Cynthia Stockley

"The Claw"

Chapter One.

Part One—The Skies Call.

“It works in me like madness, dear,

To bid me say good-bye,

For the seas call and the stars call,

And oh! the call of the sky.”

Hour after hour Zeederberg’s post-cart and all that therein was straggled deviously across the landscape, bumping along the rutty road, creaking and craking, swaggling from side to side behind the blocky hoofs of eight mules.

At five o’clock in the afternoon the heat was intense, but the sun lay in the west at last, and tiny flecks of cloud in the turquoise sky were transforming themselves into torn strips of golden fleece. The bare bleak kops of Bechuanaland were softened by amethystine tints, and the gaunt bush took feathery outlines against the horizon.

The driver of the post-cart, a big yellow Cape boy with oystery eyes, took a long swig from a black bottle which he was ready to affirm contained cold tea, though the storekeepers who filled it at every stopping place referred to its contents variously as dop, Cape smoke, and greased lightning. Afterwards he lovingly bestowed the bottle under his seat, cracked his whip, and shouted in a ferocious voice:

Hirrrrie-yoh doppers!

I sat behind the driver, on the floor of the cart crammed amongst cushions and rugs and parcels and mail-bags and luggage, aching passionately in every bone, deadly weary, and very cross. For when you are extremely tall it is not all rapture to sit for hour after hour with your length hunched beneath you like an idol of Buddha. And when you are thin, not bonily thin but temperamentally slender, you don’t care for parcels bumping into your curves as if you were made of wood, and mail-bags apparently stuffed with flints and jagged rocks piercing through the thickest cushions into your very marrow.

Hirrrrie-yoh doppers!... Slaagte... Verdommeder skepsels!...

Heaven knows what terrible significance was contained in these cabalistic words, but the eight mules immediately broke into a shambling run, the post-cart swaggled from side to side, the mail-bags hit me and stabbed me, and clouds of fine dust arose, wrapping us round in a smothering fog. Five minutes later the mules resumed their usual slouch, the fog subsided into a feathery mist, and all was as before. Slowly and deviously we straggled across the landscape. I tried for the hundredth time to arrange my rugs into the semblance of a nest, and for the hundredth time failed to do anything of the kind. There was no rest or comfort anywhere in that post-cart. In spite of my chiffon veil I could feel the fine road-dust powdering thickly on to my charming face. Mosquitoes sped down silently from strongholds in the hooped tent of the cart and without even a warning serenade took long draughts of my nice young blood through the linen sleeves of my blouse. A hundred grass ticks having at various times of outspan made convenient entry through open-work brown silk stockings, chewed at my ankles causing exquisite irritation not to be assuaged by a violent application of finger-nails.

The breeze, if heavy turgid masses of air displaced by the movement of the cart might be so called, conveyed to my face the steam arising from the mules and the extraordinarily pungent odour of native that emanated from the driver. It was something to be thankful for that the latter was so busy with the mules and his black bottle that he did not often turn his big café-au-lait-coloured countenance to me, for when he did there was something so revolting in the spirituous odour of his breath and the expression of his oystery eyes that I could feel my scalp stirring as though my hair had suddenly been brushed the wrong way. At such moments I was extremely glad that I had a small but business-like Colt slung conspicuously from my waist-belt, and that in the boudoir of a little old hunting-box in Meath there were to be found three rather nice silver cups (probably all filled with late roses) awarded to me by various ladies’ shooting clubs for making the highest aggregate of bulls-eyes. It was at such moments too that, good shot or not, I realised that I had been utterly foolish and reckless to adventure forth alone and unprotected upon this wild journey into Mashonaland.

At six o’clock the heat was still intense, and the western sky resembled a vast frameless picture daubed in primitive colours, slashed and gashed with reds and yellows. An hour later the sun shot past the horizon like a red-hot cannon-ball aimed at the other side of the world, and for a short time the land was suffused in wilder lights of orange, and the skies seemed streaked with blood. Then suddenly the heat was over, the flare died out of the picture, the far-off kops turned a faint pink colour, and the grimness of the bush was blurred in a drapery of purple chiffon. At once night unsheathed her velvet wings, and darkness fell in dim purple veils embroidered with silver stars. Some subtle scent as of flowering trees growing by a river blew through the tent of the cart. The world seemed filled with gracious dimness and made up of illimitable lovely space. An indescribable feeling of happy freedom filled my heart. It seemed to me that the lungs of my soul drew breath and expanded as they had never done in any land before. It was a sensation that came to me every morning when I saw the sun turn a gaunt country into a blue and golden world; and every evening when the sun fell and the land was wrapt in purple and silver vestments. It seemed to me then to be possible to disregard the discomforts of the day, and to forget what terrors the night might hold, by just succumbing to the charm and the magic of this wonderful great empty land. I was content to be in Africa!

Leaning back, my head against a mail-bag, my eyes half closed, I found myself suddenly remembering a brown-faced man with vivid blue eyes, with whom I had once danced at the Viceregal Lodge on the night of my “coming-out,” and who had talked to me about the lure of Africa, saying that it was worse than the call of the East. He had spoken of Africa as she, and with a mingled hatred and love that conjured up to my mind a vision of some false, beautiful vampire, who dragged men to her and fastened her claws into their hearts for ever.

“It’s a brute of a country!” he said. “Quite unfit to live in. Thank God to be back to civilisation again.” But a moment later he was talking of the veldt as tenderly as a lover might talk of the woman he loves. I remembered being intensely interested and fascinated at the time, but it was in the middle of my first real ball, and it was also my eighteenth birthday and the occasion of my first serious proposal, and I had had, very naturally, a great many other absorbing things to think about. Moreover, the dance with the blue-eyed man had come to an end, I had been whirled off by some one else, and had never seen him again. Such blue burning eyes, set in such a dark burnt face! What added more strangely to his vivid appearance were two tiny blue points of turquoise stuck in his ears.

“Shades of George Washington!” I said to myself. “Can the man be an Indian—or a Hindoo?” But who ever heard of an Indian or a Hindoo having blue eyes? Just as I was going to ask him, in the frank way that always seemed to me to be the best and simplest method of getting to the heart of things, why he wore them, I found him looking with such a deep, strange glance at me, that, most unaccountably, my lids fell over my eyes as though weighted with little heavy stones, and for a few moments I could not lift them again. Also, my gift for airy conversation suddenly deserted me and I became tongue-tied. I remember feeling glad that I was so charming to look at or he might have thought me a fool. For I had not a word to say; I could only listen eagerly to him talking about Africa like a lover. At least I felt that was the way I should like my lover to speak of me. Perhaps it was because Herriott could not talk like that that I refused him that night, though I had always intended to take him, and I knew I should vex both my people and his by not fulfilling what had been almost an accepted situation for months past.

But that was all long past—three years past to be accurate—and I had never again seen the man who talked of Africa, though I had often glanced round ball-rooms and theatres for that dark face with the burning eyes and the ridiculous blue turquoise ear-rings. Many strange things had happened since then to swallow up the memory of him, and it had been swallowed. But it was strange how often I had remembered him again since I set out on this journey to Mashonaland, and passing strange that though I had only been in Africa for a month and known the veldt for only eleven days I seemed to understand all he had said about it.

Why did I understand? I wondered. Was the lure of Africa on me too? Was this strange brown land of golden days, and crimson and orange eventides, and purple nights, calling to me? Would it keep me as he had said it always kept people who felt the lure and heard the call? At the thought I trembled a little, and felt afraid of I knew not what. Afterwards I laughed to myself at the absurdity of the thought. How could Africa keep me? I belonged to the civilised cities of the world. My home was in Paris, London, Dublin, sometimes New York. I had lived always amongst pictures, and sculpture, and books, beautiful music, lovely clothes, jewels. All these things were necessary to me. I could not contemplate life without them. Africa was only an interlude—an experience. In a few months I should be back again hunting with the Meath pack from our dear little box near Balbriggan; flying over to London for balls and Hurlingham, or with my pretty Aunt Betty van Alen in her Paris studio, entertaining her and her friends with the strange tale of my adventures in this strange land. How ridiculous to fancy that I could feel the thrilling pain of a claw in my heart—Africa’s claw! What was Africa to me or I to Africa?

I shivered. There were mists rising everywhere now, and joining the clouds of dust they wove gauzy scarfs about us and white things moved before us on the road, like spectres showing the way.

The sunshine that I loved so much was gone! It was my passion for sunshine and blue skies that had brought me for a time to this barbaric land. My passion for sunshine that I had never really been able to indulge to the full, until the crushing failure of a great bank in America had transformed me from an heiress into just an ordinary girl with a few hundreds a year whom the world no longer concerned itself particularly about.

That was one of the strange events that had occurred to change my life and swallow up many vivid memories. First my lovely and much loved mother, the one parent I could remember, had died, passing away softly in her sleep one night and looking so happy—almost gay—as she lay there dead, that it had seemed wrong to regret what had happened and the blow had thus been robbed of half its terror and pain. Then, directly afterwards, had come the banking disaster, sweeping away the great fortune my mother had left and leaving nothing from the wreckage but a few thousands to be divided between my brother Dick and me. That had been the end of my fashionable career, and when I realised it I rejoiced with an exceeding great joy, for it was a life that, as the French put it, had “never said anything to me.” Immediately the future had become far more interesting. Hundreds of people whom I had never cared a button about, but whom I had been obliged to meet and smile with, “and gladly endure,” dropped instantly out of my life and I never saw them again. The horizon became a blank canvas that I might fill in with any figures I liked against any background I chose. Well! the background I chose was sunshine, which I sought in many out-of-the-way places where sunshine abounds, and the people I let into my picture were all the odd, charming creatures I met in my travels and the delightful writers and painters and sculptors who made up the world of my Aunt Betty van Alen, herself a gifted sculptress and a beautiful Bohemian soul. She had been appointed my guardian by my mother, and we spent most of our time together, only, a true American, she never could be drawn very far from her beloved Paris. However, she was American in this, too, that she considered the world as free to women as to men, and that no harm could come to a self-reliant girl who had been well brought up and taught black from white. So that when she could not be with me herself she suffered no qualms in letting me go off on my excursions alone, and was perfectly satisfied that I should never come to any harm. She was of opinion that every true-born American girl has her head so well balanced and such a fine sense of beauty and the fitness of things that she could never step from the paths of wisdom, or stray from that straight white road that her religion and early training had laid down for her; that the more you trust an American girl the more she is trustworthy. And I think she was right. But what she never took into account with me was that though my mother was American and I had been born under the Stars and Stripes, my father’s half of me was Irish, and Irish drops in the blood spell love of adventure, love of the extraordinary in people and places and things, love of beauty, and lots of other loves, that not only cause one exquisite pleasure that is more than half pain, but lead one into many strange places where convention is not. However, I never told her or any one else of these things. Indeed it was only dimly that I realised them for myself.

On this visit to Africa, so very far away from her, Betty had unexpectedly held out rather firmly about the necessity of a chaperon, and to please her I had travelled out with a frumpy old German governess we had both known many years, who was visiting Africa to see about some property an uncle had left her in the Transvaal. All the way out I had made it quite plain to Madame von Stohl that I meant to go up to Mashonaland and see my brother Dick, that in fact it was one of my chief reasons for coming to Africa at all; and she never said a word against the idea. But lo! after I had trailed around with her to all sorts of uninteresting places in Cape Colony and the Transvaal she calmly and firmly refused to fulfil her part of the programme and go with me to Mashonaland. She said she was afraid of being eaten by Lobengula, the King of the Matabele.

The only thing to do, then, was to make my own plans and enquiries. Every one told me it was a journey of the very roughest and wildest description, and that very few women had done it before. It appeared that there were already a great number of women in Mashonaland, but they had all travelled up by waggon, with their men-folks to look after them, taking about three months to accomplish the journey. Instead of this information daunting me, as it was evidently meant to do, it made me only the more eager for such an adventure. Therefore, when I heard one man remarking to another (through the open window of the Johannesburg Hotel where we were staying) that if I took that coach journey alone it would take the curl out of my hair, I merely felt sorry for the man:—first, because he never would and never could know that my hair curled naturally, and secondly, that he should have so poor an opinion of an Irish-American girl as to think that a few rough adventures would scare her from a plan on which she had set her heart. In any case it was really no business of his. But Africa is chock full of people who mind your business for you as well as large quantities of their own. At first I was amazed and indignant at the number of utter strangers who came along and tried to interfere with my contemplated journey. Later I learned to listen, in the same spirit as it was given, to advice that was not really meant for anything but friendly information and a touching interest in the mistakes of other people. And when I smiled at them and told them that I loved adventures and couldn’t get enough of them, the men gazed at me with admiration, mingled (they told me) with a longing to start for Mashonaland by the same coach, and the women looked wistful but denied their longing to follow my example.

As for Madame von Stohl, she refused to budge from her comfortable quarters in the Johannesburg hotel. I was secretly delighted, for anything more tiresome than a fortnight’s unmitigated von Stohl in the cramped-up space of a coach I could not imagine. But I felt it my duty to reproach her. She thereupon in great irritation made some not at all agreeable remarks about the unfortunate fate of persons descended from two entirely irresponsible nations, without any sense of duty towards society, a craving for excitement, and no proper regard for the conventions of civilised life.

She said all this whilst I was packing my prettiest gowns for Fort Salisbury, and I, with the light heart of a girl who knows she is going to get her own way, responded with some cheerful reflections on heavy pudding-headed Teutons who had not an ounce of nous in the whole of their make-up, were absolutely lacking in imagination and the spirit of adventure, and simply did not know the meaning of joie de vivre. What was the use, I demanded, of sticking in Johannesburg and all the other stupid imitation towns and imagining we were seeing real Africa?

“One might just as well be in England or Germany, except that life in Europe is more comfortable and not so expensive. What I want to see—besides Dick, of course—is the illimitable veldt, and Brother Boer, and prowling lions, and Lobengula’s fifty wives.”

Elizabet von Stohl had answered that her desire was not unto these things. I then, having pitifully but very firmly told her that of course she could not help having been born a German, went out and telegraphed to Dick to come down to Johannesburg and fetch me. I thought I would give convention a fair deal. However, he wired back:

“Impossible. You must not think of coming up here at present. Country very unsettled. May be trouble with the natives at any time.”

That was ridiculous, of course. If his wife could be up there, why couldn’t I? And if he couldn’t fetch me, well, it was quite simple to buy a ticket for the coach journey and go up by myself. There was nothing monstrous in that! What did it matter about the country being unsettled if one had a revolver and was an excellent shot?

Certainly twenty pounds was an amazing price for a coach ticket. But the coach agent never said a word about its being a dangerous journey, or tried to dissuade me in any way. On the contrary he told me that it was a beautiful country, and that he was sure I should have a very agreeable time. That was something for my twenty pounds.

When I showed the ticket to Madame von Stohl she expostulated more bitterly than ever, and said she should cable to Aunt Betty, failing that, to Mr Rhodes, the Governor of Natal, Dr Jameson, and the Bishop of Grahamstown. On my suggestion that the King of Timbuctoo might also be a good man to consult she turned dark blue. Afterwards she made a gesture like the washing of hands and said that I might go my ways, for which I was very much obliged to her. And I did go them two days later behind eight prancing mules, in company with a cheerful telegraphist for Tuli, and a missionary who travelled in dancing pumps and a mackintosh. Since then the magnificent red four-wheeled coach we had set out in had been changed for “cart, carriage, wheel-barrow, and donkey-cart”; drawn sometimes by mules, sometimes by oxen; driven by men sometimes black, sometimes white, sometimes yellow, but always profane.

At Tuli we had shed the telegraphist, with regret, for he was a merry and ingenious soul, full of plots for the commissariat and the general comfort. At Palapchwe the missionary got off to call on Khama, the King of the Bechuanas, who likes missionaries, though not to eat. The poor man was minus his dancing pumps, having left them unwillingly in a mud-hole where the cart had been stuck for several hours and we had been obliged to flee for our lives from a horde of mosquitoes as large as quail.

From Palapchwe I had travelled alone, but always in the care of reliable drivers, and wherever there were telegraph stations I found that Dick, (who had come round, once he knew I was well en route) had wired to people to meet me and do all they could for me, and I had experienced nothing but kindness and hospitality from the settlers, and storekeepers and the officers at the police camps. On the third day out from Palapchwe, however, my good driver had broken his arm, and been hastily replaced by a man whom the coach agent did not know so well but hoped would be reliable. This was my friend of the oystery eyes who so vociferously bellowed—Hirrrr... rrr... rrie-yoh doppers!... Slaagte eiseltjies!

Night was on us at last. The pace of the mules grew slacker and slacker: they were reaching the end of their run, and obviously the end of their endurance. The rush of water could be plainly heard on the still air, and close ahead loomed the denser, taller bush that on the veldt invariably outlines the banks of a river.

I began to think rather wistfully of the little tin hotel or thatched store I knew must be near, where we would outspan for the night. The travellers’ bedrooms in such “hotels” were the most amazing and extraordinary places I had ever met, but they were nevertheless an improvement on my present confined quarters. I should at least be able to stretch my cramped limbs, and there would be lights and perhaps a cup of tea, and hot water to wash off the suffocating dust. These things had never yet failed me at the various halting places, and there was nearly always a woman of some kind to do her best for me.

The driver presently got down from his seat, lighted a lantern, and going to the head of the team began to guide his tired mules along the broken road. This was now little more than a wide foot-path, waggon-rutted and holed-out by the hoofs of the beasts of burden that had gone before. The stumps of trees chopped down by the axes of the Pioneers were still green and sappy in the track, and the wheels of the cart jarred against rocks that traffic had not worn down, and crushed through the houses of white ants who had not yet acquired the wisdom to build elsewhere than on the road leading to the country of Cecil Rhodes.

At last the cart stood still. The driver swinging his lantern went on alone and in a few moments was lost sight of in the bush. The mules began to quiver in an eerie way, and the trembling of them subtly communicated itself to the cart which also began to quiver and creak like an animate thing. I shivered and pulled a rug round my shoulders. It seemed we had come to a lonely and desolate spot. The trees standing black against the stars looked enormous and sinister, and there was something menacing in that sound of swift rushing water.

After a long while the driver came stumbling back, fixed his lantern on a hook in front of the cart, and began to be extremely busy with the mules. The jingle of harness falling to the ground was heard, accompanied by more creaking and shivering. My interest was aroused.

“What are you doing, driver?” I asked sharply. I knew quite well this could not be right. If the mules were unharnessed how could we reach that most desirable little tin hotel? The driver answered in a voice considerably thicker and more incoherent than the last time I had heard it (greased lightning, I had observed, frequently has this effect upon the vocal cords):

“River’s full—cart can’t cross d’ drift to-night.”

“But the little tin—the hotel—?”

“Hotels d’ other side,” was the laconic response, and he continued to undo the mules. Harness fell around him like hail.

“But what are you going to do?” I faltered.

“Going to put d’ eisels into d’ stable,” he answered stolidly, indicating with his arm a mass of blackness on his left, that might have been either a hay-stack or a cathedral, “an’ shut me in wid dem. You better come saam, Miss.” He gave a drunken chuckle. I fingered my Colt, and that gave me courage to answer in a clear voice that betrayed no sign of the panic in my soul:

“Nonsense, driver! of course there must be some decent place for me to spend the night. Take me to it at once.”

He had all the mules loose, and holding each by a small head-rein they radiated from him like the rays of a black star of which the lantern in his hand was the scarlet centre. By its light I could see his stupid brutal face clearly, though I was hidden from his vision in the dimness of the cart. However he could recognise authority when he heard its note, and looking towards me answered with a faint shade of respect in his voice if not in his words:

“You got to take your choice, Miss. Come saam into d’ stable wid me and d’ mules or else sit in d’ cart all night wid d’ lions. We can’t cross d’ river.”

“Lions!” I stammered. “But there must be some place, somewhere for me to go to—a hut—a store—something!”

Such a desperate, horrible situation was incredible. The mules were shivering with the steam still rising from them and the driver grew impatient. Apparently he acknowledged a duty to them if not to me. He came close to the cart and spoke menacingly and finally into it.

“See yere: dis is d’ Umzingwani River. No hotels yere, oney plenty of lions, worst place in Africa for lions; dat’s why I’m going to shut me up with d’ eisels. See dat place over dere?” He pointed to another grim shadow that might have represented anything in this grim place of shades—“Baas O’Flynn and Baas Jones kept a store dere. Baas O’Flynn died of d’ jim-jams, and his grave is round back of d’ hut: and a lioness fetched Baas O’Flynn out from behind the counter one day and walked off wid him in front of two kaffirs. I tell you lions is thick round here. Dat’s why dey built a stable dis side for when d’ river’s full, and dat’s why I am going to shut me up wid d’ eisels. So now you better take your choice, Miss, d’ eisels and me—or d’ lions.”

I was silent in amazement and horror, petrified with apprehension; dew was on my forehead. The driver, supposing that I was making my choice, waited for a moment or so, then getting no answer, turned his mules and moved away amidst the jingling of headstalls, muttering and chuckling to himself:

“Ach! arlright den, I told you what, if you don’t come saam wid me!”

I watched his going with despair; but my dry tongue refused to call him back. It seemed to me there could be no worse horror than to spend the night shut in a stable with that brute and the mules. And yet—lions! My backbone became a line of ice.

But I would not recall him. I watched him staggering away from me, the lantern rays flickering between the dark bodies of the mules. They seemed to go a long way off before they reached the stable, but at last I descried the inside of a brick building, narrow and manger-lined. For one moment I had a glimpse of the mules nosing eagerly to their places, then the closing of a heavy door shut out the pale vision, a bar fell heavily into its place, and I was shut and bolted into the outer darkness: alone in a wild and lonely part of Africa.

Began then for me the strangest night of all my life. In the midst of the thick darkness there suddenly and unwarrantably appeared between the branches of trees taller than any I had seen on the whole journey a wraith-like new moon, white as a milk opal. It peered through the black trees like a ghost that has lost its soul and seeks for it in desolate places. It shed no light at all, but just hovered there, peering, paling the light of the stars, and etching into view things that had better have been left hidden. It outlined some white bones that lay in an apart place at the foot of a tree, making them glisten as if they were composed of silver. It revealed the stable crouching amongst the bush like a grey monster. It showed up a spectre-like kopje on the left that I had not known was there at all and that was unlike any kopje I had ever seen, bare as a glacier with neither stock nor stone on it, nothing but one malignant-looking tree perched on its summit, leafless and crooked, holding out a forked arm that beckoned me hideously.

It is not for nothing that a superstition exists purporting bad luck to those who see the new moon through trees. There is indeed something disquietingly sinister in the sight. My Irish heart beat wildly in my breast. I was all superstitious Celt at that moment—not a drop of calm, sane American anywhere about me. My shaking hand clutched at my revolver. I had heard or read somewhere of people shooting the moon, and I wondered vaguely whether it was upon occasions such as this that the dread deed was done. Afar a wail of infinite sadness and melancholy pierced and echoed through the silence. In months to come I was to learn to hear music in the hungry jackal’s dirge, but at that time it sounded to me like the cry of some despairing soul suffering the torments of everlasting fire.

I could not keep my eyes closed. Some mysterious force compelled me to open them again and again upon the scene of terrifying ghostliness. Also, when I shut them the rush of waters seemed to surround the cart, and I expected at any moment to find myself being swept away down the strong river. In reality, nothing moved, not even a leaf on a tree. All was still, silent as the dead under the watching moon; even the little chirping cries and noises of the grass insects were hushed, or swallowed up in the smooth swift sound of rushing power. Only far away the wailing tragic cry of the jackal found many an echo and response.

Hours passed that were centuries to me, sitting Buddha-like on the floor of the cart, stiff and motionless, clutching my revolver. The moon lingered long, seeming to cling to the branches in a vain effort to stay longer, but at last she sank despairingly, and once more the clearing above the drift on the Umzingwani River was wrapt in the blackness of the nethermost pit.

It was only then that I dared change my position a little. Feeling for the hoops of the cart-hood I very slowly dragged my agonised limbs upwards, until my head touched the top of the hood. Even so I could barely stand upright, and the exquisite pain of leaping blood circulating once more in my numbed limbs was almost more than I could bear. But as I stood so, Fear, full-armed, rushed upon me again, for in the sea of darkness round me, I distinctly heard something moving:—on swift, padded feet something was stealing round the cart and breathing! Sinking down noiselessly to my former position, I peered between the mail-bags into the darkness, and once more dew stood on my forehead in little beads. Suddenly, I saw two small pale green fires that moved together, then two more exactly the same, and I knew they were the eyes of savage beasts. Paralysed with fright, I was afraid to stir, afraid almost to breathe. But my mind, still working vividly, considered the best thing to do—to sit perfectly still in the hope that they would not venture into the cart after me, or to fire my revolver into them one barrel after the other. The noise of breathing and moving was plainly made by more than one beast, and there were growlings now and horrible purring noises. I came to the conclusion that there was not one lion but probably half-a-dozen after me. To my increased horror the cart suddenly began to shake. Were they preparing to spring upon me? I grasped my revolver firmly, and with the other hand swiftly crossed myself and whispered a prayer, for indeed I believed that my last moment was come. But nothing happened. Only the coach went on shaking softly, and the snarlings and growlings in several keys continued; there was a faint jingle, too, of the harness that had been left lying on the ground. What could be happening?

I began to feel strangely sick and faint. Since morning I had eaten nothing but a very stale sandwich, and the long fast, together with the series of emotions I had gone through, began to tell upon me. My mental vision grew a little dim and unattached. I found myself thinking vaguely about things that were not at all apropos to the situation. I reflected, as drowning people are said to do, on all the things I had done and seen since first I could remember, and on all the persons I had known, including and especially Elizabet von Stohl who had so emphatically opposed this journey. I suddenly detested her exceedingly! How pleased though shocked she would be if she could know how faithfully her prognostications of evil were coming true! Would she pretend to be shocked? But she should never know. Even in my extremity I gave a desolate smile to think that if the lions did get me they would carry me off into the deep bush and leave nothing behind to tell the tale. My fate would be wrapped for ever in romantic if terrible mystery, and no one would know what naked depths of terror my soul had sounded amidst the fearsome darkness of the veldt. But I resolved that if ever I got out of this alive the eloquent reserve which marks the truly great should distinguish me also as far as my African adventures were concerned. One thing was certain: my taste for prowling lions was appeased. I also felt a diminished interest in Lobengula’s fifty wives. As for the illimitable veldt it was the limit!

And all the time the breathings and purrings and snarlings went on; and as if that were not enough they began to chew. Heaven knows what they were chewing, but I felt sure that it would very shortly be me. Suddenly I became aware that something had approached the step of the cart and was close to me. I could hear its breathing and plainly I saw the gleam of two little pale green fires. An enterprising lion had smelt me out at last and meant to do unto me as had been done unto Mr O’Flynn. The thought was too much; with the last desperate courage of the doomed I took Fate into my hands, and leaning forward fired barrel after barrel from my revolver in the direction of the little pale fires. The noise of the detonations echoing and repeating through the silent place was enormous and terrifying, but in the tingling stillness that followed, my straining ears caught the sound of fleeing padded feet and the crackling of small branches and undergrowth at gradual distances. Then my senses swam, and I sank back behind my barricade of mail-bags.

Chapter Two.

The River Calls.

“And there’s no end of voyaging

When once the voice is heard,

For the river calls, and the road calls,

And oh! the call of the bird.”

I suppose I fainted, and later perhaps I slept. At any rate it seemed, and must have been, a long while afterwards that I waked up to a sound so pleasant and comforting that I believed at first I must still be in the land of strange dreams in which my mind had been wandering. But I presently realised that though I was still lying curled up in the cart, it really was the sound of wood crackling and burning in a fire, and that the aromatic flavour in the air was the smoke of wood mingled with the curiously sweet scent of burning leaves and branches, still hissing with sap. Very softly I raised myself upon a cramped elbow and looked out of the cart. The place was transformed. The circular clearing, no longer gaunt and terrifying but a scene of tall enchanted trees and frondy ferns, was lit up with leaping rose-and-amber lights from four large fires built at the corners of a square. The post-cart, well within the radius, had a munching horse tethered to it, while stretched at full length on a rug in the firelight was a man.

He was lying carelessly at his ease, and by the flickering light of the fires looking through a number of letters and papers. One hand supported a determined-looking jaw; the rest of his face was hidden under a hat with so evil a slouch to it that it might easily have belonged to a burglar. He wore no coat; only a grey flannel shirt open at the neck, with a dark blue and crimson striped handkerchief (the kind of thing college men put on after boating or football) knotted loosely round his bare throat. His khaki riding-breeches were “hitched” round him on a leather belt from which also depended a heavy Service revolver and a knife-case. By the side of him on the rug lay a gun. He was evidently taking no risks as far as lions were concerned.

I began to have an extraordinary curiosity to see his face. Moreover I longed with a fervent longing not only to get out and sit in the warmth of those homely and attractive fires, but to speak with another human being. If he would only look up, I thought, and let me see whether or not he had an honest face! I could not trust that hat. With such a hat he might be a horse thief, an escaped convict, an I.D.B., or a pirate on a holiday, and though any of those might possibly be interesting persons to meet I felt that the time and place were hardly suitable for such a rencontre. The only thing to do was to lie perdue until I was able to come to some conclusion as to what manner of man he was. Even while I so decided he moved.

Sitting straight up he rolled the letter he had been reading into a ball and aimed it with violence and precision at the nearest fire, uttering at the same time some bad and bitter words that came quite clearly to my ears. However, I was by that time inured to bad language. Every one in South Africa uses it when they think you are not listening. Also, it is apparently the only language that mules and oxen understand for drivers never speak any other. I had become so accustomed to wicked words that I no longer took the slightest notice of them.

To my amazement I discovered that he was muttering verse to himself—bits of Stevenson:

“Sing me a song of a lad that is gone.

Say, can that lad be I?

Merry of heart he sailed on a day,

Over the sea to Skye.

* * * * *

Glory of youth glowed in his veins

Where is that glory now?”

He whipped the muffler from his neck at this and flung it down, then drove his hands into his pockets and continued his sullen chant:

“Give me again all that was there.

Give me the sun that shone.

Give me the heart, give me the eyes,

Give me the lad that is gone!”

He flung off his hat. I was able to get some idea of his general appearance then, as he passed up and down in the varying lights and shadows, and that too seemed strangely reminiscent of some one I had known. But I was disappointed to find that he didn’t look the least bit like the hero of a romance. He was not even tall. What was worse he had the most awful hair. It was black and lank like an Indian’s and distinctly thin in front, and one strand of it like a rag of black silk kept falling away from the rest and hanging down between his bad-tempered blue eyes—at least I felt sure they must be bad-tempered, and I had to come to the conclusion that they were blue, because every time he passed the fire I got a suggestion of blue. He perpetually smeared the rag of hair back from his eyes and it as perpetually fell down again. A curious thing about him was the way he moved, so softly and firmly on his feet, yet without making a sound, and when he reached the end of one of his enforced marches he swung round in the same pleasing way that the sail of a boat swings in the wind. It was hard to admit that a sort of burglar in riding-breeches could interest one by the way he walked, but I had to admit after a time, that there was a queer distinction and grace about him. He made a further remark to the stars:

“‘Give me again all that was there.’ But what for, good Lord? To let women wipe their boots on and throw in the mud! Ah, they leave one nothing! They throw down every shrine one sets up.”

I began to feel almost as safe as when the lions were prowling around.

“This terrible Africa is full of brutes!” I said to myself. “If I once get out of it, will I ever come back again? No!”

The man suddenly left off tramping, and going to each of the fires fed them in turn from a large pile of wood which he had evidently collected on arrival. Then he came to his horse and putting his arm round its neck spoke to it in a voice curiously sweet, quite unlike that in which he had been reviling women; and the horse whinnied softly to him in return.

“Dear old Belle!” he said, “you’ve had a rough time, but there’s a rest coming—a good rest coming and after that boot-and-saddle! We’ll get away from them all once more; and maybe if we have any luck, we’ll get a rest once and for all—a long, long rest—under the wide and starry sky.”

I was ashamed to hear these intimate bitter things he was confiding to his horse with his arm round her neck and his face bent. But could I help it? Only I was no longer afraid. I felt that in spite of his fierce and violent words there was nothing to fear from him.

Walking back to his rug he threw himself down once more, this time on his back, clasping his hands under his head and closing his eyes. In a few moments he was sleeping as peacefully as a child.

It really seemed after awhile that I might venture to descend. Apparently there was no danger to be anticipated from any quarter. He had guarded against lions by making fires and now he himself was asleep. There was nothing to fear but still I was horribly afraid. As quietly and carefully as possible I unknotted myself and crawled out of the cart, for I was really too stiff and weary to do anything but crawl, and when at last I stood on the ground by the step, my legs would hardly support me. However, I eventually gained the courage and strength to steal to the nearest fire and stretch my numbed fingers to the blaze. It was so big that I was able to warm myself without stooping, a fact I was intensely grateful for: I felt that I should never want to sit or kneel again for the rest of my life.

The man slept peacefully on. I could not see him clearly for the firelight dazed my eyes, but I could hear his quiet and regular breathing. Later I crept closer and gave another glance to the face I was so curious to see. At the same moment a bright flicker of light passed right over his eyes and I saw that they were open and regarding me with a wide and steady stare. Without a sound he rose to his feet.

My hands dropped to my sides, and I drew myself up to my full height, prepared (though my heart was nearly jumping out of my body) to be very calm and dignified indeed to this woman-hater who could only be nice to horses. As for him, the wind was entirely out of his sails also: he simply stood there staring at me, dumb with amazement at finding one of the hated brood of women in his camp. I might have got a good deal of malicious satisfaction out of the situation if I had not been almost stunned into confusion and astonishment myself in the revelation that the man who stood staring at me was the dark, blue-eyed man with whom I had talked about Africa three years before at the Viceregal Lodge. I recognised in a moment his extraordinarily vivid eyes with the careless lids that covered so intent a glance. And there were the little bits of blue turquoise still stuck in his ears!

I can only account for not having recognised him earlier by the fact that I had not really seen his eyes. He was one of those men whom you might pass without a glance, thinking him ordinary, until you looked in his face or he spoke to you. Then you saw at once that he was not ordinary at all, that so far from being short he was seemingly at least about three heads taller than most men, also that his hair was perfectly nice, and what was better perfectly original. In his crakey, thrilly voice he was now assuring me that he had never supposed for an instant that there was any one in the post-cart.

“And a lady, good God!—I mean it is unbelievable; but where is your driver? Do you mean to say, Madam, that you have been here alone in that cart all the evening?”

Madam! That was funny, though I did not much care about being taken for a madam. But of course he could see nothing of my face through my thick veil.

“Yes,” I said. “The driver gave me my choice between being shut into the stable with the mules or staying out here in the cart alone. I preferred this.”

“The infernal scoundrel! The—” His mouth shut, he hastily swallowed something, doubtless more profanity. “The scoundrel!” he repeated.

“The river is full. He said we could not cross to-night.”

“That is true, but his business was to make fires here and guard you. This is one of the most dangerous places in Africa. I cannot think, Madam, how you came to be on such a journey alone and unprotected. Some one is gravely to blame.”

“No, indeed,” I faltered. “No one is to blame but myself. I insisted on taking this journey against all advice. If the lions had eaten me it would have been my own fault.”

I don’t know what was the matter with me, but suddenly the remembrance of all my terrors overwhelmed me and I began to cry. I never thought I could have been so utterly silly and ridiculous, but the cause was something that I had no control over, something quite outside myself; it may have been the reaction of suddenly feeling so safe after all my misery, or that his voice was the kind of voice that stirs one up to doing things one didn’t intend to do; really I don’t know. Only, I cried quite foolishly and brokenly for a few moments like a child, and he took hold of my hands and patted them and said ever so kindly:

“There, there—don’t cry, for Heaven’s sake don’t cry—it’s all right now—you’re quite safe—I’ll take care of you. And I’ll hammer that, brute within an inch of his life to-morrow morning,” he added savagely.

He made me sit on his rug by the fire, while he went over to the cart and hauled out mail-bags and cushions and rugs, all bundled up together, and dragged them over by the fire, and in two minutes had a most delightful sort of lounge-seat ready for me. I never thought other people’s letters and parcels could be so comfortable and useful.

“Now,” said he, “have you got anything to eat or drink? I am sorry to say I haven’t a thing. I’m ‘travelling light,’ and expected to cross the river to-night and get to Madison’s for dinner.”

Of course I had a travelling basket with plenty of tinned things in it, and some stale bread. There was also tea and a little kettle which he filled from the water-bag under the cart and had over the fire in the twinkling of an eye, while I spread a napkin on the ground and laid out as invitingly as possible such provisions as I had. Then, while he was once more replenishing the fires, I pulled a little mirror from my vanity bag, and by its aid removed some of the dust which by reason of my tears had now turned to mud on my face. I arranged my veil over my hat, and my dainty, tragic brown face looked back at me from the hand-glass. I say tragic because so many people have said it before of me and I’ve got used to the word but I could never really see myself what suggested it. Only I know that I am rather original looking. I do not profess to be pretty: but I am unusual; and I have nice bones, and the shades of brown and amber in my eyes and hair are really rather charming; and I know I’ve a good line from my ear to my chin—one cannot study sculpture without getting to recognise fine lines whether in one’s self or other people.

When he came back with the kettle of boiling water, I knelt by the cloth and made the tea, while he stared at me in perfect silence. Perhaps he was surprised to see that I didn’t look much like a madam after all. He made no sign of recognition, which was rather disappointing, but I did not mind at the time as I was so frightfully hungry. So was he. There was not the faintest attempt on the part of either of us to disguise the fact that we each possessed what Dick called an “edge.” We drank our tea and fell like wolves upon the sandwiches I had made of stale bread and potted turkey. We also cleaned up a tin of sardines, about three pounds of biscuits, and a pot of strawberry jam. We ate like schoolboys and were as merry as thieves in a wood. It did not seem in the least strange to be sitting there under the stars in that wild place taking possession of a large meal with a man who did not know my name nor I his. Nothing is strange on the veldt! Besides, I felt as if I had known him all my life, even if he did not recognise me. All the same, I was aware that he never ceased to stare at me intently, with the little rag of black hair hanging between his blue eyes. He told me he was riding across country from Tuli to Fort George. He had been buying waggons and horses in the Transvaal for the Chartered Company.

“I suppose you know you have come to this part of Africa at a very bad time?” he said. “The Chartered Company is going to send an expedition into Matabeleland against Lobengula. Almost all the men in the country will be needed to fight, and while they are away in Matabeleland the ladies in Mashonaland will all be shut up in forts. That will not be very interesting. It would have been better for you to have postponed your journey until a little later.”

“Au contraire,” said I. “It is far more interesting to be in a country while history is being made than to arrive afterwards when everything is settled and dull. But why are we going to war with Lobengula?”

He laughed at the “we” which slipped in unconsciously.

“Ah! I see you are one of us already, so I can tell you all about it. Well, Loben has been behaving very badly for a long while. Ever since the Chartered Company took possession of Mashonaland he has been harassing us in various ways. But lately he has taken to serious menace. Large impis of his armed warriors have been raiding across the border laid down by agreement between the two countries, murdering the Mashonas who are under our protection, and taking up a very threatening and insolent attitude to any white men who remonstrate with him. He has paid no attention to official remonstrance, either, but broken promise after promise, so that at last we have had to take things into our own hands. If we don’t they’ll wipe out every white man in Mashonaland one of these days. So we are going to invade them and break their power once and for all. There is a chance of some interesting fighting first, though, for the Matabele are twenty thousand strong, all in fighting trim, and as ferocious as the Zulus from whom they are descended. Now, are you sorry you’ve come?”

“Not at all,” I laughed. “Afterwards, when this is all over, I may have an opportunity of seeing Lobengula’s fifty wives. That is one of my most important reasons for coming out to Africa. That and prowling lions; however, I think I’ve had more than enough of them.”

He began to laugh.

“You won’t find Lobengula’s wives very enchanting, if you do succeed in seeing them; and there are only six, by the way. But where did you get your experience of lions?”

“Here!” said I, and told him something of what I had gone through; only something. I did not think it necessary to go into details about my terror, nor to tell him I had fainted. I left him to suppose that I had been asleep when he came to camp. He looked at me keenly at this part of my story, remembering, I suppose, his pleasant remarks about women. But I returned his gaze with frank eyes.

“Ah! I heard those shots,” he said at last. “I was about two miles off then, and supposed some one was camping round here, but I could not locate them at all; no sign or smell of fire anywhere; so on finding the river full I camped here, ready to cross the drift the first thing in the morning. I looked into the post-cart, but only casually, for naturally I didn’t expect any one to be in it. I guessed that the driver had locked himself in with the mules—they usually do in such circumstances, but not when there are passengers. Those were not lions, by the way. As soon as I got here I knew by the behaviour of my horse that there had been beasts of some kind about, and when I had made fires I looked for spoor and found traces of about half-a-dozen hyenas. They must have been hungry, too, for they had chewed the mule harness to ribbons.”

He smiled at me gaily, but I felt myself turning pale.

“Hyenas! How horrible! How glad I am I did not know! I’d much rather they had been lions!”

“Thank God they were not,” he said quietly. “I’m afraid your revolver would not have been much use. Hyenas, on the contrary, hardly ever touch a human being, and are easily scared off.”

“But they laugh!” I cried, shuddering, and then sprang to my feet, for the most terrifying noise I had ever heard in my life suddenly split the stillness and rang around us. I have heard lions roar in the Zoo, and that is bad enough; but the cry of a caged lion is a dove-like call compared to the awe-inspiring, mournful, belching, hollow roar of the king of beasts when he makes his presence known to the wide and empty veldt. My companion was on his feet too.

“Don’t be afraid,” he said quietly, “but get into the cart again as quickly as possible.”

I obeyed without the least delay, another roar, closer at hand, considerably accelerating my steps. In a moment I was back in my old place on the floor; and he was swiftly untethering the horse from the back of the cart, to fasten it in front, more fully in the glare of the fires. Then he stepped into the driver’s place, and half-sitting, half-stooping, laid his rifle across the splash-board, right over the horse’s head. We waited.

“Don’t make a sound,” he said over his shoulder. There was no alarm in his voice, but rather a kind of gay elation, and my fear immediately died away. I began to watch and listen with interest for what was to happen next. There were no more roars, only an ominous stillness, that was broken presently by the restless moving and shuddering of the horse. The poor beast began to try to break loose and get away, but its master leaning forward, spoke to it in a soothing gentle voice, and the terrified creature was presently quiet, except for an occasional shudder that it could not control.

Silence again for a time that seemed hours, then at last the click of a broken twig that sounded to my straining ears like a pistol shot. There was just the faintest suspicion of a rustling of leaves. An instant later something in my companion’s intent gaze and attitude told me that the psychological moment had come. He could see something, and was taking aim. I glanced at the dim, shadowy mass of foliage towards which his rifle pointed, and for one moment saw nothing. Then something huge and pale and massive came bounding high in the air out of the shadows, and the horse cried out like a human being. The Martini-Henry cracked twice and a blinding flash of gunpowder filled the air. Later I heard my friend’s voice speaking to his leaping horse and as the smoke died away my dazed eyes saw lying stretched between the fires something that had not been there before. The only sounds to be heard were the creaking of the cart caused by the shudderings of the horse, and the chattering of my teeth. I don’t know which was the louder. But I know that I crouched beside the man’s knee and was grateful and glad for one of his strong brown hands on mine, and his crakey, thrilly voice saying close to my ear:

“There is no danger. Only we must be quiet. There’s probably another of them about. I should like to pot him too.”

Needless to say, I sat still with all my might. The great honey-coloured body fascinated my eyes, but there was something extraordinarily reassuring in the scent of mingled gunpowder and tobacco that hung about the grey flannel sleeve so close to me. We sat in silence for what must have been nearly an hour and nothing happened: no more roars, no sound anywhere but the far cry of the jackal, and the rush of the river. It was my companion who at last broke the spell, speaking in a low, absent voice, almost like a man in a reverie.

“So you have come to Africa after all, Miss Saurin!”

I could hardly believe my ears were not playing me false. It seemed the strangest thing of all the strange things that had come to pass that night that he should know my name and speak it thus. He had recognised me after all, then! In the same voice of gentle reverie he spoke again, staring not at me but straight before him.

”—And this is the way she receives you!”

“You know my name?” I faltered.

“Of course. Do you think I could ever forget your face?”

I felt my cheeks grow hot. I was not unused to hearing men say charming, flattering things, and I knew very well how to parry them. But there was something so unusual in the quiet serenity of this man’s words and the vibration of his beautiful voice that I could not lightly turn aside his strange answer. I am all woman, too, and could not refrain from feeling a little thrill of pleasure in what he said. It is surely something rather sweet to be remembered for three years by a man to whom one has spoken only once, for a few minutes, in a crowded ball-room.

“And that dance—I think you remember the dance we had together—and our talk of Africa. You said you would love to come out here, and I told you then you surely would. I think you must remember?”

There was something so appealing and yet compelling in his question that I felt obliged to answer him sincerely, though such worldly wisdom as I possessed strongly counselled me to do otherwise.

“Yes, I have always remembered,” I said, and found myself remembering other things, too, vividly: the way his words had moved me, the way my lids had fallen under his strong glance.

“And you are still Miss Saurin? Deirdre Saurin?”

It would be impossible to describe the beauty and gentleness of his voice as he so unexpectedly spoke my name. It sounded almost as if he were blessing me.

“You did not many Herriott after all? But you could not have, or he would be here. No man who married you would ever leave your side.”

That was ridiculous, of course. I felt it was ridiculous, but he said it so convincingly that I almost believed it. In fact, I was obliged to recognise that this man was very convincing indeed. You could not treat his remarks with the indifference they deserved, even if you wanted to. However, there was one thing I felt I ought to make clear to him, though it was rather embarrassing to say these things.

“I think as you know so much,” I stammered, “you ought to know a little more. I was never engaged to Lord Herriott.”

“But I was told by two different people that night, both relatives of his, that you were engaged; that the announcement was to be made immediately.”

“They had no right to say so,” I said firmly. “We were never engaged.”

“Will you tell me that he never asked you to marry him?”

“I cannot tell you more than I have,” I answered rather stiffly.

“And you think it insolence on my part to ask so much?” His voice had gone back to reverie and his eyes to the dying fires. “Do not think that, Miss Saurin. Insolence has no place near you in my mind and memory. It was no business of mine I suppose whether you refused Herriott, or why. In any case I should have left Ireland at once as I did. Only—I wish to God I had known in all these years.”

I had to realise at last that this man was making love to me, and that the fact aroused in my heart neither anger nor indignation. I felt not the slightest disposition to reprove him, but rather to go on sitting there for ever listening to his strange burning words and vibrating voice. It seemed to me suddenly that I was listening to an old song I had known all my life, but had never before heard set to music. My heart began to flutter like a wild bird in my breast and a trembling thrilled me unlike any trembling I had known through the past hours of darkness and fear. A faintness stole over my senses. I, too, had kept my gaze straight before me while we talked, but now, while I felt myself growing pale to the lips with some strange emotion, I turned my eyes his way and found him looking at me. Glance burnt glance. His blue, intent eyes searching in mine as if for something that was his. Mine reading in his—I know not what—something I had long known dimly but dared not recognise. In that moment I realised why I had come to Africa. I knew why I had refused Herriott. It was for the sake of seeing again this strange man with the voice that pulled at my heart-strings and the burning eyes that searched in mine as if for something that was his. And now, alone with him in this wild and desolate spot, where conventions and all the superficialities of life fell sheer away, and left us just simple man and woman, I was afraid of the poignant sweetness and wonder of it. I was afraid for my immortal soul.

For the second time that night, and half unconsciously, I put up my hand, and as do all good Catholics in the supreme moments of life, crossed myself. I hardly knew what I had done until I found my right hand touching the shoulder nearest him and almost as if in answer to my action, which he could not have failed to observe, he lifted his hand, which still lay upon my left hand, and pushed back from his eyes the fallen streak of hair. Afterwards he did not replace it, though mine still lay where he left it.

“You are a Catholic?” he said abruptly.

“Yes, the Saurins have always been Catholics,” I answered. Then a silence fell between us that I feared. For some reason I did not understand, I began, in a voice at first a little strained and uncertain, to tell him of the love there had always been in my family for the beautiful old faith, of how much its forms and ceremonies meant to even the most irreligious of us. I told him legends of long-dead rakes and scamps among my paternal ancestors who, forsaking their sins, had gone from their own country to fight for the faith they loved in other lands. How never a Saurin for three centuries had died without a scapular about his throat and a De profundis on his lips. I told him how my mother, coming of a rigid Protestant American family, had yet, for love of my Irish father, embraced his faith with all the fervour of the convert, and taught me to love it as she did herself. I told him things, I knew not why, that had never been told out of my family before. Whether he was interested in my facts or the soft and even flow of my voice I cannot say, but the sweet and dangerous silence was dispersed, and a kind of fragrant peace fell around us, cooling our hands and quieting our hearts.

“Catholicism was the faith of my fathers, too,” he said at last, “but I suppose we fell away from it through wandering far from our own land. I have never practised Catholicism or anything else. What religion the love of my mother put into my heart is there still, and I recognise it in great moments—at this moment—but oh, Lord! Where do these things go? The clean, fair dreams of our youth, the fine visions we began to fight with, the generosity wide as the horizon! All lost in the scuffle, buried under the mud and scum. Do you know that tag of verse—

“‘In the mud and scum of things

Something, something always sings?’

“It is something, I suppose, in the end, if we still can hear the singing. There is some rag of grace left in us, perhaps, if we can recognise a man like Rhodes when we see him, and, leaving all, go after him into the wilderness to do or die for a man with bigger dreams than our own—but it isn’t much, by God! considering what dreams we ourselves set out with!”

He seemed for the moment to have forgotten me, and to be communing with the desolation of his own soul. I offered him no word. Something told me then, that no woman can quite comfort a man for his lost dreams. At the best she may be able to create others for him; but surely they are never quite the same as those first dreams that had the freshness of the morning on them. Even as I mourned for him his mood changed, and he laughed with a laugh that turned him into a joyous boy.

“Listen to the river!” said he, laughing. “Listen to the jackals chanting their dirge of the empty stomach! Smell the rolling leagues of emptiness! Look at that beauty lying there in the grass! Oh, I tell you, this is good enough for a man! One can get back some of the old fair visions here. One might even go back to the ‘gold for silver’ creed that Whyte Melville put into some of us long ago!”

“The ‘gold for silver’ creed?”

“Do you not know your Bones and I? They were the last of my prophets.”

He began to misquote, laughing a little, but without any bitterness at all now:

“Gold for silver: old lamps for new: stack your capital in the bank that in the end pays cent for cent—the bank of human kindness, where the bonds are charity, help to the broken-down, sympathy with the bust-up, protection to the weak-kneed, encouragement to the forlorn, etc; and afterwards the inscription on your tomb or in some one’s memory:

“‘What he spent he had: what he saved he lost! What he gave he has.’

“Ah! what a long time since I heard those words, and believed that any one could be such a fool as to try and live up to them!”

“How can you say that?” I said. “It is still your creed. If ever any one protected the weak-kneed and encouraged the forlorn you have done it to-night.”

At that we both began to laugh. The shadows had fled from his brow, and his face had no more marks on it than Dick’s when he and I played together as children. Indeed, we were both as happy as children. Later he stepped down from the cart to feed the fires and fetch my rugs from where they still lay on the ground. He wrapped them round me, for the air had grown very chill, and told me to sleep. And I did, for the heavy weariness of the small morning hours had suddenly stolen upon me.

When I awoke the stars were pale in the sky, and dawn, with pearl and purple and amber on her feet, was treading the distant hills. A long line of red-legged birds streaked overhead, calling to each other as they passed. The rush of the river, which could now be plainly seen glinting between the trees, was like music on the air. A cloak of silver dew lay over grass and fern and the massed foliage of the bush; and little veldt flowers were lifting their pink faces to give forth a sweet scent. Against the faint rose and amber of the horizon a blue spiral of smoke ascended from a newly-built fire, on which the kettle was already boiling for breakfast. The only grim thing to be seen in all that fair place was the long, honey-coloured body of the dead lion, stretched upon the carpet of grass and flowers. His great shaggy head lay amidst a mass of bright wild lilies: but already little beetles and ants were busy about his blood-reddened mouth and open eyes. It was the only joyless thing to be seen, but it had no power to sadden me. I, too, was full of the glad spirit of morning, and my singing heart gave thanks as it had never done before for the magic gift of life.

Chapter Three.

Cats’ Calls.

“Originality, like beauty, is a fatal gift.”

Once more I was alone in the coach with my driver, moving onwards towards my destination—Fort Salisbury. In an hour or two I should reach Fort George, which was only a day or so from my journey’s end. My new driver, also a Cape boy, was a big, honest-looking fellow named Hendricks, one of the most trusted men in the coach service, and possessing no traits in common with the last man, except a vocabulary and an affection for “cold tea.” This man had been waiting at the other side of the river with fresh mules and another cart the morning after my adventurous night on the banks of the Umzingwani. The river had been still too full to cross by cart, so a wire apparatus for slinging mails and passengers from one bank to another had been brought into requisition. My new friend and the driver (grown curiously meek and submissive after I know not what threats and imprecations flung at him in an unknown tongue when he emerged from his fastness into the light of day) then engaged together in furthering a nerve-racking business of which I was to be the chief victim. First the mails were taken out and divided into lots weighing about 130 pounds, then each lot was placed in a sort of canvas bucket and slung across the broad sweeping stream on a piece of wire about the thickness of a clothes-line. When all the mails were over, and my luggage, I thought my turn had come and advanced with what I hoped was a nonchalant air (though my knees were trembling under me) to my fate. But the blue-eyed man was already in the bucket and whizzing across the stream. Half-way over the wire sagged hideously, and the sack touched the water. I closed my eyes with a sick feeling, and when I opened them again it was to see him just starting to recross. As he jumped from the bucket on my side of the river once more, I realised that he had been trying the wire for me. Then my nonchalance was not all assumed, as I took my turn in the horrible contrivance, for what had carried him would surely bear me safely. All the same, it was sickening to feel the slither of the bag on the wire, to see the grey-yellow water shining beneath me smooth and waveless as a mighty torrent of cod-liver oil, to experience the sag in midstream and the extra jerk of the wire to overcome it. I confess that at that moment I was not captain of my soul. I was not captain of anything, even the canvas bag! I should have given up the ghost if I had not known that a strong brown hand was on the wire, and blue keen eyes watching every movement. I think it was the most effarouchant of all my experiences, and I was still rather limp when he, having crossed once more, came to me standing by the new post-cart. He held out his hand.

“But what are you going to do?” I asked in surprise.

“Going back across the river,” said he. “I have just come over to say good-bye.”

“Are you not coming on too?”

“Not just yet. First I have a little business to transact on the other side. Later, I shall take my horse and swim a drift I know of about three miles lower down.”

I stared at him in astonishment. What business could he possibly have on the other side of the river, unless it was to skin the lion? Then I suddenly remembered his threatening words about the driver the night before, and the man’s meek mien that morning.

“I hope you are not going to beat the driver,” I said quickly.

“Good-bye,” said he, still holding out his hand.

It naturally annoyed me to have my remarks ignored in that way. I looked at him coldly.

“You will please not hurt the man on my account,” I said stiffly.

“Then I must hurt him on my own,” he calmly replied. “These men have to be taught their duty to white ladies.”

It vexed me curiously to think that he should so resent having been left alone with me all night that he must needs punish the driver for it.

“I hate brutality,” I said. “The thought of one man hitting another makes me feel sick. I think you are very vindictive.”

“I am sorry,” said he, but there was not the faintest trace of sorrow anywhere about him; in fact, he was smiling me hardily in the eyes and I saw that he had every intention of beating the man in spite of my wishes. I turned away from him to hide the vexation that surged through me, and began to arrange my rugs in the cart, but when I had finished he was still there, and with something further to remark.

“Miss Saurin, I hope you will pardon me for saying that it would be unwise of you to let any one know that your last night’s vigil included my society.”

That was really too much! I stared at him haughtily, utterly taken aback by such a remark and its inference. But he met my eyes quite unabashed. It occurred to me at the moment that he had probably never been abashed in his life, and the idea did not please me.

“I’m afraid I do not quite understand you,” I said at last in a frozen voice, “but if it is that you do not wish me to boast of having made your acquaintance—I can assure you that you need have no fear.”

Even his hardened pelt was pierced at last, though he tried to hide the fact under a sardonic grin that did not become him in the least. He threw back his rag of black hair—a sign of battle I was beginning to recognise.

“Hardly that. I was merely proffering a little friendly advice, but I remember now that you do not take kindly to advice—or you would not be here.” He grinned again, and I flushed with anger. After the terrors of the past night to fling the advice of people like Elizabet von Stohl into my teeth!

“I believe myself perfectly capable of minding my own affairs,” I said. “Further, I very much resent your inference that people would dare to talk scandal about me.”

“Evidently you do not know people as well as I do.” I merely looked over his head. “Certainly you will allow that I know my own reputation better.”

There was an opening for a dart, and I flung one with all my might.

“That is a matter that does not interest me. I do not even know your name, and probably never shall.”

But do you think that crushed him? No! “Oh, you will hear it,” he said with his careless smile, “‘blown back upon the breeze of fame,’ perhaps—of a kind. In any case we are bound to meet again.”

“Oh, will it be necessary?” I said, driven to open rudeness by his imperturbability, which I considered very much like insolence. “Will it really be necessary if I thank you now for—for the services you have been so extremely kind as to render me?” His withers remained unwrung. “You cannot escape meeting even your open enemies in this country. And it will indeed be necessary to me, even if I thank you now for the most wonderful night of my life.”

Without waiting for any newly-barbed darts I might or might not have had ready, he swiftly departed, leaving one last hardy blue smile in my eyes. A moment later he was slithering across the river on the screeching, wriggling wire.

We had left the bare, bleak kops and tall strange trees of Bechuanaland far behind now, and had crossed the last of its wild and fearful rivers. Everywhere about us stretched level country, which gave a curious impression of the sea, for the thick, hay-like grass, bleached almost to whiteness and as high as a man’s waist, swayed perpetually like pale waves. Even when the land seems a heated brazen bowl and the upper air is faint and heavy with breathlessness the veldt grass has some hidden air, some “wind from a lost country,” flitting amongst it making it sway and gently whisper.

Patches of trees grew against the horizon, but they were short and scrubby and in the nature of “bush,” though occasionally one was to be seen by itself, sprayed like an ostrich feather upon the skyline. Others, of a singularly gnarled squat type, sent all their branches up to a certain height and then flattened them out and wove them together so that the top of the tree presented the appearance of a strong, but rather stubbly, spring-mattress.

Far away on the edge of the landscape, never seeming to come nearer or recede farther, was the usual line of amethyst hills. Nearer hills were saffron coloured, and some turning pale pink in the evening light. Everywhere the eye was feasted with colour. Sard-green bushes stretched branches like candelabra high above the pale grass, and from each branch sprouted forth flowers that were like leaping scarlet and yellow flames. Creepers that had great black-pupilled crimson eyes hung from trees; and purple clematis, tangled with “old man’s beard” and some waxen white flower that gave forth an odour like opopanax, dripped and clung from huge rocks that, standing alone, looked as though they had jerked themselves loose from some mighty mountain of the moon, and dropped abruptly into the silence and solitude of this wild place. Sometimes an enormous boulder with a massive flat top would be balanced on a single narrow point, showing like a miniature Table Mountain set amongst seas of swaying grass. I imagined it would be very pleasant to sit on one of them, high above the dust and the unfragrant odour of the mules, but the rocky sides looked steep and inaccessible; and my fate was still to swaggle wearily across the landscape.

I was so tired that even the glorious hues of sunset could not comfort my soul. I drank them in, it is true, but I would rather at that time have had a cup of tea. My skin was parched with heat and dust, and I was wearied to death of being bumped and banged and sitting crumpled up in a ball.

The driver had put back the hood of the cart so that we might get what air was going, but when suddenly some large, drops of rain began to fall on me I felt, like Job, that my sorrows were too many.

“Driver!” I cried, “you don’t mean to tell me that it is now going to rain!”

“Ach! That’s nixney,” he replied. “We’ll be in Fort George before ten minutes. See the lights? Vacht till I wake them up.”

He produced the post-horn, and I hastily stopped my ears, but that did not prevent me from hearing the series of frightful blares that he gave forth. The noise cheered the mules, and they took heart of grace and threw themselves into a last desperate run. The road became smoother and the barking of dogs could be heard. I slipped on my coat and tied the ends of my veil under my chin into a big enough bow to hide behind, for I had learnt with diminishing enthusiasm what it meant to be an occupant of the mail-coach, arriving in a small township in the African wilds. I well knew that every man, woman, and dog in the place would be there to meet and examine me with curiosity. I rather liked it at first, when I could still contrive to be fresh and uncrumpled after a day amongst the mail-bags. But after a fortnight in one gown, my face decorated with tan and mosquito bites, and absolutely a crack in my best lip (the top one, of course, though the other one is charming, too) I naturally did not feel ardent about meeting a lot of people. I held a hasty consultation with the driver between his yells at the mules.

“You say there is a good hotel here, Hendricks?”

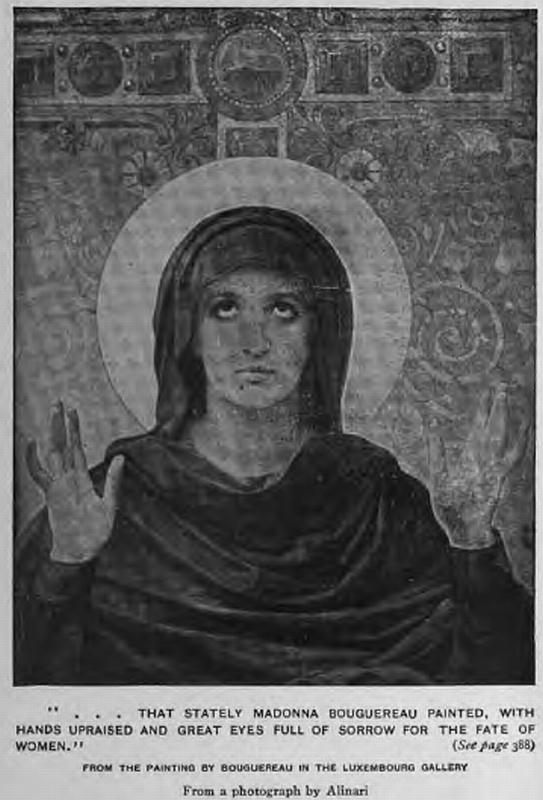

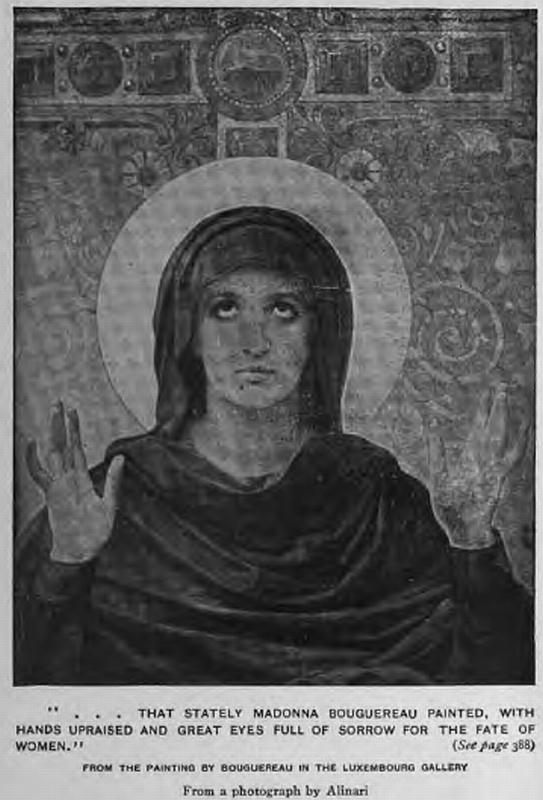

“Yah, Miss... there’s the Queen’s... and Swears’s Hotel... Mr Swears is a very good Baas... keeps a very nice bar, and a good brand of dop.”