Title: South Africa and the Transvaal War, Vol. 3 (of 8)

Author: Louis Creswicke

Release date: July 27, 2011 [eBook #36866]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BY

LOUIS CRESWICKE

AUTHOR OF “ROXANE,” ETC.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

IN SIX VOLUMES

VOL. III.—FROM THE BATTLE OF COLENSO, 15TH DEC. 1899, TO LORD ROBERTS’S ADVANCE INTO THE FREE STATE, 12TH FEB. 1900

EDINBURGH: T. C. & E. C. JACK

MANCHESTER: KENNETH MACLENNAN, 75 PICCADILLY

1900

DECEMBER 1899.

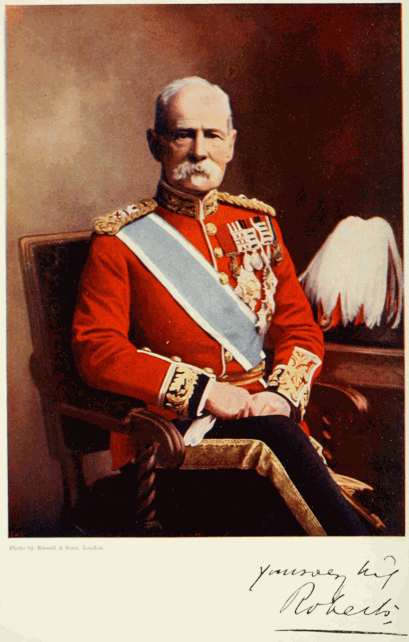

17.—Field-Marshal Lord Roberts, K.P., G.C.B., V.C., &c., appointed Commander-in-Chief in South Africa, with Lord Kitchener of Khartoum as his Chief of the Staff.

War Office issued orders under which the remaining portion of the Army A Reserve were called up; and large reinforcements were to proceed to South Africa without delay.

General Gatacre advanced from Sterkstroom to Putters Kraal.

General French established his headquarters at Arundel.

Offers of Second Contingents by the Colonies accepted.

18.—Additional Battalions of Militia embodied. There were now fifty-four Battalions of Militia embodied.

Sir Charles Warren and the Staff of the Fifth Division left Cape Town.

Reconnaissance by General French. Sortie from Ladysmith.

19.—Important order issued from the War Office, announcing that the Government had decided to raise for service in South Africa a Mounted Infantry force, to be called “The Imperial Yeomanry.” The force to be recruited from the Yeomanry.

21.—Mr. Winston Churchill arrived at Lourenço Marques after an adventurous journey.

23.—Departure of Lord Roberts from London and Southampton for the Cape.

24.—Dordrecht occupied by General Gatacre.

Sortie from Mafeking.

Two British officers captured by Boers near Chieveley.

25.—Bluejackets blew up Tugela Road bridge, and cut off Boers with their guns.

Colonel Dalgety with Mounted Police and Colonial troops held Dordrecht. (Gatacre’s Division.)

26.—Sir Charles Warren arrived at the Natal front.

Boers appeared at Victoria West.

Mafeking force attacked a Boer fort.

27.—Boers unsuccessfully bombarded Ladysmith.

28.—H.M.S. Magicienne captured German liner Bundesrath, near Delagoa Bay, with contraband of war on board.

30.—Skirmish near Dordrecht. Boers defeated with loss. Two British officers captured through mistaking Boers for New Zealanders.

JANUARY 1900.

1.—Enrolment of the first draft of the City Imperial Volunteers.

Surrender of Kuruman, after a stout resistance, to the Boers. Twelve officers and 120 police captured.

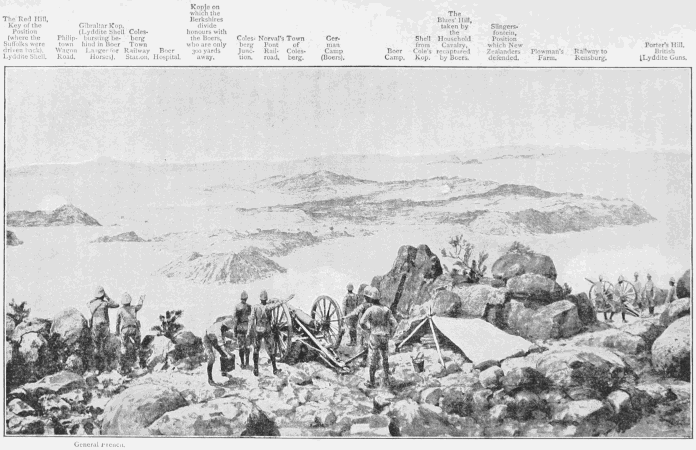

General French occupied a kopje overlooking Colesberg. Flight of Boers, leaving their wrecked guns and quantities of stores.

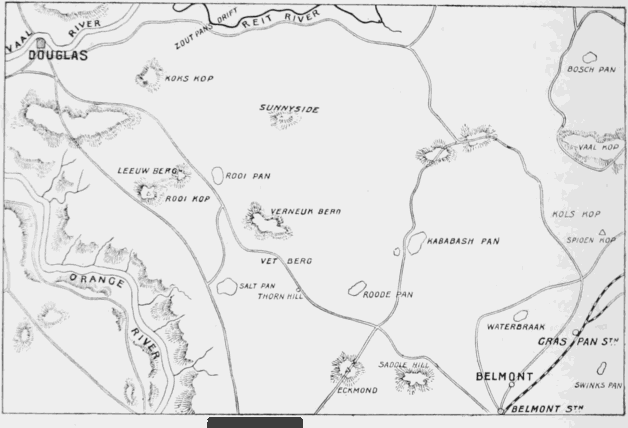

Brilliant manœuvre by Lieutenant-Colonel Pilcher at Sunnyside. Captured the entire Boer camp, made forty prisoners, advanced and occupied Douglas on Vaal River.

Colonel Plumer and Colonel Holdsworth from Rhodesia continued their march to the relief of Mafeking.

2.—Loyal inhabitants of Douglas escorted to Belmont.

General French still engaged with enemy at Colesberg.

3.—General French reinforced from De Aar. Boers being surrounded; fighting in the hills.

General Gatacre repulsed Boer attack on position commanding Molteno.

Colonel Pilcher, for “military reasons,” evacuated Douglas.

4.—General Gatacre occupied Molteno; Boers retreated to Stormberg with loss.

General French manœuvring to enclose Colesberg; further fighting.

5.—General Gatacre hotly engaged at Molteno by Boers from Stormberg; drove them off, inflicting heavy losses.

6.—Great battle at Ladysmith. Boers repulsed on every side with heavy loss.

General Buller made a demonstration in force to aid General White.

General French inflicted severe defeat on Boers at Colesberg. A Company of the 1st Suffolk Regiment captured.

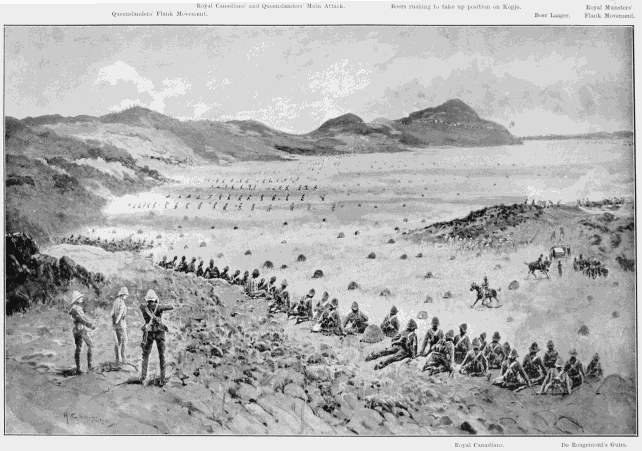

9.—British troops invaded Free State territory near Jacobsdal. The Queensland and Canadian Volunteers cleared a large belt across the Free State border.

10.—Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener arrived at Cape Town.

Forward movement for the relief of Ladysmith from Chieveley and Frere.

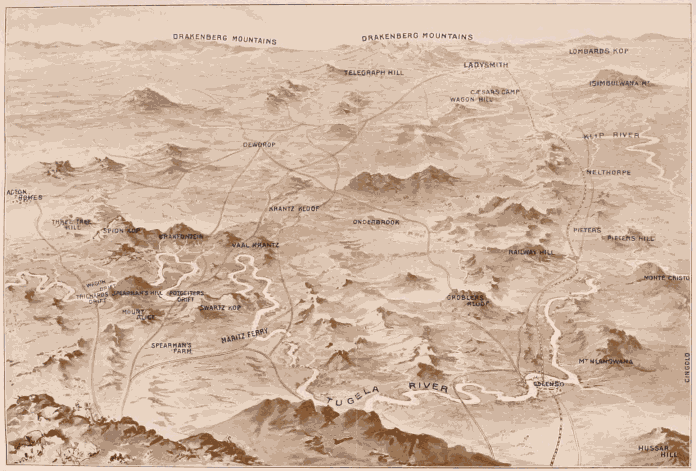

11.—Sir Redvers Buller crossed the Little Tugela, and occupied the south bank of the Tugela at Potgieter’s Drift.

Lord Dundonald and Mounted Brigade crossed the Tugela at Potgieter’s Drift.

General Gatacre made a reconnaissance in force towards Stormberg.

13.—The City Imperial Volunteers left London for South Africa.

15.—Boers attacked General French and were repulsed at Colesberg.

16.—General Lyttleton and Mounted Brigade crossed the Tugela at Potgieter’s Drift.

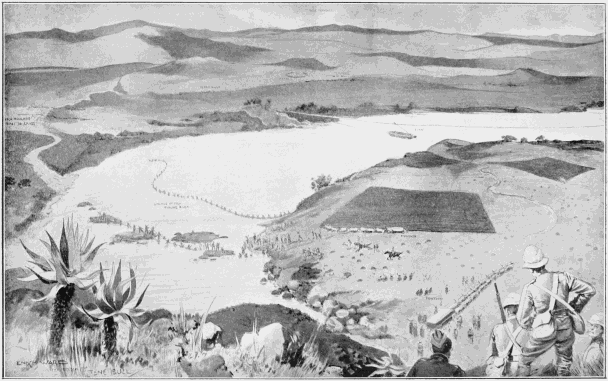

17.—Sir Charles Warren crossed, with his Division, at Trichardt’s Drift.

Lord Dundonald had an action with the Boers near Acton Homes.

18.—Tugela bridged and crossed by a Brigade and battery.

20.—Sir Charles Warren moved towards Spion Kop.

Reconnaissance by Lord Dundonald.

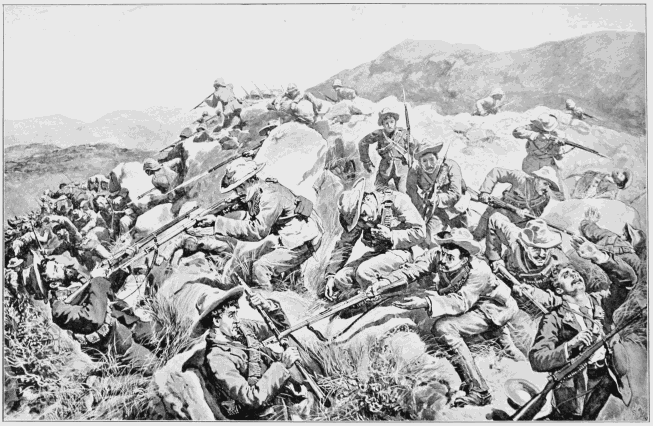

21.—Heavy fighting by Clery’s force; they attacked the Boers and captured ridge after ridge for three miles.

22—Sir Charles Warren’s entire army engaged.

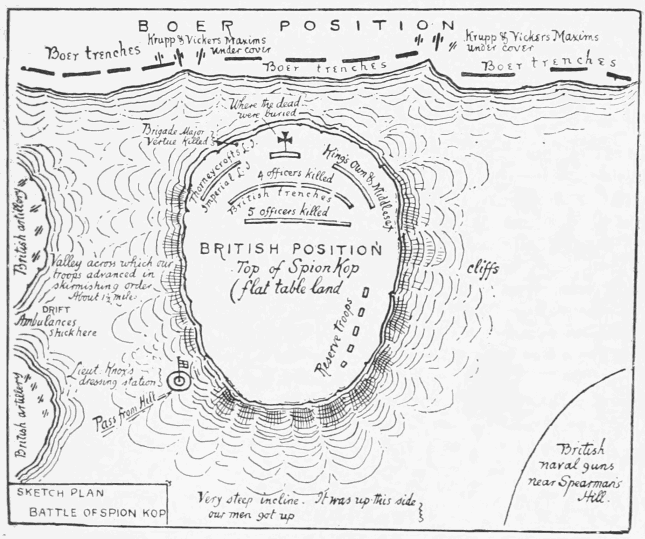

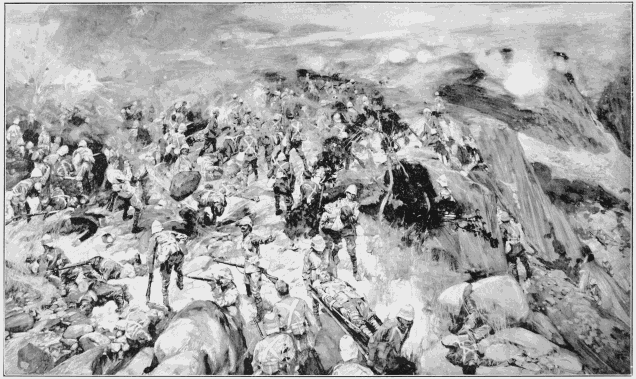

23.—Spion Kop captured by Sir Charles Warren; General Woodgate wounded.

25-27.—Abandonment of Spion Kop. Sir Charles Warren’s force withdrew to south of Tugela.

27.—Brigadier-General Brabant, commanding a Brigade of Colonial forces, joined General Gatacre.

28.—General Kelly-Kenny occupied Thebus.

30.—British force reoccupied Prieska.

FEBRUARY 1900.

3.—Telegraphic communication restored between Mafeking and Gaberones.

4.—General Macdonald occupied Koodoe’s Drift.

5.—General Buller crossed the Tugela at Manger’s Drift.

6.—General Buller captured Vaal Krantz Hill.

7.—Vaal Krantz Hill abandoned, and British force withdrew south of the Tugela.

9.—General Macdonald retired to Modder River.

Lord Roberts arrived at Modder River.

10.—Colonel Hannay’s force moved to Ramdam.

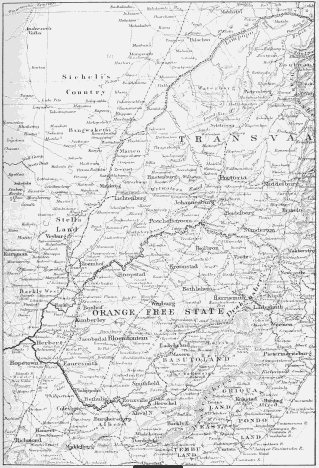

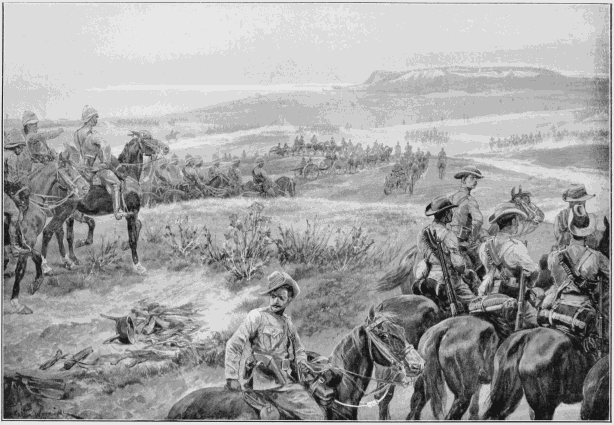

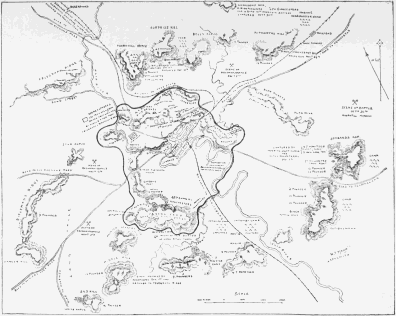

12.—General French with Cavalry Division, proceeding to the Relief of Kimberley, seized Dekiel’s Drift.

SOUTH AFRICA AND THE

TRANSVAAL WAR

—Algernon Charles Swinburne.

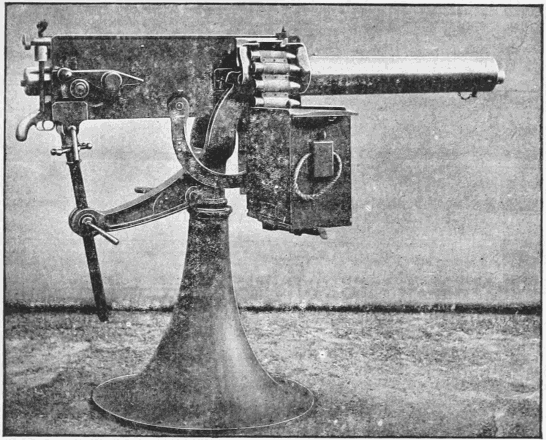

A week of disaster had terminated woefully. Three British Generals in succession—Sir William Gatacre, Lord Methuen, and Sir Redvers Buller—had advanced against strongly fortified Boer positions and suffered repulse. The hearts of the miserable loyalists, who hung in dire suspense on the result of British action, sank in despair—their dismay and their grief were pitiful. Great Britain echoed their sentiment. Disappointment was universal. General Gatacre had failed through lack of caution and mischance; the other Generals had come to grief owing to the circumstances which forced them willy nilly to hurry to the assistance of beleaguered towns in the face of overwhelming disadvantages, notably the lack of cavalry and the inefficiency of the guns. Lord Methuen had been unable to bring home his early victories owing to the absence of mounted men. Sir Redvers Buller had failed to dislodge the enemy from his strong, naturally fortified positions owing to the weakness of his artillery in comparison to that of the enemy, who had Nordenfeldt and Hotchkiss quick-firing guns in every available position. He had made a glorious attempt—owned to be magnificent; but it was not war, and in his failure[Pg 2] he recognised that it was not the game of derring-do, but the game of “slim” warfare as played by his brother Boer which must claim his attention. Now was verified the prophecy of the Polish apocalypse: “The war of the future will be a war of sieges and entrenched positions. In the war of the future the advantage will always rest with the defensive. In the war of the future, frontal attacks, without immense superiority in numbers, will be impossible.”

Every campaign, they say, has its lessons. This one we now find to be full of them, so full indeed that it has necessarily taken our Generals some time to become acquainted even with their grammar. When the war was forced upon us by the Pretoria oligarchy for the long-cherished purpose of ousting Great Britain from South Africa, many of the authorities were of opinion that a rabble of undisciplined farmers would be incapable of offering any formidable resistance to the superior military system of Great Britain. Not a hint of doubt as to the success of our arms and the effectiveness of our war apparatus was entertained. When Colonials in the summer of ’99 volunteered their services, the Government received the offers with a sniff. Later they accepted them with grateful thanks. It was never imagined that colonists could know anything of the art of war, or that they might teach a lesson or two even to that august institution the Staff College. Those who knew ventured to suggest that in South Africa the same cast-iron principles that existed in European warfare would be valueless, and that the lessons of Ingogo and Majuba in ’81 might be repeated in ’99 in all their dire and dismal reality. But these pessimists were scoffed at. They therefore waited, and hoped against hope. Now and then they feebly wondered by what process infantry, arriving two months late, when the enemy had had time to entrench the whole country at various naturally strong strategic points, would be able to overcome the disadvantages attendant on immobility. But they were silenced by a look. British pluck and endurance might be calculated upon to surmount everything and anything—some said! No one seemed to care to tackle the problem of how men on foot would be enabled to compete creditably, in anything like equal numbers, with a mounted enemy possessing more than ordinary mobility.

A mounted enemy has many advantages in his favour. He can select his own position, he can place all his force en masse into the fighting line, he can so pick his positions that one man on the defensive can make himself the equal of three men of the attacking force; and, besides, he can occupy a length of position which must extend his flanks far beyond those of the attackers on foot. These in consequence are either forced to extend to equal length, at almost certain risk of being unable to reinforce any weak point developed during the attack, and thereby cause the attack to be broken at[Pg 3] points; or they have to “contain” only a portion of the enemy in position, and perhaps leave his wings—or one wing—free to execute an outflanking movement. It is impossible when a line extends for miles, and the enemy’s strength is not discoverable before the heat of the engagement, for infantry to come from a great distance to the assistance of weak points; and by reason of this immobility it is equally impossible for infantry in the heat of action, and when the front is extended for miles, to suddenly change a plan of attack in time to save a situation.

The task set before our Generals was, therefore, almost superhuman: they were expected to make up for want of mobility with superior strategical qualifications; but, as has been said, no committee of Generals could at this juncture have decided on a strategy applicable to the complicated situation. That the Boer was a born strategist, and had able advisers, was amply proved. The amalgam of Boer methods, with Zulu theories and modern German tactics, was sufficient to try the most ingenious intelligence. For instance, the Boers in early days selected positions on the sides and tops of kopjes, and at the commencement of the campaign, at Talana Hill and at Elandslaagte, they were so perched, in accordance with the primitive principles of their race. They ignored the fact that such positions were the worst they could select against artillery fire with percussion fuses. Even for their own rifle practice such positions were also the worst, as, firing down at an angle, their bullets as a rule ran the chance of ploughing the earth without ricocheting, and served only to hit the one man aimed at. They worked, and still work, on the old Zulu principle of putting their whole strength into the fighting line, acting on the Zulu axiom, “Let it thunder—and pass.” A sound principle this, no doubt, but one which our ponderous military machinery would not allow us to adopt. To these early methods, and to his native “slimness” and cunning, the Boer now added some German erudition. The influence of German officers and German tactics began to work changes curious and inexplicable. The Boers built scientific entrenchments, no longer on the kopjes alone but also below them, thus reducing the effect of hostile artillery, save that of howitzers, and permitting their sharpshooters to sweep the plain with a hurricane from their Mausers. In addition to this they built long castellated trenches, perfect underground avenues, to allow of the invisible massing of troops at any given point. They were also provided with ingenious gun-trenches, quite hidden, along which their Nordenfeldt gun, that pumped five shells in rapid succession, could be removed swiftly from one spot to another, and thereby defeat the efforts of the British gunners to locate it.

Thus it will be seen a new complexion was put upon Boer affairs. Novel and trying conditions were imposed on those who already had[Pg 4] to cope with the problem of how to match in mobility a rival who brought to his support six legs, while the British only brought two. Whole armies consisting merely of mounted infantry and artillery had never before come into action, and it began to be understood that a war against bushwhackers, guerillas, and sharpshooters, plus the most expensive guns modernity could provide, was a matter more serious than any with which the nineteenth century had hitherto had to deal. We had to learn that sheer pluck, endurance, and brute force were unavailing, and that strategy of the hard and fast kind—the red-tape strategy of the Staff College—was about as unpractical as a knowledge of the classics to one who goes a-marketing. There is no finality in the art of war, and nations, be they ever so old and wise and important, must go on learning.

One of the newer questions was, how far personal intelligence might be distributed among a body of men? The General as a head, the Staff Officers as nerves that convey volition to the different members, we had accepted, but how far individual acumen was needed to insure success now began to be argued. Certain it was that in this campaign we had opportunities for studying the comparative value of individual discretion versus “fighting to order.” The Boers, every one of them, were working for themselves, absolutely for hearth and home, though perhaps under a general plan which certainly served to harass and annoy and keep the British army in a dilemma; while we laboured on a consolidated system which, if not obsolete, was certainly inappropriate. However, as there was no use in bemoaning our reverses, we began to congratulate ourselves on having discovered the cause of them. It was decided that first there must be more troops sent out to meet the extended nature of our operations, and that these troops must be accompanied by a sufficient number of horses to insure the necessary mobility, without which even the brute force of our numbers would be useless.

Of the successful issue of future proceedings none had a doubt. All knew that the finest strategy in the world must be useless when tools were wanting, and all felt certain that the admirable abilities of our Generals, when once the means of playing their war game came to hand, were bound to rise to the prodigious task still in store.

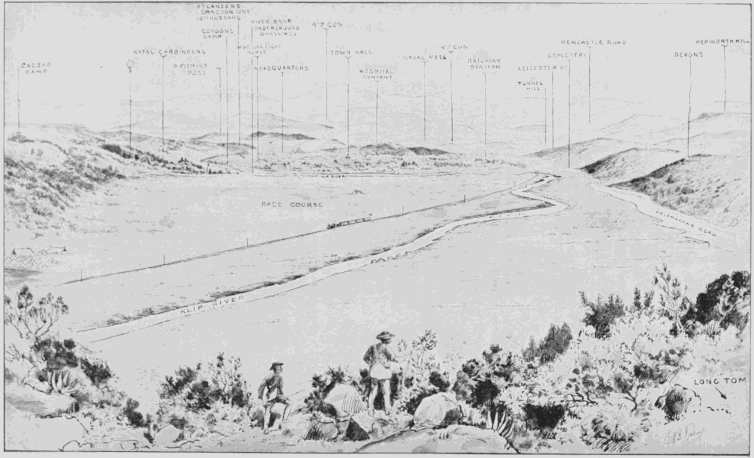

But for the dire necessity of the three gallant towns—Mafeking, Kimberley, and Ladysmith—a waiting game would have been possible and wise. The Boer stores of food and ammunition would eventually have run out, and the guns gone the way of much-used guns. Trek-oxen, instead of dragging the waggons of their masters, would have had to go to feed the hungry commandoes, and the history of slow exhaustion would have had to be told. But—again there was the great But!—those three valiant towns were holding[Pg 5] out their hands, they were crying for help, they were standing in their hourly peril hopeful and brave because they believed—they were certain—that we should never desert them!

At home the grievous news of the reverse was digested by the public with dumb, almost paralysed resignation. At first it was scarcely possible to believe that the great, the long-anticipated move for the relief of Ladysmith had proved a failure, and that the Boers were still masters of the situation, and moreover the richer by eleven of our much-needed guns. By degrees the terrible truth began to be accepted by us. By degrees the Government awakened to the fact that the fighting of the Dutchmen within the region of Natal meant more than the pitting of one Briton against two Boers, that it meant the dashing of a whole Army Corps against Nature’s strongholds, our own by right of purchase and blood, and captured from us merely by reason of neglect and delay!

To awake, however, was to act. In our misfortune it was pleasant to recall the words of Jomini, when speaking of Frederick the Great and his defeats in Silesia. “A series of fortunate events,” he said, “may dull the greatest minds, deprive them of their natural vigour, and level them with common beings. But adversity is a tonic capable of bringing back energy and elasticity to those who have lost it.” The tonic was sipped. Jomini’s theories were proved! Though Great Britain through a series of fortunate events—a long reign of comparative peace—had become lethargic and money-grubbing, she, at the first shock of adversity, regained all her elasticity, vigour, and natural spirit of chivalry. Promptly the entire nation nerved itself to prove that, as of old, it was equal to any struggle, any sacrifice. The whole country seemed with one consent to leap to arms.

The Militia, nine battalions of Infantry, was now permitted to volunteer for service in any part of the Queen’s dominions where such services might be wanted, while it was arranged that specially selected contingents of Yeomanry and Volunteers would start for the Front as soon as there were found ships sufficient to carry them.

Noble as amazing was the hurried response of the Volunteers to the intimation that their services would be accepted for the war. Hastily they pressed forward in crowds to enrol themselves. Their promptitude was goodly to look upon and to read of, for it showed that, in spite of the theories of Tolstoi and the influence of the spirit of modernity, patriotism is inherent and not a mere exotic or cultivated sentiment in the British race. We now found that though many traditions may be worn to rags, those of the British army had grown, like old tapestry, the more precious for the passage of time.[Pg 6]

Still the military position was pregnant with anxieties. A horse that is left at the post may perhaps win in the end, but his chances of success are remote. An army that lands in driblets three months after time is scarcely calculated to succeed against a rival army which has spent that interval in equipping itself for the fray. We were forced to remember that at the onset our officers were placed in the most dangerous positions, with inadequate support and no prospect of reinforcement, until their energies, mental and physical, had been sapped by undue and prolonged strain. On the north Tuli had but a handful of troops to resist an enormous and powerful enemy; Mafeking was surrounded, isolated, and able only to resist to the death the persistent attacks of shot and shell; Vryburg was allowed to be treacherously given away to the enemy; and Kimberley was left in the lurch as it were, to fight or fall according to the pluck of those who were ready to exhaust their vitality in loyalty to the Queen. On the Natal side things were still worse. The country, every inch of which is familiar to the Boer, had almost invited invasion. The whole strength of Boers and Free Staters was permitted to launch itself against an army which was entirely without reserves, and which could not be reinforced under a month. That brave and unfortunate soldier, Sir George Colley, had a theory that small, well-organised troops were worth as much again as large and desultory ones; but he took no account of peculiar facilities which are almost inherent to armies fighting on their own soil, as it were, and habits of warfare which have, so to speak, become ancestral with the Boer. From old time the Dutchman has employed his mountain fastnesses, his boulders, and his tambookie grass as screens and shelters, till in war the “tricks of the trade” have become a second nature to him, and serve in place of more complicated European methods. The small Natal army was, on Sir George Colley’s principle, allowed to pit itself against a fighting mass, dense and desultory it may be, but a fighting mass of enormous dimensions, which, whatever their failings, had weight, equipment, courage, obstinacy, and intimacy with their surroundings entirely in their favour. That the enemy was first in the field they had to thank the original promoters of war, the Peace party—the humanitarian persons who so long hampered reason by loud outcries against the shedding of blood that their own countrymen in the Transvaal were condemned to all the tortures of suspense, to be aggravated later by all the agonies of famine and disease. Their own countrywomen and their babes were saved from shot and shell to be sent defenceless and homeless to wander the world till the charity of strangers or the relief of death should overtake them, while the loyal natives were left in a state of trepidation and[Pg 7] suspense, without protection, yet forbidden to raise a hand in their own defence.

Reason now had its way. But remedies cannot be applied in a moment, and the public, which is always wise after the event, vented its anguish and its feelings of suspense by indulging in criticism, or in asking questions which, of course, could not be answered till the principal persons concerned were able to take part in the catechism. For instance, some of the riddles buzzed about in club and railway carriage were: Why did Sir Redvers Buller make a frontal attack across an open plain against an enemy admirably entrenched, and posted in a position not only made strong by art but by nature? Why was it that the Government, in spite of the warnings given by Sir Alfred Milner while he was in England in May ’99, neglected to take such precautions as would have prevented the enemy from being entirely in advance of us in the matter of time? Why, also, were the Boers permitted to arm themselves with the most expensive modern weapons, to be used against us, under the very eye of our representative in Pretoria, without our being warned of the inferior quality of our own guns, and of the impossibility of making ourselves a match for the enemy so long as the cheese-paring policy of the authorities at home was countenanced? Why, with an Intelligence Department in working order, was it never discovered that united Free State and Transvaal Dutchmen would vastly outnumber all the troops we were prepared—or, rather, unprepared—to put in the field, the troops we strove to make sufficient till the strain of reverse forced from us the acceptance of help from the Colonies, the Militia, and the Volunteers?

The great question of reinforcements filled all minds. Nothing indeed could be looked for till they should reach the Cape. Fifteen huge transports were due to arrive between the end of December and the beginning of January, bringing on the scene some 15,000 troops of all arms. The Fifth Division, under Sir Charles Warren, consisting of eight battalions of Infantry and its complement of Artillery and Engineers was expected, also the Household Cavalry Composite Regiment, the 14th Hussars, a siege train, a draft of Marines, and various odd branches of the service. Later on more troops would follow, but pending the arrival of the warrior cargoes it was impossible for our Generals to do more than act on the defensive, and consider themselves fortunate if they could prevent the further advance of the enemy to the south.

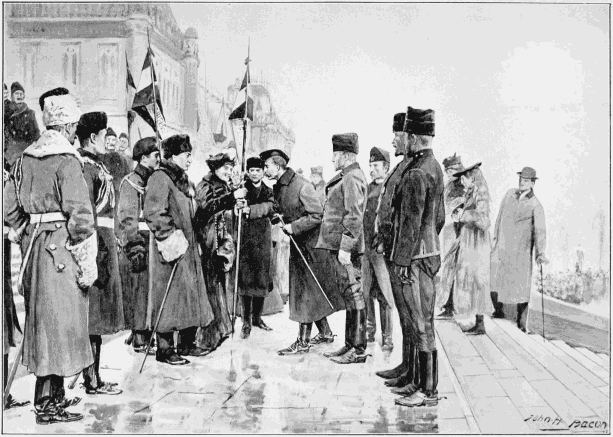

But the most momentous move of the closing year was the departure of Lord Roberts for the seat of war. Here was this gallant officer, whose life had been devoted to the service of his country, and who was at an age when many other men would have elected to stay by hearth and home, suddenly called on[Pg 8] to act in the most difficult and trying crisis. And, in the very hour that he was asked to rouse himself to meet the call of Queen and country, he was dealt a crushing blow. His gallant son, the only one, and one well worthy to have worn the laurels of his noble father, besides adding to them by his own splendid acts, was carried off, a victim to the severe wound he received at Colenso. Here was a supreme trial, so supreme indeed that none dared touch it. All, even Lord Roberts’s sincerest friends, shrunk from dwelling on the agony of mind that must have been endured by this great hero when at the same moment the voice of duty and the cry of domestic love jarred in conflict. On the one side he was called upon to brace himself to meet a political situation fraught with all manner of indescribable complications, while on the other, human nature with a thousand clinging tendrils drew him towards the numbness of mute woe or the consolation of private tears. But, like the great warrior he is, he got into harness and started off, leaving his misery in the hands of the great British people, who held it as their own. The “send off” they gave him at Waterloo Station was one of the most remarkable outbursts of public feeling on record, and this was not only due to admiration for the conqueror of Kandahar, but to profound sympathy for the man and the father who was thus laying aside his private self and placing all his magnificent ability at the service of the Empire.

It was now found desirable to remove part of the camp about ten and a half miles to the south, to get out of range of the Boer big guns which commanded the position. The wounded were daily being sent off in train-loads to Maritzburg, many of them, in spite of being shot in two or three places, cheerful and anxious to return quickly “to be in at the death,” as they sportingly described it. The funeral of Lord Roberts’s gallant son caused a sense of deep depression to prevail in all ranks, for he was not only regretted by those who held his brilliant qualities in esteem, but in sympathy with the sore affliction which had befallen the veteran “Bobs,” whose name, wherever Tommy goes, is one to conjure with. The ceremony was a most impressive one, and the pall-bearers were all men of young Roberts’s corps. These were Major Prince Christian Victor, Colonels Buchanan-Riddell and Bewicke-Copley, and Major Stuart-Wortley.

The graves of all the unfortunate slain were marked round, covered with flowers, and temporary tablets arranged till suitable memorials should be prepared.

Meanwhile the Naval guns were unceasing in their activity, and made an appalling accompaniment to the afternoon siestas[Pg 9] in which many, owing to the excessive heat, were inclined to indulge. For strategical reasons it was now found necessary to blow up the road-bridge over the Tugela, and thus prevent the Boers from advancing further to the south or spying upon our positions.

[Pg 10]Extra precautions were taken in regard to the white flag. It began to be believed at last that the Boer would take an unfair advantage of the Briton whenever he should get a chance. Strangely enough, our officers seemed to have forgotten or disregarded the object-lesson of the tragic affair of Bronker’s Spruit. Yet Boer “slimness” was then well enough established. The unfortunate Colonel Anstruther caused to be printed in the Transvaal Government Gazette a bi-lingual proclamation, informing the Boers that, in consequence of the many treacherous uses to which the white flag had been put, he would in future recognise the emblem only under the following conditions: two Boers accompanied by an officer, and all unarmed, must approach the lines bearing the white flag aloft. The British soldiers were also advised to keep well under cover whenever the flag was displayed. This showed that reliance on Boer honour would in no case be attempted. At the present date Boer morality had not improved, and it was even declared that the Free Staters had made their women boil down their national flag, so that in its pallid state it might at a little distance be mistaken for the white flag, and come in handy in case of need.

On the 20th of December a picket, consisting of seven men belonging to the 13th Hussars, was surprised some five miles from camp, in the direction of Weenen, by a party of sixty Boers. These cautiously crept round some kopjes to where the outpost was stationed. A smart tussle ensued. Two men were killed and seven horses were lost. No sooner had information of the fight reached camp than some of Bethune’s and Thorneycroft’s Mounted Infantry were despatched to the rescue, but the Boers, on perceiving these reinforcements, quickly fled and thus escaped punishment.

At this time the second advance for the relief of Ladysmith was very secretly being organised, but no one knew exactly when Sir Redvers Buller meant to move, or whether he intended to give up the idea of a frontal attack altogether. Our Generals were criticised for making frontal attacks, but Clausewitz declares that the attempt to turn the flank of the enemy can only be justified by a great superiority; this superiority may be either actual superiority of numbers, or it may follow from the way in which the lines of communication are placed. Unfortunately we had no favouring strength; the Boers outnumbered us everywhere, and not only did they exceed us numerically, but their mobility enabled them so quickly to move from front to flank positions that they were, on desire, facing us at any moment. In[Pg 11] fact the Boer army had no flank, and therefore the vast amount of after-the-event wisdom which was gratuitously handed about by “the man in the street” was absolutely wasted.

An unfortunate incident now occurred. Capt. James Rutherford and Mr. Grenfell, S.A.L.H., while visiting the pickets, disappeared. They apparently rode into the midst of the enemy’s scouts, who were everywhere prowling about, and were forced to surrender. The report of the capture was brought to the camp by native runners, who stated that the officers had been removed to Pretoria. However, for two gallant Britons lost there was one gained, for at the very time Mr. Winston Churchill had almost miraculously made himself free of his captors.

The story of his escape reads like a novel; but truth is stranger than fiction. When removed to Pretoria after the disaster to the armoured train at Chieveley, he almost gave up hope of escape; indeed he had every reason so to do, for on the 12th of December he was informed by the Transvaal Government’s Secretary for War that there was little chance of his release. Whereupon, with many doubts and misgivings, he discussed with himself the best means of struggling for freedom. The State Schools Prison was well guarded; it was surrounded by a high wall, and the sentries were vigilant in the extreme. He formed for himself a plan, however, and once when the back of the sentry was momentarily turned he took his courage in both hands as the French say, rushed at the six-foot wall, scaled it, and let himself down into a neighbouring garden before his movement could be detected. The garden was the garden of an inhabited house. There were lights in the windows; more, there were visitors on the verandah, and presently, ramblers among the paths! Moments of horror as the escaped hid in the trees seemed to become years, discovery appeared to be merely a matter of moments. But evidently the Fates decided that so useful a member of creation—warrior, writer, and politician—could not be spared by society or his country, and in a little while Mr. Churchill found himself wandering, undisguised and unrecognised, through the streets of the town. Burghers passed him, passengers brushed his shoulders. Nobody asked his business. It was evident that Fate wanted him. The stars said so, and following their direction he struck out towards the Delagoa Railroad. He knew that he dared ask his way of none; he was aware that he must make the most of the cloak of night; he was intimate enough with Boer customs to be certain that in a few hours his description would be posted throughout the two Republics. The present, and only the present, was his. He walked along the line, evading the watchers on bridges and culverts, and determining to stick to the rails, without which he might find himself lost or wandering back in the teeth of the enemy. Once free of the town,[Pg 12] he bided his time cautiously in the neighbourhood of an adjacent station. There he watched the coming of a train, and just as it steamed past him, with an alacrity and agility born of sheer despair, he made a leap towards a truck, grabbed at a hook on the edge, boarded it, and was soon burrowing deep in a cargo of coal-sacks. There he lay, grimy, exhausted, and almost distraught, but happy. He was free. Every minute the anxiety for freedom had grown within him, till now, fighting his way towards it, it had become an almost savage passion. He had decided he would never go back. No one should capture him. But this was easier to swear than to accomplish. To escape detection it was necessary again to risk his life—to leap off the train as he had leapt on it, while the machinery was in full swing and the driver ignorant of the existence of his distinguished passenger. Before dawn, therefore, he emerged from the coal-heap, and with a flying leap landed flat on the railroad. He gathered himself together, and by sunrise was concealed in a wood, his only companion for some time being a vulture. The sojourn in the cool boskage of the Transvaal was fraught with good luck, and at dusk when the fugitive emerged he was another man. At last he was able to gather his forces together for another trip on a passing train. There was always danger though—danger because it was necessary to hug the line, and where the line was, there also were railway guards, or at least humanity—inimical humanity, who most probably were plotting his ruin. Plod, plod, plod; so passed the hours, scrambling along in the dead of night through sluits and dongas in the effort to avoid the direct neighbourhood of huts, bridges, stations, and yet keep in touch with the winding iron track that led to the longed-for sea. For five days and nights he persevered, tramping after dark and sneaking under cover all day, and dimly conscious that the hue and cry had gone forth, and that every man’s hand in the enemy’s country was now turned against him. On the sixth day he managed again with amazing good fortune to safely board a train, and this time it was one going from Middleburg to Delagoa Bay. Again he burrowed among sacks and carefully hid himself, so carefully, indeed, that owing to his extreme precaution discovery was evaded. The train was searched, the sacks were prodded. Deep down, scarcely daring to breathe, lay the man they were seeking—an inch or two off—just an inch or two off. He drew a long breath and praised God for his escape. After that he passed some sixty hours in all the agonies of suspense. Famine and thirst preyed on him, and active horror lest all his exertions should be in vain, lest, at the very last moment, the whole struggle of hope and wretchedness would end in dire and fatal disaster. But he was preserved. He arrived at Lourenço Marques on the 21st of December, and from there proceeded to Natal. “I am very weak,[Pg 13] but I am free.” Such were the words of his telegram; no wired words ever meant more. “I have lost many pounds in weight, but I am lighter in heart; and I avail myself of this moment, which is a witness to my earnestness, to urge an unflinching and uncompromising prosecution of the war.” In regard to Mr. Winston Churchill’s arrival among his friends in Natal, an eye-witness wrote:—

“The 23rd of December last was a memorable day at Durban, perhaps the most memorable since that on which the Boers’ ultimatum was published. From Lourenço Marques had come the exciting intelligence that young Winston Churchill, a distinguished member of a world-renowned race, had succeeded in evading his jailers at Pretoria, and, after a series of thrilling adventures, had arrived safely at Delagoa Bay. The telegrams had further announced that the hero had immediately shipped on board the Rennie liner Induna and would land at Durban that very afternoon. The fame of Mr. Churchill as a soldier and an author was already established. The history of his gallantry both in India and at Omdurman was already well known to every good Natalian before he first stepped ashore there as one of the war correspondents of the Morning Post. His subsequent courageous conduct at Chieveley at the unfortunate incident of the armoured train and his capture by the Boers, now capped by his marvellous escape from Pretoria, had set Durban agog with excitement, and filled all and sundry with hearty desires to afford him a right royal welcome on his landing again on British soil.

“The brilliant summer sunshine, tempered by a fresh sea-breeze which sent a soft ripple across the deep blue surface of the magnificent harbour; the bold headland of the bluff contrasting vividly against the streets of iron-roofed dwellings in the township; the large numbers of ocean-going steamers and sailing craft, gay with bunting; the eager, expectant crowd of every class of society, from gaily-dressed ladies to wharf labourers, refugees, and Kaffirs in but shirts and trousers, all contributed to the completion of a picturesque panorama never to be forgotten. Long before midday did we assemble in our thousands. When it was whispered about that the Induna would berth alongside the steamer Inchanga, and that Mr. Churchill must cross the decks of the Inchanga before stepping ashore, a rush was made for her, and, in spite of all the efforts of the officers and crew, the crowd swarmed like bees on her. They took possession of every available point of vantage; they invaded the sacred precincts of the captain’s bridge; they braved the perils of the rigging; they huddled together on the ‘fo’cas’le’; they filled every boat; and, heedless of fresh paint, they clung affectionately to the ventilators and the funnel.

“After having been several times reported the Induna rounded the point at half-past two. Amid breathless expectation she steamed slowly across the harbour. Standing beside the captain on the bridge a smallish, clean-shaven man was descried, and the crowd at once recognised him as the hero whom they had assembled to honour. A thousand good British cheers broke the silence, a thousand lusty throats shouted a heartfelt welcome. But this was not all. The sturdy Natalians did not stop at shouting. The moment the Induna was moored Mr. Churchill, smiling, was seized bodily by twenty pairs of brawny arms, was patted and thumped on the back by hundreds of applauding hands, and finally, after being nearly strangled by over-zealous admirers who were waving hats and handkerchiefs and crying ‘Bravo!’ and ‘Well done!’ he was carried shoulder-high across the decks of the Inchanga and deposited in a ricksha, whence a speech was demanded. In a few modest sentences Mr.[Pg 14] Churchill good-humouredly narrated some of the more prominent episodes of his exploit, and a start was made for his hotel, the ricksha-boy being assisted more or less by some fifty amateur ricksha-men and escorted by a majority of the crowd. After picking up the editor of the Natal Mercury on the way, and installing him in state by the side of Mr. Churchill, the hotel was at last reached, and the demand for another speech having been acceded to, Mr. Churchill was permitted at four o’clock to retire from the public gaze. The same night he left Durban for the front.”

The following is a copy of the letter written by Mr. Winston Churchill to Mr. de Souza prior to escaping from prison:—

“State Schools Prison, Pretoria.

“Dear Mr. de Souza,—I do not consider that your Government was justified in holding me, a press correspondent and a non-combatant, as a prisoner, and I have consequently resolved to escape. The arrangements I have succeeded in making with my friends outside are such as to give me every confidence. But I wish, in leaving you thus hastily and unceremoniously, to once more place on record my appreciation of the kindness which has been shown me and the other prisoners by you, by the commandant, and by Dr. Gunning, and my admiration of the chivalrous and humane character of the Republican forces. My views on the general question of the war remain unchanged, but I shall always retain a feeling of high respect for the several classes of the Burghers I have met, and on reaching the British lines I will set forth a truthful and impartial account of my experiences in Pretoria. In conclusion, I desire to express my obligations to you, and to hope that when this most grievous and unhappy war shall have come to an end, a state of affairs may be created which shall preserve the national pride of the Boers and the security of the British, and put a final stop to the rivalry and enmity of both races. Regretting that circumstances have not permitted me to bid you a personal farewell, believe me, yours very sincerely,

“Winston Churchill.

“December 11, 1899.”

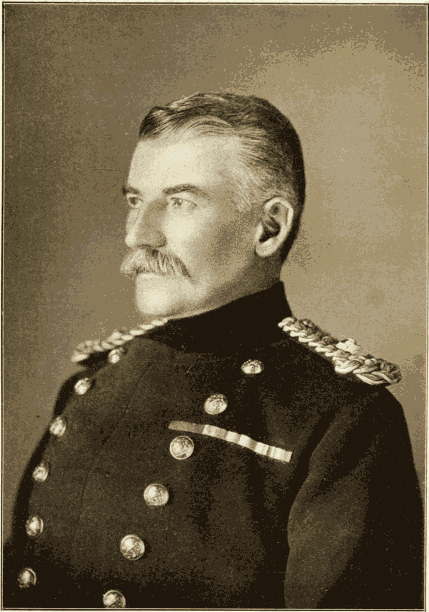

We had arrived at what might be termed a breathing spell. There was no serious movement in the direction of the Modder River, and Lord Methuen was evidently biding his time. General Gatacre felt himself too weak to take up any very active or offensive step, while General French contented himself with such harassing and cleverly annoying operations as kept the enemy, like a man with a mosquito round his nose, from napping. There was great hope of better things, however, for it was known that the Dunottar Castle had left England and was conveying to the Cape—in addition to Lord Roberts—Lord Kitchener and Major-General T. Kelly-Kenny, the Commander of the Sixth Division. Besides these were the following officers of Lord Roberts’s Staff:—Major-General G. T. Pretyman; Colonel Viscount Downe, C.I.E.; Major H. V. Cowan; Captain A. C. M. Waterfield; Major J. F. R. Henderson; Major C. V. Hume; Brevet-Major G. F.[Pg 15] Gorringe, D.S.O.; Colonel Lord Erroll; Commander the Hon. S. J. Fortescue (Naval Adviser to Lord Roberts); Captain Lord Herbert Scott; Captain Lord Settrington.

This showed that when at last we set to work we did so with a will. The forces in South Africa before the war had amounted to 25,000, which number was augmented by 55,000 on the arrival of the First Army Corps. Late in December came the Fifth Division of about 11,000, under Sir Charles Warren, followed by the Sixth Division of 10,000 men. The Seventh and Eighth Divisions of 10,000 men respectively were shortly to increase the forces at the disposal of Lord Roberts, together with some 2000 additional Cavalry, 10,000 Yeomanry, 9000 Volunteers, seven battalions of Militia, drafts for regiments at the front amounting to 10,000, and about 20,000 local forces. The first Colonial contingents consisted of about 2500 men, and these were to be followed by second contingents of like strength. The Naval Brigade was composed of about 1000; so that in all, roughly estimated, we were on the eve of putting 184,000 men into the field.

Christmas day at the Cape was solemnised with much speechifying, both from Dutch pulpits and Dutch partisans, and not a few peacefully disposed persons in this time of general goodwill lugged in Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman by the ears and quoted him to suit their purpose. That amiable worthy had said the war could have been avoided, and that cheap and incontrovertible statement the Bond got hold of and chewed and rolled on the tongue as an accompaniment to its plum-pudding and mince-pies. Of course, the war could have been avoided. Of course, it would have been quite possible to voluntarily retire from the Cape and allow South Africa to become entirely Dutch. In the same way we could give up governing India and hand it over to Russia and confine our expenses and our energies to Great Britain, the water supply, the development of national cookery, and the propagation of cabbages. But peace with dishonour was fortunately not to the taste of the British public, and those who spent their Yuletide in active service were far too devoted to the sacred duty of maintaining the prestige of the Empire to sigh for the domestic hearth and regal sirloin that might have been theirs had the Government extended its accommodating apathy a few months longer.

There were no holly decorations and displays of bunting, no rubbings of hands and vigorous snow-balling, because the South African sun blazed with the glare of beaten brass, and the thermometer stood to the height of some 100 degrees at midday. But there was a vast amount of joke-making and hearty goodwill nevertheless, and many prayers for friends and family and Queen.[Pg 16]

In Natal there were lively doings in honour of the festal season. At a time when even cracker manufacturers wax poetic, the journalistic poets thought it their duty to burst into rhyme. The Natal papers indulged in some jocose doggerel, which would have been comic had it not been deeply tragic. The lines ran thus: “To Ladysmith”—the only lines, by-the-bye, that did run there—

But Tommy was pleased and thought the stanza a capital joke. He meant to get there directly, and merely quoted the proverb about “slow and shure”—there were so many Irishmen about, fine fellows, who believed in themselves and they were shure about everything. They had nothing to do with doubt, for doubt, after all, is the mother of diffidence!

And some of these rollicking youngsters managed to retain their native good-humour in most distressing circumstances. A good story was told of one gallant private in hospital who had lost his leg but persisted in apostrophising the missing limb whenever it ached. “Be aisy wid ye. Can’t ye be quiet? Ye’ll niver take me into the foight again. Ohovo!”

Other examples of amazing good-temper and pluck on the part of the wounded filled all eye-witnesses with pathetic admiration. One man, a quondam music-hall singer, carried his jocose art into his sick-bed. A Boer prisoner had lost his arms, and the poor fellow helplessly shook his head when offered tobacco. But the music-hall singer saw the shake of the head and tearful eye that accompanied it. In a moment, with gymnastic dexterity, he had placed his arms round the Boer and performed the office of the missing ones, giving the fellow the advantage of a good smoke. Another of our men who had lost his right arm co-operated with a Boer who had lost his left, and between them they rolled cigarettes to the great satisfaction of both. While they were in hospital another sufferer pretended to be in no way depressed by the loss of his arm, and ventured on mild whimsicalities regarding the economy of being able to share a single pair of gloves with any right-handed man who might also have lost a limb!

On the whole, well or ill, Tommy was temporarily in clover. The fat of the land was being sent out by fervent admirers at home. Indeed he was getting somewhat inundated with worsted goods which the fair hands of his countrywomen had been devotedly manufacturing. Jack Tar, despite his magnificent work, was not so highly distinguished, at least so he thought, and occasionally[Pg 17] vented his disgust into private ears. But, as one of them said, they’d had a treat for Christmas—the treat of a wash! It was bathing under difficulties, however, for one half of the men had to keep guard with loaded rifles while the other half wallowed in water that, in harmony with the general scheme of things in camp, was also of kharki hue!

Tommy at the front was externally scarcely the Tommy of our acquaintance. His bright spick and span exterior was gone. Kharki had sobered him and planed down his individuality. His uniform no longer sat without a crease. It was washed and worn and shrunken from hard and honourable usage, and his carriage was no longer the carriage of Tommy on parade. He seemed to have taken a leaf out of Jack’s book, and the slight slouch became him well. It gave him the air of a workman and an individual, and seemed to point to the fact that there was no longer occasion for him to be judged by appearances. We knew the inner man now. He did his duty grandly, and his splendid courage and perseverance had made him independent of the pomp and panoply of war. In the matter of “grit” they were all alike. But in externals they had curious differences, their characteristics varying considerably according to the regiment to which they belonged. Some were dapper still—the newly arrived ones—with hair clipped to an eighth of an inch for head and half an inch for moustache; others had succumbed to circumstances, and had grown beards of odd sizes and shapes and colours (scumbled in all cases with dust), while the youngsters displayed an unhappy medium, styled by an officer “pieces of unexpected wool,” on promiscuous parts of their faces! Still, when all was said, joviality and “grit” put an identical veneer on them all!

The officers too were transmogrified. They were dressed exactly like the men. Tan brown belts, swords, and revolvers were no longer in evidence. When going off to war, or any other duty at all under arms, each officer arrayed himself in his servant’s belt and equipment—stained with clay paste to the prevalent dust or kharki colour—and took with him his servant’s rifle and one hundred rounds of ammunition. There was a difference without a distinction. The officer carried a field-glass, and this when not in use was concealed in a coat-pocket. Every precaution was now adopted to prevent them from inviting an undue share of attention. The mounted officers had carbines—neat, handy weapons, which slipped into a leather carbine bucket in the saddle, on the other side of which went the very necessary wire-cutters. Barbed wire entanglements were so much a part of the Boer programme—“to cheer you up in crossing the drifts,” some one said—that the cutters became an essential part of warlike gear. A strange innovation this; very[Pg 18] small but very full of meaning. The Boers were teaching us a great deal. We were beginning to understand, almost to admire, their curious modes of warfare—their strange ability to “sit tight,” wire themselves in, and yet to fly away! Years ago, when some tactician ventured to say that the war of the future embraced only the question of long-range rifles and wire-entangled trenches, we were inclined to pooh-pooh! Now we were beginning to see wisdom in this stubborn and persistent, and yet skittishly mobile foe! When we looked at our wire nippers and their strong entrenchments we began to formulate the war motto of the future, which resolves itself into five words: “Six legs and a spade!” The sword, the bayonet, the cavalry charge were passing away for ever. Here the dignified charger was ill-matched with the nimble steed of the country, and many officers were only too glad to supplement their English horses with Basuto ponies—to secure four serviceable and sure legs, as the climate and other circumstances contrived to wear out those of their British beasts. Fortunately there was still a plentiful choice in horse-flesh, what with British and Australian and Argentine specimens, but the Basuto ponies were the most knowing and handy for the purposes required. The imported horse, it was discovered, needed a long and probationary period to make him at home on the South African veldt. Like other aristocratical creatures, he was unequal to the hand-to-mouth existence of the African-born animal, who, by habit and instinct, could shift for himself. He was neither knowing nor cautious, having been unaccustomed to ground honeycombed with mole-holes, sluits, and other obstacles, or to the trick of rolling on the veldt and picking up his meals haphazard from the first bush he came across. Hence it became evident that horses in plenty must be forthcoming if we were ever to remedy our deficiencies and make our progress something other than the steam-roller style of progress to which we had been accustomed.

Plucky little Mafeking continued to hold its own, and not merely to hold its own, but to make itself dauntlessly aggressive. Continual sorties took place, and indeed formed part of the routine of daily life. Commandant Cronje now sent in a communication disputing the right of the British to use dynamite in any way in the operations for the defence of the town; but Colonel Baden-Powell was inclined for deeds, not arguments, so Cronje was silenced. The town was enlivened by a great concert, in which the National Anthem was sung with fervour and intense significance. This showed without doubt that Mafeking meant to fight so long as breath should last. In regard to provisions and water, the garrison was getting on well. The art of dodging shells, said one officer, was being carried to a state of great perfection, and the fighting was being conducted in strict accordance with military etiquette, Commandant Cronje always giving due notice of bombardment!

For some time after Colonel Walford’s gallant defence of Cannon Kopje on the 31st October, nothing much occurred. The losses from this attack were more than at first supposed. Captain the Hon. H. Marsham, as we know, was killed, and Captain Pechell, who was hit in the abdomen by a piece of shell, succumbed to his injuries. Sergeant Lloyd, who did splendid service with the Red Cross company, was struck while attending to the wounded, and died. Trooper Nicholas, whose arm was shattered, succumbed owing to shock to the system. A trooper who was hit by a bullet in the collar-bone escaped death miraculously. Fortunately, Lieutenants Brady and Dawson, who were also injured, were getting on well.

Among the marvellous escapes recorded, and these were not a few, was one of a negro who was shot through the brain by a bullet. The projectile passed through one temple and lodged in the other, yet the man still survived, and showed a decided intention to recover. There is an old story of a Jamaica negro who fell from a tree without injury, and when asked how he escaped, he explained his good fortune by saying, “Tank God, me fall on me head!” The invulnerability of the nigger cranium in that case, as in this, had its advantages, and it would be interesting if some of our[Pg 20] specialists—say Dr. Horsley—would account for the rough-and-tumble superiority of blacks over whites.

On the 1st of November a lamentable incident occurred. Parslow, the correspondent of the Daily Chronicle, was shot by a member of the garrison. The following is an extract from a letter relating to the sad affair, which was in the possession of the Editor of the Daily Chronicle:—

“Mafeking, November 19.—One item, the most unpleasant of the whole beleaguerment, occupied attention during last week—that is, the court-martial of Lieutenant Murchison for the murder of Mr. Parslow, special war correspondent of the London Daily Chronicle. He was a genial, good-humoured young fellow, and asked Murchison, an artilleryman of ability and undoubted courage, to dine with him. After dinner Mr. Parslow strolled with Murchison across the Market Square towards Dixon’s Hotel, the headquarters of the Staff, the ostensible purpose being for both of them to obtain a copy of the orders for the day, usually issued about that time—half-past nine or ten o’clock P.M. Some words ensued apparently during the few minutes occupied in reaching Dixon’s. Parslow left his companion in the passage of the hotel, and was passing out, when it is alleged that Murchison drew his revolver and shot him dead, the bullet entering his head on the occipital protuberance an inch or an inch and a half behind the left ear, and lodging against the base of the skull. The case is completed, and the court closed to consider the verdict.”

The young journalist was exceedingly popular and deeply regretted. He was buried with military honours on the evening of[Pg 21] the 2nd. His coffin was covered with the Union Jack, and carried to the grave by Major Baillie of the Morning Post, Mr. Angus Hamilton of the Times, Mr. Hellawell of the Daily Mail, Mr. Reilly of the Pall Mall Gazette, and the correspondent of the Press Association. The funeral was attended by many members of the Staff, who were desirous of showing their esteem for the promising and gallant writer.

The enemy now engaged in hostilities under the command of the son of Cronje, who was said to have had, in the interval, a passage d’armes with his father, the General, the younger man having taunted the elder for not having succeeded in reducing Mafeking to submission. Whereupon Cronje fils undertook to do the great deed himself, and in setting about it managed to get killed. The Boers again stormed the place, and were driven back in confusion by the magnificent energy of the British South African Police, leaving strewn on the field of action an enormous number of dead and wounded. Their removal occupied two hours. Captain Goodyear, commanding a squad of Cape “boys,” made a dashing sortie, and received a wound in the leg, but he nevertheless captured the brickfields, and held them against the enemy, thus preventing him from utilising them for sniping operations.

Sunday the 5th of November was, as usual, observed as a day of truce. The enemy made an effort to defy the rules of Sabbath etiquette, and were informed, under a flag of truce, that if they should continue to erect works commanding the brickfields, the guns would open fire on them. This warning had the desired effect. The memory of Guy Fawkes, together with the news of our victories in Natal, was honoured by an exhibition of fireworks—a display which some thought rather de trop considering the nature of the daily operations in the town. On the following day the Boers made themselves unpleasantly obstreperous by saluting the place with quick-firing guns, weapons whose shells burst almost simultaneously with the report, thus depriving those aimed at of the chance of running to cover.

The air of Mafeking is said to be equal to champagne, and perhaps to its stimulating influence the garrison owed its sprightliness and activity. The little township “ran” a journal of its own, and though not so effervescent as The Lyre of Ladysmith, it had its humorous side. The Mafeking Mail, as it was called, was issued daily—shells permitting. Quoting from the Mail of the 1st of November, a facsimile of which was reproduced by the Daily Telegraph, we read that—

“We have borne the much-feared bombardment for a fortnight, and still Mafeking stands. From what we have experienced we do not consider ourselves too optimistic in anticipating a successful ending to the contest. For[Pg 22] the first time in the history of Boer warfare have the Boers been defeated at every turn by a force far inferior in point of numbers. Since the first attack on Saturday, October 14th, they fly directly our guns are heard. Safely out of range they fire into the town, but they do not appear to be pining for another attempt at storming Mafeking. In the ‘general orders’ issued last Sunday the following occurs:—‘The Colonel Commanding having made a careful inspection of the defences of the town and the native stadt, is now of opinion that no force that the Boers are likely to bring against us could possibly effect an entrance at any point.’ Now, this is like the advertisements say a certain cocoa is—grateful and comforting, and we feel that having got so far through the ordeal, we have only to remain steadfast, as the matter of a little time will see decided the first great step towards the settlement of the future of South Africa. There is no doubt that the attention of Great Britain, the Colonies, in fact, the whole world, is now riveted upon this little spot, which is now playing a prominent part in the most important epoch in the history of this wonderful continent. We know there is no need to urge the claims of our country and kindred upon our gallant garrison. Being in such close touch with each other that nothing but the exceptional circumstances thrust upon us could have made possible, we are in a position to judge and recognise the steady determination that British blood and British pluck exhibit when such a crisis as the present arises, and we know that the memory of Bronkhurst Spruit, Majuba, and Potchefstrom will make that determination, supported by the knowledge of our grand successes of the past fortnight, more firm, more strong, and more united than has been before, and this, with the grand soldier who is in command here, will render certain the first stages towards the complete crushing of the enemy.

“There is no doubt that there was landed in South Africa by Sunday last a body of 57,000 men, including probably twelve or fourteen regiments of cavalry, twenty or twenty-two batteries of artillery, and forty regiments of infantry, besides, most likely, a body of mounted infantry. Of this force there will be not less than 15,000 disembarked at Cape Town and despatched on the road here. They may now be settling accounts with the Boers outside Kimberley, in which case Vryburg might be reached by Sunday, allowing for some delay at Fourteen Streams. When our troops reach Vryburg the air of Mafeking will not suit Cronje sprinters, so by this day week we may begin to wish them a pleasant journey back to the Transvaal. It will then be merely an interchange of courtesy if we return the visit.

“When the big gun with which the enemy hoped to pulverise us, and which has sent more shells in the neighbourhood of the hospital and women’s laager than in any other parts of the town, is taken by our troops, we think it only fair to Mafeking that it should be brought here. It will make a good memorial and be an object lesson to succeeding generations, who, reading the history of our bombardment, and seeing the weapon employed against our women and children, will be able to judge of the nineteenth-century Boer’s fitness to dominate such a territory as the Transvaal. Let it be placed, say, in the space opposite the entrance to the railway station, raised on end, with the unexploded shells piled at its base, with a description of Colonel Baden-Powell’s clever defence of the place. We hope the Colonel will bear the town in mind when the disposal of the gun is under discussion.

“Major Lord E. Cecil, C.S.O., last evening issued the following under the heading of ‘General Orders’:”—

[Here was recorded Colonel Baden-Powell’s appreciation of the action of Colonel Walford and his gallant men, which has been previously quoted.]

The perusal of the opening paragraphs of the Mafeking Mail serves to enlighten us as to the degrees of hope deferred through which the plucky inhabitants had to pass. The pathos of the expression, “So by this day week we may begin to wish them a pleasant journey back to the Transvaal,” can only be understood by comparing the date to which it referred with that of the relief of the noble garrison—the 17th of May 1900!

On the 7th of November, the force under Major Godley and Captain Vernon made a successful sortie, the excellent management of which was recognised in an order issued by Colonel Baden-Powell:—

“The surprise against the enemy to the westward of the town was smartly and successfully executed at dawn this morning by a force under the direction of Major Godley. Captain Vernon’s squadron of the Protectorate Regiment carried this operation out with conspicuous coolness and steadiness. The gunners, under Major Panzera, fought and worked their guns well under a very trying fire from the enemy. The Bechuanaland Rifles are to be congratulated on the efficient services rendered by them under Captain Cowan in this their first engagement in the field. The enemy appeared to have suffered severely, while our casualties were luckily very light. This is largely due to the fact that Major Godley delivered his blow suddenly and quickly, and withdrew his force again in good time and order. The Colonel Commanding has much pleasure in placing on record a plucky piece of work by Gunners R. Cowan and F. H. Godson. The Hotchkiss gun, of which they had charge, was overturned and its trail-hook broken in course of action. In spite of a very heavy fire from the enemy’s one-pound Maxim and seven-pound Krupp, these men attached the trail to the limber by ropes, and brought the gun safely away.”

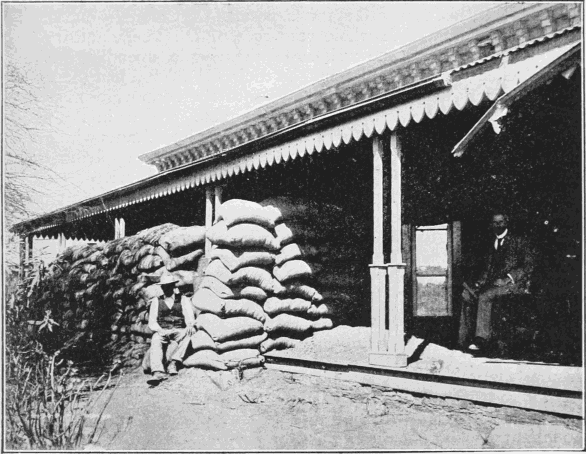

At this time the town was surrounded by some 2000 Boers, and a heavy shell-fire was daily exchanged. The damage done, however, was slight, except in the case of the Convent, which seemed to be a favourite mark for the Boer gunners. The trenches of the besiegers had been moved to about 2000 yards of the town, and from here the enemy fired with rifles, but with indifferent success. The Boers, in fact, were getting disheartened. Colonel Baden-Powell was proving himself prepared to enter into a competitive examination on the subject of “slimness” with them, and they were somewhat disturbed at the intellectual strain demanded for rivalry against so smart a pupil. All manner of efforts were made, and there was even a Dutch council of war as to the propriety of making a midnight attack upon the place. But the wily Colonel was ready for them. He took care that lanterns should be placed[Pg 24] in suitable positions to illumine the paths of the would-be assailants, and when they turned on these lanterns the attention of their guns and broke them, more were immediately found to take their place. There was also the British bayonet in reserve, and a hint which they did not care to prove as a certainty—that dynamite was somewhere or other arranged in a ring round the place, so that at a given sign the too pressing attentions of intruders might be disposed of. These some one called “the B. P. Surprise Packets,” which were arranged on the lucky-tub principle, ready for those who might venture on an experimental dive. The exact locality was not disclosed, in order that their whereabouts might prove a never-ending source of wonder and interest to the besiegers.

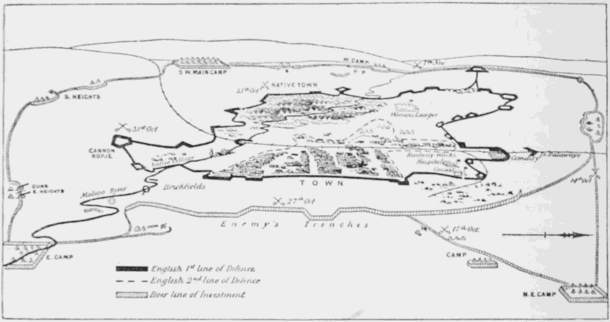

As before said, continual sorties took place, and Colonel Baden-Powell succeeded in capturing mules and horses from the enemy and generally harassing him. Great expectations sustained the gallant little party that Colonel Plumer’s force would shortly make its way from the north and join hands with Colonel Baden-Powell. Early in November the opposing forces stood thus:[Pg 25]—

| Colonel Baden-Powell, with 500 Cavalry, 200 Cape Mounted Police, and B.S.A. Company’s Mounted Police, 60 Volunteers, six machine-guns, two 7-pounders, and 200 to 300 townsmen used to arms | 1500 |

| 1000 Transvaal Boers under Commandant Cronje, and 500 Boers at Maritzani | 1500 |

But later, some of the Boers were drawn off for service in the south.

Of the diminutive town of Kuruman and its gallant struggle little can be said. The garrison—consisting of seventy-five British subjects, including the men that came from Bastards—under the command of Captain Baker stood out valiantly, fighting with rare obstinacy, and hoping that British success elsewhere would speedily draw off the intermittent attentions of the Boers. From the 13th to the 20th of November a strong party of Dutchmen kept up incessant pressure, but they were forced to retreat, though both sides suffered loss. On the part of the British one special constable was killed.

The official details of the defence showed that the Mission Station which was formerly the centre of Dr. Moffat’s long work among the natives of that part of Africa was the point of resistance to the Boer attack. When the Dutch commandant notified the magistrate of his intention to occupy the place, the latter replied that he had orders to defend it. Thereupon he collected twenty natives and thirty half-castes, with whose aid he barricaded the Mission Chapel, and there resisted the assault of 500 Boers for six days and nights, after which the Boers abandoned the attack.

To look back on the amazing valour of the tiny garrison, unsuccessful though it was, makes every British heart swell with pride. On the outbreak of hostilities, Mr. Hilliard, the Resident Magistrate, called a meeting of the inhabitants, and eloquently urged them to remain loyal. This, as we know, they did, with the result that the place resisted the Boers and routed them, and, moreover, set a most salutary example of loyalty to the surrounding districts of Cape Colony. The following extracts from five short letters (all dated November 24), written by Mr. and Mrs. Hilliard to relatives, will be of interest, as showing the gallant spirit that sustained these brave people, and the love for Queen and country that was so practically displayed by them. Mr. Hilliard said:—“Just a short letter to say we have been fighting the Boers here from the 13th to the 18th, and have driven them back with heavy loss. I received a letter from their ‘Fighting General,’ Visser, on Sunday the 12th, saying that if I did not surrender the town voluntarily, he would take it by main force. I replied that if he did he would have to[Pg 26] take the consequences of his illegal act, as my Government had not instructed me to evacuate the town. The enemy has drawn off towards Vryburg.” In another letter he said:—“We are going strong; the brave little garrison is so good and cheerful. The army has gone, but may return, so we are prepared.” In yet another he wrote:—“We are all right up to now, and shall stick to our dear old flag till the last, whatever happens. May God defend the right and our dear Queen. Three cheers for all.” Mrs. Hilliard wrote:—“On Monday, November 13, the Boers attacked Kuruman. Our men fought bravely for six days, after which the Boers departed, and we don’t know if they intend returning or not. Charlie is at the Police Camp, and looks well and happy. He is very proud of our men. Our men are still on the alert, and are strengthening their forts, as the Boers will not return without a cannon. They quite expected this place to be handed over to them at once, as Vryburg was.”

This state of affairs continued till the end of the year. On the 1st of January the plucky little garrison was at last forced to surrender. This, they said, they would never have done had they possessed a single cannon. The Boer artillery knocked to pieces the improvised fort before the white flag was hoisted over the ruins. Four men were killed and eighteen wounded in the splendid but hopeless effort to hold the open village against a foe provided with artillery and superior in numbers. The Boers numbered twelve hundred against some seventy-five practically helpless men! So the unequal tug-of-war came to an end—we may say, an honourable end.

In Northern Rhodesia, British subjects were practically isolated. The telegraph to the south was cut, and the railway—some four hundred miles of it—was damaged in various places. To show the state of remoteness in which the unfortunate inhabitants found themselves, it is sufficient to say that a telegram from London to Buluwayo took sixteen days in transit. Letters from Port Elizabeth were received about three weeks after being posted. It may easily be imagined what dearth of news prevailed, and how even such news as it was, was falsified by rumour. But the excellent fellows kept heart, although they were, as one of them said, “absolutely ignored by the British Government, and had not a red coat in the country.” He went on to say, “We have any quantity of men of grit, and about a thousand fellows have volunteered to fight out of a total population of men, women, and children of six thousand at most.”

So little could reach us as to the doings of Colonel Plumer’s splendid little force, that the following letter from Trooper Young, a barrister, who joined at the outbreak of the war, may be[Pg 27] quoted. It supplies some early links in the chain of the brave history:—

“Fort Tuli, South Africa, November 9, 1899.

“I’ve had a bit of an exciting time since I last wrote—almost too exciting at one time. Last time I wrote was when we were leaving Tuli for Rhodes Drift. We arrived there all right after much marching and counter-marching, mostly by night. The second night of it, for the small portion we had for sleep I struck a guard; so by the third night I was in a wretched state from want of sleep. I was always dropping off to sleep on my horse and suddenly waking up. Moreover, I began to see all sorts of strange things. Brooks and trees were transformed into houses and gardens, and then I would come-to with a start and pinch myself and try to keep awake—a very unpleasant experience. When we reached Rhodes Drift, our squadron was quartered there alone, and we had a couple of brushes with the enemy to start with.

“I missed the first, in which we had much the best of it. We only had one man hit, and that only slightly, and in return we bowled over a couple of Dutchmen (others may have been wounded), stampeded their horses, over a hundred in number (we surprised their grazing guard), killed or wounded twenty of the horses, and jumped seven. The next fight was warm for a bit. We had only half the squadron—about forty-five men—who were reconnoitring round the enemy’s fort dismounted. This was only three miles from our camp and in British territory. We had four men wounded, and did an equal amount of damage to them, if not more. We got off very cheap, for their fire was very hot, and very close too. The third fight came off on November 2, and that was a scorcher. On the night before it I was on guard. It was a beastly night, raining and blowing hard, so I got very little sleep when it was my turn off. In the day I was in charge of the grazing guard with three other men.

“About one o’clock I got orders to bring in the horses, which I did, and had just got all the horses tied up when the Dutch started firing on us. I’d just got into a nice position behind a good big rock when I was ordered to ride out to warn our outlying pickets. There were three of them, four men in each, about a mile or a mile and a half away. A risky job it was too. Two of us were sent. I asked the other man which he would go to. He chose the one I had wanted, so I had the worst job—two pickets to warn, and had to ride right through the line of fire. As I started, one of our officers shouted, ‘Don’t spare your horse; ride like h—ll;’ and I did too. Directly I got out, ping-ping came two bullets, a bit high, but others soon followed much closer. I got out, though, all right, warned the two pickets, and came in with them. We got a bit of a fusillade on us when we got near the fort, but had no[Pg 28] casualties. The man who rode to the other picket had his horse shot under him; so I scored—not for long, though, for my own horse was shot soon after.

“When I got back, I found we were having a very hot time. Our position was a couple of small kopjes close together. On two sides there was an open space for about 600 or 700 yards. On the other two sides there was a lot of bush and a ridge running round us, which we were not strong enough to occupy. The Boers had in the field between 300 and 400 men, so we thought; we afterwards found that that was not overstating their number. Moreover, they had 250 men and one gun at Brice’s Store, about six miles away on the Tuli road, and strong reinforcements at their camp. They gave us the devil of a time. At first they fired mostly at the horses. They, poor beasts, had no cover, and nearly every one was hit. A few broke loose and bolted. Later, they turned their attention to us. Luckily, their shell-fire was very wild, or we should have suffered heavily. As it was, we had not a man even wounded; but it was a miracle we did not, for at times their rifle-fire was very heavy, and now and then they got a good shell in. I had a narrow shave. A shell burst just near me, and one of the splinters struck a stone and sent a piece of it bang against my leg. It cut right through my putties, three folds of them. I made certain I was wounded, and was much relieved to find there was no damage done.

“When the evening came, we had two alternatives—to stay where we were and wait to be cut up, or try to go through to Tuli. It was finally decided to do the latter, and it was undoubtedly the right thing to do. If we had remained, we should have been surrounded the next day, and every one slaughtered. With ninety men against a thousand we should have had no show; still, it was a very bitter pill having to sneak off at night, leaving everything behind (including the few horses left alive), our kit and waggons, even the ambulance waggon. It was horrible saying good-bye to our horses. My poor little Whiskey was wounded and very unhappy; we were not allowed to shoot the wounded ones, as we had to sneak off as quietly as possible. It was very sad work. Luckily we had no man hit. I don’t know what we should have done if we had. I suppose we should have remained there and taken the inevitable consequences, as we would not have left them. We left at 8 P.M., and arrived at Tuli at 1 P.M. next day, only two halts, one and a half in the night for sleep, and another of half-an-hour for breakfast, which for me and most of us consisted of water. I had nothing to eat except one small cookie from 8 A.M. the morning of the fight to 2 P.M. the next day.