Title: The Outline of History: Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind

Author: H. G. Wells

Editor: Sir Ernest Barker

Harry Johnston

Sir E. Ray Lankester

Gilbert Murray

Illustrator: J. F. Horrabin

Release date: April 12, 2014 [eBook #45368]

Most recently updated: February 21, 2018

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif, Adam Buchbinder and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

THE OUTLINE OF HISTORY

|

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed. No attempt has been made to correct or normalize the spelling of non-English words. Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text. The illustrations have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading. In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol

Introduction (etext transcriber's note) |

| ¶ Mr. WELLS has also written the following novels: | |

| LOVE AND MR. LEWISHAM KIPPS MR. POLLY THE WHEELS OF CHANCE THE NEW MACHIAVELLI ANN VERONICA TONO BUNGAY MARRIAGE BEALBY THE PASSIONATE FRIENDS THE WIFE OF SIR ISAAC HARMAN THE RESEARCH MAGNIFICENT MR. BRITLING SEES IT THROUGH THE SOUL OF A BISHOP JOAN AND PETER THE UNDYING FIRE | |

| ¶ The following fantastic and imaginative romances: | |

| THE WAR OF THE WORLDS THE TIME MACHINE THE WONDERFUL VISIT THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU THE SEA LADY THE SLEEPER AWAKES THE FOOD OF THE GODS THE WAR IN THE AIR THE FIRST MEN IN THE MOON IN THE DAYS OF THE COMET THE WORLD SET FREE | |

| And numerous Short Stories now collected in One Volume under the title of | |

| THE COUNTRY OF THE BLIND | |

| ¶ A Series of books on Social, Religious, and Political questions: | |

| ANTICIPATIONS (1900) MANKIND IN THE MAKING FIRST AND LAST THINGS NEW WORLDS FOR OLD A MODERN UTOPIA THE FUTURE IN AMERICA AN ENGLISHMAN LOOKS AT THE WORLD WHAT IS COMING? WAR AND THE FUTURE IN THE FOURTH YEAR GOD THE INVISIBLE KING | |

| ¶ And two little books about children’s play, called | |

| FLOOR GAMES and LITTLE WARS | |

Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind

BY

H. G. WELLS

WRITTEN WITH THE ADVICE AND EDITORIAL HELP OF

MR. ERNEST BARKER,

SIR H. H. JOHNSTON, SIR E. RAY LANKESTER

AND PROFESSOR GILBERT MURRAY

AND ILLUSTRATED BY

J. F. HORRABIN

VOLUME I

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1920

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1920,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

By H. G. WELLS.

Set up and electrotyped. Published November, 1920.

NORWOOD PRESS

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

“A philosophy of the history of the human race, worthy of its name, must begin with the heavens and descend to the earth, must be charged with the conviction that all existence is one—a single conception sustained from beginning to end upon one identical law.”—Friedrich Ratzel.

THIS Outline of History is an attempt to tell, truly and clearly, in one continuous narrative, the whole story of life and mankind so far as it is known to-day. It is written plainly for the general reader, but its aim goes beyond its use as merely interesting reading matter. There is a feeling abroad that the teaching of history considered as a part of general education is in an unsatisfactory condition, and particularly that the ordinary treatment of this “subject” by the class and teacher and examiner is too partial and narrow. But the desire to extend the general range of historical ideas is confronted by the argument that the available time for instruction is already consumed by that partial and narrow treatment, and that therefore, however desirable this extension of range may be, it is in practice impossible. If an Englishman, for example, has found the history of England quite enough for his powers of assimilation, then it seems hopeless to expect his sons and daughters to master universal history, if that is to consist of the history of England, plus the history of France, plus the history of Germany, plus the history of Russia, and so on. To which the only possible answer is that universal history is at once something more and something less than the aggregate of the national histories to which we are accustomed, that it must be approached in a different spirit and dealt with in a different manner. This book seeks to justify that answer. It has been written primarily to show that history as one whole is amenable to a more broad and comprehensive handling than is the history of special nations and periods, a broader handling that will bring it within the normal limitations of time and energy set to the reading and education of an ordinary citizen. This outline deals with ages and races and nations, where the ordinary history deals with reigns and pedigrees and campaigns; but it will not be found to be more crowded with names and dates, nor more difficult to follow and understand. History is no exception amongst the sciences; as the gaps fill in, the outline simplifies; as the outlook broadens, the clustering multitude of details dissolves into general laws. And many topics of quite primary interest to mankind, the first appearance and the growth of scientific knowledge for example, and its effects upon human life, the elaboration of the ideas of money and credit, or the story of the origins and spread and influence of Christianity, which must be treated fragmentarily or by elaborate digressions in any partial history, arise and flow completely and naturally in one general record of the world in which we live.

The need for a common knowledge of the general facts of human history throughout the world has become very evident during the tragic happenings of the last few years. Swifter means of communication have brought all men closer to one another for good or for evil. War becomes a universal disaster, blind and monstrously destructive; it bombs the baby in its cradle and sinks the food-ships that cater for the non-combatant and the neutral. There can be no peace now, we realize, but a common peace in all the world; no prosperity but a general prosperity. But there can be no common peace and prosperity without common historical ideas. Without such ideas to hold them together in harmonious co-operation, with nothing but narrow, selfish, and conflicting nationalist traditions, races and peoples are bound to drift towards conflict and destruction. This truth, which was apparent to that great philosopher Kant a century or more ago—it is the gist of his tract upon universal peace—is now plain to the man in the street. Our internal policies and our economic and social ideas are profoundly vitiated at present by wrong and fantastic ideas of the origin and historical relationship of social classes. A sense of history as the common adventure of all mankind is as necessary for peace within as it is for peace between the nations.

Such are the views of history that this Outline seeks to realize. It is an attempt to tell how our present state of affairs, this distressed and multifarious human life about us, arose in the course of vast ages and out of the inanimate clash of matter, and to estimate the quality and amount and range of the hopes with which it now faces its destiny. It is one experimental contribution to a great and urgently necessary educational reformation, which must ultimately restore universal history, revised, corrected, and brought up to date, to its proper place and use as the backbone of a general education. We say “restore,” because all the great cultures of the world hitherto, Judaism and Christianity in the Bible, Islam in the Koran, have used some sort of cosmogony and world history as a basis. It may indeed be argued that without such a basis any really binding culture of men is inconceivable. Without it we are a chaos.

Remarkably few sketches of universal history by one single author have been written. One book that has influenced the writer very strongly is Winwood Reade’s Martyrdom of Man. This dates, as people say, nowadays, and it has a fine gloom of its own, but it is still an extraordinarily inspiring presentation of human history as one consistent process. Mr. F. S. Marvin’s Living Past is also an admirable summary of human progress. There is a good General History of the World in one volume by Mr. Oscar Browning. America has recently produced two well-illustrated and up-to-date class books, Breasted’s Ancient Times and Robinson’s Medieval and Modern Times, which together give a very good idea of the story of mankind since the beginning of human societies. There are, moreover, quite a number of nominally Universal Histories in existence, but they are really not histories at all, they are encyclopædias of history; they lack the unity of presentation attainable only when the whole subject has been passed through one single mind. These universal histories are compilations, assemblies of separate national or regional histories by different hands, the parts being necessarily unequal in merit and authority and disproportionate one to another. Several such universal histories in thirty or forty volumes or so, adorned with allegorical title pages and illustrated by folding maps and plans of Noah’s Ark, Solomon’s Temple, and the Tower of Babel, were produced for the libraries of gentlemen in the eighteenth century. Helmolt’s World History, in eight massive volumes, is a modern compilation of the same sort, very useful for reference and richly illustrated, but far better in its parts than as a whole. Another such collection is the Historians’ History of the World in 25 volumes. The Encyclopædia Britannica contains, of course, a complete encyclopædia of history within itself, and is the most modern of all such collections.[1] F. Ratzel’s History of Mankind, in spite of the promise of its title, is mainly a natural history of man, though it is rich with suggestions upon the nature and development of civilization. That publication and Miss Ellen Churchill Semple’s Influence of Geographical Environment, based on Ratzel’s work, are quoted in this Outline, and have had considerable influence upon its plan. F. Ratzel would indeed have been the ideal author for such a book as our present one. Unfortunately neither he nor any other ideal author was available.[2]

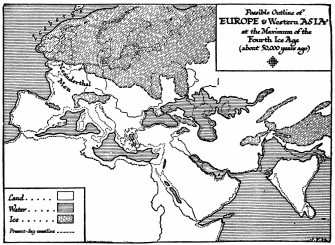

The writer will offer no apology for making this experiment. His disqualifications are manifest. But such work needs to be done by as many people as possible, he was free to make his contribution, and he was greatly attracted by the task. He has read sedulously and made the utmost use of all the help he could obtain. There is not a chapter that has not been examined by some more competent person than himself and very carefully revised. He has particularly to thank his friends Sir E. Ray Lankester, Sir H. H. Johnston, Professor Gilbert Murray, and Mr. Ernest Barker for much counsel and direction and editorial help. Mr. Philip Guedalla has toiled most efficiently and kindly through all the proofs. Mr. A. Allison, Professor T. W. Arnold, Mr. Arnold Bennett, the Rev. A. H. Trevor Benson, Mr. Aodh de Blacam, Mr. Laurence Binyon, the Rev. G. W. Broomfield, Sir William Bull, Mr. L. Cranmer Byng, Mr. A. J. D. Campbell, Mr. A. Y. Campbell, Mr. L. Y. Chen, Mr. A. R. Cowan, Mr. O. G. S. Crawford, Dr. W. S. Culbertson, Mr. R. Langton Cole, Mr. B. G. Collins, Mr. J. J. L. Duyvendak, Mr. O. W. Ellis, Mr. G. S. Ferrier, Mr. David Freeman, Mr. S. N. Fu, Mr. G. B. Gloyne, Sir Richard Gregory, Mr. F. H. Hayward, Mr. Sydney Herbert, Dr. Fr. Krupicka, Mr. H. Lang Jones, Mr. C. H. B. Laughton, Mr. B. I. Macalpin, Mr. G. H. Mair, Mr. F. S. Marvin, Mr. J. S. Mayhew, Mr. B. Stafford Morse, Professor J. L. Myres, the Hon. W. Ormsby-Gore, Sir Sydney Olivier, Mr. R. I. Pocock, Mr. J. Pringle, Mr. W. H. R. Rivers, Sir Denison Ross, Dr. E. J. Russell, Dr. Charles Singer, Mr. A. St. George Sanford, Dr. C. O. Stallybrass, Mr. G. H. Walsh, Mr. G. P. Wells, Miss Rebecca West, and Mr. George Whale have all to be thanked for help, either by reading parts of the MS. or by pointing out errors in the published parts, making suggestions, answering questions, or giving advice. The amount of friendly and sympathetic assistance the writer has received, often from very busy people, has been a quite extraordinary experience. He has met with scarcely a single instance of irritation or impatience on the part of specialists whose domains he has invaded and traversed in what must have seemed to many of them an exasperatingly impudent and superficial way. Numerous other helpful correspondents have pointed out printer’s errors and minor slips in the serial publication which preceded this book edition, and they have added many useful items of information, and to those writers also the warmest thanks are due. But of course none of these generous helpers are to be held responsible for the judgments, tone, arrangement, or writing of this Outline. In the relative importance of the parts, in the moral and political implications of the story, the final decision has necessarily fallen to the writer. The problem of illustrations was a very difficult one for him, for he had had no previous experience in the production of an illustrated book. In Mr. J. F. Horrabin he has had the good fortune to find not only an illustrator but a collaborator. Mr. Horrabin has spared no pains to make this work informative and exact. His maps and drawings are a part of the text, the most vital and decorative part. Some of them, the hypothetical maps, for example, of the western world at the end of the last glacial age, during the “pluvial age” and 12,000 years ago, and the migration map of the Barbarian invaders of the Roman Empire, represent the reading and inquiry of many laborious days.

The index to this edition is the work of Mr. Strickland Gibson of Oxford. Several correspondents have asked for a pronouncing index and accordingly this has been provided.

The writer owes a word of thanks to that living index of printed books, Mr. J. F. Cox of the London Library. He would also like to acknowledge here the help he has received from Mrs. Wells. Without her labour in typing and re-typing the drafts of the various chapters as they have been revised and amended, in checking references, finding suitable quotations, hunting up illustrations, and keeping in order the whole mass of material for this history, and without her constant help and watchful criticism, its completion would have been impossible.

| BOOK I THE MAKING OF OUR WORLD | ||

|---|---|---|

| PAGE | ||

| Chapter I. The Earth in Space and Time | 3 | |

| Chapter II. The Record of the Rocks | ||

| § 1. | The first living things | 7 |

| § 2. | How old is the world? | 13 |

| Chapter III. Natural Selection and the Changes of Species | 16 | |

| Chapter IV. The Invasion of the Dry Land by Life | ||

| § 1. | Life and water | 23 |

| § 2. | The earliest animals | 25 |

| Chapter V. Changes in the World’s Climate | ||

| § 1. | Why life must change continually | 29 |

| § 2. | The sun a steadfast star | 34 |

| § 3. | Changes from within the earth | 35 |

| § 4. | Life may control change | 36 |

| Chapter VI. The Age of Reptiles | ||

| § 1. | The age of lowland life | 38 |

| § 2. | Flying dragons | 43 |

| § 3. | The first birds | 43 |

| § 4. | An age of hardship and death | 44 |

| § 5. | The first appearance of fur and feathers | 47 |

| Chapter VII. The Age of Mammals | ||

| § 1. | A new age of life | 51 |

| § 2. | Tradition comes into the world | 52 |

| § 3. | An age of brain growth | 56 |

| § 4. | The world grows hard again | 57 |

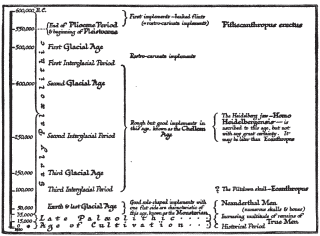

| § 5. | Chronology of the Ice Age | 59 |

| BOOK II THE MAKING OF MEN | ||

| Chapter VIII. The Ancestry of Man | ||

| § 1. | Man descended from a walking ape | 62 |

| § 2. | First traces of man-like creatures | 68 |

| § 3. | The Heidelberg sub-man | 69 |

| § 4. | The Piltdown sub-man | 70 |

| § 5. | The riddle of the Piltdown remains | 72 |

| Chapter IX. The Neanderthal Men, an Extinct Race. (The Early Palæolithic Age) | ||

| § 1. | The world 50,000 years ago | 75 |

| § 2. | The daily life of the first men | 79 |

| § 3. | The last Palæolithic men | 84 |

| Chapter X. The Later Postglacial Palæolithic Men, the First

True Men. (Later Palæolithic Age) | ||

| § 1. | The coming of men like ourselves | 86 |

| § 2. | Subdivision of the Later Palæolithic | 95 |

| § 3. | The earliest true men were clever savages | 98 |

| § 4. | Hunters give place to herdsmen | 101 |

| § 5. | No sub-men in America | 102 |

| Chapter XI. Neolithic Man in Europe | ||

| § 1. | The age of cultivation begins | 104 |

| § 2. | Where did the Neolithic culture arise? | 108 |

| § 3. | Everyday Neolithic life | 109 |

| § 4. | How did sowing begin? | 116 |

| § 5. | Primitive trade | 118 |

| § 6. | The flooding of the Mediterranean Valley | 118 |

| Chapter XII. Early Thought | ||

| § 1. | Primitive philosophy | 122 |

| § 2. | The Old Man in religion | 125 |

| § 3. | Fear and hope in religion | 126 |

| § 4. | Stars and seasons | 127 |

| § 5. | Story-telling and myth-making | 129 |

| § 6. | Complex origins of religion | 130 |

| Chapter XIII. The Races of Mankind | ||

| § 1. | Is mankind still differentiating? | 136 |

| § 2. | The main races of mankind | 140 |

| § 3. | Was there an Alpine race? | 142 |

| § 4. | The Heliolithic culture of the Brunet peoples | 146 |

| § 5. | How existing races may be related to each other | 148 |

| Chapter XIV. The Languages of Mankind | ||

| § 1. | No one primitive language | 150 |

| § 2. | The Aryan languages | 151 |

| § 3. | The Semitic languages | 153 |

| § 4. | The Hamitic languages | 154 |

| § 5. | The Ural-Altaic languages | 156 |

| § 6. | The Chinese languages | 157 |

| § 7. | Other language groups | 157 |

| § 8. | Submerged and lost languages | 161 |

| § 9. | How languages may be related | 163 |

| BOOK III THE DAWN OF HISTORY | ||

| Chapter XV. The Aryan-speaking Peoples in Prehistoric Times | ||

| § 1. | The spreading of the Aryan-speakers | 167 |

| § 2. | Primitive Aryan life | 169 |

| § 3. | Early Aryan daily life | 176 |

| Chapter XVI. The First Civilizations | ||

| § 1. | Early cities and early nomads | 183 |

| § 2A. | The riddle of the Sumerians | 188 |

| § 2B. | The empire of Sargon the First | 191 |

| § 2C. | The empire of Hammurabi | 191 |

| § 2D. | The Assyrians and their empire | 192 |

| § 2E. | The Chaldean empire | 194 |

| § 3. | The early history of Egypt | 195 |

| § 4. | The early civilization of India | 201 |

| § 5. | The early history of China | 201 |

| § 6. | While the civilizations were growing | 206 |

| Chapter XVII. Sea Peoples and Trading Peoples | ||

| § 1. | The earliest ships and sailors | 209 |

| § 2. | The Ægean cities before history | 213 |

| § 3. | The first voyages of exploration | 217 |

| § 4. | Early traders | 218 |

| § 5. | Early travellers | 220 |

| Chapter XVIII. Writing | ||

| § 1. | Picture writing | 223 |

| § 2. | Syllable writing | 227 |

| § 3. | Alphabet writing | 228 |

| § 4. | The place of writing in human life | 229 |

| Chapter XIX. Gods and Stars, Priests and Kings | ||

| § 1. | Nomadic and settled religion | 232 |

| § 2. | The priest comes into history | 234 |

| § 3. | Priests and the stars | 238 |

| § 4. | Priests and the dawn of learning | 240 |

| § 5. | King against priests | 241 |

| § 6. | How Bel-Marduk struggled against the kings | 245 |

| § 7. | The god-kings of Egypt | 248 |

| § 8. | Shi Hwang-ti destroys the books | 252 |

| Chapter XX. Serfs, Slaves, Social Classes, and Free Individuals | ||

| § 1. | The common man in ancient times | 254 |

| § 2. | The earliest slaves | 256 |

| § 3. | The first “independent” persons | 259 |

| § 4. | Social classes three thousand years ago | 262 |

| § 5. | Classes hardening into castes | 266 |

| § 6. | Caste in India | 268 |

| § 7. | The system of the Mandarins | 270 |

| § 8. | A summary of five thousand years | 272 |

| BOOK IV JUDEA, GREECE, AND INDIA | ||

| Chapter XXI. The Hebrew Scriptures and the Prophets | ||

| § 1. | The place of the Israelites in history | 277 |

| § 2. | Saul, David, and Solomon | 286 |

| § 3. | The Jews a people of mixed origin | 292 |

| § 4. | The importance of the Hebrew prophets | 294 |

| Chapter XXII. The Greeks and the Persians | ||

| § 1. | The Hellenic peoples | 298 |

| § 2. | Distinctive features of the Hellenic civilization | 304 |

| § 3. | Monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy in Greece | 307 |

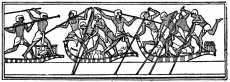

| § 4. | The kingdom of Lydia | 315 |

| § 5. | The rise of the Persians in the East | 316 |

| § 6. | The story of Crœsus | 320 |

| § 7. | Darius invades Russia | 326 |

| § 8. | The battle of Marathon | 332 |

| § 9. | Thermopylæ and Salamis | 334 |

| § 10. | Platæa and Mycale | 340 |

| Chapter XXIII. Greek Thought and Literature | ||

| § 1. | The Athens of Pericles | 343 |

| § 2. | Socrates | 350 |

| § 3. | What was the quality of the common Athenians? | 352 |

| § 4. | Greek tragedy and comedy | 354 |

| § 5. | Plato and the Academy | 355 |

| § 6. | Aristotle and the Lyceum | 357 |

| § 7. | Philosophy becomes unworldly | 359 |

| § 8. | The quality and limitations of Greek thought | 360 |

| Chapter XXIV. The Career of Alexander the Great | ||

| § 1. | Philip of Macedonia | 367 |

| § 2. | The murder of King Philip | 373 |

| § 3. | Alexander’s first conquests | 377 |

| § 4. | The wanderings of Alexander | 385 |

| § 5. | Was Alexander indeed great? | 389 |

| § 6. | The successors of Alexander | 395 |

| § 7. | Pergamum a refuge of culture | 396 |

| § 8. | Alexander as a portent of world unity | 397 |

| Chapter XXV. Science and Religion at Alexandria | ||

| § 1. | The science of Alexandria | 401 |

| § 2. | Philosophy of Alexandria | 410 |

| § 3. | Alexandria as a factory of religions | 410 |

| Chapter XXVI. The Rise and Spread of Buddhism | ||

| § 1. | The story of Gautama | 415 |

| § 2. | Teaching and legend in conflict | 421 |

| § 3. | The gospel of Gautama Buddha | 422 |

| § 4. | Buddhism and Asoka | 426 |

| § 5. | Two great Chinese teachers | 433 |

| § 6. | The corruptions of Buddhism | 438 |

| § 7. | The present range of Buddhism | 440 |

| BOOK V THE RISE AND COLLAPSE OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE | ||

| Chapter XXVII. The Two Western Republics | ||

| § 1. | The beginnings of the Latins | 445 |

| § 2. | A new sort of state | 454 |

| § 3. | The Carthaginian republic of rich men | 466 |

| § 4. | The First Punic War | 467 |

| § 5. | Cato the Elder and the spirit of Cato | 471 |

| § 6. | The Second Punic War | 475 |

| § 7. | The Third Punic War | 480 |

| § 8. | How the Punic War undermined Roman liberty | 485 |

| § 9. | Comparison of the Roman republic with a modern state | 486 |

| Chapter XXVIII. From Tiberius Gracchus To the God Emperor in Rome | ||

| § 1. | The science of thwarting the common man | 493 |

| § 2. | Finance in the Roman state | 496 |

| § 3. | The last years of republican politics | 499 |

| § 4. | The era of the adventurer generals | 505 |

| § 5. | Caius Julius Cæsar and his death | 509 |

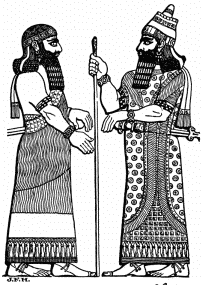

| § 6. | The end of the republic | 513 |

| § 7. | Why the Roman republic failed | 516 |

| Chapter XXIX. The Cæsars between the Sea and the Great Plains of the Old World | ||

| § 1. | A short catalogue of emperors | 52 |

| § 2. | Roman civilization at its zenith | 529 |

| § 3. | Limitations of the Roman mind | 539 |

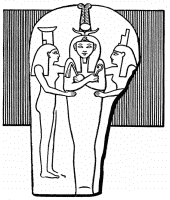

| § 4. | The stir of the great plains | 541 |

| § 5. | The Western (true Roman) Empire crumples up | 552 |

| § 6. | The Eastern (revived Hellenic) Empire | 560 |

| BOOK VI CHRISTIANITY AND ISLAM | ||

| Chapter XXX. The Beginnings, the Rise, and the Divisions of Christianity | ||

| § 1. | Judea at the Christian era | 569 |

| § 2. | The teachings of Jesus of Nazareth | 573 |

| § 3. | The universal religions | 582 |

| § 4. | The crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth | 584 |

| § 5. | Doctrines added to the teachings of Jesus | 586 |

| § 6. | The struggles and persecutions of Christianity | 594 |

| § 7. | Constantine the Great | 598 |

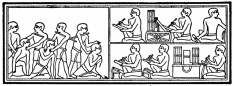

| § 8. | The establishment of official Christianity | 601 |

| § 9. | The map of Europe, A.D. 500 | 605 |

| § 10. | The salvation of learning by Christianity | 609 |

| Chapter XXXI. Seven Centuries in Asia (CIRCA 50 B.C. TO A.D. 650) | ||

| § 1. | Justinian the Great | 614 |

| § 2. | The Sassanid Empire in Persia | 616 |

| § 3. | The decay of Syria under the Sassanids | 619 |

| § 4. | The first message from Islam | 623 |

| § 5. | Zoroaster and Mani | 624 |

| § 6. | Hunnish peoples in Central Asia and India | 627 |

| § 7. | The great age of China | 630 |

| § 8. | Intellectual fetters of China | 635 |

| § 9. | The travels of Yuan Chwang | 642 |

| PAGE | |

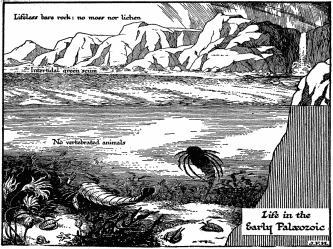

| Life in the Early Palæozoic | 11 |

| Time-chart from Earliest Life to 40,000,000 Years Ago | 14 |

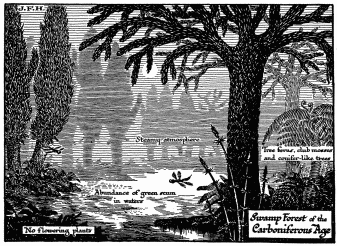

| Life in the Later Palæozoic Age | 19 |

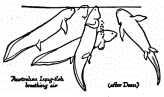

| Australian Lung Fish | 26 |

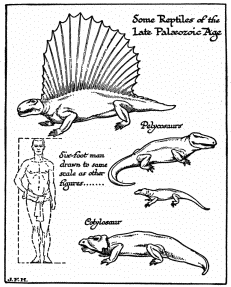

| Some Reptiles of the Late Palæozoic Age | 27 |

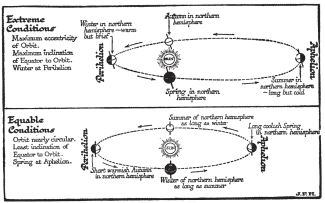

| Astronomical Variations Affecting Climate | 33 |

| Some Mesozoic Reptiles | 40 |

| Later Mesozoic Reptiles | 42 |

| Pterodactyls and Archæopteryx | 45 |

| Hesperornis | 48 |

| Some Oligocene Mammals | 53 |

| Miocene Mammals | 58 |

| Time-diagram of the Glacial Ages | 60 |

| Early Pleistocene Animals, Contemporary with Earliest Man | 64 |

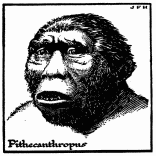

| The Sub-Man Pithecanthropus | 65 |

| The Riddle of the Piltdown Sub-Man | 71 |

| Map of Europe 50,000 Years Ago | 77 |

| Neanderthal Man | 78 |

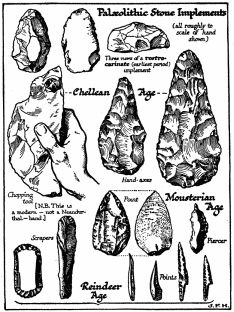

| Early Stone Implements | 81 |

| Australia and the Western Pacific in the Glacial Age | 82 |

| Cro-magnon Man | 87 |

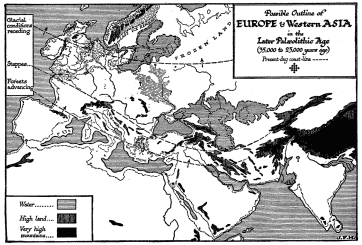

| Europe and Western Asia in the Later Palæolithic Age | 89 |

| Reindeer Age Articles | 90 |

| A Reindeer Age Masterpiece | 93 |

| Reindeer Age Engravings and Carvings | 94 |

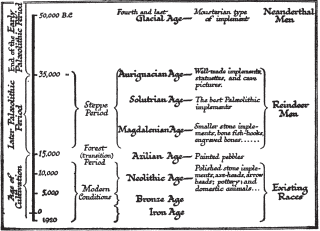

| Diagram of the Estimated Duration of the True Human Periods | 97 |

| Neolithic Implements | 107 |

| Restoration of a Lake Dwelling | 111 |

| Pottery from Lake Dwellings | 112 |

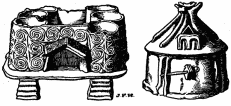

| Hut Urns | 115 |

| A Menhir of the Neolithic Period | 128 |

| Bronze Age Implements | 132 |

| Diagram Showing the Duration of the Neolithic Period | 133 |

| Heads of Australoid Types | 139 |

| Bushwoman | 141 |

| Negro Types | 142 |

| Mongolian Types | 143 |

| Caucasian Types | 144 |

| Map of Europe, Asia, Africa 15,000 Years Ago | 145 |

| The Swastika | 147 |

| Relationship of Human Races (Diagrammatic Summary) | 149 |

| Possible Development of Languages | 155 |

| Racial Types (after Champollion) | 163 |

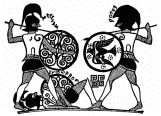

| Combat between Menelaus and Hector | 176 |

| Archaic Horses and Chariots | 178 |

| The Cradle of Western Civilization | 185 |

| Sumerian Warriors in Phalanx | 189 |

| Assyrian Warrior (temp. Sargon II) | 193 |

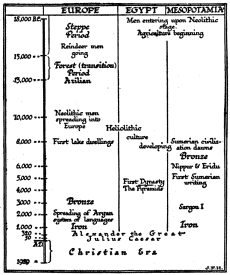

| Time-chart 6000 B.C. to A.D. | 196 |

| The Cradle of Chinese Civilization (Map) | 202 |

| Boats on Nile about 2500 B.C. | 211 |

| Egyptian Ship on Red Sea, 1250 B.C. | 212 |

| Ægean Civilization (Map) | 214 |

| A Votary of the Snake Goddess | 215 |

| American Indian Picture-Writing | 225 |

| Egyptian Gods—Set, Anubis, Typhon, Bes | 236 |

| Egyptian Gods—Thoth-lunus, Hathor, Chnemu | 239 |

| An Assyrian King and His Chief Minister | 243 |

| Pharaoh Chephren | 248 |

| Pharaoh Rameses III as Osiris (Sarcophagus relief) | 249 |

| Pharaoh Akhnaton | 251 |

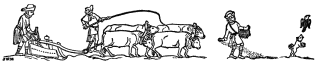

| Egyptian Peasants (Pyramid Age) | 257 |

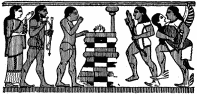

| Brawl among Egyptian Boatmen (Pyramid Age) | 260 |

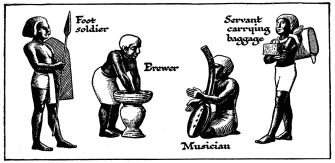

| Egyptian Social Types (From Tombs) | 261 |

| The Land of the Hebrews | 280 |

| Aryan-speaking Peoples 1000-500 B.C. (Map) | 301 |

| Hellenic Races 1000-800 B.C. (Map) | 302 |

| Greek Sea Fight, 550 B.C. | 303 |

| Rowers in an Athenian Warship, 400 B.C. | 306 |

| Scythian Types | 319 |

| Median and Second Babylonian Empires (in Nebuchadnezzar’s Reign) | 321 |

| The Empire of Darius | 329 |

| Wars of the Greeks and Persians (Map) | 333 |

| Athenian Foot-soldier | 334 |

| Persian Body-guard (from Frieze at Susa) | 338 |

| The World According to Herodotus | 341 |

| Athene of the Parthenon | 348 |

| Philip of Macedon | 368 |

| Growth of Macedonia under Philip | 371 |

| Macedonian Warrior (bas-relief from Pella) | 373 |

| Campaigns of Alexander the Great | 381 |

| Alexander the Great | 389 |

| Break-up of Alexander’s Empire | 393 |

| Seleucus I | 395 |

| Later State of Alexander’s Empire | 398 |

| The World According to Eratosthenes, 200 B.C. | 405 |

| The Known World, about 250 B.C. | 406 |

| Isis and Horus | 413 |

| Serapis | 414 |

| The Rise of Buddhism | 419 |

| Hariti | 428 |

| Chinese Image of Kuan-yin | 429 |

| The Spread of Buddhism | 432 |

| Indian Gods—Vishnu, Brahma, Siva | 437 |

| Indian Gods—Krishna, Kali, Ganesa | 439 |

| The Western Mediterranean, 800-600 B.C. | 446 |

| Early Latium | 447 |

| Burning the Dead: Etruscan Ceremony | 449 |

| Statuette of a Gaul | 450 |

| Roman Power after the Samnite Wars | 451 |

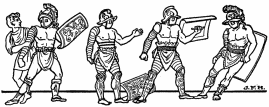

| Samnite Warriors | 452 |

| Italy after 275 B.C. | 453 |

| Roman Coin Celebrating the Victory over Pyrrhus | 455 |

| Mercury | 457 |

| Carthaginian Coins | 468 |

| Roman As | 471 |

| Rome and its Alliances, 150 B.C. | 481 |

| Gladiators | 489 |

| Roman Power, 50 B.C. | 506 |

| Julius Cæsar | 512 |

| Roman Empire at Death of Augustus | 518 |

| Roman Empire in Time of Trajan | 524 |

| Asia and Europe: Life of the Period (Map) | 544 |

| Central Asia, 200-100 B.C. | 547 |

| Tracks of Migrating and Raiding Peoples, 1-700 A.D. | 555 |

| Eastern Roman Empire | 561 |

| Constantinople (Maps to show value of its position) | 563 |

| Galilee | 571 |

| Map of Europe, 500 A.D. | 608 |

| The Eastern Empire and the Sassanids | 620 |

| Asia Minor, Syria, and Mesopotamia | 622 |

| Ephthalite Coin | 629 |

| Chinese Empire, Tang Dynasty | 633 |

| Yuan Chwang’s Route from China to India | 643 |

THE earth on which we live is a spinning globe. Vast though it seems to us, it is a mere speck of matter in the greater vastness of space.

Space is, for the most part, emptiness. At great intervals there are in this emptiness flaring centres of heat and light, the “fixed stars.” They are all moving about in space, notwithstanding that they are called fixed stars, but for a long time men did not realize their motion. They are so vast and at such tremendous distances that their motion is not perceived. Only in the course of many thousands of years is it appreciable. These fixed stars are so far off that, for all their immensity, they seem to be, even when we look at them through the most powerful telescopes, mere points of light, brighter or less bright. A few, however, when we turn a telescope upon them, are seen to be whirls and clouds of shining vapour which we call nebulæ. They are so far off that a movement of millions of miles would be imperceptible.

One star, however, is so near to us that it is like a great ball of flame. This one is the sun. The sun is itself in its nature like a fixed star, but it differs from the other fixed stars in appearance because it is beyond comparison nearer than they are; and because it is nearer men have been able to learn something of its nature. Its mean distance from the earth is ninety-three million miles. It is a mass of flaming matter, having a diameter of 866,000 miles. Its bulk is a million and a quarter times the bulk of our earth.{v1-4}

These are difficult figures for the imagination. If a bullet fired from a Maxim gun at the sun kept its muzzle velocity unimpaired, it would take seven years to reach the sun. And yet we say the sun is near, measured by the scale of the stars. If the earth were a small ball, one inch in diameter, the sun would be a globe of nine feet diameter; it would fill a small bedroom. It is spinning round on its axis, but since it is an incandescent fluid, its polar regions do not travel with the same velocity as its equator, the surface of which rotates in about twenty-five days. The surface visible to us consists of clouds of incandescent metallic vapour. At what lies below we can only guess. So hot is the sun’s atmosphere that iron, nickel, copper, and tin are present in it in a gaseous state. About it at great distances circle not only our earth, but certain kindred bodies called the planets. These shine in the sky because they reflect the light of the sun; they are near enough for us to note their movements quite easily. Night by night their positions change with regard to the fixed stars.

It is well to understand how empty space is. If, as we have said, the sun were a ball nine feet across, our earth would, in proportion, be the size of a one-inch ball, and at a distance of 323 yards from the sun. The moon would be a speck the size of a small pea, thirty inches from the earth. Nearer to the sun than the earth would be two other very similar specks, the planets Mercury and Venus, at a distance of 125 and 250 yards respectively. Beyond the earth would come the planets Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, at distances of 500, 1806, 3000, 6000, and 9500 yards respectively. There would also be a certain number of very much smaller specks, flying about amongst these planets, more particularly a number called the asteroids circling between Mars and Jupiter, and occasionally a little puff of more or less luminous vapour and dust would drift into the system from the almost limitless emptiness beyond. Such a puff is what we call a comet. All the rest of the space about us and around us and for unfathomable distances beyond is cold, lifeless, and void. The nearest fixed star to us, on this minute scale, be it remembered,—the earth as a one-inch ball, and the moon a little pea—would be over 40,000 miles away.

The science that tells of these things and how men have come{v1-5} to know about them is Astronomy, and to books of astronomy the reader must go to learn more about the sun and stars. The science and description of the world on which we live are called respectively Geology and Geography.

The diameter of our world is a little under 8000 miles. Its surface is rough; the more projecting parts of the roughness are mountains, and in the hollows of its surface there is a film of water, the oceans and seas. This film of water is about five miles thick at its deepest part—that is to say, the deepest oceans have a depth of five miles. This is very little in comparison with the bulk of the world.

About this sphere is a thin covering of air, the atmosphere. As we ascend in a balloon or go up a mountain from the level of the sea-shore the air is continually less dense, until at last it becomes so thin that it cannot support life. At a height of twenty miles there is scarcely any air at all—not one hundredth part of the density of air at the surface of the sea. The highest point to which a bird can fly is about four miles up—the condor, it is said, can struggle up to that; but most small birds and insects which are carried up by aeroplanes or balloons drop off insensible at a much lower level, and the greatest height to which any mountaineer has ever climbed is under five miles. Men have flown in aeroplanes to a height of over four miles, and balloons with men in them have reached very nearly seven miles, but at the cost of considerable physical suffering. Small experimental balloons, containing not men, but recording instruments, have gone as high as twenty-two miles.

It is in the upper few hundred feet of the crust of the earth, in the sea, and in the lower levels of the air below four miles that life is found. We do not know of any life at all except in these films of air and water upon our planet. So far as we know, all the rest of space is as yet without life. Scientific men have discussed the possibility of life, or of some process of a similar kind, occurring upon such kindred bodies as the planets Venus and Mars. But they point merely to questionable possibilities.

Astronomers and geologists and those who study physics have been able to tell us something of the origin and history of the earth. They consider that, vast ages ago, the sun was a spinning, flaring{v1-6} mass of matter, not yet concentrated into a compact centre of heat and light, considerably larger than it is now, and spinning very much faster, and that as it whirled, a series of fragments detached themselves from it, which became the planets. Our earth is one of these planets. The flaring mass that was the material of the earth broke as it spun into two masses, a larger, the earth itself, and a smaller, which is now the dead, still moon. Astronomers give us convincing reasons for supposing that sun and earth and moon and all that system were then whirling about at a speed much greater than the speed at which they are moving to-day, and that at first our earth was a flaming thing upon which no life could live. The way in which they have reached these conclusions is by a very beautiful and interesting series of observations and reasoning, too long and elaborate for us to deal with here. But they oblige us to believe that the sun, incandescent though it is, is now much cooler than it was, and that it spins more slowly now than it did, and that it continues to cool and slow down. And they also show that the rate at which the earth spins is diminishing and continues to diminish—that is to say, that our day is growing longer and longer, and that the heat at the centre of the earth wastes slowly. There was a time when the day was not a half and not a third of what it is to-day; when a blazing hot sun, much greater than it is now, must have moved visibly—had there been an eye to mark it—from its rise to its setting across the skies. There will be a time when the day will be as long as a year is now, and the cooling sun, shorn of its beams, will hang motionless in the heavens.

It must have been in days of a much hotter sun, a far swifter day and night, high tides, great heat, tremendous storms and earthquakes, that life, of which we are a part, began upon the world. The moon also was nearer and brighter in those days and had a changing face.[3]

§ 1. The First Living Things. § 2. How Old Is the World?

WE do not know how life began upon the earth.[4]

Biologists, that is to say, students of life, have made guesses about these beginnings, but we will not discuss them here. Let us only note that they all agree that life began where the tides of those swift days spread and receded over the steaming beaches of mud and sand.

The atmosphere was much denser then, usually great cloud masses obscured the sun, frequent storms darkened the heavens. The land of those days, upheaved by violent volcanic forces, was a barren land, without vegetation, without soil. The almost incessant rain-storms swept down upon it, and rivers and torrents carried great loads of sediment out to sea, to become muds that hardened later into slates and shales, and sands that became sandstones. The geologists have studied the whole accumulation of these sediments as it remains to-day, from those of the earliest ages to the most recent. Of course the oldest deposits are the most distorted and changed and worn, and in them there is now no certain trace to be found of life at all. Probably the earliest{v1-8} forms of life were small and soft, leaving no evidence of their existence behind them. It was only when some of these living things developed skeletons and shells of lime and such-like hard material that they left fossil vestiges after they died, and so put themselves on record for examination.

The literature of geology is very largely an account of the fossils that are found in the rocks, and of the order in which layers after layers of rocks lie one on another. The very oldest rocks must have been formed before there was any sea at all, when the earth was too hot for a sea to exist, and when the water that is now sea was an atmosphere of steam mixed with the air. Its higher levels were dense with clouds, from which a hot rain fell towards the rocks below, to be converted again into steam long before it reached their incandescence. Below this steam atmosphere the molten world-stuff solidified as the first rocks. These first rocks must have solidified as a cake over glowing liquid material beneath, much as cooling lava does. They must have appeared first as crusts and clinkers. They must have been constantly remelted and recrystallized before any thickness of them became permanently solid. The name of Fundamental Gneiss is given to a great underlying system of crystalline rocks which probably formed age by age as this hot youth of the world drew to its close. The scenery of the world in the days when the Fundamental Gneiss was formed must have been more like the interior of a furnace than anything else to be found upon earth at the present time.

After long ages the steam in the atmosphere began also to condense and fall right down to earth, pouring at last over these warm primordial rocks in rivulets of hot water and gathering in depressions as pools and lakes and the first seas. Into those seas the streams that poured over the rocks brought with them dust and particles to form a sediment, and this sediment accumulated in layers, or as geologists call them, strata, and formed the first Sedimentary Rocks. Those earliest sedimentary rocks sank into depressions and were covered by others; they were bent, tilted up, and torn by great volcanic disturbances and by tidal strains that swept through the rocky crust of the earth. We find these first sedimentary rocks still coming to the surface of the{v1-9} land here and there, either not covered by later strata or exposed after vast ages of concealment by the wearing off of the rock that covered them later—there are great surfaces of them in Canada especially; they are cleft and bent, partially remelted, recrystallized, hardened and compressed, but recognizable for what they are. And they contain no single certain trace of life at all. They are frequently called Azoic (lifeless) Rocks. But since in some of these earliest sedimentary rocks a substance called graphite (black lead) occurs, and also red and black oxide of iron, and since it is asserted that these substances need the activity of living things for their production, which may or may not be the case, some geologists prefer to call these earliest sedimentary rocks Archæozoic (primordial life). They suppose that the first life was soft living matter that had no shells or skeletons or any such structure that could remain as a recognizable fossil after its death, and that its chemical influence caused the deposition of graphite and iron oxide. This is pure guessing, of course, and there is at least an equal probability that in the time of formation of the Azoic Rocks, life had not yet begun.

Long ago there were found in certain of these ancient first-formed rocks in Canada, curious striped masses, and thin layers of white and green mineral substance which Sir William Dawson considered were fossil vestiges, the walls or coverings of some very simple sort of living thing which has now vanished from the earth. He called these markings Eozoon Canadense (the Canadian dawn-animal). There has been much discussion and controversy over this Eozoon, but to-day it is agreed that Eozoon is nothing more than a crystalline marking. Mixed minerals will often intercrystallize in blobs or branching shapes that are very suggestive of simple plant or animal forms. Any one who has made a lead tree in his schooldays, or lit those queer indoor fireworks known as serpents’ eggs, which unfold like a long snake, or who has seen the curious markings often found in quartz crystals, or noted the tree-like pattern on old stone-ware beer mugs, will realize how closely non-living matter can sometimes mock the shapes of living things.

Overlying or overlapping these Azoic or Archæozoic rocks come others, manifestly also very ancient and worn, which do{v1-10} contain traces of life. These first remains are of the simplest description; they are the vestiges of simple plants, called algæ, or marks like the tracks made by worms in the sea mud. There are also the skeletons of the microscopic creatures called Radiolaria. This second series of rocks is called the Proterozoic (beginning of life) series, and marks a long age in the world’s history. Lying over and above the Proterozoic rocks is a third series, which is found to contain a considerable number and variety of traces of living things. First comes the evidence of a diversity of shellfish, crabs, and such-like crawling things, worms, seaweeds, and the like; then of a multitude of fishes and of the beginnings of land plants and land creatures. These rocks are called the Palæozoic (ancient life) rocks. They mark a vast era, during which life was slowly spreading, increasing, and developing in the seas of our world. Through long ages, through the earliest Palæozoic time, it was no more than a proliferation of such swimming and creeping things in the water. There were creatures called trilobites; they were crawling things like big sea woodlice that were probably related to the American king-crab of to-day. There were also sea-scorpions, the prefects of that early world. The individuals of certain species of these were nine feet long. These were the very highest sorts of life. There were abundant different sorts of an order of shellfish called brachiopods. There were plant animals, rooted and joined together like plants, and loose weeds that waved in the waters.

It was not a display of life to excite our imaginations. There was nothing that ran or flew or even swam swiftly or skilfully. Except for the size of some of the creatures, it was not very different from, and rather less various than, the kind of life a student would gather from any summer-time ditch nowadays for microscopic examination. Such was the life of the shallow seas through a hundred million years or more in the early Palæozoic period. The land during that time was apparently absolutely barren. We find no trace nor hint of land life. Everything that lived in those days lived under water for most or all of its life.

![]()

Life in the Early Palæozoic

Note its general resemblance, except for size, to the microscopic summer

ditch-water life of to-day.

Between the formation of these Lower Palæozoic rocks in which the sea scorpion and trilobite ruled, and our own time, there have intervened almost immeasurable ages, represented by layers{v1-12} and masses of sedimentary rocks. There are first the Upper Palæozoic Rocks, and above these the geologists distinguish two great divisions. Next above the Palæozoic come the Mesozoic (middle life) rocks, a second vast system of fossil-bearing rocks, representing perhaps a hundred millions of swift years, and containing a wonderful array of fossil remains, bones of giant reptiles and the like, which we will presently describe; and above these again are the Cainozoic (recent life) rocks, a third great volume in the history of life, an unfinished volume of which the sand and mud that was carried out to sea yesterday by the rivers of the world, to bury the bones and scales and bodies and tracks that will become at last fossils of the things of to-day, constitute the last written leaf.

(It is, we may note, the practice of many geologists to make a break between the rest of the Cainozoic system of rocks and those which contain traces of humanity, which latter are cut off as a separate system under the name of Quaternary. But that, as we shall see, is rather like taking the last page of a book, which is really the conclusion of the last chapter, and making a separate chapter of it and calling it the last chapter.)

These markings and fossils in the rocks and the rocks themselves are our first historical documents. The history of life that men have puzzled out and are still puzzling out from them is called the Record of the Rocks. By studying this record men are slowly piecing together a story of life’s beginnings, and of the beginnings of our kind, of which our ancestors a century or so ago had no suspicion. But when we call these rocks and the fossils a record and a history, it must not be supposed that there is any sign of an orderly keeping of a record. It is merely that whatever happens leaves some trace, if only we are intelligent enough to detect the meaning of that trace. Nor are the rocks of the world in orderly layers one above the other, convenient for men to read. They are not like the books and pages of a library. They are torn, disrupted, interrupted, flung about, defaced, like a carelessly arranged office after it has experienced in succession a bombardment, a hostile military occupation, looting, an earthquake, riots, and a fire. And so it is that for countless generations this Record of the Rocks lay unsuspected beneath the{v1-13} feet of men. Fossils were known to the Ionian Greeks in the sixth century B.C.,[5] they were discussed at Alexandria by Eratosthenes and others in the third century B.C., a discussion which is summarized in Strabo’s Geography (?20-10 B.C.). They were known to the Latin poet Ovid, but he did not understand their nature. He thought they were the first rude efforts of creative power. They were noted by Arabic writers in the tenth century. Leonardo da Vinci, who lived so recently as the opening of the sixteenth century (1452-1519), was one of the first Europeans to grasp the real significance of fossils,[6] and it has been only within the last century and a half that man has begun the serious and sustained deciphering of these long-neglected early pages of his world’s history.

Speculations about geological time vary enormously.[7] Estimates of the age of the oldest rocks by geologists and astronomers starting from different standpoints have varied between 1,600,000,000, and 25,000,000. The lowest estimate was made by Lord Kelvin in 1867. Professor Huxley guessed at 400,000,000 years. There is a summary of views and the grounds upon which the estimates have been made in Osborn’s Origin and Evolution of Life; he inclines to the moderate total of 100,000,000. It must be clearly understood by the reader how sketchy and provisional all these time estimates are. They rest nearly always upon theoretical assumptions of the slenderest kind. That the period of time has been vast, that it is to be counted by scores and possibly by hundreds of millions of years, is the utmost that can be said with certainty in the matter. It is quite open to the reader to divide every number in the appended time diagram by ten or multiply it by two; no one can gainsay him. Of the relative amount of time as between one age and another we have, however, stronger evidence; if the reader cuts{v1-14} down the 800,000,000 we have given here to 400,000,000, then he must reduce the 40,000,000 of the Cainozoic to 20,000,000. And be it noted that whatever the total sum may be, most geologists are in agreement that half or more than half of the whole of geological time had passed before life had developed to the Later Palæozoic level. The reader reading quickly through these opening chapters may be apt to think of them as a mere swift prelude{v1-15} of preparation to the apparently much longer history that follows, but in reality that subsequent history is longer only because it is more detailed and more interesting to us. It looms larger in perspective. For ages that stagger the imagination this earth spun hot and lifeless, and again for ages of equal vastness it held no life above the level of the animalculæ in a drop of ditch-water.

Not only is Space from the point of view of life and humanity empty, but Time is empty also. Life is like a little glow, scarcely kindled yet, in these void immensities.{v1-16}

NOW here it will be well to put plainly certain general facts about this new thing, life, that was creeping in the shallow waters and intertidal muds of the early Palæozoic period, and which is perhaps confined to our planet alone in all the immensity of space.

Life differs from all things whatever that are without life in certain general aspects. There are the most wonderful differences among living things to-day, but all living things past and present agree in possessing a certain power of growth, all living things take nourishment, all living things move about as they feed and grow, though the movement may be no more than the spread of roots through the soil, or of branches in the air. Moreover, living things reproduce; they give rise to other living things, either by growing and then dividing or by means of seeds or spores or eggs or other ways of producing young. Reproduction is a characteristic of life.

No living thing goes on living forever. There seems to be a limit of growth for every kind of living thing. Among very small and simple living things, such as that microscopic blob of living matter the Amæba, an individual may grow and then divide completely into two new individuals, which again may divide in their turn. Many other microscopic creatures live actively for a time, grow, and then become quiet and inactive, enclose themselves in an outer covering and break up wholly into a number of still smaller things, spores, which are released and scattered and again grow into the likeness of their parent. Among more complex creatures the reproduction is not usually such simple division, though division does occur even in the case of many creatures{v1-17} big enough to be visible to the unassisted eye. But the rule with almost all larger beings is that the individual grows up to a certain limit of size. Then, before it becomes unwieldy, its growth declines and stops. As it reaches its full size it matures, it begins to produce young, which are either born alive or hatched from eggs. But all of its body does not produce young. Only a special part does that. After the individual has lived and produced offspring for some time, it ages and dies. It does so by a sort of necessity. There is a practical limit to its life as well as to its growth. These things are as true of plants as they are of animals. And they are not true of things that do not live. Non-living things, such as crystals, grow, but they have no set limits of growth or size, they do not move of their own accord and there is no stir within them. Crystals once formed may last unchanged for millions of years. There is no reproduction for any non-living thing.

This growth and dying and reproduction of living things leads to some very wonderful consequences. The young which a living thing produces are either directly, or after some intermediate stages and changes (such as the changes of a caterpillar and butterfly), like the parent living thing. But they are never exactly like it or like each other. There is always a slight difference, which we speak of as individuality. A thousand butterflies this year may produce two or three thousand next year; these latter will look to us almost exactly like their predecessors, but each one will have just that slight difference. It is hard for us to see individuality in butterflies because we do not observe them very closely, but it is easy for us to see it in men. All the men and women in the world now are descended from the men and women of A.D. 1800, but not one of us now is exactly the same as one of that vanished generation. And what is true of men and butterflies is true of every sort of living thing, of plants as of animals. Every species changes all its individualities in each generation. That is as true of all the minute creatures that swarmed and reproduced and died in the Archæozoic and Proterozoic seas, as it is of men to-day.

Every species of living things is continually dying and being born again, as a multitude of fresh individuals.{v1-18}

Consider, then, what must happen to a new-born generation of living things of any species. Some of the individuals will be stronger or sturdier or better suited to succeed in life in some way than the rest, many individuals will be weaker or less suited. In particular single cases any sort of luck or accident may occur, but on the whole the better equipped individuals will live and grow up and reproduce themselves and the weaker will as a rule go under. The latter will be less able to get food, to fight their enemies and pull through. So that in each generation there is as it were a picking over of a species, a picking out of most of the weak or unsuitable and a preference for the strong and suitable. This process is called Natural Selection or the Survival of the Fittest.[8]

It follows, therefore, from the fact that living things grow and breed and die, that every species, so long as the conditions under which it lives remain the same, becomes more and more perfectly fitted to those conditions in every generation.

But now suppose those conditions change, then the sort of individual that used to succeed may now fail to succeed and a sort of individual that could not get on at all under the old conditions may now find its opportunity. These species will change, therefore, generation by generation; the old sort of individual that used to prosper and dominate will fail and die out and the new sort of individual will become the rule,—until the general character of the species changes.

Suppose, for example, there is some little furry whitey-brown animal living in a bitterly cold land which is usually under snow. Such individuals as have the thickest, whitest fur will be least hurt by the cold, less seen by their enemies, and less conspicuous as they seek their prey. The fur of this species will thicken and its whiteness increase with every generation, until there is no advantage in carrying any more fur.

![]()

Diagram of Life in the Later Palæozoic Age.

Life is creeping out of the water. An insect like a dragon fly is shown.

There were amphibia like gigantic newts and salamanders, and even

primitive reptiles in these swamps.

Imagine now a change of climate that brings warmth into the land, sweeps away the snows, makes white creatures glaringly visible during the greater part of the year and thick fur an encumbrance. Then every individual with a touch of brown in its colouring and a thinner fur will find itself at an advantage, and very white and heavy fur will be a handicap. There will be{v1-20} a weeding out of the white in favour of the brown in each generation. If this change of climate come about too quickly, it may of course exterminate the species altogether; but if it come about gradually, the species, although it may have a hard time, may yet be able to change itself and adapt itself generation by generation. This change and adaptation is called the Modification of Species.

Perhaps this change of climate does not occur all over the lands inhabited by the species; maybe it occurs only on one side of some great arm of the sea or some great mountain range or such-like divide, and not on the other. A warm ocean current like the Gulf Stream may be deflected, and flow so as to warm one side of the barrier, leaving the other still cold. Then on the cold side this species will still be going on to its utmost possible furriness and whiteness and on the other side it will be modifying towards brownness and a thinner coat. At the same time there will probably be other changes going on; a difference in the paws perhaps, because one half of the species will be frequently scratching through snow for its food, while the other will be scampering over brown earth. Probably also the difference of climate will mean differences in the sort of food available, and that may produce differences in the teeth and the digestive organs. And there may be changes in the sweat and oil glands of the skin due to the changes in the fur, and these will affect the excretory organs and all the internal chemistry of the body. And so through all the structure of the creature. A time will come when the two separated varieties of this formerly single species will become so unlike each other as to be recognizably different species. Such a splitting up of a species in the course of generations into two or more species is called the Differentiation of Species.

And it should be clear to the reader that given these elemental facts of life, given growth and death and reproduction with individual variation in a world that changes, life must change in this way, modification and differentiation must occur, old species must disappear, and new ones appear. We have chosen for our instance here a familiar sort of animal, but what is true of furry beasts in snow and ice is true of all life, and equally true of the soft{v1-21} jellies and simple beginnings that flowed and crawled for hundreds of millions of years between the tidal levels and in the shallow, warm waters of the Proterozoic seas.

The early life of the early world, when the blazing sun rose and set in only a quarter of the time it now takes, when the warm seas poured in great tides over the sandy and muddy shores of the rocky lands and the air was full of clouds and steam, must have been modified and varied and species must have developed at a great pace. Life was probably as swift and short as the days and years; the generations, which natural selection picked over, followed one another in rapid succession.

Natural selection is a slower process with man than with any other creature. It takes twenty years or more before an ordinary human being in western Europe grows up and reproduces. In the case of most animals the new generation is on trial in a year or less. With such simple and lowly beings, however, as first appeared in the primordial seas, growth and reproduction was probably a matter of a few brief hours or even of a few brief minutes. Modification and differentiation of species must accordingly have been extremely rapid, and life had already developed a very great variety of widely contrasted forms before it began to leave traces in the rocks. The Record of the Rocks does not begin, therefore, with any group of closely related forms from which all subsequent and existing creatures are descended. It begins in the midst of the game, with nearly every main division of the animal kingdom already represented.[9] Plants are already plants, and animals animals. The curtain rises on a drama in the sea that has already begun, and has been going on for some time. The brachiopods are discovered already in their shells, accepting and consuming much the same sort of food that oysters and mussels do now; the great water scorpions crawl among the seaweeds, the trilobites roll up into balls and unroll and scuttle away. In that ancient mud and among those early weeds there was probably as rich and abundant and active a life of infusoria and the like as one finds in a drop of ditch-water to-day. In the ocean waters, too, down to the utmost downward limit to{v1-22} which light could filter, then as now, there was an abundance of minute and translucent, and in many cases phosphorescent, beings.

But though the ocean and intertidal waters already swarmed with life, the land above the high-tide line was still, so far as we can guess, a stony wilderness without a trace of life.{v1-23}

§ 1. Life and Water. § 2. The Earliest Animals.

WHEREVER the shore line ran there was life, and that life went on in and by and with water as its home, its medium, and its fundamental necessity.

The first jelly-like beginnings of life must have perished whenever they got out of the water, as jelly-fish dry up and perish on our beaches to-day. Drying up was the fatal thing for life in those days, against which at first it had no protection. But in a world of rain-pools and shallow seas and tides, any variation that enabled a living thing to hold out and keep its moisture during hours of low tide of drought met with every encouragement in the circumstances of the time. There must have been a constant risk of stranding. And, on the other hand, life had to keep rather near the shore and beaches in the shallows because it had need of air (dissolved of course in the water) and light.

No creature can breathe, no creature can digest its food, without water. We talk of breathing air, but what all living things really do is to breathe oxygen dissolved in water. The air we ourselves breathe must first be dissolved in the moisture in our lungs; and all our food must be liquefied before it can be assimilated. Water-living creatures which are always under water, wave the freely exposed gills by which they breathe in that water, and extract the air dissolved in it. But a creature that is to be exposed for any time out of the water, must have its body and its breathing apparatus protected from drying up. Before the seaweeds could creep up out of the Early Palæozoic seas into{v1-24} the intertidal line of the beach, they had to develop a tougher outer skin to hold their moisture. Before the ancestor of the sea scorpion could survive being left by the tide it had to develop its casing and armour. The trilobites probably developed their tough covering and rolled up into balls, far less as a protection against each other and any other enemies they may have possessed, than as a precaution against drying. And when presently, as we ascend the Palæozoic rocks, the fish appear, first of all the backboned or vertebrated animals, it is evident that a number of them are already adapted by the protection of their gills with gill covers and by a sort of primitive lung swimming-bladder, to face the same risk of temporary stranding.

Now the weeds and plants that were adapting themselves to intertidal conditions were also bringing themselves into a region of brighter light, and light is very necessary and precious to all plants. Any development of structure that would stiffen them and hold them up to the light, so that instead of crumpling and flopping when the waters receded, they would stand up outspread, was a great advantage. And so we find them developing fibre and support, and the beginning of woody fibre in them. The early plants reproduced by soft spores, or half-animal “gametes,” that were released in water, were distributed by water and could only germinate under water. The early plants were tied, and most lowly plants to-day are tied, by the conditions of their life cycle, to water. But here again there was a great advantage to be got by the development of some protection of the spores from drought that would enable reproduction to occur without submergence. So soon as a species could do that, it could live and reproduce and spread above the high-water mark, bathed in light and out of reach of the beating and distress of the waves. The main classificatory divisions of the larger plants mark stages in the release of plant life from the necessity of submergence by the development of woody support and of a method of reproduction that is more and more defiant of drying up. The lower plants are still the prisoner attendants of water. The lower mosses must live in damp, and even the development of the spore of the ferns demands at certain stages extreme wetness. The highest plants have carried freedom from{v1-25} water so far that they can live and reproduce if only there is some moisture in the soil below them. They have solved their problem of living out of water altogether.

The essentials of that problem were worked out through the vast æons of the Proterozoic Age and the early Palæozoic Age by nature’s method of experiment and trial. Then slowly, but in great abundance, a variety of new plants began to swarm away from the sea and over the lower lands, still keeping to swamp and lagoon and watercourse as they spread.

And after the plants came the animal life.

There is no sort of land animal in the world, as there is no sort of land plant, whose structure is not primarily that of a water-inhabiting being which has been adapted through the modification and differentiation of species to life out of the water. This adaptation is attained in various ways. In the case of the land scorpion the gill-plates of the primitive sea scorpion are sunken into the body so as to make the lung-books secure from rapid evaporation. The gills of crustaceans, such as the crabs which run about in the air, are protected by the gill-cover extensions of the back shell or carapace. The ancestors of the insects developed a system of air pouches and air tubes, the tracheal tubes, which carry the air all over the body before it is dissolved. In the case of the vertebrated land animals, the gills of the ancestral fish were first supplemented and then replaced by a bag-like growth from the throat, the primitive lung swimming-bladder. To this day there survive certain mudfish which enable us to understand very clearly the method by which the vertebrated land animals worked their way out of the water. These creatures (e.g. the African lung fish) are found in tropical regions in which there is a rainy full season and a dry season, during which the rivers become mere ditches of baked mud. During the rainy season these fish swim about and breathe by gills like any other fish. As the waters of the river evaporate, these fish bury themselves in the mud, their gills go out of action, and the creature keeps itself alive until the waters return by swallowing air, which passes into its swimming-bladder. The Australian lung fish,{v1-26} when it is caught by the drying up of the river in stagnant pools, and the water has become deaerated and foul, rises to the surface and gulps air. A newt in a pond does exactly the same thing. These creatures still remain at the transition stage, the stage at which the ancestors of the higher vertebrated animals were released from their restriction to an under-water life.

The amphibia (frogs, newts, tritons, etc.) still show in their life history all the stages in the process of this liberation. They are still dependent on water for their reproduction; their eggs must be laid in sunlit water, and there they must develop. The young tadpole has branching external gills that wave in the water; then a gill cover grows back over them and forms a gill chamber. Then, as the creature’s legs appear and its tail is absorbed, it begins to use its lungs, and its gills dwindle and vanish. The adult frog can live all the rest of its days in the air, but it can be drowned if it is kept steadfastly below water. When we come to the reptile, however, we find an egg which is protected from evaporation by a tough egg case, and this egg produces young which breathe by lungs from the very moment of hatching. The reptile is on all fours with the seeding plant in its freedom from the necessity to pass any stage of its life cycle in water.

![]()

Australian Lung fish breathing air

The later Palæozoic Rocks of the northern hemisphere give us the materials for a series of pictures of this slow spreading of life over the land. Geographically, all round the northern half of the world it was an age of lagoons and shallow seas very favourable to this invasion. The new plants, now that they had acquired the power to live this new aerial life, developed with an extraordinary richness and variety.

![]()

Some Reptiles of the Late Palæozoic Age

There were as yet no true flowering plants,[10] no grasses nor trees that shed their leaves in winter;[11] the first “flora” consisted{v1-27} of great tree ferns, gigantic equisetums, cycad ferns, and kindred vegetation. Many of these plants took the form of huge-stemmed trees, of which great multitudes of trunks survive fossilized to this day. Some of these trees were over a hundred feet high, of orders and classes now vanished from the world. They stood with their stems in the water, in which no doubt there was a thick tangle of soft mosses and green slime and fungoid growths that left few plain vestiges behind them. The abundant remains{v1-28} of these first swamp forests constitute the main coal-measures of the world to-day.

Amidst this luxuriant primitive vegetation crawled and glided and flew the first insects. They were rigid-winged, four-winged creatures, often very big, some of them having wings measuring a foot in length. There were numerous dragon flies—one found in the Belgian coal-measures had a wing span of twenty-nine inches! There were also a great variety of flying cockroaches. Scorpions abounded, and a number of early spiders, which, however, had no spinnerets for web making.[12] Land snails appeared. So too did the first-known step of our own ancestry upon land, the amphibia. As we ascend the higher levels of the Later Palæozoic record, we find the process of air adaptation has gone as far as the appearance of true reptiles amidst the abundant and various amphibia.

The land life of the Upper Palæozoic Age was the life of a green swamp forest without flowers or birds or the noises of modern insects. There were no big land beasts at all; wallowing amphibia and primitive reptiles were the very highest creatures that life had so far produced. Whatever land lay away from the water or high above the water was still altogether barren and lifeless. But steadfastly, generation by generation, life was creeping away from the shallow sea-water of its beginning.{v1-29}

§ 1. Why Life Must Change Continually. § 2. The Sun a Steadfast Star. § 3. Changes from Within the Earth. § 4. Life May Control Change.

THE Record of the Rocks is like a great book that has been carelessly misused. All its pages are torn, worn, and defaced, and many are altogether missing. The outline of the story that we sketch here has been pieced together slowly and painfully in an investigation that is still incomplete and still in progress. The Carboniferous Rocks, the “coal-measures,” give us a vision of the first great expansion of life over the wet lowlands. Then come the torn pages known as the Permian Rocks (which count as the last of the Palæozoic), that preserve very little for us of the land vestiges of their age. Only after a long interval of time does the history spread out generously again.

It must be borne in mind that great changes of climate have always been in progress, that have sometimes stimulated and sometimes checked life. Every species of living thing is always adapting itself more and more closely to its conditions. And conditions are always changing. There is no finality in adaptation. There is a continuing urgency towards fresh change.

About these changes of climate some explanations are necessary here. They are not regular changes; they are slow fluctuations between heat and cold. The reader must not think that because the sun and earth were once incandescent, the climatic history of the world is a simple story of cooling down. The centre of the earth is certainly very hot to this day, but we feel nothing of that internal heat at the surface; the internal heat, except{v1-30} for volcanoes and hot springs, has not been perceptible at the surface since first the rocks grew solid. Even in the Azoic or Archæozoic Age there are traces in ice-worn rocks and the like of periods of intense cold. Such cold waves have always been going on everywhere, alternately with warmer conditions. And there have been periods of great wetness and periods of great dryness throughout the earth.

A complete account of the causes of these great climatic fluctuations has still to be worked out, but we may perhaps point out some of the chief of them.[13] Prominent among them is the fact that the earth does not spin in a perfect circle round the sun. Its path or orbit is like a hoop that is distorted; it is, roughly speaking, elliptical (ovo-elliptical), and the sun is nearer to one end of the ellipse than the other. It is at a point which is a focus of the ellipse. And the shape of this orbit never remains the same. It is slowly distorted by the attractions of the other planets, for ages it may be nearly circular, for ages it is more or less elliptical. As the ellipse becomes most nearly circular, then the focus becomes most nearly the centre. When the orbit becomes most elliptical, then the position of the sun becomes most remote from the middle or, to use the astronomer’s phrase, most eccentric. When the orbit is most nearly circular, then it must be manifest that all the year round the earth must be getting much the same amount of heat from the sun; when the orbit is most distorted, then there will be a season in each year when the earth is nearest the sun (this phase is called Perihelion) and getting a great deal of heat comparatively, and a season when it will be at its farthest from the sun (Aphelion) and getting very little warmth. A planet at aphelion is travelling its slowest, and its fastest at perihelion; so that the hot part of its year will last for a much less time than the cold part of its year. (Sir Robert Ball calculated that the greatest difference possible between the seasons was thirty-three days.) During ages when the orbit is most nearly circular there will therefore be least extremes of{v1-31} climate, and when the orbit is at its greatest eccentricity, there will be an age of cold with great extremes of seasonal temperature. These changes in the orbit of the earth are due to the varying pull of all the planets, and Sir Robert Ball declared himself unable to calculate any regular cycle of orbital change, but Professor G. H. Darwin maintained that it is possible to make out a kind of cycle between greatest and least eccentricity of about 200,000 years.