Title: Being Well-Born: An Introduction to Eugenics

Author: Michael F. Guyer

Editor: M. V. O'Shea

Release date: May 21, 2012 [eBook #39751]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive.)

BEING WELL-BORN

AN INTRODUCTION TO EUGENICS

By

MICHAEL F. GUYER, Ph. D.

Professor of Zoology, The University of Wisconsin

Childhood and Youth Series

Edited by M. V. O’SHEA

Professor of Education, The University of Wisconsin

INDIANAPOLIS

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright 1916

The Bobbs-Merrill Company

PRESS OF

BRAUNWORTH & CO.

BOOKBINDERS AND PRINTERS

BROOKLYN, N. Y.

TO MY WIFE

HELEN M. GUYER

The writer recalls that when he was a young boy, he heard the grown-up people in the community earnestly and incessantly debating the question: Does heredity play a greater part in shaping one’s mind and body than does his environment? From that day to this he has listened to men and women in every walk of life discussing the relation of heredity to environment in determining human traits. Teachers and parents are constantly asking: “Are such and such characteristics in my children due to their inheritance or to the way they have been trained?” Students of juvenile delinquency and of mental defect and deficiency are searching everywhere for light on this matter. It is not to be wondered at that practically all people are peculiarly interested in this problem, since it concerns intimately one’s personal traits, and it constantly confronts any one who is responsible for the care and culture of the young.

It is suggestive to note how people differ in their views regarding the extent to which a child’s physical and mental qualities and capacities are fixed definitely by his inheritance. The writer has often heard students in university classes discuss the subject; and their handling of the problem has shown how superficially and even superstitiously most persons regard the mechanism and functions of heredity. It is significant also to observe what extreme views many people hold regarding the possibility of affecting a child’s traits and abilities by subjecting him to specific influences during his prenatal life. In any group of one hundred persons chosen at random, probably seventy-five will believe in specific prenatal influence. Many of them will believe in birthmarks due to peculiar experiences of the mother. A popular book recently published asserts among other things that if a mother will look upon beautiful pictures and listen to good music during the prenatal period of her child, the latter will possess esthetic traits and interests in high degree. On the other hand, people generally do not seem to think that degenerate parents beget only degenerate children. Alcoholics, feeble-minded persons and the like are permitted to bring children into the world.

Very few people have any precise knowledge of the mechanism of heredity. The whole thing is inscrutable to them, and is shrouded in mystery. Superstition flourishes among even intelligent persons in respect to heredity, and errors due to education, and tragedies resulting from vicious social organization are all alike ascribed to its uncontrollable forces. Most people are none the wiser because they do not know to what extent the physical and mental defects and deviations of individuals are due to inheritance or to the malign influences of the individual’s environment and training.

Professor Guyer, who has studied the whole problem in a thoroughgoing, scientific way, has prepared this book with a view to illuminating some of the mysteries that surround the subject of heredity, and to dispelling the illusions that persist regarding it. He shows the method which nature follows in the development of the individual. He presents the laws which have become established respecting the extent to which and the manner in which immediate and remote ancestors contribute to the child’s physical and mental organism. He answers many questions which those who are engaged in social work or in education in the home or the school are asking to-day. He discusses subjects upon which every serious-minded person wishes to be informed. He has thus made a book which is both of theoretical and of practical interest.

He has written in a style which should make his book attractive to the parent and the teacher as well as to the student of the complicated mechanism of inheritance. Only a few special terms are used, and these should not give any reader trouble, because the treatment throughout is so concrete that the meaning of the terms will be easily grasped. Further, the book is illustrated, with many attractive and instructive illustrations which will show at a glance the working of the principles of inheritance which are developed in the text.

This book may be heartily commended to all who are interested in questions of human nature, education and social reform. It should enable the parent, the teacher and the legislator to understand more clearly than most of them now do in how far children’s traits and possibilities are or can be fixed by inheritance as contrasted with environmental conditions and nurture in home, school, church and institutional life.

M. V. O’Shea.

Madison, Wisconsin.

One of the most significant processes at work in society to-day is the awakening of the civilized world to the rights of the child; and it is coming to be realized that its right of rights is that of being well-born. Any series of publications, therefore, dealing primarily with the problems of child nature may very fittingly be initiated by a discussion of the factor of well-nigh supreme importance in determining this nature, heredity.

No principles have more direct bearing on the welfare of man than those of heredity, and yet on scarcely any subject does as wide-spread ignorance prevail. This is due in part to the complexity of the subject, but more to the fact that in the past no clear-cut methods of attacking the manifold problems involved had been devised. Happily this difficulty has at least in part been overcome.

It is no exaggeration to say that during the last fifteen years we have made more progress in measuring the extent of inheritance and in determining its elemental factors than in all previous time. Instead of dealing wholly now with vague general impressions and speculations, certain definite principles of genetic transmission have been disclosed. And since it is becoming more and more apparent that these hold for man as well as for plants and animals in general, we can no longer ignore the social responsibilities which the new facts thrust upon us.

Since what a child becomes is determined so largely by its inborn capacities it is of the greatest importance that teachers and parents realize something of the nature of such aptitudes before they begin to awaken them. For education consists in large measure in applying the stimuli necessary to set going these potentialities and of affording opportunity for their expression. Of the good propensities, some will require merely the start, others will need to be fostered and coaxed into permanence through the stereotyping effects of proper habits; of the dangerous or bad, some must be kept dormant by preventing improper stimulation, others repressed by the cultivation of inhibitive tendencies, and yet others smothered or excluded by filling their place with desirable traits before they themselves come into expression.

We must see clearly, furthermore, that even the best of pedagogy and parental training has obvious limits. Once grasp the truth that a child’s fate in life is frequently decided long before birth, and that no amount of food or hospital service or culture or tears will ever wholly make good the deficiencies of bad “blood,” or in the language of the biologist, a faulty germ-plasm, and the conviction must surely be borne home to the intelligent members of society that one thing of superlative importance in life is the making of a wise choice of a marriage mate on the one hand, and the prevention of parenthood to the obviously unfit on the other.

In the present volume it is intended to examine into the natural endowment of the child. And since full comprehension of it requires some understanding of the nature of the physical mechanism by which hereditary traits are handed on from generation to generation, a small amount of space is given to this phase. Then, that the reader may appreciate to their fullest extent the facts gathered concerning man, a review of the more significant principles of genetics as revealed through experiments in breeding plants and animals has been undertaken. The main applications of these principles to man is pointed out in a general discussion of human heredity. Finally, inasmuch as all available data indicate that the fate of our very civilization hangs on the issue, the work concludes with an account of the new science of eugenics which is striving for the betterment of the race by determining and promulgating the laws of human inheritance so that mankind may intelligently go about conserving good and repressing bad human stocks.

In order to eliminate as many errors as possible and to avoid oversights I have submitted various chapters to certain of my colleagues and friends who are authorities in the special field treated therein. While these gentlemen are in no way responsible for the material of any chapter they have added greatly to the value of the whole by their suggestions and comments. Thus I am indebted to Professor Leon J. Cole for reading the entire manuscript; to Professors A. S. Pearse and F. C. Sharp for reading Chapter VII; to Professor C. R. Bardeen for reading special parts; to Doctor J. S. Evans for reading Chapter VI and part of V; to Doctor W. F. Lorenz, of the Mendota Hospital, for reading Chapter VIII; to Judge E. Ray Stevens for reading Chapter IX, and to Helen M. Guyer for several readings of the entire manuscript.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to all of these readers, to various publishers and periodicals for the use of certain of the illustrations, to the authors of the numerous books and papers from which much of the material in such a work as this must necessarily be selected, and to my artist, Miss H. J. Wakeman, for her painstaking endeavors to make her work conform to my ideas of what each diagram should show.

M. F. G.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Heredity | 1 |

| Blood heritage—Kind determined by origin—Ancestry a network—Ancestry in royalty—Offspring derived from one parent only—Dual ancestry an aid in studying heredity—Reversion—Telegony—Prenatal influences apart from heredity—Parent body and germ not identical—A hereditary character defined—Hereditary mingling a mosaic rather than a blend—Determiners of characters, not characters themselves, transmitted—Our knowledge of heredity derived along three lines—The method of experimental breeding—The statistical method—Galton’s law of regression—Correlations between parents and offspring—The biometrical method, statistical, not physiological—Mental as well as physical qualities inheritable. | ||

| II | The Bearers of the Heritage | 20 |

| The cell the unit of structure—Unicellular organisms—Importance of cell-theory—Heredity in unicellular forms—Reproduction and heredity in colonial protozoa—Conjugation—Specialization of sex-cells—The fertilized ovum—Advancement seen in the Volvox colony—Natural death—Specialization in higher organisms—Sexual phenomena in higher forms—Cell-division—Chromosomes constant in number and appearance—Significance of the chromosomes—Cleavage of the egg—Chief processes operative in building the body—The origin of the new germ-cells—Significance of the early setting apart of the germ-cells—Individuality of chromosomes—Pairs of chromosomes—Reduction of the number of chromosomes by one-half—Maturation of the sperm-cell—Maturation of the egg-cell—Parallel between the two processes—Fertilization—Significance of the behavior of the chromosomes—A single set of chromosomes sufficient for the production of an organism—The duality of the body and the singleness of the germ—The cytoplasm in inheritance—Chromosomes possibly responsible for the distinctiveness of given characters—Sex and heredity—Many theories of sex determination—The sex-chromosome—Sex-linked characters in man—In lower forms. | ||

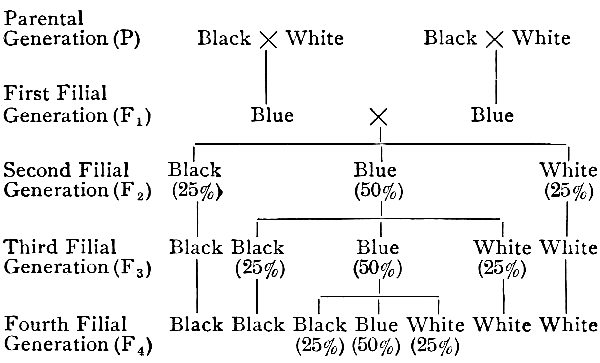

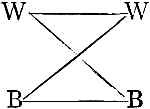

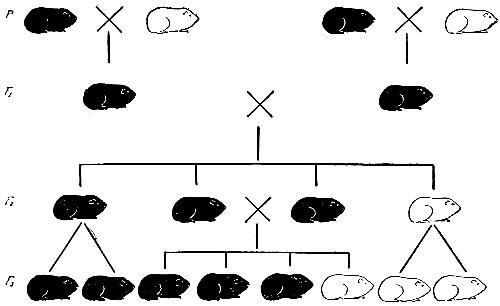

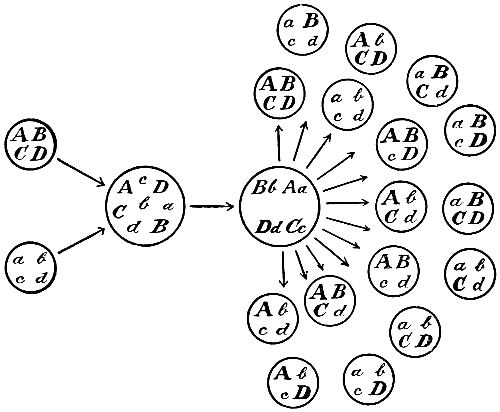

| III | Mendelism | 67 |

| New discoveries in the field of heredity—Mendel—Rediscovery of Mendelian principles—Independence of inheritable characters—Illustration in the Andalusian fowl—The cause of the ratio—Verification of the hypothesis—Dominant and recessive—Segregation in the next generation—Illustrated in guinea-pigs—Terminology—The theory of presence and absence—Additional terminology—Dominance not always complete—Modifications of dominance—Mendel’s own work—Dihybrids—Getting new combinations of characters—Segregations of the determiners—Four kinds of gametes in each sex—The 9:3:3:1 ratio—Phenotype and genotype—The question of blended inheritance—Nilsson-Ehle’s discoveries—Such cases easily mistaken for true blends—Skin-color in man—Questionable if real blends exist—The place of the Mendelian factors in the germ-cell—Parallel between the behavior of Mendelian factors and chromosomes—A single chromosome not restricted to carrying a single determiner. | ||

| IV | Mendelism in Man | 97 |

| Probably applicable to many characters in man—Difficult to get correct data—A generalized presence-absence formula—Indications of incomplete dominance—Why after the first generation only half the children may show the dominant character—Eye-color in man—Hair-color—Hair-shape—Irregularities—Digital malformations—Eye defects—Other defects inherited as dominants—Recessive conditions more difficult to deal with—Albinism—Other recessive conditions in man—Breeding out defects—Other inheritable conditions in man. | ||

| V | Are Modifications Acquired Directly by the Body Inherited? | 121 |

| Which new characters are inherited?—Examples of somatic modifications—Use and disuse—The problem stated—Special conditions in mammals—Three fundamental questions—External influences may directly affect the germ-cells—Such effects improbable in warm-blooded animals—Poisons may affect the germ-plasm—How can somatic modifications be registered in germ-cells?—Persistence of Mendelian factors argues against such a mode of inheritance—Experiments on insects—On plants—On vertebrates—Epilepsy in guinea-pigs—Effects of mutilations not inherited—Transplantation of gonads—Effects of body on germ, general not specific—Certain characters inexplicable as inherited somatic acquirements—Neuter insects—Origin of new characters in germinal variation—Sexual reproduction in relation to new characters—Many features of an organism characterized by utility—Germinal variation a simpler and more inclusive explanation—Analysis of cases—Effects of training—Instincts—Disease—Reappearance not necessarily inheritance—Prenatal infection not inheritance—Inheritance of a predisposition not inheritance of a disease—Tuberculosis—Two individuals of tubercular stock should not marry—Special susceptibility less of a factor in many diseases—Deaf-mutism—Gout—Nervous and mental diseases—Other disorders which have hereditary aspects—Induced immunity not inherited—Social, ethical and educational significance of non-inheritance of somatic modifications—No cause for discouragement—Improved environment will help conserve superior strains when they do appear. | ||

| VI | Prenatal Influences | 159 |

| All that a child possesses at birth not necessarily hereditary—The myth of maternal impressions—Injurious prenatal influences—Lead poisoning—The expectant mother should have rest—Too short intervals between children—Expectant mothers neglected—Alcoholism—Unreliability of most data—Alcohol a germinal and fetal poison—Various views of specialists on the effects of alcoholism on progeny—The affinity of alcohol for germinal tissue—Innate degeneracy versus the effects of alcohol—Experimental alcoholism in lower animals—Further remarks on the situation in man—Much inebriety in man due to defective nervous constitution—Factors to be reckoned with in the study of alcoholism—Venereal diseases—The seriousness of the situation—Infantile blindness—Syphilis—Some of the effects—A blood test—Many syphilitics married—Why permit existing conditions to continue?—Ante-nuptial medical inspection—The perils of venereal disease must be prevented at any cost—Bad environment can wreck good germ-plasm. | ||

| VII | Responsibility for Conduct | 195 |

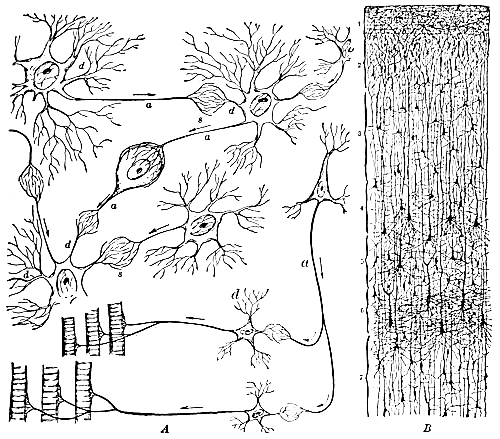

| All mental process accompanied by neural process—Gradations in nervous response from lower organisms to man—Behavior of many animals often an automatic adjustment to simple external agents—Tropisms—Certain apparently complex volitions probably only tropisms—Complicating factors—Many tropic responses apparently purposeful—Tropisms grade into reflex actions and instincts—Adjustability of instincts opens the way for intelligent behavior—Modification of habits possible in lower animals—Some lower vertebrates profit by experience—Rational behavior—Conceptual thought probably an outgrowth of simpler psychic states—The capacity for alternative action in higher animals—The elemental units of the nervous system are the same in lower and higher animals—Neuron theory—Establishment of pathways through the nervous system—Characteristic arrangements of nerve cells subject to inheritance—Different parts of the cortex yield different reactions—Skill acquired in one branch of learning probably not transferred to another branch—Preponderance of cortex in highest animals—Special fiber tracts in the spinal cord of man and higher apes—Great complexity in associations and more neurons in the brain of man—The nervous system in the main already staged at the time of birth—Many pathways of conduction not yet established—The extent of the modifiable zone unknown—Various possibilities of reaction in the child—Probable origin of altruistic human conduct—Training in motive necessary—Actual practise in carrying out projects important—Interest and difficulty both essential—The realization of certain possibilities of the germ rather than others is subject to control—We must afford the opportunity and provide the proper stimuli for the development of good traits—Moral responsibility. | ||

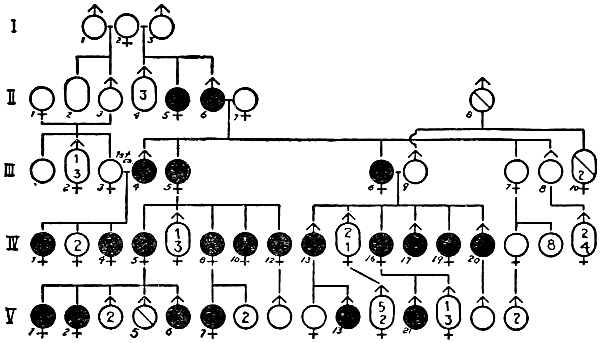

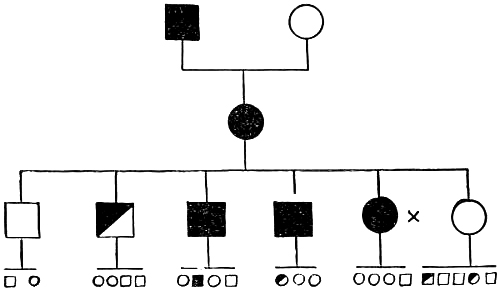

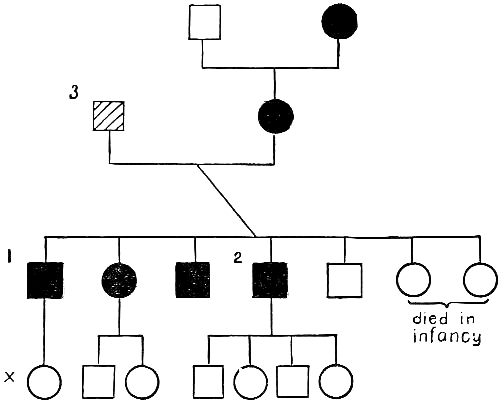

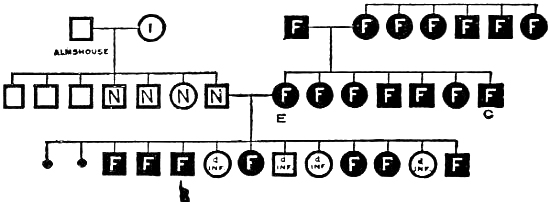

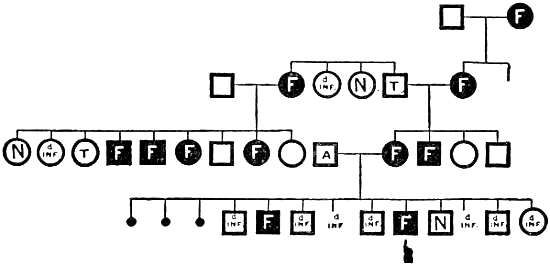

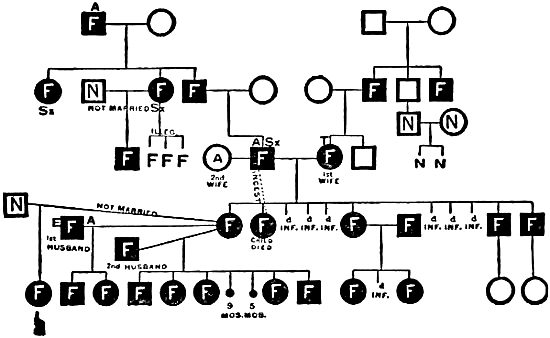

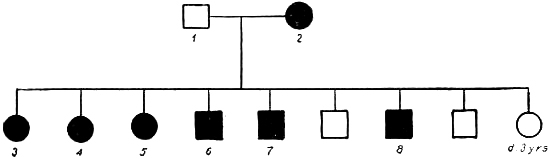

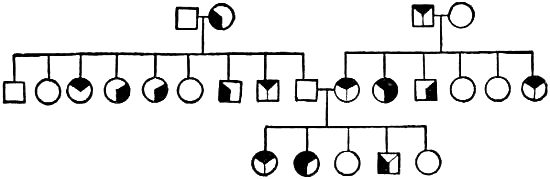

| VIII | Mental and Nervous Defects | 228 |

| Prevalence of insanity—Imperfect adjustments of the brain mechanism inheritable—Many mental defectives married—Disproportionate increase in number of mental defectives—Protests voiced by alienists—Examples of hereditary feeble-mindedness—Difficult to secure accurate data—Feeble-mindedness and insanity not the same—Many types of insanity—Not all insanities of the same eugenical significance—Difficulties of getting genealogies of specific forms of insanity—Certain forms of insanity seem to behave as Mendelian recessives—Grades of feeble-mindedness—About two-thirds of feeble-mindedness inherited—Some results of non-restraint of the feeble-minded—Not all cases of mental deficiency inherited—Epileptics—Feeble-mindedness probably a recessive—Many apparently normal people are carriers of neuropathic defects—Tests for mental deficiency—The backward child in school—The exceptionally able child—Cost of caring for our mentally disordered—Importance of rigid segregation of the feeble-minded—Importance of early diagnosis of insanity—Opinion of competent psychiatrists essential—Some insanities not hereditary—Importance of heredity in insanity not appreciated. | ||

| IX | Crime and Delinquency | 263 |

| Heredity and environment in this field—Feeble-mindedness often a factor—Many delinquent girls mentally deficient—Institutional figures misleading—Many prisoners mentally subnormal—Inhibitions necessary to social welfare—The high-grade moron a difficult problem—Degenerate strains—Intensification of defects by inbreeding—Vicious surroundings not a sufficient explanation in degenerate stocks—Not all delinquents defectives—No special inheritable crime-factor—What is a born criminal?—Epileptic criminal especially dangerous—The mental disorders most frequently associated with crime—Bearing of immigration on crime and delinquency—Sexual vice—School instruction in sex-hygiene—Mere knowledge not the crux of the sex problem—Early training in self-restraint an important preventive of crime and delinquency—Multiplication of delinquent defectives must be prevented. | ||

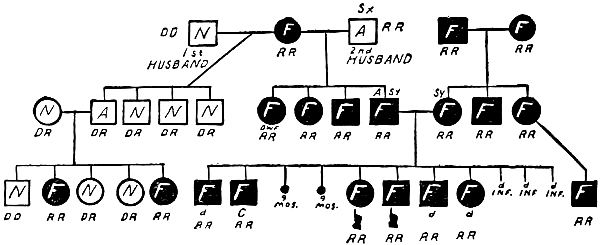

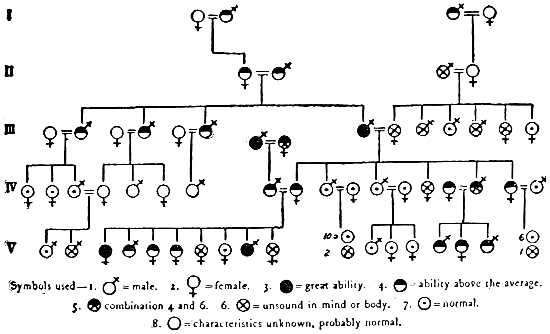

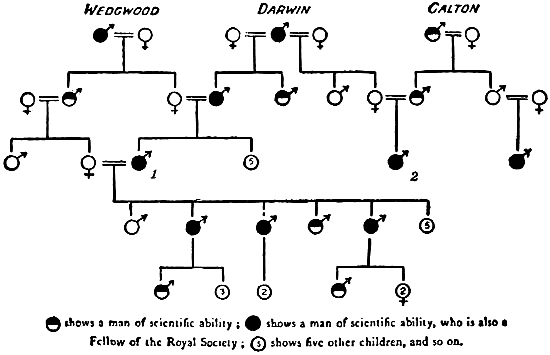

| X | Race Betterment Through Heredity | 289 |

| Questionable charity—Past protests—An increasing flood of defectives—Natural elimination of defectives done away with—Why not prevent our social maladies?—Eugenics defined—Improved environment alone will not cure racial degeneracy—Heredity and environment—Inter-racial marriage—Human conservation—Kindness in the long run—The problem has two phases—Constructive eugenics must be based on education—Inferior increasing more rapidly than superior stocks—An unselected population may contain much valuable material—The lack of criteria for judging fitness—The college graduate—Native ability, independence and energy eugenically desirable—Four children to each marriage required to maintain a stock—Factors contributing to low birth-rate in desirable strains—The educated public must be made to realize the situation—Utilization of family pride as a basis for constructive eugenics—The tendency for like to marry like—Public opinion as an incentive to action—Choosing a marriage mate means choosing a parent—The best eugenic marriage also a love match—The elimination of the grossly unfit urgent—Suggested remedies—Inefficacy of laws which forbid marriage of mental defectives—Systems of mating impracticable in the main—Corrective mating presupposes knowledge of eugenics—Segregation has many advocates—Sterilization as a eugenic measure—To what conditions applicable—In insanity—In feeble-mindedness—In cases of epilepsy—Sterilization laws—Social dangers in vasectomy—Our present knowledge insufficient—Sterilization laws on trial—An educated public sentiment the most valuable eugenic agent—The question of personal liberty—Education of women in eugenics needed—Much yet to be done—A working program—Which shall it be? | ||

| Glossary | 343 | |

| References for Further Reading and Study | 355 | |

| Index | 361 |

BEING WELL-BORN

HEREDITY

It is a commonplace fact that offspring tend to resemble their parents. So commonplace, indeed, that few stop to wonder at it. No one misunderstands us when we say that such and such a young man is “a chip off the old block,” for that is simply an emphatic way of stating that he resembles one or the other of his parents. The same is true of such familiar expressions as “what’s bred in the bone,” “blood will tell,” and kindred catch phrases. All are but recognitions of the same common fact that offspring exhibit various characteristics similar to those of their progenitors.

Blood Heritage.—To this phenomenon of resemblance in successive generations based on ancestry the term heredity is applied. In man, for instance, there is a marked tendency toward the reappearance in offspring of structures, habits, features, and even personal mannerisms, minute physical defects, and intimate mental peculiarities like those possessed by their parents or more remote forebears. These personal characteristics based on descent from a common source are what we may call the blood heritage of the child to discriminate it from a wholly[Pg 2] different kind of inheritance, namely, the passing on from one generation to the next of such material things as personal property or real estate.

Kind Determined by Origin.—It is inheritance in the sense of community of origin that determines whether a given living creature shall be man, beast, bird, fish, or what not. A given individual is human because his ancestors were human. In addition to this stock supply of human qualities he has certain well-marked features which we recognize as characteristics of race. That is, if he is of Anglo-Saxon or Italian or Mongolian parentage, naturally his various qualities will be Anglo-Saxon, Italian, or Mongolian. Still further, he has many distinctive features of mind and body that we recognize as family traits and lastly, his personal characteristics such as designate him to us as Tom, Harry, or James must be added. The latter would include such minutiæ as size and shape of ears, nose or hands; complexion; perhaps even certain defects; voice; color of eyes; and a thousand other particulars. Although we designate these manifold items as individual, they are in reality largely more or less duplicates of similar features that occur in one or the other of his progenitors, features which he would not have in their existing form but for the hereditary relation between him and them.

“O Damsel Dorothy! Dorothy Q.!

Strange is the gift that I owe to you;

·····

What if a hundred years ago

Those close-shut lips had answered ‘No,’

·····

[Pg 3]Should I be I, or would it be

One-tenth another, to nine-tenths me?”

“Soft is the breath of a maiden’s yes;

Not the light gossamer stirs with less;

But never a cable that holds so fast

Through all the battles of wave and blast,

And never an echo of speech or song

That lives in the babbling air so long!

There were tones in the voice that whispered then

You may hear to-day in a hundred men.”

When life steps into the world of matter there comes with it a sort of physical immortality, so to speak; not of the individual, it is true, but of the race. But the important thing to note is that the race is made up, not of a succession of wholly unrelated forms, but a continuation of the same kind of living organisms, and this sameness is due to the actual physical descent of each new individual from a predecessor. In other words, any living organism is the kind of organism it is in virtue of its hereditary relation to its ancestors.

It is part of the biologist’s task to seek a material basis, a continuity of actual substance, for this continuity of life and form between an organism and its offspring. Moreover, inasmuch as the offspring is never precisely similar to its progenitors he must determine also what qualities are susceptible of transmission and in what measure.

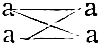

Ancestry a Network.—From the fact that each child has all of the ancestors of its mother as well as of its father, arises the great complications which are met with in determining the lineage of an individual.[Pg 4] A person has two parents, four grandparents, eight great grandparents, and thus following out pedigree it is plain to be seen that through this process of doubling in each generation, in the course of a few centuries one’s ancestry is apparently enormous. By actual computation, according to Professor D. S. Jordan, if we count thirty generations back to the Norman invasion of England in 1066, at this ratio of duplication, the child of to-day would have had at that time an ancestry of 8,598,094,592 persons. But we know that the total number of inhabitants in England during the time of William the Conqueror was but a small fraction of this enormous aggregate. This means that we shall have to modify our inference that a child has twice as many ancestors as its parents; a condition which at first sight seems evident, but which is not literally true. The fact is that the parents of the child, in all probability, have many ancestors in common—a state of affairs which is brought about through the intermarriage of relatives, and this is especially frequent among remoter descendants of common progenitors. Time after time in genealogy strains of blood have crossed and recrossed until it is not improbable that a man of to-day who is of English origin has the blood in his veins from every inhabitant of England who lived during the time of William the Conqueror and left fruitful descendants. Instead of conceiving of ancestry as an ever branching and widening tree-like system as it recedes into the past, it is more accurate, therefore, to regard it in the light of an elaborate meshwork. The “family tree” in reality becomes the family net.

[Pg 5]Ancestry in Royalty.—The pedigrees of royal families have proved to be of much importance in the study of human inheritance, not that royal traits are any more heritable than any other, but simply because the records have been carefully kept so that they are the most comprehensive and easily followed pedigrees available. The netlike weave of ancestry is particularly well exemplified in some of these families because of much close intermarriage. Their heritage typifies on an intensified scale the heritage of the mass of mankind. For example, if we go six generations back in the ancestry of Frederick the Great instead of the expected sixty-four individual ancestors we find only forty; or in a still more closely woven stock, in the Spanish royal line of Don Carlos we find in six generations instead of sixty-four individual ancestors, only twenty-eight. While the present German emperor might have had four thousand ninety-six ancestors in the twelfth generation back, it is estimated that owing to intermarriage he probably had only five hundred thirty-three.

Offspring Derived from One Parent Only.—So far in our reckoning of heredity we have counted elements from both father and mother, and the complications which arise from such a double ancestry are manifestly very perplexing ones. If we could do away with the elements of sex and find offspring that are derived from one parent only, it would seemingly simplify our problem very much for we should thus have a direct line of descent, free from intermingling. This, in fact, occurs to a greater or less extent among lower animals in a number of instances. There may[Pg 6] be only female forms for a number of generations and the eggs which they produce develop directly into new individuals. Moreover, many of the simpler organisms have the power of dividing their bodies into two and thus giving rise to two new forms, each of which resembles the parent. This shows plainly that we may have inheritance without the appearance of any male ancestor at all, hence sex is not always a necessary factor in reproduction or heredity. The development of eggs asexually, that is, without uniting first with a male cognate, is termed parthenogenesis. The ordinary plant louse or aphid which is frequently found upon geraniums is a familiar example of an animal which reproduces largely in this way. During the summer only the females exist and they are so astonishingly fertile that one such aphid and her progeny, supposing none dies, will produce one hundred million in the course of five generations. In the last broods of the fall, males and females appear and fertile eggs are produced which lie dormant through the winter to start the cycle of the next year. Again, the eggs of some kinds of animals which normally have to unite with a male germ before they develop, can be made to develop by merely treating them with chemical solutions. The difference between an offspring derived in such a manner, and one which has developed from an egg fertilized by the male is that it is made up of characteristics from only one source, the maternal.

Dual Ancestry an Aid in Studying Heredity.—Although we have the factors of heredity in a more simplified form in the case of asexual transmission,[Pg 7] as a matter of fact most of our insight into the problems of heredity has been attained from a study of sexually reproducing forms, because the very existence of two sets of more or less parallel features offers a kind of checking up system by which we can follow a given characteristic.

Reversion.—Occasionally, however, plants and animals do not develop the complete individuality we might expect, but stop short at or re-attain some ancestral stage along the line of descent, and thus come to resemble some progenitor perhaps many generations back of their own time. Thus it is well known that as regards one or more characteristics a child may resemble a grandparent or often some remote ancestor much more closely than it does its immediate parent. The reappearance of such ancestral traits the student of heredity designates as Reversion or Atavism.

Reversion may occur apparently in any class of plants or animals. It is especially pronounced among domesticated forms, which through man’s selection have been produced under more or less artificial conditions. For example, among fancy breeds of pigeons, there may be an occasional return to the old slaty blue color of the ancestral rock-pigeon, with two dark cross-bars on the wings, from which all modern breeds have been derived. This is almost sure to happen if the fancy varieties are inter-crossed for two or three generations. Another example of reversion frequently cited is the occasional reappearance in domestic poultry of the reddish or brownish color pattern of the ancestral jungle-fowl to which, among[Pg 8] modern forms, the Indian game seems most nearly related in color. Still another example is the cross-bars or stripes occasionally to be seen on the forelegs of colts, particularly mules, reminiscent of the extinct wild progenitors which were supposedly striped.

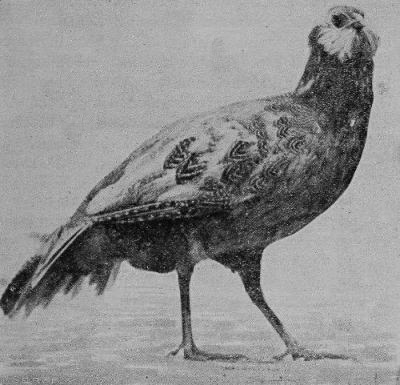

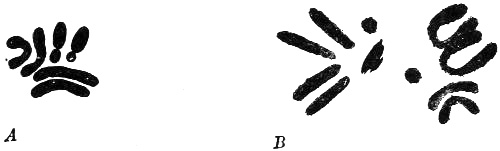

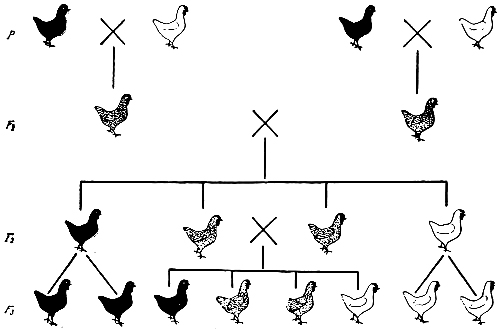

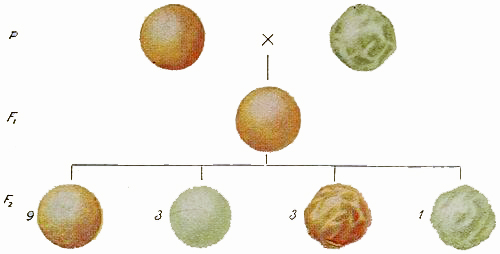

Fig. 1, p. 9, is a picture of a hybrid between the common fowl and the guinea-fowl. The chevron-like markings on certain feathers show a reversion to a type of color pattern that is prevalent among both the primitive pheasants (the domestic chicken is a pheasant) and the primitive guinea-fowls. Although the common spotted guinea-fowl may be crossed with a black chicken which shows no trace of barring, nevertheless the hybrid offspring are likely to bear a chevron-like pattern such as that shown in the picture.

There has been much quibbling over the relative meanings of reversion and atavism. The general idea, whichever term we use, is that there is a “throwing back” in a noticeable degree through inheritance to some ancestral condition beyond the immediate parents. A few recent authors have taken the term atavism in a restricted sense and use it to signify specifically those not uncommon cases in which a particular character of an offspring resembles the corresponding character of a grandparent instead of a parent. Such, for example, as the blue eye-color of a child with brown-eyed parents, each of whom in turn has had a blue-eyed parent. The tendency of other authors is to abandon the term entirely because of the diversity of meaning that has been attached to it in the past.

Fig. 1

Hybrid between the guinea-fowl and the common fowl,showing in many feathers reversion to a primitive chevron-like barring.

Certain classes of so-called reversions, such as the case of the eye-color just cited, are readily explicable on Mendelian principles as we shall see in a later chapter, but probably not all kinds of phenomena described as reversion can be so explained. For example, some seem to be cases of suppressed development. The word reversion, indeed, must be looked on[Pg 10] as a convenient descriptive term rather than as the name of a single specific condition.

Telegony.—There is yet a wide-spread belief in the supposed influence of an earlier sire on offspring born by the same mother to a later and different sire. This alleged phenomenon is termed telegony. For example, many dog-breeders assert that if a thoroughbred bitch has ever had pups by a mongrel father, her later offspring, although sired by a thoroughbred, will show taints of the former mongrel mating. In such cases the female is believed to be ruined for breeding purposes. Other supposed instances of such influences have been cited among horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, cats, birds, pets of various kinds and even men. The historic case most frequently quoted is that of Lord Morton’s mare which bore a hybrid colt when bred to a quagga, a striped zebra-like animal now extinct. In later years the same mare bore two colts, sired by a black Arabian horse. Both colts showed stripes on the neck and other parts of the body, particularly on the legs. It was inferred that this striping was a sort of after effect of the earlier breeding with the quagga. In recent times, however, Professor Ewart has repeated the experiment a number of times with different mares using a Burchell zebra as the test sire. Although his experiments have been devised so as to conduce in every way possible to telegony his results have been negative. Moreover, it has been pointed out that the stripes on the legs of the two foals alleged to show telegony could not have been derived from the quagga sire for, unlike zebras, quaggas did not have their legs striped. Furthermore[Pg 11] it is known that the occurrence of dark brown stripes on the neck, withers and legs of ordinary colts is not uncommon, some cases of which have exhibited more zebra-like markings than those of the colts from Lord Morton’s mare. It seems much more probable, therefore, that the alleged instances are merely cases of ordinary reversion to the striped ancestral color pattern which probably characterized the wild progenitors of the domesticated horse.

Various experiments on guinea-pigs, horses, mice and other forms, especially devised to test out this alleged after-influence of an earlier sire, have all proved negative and the general belief of the biologist to-day is that telegony is a myth.

Prenatal Influences Apart from Heredity.—In discussing the problems of heredity it is necessary to consider also the possibilities of external influences apart from lineage which may affect offspring through either parent. Although modifications derived directly by the parent, and prenatal influences in general, are of extremely doubtful value as of permanent inheritable significance, nevertheless they must be reckoned with in any inventory of a child’s endowment at birth. Impaired vitality on the part of the mother, bad nutrition and physical vicissitudes of various kinds all enter as factors in the birthright of the child, who, moreover, may bear in its veins slumbering poisons from some progenitor who has handed on blood taints not properly attributable to heredity. Of such importance is this kind of influence to the welfare of the immediate child that it will be necessary to discuss it in considerable detail in a later chapter.

[Pg 12]Parent Body and Germ Not Identical.—Inasmuch as each new individual appears to arise from material derived from its parent, taking the evidence at its face value one might suppose that any peculiarity of organization called forth in the living substance of the parent would naturally be repeated in the offspring, but a closer study of the developing organism from its first inception to maturity shows this to be probably a wrong conclusion. The parent-body and the reproductive substance contained in that body are by no means identical. It becomes an important question to decide, in fact, how much effect, if any, either permanent or temporary, the parent-body really has on the germ.

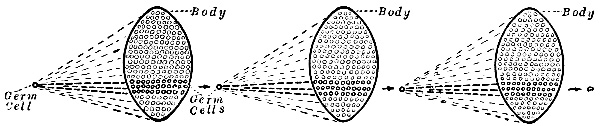

A given fertile germ (Fig. 2, p. 13) gives rise by a succession of divisions to a body which we call the individual, but such a germ also gives rise to a series of new germ-cells which reside in that individual, and it is these germ-cells, not something derived from the body, that pass on the determiners of distinguishing features or qualities from generation to generation. It is only by grasping the significance of this fact that we can understand how in certain cases a totally different set of characters may appear in an offspring than those manifested in either parent.

An Hereditary Character Defined.—By a character, in discussions in heredity, is meant simply a trait, feature or other characteristic of an organism. Where we can pick out a single definable characteristic which acts as a unit in heredity, for greater accuracy we term it a unit-character. Many traits are known to be inherited on a unit basis or are capable of being[Pg 13] analyzed into factors which are so inherited. These unit-characters are in large measure inherited independently of one another apparently, although cases of characters inherited as a unit along with other characters are known.

Hereditary Mingling a Mosaic Rather Than a Blend.—The independence of unit-characters in inheritance leads us to the important conclusion that the mingling of two lines of ancestry into a new individual is in no sense bringing them into the “melting pot,” as it has been picturesquely expressed, but it is rather to be regarded as the mingling of two mosaics, each particle of which retains its own individuality, and which, even if overshadowed in a given generation, may nevertheless manifest its qualities undimmed in later generations when conditions favorable to its expression transpire.

Fig. 2

Diagram illustrating germinal continuity. Through a series of divisions a germ-cell gives rise to a body or a soma and to new germ-cells. The latter, not the body, give rise in turn to the next generation.

Determiners of Characters, Not Characters Themselves, Transmitted.—The fact should be thoroughly understood that the actual thing which is transmitted by means of the germ in inheritance is not the character itself, but something which will determine the[Pg 14] character in the offspring. It is important to remember this, for often these determiners, as they are called, may lie unexpressed for one or more generations and may become manifest only in later descendants. The truth of the matter is, the child does not inherit its characters from corresponding characters in the parent-body, but parent and child are alike because they are both products of the same line of germ-plasm, both are chips from the same old block.

METHODS OF STUDYING HEREDITY

Before entering into details it will be well to get some idea of the methods which are commonly employed in arriving at conclusions in the field of heredity. Some of these are extremely complex and all that we can do in an elementary presentation is to get a glimpse of the procedures.

Our Knowledge of Heredity Derived Along Three Lines.—Our modern conceptions of heredity have been derived mainly from three distinct lines of investigation: First, from the study of embryology, in which the biologist concerns himself with the genesis of the various parts of the individual, and the mechanism of the germs which convey the actual materials from which these parts spring; second, through experimental breeding of plants and animals to compare particular traits or features in successive generations; and third, through the statistical treatment of observations or measurements of a large number of parents and their offspring with reference to a given characteristic in order to determine the average [Pg 15]extent of resemblance between parents and children in that particular respect.

The Method of Experimental Breeding.—A tremendous impetus was given to the method of experimental breeding when it was realized that we can itemize many of the parts or traits of an organism into entities which are inherited independently one of another. Such traits, or as we have already termed them, unit-characters, may be not only independently heritable but independently variable as well. The experimental method seeks to isolate and trace through successive generations the separate factors which determine the individual unit-characters of the organism. In this attempt cross-breeding is resorted to. Forms which differ in one or more respects are mated and the progeny studied. Next these offspring are mated with others of their own kind or mated back with the respective parent types. In this way the behavior of a particular character may often be followed and the germinal constitutions of the individuals concerned can be formulated with reference to it. Inasmuch as we shall give much consideration to this method in the chapter on Mendelism we need not consider it further here.

The Statistical Method.—The statistical method seeks to obtain large bodies of facts and to deal with evidence as it appears through mathematical analysis of these facts. The attempt of its followers is to treat quantitatively all biological processes with which it is concerned. Historically Sir Francis Galton was the first to make any considerable application of statistical methods to the problems of heredity and variation. In[Pg 16] his attempts to determine the extent of resemblance between relatives of different degree as regards bodily, mental and temperamental traits, he devised new methods of statistical analysis which constitute the basis of modern statistical biology, or biometry as it is termed by its votaries. Professor Karl Pearson in particular has extended and perfected the mathematical methods of this field and stands to-day as perhaps its most representative exponent. The system is in the main based on the calculus of probability. The methods often are highly specialized, requiring the use of higher mathematics, and are therefore only at the command of specially trained workers.

Just as insurance companies can tell us the probable length of human life in a given social group, since although uncertain in any particular case, it is reducible in mass to a predictable constant, so the biometrician with even greater precision because of his improved methods can often, when a large number of cases are concerned, give us the intensity of ancestral influence with reference to particular characters.

For example, it is clear that by measuring a large number of adult human beings one can compute the average height or determine the height which will fit the greatest number. There will be some individuals below and some above it, but the greater the divergence from this standard height the fewer will be the individuals concerned.

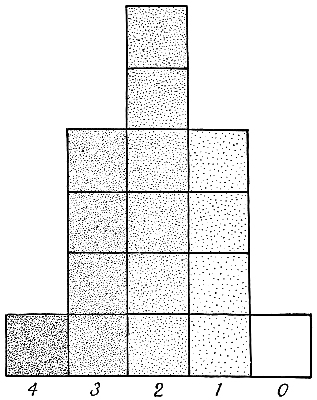

Galton compared the heights of 204 normal English parents and their 928 adult offspring. In order to equalize the measurements of men and women he found he had to multiply each female height by 1.08.[Pg 17] Then, to take both parents into account when comparing height of parents to that of children he added the height of the father to the proportionately augmented height of the mother and divided by two, thus securing the height of what he termed the “mid-parent.” He found that the mid-parental heights of his subjects ranged from 64.5 to 72.5 inches, and that the general mode was about 68.5 inches. It should be mentioned that the mode, in a given population, represents the group containing the largest number of individuals of one kind; it may or may not coincide with the average. The children of all mid-parents having a given height were measured next and tabulated with reference to these mid-parents. The results of Galton’s measurements may be expressed simply as follows:

| MODE | |||||||||

| Height of mid-parent in inches | 64.5 | 65.5 | 66.5 | 67.5 | 68.5 | 69.5 | 70.5 | 71.5 | 72.5 |

| Average height of offspring | 65.8 | 66.7 | 67.2 | 67.6 | 68.3 | 68.9 | 69.5 | 69.9 | 72.2 |

The Law of Regression.—It is plain from this table that the offspring of short mid-parents tend to be under average or modal height though not so far below as their parents. Likewise children of tall parents tend to be tall but less tall than their parents. This fact illustrates what is known as Galton’s law of regression; namely, that if parents in a given population diverge a certain amount from the mode of the population as a whole, their children, while tending to[Pg 18] resemble them, will diverge less from this mode. It is clear that the extent of regression is an inverse measure of the intensity of inheritance from the immediate parents; if the deviation of the offspring from the general mode were nearly as great as that of their parents then the intensity of the inheritance must be high; if but slight—that is, if the offspring regressed nearly to the mode—then the intensity of the inheritance must be ranked as low. In the example in question it must be ranked as relatively high. Computations show that as regards stature the fraction two-thirds represents approximately the amount of resemblance between the two generations where both parents are considered.

Correlations Between Parents and Offspring.—In modern researches the conception of mid-parent and mid-grandparent as utilized by Galton has been largely abandoned. It has been found more convenient as well as more accurate to keep the measurements of the two parents separate and to deal with correlations between fathers and sons, fathers and daughters, mothers and sons, mothers and daughters, brother and brother, etc. Professor Pearson and his pupils have found for a number of characters that the correlation between either parent and children, whether sons or daughters, is relatively close. The correlation between brother and brother, sister and sister, and brother and sister, usually ranges a little higher than the corresponding relation between parents and children.

The Biometrical Method, Statistical, Not Physiological.—While biometry may in certain cases go far toward showing us the average intensity of the[Pg 19] inheritance of certain characters it can not replace the method of the experimental breeder which deals with particular characters in individual pedigrees. It must be borne in mind that the biometrical method is a statistical and not a physiological one and that it is applicable only when large numbers of individuals are considered in mass. It is most valuable in cases where we are unable sharply to define single characters, due probably to the concurrent action of a number of independent causes, or where experiment is impossible so that we have to depend solely on numerical data gained by observation.

Mental Qualities Inheritable.—Galton showed by this method long ago, and Pearson and his school have extended and more clearly established the work, that exceptional mental qualities tend to be inherited. While on the average the children of exceptional parents tend to be less exceptional than their parents, still they are far more likely to be exceptional than are the children of average parents. By this method Professor Pearson has shown that such mental and temperamental attributes as ability, vivacity, conscientiousness, temper, popularity, handwriting, etc., are as essentially determined as are physical features through the hereditary endowment.

THE BEARERS OF THE HERITAGE

Before we can make any detailed analysis of the inheritance of characters we should have some general idea of the physical structure of animals and particularly some familiarity with the development of an individual from the egg, as well as some knowledge of the nature of the germ-cells.

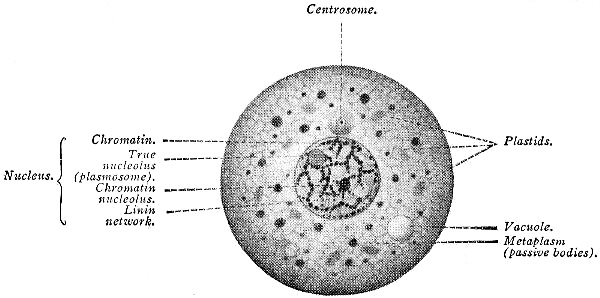

The Cell the Unit of Structure.—If we examine one of the higher animals, as, for example, the horse, the dog, or man, we find that it is made up of a large number of constituents, such as bones, muscles, nervous elements, blood and other tissues. Each kind of tissue is composed of a number of living units, ordinarily microscopic in size, which are known as cells. A careful examination of various cells reveals that although they may differ greatly in size, shape and minor details, they all alike possess certain well-marked characteristics. Each when reduced to its fundamental form is seen to consist of a small mass of living matter termed protoplasm in which may usually be distinguished two regions—the cell-body or cytoplasm, and the nucleus (Fig. 3, p. 21). Any cell, whether it be of the brain, of the liver, or from any organ of an animal or plant, has this same fundamental structure. In addition, a limiting membrane or wall of some kind is generally present, although it is not a necessary constituent of all cells.

Fig. 3

Diagram of a cell showing various parts.

Unicellular Organisms.—While such a structure as a tree or a horse is composed of countless millions of cells, on the other hand numerous organisms, both plant and animal, exist which consist of only one cell. Yet this cell is just as characteristically a cell as are[Pg 22] the components of a complex animal or plant. It has the necessary parts, the cell body and the nucleus. Moreover it exhibits all of the fundamental activities of life, though in a simplified form, that a complex higher organism does.

Importance of Cell-Theory.—This discovery that every living thing is a single cell or an aggregation of cooperating cells and cell-products is one of our most important biological generalizations because it has brought such a wide range of phenomena under a common point of view. In the first place, the structure of both plants and animals is reducible to a common fundamental unit of organization. Moreover, both physiological and pathological phenomena are more readily understood since we recognize that the functions of the body in health or disease are in large measure the result of the activities of the individual cells of the functioning part. Then again, the problems of embryological development have become much more sharply defined since it could be shown that the egg is a single cell and that it is through a series of divisions of this cell and subsequent changes in the new cells thus formed that the new organism is built up. And lastly, the problem of hereditary transmission has been rendered more definite and approachable by the discovery that the male germ is likewise a single cell, that fertilization of the egg is therefore the union of two cells, and that in consequence the mechanism of inheritance must be stowed away somehow in these two cells.

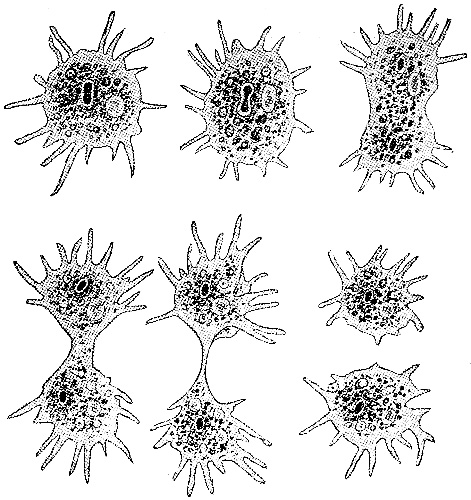

Heredity in Unicellular Forms.—In unicellular animals one can readily see how it is possible for an[Pg 23] individual always to give rise to its own kind. One of the simplest of the single-celled animals is the Ameba (Fig. 4, p. 24).

The ameba eats and grows as do other animals. Sooner or later it reaches a size beyond which it can not increase advantageously, yet it is continuously taking in new food material which stimulates it to further growth. Here then is a problem. The ameba solves this difficulty by dividing to form two amebæ. Such a division is illustrated in Fig. 4, p.24. First the nucleus divides, then the cell-body. When the two new amebæ separate completely each renews the occupation of eating and growing. But what has become of the parent? Here, where once existed a large adult ameba are two young amebæ. The parent individual as such has disappeared, yet there has been no death, for we have simply two bits of living jelly in place of one. They will in turn repeat the same process, so will their offspring, and thus, barring accident, this growth and reproduction, or overgrowth as we may regard it, may go on forever, as far as we know. Here the problem of heredity, or the resemblance of offspring to parent, is not a very complicated one. The substance of the cell-body and cell-nucleus divides into two similar halves, so that each descendant has the substance of the parent in its own body, only it has but half as much. It differs from the parent, not in quality or kind, but in size.

Fig. 4

Six successive stages in the division of Ameba polypodia (after Schulze). The nucleus is seen as a dark spot in the interior.

Reproduction and Heredity in Colonial Protozoa.—There are enormous numbers of these single-celled animals existing in all parts of the world. Some are simple like the ameba, others are very complex in structure. Many, after division, move apart and pursue wholly independent courses of existence. On the other hand we find a modification appearing in some which is of the greatest importance. After division instead of moving apart the two cells may remain side[Pg 25] by side and divide further to form two more, these in turn may divide and thus the process goes on until there is formed what is known as a colony. Each cell of such a colony resembles the original ancestral cell because each is a part of the actual substance of that cell. As in the ameba, the first two cells are the ancestral cell done up in two separate packets, and thus finally the full quota of cells must be so many separate packets of the same kind of material. Inasmuch as each is but a repetition of its original ancestor, it can, and at times does, produce a colony of the same kind as that ancestor produced.

Conjugation.—At longer or shorter intervals, however, we find that two individuals, on the disruption of the old colony, instead of continuing the routine of establishing new colonies through a series of cell divisions, very radically alter their behavior. They unite and fuse into a single larger individual. This process is called conjugation. We find it occurring even in some species of ameba. The conjugating cells in some colonies are alike in size and appearance, in others different.

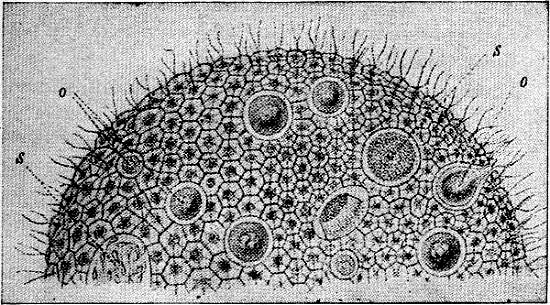

Specialization of Sex-Cells.—A beautiful sphere-shaped colony known as Volvox is to be found occasionally in roadside pools. Depending on the species of Volvox to which it belongs, the colony may be made up of from a few hundred to several thousand individuals arranged in a single layer about the fluid-filled center of the sphere and bound together by a clear jelly-like inter-cellular substance. Each individual cell also connects with its neighbors by means of thin threads of living matter. One of the largest[Pg 26] species is Volvox globator, one edge of which is represented in Fig. 5, p. 27. Mutual pressure of the cells gives them a polygonal shape when viewed from the surface. Each cell, with a few exceptions to be noted immediately, bears two long flagella, whip-like structures which project out into the water. The lashing of these flagella gives the ball a rotary motion and thus it moves about. When the colony has reached its adult condition and is ready to reproduce itself, certain cells without flagella and somewhat larger than the ordinary cells become more rounded in outline and increase considerably in size through the acquisition of food materials. They are then known as egg cells or ova. Each ovum finally enters on a series of cell-divisions forming a mass of smaller and smaller cells which gradually assumes the form of a hollow sphere like the parent colony. The young colonies thus formed drop into the interior of the parent colony to escape later to the outside as independent swimming organisms when the old colony dies and disintegrates.

The Fertilized Ovum Termed a Zygote.—After a number of generations of such asexual reproduction, sexual reproduction occurs. The ova arise as usual. Certain members of the colony, on the other hand, go to the other extreme and divide up into bundles of from sixty-four to one hundred twenty-eight minute slender cells, each provided with flagella for locomotion. When mature these small flagellate cells, now known as spermatozoa, escape into the interior of the parent colony and swim about actively. Ultimately each ovum is penetrated by a spermatozoon, the two cells fuse completely and thus form the single [Pg 27]fertilized ovum or zygote. The body-cells of the mother colony finally disintegrate. After a period of rest each zygote, through a series of cell-divisions, develops into an adult Volvox. In some species of Volvox a still further advance is seen, in that instead of both kinds of gametes being produced in the same colony, the ova may be produced by one colony and the spermatozoa by another. Here, then, we have the foreshadowings of two sexes as separate individuals, a phenomenon of universal occurrence among the highest forms of animal life.

Fig. 5

Volvox globator (from Hegner after Oltmanns). Half of a sexually reproducing colony: o, eggs; s, spermatozoa.

Advancement Seen in the Volvox Colony.—In the Volvox colony there is a distinct advance over the conditions met with in various lower protozoan colonies in that only certain individuals of the colony[Pg 28] take part in the process of reproduction and these individuals are of two distinct types; one is a larger, food-laden cell or egg and the other a small, active, fertilizing cell. The motile forms are produced in much greater numbers than the eggs, plainly because they have to seek the egg and many will doubtless perish before this can be accomplished. This disparity in number is only a means of insuring fertilization of the egg. The remaining cells of the body carry on the ordinary activities of the colony such as locomotion and nutrition and have ceased to take any part in the production of new colonies.

Natural Death Appears With the Establishment of a Body Distinct from the Germ.—Volvox is an organism of unusual interest because in it we see a prophecy of what is to come. Although still regarded as a colony of single-celled individuals, it represents in reality a transition between the whole group of unicellular animals termed protozoa and the many celled animals characterized by the possession of distinct tissues, known as Metazoa. Moreover, it shows an interesting stage in the establishment of a body or soma distinct from special reproductive cells which have taken on the function of reproducing the colony. In such colonial forms natural death is found appearing for the first time, the reproductive cells alone continuing to perpetuate the species. Then again Volvox represents an important step in the establishment of sex in the animal kingdom for in its sexual reproduction the conjugating cells known as gametes are no longer alike in appearance but have become differentiated into definite ova and spermatozoa.

[Pg 29]In Volvox as in the other organisms which we have studied we find that all of the cells including the germ-cells are produced by the repeated division of a parent cell, and consequently each must contain the characteristic living substance of that parent. Many other forms might be cited to illustrate reproduction in single-celled animals, whether free or in colonies, but all such cases would be practically but repetitions or modifications of those we have already examined.

Specialization in Higher Organisms.—If we pass on to the higher animals and plants which are not single cells or colonies of similar cells but organisms made up of many different kinds of cells, we find a pronounced extension of the phenomenon met with in Volvox. Instead of each cell executing independently all of the life relations, certain ones are set apart for the performance of certain functions to the exclusion of other functions which are carried on by other members of the aggregation. Thus the organism as a whole has all the life relations carried on, but, as it were, by specialists.

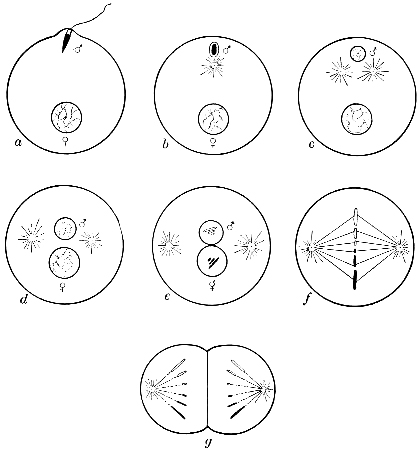

Sexual Phenomena in Higher Forms.—In the reproduction of multicellular organisms, one sees likewise but a continuation of the phenomena exhibited in Volvox. Ordinarily, each new form is produced by the successive divisions of a single germ-cell which in the vast majority of cases has conjugated with another germ-cell. In the development of the egg, as the divisions proceed, groups of cells become modified for their particular work until the entire organism is completed. During development certain cells are set apart for reproduction of the form just as they were in[Pg 30] Volvox. These two kinds of reproductive cells in multicellular organisms are derived ordinarily from two separate individuals known as male and female, though there are some exceptions. The main difference between these cells which will have to unite to form a single fertile germ-cell, is that they have specialized in different directions; one is small and active, the other large, food-laden and passive. But with two such germ-cells coming as they do from two individuals, one the male, the other the female, it is obvious that the actual living substance of which each germ is composed will be distinctive of its own parental line and that when the germs unite these distinctive factors commingle, hence the complications of double ancestry arise.

Structure of the Cell.—Before we can understand certain necessary details of the physical mechanism of inheritance we must inquire a little further into the finer structure of the cell and into the nature of cell division. A typical cell, as it would appear after treatment with various stains which bring out the different parts more distinctly, is shown in Fig. 3, p. 21. Typical, not that any particular kind of living cell resembles it very closely in appearance, but because it shows in a diagrammatic way the essential parts of a cell. In the diagram, there are two well-marked regions; a central nucleus and a peripheral cell-body or cytoplasm. Other structures are pictured but only a few of them need command our attention at present. At one side of the nucleus one observes a small dot or granule surrounded by a denser area of cytoplasm. This body is called the[Pg 31] centrosome. The nucleus in this instance is bounded by a well-marked nuclear membrane and within it are several substances. What appear to be threads of a faintly staining material, the linin, traverse it in every direction and form an apparent network. The parts on which we wish particularly to rivet our attention are the densely stained substances scattered along or embedded in the strands of this network in irregular granules and patches. This substance is called chromatin. It takes its name from the fact that it shows great affinity for certain stains and becomes intensely colored by them. This deeply colored portion of the cell, the chromatin, is by most biologists regarded as of great importance from the standpoint of heredity. One or more larger masses of chromatin or chromatin-like material, known as chromatin nucleoli, are often present, and not infrequently a small spheroidal body, differing in its staining reactions from the chromatin-nucleolus and sometimes called the true nucleolus, exists.

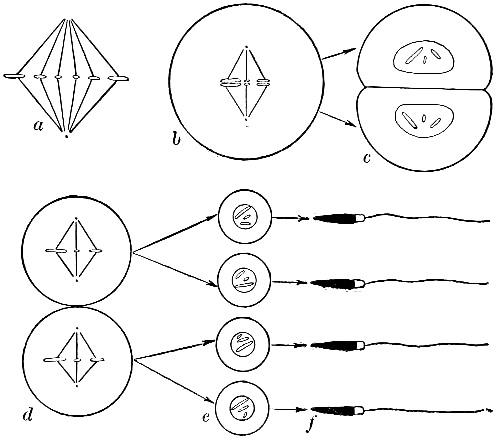

Cell-Division.—In the simplest type of cell-division the nucleus first constricts in the middle, and finally the two halves separate. This separation is followed by a similar constriction and final division of the entire cell-body, which results in the production of two new cells. This form of cell-division is known as simple or direct division. Such a simple division, while found in higher animals, is less frequent and apparently much less significant than another type of division which involves profound changes and rearrangements of the nuclear contents. The latter is termed[Pg 32] mitotic or indirect cell-division. Fig. 6, p. 33, illustrates some of the stages which are passed through in indirect cell-division. The centrosome which lies passively at the side of the nucleus in the typical cell (Fig. 6a, p. 33) awakens to activity, divides and the two components come to lie at the ends of a fibrous spindle. In the meantime, the interior of the nucleus is undergoing a transformation. The granules and patches of chromatin begin to flow together along the nuclear network and become more and more crowded until they take on the appearance of one or more long deeply-stained threads wound back and forth in a loose skein in the nucleus (Fig. 6b, p. 33). If we examine this thread closely, in some forms it may be seen to consist of a series of deeply-stained chromatin granules packed closely together intermingled with the substance of the original nuclear network.

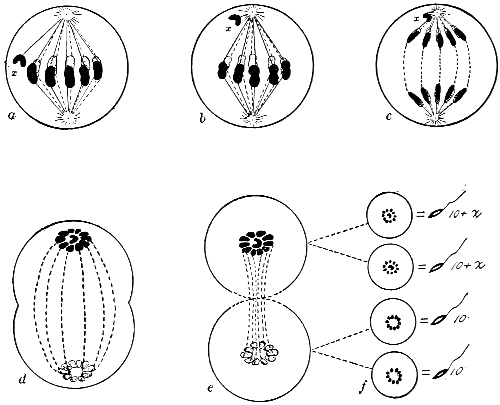

As the preparations for division go on the coil in the nucleus breaks up into a number of segments which are designated as chromosomes (Fig. 6c, p. 33). The nuclear membrane disappears. The chromosomes and the spindle-fibers ultimately become related in such a way that the chromosomes come to lie at the equator of the spindle as shown in Fig 6d, p. 33. Each chromosome splits lengthwise to form two daughter chromosomes which then diverge to pass to the poles of the spindle (Figs. 6e and f, p. 33). Thus each end of the spindle comes ultimately to be occupied by a set of chromosomes. Moreover each set is a duplicate of the other, because the substance of any individual chromosome in one group has its counterpart in the other. In fact this whole complicated system of indirect division [Pg 33]is regarded by most biologists as a mechanism for bringing about the precise halving of the chromosomes.

Fig. 6

Diagram showing representative stages in mitotic or indirect cell-division: a, resting cell with reticular nucleus and single centrosome; b, the two new centrosomes formed by division of the old one are separating and the nucleus is in the spireme stage; c, the nuclear wall has disappeared, the spireme has broken up into six separate chromosomes, and the spindle is forming between the two centrosomes; d, equatorial plate stage in which the chromosomes occupy the equator of the spindle; e, f, each chromosome splits lengthwise and the daughter chromosomes thus formed approach their respective poles; g, reconstruction of the new nuclei and division of the cell body; h, cell-division completed.

[Pg 34]The chromosomes of each group at the poles finally fuse and two new nuclei, each similar to the original one, are constructed (Figs. 6g and h, p. 33). In the meantime a division of the cell-body is in progress which, when completed, results in the formation of two complete new cells.

As all living matter if given suitable food, can convert it into living matter of its own kind, there is no difficulty in conceiving how the new cell or the chromatin material finally attains to the same bulk that was characteristic of the parent cell. In the case of the chromatin, indeed, it seems that there is at times a precocious doubling of the ordinary amount of material before the actual division occurs.

Chromosomes Constant in Number and Appearance.—With some minor exceptions, to be noted later, which increase rather than detract from the significance of the facts, the chromosomes are always the same in number and appearance in all individuals of a given species of plants or animals. That is, every species has a fixed number which regularly recurs in all of its cell-divisions. Thus the ordinary cells of the rat, when preparing to divide, each display sixteen chromosomes, the frog or the mouse, twenty-four, the lily twenty-four, and the maw-worm of the horse only four. The chromosomes of different kinds of animals or plants may differ very much in appearance. In some they are spherical, in others rod-like, filamentous or perhaps of other forms. In some organisms the chromosomes of the same nucleus may differ from one[Pg 35] another in size, shape and proportions, but if such differences appear at one division they appear at others, thus showing that in such cases the differences are constant from one generation to the next.

Significance of the Chromosomes.—The question naturally arises as to what is the significance of the chromosomes. Why is the accurate adjustment which we have noted for their division necessary? The very existence of an elaborate mechanism so admirably adapted to their precise halving, predisposes one toward the belief that the chromosomes have an important function which necessitates the retention of their individuality and their equal division. Many biologists accept this along with other evidence as indicating that in chromatin we have a substance which is not the same throughout, that different regions of the same chromosome have different physiological values.

When the cell prepares for divisions, the granules, as we have seen, arrange themselves serially into a definite number of strands which we have termed chromosomes. Judging from all available evidence, the granules are self-propagating units; that is, they can grow and reproduce themselves. So that what really happens in mitosis in the splitting of the chromosomes is a precise halving of the series of individual granules of which each chromosome is constituted, or in other words each granule has reproduced itself. Thus each of the two daughter cells presumably gets a sample of every kind of chromosomal particle, hence, the two cells are qualitatively alike. To use a homely illustration we may picture the individual chromosomes to ourselves as so many separate trains of freight cars,[Pg 36] each car of which is loaded with different merchandise. Now, if every one of the trains could split along its entire length and the resulting halves each grow into a train similar to the original, so that instead of one there would exist two identical trains, we should have a phenomenon analogous to that of a dividing chromosome.

Cleavage of the Egg.—It is through a series of such divisions as these that the zygote or fertilized egg-cell builds up the tissues and organs of the new organism. The process is technically spoken of as cleavage. Cleavage generally begins very shortly after fertilization. The fertile egg-cell divides into two, the resulting cells divide again and thus the process continues, with an ever-increasing number of cells.

Chief Processes Operative in Building the Body.—Although of much interest, space will not permit of a discussion in detail of the building up of the special organs and tissues of the body. It must suffice merely to mention the four chief processes which are operative. These are, (1) infoldings and outfoldings of the various cell complexes; (2) multiplication of the component cells; (3) special changes (histological differentiation) in groups of cells; and (4) occasionally resorption of certain areas of parts.

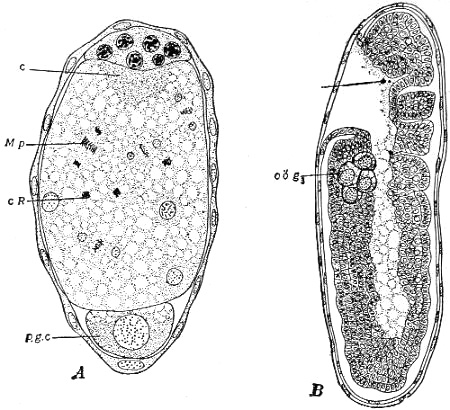

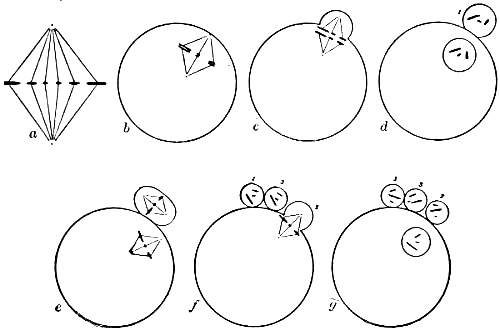

The Origin of the New Germ-Cells.—On account of the unusual importance from the standpoint of inheritance, which attaches to the germ-cells, a final word must be said about their origin in the embryo. While the evidence is conflicting in some cases, in others it has been well established that the germ-cells are set apart very early from the cells which are to[Pg 37] differentiate into the ordinary body tissues. Fig. 7A, p. 38, shows a section through the eight-celled stage of Miastor, a fly, in which a single large, primordial germ-cell (p. g. c.) has already been set apart at one end of the developing embryo. The nuclei of the rest of the embryo still lie in a continuous protoplasmic mass which has not yet divided up into separate cells. The densely stained nuclei at the opposite end of the section are the remnants of nurse-cells which originally nourished the egg. Fig. 7B, p. 38, is a longitudinal section through a later stage in the development of Miastor; the primitive germ-cells (oög) are plainly visible. Still other striking examples might be cited. Even in vertebrates the germ-cells may often be detected at a very early period.

Significance of the Early Setting Apart of the Germ-Cells.—It is of great importance for the reader to grasp the significance of this early setting apart of the germ-cells because so much in our future discussion hinges on this fact. The truth of the statement made in a previous chapter that the body of an individual and the reproductive substance in that body are not identical now becomes obvious. For in such cases as those just cited one sees the germinal substance which is to carry on the race set aside at an early period in a given individual; it takes no part in the formation of that individual’s body, but remains a slumbering mass of potentialities which must bide its time to awaken into expression in a subsequent generation. Thus an egg does not develop into a body which in turn makes new germ-cells, but body and germ-cells are established at the same time, the body[Pg 38] harboring and nourishing the germ-cells, but not generating them (Fig. 2, p. 13). The same must be true also in many cases where the earliest history of the germ-cells can not be visibly followed, because in any event, in all higher animals, they appear long before the embryo is mature and must therefore be descendants of the original egg-cell and not of the functioning tissues of the mature individual. This need not necessarily mean that the germ-cells have remained wholly unmodified or that they continue uninfluenced by the conditions which prevail in the body, especially in the nutritive blood and lymph stream, although as a matter of fact most biologists are extremely skeptical as to the probability that influences from the body beyond such general indefinite effects as might result from under-nutrition or from poisons carried in the blood, modify the intrinsic nature of the germinal substances to any measurable extent.

Fig. 7

A—Germ-cell (p. g. c.) set apart in the eight-celled stage of cleavage in Miastor americana (after Hegner). The walls of the remaining seven somatic cells have not yet formed though the resting or the dividing (M p) nuclei may be seen; c R, chromatin fragments cast off from the somatic cells.

B—Section lengthwise of a later embryo of Miastor; the primordial egg-cells (oög3) are conspicuous (after Hegner).

[Pg 39]Germinal Continuity.—The germ-cells are collectively termed the germinal protoplasm and it is obvious that as long as any race continues to exist, although successive individuals die, some germinal protoplasm is handed on from generation to generation without interruption. This is known as the theory of germinal continuity. When the organism is ready to reproduce its kind the germ-cells awaken to activity, usually undergoing a period of multiplication to form more germ-cells before finally passing through a process of what is known at maturation, which makes them ready for fertilization. The maturation process proper, which consists typically of two rapidly succeeding divisions, is preceded by a marked growth in size of the individual cells.

Individuality of Chromosomes.—Before we can understand fully the significance of the changes which go on during maturation we shall have to know more[Pg 40] about the conditions which prevail among the chromosomes of cells. As already noted each kind of animal or plant has its own characteristic number and types of chromosomes when these appear for division by mitosis. In many organisms the chromosomes are so nearly of one size as to make it difficult or impossible to be sure of the identity of each individual chromosome, but on the other hand, there are some organisms known in which the chromosomes of a single nucleus are not of the same size and form (Fig. 8, p. 41). These latter cases enable us to determine some very significant facts. Where such differences of shape and proportion occur they are constant in each succeeding division so that similar chromosomes may be identified each time. Moreover, in all ordinary mitotic divisions where the conditions are accurately known, these chromosomes of different types are found to be present as pairs of similar elements; that is, there are two of each form or size.