Title: Some Zulu Customs and Folk-lore

Author: L. H. Samuelson

Release date: August 4, 2014 [eBook #46501]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net. This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive

(http://archive.org).

It is hoped that the following short stories, which the writer has endeavoured to tell in the simplest language, will give some idea of the inner feelings and belief of a people whose individuality is, despite the number of years we have been in contact with them, little known to the large majority of us. Even among those well versed in the language and the practical or legal customs of the natives, there are few who are acquainted with the undercurrents of thought, and the many traditions and superstitions, which are accepted without question by the Zulus, and which form an essential part of the mental life of all among them who have not had their ideas modified to some extent by European teaching, and vi which continue to have a strong hold upon the larger number even of those who have had the advantages of some kind of education at the hands of the missionaries and other teachers. The common estimate of the African native is that he is a being with no ideas above his cattle and his physical wants; but a more intimate acquaintance with their life, such as the writer had from being amongst them for many years at her father’s mission station in Zululand, will reveal that the native has an ideal life of his own. This, it is true, is in many instances of a crude and savage character; yet it rises a little, if only a little, above what is “of the earth, earthly,” and, though it may possibly provoke a smile on account of its crudeness or simplicity, it will at times strike a chord of sympathy as a touch of nature—as an aspiration, however feeble, to penetrate beyond the veil which hides the unseen world from human eyes.

vii Those who have made the folklore of savage or half-civilized peoples their study cannot fail to be struck with the strange analogy between some of the superstitions of the Zulus and those of many other nations. Vague and undefined as some of their native ideas are, there is still a belief in the existence of a spirit world around them by which their lives are affected, and a groping after a knowledge of influences beyond human power, which direct the destinies of mortal man, and of mysterious forces which can be brought into play by men peculiarly gifted. In their custom of sacrificing to the spirits, to induce them to restore the health of a patient, and their belief in the powers of wizards, we find them under the thraldom of the same superstitions which have become familiar to us in so many and such diverse directions—from the ancient Greeks to the modern spiritualists—and which have at times played so great a part in the viii history of the world. Their belief in the “spirits of their fathers” watching over them is similar to the idea underlying Chinese ancestral worship, and the wizard’s powers of killing or injuring do not differ in essentials from the so-called spirit healing of enlightened America or the working of the “evil eye” still believed in by the ignorant among the peasantry of Italy. If, therefore, in reading of the Zulu superstitions we are provoked at times to smile, it must be rather at the form than at the substance. The superstitions are the same that have ever existed, and that, despite all our advancement, still find adherents among civilized communities, though among these they are expressed in more delicate language and acted upon in less savage ways. With the large mass of Europeans such superstitions, thanks to modern enlightenment, are taken at their true value; but so long as there are among ourselves people who believe in planchettes, we ix cannot quite afford to look with supercilious contempt upon the African who believes in wizards. And there is one point of view in which a knowledge of what he believes is of material importance. To him, these superstitions are realities. He accepts them as facts of which he has to take account, and which will be acted upon by the society in which his lot is cast. To estimate his true character, and form any accurate idea of the manner in which his mind will work, some knowledge not only of his customs but also of his social habits and beliefs is thus essential.

The author therefore trusts that the present small work may prove not only of some scholastic value, but may also be of practical use to the missionary, the administrator, and, indeed, to all who come into contact with the little understood “Native,” or who are interested in his progress and well-being.

x The Author of these sketches is deeply indebted to Miss A. Werner for the pains she took to introduce a few of them, through the “Journal of the African Society,” to the notice of many of those gentlemen who, having held the highest positions in South Africa, or been in supreme power over the Zulu Nation, know how important it is that those who hold the destinies of this interesting people in their hands should understand as much as possible of the bias of their minds and the springs of their conduct. But for their generous expression of this opinion, it is doubtful whether this little volume would ever have struggled to the light. To them she is profoundly grateful, as she is also to those whose ready support has enabled her to bring her venture to a successful issue. She wishes also to acknowledge the valuable assistance received from the ex-President of the Folk-lore Society and the Secretaries of the Royal Colonial Institute and the African Society.

| PAGE | |

| A Zulu Wedding | 1 |

| How Twins were Treated | 7 |

| “Sending Home,” I. | 11 |

| “Sending Home,” II. | 13 |

| Departed Spirits | 18 |

| Sacrificing to Spirits | 20 |

| The Death of a Chief | 24 |

| Inkata | 27 |

| The Zulu Annual Feast | 30 |

| The Doctoring of an Army | 39 |

| Finding out Wizards | 44 |

| A Fire Extinguisher | 47 |

| Rain Doctors | 48 |

| Rainbow, Lightning, and Eclipses | 50 |

| Praying for the Corn | 53 |

| Old Wives’ Tales | 56 |

| xii King Mpande’s Snake Charmer | 62 |

| How Death came into the World | 66 |

| The Zulu’s Choicest Bit of Meat | 68 |

| A Friendly Way of Obtaining Food | 69 |

| Peacemaking over a Pinch of Snuff | 71 |

| Rules of a Zulu Hunt | 75 |

| Bongoza’s Smartness | 77 |

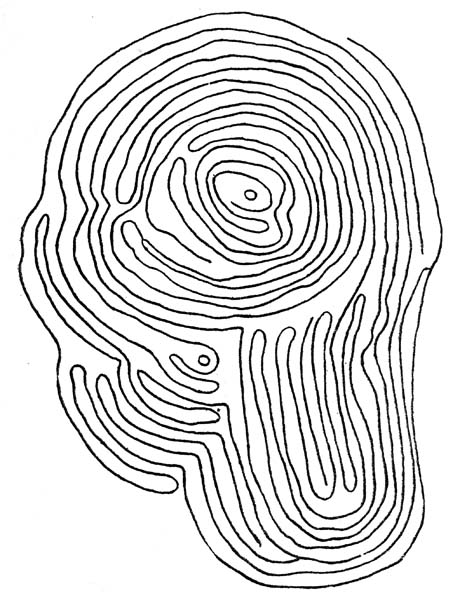

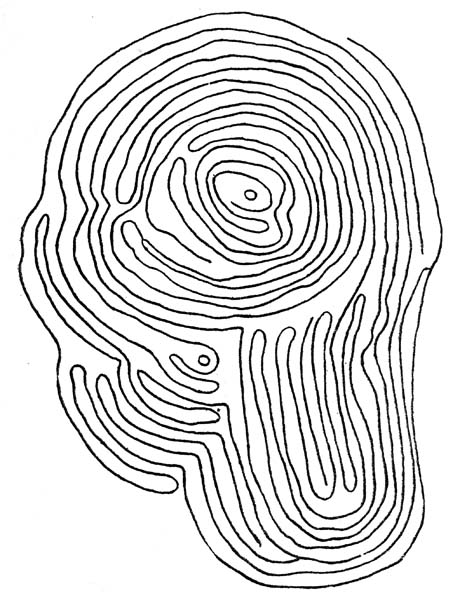

| Zulu Labyrinths and War Game | 81 |

NOTE.—The valuable footnotes signed “Ed.” are taken by permission from Miss Werner’s Paper in the “Journal of the African Society.”

There is much ceremony connected with a heathen Zulu wedding. A month or more before the time the bridegroom-elect has to compose a song to be sung by him and his party. Then he invites all the young men in the neighbourhood to come and learn it; he also composes a tune to suit it, which they all have to practise singing together, whilst dancing and manœuvring about, beating time with their feet. All his sisters, with their friends, join in as well. The song is generally made up of a very few words, something like a round in three or four parts. Here is one, for example:—

“Kusiqingile. Sesipiwe amabosho.” (We are in a fix. We are now supplied with cartridges.)

I was once present at a wedding where the following was sung: “Wen ‘obem’ ugwai, 2 Kauseikuza ini?” (You who take snuff. Will you never die?) This was the bridegroom’s song. He had managed to set it to quite a nice tune, and it went with a swing, the men keeping time beautifully with their feet, and flourishing their sticks in the air.

The bride-elect, too, has to go through the same preparations a month beforehand. She composes her song, and makes a tune for it, then all her friends have to come and learn it. The afternoons are generally set apart for this, and nice moonlight nights, when they can keep it up till the small hours of the morning. The words of the song may be: “Yek’ ubugontshi! Ngashiy’ umame.” (What trouble! I left mother.) Or, “Kuya ngotando. Ngishiy’abakwetu.” (It is my choice. I left my people.) After the day has been fixed for the Umtimba and everything is ready for it, the father sends two cows on ahead the day before, to be put for the bride in the cattle kraal of her future home. This is a sign that she will be leaving her home in the afternoon with her “udwendwe” (bridesmaids and party); and a hut is then prepared at once to receive them when they arrive in the evening—the eve of her wedding day. When the udwendwe reaches the kraal, a great noise of singing and clapping of hands is heard, this being the signal of their arrival. Most girls carry small stones in their hands so as to make a louder noise. Clapping at the gate, they are met by someone who invites them to enter, and leads the way to the hut prepared 3 for them. In this hut they sit up all night, singing and talking, until about dawn, when they make a move towards a bush, chosen in the neighbourhood, where they settle down to breakfast. In this place they spend the greater part of the forenoon, cooking and feasting, Meat and beer is sent to them from the bride’s future home. At about 8 in the morning the first messenger is sent by the bridegroom to invite the bride to come up; but he doesn’t return, nor is he expected to do otherwise than remain there, for this is a part of the marriage ceremony. The bridegroom again sends another messenger with the same message; he also remains, and others are sent again soon after. This goes on till there are about forty or fifty men sent off to fetch the bride and party. Lastly a beast is sent down, and that makes the bride think it is about time she prepared to move. She then begins to put on her bridal ornaments which consist chiefly of a new skin skirt, made of an ox-hide, well greased and perfumed with “amaka,” white ox tails on her arms and wrists, white and green beads (buma) round her neck, waist and ankles, sakabula feathers (Umnyakanya) on her head—a veil of beads (Invakaza) over her face, and a knife or an assagai in her hand, to flourish about whilst dancing. When the bridesmaids have finished assisting her they put on their finery; then they surround the bride and screen her with mats, so that no one can possibly see her before she appears before her future husband, whose 4 part it is to see her first. She is thus carefully hidden all the way, but now and then she puts up her knife just to show whereabouts in the crowd she is. The bridegroom is generally found seated with some of his best friends on the ground in the cattle kraal or outside it, and the bride is brought before him in this fashion. When very near, the crowd falls back and the maids are allowed to come forward with their screened-up treasure, which is unveiled before him by drawing aside the mats. She kneels down and whispers the usual few words into his ears, which are: “Sengifikile. Ungipate kahle. Ungilahle nami sengiyakukulahla.” (I have now come. You’ll treat me well. You’ll bury me and I’ll bury you.) To which he answers: “Kulungile pelanawe ungipate kahle.” (Agreed. You treat me well too.) After this the maids have their say (pela nawe), warning him to treat her kindly and lovingly or he may live to suffer for it, &c. They may say anything to him at this time. Then the old women come forward dancing in and out amongst the girls. They carry a mealie cob stuck on the point of an assagai. This they flourish about in the air for luck and prosperity. While this is going on the bridegroom and party hurry off to deck themselves out in their finery. This is always done after the bride has arrived. He wears a grand umutsha (kilt), made of cowhide and skin of an intsimangu (monkey), also white ox tails round his legs and arms, isaka (head ornament) of sakabula (long-tailed finch) feathers on his head, 5 and he carries a knobkerrie and courting shield in his hand. If he is an ikehla (man with ring on his head) he has to wear a neat little isiqova (tuft) on his forehead, made of pretty feathers, and a longer one at the back of his head.

When the bridegroom comes forward again with all his escort the dancing begins in earnest. His song is then rendered for the admiration of the bridal party and visitors. They go on dancing and singing it till they are fairly exhausted; then they sit down and rest, while the bride, assisted by her maids, goes through her song in all its charming variations, the old women manœuvring in and out of the crowd with the most graceful movements imaginable. When the bride has finished her part, the bridegroom comes in again with his, and they sing and dance together until dusk, when all the people return to their homes. Beer only is provided on that day—nothing else.

The next day the wedding feast takes place; this is called “Ukuqolisca” (breakfast or reception). Only relations and invited guests join in this. The bride on this day gives away all her girlish ornaments of beads, &c., to her sisters and her husband’s sisters. She puts all the necklaces in a vessel and pours water over them, then takes them out, one by one, and throws them on the girls. This is the way she gives them away.

On the third day the final part of the ceremony takes place. The bride has to try to run back to her home, with a child on her back belonging to 6 her new home, for there are often several families in one kraal. If she is a good runner and manages to get there without being caught she wins a cow; but this is a very difficult thing to do, for she is carefully watched, and the weight of the child on her back is a great hindrance. If she is lucky enough to win the prize her husband has to give it, to bring her back again, and that adds to the number of the lobola (dowry) cattle.

Zulus used to consider it unlucky to have twins, and worse still to have triplets. The latter were always thought to be monkeys, and killed as soon as they were born. Only one of the former was allowed to live. Sometimes parents found it difficult to decide which one to keep, although the rule was to kill the younger of the two. The greatest difficulty arose when the youngest one happened to be a girl; for by killing her a fortune was lost—it meant losing ten or twenty head of cattle.

Once a Zulu woman was in a difficulty of this kind. She had two lovely black babes, and loved both dearly, so she made up her mind to break the rule and keep them. But she and her husband suffered severely for it. They were continually reminded of having dared to break the rule of their country, and at last, when the twins were ten years old, and looked handsome and promising, their superstitious and envious neighbours threatened to report it to King Mpande. The parents’ hearts sank within them, so they decided to take the boy to a mission station near, and offer him to “The Great-great-one,” meaning God. He was accepted and taught. In time he became a Christian. His 8 parents often went to see him, and his sister brought him presents of mealies and sweet potatoes. Five or six years went by, but still the fact that the old man had spared his son was not forgotten. At last the threat was carried out. He was reported at headquarters, and accused of being a wizard as well, because he was lucky in whatever he undertook. He and his five wives were very industrious; they always planted large patches of mealies, Kafir corn (mabele), pumpkins, and sweet potatoes, so that they often had plenty of food and to spare when others were hard up. They were given to hospitality, and always pleased to help those in need, so it seemed rather strange that they had enemies. They had ten nice young daughters who could sing and dance well, and about the same number of sons, who were good hunters and kept them supplied with game. The chief men of that district were very jealous of this wealthy old farmer, and advised the king to do away with him and take his property. The king gave his consent, and almost immediately a band of men were told off to go and kill him, and to bring back his cattle and daughters. A company of the famous old “Ndhlondhlo” regiment set off, well armed with assagais, knobkerries, and shields. As they went along they flourished their weapons in the air with great pride. It was a good two days’ journey they had to take, to this place in the thorn country. They arrived there about the middle of the second night and halting a few yards away, 9 surrounded the kraal and lay down to rest in the high grass till dawn. As soon as it was light they got up and closed in round the kraal. The two men who were best acquainted with the owner, and who had often visited him, went up to the chief hut to inquire if he was stirring, for they said they were out hunting rather early, and would be grateful for a pinch of snuff to freshen them up a little. The kind old man, desirous to please as usual, opened the door of his hut at once and came out with his snuff-box. While he was in the act of giving them some, a volley was discharged at him, and he fell down dead on the spot. Women and children came running out in confusion from all the other huts to see what was the matter; then two of the chief women were also killed. The other three were left to bury their husband, which they were soon made to do, being ordered to carry him off and throw him into a donga. The mealie pits were opened and destroyed. Then two fine beasts were butchered for breakfast. The men had rather more than they could eat, so they invited the girls to make a good meal, for they had a two days’ journey before them to the king’s kraal. The girls answered, “You invite us to eat while our parents’ blood is still fresh on the ground! We will not eat. Would that we could die too, and escape being made slaves to the king who has ruined our happy home. Oh! ye spirits of our ancestors, pity us and take us out of this cruel misery!”

10 The twin boy, having heard in the early hours of the morning the fate of his people, hid in a cupboard at the mission house. He was called for, but he was nowhere to be found. The mission house was searched through and through, but fortunately no one thought he might be in the cupboard. When they had satisfied themselves that he was not there, they went off with the girls. It was pitiful to hear their cries. The men had no mercy, but went along joking and praising themselves for having managed so remarkably well. Such was life in Zululand before the Zulu war!

Soon after this affair another Zulu woman had twin girls, and the parents, having learnt a sad lesson, determined to observe the custom of their country. The younger one was killed, although she looked the healthier and finer. She was left to starve to death in a cold corner of the hut, while the other one was cuddled up and kept warm and fed. Strange to say, the chosen one pined and died a fortnight later, and the mother regretted not having kept the younger.

This custom is no longer observed. It is now considered lucky to have twins, especially if they are girls; for it means twenty head of cattle for the family at her marriage.

There are many, no doubt, who know of the old cruel Zulu custom of “Ukugodusa” (sending home), i.e., doing away with the aged people. If a man was too old and feeble to go to the king’s kraal occasionally, and join his regiment whenever called out, the king would pick out a troop of men and say, “Hamba niye kum’godusa”—meaning “go and send him home.” Then this troop of men would travel miles away to the man’s kraal, taking good care to get there by night, and to surround it, so as to pounce upon the poor old fellow as soon as he came out of his hut in the morning, and take him away to bury alive or otherwise kill him. The victim simply had to go away obediently, knowing it was the king’s order, as well as the custom of his country. So all Zulu men, old and young, used to make a point of meeting at the king’s kraal, “Komkulu” (at the great one’s), especially at Christmas time, to show that they were still of service. If through illness they had to stay at home, and it could be proved that they were indisposed, the king excused them; but they were most careful not to let it happen again.

12 When women became helpless, and needed looking after, they, too, had to be “sent home,” and that was done by their own people. Even their own sons would order it to be done, and assist in the cruel performance. Here is one example of it. Once, two sons, wanting to get rid of their aged mother, tempted her out for a long walk to some dongas (dry watercourses with deep holes in the banks). (Zulu.) They took her to the deepest one and pushed her into it. The poor old creature hurt her ankle very badly, and could not get out again. She was in that donga two days and two nights, without food or a drop of water to drink. Maddened by hunger she made a despairing effort to scramble out, and fortunately managed it at last. Once on the level she found some wild berries and fruit, of which she made a good meal. This gave her a little strength to decide on her next move. Not daring to venture anywhere near her home again, she took a long journey to a mission station, and there begged to be taken in. The missionary and his family were very good to her, and gave her a home and taught her. In time she became a Christian, and it was most touching to hear her saying her prayers early in the morning. She prayed most earnestly for her sons who had forsaken her.

Another old woman was daily threatened to be “sent home,” but a certain missionary’s wife and daughters who used to visit the kraal begged that she should be spared. They took her some covering 13 occasionally, for she was helpless and often would sleep too near the fireplace and burn her blankets. Years went on in this way, until the missionary family had to take a trip to Durban to get supplies for the year. Then the mischief was done. On their return, great was their distress at finding the old woman no more. Her people had taken her to a very deep ant-bear hole and made her go in. Before obeying she meekly asked for a last pinch of snuff, which they could not deny her. She sat down to take her snuff, then stepped into the ant-bear hole. They filled it up with earth and buried her alive.

“Ukugodusa,” one is thankful to know, is out of date now, as well as illegal.

I feel that it would, perhaps, be wise to give one more proof to show that the above was a real custom amongst the Zulus, even as lately as in the days of King Cetshwayo. A poor old woman named Madokodo was another victim, besides Mfoto whom I mentioned before. Sometime in the beginning of 1869 Madokodo, on account of her old age, was thrown into a donga, or pit, by one of her sons and his friends, to get her out of the way, or send her home (godusa), as this was called. 14 The poor old body was not in her second childhood (as Mfoto was), but was healthy and strong. She was in this pit for a few days, trying to get out, but kept falling back again. When night came she was in terror of the wolves and tigers which were prowling about the place; but she knew there was a Great God above, and she prayed for His protection. At last she managed to scrape a few holes in the donga with her finger nails, and made steps to climb up by, and the Great Almighty (Usomandhla) gave her strength to get out. Then she went to a great friend of hers, who fed her and kept her in a secret corner of her kraal until she got over her shock and became strong again. Madokodo then went to one of her other sons by night, and he was much pleased as well as surprised to see his mother alive; but, fearing the elder and cruel brother might find her and try to carry out this cruel custom again, he thought it best not to keep her with him long, so he proposed taking her to a mission station and giving her to the missionary. The mother agreed to this, and the two went off together, travelling a good many miles till they reached St. Paul’s Mission Station, the missionary there being my father, Rev. S. M. Samuelson. Arriving at the door of our house, poor old Madokodo, lame and footsore, called out in a pleading voice, “Ngitola Baba,” “Ngitola Nkosi Yame!” which means, “Adopt me, Father,” “Adopt me, my Master.” My father inquired into the matter, and all was related, her loving son supporting her. Nothing could be done 15 but to save the poor old soul from future trouble, and to try to win her for Christ’s Kingdom. My father took her under his care on August 13th, 1869, and the son took leave of his mother and returned home again. Madokodo slept in the kitchen, and my mother took great interest in her, for she was very intelligent, industrious and tidy. After a while Madokodo expressed a wish to join the Catechumen class, and be prepared for Baptism. She was very earnest; for early in the morning, just about sunrise, we children heard her deep, pleading voice in prayer whilst we were still in our beds, “Baba wami Opezulu, ovele wa ngibheka, osangibhekile namanje, ngitola Mdali wami, tola nabanta bami, utetelele nalo ongilahlileyo!” (My Father above, Thou Who hast taken care of me from the very first, and Who art still caring for me, adopt me, my Creator, adopt also my children, and forgive the one who has thrown me away.”) Then she would always finish with “The Lord’s Prayer,” which she had by then learnt. At the end of eight months she was baptized, and received the name Eva. She was, I believe, the first old woman who became a Christian at St. Paul’s, and she was very happy after that, and helped in the mission work by setting an excellent example to the younger converts. News of the aged woman’s conversion and baptism spread all over the country like wildfire, for Zulus, as a rule, are great news carriers. Her wicked son heard of it, for he had hoped she had reached her destination 16 long ago, as he had “sent her home.” The middle-aged people bore her a grudge on account of her having become a Christian at her age, and, fearing others might do the same, clubbed together and made plans to get her out of the way; so they accused her of witchcraft and reported her to King Cetshwayo. Eva at this time had had someone to help to build her a small hut, and she was cutting some high grass (tambootie) near a certain kraal, with which to thatch it. Meanwhile, illness (influenza colds) breaking out at this kraal, poor old Eva was accused of having caused this. The King, through his Prime Minister, Mnyamana, granted permission to have her killed. On the 4th of June, 1870 (Trinity Sunday), as we were just coming out of church, we were surprised by a large party of men (thirty in number) meeting us outside the church door, armed with assagais and knobkerries, with a demand from the King that Eva should be handed over to them to be killed! Eva ran to her protector (my father), calling out, “Save me, save me!” and caught hold of him round the waist, and the men pulling her away by force nearly tore his coat tails off. Then my younger brother Robert (R. C. Samuelson) interfered, and took hold of the woman, calling out, “Muyeke bo!” (leave her); then one man, indignant with this interference, lifted up his knobkerrie over Robert’s head, shouting: “Ngase ngiliqumuze ikanda kona manje” (I will break your skull 17 this moment); then, of course, the poor woman had to go. She was driven by these thirty men six miles into the thorn country to a river called Idango, near the Umhlatuzi river. We sat on the mountain, all of us, watching the long procession, Eva leading, the row of cruel humanity following in a long string. We watched and prayed broken-hearted, for we all loved poor old Eva; but it was a comfort to know she was a Christian! At last when we could see them no more we returned home, too dispirited to dine that day. In the evening someone told us she had met her fate bravely. As she went along she prayed to be received in the Heavenly Home of rest, where all unkindness and cruelty will end! At Idango river they drove her to a very big pond, where crocodiles were often seen; there they lifted up their kerries to brain her. She then said, “Ngogoduka impela namhla!” (“I will, of a surety (indeed), go home to-day!”) They then killed her and threw her into the pond for the crocodiles to eat.

Such was life in Zululand before the Zulu war. And yet on the whole things had, in a way, improved since Tshaka’s and Dingane’s days. The life of a missionary with his family was not at all an enviable one, although the natives had great respect for them, knowing as they did that they lived in their country as friends and messengers of the Gospel. They liked the missionary, although they objected to his religion.

The Zulus have a belief in the re-embodiment of departed spirits. Of this I remember having a practical illustration when, as a child, I was travelling about their country with my mother. We were about to visit a chief named Mqayikana. His kraal was close to the road, and as we were passing it we saw a nasty looking green snake. I picked up a stone and threw it at the reptile. In a moment a number of natives ran up and, seeing the snake, called out: “Leave it alone. It is the spirit of Mqayikana’s father which has come to visit us. We killed a fat beast as an offering to it to-day, and prayed that it might come and taste the meat. For our chief Mqayikana is very ill, and we want to induce his father not to call him away just yet.” I was young, and possibly a little indiscreet in those days, and replied: “Nonsense! The snake is an accursed creature, and ought never to be spared,” and I threw another stone at it, just bruising its tail. “Stop! Stop! or you will suffer for it. As it is, your white skin alone has saved you. If you had been black you would never eat corn any more. You would have to die the death!” Seeing that the men were in earnest and really 19 excited, I thought it best to leave the snake alone. Had I not done so I might have been smelt out as a witch later on if anything had happened to Mqayikana. We sent the chief a small peace-offering in the shape of a packet of sugar, apologising for my unintentional rudeness to his father’s ghost, and I am glad to say he proved himself not only forgiving but friendly, sending us a fine sheep, and even inviting us to come and take a pinch of snuff with him—a token of friendship among the Zulus; but we, perhaps not imprudently, begged to be excused.

The heathen Zulus still keep up this custom, chiefly in times of illness and death. The phrase means slaughtering cattle for departed ancestors, whose spirits appear in the form of a certain snake, which they hold sacred. It is called “Inyandezulu”, and its colour is green with brown under the belly. No native in old days would have dared to kill this snake, for he would have been punished by death. If any one is taken seriously ill at a kraal, the doctor, who is sent for immediately, after having examined his patient orders the relations to make a sacrifice to the “Amadhlozi”(spirits), and pray for the recovery of the invalid. Then a beast has to be chosen from the herd for the purpose, or a sheep or goat from the flock. While the animal is being slaughtered, the chief man calls on the “Amadhlozi”, saying, “Watch over us, O ye spirits of our fathers, I implore! Take not this our child away from us yet. Here we are slaughtering this for you. Come into the hut to-night and feast on it, I pray. Then let your anger be turned from us, and let us keep our child. 21 Oh! look on us with pity, and hear us!” After that the slaughtered animal is cut up in pieces and hung up in a hut; even the blood is put there in an earthen vessel. A dish of water is also taken in and placed on the floor, and a snuff box full of snuff beside it. They firmly believe that the “Idhlozi” comes in at night, has a wash, a pinch of snuff, and a taste of the meat and blood, and then returns into its hole again in a more forgiving mood. When the hut is entered in the morning nothing is seen of the “Idhlozi”, not even any marks on the meat to show that it has tasted it at all, still they firmly believe the hut has been visited. The “usu” (paunch) is then taken out and given to the doctor for medical use. He has it boiled together with herbs and medicines, then he steams his patient with the mixture, and administers some of it inwardly. The “insonyama” (right flank) is then cooked for the invalid, and he has to have a piece of it to eat every day as long as it is good. It is hung up in his hut, and there it hangs till it is quite high. It is looked upon as a charm. The rest of the meat can be eaten by the members of the kraal after it has been kept over night in the hut for the “Idhlozi” (spirit). Another beast has to be killed for the doctor’s special use while attending his patient. If the patient dies, an “Umtakati” (wizard) is blamed for it, and an “Ungoma” (witch doctor) is at once engaged to find him out. The doctor has nothing to do with that. He receives his fee and 22 goes home. Soon after he leaves, the burial takes place privately. No outsiders are allowed to be present. The corpse is made to sit up, and tied in this posture. It is taken out to the grave, which is dug outside the hut, and seated in it. A stone is placed on the head to steady it, and all the deceased’s possessions, clothing, mats, blankets, etc., are brought out and put into the grave—no one dares to keep any of them, for they are superstitious about it, believing that to use them would cause more deaths. There is no ceremony over the grave. Soon after it has been filled in, a mass of thorny bushes is stuck over it to keep “Abatakati” (wizards) from taking the body out to use in killing others. People then come in great numbers all round the kraal, crying out as loud as they can, “Maye babo! wafa wen ’owakiti” (“Woe, father! you died, you of our house”). They don’t speak to the mourners that day, but return home after having had a good cry. All the relations who were at the funeral hurry off to the river soon after it is over to have a bathe. When they return, another beast is killed as a sacrifice to the “Idhlozi”, with earnest prayers for the safety of the rest of the family. While it is being kept in the hut for “Idhlozi” to taste, all the members of that kraal have to chew medicines before partaking of anything, even a pinch of snuff. These medicines are used as a preventive against death.

The natives mourn in this way. They throw aside all their ornaments for at least two months. 23 They also have their heads shaved. They do not, as a rule, go out visiting during the two months of mourning, and they are not expected to go to dances or any festivities. They keep at home quietly. Absent relatives are all expected to come home for a couple of days to take medicine, and the comforting doctor comes with some of a soothing character. After ten days are over, visitors may come to “kala” (sympathize). They come quietly into the house of mourning, and sit down mute with their heads bent low for some time, and with arms crossed over the shoulders. At last a feeble voice is heard to say “Sanibona” (“We see you”): they answer, “Haw! sikubona ngapi ufelwe nje. Siya kala wena wakiti!” (Oh! how do we see you having lost. We sympathize with you”). The visitors sit about an hour or two in the same position, quietly, as no conversation is permitted on such an occasion. They then go out without saying a word of farewell, only casting sad looks towards the mourners. During the two months of mourning a smelling Doctor is engaged to find out the witch or wizard, and the way this is done will be seen in the “Ingoboco” (Chief Witch Doctor) story. Any one not calling to “kala” after the tenth day is at once suspected as “Umtakati.” So all make a point of showing themselves. Still the majority of them go out of kindness, for they do possess true and sympathizing hearts.

As soon as a man holding the position of chief, or head of a kraal, is dead, the corpse is placed in a sitting posture with the back to the central post of his hut, the limbs being doubled up and tied together. A messenger is then sent out to call all the wives and friends of the deceased, and they, being collected in one place, set up a loud wailing, sufficient one would say to “waken the dead.” The next thing is to separate the cows from their calves, so that they also make a most deafening noise, the calves lowing for their mothers, the cows lowing for their calves.

The first outburst of grief having subsided, the sons and friends proceed to dig the grave. The eldest son begins first, as, according to native belief, the ground will then soften and yield more easily to the other diggers. He then hands on the hoe, which is the digging tool most generally used, to the son who is next in importance to himself, and so it is passed on in rotation till the grave is ready. The eldest son (inkosana), after 25 doing his part, takes the barbed assagai which belonged to his father as head of the house, and stands holding it with the point to the ground until the work of digging is finished. A barbed assagai is handed down from generation to generation in native families, the holder being always the chief or head of the family or the acknowledged heir and successor, and in cases of disputed succession it is of the greatest importance to ascertain who held the assagai at the grave, and who began the digging, as well as who is the present possessor of the assagai.

After the hole has been dug stones are placed in the grave for the body to be seated on, and it is set there by one of the sons of the chief wife, the man whose right it is to do this holding an important position on the right-hand side of the kraal.

When the grave has been filled in, the relations and friends go through the “ukugeza” or cleansing ceremony, taking a small portion of a powder made of three kinds of bitter roots. Through the taking of this powder it is supposed that death will be averted from the friends of the deceased, and that any ill effects which might arise from his death will be prevented. After this they all go down to the river and bathe, and the wailing is over.

They then go into mourning for periods of time which vary from a few weeks to a whole year, according to the rank of the person mourned.

26 The wife, children, and nearest relations show their mourning by allowing their hair to grow long. When the appointed time is over all the family and friends are again assembled and, the doctor being in attendance, a goat is killed, this being essential in the latest stage of the ceremonies. A decoction of bitter roots is made, and the gall of the goat emptied into it. The whole is then worked up into a froth, whilst the spirit of the dead man is called upon to take care of his children and to supply all their needs. Some of the mixture is sprinkled upon those who are present, the young people cut their hair short, and the old ones shave their heads; a bathe in the river follows, and the mourning is over.

When the head of a kraal dies, the whole kraal is removed to a fresh site. It must, however, remain for a year if he was a king or an hereditary chief, because in that case he would be buried there, and his grave must be carefully guarded against witches for that space of time.

The graves of the kings in the Zulu country have always been watched, a kraal being erected near for the purpose. Should it happen that the inkosikazi (chief wife) has had no male issue, the head of the family can, on the marriage of his eldest daughter, use the ukulobola cattle received for her to buy a wife for himself or for some of his sons, and thus raise up male issue to be heirs to such head man’s principal house.

Before giving a description of an Inkata I must explain that it is not at all the same thing as the ordinary grass pad for supporting burthens on the head which goes by that name.[1] The Inkata now described is a larger thing, made of certain fibres which are very strong and binding. The doctor 28 specially deputed to make it knows exactly what fibres to use. He makes it in secret, sprinkles it with various concoctions, and finally winds the skin of a python round it, as this reptile is considered the most powerful of animals, coiling itself round its prey and squeezing it to death, as it does. When the Inkata is finished all the full-grown men as well as the principal women of the tribe are summoned, and are sprinkled and given powders of various dried herbs to swallow. The men then go down to a river and drink certain mixtures, bathe in the river, and return to the kraal where the Inkata is made. They are then sprinkled a second time, and return to their homes.

After this the Inkata is handed over by the doctor to the chief’s principal wife, and entrusted to her and to two or three others, to be withdrawn from the common gaze. It is taken great care of and passed on from generation to generation as part of the chief’s regalia. The Inkata is looked upon as the good spirit of the tribe, binding all together in one, and attracting back any deserter.

The king or chief uses it on all great occasions—more especially on those of a civil nature. For instance, when a new chief is taking up the reins of government, the Inkata is brought out of its hiding-place, a circle is formed by the tribe, and it is placed on the ground in the centre. The new chief then, holding his father’s weapons, stands on the Inkata while he is being proclaimed by his people. After this it is carefully put away again.

29 In case of the king being taken ill the doctor seats him on the Inkata while he is “treating” him (elapa). It is also used in a variety of other royal ceremonies, and is looked upon as more sacred than the English Crown. It is, in fact, the guardian spirit or totem of a Zulu tribe. Yet, strange to say, it appears that nothing was known to the Judges of the Native High Court as to the existence of the Inkata, in a very important case[2] not long since tried there, when it was what might be termed the very essence of the case, and possibly injustice resulted from this ignorance of native laws and customs.

|

The word seems to be almost universal in the Bantu languages:—Nyanja, nkata; Luganda, enkata; Swahili, kata; Suto, khare. What is most curious is that, so far away as the Gold Coast we find an indication of ceremonial usages connected with this article. See the Journal of the African Society for July, 1908, p. 407. The Fanti word for it is ekar, which may be a merely accidental resemblance, or may point to a fundamental identity of roots in the West African and the Bantu languages. Possibly the root idea of-kata is “something coiled or rolled up,” and this may be the only connection between the head-pad and the charm. The Baronga (Delagoa Bay) have a similar tribal talisman called mhamba, which is a set of balls, each containing the nail-parings and hair of a deceased chief, kneaded up with the dung of the cattle slaughtered at his funeral, and no doubt some kind of pitch to give it consistency. These balls are then enclosed in plaited leather thongs. The custom of thus preserving relics of dead chiefs is found elsewhere: the Cambridge Ethnological Museum possesses a set of the “regalia” of Unyoro, which would come under the same category.—Ed. |

|

Rex v. Tshingumusi, Mbopeyana, and Mbombo. 1909. |

This feast was always arranged to take place at about Christmas time. Men of all ages were requested to go; even young boys had to appear at it from all parts of Zululand. Those who were missed at this great gathering, and who were reported as being too aged to take the long journey, were ordered to be “sent home” by the king. Everyone had to bring his ornaments to adorn his person, and deck himself out suitably. These ornaments consisted of different coloured ox tails, feathers, and beads. Those who had distinguished themselves in battle wore horns of bravery besides, and certain kinds of roots round their necks. They also had to take food with them—enough to last for a week or longer—for the gathering always lasted four days at the least, and most of the people had to take long journeys to get to it. There were four different ceremonies to go through at that time in connection with “Ukunyatela” (feast of first fruits), and “Umkosi” (the feast). On the first day the ceremony of strangling a black bull and pulling it to pieces by mere force was performed. Mbonambi, the best and strongest regiment, was picked out to 31 do this. Sometimes the black bull picked out for the purpose would happen to be grazing by the river, and the poor beast had to be attacked and pulled to pieces there; or sometimes it would take place in the king’s cattle kraal, and he would be present looking on. If done by the river side, all parts of the ox had to be carried home and placed before the king, so that he could see that it had been done without the assistance of knives, choppers or assagais. The beef was not to be eaten on any account. The next to handle it were the doctors. They brought a mixture of all sorts of medicines with which to smear the meat; but the king must have a dose of it first. This was to give him a brave and cruel heart. When the king had taken his dose, the doctors used their mixed medicines to smear over all the beef and prepare it for roasting. Meanwhile the king’s regiment, the Ingobamakosi (bend or humble), was busy getting wood to use for the purpose. This was supposed to be a great honour, and the king would pick a regiment specially for it. The doctors finished their allotted task and the Ingobamakosi arrived with the wood. They then cut strips of beef and roasted it until it was black. This was done by the Ingobamakosi at the last feast before the Zulu war. For, being the king’s favourite regiment, he granted them more privileges than all the other regiments put together, and they were greatly envied on that account. It was galling to the rest that this 32 young and proud corps was picked to roast the daubed beef! for it gave them the right to have the first taste of the medicines after the king. If they went to battle, these would give them courage and make them fight to the last. They would never think of retreating. The men did not take the medicines in the same manner as the king. An officer would take a strip of roasted meat, bite a small piece off, suck the juice and swallow that only, spitting the meat out again, then pass the rest of the meat on to his men, and they would do the same. Then all the other regiments would follow suit. The meat was not passed in at all a polite way; it was simply tossed up high into the air, and the next one had to catch it, take a bite, and toss it up again. After this the bones and horns of the beast had to be burnt to cinders. During these four days all the young lads old enough to join a corps had to “kreza.” This is to draw the milk into their mouths and drink it warm, preparing themselves thereby to be made into a corps. The king would meanwhile choose a fitting name for the new regiment.

A month before the feast the king generally sent a party of four men and two boys to the beach to look for a certain vegetable marrow growing near the sea. This species grows wild there, and has never been cultivated. Sometimes the marrow would be ready to pick early in the season and sometimes late; and the time to begin the annual feast greatly depended upon this. They 33 could not commence operations without knowing that the vegetable was ready, for it had to be used on the second day. Therefore the party sent off in search of it had to stay on the coast until it was fit to pick; they were on no account whatever to return without it. On its arrival all is ready for the second day’s performance, which proceeds as follows: The king and party rise very early and enter the great cattle kraal. Here the marrow is presented to the king, who receives and inspects it very carefully, and says a few words in a low voice over it, all the chief men standing round about him expectantly. Then the ceremony of tossing the marrow commences. The king throws it up in the air five or six times, catching it again like a ball, after that he throws it to the men, when it breaks perhaps into two or three pieces, and these again he throws to the men, and they by turns go through the same performance. Then they throw the broken pieces over the kraal to all the different regiments drawn up round it awaiting their turn at the tossing. This goes on until all have touched the marrow and broken it into small pieces. Then the king picks out of his herd another black bull, fiercer than the one of the day before, to be treated in the same way. It is said that it gives the warriors bravery and cruelty. At noon, when all the ceremonies are over, the king declares the “Feast of first fruits” at an end. He allows reed instruments (umtshingo and ivenge) to be played all through the country, 34 so that all people may know they may now begin to eat green mealies, vegetable marrows, and pumpkins. Before the umtshingo and ivenge are heard no one may touch anything fresh out of the gardens, no matter how long the fruit or vegetables have been ripe (even if the people are starving), on penalty of death, or, later on, a heavy fine. It was against the laws of the country, too, to play the reed instruments before the king gave the order, being considered a greater offence even than eating green mealies before “Ukunyatela” (to tread) had taken place, for it was misleading the people; therefore the punishment for this offence was certain death. Umtshingo is the long hollow reed the natives play tunes on. It is a kind of flute; there is no string to it. The ivenge is a short one with only two notes. Two of these instruments have to be played together to make a tune at all. The favourite air played on them is, “Ucakide ka bon’ indod’ isegunjini” (the weasel doesn’t see the man who is in the corner). Some natives can play several nice tunes on the long reed.

The great dance commences about 3 p.m. All have to “vunula” first (put on their ornaments). They, of course, grease themselves well to make their dark bodies sleek and supple. All chiefs have black feathers of the indwa bird stuck in the centre of their head ring, just above the forehead. The younger chiefs wear black ostrich feathers in the same way. The grand old Mbonambi regiment carried plumes of black ostrich 35 feathers. A shape of straw was first made (like the crown of a hat) and the feathers were neatly stitched on to cover it all. These plumes looked very graceful as the men came dancing and bowing before the king. All the regiments would simultaneously beat their shields with knobkerries, and the noise would re-echo over the mountains like a fearful peal of thunder. The regimental ornaments varied a great deal, as they were chosen to mark the different corps. The rest of the afternoon, until dark, was spent in dancing and singing “Ingoma ye nkosi” (National Anthem). The words were as follows:—

It sounded really grand to hear thousands of men singing it, dancing, and keeping time with their feet, the words giving somewhat the effect of a “round,” and the trampling of feet resembling distant thunder. The next morning, on looking round at the fields where the dance had taken place, one would find the grass beaten into the ground.

The third day is usually spent in feasting and drinking beer. The king orders his chiefs to deal out a certain number of cattle to each regiment for slaughter early in the morning, so as to give them 36 plenty of time to prepare the meat, and to have it cooked by noon, when the feast commences. After all the meat has been devoured beer is brought round, and those who serve it out have to taste it first in front of everybody to show that it has not been poisoned. This is a standing rule at all beer drinks. No one will drink the beer before it has been tasted. The men sit down in circles, and the one who heads the circle has the first drink, and passes the earthen vessel to the next, and it travels all round the circle and comes back to him again, then he takes another drink and passes it; this is repeated till there is no beer left. Talking goes on all the time—relating anecdotes, questioning and arguing as to which regiment danced the best, looked the best, or distinguished itself the most in any way. Now and then an “Imbhongi” (jester) comes forward, shouting praises to the king, and jumping about like a maniac, with long horns fixed on his forehead. He acts the wild bull, tearing the ground up with his horns, then leaps into the air, shouting the king’s praises all the time. The people have to show their approval by praising and thanking him for his wonderful feats of agility. This afternoon the doctors are uncommonly busy preparing “Imshikaqo yemiti” (the mixture of medicines), to be ready for use the next day. The officers also are busy choosing places where the doctoring is to be done.

On the fourth day each man in every regiment has to take the mixture of medicines, which acts as 37 an emetic. In order to be fully prepared for the effects of the medicine, each regiment, in its allotted place, digs a deep trench. This is done very early in the morning. It is said by many who took this mixture that it made their hearts feel very bad indeed, full of cruelty and daring. This is the day, too, when the men felt most inclined to fight in order to try their strength. They would break out quite unexpectedly, without waiting orders from their king. At the last feast given before the Zulu war the ground was actually strewn with the dying and the dead. The blood of the favourite Ingobamakosi regiment being heated and poisoned by the “Imshikaqo,” they dashed forward to try their strength against another noted regiment, which, jealous of them, had been constantly provoking them to fight.

Late in the afternoon of this great doctoring day the chiefs had to call up their men to stand before the king and hear the new laws given out. Soon after this, “ukubuta” (collecting) takes place. The boys who have come to “Kreza” (milk into their mouths), come forward to be “Butwa” (made into a regiment). The name is chosen and given out. So the lads go home holding their heads up high with pride, shouting as they go along, “We are soldiers of the king.” After this has been done the king addresses the people, and fines those heavily who have been fighting and shedding blood. Then he praises those who have behaved best, and finally bids them all go home in peace. A good many 38 men generally volunteered to stay on and “konza” (serve the king). There was always plenty of work for them to do in the fields, weeding mealies and minding amabele (Kafir corn) gardens—keeping the destructive little birds away from eating them. There was also a good deal of fencing to be done, for the king’s kraal was an uncommonly large one, and had always to be kept neat and tidy. The men who volunteered to stay and work had to keep themselves in food. Very often they would run short and live only on water for days. Their people had to come long distances with it, carrying it on their heads, and sometimes they could ill be spared from home. They got no pay for their work, but a beast was given them occasionally for slaughter when all the work was finished. By the time they had to leave, a good many of them were reduced to mere skeletons, and could barely manage to drag themselves home.

The annual feast is now a thing of the past, as there is no king, so is also the “Feast of the first fruits.” The only part of it they keep up is taking a dose of the mixture each year before eating green mealies or vegetables. This they regard as a help towards making the green food agree with them, and that is all.

This was a most important ceremony among the Zulus while they were still under their own rulers. The natives of Zululand, as all who know anything of their history will admit, were the bravest and most warlike of the coloured races, and were always ready to fight for their king and country. They never shirked their duty as soldiers, they were all trained to arms from boyhood, and felt it a disgrace not to go out against the foe whenever called upon to do so.

The ceremony of Ukuqwamba was invariably performed when there was to be war, and was supposed to make the men both brave and invulnerable.

A proclamation went forth to all the men, in the word “Maihlome” (Let them arm), and in a very short time the whole manhood of the nation mobilized and proceeded, fully equipped for war, to the chief kraal of the sovereign, encamping within a short distance. No women were permitted to come near, all supplies of food or other necessaries being brought by men or boys specially deputed 40 for this service. The army, having assembled at its rendezvous, was then formed into a crescent, and the national war-doctor marched up in all his war-paint, when a very wild black bull was brought in, seized by some warriors selected for the occasion, and held down by them, while the doctor killed it by a blow with his axe on the nape of the neck. Meanwhile a large fire was lighted, and kept up while the beast was being flayed. Then its flesh was cut into long narrow strips, which were roughly roasted in the fire under the superintendence of the doctor, rubbed with a powder made of various roots and herbs and portions of the skins of lions and other fierce animals, and tossed up into the air among the soldiers, who had to catch them in their mouths, bite off a piece, and pass the rest on, till everyone had had a mouthful. Any piece which might chance to fall on the ground was left there.

The doctor’s attendants now brought him vessels full of a liquid composed of various medicines pounded and mixed with water, and the doctor sprinkled the warriors with it, shouting the while, “Umabope kabope, Umabope kabope” (let the Mabope tie up, that is, concentrate the strength of the army).[3] All were now ready, and without 41 further delay set out to fight. The “tshela” (tela) or sprinkling was repeated in case of a reverse, but not the killing of a bull.[4]

The whole body was now drawn up in a crescent, representing the two horns of a bull about to thrust at the enemy, while the central part represented the face of the bull, which would drive them away.

The war-doctor brings with him all the things required for carrying out the rites I have described, namely, an axe with a sharp point, a knife, the different medicines, and the sprinkler. This should be made of the tail of the gnu, or if this cannot be obtained, the tail of a black bull is used. All these things the doctor keeps in his own possession, carefully wrapped up in a mat.

The whole of these ceremonies were gone through just before the Zulu war of 1879, and in addition to this the fighting men partook of a medicinal charm which was to repel the enemy (Intelezi yempi).

We must not forget the women-folk who were left behind. Married women always wear a skirt 42 made of ox-hide, the hair having been scraped off. In ordinary life the upper edge of this is rolled outward, round the hips, but during war they turn the roll inside. The young girls throw ashes over their bodies, a sign of mourning, as wearing sackcloth and ashes was among the Hebrews. The old women take their brooms and run along the roads sweeping with them, thus indicating that they would make a clean sweep of their enemies in all directions. This they call Ukutshaluza.

Women also drink similar medicines to those taken by the men, but the preparation of them is somewhat different. A big fire is lighted outside the kraal, and a pot containing a number of roots possessing magical properties is put on, and left to simmer slowly till next morning, when the fresh milk of a cow is added, to whiten it. This is supposed to bring good luck. When it is ready, all the women and children sit round the pot, dip their fingers in it, and lick off the mixture. This is the Ukuncinda, or ceremony of sucking. After this, a cow is slaughtered for them to eat. Then they begin to sweep, smear the floors of their huts with cow-dung, and make all tidy. This is evidently to prepare for the return of the soldiers. Beer is made, and snuff ground, and all the snuff-boxes filled up, so that nothing shall be wanting.

The Zulus “fight and die”; there is no turning back, no retreating—for that only means death in the end, an inglorious death instead of a glorious one. Any who turned back would be killed by 43 order of the king or chief. This was the law of the country in war-time.

When attacking, the whole body of men made one big rush forward, shouting their clan name or war-cry, “Usutu!” or “Mandhlakazi!”[5] &c., as the case might be.

On camping out for the night a watchword was always agreed upon, unknown, of course, to the enemy, and to every passer-by they cried, “Who goes there?” their own people, on giving the word, being allowed to go safely on their way. This, of course, is the same procedure as would be followed among other nationalities.

|

Umabope is explained in Colenso’s Dictionary (p. 333) as “a climbing plant with red roots, bits of which are much worn about the neck.” A note adds: “The root is chewed by Zulus when going to battle, the induna giving the word ‘Lumani (bite) umabope!’ which they do for a few minutes and then spit it out again, saying ‘Nang’umabope!’ (here is the umabope). The notion is that the foe will be bound in consequence to commit some foolish act.” (The verb bopa means “tie.”) |

|

The nearest translation that can be given in English of the word Ukuqwamba would be “Talisman,” and “Ukuqwanjiswa kwempi” may be rendered “The consecration of an army.” |

|

Usutu is the name of the royal clan to which Cetshwayo belonged—Mandhlakazi being the house of Zibebu.—Ed. |

The office of Detector of Wizards was held by the Chief of Izanusi. He was the one chosen by the king to decide abatakati (wizard) cases. A big Umkamba tree, standing with its wide outstretched branches between Mahlabatini and Ulundi Military Kraals, was the place where he took the appeal cases. (The former was Mpande’s headquarters and the latter Cetshwayo’s.) He heard only the most complicated cases in which the majority of people were dissatisfied with the inferior Zanusi’s (detector of wizards) decision. I happened to be paying a short visit to these kraals during Cetshwayo’s reign, when one morning early I saw a great number of people collected under the Umkamba tree, and on asking a native standing by what these men were assembled for was told that the king’s chief, Sangoma, was about to “Bul’ingoboco” (inquire into the wizard’s case whether the right judgment had been given). Then my friend and I went near the place to observe the proceedings. We saw the demoniacal Umgoma standing with his dreaded magic wand in his right hand, a 45 black tail of “Inkonkoni” (gnu), and making fearful deep noises in his throat (bodhla), calling the spirits to help him to touch the right man with his wand. While doing this he would be walking round and round the people, now and then making sudden leaps into the air like a maniac, flourishing his dreaded wand, and all the accused would be awaiting the final touch with fear and trembling. The Imigoma (doctors) who had partly heard the cases would also be present, as well as relations of the accused, but none of them were supposed to say anything to the Ingoboco man: the amadhlozi (spirits) were to instruct him in everything. After having gone on till thoroughly exhausted with the antics described, he suddenly stops near his victim, whom he touches on the head with the Inkonkoni tail. The poor man has then to be taken off at once without even a word of remonstrance or a last farewell from his relations. He is driven off to Kwankata, a precipice over a deep pond in the Mfolozi River, which is full of crocodiles. This place is at no great distance from Ulundi. Having reached it the poor victim would be first stoned, then thrown down the precipice into the pond, where the crocodiles were always in readiness to receive him. They really lived on human beings.

Happily the morning we were watching Ingoboco the victim escaped most marvellously by running off at once to the king, who was standing in the cattle kraal, and throwing himself down at his feet, pleading for mercy, which was granted at once 46 as a reward for his pluck and running powers. I am told that several others managed to save themselves in the same way, for it was quite an understood thing that if a man reached the king, outstripping all his pursuers, he would be saved. This also held good if a man reached King Mpande’s grave in safety. No one would dare to touch him there.

Icimamlilo is the name of a compound which is in use among the heathen Zulus in cases of murder or homicide, and so well is this known that if any person were found using it after a murder had been committed, that person would be strongly suspected of the crime. It consists of four or five kinds of very bitter roots, with pieces of the flesh of the following animals: a lion, a baboon, a jackal, a hyena, and an elephant, also a kind of hawk. All of these ingredients are essential, there are others which may be added, but which are not absolutely necessary. After all these things have been burnt to ashes and thoroughly mixed, the murderer or homicide swallows some of the powder, and mixing the rest with water sprinkles himself and goes off for a bathe; then the purification is complete, and any evil effects upon the system which, according to native superstition may follow the killing of a human being, are counteracted. This custom of purification is still strictly kept up by the heathen natives, as a preventive against their own death, which they believe might otherwise naturally take place as a consequence of having killed another.

In common with other backward races the Zulus have faith in the power of the rain doctors to make, or to draw, rain, and also to prevent it from falling. The Zulu kings generally kept rain doctors; but as these men, when they did not make enough rain to please their royal masters, were in danger of being fined or even put to death, they were obliged to invent a good many excuses for their failures. The most common was that they felt sure somebody was practising witchcraft, that is to say, putting pegs dipped in medicine into the ground, or tying knots in the grass on the mountain-tops and sprinkling them with medicines, either of which proceedings would stop the rain. Then the king would send messengers round the country commanding his subjects to find out where pegs had been driven in, or knots tied in the grass, and the owner of the kraal in whose neighbourhood this was found to have been done was liable to be killed or fined, at the king’s discretion. In a dry season people were constantly in fear of this happening, for they knew that any who wished to injure them would drive in pegs near their kraals and then report them to the king for having done it.

49 Cetshwayo once had a rain doctor of whom he thought a great deal; but one year when there was a terrible drought he lost faith in him, and then someone accused him to the king of having wilfully prevented the rain from falling. Of course this made his majesty furiously angry, and he ordered the unfortunate man to be killed and thrown into the river, together with his hut and everything he possessed. No sooner was this order carried out than the rain fell in torrents. Such is the story told by the natives, but I cannot vouch for the truth of it.[6]

The Zulus used to consider the Basuto rain doctors the best of any, and the king sometimes engaged some of them to come to Zululand when rain was wanted. One year a large number of them arrived, laden with roots and other medicines, from Basutoland. Some carried calabashes filled with liquids, which were rolled about on the ground at the cattle-kraal to bring thunder, and bundles containing charms to bring lightning and rain were stuck upright in the ground. These performances went on for some weeks, until at last the rain came, and the Zulus were satisfied that it was caused by the hard work of the Basuto doctors. These men were kept well supplied with beef and beer all the time they were in the country, and handsome presents were given them when they left it to return to their own land.

|

This story scarcely seems to be consistent with Cetshwayo’s character. He was certainly a sceptic as regards witchcraft.—Ed. |

The Zulus believe in a glorious being whom they call the Queen of Heaven, of great and wondrous beauty, and the rainbow is supposed to be an emanation of her glory. This “Queen of Heaven” (Inkosikazi) is a different person from the Heavenly Princess, to whom the young girls pray regularly once a year, as described on another page.[7]

51 Some believe that there is a gorgeously coloured animal at the point where the rainbow appears to come in contact with the earth, and that it would cause the death of any who caught sight of it.[8]

The natives as a rule are very superstitious about the lightning; if it has struck anything they say “the heavens did it,” they dare not speak of it by name. A person killed by lightning is buried without ceremony, and there is no mourning for him; a tree which has been struck may not be used for fuel; the flesh of any animal so killed is not to be eaten; huts which have been injured by lightning are abandoned, and very often the whole kraal is removed. Persons living in such a kraal 52 may not visit their friends, nor may their friends visit them, until they have been purified and pronounced clean by the doctor. They are not allowed to dispose of their cattle until they also have been attended to by the doctor: even the milk is considered unclean, and people abstain from drinking it.

An eclipse or an earthquake foretells a great calamity, and the natives are terrified whenever an eclipse takes place. The defeat of Cetshwayo by Usibebu a few hours after an earthquake, which was felt all through Zululand in 1883, naturally confirmed them in the belief that it is an evil omen.[9]

|

The rainbow is called utingo lwenkosikazi, “The Queen’s Bow.” See Callaway, Nursery Tales and Traditions of the Zulus, p. 193. Utingo, however, is not “a bow” in our sense (at any rate not in current Zulu speech), but a bent stick or wattle, such as is used in making the framework of a hut. It is difficult to ascertain anything about this inkosikazi; but the Zulu women hold dances on the hills in honour of some Inkosazana—an echo, it may be, of the story of Jephtha’s daughter. Mr. Dudley Kidd (The Essential Kafir, p. 112) seems to have confused her with Nomkubulwana, who, as Miss Samuelson expressly tells us, is not the same person. It is not clear whether she is identical with the mysterious being called “Inkosazana,” of whom the late Bishop Callaway says: “The following superstition ... appears to be the relic of some very old worship” (Religious System of the Amazulu, p. 253). She was supposed to appear, or rather to be heard speaking (for she was never seen), in lonely places, and predicted the future, or gave directions which had to be obeyed by the people. “It is she who introduces many fashions among black men. She orders the children to be weaned earlier than usual.... Sometimes she orders much beer to be made and poured out on the mountain. And all the tribes make beer, each chief and his tribe; the beer is poured on the mountain; and they thus free themselves from blame.... I never heard that they pray to her for anything, for she does not dwell with men, but in the forest, and is unexpectedly met with by a man who has gone out about his own affairs, and he brings back her message.”—Ed. |

|

The Congo people believe the rainbow to be a snake (chama) as do the Yorubas (Oshumare). (See Mr. Dennett’s At the Back of the Black Man’s Mind (p. 142), and Nigerian Studies (p. 217).—Ed. |

|

The earthquake referred to took place in 1883, during the night which preceded Cetshwayo’s defeat by Usibebu at Ulundi. My sister (Mrs. Faye) and I were camped out some ten miles from Melmoth, when, about midnight, the wagonette in which we were sleeping was shaken and began to move down hill, but was fortunately stopped after a few yards by a block of wood lying in the grass. The natives who were near us exclaimed that it meant a calamity to the Zulu nation. And in the morning, when we got down from the wagonette, we found a great number of men sitting about looking sad, with their arms over their shoulders (meaning “we are lost”). They told us that Cetshwayo had been killed by Usibebu; in fact, the latter had made a clean sweep of the royal kraal and all the king’s men. In less than an hour later we saw numbers of people, some running, some limping, some crawling past us, who had just managed to escape with their lives. Cetshwayo, wounded badly in the leg, was saved, and taken for protection to Eshowe, where he died early in the following year. (See Mr. Gibson’s The Story of the Zulus, p. 256, new edition.) |

A description of an old Zulu custom which is now slowly dying out may be found interesting. It is generally observed at the season when the mealies and mabele (Kafir corn) are coming into flower.

The Zulus believe that there is a certain Princess in Heaven, who bears the name of Nomkubulwana (Heavenly Princess), and who occasionally visits their cornfields and causes them to bear abundantly. For this princess they very often set apart a small piece of cultivated land as a present, putting little pots of beer in it for her to drink when she goes on her rounds. They often sprinkle the mealies and mabele with some of the beer, for luck to the harvest.

There is one day appointed specially for girls, when they go out fasting on to the hills, and spend the whole day weeping, fasting, and praying, as they think that the more they fast and weep the more likely they are to be pitied by the princess. On that day they have to wear men’s clothing (umutsha) made of skins, and all men and boys are 54 to keep out of their way, neither speaking to them nor looking at them.

They start very early, as by sunrise they must be by the riverside, ready to begin praying and weeping.[10]

Digging deep holes in the sand, they make two or three little girls sit in them, and fill them in again, till nothing but their heads are left showing above ground. There they must remain, weeping 55 and praying for some time. Girls about six years old are generally chosen for this purpose, as they cry the most (rather from fright than anything else), and so are most likely to catch the ear of the heavenly princess.

When the older girls think the poor little things have done their fair share, they help them out and let them run home.

The big girls then go to the mountains and weep; after that to their gardens, round which they walk, screaming to the heavenly princess to have pity on them and give them a good harvest.

After this they sprinkle the gardens with beer, and set little pots of it here and there for the princess.

About sunset the ceremonies are over, and they all go back to the river to bathe, after which they return to their homes and break their fast. Any girls refusing to join with the others on Nomkubulwana’s day would lose caste, unless prevented by illness. Of course Christian girls are not expected to join, this being an entirely heathen rite.

|

Cf. an account of this custom (umtshopi) in Colenso’s Zulu Dictionary, p. 614. A similar observance, intended to avert disease, is described by Mrs. Hugh Lancaster Carbutt in the (South African) Folk-Lore Journal for January, 1880 (Vol. II., p. 12), as follows: “Among the charms to prevent sickness from visiting a kraal is the umkuba, or custom of the girls herding the cattle for a day. [Umkuba means “custom,” it is not the name of this particular rite.] No special season of the year is set apart for this custom. It is merely enacted when diseases are known to be prevalent. On such an occasion all the girls and unmarried women of a kraal rise early in the morning, dress themselves entirely in their brothers’ skins [i.e., skin kilts (umutsha)], and, taking their knobkerries and sticks, open the cattle-pen or kraal, and drive the cattle away from the vicinity of the homestead, none of these soi-disant herds returning home, or going near a kraal, until sunset, when they bring the cattle back. No one of the opposite sex dare go near the girls on this day, or speak to them.”—We have reproduced the passage in full, as the periodical which contains it is now very scarce. It should be noted that at ordinary times it would be contrary to custom—indeed, highly improper, if not sacrilegious—for any woman or girl to approach the cattle-kraal, to say nothing of herding the cattle. The idea is, no doubt, to compel the assistance of the Unseen by some flagrant outrage on decency, actual or threatened.—Ed. |

In addition to the many beliefs amongst the Zulus, of which I have given some examples, which may be properly called superstitious, there are a large number of curious half-beliefs and traditions, something of the nature of “old wives’ tales,” to which allusion is made more or less seriously in the ordinary course of Zulu conversation, and which often come as a surprise to the uninitiated European. I remember being much struck with some of these many years ago (as far back as in 1872), when my father took me as a child for a journey through Zululand on a visit to the great kraal of the celebrated King Mpande. On the way, as I was getting somewhat tired, a friendly Zulu told me to press my foot on an aloe (icena), and I should not be tired any longer. I saw no particular harm in obeying the injunction, and whether it was from the effect of the “icena,” or a thought cure wrought by the friendly Zulu, I certainly managed to get on.

On the same journey I was struck by a curious idea the Zulus have (somewhat akin to our “watched pot never boils”) as to disturbing the ordinary processes of the vegetable kingdom. I 57 noticed some fine varieties of pumpkins, melons, and marrows, and, being curious to know their names, I pointed my finger at them. “Musa, musa” (don’t, don’t), shouted my native conductor, “they will never ripen if you point at them. You ought always to bend your fingers and point with your knuckles towards vegetables.” “Oh,” said I, “you might perhaps pick me that pumpkin (indicating one of the best), as it is the only one I pointed at, and it will prevent its rotting,” and he at once fell in with my suggestion, adding a few marrows growing near the pumpkin, which had also been in peril. Some of our mistakes in dealing with the Zulus might at times lead to serious consequences; but fortunately, as a rule they take them good naturedly, and attribute them to our ignorance.