Title: Dumas' Paris

Author: M. F. Mansfield

Release date: January 31, 2011 [eBook #35125]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

Dumas’ Paris

| UNIFORM VOLUMES | ||

| Dickens’ London | ||

| By Francis Miltoun | ||

| Library 12mo, cloth, gilt top | $2.00 | |

| The Same, ¾ levant morocco | 5.00 | |

| Milton’s England | ||

| By Lucia Ames Mead | ||

| Library 12mo, cloth, gilt top | 2.00 | |

| The Same, ¾ levant morocco | 5.00 | |

| Dumas’ Paris | ||

| By Francis Miltoun | ||

| Library 12mo, cloth, gilt top | net | 1.60 |

| postpaid | 1.75 | |

| The Same, ¾ levant morocco | net | 4.00 |

| postpaid | 4.15 | |

| L. C. PAGE & COMPANY New England Building Boston, Mass. | ||

Alexandre Dumas

Dumas’ Paris

By

Francis Miltoun

Author of “Dickens’ London,” “Cathedrals of Southern

France,” “Cathedrals of Northern France,” etc.

With two Maps and many Illustrations

Boston

L. C. Page & Company

MDCCCCV

Copyright, 1904

By L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

All rights reserved

Published November, 1904

COLONIAL PRESS

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, Mass., U.S.A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A General Introduction | 1 |

| II. | Dumas’ Early Life in Paris | 14 |

| III. | Dumas’ Literary Career | 33 |

| IV. | Dumas’ Contemporaries | 68 |

| V. | The Paris of Dumas | 83 |

| VI. | Old Paris | 126 |

| VII. | Ways and Means of Communication | 147 |

| VIII. | The Banks of the Seine | 165 |

| IX. | The Second Empire and After | 178 |

| X. | La Ville | 195 |

| XI. | La Cité | 235 |

| XII. | L’Université Quartier | 244 |

| XIII. | The Louvre | 257 |

| XIV. | The Palais Royal | 266 |

| XV. | The Bastille | 278 |

| XVI. | The Royal Parks and Palaces | 297 |

| XVII. | The French Provinces | 321 |

| XVIII. | Les Pays Étrangers | 360 |

| Appendices | 373 | |

| Index | 377 |

| PAGE | |

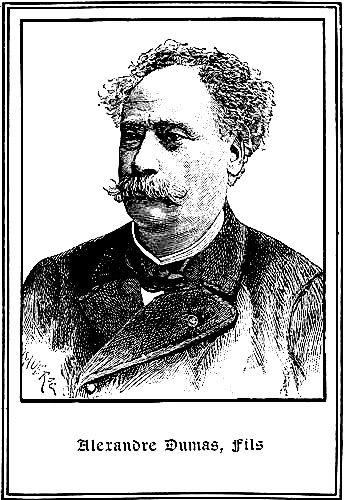

| Alexandre Dumas | Frontispiece |

| Dumas’ House at Villers-Cotterets | 7 |

| Statue of Dumas at Villers-Cotterets | 14 |

| Facsimile of Dumas’ Own Statement of His Birth | 26 |

| Facsimile of a Manuscript Page from One of Dumas’ Plays | 37 |

| D’Artagnan | 48 |

| Alexandre Dumas, Fils | 64 |

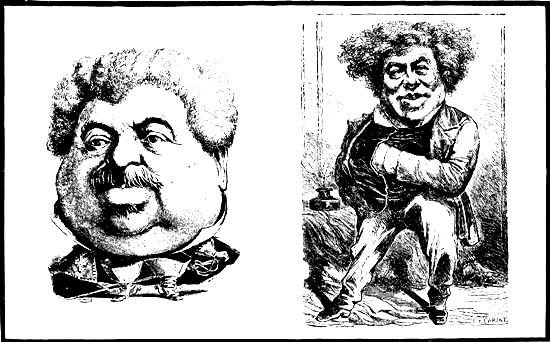

| Two Famous Caricatures of Alexandre Dumas | 68 |

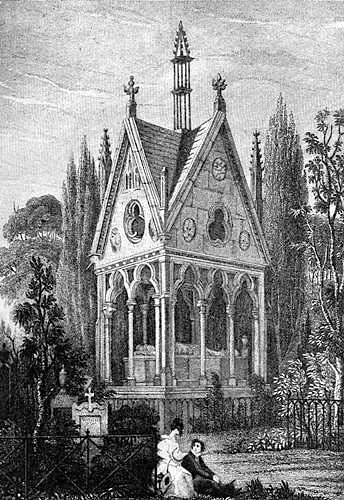

| Tomb of Abelard and Héloïse | 82 |

| General Foy’s Residence | 84 |

| D’Artagnan, from the Dumas Statue by Gustave Doré | 123 |

| Pont Neuf—Pont au Change | 135 |

| Portrait of Henry IV. | 143 |

| Grand Bureau de la Poste | 154 |

| The Odéon in 1818 | 167 |

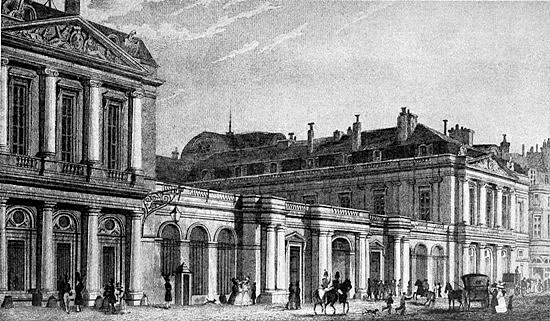

| Palais Royal, Street Front | 183 |

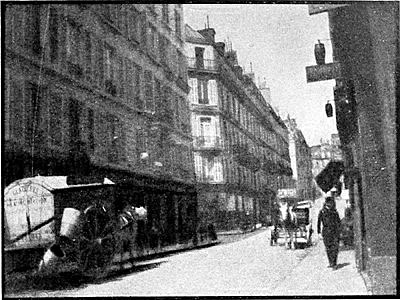

| 77 Rue d’Amsterdam—Rue de St. Denis | 188 |

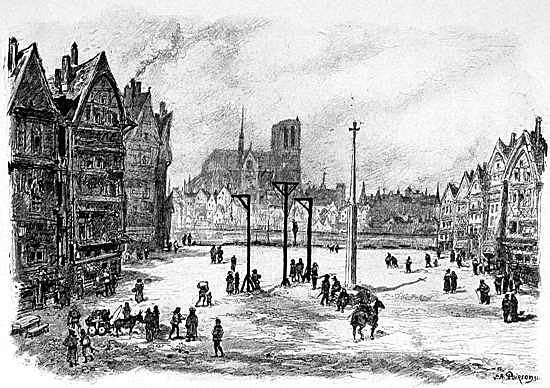

| Place de la Grève | 197 |

| Tour de St. Jacques la Boucherie (Méryon’s Etching, “Le Stryge”) | 198 |

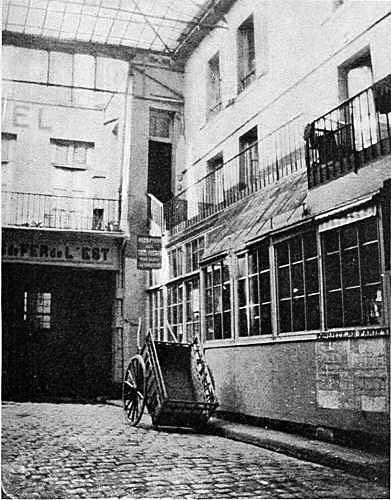

| Hôtel des Mousquetaires, Rue d’Arbre Sec | 207 |

| [Pg viii]D’Artagnan’s Lodgings, Rue Tiquetonne | 214 |

| 109 Rue du Faubourg St. Denis (Déscamps’ Studio) | 221 |

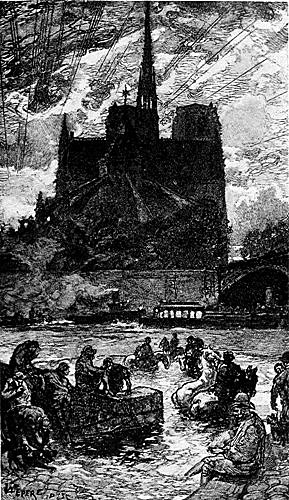

| Nôtre Dame de Paris | 235 |

| Plan of La Cité | 236 |

| Carmelite Friary, Rue Vaugirard | 246 |

| Plan of the Louvre | 257 |

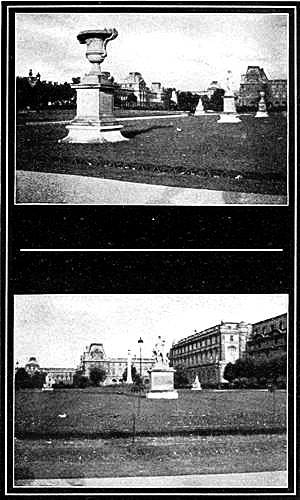

| The Gardens of the Tuileries | 265 |

| The Orleans Bureau, Palais Royal | 268 |

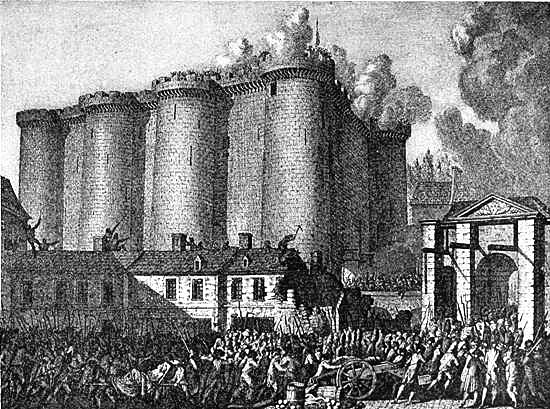

| The Fall of the Bastille | 284 |

| Inn of the Pont de Sèvres | 302 |

| Bois de Boulogne—Bois de Vincennes—Forêt de Villers-Cotterets | 315 |

| Château of the Ducs de Valois, Crépy | 318 |

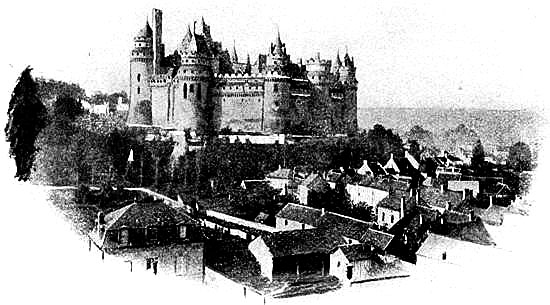

| Castle of Pierrefonds | 324 |

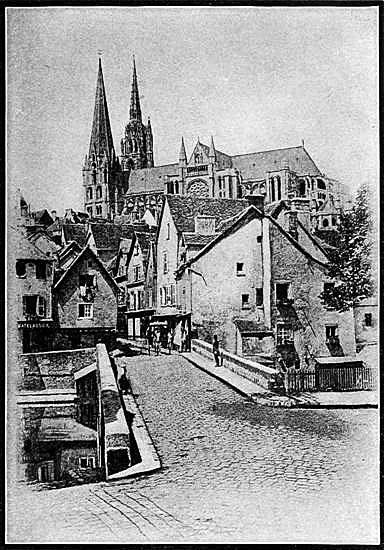

| Nôtre Dame de Chartres | 329 |

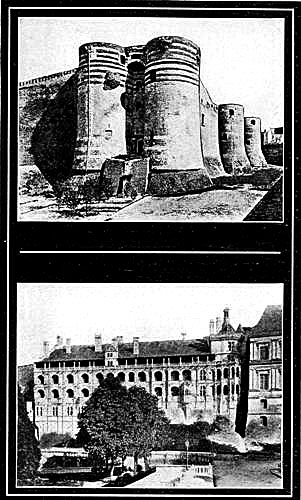

| Castle of Angers—Château of Blois | 333 |

There have been many erudite works, in French and other languages, describing the antiquities and historical annals of Paris from the earliest times; and in English the mid-Victorian era turned out—there are no other words for it—innumerable “books of travel” which recounted alleged adventures, strewn here and there with bits of historical lore and anecdotes, none too relevant, and in most cases not of undoubted authenticity.

Of the actual life of the people in the city of light and learning, from the times of Napoleon onward, one has to go to the fountainhead of written records, the acknowledged masterworks in the[Pg 2] language of the country itself, the reports and annuaires of various sociétês, commissions, and what not, and collect therefrom such information as he finds may suit his purpose.

In this manner may be built up a fabric which shall be authentic and proper, varied and, most likely, quite different in its plan, outline, and scope from other works of a similar purport, which may be recalled in connection therewith.

Paris has been rich in topographical historians, and, indeed, in her chroniclers in all departments, and there is no end of relative matter which may be evolved from an intimacy with these sources of supply. In a way, however, this information ought to be supplemented by a personal knowledge on the part of the compiler, which should make localities, distances, and environments—to say nothing of the actual facts and dates of history—appear as something more than a shrine to be worshipped from afar.

Given, then, these ingredients, with a love of the subject,—no less than of the city of its domicile,—it has formed a pleasant itinerary in the experiences of the writer of this book to have followed in the footsteps of Dumas père, through the streets that he knew and loved, taking note meanwhile of such contemporary shadows as were thrown[Pg 3] across his path, and such events of importance or significance as blended in with the scheme of the literary life of the times in which he lived, none the less than of those of the characters in his books.

Nearly all the great artists have adored Paris—poets, painters, actors, and, above all, novelists.

From which it follows that Paris is the ideal city for the novelist, who, whether he finds his special subjects in her streets or not, must be inspired by this unique fulness and variety of human life. Nearly all the great French novelists have adored Paris. Dumas loved it; Victor Hugo spent years of his time in riding about her streets on omnibuses; Daudet said splendid things of it, and nearly, if not quite, all the great names of the artistic world of France are indissolubly linked with it.

Paris to-day means not “La Ville,” “La Cité,” or “L’Université,” but the whole triumvirate. Victor Hugo very happily compared the three cities to a little old woman between two handsome, strapping daughters.

It was Beranger who announced his predilection for Paris as a birthplace. Dumas must have felt something of the same emotion, for he early gravitated to the “City of Liberty and Equality,” in[Pg 4] which—even before the great Revolution—misfortune was at all times alleviated by sympathy.

From the stones of Paris have been built up many a lordly volume—and many a slight one, for that matter—which might naturally be presumed to have recounted the last word which may justifiably have been said concerning the various aspects of the life and historic events which have encircled around the city since the beginning of the moyen age.

This is true or not, according as one embraces a wide or a contracted horizon in one’s view.

For most books there is, or was at the time of their writing, a reason for being, and so with familiar spots, as with well-worn roads, there is always a new panorama projecting itself before one.

The phenomenal, perennial, and still growing interest in the romances of Dumas the elder is the excuse for the present work, which it is to be hoped is admittedly a good one, however far short of exhaustiveness—a much overworked word, by the way—the volume may fall.

It were not possible to produce a complete or “exhaustive” work on any subject of a historical, topographical or æsthetic nature: so why claim it?[Pg 5] The last word has not yet been said on Dumas himself, and surely not on Paris—no more has it on Pompeii, where they are still finding evidences of a long lost civilization as great as any previously unearthed.

It was only yesterday, too (this is written in the month of March, 1904), that a party of frock-coated and silk-hatted benevolent-looking gentlemen were seen issuing from a manhole in the Université quartier of Paris. They had been inspecting a newly discovered thermale établissement of Roman times, which led off one of the newly opened subterranean arteries which abound beneath Paris.

It is said to be a rival of the Roman bath which is enclosed within the walls of the present Musée Cluny, and perhaps the equal in size and splendour of any similar remains extant.

This, then, suggests that in every land new ground, new view-points, and new conditions of life are making possible a record which, to have its utmost value, should be a progressively chronological one.

And after this manner the present volume has been written. There is a fund of material to draw upon, historic fact, pertinent and contemporary side-lights, and, above all, the environment which haloed itself around the personality of Dumas,[Pg 6] which lies buried in many a cache which, if not actually inaccessible, is at least not to be found in the usual books of reference.

Perhaps some day even more will have been collected, and a truly satisfying biographical work compiled. If so, it will be the work of some ardent Frenchman of a generation following that in which Alexandre Dumas lived, and not by one of the contemporaries of even his later years. Albert Vandam, perhaps, might have done it as it should have been done; but he did not do so, and so an intimate personal record has been lost.

Paris has ever been written down in the book of man as the city of light, of gaiety, and of a trembling vivacity which has been in turn profligate, riotous, and finally criminal.

All this is perhaps true enough, but no more in degree than in most capitals which have endured so long, and have risen to such greatness.

With Paris it is quantity, with no sacrifice of quality, that has placed it in so preëminent a position among great cities, and the life of Paris—using the phrase in its most commonly recognized aspect—is accordingly more brilliant or the reverse, as one views it from the boulevards or from the villettes.

DUMAS’ HOUSE AT VILLERS-COTTERETS

French writers, the novelists in particular, have [Pg 7]well known and made use of this; painters and poets, too, have perpetuated it in a manner which has not been applied to any other city in the world.

To realize the conditions of the life of Paris to the full one has to go back to Rousseau—perhaps even farther. His observation that “Les maisons font la ville, mais le citoyens font la cité,” was true when written, and it is true to-day, with this modification, that the delimitation of the confines of la ville should be extended so far as to include all workaday Paris—the shuffling, bustling world of energy and spirit which has ever insinuated itself into the daily life of the people.

The love and knowledge of Alexandre Dumas père for Paris was great, and the accessory and detail of his novels, so far as he drew upon the capital, was more correct and apropos. It was something more than a mere dash of local colour scattered upon the canvas from a haphazard palette. In minutiæ it was not drawn as fine as the later Zola was wont to accomplish, but it showed no less detail did one but comprehend its full meaning.

Though born in the provincial town Villers-Cotterets,—seventy-eight kilomètres from Paris on the road to Soissons,—Dumas came early in touch with the metropolis, having in a sort of runaway[Pg 8] journey broken loose from his old associations and finally becoming settled in the capital as a clerk in the Bureau d’Orleans, at the immature age of twenty. Thus it was that his impressions and knowledge of Paris were founded upon an experience which was prolonged and intimate, extending, with brief intervals of travel, for over fifty years.

He had journeyed meantime to Switzerland, England, Corsica, Naples, the Rhine, Belgium,—with a brief residence in Italy in 1840-42,—then visiting Spain, Russia, the Caucasus, and Germany.

This covered a period from 1822, when he first came to Paris, until his death at Puys, near Dieppe, in 1870; nearly a full half-century amid activities in matters literary, artistic, and social, which were scarce equalled in brilliancy elsewhere—before or since.

In spite of his intimate association with the affairs of the capital,—he became, it is recalled, a candidate for the Chamber of Deputies at the time of the Second Republic,—Dumas himself has recorded, in a preface contributed to a “Histoire de l’Eure,” by M. Charpillon (1879), that if he were ever to compile a history of France he should first search for les pierres angulaires of his edifice in the provinces.

[Pg 9]This bespeaks a catholicity which, perhaps, after all, is, or should be, the birthright of every historical novelist.

He said further, in this really valuable and interesting contribution, which seems to have been entirely overlooked by the bibliographers, that “to write the history of France would take a hundred volumes”—and no doubt he was right, though it has been attempted in less.

And again that “the aggrandizement of Paris has only been accomplished by a weakening process having been undergone by the provinces.” The egg from which Paris grew was deposited in the nest of la cité, the same as are the eggs laid par un cygne.

He says further that in writing the history of Paris he would have founded on “Lutetia (or Louchetia) the Villa de Jules, and would erect in the Place de Notre Dame a temple or altar to Ceres; at which epoch would have been erected another to Mercury, on the Mount of Ste. Geneviève; to Apollo in the Rue de la Barillerie, where to-day is erected that part of Tuileries built by Louis XIV., and which is called Le Pavillon de Flore.

“Then one would naturally follow with Les Thermes de Julien, which grew up from the Villa[Pg 10] de Jules; the reunion under Charlemagne which accomplished the Sorbonne (Sora bona), which in turn became the favourite place of residence of Hugues Capet, the stronghold of Philippe-Auguste, the bibliothèque of Charles V., the monumental capital of Henri VI. d’Angleterre; and so on through the founding of the first printing establishment in France by Louis XI.; the new school of painting by François I.; of the Académie by Richelieu; ... to the final curtailment of monarchial power with the horrors of the Revolution and the significant events which centred around the Bastille, Versailles, and the Tuileries.”

Leaving the events of the latter years of the eighteenth century, and coming to the day in which Dumas wrote (1867), Paris was truly—and in every sense—

“The capital of France, and its history became not only the history of France but the history of the world.... The city will yet become the capital of humanity, and, since Napoleon repudiated his provincial residences and made Paris sa résidence impériale, the man of destiny who reigns in Paris in reality reigns throughout the universe.”

There may be those who will take exception to these brilliant words of Dumas. The Frenchman has always been an ardent and soi-disant bundle of[Pg 11] enthusiasm, but those who love him must pardon his pride, which is harmless to himself and others alike, and is a far more admirable quality than the indifference and apathy born of other lands.

His closing words are not without a cynical truth, and withal a pride in Paris:

“It is true that if we can say with pride, we Parisians, ‘It was Paris which overthrew the Bastille,’ you of the provinces can say with equal pride, ‘It was we who made the Revolution.’”

As if to ease the hurt, he wrote further these two lines only:

“At this epoch the sister nations should erect a gigantic statue of Peace. This statue will be Paris, and its pedestal will represent La Province.”

His wish—it was not prophecy—did not, however, come true, as the world in general and France and poor rent Alsace et Lorraine in particular know to their sorrow; and all through a whim of a self-appointed, though weakling, monarch.

The era of the true peace of the world and the monument to its glory came when the French nation presented to the New World that grand work of Bartholdi, “Liberty Enlightening the World,” which stands in New York harbour, and whose smaller replica now terminates the Allée des Cygnes.

The grasp that Dumas had of the events of [Pg 12]romance and history served his purpose well, and in the life of the fifties in Paris his was a name and personality that was on everybody’s lips.

How he found time to live the full life that he did is a marvel; it certainly does not bear out the theory of heredity when one considers the race of his birth and the “dark-skinned” languor which was supposedly his heritage.

One edition of his work comprises two hundred and seventy-seven volumes, and within the year a London publisher has announced some sixty volumes “never before translated.” Dumas himself has said that he was the author of over seven hundred works.

In point of time his romances go back to the days of the house of Valois and the Anglo-French wars (1328), and to recount their contents is to abstract many splendid chapters from out the pages of French history.

It would seem as though nearly every personage of royalty and celebrity (if these democratic times will allow the yoking together of the two; real genuine red republicans would probably link royalty and notoriety) stalked majestically through his pages, and the record runs from the fourteenth nearly to the end of the nineteenth century, with the exception of the reign of Louis XI.

[Pg 13]An ardent admirer of Sir Walter Scott has commented upon this lapse as being accounted for by the apparent futility of attempting to improve upon “Quentin Durward.” This is interesting, significant, and characteristic, but it is not charitable, generous, or broad-minded.

At fifteen (1817), Dumas entered the law-office of one Mennesson at Villers-Cotterets as a saute-ruisseau (gutter-snipe), as he himself called it, and from this time on he was forced to forego what had been his passion heretofore: bird-catching, shooting, and all manner of woodcraft.

When still living at Villers-Cotterets Dumas had made acquaintance with the art of the dramatist, so far as it was embodied in the person of Adolphe de Leuven, with whom he collaborated in certain immature melodramas and vaudevilles, which De Leuven himself took to Paris for disposal.

“No doubt managers would welcome them with enthusiasm,” said Dumas, “and likely enough we shall divert a branch of that Pactolus River which is irrigating the domains of M. Scribe” (1822).

Later on in his “Mémoires” he says: “Complete humiliation; we were refused everywhere.”

STATUE OF DUMAS AT VILLERS-COTTERETS

[Pg 15]From Villers-Cotterets the scene of Dumas’ labours was transferred to Crépy, three and a half leagues distant, a small town to which he made his way on foot, his belongings in a little bundle “not more bulky than that of a Savoyard when he leaves his native mountains.”

In his new duties, still as a lawyer’s clerk, Dumas found life very wearisome, and, though the ancient capital of the Valois must have made an impress upon him,—as one learns from the Valois romances,—he pined for the somewhat more free life which he had previously lived; or, taking the bull by the horns, deliberated as to how he might get into the very vortex of things by pushing on to the capital.

As he tritely says, “To arrive it was necessary to make a start,” and the problem was how to arrive in Paris from Crépy in the existing condition of his finances.

By dint of ingenuity and considerable activity Dumas left Crépy in company with a friend on a sort of a runaway holiday, and made his third entrance into Paris.

It would appear that Dumas’ culinary and gastronomic capabilities early came into play, as we learn from the “Mémoires” that, when he was not yet out of his teens, and serving in the notary’s[Pg 16] office at Crépy, he proposed to his colleague that they take this three days’ holiday in Paris.

They could muster but thirty-five francs between them, so Dumas proposed that they should shoot game en route. Said Dumas, “We can kill, shall I say, one hare, two partridges, and a quail.... We reach Dammartin, get the hinder part of our hare roasted and the front part jugged, then we eat and drink.” “And what then?” said his friend. “What then? Bless you, why we pay for our wine, bread, and seasoning with the two partridges, and we tip the waiter with the quail.”

The journey was accomplished in due order, and he and his friend put up at the Hôtel du Vieux-Augustins, reaching there at ten at night.

In the morning he set out to find his collaborateur De Leuven, but the fascination of Paris was such that it nearly made him forswear regard for the flight of time.

He says of the Palais Royale: “I found myself within its courtyard, and stopped before the Theatre Français, and on the bill I saw:

“‘Demain, Lundi

Sylla

Tragédie dans cinq Actes

Par M. de Jouy’

[Pg 17]“I solemnly swore that by some means or other ... I would see Sylla, and all the more so because, in large letters, under the above notice, were the words, ‘The character of Sylla will be taken by M. Talma.’”

In his “Mémoires” Dumas states that it was at this time he had the temerity to call on the great Talma. “Talma was short-sighted,” said he, “and was at his toilet; his hair was close cut, and his aspect under these conditions was remarkably un-poetic.... Talma was for me a god—a god unknown, it is true, as was Jupiter to Semele.”

And here comes a most delicious bit of Dumas himself, Dumas the egotist:

“Ah, Talma! were you but twenty years younger or I twenty years older! I know the past, you cannot foretell the future.... Had you known, Talma, that the hand you had just touched would ultimately write sixty or eighty dramas ... in each of which you would have found the material for a marvellous creation....”

Dumas may be said to have at once entered the world of art and letters in this, his third visit to Paris, which took place so early in life, but in the years so ripe with ambition.

Having seen the great Talma in Sylla, in his dressing-room at the Theatre Français, he met[Pg 18] Delavigne, who was then just completing his “Ecole des Viellards,” Lucien Arnault, who had just brought out “Regulus;” Soumet, fresh from the double triumph of “Saul” and “Clymnestre;” here, too, were Lemercier, Delrien, Viennet, and Jouy himself; and he had met at the Café du Roi, Theadlon, Francis, Rochefort, and De Merle; indeed by his friend De Leuven he was introduced to the assemblage there as a “future Corneille,” in spite of the fact that he was but a notary’s clerk.

Leaving what must have been to Dumas the presence, he shot a parting remark, “Ah, yes, I shall come to Paris for good, I warrant you that.”

In “The Taking of the Bastille” Dumas traces again, in the characters of Pitou and old Father Billot, much of the route which he himself took on his first visit to Paris. The journey, then, is recounted from first-hand information, and there will be no difficulty on the part of any one in tracing the similarity of the itinerary.

Chapter I., of the work in question, brings us at once on familiar ground, and gives a description of Villers-Cotterets and its inhabitants in a manner which shows Dumas’ hand so unmistakably as to remove any doubts as to the volume of assistance he may have received from others, on this particular book at least.

[Pg 19]“On the borders of Picardy and the province of Soissons, and on that part of the national territory which, under the name of the Isle of France, formed a portion of the ancient patrimony of our kings, and in the centre of an immense crescent, formed by a forest of fifty thousand acres, which stretches its horns to the north and south, rises, almost buried amid the shades of a vast park planted by François I. and Henri II., the small city of Villers-Cotterets. This place is celebrated from having given birth to Charles Albert Demoustier, who, at the period when our present history commences, was there writing his Letters to Emilie on Mythology, to the unbounded satisfaction of the pretty women of those days, who eagerly snatched his publications from each other as soon as printed.

“Let us add, to complete the poetical reputation of this little city, whose detractors, notwithstanding its royal château and its two thousand four hundred inhabitants, obstinately persist in calling it a mere village—let us add, we say, to complete its poetical reputation, that it is situated at two leagues distance from Laferte-Milan, where Racine was born, and eight leagues from Château-Thierry, the birthplace of La Fontaine.

“Let us also state that the mother of the author[Pg 20] of ‘Britannicus’ and ‘Athalie’ was from Villers-Cotterets.

“But now we must return to its royal château and its two thousand four hundred inhabitants.

“This royal château, begun by François I., whose salamanders still decorate it, and finished by Henri II., whose cipher it bears entwined with that of Catherine de Medici and encircled by the three crescents of Diana of Poictiers, after having sheltered the loves of the knight king with Madame d’Etampes, and those of Louis Philippe of Orleans with the beautiful Madame de Montesson, had become almost uninhabited since the death of this last prince; his son, Philippe d’Orleans, afterward called Egalité, having made it descend from the rank of a royal residence to that of a mere hunting rendezvous.

“It is well known that the château and forest of Villers-Cotterets formed part of the appanage settled by Louis XIV. on his brother Monsieur, when the second son of Anne of Austria married the sister of Charles II., the Princess Henrietta of England.

“As to the two thousand four hundred inhabitants of whom we have promised our readers to say a word, they were, as in all localities where two[Pg 21] thousand four hundred people are united, a heterogeneous assemblage.

“Firstly: Of the few nobles, who spent their summers in the neighbouring châteaux and their winters in Paris, and who, mimicking the prince, had only a lodging-place in the city.

“Secondly: Of a goodly number of citizens, who could be seen, let the weather be what it might, leaving their houses after dinner, umbrella in hand, to take their daily walk, a walk which was regularly bounded by a deep, invisible ditch which separated the park from the forest, situated about a quarter of a league from the town, and which was called, doubtless on account of the exclamation which the sight of it drew from the asthmatic lungs of the promenaders, satisfied at finding themselves not too much out of breath, the ‘Ha, ha!’

“Thirdly: Of a considerably greater number of artisans who worked the whole of the week and only allowed themselves to take a walk on the Sunday; whereas their fellow townsmen, more favoured by fortune, could enjoy it every day.

“Fourthly and finally: Of some miserable proletarians, for whom the week had not even a Sabbath, and who, after having toiled six days in the pay of the nobles, the citizens, or even of the artisans, wandered on the seventh day through the[Pg 22] forest to gather up dry wood or branches of the lofty trees, torn from them by the storm, that mower of the forest, to whom oak-trees are but ears of wheat, and which it scattered over the humid soil beneath the lofty trees, the magnificent appanage of a prince.

“If Villers-Cotterets (Villerii ad Cotiam Retiæ) had been, unfortunately, a town of sufficient importance in history to induce archæologists to ascertain and follow up its successive changes from a village to a town and from a town to a city—the last, as we have said, being strongly contested, they would certainly have proved this fact, that the village had begun by being a row of houses on either side of the road from Paris to Soissons; then they would have added that its situation on the borders of a beautiful forest having, though by slow degrees, brought to it a great increase of inhabitants, other streets were added to the first, diverging like the rays of a star and leading toward other small villages with which it was important to keep up communication, and converging toward a point which naturally became the centre, that is to say, what in the provinces is called Le Carrefour,—and sometimes even the Square, whatever might be its shape,—and around which the handsomest buildings of the village, now become a burgh, were[Pg 23] erected, and in the middle of which rises a fountain, now decorated with a quadruple dial; in short, they would have fixed the precise date when, near the modest village church, the first want of a people, arose the first turrets of the vast château, the last caprice of a king; a château which, after having been, as we have already said, by turns a royal and a princely residence, has in our days become a melancholy and hideous receptacle for mendicants under the direction of the Prefecture of the Seine, and to whom M. Marrast issues his mandates through delegates of whom he has not, nor probably will ever have, either the time or the care to ascertain the names.”

The last sentence seems rather superfluous,—if it was justifiable,—but, after all, no harm probably was done, and Dumas as a rule was never vituperative.

Continuing, these first pages give us an account of the difficulties under which poor Louis Ange Pitou acquired his knowledge of Latin, which is remarkably like the account which Dumas gives in the “Mémoires” of his early acquaintance with the classics.

When Pitou leaves Haramont, his native village, and takes to the road, and visits Billot at “Bruyere aux Loups,” knowing well the road, as he did that[Pg 24] to Damploux, Compiègne, and Vivières, he was but covering ground equally well known to Dumas’ own youth.

Finally, as he is joined by Billot en route for Paris, and takes the highroad from Villers-Cotterets, near Gondeville, passing Nanteuil, Dammartin, and Ermenonville, arriving at Paris at La Villette, he follows almost the exact itinerary taken by the venturesome Dumas on his runaway journey from the notary’s office at Crépy-en-Valois.

Crépy-en-Valois was the near neighbour of Villers-Cotterets, which jealously attempted to rival it, and does even to-day. In “The Taking of the Bastille” Dumas only mentions it in connection with Mother Sabot’s âne, “which was shod,”—the only ass which Pitou had ever known which wore shoes,—and performed the duty of carrying the mails between Crépy and Villers-Cotterets.

At Villers-Cotterets one may come into close contact with the château which is referred to in the later pages of the “Vicomte de Bragelonne.” “Situated in the middle of the forest, where we shall lead a most sentimental life, the very same where my grandfather,” said Monseigneur the Prince, “Henri IV. did with ‘La Belle Gabrielle.’”

So far as lion-hunting goes, Dumas himself at an early age appears to have fallen into it. He[Pg 25] recalls in “Mes Mémoires” the incident of Napoleon I. passing through Villers-Cotterets just previous to the battle of Waterloo.

“Nearly every one made a rush for the emperor’s carriage,” said he; “naturally I was one of the first.... Napoleon’s pale, sickly face seemed a block of ivory.... He raised his head and asked, ‘Where are we?’ ‘At Villers-Cotterets, Sire,’ said a voice. ‘Go on.’” Again, a few days later, as we learn from the “Mémoires,” “a horseman coated with mud rushes into the village; orders four horses for a carriage which is to follow, and departs.... A dull rumble draws near ... a carriage stops.... ‘Is it he—the emperor?’ Yes, it was the emperor, in the same position as I had seen him before, exactly the same, pale, sickly, impassive; only the head droops rather more.... ‘Where are we?’ he asked. ‘At Villers-Cotterets, Sire.’ ‘Go on.’”

That evening Napoleon slept at the Elysée. It was but three months since he had returned from Elba, but in that time he came to an abyss which had engulfed his fortune. That abyss was Waterloo; only saved to the allies—who at four in the afternoon were practically defeated—by the coming up of the Germans at six.

Among the books of reference and contemporary[Pg 26] works of a varying nature from which a writer in this generation must build up his facts anew, is found a wide difference in years as to the date of the birth of Dumas père.

As might be expected, the weight of favour lies with the French authorities, though by no means do they, even, agree among themselves.

His friends have said that no unbiassed, or even complete biography of the author exists, even in French; and possibly this is so. There is about most of them a certain indefiniteness and what Dumas himself called the “colour of sour grapes.”

The exact date of his birth, however, is unquestionably 1802, if a photographic reproduction of his natal certificate, published in Charles Glinel’s “Alex. Dumas et Son Œuvre,” is what it seems to be.

Dumas’ aristocratic parentage—for such it truly was—has been the occasion of much scoffing and hard words. He pretended not to it himself, but it was founded on family history, as the records plainly tell, and whether Alexandre, the son of the brave General Dumas, the Marquis de la Pailleterie, was prone to acknowledge it or not does not matter in the least. The “feudal particle” existed plainly in his pedigree, and with no discredit to any concerned.

FACSIMILE OF DUMAS’ OWN STATEMENT OF HIS BIRTH

[Pg 27]General Dumas, his wife, and his son are buried in the cemetery of Villers-Cotterets, where the exciting days of the childhood of Dumas, the romancer, were spent, in a plot of ground “conceded in perpetuity to the family.” The plot forms a rectangle six metres by five, surrounded by towering pines.

The three monuments contained therein are of the utmost simplicity, each consisting of an inclined slab of stone.

The inscriptions are as follows:

| FAMILLE | ALEXANDRE | DUMAS | ||

| Thomas-Alexandre | Marie-Louise-Elizabeth | Alexandre Dumas | ||

| Dumas | Labouret | né à Villers-Cotterets | ||

| Davy de la Pailleterie | Épouse | le 24 juillet 1802 | ||

| général dé division | du général de division | décédé | ||

| né à Jeremie | Dumas Davy | le 5 décembre 1870 | ||

| Ile et Côte de Saint | de la Pailleterie | à Puys | ||

| Dominique | née | transféré | ||

| le 25 mars 1762, | à Villers-Cotterets | à | ||

| décédé | le 4 juillet 1769 | Villers-Cotterets | ||

| à Villers-Cotterets | décédée | le | ||

| le 27 février 1806 | le 1er aout 1838 | 15 avril 1872 |

There would seem to be no good reason why a book treating of Dumas’ Paris might not be composed entirely of quotations from Dumas’ own works. For a fact, such a work would be no less valuable as a record than were it evolved by any[Pg 28] other process. It would indeed be the best record that could possibly be made, for Dumas’ topography was generally truthful if not always precise.

There are, however, various contemporary side-lights which are thrown upon any canvas, no matter how small its area, and in this instance they seem to engulf even the personality of Dumas himself, to say nothing of his observations.

Dumas was such a part and parcel of the literary life of the times in which he lived that mention can scarce be made of any contemporary event that has not some bearing on his life or work, or he with it, from the time when he first came to the metropolis (in 1822) at the impressionable age of twenty, until the end.

It will be difficult, even, to condense the relative incidents which entered into his life within the confines of a single volume, to say nothing of a single chapter. The most that can be done is to present an abridgment which shall follow along the lines of some preconceived chronological arrangement. This is best compiled from Dumas’ own words, leaving it to the additional references of other chapters to throw a sort of reflected glory from a more distant view-point.

The reputation of Dumas with the merely casual reader rests upon his best-known romances, “Monte[Pg 29] Cristo,” 1841; “Les Trois Mousquetaires,” 1844; “Vingt Ans Après,” 1845; “Le Vicomte de Bragelonne,” 1847; “La Dame de Monsoreau,” 1847; and his dramas of “Henri III. et Sa Cour,” 1829, “Antony,” 1831, and “Kean,” 1836.

His memoirs, “Mes Mémoires,” are practically closed books to the mass of English readers—the word books is used advisedly, for this remarkable work is composed of twenty stout volumes, and they only cover ten years of the author’s life.

Therein is a mass of fact and fancy which may well be considered as fascinating as are the “romances” themselves, and, though autobiographic, one gets a far more satisfying judgment of the man than from the various warped and distorted accounts which have since been published, either in French or English.

Beginning with “Memories of My Childhood” (1802-06), Dumas launches into a few lines anent his first visit to Paris, in company with his father, though the auspicious—perhaps significant—event took place at a very tender age. It seems remarkable that he should have recalled it at all, but he was a remarkable man, and it seems not possible to ignore his words.

“We set out for Paris, ah, that journey! I recollect it perfectly.... It was August or [Pg 30]September, 1805. We got down in the Rue Thiroux at the house of one Dollé.... I had been embraced by one of the most noble ladies who ever lived, Madame la Marquise de Montesson, widow of Louis-Philippe d’Orleans.... The next day, putting Brune’s sword between my legs and Murat’s hat upon my head, I galloped around the table; when my father said, ‘Never forget this, my boy.’... My father consulted Corvisart, and attempted to see the emperor, but Napoleon, the quondam general, had now become the emperor, and he refused to see my father.... To where did we return? I believe Villers-Cotterets.”

Again on the 26th of March, 1813, Dumas entered Paris in company with his mother, now widowed. He says of this visit:

“I was delighted at the prospect of this my second visit.... I have but one recollection, full of light and poetry, when, with a flourish of trumpets, a waving of banners, and shouts of ‘Long live the King of Rome,’ was lifted up above the heads of fifty thousand of the National Guard the rosy face and the fair, curly head of a child of three years—the infant son of the great Napoleon.... Behind him was his mother,—that woman so fatal to France, as have been all the daughters of the Cæsars, Anne of Austria, Marie Antoinette,[Pg 31] and Marie Louise,—an indistinct, insipid face.... The next day we started home again.”

Through the influence of General Foy, an old friend of his father’s, Dumas succeeded in obtaining employment in the Orleans Bureau at the Palais Royal.

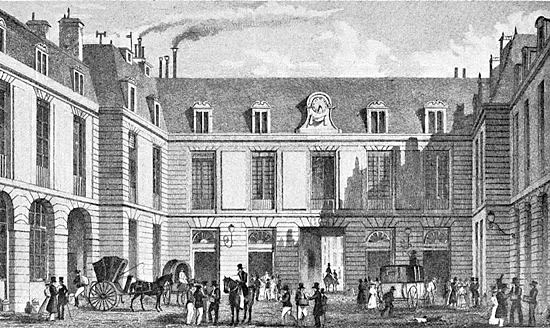

His occupation there appears not to have been unduly arduous. The offices were in the right-hand corner of the second courtyard of the Palais Royal. He remained here in this bureau for a matter of five years, and, as he said, “loved the hour when he came to the office,” because his immediate superior, Lassagne,—a contributor to the Drapeau Blanc,—was the friend and intimate of Désaugiers, Théaulon, Armand Gouffé, Brozier, Rougemont, and all the vaudevillists of the time.

Dumas’ meeting with the Duc d’Orleans—afterward Louis-Philippe—is described in his own words thus: “In two words I was introduced. ‘My lord, this is M. Dumas, whom I mentioned to you, General Foy’s protégé.’ ‘You are the son of a brave man,’ said the duc, ‘whom Bonaparte, it seems, left to die of starvation.’... The duc gave Oudard a nod, which I took to mean, ‘He will do, he’s by no means bad for a provincial.’” And so it was that Dumas came immediately under the[Pg 32] eye of the duc, engaged as he was at that time on some special clerical work in connection with the duc’s provincial estates.

The affability of Dumas, so far as he himself was concerned, was a foregone conclusion. In the great world in which he moved he knew all sorts and conditions of men. He had his enemies, it is true, and many of them, but he himself was the enemy of no man. To English-speaking folk he was exceedingly agreeable, because,—quoting his own words,—said he, “It was a part of the debt which I owed to Shakespeare and Scott.” Something of the egoist here, no doubt, but gracefully done nevertheless.

With his temperament it was perhaps but natural that Dumas should have become a romancer. This was of itself, maybe, a foreordained sequence of events, but no man thinks to-day that, leaving contributary conditions, events, and opportunities out of the question, he shapes his own fate; there are accumulated heritages of even distant ages to contend with. In Dumas’ case there was his heritage of race and colour, refined, perhaps, by a long drawn out process, but, as he himself tells in “Mes Mémoires,” his mother’s fear was that her child would be born black, and he was, or, at least, purple, as he himself afterward put it.

Just how far Dumas’ literary ability was an inheritance, or growth of his early environment, will ever be an open question. It is a manifest fact that he had breathed something of the spirit of romance before he came to Paris.

Although it was not acknowledged until 1856, “The Wolf-Leader” was a development of a legend told to him in his childhood. Recalling then the incident of his boyhood days, and calling into recognition his gift of improvisation, he wove a tale which reflected not a little of the open-air life of the great forest of Villers-Cotterets, near the place of his birth.

Here, then, though it was fifty years after his birth, and thirty after he had thrust himself on the great world of Paris, the scenes of his childhood were reproduced in a wonderfully romantic[Pg 34] and weird tale—which, to the best of the writer’s belief, has not yet appeared in English.

To some extent it is possible that there is not a little of autobiography therein, not so much, perhaps, as Dickens put into “David Copperfield,” but the suggestion is thrown out for what it may be worth.

It is, furthermore, possible that the historic associations of the town of Villers-Cotterets—which was but a little village set in the midst of the surrounding forest—may have been the prime cause which influenced and inspired the mind of Dumas toward the romance of history.

In point of chronology, among the earliest of the romances were those that dealt with the fortunes of the house of Valois (fourteenth century), and here, in the little forest town of Villers-Cotterets, was the magnificent manor-house which belonged to the Ducs de Valois; so it may be presumed that the sentiment of early associations had somewhat to do with these literary efforts.

All his life Dumas devotedly admired the sentiment and fancies which foregathered in this forest, whose very trees and stones he knew so well. From his “Mémoires” we learn of his indignation at the destruction of its trees and much of its natural beauty. He says:

[Pg 35]“This park, planted by François I., was cut down by Louis-Philippe. Trees, under whose shade once reclined François I. and Madame d’Etampes, Henri II. and Diane de Poitiers, Henri IV. and Gabrielle d’Estrées—you would have believed that a Bourbon would have respected you. But over and above your inestimable value of poetry and memories, you had, unhappily, a material value. You beautiful beeches with your polished silvery cases! you beautiful oaks with your sombre wrinkled bark!—you were worth a hundred thousand crowns. The King of France, who, with his six millions of private revenue, was too poor to keep you—the King of France sold you. For my part, had you been my sole possession, I would have preserved you; for, poet as I am, one thing that I would set before all the gold of the earth: the murmur of the wind in your leaves; the shadow that you made to flicker beneath my feet; the visions, the phantoms, which, at eventide, betwixt the day and night, in the doubtful hour of twilight, would glide between your age-long trunks as glide the shadows of the ancient Abencerrages amid the thousand columns of Cordova’s royal mosque.”

What wonder, with these lines before one, that the impressionable Dumas was so taken with the[Pg 36] romance of life and so impracticable in other ways.

From the fact that no thorough biography of Dumas exists, it will be difficult to trace the fluctuations of his literary career with preciseness. It is not possible even with the twenty closely packed volumes of the “Mémoires”—themselves incomplete—before one. All that a biographer can get from this treasure-house are facts,—rather radiantly coloured in some respects, but facts nevertheless,—which are put together in a not very coherent or compact form.

They do, to be sure, recount many of the incidents and circumstances attendant upon the writing and publication of many of his works, and because of this they immediately become the best of all sources of supply. It is to be regretted that these “Mémoires” have not been translated, though it is doubtful if any publisher of English works could get his money back from the transaction.

Other clues as to his emotions, and with no uncertain references to incidents of Dumas’ literary career, are found in “Mes Bêtes,” “Ange Pitou,” the “Causeries,” and the “Travels.” These comprise many volumes not yet translated.

FACSIMILE OF A MANUSCRIPT PAGE FROM ONE OF DUMAS’ PLAYS

Dumas was readily enough received into the folds[Pg 37] of the great. Indeed, as we know, he made his entrée under more than ordinary, if not exceptional, circumstances, and his connection with the great names of literature and statecraft extended from Hugo to Garibaldi.

As for his own predilections in literature, Dumas’ own voice is practically silent, though we know that he was a romanticist pure and simple, and drew no inspiration or encouragement from Voltairian sentiments. If not essentially religious, he at least believed in its principles, though, as a warm admirer has said, “He had no liking for the celibate and bookish life of the churchman.”

Dumas does not enter deeply into the subject of ecclesiasticism in France. His most elaborate references are to the Abbey of Ste. Genevieve—since disappeared in favour of the hideous pagan Panthéon—and its relics and associations, in “La Dame de Monsoreau.” Other of the romances from time to time deal with the subject of religion more or less, as was bound to be, considering the times of which he wrote, of Mazarin, Richelieu, De Rohan, and many other churchmen.

Throughout the thirties Dumas was mostly occupied with his plays, the predominant, if not the most sonorous note, being sounded by “Antony.”

As a novelist his star shone brightest in the [Pg 38]decade following, commencing with “Monte Cristo,” in 1841, and continuing through “Le Vicomte de Bragelonne” and “La Dame de Monsoreau,” in 1847.

During these strenuous years Dumas produced the flower of his romantic garland—omitting, of course, certain trivial and perhaps unworthy trifles, among which are usually considered, rightly enough, “Le Capitaine Paul” (Paul Jones) and “Jeanne d’Arc.” At this period, however, he produced the charming and exotic “Black Tulip,” which has since come to be a reality. The best of all, though, are admittedly the Mousquetaire cycle, the volumes dealing with the fortunes of the Valois line, and, again, “Monte Cristo.”

By 1830, Dumas, eager, as it were, to experience something of the valiant boisterous spirit of the characters of his romances, had thrown himself heartily into an alliance with the opponents of Louis-Philippe. Orleanist successes, however, left him to fall back upon his pen.

In 1844, having finished “Monte Cristo,” he followed it by “Les Trois Mousquetaires,” and before the end of the same year had put out forty volumes, by what means, those who will read the scurrilous “Fabrique des Romans”—and properly discount it—may learn.

[Pg 39]The publication of “Monte Cristo” and “Les Trois Mousquetaires” as newspaper feuilletons, in 1844-45, met with amazing success, and were, indeed, written from day to day, to keep pace with the demands of the press.

Here is, perhaps, an opportune moment to digress into the ethics of the profession of the “literary ghost,” and but for the fact that the subject has been pretty well thrashed out before,—not only with respect to Dumas, but to others as well,—it might justifiably be included here at some length, but shall not be, however.

The busy years from 1840-50 could indeed be “explained”—if one were sure of his facts; but beyond the circumstances, frequently availed of, it is admitted, of Dumas having made use of secretarial assistance in the productions which were ultimately to be fathered by himself, there is little but jealous and spiteful hearsay to lead one to suppose that he made any secret of the fact that he had some very considerable assistance in the production of the seven hundred volumes which, at a late period in his life, he claimed to have produced.

The “Maquet affaire,” of course, proclaims the whilom Augustus Mackeat as a collaborateur; still the ingenuity of Dumas shines forth through the[Pg 40] warp and woof in an unmistakable manner, and he who would know more of the pros and cons is referred to the “Maison Dumas et Cie.”

Maquet was manifestly what we have come to know as a “hack,” though the species is not so very new—nor so very rare. The great libraries are full of them the whole world over, and very useful, though irresponsible and ungrateful persons, many of them have proved to be. Maquet, at any rate, served some sort of a useful purpose, and he certainly was a confidant of the great romancer during these very years, but that his was the mind and hand that evolved or worked out the general plan and detail of the romances is well-nigh impossible to believe, when one has digested both sides of the question.

An English critic of no inconsiderable knowledge has thrown in his lot recently with the claims of Maquet, and given the sole and entire production of “Les Trois Mousquetaires,” “Monte Cristo,” “La Dame de Monsoreau,” and many other of Dumas’ works of this period, to him, placing him, indeed, with Shakespeare, whose plays certain gullible persons believe to have been written by Bacon. The flaw in the theory is apparent when one realizes that the said Maquet was no myth—he was, in fact, a very real person, and a literary personage of a [Pg 41]certain ability. It is strange, then, that if he were the producer of, say “Les Trois Mousquetaires,” which was issued ostensibly as the work of Dumas, that he wrote nothing under his own name that was at all comparable therewith; and stranger still, that he was able to repeat this alleged success with “Monte Cristo,” or the rest of the Mousquetaire series, and yet not be able to do the same sort of a feat when playing the game by himself. One instance would not prove this contention, but several are likely to not only give it additional strength, but to practically demonstrate the correct conclusion.

The ethics of plagiarism are still greater and more involved than those which make justification for the employment of one who makes a profession of library research, but it is too involved and too vast to enter into here, with respect to accusations of its nature which were also made against Dumas.

As that new star which has so recently risen out of the East—Mr. Kipling—has said, “They took things where they found them.” This is perhaps truthful with regard to most literary folk, who are continually seeking a new line of thought. Scott did it, rather generously one might think; even Stevenson admitted that he was greatly indebted to Washington Irving and Poe for certain[Pg 42] of the details of “Treasure Island”—though there is absolutely no question but that it was a sort of unconscious absorption, to put it rather unscientifically. The scientist himself calls it the workings of the subconscious self.

As before said, the Maquet affaire was a most complicated one, and it shall have no lengthy consideration here. Suffice to say that, when a case was made by Maquet in court, in 1856-58, Maquet lost. “It is not justice that has won,” said Maquet, “but Dumas.”

Edmond About has said that Maquet lived to speak kindly of Dumas, “as did his legion of other collaborateurs; and the proudest of them congratulate themselves on having been trained in so good a school.” This being so, it is hard to see anything very outrageous or preposterous in the procedure.

Blaze de Bury has described Dumas’ method thus:

“The plot was worked over by Dumas and his colleague, when it was finally drafted by the other and afterward rewritten by Dumas.”

M. About, too, corroborates Blaze de Bury’s statement, so it thus appears legitimately explained. Dumas at least supplied the ideas and the esprit.

In Dumas’ later years there is perhaps more [Pg 43]justification for the thought that as his indolence increased—though he was never actually inert, at least not until sickness drew him down—the authorship of the novels became more complex. Blaze de Bury put them down to the “Dumas-Legion,” and perhaps with some truth. They certainly have not the vim and fire and temperament of individuality of those put forth from 1840 to 1850.

Dumas wrote fire and impetuosity into the veins of his heroes, perhaps some of his very own vivacious spirit. It has been said that his moral code was that of the camp or the theatre; but that is an ambiguity, and it were better not dissected.

Certainly he was no prude or Puritan, not more so, at any rate, than were Burns, Byron, or Poe, but the virtues of courage, devotion, faithfulness, loyalty, and friendship were his, to a degree hardly excelled by any of whom the written record of cameraderie exists.

Dumas has been jibed and jeered at by the supercilious critics ever since his first successes appeared, but it has not leavened his reputation as the first romancer of his time one single jot; and within the past few years we have had a revival of the character of true romance—perhaps the first true revival since Dumas’ time—in M. Rostand’s “Cyrano de Bergerac.”

[Pg 44]We have had, too, the works of Zola, who, indomitable, industrious, and sincere as he undoubtedly was, will have been long forgotten when the masterpieces of Dumas are being read and reread. The Mousquetaire cycle, the Valois romances, and “Monte Cristo” stand out by themselves above all others of his works, and have had the approbation of such discerning fellow craftsmen as George Sand, Thackeray, and Stevenson, all of whom may be presumed to have judged from entirely different points of view. Thackeray, indeed, plainly indicated his greatest admiration for “La Tulipe Noire,” a work which in point of time came somewhat later. At this time Dumas had built his own Chalet de Monte Cristo near St. Germain, a sort of a Gallic rival to Abbotsford. It, and the “Théâtre Historique,” founded by Dumas, came to their disastrous end in the years immediately following upon the Revolution of 1848, when Dumas fled to Brussels and began his “Mémoires.” He also founded a newspaper called Le Mousquetaire, which failed, else he might have retrenched and satisfied his creditors—at least in part.

He travelled in Russia, and upon his return wrote of his journey to the Caspian. In 1860 he obtained an archæological berth in Italy, and edited a Garibaldian newspaper.

[Pg 45]By 1864, the “Director of Excavations at Naples,” which was Dumas’ official title, fell out with the new government which had come in, and he left his partisan journal and the lava-beds of Pompeii for Paris and the literary arena again; but the virile power of his early years was gone, and Dumas never again wielded the same pen which had limned the features of Athos, Porthos, Aramis, and D’Artagnan.

In 1844 Dumas participated in a sort of personally-conducted Bonapartist tour to the Mediterranean, in company with the son of Jerome Napoleon. On this journey Dumas first saw the island of Monte Cristo and the Château d’If, which lived so fervently in his memory that he decided that their personality should be incorporated in the famous tale which was already formulating itself in his brain.

Again, this time in company with the Duc de Montpensier, he journeyed to the Mediterranean, “did” Spain, and crossed over to Algiers. When he returned he brought back the celebrated vulture, “Jugurtha,” whose fame was afterward perpetuated in “Mes Bêtes.”

That there was a deal of reality in the characterization and the locale of Dumas’ romances will not be denied by any who have acquaintance therewith.[Pg 46] Dumas unquestionably took his material where he found it, and his wonderfully retentive memory, his vast capacity for work, and his wide experience and extensive acquaintance provided him material that many another would have lacked.

M. de Chaffault tells of his having accompanied Dumas by road from Sens to Joigny, Dumas being about to appeal to the republican constituency of that place for their support of him as a candidate for the parliamentary elections.

“In a short time we were on the road,” said the narrator, “and the first stage of three hours seemed to me only as many minutes. Whenever we passed a country-seat, out came a lot of anecdotes and legends connected with its owners, interlarded with quaint fancies and epigrams.”

Aside from the descriptions of the country around about Crépy, Compiègne, and Villers-Cotterets which he wove into the Valois tales, “The Taking of the Bastille,” and “The Wolf-Leader,” there is a strong note of personality in “Georges;” some have called it autobiography.

The tale opens in the far-distant Isle of France, called since the English occupation Mauritius, and in the narrative of the half-caste Georges Munier are supposed to be reflected many of the personal incidents of the life of the author.

[Pg 47]This story may or may not be a mere repetition of certain of the incidents of the struggle of the mulatto against the barrier of the white aristocracy, and may have been an echo in Dumas’ own life. It is repeated it may have been this, or it may have been much more. Certain it is, there is an underlying motive which could only have been realized to the full extent expressed therein by one who knew and felt the pangs of the encounter with a world which only could come to one of genius who was by reason of race or creed outclassed by his contemporaries; and therein is given the most vivid expression of the rise of one who had everything against him at the start.

This was not wholly true of Dumas himself, to be sure, as he was endowed with certain influential friends. Still it was mainly through his own efforts that he was able to prevail upon the old associates and friends of the dashing General Dumas, his father, to give him his first lift along the rough and stony literary pathway.

In this book there is a curious interweaving of the life and colour which may have had not a little to do with the actual life which obtained with respect to his ancestors, and as such, and the various descriptions of negro and Creole life, the story [Pg 48]becomes at once a document of prime interest and importance.

Since Dumas himself has explained and justified the circumstance out of which grew the conception of the D’Artagnan romances, it is perhaps advisable that some account should be given of the original D’Artagnan.

Primarily, the interest in Dumas’ romance of “Les Trois Mousquetaires” is as great, if not greater, with respect to the characters as it is with the scenes in which they lived and acted their strenuous parts. In addition, there is the profound satisfaction of knowing that the rollicking and gallant swashbuckler has come down to us from the pages of real life, as Dumas himself recounts in the preface to the Colman Lévy edition of the book. The statement of Dumas is explicit enough; there is no mistaking his words which open the preface:

“Dans laquelle

Il est établi que, malgré leurs noms en os et en is,

Les héros de l’histoire

Que nous allons avoir l’honneur de raconter à nos lecteurs

N’ont rien de mythologique.”

The contemporary facts which connect the real Comte d’Artagnan with romances are as follows:

Charles de Batz de Castlemore, Comte [Pg 49]d’Artagnan, received his title from the little village of Artagnan, near the Gascon town of Orthez in the present department of the Hautes-Pyrénées. He was born in 1623. Dumas, with an author’s license, made his chief figure a dozen years older, for the real D’Artagnan was but five years old at the time of the siege of La Rochelle of which Dumas makes mention. On the whole, the romance is near enough to reality to form an ample endorsement of the author’s verity.

D’ARTAGNAN

The real D’Artagnan made his way to Paris, as did he of the romance. Here he met his fellow Béarnais, one M. de Treville, captain of the king’s musketeers, and the illustrious individuals, Armand de Sillegue d’Athos, a Béarnais nobleman who died in 1645, and whose direct descendant, Colonel de Sillegue, commanded, according to the French army lists of a recent date, a regiment of French cavalry; Henry d’Aramitz, lay abbé of Oloron; and Jean de Portu, all of them probably neighbours in D’Artagnan’s old home.

D’Artagnan could not then have been at the siege of La Rochelle, but from the “Mémoires de M. d’Artagnan,” of which Dumas writes in his preface, we learn of his feats at arms at Arras, Valenciennes, Douai, and Lille, all places where once and again Dumas placed the action of the novels.

[Pg 50]The real D’Artagnan died, sword in hand, “in the imminent deadly breach” at Maestricht, in 1673. He served, too, under Prince Rupert in the Civil War, and frequently visited England, where he had an affaire with a certain Milady, which is again reminiscent of the pages of Dumas.

This D’Artagnan in the flesh married Charlotte Anne de Chanlecy, and the last of his direct descendants died in Paris in the latter years of the eighteenth century, but collateral branches of the family appear still to exist in Gascony, and there was a certain Baron de Batz, a Béarnais, who made a daring attempt to save Marie Antoinette in 1793.

The inception of the whole work in Dumas’ mind, as he says, came to him while he was making research in the “Bibliothèque Royale” for his history of Louis XIV.

Thus from these beginnings grew up that series of romances which gave undying fame to Alexandre Dumas, and to the world of readers a series of characters and scenes associated with the mediæval history of France, which, before or since, have not been equalled.

Alexandre Dumas has been described as something of the soldier, the cook, and the traveller, more of the journalist, diplomatist, and poet, and, more than all else, the dramatist, romancer, and[Pg 51] raconteur. He himself has said that he was a “veritable Wandering Jew of literature.”

His versatility in no way comprised his abilities, and, while conceit and egoism played a not unimportant share in his make-up, his affability—when he so chose—caused him to be ranked highly in the estimation of his equals and contemporaries. By the cur-dogs, which always snap at the heels of a more splendid animal, he was not ranked so high.

Certain of these were for ever twitting him publicly of his creed, race, and foibles. It is recorded by Theodore de Bauville, in his “Odes,” that one Jacquot hailed Dumas in the open street with a ribald jeer, when, calmly turning to his detractor, Dumas said, simply: “Hast thou dined to-day, Jacquot?” Then it was that this said Jacquot published the slanderous brochure, “La Maison Dumas et Cie,” which has gone down as something considerable of a sensation in the annals of literary history; so much so, indeed, that most writers who have had occasion to refer to Dumas’ literary career have apparently half-believed its accusations, which, truth to tell, may have had some bearing on “things as they were,” had they but been put forward as a bit of temperate criticism rather than as a sweeping condemnation.

[Pg 52]To give the reader an idea of the Dumas of 1840, one can scarcely do better than present his portrait as sketched by De Villemessant, the founder and brilliant editor of the Figaro, when Dumas was at the height of his glory, and a grasp of his hand was better than a touch of genius to those receiving it:

“At no time and among no people had it till then been granted to a writer to achieve fame in every direction; in serious drama and in comedy, and novels of adventure and of domestic interest, in humourous stories and in pathetic tales, Alexandre Dumas had been alike successful. The frequenters of the Théâtre Français owed him evenings of delight, but so did the general public as well. Dumas alone had had the power to touch, interest, or amuse, not only Paris or France, but the whole world. If all other novelists had been swallowed up in an earthquake, this one would have been able to supply the leading libraries of Europe. If all other dramatists had died, Alexandre Dumas could have occupied every stage; his magic name on a playbill or affixed to a newspaper feuilleton ensured the sale of that issue or a full house at the theatre. He was king of the stage, prince of feuilletonists, the literary man par excellence, in that Paris then so full of intellect. When he opened [Pg 53]his lips the most eloquent held their breath to listen; when he entered a room the wit of man, the beauty of woman, the pride of life, grew dim in the radiance of his glory; he reigned over Paris in right of his sovereign intellect, the only monarch who for an entire century had understood how to draw to himself the adoration of all classes of society, from the Faubourg St. Germain to the Batignolles.

“Just as he united in himself capabilities of many kinds, so he displayed in his person the perfection of many races. From the negro he had derived the frizzled hair and those thick lips on which Europe had laid a delicate smile of ever-varying meaning; from the southern races he derived his vivacity of gesture and speech, from the northern his solid frame and broad shoulders and a figure which, while it showed no lack of French elegance, was powerful enough to have made green with envy the gentlemen of the Russian Life-Guards.”

Dumas’ energy and output were tremendous, as all know. It is recorded that on one occasion,—in the later years of his life, when, as was but natural, he had tired somewhat,—after a day at la chasse, he withdrew to a cottage near by to rest until the others should rejoin him, after having finished their sport. This they did within a reasonably short time,—whether one hour or two is not stated with[Pg 54] definiteness,—when they found him sitting before the fire “twirling his thumbs.” On being interrogated, he replied that he had not been sitting there long; in fact, he had just written the first act of a new play.

The French journal, La Revue, tells the following incident, which sounds new. Some years before his death, Dumas had written a somewhat quaint letter to Napoleon III., apropos of a play which had been condemned by the French censor. In this epistle he commenced:

“Sire:—In 1830, and, indeed, even to-day, there are three men at the head of French literature. These three men are Victor Hugo, Lamartine, and myself. Although I am the least of the three, the five continents have made me the most popular, probably because the one was a thinker, the other a dreamer, while I am merely a writer of commonplace tales.”

This letter goes on to plead the cause of his play, and from this circumstance the censorship was afterward removed.

A story is told of an incident which occurred at a rehearsal of “Les Trois Mousquetaires” at the “Ambigu.” This story is strangely reminiscent of another incident which happened at a rehearsal of Halévy’s “Guido et Génevra,” but it is still worth[Pg 55] recounting here, if only to emphasize the indomitable energy and perspicacity of Dumas.

It appears that a pompier—that gaudy, glistening fireman who is always present at functions of all sorts on the continent of Europe—who was watching the rehearsal, was observed by Dumas to suddenly leave his point of vantage and retire. Dumas followed him and inquired his reason for withdrawing. “What made you go away?” Dumas asked of him. “Because that last act did not interest me so much as the others,” was the answer. Whereupon Dumas sent for the prompt-book and threw that portion relating to that particular tableau into the fire, and forthwith set about to rewrite it on the spot. “It does not amuse the pompier,” said Dumas, “but I know what it wants.” An hour and a half later, at the finish of the rehearsal, the actors were given their new words for the seventh tableau.

In spite of the varied success with which his plays met, Dumas was, we may say, first of all a dramatist, if construction of plot and the moving about of dashing and splendid figures counts for anything; and it most assuredly does.

This very same qualification is what makes the romances so vivid and thrilling; and they do not falter either in accessory or fact.

[Pg 56]The cloaks of his swashbucklering heroes are always the correct shade of scarlet; their rapiers, their swords, or their pistols are always rightly tuned, and their entrances and their exits correctly and most appropriately timed.

When his characters represent the poverty of a tatterdemalion, they do it with a sincerity that is inimitable, and the lusty throatings of a D’Artagnan are never a hollow mockery of something they are not.

Dumas drew his characters of the stage and his personages of the romances with the brilliance and assurance of a Velasquez, rather than with the finesse of a Praxiteles, and for that reason they live and introduce themselves as cosmopolitans, and are to be appreciated only as one studies or acquires something of the spirit from which they have been evolved.

Of Dumas’ own uproarious good nature many have written. Albert Vandam tells of a certain occasion when he went to call upon the novelist at St. Germain,—and he reckoned Dumas the most lovable and genial among all of his host of acquaintances in the great world of Paris,—that he overheard, as he was entering the study, “a loud burst of laughter.” “I had sooner wait until monsieur’s visitors are gone,” said he. “Monsieur has[Pg 57] no visitors,” said the servant. “Monsieur often laughs like that at his work.”

Dumas as a man of affairs or as a politician was not the success that he was in the world of letters. His activities were great, and his enthusiasm for any turn of affairs with which he allied himself remarkable; but, whether he was en voyage on a whilom political mission, at work as “Director of Excavations” at Pompeii, or founding or conducting a new journal or a new playhouse, his talents were manifestly at a discount. In other words, he was singularly unfit for public life; he was not an organizer, nor had he executive ability, though he had not a little of the skill of prophecy and foresight as to many turns of fortune’s wheel with respect to world power and the comity of nations.

Commenting upon the political state of Europe, he said: “Geographically, Prussia has the form of a serpent, and, like it, she appears to be asleep, in order to gain strength to swallow everything around her.” All of his prophecy was not fulfilled, to be sure, but a huge slice was fed into her maw from out of the body of France, and, looking at things at a time fifty years ahead of that of which Dumas wrote,—that is, before the Franco-Prussian War,—it would seem as though the serpent’s appetite was still unsatisfied.

[Pg 58]In 1847, when Dumas took upon himself to wish for a seat in the government, he besought the support of the constituency of the borough in which he had lived—St. Germain. But St. Germain denied it him—“on moral grounds.” In the following year, when Louis-Philippe had abdicated, he made the attempt once again.

The republican constituency of Joigny challenged him with respect to his title of Marquis de la Pailleterie, and his having been a secretary in the Orleans Bureau. The following is his reply—verbatim—as publicly delivered at a meeting of electors, and is given here as illustrating well the earnestness and devotion to a code which many Puritan and prudish moralists have themselves often ignored:

“I was formerly called the Marquis de la Pailleterie, no doubt. It was my father’s name, and one of which I was very proud, being then unable to claim a glorious one of my own make. But at present, when I am somebody, I call myself Alexandre Dumas, and nothing more; and every one knows me, yourselves among the rest—you, you absolute nobodies, who have come here merely to boast, to-morrow, after having given me insult to-night, that you have known the great Dumas. If such were your avowed ambition, you could have[Pg 59] satisfied it without having failed in the common courtesies of gentlemen. There is no doubt, either, about my having been a secretary to the Duc d’Orleans, and that I have received many favours from his family. If you are ignorant of the meaning of the phrase, ‘The memories of the heart,’ allow me, at least, to proclaim loudly that I am not, and that I entertain toward this family of royal blood all the devotion of an honourable man.”

That Dumas was ever accused of making use of the work of others, of borrowing ideas wherever he found them, and, indeed, of plagiarism itself,—which is the worst of all,—has been mentioned before, and the argument for or against is not intended to be continued here.

Dumas himself has said much upon the subject in defence of his position, and the contemporary scribblers of the time have likewise had their say—and it was not brief; but of all that has been written and said, the following is pertinent and deliciously naïve, and, coming from Dumas himself, has value:

“One morning I had only just opened my eyes when my servant entered my bedroom and brought me a letter upon which was written the word urgent. He drew back the curtains; the weather—doubtless[Pg 60] by some mistake—was fine, and the brilliant sunshine entered the room like a conqueror. I rubbed my eyes and looked at the letter to see who had sent it, astonished at the same time that there should be only one. The handwriting was quite unknown to me. Having turned it over and over for a minute or two, trying to guess whose the writing was, I opened it and this is what I found:

“‘Sir:—I have read your “Three Musketeers,” being well to do, and having plenty of spare time on my hands—’

“(‘Lucky fellow!’ said I; and I continued reading.)

“‘I admit that I found it fairly amusing; but, having plenty of time before me, I was curious enough to wish to know if you really did find them in the “Memoirs of M. de La Fère.” As I was living in Carcassonne, I wrote to one of my friends in Paris to go to the Bibliothèque Royale, and ask for these memoirs, and to write and let me know if you had really and truly borrowed your facts from them. My friend, whom I can trust, replied that you had copied them word for word, and that it is what you authors always do. So I give you fair notice, sir, that I have told people all about it [Pg 61]at Carcassonne, and, if it occurs again, we shall cease subscribing to the Siècle.

“‘Yours sincerely,

“‘——.’

“I rang the bell.

“‘If any more letters come for me to-day,’ said I to the servant, ‘you will keep them back, and only give them to me sometime when I seem a bit too happy.’

“‘Manuscripts as well, sir?’

“‘Why do you ask that question?’

“‘Because some one has brought one this very moment.’

“‘Good! that is the last straw! Put it somewhere where it won’t be lost, but don’t tell me where.’

“He put it on the mantelpiece, which proved that my servant was decidedly a man of intelligence.

“It was half-past ten; I went to the window. As I have said, it was a beautiful day. It appeared as if the sun had won a permanent victory over the clouds. The passers-by all looked happy, or, at least, contented.

“Like everybody else, I experienced a desire to take the air elsewhere than at my window, so I dressed, and went out.

“As chance would have it—for when I go out[Pg 62] for a walk I don’t care whether it is in one street or another—as chance would have it, I say, I passed the Bibliothèque Royale.

“I went in, and, as usual, found Pâris, who came up to me with a charming smile.

“‘Give me,’ said I, ‘the “Memoirs of La Fère.”’

“He looked at me for a moment as if he thought I was crazy; then, with the utmost gravity, he said, ‘You know very well they don’t exist, because you said yourself they did!’

“His speech, though brief, was decidedly pithy.

“By way of thanks I made Pâris a gift of the autograph I had received from Carcassonne.

“When he had finished reading it, he said, ‘If it is any consolation to you to know it, you are not the first who has come to ask for the “Memoirs of La Fère”; I have already seen at least thirty people who came solely for that purpose, and no doubt they hate you for sending them on a fool’s errand.’

“As I was in search of material for a novel, and as there are people who declare novels are to be found ready-made, I asked for the catalogue.

“Of course, I did not discover anything.”

Every one knows of Dumas’ great fame as a gastronome and epicure; some recall, also, that he himself was a cuisinier of no mean abilities. How[Pg 63] far his capacities went in this direction, and how wide was his knowledge of the subject, can only be gleaned by a careful reading of his great “Dictionnaire de Cuisine.” Still further into the subject he may be supposed to have gone from the fact that he also published an inquiry, or an open letter, addressed to the gourmands of all countries, on the subject of mustard.