front cover

front cover

TRÜBNER’S

ORIENTAL SERIES.

VII.

Ballantyne Press

BALLANTYNE, HANSON AND CO.

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

MECCA

MECCA

SELECTIONS FROM THE ḲUR-ÁN

BY

EDWARD WILLIAM LANE,

HON. DOCTOR OF LITERATURE, LEYDEN;

CORRESPONDENT OF THE INSTITUTE OF FRANCE;

HON. MEMBER OF THE GERMAN ORIENTAL SOCIETY, THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY,

THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LITERATURE, ETC.;

AUTHOR OF “THE MODERN EGYPTIANS,” AND “AN ARABIC-ENGLISH LEXICON;”

TRANSLATOR OF “THE THOUSAND AND ONE NIGHTS.”

A New Edition, Revised and Enlarged,

WITH AN INTRODUCTION,

BY

STANLEY LANE POOLE.

LONDON:

TRÜBNER & CO., LUDGATE HILL.

1879.

[All rights reserved.]

[Pg v]

PREFACE.

There are several translations of the Ḳur-án in several

languages; but there are very few people who have the

strength of mind to read any of them through. The

chaotic arrangement and frequent repetitions, and the

obscurity of the language, are sufficient to deter the most

persistent reader, whilst the nature of a part of its contents

renders the Ḳur-án unfit for a woman’s eye.

Yet there always has been a wish to know something

about the sacred book of the Mohammadans, and it was

with the design of satisfying this wish, whilst avoiding

the weariness and the disgust which a complete perusal

of the Ḳur-án must produce, that Mr. Lane arranged the

‘Selections’ which were published in 1843. In spite of

many printer’s errors, due to the author’s absence from

England, the book was so far successful that the edition

was exhausted, and it is now very difficult to obtain

a copy. But partly owing to the obstructions to the

reading offered by an interwoven native commentary,

and partly by reason of the preference shown for the

doctrinal over the poetical passages, the book went

into scholars’ hands rather than into the libraries of

[Pg vi]

the general reading public. It has proved of considerable

service to students of Arabic, who have found

it the most accurate rendering in existence of a large part

of the Ḳur-án; and even native Muslims of India, ignorant

of Arabic, have used Lane’s ‘Selections’ as their Bible.

In this edition I have endeavoured rather to carry out

the original intention of the translator. Experience has

shown that the first plan was over-learned to commend

itself to the average reader, for whom Mr. Lane had

destined the book; in this edition I have therefore

omitted many of the notes, which will not be missed

by the reader for whom the book is intended, and for

which the Arabic scholar has only to refer to the first

edition, or to Sale’s Koran, whence most of them were

derived. Again, the text of the first edition was obscured

and interrupted by an interwoven commentary, which

destroyed the pleasure of the language and often made the

meaning less intelligible than before. This commentary

has been thinned. Where it added nothing to the text, it

has been erased; where it gave a curious or valuable explanation,

it has been thrown into a footnote; where it

merely supplied a necessary word to complete the sense,

that word has been left in the text distinguished by a different

type[1]. Once more, the early and wilder soorahs

were almost wholly omitted in the first edition, whilst

the later more dogmatic and less poetical soorahs were

perhaps too fully represented. I have endeavoured to

establish the balance between the two.

[Pg vii]

In this edition the Selections are divided into two parts.

The first is Islám; the second, other religions as regarded

in Islám. In the first are grouped, under distinctive

headings, the more important utterances of Moḥammad on

what his followers must believe and do; in the second are

his versions of the history of the patriarchs and other personages

of the Jewish and Christian writings.

It is only in the First Part that I have made much alteration,

either by adding fresh extracts (distinguished by a

sign), or by making a few merely verbal alterations in the

original extracts, or by the suppression or transposition of

the commentary. Any alterations that go beyond this—new

renderings, for instance—are duly recorded in the

footnotes.

The Second Part is almost unchanged from the first

edition. In this part the interwoven commentary is left

entire, for the traditions of the commentators about Abraham

and Moses and Christ are as curious as the traditions

of Moḥammad, and about as credible; and the narrative

style of the Second Part allows the introduction of parentheses

more easily than the rhetorical form which many

of the extracts in the First Part present.

Mr. Lane’s Introduction was abridged from Sale’s Preliminary

Discourse, with but little addition from his own

knowledge. Sale’s Discourse abounds in information, but

it is too detailed and lengthy for the purpose of this

volume. I have, then, substituted a short sketch of the

beginnings of Islám. I have tried to bring home to the

reader the little we know of the early Arabs; then to draw

the picture of the great Arab prophet and his work; to

[Pg viii]

show what are the salient points of Islám; and finally

to explain something of the history of the Ḳur-án and its

contents. I am conscious of having drawn the picture

with a weak hand, but I hope the sketch may serve as a

not quite useless introduction to a volume of typical selections

from a book which, in the peculiar character of its

contents and the extraordinary power of its influence, has

not its parallel in the world.

S. L. P.

June 1878.

[Pg ix]

CONTENTS.

| INTRODUCTION. |

PAGE

|

| I. |

THE ARABS BEFORE MOḤAMMAD |

xi |

| II. |

MOḤAMMAD |

xxxvii |

| III. |

ISLÁM |

lxxvii |

| IV. |

THE ḲUR-ÁN |

c |

| PART THE FIRST. |

| I. |

THE OPENING PRAYER |

3 |

| II. |

PREMONITION |

4 |

| III. |

GOD |

5 |

| IV. |

MOḤAMMAD AND THE ḲUR-ÁN |

13 |

| V. |

THE RESURRECTION, PARADISE, AND HELL |

21 |

| VI. |

PREDESTINATION |

32 |

| VII. |

ANGELS AND JINN |

33 |

| VIII. |

TRUE RELIGION AND FALSE |

34 |

| IX. |

BELIEVERS AND UNBELIEVERS |

38 |

| PART THE SECOND. |

| I. |

PROPHETS, APOSTLES, AND DIVINE BOOKS |

47 |

| II. |

ADAM AND EVE |

49 |

| III. |

ABEL AND CAIN |

53 |

| IV. |

NOAH AND THE FLOOD |

55 |

| V. |

´ÁD AND THAMOOD |

60 |

| VI. |

DHU-L-ḲARNEYN |

63 |

| VII.[Pg x] |

ABRAHAM, ISHMAEL, ISAAC |

66 |

| VIII. |

JACOB, JOSEPH AND HIS BRETHREN |

77 |

| IX. |

JOB |

93 |

| X. |

SHO´EYB |

95 |

| XI. |

MOSES AND HIS PEOPLE |

97 |

| XII. |

SAUL, DAVID, SOLOMON |

132 |

| XIII. |

JONAH |

146 |

| XIV. |

EZRA |

148 |

| XV. |

THE MESSIAH |

149 |

| |

INDEXES |

167 |

[Pg xi]

INTRODUCTION.

I.—THE ARABS BEFORE MOḤAMMAD.

‘Oh, our manhood’s prime vigour! No spirit feels waste,

Not a muscle is stopped in its playing nor sinew unbraced.

Oh, the wild joys of living! the leaping from rock up to rock,

The strong rending of boughs from the fir-tree, the cool silver shock

Of the plunge in the pool’s living water, the hunt of the bear,

And the sultriness showing the lion is couched in his lair.

And the meal, the rich dates yellowed over with gold-dust divine,

And the locust flesh steeped in the pitcher, the full draught of wine,

And the sleep in the dried river-channel where bulrushes tell

That the water was wont to go warbling so softly and well.

How good is man’s life, the mere living! how fit to employ

All the heart and the soul and the senses for ever in joy!’

—Browning, Saul.

Between Egypt and Assyria, jostled by both, yielding to

neither, lay a strange country, unknown save at its marches

even to its neighbours, dwelt-in by a people that held

itself aloof from all the earth—a people whom the great

empires of the ancient world in vain essayed to conquer,

against whom the power of Persia, Egypt, Rome, Byzantium

was proven impotence, and at whose hands even the

superb Alexander, had he lived to test his dream, might

for once have learnt the lesson of defeat. Witnessing the

struggle and fall of one and another of the great tyrannies

of antiquity, yet never entering the arena of the fight;—swept

on its northern frontier by the conflicting armies of

Khusru and Cæsar, but lifting never a hand in either

cause;—Arabia was at length to issue forth from its silent

mystery, and after baffling for a thousand years the curious

gaze of strangers, was at last to draw to itself the

fearful eyes of all men. The people of whom almost

[Pg xii]

nothing before could certainly be asserted but its existence

was finally of its own free will to throw aside the veil, to

come forth from its fastnesses, and imperiously to bring

to its feet the kingdoms of the world.

It is not all Arabia of which I speak. The story to

tell has nothing as yet to say to the ‘happy’ tilled lands of

the south, nor to the outlying princedoms of El-Ḥeereh and

Ghassán bordering the territories and admitting the suzerainty

of Persia and Rome. These lands were not wrapped

in mystery: the Himyerite’s kingdom in the Yemen, the

rule of Zenobia at Palmyra, were familiar to the nations

around. But the cradle of Islám was not here.

Along the eastern coast of the Red Sea, sometimes

thrusting its spurs of red sandstone and porphyry into the

waves, sometimes drawing away and leaving a wide stretch

of lowland, runs a rugged range of mountain. One above

another, the hills rise from the coast, leaving here and there

between them a green valley, where you may see an Arab

settlement or a group of Bedawees watering their flocks.

Rivers there are none; and the streams that gather from

the rainfall are scarcely formed but they sink into the

parched earth. Yet beneath the dried-up torrent-beds a

rivulet trickles at times, and straightway there spreads a

rich oasis dearly prized by the wanderers of the desert.

All else is bare and desolate. Climb hill after hill, and

the same sight meets the eye—barren mountain-side, dry

gravelly plain, and the rare green valleys. At length

you have reached the topmost ridge; and you see, not

a steep descent, no expected return to the plain, but a

vast desert plateau, blank, inhospitable, to all but Arabs

unindwellable. You have climbed the Ḥijáz—the ‘barrier’—and

are come to the steppes of the Nejd—the ‘highland.’

In the valleys of this barrier-land are the Holy

Cities, Mekka and Medina. Here is the birthplace of

Islám: the Arab tribes of the Ḥijáz and the Nejd were

the first disciples of Moḥammad.

One may tell much of a people’s character from its

[Pg xiii]

home. Truism as it seems, there is yet a meaning in the

saying that the Arabs are peculiarly the people of Arabia.

Those who have travelled in this wonderful land tell us of

the quickening influence of the air and scene of the desert.

The fresh breath of the plain, the glorious sky, the still

of the wide expanse, trod by no step but your own, looked

upon only by yourself and perhaps yonder solitary eagle

or the wild goat leaping the cliffs you have left behind,

the absolute stillness and aloneness, bring about a strange

sense of delight and exultation, a bounding-up of spirits

held in long restraint, an unknown nimbleness of wit and

limb. The Arabs felt all this and more in their bright

imaginative souls. A few would settle in villages, and

engage in the trade which came through from India

to the West; but such were held in poor repute by the

true Bedawees, who preferred above all things else the free

life of the desert. It is a relief to turn from the hurry

and unrest of modern civilisation, from the never-ending

strife for wealth, for ‘position,’ for pleasure, even for

knowledge, and look for a moment on the careless life of

the Bedawee. He lived the aimless, satisfied life of some

child; he sought no change; he was supremely content

with the exquisite sense of simple existence; he was

happy because he lived. He wished no more. He

dreaded the dark After-death; he thrust it from his

thoughts as often as it would force itself unwelcome upon

him. Utterly fearless of man and fortune, he took no

thought for the morrow: whatever it brought forth, he

felt confidently his strength to enjoy or endure; only let

him seize the happiness of to-day while it shall last, and

drain to the dregs the overbrimming cup of his life. He

was ambitious of glory and victory, but it was not an

ambition that clouded his joy. Throughout a life that

was full of energy, of passion, of strong endeavour after

his ideal of desert perfectness, there was yet a restful sense

of satisfied enjoyment, a feeling that life was of a surety

well worth living.

[Pg xiv]

For the Arab had his ideal of life. The true son of the

desert must in the old times do more than stretch his

limbs contentedly under the shade of the overhanging

rock. He must be brave and chivalrous, generous, hospitable;

ready to sacrifice himself and his substance for his

clan; prompt to help the needy and the traveller; true to

his word, and, not least, eloquent in his speech.

Devotion to the clan was the strongest tie the Arab

possessed. Though tracing their descent from a common

traditional ancestor, the great northern family of Bedawees

was split up into numerous clans, owning no

central authority, but led, scarcely governed, each by its

own chief, who was the most valiant and best-born man

in it. The whole clan acted as one being; an injury done

to one member was revenged by all, and even a crime

committed by a clansman was upheld by the whole brotherhood.

Though a small spark would easily light-up war

between even friendly clans, it was rarely that those of

kin met as enemies. It is told how a clan suffered

long and oft-repeated injuries from a kindred clan without

one deed of revenge. ‘They are our brothers,’ they

said; ‘perhaps they will return to better feelings; perhaps

we shall see them again as they once were.’ To be brought

to poverty or even to die for the clan, the Arab deemed

his duty—his privilege. To add by his prowess or his

hospitality or his eloquence to the glory of the clan was

his ambition.

A mountain

2 we have where dwells he whom we shelter there,

lofty, before whose height the eye falls back blunted:

Deep-based is its root below ground, and overhead there soars

its peak to the stars of heaven whereto no man reaches.

A folk are we who deem it no shame to be slain in fight,

though that be the deeming thereof of Salool and ´Ámir;

Our love of death brings near to us our days of doom,

but their dooms shrink from death and stand far distant.

There dies among us no lord a quiet death in his bed,

and never is blood of us poured forth without vengeance.

[Pg xv]

Our souls stream forth in a flood from the edge of the whetted swords:

no otherwise than so does our spirit leave its mansion.

Pure is our stock, unsullied: fair is it kept and bright

by mothers whose bed bears well, and fathers mighty.

To the best of the uplands we wend, and when the season comes

we travel adown to the best of fruitful valleys.

Like rain of the heaven are we: there is not in all our line

one blunt of heart, nor among us is counted a niggard.

We say nay when so we will to the words of other men,

but no man to us says nay when we give sentence.

When passes a lord of our line, in his stead there rises straight

a lord to say the say and do the deeds of the noble.

Our beacon is never quenched to the wanderer of the night,

nor has ever a guest blamed us where men meet together.

Our Days

3 are famous among our foemen, of fair report,

branded and blazed with glory like noble horses.

Our swords have swept throughout all lands both west and east,

and gathered many a notch from the steel of hauberk-wearers;

Not used are they when drawn to be laid back in the sheaths

before that the folk they meet are spoiled and scattered.

If thou knowest not, ask men what they think of us and them

—not alike are he that knows and he that knows not.

The children of Ed-Dayyán are the shaft of their people’s mill,

—around them it turns and whirls, while they stand midmost.

4

The renown of the clan was closely wrapped up with

the Arab chieftain’s personal renown. He was keenly

sensitive on the point of honour, and to that notion he

attached a breadth of meaning which can scarcely be

understood in these days. Honour included all the different

virtues that went to make up the ideal Bedawee.

To be proved wanting in any of these was to be dishonoured.

Above all things, the man who would ‘keep

[Pg xvi]

his honour and defile it not’ must be brave and hospitable—

A rushing rain-flood when he gave guerdons:

when he sprang to the onset, a mighty lion.

The Arab warrior was a mighty man of valour. He

would spend whole days in the saddle, burdened with heavy

armour, in the pursuit of a foe, seeking the life of the

slayer of his kin, or sweeping down upon the caravan of

rich merchandise which his more peaceful countrymen

of the towns were carrying through the deserts. The

Arab lived mainly by plunder. His land did not yield

him food—unless it were dates, the Bedawee’s bread—and

he relied on the success of his foraging expeditions for his

support. These he conducted with perfect good-breeding;

he used no violence when it could be avoided; he merely

relieved the caravan from the trouble of carrying any

further the goods that he was himself willing to take

charge of, urging, if necessary, the unfair treatment of his

forefather Ishmael as an excellent reason for pillaging the

sons of Isaac. ‘When a woman is the victim, no Bedouin

brigand, however rude, will be ill-mannered enough to

lay hands upon her. He begs her to take off the garment

on which he has set his heart, and he then retires to a

distance and stands with eyes averted, lest he should do

violence to her modesty.’

The poems of the early Arabs are full of the deeds of

their warriors, the excitement of the pitched battle, the

delight of the pursuit, the nightly raid on the camp, the

trial of skill between rival chiefs, and the other pictures

of a warrior’s triumph. Here we find little of

the generosity of war: mercy was rarely exercised and

hatred was carried to its extremest limits; quarter was

neither asked nor given; to despatch a wounded man was

no disgrace; the families of the vanquished were enslaved.

Notwithstanding his frank genial nature, the Arab was of

a dangerously quick temper, derived, he boasted, from the

flesh he lived on of the camel, the surliest and most ill-conditioned

[Pg xvii]

of beasts. If he conceived himself insulted,

he was bound to revenge himself to the full, or he would

have been deemed dishonoured for ever. And since his

fiery temper easily took offence, the history of the early

Arabs is full of the traditions of slight quarrels and their

horrible results—secret assassination and the long-lasting

blood-feud.

Many the warriors, noon-journeying, who, when

night fell, journeyed on and halted at dawning—

Keen each one of them, girt with a keen blade

that when one drew it flashed forth like the lightning—

They were tasting of sleep by sips, when, as

they nodded, thou didst fright them, and they were scattered.

Vengeance we did on them: there escaped us

of the two houses none but the fewest.

And if Hudheyl

5 broke the edge of his

6 sword-blade—

many the notch that Hudheyl gained from him!

Many the time that he made them kneel down on

jagged rocks where the hoof is worn with running!

Many the morning he fell on their shelter,

and after slaughter came plunder and spoiling!

Hudheyl has been burned by me, one valiant

whom Evil tires not though they be wearied—

Whose spear drinks deep the first draught, and thereon

drinks deep again of the blood of foemen.

Forbidden was wine, but now it is lawful:

hard was the toil that made it lawful!

Reach me the cup, O Sawád son of ´Amr!

my body is spent with gaining my vengeance.

To Hudheyl we gave to drink Death’s goblet,

whose dregs are disgrace and shame and dishonour.

The hyena laughs over the slain of Hudheyl, and

the wolf—see thou—grins by their corpses,

And the vultures flap their wings, full-bellied

treading their dead, too gorged to leave them.

The contempt which the Arab, with a few noble exceptions,

felt for the gentler virtues is seen in these lines:—

Had I been a son of Mázin, there had not plundered my herds

the sons of the Child of the Dust, Dhuhl son of Sheybán!

[Pg xviii]

There had straightway arisen to help me a heavy-handed kin,

good smiters when help is needed, though the feeble bend to the blow:

Men who, when Evil bares before them his hindmost teeth,

fly gaily to meet him, in companies or alone.

They ask not their brother, when he lays before them his wrong

in his trouble, to give them proof of the truth of what he says.

But as for my people, though their number be not small,

they are good for nought against evil, however light it be;

They requite with forgiveness the wrong of those that do them wrong,

and the evil deeds of the evil they meet with kindness and love;

As though thy Lord had created among the tribes of men

themselves alone to fear Him, and never one man more.

Would that I had in their stead a folk who, when they ride forth,

strike swiftly and hard, on horse or on camel borne!

A point on which the temper of the Bedawee was easily

touched was his family pride. The Arab prized good blood

as much in men as in his horses and camels. In these

he saw the importance of breed, and in men he firmly believed

the same principle held good. With the tenacious

memory of his race, he had no difficulty in remembering

the whole of a complicated pedigree, and he would

often proudly dwell on the purity of his blood and the

gallant deeds of his forefathers. He would challenge

another chief to prove a more noble descent, and hot

disputes and bitter rivalries often came of these comparisons.

But if noble birth brought rivalry and hatred, it

brought withal excellent virtues. The Arab nobleman

was not a man who was richer and more idle and luxurious

than his inferiors: his position, founded upon descent,

depended for its maintenance on personal qualities. Rank

brought with it onerous obligations. The chief, if he

would retain and carry on the repute of his line, must not

only be fearless and ready to fight all the world; he must

be given to hospitality, generous to kith and kin, and

to all who cry unto him. His tent must be so pitched

in the camp that it shall not only be the first that the

enemy attacks, but also the first the wayworn stranger

approaches; and at night fires must be kindled hard by to

guide wanderers in the desert to his hospitable entertain

[Pg xix]ment.

If a man came to an Arab noble’s tent and said, ‘I

throw myself on your honour,’ he was safe from his enemies

until they had trampled on the dead body of his host.

Nothing was baser than to give up a guest; the treachery

was rare, and brought endless dishonour upon the clan in

which the shame had taken place. The poet extols the

tents—

Where dwells a kin great of heart, whose word is enough to shield

whom they shelter when peril comes in a night of fierce strife and storm;

Yea, noble are they: the seeker of vengeance gains not from them

the blood of his foe, nor is he that wrongs them left without help.

The feeling lasted even under the debased rule of

Muslim despots; for it is related that a governor was once

ordering-out some prisoners to execution, when one of

them asked for a drink of water, which was immediately

given him. He then turned to the governor and said,

‘Wilt thou slay thy guest?’ and was forthwith set free.

A pledge of protection was inferred in the giving of hospitality,

and to break his word was a thing not to be

thought upon by an Arab. He did not care to give an

oath; his simple word was enough, for it was known to

be inviolable. Hence the priceless worth of the Arab

chief’s word of welcome: it meant protection, unswerving

fidelity, help, and succour.

There was no bound to this hospitality. It was the

pride of the Arab to place everything he possessed at

the service of the guest. The last milch-camel must be

killed sooner than the duties of hospitality be neglected.

The story is told of Ḥátim, a gallant poet-warrior of the

tribe of Ṭayyi, which well illustrates the Arab ideal of

hostship. Ḥátim was at one time brought to the brink of

starvation by the dearth of a rainless season. For a whole

day he and his family had eaten nothing, and at night, after

soothing the children to sleep by telling them some of those

stories in which the Arabs have few rivals, he was trying

by his cheerful conversation to make his wife forget her

[Pg xx]

hunger. Just then they heard steps without, and a corner

of the tent was raised. ‘Who is there?’ said Ḥátim. A

woman’s voice replied, ‘I am such a one, thy neighbour.

My children have nothing to eat, and are howling like young

wolves, and I have come to beg help of thee.’ ‘Bring them

here,’ said Ḥátim. His wife asked him what he would do,

for if he could not feed his own children, how should he find

food for this woman’s? ‘Do not disturb thyself,’ he answered.

Now Ḥátim had a horse renowned far and wide for

the purity of his stock and the fleetness and beauty of his

paces. He would not kill his favourite for himself nor

even for his own children; but now he went out and slew

him, and prepared him with fire for the strangers’ need. And

when he saw them eating with his wife and children, he

exclaimed, ‘It were a shame that you alone should eat

whilst all the camp is perishing of hunger;’ and he went

and called the neighbours to the meal, and in the morning

there remained of the horse nothing but his bones. But

as for himself, wrapped in his mantle, he sat apart in a

corner of the tent.

This Ḥátim is a type of the Arab nature at its noblest.

Though renowned for his courage and skill in war, he

never suffered his enmity to overcome his generosity. He

had sworn an oath never to take a man’s life, and he

strictly observed it, and always withheld the fatal last blow.

In spite of his clemency, he was ever successful in the

wars of his clan, and brought back from his raids many a

rich spoil, only to spend it at once in his princely fashion.

His generosity and faithful observance of his word at

times placed him in positions of great danger; but the

alternative of denying his principles seems never to have

occurred to his mind. For instance, he had imposed upon

himself as a law never to refuse a gift to him that asked it

of him. Once, engaged in single combat, he had disarmed

and routed his opponent, who then turned and said, ‘Ḥátim,

give me thy spear.’ At once he threw it to him, leaving

himself defenceless; and had he not met an adversary

[Pg xxi]

worthy of himself, this had been the last of his deeds.

Happily Ḥátim was not the only generous warrior of the

Arabs, and his foe did not avail himself of his advantage.

When Ḥátim’s friends remonstrated with him on the rashness

of an act which, in the spirit of shopkeepers, they

regarded as quixotic, Ḥátim said, ‘What would you have

me to do? He asked of me a gift!’

It was Ḥátim’s practice to buy the liberty of all captives

who sought his aid: it was but another application of the

Arab virtue of hospitality. Once a captive called to him

when he was on a journey and had not with him the

means of paying the ransom. But he was not wont to

allow any difficulties to baulk him of the exercise of his

duty, and he had the prisoner released, stepping meanwhile

into his chains until his own clan should send the

ransom.

Brave, chivalrous, faithful, and generous beyond the

needful of Arab ideal—so that his niggard wife, using the

privilege of high dames, repudiated him because he was

ever ruining himself and her by his open hand—Ḥátim

filled up the measure of Arab virtue by his eloquence,

and such of his poems as have come down to us reflect

the nobility of his life. As a youth he had shown a

strong passion for poetry, and would spare no means of

doing honour to poets. His grandfather, in despair at the

boy’s extravagance, sent him away from the camp to guard

the camels, which were pastured at a distance. Sitting there

in a state of solitude little congenial to his nature, Ḥátim

lifted his eyes and saw a caravan approaching. It was the

caravan of three great poets who were travelling to the

court of the King of El-Ḥeereh. Ḥátim begged them to alight

and to accept of refreshment after the hot and dreary journey.

He killed them a camel each, though one would have more

than sufficed for the three; and in return they wrote him

verses in praise of himself and his kindred. Overjoyed at

the honour, Ḥátim insisted on the poets each accepting a

hundred camels; and they departed with their gifts. When

[Pg xxii]

the grandfather came to the pasturing and asked where

the camels were gone, Ḥátim answered, ‘I have exchanged

them for a crown of honour, which will shine for all time

on the brow of thy race. The lines in which great poets

have celebrated our house will pass from mouth to mouth,

and will carry our glory over all Arabia.’ 7

This story well illustrates the Arab’s passionate love

of poetry. He conceived his language to be the finest

in the world, and he prized eloquence and poetry as the

goodliest gifts of the gods. There were three great events

in Arab life, when the clan was called together and great

feastings and rejoicings ensued. One was the birth of a

son to a chief; another the foaling of a generous mare;

the third was the discovery that a great poet had risen

up among them. The advent of the poet meant the immortality

of the deeds of the clansmen and the everlasting

contumely of their foes; it meant the raising up of the

glory of the tribe over all the clans of Arabia, and the

winning of triumphs by bitterer weapons than sword and

spear—the weapons of stinging satire and scurrilous squib.

No man might dare withstand the power of the poets

among a people who were keenly alive to the point of an

epigram, and who never forgot an ill-natured jibe if it

were borne upon musical verse. Most of the great heroes

of the desert were poets as well as warriors, and their

poesy was deemed the chiefest gem in their crown, and,

like their courage, was counted a proof of generous birth.

The Khalif ´Omar said well, ‘The kings of the Arabs are

their orators and poets, those who practise and who celebrate

all the virtues of the Bedawee.’

This ancient poetry of the Arabs is the reflection of the

people’s life. Far away from the trouble of the world,

barred by wild wastes from the stranger, the Bedawee

[Pg xxiii]

lived his happy child’s life, enjoying to the uttermost the

good the gods had sent him, delighting in the face that

Nature showed him, inspired by the glorious breath of the

deserts that were his home. His poetry rings of that

desert life. It is emotional, passionate, seldom reflective.

Not the end of life, the whence and the whither, but the

actual present joy of existence, was the subject of his song.

Vivid painting of nature is the characteristic of this poetry:

it is natural, unpolished, unlaboured. The scenes of the

desert—the terrors of the nightly ride through the hill-girdled

valley where the Ghools and the Jinn have their

haunts; the gloom of the barren plain, where the wolf,

‘like a ruined gamester,’ roams ululating; the weariness

of the journey under the noonday sun; the stifling of the

sand-storm, the delusions of the mirage; or again, the

solace of the palm-tree’s shade, and the delights of the

cool well;—such are the pictures of the Arab poet. The

people’s life is another frequent theme: the daily doings

of the herdsman, the quiet pastoral life, on the one hand;

on the other, the deeds of the chiefs—war, plunder, the

chase, wassail, revenge, friendship, love. There were

satires on rival tribes, panegyrics on chiefs, laments for

the dead. This poetry is wholly objective, artless, childlike;

it is the outcome of a people still in the freshness of

youth, whom the mysteries and complications of life have

not yet set a-thinking. ‘Just as his language knows but

the present and the past, so the ancient Arab lived but in

to-day and yesterday. The future is nought to him; he

seizes the present with too thorough abandonment to have

an emotion left for anything beyond. He troubles himself

not with what fate the morrow may bring forth, he

dreams not of a beautiful future,—only he revels in the

present, and his glance looks backward alone. Rich in

ideas and impressions, he is poor in thought. He drains

hastily the foaming cup of life; he feels deeply and passionately;

but it is as if he were never conscious of the

coming of the thoughtful age which, while it surveys the

[Pg xxiv]

past, as often turns an anxious look to the unknown

future.’

It is very difficult for a Western mind to enter into the

real beauty of the old Arab poetry. The life it depicts is

so unlike any we can now witness, that it is almost removed

beyond the pale of our sympathies. The poetry is

loaded with metaphors and similes, which to us seem far-fetched,

though they are drawn from the simplest daily

sights of the Bedawee. Moreover, it is only in fragments

that we can read it; for the change in the whole character

of Arab life and in the current of Arab ideas which

followed the conquests of Islám extinguished the old

songs, which were no longer suitable to the new conditions

of things; and as they were seldom recorded

in writing, we possess but a little remnant of them.8

Yet ‘these fragments may be broken, defaced, dimmed,

and obscured by fanaticism, ignorance, and neglect; but

out of them there arises anew all the freshness, bloom,

and glory of desert-song, as out of Homer’s epics rise the

glowing spring-time of humanity and the deep blue

heavens of Hellas. It is not a transcendental poetry, rich

in deep and thoughtful legend and lore, or glittering in

the many-coloured prisms of fancy, but a poetry the chief

task of which is to paint life and nature as they really

are; and within its narrow bounds it is magnificent. It

is chiefly and characteristically full of manliness, of vigour,

and of a chivalrous spirit, doubly striking when compared

with the spirit of abjectness and slavery found in some

other Asiatic nations. It is wild and vast and monotonous

as the yellow seas of its desert solitudes; it is daring and

noble, tender and true.’ 9

[Pg xxv]

There was one place where, above all others, the Ḳaṣeedehs

of the ancient Arabs were recited: this was ´Okáḍh, the

Olympia of Arabia, where there was held a great annual

Fair, to which not merely the merchants of Mekka and the

south, but the poet-heroes of all the land resorted. The

Fair of ´Okáḍh was held during the sacred months,—a sort

of ‘God’s Truce,’ when blood could not be shed without a

violation of the ancient customs and faiths of the Bedawees.

Thither went the poets of rival clans, who had as

often locked spears as hurled rhythmical curses. There

was little fear of a bloody ending to the poetic contest, for

those heroes who might meet there with enemies or blood-avengers

are said to have worn masks or veils, and their

poems were recited by a public orator at their dictation.

That these precautions and the sacredness of the time could

not always prevent the ill-feeling evoked by the pointed

personalities of rival singers leading to a fray and bloodshed

is proved by recorded instances; but such results

were uncommon, and as a rule the customs of the time

and place were respected. In spite of occasional broils

on the spot, and the lasting feuds which these poetic

contests must have excited, the Fair of ´Okáḍh was a

grand institution. It served as a focus for the literature

of all Arabia: every one with any pretensions to poetic

power came, and if he could not himself gain the applause

of the assembled people, at least he could form one of the

critical audience on whose verdict rested the fame or the

shame of every poet. The Fair of ´Okáḍh was a literary

congress, without formal judges, but with unbounded

influence. It was here that the polished heroes of the

desert determined points of grammar and prosody; here

the seven Golden Songs were recited, although (alas for

the charming legend!) they were not afterwards ‘suspended’

on the Kaạbeh; and here ‘a magical language, the language

of the Ḥijáz,’ was built out of the dialects of Arabia,

and was made ready to the skilful hand of Moḥammad,

that he might conquer the world with his Ḳur-án.

[Pg xxvi]

The Fair of ´Okáḍh was not merely a centre of emulation

for Arab poets: it was also an annual review of Bedawee

virtues. It was there that the Arab nation once-a-year

inspected itself, so to say, and brought forth and

criticised its ideals of the noble and the beautiful in life

and in poetry. For it was in poetry that the Arab—and

for that matter each man all the world over—expressed

his highest thoughts, and it was at ´Okáḍh that these

thoughts were measured by the standard of the Bedawee

ideal. The Fair not only maintained the highest standard

of poetry that the Arabic language has ever reached: it

also upheld the noblest idea of life and duty that the

Arab nation has yet set forth and obeyed. ´Okáḍh was

the press, the stage, the pulpit, the Parliament, and the

Académie Française of the Arab people; and when, in his

fear of the infidel poets (whom Imra-el-Ḳeys was to usher

to hell), Moḥammad abolished the Fair, he destroyed the

Arab nation even whilst he created his own new nation of

Muslims;—and the Muslims cannot sit in the places of

the old pagan Arabs.

It is very difficult for the Western mind to dissociate the

idea of Oriental poetry from the notion of amatory odes, and

sonnets to the lady’s eyebrow: but even the few extracts

that have been given in this chapter show that the Arab

had many other subjects besides love to sing about, and

though the divine theme has its place in almost every poem,

it seldom rivals the prominence of war and nature-painting,

and it is treated from a much less sensual point of view

than that of later Arab poets. Many writers have drawn

a gloomy picture of the condition of women in Arabia

before the coming of Moḥammad, and there is no doubt

that in many cases their lot was a miserable one. There

are ancient Arabic proverbs that point to the contempt in

which woman’s judgment and character were held by the

Arabs of ‘the Time of Ignorance,’ and Moḥammad must

have derived his mean opinion of women from a too general

impression among his countrymen. The marriage tie was

[Pg xxvii]

certainly very loose among the ancient Arabs. The ceremony

itself was of the briefest. The man said khiṭb (i.e.

I am an asker-in-marriage), and the giver-away answered

nikḥ (i.e., I am a giver-in-marriage), and the knot was thus

tied, only to be undone with equal facility and brevity.

The frequency of divorce among the Arabs does not speak

well for their constancy, and must have had a degrading

effect upon the women. Hence it is argued that women

were the objects of contempt rather than of respect among

the ancient Arabs.

Yet there is reason to believe that the evidence upon

which this conclusion is founded is partial and one-sided.

There was a wide gulf between the Bedawee and the town

Arab. It is not impossible that the view commonly entertained

as to the state of women in preïslamic times is

based mainly on what Moḥammad saw around him in

Mekka, and not on the ordinary life of the desert. To

such a conjecture a curiously uniform support is lent by

the ancient poetry of the desert; and though the poets

were then—as they always are—men of finer mould than

the rest, yet their example, and still more their poems

passing from mouth to mouth, must have created a widespread

belief in their principles. It is certain that the

roaming Bedawee, like the mediæval knight, entertained

a chivalrous reverence for women, although he, too, like

the knight, was not always above a career of promiscuous

gallantry; but there was always a certain glamour of

romance about the intrigues of the Bedawee. He did not

regard the object of his love as a chattel to be possessed,

but as a divinity to be assiduously worshipped. The poems

are full of instances of the courtly respect displayed by

the heroes of the desert toward defenceless maidens, and

the mere existence of so general an ideal of conduct in the

poems is a strong argument for Arab chivalry: for with

the Arabs the abyss between the ideal accepted of the

mind and the attaining thereof in action was narrower

than it is among ‘more advanced’ nations.

[Pg xxviii]

Whatever was the condition of women in the trading

cities and villages, it is certain that in the desert woman

was regarded as she has never since been among Muslims.

The modern ḥareem system was there as yet undreamt

of; the maid of the desert was unfettered by the

ruinous restrictions of modern life in the East. She was

free to choose her own husband, and to bind him to have

no other wife than herself. She might receive male

visitors, even strangers, without suspicion: for her virtue

was too dear to her and too well assured to need the

keeper. It was the bitterest taunt of all to say to a

hostile clan that their men had not the heart to give

nor their women to deny; for the chastity of the women

of the clan was reckoned only next to the valour

and generosity of the men. In those days bastardy was

an indelible stain. It was the wife who inspired the

hero to deeds of glory, and it was her praise that he most

valued when he returned triumphant. The hero of desert

song thought himself happy to die in guarding some women

from their pursuers. Wounded to the death, ´Antarah

halted alone in a narrow pass, and bade the women press

on to a place of safety. Planting his spear in the ground,

he supported himself on his horse, so that when the pursuers

came up they knew not he was dead, and dared not

approach within reach of his dreaded arm. At length the

horse moved, and the body fell to the ground, and the

enemies saw that it was but the corpse of the hero that

had held the pass. In death, as in a life sans peur et sans

reproche, ´Antarah was true to the chivalry of his race.

There are many instances like this of the knightly

courtesy of the Arab chief in ‘the Time of Ignorance.’

In the old days, as an ancient writer says, the true Arab

had but one love, and her he loved till death, and she him.

Even when polygamy became commoner, especially in the

towns, it was not what is meant by polygamy in a modern

Muslim state: it was rather the patriarchal system of

Abram and Sarai.

[Pg xxix]

There is much in the fragments of the ancient poetry

which reflects this fine spirit. It is ofttimes ‘tender and

true,’ and even Islám could not wholly root out the

real Arab sentiment, which reappears in Muslim times

in the poems of Aboo-Firás. Especially valuable is the

evidence of the old poetry with regard to the love of

a father for his daughters. Infanticide, which is commonly

attributed to the whole Arab nation of every age

before Islám, was in reality exceedingly rare in the

desert, and after almost dying out only revived about

the time of Moḥammad. It was probably adopted by

poor and weak clans, either from inability to support

their children, or in order to protect themselves from the

stain of having their children dishonoured by stronger

tribes, and the occasional practice of this barbarous and

suicidal custom affords no ground for assuming an unnatural

hatred and contempt for girls among the ancient

Arabs. These verses of a father to his daughter tell a

different story:—

If no Umeymeh were there, no want would trouble my soul,

no labour call me to toil for bread through pitchiest night;

What moves my longing to live is but that well do I know

how low the fatherless lies, how hard the kindness of kin.

I quake before loss of wealth lest lacking fall upon her,

and leave her shieldless and bare as flesh set forth on a board.

My life she prays for, and I from mere love pray for her death—

yea death, the gentlest and kindest guest to visit a maid.

I fear an uncle’s rebuke, a brother’s harshness for her;

my chiefest end was to spare her heart the grief of a word.

Once more, the following lines do not breathe the spirit

of infanticide:—

Fortune has brought me down (her wonted way)

from station great and high to low estate;

Fortune has rent away my plenteous store:

of all my wealth, honour alone is left.

Fortune has turned my joy to tears: how oft

did Fortune make me laugh with what she gave!

But for these girls, the Ḳaṭa’s downy brood,

unkindly thrust from door to door as hard,

Far would I roam and wide to seek my bread

in earth that has no lack of breadth and length;

[Pg xxx]

Nay, but our children in our midst, what else

but our hearts are they walking on the ground?

If but the wind blow harsh on one of them,

mine eye says no to slumber all night long.

Hitherto we have been looking at but one side of Arab

life. The Bedawees were indeed the bulk of the race, and

furnished the swords of the Muslim conquests; but there

was also a vigorous town-life in Arabia, and the citizens

waxed rich with the gains of their trafficking. For through

Arabia ran the trade-route between East and West: it was

the Arab traders who carried the produce of the Yemen to

the markets of Syria; and how ancient was their commerce

one may divine from the words of a poet of Judæa

spoken more than a thousand years before the coming of

Moḥammad.

Wedan and Javan from San´a paid for thy produce:

sword-blades, cassia, and calamus were in thy trafficking.

Dedan was thy merchant in saddle-cloths for riding;

Arabia and all the merchants of Kedar, they were the merchants of thy

hand:

in lambs and rams and goats, in these were they thy merchants.

The merchants of Sheba and Raamah, they were thy merchants,

with the chief of all spices, and with every precious stone, and gold,

they paid for thy produce.

Haran, Aden, and Canneh, the merchants of Sheba, Asshur and Chilmad

were thy merchants;

They were thy merchants in excellent wares,

in cloth of blue and broidered work,

in chests of cloth of divers colours, bound with cords and made fast

among thy merchandize.

10

Mekka was the centre of this trading life, the typical

Arab city of old times—a stirring little town, with its

caravans bringing the silks and woven stuffs of Syria and

the far-famed damask, and carrying away the sweet-smelling

produce of Arabia, frankincense, cinnamon, sandal-wood,

aloe, and myrrh, and the dates and leather

[Pg xxxi]

and metals of the south, and the goods that come to

the Yemen from Africa and even India; its assemblies

of merchant-princes in the Council Hall near the

Kaạbeh; and again its young poets running over with

love and gallantry; its Greek and Persian slave-girls

brightening the luxurious banquet with their native songs,

when as yet there was no Arab school of music, and the

monotonous but not unmelodious chant of the camel-driver

was the national song of Arabia; and its club, where

busy men spent their idle hours in playing chess and

draughts, or in gossiping with their acquaintance. It

was a little republic of commerce, too much infected with

the luxuries and refinements of the states it traded with,

yet retaining enough of the free Arab nature to redeem it

from the charge of effeminacy.

Mekka was a great home of music and poetry, and

this characteristic lasted into Muslim times. There

is a story of a certain stonemason who had a wonderful

gift of singing. When he was at work the young

men used to come and importune him, and bring him

gifts of money and food to induce him to sing. He

would then make a stipulation that they should first help

him in his work; and forthwith they would strip off their

cloaks, and the stones would gather round him rapidly.

Then he would mount a rock and begin to sing, whilst the

whole hill was coloured red and yellow with the variegated

garments of his audience. Singers were then held in the

highest admiration, and the greatest chiefs used to pay

their court to ladies of the musical profession. One of

them used to give receptions, open to the whole city, in

which she would appear in great state, surrounded by her

ladies-in-waiting, each dressed magnificently, and wearing

‘an elegant artificial chignon.’ It was in this town-life that

the worse qualities of the Arab came out; it was here that

his raging passion for dicing and his thirst for wine were

most prominent. In the desert there was little opportunity

for indulging in either luxury; but in a town which

[Pg xxxii]

often welcomed a caravan bringing goods to the value of

twenty thousand pound, such excesses were to be looked

for. Excited by the song of the Greek slave-girl and the

fumes of mellow wine, the Mekkan would throw the dice

till, like the Germans of Tacitus, he had staked and lost

his own liberty.

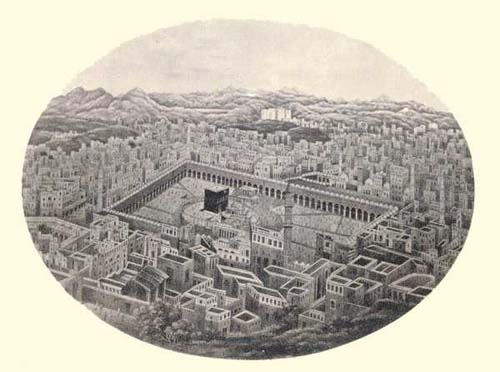

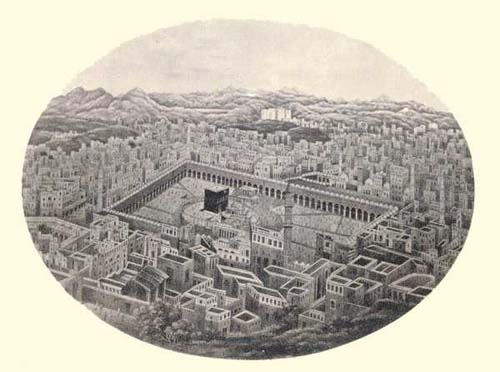

But Mekka was more than a centre of trade and of

song. It was the focus of the religion of the Arabs.

Thither the tribes went up every year to kiss the black

stone which had fallen from heaven in the primeval

days of Adam, and to make the seven circuits of the

Kaạbeh naked,—for they would not approach God in the

garments in which they had done their sins,—and to perform

the other ceremonies of the pilgrimage. The Kaạbeh,

a cubical building in the centre of Mekka, was the most

sacred temple in all Arabia, and it gave its sanctity to all

the district around. It had been, saith tradition, first

built by Adam from a heavenly model, and then rebuilt

from time to time by Seth and Abraham and Ishmael, and

less reverend persons, and it contained the sacred things of

the land. Here was the black stone, here the great god of

red agate, Hubal, and the three hundred and sixty idols,

one for each day of the year, which Moḥammad afterwards

destroyed in one day. Here was Abraham’s stone

and that other which marked the tomb of Ishmael, and hard

by Zemzem, the god-sent spring which gushed from the

sand when the forefather of the Arabs was perishing of

thirst.

The religion of the ancient Arabs, little as we know of

it, is especially interesting, inasmuch as the Arabs longest

retained the original Semitic character, and hence probably

the original Semitic religion: and so in the ancient religion

of Arabia we see the religion once professed by

Chaldeans, Canaanites, Phœnicians. This ancient religion

‘rises little higher than animistic polydaemonism. It is a

collection of tribal religions standing side by side, only

loosely united, though there are traces of a once closer

[Pg xxxiii]

connection.’ 11 The great objects of worship were the sun

and the stars and the three moon-goddesses—El-Lát the

bright moon, Menáh the dark, and El-´Uzzà the union of

the two; whilst a lower cultus of trees, stones, and mountains,

supposed to be dwelt-in by souls, shows that the

religion had not yet quite risen above simple fetishism. At

the time of Moḥammad the Arabs worshipped numerous

images, which may have been merely a development from

the previous stone-worship, or may have been introduced

from intercourse with Christians. There are traces of a

belief in a supreme God behind this pantheon, and the

moon-goddesses and other divinities were regarded as

daughters of the most high God (Alláh ta´ála)—a conception

also possibly derived from Christianity. The various

deities (but not the Supreme Allah) had their fanes, where

human sacrifices, though rare, were not unknown; and

their cultus was superintended by a hereditary line of

seers, who were held in great reverence, but never developed

into a priestly caste.

Besides the tribal gods, individual households had their

special Penates, to whom was due the first and the last

salám of the returning or outgoing host. But in spite of

all this superstitious apparatus the Arabs were never a

religious people. In the old days, as now, they were reckless,

skeptical, materialistic. They had their gods and

their divining-arrows, but they were ready to demolish

both if the responses proved contrary to their wishes. A

great majority believed in no future life nor in a reckoning-day

of good and evil. If a few tied camels to the graves

of the dead that the corpse might ride mounted to the

judgment-seat, it must have been the exception; and if

there are some doubtful traces of the doctrine of metempsychosis,

this again must have been the creed of the very

few.

[Pg xxxiv]

Christianity and Judaism had made but small impress

upon the Arabs. There were Jewish tribes in the north,

and there is evidence in the Ḳur-án and elsewhere that the

traditions and rites of Judaism were widely known in

Arabia. But the creed was too narrow and too exclusively

national to commend itself to the majority of the

people. Christianity fared even worse. Whether or not

St. Paul went there, it is at least certain that very little

effect was produced by the preaching of Christianity in

Arabia. We hear of Christians on the borders, and even

two or three among the Mekkans, and bishops and churches

are spoken of at Dhafár and Nejrán. But the Christianity

that the Arabs knew was, like the Judaism of the northern

tribes, a very imperfect reflection of the faith it professed

to set forth. It had become a thing of the head instead

of the heart, and the refinements of monophysite and

monothelite doctrines gained no hold upon the Arab

mind.

Thus Judaism and Christianity, though they were well

known, and furnished many ideas and ceremonies to

Islám, were never able to effect any general settlement in

Arabia. The common Arabs did not care much about any

religion, and the finer spirits found the wrangling dogmatism

of the Christian and the narrow isolation of the Jew

little to their mind. For there were before the time of

Moḥammad men who were dissatisfied with the low

fetishism in which their countrymen were plunged, and

who protested emphatically against the idle and often cruel

superstitions of the Arabs. Not to refer to the prophets,

who, as the Ḳur-án relates, were sent in old time to the tribes

of ´Ád and Thamood to convert them, there was, immediately

before the preaching of Moḥammad, a general feeling

that a change was at hand; a prophet was expected, and

women were anxiously hoping for male children if so be

they might mother the Apostle of God; and the more

thoughtful minds, tinged with traditions of Judaism, were

[Pg xxxv]

seeking for what they called ‘the religion of Abraham.’

These men were called ‘Ḥaneefs,’ or skeptics, and their

religion seems to have consisted chiefly in a negative position,

in denying the superstition of the Arabs, and in only

asserting the existence of one sole-ruling God whose absolute

slaves are all mankind, without being able to decide

on any minor doctrines, or to determine in what manner

this one God was to be worshipped. So long as the Ḥaneefs

could give their countrymen no more definite creed than

this, their influence was limited to a few inquiring and

doubting minds. It was reserved for Moḥammad to formulate

the faith of the Ḥaneefs in the dogmas of Islám.

For the leader of these few ‘skeptics’ was Zeyd ibn ´Amr,

to whom Moḥammad often resorted, and another, Waraḳah,

was the cousin of the Prophet and his near neighbour: and

thus the Ḥaneefs were the forerunners of the man who

was to change the destinies of the Arabs.

We can no longer see the true Arab as he was in ‘the

Time of Ignorance,’ and we cannot but regret our loss;

for the Pagan Arab is a noble type of man, though

there be nobler. There is much that is admirable in

his high mettle, his fine sense of honour, his knightliness,

his ‘open-handed, both-handed,’ generosity, his

frank friendship, and his manly independent spirit;

and the faults of this wild reckless nature are not

to be weighed against its many excellencies. When

Moḥammad turned abroad the current of Arab life, he

changed the character of the people. The mixture with

foreign nations, and the quiet town-life that succeeded to

the tumult of conquest, gradually effaced many of the

leading ideas of the old Arab nature, and the remnant that

still dwell in the land of their fathers have lost much of

that nobleness of character which in their ancestors covered

a multitude of sins. Moḥammad in part destroyed the

Arab and created the Muslim. The last is no amends for

the first. The modern Bedawee is neither the one nor the

[Pg xxxvi]

other; he has lost the greatness of the old type without

gaining that of the new. As far as the Arabs alone are

concerned, Moḥammad effected a temporary good and a

lasting harm. As to the world at large, that is matter for

another chapter.

[Pg xxxvii]

II.—MOḤAMMAD.

For every fiery prophet in old times,

And all the sacred madness of the bard,

When God made music through them, could but speak

His music by the framework and the chord;

And as he saw it he hath spoken truth.

—The Holy Grail.

A prophet for the Arabs must fulfil two conditions if

he will bring with his good tidings the power of making

them accepted: he must spring from the traditional centre

of Arabian religion, and he must come of a noble family

of pure Arab blood. Moḥammad fulfilled both. His

family was that branch of the Ḳureysh which had raised

Mekka to the dignity of the undisputed metropolis of

Arabia, and which, though impoverished, still held

the chief offices of the sacred territory. Moḥammad’s

grandfather was the virtual chief of Mekka; for to him

belonged the guardianship of the Kaạbeh, and he it was

who used the generous privilege of giving food and

water to the pilgrims who resorted to the ‘House of God.’

His youngest son, after marrying a kinswoman belonging

to a branch of the Ḳureysh, settled at Yethrib (Medina),

died before the birth of his son (571), and this son,

Moḥammad, lost his mother when he was only six years

old. The orphan was adopted by his grandfather, ´Abd-el-Muṭṭalib;

and a tender affection sprang up between

the chief of eighty years and his little grandson.

Many a day the old man might be seen sitting at his

wonted place near the Kaạbeh, and sharing his mat

with his favourite. He lived but two years more; and

at his dying request, his son Aboo-Ṭálib took charge of

[Pg xxxviii]

Moḥammad, for whom he too ever showed a love as of

father and mother.

Such is the bare outline of Moḥammad’s childhood;

and of his youth we know about as little, though the

Arabian biographies abound in legends, of which some

may be true and most are certainly false. There are

stories of his journeyings to Syria with his uncle,

and his encounter with a mysterious monk of obscure

faith; but there is nothing to show for this tale, and

much to be brought against it. All we can say is,

that Moḥammad probably assisted his family in the war

of the Fijár, and that he must many a time have frequented

the annual Fair of ´Oḳádh, hearing the songs of the desert

chiefs and the praise of Arab life, and listening to the

earnest words of the Jews and Christians and others who

came to the Fair. He was obliged at an early age to earn

his own living; for the noble family of the Háshimees, to

which he belonged, was fast losing its commanding

position, whilst another branch of the Ḳureysh was

succeeding to its dignities. The princely munificence of

Háshim and ´Abd-el-Muṭṭalib was followed by the poverty

and decline of their heirs. The duty of providing the

pilgrims with food was given up by the Háshimees to

the rival branch of Umeyyeh, whilst they retained only the

lighter office of serving water to the worshippers. Moḥammad

must take his share in the labour of the family,

and he was sent to pasture the sheep of the Ḳureysh on

the hills and valleys round Mekka; and though the people

despised the shepherd’s calling, he himself was wont to

look back with pleasure to these early days, saying that

God called never a prophet save from among the sheep-folds.

And doubtless it was then that he developed

that reflective disposition of mind which at length

led him to seek the reform of his people, whilst in his

solitary wanderings with the sheep he gained that marvellous

eye for the beauty and wonder of the earth and

sky which resulted in the gorgeous nature-painting of

[Pg xxxix]

the Ḳur-án. Yet he was glad to change this menial

work for the more lucrative and adventurous post of

camel-driver to the caravans of his wealthy kinswoman

Khadeejeh; and he seems to have taken so kindly to the

duty, which involved responsibilities, and to have acquitted

himself so worthily, that he attracted the notice of

his employer, who straightway fell in love with him, and

presented him with her hand. The marriage was a singularly

happy one, though Moḥammad was scarcely twenty-five

and his wife nearly forty, and it brought him that repose

and exemption from daily toil which he needed in order

to prepare his mind for his great work. But beyond

that, it gave him a loving woman’s heart, that was the

first to believe in his mission, that was ever ready to console

him in his despair and to keep alive within him the

thin flickering flame of hope when no man believed in

him—not even himself—and the world was black before

his eyes.

We know very little of the next fifteen years. Khadeejeh

bore him sons and daughters, but only the daughters

lived. We hear of his joining a league for the protection

of the weak and oppressed, and there is a legend of his

having acted with wise tact and judgment as arbitrator in

a dispute among the great families of Mekka on the occasion

of the rebuilding of the Kaạbeh. During this time,

moreover, he relieved his still impoverished uncle of the

charge of his son ´Alee—afterwards the Bayard of Islám,—and

he freed and adopted a certain captive, Zeyd; and

these two became his most devoted friends and disciples.

Such is the short but characteristic record of these fifteen

years of manhood. We know very little about what

Moḥammad did, but we hear only one voice as to what

he was. Up to the age of forty his unpretending modest

way of life had attracted but little notice from his townspeople.

He was only known as a simple upright man,

whose life was severely pure and refined, and whose true

desert sense of honour and faith-keeping had won him

the high title of El-Emeen, ‘the Trusty.’

[Pg xl]

Let us see what fashion of man this was, who was about

to work a revolution among his countrymen, and change

the conditions of social life in a vast part of the world.

The picture12 is drawn from an older man than we have yet

seen; but Moḥammad at forty and Moḥammad at fifty or

more were probably very little different. ‘He was of the

middle height, rather thin, but broad of shoulders, wide of

chest, strong of bone and muscle. His head was massive,

strongly developed. Dark hair, slightly curled, flowed in

a dense mass down almost to his shoulders. Even in

advanced age it was sprinkled by only about twenty grey

hairs—produced by the agonies of his “Revelations.” His

face was oval-shaped, slightly tawny of colour. Fine,

long, arched eyebrows were divided by a vein which

throbbed visibly in moments of passion. Great black

restless eyes shone out from under long, heavy eyelashes.

His nose was large, slightly aquiline. His teeth, upon

which he bestowed great care, were well set, dazzling

white. A full beard framed his manly face. His skin

was clear and soft, his complexion “red and white,” his

hands were as “silk and satin,” even as those of a woman.

His step was quick and elastic, yet firm, and as that of

one “who steps from a high to a low place,” In turning

his face he would also turn his full body. His whole gait

and presence were dignified and imposing. His countenance

was mild and pensive. His laugh was rarely more

than a smile....

‘In his habits he was extremely simple, though he

bestowed great care on his person. His eating and drinking,

his dress and his furniture, retained, even when he

had reached the fulness of power, their almost primitive

nature. The only luxuries he indulged in were, besides

arms, which he highly prized, a pair of yellow boots, a

present from the Negus of Abyssinia. Perfumes, however,

he loved passionately, being most sensitive of smell.

Strong drinks he abhorred.

[Pg xli]

‘His constitution was extremely delicate. He was nervously

afraid of bodily pain; he would sob and roar under

it. Eminently unpractical in all common things of life,

he was gifted with mighty powers of imagination, elevation

of mind, delicacy and refinement of feeling. “He is

more modest than a virgin behind her curtain,” it was said

of him. He was most indulgent to his inferiors, and would

never allow his awkward little page to be scolded, whatever

he did. “Ten years,” said Anas, his servant, “was I

about the Prophet, and he never said as much as ‘uff’ to

me.” He was very affectionate towards his family. One

of his boys died on his breast in the smoky house of the

nurse, a blacksmith’s wife. He was very fond of children.

He would stop them in the streets and pat their little

cheeks. He never struck any one in his life. The worst

expression he ever made use of in conversation was,

“What has come to him?—may his forehead be darkened

with mud!” When asked to curse some one he replied,

“I have not been sent to curse, but to be a mercy to mankind.”

“He visited the sick, followed any bier he met,

accepted the invitation of a slave to dinner, mended his

own clothes, milked his goats, and waited upon himself,”

relates summarily another tradition. He never first withdrew

his hand out of another man’s palm, and turned not

before the other had turned.... He was the most faithful

protector of those he protected, the sweetest and most

agreeable in conversation; those who saw him were suddenly

filled with reverence; those who came near him

loved him; they who described him would say, “I have

never seen his like either before or after.” He was of

great taciturnity; but when he spoke it was with emphasis

and deliberation, and no one could ever forget what he

said. He was, however, very nervous and restless withal,

often low-spirited, downcast as to heart and eyes. Yet he

would at times suddenly break through these broodings,

become gay, talkative, jocular, chiefly among his own. He

would then delight in telling little stories, fairy tales, and

[Pg xlii]

the like. He would romp with the children and play

with their toys.’

‘He lived with his wives in a row of humble cottages,

separated from one another by palm-branches, cemented

together with mud. He would kindle the fire, sweep the

floor, and milk the goats himself. ´Áïsheh tells us that

he slept upon a leathern mat, and that he mended his

clothes, and even clouted his shoes, with his own hand.

For months together ... he did not get a sufficient meal.

The little food that he had was always shared with those

who dropped in to partake of it. Indeed, outside the Prophet’s

house was a bench or gallery, on which were always

to be found a number of the poor, who lived entirely on

his generosity, and were hence called the “people of the

bench.” His ordinary food was dates and water or barley-bread;

milk and honey were luxuries of which he was

fond, but which he rarely allowed himself. The fare of

the desert seemed most congenial to him, even when he

was sovereign of Arabia.’ 13

Moḥammad was full forty before he felt himself called

to be an apostle to his people. If he did not actually worship

the local deities of the place, at least he made no public

protest against the fetish worship of the Ḳureysh. Yet

in the several phases of his life, in his contact with traders,

in his association with Zeyd and other men, he had gained

an insight into better things than idols and human sacrifices,

divining-arrows and mountains and stars. He

had heard a dim echo of some ‘religion of Abraham;’

he had listened to the stories of the Haggadah: he

knew a very little about Jesus of Nazareth. He seems

to have suffered long under the burden of doubt and self-distrust.

He used to wander about the hills alone, brooding

over these things; he shunned the society of men, and

‘solitude became a passion to him.’

At length came the crisis. He was spending the

[Pg xliii]

sacred months on Mount Ḥirá, ‘a huge barren rock,

torn by cleft and hollow ravine, standing out solitary in

the full white glare of the desert sun, shadowless, flowerless,

without well or rill.’ Here in a cave Moḥammad

gave himself up to prayer and fasting. Long months or

even years of doubt had increased his nervous excitable

disposition. He had had, they say, cataleptic fits during

his childhood, and was evidently more delicately and

finely constituted than those around him. Given this

nervous nature, and the grim solitude of the hill where he

had almost lived for long weary months, blindly feeling

after some truth upon which to rest his soul, it is not difficult

to believe the tradition of the cave, that Moḥammad

heard a voice say, ‘Cry!’ ‘What shall I cry?’ he answers—the

question that has been burning his heart during

all his mental struggles—

Cry

14! in the name of thy Lord, who hath created;

He hath created man from a clot of blood.

Cry! and thy Lord is the Most Bountiful,

Who hath taught [writing] by the pen:

He hath taught man that which he knew not.

Moḥammad arose trembling, and went to Khadeejeh, and

told her what he had seen; and she did her woman’s part,

and believed in him and soothed his terror, and bade him

hope for the future. Yet he could not believe in himself.

Was he not perhaps mad, possessed by a devil? Were

these voices of a truth from God? And so he went again

on his solitary wanderings, hearing strange sounds, and

thinking them at one time the testimony of Heaven,

at another the temptings of Satan or the ravings of

madness. Doubting, wondering, hoping, he had fain

put an end to a life which had become intolerable in its

changings from the heaven of hope to the hell of despair,

when again he heard the voice, ‘Thou art the messenger

of God, and I am Gabriel.’ Conviction at length seized

[Pg xliv]

hold upon him; he was indeed to bring a message of good

tidings to the Arabs, the message of God through His

angel Gabriel. He went back to Khadeejeh exhausted in

mind and body. ‘Wrap me, wrap me,’ he said; and the

word came unto him—

O thou enwrapped in thy mantle

Arise and warn!

And thy Lord,—magnify Him!

And thy raiment,—purify it!

And the abomination,—flee it!

And bestow not favours that thou mayest receive again with increase,

And for thy Lord wait thou patiently.

There are those who see imposture in all this; for such

I have no answer. Nor does it matter whether in a hysterical

fit or under any physical disease soever Moḥammad

saw these visions and heard these voices. We are not

concerned to draw the lines of demarcation between

enthusiasm and ecstasy and inspiration. It is sufficient

that Moḥammad did see these things—the subjective

creations of a tormented mind. It is sufficient

that he believed them to be a message from on high, and

that for years of neglect and persecution and for years of

triumph and conquest he acted upon his belief.

Moḥammad now (612) came forward as the Apostle of

the One God to the people of Arabia: he was at last well

assured that his God was of a truth the God, and that He

had indeed sent him with a message to his people, that

they too might turn from their idols and serve the living

God. He was in the minority of one, but he was no

longer afraid; he had learnt that self-trust which is the

condition of all true work. At first he spoke to his near

kinsmen and friends; and it is impossible to overrate the