Title: The Life of a Conspirator

Author: Thomas Longueville

Release date: May 4, 2012 [eBook #39612]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Robert Cicconetti, Pat McCoy, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries (http://www.archive.org/details/toronto)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/lifeofconspirato00longuoft |

[Pg i]

[Pg ii]

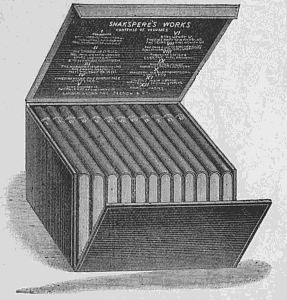

SIR EVERARD DIGBY

From a portrait belonging to W. R. M. Wynne, Esq. of Peniarth, Merioneth

[Pg iii]

BEING A BIOGRAPHY OF SIR EVERARD DIGBY

BY

ONE OF HIS DESCENDANTS

BY THE AUTHOR OF

“A LIFE OF ARCHBISHOP LAUD,”BY A ROMISH RECUSANT, “THE

LIFE OF A PRIG, BY ONE,”ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRÜBNER & CO., Ltd.

PATERNOSTER HOUSE, CHARING CROSS ROAD

1895

[Pg iv]

[Pg v]

The chief difficulty in writing a life of Sir Everard Digby is to steer clear of the alternate dangers of perverting it into a mere history of the Gunpowder Plot, on the one hand, and of failing to say enough of that great conspiracy to illustrate his conduct, on the other. Again, in dealing with that plot, to condemn all concerned in it may seem like kicking a dead dog to Protestants, and to Catholics like joining in one of the bitterest and most irritating taunts to which they have been exposed in this country throughout the last three centuries. Nevertheless, I am not discouraged. The Gunpowder Plot is an historical event about which the last word has not yet been said, nor is likely to be said for some time to come; and monographs of men who were, either directly or indirectly, concerned in it, may not be altogether useless to those who desire to make a study of it. However faulty the following pages may be in fact or in inference, they will not have been written in vain if they have the effect of eliciting from others that which all students of historical subjects ought most to desire—the Truth.

I wish to acknowledge most valuable assistance[Pg vi] received from the Right Rev. Edmund Knight, formerly Bishop of Shrewsbury, as well as from the Rev. John Hungerford Pollen, S.J., who was untiring in his replies to my questions on some very difficult points; but it is only fair to both of them to say that the inferences they draw from the facts, which I have brought forward, occasionally vary from my own. My thanks are also due to that most able, most courteous, and most patient of editors, Mr Kegan Paul, to say nothing of his services in the very different capacity of a publisher, to Mr Wynne of Peniarth, for permission to photograph his portrait of Sir Everard Digby, and to Mr Walter Carlile for information concerning Gayhurst.

The names of the authorities of which I have made most use are given in my footnotes; but I am perhaps most indebted to one whose name does not appear the oftenest. The back-bone of every work dealing with the times of the Stuarts must necessarily be the magnificent history of Mr Samuel Rawson Gardiner.

[Pg vii]

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

| The portrait of Sir Everard Digby—Genealogy—His father a literary man—His father’s book—Was Sir Everard brought up a Protestant?—At the Court of Queen Elizabeth—Persecution of Catholics—Character of Sir Everard—Gothurst—Mary Mulsho—Marriage—Knighthood | 1-14 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Hospitality at Gothurst—Roger Lee—Sir Everard “Catholickly inclined”—Country visiting 300 years ago—An absent host—A good hostess—Wish to see a priest—Priest or sportsman?—Father Gerard—Reception of Lady Digby—Question of Underhandedness—Illness of Sir Everard—Conversion—Second Illness—Impulsiveness of Sir Everard | 15-32 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The wrench of conversion—Position of converts at different periods—The Digbys as converts—Their chapel—Father Strange—Father Percy—Chapels in the days of persecution—Luisa de Carvajal—Oliver Manners—Pious dodges—Stolen waters—Persecution under Elizabeth | 33-48 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The succession to the Crown—Accession of James—The Bye Plot—Guy Fawkes—Father Watson’s revenge on the Jesuits—Question as to the faithlessness of James—Martyrdoms and [Pg viii]persecutions—A Protestant Bishop upon them | 49-69 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Catholics and the Court—Queen Anne of Denmark—Fears of the Catholics—Catesby—Chivalry—Tyringham—The Spanish Ambassador—Attitude of foreign Catholic powers—Indictments of Catholics—Pound’s case—Bancroft—Catesby and Garnet—Thomas Winter—William Ellis—Lord Vaux—Elizabeth, Anne, and Eleanor Vaux—Calumnies | 70-96 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Roger Manners—A pilgrimage—Harrowden—Catesby informs Sir Everard of the Conspiracy—Scriptural precedents—Other Gunpowder Plots—Mary Queen of Scots, Bothwell and Darnley—Pretended Jesuit approval | 97-113 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| A Latin Book—Immoderate friendships—Principles—Second-hand approval—How Catesby deceived Garnet—He deceived his fellow-conspirators—A liar | 114-129 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Garnet’s unfortunate conversation with Sir Everard—Garnet’s weakness—How Garnet first learned about the Plot—Secresy of the Confessional—Catesby and the Sacraments—Catesby a Catholic on Protestant principles—Could Garnet have saved Sir Everard?—Were the conspirators driven to desperation?—Did Cecil originate the Plot? | 130-148 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Financial aspects of the Gunpowder Plot—Sir Everard’s relations to his wife—Little John—Secret room at Gothurst—Persecution of Catholics in Wales—The plan of Campaign—Coughton—Guy Fawkes—His visit to Gothurst | 149-168 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| White Webbs—Baynham’s Mission—All-Hallows at Coughton—All Souls at Gothurst—An unwelcome Guest—The remains of feudalism—Start from Gothurst—Arrival at Dunchurch—What was going on in London—Tresham—The hunting-party—A card-party—Arrival of the fugitives—The discovery [Pg ix]in London—The flight | 169-191 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Catesby lies to Sir Everard—Expected help from Talbot—The hunting-party repudiates the conspirators—The future Earl of Bristol—The start—Warwick—Norbrook—Alcester—Coughton—Huddington—Talbot refuses to join in the Insurrection—Father Greenway—Father Oldcorne—Whewell Grange—Shadowed—No Catholics will join the conspirators—Don Quixote | 192-218 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Holbeche House—Sir Everard deserts—Sir Fulke Greville—The Hue-and-Cry—Hunted—In cover—Caught—Journey to London—Confiscation—The fate of the conspirators at Holbeche—The Archpriest—Denunciations—Letter of Sir Everard—Confession | 219-236 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Threats of torture—Search at Mrs Vaux’s house—Lady Digby’s letters to Salisbury—Sir Everard to his wife—Sir Everard writes to Salisbury—Death of Tresham—Poem—Examinations | 237-251 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Father Gerard’s letter to Sir Everard—Sir Everard exonerates Gerard—Sir Everard’s letter to his sons | 252-267 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The trial—Appearance of the prisoners from different points of view—Sir Edward Philips—Sir Edward Coke—His description of the punishment for High Treason—Sir Everard’s speech—Coke’s reply—Earl of Northampton—Lord Salisbury—Sentence | 268-288 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Waiting for death—Poem—Kind words for Sir Everard—The injury he did to the Catholic cause—Two happy days—Procession to the scaffold—Sir Everard’s last speech—Execution—Epilogue | 289-306 |

[Pg x]

[Pg 1]

Nothing is so fatal to the telling of an anecdote as the prelude:—“I once heard an amusing story,”&c., and it would be almost as unwise to begin a biography by stating that its subject was a very interesting character. On the other hand, perhaps I may frighten away readers by telling them at starting, this simple truth, that I am about to write the history of a young man of great promise, whose short life proved a miserable failure, who terribly injured the cause he had most at heart, for which he gave his life, a man of whom even his enemies said, when he had met his sad fate:—“Poor fellow. He deserved it. But what a pity!”

If the steady and unflinching gaze of one human being upon another can produce the hypnotic state, it may be that, in a much lesser degree, there is some subtle influence in the eternal stare of the portrait of an ancestor. There is no getting away from it unless you leave the room. If you look at your food, talk to a friend, or read a book, you know and feel that his eyes are still rivetted upon you; and[Pg 2] if you raise your own, again, towards his, there he is, gravely and deliberately gazing at you, or, you are half inclined to think, through you at something beyond and behind you, until you almost wish that you could be thrown into some sort of cataleptic condition, in which a series of scenes could be brought before your vision from the history of the long-dead man, whose representation seems only to exist for the purpose of staring you out of countenance.

In a large country house, near the west coast of Wales, and celebrated for its fine library, hangs a full-length portrait which might well impel such a desire. It represents a tall man, with long hair and a pointed beard, in a richly-chased doublet, a lace ruff and cuffs, very short and fringed trunk hose, and a sword by his side. He has a high forehead, rather raised and arched eyebrows, a long nose, hollow cheeks, and a narrow, pointed chin. His legs are thin; his left hand is placed upon his hip; and with his right he holds a cane, which is resting on the ground. At the bottom of the picture is painted, in Roman characters, “Sir Everard Digby, Knight, OB. 1606.”

Few people care for genealogies unless their own names are recorded in them. The keenest amateur herald in matters relating to his own family, will exhibit an amazing apathy when the pedigree of another person is offered for his inspection; the shorter, therefore, my notice of Sir Everard Digby’s[Pg 3] descent, the better. He was descended from a distinguished family. It had come over from Normandy with William the Conqueror, who had granted it lands at Tilton, which certainly were in its possession in the sixteenth century, though whether the subject of my biography inherited them, I am not quite sure. The first Sir Everard Digby lived in the reigns of Henry I. and Stephen.[1] This powerful family sided with Henry VII. against Richard III.; and on one occasion, King Henry VII.[2] “did make Knights in the field seven brothers of his house at one time, from whom descended divers houses of that name, which live all in good reputation in their several countries. But this Sir Everard Digby was the heir of the eldest and chiefest house, and one of the chiefest men in Rutlandshire, where he dwelt, as his ancestors had done before him, though he had also much living in Leicestershire and other shires adjoining.”He was the fourteenth in direct eldest male descent from Almar, the founder of the family in the eleventh century. Five of his forefathers had borne the name of Everard Digby, one of whom was killed at the battle of Towton in 1461. Sir Everard’s father had also [Pg 4]been an Everard, and done honour to the name; but literature and not war had been the field in which he had succeeded. He published four books.[3] The only one of these in my possession is his Dissuasive from taking the Goods and Livings of the Church. It is dedicated “To the Right Honourable Sir Christopher Hatton, Lord High Chancellor of England, &c.”

The author’s style may be inferred from the opening of his preface:—“If my pen (gentle reader) had erst bin dipped in the silver streames flowing from Parnassus Hill, or that Apollo with his sweet-sounding harp would vouchsafe to direct the passage thereof unto the top of the high Olympus; after so general a view of great varietie far and neere, I might bouldly begin with that most excellent Poet Cicelides Musę paulo maiora canamus.”I leave my readers to judge how many modern publishers would read any further, if such a book were offered to them in these days! Still, it is interesting as showing the style of the times.

Father Gerard, an intimate friend of the Sir Everard Digby whose life I am writing, mentions[4] “the piety of his parents,”and that “they were ever the [Pg 5]most noted and known Catholics in that country” (Rutlandshire); and Mr Gillow, in his Bibliographical Dictionary of English Catholics[5], states that they “had ever been the most staunch and noted Catholics in the county of Rutland.”But here I am met with a difficulty. Would a Catholic have written such a passage as the following, which I take from the Dissuasive? It refers to that great champion of Protestantism and Anglicanism, Queen Elizabeth.

“I cannot but write truely,”he says, “that which the Clergie with the whole realme confesse plainely: That we render immortell thankes unto Almightie God, for preserving her most Roiall Majestie so miraculouslie unto this daie, giving her a most religious heart (the mirror of all Christian princes) once and ever wholly consecrated to the maintaining of his divine worship in his holy Temple. From this cleare Christall fountaine of heavenlie vertue, manie silver streames derive their sundrie passages so happelie into the vineyarde of the Lorde, that neither the flaming fury of outward enimies, nor the scorching sacrilegious zeale of domesticall dissimulation, can drie up anie one roote planted in the same, since the peaceable reigne of her most Roial Majestie.”

The writer of the notice of Sir Everard Digby in the Biographia Britannica[6] appears to have believed his father to have been a Protestant; but on what grounds he does not state. So familiar a friend [Pg 6]as Father Gerard is unlikely to have been mistaken on this point. Possibly, however, in speaking of his “parents,”he may have meant his forefathers rather than his own father and mother. This seems the more likely because, after his father’s death, when he was eleven years old, Sir Everard was brought up a Protestant. In those times wards were often, if not usually, educated as Protestants, even if their fathers had been Catholics; but if Sir Everard’s mother had been remarkable for her “piety”as a Catholic, and one of the “noted and known Catholics”in her county, we might expect to find some record of her having endeavoured to induce her son to return to the faith of his father, as she lived until after his death. The article in the Biographia states that Sir Everard was “educated with great care, but under the tuition of some Popish priests”: Father Gerard, on the contrary, says that he “was not brought up Catholicly in his youth, but at the University by his guardians, as other young gentlemen used to be”; and in his own Life,[7] he speaks of him as a Protestant after his marriage. Lingard also says[8] that “at an early age he was left by his father a ward of the crown, and had in consequence been educated in the Protestant faith.” I can see no reason for doubting that this was the case.

[Pg 7]

At a very early age, Everard Digby was taken to the Court of Queen Elizabeth, where he became “a pensioner,”[9] or some sort of equivalent to what is now termed a Queen’s page. He must have arrived at the Court about the time that Essex was in the zenith of his career; he may have witnessed his disgrace and Elizabeth’s misery and vacillation with regard to his trial and punishment. He would be in the midst of the troubles at the Court, produced by the rivalry between Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Charles Blount; he would see his relative, Cecil, rapidly coming into power; he could scarcely fail to hear the many speculations as to the successor of his royal mistress.

He may have accompanied her[10] “hunting and disporting”“every other day,”and seen her “set upon jollity”; he may have enjoyed the[11] “frolyke”in “courte, much dauncing in the privi chamber of countrey daunces befor the Q. M.”; very likely he may have been in attendance upon the Queen when she walked on[12] “Richmond Greene,”“with greater shewes of ability, than”could “well stand with her years.”During the six years that he was at Court, [Pg 8]he probably came in for a period of brilliancy and a period of depression, although there is nothing to show for certain whether he had retired before the time thus described in an old letter[13]:—“Thother of the counsayle or nobilitye estrainge themselves from court by all occasions, so as, besides the master of the horse, vice-chamberlain, and comptroller, few of account appeare there.”If Lingard is right, however,[14] he gave up his appointment at Court the year before Elizabeth’s death, and thus luckily escaped the time when, as he describes her, she was[15] “reduced to a skeleton. Her food was nothing but manchet bread and succory pottage. Her taste for dress was gone. She had not changed her clothes for many days. Nothing could please her; she was the torment of the ladies who waited on her person. She stamped with her feet, and swore violently at the objects of her anger.”

One thing that may have had a subsequent influence upon Digby, while he was at the Court of Elizabeth, was the violence shown towards Catholics. In the course of the fourteen years that followed the defeat of the Spanish Armada before the death of the Queen,[16] “the Catholics groaned under the presence of incessant persecution. Sixty-one clergymen, forty-seven laymen, and two gentlemen, suffered capital punishment for some or other of the spiritual felonies and treasons [Pg 9]which had been lately created.”Although he had been brought up a Protestant, “this gentleman,”says Gerard,[17] “was always Catholicly affected,”and the severe measures dealt out to Catholics whilst he was at Court may have disgusted him and induced him to leave it.

I have shown how Father Gerard states[18] that Sir Everard Digby was educated “at the University by his guardians, as other young gentlemen used to be.” It is to be wished that he had informed us at what University and at what College; when he went there and when he left; as his attendance at Court, together with a very important event, to be noticed presently, which took place, or is said to have taken place, when he was fifteen, make it difficult to allot a vacant time for his University career.

The young man,—he did not live to be twenty-five,—whose portrait we have been looking at, is described in the Biographia Britannica[19] as having been “remarkably handsome,”“extremely modest and affable,” and “justly reputed one of the finest gentlemen in England.”His great personal friend, the already-quoted Father Gerard,[20] says that he was “as complete a man in all things that deserved estimation, or might win him affection, as one should see in a kingdom. He was of stature about two yards high,”“of countenance” “comely and manlike.”“He was skilful in all [Pg 10]things that belonged to a gentleman, very cunning at his weapon, much practised and expert in riding of great horses, of which he kept divers in his stable with a skilful rider for them. For other sports of hunting or hawking, which gentlemen in England so much use and delight in, he had the best of both kinds in the country round about.”“For all manner of games which are also usual for gentlemen in foul weather, when they are forced to keep house, he was not only able therein to keep company with the best, but was so cunning in them all, that those who knew him well, had rather take his part than be against him.”“He was a good musician, and kept divers good musicians in his house; and himself also could play well of divers instruments. But those who were well acquainted with him”—and no one knew him better than Father Gerard himself—“do affirm that in gifts of mind he excelled much more than in his natural parts; although in those also it were hard to find so many in one man in such a measure. But of wisdom he had an extraordinary talent, such a judicial wit and so well able to discern and discourse of any matter, as truly I have heard many say they have not seen the like of a young man, and that his carriage and manner of discourse were more like to a grave Councillor of State than to a gallant of the Court as he was, and a man of about twenty-six years old (which I think was his age, or thereabouts).”In this Father Gerard was mistaken. Sir Everard Digby did not live to be twenty-[Pg 11]six, or even twenty-five. Gerard continues:—“And though his behaviour were courteous to all, and offensive to none, yet was he a man of great courage and of noted valour.”

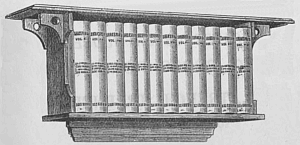

GOTHURST

The home of Sir Everard Digby; now called Gayhurst

We began by examining a portrait: let us now take a look at an old country-house. Turning our backs on Wales, a country which has little to do with my subject, we will imagine ourselves in Buckinghamshire, about half way between the towns of Buckingham and Bedford, and about three miles from Newport Pagnell, a little way from the high road leading in a north-westerly direction. There stands the now old, but at the time of which I am writing, the comparatively new house, known then as Gothurst.

Perhaps one of the chief attractions in Elizabethan architecture is that, by combining certain features of both classical and gothic architecture, it is a result, as well as an example, of that spirit of compromise so dear to the English nation. If somewhat less picturesque, and less rich and varied in colour, than the half-timbered houses of Elizabethan architecture, the stone buildings of the same style are more massive and stately in their appearance, and the newly-hewn stone of Gothurst[21] presented a remarkably fine front, with its pillared porch, its lengthy series of mullioned windows, and its solid wings at [Pg 12]either side. It was built upon rising ground, which declined gradually to the rich, if occasionally marshy, meadows bordering on the river Ouse.[22] It was a large house, although, like many others built in the same style, the rooms were rather low in proportion to their size.[23] The approach was through a massive gateway,[24] from which an avenue of yews—which had existed in the time of the older house that formerly stood on the same site—led up to the square space in front of the door. Near the gateway was the old church, which was then in a very indifferent state of repair,[25] and below this were three pieces of water. Beyond them ran the river Ouse, and on the opposite side stood the old tower and church of Tyringham. If the house was new, it was very far from being the pretentious erection of a newly-landed proprietor. Yet the estate on which it stood had more than once been connected with a new name, owing to failures in the male line of its owners and the marriages of its heiresses, since it had been held by a De Nouers, under the Earl of Kent, half-brother to William the Conqueror. It [Pg 13]had passed[26] by marriage to the De Nevylls in 1408; it had passed in the same way to the Mulshos in the reign of Henry VIII., and I am about to show that, at the end of the sixteenth century, it passed again into another family through the wedding of its heiress.

Mary Mulsho, the sole heiress of Gothurst, was a girl of considerable character, grace, and gravity of mind, and she was well suited to become the bride of the young courtier, musician, and sportsman excelling “in gifts of mind,”described at the beginning of this chapter. It can have been no marriage for the sake of money or lands; for Everard Digby was already a rich man, possessed of several estates, and he had had a long minority; moreover, there is plenty of evidence to show that they were devotedly attached to one another.

The exact date of their marriage I am unable to give. Jardine says[27] that Sir Everard “was born in 1581,”and that “in the year 1596 he married”; and, if this was so, he can have been only fifteen on his marriage. Certainly he was very young at the time, and Jardine may be right; for, at the age of twenty-four, he said that a certain event, which is known to have taken place some time after their marriage, had happened seven or eight years earlier than the time at which he was speaking.[28] I have made inquiries in local registers and at the Herald’s College, without obtaining any further light upon the question of the [Pg 14]exact date of his wedding. One thing is certain, that his eldest son, Kenelm, was born in the year 1603. In that same year Everard Digby was knighted by the new king, James I. He may have been young to receive that dignity; but, as a contemporary writer[29] puts it, “at this time the honour of knighthood, which antiquity preserved sacred, as the cheapest and readiest jewel to preserve virtue with, was promiscuously laid on any head belonging to the yeomandry (made addle through pride and contempt of their ancestors’ pedigree), that had but a court-friend, or money to purchase the favour of the meanest able to bring him into an outward room, when the king, the fountain of honour, came down, and was uninterrupted by other business; in which case it was then usual for the chamberlain or some other lord to do it.”It is said that, during the first three months of the reign of James I., the honour of knighthood was conferred upon seven hundred individuals.[30]

We find Sir Everard and Lady Digby, at this period of our story, possessed of everything likely to insure happiness—mutual affection, youth, intelligence, ability, popularity, high position, favour at Court, abundance of wealth, and a son and heir. How far this brilliant promise of happiness was fulfilled will be seen by and bye.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Harleian MSS., 1364.

[2] Narrative of the Gunpowder Plot, Father Gerard, p. 87.

N.B.—“The Narrative of the Gunpowder Plot,”and “The Life of Father John Gerard,”are both published in one volume, entitled The Condition of Catholics under James I., edited by Father John Morris, S.J.: Longmans, Green & Co., 1871. It will be to this edition that I shall refer, when I quote from either of these two works.

[3] See Bibliographia Britannica, Vol. iii. p. 1697. The books were:—I. Theoria Analytica ad Monarchiam Scientiarum demonstrans. II. De Duplici Methodo, libri duo, Rami Methodum refutantes. III. De Arte Natandi; libri duo. IV. A Dissuasive from taking the Goods and Livings of the Church, &c.

[4] Narrative of the G. P., p. 88.

[5] P. 62.

[6] Vol. iii. p. 1697.

[7] Life of Father John Gerard, p. clii.

[8] History of England, Vol. vii. chap. i.

[9] S. P. James I., Gun. P. Book, Part II. No. 135, Exam, of Sir E. Digby—“He confesseth that he was a pencon to Quene Elizabeth about six yeres, and tooke the othe belonging to the place of a pencioner and no other.”

[10] Lord Henry Howard to Worcester.

[11] Letter of Lord Worcester, Lodge III. p. 148.

[12] MS. Letter. See Lingard, Vol. vi. chap. ix.

[13] MS. Letter. See Lingard, Vol. vi. chap. ix.

[14] History, Vol. vii. chap. i.

[15] Ib., Vol. vi. chap. ix.

[16] Lingard, Vol. vi. chap. iii.

[17] Narrative of the G. P., p. 88.

[18] Ib.

[19] Vol. iii. p. 180.

[20] Narrative of the G. P., p. 88.

[21] “Antiently Gaythurst,”says Pennant in his Journey. It is now called Gayhurst.

[22] See Pennant’s Journey from Chester to London, p. 437, seq. Also Lipscomb’s History and Antiquities of Bucks, Vol. iv. 158, seq.

[23] The house is still standing, and is the residence of Mr Carlile. The further side was enlarged, either in the eighteenth or very early in the nineteenth century, in the style of Queen Anne; but this in no way spoils the effect of the remarkably fine old Elizabethan front.

[24] This has disappeared.

[25] Poem on Everard Digby, written by the present owner of Gothurst, and privately printed.

[26] See Pennant’s Journey, p. 438.

[27] Criminal Trials, Vol. ii. p. 30.

[28] S. P. Dom. James I., Gunpowder Plot Book, Part II. No 135, B.

[29] Osborne’s Traditional Memorials, p. 468. I quote from a footnote on page 147 of the Somers Tracts, Vol. ii.

[30] See Lingard, Vol. vii. chap. i.

Young as he was, Sir Everard Digby’s acquaintance was large and varied, and Gothurst was a very hospitable house. Its host’s tastes enabled him thoroughly to enjoy the society of his ordinary country neighbours, whose thoughts chiefly lay in the direction of sports and agriculture; but he still more delighted in conversing with literary and contemplative men, and when his guests combined all these qualities, he was happiest. One such, who frequently stayed at Gothurst, is thus quaintly described by Father Gerard.[31] Roger Lee “was a gentleman of high family, and of so noble a character and such winning manners that he was a universal favourite, especially with the nobility, in whose company he constantly was, being greatly given to hunting, hawking, and all other noble sports. He was, indeed, excellent at everything, &c.”In short, he appears to have been exactly the kind of man to make a congenial companion for Sir Everard.[32]

[Pg 16]So intimate was he at Gothurst, even during the life of Lady Digby’s father, who had died at the time of which I am about to write, that, on his visits there, he frequently took with him a friend, who, like himself, was an intelligent, highly-educated, and agreeable man, of good family, fond of hawking, hunting, and other sports, and an excellent card-player.

Both Lee and his companion were Catholics, and, as I explained in the last chapter, Sir Everard Digby, although brought up a Protestant, was “Catholickly inclined, and entertained no prejudice whatever against those of the ancient faith”; indeed, in one of his conversations with Lee he went so far as to ask him whether he thought his friend would be a good match for his own sister, observing that he would have no objection to her marrying a Catholic; “for he looked on Catholics as good and honourable men.” Considering the pains, penalties, and disabilities to which recusants, as they were called, were then exposed, this meant very much more than a similar remark would mean in our times. And not only was he unprejudiced, for he took a keen interest in the religion of Catholics, and the three men talked frequently on that subject, the speakers being usually Lee and Digby, the friend putting in a word occasionally, but for the most part preferring to stand by as a listener.

None of Lady Digby’s family were Catholics;[33] her [Pg 17]father had been an ardent Protestant, and possibly, as is not uncommonly the case, the long conversations about Catholicism would have more interest to one who had been brought up in an extreme Protestant atmosphere, than to those who had been accustomed to mix among people of both religions. At any rate, it is pretty evident that the young wife often sat by while her husband and his guests talked theology, and that she had gradually begun to form her own ideas upon the subject.

In considering life at a hospitable country house, nearly three hundred years ago, it is well to try to realise the difference between the conditions under which guests can now be obtained and those then existing. Visitors, and letters to invite them, are now conveyed by railway, and our postal arrangements are admirable; then, the public posts were very slow and irregular, many of the roads were what we should call mere cart-tracks, and it took weeks to perform journeys which can now be accomplished in twenty-four hours.

Our present system of filling our country houses just when we please, and then taking a quiet time alone, or visiting at other country houses, or betaking ourselves to some place for amusement, was impossible early in the seventeenth century; at that period, the only chance of seeing friends, except those living close at hand, was to receive them whenever they found it convenient to come, and to make country[Pg 18] houses, as it were, hotels for such acquaintances who chanced to be passing near them on their journeys. People who were on visiting terms not uncommonly rode or drove up to each other’s houses, without special invitation; and, even when invited, if the distance were great, owing to the condition of the roads and the frequent breakdowns in the lumbersome vehicles, it rarely could be foreseen when a destination would be reached. Yet a welcome was generally pretty certain, for, before the days of newspapers, to say nothing of circulating libraries, hosts and hostesses were not hypercritical of the guests who might come to relieve their dulness, and the vestiges still remaining of the feudal hospitality of the baron’s great halls made them somewhat liberal and unfastidious as to the social standing of those whom they received; nor was it very rare for unknown travellers, who asked leave to take a short rest at a strange house, to meet with a cordial welcome and liberal entertainment.

There was nothing out of the common, therefore, in guests so well known at Gothurst as Roger Lee and his favourite companion riding up to that house unexpected, yet certain of being gladly received; but, on a certain occasion, they were both disappointed on reaching its arched and pillared doorway, at being told that their host had gone to London. The kind and graceful reception given by their hostess, however, did much to make up for his absence.

The long, if rather low rooms, with their wide,[Pg 19] mullioned windows, the good supply, for those times, of books, and the picturesque grounds, with the river flowing through them, made Gothurst a charming house to stay at, and Sir Everard’s man-cook[34] no doubt made the creature comforts all that could be desired. For those who cared for sport, there was plenty of agreeable occupation, for there were hawks and hounds and well-filled stables. The young hostess, who had been brought up among men who spent their lives in country amusements, could converse about horses, dogs, and hunting if required; most probably, too, she often carried a hawk on her wrist; and, as she shared her husband’s tastes for literature and serious reflection, she could suit herself to almost any company.

Her two guests were prepared to talk about any topic that might seem most pleasing to their hostess, and it was soon clear that she wished to renew the conversations about religion which she had listened to with so much attention when her friends had been last in her house in the company of her husband. They were no less ready to discuss the same subject with her, and the more she listened to them, the more she questioned them, and the more she thought over their replies to her difficulties, doubts, and objections, the more inclination did she feel towards the creed they professed. She was well aware that her husband, at [Pg 20]the very least, had a high respect for it; that he already admitted the truth of a great part of it, and that, in discussing it with Lee and his friend, he had propounded arguments against it rather as those of others than as his own; and when, after considerable solitary reflection while her visitors were out of doors, she felt very nearly assured that the Almighty could not approve of people professing a variety of creeds; that of several religions, all teaching different doctrines, only one could be right; that if God had revealed a right religion, he must have ordained some one body of men to teach it, and that there was only one body which seemed to have any claim to such tremendous authority, and that the Roman Catholic Church. These thoughts made her earnestly wish to talk the matter over with one of its priests, and consult him on the question of her own position in respect to so all-important a subject.

To meet with a priest was not easy in those times. Such priests as there were in England rarely, if ever, declared themselves, except to Catholics or would-be Catholics; for to make such a declaration, in this country, amounted to self-accusation of the crime of High Treason. Her two guests were Catholics, and would undoubtedly know several priests, and where they could be found; but to reveal their names or their whereabouts would be dangerous, both to those priests and to themselves, and Lady Digby felt some hesitation in interrogating them on such points. At last,[Pg 21] rather than place one of her husband’s favourite companions in a position which might be unwelcome or even compromising, she determined to consult, not Roger Lee, but the friend he had brought with him. When she had delicately and nervously told him of her wish to see a priest, she was far from reassured by observing that he was with difficulty repressing a smile.[35] Could it be that he thought her a silly woman, hurriedly contemplating a change of religion on too scanty consideration? Or was the finding of a priest so difficult a thing just then as to make a wish to attempt it absurd? His expression, however, soon changed, and he told her, gravely enough, that he thought her desire might very possibly be fulfilled; at any rate, he promised to speak to Roger Lee about it. “In the meantime,”he added, “I can teach you the way to examine your conscience, as I myself was taught to do it by an experienced priest.”She was inclined to smile, in her turn, at such an offer from a mere sportsman; so, thanking him, she allowed the subject to drop.

He had not left her very long before Roger Lee entered the room, and, as he immediately told her that he had heard of her wish to have some conversation with a priest, it was clear that his friend had lost no time in informing him of it. Her surprise may be imagined when Lee proceeded to tell her that his companion was himself a priest!

[Pg 22]At first she refused to believe it.[36] “How is it possible he can be a priest?”she asked, “has he not lived rather as a courtier? Has he not played cards with my husband, and played well too, which is impossible for those not accustomed to the game? Has he not gone out hunting, and frequently in my hearing spoken of the hunt, and of hawks in proper terms, without tripping, which no one could but one who has been trained to it?”

She gave many other reasons for disbelieving that he could be a cleric; and, finally, only accepted the fact on Roger Lee’s reiterated and solemn assurances.

“I pray you,”she then said, “not to be angry with me, if I ask further whether any other Catholic knows him to be a priest but you. Does ... know him?”

“Yes,”replied Lee, “and goes to confession to him.”

Then she asked the same question concerning several other Catholics living in the county, or the adjoining counties—among others, a lady who lived about ten miles from Gothurst.

“Why,”said Lee, “she not only knows him as a priest, but has given herself, and all her household, and all that she has, to be directed by him, and takes no other guide but him.”

At this, she admitted that she was thoroughly satisfied. Whereupon Lee remarked of his friend—

[Pg 23]

“You will find him, however, quite a different man when he has put off his present character.”

“This,”wrote the priest himself, who was Father John Gerard, second son of[37] Sir Thomas Gerard,[38] a Lancashire Knight, and an ancestor of the present Lord Gerard. “This she acknowledged the next day, when she saw me in my soutane and other priestly garments, such as she had never before seen. She made a most careful confession, and came to have so great an opinion of my poor powers, that she gave herself entirely to my direction, meditated great things, which, indeed, she carried out, and carries out still.”

I can fancy certain people, on reading all this, saying, “How very underhand!”I would ask them to bear in mind that for Father Gerard to have acted otherwise, and to have gone about in “priestly garments,”under his own name, would have been the same thing as to have gone to the common hangman and to have asked him to be so obliging as to put the noose round his neck, and then to cut him down as quickly as possible in order that he might relish to the full the ghastly operation of disembowelling and quartering. To this it may be replied that to conceal his identity might be all very well, but that it was quite another thing to stay at the house of a [Pg 24]friend under that concealment, and, in the character of a layman and a guest, to decoy his host’s wife from her husband’s religion, in that host’s and husband’s absence, thus betraying his friendship and violating his hospitality.

My counter-reply would be, that his host had frequently discussed religious questions with both himself and Lee, and had shown, at least, a very friendly feeling towards Catholics in general and their religion; that, as has already been proved, he had in so many words declared himself free from any objection to the marriage of his own sister with a Catholic; nay, that he wished to see her[39] “married well, and to a Catholic, for he looked on Catholics as honourable men;”and that Lady Digby had determined to become a Catholic after due consideration and without any unfair external influence. As to his revealing his priestly character to her and exercising his priestly functions on her behalf, it must be observed that she had expressed a particular wish to see and to converse with a priest, without any such action on her part having been suggested to her by either Gerard or Lee, and that, if Gerard had continued to conceal his own priesthood, she would have simply been put to the trouble, and possibly the dangers, of searching for some other priest. If it be further objected that he ought at least to have waited until her husband’s return, I must so far repeat myself as [Pg 25]to point out that a man who had stated that he would have no objection whatever to his sister’s being married to a Catholic, might be fairly assumed to have no objection to finding himself also married to a Catholic. Again, since Lady Digby was convinced that her soul would only be safe when in the fold of the Church, it would be natural that she should not like to admit of any delay in her reception into it. This being the case, the guests had their duties to their hostess, as well as to their host. It is unnecessary to enter here into the question whether wives should inform their husbands, and grown-up sons and daughters their parents, before joining the Roman Catholic Church; I may, however, be allowed to say that I believe it to be the usual opinion of priests, as well as laymen, as it certainly is of myself, that in most cases, although possibly not absolutely in every case, their doing so is not only desirable, but a duty, provided no hindrance to the following of the dictates of their consciences will result from so doing. Where it would have such an effect, our Lord’s teaching is plain and unmistakeable—“He that loveth father or mother more than me, is not worthy of me.”

Some Protestants are under the impression that a conversion like Lady Digby’s, in which she consulted, and was received into the Church by, a “priest in disguise”is “just the sort of thing that Roman Catholics like.”There could be no greater mistake![Pg 26] It is just what they do not like. The secrecy of priests in the reign of James I. was rendered necessary by persecution: so was that of the laity in housing and entertaining them: so also were the precautions to conceal the fact that mass was said in private houses, and that rooms were used as chapels.

Now I would not pretend for a moment that such a condition of things was wholesome for either priests, Jesuits, laymen, or laywomen. There are occasions on which secrecy may be a dire necessity, but it is, at best, a necessary evil, and its atmosphere is unnatural, cramping, dangerous, and demoralising, although the persecution producing it may lead to virtue, heroism, and even martyrdom. The persecutions of the early Christians by the Romans gave the Church hundreds of saints and martyrs; yet surely those persecutions did not directly tend to the welfare of Christianity; and I suppose that the authorities of the established Church in this country would scarcely consider that Anglicanism would be in a more wholesome condition if every diocese and cure were to be occupied by a bishop or priest of the Church of Rome under the authority of the Pope, although the privations of the dispossessed Anglican clergy, and the inconveniences of the Anglican laity, might be the means of bringing about many individual instances of laudable self-denial, personal piety, and religious zeal. On the same principle, I think that a Catholic student, with an elementary knowledge of the[Pg 27] subject, when approaching the history of his co-religionists in England during the reign of James I., would have good grounds for expecting that, while many cases of valiant martyrdom and suffering for the faith would embellish the pages he was about to read, those pages would also reveal that the impossibility of priests and religious living a clerical life, and the necessity of their joining day by day in the pursuits and amusements of laymen—laymen, often, of gaiety and fashion, if nothing more—had led to serious irregularities in discipline; that the frequent intervals without mass, or any other religious service or priestly assistance, had had the effect of rendering the laity deficient in the virtues which religious exercises and sacraments are supposed to inculcate; that the constant and inevitable practice of secrecy and concealment had induced a habit of mind savouring of prevarication, if not of deception, and that in the embarrassing circumstances and among the harassing surroundings of their lives, clergy as well as laity had occasionally acted with neither tact nor discretion. No one is more alive to the sufferings or the injustices endured by English Catholics in the early part of the seventeenth century, or more admires the courage and patience shown by many, if not most, of those who bore them, than myself; and it is only in fairness to those sufferers, and with a desire to look at their actions honestly, and, as much as may be, impartially, that I approach the subject in this spirit. I have laid the more emphasis[Pg 28] on the dangers of secrecy, be it ever so unavoidable or enforced, because of their bearing upon a matter which will necessarily figure largely in the forthcoming pages.

Lady Digby had no sooner been received into the Church than she became exceedingly anxious for the conversion of her husband, but news now arrived which made her anxious about him on another account. A messenger brought the tidings that Sir Everard was very seriously ill in London, and Lady Digby at once determined to start on the journey of some forty-five or fifty miles in order to nurse him. Her guests volunteered to go to him also, and they were able to accomplish the distance, over the bad roads of that period, much more rapidly than she was.

I will let Father Gerard give an account of his own proceedings with Digby for himself.[40] “I spoke to him of the uncertainty of life, and the certainty of misery, not only in this life, but especially in the next, unless we provided against it; and I showed him that we have here no abiding city, but must look for one to come. As affliction often brings sense, so it happened in this case, for we found little difficulty in gaining his goodwill.

“He prepared himself well for confession after being taught the way; and when he learnt that I was a priest, he felt no such difficulty in believing as his wife had done, because he had known similar [Pg 29]cases, but he rather rejoiced at having found a confessor who had experience among persons of his rank of life, and with whom he could deal at all times without danger of its being known that he was dealing with a priest. After his reconciliation he began on his part to be anxious about his wife, and wished to consult with us how best to bring her to the Catholic religion. We both smiled at this, but said nothing at the time, determining to wait till his wife came up to town, that we might witness how each loving soul would strive to win the other.”

When Digby had recovered and had returned to Gothurst with his wife, they both paid a visit to Father Gerard at the country house, some distance from their own home, at which he lived as chaplain. This was probably Mrs Vaux’s house at Stoke Pogis, of which we shall have something to say a little later. While there, he was taken ill even more seriously than before. His life became in danger, and the best doctors in Oxford were sent for to his assistance. They despaired of curing him, and “he began to prepare himself earnestly for a good death.”His poor young wife, being told that her husband could not recover, began “to think of a more perfect way of life,”in case she should be left a widow. It may be thought that she might at least have waited to do this until after the death of her husband, but it is possible, and even probable, although not mentioned by Father Gerard, that Sir Everard himself desired[Pg 30] her to consider what manner of life she would lead when he should be gone. She would be a very young widow with a large property, and Sir Everard would doubtless feel anxious as to what would become of her.[41] “For some days,”says Father Gerard, “she gave herself to learn the method of meditation, and to find out God’s will with regard to her future life, how she might best direct it to his glory. This was her resolution, but God had otherwise arranged, and for that time happily.”

Gerard himself was, humanly speaking, the means of prolonging Digby’s life, for, in spite of the verdict of the great physicians from Oxford, that nothing could save him, Father Gerard refused to give up all hope, and persuaded him to send for a certain doctor of his own acquaintance from Cambridge. “By this doctor, then, he was cured beyond all expectation, and so completely restored to health that there was not a more robust or stalwart man in a thousand.”

Not very long after he had become a Catholic, Digby was roughly reminded of the illegality of his position, by a rumour that his friend, Father Gerard, who had gone to a house to visit, as a priest, a person who was dying, was either on the point of being, or was actually, in the hands of pursuivants. This news distressed him terribly. He immediately told his wife that, if Father Gerard [Pg 31]were arrested, he intended to take a sufficient number of friends and servants to rescue him, and to watch the roads by which he would probably be taken to London; and that “he would accomplish”his “release one way or another, even though he should spend his whole fortune in the venture.”The danger of such an attempt at that period was obvious. Certainly his desire to set free Father Gerard was most praiseworthy, but whether, had he attempted it in the way he proposed, he would have benefitted or injured the Catholic cause in England, may be considered at least doubtful. A rescue by an armed force would have meant a free fight, probably accompanied by some bloodshed, with this result, that, if successful, the perpetrators would most likely have been discovered, and sooner or later very severely dealt with as aggressors against the officers of the law in the execution of their duty, and that, if unsuccessful, the greater proportion of the rescuing party would have met their deaths either on the field at the time, or on the gallows afterwards. To attempt force against the whole armed power of the Crown seemed a very Quixotic undertaking, and the idea of dispersing the whole of his wealth, whether in the shape of armed force or other channels, in a chimerical effort to set free his friend, however generous in intent, scarcely recommends itself as the best method of using it for the good of the cause he had so much at heart. This incident shows[Pg 32] Digby’s hastiness and impetuosity. Fortunately, the report of Father Gerard’s arrest turned out to be false; so, for the moment, any excited and unwise action on Sir Everard’s part was avoided.

FOOTNOTES:

[31] Life of Father John Gerard, p. cxxxvi.

[32] I write of Sir Everard and Lady Digby; but it is improbable that he had received knighthood at the period treated of in this chapter.

[33] Life of Father John Gerard, p. cl.

[34] Even his under-cook was a man. Cal. Sta. Pa. Dom., 1603-10, p. 266.

[35] Life of Gerard, p. cli.

[36] Life of Father John Gerard; p. cli.

[37] This Sir T. Gerard was committed to the Tower on an accusation “of a design to deliver Mary Queen of Scots out of her confinement.”—Burke’s Peerage, 1886, p. 576.

[38] Life of Gerard, p. clii.

[39] Life of Father John Gerard, p. cli.

[40] Life of Father John Gerard, p. cliii.

[41] Life of Father John Gerard, p. cliii.

A change of religion causes, to most of those who make it, a very forcible wrench. It may be, probably it usually is, accompanied by great happiness and a sensation of intense relief; no regrets whatever may be felt that the former faith, with its ministers, ceremonies, and churches have been renounced for ever; on the contrary, the convert may be delighted to be rid of them, and in turning his back upon the religion of his childhood, he may feel that he is dismissing a false teacher who has deceived him, rather than that he is bidding farewell to a guide who has conducted him, however unintentionally, unwittingly, or unwillingly, to the gate of safety. Yet granting, and most emphatically granting, all this, we should not forget that there is another view of his position. Let his rejoicing be ever so great at entering that portal and leaving the land of darkness for the regions of light, be the welcome he receives from his future co-religionists as warm as it may, and be his confidence as great as is conceivable, the convert is none the less forsaking a well-known country for one that is new to[Pg 34] him, he is leaving old friends to enter among strangers, and he is exchanging long-formed habits for practices which it will take him some time to understand, to acquire, and to familiarize.

A convert, again, is not invariably free from dangers. Let us take the case of Sir Everard Digby. A man with his position, popularity, wealth, intellect, and influence, was a convert of considerable importance from a human point of view, and he must have known it. If he lost money and friends by his conversion, much and many remained to him, and among the comparatively small number of Catholics he might become a more leading man than as a unit in the vast crowd professing his former faith; and although, on the whole, the step which he had taken was calculated to be much against his advancement in life, there are certain attractions in being the principal or one of the principal men of influence in a considerable minority. I am not for a moment questioning Digby’s motives in becoming a Catholic; I believe they were quite unexceptionable; all that I am at the moment aiming at is to induce the reader to keep before his mind that the position of an influential English convert, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, like most other positions, had its own special temptations and dangers, and my reasons for this aim will soon become obvious.

In comparing the situation of a convert to Catholic[Pg 35]ism in the latter days of Elizabeth or the early days of James I., with one in the reign of Victoria, we are met on the threshold with the fact that terrible bodily pains, and even death itself, threatened the former, while the latter is exposed to no danger of either for his religion. In the matter of legal fines and forfeitures, again, the persecution of the first was enormous, whereas the second suffers none. But of these pains and penalties I shall treat presently. Just in passing I may remark that many a convert now living has reason for doubting whether any of his forerunners in the times of Elizabeth or James I. suffered more pecuniary loss than he. One parent or uncle, by altering a will, can cause a Romish recusant more loss than a whole army of pursuivants.

Looking at the positions of converts at the two periods from a social point of view, we find very different conditions. Instead of being regarded, as he is now, in the light of a fool who, in an age of light, reason, and emancipation from error, has wilfully retrograded into the grossest of all forms of superstition, the convert, in the reigns of Elizabeth and James, was known to be returning to the faith professed by his fathers, one, two, or, at most, three generations before him. It was not then considered a case of “turning Roman Catholic,”but of returning to the old religion, and even by people who cared little, if at all, about such matters, he was rather respected than otherwise.

Now it is different. During the two last genera[Pg 36]tions, so many conversions have apparently been the result of what is known as the Oxford Movement, or of Ritualism, that converts are much associated in men’s minds with ex-clergymen, or with clerical families; and to tell the truth, at least a considerable minority of Anglicans of good position, while they tolerate, invite to dinner, and patronise their parsons, in their inmost hearts look down upon and rather dislike the clergy and the clergy-begotten.

At present, again, a prejudice is felt in England against an old Catholic, prima facie, on the ground that he is probably either an Irishman, of Irish extraction, or of an ancient Catholic English family rendered effete by idleness, owing to religious disabilities, or by a long succession of intermarriages. It would be easy to prove that these prejudices, if not altogether without foundation in fact, are immensely and unwarrantably exaggerated, but my object, at present, is merely to state that they exist. Three hundred years ago, whatever may have been the prejudices against Catholics, old or new, they cannot have arisen on such grounds as these, and if Protestants attributed the tenacity of the former and the determined return of the latter to their ancient faith rather to pride than to piety, there is no doubt which motive would be most respected in the fashionable world.

The conduct of the Digbys, immediately after their conversion, was most exemplary. They threw[Pg 37] themselves heart and soul into their religion, and Father Gerard, who had received them into the Church, writes[42] of Sir Everard in the highest terms, saying:—“He was so studious a follower of virtue, after he became a Catholic, that he gave great comfort to those that had the guiding of his soul (as I have heard them seriously affirm more than once or twice), he used his prayers daily both mental and vocal, and daily and diligent examination of his conscience: the sacraments he frequented devoutly every week, &c.”“Briefly I have heard it reported of this knight, by those that knew him well and that were often in his company, that they did note in him a special care of avoiding all occasions of sin and of furthering acts of virtue in what he could.”

He read a good deal in order to be able to enter into controversy with Protestants, and he was the means of bringing several into the Church—“some of great account and place.”As to his conversation, “not only in this highest kind, wherein he took very great joy and comfort, but also in ordinary talk, when he had observed that the speech did tend to any evil, as detraction or other kind of evil words which sometimes will happen in company, his custom was presently to take some occasion to alter the talk, and cunningly to bring in some other good matter or profitable subject to talk of. And [Pg 38]this, when the matter was not very grossly evil, or spoken to the dishonour of God or disgrace of his servants; for then, his zeal and courage were such that he could not bear it, but would publicly and stoutly contradict it, whereof I could give divers instances worth relating, but am loth to hold the reader longer.”Finally, in speaking of those “that knew him”and those “that loved him,”Father Gerard says, “truly it was hard to do the one and not the other.”

Like most Catholics living in the country, and inhabiting houses of any size, the Digbys made a chapel in their home, “a chapel with a sacristy,” says Father Gerard,[43] “furnishing it with costly and beautiful vestments;”and they “obtained a Priest of the Society”(of Jesus) “for their chaplain, who remained with them to Sir Everard’s death.”Of this priest, Gerard says[44] that he was a man “who for virtue and learning hath not many his betters in England.”This was probably Father Strange,[45] who usually passed under the alias of Hungerford. He was the owner of a property, some of which, in Gloucestershire, he sold,[46] and “£2000 thereof is in the Jesuites’ bank”said a witness against him. He was imprisoned, after Sir Everard Digby’s death, for [Pg 39]five or six years.[47] In an underground dungeon in the Tower[48] “he was so severely tortured upon the rack that he dragged on the rest of his life for thirty-three years in the extremest debility, with severe pains in the loins and head. Once when he was in agony upon the rack, a Protestant minister began to argue with him about religion; whereupon, turning to the rack-master, Father Strange[49] “asked him to hoist the minister upon a similar rack, and in like fetters and tortures, otherwise, said he, we shall be fighting upon unequal terms; for the custom everywhere prevails amongst scholars that the condition of the disputants be equal.”

Another Jesuit Father, at one time private chaplain to Sir Everard Digby, was Father John Percy,[50] who afterwards, under the alias of Fisher, held the famous controversy with Archbishop Laud in the presence of the king and the Countess of Buckingham, to whom he acted as chaplain for ten years. He also had been fearfully tortured in prison, in the reign of Elizabeth; and if he recounted his experiences on the rack to Sir Everard Digby, the hot blood of the latter would be stirred up against the Protestant Governments that could perpetrate or tolerate such iniquities.

In trying to picture to himself the “chapel with a sacristy”made by the Digbys at Gothurst, a [Pg 40]romantic reader may imagine an ecclesiastical gem, in the form of a richly-decorated chamber filled with sacred pictures, figures of saints, crucifixes, candles, and miniature shrines. Before taking the trouble of raising any such representation before the mind, it would be well to remember that, in the times of which we are treating, that was the most perfect and the best arranged chapel in which the altar, cross, chalice, vestments, &c., could be concealed at the shortest possible notice, and the chamber itself most quickly made to look like an ordinary room. The altar was on such occasions a small slab of stone, a few inches in length and breadth, and considerably less than an inch in thickness. It was generally laid upon the projecting shelf of a piece of furniture, which, when closed, had the appearance of a cabinet. Some few remains of altars and other pieces of “massing stuff,” as Protestants called it, of that date still remain, as also do many simple specimens used in France during the Revolution of last century, which have much in common with them. To demonstrate the small space in which the ecclesiastical contents of a private chapel could be hidden away in times of persecution, I may say that, even now, for priests who have the privilege of saying mass elsewhere than in churches or regular chapels—for instance, in private rooms, on board ship,[51] or in the ward of a hospital—altar, chalice, [Pg 41]paten, cruets, altar-cloths, lavabo, alb, amice, girdle, candlesticks, crucifix, wafer-boxes, wine-flask, Missal, Missal-stand, bell, holy-oil stocks, pyx, and a set of red and white vestments (reversible)—in fact, everything necessary for saying mass, as well as for administering extreme unction to the sick, can be carried in a case 18 inches in length, 12 inches in width, and 8 inches in depth. Occasionally, as we are told of the Digbys, rich people may have had some handsome vestments; but a private chapel early in the sixteenth century must have been a very different thing from what we associate with the term in our own times, and however well furnished it may have been as a room, it must have been almost devoid of “ecclesiastical luxury.”

Here and there were exceptions, in which Catholics were very bold, but they always got into trouble. For instance, when Luisa de Carvajal came to England, she was received at a country house—possibly Scotney Castle, on the borders of Kent and Sussex—the chapel of which[52] “was adorned with pictures and images, and enriched with many relics. Several masses were said in it every day, and accompanied by beautiful vocal and instrumental music.”It was “adorned not only with all the [Pg 42]requisites, but all the luxuries, so to speak, of Catholic worship;”and Luisa could walk “on a spring morning in a pleached alley, saying her beads, within hearing of the harmonious sounds of holy music floating in the balmy air.”What was the consequence? “The beautiful dream was rudely dispelled. One night, after she had been at this place about a month, a secret warning was given to the master of this hospitable mansion, that he had been denounced as a harbourer of priests, and that the pursuivants would invade his house on the morrow. On the receipt of this information, measures were immediately taken to hide all traces of Catholic worship, and a general dispersion took place.”I only give this as a typical case to show how necessary it then was to make chapels and Catholic worship as secret as possible.

Sir Everard Digby was anxious that others, as well as himself, should join the body which he believed to be the one, true, and only Church of God, and of this I have nothing to say except in praise. An anecdote of his efforts in this direction, however, is interesting as showing, not only the necessities of the times, but also something of the character and disposition of the man. In studying a man’s life, there may be a danger of building too much upon his actions, as if they proved his inclinations, when they were in reality only the result of exceptional circumstances, and I have no wish to force the inferences, which I myself[Pg 43] draw from the following facts, upon the opinions of other people; I merely submit them for what they are worth.

Father Gerard says[53] that Sir Everard “had a friend for whom he felt a peculiar affection,”namely, Oliver Manners, the fourth son of John, fourth Earl of Rutland, and said by Father J. Morris[54] to have been knighted by King James I. “on his coming from Scotland,”on April 22nd, 1603, but by Burke,[55] “at Belvoir Castle, 23rd April 1608.”He was very anxious that this friend should be converted to the Catholic faith, and that, to this end, he should make the acquaintance of Father Gerard; “but because he held an office in the Court, requiring his daily attendance about the King’s person, so that he could not be absent for long together,”this “desire was long delayed.”At last Sir Everard met Manners in London at a time when he knew that Father Gerard was there also, “and he took an opportunity of asking him to come at a certain time to play at cards, for these are the books gentlemen in London study both night and day.”Instead of inviting a card-party, Digby invited no one except Father Gerard, and when Manners arrived, he found Gerard and Digby “sitting and conversing very seriously.”The latter asked him “to sit down a little until the rest should arrive.”After a short silence Sir Everard said:—

[Pg 44]

“We two were engaged in a very serious conversation, in fact, concerning religion. You know that I am friendly to Catholics and to the Catholic faith; I was, nevertheless, disputing with this gentleman, who is a friend of mine, against the Catholic faith, in order to see what defence he could make, for he is an earnest Catholic, as I do not hesitate to tell you.”At this he turned to Father Gerard and begged him not to be angry with him for betraying the fact of his being a Romish recusant to a stranger; then he said to Manners, “And I must say he so well defended the Catholic faith that I could not answer him, and I am glad you have come to help me.”

Manners “was young and confident, and trusting his own great abilities, expected to carry everything before him, so good was his cause and so lightly did he esteem”his opponent, “as he afterwards confessed.” After an hour’s sharp argument and retort on either side, Father Gerard began to explain the Catholic faith more fully, and to confirm it with texts of Scripture, and passages from the Fathers.

Manners listened in silence, and “before he left he was fully resolved to become a Catholic, and took with him a book to assist him in preparing for a good confession, which he made before a week had passed.” He became an excellent and exemplary Christian, and his life would make an interesting and edifying volume.

[Pg 45]All honour to Sir Everard Digby for having been the human medium of bringing about this most happy and blessed conversion! It might have been difficult to accomplish it by any other method. In those days of persecution, stratagem was absolutely necessary to Catholics for their safety sake, even in everyday life, and still more so in evangelism. As to the particular stratagem used by Digby in this instance, I do not go so far as to say that it was blame-worthy; I have often read of it without mentally criticising it; I have even regarded it with some degree of admiration; but, now that I am attempting a study of Sir Everard Digby’s character, and seeking for symptoms of it in every detail that I can discover of his words and actions, I ask myself whether, in all its innocence, his conduct on this occasion did not exhibit traces of a natural inclination to plot and intrigue. Could he have induced Manners to come to his rooms by no other attraction than a game of cards, which he had no intention of playing? Was it necessary on his arrival there to ask him to await that of guests who were not coming, and had never been invited? Was he obliged, in the presence of so intimate a friend, to pretend to be only well-disposed towards Catholics instead of owning himself to be one of them? Need he have put himself to the trouble of apologising to Father Gerard for revealing that he was a Catholic? In religious, as in all other matters, there are cases in which artifice may be harmless or[Pg 46] desirable, or even a duty, but a thoroughly straightforward man will shrink from the “pious dodge”as much as the kind-hearted surgeon will shrink from the use of the knife or the cautery.

Necessary as they may have been, nay, necessary as they undoubtedly were, the planning, and disguising, and hiding, and intriguing used as means for bringing about the conversions of Lady Digby, Sir Everard Digby, and Oliver Manners, though innocent in themselves, placed those concerned in them in that atmosphere of romance, adventure, excitement, and even sentiment, which I have before described, and it is obvious that such an atmosphere is not without its peculiar perils.

It is certainly very comfortable to be able to preach undisturbed, to convert heretics openly, and to worship in the churches of the King and the Government; yet even in religion, to some slight degree, the words of a certain very wise man may occasionally be true, that[56] “stolen waters are sweeter, and hidden bread is more pleasant.”Nothing is more excellent than missionary work; but it is a fact that proselytism, when conducted under difficulties and dangers, whether it be under the standard of truth or under the standard of error, is not without some of the elements of sport; at any rate, if it be true, as enthusiasts have been heard to assert, that even the hunted fox is a partaker in the pleasures of the chase, [Pg 47]the Jesuits had every opportunity of enjoying them during the reigns of Elizabeth and James I.

Besides a consideration of the personal characteristics of Sir Everard Digby, and the position of converts to Catholicism in his times, it will be necessary to take a wider view of the political, social, and religious events of his period. Otherwise we should be unable to form anything like a fair judgment either of his own conduct, or of the treatment which he received from others.

The oppression and persecution of Catholics by Queen Elizabeth and her ministers was extreme. It was made death to be a priest, death to receive absolution from a priest, death to harbour a priest, death even to give food or help of any sort to a priest, and death to persuade anyone to become a Catholic. Very many priests and many laymen were martyred, more were tortured, yet more suffered severe temporal losses. And, what was most cruel of all, while Statutes were passed with a view to making life unendurable for Catholics in England itself, English Catholics were forbidden to go, or to send their children, beyond the seas without special leave.

The actual date of the Digbys’ reception into the Catholic Church is a matter of some doubt. It probably took place before the death of Elizabeth. That was a time when English Catholics were considering their future with the greatest anxiety. Politics[Pg 48] entered largely into the question, and where politics include, as they did then, at any rate, in many men’s minds, some doubts as to the succession to the crown, intrigue and conspiracy were pretty certain to be practised.

FOOTNOTES:

[42] A Narrative of the Gunpowder Plot, p. 89.

[43] Life of Father John Gerard, p. clv.

[44] A Narrative of the Gunpowder Plot, p. 89.

[45] Father H. Garnet and the Gunpowder Plot, by Father Pollen, p. 15.

[46] Records of the English Province. S.J. Series, ix. x. xi., p. 3.

[47] Ib., p. 5, and Stoneyhurst MSS.

[48] Ib., p. 3.

[49] Ib., p. 4.

[50] Records, S.J. Series, i., p. 527.

[51] In his Mores Catholici (Cincinnati, 1841, Vol. II. p. 364), Kenelm H. Digby says that "Portable altars were in use long before the eleventh century. St Wulfran, Bishop of Sens, passing the sea in a ship, is said to have celebrated the sacred mysteries upon a portable altar."

[52] The Life of Luisa de Carvajal, by Lady G. Fullerton, p. 154, seq.

[53] Life of Father John Gerard, p. clxvi. seq.

[54] Ib., footnote to p. cciii.

[55] Peerage, 1886, p. 1173.

[56] Proverbs ix. 17.

The responsibility of the intrigues in respect to the claims to the English throne, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, rests to some extent upon Queen Elizabeth herself. As Mr Gardiner puts it:—[57] “She was determined that in her lifetime no one should be able to call himself her heir.”It was generally understood that James would succeed to the throne; but, so long as there was the slightest uncertainty on the question, it was but natural that the Catholics should be anxious that a monarch should be crowned who would favour, or at least tolerate them, and that they should make inquiries, and converse eagerly, about every possible claimant to the throne. Fears of foreign invasion and domestic plotting were seriously entertained in England during the latter days of Elizabeth, as well as immediately after her death. “Wealthy men had brought in their plate and treasure from the country, and had put them in places of safety. Ships of war had been stationed in [Pg 50]the Straits of Dover to guard against a foreign invasion, and some of the principal recusants had, as a matter of precaution, been committed to safe custody.”[58]

When James VI. of Scotland, the son of the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots, ascended the throne, rendered vacant by the death of Elizabeth, as James I. of England, no voice was raised in favour of any other claimant, and[59] “the Catholics, flattered by the reports of their agents, hailed with joy the succession of a prince who was said to have promised the toleration of their worship, in return for the attachment which they had so often displayed for the house of Stuart.”King James owed toleration, says Lingard, “to their sufferings in the cause of his unfortunate mother;”and “he had bound himself to it, by promises to their envoys, and to the princes of their communion.”

The opinion that the new king would upset and even reverse the anti-Catholic legislation of Elizabeth was not confined to the Catholic body: many Protestants had taken alarm on this very score, as may be inferred from a contemporary tract, entitled[60] Advertisements of a loyal subject to his gracious Sovereign, drawn from the Observation of the People’s Speeches, in which the following passage occurs:—“The plebes, I wotte not what they call them, but some there bee [Pg 51]who most unnaturally and unreverentlie, by most egregious lies, wound the honour of our deceased soveraigne, not onlie touching her government and good fame, but her person with sundry untruthes,” and after going on in this strain for some lines it adds:—“Suerlie these slanders be the doings of the papists, ayming thereby at the deformation of the gospell.”[61]

On the other hand, there were both Catholics and Puritans who were distrustful of James. Sir Everard cannot have been long a Catholic, when a dangerous conspiracy was on foot. Sir Griffin Markham, a Catholic, and George Brooke, a Protestant, and a brother of Lord Cobham’s, hatched the well-known plot which was denominated “the Bye,”and, among many others who joined it, were two priests, Watson and Clarke, both of whom were eventually executed on that account. Its object appears to have been to seize the king’s person, and wring from him guarantees of toleration for both Puritans and Catholics. Father Gerard acquired some knowledge [Pg 52]of this conspiracy, as also did Father Garnet, the Provincial of the Jesuits, and Blackwell, the Archpriest; and they insisted upon the information being laid instantly before the Government. Before they had time to carry out their intention, however, it had already been communicated, and the complete failure of the attempt is notorious. The result was to injure the causes of both the Catholics and the Puritans, and James never afterwards trusted the professions of either.

So far as the Catholics were concerned, the “Bye” conspiracy unfortunately revealed another; for Father Watson, in a written confession which he made in prison, brought accusations of disloyalty against the Jesuits. It was quite true that, two years earlier, Catesby, Tresham, and Winter—all friends of Sir Everard Digby’s—had endeavoured to induce Philip of Spain to invade England, and had asked Father Garnet to give them his sanction in so doing; but Garnet had “misliked it,”and had told them that it would be as much “disliked at Rome.”[62]