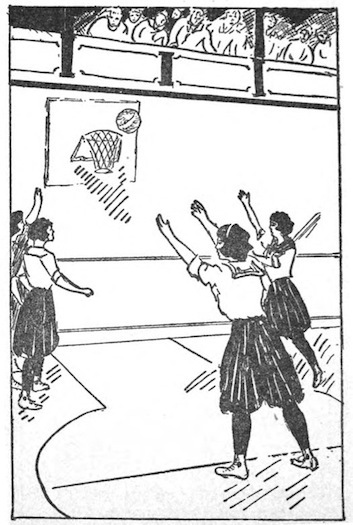

THE BALL ROSE AND FLEW DIRECTLY AT THE BASKET.

Title: The Girls of Central High at Basketball; Or, The Great Gymnasium Mystery

Author: Gertrude W. Morrison

Release date: November 2, 2011 [eBook #37912]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Print project.)

THE BALL ROSE AND FLEW DIRECTLY AT THE BASKET.

CONTENTS:

The referee’s whistle sounded sharply, and the eighteen girls of Central High engaged in playing basketball, as well as an equal number strung along the side lines, stopped instantly and turned their eyes on Mrs. Case, the physical instructor.

“Hester Grimes! you are deliberately delaying the game. I have reprimanded you twice. The third time I will take you out of the team for the week——”

“I didn’t, either!” cried the person addressed, a rather heavily built girl for her age, with a sturdy body and long arms—well developed in a muscular way, but without much grace. She had very high color, too, and at the present moment her natural ruddiness was heightened by anger.

“You are breaking another rule of the game by directly addressing the referee,” said Mrs. Case, grimly. “Are you ready to play, or shall I take you out of the game right now?”

The red-faced girl made no audible reply, and the teacher signalled for the ball to be put into play again. Three afternoons each week each girl of Central High, of Centerport, who was eligible for after-hour athletics, was exercised for from fifteen to thirty minutes at basketball. Thirty-six girls were on the ground at a time. Every five minutes the instructor blew her whistle, and the girls changed places. That is, the eighteen actually playing the game shifted with the eighteen who had been acting as umpires, judges, timekeepers, scorers, linesmen and coaches. This shifting occupied only a few seconds, and it put the entire thirty-six girls into the game, shift and shift about. It was in September, the beginning of the fall term, and Mrs. Case was giving much attention to the material for the inter-school games, to be held later in the year.

Hester Grimes had played the previous spring on the champion team, and held her place now at forward center. But although she had been two years at Central High, and was now a Junior, she had never learned the first and greatest truth that the physical instructor had tried to teach her girls:

“Keep your temper!”

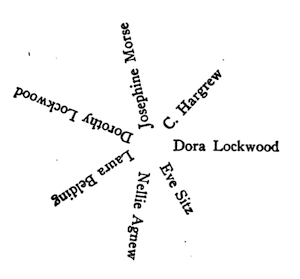

Since spring several of the girls playing on the first team of Central High had left school, graduating as seniors. The work now was to whip this team into shape, and finally Mrs. Case and the girls themselves, voting upon the several names in their capacity as members of the Girls’ Branch Athletic League, had settled upon the following roster of names and positions as the “make-up” of the best-playing basketball team of Central High:

Josephine Morse, goal-keeper

Evangeline Sitz, right forward

Dora Lockwood, left forward

Hester Grimes, forward center

Laura Belding, jumping center

Lily Pendleton, back center

Dorothy Lockwood, right guard

Nellie Agnew, left guard

Bobby Hargrew, goal guard

The basketball court of Central High was located in the new Girls’ Athletic Field, not far from the school building itself, and overlooking beautiful Lake Luna and the boathouses and rowing course. At the opening of Central High this fall the new field and gymnasium had first come into use.

The athletic field, gymnasium and swimming pool were the finest in the State arranged for girls’ athletics. They had been made possible by the generosity of one of the very wealthy men of Centerport, Colonel Richard Swayne, and his interest in the high school girls and their athletics had been engaged by one of the girls themselves, Laura Belding by name, but better known among her schoolfellows and friends as “Mother Wit.”

The play went on again under the keen eye of the instructor. Mrs. Case believed most thoroughly in the efficiency of basketball for the development and training of girls; but she did not allow her charges to play the game without supervision. Lack of supervision by instructors is where the danger of basketball and kindred athletics lies.

The game is an excellent one from every point of view; yet within the last few years it has come into disfavor in some quarters, and many parents have forbidden their daughters to engage in it. Like bicycling in the past, and football with the boys, basketball has suffered “a black eye” because of the way it has been played, not because of the game itself.

But the Girls’ Branch played the game under sound rules, and under the keen oversight of the instructor engaged by the Board of Education of Centerport for that purpose. Basketball is the first, or one of the first vigorous team games to become popular among women and girls in this country, and under proper supervision will long remain a favorite pastime.

The rules under which the girls of Central High played the game were such as brought into basketball the largest number of players allowed. Whereas there were often in the games on Central High courts only right forward, left forward, center, right guard and left guard, with possibly a jumping center—these games being engaged in by the girls for their own amusement—in the regular practice and when the representative team played the teams of other schools, the girls on the field numbered nine upon a side.

Thus conforming with the new rules, Mrs. Case, and the physical instructors of the other highs of Centerport and the neighboring cities, made the interest in basketball more general and enabled a greater number of ambitious girls to gain coveted positions on the first team.

Suddenly Mrs. Case’s whistle stopped the play again. And as the bustle and activity subsided, two girls’ voices rose above all.

“You just see! It’s only Hester who gets scolded——”

“It’s not so! If she’d play fair——”

“Miss Pendleton and Miss Agnew are discussing something of much importance—much more important than the game,” said the referee, tartly.

“Well, she said——” began Nellie Agnew, who was usually a very quiet girl, but who was flushed and angry now as she “looked daggers” at Lily Pendleton, who was Hester Grimes’s chum.

“That will do, Nellie!” exclaimed the instructor. “You girls evidently have not taken to heart what I have been telling you. The only way to play this—or any other team game—is to work together and talk as little as possible. And by no means allow your tempers to become heated.

“We have formed a new line-up for the fall series of games with East and West High, and the highs of Keyport and Lumberport. It would be too bad to change the make-up of the team later; but I want girls on our champion team, who play the first class teams of other schools, who know how to keep cool and to keep their mouths shut. Now! don’t let me have to repeat this again to-day at least. Time!”

Hester Grimes turned and gave Nellie Agnew an angry look and then went on playing. The girls officiating at the lines changed with the actual players. Later they shifted again, which brought the first team into the field once more with the ball.

When the practice was over Mrs. Case stopped Hester Grimes before she could run off the field. She spoke to her in a low voice, so that no other girl could hear; but she spoke firmly:

“Hester, you are making a bad impression upon the teachers as well as on the minds of your fellow pupils by your indulgence in bad temper.”

“Nobody else calls me down for it but you, Mrs. Case,” declared the big girl, bitterly.

“You are a good scholar—you do not fail at your books,” Mrs. Case continued, quietly. “You do not have occasion in the classroom to often show your real disposition. Here, in matters of athletics, it is different. Your deportment does not suit me——”

“It never has, Mrs. Case,” exclaimed the red-faced girl. “You have criticized me ever since you came here to Central High——”

“Stop, Hester! How dare you speak that way to a teacher? I shall certainly report you to Mr. Sharp if you take my admonition in such a spirit. I have finished with you. If you do not show improvement in deportment on the athletic field I shall shut you out of practice entirely.”

The instructor spoke sharply and her face was clouded. She was a very brisk, decisive woman, and she considered that she had been patient with Hester Grimes long enough.

Hester was the only daughter of a very wealthy wholesale butcher, and from her babyhood had been indulged and given her way. She was one of those girls who fairly “boss” their parents and everybody around their homes. She had bought the friendliness of some weak girls by her display and the lavish use of spending money. Perhaps, however, Lily Pendleton was really the only girl who cared for Hester.

Most of the girls who had been relieved from basketball practice had run in to change to their street clothing. On the lower floor of the gymnasium building was the swimming pool, shower baths, and dressing room, besides the lockers for field materials, the doctor’s and instructor’s offices, and the hair-drying room. Above was the gymnasium proper with all the indoor apparatus allowed by the rules of the Girls’ Branch.

Each girl had her own locker and key, the key to be handed in at the instructor’s office when she left the building. When Hester came into the long dressing room there was a chatter of voices and laughter. There was no restriction on talking in here.

Lily met her chum at the door. The former was naturally a pale girl, rather pretty, but much given to aping fashions and frocks of grown women.

“I’d like to box that Bobby Hargrew’s ears,” she said, to her angry chum. “She was just saying that you’d queer the team again before you got through. She’s always hinting that you lost that last game we played East High last spring.”

“I’ll just fix her for that—the mean little thing!” snapped Hester, and being just in the mood for quarreling she stalked over to where little Clara Hargrew was talking to a group of friends, among whom were Nellie Agnew and the Lockwood twins.

“So you’re slandering me, as usual, are you, Miss?” demanded Hester, her face very fiery and her voice very loud.

“Meaning me?” demanded Bobby, shaking her curly head, and grinning impishly at the bigger girl.

“Who else would I mean, Miss?” pursued Hester.

“I couldn’t slander you, Hessie,” said the mischief-loving Bobby.

“You are a trouble-maker all the time, Bobby Hargrew——” began the older girl, but Bobby broke in with:

“If I made anywhere near as much trouble as you do about this gymnasium, Hessie, I’d talk soft.”

“Now, Bobby,” cautioned Nellie Agnew, laying a quick hand upon the smaller girl’s arm and drawing her away.

But Hester, quite beside herself, lifted her palm and struck at Bobby. Perhaps the agile girl dodged; or maybe Nellie deliberately stepped forward. Anyhow, the stroke intended for Bobby landed full upon Nellie’s cheek. Hester was strong and her hand heavy. The print of her palm left a white patch for a moment upon the plump cheek of the doctor’s daughter.

“Now you’ve done it, Hessie!” cried Bobby, angrily. “See what you’ve done!”

“I didn’t——” began Hester, rather startled by the result of her blow; but the tears of anger and pain had sprung to Nellie’s eyes and for once the peacemaker showed some spirit.

“It served you just right! You’re always interfering,” flashed out Hester.

“You are a bad and cruel girl,” said Nellie, sobbing, but more in anger than pain.

“Bah! you run and tell Mrs. Case now. That will be about your style.”

“I shall tell my father,” said Nellie, firmly, and turned away that her enemy might not exult longer in her tears.

“And he’s our physician and I guess he’ll have something to say about your actions, Hessie!” cried Bobby Hargrew. “You’re not fit to play with nice girls, anyway.”

“And you’re one of the ‘nice’ ones, I suppose, Miss?” scoffed Hester.

“I hope I am. I don’t lose my temper and queer my team-mates’ play. And nobody ever caught me doing mean things—and you’ve been caught before. If it wasn’t for Gee Gee favoring you, you’d have been asked to leave Central High before now,” cried Bobby.

“That’s so, too,” said one of the twins, quite as angry as Bobby, but more quietly.

“I should worry!” laughed Hester, loudly and scornfully. “What if I did leave Central High? You girls are a lot of stuck-up ninnies, anyway! I hate you all, and I’ll get square with you some day—you just see if I don’t!”

It was perhaps an empty threat; yet it was spoken with grim determination on Hester Grimes’s part. And only the future could tell if she would or would not keep her promise.

The Girls’ Branch Athletic League of Central High had been in existence only a few months. Gymnasium work, folk dancing, rowing and swimming, walking and some field sports had been carried to a certain point under the supervision of instructors engaged by Centerport’s Board of Education before the organization of the girls themselves into an association which, with other school clubs, held competitions in all these, and other, athletics for trophies and prizes.

Centerport, a lively and wealthy inland city located on the shore of Lake Luna, boasted three high schools—the East and West Highs, and the newer and large Central High, which was built in “the Hill” section of the town, the best residential district, on an eminence overlooking the lake and flanked on either side and landward, as well, by the business portions of the city. The finest estates of the Hill district sloped down to the shore of the lake.

Public interest had long since been aroused in the boys’ athletics; but that in girls’ similar development had lagged until the spring previous to the opening of our story.

In the first volume of this series, entitled “The Girls of Central High; Or, Rivals for All Honors,” was related the organization of the Girls’ Branch, and the early difficulties and struggles of a group of girl sophomores, most of whom were now on the roster of the basketball team as named in our first chapter. Laura Belding was the leading character in that first volume, and her quick-wittedness and loyalty to the school and to the athletic association really brought about, as has been intimated, the building of a fine gymnasium for the girls of Central High and the preparation of the athletic field connected therewith.

In “The Girls of Central High on Lake Luna; Or, The Crew That Won,” the second volume of the series, was narrated the summer aquatic sports of the girls and their boy friends; and in that story the Lockwood twins, Dora and Dorothy, came to the fore as champion canoeists among the girls, as well as efficient members of the crew of the eight-oared shell, which won the prize cup offered by the Luna Boat Club to the champion shell rowed by high school girls.

Lake Luna was a beautiful body of water, all of twenty miles in length, with Rocky River flowing into it from the west at Lumberport, and Rolling River carrying off her overflow at the east end of the lake, where stood the third of the trio of towns—Keyport. Both Lumberport and Keyport had a well conducted high school, and the girls in both were organized for athletics as were the three chief schools of Centerport.

South of Centerport was a range of low hills, through which the two railroads which tapped the territory wound their way through deep cuts and tunnels. In the middle of the lake was Cavern Island, a very popular amusement park at one end, but at its eastern end wild and rocky enough. The northern shore of the lake was skirted by farms and deep woods, with a goodly mountain range in the distance.

The girls who had been in the first class at basketball practice began to troop out of the gymnasium in their street apparel. Chetwood Belding and his chum, Lance Darby, were waiting for Laura and Jess Morse. With them was a gangling, goose-necked youth, dressed several degrees beyond the height of fashion. This was Prettyman Sweet, the acknowledged “glass of fashion and mould of form” among the boys of Central High.

“Hullo! here’s Pretty!” cried Bobby Hargrew, dancing out behind Laura and Jess. “You’re never waiting to beau me home, are you, Mr. Sweet?”

“I—oh—ah——” stammered Purt, in much confusion. “It weally would give me pleasure, Miss Bobby; but I weally have a pwior engagement—ah!”

Just then Hester and Lily came out of the door. Bobby dodged Hester in mock alarm. Lily stopped in the shelter of the doorway to powder her nose, holding up a tiny mirror that she might do it effectively, and then dropping both mirror and “powder rag” into the little “vanity case” she wore pendant from her belt.

Purt Sweet approached Miss Pendleton with a mixture of diffidence and dancing school deportment that made Bobby shriek with laughter.

“Oh, joy!” whispered the latter to Nellie, who appeared next with the Lockwood twins. “Purt has found a shrine before which to lay his heart’s devotion. D’ye see that?” pointing derisively to Lily and young Sweet turning the first corner.

Hester was strolling away by herself. Nellie said, quickly:

“Let’s not go this way. I don’t want to meet that girl again to-night.”

“Much obliged to you, Nell, for taking my slapping. But Hester never really meant to hit me, after all. You got in the way, you know.”

“You’d better behave,” said one of the twins admonishingly. “You made this trouble, Bobby.”

“There you go!” cried Bobby, with apparent tears. “Nobody loves me; Hester tried to slap me, and Pretty Sweet wouldn’t even walk with me. Oh, and say!” she added, with increased hilarity, “what do you suppose the boys are telling about Pretty now?”

“Couldn’t say,” said Dora Lockwood. “Something ridiculous, I venture to believe.”

“It’s funny,” giggled Bobby. “You see, Purt thinks he’s really getting whiskers.”

“No!” exclaimed Dorothy.

“Sure. You watch him next time you have a chance. He’s always feeling to see if his side-tapes have sprouted. He has got a little yellow fuzz on his upper lip—honest!

“Well, Purt went into Jimmy Fabro’s shop the other day—you know, that hair-cutting place right behind Mr. Betting’s store, on the side street? Well, Purt went in and took a chair. Jimmy was alone.

“‘What you want—hair cut again this week, Pretty?’ asked Jimmy.

“‘No—o,’ says Purt. ‘Sh—sh—shave.’

“Jimmy grunted, dropped back the chair, muffled Purt up in the towels, and then squinted up and down his victim’s cheeks. Finally he mumbled something about being ‘right back’ and ran into Mr. Belding’s and came back with a watchmaker’s glass stuck in his eye. Then he squinted up and down Purt’s face some more and finally mixed a big mug of lather—and lathered Purt’s eyebrows!”

“Oh! what for?” demanded Dora Lockwood.

“That’s what Purt asked him,” giggled Bobby. “Jimmy said in his gruff way:

“‘I’m hanged if I can see hair anywhere else on your face, Pretty. You want your eyebrows shaved off, don’t ye, Pretty?’ So, Chet says, Purt’s been trying to shave himself since then in a piece of broken mirror out in the wood shed, and with a jack-knife.”

Although Nellie Agnew laughed, too, at Bobby’s story, she was in no jolly mood when she parted from the other girls and entered Dr. Agnew’s premises.

The doctor, Nellie’s father, was a broadly educated physician—one of the small class of present day medical men who, like the “family doctor” of a past generation, claimed no “specialty” and treated everything from mumps to a broken leg. He was a rather full-bodied man, with a pink, wrinkled face, cleanly shaven every morning of his life; black hair with silver threads in it and worn long; old-fashioned detachable cuffs to his shirts, and a black string tie that went around his collar twice, the ends of which usually fluttered in the breeze.

There had long since been established between the good doctor and his daughter a confidential relation very beautiful to behold. Mrs. Agnew was a very lovely woman, rather stylish in dress, and much given to church and club work. Perhaps that is why Dr. Agnew had made such a comrade of Nellie. She might, otherwise, have lacked any personal guide at a time in her life when she most needed it.

It was no new thing, therefore, that Nellie should follow the doctor into the office that evening after dinner, and perch on the broad arm of his desk chair while he lit the homely pipe that he indulged in once a day—usually before the rush of evening patients.

When Nellie had told her father all about the unpleasant quarrel at the gymnasium the doctor smoked thoughtfully for several minutes. Then he said, in his clear, quiet voice—the calm quality of which Nellie had herself inherited:

“Do you know what seems to me to be the kernel in the nut of these school athletics, Nell?”

“What is it, Daddy Doctor?”

“Loyalty. That’s the kernel—loyalty. If your athletics and games don’t teach you that, you might as well give ’em up—all of you girls. The feminine sex is not naturally loyal; now, don’t get mad!” and the doctor chuckled. “It is not a natural virtue—if any virtue is humanly natural—of the sex. It’s only the impulsive, spitfire girls who are naturally loyal—the kind who will fight for another girl. Among boys it is different. Now, I am not praising boys, or putting them an iota higher than girls. Only, long generations of working and fighting together has made the normal male loyal to his kind. It is an instinct—and even our friends who call themselves suffragettes have still to acquire it.

“But this isn’t to be a lecture, Nell. It’s just a piece of advice. Show yourself loyal to the other girls of Central High, and to the betterment of basketball and the other athletics, by——”

“By what?” cried Nellie.

“By paying no attention to Hester Grimes, or what she does. After all, her shame, if she is removed from your basketball team, is the shame of her whole class, and of the school as well. Ignore her mean ways if you can. Don’t get in the way of her hand again, Nell,” and his eyes twinkled. “Remember, that blow was not intended for you, in the first place. And I am not sure that Clara Hargrew would not sometimes be the better for the application of somebody’s hand—in the old-fashioned way! No, Nell. Say nothing. Make no report of the affair. If Hester is disloyal, don’t you be. Keep out of her way as much as possible——”

“But she spoiled our games with the other schools last spring, and she will do so again,” complained Nellie.

“Then let Mrs. Case, or somebody else, be the one to set the matter in motion of removing Hester from the team. That’s my advice, Miss.”

“And of course I shall take it, Daddy Doctor,” said Nellie slowly. “But I did think it was a chance for us to get rid of Hester. She is such a plague.”

The doctor’s eyes twinkled. “I wonder why it is that we always want to shift our burdens on other folks’ shoulders? Do you suppose either the East or West Highs would find Hester any more bearable if she attended them instead of Central?”

The girls of Central High had something of more moment than Hester Grimes’s “tantrums” to think of the next day. Bobby Hargrew came flying up the path to the doctor’s porch long before school time. Nellie saw her and ran out to see what she wanted.

“What do you s’pose?” cried Bobby.

“Couldn’t guess, Chicken-little,” laughed Nellie. “Has the sky fallen?”

“Almost as bad,” declared Bobby, twinkling, but immediately becoming grave. “The gymnasium——”

“Not burned!”

“No, no! But it’s been entered. And by some awfully mean person. The apparatus on the upper floor has been partly destroyed, and the lockers broken into downstairs and lots of the field materials spoiled. Oh, it’s dreadfully mean, Nellie! They even sawed through the rungs of the hanging ladders a little way, so that if anybody swung on them they’d break.

“And with all the harm they did, nobody can tell how they got into the building, or out again. The watchman sleeps on the premises. You know, he’s not supposed to keep awake all night, for the same man keeps the field in repair during the day. But my father says that Jackway, the watchman, must have slept like the dead if he didn’t hear the marauders while they were damaging all that apparatus.

“It’s just too mean,” concluded Bobby. “There isn’t a basketball that isn’t cut to pieces, and the tennis ball boxes were broken open and the balls all thrown into the swimming pool. Tennis rackets were slashed, hockey sticks sawed in two, and other dreadful things done. It shows that whoever did it must have had a grudge against the athletic association and us girls—must have just hated us!”

“And who hates us?” cried Nellie, the question popping out before she thought.

Bobby turned rather white, though her eyes shone. She tapped Nellie on the shoulder with an insistent index finger.

“You and I know who says she hates us,” whispered the younger girl.

Franklin Sharp, principal of Central High, had something particular to say that morning at Assembly. At eight-thirty o‘clock the gongs rang in each room and the classes marched to the hall as usual. But there was an unusual amount of excitement, especially on the girls’ side of the great hall.

The news Bobby Hargrew had brought to Nellie Agnew had spread over the Hill long before schooltime. Bobby, running from house to house, had scattered the news like burning brands; and wherever she dropped a spark a flame of excitement had sprung up and spread.

And how many of the girls had whispered the same thing! What Hester Grimes had said the previous afternoon had been heard by a dozen girls; a hundred had learned of it before the gymnasium had cleared that afternoon; now the whole school—on the girls’ side, at least—knew that Hester had declared her hatred of the girls of Central High before the damage was done in the gymnasium.

This gossip could not fail to have flown to Principal Sharp’s ears. He was eminently a just man; but he seldom interfered in the girls’ affairs, preferring to let his assistant, Miss Grace G. Carrington (otherwise “Gee Gee” among the more thoughtless of her pupils) govern the young ladies. But what the principal said on this occasion seemed to point to the fact that he had taken cognizance of the wild supposition and gossip that was going the round of the girl’s classes.

“A cruel and expensive trick has been perpetrated by some irresponsible person with pronounced criminal instincts,” declared Mr. Sharp, seriously. “This is not the outburst of some soul prone to practical joking, so-called; nor is it the mere impish mischievousness of a spirit with a grudge against its fellows. The infamous actions of the person, or persons, in the girls’ gymnasium last night show degeneracy and a monkeyish wickedness that can be condoned in no particular.

“We can declare with confidence that no pupil of Central High could have accomplished the wicked work of last night. It would have been beyond the physical powers of any of our young ladies to have broken into the building; and we are equally confident that no young gentleman on our roster is at that early stage of evolution in which he would consider such work at all amusing.

“Of course, there will be an investigation made—not alone by the school authorities, but by the police. The matter is too serious to ignore. The damage done amounts to several hundreds of dollars. And the mystery of how the culprit or culprits entered the building, with the doors and windows locked and Jackway asleep in his bed in the doctor’s office, must likewise be explained.

“Meanwhile, young ladies and gentlemen, let no wild romances or unsubstantiated rumors shake your minds. We none of us know how the criminal entered the gymnasium, or who he is. Let the matter rest there until the investigation is completed and the actual wrong-doer brought to book. I hope I make myself clear? That is all. You are dismissed to classes.”

But, to himself, perhaps the principal said: “Meanwhile I will go out and stop the water from running down hill!” For the gossip having once begun to grow, there was no stopping it. Some of the girls had already begun to look askance at Hester when they passed her. Others whispered, and wondered, and surmised—and the wonder grew like the story of the man who ate the three black crows.

Hester, however, did not realize what all this meant. She was still angry with Nellie, and Bobby, and the others whom she considered had crossed her the previous afternoon. And especially was she angry with Mrs. Case, the physical instructor.

“I don’t much care if the stuff in the gymnasium was all cut up,” she declared, to her single confidant, Lily Pendleton.

“Oh, Hester! Don’t let them hear you say it!” cried her chum, who had heard some of the whispers against Hester, but had not dared repeat them to her chum for fear of an outbreak of the latter’s unfortunate temper.

“What do I care for ’em?” returned Hester, and went off by herself.

Hester Grimes was not entirely happy. She would not admit it in her own soul, but she was lonely. Even Lily was not always at her beck and call as she once had been. To tell the truth, Lily Pendleton seemed suddenly to have “a terrible crush” on Prettyman Sweet.

“And goodness only knows what she sees in that freak to want to walk with him,” muttered Hester, in retrospection.

Lily and Purt were pupils in the same dancing class and just at present dancing was “all the rage.” Hester did not care for dancing—not even for the folk dancing that Mrs. Case taught the girls of Central High. She liked more vigorous exercises. She played a sharp game of tennis, played hockey well, was a good walker and runner, and liked basketball as well as she liked anything.

“And here these Miss Smarties and Mrs. Case want to put me off the team,” thought Hester Grimes, walking down toward the athletic field and the gym. building after school that day.

There was little to go to the gym. for just now, with the fixtures cut up and broken. But Hester felt a curiosity to see the wreck. And there were other girls from Central High who seemed to feel the same. Some were ahead of her and some came after. They exclaimed and murmured and were angry or excited, as the case might be; but Hester mooned about in silence, and the only soul she spoke to in the building was Bill Jackway.

The latter looked very much worried. He was a steady, quiet, red-haired man, with pale blue eyes and a wandering expression of countenance at most times. But he was a good and careful worker and kept the athletic field in good shape and the gym. well swept and dusted.

Jackway had never been married; but his sister had married a man named Doyle and was now a widow with two children. When Jackway got an hour or two off from the gym. he went to see his sister, and played with the baby, Johnny. Johnny, who was a sturdy little fellow of three, had been brought to-day to see his uncle by his gangling big brother, Rufe Doyle. Rufe was a second edition of his uncle, Bill Jackway, without Bill’s modicum of sense. A glance at Rufe told the pitiful story. As his Irish father had said, Rufe was “an innocent.” But he loved Baby Johnny and took great care of him.

“Johnny’s growing like a weed, Rufie,” said Hester, kindly enough, as she pinched the little fellow’s cheek softly. “You take such good care of him.”

Rufe threw back his head, opened his mouth wide, and roared his delight at this compliment.

“Yes, ma’am!” he chuckled, when his paroxysm was over. “Johnny ain’t much out of my sight when he’s awake. Is he, Uncle Bill?”

“No, Rufus,” replied Jackway, sadly.

“I’m pretty smart to take care of Johnny so well—ain’t I, Uncle Bill?” demanded the weak-minded boy again.

“You are smart enough when you want to be, Rufus,” muttered Jackway, evidently in no very social mood.

“You’re worried about what happened last night, aren’t you?” demanded Hester, sharply.

“Yes, ma’am; I be,” admitted the watchman.

“You needn’t be. They’ll never blame you,” returned Hester, brusquely, and went out.

She wandered into the park at the foot of Whiffle Street and sat down. Here Rufus Doyle followed her with Baby Johnny. There had been heavy rains for the past week—until the day before. The gutters had run full and the park squad of “white wings” were raking the beaten leaves into windrows and flushing the sand and debris into the sewers. One basin cover had been laid back and left an open trap for unwary feet.

Rufus Doyle was trying to coax a gray squirrel near for Johnny to admire. But Johnny was not particularly interested in bunny. Hester saw the toddler near the open hatch of the sewer basin one moment; the next he had disappeared, and it seemed to her as though a faint cry rang in her ears.

She leaped up from the bench.

“Johnny!” she called.

Rufus was still engaged with the squirrel. Nobody seemed to have noticed the disappearance of the baby. Hester dashed to the open basin and peered down into the swirling brown water.

Again that cry—that weak, bubbling wail from out the darkness of the sewer basin. Something swirled past Hester’s strained vision in the dervish dance of the debris floating in the murky water. It was a tiny hand, stretched forth from a skimpy blue-cloth sleeve.

It was Johnny Doyle’s hand; but the child’s body—the rest of it—was under water!

The water was not more than six feet below the surface of the ground; but deep, deep down was the entrance of the big drain that joined the main sewer taking the street water and sewerage from the whole Hill section. Johnny was being sucked down into that drain.

The girl, her mind keenly alert to all this, shrieked unintelligible cries for help—unintelligible to herself, even. She could not have told afterward a word she said, or what manner of help she demanded; but she knew the boy was drowning and that she could swim!

With her clothing to hold her up a bit Hester believed she could swim or keep afloat even in that swirling eddy. The appealing little hand had no more than waved blindly once, than Hester gathered her rather full skirts about her and jumped, feet first, into the sewer-basin.

That was no pleasant plunge, for, despite her skirts, Hester went down over her head. But her hands, thrashing about in the water, caught the baby’s dress. She came up with Johnny in her arms, and when she had shaken the water from her eyes so that she could see, above was the brown face of one of the street cleaners. He was lowering a bucket on a rope, and yelling to her.

What he said Hester did not know; but she saw her chance, and placed little Johnny—now a limp, pale rag of a boy—in the bucket, and the man drew him up with a yell of satisfaction.

Hester was not frightened for herself. She felt the tug of the eddy at her feet; but she trod water and kept herself well above the surface until the man dropped the bucket down again. Then she saw the wild eyes and pallid, frightened face of Rufus at the opening, too; and a third anxious countenance. She knew that this belonged to Nellie Agnew’s father.

“Hang on, child!” exclaimed the physician, heartily. “We’ll have you out in a jiffy.”

Hester clung to the rope and was glad to be dragged out of the filthy basin. She sat on the ground, almost breathless, for a moment. Rufe, with a wild cry, had sprung to Johnny. But the doctor put the half-witted lad aside and examined the child.

“Bless him! he isn’t hurt a mite,” declared Dr. Agnew, cheerfully. “Run, get a taxi, Rufe! Quick, now! I’ll take you and Johnny, and Miss Hester, too, home in it.”

Everybody was used to obeying the good doctor’s commands, and Rufus Doyle ran as he was told. Hester was on her feet when the cab returned, and Dr. Agnew was holding the bedraggled and still unconscious Johnny in his arms.

“We’ll take you home first, Hester,” said Dr. Agnew. “You live nearest.”

“No, no!” exclaimed Hester. “Go by the way of Mrs. Doyle’s house. The baby ought to be ’tended to first.”

“Why, that’s so,” admitted the physician, and he looked at her a little curiously.

Hester whisked into the cab and hid herself from the curious gaze of the few passers-by who had gathered when the trouble was all over. The taxi bore them all swiftly to the Doyles’ humble domicile. It was on a street in which electric cabs were not commonly driven, and Rufe was mighty proud when he descended first into a throng of the idle children and women of the neighborhood.

Of course, the usual officious neighbor, after one glance at Johnny’s wet figure, had to rush into the house and proclaim that the boy had been drowned in the lake. But the doctor was right on her heels and showed Mrs. Doyle in a few moments that Johnny was all right.

With a hot drink, and warm blankets for a few hours, and a good sleep, the child would be as good as new. But when the doctor came out of the house he was surprised to find the cab still in waiting and Hester inside.

“Why didn’t you go home at once and change your clothing?” demanded Dr. Agnew, sharply, as he hopped into the taxi again.

“Is Johnny all right?” asked Hester.

“Of course he is.”

“Then I’ll go home,” sighed Hester. “Oh, I sha’n’t get cold, Doctor. I’m no namby-pamby girl—I hope! And I was afraid the little beggar would be in a bad way. He must have swallowed a quantity of water.”

“He was frightened more than anything else,” declared Dr. Agnew, aloud. But to himself he was thinking: “There’s good stuff in that girl, after all.”

For he, too, had heard the whispers that had begun to go the rounds of the Hill, and knew that Hester Grimes was on trial in the minds of nearly everybody whom she would meet. Some had already judged and sentenced her, as well!

If Hester had arrived at the Grimes’s house in two cabs instead of one it would have aroused her mother to little comment; for, for some years now, her daughter had grown quite beyond her control and Mrs. Grimes had learned not to comment upon Hester’s actions. Yet, oddly enough, Hester was neither a wild girl nor a silly girl; she was merely bold, bad tempered, and wilful.

Mrs. Grimes was a large, lymphatic lady, given to loose wrappers until late in the day, and the enjoyment of unlimited novels. “Comfort above all” was the good lady’s motto. She had suffered much privation and had worked hard, during Mr. Grimes’s beginnings in trade, for Hester’s father had worked up from an apprentice butcher boy in a retail store—was a “self-made man.”

Mr. Grimes was forever talking about how he had made his own way in the world without the help of any other person; but he was, nevertheless, purse-proud and arrogant. Hester could not fail to be somewhat like her father in this. She believed that Money was the touchstone of all good in the world. But Mrs. Grimes was naturally a kindly disposed woman, and sometimes her mother’s homely virtues cropped out in Hester—as note her interest in the Doyles. She was impulsively generous, but expected to find the return change of gratitude for every kindly dollar she spent.

They had a big and ornate house, in which the servants did about as they liked for all of Mrs. Grimes’s oversight. The latter admitted that she knew how to do a day’s wash as well as any woman—perhaps would have been far more happy had she been obliged to do such work, too; but she had no executive ability, and the girls in the kitchen did well or ill as they listed.

Now that Hester was growing into a young lady, she occasionally went into the servants’ quarters and tried to set things right in imitation of her father’s blustering oversight of his slaughter house—without Mr. Grimes’s thorough knowledge of the work and conditions in hand. So Hester’s interference in domestic affairs usually resulted in a “blow-up” of all concerned and a scramble for new servants at the local agencies.

Under these circumstances it may be seen that the girl’s home life was neither happy nor inspiring. The kindly, gentle things of life escaped Hester Grimes. She unfortunately scorned her mother for her “easy” habits; she admired her father’s bullying ways and his ability to make money. And she missed the sweetening influence of a well-conducted home where the inmates are polite and kind to one another.

Hester was abundantly healthy, possessed personal courage to a degree—as Dr. Agnew had observed—was not naturally unkind, and had other qualities that, properly trained and moulded, would have made her a very nice girl indeed. But having no home restraining influences, the rough corners of Hester Grimes’s character had never been smoothed down.

Her friendship with Lily Pendleton was not like the “chumminess” of other girls. Lily’s mother came of one of the “first families” of Centerport, and moved in a circle that the Grimeses could never hope to attain, despite their money. Through her friendship with Lily, who was in miniature already a “fine lady,” Hester obtained a slight hold upon the fringe of society. But even Lily was lost to her at times.

“Why ain’t I seen your friend Lily so much lately?” asked Mrs. Grimes, languidly, the evening of the day Hester had plunged into the sewer and rescued little Johnny Doyle.

“Oh, between dancing school and Purt Sweet, Lil has about got her silly head turned,” said Hester, tossing her own head.

“My goodness me!” drawled Mrs. Grimes, “that child doesn’t take young Purt Sweet seriously, does she?”

“Whoever heard of anybody’s taking Pretty seriously?” laughed Hester. “Only Pretty himself believes that he has anything in his head but mush! Last time Mrs. Pendleton had an evening reception, Purt got an invite, and went. Something happened to him—he knocked over a vase, or trod on a lady’s dress, or something awkward—and the next afternoon Lil caught him walking up and down in front of their house, trying to screw up courage enough to ring the bell.

“‘What’s the matter, Purt?’ asked Lily, going up to him.

“‘Oh, Miss Lily!’ cries Purt. ‘What did your mother say when you told her I was sorry for having made a fool of myself at the party last night?’

“‘Why,’ says Lil, ‘she said she didn’t notice anything unusual in your actions.’

“Wasn’t that a slap? And now Lil is letting Purt run around with her and act as if he owned her—just because he’s a good dancer.”

“My dear!” yawned her mother. “I should think you’d join that dancing class.”

“I’ll wait till I’m asked, I hope,” muttered Hester. “Everybody doesn’t get to join it. We’re not in that set—and we might as well admit it. And I don’t believe we ever will be.”

“I’m certainly glad!” complained her mother, rustling the leaves of her book. “Your father is always pushing me into places where I don’t want to go. He had a deal in business with Colonel Swayne, and he insisted that I call on Mrs. Kerrick. They’re awfully stuck-up folks, Hess.”

“I see Mrs. Kerrick’s carriage standing at the Beldings’ gate quite often, just the same,” muttered Hester.

“Yes—I know,” said her mother. “They make a good deal of Laura. Well, they didn’t make much of me. When I walked into the grounds and started up the front stoop, a butler, or footman, or something, all togged up in livery, told me that I must go around to the side door if I had come to see the cook. And he didn’t really seem anxious to take my card.”

“Oh, Mother!” exclaimed Hester.

“You needn’t tell your father. I don’t blame ’em. They’ve got their own friends and we’ve got ourn. No use pushing out of our class.”

“You should have gone in the carriage,” complained Hester.

“I don’t like that stuffy hack,” said her mother. “It smells of—of liv’ry stables and—and funerals! If your father would set up a carriage of his own——”

“Or buy an automobile instead of hiring one for us occasionally,” finished Hester.

For with all his love of display, the wholesale butcher was a thrifty person.

With Lily so much interested for the time in other matters, Hester found her only recreation at the athletic field; and for several days after the mysterious raid upon the girls’ gymnasium there was not much but talk indulged in about the building. Then new basketballs were procured and the regular practice in that game went on.

In a fortnight would come the first inter-school match of the fall term—a game between Central High girls and the representative team of East High of Centerport. In the last match game the East High girls had won—and many of the girls of Central High believed that the game went to their competitors because of Hester Grimes’s fouling.

There was more talk of this now. Some of the girls did not try to hide their dislike for Hester. Nellie Agnew did not speak to her at all, and the latter was inclined to accuse Nellie of being the leader in this apparent effort to make Hester feel that she was looked upon with more than suspicion. The mystery of the gymnasium raid overshadowed the whole school; but the shadow fell heaviest on Hester Grimes.

“She did it!”

“She’s just mean enough to do it!”

“She said she hated us!”

“It’s just like her—she spoils everything she can’t boss!”

She could read these expressions on the lips of her fellow students. Hester Grimes began to pay for her ill-temper, and the taste of this medicine was bitter indeed.

It would have been hard to tell how the suspicion took form among the girls of Central High that Hester Grimes knew more than she should regarding the gymnasium mystery. Whether she had spoiled the paraphernalia herself, or hired somebody to do it for her, was the point of the discussion carried on wherever any of the girls—especially those of her own class—met for conference.

Older people scoffed at the idea of a girl having committed the crime. And, indeed, it was a complete mystery how the marauder got into the building and out again. Bill Jackway, the watchman, was worried almost sick over it; he was afraid of losing his job.

Bobby Hargrew was about the only girl in Central High who “lost no sleep over the affair,” as she expressed it. And that wasn’t because she was not keenly interested in the mystery. Indeed, like Nellie, she had seen at the beginning that suspicion pointed to Hester Grimes. And perhaps Bobby believed at the bottom of her heart that Hester had brought about the destruction. Bobby and Hester had forever been at daggers’ points.

Bobby, however, was as full of mischief and fun as ever.

“Oh, girls!” she exclaimed, to a group waiting at the girls’ entrance to the school building one morning. “I’ve got the greatest joke on Gee Gee! Listen to it.”

“What have you done now, you bad, bad child?” demanded Nellie. “You’ll miss playing goal guard against East High if you don’t look out. Miss Carrington is watching you.”

“She’s always watching me,” complained Bobby. “But this joke can’t put a black mark against me, thank goodness!”

“What is it, Bobby?” asked Dorothy Lockwood.

“Don’t keep us on tenter-hooks,” urged her twin.

“Why, Gee Gee called at Alice Long’s yesterday afternoon. You know, she is bound to make a round of the girls’ homes early in the term—she always does. And Alice Long was able to return to school this fall.”

“And I’m glad of that,” said Dorothy. “She’ll finish her senior year and graduate.”

“Well,” chuckled Bobby, “Gee Gee appeared at the house and Tommy, Short and Long’s little brother, met her at the door. Alice wasn’t in, and Gee Gee opened her cardcase. Out fluttered one of those bits of tissue paper that come between engraved cards—to keep ’em from smudging, you know. Tommy jumped and picked it up, and says he:

“‘Say, Missis! you dropped one of your cigarette papers.’ Now, what do you know about that?” cried Bobby, as the other girls went off into a gale of laughter. “Billy heard him, and it certainly tickled that boy. Think of Gee Gee’s feelings!”

Not alone Bobby, but all the members of the basketball team were doing their very best in classes so as to have no marks against them before the game with the East High girls.

Mrs. Case coached them sharply, paying particular attention to Hester. It was too bad that this robust girl, who was so well able to play the game, should mar her playing with roughness and actual rudeness to her fellow-players. And warnings seemed wasted on her.

Hester never received a demerit from Miss Carrington. In class she was always prepared and there was little to ruffle her temper. The instructors—aside from Mrs. Case—seldom found any fault with Hester Grimes.

The game with the crack team of the East High girls was to be played on the latter’s court. The girls of Central High had been beaten there in the spring; this afternoon they went over—with their friends—with the hope of returning the spring defeat.

Bobby had been in the audience and led the “rooting” among the girls for Central High at the former game. Now she had graduated from a mere basketball “fan” to a very alert and successful goal guard.

This was Eve Sitz’s first important game, too; but the Swiss girl was of a cool and phlegmatic temperament and Laura Belding, as captain, had no fears for her.

The audience was a large one, and was enthusiastic from the start. The girls of Central High always attended the boys’ games in force and applauded liberally for their own school team; so Chet Belding and Lance Darby, with a crowd of strong-lunged Central High boys at their backs, cheered their girl friends when they came on the field with the very effective school yell:

“C-e-n, Central High!

C-e-n-t-r-a-l, Central High!

C-e-n-t-r-a-l-h-i-g-h, Central High!

Ziz-z-z-z——

Boom!”

The teams took their places after warming up a little, their physical instructors acting as coaches, while the physical instructor for West High School of Centerport was referee. The officials on the lines were selected from the competing schools.

It was agreed to play two fifteen-minute halves and the ball was put into play by the referee. The girls of Central High played like clockwork for the first five minutes and scored a clean goal. Their friends cheered tumultuously.

When the ball was put into play again there was much excitement. “Shoot it here, Laura! I’m loose!” shouted Bobby, whose slang was always typical of the game she was playing.

“Block her! Block her!” cried the captain of the East High team.

Most of the instructions were supposed to be passed by signal; but the girls would get excited at times and, unless the referee blew her whistle and stopped the play, pandemonium did reign on the court once in a while. Suddenly the ball chanced to be snapped to Hester’s side of the court. Her opponent got it, and almost instantly the referee’s whistle blew.

“That Central High girl at forward center is over-guarding.”

“No, I’m not!” snapped Hester.

The lady who acted as referee was a bit hot-tempered herself, perhaps. At least, this flat contradiction brought a most unexpected retort from her lips:

“Central High Captain!”

“Yes, ma’am?” gasped Laura Belding.

“Take out your forward center and put in a substitute for this half.”

“But, Miss Lawrence!” cried Laura, aghast.

“You are delaying play, Miss Belding,” said the referee, sharply.

Laura looked at Hester with commiseration; but she did not have to speak. The culprit, with a red and angry visage, was already crossing the court toward the dressing rooms. Laura put in Roberta Fish, and play went on.

But the Central High team was rattled. East High got two goals—one from a foul—and so stood in the lead at the end of the half. The visiting team did not work so well together with the substitute player, and the captain of East High, seeing this fact, crowded the play to Roberta Fish’s side.

“My goodness!” whispered Bobby Hargrew, as they ran off the field at the end of the half. “I hope that’s taught Hester a lesson. And this is once when we need Hester Grimes badly.”

“I should say we did,” panted Laura.

“We’ve got to play up some to win back that point we lost, let alone beating them,” cried Jess Morse.

Nellie Agnew was the first to enter the dressing room assigned to the Central High girls. She looked around the empty room and gasped.

“What’s the matter, Nell?” cried Bobby, crowding in.

“Where is she?” demanded the doctor’s daughter.

“Hessie has lit out!” shouted Bobby, turning back to the captain and her team-mates.

“She’s got mad and gone home!” declared Jess Morse. “Her hat and coat are gone.”

“Now what will we do?” cried Dorothy Lockwood.

And the question was echoed from all sides. For without Hester it did not seem possible that the Central High team could hold its own with its opponents.

The dressing room buzzed like an angry beehive for a minute. It was Laura Belding, captain of the team, who finally said:

“Hester surely can’t have deserted us in this way. She knows that Roberta is not even familiar with our secret signals.”

“She’s gone, just the same,” said her chum, Jess. “That’s how mean Hester Grimes is.”

“Well, I declare! I don’t know that I blame her,” cried Lily Pendleton.

“You don’t blame her?” repeated Nellie. “I don’t believe you’d blame Hester no matter what she did.”

“She hasn’t done anything,” returned Lily, sullenly.

“How about the gym. business——”

Bobby Hargrew began it, but Laura shut her off by a prompt palm laid across her mouth.

“You be still, Bobby!” commanded Nellie Agnew.

“You’re all just as unfair to Hessie as you can be,” said Lily with some spirit. “And now this woman from West High had to pick on her——”

“Don’t talk so foolishly, Lil,” said Dora Lockwood. “You know very well that Hester has been warned dozens of times not to talk back to the referee. Mrs. Case warns her almost every practice game about something. And now she has got taken up short. If it wasn’t for what it means to us all in this particular game, I wouldn’t care if she never played with us.”

“Me, too!” cried Jess, in applause. “Hester is always cutting some mean caper that makes trouble for other folk.”

“We can’t possibly win this game without her!” wailed Dorothy.

“I’ll do my very best, girls,” said Roberta Fish, the substitute player at forward center.

“Of course you will, Roberta,” said Laura, warmly. “But we can’t teach you all our moves in these few moments—Ah! here is Mrs. Case.”

Their friend and teacher came in briskly.

“What’s all this? what’s all this?” she cried. “Where is Hester?”

“She took her hat and coat and ran out before we came in, Mrs. Case,” explained Laura.

“Not deserted you?” cried the instructor.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“But that is a most unsportsmanlike thing to do!” exclaimed the instructor, feeling the desertion keenly. That one of her girls should act so cut Mrs. Case to the heart. She took great pride in the girls of Central High as a body, and Hester’s desertion was bad for discipline.

“You must do the best you can, Laura, with the substitute,” she said, at last, and speaking seriously. “I will inform Miss Lawrence that you will put in Roberta for the second half, too. Nothing need be said about Hester’s defection.”

“I am afraid we can’t win with me in Hessie’s place,” wailed Roberta.

“You’re going to do your very best, Roberta,” said Mrs. Case, calmly. “You always do. All of you put your minds to the task. Your opponents are only one point ahead of you. The first five-minutes’ play in the first half was as pretty team work on your part as I ever saw.”

“But we can’t use our secret signals,” said Laura.

“Play your very best. Do not put Roberta into bad pinches——”

“But the captain of the East High team sees our weak point, and forces the play that way,” complained Jess Morse.

“Of course she does. And you would do the same were you in her place,” said Mrs. Case, with a smile. “But above all, if you can’t win gracefully, do lose gracefully! Be sportsmanlike. Cheer the winners. Now, the whistle will sound in a moment,” and the instructor hurried away to speak to the referee.

“Oh, dear me!” groaned Roberta. “My heart’s in my mouth.”

“Then it isn’t where Sissy Lowe, one of the freshies, said it was in physiology class yesterday,” chuckled Bobby Hargrew.

“How was that, Bobby?” queried Jess.

“Sissy was asked where the heart was situated—what part of the body—and she says:

“‘Pleathe, Mith Gould, ith in the north thentral part!’ Can you beat those infants?” added Bobby as the girls laughed.

But they were in no mood for laughter when they trotted out upon the basketball court at the sound of the referee’s whistle. They took their places in silence, and the roars of the Central High boys, with their prolonged “Ziz—z—z—z——Boom!” did not sound as encouraging as it had at the beginning of the first half.

Basketball is perhaps the most transparent medium for revealing certain angles of character in young girls. At first the players seldom have anything more than a vague idea of the proper manner of throwing a ball, or the direction in which it is to be thrown.

The old joke about a woman throwing a stone at a hen and breaking the pane of glass behind her, will soon become a tasteless morsel under the tongue of the humorist. Girls in our great public schools are learning how to throw. And basketball is one of the greatest helps to this end. The woman of the coming generation is going to have developed the same arm and shoulder muscles that man displays, and will be able to throw a stone and hit the hen, if necessary!

The girl beginner at basketball usually has little idea of direction in throwing the ball; nor, indeed, does she seem to distinguish fairly at first between her opponents and her team mates. Her only idea is to try to propel the ball in the general direction of the goal, the thought that by passing it from one to another of her team mates she will much more likely see it land safely in the basket never seemingly entering her mind.

But once a girl has learned to observe and understand the position and function of team mates and opponents, to consider the chances of the game in relation to the score, and, bearing these things in mind, can form a judgment as to her most advantageous play, and act quickly on it—when she has learned to repress her hysterical excitement and play quietly instead of boisterously, what is it she has gained?

It is self-evident that she has won something beside the mere ability to play basketball. She has learned to control her emotions—to a degree, at least—through the dictates of her mind. Blind impulse has been supplanted by intelligence. Indeed, she has gained, without doubt, a balance of mind and character that will work for good not only to herself, but to others.

Indeed, it is the following out of the old fact—the uncontrovertible fact of education—that what one learns at school is not so valuable as is the fact that he learns how to learn. Playing basketball seriously will help the girl player to control her emotions and her mind in far higher and more important matters than athletics.

To see these eighteen girls in their places, alert, unhurried, watchful, and silent, was not alone a pleasing, but an inspiring sight. Laura and her team mates—even Roberta—waited like veterans for the referee to throw the ball. Laura and her opposing jumping center were on the qui vive, muscles taut, and scarcely breathing.

Suddenly the ball went up. Laura sprang for it and felt her palms against the big ball. Instantly she passed it to Jess Morse and within the next few seconds the ball was in play all over the back field—mostly in the hands of Central High girls.

They played hard; but nobody—not even Roberta—played badly. The East High girls were strong opponents, and more than once it looked as though the ball would be carried by them into a goal. However, on each occasion, some brilliant play by a Central High girl brought it back toward their basket and finally, after six and a half minutes, the visiting team made a goal.

The Central High girls were one point ahead.

The ball went in at center again and there was a quick interchange of plays between the teams. Suddenly, while the ball was flying through the air toward East High’s basket, the referee’s whistle sounded.

“Foul!” she declared, just as the ball popped into the basket.

A murmur rose from the East High team. Madeline Spink, the captain, said quietly:

“But the goal counts for us, does it not, Miss Lawrence?”

“It counts as a goal from a foul,” replied the referee, “which means that it is no goal at all, and the ball is in play.”

The East High girls were more than a little disturbed by the decision. It was a nice point; for on occasion a goal thrown from the foul line counts one. It broke up, for the minute, the better play of the East High team, and the instant the Central High girls got the ball they rushed it for a goal.

There was great excitement at this point in the game. If Central High won two clean points it would hardly be possible for East High to recover and gain the lead once more. Laura signalled her players from time to time; but she was hampered whenever the ball came near Roberta, or the time was ripe for a massed play. The substitute did not know all the secret signals.

Had Hester Grimes only been in her place! Her absence crowded the Central High team slowly to the wall. In the very moment of success, when a clean goal was about to be made, they failed and their opponents got the ball. Again it was passed from hand to hand. One girl bounced the ball and a foul was called. Again the Central Highs rushed it, and from the foul line made another goal.

Two points ahead, and the boys in the audience cheered madly. No harder fought battle had ever been played upon that court.

“Shoot it over, Jess!” roared Chet, at one point, rising and waving to his particular girl friend, madly. “Look out! they’ll get you!”

“Look out, Laura! don’t let ’em get you——Aw! that’s too bad,” grumbled Lance Darby, quite as interested in the work of Chet’s sister on the court.

“Hi! no fair pulling! Say! where’s the referee’s eyes?” demanded Chet, the next moment, in disgust.

“Behind her glasses,” said his chum. “I never did believe four eyes were as good as two.”

The ball came back to center again and there was little delay before it was put in play. Only three minutes remained. The eighteen girls were as eager as they could be. Madeline Spink and her team mates were determined to tie the score at least. A clean goal would do it.

They rushed the play and carried the ball into Roberta’s country. Roberta never had a chance! In a moment the ball was hurtling toward the proper East High girl, and no guarding could save it.

A cheer from the audience—those interested in the East High girls—announced another clean goal. The score was tied and two minutes to play!

“Do not delay the game, young ladies!” warned the referee.

They were in position again and the ball was thrown up. No fumbles now. Every girl was playing for all that there was in her! A single point would decide the rivalry of the two schools at the beginning of the playing season. To lead off with this first game would encourage either team immeasurably.

East High led off first; but quickly Laura and her team mates got the ball again and pushed it toward the basket. There was no rough play. The umpires, as well as the referee, watched sharply. It was a sturdy, vigorous, but fair game. This was a time when Hester’s hot temper might have brought the team disgrace; and for a moment Laura was, after all, glad that the delinquent had gone home.

Then, suddenly, from full field and a fair position, the ball rose and flew directly for the basket. While in mid-air the whistle was blown. Time was called and the game was ended.

The spectators, as well as the players, held their breath and watched the flying ball. Although the whistle had blown, the goal—if the ball settled into the basket—would count for the visiting team. This one unfinished play would give the girls of Central High two clear points in the lead if all went well.

The course of the flying ball was watched by all eyes, therefore. Chet Belding and his mates began their chant, believing that the ball was sure to go true to the basket.

But they began too soon. The ball hit the ring of the basket, hovered a moment over it, and then fell back and rolled into the court! Chet’s chant of praise changed to a groan. The game was over—and it was a tie.

Disappointed as the girls of Central High were, they cheered their opponents nobly, and the East High girls cheered them. The audience had to admit that the game had been keenly fought and—after Hester was put out of it—as cleanly as a basketball game had ever been played on those grounds.

Miss Lawrence, the referee, came to the Central High girls’ dressing room and complimented Laura and her team on their playing.

“I was sorry to put off your forward center, Miss Belding, in the first half. If you had brought her into the field in the second half your team, without doubt, would have won,” said the referee. “That girl is a splendid player, but she needs to learn to control her temper.”

“That’s always the way!” cried Nellie Agnew, when the West High instructor was gone. “Hester spoils everything.”

“She crabs every game we play,” growled Bobby, both sullen and slangy.

“She ought to be put off the team for good,” said one of the twins.

“That’s so,” chimed in her sister.

“We’ll never win this season if Hessie is included in this team,” declared Jess Morse.

Even Lily Pendleton could find nothing to say now in favor of her chum. She hurried away from the others girls, and the seven remaining seriously discussed the situation. It was Nellie, despite her promise to her father, who came out boldly and said:

“Let’s put her off the team altogether.”

“We can’t do it,” objected Laura.

“Ask Mrs. Case to do it, then,” said Jess.

“But who’ll ask her? Hester will be awfully mad,” said Eve Sitz.

“I wouldn’t want to be the one to do the asking,” admitted the bold Bobby.

The seven regular members of the basketball team were alone now. Dorothy Lockwood said:

“I wouldn’t want to be the one to sign a petition. But that is what we ought to do—sign a petition to Mrs. Case asking her to remove Hester.”

“What do you say, Mother Wit?” demanded Jess Morse of Laura.

“I vote for the petition,” said Laura, gravely.

“And who’ll sign it?” cried Dorothy.

“All of us.”

“Not me first!” declared Dora.

“We’ll make it a ‘round robin,’” said Laura, smiling. “All seven of us will sign in a circle, but nobody need take the lead in making the request. If we are all agreed Jess can write the petition to Mrs. Case.”

“I’ll do it!” declared Jess Morse.

With some corrections from her chum, Josephine finally prepared and presented for their signatures the petition, and having read it the girls, one after the other, signed her name in the manner Mother Wit had suggested. The petition and Round Robin was as follows:

“We, the undersigned members of Basketball Team No. 1, of Central High, Girls’ Branch Athletic League, after due and ample discussion of the facts, conclude that the retention of Hester Grimes as a member of the said team is a detriment thereto, and that her membership will, in the future, as in the past, cause the team to lose games in the Trophy Series of Inter-School Games. We therefore ask that the aforesaid Hester Grimes be removed from the team and that some other player be nominated in her stead.”

In signing the paper in this fashion no one girl could be accused of leading in the demand for Hester’s removal. Lily had gone, so that nobody would tell Hester just what each girl said, or who signed first. That Nellie Agnew had taken the lead in this petition against her schoolmate the doctor’s daughter herself knew, if nobody else did. She felt a little conscience-stricken over it, too, for she had told Daddy Doctor that she would be guided by his advice in the matter of Hester Grimes.

And after supper that night her father said something that made Nellie feel more than ever condemned.

“Do you know, Nell,” he said, thoughtfully, pulling on his old black pipe as she perched as usual on the broad arm of his chair. “Do you know there is good stuff in that girl Hester?”

“In Hester Grimes?” asked Nellie, rather flutteringly.

“Yes. In Hester Grimes. I guess you didn’t hear about it. And it slipped my mind. But when I was over to see little Johnny Doyle again to-day I found Hester there and the Doyles think she’s about right—especially Rufus.”

“Rufus isn’t just right in his mind—is he?” asked Nellie, her eyes twinkling a little.

“I don’t know. In some things Rufe is ’way above the average,” chuckled her father. “He is cunning enough, sure enough! But to get back to Hester. I never told you how she jumped into the sewer-basin and saved Johnny’s life?”

“No! Never!” gasped Nellie.

The physician told her the incident in full. He told her further that Hester had done a deal, off and on, for the Widow Doyle and her children.

“Oh, I wish I had known!” cried Nellie, in real contrition.

“What for?” demanded the doctor.

But she would not tell him. She knew that the petition had been mailed to Mrs. Case that very evening. Her name was on it, and in her own heart Nellie knew that she had had as much to do with the scheme to put Hester Grimes off the basketball team as any girl.

“Perhaps, if the girls had known what Hester did for Johnny they wouldn’t have been so bitter against her,” thought the doctor’s daughter. “I know I would never have signed that hateful paper. Oh, dear! why did Daddy Doctor have to find out that there was some good in Hester, and tell me about it?”

Hester Grimes, as the doctor said, had appeared late that afternoon at the Doyles’ little tenement. She had gone there from the basketball game instead of going directly home.

To tell the truth, she did not wish to be questioned by her mother, nor did she want to meet Lily. If she had felt hatred against her mates in Central High before, that feeling in her heart was now doubled!

For, as all anger is illogical (indignation may not be) Hester turned upon the girls and blamed them for the referee’s decision. Because Miss Lawrence had put her out of the game Hester would have been glad to know that her team mates had gone to pieces and been defeated.

She had managed to recover outwardly from her disappointment and anger, however, when she arrived at the domicile of her humble acquaintances. Mrs. Doyle knitted jackets, and Hester had ordered one for her mother.

“Ma is always lolling around and complaining of feeling draughts,” said Hester. “So I’ll give her one of these ‘snuggers’ to keep her shoulders warm. She’s always snuffing with a cold when it comes fall and the furnace fire is not lit.”

“Lots o’ folks are having colds just now,” complained Mrs. Doyle. “Johnny’s snuffling with one.”

“Oh, he’ll be all right—won’t he, Rufie?” said Hester, chucking the baby under his plump little chin, but speaking to his faithful nurse.

“In course he will, Miss Hester,” cried Rufus, and then opened his mouth for a roar of laughter, that made even the feverish Johnny crow.

“Rufus never gets tired of minding Johnny,” said the widow, proudly. “But he does miss his Uncle Bill.”

Rufe’s face clouded over. “He ain’t never home no more,” he said, complainingly.

“But you can go over to see him at the gymnasium,” said Hester.

“Not no more he can’t, Miss,” said the widow. “Rufus used to go over to see Uncle Bill evenings; but Uncle Bill can’t have him there no more.”

“Why not?” asked Hester, quickly; and yet she flushed and turned her own gaze away and looked out of the window.

“Bill’s had some trouble there. He’s afraid the Board of Education would object. Somebody got into the building——”

“I heard about it,” said Hester, quickly.

“Wisht Uncle Bill had another job,” grumbled Rufus.

“Rufie’s real bright about some things,” whispered his mother. “And sharp ain’t no name for it! He is pretty cute. You can’t say much before him that he don’t remember, and repeat.”

“Wisht that old gymnasium building would burn up; then Uncle Bill could come home,” muttered Rufe.

Mrs. Doyle went to see to her fire. Hester beckoned the boy to the window and whispered to him. Gradually Rufe’s face lit up with one of his flashes of cunning. Money passed from the girl’s hand to that of the half-witted youth.

Just then Dr. Agnew appeared and Hester took her departure.

On the following morning Franklin Sharp, the principal of Central High, called a conference of his teachers at the first opportunity. He was very grave indeed when he told them that another raid had been made upon the girls’ gymnasium.

“Not so much damage is reported as was done before. But, then, the paraphernalia before destroyed was not all removed. But this time the scoundrel—or scoundrels—tried arson.

“A fire was built in a closet on the upper floor. Bill Jackway smelled smoke and got up to see what it was. He found no trace of the firebug—can discover no way in which he got out——”

“But how did he get in?” asked one of the teachers.

“That is plain. It had rained early in the evening. Footprints are still visible leading across a soft piece of ground from the east fence to a window. The window was open, although Bill swears it was shut and locked when he went to bed at ten o’clock. That is how the marauder entered the building. How he got out is a mystery,” declared the principal.

“It is a very dreadful thing,” complained Miss Carrington. “I do not see what we can do about it.”

“We must do something,” said Miss Gould, with vigor.

“Suppose you suggest a course of procedure, Miss Gould?” said the principal, his eyes twinkling.

“I think it would be well,” said Miss Gould, “to sift every rumor and story regarding this matter. There is much gossip among the girls. I have heard of a threat that one girl made in the gymnasium——”

“That is quite ridiculous, Miss Gould!” cried Miss Carrington, with some heat. “You have been listening to a base slander against one of my very best pupils.”

“You mean this Hester Grimes, Henry Grimes’s daughter?” said the principal, sternly.

“That is the girl,” admitted Miss Gould. “I know little about her——”

“And I know a good deal,” interposed Mrs. Case, grimly. “Miss Carrington finds her good at her books, and her deportment is always fair in classes. I find her the hardest girl to manage in all the school. She has a bad temper and she has never been taught to control it. It has gone so far that I fear I shall have to shut her out of some of the athletics,” and she related all that had happened at the basketball game with the East High girls the afternoon before.

“I do not approve of these contests,” said Miss Carrington, primly. “They are sure to cause quarreling.”

“If they do, then there is something the matter with the girls,” declared Mr. Sharp, briskly.

“And I have received this request from the girls of the team—seven of them—this morning,” continued Mrs. Case, producing the “round robin.” “The only girls beside Hester who did not sign it is a girl who always chums with her—the only really close friend Hester has to my knowledge in the school.

“Now, I should like very much to be instructed what to do about this? The girls are perfectly in the right. Hester is not dependable on the team. There should be another girl in her place——”

“Oh, but it is quite unfair!” cried Miss Carrington. “And remember her father is quite an important man. There will be trouble if Hester is put down in these tiresome athletics; or if this story that is going about is repeated to Mr. Grimes I can’t imagine what he would do.”

“Mr. Grimes does not run the Board of Education, nor does he control our actions,” declared Mr. Sharp. “We must take cognizance of these matters at once. I believe you should remove Hester from the team, as requested, Mrs. Case. You have ample reason for so doing. And this matter of the attempt to burn the gymnasium must be investigated fully.”

“But no girl could do these things in the gymnasium,” cried Miss Carrington, with considerable asperity.

“But she could get somebody else to do them—especially a girl who is allowed as much spending money as Hester Grimes,” said the principal. “I can imagine no sane person committing such a crime. It is wilful and malicious mischief, and could only be inspired by hatred, or—an unbalanced mind. That is my opinion.”

For some reason, that lively young “female Mercury,” as Jess Morse sometimes dubbed her, Bobby Hargrew, did not hear of this new raid upon the girls’ gym. early that morning; so, like the other pupils of Central High, she could not visit the athletic building until after school. She went then with Nellie and Laura and Jess, and the quartette were almost the first girls to enter the building that day.

“It’s a dreadful thing,” said Laura, in discussing the affair.

The girls were all noticeably grave about the matter this time. There was little excitement, or talk of “how horrid it was” and all that. There was a gravity in their manner which showed that the girls of Central High were quite aware that the case was serious in the extreme.

One of their number was accused of being the instigator of these raids on the gymnasium. True, or false, it was an accusation that could not be lightly overlooked. Laura Belding was particularly grave; and Nellie Agnew had cried about it.

The four friends went out into the field and examined the footprints in the earth.

“Those were never Hessie’s ‘feetprints,’ for, big as her feet are, she never wears boots like those!” giggled Bobby.

“He was a shuffler—that fellow,” said Jess. “See how blurred the marks are at the heel?”

“And he shuffled right up to this window—And how do you suppose he opened it, if, as Mr. Jackway says, it was locked on the inside?”

“Mystery!” said Bobby.

“Give it up,” added Jess. “What do you say, Mother Wit?”

“That is the way he opened it,” said Laura, softly, looking up from the foot prints.

“What’s that?” cried Jess.