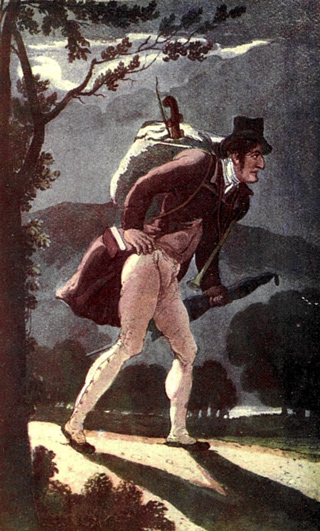

Drawn by Rowlandson

Quæ Genus on his Journey To London.

Title: The History of Johnny Quæ Genus, the Little Foundling of the Late Doctor Syntax.

Author: William Combe

Illustrator: Thomas Rowlandson

Release date: March 10, 2013 [eBook #42299]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Mary Akers and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

THE ILLUSTRATED POCKET LIBRARY

OF PLAIN AND COLOURED BOOKS

THE HISTORY OF

JOHNNY QUÆ GENUS

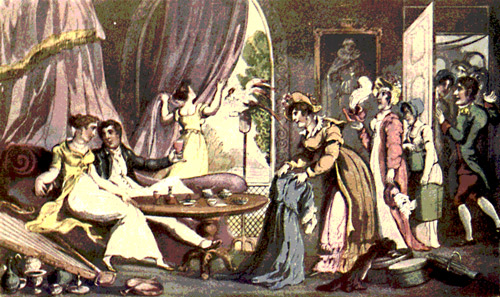

Drawn by Rowlandson

Quæ Genus on his Journey To London.

WITH TWENTY-FOUR

COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS

BY THOMAS ROWLANDSON

A NEW EDITION

METHUEN & CO.

LONDON

1903

NOTE

THIS Issue is founded on the Edition

published by R. Ackermann in the

year 1822

HISTORY

OF

QUÆ GENUS, ETC.

THE favour which has been bestowed on the different Tours of Doctor Syntax, has encouraged the Writer of them to give a History of the Foundling, who has been thought an interesting Object in the latter of those Volumes; and it is written in the same style and manner, with a view to connect it with them.

This Child of Chance, it is presumed, is led through a track of Life not unsuited to the peculiarity of his Condition and Character, while its varieties, as in the former Works, are represented by the Pencil of Mr. Rowlandson with its accustomed characteristic Felicity.

The Idea of an English Gil Blas predominated through the whole of this Volume; which must be vi considered as fortunate in no common degree, if its readers, in the course of their perusal, should be disposed to acknowledge even a remote Similitude to the incomparable Work of Le Sage.

The AUTHOR.

THIS prolonged work is, at length, brought to a close.—It has grown to this size, under rare and continuing marks of public favour; while the same mode of Composition has been employed in the last, as in the former Volumes. They are all equally indebted to Mr. Rowlandson's talents.

It may, perhaps, be considered as presumption in me, and at my age, to sport even with my own Dowdy Muse, but, from the extensive patronage which Doctor Syntax has received, it may be presumed that, more or less, he has continued to amuse: And I, surely, have no reason to be dissatisfied, when Time points at my eightieth Year, that I can still afford some pleasure to those who are disposed to be pleased.

The AUTHOR.

May 1, 1821.

| Besides, as most folk do agree To find a charm in novelty, 'Tis the first time that Grammar rule Which makes boys tremble when at school Did with the name an union crave Which at the font a sponsor gave. But whether 'twas in hum'rous mood Or by some classic whim pursued, Or as, in Eton's Grammar known, It bore relation to his own, Syntax, it was at Whitsuntide, And a short time before he died, In pleasant humour, after dinner, Surnam'd, in wine, the little sinner. |

|

| And thus, amid the table's roar, Gave him from good, old Lilly's store, A name which none e'er had before. |

} |

| —'Squire Worthy, who, perchance was there Promis'd the Doctor's wish to share, That want, at least might not annoy The progress of the Foundling Boy. "—Syntax," He said, "We'll try between us To make the fortune of Quæ Genus: You feed his mind with learning's food, And I'll protect him if he's good." 3 "While I," said smiling Dickey Bend, "Will add my mite as Johnny's friend; Nor shall he want the scraps of knowledge Which he can pick up at my College." —Thus, as they did the bumper ply To Johnny's future destiny, The warm, almost parental heart Of Mrs. Syntax bore its part; And her cheek wore a smile of joy As she beheld th' unconscious boy, Who, careless of the kind debate, Play'd with the cherries on his plate. |

| But the good lady took him home And kept him many a year to come; When he grew up a charming youth, In whom simplicity and truth 4 Did o'er his ev'ry thought preside; While, with such an anxious guide, Life smil'd and seem'd to promise fair, That it would answer to the care Which her affection had bestow'd, To set him on his future road: But when she died poor John was hurl'd Into a bustling, tricking world. He had, 'tis true, all she could leave; She gave him all there was to give; Of all she had she made him heir, But left it to a lawyer's care: No wonder then that he was cheated And her fond anxious hopes defeated: So that instead of his possessing The fruits of her last, dying blessing; |

|

| He had, as it turn'd out, to rue What foul rascality could do; And his own wild vagaries too. |

} |

| Thus I proceed,—my humble strain Has hap'ly pleas'd.——I may be vain,— But still it hopes to please again. |

} |

| In this great overwhelming town, Certain receptacles are known, Where both the sexes shew their faces To boast their talents and get places: Not such as kings and courts can give, Not such as noble folk receive, 5 But those which yield their useful aid To common wants or gen'ral trade, Or finely furbish out the show That fashion does on life bestow. Here those who want them may apply For toiling powers and industry, On whom the nervous strength's bestow'd To urge the wheel or bear the load. Here all who want, may pick and chuse Each service of domestic use: The laundry, kitchen, chamber, dairy, May always find an Ann or Mary, While in th' accommodating room, He who wants coachman, footman, groom, Or butler staid, may come and have, With such as know to dress and shave. —The art and skill may here be sought In ev'ry thing that's sold and bought, In all the well spread counter tells Of knowledge keen in yards and ells; Adepts in selling and in buying And perfect in the modes of lying; Who flatter misses in their teens, And harangue over bombazeens, Can, in glib words, nor fear detection, Arrange each colour to complexion: Can teach the beau the neckcloth's tie, With most becoming gravity; Or with a consequential air, Turn up the collar to a hair. —Besides, your nice shop-women too, May at a call be brought to view, Who, with swift fingers, so bewitching, Are skill'd in ev'ry kind of stitching; Can trim the hat, arrange the bonnet, And place the tasty ribbon on it. 6 In short, here all to service bound, May in their various shapes be found. —From such who may display their charms, By smirking looks and active arms, To those in kitchen under ground Amid black pots and kettles found: From such as teach the early rules, Or in the male or female schools, To those of an inferior breed, Who ne'er have known to write or read: From those who do the laws perplex In toil at an attorney's desk, To such as pass their busy lives In cleaning shoes or cleaning knives. |

|

| To these, perhaps, an added score Might swell the tiresome list or more, But here description says, "give o'er." |

} |

| In such enregistering shop One morn a figure chanc'd to pop; (But here I beg it may be guess'd, Of these same shops it was the best, |

|

| His hat was rather worse for wear, His clothing, too, was somewhat bare, His boots might say, "we've travell'd far." |

} |

| His left hand an umbrella bore And something like a glove he wore: Clean was his very sun-burnt skin Without a long hair on his chin, While his lank face, in ev'ry feature, Proclaim'd a keen, discerning nature; |

|

| And when he spoke there was an air Of something not quite common there: His manner good, his language fair. |

} |

| A double cape of curious make, Fell from his shoulders down his back, 7 As if art did the folds provide A very awkward hump to hide; But, if 'twere so, the cunning fail'd, For still the treach'rous bunch prevail'd. |

|

| By chatting here and talking there, He did his curious mind prepare With all the means by which to gain The end his wishes would obtain;— Then with half-humble, solemn face, He sought the ruler of the place, Who boasted an establish'd fame, And Sharpsight was his well-known name. But ere we in our way proceed To tell of many a future deed, It may, we doubt not, be as well, To save all guess-work, just to tell, Of the part now upon the stage Quæ Genus was the personage. Fortune's dark clouds, for some time past That learned title had o'ercast, And he had borrow'd names in plenty, He might have gone by more than twenty; |

|

| But now arriv'd in this great town Without a fear of being known He thought he might assume his own: |

} |

| And he had weighty reasons too For what he was about to do, Which, we believe, a future page Will reconcile as reasons sage. At length his statement he began, When thus the conversation ran. |

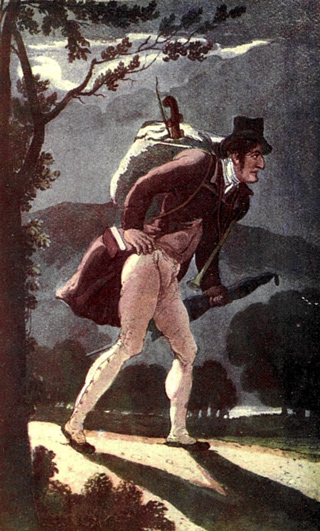

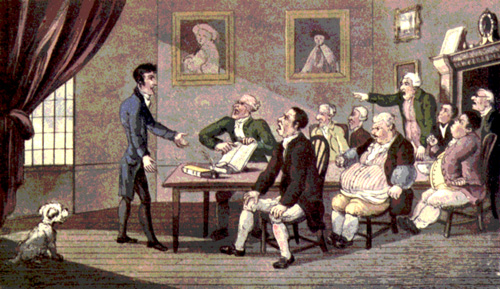

Drawn by Rowlandson

Quæ Genus, in search of Service.

| "In answer to your just desire, Permit me fairly to enquire, Which to my ledger is transmitted, For what your qualities are fitted? And, in good faith, I wish to know, What you have done, and what can do? Nay, to whose word I may refer For your good name and character. Such is essential to the case, Such are the first steps to a place, Of whate'er kind that place may be, Whether of high or low degree; Without them no access to station, No character, no situation. —What you assert, you say is true, I'm sure, my friend, I wish so too: 9 For what you ask, as you describe, Is ask'd by all the serving tribe: 'Tis that to which they all pretend, But those I never can commend |

|

| In honour to my own good name, And to this room's establish'd fame, But what the rigid truth may claim. |

} |

| Though as you look this place around, But common folk are to be found: Coachmen who sit without a whip; Footmen, without a call to skip; Gardeners who have lost their spade, And Journeymen without a trade; Clerks whose pens have long been idle; With grooms quite dull, who ask a bridle; Cooks who exclaim for roast and boil'd, And nurs'ry-maids without a child; Young, sprightly girls who long to clamber From drawing-rooms to upper chamber, Ready the drudg'ry to assail Of scrubbing-brush, and mop and pail; Stout porters who for places tarry, Whose shoulders ache for loads to carry; But character they must maintain, Or here they come, and pay in vain. In short, were I to count them o'er, I could name twenty kinds or more, Who patient and impatient wait About this busy, crowded gate. —But you might higher claimants see Within this crowded registry, Who do not at the desk appear, Nor e'er are seen in person here; But they are charged a larger fee, Both for success and secrecy. 10 Thus you must see how much depends, To gain your object and your ends, That you should truly let me know What you have done,—what you can do; And I, once more, beg to refer To your good name and character." |

| "I do profess I can engage With noble, simple, and with sage. Though young as yet, I've been so hurl'd About what you would call the world, That well I know it, yet 'tis true, I can be very honest too. —Of the good name which you demand, I tell you—I've not one at hand. Of friends, I once had ample store, But those fair, prosp'rous days are o'er, And I must mourn it to my cost That friends are dead, and gone, and lost; But if to conscience 'tis referr'd, My conscience says, Sir, take his word. —Of character, though I have none, Perhaps, Sir, I can purchase one: I, from a corner of my coat, May just pluck out a pretty note; Which, with a view to gain an end, Might, in an urgent want, befriend. |

|

| Now, if to place me, you contrive, Where I may have a chance to thrive; I'll give this note, if I'm alive. |

} |

| It may be rather worth your while; Perhaps it may awake a smile." |

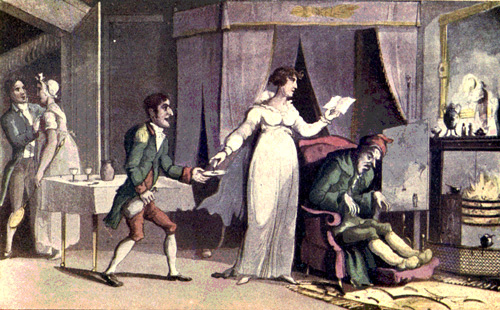

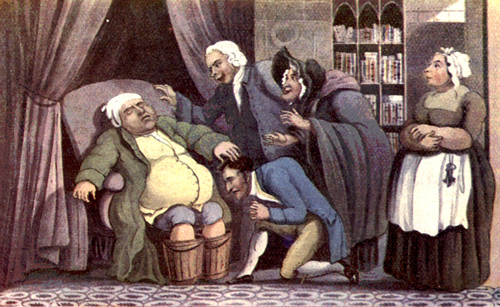

Drawn by Rowlandson

Quæ Genus reading to Sir Jeffrey Gourmand.

| "I know it well, as you will see, It tells my infant history: This leaf will partly save the task Of answ'ring what you're pleas'd to ask. |

|

| That little infant whom you see In basket laid,—that, Sir, is me, Now grown to sad maturity. |

} |

| —It was within an Inn of Court, Where busy Lawyers plead and sport; Upon those stairs and thus enclos'd, My new-born figure was expos'd. |

|

| Of mercy they had little share Whose cruel purpose plac'd me there, And left me to the Lawyer's care; 18 |

} |

| For, had th' Attorney been in town, Who did those very chambers own, I doubt what might have been my fate: The thing was strange—the hour was late; The work-house might be distant far, And dubious been the nursings there. But one, perchance, possess'd the floor When I was laid beside the door, Who would have felt a crying sin Had he not ta'en the stranger in. When I this pictur'd figure view, So innocent—so helpless too, A smile's contending with a tear, On seeing what I now appear: A pretty figure for a casket,— A little Falstaff in the basket." |

| "This is most strange, I do declare! But pray what figure did she bear While you th' unwilling servant were?" |

} |

| "Well, well, go on," Sir Jeff'ry said, While his glad, twinkling eyes betray'd, How much Quæ Genus pleas'd his fancy At this so flatt'ring necromancy. —While the Knight his cold coffee quaffing, But still at his own fancies laughing, |

|

| Exclaim'd, "proceed, but be it known, I wish the lady's hist'ry done, And then you will conclude your own." |

} |

| "But one more question I've to ask, Ere you perform your promis'd task, And tell me from all shuffling free, The items of your history, Up to the moment when you stand A candidate for my command. And now Quæ Genus tell the name Of this same universal dame, Whom you, poor fellow, have been serving, And, as you state it, almost starving. —If in your tale she does agree, It is a tale of mystery; Some fairy fable, I suppose, That paints, in emblems, human woes, And does in figur'd words, apply To your peculiar history. It is not in the usual way That such as you their state display; It is not in such borrow'd guise That they unfold their histories, With here and there a little bit Of droll'ry to shew off their wit; 23 It is not in this form I see Those who may wear my livery; But your's I feel a diff'rent case From those who come to seek a place; Or when the register may send him, With, 'Sir, we beg to recommend him.' I now bethink me of the sage Who lov'd you in your tender age; |

|

| And when I see you have a claim To share the page that marks his fame, Syntax, that highly honour'd name |

} |

| A passport is, my good Quæ Genus, To the familiar talk between us. From that relation which you share, No longer stand, but take a chair, And now proceed, without delay, To close the tale in your own way. |

| "Miss-Fortune is the name she bears, Her rent-roll's form'd of sighs and tears: 24 She doth not live or here or there, I fear, Sir, she lives ev'ry where. I'm sure that I know not the ground Where her sad influence is not found; |

|

| But if a circle should appear Beyond her arbitrary sphere, I feel and hope, Sir, it is here. |

} |

| —This worn-out coat, Sir, which you see, Is the kind Lady's livery: I once was fat, but now am thin, Made up of nought but bone and skin; I once was large but now am small, From feeding in her servants'-hall, And the hump I shall ever bear Is an example of her care. As for the blessed Dame's beginning, I've heard that it began in sinning, And I have learn'd that she will end When this vile world has learn'd to mend; But if we guess when that may be, We may guess to eternity." |

| "Though in a diff'ring point of view, I know her just as well as you; And hang the hag she plagues me too. |

} |

| Need I, good fellow, need I tell ye, She deck'd me out with this great belly; 'Tis she, by way of friendly treat, Has given this pair of gouty feet; Nay sometimes when her whim commands Miss-Fortune robs me of my hands: 'Tis she with her intention vile That makes me overflow with bile; And tho' my table's spread with plenty Of ev'ry nice and costly dainty, She sometimes envies me a bite, And takes away my appetite. She does not meddle with my wealth, But then she undermines my health; She never in my strong box looks, Nor pries into my banker's books; My ample fortune I contrive To guard with care and make it thrive, I check her power to destroy it, But then she says, 'you sha'n't enjoy it; 26 I will take care you shall endure The ills and pains gold cannot cure.' Or leagu'd with wrinkled age at least, She strives to interrupt the feast. —But with her malice I contend, Where she's a foe, I'm oft a friend, And, with the weapons I can wield, I sometimes drive her from the field. Nay when she does the victim clasp, I snatch it from her cruel grasp. And thus you see, or more or less, I make her prove my happiness." |

| "And she shall 'wake it now, Quæ Genus! An instant contract's made between us. I break that which she made with you, And gladly you abjure it too. I have no doubt, my friend, to venture; Into my service you shall enter, Your ills at present shall be o'er, Miss-Fortune you shall serve no more. At least, I say, while you contrive By your good deeds with me to live: 27 I'll save you from your late disaster And change your mistress for a master. I want no bowings, no grimaces, No blessings that I've chang'd your places. —I now remind you to relate All that has been your various fate, Nay, all that you have ever known, Since time and freedom were your own. —I tell you, Johnny, speak the truth; I know what follies wait on youth: I know where erring passion leads, On what a slipp'ry ground it treads: I can remember that I fail'd When the gay, tempting world prevail'd; Nor shall I now the thought conceal, Which reason tells me to reveal. What Heaven forgives should be forgiven By all who look with hope tow'rds Heaven: |

|

| But I expect not faults alone, I trust in what you may have done, There may work out a little fun. |

} |

| —If I guess right your lively eye Was not exactly made to cry, But sometimes call forth pleasantry; |

} |

| Of diff'ring thoughts to ope the vein, Let pleasure forth or lessen pain. But still do not your mischiefs hide, Throughout your tale, be truth your guide; Nor make Miss-Fortune though she starves, Worse, by the bye, than she deserves, For after all her misdeeds past, The Dame may do you good at last. —Deceive me, and you will offend, Deceive me, and you lose a friend: Try to deceive me and again You'll join Miss-Fortune's pale-fac'd train. 28 |

|

| Proceed then, and, without a fear, Pour thy misdoings in my ear And I will with indulgence hear. |

} |

| I'll not discard you for the evil, Though you should prove a little devil, Though to your hump you should not fail, To add your horns and hoofs and tail; Though you should prove a bag of sin, And hump'd without be hump'd within, Here you shall have your home, your food; Kick at Miss-Fortune, and be good." |

| "The Volume that now lies before ye, Tells you thus far, Sir, of my story; Which would be upon this occasion A work of supererogation; Though I shall beg leave to repeat, I'm not the new-born of the street; But as it never yet appear'd, At least, as I have ever heard, To such unknown, unfather'd heirs, I am a Foundling of the stairs, Without a mark upon the dress, By which there might be form'd a guess, Whether I should the offspring prove Of noble or of vulgar love; 29 Whether thus left in Inn of Court Where Lawyers live of ev'ry sort; Love in a deep full-bottom clad, Gave me a grave black-letter'd dad, Who, if 'twere so, might not agree To have a child without a fee; And, therefore, would not plead my cause, But left me to the vagrant laws Of chance, who did not do amiss, But sued in Formâ Pauperis, And, in a Court where Mercy reign'd, The little Foundling's cause was gain'd: Syntax was judge, and pity's power Sav'd me in that forsaken hour. He with that truly Christian spirit, Which Heaven gave him to inherit, Fondly embrac'd me as his own; But ere three transient years were gone, I lost my friend, but found another, A father he, and she, a mother; For such at least they both have prov'd, And as their child the stranger lov'd. O, rest her soul!—to her 'tis given To share his happy lot in Heaven. I seem'd to be her utmost pride, And Johnny trotting by her side, Fill'd with delight her glancing eye In warm affection's sympathy. This fond, this kind, this fost'ring friend Did to my ev'ry want attend; Her only fault, she rather spoil'd As he grew up, the darling child; But though her care was not confin'd Or to his body, or his mind, Though, with a fond parental view, She gave to both th' attention due, 30 Ne'er would she her displeasure fix On his most wild, unlucky tricks. So that at church he held grave airs, Pronounc'd Amen, and said his pray'rs, And on a Sunday evening read A sermon ere they went to bed, Throughout the week, he was quite free For mischief with impunity. —If on the folk I squirted water, How she would shake her sides with laughter; If the long-rotten eggs were thrown At Mary, Sally, or at Joan; If any stinging stuff was put Into the hasty trav'ller's boot; If the sly movement of the heel Should overturn the spinning-wheel. —If holly plac'd beside the rose Should wound the gay sheep-shearer's nose, Or 'neath the tail a thorn-bush pricking, Should set Dame Dobbins' mare a kicking, And overthrow the market load, While beans and peas o'erspread the road, If the poor injur'd made complaint To Madam of her wily saint, She would reply, 'pray cease your noise, These are the tricks of clever boys, It is my pleasant Johnny's fun, Tell me the damage, and have done.' —When I became a rosy boy, My growth encreas'd her growing joy; But now such gamesome hours were o'er I play'd my childish tricks no more. My little heart 'gan to beat high, And with heroic ardor try The tempting danger to pursue, And do what others could not do: 31 I sought to climb the highest tree, Where none would dare to follow me, Or the gay sporting horse to ride, Which no school-fellow dare bestride. My feats were sometimes rather scaring, But the Dame lov'd to see me daring; As by my running, leaping, walking, I us'd to set the parish talking, And, to the good old women's wonder, I fear'd not lightning nor thunder. |

|

| She thought, in future time, my name By some achievement bold, might claim A loud blast in the trump of fame. |

} |

| "Oft I my loss, in secret, wept, And when my eyelids should have slept, Nay, when those eyelids should have clos'd And I in strength'ning sleep repos'd, They remain'd wakeful oft and shed Their dews upon my troubled bed. Though Master Gripe-all, it was known Shew'd me a kindness not his own; And did with all indulgence treat me, As the best means, at length, to cheat me. He strove my early grief to soothe, Call'd me his dear, delightful youth; 37 Gave me a pretty horse to ride, With money in my purse beside; Let me employ the taylor's art To deck me out and make me smart, Let me just study when I pleas'd, Nor e'er my mind with learning teas'd. But still a gnawing discontent Prey'd on me wheresoe'er I went. —Of Phillis too I was bereft, One real pleasure that was left: A fav'rite spaniel of my friend, That did on all my steps attend, |

|

| At eve was frisking, fond and gay, But on the sad succeeding day, A poison'd, swollen form it lay. |

} |

| It might be chance, but while I griev'd, The following letter I received, Which was thrown o'er a hedge the while I sat half weeping on a stile. The writer I could never tell; But he who wrote it meant me well; And I've no doubt that it contain'd The thoughts which through the country reign'd." |

| "I'm a poor man, but yet can spell, And I lov'd Madam Syntax well: —But I've a sorry tale to tell. |

} |

| Young 'Squire you're in the Devil's hands, Or one who yields to his commands, And who, I'm certain, would be bold In bloody deeds, if 'tis for gold. Halters he fears, but the base wretch Fears no one mortal but Jack Ketch: Yet what with quirks and such like flaws, He can contrive to cheat the laws: 38 Though Madam's hand the will might sign, It is no more her will than mine. Some say, as she lay on her bed, The deed was sign'd when she was dead, And I've heard some one say, whose name I must not give to common fame, He'd lay ten pounds and say, 'have done,' You liv'd not on to twenty-one; And if you die before, 'tis known, That Madam's money's all his own. Nay, how he did the will compose, 'Tis Beelzebub alone who knows! He in a lonely mansion lives, But there the cunning villain thrives: Yes, he gets on, as it appears, By setting people by the ears: Though I have heard Nan Midwife say, Who sometimes travels late that way, That 'neath the yew, near the house wall, Where the dark ivy's seen to crawl, A cat she once saw which was half As big as any full-grown calf, And with her tail beat down the bushes, As if they were but slender rushes; Has often felt sulphureous steam, And seen bright lines of lightning gleam. These things the good, old woman, swears She sometimes smells and sees and hears, While thus all trembling with affright, She scarce can get her bald mare by't. —Run off, young 'Squire, for much I fear You'll be cut off, if you stay here. My service thus I do commend, From, Sir, your very humble friend: And hope you will take in good part, What comes from poor but honest heart!" 39 |

| "One day as I was riding out, Prowling the country round about, A guide-post stood, in letter'd pride, Close by the dusty high-road side: With many towns for passage fam'd, Oxford upon its points was nam'd, Which instant call'd me to attend To my kind patron Doctor Bend: And then there 'rose within my breast A thought that reason did suggest, And not th' effect of boyish whim, 'Th' Attorney quit and fly to him.'— —Soon after, by a lucky chance, I heard what made my heart to dance, That Cerberus would be from home, At least for sev'ral days to come, Though, when of me he took his leave, He said, 'expect me home at eve, But, as talk may the way beguile,' He added, 'ride with me a mile.' —This was the very thing I wish'd, For now I felt the fox was dish'd. He rode on first and bade me follow, 'Twas then that I began to hollow; I had but one white lie to tell And all things would be going well. I said it was my guardian's whim That I should make the tour with him, 40 And ask'd for a clean shirt or so As I had such a way to go. Thus my great-coat, most closely roll'd, Did all the useful package hold, And to the saddle strongly tied I was completely satisfied, As nought appear'd, thus pack'd together, But a protection from the weather, So that the lawyer's lynx's eye Was clos'd on curiosity: For Madam Gripe-all's ready care Did, to my wish, the whole prepare. Indeed, whatever she might be, Her kindness never fail'd to me. She frequently would call me son, And say she lov'd me as her own; Nay, when the clock struck, she would say, 'Kiss me as often, dear, I pray As that same clock is heard to strike, And oft'ner, dearest, if you like.' |

|

| Though such favour ne'er was shown, But when we both were quite alone, And seldom when the clock struck one. |

} |

| Her fondness I could well have stinted, For, to say truth, she smelt and squinted: But I remember'd that she cried, When my poor, little Phillis died. |

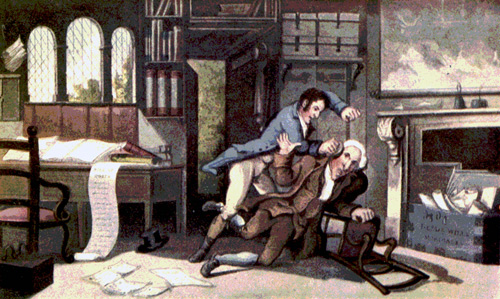

Drawn by Rowlandson

Quæ Genus at Oxford.

| "I told a simple, artless tale, That seem'd completely to prevail, As I beheld his face the while Beam with a kind, approving smile. ''Tis a bold trick,' the Doctor said, 'Which you, my lively spark, have play'd, But since to College you are come, I'll try to make the place your home; Where I should hope you need not fear To be cut short in your career; I think, at least, we may engage To keep you safe till you're of age, When I shall leave you to the struggling With Gripe-all's artifice and juggling: But still the cunning lawyer knows I have good friends 'mong some of those Who lead the bar or have a seat Where the keen eye detects a cheat. He will, I doubt not, swear and curse, Nay, he may say you've stole his horse; But if he meets with no disaster, In two days he shall see his master, And John will have a strict command To give a letter to his hand 42 Which I shall with due caution write Before I seek my bed to-night, And if my mental eye sees clear Will fix my friend Quæ Genus here.' John met the lawyer on the road, Just as he reach'd his own abode, And ere at home he could have heard Of my escape a single word: Told him at once all he could tell, That I at Oxford was, and well, Where as I stay'd, I had of course, With many thanks return'd his horse, John said, he rather look'd confus'd As the epistle he perus'd. —Whether it bore a kind request I should with Alma Mater rest, Or any hint that might apply To the High Court of Chancery: |

|

| If soothing it contain'd or threat, I never knew or I forget,— With all submission it was met. |

} |

| To all it ask'd he did agree, And sent his kind regards to me, While he his counsel did commend Not to run off from Doctor Bend, Nor e'er be govern'd by the whim That made me run away from him. |

|

| "Thus soon in Scholar's cap and gown, I was seen saunt'ring up and down The High-Street of fair Oxford Town. |

} |

| And though I stood not first in fame, I never bore an idler's name. I was content, nay 'twas my pride The Doctor ne'er was heard to chide, 43 Which, as your Oxford youths can tell, Was getting onward rather well. My friends, the Worthies, near the Lake, Lov'd me for Doctor Syntax' sake, And, free from e'en a speck of care, I pass'd a short-liv'd Summer there. —But time, as it is us'd, roll'd on, And I, at length, was twenty-one. |

|

| "I now became a man of cares To bear the weight of my affairs, To know my fortune's full amount, And to arrange a clear account Between the vile, rapacious elf, The Lawyer Gripe-all and myself. |

|

| —No sooner to the place I came, Soon as was heard my well-known name, The bells my coming did proclaim, |

} |

| And had I stay'd the following day, I would have made the village gay! Thus Gripe-all was full well prepar'd And put at once upon his guard. I went unwittingly alone To claim my right and ask my own, Though arm'd, to cut the matter short, With an enliv'ning dose of Port, While he was ready to display The spirit of the law's delay. —A step, he said, he could not stir Without Baptismal Register, And many a proof he must receive, Which well he knew I could not give; And till these papers I could shew, He must remain in Statu quo. But still, as a kind, gen'rous friend, And from respect to Doctor Bend, 44 He would, though cash did not abound, Advance me then four hundred pound. I took the notes and thought it best To wait the settling of the rest; But soon I saw, as I'm alive, That I had sign'd receipt for five. My fingers caught the fraudful paper, At which he 'gan to fume and vapour, And let loose language full of ire, Such as 'you bastard, rascal, liar,' On which I caught him by the nose, And gave the wretch some heavy blows, Nay, as the blood ran down his face, I dash'd the ink all in his face, So that his figure might have done E'en for the pit of Acheron. Inky black and bloody red Was o'er his ghastly visage spread, As he lay senseless on the floor, And, as I then thought, breath'd no more. —The office, now a scene of blood, Most haply in the garden stood, So that our scene of sanguine riot Did not disturb domestic quiet: The notes were in my pocket stor'd, And the receipt was in the hoard; But as I now believ'd him dead, I thought of being hang'd—and fled. Nor did I make the whisky wait Which then stood at the garden gate. The driver who there held the reins, Took me through many secret lanes And woodland roads, that might evade Pursuit, if any should be made. He had an humble play-mate been When I was sportive on the green; 45 But now, like me, to manhood grown, Was as a skilful driver known; And would have gone to serve Quæ Genus Though fire and water were between us. I told him all the fears I felt, And how I had with Gripe-all dealt; |

|

| Nay, urg'd him, if I were pursued, To cheat the blood-hounds, if he could, All which he mainly swore he would. |

} |

| Nay, hop'd I'd given him such a drubbing, As to send him Beelzebubbing; Though, first or last, he sure would go To his relations down below. |

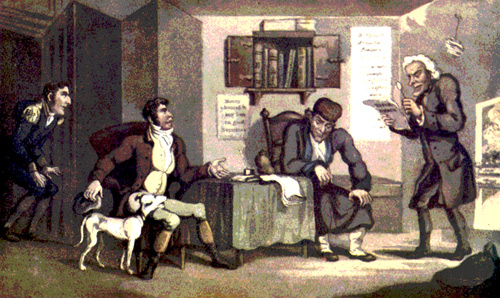

Drawn by Rowlandson

Conflict between Quæ Genus & Lawyer Gripe-All.

| "The fever wag'd a painful strife, A struggling chance 'tween Death and Life, That play'd upon my yielding spine, Which did to outward curve incline: I felt the mark would ne'er forsake Its cruel seat upon my back; I bent beneath the foul disaster That ne'er would yield to any plaister: Nor medicine, nor knife can cure it, And must struggle to endure it. Thus when restor'd to health and vigour, I was become a crook-back'd figure: My former round and healthful face Had lost its plump, its rosy grace, And was reduc'd from this same cause To pale and lean and lantern jaws, That none who once Quæ Genus knew Would recollect him on the view; Nor e'en would recognition wait Though he should pass by Gripe-all's gate. |

|

| When in the glass I chanc'd to view, The figure I now scarcely knew, I shudder'd and despis'd it too. |

} |

| —'At length,' said Julep, 'I commend, Ere you depart, a worthy friend, 47 A lawyer too, nay, do not start, Whose well-stor'd head and honest-heart, Throughout his life were ne'er disjoin'd, And in his practice are combin'd The cause of truth and right to aid; Who ne'er has heard the poor upbraid His conscious dealings, while 'tis known, The wealthy do his virtues own. Thus, as your fate has been accurs'd, Of legal dealers, with the worst; You now may, as by all confess'd, Obtain good counsel from the best. |

| 'My dress and name I'll do anon, The fever all the rest has done; |

|

| For Doctor Bend I would defy The fondled Foundling to descry, In his mis-shapen misery. |

} |

| Johnny Quæ Genus, now adieu! Jack Page I substitute for you!' |

| "You must, Sir Jeff'ry, often see The strange effects of vanity; Another you will find in me. |

} |

| You'll scarce believe as I relate The folly which I now must state: That I've been such a silly elf I now can scarce believe myself: 50 And I could wish I dare conceal What duty bids me to reveal. —Did not calm prudence whisper now To my existing state to bow, To tell it all to such a friend As I had found in Doctor Bend, |

|

| Or a quick pilgrimage to make To Worthy-Hall beside the Lake, Where, for dear Doctor Syntax' sake, |

} |

| The troubled Foundling would receive All that protecting care could give. This was the counsel Make-peace gave, A lawyer who was not a knave; Who would advise without a fee, And felt for human misery. —This Reason said in lessons strong, As I pac'd my still way along, When the dull sound of my own feet And Philomela's sonnet sweet Did on the gen'ral silence break, And seem'd to keep the night awake. Then Vanity sat pick-a-pack Perch'd on the hump upon my back, And whisper'd into either ear, 'Such humbling counsels do not hear. Where poor Quæ Genus has been known His alter'd form must ne'er be shown: With this sad shape he never can Hold himself forth a gentleman: No art can furnish you a cloak To hide from pity or from joke. If passing on a river's ridge, Or, perchance lolling o'er a bridge, You gaze upon the stream below Whose crystal mirror's seen to flow, 51 Would not the picture meet your eye Of your own sad deformity? At Oxford you would be the talk Of the High-street or Christ-Church-walk, While many quizzing fools look round To view your rising back begown'd. —How would you bear the wond'ring ken Of the good folk of Sommerden, While they with pitying looks lament The once straight form, but now so bent! Then leave the world where you have been, Where I would be no longer seen, Nor let the jealous eye compare, What you once was with what you are. |

|

| Might I advise, I'd sooner die Unknown, in humble privacy, Again,' said whisp'ring vanity, |

} |

| 'Than e'er appear where I was known For graces which were then my own, That pity or that scorn might point At such a form, so out of joint.' |

|

| "I need not say how many days I sought the bye and secret ways, |

|

| For ever list'ning to the tongue That whisper'd soft and pleaded strong, To set each better feeling wrong. |

} |

| Hence I resign'd myself to chance, Left fortune, friends, inheritance, And madly felt that I was hurl'd Thus mark'd to wander through the world. To snatch at, and at once receive, Whate'er the world might chance to give. |

|

| 'Twas not a whimsy of the brain, That did the idle scheme sustain, 'Twas something which I can't explain. 52 |

} |

| All feeling center'd in the pack That had thus risen on my back; And as I felt the burden there, It seem'd the seat of ev'ry care, Of ev'ry painful thought brimfull, Like Old Pandora's Ridicule. |

|

| But as every single note Which I from Gripe-all's grasp had got, Was still secure within my coat, |

} |

| I had sufficient means and more To travel all the kingdom o'er |

|

| With staff in hand, and well-shod feet, And oil'd umbrella form'd to meet The show'rs that might my passage greet. |

} |

| One pocket did a bible hold, The other held the story told, Which good Æneas did rehearse To Dido, in immortal verse; While from a loop before descended A flute that oft my hours befriended: Thus I with verse, with prose or fist, Was scholar, fiddler, methodist. As fit occasion might demand, I could let Scripture Phrase off-hand, Or fine re-sounding verses quote, Or play a tune in lively note. Thus qualified to cut and carve, I need not fear that I should starve; While in some future lucky stage Of my uncertain pilgrimage, I might have hopes, remov'd from strife, To be a fixture for my life. |

| "I wish'd to figure as Othello, But he was a fine, straight-made fellow, Whom, with a shape, so crook'd, so bent, I could not dare to represent, And though his face was olive brown, No injury his form had known; While mine, in its unseemly guise, Fair Desdemona must despise: |

|

| Nor could it be a bard's design, That love-sick maids should e'er incline To such an outrag'd shape as mine. |

} |

| My voice possess'd a tender strain, That could express a lover's pain; But such a figure never yet Was seen to win a Juliet. Nay ladies lolling in a box, Would think it a most curious hoax, If through their glasses they should see Lord Townly such an imp as me. Thus for a month or more, Jack Page Fretted and strutted on the stage, Sometimes affording Richard's figure In all its native twist and vigour; Or bearing kick, or smack, or thump From Harlequin upon his hump. 56 Though I say not, I was ill-paid For the fine acting I display'd. Nay, had I less mis-shapen been, I might to the Theatric scene, Have turn'd my strange life's future views, And courted the Dramatic Muse. |

| "I think, Sir Jeff'ry you may guess, The plot my Farce aims to possess,— A kind of praise of ugliness; |

} |

| Where Beauty is not seen to charm, Nor fill the heart with fond alarm; Where finest eyes may gleam in vain, May wake no joy, or give no pain: And though the beaming smiles may grace The rosy bloom of Delia's face, Here they excite no am'rous passion, Nor call forth tender inclination: 57 Such the desire, that ev'ry day, Amuses Cupid when at play, But other objects must engage The scenes I offer'd to the stage: Lame legs, club feet, and blinking eyes, With such like eccentricities, Call'd forth my amorous desire, And set my actors all on fire. With me no Damon longs to sip The sweets of Cath'rine's pouting lip, But smoke-dried Strephon seeks the bliss Of a well-guarded, snuffy kiss, Where the long nose, delightful wonder, Scarce from the chin can keep asunder; Where lovers' hearts ne'er feel a thump, But when they view each other's hump. |

| "To you, Sir, it was never known To feel the state which I must own: No home, not knowing where to go, How I should act and what to do. Just as a ship whose rudder's lost, Nor within sight of any coast; Without the power to stand the shock Of tempest, or to shun the rock. From the strange nature of my birth, I knew no relative on earth, Nor to my giddy thoughts was given To look with any hope to Heaven. To London I propos'd to go, Where not a being did I know: To me it was an unknown shore, Where I had never been before, At least, since of all care bereft, I was a helpless Foundling left. Thus, as I thought, behold I stood, Beside a mill-dam's spreading flood; |

|

| The waters form'd to drive the mill With its tremendous wheel, stood still, While evening glimmer'd on the hill. |

} |

| One plunge I said and all is o'er, My hopes and fears will be no more; An unknown child, an unknown man, And I shall end as I began. Nor can I say what would have follow'd, I, and my hump, might have been swallow'd In the deep, wat'ry gulph beneath, Had I not heard a hautbois breath 59 A lively, but an uncouth strain, As it appear'd from rustic swain, Which, as it dwelt upon my ear, Told me that merriment was near, And did at once dispel the gloom That might have sought a wat'ry tomb. I turn'd my footsteps tow'rds the sound That was now heard the valley round; When soon upon the rural green, The sight of busy mirth was seen. |

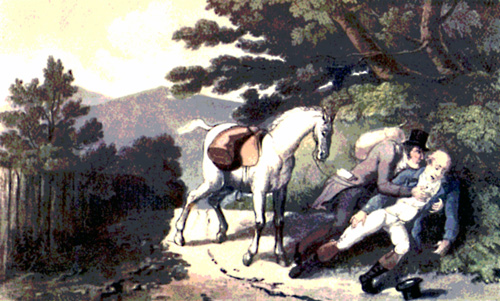

Drawn by Rowlandson

Quæ Genus at a sheep shearing.

Quæ Genus assisting a Traveller.

| "To Reason I attention lent; Th' advice was good,—and, strait or bent, I now resolv'd to be content. |

} |

| "Thus, as I urg'd my onward way, In spirits rather growing gay, |

|

| With saddle bags and all alone, A sprightly horse came trotting on, As if he had his rider thrown. 63 |

} |

| The beast I, with some trouble, caught, And then its fallen master sought, Whom, within half a mile I found All pale and stretch'd upon the ground: When I approach'd, as in surprise, He gave a groan and op'd his eyes. A crystal brook ran murm'ring by, Its cooling fluid to supply, And soon its sprinklings did afford The power that banish'd strength restor'd. Thus, when re-mounted on his steed, We did, in progress slow, proceed: I cautious pac'd it by his side With tighten'd rein the horse to guide; And with attentive eye, prevent Another downfall accident. |

|

| "We might have gone a mile or more, When we beheld a lofty tower That did in stately form arise, A welcome sight to anxious eyes, Marking a spot where might be found Some styptic to a bleeding wound. |

|

| I shall be brief,—the Horseman's head Was soon repos'd on downy bed; The Surgeon came and he was bled: |

} |

| The lancet was by blisters follow'd, And potions, in due order, swallow'd. He look'd his thanks, then squeez'd my hand, Bade me, what gold could pay, command; Of all I wish'd to take my fill, Enjoy myself, nor fear the bill. I took my patient at his word, And what the Blue Bell could afford, (An Inn of good repute and worth, Well known to all who travel North,) 64 As it was his desire, enjoy'd, Till with good living I was cloy'd. But his sick bed I did amuse, I told him tales and read the news; So that with emphasis he swore He almost griev'd his ills were o'er. |

| "'A Trav'ller is the name I bear, A well-known, useful character, Who, through the kingdom's wide-stretch'd bounds, Ne'er fails to make his yearly rounds. 65 I for a London house of trade Employ my necessary aid, By which its commerce I extend From Dover to the far Land's End. Well mounted, or perhaps in chaise, We quietly pursue our ways; Lift our heads high, and look so grand When we have payments to demand, But bow, and handsome speeches give When we have orders to receive: Thus suiting manners, as you see To our commercial policy. Nay, when the busy day is o'er, We meet at night, perhaps a score; And, in return, give our commands To humble host, who cringing stands, In order to prepare the best For the be-bagg'd and trav'lling guest, |

|

| And bring us wine to aid our cheer; While, with stump'd pens behind the ear, Good folks in town may drink their beer— |

} |

| Nay, may be boasting of our labours In smoking clubs of sober neighbours. |

| "I seiz'd the time and told my tale, At least, as much as might avail Some settlement in town to find, That suited both my means and mind; When by advice, and, which was better, By a most urgent, friendly letter, Arriv'd in London,—I soon found I did not tread on hostile ground: |

|

| Nay, ere a week was pass'd and gone, Fortune, I hop'd had ceas'd to frown, As I did now a station own, 67 |

} |

| With promis'd comfort by my side, That gave me gains, nor hurt my pride. But my misfortunes were not past, Though this I hope will be my last, Or I'll avenge me of the pack, The foe I carry on my back; From London Bridge I'll dash me plump,— And drown th' incorrigible Hump. |

| "Thus, Sir, I've told my tedious story, And now a suppliant stand before you: But in my story, right or wrong, Truth was the rudder of my tongue. —I've done, and, in all patience, wait, To know how you may rule my fate; |

|

| And if my hist'ry will commend Quæ Genus, (such may be his end,) To you, Sir Jeff'ry, as his friend." |

} |

| SILENCE for some short time ensu'd, Ere conversation was renew'd. |

|

| —Sir Jeff'ry first strok'd down his chin, With something 'twixt a yawn and grin, And then thought proper to begin. |

} |

| "Things at the worst, 'tis said, must mend, And I will prove your real friend, 70 If you, hereafter, have the sense To merit my full confidence: And now, I think, you may prepare To take my household to your care. Your pride must not offended be At putting on a livery, As that will be the best disguise To hide you from all prying eyes; Quæ Genus, too, you now must yield, That learned name should be conceal'd; Ezekiel will suspicion smother, As well, I think, as any other, Till I have due enquiry made If Gripe-all be alive or dead, And how far I may recommend The runaway to Doctor Bend. Do what is right—and laugh at fear; The mark you carry in your rear Will never intercept the view Fortune may have in store for you. No more let vanity resent The stroke by which your form is bent! How many in the world's wide range Would willingly their figures change For such as yours, and give their wealth To get your hump and all its health. Look at my legs—my stomach see, And tell me, would you change with me? |

|

| Nay, when your healthy form I view, Though all be-hump'd, I'd change with you, And give you half my fortune too. |

} |

| Lament no more your loss of beauty, But give your thoughts to do that duty Which my peculiar wants require, And more you need not to desire. 71 I feel I cannot pay too high For care and for fidelity: Let me see that—my heart engages To give you something more than wages —Your duties will be found to vary, As Steward, Nurse, and Secretary: Thus you will soon my wants attend Less as a servant than a friend. You may suppose I little know Of what is going on below; My leading wishes are, to prove That I am duly serv'd above, And you, as may be daily seen, Must play the active game between." |

Drawn by Rowlandson

Quæ Genus, in the Sports of the Kitchen.

| "O may I never, never be A servant out of livery, Which is th' ambitious, hop'd-for lot Of all who wear the shoulder knot! |

|

| O may I never quit my place Behind the chair, nor shew my face, The sideboard's glitt'ring show to grace, |

} |

| If, when my master ceas'd to dine, I ever stole a glass of wine! O, may my food be pitch and mustard, If ever I took tart or custard, If e'er I did my finger dip In some nice sauce and rub my lip! If turnpike tolls I e'er enlarg'd,— May I this moment be discharg'd!" |

| "May I be flogg'd with thorny briars If e'er I heard such cursed liars, |

|

| And should I venture now to say I ne'er purloin'd or corn or hay, I should be liar big as they! |

} |

| Nay, 'tis such folly to be lying, And all these trifling tricks denying, Which, ere a fortnight's past and over, Mr. Ezekiel must discover. Sir Jeff'ry's keen look never sees What are but clever servants' fees, And he would feel it to his sorrow, Were he to change us all to-morrow; For the new steward soon will see No master's better serv'd than he. 75 There's not a carriage about town That looks genteeler than our own; Or horses with more sprightly air, Trot through the street or round a square. I say that we all do our duty, And if we make a little booty, We never hear Sir Jeff. complain: And wherefore should one give him pain? If better servants he should seek, He must be changing ev'ry week; And I am sure that kind of strife Would spoil the quiet of his life: Nay, as you know, there is no question Would operate on his digestion; And when that fails, it is a point That puts the rest all out of joint. Thus all our trifling, secret gains Save him a multitude of pains: And when our daily work is done, If we kick up a little fun, No harm proceeds—no ill is meant— He's not disturb'd—and all's content. —Nay, now my friends, I'll club my shilling, And you, I'm sure, will be as willing To drink—that bus'ness may go on In the same temper it has done, And, without any treach'rous bother, That we may understand each other: That, without boasting or denying, We need not to continue lying; And that, disdaining needless fuss, Ezekiel may be one of us." |

| At length, in office thus install'd, And each was gone where duty call'd, |

|

| He, with a pressing arm, embrac'd The busy cook's well-fatten'd waist, As with her pin she plied the paste; |

} |

| When from her active tongue he drew The duties which he had to do, And how he might their claims divide, Nor lean too much to either side. —Our hero, who now felt his ground, Thought not of change in what he found; And that to enter on reform Would be but to excite a storm, Disturb the Knight's desir'd repose And fill a kitchen full of foes. He plainly saw his station bound him To be at peace with all around him: But, as the diff'rent int'rests drew, He rather trembled at the view. |

| 'Twas in this case our hero stood: He might be bad—he might be good; If good, he must the kitchen sweep— If bad, its tricks a secret keep; But if he would preserve his cloth, He must determine to be both. |

|

| Thus, as he took a thoughtful view, He saw, his int'rest to pursue, He must divide himself in two. |

} |

| Above to stick to rigid plan— Below to join the lively clan: In what Sir Jeff'ry did entrust To his sole province, to be just; 78 But ne'er to interrupt the show That was kept up by friends below: At least, he was resolv'd to try This system of philosophy; To be a favourite with all, In drawing room and servants' hall. From all that he at present view'd, No other plan could be pursu'd; No other method could he trace, To be at ease and keep his place. |

|

| Up-stairs to serious care he went, Down-stairs to stolen merriment, And thus the day and night were spent. |

} |

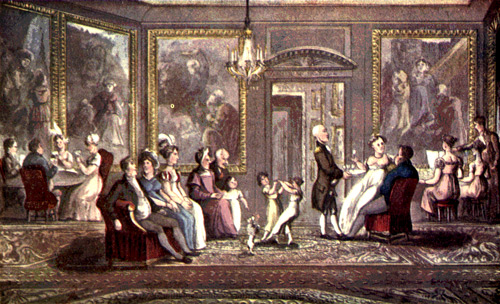

Drawn by Rowlandson

Quæ Genus, in the service of Sir. Jeffery Gourmand.

| In this wide world, how oft is seen A phantom with alluring mien, 79 Y'clep'd Temptation, whose sweet smiles Too oft the stoutest heart beguiles. Whate'er its forms, they seldom fail Sooner or later to prevail. If it assumes a golden shower, Or sits in any seat of power, How numerous the slavish band Who offer to obey command: Still, some examples may be shown Of those whose virtues would disown Its influence, and refuse to fly, Or yield the palm of victory. But where's the heart that e'er disdains The pow'r that dwells where beauty reigns? If such a question we propose, Ezekiel was not one of those; And thus below-stairs he began To break upon his up-stairs plan: |

|

| Nay, this same rigid rule of right, In his close duties to the Knight, He now thought might be drawn too tight; |

} |

| And that, in trifles, to his feeling, He might be safe in double dealing, And in the drawing-room apply The aid of kitchen policy: But he as soon would think of murther As to proceed an atom further. How he thus happen'd to decline From his strict, philosophic line; Why he relax'd from law severe In the Knight's upper atmosphere, Will not surprise one human creature Who the world knows, or human nature, Or recollects the joy or smart When passion first invades the heart. 80 |

|

| There were two objects most bewitching, That sparkled all around the kitchen; Though so bright was every kettle, Or plate or pan of various metal, That each might gaze upon a face As if they peep'd into a glass: Though fire-irons did reveal The shining of the polish'd steel,— Yet these superior pow'rs display'd, Than aught by human artist made: In short, to state what they could be, And silence curiosity, They were two eyes which lustre shed Where'er the owner turn'd her head; Though they gave not the only grace That play'd on Molly's charming face. But whether 'twas her lips or nose, Or the fine curve of auburn brows, That aided the commanding eye In its well-play'd artillery, Howe'er that be—in his warm heart Ezekiel had receiv'd the dart, And as its ruling power he felt, Each steady purpose 'gan to melt:— |

|

| For her he might his virtue stake And let his yielding conscience quake, Nay, cheat Sir Jeff'ry for her sake. |

} |

| Madge now scream'd out at her disaster, And swore that she would tell her master, But our Ezekiel found a plaister; |

} |

| Though what the plaister was he found To silence tongues and cure the wound, We must not nice enquiry make For virtue's and our hero's sake. 82 But we may tell, for this we know, That all was still and calm below; Though as the faithful verse will prove He shap'd another plan above, Form'd to controul all household feud, And be as honest as he could; Thus give to things another face To live at ease and keep his place. —Two int'rests into one were thrown, Those of Sir Jeff'ry and his own: The former strictly to maintain, Nor yet the latter to disdain; The Knight's confiding grace to keep, Nor let his own advantage sleep; The kitchen's jovial mirth to boast, But leave the cook to rule the roast; To be of Molly's smiles possest, Though never to offend the rest: And here we fear is the beginning, The first short lesson of his sinning. |

| There is a proverb so well known It would be ign'rance not to own The having heard and felt its truth E'en in the days of early youth, That, if we chance with those to live Whose lives a bad example give, They will convey, as we shall find, A foul contagion to the mind. Thus for a time Ezekiel stood Firm as the tree that crowns the wood, But, after mocking ev'ry blast, Will sometimes bend and fall at last. Though whether he began to shake, Or only suffer'd twigs to break, |

|

| But still retain'd his fibres bound, In firm defiance to the ground, While the main trunk, tho' shook, was sound, |

} |

| Is what the curious mind shall know, And no far distant page will show. 84 Thus the humble verse will trace His future honour or disgrace; As intermingled they must be With scenes of household history. |

|

| When good Sir Jeff'ry's gout was kind And to his bed he was confin'd; No dainty dinner to be got, And nought but messes in the pot, The kitchen folk, then quite at leisure, Would think of more than common pleasure; Then butlers of the higher station, And valets to gay men of fashion, Invited were, to join the ball Now given in the servants' hall, With ladies' maids who titles bore Of mistresses—whose gowns they wore; And sometimes a smart tradesman, too, Would pop in to say—how do ye do. |

|

| —Here all home secrets were betray'd— The various tricks which servants play'd, And how their fortunes could be made. |

} |

| When one grave man his silence broke, And thus to our Ezekiel spoke:— "Had I," says he, "so fine a place, As your superior manners grace; Had I a rich man in my keeping, Who passes half his time in sleeping; Whose purse is always in your view, And lets you pay his tradesmen too; While, that he may enjoy his ease, He makes you guardian of his keys, My growing fortune soon should flow, And in a way he ne'er should know. If by his bed you are his nurse, And have the jingling of his purse; 85 If, when the doctor comes to see him, And you are calmly told to fee him, You must be nam'd the veriest elf If, then, you do not fee yourself: Nay, when his fingers, cramp'd with gout, Cannot well take a sovereign out, And he should bid you take out four, Contrive to grapple five or more. 'Tis when he's sick with aches and ails, When pain torments and mem'ry fails, When the night's pass'd his bed beside, Then Fortune tells you to provide For future wants,—and bless the hour That gives the means into your power: Nor ever fail, on some pretence, To rail against the rash expense Which doctors and their varlets bring To patients, sick and suffering, Till you can get him to exclaim— 'Expense is a mere idle name; Of cost let your complainings cease, I care not so it gives me ease:' Then offer up your thanks to Heaven That to his fortune it is given To be thus blest with ample wealth, At any cost to purchase health. This is your harvest; I shall tell Another story when he's well: That time's but short,—though let him see That then you're all economy. When he can settle an account, And look into the just amount, Then, then let ev'ry thing appear Just as it ought—correct and clear. Thus let your speculations rove When well below, when sick above, 86 And all I'm worth I now would stake You will, in time, a fortune make. Rich as he is, and careless too, With such a confidence in you, Sir Jeffery will never feel Your happy turn in fortune's wheel." |

| Here this fine conversation ended, But not, perhaps, as was intended, Which strong temptations might display To lead th' unsettled mind astray; And, for a time, as fancy play'd, Now beaming light, now seeking shade, Ezekiel hover'd o'er the plan Of specious rogue or honest man. Perhaps a smart, neat, pleasant shop, Did on his pericranium pop, With his warm, faithful wish to crown, The lovely Molly then his own: Such interests might his purpose guide, Till he was questioned by his pride;— "—But can this be a proper plan For one bred like a gentleman? |

|

| 'Tis true I cannot change the show Of kitchen policy below, There I must yield, I'm bound to know: |

} |

| But, in the regions above, The whole in rectitude shall move; To the Knight's goodness I may trust, And faithful will I be and just; 89 Nor ever take or e'en receive But what his favour's pleas'd to give; Nor shall reproach my mind disgrace Whene'er I look him in the face." Such were his thoughts,—the grocer fail'd. Thus honesty at length prevail'd, And sav'd him, as things shortly stood, From baseness of ingratitude. |

| "This soup, my friend's a special treat, Fit for an Emperor to eat, And now, my pleasure to pursue, I trust I have a treat for you. I've spar'd no pains to know the fate That on your future hopes may wait, And what I shall proceed to tell May altogether please you well, Unless you are resolv'd to try New whims and tricks of foolery, On which, however will depend, Whether your master is your friend. If, at all points, the news I bring May not be quite so flattering; Yet surely it deserves at least, To be thought good, if not the best. —You need no longer stand in awe Of any terrors of the law, The beating you to Gripe-all gave Did little harm to that same knave, 90 For he surviv'd to play a prank, By robbing of a country bank, And fled, as his late neighbours say, To flourish in America. Thither your fortune too is gone, But then your fears are also flown. Time, it is hop'd may make amends, Fortune and you may still be friends; Nor shall I my best wishes smother To introduce you to each other. My growing favour you will see, So lay aside your livery: Hence you will need not a disguise 'Gainst curious thoughts and prying eyes: Your former title you may claim, Again Quæ Genus is your name: Be faithful, and you soon shall know The kindness I may yet bestow. |

|

| Nay, be but honest, while I live Your upright service shall receive All that my grateful hand should give: |

} |

| Nor doubt my purpose as sincere,— More may be meant than meets the ear." |

| Of words there was a mute hiatus, And of the noon-tide apparatus The table quickly was bereft, While with some new-born pamphlet left, Sir Jeffery calmly was proceeding To gratify his usual reading, When our Quæ Genus bore away The fragments of the lighten'd tray, And sought his pantry's cool retreat, Where, lolling on a welcome seat, He let his busy fancy range Throughout the unexpected change, 92 That did upon his fortune wait; And still, though humble was his state, Scarce could he think it a disaster To wait the will of such a master; Nor did his pride reluctant bend, Since that same master was his friend. All that indulgence could bestow Sir Jeff'ry did not fail to show; And, when alone, it seem'd to please The knight to set him at his ease, And shrink the distance to a span Between the master and the man. |

|

| —Nay, here it cannot be denied That it was soothing to his pride To lay the shoulder-knot aside. |

} |

| The liv'ried dress of red and brown He thus was call'd on to disown: In blue and buff, or buff and blue He now appear'd to daily view. The knight allow'd the taylor's art By all its power to make him smart; And Snip with his consummate skill, In working drapery to his will, By his contrivance gave the cape A flow to soften down the shape, So that the hump could scarce be said His general figure to degrade, Nor, to a common view, be seen To indispose his pleasing mien. |

| THE various, the uncertain views Which the all-anxious world pursues, While it directs its searching eye To what is call'd prosperity, Compose the gen'ral, pictur'd strife That forms the daily scene of life; And make up the uncertain measure Of power, of riches, and of pleasure; |

|

| Which, whatsoe'er may be our state, Do on the varying projects wait Of lowly poor or princely great: |

} |

| For as all worldly things move on We weigh them by comparison. Thus he who boasts his little all At a street-corner on a stall, Tempting the gaze of wandering eyes To view the transient merchandise, Will look to Fortune's smile to bless His humble trading with success, As he whose freighted vessel sails O'er distant seas with doubtful gales. Nay, in Ambition's humble school Perceive we not the love of rule, O'er rustic swains to bear the rod And be a village demi-god? To gain command and take the lead Where mean submission courts a head, 94 Does in the lowest class prevail Of vulgar thoughts to turn the scale, As that which on their wishes wait, Whose object is to rule the state. —Seek you for pleasure as it flows, In ev'ry soil the flow'ret grows; From the pale primrose of the dale Nurs'd only by the vernal gale, |

|

| To the rich plant of sweets so rare Whose tints the rainbow colours share And drinks conservatorial air. |

} |

| But, 'tis so subject to the blast, It cannot promise long to last; Though still it 'joys the fragrant day, Till nature bids it pass away. The rude boy turns the circling rope, Or flies a kite or spins a top, When, a stout stripling, he is seen With bat and ball upon the green; The later pleasures then await On humble life whate'er its state, And are with equal ardor sought As those with high refinement wrought, Where birth and wealth and taste combine To make the festive brilliance shine. |

| "Consider, man, weigh well thy frame; The king, the beggar, is the same, |

|

| Dust form'd us all,—each breathes his day, Then sinks into his mortal clay." Thus wrote the fabling Muse of Gay. |

} |

| Such thoughts as these of moral kind Quæ Genus weigh'd within his mind: |

|

| For wherefore should it not be thought That, as his early mind was taught, It might be with sage maxims fraught? |

} |

| —Thus seated, or as he stood sentry, Sole guardian of the butler's pantry, Which lock'd up all the household state, The cumbrance rich of massy plate, And all the honour that could grace The power of superior place, That did acknowledg'd rank bestow O'er all the kitchen-folk below; What wonder that his mind should range On hopes that waited on the change Which unexpected Fortune's power Seem'd on his present state to shower. Though while his wand'ring mind embrac'd The present time as well as past, The visions of the future too Gave a fair prospect to his view. But life this well-known feature bears, Our hopes' associates are our fears, And ever seem, in reason's eye, As struggling for the mastery, 97 In which they play their various part, To gain that citadel the heart. |

| The Knight most gen'rous was and free, And kind as kindest heart could be, So that Quæ Genus scarce could trace The humbling duties of his place. Whate'er he did was sure to please, No fretful whims appear'd to tease; And while with fond attention shown, He did each willing duty own, Sir Jeff'ry frequent smiles bestow'd, And many a kind indulgence show'd, And oftentimes would wants repress To make his fav'rite's labours less: |

|

| Nay, when he dawdled o'er his meat, Would nod and bid him take a seat To share the lux'ry of the treat.98 |

} |

| —He fancied, and it might be true, That none about him e'er could do What his peculiar wants required, And in the way he most desired, As his Quæ Genus, thus he claim'd him, Whene'er to other folk he nam'd him. Indeed, he took it in his head That no one else could warm his bed, And give it that proportion'd heat That gave due warmth to either sheet. |

| What could our Hero more desire, What more his anxious wish require, When with a calm and reas'ning eye He ponder'd o'er his destiny, As he unwound the tangled thread That to his present comforts led, And serv'd as a directing clue In such strange ways to guide him through? —To what new heights his hopes might soar, It would be needless to explore: For now the threat'ning time appears When he is troubled with his fears. His hopes have triumph'd o'er the past; But then the present may not last; And what succession he might find Harass'd with doubts his anxious mind. —Of the gross, cumbrous flesh the load Sir Jeffery bore did not forebode Through future years a ling'ring strife Between the powers of death and life; The legs puff'd out with frequent swell, Did symptoms of the dropsy tell; The stiffen'd joints no one could doubt Were children of a settled gout; And humours redd'ning on the face, Bespoke the Erysipelas. Indeed, whene'er Quæ Genus view'd, With rich and poignant sauce embued, 100 As dish to dish did there succeed, Which seem'd by Death compos'd to feed With fatal relishes to please The curious taste of each disease, That did Sir Jeffery's carcase share And riot on the destin'd fare: When thus he watch'd th' insidious food, He fear'd the ground on which he stood. —Oft did he curse the weighty haunch Which might o'ercharge Sir Jeff'ry's paunch; And to the turtle give a kick, Whose callipash might make him sick. He only pray'd Sir Jeff'ry's wealth Might keep on life and purchase health. "Let him but live," he would exclaim, "And fortune I will never blame." Money is oft employ'd in vain, To cure disease and stifle pain; And though he hop'd yet still he fear'd Whene'er grave Galen's self appear'd; For when the solemn Doctor came, (Sir Midriff Bolus was his name,) He often in a whisper said, "I wonder that he is not dead, Nay, I must own, 'tis most surprising, That such a length of gormandising Has not ere this produc'd a treat For hungry church-yard worms to eat, And 'tis the skill by which I thrive That keeps him to this hour alive. |

|

| Nay, though I now Sir Jeffery see In spirits and such smiling glee, I tremble for to-morrow's fee." |

} |

| —When this brief tale he chose to tell And ring his patient's fun'ral bell, 101 Quæ Genus fail'd not to exclaim, As he call'd on the Doctor's name, "O tell me not of the disaster That I must feel for such a master, Nay, I may add, for such a friend Were I to go to the world's end, Alas, my journey would be vain, Another such I ne'er should gain!" |

|

| Sir Midriff, member of the college, And of high standing for his knowledge, In lab'ring physic's mystic sense And practical experience, As common fame was pleas'd to say, Expected more than common pay. Now, as Sir Jeff'ry never thought His health could be too dearly bought, Whene'er the healing Knight was seen, Wrapt up within the Indian screen, To shape the drugs that might becalm Some secret pain or sudden qualm; Or when there was a frequent question, Of bile's o'erflow and indigestion, Or some more serious want had sped Sir Jeff'ry Gourmand to his bed, Quæ Genus fail'd not to convey (For he had learn'd the ready way), The two-fold fee, by strict command, Into Sir Midriff's ready hand. Thus, in this kind of double dealing, The Doctor had a pleasant feeling, That seem'd to work up a regard For him who gave the due reward, And knew so well to shape the fee From the sick chamber's treasury. 102 |

|

| Thus when our Hero told his pain And did his future fears explain, Galen replied,—"Those fears restrain, |

} |

| To this grave promise pray attend, Sir Midriff Bolus is your friend." |

| But something yet remains to know:— To manage two strings to your bow, A maxim is, which ev'ry age Has rend'red venerably sage, And forms a more than useful rule In the world's universal school. Sir Jeffery, we make no doubt, In various ways had found it out: 103 It might have help'd him on to wealth, And now to aid the wants of health, |

|

| He kept the adage in his view, And as one Doctor might not do, It now appears that he had two. |

} |

| The one, in order due, has been Brought forth on the dramatic scene, Ranks high in bright collegiate fame, And M. D. decorates his name. He never ventures to prescribe But what is known to all the tribe, Who hold the dispensarial reign Beneath the dome of Warwick-Lane. The other, steering from the track Of learned lore, was styl'd a Quack; Who, by a secret skill, composes For many an ill his sovereign doses: But whether right or wrong, the town Had given his nostrums some renown. Salves for all wounds, for each disease Specifics that could give it ease, Balsams, beyond all human praise, That would prolong our mortal days. All these, in many a puffing paper, Are seen in striking forms to vapour, As, in the Magazines they shine, The boast of Doctor Anodyne. His office was advice to give In his own house from morn till eve, And a green door, within a court, Mark'd out the place of snug resort, Where patients could indulge the feeling That might dispose them to concealing The nervous hope, the sly desire To eke out life's expiring fire, 104 Without the danger to expose Their secret or to friends or foes. Sir Jeffery was one of these Who thought it was no waste of fees, Though they were toss'd about by stealth, If he could think they purchas'd health: But here, who will not say, it seems He guarded life by two extremes. Sir Midriff told him he must starve, And Anodyne to cut and carve: But though the first he nobly paid, It was the latter he obey'd. Full often was his Merc'ry sent To bring back med'cine and content; |

|

| Permission, what he wish'd, to eat, And physic to allay the heat Brought on by a luxurious treat; |

} |

| To give the stomach strength to bear it, With some enliv'ning dose to cheer it. But still our Hero's watchful eye Saw that this sensuality Was bringing matters to an end, That he too soon should lose his friend; And in what way he should supply The loss when that same friend should die, Did often o'er his senses creep When he should have been fast asleep. Sir Midriff to his promise swore, And Anodyne had promis'd more, Both had prescrib'd or more or less, A future vision of success: But time has still some steps to move, Before they their engagements prove; Ere our Quæ Genus we shall see In a new line of history. 105 |

|

| Sir Jeffery now began to droop, Nor was he eager for his soup: |

|

| He blunder'd on the wrong ragout, Nor harangu'd o'er a fav'rite stew, Scarce wild-duck from a widgeon knew. |

} |

| No longer thought it an abuse, To see St. Mich: without a goose. Unless prepar'd with cordial strong, He hardly heard the jovial song, Or hearing, had not strength to move And strike the table to approve. Nay, sometimes his unsteady hand Could not the rubied glass command, But forc'd him slowly to divide The rosy bumper's flowing tide. Beside him oft Quæ Genus sat An hour, and not a word of chat; And when he was in sleepy taking The news would scarcely keep him waking. |

| Thus did the differing doctors fail, Nor could their varying skill prevail: 106 They neither could set matters right, Or quicken a pall'd appetite. More weak and weak Sir Jeffery grew, Nay, wasted to the daily view, And, as his faithful servant found, Between two stools he fell to ground. |

|

| But still he smelt the sav'ry meat, He sometimes still would eye the treat, And praise the dish he could not eat. |

} |

| One day, when in a sunshine hour, To pick a bit he felt the power, Just as he did his knife apply To give a slice of oyster-pie, Whether the effort was too great To bear the morsel to his plate; Or if, from any other cause, His nature made a gen'ral pause, He gave a groan, it was his last, And life and oyster-pies were past. |

| Mutes marching on, in solemn pace, With gladden'd heart and sorrowing face, Who, clad in black attire, for pay Let out their sorrows by the day: The nodding plumes and 'scutcheon'd hearse Would make a pretty show in verse; But 'tis enough, Sir Jeffery dead, That his remains, enshrin'd in lead, And, cloth'd in all their sad array, To mingle with their native clay, Were safe convey'd to that same bourne From whence no travellers return. |

|

| —We must another track pursue, Life's varying path we have in view,— Our way Quæ Genus is with you! |

} |

| AS our enlighten'd reason ranges O'er man and all his various changes, What sober thoughts the scenes supply, To hamper our philosophy; To make the expanding bosom swell With the fine things the tongue can tell! And it were well, that while we preach, We practice, what we're fain to teach. O, here might many a line be lent, To teach the mind to learn content, And with a manly spirit bear The stroke of disappointing care; Awake a just disdain to smile On muckworm fortune base and vile, Look on its threatnings to betray, As darksome clouds that pass away, And call on cheering hope to see Some future, kind reality. —All who Sir Jeffery knew could tell Our Hero serv'd him passing well; |

|

| Nay to the care which he bestow'd The Knight a lengthen'd period ow'd, And such the thanks he oft avow'd. |

} |

| Quæ Genus never lost his views Of duty and its faithful dues; His honour no one could suspect, Nor did he mark with cold neglect 109 |

|

| Those services which intervene In a sick chamber's sickly scene: His duty thought no office mean, |

} |

| And to Sir Jeffery's closing sigh All, all was warm fidelity. Nay, thus the Knight would frequent own A grateful sense of service done; And oft, in words like these, he said, That duty shall be well repaid. "Quæ Genus, know me for your friend, I to your welfare shall attend; Your friend while I retain my breath, And when that's gone, your friend in death." That death he felt as a disaster, For, to speak truth, he lov'd his master, Nor did he doubt that a reward Would prove that master's firm regard. |

| Our Hero thought it wond'rous hard Thus to be foil'd of his reward, That which, in ev'ry point of view, He felt to be his honest due; 111 And both his master and his friend Did to his services intend; Which, as the sun at noontide clear, Does by the codicil appear: |

|

| But when he ask'd Sir Jeffery's heir (Who did so large a fortune share) The blank hiatus to repair, |

} |

| Which he with truth could represent As an untoward accident, The wealthy merchant shook his head And bade him go and ask the dead. Quæ Genus ventur'd to reply While his breast heav'd a painful sigh, "The dead, you know, Sir, cannot speak, But could the grave its silence break, I humbly ask your gen'rous heart, Would not its language take my part, Would it not utter, 'O fulfil The purpose of the codicil?' Would it not tell you to supply The blank with a due legacy?" The rich man, turning on his heel, Did not the rising taunt conceal. "All that the grave may please to say, I promise, friend, I will obey." |