Title: The Flaming Sword in Serbia and Elsewhere

Author: M. A. Stobart

Release date: July 7, 2013 [eBook #43124]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Moti Ben-Ari and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/flamingswordinse00stobrich |

THE FLAMING SWORD

By MRS. ST. CLAIR STOBART

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

MCMXVI

in admiration of the courage with which he and the nation which he represents have, in spite of all temptations, upheld the Ideal of Spiritual Freedom, and in fervent hope that this Ideal will soon be realised in that Greater Serbia which will arise from the sepulchre of the Past.

I have written this book in the first person, because it would be an affectation to write in the neuter person about these things which I have felt and seen.

But if the book has interest, this should lie, not only in the personal experiences, but in the effect which these have had upon the beliefs of a modern woman who is probably representative of other women of her century.

I believe that humankind is at the parting of the ways. One way leads to evolution—along spiritual lines—the other to devolution—along lines of materialism; and the sign-post to devolution is militarism. For militarism is a movement of retrogression, which will bring civilisation to a standstill—in a cul-de-sac.

And I believe that militarism can only be destroyed with the help of Woman. In countries where Woman has least sway, militarism is most dominant. Militarism is maleness run riot.

Man's dislike of militarism is prompted by sentiment, or by a sense of expediency. It is not due to instinct; therefore it is not forceful. The charge of human life has not been given by Nature to Man. Therefore, to Man, the preservation of life is of less importance than many other things. Nature herself sets an example of recklessness with males; she creates, in the insect world, millions of useless male lives for one that is to serve the purpose of maleness. It is said that the proportion of male may-flies to female is six thousand to one. Nature behaves similarly—though with more moderation—with male human babies. More males than females are born, but fewer males survive. Is war perhaps[viii] another extravagant device of Nature; or is society, which encourages war, blindly copying Nature for the same end?

On the other hand, Woman's dislike of militarism is an instinct.

Life—for Woman—is not a seed which can be sown broadcast, to take root, or to perish, according to chance. For Woman, life is an individual charge; therefore, for Woman, the preservation of life is of more importance than many other things.

By God and by Man, the care of life is given to Woman, before and after birth. With all her being, Woman—primitive Woman—has defended that life as an individual concrete life; and with all her being, Woman—modern Woman—must now, in an enlarged sphere, defend the abstract life of humankind.

Therefore, it is good that Woman shall put aside her qualms, and go forth and see for herself the dangers that threaten life.

Therefore it is good that Woman shall record, as Woman, and not as neuter, the things which she has felt, and seen, during an experience of militarism at first hand.

This book is in five parts.

Part I. deals with preliminaries and military hospital work in Bulgaria, Belgium, France, and Serbia.

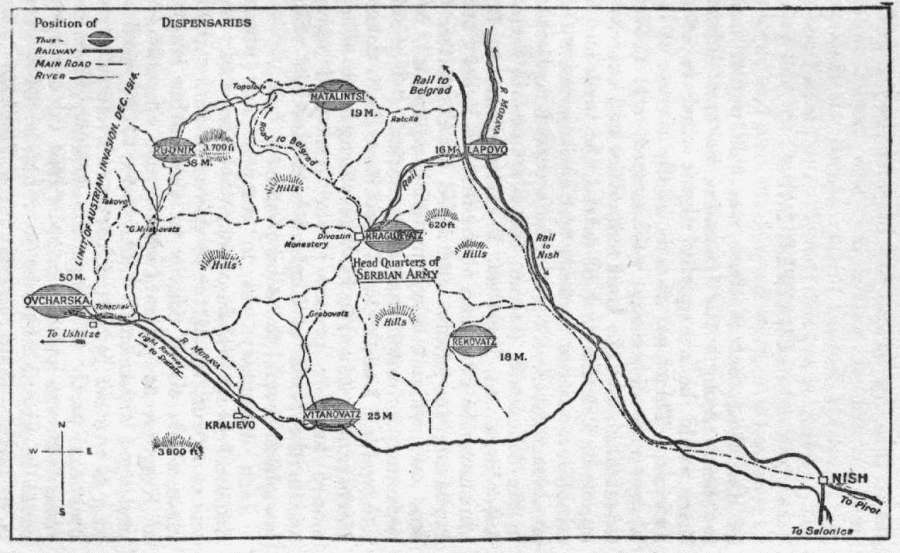

Part II. deals with roadside tent dispensary work in Serbia.

Part III. is a diary of the Serbian retreat.

Part IV. discusses:

(a) The war work of women.

(b) Serbian character.

(e) The evils of war.

Part V. comprises maps and letters and lists of

personnel.

The title of the book is taken from Genesis iii. 22-24. Readers will understand that Part III. does not attempt to deal with the Serbian retreat as a whole; materials for this were not available. It describes the day to day doings of one small segment of the historical mosaic. The book has many imperfections, but if something of the spirit of the Serbian nation shines through its pages, it will have served its purpose.

To go through the horrors of war, and keep one's reason—that is hell. Those who have seen the fiery Moloch, licking up his human sacrifices, will harbour no illusions; they will know that the devouring deity of War is an idol, and no true God. The vision is salutary; it purges the mind from false values, and gives courage for the exorcism of abominations still practised by a world which has no knowledge of the God of Life. The abominations which are now practised in Europe, by twentieth century man, are no less abominable than those practised of old in the Valley of Hinnom. The heathen passed their sons and daughters through the fire, to propitiate their deity; the Lord God condemned the practice. We Christians pass our sons and daughters through the fire of bloody wars, to propitiate our deities of patriotism and nationalism. Would the Lord God not also condemn our practice? But we, alas! have no Josiah to act for the Lord God (2 Kings xxiii.). The heathen wept at the destruction of Baal, but the worship of the pure God prevailed. No one believes that his god is false, till it has been destroyed. Therefore, we must destroy militarism, in and through this war, and future generations will justify the deed.

I am neither a doctor nor a nurse, but I have occupied myself within the sphere of war for the following reasons.

After four years spent on the free veldt of the South African Transvaal, I returned to London (in 1907) with my mind cleared of many prejudices. The[2] political situation into which I found myself plunged, was interesting. Both men and women were yawning themselves awake; the former after a long sleep, the latter for the first time in history. The men had been awakened by the premonitory echo of German cannons, and were, in lounge suits, beginning to look to their national defences. Women probably did not know what awakened them, but the same cannons were responsible.

For self-defence is the first law of sub-conscious nature; and the success of Prussian cannons would mean the annihilation of woman as the custodian of human life.

It was natural that woman's first cry should be for the political vote: influence without power is a chimera. But it was also natural that at a moment when national defence was the rallying shibboleth for men, the political claims of women should be by men disregarded. Political power without national responsibility would be unwisdom and injustice.

But was woman incapable of taking a responsible share in national defence?

I believed that prejudice alone stood in woman's way. Prejudice, however, is not eliminated by calling it prejudice. Practical demonstration that prejudice is prejudice, will alone dissipate the phantom.

But what form should woman's share in national defence assume? In these days of the supremacy of mechanical over physical force, woman's ability as a fighting factor could have been shown. But there were three reasons against experimenting in this direction.

Firstly, it would have been difficult to obtain opportunities for the necessary proof of capacity.

Secondly, woman could not fight better than man, even if she could fight as well, and, as an argument for the desirability of giving woman a share in national[3] responsibility, it would be unwise to present her as a performer of less capacity than man. The expediency of woman's participation in national defence could best be proved by showing that there was a sphere of work in which she could be at least as capable as man.

Thirdly, and of primary importance, if the entrance of women into the political arena is an evolutionary movement—forwards and not backwards—woman must not encumber herself with legacies of male traditions likely to compromise her freedom of evolvement along the line of life.

If the Woman's Movement has, as I believe, value in the scheme of creation, it must tend to the furtherance of life, and not of death.

Now, militarism means supremacy of the principle that to produce death is, on occasions—many occasions—more useful than to preserve life. Militarism has, in one country at least, reached a climax, and I believe it is because we women feel in our souls that life has a meaning, and a value, which are in danger of being lost in militarism, that we are at this moment instinctively asking for a share in controlling those human lives for which Nature has made us specially responsible. "Intellect," says Bergson, "is characterised by a natural inability to comprehend life." Woman may be less heavily handicapped in an attempt to understand it?

It may well have been the echo of German cannons which aroused woman to self-consciousness.

Demonstration, therefore, of the capacity of woman to take a useful share in national defence must be given in a sphere of work in which preservation, and not destruction of life, is the objective. Such work was the care of the sick and wounded.

In a former book, War and Women, an account has been given of the founding of the "Women's Convoy Corps," as the practical result of these ideas. The work which was accomplished by members of this[4] Corps, in Bulgaria, during the first Balkan War, 1912-13, afforded the first demonstration of the principle that women could efficiently work in hospitals of war, not only as nurses—that had already been proved in the Crimean War—but as doctors, orderlies, administrators, in every department of responsibility, and thus set men free for the fighting line.

I had hoped that, as far as I was concerned, it would never be necessary again to undertake a form of work which is to me distasteful. But when the German War broke out in August, 1914, I found to my disappointment, that the demonstration of 1912-13 needed corroboration. For I had one day the privilege of a conversation with an important official of the British Red Cross Society, and, to my surprise, he repeated the stale old story that women surgeons were not strong enough to operate in hospitals of war, and that women could not endure the hardships and privations incidental to campaigns.

I reminded him of the women at Kirk Kilisse. "Ah!" he replied, "that was exceptional." I saw at once that he, and those of whom he was representative, must be shown that it was not exceptional. But where there is no will to be convinced, the only convincing argument is the deed. Action is a universal language which all can understand.

I must, therefore, once more enter the arena; for my previous experience of war had corroborated my belief that the co-operation of woman in warfare, is essential for the future abolition of war; essential, that is, for the retrieval of civilisation. For these reasons I must not shirk.

I had gone to Bulgaria with open mind, prepared to judge for myself whether it was true that war calls forth valuable human qualities which would otherwise lie dormant, and whether it was true that the purifying influence of war is so great, that it compensates the human race for the disadvantages of war. My mind had been open for impressions of so-called glories of war.

But the glories which came under my notice in Bulgaria, were butchered human beings, devastated villages, a general callousness about the value of human life, that was for me a revelation. This time I should go out with no illusions about these martial glories.

But how should I go? To my satisfaction I found that the Bulgarian "first step" had led to an easy staircase, and when I offered the services of a Woman's Unit to the Belgian Red Cross, I was at once invited to establish a hospital in Brussels.

The St. John Ambulance Association, at the instigation of Lady Perrott, and the Women's Imperial Service League (which, with Lady Muir Mackenzie as Vice-Chairman, had been organised with the view of helping to equip women's hospital units), together with many other generous friends, provided money and equipment, and a Woman's Unit was assembled.

I went to Brussels in advance of the unit, to make arrangements, and was given, as hospital premises, the fine buildings of the University.

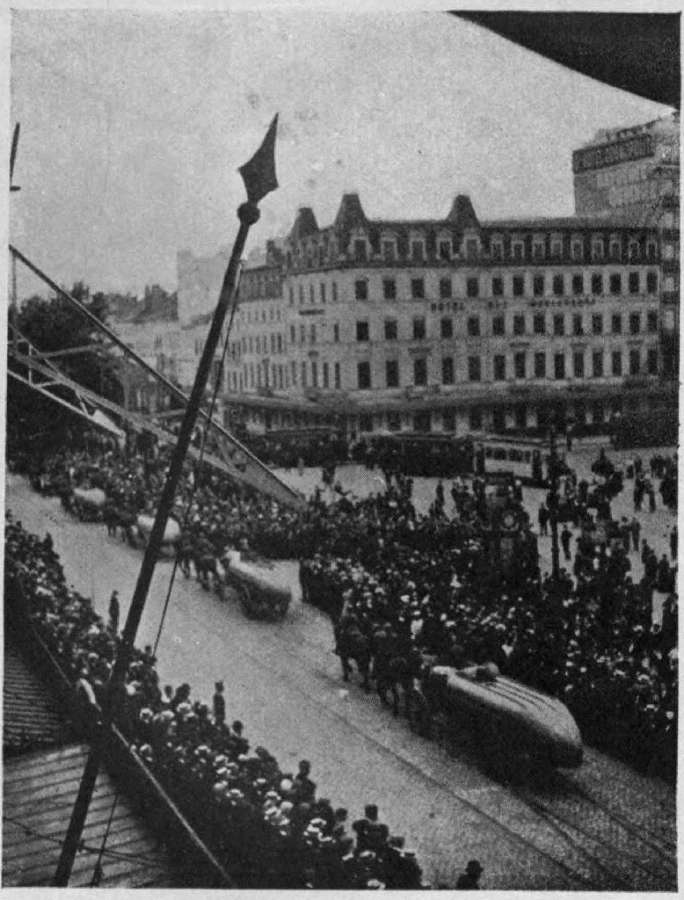

The day after arrival, I had begun the improvisation[6] of lecture and class-rooms into wards, when, that same day, the work was interrupted by the entry of the Germans, who took possession of the Belgian Capital. During three days and nights the triumphant army, faultlessly equipped, paraded through the streets. For some hours I watched it from the second floor window of a restaurant in the Boulevard des Jardins Botaniques, together with my husband, who was to act as Hon. Treasurer, and the Vicar of the Hampstead Garden Suburb, who was to act as Chaplain to our unit. And my mind at once filled with presage of the tough job which the Allies had undertaken.

The picture upon which we looked was indeed remarkable. Belgium had been "safeguarded" from aggression, by treaties with the most civilised nations of the world. But here now were the legitimate inhabitants of the capital of Belgium standing in their thousands, gazing helplessly, in dumb bewilderment, whilst the army of one of these "most civilised" Governments streamed triumphantly, as conquerors, through their streets. And in all those streets, the only sounds were the clamping feet of the marching infantry, the clattering hoofs of the horses of the proud Uhlans and Hussars, and the rumbling of the wagons carrying murderous guns.

The people stood silent, with frozen hearts, beholding, as fossils might, the scenes in which they could no longer move.

For them, earth, air, sky, the whole world outside that never-ending procession, seemed expunged. No one noticed whether rain fell, or the sun shone, whilst that piteous pageant of triumphant enmity, passed, in ceaseless cinema, before their eyes.

All idea of establishing a hospital for the Allies had to be abandoned. The Croix Rouge was taken over by the Germans, and hospitals would be commandeered for German soldiers. My one desire was to get in[7] touch with my unit; for they might, I thought, in response to the cable sent by the Belgian Red Cross, on the night of our arrival, be already on their way to join me, and might be in difficulties, surrounded by the Germans. Whatever personal risk might be incurred, I must leave Brussels.

The Consuls advised me to remain: they said I should not be able to obtain a passport from the German General. When I remonstrated, they shrugged their shoulders and said, "Well, go and ask him yourself!" I went, and obtained an officially stamped passport for myself and my two companions, who gallantly, and against my wishes, insisted on accompanying me, and sharing the risks of passing through the enemy's lines.

But, notwithstanding our stamped passport, we were, at Hasselt, arrested as spies, and at Tongres we were condemned to be shot within twenty-four hours. The story of our escape and eventual imprisonment, at Aachen, has been told elsewhere, but one remark of the German Devil-Major Commandant at Tongres, is so illuminative of the spirit of militarism that it bears repetition.

The Major said, "You are spies"; he fetched a big book from a shelf, opened it, and pointing on a certain page, he continued, "and the fate of spies is to be shot within twenty-four hours. Now you know your fate." I answered cheerily, as though it were quite a common occurrence to hear little fates like that, "but, mein Herr Major, I am sure you would not wish to do such an injustice. Won't you at least look at our papers, and see that what we have told you is true; we were engaged in hospital work when," etc. He then replied, and his voice rasped and barked like that of a mad dog, "You are English, and, whether you are right or wrong, this is a war of annihilation."

I shall always be grateful for that phrase, for I recognised in it an epitome of the spirit of militarism, carried, as the Prussian arch-representatives of war[8] carry it, to its logical extreme. For, according to modern militarism, war aims at annihilation of the enemy, and the enemy includes not only the combatants—these are the least offensive element—but the non-combatants, the men who represent the rival commerce, the women who represent the rival culture, and the men and women who represent codes of honour and humanity which are the beacons of the rival civilisation—at one and all of these, is aimed the blow which is delivered through the medium of the proxies in the field.

We three non-combatants—namely (a) a minister of the Holy Church, (b) a university man, who had officiated as judge in Burma, and (c) a woman engaged in hospital work, were now condemned to death, not because we represented a military danger, but because we represented, although in humble degree, those qualities of the rival nation, which had brought that nation to the front of civilisation. War aims at the annihilation, not of that which is bad, but of that which is best.

The Devil-Major, as we called him, then made us follow him upstairs, to the top floor, to a room in which we were to spend the night—the last night? He ordered me to be separated from the others, in another room, but I was responsible for the position of my companions, and without my influence—as a woman—death for them was certain, and I resisted the separation successfully. The Major then drove us into a room that was bare, except for verminous straw upon the floor. He refused to give us food, though we had not eaten since the day before, but water in tin cans was brought to us to drink, and we were told to lie down on the dirty straw.

The Devil-Major then warned the guards that if we moved, or talked to each other, they were to shoot us, then he left us for the night.

Sleep was impossible, owing to the ceaseless chiming[9] of half-a-dozen church clocks, which seemed purposely to have clustered within a few hundred yards of us. The bells were all hopelessly out of tune, the tuners being presumably at the front; and every quarter of an hour all the bells of all the clocks, played different tunes, which lasted almost till the next quarter's chime was due. The discord was a nightmare for sensitive ears, but the harsh jangle of these bells, as they tumbled over each other, brutally callous to the jarring sounds, and to the irrelevancy of the melodies they played, seemed in keeping with the discordance—illustrated by our position—between the ideal of life, designed by God the Spirit, and the botching of that design, by murderous man.

Was our position, I wondered, another of the glories of war? These glories, exhibited at that time in Belgium, were, as I noticed, all of one stamp—devastation, murder of women and children, rapine, every form of demoniacal torture. All these glories are visualised, and not exaggerated, in the cartoons of Raemaekers.

But we three escaped by miracles, and returned safely to England.

I found that my unit had not yet left London, and I was able in a short time, with them, to accept an invitation from the Belgian Red Cross to go to Antwerp. We went out under the auspices of the St. John Ambulance Association, and established our hospital in the big Summer Concert Hall, in the Rue de l'Harmonie. Here once again the glories of war were manifested.

After three weeks' work upon the maimed and shattered remnants of manhood that were hourly brought to us from the trenches, the German bombardment of the city began. For eighteen hours our hospital unit was under shell fire, and I had the opportunity of seeing women—untrained to such scenes—during the nerve-racking strain of a continuous bombardment. They took no notice of the shells, which whizzed over our heads, without ceasing, at the rate of four a minute, and dropped with the bang of a thousand thunderclaps, burning, shattering, destroying everything around us.

The story of how these women rescued their wounded, carried them without excitement, as calmly as though they were in a Hyde Park parade, on stretchers, and when stretchers failed, upon their backs, from the glass-roofed hospital, down steep steps, to underground cellars, has also been told elsewhere.

We saved our wounded, but in the picture of the murderous shells, dropping at random, here, there, and everywhere; of the beautiful city of Antwerp in flames, its peaceful citizens, its women and children, with little bundles of household treasures in their arms, fleeing terror-stricken from their homes into the unknown: in all this it was difficult to see glory, except the glory triumphant of the enemy's superior make of guns—superior machinery.

We lost, of course, all our hospital material, but once again, thanks to the Women's Imperial Service League and to the St. John Ambulance Association, now in conjunction with the British Red Cross Society, who also assisted us; thanks also again to friends and sympathisers, we were enabled to collect fresh equipment, and as, alas! hospitals could no longer be worked in Belgium, we offered our services to the French Red Cross, and were invited to establish our hospital in Cherbourg.

At this port, every day, arrived boat-loads of wounded from the northern battlefields. Their uniforms indistinguishable with blood, maimed, blinded, shattered in mind and body, these human derelicts were lifted from the dark ship's-hold, on stretchers, to the quay, and thence were transported to hospitals for amputations, a weary convalescence, or perhaps death. It was again a little difficult to recognise the glory of it all. And then came Serbia.

We had been working for four months at Cherbourg, when I read one day that an epidemic of typhus had broken out in Serbia; that the hospitals were overcrowded with sick and wounded; that one-third of the Serbian doctors had died, either of typhus, or at the front, and that nursing and medical help were badly needed. I knew from the moment when I read that report, that I should go, but I confess that I tried, at the beginning, to persuade myself that my first duty was to the Cherbourg hospital. I dreaded the effort of going to London, of facing the endless red tape, snubs, opposition, the collecting of money, and a unit, difficulties of all sorts with which I was now familiar. One of my plays was going to be acted at the theatre in Cherbourg,[12] at a charity matinée, and I wanted to see it. Also, after a winter of continuous rain, the sun had begun its spring conjuring tricks, and one morning before breakfast, as I was walking in the woods, I noticed that through the damp earth, and the dead beech leaves, myriads of violets, ferns and primroses were showing their green leaf-buds. I felt a momentary twinge of joy; and that decided me. This would be a pleasant place in Spring; many women would be glad to do my work.

The wounded were no longer coming south in such numbers as at first, owing probably to the dangers of the sea voyage; the hospital was in thorough order, and the administration could be left in capable hands. The call had come, and I could no more ignore it, than the tides can ignore the tugging of the moon.

I went to London (in February, 1915) to see if I was right in my surmise as to the need for help in Serbia, and I was at once asked by the Serbian Relief Fund, to organise and to direct a hospital unit, also to raise a portion of the funds. We were to go to Serbia as soon as Admiralty transport could be procured. This involved considerable delay, and it was not till April 1st that we set sail from Liverpool for Salonica.

The unit numbered forty-five, and comprised seven women doctors—Mrs. King-May Atkinson, M.B., Ch.B., Miss Beatrice Coxon, D.R.C.P.S.R., Miss Helen B. Hanson, M.D., B.S., D.P.H., Miss Mabel Eliza King-May, M.B., Ch.B., Miss Edith Maude Marsden, M.B., Ch.B., Miss Catherine Payne, M.B., Miss Isobel Tate, M.D., N.U.I.—eighteen trained nurses, together with cooks, orderlies, chauffeurs, and interpreters. The principle that women could successfully conduct a war hospital in all its various departments, had now been amply proved, and had been conceded even by the sceptical. The original demonstration had already borne ample fruit. Units of Scottish women were doing excellent work in France, and also in Serbia, and even in London, women doctors had now been given staff rank in military hospitals. The principle was firmly established, and I thought, therefore, that no harm would now be done by accepting the services of a few men orderlies and chauffeurs.

Amongst the applications for the post of orderly, were some Rhodes scholars; and an interesting reversal of traditional procedure occurred. At the last moment, the scholars asked to be excused, because, owing to the additional risks of typhus involved in the expedition to Serbia, they must first obtain permission to run the risk, from their relatives in America, and for this, they said, there would not now be time. Our women, on the other hand, braved their relatives, knowing that a woman's worst foes, where her work is concerned, are often those of her own household.

Determined, however, to dodge the typhus if possible, I proposed to the Serbian Relief Fund that our hospital should be housed—both staff and patients—entirely in tents. It was only a question of raising more money; and this was obtained through friends and sympathetic audiences.

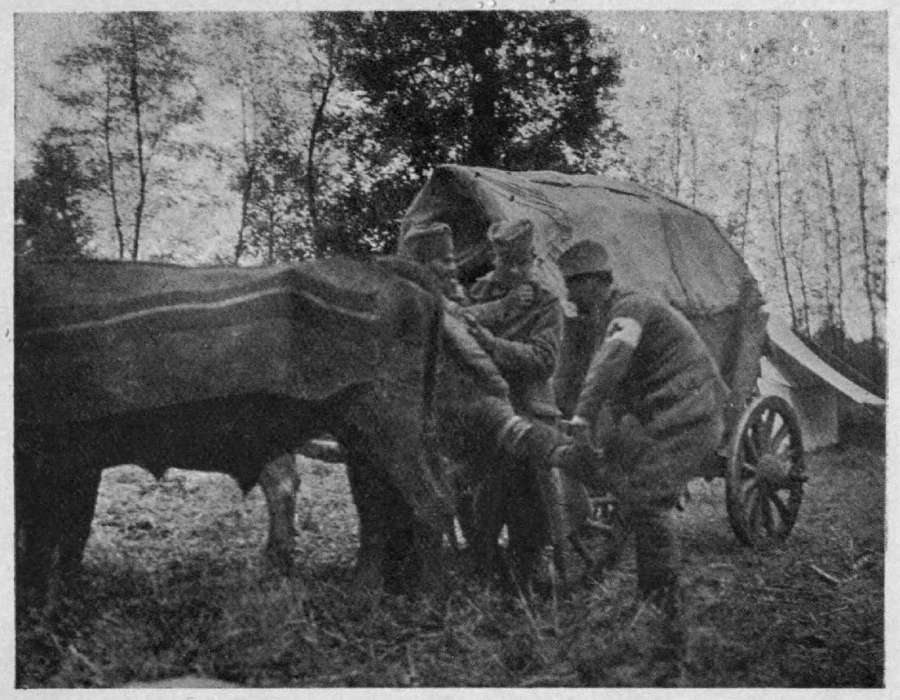

Typhus infection is carried by lice, and these would naturally be more difficult to eliminate within already infected houses than in tents in the open air. Also by the use of tents we should render ourselves mobile, and be more likely to be of service in emergency; this was later amply proved.

The Committee of the Serbian Relief Fund agreed to the proposal, and sixty tents, mostly double-lined, were specially made to order, by Messrs. Edgington of Kingsway, for wards, staff, X-ray, kitchens, dispensary, lavatories, baths, sleeping, etc., etc., with camp beds and outfit.

Lady Grogan and Mrs. Carrington Wilde, who were giving up their lives to Serbian Relief Fund work, did wonders for our unit, and in every way helped to make things easy for us. Mr. B. Christian, chairman, also gave wholehearted support, and the Women's Imperial Service League, with Lady Muir Mackenzie, Lady Cowdray, Mrs. Carr Ellison, Lady Mond, Mrs. Ronald McNeill, and their indefatigable secretary, Mrs. McGregor, were of invaluable service.

The Admiralty transport, for which during six precious weeks we had waited impatiently, was an old two thousand ton boat, of the Royal Khedivial Mail Line, only accustomed to carrying passengers from one port to another, short distances on the Mediterranean coast, and she could only give us nineteen places. It was arranged, therefore, for the remainder of the unit to follow overland, and to arrive, if possible, simultaneously at Salonica.

The captain of our boat received twenty-four hours' notice of the fact that he was to carry to Salonica a[15] couple of hundred members of various hospital units. His chief steward, to whom would have been entrusted the purchase of food stores, was laid up with a broken leg, and the captain had been obliged himself to go from house to house, in Liverpool, to find a crew. We were lucky, therefore, to get any food or any crew at all, and still more lucky in the captain, who, by his courtesy, and concern for our welfare, compensated for little deficiencies in the ménu. Besides, one was thankful to be on the way to work, after so much delay.

But after having waited six weeks for the boat, I nearly lost it at the last moment. The cabby who drove me and two others from the station at Liverpool, to the dock, was a fool, and couldn't find the dock in which the Saidieh was berthed, and for half an hour, in the rain, our four-wheeler crawled up and down, and in and out of a tangled maze of nine miles of docks. The horse, the cab, and the cabby were all extraordinarily old, and when we were at the point farthest from possibility of help, they all three collapsed. We patched up the horse and cab, but had more difficulty with the cabby. He couldn't see why we were so fastidious about sailing in one boat rather than in another, and time after time he drove, with triumphant flourish of whip, through the dock gates, and stopped in front of an old coal barge, and was much hurt by our refusal to get on board. But all this worked a miracle, for when at last we hit upon the right dock, a short time before the departure of the Saidieh, I was, for the first time in my life, thankful to find myself on board a steamer.

No places had been reserved for our party, but after a general scramble with the members of portions of six other hospital units, mostly women, voyaging with us, we all settled down comfortably to sea-sickness and submarines. The rough weather provided us with the former, but saved us from the latter.[16] Submarines were supposed to be waiting for us off the Scilly Isles, and at first we were afraid that the Saidieh would be sunk; but later we were afraid she wouldn't.

The units, which kept to themselves in a remarkable way, were a source of much abstract interest to each other, and to me. It was particularly satisfactory to notice the unstinting way in which the principle of women's work in all departments, responsible as well as irresponsible, of a war hospital, was—as represented on this ship—now acknowledged. The woman administrator, the woman surgeon, the woman orderly, in addition, of course, to the woman nurse, who had been the first to win her position in war work.

I should like incidentally to suggest that uniform for women employed in public work, should be as compulsory always, as it is for men. Occasional hobble skirts, and low-cut blouses, reminiscent of the indecorums of the Society puppet, struck a peculiarly jarring note amongst a boat-load of people prepared for life-and-death realities, on a mission of humanity.

Of all these doctors, nurses, orderlies, administrators, chauffeurs, interpreters, how many would return? One should be taken and the other left? Laughing, singing, acting, reading, playing cards, flirting, quarrelling—how many were doing these things for the last time? Towards what fate were each and all being borne? Were we, as adjuncts of the Serbian Army, sailing to life or death, to victory or defeat?

How quickly all grew accustomed to, and ignored, the grandeur of moon, stars, planets, the wonders of a firmament new to most, because generally hidden by chimney-tops and smoke, and, conscious only of a little shrunken circle, grew absorbed in trifles. The vastness, the peace, the tumult, the joy of Nature, all[17] unseen; the main interests, hair washing, gossip, fancy dress, bridge parties, quality of cigars, and food. Nobility of character curiously hidden, but ready to spring forth when pressed by the button of emergency.

A little excitement at first, from rumours of submarines, then boat drill, a sense of adventure, half enjoyable, half unpleasant, followed by the comfortable assurance that danger is passed, and enjoyment now legitimate, for those who are not kept low by sea-sickness. New friends and sudden confidences, as suddenly regretted; the inevitable Mrs. Jarley's waxworks, badly acted, but applauded; vulgar songs, mistaken for humour; real talent shy in coming forward, false coin in evidence; pride in attention from the captain; the small ambitions, to be top dog at games, to win a reputation as bridge player, to become sunburnt: all pursued with the same vigour with which work will later be attacked.

Danger from above, from below, from all around, but none so harmful as the tongue of a jealous comrade.

The story of one voyage is the story of all voyages. It is the story of mankind caricatured at close quarters, reflected on a distorting mirror.

The ship's first officer was a Greek; he was keenly on the side of the Allies. He hoped shortly to enlist, and he told me that it was his firm conviction that if Greece did not join the Allies immediately the people would revolt against the King.

The third officer, also a Greek, was a rabid pro-German. His presence on board seemed particularly undesirable; but the wonder was that there were not more undesirables on the ship, for anyone could have entered it at Liverpool.

Rough weather continued till we reached Gibraltar, on April 8th, and, after one fine day, resumed sway till the 11th, when we sailed past the Greek coast.

We reached Salonica on April 15th, the various units full of eagerness to learn their respective destinations.

We were met by the Serbian Consul, Monsieur Vintrovitch, and by the English Consul-General, Mr. Wratislaw, also by Mr. Chichester, who has since, alas, succumbed to typhoid.

There was disappointment amongst members of our unit, when they learned that we were to establish our hospital at Kragujevatz. They would have preferred Belgrade, as being nearer to the supposed front. Fronts, however, are movable, and as Kragujevatz was the military headquarters, we were, I knew, much more likely to get the work we wanted, if we were immediately under the official army eye; I was, therefore, more than content to go to Kragujevatz.

We spent that night on board, at the kind invitation of the captain, as there was a scrimmage for rooms in the hotels. We then had comfortable time next day in which to find quarters. The portion of the unit travelling via Marseilles arrived, excellently timed, by Messageries boat, on Saturday, the 17th. We spent the next few days struggling with, or trying to find, quay officials, and getting the stores and equipment unloaded, and placed in railway trucks. It was difficult to hit upon a working day at the dock, for we were now in one of those happy lands in which eight days out of every seven, are holidays. Friday was a fast day—no work; Saturday was a feast day—no work; Sunday was Sunday—no work; Monday came after Sunday, Saturday and Friday—therefore no work, a day of recovery was necessary after so many holidays. One had to be awake all night, to discover an odd moment when a little work was likely to be smuggled into the day's routine of happy idleness.

But by the evening of Monday, the 19th, everything—tents, equipment, stores, etc.—was on the trucks and ready to travel with us. And I, with eleven members, as advance party, left Salonica at 8 a.m. for Kragujevatz. We had all duly, the night before, performed the rite of smearing our bodies with paraffin, as a supposed precaution against the typhus lice. But it is probably a mistake to think that paraffin kills lice. Paraffin is a good cleanser, and lice, which flourish in dirt, respect their enemy, but are not killed by it.

The railway journey was interesting, especially to those amongst us who had never before been away from England.

We were amused to see real live storks nesting on the chimney-tops. So the German nursery tale, that babies are brought into the world by storks, down the bedroom chimney, must be true. German fables will probably in future teach that babies are brought through the barrels of rifles, double barrels being a provision of Providence for the safe arrival of twins, which will be much needed for the repopulation of the country.

We reached Skoplye at 9 p.m. Sir Ralph Paget kindly came to the train to greet us, and whilst we had some very light refreshments at the station, he stayed and talked with us. Lady Paget was then, we were thankful to hear, recovering from the attack of typhus which she had contracted during her hospital work at Skoplye.

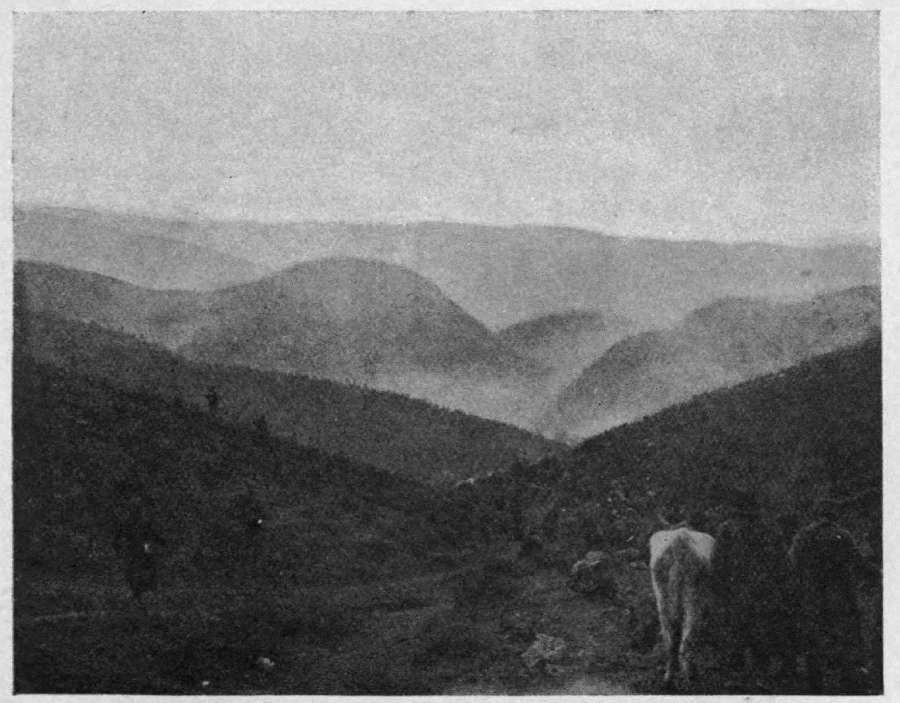

The country through which we passed, was magnificent; mountains, rivers, gorges, and picturesque houses—one-storied, of sun-dried brick—with clear air, warm sunshine, and blossoming fruit trees. Occasionally a ruined village, or a new bridge replacing one that had lately been destroyed by Bulgarian raids, or newly dug graves of those killed in the last raid, were reminders that man, with his murderous works, would see to it that enjoyment of Nature's[20] works should not enter for long into our programme.

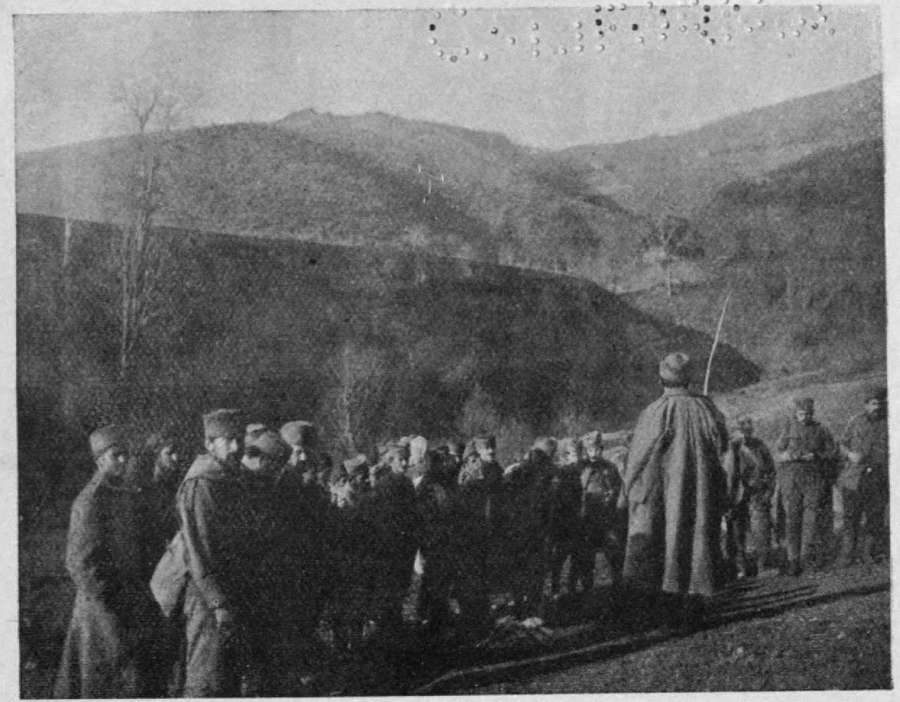

We reached Nish at 7.30 next morning, April 21st. At the station we were met by Dr. Karanovitch, Chief Surgeon of the Army; Dr. Grouitch, Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs; Mr. Blakeney, British Vice-Consul; Professor Todorovitch, Secretary to the Chief Surgeon; Mr. Petcham, Official of Foreign Affairs; and Dr. Soubotitch, President of the Red Cross Society.

All were most courteous and hospitable, and during the one and a half hour's halt they took us to breakfast at the Red Cross Hospital, and later accompanied us to the station to speed us on our last stage of the journey to Kragujevatz.

We left Nish at 10 a.m., and reached Kragujevatz at 7 p.m. The scenery was superb, and we were sorry when the journey came to an end. At the station, we were met by Colonel Dr. Guentchitch, the head of the Army Medical Service. He had most thoughtfully arranged sleeping quarters for the staff in the empty wards of a hospital; but it seemed wiser, and less trouble to all concerned, for us to stay for the night in our train, in a siding.

On arrival, the Colonel drove me and the Treasurer and two of our doctors to see a proposed site for our camp hospital—the racecourse, then disused, above the town. Excellent—nothing more suitable was likely to be found. The unit was then invited to dine at the officers' club mess. Here we met Colonel Harrison, British Military Attaché, and also Colonel Hunter, who was in charge of the Royal Army Medical Corps mission. The French and Russian attachés were also there.

It was homely to meet once more the genus military attaché; it was indeed difficult to imagine conducting a hospital without them. For at Kirk[21] Kilisse, when we arrived in a starving condition, the British attaché had found us food, and the Italian attaché, whom, in the dark, I had mistaken for some one else, had sportingly acted up to the character of the some one else, and had provided us with straw for mattresses.

Though some folks find Serbian cooking too rich, the dishes have a distinctive and pleasing character of their own, and the dinner, after two days of cold meals, was much enjoyed. It was delightful to find that the Serbian officers, both medical and military, were cultured men of quick and sympathetic intelligence. I knew at once that I should like them. Most of them spoke German, a few talked French, but all could converse fluently in either one or the other language, in addition, of course, to their own. One is always reminded abroad that all other nations are better educated than we are. We are still so insular, and are still, with the pride of ignorance, proud of our defect. We have not yet reached the stage of realising that we can never take a leading part in the councils of Europe, till we can converse, without interpreters, with the leading minds of Europe.

Next day Colonel Guentchitch took us to see alternative camp sites, but nothing half as suitable as the racecourse was available, and upon this we decided.

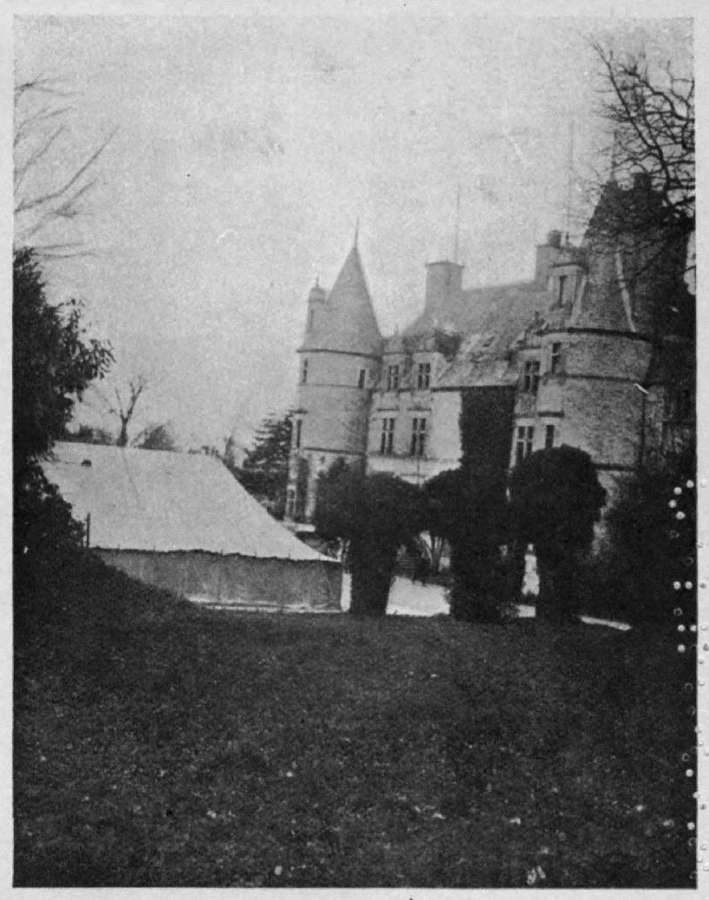

By the evening of Thursday, April 22nd, we had unpacked, and pitched some small ridge tents in which to spend the night, refusing the kind offer of sleeping accommodation in the town, though we again accepted the officers' hospitality for the evening meal.

The next day was spent in pitching the camp, and the authorities were pleased, and surprised, because we refused all offers of help in putting up the tents. We had gone to Serbia to help the[22] Serbians, and not to be a nuisance. Foreign units which arrive and expect to have everything done for them, are more bother than they are worth.

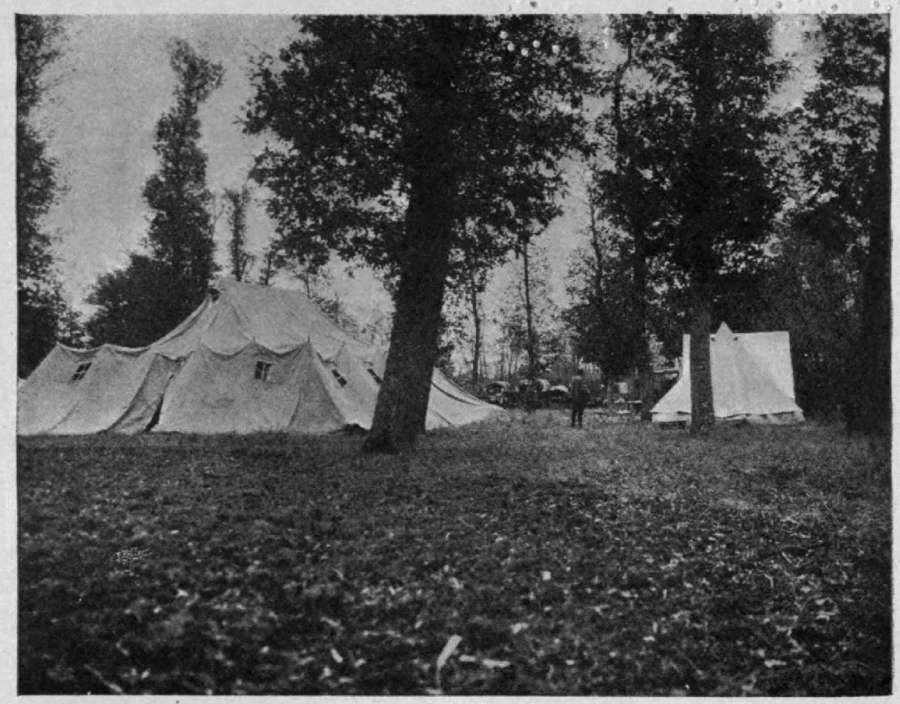

The remainder of the unit, with Dr. King-May, arrived from Salonica, and under the supervision of Dr. Marsden and Miss Benjamin (head orderly) a small town of tents, gleaming white in the brilliant sunshine, soon appeared in the local geography.

One long wide street of tents for the staff, then a large interval of open grass space, and another avenue of ward tents, with a connecting base line of tents for offices, kitchens, X-ray, and dispensary.

The camp was finely situated. We were surrounded on all sides by hills, not ordinary dead hills, these were alive with picturesque villages, half-hidden amongst orchards of plum and apple trees. On the far side of the white, one-storied town of Kragujevatz, the hills to the east, and south, seemed to be in poetic partnership with the clouds, and all day long, with infinite variety, reflected rainbow colours and storm effects—an endless source of joy.

At night, when the tents were lighted by small lanterns, and nothing else was visible but the stars, the camp looked like a fairy city.

The cuckoo had evidently not been present during Babel building, for all day long, and sometimes at night, he cuckooed in broad English—a message from our English spring. But the climax of surprises came when we found ourselves kept awake by the singing of the nightingales. Was this the Serbia of which such grim accounts had reached us?

We were ready to open our hospital either for the wounded, or for typhus patients, and we gave the authorities their choice. Colonel Guentchitch promptly decided that he would rather not start a new typhus centre; he wished us to take wounded. We began with fifty, and these were in a few days increased to one hundred and thirty.

And at once I realised, that the impression which even now largely prevails in Western Europe as to the bellicose character of the Serbian nation, is wrong.

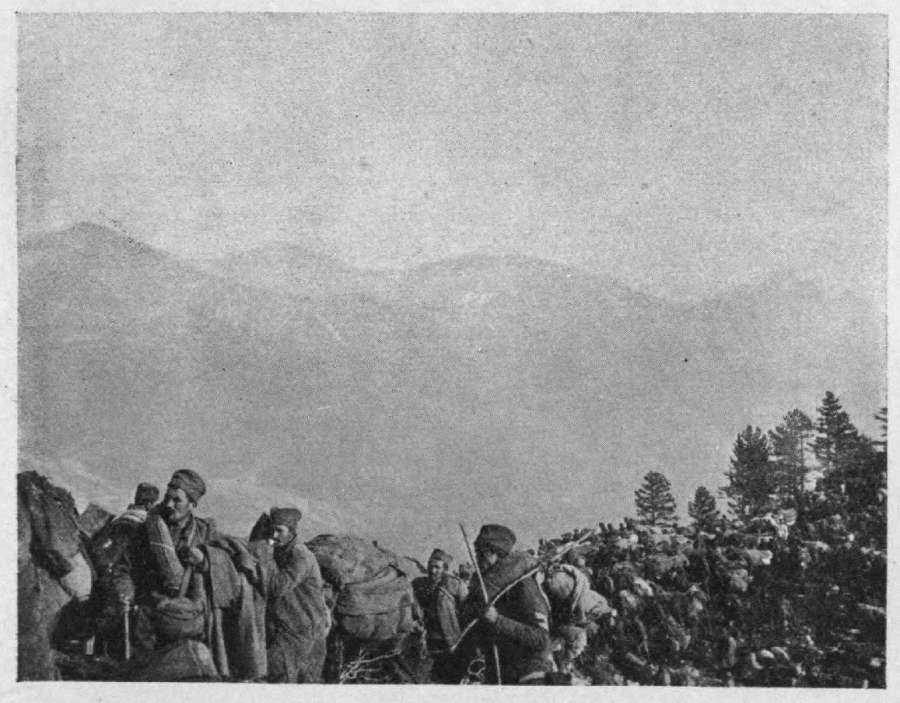

The average Serbian peasant-soldier is not the truculent, fierce, fighting-loving savage so often represented. He does not love fighting, but he loves,[24] with all the enthusiasm of a poetic nature, his family, his home, his hectares of land, and his country. He has fought much in the past, but in defence of these possessions which he prizes. No one can accuse the Serbian soldier of cowardice, yet his dislike of fighting, and his love of home, were so marked, that it was easy to distinguish, by his brisk walk, and cheerful countenance, or by his slow gait, and depressed attitude, whether a drab-dressed soldier, with knapsack, walking along the road, was going Kod kutche (home) or—his ten days' leave at an end—was going once more y commando (to the front).

Our wounded were the most charming patients imaginable, and it was always a joy to go into the wards and have a talk with them. They were alertly intelligent, with a delightful sense of humour, and a total absence of vulgarity or coarseness. They were all so chivalrous, courteous and delicate in their behaviour to the nurses, and to us women generally, and so full of affection and gratitude for the help given to them, that it was difficult to realise that these were not officers, but peasants, with little knowledge of the world outside their own national history.

With this every Serbian peasant is familiar, because it is handed down from generation to generation, in ballads and heroic legends, by the bards or guslars.

Our patients were all wonderfully cheerful and happy, and the convalescents enjoyed their meals in a tent which had been given by the men working on a ranch in British Columbia. Popara (a national dish—a sort of porridge of bread and lard), and eggs, bread, and pekmez (plum jam), and tea or coffee for breakfast; a rich stew of meat and vegetables, or a roast, and pudding or pastry for dinner; and again, meat, and stew, or soup, and pudding for supper.[25] On Fridays, however, the soldiers always refused meat.

Colonel Nicolaivitch (now Serbian Military Attaché in London) told me the other day that, on one of his visits to our Kragujevatz camp, he had been talking in one of the wards, with a man who was sitting up in bed with a bandaged head. He was much enjoying his dinner, and the Colonel said, "I expect you would like to stay in this hospital half a year?" "No," replied the man promptly, "a whole year."

The men are not accustomed to play games, except with cards. A card game called "Jeanne d'Arc" was the favourite. But they loved "Kuglana": this was a game like skittles, played with nine pins and a large wooden ball, which was swung between two tall posts. It was made for us at the arsenal, and gave our convalescents much joy and recreation.

I was a little surprised at the matter-of-fact way in which the men all accepted women doctors, and surgical operations by women. Indeed, they highly approved, because women were, they said, more gentle, and yet as effective as men doctors.

I was also surprised that at first, in April, when the weather was cold, they did not fear the tents and the open-air life. But the ward-tents, being double-lined, were as warm as could be wished at night, or when it rained; and in sunny weather, when the sides were lifted, gave an open-air treatment which was at once appreciated.

Camp hours were:—

Reveillé at 5.30 a.m.

Breakfast at 6 (the sun was very hot in the middle of the day and it was better to get the heaviest part of the work done in the cooler hours).

Lunch at 11.30.

Tea at 4.

Supper at 6.30 (as the town was out of bounds it[26] seemed wise to avoid the possibility of dull evenings by going early to bed).

Lights out at 9.

Much attention was attracted by our novel form of hospital, and all day long, visitors, official and otherwise, flocked to see all the arrangements. These seemed to be highly approved.

The kitchen department was under the supervision of Miss M. Stanley; dispensary under Miss Wolseley; laundry, Miss Johnstone; linen, Mrs. Dearmer. The X-ray Department was managed by Dr. Tate and Mr. Agar. The Secretary was Miss McGlade, and the Hon. Treasurer, John Greenhalgh.

The sanitation was in the hands of Miss B. Kerr, and was a subject of interested and invariably of favourable criticism. And it required some system to cope successfully with open-air sanitation, on a fixed spot, for more than two hundred people. Colonel Hunter, sometimes twice a day, brought visitors to whom he was anxious to show certain features in the scheme of which he specially approved. He told me that we were useful to him as object-lessons, and he cabled home in favourable terms to the War Office, concerning our hospital work, and also, later, concerning the dispensary scheme, with which he was well pleased.

It soon, indeed, came to be considered quite the correct thing for visitors to Kragujevatz to come up and visit the camp, and the only relief from the monotony of showing people round, was the variety of language which had to be employed. Sometimes, simultaneously, a Serbian, who, in addition to his own language, only spoke German, another who only spoke French, another who could only talk Serbian, and perhaps an Englishman who could only talk English—these must all be entertained together. It was like the juggler's feat with balls in the air.

Almost everybody of note in Serbia visited us at[27] one time or another, and our visitors' book, now, alas! in the hands of the Germans, was an interesting record.

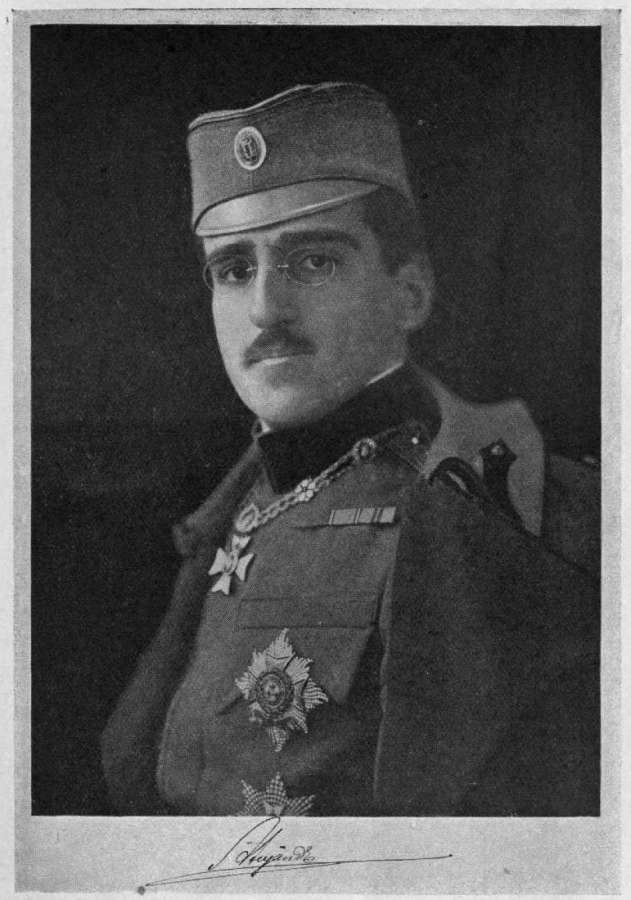

His Royal Highness the Crown Prince (Alexander) honoured us with a visit as soon as he learnt that he would be able to converse in French or German. He speaks good English, but has presumably not had the same opportunities of practice in this language. But in the visitors' book, which he took back to the palace for the purpose, he wrote a page and a half, in excellent English, describing his impression of the work of the hospital, and expressing his gratitude for the help given to his brave soldiers.

A fine fellow this Prince: straightforward, unostentatious, full of sympathy and quick intelligence; in every way worthy of a throne. He looked at every detail of the camp with critical interest, then as he walked, in the scorching sun, from the hospital quarters to the tents reserved for the staff, he asked, as he looked around, "Have you no sun-shelters?" We had none, and he immediately turned to a member of his staff, and told him to see that "ladniaks," or arbours, made of young trees, and dead branches, were at once arranged for us.

Accordingly, in a few days, a procession of wagons arrived, carrying a whole forest of young trees for props, and dead branches for roof and sides; and arbours were erected, and much comfort to us all was the result.

On the evening of the Prince's visit, the convalescent soldiers celebrated the event by giving us an impromptu entertainment after supper. Dressed in their light-coloured pyjamas, scarlet bed-jackets, and big mushroom-shaped straw hats, they formed, outside our mess tent, a picturesque group, silhouetted against the white tents which were aglow with fairy lamps, and looked like inflated stars.

The Serbian national instrument is the gusla, a one-stringed banjo, played with a bow; the sound[28] is like the plaintive buzzing of a bumble bee, when, round and round a room, it blindly seeks an exit.

Accompanying himself upon the gusla, one soldier after the other sang, or rather chanted, in mournful monotone, the old poetic legends in which the tragic history of their country has been transmitted from one generation to another; or they sang together, in parts; or they recited stirring tragedies—always tragedies—of which Serbian history is composed.

It is wise to allow plenty of time for a Serbian concert, as no self-respecting guslar cares to deal with less than half-a-dozen centuries of his national history at one sitting. One guslar, at this concert, caused us some embarrassment. He wouldn't leave off "guslaring." We tried every inducement. He paid no heed; and I saw, with despair, that he meant to carry his country safely into freedom from Turkish tyranny, and that meant another 500 years. The moon came and went; but moons might come, and moons might go, he went on for ever. Finally, in desperation, we all clapped vigorously. Good! He stopped, placed his gusla on the ground, and joined heartily in the clapping—but for a moment only. We weren't quick enough, and before we could take away his instrument, he had picked it up and begun again, and we were back again at the year 1389.

Every Serbian peasant is a poet, and one of these soldiers recited a portion of a fine dramatic poem which he had just written and presented to me. The poem began as an epic of Serbian history, past and present, and ended in a pæan of gratitude to the Stobart Hospital.

Tragedy, always dominant in Serbian history, gives a sad dignity to Serbian music, and, in contrast, the songs sung by the unit, as interludes in the Serbian concert, seemed commonplace.

The fitful moon had now set; the soldiers sat on benches placed one behind the other, and in the darkness, their faces were almost invisible. But here[29] and there a lighted cigarette illumined the war-worn face, and showed the result of hardships and suffering. We did not then know that the future was to bring a fate more terrible still.

But no entertainment in Serbia can be reckoned a success, if it does not end in a spontaneous burst of kolo dancing. Two men, with arms linked, will suddenly begin dancing a slow shuffling step. Another man will, as suddenly, produce, as though from the skies, a gusla, or a violin, or a flute, and will start playing, and will play over, and over, and over again, a dozen bars of the same melancholy tune. This has a remarkable effect. Immediately, everybody within sound of the music will, one after the other, join in, in pied piper style, and, linking arms, form a circle round the proud musician.

There are many varieties of steps, both quick and slow, and the dance can be extremely graceful in effect. But whether it is well or badly danced, the kolo is always dignified, with total absence of rowdyism, vulgarity, or sensuousness.

The kolo and the gusla are to Serbia, what the reel and the bagpipes are to Scotland. The kolo, like Serbian music and Serbian literature, reflects the spirit of their tragic history; even when the steps grow quicker with increased excitement, the feet are scarcely lifted from the ground; the movements are never movements of joy; the high kick, the leap, the spring, indicative of a light heart, are always absent.

On this evening, after an hour of the concert, the men suddenly broke into kolo. To their intense delight, Maika (mother), their name for the Directress, boldly joined the circle. "Dobro (well done), Maika! dobro! dobro!" they all shouted in chorus. Nurses, doctors, and orderlies all promptly followed suit, and as a finale to a successful evening, the various national anthems of the Allies were sung, and "lights out" bell rang the "Amen."

One of our most frequent and most welcome visitors was Colonel Dr. Lazaravitch Guentchitch, Head of the Serbian Army Medical Service. He had held this post also during the wars of 1912-13-14. He was brimful of quick and generous sympathy and insight; efficient and businesslike, with a delightful sense of humour and absence of red tape, it was always a real pleasure to talk with him. Taken one with another, indeed, the Serbian officials whom I had the privilege to meet were—unlike most officials in other countries—human.

Our most frequent visitor was Major Dr. Protitch, Director of the Shumadia Military Hospital. He was our official inspector, and was responsible for the evacuation of the convalescent wounded. He came always officially, once a day, during all the six months of our work at Kragujevatz, and he never came once too often.

Nothing that could be done for our comfort, or to show the sympathy and generosity of the officials, was forgotten by him. One morning, soon after the establishment of the camp, I saw a man carrying a spade, and another wheeling a barrow filled with earth, coming towards my tent. When they were in front of it, they stopped. I wondered what they were going to do, and I tried to remember the Serbian words for "What's your business?" when Major Protitch came up. He smiled, and told me that he had heard me say that I was fond of flowers, and that at home, in England, I had a garden of my own. He was therefore going to plant a little garden in front of my tent, and in front of one of every two[31] tents, all up the line, to remind us of our homeland. Barrow loads of earth were accordingly deposited, and were then planted with violas, carnations, cinerarias, and many varieties of gay flowers. The gardens were in shape and size suspiciously like graves: they were, alas! as shown by later events, symbolic of the graves of many Serbian hopes.

One day Major Protitch invited me and our Treasurer to his Slava feast. Slava is the anniversary of the day on which the ancestors of the family were converted to Christianity. We were to be present at the inauguration ceremony in celebration of his patron saint day. Madame Protitch was in deep mourning, and for that reason there were to be no other guests.

At 9 a.m. the Major and his wife, their small son of five years old, and the priest, and verger, were waiting for us, round a table, in a wood, outside the little shooting box club-house, which the Major and his wife had improvised as summer quarters, at the southern end of our racecourse. After we had wished them "Sretna Slava" (happy feast day) and shaken hands, the priest led the way into the house, and we all followed. A tiny room was arranged, in excellent taste, as living and bedroom. On a small table in the middle of the room, were two large cakes, a long, fat, brown, unlighted candle, a crucifix, and a saucer of water. In the latter was a sprig of a faded flower called boziliac.

The priest, who had long hair, and wore a blue embroidered robe, said a short prayer, and the verger, a Serbian peasant in ordinary dress, without a collar—probably because the weather was hot—said the response. Then the big candle was lighted by the little son, who was nervous, and received surreptitious help from his father. Then came more prayers by the priest, and responses by the verger, who seemed to play quite as important a[32] part as the priest; the family only crossed themselves vigorously at intervals.

Next, the priest immersed the crucifix in the water in the saucer, and with the wet crucifix sprinkled the Major, and the boy, and various objects on the table and about the room. He did not sprinkle the wife, she was scrupulously omitted from all the proceedings. The priest then made the sign of the cross on both the cakes; took one cake and held it upside down, and without severing it, made two cross cuts, and poured a little red wine into the cuts. When this had soaked in, he turned it right side up again. Then he and the two honoured males, together held the cake again, and turned it slowly round and round in their hands, the wife still looking on.

The priest then took the cake and held it sideways, almost, but not quite severed, to show the cross cuts; he held it thus for the father and son to kiss, removed it, and gave it to them again to kiss, and once again for the third time; the cake had then done its duty, and was replaced on the table.

Then came more prayers, the congregation standing. After this the priest shook hands with Major Protitch, and the boy, and the religious ceremony, in which the wife had had no share, was over. She was only servitor, and now she handed first to the priest, the other cake, made by herself, of corn, and nuts, and sugar. He helped himself with a spoon to a small portion; the cake was then handed to me. I found it delicious, and should have liked more; and then to the others. Madame Protitch then handed round other cakes, and cognac, and the priest bade us farewell, and departed. After that we were given orange, sliced, and spiced, and water, and Turkish coffee. And then we talked, in German. Our hosts told us that a cake of corn, and nuts, is always made, at funerals, for the dead, and as the patron saint is dead, he gets the benefit on his name day. But there[33] is one unfortunate patron saint, who is an archangel, and therefore he is not dead, and because he is not dead, he is not entitled to this cake. Who'd be an archangel? But this means, of course, that the people who have this star turn, for their patron saint, cannot have this fascinating corn and nut-cake on their Slava day—all distinctly discouraging to the worship of archangels.

I asked Madame Protitch how she liked being left out of all the blessings. She was surprised at my surprise, and I remembered having read that, in Serbia, the formula used by a man on introducing his wife used to be: "This is my wife, God forgive me." And in describing his children, a father would say: "I have three sons and—God forgive me—three daughters."

The extreme modesty on the part of the husband concerning his wife, may be due to the fact that a wife was considered to be the property of the man, and it is, of course, unbecoming to boast of one's possessions. One should minimise their value as far as possible. Mothers, who are not regarded as property, are always spoken of, and treated by men with extreme respect.

That was, however, not an appropriate moment for feminist propaganda—it's extraordinary how few moments ever are appropriate for this. I therefore contented myself with saying that in England we were beginning to have different ideas about the relative position of women, and of men. I should have liked to add that the world is on its way to the discovery that the highest interests of men, and of women are identical, and that it is only the lowest interests of men, that clash with the highest interests of women.

But in some ways the Serbians are ahead of other European nations in their respect for women. Major Protitch told me that the Government were intending to give recognition to the peasant women[34] who, by working on the farms during the prolonged absence of their men folk, at the front, had saved the country from famine. Our Government might well take a hint in this respect. Who could say that there was no woman's movement in Serbia? It is a woman's movement, moved by men.

Another frequent visitor was the British Military Attaché, Colonel Harrison. He dined with us almost every night during four months—a compliment to the cooking—and until he was invalided home—not as a result of the cooking. He was a good friend to Serbia. He had the preceding autumn been one of the factors, behind the scenes, partially responsible for the sudden turn in the fortunes of the Serbian Army. An interesting book might be written if the true origins of great events were traced and revealed. We should have to re-learn many pages of history.

It was largely due to the agitation of Colonel Harrison, who cabled continuously for ammunition to be sent, that the tables had been turned on the Austrians. The latter were expecting the usual feeble volleys, from the depleted Serbian cannons, but instead, on a certain occasion, a fierce cannonade, with live ammunition, suddenly thundered from the guns, and the Austrians were so surprised and dismayed that they fled, and Serbia was—temporarily—saved.

But we had the satisfaction of seeing for ourselves that ammunition was now being made in large quantities, for Kragujevatz was the home of a large and excellently appointed arsenal. The director, who stood about six feet four—a magnificently fine fellow—showed me round the arsenal one day, and gave me various souvenirs, and then he paid a return visit to our camp. As a memento of this, he presented me with a beautiful big bell, cast from cannons taken from the Austrians; it was inscribed, and will[35] always be a precious possession. During six months in our camp on the racecourse of Kragujevatz, this bell, with loud but musical voice, summoned the unit from and to their beds, and to their meals and prayers; later it journeyed over the mountains of Montenegro and Albania, hidden in a sack. Its voice was then hushed, for on the mountains there were no beds, few meals, and prayers were spontaneous; and now it hangs in an English home as gong, calling us to meals; but it also serves as muezzin, calling to that form of prayer which is the only effective prayer—determination—on Serbia's behalf.

Another visitor was Sir Thomas Lipton. He and his yacht had brought hospital units to Serbia, and he was now touring to see the country. The officials, when he was expected at Kragujevatz, asked me if I would meet him at the station, at 5.17 a.m. He and I had recently lunched as co-guests of Sir Ralph Paget, at Nish, and afterwards Sir Thomas had shortened a tedious night railway journey by telling amusing stories of his life's experiences. Also, at a reception given by Lady Cowdray to our unit before we left for Serbia, he had been present, and had said kind words to and about us. He was thus an old friend. I always rose at 4.30, to set things going, and to make sure of the joy of seeing the sun rise—getting up at four, therefore, to meet him, was no hardship.

The sunrise rewarded me as usual. A blaze of crimson over the eastern hills, followed by a glare of yellow, melting into rainbow colours. I met the train, and Sir Thomas and his suite breakfasted with us. I hope we gave him porridge, but I've forgotten. But we showed him the camp; then he lunched at the officers' mess, inspected the arsenal in the afternoon, and came back to us for tea and supper.

In the evening, in his honour, we gave a little[36] supper party, which included Colonels Guentchitch and Popovitch, and Captain Yovan Yovannovitch, of the Intelligence Department, Mr. Robinson of The Times, and Mr. Stanley Naylor of The Daily Chronicle. Sir Thomas seemed to like the cheery, homely atmosphere of the corporate supper-table, at which all members of our unit—doctors, nurses, orderlies, chauffeurs, interpreters, myself and guests—messed, as always, together. He made one of his happy speeches, and response was made. After supper we gave an open-air concert, on the grass space between the hospital and the staff tents. The night was warm and lovely; the moon was bright, and all Kragujevatz, invited or not invited, considered it the correct thing to come to the concert.

The Crown Prince had kindly lent us his band, and, in addition to excellent music by them, the programme included part songs by a company of theological students, who were now working in hospitals in Kragujevatz (in lieu of military service), also songs and recitations by other people.

Our own convalescent soldiers were too shy to perform, but in their bright-coloured dressing-gowns, or with blankets pinned round them, they formed a patch of picturesqueness amongst the audience. But they were not too shy to join in the final impromptu kolo dance. As usual, at the right moment, the guslar and the kolo-starter dropped from the skies, and for a few minutes all Kragujevatz were linked arm in arm, in happy abandonment of care and sorrow, in the magic kolo circle. But the happiness was of short duration. Has there ever been a time during the last five hundred years when Serbia could rejoice with a light heart? Will the time ever come when Serbian swords can be beaten into ploughshares, and their bayonets into pruning hooks?

Even amongst our comparatively cheerful patients,[37] during this temporary lull in the fighting, tragedies were occurring in the usual humdrum fashion. One man who was badly wounded, and unable to leave his bed, received a letter from home, telling him that his wife, two children, and a brother, had just died of typhus, and that two other children, and his mother, all members of the same zadruga (family community) were dangerously ill with the same disease.

A few hundred yards beyond our camp, four thousand newly dug graves, containing typhus victims, testified to the virulence of this one disease in this one town. With curious ingenuity, the typhus fiend stepped in to carry on the destruction of human life, during the interlude when the fighting fiend was in abeyance. Is it a wonder that the Serbian peasant forgets to see the hand of God in all his suffering? For many centuries the hand of the Turk has been too plainly the direct cause of his tragedies. There has been no desire to seek for further causes. Even those of us who have made it our business to search diligently for God, have not always found Him; but perhaps we are like the players in "hunt the thimble" game, we cannot find God, because He is in too conspicuous a place—in our own hearts.

But for centuries, the salvation of the Serbian peasant has been working itself out on larger lines than those of a narrow theology; the struggle of his nation has been for that which is the basis of Christian faith—for Freedom. For the outer frills, the rituals of that faith, the Serbian peasant has had no time. With us, in England, this situation is reversed. We have had plenty of time to attend to the frills, and have perhaps lost sight of that which is the basis of our common faith.

It is undoubtedly true that in Serbia, religion, if by religion is meant theological doctrine, and adherence to ritual, has little hold upon the people.[38] But during centuries of oppression, religious teaching has been necessarily confined to the monks, and they, to avoid persecution, have been obliged to seclude themselves amongst the mountains. And so it has come about, as usual, that the praying men have been content with prayer, and the men of action with action. Neither of them has perceived that a combination of prayer, and action, is necessary for the fulfilment of divine destiny.

Amongst the Serbian soldiers many primitive notions still prevailed. One day, after one of the big thunder-storms which were frequent during the spring and summer months, I asked the men in one of the wards, what was their idea of the origin of thunder? "God must have something to do in Heaven," replied one man. "We work on earth and He must work above, so He makes thunder and lightning. He mustn't sit up there and do nothing."

"No, no," answered another; "it is not God that makes thunder, it's St. Ilyia; it's he who works the thunder and lightning."

I asked who was St. Ilyia? Didn't I know St. Ilyia? He was a workman, paid by the day, to work on the land. One evening late, as he was on his way home, he met a devil. The devil reminded him that he, the devil, had been best man at his, Ilyia's, wedding. "And I now congratulate you," the devil added mockingly, "that your wife has run away with another man." Ilyia was furious, but said nothing, and walked on. Soon he met another devil. This one reminded him that he had been first witness at his wedding, and he, too, added mockingly, "I congratulate you that your wife has run away with another man." Ilyia was still more furious, but he walked on. Soon he met a third devil. This devil reminded him that he had been godfather to his, Ilyia's, child, and he also added mockingly, "I congratulate you that your wife has run away with another man."

Mad with anger, Ilyia rushed home determined to[40] kill the guilty pair. He went into his bedroom, and saw a man and woman in the bed. He did not stop to look, but he killed them both. They were his father and mother. For a punishment, God made him serve as ferryman, to carry people across the river in his own village. He must give to each passenger a melon seed. One day there came a passenger—a devil—in such a hurry he wouldn't take the seed. "Why won't you take it? But you must," urged Ilyia. "No," replied the devil, "I am in a hurry to spoil a wedding, and I have no time to wait." Immediately, in answer, Ilyia killed the devil, and threw his body into the water. God, however, pardoned Ilyia, and took him to heaven as His servant, but he must work the thunder and lightning. So he kept killing all the devils with his lightning. But one deformed devil always managed to hide away, and one day this poor devil managed to get to God, and asked Him why He allowed all the devils to be killed. It is the devils, he argued, who bring the wars which cause deformities, and the devils who cause all sickness and poverty, and as it is only the sick and the poor who pray to God—why get rid of them?

The argument seemed to appeal to God, for He replied, Very well, He would at any rate not let him, the deformed devil, be killed by Ilyia.

But Ilyia still tries to kill him, and whenever it thunders and lightens, that is Ilyia trying to kill the deformed devil.

There were several points in this story, upon which I should have liked enlightenment; but when I began asking questions, I was told, simply, that it was so, and that it always had been. How, then, could I doubt? And I assured them that I did not doubt.

Then another man said that there had been a thunderstorm last night, because Italy was now going[41] to join in the fighting; the thunder and lightning was a sign that another land was going to shed its blood. I had thought of that myself, and was glad that they voiced my thought. Much more interesting and reasonable to believe in concrete causes.

During the night, whilst the thunder-storms had been immediately overhead, many of the wounded left their beds, and stood and prayed to God not to let them be killed—presumably by Ilyia, as deformed devils.

It was not strange that a relationship between politics and weather in Serbia should be assumed, for violence was the keynote of both. When the sun shone, its heat was fierce, it scorched the body through thick clothes; when rain fell, it poured in waterspouts, as though the skies had burst a dam. The wind blew tornadoes, and with the brutality of a gigantic peg-top, whirled everything within reach, into space, at the rate of eighty miles an hour. Thunder and lightning had the force of up-to-date artillery, and the mud was—Balkan.

One Sunday afternoon, I was standing with our chaplain, outside the tent in which, in two minutes' time, he was to conduct the evening service. We were choosing the hymns, but we were suddenly interrupted by a whirlwind of dust, which nearly blinded us, and before we could close our books, and with a suddenness which is, as a rule, only permitted on the stage, a tornado, rushing at the rate of eighty miles an hour, hurled itself point-blank at our camp, and though everybody immediately rushed to tighten tent ropes, within fifteen seconds, fifteen tents were blown flat upon the ground, and chairs, tables, hairbrushes, garments of all sorts, a menagerie of camp equipment, and personal effects, were flying over the plain, beyond possibility of recovery. There was no church service that evening.

After a day or two of rain, skirts became a folly[42] and indecency. I was at first shy, as a guest in a foreign country, of casting the recognised symbol of feminine respectability. But my work required me to be constantly on the tramp, around the extensive camp, and one day, when my skirt had become soaked, and bedraggled, and I could no longer walk in it, I took it off. I found that with my long boots and a longish tunic coat, over breeches which matched the coat, the effect was respectable, and was approved by the rest of the unit, who soon followed the example on wet days. But it was a little bit of a shock to me when, on that first morning of audacity, a car drove up to the camp, and out stepped the representatives of three nations—viz., Sir Ralph Paget (British Commissioner), Dr. Grouitch (Serbian Foreign Secretary), and Mr. Strong, who was on a mission to report for Mr. Rockefeller on the condition of Serbian hospitals. But they didn't seem as shocked as might have been expected; and I became more than ever confirmed in the belief that even if skirts are retained by women for decorative purposes, they will have to be abandoned by workers. The question of women's work is largely a question of clothes.

But the Serbian soldiers would never sympathise with us in our abhorrence of mud. "No, no, mud was 'Dobro, dobro' (good, good), because mud meant rain for crops; also mud had saved them from the Austrians who, in November last, had not been able to advance their big guns further, on account of the mud. Yes, mud was 'Dobro, dobro.'"

There never was in any language a word so omnipotent, so deep-reaching as this word "Dobro." Of what use to worry with phrase books, grammars and dictionaries; why trouble to learn a difficult language, written in arbitrary characters, when one simple word could open all the gates of understanding! With "Dobro" on the tip of the tongue—every tongue—Serbian and English tongues alike, how could there be "confusion of tongues"? The heritage of Babel could be flouted. Diagnosis by doctors, nursing, treatment, orders, warnings, instructions from and to one and all, within and without the camp; interchange of ideas; even proposals and acceptance or refusal of marriage; all could be understood by means of the blessed word "Dobro" and its negative "Ne-dobro," spoken with appropriate variations of accent.

Is it a wonder that good understanding prevailed between Serbians and English? Misunderstandings arise from words. In Serbia there only was one word—"Dobro"; and I'm longing for the day—"Der Tag"—when we can go back to Serbia and find that all is indeed once more "Dobro, dobro."

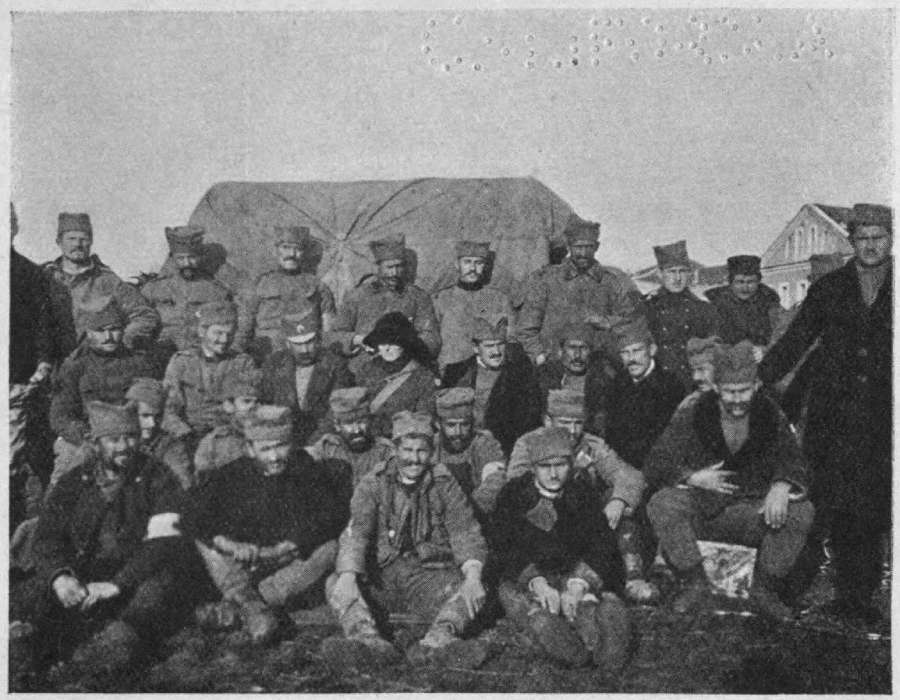

When we first arrived in Serbia, we were much interested in the sight of many thousands of Austrian prisoners of war, working in every department of life, and living in apparent freedom. Those who were officers were often employed in hospitals. In Dr. Protitch's hospital, one of the prisoners had been Professor of Mathematics, at the University of Prague. His work now was to count the dirty linen, and he did it very badly. I suppose even the Professor's mathematics couldn't make ninety nightshirts that came back from the wash, equal to one hundred that went out.

We had no commissioned officers in our hospital, but forty Austrian so-called prisoners helped us in the rough work of the camp, as trench diggers, stretcher bearers and ward orderlies, etc. These men were working in a camp hospital controlled by women; they were working for the enemies of their country, yet they were quite unguarded, and slept at night, in tents, like the rest of us. But after the first wonder had evaporated, thoughts of the possible mischief they might do, never entered our minds. It showed the artificiality of war. These men—forty[44] thousand or more—were told that by the rules of the game, they were prisoners, and therefore must keep off Tom Tiddler's ground, and they obeyed the rules with scarcely any supervision.

There were Serbian Austrians, and Austrian Austrians. The latter spoke only German, and were less to be trusted politically than the former, who talked only Serbian. The Serbian Austrians were to all intents Serbians, and dreaded nothing so much as the prospect of being retaken by the Austrians—their former masters.

The main distinction between the two is that of religion, Croats or Serbian Austrians are Catholics, whereas the others belong to the Greek Church. But all alike were excellent workers, and very happy in their work. Both they and we grieved terribly when later, owing to political causes, all our Catholic prisoners were removed from their positions of freedom, and happy work in our hospital, and were sent, under strict escort, to dig tunnels on the railway to Roumania, or to other work in which supervision was feasible.

Amongst these orderlies working for us, was a funny old man called Jan. He had a wife and children somewhere in Serbia, and he developed a chronic habit of coming to ask for leave to go and see them. On one occasion when he came to say good-bye to "Maika" (mother), I noticed that he was hugging two bottles, which were carefully wrapped in paper. I asked him what he was carrying, and he answered proudly, "Medicine for my little ones." "Dear! dear! are they ill?" I asked with some concern; "I am sorry." "Oh! no. They're not ill. I am only taking them the medicine as a treat." He had apparently explained his idea to our dispenser, and she had given him something harmless to satisfy his fatherly instinct of giving joy. A side-light on the scarcity of medicines.

Our hospital received several visits from German and Austrian aeroplanes. Kragujevatz was one of their main objectives, on account of the arsenal and the Crown Prince.