that true?"

"Perhaps it is, uncle."

"In other words, the murder and all the infamous details which accompanied it must have been—don't let us hesitate to use the word—must have been cinematographed by some unseen witness from whom I obtained that precious film: and my invention consists solely in reproducing the film in the thickness of a gelatinous layer of some kind or other. A wonderful, but a credible discovery. Are we still agreed?"

"Yes, uncle, quite."

"Very well. But now I am claiming something very different. I am claiming to have[Pg 54] witnessed an evocation of the battle of Trafalgar! If so, the French and English frigates must have foundered before my eyes! I must have seen Nelson die, struck down at the foot of his mainmast! That's quite another matter, is it not? In 1805 there were no cinematographic films. Therefore this can be only an absurd parody. Thereupon all your emotion vanishes. My reputation fades into thin air. And you laugh! I am to you nothing more than an old impostor, who, instead of humbly showing you his curious discovery, tries in addition to persuade you that the moon is made of green cheese! A humbug, what?"

We had left the wall and were walking towards the door of the garden. The sun was setting behind the distant hills. I stopped and said to Noël Dorgeroux:

"Forgive me, uncle, and please don't think that I am over lacking in the respect I owe you. There is nothing in my amusement that need annoy you, nothing to make you suppose that I suspect your absolute sincerity."

"Then what do you think? What is your conclusion?"

"I don't think anything, uncle. I have arrived at no conclusion and I am not even trying to do so, at present. I am out of my depth, per[Pg 55]plexed, at the same time dazed and dissatisfied, as though I felt that the riddle was even more wonderful than it is and that it would always remain insoluble."

We were entering the garden. It was his turn to stop me:

"Insoluble! That is really your opinion?"

"Yes, for the moment."

"You can't imagine any theory?"

"No."

"Still, you saw? You have no doubts?"

"I certainly saw. I saw first three strange eyes that looked at us; then I witnessed a scene which was the murder of Miss Cavell. That is what I saw, just as you did, uncle; and I do not for a moment doubt the undeniable evidence of my own eyes."

He held out his hand to me:

"That's what I wanted to know, my boy. And thank you."

I have given a faithful account of what happened that afternoon. In the evening we dined together by ourselves, Bérangère having sent word to say that she was indisposed and would not leave her room. My uncle was deeply absorbed in thought and did not say a word on what had happened in the Yard.

[Pg 56]I slept hardly at all, haunted by the recollection of what I had seen and tormented by a score of theories, which I need not mention here, for not one of them was of the slightest value.

Next day, Bérangère did not come downstairs. At luncheon, my uncle preserved the same silence. I tried many times to make him talk, but received no reply.

My curiosity was too intense to allow my uncle to get rid of me in this way. I took up my position in the garden before he left the house. Not until five o'clock did he go up to the Yard.

"Shall I come with you, uncle?" I suggested, boldly.

He grunted, neither granting my request nor refusing it. I followed him. He walked across the Yard, locked himself into his principal workshop and did not leave it until an hour later:

"Ah, there you are!" he said, as though he had been unaware of any presence.

He went to the wall and briskly drew the curtain. Just then he asked me to go back to the workshop and to fetch something or other which he had forgotten. When I returned, he said, excitedly:

"It's finished, it's finished!"

"What is, uncle?"

[Pg 57]"The Eyes, the Three Eyes."

"Oh, have you seen them?"

"Yes; and I refuse to believe . . . no, of course, it's an illusion on my part. . . . How could it be possible, when you come to think of it? Imagine, the eyes wore the expression of my dead son's eyes, yes, the very expression of my poor Dominique. It's madness, isn't it? And yet I declare, yes, I declare that Dominique was gazing at me . . . at first with a sad and sorrowful gaze, which suddenly became the terrified gaze of a man who is staring death in the face. And then the Three Eyes began to revolve upon themselves. That was the end."

I made Noël Dorgeroux sit down:

"It's as you suppose, uncle, an illusion, an hallucination. Just think, Dominique has been dead so many years! It is therefore incredible . . ."

"Everything is incredible and nothing is," he said. "There is no room for human logic in front of that wall."

I tried to reason with him, though my mind was becoming as bewildered as his own. But he silenced me:

"That'll do," he said. "Here's the other thing beginning."

[Pg 58]He pointed to the screen, which was showing signs of life and preparing to reveal a new picture.

"But, uncle," I said, already overcome by excitement, "where does that come from?"

"Don't speak," said Noël Dorgeroux. "Not a word."

I at once observed that this other thing bore no relation to what I had witnessed the day before; and I concluded that the scenes presented must occur without any prearranged order, without any chronological or serial connection, in short, like the different films displayed in the course of a performance.

It was the picture of a small town as seen from a neighbouring height. A castle and a church-steeple stood out above it. The town was built on the slope of several hills and at the intersection of the valleys, which met among clumps of tall, leafy trees.

Suddenly, it came nearer and was seen on a larger scale. The hills surrounding the town disappeared; and the whole screen was filled with a crowd swarming with lively gestures around an open space above which hung a balloon, held captive by ropes. Suspended from the balloon was a receptacle serving probably for the production of hot air. Men were issuing from[Pg 59] the crowd on every hand. Two of them climbed a ladder the top of which was leaning against the side of a car. And all this, the appearance of the balloon, the shape of the appliances employed, the use of hot air instead of gas, the dress of the people; all this struck me as possessing an old-world aspect.

"The brothers Montgolfier," whispered my uncle.

These few words enlightened me. I remembered those old prints recording man's first ascent towards the sky, which was accomplished in June, 1783. It was this wonderful event which we were witnessing, or, at least, I should say, a reconstruction of the event, a reconstruction accurately based upon those old prints, with a balloon copied from the original, with costumes of the period and no doubt, in addition, the actual setting of the little town of Annonay.

But then how was it that there was so great a multitude of townsfolk and peasants? There was no comparison possible between the usual number of actors in a cinema scene and the incredibly tight-packed crowd which I saw moving before my eyes. A crowd like that is found only in pictures which the camera has secured direct, on a public holiday, at a march-past of troops or a royal procession.

[Pg 60]However, the wavelike eddying of the crowd suddenly subsided. I received the impression of a great silence and an anxious period of waiting. Some men quickly severed the ropes with hatchets. Etienne and Joseph Montgolfier lifted their hats.

And the balloon rose in space. The people in the crowd raised their arms and filled the air with an immense clamour.

For a moment, the screen showed us the two brothers, by themselves and enlarged. With the upper part of their bodies leaning from the car, each with one arm round the other's waist and one hand clasping the other's, they seemed to be praying with an air of unspeakable ecstasy and solemn joy.

Slowly the ascent continued. And it was then that something utterly inexplicable occurred: the balloon, as it rose above the little town and the surrounding hills, did not appear to my uncle and me as an object which we were watching from an increasing depth below. No, it was the little town and the hills which were sinking and which, by sinking, proved to us that the balloon was ascending. But there was also this absolutely illogical phenomenon, that we remained on the same level as the balloon, that it retained the same dimensions and that the two brothers[Pg 61] stood facing us, exactly as though the photograph had been taken from the car of a second balloon, rising at the same time as the first with an exactly and mathematically identical movement!

The scene was not completed. Or rather it was transformed in accordance with the method of the cinematograph, which substitutes one picture for another by first blending them together. Imperceptibly, when it was perhaps some fifteen hundred feet from the ground, the Montgolfier balloon became less distinct and its vague and softened outlines gradually mingled with the more and more powerful outlines of another shape which soon occupied the whole space and which proved to be that of a military aeroplane.

Several times since then the mysterious screen has shown me two successive scenes of which the second completed the first, thus forming a diptych which displayed the evident wish to convey a lesson by connecting, across space and time, two events which in this way acquired their full significance. This time the moral was clear: the peaceable balloon had culminated in the murderous aeroplane. First the ascent at Annonay. Then a fight in mid-air, a fight between the monoplane which I had seen develop from the old-fashioned balloon and the biplane upon which I beheld it swooping like a bird of prey.

[Pg 62]Was it an illusion or a "faked representation?" For here again we saw the two aeroplanes not in the normal fashion, from below, but as if we were at the same height and moving at the same rate of speed. In that case, were we to admit that an operator, perched on a third machine, was calmly engaged in "filming" the shifting fortunes of the terrible battle? That was impossible, surely!

But there was no good purpose to be served by renewing these perpetual suppositions over and over again. Why should I doubt the unimpeachable evidence of my eyes and deny the undeniable? Real aeroplanes were manoeuvring before my eyes. A real fight was taking place in the thickness of that old wall.

It did not last long. The man who was alone was attacking boldly. Time after time his machine-gun flashed forth flames. Then, to avoid the enemy's bullets, he looped the loop twice, each time throwing his aeroplane in such a position that I was able to distinguish on the canvas the three concentric circles that denote the Allied machines. Then, coming nearer and attacking his adversaries from behind, he returned to his gun.

The Hun biplane—I observed the iron cross—dived straight for the ground and recovered[Pg 63] itself. The two men seemed to be sitting tight under their furs and masks. There was a third machine-gun attack. The pilot threw up his hands. The biplane capsized and fell.

I saw this fall in the most inexplicable fashion. At first, of course, it seemed swift as lightning. And then it became infinitely slow and even ceased, with the machine overturned and the two bodies motionless, head downwards and arms outstretched.

Then the ground shot up with a dizzy speed, devastated, shell-holed fields, swarming with thousands of French poilus.

The biplane came down beside a river. From the shapeless fuselage and the shattered wings two legs appeared.

And the French plane landed almost immediately, a short way off. The victor stepped out, pushed back the soldiers who had run up from every side and, moving a few yards towards his motionless prey, took off his mask and made the sign of the cross.

"Oh," I whispered, "this is dreadful! And how mysterious! . . ."

Then I saw that Noël Dorgeroux was on his knees, his face distorted with emotion:

"What is it, uncle?" I asked.

Stretching towards the wall his trembling[Pg 64] hands, which were clasped together, he stammered:

"Dominique! I recognize my son! It's he! Oh, I'm terrified!"

I also, as I gazed at the victor, recovered in my memory the time-effaced image of my poor cousin.

"It's he!" continued my uncle. "I was right . . . the expression of the Three Eyes. . . . Oh! I can't look! . . . I'm afraid!"

"Afraid of what, uncle?"

"They are going to kill him . . . to kill him before my eyes . . . to kill him as they actually did kill him . . . Dominique! Dominique! Take care!" he shouted.

I did not shout: what warning cry could reach the man about to die? But the same terror brought me to my knees and made me wring my hands. In front of us, from underneath the shapeless mass, among the heaped-up wreckage, something rose up, the swaying body of one of the victims. An arm was extended, aiming a revolver. The victor sprang to one side. It was too late. Shot through the head, he spun round upon his heels and fell beside the dead body of his murderer.

The tragedy was over.

My uncle, bent double, was sobbing pitifully[Pg 65] a few paces from my side. He had witnessed the actual death of his son, foully murdered in the great war by a German airman!

Bérangère next day resumed her place at meals, looking a little pale and wearing a more serious face than usual. My uncle, who had not troubled about her during the last two days, kissed her absent-mindedly. We lunched without a word. Not until we had nearly ended did Noël Dorgeroux speak to his god-child:

"Well, dear, are you none the worse for your fall?"

"Not a bit, god-father; and I'm only sorry that I didn't see . . . what you saw up there, yesterday and the day before. Are you going there presently, god-father?"

"Yes, but I'm going alone."

This was said in a peremptory tone which allowed of no reply. My uncle was looking at me. I did not stir a muscle.

Lunch finished in an awkward silence. As he was about to leave the room, Noël Dorgeroux turned back to me and asked:

"Do you happen to have lost anything in the Yard?"

[Pg 67]"No, uncle. Why do you ask?"

"Because," he answered, with a slight hesitation, "because I found this on the ground, just in front of the wall."

He showed me a lens from an eye-glass.

"But you know, uncle," I said, laughing, "that I don't wear spectacles or glasses of any kind."

"No more do I!" Bérangère declared.

"That's so, that's so," Noël Dorgeroux replied, in a thoughtful tone. "But, still, somebody has been there. And you can understand my uneasiness."

In the hope of making him speak, I pursued the subject:

"What are you uneasy about, uncle? At the worst, some one may have seen the pictures produced on the screen, which would not be enough, so it seems to me, to enable the secret of your discovery to be stolen. Remember that I myself, who was with you, am hardly any wiser than I was before."

I felt that he did not intend to answer and that he resented my insistence. This irritated me.

"Listen, uncle," I said. "Whatever the reasons for your conduct may be, you have no right to suspect me; and I ask and entreat you to give[Pg 68] me an explanation. Yes, I entreat you, for I cannot remain in this uncertainty. Tell me, uncle, was it really your son whom you saw die, or were we shown a fabricated picture of his death? Then again, what is the unseen and omnipotent entity which causes these phantoms to follow one another in that incredible magic lantern? Never was there such a problem, never so many irreconcilable questions. Look here, last night, while I was trying for hours to get to sleep, I imagined—it's an absurd theory, I know, but, all the same, one has to cast about—well, I remembered that you had spoken to Bérangère of a certain inner force which radiated from us and emitted what you have named the B-rays, after your god-daughter. If so, might one not suppose that, in the circumstances, this force, emanating, uncle, from your own brain, which was haunted by a vague resemblance between the expression of the Three Eyes and the expression of your own, might we not suppose that this force projected on the receptive material of the wall the scene which was conjured up in your mind? Don't you think that the screen which you have covered with a special substance registered your thoughts just as a sensitive plate, acted upon by the sunlight, registers forms and outlines? In that case . . ."

[Pg 69]I broke off. As I spoke, the words which I was using seemed to me devoid of meaning. My uncle, however, appeared to be listening to them with a certain willingness and even to be waiting for what I would say next. But I did not know what to say. I had suddenly come to the end of my tether; and, though I made every effort to detain Noël Dorgeroux by fresh arguments, I felt that there was not a word more to be said between us on that subject.

Indeed, my uncle went away without answering one of my questions. I saw him, through the window, crossing the garden.

I gave way to a movement of anger and exclaimed to Bérangère:

"I've had enough of this! After all, why should I worry myself to death trying to understand a discovery which, when you think of it, is not a discovery at all? For what does it consist of? No one can respect Noël Dorgeroux more than I do; but there's no doubt that this, instead of a real discovery, is rather a stupefying way of deluding one's self, of mixing up things that exist with things that do not exist and of giving an appearance of reality to what has none. Unless . . . But who knows anything about it? It is not even possible to express an opinion. The whole thing is an ocean of mystery, over[Pg 70]hung by mountainous clouds which descend upon one and stifle one!"

My ill-humour suddenly turned against Bérangère. She had listened to me with a look of disapproval, feeling angry perhaps at my blaming her god-father; and she was now slipping towards the door. I stopped her as she was passing; and, in a fit of rancour which was foreign to my nature, I let fly:

"Why are you leaving the room? Why do you always avoid me as you do? Speak, can't you? What have you against me? Yes, I know, my thoughtless conduct, the other day. But do you think I would have acted like that if you weren't always keeping up that sulky reserve with me? Hang it all, I've known you as quite a little girl! I've held your skipping-rope for you when you were just a slip of a child! Then why should I now be made to look on you as a woman and to feel that you are indeed a woman . . . a woman who stirs me to the very depths of my heart?"

She was standing against the door and gazing at me with an undefinable smile, which contained a gleam of mockery, but nothing provocative and not a shade of coquetry. I noticed for the first time that her eyes, which I thought to be[Pg 71] grey, were streaked with green and, as it were, flecked with specks of gold. And, at the same time, the expression of those great eyes, bright and limpid though they were, struck me as the most unfathomable thing in the world. What was passing in those limpid depths? And why did my mind connect the riddle of those eyes with the terrible riddle which the three geometrical eyes had set me?

However, the recollection of the stolen kiss diverted my glance to her red lips. Her face turned crimson. This was a last, exasperating insult.

"Let me be! Go away!" she commanded, quivering with anger and shame.

Helpless and a prisoner, she lowered her head and bit her lips to prevent my seeing them. Then, when I tried to take her hands, she thrust her outstretched arms against my chest, pushed me back with all her might and cried:

"You're a mean coward! Go away! I loathe and hate you!"

Her outburst restored my composure. I was ashamed of what I had done and, making way for her to pass, I opened the door for her and said:

"I beg your pardon, Bérangère. Don't be[Pg 72] angrier with me than you can help. I promise you it shan't occur again."

Once more, the story of the Three Eyes is closely bound up with all the details of my love, not only in my recollection of it, but also in actual fact. While the riddle itself is alien to it and may be regarded solely in its aspect of a scientific phenomenon, it is impossible to describe how humanity came to know of it and was brought into immediate contact with it, without at the same time revealing all the vicissitudes of my sentimental adventure. The riddle and this adventure, from the point of view with which we are concerned, are integral parts of the same whole. The two must be described simultaneously.

At the moment, being somewhat disillusionized in both respects, I decided to tear myself away from this twofold preoccupation and to leave my uncle to his inventions and Bérangère to her sullen mood.

I had not much difficulty in carrying out my resolve in so far as Noël Dorgeroux was concerned. We had a long succession of wet days. The rain kept him to his room or his laboratories; and the pictures on the screen faded from my mind like diabolical visions which the brain re[Pg 73]fuses to accept. I did not wish to think of them; and I thought of them hardly at all.

But Bérangère's charm pervaded me, notwithstanding the good faith in which I waged this daily battle. Unaccustomed to the snares of love, I fell an easy prey, incapable of defence. Bérangère's voice, her laugh, her silence, her day-dreams, her way of holding herself, the fragrance of her personality, the colour of her hair served me as so many excuses for exaltation, rejoicing, suffering or despair. Through the breach now opened in my professorial soul, which hitherto had known few joys save those of study, came surging all the feelings that make up the delights and also the pangs of love, all the emotions of longing, hatred, fondness, fear, hope . . . and jealousy.

It was one bright and peaceful morning, as I was strolling in the Meudon woods, that I caught sight of Bérangère in the company of a man. They were standing at a corner where two roads met and were talking with some vivacity. The man faced me. I saw a type of what would be described as a coxcomb, with regular features, a dark, fan-shaped beard and a broad smile which displayed his teeth. He wore a double eye-glass.

Bérangère heard the sound of my footsteps, as I approached, and turned round. Her atti[Pg 74]tude denoted hesitation and confusion. But she at once pointed down one of the two roads, as though giving a direction. The fellow raised his hat and walked away. Bérangère joined me and, without much restraint, explained:

"It was somebody asking his way."

"But you know him, Bérangère?" I objected.

"I never saw him before in my life," she declared.

"Oh, come, come! Why, from the manner you were speaking to him . . . Look here, Bérangère, will you take your oath on it?"

She started:

"What do you mean? Why should I take an oath to you? I am not accountable to you for my actions."

"In that case, why did you tell me that he was enquiring his way of you? I asked you no question."

"I do as I please," she replied, curtly.

Nevertheless, when we reached the Lodge, she thought better of it and said:

"After all, if it gives you any pleasure, I can swear that I was seeing that gentleman for the first time and that I had never heard of him. I don't even know his name."

We parted.

[Pg 75]"One word more," I said. "Did you notice that the man wore glasses?"

"So he did!" she said, with some surprise. "Well, what does that prove?"

"Remember, your uncle found a spectacle-lens in front of the wall in the Yard."

She stopped to think and then shrugged her shoulders:

"A mere coincidence! Why should you connect the two things?"

Bérangère was right and I did not insist. Nevertheless and though she had answered me in a tone of undeniable candour, the incident left me uneasy and suspicious. I would not admit that so animated a conversation could take place between her and a perfect stranger who was simply asking her the way. The man was well set-up and good-looking. I suffered tortures.

That evening Bérangère was silent. It struck me that she had been crying. My uncle, on the contrary, on returning from the Yard, was talkative and cheerful; and I more than once felt that he was on the point of telling me something. Had anything thrown fresh light on his invention?

Next day, he was just as lively:

[Pg 76]"Life is very pleasant, at times," he said.

And he left us, rubbing his hands.

Bérangère spent all the early part of the afternoon on a bench in the garden, where I could see her from my room. She sat motionless and thoughtful.

At four o'clock, she came in, walked across the hall of the Lodge and went out by the front door.

I went out too, half a minute later.

The street which skirted the house turned and likewise skirted, on the left, the garden and the Yard, whereas on the right the property was bordered by a narrow lane which led to some fields and abandoned quarries. Bérangère often went this way; and I at once saw, by her slow gait, that her only intention was to stroll wherever her dreams might lead her.

She had not put on a hat. The sunlight gleamed in her hair. She picked the stones on which to place her feet, so as not to dirty her shoes with the mud in the road.

Against the stout plank fence which at this point replaced the wall enclosing the Yard stood an old street-lamp, now no longer used, which was fastened to the fence with iron clamps. Bérangère stopped here, all of a sudden, evi[Pg 77]dently in obedience to a thought which, I confess, had often occurred to myself and which I had had the courage to resist, perhaps because I had not perceived the means of putting it into execution.

Bérangère saw the means. It was only necessary to climb the fence by using the lamp, in order to make her way into the Yard without her uncle's knowledge and steal a glimpse of one of those sights which he guarded so jealously for himself.

She made up her mind without hesitation; and, when she was on the other side, I too had not the least hesitation in following her example. I was in that state of mind when one is not unduly troubled by idle scruples; and there was no more indelicacy in satisfying my legitimate curiosity than in spying upon Bérangère's actions. I therefore climbed over also.

My scruples returned when I found myself on the other side, face to face with Bérangère, who had experienced some difficulty in getting down. I said, a little sheepishly:

"This is not a very nice thing we're doing, Bérangère; and I presume you mean to give it up."

She began to laugh: