GEORGE CRUIKSHANK'S

OMNIBUS.

PREFACE.

"DE OMNIBUS REBUS ET QUIRUSDAN ALIIS."

PUBLISHED BY TILT & BOGUE, 86, FLEET STREET

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK'S

OMNIBUS.

ILLUSTRATED WITH ONE HUNDRED ENGRAVINGS ON STEEL

AND WOOD.

"De Omnibus rebus et quibusdam aliis."

EDITED BY LAMAN BLANCHARD, ESQ.

LONDON:

TILT AND BOGUE, FLEET STREET.

MDCCCXLII.

LONDON:

BRADBURY AND EVANS, PRINTERS, WHITEFRIARS.

[v]

CONTENTS.

| | PAGE |

| "Our Preface" described. |

| My Portrait | 1 |

| My last pair of Hessian Boots | 8 |

| Epigram | 13 |

| Love seeking a Lodging | 14 |

| Frank Heartwell; or, Fifty Years Ago, | 15, 39, 76, |

| | 112, 144, 177, |

| | 210, 246, 282. |

| Monument to Napoleon | 26 |

| Photographic Phenomena; or, the New School of Portrait Painting | 29 |

| Commentary on the New Police Act—Punch v. Law | 33 |

| Original Poetry, by the late Sir Fretful Plagiary, Knt. "Ode to the Human Heart," | |

| "On Life et cetera," &c. | 35 |

| Love has Legs | 52 |

| Bernard Cavanagh, the Irish Cameleon | 53 |

| The Ass on the Ladder | 54 |

| Omnibus Chat | 59 |

| Scene near Hogsnorton | 61 |

| Chancery Lane Enigma | ib. |

| Sonnets to Macready | 63 |

| Large Order to a Homœopathic Apothecary, &c. | 64 |

| "My Vote and Interest." | |

| A Communication from Mr. Simpleton Schemer, of Doltford Lodge, Crooksley | 65 |

| The Census | 72 |

| Love's Masquerading | 75 |

| The Livery—Out of London | 89 |

| Omnibus Chat | 92 |

| Legend of Van Diemen's Land | 92 |

| The Girl and the Philosopher | 94 |

| The Grave of the Suicide (who thought better of it). | ib. |

| A Rigid Sense of Duty | 95 |

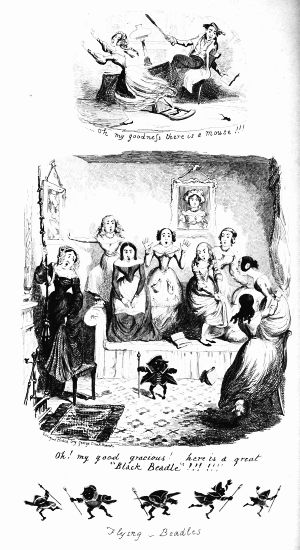

| Frights | 97 |

| A Peep into a Leg-of-Beef Shop | 100 |

| A Few Notes on Unpaid Letters | 102 |

| First Discovery of Van Demon's Land | 104 |

| The Muffin Man | 120 |

| A Tiger Hunt in England | 121 |

| Omnibus Chat | 124 |

| Ingenious Rogueries | 124 |

| The Sister Sciences of Botany and Horticulture | 126 |

| Photogenic Pictures, No. II. | 127 |

| A Negro Boy in the West Indies | ib. |

| Legend of the Kilkenny Cats | 128 |

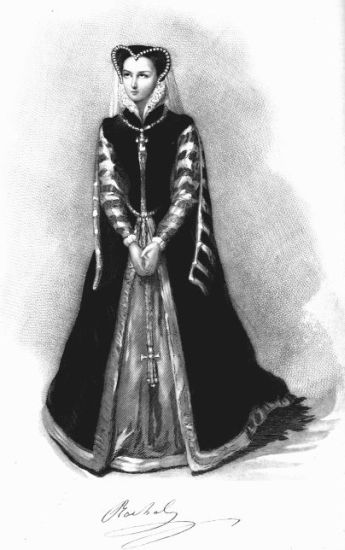

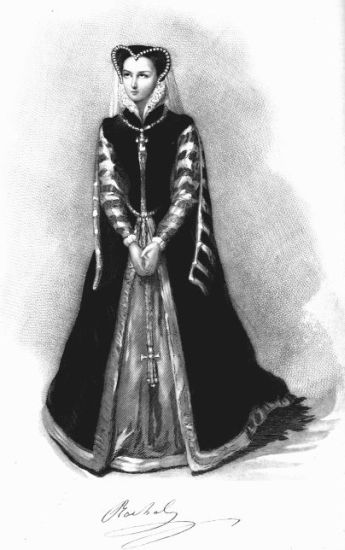

| Mademoiselle Rachel | 129 |

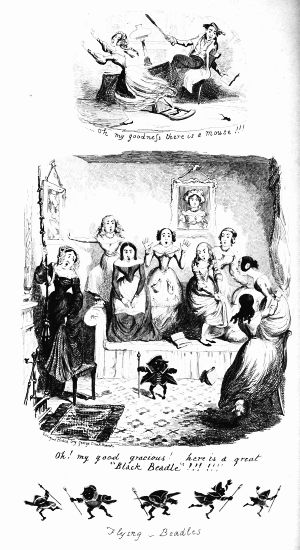

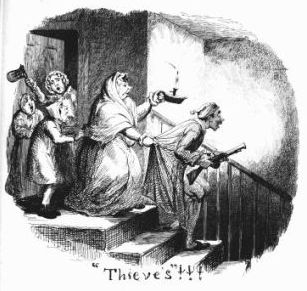

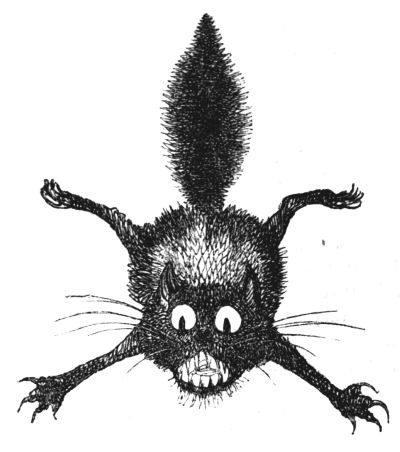

| Frights!—No. II. | 130 |

| A Short Cruise at Margate | 132 |

| Epigrams | 134 |

| Passionate People | 135 |

| Our New Cooks | 141 |

| A Song of Contradictions | 143 |

| A Warm Reception | 151 |

| Tea-Table Tattle | 152 |

| Omnibus Chat | 155 |

| The Fashions | ib. |

| Playbills and Playgoing | ib. |

| A Romance of the Orchestra | 156 |

| One of the Curiosities of Literature | 157 |

| An Incident of Travel | 158 |

| Here's a Bit of Fat for You | 159 |

| Heiress Presumptive | ib. |

| Letter from Mrs. Toddles | 160 |

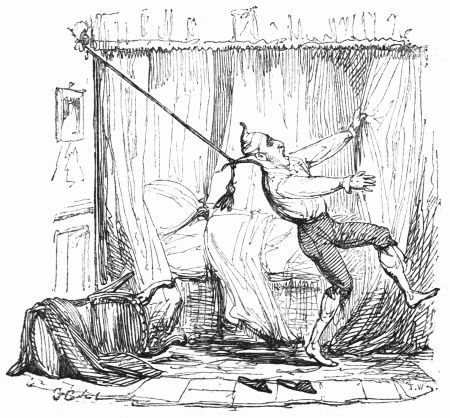

| Frights!—No. III. Haunted Houses, &c. | 161 |

| Little Spitz; by Michael Angelo Titmarsh | 167 |

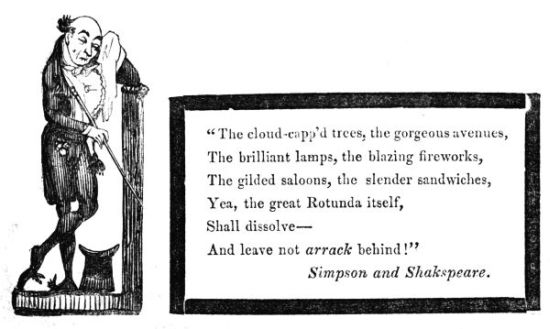

| Last Night of Vauxhall; by Laman Blanchard | 172 |

| A Tale of the Times of Old | 176 |

| An Anacreontic Fable | ib. |

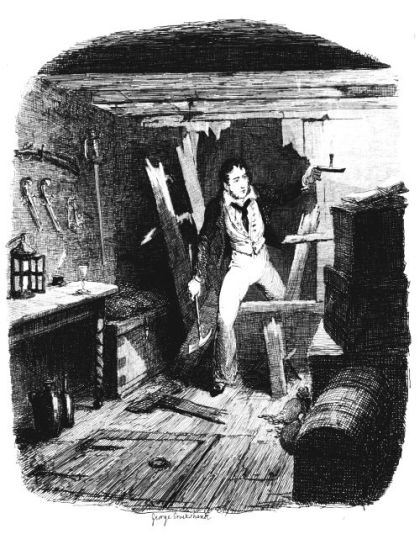

| How to Raise the Wind; by Captain Marryatt, R.N. | 182 |

| Peep at Bartholomew Fair; by Alpha | 188 |

| Omnibus Chat[vi] | 191 |

| Association of Ideas | ib. |

| Boys at School | 194 |

| The Laceman's Lament | ib. |

| The Height of Impudence | 195 |

| Mrs. T. again | 196 |

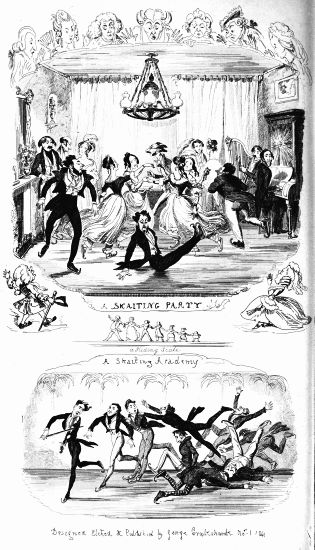

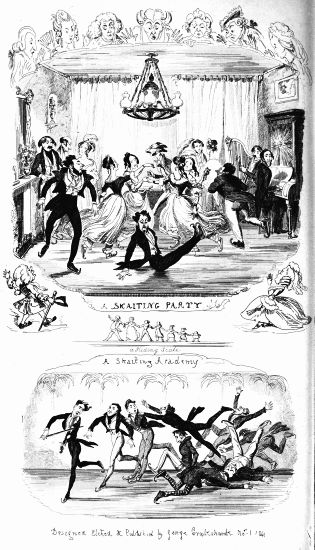

| The Artificial Floor for Skating | 197 |

| Duns Demonstrated; by Edward Howard, Author of "Rattlin the Reefer" | 199 |

| The Second Sleeper Awakened. Translated by Ali | 202 |

| Just Going Out; by Laman Blanchard | 204 |

| A Theatrical Curiosity | 216 |

| Sliding Scales | 217 |

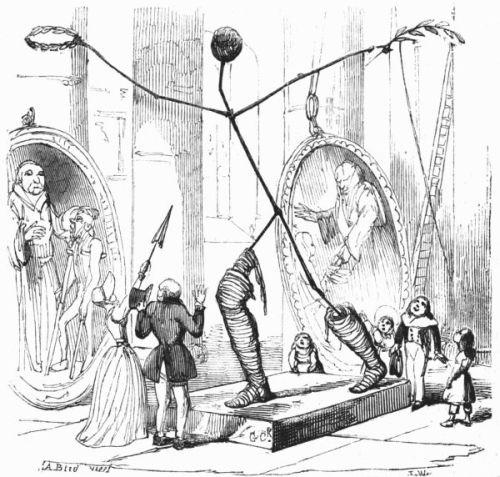

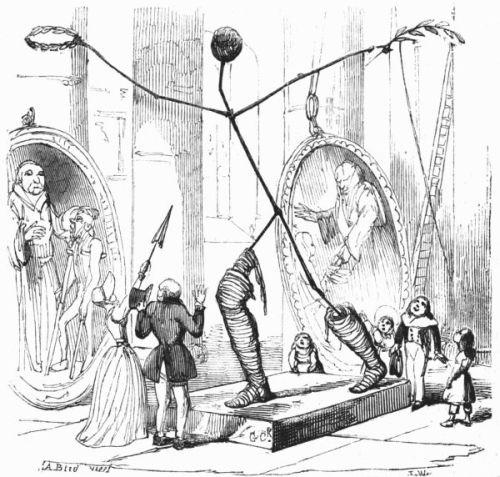

| Sketches Here, There, and Everywhere; by A. Bird. A Stage-coach Race | 218 |

| Another Curiosity of Literature | 222 |

| A Horrible Passage in My Early Life | 223 |

| Two of a Trade | 225 |

| Omnibus Chat | 226 |

| The Two Naval Heroes | ib. |

| Tar and Feathers | 227 |

| An Acatalectic Monody | 228 |

| Third Meeting of the Bright-ish Association for the Advancement of Everything | ib. |

| Rum Corks in Stout Bottles | 229 |

| A Highway Adventure | 230 |

| Bearded like the Pard | ib. |

| Some Account of the Life and Times of Mrs. Sarah Toddles; by Sam Sly | 231 |

| The Fire at the Tower of London | 233 |

| Miss Adelaide Kemble | 238 |

| Jack Gay, Abroad and at Home; by Laman Blanchard | 240 |

| The King of Brentford's Testament; by Michael Angelo Titmarsh | 244 |

| The Fire King Flue | 254 |

| A Passage in the Life of Mr. John Leakey | 255 |

| Omnibus Chat | 260 |

| The Clerk, a Parody | ib. |

| The British Association | 261 |

| Playing on the Piano | 262 |

| November Weather | 263 |

| Mrs. Toddles | ib. |

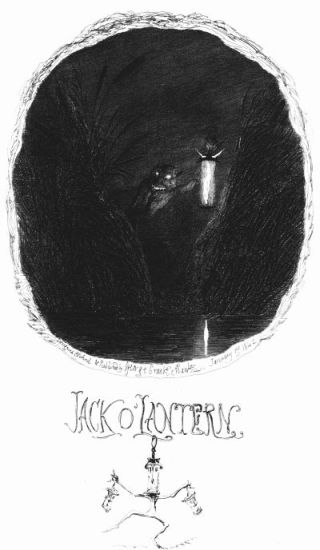

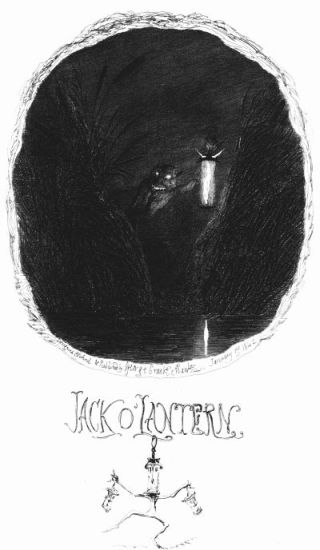

| Jack-o'lantern | 265 |

| Christmas. By Sam Sly | 266 |

| A Snap-Dragon. By Charles Hookey Walker, Esq. | 267 |

| Sonnet to "Some One" | ib. |

| The Homœopathist's Serenade. By Dr. Bulgardo | ib. |

| What do you do that for? | 268 |

| Lines by a Y—g L—y of F—sh—on | 271 |

| The Frolics of Time. A Striking Adventure. By Laman Blanchard, Esq. | 272 |

| A Peep (Poetic) at the Age. By A. Bird | 276 |

| A Still-life Sketch | 277 |

| A Tale of an Inn | 278 |

| "Such a Duck!" | 281 |

| The Postilion | 289 |

| "The Horse by the Head" | 292 |

| A Floating Recollection | 293 |

| The Pauper's Chaunt | 294 |

| Sketches Here, There, and Everywhere | 295 |

| Mrs. Toddles | 299 |

| Sonnet to Mrs. Toddles | 300 |

| Postscript | 304 |

[vii]

LIST OF ETCHINGS ON STEEL.

"DE OMNIBUS REBUS ET QUIBUSDAM ALIIS."

| | PAGE |

| PREFACE | to face title |

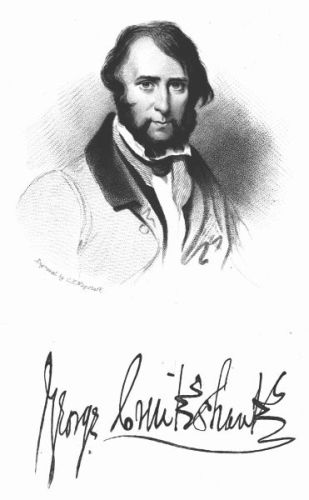

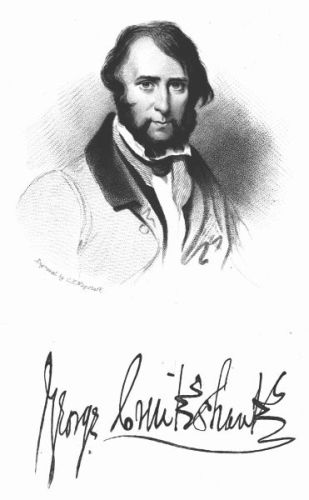

| PORTRAIT OF GEORGE CRUIKSHANK | 1 |

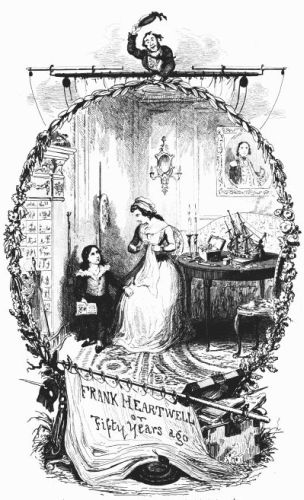

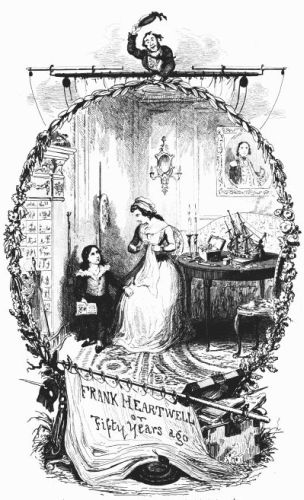

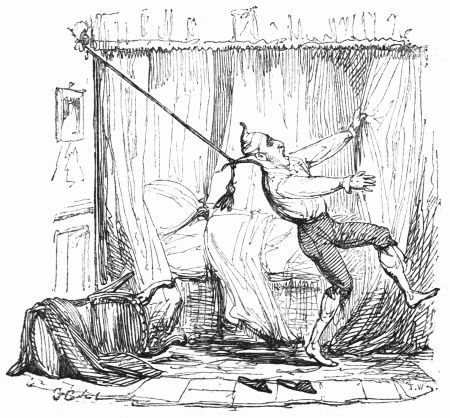

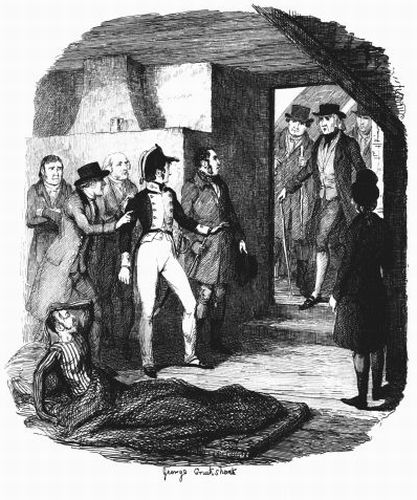

| FRANK HEARTWELL, OR FIFTY YEARS AGO. | 15 |

| COMMENTARY UPON THE NEW POLICE ACT, NO. I. | 33 |

| COMMENTARY UPON THE NEW POLICE ACT, NO II. | 34 |

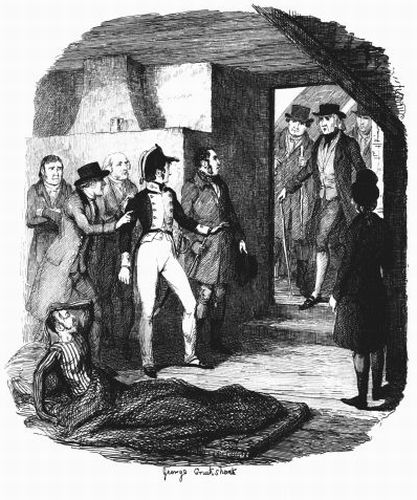

| FRANK HEARTWELL'S FIRST INTERVIEW WITH BRADY | 47 |

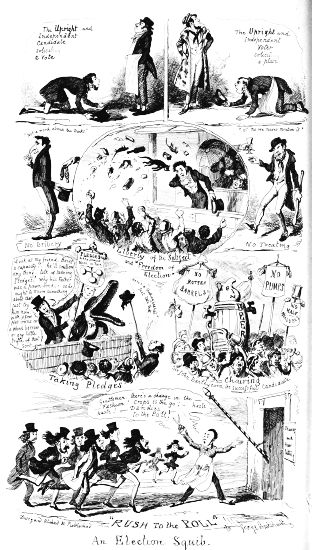

| "RUSH TO POLL"—AN ELECTION SQUIB | 65 |

| FRANK HEARTWELL AND SAMBO, IN THE HOLD OF THE TENDER | 85 |

| FRIGHTS, NO. I.—"FLYING BEADLES" | 97 |

| FRANK HEARTWELL, BEN, AND SAMBO, AMUSING THE NATIVES | 116 |

| PORTRAIT OF RACHEL IN THE CHARACTER OF MARIE STUART | 129 |

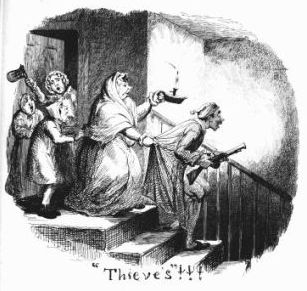

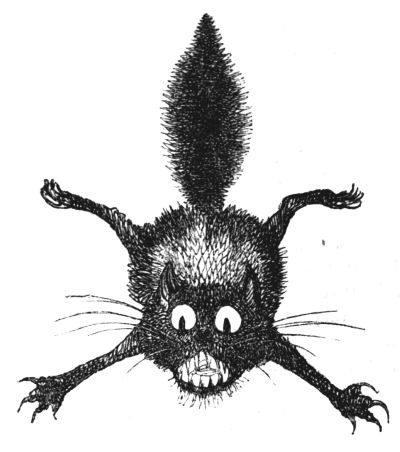

| FRIGHTS, NO. II.—"THIEVES."—"THE STRANGE CAT" | 130 |

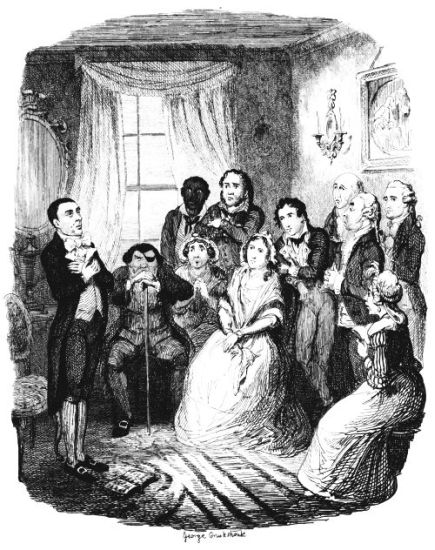

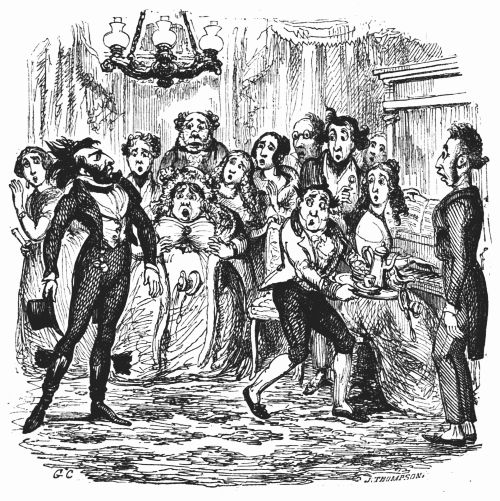

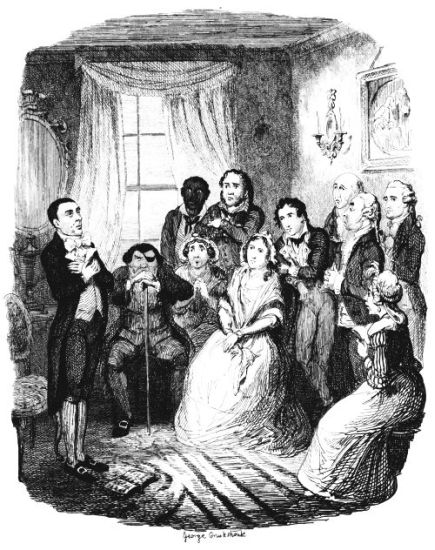

| RICHARD BROTHERS, THE PROPHET, AT MRS. HEARTWELL'S | 147 |

| FRIGHTS, NO. III.—"GHOSTS" | 161 |

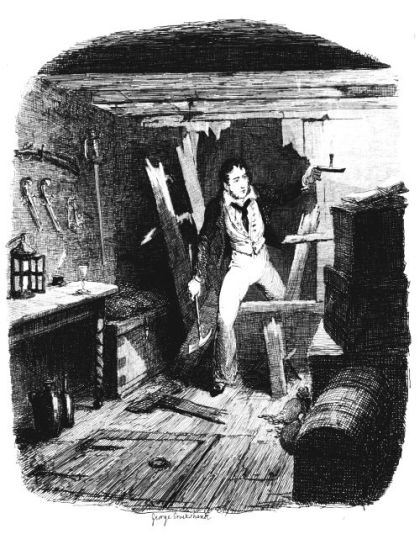

| FRANK HEARTWELL DISCOVERING TREASURE | 181 |

| A SKATING PARTY | 197 |

| FRANK HEARTWELL PREPARING TO SWIM TO THE WRECK | 214 |

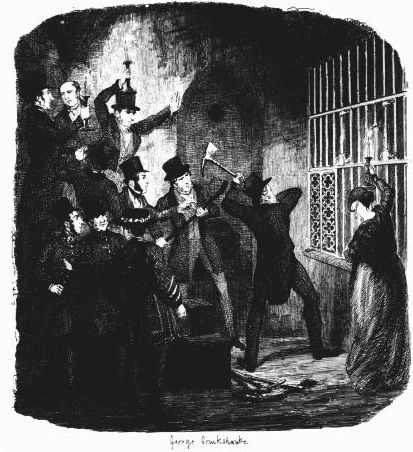

| BREAKING INTO "THE JEWEL ROOM" AT THE TOWER | 233 |

| PORTRAIT OF MISS ADELAIDE KEMBLE | 238 |

| FRANK HEARTWELL SEIZING BRADY | 252 |

| JACK O'LANTERN | 265 |

| FRANK HEARTWELL | 287 |

[viii]

LIST OF WOOD-CUTS.

| | PAGE |

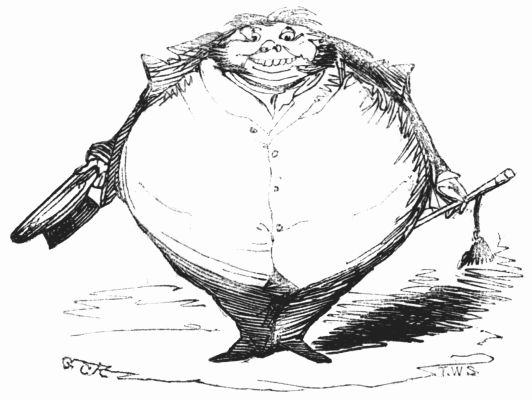

| 1. The peep-show | Preface |

| 2. Bust of Shakspeare with pipe | 2 |

| 3. G. C. in a drawing-room | 4 |

| 4. G. C. and a cabman | 5 |

| 5. A pair of bellows | 6 |

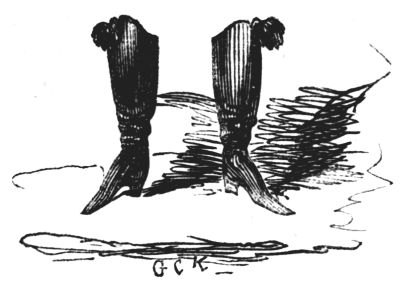

| 6. My last pair of Hessians | 8 |

| 7. A pair of shoes | 13 |

| 8. Love seeking a lodging | 14 |

| 9. Monument to Napoleon | 26 |

| 10. Photographic painting | 29 |

| 11. The sun painting all the world and his wife | 32 |

| 12. Love has legs | 52 |

| 13. The ass climbing the ladder | 54 |

| 14. The ass on the ladder | 54 |

| 15. The boy on the ladder | 54 |

| 16. Ditto | 56 |

| 17. A large order | 64 |

| 18. Love masquerading | 75 |

| 19. Foot-boy and bread | 90 |

| 20. Footman and pups | 91 |

| 21. Coachman and dumplings | 92 |

| 22. A rigid sense of duty | 95 |

| 23. Mrs. Toddles | 96 |

| 24. Leg-of-beef shop | 100 |

| 25. The Flying Dutchman | 106 |

| 26. Kangaroo dance | 109 |

| 27. Kangaroo and fiddler | 111 |

| 28. The muffin-man | 120 |

| 29. The strange cat | 131 |

| 30. The round hat and the cocked hat | 132 |

| 31. Sailor chasing Napoleon | 134 |

| 32. A passionate man | 138 |

| 33. T tree | 152 |

| 34. Emperor of China cutting off his own nose | 153 |

| 35. Chinese cavalry | 153 |

| 36. Tea-pot | 154 |

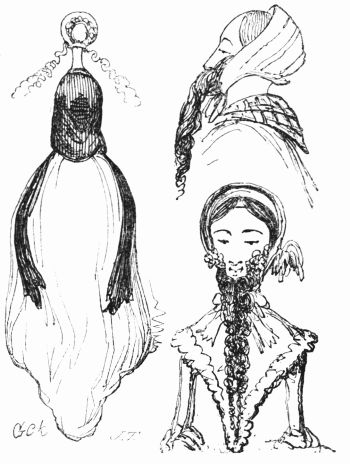

| 37. The fashions | 155 |

| 38. The boy's revenge | 159 |

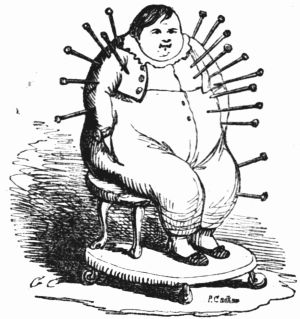

| 39. The living pincushion | 159 |

| 40. Mrs. Toddles | 160 |

| 41. Materials for making a ghost | 163 |

| 42. The ghost | 163 |

| 43. The bell-pull and the pigtail | 166 |

| 44. Little Spitz | 167 |

| 45. Last night of Vauxhall—the balloon | 172 |

| 46. Simpson à la Shakspeare | 175 |

| 47. Cupid with an umbrella | 176 |

| 48. Love breaking hearts | 176 |

| 49. Height of impudence | 195 |

| 50. Mrs. Toddles at Margate | 196 |

| 51. Ditto | 196 |

| 52. The Dun | 200 |

| 53. The Second Sleeper | 202 |

| 54. Sliding Scale | 217 |

| 55. Mile-stones—on the Rail-road | 222 |

| 56. Butcher's Boy | 225 |

| 57. Tar and Feathers | 227 |

| 58. Corks | 229 |

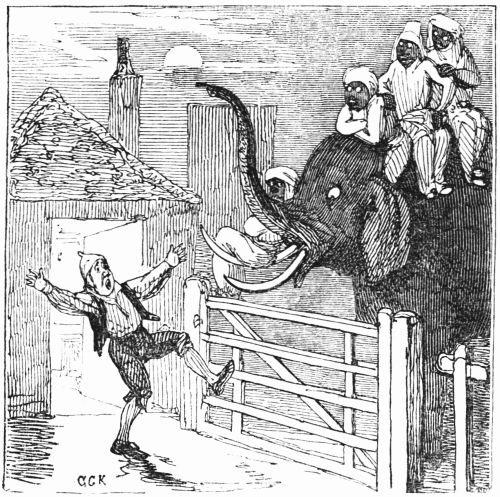

| 59. Turnpikeman and the Elephant | 230 |

| 60. Three Figures of Fashion | 230 |

| 61. Plan of the Tower of London | 233 |

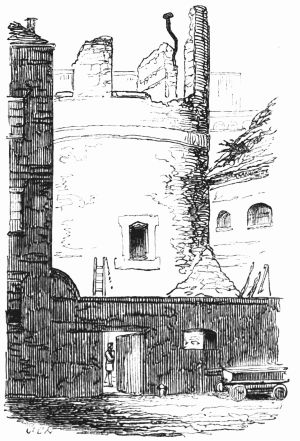

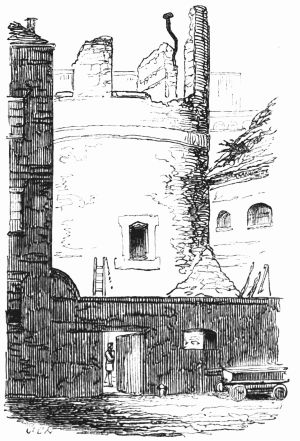

| 62. Bowyer Tower | 235 |

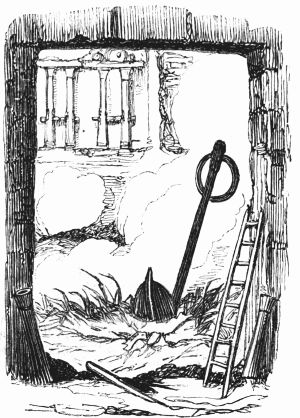

| 63. Camperdown Anchor | 235 |

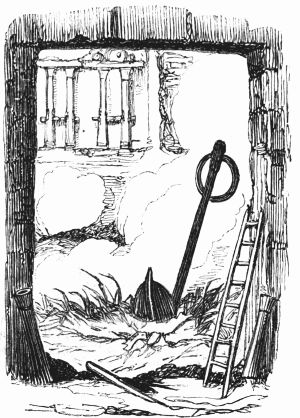

| 64. Lady Jane's Room | 236 |

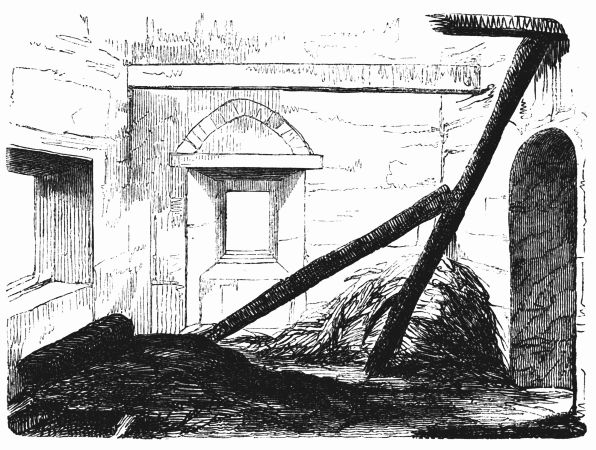

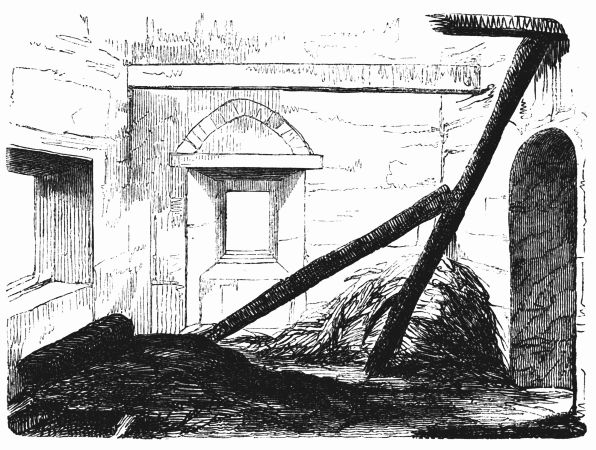

| 65. The Fire-king Flue | 236 |

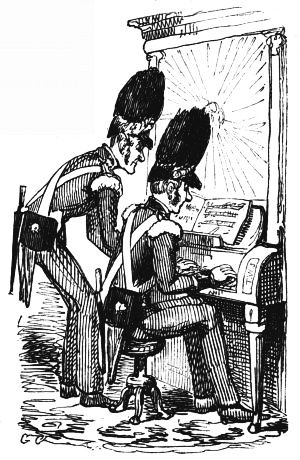

| 66. Grenadiers playing on the Piano | 262 |

| 67. Fireman playing on a Piano | 263 |

| 68. Colonel Walker (or Talker) | 264 |

| 69. Mrs. Toddles in a Fit | 264 |

| 70. Such a Duck | 281 |

| 71. The Horse by the Head | 292 |

| 72. Sheer Tyranny | 294 |

| 73. Sheer Kindness | 294 |

| 74. Pope's Guard | 296 |

| 75. Building an Angel | 297 |

| 76. Mrs. Toddles in the Dickey | 299 |

| 77. Mrs. T. and the Colonel dancing | 299 |

| 78. As Broad as it's Long | 300 |

[ix]

OUR PREFACE.

We have been entreated by a great many juvenile friends to "tell 'em all about our

Engraved Preface in No. I.;" and entreaties from tender juveniles we never could resist.

So, for their sakes, we enter into a little explanation concerning the great matters crowded

into "our Preface." All children of a larger growth are, therefore, warned to skip this

page if they please—it is not for them, who are, of course, familiar with the ways of the

world—but only for the little dears who require a Guide to the great Globe they are

just beginning to inhabit.

Showman.—"Now then, my little masters and missis, run home to your mammas, and cry till they

give you all a shilling apiece, and then bring it to me, and I'll show you all the pretty pictures."

So now, my little masters and misses, have you each got your No. 1 ready? Always take

care of that. Now then, please to look at the top of the circular picture which represents

the world, and there you behold Her Majesty Queen Victoria on her throne, holding a court,

with Prince Albert, in his field-marshal's uniform, by her side, and surrounded by ladies,

nobles, and officers of state. A little to the right are the heads of the Universities, about

to present an address. Above the throne you behold the noble dome of St. Paul's, on each

side of which may be seen the tall masts of the British navy. Cast your eyes, my pretty

dears, below the throne, and there you behold Mr. and Mrs. John Bull, and three little

Bulls, with their little bull-dog; one little master is riding his papa's walking-stick, while

his elder brother is flying his kite—a pastime to which a great many Bulls are much attached.

Miss Bull is content to be a little lady with a leetle parasol, like her mamma. To

the right of the kite you behold an armed man on horseback, one of those curious figures

which, composed of goldbeater's skin, used to be sent up some years ago to astonish the

natives; only they frightened 'em into fits, and are not now sent up, in consequence of being

put down. And now you see "the world goes round." Turn your eyes a little to the right

to the baloon and parachute, and then look down under the smoke of a steamer, and you

behold a little sweep flourishing his brush on the chimney-top, and wishing perhaps that

he was down below there with Jack-in-the-green. Now then, a little more to the right—where

you see a merry dancing-group of our light-heeled and light-hearted neighbours,

the leader of the party playing the fiddle and dancing on stilts, while one of his countrymen

is flying his favourite national kite—viz., the soldier. In the same vicinity, are

groups of German gentlemen, some waltzing, and some smoking meerschaums; near these

are foot-soldiers and lancers supporting the kite-flyer. Now, near the horse, my little

dears, you will see the mule, together with the Spanish muleteers, who, if not too tired,

would like to take part in that fandango performed to the music of the light guitar.

Look a little to the left, and you behold a quadrille-party, where a gentleman in black is

pastorale-ing all the chalk off the floor; and now turn your eyes just above these, and

you behold a joyful party of convivialists, with bottles in the ice-pail and bumpers raised,

most likely to the health of our gracious Queen, or in honour of the Great Captain of

the Age. And now, my little dears, turn your eyes in a straight line to the right, and

you will perceive St. Peter's at Rome, beneath which are two young cardinals playing at[x]

leap-frog, not at all frightened at the grand eruption of Mount Vesuvius which is going

on in the distance. From this you must take a leap on to the camel's back, from which

you will obtain a view of the party sitting just below, which consists of the grand Sultan

smoking desperately against Ali Pacha. Now, look a little lower down, and you will

see a famous crocodile-catcher of the Nile, said to bear a striking resemblance to Commodore

Napier; and now, look upwards again to the farthest verge, and you behold the

great Pyramid, and a wild horseman chasing an ostrich not so wild as himself. Now,

the world goes round a little more, and you see some vast mountains, together with the

temples of Hindostan; and upon the palm-tree you will find the monkeys pulling one

another's tails, being very uneducated and having nothing else to do: here, also, you will

discern the Indian jugglers, one throwing the balls, and another swallowing the sword, a

very common thing in these parts. And now, my little dears, you can plainly see several

very independent gentlemen and loyal subjects standing on their heads in presence of the

Emperor of ever so many worlds, and the brother of the sun and moon; and behind

these, hiding the wall of China, you will see a quantity of steam, (for they are in hot

water there,) that issues from the tea-kettles. Leaving his Celestial Majesty smoking his

opium, and passing the junks, temples, and pagodas, you see a Chinese joss upon his

pedestal; and now you can descend and join that pretty little tea-party, where you will

recognise some of your old acquaintances on tea-cups; only, if you are afraid of the

lion which you see a long way off, you can turn to the left, and follow the tiger that is

following the elephant like mad: and now, my little dears, you can jump for safety into

that palanquin carried by the sable gentry, or perhaps you would join the party of Persians

seated a little lower, only they have but one dish and no plates to eat out of. Just above

this dinner-party you behold some live venison, or a little antelope eating his grass for

dinner while a boa-constrictor is creeping up with the intention of dining upon him; so

you had better make your way to that giraffe, who is feeding upon the tops of trees,

which habit is supposed to have occasioned the peculiar shape of that remarkable quadruped;

and now you fall again in the way of that ramping lion, from whose jaws a black

is retreating only to encounter a black brother more savage than the wild beast. And now,

if your eye follows that gang of slaves, chained neck to neck, who are being driven off

to another part of the world, you will see what treatment they are doomed to experience

there, in the flogging which is being administered to one of their colour—that is to say,

black as the vapour issuing from that mountain in the distance; it is Chimborao,

or Cotapaxi, I can't say exactly which, but it shall be whichever you please, my pretty

little dears. In the smoke of it an eagle is carrying off a lamb—do you see?—Stop, let

me wipe the glasses!—Ah, yes, and now you can clearly behold a gentleman of the

United States smoking his cigar in his rocking-chair. A little behind is another gentleman

driving his sleigh, and in front you won't fail to see an astonishing personage, who

has just caught a cayman, or American crocodile, which he is balancing on his walking-stick,

on purpose to amuse little boys and girls like you. At his side is the celebrated

runaway nigger represented by Mr. Mathews, who says, "Me no likee confounded

workee; me likee to sit in a sun, and play fiddle all day." Over his head is a steam-vessel,

and at his feet an Indian canoe; towards it a volume of smoke is ascending from a fire,

round which some savages are dancing with feeling too horrible to think of. So instead

of stopping to dinner here, my little masters and misses, you would much rather, I dare

say, take pot-luck with that group of gipsies above, who are going to regale upon a pair

of boiled fowls, which I hope they came honestly by. Talking of honesty, we start upwards

to the race-course; and now goes the world round again, until you get sight of a gentleman

with a stick in his hand, who has evidently a great stake in the race, and who is so rejoiced

at having won, that he is unconscious of what he is all the while losing in the abstraction

of his pocket-book. And now we are in the midst of the fair, where we see the best

booth, and merry doings in the shape of a boxing-match; but as "music has charms,"

turn your eyes and your ears too some little distance downwards in the direction of the

organ player and the tambourine, where you will find some jovial drinkers, not far from

the harp and violin of the quadrille-party. I hope their music won't be drowned by the

noise of that Indian, to the left, beating the tom-tom, while the nautch-girls are dancing

as if they couldn't help it, all to amuse the mighty Emperor of all the Smokers and

Prince of Tobacco, who is seated, hookah in hand, in the centre of the globe—where we

must leave him to his enjoyment, tracing our way back to the jovial drinking-party,

where you will see Jack capering ashore, and getting on perhaps a little too fast, while

the donkey-boy above him can't get on at all, and the fox-hunter, still higher up, seems

to be in danger of getting off—especially if his horse should happen to be startled by his

brother-sportsman's gun behind him. And now, my little dears, the gun has brought

us round again to the royal guards, where the band is playing, in glorious style, God

save the Queen! And thus ends, where it began, my History of the World!

[1]

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK'S

OMNIBUS.

"MY PORTRAIT."

I respectfully beg leave to assure all to whom "My Portrait" shall

come, that I am not now moved to its publication, for the first time, by any

one of the ten thousand considerations that ordinarily influence modest men

in presenting their "counterfeit presentments" to the public gaze. Mine

would possibly never have appeared at all, but for the opportunity thus

afforded me of clearing up any mistakes that may have been originated by

a pen-and-ink sketch which recently appeared in a publication entitled

"Portraits of Public Characters."

The writer of that sketch was evidently animated by a spirit of

kindness, and to kindness I am always sensitively alive; but he has been

misinformed—he has represented me "as I am not," instead of "as I

am;" and although it is by no means necessary that I should offer

"some account of myself" in print, it is desirable that I should, without

fatiguing anybody, correct some half-dozen of the errors into which my

biographer has fallen.

A few words of extract, and a few more of comment, and my object, as

the moralist declares when he seeks to lure back one sinner to the paths

of virtue, will be fully attained.

The sketch, which professes to be "my portrait," opens thus:—

(1.) "I believe Geo. Cruikshank dislikes the name of artist, as being too common-place."

I have my dislikes; but it happens that they always extend to things,

and never settle upon mere names. He must be a simpleton indeed who

dislikes the name of artist when he is not ashamed of his art. It is possible

that I may once in my life, when "very young," have said that I

would rather carry a portmanteau than a portfolio through the streets;

and this, perhaps from a recollection of once bearing a copper-plate,

not sufficiently concealed from the eyes of an observant public, under my

arm, and provoking a salutation from a little ragged urchin, shouting at

the top of his voice, hand to mouth—"There goes a copper plate en-gra-ver!"

It is true, that as I walked on I experienced a sense of the uncomfortableness

of that species of publicity, and felt that the eyes of

Europe were very inconveniently directed to me; but I did not, even in

that moment of mortification, feel ashamed of my calling: I did not

"dislike the name of artist."

(2.) "When a very young man, it was doubtful whether the weakness of his eyes would not

prove a barrier to his success as an artist."

When a very young man, I was rather short-sighted, in more senses than

one; but weak eyes I never had. The blessing of a strong and healthy[2]

vision has been mine from birth; and at any period of time since that

event took place, I have been able, even with one eye, to see very clearly

through a millstone, upon merely applying the single optic, right or

left, to the centrical orifice perforated therein. But for the imputation

of weakness in that particular, I never should have boasted of my capital

eye; especially (as an aged punster suggests) when I am compelled to use

the capital I so often in this article.

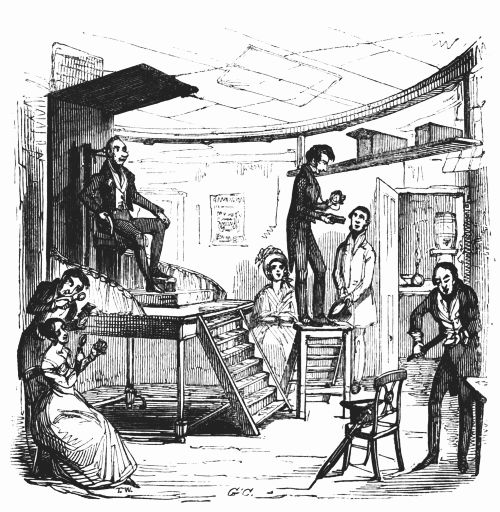

(3.) "The gallery in which George first studied his art, was, if the statement of the author

of 'Three Courses and a Dessert' may be depended on, the tap-room of a low public-house,

in the dark, dirty, narrow lanes which branch off from one of the great thoroughfares towards

the Thames. And where could he have found a more fitting place? where could he have met

with more appropriate characters?—for the house was frequented, to the exclusion of everybody

else, by Irish coal-heavers, hodmen, dustmen, scavengers, and so forth!"

I shall mention, en passant, that there are no Irish coal-heavers: I

may mention, too, that the statement of the author adverted to is not

to be depended on; were he living, I should show why. And now to the

scene of my so-called "first studies." There was, in the neighbourhood

in which I resided, a low public-house; it has since degenerated into

a gin-palace. It was frequented by coal-heavers only, and it stood

in Wilderness-lane, (I like to be particular,) between Primrose-hill

and Dorset-street, Salisbury-square, Fleet-street. To this house of

inelegant resort, (the sign was startling, the "Lion in the Wood,")

which I regularly passed in my way to and from the Temple, my attention

was one night especially attracted, by the sounds of a fiddle, together

with other indications of festivity; when, glancing towards the tap-room

window, I could plainly discern a small bust of Shakspeare placed over

the chimney-piece, with a short pipe stuck in its mouth, thus—

This was not clothing the palpable and the familiar with golden

exhalations from the dawn, but it was reducing the glorious and immortal

beauty of Apollo himself to a level with the common-place and the vulgar.

Yet there was something not to be quarrelled with in the association

of ideas to which that object led. It struck me to be the perfection

of the human picturesque. It was a palpable meeting of the Sublime and

the Ridiculous; the world of Intellect and Poetry seemed thrown open to

the meanest capacity; extremes had met; the highest and the lowest had

united in harmonious fellowship. I thought of what the great poet had

himself been, of the parts that he had played, and the wonders he had

wrought, within a stone's-throw of that very spot; and feeling that even

he might have well wished to be there, the pleased spectator of that

lower world, it was impossible not to recognise the fitness of the pipe.

It was the only pipe that would have become the mouth of a poet in that

extraordinary scene; and without it, he himself would have wanted majesty

and the right to be present. I fancied that Sir Walter Raleigh might have

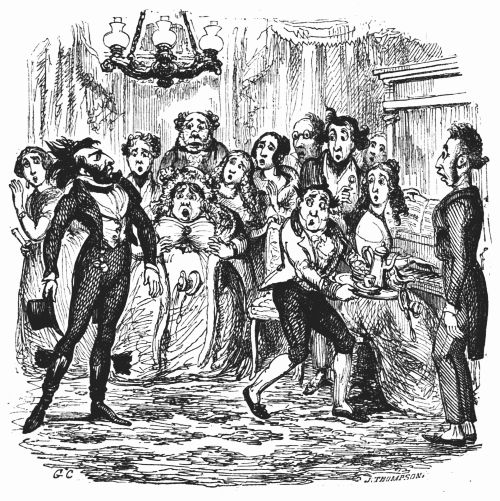

filled it for him. And what a scene was that to preside over and to contemplate[1]! What

a picture of life was there! It was as though Death were dead! It was all[3]

life. In simpler words, I saw, on approaching the window and peeping

between the short red curtains, a swarm of jolly coal-heavers! Coal-heavers

all—save a few of the fairer and softer sex—the wives of some

of them—all enjoying the hour with an intensity not to be disputed, and

in a manner singularly characteristic of the tastes and propensities of aristocratic

and fashionable society;—that is to say, they were "dancing

and taking refreshments." They only did what "their betters" were

doing elsewhere. The living Shakspeare, had he been, indeed, in the

presence, would but have seen a common humanity working out its

objects, and have felt that the omega, though the last in the alphabet,

has an astonishing sympathy with the alpha that stands first.

This incident, may I be permitted to say, led me to study the characters

of that particular class of society, and laid the foundation of scenes

afterwards published. The locality and the characters were different, the

spirit was the same. Was I, therefore, what the statement I have quoted

would lead anybody to infer I was, the companion of dustmen, hodmen,

coal-heavers, and scavengers? I leave out the "and so forth" as superfluous.

It would be just as fair to assume that Morland was the companion

of pigs, that Liston was the associate of louts and footmen, or that Fielding

lived in fraternal intimacy with Jonathan Wild.

(4.) "With Mr. Hone" (afterwards designated "the most noted infidel of his day")

"he had long been on terms not only of intimacy, but of warm friendship."

A very select class of associates to be assigned to an inoffensive artist

by a friendly biographer; coal-heavers, hodmen, dustmen, and scavengers

for my companions, and the most noted infidel of his day for my intimate

friend! What Mr. Hone's religious creed may have been at that

time, I am far from being able to decide; I was too young to know

more than that he seemed deeply read in theological questions, and,

although unsettled in his opinions, always professed to be a Christian.

I knew also that his conduct was regulated by the strictest morality. He

had been brought up to detest the Church of Rome, and to look upon

the "Church of England" service as little better than popish ceremonies;

and with this feeling, he parodied some portions of the Church service for

purposes of political satire. But with these publications I had nothing

whatever to do; and the instant I heard of their appearance, I entreated

him to withdraw them. That I was his friend, is true; and it is true,

also, that among his friends were many persons, not more admired for their

literary genius, than esteemed for their zeal in behalf of religion and morals.

(5.) "Not only is George a decided liberal, but his liberalism has with him all the

authority of a moral law."

I have already said, that I never quarrel with names, but with things;

yet as so many and such opposite interpretations of the terms quoted are

afloat, and as some of them are not very intelligible, I wish explicitly to

enter my protest against every reading of the word "liberal," as applicable

to me, save that which I find attributed to it in an old and seemingly

forgotten dictionary—"Becoming a gentleman, generous, not mean."

(6.) "Even on any terms his genius could not, for some time past, be said to have been

marketable, Mr. Bentley the bookseller having contrived to monopolise his professional labours

for publications with which he is connected."

This assertion was to a certain extent true, while I was illustrating[4]

Oliver Twist and Jack Sheppard, works to which I devoted my best

exertions; but so far from effecting a monopoly of my labours, the

publisher in question has not for a twelvemonth past had from me more

than a single plate for his monthly Miscellany; nor will he ever have

more than that single plate per month; nor shall I ever illustrate any

other work that he may publish.

(7.) "He sometimes sits at his window to see the patrons of 'Vite Condick Ouse' on their

way to that well-known locality on Sundays," &c.

As my "extraordinary memory" is afterwards defined to be "something

resembling a supernatural gift," it ought to enable me to recollect

this habit of mine; yet I should have deemed myself as innocent of such

a mode of spending the Sabbath as Sir Andrew Agnew himself, but for this

extraordinary discovery. I am said to have "the most vivid remembrance

of anything droll or ludicrous;" and yet I cannot remember sitting at the

window "on a Sunday" to survey the motley multitude strolling towards

"Vite Condick Ouse." I wish the invisible girl would sell me her secret.

(8.) "He is a very singular, and, in some respects, eccentric man, considered, as what he

himself would call, a 'social being.' The ludicrous and extraordinary fancies with which

his mind is constantly teeming often impart a sort of wildness to his look, and peculiarity to his

manner, which would suffice to frighten from his presence those unacquainted with him. He

is often so uncourteous and abrupt in his manner as to incur the charge of seeming rudeness."

Though unaccustomed to spend the Sabbath day in the manner here[5]

indicated, I have never yet been regarded as Saint George; neither,

on the other hand, have I ever before been represented as the Dragon!

Time was, when the dove was not more gentle; but now I "frighten

people from my presence," and the isle from its propriety. The "Saracen's

Head" is all suavity and seductiveness compared to mine. Forty thousand

knockers, with all their quantity of fright, would not make up my sum.

I enter a drawing-room, it may be supposed, like one prepared to go the

whole griffin. Gorgons, and monsters, and chimeras dire, are concentrated

by multitudes in my person.

The aspect of Miss Jemima Jones, who is enchanting the assembled

party with "See the conquering hero comes," instantaneously assumes the

expression of a person singing "Monster, away." All London is Wantley,

and all Wantley is terror-stricken wherever I go. I am as uncourteous

as a gust of wind, as abrupt as a flash of lightning, and as rude as the billows

of the sea. But of all this, be it known that I am "unconscious."

This is acknowledged; "he is himself unconscious of this," which is true

to the very letter, and very sweet it is to light at last upon an entire and

perfect fact. But enjoying this happy unconsciousness—sharing it moreover

with my friends, why wake me from the delusion! Why excite

my imagination, and unstring my nerves, with visions of nursery-maids

flying before me in my suburban walks—of tender innocents in arms

frightened into fits at my approach, of five-bottle men turning pale in my

presence, of banquet-halls deserted on my entrance!

(9.) "G. C. is the only man I know moving in a respectable sphere of

life who is a match for the under class of cabmen. He meets them on their

own ground, and fights them with their own weapons. The moment they begin

to swagger, to bluster, and abuse, he darts a look at them,

which, in two cases out of three, has the effect of reducing them to a

tolerable state of civility; but if looks do not produce the desired

results—if the eyes do not operate like oil thrown on the troubled

waters, he talks to them in tones which, aided as his words and lungs

are by the fire and fury darting from his eye, and the vehemence of his

gesticulation, silence poor Jehu effectually," &c.

Fact is told in fewer words than fiction. It so happens that I never

had a dispute with a cabman in my life, possibly because I never provoked

one. From me they are sure of a civil word; I generally open the door to

let myself in, and always to let myself out; nay, unless they are very

active indeed, I hand the money to them on the box, and shut the door to

save them the trouble of descending. "The greatest is behind"—I

invariably pay them more than their fare; and frequently, by the

exercise of a generous forgetfulness, make them a present of an umbrella,

pair of gloves, or a handkerchief. At times, I have gone so far as to

leave them a few sketches, as an inspection of the albums of their wives

and daughters (they have their albums doubtless) would abundantly

testify.

[6]

(10.) "And yet he can make himself exceedingly agreeable both in conversation and

manners when he is in the humour so to do. I have met with persons who have been loaded

with his civilities and attention. I know instances in which he has spent considerable time

in showing strangers everything curious in the house; he is a collector of curiosities."

No single symp—— I was about to say that no single symptom

of a curiosity, however insignificant, is visible in my dwelling, when by

audible tokens I was (or rather am) rendered sensible of the existence

of a pair of bellows. Well, in these it must be admitted that we

do possess a curiosity. We call them "bellows," because, on a close

inspection, they appear to bear a much stronger resemblance to "bellows"

than to any other species of domestic implement; but what in reality

they are, the next annual meeting of the great Scientific Association

must determine; or the public may decide for themselves when admitted

hereafter to view the precious deposit in the British Museum. In the mean

time, I vainly essay to picture the unpicturable.

Eccentric, noseless, broken-winded, dilapidated, but immortal, these

bellows have been condemned to be burnt a thousand times at least; but

they are bellows of such an obstinate turn of mind that to destroy them

is impossible. No matter how imperative the order—how immediate

the hour of sacrifice, they are sure to escape. So much for old maxims;

we may "sing old Rose," but we cannot "burn the bellows." As often as

a family accident happens—such as the arrival of a new servant,

or the sudden necessity for rekindling an expiring fire, out come the

bellows, and forth go into the most secret and silent corners of the

house such sounds of wheezing, squeaking, groaning, screaming, and

sighing, as might be heard in a louder, but not more intolerable key,

beneath the roaring fires of Etna. Then, rising above these mingled

notes, issues the rapid ringing of two bells at once, succeeded by a

stern injunction to the startled domestic "never on any account to use

those bellows again," but, on the contrary, to burn, eject, and destroy

them without reservation or remorse. One might as well issue orders to

burn the east wind. A magic more powerful even than womanly tenderness

preserves them; and six weeks afterwards forth rolls once more that

world of wondrous noises. Let no one imagine that I have really sketched

the bellows, unless I had sketched their multitudinous voice. What

I have felt when drawing Punch is, that it was easy to represent his

eyes, his nose, his mouth; but that the one essential was after all

wanting—the squeak. The musician who undertook to convey by a

single sound a sense of the peculiar smell of the shape of a drum, could

alone picture to the eye the howlings and whisperings of

the preternatural bellows. Now you hear a moaning as of one put to the

torture, and may detect both the motion of the engine and the cracking[7]

of the joints; anon cometh a sound as of an old beldame half inebriated,

coughing and chuckling. A sigh as from the depths of a woman's heart

torn with love, or the "lover sighing like furnace," succeeds to this; and

presently break out altogether—each separate note of the straining pack

struggling to be foremost—the yelping of a cur, the bellowing of a schoolboy,

the tones of a cracked flute played by a learner, the grinding of notched

knives, the slow ringing of a muffled muffin-bell, the interrupted rush of

water down a leaky pipe, the motion of a pendulum that does not know

its own mind, the creaking of a prison-door, and the voice of one who

crieth the last dying speech and confession; together with fifty thousand

similar sounds, each as pleasant to the ear as "When am I to have the

eighteen-pence" would be, to a man who never had a shilling since the day

he was breeched. The origin of the bellows, I know not; but a suspicion

has seized me that they might have been employed in the Ark had there

been a kitchen-fire there; and they may have assisted in raising a flame

under the first tea-kettle put on to celebrate the laying of the first stone

of the great wall of China. They are ages upon ages older than the bellows

of Simple Simon's mother; and were they by him to be ripped open,

they could not possibly be deteriorated in quality. The bellows which

yet bear the inscription,

"Who rides on these bellows?

The prince of good fellows,

Willy Shakspeare,"

are a thing of yesterday beside these, which look as if they had been

industriously exercised by some energetic Greek in fanning the earliest

flame of Troy. To descend to later days, they must have invigorated the

blaze at which Tobias Shandy lighted his undying pipe, and kindled a

generous blaze under that hashed mutton which has rendered Amelia immortal.

But "the days are gone when beauty bright" followed quick upon

the breath of the bellows: their effect at present is, to give the fire a bad

cold; they blow an influenza into the grate. Empires rise and fall, and

a century hence the bellows may be as good as new. Like puffing, they

will know no end.

(11.) And lastly—for the personality of this paragraph warns me to conclude—"In person

G. C. is about the middle height and proportionably made. His complexion is something

between pale and clear; and his hair, which is tolerably ample, partakes of a lightish hue.

His face is of the angular form, and his forehead has a prominently receding shape."

As Hamlet said to the ghost, I'll go no further! The indefinite complexion,

and the hair "partaking" of an opposite hue to the real one,

may be borne; but I stand, not upon my head, but on my forehead! To

a man who has once passed the Rubicon in having dared to publish his

portrait, the exhibition of his mere profile can do no more injury than

a petty larceny would after the perpetration of a highway robbery. But

why be tempted to show, by an outline, that my forehead is innocent of a

shape (the "prominently receding" one) that never yet was visible in

nature or in art? Let it pass, till it can be explained.

"He delights in a handsome pair of whiskers." Nero had one flower

flung upon his tomb. "He has somewhat of a dandified appearance."

Flowers soon fade, and are cut down; and this is the "unkindest cut of

all." I who, humbly co-operating with the press, have helped to give

permanence to the name of dandy—I who have all my life been breaking[8]

butterflies upon wheels in warring against dandyism and dandies—am at

last discovered to be "somewhat" of a dandy myself.

"Come Antony, and young Octavius, come!

Revenge yourselves—"

as you may;—but, dandies all, I have not done with you yet. To

resume. "He used to be exceedingly partial to Hessian boots." I confess

to the boots; but it was when they were worn even by men who walked

on loggats. I had legs. Besides, I was very young, and merely put

on my boots to follow the fashion. "His age, if his looks be not deceptive,

is somewhere between forty-three and forty-five." A very obscure and

elaborated mode of insinuating that I am forty-four. "Somewhere between!"

The truth is—though nothing but extreme provocation should

induce me to proclaim even truth when age is concerned,—that I am

"somewhere between" twenty-seven and sixty-three, or I may say sixty-four;—but

I hate exaggeration.

Exit, G. Ck.

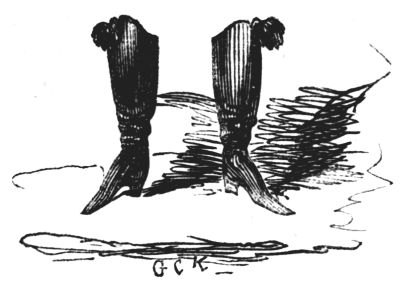

MY LAST PAIR OF HESSIAN BOOTS.

"Ah! sure a pair was never seen

So justly formed—"

Hoby would say, that as "all are not men who bear the human form,"

so all are not boots that bear the pedal shape. All boots, for example,

are not Hessians; nor are all Hessians like my last pair. Mathews used

to tell a story of some French Hoby, who, having with incredible genius

constructed a pair of boots, which Tom Thumb when a little boy could

no more have got on than Cinderella's sister could the magic slipper,

refused to part with them for any sum of money—he had "made them

in a moment of enthusiasm." Myriads of such moments were consumed in

the construction of my last pair. The boots published by Mr. Warren in

magazines and country newspapers, exhibiting the grinning portrait of a

gentleman in the interesting act of shaving, or a cat bristling up and

outwondering Katerfelto, were vulgar in form, and dull of polish, beside

mine Hessians. Pleasant it was, just as I was budding into life, to draw

them on, and sit with one knee crossing the other, to contemplate my

favourite leg. I used to wish myself a centipede, to wear fifty pairs of

Hessians at a time.

To say that the boots "fitted like gloves" would be to pay the most

felicitous pair of white kids a compliment. They had just as many natural

wrinkles as they ought to have; and for the tassels—we have all

seen the dandies of that day take out a comb, and comb the tassels of

their fire-bucket-looking boots as often as they got into disorder; but

mine needed no aid from such trickery and finessing.

[9]

I had strolled forth at the decline of a day in spring, and had afterwards

dined at Long's—my boots and I. They had evidently been the admiration

of every observer. I was entirely satisfied with them, and consequently

with myself. Returned home, a pair of slippers was substituted

for them, and with my feet on the fender and the vapour of a cigar

enwrapping me like a dressing-gown, I sat contemplating "my boots."

Thought reverted to the fortunes of my Lord Marquis of Carabas, and

I saw in my Hessians a brighter destiny than Puss in hers won for him.

I thought too of the seven-leagued boots of my ancient friends the Ogres,

and felt that I could take Old and New Bond Streets at a step.

That night those boots melted into thin air. There was "nothing like

leather" visible there in the morning. My golden vision had vanished

as suddenly as Alnaschar's—only his perished amidst the crash and clatter

of a basket of crockery kicked into the clouds; mine had stolen away in

solemn silence. Not a creak was heard, yet the Hessians were gone.

It was the remark of my housekeeper that boots could not go without

hands. Such boots I thought might possibly have walked off by themselves.

But when it was discovered that a window-shutter had been

forced open, and sundry valuables carried away, it was plain that some

conceited and ambitious burglar had eloped with my boots. The suspicion

was confirmed by the detection of a pair of shoes conscientiously

left behind, on the principle that exchange is no robbery. Ugh!—such

shoes. Well might I declare that nothing like leather was visible.

What odious feet had been thrust into my desecrated Hessians! I put my

legs into mourning for their loss; and, convinced that I should never

procure such another pair, sank from that moment into mere Wellingtons.

It was not long after this, that, seated in a coffee-room in Piccadilly,

my attention was drawn to the indolent and comfortable attitude of a

person, who, with his legs stretched conspicuously along the cushioned

bench, was reading a newspaper. How it was I can hardly tell; but

my eye was irresistibly attracted to his boots, just as Othello's was to the

handkerchief bound round the wounded limb of Cassio. He seemed to be

proud of them; they were ostentatiously elevated into view. The boots

were Hessians. Though not now worn in their very "newest gloss,"

they were yet in excellent, I may say in enviable condition. My anxious

glance not only wandered over their polished surface, but seemed to penetrate

to their rich bright linings, the colour whereof was now no more a

secret to me than were those silken tassels that dangled to delight the

beholder. I knew my boots again. The wearer, having the newspaper

spread before his face, could not notice any observation directed to his

lower extremities; my opportunity of inspection therefore was complete.

They were my Hessians. My first impulse was to ring the bell for a

boot-jack, and claim them upon the spot; but before I could do so the

stranger suddenly sprang upon his feet, seized his hat, and with one complacent

glance at those tasselled habiliments, which were far from having

lost all their "original brightness," swaggered out of the coffee-room.

Curiosity prompted me to follow—I caught a glimpse of the bright

backs of my boots as they flashed round the corner of a neighbouring street.

Pursuing them, I surveyed the wearer; and now perceived that not even[10]

those incomparable Hessians could transform a satyr into Hyperion, or

convert a vulgar strut into the walk of a gentleman. Those boots

were never made for such limbs—never meant to be "sported" after

so villanous a fashion. You could see that his calves were indifferently

padded, and might have sworn the swaggerer was a swell blackleg—one

of the shabby-genteel, and visibly-broken-down class. Accordingly,

after a turn or two, it was anything but surprising to see him squeeze

himself into a narrow passage over the door of which was written the

word "Billiards." I heard my boots tramping up the dingy staircase

to which the passage led—and my feet, as though from sympathy, and

what the philosopher calls the "eternal fitness of things," were moving

after them—when the "cui bono?" forcibly occurred to my mind! If I

should demand my Hessians, was there a probability of obtaining them?

and if I should obtain them, was there a possibility of my ever wearing

them again? Could I think of treading in the boots of a blackleg, albeit

they never were his own? No, I gave them up to the profanation which

was their destiny. I called up Hamlet's reflection on the vile uses to

which we may return; and as for the gambler, who in once virtuous

boots threaded the paths of vice and depravity, I kicked him—"with my

mind's toe, Horatio"—and passed on.

Shakspeare, in one of the most touching and beautiful of his sonnets, tells

us how he bemoaned his outcast state,

"And troubled deaf heaven with his bootless cries;"

but with no such cries of mine is the reader doomed to be troubled.

Indeed, when I parted from my Hessians on the occasion referred to, I

never dreamed of mentioning them more. I had heard, as it seemed, their

last creak. Not only were they out of sight, but out of mind. It

appeared just as likely that I should ever again be excited on their account,

as that I should hang them up à-la-General-Bombastes, and make war

upon their adventurous displacer. Yet it was not three months after

the event recorded, that in the city, in broad-daylight, my hat was all

but lifted off by the sudden insurrection of my hair, on recognising my

boots again. Yes, the very boots that once were mine, "et nullus error!"

or, as we say in English, "and no mistake!" As easily to be identified

were they as the freckled, wrinkled, shrunken features of a beloved friend,

parted from in plump youth. I knew my boots, if I may so say, by their

expression. Altered as they were, to me were they the same:—"alike,

but oh! how different."

"The light of other days had faded."

It could not be said of either Hessian, that it figured on a "leg" this time.

The wearer was evidently a collector in the "cast-off" line—had been

respectable, and was still bent on keeping up appearances. This was

plainly indicated by the one tassel which the pair of boots yet boasted

between them—a brown-looking remnant of grandeur, and yet a lively

compromise with decay. The poor things were sadly distorted; the

heels were hanging over, illustrating the downward tendency of the

possessor; and there was a leetle crack visible at the side. They

were Dayless and Martinless—dull as a juryman—worn out like a cross-examined

witness. They would take water like a teetotaller. There was[11]

scarcely a kick left in them. They were in a decline of the galloping sort;

and appeared just capable of lasting out until an omnibus came by. A

walk of a mile would have ensured emancipation to more than one of

the toes that inhabited them.

My once "lovely companions" were faded, but not gone. It was my

fortune to meet them again soon afterwards, still further eastward. The

recognition, as before, was unavoidable. They were the boots, but "translated"

out of themselves; another pair, yet the same. The heels were

handsomely cobbled up with clinking iron tips, and a worsted tassel

of larger dimensions had been supplied to match the remaining silk one.

The boots thus regenerated rendered a rather equivocal symmetry to the

legs of an attorney's clerk, whose life was spent in endless errands with

copies of writs to serve, and in figuring at "free-and-easys" and spouting-clubs.

They were well able to bear him on his daily and nightly

rounds, for the new soles were thicker than any client's head in Christendom.

This change led me naturally enough into some profound speculations

upon "wear and tear," and much philosophical musing on the

absorption and disappearance of soles and heels after a given quantity of

perambulation. But while I was wondering into what substances and

what shapes the old leather might be passing, and also how much of my

own original self (for we all become other people in time) might yet be

remaining unto me, I lost sight for ever of the lawyer's clerk, but not

of my boots—for I suspect he effected some legal transfer of them to a

client who was soon as legally transferred to the prison in Whitecross-street;

since, passing that debtors' paradise soon after, I saw the identical

boots (the once pale blue lining was now of no colour) carried out by

an aged dame, who immediately bent her steps, like one well acquainted

with the way, towards "mine uncle's" in the neighbourhood.

Hessians that can escape from a prison may work their way out of a

pawnbroker's custody; and my Hessians had something of the quality of

the renowned slippers of Bagdad,—go where they might, they were sure

to meet the eye of their original owner. The next time I saw the boots,

they were on the foot-board of a hackney-coach; yea, on the very feet

of the Jarvey. But what a falling-off! translation was no longer the

word. They had suffered what the poet calls a sea-change. The tops were

cut round; the beautiful curve, the tassels, all had vanished. One boot

had a patch on one side only; the other, on both. I thought of the

exclamation of Edmund Burke,—"The glory of Europe is extinguished

for ever!" Instinct told me they were the boots; but—

"The very Hoby who them made,

Beholding them so sore decay'd,

He had not known his work."

I hired the coach, and rode behind my own boots: the speculative fit again

seized me. I recollected how

"All that's bright must fade,"

and "moralized the spectacle" before me. How many had I read of—nay

seen and known—who had started in life like my boots,—bright,

unwrinkled, symmetrical,—and who had sunk by sure degrees, by

wanderings farther and farther among the puddles and kennels of[12]

society, even into the same extremity of unsightly and incurable

distortion.

——"Not Warren, nor Day and Martin,

Nor all the patent liquids o' the earth,

Shall ever brighten them with that jet black

They owed in former days."

My very right to my own property had vanished. They had ceased to

be my boots; they were ceasing to be boots. They cost me something

nevertheless; for having in my perturbation merely told the driver to

"drive on," he took me to Bayswater instead of Covent-garden; and,

as the price of my abstraction, abstracted seven-and-six-pence as his fare.

From a hackney-coachman they seem to have descended to the driver

of what had once been a donkey; to one who cried "fine mellow

pears," "green ripe gooseberries," and other hard and sour assistants

in the destruction of the human race. This I discovered one day by

seeing "my boots" dragged to a police-office (their owner in them), where

indeed one of the pair—if pair they might still be called—figured as a

credible witness; it having been employed as a weapon, held by the solitary

strap that yet adhered to it, for inflicting due punishment on the head

of its master's landlord, a ruffian who had had the brutal inhumanity to

tap at the door of an innocent tenant, and ask for his rent.

It is probable that in this skirmish they sustained some damage, and

required "renovation" once more; for I subsequently saw them at one of

those "cobbler's-stalls" which are fast disappearing (the stall becoming

a shop, and the shop an emporium), with an intimation in chalk upon

the soles—"to be sold." Of the original Hessians nothing remained but

a portion of the leggings. They had been soled and re-soled; the old

patches had disappeared; and there was now a patch upon the new fronts

which they had acquired. Having had them from the last, to the last I

resolved to track them; and now found them in the possession of a good

ancient watchman of the good ancient time in Fleet-street, from whose feet,

however, they were one night treacherously stolen as he sat quietly

slumbering in his box. The boots wandered once more into vicious paths,

having become the property of a begging-letter impostor of that day, in

whose company they were seen to stagger out of a gin-shop—then to run

away with their tenant—to bear him, all unconscious of kennels, on both

sides of the road, faster than lamplighter or postman can travel—and finally

to trip him up against the machine of a "needy knifegrinder" (his nose

coming into collision with the revolving stone), who, compassionating

the naked feet of his seemingly penniless and sober fellow-lodger, had that

very morning presented him with part of a pair of boots, as being better

than no shoe-leather. This fragmentary donation was the sad remnant of

my Hessians—the "last remains of princely York."

When we give a pair of old boots to the poor, how little do we consider

into what disgusting nooks and hideous recesses they may carry their new

owner! Let no one shut up the coffers of his heart, or check even momentarily

the noble impulse of charity; but it is curious to note what purposes

a bashful maiden's left-off finery may be made to serve on the stage of a

show at Greenwich fair; how an honest matron's muff, passed into other

hands, may be implicated in a case of shop-lifting; how the hat of a great[13]

statesman may come to be handed round to ragamuffins for a collection of

half-pence for the itinerant conjuror; or how the satin slippers of a

countess may be sandalled on the aching feet of a girl whose youth is one

weary and wretched caper upon stilts!

"My Hessians"—neither mine, nor Hessians, now—were on their last

legs. Theirs had not been "a beauty for ever unchangingly bright."

They had experienced their decline; their fall was nigh. Their earliest

patchings suggested, as a similitude, the idea of a Grecian temple, whose

broken columns are repaired with brick; the brick preponderates as

ruin prevails, until at length the original structure is no more. The

boots became one patch! Such were they on that winter-morn, when

a ruddy-faced "translator" sat at his low door, on a low stool, the boots

on his lap undergoing examination. After due inspection, his estimate

of their value was expressed by his adopting the expedient of Orator

Henley; that is to say, by cutting the legs off, and reducing what remained

of their pride to the insignificance of a pair of shoes; which, sold in that

character to a match-vender, degenerated after a few weeks into slippers.

Sic transit, &c.

Of the appropriation of the amputated portion no very accurate account

can be rendered. Fragments of the once soft and glossy leather furnished

patches for dilapidated goloshes; a pair or two of gaiter-straps were

extricated from the ruins; and the "translator's" little boy manufactured

from the remains a "sucker," of such marvellous efficacy that his father

could never afterwards keep a lapstone in the stall.

As for the slippers, improperly so called, they pinched divers corns,

and pressed various bunions in their day, as the boots, their great

progenitors, had done before them, sliding, shuffling, shambling, and

dragging their slow length along; until in the ripeness of time, they,

with other antiquities, were carried to Cutler-street, and sold to a

venerable Jewess. She, with knife keen as Shylock's, ripped off the

soles—all besides was valueless even to her—and, not without

some pomp and ceremony, laid them out for sale on a board placed upon a

crippled chair. Yes, for sale; and to that market for soles there soon

chanced to repair an elderly son of poverty; who, having many little feet

running about at home made shoes for them himself. The soles became his;

and thus of the apocryphal remains of my veritable Hessians, was there

just sufficient leather left to interpose between the tender feet of a

child, and the hard earth, his mother!

and thus of the apocryphal remains of my veritable Hessians, was there

just sufficient leather left to interpose between the tender feet of a

child, and the hard earth, his mother!

ON A WICKED SHOEMAKER.

You say he has sprung from Cain;—rather

Confess there's a difference vast:

For Cain was a son of the first father

While he is "a son of the last."

[14]

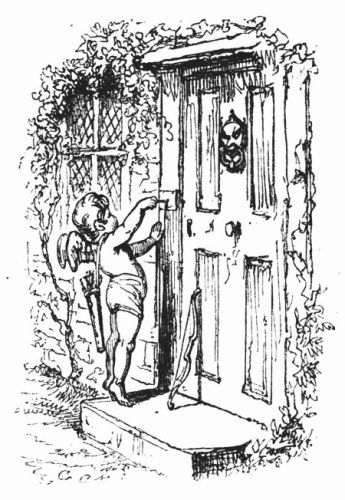

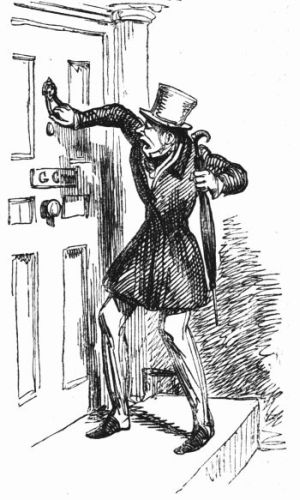

LOVE SEEKING A LODGING.

At Leila's heart, from day to day,

Love, boy-like, knock'd, and ran away;

But Love grown older, seeking then

"Lodgings for single gentlemen,"

Return'd unto his former ground,

And knock'd, but no admittance found—

With his rat, tat, tat.

His false alarms remember'd still.

Love, now in earnest, fared but ill;

For Leila in her heart could swear,

As still he knock'd, "There's no one there."

A single god, he then essay'd

With single knocks to lure the maid—

With his single knock.

Each passer-by, who watch'd the wight,

Cried "Love, you won't lodge there to-night!"

And love, while listening, half confess'd

That all was dead in Leila's breast.

Yet, lest that light heart only slept,

Bold Love up to the casement crept—

With his tip, tap, tap.

No answer;—"Well," cried Love, "I'll wait,

And keep off Envy, Fear, and Hate;

No other passion there shall dwell,

If I'm shut out—why, here's a bell!"

He rang; the ring made Leila start,

And Love found lodgings in her heart—

With his magic ring.

Designed Etched & Published by George Cruikshank May 1st 1841

[15]

FRANK HEARTWELL; OR FIFTY YEARS AGO.

BY BOWMAN TILLER.

CHAPTER I.

It was about half a century ago in the closing twilight of an autumnal

evening at that period of the season when the falling of the sear and

yellow leaves indicated the near approach of winter, that a lady was seated

at work in one of those comfortable parlours which, as far as the memory

of living man can go back, were at all times considered essential to an Englishman's

ideas of enjoyment, and which certainly were not and are not

to be found, approaching to the same degree of commodious perfection, in

any other part of the world. By her side sat a beautiful boy some seven

or eight years of age, whose dark glossy ringlets hung clustering down his

shoulders over the broad and open white cambric collar of his shirt. His

full and fair face bore the ripened bloom of ruddy health, and his large

blue eyes, even though a child, were strongly expressive of tenderness and

love. The lady herself was fair to look upon, possessing a placid cast of

countenance which, whilst it invited esteem and confidence, calmly repelled

impertinence or disrespect; her eyes, like those of her son, were

mild and full, and meltingly blue, and through the shades of long dark

lashes discoursed most eloquently the language of affectionate solicitude

and fond regard; and it was impossible to look upon them, or be looked

upon by them, without experiencing a glow of pleasure, warming and

nourishing all the better feelings and purposes of the heart. In age she

was twenty-six, but matronly anxiety gave her the appearance of being

some two or three years older; her figure was faultless, and the tight

sleeve of her gown fitting closely to her arm, and confined with a bracelet

of black velvet at the wrist, displayed the form of a finely moulded

limb; and the painter or the sculptor would have been proud to copy

from so admirable a model.

The floor of the room was covered with a soft Turkey carpet, which,

though somewhat faded, still retained in many parts its richness of colours.

The panelled walls were of oak that had endured for more than one generation;

and though time had thrown his darkened shadows over them,

as if to claim them for his own, art had been called in aid, if not to defeat

his claims, yet to turn them to advantage; for the blackened wood was

polished to a mirror-like brightness, and instead of dispensing gloom, its

reflections were light and cheerful. Suspended in the upper compartments

and surrounded with oval frames, tastefully carved and gilt, were well

executed portraits by the celebrated masters of those and earlier days.

Between the two windows, where the whole of the light was thrown

upon the person, hung suspended a pier looking-glass in a well-carved

mahogany frame surrounded by the plume of the Prince of Wales, bearing

the appropriate motto for the reflecting tablet itself, "Ich Dien;" and

at the corners, in open work, were cut full-ripe ears of corn in their

golden glory, sheaved together with true-love knots.

[16]

In one angle of the room stood a lofty circular dumb-waiter, its planes

decreasing as they rose in altitude and bearing a display of wine-glasses

with those long white tortuous spiral columns, which, like the screw of

Archimedes, has puzzled older heads than those of childhood to account

for the everlasting turns. There were, also, massive articles of plate of

various periods, from the heavy spoons with the sainted apostles effigied

at the extremity of the handles, to the silver filigree wrought sugar-stand,

with its basin of blue enamelled glass. There were also numerous figures

of ancient China, more remarkable for their fantastic shapes than either

for ornament or for use.

The tables were of dark mahogany, the side slabs curiously deviced,

and the legs assuming something of an animal form with the spreading

paw of the lion or the tiger on each foot. One table, however, that was

carefully placed so as to be remote from danger, had a raised open-work,

about two inches in height, round the edges of its surface, to protect and

preserve the handsome and much-prized tea-service, which had been brought

by a seafaring ancestor as a present from the "Celestial Empire."

A commodious, soft-cushioned, chintz-covered sofa occupied one side of

the parlour, and the various spaces were filled with broad and high-backed

mahogany chairs, whose capacious seats were admirable representatives of

composure and ease. But there was one with wide-spreading arms, that

seemed to invite the weary to its embrace; it was stuffed with soft material,

and covered entirely with thick yellow taffeta, on which many an

hour of laborious toil had been expended to produce in needle-work imitations

of rich fruit and gorgeous flowers; it was a relic of antiquity, and

the busy fingers that had so skilfully plied the task had long since yielded

to mouldering decay.

The fire-place was capacious, and its inner sides were faced with earthenware

tiles, on which were represented scenes and sketches taken from

scripture history. It is true that some of the delineations bore a rather

incongruous character: the serpent erecting itself on the tip of its tail to

beguile Eve; the apple, whose comparative dimensions was calculated

to set the mouth of many a schoolboy watering; and not unfrequently a

mingling of the Selectæ e Profanis amongst the groups caused curious

speculations in the youthful mind. But who can call to recollection the

many evening lectures which this constant fund of instruction and amusement

afforded, without associating them with pleasing remembrances of

innocence and peace?

The fire-grate was large, and of the old-fashioned kind, somewhat of

a basket-like form, small at the bottom, but spreading out into wider

range as its side boundaries ascended.

Lighted tapers were on the table, together with a lady's work-box, and

the small, half-rigged model of a vessel, which the boy had laid down

that he might peruse the history and voyages of Philip Quarll, and now,

sitting by his mother's knee, he was putting questions to her relative

to the sagacious monkeys who were stated to have been poor Philip's

personal attendants and only friends.

Emily Heartwell was, in every sense of the term, the "beloved" wife of

a lieutenant in the British royal navy, who had bravely served with great[17]

credit to himself and advantage to the honour of his country's flag; but

unfortunately becoming mixed up with the angry dissensions that had arisen

amongst political partisans through the trial of Admiral Keppel by court-martial,

he remained for some length of time unemployed, but recently,

through the influence and intervention of his former commander and

patron, Sir George (afterwards Lord) Rodney, he had received an appointment

to a ship-of-the-line that was then fitting out to join that gallant

admiral in the West Indies.

The father of Lieutenant Heartwell had risen from humble obscurity to

the command of a West Indiaman; and his son having almost from his

childhood accompanied him in his voyages, the lad had become early

initiated in the perils and mysteries of a seaman's life, so that on parting

with his parent he was perfectly proficient in all the important duties that

enable the mariner to counteract the raging of the elements, and to navigate

his ship in safety from port to port. What became of the father was

never accurately known. He was bound to Jamaica with a valuable

cargo of home manufactures; he was spoken off the Canaries, and reported

all well; but from that day no tidings of him had been heard,

and it was supposed that the ship had foundered at sea, and all hands

perished.

By some fortuitous circumstance, young Heartwell had been brought

under the especial notice of the intrepid Rodney, who not only placed

him on the quarter-deck of his own ship, but also generously patronised

and maintained him through his probationary term, and at its close, though

involved in difficulties himself, first procured him a lieutenant's commission,

and then presented him with a handsome outfit, cautioning him most

seriously, as he was a good-looking fellow, not to get entangled by

marriage, at least, till he had attained post-rank, or was regularly laid

up with the gout, when he was perfectly at liberty to take unto himself

a wife.

But the lieutenant had a pure, unsophisticated mind, sensibly alive

to all the blandishments of female beauty, but with discretion to avoid

that which he considered meretricious, and to prize loveliness of feature

only when combined with principles of virtue rooted in the heart. Ardently

attached to social life, it can excite but little wonder that on mature

acquaintance with the lady who now bore his name, he had forgotten

the injunction of his commander; and, being possessed of a little property,

the produce of well-earned prize-money, he offered himself to the acceptance

of one who appeared to realise his most fervent expectations;

and, when it is considered that to a remarkably handsome person the

young lieutenant united some of the best qualities of human nature, my

fair readers will at once find a ready reason for his suit not being rejected.

In short, they were married. The father of Mrs. Heartwell, a pious

clergyman, performed the ceremony, and certainly in no instance could

there have been found two persons possessing a stronger attachment,

based on mutual respect and esteem.

An uncle, the brother of the lieutenant's father had, when a boy, gone

out to the East Indies, but he kept up very little communication with his

family, and they had for some time lost sight of him altogether, when[18]

news arrived of his having prospered greatly, and the supposition was

that he had amassed a considerable fortune. As this intelligence, however,

was indirect, but little credit was given to it, and it probably would have

passed away from remembrance, or at least been but little thought of,

had not letters arrived announcing the uncle's death, and that no will

could be discovered.

The lieutenant, as the only surviving heir, was urged to put in his

claim; and, though he himself was not very sanguine in his expectations

that his uncle had realised a large fortune, yet it gratified him to think

that there might be sufficient to assist in securing a respectable and comfortable

maintenance for his wife and child during his absence. From an

earnest desire to surprise Mrs. Heartwell with the pleasing intelligence,

he had for the first time since their union refrained from informing her

of his proceedings; and on the afternoon of the day on which our narrative

opens, he had appointed to meet certain parties connected with the

affair at the office of Mr. Jocelyn Brady, a reputed clever solicitor in

Lincoln's Inn, when the whole was to be finally arranged, and the deeds

and papers placed in his possession in the presence of witnesses.

Cherishing not only the hope, but also enjoying the conviction, that in

a short time he should be able to gladden her heart, the lieutenant imprinted

a warm and affectionate kiss on the lips of his wife, and pressing his

boy in his arms with more than his usual gaiety, he bade them farewell

for a few hours, promising at his return to communicate something that

would delight and astonish them.

But, notwithstanding the hilarity of her husband, an unaccountable

depression weighed heavily on the usually cheerful spirits of Mrs. Heartwell;

and, whilst returning the embrace of her husband, a presentiment

of distress, though she knew not of what nature or kind, filled her bosom

with alarm; and a heavy sigh—almost a groan—burst forth before she had

time to exercise consciousness, or to muster sufficient energy to restrain

it. The prospect of, and the near approach to, the hour of their separation,

had certainly oppressed her mind, but she would not distress her husband

by openly yielding to the manifestation of grief that might render their

parting more keenly painful. She had vigorously exerted all her fortitude

to bear up against the anticipated trial which awaited her, of bidding

a long adieu to the husband of her affections and the father of her child;

but the pressure which now inflicted agony was of a different character

to what she had hitherto experienced. It was a foreboding of calamity

as near at hand, an undefined and undefinable sensation, producing

faintness of spirit and sickness of heart; her limbs trembled, her breath

faltered, and she laid her head upon his shoulder and burst into convulsive

sobbings, that shook her frame with violent agitation.

I am no casuist to resolve doubtful cases, but I would ask many

thousands who have to struggle with the anxious cares, the numerous

disappointments, and all the various difficulties that beset existence,

whether they have not had similar distressing visitations, previous to the

arrival of some unforeseen calamity. What is it, then, that thus operates

on the faculties to produce these symptoms? It cannot be a mere affection

of the nervous system, caused by alarming apprehensions of the future,[19]

for, in most instances, nothing specific has been known or decided.

May it not, therefore, be looked upon as a wise and kind ordination of

providence, to prepare the mind for disastrous events that are to follow?

The lieutenant raised the drooping head of his wife, earnestly gazed on

her expressive countenance, kissed away her tears, and then exclaimed,

"How is this, Emily? what! giving way to the indulgence of sorrow at

a moment when prosperity is again extending the right hand of good-fellowship?

We have experienced adverse gales, my love, but we have

safely weathered them; and now that we have the promise of favourable

breezes and smooth sailing, the prospect of renewed joy should gladden

your heart."

"But are you not soon to leave me, Frank?" returned Mrs. Heartwell,

as she strove to subdue the feelings which agitated her, "and who

have I now in the wide world but you?"

The lieutenant fervently and fondly pressed her to his heart, whilst

with a mingled look of gentle reproach and ardent affection he laid his

disengaged hand on the head of his boy, who raising his tear-suffused eyes

to the countenance of his mother, as he endeavoured to smile, uttered,

"Do not be afraid mama, I will protect you till papa comes back!"

The silent appeal of her husband and the language of her child

promptly recalled the wife and the parent to a sense of her marital and

maternal duties—she instantly assumed a degree of cheerfulness; and the

lieutenant engaging to be home as early as practicable, took his departure

to visit his professional adviser.

The only male attendant (and he was looked upon more in the character