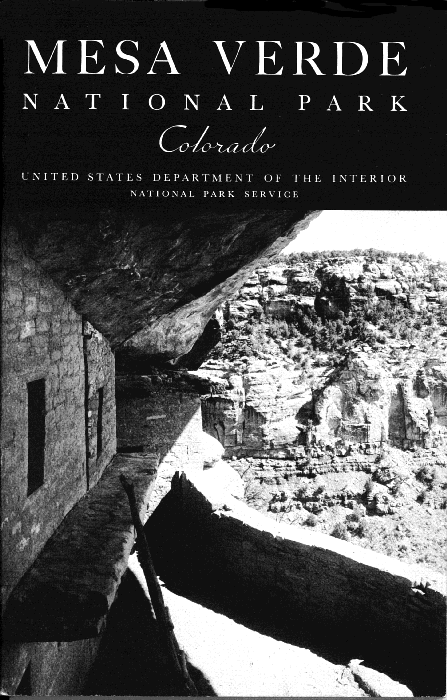

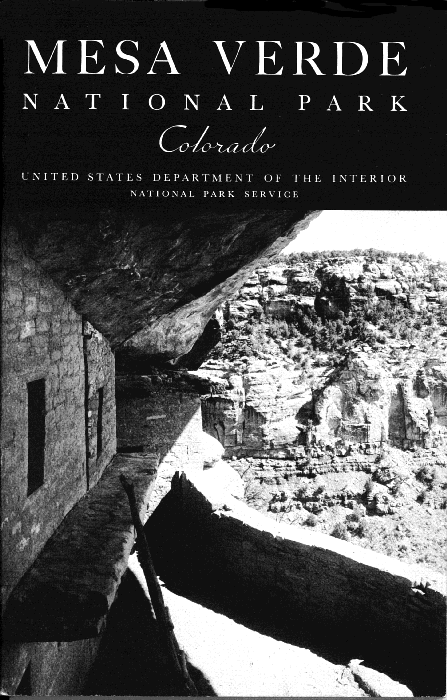

Title: Mesa Verde [Colorado] National Park

Creator: United States. Department of the Interior

Release date: April 22, 2011 [eBook #35936]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Tom Cosmas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

United States Department of the Interior

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

UNITED STATES

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[1] Approximate dating. Exact dating by the methods of tree-ring chronology is yet to be accomplished.

A complete copy of the rules and regulations for governing the park may be seen at the office of the superintendent.

Automobiles.—Secure automobile permit, fee $1 per car. Speed limit 35 miles per hour on entrance highway, 20 miles per hour in headquarters area and on ruin roads. Drive carefully; free wheeling is prohibited within the park.

Fires.—Confine fires to designated places. Extinguish completely before leaving camp, even for temporary absences. Do not guess your fire is out—KNOW IT.

Firewood.—Use only the wood that is stacked and marked "firewood" near your campsite. By all means do not use your ax on any standing tree or strip bark from the junipers.

Grounds.—Burn all combustible rubbish before leaving your camp. Do not throw papers, cans, or other refuse on the ground or over the canyon rim. Use the incinerators which are placed for this purpose.

Hiking.—Do not venture away from the headquarters area unless accompanied by a guide or after first having secured permission from a duly authorized park officer.

Hunting.—Hunting is prohibited within the park. This area is a sanctuary for all wildlife.

Noise.—Be quiet in camp after others have gone to bed. Many people come here for rest.

Park Rangers.—The rangers are here to help and advise you as well as to enforce regulations. When in doubt, ask a ranger.

Ruins and Structures.—Do not mark, disturb, or injure in any way the ruins or any of the buildings, signs, or other properties within the park.

Trees, Flowers, and Animals.—Do not carve initials upon or pull the bark from any logs or trees. Flowers may not be picked unless written permission is obtained from the superintendent or park naturalist. Do not harm or frighten any of the wild animals or birds within the park. We wish to protect them for your enjoyment.

Visitors.—Register and secure permit at the park entrance. Between travel seasons, registration and permit are arranged for at park headquarters.

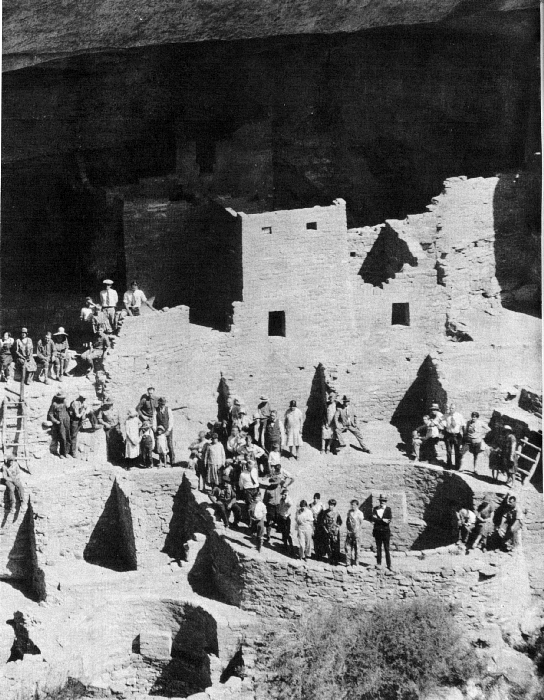

Grant photo.

|

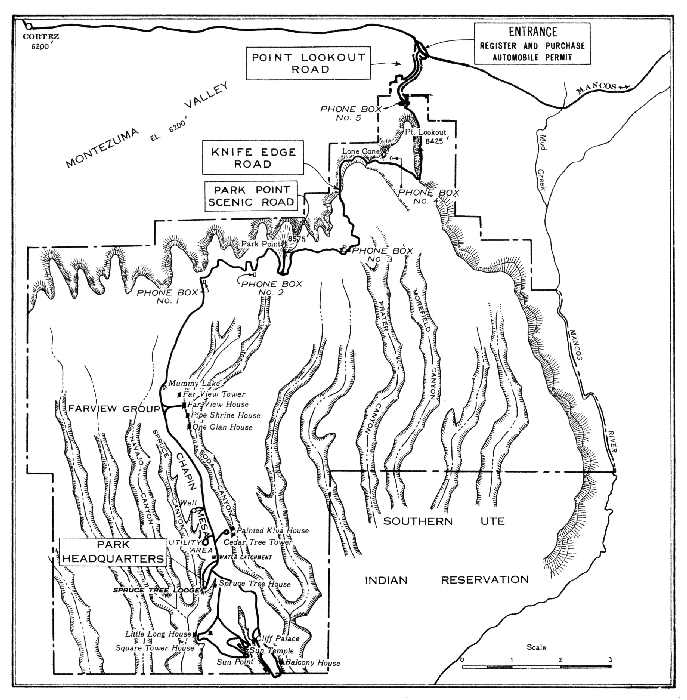

The mesa verde, or green mesa, so-called because its juniper and piñon trees give it a verdant tone, is 15 miles long by 8 miles wide. Rising abruptly from the valley on the north side, its top slopes gradually southward to the high cliffs bordering the canyon of the Mancos River on the south. Into this valley open a number of large high-walled canyons through which occasionally, in times of heavy rain, raging torrents of water flow into the Mancos. In the shelter of the caves that have been eroded in the sides of these canyons are some of the best-preserved cliff dwellings in America, built many centuries ago by a tribe of peace-loving Indians who prized the security offered by the almost inaccessible caves. In order to preserve these cliff dwellings Mesa Verde National Park was created, but they are not the only attractions in the area. In the winter the park is closed to travel by deep snow, but in the early spring the blanket of snow is replaced by a mantle of flowers that change with the seasons, and to the story of the prehistoric inhabitants is added an absorbing story of nature that is peculiar to this mesa and canyon country.

"The Mesa Verde region", writes Arthur Chapman, "has many attractions besides its ruins. It is a land of weird beauty. The canyons which seam the mesa, all of which lead toward the distant Mancos River, are, in many cases, replicas of the Grand Canyon of the Colorado. While the summer days are warm, the nights are cool, and the visitor should bring plenty of wraps besides the clothing and shoes necessary for the work of climbing around among the trails. It is a country for active footwork, just as it was in the days of the cliff dwellers themselves. But when one has spent a few days among the cedars and piñon pines of the Mesa Verde, well named Green Table by the Spaniards of early days, he becomes an enthusiast and will be found among those who return again and again to [Pg_02] this most unique of national parks to study its mysteries and its beauties from all angles."

The northern edge of the mesa terminates in a precipitous bluff, averaging 2,000 feet above the Montezuma Valley. The general slope of the surface is to the south, and as the main entrance highway meanders back and forth in heading each smaller canyon, many times skirting the very brink of the great northern fault line, tremendous expanses of diversified terrain are brought into view, first in Colorado and Utah, then in Arizona and New Mexico.

A new scenic road approximately 1 mile in length branches from the main highway at a point 10.2 miles beyond the entrance checking station and ascends to the crest of Park Point, the highest part of the Mesa Verde National Park, which attains an elevation of 8,572 feet above sea level.

From this majestic prominence the great Montezuma Valley, dotted with artificial lakes and fertile fields, appears as from an airplane, while to the north are seen the Rico Mountains and the Lone Cone of Colorado, and to the east, the La Plata Mountains. To the west the La Sals, the Blues, and Bears Ears, of Utah, dominate the horizon. Some of these landmarks are more than 115 miles distant. Southward numerous deep canyons, in which the more important cliff dwellings are found, subdivide the Mesa Verde into many long, narrow tonguelike mesas. The dark purplish canyon of the Mancos River is visible in the middle foreground, and beyond, above the jagged outline of the mesa to the south, the Navajo Reservation, surrounded by the deep-blue Carrizos of Arizona and the Lukachukai and Tunichas of New Mexico.

In the midst of this great mountain-enclosed, sandy plain, which, seen from the mesa, resembles a vast inland sea surrounded by dark, forbidding mountains, rises Ship Rock (45 miles distant), a great, jagged shaft of igneous rock, 1,860 feet high, which appears for all the world like a great "windjammer" under full sail. Toward evening the illusion is perfect.

The distance from Park Point to Spruce Tree Camp, the park headquarters, is 10.5 miles. The entire road from the park entrance to headquarters, 20 miles, is gravel surfaced and oil treated, full double width, and cars may pass at any point thereon.

Although there are hundreds of cliff dwellings within the Mesa Verde National Park, the more important are located in Rock, Long, Wickiup, Navajo, Spruce, Soda, Moccasin, and tributary canyons. Surface ruins of a different type are widely distributed over the narrow mesas separating the numerous canyons. A vast area surrounding the park contains more or [Pg_03] less important ruins of these early inhabitants, most important and easiest of access from the park being the Aztec Ruins and Chaco Canyon National Monuments, New Mexico; the Yucca House National Monument, Colorado; and the Hovenweep National Monument, Colorado-Utah.

Although the Spaniards were in the Mesa Verde region as early as 1765 and the Americans as early as 1859, it was not until 1872 that the first settlement was made. In that year the Mancos Valley, lying at the foot of the Mesa Verde, was settled, but because of the fact that the mesa [Pg_04] itself was a stronghold of the warlike Ute Indians, many years passed before the cliff dwellings were discovered.

The ruins in the Mancos Canyon were discovered as early as 1874 when W. H. Jackson, who led a Government party, found there many small dwellings broken down by the weather. The next year he was followed by Prof. W. H. Holmes, later chief of the Bureau of American Ethnology, who drew attention to the remarkable stone towers also found in this region. Had either of the explorers followed up the side canyons of the Mancos they would have then discovered ruins which, in the words of Baron Gustav Nordenskiöld, the talented Swedish explorer, are "so magnificent that they surpass anything of the kind known in the United States."

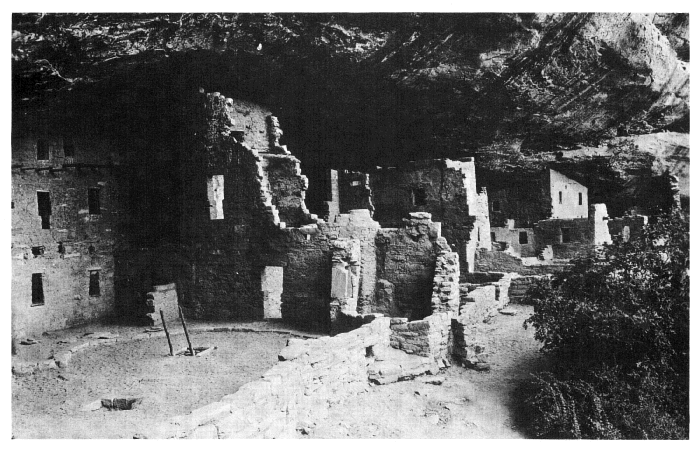

The largest cliff ruin, known as Cliff Palace, was discovered by Richard Wetherill and Charlie Mason while hunting cattle one December day in 1888. Coming to the edge of a small canyon they first caught sight of a village under the overhanging cliff on the opposite side, placed like a picture in its rocky frame. In their enthusiasm they thought it was a palace. With the same enthusiasm the visitors of today involuntarily express their pleasure and surprise as they first view this spectacular ruin.

Later these two men explored this ruin and gave it the name of Cliff Palace, an unfortunate designation, for it is in no respect a palace, but a community house, containing more than 200 living rooms, former abodes of families, and 23 ceremonial rooms or kivas. They also discovered other community dwellings, one of which was called Spruce Tree House, from a large spruce tree, since cut down, growing in front of it. This had eight ceremonial rooms and probably housed 300 inhabitants.

The findings of these two ruins did not complete the discoveries of ancient buildings in the Mesa Verde; many other ruins were found by the Wetherill brothers and other early explorers. They mark the oldest and most congested region of the park, but the whole number of archeological sites may reach into the thousands.

Only a few of the different types of ruins that have already been excavated, repaired, and made accessible to the visitor are considered herein. This excavation and repair was the work of the late Dr. J. Walter Fewkes, formerly chief of the Bureau of American Ethnology, with the exception of Balcony House, which was done by Jesse L. Nusbaum. Hundreds of sites await scientific investigation, being accessible now only on foot or horseback.

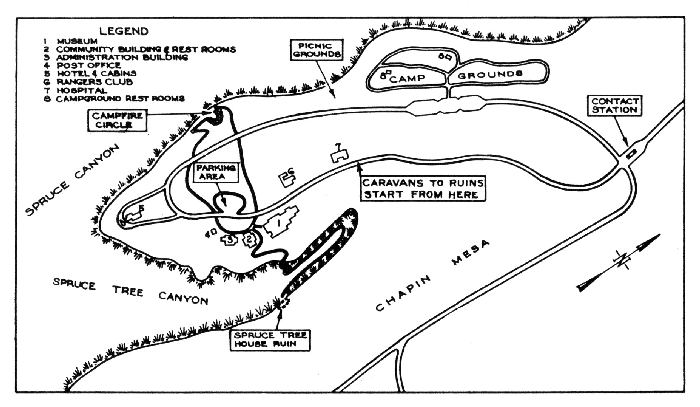

Spruce Tree House, located in a large cave just across Spruce Tree Canyon from the museum, has been made readily accessible by a short winding trail. This is the only excavated cliff dwelling in the park that may be visited without going on a conducted tour, and is open to the public at all times. A ranger is always on duty to protect the ruin from vandalism and to give information to the visitors.

The total length of Spruce Tree House is 216 feet, and its greatest width is 89 feet. During the excavation of the ruin in 1907, Dr. Fewkes counted 8 ceremonial rooms, or kivas, and 114 rooms that had been used for living, storage, and other purposes. At least 14 seemed to have been storage and burial rooms so that probably not more than 100 were used as dwellings. If it is considered that a family occupied each room, the population would have been large, but it is doubtful if all of the rooms were occupied at one time. An average of 2 or 3 persons to the room, making a total of not more than 300 for the entire village, would no doubt be a fair estimate.

Two hundred feet north of Spruce Tree House the canyon comes to an abrupt box end. A splendid spring flows from the base of the sandstone cliff, and it was to this spring that the cliff-dweller women went for water carrying it back to their homes in their big water jars. At the south end of the cave a trail, consisting of small toeholds cut in the cliff, led to the mesa top above. This trail was used by the men as they went to their mesa-top fields, where they raised corn, beans, and squash, and by the hunters as they went in search of deer and mountain sheep that lived in the forests above.

The rooms of Spruce Tree House are divided into two groups by a court or street running from the front to the back of the cave, at a point just south of the center of the village. The majority of the rooms are north of this street, and some of the walls show the finest work in the entire structure. The stones were well shaped and smoothed; the mud mortar was carefully worked into the crevices and compressed with thin stone wedges. Over many of the walls was spread a thin coat of reddish plaster, often decorated with paintings. These rooms, standing as when they were constructed 700 years ago, are mute evidence of the cleverness of the masons who built them.

Spruce Tree House has more walls that reach the top of the cave than any other ruin in the park. All through the central part the walls were three stories high, the top of the cave serving as the roof of the upper rooms. One-and two-story structures usually required a ceiling of heavy rafters, running lengthwise of the rooms. These were covered with a crosswise [Pg_07] layer of small poles and withes as a support for an average 3-inch floor of clay. Very often a small hatchway was left in one corner of the ceiling. A short ladder leaning in the corner of the lower room gave access to the room above.

Very few of the houses were equipped with fire pits. Most of the cooking was done in the open courts. Small fire pits can be found along the walls and in the corners of the courts and passageways.

Spruce Tree House has eight of the circular, subterranean rooms that were set aside for ceremonial purposes. Similar rooms are still in use in the present day Pueblo Indian villages and are known as kivas.

Usually the kiva roofs have collapsed, but in Square Tower House two kivas have the original roofs almost intact. Following the plan of these original roofs, three of the kivas in Spruce Tree House have been reroofed. Details of construction may be noted by descending the ladder into one of these restored kivas.

Kivas in the Mesa Verde are always underground and generally circular in shape. The average diameter is 12 to 13 feet and the depth is such that the roof would clear a man's head. At a point about 3 feet above the floor is a narrow ledge running entirely around the room. This ledge is known as the banquette and its exact use is unknown. On this ledge were built six stone buttresses or pilasters, 2 to 3 feet in height, which served as roof supports. Short beams were placed from pilaster to pilaster around the room, and additional series of beams were laid to span the angles formed by the lower series. Normally five or six sets of beams extended this cribwork almost to the ground level. Horizontal beams were then placed across the top and the whole structure was covered with bark and earth. A small square hole in the center of the roof provided an entrance which also served for a smoke vent.

On the south side of the kiva the banquette is wider between two of the pilasters than anywhere else around the room. This deep recess is often referred to as an altar, although its exact use is not known. Just back of the wall of this deep recess is a vertical shaft that leads down to meet a horizontal shaft that opens into the kiva just above the floor. This is the ventilator shaft. The fire, burning in the small pit in the center of the room, sent the smoke up through the hole in the roof, and the fresh air was drawn down through the ventilator shaft. Between the ventilator and the fire pit a small wall, known as the "deflector", was constructed to keep the fresh air current from blowing on the fire.

[Pg_08] Two or three feet from the fire pit, and in a straight line with the ventilator shaft, the deep recess, the deflector, and the fire pit is a small hole in the floor of the kiva. This hole is usually about 3 inches in diameter and from 4 to 6 inches deep; its walls and bottom often covered with a smooth layer of mud. In the present-day kivas this hole is known as the "sipapu", and is considered to be the symbolic entrance to the underworld. The kiva was a combination ceremonial, club, and work room for the men. Even in the present-day villages the women are rarely ever allowed to enter the kivas because of the fact that the men take almost entire charge of the religious work. It is believed that each clan had its own kiva. It may be noted that in almost every case the kiva is surrounded by a group of living rooms. The members of the clan no doubt lived in these rooms and the men held their ceremonies in the adjoining kiva. Two of the kivas in Spruce Tree House have side entrances that lead to nearby rooms. These rooms may have been the homes of the priests, or dressing rooms for them.

Twenty-one of the roof beams in Spruce Tree House have been dated by tree-ring chronology. These dates show that the houses were constructed during the years between 1230 A.D. and 1274 A.D. In 1276 A.D. a 24-year period of drought began that caused the cliff dwellers to move to regions where there was a more permanent supply of water. In those same regions are the homes of the modern Pueblo Indians and no doubt some of these people are the descendants of the cliff dwellers.

Cliff Palace lies in an eastern spur of Cliff Canyon under the roof of an enormous cave that arches 50 to 100 feet above it. The floor of the cave is elevated about 200 feet above the bottom of the canyon and is just under the rim of the mesa. The entrance of the cave faces west, toward a great promontory upon which stands Sun Temple.

The total length of the cave is over 300 feet and its greatest depth is just under 100 feet. The vaulted roof is so high that the cave is always light and airy, offering a perfect home site to the cliff dwellers who were seeking protection from the elements as well as from their enemies.

Fortunately, the configuration of the cliffs above the ruin makes it possible to get a fine bird's-eye view from the rim of the mesa. Views obtained from the heads of the two trails are most striking and give an idea of the setting and size of the building before it is entered for closer [Pg_09] inspection. The most spectacular view of Cliff Palace is from Sun Temple, across the canyon. This is the only spot from which the entire ruin may be seen.

Cliff Palace is the largest known cliff dwelling. Dr. Fewkes, who excavated the ruin in 1909, placed the number of living rooms at slightly more than 200. Very few of the walls reached the top of the cave because of its great height, but many of the structures were as high as two and three stories. Near the south end of the ruin is the tallest structure, a four-story tower that reaches the cave roof. Ground space appropriate for building purposes was at a premium in the cave. To provide for an increasing population, second-, third-, and even fourth-story rooms were superimposed on the original single-story structures which predominated in the initial cliff-dweller occupation of this site.

When the cliff dwellers started building in the cave they were confronted with the problem of an uneven floor. The floor of the cave slanted from the back to the front and was covered with huge, angular boulders that had fallen from the cave roof. This problem the cliff dweller solved by erecting terraces and filling in the irregular places. The open spaces between the boulders were excellent for kivas, as there was not a great deal of excavation necessary. After the kiva walls were built the extra space was filled in with trash and dirt. When the flat kiva roof was added a level court resulted. Around this court the homes were constructed, often on the rough surfaces of the big boulders. Because of the uneven floor and the terracing that was necessary, six distinct terrace levels resulted.

Twenty-two kivas are located in the cave and another, lying about 50 feet from the western end, and thought to have been used by men living in the cave, brings the total to 23. Twenty of these conform to the plan of the typical Mesa Verde kiva, but three seem to be of a different type. These three, instead of being round, are square with rounded corners. The banquette is missing as well as the pilasters or roof supports.

Because of the fact that the inhabitants of Cliff Palace were forced to store enough corn each fall to last until the next harvest a great many storage rooms were constructed. Any small nook or cranny that was too small for a home was utilized for that purpose. Far back in the cave a number were constructed of large, thin sandstone slabs. These slabs were [Pg_10] placed on end to form small rectangular rooms. When the door slabs were in place and all of the crevices were well chinked with mud the grain was safe from the rodents. High up under the roof of the cave, at the back, was a long narrow shelf that was also utilized for storage space. A wall was built along the front of the ledge to the cave roof, and the space back of the wall was divided into 14 small storage rooms. A ladder on the roof of one of the houses below gave access to the ledge.

In the third floor room of the four-story tower is the finest painting yet found in the Mesa Verde. The entire inner surface of the four walls was covered with bright red designs on a white background. The designs are similar to those found on cliff-dweller pottery. The white color was obtained by mixing finely ground gypsum with water to form a smooth paste; the red was obtained by treating hematite, or red ochre, in the same manner.

The outstanding structure in Cliff Palace is the two-story round tower that stands just south of the center of the cave. Every stone in this tower is rounded to conform to the curvature of the walls and the graceful taper toward the top makes it one of the finest examples of masonry work in the region. When the early explorers first entered this tower the only object found was the most beautiful stone ax they ever discovered. Whether this tower was a home or whether it was constructed for some special purpose is a matter of conjecture.

Because of the fact that Cliff Palace is the largest of all cliff dwellings, its population is of special interest. A close inspection of the rooms in the ruin shows that they are smaller, on the average, than the rooms in any of the other large cliff dwellings. When judged from our modern standards, it is difficult to imagine more than a couple of people living in each one. Our modern ideas, however, will not help us in understanding the people who once lived in Cliff Palace.

More than anything else the cliff dwellers desired security from their enemies. Their next desire was safety from the elements. When it is considered that these were the motivating influences, it can easily be understood that such minor matters as space and comfort would receive little consideration. Since the inhabitants were an easy-going, peace-loving group it can be imagined that crowded living conditions would not be [Pg_11] objectionable. In addition it must be considered that the rooms were used principally as sleeping quarters. All activities were carried on in the open courts and on the terraced roof tops. Even the cooking was done over open fires outside the houses.

An average of two to the room would give a population of 400; an average of three would place 600 in the cave. If every room were occupied at one time and if the average of two or three to the room is not too high, it would seem that a total population of 500 would not be too great for Cliff Palace.

Balcony House lies in Soda Canyon about 2½ miles southeast of Spruce Tree Camp, and is reached by a continuation of the Cliff Palace Road. It is one of the most picturesque of the accessible ruins in the park and occupies a better position for defense than most of the other ruins on the mesa. A few defenders could have repelled a large attacking force. Additional precautions have been taken at the south end of the ruin for the strengthening of its defenses, where the only means of reaching it is through a fortified narrow cleft. The south part of the ledge was walled up to a height of about 15 feet, the lower part of the wall closing the cleft being pierced by a narrow tunnel. Through this tunnel a man may creep on hands and knees from the cliff dwelling to the south part of the ledge, which affords a footing, with a precipice to the left and the cliff to the right, for about 100 paces. The ledge here terminates in the perpendicular wall of the canyon. The ruined walls of a defensive structure, built to cut off approach on this side, may still be traced.

At the north end of the ruin the foundation gave the builders considerable trouble, but the difficulties were skillfully overcome. A supporting wall was erected on a lower ledge, to form a stable foundation for the outer wall of the upper rooms, where the higher ledge was too narrow or abrupt for building purposes.

South of the rooms fronted by this wall is a small open court, bounded at the back by a few very regular and well-preserved rooms which rise to the roof of the cave. The poles supporting the floors of these upper-story rooms project about 2 feet to provide support for a balcony. Split poles, laid parallel with the front wall, were covered at right angles with rods of cedar bast and generously plastered with clay to form the floor of the balcony, which served as a means of outside communication between the rooms of the upper story. A low, thick parapet wall built on the edge of the precipice encloses the canyon side of the northern court. [Pg_12] The funds for the excavation and repair of Balcony House in 1911 were largely furnished by the Colorado Cliff Dwellers Society, an organization founded and directed by Mrs. Gilbert McClurg, of Colorado Springs, Colo. The original purpose of this society was to stimulate interest in legislation for the preservation and protection of the prehistoric remains of the Mesa Verde. This society advanced the creation of Mesa Verde National Park in 1906.

Square Tower House Ruin is situated in an eastern spur of Navajo Canyon, opposite a great bluff called Echo Cliff. An ancient approach to the ruin from the canyon rim is visible to the south of the dwelling. Footholes for ascent and descent had been cut in the cliff by the Indians which enabled them to reach the level on which the ruin is situated. The footpath now used by visitors parallels the ancient trail. Along the top of the talus this pathway splits into an upper and lower branch. The former, hugging the cliff, passes through the "Eye of the Needle"; the latter is lower down on the talus and is used by the stouter and older visitors.

The Square Tower House cave is shallow, its back wall perpendicular, with roof slightly overhanging. At the extreme eastern end of the ruin the vertical cliff suddenly turns at right angles, forming an angle in which, high above the main ruin, there still remain walls of rooms. To these rooms, which are tucked away just under the canyon rim, with only their front walls visible, the name "Crow's Nest" is given. Logs, with their ends resting in notches cut in the rock actually support walls of masonry, as seen in the angle of this cliff. This is a well-known method of cliff-house construction.

This ruin measures about 138 feet from its eastern to its western end. There are no streets or passageways as at Spruce Tree House and Cliff Palace. The rooms are continuous and compactly constructed, the walls being united from one end of the cave to the other, excepting for the spaces above the kivas. The absence of a cave recess to the rear of the ruin is significant as it allowed the cliff to be used as the back wall of rooms. Rooms in Square Tower House do not differ radically from those of Spruce Tree House and other cliff dwellings. They have smaller windows, door openings, and supports of balconies. The rectangular rooms were constructed above the ground; the circular rooms were subterranean. The former were devoted to secular and the latter to ceremonial purposes.

The tower is, of course, the most conspicuous as well as the most interesting architectural feature of the ruin, being visible for a long distance as [Pg_13] one approaches Square Tower House. Its foundation rests on a large boulder situated in the eastern section of the cave floor. This tower has three walls constructed of masonry, the fourth being the perpendicular rear wall of the cave. The masonry of the tower stands about 35 feet above the foundation, but the foundation boulder on which it stands increases its height over 5 feet.

On a projecting rock on the west side above the tower is the wall of a small, inaccessible room which may have been used as a lookout or as an eagle house.

The lowest story of the tower is entered from plaza B, and on the east side there are three openings, situated one over another, indicating the first, second, and third stories, but on the south side of the tower there are only two doorways. The roof of the lowest room is practically intact, showing good workmanship, but about half of its floor is destroyed. The upper walls of the second-story room have the original plaster, reddish dado below and white above. Although the third and fourth stories are destitute of floors, they are plastered.

Some of the best preserved circular ceremonial chambers (kivas) in the Southwest are to be seen in Square Tower House. The majority of the kivas belong to the pure type, distinguished by mural pilasters supporting a vaulted roof.

Kiva A is particularly instructive on account of the good preservation of its roof. Its greatest diameter is 13 feet 6 inches; or, measuring inside the banquettes, 11 feet 1 inch. The interior is well plastered with many layers of brown plaster. The pilasters are six in number, one of which is double. Two depressions are visible in the smooth floor, in addition to a fireplace and a sipapu. These suggest ends of a ladder, but no remains of a ladder were found in the room.

Kiva B is the largest ceremonial chamber in Square Tower House, measuring 16 feet 9 inches in diameter over all. This kiva is not only one of the best preserved, but also one of the most instructive in Square Tower House, since half of the roof, with the original cribbing, is still in place, extending completely around the periphery. It has six pilasters and as many banquettes. Where the plaster had not fallen, it was found to have several layers.

The perpendicular cliff back of Square Tower House has several different forms of incised petroglyphs. From the fact that these usually occur on the cliff above the kiva roofs, they may be regarded as connected in some way with a religious symbolism. A few petroglyphs are also found on stones set in the walls of the rooms.

The ruin formerly called Willow House, but now known as Oak Tree House, lies on the north side of Fewkes Canyon, in a symmetrical cave and has an upper and a lower part. The two noteworthy features of Oak Tree House are the kivas and the remnant of the wall of a circular room made of sticks plastered with adobe but destitute of stone masonry.

Oak Tree House has seven kivas and may be called a large cliff dwelling. One of the kivas has a semicircular ground plan with a rectangular room on the straight side. There are no pilasters or banquettes in this kiva. The floor of another kiva was almost wholly occupied by a series of grinding bins, indicating a secondary use. The excavation work on Oak Tree House has not yet been completed, but a small collection of specimens at one end of the ruin shows the nature of the objects thus far found.

Looking across Cliff Canyon from Sun Point one can see the fine ruin called Sun Set House, formerly known as Community House. This ruin, like many other cliff dwellings, has an upper and a lower house, the former being relatively larger than is usually the case. Although Sun Set House is accessible, it has never been excavated.

The cliff houses considered in the preceding pages are habitations. There are also specialized buildings on the Mesa Verde which were never inhabited but were used for other purposes. Two of these presumably were devoted solely to ceremonial purposes and are known as Sun Temple and Fire Temple.

Sun Temple is situated west of Cliff Palace, on the promontory formed by the confluence of Cliff and Fewkes Canyons. Up to the year 1915 the site of Sun Temple was a mound of earth and stones, all showing artificial working or the pecking of primitive stone hammers. This mound had a circular depression in the middle and its surface was covered with trees and bushes. No high walls projected above the ground nor was there any intimation of the size or character of the buried building. It was believed to be a pueblo or communal habitation. Excavation of this mound brought into view one of the most unusual buildings in the park.

[Pg_16] Sun Temple is a type of ruin hitherto unknown in the park. The building excavated shows excellent masonry and is the most mysterious form yet discovered in a region rich in prehistoric remains. Although at first there was some doubt as to the use of this building, it was early recognized that it was not constructed for habitation, and it is now believed that it was intended for the performance of rites and ceremonies; the first of its type devoted to religious purposes yet recognized in the Southwest.

The ruin was purposely constructed on a commanding promontory in the neighborhood of large inhabited cliff houses. It sets somewhat back from the edge of the canyon, but near enough to make it clearly visible from all sides, especially the neighboring mesas. It must have presented an imposing appearance rising on top of a point high above inaccessible, perpendicular cliffs. No better place could have been chosen for a religious building in which the inhabitants of many cliff dwellings could gather and together perform their great ceremonial dramas.

The ground plan of the ruin has the form of the letter D. The building is in two sections, the larger of which, taken separately, is also D-shaped. This is considered the original building. The addition enlarging it is regarded as an annex. The south wall, which is straight and includes both the original building and the annex, is 131.7 feet long. The ruin is 64 feet wide.

There are about 1,000 feet of walls in the whole building. These walls average 4 feet in thickness, and are double, enclosing a central core of rubble and adobe. They are uniformly well made.

The fine masonry, the decorated stones that occur in it, and the unity of plan stamp Sun Temple as the highest example of Mesa Verde architecture.

The walls were constructed of the sandstone of the neighborhood. Many stone hammers and pecking stones were found in the vicinity.

On the upper surface of a large rock protruding from the base of the southwest corner of the building a peculiar depression, surrounded by radiating ridges, was found. To primitive minds, this may have appeared as a symbol of the sun and, therefore, deemed an object of great significance, to be protected as a shrine. This natural impression may have prompted Dr. Fewkes in the naming of this ruin.

There are three circular rooms in Sun Temple which from their form may be identified as ceremonial in function, technically called kivas. Two [Pg_17] of these, free from other rooms, are situated in the plaza that occupies the central part of the main building, and one is embedded in rooms of the so-called "annex." Adjoining the last mentioned, also surrounded by rooms, is a fourth circular chamber which is not a kiva. This room, found to be almost completely filled with spalls or broken stones, perhaps originally served as an elevated tower or lookout.

The kiva that is situated in the west section of Sun Temple has a ventilator stack attached to the south side, recalling the typical ventilator of a Mesa Verde cliff kiva, and there are indications of the same structure in the two circular chambers in the court. These kivas, however, have no banquettes or pilasters to support a vaulted roof, and no fragments of roof beams were found in the excavations made at Sun Temple. East of Sun Temple, where formerly there was only a mound of stone and earth, there were found the remains of a low circular structure of undetermined use.

Most of the peripheral rooms of Sun Temple open into adjoining rooms, a few into the central court, but none has external openings. Some of the rooms are without lateral entrances, as if it were intended to enter them through a hatch in the roof.

Not only pits indicative of the stone tools by which the stones forming the masonry of Sun Temple were dressed appear on all the rocks used in its construction, but likewise many bear incised symbols. Several of these still remain in the walls of the building; others have been set in cement near the outer wall of the eastern kiva. It is interesting to record that some of the stones of which the walls were constructed were probably quarried on the mesa top not far from the building, but as the surface of the plateau is now forested, the quarries themselves are hidden in accumulated soil and are difficult to discover.

Sun Temple is believed to be among the latest constructed of all the aboriginal buildings in the park, probably contemporaneous with late building activities in Balcony House, Spruce Tree House, and Cliff Palace.

Because of the absence of timbers or roof beams it is impossible to tell when Sun Temple was begun, how long it took for its construction, or when it was deserted. There are indications that its walls may never have been completed, and from the amount of fallen stones there can hardly be a doubt that when it was abandoned they had been carried up in some places at least 6 feet above their present level. The top of the wall had been worn down at any rate 6 feet in the interval between the time it was abandoned and the date of excavation of the mound. No one can tell the length of this interval in years.

[Pg_18] We have, however, knowledge of the lapse of time, because the mound had accumulated enough soil on its surface to support growth of large trees. Near the summit of the highest wall in the annex there grew a juniper tree of great antiquity, alive and vigorous when excavation work was begun. This tree undoubtedly sprouted after the desertion of the building and grew after a mound had developed from fallen walls. Its roots penetrated into the adjacent rooms and derived nourishment from the soil filling them.

Necessarily, when these roots were cut off the tree was killed. It was then cut off about a foot above the ground, the stump remaining. A cross section of this stump was examined by Gordon Parker, supervisor of the Montezuma National Forest, who found that it had 360 annual rings without allowing for decayed heartwood which would add a few more years to its age.

It is not improbable that this tree began to grow on the top of the Sun Temple mound shortly after the year 1540, when Coronado first entered New Mexico. How long an interval elapsed for crumbling walls to form the mound in which it grew, and how much earlier the foundations of the ruined walls were laid, no one can tell. A conservative guess of 350 years for the interval between construction and the time the cedar began to sprout would carry the antiquity of Sun Temple back to about 1200 A.D.

The argument that appeals most strongly to many in supporting the theory that Sun Temple was a ceremonial building is the unity shown in its construction. A preconceived plan existed in the minds of the builders before they began work on the main building. Sun Temple was not constructed haphazardly, nor was its form due to addition of one clan after another, each adding rooms to a preexisting nucleus. There is no indication of patching one building to another, so evident at Cliff Palace and other large cliff dwellings. The construction of the recess in the south wall, situated exactly, to an inch, midway in its length, shows it was planned from the beginning.

We can hardly believe that one clan could have been numerous enough to construct a house so large and massive. Its walls are too extensive; the work of dressing the stones too great. The construction of Sun Temple presumably represents the cooperative efforts of many clans from adjacent cliff dwellings uniting in a common purpose. Such a united effort represents a higher state of sociological development than a loosely connected population of a cliff dwelling.

On the theory that this building was erected by people from several neighboring cliff dwellings for ceremonies held in common, we may suppose that the builders came daily from their dwellings in Cliff Palace and other houses and returned at night, after they had finished work, to their homes. The trails down the sides of the cliffs which the workmen used are still to be seen. The place was frequented by many people, but there is no evidence that any one clan dwelt near this mysterious building during its construction.

The argument that cliff dwellers in the neighborhood built Sun Temple and that incoming aliens had nothing to do with its construction seems very strong. The architectural differences between it and Cliff Palace are not objections, for the architectural form of Sun Temple may be regarded as a repetition, in the open, of a form of building that developed in a cliff house; the rounded north wall conforms with the rear of a cave and the straight south wall reproduces the front of a cliff dwelling. The recess midway in the south wall of Sun Temple could be likened without forcing the comparison to a similar recess which occurs at the main entrance into Cliff Palace.

Sun Temple was not built by an alien people, but by the cliff dwellers as a specialized building mainly for religious purposes, and, so far as known, is the first of its type recognized in the Mesa Verde area.

Fire Temple is one of the most remarkable cliff houses in the park, if not in the whole Southwest. It is situated in a shallow cave in the north wall of Fewkes Canyon, near its head, and can readily be seen from the road along the southwest rim of the canyon. This ruin was formerly called Painted House, but when it was excavated in May 1920 evidence was obtained that it was a specialized building and not a habitation. The facts brought to light point to the theory that it was consecrated to the fire cult, one of the most ancient forms of worship.

The ruin is rectangular in form, almost completely filling the whole of its shallow cave, and the walls of the rooms extend to the roof. A ground plan shows a central court 50 feet long and about 25 feet broad, flanked at each end with massive-walled buildings two stories high. The walls of these rooms are well constructed, plastered red and white within and on the side turned to the court. The white plaster is adorned with symbolic [Pg_20] figures. The beams used in the construction of the ceiling of the lower room are missing, but the walls show clearly that the structure was formerly two stories high. No beams were used in the construction of the floors, the lower story having been filled in with fragments of rocks on which was plastered a good adobe floor.

The court or plaza was bounded by a low wall on the south side, the buildings enclosing the east and west ends, where there was a banquette. The north side of the court was formed by the solid rocks of the cliff, but on the lower part a narrow masonry wall had been laid up about head high, projecting from the cliff a foot and less on the top. The wall was formerly plastered red below and white above, triangular figures and zigzag markings recalling symbols of lightning on the line of the junction of the red and white surfaces.

In the center of the court on a well-hardened adobe floor there is a circular walled fire pit containing an abundance of ashes, and on either side of it are foundations of small rectangular structures. The function of the rectangular enclosures, lying one on each side of the fire pit, is unknown. The middle room of the lowest tier of rooms just west of the main court has a number of painted symbols and zoormorphic figures upon its walls. These paintings, in red, still remain in a fair state of preservation, and consist of five symbols, supposedly of fire, and many pictures of mountain sheep and other animals.

Just west of Fire Temple there is a group of rooms which were evidently habitations, since household utensils were found in them. One of these rooms has in the floor a vertical shaft which opens outside the house walls like a ventilator. The former use of this structure is unknown. Although the Fire Temple was not inhabited, there were undoubtedly dwellings nearby.

A hundred feet east of the Fire Temple there are two low caves, one above the other. This cliff dwelling is called New Fire House. The rooms in the lower cave were fitted for habitation, consisting of two, possibly three, circular ceremonial rooms and a few secular rooms; but the upper cave is destitute of the former. The large rooms of the upper house look like granaries for the storage of provisions, although possibly they also were inhabited. In the rear of the large rooms identified as granaries was found a small room with a well-preserved human skeleton accompanied with mortuary pottery. One of these mortuary offerings is a fine mug made of black and white ware beautifully decorated. In the rear of the cave were three well-constructed grinding bins, their metates still in place.

[Pg_21] The upper house is now approached from the lower by foot holes in the cliff and a ladder. Evidences of a secondary occupation of one of the kivas in the lower house appear in a wall of crude masonry without mortar, part of a rectangular room built diagonally across the kiva. The plastering on the rear walls of the lower house is particularly well preserved. One of the kivas, has, in place of a deflector and ventilator shaft, a small rectangular walled enclosure surrounded by a wall, recalling structures on the floor of the kivas of Sun Temple. The meaning of this departure from the prescribed form of ventilator is not apparent.

Hidden in the timber about one-half mile east of the main entrance highway, and 1 mile north of Park Headquarters, stands a prehistoric tower. This ruin has been named Cedar Tree Tower because of the ancient juniper tree that grows adjacent to the north wall. The excavation of the tower and the area about its base led to the discovery that although it appeared to stand alone there were two subterranean rooms connected with its base. The larger of these rooms is a kiva, typical of the Mesa Verde cliff dwelling. Communication between kiva and tower was by means of a subterranean passage. This passage bifurcates, one branch opening through the tower floor, the other into a small square room. In the middle of the solid rock floor of the tower a circular hole, or sipapu, symbolic of the entrance to the underworld, had been drilled.

The masonry is excellent and the massive character and workmanship of the walls indicate some important use. No living rooms were found adjacent to the tower. The walls of the tower are uniformly two feet in width and they still stand to the height of 12 feet.

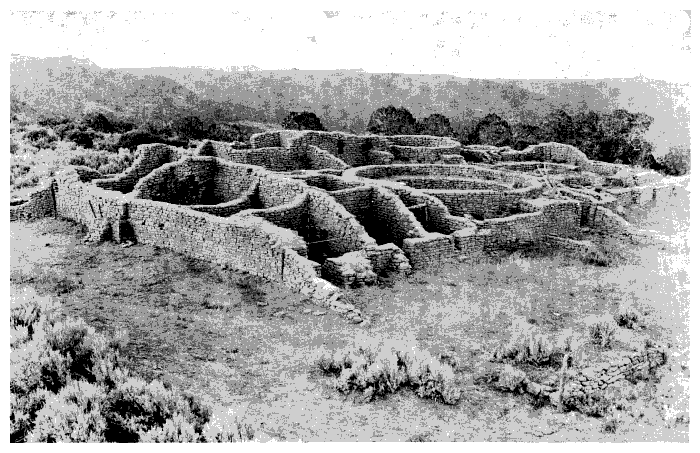

Archeological investigations have shown that the inhabitants of the Mesa Verde built compact pueblo-style structures on the open mesa land separating the deep canyons. Lacking natural protection of the caves and cliffs of the canyons, a closely knit and compact structure was necessary for defensive purposes. Not having to conform to the irregular contours of the cave as in the cliff-house type, the structure assumed a roughly rectangular shape in the open, with the kivas within protected by the adjacent outside living and storage rooms. The roofed-over kivas formed small open courts within the higher outside walls. Structurally, there is but little difference between the cliff house and the pueblo; undoubtedly they belong to the same culture and period.

[Pg_23] Four and a half miles north of Spruce Tree Camp the park road passes near 16 major and many minor mounds. This is the so-called Mummy Lake group, a misnomer, since the walled depression at the crest of the slope above the group was never used as a reservoir, also since mummies are never found where the least dampness occurs. In the spring of the year water is still conducted to the depression by the drainage ditches which the early cowmen in the park constructed in their efforts to impound sufficient water for their stock.

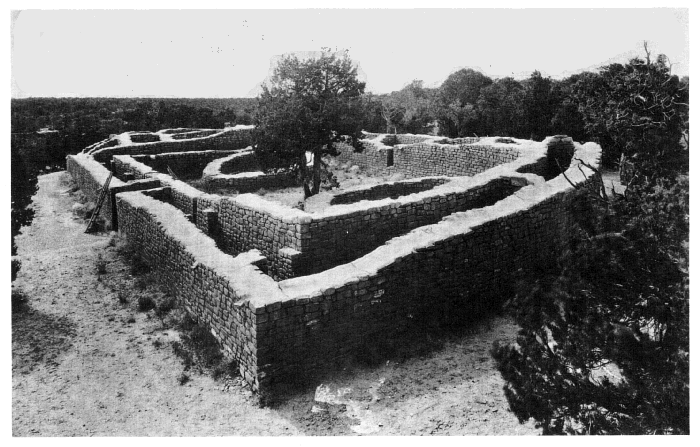

The first unit of this group to be excavated was named Far View House because of the wonderful panorama of diversified terrain that is visible in Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona from the walls of the ruin. At the beginning of the work, this mound appeared very much as any of the other adjacent major mounds, no sign of standing wall appearing above the even contour of the ruin. Heavy growths of sagebrush covered the whole area. Three months' time was devoted to the excavation in revealing the rectangular pueblo, 100 by 113 feet in size, now seen. The slow crumbling of the heavy dirt-covered roofs and the walls, together with the annual deposit of wind-blown sand from the San Juan country early each spring, gradually filled the rooms to the level of the standing walls, after which destructive elements and forces can little change the contour of any ruin.

The external features of Far View House are apparent as we approach its walls; mounting to the top of the highest wall we can best observe the general plan. This pueblo is rectangular in shape, consisting of concentrated rooms with a court surrounded by a wall annexed to the south side. On its southeast corner, a little less than 100 feet away, lies the cemetery from which have been taken a number of skeletons with their offerings of food bowls and other objects, such as was the custom of these people to deposit in the graves of their dead.

At its highest point on the north wall the pueblo had three stories, but on the southern side there was but a single story. This building was terraced, one tier of rooms above another. In the corner of the interior of the highest room may still be seen the ancient fireplaces and stones for grinding corn, set in their original positions as used by the former inhabitants. There are no external windows or passages, except on the south side where midway in length is a recess in which was placed a ladder in order to be hidden from view. The inhabitants evidently used the roof of the lowest terrace for many occupations. A bird's-eye view shows that all the rooms, now roofless, fall into two groups.

[Pg_24] In the center of this mass of rooms is a kiva 32 feet in diameter, and around it are three smaller kivas. The size of the large kiva is noteworthy. In the cliff dwellings the kivas were necessarily small because of the limited floor space, but in the surface villages, where unlimited space was available, they were often large. This arrangement of one large kiva and several small ones is common. It might indicate that each clan had a small kiva of its own but that in the major ceremonies, when all of the clans worked together, the large ceremonial room was used. The structural details of the large kiva are identical with those of the smaller ones. The only variation is in the size.

The rooms surrounding these circular ones vary somewhat in form but are, as a rule, rectangular, the shapes of those near the kivas being triangular to fill the necessary spaces. The contents of the rectangular rooms show that they were living rooms. Artifacts were found and indications of various industries as well as marks of smoke from their fireplaces appear on the walls. From the nature of this evidence there is no doubt that Far View House was once inhabited by the people living the same way as those who used the cliff dwellings.

The court added to the pueblo on its south side is enclosed by a low wall. Here were probably performed, in ancient times, the many religious dances and festivals.

Far View House is but one of the 16 pueblos in the Mummy Lake group, and at the period of maximum development could have housed a large population. To the north and east, where the two branches of Soda Canyon join, another large village or group has been located, and one can almost trace the trail across the west fork of Soda Canyon to the neighboring village and imagine the dusky visitors going from one to the other in prehistoric times. Each narrow tonguelike mesa of the Mesa Verde has its ruins of either isolated pueblo structures, or adjacent groups, denoting the widespread distribution of the mesa pueblo builders.

Pottery is the best index as to the chronological sequence of the ruins in the Southwest, and in examining the pottery of some of the mesa-type pueblos it is found that some contain pottery antedating that of the cliff-house culture, while others contain similar types. Undoubtedly, they were simultaneously inhabited, in part at least, and the transitory period was of long duration; but the period in prehistoric time when they were built and later deserted has not been determined. We cannot say from data now at hand when this took place, documentary history affording no help.

[Pg_25] The aborigines who lived near these ruins when discovered in 1874 were Utes, a Shoshonean stock who disclaimed all knowledge of the people who constructed these buildings. They avoided them as uncanny and even now can only with difficulty be induced to enter them. They have dim legends of conflicts between the earliest Utes and cliff dwellers. Unfortunately, however, such legendary evidence is not reliable, as the general mythology of these people has been much distorted due to foreign contacts and the passage of time.

During the season of 1922 excavation and repair work in the vicinity of Far View House was carried on simultaneously. Among the ruins excavated were Pipe Shrine House, One Clan House, Far View Tower, and Megalithic House.

In 1922 one of the Late Basket Maker pit houses was excavated on the mesa above Square Tower House. This structure is known as Earth Lodge A. Although it once had a mud and pole roof almost as high as a man's head, nothing now remains but the underground part of the house. None of these pit houses have ever been found that have not been burned, and only a few pieces of charcoal remain as evidence of the former roof. The pit is 30 inches deep and 18 feet in diameter. In the center is a fire pit. In the floor are also four holes, forming a large square, in which the roof supports once stood. The walls of the pit were formerly plastered with a thick layer of mud, but only a few patches of this remain. Around the edge of the room, at floor level, were a number of small storage bins made of thin stone slabs. No side entrance was located during excavation. In some of the pit houses evidence has shown that entrance was often made by means of a ladder through the smokehole in the roof.

This was a typical home of the Lake Basket Makers who were living in this region when the Pueblo Indians arrived about 700 A. D. These pit houses passed out of existence as soon as the masonry wall was perfected.

Of all the ruins in Mesa Verde National Park only 28 have been named and only 30 excavated. No survey of the unexcavated sites has been made, and the total number of ruins is unknown. Several hundred cliff dwellings have been discovered, and new ones will probably be found in the more remote canyons. The surface pueblos outnumber the cliff [Pg_26] dwellings, and a careful search would reveal many that are now hidden by a thick growth of underbrush. The earth lodges of the Late Basket Makers are so common that hundreds will be brought to light by careful search. Dozens of them can be located in a half-hour walk over any of the mesas.

Dr. A. E. Douglass, director of Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, established the tree-ring chronology for dating Southwestern ruins. This chronology is based upon the facts that solar changes affect our weather and weather in turn the trees of the arid Southwest, as else-where, and that such affects are recorded in the variation of tree-ring growth during wet and dry years. Thus the tree-ring record of living trees has been extended into the past by arranging beams from historic pueblos in their proper sequence so that the inner rings of one match the outer rings of its predecessor, and in turn match the rings of the living trees. After completing the series from living trees and pueblos, of known dates, the record has been continued through the cross-sections of prehistoric beams of fir and pine that were chopped with the stone axes. The continuation of this chronology is only limited by the finding of earlier beams than those used in the established chronology.

The National Geographic Society tree-ring expedition took, in all, 49 beam sections from ruins within Mesa Verde National Park. During 1932 and 1933 further tree-ring research was carried on in this area and additional dates have been secured. Presuming that the year of cutting the timber was the year of actual use in construction, the following dates have been established for the major cliff dwellings:

| Mug House, A. D. 1066 | Long House, A. D. 1204-11 | |

| Cliff Palace, A. D. 1073-1273 | Square Tower House, A. D. 1204-46 | |

| Oak Tree House, A. D. 1112-84 | Spruce Tree House, A. D. 1230-74 | |

| Spring House, A. D. 1115 | New Fire House, A. D. 1259 | |

| Hemenway House, A. D. 1171 | Ruin No. 16, A. D. 1261 | |

| Balcony House, A. D. 1190-1272 | Buzzard House, A. D. 1273 |

Since considerable tree-ring material from these ruins remains yet to be examined, the dates given above are not final. On the basis of present evidence, Cliff Palace, the largest and most complex cliff house within the park, shows an occupancy of 200 years.

[Pg_27] It is an interesting fact that all of the dates fall just short of the beginning of the great drought, which the tree-ring chronology shows commenced in 1276 and extended to 1299, a period of 24 years.

[2] The Secret of the Southwest Solved by Talkative Tree Rings, by A. E. Douglass: National Geographic Magazine. December 1929.

In 1923 Roy Henderson and A. B. Hardin discovered the largest and finest watchtower that had yet been found. The tower was circular, 25 feet in height and 11 feet in diameter. Loopholes at various levels commanded the approach from every exposed quarter.

During the winter of 1924 the north refuse space of Spruce Tree House was excavated. Two child burials were found, one partially mummified, the other skeletal only. With one was found a mug, a ladle, a digging stick, and two ring baskets that had held food. Several corrugated jars were found, together with miscellaneous material. A layer of turkey droppings a foot thick indicated the space had been used as a turkey pen.

During January and February of 1926, when snow was available as a water supply, excavations were carried on in Step House Cave, by Superintendent Jesse L. Nusbaum. In 1891 Nordenskiöld had found many fine burials in this cave and it had suffered greatly from pothunting. The cliff dweller refuse at the south end of the cave had not been thoroughly cleaned out, however, and it was under this layer of trash that the important discovery was made. Three of the Late Basket Maker pit houses were found, giving the first evidence that these people had used the caves before the cliff dwellers. Very few artifacts were found because of the earlier pothunting. In 1926 also a low, deep cave opposite Fire Temple was excavated, and a small amount of Basket Maker material found. Most interesting were two tapered cylinders of crystallized salt that still bore the imprint of the molder's hands. While bracing a slipping boulder in Cliff Palace, Fred Jeep found, in 1916, a sandal of the Early Basket Maker type that indicates a former occupancy of the cave by the first group of Agricultural Indians in this region.

In 1927 Bone Awl House was excavated. A series of unusually fine bone awls was found that suggested the name for the ruin. Much miscellaneous material was also found. Another small cliff dwelling nearby was cleaned out. One baby mummy and an adult burial were found, as well as some pottery and bone and stone tools. This ruin is reached by a spectacular series of 104 footholds that the cliff dwellers had cut in the almost perpendicular canyon wall.

During March of 1928 and the winter of 1929 restricted excavations were conducted in ruins 11 to 19, inclusive, on the west side of Wetherill Mesa. [Pg_28] Several burials were found, all in poor condition because of dampness. Outstanding was an unusual bird pendant of hematite with crystal eyes set into drilled sockets with piñon gum. Forty-two bowls were reconstructed from the sherds found.

In the summer of 1929 Mr. and Mrs. Harold S. Gladwin and associates of Gila Pueblo, Globe, Ariz., assisted by Deric Nusbaum, conducted an archeological survey of small-house ruins on Chapin Mesa and in the canyon heads along the North Rim. The survey covered 250 sites. One hundred sherds were collected from each site and studied to identify the pottery types, the sequence of their development, and their relationship to pottery types of other southwestern archeological areas.

The forest fire of 1934 revealed many hitherto unknown ruins. Two splendid watchtowers were found on the west cliff of Rock Canyon. In a small area at the head of Long Canyon 10 new Early Pueblo ruins were located and no doubt scores of others will be found upon more careful search. In the heads of the small canyons many dams and terraces were noted.

In the stabilization program that was carried on in 1934-35 a number of artifacts were found. A certain amount of debris had to be moved in order that the weakened walls and slipping foundations might be strengthened and varied finds resulted. Axes, bone awls, sandals, pottery, planting sticks, and similar articles were most common, but a few burials were also found.

In August 1934 the undisturbed skeleton of an old woman was found on the bare floor of a small ruin just across the canyon from the public campgrounds. This skeleton, of particular importance because of fusion of the spinal column, had apparently remained exposed and undisturbed through more than seven centuries.

Because of the fact that no detailed, comprehensive survey has ever been made of the archeological resources of the park, the findings of new ruins, artifacts, and human remains are more or less regularly reported at the park museum.

The so-called "Mesa Verde cliff dwellers" were not the first of the prehistoric southwestern cultures, nor were they the first human occupants of the natural caves that abound in the area of the park. Centuries before the cliff-dweller culture with its complex social organizations, agriculture, and highly developed arts of masonry, textiles, and ceramics, it is thought that small groups of primitive Mongoloid hunters crossed from the north-* [Pg_29] eastern peninsula of Asia to the western coast of Alaska. The Bering Strait, with but 60 miles of water travel, offered the safest and easiest route.

Just when these migrations to the east had their origin and how long they continued cannot definitely be said, but it is thought the earliest Mongoloid hunters were in northwestern America about twelve to fifteen thousand years ago. When Columbus "discovered" America the continent was inhabited from Alaska to the Strait of Magellan and from the Pacific to the Atlantic coasts.

For perhaps several thousand years following the first migrations little of great significance developed. There undoubtedly was cultural progress, but it was slow, and in the long perspective of time its evidences are hardly discernible. With the knowledge and benefits of agriculture, which was probably developed first in Mexico, hunting gave way to husbandry, nomadism to sedentary life, and there followed a great period of change and advancement. The introduction of corn or Indian maize into what is now the southwestern United States may be called the antecedent condition for all advanced cultures of the area.

Evidence has not yet been established that the first of the maize-growing Indians of the Southwest were permanent occupants of the Mesa Verde. Nevertheless, in the Cliff Palace cave, well below the horizon or floor level of the cliff dwellers, archeologists have found a yucca fiber sandal of a distinctive type which is associated only with the first agricultural civilization. From this evidence it would be reasonable to assume that the caves of Mesa Verde at least offered temporary shelter, if not permanent homes, to the people of this period.

The earliest culture so far definitely identified as having permanent habitation on the Mesa Verde is the Basket Maker III or the Second Agricultural Basket Maker first found in Step House cave on the west side of the park below the debris of the latter cliff-house occupation. Recent excavations and archeological surveys furnish conclusive evidence that the second agricultural people were most numerous in the area now included in this national park, and they constructed their roughly circular subterranean rooms not only in the sandy floor of the caves but also in the red soil on the comparatively level mesas separating the numerous canyons. Late Basket Maker House A, formerly known as Earth Lodge A, is an example of this early type of structure. Up to this time excavations have failed to uncover a single house structure of this type not destroyed by fire.

These early inhabitants made basketry, excelled in the art of weaving, and it is believed were the first of the southwestern cultures to invent fired [Pg_30] pottery. The course of this invention can be traced from the crude sun-dried vessel tempered with shredded cedar bark to the properly tempered and durable fired vessel.

Then followed a long development in house structure, differing materially from this earlier type. Horizontal masonry replaced the cruder attempts of house-wall construction; rectangular or squarish forms replaced the somewhat circular earlier type; and gradually the single-room structures were grouped into ever-enlarging units which assumed varying forms of arrangement as the development progressed. The art of pottery making improved concurrently with the more complex house structure. This later period represents the intermediate era of development from the crude Late Basket Maker dwellings to the remarkable structures of the "Cliff House Culture."

During this period of transition new people penetrated the area. The Basket Makers throughout the course of their development were consistently a long-headed group. The appearance of an alien group is recorded through the finding of skeletons with broad or round skulls and a deformed occiput. These new people, the Pueblos, took over, changed, and adapted to their own needs the material culture of the earlier inhabitants.

The Pueblos were not content with the crude buildings and earth lodges that sufficed as homes during the earlier periods. For their habitations they shaped stones into regular forms, sometimes ornamenting them with designs, and laid them in mud mortar, one on another. Their masonry has resisted the destructive forces of the elements for centuries.

The arrangement of houses in a cliff dwelling the size of Cliff Palace is characteristic and is intimately associated with the distribution of the social divisions of its former inhabitants.

The population was composed of a number of units, possibly clans, each of which had its more or less distinct social organization, as indicated in the arrangement of the rooms. The rooms occupied by a clan were not necessarily connected, and generally neighboring rooms were distinguished from one another by their uses. Thus, each clan had its men's room, which is called the "kiva." Each clan had also a number of rooms, which may be styled the living rooms, and other enclosures for granaries. The corn was ground into meal in another room containing the metate set in a stone bin or trough. Sometimes the rooms had fireplaces, although these were generally in the plazas or on the housetops. All these different rooms, taken together, constituted the houses that belonged to one clan.

The conviction that each kiva denotes a distinct social unit, as a clan or a family, is supported by a general similarity in the masonry of the kiva walls [Pg_31] and that of adjacent houses ascribed to the same clan. From the number of these rooms it would appear that there were at least 23 social units or clans in Cliff Palace.

Apparently there is no uniformity or prearranged plan in the distribution of the kivas. As religious belief and custom prescribed that these rooms should be subterranean, the greatest number were placed in front of the rectangular buildings where it was easiest to construct them. When necessary, because of limited space or other conditions, kivas were also built far back in the cave and enclosed by a double wall of masonry, with the walls being spaced about two and a half to three feet apart. The section between the walls was then backfilled with earth or rubble to the level of the kiva roof. In that way the ceremonial structure was artificially made subterranean, as their beliefs required.

In addition to their ability as architects and masons, the cliff dwellers excelled in the art of pottery making and as agriculturists. Their decorated pottery—a black design on pearly white background—will compare favorably with pottery of the other cultures of the prehistoric Southwest.

As their sense of beauty was keen, their art, though primitive, was true; rarely realistic, generally symbolic. Their decoration of cotton fabrics and ceramic work might be called beautiful, even when judged by our own standards. They fashioned axes, spear points, and rude tools of stone; they wove sandals, and made attractive basketry.

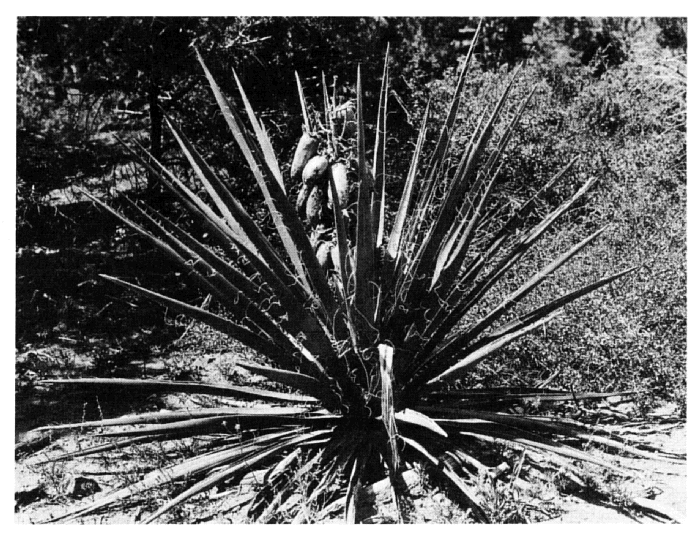

The staple product of the cliff dwellers was corn; they also planted beans and squash. This limited selection was perhaps augmented by piñon nuts, yucca fruit, and other indigenous products found in abundance. Nevertheless, successful agriculture on the semiarid plateau of the Mesa Verde must have been dependent upon hard work and diligent efforts. Without running streams irrigation was impossible and success depended upon the ability of the farmer to save the crop through the dry period of June and early July.

Rain at the right time was the all-important problem, and so confidently did they believe that they were dependent upon the gods to make the rain fall and the corn grow that their prayers for rain probably developed into their most important ceremonies.

From Dr. A. E. Douglass's tree-ring chronology the earliest date so far established for the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings is 1066 A.D. and the latest date 1274 A.D. While it should not be imagined that these are the all-inclusive dates representing the total time of the cliff-dweller culture, it is interesting to note that this same tree-ring story tells us that a great drought [Pg_32] commenced in 1276 and extended for a 24-year period to 1299. It may logically be presumed that the prehistoric population was gradually forced to withdraw from the area as the drought continued and to establish itself near more favorable sources of water supply.

The so-called "Aztec ruin", which is situated on the banks of the Animas River in northwestern New Mexico, substantiates this hypothesis of the voluntary desertion of the cliff dwellings. In this ruin is found unmistakable evidence of a secondary occupation which has been definitely identified as a Mesa Verde settlement.

It is thought that certain of the present-day Pueblo Indians are descendants, in part at least, of the cliff dwellers. Many of these Indian towns or pueblos still survive in the States of New Mexico and Arizona, the least modified of which are the villages of the Hopi, situated not far from the Grand Canyon National Park.

The fauna and flora of Mesa Verde should be particularly interesting to visitors. A combination of desert types from the lower arid country and mountain types, usually associated with regions of greater rainfall, occur here. The desert types are highly specialized to cope with their environment, particularly the plant and smaller animal life.

Rocky Mountain mule deer are perhaps the only big game to be found abundantly in the park. They are often seen. Their numbers in the park, however, vary greatly according to the season. It is hoped to reintroduce the native species of Rocky Mountain bighorn as soon as range sufficient for the needs of this species has been added to the park. Occasionally a black bear is reported.

Cougars, or mountain lions, and bobcats are part of the wildlife of the park and, strange to say, are occasionally seen in broad daylight. In other national parks these animals are rarely seen even by rangers. Coyotes and foxes are not as numerous as they once were on the mesa. As a result of the reduction of the predators, many of the smaller animals, such as rabbits, porcupines, and prairie dogs, have greatly increased. Rock and ground squirrels and the Colorado chipmunk are present in great numbers.

More than 200 varieties of birds have been recorded. The species range from the majestic golden eagle, the largest bird, down to a variety of dainty humming birds.

Game birds are represented by the dusky grouse. No wild turkeys are now to be found in the park, although it is believed that they were once [Pg_33] here. The cliff dwellers domesticated the turkey, and their bones, feathers, and droppings are found in all the ruins. At present the reintroduction of wild turkeys to Mesa Verde is under consideration.

Among the interesting animal residents of Mesa Verde are the reptiles. The lizards are represented by the horned lizard, the western spotted or earless lizard, the collared lizard, the striped race runner, utas, rock swifts, and sagebrush swifts. Among the snakes are found the bull snake, the smooth green snake, the western striped racer, the rock snake, and the prairie rattlesnake. The latter, the only poisonous species on the Mesa Verde, lives among the rocks in the lower canyons.

Mesa Verde receives considerably more rainfall than true desert areas, and vegetation typical of the upper sonoran or transition zone is moderately luxuriant. This heavy cover of vegetation accounts for its name, which means "Green Tableland." The dense forest consists of piñon pine, juniper, Douglas fir, and western yellow pine. The north-facing slopes and moist canyons contain quaking aspen and box elders, with willows and cottonwoods growing along the Mancos River. The heavy covering of [Pg_34] scrub oak and mountain mahogany over the higher elevations of the park makes this region a most colorful one during the fall months.

Among the fruit-bearing shrubs and trees are the service berry, choke cherry, Oregon grape, and elderberry.

An abundance of wild flowers, varying in color with the growing season, include principally the Mariposa lily, Indian paint brush, pentstemon, lupine, wild sweet pea, and a great variety of the compositae family.

Mesa Verde National Park may be reached by automobile from Denver, Colorado Springs, Pueblo, and other Colorado points. Through Pueblo one road leads to the park by way of Canon City, from where one may look down into the Royal Gorge, the deepest canyon in the world penetrated by a railroad and river. This road passes through Salida and on through Gunnison and Montrose, and then south through Ouray, Silverton, and Durango. This route passes through some of Colorado's most magnificent mountain scenery. Another road leads south from Pueblo through Walsenburg, across La Veta Pass, on through Alamosa, Del Norte, Pagosa Springs, and Durango, crossing Wolf Creek Pass en route. Both roads lead west from Durango to Mancos and on into the park.

Motorists coming from Utah turn southward from Green River or Thompsons, crossing the Colorado River at Moab, proceeding southward to Monticello, thence eastward to Cortez, Colo., and the park.

From Arizona and New Mexico points, Gallup, on the National Old Trails Road, is easily reached. The auto road leads north from Gallup through the Navajo Indian Reservation and a corner of the Ute Indian Reservation. At Shiprock Indian Agency, 98 miles north of Gallup, the San Juan River is crossed.

Mesa Verde National Park is approached by rail both from the north and from the south: From the north via the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad main transcontinental line through Grand Junction, and branch lines through Montrose or Durango; from the south via the main transcontinental line of the Santa Fe Railroad through Gallup, N. Mex.

The lines of the Denver & Rio Grande Western System traverse some of the most magnificent scenery of the Rocky Mountain region, a fact which gives the journey to Mesa Verde zestful travel flavor. Two main-line routes are provided to the Grand Junction gateway.

[Pg_35] The Royal Gorge Route goes through the Grand Canyon of the Arkansas, now spanned by an all-steel suspension bridge, 1,053 feet above the tracks in the Royal Gorge. This route crosses Tennessee Pass (altitude, 10,240 feet) and follows the Eagle River to its junction with the Colorado River at Dotsero, thence to Grand Junction.

Service was inaugurated in June 1934 via the new James Peak Route of the D. & R. G. W., utilizing the Moffat Tunnel (altitude at apex, 9,239 feet), 6.2-mile bore which pierces the Continental Divide 50 miles west of Denver. This route follows the Colorado River from Fraser, high on the west slope of the continent, through Byers Canyon, Red Gorge, Gore Canyon, and Red Canyon, thence over the Dotsero Cut-off to Dotsero, where it joins the Royal Gorge Route. The new line saves 175 miles in the distance from Denver to Grand Junction.

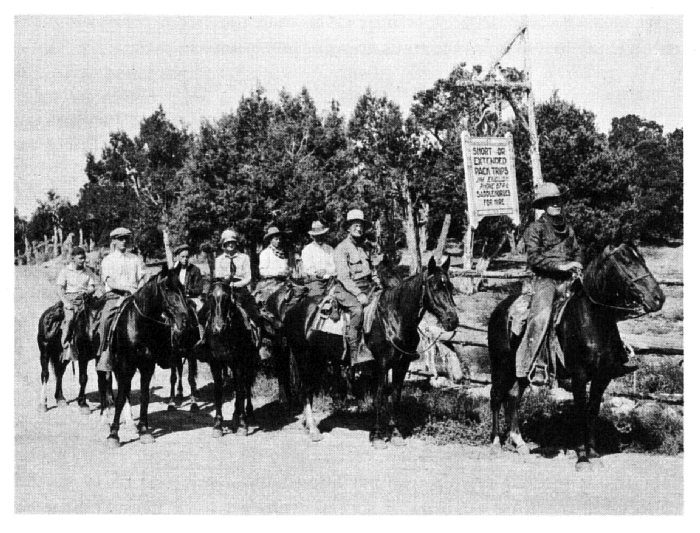

The Rio Grande Motor Way, Inc., of Grand Junction, Colo., from June 15 to September 15, operates a daily motor service from Grand Junction, Delta, Montrose, Ouray, Silverton, Durango, and Mancos, Colo., to Spruce Tree Lodge in Mesa Verde National Park. This motor bus leaves Grand Junction at 6:45 a.m., via the scenic Chief Ouray Highway, stopping en route at other places mentioned, crossing beautiful Red Mountain Pass (altitude, 11,025 feet), arriving at Spruce Tree Lodge at 7 p.m. The stage leaves the park at 7 a.m., when there are passengers, arriving at Grand Junction at 5:40 p.m. The round trip fare between Grand Junction and the park is $18.65.