Title: Charles Auchester, Volume 1 (of 2)

Author: Elizabeth Sara Sheppard

Release date: February 22, 2012 [eBook #38949]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

CHARLES AUCHESTER

Volume I.

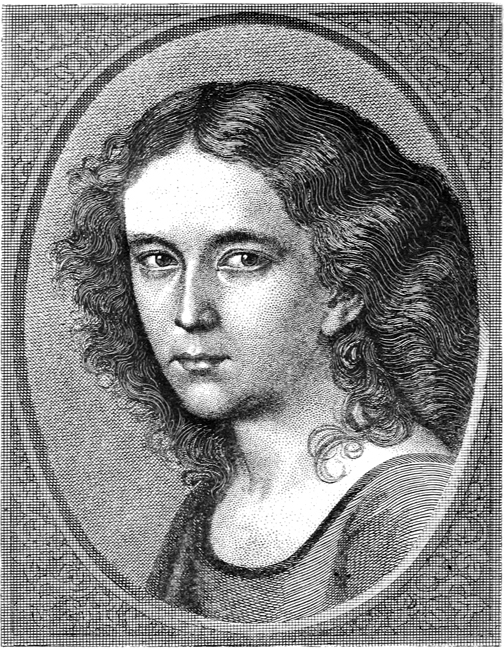

MENDELSSOHN

FROM AN ORIGINAL PORTRAIT—1821.

BY

WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES

By GEORGE P. UPTON

AUTHOR OF "THE STANDARD OPERAS," "STANDARD ORATORIOS," "STANDARD CANTATAS," "STANDARD SYMPHONIES," "WOMAN IN MUSIC," ETC.

In Two Volumes

Volume I.

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG AND COMPANY

1891

Copyright,

By A. C. McClurg and Co.

a.d. 1891.

The romance of "Charles Auchester," which is really a memorial to Mendelssohn, the composer, was first published in England in 1853. The titlepage bore the name of "E. Berger," a French pseudonym, which for some time served to conceal the identity of the author. Its motto was a sentence from one of Disraeli's novels: "Were it not for Music, we might in these days say, The Beautiful is dead." The dedication was also to the same distinguished writer, and ran thus: "To the author of 'Contarini Fleming,' whose perfect genius suggested this imperfect history." To this flattering dedication, Mr. Disraeli replied in a note to the author: "No greater book will ever be written upon music, and it will one day be recognized as the imaginative classic of that divine art."

Rarely has a book had a more propitious introduction to the public; but it was destined to encounter the proverbial fickleness of that public. The author was not without honor save in her own country. It was reserved for America first to recognize her genius. Thence her fame travelled back to her own home; but an early death prevented her from enjoying the fruits of her enthusiastic toil. Other works followed from her busy pen, among them "Counterparts,"—a musico-philosophical romance, dedicated to Mrs. Disraeli, which had a certain success; "Rumor," of which Beethoven, under the name of Rodomant, 6 is supposed to have been the hero; "Beatrice Reynolds," "The Double Coronet," and "Almost a Heroine:" but none of them achieved the popularity which "Charles Auchester" enjoyed. They shone only by the reflected light of this wonderful girl's first book. The republication of this romance will recall to its readers of an earlier generation an old enthusiasm which may not be altogether lost, though they may smile as they read and remember. It should arouse a new enthusiasm in the younger generation of music-lovers.

Elizabeth Sheppard, the author of "Charles Auchester," was born at Blackheath, near London, in 1837. Her father was a clergyman of the Established Church, and her mother a Jewess by descent,—which serves to account for the daughter's strong Jewish sympathies in this remarkable display of hero-worship. Left an orphan at a tender age, she was thrown upon her own resources, and chose school-teaching for her profession. She was evidently a good linguist and musician, for she taught music and the languages before she was sixteen. She had decided literary ambition also, and wrote plays, poems, and short stories at an age when other children are usually engaged in pastimes. Notwithstanding the arduous nature of her work and her exceedingly delicate health, she devoted her leisure hours to literary composition. How this frail girl must have toiled is evidenced by the completion of "Charles Auchester" in her sixteenth year. In her seventeenth she had finished "Counterparts,"—a work based upon a scheme even more ambitious than that of her first story. When it is considered that these two romances were written at odd moments of leisure intervening between hours of wearing toil in the school-room, and that she was a mere child and very frail, it will be admitted that the history of literary effort hardly records a parallel case. Nature however always exacts the penalty for such mental excesses. This little creature of "spirit, fire, and dew" died on March 13, 1862, at the early age of twenty-five. 7

Apart from its intrinsic merits as a musical romance, there are some features of "Charles Auchester" of more than ordinary interest. It is well known that Seraphael, its leading character, is the author's ideal of Mendelssohn, and that the romance was intended to be a memorial of him. More thoroughly to appreciate the work, and not set it down as mere rhapsody, it must be remembered that Miss Sheppard wrote it in a period of Mendelssohn worship in England as ardent and wellnigh as universal as the Handel worship of the previous century had been. It was written in 1853. Mendelssohn had been dead but six years, and his name was still a household word in every English family. He was adored, not only for his musical genius, but also for his singular purity of character. He was personally as well known in England as any native composer. His Scotch Symphony and Hebrides Overture attested his love of Scotch scenery. He had conducted concerts in the provinces; he appeared at concerts in London in 1829 and in subsequent years, and was the idol of the drawing-rooms of that day. Some of his best works were written on commissions from the London Philharmonic Society. He conducted his "Lobgesang" at Birmingham in 1840, and he produced his immortal "Elijah" in the same town in 1846,—only a year before his death. There were numerous ties of regard, and even of affection, binding him to the English people. From a passing remark in the course of the romance, we learn that it opens about the year 1833, when Mendelssohn was in his prime; and as it closes with his death, it thus covers a period of fourteen years,—the most brilliant and productive part of his life.

Curious critics of "Charles Auchester" have found close resemblances between its characters and other musicians. There is good reason to believe that Starwood Burney was intended for Sterndale Bennett, not only from the resemblance of the names in sound and meaning, but also from many other events common to each. It requires, 8 however, some stretch of the imagination to believe that Charles Auchester was intended as a portrait of Joachim the violinist; that Aronach, the teacher at the St. Cecilia School, was meant for Zelter; Clara Benette for Jenny Lind; and Laura Lemark for Taglioni. It is altogether likely that the author in drawing these characters had the types in mind, and without intending to produce a parallel or to preserve anything like synchronism, invested them with some of the characteristics of the real persons, all of whom, it may be added, except Taglioni, were intimately associated with Mendelssohn.

All this lends the charm of human interest to the book; but, after all, it is the author's personality that invests it with its rare fascination. It would not bear searching literary criticism; fortunately, no one has been so ungracious as to apply it. It is more to the purpose to remember that here is a young girl of exquisite refinement, rare intellectuality, and the most overwhelming enthusiasm, who has written herself into her work with all her girlish fancies, her great love for the art, her glowing imagination, and that rapturous devotion for the hero of her exalted world which is characteristic of her sex at sixteen. And in doing this she has pictured her dreams with most glowing colors, and told them with delicate naïveté and exuberant passion. In a word, she has expressed the very spirit of music in language, and in a language so pure and adoring as to amount to worship. In Disraeli's words, it is "the imaginative classic of the divine art." To those who have not lost their early enthusiasms, this little book will come like the perfume of a flower, or some tone of a well-remembered voice, recalling the old days and reviving an old pleasure. To those who have lost such emotions, what is left but Lethe?

In preparing the work for publication, I have added some brief notes, indicating the connection between the real and the ideal, and making the meaning of the text clearer to the general reader of to-day. Anything which 9 will throw light upon this charming romance should be welcome, and the more so that the gifted author has been strangely neglected both in musical and general biographical dictionaries. It is to be hoped that an adequate sketch of her life may some day appear.

George P. Upton.

Chicago, 1891.

CHARLES AUCHESTER.

I never wrote a long letter in my life. It is the manual part I dislike,—arranging the paper, holding the pen in my fingers, and finding my arm exhausted with carrying it to and from the inkstand. It does not signify, though; for I have made arrangements with my free-will to write more than a letter,—a life, or rather the life of a life. Let none pause to consider what this means,—neither quite Germanly mysterious, nor quite Saxonly simple, like my origin.

There are many literal presentations of ordinary personages in books which, I am informed, and I suppose I am to assure myself, are introduced expressly to intensify and illustrate the chief and peculiar interest where an interest is, or to allure the attention of the implicit, where it is not. But how does it happen that the delineations of the gods among men, the heroic, gifted few, the beings of imaginative might or genius, are so infinitely more literal? Who—worshipping, if not strong enough to serve, the Ideal—can endure the graceless ignorance of his subject betrayed by many a biographer, accepted and accomplished in his style? Who, so worshipping, can do anything but shudder at the meagre, crude, mistakable portraits of Shakspeare, 12 of Verulam, of Beethoven? Heaven send my own may not make me shudder first, and that in my attempt to recall, through a kind of artistic interlight, a few remembered lineaments, I be not self-condemned to blush for the spiritual craft whose first law only I had learned.

I know how many notions grown persons entertain of their childhood as real, which are factitious, and founded upon elder experience, until they become confounded with it; but I also feel that in great part we neglect our earliest impressions, as vague, which were the truest and best we ever had. I believe none can recall their childish estimate or essence without identifying within their present intimate selves. In my own case the analogy is perfect between my conceptions then and my positive existence now. So every one must feel who is at all acquainted with the liabilities of those who follow art.

The man of power may manage to merge his individuality in his expansive association with the individuality of others; the man of science quenches self-consciousness in abstraction; and not a few who follow with hot energy some worldly calling, become, in its exercise, as itself, nor for a solitary moment are left alone with their personality to remember even that as separate and distinctly real.

But all artists, whether acknowledged or amateur, must have proved that, for themselves, the gauge of immortality, in life as in art, consists in their self-acquaintance, their self-reliance, their exact self-appreciation with reference to their masters, their models, their one supreme ideal.

I was born in a city of England farthest from the sea, within whose liberties my grandfather and father had resided, acquiring at once a steady profit and an honorable commercial fame. Never mind what they were, or 13 in which street or square their stocked warehouses were planted, alluring the eyes and hearts of the pupils of Adam Smith. I remember the buildings well; but my elder brother, the eldest of our family, was established there when I first recall them, and he was always there, residing on the premises. He was indeed very many years my senior, and I little knew him; but he was a steady, excellent person, with a tolerable tenor voice and punctilious filial observances towards our admirable mother. My father was born in England; but though his ancestors were generally Saxon, an infusion of Norman blood had taken place in his family a generation or two behind him, and I always suspected that we owed to the old breeding of Claire Renée de Fontenelle some of our peculiarities and refinements; though my father always maintained that they flowed directly from our mother. He was travelling for the house upon the Continent when he first found her out, embedded like a gem by a little German river; and she left with him, unrepiningly, her still but romantic home, not again to revisit it.

My mother must have been in her girlhood, as she was in her maturest years, a domestic presence of purity, kindliness, and home-heartedness; she had been accustomed to every kind of household manœuvre, and her needlework was something exquisite. From her German mother she inherited the quietness of which grace is born, the prudence with which wisdom dwells, and many an attribute of virtue; but from her father she inherited the right to name herself of Hebrew origin. Herein my chief glory lies; and whatever enlightenment my destiny has boasted, streams from that radiant point. I know that there are many who would as genuinely rejoice in descent from Mahomet, from Attila, or from Robin Hood, as from any of Israel's children; but I 14 claim the golden link in my genealogy as that which connects it with eternity and with all that in my faith is glorious.[1]

My mother had lived in a certain seclusion for some years before I first began to realize; for my father died before my first year's close. We still resided near the house of business,—not in it, for that was my brother's now, and Fred had lately brought home a wife. But we were quite settled and at home in the house I first remember, when it breaks, picture-like, on my dawning memory. I had three sisters: Clotilda was the oldest, and only a year younger than Fred. She was an extraordinarily clever person, though totally destitute of art or artistic yearnings. She had been educated unwontedly, and at least understood all that she had learned. Her favorite pursuits were reading, and comparing lexicons and analyses of different languages, and endeavoring to find common roots for all; but she could and did work perfectly, write a fine, close hand, and very vigorously superintend the household in my mother's absence or indisposition. She had rather a queer face, like one of the Puritan visages in antique portraits; but a very cheerful smile, and perfect composure of manner,—a great charm in mine eyes, O ye nymphs and graces! Millicent, three years younger, was a spirit of gentleness,—imperceptibly instructing me, she must be treated with a sort of awe. Her melancholy oval face and her pale eyelids showed more of the Hebrew than any of us excepting myself; only I was plain, and she remarkably 15 pleasing. Lydia, my youngest sister, was rather showy than brilliant, and rather bright than keen,—but not much of either; and yet she was always kind to me, and I should have grieved to miss her round brown eyes at our breakfast-table, or her loud, ringing laugh upstairs from the kitchen; for she had the pantry key.

Both Millicent and Lydia played and sang, if not very powerfully, yet with superior taste. Millicent's notes, not many in number, were as the notes of a cooing dove. Before I was five years old I used to sit upon the old grand piano and watch their faces while they sang on Sunday evenings,—my mother in a tremulous soprano, with Fred's tenor, and the bass of a friend of his. This did not please me; and here let me say that musical temperament as surely asserts itself in aversion to discordant, or not pure, as in desire for sweet and true sounds. I am certain this is true. I was always happy when Millicent sang alone, or even when she and Lydia mixed their notes; for both had an ear as accurate for tune and for time as can be found in England, or indeed in Germany. But oh! I have writhed beneath the dronings of Hatchardson's bass, on quartet or chorale an audible blemish, and in a rare composition now and then, the distorting and distracting point on which I was morbidly obliged to fasten my attention. We had no other music, except a little of the same kind, not quite so good, from various members of families in the neighborhood professing to play or sing. But I will not dwell on those, for they are displaced by images more significant.

I can never recollect a time when I did not sing. I believe I sang before I spoke. Not that I possessed a voice of miraculous power, but that everything resolved itself into a species of inward rhythm, not responsive to 16 by words, but which passed into sound, tone, and measure before I knew it was formed. Every sight as well as all that touched my ears produced this effect. I could not watch the smoke ascending, nor the motions of the clouds, nor, subtler yet, the stars peeping through the vaulted twilight, without the framing and outpouring of exuberant emotion in strains so expressive to my own intelligence that it was entranced by them completely. I was a very ailing child for several years, and only the cares I received preserved me then; but now I feel as if all healthfulness had been engendered by the mere vocal abstraction into which I was plunged a great part of every day. I had been used to hear music discussed, slightly, it is true, but always reverently, and I early learned there were those who followed that—the supreme of art—in the very town we inhabited,—indeed, my sisters had taken lessons of a lady a pupil of Clementi; but she had left for London before I knew my notes.

Our piano had been a noble instrument,—one of the first and best that displaced the harpsichords of Kirkman.[2] Well worn, it had also been well used, and when deftly handled, had still some delights extricable. It stood in our drawing-room, a chamber of the red-brick house that held us,—rather the envy of our neighbors, for it had a beautiful ceiling, carved at the centre and in the corners with bunches and knots of lilies. It was a high and rather a large room. It was filled with old furniture, rather handsome and exquisitely kept, and 17 was a temple of awe to me, because I was not allowed to play there, and only sometimes to enter it,—as, for example, on Sundays, or when we had tea-parties, or when morning callers came and asked to see me; and whenever I did enter, I was not suffered to touch the rug with my feet, nor to approach the sparkling steel of the fire-irons and fender nearer than its moss-like edge. Our drawing-room was, in fact, a curious confusion of German stiffness and English comfort; but I did not know this then.

We generally sat in the parlor looking towards the street and the square tower of an ancient church. The windows were draped with dark-blue moreen, and between them stood my mother's dark-blue velvet chair, always covered with dark-blue cloth, except on Sundays and on New Year's day and at the feast of Christmas.

The dark-blue drugget covered a polished floor, whose slippery, uncovered margin beneath the wainscot has occasioned me many a tumble, though it always tempted me to slide when I found myself alone in the room. There were plenty of chairs in the parlor, and a few little tables, besides a large one in the centre, over which hung a dark-blue cover, with a border of glowing orange. I was fond of the high mantelshelf, whose ornaments were a German model of a bad Haus, and two delicate wax nuns, to say nothing of the china candlesticks, the black Berlin screens, and the bronze pastille-box.

Of all things I gloried in the oak closets—one filled with books, the other with glass and china—on either side of the fireplace; nor did I despise the blue cloth stools, beautifully embroidered by Clo, just after her sampler days, in wool oak-wreaths rich with acorns. I used to sit upon these alternately at my mother's feet, 18 for she would not permit one to be used more than the other; and I was a very obedient infant.

My greatest trial was going to church, because the singing was so wretchedly bad that it made my ears ache. Often I complained to my mother; but she always said we could not help it if ignorant persons were employed to praise God, that it ought to make us more ready to stand up and sing, and answer our very best, and that none of us could praise him really as the angels do. This was not anything of an answer, but I persisted in questioning her, that I might see whether she ever caught a new idea upon the subject. But no; and thus I learned to lean upon my own opinion before I was eight years old, for I never went to church till I was seven. Clo thought that there should be no singing in church,—she had a dash of the Puritan in her creed; but Lydia horrified my mother oftentimes by saying she should write to the organist about revising the choir. But here my childish wisdom crept in, and whispered to me that nothing could be done with such a battered, used-up, asthmatic machine as our decrepit organ, and I gave up the subject in despair.

Still, Millicent charmed me one night by silencing Fred and Mr. Hatchardson when they were prosing of Sternhold and Hopkins, and Tate and Brady,[3] and singing-galleries and charity-children, by saying,—

"You all forget that music is the highest gift that God bestows, and its faculty the greatest blessing. It must be the only form of worship for those who are musically endowed,—that is, if they employ it aright."

Millicent had a meek manner of administering a wholesome truth which another would have pelted at the hearer; but then Millicent spoke seldom, and never 19 unless it was necessary. She read, she practised, she made up mantles and caps à ravir, and she visited poor sick people; but still I knew she was not happy, though I could not conceive nor conjecture why. She did not teach me anything, and Lydia would have dreamed first of scaling Parnassus. But Clo's honorable ambition had always been to educate me; and as she was really competent, my mother made no objection. I verily owe a great deal to her. She taught me to read English, French, and German between my eighth and tenth years; but then we all knew German in our cradles, as my mother had for us a nurse from her own land. Clo made me also spell by a clever system of her own, and she got me somehow into subtraction; but I was a great concern to her in one respect,—I never got on with my writing. I believe she and my mother entertained some indefinite notion of my becoming, in due time, the junior partner of the firm. This prescience of theirs appalled me not, for I never intended to fulfil it, and I thought, justly enough, that there was plenty of time before me to undo their arrangements. I always went to my lessons in the parlor from nine till twelve, and again in the afternoon for an hour, so that I was not overworked; but even when I was sitting by Clo,—she, glorious creature! deep in Leyden or Gesenius—I used to chant my geography or my Telemachus to my secret springs of song, without knowing how or why, but still chanting as my existence glided.

I had tolerable walks in the town and about through the dusty lanes with my sisters or my nurse, for I was curious; and, to a child, freshness is inspiration, and old sights seen afresh seem new.

I liked of all things to go to the chemist's when my mother replenished her little medicine-chest. There 20 was unction in the smell of the packeted, ticketed drugs, in the rosy cinnamon, the golden manna, the pungent vinegar, and the aromatic myrrh. How I delighted in the copper weights, the spirit-lamp, the ivory scales, the vast magazines of lozenges, and the delicate lip-salve cases, to say nothing of the glittering toilet bagatelles, and perfumes and soaps! I mention all this just because the only taste that has ever become necessary to me in its cultivation, besides music, is chemistry, and I could almost say I know not which I adhere to most; but Memory comes,—

"And with her flying finger sweeps my lip."

I forbear.

I loved the factories, to some of which I had access. I used to think those wheels and whirring works so wonderful that they were like the inside of a man's brain. My notion was nothing pathetic of the pale boys and lank girls about, for they seemed merely stirring or moveless parts of the mechanism. I am afraid I shall be thought very unfeeling; I am not aware that I was, nevertheless.

I sometimes went out to tea in the town; I did not like it, but I did it to please my mother. At one or two houses I was accustomed to a great impression of muffins, cake, and marmalade, with coffee and cream; and the children I met there did nothing adequately but eat. At a few houses, again, I fared better, for they only gave us little loaves of bread and little cups of tea, and we romped the evening long, and dramatized our elders and betters until the servants came for us. But I, at least, was always ready to go home, and glad to see my short, wide bed beside my mother's vast one, and my spotless dimity curtains with the lucid muslin frills; and how often I sang the best tunes in my head 21 to the nameless effect of rosemary and lavender that haunted my large white pillow!

We always went to bed, and breakfasted, very early, and I usually had an hour before nine wherein to disport myself as I chose. It was in these hours Millicent taught me to sing from notes and to discern the aspect of the key-board. Of the crowding associations, the teeming remembrances, just at infancy and early childhood, I reject all, except such as it becomes positively necessary I should recall; therefore I dwell not upon this phase of my life, delightful as it was, and stamped with perfect purity,—the reflex of an unperverted temperament and of kindly tenderness.

We had a town-hall,—a very imposing building of its class, and it was not five minutes' walk from the square-towered church I mentioned. It was, I well knew, a focus of some excitement at election times and during the assizes, also in the spring, when religious meetings were held there; yet I had never been in it, and seldom near it,—my mother preferring us to keep as clear of the town proper as possible. Yet I knew well where it stood, and I had an inkling now and then that music was to be heard there; furthermore, within my remembrance, Millicent and Lydia had been taken by Fred to hear Paganini within its precincts. I was too young to know anything of the triennial festival that distinguished our city as one of the most musical in England, at that time almost the only one, indeed, so honored and glorified. I said, what I must again repeat, that I knew nothing of such a prospective or past event until the end of the summer in which I entered my eleventh year.

I was too slight for my health to be complete, but very strong for one so slight. Neither was I tall, but I had an innate love of grace and freedom, which governed my motions; for I was extremely active, could leap, spring, and run with the best, though I always hated walking. I believe I should have died under any other care than that expanded over me, for my mother abhorred the forcing system. Had I belonged to those 23 who advocate excessive early culture, my brain would, I believe, have burst, so continually was it teeming. But from my lengthy idleness alternating with moderate action, I had no strain upon my faculties.

How perfectly I recollect the morning, early in autumn, on which the festival was first especially suggested to me! It was a very bright day, but so chilly that we had a fire in the parlor grate, for we were all disposed to be very comfortable as part of our duty. I had said all my lessons, and was now sitting at the table writing a small text copy in a ruled book, with an outside marbled fantastically brown and blue, which book lay, not upon the cloth, of course, but upon an inclined plane formed of a great leather case containing about a quire of open blotting-paper.

My sister Clotilda was over against me at the table, with the light shaded from her eyes by a green fan screen, studying, as usual, in the morning hours, a Greek Testament full of very neat little black notes. I remember her lead-colored gown, her rich washing silk, and her clear white apron, her crimson muffetees and short, close black mittens, her glossy hair rolled round her handsome tortoise-shell comb, and the bunch of rare though quaint ornaments—seals, keys, rings, and lockets,—that balanced her beautiful English watch. What a treasure they would have been for a modern châtelaine! my father having presented her with the newest, and an antique aunt having willed her the rest. She was very much like an old picture of a young person sitting there.

For my part, I was usually industrious enough, because I was never persecuted with long tasks; my attention was never stretched, as it were, upon a last, so that it was no meritorious achievement if I could bend it towards all that I undertook, with a species of elasticity 24 peculiar to the nervous temperament. My mother was also busy. She sat in her tall chair at the window, her eyes constantly drawn towards the street, but she never left off working, being deep in the knitting of an enormous black silk purse for Lydia to carry when she went to market. Millicent was somewhere out of the room, and Lydia, having given orders for dinner, had gone out to walk.

I had written about six lines in great trepidation—for writing usually fevered me a little, it was such an effort—when my great goose-quill slipped through my fingers, thin as they were, and I made a desperate plunge into an O. I exclaimed aloud, "Oh, what a blot!" and my lady Mentor arose and came behind me.

"Worse than a blot, Charles," she said, or something to that effect. "A blot might not have been your fault, but the page is very badly written; I shall cut it out, and you had better begin another."

"I shall only blot that, Clo," I answered; and Clo appealed to my mother.

"It is very strange, is it not, that Charles, who is very attentive generally, should be so little careful of his writing? He will never suit the post of all others the most important he should suit."

"What is that?" I inquired so sharply that my mother grew dignified, and responded gravely,—

"My dear Clotilda, it will displease me very much if Charles does not take pains in every point, as you are so kind as to instruct him. It is but little such a young brother can do to show his gratitude."

"Mother!" I cried, and sliding out of my chair, I ran to hers. "I shall never be able to write,—I mean neatly; Clo may look over me if she likes, and she will know how hard I try." 25

"But do you never mean to write, Charles?"

"I shall get to write somehow, I suppose, but I shall never write what you call a beautiful hand."

My mother took my fingers and laid them along her own, which were scarcely larger.

"But your hands are very little less than mine; surely they can hold a pen?"

"Oh, yes, I can hold anything!" And then I laughed and said, "I could do something with my hands too." I was going to finish, "I could play;" but Lydia had just turned the corner of the street, and my mother's eyes were watching her up to the door. So I stood before her without finishing my explanation. She at length said, kindly, "Well, now go and write one charming copy, and then we will walk."

I ran back to my table and climbed my chair, Clo having faithfully fulfilled her word and cut out the offending leaf.

But I had scarcely traced once, "Do not contradict your elders," before Lydia came in, flushed and glowing, with a basket upon her arm. She exhibited the contents to my mother,—who, I suppose, approved thereof, as she said they might be disposed of in the kitchen,—and then, with a sort of sigh, began, before she left the room, to remove her walking dress.

"Oh! it is hopeless; the present price is a guinea."

"I was fearful it would be so, my dear girl," replied my mother, in a tone of mingled condolence and authority she was fond of assuming. "It would be neither expedient nor fitting that I should allow you to go, though I very much wish it; but should we suffer ourselves such an indulgence, we should have to deprive ourselves of comforts that are necessary to health, and thus to well being. I should not like dear Millicent 26 and yourself, young as you are, to go alone to the crowded seats in the town-hall; and if I went with you, we should be three guineas out of pocket for a month."

This was true; my mother's jointure was small, and though we lived in ease, it was by the exercise of an economy rigidly enforced and minutely developed. It was in my own place, indeed, I learned how truly happy does comfort render home, and how strictly comfort may be expressed by love from prudence, by charity from frugality, and by wit from very slender competence.

"I do not complain, dear mother," Lydia resumed, in a livelier vein; "I ventured to ask at the office because you gave me leave, and Fred thought there would be back seats lowered in price, or perhaps a standing gallery, as there was at the last festival. But it seems the people in the gallery made so much uproar last time that the committee have resolved to give it up."

This was getting away from the point, so I put in, "Is the festival to be soon, then, Lydia?"

"Yes, dear; it is only three weeks to-day to the first performance."

"Will it be very grand?"

"Oh, yes; the finest and most complete we have ever had."

Then Lydia, having quite recovered her cheerfulness, went to the door, and speedily was no more seen. No one spoke, and I went on with my copy; but it was hard work for me to do so, for I was in a pricking pulsation from head to foot. It must have been a physical prescience of mental excitement, for I had scarcely ever felt so much before. I was longing, nay, crazy, to finish my page, that I might run out and find Millicent, who, child as I was, I knew could tell me what I wanted to hear better than any one of them. My eagerness 27 impeded me, and I did not conclude it to Clo's genuine satisfaction after all. She dotted all my i's and crossed my t's, though with a condescending confession that I had taken pains,—and then I was suffered to go; but it was walking time, and my mother dressed me herself in her room, so I could not catch Millicent till we were fairly in the street.

I do not pretend to remember all the conversations verbatim which I have heard during my life, or in which I have taken a part; still, there are many which I do remember word by word, and every word. My conversation that morning with Millicent I do not remember,—its results blotted it out forever; still, I am conscious it was an exposition of energy and enthusiasm, for hers kindled as she replied to my ardent inquiries, and, unknowingly, she inflamed my own. She gave me a tale of the orchestra, its fulness and its potency; of the five hundred voices, of the conductor, and of the assembly; she assured me that nothing could be at all like it, that we had no idea of its resources or its effects.

She was melancholy, evidently, at first, but quite lost in her picturesque and passionate delineation, I all the while wondering how she could endure to exist and not be going. I felt in myself that it was not only a sorrow, but a shame, to live in the very place and not press into the courts of music. I adored music even then,—ay! not less than now, when I write with the strong heart and brain of manhood. I thought how easily Millicent might do without a new hat, a new cloak, or live on bread and water for a year. But I was man enough even then, I am thankful to say, to recall almost on the instant that Millicent was a woman, a very delicate girl, too, and that it would never do for her to be crushed 29 among hundreds of moving men and women, nor for Fred to undertake the charge of more than one—he had bought a ticket for his wife. Then I returned to myself.

From the first instant the slightest idea of the festival had been presented to me, I had seized upon it personally with the most perfect confidence. I had even determined how to go,—for go I felt I must; and I knew if I could manage to procure a ticket, Fred would take me in his hand, and my mother would allow me to be disposed of in the shadow of his coat-tails, he was always so careful of us all. As I walked homewards I fell silent, and with myself discussed my arrangements; they were charming. The town-hall was not distant from our house more than a quarter of a mile. I was often permitted to run little errands for my sisters: to match a silk or to post a letter. My pecuniary plan was unique: I was allowed twopence a week, to spend as I would, though Clo protested I should keep an account-book as soon as I had lived a dozen years. From my hatred of copper money I used to change it into silver as fast as possible, and at present I had five sixpences, and should have another by the end of another week. I was to take this treasure to the ticket office, and request whatever gentleman presided to let me have a ticket for my present deposit, and trust—I felt a certain assurance that no one would refuse me, I know not why, who had to do with the management of musical affairs. I was to leave my sixpences with my name and address, and to call with future allowances until I had refunded all. It struck me that not many months must pass before this desirable end might accomplish itself.

I have often marvelled why I was not alarmed, nervous as I was, to venture alone into such a place, with 30 such a purpose; but I imagine I was just too ignorant, too infantine in my notions of business. At all events, I was more eager than anxious for the morrow, and only restless from excited hope. I never manœuvred before, I have often manœuvred since, but never quite so innocently, as I did to be sent on an errand the next morning. It was very difficult, no one would want anything, and at last in despair I dexterously carried away a skein, or half a skein, of brown sewing silk, with which Lydia was hemming two elegant gauze veils for herself and for Millicent. The veils were to be worn that day I knew, for my mother had set her heart upon their excluding a "thought" of east in the autumnal wind, and there was no other silk; I managed to twist it into my shoe, and Lydia looked everywhere for it, even into the pages of Clo's book,—greatly to her discomfiture. But in vain, and at last said Lydia, "Here, Charles, you must buy me another," handing me a penny. Poor Lydia! she did not know how long it would be before I brought the silk; but imagining I should be back not directly, I had the decency to transfer my pilfered skein to the under surface of the rug, for I knew that they would turn it up as usual in a search. And then, without having been observed to stoop, I fetched my beaver broad brimmer and scampered out.

I scampered the whole way to the hall. It was a chilly day, but the sun had acquired some power, and it was all summer in my veins. I believe I had never been in such a state of ecstasy. I was quite lightheaded, and madly expected to possess myself of a ticket immediately, and dance home in triumph. The hall! how well I remember it, looking very still, very cold, very blank; the windows all shuttered, the doors all closed. But never mind; the walls were glorious! 31 They glittered with yellow placards, the black letters about a yard long announcing the day, the hour, the force,—the six-foot long list of wonders and worthies. I was something disappointed not to find the ticket-office a Spanish castle suddenly sprung from the stonework of the hall itself, but it was some comfort that it was in St. Giles' Street, which was not far.

I scampered off again,—I tumbled down, having lost my breath, but I sprang again to my feet; I saw a perfect encampment of placards, and I rushed towards it. How like it was to a modern railway terminus, that ticket-office!—in more senses than one, too. The door was not closed here, but wide open to the street: within were green-baize doors besides, but the outer entrance was crowded, and those were shut,—not for a minute together, though, for I could not complain of quiet here. Constantly some one hurrying past nearly upset me, bustling out or pushing in. They were all men, it is true; but was I a girl? Besides, I had seen a boy or two who had surveyed me impertinently, and whom I took leave to stare down. A little while I stood in the entry, bewildered, to collect my thoughts,—not my courage,—and then, endeavoring to be all calmness and self-possession, I staggered in. I then saw two enclosed niches, counter-like: the one had a huge opening, and was crammed with people on this side; the other was smaller, an air of eclecticism pervaded it; and behind each stood a man. There was a staircase in front, and painted on the wall to its left I read: "Committee-room upstairs; Balloted places,"—but then I returned to my counters, and discovered, by reading also, that I must present myself at the larger for unreserved central seats. It was occupied so densely in front just now that it was hopeless to dream of an approach 32 or appeal; I could never scale that human wall. I retreated again to the neighborhood of the smaller compartment, and was fascinated to watch the swarming faces. Now a stream poured down the staircase, all gentlemen, and most of them passed out, nodding and laughing among themselves. Not all passed out. One or two strolled to the inner doors and peeped through their glass halves, while others gossiped in the entry. But one man came, and as I watched him, planted himself against the counter I leaned upon,—the mart of the reserved tickets. He did not buy any though, and I wondered why he did not, he looked so easy, so at home there. Not that I saw his face, which was turned from me; it struck me he was examining a clock there was up on the staircase wall. I only noticed his boots, how bright they were, and his speckled trousers, and that his hand, which hung down, was very nicely covered with a doeskin glove.

Before he had made out the time, a number of the stones in the human partition gave way at once,—in other words, I saw several chinks between the loungers at the larger counter. I closer clasped my sixpences, neatly folded in paper, and sped across the office. Now was my hour. I was not quite so tall as to be able to look over and see whom I addressed; nevertheless, I still spoke up.

I said, "If you please, sir, I wish to speak to you very particularly about a ticket."

"Certainly," was the reply instantly thrown down upon me. "One guinea, if you please."

"Sir, I wish to speak about one, not to buy it just this minute; and if you allow me to speak,"—I could not continue with the chance of being heard, for two more stones had just thrust themselves in and hid my chink; 33 they nearly stifled me as it was, but I managed to escape, and stood out clear behind. I stood out not to go, but to wait, determined to apply again far more vigorously.

I listened to the rattling sovereigns as they dropped; and dearly I longed for some of that money, though I never longed for money before or since. Then suddenly reminded, I turned, to see whether that noticeable personage had left the smaller counter. He was there. I insensibly moved nearer to him,—so attractive was his presence. And as I believe in various occult agencies and physical influences, I hold myself to have been actually drawn towards him. He had a face upon which it was life to look, so vivid was the intelligence it radiated, so interesting was it in expression, and if not perfect, so pure in outline. He was gazing at me too, and this, no doubt, called out of me a glance all imploring, as so I felt, yea, even towards him, for a spark of kindliest beam seemed to dart from under his strong dark lashes, and his eyes woke up,—he even smiled just at the corners of his small, but not thin lips. It was too much for me. I ran across, and again took my stand beside him. I thought, and I still think, he would have spoken to me instantly; but another man stepped up and spoke to him. He replied in a voice I have always especially affected,—calm, and very clear, but below tone in uttering remarks not intended for the public. I did not hear a word. As soon as he finished speaking, he turned and looked down upon me; and then he said, "Can I do anything for you?"

I was so charmed with his frank address, I quite gasped for joy: "Sir, I am waiting to speak to the man inside over there about my ticket."

"Shall I go across and get it?" 34

"Why, no, sir. I must speak to him—or if you would tell me about it."

"I will tell you anything; say on."

"Sir, I am very poor, and have not a guinea, but I shall have enough in time, if you will let me buy one with the money I have brought, and pay the rest by degrees."

I shall never forget the way he laid his hand on my shoulder and turned me to the light,—to scrutinize my developments, I suspect; for he stayed a moment or two before he answered, "I do think you look as if you really wanted one, but I am afraid they will not understand such an arrangement here."

"I must go to the festival," I returned, looking into his eyes, "I am so resolved to go; I will knock the door down if I cannot get a ticket. Oh! I will sell my clothes, I will do anything. If you will get me a ticket, sir, I will promise to pay you, and you can come and ask my mother whether I ever break my word."

"I am sure you always keep it, or you would not love music so earnestly; for you are very young to be so earnest," he responded, still holding me by the arm, that thrilled beneath his kindly pressure. "Will you go a little walk with me, and then I can better understand you or what you want to do?"

"I won't go till I have got my ticket."

"You cannot get a ticket, my poor boy; they are not so easily disposed of. Why not ask your mother?"

"My sister as good as did; but my mother said it was too expensive."

"Did your mamma know how very much you wished it?"

"We do not say mamma, she does not like it; she likes 'liebe Mutter.'" 35

"Ah! she is German. Perhaps she would allow you to go, if you told her your great desire."

"No, sir; she told Lydia that it would put her out of pocket."

My new friend smiled at this.

"Now, just come outside; we are in the way of many people here, and I have done my business since I saw that gentleman I was talking to when you crept so near me."

"Did you know I wanted to come close to you, sir?"

"Oh, yes! and that you wanted to speak. I know the little violin face."

These words transported me. "Oh! do you think I am like a violin? I wish I were one going to the festival."

"Alas! in that sense you are not one, I fear."

I burst into tears; but I was very angry with myself, and noiselessly put my whole face into my handkerchief as we moved to the door. Once out in the street, the wind speedily dried these dews of my youth, and I ventured to take my companion's hand. He glanced down at mine as it passed itself into his, and I could see that he was examining it. I had very pretty hands and nails,—they were my only handsome point; my mother was very vain of them. I have found this out since I have grown up.

"My dear little boy, I am going to do a very daring thing."

"What is that, sir?"

"I am going to run away with you; I am going to take you to my little house, for I have thought of something I can only say to you in a room. But if you will 36 tell me your name, I will carry you safe home afterwards, and explain everything to the 'liebe Mutter.'"

"Sir, I am so thankful to you that I cannot do enough to make you believe it. I am Charles Auchester, and we live at No. 14 Herne Street, at a red house with little windows and a great many steps up to the door."

"I know the house, and have seen a beautiful Jewess at the window."

"Everybody says Millicent is like a Jewess. Sir, do you mind telling me your name? I don't want to know it unless you like to tell it me."

"My name is not a very pretty one,—Lenhart Davy."[4]

"From David, I suppose?" I said, quickly. My friend looked at me very keenly.

"You seem to think so at least."

"Yes, I thought you came from a Jew, like us,—partly, I mean. Millicent says we ought to be very proud of it; and I think so too, because it is so very ancient, and does not alter."

I perfectly well remember making this speech. Lenhart Davy laughed quietly, but so heartily it was delightful to hear him.

"You are quite right about that. Come! will you trust me?"

"Oh! sir, I should like to go above all things, if it is not very far,—I mean I must get back soon, or they will be frightened about me."

"You shall get back soon. I am afraid they are frightened now,—do you think so? But my little house is on the way to yours, though you would never find it out."

He paused, and we walked briskly forwards. 38

Turning out of the market-place, a narrow street presented itself: here were factories and the backs of houses. Again we threaded a narrow turning: here was an outskirt of the town. It fronted a vast green space; all building-ground enclosed this quiet corner, for only a few small houses stood about. Here were no shops and no traffic. We went on in all haste, and soon my guide arrested himself at a little green gate. He unlatched it; we passed through into a tiny garden, trim as tiny, pretty as trim, and enchantingly after my own way of thinking. Never shall I forget its aspect,—the round bed in the centre, edged with box as green as moss; the big rose-tree in the middle of the bed, and lesser rose-trees round; the narrow gravel walk, quite golden in the sun; the outer edge of box, and outer bed of heaths and carnations and glowing purple stocks. But above all, the giant hollyhocks, one on each side of a little brown door, whose little latticed porch was arched with clematis, silvery as if moonlight "Minatrost" were ever brooding upon that threshold.

I must not loiter here; it would have been difficult to loiter in going about the garden, it was so unusually small, and the house, if possible, was more diminutive. It had above the door two tiny casement windows, only two; and as my guide opened the little door with a key he brought out of his pocket, there was nothing to delay our entrance. The passage was very narrow, but 39 lightsome, for a door was open at the end, peeping into a lawny kind of yard. No children were tumbling about, nor was there any kitchen smell, but the rarest of all essences, a just perceptible cleanliness,—not moisture, but freshness.

We advanced to a staircase about three feet in width, uncarpeted, but of a rich brown color, like chestnut skins; so also were the balusters. About a dozen steps brought us to a proportionate landing-place, and here I beheld two other little brown doors at angles with one another. Lenhart Davy opened one of these, and led me into a tiny room. Oh, what a tiny room! It was so tiny, so rare, so curiously perfect that I could not help looking into it as I should have done into a cabinet collection. The casements were uncurtained, but a green silk shade, gathered at the top and bottom, was drawn half-way along each. The walls were entirely books,—in fact, the first thing I thought of was the book-houses I used to build of all the odd volumes in our parlor closet during my quite incipient years. But such books as adorned the sides of the little sanctum were more suitable for walls than mine, in respect of size, being as they were, or as far as I could see, all music-books, except in a stand between the casements, where a few others rested one against another. There was a soft gray drugget upon the floor; and though, of course, the book-walls took up as much as half the room (a complete inner coat they made for the outside shell), yet it did not strike me as poking, because there was no heavy furniture, only a table, rather oval than round, and four chairs; both chairs and table of the hue I had admired upon the staircase,—a rich vegetable brown. On the table stood a square inkstand of the same wood, 40 and a little tray filled with such odds as rubber, a penknife, sealing-wax, and a pencil. The wood of the mantelshelf was the same tone, and so was that of a plain piano that stood to the left of the fireplace, in the only nook that was not books from floor to ceiling; but the books began again over the piano. All this wood, so darkly striking the eye, had an indescribably soothing effect (upon me I mean), and right glad was I to see Mr. Davy seat himself upon a little brown bench before the piano and open it carefully.

"Will you take off your hat for a minute or two, my dear boy?" he asked, before he did anything else.

I laid the beaver upon the oval table.

"Now, tell me, can you sing at all?"

"Yes sir."

"From notes, or by ear?"

"A great deal by ear, but pretty well by notes."

"From notes," he said, correctingly, and I laughed.

He then handed me a little book of chorales, which he fetched from some out-of-the-way hole beneath the instrument. They were all German: I knew some of them well enough.

"Oh, yes, I can sing these, I think."

"Try 'Ein' feste Burg ist unser Gott.'[5] Can you sing alto?"

"I always do. Millicent says it is proper for boys."

He just played the opening chord slentando, and I began. I was perfectly comfortable, because I knew what I was about, and my voice, as a child's, was perfect. I saw by his face that he was very much surprised, as well as pleased. Then he left me alone to sing another, and then a third; but at last he struck in with a 41 bass,—the purest, mellowest, and most unshaken I have ever heard, though not strong; neither did he derange me by a florid accompaniment he made as we went along. When I concluded the fourth, he turned, and took my hand in his.

"I knew you could do something for music, but I had no idea it would be so very sweetly. I believe you will go to the festival, after all. You perceive I am very poor, or perhaps you do not perceive it, for children see fairies in flies. But look round my little room. I have nothing valuable except my books and my piano, and those I bought with all the money I had several years ago. I dare say you think my house is pretty. Well, it was just as bare as a barn when I came here six months ago. I made the shelves (the houses for my precious books) of deal, and I made that table, and the chairs, and this bench, of deal, and stained each afterwards; I stained my shelves too, and my piano. I only tell you this that you may understand how poor I am. I cannot afford to give you one of these tickets, they are too dear, neither have I one myself; but if your mother approves, and you like it, I believe I can take you with me to sing in the chorus."

This was too much for me to bear without some strong expression or other. I took my hat, hid my face in it, and then threw my arms round Lenhart Davy's neck. He kissed me as a young father might have done, with a sort of pride, and I was able to perceive he had taken an instant fancy to me. I did not ask him whether he led the chorus, nor what he had to do with it, nor what I should have to do; but I begged him joyously to take me home directly. He tied on my hat himself, and I scampered all the way downstairs and round the garden 42 before he came out of his shell. He soon followed after me, smiling; and though he asked me no curious question as we went along, I could tell he was nervous about something. We walked very fast, and in little less than an hour from the time I left home, I stood again upon the threshold.

Of all the events of that market-day, none moved me more enjoyably than the sight of the countenances, quite petrified with amazement, of my friends in the parlor. They were my three sisters. Clo came forward in her bonnet, all but ready for a sortie; and though she bowed demurely enough, she began at me very gravely,—

"Charles, I was just about to set out and search for you. My mother has already sent a servant. She herself is quite alarmed, and has gone upstairs."

Before I could manage a reply, or introduce Lenhart Davy, he had drawn out his card. He gave it to the "beautiful Jewess." Millicent took it calmly, though she blushed, as she always did when face to face with strangers, and she motioned him to the sofa. At this very instant my mother opened the door.

It would not be possible for me to recover that conversation, but I remember how very refined was the manner, and how amiably deferential the explanation of my guide, as he brought out everything smooth and apparent even to my mother's ken. Lydia almost laughed in his presence, she was so pleased with him, and Millicent examined him steadfastly with her usually shrinking gray eyes. My mother, I knew, was displeased with me, but she even forgave me before he had done speaking. His voice had in it a quality (if I may so name it) of 44 brightness,—a metallic purity when raised; and the heroic particles in his blood seemed to start up and animate every gesture as he spoke. To be more explicit as to my possibilities, he told us that he was in fact a musical professor, though with little patronage in our town, where he had only a few months settled; that for the most part he taught, and preferred to teach, in classes, though he had but just succeeded in organizing the first. That his residence and connection in our town were authorized by his desire to discover the maximum moral influence of music upon so many selected from the operative ranks as should enable him by inference to judge of its moral power over those same ranks in the aggregate. I learned this afterwards, of course, as I could not apprehend it then; but I well recall that his language, even at that time, bound me as by a spell of conviction, and I even appreciated his philanthropy in exact proportion to his personal gifts.

He said a great deal more, and considerably enlarged upon several points of stirring musical interest, before he returned to the article of the festival. Then he told us that his class would not form any section of the chorus, being a private affair of his own, but that he himself should sing among the basses, and that it being chiefly amateur, any accumulation of the choral force was of consequence. He glanced expressly at my mother when he said,—

"I think your little boy's voice and training would render him a very valuable vote for the altos, and if you will permit me to take charge of him at the rehearsals, and to exercise him once or twice alone, I am certain Mr. St. Michel will receive him gladly."

"Is Mr. St. Michel the conductor, Mr. Davy, then?" replied my mother with kindness. "I remember seeing 45 him in Germany when a little theatre was opened in our village. I was a girl then, and he very young."

"Yes, madam. Application was made to the wonderful Milans-André, who has been delighting Europe with his own compositions interpreted by himself; but he could not visit England at present, so St. Michel will be with us, as on former occasions. And he is a good conductor, very steady, and understands rehearsal."

Let me here anticipate and obviate a question. Was not my mother afraid to trust me in such a mixed multitude, with men and women her inferiors in culture and position? My mother had never trusted me before with a stranger, but I am certain, at this distance of time, she could not resist the pure truthfulness and perfect breeding of Lenhart Davy, and was forced into desiring such an acquaintance for me. Perhaps, too, she was a little foolish over her last-born, for she certainly did indulge me in a quiet way, and with a great show of strictness.

As Lenhart Davy paused, she first thanked him, then rang the bell, was silent until she had ordered refreshments, sat still even then a few minutes, and presently uttered a deliberate consent. I could not bear it. I stood on one foot for an instant behind Clo's chair, and then flung myself into the passage. Once upstairs, I capered and danced about my mother's bed-room until fairly exhausted, and then I lay down on my own bed, positively in my coat and boots, and kicked the clothes into a heap, until I cried. This brought me to, and I remembered with awe the premises I had invaded. I darted to my feet, and was occupied in restoring calm as far as possible to the tumbled coverlid, when I was horrified at hearing a step. It was only Millicent, with tears in her good eyes. 46

"I am so glad for you, Charles," she said; "I hope you will do everything in your power to show how grateful you are."

"I will be grateful to everybody," I answered. "But do tell me, is he gone?"

"Dear Charles, do not say 'he' of such a man as Mr. Davy."

Now, Millicent was but seventeen; still, she had her ideas, girlishly chaste and charming, of what men ought to be.

"I think he is lovely," I replied, dancing round and round her, till she seized my hands.

"Yes, Mr. Davy is gone; but he is kindly coming to fetch you to-morrow, to drink tea with him, and mother has asked him to dine here on Sunday. He showed her a letter he has from the great John Andernach, because mother said she knew him, and she says Mr. Davy must be very good, as well as very clever, from what Mr. Andernach has written."

"I know he is good! Think of his noticing me! I knew I should go! I said I would go!" and I pulled my hands away to leap again.

The old windows rattled, the walls shook, and in came Clo.

"Charles, my mother says if you do not keep yourself still, she will send a note after Mr. Davy. My dear boy, you must come and be put to rights. How rough your head is! What have you been doing to make it so?" and she marched me off. I was quelled directly, and it was indeed very kind of them to scold me, or I should have ecstasized myself ill.

It was hard work to get through that day, I was so impatient for the next; but Millicent took me to sing a little in the evening, and I believe it sent me to sleep. I 47 must mention that the festival was to last three days. There were to be three grand morning performances and three evening concerts; but my mother informed me she had said she did not like my being out at night, and that Lenhart Davy had answered, the evening concerts were not free of entrance to him, as there was to be no chorus, so he could not take me. I did not care; for now a new excitement, child of the first and very like its parent, sprang within my breast. To sing myself,—it was something too grand; the veins glowed in my temples as I thought of my voice, so small and thin, swelling in the cloud of song to heaven: my side throbbed and fluttered. To go was more than I dared to expect; but to be necessary to go was more than I deserved,—it was glory.

I gathered a few very nice flowers to give Lenhart Davy, for we had a pretty garden behind the house, and also a bit of a greenhouse, in which Millicent kept our geraniums all the winter. She was tying up the flowers for me with green silk when he knocked at the door, and would not come in, but waited for me outside. Amiable readers, everybody was old-fashioned twenty years ago,[6] and many somebodies took tea at five o'clock. Admirable economy of social life, to eat when you hunger, and to drink when you thirst! But it is polite to invent an appetite for made-dishes, so we complain not that we dine at eight nowadays; and it is politic too, for complexions are not what they used to be, and maiden heiresses, with all their thousands, cannot purchase Beauty Sleep! Pardon my digression while Davy is waiting at the door. I did not keep him so long, be certain. We set out. He was very much pleased with my flowers, and as it was rather a chilly 48 afternoon, he challenged me to a race. We ran together, he striding after me like a child himself in play, and snapping at my coat; I screamed all the while with exquisite sensation of pleasurable fun. Then I sped away like a hound, and still again he caught me and lifted me high into the air. Such buoyancy of spirits I never met with, such fluency of attitude; I cannot call them or their effect animal. It was rather as if the bright wit pervaded the bilious temperament, almost misleading the physiologist to name it nervous. I have never described Lenhart Davy, nor can I; but to use the keener words of my friend Dumas, he was one of the men the most "significant" I ever knew.

Arrived at his house,—that house, just what a house should be, to the purpose in every respect,—I flew in as if quite at home. I was rather amazed that I saw no woman-creature about, nor any kind of servant. The door at the end of the passage was still open; I still saw out into the little lawny yard, but nobody was stirring. "The house was haunted!"

I believe it,—by a choir of glorious ghosts!

"Dear alto, you will not be alarmed to be locked in with me, I hope, will you?"

"Frightened, sir? Oh, no, it is delicious." I most truly felt it delicious. I preceded him up the staircase,—he remaining behind to lock the little door. I most truly felt it delicious. Allow me again to allude to the appetite. I was very hungry, and when I entered the parlor I beheld such preparation upon the table as reminded me it is at times satisfactory as well as necessary to eat and drink. The brown inkstand and company were removed, and in their stead I saw a little tray, of an oval form, upon which tray stood the most exquisite porcelain service for two I have ever seen. The china was small and very old,—I knew that, for we were rather curious in china at home; and I saw how very valuable these cups, that cream-jug, those plates must be. They were of pearly clearness, and the crimson and purple butterfly on each rested over a sprig of honeysuckle entwined with violets. 50

"Oh, what beautiful china!" I exclaimed; I could not help it, and Lenhart Davy smiled.

"It was a present to me from my class in Germany."

"Did you have a class, sir, in Germany?"

"Only little boys, Charlie, like myself."

"Sir, did you teach when you were a little boy?"

"I began to teach before I was a great boy, but I taught only little boys then."

He placed me in a chair while he left the room for an instant. I suppose he entered the next, for I heard him close at hand. Coming back quickly, he placed a little spirit-lamp upon the table, and a little bright kettle over it; it boiled very soon. He made such tea!—I shall never forget it; and when I told him I very seldom had tea at home, he answered, "I seldom drink more than one cup myself; but I think one cannot hurt even such a nervous person as you are,—and besides, tea improves the voice,—did you know that?"

I laughed, and drew my chair close to his. Nor shall I ever forget the tiny loaves, white and brown, nor the tiny pat of butter, nor the thin, transparent biscuits, crisp as hoar-frost, and delicate as if made of Israelitish manna. Davy ate not much himself, but he seemed delighted to see me eat, nor would he allow me to talk.

"One never should," said he, "while eating."

Frugal as he was, he never for an instant lost his cheery smile and companionable manner, and I observed he watched me very closely. As soon as I had gathered up and put away my last crumb, I slipped out of my chair, and pretended to pull him from his seat.

"Ah! you are right, we have much to do."

He went out again, and returned laden with a wooden tray, on which he piled all the things and carried them downstairs. Returning, he laughed and said,— 51

"I must be a little put out to-night, as I have a visitor, so I shall not clear up until I have taken you home."

"My mother is going to send for me, sir; but I wish I might help you now."

"I shall not need help,—I want it at least in another way. Will you now come here?"

We removed to the piano. He took down from the shelves that overshadowed it three or four volumes in succession. At length, selecting one, he laid it upon the desk and opened it. I gazed in admiration. It was a splendid edition, in score, of Pergolesi's "Stabat Mater." He gathered from within its pages a separate sheet—the alto part, beautifully copied—and handed it to me, saying, "I know you will take care of it." So I did. We worked very hard, but I think I never enjoyed any exercise so much. He premised, with a cunning smile, that he should not let me run on at that rate if I had not to be brushed up all in a hurry; but then, though I was ignorant, I was apt and very ardent. I sang with an entire attention to his hints; and though I felt I was hurrying on too fast for my "understanding" to keep pace with my "spirit," yet I did get on very rapidly in the mere accession to acquaintance with the part. We literally rushed through the "Stabat Mater," which was for the first part of the first grand morning, and then, for the other, we began the "Dettingen Te Deum." I thought this very easy after the "Stabat Mater," but Davy silenced me by suggesting, "You do not know the difficulty until you are placed in the choir." Our evening's practice lasted about two hours and a half. He stroked my hair gently then, and said he feared he had fatigued me. I answered by thanking him with all my might, and begging to go on. He shook his head. 52

"I am afraid we have done too much now. This day week the 'Creation,'—that is for the second morning; and then, Charles, then the 'Messiah,'—last and best."

"Oh, the 'Messiah'! I know some of the songs,—at least, I have heard them. And are we to hear that? and am I to sing in 'Hallelujah'?" I had known of it from my cradle; and loving it before I heard it, how did I feel for it when it was to be brought so near me? I think that this oratorio is the most beloved of any by children and child-like souls. How strangely in it all spirits take a part!

Margareth, our ancient nurse, came for me at half-past eight. She was not sent away, but Davy would accompany us to our own door. Before I left his house, and while she was waiting in the parlor, he said to me, "Would you like to see where I sleep?" and called me into the most wonderful little room. A shower-bath filled one corner; there was a great closet one whole side, filled with every necessary exactly enough for one person. The bed was perfectly plain, with no curtains and but a head-board, a mattress, looking as hard as the ground, and a very singular portrait, over the head, of a gentleman, in line-engraving, which does not intellectualize the contour. This worthy wore a flowing wig and a shirt bedecked with frills.

"That is John Sebastian Bach," said Lenhart Davy,—"at least, they told me so in Dresden. I keep it because it means to be he."

"Ah!" I replied; for I had heard the jaw-breaking name, which is dearer to many (though they, alas! too few, are scattered) than the sound of Lydian measures.

If I permit myself to pay any more visits to the nameless cottage, I shall never take myself to the festival; but I must just say that we entertained Davy the next Sunday at dinner. I had never seen my mother enjoy anybody's society so much; but I observed he talked not so much as he listened to her, and this may have been the secret. He went very early, but on the Tuesday he fetched me again. It was not in vain that I sang this time either,—my voice seemed to deliver itself from something earthly; it was joy and ease to pour it forth.

When we had blended the bass and alto of the "Creation" choruses, with a long spell at "The heavens are telling," Davy observed, "Now for the 'Messiah,' but you will only be able to look at it with me; to-morrow night is rehearsal at the hall, and your mother must let you go." Rehearsal at the hall! What words were those? They rang in my brain that night, and I began to grow very feverish. Millicent was very kind to me; but I was quite timid of adverting to my auspices, and I dared not introduce the subject, as none of them could feel as I did. My mother watched me somewhat anxiously,—and no wonder; for I was very much excited. But when the morrow came, my self-importance made a man of me, and I was calmer than I had been for days. 54

I remember the knock which came about seven in the evening, just as it was growing gray. I remember rushing from our parlor to Lenhart Davy on the doorstep. I remember our walk, when my hands were so cold and my heart was so hot, so happy. I remember the pale, pearly shade that was falling on street and factory, the shop-lit glare, the mail-coach thundering down High Street. I remember how I felt entering, from the dim evening, the chiaro-oscuro of the corridors, just uncertainly illustrated by a swinging lamp or two; and I remember passing into the hall. Standing upon the orchestra, giddy, almost fearful to fall forwards into the great unlighted chaos, the windows looked like clouds themselves, and every pillar, tier, and cornice stood dilated in the unsubstantial space. Lenhart Davy had to drag me forwards to my nook among the altos, beneath the organ, just against the conductor's desk. The orchestra was a dream to me, filled with dark shapes, flitting and hurrying, crossed by wandering sounds, whispers, and laughter. There must have been four or five hundred of us up there, but it seems to me like a lampless church, as full as it could be of people struggling for room.

Davy did not lose his hold upon me, but one and another addressed him, and flying remarks reached him from every quarter. He answered in his hilarious voice; but his manner was decidedly more distant than to me when alone with him. At last some one appeared at the foot of the orchestra steps with a taper; some one or other snatched it from him, and in a moment a couple of candles beamed brightly from the conductor's desk. It was a strange, candle-light effect then. Such great, awful shadows threw themselves down the hall, and so many faces seemed darker than they had, clustered 55 in the glooming twilight. Again some hidden hand had touched the gas, which burst in tongues of splendor that shook themselves immediately over us; then was the orchestra a blaze defined as day. But still dark, and darkening, like a vast abyss, lay the hall before us; and the great chandelier was itself a blot, like a mystery hung in circumambient nothingness.

I was lost in the light around me, and striving to pierce into that mystery beyond, when a whisper thrilled me: "Now, Charles, I must leave you. You are Mr. Auchester at present. Stand firm and sing on. Look alone at the conductor, and think alone of your part. Courage!" What did he say "courage" for? As if my heart could fail me then and there!

I looked steadfastly on. I saw the man of many years' service in the cause of music looking fresh as any youth in the heyday of his primal fancy. A white-haired man, with a patriarchal staff besides, which he struck upon the desk for silence, and then raised, in calm, to dispel the silence.

I can only say that my head swam for a few minutes, and I was obliged to shut my eyes before I could tell whether I was singing or not. I was very thankful when somebody somewhere got out as a fugue came in, and we were stopped, because it gave me a breathing instant. But then again, breathless,—nerveless, I might say, for I could not distinguish my sensations,—we rushed on, or I did, it was all the same; I was not myself yet. At length, indeed, it came, that restoring sense of self which is so precious at some times of our life. I recalled exactly where I was. I heard myself singing, felt myself standing; I was as if treading upon air, yet fixed as rock. I arose and fell upon those surges of sustaining sound; but it was as with an undulating 56 motion itself rest. My spirit straightway soared. I could imagine my own voice, high above all the others, to ring as a lark's above a forest, tuneful with a thousand tones more low, more hidden; the attendant harmonies sank as it were beneath me; I swelled above them. It was my first idea of paradise.

And it is perhaps my last.

Let me not prose where I should, most of all, be poetical. The rehearsal was considered very successful. St. Michel praised us. He was a good old man, and, as Davy had remarked, very steady. There was a want of unction about his conducting, but I did not know it, certainly not feel it, that night. The "Messiah" was more hurried through than it should have been, because of the late hour, and also because, as we were reminded, "it was the most generally known." Besides, there was to be a full rehearsal with the band before the festival, but I was not to be present, Davy considerately deeming the full effect would be lost for me were it in any sense to be anticipated.

I feel I should only fail if I should attempt to delineate my sensations on the first two days of performance, for the single reason that the third morning of that festival annihilated the others so effectually as to render me only master at this moment of its unparalleled incidents. Those I bear on my heart and in my life even to this very hour, and shall take them with me, yea, as a part of my essential immortality.

The second night I had not slept so well as the first, but on the third morning I was, nathless, extraordinarily fresh. I seemed to have lived ages, but yet all struck me in perfect unison as new. I was only too intensely happy as I left our house with Davy, he having breakfasted with us.

He was very much pleased with my achievements. I was very much pleased with everything; I was saturated with pleasure. That day has lasted me—a light—to this. Had I been stricken blind and deaf afterwards, I ought not to have complained,—so far would my happiness, in degree and nature, have outweighed any other I can imagine to have fallen to any other lot. Let those who endure, who rejoice, alike pure in passion, bless God for the power they possess—innate, unalienable, intransferable—of suffering all they feel.

I shall never forget that scene. The hall was already crowded when we pressed into our places half an hour before the appointed commencement. Every central speck was a head; the walls were pillared with human beings; the swarm increased, floating into the reserved places, and a stream still poured on beneath the gallery.