Title: The Lure of Old London

Author: Sophie Cole

Release date: June 6, 2012 [eBook #39932]

Most recently updated: July 19, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Ian Deane and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Ian Deane

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

AUTHOR OF

"A LONDON POSY," "THE LOITERING HIGHWAY," ETC.

WITH 8 ILLUSTRATIONS

MILLS & BOON, LIMITED

49 RUPERT STREET

LONDON, W. 1

Published 1921

FROM MILLS & BOON'S LIST

—

BY CHELSEA REACH

By REGINALD BLUNT

With 24 Illustrations. Demy 8vo. 10s. 6d. net

MY SOUTH AFRICAN YEAR

By CHARLES DAWBARN

With 30 Illustrations from Photographs. Demy 8vo.

10s. 6d. net

SOMERSET NEIGHBOURS

By ALFRED PERCIVALL

Demy 8vo. 8s. 6d. net

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

By FRANK ILSLEY PARADISE

With a Frontispiece. Crown 8vo. 5s. net

THE STREET THAT RAN AWAY

By ELIZABETH CROLY

With 4 Illustrations in Colour. Crown 8vo. 5s. net

LETTERS TO MY GRANDSON

ON THE WORLD ABOUT HIM

By the Hon. STEPHEN COLERIDGE

Crown 8vo. 4s. net

SWITZERLAND IN WINTER

By WILL and CARINE CADBY

With 24 Illustrations. F'cap, 8vo. 4s. net

FACING PAGE

TO

THE FRIEND WHO WANDERED WITH ME IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF GEORGE AND MRS. DARLING

PEOPLE who are kind enough to read my stories sometimes tell me they like them on account of their London atmosphere. This is reassuring, because London is, to me, what "King Charles' head" was to "Mr. Dick," and when my publisher suggested that I should write this volume I mounted my hobby-horse with glee.

The objects of the journeys recorded were chosen haphazard. With a myriad places clamouring for notice, and each place brimful of interest, one takes the first that comes, reflecting that what one doesn't see to-day can be seen to-morrow, regretful only that, no matter how many to-morrows may remain, there will not be enough to exhaust the charms of London. London has moods for each hour and surprises round every corner. It may be the enchantress, or the "stony-hearted step-mother," but one part it can never play—that of the bore. "Strange stories," says Walter Thornbury, in his introduction to "Old and New London," "about strange men grow like moss in every crevice of the bricks." To people the streets with the shades of those "strange men" is a fascinating pastime which I owe, in large measure, to the guidance of that wonderful and inexhaustible book.

If, in this humble little volume of my own, I dared aspire to do anything more than please myself, it would be to share with some lovers of London those moods of curious happiness which one finds in the haunts of London's ghosts.[1]

WHEN the Countess of Corbridge sent the quarterly cheque for fifty pounds to her brother, the Hon. George Tallenach, she always addressed the envelope to Carrington Mansions, Mayfair. As a matter of fact, the Honourable George lived in Carrington Mews, Shepherd Market, and derived a certain ironic pleasure from the contemplation of his sister's snobbishness. But then the Honourable George had never acted up to the traditions of his family. His Bohemianism, coupled with an inability to settle down to any calling, had been the despair of that family ever since he was ploughed at Oxford. And now, at the age of sixty-five, he was a pensioner on the bounty of the Countess of Corbridge, living in a workman's flat in Carrington Mews, an adept in the art of poetic loafing, an inveterate gossip and roamer of the streets, a kindly old vagabond with well-brushed shabby clothes, a clean collar and a spotless pocket handkerchief, the love of London in his bones, and of his fellows in his heart.[2]

Mrs. Darling, the pensioned widow of a night watchman, who lived in the flat below, was in the habit of rendering the Honourable George small services. It was she to whom he applied in any domestic emergency—she mended his socks and kept his handkerchiefs a good colour, sewed on his buttons, and inculcated a policy of thrift towards the end of the quarter when funds were getting low.

Such a period was imminent now, and when Mrs. Darling brought in a pile of snowy handkerchiefs and deposited them on the table this warm September morning, the Honourable George, faced with the prospect of three lean weeks, propounded to her a scheme he had devised for a cheap form of enjoyment.

"Mrs. Darling," he began, "I have noticed with regret your lamentable ignorance of the place in which you live."

"Me ignorant of Shepherd Market. I don't think!" declared Mrs. Darling indignantly. "I 'aven't lived in it for thirty-five years for nothink. Why, there isn't a shop or a person I——"

"Not so fast, Mrs. Darling. I was referring to London as a whole, of which Shepherd Market is as a needle in a haystack. And your knowledge even of the Market and its surroundings is purely superficial. I suppose you are not aware that Shepherd Market is the place where the fair,[3] which gave Mayfair its name, was held up to the middle of the eighteenth century, and that the Market itself is nearly two hundred years old. No doubt you are also in ignorance of the fact that Kitty Fisher lived in Carrington Street: Kitty, the celebrated courtesan who married John Norris and gave herself up to repairing two dilapidated fortunes, thus proving the inaccuracy of the statement that the leopard cannot change its spots, and challenging the baseness and the scurvy malevolence of those 'little scribblers' who accused her of having 'neither sense nor wit, but only impudence'."

"Well, sir, I must admit I didn't know all them things."

"Of course you didn't; but cheer up, it isn't too late to learn. What d'you say to our having some outings together? Suppose we make a start this afternoon? London's at its best on these calm autumn days."

"What, me and you?"

"Yes—why not?"

"'Spose we met any of yer grand friends? Me, in my ole plush coat I've 'ad this ten years. It's true I got a new 'at, ten and eleven at Selfridge's bargain basement, but a hat ain't everythink."

"No, you certainly want more than that. But clothes, also, aren't everything. It's your[4] company I hanker after, Mrs. Darling. I seek a virgin mind on which to make first impressions. I'm tired of people who know everything. In seeing things through your eyes I shall——"

But Mrs. Darling interrupted the speaker to remark with a scandalised air that there wasn't much of the virgin about her, seeing she'd been married thirty-three years, and a widow too, not to speak of being the mother of four children.

This drew forth from the Honourable George a charge of frivolity coupled with a long-winded explanation of his newly conceived idea, and an equally long-winded explanation of the benefit Mrs. Darling might derive from it. The listener, who had been standing first on one leg, then on the other, her mind racked by a suspicion that the potatoes would be reduced to pulp, made a reckless promise at the first pause, and then beat a precipitate retreat to her flat below.

"'E gets worse and worse," she meditated, as she strained off the potatoes—just in time. "Talk about balmy—if this don't take the bun! But if it gives 'im any pleasure, it won't do me no 'arm. I'll go this once, just to pacify 'im. I bet 'e won't ask me again!" and Mrs. Darling's smile had a quality of grim humour.

The Honourable George, always a favourite with the opposite sex, had had many love affairs of a more or less light nature, loves of a day, a[5] week, or a month. But existing with, and surviving these ephemeral distractions, was "Agatha," the woman he had always meant some day to ask in marriage. Owing, however, to the Honourable George's thriftless habits, that day had never arrived, and "Agatha," who had allowed all her birds in the hand to escape in favour of that elusive bird in the bush, was at the age of sixty still a spinster, finding her interests in church work, dogs, and other people's babies. At regular intervals she had letters from George. George, who was apt to ride rough-shod over her well-bred susceptibilities with his racy comments on people and things. George, who shocked her and saved her from old maidishness, whose letters came into the prim little country house with a refreshing breath of Bohemianism, providing an antidote to dry rot, and a healthy interest in men and things outside her narrow circle. The following letters are those particular ones which gave the account of his peregrinations with Mrs. Darling.[6]

CARRINGTON MEWS,

SHEPHERD MARKET,

13th September.

DEAR Agatha,—I've got a new pal! Her name may have appeared in my letters before, in connection with the histories of my neighbours in the other flats, the mending of my vests and pants, and cheap lunches at home when she provides me with a portion of her beef-steak pie for ninepence. Her name is Darling, which necessitates the painstaking use of the "Mrs." for fear of a misunderstanding. She is a widow, and a person of kindly sympathies but limited intelligence outside the domain of domestic affairs. She is Cockney to the finger tips, yet London, to her, is as unexplored and as unknown as one of the stars. The temptation, when one day I realised this, was irresistible. Obviously, it was meant that I was destined to take the work of her education in hand, and to-day we made a start with our immediate surroundings.[7]

It seems hardly credible that Mrs. Darling never went out to buy a pound of potatoes that she did not pass "Ducking Pond Mews" in Shepherd Street, yet it had never occurred to her to wonder how it got its title, much less to make any effort to find out. She said she supposed there had been a pond there, some time, and when I told her it was what, in contemporary papers, was described as "an extensive basin of water," she said, "A penny plain and tuppence coloured". Mrs. D. is very averse to anything of the nature of "side" in conversation, and so I did not go on to quote the article which spoke of a "commodious house and a good disposure of walks". I thought, though, it would interest her to know that, by payment of the small sum of twopence, lovers of a certain polite and humane sport could in those old days witness the torture of the duck when it was put in the pond and hunted by dogs who were driven in after it. Also that Charles II and some of his nobility were in the habit of frequenting those sports.

She said she wasn't a bit surprised. She never had thought much of royalty; all the same, it didn't do to believe everything you were told.

This was a trifle discouraging, and we walked on in silence for a few minutes, pausing to glance down East Chapel Street, where is the many-paned [8] window of the "Serendipity" shop, with its old coloured prints and the original editions of seventeenth-century poets, bound in vellum; then on to the East Yard, which exists exactly as it was in the old coaching days.

Do you know, Agatha, that I live in one of the most unique spots in London? We are hemmed in by an aristocracy of houses, places and people, yet we are as far apart from it all as if the walls of Jericho came between. There's no approaching by degrees. One steps through one of those low arches in Curzon Street into this quaint little island of loiterers in the twinkling of an eye. A world of cobbled-paved streets, culs de sac, devious by-ways, and shops which in their meditative unconcern seem to trust in Providence to send them customers. A world from which one sometimes awakens in Piccadilly with a feeling of having slept as long as Rip Van Winkle himself.

I suggested the wax effigies at Westminster Abbey with diffidence. To my relief, however, the old lady received the proposal favourably, and on our way I imparted to her a dark intention which I had cherished for years. It was to spend a night in the Abbey. I should choose the warmest night in summer, and I should go provided with a packet of sandwiches and a flask of whisky. Imagine the thrill on a moonlight[9] night, when the figures on the tombs in the long aisles would be like creatures on a stage frozen into stone at some moment of dramatic intensity. Pointing, beckoning, warning, praying, weeping and exhorting. "The dust of the dead"—a fine phrase that. One would see it rise like incense in the moonbeams, and the vast silences would be thick with whispered thoughts. Perhaps now and again there would come a sound which had nothing to do with the dead—the footfall of a watchman.

Mrs. Darling asked if it had occurred to me that the watchman might give me in charge. I assured her that I had not left such a contingency out of my calculations. I should well tip the watchman, and a drink out of my flask on top of the tip would make a friend of him for life. No doubt he would be glad of a talk to relieve the monotony of his job, and the talk of a night watchman in Westminster Abbey would be worth listening to. He could tell me something of those suspected secret places which are not shown to visitors. He might even let me see them for myself. He would know the Abbey as it is impossible for the ordinary public to know it. The ordinary public no more knows the Abbey than does a person, who stands on the kerb to watch the King pass on his way to some State function, know the man inside the King.[10] The Abbey should be seen when the voices of glib guides, and the shuffling footsteps of visitors bored with sight-seeing, have ceased. Then, when the echoes of the last footsteps have died away, when the last door has banged, and the last key been turned in the last lock, then the Abbey puts aside its mask and communes with its dead. What a strange silence that must be, when the thoughts of kings and queens, statesmen and warriors, poets and priests, fill every corner of the ancient building with their noiseless vigilance!

Mrs. Darling said that, even if I escaped being taken to the police station, I should certainly get an attack of rheumatism, but I explained that sensations invariably have their price, and that I shouldn't grudge paying for this particular one.

We left the daylight of the Broad Sanctuary for the gloom of the vast interior, and I suggested that we should explore the chapels before doing the wax effigies in the Islip Chamber.

As we walked down the north transept the old lady asked me if it was true that "Old Parr" was buried in the Abbey, and I took her to read the inscription on the stone in Poet's Corner. "Old Parr's" qualification for hob-nobbing with the élite in art and literature lies in the fact that he died at the age of 152, and lived in the reigns of ten sovereigns, an achievement great enough,[11] it was considered, to earn him the right to such distinguished burial. How came it, I wonder, that this solitary human being was endowed with such powers of resistance to natural decay? There must have been something weird about that old man. Taylor, the poet, in his description of him, says:—

"From head to heel, his body hath all over

A quick set, thick set, natural, hairy cover."

Was Old Parr a throw-back to our ancestor the ape?

Mrs. Darling said he must have outlived all his relations and been very lonely, and to reassure her I mentioned that if he outlived old ties he also made new ones, marrying his second wife (only his second) at the age of 120, and having by her one child.

Mrs. D. retorted that he ought to have been ashamed of himself, which struck me as inconsistent. Parr's first wife had no doubt been dead a great many years, and all those years he had presumably been waiting for the end which never came. When, at the age of 120, he found himself still alive, and still hale and hearty, he would begin to think it was about time to accept things as they were and start life all over again. That my thoughts in Poet's Corner, by the way, concerned themselves with "Old Parr" to the exclusion of Garrick, Johnson, Thackeray, Dickens,[12] Coleridge, and Spenser, the "Prince of Poets," must have been Mrs. D.'s fault.

I prefer Monday for a visit to the chapels, not because one saves sixpence, but because I never follow in the footsteps of a guide without a humiliating sense of being one of a hungry mob of chickens round the man with the bag of grain. It is much more exciting to go pecking about on your own, and on Mondays you can loiter unmolested where you will, and for as long as you will.

The north aisle of Henry VII's Chapel, where Queen Elizabeth is buried, invariably draws me, and I led the way there, first. Strangely enough, it is often empty, and always quiet. One's thoughts of Elizabeth mingle curiously with those of her hated half-sister, "Bloody Queen Mary," who is buried below Elizabeth, and who was, according to Sandford, "interred without any monument or other remembrance".

It is strange to note the unequal distribution of favours in the matter of burial. Charles II, for instance, has nothing more than his name and the dates of his birth and death recorded in small letters on the pavement of the chapel in the south aisle. Pepys says of Charles, "He was very obscurely buried at night without any manner of pomp, and soon forgotten after all his vanity".[13]

Addison is near Queen Elizabeth, and close to his friend Charles Montague, first Earl of Halifax. Reference to the fact is quaintly made in the two concluding lines of the Addison's epitaph:—

"Oh for ever gone; take this last adieu,

And sleep in peace next thy lov'd Montague."

The place is narrow and rather dark. It would have been more befitting Elizabeth's magnificence had she been laid amidst the colour and pomp of the chapel of Henry VII. One would think, too, that she had a restless neighbour in "Bloody Queen Mary". The words of the Latin inscription perhaps make a mute appeal for charity for the latter when they say, "Consorts both in throne and grave, in the hope of one resurrection".

Against the east wall is a sarcophagus containing bones found at the foot of a staircase in the Bloody Tower, and supposed to be those of the two princes who were murdered in the Tower by their uncle. Yes, Elizabeth has eerie company, and somehow, in the cold grey light of this dim corner of the Abbey, it is not the Elizabeth described by Green, the historian, as that "brilliant, fanciful, unscrupulous child of earth, and the Renaissance," of whom we think, but the dying, lonely woman who, her mind unchanged, her old courage gone, "called for a sword to be constantly[14] beside her, and thrust it from time to time through the arras as if she heard murderers stirring there". What a subject for a picture!

The quarters were struck by the chiming of the Abbey clock inside, and the booming of Big Ben outside, and as we wandered from chapel to chapel I was wooing those lurking beauties of the building which wait patiently for the day, the hour, and the man who is to find out their loveliness. The ordinary visitor is mostly too engaged in picking up crumbs of information to have leisure to lift his eyes to the sculptured figures which stand aloft in the blue haze of encroaching twilight. Neither does he catch the secret flame of some obscure window which suddenly shines out like a sinking sun through the forest of pillars and arches, nor notice the jealous little doors to which only the privileged have the key. I found one such this afternoon in the Chapel of Edward the Confessor, but when I put my eye to the keyhole, nothing but darkness rewarded my curiosity. Mrs. Darling asked me if I'd ever had any luck with keyholes, and I was obliged to admit that I hadn't—still, one never knows.

There was no need to peer through the keyhole of the door leading to the Islip Chamber, because for the moderate sum of threepence we were admitted without parley.

The guide pushed back a door into darkness,[15] touched a button, and behold a flight of steps leading up to the strange lodging of the life-sized dolls.

Charles the Second was the first to confront us, his bold black eyes meeting Mrs. Darling's inquisitive glance with a sinister challenge.

"Of a tall stature and of sable hue,

Much like the son of Kish that lofty grew."

"I wouldn't trust 'im a inch further than I could see 'im," was Mrs. Darling's comment on the "Merry Monarch".

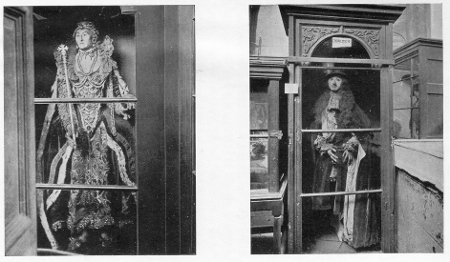

I complimented her on being a good judge of character. The guide had turned on the electric lights, which were fixed to shine on the silent company standing in their glass cases. William III and Mary in their purple velvet and brocades, their real point de rose and imitation jewels. The Duke of Buckingham, who died at the age of nineteen, lies on a bier in the centre of the room. The effigy lay in state at his mother's house, and one reads that she invited all her friends to see it, stating that "she could carry them in conveniently by a back door". Plain Queen Anne and "La Belle Stuart," the Duchess of Richmond, loved, in vain, by Charles II, and jealous for the posthumous reputation of her beauty. She left orders that her effigy, "as well done as could be," should be placed "under[16] clear crown glass and none other". She should have been content to go down to posterity as the figure of Britannia on the coins.

Mrs. Darling thought the Duchess would "'ave a bit of a shock if she could see 'erself now," and, indeed, I have rarely seen a more cynical comment on the glory that passes than is to be found in these weird figures in their dingy finery. Yet they have a dignity, and an exciting interest. One can approach unmolested and share the privilege of the cat who may look at a king. One may try to pierce the secrets hidden or betrayed by those waxen masks. There is Queen Elizabeth, for instance (to my mind the most arresting figure in the collection); the face is taken from a death mask, and there is something disquieting in the eyes, awful with the horror of death. A strange face, possessing in its smallness the curiously repellant qualities of great age: a face to which the kindly homeliness of Nelson's in the next case made reassuring contrast.

WAX EFFIGIES OF QUEEN ELIZABETH AND CHARLES THE SECOND.

Mrs. Darling said "Elizabeth didn't look 'uman," and I suppose one touches on the tragedy of her life when one says that it is always as a queen, rather than as a woman, one regards her. Yet she had her feminine vanities. I have always been impressed by the account of her travelling from Richmond to Chelsea by[17] night because the torchlight was more kind to her wrinkles than was the daylight.

The bell was tolling for afternoon service, the voice of a guide could be heard echoing in the chapels below, and we had the place to ourselves. Mrs. Darling returned and had another look at Charles II, just, as she expressed it, to "wonder what any woman could see in him," and, for the moment, I was alone with those waxen men and women who stared at me across the ages. There is something oddly intimate about a wax figure, and I was making strides in the acquaintance of Queen Elizabeth and Nelson when the verger returned with the intimation that sight-seers must depart, as Evensong was about to begin. Remorselessly he switched off the lights and we clattered down the wooden stairway, leaving the little company of strangely assorted ghosts to their dreams, and maybe an interchange of thoughts as the outcome of their long broodings.

It occurred to me as we came into the sunlight again, that while we were about it we would go and see the older figures which have been placed in the Norman Undercroft. And so we turned into Dean's Yard, and from thence to the cloisters, pausing now and again to read the inscriptions on the tombstones over which we walked. The lettering on some of them had been[18] freshly chiselled, and the names stood out, giving, it seemed, new life to the memories of those who lay beneath.

Mrs. Darling complained that I might have taken her to a more cheerful place, giving it as her opinion that Westminster Abbey was "nothink more than a bloomin' churchyard". I had to remind her that it is we who, in that place, are the ghosts, and the ghosts who are the real people. The present no longer exists for us. We left it, half an hour ago, to adventure into the dim old ages.

"Speak for yourself, sir," said she. "The present's good enough for me. You got a white mark on yer coat leaning up against the wall, and there's the old chap waiting what you asked to take us underground."

The verger approached with a bunch of keys, leading the way through the "dark cloister" to a door above which was an iron grating. At its opening, a gloomy dungeon-like interior was disclosed, but he put up his hand, and in a moment the Undercroft was flooded with electric light. It is of spacious proportions and of Norman architecture, having a clean-swept empty appearance. On the floor are some glass cases containing the oldest of the effigies, the actual figures which were carried at the funerals. Here is Katherine of Valois. I never hear her name[19] without remembering a passage in Pepys' Diary, where he says: "To Westminster Abbey and there did see all the tombs very finely, having one with us alone ... and here we did see, by particular favour, the body of Queen Katherine of Valois, and I had the upper part of her body in my hands, and I did kiss her mouth, reflecting upon it that I did kiss a queen, and that this was my birthday, thirty-six years old."

"Well, who'd er thought they'd come to this!" exclaimed Mrs. Darling, as she gazed at the "ragged regiment". "Wot a show up! Why, this one ain't decent," pointing to the nude figure of Prince Henry of Wales.

The verger explained that these historic dolls had been discovered lying in the cellars under the Dean's house, and how I envied the finder! If only I could get free permission to roam the Abbey and its precincts night and day, open every door I came to, go down every cellar, explore every passage, mount every stairway, I should want to live for ever. I said as much to Mrs. Darling, and she remarked that it wouldn't surprise her to hear that, when I got to heaven, I'd been given "some nosey job".

Quite an inspiring idea! and I warned her that next time she came to the Abbey she might see my ghost peeping through a keyhole.

She shook her head. "You ain't ever likely[20] to meet me 'ere," she said, "for if I must speak the truth, sir, I think it's very dry."

I told her that was because she didn't realise the living, human side of the people in whose likeness the effigies had been made, and I captured her attention with gossip about Henry VII, whose mother was not quite fourteen when she gave birth to him, and whose usurious disposition led him to think first of marrying his own daughter-in-law, then a lady who was insane. The information that on his death-bed he had discharged the debts of all prisoners in London who owed no more than forty shillings, roused a cynical comment from the old lady to the effect that Henry VII did his devil-dodging at the expense of his heirs.

We left the dark cloister as we talked and turned into the vaulted passage leading to the corner which I have sometimes heard described as "The Monk's Garden". Surely there is no more peaceful spot in all London. The little fountain in the enclosure bubbles all day long to the silence, the huge plane tree above it spreads wide arms to the old arcade, and ferns unfold their green fronds to the sunshine. It is a place in which to meditate kindly on the weaknesses of poor human nature, and to dwell with reverence on its greatness.

I felt impelled to set Henry VII right with[21] Mrs. Darling, and suggested we should return to visit his chapel, but the words fell on stony soil. Mrs. D.'s face assumed the expression with which I associated "dryness," and I proposed instead an adjournment to one of the neighbouring tea-shops. The old lady at once became alert, and taking the lead, towed me reluctantly through Dean's Yard into the roar of Victoria Street.

But I could not so easily shake the dust of the Abbey from my feet. I felt as one of those wax effigies would feel could he come to life, and stepping from out of his glass case, take a walk to Charing Cross. Then a strange idea occurred. Suppose I was one of them? It was possible, if the theory of a former existence holds water. I might be a Charles II, a Henry VII, a Nelson! On second thoughts, though, I am more inclined to class myself with the artistic fraternity—a Garrick, a Beaumont, or a Ben Jonson—"O, rare Ben Jonson!" Yes, I find in myself traits distinctly reminiscent of the poet who used his pen as Hogarth used his brush——

"That's the second time you done it, sir." Mrs. Darling's voice brought me back to the twentieth century with an unpleasant jar.

"Done what?" I asked.

"Run into somebody through not lookin' where yer goin'. That telegraph boy didn't 'arf[22] size you up. I shouldn't like to repeat wot 'e said."

"I wouldn't ask it of you," I hastened to assure her.

She had come to a halt before the window of an A.B.C. shop. "Look!" she exclaimed, "Crumpets! 'Ow funny!"

I told her I didn't see the joke, and she said that came of my not keeping my ears open—the telegraph boy had referred to a certain person being "balmy on the crumpet!"

I feigned unconsciousness of the deduction. There are occasions when Mrs. D.'s perverted sense of humour needs keeping in check, and to quote "Charley's Aunt," it was "such a damned silly joke".

I am sorry to have to end my yarn on this prosaic note, but that is the way of things in an existence where the necessity to blow your nose or change your socks breaks in on the most exalted moments.

Believe me, dear Agatha,[23]

Your devoted,

GEORGE.

CARRINGTON MEWS,

SHEPHERD MARKET,

24th September.

DEAR Agatha,—I was glad to hear, by the way, that you had been incited to unearth Pepys from a neglected corner of your bookcase. The old chap's vitality is infectious. One can scarcely turn a leaf anywhere but one is interested, amused, or receives the benefit of a shock to one's sense of the proprieties. This morning I opened him haphazard and read, "So over the fields to Southwark. I spent half an hour in St. Mary Overy's Church, where are fine monuments of great antiquity". I took it as a leading, and this afternoon Mrs. Darling and I paid a visit to Southwark Cathedral.

The building lies in a hollow, and as one goes down the steps to the churchyard one leaves behind the rumble of traffic on its way to London Bridge over the cobbles. Inside we found the length of the long narrow nave dim and grey, but in the neighbourhood of the clerestory a[24] golden light diffused itself, falling in patches on the groined roof. At the tomb of John Gower, the poet, who died in 1408, we paused. It occurred to me that it might interest Mrs. D. to hear that it was not till his old age, when his hair was grey, that wearying of his solitary state, John Gower took a wife.

The old lady stared at the stone effigy with the long hair bound by a chaplet of red roses, the short curled beard, the clasped hands, and stiff-buttoned habit falling in straight prim lines to the feet. "They do say," she remarked parenthetically, that "it's a pore 'eart wot never rejoices; but perhaps 'e couldn't get anyone to 'ave 'im."

Conscious of a possible application to my own celibate state, I left John Gower and drew Mrs. D.'s attention to the tomb of John Trehearn, gentleman servant to Queen Elizabeth and James I. On a table is recorded the king's testimony to the worth of his servant:—

Had kings power to lend their subjects breath,

Trehearn, thou shoulds't not be cast down by death.

John's wife stands by his side, her head reaching but to his shoulder. John has an apprehensive expression, and his little wife's prim pursed mouth argues badly for John's happiness and peace of mind. Mrs. Darling,[25] who, as you will have discovered by this time, is a good judge of character, said that perhaps, after all, there were worse things than bachelorhood. I was not in a position to argue the point, and we walked on into the retro-choir, where lies a curious skeleton effigy, which represents the ferryman, father of St. Mary Overie, the patron saint of the church.

The ferryman, it seems, was a penurious old rascal who feigned death for twenty-four hours, expecting his servants to fast till his funeral and thus save him the cost of a day's food. The servants, however, who were half starved, seized the opportunity to break open the larder and feast instead of fast, and the old ferryman rose in his winding sheet, a candle in each hand, bent on chastising the miscreants. One of them, imagining it was the devil himself, picked up the butt end of an oar and aimed with it a blow which brought the death his master had feigned. His daughter, whose lover was killed in an accident following the homicide of her father, entered a convent, and gave the money her father had amassed to build a house of sisters on the ground where part of the present church now stands.

There are two windows in the retro-choir of sinister significance. They represent six clergy of the sixteenth century, and at the base of one of the windows are the names of Laurence[26] Saunders, Rector of All Hallows, Bread Street; Robert Ferrier, Bishop of St. David's; Robert Taylor, Rector of Hadley, Suffolk; and after each name is the awful and laconic statement, "Burnt". On the other windows the names and dates are almost indecipherable, but below the central figure stands out one word of awful import, "Smithfield". The windows have no artistic merit, and there is nothing arresting in the presentment of those six men who endured the tortures of the damned for their faith, yet somehow they seemed from their dark corner at the east end of the retro-choir to dominate the place. One saw those windows directly one entered—far-off bits of colour at the base of long tunnels framed by the sharply-pointed Gothic arches, and the remembrance of them remained, mingling strangely with thoughts of poets and playwrights. Edmund, brother of William Shakespeare, John Fletcher, and Philip Massinger are buried in the choir. Of the two last named one doesn't know which had the more tragic end. Fletcher, the friend of William Shakespeare, who, according to an old record, had during the great plague been invited by a knight of Norfolk or Suffolk into the country, and who "stayed in London but to make himself a suit of clothes, and when it was making, fell sick and died. This," continues John Aubrey,[27] the writer of the record, "I heard from the tailor, who is now a very old man, and clerk of St. Marie Overie."

Massinger, the poet and playwright, died in 1639. The register of that year records, "Buried, Philip Massinger, a stranger". Poor Philip Massinger, who, after writing forty popular plays, was buried, a pauper, at the expense of the parish. Apparently he had been preaching that which he had been unable to practise when he wrote his play entitled "A New Way to Pay Old Debts".

Edmund Shakespeare, described as "A Player," died before his brother William, and perhaps Edmund was in William's thoughts when he wrote:—

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come.

Whoever before, whoever again, will express with such heart-searching simplicity the secret fear which besets us all, that "dread of something after death, the undiscovered country from whose bourne no traveller returns"?

I have strange and uncanny suspicions about Shakespeare. One knows so little about the man himself, and at times I have wondered if he were some supernatural being sent, perhaps, from another and more enlightened world, to be the mouthpiece of poor dumb humanity in this.[28]

It is invariably reserved for Mrs. Darling to bring me up bump against prosaic facts in the midst of such speculations. We were standing before the monument erected to the memory of that incredible genius, and she greeted the alabaster figure which reclines against a topographical background as an old friend. She knew all about the ghost in "'Amblet" and something about someone who committed a murder in "Macbeth". She said, referring to the nude appearance of the poet's legs, that it was hard on the men of those days who were knock-kneed, they must have felt very cold with nothing more on their nether limbs than what she described as a "pair 'er bathin' drawers". A supercilious young woman standing near turned her lorgnette on the old lady, and fearing recriminations on the part of Mrs. D., should she discover that she was an object of derision, I drew her with me to examine some old bosses which I had noticed, stacked like winter logs in a corner near.

A verger explained that they were removed from the roof of the old nave when the church was restored. He said they were all of religious significance. A gross countenance in the act of swallowing a problematical morsel represented, for instance, the devil consuming Judas, whilst a hideous face with a lolling, twisted tongue,[29] signified the liar. There were subjects of beauty, too, and as the man proceeded with his glib interpretation of those child-like specimens of mediæval art, I pictured the wood carvers, high up in vaulted roofs, giving the reins to their varied imaginations—beautiful, devout, ugly, or grotesque; at times even bestial. What matter! No one of the worshippers below would see the result of those patient hours of work—only the sunbeams, finding entrance as they travelled from east to west, or the light of the moon, stealing like a thief in the night into the darkness and silence, touching here a rafter, there a bit of carving. And so the artist could please himself and weave his own fancies, devout or profane, beautiful or monstrous, up there all alone in the roof, and if the demons and devils he created leered at the congregations beneath, the angels smiled at them too, and meanwhile no one was the wiser or any the worse.

And now here were the old bosses which had lived solitary and unknown in the dizzy altitudes above the nave, brought down to earth to be stared at and talked about. Did they appreciate the change? And would their creators, could they have foreseen such an anti-climax, have made them different?

I suggested to Mrs. Darling that we should go and have a look at "The George Inn" while we[30] were in the neighbourhood of the Borough High Street. A policeman of whom I inquired said he had a sort of notion he had heard of it. "Down one of those side streets that look as if there's nothing in them," he volunteered. "About the third or fourth turning."

We found the place easily, owing to the forethought of the proprietor, who had placed a notice at the entrance of the yard warning passers-by not to be misled by the appearance of its leading to nothing. The George Hotel (I was sorry he had adopted that pretentious title in place of the old word "inn") was there, the notice stated, and with thoughts of stage coaches, Sam Weller, and Mr. Pickwick I turned into the yard.

Yes, there it was, tucked away in its funny little corner, conscious, it seemed, of being left behind and forgotten in the present-day rush of life. There were the old wooden galleries, one above another, running the length of its long, flat-windowed front, the sloping, red-tiled roof with its garret windows, the coffee-room with its faded red curtains, and the entrance by a low door down a step. A waggon, with some porters in attendance, stood in front of the Great Northern Goods Depot at the farther end of the yard, but no signs of life about "The George," save a charwoman with a pail in the lower of the two galleries. This was probably owing to the[31] fact that it was closing time: surely an opportunity for the ghosts to put in an appearance! Perhaps, though, they preferred the bustle of customers and clink of glasses. For myself, I must confess that the sight of a closed "pub" has an effect as depressing as that which attends a walk in the City streets between three and four o'clock on a Christmas afternoon.

I apologised to Mrs. Darling for not being able to offer her a drink at "The George," and we retraced our steps towards London Bridge. Some day, Agatha, I will take you to London Bridge about 4.30 on a November afternoon, when there is just the right kind of sunset to fit the picture. It was the right kind this afternoon—one of those skies suffused with rose-coloured clouds which come on like the reinforcements of a vast army under the smoke of artillery, sullenly beautiful with a mood which found its response in the river glazed with a reflection of colour over its black oily depths. Of all the sights of London this, to myself, is the most inspiring, and judging by the row of loiterers one invariably finds leaning over the parapet, there are others who fall under its spell. London Bridge says to the big ships which the Tower Bridge has opened its arms to receive, "Thus far and no farther," and there they lie in the Pool, whilst the cranes, like giant fishing-rods, angle[32] for their booty. Villainous-looking little tugs, with sinister green lights, belch black smoke which mingles with the white steam and yellow smoke from the funnels of the large boats. Amidst coils of rope, bales of goods, and a smutty mirk, the wharf workers and sailors move like ants to the accompaniment of clanking chains and the hooting of sirens. On the sides of the ships are painted strange-looking foreign names, Dutch, Norwegian, and Greek, and Mrs. Darling awoke with surprise to the knowledge that tea from India was deposited almost on her doorstep.

Whilst we stood there a big boat moved out into mid-stream, making a stately course through the smoke-veiled sunset towards where the Tower Bridge was opening its portals with a welcome to the high seas beyond. As the vessel neared the bridge, it was as if the artist who was painting the picture had touched it here and there with the point of a luminous pencil. The pencil travelled along the blackened wharves, dotting them with pin-pricks of light, and the men on the barges and boats below began to hang out their lanthorns. It was an epic, this passing of the ship through the gates of Old Father Thames. The lights shone out to give it good speed, and the smouldering fires of sunset followed in its wake. The majesty of the scene[33] filled one with a sense of elation, and I said to myself, "It is not for nothing that London is called 'the Heart of the Empire'".

Mrs. Darling asked me if it was true that houses were built on old London Bridge, and I quoted the description of the place by a contemporary writer: "The street," he says, "was dark, narrow, and dangerous, the houses overhanging the road so as to almost shut out the daylight," adding the information that "arches of timber crossed the street to keep the shaky old tenements from falling on each other." "London Bridge," declared an old proverb, "was made for wise men to go over and fools to go under," but when one reads such statements as "in 1401 another house on the bridge fell down, drowning five of its inhabitants," it occurs to one that there was almost as much danger overhead as below, where fifty watermen were computed to be drowned every year.

What a picture those old records paint! There can be no pictures like it in the London of to-day. Add the ghastly touch of a row of rotting heads spiked on the battlements, and you are set wondering anew at the weird psychology of the dark ages.

I told Mrs. D. the story of Sir Thomas More's head, which his daughter bribed a man to remove from the spike on the bridge and drop into a boat[34] below where she sat, and the old lady said, "It must 'ave bin a good shot". The person responsible for Mrs. D.'s anatomy left out the bump of reverence; sentiment is also foreign to her composition, whilst her scepticism of anything she cannot actually see and touch is a deeply ingrained quality. Sir Thomas More, Henry VIII, Charles II, the Christian martyrs, are, in her estimation, to be taken with a grain of salt. She makes no distinction between them and "'Amblet" or the creations of Bunyan's brain. Tradition is a dead letter to her, and although she takes a marked interest in the Plague and the Great Fire, I have a suspicion if she were asked to "have a bit" on the actuality of those happenings, she would lay odds for, with a sensation of risk.

Another story of a head, instinct with the fee-faw-fum spirit of the times, is that about good old John Fisher, who would not recognise the spiritual claims of Henry VIII. Fisher's head was parboiled before being spiked, and, according to Walter Thornbury, in his "Old and New London," "the face for a fortnight remained so ruddy and lifelike and such crowds collected to see the so-called miracle, that the king, in a rage, at last ordered the head to be thrown down into the river".

But, dear lady, I am burning the midnight oil[35] and must to bed. Do I dream, or does the old watchman pass my window crying:—

Maids in your smocks,

Look to your locks,

Your fire and your light,

And give you good night?

Anyhow, it is a relief to turn from those ghastly trophies on the battlements of the Bridge to this kindly warning with its concluding benediction.

I echo the latter, and am ever yours,[36]

GEORGE.

CARRINGTON MEWS,

7th October.

DEAR Agatha,—I'm glad you were interested in the account of my outing with Mrs. Darling. Your reference to Verdant Green was apposite but not quite kind. I bear no malice, however: witness the continuation of the history of my wanderings.

I have been reading "Pepys' Diary" for what Mrs. Darling would call the "umpteenth" time. Strangely enough, I had never visited his tomb, and it occurred to me that Mrs. Darling and I might make a day of it, starting with Bankside and working round to Hart Street, Seething Lane, by way of Upper Thames Street. We got off our 'bus at Southwark Street because I wanted to see some ancient alms-houses I had been told were tucked away in a side turning near. Alms-houses have an atmosphere of their own which I always find congenial to my age and aspirations—a roof to cover one, food and light, and time to idle: what more could one want! Mrs. Darling[37] didn't agree with me. She is not the kind of woman to grow old gracefully. She runs across roads, and would no more dream of sitting over the fire doing nothing for half an hour than she would contemplate wearing caps—I refer to old ladies' caps, not the cloth variety which is the approved head-dress for ladies of her class when doing the morning's shopping.

We found Hopton's Alms-house in Holland Street almost by chance. It is so easy to pass along the end of the street without discovering anything unusual. One sees nothing but an iron railing and a hint of green, and had I not been on the look out, I should have gone my way unconscious of Hopton and the little oasis he had created for his old men and women in this corner of the busy city.

We found that the iron railing shut off a little world of "God's Houses," as they call them in Belgium, from the squalid road and the tall ugly buildings opposite. On a tablet was inscribed the laconic statement, "Chas. Hopton, Esq.: Sole founder of this charity. Anno 1752," and when the winter's gales roar down the chimneys at nights, or the rain beats against the casements, I hope the pensioners sometimes give Charles a grateful thought.

The houses are built in blocks round three sides of a green which is traversed by paved paths and[38] set with trees, one tree in each section. The grass was very green, and pigeons were assembled on the tiled roofs. There were wooden benches placed at intervals, and a sleek cat sat on one of them, whilst some caged birds sang unconcernedly over its head.

I spoke to an old man who stood at the door of one of the houses, and he took us to the back of his dwelling to show us his little garden, in which a few chrysanthemums were making a brave struggle against the city smoke. Each house, he pointed out, had its allotment, but the overshadowing warehouses and factories made gardening a rather thankless task.

Continuing our way we turned into a side street of mean houses, at the end of which the vicinity of the river was disclosed by the rattle and clank of huge cranes as they made their lazy circular movements against the sky.

We were in Shakespeare's world, and Bear Garden's Alley must have been named after the Bear Garden, which was almost next door to the Globe Theatre, where Shakespeare acted. Rose Alley, too, was reminiscent of the Rose Theatre, where Ben Jonson's plays were performed. But what has this dingy wharf to do with the rural scene amidst which those old theatres were placed? Surely there never could have been fields and country lanes in this neighbourhood of[39] slums, factories, and warehouses! Fields and lanes which would be sweet with the scents of summer evenings, and which Shakespeare must have walked, thinking perhaps of "a bank where wild thyme grows, quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine".

It was low tide, and the river flowing oilily between its banks was of the same hue as the mud. A fog haze lurked in the background all round, and on the opposite side a red-painted barge stood out as if having caught the warmth of a hidden sun. A few moments ago there had been no St. Paul's, but now there grew the vague outline of a vast circumference suspended in the air high above the warehouses opposite. Minute by minute, as the veil-thinned details were born, the sun found the gold cross, and the dome washed with purple rose as at the touch of an enchanter's wand into the sun-rayed vista.

"That's a place I never bin to," observed Mrs. Darling with an air of conscious virtue. I did not suggest that she should make good the omission. To tell the truth, the outside of St. Paul's makes me happier than the inside. To see its purple dome float in majesty above the sea of house-tops, as unsubstantial as an opium-eater's dream, or to meet its august presence face to face half-way up Ludgate Hill, when the pigeons are wheeling round it like bits[40] of tinder blown from an unseen fire, is to find that "thing of beauty" which is a "joy for ever". But to go inside is to lose one's identity in a homeless immensity and a wilderness of echoes.

I was reluctant to leave the river-side. It is an ideal spot for "loafing". The men employed on wharves and barges are a class apart from the ordinary workman, it always seems to me. They may not be conscious of it, but the meditative spirit of the lazy tide, the slow-moving barges, and those silent activities of the river's life have instilled in them a poetical and contemplative outlook on existence which no other calling can inspire.

We crossed the river by the temporary bridge, and turning to the right made our way along Upper Thames Street. As we went I meditated on "What's in a name?" the question being suggested by the quaint nomenclature of the courts and alleys of the city. From the stores of my memory I could produce Hanging Sword Alley, Dark House Lane, Passing Alley, Pudding Lane, Hen and Chicken's Court, World's End Passage, Fig Tree Court, Green-Arbour Court, Boss Alley, Maypole Alley, Crucifix Lane, Sugar Loaf Court. And last week I came across a book dated 1732 in which was an alphabetical table of all the streets, courts, lanes, alleys,[41] yards, rows, within the bills of mortality. Some day I'm going to take that old book with me and go on a voyage of discovery. Are Dirty Lane and Deadman's Place still to be found in the parish of Southwark? Is Coffin Alley still in St. Sepulchre's? I'm afraid not, and I'm quite sure that Damnation Alley no longer graces St. Martin's in the Fields.

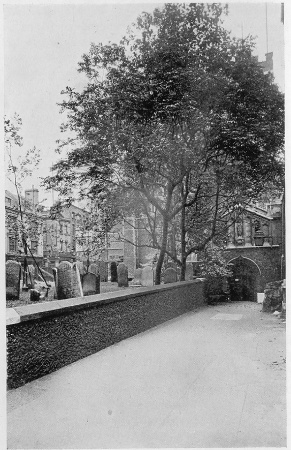

By way of Fish Street Hill, Eastcheap, Great Tower Street, and Mark Lane we approached St. Olave's in Hart Street. As, however, I wanted to look through the railings at the old churchyard, we turned the corner into Seething Lane, where, on top of the iron gate, is a sinister memento of the Plague. They were weird times, those old days, with their childish spirit of fee-faw-fum, and the skulls and crossbones on top of the gate bring a breath from the dark ages into some moment of to-day. Probably not one person in a hundred notices the skulls or pauses to look through the iron railings and reflect that Pepys himself must have walked down that very pathway between the gravestones on that occasion of which he wrote. "This is the first time I have been in the church since I left London for the Plague," he says, "and it frighted me indeed to go through the church, more than I thought it could have done, to see so many graves lie so high upon the churchyard. I was much troubled[42] at it, and do not think to go through it again a good while." Later he records the reassurance he had experienced in seeing those same graves mantled in snow.

I believe it was the custom when making the entry to add the letter P after the names of those who had perished by the Black Death, but I have never had the privilege of seeing the registers. Mary Ramsey, who is supposed to have brought the Plague into London, is buried in the churchyard.

The church is square, with a columned nave, and the old glass in the large east window sheds a mellow light on some painted figures on a tomb near. The building does not wear its history on its sleeve, but Samuel Pepys (the only man who ever told the unromantic truth about himself) could, if he would, paint pictures of some of the scenes those old walls have witnessed. His body lies beneath the altar, and high above it, on the north-east wall, is the monument to his wife. She has a girl-like, engaging face, the head bent slightly forward as if in the act of listening for some message from her lord and master who lies so silent below.

It is certain that when Pepys was so frank with himself about his weaknesses, he never imagined he was going to have an audience which would last through the centuries. I[43] wondered as I looked at the sculptured face with its expression a little wistful, and a little supercilious, which of us would care to purchase notoriety at such a price?

Mrs. Darling inquired curiously about the nature of those self-revelations, and as we consumed our chops and baked potatoes, and drank our ale at a little restaurant near, I told her of a certain Cock Tavern opposite the Temple, where Pepys in his diary mentions bringing Mrs. Knipp (an actress of whom his wife was jealous), and where they "drank, eat a lobster and sang and mighty merry till almost midnight". And how these meetings went on until Mrs. Pepys came to the bedside of her husband one night and threatened to pinch him with red-hot tongs.... Whereupon Mrs. Darling found a resemblance between the Essayist and "that other old gentleman in the waxworks". "Saucy kippers," she called them both, bracketing King Charles with the roving Samuel.

In justice to poor Samuel, however, I told the old lady how he had said, "My wife seemed very pretty to-day, it being for the first time I had given her leave to wear a black patch". How on another occasion he records, "Talking with my wife, in whom I never had greater content, blessed be God!" How he had given her five pounds to buy a petticoat, and how he states[44] that he is "as happy a man as any in the world.... And all do impute almost wholly to my late temperance, since my making of my vows against wine and play."

Mrs. Darling, who had finished her second glass of ale and felt cheerful, pulled on her woollen gloves and set her ten-and-elevenpenny hat at a more jaunty angle. Men, she declared, were "rovin' by nature," and if a woman wanted to be happy there were "some things she got to shut her eyes to". Half the women who grumbled about their husbands had in her opinion got nobody but themselves to thank for it. The theme is a favourite one of the old lady's, and she continued her discourse as we made our way to Houndsditch—a "melancholy" spot, according to Shakespeare, taking its name from the old city ditch full of dead dogs. A region of small wholesale shops in the drapery line which made no pretentions at setting out the wares to advantage, everything being conducted on strict business principles which left no room for trifling. One came across such announcements as "Grand Order of Israel Friendly Society," and names of such Biblical association as Abraham Lazarus, Isaac Levi, and Simon Solomon. You might by favour purchase a solitary blouse or a dozen of buttons, but it was not with such casual purchasers the little shops wished to trade.[45]

We happened on a gateway over which was inscribed, "Phil's Buildings, Clothes and General Market". A man who had been sitting unnoticed in a pay-box thrust his head out of the little window. "Want anyone in there, sir?" he asked.

"No, I want to see the place."

"Penny, please."

I produced two, and we found ourselves in a yard on each side of which were empty houses, apparently used as warehouses for second-hand clothes. Beyond was a little market-place where men were ranging their goods on long forms under a zinc roof. All round lay huge bundles of wearing apparel—one bundle would contain men's underwear, another trousers, another coats, not to mention piles of old boots, hats, and indiscriminate rubbish.

Through the unglazed windows of the empty houses could be seen a salesman fitting a customer with an overcoat, and a ticket hanging from the window-sill gave the information that paper and string cost 2d.

Mrs. Darling said there might be bargains to be had if the buyer was "in the know," the prices placed upon the garments having no relation to what the seller expected to get (unless "a mug" came along). Bargaining was the very spirit of the place, and a good Jew would feel defrauded[46] of his sport if a customer made no attempt to beat him down.

There was a market every day at two o'clock, the Jew in the pay-box told us, and on being questioned he was quite ready to talk about the slums near. A neighbourhood where you wanted a protector after dark—a person like himself, for instance, who knew every man and woman in the place, and who, for a consideration, would take the gentleman round and show him such things as he had never dreamed of. There was the house which had been raided by the police and three of them shot—he could show the bullet marks in the wall. Then there was Mitre Court, where "Jack the Ripper" had followed on the very heels of the policeman on his beat and murdered a poor creature within ear-shot and almost eye-shot of the man in blue, and never a sound of the horrible outrage to break the silence of the night.

There are other sinister associations connected with the spot, and as I listened I remembered the houses near which were built on one of the plague pits. When the workmen were digging foundations they came upon hundreds of bodies, being able to distinguish the women by their long hair. There was an outcry about the fear of contagion, and the bodies were removed and buried all together in a deep hole dug for the[47] purpose at the upper end of Rose Alley. I should not like to live in a house built on a plague pit.

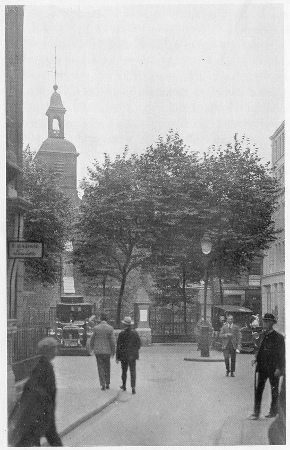

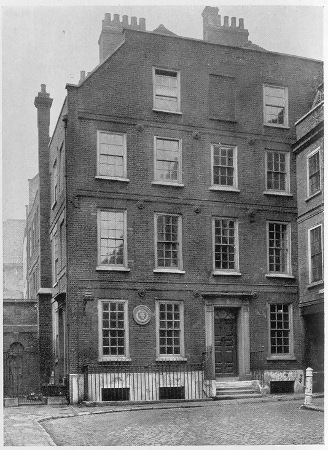

GREAT ST. HELEN'S.

"Great St. Helen's" in Bishopgate Street was a pleasant change from the horrors to which we had just been listening. The churchyard was carpeted with dead leaves and the church inside was vague with a coloured dusk. The glowing windows shut out the light, but through one of plain glass the sun entered, making a rainbow bridge high up across the nave towards the Figure of the Good Shepherd on the opposite window.

As we walked round, trying in the semi-darkness to read the inscriptions on the tombs of Sir John Crosby, grocer and woolstapler, who built Crosby Hall; Thomas Gresham, founder of the Royal Exchange; and Julius Cæsar, Privy Counsellor to James I, the sunbeams which had penetrated here and there through cracks and crevices were crossing swords in the gloom of the old building, finding out a crimson cushion, a sculptured face or hands folded in prayer, and lighting, as it were, candles in odd corners.

Not a vestige remains of the old priory of St. Helen's, and the nuns' gratings on the north side, which communicated with the old crypt, have now nothing but darkness to reveal to the curious who peer through them. On the same[48] side of the church is a walled-up door, and a little circular stone staircase which invites ascent, then confronts the explorer with impenetrable gloom and "no thoroughfare". The old building has lost a limb, and "Finis" is, it seems, writ suddenly in the middle of an exciting chapter.

Mrs. Darling suffers from an infirmity which she describes as "bad feet," so instead of going on to the Charterhouse, as we had intended, we had tea, then home by 'bus.

Mrs. Darling, over her third cup, became expansive, and addressed me as "Old sport". I must certainly give a little time to the study of Cockney slang. I have arrived at the conclusion that it very effectively fills gaps left by the vocabulary of the more cultured and colourless classes.

"Old sport." Not half a bad term. There are moods in which I could apply it to yourself, and occasions on which I really think you might accept it as a compliment.

Yours with the best of intentions,[49]

GEORGE.

CARRINGTON MEWS,

1st November.

DEAR Agatha,—Yes, I am sure you would find the study of Pepys a profitable one. Why not read him to the Mothers' Meeting instead of "The Parent's Friend" or "How to Keep your Husband out of the 'Pub'"? The old chap can be as smug and moral as Sandford and Merton, and his instructiveness is always involuntary.

But to the continuation of the story of my wanderings.

Smithfield, apart from its terrible associations with the Christian martyrs, is not a pleasant place to visit. On every side one is confronted by corpses sewn up in muslin shrouds, whilst ghoulish men in greasy overalls, their hands smeared with blood, superintend the packing of dead flesh into huge vans. A vegetarian could not find a happier spot in which to point the moral of his message. Mrs. Darling said it made her feel as if she could never look a bullock or a[50] sheep in the face again, and the mutton chop I had had for lunch haunted my digestion.

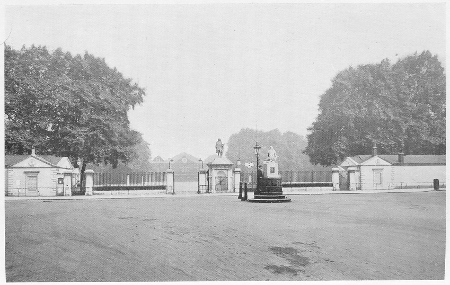

It was a relief to leave these horrors for Charterhouse Square, a sad enclosure behind iron railings where the yellow leaves lay thick on the grass and the benches stood empty under the avenue of limes.

The sparrows and starlings were as vociferous as they only can be on a November afternoon when dusk is approaching. Their notes made a volume of soft whistling sound which flowed like a tide in the still, cold air. It followed us through the gateway and into the courtyard, becoming muffled as we went, then giving place to the perfect peace and quiet of the old buildings and their surroundings.

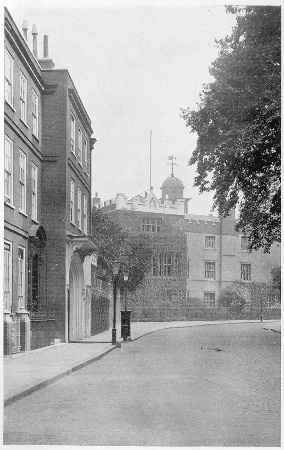

Charterhouse has experienced three phases—first, the Carthusian monastery, then the residence of members of the nobility, lastly, the alms-house for old gentlemen; and it is in this latter capacity that its appeal has always lain for myself, or rather, perhaps, I should say it is the alms-house grafted on that background of ancient history which stirs the imagination.

THE CHARTERHOUSE.

In 1611, at the close of the occupation of the Duke of Norfolk and Lord Thomas Howard, it was bought and endowed as a hospital and school by Mr. Thomas Sutton. The school was removed in 1872, and the number of pensioners[51] ("bachelors or widowers over sixty, gentlemen by descent and in poverty") has been reduced from eighty to fifty.

Mrs. Darling, who has a kindly feeling for "old chaps" (witness her good offices to the writer), was very particular in her enquiries as to what was done for the comfort of these particular old gentlemen, and, judged by the answers of the guide, they have a quite enviable time. I shouldn't mind being one myself.

A comfortable bed-sitting-room, with a fire to go to bed by (each pensioner is allowed two tons and a quarter of coal a year), good food, and forty pounds a year pocket money: what more could one want in those later years when desires become fewer with the growing restfulness of old age! Mrs. Darling was of the opinion that the banning of her sex was to be traced to the monkish associations of the place, and considered it a thing to be deprecated. Men, left to themselves, she declared, got "very narrer-minded and dull". They needed a woman to sharpen their wits "jest the same as a cat needs somethink to sharpen 'is claws on".

We went through a paved passage where are the memorial tablets to some of the old school boys since become famous—Thackeray, Wesley, Sir Henry Havelock, Addison, and Steele—and the guide opening a door at the end, we caught[52] a glimpse of stained glass windows and the dark heavy interior of the Jacobean chapel. In the silence we could hear the tick-tock of the chapel clock, that same old clock which seems the familiar spirit of such places.

I suppose, Agatha, the Charterhouse chapel spells to you, as it does to me, Colonel Newcome, and in the raw dusk of the November afternoon I seemed, in the words of Thackeray, to hear "the old reverend blackgowns coughing feebly in the twilight——"

There were candles in those days; now, the guide touches a button and the place is illumined by electric lights—not too many, however—just enough to throw shadows across the aisles and burnish the carvings on the pensioners' seats. As we stared at the founder's tomb, and heard of the customs appertaining to the 12th of December, fiction became merged in fact, and Colonel Newcome grew from out the shadows of the past, a figure as convincing as any of those buried beneath the old flagstones.

"His dear old head was bent down over his prayer-book; there was no mistaking him. He wore the black gown of the pensioners of the Hospital of Grey Friars. His Order of the Bath was on his breast. He stood there amongst the poor brethren, uttering the responses to the psalm. The steps of this good man had been[53]] ordered thither by Heaven's decree: to this alms-house! Here it was ordained that a life all love, and kindness, and honour should end!"

The guide stood back for us to leave, switched off the lights, and closed the door on the vision of those "reverend blackgowns coughing feebly in the twilight". But carrying the remembrance of them with us, we followed him to Norfolk House. The bare boards of the great oak staircase have a well-scrubbed appearance, and everywhere was silence, a dead magnificence, and chill austerity. One can imagine the brothers' rooms, homelike in the cheerful blaze of their fires, but Norfolk House, with its great staircase, its library and tapestry room, its tiny picture gallery and terrace, possesses the tragic aloofness of things which, having survived their uses, remain to be stared at as relics. The guide switched on the lights as he went, and there sprang to view the library with its book-lined walk—old books of Jesuit travel and divinity which are never opened from one year's end to another. In their dim bindings they make a scholarly background for the Chippendale furniture, and the portrait of the man who had bequeathed them to the institution presides wistfully over the neglected feast of letters. From thence into the governor's room, with its[54] painted Florentine mantelpiece, its faded tapestries, leaden-paned diamond windows, and the arms of the Norfolk family emblazoning the ceiling.

All came to view with the switching on of the lights, then faded into the dusk again at the touch of a button. Our footsteps echoed hollow down the great dim staircase, and we entered the dining-hall, the most ancient of the buildings of pre-Reformation date. Here was the warmth of human contact again: the embers of a fire glowed on the wide hearth under the carved stone chimney piece, and Mrs. Darling said she could smell stewed rabbit and apple tart. She seemed quite pleased with this unofficial testimony to the kind of fare provided for the brothers, and when the guide told her that ale was allowed to all, and whisky to some, her opinion of the administration of the charity went up by leaps and bounds.

Mrs. Darling has no sympathy with the Pussyfoot movement. The late Mr. Darling, it seems, was, like Peggotty's husband, "a little near" when he was sober, and but for his habit of now and again taking too much his wife would never have got a new hat or frock. "Why this very ole plush jacket he bought me the day after 'e'd got drunk and give me a black eye!" she stated triumphantly, "an' it wasn't on'y wot[55] 'e give me neither. It wos wot I used ter pinch when I turned out 'is pockets! I got as much as ten bob at a time, an' he daren't say 'e'd lost anythink, because I'd 'ave said 'e'd kep' bad company and bin robbed!"

Mrs. Darling has an ironic sense of humour you will observe.

I think, of all the pictures provided by the Charterhouse, the one which gave me the greatest enjoyment was that which met our eyes when the guide opened the door of the "brothers'" library. He had first taken the precaution to see that the room was unoccupied, so I imagine it is not exactly on the list of those parts of the buildings free to the public. The place is a long, low-ceiled apartment (originally the monks' refectory), pillared and wainscotted, with square lozenge-paned windows through which the light of the fading afternoon entered reluctantly. It must, at any time, be a dark room, the outstanding bookcases dividing it into aisles, at the end of which were the dusty old windows.

But in the twilight, with a ruby fire glowing on the hearth, a large crimson Turkey rug before it, and a semi-circle of empty wooden chairs ranged round, it struck a note of comfort and homeliness very welcome after our wanderings through rooms given over to ghosts. Not that[56] those same ghosts did not lurk here too. The empty wooden chairs with their stiff, outstretched arms, had a suggestion of waiting for a company other than the black-robed pensioners who, apparently, were fonder of their own bed-sitting-rooms than this ancient apartment with its monkish associations.

But the guide was waiting for us: there is no time allowed for dreaming in these places. One must do that afterwards at home, and I sometimes think, Agatha, that more even than my enjoyment in the actual visits to these old scenes, is the pleasure of talking to you about them in these letters.

A solitary gas lamp was flickering here and there in the cloisters when we came outside, and we found the sparrows and starlings still continuing their concert with indefatigable energy. As they flew round and round the trees it was difficult to distinguish between birds and falling leaves. The dusk was peopled with both.

The proximity to St. Bartholomew's suggested a visit, and we walked a few yards down Aldersgate Street and from thence into Cloth Fair. Of the original Cloth Fair there is very little left now. On every side you see empty spaces where, not many years ago, had been tortuous streets and courts of ancient houses that must have witnessed the reign of many a king and[57] queen—houses that stood there long before the Christian martyrs were burnt at Smithfield, and first plague, then fire, ravaged the city. Could they have told their terrible secrets those ancient dwellings might have recounted stories as terrorising as the most blood-curdling of nightmares.

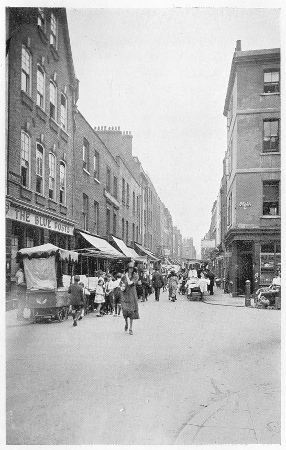

A BIT OF OLD SMITHFIELD.

Of the particular row of houses which had always appealed to me by reason of their contiguity to the churchyard, part of one only remains. Many a time have I stood and stared at the dingy backs of those unwholesome dwellings, wondering what it must feel like to live in a room with a discoloured tombstone peeping in at the window. Familiarity, one imagines, would breed contempt, but there would be times during sleepless nights, or in some hour of depression, when the horrid nearness of that sooty churchyard, with its mouldering bodies under the rank grass and refuse, would foster the evil imaginations of madness.

However, the houses, and many of their like, have gone now, and Cloth Fair and Little Britain, with the exception of little bits here and there such as in East Passage, make space for business premises and warehouses. In the midst of it all stands St. Bartholomew the Great, a thing of mutilated limbs—witness the scars on portions of its walls where its members have been[58] dissevered, and where in their place mundane buildings have crowded up to within a few yards of it. Yet there it stands, in dignified aloofness from the intrusive neighbours who nudge its elbows with irreverent and familiar touch. They may rub shoulders with it at every point, but between them and it is no more intimacy than there is between Rahere, its founder, and the sight-seer who, gazing at his tomb, learns the story of his conversion from jester to monk. The strange story of a vision of St. Bartholomew, in which the Saint, with a practical regard to detail, ordered Rahere to build a church in Smithfield, a behest the noble fulfilment of which is made evident in the old walls that have weathered so many centuries, and the Hospital next door.

St. Bartholomew's is one of those buildings which has, like some people, to be known to be loved. At first one is almost repelled by its austere and dignified beauty. It is unapproachable with the unapproachableness of the great. It is dim, too, with the pathetic dimness of a lonely old age, and one's sense of reverence is violated when one learns that the Lady Chapel was at one time tenanted by a fringe manufacturer, and the north transept used as a blacksmith's forge.

But the age of vandalism is past, and within[59] the old walls law and order are restored. The ring of the blacksmith's hammer has given place to the solemn notes of the organ, the blaze of the forge fire to the soft light of altar candles. The fret and hurry of life no more cross the threshold, and you can meditate undisturbed.

Mrs. Darling was obviously bored. Historical details and dates leave her cold. She does not belong to the class of sight-seers who, hungry for information, follow sheep-like in the wake of the guide. She wanders off on her own and has a curious faculty for seizing on some unimportant detail which makes a personal appeal to her. Charterhouse will always mean for her the figure of one of the old pensioners we saw in the cloisters. A funny old chap in a large slouch felt hat, a dirty trench coat, and with his trousers sagging about his ankles—that and the smell of stewed rabbit and apple tart, together with rumours of nips of whisky and glasses of ale, will stand out in her memory from an undigested mass of "dry" facts and a background of empty echoing rooms and old grey walls, which latter, as she expressed it, "give her the pip". The history of The Priory of St. Bartholomew made her tired, and I suggested an adjournment.

As we passed St. Bartholomew's Hospital I pointed out to her the brass plate in the wall on which was inscribed the names of some who,[60] within a few feet of the spot, had suffered for their faith at the stake in 1556-1557. Smithfield will always be a place of shuddering associations, and even the prosaic market front and the cold-storage premises, with their rows of lighted windows starring the blue dusk, seemed in some strange fashion implicated in its awful memories. As late as March, 1849, when excavations were being made for a new sewer, there were discovered, three feet below the surface, immediately opposite the entrance to the church, charred human bones and the remains of some oak posts partially consumed by fire. From whence did the courage of those heroic citizens of old come? Life has no greater mystery than the undaunted spirit with which they faced the hellish tortures of fire and the rack.

At the top of Giltspur Street I paused with a sudden recollection of having heard that there still existed the quaint statue of the Fat Boy who used to stand at Pie Corner, where the Great Fire ceased. The incident appealed to Mrs. Darling's curious faculty for selection. She said she would like to see that fat boy, and we promptly went in search of him.

There were no signs of Pie Corner, the spot where it should have been being occupied by the shop of a foot specialist. It was Mrs. Darling who discovered the Fat Boy standing[61] in a little brick alcove, over the door, which had apparently been made for his reception.

He was not a model of symmetry or beauty, but Mrs. Darling promptly annexed him as she had annexed the old pensioner of the sagging trousers and slouched hat, and somewhere in the lumber-room of the old lady's memory the Fat Boy took his place with Charles II, the aforesaid old pensioner, and Samuel Pepys, to whom she invariably refers as "that saucy ole man with the curls".

The fact that the Great Fire broke out at the king's baker's in Pudding Lane and ended at Pie Corner struck her as something more than a coincidence. It was all very well for people to talk about "chance," she didn't believe in chance. The very fact of the coincidence of names suggested, to her mind, a well-thought-out plan. She would have sympathised with the Rev. Samuel Vincent, who, writing at the time, said, "This doth smell of a Popish design, hatcht in the same place where the Gunpowder Plot was contrived".

By the way, I never think of the Great Fire without remembering the description of an eyewitness of the burning of Guild Hall: "And amongst other things that night, the sight of Guildhall was a fearful spectacle, which stood, the whole body of it together, in view for several[62] hours together, after the fire had taken it, without flames (I suppose because the timber was such solid oak), like a bright shining coal, as if it had been a palace of gold, or a great building of burnished brass". You won't beat that for a bit of word painting.

We walked on through the Old Bailey and into Fleet Street, where Shoe Lane reminded me of the fact that the man who was responsible for the phrase, "Before you could say Jack Robinson," was a tobacconist named Herdom, who lived at 98 Shoe Lane some hundred years ago.

The following verse is ascribed to him:—

Says the lady, says she, "I've changed my state."

"Why, you don't mean," says Jack, "that you've got a mate?

You know you promised me". Says she, "I couldn't wait,

For no tidings could I gain of you, Jack Robinson,

And somebody one day came to me and said

That somebody else had somewhere read,

In some newspaper, that you were somewhere dead".

"I've not been dead at all," says Jack Robinson,

the pathetic naïveté of which statement marks the simple sailorman.