Gordon Stables

"In Touch with Nature"

"Tales and Sketches from the Life"

Chapter One.

Rowan-Tree Cottage.

“The merry homes of England!

Around their hearths by night,

What gladsome looks of household love

Meet in the ruddy light!

There, woman’s voice flows forth in song

Or childhood’s tale is told,

Or lips move tunefully along

Some glorious page of old.”

Mrs Hemans.

“You’re my Maggie May, aren’t you?”

There was a murmured “Yes,” and a tired and weary wee head was laid to rest on my shoulder.

We were all sitting round the log fire that burned on our low hearth, one wild night in winter. Outside such a storm was raging as seldom visits the southern part of these islands. It had been hard frost for days before, with a bright and cloudless sky; but on the morning of this particular day the blue had given place to a uniform leaden grey. The cloud canopy lowered, the horizon neared, then little pellets of snow began to fall no larger than millet-seeds, till they covered all the hard ground, and powdered the lawn, and lay on the laurel-leaves, and on the ivy that the sparrows so love. Gradually these pellets gave place to broad dry flakes of snow.

“How beautiful it was, falling so silently all day long,

All night long, on the mountains, on the meadows,

On the roofs of the living, on the graves of the dead.”

Yes, silently it had come down, and by sunset it was some inches deep on every tree; and very lovely were the Austrian pines and spruce-firs on the lawn, with their branches bending earthwards under their burdens of snow.

But later in the evening a change had come over the spirit of the scene, and a wild wind had begun to blow from the east. It blew first with a moaning, mournful sound, that saddened one’s heart to listen to; but soon it gathered force, and shrieked around the cottage, and tore through the leafless branches of the tall lime-trees with a noise that made both Frank and me think of gales and storms in the wide Atlantic.

Little Ida, our youngest tottie, was sitting on the hearth painting impossible birds of impossible colours, and using Sir John the Grahame’s back as an easel. She shook her paint-brush at me as she remarked seriously, “She is my Maggie May, and ma’s Maggie May, and Uncle Flank’s Maggie May, and Sil John the Glahame’s Maggie May.” My wife looked up smiling from her sewing.

“Quite right, child,” she said, “she is all our Maggie Mays.”

“O! ma,” remonstrated Ida, “that’s not dood glammer. There touldn’t be two Maggie Mays, tould there, pa?”

“Quite impossible,” I replied; “but how would you say it?”

“I would say—‘She is all of us’s Maggie May.’”

Having put our grammar to rights, Ida went quietly on painting.

Maggie May, it will be gathered from the above, was a pet in the family circle: she certainly was at present, though not the baby either.

The facts of the case are as follows: Maggie May was an invalid. Not very long before this she had been lying on a bed of pain and illness, from which none of us had expected to see her rise. She was but a fragile flower at the best, but as her recent indisposition had been partly attributable to me, I had tenfold interest in getting her well and strong again.

It happened thus: our bonnie black mare Jeannie has been allowed to have a deal of her own way, and never starts anywhere till she has had a couple of lunch biscuits and a caress. After this she will do anything. I had driven the two girls over to a farm about eight miles from our cottage, and on the way back had occasion to call on a friend. “Stand quiet,” I said; “Jeannie, I won’t be long, and I’ll bring you a biscuit.” Jeannie tossed her tail and moved her ears knowingly as much as to say, “All right, master. Don’t forget. A bargain is a bargain.”

But woe is me! I did forget, completely; and when I jumped into the phaeton Jeannie refused to budge.

Well, I suppose I lost my temper. I flicked her with the whip. Then the mare lost hers. She screamed with rage, and next moment she was tearing along the road with the bit in her teeth at a fearful speed. All my efforts to control the speed of the runaway were in vain. Little Ida clung in terror to me; Maggie May sat firm, but pale.

On we rushed, luckily meeting nothing on the road. A whole mile was speedily pat behind us. But half a mile further on was the dismal dell called Millers’ Dene, with the descent to it dangerous even at a walking pace. To attempt to take it, at the rate we were now moving, would be certain destruction. Could I check the mare before we reached the brow of the hill? I tried my utmost, but utterly failed.

Then my mind was made up. There were broad hedges at each side of the road, and no ditch between.

Summoning all my calmness and strength then, for a supreme effort, and just as we had reached the end of the level road, and the dreadful dene (a glen or ravine) lay deep down before us, with a sudden wrench I swerved the mare off the road and put her at the hedge.

It was a desperate remedy, but so far successful, and the only one really hurt was poor Maggie May.

It was one of those adventures one never forgets.

The child had received a terrible shock, and for weeks hovered ’twixt death and life. No wonder then that we made much of her, now we had her back amongst us once again; and that each of us did our best to nurse back the life and joy she had been almost bereft of for ever.

This needed all the more care, in that the shock had been purely nervous, and her mind, always sensitive, sympathised with her body.

Very pleasant, quiet, and delightful were the evenings we now spent at Rowan-Tree Cottage. We cared very little to-night, for instance, for the wild wind that was raging without, albeit we sometimes thought—not without a kind of shudder—of sailors far at sea, or of travellers belated in crossing the moors.

Uncle Frank—as we all called him—and I had constituted ourselves the story-tellers at these little fireside reunions. A right jolly, jovial sailor was Frank, with a big rough beard, tinged with grey, a weather-beaten face as brown as the back of a fiddle, and blue eyes that swam in fun and genuine good nature.

Frank had been everywhere by sea and land, and I myself have seen a bit of the world. It would have been strange indeed, then, if we could not have told stories and described scenes and events, from our experience, that were bound to interest all who listened.

Sometimes these experiences would be related in the form of conversations; at other times, either Frank or I had written our stories, and read them to our little audience.

Stories were interspersed with songs and the music of the fiddle. Frank was our sweet singer for the most part; he was also our musician. Flaying, however, on his part was never what you might call premeditated; something in the air, you might say, or in the state of our feelings, rendered music at times a necessity; then Frank would take up his instrument as quietly and mechanically as if it had been that meerschaum of his which, being a sailor, he was allowed to smoke.

Now, in the evenings, with his fiddle in his hand, Uncle Frank was simply complete. “An accomplished player?” did you ask. Perhaps not; certainly not what is called a trick-player. But the fiddle—O! call it not a violin—the fiddle when in Frank’s hand spoke and sang. They say that a good rider ought to appear part and parcel of the horse he bestrides. Frank seemed part and parcel of the instrument in his grasp. Bending lovingly over it, his brown beard floatingly on its breast, while he played, the fiddle verily seemed inspired with Frank’s own feelings and genius. And while you listened to the melting notes of some old Irish melody, the green hills of Erin would rise up before your mind’s eye, and the fiddle sang to you of the sorrows of that unhappy isle. Or the strains carried you away back through the half-forgotten past, to the days of chivalry and romance, when—

“The harp that once through Tara’s halls

The soul of music shed.”

But in a moment the scene was changed, and Frank was playing a wild Irish jig which at once transported you to Donnybrook Fair. Paddy in all his glory is there; you think you can see him dancing on the village green, as he twirls his shilelagh or smokes his dudheen.

But anon Frank’s fiddle, like the wand of a fairy, wafts us away to Scotland, and the tears come to our eyes as we listen to some plaintive wail of the days of auld lang syne, some sweet sad “lilt o’ dool and sorrow.”

Or we are transported to the times of the Jacobite rebellions, and as that spirited march or that wild thrilling pibroch falls on our ears we cannot help thinking that, had we lived in those old days, and heard such music then, we too might have fought for “Bonnie Prince Charlie.”

It would be difficult to give the reader any very definite idea of the appearance of our cottage outside or inside. Though not very far from the village, it was so buried in trees of every sort—elms, oaks, lindens, chestnuts, pines, and poplars—that no photographer, or artist either, could ever sketch it. Much less can I. But just imagine to yourself all kinds of pretty shrubberies, and half-wild lawns, and rustic rose-clad arches, and quaint old gables, and verandahs over which the sweet-scented mauve wistaria fell in clusters in spring, when the yellow laburnum and the lilacs were in bloom. Let flowers peep out from every corner and nook—the snowdrop, the crocus, daffodil and primrose in April, with wild flowers on the lawns in summer, and syringas and roses even in the hedges; and people the whole place with birds of every size, from the modest wee wren or little tit to the speckled mavis and orange-billed blackbird, that sang every morning to welcome the sunrise; let wild pigeons croodle among the ivy that creeps around the poplar-trees, and nightingales make spring nights melodious; and imagine also all kind of coaxing walks, that seemed to lead everywhere, but never land one anywhere in particular; and you will have some faint notion what Rowan-Tree Cottage was like.

To be sure our place was most lovely in spring and summer, but it had a beauty of its own even in winter, when the snow lay thick on the lawns and terraces, and seemed to turn the trees into coral. We had pets out of doors as well as pets inside—wild pets as well as tame ones.

The former were chiefly the birds, but there were splendid great brown squirrels also, that used to run about the lawn with their immensities of tails trailing over the daisies, and that, if they heard a footstep, simply got up on one end the better to see who was coming: if it was any of us, they were in no hurry to disappear; but if a stranger hove in sight, then they fled up a neighbouring elm-tree with a celerity that was surprising.

There were tame dormice too, that peeped out from among the withered leaves or climbed about on the may-trees close beside our garden hammocks. They easily knew the shape of a stranger, or the voice of one either, and used to slide slily away if any person unfamiliar to them appeared on the scene.

“Listen to the wind,” said mamma; “why it seems to shake the very house!”

“It sounds like wild wolves howling round the door,” said Frank.

“But see how brightly the fire is glowing,” I remarked, in order to give a less dismal tinge to the situation.

Frank got up and went to the door to look out, but speedily returned. “Why,” he said, “it is almost impossible to breathe outside. It puts me in mind of some nights I spent during the winter of 187-, in the Polar Regions.”

“Tell us all about it, Frank; but first and foremost just put a few more logs on the fire.”

Frank quietly did as he was told, and presently such a glorious gleam was shed abroad as banished every feeling of gloom from our hearts.

Sir John the Grahame, our great wolfhound, who had been dreaming on the hearth and doing duty as Ida’s easel, begged leave to withdraw, and Ida herself drew her footstool back.

Frank took his fiddle and sat for some time gazing thoughtfully at the fire, with a smile on his face, playing meanwhile a low dreamy melody that we could have listened to long enough.

The air he was playing we had never heard before, but it seemed to refresh his memory and bring back the half-forgotten scenes of long ago. “If,” he began at last, still looking at the fire as if talking to that, “if you will take a map of the world—”

But stay. Frank’s story deserves a chapter all to itself, and it shall have it too.

Chapter Two.

A Christmas in the Arctic Ocean.

“Here Winter holds his unrejoicing Court,

Here arms his winds with all-subduing frost,

Moulds his fierce hail, and treasures up his snows,

Throned in his palace of cerulean ice.”

Thomson.

“If you will take a map of the world,” began Frank, “and with a pin or a needle to direct you, follow one of the lines of longitude running south and north through England, up towards the mysterious regions round the Pole, you will find that this line will run right away through Scotland, through the distant Orkney and Shetland, past the lonely Faroe Isles till, with Iceland far on the left, you cross the Arctic Circle. Go north still, and still go north, and presently you will find yourself near to a little island called Jan Mayen, that stands all by itself—oh! so desolate-looking—right in the centre of the Polar ocean. In that lonely isle of the sea I spent my Christmas many years ago.

“What took me there, you ask me, Ida? I will tell you. I was one of the officers of a strongly built but beautiful steam yacht, and we had spent nearly all the summer cruising in the Arctic seas. For about three weeks we sojourned near an island on the very confines of the No-Man’s land around the Pole, and nearly as far to the nor’ard as any soul has ever yet reached.

“We named this island the Skua, after our good yacht—a wild mountainous island it was, with never a trace of living vegetable life on it, but, marvellous to relate, the fossil remains of sub-tropical trees.

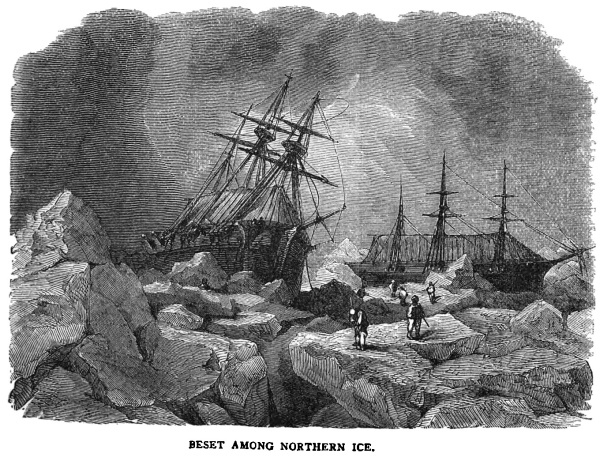

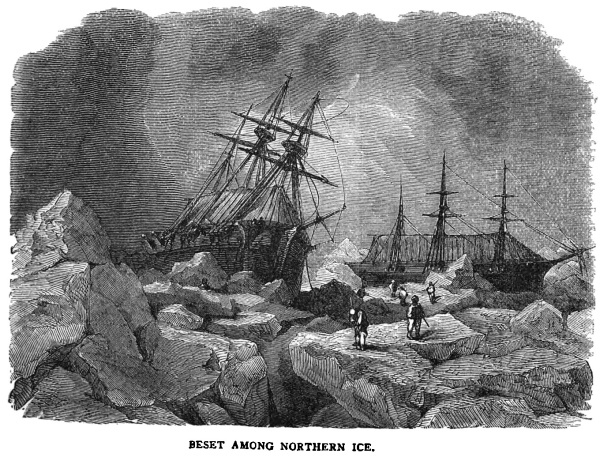

“I say we sojourned there, but this need not give you the idea that we stopped there of our own free will, for the truth is we were caught in a trap—a large one sure enough, but still a trap. We found ourselves one morning in the midst of an ocean lake, or piece of open water in the ice-field, as nearly circular as anything, and about four miles in width. We wanted to get out, but everywhere around us was a barrier of mountainous icebergs. So, baffled and disappointed, we took up a position in the centre of the lake, blew off steam, banked our fires, and waited patiently for a turn in events.

“In three weeks’ time a dark bank of mist came rolling down upon us, and so completely enveloped our vessel that a man could not see his comrade from mast to mast.

“That same night a swell rose up in the lake, and the yacht rocked from side to side as if she had been becalmed in the rolling seas of the tropics, while the roar of the icebergs dashing their sides together, fell upon our ears like the sound of a battle fought with heavy artillery.

“But next day the swell went down, the motion had ceased, and we found to our joy that the great bergs had separated sufficiently to allow us to force a passage southwards through the midst of them. A very precarious kind of a passage it was, however, with those terrible ice-blocks, broader than the pyramids, taller than churches, at every side of us.

“South and south we now steamed, and the bergs got smaller and smaller, and beautifully less, till we came into the open sea, and so headed away more to the west.

“‘Boys,’ said our good captain one day, ‘this is a splendid breakfast.’ And a splendid breakfast it was. We had all sorts of nice things, beefsteaks and game pasties, fresh fish, and sea-birds’ eggs—the latter so beautiful in shape and colour that you hesitated a moment before you broke the shell, to say nothing of fragrant tea and coffee, and guava jam and marmalade to finish up with.

“‘Boys,’ said the captain again, as he helped himself to an immense piece of loon pie, ‘it is far too soon to go back to England yet, isn’t it?’

“‘Yes, much too soon.’

“‘Well, I’ve got an idea. Let us bear still more to the westward, and have a look at the island of Jan Mayen. We’ll get some fun there, I’ll be bound; it used to be quite uninhabited, you know, but I was told before leaving our own country that the Yankees—enterprising fellows—had resolved to build a walrus station there for summer months. Now, wherever you find Yanks in these seas, you find Yacks (a tribe of Innuits, of somewhat migratory tendencies). And between the two of them we ought to enjoy ourselves. Shall we go?’

“‘By all means,’ cried everybody.

“Well, we made the island easily enough, in about ten days’ time, and after sailing about halfway round it without seeing anything at all except immense cliffs of snow-capped rocks, against which the waves were beating with a noise like distant thunder, we found a kind of bay, with a beach on which boats could land. Into this we steamed boldly enough, and presently the noise of the anchor cable rattling over the bows seemed suddenly to awaken—it was early morning—the inhabitants of a curious little village that stood near the head of the bay. There was only one long low wooden hut, all the rest of the buildings being primitive in the extreme; indeed, they looked far more like gigantic mole-heaps than the residences of human beings.

“But forth the inhabitants all swarmed; at all events, to the number, I should think, of ’twixt thirty and forty, and a stranger-looking group of individuals it has never been my lot to witness.

“I guessed then, and I found afterwards I was right, that they consisted of men, women, and children; but the fun of the thing was that they were all dressed perfectly alike and looked alike, differing only in size. The dress of the men was composed of skins entirely; they were about five feet high, and broad in proportion. The dress of the women was identical; they were six inches shorter: and the children were all dressed just like their papas and mammas, so they looked like tiny old men and women. And when we landed and stood on the beach among these strange but harmless creatures we found them funnier-looking still; for they all had round, brown faces, all flat noses, and all little beads of eyes that seemed to twinkle with merriment, although nearly hidden by brown cheeks that seemed to shake every time they spoke.

“Amongst these strange people there was one tall figure who stood aside, all by himself, and didn’t laugh in the least. A Yankee he was, six feet four in his boots, if an inch. He was dressed from top to toe in the skin of a polar bear.

“‘Gentlemen,’ he said, presently, ‘if you’re quite done guffawing, perhaps you’ll permit me to welcome you to the island of Jan Mayen.’

“We were serious in a moment, took off our caps and apologised, and ten minutes afterwards we were rowing the Yankee off to breakfast.

“He told us, in the course of conversation, that he was head of the walrus station; that during his stay in the island they had got no end of ivory and blubber; that there was capital sport; and ended by saying:

“‘And now that ye’re come, gentlemen, I hope ye’ll stop and spend next Christmas with me.’

“We laughed at the very idea of spending Christmas in such a place; but little we knew.

“The Yankee was right, the sport was glorious; all sorts of Arctic birds and beasts fell to our guns, and weeks went by, and still we postponed our departure; but at last, one day, we determined to start.

“When we awoke, however, on the following morning, it was to find that during the night an immense shoal of heavy icebergs had floated in from the sea and entirely hemmed us in. The same day the frost set in.

“The captain first pulled a long face, then he laughed.

“‘Boys,’ he said, ‘we must make the best of a bad job. We are bound to stop here till spring.’

“October flew past, November died away, and before we knew where we were Christmas week came round. You see the time had gone quickly because we really had been enjoying ourselves.

“Yet I, for one, could not help contrasting my present position with what it would have been at home in old England. How different it was here! yet the very difference made it quite charming. Suppose that you had stood on the deck of our brave yacht and looked around; you would have seen that the whole bay was frozen over with thick black ice. No need for boats now, we could skate to the shore. Behind us, seaward, across the month of the bay, stretched a rugged wall of serrated icebergs; on each side of the bay were the ice-clad rocks; shoreward, as you turned your eye, there was first the Innuit village, then the land rose gradually upwards, a snow-clad valley rock-bound, till, in the far distance, behold a vast, towering mountain of ice.

“Now remember that we never saw the sun at this time; we had no day at all, nor had had for a whole month. But who can picture the glory of that Arctic night? My pen seems to quiver in my hand when I attempt to describe it to you. During this Christmas week we had no moon. We did not miss the moon any more than we missed the sun. But we had the stars; and somehow, away up in these regions of the Pole, we seemed nearer to the heavens; anyhow, those stars appeared as large as saucers and as bright as suns, and the sky’s blue between them was blue.

“We had the stars, then, but we had something else; we had the Aurora Borealis, in all its splendour of colour and shape. At home we see the Aurora on clear frosty nights only, as a bow of white scintillating lights above the northern horizon. Here we were dwelling in the very home of the Aurora; it stretched from east to west above us, a broad belt of radiant coloured lights. It was a gorgeous scene.

“I have said that the bay in which our yacht lay was all frozen over; but this is not strictly true, because there was one portion of it, about half an acre in extent, and lying close under the barrier of icebergs, which was always kept open. This piece of open water was not only our fishing-ground, but it was a breathing-spot for many sea-mammals.

“During this happy but strange Christmas week we had all sorts of fun on board, and all kinds of games on the ice. Skating under the Aurora! why, you should have seen us; a merrier party you never looked upon.

“‘Boys,’ said the captain one morning, ‘I’m going to give those Innuits a Christmas dinner.’

“‘Hurrah!’ we all cried. ‘What fun it will be!’

“Christmas came at last, and preparations had been made to spend it cheerfully for more than a week beforehand.

“After service—and how impressive the service was, held on the deck of that Aurora-lighted ship, I shall never forget—after service, we all rushed down to dinner. We were to have ours early, because the Yacks’ entertainment was to be the great event of the twenty-four hours.

“After our dinner we had songs and pleasant talk—the pleasantest of talk; for we chatted of the dear ones at home, who probably at that very moment were fondly thinking of us. The men forward enjoyed themselves in like manner. Then the cry was ‘Hurrah! for the shore.’

“A large marquee, which we had on board, had been erected, and in this tent we found all the male and female Yacks assembled. Expectant Captain Bob, who commanded the Innuits, and was the merriest of them all, sat at the head of the great deal table, and on one side of him was his wife, Oily, on the other his pet sister, Shiny. Both Shiny and Oily were all on the titter with joy.

“When the great pudding was carried in on a hand-barrow and placed in front of Captain Bob, the astonishment on the faces of these funny little folk was extreme; but when the brandy was ignited on the top of the pudding, then up started Captain Bob and every Yack in the room, and a wild rush was made for the door. But peace was soon restored, and this king of puddings served. It was well it was a large one; it was well there were two more of the same size to follow, and I do believe if there had been half a dozen they would have found room for them. No wonder that when they had eaten and drunk until more than satisfied they rose up to dance. As they danced, too, they chanted a wild, unearthly kind of a song, each verse ending in ‘Ee-ay-ee,’ from the women, and ‘Oh! ah! oh!’ from the men.

“At last there was a dead silence, and all the Yacks flocked together, and presently out from their midst came Captain Bob—not willingly, for Oily and Shiny were shoving him along, yard by yard, with many a slap on his sheepish shoulders.

“‘Go ’long wid you,’ they were saying; ‘de capitan man not eat ye. Plenty quick go.’

“‘What is it, Bob?’ said the captain.

“‘They want more pudding,’ said shy Bob.

“‘Ah!’ cried Captain Browning, laughing; ‘I thought that would be the cry. Steward, bring up the last two puddings, positively the last.’

“The puddings were cold—they were frozen; and this is how they were served: they were simply rolled like bowling balls into the midst of them.

“And here I drop the curtain. We went away and left them scrambling over their frozen fare.

“When spring returned, with many a blessing following us, we steamed away south, and in due time reached dear old England once again; but no one who was on board the saucy Skua is likely to forget that Christmas we spent in the Arctic Sea.”

“So now good-night, Maggie May, and good-night all,” said Uncle Frank, getting up and laying his fiddle as carefully aside as if it had been a living, breathing thing.

“I’ll sleep soundly to-night,” he added.

“The wind in the trees won’t keep you awake,” I said, laughing.

“Quite the reverse, lad,” replied Frank; “I shall take it for the sound of the waves, and dream I am far away at sea.”

And after he had gone aloft, as he called it, we could hear that deep manly voice of his, trolling forth a verse of that grand old hymn:

“Rocked in the cradle of the deep,

I lay me down in peace to sleep;

Secure I rest upon the wave,

For Thou, O Lord! hast power to save.”

Chapter Three.

Birds and Beasts in Winter.—The Owl and the Weasel.

“O! Nature, a’ thy shows and forms

To feeling pensive hearts have charms,

Whether the summer kindly warms

Wi’ life and light,

Or winter howls in gusty storms

The lang dark night.”

Burns.

Our birds out of doors had all a pitiful tale to tell next morning. Not that they had any reason to complain of the boisterousness of the weather, for the wind, after blowing the snow into the most fantastic of wreaths that blocked the roads and walks, and shut us quite up and away from the village, had retired to the cave of its slumber, wherever that may be. The sun, moreover, was shining from a sky of brightest blue, and the trees were like trees of coral, yet the frost was intense.

So while Buttons proceeded to feed the dogs—always an interesting operation—and I stood by looking on, the birds came round us in flocks. The robin, of course, was the tamest; he would almost eat from my hand: later on he did.

This was our own particular robin, who had come backwards and forwards for years, and knew every one of us, I verily believe, by name.

“It is terrible weather, isn’t it,” he said to me confidentially; “there is nothing to eat; everything is covered up, and the worms have all gone down a yard beneath the earth to keep themselves cosy. My feet are almost frozen!”

“That is right,” he added; “I cannot live without a little animal food, and this shredded morsel of sheep’s-head is delicious. Some feed their birds in winter on crumbs alone. They ought to study their habits, and add a bit of meat now and then. There, don’t go away till I finish my breakfast, because, the moment you are off, down comes Mr Thrush and gobbles up the lot.”

“But,” I said, “you’re not afraid of the sparrows.”

“I’m not afraid of a few of them, though five is more than I can fight, and often ten come. They are cowardly creatures in the main.”

“Now, Buttons,” I said, “as soon as you have fed the dogs give them all a romp in the snow; then set up the birds’ sheaf.”

I alluded to a custom we have at our place of giving the birds a Christmas-tree, whenever there is snow on the ground. It is a plan taught us by the Norwegians, and I would rejoice to think it was universally adopted; for surely we ought to feed well in winter the birds that amuse and delight us when summer days are fine.

The Christmas-tree is simply a little sheaf of oats or wheat tied to the top of a small spruce-fir. It is positively a treat to see with what delight they cluster round it.

Another good plan—which gives much amusement, as witnessed from the dining-room window—is to tie up a little sheaf of oats by a string to the branch of a tree.

Tie also up some scraps of meat, and, if you have it, a few poppy-heads for the tits. The poppy-heads must be gathered and garnered in autumn, being cut down before they are too ripe, and with long stalks attached to them.

I am not sure that the seeds are not almost capable of intoxicating the birds, but they do so luxuriate in them, that I have not the heart to deny them the delight.

Here is an excerpt from my diary of this winter before the snowstorm came on:

“December 19.—It is a bright beautiful day. The garden-paths are hard. The grass on lawns and borders is crisp and white with the hoar-frost that has fallen during the night. Though it is past midday, the sun makes no impression on it. There isn’t the slightest breath of wind, nor is there a leaf left on the lofty trees to stir if it did blow. A still, quiet, lovely winter’s day.

“But I do not think the birds are at all unhappy yet. The blackbirds and the thrushes are still wild. They have not come near the door yet to beg for food. But the sparrows have, and eke cock-robin. The latter has just eaten about a yard of cold boiled macaroni, and now sits on an apple-tree and sings loud and clearly a ringing joyous song of thanksgiving. I cannot help believing that he looks upon poor me as only an instrument in the hands of the kind Providence, who seeth even the sparrow fall.

“Perhaps even the sparrows are thankful, though music is not much in their line. These gentry are not particular what they eat, and it is surprising how soon they make away with a soaked dog’s biscuit, if one be left in their way, or a pound or two of the boiled liver that Hurricane Bob is so very fond of. The old nests of these birds are still up in the wistaria-trees that cover the front, or one of the fronts, of the cottage. Those nests are crowded with the birds at night. They have used them now for two seasons, simply re-lining them. Memo: to pull them all down as soon as the days get warmer; laziness should not be encouraged even in sparrows.

“December 21.—The weather is still hard and calm. Cock-robin had a sad story to tell me this morning. He looked all wet and draggled and wretched, quite a little mop of a robin.

“‘Whatever have you been doing, Cockie?’ I asked. ‘Have you had an accident?’

“‘Accident, indeed!’ replied Cockie. ‘No, it was no accident, but a daring premeditated attempt at parricide.’

“‘Parricide,’ I cried, ‘you don’t mean to say that your son—’

“‘O! but I do though,’ interrupted Cockie. ‘You know, sir, that he follows me to the door, and attempts to take the bit out of my mouth, and you’ve seen me fling him a piece of meat.’

“‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘and then try to chase him away, and the young rascal runs backwards, and sings defiance in your face.’

“‘True, sir; and to-day, when I tried to reason with him, he flew right at me—at his father, sir—and toppled me heels over head into the water-vat, and I’m sure I’ve caught a frightful cold already.’

“‘There’s a fire in my study, Cockie, if you care to go in.’

“‘No, thank you, sir, I’ll sit in the sun.’

“December 22.—The weather gets colder and colder. I interviewed a speckle-breasted thrush to-day, who had come to the garden-room-door to be fed.

“‘On winter nights,’ I asked, ‘do you not suffer very much from the cold?’

“The bird looked at me for a moment with one big bright eye and said:

“‘No, not as a rule. You see we retire early, always seeking shelter at sunset, and generally going to the self-same spot night after night, for weeks or months; for all the winter through we can do with quite a deal of sleep. Yes, as you say, we make up for it in spring and early summer, when we sing all the livelong day and seldom have more than four hours of rest. We rest in winter under the shelter of a hedge or tree, or eave, away from the prevailing wind.

“‘In winter we are more warmly feathered all over, though our garments are less gay than in summer, when we have to appear on the stage, as it were. Even our heads are well clad, and when perched on a bough our toes are covered, and we hardly feel the cold a bit.

“‘But at times in winter it is bad enough, for when the snow covers the frozen ground we get but little warmth-giving food. This alone prevents us from sleeping soundly; and sometimes the wind gets high and rages through the trees, and we get blown right off our perches. Then, as it is all dark, we are glad to huddle in anywhere, and many of us get snowed up, and never see the glad sunshine any more.

“‘Wet is even worse than snow, and if there is wind as well as wet we are very numbed and wretched. Then the night seems so long, and we are so glad when day breaks at last, and the warm sunshine streams in through the bushes.’”

Our little village was so truly small and so unsophisticated, that with the exception of the clergyman and doctor it could boast of nothing at all in the shape of society, while the families in the country districts were mostly honest farmer-folk, who had seen but little of the outside world, and only heard of it by reading the weekly paper. Their talk was chiefly about growing crops and live stock, so that, interesting though this might be, neither my friend Frank nor myself had much temptation to leave home on winter evenings.

But we had plenty to talk about nevertheless, and I cannot help saying that it would be a blessing to themselves if the thousands of country families, situated as we were, would cultivate the art of instructive conversation and story-telling. Science gossip is infinitely to be preferred to fireside tattle about one’s neighbours, to say nothing of its being free from ill-nature, and elevating to the mind instead of depressing.

About a week before Christmas, my wife was busy one evening trimming an opera-cloak for Maggie May—would she ever wear it, I wonder—with some kind of grebe.

“Is it grebe?”

“Yes, it is the skin of a grebe of some kind,” was the reply; “but there are so many different kinds, in this country find America.”

“A kind of duck, isn’t it?”

“Or a kind of gull?”

“Betwixt and between, one might say. Grebes are nearly allied to the great Northern Diver, but their feet are not, like his, quite webbed. They frequent the seashore and rivers by the sea, and live on fish, frogs, and molluscs of any sort. Their nests are often built to float among the reeds, and to rise and fall with the tide.”

“When I get an opela-cloak,” said Ida, “I’ll have it tlimmed with elmine.”

“Why with ermine, Ida?”

“Because the Queen had elmine on, in the waxwork.”

“Yes; and the ermine is only a weasel after all, and all summer it wears a dress of red-brown fur, which speedily gets bleached to white, when the thermometer stands below zero.”

“No, Frank, I haven’t seen my weasel for some time. He is dozing in some snug corner, you may be sure; and really, Frank, I believe the subject of hibernation is but very imperfectly understood. I don’t want to go into the matter at present physiologically, except to say that it seems to be a provision of Nature for the protection of species; and that a variety of animals and creatures of all kinds that we little wot of, hibernate, more or less completely. We see sometimes, in the dead of winter, a beautiful butterfly—a red Admiral, perhaps—suddenly appear and dance about on a pane of glass. We wonder at it. It is not a butterfly’s ghost at all, but a real butterfly, who had gone to sleep in a snug corner of the room, and has now awakened probably only to die.

“I found an immense knot of garden worms, the other day, deep down in garden mould. They were sleeping away the cold season.

“But, talking about weasels, I’ll tell you a story, Ida.”

The Owl and the Weasel.

“From yonder ivy-mantled tower,

The moping owl doth to the moon complain,

Of such as, wandering near her secret bower,

Molest her ancient solitary reign.”

“By what you tell me,” I said, “I can now guess where all my wild rabbits have gone.”

I was talking to a weasel. And indeed the weasel seemed talking to me, for he stood upon his hind-legs, on the balcony, staring in at me through the French window that opens from my study on to the long shady lawn. As I did not move, he had a good look at me, and I think he felt satisfied that I was not likely to harm him.

“Yes,” I continued; “under that verandah, under the wooden balcony where you now stand, used to dwell six wild rabbits, and did I not delight to see them gambolling on the grass on the early summer mornings, the while the blackbirds, the thrush, and the mavis enjoyed the bath placed on purpose for them under the shade of the scented syringas.”

“Well,” replied the weasel, with a little toss of the head, “I dwell there now, and very comfortable I find the quarters.”

“And the rabbits?” I inquired.

“Good morning!” said the weasel, and it departed.

The weasel often came to see me in this fashion, and sometimes, when I took my chair outside of an evening, he would suddenly appear at the far end of the balcony.

“O, you’re there, are you?” he would seem to say, quite saucily. “Well, don’t trouble yourself getting up; I sha’n’t stop.”

I had often wished to have a tame weasel; but though my present visitor was not afraid of me, and I know it took the milk I used to put down for it in a small bit of broken basin, I could never make a real pet of it.

But one bright lovely day I was passing along in the country on my tricycle. It was a lonesome upland, where I was travelling, with neither hedge nor ditch on either side of the road, only green grass and trees, with here and there a bush of golden furze. I was going along at no extra speed, but thoroughly enjoying myself; still, I put on all the power I could after a time, and seemed to fly towards what appeared to be an immense black snake hurrying across the broad pathway. This snake, however, on a nearer inspection, resolved itself into one mother weasel and five young ones, all in a row. Seeing me dismount, the old mother hurriedly snatched up one of her little ones, perhaps her favourite, and in a few moments they were out of sight, far away in the thicket. Nay, not all of them, for here was one entangled in the rank grass by the pathway. What should I do with it? If its mother did not return it would very likely be left to perish. “Ah! I have it,” I thought, “I will take it home and tame it and keep it as a pet.” It needed some taming, too, young as it was; this I soon found when I commenced to capture it, but not without considerable risk to my fingers; but at last I had it secure in my tricycle basket.

I must at once confess that I was not successful in my endeavours to domesticate this poor wee weasel. As far as a cage could be, its abode was palatial; it had the warmest and softest of nests, and everything to tempt its palate that I could think of; but although it came to know and not fear me in a very few weeks, yet it never seemed perfectly content, and seemed to long for the wild woods—and its mother.

And at last the poor little mite died, and I buried it in a tiny box under a bush, and vowed to myself as I did so that I would never take any wild thing away from its mother again.

Some people would tell you that you ought to destroy stoats and weasels whenever you see them. I myself think you ought not, because, although they do sometimes treat themselves to a young leveret, or even a duckling or chicken, they should be forgiven for this when we consider the amount of good they do, by destroying such grain-eating animals as rats and mice, to say nothing of our garden-pests, the moles.

Even the owl is a very useful bird of prey, because he works by night, when hawks have gone to sleep. Like many human thieves and robbers, mice like to ply their pilfering avocation after nightfall, and they might do so with impunity were it not for those members of the feathered vigilance committee—the owls.

Now, so long as an owl does his duty, I think he has a right to live, and even to be protected; but even an owl may forget himself sometimes, and be guilty of indiscretion. When he does so, he has only himself to blame if evil follow.

There was once a particularly well-to-do and overweeningly ambitious owl, who lived in an old castle, not far from the lovely village of Fern Dene.

“Oh!” he said to himself one bright moonlight night, as he sat gazing down on the drowsy woodland and the little village with its twinkling lights; “I should like a repetition of last night’s feast—a tasty young weasel. Oh! I would never eat mouse again, if I could always have weasel.” And he half closed his old eyes with delight as he spoke.

“And why not?” he continued, brightening up; “there were five of them, and I only had one. So here I go.”

And away flew the owl out of the topmost window of the tower, and flapping his great lazy wings in the air, made directly over the trees to the spot where the weasel had her nest.

“I shouldn’t wonder,” said one bat to another, “if our friend Mr Owl finds more than his match to-night.”

Farmer Hodge, plodding wearily homewards through the moonlight, about half an hour after, was startled by a prolonged and mournful shriek that seemed close to his ear, while at the same time he saw something dark rising slowly into the sky. He watched it for many minutes; there was another scream, but a fainter one higher up in the air; then the something dark grew darker and larger, and presently fell at his feet with a dull thud. “What could it be?” he wondered as he stooped to examine it. Why a great barn-owl with a weasel fast to its neck. Were they dead? Yes, both were dead; but one had died bravely doing its duty and defending its homestead; the other was a victim to unlawful ambition.

Chapter Four.

Away in the Woods.

“Come to the woods, in whose mossy dells,

A light all made for the poet dwells;

A light, coloured softly by tender leaves,

Whence the primrose a mellower glow receives.

“The stock-dove is there in the beechen tree,

And the lulling tone of the honey-bee;

And the voice of cool waters, ’midst feathery fern,

Shedding sweet sounds from some hidden urn.”

“I went up with the dogs this morning,” I said one evening, “to see how my woodland study looked in winter.”

“You did not do any work?”

“I did indeed. It was so warm under my great oak-tree, that I could not resist the temptation of sitting down and writing fully half a chapter of a new tale.”

It is a clear sunny day, with the ground flint-hard with the frost. The leaves are still on the bramble-bushes, so dear to school-children when autumn days ripen the big luscious-looking black and bronze berries. The leaves also closely cover yonder little beech-trees. The furze is of a dark olive-green colour, covered here and there with patches of white, where the hoar-frost lodges, and with spots of brightest yellow when the blossoms still flourish. There are buds on the leafless twiglets of the oak, though the tree still soundly sleeps, and the ground is everywhere covered with moss and broken mast. Not a sound is there to break the stillness of the winter’s morning, save now and then the peevish twitter of a bird among the thorns, or the cry of a startled blackbird, while now and then a rabbit goes scurrying across the glade, stopping when at a safe distance to eye me wonderingly. How different it all is from Nature here in her summer garb.

My Woodland Study in Summer.

It is an open glade in the middle of a pine-wood. Not all green and level is this glade, with trees standing round in a circle, like the clearings in forests of the Far West, which I used to read of in the novels of Cooper and that so bewitched me when a boy. No, for judging from the rough and rutty pathway that leads up to it, and from the numerous banks and hillocks in it, there can be no doubt that, in far distant days of the past, gravel must have been dug and carted hence.

The wood itself—glade and all—stands on a hill. At any time of the day I have but to ascend one of these furze-clad banks to catch a view the beauty of which can hardly be surpassed by any other scene in bonnie Berkshire. It is warm to-day—’tis the 1st of August—and there lies a greyish-purple haze over all the landscape, that tones and softens it. The nearer trees, just beyond the field down there where the sheep are feeding, the stately ashes, the spreading elms and planes, and the towering poplars, stand out green and clear in the sunshine; but the hills beyond the valley of the Thames and the trees along its banks have a blotted, blurred, and unfinished look about them, but are very charming to behold nevertheless, all the more in that, here and there, you catch glimpses of the silvery river itself, reflecting the glorious sunshine.

Down yonder is the road that leads past my pine-wood. You could not help noticing that it is very beautiful. It is a road of yellow gravel, bounded on each side, first by broad grassy banks on which rich white clover blooms and yellow celandines are conspicuous, and next by a wild indescribable tangle of a hedge. It had been originally blackthorn, but has been so cut back that many other bushes and weeds far less easily offended have asserted their independence, and tower over it or swamp it. Yes, but, taken as a whole, it must be confessed they swamp it in beauty. Yonder are patches of dark-leaved nettles, yonder clumps of orange-brown seedling docks, side by side with lofty spreading pink-eyed iron-weed. Yonder is a canopy of that marvellous creeper the white briony: very small are their little greenish-white flowerets, but what a show their myriads make, and the clusters of its berries, green and crimson, rival in beauty those of the blue-petalled woody nightshade that are growing there as well. High over the hedgerow stands the yellow tansy and the wild parsley, while in it, under it, and scattered hero and there are the crimson glow of field poppies, the orange gleam of leopard’s bane, and starry lights from ox-eyed daisies.

The banks or hillocks in my woodland study—among which you may wander as in a labyrinth, lose your way, and finally perhaps, much to your surprise, find yourself back again at the very place whence you started—are clothed with tall furze-bushes; their yellow blossoms have faded and fallen, and downy seed-pods that crackle in the sunshine, as they split and scatter their seeds, have taken their place, but the beauty of these blossoms is hardly missed, for over and through the dark-green furze the brambles creep and trail, dotting them over with clusters of pink-white bloom.

If you went close to these trailing brambles, you would find that each cluster of bloom had a bee or two at work on it. There are plenty of the bees of commerce there, dressed in homespun garb of unassuming grey or brown, quite suitable for the work they have to do—make honey for the humble cottagers that dwell in the village nestling among the trees down yonder. But besides these, there are great gaudy bees that go droning from blossom to blossom, clad in velvet, with stripes of orange, white, or red, each arrayed in his own tartan, one might say, each belonging to his own clan or ilk. Here is a great towering thistle—emblem of Scotland, pride of her sons. How beautiful the broad mauve-coloured, thorn-protected flowers are, and on each of them is one of the aforesaid big tartan bees, and on some there are two revelling in the nectar there distilled! Now do those Scottish thistles exude a kind of whisky, I wonder, or rather a kind of Athole brose (a mixture of honey and whisky). Whether they do or not, one thing must be patent to the eyes of all observers—those tartan bees do positively become intoxicated on those Scottish thistle-tops; from other flowers they gather honey in quite a business sort of a way, but once they alight upon the thistle they are down for the day. They soon become so drowsy that they don’t care to move, and if you go near them they hold up their forelegs and shako them at you in a deprecating sort of a way.

“For goodness’ sake,” they seem to say, “don’t come here to disturb us; go away and look after your business, if you happen to have any, only don’t come here.”

If you are an early bird, you may find some of those bees asleep on the thistle-tops at six o’clock in the morning, the down on their backs all bedraggled, and dew on their wings, evidence enough that they have not been home at all, and mean to make another day of it.

Shrub-like oaks, stunted willows, and dark-berried elders also grow on the banks among the furze and the bramble, and here and there a patch of purple heath.

Between the little hills the ground is level, but carpeted over with grass and moss, and a profusion of dwarfed wild flowers of every tint and colour under the sun.

The wood itself is of fir and larch pine, with here and there a gigantic and widely spreading oak. There are dark spruce thickets too, much frequented by wood-pigeons—I can hear their mournful croodling now—and there are darker thickets still, where the brown owl sits blinking and nodding all day long, till gloaming and starlight send him out, with the bat, to see after supper.

It is under the shadow of a splendid oak-tree, which overhangs a portion of my glade, that I mostly write, and under it my little tent is pitched, the shelter of which I only court when a shower comes on, being, like every other wild creature, a thorough believer in the benefits of a life spent in the fresh open air.

Yonder hangs a hammock in which, when tired, I may lounge with a book, or, soothed by the sweet breath of the pine-trees, and lulled by the whisper of wind and leaf, sleep.

But when work is done, hammock, tent and all are packed upon or behind my tricycle, which, like a patient steed, stands there waiting to bear me to my home in the valley.

My woodland study is fully five-hundred feet above the level of the sea, and yet it is easy to see from the size, shape and surface of the pebbles all around me, that this glade was once upon a time a portion of the ocean’s bed; that glass-green waves once rippled over those banks where the furze now grows; that congers and flat fish once wriggled over the gravel where those thistles are blooming; and that thorny-backed crabs used to lie perdu in the holes where dormice now sleep in winter.

I pick up one of those pebbles and throw it—well, just in yonder among the whins; where the stone has alighted a wild old fox has a den, and she has cubs too in spring-time; so I am not the only wild creature that frequents these solitudes. Oh no; for apart from the birds, who all know me, and do pretty much as they please, there are mice and moles in the grass, and high aloft orange-brown squirrels that leap from tree to tree, besides rabbits in dozens that scurry around the hillocks and play at hide-and-seek. At this very moment up on yonder bank sits a hare; his ears are very much pricked, and he is looking towards me, but as he is chewing something, in a reflective kind of way, he cannot be very much alarmed. And only last evening I saw a large hedgehog trotting across my glade, dragging behind him a long green snake, a proof, methinks, that innocent hoggie is fond of something more solid than black beetles and juicy slugs as a change of diet.

With the exception of an occasional keeper, wandering in pursuit of game, no human being ever disturbs the sanctity of my woodland study; and no sound falls on my ears, except the distant roar of a passing train, the song of linnets, and croodle of turtle-dove and cushat.

Sometimes, in blackberry season, far down in yonder copse, I can hear the laughing voices of children at work among the brambles. Just under a furze-bush, not five yards from the spot where I am now reclining, a pheasant some time ago brought forth a brood of young. She never used to move when I went close to her, only looked up in my face, as much as to say, “I don’t think you are likely to disturb me, but I mean to stick to my nest whatever happens.”

There is something new to be seen and studied in this woodland haunt of mine all the year through. What a wondrous volume is this book of Nature! I honestly declare that if I thought I had any chance of living for, say a couple of thousands of years, I would go in for the study of natural history in downright earnest, and at the end of even that time, I daresay, I should feel just as ignorant as I do now.

But I don’t come to my woodland study to laze, be assured; a good deal of honest work is done in this sylvan retreat, as many a London editor can testify. Only, there are half-hours on some days when a drowsy, dreamy sensation steals over me, and I pitch my pen away and lie on the moss and chew the white ends of rushes, and think.

It is, say, a beautiful day in mid-July. There are wondrous clouds up yonder, piled mass on mass, with rifts of bright blue between, through which the sun shines whenever he gets a chance. There is a strip of sunshine, even now, glittering on those feathery seedling grasses, and varnishing them as it were. It is gone, and a deal of beauty goes with it.

It is close and sultry and silent, and with half-shut eyes I take to studying the liliputians that alight with fairy feet on my manuscript, or creep and crawl across it.

Here is a gnat—the Culm communis—a vast deal too communis in these wilds, especially at eventide, but my hands have long ago been rendered proof against their bites à la Pasteur. This is a new-born culex; he hardly knows what the world is all about yet. But how fragile his limbs, how delicate his wings! These last are apt to get out of order, a breath of wind may do damage, a raindrop were fatal. This gnat has lost a leg, but that does not seem to interfere in the least degree with his enjoyment of life. He is a philosopher, five legs are fun enough; so away he flies.

Here are some small spiders—crimson ones. There are other tiny ones, too tiny yet to build a web, so they stalk for wee unwary flies.

Here comes a great mother spider, quite a Jumbo among the others; she walks quickly across the sheet, but, strange to say, half a dozen pin-head young ones are clinging to her, and now and then she drops one, and it quite unconcernedly goes to work to make its own living. Fancy human parents getting rid of their offspring in this way! No such luck, many will add.

Skipjacks go jumping about on my paper, clicking like little watches; the very clowns of insect-life are these. Elateridae is the long name they go by in history.

Here is a little scoundrel no bigger than the dot of the letter “i,” but when I touch him with the point of a blade of grass, hey! presto! he has jumped high in air and clean over twenty lines of my ruled foolscap—i.e., more than a hundred times the length of himself. How I envy him the ability and agility to jump so!

Here is a wee Anobium, as big as a comma; he can’t jump, but he knows his way about, and when I touch him he shams dead. He has a big brother, called the death-watch, and he does the same.

But here comes a bigger jumper, and here another; one is yellow and the other brown. In a day or two the yellow one will be as dark as the other. They are Aphrophorae. They were born in a spittle, for so the country folks term the frothy morsels of secretion we see clinging to such herbs as sour-dock. Let them hop; I am not going to take their lives on this lovely day, albeit they do much harm to my garden crops.

But here is a bigger arrival, a Saltatorial gryllide, a lovely large sea-green grasshopper; his immense ornamental hinder legs put you in mind of steam propellers. He is on my blotting-paper, watching me with his brown wise-looking eyes, ready for a leap at a moment’s notice. I lift my hand to brush a gnat from my ear: whirr! he is off again and out of sight. He doesn’t care where he flies to, and when he does spring away into infinity he can’t have the slightest notion where he will land. What a happy-go-lucky kind of life! What a merry one! He toils not, neither does he spin; he travels where and when he pleases; there is food for him wherever he goes, and nothing to pay for it. A short life, you say? There is no one can prove that, for one hour may seem as long to him as a year to you or to me. To be sure a bird may bolt him, but then he dies in the sunshine and it is all over in a moment.

Here is a tiny elongated Coleopterite who, as soon as he alights for a rest, folds away his wings under his tippet (elytra). He does not bite them off as some silly she-ants do. For as soon as the sun blinks out again this insect will unfold his wings and be off once more, and he may perhaps alight in some human being’s eye before evening and be drowned in a tear.

There are some of an allied species, but so very very tiny that when they get on to my manuscript while I am writing, they are as bewildered as I have been before now on an Arctic ice-field. Perhaps they get a kind of snow-blind. At all events they feel their way about, and if they chance to come to a word I have just written, they dare not cross it for fear of getting drowned—every stroke of my pen is to one of these wee mites a blue rolling river of ink. So they’ve got to walk round.

Here is a new-born Aphis (green-fly). It is still green. It has not been bronzed yet, and its wings are the most delicate gauze. It does not seem to know a bit what to do, or where to go, or what it has been put into the world for, any more than a human philosopher.

This wee thing takes advantage of a glint of sunshine and essays to fly, but a puff of wind catches him, and, as “the wind bloweth where it listeth,” he has to go with it. He will be blown away and away, thousands and thousands of midges’ miles away. He will never come back to this part of the wood, never see any of his relations—if he has any—again. Away and away, to the back of the north wind perhaps; he may be swallowed by a bat or a sand-marten; he may be impaled on a thorn or drowned in a dewdrop, or alight on the top of a pond and get gobbled up by a minnow; but, on the other hand, he may be blown safe and sound to some far-off land beyond the Thames, settle down, get married, and live happy for ever afterwards.

Clack—clack—clack—clack! A great wild pigeon has alighted on the pine-tree above me. I have been so quiet, she does not know I am here. I cough, and click—clack—click go her wings, and off she flies sideways, making a noise for all the world like the sound of that whirling toy children call “a thunder-spell.”

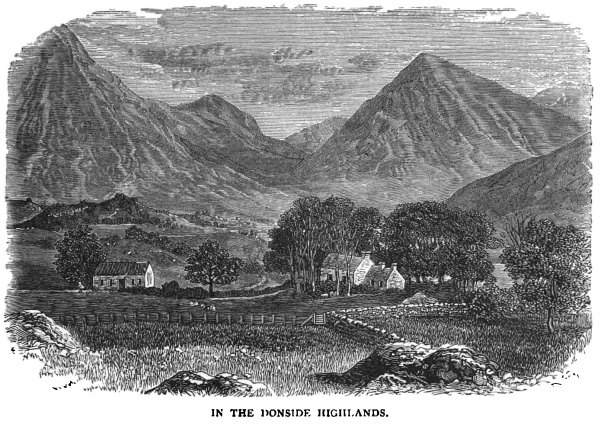

But she has knocked down a cone. It is still green, but somehow the sight of it takes me far away north to bonnie Scotland, and I am roaming, a boy once more, on a wild moorland, where grow, here and there, tiny pine-trees—seedlings, that owe their habitat, if not existence, to the rooks, who have carried cones like these from the forests. Like Byron, “I rove a young Highlander o’er the dark heath.”

“I arise with the dawn, with my dog as my guide,

From mountain to mountain I’m bounding along,

I am breasting the billows of Dee’s rushing tide,

And hear at a distance the Highlander’s song.”

I close my eyes, and it all comes back, that wild and desolate but dearly-loved scene; the banks where lizards bask; the “pots” and the ponds in that broad moor, where teal-ducks swim, and near which the laughing snipe has her nest; I hear the wild whistle of the whaup or curlew, and the checker of the stone-hatch in the cairn. I am wading among crimson heath and purple heather, where the crowberry and cranberry grow in patches of green. And now I have wandered away to the deep, dark forest itself; and near to a kelpie’s pool, by the banks of a stream, I lay me down to rest. There are myriads of bees in the lime-trees above, through which the sunshine shimmers, lighting up the leaves to a tenderer green, but the bees begin to talk, and the murmuring stream begins to sing, and presently I find myself in Elfin-land, in the very midst of a fairy revel.

The “Midsummer Night’s Dream” is a masterpiece of art, but nothing to this. That was a mere phantasy; this is a reality. This is—

“Pa! papa!”

I start up. I am still in my woodland study. But a sweet young face is bending over me, and tender eyes are looking into mine.

“Pa, dear, how sound you have been asleep! Do you know it is nearly sunset?”

“Have I? Is it?” I reply, smiling. “I thought, Ida, you were queen of Elfin-land.”

It is my tiny daughter who has come toddling up to the wood to seek for me.

Three minutes after this, we are tooling down the hill homewards, and Ida—my own little queen of the elves—is seated on the cycle beside me.

Chapter Five.

Summer Life in Norland Seas.

“To the ocean now I fly

And those Norland climes that lie

Where Day never shuts his eye.”

“And nought around, howe’er so bright,

Could win his stay, or stop his flight

From where he saw the pole-star’s light

Shine o’er the north.”

It was no wonder that, with the snow lying deep around our dwelling, and the storm-wind rattling our windows of a night, and howling and “howthering” around the chimnies, both Frank’s thoughts and my own should be carried away to the wild regions of the Pole, where both of us had spent some years of our lives; or that I should have been asked one night to relate some of my experiences of Greenland seas and their strange animal inhabitants, seals and bears among the rest.

I related, among other things—

How Seals are Caught in Greenland.

“That sealing trip,” I said, “I shall never forget. My particular friend the Scotch doctor, myself, and Brick the dog, were nearly always hungry; many a midnight supper we went in for, cooked and eaten under the rose and forecastle.”

Friday night was sea-pie night, by the universal custom of the service. The memory of that delicious sea-pie makes my month water even now, when I think of it.

The captain came down one morning from the crow’s-nest—a barrel placed up by the main truck, the highest position in the ship from which to take observations—and entered the saloon, having apparently just taken leave of his senses. He was “daft” with excitement; his face was wreathed in smiles, and the tears of joy were standing in his eyes.

“On deck, my boys, on deck with you, and see the seals!”

The scene we witnessed on running aloft into the rigging was peculiarly Greenlandish. The sun had all the bright blue sky to himself—not the great dazzling orb that you are accustomed to in warmer countries, but a shining disc of molten silver hue, that you can look into and count the spots with naked eye. About a quarter of a mile to windward was the main icepack, along the edge of which we were sailing under a gentle topsail breeze. Between and around us lay the sea, as black as a basin of ink. But everywhere about, as far as the eye could see from the quarter-deck, the surface of the water was covered with large beautiful heads, with brilliant earnest eyes, and noses all turned in one direction—that in which our vessel was steering, about south-west and by south. Nay, but I must not forget to mention one peculiar feature in the scene, without which no seascape in Greenland would be complete. Away on our lee-bow, under easy canvas, was the Green Dutchman. This isn’t a phantom ship, you must know, but the most successful of all ships that ever sailed the Northern Ocean. Her captain—and owner—has been over twenty years in the came trade, and well deserves the fortune that he has made by his own skill and industry.

If other proof were wanting that we were among the main body of seals, the presence of that Green Dutchman afforded it; besides, yonder on the ice were several bears strolling up and down, great yellow monsters, with the ease and self-possession of gentlemen waiting for the sound of the last dinner gong or bugle. Skippers of ships might err in their judgment, the great Green Dutchman himself might be at fault, but the knowledge and the instinct of Bruin is infallible.

We were now in the latitude of Jan Mayen; the tall mountain cone of that strange island we could distinctly see, raised like an immense shining sugar-loaf against the sky’s blue. To this lonely spot come every year, through storm and tempest, in vessels but little bigger or better than herring-boats, hardy Norsemen, to hunt the walrus for its skin and ivory, but by other human feet it is seldom trodden. It is the throne of King Winter, and the abode of desolation, save for the great bear that finds shelter in its icy caves, or the monster seals and strange sea-birds that rest on its snow-clad rocks. At this latitude the sealer endeavours to fall in with the seals, coming in their thousands from the more rigorous north, and seeking the southern ice, on which to bring forth their young. They here find a climate which is slightly more mild, and never fail to choose ice which is low and flat, and usually protected from the south-east swell by a barrier of larger bergs. The breeding takes place as soon as the seals take the ice, the males in the meantime removing in a body to some distant spot, where they remain for three weeks or so, looking very foolish—just, in truth, as human gentlemen would under like circumstances—until joined by the ladies. The seal-mothers are, I need hardly say, exceedingly fond of their young. At all other times timid in the extreme, they will at this season defend them with all the ferocity of bears. The food of the seals in nursing season consists, I believe, of the small shrimps with which the sea is sometimes stained for miles, like the muddy waters of the Bristol Channel, and also, no doubt, of the numerous small fishes to be found burrowing, like bees in a honeycomb, on the under surface of the pieces of ice. The wise sealer “dodges” outside, or lies aback, watching and wary, for a fortnight at least, until the young seals are lumpy and fat, then the work of death begins. I fear I am digressing, but these remarks may be new to some readers.

“The Green Dutchman has filled her fore-yard, sir, and is making for the ice;” thus said the first mate to the captain one morning.

“Let the watch make sail,” was the order, “and take the ice to windward of her.”

The ship is being “rove” in through the icebergs, as far and fast as sail will take her. Meanwhile, fore and aft, everybody is busy on board, and the general bustle is very exciting. The steward is serving out the rum, the cook’s coppers are filled with hams, the hands not on deck are busy cleaning their guns, sharpening their knives, getting out their “lowrie tows” (dragging-ropes), and trying the strength of their seal-club shafts by attempts to break them over their hardy knees. The doctor’s medical preparations are soon finished; he merely pockets a calico bandage and dossel of lint, and straps a tourniquet around his waist, then devotes his attention exclusively to his accoutrements. Having thus arranged everything to his entire satisfaction, he fills a sandwich-case, then a brandy-flask and baccy-pouch, and afterwards eats and drinks as long as he can—to pass the time, he says—then, when he can’t eat a morsel more, he sits and waits and listens impatiently, beating the devil’s tattoo with his boot on the fender. Presently it is “Clew up,” and soon after, “All hands over the side.”

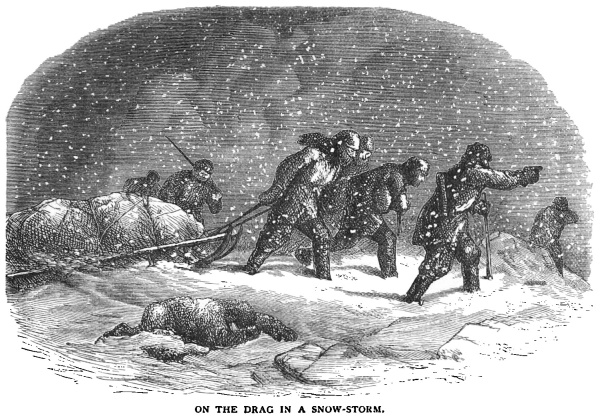

The day was clear and bright and frosty, and the snow crisp and hard. There was no sinking up to the knees in it. You might have walked on it with wooden legs. Besides, there was but little swell on, so the movement of the bergs was slow, and leaping easy.

Our march to the sealing-ground was enlivened by a little logomachy, or wordy war, between the first mate and the doctor. The latter began it:

“Harpooneers and clubmen,” he cried, “close up behind me, here; I’m gaun to mak’ a speech; but keep movin’ a’ the time—that’s richt. Well, first and foremost, I tell ye, I’m captain and commander on the ice; d’ye hear?”

“You commander!” exclaimed the mate; “I’ll let ye ken, my lad, that I’m first officer o’ the ship.”

“Look here, mate,” said the doctor, “I’ll no lose my temper wi’ ye, but if ye interrupt me again, by ma sang, ye’ll ha’ to fecht me, and ye ken ye havena the biceps o’ a daddy-lang-legs, nor the courage o’ a cockney weaver, so keep a calm sough.—Now, men,” he continued, “I, your lawfully constituted commander, tell ye this: there is to be nae cruelty, this day, to the innocent lambs we’re here to kill. Mind ye, God made and cares for a’ His creatures. But I’m neither going to preach or pray, but I’ll put it to ye in this fashion. If I see one man Jack of ye put a knife in a seal that he hasna previously clubbed and killed, I’ll simply ca’ that man’s harns oot (dash his brains out) to begin wi’, and if he does it again, I’ll stop his ’bacca for the entire voyage, and his grog besides.”

Probably the last threat was more awful to a sailor than actual braining. At all events, it had the desired effect, for during the whole of that day I saw nothing among our men but slaughter as humane as slaughter could be made. Even then, however, there was much to harrow the feelings of any one at all sensitive. For the young Greenland seal is such an innocent little thing, so beautiful, so tender-eyed, and so altogether like a baby in a blanket, that killing it is revolting to human nature. Besides, they are so extremely confiding. Raise one in your arms—it will give a little petted grumble, like a Newfoundland puppy, and suck your fingers; not finding its natural sustenance in that performance, it will open its mouth, and give vent to a plaintive scream for its ma, which will never fail in bringing that lady from the depths beneath, eager-eyed and thirsting for your life.

Towards the middle of the day I strolled among the crew of the P—e. The men were wildly excited, half-drunk with rum, and wholly with spilling blood, singing and shouting and blaspheming, striking home each blow with a terrible oath, flinching before the blood had ceased to flow, and sometimes, horrible to say, flinching the unhappy innocents alive. All sorts of shocking cruelties were perpetrated, in order to make puppies scream, and thus entice the mother to the surface to be shot or clubbed. I saw one fellow— Pah! I can’t go on.

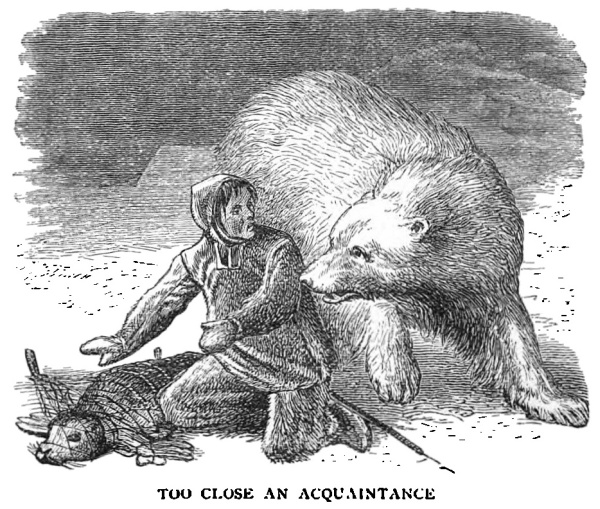

Blood shows to advantage on ice. Here there were oceans of it. The snow was pure and white and dazzling in the morning—I leave it to the imagination of the sentimental to guess its appearance at eventide. The stout Shetlandmen, with their lowrie tows, dragged the skins to the ship. There were no regular meals any day during sealing. The crew fed and drank alike, when they could and what they could. There was but little sport in all this—a certain wild excitement, to be sure, quite natural under the circumstances, for were we not engaged in one of the lawful pursuits of commerce and making money? The bears were having fine times of it, for there was but little inclination on our part to pursue them, while there were seals to slay; and Bruin seemed to know this, and was correspondingly bold and impertinent, although never decidedly aggressive; for compared to seals men are merely skin and bone, and Bruin has a penchant for adiposity.

In ten days there was not a seal left, for ships had collected from all quarters—like war-horses scenting the battle from afar, or like sea-gulls on “making-off” days—to assist in the slaughter. By-the-by, what peculiar instinct or what sense is it that enables those sea-gulls to determine the presence of carrion in the water at almost incredible distances? On making-off days—that is, idle days at sea—when, there being nothing else to do, the hands are employed in separating the blubber from the skins, putting them in different tanks and casting the offal overboard, there shall not be a single gull in sight from the crow’s-nest, even within ken of the telescope; but when, twenty minutes afterwards, the work is well begun, the sea shall be white with those gulls, singly or in clusters fighting for the dainty morsels of flesh and blubber.

We got frozen in after this, and in a fortnight’s time we found ourselves forsaken by the bears, and even by the birds, both of which always follow the seals.

What a lonely time we had of it for the next month, in the centre of that silent, solitary icepack! But for the ships that lay here and there, frozen in like ourselves, it might have been mistaken for some snow-clad moorland in the dead of winter. And all the time there never was a cloud in the blue sky, even as big as a man’s hand; the sun shone there day and night but gave no heat, and the silence was like the silence of space—we could have heard a snow-flake fall.

Once a week, at least, a gale of wind might be blowing, hundreds of miles away from where we were—it was always calm in the pack—then the great waves would come rolling in beneath the ice, though of course we could not see them, lifting up the giant bergs, packing and pitching the light bay-ice over the heavy, and grinding one against the other or against our seemingly doomed ship with a shrieking, deafening noise, that is quite indescribable. We thus lived in a constant state of suspense, with our traps always packed and ready to leave the vessel if she were “nipped.” One ship had gone down before our very eyes, and another lay on the top of the ice on her beam ends, with the keel exposed.

But clouds and thaw came at last, and we managed, by the aid of ice-saws and gunpowder, to cut a canal and so get free and away into the blue water once more.

“Were you not glad?” said Maggie May.

“Yes, glad we all were, yet I do not regret my experience, for in that solitary ice-field we were indeed alone with Nature. And, Maggie May, being alone with Nature is being alone with God.”

“Ah! Frank,” I added, “it is amid such scenes as these, and while surrounded with danger, that one learns to pray.”

“True, lad, true,” said Uncle Frank solemnly, “and strange and many are the wonders seen by those who go down to the sea in ships.”

Chapter Six.

Face to Face with Ice-Bears.

“Why, ye tenants of the lake,

For me your wat’ry haunts forsake?

Tell me, fellow-creatures, why

At my presence thus you fly?

Conscious, blushing for our race,

Soon, too soon, your fears I trace;

Man, your proud usurping foe,

Would be lord of all below,

Plumes himself in Freedom’s pride,

Tyrant stern to all beside.”

Burns.

“If ever a true lover of Nature lived,” said Frank one winter’s evening, as we all sat round the fire as usual, “it was your Scottish bard, the immortal Burns.”

“Yes,” I said, “no one was ever more sensible than he that a great gulf is fixed between our lower fellow-creatures and us—a gulf formed and deepened by ages of cruelty towards them. We fain—some of us at least—would cross that gulf and make friends with the denizens of field and forest, but ah! Frank, they will not trust us. I can fancy the gentle Burns walking through the woods, silently, on tiptoe almost, lest he should disturb any portion of the life and love he saw all about him, or cause distress to any one of God’s little birds or beasts. See the wounded hare limp past him!—poor wee wanderer of the wood and field—look at the tears streaming over the ploughman’s cheeks as he says:

“‘Seek, mangled wretch, some place of wonted rest—

No more of rest, but now thy dying bed!

The sheltering rushes whistling o’er thy head,

The cold earth with thy bleeding body prest.’”

“And what,” said Frank, “can equal the pitiful pathos and simplicity of his address to the mouse whose nest in autumn has been turned up by the ploughshare?

“‘Thy wee bit housie too in ruin,

It’s silly wa’s, the winds are strewin’,

An’ naething, now to big a new ane

O’ foggage green,

An bleak December’s winds ensuin’,

Both snell and keen.’”

(Big means build; snell means keen.)

“Yes, Frank, and he says in that same sweet and tender poem:

“‘I’m truly sorry man’s dominion,

Has broken Nature’s social union,

An’ justifies that ill-opinion

Which makes thee startle

At me, thy poor earth-born companion,

An’ fellow-mortal!’”

“Well,” replied Frank, “I’m very much of Burns’s way of thinking; I would like to be friends with all my fellow-mortals, and have reason to believe it is really man’s cruelty that has broken the spell that should bind us.

“Why, away up in the north, the biggest beast in the sea is the simplest and the best-natured. I mean the whale. The birds are so tame you can almost catch them alive, and even bears will pass you by if you do not seek to molest them.”

“Tell us some bear stories, Frank.”

Frank accordingly cleared his throat.

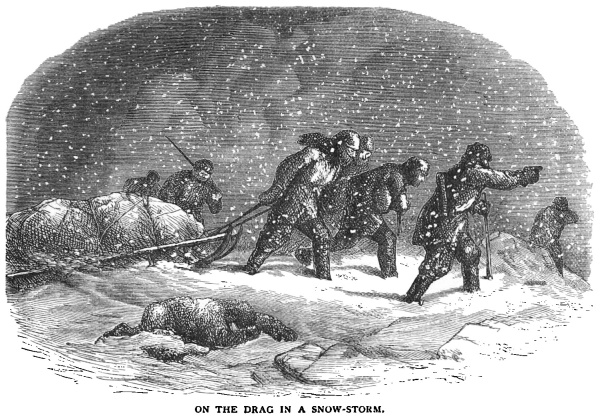

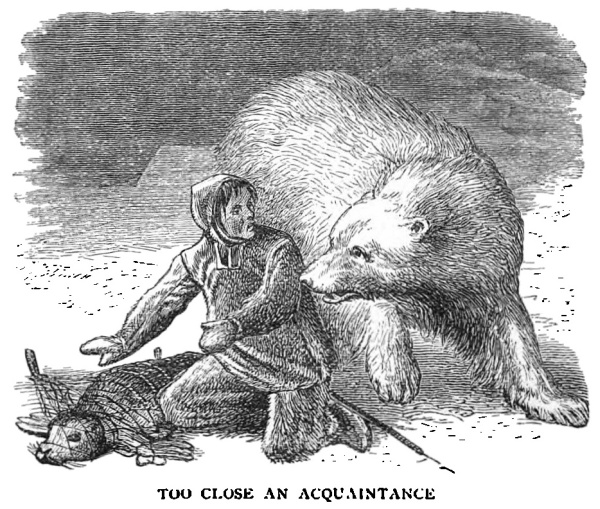

“What I tell you, then, about Polar bears,” he said, “you may believe. My facts are true facts, not ordinary facts, and I gained my experience myself, and neither from books nor from imagination. But talking about books,” he continued, pulling one down from the shelf and spreading it open before him, “here is one on natural history, and as there are pictures in it, it will be sure to please you. The book is not an old one, and is a reputed authority. Well, look at that. That is supposed to be a Polar bear just come out of a cave, and having a sniff round. It is more the shape of a dormouse that has lost its tail in a trap.