Title: The Missing Link in Modern Spiritualism

Author: A. Leah Underhill

Release date: August 13, 2012 [eBook #40485]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell, eagkw and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY

A. LEAH UNDERHILL,

OF THE FOX FAMILY.

REVISED AND ARRANGED BY A LITERARY FRIEND.

NEW YORK:

THOMAS R. KNOX & CO.,

(Successors to James Miller,)

813 Broadway.

1885.

Copyright, 1885, by

A. LEAH UNDERHILL.

TROW’S

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY,

NEW YORK.

Dedication.

TO MY HUSBAND,

DANIEL UNDERHILL,

WHO,

BEFORE I HAD OTHER CLAIMS THAN THOSE OF TRUTH AND RIGHT,

NOBLY SUSTAINED ME WHEN OLDER FRIENDS WAVERED,

THIS NARRATIVE IS DEDICATED,

NOT LESS GRATEFULLY THAN LOVINGLY.

The author of this volume, having written it from

time to time, from her recollections and documentary

materials, which include bushels of letters—but unwilling

to commit it to the press in the disjointed condition which

was a natural consequence of her own want of much practice

of the pen—did me the honor of requesting my aid

in revising and arranging it for publication. Her honesty

and sincerity of character have caused her to insist upon a

preface to that effect. Though deeming this a superfluous

scruple on her part, I am induced to comply with her wish

for a different reason; and that is, the opportunity it affords

of bearing my testimony to the remarkable accuracy

of her memory and of her truthfulness, as those qualities

have proved themselves throughout the intimate intercourse

of many weeks, during which she has often had to

repeat the same recollections of facts and incidents, under

what was almost legal cross-examination, without ever the

slightest variation in their details, and without ever allowing

anything to pass which might be in the least degree[vi]

tainted with inaccuracy or mistake. As she is so well

known to so many friends, it is superfluous for me to express

on this page, which will meet her eye for the first

time in print, the high and affectionate esteem and respect

with which that intimate intercourse, with all its opportunities

for observation and judgment, have inspired the

Editor.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Hydesville | 5 |

| “Mysterious Noises” heard in the House of John D. Fox, in Hydesville (Town of Arcadia), near Newark, Wayne County, N. Y.—Statements of Witnesses. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Hydesville (Continued) | 20 |

| The Last Digging in the Cellar—Mob Antagonism—Noble Friends—Experiences and Theories—Antecedents of the House—Franklin. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Rochester | 30 |

| My First Knowledge of the Matter—Hasten to Hydesville—Rapping on a Canal Boat—Experiences—Mother Comes to Rochester—Calvin Brown—Devious Route of Projectiles Up-stairs from Cellar to Garret—A Death-knell Sounded all Night on the Keys of a Locked Piano. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Rochester (Continued) | 47 |

| Ventriloquism—“Proclaim these Truths to the World”—The Call for the Alphabet—Voices in Raps—God’s Telegraph between the two Worlds—An Eviction—Committee of Five—No Money Accepted—Improper Questions to Spirits—“Done”—Struggle against the “Uncanny Thing”—Benjamin Franklin.[viii] | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Rochester (Continued), November, 1848 | 57 |

| Light Articles made Immovable—The Coffins—Adieu of the Spirits—Their Return—First Steps toward Public Investigation—“Hire Corinthian Hall”—First Committee of Investigation—Second—Third or “Infidel” Committee—Behavior of a Great Dining-table—The Tar and Torpedo Mob. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Mediumistic Vein in Our Family | 74 |

| Some Family Antecedents—Our Great-grandmother—Phantom Prophetic Funerals—Vision of a Tombstone Nine Years in Advance, etc. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Mediumistic Vein in Our Family (Continued) | 89 |

| Marvellous Writing by a Baby Medium. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Rochester (Continued) | 100 |

| “Repeat the Lord’s Prayer”—First Money Accepted—Muscular Quakerism—Letter from George Willets—Letter from John E. Robinson—Caution against Consultation of Spirits about Worldly Interests. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Albany and Troy. 1850 | 115 |

| Excursion to Albany—Delavan House and Van Vechten Hall—Rev. Dr. Staats and the Judges—High Class of Minds Interested—President Eliphalet Nott—Pecuniary Arrangements—Excursion to Troy—Trojan Ladies—Mob Attempts on Life of Margaretta. | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| New York. 1850 | 128 |

| “The Rochester Knockings at Barnum’s Hotel”—Hard Work—Our Visitors—A Poisoned Bouquet—Hair of the Emperor Napoleon I.—Hair of John C. Calhoun—Investigation at Residence of Rev. Rufus W. Griswold, by the Leading Literary Celebrities of New York.[ix] | |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Return to Rochester | 142 |

| Letters and Newspaper Articles Respecting our New York Campaign—Letter from Amy Post—Letters from John E. Robinson—Article from a Sunday Newspaper—From the New York Day-Book—Letter from Dr. C. D. Griswold—Letter from Jacob C. Cuyler—Article by Horace Greeley—Poem from the Sunday Dispatch. | |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Buffalo. 1850-51. | 165 |

| Urged to Return to New York—Visit to Buffalo—Attempt by a Pretended Friend to Frighten us Away—Thunderbolt from the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser—The “Females”—Knee-joint Theory—Our Reply Challenging Investigation of it—The Doctors’ Day—Mrs. Patchen’s Peculiarity. | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Buffalo (Continued) | 179 |

| Investigations upon Investigations—A Meeting at the Phelps House—Manifestations with Bells, etc.—Mr. Albro’s Report—A Death Scene—Letter from Me to the Commercial Advertiser, and how I forced its Insertion—Article from the Buffalo Daily Republic—Letter from Mr. Greeley—Mr. E. W. Capron—Departure from Buffalo. | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Buffalo (Continued) | 197 |

| Letters from John E. Robinson and Welcome Whittaker. | |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Extracts from D. M. Dewey’s History | 206 |

| Letters from Rev. Charles Hammond and John E. Robinson. | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Ohio Campaign | 219 |

| Return to Rochester—Attempted Burglary—Summons to Ohio—“Rev.” C. C. Burr—“Toe-ology”—Gold Medals and Jewelled Watch—First Public Speech—Committee Investigations as usual—Calvin’s Illness, and henceforth Mrs. Brown—First Spiritual Convention.[x] | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Miscellaneous Letters Connected with the Ohio Campaign | 231 |

| N. S. Wheeler—E. S. Brownfield—Chillicothe Committee—Charles F. Whippo—M. L. Wright—D. A. Eddy—Extracts from the Press—“A Fair Challenge from Mrs. Fish” and Sequel—Columbus Committee—D. A. Eddy—M. L. Wright—Interesting Letter from Dear Amy Post—Article from the Cleveland Plaindealer. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| New York City, from January, 1852 | 250 |

| Competing Claims upon Us—Decision in Favor of New York as Residence—Death of Calvin R. Brown—Remains Removed to Rochester for Burial—Personal Friendships—Alice and Phœbe Cary—Course of Test Experiments at Dr. Gray’s—The Monday Evening Circle—Rules of Séances. | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| New York City (Continued) | 269 |

| Our Brilliant Success with the Superior Intellectual Classes—Whiskey at Washington—Cognizance of Domestic Secrets—Discomfiture of Anderson, “the Wizard of the North”—Remarkable Experience with a very Notorious Person. | |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Phosphorus | 282 |

| Spirit Lights Visible at Dark Séances—Private Circle in Jersey City in 1857—Solid Granules of Phosphorus Appearing in Earth which I had Touched—Surprising and Distressing Letter—The Good Spirits and Daniel Underhill to the Rescue—Benjamin Franklin—Marriage to D. Underhill, November 2, 1858, and Close of my Public Mediumship—Analogous Phenomena in Private at Home. | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Boston and the Harvard Professors, 1857 | 297 |

| Agreement for an Investigation by a Committee of Harvard Professors—Expulsion of a Student from the Divinity School for the Crime of Mediumship—Professor Felton—Agassiz—Varley, the Electrician of the Atlantic Telegraph Company.[xi] | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Boston and the Harvard Professors (Continued) | 312 |

| Disinterested Judgments upon the Sham Investigation—Our Part in the Proceedings—More Fair Investigation by the Collective Representatives of the New England Press—Investigation by a Body of Unitarian Clergymen—Our Triumphant Return Home—Theodore Parker. | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Robert Dale Owen and Professor Felton, President of Harvard College | 326 |

| Masterly Letter from Mr. Owen. | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Experiences of Robert Dale Owen through the Mediumship of the Author | 339 |

| Moving a Ledge of Rock on the Sea-shore—Raps on the Water, and in the Living Wood—Seeing the Raps—Moving Ponderable Bodies by Occult Agency—Crucial Test—A Heavy Dinner-table Suspended in the Air by Occult Agency. | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Experiences of the Author with Robert Dale Owen (Continued) | 348 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Spirit Cures—Mr. Capron’s Wife | 361 |

| Statement by E. W. Capron—Wife of General Waddy Thompson, of South Carolina—Wife of Mr. Davis, of Providence, R. I. | |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Miscellaneous Letters | 368 |

| J. Heddon—S. Chamberlain—John E. Robinson—A. Underhill—George Lee, M.D. | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Miscellaneous Letters (Continued) | 386 |

| E. F. Norton—John E. Robinson—Governor N. P. Tallmadge—Pauline M. Davis—Same—John E. Robinson—Prof. J. J. Watson.[xii] | |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Some Observations on Mediumship | 403 |

| Mysteries of Mediumship—To Prove the Immortality of the Soul—Passivity and Harmony at Séances—Honest and Candid Scepticism—Imaginary and Self-induced Mediumship—Deceptive Communications—Cautions—Rappings—Spirits made Visible—Beware of Fraudulent Mediums—Not all Spirits Reliable—Cabinets. | |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Miscellaneous Incidents | 415 |

| Felicia Hemans—Spirit Dictations of Music. | |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Miscellaneous Incidents (Continued) | 421 |

| Crowd of Spirits made Visible by Lightning—Scarcely Credible but True—A Game of Euchre—Margaret’s Dream—Mistaken Names Corrected by Spirits—An Unwilling Convert made Grateful and Happy—A Spirit Knows better than the Postmaster—Opening of a Combination Lock—A Visitor Magnetized into a Medium Himself—Curious Story about a Mutilated Limb—Disturbance in the Troup Street Cottage—A Caution against Cruelty to Orphan Children—Mrs. Hopper’s Mysterious End—“Touch Samantha”—“I felt my Handkercher Tied Tighter every Minit”—“No Brimstone yet”—Kitchen Work by Night—‘Sich a Gittin’ up Stairs’—The Death of Isaac T. Hopper—William M. Thackeray—“Witch Stories”—George Thompson—A Child’s Letter—Extracts from D. Underhill’s Minute Book—Practical Jokes Performed and Rebuked—A Prophetic Dream—James A. Garfield—“Incident” Related by the Editor. | |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Action of Spirits through the Mediumship of a Five-month’s-old Infant | 464 |

| Various Manifestations around the Baby—Writing in Greek through his Hand. | |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| “The Missing Link” | 471 |

| Finale | 475 |

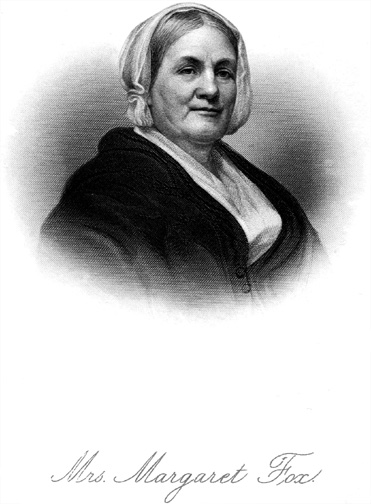

| Mrs. Margaret Fox | Frontispiece. |

| PAGE | |

| John D. Fox | 10 |

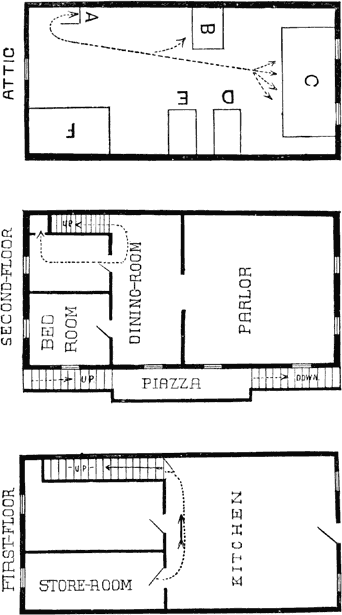

| Diagram, Prospect Street House | 42 |

| Autograph Illustrations of a Baby’s Mediumship | 90 |

| Mrs. Margaretta Fox Kane | 122 |

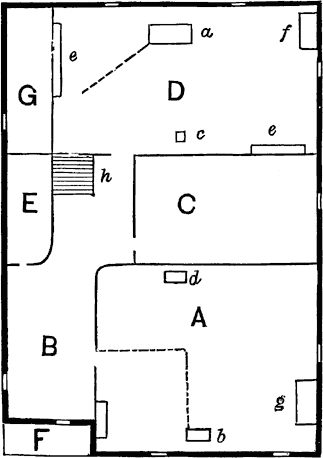

| Diagram, Trout Street House | 209 |

| Cleveland (Ohio) Gold Medal | 225 |

| Autograph Letter of Alice Cary | 265 |

| Autograph Letter of Same | 266 |

| Autograph Letter of John W. Edmonds | 267 |

| Autograph Letter of Horace Greeley | 268 |

| Daniel Underhill | 292 |

| Mrs. Katie Fox Jencken | 465 |

| Greek Writing by a Five-month’s-old Infant | 470 |

| A. Leah Underhill (the Author) | 475 |

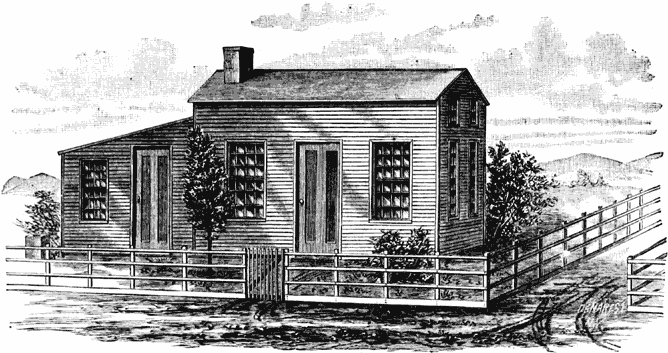

| The Hydesville House | 477 |

Note.—The steel-engraved portraits of the Fox family are from paintings, of dates very different from those referred to on the pages which they face. With the exception of the parents (Mr. and Mrs. Fox), they represent the three “Fox girls” (as they were called) at ages more matured than would correspond to the text of the pages which they accompany. Photography was not so advanced and universal as at the present day.

It is not that the history of Spiritual Manifestations in this century and country has not again and again been written, nor that a library of the splendid literature of Spiritualism—narrative, philosophical, and religious—does not already exist, that I have deemed it a duty to give this history to the world.

It happens that nobody else possesses—both in vivid personal recollections and in stores of documentary material—the means and the data necessary for the task of giving a correct account of the initiation of the movement known as Modern Spiritualism; and the now hastening lapse of years gives warning that if to place it on record is a duty—as many friends have often urged—it is a duty not to be much longer delayed.

Many mistakes and material omissions have been made in former summary accounts from pens of friends, as well as misstatements from those of foes; nor could any one heretofore form any clear or complete idea of the early years of the epochal period which dates from March 31, 1848.

Since that day, starting from a small country village of Western New York, Spiritualism has made its way—against tremendous obstacles and resistances, but under an impulse and a guidance from higher spheres—round the civilized globe. Starting from three sisters, two of[2] them children, and the eldest a little beyond that age, clustered round a matchless mother (whose revered portrait does honor to my title-page), its ranks of believers, private or publicly avowed, have grown within thirty-six years to millions whose number no man positively knows, but which, I think, cannot be less than as many as it counts of years. Beginning in a small house, temporarily occupied while another was building, it has established itself in sovereign palaces; and the latest reports from England represent it as fast growing, under the encouraging influence of the reigning royal family, even into social fashionableness. As in the story of the weary forty years’ wandering of the children of Israel in the desert—fed by food and led by light, both from heaven—so does Spiritualism seem to be now nearing the borders of its Promised Land. It is but a few years since it was a favorite topic for scoff or sneer by the press, while now it is but rarely that here and there is to be found some writer so far lagging behind the march of the age as still to yield, in that way, to the force of former foolish habit. How far and how deeply it has modified the old teachings of the pulpit is patent to all observant eyes; while among the priesthood in the divine temple of Science, the number and unsurpassed rank of those who, under its influence, have abandoned the materialism of their old philosophies, after exhaustive investigation of the facts and truths of Spiritualism, is such as to stamp with the disgrace of simple ignorance those who may still dare to deny and deride;—even as history has fixed the fate of those professors and priests who refused to take a look through Galileo’s telescope; or of those doctors who, being past the age of forty, could never, to their dying day, accept Harvey’s demonstrations of the circulation of the blood.

It will be seen in the following pages how a vein of that[3] mysterious something which, in our generation of “the Fox family,” has come to be called “mediumship,” is perceptible, cropping out in old stories, running through ancestral generations, and how it reappears most marvellously in an infant in the next one succeeding to us. It will also appear how long and strenuously we resisted its influence and its manifestations, and struggled against the absolute persecutions which at last forced us into publicity.

I conclude this Introduction by a brief allusion to the reasonable question which has been so often asked, Cui bono?—or what is the use of the manifestations of Spiritualism?

It is that they demonstrate the reality of the survival of man’s spirit, or inner self, after that “death” which is but birth into another stage of progressed and progressive life, in unchanged personality and identity; or, in other words, that immortality of the soul (heretofore a mere dogma of unproved and unprovable “faith”), which is the foundation corner-stone of all religions and of all Religion. In the words of Paul, to “faith” they “add knowledge.” They thus not only console bereavement, snatch from death its sting, and from the grave its victory, but through the concurrent teachings of all good and advanced spirits they make us feel the real reality of the brotherhood of mankind, and the common fatherhood of that supreme, unnamed, and unnamable Infinitude of Love, Wisdom, and Power, who is addressed in Pope’s Universal Prayer, as—

“Mysterious Noises” heard in the house of John D. Fox, in Hydesville (Town of Arcadia), near Newark, Wayne County, N. Y.—Statements of Witnesses.

The following statements were made by the different persons whose names are signed to them, and taken down in writing as they made them; after which they were carefully read, and signed by them. They comprise but a small number of those who heard these noises, or have been knowing to these transactions; but they are deemed sufficient to satisfy the public mind in regard to their truthfulness.

“We moved into this house on December 11, 1847, and have resided here since that date. We formerly lived in the city of Rochester, N. Y. We were first disturbed by these[6] noises about a fortnight ago. It sounded like some one knocking in the east bedroom, on the floor; we could hardly tell where to locate the sounds, as sometimes it sounded as if the furniture was moved, but on examination we found everything in order. The children had become so alarmed that I thought best to have them sleep in the room with us. There were four of us in family, and sometimes five.

“On the night of the first disturbance we all got up, lighted a candle and searched the entire house, the noises continuing during the time, and being heard near the same place. Although not very loud, it produced a jar of the bedsteads and chairs that could be felt when we were in bed. It was a tremulous motion, more than a sudden jar. We could feel the jar when standing on the floor. It continued on this night until we slept. I did not sleep until about twelve o’clock. On March 30th we were disturbed all night. The noises were heard in all parts of the house. My husband stationed himself outside of the door while I stood inside, and the knocks came on the door between us. We heard footsteps in the pantry, and walking down-stairs; we could not rest, and I then concluded that the house must be haunted by some unhappy, restless spirit. I had often heard of such things, but had never witnessed anything of the kind that I could not account for before.

“On Friday night, March 31, 1848, we concluded to go to bed early and not permit ourselves to be disturbed by the noises, but try and get a night’s rest. My husband was here on all these occasions, heard the noises, and helped search. It was very early when we went to bed on this night; hardly dark. I had been so broken of my rest I was almost sick. My husband had not gone to bed when we first heard the noise on this evening. I had just lain[7] down. It commenced as usual. I knew it from all other noises I had ever before heard. The children, who slept in the other bed in the room, heard the rapping, and tried to make similar sounds by snapping their fingers.

“My youngest child (Cathie) said: ‘Mr. Splitfoot, do as I do,’ clapping her hands. The sound instantly followed her with the same number of raps; when she stopped the sound ceased for a short time. Then Margaretta said, in sport: ‘Now do just as I do; count one, two, three, four,’ striking one hand against the other at the same time, and the raps came as before. She was afraid to repeat them. Then Cathie said, in her childish simplicity: ‘O mother, I know what it is; to-morrow is April-fool day, and it’s somebody trying to fool us.’ I then thought I could put a test that no one in the place could answer. I asked the noise to rap my different children’s ages, successively. Instantly each one of my children’s ages was given correctly, pausing between them sufficiently long to individualize them until the seventh, at which a longer pause was made, and then three more emphatic raps were given, corresponding to the age of the little one that died, which was my youngest child. I then asked: ‘Is this a human being that answers my questions so correctly?’ There was no rap. I asked: ‘Is it a spirit? If it is, make two raps?’ Two sounds were given as soon as the request was made. I then said: ‘If it was an injured spirit, make two raps,’ which were instantly made, causing the house to tremble. I asked, ‘Were you injured in this house?’ The answer was given as before. ‘Is the person living that injured you?’ Answered by raps in the same manner. I ascertained by the same method that it was a man, aged thirty one-years; that he had been murdered in this house, and his remains were buried in the cellar; that his family consisted of a wife and five children, two sons and three daughters, all living at[8] the time of his death, but that his wife had since died. I asked: ‘Will you continue to rap if I call in my neighbors that they may hear it too?’ The raps were loud in the affirmative. My husband went and called in Mrs. Redfield (our nearest neighbor). She is a very candid woman. The girls were sitting up in bed clinging to each other and trembling with terror. I think I was as calm as I am now. Mrs. Redfield came immediately (this was about half past seven), thinking she would have a laugh at the children; but when she saw them pale with fright and nearly speechless, she was amazed, and believed there was something more serious than she had supposed. I asked a few questions for her, and was answered as before. He told her age exactly. She then called her husband, and the same questions were asked and answered. Then Mr. Redfield called in Mr. Duesler and wife, and several others. Mr. Duesler then called in Mr. and Mrs. Hyde, also Mr. and Mrs. Jewell. Mr. Duesler asked many questions, and received answers. I then named all the neighbors I could think of, and asked if any of them had injured him, and received no answer. Mr. Duesler then asked questions and received answers. He asked, ‘Were you murdered?’ Raps affirmative. ‘Can your murderer be brought to justice?’ No sound. ‘Can he be punished by the law?’ No answer. He then said: ‘If your murderer cannot be punished by the law, manifest it by raps,’ and the raps were made clearly and distinctly. In the same way Mr. Duesler ascertained that he was murdered in the east bed-room about five years ago, and that the murder was committed by a Mr. ——, on a Tuesday night, at twelve o’clock; that he was murdered by having his throat cut with a butcher knife; that the body was taken down cellar; that it was not buried until the next night; that it was taken through the buttery, down the stairway, and that it[9] was buried ten feet below the surface of the ground. It was also ascertained that he was murdered for his money, by raps affirmative. ‘How much was it, one hundred?’ No rap. ‘Was it two hundred?’ etc.; and when he mentioned five hundred the raps replied in the affirmative. Many called in who were fishing in the creek, and all heard the same questions and answers. Many remained in the house all night. I and my children left the house. My husband remained in the house with Mr. Redfield all night. On the next Saturday the house was filled to overflowing. There were no sounds heard during the day, but they commenced again in the evening. It was said there were over three hundred persons present at the time. On Sunday morning the noises were heard throughout the day by all who came to the house. On Saturday night, April 1st, they commenced digging in the cellar; they dug until they came to water, and then gave it up. The noise was not heard on Sunday evening nor during the night. Stephen B. Smith and wife (my daughter Maria), and my son, David S. Fox and wife, slept in the room this night. I have heard nothing since that time until yesterday. In the forenoon of yesterday there were several questions answered in the usual way, by rapping. I have heard the noise several times to-day.

“I am not a believer in haunted houses or supernatural appearances. I am very sorry that there has been so much excitement about it. It has been a great deal of trouble to us. It was our misfortune to live here at this time; but I am willing and anxious that the truth should be known, and that a true statement should be made. I cannot account for these noises; all that I know is, that they have been heard repeatedly, as I have stated. I have heard this rapping again this (Tuesday) morning, April 4th. My children also heard it. I certify that the foregoing[10] statement has been read to me, and that the same is true; and that I should be willing to take my oath that it is so, if necessary.

(Signed) “Margaret Fox.

“April 11, 1848.”

“I have heard the above statement of my wife, Margaret Fox, read, and hereby certify that the same is true in all its particulars. I heard the same rappings which she has spoken of, in answer to the questions, as stated by her. There have been a great many questions besides those asked, and answered in the same way. Some have been asked a great many times, and they have always received the same answers. There has never been any contradiction whatever.

“I do not know of any way to account for these noises, as being caused by any natural means. We have searched every nook and corner in and about the house, at different times, to ascertain if possible whether anything or anybody was secreted there that could make the noise, and have not been able to find anything which would or could explain the mystery. It has caused a great deal of trouble and anxiety.

“Hundreds have visited the house, so that it is impossible for us to attend to our daily occupations; and I hope that, whether caused by natural or supernatural means, it will be ascertained soon. The digging in the cellar will be resumed as soon as the water settles; and then it can be ascertained whether there are any indications of a body ever having been buried there; and if there are, I shall have no doubt but that it is of supernatural origin.

(Signed) “John D. Fox.

“April 11, 1848.”

“I live in this place. I moved from Cayuga County here, last October. I live within a few rods of the house in which these sounds have been heard. The first I heard anything about them was a week ago last Friday evening (March 31st). Mrs. Redfield came over to my house, to get my wife to go over to Mr. Fox’s. Mrs. R. appeared to be very much agitated. My wife wanted me to go over with them, and I accordingly went. When she told us what she wanted us to go over there for, I laughed at her and ridiculed the idea of there being anything mysterious about it. I told her it was all nonsense, and that we would find out the cause of the noise, and that it could easily be accounted for. This was about nine o’clock in the evening. There were some twelve or fourteen persons present when I left them. Some were so frightened that they did not want to go into the room. I went into the room and sat down on the bed. Mr. Fox asked a question, and I heard the rapping, which they had spoken of, distinctly. I felt the bedstead jar when the sounds were produced. Mr. Fox then asked if it would answer my questions if I asked any; and it rapped three times. I then asked if it was an injured spirit, and it rapped. I asked if it had come to hurt any one who was then present. It did not rap. I then reversed the question, and it rapped. I asked if my father or I had injured it (as we had formerly lived in that house), and there was no noise. ‘If we have not injured you, manifest it by rapping,’ and we all heard three distinct raps. I then asked if such or such a one had injured it (meaning the several families who had formerly lived in the house), and there was no noise. Upon asking the negatives of those questions the[12] rapping was heard. I then asked if Mr. —— (naming a person who had lived in the house at a former period) had injured it; and if so, to manifest it by rapping, and it made three raps louder than usual; and at the same time the bedstead jarred more than it had before. I then inquired if it was murdered for money, and the sounds were heard. Questions and answers as to different sums of money were then given as stated by Mr. Fox. All in the room said they heard the sounds distinctly.

“After that, I went over and got Artemus W. Hyde to come over. I then asked over nearly all the same questions, and got the same answers. Mr. Redfield went after David Jewell and wife, and Mr. and Mrs. Hyde also came in. After they came, I asked the same questions over again, and got the same answers. I asked if it was murdered by being struck on the head, and there were no sounds; I then reversed the question, and the rapping was heard. I then asked if it was stabbed in the side, and there was no answer. Upon asking the negative of this the rapping was heard. It usually rapped three times in giving an affirmative answer to my questions. I then asked if it had its throat cut, and it rapped as usual. Then, if it was with a butcher knife, and the rapping was heard. In the same way it was ascertained that it was asleep at the time, but was awakened when the knife entered its throat; that it struggled and made some noise and resistance. Then I asked if there was any one in the house at the time but him, and it did not rap. I then asked if they two were alone, and the rapping was heard. I then asked if Lucretia Pulver was there at the time, and there was no rapping. If she had gone away that night, and if Mrs. —— was gone away also, and the rapping was heard each time. There was no rapping heard, only when we asked questions. I then asked if any one in[13] Hydesville knew of the murder at the time except ——, and it rapped. Then I asked about a number of persons, if they knew it, and there was no rapping until I came to Mrs. ——, and when I came to her name the rapping was heard. Then if any one but —— and wife knew of it, and I got no rap. Then if they were all that knew of the murder, and it rapped. I asked if the body was put into the cellar, and it rapped. I then asked if it was buried in different points of the cellar, and to all my questions there was no rapping, until I asked if it was near the centre, and the rapping was heard. Charles Redfield then took a candle and went down cellar. I told him to place himself in different parts of the cellar, and as he did so I asked the question if a person was over the place where it was buried, and I got no answer until he stood over a certain place in the cellar, when it rapped. He then stepped one side, and when I asked the question there were no noises. This we repeated several times, and we found that whenever he stood over the one place the rapping was heard, and when he moved away from that one place, there was no rapping in answer.”

Note.—The remainder of Mr. Duesler’s statement does not vary from that of my mother and others, and, for want of room, is omitted. It was dated April 12, 1848.

“I lived in this house all one winter, in the family of Mr. ——. I worked for them a part of the time, and a part of the time I boarded and went to school. I lived there about three months. During the latter part of the time I was there I heard these knockings frequently: in the bedroom, under the foot of the bed. I heard it a number of nights, as I slept in the bedroom nearly all the time that I stayed there. One night I thought I heard a man[14] walking in the buttery. This buttery is near the bedroom, with a stairway between the two. Miss Amelia Losey stayed with me that night. She also heard the noise, and we were both much frightened, and got up and fastened down the windows, and fastened the door. It sounded as if a person walked through the buttery, down cellar, and part way across the cellar bottom, and then the noise ceased. There was no one else in the house at the time except my little brother, who was asleep in the same room with us. This was about twelve o’clock I should think. We did not go to bed until after eleven, but had not been asleep when we heard it striking. Mr. and Mrs. —— had gone to Loch Berlin, to be gone till the next day. One morning about a week after this Mrs. —— sent me down cellar to shut the outside door (which fastens on the inside). In going across the cellar I sank knee deep in the centre of the cellar. It appeared to be uneven and very loose. After I got up-stairs Mrs. —— asked me what I screamed for. When I told her, she laughed at me for being frightened, and said it was only where rats had been at work in the ground.

“A day or two after this, Mr. —— carried a lot of dirt into the cellar, just at night, and was at work there some time. Mrs. —— told me that he was filling up the rat-holes.

“A few days before I first heard the noises, or anything of the kind had ever occurred, a foot-pedlar called there about two o’clock in the afternoon. Mrs. —— then told me that Mr. —— thought they would not want me any longer, and that I might go home; but, if they wanted me again they would send for me. Mrs. —— was going to Loch Berlin, to stay that night. This was the first I had heard of it. I wanted to buy some things of the pedlar, but had no money with me, and he said he would call at[15] our house the next morning and sell them to me. I never saw him after that. Three days after this they sent for me to come and board with them, and go to school. I accordingly came, and went to school about one week, when she wanted I should stay out of school and do house-work, as she had a couple of coats to make over for her husband. She said they were too large for her husband, and out of fashion, and she must alter them. They were ripped to pieces when I first saw them. I should think the pedlar was about thirty years old. I heard him conversing with Mrs. —— about his family. He told her how many children he had, in answer to her inquiry. I do not recollect how many he said he had. Mrs. —— told me that he (the pedlar) was an old acquaintance of theirs. A short time after this Mrs. —— gave me a thimble, which she said she had bought of the pedlar, and paid him fifty cents for. Some time after I had left her I visited her again; and she said the pedlar had been there again, and showed me another thimble, which, she said, she had bought of the same pedlar. She said he had cheated her; that he had sold it to her for pure silver, but it was only German silver. She also showed me some other things which she said she had bought of him.

“I did not (and do not now) know what to think of the noises I have heard. The dog would sit under the bedroom window and howl all night long. Mr. and Mrs. —— appeared to be very good folks, only they were rather quick-tempered.

“This pedlar carried a trunk and a basket, I think, with vials of essence in it. He wore a black coat and light-colored pants.

“I am willing to swear to the above statement, if necessary.

“Lucretia Pulver.

“April 11, 1848.”

“I was acquainted with Mr. and Mrs. ——. I called on them frequently. My warping bars were in their chamber, and I used to go there to do my work. One morning when I went there Mrs. —— told me that she felt very badly; that she had not slept much, if any, the night before. When I asked her what the matter was, she said she didn’t know but it was the fidgets; but she thought she heard something walking about from one room to another, and that she and Mr. —— got up and fastened the windows down. She felt safe after that. I heard her speak about hearing sounds after that, which she could not account for.

“Anna Pulver.

“April 11, 1848.”

It will be sufficient to sum up the important bearings of this subject by quoting a few more extracts from the numerous certificates contained in the little pamphlet published by E. E. Lewis, Esq., of Canandaigua, N. Y.

“Mr. and Mrs. Weekman lived in this house for a year and a half, and were frequently startled by the rappings, walking, etc. On several occasions they sought diligently to discover the cause. He stood with his hand on the latch, and when the knockings were repeated, suddenly opened the door and ran into the yard and entirely around the house; but nothing was ascertained by him.”

Mrs. Weekman says: “We heard great noises during the night; sometimes a sound as if a person was walking in the cellar. (There was nothing but a single board floor, between the cellar and the upper room, so that the sound made in one was easily heard in the other.) One night one of our little girls, who slept in the room where the noises[17] were heard, awoke us all by her screaming very loudly. My husband and myself, and our hired girl, all went to the room to see what was the matter with her. The child sat up in bed, crying and screaming, and it was some time before we could quiet her enough to get answers to our questions. She said ‘something had been moving around her and over her head and face: that it was cold, and that she felt it all over her.’ This was between twelve and one o’clock. We took her into bed with us, and it was a long time before we could get her to sleep in that bed again. At one time Mr. Weekman heard his name called. (I was away that night, sitting up with a sick person.) He was awakened, and supposed some one wanted him. He sat up in bed for some time, but heard no more. We never found out what or who called him. So many have heard these noises that it seems there must be something unusual.”

Mrs. Jane C. Lape “lived in the family of Mrs. Weekman at the time she states. There was but one door in the bedroom. When I was doing my work, I saw a man in the bedroom joining the kitchen. I saw the man distinctly. I was frightened. I had been in the kitchen a long time, and knew that nobody could have gone into that room. The man stood facing me when I saw him. He did not speak, nor did I hear any noise at any time. He had on light pants, black frock-coat, and cloth cap. He was of medium size. I knew of no person in that vicinity who would answer that description. Mrs. Weekman was in another part of the house at that time. I left the room, and when I returned with Mrs. Weekman there was no person there. She thought it was some person who wanted to frighten me; but we were never able to ascertain who or what it was. I have always thought and still do think that it was supernatural. I had never been a believer in such things until I saw this.”[18]

“We, the undersigned, do hereby certify that during the summer of 1844, we lived near the house now occupied by John D. Fox; that it was then occupied by —— ——; and that, during the summer, the water in that well was very offensive and bad. We further certify that said well is within thirty feet of the centre of the cellar under said house.

“(Signed) Norman Ayres.

John Irish.

“Arcadia, April 18, 1848.”

In my brother’s statement (see pamphlet by E. E. Lewis, Esq.) was given a correct account of the digging to find the body of the murdered man in the cellar.

“I live about two miles from the house my father, John D. Fox, now occupies, and where these strange noises were heard. It was a week ago last Friday, March 31st, when they told me about it. I advised them to make a thorough search, and I thought they would find a cause for it. I heard no noise, and after remaining a short time, returned home. The next morning, April 1, 1848, they sent for me to come again, and they told me the noises had been heard all night. I went early in the evening; heard the rapping distinctly. Many questions were asked and answered by the rapping.”

(It is not necessary to here repeat all of David’s statement, as the entire substance of it is given in nearly all the other certificates.)

“A large collection of people had assembled, more than could get into the house; committees were chosen, and placed in different parts of the house, that no deception might be practised by any one. These committees were[19] composed of neighbors and friends, whom we knew to be strictly honest. I remained in the house until about one o’clock in the morning. The noises had ceased a little before twelve. After some of the crowd had left, we commenced digging in the cellar. Before digging I asked the question: ‘In what part of the cellar was your body buried?’ naming the different corners of the cellar. No response was made. ‘Was it in the centre?’ The rapping answered affirmatively. Mr. Carlos Hyde went down in the cellar, walked over the bottom, asking at every point if he was over the right place, but no rappings were heard until he stood in the centre of the cellar. It then rapped so that those in the cellar as well as those in the room above could hear it. We dug about three feet deep, when the water came in so fast we had to stop. I was here again on Monday, April 3d, and we commenced digging again in the cellar, and baling out the water; but we found it impossible to make any headway.

“On Tuesday evening they began digging again. I got a pump, and we took up the floor and put it in the hole, and began to pump and bale out the water at the same time. We could not lower the water much and had to give it up. The water is in the hole, although it is lowering gradually. I thought, from there being so many respectable people present, and they having heard the same sounds that I did, that there must be something in it. I never believed in haunted houses or anything of that kind. I have heard of such things, but never saw or heard anything but what I could account for on reasonable grounds. I cannot account for this noise as being produced by any human agency. I am perfectly willing to take my oath as to the truth of the statements which I have here made, if it is thought necessary.

“(Signed) David S. Fox.

“Tuesday, April 11, 1848.”

The Last Digging in the Cellar—Mob Antagonism—Noble Friends—Experiences and Theories—Antecedents of the House—Franklin.

It was late in July, 1848. The old house at Hydesville was not occupied by any one, save the “murdered man.” Many went there alone, or in small parties; and often the rappings were heard.

We, too, visited the old house, went down into the cellar, and called on the spirits to answer our questions and direct us aright.

Notwithstanding all the bitter conflicts we had passed through in Rochester, we had come to the conclusion that good spirits (as well as bad ones) could manifest themselves to us. We were greatly favored in our early associations with a class of progressive philanthropic people among our neighbors, whose highest aim was to benefit the world, and who urged us to go forth and do our duty. We learned from them to take a more liberal view, as they had taught us many valuable lessons of forbearance and perseverance. When I saw my dear good brother bow with the others, and ask questions of the Spirits, my soul and all within me was lifted beyond the scoffs and ridicule which I knew we must submit to if we performed the heavy duties incumbent upon us. There had been great excitement for a time, but little now was said in that vicinity about it, as there had been so much ridicule attached to the occurrences of the past, that the leaders[21] shrank from further publicity. But, during this time, we were having our experiences in Rochester, where I resided.

It was now directed by the Spirits that the digging should be resumed. (It was the dry season of the year, and the water in the Ganargua[1] was low.) My brother declared that he could not again enter upon so hazardous an undertaking. He believed himself capable of acting on his own judgment in the matter. But for once he found, to his utter discomfiture, that the mighty powers that seemed to rule our destiny were not to be defeated. The Spirits directed that he should invite certain gentlemen to assist in the digging. They spelled out the names of many Rochester friends, viz., Henry Bush, Lyman Granger, Mr. Post, Dr. Faulkner, and Rev. A. H. Jervis. The above-named were old and tried friends, and we felt no hesitation in calling upon them; but when David was requested to invite gentlemen living in the vicinity of Hydesville, with whom he had little or no acquaintance, he positively refused to do their bidding. The friends in Rochester received this announcement with apparent satisfaction. All came at the appointed time. Mr. and Mrs. Granger and daughter, Mr. and Mrs. Bush, Mrs. Jervis, Dr. Faulkner and his little son, etc. I doubt if either of these gentlemen had ever used the pickaxe and spade before; but they came willing to perform their duty. Brother David still declared that he could not, and would not, make himself so ridiculous as to invite men who would laugh at him for entertaining such an idea; but still the Spirits commanded him to obey instructions, and nightly they would go through the performance of representing the murder scene. (This occurrence was in my brother’s house.) Gurgling, strangling, sawing, planing, and boring; representing[22] the enactment of the horrid crime said to have been committed in the Hydesville house.

Our friends urged David to act in accordance with the request of the “Spirits,” but he could not make up his mind to do so. He walked from room to room, and in secret prayed that this terrible injunction might be removed. He cried, with uplifted hands, to God, to have compassion on our family; and then, in despair, would say: “Better to die together, than to live so disgraced.” The sight of his grief and despair was heart-rending; but the Spirits were inexorable. The day appointed for the digging arrived. During the previous, night all was in an uproar. The sounds as of broken crockery were heard, and as if heavy weights were dragged across the floor. Sawing, planing, digging, boring, groaning, and whispering close to our ears. This continued until the bright, beautiful dawn of the morning warned us that it was time to prepare for the labors of the day. We were commanded by the Spirits thus—“Go forth and do your duty, and good will come of it.” Chauncy Culver, my brother’s wife’s brother, called in, and David said: “Chauncy, you are politely invited to join us in the digging to-day.” He answered, “I am willing to do so, Dave.” Others who had been named, but not invited, dropped in by chance, and all united with us; but the great burden fell upon David’s shoulders. Chickens were cooked, puddings, pies, cakes, and sweet-meats were prepared by my brother’s wife, Elizabeth, and my sister Maria. Our living was sumptuous, and we had very little opposition during the first day’s work. The earth was hard and dry, and the digging tiresome; but the party worked diligently until near noon, when they came to a quantity of charcoal and traces of lime (this was between four and five feet below the cellar bottom), some hair of a reddish or sandy hue,[23] and some teeth, which showed, beyond all question, that the earth had at some time, and for some purpose, been disturbed. The party worked on until it began to grow dark, and the first day’s work was ended. We returned to David’s home, about two miles from the Hydesville house, well satisfied with our day’s work, and the friends felt that they had done all in their power to get at the truth of the Spirits’ declaration.

We made two large beds on opposite sides of the parlor; the women and children rested upon one of them, and the men on the other; Dr. Faulkner and his little son being in the parlor bedroom. All heard the manifestations that night; and they were most wonderful in character. This arrangement of the beds was directed by the Spirits, that they might gratify all by making manifestations during the night.

The next day we resumed our labor. The ladies accompanied their husbands and friends. We had started as early as possible. Mr. S. B. Smith, my sisters husband, my brother David, and some of the neighbors turned out five or six wagons to convey us to our destination, forming quite a procession of our own; but as we came to the turn of the hill, from whence we could see in all directions, there were vehicles of every description wending their way to the “haunted house.” Shouts of ribaldry and roars of laughter fell upon our ears like the death-knell of some poor soul—who might almost begin to feel himself guilty of crimes he had never committed.

We entered the cellar. On came the noisy rabble. Our noble, pale-faced, honorable men stood firm in their duty. Mark the contrast, dear readers: many of those noble souls now stand in the higher ranks in glory. They have passed through the fiery furnace, entered the “golden gate” of the new Jerusalem; and to them offer your praises and[24] admiration. Such men and women as those dared to stand before the world and battle for the right. It was such as they who fought and won the great battle against slavery and contributed to its overthrow. May they continue to live in the memories of the children of earth.

Through the second day the digging was frequently interrupted by the rude entrance of some of the outside crowd. We (the women) formed a guard around the place where the work was in progress, to protect the men thus engaged. We had candles in our hands, with which to light the laborers, when suddenly one of the workers cried out, “Great God! here are the pieces of a broken bowl!” (The Spirit always said that the bowl which caught his blood was buried; and he represented nightly the sound of pouring blood into a vessel or bowl, dropping slower and slower, until at last it ceased entirely; and then the sound would come as if the bowl were thrown and broken in pieces.) Several bones were found which doctors pronounced human bones, stating to what parts of the body they belonged. One, I remember, was said to be from the ankle, two from the hands, and some from the skull, etc. (Some persons, who never saw these bones, argued that they were not human bones, hair, and teeth which were there found. But I ask, in the name of common sense, how did they happen to be there, nearly six feet beneath the cellar bottom?)

In the afternoon the crowd outside grew more bold, and among them were sympathizers with the man who was accused by the general public opinion. We pitied him, and regretted that he had been named; but we never knew that such a man had lived, until the neighbors had brought out the fact by putting questions which were answered by the rappings.

These spectators were becoming more and more excited,[25] and crowded into the cellar. Some called us crazy. They reached over the heads of the women and spat upon and dropped sticks and stones on those who were digging. We still stood firm in the defence of our friends, the laboring party; and they worked on until they struck what seemed to be a board. This sounded hollow, and its location was beneath the sand and gravel. They procured an augur and bored through the obstruction, when the augur dropped to the handle. They then obtained bits, and attached them to long sticks, and with them bored several inches, when the bit would drop to the depth of a foot or more. In this way they lost two of the bits, which dropped through and were not recovered. By this time the excitement was overwhelming. The cellar was filled with people. Some cried, “Drag out the women! drag them out!” Others said, “Don’t hurt the women, drag out the men!” The floor over our heads creaked with the weight of the multitude. It grew dark. Our friends could work no longer, and reluctantly retired. How we all reached the outside, amid the shouts and the roar of the excited crowd, I cannot explain; but at length we stood together in the door-yard, awaiting our conveyances, and no word of disrespect was spoken to any of us. The Spirits said: “Dear faithful friends, your work here is done. God will reward you.”

“Yes,” said that noble-looking man, Henry Bush, with the acquiescence of all, “our work is done.”

We all returned to David’s (the old homestead). That night and the following day our friends returned to Rochester. We remained a few days with our family.

I must pass over many interesting circumstances, or it will be wholly impossible to put our story in one volume: but I deem it due to my family that some facts should be stated in this history.[26]

After the public parts we had been forced to perform at Hydesville, the news spread far and wide. The crowd of people came in wagons from every direction before the harvest had been gathered. Some drove through the gate, but others took down the fences, and drove through the grain fields, and peppermint beds, regardless of the destruction they were perpetrating. Against all this destruction of his property, David was defenceless. He saw and felt how utterly useless it was for him to attempt to remonstrate with such an element.

It was late in the afternoon when a tired horseman came galloping up the carriage road, to inform my brother that a party consisting of several wagon-loads were on their way to mob us. At this announcement we were much frightened, and knew not what to do. Intimations of such a design had reached us previously, and powder and shot had been provided for our defence. The boys and hired men had gathered piles of stones behind the house, and at first it was considered to be our wisest way to defend ourselves as best we could.

The sun was low and we dreaded the night coming on. What could we do? Mother called us all into the parlor bedroom, and there we knelt, with fear, and prayed to God for protection. The Spirits spelled out to us, “You will not be harmed. God will protect you.” We stood for a moment and counselled together. The package of powder flew from the top of the bureau and hit Cathie on the forehead, and that of the shot came and struck me on the shoulder. My brother took the guns and fired them off, and threw the powder and shot into the peppermint patch, saying, “I will not raise a hand against them. If God has sent this upon us, for the good of mankind, he is able to protect us. I will trust him.”

The windows were fastened down as best we could.[27] The dog began to bark fearfully. We heard the distant shouts and snatches of songs, and knew they would soon be upon us. They drove up the road, into the yard, and one woman jumped through the window of the kitchen, hoops and all. She was in the kitchen before any of us knew they had entered the door-yard. David left us alone in the parlor, walked into the kitchen, and said to the woman, “If you had knocked I would have opened the door for you; it was not locked.” He then opened all the doors, walked out to the crowd, and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, walk in. You are welcome to search the house from garret to cellar, if you will do so respectfully.” One man, the leader of the crowd, exclaimed, in a manner of the utmost surprise: “My God! Dave Fox, is it you they have said so much about? No, we won’t come in now. We’ll go home and dress ourselves and come another time.”

Thus ended this mob against the Spiritualists, as all others subsequently have ended. The Spirits, therefore, fulfilled their promise and protected us from all harm.

I might fill many a page with the experiences of the family in that house at Hydesville, during the period of about three months and three weeks preceding that March 31, 1848, on which the neighbors were first called in. From the very first night of their taking possession of it, they were disturbed and puzzled with the strange knockings and other noises. They had gone into it only as a temporary home, while my father was building the new house on the homestead farm, and the carpenter had estimated a couple of months as sufficient time for his work. All sorts of natural theories were imagined as to the cause of the sounds, nor did they, for some time, think of Spirits or of anything supernatural, or even important. Father insisted, at one time, that they proceeded from a cobbler in[28] the neighborhood, hammering leather, and working late in the night. Then it was “some boards that must be loose and shaken by the wind.” Then it appeared that “there must be dancing going on at Mr. Duesler’s, or some other house within hearing;” then “the house must be full of rats”—though mother declared she had never seen a rat in it. Again, when the knocks would break out suddenly, close to some of the family, or at the table, one of the girls would charge the other with having caused them, saying, “Now you did that,” etc., etc. Father had always been a regular Methodist, in good standing, and was invariable in his practice of morning prayers; and when he would be kneeling upon his chair, it would sometimes amuse the children to see him open wide his eyes, as knocks would sound and vibrate on his chair itself. He expressed it graphically to mother: “When I am done praying, that jigging stops.” My daughter Lizzie used to declare that when she was writing, there would sometimes come a strong ticking on the paper. One night loud screams were heard from the children, Maggie and Cathie, in bed. “O mother, come quick. Somebody has lain down across the bed.” They were often so frightened that mother would have to take them to lie on both sides of her in her bed, and sometimes they would go, one to father’s bed and the other to mother’s. But these frights were attributed to bad dreams. Indeed, it now seems strange that so little serious impression was made on their minds for so long a time by these strange things, so persistent, so varied, and so inexplicable, which they instinctively abstained from talking about to the neighbors.

It was not till March 31st that they seemed to have culminated to the point which exhausted their patience, and which at last drove them to do so. On the preceding[29] night they had been kept awake nearly all night by the knocking and heavy poundings about the house; and up to three o’clock in the morning they were occupied pursuing the sounds about from place to place, puzzling over them, and baffled in every attempt to discover a cause. The door would be pounded upon from the outside, and father would take hold of the handle, and on the return of the knocking would suddenly fling the door open, only to discover nothing. He and mother stood on the opposite sides of it, and each would hear the knocking on the side opposite to themselves, as though made by powerful muffled knuckles. Yet on neither side could be found traces of any person or thing to have produced them, while both would feel the strong vibrations of the wooden door.

It was afterward learned that, for several years back, strange noises had been heard by successive occupants of that house, none of whom had remained long as its tenants. Prior to its occupation by a certain family there had been no such disturbances; subsequently to then, they had been experienced by all their successors. It would be easy for me to name families of the highest respectability, and who are still my good friends, who would attest this.[2]

[1] The old Indian name of the creek.

[2] It would seem that none of the families who, in the course of several years, had preceded the Fox family in the occupancy of this haunted house, combined the highly mediumistic nature with the other characteristics specially qualifying them for the great work for which the time was ripe, so that the manifestations, which appealed for attention, had knocked in vain at doors which could not open to them. Dr. Franklin, great philosopher and inventor of his time, was also, in the Spirit life, one of the inventors of this mode of communication between the two worlds, through knockings given in correspondence with the letters of the alphabet. Through another medium, besides the author of this volume, he has told me that out of “millions” he at last found in the Fox family the instruments he wanted for its practical application and introduction. This narrative curiously shows how hard and long they too struggled against the mission to which the Spirits were leading and at last forcing them, as will be seen below. I asked him if Spirits had influenced them to take the Hydesville house. His reply was a curious one. Instead of three consecutive and decided raps, which would have expressed assent, he on two occasions answered with only two raps, followed after a moment’s pause with a third, completing a qualified affirmative. “You mean that it was partially so?” I said; which was immediately answered with an unqualified assent; and he added, “It was many, not one alone,” thus disclaiming the credit of its sole and individual authorship.—Ed.

My First Knowledge of the Matter—Hasten to Hydesville—Rapping on a Canal Boat—Experiences—Mother Comes to Rochester—Calvin Brown—Devious Route of Projectiles Up-stairs from Cellar to Garret—A Death-knell Sounded All Night on the Keys of a Locked Piano.

This volume is not meant to be an autobiography, though I regret to be compelled to speak so much of myself in giving an account of the inauguration of the movement known as “Modern Spiritualism,” through the three sisters of the Fox family, of whom I was the eldest, and already married when my two sisters, Margaretta and Catharine, were children. I was not with the family, but at my own house in Rochester, during most of the events related above.

I was myself also at that time but little more than a child, for when I was married at Rochester, N. Y., I could count but fourteen years and five months. It will be seen below how I was twice widowed before the age of twenty-four,[31] though my second marriage was on the supposed death-bed of one who had been a brother to us all from childhood, and who merely desired to bequeath me his name.

Mr. Fish discovered when too late that he had married a child, and soon became indifferent to his home and family. He left Rochester under a pretence of going on business to the West. The next I heard of him was that he had married a rich widow in the State of Illinois.

As he had left little means for the support of myself and child, I turned my attention to teaching music. I had many friends who assisted me in getting pupils, and I was delighted to find myself entirely independent. One day (early in May, 1848), I was at the house of Mr. Little, enjoying myself with the young ladies, when Mrs. Little came in with the proof-sheet of a pamphlet issued by E. E. Lewis, Esq., of Canandaigua, N. Y. Mrs. Little knew my maiden name was Fox; that my parents (at the time) were in Arcadia, Wayne County, N. Y., and concluded I must be the daughter of John D. Fox. She then introduced the printer, and he commenced questioning me about my family relations. He said, “Is your mother’s name Margaret? Have you a brother David?” I replied, yes. I began to be startled by his questions, and said, “For mercy’s sake, what has happened?” He answered by placing the proof-sheet in my hands, which gave me the first idea I ever had of the manifestations which had been taking place at the dwelling of our family in Hydesville. I read it, and cried over it. I knew not what to think, but I said to them all, “If my father, mother, and brother David have certified to such a statement, it is true.” All who heard me thus declare believed it, and never wavered for a moment. As soon as I could collect my thoughts, I called on Mrs. Granger and Mrs. Grover, old friends of mine and[32] of our family, and related to them the account which I had read in the proof-sheet.

I told them I should take the night boat for Newark, Wayne County. I would visit my family, and learn for myself about the mysterious affair. They concluded to go with me. We were, at that time, obliged to travel by the Erie Canal packet-boat, as the direct railroad between Syracuse and Rochester had not yet been built. It took a few hours longer then than now to make that journey. When we arrived at Hydesville, which is about two miles from our old homestead, we found the house deserted. My brother had persuaded the family to leave the old “haunted house,” and live with him until their new house was finished.

We drove to brother David’s, where we found mother completely broken down by the recent events. She never smiled; but her sighs and tears were heart-rending. We begged her to hope for the best, and try to think differently; but she could not. She wished we could all die; and it was, at the time, impossible to cheer her by anything we could say or do. She was only about middle age, and her health had always been good; and she was, by nature, very cheerful.

I with the ladies who accompanied me remained about two weeks, when we concluded to take Katie and Lizzie (my daughter) with us and return home to Rochester, as mother thought the former to be the one followed mostly by the sounds; and we hoped, by separating the two children (Maggie and Katie), that we could put a stop to the disturbance.

We had not gone many miles on the canal, however, when we became aware that the rapping had accompanied us. Perfect consternation came upon us. I knew not what to do. We did not wish our friends to know that[33] the rapping had followed us; and we remained, as much as possible, by ourselves.

When we went to the dinner-table with the other passengers, the Spirits became quite bold and rapped loudly; and occasionally one end of the table would jump up and nearly spill the water out of our glasses; but there was so much noise on the boat going through the locks and other disturbances, that only we, who recognized the special sounds, knew of them. We arrived at home about 5 P.M. I sat down to think over the occurrences of the day and of other days during my visit.

The two girls had gone into the garden. All at once came a dreadful sound, as if a pail of bonnyclabber had been poured from the ceiling and fallen upon the floor near the window. The sound was horrible enough, but, in addition, came the jarring of the windows and of the whole house, as if a heavy piece of artillery had been discharged in the immediate vicinity. I was so paralyzed by fear that I could not move, and sat stupefied; again came the same terrible sound, with all the jarring, as at first; and yet again it came; when I sprang from the sofa on which I had been seated and rushed out into the garden where the children were. They immediately cried out, “Why, what is the matter with you, Leah? how pale you look!” I made some evasive reply, as I did not wish to alarm them.

We went to bed at an early hour, being tired and much excited. The children had expressed great fear, and I went to bed with them. No sooner had I extinguished the light, than the children screamed, and Lizzie said she felt a cold hand passing over her face, and another over her shoulder down her back. She screamed fearfully, and I feared she would go into spasms. Katie was also much frightened. For my part I was equally terror-stricken.[34] I arose from my bed and sought the Bible, from which I read a chapter. But while I was reading the girls felt some touches. I had never felt them; and I could not realize that they were not in some way mistaken.

It was now late in the night and all was silent. We thought we would try to sleep, as we were tired and excited. But the instant we extinguished our light the Bible flew from under my pillow—where I had placed it, supposing that the sacred volume would be respected. The box of matches was shaken in our faces, and such a variety of performances ensued that we gave up in despair to our fate, whatever it might be. We called on each other, if either was silent a few moments, that we might know that we were all alive. Finally, when the night was nearly spent, the disturbance ceased, and we fell asleep. We did not awake until very late in the morning. The sun shone brightly, and the birds sang sweetly in the trees of the public square. (Our residence then was on Mechanics’ Square.) The June roses were just out, and all nature was in her loveliest hues. We could not make the disturbances of the past night seem real to us. I doubted everything, but kept my own counsel; and as the shades of evening fell upon the scene, which had been a day of such brightness and beauty, I made up my mind that I would go on as usual and try to forget, as far as possible, the frightful occurrences of the previous night. In the evening my friend Jane Little and two or three other friends called in to spend an hour or so with us. We sang, and I played on the piano; but even then, while the lamp was burning brightly, I felt the deep throbbing of the dull accompaniment of the invisibles, keeping time to the music as I played; but I did not wish to have my visitors know it, and the Spirits seemed kind enough not to make[35] themselves heard so that others would observe what was so apparent to me.

All seemed quiet when we retired for the night, at about ten o’clock. We slept quietly for about two hours, when we were awakened by the most frightful manifestations. The house was in a perfect uproar. Tables and everything in the room below us were being moved about. Doors were opened and shut, making the greatest possible noises. They then walked up-stairs and into the room next to us (our bedroom was an open recess off from this room). There seemed to be many actors engaged in the performance, and a large audience in attendance.

The representation of a pantomime performance was perfect.

After the first scene, there was great applause by the Spirit audience. Immediately following, one Spirit was heard to dance as if with clogs, which continued fully ten minutes. This amused the audience very much; and a loud clapping of hands followed. After this we heard nothing more except the representation of a large crowd walking away down-stairs, through the rooms, closing the doors heavily after them. It is useless to attempt to record all the manifestations which occurred nightly during the last few weeks that we remained in that house. I came to the conclusion that it was haunted, and decided to move out of it as soon as I could find another house that suited me.

There was a house on Prospect Street, nearly finished, and I engaged it. I was particular to tell the agent that I wanted a house in which no crime had been committed. For I believed that the house I was then living in, like the one at Hydesville, was haunted; and I presumed that in this case as in the other it must have had its origin in hidden crime. He smiled as he remarked that he “thought that I would have no difficulty on that account.”[36] We moved into this house as soon as possible, and congratulated ourselves on our good fortune in finding a place that had never before been tenanted.

Two houses stood on one foundation. On the ground floor was a kitchen, cellar, and pantry. The staircase led from the kitchen to the second floor. On the outside, a front and rear flight of steps led to a balcony from which we could enter the parlor and dining-room, on the second floor. Another flight of steps led from the dining-room to the third floor, which was one room the entire length and breadth of the house. In this last-named room we put up three beds, and one bed in the room on the parlor floor. I partitioned off a small room in one corner of the upper floor with chintz curtains. This lessened the size of the large room and afforded us a store-room. In the rear of the house was an old cemetery, called “the Buffalo Burying-ground.” This cemetery was separated from our lot by a high fence. I remember I disliked the idea of seeing those tall monuments every time I went into the pantry. (The entrance into the dining-room from the kitchen was through the pantry.)

Nothing occurred, during the first night of our occupancy of this house, of an unusual character, and we slept undisturbed.

I had written to our family at Arcadia, and told them what was transpiring with us nightly. This worried mother, and she determined to come immediately, and find some plan for suppressing it, if it could possibly be done. She, with Margaretta, arrived the next day, and we rejoiced to tell her that we had occupied the new house one night, and no sounds had been heard to disturb us. After supper we remained at the table a long time, until mother suggested that it was getting late, and we had better retire for the night.[37]

All was quiet until about midnight, when we distinctly heard footsteps coming up the stairs, walking into the little room I had partitioned off with curtains, which seemed admirably adapted to their purposes. We could hear them shuffling, giggling, and whispering, as if they were enjoying themselves at some surprise they were about to give us. Occasionally they would come and give our bed a tremendous shaking, lifting it (and us) entirely from the floor, almost to the ceiling, and then let us down with a bang; then pat us with hands. Then they would retire to the little room, which we subsequently named “the green room.” At length we were quiet, and all fell asleep and slept until late in the morning.

The sun shone brightly in through the window, and mother exclaimed: “Can it be possible? Is it really true? How can we live and endure it? We cannot much longer stay here alone nights. We must have somebody to stay with us.” Fillmore Grover came to take his lesson, and mother asked him to tell Calvin she would like to have him call and see her. (Calvin Brown’s mother had been left a widow when quite young. She was the daughter of Daniel Hopkins, of Canada West, and belonged to the Society of Friends. She married out of the society, which was then against their discipline. She placed her oldest child, Calvin, in a military school; and when she found herself gradually failing in strength, she wrote to her father, who came and took her home, with her three younger children. She returned once to Rochester, and requested mother to look after Calvin, and care for him as she would for her own child, if she should not recover. His mother died, and he called my parents father and mother; the same as the rest of us.)

He called at about two o’clock. We all sat down and related what had happened and what we had witnessed[38] during the past night. He promised to come and stay there at night; but he advised us to ask no questions, nor give them any encouragement, as he considered them evil spirits. To this we all agreed.

He came that night, and we were allowed to rest quietly until about two o’clock, when we were all awakened by a disturbance in the “green room.” Everything seemed to be in commotion, but, as Calvin was in the house, I felt more confidence in myself. I asked them to please behave themselves. At this, one Spirit walked around, as if on his bare feet. He answered my question by stamping on the floor. I was amused—although afraid. He seemed so willing to do my bidding that I could not resist the temptation of speaking to him as he marched around my bed. I said, “Flat-Foot,[3] can you dance the Highland fling?” This seemed to delight him. I sang the music for him, and he danced most admirably. This shocked mother, and she said, “O Leah, how can you encourage that fiend, by singing for him to dance?” I soon found that they took advantage of my familiarity, and gathered in strong force around us. And here language utterly fails to describe the incidents that occurred. Loud whispering, giggling, scuffling, groaning, death-struggles, murder scenes of the most fearful character—I forbear to describe them. Mother became so alarmed that she called to Calvin to come up-stairs. He came—angry at the Spirits, and declared that “he would conquer, or die in the attempt.” This seemed to amuse them. They went to his bed, raised it up and let it down, and shook it violently. He was still determined not to yield to them.

Before Calvin came up-stairs, and during a short lull in their performances, we quickly removed our beds to the[39] floor, hoping thereby to prevent them from raising us up and letting us down with such violence. Calvin said, as he came up, that we were foolish to make our beds on the floor, as it pleased the Spirits to see how completely they had conquered us. So he laid down on his bed, and quietly waited developments. Mother said, “Calvin, I wish your bed was on the floor, too. We have not been disturbed since we left the bedstead.” Calvin remarked, “They are up to some deviltry now. I hear them.” He no sooner uttered these words, than a shower of slippers came flying at him as he lay in his bed. He bore this without a murmur. The next instant he was struck violently with his cane. He seized it and struck back, right and left, with all his strength, without hitting anything; but received a palpable bang in return for every thrust he made. He sprang to his feet and fought with all his might. Everything thrown at him he pitched back to them, until a brass candlestick was thrown at him, cutting his lip. This quite enraged him. He pronounced a solemn malediction, and, throwing himself on the bed, vowed he would have nothing more to do with “fiendish Spirits.”

He was not long permitted to remain in quiet there. They commenced at his bedstead and deliberately razed it to the floor, leaving the head-board in one place, the foot-board in another, the two sides at angles, and the bed-clothes scattered about the room. He was left lying on his mattress, and for a moment there was silence; after which some slight movements were heard in the “green room.” I had stowed a large number of balls of carpet-rags in an old chest standing on the floor, with two trunks and several other articles on the top of it. It seemed but the work of a moment for them to get at the carpet-balls, which came flying at us from every direction, hitting us in the same place every time. They took us[40] for their target, and threw with the skill of an archer. Darkness made no difference with them, and if either of us attempted to remonstrate against such violence, they would instantly give the remonstrant the benefit of a ball.