Title: Recollections of Windsor Prison;

Author: of Vermont John Reynolds

Release date: April 4, 2012 [eBook #39370]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This book was produced from scanned images of public

domain material from the Google Print project.)

CONTAINING

Sketches of its History and Discipline;

WITH

APPROPRIATE STRICTURES,

AND

MORAL AND RELIGIOUS REFLECTIONS.

BY JOHN REYNOLDS.

Third Edition.

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY A. WRIGHT.

1839.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1834,

BY ANDREW WRIGHT,

in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

"Lest men suspect your tale untrue,

Keep probability in view."

In following this suggestion of the poet, I have been compelled to "extenuate," and I have had no temptation to "set down aught in malice." The world of gloomy horrors through which my memory has been roving for the materials of this volume, cannot receive a deepening shade from either reality or fiction; and my conscientious and prudential object has been, to take the brightest truths which my subjects have required, and let the darker ones remain untold. For the correctness of the facts which I have recorded, as to all essential points, I hold myself responsible; and as to my strictures and reasonings, I am willing they should pass for just what they are worth.

In sending these Recollections abroad, I am governed by principles which are equally remote from the considerations of either hope or fear. All my hopes, from my fellow men, are gone out in the cold and gloomy damps of despair; and having long endured their deepest scorn, I have nothing more to fear from them. My sole object is to plead the cause of suffering humanity, and drag iniquity from her dark retreats out into the view of mankind. I have also aimed to rend the mask from spiritual wickedness; and rouse the energies of benevolence in favor of the wretched. My cause is a good one—would to God it could find an abler advocate!

In noticing the opinions of others, I have been unrestrained, but candid; and in touching the conduct of some, I have endeavored to render to each his due—praise, to whom praise, and censure, to whom censure—and I am willing to step into the same scale myself.

(p. iv) I am well aware that this book will create me enemies, and put the tongue of slander in motion; but none of these things move me. The bird that is wounded will flutter. On the other hand, I expect to obtain some friends by this work; but this has been no inducement with me to publish it. Finally, I can assure both friends and foes, that, if any good should result from this volume to the cause of benevolence in any way, I may take my pen again. At any rate, I shall have the satisfaction of having done my duty, and performed my vow; and this satisfaction is of more value to me than any other reward which may result from my labors.

THE AUTHOR.

Boston, April, 1834.

Egypt is said to have been the cradle of letters; and happy had it been for her history, if she had never cradled any thing worse. There are the first and oldest pyramids, the sphynxes, and the labyrinths; and there was erected the first prison of which history has taken notice. A cruel and heartless people, they deserve the infamy of corrupting the principles of penal justice, and of transforming their prisons into theatres of the most fiend-like barbarity, and unhallowed revenge.

With the same spirit which led the scholar to pry into the hieroglyphic mysteries of this land of wonders, has the genius of her prison discipline been copied by the nations of the earth, till the whole world is filled with these terrestrial hells. But as this sketch leads me rather to the contemplation of Penitentiaries than prisons in general, I shall turn my thoughts to them in particular.

These lurid and doleful mansions, owe their existence to the sinfulness and depravity of man; and they are designed, by a mild and salutary process, to reform the sons of guilt and crime. Long experience had demonstrated, that sanguinary measures produced no good effect on the (p. 6) sufferers, but rather made them worse. Humanity, too, recoiled from the cruelty of such inflictions as the lash, and the brand; and as the effect of such severity was no argument for its continuance, humane legislators devised the Penitentiary system, by which criminals are confined to labor, and should be allowed full opportunities of reflecting on their conduct, and of reforming their lives. And as the design is to have them treated with kindness, and allowed all the means of moral and religious instruction and improvement, that man can furnish, the benevolent hope of the community is, that their sufferings, thus tempered with mercy and humanity, will be salutary and reforming in its effects. Mercy and benevolence were the inspiring angels of this system, and could it ever be brought practically to bear on offending man, it would produce a salutary reform in his heart and life.

But the great difficulty with which this system has to contend, is, the absolute impossibility of finding proper persons to carry it into effect. The life and soul of it is unmingled mercy, and men, qualified by gentleness of temper and benevolence of heart, to administer its laws, are not to be found on earth. Man, in his ruined and fallen nature, is a savage, and the milk of human tenderness was never drawn from the breast of a tiger. To give a full practical demonstration of the tendency and effects of the Penitentiary discipline, as it exists in the speculations of the philanthropist, God must become the director, and angels the ministering spirits of its administration. Such a system, in the faultlessness of perfection, is now in practical operation on the entire community of fallen and impenitent spirits; and the success of the past demonstrates the rationality of the expectation of universal success. On this the mind rests with perfect pleasure, and is relieved by it from the painfulness of witnessing the inefficiency of human means, to reform the votaries of guilt.

(p. 7) There can be no moral truth more fully demonstrated than this, that nothing but goodness can beget goodness. Material substances communicate their own properties to each other, and moral qualities impregnate, with their own nature, the objects on which they exert an influence.—Hence the baleful influence of tyranny on the human mind. Hence the contagion of vice. And hence the reason of the truth, that "we love God because he first loved us."

Where, in all history, can an instance be found of a single reformation from guilt, by any other than gentle and clement means? The blaze of retributive vengeance may awe the propensities to crime into inaction; but it cannot uproot them. The terrors of the Lord may make men afraid, but it is the goodness of God that leads to reformation. This is the secret of the Lord, which is with them that fear him. This is the golden key which opens the cause of that success, which has, visibly, in so many cases, marked the progress of the gospel of the grace of God; and which is, in all others, attaining the same happy result, by a process so silent and slow, as to evade the careless observation of the unreflecting multitude. This is the philosophy of the divine administration, and it is one of those simple sciences which the pride of man is reluctant to learn; but which the humility of Christ will dispose him to receive, and by which his nature is to be renewed and adorned.

A ray of this science darkened by the dusky medium through which it passed, shot from the throne of blended goodness and intelligence, and crossed the mind of that philanthropist who conceived the ideal theory of an effective Penitentiary discipline, in the hands of man. A gleam of sacred light seemed to spread over the anticipated results of the embryo experiment, as he resolved it in his enthusiastic mind; but it was like the gleam of the north, (p. 8) which shoots on the eye, and is immediately lost in its vivid expansion. It is a vain and idle theory; splendid, indeed, but impracticable; lovely, but visionary; and can never go into perfect operation till the occasion for it shall have ceased. In all but intelligent and sympathizing hands, this system of benevolence must necessarily be perverted; and as "man's inhumanity to man makes countless thousands mourn," the same uncomely traits of character will continue, till the Spirit of God shall have humanized mankind, and obviated the necessity of corrective discipline.

Another obstacle, not only to the exhibition of a perfect Penitentiary, but to so good a one as might exist, even in the present state of human depravity, is, the well known fact, that merciful men cannot be obtained to enforce its discipline; none but the true sons of an uncompromising and iron-hearted severity, will consent to perform for any considerable time, the unenviable task of inflicting pain on a fellow creature. Hence this duty is too frequently assigned, from necessity, to those who find in it the highest enjoyment of which their dreadful natures are capable. There are numbers of very bright exceptions to this remark, and I shall notice them with pleasure when I come to treat of the character of the keepers. Could such men as may be found on earth—those brighter fragments of ruined humanity, which are frequently to be met with,—be placed at the head and in the offices of our Penitentiaries, and could they be removed at that very hour when the too frequent perception of suffering begins to corrupt and deaden their moral feelings, many of the evils which now grow out of the perversion of those means of good, might be obviated, even if no salutary results could be produced. And this I am confident is an improvement in those places for which the demand is impressive and thrilling.

Another reason why prisons do not effect more good, or prevent more evil, is, the design of them is lost sight of. (p. 9) Instead of an altar to God, the keepers erect one to Mammon; and among the sacrifices at this altar are found the health, peace, and life of the convicts. Here, surely, reform is called for in a voice as sacred as it is loud and awful. Remove that altar; subsidize no longer the blood of souls in the interdicted worship of an idol; but allow the subjects of penal bondage time and opportunity for reflection; for reading the Holy Bible; for prayer; for public and social worship;—and furnish them with all the means and facilities of moral and religious improvement which intelligent piety can suggest.

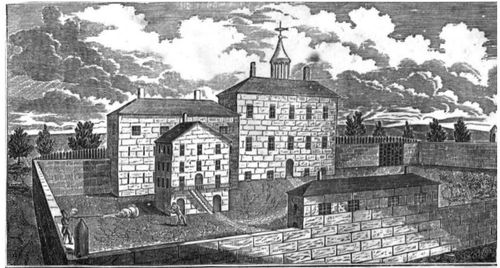

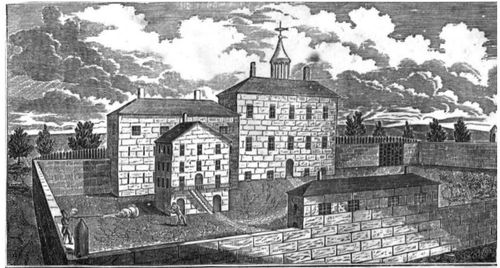

The foundation of this prison was laid in 1809. It is built of stone throughout, has three stories, and thirty-five rooms or cells, with strong and massy iron doors. The cells on the ground are small, with small apertures or windows; those in the second story are generally larger, but with similar apertures; and those in the upper story are all larger, and have grated windows, much larger than those in the other stories. In this story are two rooms which are used as hospitals. The furniture of the rooms are straw beds, with convenient and comfortable clothing, small seats and a few books. The ground story is for the prisoners when they first enter the prison. After some time, if they conduct in a satisfactory manner, they are moved to the second story; from which, in due time, if they merit the favor, they are permitted to ascend to the third. If any of the prisoners, in the second and third stories, transgress the laws, they are put down one story as a part of their punishment.

Some of the small cells in the first and second stories are used as solitary cells for the punishment of offenders. The apertures of these are closed, so that they are as dark as midnight. While the offender is in these, he has only one blanket to sleep on, in the coldest weather in the winter, and in the summer, nothing but the stone floor. His only (p. 11) sustenance is a piece of bread once a day, weighing from four to six ounces. Some prisoners have been confined in these places more than thirty days, though the usual time varies from six to twelve. Many have frozen their feet there, and in many a constitution, the seeds of decay and death have there been planted.

The furniture of the hospitals is of a piece with that of the other parts of the prison, and only one degree more comfortable. The beds are straw; the clothes are clean; the food various, according to the complaints of the sick, but never rises to the claims of humanity. In the winter, the patients are blessed with a stove, and are kept comfortably warm. This is the dying place, but some are denied the comfort of even this, and die before they can get admittance. According to the laws of the prison, however, this is the only place in which medicine must be given, and the appointed department for all that are sick. But laws are only ropes of sand. The laws of the prison are merciful, but neither the rains of spring, the dews of morning, nor the sunbeams of heaven, can either soften or fertilize a rock.

It was the original design that the whole prison should be kept warm, and large stoves were provided for this purpose; but it was found impossible to do this by the means used, and after a few years, the coldest part of the winter found not a spark of fire in any of the halls. Much is suffered on account of the cold; but it is a place of punishment, and this is the kind and feeling argument with which the keepers meet the entreaties of the shivering prisoners. Many a time have I made large balls by scraping the frost with my hand from the stone sides of my cell; and thousands of times have my hands been so chilled, that I had to tax my ingenuity to turn over the pages of my bible.

Adjoining the prison is a large brick house, for the use of the keepers and guard. At some distance in the rear, (p. 12) is a large brick shop, in which the prisoners are employed during the day, at their labor, which was at first making nails and other smith work, but has since been changed to manufacturing cotton cloth, ginghams, plaids, &c. This shop is kept warm and clean.

Another brick building between the shop and prison was erected for store rooms, lumber rooms, &c., and for a chapel. This part of it was very convenient, and spoke much for the pious feelings of the individuals who erected it. It was used, however, only a few years for the worship of God, when "a new king arose who knew not Joseph," and the voice of the preacher and the utterance of prayer departed from this temple, and the buyers and sellers, and money changers occupied the place of the priest, and polluted the sacred altar. It was painful to tread on these sacred ruins, and to hear the clack of looms where the soul had hung with transport on the sacred sounds of instruction, and been melted with the holy ardors of devotional feeling. "By what spirit," I often asked, "was this ruin made? Was it the spirit of piety?"—No! The genius of this change came not from Jordan's waves, nor from Zion's holy hill; the hand that smote this altar of religion and extinguished the last cheering light of the contrite soul was nerved by the same spirit that led the guilty rabble to smite the condemned Redeemer, and place on his innocent head a crown of thorns.

Another brick building east of this, used as an office for the master weaver, and a carpenter's shop, &c. is all that had been erected previously to the building of the new prison for solitary confinement, in 1830. Around all these is a wall about sixteen feet high, and three feet thick at the base, which completes the Establishment.

The government of the prison was, at first, vested in a Board of Visiters, who appointed the subordinate officers, made the By-Laws of the Institution, and made report of (p. 13) their doings to the Legislature every year. The officers of their appointment were the head keeper and three or more assistant keepers—five guard—a master weaver—a physician—a chaplain—and a contractor. One of the Visiters attended at the prison one day in every week to give directions about the work, and to see that the By-Laws were obeyed and enforced.

After some years this form of the government was changed, and the duty of the Board of Visiters committed to one man, denominated the Superintendent. Another change soon after gave the appointment of a Warden to the Legislature, and the appointment of the inferior officers to him, leaving the Superintendent to act only as contractor. After eight years the office of Warden was destroyed by the Legislature, and all authority recommitted to the Superintendent.

These changes in the government did not effect, in any degree, the spirit by which the prison was governed; and while each form had its peculiarities and excellencies, they all had their defects. The principal defects were the investing of the Visiters and Wardens, and Superintendents with the power to appoint physicians and chaplains. These are high and important offices, and ought not to be answerable to any power but supreme. The physician, depending on the pleasure of a petty officer for his appointment, is too often the mere tool of that officer, to the injury of his moral principles, and at the expense of the health and life of too many of the prisoners. Whereas if the physician held his office from the Legislature, he would have power to open and shut, which he has not now; and both health and life, which are now lost, might be preserved.

The Chaplain, also, should hold his office from the highest source in the state. In such a place, his is the most important office, and he ought to have authority to do all things pertaining to it, without any reference to the pleasure (p. 14) of a man who, perhaps, despises both him and his office, and believes in no God higher than himself. The gospel ought to be fully taught and explained, and exemplified by the Chaplain; and he ought to be elevated, in his authority, above the control of those who can now say to him—"Come at such a moment, or not at all."

Another reason why the Legislature ought to appoint the Chaplain is, that then, sectarian policy would not have so much influence. The Legislature is composed of members of all churches, and they would, as they do their own chaplain, appoint without any reference to sect; and then one man living in Windsor, could not consult the finances of his own party, in appointing a clergyman for the prison.

The By-Laws of the prison have never been very materially altered, since they were first composed. A copy of them is laid before the Legislature every year, and being sanctioned by that body, they become, virtually, the laws of the state for that Institution. They are wisely adapted to the circumstances of the prison, and are as merciful as they are wise; but they are disregarded, and never adverted to but when they direct the infliction of punishment on the prisoners. They are trampled under foot by every keeper and guard, from the highest to the lowest. They are read once in every month to the prisoners, but those parts which relate to the conduct of the officers, are wisely omitted in reading, lest the prisoners should know when they err, and be able to convict them from the law. I do not say this from conjecture, I know it; for the hand that is writing this word, copied them every year, and I also read to the prisoners the parts directed to be read; and I have often heard the keeper say, that the prisoners ought not to know what laws relate to the officers. I shall have occasion, in the course of these sketches, to quote largely from these By-Laws, and what has been written here will suffice for my present purpose.

(p. 15) The prisoners go to their work at sunrise, and retire at sunset. They have a task, and for what they do over it, they receive a compensation. Their food is coarse, but good and wholesome. They wear party-colored clothes, half green and half scarlet, and are kept clean. They are not allowed to converse together while at work, nor can they leave their employment and go into the yard, or any part of the shop without permission of the keeper. When they are out of the shops they are under the care of the guard on the wall, and they are not suffered to ramble, but must do their errand and return into the shop.

They can see their friends, when they call, in the presence of a keeper, and write and receive letters, if they contain nothing objected to by the Warden or head officer. They have such books as they purchase for themselves, and once they had a social library, which would have been more useful, if many very improper books had not been in it. Why these were admitted, the guardians of the morals of the place must answer. No newspapers were allowed to be introduced, not even religious ones; but tracts and religious pamphlets were not objected to.

There is always a keeper in every shop while the prisoners are at work, and he is armed with a sword. A guard is placed on the wall during the day, armed with a gun, loaded with a ball and buck shot; and at night there is one in the entrance of the prison to prevent escapes.

Such is the general history of the prison up to 1830, when a new prison, on the plan of solitary confinement, was erected. This contains about one hundred and seventy small cells, in which the prisoners are confined separately during the night. No radical alteration, I apprehend, has been made in the government of the place, in any other respect. The design of this change was, to prevent the prisoners from corrupting each other's minds by social intercourse. The principle laid down by the votaries of this (p. 16) plan, is, that vice is contagious, and wicked men become worse by association. The more abandoned, it is said, will draw down others to their own degree of guilt, if permitted to associate together, and thus baffle all the efforts of piety and virtue for their reformation. Hence the presumptive necessity for a prison on a new construction, and hence the prison for solitary confinement in Windsor. I hope it will be so managed as to prove a less curse to humanity than the old one, though it is like hoping against hope. In respect to its reforming effect, I shall say more in another article; but I will remark here, that reformation is a moral work, and depends not on the shape of the person's room. It is a work of mercy, and nothing but mercy can effect it. Man is a social being, and the laws of his nature are violated by dooming him to solitude. The genius of crime dwells in the dark places of retirement, and always communes with its followers alone. Social life, on the contrary, is the garden of every virtue, in which nothing but flowers are permitted to flourish, and nothing but good fruit permitted to ripen when properly cultivated.

I ought to touch this subject with a delicate hand. Many giants of speculation have been this way, and they have laid down principles from which I am compelled to dissent. I am well aware of the charm of greatness, and of the danger of appearing singular with those on whom the mantle of popular veneration has been seen to fall; and I feel that in the strictures which I am commencing, I shall gain no applause from those who are kindly delivered from labor of thinking for themselves. This weighs, however, but little with me. A being who has visited the moon knows more about it than astronomers have ever taught. A man who has burned his finger knows more of the effect of fire on flesh, than the most eloquent lecturer who has had no experience. Confident, then, that my own experience may be safely trusted, I shall follow it cheerfully, whether it lead me in the path which speculation has trodden, or across it. Bacon lays it down as a principle in philosophy, that man is ignorant of every thing antecedent to observation, and that experience is at the bottom of all our knowledge. To this principle I bow in submission, and take it for granted that what I have experienced I know.

Sustained then by my own personal experience and observation, I say fearlessly, that the solitary confinement plan, is an unwise, unfeeling, and ruinous innovation upon the Penitentiary discipline. Every body knows that it adds to the terror of such places; evinces a cruel recklessness of the feelings and personal comfort of the prisoner; and has the effect to convince him that the government is not his friend. This destroys his confidence in its mercy, and creates in him a disposition for revenge, which will eternally baffle all efforts for his reformation. (p. 18) He may, indeed, be awed with the gloomy horrors of the law, but cannot, by such means, be regenerated into a love of virtue. No; before you can do any thing towards reforming a sinner, you must convince him of your real friendship for him, which can be done only by being friendly; and it is not being friendly to inflict pain without a benevolent motive. The construction of ordinary prisons is full cruel enough to fill the soul with terror; no friend would build even such a place as Windsor prison was, for one he loved, and no human being could suppose that love and friendship for the human race, had any thing to do in forming its plan. Should an angel from some happy world, in his flight near our earth, pause and contemplate the old prison at Windsor, he would hasten back and inform his companions that he had seen a hell. That place was designed or ignorantly constructed, as a fit house in which Revenge might feed in luxury on the tears of distress, and dance to the groans of despair. Every prisoner could read the spirit of the place in the massy walls—the iron grates and doors—and the noonday twilight of the cells; and the impression on every mind was, that the spirits of the infernal world had been erecting a very appropriate Temple for their chief. This is neither fiction, fancy, nor poetry, but solemn literal truth. The deathly chill which it threw on my spirits when I entered it, makes me shudder to this hour. But the new prison caps the climax of relentless invention, and sets description at defiance. Now, I say, that no prisoner can suppose by any reach of rational candor, that the builders of this new prison, were his friends; and hence all efforts, purporting to spring from a tender regard for his good, will be appreciated accordingly.

But it may be said, that the contagious nature of vice rendered it necessary to separate the prisoners into small solitary cells, to prevent their social intercourse, and its (p. 19) supposed consequence, their reciprocal progression in vice. To this I reply, and I will appeal to the facts in the case in support of my position, that the practical effect of such a separation goes to prove, that it is only a refinement of cruelty. The more completely you put one man into the power of another, the more perfectly do you create a tyrant, and prostrate a sufferer. Solitary cells and flogging, go hand in hand. Thus, the more certainly is the sufferer convinced that the authority is his enemy, and the more certainly is his reformation rendered impossible. The evils of solitary cells are far greater than the evils they were designed to remedy. I appeal to the experiment. I have only one more observation to make on this head, and I make it with a design to have it remembered. It is this—Benevolence will appear benevolence, and nothing but apparent benevolence will turn a sinner from the error of his ways, and lead him to purify his heart.

The unanimous opinion of all ages and countries has been, that prison keepers are tyrants. Regarding the prisons of earth and the prison of gehenna, in the same light, the directors and servants of both have been considered as drinking at the same fountain, and as possessing the same traits of moral character. This opinion, however, like many others which have obtained in the world, is not universally true, for there are prison keepers who possess every moral excellence, and who are more like angels of mercy, than fiends of darkness. But it is to be lamented that these exceptions are rare, and that it is too (p. 20) generally true, for the honor of humanity, that the term gaoler is synonymous with despot.

From this general truth, a very humbling inference necessarily follows. We cannot resist the conclusion to which it leads the reflecting mind, that cruelty is a radical element in the moral nature of fallen man, and never fails to develop itself when circumstances permit. Human nature is, in its fallen and unregenerate condition, only a cluster of shapeless and uncomely fragments, and presents every where the same bold and darkened outlines of depravity; and to adventitious circumstances is to be principally attributed the small complexional difference in the filling up of the picture. Like the mouldering, moss-grown ruins of some temple, which was once the wonder of the world, man is only the wreck of what he was when his heart was the throne of Deity, and his soul the image of his glorious Creator. Then, holiness was his element, but now sin. Then, angels sought, but now they shun his society. Then, like a field warmed by the sun, moistened by the rain, and fully prepared by the tiller's hand, he brought forth fruit unto God; but now he exhibits the sterility of a desert, in respect to what is good, but the fruitfulness of a garden in respect to evil. Then, mercy and gentleness were the seraph principles of his conduct, but now he is the cruel and savage playmate of the tiger.

This, I am aware, is a very repulsive truth, and one to which the pride of man will not readily subscribe. It is, notwithstanding, a truth, stereotyped on every page of his moral history; and it applies equally to the little Satan of a family and to the tyrant of a world. The seeds are in every breast, and they never fail to germinate under auspicious circumstances. Invest man with authority, and you commission a despot; and nothing but the restraining principles of the gospel, will prevent him from becoming a curse to those who are in his hands. The history (p. 21) of Hazael fully confirms the truth of this remark. He was sent to Elisha the prophet to inquire whether Benhadad the king of Syria would recover from a disease with which he was afflicted. As soon as he came into the presence of the prophet, Elisha fastened his eyes steadfastly on his countenance and wept. The astonished Syrian inquired the cause of his weeping. "I weep," said the man of God, "because I know the evil that thou wilt do unto the children of Israel; their strong holds wilt thou set on fire, and their young men wilt thou slay with the sword; and wilt dash their children, and rip up their women with child." Indignant at the imputation of such monstrous cruelty to him, Hazael replied, "Is thy servant a dog that he should do this great thing!" "But," said the prophet, "the Lord hath shewed me that thou shall be king over Syria." While he was only an inferior officer, Hazael's soul shuddered at the bare mention of those cruelties which in a more elevated rank he was going to commit; but when informed that he was to become the king of Syria, the unhallowed principles of his nature began to quicken into exercise. The first act of his life after this was the murder of his master, and the language of the prophet is the history of his future life.

This is by no means a solitary exemplification of the truth which I have asserted. Nero, when he ascended the throne, is said to have been a merciful man; and when he was called upon to sign a death warrant, he is said to have expressed his regret that he had learned to write. Such was Nero once, but what was his character afterwards? His history is written in the blood of his murdered mother, and of Seneca his tutor; and in the tears, and cries, and broiling flesh of a thousand martyrs. Here is a fair specimen of the effect of unbridled authority on the nature of man; and while it holds up a hydra monster to the execration of all mankind, it says to all of us, in language of (p. 22) the most thrilling import, "Let him that thinketh he standeth take heed lest he fall."

Having made these general observations on the nature of man, and the influence of circumstances upon him, I shall enter upon the subject of this sketch.

Perhaps no prison on earth ever had better keepers than the one in Windsor. Though many of these have been as bad as humanity under such circumstances could possibly become, and though much of their conduct cannot be contemplated without the deepest horror of soul, the number of such monsters has been comparatively small. The frequent changes which take place in the officers, and the shortness of their residence there, are very fortunate circumstances, not at all favorable to the production of perfect tyrants. The longer a keeper stays there, the more cruel and heartless he becomes. This is a truth which experience has taught to every observing prisoner. Hence it is equally true that prisons grow worse as they grow older. They all had their origin in a merciful design, but by the authority with which the officers are clothed, they become little empires, and gradually sink down into the gloom of unalleviated despotism.

There are but few of the keepers who continue there over one or two years, some not so long, and but now and then one who stays five or six years. These are invariably the most hardened, and having the most power, they give tone to the conduct of the others and gradually induce them towards their own degree of severity. Influenced by them, many a young keeper and guard have been led to stain their souls with deeds of cruelty, which they could not think of afterwards without horror. The truth of the case is this—there are a few of the officers who have fully reached that dark eminence of perfect inhumanity, which is ascribed to a fallen spirit; and from (p. 23) this unenviable distinction there is a gradual softening down to the common level of human character.

These, according to their authority and moral temperament, exert a malignant influence on the administration of the prison, and on the peace and comfort of the prisoners. Generally taken from the very humblest employments, illiterate, and destitute of a proper acquaintance with mankind, and invested with an authority little less than absolute, extending virtually to the life or death of their subjects, they are intoxicated with their power, and seek every possible occasion to display it. To speak civilly to a prisoner is considered beneath their dignity; and their cup of joy is full only when they can say—"I have sent the rascal to the solitary cell." Armed with a sword, and placed over one of the shops, they ape the monarch and claim the homage of a god.

The same spirit accompanies the stripling when he ascends the wall to act the soldier in his turn. Though serving for a stipend of eight dollars a month, and doomed by a decree which he is unable to violate, to the lowest walks in society, he fancies now that he is somebody, and makes all who are under his shadow feel the full weight of his self-importance. Over one entire quarter of an acre of this world, strongly walled in, he holds divided empire with his brother on the other side; he imagines that his bench is a throne, his gun a sceptre, and the limit of his dominions the everlasting hills. It is not easy to treat this subject with seriousness, and yet it is too solemn to be trifled with. See him pacing his post like a private in the army. Be careful how you smile, for he has the instrument of death in his hand, and he it was who took the life of Fane.[1]

But these servants of the prison are not only inhuman and vain, there is no meanness to which they will not stoop; and they delight in all those little vexations with which they can perplex the prisoners. They are employed in (p. 24) making little rules and regulations for the prisoners, when they are in the yard, and these are so numerous, that no one can remember them, and so contradictory, that to obey one, at least half a dozen must be violated. Their common language to their subjects is—"Go here!—go there!—do this!—do that!—shut your head!—mind your business!—what are you doing!—out of the vault!—you shall go to the solitary for that!"

Nor is such mean and cruel conduct peculiar to the subordinate powers, they often are found in, and are copied from, the highest. I have seen those who occupied the chief seats in the synagogue, try every expedient to vex the prisoners into a war of words, and having accomplished their object, punish them for those very words which they provoked them to utter. I have heard them insult the prostrate objects of their power with words which I should blush to write. I have know them authorize vexatious regulations which the heart of Verres could not have enforced. I have seen one of these gather a number of prisoners around him, and though he had a wife and daughters, lead and give spirit to a conversation, which would have imprinted a blush on the cheek of impurity itself.

This conduct is the more conspicuous from the fact, that the laws of the prison require every officer, and the head one especially, to have an especial reference, in all things, to the good and moral reformation of the prisoners. This also renders their conduct the more criminal; and to this as one of the principal causes must be referred the hardening effect of state-prison discipline upon its subjects.—They know the laws by which the keepers are bound; they know that the community and the government of the state require them to be merciful, and to treat the convicts as if they considered them human beings; and when they see these officers so outrageously sinful against the most solemn obligations, and the most sacred and obligatory laws, (p. 25) and yet as cruel to them for trifling and shadowy offences, as if they themselves were immaculate, they cannot help despising them in their hearts, and kindling with a flame which sets reformation at defiance. And it is not too much to say, that many a prisoner has been hardened in crime by the example of those very men who were commissioned to reform him. If I had the power, and desired to have the angel Gabriel become a devil, I would send him to Windsor prison for three years.

But I should do violence to my own feelings, and injustice to this part of my subject, were I not to give a very different character to some who have held offices in this Institution. As there are a few who have reached the climax of depravity, so there are some who have exhibited characters which do honor to human nature. Like stars in the dark, they were the angel spirits of that "house of wo and pain." They were warmed with the pure glow of benevolent and christian feeling; and if all the keepers had manifested the same temper and sympathy for the suffering, many a mountain of grief would have been rolled from their bleeding breasts—many a refractory spirit would have been charmed into obedience—many a hard heart would have been softened into tenderness—many a guilty soul would have been washed into purity—many a mother's heart would have been gladdened with the return of a prodigal child—and many a wife would have been blessed with a husband reclaimed. To these, I owed much of my comfort while I was a prisoner. I remember them with gratitude, and I am sure that they will have the blessing of the merciful.

From the account already given, it would readily be inferred, that the officers of the prison are not professors of religion. This inference would not be true unless a few exceptions should be made. I recollect only four, however, among the inferior officers, to whom the inference would (p. 26) not fully apply. In respect to these it is right to say, that they exhibited as much of the spirit of their profession, as could be intelligently expected from any in their situation. The same remark is true of the head ones, many of whom had been baptized. Christians, as well as others, are influenced by circumstances, and authority is the worst circumstance in which any christian can be placed. A small historic sketch will fully illustrate the influence of power, even on sanctified humanity. One of the prisoners was a restorationist. A friend of his, a very respectable clergyman of that faith, sent him a book in defence of the doctrine of future retribution, against the writings of Rev. W. Balfour. He had received many similar books from the same source, but this was objected to, and kept from him full six weeks, but not returned to the sender, nor any information given either way. At length a keeper informed him that there was a letter for him in the house, from Rev. S. C. Loveland, and a book entitled "Hudson's Reply," which the officer at the head of affairs refused to let him have. This keeper was a man of too noble a soul to be cramped by the unfeeling regulations of a religious exclusive, and he gave the prisoner an opportunity to read them and then return them to him. After this he found means of obtaining them on the express condition, that he would not lend them to any of his fellow prisoners. This same man, at another time, refused to let a prisoner have a book on the subject of religion, which was written and sent to him by his father.

This officer must have had a very conscientious regard for the moral and religious good of the prisoners; but how he could exclude religious books from them, and yet permit them to purchase and read the lowest, dirtiest and most infamous books that ever corrupted either sex, or disgraced the literature of any age or country, he can tell as truly as I can conjecture. This is not a solitary instance (p. 27) of religious inconsistency in the officers; I could mention more, but my limits will not permit. It shews what mankind are—a selfish, exclusive, unfeeling, and despotic community. Every view which we can take of man, as he comes into contact with circumstances, goes to confirm the maxim, that if he has power he will use it. From the same volume we learn the impolicy of creating spiritual superiors. Christians are brethren. Among them is no allowable pre-eminence. They are to call no man on earth either master, or father. This is the command of Christ himself, and from the authority with which it is clothed, is obvious the greatness of the crime of disobeying it. Hence the fact that a spiritual despotism is the worst that can exist. Look to Rome; look to England; look into the cells of the Inquisition. May the Lord never, in his anger, curse these United States with a church establishment. Political tyranny is horrid enough, but from spiritual tyranny, good God deliver us!

There was once an important officer in the prison who was a Deist. He despised all religion, and even insulted and abused the Chaplain. Frequently did he keep some of the prisoners employed in chopping wood on the Sabbath; and when spoken to about this profanation of the Christian's sacred day, his reply was—"Monday is a good day, Tuesday is a good day, Sunday is a good day, I see no difference in them." There was not a single good thing in this man's official conduct. He despised almost every thing that is called good. The prisoners he regarded as an inferior race of animals, and rebuked the Chaplain for calling them "brethren." He was too bad even for that office, and as he purchased an ox for the prisoners to eat, which had died of disease in the heat of summer, the Superintendent gave him a very sudden and peremptory discharge. "I give you," said he, "till to-morrow morning (p. 28) to clear out, and take away your things." This was good tidings of great joy to all, and the prison rung with Jubilee.

I knew another high officer in the prison, who was also a Deist; but he was a most excellent man, and by a kind and fatherly administration, he endeared himself to every prisoner. His conduct would have done honor to the highest professions of Christianity. He adorned many of the doctrines of the gospel. He was not only an honest man, he was also a benevolent one. In all things he was influenced by principle, and did as he would be done by; and he did more to bless the prisoners with the preaching of the gospel, than many who prided themselves on their Christianity.

Among many of the inferior officers of the prison, who made no profession of religion, there was but one sentiment in respect to those prisoners who professed to be Christians, and this was, that they were all hypocrites.—They dealt out to them a very superior share of their contempt, and always ridiculed their professions. If one of them was particular in reading the Scriptures, that was made the subject of light remark; and if in prayer one of them spoke so as to be heard, he was impudently ordered to stop. And once, in particular, a keeper told one of the serious convicts, that he would act a more wise part, if he would say nothing about his religion, but leave off praying and be like the other prisoners. Another prisoner was put in the solitary cell for reading his bible in the shop, where many a one had been allowed to read books, undisturbed, with which no virtuous female would pollute her fingers. The common vulgar cant, with which the keepers used to assail the piety of the prisoners, was as follows,—"They want to get out I guess—they are coming the religious lock—they are going to pray themselves out—they are mighty pious just now, pity they had not thought of this before." Such remarks as these were as frequent as (p. 29) the mention of the prisoner's piety, or the sight of one who was known to read his bible and pray; and not only the servants, but their masters often joined in such unmanly and inhuman sarcasms. "The tender mercies of the wicked are cruel."

This view presents human nature in its most degraded state, and in its darkest complexion. Here is man doubly fallen; here are the fragments of moral ruin in their most hideous array. A field, once green with inspiring promise, but now withering under a second blight. A splendid and glorious creation in baleful ruin. An ocean, once pure as a dew drop and smooth as a sea of glass, but now torn by conflicting waves, and casting up mire and dirt. The view is too painful! My heart sickens within me!

But it affords some relief to the mind, in dwelling on this gloomy prospect, to find here and there a ruin less ruined than others—a lonely column not fallen; a prostrate pillar not covered with moss nor buried in the earth. The soul of man is not susceptible of utter ruin. Immortal, it cannot die; the inspiration of the Almighty, and glorious once in his own image, it may grow dim, but not utterly dark; it may sink, but will rise again; it may wander, but will not be finally lost. My remarks on this subject, therefore, will be designed to shew, that there are, in this mass of dark, polluted, and fallen mind, some redeeming traits remaining unruined; something to admire and commend—something to imitate and love. In doing this, I shall (p. 30) relate some of the many historic incidents, which will prove the existence, and illustrate the nature of those moral and intellectual principles, which have hitherto survived that annihilating process to which they have been exposed.

The first incidents which I shall relate, will show that the prisoners have sympathy for, and take pleasure in relieving the distressed.

A female who had a husband in the prison, came with her two children, three hundred miles to see him. By the time she arrived, she had spent all her money, and had suffered on the road. As soon as this was known, the prisoners made up a purse of fourteen dollars, and gave it to her, besides giving her cloth to dress both of her children.

Another time a father and mother came there to see their son, and being destitute, a purse of eight dollars was made up for them.

Another occasion for the charity of the prisoners was as follows:—The sentences of two of the prisoners had expired, but not having the money to pay the cost of their prosecution, they were not permitted by the keeper to leave the prison. When this was known, the sum required was immediately made up and given to them, and they were discharged.

By another train of incidents, it will appear, that they are pleased with religious worship, and love to hear the preaching of the gospel.

They always attend when there is preaching, and listen with a degree of interest and earnestness, which no preacher has failed to notice.

When, after years of earnest application, they obtained leave to form a choir of singers for religious purposes, they furnished their own books and instruments, not being able to get them of the keepers.

(p. 31) On another occasion, a company of them bought a lot of tracts for gratuitous distribution in the prison.

As an expression of their sense of the importance of preaching, and of the faithfulness of their Chaplain, they gave him money to purchase him a coat.

At another time, they contributed about twenty dollars to a society which had been formed to send the gospel to prisons.

A cluster of promiscuous incidents which I am now going to group together, will demonstrate the existence of other excellent qualities.

Husbands and children are particularly careful to keep their earnings, and at convenient times, send them to their parents and families. Others are diligent at work, that they may have the means of making a decent appearance when they get their liberty. Some apply themselves to books, and a few have made astonishing progress in the sciences. I knew one who made himself master of Euclid's Elements, Ferguson's Astronomy, Stuart's Intellectual and Paley's Moral Philosophy. Another made himself acquainted with most of the branches in a liberal education. And many others became very good common scholars. Not a few of them are chaste and moral in their conversation, and civil and exemplary in all their conduct. And that they are not so lost to the virtues of our nature, as some who are in different circumstances, is evident from the fact, that they are proverbially, an industrious community.

I dwell with pleasure on these virtues, which still smile and diffuse their fragrance in the midst of surrounding desolation; and some of them are found in every breast of that unhappy multitude. The fact is, there are a great many principles of moral excellence, which go to the formation of a perfect character; and it is never that all of these can be found destroyed, or uprooted, in any one (p. 32) individual. That monster over whose breast has been hung the pall of every virtue, never was and never can be found. Some seed, some root, some germ, remains to repair the desolation, and to smile in perfect growth and endless beauty, where ruin has been the deepest. Hence the hope of reformation. Hence the strongest argument to attempt it, both in ourselves and others. The pulse of spiritual or moral health is still beating in all those guilty souls, and proper attention would soon restore them to its blissful enjoyment.

On the other hand, they exhibit many of the very worst passions and principles of fallen nature, in their worst and most appalling light. Against this charge nothing can be said in their vindication. My only object in introducing this sketch, is, to show, that though many of the virtues of the upright heart have been destroyed from theirs, all of them have not. There are some good and excellent qualities remaining in every one of them; and I wish to turn the thoughts and efforts of our Benevolent Societies to their improvement. This is an inviting field for them to labor in, and they could not labor here in vain. Christ came from heaven to save prisoners, and the servants of Christ ought to be willing to follow his example and visit prisons too. He might have kept better company in heaven, or gone on an embassy to less guilty worlds, but he came to us, to sinners, to prisoners, to save us from sin, and free us from chains.

In a state prison, almost every action of the prisoners, not particularly mentioned in the By-Laws, is either a crime or not, according to the whim that happens to be in the breast of the keeper at the time it is done. Hence there are many actions punished, and sometimes very severely, which were not known to have been improper at the time they were committed, but which, by a very common post facto process, became crimes afterwards. Any thing which a prisoner does or neglects to do, is, if the guard or keeper who notices it, has any spite to gratify, dressed up in a criminal suit and made a pretext for punishment. To smile or look sober, to speak or keep silence, to walk or sit still, is alike criminal when convenience requires.

It is, also, a rule of conduct with the keepers, to punish all for the crime of one. Instances of this are very common. I will mention some of them.

There was a little upstart dandy among the prisoners, who on one occasion, had his hair cut by order of his keeper a little shorter than his vanity desired. Displeased with this, he immediately had all his hair cut down to one quarter of an inch; and on account of this criminal vanity and resentment in him, every head in the prison was scissored down to a quarter of an inch for more than two years.

To make his displeasure fall with full force on one of the prisoners, the Warden once took every book out of the work shops and ordered that no prisoner should rest from his work two minutes at a time, from morning till night.

Because some of the prisoners have pretended that they were sick when they were not, every sick man is neglected.

(p. 34) Another fact in relation to crimes is, that some of the keepers have given their countenance and aid to the prisoners in the commission of them, and shared with them the profits of their wickedness. It is well known that some of the keepers have assisted the prisoners to get materials into the cells for weaving suspenders; and when woven, they have sold them and divided the money. Fine keepers! Fit men to reform the guilty! Assist the prisoners to steal, and divide the plunder!

But when we come to those crimes which are specified in the By-Laws, the most frequent grow out of the following sources:—

1. Defects in the work. For the smallest defect here, the prisoner is often made to feel severely. What is so small that none but a malignant eye would notice it, some variation in the shade, something that could not have been avoided, is too often carried on to the books as a great crime, for which only ten days in the solitary cell can atone.

2. Not keeping a proper distance in walking. The laws require the prisoners to keep six feet apart in going to and returning from their cells and meals. This requires no small share of practical trigonometry, and if a prisoner should not be pretty good to learn, before he can possibly keep in the right spot, the guard will have an opportunity to give him a number of solitary lectures. Many a man, who thought he was exactly right, not knowing so well as the more learned guard, has been sent into punishment, and made to feel how sad a thing it is, not to understand the six feet trigonometry.

3. Insolence is another crime. This is committed very frequently, as an accent or emphasis is sufficient for this purpose. The keepers and guard are very tenacious of their dignity, and what the governor of the state would consider respectful language, if addressed to him, they (p. 35) consider insolence. If one should turn over the pages of the black book, he would find this crime written to the sorrow of many a prisoner.

4. Not performing the task. This crime is generally found against learners, who have not had time to become masters of their work. This, however, is no excuse, the task is fixed and must be done. Nor is it of any avail that the materials have been poor, the complaint is,—the work is not done, and nothing but the grave can hide from, or avert the penalty.

5. Speaking together without liberty. Many are punished for this crime, and very justly in many instances no doubt, but not in all. If a prisoner is seen to move his lips this crime is written against him, and suffer he must.

6. The other crimes might be ranged under the heads of "wasting the materials"—"attempting to escape"—"resisting the authority," &c., all of which are frequently found in the books against the prisoners; and I know not that any criminal of these stamps has had much reason to complain, that his sufferings have been too severe.

This is the proper place to state the absolute authority of the keepers and guard over the destinies of the convicts. If one is reported, he must be punished, and that too without a hearing, and often without knowing the crime alleged against him. If he should ask the officer what his crime is, the answer would be, "you know what it is." After he finds out the crime, and desires to be released from punishment, the one who reported him must be consulted; and after he is willing, the sufferer must avow that he is guilty, and promise to reform, before he can get out. Innocent or guilty, it makes no difference, he must say—"I am guilty," or he will plead in vain to be released; and many a one has lied by compulsion, in order to get rid of further suffering. This was his only (p. 36) alternative, he must spot his soul with falsehood, or die a martyr to truth.

The punishments are of different kinds; the most common is that of confinement in the solitary cell. This is cruel and dreadful. The want of food reduces the strength and takes away the flesh, so that when the sufferer comes out, his face is often pale as death, his frame only a skeleton, and he unable to walk without reeling. He has only a small piece of bread once in twenty-four hours, with a pail of water; and no bed but the rock. In the winter he has a blanket, but such is the degree of cold to which he is exposed, that he has to keep walking and stamping night and day, to keep from freezing to death. And having no proper nourishment to sustain him, he becomes, under the joint influence of cold, fatigue, and hunger, a miracle of suffering, over which Satan himself might weep. Day after day, and night after night, he drags along his heavy and burdensome existence, friendless and unpitied, the sport of his unfeeling keepers, and the victim of an eternity of torment. I know what this suffering is, for I have experienced it. Seven days and seven nights, in the dead of winter, I hung on the frozen mountain of this misery, and died a thousand deaths. Every day was an eternity, and every night forever and ever; and all this I endured because I incautiously smiled once in my life, when I happened to feel less gloomy than usual. But my suffering was nothing compared with others. Some spend twelve, some twenty, and some over thirty days there. My heart chills at the thought! If God is not more merciful than man, what will become of us?

Another kind of punishment is the block and chain. This is a log of wood, weighing from thirty to sixty pounds, to which a long chain is fastened, the other end of which is fastened around the sufferer's ancle. This he carries with him wherever he goes, and performs, with it, his daily (p. 37) task. This is not much used, it being less severe than the solitary cell. Some have carried these for several weeks, and even months.

The iron jacket is another form of punishment, inflicted only once in a great while. This is a frame of iron which confines the arms down, and back, and prevents the person from lying down with any comfort. This is generally accompanied with one of the other kinds of punishment, as it is not considered much inconvenience alone.

Connected with these several kinds of punishment is the putting the convict down from one of the upper stories if he is up there. The whole administration of the prison is clothed with terror, and there is no end to its vengeance. The first form of suffering is only the first lash, and each additional form comes in regular succession. This is the second lash. The third is this—the number of times that the prisoner has been in punishment, is always brought up when an application is made for a pardon. The Reporter of characters takes a full share of gratification in adverting to these, when a certificate of the conduct is given. I cannot mention this man's conduct without indignation. I hope he will find room for repentance, and obtain pardon from his God for his many vexatious acts in relation to the prisoners. I know of no man in whose breast so little humanity prevails. Every prisoner will carry to judgment a charge against him. One drop of human sympathy never flowed in his veins. A mountain of ice has frozen around his heart. His acts of inhumanity would fill volumes, and it would require years to record them. I pity him from my soul, and though I have felt more than once, the weight of his mercy, I freely pardon him. If he should ever look on this page, I hope he will remember how unjustly he abused me, because he had the power, and I could not help myself. I wish also that he would think of Plumley, and the three times convicted sufferer of Woodstock Green.

(p. 38) Besides those already mentioned, it may not be out of place to touch on a few of what may be called extra judicial inflictions, or those which are felt by the prisoners without the usual process of a "report in writing." These are—not sending their letters, nor admitting those sent to them—adding a yard to the task of a man, who did not feel like doing more than was required of him, and making him use the finest and most difficult materials—imposing the worst work, and allowing only the poorest tools. These, and many other vexatious practices, are as common as the return of day and night; so that the prison at Windsor is one of those gloomy and dreadful places, which image to the mind that house of woe and pain, where are weeping and wailing, and gnashing of teeth; where the worm dieth not and the fire is not quenched; and into which the wicked will be turned, and all the nations that forget God.

That the reader may have a full view of this subject, I shall give in the next chapter a multitude of cases, which will fully illustrate this very important and affecting part of my sketches.

The case of Samuel E. Godfrey is one of deep and thrilling interest to every feeling heart. It is one of those numerous cases which stain the records of humanity, in which the guilt of a criminal is extenuated by the circumstances of its existence, and lost in the intensity of his sufferings. The fertile regions of Fancy cannot produce a theme more fruitful in incidents, and more painful in its melancholy details. It presents to our minds two principal sufferers, one pure and stainless as the mountain snow—a (p. 39) forlorn and destitute female; religion warming her crimeless heart, and virtue sparkling in her tearful eyes, she deserted not, in the hour of his afflictions, the companion of her better days, but hung, like an angel of mercy, on the bosom of his grief, and shared in every pang of his soul. The other claims not our sympathies as for an innocent sufferer, for crime had been on his hands, and guilt had made its stains on his heart. I do him no injustice by this statement; but I should stain my own conscience were I not to add, that he was a criminal by aggravation, and that had others acted more in accordance with the dictates of either religion or moral honesty, he would not have reddened his hands with the blood of his fellow-man, nor ended his days on a gallows.

In rescuing the history of this unfortunate sufferer from the grave of oblivion, I have but one motive, and this is, to do good. It contains volumes of instruction, and much of this is needed at the present day. Societies are formed and forming, with a view to improve the condition of suffering criminals by such a change in the discipline of prisons, as may conduce to their reformation; and these societies have a right to such information, as may enable them to act intelligently and efficiently. I also desire by this piece of history, to hold up the yet unpunished authors of the most unearthly sufferings, to the indignant scorn and righteous reprobation of all mankind. It is too often the case that the crimes of men in authority are sanctified by the duties of their office, and they screened from the arm of the law and the force of public contempt, by the necessity of the case. But the time has come to vindicate the sacred purity of public stations from this charge, by taking the robe from every unworthy incumbent, and inculcating the sentiment, both by precept and by practice, that there is no sanctuary for crime, and no justification for guilt.

(p. 40) With the history of Godfrey previous to the unhappy event which conducted him to the scaffold, I have nothing to do. At this time he was confined in the prison on a sentence of three years for a petty crime committed in Burlington near the close of the war. He had served about half of this term, and his conduct had been such as to justify an expectation of pardon, an application for which was pending before the executive, when the gloomy event transpired which sealed his dreadful doom. His wife, one of the most amiable of women, had gone to lay his petition before the Governor and Council, and plead the cause of her husband. Hope was beginning to play around the darkness of his cell, and the anticipations of liberty were beginning to inspire his breast. His arms were almost thrown out to embrace the companion of his bosom and the friends of his heart. In the ear of fancy he heard the voice of his keeper saying—"Godfrey, you are free!" At this moment, by a sudden turn in the scale of his destiny, all the future was darkened, and the taper of life began to grow dim with despair. Driven to desperation by the unjust and cruel treatment of a petty officer of the prison, he committed the fatal deed, which gave rise to that train of sufferings, and developed those traits of unfeeling cruelty in his persecutors, which I am going to describe; and which terminated his mortal existence on the gallows.

His employment was weaving; a given number of yards each day was his task. At the time under consideration, he took what he had woven and handed it over to his keeper, and as usual, he was found to have done his task, and performed as much labor as was required of any of the prisoners, and to have done his work well. While he was conversing with the keeper on the subject of his labor he remarked that he had done more than he meant to.—This gave offence, and he immediately corrected the expression, (p. 41) and gave, as what he designed to say, that he had wove more than he thought he had. But this did not give satisfaction; and the master weaver coming up at the time, a consultation was held with him by the keeper, which resulted in a complaint against Godfrey to the Warden, for "insolence." This complaint was made by the advice of the master weaver, who wrote it with his own hand, as he acknowledges in his testimony before the court. "I advised Mr. Rodgers to report him, and wrote the report." These are his own words, and as a reason for his conduct, he further says; "I had understood that there was a combination among the prisoners not to weave over a certain quantity."

Such was the crime alleged in the complaint, which I desire to have noticed very particularly. It was not that he had not performed his full task. It was not that his work was not well done. But it was that he said—"I have done more than I meant to," which he immediately softened by saying—"I mean I have done more than I thought I had." And when I shall have informed you what the consequence of such a complaint was, what the punishment it procured, you will be able to appreciate the character of those who entered the complaint, and the greatness of the provocation it gave to the unhappy victim to commit the assault which followed.

The laws of the prison were very severe. When any one was reported to the Warden for any crime, he was, without any hearing, committed to a solitary cell, as dark as a tomb, and confined there on bread and water for a number of days, seldom less than a week, at the pleasure of the keepers. The cell is stone; the prisoner is allowed no bed or blanket, and only four ounces of bread a day; and before he can be released from this grave of the living, he must humble himself, plead guilty, whether he is or not, acknowledge the justice of his sufferings, and promise to (p. 42) do better for the time to come. To such suffering and ignominy was Godfrey doomed for that shadow of a crime, and who can wonder at the rashness and desperation to which he was driven.

Soon after the complaint was sent to the Warden the prisoners were called to dinner, and Godfrey with the rest. After the tables were dismissed, as Godfrey was going out of the dining room, the Warden, who was present, ordered him to stop. Knowing by this that he was reported, and the thought of the punishment to which he had been so unjustly and unfeelingly devoted, crossing his mind, he became enraged, and resolved to be avenged on his persecutor before he submitted to the authority of the Warden.

Fired with this rash determination, he entered the shop, took a leg of one of the loom seats, which he cut away with a knife that he had taken for this purpose from a shoe-bench; and with the knife and club, he went into an affray with Rodgers the keeper, who had complained of him. He struck at him a few times, but without effect, his club catching in some yarn which was hung overhead. Seeing the affray, Mr. Hewlet, the Warden, went to the assistance of Rodgers, which brought Godfrey between them. Armed with sharp and heavy swords, they began to play upon their victim, and soon the floor began to drink the blood which, with those instruments of death, they had drawn from his mangled head. So unmercifully did they cut and bruise him that one of the prisoners laid hold of Mr. Hewlet, and begged of him for God's sake not to commit murder. It was during this struggle that Mr. Hewlet received a stab in his side, but from what hand no one could say positively, though no one doubts it was done by Godfrey. That it was done, however, without malice, and that he had no recollection of the act afterwards, ought not to be questioned after his dying testimony. The first that was seen of the knife was when it was lying on the floor in the blood. Faint with the blows he had endured, (p. 43) and from the loss of blood, Godfrey sunk down from the unequal conflict on the sill of a loom. Mr. Hewlet putting his hand up to his side, said he was wounded, and was led into the house, and the affray ended.

Mr. Hewlet had been afflicted with the consumption for years, and no one who knew him thought he would live long; and he was evidently sensible himself that his end was nigh. He would frequently complain of pains in his breast, on which he would often lay his hand and say, "I am all gone." In this state of health, the wound he received in his side inflaming, he lingered about six weeks and expired. From a post mortem examination, it was found that the knife had entered in the direction, and near the left lobe of the liver; and as that was entirely consumed, it was the opinion of the surgeons, that the knife had entered it, and produced an inflammation which was the cause of his death. It was the unanimous opinion of the surgeons that Mr. Hewlet's death was caused by the wound.

Godfrey was taken from the scene of the affray, and lodged in the place of punishment, and no attention of any kind was paid to the wounds in his head. No doubt many would have rejoiced if he had died, and nothing but the utmost care on his part prevented his wounds inflaming, and leading to a fatal result. He used to keep his head bound up with a piece of cotton cloth, and constantly wet with urine, the only medicine he could obtain; and by this means he preserved his life to endure more indignity and suffering, and die under the hand of the executioner.

As soon as Mr. Hewlet died, complaint was entered to the Grand Jury against Godfrey and an indictment for murder found against him. Immediately after this was done, the keepers and guard began to torment him with the most unfeeling allusions to his anticipated death. They insulted his sufferings—told him that they should soon see him on (p. 44) the gallows—and exulted above measure when they could kindle his worst feelings, and draw from him an angry expression. This was the theme of their cruel tongues continually, and I here affirm, without fear of contradiction, that greater outrage was never practiced on the feelings of a criminal by a mean and unprincipled mob, than Godfrey endured from those who had been placed over him as guards, and who were under a solemn oath to treat all the prisoners with kindness and humanity.

Nor was this feeling and disposition to torment a degraded sufferer, confined to the petty servants of the prison; it marked the conduct of all, and even the highest officers of the Institution seemed to take an infernal satisfaction in creating terrors to harass his mind. At one time they would dwell on the certainty that he would be hung, and at another inform him that his gallows should be erected over the large gate of the prison-yard, and so high that all the prisoners and all the village might see him. Surrounded by such fiends incarnate, he groaned away his dreadful hours till the time arrived for his trial.

There were many individuals who felt an interest in the issue of this trial, and who had serious doubts as to his being guilty of murder. Among these were Messrs. Hutchinson and Marsh, who volunteered their services as his counsel. They defended him with a zeal and eloquence which did them honor. But the die was cast against him, and he was condemned to suffer as a murderer. It was the opinion of some that he would be found guilty of only manslaughter, and then his sentence would be imprisonment for a great number of years or for life. This was mentioned to him, as a source of comfort, by his friends, but he always spoke of returning to the prison with the utmost horror. "No," said he, "not the prison, but the gallows,—if I cannot have liberty, give me death,—I would rather die than go back to prison for six months."

(p. 45) It is said that adversity is woman's hour—that female loveliness shines brightest in the dark. I have no doubt that this is always the case; in the present instance I know it was. Godfrey had a wife, and the best man on earth never deserved a better one. With a fortitude that affliction could not for a moment weaken, she hung around his sorrows, and flew with angel swiftness to relieve his burdened soul. She went to the governor and obtained a short reprieve for her condemned husband; and his counsel interposed and obtained for him another trial.

He was now remanded to the prison to wait a year before the court was to meet and give him a re-hearing. I have no doubt that he would have chosen death rather than this, had not the seraph tenderness of his wife thrown a charm around his being.

During this year he experienced the same vexations that had attended him before his trial. And the tiger hearts of his keepers even improved on their former cruelty, and created in his mind the spectre which haunted his midnight hours, and painted before his terrified imagination his lifeless body quivering under the dissecting knife.—They also most basely and falsely threw out to him insinuations against the purity of his wife. And as if impatient for his blood, they contrived to shed some of it before hand, as a kind of first fruits to their unholy thirst for vengeance. This was done by provoking him into a rage, and then falling upon him with a sharp sword and forcing the edge of it by repeated blows against his hand, with which he aimed to defend himself, and of which he then lost the use.

At length the year rolled away, and he was placed again at the bar of his country, to answer to a charge which involved his life. The same noble spirits continued his counsel; but the verdict was given against him, and sentence of death was again pronounced. Unwilling to abandon (p. 46) him yet, his counsel obtained for him another hearing, at another court which was to sit in one year from that time, and till then he was obliged to return to the bosom of his tormentors.

During this year he found one friend in Mr. Adams, his keeper. This man had the milk of human kindness in his breast, and he treated his prisoner in such a manner as to obtain his warmest gratitude, and deserve the respect of all mankind. During this year, few incidents transpired worthy of notice. Godfrey had a good room, and was allowed a few tools with which he manufactured some toys, the sale of which gave him the means of supplying himself with such little articles of comfort as his situation required. This was the last year of his life. At the session of the court he was again convicted, and the sentence of death was soon after executed upon him.

Previous to his execution he dictated a brief history of his life, and his dying speech, which were printed and read with great avidity. In his dying speech, he makes a solemn and earnest request, that his remains may be permitted to rest in peace, and not be disturbed by those "human vultures," who were anxious to do to his body what they could not do to his soul. He had no fear of death, but he shuddered at the thought of being dissected by the doctors. But those who had no feelings of compassion for him while he was living, disregarded his dying request, and his bones were afterwards found bleaching in the storms of heaven, on a lonely spot where they had been thrown to avoid detection.