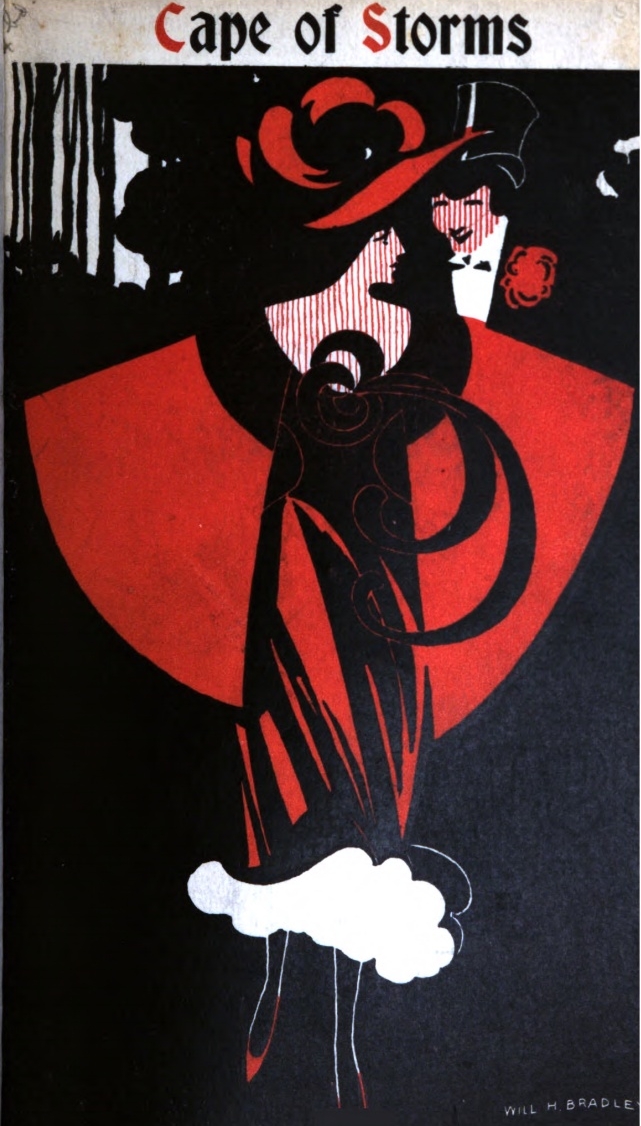

Title: Cape of Storms: A Novel

Author: Percival Pollard

Release date: May 24, 2012 [eBook #39781]

Most recently updated: April 3, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marc D'Hooghe (Images generously made available by the Hathi Trust)

"So this old mariner, Bartholomew Diaz, called that place the cape of torments and of storms and blessed his Maker that he was safely gone by it. And even so, in the lives of us all, there is a Cape of Storms, the which to pass safely is delightful fortune, and on which to be wrecked is the common fate. For it often happens that this Corner Dangerous holds a woman's face." * * *

—An Unknown Author

1894

ST. JOSEPH

FRIDENAU

CHICAGO

1895

"Life is a cup that is better to sip than to drain; the taste of the dregs is very bitter in the mouth." I shall never forget those words of our dear minister's, I suppose, because so much that has happened since he first uttered them to us as we sat in his Sunday-school class has shown me the truth of them. Dick himself, I remember, was especially loth to believe Mr. Fairly's monition; indeed, none of us young bloods cared to think that there was anything in the life before us that was not altogether worth living, and when Dick spoke up plainly and quite proudly, arguing against the pastor's words, we were all silent approvers of his challenge. Dick was always the bravest boy in the village; and we had long since come to be admirers rather than rivals. But Mr. Fairly only shook his head and smiled a little—he had a wonderful smile, and his eyes were always shining with kindness—and patted Dick on the head, with a gentle, "Well, well, my boy, let us hope so; let us hope so. Perhaps you will be fortunate above your fellows."

The incident dwells in my memory for many reasons. It was, as I have said, a curiously prophetic sentence of our pastor's; besides that, it was the last Sunday that we were all together in Lincolnville, we boys who had played, and fought and learned together. Early in the week, Dick—somehow, long after the world has come to know him only as Richard Lancaster, I am still unable to think of him as anything but the "Dick" of my boyhood—was to leave the village for the world; he was going to begin a life for himself, up there in that mysteriously magnetic maelstrom—the town. Like Dick Whittington of old, and every fresh young blood every day of this world's life, he was going up to town to conquer. Before him lay the beautiful pathway into a glorious future; promises and pleasures were like hedges to that way that he was going to tread. He was all eagerness, all hope, all ambition. And, to be just, perhaps there was never a boy went up to town from Lincolnville who had better cause to be full of pleasant hopes for his future than Dick. Certainly, it was the first time the little place had evolved such a talent; and it felt a pardonable pride in the boy; it expected, perhaps, even more than he did, and was looking forward to the reflected glory of being his native village.

If you have traveled through the West at all, and have anything more than a car-window acquaintance with the great Middle West, you know Lincolnville fairly well, I think. Not that you may ever have been to the village itself, but because it is a type of thousands of other villages scattered throughout the country.

It is the county-seat, and is built upon the checker-board plan, with a sort of hollow square in the middle, filled, as an Irishman might say, with a park. The sides of this square form the business heart of the place; each street that runs away from the square is lined with pretty dwelling-houses of frame or brick, so that the village looks like an octopus with four large tentacles stretching toward every point of the compass. The streets are fringed with shade trees of every sort, and in midsummer the place looks like a veritable nest of green and cool bowers. The county is strictly and agricultural one; the farmers come to "town," as they call it, every Saturday; at least, hitch their horses to the iron railing that surrounds the park, and spend the day selling produce, buying dry goods, implements or other necessaries. The face of the village rarely changes; there is an occasional fire on the "square," mayhap, and then the newer building that fills the gap is in decided improvement over the old one; young men are forever going out into the world, and old men are for ever coming back thither to die; for the rest, one might fancy that, if you came into the world again a hundred years from now, you would find the same farmers doing their "trading" at exactly the same stores that they now favor. On occasions of a political convention, or a circus, the town takes on a festive aspect, and the roads leading to the square are filled, all day long, with wagons that have come from the further edges of the county. During the three or four days of the County Fair, too, there is great activity between the village and the Fair Grounds, and, if it be a dry summer, the air between those places is merely one huge cloud of dust. Occasionally the pretty little Opera House has an entertainment that draws out such of the citizens as have no very severe religious scruples against the theatre. For the rest, the place is an admirable home of quiet. Young blood chafes at this quiet; old blood finds there the peace it seeks.

In the very nature of things, a place of this sort is chiefly concerned with its own affairs; the main theme of conversation are its own people. Everyone is perfectly acquainted with his neighbor's affairs, and not infrequently, in fact, is able to inform that neighbor of certain details relating to the latter, that had until then been unknown to him. So it was that, at the time of Dick's leaving Lincolnville, the good people of that place knew, much better than he did himself, the surety of his engagement to Dorothy Ware. He himself would have been only too glad to be as sure as they were, when he heard the rumors he was given to smiling rather sardonically.

He came to me once, I remember, and looked at me for a long time with those clear, grey eyes of his. "Tell me, old man," he said, "do you think she cares for me?" It is a stupid question, this; but almost every boy who is in love puts it to some friend or other, in the quest for confirmation of his fears or hopes. "Why, Dick," I said—still more foolishly, perhaps, now that I look back on it—"Why, Dick, of course she does. We all do." "Oh," he flung in, impatiently, "I don't mean that!" I knew what he meant; but who shall tell, being a man, whether a girl cares or not? Although, if ever a boy was made to be well beloved, surely it was Dick.

He was always a high-spirited youngster; some of his tricks are still legends of the old high-school in his native place. He never liked to fight, being naturally mild of temper; but when he was roused beyond endurance lie was a veritable Daniel. His father died when he was only four years old; to his mother he was the most devoted of sons.

It was when he was about ten years old that his talent for drawing first proved itself. It came to him in the way that it has come to many who have since made the world listen to their names—on the old black-board in the schoolroom. It was a caricature of Mr. Fairly, I remember, who was always very tall and very thin, and whose face was like that of a French general's under the empire. Dick exaggerated all these peculiarities most deftly with his chalk, and then it so happened that Mr. Fairly himself walked in and found the caricature. He only looked at Dick quietly, and put his hand down on his shoulder with a subdued, "I am a good deal older than you, my boy, a good deal older. You're sorry, aren't you?" And something in our minister's tone must have touched Dick, for the boy put his head down and said: "Yes, sir," with a little choke in his voice. Nor do I think that from that day to this Dick has ever drawn or painted in caricature. But in all other ways he developed his talent day by day with really wonderful results. He always had a rare notion of color; the autumn foliage thereabouts gave him the most startling effects. He used to go out into the woods in mid-summer and mid-winter—it made little difference to him—and come back with some of the prettiest bits of landscape work I have ever seen. There were, it is true, certain palpable crudities in his work, due to the lack of any training save that of his instincts, but those would undoubtedly disappear as soon as he came under the influence of a proper instructor. It was for this that he was going to leave the village and become of the greater world in town. His mother had rebelled at first; she was growing old, and she feared the thought of losing sight of him; but there was no restraining his ambition. To remain cooped up in that little corral of a place all his life—oh, no; that was not at all the thing for Dick Lancaster. That great world, out there, that he had read and heard so much about, that was where he ought to be; and it was there he wanted to wager and to win; what was there left in Lincolnville? He could do nothing more there; his life was beginning to be a mere stagnation. He must out and away. This longing for shaking off the shackles of that narrow village life was, as much as ambition, the spur that sent him out into the larger world. And I do not wonder at him. Those small places are not fit arenas for the disporting of ambitions or freedoms.

At this time, Dick was a little over one-and-twenty. He was handsome in a dark, olive-skinned sort of way, and his eyes had the longest lashes I have ever seen in a man. His hair curled a little, though he was forever trying to comb and coax the curl away; he hated it, saying that curls were all right for a girl, perhaps, but not for a man. He was, but for the fact that he was very fond of good cigars, a veritable Pierrot. He had always been very closely under his mother's influence; even his association with the boys of his own age and class had not been enough to taint him at all. He had a fancy that, now as I consider it, after all these years, seems a most pathetic one, that the world was a very beautiful place in which the wicked were always punished, if not by actual stripes, at least by the disdain of their fellow-men. It seems strange, perhaps, that a young man of his age should still hold such notions, but you must remember that in the quieter villages of our country it is possible to hold these fancies all one's life; the town is the great disenchanter. Dick considered that he had two things to live for—his ambition and Dorothy Ware.

It was beautiful, the way the boy sometimes rhapsodized; beautiful, and yet in the light of after events, sad. "One day, you know," he said in one of his bursts of enthusiasm, "I will be known all the world over as a great painter. People will come to my studio and wonder at it, and the work in it. They will invite me everywhere. I will be a lion. But I shall always place my work first; admiration shall go into the last place. And there will be Dorothy! Dear Dorothy! I haven't asked her yet, you know, but I hope—oh, yes, I hope—that it will be all right between us. Dorothy will help me in everything; when I begin to flag, or to lose spirit, she will spur me on. She will represent me to the great world of society when I am hard at work; she will be my veritable Alter Ego. And some day—some day, when I feel that my brush and my hand have in them the passion for my masterpiece, I will paint her face—her face!" He took up a photograph that lay on the table before him and looked at it steadily for an instant or two. "Sweet face!" he went on, "how shall mere paint ever represent you? There must be love, too. Love and paint. The one is a mere trick of the hand and eye; the other is mine and mine alone. For no one can love her as I do."

As for Miss Dorothy Ware, she was eighteen and beautiful. I do not know that any woman really needs a fuller description than that. As for her wit, it is too early in this chronicle to speak of that; nor do I, personally, differ much from Théophile Gautier, when he states that a woman who has wit enough to be beautiful has all she needs.

Miss Ware's father had made a great deal of money by the very simple process of growing old; he had been one of the pioneer settlers in that county and his had been most of the land that the village now stood on. Miss Ware herself, while sensible of her riches, was unspoilt by them. By nature she was of the disposition that one can call nothing else but "sweet;" she was tender and gracious; she was fond of fun, so long as that fun annoyed no one else; in a word, she was considerate and gentle and lovable. She had been brought up in the south, and she had retained a trace of the southern accent, so that her speech was in itself a charm; she had natural talents for looking pretty under all circumstances; some might have said that she had the instincts of a coquette, but I do not believe it of her. She was devoted to children and dumb animals. And whoso has those instincts is intrinsically good. But Miss Ware held that she had by no means had enough of this world's pleasures to begin thinking of so solemn a thing as marriage. Like a large number of the girls of today, she was, first and foremost, "out for a good time," as the slang of the time has it. She had certainly the intention of some day marrying the man she loved and making him as happy as she could; but in the meanwhile she wanted to test the world's ability to furnish entertainment quite a little while yet. Which was why, although she was very fond of Dick, she had invariably put him off, when he grew importunate, with a laugh. "Why, Dick," she would say, "don't you know you're absurd to think of such a thing? We're just children yet. Oh, I know we're of age, but what of that? You don't mean to tell me that you think your life has shaped, or even begun to shape itself yet? No. And as for me, I'm going to skirmish around a while yet before I settle down and become old married people! Be sensible, Dick!" And Dick, with a sigh in his heart, was, perforce, fain to say that he would try. "Skirmish around!" It grated on him, somehow, that phrase; it seemed to hold for him visions of innumerable flirtations; of contact with the world, the flesh and the devil, with the brushing off of the faint, roseate bloom of innocence.

It was on the day before Dick's departure for town that Lincolnville received the news of another intended going abroad. The Wares' were to sail for Europe before the month was out. Mrs. Ware had long been an invalid; for years the doctors had advised travel, but her husband's objections to any sort of change had hitherto prevailed against her wishes. But now the really dangerous state of Mrs. Ware's health, added to the entreaties of Dorothy, who longed, as do all American girls, for a glimpse of the old country, had brought the old gentleman to acquiescence. He would not go himself; he was getting too old for such a trip; but his wife and daughter should go, if they had set their hearts on it. So that, with the prospective departure of both Richard Lancaster and the girl that rumor had him engaged to, the tongues of the gossips had plenty to do on that day. When Dick first heard the news about the Wares' he was inclined to be downhearted; then it struck him that it would give him an opportunity for another effort at getting from Dorothy at least the promise of a promise.

Than Lincolnville in mid-summer I know few fairer places; there is a cool, green quiet all about that makes for peace and gentleness, and in the whispering of the breeze as it curls through the thick foliage of the spreading trees there is the note of happiness. Happiness, indeed, lies nearer to man in one of these small, serene villages, than anywhere else in the world, save in solitude; but it is rarely that man sees the sleeping beauty that he has sought all his life long. Dick, as he walked along toward the Ware house that splendid afternoon, caught something of the warm, comfortable languor that was in the air, and looked about him with a note of regret in his regard. "How pretty it all is!" he thought, looking at the familiar houses, with their well-kept lawns and ivy-covered verandahs, "how pretty! And yet—" he sighed, and then smiled with a proud lift of the head—"there are other things!"

He found Miss Ware seated in a hammock on what was known as the front-porch. It was a long, low, cool stretch of verandah, reminding one of the style of architecture in vogue in the old south. It was all harbored in vines that were so luxurious they hardly gave the breeze a fair chance to penetrate; on the other hand, the sun's rays were safely guarded against.

Young Lancaster drew up a chair, after she had smiled and reached him one of her hands. He looked at her critically for a moment.

"Dorothy," he said, "I have never seen you looking so pretty."

"I have never felt so happy, Dick," she said.

"Because you are going away?"

"Yes. And you?"

"I am happy, too. And yet, I am rather sorry. I have lived here all my life; this is the first time that I am going away from home. There is something solemn about it; but then—the end, oh, the end—justifies it all. That is not the chief reason why I am not altogether satisfied to go away. Dorothy, don't you know the other reason?"

She opened her eyes a little, and smiled a trifle at the corners of her mouth. "I, Dick, why, how should I know?" Then she saw that he looked hurt and she changed her tone. "Dick," she went on, "why won't you be sensible about it? I suppose you mean about me? Why, Dick, you know I like you, don't you? I've always liked you and admired you, but—dear me, can I help it if I feel sure that I don't like anyone yet—in that way? I'd like to, perhaps, but—well, I don't. What can I do?" She looked at him appealingly and reproachfully.

"I know, I know," he said, soothingly, "I'm an impetuous, thoughtless idiot, I'm afraid, and I hurt you. And, oh, Dorothy! don't you know I'd rather suffer torments unspeakable than hurt you?" He put out his hand and touched the one hand of hers that swung beside him, over the edge of the hammock. "But yet, dear," he went on, "if I only had a word from you to remember, be it ever so slight, I would fight so much better against the world. For it is the same to-day as it was in the middle ages; we go to our crusades, all of us, and if we have a sweetheart who will give us her love as an armor, we fight the better fight. Our crusades have a different air, to be sure, but the idea is the same. Don't you know, Dorothy, that if you only gave, me some little thing to cling to, I would feel a hundred times stronger. Come, Dorothy, it costs you little to say it!"

"But if I say that word, I must live up to it."

"True; your fair conscience would let you do nothing less. And yet, there are words so slight that they would cost you scarcely anything, while to me they would be coats of mail."

For a time there was silence, both looking out over the street where the school children were passing homewards. A buggy rattled by, throwing clouds of dust; then there was quiet again. "If you could say to me, Dorothy, 'Dick, I won't marry anyone until I see you again, until I come home again. And I'll try to like you—that way,' why, that would be enough for me."

She held up her right hand with a pretty little gesture. "I do solemnly swear," she said. Then she went on more seriously, "Why, yes, Dick, I'll promise that. Small chance of my getting married for a few years, anyway, so I won't have such a very awful time living up to that promise. Now, do you think, sir, that you're engaged to me?"

"No, no, dear; not at all. But you've let me hope, haven't you? That's all I want. You don't know how much happier I'll feel all the time you're away. How long, by the way, do you think you'll be abroad?"

"A year, at the least. I want to see it all, you know, when I do get the chance. Mamma'll want to stay in Carlsbad or Ems, or somewhere all the time; but I'm going to get her well real soon, you see if I don't, and then we'll just travel for fun and nothing else. Dick, wouldn't it be great if you could go along?"

"It would, for a fact," he assented, "but it's too good to be true. Besides I'm going to have some fun of my own!"

"Your work, you mean?"

"Yes. Isn't it fun to succeed? And I'm going to succeed! The fighting for success will be fun, and the victory will be fun!" His eyes flashed with a fierce battle-light. Today this fire of ambition is the only thing that at all takes the place of the blood fervor that spurred on the knights of the olden times. "Dorothy," he said, presently, with a sudden softness in his voice, "will you wish me luck?"

She gave him, for answer, her right hand, and looked at him wistfully. She was wondering, perhaps, why it was that she did not love this lovable boy. "I wish you all the success in the world," she said quietly. And then, as he turned to go, she called after him, in the old formula they had used to each other a thousand times as boy and girl—"Good-bye, Dick. Be good!"

The love affairs of a boy and a girl, you may think, are hardly the things that matter very much in the world of today. But the boy and girl of today are the man and the woman of tomorrow; and between these stages there is only the little gulf, so easily crossed, wherein runs the river of knowledge of the world we live in. As soon as we have crossed that we are become men and women, and are left of our childhood nothing but the wish that it were ours again.

Although the western windows were open, it was decidedly warm in the offices of the Weekly Torch. The offices were on the tenth floor in one of the town's best known sky-scrapers—the Aurora. There was a view, through the windows, of innumerable roofs and streets; here and there the tower of a railway station or a new hotel protruded—in the words of A.B. Wooton owner of the Torch—"like a sore thumb." Mr. Wooton was at that moment engaged in the diverting pastime of having his feet stretched over the side of his desk; and watching the smoke of his cigarette curl out of the window. Besides his own, there were three other desks, of the roller-top pattern, in the room, the door of which was marked "Editorial Rooms," but was rarely, if ever, seen closed. As a usual thing the outer door to the corridor was, in the summer-time at least, also left wide open; you could see from the window clear to the outer door. Indeed, it was one of Wooten's special talents, this ability of his to see at a glance, from his seat by the window, who it was that was coming in through the farther door. At one of the other desks a man was smoking a pipe and shoving a pencil rapidly over sheet of paper. Presently this man laid his pencil down, took his pipe out of his mouth and knocked the ashes over into the cuspidor. Then he leaned back in his chair and inquired,

"Who was it?"

"Young fellow from the Art Institute," said Wooten. "Sketches to show; wants to do illustrating; same old gag. They all come to it. Paint and fame come altogether too high, and a fellow's got to live. Although, as the Frenchman remarked, 'Je ne vois pahs la nécessité.'" The ability to hideously mispronounce French with a sort of bravado that almost made it seem correct was one of Wooten's peculiarities.

The other man gave a mock shudder. "If your morals," he said, "were as bad as your French, you wouldn't be fit to print. Was his stuff any good?"

"Very fair. Got a thing or two to learn about working for reproduction, as all these art-school men have; but he's got it in him. I told him to go and see young Belden, on the Chronicle, to get a few points about reproduction. I believe I'll be able to use him. If he's cheap." Wooton laughed, and threw the stub of his cigarette out of the window. Then he began throwing the papers on his desk all in a heap and looking into, under and around them. "Confound the luck," he began; then, turning to the other man, "Got a cigarette, Van?"

Van, whose full name was Vanstruther, and whom his intimates called alternately "Tom" and "Van," threw a box over to the other's desk, laughing. "I swear," he said, "it's my firm belief that if a man were to put you in a story and try to draw you with a single stroke he would only have to say that you spent your life between buying and losing cigarettes."

"And matches," added the other calmly. "Got one?"

"Jupiter! If this thing goes on I'm going to strike for higher rates. It's not in the contract that I furnish the office with smokes!"

"No. But the stuff you write, Van, is what drives me to cigarettes. So you make your own bed, you see. Hallo! Here's alone female to see me! Wonder who?"

He got up and went towards the door. "Did you wish to see me?" he inquired.

"The editor?" She hesitated a little but he assured her with a slight nod that she had found her man, and she followed him towards his desk. She took a seat beside him, and they began conversing in a tone so low that Vanstruther could only catch a stray word now and again. Presently she got up. "Very well then," she was saying, "you have my address; if anything should turn up, you will let me know, won't you?" With a little rustling of skirts she was gone. Presently they could here her voice saying "Down!" to the elevator boy.

"What was her game?" asked Vanstruther.

"Wanted to contribute poetry as a regular department. You can't fling a club around a corner anywhere in this town without hitting one of her kind, nowadays!"

"Then why didn't you tell her right away you weren't using anything of that sort?"

"Why, you infernal idiot, didn't you look at her?"

"No. Choice?"

"Very." He put a slip of paper into a pigeon hole, remarking as he did so, "Filed for future reference."

From the next room came a gruff voice, "Column of editorial to fill yet, Mr. Wooton."

"That foreman of mine's like Banquo's ghost," muttered Wooton, as he put his pen into the ink and bent down over the desk. For a while there was only the sound of pen and pencil going over paper, and the click of the type in the next room. Then there was a heavy step heard in the passage outside, and presently Wooton muttered: "The Lord's giving us this day our daily loafers, I see. I wonder why it is," he went on aloud, as a tall, heavy-set man, with a military mustache and eyeglasses in front of mild blue eyes, came into the room, "that you fellows always show up on Friday. Which, being the day we go to press—what's that? More copy? Oh, all right!" The foreman was taking all the written sheets from his desk and pleading for more. The new comer was evidently used to this sort of greeting; he calmly picked a cigarette from the box on Vanstruther's desk, lit it and sat down on a chair that was drawn up to the table-where the "exchanges" lay piled in heaps. He finally found what he had been apparently looking for—a paper with a very gaudy and risky picture on the front of the cover; he folded it to his satisfaction and began to look through it. "Say, Van," he began, presently, "what's this I hear about their going to play the Ober-Ammergau Passion Play here? Anything in it?"

Vanstruther was terribly busy. "Haven't heard," was all he said.

"I heard that it was all fixed," the other went on. "They've even got the man to play the leading part. Fellow called Tom Vanstruther. They say he's going to play the part without a makeup, and—"

"Oh, look here," said Vanstruther, half turning around in his chair, "you go to the devil, will you?"

The other man took out a huge cigar-holder, inserted his cigarette and curled his mustache. "Van's still a little sore about that," he said, turning to Wooton, who merely nodded his head. There came again the sound of footsteps in the outer hall, and Wooton, peering forward a little, broke into a cheery "Hallo, Dante Gabriel Belden, glad to see you! Come in. By the way, I just sent a young fellow who has your disease over to see you this morning. Wants to learn the reproduction rules of the game. See him?"

"Yes. Had a little talk with him. Clever chap. Tell you about him in a minute. Hallo, Van, how are the other three hundred and ninety-nine? Hallo, Stanley, haven't they got you under the vagrancy ordinance yet?"

The man with the huge mustache and the lengthy cigar-holder shook his head and said, "Not yet. But I understand they're on the trail. Well, how is Art, and what are the books you have lately bought, and what is the latest of your schemes that has died?"

"Oh, give them to me one at a time. Hang it, Wooton, why do you allow this man to come up here, anyway, to wear out your furniture and the patience of us all?"

"Oh," said Wooton, "he's an amusing animal, and I forgive any man anything if only he will amuse me."

"That's beastly bad morals!" said the artist.

"Morals!" echoed Wooton, with a bland smile, "my dear boy, you want to take a pill. No; take two! Morals in this day and age; moreover, on the borders of Bohemia, to talk about morals! Jove, I see myself forced to seek the solace of the deadly cigarette." He lit one of those slender rolls of tobacco and paper and went on, "However you haven't answered Stanley's questions yet. For you must know, Van, that Belden is one of the most extravagant and insatiable hunters of art books in all this town. Ever been in his flat? Well, it's a series of rooms, completely lined with books and pictures, with a very small hole in the middle of each room. Said hole being usually filled—to use an Irishism—with a center-table loaded to the guards with art portfolios. I don't believe there's a book or art store in town that the man doesn't owe large bills to; and I know, for a fact, that when it comes to be a question between a new overcoat and a new art book, he always takes the latter. And as for his schemes—well, I will admit they're all good, but, like the good, they die young. While they have the merit of exceeding novelty, they ride him like the plague; but presently a new idol comes and the old one falls into decay. Tell us, Dante, about the newest scheme!"

"H'm," replied the artist, "I don't see that you've left me anything to tell. I've got a new book of Vierge's stuff that you fellows want to come up and see one of these days; that's about all that I can think of."

"Thank you for the pressing invitation," said Wooton.

"Oh, and about that fellow you sent up to see me," Belden continued, "I liked his stuff immensely. He needs a little experience and hard luck on the practical side of getting his stuff made into cuts, and he'll be all right. The fact is, Wooton, seeing you like the fellow's sketches fairly well, and I'm rushed to death with other work, I've thought of turning my work for the Torch over to him. Would you object?"

"Not a bit, provided he does it as well; and he won't have to get much of a move on to do that. And then they're cheaper when they're green!"

Belden groaned. "You're the most awful specimen of materialism I ever hope to run up against. Then you don't object to this fellow—what's his name again, Lancaster, isn't it?—doing your sketches? All right, I'll train him a bit for you. And then I guess it would be a good scheme for him to have a desk here in your office somewhere, so that he can have a workshop and be right at hand for you. It isn't as if he had a studio of his own."

"That'll be all right; we've got plenty of room. But while you're training him, old man, I hope you won't inoculate him with that villainous style of dressing you adopt at the end of your pen. You're very hot people on everything that's got to be done in a hurry, and you're great on fine work of the etching order, but when it comes to making people look like the men and women one would care to be seen with, you're simply not in this county, that's all there is about it. I've always claimed, you know," he went on, turning a little so that he faced Vanstruther and Stanley, "that the great fault common to all the black-and-white artists in this town was that they couldn't define the difference between a gentleman and a hoodlum. They talk to me about technique, and drawing, and all the rest of it, none of which, I will admit, I know a mortal thing about; but all I answer is that I'm going from the point of view of the man who doesn't know how the drawing is made, but who does know how it looks when it's finished. The people of today look at nearly everything for it's merely superficial aspect; and the finer people look to our artists to display taste in clothing their pictorial creatures. If you only dress your people well, they'll want your drawings so that they can get fashion pointers from them. Now-a-days an illustrator has got to be more than a mere manipulator of pen and ink; he has got to keep an eye on the fashions, and even a little ahead of them. At least, that's what the man I'm looking for should be."

Stanley muttered, around the edges of his mustache, so that only Vanstruther could hear, "Yes; and he'd want to pay him as much as ten dollars a week!"

Belden laughed, and got up. "Why don't you put all that into a lecture, Wooton, and give the fellows over at the Institute a glimpse of this higher knowledge of yours. However, I've got to be going. I'll send that man Lancaster over here in a day or so. Goodbye, people!"

"There's one of the cleverest fellows with a pen in this town," said Wooten, as soon as the artist's footsteps had died away down the corridor, "but he's utterly spoiled himself by the work he's been doing of late years. He's a very fast worker, and one of the best men a daily paper ever got hold of. Then, too, I've seen copy-work of his—that is, from photographs or paintings—done in pen-and-ink, that had all the fine detail and effect of an etching. But, for the sake of the money there is in it, he does blood and thunder illustrations for a paper of that sort. After a man has done that sort of thing for a year or two, it gets into his style. I don't believe he'll ever be able to do anything else, now. Of course, he'll aways make good money, because his speed and capacity for work are simply invaluable; but art, as far as he is concerned, must be weeping large salty tears."

"This picture of you, A.B. Wooton, pleading the cause of art," remarked Stanley, "is one of the most affecting I have ever beheld. It really makes me feel—hungry."

"Your invitation, sir," said Wooton, walking over toward the closet and getting his hat, "is cordially accepted. Come on, Van; we are invited to lunch by the Honorable Mr. Stanley, exchange reader to the Torch. Never linger in a case like this!"

"For consummate nerve," Stanley suggested, "you really take the medal, A.B. However, seeing I made a little borrow from the old lady yesterday, I will go you one lunch on the strength of it. But I do hope you men had late breakfasts."

Just before they were ready to pass out, Tony, the office boy came in. "Say," he said to Wooton, in a low tone, "you remember that letter I took to the house day before yesterday? Well, does the quarter walk to-day?"

"Which," Wooton explained, as he handed the boy a quarter, "is Tony's peculiar way of inquiring whether he is going to get that twenty-five cents or not." Tony grinned and went back to his desk were he was busy addressing wrappers.

When the three men came back from lunch, they found a young man, holding a black leather case in his hand, such as bank messengers carry, sitting patiently in a chair in the outer office. He got up when they entered, and handed Wooton a paper. Wooton took it to the light, read it slowly, and handed it back. "Tell him to send that around again on the tenth, will you." Then he walked into the composing room and began talking to the foreman. The collector put the slip of paper back into his portfolio and went out.

"Van," said Wooton, as they sat down at his desk, presently, "I wish you'd try and hurry that stuff of yours along a little, will you? I've got to go to a tea at Mrs. Stewart's at four, and the ghost tells me that your page is half a column shy yet."

Vanstruther nodded silently, while Stanley inquired, "Excuse my ignorance Mr. Wooten, but who is Mrs. Stewart?"

"What? You don't know the great and only Annie McCallum Stewart? Oh, misericordia, can such things be?"

"They are."

"Well, Mrs. Stewart is a remarkably clever woman. One of the cleverest women our society affords, in fact. She is the daughter of one of the town's best known and most popular doctors, and everyone in society knew her so well when she was only Annie McCallum that now, when she is married to Stewart, one still uses her old name as well as her new one. That's all the result of individuality. She has read a great deal, and kept her eyes open a great deal. She has a husband who is ridiculously fond of her, and otherwise as blind as a bat. She, on the other hand, has a mania for young men. Whenever you see her with a young man of any sort of looks, somebody will tell you that Annie McCallum Stewart has got a new youth in the net. She likes to lure them up into her 'den,' as she calls it, and talk to them about the higher life. Then they fall in love with her and she forgives them and elaborates upon the beauties of pure Platonism. In a word, Stanley, she's one of the most perfect forms of the mental flirt I ever come across."

"H'm. Is your tea today to be in duet form, or is it a general scramble?"

"Oh, it's a general all-comers' game. But I always like to go to that house; she interests me immensely. I'm always wondering how near she really can skate to the edge without breaking over."

"Yes," acquiesced the other, reflectively, "that is an interesting speculation. Hallo, here's another friend of yours!"

The new-comer laid an envelope on Wooton's desk and waited. The latter opened it hastily, and then said, "I sent that down by this morning's mail."

The man had hardly gone before Stanley laid down the paper he had been paging through and said, looking steadily at Wooton, "Jupiter, but you do that easily! If I could do that only half as well I'd count myself as free from debts for the rest of my life. It's my solemn belief that you can tell a collector from an ordinary mortal as soon as he steps inside the door. I've heard you tell a man, who had only just turned inside the outer office, that you were 'going to send that down in the morning,' and I've seen you look the enemy calmly in the face and tell him that you had fixed that up with his employer about an hour ago. And you do it as easily as if you were lighting a cigarette. Another man might get embarrassed, and hesitate, or feel guilty! But you! Not in a hundred years! You never quail worth a cent. It's positive genius, my boy, positive genius!"

"No; it's only business, that's all."

"H'm, by the way, speaking of business, aren't you running the game a trifle extravagantly here? I don't want to mix in, of course, but is the thing paying so well as—"

The other interrupted him. "My dear fellow," he said, "it's evident you haven't any idea how well this thing is paying. Why, man, look at me! Do I economise much? No. Well, I don't have to, that's why! But come on and let's saunter down street. Van's finished, and they've got all the copy they want, and I expect there are a few pretty girls out today. Let's go and take a glimpse at the parade on the Avenue. And then I'll go down to that tea."

There were several callers at the office after they had left; some bill-collectors, a society man who left the announcement for some forthcoming dances; a boy to buy ten copies of last week's paper; a printer looking for work; and the mail-carrier. Towards six o'clock the foreman and the compositors left; then Tony, the office-boy, shut up his desk, and went out, locking the door behind him. The Weekly Torch had gone to rest for the day.

In the very air and life that prevailed in the office of the Torch there was, as one may suppose, something strange, and at first repugnant to Dick Lancaster. To one of his bringing up, his earnest intentions, his thirst for real things, it seemed that all this was very like a gaudy sham, a bubble of pretense, of surface prattle. He could scarcely believe that the flippancy of these men was serious with them; their talk, their point of view astonished and horrified him. If they were to be believed, life was nothing but a skimming of more or less uneven surfaces; the only thing to be tried for was pleasure, and there was no moral line at all. And then again he rebuked himself for being, perhaps, a homesick young idiot, overgiven to morbid speculation. That was not what he had come to town for; he was going to do some good work and make a name and fame for himself.

He had found, very early in his career, that in order to get upon the first steps of the ladder he must become an illustrator. If he had had the means that would have enabled him to wait through studio-work, a trip to Paris, and the dreary years ere orders came from dealers, he would have clung to paint at any risk; but he saw himself forced to earn some bread-and-butter even while he waited for his dreams to come true. So, with some slight reluctance at first, to be sure, but afterwards with all his energy, he applied himself to pen and ink work. In course of time, as we have seen, he became the staff-artist of the Torch, He was making a very fair living for so young a man, and he made a great many acquaintances. And life every day showed him a new aspect.

One of the men he had so far taken the greatest liking to was Belden, the artist, who had, to all intents and purposes, put him into his present position with the Torch, Belden, whose name was Daniel Grant Belden, but whom his friends chaffingly called, on account of the similarity of the initials, Dante Gabriel, was one of the most happy-go-lucky individuals that ever breathed. His mania for art books kept him more or less hard-up; yet he undoubtedly had one of the finest collections, in that sort, in town. He got orders for work from a publisher; he took the manuscript that he was to illustrate home with him; he kept it three weeks; then, without having read it, he returned it saying he was too busy to attempt the commission. And if ever there was one in this present day of ours, he was a Bohemian. The peculiar part of it was that in addition to being a Bohemian by instinct, he was one by intention. He read Henri Murger with avidity, and thought of him always. On the street he was a curious object; his overcoat was a trifle shiny, and his hat was always an old, or at least, a misused one; his trousers were too tight at the knees; his boots rarely polished. He usually walked with a long, quick stride; and a long, peculiar cigar, of the sort the Wheeling people call "stogy," was almost always in his mouth. You rarely saw him on the Elevated except with an armful of books and papers. He would come home at one in the morning and sit down at his wide drawing table and work until dawn. Then, with not much more than his coat hastily thrown off, he would fling himself on the couch and be fast asleep in an instant. Often, too, he would go fast to sleep while his pen was traveling over the paper; in ten minutes, or sometimes half an hour, he would wake up and continue the stroke that had been interrupted; his pen would have not spilled a single drop. He did all his own cooking, and marvelous were the meals that resulted. He liked nothing better than to fill his rooms with a number of choice, congenial souls. They would talk art-shop for hours, or listen to music; he knew a great many clever young fellows who were gifted in playing the piano, the flute or the violin; and while his own musical tastes were barbaric, and called, chiefly, for the spirited rendition of darky-minstrelsies, he gave the rest of his company the freedom of their choice, also, and sat patiently through the most beautiful of operatic strains. Sunday was the day singled out more especially for those pleasant little "evenings" at Belden's flat.

Dick Lancaster had been asked up to these evenings a great many times before he ever went. For long, he could not make up his mind to it; in spite of all the thousand and one laxities that he saw in the daily life around him, to devote oneself to anything in the nature of sheer pleasure, on Sunday, still seemed to him a decided mis-step.

But one day, toward the beginning of winter, Belden, who had been in to call on his young protégée at the Torch office, said to him,

"Look here, Dick, why don't you come up some Sunday evening and join our gang? Goodness, you can't afford to be as straight-laced as all that, in this town. Besides, we don't do anything that's against the law and the prophets, you know. We talk a little shop, and some man reads something, perhaps, and Stanley plays a thing or two on the violin. Then we go out and help ourselves to whatever I may happen to have in the larder. And then you go home, or you bunk up there, and where's the harm done? Look at it sensibly, my boy; we are all slaves in the same bondage, in this town, and Sunday is our one off-day; you don't mean to say we're heathens and creatures of the devil if we seek the sweetest rest we can on that day? To some men, rest means church; to me and most of the men you know, it means relaxation, and relaxation means recreation. The others get their music in church, I get mine at home. Now, Dick, say you'll come up next Sunday."

And Dick, looking at Belden as if to make out whether that artist were an emissary of the Evil One or merely a man of the present day, coughed a little, and then said, rather sheepishly, "Very well, I'll come—to please you, Belden." He felt, the next minute, as if he had slipped and fallen; he grew a little faint; he thought he could hear the sound of the church bells as they used to come singing over the meadows in Lincolnville; he saw himself and his mother sitting side by side in the old pew, listening to the pleasant voice of Mr. Fairly droning out his prayer; then he shook himself together and blushed at his fancies. Belden had gone already, but Dick felt as if he would run after him and tell him, "No, no, I cannot, must not come!" He ran to the door; the corridor was empty; Belden was half way down the next block by this time. Then he solaced himself with the thought, "Surely it can be no great harm after all—besides, I have promised!"

He bent down over the drawing-board once more, but he could no longer chain his thoughts to the work before him. They flew round and round in a curious circling way about this new life that he had become a part of. It was, he was forced to admit to himself, not as beautiful a thing as he had expected; but it was certainly novel, and it interested him immensely, it kept his curiosity excited, it touched his senses. As he began to consider that quiet country village that he had left, out yonder on the plains, and this busy beehive of a metropolis, he came, also, to consider the men he was beginning to know. He leaned back in the chair, smiling a little. The office was nearly empty at this time; it was during the noon hour, and Dick was alone in the outer office. He passed over, in his thoughts, the men that he was thrown with in the Torch office. There was Wooton himself: tall, thin, with a face that was all profile—a wonderfully pure profile—with a mouth almost too small for a man, a nose that bent a little like those of the Cæsars. Dick did not know, yet, what to make of Wooton. The man had a wonderful charm; he could talk most entertainingly, most logically and he had some curiously interesting theories. There was a sort of laisser-aller negligence in his manner; his manners were admirable, and there was some occult fascination about him that one could scarcely define. As Dick considered him, he remembered that on several occasions, he had listened to Wooton's dissertations on subjects that otherwise would have offended him, merely because the man's charm of person and speech were so alluring. As to whether it was genuine or a mere veneer, well, how could one tell as soon as this? Time, which tells so many things, would doubtless tell that too.

Then Vanstruther! He had a blonde beard that came to a point, and he always wore glasses. For the rest, Dick knew but little of him save what he had heard. Vanstruther "did" the more important of the society events for the Torch, and himself moved and had his nightly being in the smartest circles in town. The peculiar part of it was that he was married, and had several children; barring the hour or so a day that he spent in the office of the Torch he was the most devoted husband and father in the world, and spent the most of his day at home, where in his little study-room he sat in front of a typewriter stand and manufactured at lightning speed—what do you suppose?—dime novels. This was, among the man's intimates, a more or less open secret; but to the world at large, and particularly the world of society, he was known merely as a delightful person, socially, and something of a flaneur, intellectually.

As for Stanley—the man's full name was Laurence Stanley—Dick had somehow taken a dislike to him. He knew little of him except that he was a professional do-nothing, who lived off his wife's money, speculated occasionally, and appeared a great deal in society. No one ever saw his wife, who was an invalid. He talked with inveterate cynicism; it was this that made him repugnant to young Lancaster. He had a sneer and a cigarette always with him, and Dick hated both.

The tip-tapping of a light foot-step over the oil-cloth brought Dick back from the land of day-dreams. It was rather a pretty woman that stood before him, and she was gowned in a manner that even with his inexperience he knew to be distinctly up-to-date, and that he certainly admitted as attractive from an artistic standpoint. She looked past him into the inner office, lifted her eyebrows a trifle and inquired: "Is Mr. Wooton not in?"

"Not just now," responded Dick, getting up, "but he will be back in a very little while. If you would care to wait—" He took hold of the back of a revolving chair that stood close by.

"No," she declared, "I only had a minute. Will you tell him Mrs. Stewart was up? Or, stay; I'll write him a line."

Dick gave her some letterheads, and pen and ink; she sat down at his desk and began writing, with a good deal of scratching and scraping. "There," she said when she had addressed the envelope, "If you will please give him that as soon as he comes in. Thank you. Do you do this?" She pointed with one gloved finger to the drawing he had been busy on. He bowed silently. She looked at him with a quick, comprehensive glance, smiled a trifle, and swept out of the door.

"So that is Mrs. Annie McCallum Stewart!" was Dick's first mental exclamation, "well, she's certainly not an ordinary woman. Wonder if I'll ever get to know her?"

With which speculation he turned to his work. When Wooton returned, and had read the note, he broke into a low chuckle, "That's like her! Just like her. What do you suppose she says?"

Dick was the only other person in the outer office, so he was forced to take the question as addressed to himself. "I have no idea," he declared.

"She says she is getting awfully tired of her present lot of young men, and wants me, for goodness sake, to bring down some one different, and bring him soon. She says she is tired to death of the man who has lived and seen and heard everything, and she is dying for a man who is as like Pierrot as two peas!" Wooton tore the letter up mechanically, and put the pieces into the waste-basket. "Well," he went on, "I wish I could—" he stopped and looked at Dick, breaking out the next instant into a broad grin, "Jupiter!" he added, "you're just the man! Do you want to join the noble army of martyrs in ordinary to the extraordinary Annie? She'll do you lots of good; she'll be a pocket education in the philosophy of today, and she'll put you through all manner of interesting paces. Seriously, she's a woman who can do a man a lot of good, socially. And society never does a man much harm; it broadens him, and gives him finish. Now, you're just the sort of youth she'll like immensely; and yet she'll soon find out that you've heard about her and her ways. Never mind; she won't like you any the worse for that; she's too much a woman of the world. What do you think? The next time I go down to tea at her house I'll take you along, eh? All you've got to do is to be clever and amusing and different to the others; Mrs. Stewart is like the rest of society in that she demands something of the people she takes up, but she doesn't demand such impossibilities. I'll write and tell her I've got the very man!" He went on into the inner office, before Dick had time to say anything in reply. And, to tell the truth, the idea rather interested him. He had seen her, and had felt interested in her; he had heard so much about her; and now he was going to meet her! As to being clever and amusing, he thought he was likely to fail miserably; but he might, unconsciously perhaps, succeed in being what Wooten called "different."

Just then Wooton gave a sudden exclamation. "This is Wednesday, isn't it? Well, that is her afternoon. You'd better shut up your desk for today; go up to your rooms and get an artistic twirl or two to your locks, and then come down to the smoking-room of the Cosmopolitan Club about quarter to four; I'll be there waiting for you. Then we'll go on down to Mrs. Stewart's together."

The days were getting very short now, and darkness was already hovering over the town as Dick passed through the portals of the Cosmopolitan. When they came out together, Wooton and he, it seemed to Dick that the town was in one of its most characteristic tempers. It was in the beginning of winter; the air was a little damp, and smoke hung in it so that it begrimed in an incredibly short space of time. The buildings, in the twilight that was half of the day's natural dusk and half the murkiness of the smoke, loomed against the hardly denned sky like some towering, threatening genii. The electric lights were beginning to peer through the gloom. The sidewalks were alive with a never-tiring throng, men and women jostling each other, never stopping to apologize; all intent not so much on the present as on something that was always just a little ahead. This, the onlooker mused, was what it meant to "get ahead," a blind physical rush in the dark, a callous indifference to others, a selfish brutality, a putting into effect the doctrine of the survival of the fittest. The streets clanged with the roll of wheels; carriages with monograms on the panels rolled by with clatter of chains and much spattering of mud; huge drays drawn by four, and sometimes six-horse teams, and blazening to the world the name of some mercantile genius whom soap or pork had enriched, thundered heavily over the granite blocks; the roar and underground buzz of the cable mingled with the deafening ringing of the bell that announced the approach of the cable trains; overhead was the thunderous noise of the Elevated. It was all like a huge cauldron of noise and dangers. Dick declared to himself that it was the modern Inferno. And yet, as he passed toward the station of the Elevated with Wooton, Dick began to understand something of the fascination that the place, even in its most noisome aspects, was able to exert. In the very rush and roar, in the ceaseless hum and murmur and groaning, there was epitomized the eager fever of life, its joys and its pains. Here, after all, was life. And it was life that Dick had come to taste.

There was a quick ride on the Elevated, Dick catching various glimpses of unsightly buildings that showed their undress uniform, of dim-lit back rooms where one caught hints of dismal poverty, of roofs that seemed to shudder under the banner of dirty clothes fluttering in the breeze. The town seemed, from this view, like the slattern who is all radiant at night, at the ball, but who, next morning, is an unkempt, untidy hag.

Mrs. Annie McCallum Stewart rose rather languidly as they were announced. Dick noticed that in some mysterious way she managed to give a peculiar grace to almost her every movement; there was something of a tigress in the way she walked. She gave her hand to Wooton—"Delightful of you to come so soon," she murmured.

"One of the things I live for, my dear Mrs. Stewart," said Wooton, "is to surprise people. Knew you didn't expect me, so I came. Brought a dear friend of mine, Mrs. Stewart, Mr. Lancaster. Want you to like him."

"My only prejudice against you, Mr. Lancaster," was Mrs. Stewart's smiling reply, "is that you come under Mr. Wooton's protection. I pretend I'm immensely fond of him, but I'm not; I'm only afraid of him; he's too clever." And, still laughing at Wooton in such a way as to show the exquisite perfection of her teeth, she presented young Lancaster to several of the others who were sitting about the room, chatting and sipping tea. He had a vague idea of several stiff young men bowing to him, of an equal number of splendidly appareled, but unhandsome girls, looking at him with supercilious nods, and of hearing names that faded as easily as they touched him. He found himself, presently, sitting on a low divan, opposite to a girl with dreamy blue eyes behind pince-nez eyeglasses. He hadn't caught her name; he knew no more of her tastes, of the things she was likely to converse about than did the Man in the Moon. But he instinctively opined that it was necessary to seem rather than to be, to skim rather than to dive.

"I've been 'round the circle," he said, trying a smile, "and I'm delivered up to you. I hope you'll treat me well."

The girl with the blue eyes looked at him a moment in silence. Then she said, abruptly: "This is the first time that you've been down here, isn't it? I knew it! Well, these things are not bad—when you get used to them. Now, you're not used to them. Confess, are you?"

Dick shook his head. "I am innocent as a lamb," he said, with mock apology.

The girl went on: "Well, that may do as a novelty. Annie's great on new blood, you know. Shouldn't wonder if she took you up. How are you on theosophy?"

Dick stared. What sort of a torrent of curiosity was this that was gushing forth from this peculiar creature? "To tell you the truth," he hazarded, "I am not 'on' at all."

She smiled. "Ah, that's bad. However, I dare say there's something else. Now, how are you on art?"

"I know a little something." He smiled to himself, wondering how much of the actual practical knowledge of art there was in all that room, outside of what he himself possessed.

"Ah, a little something. Well, that's all that's needed, nowadays. The great point is to know 'a little something' about everything. To know anything thoroughly is to be a bore. A man of that sort is always didactic on the one subject he is familiar with, and absolutely stupid on all other things. However, what's the use of considering those people? They're quite impossible." She began tapping the carpet with her slipper. "Speaking of impossible people," she went on, "there's Mrs. Tremont. Over there with the grey waist. Intellectually, she's impossible; socially she is the possible in essence. She was a Miss Alexander, of Virginia; then she married Tremont, and lived in Boston long enough to get Boston superciliousness added to the natural haughtiness given to her in her birth. She talks pedigree, and dreams of precedence. She goes everywhere, and I fancy she thinks that when she hands St. Peter her card that personage will bow in deference and announce her name in particularly awestruck tones. The girl who is talking to the tall man with the military mustache is Miss Tremont. She is her mother, plus the world and the devil."

Dick interrupted her, as she paused to sip her tea. "Yes," he said, "and now tell me who you are?"

She, lifted her eyebrows a trifle. "You have audacity," she said, "and I begin to think you are clever. Audacity is successful only when one is clever. When one is stupid, audacity is a crime. Who am I? Well—" she smiled again at the thought of his assurance. "Why not ask my enemies? But you don't know who is my enemy, who is my friend. Well, I am the Philistine in this circle of the elect. I'm a cousin of Mrs. Stewart's, and I come because I am fond of being amused. She herself amuses me most. She seems to be so tremendously in earnest, and she's so unfathomably insincere. She hates me, you know, because I didn't marry John Stewart when he proposed to me. Then, I never did anything, or had a fad, or was eccentric, so I don't really belong here; but, as I said before, the house amuses me, and I come. I don't know why I tell you this, but I don't care very much, and besides, I believe you're still genuine. It's so pathetic to be genuine; it reminds me of a baby rabbit—blind eyes and fuzz. I'm not sure, but it's my idea, that if you want to keep Mrs. Stewart's good graces you'll have to do nothing harder than stay genuine. It's so novel. Most of us, today, couldn't be genuine again any more than we could be born again. Ah, here's my dear cousin approaching. I suppose she comes to rescue you from my clutches. If you want to please her immensely, tell her I bored you to death. She'll have the thought for desert all week."

Mrs. Stewart sailed toward them with a queenly sweep that was decidedly imposing. She had decided to have a chat with young Lancaster. When she had seen him in the office of the Torch, and now, when he first entered the room, she had seen at a glance that he was handsome enough not to need cleverness; but she was curious to see whether he would interest her in other than visual ways. "You've been most fortunate," she said to Dick, as she reached them, "with Miss Leigh to interpret us for you. Has she told you, I wonder, that she is my favorite cousin? But now, I want to talk to you about art. If Miss Leigh will surrender you to me—?"

"I've been talking to Mr. Wooton about you," she said as she bore him away in triumph, "and he tells me you've only been in town for a few weeks. You still have vivid impressions, I suppose. When one has lived here for years and years, one's impressionability gets hardened. It takes something very forcible to really rouse us. And even then we prefer to let some one of us experience the sensation; it is so much easier to take another's word for it, and follow in the rut. That is how most of our present day fads come about. Some one gets pierced between the casings of the armour of indifference, and the rest of us take the cue and join in the chorus of ecstasy. We don't go to hear Patti or Paderewski, you know, because, we really feel their art deeply; it is because someone once felt it and it became the fashion." While she talked, she had led him into a window-nook and motioned him to a fauteuil that covered the crescent-shaped niche. As she sat down, the lines of her figure could be traced through the perfect fit of her gown. He noticed what finish, what art there was about the picture she made as she sat there, beside him. Her gown was a delicate shade of gray; the crepe seemed to love her as a vine loves a tree, so closely did it follow and cling to the lines of her hips, her waist, her shoulders. Over her sleeves, immensely wide, as the fashion of the time decreed, fell lapels of silk. She had on low shoes, and above them he could see the neat contour of her ankles, also clad in gray. "However," she went on, "I did not intend to talk of the fashion; I wanted to ask you how the town struck your artistic side. Don't you find as great pictures in a street full of life as in a valley full of shadow? Isn't there more of the history of today in the faces of the people you meet on the Avenue than in a stretch of blue sky, a white sail, and a background of Venice?"

"I see you're something of a realist?"

"Don't! Please don't! That word gets on my nerves. I suppose my amiable cousin, Miss Leigh, told you we were all blue-stockings, and dilettantes. I assure you we've got beyond the Realism versus Romance stage of disputation. Really, you don't know how you disappointed me with that question. Mr. Wooton told me you were original!"

Dick flushed a little. "He also told me," he retorted, "that you were extraordinary. I begin to believe him." His tone had a suspicion of pique in it. But Mrs. Stewart beamed.

"Ah," she said, "I like you when you look like that. That's—h'm, now what is that?—anger, I suppose? It's really so long since I had a real emotion that I don't know how it's done. Do you know, I think you and I are going to be great friends! Yes, I feel I'm going to like you immensely. Won't you try to like me?" She leaned over toward him, and his shy young eyes caught the faint flutter of lace on her breast with something of dim bewilderment. Her lips were parted, and her teeth shone like twin rows of pearls. She went on, before he had time to do more than begin a stammer of embarassment, "Yes, just as long as you stay real, and genuine, I want you to come and see me very often; as often as you possibly can. I imagine that talking to you is going to be like dipping in the fountain of youth. Tell me, you people out there in the country, how do you keep so young?"

"Ask me that, Mrs. Stewart, when I have found out how it is that you in town lose your youth so soon."

"True. You will be the better judge. But you never told me how it strikes the artist in you, this town of ours."

"I haven't had time to think yet how it strikes me. I'm busy finding out all about it. Just at present it's all like the genius that came from the fisherman's vessel in the Arabian Nights: it is a huge coil of smoke that stifles me with its might and its thickness. I know there are wonderful color-effects all about me, but my nerves are still so eager for the mere taste of it all that I can't digest anything. Besides—" he stopped and sighed a little—"I must not begin to think of paint for years. I'm a mere apprentice. I just scratch and rub, and scratch and rub, as a brother artist puts it."

"But one sees some very pretty effects in black-and-white. Look at Life, for instance—"

"No, Mrs. Stewart, if you would be loyal to me, don't look at the aforesaid 'loathsome contemporary,' as they say out West." It was Wooton who had approached, and interrupted Mrs. Stewart with an easy nonchalance that, in almost any other man, would have been an unpardonable rudeness. He threw himself on a chair and continued: "Mrs. Stewart, you have wounded me sorely. I bring you a disciple and what do you do? You buttonhole him, as it were, and preach treason to him. For, you must confess, that to tell people to look at Life when they might be looking at—h'm—another periodical, whose name I reverence too highly to mention before a traitoress, is High Treason."

For reply, Mrs. Stewart tapped Wooton lightly on the lips with a large ivory paper-cutter that she had been toying with. "As I was saying, when rudely interrupted, look at—"

"My dear Mrs. Stewart, why this feverish desire to look at life? I ask you both, is life pretty? Remember M. Zola and Mr. Howells. They are supposed to give us life, are they not? Well, the one flushes a sewer, and the other hands us weak tea. I prefer not to contemplate life. I am obliged to read the morning papers because it is become necessary to know today the unpleasantness that happened yesterday. But otherwise I assure you that life—"

This time, Mrs. Stewart tapped him quite smartly with the paper-cutter.

"You know very well that puns have been out of fashion for more years than you have been of age. We were talking about art, and incidentally about a paper that encourages art, and you begin a dissertation on life! What do you mean?"

Wooton mockingly stifled an effort to yawn. "As if I ever, by the vaguest chance, meant anything! I hate to be asked what I mean. If I knew, I would probably not tell, and if I do not know why should I lie? The safest course in this world is never to mean anything and to say everything. If I had my life to live over again—"

Mrs. Stewart looked at him with a shudder, lifting her shoulders, while her mouth showed a smile. "Why speak of anything so unpleasant?"

"Ah, had you there, Wooton, eh!" It was Vanstruther, who had strolled over to pay his respects to Mrs. Stewart. She held out a hand; he pressed it lightly. He nodded to Lancaster, and then looked through the half-drawn portiers to where in the black-and-gold drawing-room the others were sitting and standing in colorful groups. Someone was at the piano playing a mazurka of Chopin's. There was a faint click of cups touching saucers; the high notes of the women and the low drawl of the men. Vanstruther looked at them all slowly, and then turned to Mrs. Stewart again. "All in?" he inquired.

Mrs. Stewart nodded and smiled.

"I've not been at your house for so long," Vanstruther continued, "that I'm a little out of the running. Several people here that are new to me. Now, that girl in black?"

"Talking to young Hexam? That's Madge Winters. You remember young Winters who was runner-up in the tennis tournament last season?—sister of his. She's just back from Japan. Has some idea of doing a sort of Edmund Russell gospel of the beautiful a la Japan course of readings. Her brother amused me once and I'm going to do what I can for her. Now, who else is there? Let me see: I don't think you ever met Miss Farcreigh before—she's talking to the man at the piano. Delightful girl—her father's the big Standard Oil man, you know—and collects china. Sings a little, too. But chiefly I like her because she's pretty and a great catch. There's a German prince madly in love with her, but her father objects to him because his majesty never did a stroke of work in his life. I believe you know all the others."

"Thank you, yes." Vanstruther turned to Dick and said to him, with a smile at Mrs. Stewart, "You may find eccentric people here, Lancaster, but you will never find unpleasant ones."

"That's where Mrs. Stewart makes the inevitable mistake," drawled Wooton. "There should be one or two unpleasant ones, merely for the sake of the others. If it were not for the unpleasant people in the world, it would hardly be worth while being the other kind."

"You're as unpleasant as need be," was Mrs. Stewart's reply.

"Delighted!" murmured Wooton. "To have done a duty is always a delight. I have done several. I have brought you a new disciple, I have leavened your heaven with intrusion of myself, and now—now I must really go. My virtues are still like incense in my nostrils. Allow me to waft myself gently away before they grow rank and stale."

Dick rose at the same moment. "Oh," Wooton said to him, "you're not obliged to go yet. Stay and let Mrs. Stewart enchant you with the nectar of proximity! I've got to be down at the Midwinter dance tonight, so I must be off now."

But Dick, in spite of the other's protestations, insisted that he must really go also. He assured Mrs. Stewart that lie had enjoyed himself immensely, promised to come soon and often, and was presently whirling down-town again with Wooton. The latter had bought an evening paper and was carefully perusing the sporting columns. Dick closed his eyes, trying to recall the picture he had just left: the dim-lit drawing-room, with its well-dressed, graceful people; Mrs. Stewart's fascinating voice and figure; the flippant frivolity of all their discourse; the useless sham of all their isms and fads; the clever ease with which everything seemed to be taken for granted, and nothing was ever truly analyzed—how like a phantasmagoria of repellant things it all was, and yet how fascinating! Everyone appeared to know everything; no surprise was ever expressed; no emotion was ever visible. It was fully expected that everyone was possessed of no real aim in life save the riding of a hobby; it was agreed that to appear ignorant of anything was to be vulgar. And yet, in that circle, Dick was hailed as "so delightfully genuine," and was told that he would stand high at court as long as he remained so! Surely these were strange days, and stranger ways! That phrase of Mrs. Stewart's about young Winters grated harshly, too—"He amused me once!"

Was life merely an effort at being forever amused?

Almost, it seemed so.

The room was dim with smoke. Through the faint veil that curled incessantly toward the ceiling the pictures on the wall took on a misty haze that heightened rather than spoilt their effect. It was not a large room, but the walls were covered with pictures of every sort. It was impossible to escape observing the artistic carelessness that had prevailed in the arrangement of the furniture. Bookcases lined the lower portion of each wall; then came pictures. There was an original by Blum; a marvelously executed facsimile of a black-and-white by Abbey; a Vierge, and a Myrbach. Not the least remarkable Mature of these ornaments was the manner of their framing, A Parisienne, by Jules Cheret, for instance, all skirts and chic, looked as if she had just burst through the confines of a prison-wall of a daily paper. The carelessly serrated edges, then the white matting, and the brown frame gave a whole that was worth looking at twice. An etching—one of Beardsley's fantasies—was framed all in black; it was more effective than the original.

Over the mantel were scattered photographs of stage divinities in profusion. Many of them had autographs scrawled across the face of the picture. In a niche in the wall a human skull, with a clay pipe stuck jauntily between the teeth, looked out over the smoke.

From the next room, beyond the open portieres, came the sound of a violin and a piano.

The air of Mascagni's "Intermezzo" died away, and for it was substituted a slow dirge-like melody. Belden, in the front room, broke out into an explosive, "Ah, that's the stuff! Everybody sing: 'For they're hangin' Danny Deever in the mohn-nin'.'" The wail of that solemn ballad went echoing through the house, all the men present joining in. Belden, who had been lying at full length on the floor, explaining the beauties of a charcoal drawing by Menzel to a group of three other artists—Marsboro, of the Telegraph, Evans, of the Standard, and a younger man, Stevely, who was still going to the Art School—had jumped to his feet and was slowly waving a pencil in mock leadership of a chorus. Vanstruther, who was stealing an evening from society for Bohemia's sake, was far back in a huge rocking chair; a fantastic work by Octave Uzanne on his knee, and his legs stretched out over the center table; he now held his pipe in his hand and hummed the refrain in a deep bass.

"Go on," urged Belden, as the last notes moaned themselves away in the smoke, "go on, give us something else!" But Stanley laid his violin down on a bookcase and declared that his arm was tired.

Vanstruther pulled at his pipe again, until he was sure he still had fire. Then he declared, oracularly, "Stanley, you look tremendously religious tonight. Been jilted?

"No, shaved. You confirm an impression I have that a man never feels so religious as when he has just been shaved. I assure you that in this way I could really read one of your 'shockers,' Van, and feel that I was doing my duty."

"Oh," Belden cut in, going over to one of the bookcases, "anything to stop Stanley from hearing himself talk. It makes him drunk. Seeing we had a ballad of Kipling's just now, suppose some one reads something of his. Then someone else can sit still, and think of his sins, while the pen-and-ink men make sketches of him. How'll that do, eh?

"All right." It was Vanstruther, whose voice came from over the smoke. "I'll read if you like; and Stanley can get a far-away expression into his countenance, while you other fellows put his ephemeral beauty on paper. What'll it be?"

Stanley, who was rolling himself onto a sofa in the corner, murmured, while he rolled a cigarette with a deft motion of his fingers, "Oh, give us that yarn about the things in a dead man's eye, what's the title again—'At the End of the Passage', isn't it? I'm in the mood for something of that pleasant sort. By the way, aren't we a man shy, Belden?"

"Yes. Young Lancaster hasn't arrived yet. I had a great time getting him to say he would come; he has scruples about Sunday, and all that sort of thing; but he'll turn up pretty soon, I know. Here's the book, Van." He handed the volume across the table. Stanley, after a few chaffing remarks had passed back and forth, was arranged into a position that would give the artists a sharp profile to work from. The artists began sharpening pencils, and pinning paper on drawing boards. And then, for a time, there was nothing but the sounds of pens and pencils going over paper, and Vanstruther's voice reading that story of Indian heat and hopelessness. In the other room McRoy, the man who had been playing Stanley's piano accompaniment, was reading Swinburne to himself.

The bell rang suddenly. Belden threw his sketch down and opened the door. "Lancaster, I suppose," he said. Then they heard his voice in the hall, greeting the newcomer, who was presently ushered in and airily made known to such of the men as he had not yet been introduced to.

"You've just missed a treat, my boy," said Belden, pushing Dick into a chair. "Vanstruther has been reading us a yarn of Kipling's. You're fond of Kip., I suppose?"

While Dick said, "Oh, yes, indeed," Stanley put in.

"It's lucky for you you are, because Belden here swears by the trinity of Kipling, Riley and Henri Murger. He has occasional flirtations with other authors, but he generally comes back to those three. But then, when you get to know Belden better, you will realize that he has what is technically known as 'rats in his garret.' Do you know what he once did, just to illustrate? Walked miles in a bleak country district that he might reach a certain half-disabled bridge and there sit, reading De Quincey's 'Vision of Sudden Death' by moonlight! The man who can do that can do anything that's weird."

"There's only one way to stop your tongue, Stanley," Belden remarked humoredly, "and that is to ask you to play for us again. Lancaster has never heard you yet, you know."

Stanley looked out into the other room. "What do you say, Mac? Shall we tune our harps again?"

"Just as cheap," said the other, without looking up from his book.