Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

No attempt has been made to correct or normalize the

spelling of non-English words.

Some typographical errors have been corrected;

a list follows the text.

Some illustrations

have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol  will bring up a larger version of the image.

will bring up a larger version of the image.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Index

(etext transcriber's note) |

OLD

CONTINENTAL

TOWNS

Uniform with this Volume

(All very fully Illustrated)

| The Cathedrals of England and Wales |

| By T. Francis Bumpus (3 vols.) | 6s. net each |

| The Cathedrals of Northern France |

| By T. Francis Bumpus | 6s. net |

| The Cathedrals of Northern Germany and the Rhine |

| By T. Francis Bumpus | 6s. net |

| The Cathedrals of Northern Spain |

| By Charles Rudy | 6s. net |

| The Cathedrals and Churches of Northern Italy |

| By T. Francis Bumpus | (9×6½. 16s. net) |

| The Cathedrals of Central Italy |

| By T. Francis Bumpus | 6s. net |

| London Churches Ancient and Modern |

| By T. Francis Bumpus (2 vols.) | 6s. net each |

| The Abbeys of Great Britain |

| By H. Claiborne Dixon | 6s. net |

| The English Castles |

| By Edmond B. d’Auvergne | 6s. net |

| A History of English Cathedral Music |

| By John S. Bumpus (2 vols.) | 6s. net each |

| The Cathedrals of Norway, Sweden and Denmark |

| By T. Francis Bumpus | (9×6½. 16s. net) |

| Old English Towns (First Series) |

| By William Andrews | 6s. net |

| Old English Towns (Second Series) |

| By Elsie Lang | 6s. net |

| The Cathedrals and Churches of Belgium |

| By T. Francis Bumpus | 6s. net |

ROUEN, 1822.

A STREET SHOWING THE TOWER OF THE CATHEDRAL.

OLD CONTINENTAL

TOWNS

BY

WALTER M. GALLICHAN

Author of

“The Story of Seville,” “Fishing and Travel

in Spain,” “Cheshire,” etc.

LONDON

T. WERNER LAURIE

CLIFFORD’S INN

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ROUEN. | A Street showing the Tower

of the Cathedral, 1822 | Frontispiece |

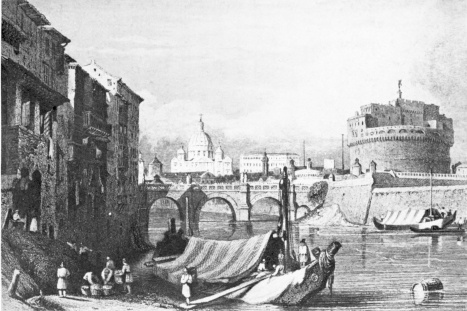

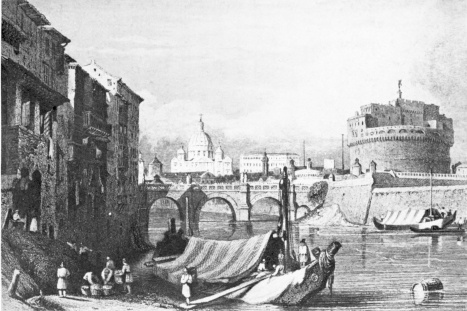

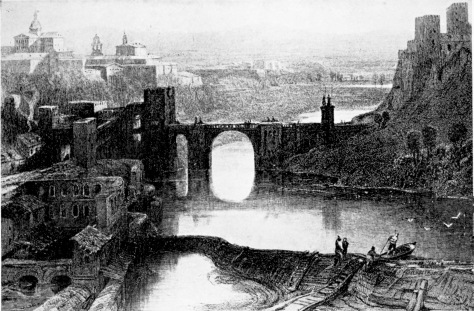

ROME. | The Bridge and Castle of St

Angelo, 1831 | To face page | 2 |

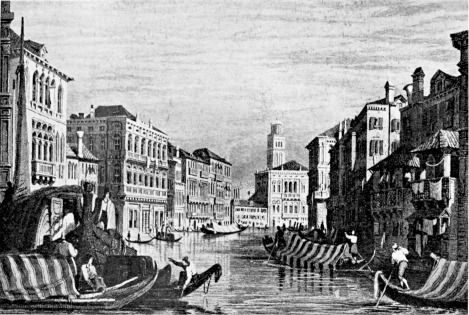

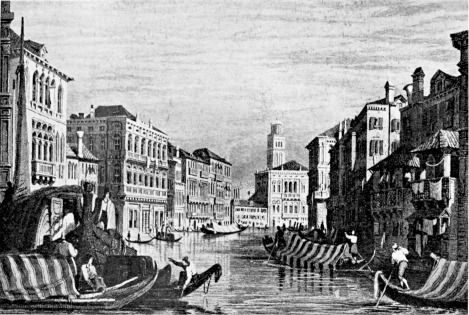

VENICE. | The Grand Canal, 1831 | " | 30 |

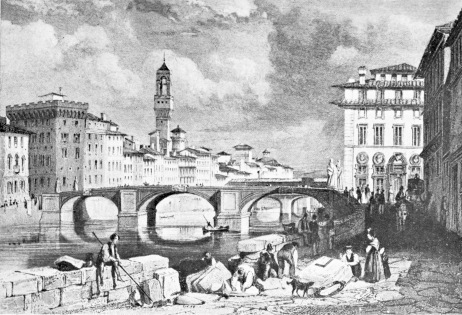

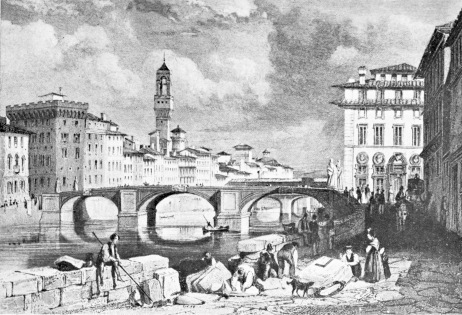

FLORENCE. | Ponte Santa Trinita, 1832 | " | 58 |

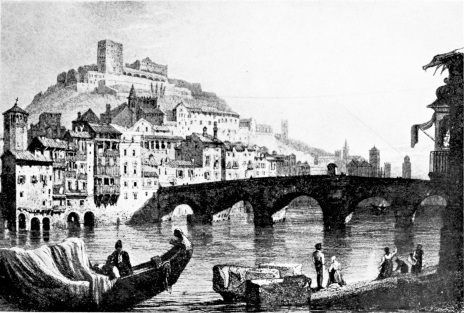

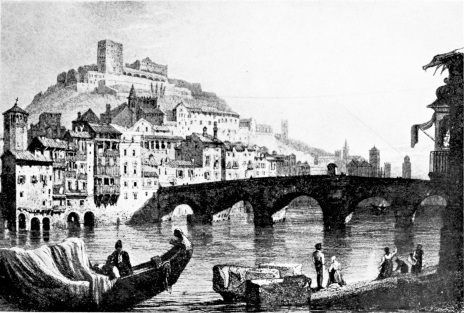

VERONA. | 1830 | " | 72 |

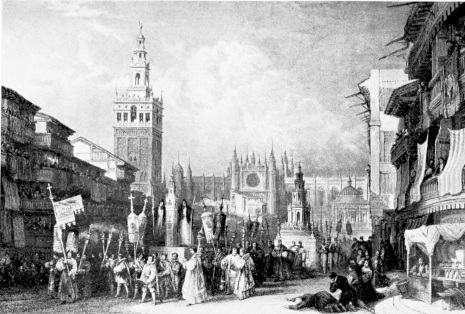

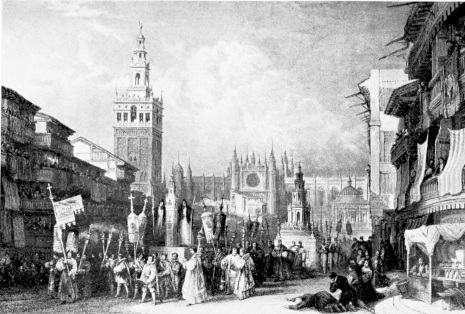

SEVILLE. | Plaza Real and Procession of

the Corpus Christi, 1836 | " | 80 |

CORDOVA. | The Prison of the Inquisition,

1836 | " | 98 |

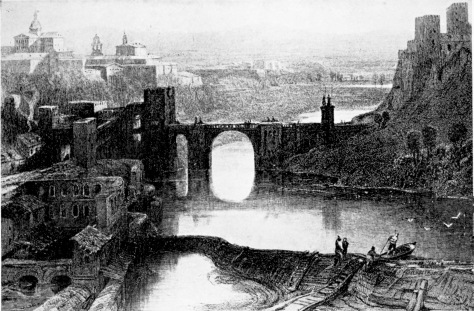

TOLEDO. | 1837 | " | 120 |

OPORTO. | From the Quay of Villa Nova,

1832 | " | 152 |

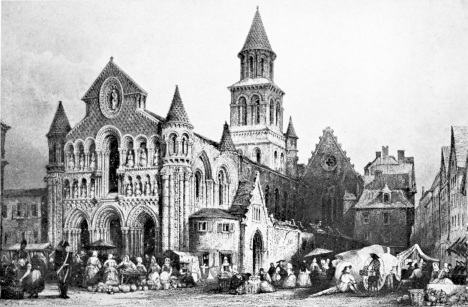

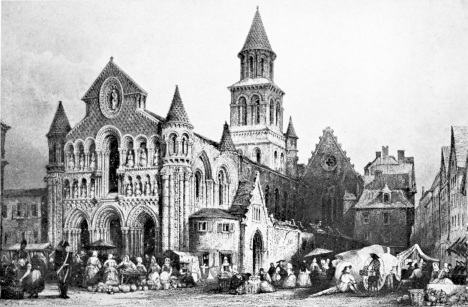

POITIERS. | The Church of Notre Dame,

1845 | " | 164 |

GHENT. | 1832 | " | 202 |

ANTWERP. | The Cathedral, 1832 | " | 212 |

COLOGNE. | St Martin’s Church, 1826 | " | 230 |

NUREMBERG. | 1832 | " | 242 |

PRAGUE. | The City and Bridge, 1832 | " | 260 |

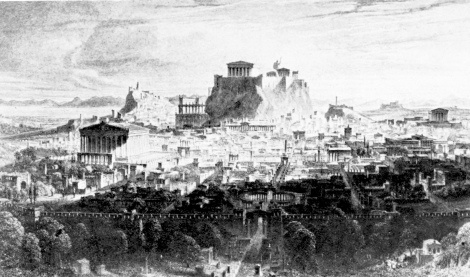

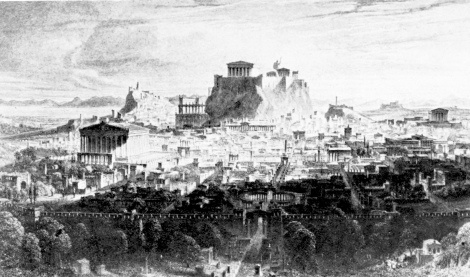

ATHENS. | A supposed appearance if restored,

1824 | " | 266 |

{1}

OLD CONTINENTAL TOWNS

ROME

THE story of Rome is a mighty chronicle of such deep importance towards

an understanding of the growth of Europe, that a feeling almost of

helplessness assails me as I essay to set down in this limited space an

account of the city’s ancient grandeur and of its monuments. It is with

a sense of awe that one enters Rome. The scene gives birth to so much

reflection, the pulse quickens, the imagination is stirred by the annals

of Pompey and Cæsar, and the mighty names that resound in the history of

the wonderful capital; while the ruins of the days of power and pomp are

as solemn tokens of the fate of all great civilisations.

The surroundings of Rome, the vast silent Campagna, that rolling tract

of wild country, may be likened to an upland district of Wales. Here are

scattered relics of the resplendent{2} days, in a desert where the sirocco

breathes hotly; where flocks of sheep and goats wander, and foxes prowl

close to the ancient gates. Eastward stand the great natural ramparts of

purple mountains, whence the Tiber rolls swiftly, and washing Rome,

winds on through lonely valleys.

Dim are the early records of the city. Myth and legend long passed as

history in the chronicles of the founding of Rome. We learn now from the

etymologists and modern historians that the name of Rome was not derived

from Roma, the mother of Romulus, nor from ruma, but, according to

Niebuhr, from the Greek rhoma, signifying strength; while Michelet

tells us that city was called after the River Rumo, the ancient name of

the Tiber.

ROME, 1831.

THE BRIDGE AND CASTLE OF ST. ANGELO.

Romulus, the legendary founder, was supposed to have lived B.C. 752. The

growth of the community on the Seven Hills began, according to the old

annalists, with a settlement of shepherds. We are told that after the

death of Romulus, the first king, the city was ruled by Numa Pompilius.

This sovereign instituted nine guilds of industry, and united the mixed

population. Tarquinius Superbus, the despotic king, reigned with

fanatical religious austerity,{3} and after his banishment Rome became a

republic.

The first system of rule was sacerdotal, the second aristocratic, and

the third a state of liberty for the plebeians. Then came the Gauls who

burned the city to the ground and harried the whole country. Hannibal

and Scipio arose, and we enter upon the period of the great Punic Wars,

followed by the stirring epoch of Cæsar and Pompey.

How shall we separate myth and simple tradition from the veracious

chronicles of the Roman people? What were the causes of the downfall of

their proud city, and the decadence of the great race that invaded all

quarters of Europe? These are the questions which fill the mind as we

wander to-day in Rome. We are reminded of the menace of wealth, the

insecurity of prosperity, and the devastating influence of militarism

and the lust of conquest. We meditate, too, on the spirit of persecution

that flourished here, the love of ferocity, and the cruelty that

characterised the recreations of the city under the emperors.

With all its eminence in art and industry, in spite of its high

distinction in the science of warfare, and its elaborate jurisprudence

and{4} codes, Rome, at one time terrorised by Nero, at another humanely

governed by Aurelius, was in its last state a melancholy symbol of

decrepitude and failure. The final stage of degradation was worse than

the primitive period of barbarism and superstition.

In the Middle Ages, at the time when most of the wealth went to the

Popes of Avignon, the city had fallen into pitiful decay. The majestic

St Peter’s was threatened by destruction through lack of repair; the

Capitol was described as on a level with “a town of cowherds.”

The monarchy of Rome is said to have endured for about two hundred and

forty years. The city extended then over a wide area, and was protected

by walls and towers. The Coliseum, the Pantheon, and the Forum were

built as Rome grew in might and magnificence, and the Roman style of

architecture became a model for the world. Happily these structures have

survived. The Rome of pagan days and the Rome of the Renaissance are

mingled here strangely, and the pomp and affluence of former times

contrasts with the poverty of to-day that meets us in the streets.

Note the faces of the people; here are features stern and regular,

recalling often old{5} prints of the Romans of history. The dress of the

poorer women is ancient, while that of the upper classes is as modern as

the costumes of Paris, Berlin, or London. On days of fête it is

interesting to watch these people at play, all animated with a southern

gaiety which the northerner may envy. The life of Rome is outdoor; folk

loiter and congregate in the streets; there is much traffic of vehicles

used for pleasure. Over the city stretches “the Italian sky,” ardently

blue—the sky that we know from paintings before we have visited

Rome—and upon the white buildings shines a hot sun from which we shrink

in midsummer noons.

It is hard to decide which appeals to us the more strongly in Rome—the

relics of Cæsar’s empire or the art of the Middle Ages. The Coliseum

brings to mind “the grandeur that was Rome,” in the days of the pagan

majesty, while St Peter’s, with its wealth of gorgeous decoration and

great paintings, reminds us of the supreme power of the city under the

popes.

In the Coliseum there is social history written in stone. We look upon

the tiers rising one above the other, and picture them in all the

splendour of a day of cruel carnival. We{6} may see traces of the lifts

that brought the beasts to the arena from the dens below.

Ad leones! The trumpet blares, and a victim of the heretical creed is

led into the amphitheatre to encounter the lions. How often has this

soil been drenched in blood. How often have the walls echoed with the

plaudits of the Roman populace, gloating upon a spectacle of torture, or

aroused to ecstasy by the combats of gladiators.

Silence broods in the arena, and in every interstice the maidenhair fern

grows rife among the decaying stones. The glory has departed, but the

shell of the Flavian amphitheatre remains as a monument of Rome’s

imperial days. Here were held the chariot races, the competitions of

athletes, the tournaments on horseback, the baiting of savage brutes,

the wrestling bouts, throwing the spear, and the fights of martyrs with

animals. Luxury and cruelty rioted here on Roman holidays.

For a comprehensive view of the Coliseum, you should climb the Palatine

Hill. The hundreds of arches and windows admit the sunlight, and the

building glows, “a monstrous mountain of stone,” as Michelet describes

it. Tons of the masonry have been removed by{7} vandals. The fountain in

which the combatants washed their wounds remains, and the walls of the

circus rise to a height of a hundred-and-fifty-seven feet. In yonder

“monument of murder” there died ten thousand victims in a hundred days

during the reign of Trajan.

The triumph of Christianity is symbolised in St Peter’s. An impartial

chronicler cannot close his eyes to the truth written in the great

cathedral. Both pagans and Christians persecuted in turn to the glory of

their deities. Force was worshipped alike by emperor and pope. Pagans

tortured martyrs in the arena; the Christians burned them in the square.

In 1600 Giordano Bruno was tied to the stake, and consumed in the

flames, by decree of the Church, after two years of imprisonment. His

offence was the writing of treatises attempting to prove that the earth

is not flat, and that God is “the All in All.” He also dared to opine

that there may be other inhabited worlds besides our own. Bruno’s last

words have echoed through the ages: “Perhaps it is with greater fear

that you pass the sentence upon me than I receive it.”

Under Innocent IV. the Inquisition was established as a special tribunal

against heretics.{8} Men of science soon came under its penalties.

Copernicus was a teacher of mathematics in Rome, when he conceived his

theory, “The Revolutions of the Heavenly Bodies,” which he dedicated to

Pope Paul. Fearing the awful penalties of the Holy Office, he withheld

publication of the work for many years, only seeing a copy of the

printed volume in his last hours. The book was condemned by the

Inquisition and placed on the index.

About a century later, Galileo wrote his “System of the World,” an

exposition and defence of the theories of Copernicus. The Inquisition

dragged him before its tribunal at Rome, where he was charged with

heresy and compelled to recant or die. We know that he chose

recantation, or the fate of Bruno would have been his. For ten years

Galileo pined in the dungeon, and his body was flung into a dishonoured

grave.

Not a man in Rome was safe from the Inquisition. Its courts travestied

justice; its terrified witnesses lied, and the accusers were

intimidated. Suspicion alone was sufficient to compel arrest and trial,

and there was no possible appeal, and no hope of pity or leniency. The

Church urged that while unbelief existed,{9} the Inquisition was a

necessity, and the chief means of stamping out heretical doctrine. And

yet, a few years ago, an International Free-thought Congress was held

under the shadow of St Peter’s. How truly, “it moves!”

The Renaissance, with its mighty intellectual impetus, its reverence for

the arts and culture, and its resistance against the absolutism of the

Papacy came as the salvation of Rome from the terrors and the stagnation

of the dark days.

The birth of Michael Angelo, in 1474, came with a new era of

enlightenment. Angelo, painter, sculptor, poet, and philosopher, was

commissioned by Pope Julius II. to carve a great work in Rome, and to

adorn the Sistine Chapel with frescoes. Three years were spent on these

superb paintings. This is the most wonderful ceiling painting in the

world. In the centre are pictures of scenes of the Creation and Fall; in

compartments are the prophets, and other portions represent the

ancestors of the Virgin Mary and historical characters.

The figures are colossal, and wonderful in their anatomy, revealing the

artist’s richness of imagination, as well as his unsurpassed technical

skill. To see to advantage the frescoes of the roof, it is necessary to

lie flat on the back, and{10} gaze upwards. The human figure is superbly

imaged in “The Temptation, Fall and Expulsion.” The largest figures in

the whole composition are among the prophets and sibyls.

“Here, at last, here indeed for the first time,” writes Mr Arthur

Symons, in his “Cities,” “is all that can be meant by sublimity; a

sublimity which attains its pre-eminence through no sacrifice of other

qualities; a sublimity which (let us say it frankly) is amusing. I find

the magnificent and extreme life of these figures as touching, intimate,

and direct in its appeal, as the most vivid and gracious realism of any

easel picture.”

The vast picture of “The Last Judgment,” on the wall of the Sistine

Chapel, was painted by Michael Angelo when he was growing old. The work

occupied about seven years. It is full of figures in every kind of

action, and most of them are nude. Their nakedness affronted Paul IV.,

who commanded Da Volterra, a pupil of Angelo, to paint clothing on some

of the forms, thus marring the beauty of the work.

In the Pauline Chapel of the Vatican are two mural paintings by Michael

Angelo, “The Crucifixion of St Peter,” and “The Conversion of St Paul.{11}”

“I could only see and wonder,” writes Goethe, referring to the works of

Angelo in a letter from Rome. The mental confidence and boldness of the

master, and his grandeur of conception, are beyond all expression.

Sir Joshua Reynolds spent some time in Rome, in 1750, and recorded the

result of his study of the work of Raphael and Michael Angelo. It was in

the cold chambers of the Vatican that Reynolds caught the chill which

brought about his deafness. He made many copies of parts of the

paintings of Angelo. “The Adonis” of Titian in the Colonna Palace, the

“Leda,” by Coreggio, and the works of Raphael, were closely studied by

the English painter. Before he left Rome he declared that the art of

Angelo represented the highest perfection.

Many critics affirm that St Peter’s is somewhat disappointing,

architecturally considered, while some critics maintain that it is one

of the finest churches in the world. The colonnades, with their gallery

of sculptured images, are stately and impressive. It is the huge façade

that disappoints. Nevertheless, St Peter’s is a stupendous temple, with

a dignity and majesty of its own. The interior is garish; we miss the

dim religious light and the atmosphere of{12} sober piety so manifest in

the cathedrals of Spain. As a repository of masterpieces St Peter’s is

world-famous. Here is “The Virgin and Dead Christ,” the finest of

Michael Angelo’s early statues.

Angelo spent various periods in Rome, after his first stay of five

years. He was in the city at the age of sixty, and much of his work was

executed when he was growing old. It was in the evening of his days that

he became the close friend of Vittoria Colonna, the inspirer of his

poetry, and after her death, in 1547, he entered upon a spell of

ill-health and sadness. But his activities were marvellous, even in old

age. In 1564 he planned the Farnese Palace for Paul III., and directed

the building of the Church of Santa Maria.

Immensity is the chief impression of the interior of St Peter’s. Even

the figures of cherubs are gigantic. The great nave with its marble

pavement and huge pillars, is long-drawn from the portal to the altar,

and the space within the great dome is bewildering in its vastness.

The bronze statue of St Peter, whose foot is kissed yearly by thousands

of devotees, is noted here among the numerous images. At the altar we

shall see Canova’s statue of Pius VI.,{13} the chair of St Peter, and tombs

of the Popes Urban and Paul.

Michael Angelo designed the beautiful Capello Gregoriana. His lovely

“Pieta” is the Cappella della Pieta, and this is the most splendid work

within the building. Tombs of popes are seen in the various chapels. In

the resplendent choir chapel is Thorvaldsen’s statue of Pius VII.

The Vatican is a great museum of statuary, the finest collection in

existence to-day. On the site of the building once stood a Roman

emperor’s palace, which was reconstructed as a residence for Pope

Innocent III. Besides the statues in the Vatican and the cathedral,

there are many remarkable works of sculpture in the Villa Albani and the

Capitoline. In the Capitoline Museum are, the “Dying Gladiator,” the

“Resting Faun,” and the “Venus.”

Days may be spent in inspecting the minor churches of Rome. Perhaps the

most interesting is San Giovanni Laterano, built on the site of a Roman

imperial palace, and dating from the fourteenth century. The front is by

Galileo, very highly decorated. Within, the chapels of the double aisles

are especially interesting for their lavish embellishment. The{14} apse is

a very old part of the structure, and the Gothic cloister has grace and

dignity, with most admirable carved columns. It is a debated question

whether the ceiling of this church was painted by Michael Angelo or

Della Porta.

The Lateran Palace, close to San Giovanni, has a small decorated chapel

at the head of a sacred staircase, said to have been trodden by Christ

when he appeared before Pilate, and brought here from Jerusalem.

The Churches of San Clemente, Santi Giovanni Paolo, Santa Maria in Ara

Coeli are among the other churches of note.

The memorials of pagan and Christian times stand side by side in Rome,

and in roaming the city it is difficult to direct one’s steps on a

formal plan. Turning away from an arch or a temple of Roman origin, you

note a Renaissance church, and are tempted to enter it. If I fail to

point out here many buildings which the visitor should see, it is

because the number is so great.

The part of the city between the Regia and the Palatine Hill is very

rich in antiquities. It is said that Michael Angelo carried away a great

mass of stone from the Temple of Vesta to build a part of St Peter’s;

but I do not{15} know upon what authority this is stated. A few blocks of

stone are, however, all that remain of the buildings sacred to the

vestals.

The tall columns seen as we walk to the Palatine Hill, are relics of the

temple of Castor and Pollux. Behind the Regia is the temple of Julius

Cæsar, built by Augustus; and here Mark Antony delivered his splendid

oration. Near to this temple is the Forum, with traces of basilicas, and

a few standing columns. The whole way to the Capitoline abounds in

ancient stones of rich historical interest. Here are the walls of the

Plutei, with reliefs representing the life of Trajan, the grand arch of

Septimus Severus, the columns of the Temple of Saturn.

The Palatine Hill is crowned with the ruins of the Palace of the Cæsars.

Mural decorations still remain on the walls of an apartment. Here will

be seen relics of a school, a temple dedicated to Jupiter, and portions

of the famous wall of the mythical Romulus. These are but a few of the

antiquities of the Palatine, whence the eye surveys Rome and the rolling

Campagna.

In the quarter of the Coliseum are ancient baths, once sumptuously

fitted and adorned with images, now removed to the museum of the{16} city.

Trajan’s Column towers here to about one hundred-and-fifty feet. Then

there is the Pantheon, a classic building wonderfully preserved. All

these are but a few of the ancient edifices of Rome.

Among the more important museums and picture galleries are the splendid

Vatican, at which we have glanced, the Capitol Museum, the Palazzo del

Senatore, with works by Velazquez, Van Dyck, Titian, and other masters,

the National Museum, the Villa Borghese, the Dorian Palace, and the

Kircheriano.

The art annals of the Rome of Christian times are of supreme interest.

The greatest of the painters who came to study in Rome was Velazquez,

who was offered the hospitality of Cardinal Barberini in the Vatican. He

stayed, however, in a quieter lodging, at the Villa Medici, and

afterwards in the house of the Spanish ambassador. Velazquez paid a

second visit to Rome in 1649, where he met Poussin, and Salvator Rosa.

To Rosa he remarked, “It is Titian that bears the palm.”

The Spanish painter was made a member of the Roman Academy; and at this

time he painted the portrait of Innocent X., which occupies a position

of honour in the Dorian{17} Palace. Reynolds described this as “the finest

piece of portrait-painting in Rome.” Velazquez’ portrait of himself is

in the Capitoline Museum in the city.

The art records of Rome are so many that I cannot attempt to refer to

more than a small number of them. Literary associations, too, crowd into

the mind as we walk the lava-paved streets of the glowing capital.

Goethe sojourned long in Rome, and wrote many pages of his impressions.

In 1787 he writes of the amazing loveliness of a walk through the

historic streets by moonlight, of the solemnity of the Coliseum by

night, and the grandeur of the portico of St Peter’s. He praises the

climate in spring, the delight of long sunny days, with noons “almost

too warm”; and the sky “like a bright blue taffeta in the sunshine.” In

the Capitoline Museum he admired the nude “Venus” as one of the finest

statues in Rome. “My imagination, my memory,” he writes, “is storing

itself full with endlessly beautiful subjects.... I am in the land of

the arts.”

Full of rapture are the letters of Shelley from Rome: “Since I last

wrote to you,” he says to Peacock, “I have seen the ruins of Rome, the{18}

Vatican, St Peter’s, and all the miracles of ancient and modern art

contained in that majestic city. The impression of it exceeds anything I

have ever experienced in my travels.... We visited the Forum, and the

ruins of the Coliseum every day. The Coliseum is unlike any work of

human hands I ever saw before. It is of enormous height and circuit, and

the arches, built of massy stones, are piled on one another, and jut

into the blue air, shattered into the forms of overhanging rocks.”

Shelley was entranced by the arch of Constantine. “It is exquisitely

beautiful and perfect.” In March 1819, he writes: “Come to Rome. It is a

scene by which expression is overpowered, which words cannot convey.”

The Cathedral scarcely appealed to Shelley; he thought it inferior

externally to St Paul’s, though he admired the façade and colonnade.

More satisfying to the poet’s æsthetic taste was the Pantheon, with its

handsome fluted columns of yellow marble, and the beauty of the

proportions in the structure.

The Pantheon is generally admitted to be the most noble of the ancient

edifices of the city. It was erected by Agrippa 27 B.C., and sumptuously

adorned with fine marbles. The dome is{19} vast and nobly planned, and the

building truly merits Shelley’s designation, “sublime.”

Keats was buried in the Protestant cemetery in Rome, in a tomb bearing

the inscription: “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.” His loyal

and admiring friend, Shelley, wrote a truer memorial of the young poet:

“Go thou to Rome—at once the paradise,

The grave, the city, and the wilderness;

And where its wrecks like shattered mountains rise,

And flowering weeds, and fragrant copses dress

The bones of desolation’s nakedness

Pass, till the spirit of the spot shall lead

Thy footsteps to a slope of green access,

Where, like an infant’s smile, over the dead

A light of laughing flowers along the grass is spread.”

In 1850 Robert Browning and his wife were in Rome, and it was then that

Browning wrote the beautiful love poem, “Two in the Campagna,” telling

of the joy of roaming in:

“The champaign with its endless fleece

Of feathery grasses everywhere!

Silence and passion, joy and peace

An everlasting wash of air——”

Poets and painters have through the centuries drawn inspiration from

this wondrous city of splendid monuments and ancient grandeur. How{20} true

was Goethe’s statement that wherever you turn in Rome there is an object

of beauty and arresting interest.

The appeal of the city is strong, the variety bewildering, whether you

elect to muse upon the remains of the imperial days, or to study the

Renaissance art of the Christian churches. It is well, if possible, to

make a survey of the antiquities in chronological order, beginning with

an inspection of the ruins of the Romulean wall and the traces of the

oldest gates. Then the Forum should be visited in its valley, and the

art of the temple of Saturn, the Basilica Julia, and the Arch of Fabius

examined. The Temple of Vespasian, the Palace of Caligula, Trajan’s

Column, and the numerous arches will all arouse memories of the emperors

and the splendid purple days.

The Campagna is not only a wilderness, but it is rich in historic

memories. Here lived the cultured Cynthia, the friend of Catullus, the

poet, and of Quintilius Varus. Numerous villas dotted the Campagna in

the days of the emperors, and here, during the summer heats, retired

many of the wealthy citizens of Rome. Valuable antiquities, vases, urns,

and figures, have been unearthed from this classic soil.{21}

ASSISI

“THERE was a man in the city of Assisi, by name Francis, whose memory is

blessed, for that God, graciously presenting him with blessings of

goodness, delivered him in His mercy from the perils of this present

life, and abundantly filled him with the gifts of heavenly grace.”

So speaks Saint Bonaventura of the noble character of the holy man of

Assisi, whose figure arises before us as we tread the streets of the

town of his birth. For Assisi is a place of pilgrimage, filled with

fragrant memories of that saint of whom even the heterodox speak with

loving reverence. St Francis stands distinct in an age of fanatic

religious zeal, as an example of tolerance, a lover of mercy, and a

practical follower of the teaching of Christian benevolence.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, Pope Innocent III. offered

indulgences to the faithful who would unite in a crusade against the

Albigensian heretics of Languedoc. For{22} twenty years blood was shed

plentifully in this war upon heresy; for twenty years the hounds of

persecution were let loose on the hated enemies of papal absolutism.

“Kill all; God will know,” was the answer of the Pope’s legate during

this massacre, when asked by the crusaders how they could recognise the

heretics. While Languedoc and Provence were ravaged by the truculent

persecutors, and fires were lighted to burn the bodies of men, women and

children, St Francis lived in Assisi, preaching humanity and good will.

There is no testimony that he protested expressly against the

Albigensian crusades; but we know from his life and his writings that he

detested cruelty and violence, and never directly counselled

persecution.

In “The Golden Legend” we read that “Francis, servant and friend of

Almighty God, was born in the city of Assisi, and was made a merchant in

the twenty-fifth year of his age, and wasted his time by living vainly,

whom our Lord corrected by the scourge of sickness, and suddenly changed

him into another man, so that he began to shine by the spirit of

prophecy.”

Putting on the rags of a beggar, St Francis went to Rome, where he sat

among the mendi{23}cants before St Peter’s. Then began the miraculous cures

of lepers whose hands he kissed, and his many works of charity and

healing. He extolled “holy poverty,” and called poverty his “lady.” When

he saw a worm lying on the path, the compassionate saint removed it, so

that it should not be trodden on by passers-by. The birds he called his

brothers and sisters; he fed them, bade them sing or keep silence, and

they obeyed him. All birds and beasts loved him; and he taught the birds

to sing praises to their creator. St Francis was perhaps the first

eminent Christian who showed pity and love for the lower animals. In the

morass of Venice, he came upon a great company of singing-birds, and

entering among them, caused them to sing lauds to the Almighty.

St Francis taught asceticism to his followers, but it was the asceticism

of joy rather than of grief and pain. The saint had in him the qualities

of poet and artist as well as of pious mystic. He lived for a time the

life of the luxurious, and found it profitless and hollow; he passed

through the ordeal of the temptations that beset a young man born of

wealthy parents.

“The more thou art assailed by temptations,{24} the more do I love thee,”

said the blessed St Francis to his friend Leo. “Verily I say unto thee

that no man should deem himself a true friend of God, save in so far as

he hath passed through many temptations and tribulations.”

Flung into the prison of Perugia, he rejoiced and sang, and when the

vulgar threw dirt upon him and his friars, he did not resent their

rudeness.

Trudging bare-footed through Umbria, scantily clothed, and subsisting

upon crusts offered by the charitable, St Francis set an example of the

holiness of poverty which impressed the peasants and excited their

veneration for the preacher and his gospel.

He worked as a mason, repairing the decayed Church of St Damian, and

preached a doctrine of labour and industry, forsaking all that he had so

that he might reap the ample harvest of Divine blessing. In winter the

saint would plunge into a ditch of snow, that he might check the

promptings of carnal desire. He refused to live under a roof at Assisi,

preferring a mere shelter of boughs, with the company of Brother Giles

and Brother Bernard. A cell of wood was too sumptuous for him.

As St Francis grew in holiness there appeared{25} in him the stigmata of

Christ’s martyrdom. In his side there was the wound of the spear; in his

hands and feet were the marks of the nails. St Bonaventura relates that

after his death, the flesh of the saint was so soft that he seemed to

have become a child again, and that the wound in the side was like a

lovely rose.

He died, according to this historian, in 1226, on the fourth day of

October. His remains were interred in Assisi, and afterwards removed to

“the Church built in his honour,” in 1230.

After the canonisation of the holy St Francis many miracles happened in

Italy. In the church of his name in Assisi, when the Bishop of Ostia was

preaching, a huge stone fell on the head of a devout woman. It was

thought that she was dead, but being before the altar of St Francis, and

having “committed herself in faith” to him, she escaped without any

hurt. Many persons were cured of disease by calling upon the blessed

name of the Saint of Assisi, and mariners were often saved from wrecks

through his intervention.

St Francis lived when the fourth Lateran Council gave a new impetus to

persecution, by increasing the scope and power of the inquisition. This

gentlest of all the saints was sur{26}rounded by a host of influences that

made for religious rancour, and yet he preached a doctrine of love, and

was, so far as we can learn, quite untouched by the persecuting zeal

that characterised so many of his sainted contemporaries. It is with

relief, after the contemplation of the cruelty of his age, that we greet

the tattered ascetic of Assisi, as, in imagination, we see him pass up

the steps of the house wherein Brother Bernard was a witness of his

ecstasy.

The little city of Assisi stands on a hill; a mediæval town of a

somewhat stern character meets the eye as we approach it. Outside the

town is a sixteenth-century church, Santa Maria degli Angeli, which will

interest by reason of the Portinucula, a little chapel repaired by St

Francis. It was around this church that the first followers of the saint

lived in hovels with wattled roofs. Here was the garden in which the

holy brother delighted to wander, and to watch his kindred the birds,

and here are the rose bushes without thorns, that grew from the saint’s

blood.

Entering Assisi, we soon reach the Church of San Francisco, in which is

the reputed tomb of St Francis. This is not a striking edifice, but its

charm is in the pictures of Giotto. Poverty,{27} Chastity, and Obedience

are the subjects of these frescoes. Ruskin copied the Poverty, and made

a long study of these works. The picture symbolises the Lady of Poverty,

the bride of St Francis, who is given to him by Christ. This is one of

Giotto’s chief pictures. Chastity is a young woman in a castle; she is

worshipped by angels, and the walls of the fortress are surrounded by

men in armour. In another fresco St Francis is dressed in canonical

garb, attended by angels, who sing praise to him. It is said that Dante

suggested this subject to Giotto.

The frescoes of Simone, in a chapel of the lower church, are of much

interest to the art student. They are richly coloured and very

decorative, and have been considered by some authorities as equal to the

works of Giotto at Assisi. Simone was a painter of the Sienese School,

and according to Vasari, he was taught by Giotto. His “Annunciation” is

a rich work, preserved in the Uffizi Palace at Florence.

The twenty-eight scenes in the history of St Francis are in the upper

church, and in these we see again Giotto’s noblest art in the harmonious

grouping and the fluidity of his colour.{28}

The Cathedral of San Rufino is a handsome church. Here St Francis was

baptised, and in this edifice he preached.

The father of the saint was a woollen merchant, and his shop was in the

Via Portica. The house still stands, and may be recognised by its highly

decorated portal. This was not the birthplace of St Francis, for the

Chiesa Nuova, built in 1615, covers the site of the house.

In the Church of St Clare you are shown the “remains” of Saint Clare, in

a crypt, lying in a glass case.

When Goethe was in Assisi, the building that interested him more than

any other was the Temple of Minerva, built in the time of Augustus.

“At last we reached what is properly the old town, and behold before my

eyes stood the noble edifice, the first complete memorial of antiquity

that I had ever seen.... Looking at the façade, I could not sufficiently

admire the genius-like identity of design which the architects have here

as elsewhere maintained. The order is Corinthian, the inter-columnar

spaces being somewhat above the two modules. The bases of the columns,

and the plinths seem to{29} rest on pedestals, but it is only an

appearance.” Goethe concludes his description: “The impression which the

sight of this edifice left upon me is not to be expressed, and will

bring forth imperishable fruits.{30}”

VENICE

THE very name breathes romance and spells beauty. Poets, artists, and

historians without number have revealed to us the glories of this city.

Dull indeed must be the perception of loveliness of form and colour in

the mind of the man who is not deeply moved by the contemplation of the

Stones of Venice. Yet it seems to me that no city is so difficult to

describe; everything has been said, every scene painted by master hands.

One’s impression must read inevitably like that which has been written

over and over again. And in a brief enumeration of the buildings to be

seen by the visitor, how can the unhappy writer avoid the charge of

baldness and inefficiency?

VENICE, 1831.

THE GRAND CANAL.

Well, then, to say that Venice is supremely beautiful among the towns of

Italy is to set down a commonplace. It is a town in which the

matter-of-fact man realises the meaning of romance and poetry; a town

where the phlegmatic become sentimental, and the poetic are stirred to

ecstasies. George Borrow wept{31} at beholding the beauty of Seville by

the Guadalquivir in the evening light. “Tears of rapture” would have

filled his eyes as he gazed upon the splendours of the Grand Canal.

Some of the many writers upon Venice have found the scene “theatrical”;

others assert that the influence of Venice is sad, while others again

declare that the city provokes hilarity of spirits in a magical way.

Whatever the nature of the spell, it is strong, and few escape it.

Ruskin, Byron, the Brownings, and Henry James, are among the souls to

whom Venice has appealed with the force of a personality.

The spirit of Venice has been felt by thousands of travellers. Its

pictures—for every street is a picture—remain deeply graven on the

mind’s tablet.

Perhaps there is nothing made by man to float upon the waters more

graceful in its lines than a gondola. To think of Venice, is to recall

these gliding, swan-like, silent craft, that ply upon the innumerable

waterways. Like ghosts by night they steal along in the deep shadows of

the palaces, impelled by boatmen whose every attitude is a study in

lissome grace. To lie in a gondola, while the attendant noiselessly

propels the stately skiff with his{32} pliant oar, is to realise romance

and the perfection of leisurely locomotion.

What can be said of the sunsets, the almost garish colouring of sea and

sky, and the witchery of reflection upon tower and roof? What can be

written for the thousandth time of the resplendent churches, the rich

gilding, the noble façades, the hundred picturesque windings of the

canals between houses, each one of them a subject for the artist’s

brush? Is there any other city that grips us in every sense like Venice?

The eyes and the mind grow dazed and bewildered with the beauty and the

colour, till the scene seems almost unreal, a fantasy of the brain under

the influence of a drug.

The student of life and the philosopher will find here matter for

cogitation, tinged maybe with seriousness, even sadness. Venetian

history is not all glorious, and the city to-day has its social evils,

like every other populous place on the globe. There are beggars, many of

them, artistic beggars, no doubt; but they are often diseased and always

unclean. Yet even the dirty faces of the alleys, in this city of

loveliness, have, according to artists, a value and a harmony. There is

the same obvious,{33} sordid poverty here as in London or Manchester. But

the dress of the people, even if ragged, is bright, and the faces, even

though wrinkled and haggard, fit the scene and the setting in the

estimate of the painter.

If your habit is analytic and critical, you will find defects in the

modern life of Venice that cannot be hidden. The city is not prosperous

in our British sense of the word. There is an air of decayed grandeur,

an impression that existence in this town of exquisite art is not

happiness for the swarm of indigents that live in the historic purlieus.

On the other hand, there is the climate, a soft, sleepy climate, not

very healthy perhaps, but usually kindly. The sun is generous, the sky

rarely frowns. Life passes lazily, dreamily, on the oily waters of the

canals, in the piazza, and in those tall tumble-down houses built on

piles. No one appears to hurry about the business of money-getting; no

one apparently is eager to work, except perhaps the unfortunate

mendicants and the persuasive hawkers, who do indeed toil hard at their

occupations.

When the evening breeze bears the interesting malodours of the canals,

with other indescribable and characteristic smells, and the{34} sun sinks

in crimson in a flaming sky, and music sounds from the piazza and the

water, and the gondolas glide and pass, and beautiful women smile and

stroll in streets bathed in gold, you will think only of the loveliness

of Venice, and forget the terrors of its history and the misery of

to-day. And it is well, for one cannot always grapple with the problems

of life; there must be hours of sensuous pleasure. Sensuous seems to me

the right word to convey the influence of Venice upon a summer evening,

when, a little wearied by the heat of the day, you loll upon a bridge,

smoking a cigar, and drinking in languidly the beauty of the scene,

while a grateful breeze comes from the darkening sea.

Go to the Via Garibaldi, if you wish to lounge and to study the

Venetians of “the people.” Here the natives come and go and saunter. The

women are small, like the women of Spain, dark in complexion, and in

manner animated. They are very feminine; often they are lovely.

You will be struck with the gaiety of the people, a sheer

lightheartedness more evident and exuberant than the gaiety of Spanish

folk. Perhaps the struggle for existence is less keen than it seems

among the inhabitants of the more{35} lowly quarters of the city. At

anyrate, the Venetians are lovers of song and laughter. A flower

delights a woman, a cigarette is a gift for a man. They are able to

divert themselves in Venice without sport, and with very few places of

amusement.

“The place is as changeable as a nervous woman,” writes Mr Henry James,

“and you know it only when you know all the aspects of its beauty. It

has high spirits or low, it is pale or red, grey or pink, cold or warm,

fresh or wan, according to the weather or the hour.”

Having given a faint presentment of the beauties of Venice, I will refer

to some of the chief episodes of its great history. In the earliest

years of its making, we are upon insecure ground in attempting to write

accurately upon Venetia. The city probably existed when the Goths swept

down upon Italy, about 420, and it fell a century later into the hands

of the fierce Lombards. Under the Doges (dukes) the land was wrested

here and there from the waves, the mudbanks protected with piles and

fences, and the great buildings began to arise from a foundation of

apparent instability.

The ingenuity of the architect and the builder in constructing this city

is nothing short of{36} marvellous. In the sixth century the town was no

doubt a collection of huts on sandbanks, intersected by tidal streams.

There were meadows and gardens by the verge of the sea, and the

inhabitants made the most of every yard of firm soil. St Mark’s

Cathedral was built in the tenth century, to serve as a resting-place

for the bones of the saint.

Under the wise rule of Pietro Tribuno, Venice withstood the attack of a

Hungarian horde. The city was walled in and fortified, and the natives

gathered at Rialto. The resistance was successful. The Doge who saved

the city was one of the most honoured of all the rulers of Venice as a

brave general and a man of scholarly parts.

Genoa and Pisa, formed into a powerful republic, warred with Venice in

the eleventh century; but the Venetians won in the protracted warfare.

Wars in Italy and wars in the East followed, and internal trouble

reigned intermittently in the city.

The discovery of America by Columbus, and the opening up of trade with

Hindustan, affected Venice injuriously. Until then the city had held a

monopoly as a market for the products of the Orient. Her great power

and{37} wealth were imperilled by the discoveries of Columbus, the Genoese

voyager, and by the rounding of Cape Horn by the Portuguese adventurers.

Spain and Portugal were reaping the splendid golden harvest while Venice

was impoverished. Consternation filled the minds of the citizens. The

great Republic had reached the height of its glory in the fifteenth

century, but from the falling off of her commerce she never recovered.

It is curious that in the period of decline, Venice expended much wealth

in works of art, and in the embellishment of the buildings and palaces.

Several of the city’s greatest painters flourished at this time.

The Doge’s Palace, often burned down, was rebuilt in its present

grandeur. St Mark’s was constantly repaired, decorations were added, and

internal parts reconstructed. The palaces of the rich sprang up by the

waterways of this city in the sea.

Printing was already an art and industry in Venice. John of Spires used

movable type, and succeeding him were many distinguished printers, whose

presses supplied the civilised world with books.

A terrible plague devastated the city in 1575.{38} Among the victims were

the great painter, Titian, then nearly a hundred years of age. The

epidemic spread all over Venice.

When Pope Paul V. endeavoured to bring the citizens under his autocratic

rule, they resisted with much firmness. One of the causes of offence was

that the Venetians favoured the principle of toleration in religious

beliefs, and permitted the heretical to worship according to their

consciences. The Pope, after fruitless negotiations, excommunicated

Venice, sending his agents with the documents. With all vigilance, the

government of the city forbade the exposure of any papal decree in the

streets, while the Doge stoutly asserted that the people of Venice

regarded the bull with contempt.

Nearly all Europe sided with Venice in this conflict between Pope and

Doge. England was prepared to ally herself with France, and to assist

Venice. Months passed without developments. Venice remained Catholic,

but refused to become a vassal of the Pope of Rome. Paul was enraged and

humiliated. One cannot admire his action; yet pity for the proud,

sincere, and baffled Pontiff tinges one’s view of the struggle. Venice

even refused to request{39} the abolition of the ban. She remained quietly

indifferent to the thunderings of the See, and haughtily criticised the

overtures of reconciliation offered through the French cardinals.

Finally, with dignity and yet a touch of farce, the Senate handed over

to the Pope’s emissaries certain offenders, “without prejudice,” to be

held by the King of France.

Paolo Sarpi, the priest and born diplomat, was the hero of Venice during

this quarrel with Rome. Sarpi was a man of unassailable virtue and

integrity, a tactful leader of men, and possessed of intrepidity. He

was, not unnaturally, detested by the adherents of the Pope for his

defence of Venetian rights and privileges. One night, crossing a bridge,

Brother Paolo was attacked by ruffians, and stabbed with daggers. The

assailants had been sent from Rome to kill the obnoxious priest. But the

scheme failed, for Paolo Sarpi recovered from his wounds, and the

attempt upon his life endeared him still more deeply to the hearts of

the Venetians.

Some years after he died in his bed, lamented by high and low in the

city. Before the Church of Santa Fosca stands a memorial to this brave

citizen.{40}

The Venice of the eighteenth century was a decaying city, with an

enervated, apathetic population, given to gaming, and improvident in

their lives. Many of the noble families sank into penury. Still the

people sang and danced and held revelry; nothing could quench their

passion for enjoyment. The Republic was now the prey of the great

imperialist Napoleon, who adroitly acquired Venice by threats of war

followed by promises of democratic rule. A few shots were fired by the

French; then the Doge offered terms, which gave the city to the Emperor,

while the citizens held rejoicings at the advent of a new government.

A few months later Venice was given to Austria by the Treaty of

Campoformio. Between the French and the Austrians the city passed

through a troublous period of many years. Venice was now a fallen state.

But what a memorial it is! The city is like a huge volume of history,

and we linger over its enchanting pages. Let us now look upon the

monuments that reveal to us the soul and genius of Venice of the olden

times.

Several of the most important buildings in Venice border the fine square

of San Marco, a favourite evening gathering-place of the Venetians.{41}

Dominating the piazza is the Cathedral of San Marco, with its

magnificent front, a bewildering array of portals, decorated arches,

carvings in relief, surmounted by graceful towers and steeples. The

style is Byzantine, and partly Roman, designed after St Sophia at

Constantinople. In shape the edifice is cruciform, with a dome to each

arm of the cross. High above the cathedral roof rises the noble

Campanile.

Over the chief portal are four bronze horses, brought here in 1204 from

Byzantium. The steeds are beautifully modelled, and the work is ascribed

to Lysippos, a sculptor of Corinth. Napoleon took the horses to Paris,

but they were restored to Venice in 1815.

The mosaic designs of the façade represent “The Last Judgment,” among

other Scriptural subjects, while one of the mosaics depicts San Marco as

it was in the early days. A number of reliefs and images adorn the

arches of each of the five doorways of the main entrance.

Within the decorations are exquisite. Ruskin writes: “The church is lost

in a deep twilight, to which the eye must be accustomed for some moments

before the form of the building can{42} be traced; and then there opens

before us a vast cave, hewn out into the form of a cross, and divided

into shadowy aisles by many pillars. Round the domes of its roof the

light enters only through narrow apertures like large stars; and here

and there a ray or two from some far-away casement wanders into the

darkness, and casts a narrow phosphoric stream upon the waves of marble

that heave and fall in a thousand colours along the floor. What else

there is of light is from torches or silver lamps, burning ceaselessly

in the recesses of the chapels; the roof sheeted with gold, and the

polished walls covered with alabaster, give back at every curve and

angle some feeble gleaming to the flames, and the glories round the

heads of the sculptured saints flash out upon us as we pass them, and

sink again into the gloom.”

In the vestibule of the cathedral, the mosaic decoration depicts Old

Testament scenes. In the apse are represented a figure of the Lord, with

St Mark, and the acts of St Peter and St Mark. The mosaics of the east

dome represent Jesus and the prophets. Tintoretto’s design is in an

adjoining archway, and in the centre dome is “The Ascension.” The

western dome has “The Descent of the Holy Ghost,” and an arch{43} here is

decorated with “The Last Judgment.” There are more mosaics in the

aisles, illustrating “The Acts of the Apostles.”

The high altar is a superb example of sculpture. The roof is supported

by marble columns, carved with scenes from the lives of Christ and the

Virgin Mary. The figures date from the eleventh century. A magnificent

altarpiece of gold-workers’ design is shown for a fee. The upper part is

the older, and it was executed in Constantinople. The lower portion is

the work of Venetian artists of the twelfth century.

The baptistery contains early mosaics, a monument of one of the Doges of

Venice; and the stone upon which John the Baptist is stated to have been

beheaded is kept here.

“The Legend of San Marco” is the design in the Cappella Zen, adjoining

the baptistery. Here are the tomb of Cardinal Zen, a Renaissance work in

bronze, and a handsome altar.

In his rapturous description of the interior of San Marco, Ruskin

continues: “The mazes of interwoven lines and changeful pictures lead

always and at last to the Cross, lifted and carved in every place and

upon every stone; sometimes with the serpent of eternity wrapt round

it,{44} sometimes with doves beneath its arms, and sweet herbage growing

forth from its feet.”

Venetian architecture has a character of its own. We find the Oriental

influence in most of the buildings of Venice; the ogee arch is commonly

used, and the square billet ornament is a distinguishing mark. The first

Church of San Marco was built in 830.

The Palace of the Doge is in the Piazza. Its architecture has been

variously described and classified. It has strong traces of Moorish

influence, while in many respects it is Gothic. The decorated columns of

the arcades are very beautifully designed. Archangels and figures of

Justice, Temperance, and Obedience adorn the building, and there is an

ancient front on the south side. Enter through the Porta della Carta,

and you will find a court of wonderful interest, with rich façades and

the great staircase, which is celebrated as the crowning-place of the

Doges.

The architecture of the interior of the palace is of a later date than

that of the exterior. In the big entrance hall are Tintoretto’s

portraits of legislators of Venice. From here enter the next apartment,

which contains a magnificent painting of “Faith” by Titian. In another{45}

hall are four more of Tintoretto’s works, and one by Paolo Veronese. The

Sala del Collegio is one of the principal chambers of the palace and its

ceiling was painted by Veronese. Here is the Doge’s throne.

Tintoretto and Palma were the artists who executed the paintings in the

Hall of the Senators. The adjoining chapel is decorated with another of

Tintoretto’s pictures. Pass to the Hall of the Council of Ten, where the

rulers of the city sat, and note the gorgeous ceiling by Paolo Veronese.

A staircase leads to the Hall of the Great Council below. From the

window there is an inspiriting view. The walls are hung with portraits,

but the glory of this hall is Tintoretto’s “Paradise,” an immense

painting.

Before leaving the Palace of the Doges, I will devote a few lines to the

Schools of Venice of the sixteenth century. Unfortunately most of the

works of Giorgione, the most characteristic painter of Venice, have

disappeared. He was the founder of a tradition, and the teacher of many

painters, including Palma, while his work influenced a number of his

contemporaries. Titian, born in 1477, was one of Giorgione’s admirers,

and his early work shows his influence.{46} The pictures of the great

Venetian master are one of the glories of the city. Some of his

paintings are in the Academy, in the Church of Santa Maria dei

Friari—where there is a monument to the artist—in the Church of Santa

Maria della Salute, and in the private galleries of the city.

In the Academy collection, in a large building in the square of St

Mark’s, are Titian’s much-restored “Presentation” and the “Pieta,” among

the finest specimens of the Venetian School of painters. The celebrated

“Assumption” has been also restored.

“There are many princes; there is but one Titian,” said Charles V. of

Spain, who declared that through the magic of the Venetian painter’s

pencil, he “thrice received immortality.” Forty-three examples of the

art of Titian are in the Prado Gallery of Madrid. Sanchez Coello, Court

artist to Philip II. was one of the students of the Italian master;

indeed several of the great painters of Spain were influenced by Titian,

and none of them revered him more than Velazquez.

Tintoretto’s “Miracle of St Mark” and “Adam and Eve” are two instances

of his genius for colour, in the Academy, calling for{47} special study,

and another of his works is to be seen in Santa Maria della Salute. We

have just looked at a number of this painter’s pictures in the Doge’s

Palace.

It has been said that Tintoretto inspired El Greco, whose pictures we

shall see in Toledo. Tintoretto was a pupil of Titian, basing his

drawing on the work of Michael Angelo, and finding inspiration for his

colour in the painting of Titian. He was a most industrious and prolific

artist.

Paolo Veronese, though not a native of Venice, was one of the school of

that city. He surpassed even Tintoretto in the use of colour, and

adorned many ceilings and altars, besides painting canvases. The “Rape

of Europa” and others of Paolo’s mythical subjects display his gift of

colour and richness of imagination.

Among the later Venetian painters, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo is perhaps

the most remarkable. His conceptions were bizarre, and his fanciful

style is manifest in his picture of the “Way to Calvary,” preserved in

Venice. Canaletto may be mentioned as the last of the historic painters

of Venice.

The work of Bellini must on no account be forgotten before we leave the

subject of{48} Venetian art. His “Madonna Enthroned” is in the Academy,

among other of the masterpieces of his brush; and one of his most

exquisite paintings is in the Church of the Friari.

Let us also remember the splendid treasures of the art of Carpaccio, as

seen in the picture of “Saint Ursula” in the Academy, and in the

delightful paintings of San Giorgio, which moved Ruskin to rapture.

The many churches of Venice contain pictures of supreme interest. Most

of them are in a poor light, and can only be examined with difficulty.

San Zanipolo is a church of Gothic design, built by the Dominicans,

abounding in tombs and monuments. San Zaccaria has Bellini’s altarpiece

“The Madonna and Child.”

Many of the palaces, especially those of the Grand Canal, are

exceedingly beautiful in design, whether the style is Renaissance or

Byzantine-Romanesque. Among the oldest are the Palazzo Venier, the

Palazzo Dona, and the Palazzo Mesto; while for elegance the following

are notable: Dario, the three Foscari palaces, the Pesaro, the Turchi,

and Ca d’ Oro, and the Loredan.

Some of these historic houses are associated{49} with men of genius of

modern times. Wagner lived in the Palazzo Vendramin Calergi. In 1818

Byron resided in the Palazzo Mocenigo, and Browning occupied the Palazzo

Rezzonico.

Robert Browning and his wife had a passionate love for Venice. As a

young man the poet visited the city, and returned to England thrilled by

his impressions. Mrs Bridell Fox, his friend, says that: “He used to

illustrate his glowing descriptions of its beauties—the palaces, the

sunsets, the moonrises, by a most original kind of etching. Taking up a

bit of stray notepaper, he would hold it over a lighted candle, moving

the paper about gently till it was cloudily smoked over, and then

utilising the darker smears for clouds, shadows, water, or what not,

would etch with a dry pen the forms of lights on cloud and palace, on

bridge or gondola, on the vague and dreamy surface he had produced.”

William Sharp—from whose “Life of Browning” I cull the passage just

quoted—tells us that his friend selected the palace on the Grand Canal

as a corner for his old age. Browning was “never happier, more sanguine,

more joyous than here. He worked for three or four hours each morning,

walked daily for{50} about two hours, crossed occasionally to the Lido with

his sister, and in the evenings visited friends or went to the opera.”

In 1889 Robert Browning died in Venice, on a December night, as “the

great bell of San Marco struck ten.” He had just received news of the

success of his “Asolando.” The poet was honoured in the city by a

splendid and solemn funeral procession of black-draped gondolas,

following the boat that held his body. Would he not have chosen to die

in the Venice that he loved with such intense fervour?

Among the statuary in the streets is the image of Bartolomeo Colleoni on

horseback, “I do not believe that there is a more glorious work of

sculpture existing in the world,” writes Ruskin of this statue, which

stands in front of SS. Giovanni e Paolo. In the Piazzetta by the Palace

of the Doges are the two columns, which everyone associates with Venice,

bearing images of the flying lion of St Mark, and of St Theodore

treading upon a crocodile.

One other public building must be seen by the visitor. This is the

beautiful library opposite the Doge’s Palace, an edifice that John

Addington Symonds praises as one of the chief achievements of Venetian

artists. The cathedral,{51} the ducal palace, the library, and the Academy

of Arts are certainly four impressive and splendid buildings.

If you have seen the old roofed bridge that spans the river at the head

of the Lake of Lucerne, you will have an impression of the famous Rialto

of Venice. The historic bridge is charged with memories of the days when

“Venice sate in state throned on her hundred isles,” and citizens asked

of one another, in the words of Solanio, in The Merchant of Venice.

“Now, what news on the Rialto?” The bridge is mediæval in aspect, and

romantic in its associations. You cannot lounge there without an

apparition of Shylock, raving at the loss of the diamond that cost him

two thousand ducats in Frankfort.

All around this “Queen of Cities” are places of supreme interest to the

student of architecture and the lover of natural beauty. Padua, and

Vicenza, with its rare monuments of Palladio, Murano, Torcello, and

other towns and villages with histories are within access of Venice. But

do not hasten from Venezia. It is a town in which one should roam and

loiter for long days.{52}

PERUGIA

A WHITE town, perched high on a bleak hill, is one’s first impression of

Perugia. The position of the capital of Umbria is menacing, and without

any confirmation of history, one surmises that this was once a Roman

fortified town. After being built and held by the Etruscans, Perugia was

taken by the Roman host, and called Augusta Perusia. For centuries the

town was the terror of Umbria. Its citizens appear to have been a

superior order of bold banditti, continually making raids on the

surrounding towns and villages, and returning with spoil.

Mediæval traditions of Perugia are a romance of battle within and

without the town. At one time one faction held sway, at another a rival

faction gained the upper hand, and the natives spent much time and

energy in endeavouring to kill one another. The story is perhaps more

melodramatic than tragic. It reads almost like a novel of sensational

episodes, related by{53} a fertile and imaginative writer in order to

thrill his readers.

Pope Paul III. was the subduer of Perugia. He dominated the town with a

citadel, now destroyed, and broke the power of its martial inhabitants

with the sword and the chain.

The surroundings of the town are bare, except for the olive groves which

give a cold green to a landscape somewhat devoid of warm colouring. You

either climb tediously up a long hill to the city, or ascend in an

incongruous electric tramcar. Entering the place, the chances are that

your sense of smell will be affronted somewhat rudely, for Perugia is

not very modern in its sanitary system.

Assisi is seen in the distance, bleached on its slope, and there are

far-off prospects of high mountains. The Prefeturra terrace is over

sixteen hundred feet above the sea, and is a fine view-point.

The setting of Perugia makes no appeal to the lover of sylvan charms. It

stands on an arid height, constantly attacked by the wind, and in dry

weather the town is very dusty. But there is hardly a narrow street nor

a corner without quaintness and beauty for the eye that can appreciate

them. Almost every{54}where are glimpses of elegant spires and tall

belfries.

The cathedral, dedicated to San Lorenzo, is a fourteenth-century

edifice, with an aged aspect, and not much beauty in its decorations. In

the Chapel of San Bernardino is “The Descent from the Cross,” by

Baroccio. This artist was a follower of Coreggio, fervent in his piety,

and devoted to his art. He was born in Urbino, and painted several

pictures in Rome. The example in the cathedral is one of his best-known

paintings. Signorelli designed an altarpiece for this church. Three

popes were buried here, Innocent III., Urban IV., and Martin IV.

Close to San Lorenzo is the Canonica, a palace of the popes, a huge,

heavy building. The fortress-like Palazzo Pubblico is still used as the

town hall. Its history is stirring. Many trials have been held in its

halls, and we read that culprits were sometimes hurled to death from one

of the windows.

The upper part of the Palazzo is a gallery of paintings, the works

representing the Umbrian School. Here we may study Perugino, Fiorenzo di

Lorenzo, Bonfigli, and other masters of the fifteenth century. Perugino

instituted a school of painting in the town. In the Sistine Chapel,{55} in

Florence, we may see some of his frescoes. We shall see presently

examples of his works in other buildings in Perugia.

Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, Bonfigli, and Pinturicchio are represented in the

secular buildings and churches of the town. An altarpiece by Giannicola,

one of Perugino’s pupils, should be noticed.

But perhaps the most important of the paintings are Fra Angelico’s

“Madonna and Saints,” “Miracles of San Nicholas,” and “The

Annunciation.”

Perugino’s frescoes in the Exchange (Collegio del Cambio) are very

beautiful, depicting the virtues of illustrious Greeks and Romans.

“Perugino’s landscape backgrounds,” writes Mr Robert Clermont Witt, in

“How to look at Pictures,” “with their steep blue slopes and winding

valleys are as truly representative of the hill country about Perugia as

are Constable’s leafy lanes and homesteads of his beloved eastern

counties.”

In the museum of the University, we shall find a number of antiquities

of pre-Roman and Roman times. The Church of San Severo must be visited,

for it contains a priceless early work by Raphael.{56}

The Piazzi del Municipio was the scene of many conflicts in the

troublous days of Perugia. Here the austere Bernardino used to preach,

and here were held the pageants of the popes upon their visits to the

town. Around this piazzi is a network of narrow, ancient thoroughfares,

with many curious houses.

The Piazzi Sopramuro is one of the oldest parts of the town. In this

vicinity is the ornate, massive Church of San Domenico, with a

magnificent window, and the Decorated monument of Benedict XI.

Passing through the Porta San Pietro, we approach the Church of San

Pietro, considered to be the oldest sacred building in the town. It has

a splendidly ornamented choir, and in the sacristy are some remarkable

works of Perugino. The belfry of this church is of very graceful design.

About three miles from Perugia, towards Assisi, are some Etruscan tombs,

with buried chambers, a vestibule, and several statues. This monument is

of deep interest. It is a family cemetery of great antiquity, and the

carvings are of exquisite art.{57}

FLORENCE

Firenze la bella, the pride of its natives, the dream of poet and

painter and the delight of a multitude of travellers, lies amid graceful

hills, clothed with olive gardens and dotted with white villas. In the

clear distance are the splendid Apennines. Climb to the terrace of San

Miniato, and you will gain a wide general view of this great and

beautiful city of culture and the arts. The wonderful campanile of

Giotto rises above the surrounding buildings, rivalling the height of

the cathedral; the sunlight glows on dome and tower, and the valleys and

glens lie in deep shadow, stretching away to the slopes of the

mountains.

Very lovely, too, is the prospect from the Boboli Gardens, and finer

still the outlook from Fiesole, whence the eye surveys the Cathedral,

the Baptistery, the Campanile, the noble churches of Bruneschi, the

Pitti Palace, and many fair buildings of the Middle Ages.

Gazing over Florence from one of the elevations of the environs, a vast

pageant of history{58} seems revealed, and men of illustrious name pass in

long procession in the vision of the mind. How numerous are the great

thinkers and artists associated with the city from Savonarola to the

Brownings! We recall Dante, Giotto, Boccaccio, Michael Angelo—the roll

seems inexhaustible. Almost all the famous men of Italy are connected

with the culture-history and the political annals of Florence. The city

inspires and holds us with a spell; we are impelled to wander day after

day in the narrow streets, to linger in the fragrant gardens, to roam in

the luxuriant valleys of the surrounding country, and to climb the hill

of classic Fiesole.

Rich and beautiful is the scenery between Florence and Bologna, with its

glimpses of the savage Apennines. The glen of Vallombrosa is one of the

loveliest spots in the vicinity, where the old monastery broods amid

beech and chestnut-trees. It was this scene that Milton recalled when he

wrote the lines:

“Thick as autumnal leaves that strew the brooks

In Vallombrosa....”

FLORENCE.

PONTE SANTA TRINITA, 1832.

The history of the city is of abundant interest. Florence was probably

an important station in the days of the Roman Triumviri. Totila{59} the

Goth besieged and destroyed the town, and Charlemagne restored it two

hundred and fifty years later. Machiavelli states that from 1215

Florence was the seat of the ruling power in Italy, the descendants of

Charles the Great governing here until the time of the German emperors.

In the struggle between the Church and the State, the city took sides

with the popular party for the time being. There were, however, constant

factions within Florence, due to the quarrels of the Buondelmonti and

Uberti families. Frederick II. favoured the Uberti cause, and with his

help, the Buondelmontis were expelled. Then came the remarkable period

of the Guelfs and the Ghibellines, the former standing for the Pope, and

the latter siding with the Emperor. Florence favoured the Guelfs, and

the Ghibellines resolved to destroy the city; but the Guelf party again

won ascendancy in Florence. The trouble was, however, not at an end. For

years Florence was disturbed by the conflicting aims of these intriguing

parties.

Grandees and commoners warred in Florence in the fourteenth century, and

efforts were made by the aristocratic rulers to curtail the liberties of

the people. This was frustrated by the{60} commoners, and the government

was reformed on a more democratic basis. Peace followed during a period

of about ten years, but calamity befell Florence in the form of the

pestilence described by Boccaccio. Ninety-six thousand persons are said

to have died from the ravages of this plague.

As early as the twelfth century there were many signs in Florence of

intellectual liberty. The doctrine of the eternity of matter was openly

discussed, and on to the days of Savonarola civilising forces were at

work in this centre of culture.

Girolamo Savonarola arose at the end of the fifteenth century, and his

reforming influence soon spread through Italy. “The church is shaken to

its foundations,” he cries. “No more are the prophets remembered, the

apostles are no longer reverenced, the columns of the church strew the

ground because the foundations are destroyed—in other words because the

evangelists are rejected.” Such heresy as this brought Savonarola to the

stake.

Greater among the mighty of Florence was Dante, born in a memorable age

of art and invention. “The Vita Nuova,” inspired by the gentle damsel,

Beatrice, was written when Dante{61} had met his divinity at a May feast

given by her father, Folco Portinari, one of the chief citizens of

Florence. Beatrice died in 1290 at the age of twenty-four. Boccaccio

states that the poet married Gemma Donati about a year after the death

of Beatrice. Dante died in 1321, and was buried in Ravenna.

For me the chief appeal in Seville, Antwerp, or any old Continental town

is in the human associations. In Florence, roaming in the ancient

quarters, the figure of Dante, made so familiar by many paintings,

arises with but little effort of the imagination, for the streets have

not greatly changed in aspect since his day. The atmosphere remains

mediæval.

Can we not see the moody poet, driven from his high estate by the

quarrels of the ruling houses, pacing the alleys, repeating to himself:

“How hard is the path!” Can we not picture him in company with Petrarch,

who, after the merry-making in the palace, remarked that the wise poet

was quite eclipsed by the mountebanks who capered before the guests? And

do we not hear Dante’s muttered “Like to like!”

Two great English poets, Chaucer and Milton, made journeys to Florence.

Giovanni Boccaccio was born in 1313, in{62} Certaldo, a small town some

leagues from Florence. He spent a few years in France and in the south

of Italy, returning to Florence at the age of twenty-eight. Boccaccio

was the close friend and the biographer of Dante, and a contemporary of

Petrarch.

In the time of Lorenzo de Medici, Florence was a prosperous city and a

seat of learning. Machiavelli writes of Lorenzo: “The chief aim of his

policy was to maintain the city in ease, the people united, and the

nobles honoured. He had a marvellous liking for every man who excelled

in any branch of art. He favoured the learned, as Messer Agnola da

Montepulciano, Messer Cristofano Landini, and Messer Demetrio; the Greek

can bear sure testimony whence it came that the Count Giovanni della

Mirandola, a man almost divine, withdrew himself from all the other

countries of Europe through which he had travelled, and attracted by the

munificence of Lorenzo, took up his abode in Florence. In architecture,

music, and poetry, he took extraordinary delight.... Never was there any

man, not in Florence merely, but in all Italy, who died with such a name