TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

—The transcriber of this project created the book cover image using the front cover of the original book. The image is placed in the public domain.

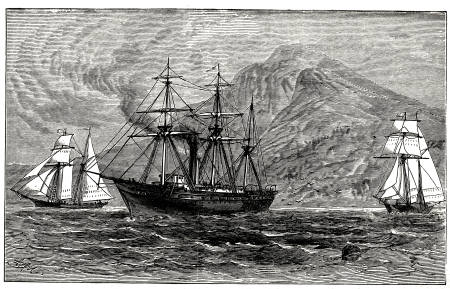

The Academy Squadron off Barcelona. Page 12.

YOUNG AMERICA ABROAD—SECOND SERIES.

Vine and Olive;

OR,

YOUNG AMERICA IN SPAIN AND

PORTUGAL.

A Story of Travel and Adventure.

BY

WILLIAM T. ADAMS

(OLIVER OPTIC),

AUTHOR OF “OUTWARD BOUND,” “SHAMROCK AND THISTLE,” “RED CROSS,”

“DIKES AND DITCHES,” “PALACE AND COTTAGE,” “DOWN THE

RHINE,” “UP THE BALTIC,” “NORTHERN LANDS,”

“CROSS AND CRESCENT,” “SUNNY

SHORES,” ETC.

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS.

New York:

CHARLES T. DILLINGHAM.

COPYRIGHT:

By WILLIAM T. ADAMS.

1876.

TO MY FRIEND,

HENRY RUGGLES, Esq.,

“CONSULADO DE LOS ESTADOS UNIDOS, EN BARCELONA,

EN TIEMPOS PASADOS,”

WHEN WE “ASSISTED” TOGETHER AT A BULL-FIGHT IN

MADRID, VISITED EL ESCORIAL AND TOLEDO,

AND WITH WHOM THE AUTHOR

RELUCTANTLY PARTED

AT CASTILLEJO,

THIS VOLUME

IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED.

PREFACE.

Vine and Olive, the fifth volume of the second series of “Young America Abroad,” contains the history of the Academy Squadron during the cruise along the shores of Spain and Portugal, and the travels of the students in the peninsula. As in the preceding volumes, the professor of geography and history discourses on these subjects to the pupils, conveying to them a great deal of useful information concerning the countries they visit. The surgeon of the ship is a sort of encyclopædia of travel; and, while he is on shore with a couple of the juvenile officers, he enlightens them by his talk on a great variety of topics; and the description of “sights” is given in these conversations, or in the “waits” between the speeches. In addition to the cities of the peninsula on the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, the young travellers cross the country from Barcelona to Lisbon, visiting on the way Saragossa, Burgos, the Escurial, Madrid, Toledo, Aranjuez, Badajos, and Elvas. In another excursion by land, they start from Malaga, and take in Granada and the Alhambra, Cordova, Seville, and Cadiz. Besides the ports mentioned, the party vessels visit Valencia, Alicante,—from which they make an excursion to Elche to see its palms—Carthagena, and Gibraltar.

The author has visited every country included in the titles of the eleven volumes of the two series of which the present volume is the last published. He has been abroad twice for the sole purpose of obtaining the materials for these books; his object being to produce books that would instruct as well as amuse.

The story of the incendiaries and of the young Spanish officer of[6] the Tritonia, interwoven with the incidents of travel, is in accordance with the plan adopted in the first, and followed out in every subsequent volume of the two series. Doubtless the book will have some readers who will skip the lectures of the professor and the travel-talk of the surgeon, and others who will turn unread the pages on which the story is related; but we fancy the former will be larger than the latter class. If both are suited, the author need not complain; though he especially advises his young friends to read the historical portions of the volume, because he thinks that the maritime history of Portugal, for instance, ought to interest them more than any story he can invent.

The titles of all the books of this series were published ten years ago. The boys and girls who read the first volume are men and women now; and the task the author undertook then will be finished in one more volume.

With the hope that he will live to complete the work begun so many years ago, the author once more returns his grateful acknowledgments to his friends, old and young, for the favor they have extended to this series.

Towerhouse, Boston, Oct. 19, 1876.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE. | ||

| I. | Something about the Marines | 11 |

| II. | At the Quarantine Station | 26 |

| III. | A Grandee of Spain | 41 |

| IV. | The Professor’s Talk about Spain | 53 |

| V. | A Sudden Disappearance | 79 |

| VI. | A Look at Barcelona | 87 |

| VII. | Fire and Water | 102 |

| VIII. | Saragossa and Burgos | 116 |

| IX. | The Hold of the Tritonia | 133 |

| X. | The Escurial and Philip II. | 145 |

| XI. | The Cruise in the Felucca | 159 |

| XII. | Sights in Madrid | 173 |

| XIII. | After the Battle in the Felucca | 187 |

| XIV. | Toledo, and Talks about Spain | 202 |

| XV. | Trouble in the Runaway Camp | 221 |

| XVI. | Bill Stout as a Tourist | 233 |

| XVII. | Through the Heart of Spain | 245 |

| XVIII.[8] | Africa and Repentance | 261 |

| XIX. | What Portugal has done in the World | 274 |

| XX. | Lisbon and its Surroundings | 292 |

| XXI. | A Safe Harbor | 305 |

| XXII. | The Fruits of Repentance | 319 |

| XXIII. | Granada and the Alhambra | 333 |

| XXIV. | An Adventure on the Road | 349 |

| XXV. | Cordova, Seville, and Cadiz | 358 |

| XXVI. | The Capture of the Beggars | 373 |

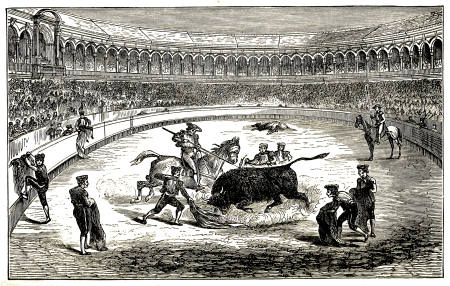

| XXVII. | The Bull-Fight at Seville | 390 |

VINE AND OLIVE;

OR,

YOUNG AMERICA IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL.

CHAPTER I.

SOMETHING ABOUT THE MARINES.

“Land, ho!” shouted the lookout in the foretop of the Tritonia.

“Where away?” demanded the officer of the deck, as he glanced in the direction the land was expected to be found.

“Broad on the weather bow,” returned the seaman in the foretop.

“Mr. Raimundo,” said the officer of the deck, who was the third lieutenant, calling to the second master.

“Mr. Scott,” replied the officer addressed, touching his cap to his superior.

“You will inform the captain, if you please, that the lookout reports land on the weather bow.”

The second master touched his cap again, and hastened to the cabin to obey the order. The academy squadron, consisting of the steamer American Prince and the topsail schooners Josephine and Tritonia,[12] were bound from Genoa to Barcelona. They had a short and very pleasant passage, and the students on board of all the vessels were in excellent spirits. Though they had been seeing sights through all the preceding year, they were keenly alive to the pleasure of visiting a country so different as Spain from any other they had seen. The weather was warm and pleasant for the season, and the young men were anxiously looking forward to the arrival at Barcelona. On the voyage and while waiting in Genoa, they had studied up all the books in the library that contained any thing about the interesting land they were next to visit.

The Tritonia sailed on the starboard, and the Josephine on the port quarter, of the American Prince. The two consorts had all sail set, and were making about eight knots an hour, which was only half speed for the steamer, to which she had been reduced in order to keep company with the sailing vessels. Though the breeze was tolerably fresh, the sea was smooth, and the vessels had very little motion. The skies were as blue and as clear as skies can ever be; and nothing could be more delicious than the climate.

In the saloon of the steamer and the steerage of the schooners, which were the schoolrooms of the academy squadron, one-half of the students of the fleet were engaged in their studies and recitations. A quarter watch was on duty in each vessel, and the same portion were off duty. But the latter were not idle: they were, for the most part, occupied in reading about the new land they were to visit; and the more ambitious were preparing for the next recitation. Their positions on[13] board for the next month would depend upon their merit-roll; and it was a matter of no little consequence to them whether they were officers or seamen, whether they lived in the cabin or steerage. Some were struggling to retain the places they now held, and others were eager to win what they had not yet attained.

There were from two to half a dozen in each vessel who did only what they were obliged to do, either in scholarship or seamanship. At first, ship’s duty had been novel and pleasant to them; and they had done well for a time,—had even struggled hard with their lessons for the sake of attaining creditable places as officers and seamen. They had been kindly and generously encouraged as long as they deserved it; but, when the novelty had worn away, they dropped back to what they had been before they became students of the academy squadron. Mr. Lowington labored hard over the cases of these fellows; and, next to getting the fleet safely into port, his desire was to reform them.

In the Tritonia were four of them, who had also challenged the attention and interest of Mr. Augustus Pelham, the vice-principal in charge of the vessel, who had formerly been a student in the academy ship, and who had been a wild boy in his time. The interest which Mr. Lowington manifested in these wayward fellows had inspired the vice-principal to follow his example. Possibly the pleasant weather had some influence on the laggards; for they seemed to be very restive and uneasy under restraint as the squadron approached the coast of Spain. All four of them were in the starboard watch, and in the second part thereof, where they had been put so that the vice-principal could[14] know where to find them when he desired to watch them at unusual hours.

The third lieutenant was the officer of the deck, assisted by the second master. The former was planking the weather side of the quarter deck, and the latter was moving about in the waist. The captain came on deck, and looked at the distant coast through his glass; but it was an old story, and he remained on deck but a few minutes. Raimundo, the officer in the waist, was a Spaniard, and the shore on the starboard was that of “his own, his native land.” But this fact did not seem to excite any enthusiasm in his mind: in fact, he really wished it had been somebody else’s native land, and he did not wish to go there. He bestowed more attention upon the four idlers, who had coiled themselves away in the lee side of the waist, than upon the shadowy shore of the home of his ancestors. He was a sharp officer; and this was his reputation on board. He could snuff mischief afar off; and more than one conspiracy had been blighted by his vigilance. He seemed to be gazing at the clear blue sky, and to be enjoying its azure transparency; but he had an eye to the laggards all the time.

“I wonder what those marines are driving at,” said he to himself, after he had studied the familiar phenomenon for a while, and, as it appeared, without any satisfactory result. “I never see those four fellows talking together as long as they have been at it, without an earthquake or some sort of a smash following pretty soon after. I suppose they are going to run away, for that is really the most fashionable sport on board of all the vessels of the fleet[15].”

Perhaps the second master was right, and perhaps he was wrong. Certainly running away had been the greatest evil that had tried the patience of the principal; but there had been hardly a case of it since the squadron came into the waters of the Mediterranean, and he hoped the practice had gone out of fashion. It had been so unsuccessful, that most of the students regarded it as a played-out expedient.

Raimundo was one of those whom this nautical institution had saved to be a blessing, instead of a curse, to the community; but he was truly reformed, and, over and above his duty as an officer, he was sincerely desirous to save the “marines” from the error of their ways. He did not expect them to uncover their plans all at once, and he was willing to watch and wait.

Having viewed the marines from the officer’s side of the question, we will enter into the counsels of those who were the subjects of this official scrutiny. After the first few months of life in the squadron, these four fellows had been discontented and dissatisfied. They had been transferred from one vessel to another, in the hope that they might find their appropriate sphere; but there seemed to be no sphere below—at least, as far as they had gone—where they could revolve and shine. They had been “sticks,” wherever they were. One country seemed to be about the same as any other to them. They did not like to study; they did not like to “knot and splice;” they did not like to stand watch; they did not like to read even stories, fond as they were of yarns of the coarser sort; they did not like to do any thing but eat, sleep, and loaf about the deck, or, on shore, but to dissipate and indulge in rowdyism.[16] Two of them had been transferred to the Tritonia from the Prince at Genoa, and the other two had been in the schooner but two months.

“I’m as tired as death of this sort of thing,” said Bill Stout, the oldest and biggest fellow of the four.

“I had enough of it in a month after I came on board,” added Ben Pardee, who was lying flat on his back, and gazing listlessly up into the clear blue sky; “but what can a fellow do?”

“Nothing at all,” replied Lon Gibbs. “It’s the same thing from morning to night, from one week’s end to the other.”

“Can’t we get up some sort of an excitement?” asked Bark Lingall, whose first name was Barclay.

“We have tried it on too many times,” answered Ben Pardee, who was perhaps the most prudent of the four. “We never make out any thing. The fellows in the Tritonia are a lot of spoonies, and are afraid to say their souls are their own.”

“They are good little boys, lambs of the chaplain’s fold,” sneered Lon Gibbs. “There is nothing like fun in them.”

“We are almost at the end of the cruise, at any rate,” said Bark Lingall, who seemed to derive great comfort from the fact. “This slavery is almost at an end.”

“I don’t know about that,” added Bill Stout.

“Spain and Portugal are the last countries in Europe we are to visit; and we shall finish them up in three or four weeks more.”

“And what then? we are not to go home and be discharged, as you seem to think,” continued Bill Stout. “We are to go to the West Indies, taking in a lot of islands on the way—I forget what they are[17].”

“I can stand it better when we are at sea,” said Ben Pardee. “There is more life in it as we are tumbling along in a big sea. Besides, there will be something to see in those islands. These cities of Europe are about the same thing; and, when you have seen one, you have seen the whole of them.”

“I don’t know about that,” suggested Lon Gibbs, who, from the chaplain’s point of view, was the most hopeful of the four; for his education was better than the others, and he had some taste for the wonders of nature and art. “Spain ought to be worth seeing to fellows from the United States of America. I suppose you know that Columbus sailed from this country.”

“Is that so?” laughed Bark Lingall. “I thought he was an Italian; at any rate, we saw the place where he was born, or else it was a fraud.”

“I think you had better read up your history again, and you will find that Columbus was born in Italy, but sailed in the service of Spain,” replied Lon Gibbs.

“That will do!” interposed Bill Stout, turning up his nose. “We don’t want any of that sort of thing in our crowd. If you wish to show off your learning, Lon, you had better go and join the lambs.”

“That’s so. It’s treason to talk that kind of bosh in our company. We have too much of it in the steerage to tolerate any of it when we are by ourselves,” said Ben Pardee.

“I thought you were going to do something about it,” added Bill Stout. “We are utterly disgusted, and we agreed that we could not stand it any longer. We shall go into the next place—I forget the name of it[18]”—

“Barcelona,” added Lon Gibbs, who was rather annoyed at the dense ignorance of his friend.

“Barcelona, then. I suppose it is some one-horse seaport, where we are expected to go into ecstasies over tumble-down old buildings, or pretend that we like to look at a lot of musty pictures. I have had enough of this sort of thing, as I said before. I should like to have a right down good time, such as we had in New York when we went round among the theatres and the beer-shops. That was fun for me. I’m no book-worm, and I don’t pretend to be. I won’t make believe that I enjoy looking at ruins and pictures when it is a bore to me. I will not be a hypocrite, whatever else I am.”

Bill Stout evidently believed that he had some virtue left; and, as he delivered himself of his sentiments, he looked like a much abused and wronged young man.

“Here we are; and in six or eight hours we shall be in Barcelona,” continued Ben Pardee.

“And it is no such one-horse place as you seem to think it is,” added Lon Gibbs. “It is a large city; in fact, the second in size in Spain, and with about the same population as Boston. It is a great commercial place.”

“You have learned the geography by heart,” sneered Bill Stout, who had a hearty contempt for those who knew any thing contained in the books, or at least for those who made any display of their knowledge.

“I like, when I am going to any place, to know something about it,” pleaded Lon, in excuse for his wisdom in regard to Barcelona.

“Are there any beer-shops there, Lon?” asked Bill.

“I don’t know[19].”

“Then your education has been neglected.”

“Spain is not a beer-drinking country; and I should say you would find no beer-shops there,” continued Lon. “Spain is a wine country; and I have no doubt you will find plenty of wine-shops in Barcelona, and in the other cities of the country.”

“Wine-shops! that will do just as well, and perhaps a little better,” chuckled Bill. “There is no fun where there are no wine or beer shops.”

“What’s the use of talking?” demanded Bark Lingall. “What are the wine or the beer shops to do with us? If we entered one of them, we should be deprived of our liberty, or be put into the brig for twenty-four hours; and that don’t pay.”

“But I want to break away from this thing altogether,” added Bill Stout. “I have been a slave from the first moment I came into the squadron. I never was used to being tied up to every hour and minute in the day. A fellow can’t move without being watched. What they call recreation is as solemn as a prayer-meeting.”

“Well, what do you want to do, Bill?” asked Ben Pardee, as he glanced at the second master, who had halted in his walk in the waist, to overhear, if he could, any word that might be dropped by the party.

“That’s more than I am able to say just at this minute,” replied Bill, pausing till the officer of the watch had moved on. “I want to end this dog’s life, and be my own master once more. I want to get out of this vessel, and out of the fleet.”

“Would you like to get into the steamer?” asked Lon Gibbs.

“I should like that for a short time; but I don’t think I should be satisfied in her for more than a week or two. It was just my luck, when I got out of the Young America, after she went to the bottom, to have the American Prince come to take her place, and leave me out in the cold. No, I don’t want to stay in the steamer; but I should like to be in her a few days, just to see how things are done. All the fellows have to keep strained up in her, even more than in the Tritonia; and that is just the thing I don’t like. In fact, it is just the thing I won’t stand much longer.”

“What are you going to do about it? How are you going to help yourself?” inquired Lon Gibbs. “Here we are, and here we must stay. It is all nonsense to think of such a thing as running away.”

“I want some sort of an excitement, and I’m going to have it too, if I am sent home in some ship-of-war in irons.”

“You are getting desperate, Bill,” laughed Ben Pardee.

“That’s just it, Ben; I am getting desperate. I cannot endure the life I am leading on board of this vessel. It is worse than slavery to me. If you can stand it, you are welcome to do so.”

“We all hate it as bad as you do,” added Bark Lingall, who had the reputation of being the boldest and pluckiest of the bad boys on board of the Tritonia.

“I don’t think you do. If you did, you would be as ready as I am to break the chains that bind us.”

“We are ready to do any thing that will end this dog’s life,” replied Bark. “We will stand by you, if you will only tell us what to do[21].”

“I think you are ready for business, Bark; but I am not so sure of the others,” he added, glancing into the faces of Lon Gibbs and Ben Pardee.

“I don’t believe in running away,” said the prudent Ben.

“Nor I,” added Lon.

“I knew you were afraid of your own shadows,” sneered Bill.

“We are not afraid of any thing; but so many fellows have tried to run away, and made fools of themselves, that I am not anxious to try it on. The principal always gets the best of it. There were the two fellows, De Forrest and Beckwith, who had been cabin officers, that tried it on. Lowington didn’t seem to care what became of them. But in the end they came back on board, like a couple of sick monkeys, went into the brig like white lambs, and to this day they have to stay on board when the rest of the crew go ashore, in charge of the big boatswain of the ship.”

“Well, what of it? I had as lief stay on board as march in solemn procession with the professors through the old churches of the place we are coming to—what did you say the name of it was?”

“Barcelona,” answered Lon.

“But that’s not the thing, Bill,” protested Ben. “It is not so much the brig and the loss of all shore liberty as it is the being whipped out at your own game.”

“That’s the idea,” added Lon. “When those fellows came on board, though they had been absent for weeks, the principal only laughed at them as he ordered them into the brig. There was not a fellow in the ship who did not feel that they had made fools of themselves. I[22] would rather stay in the brig six months than feel as I know those fellows felt at that moment.”

“I don’t think of running away,” continued Bill. “I have a bigger idea than that in my mind.”

“What is it?” demanded the others, in the same breath.

“I won’t tell you now, and not at all till I know that you can bear it. Desperate cases require desperate remedies; and I’m not sure that any of you are up to it yet.”

No amount of teasing could induce Bill Stout to expose the dark secret that was concealed in his mind; and at noon the watch was relieved, so that they had no other opportunity to talk till the first dog-watch; but the secret came out in due time, and it was nothing less than to burn the Tritonia. Bill believed that her ship’s company could not be accommodated on board of the other vessels, which were all full, and therefore the students would be sent home. At first Bark Lingall was horrified at the proposition; but having talked it over for hours with Bill Stout alone, for the conspirator would not yet trust the secret with Ben Pardee and Lon Gibbs, he came to like the plan, and fully assented to it. He would not consent to do any thing that would expose the life of any person on board. It was not till the following day that Bark came to the conclusion to join in the conspiracy. Towards night, as it was too late to go into port, the order had been signalled from the Prince to stand off and on; and this was done till the next morning.

The plan was discussed in all its details. It was believed that the vessels would be quarantined at Barcelona,[23] and this would afford the best chance to carry out the wicked plot. One of their number was to conceal himself in the hold; and, when all hands had left the vessel, he was to light the fire, and escape the best way he could. If the fleet was not quarantined, the job was to be done when the ship’s company landed to see the city.

At eight bells in the morning, the signal was set on the Prince to stand in for Barcelona. The conspirators found no opportunity to broach the wicked scheme to Ben and Lon. For the next three hours the starboard watch were engaged in their duties. As may be supposed, Bill Stout and Bark Lingall, with their heads full of conspiracy and incendiarism, were in no condition to recite their lessons, even if they had learned them, which they had not done. They were both wofully deficient, and Bill Stout did not pretend to know the first thing about the subject on which he was called upon to recite. The professor was very indignant, and reported them to the vice-principal. Mr. Pelham found them obstinate as well as deficient; and he ordered them to be committed to the brig, and their books to be committed with them. They were to stand their watches on deck, and spend all the rest of the time in the cage, till they were ready to recite the lessons in which they had failed. The “brig” was the ship’s prison.

Mr. Marline, the adult boatswain, took charge of them, and locked them up. The position of the brig had been recently changed, and it was now under the ladder leading from the deck to the steerage. The partitions were hard wood slats, two inches thick and three inches apart. Two stools were the only furniture[24] it contained, though a berth-sack was supplied for each occupant at night. Their food, which was always much plainer than that furnished for the cabin and steerage tables, was passed in to them through an aperture in one side, beneath which was a shelf that served for a table.

Bark looked at Bill, and Bill looked at Bark, when the door had been secured, and the boatswain had left them to their own reflections. Neither of them seemed to be appalled by the situation. They sat down upon the stools facing each other. Bark smiled upon Bill, and Bill smiled in return. This was not the first time they had been occupants of the brig.

“Here we are,” said Bill Stout, in a low tone, after he had made a hasty survey of the prison. “I think this is better than the old brig, and I believe we can be happy here for a few days.”

“What will become of our big plan now, Bill?” asked Bark.

“Hush!” added Bill in his hoarsest whisper, as he looked through the slats of the prison to see if any one was observing them.

“What’s the matter now?” demanded Bark, rather startled by the impressive manner of his companion.

“Not a word,” replied Bill, as he pointed and gesticulated in the direction of the flooring under the ladder.

“Well, what is it?” demanded Bark.

“Don’t you see?” and again he pointed as before.

“I don’t see any thing.”

“Then you are blind! Don’t you see that the new brig has been built over one of the scuttles that lead down into the hold?”

“I see it now. I didn’t know what you meant when you pointed so like Hamlet’s ghost[25].”

“Don’t say a word, or look at it,” whispered Bill, as he placed his stool over the trap, and looked out into the steerage.

The vice-principal passed the brig at this moment, and nothing more was said.

CHAPTER II.

AT THE QUARANTINE STATION.

While these events were transpiring below, the signal had come from the Prince to shorten sail on the schooners, for the squadron was within half a mile of the long mole extending to the southward of the tongue of land that forms the easterly side of the harbor of Barcelona. A signal for a pilot was exhibited on each vessel of the fleet, but no pilot boat seemed to be in sight. As the bar could not be far distant, it was not deemed prudent to advance any farther; and the steamer had stopped her engine.

“Signal on the steamer to heave to, Mr. Greenwood,” said Rolk, the fourth master, as he touched his cap to the first lieutenant, who was the officer of the deck.

“I see it,” replied Greenwood. “Haul down the jib, and back the fore-topsail!”

The necessary orders were given in detail, and in a few moments the three vessels of the fleet were lying almost motionless on the sea. Greenwood took a glass from the beckets at the companion-way, and proceeded to a make a survey of the situation ahead. But there was nothing to be seen except the mole, and the high fortified hill of Monjuich on the mainland, across the harbor.

“Where are your pilots, Raimundo?” asked Scott of the second master; and both of them were off duty at this time.

“You won’t see any pilots yet awhile,” replied the young Spaniard.

“Are they all asleep?”

“Do you think they will be weak enough to come on board before the health officers have given their permission for the vessels to enter the harbor?” added Raimundo. “If they did so they would be sent into quarantine themselves.”

“They are prudent, as they ought to be,” added Scott. “I suppose you begin to feel at home about this time; don’t you, Don Raimundo?”

“Not half so much at home as I do when I am farther away from Spain,” replied the second master, with a smile that seemed to be of a very doubtful character.

“Why, how is that?” asked Scott. “This is Spain, the home of your parents, and the land that gave you birth.”

“That’s true; but, for all that, I would rather go anywhere than into Spain. In fact, I don’t think I shall go on shore at all,” added Raimundo, and there was a very sad look on his handsome face.

“Why, what’s the matter, my Don?”

“I thought very seriously of asking Mr. Lowington to grant me leave of absence till the squadron reaches Lisbon,” replied the second master. “I should have done so if it had not been for losing my rank, and taking the lowest place in the Tritonia.”

“I don’t understand you,” answered Scott, puzzled by the sudden change that had come over his friend;[28] for, being in the same quarter watch, they had become very intimate and very much attached to each other.

“Of course you do not understand it; but when I have the chance I will tell you all about it, for I may want you to help me before we get out of the waters of Spain. But I wish you to know, above all things, that I never did any thing wrong in Spain, whatever I may have done in New York.”

“Of course not, for I think you said you left your native land when you were only ten years old.”

“That’s so. I was born in this very city of Barcelona; and I suppose I have an uncle there now; but I would not meet him for all the money in Spain,” said Raimundo, looking very sad, and even terrified. “But we will not say any thing more about it now. When I have a chance, I will tell you the whole story. I am certain of one thing, and that is, I shall not go on shore in Barcelona if I can help it. There is a boat coming out from behind the mole.”

“An eight-oar barge; and the men in her pull as though she were part of a funeral procession,” said the first lieutenant, examining the boat with the glass. “She has a yellow flag in her stern.”

“Then it is the health officers,” added Raimundo.

All hands in the squadron watched the approaching boat; for by this time the quarantine question had excited no little interest, and it was now to be decided. The oarsmen pulled the man-of-war stroke; but the pause after they recovered their blades was so fearfully long that the rowers seemed to be lying on their oars about half of the time. Certainly the progress of the barge was very slow, and it was a long time before it[29] reached the American Prince. Then it was careful not to come too near, lest any pestilence that might be lurking in the ship should be communicated to the funereal oarsmen or their officers. The boat took up its position abreast of the steamer’s gangway, and about thirty feet distant from her.

A well-dressed gentleman then stood up in the stern-sheets of the barge, and hailed the ship. Mr. Lowington, in full uniform, which he seldom wore, replied to the hail in Spanish; and a long conference ensued. When the principal said that the squadron came from Genoa, the health officer shook his head. Then he wanted to know all about the three vessels, and it appeared to be very difficult for him to comprehend the character of the school. At last he was satisfied on all these points, and understood that the academy was a private enterprise, and not an institution connected with the United States Navy.

“Have you any sickness on board?” asked the health officer, when the nature of the craft was satisfactorily explained.

“We have two cases of measles in the steamer, but all are well in the other vessels,” replied Mr. Lowington.

“Sarampion!” exclaimed the Spanish officer, using the Spanish word for the measles.

At the same time he shrugged his shoulders like a Frenchman, and vented his incredulity in a laugh.

“Viruelas!” added the officer; and the word in English meant smallpox, which was just the disease the Spaniards feared as coming from Genoa.

Mr. Lowington then called Dr. Winstock, the surgeon,[30] who spoke Spanish fluently, and presented him to the incredulous health officer. A lengthy palaver between the two medical men ensued. There appeared to be some sort of freemasonry, or at least a professional sympathy, between them, for they seemed to get on very well together. The cases of measles were very light ones, the two students having probably contracted the disease in some interior town of Italy where they passed the night at a hotel. They had been kept apart from the other students, and no others had taken the malady.

The health officer declared that he was satisfied for the present with the explanation of the surgeon, and politely asked to see the ship’s papers, which the principal held in his hand. The barge pulled up a little nearer to the steamer; a long pole with a pair of spring tongs affixed to the end of it was elevated to the gangway, between the jaws of which Mr. Lowington placed the documents. They were carefully examined, and then all hands were required to show themselves in the rigging. This order included every person on board, not excepting the cooks, waiters, and coal-heavers. In a few moments they were standing on the rail or perched in the rigging, and the health officer and his assistants proceeded to count them. The number was two short of that indicated in the ship’s papers, for those who were sick with the measles were not allowed to leave their room.

The health officer then intimated that he would pay the vessel a visit; and all hands were ordered to muster at their stations where they could be most conveniently inspected. Every part of the vessel was then carefully examined, and the Spanish doctors minutely overhauled[31] the two cases of measles. They declared themselves fully satisfied that there was neither yellow fever nor smallpox on board of the steamer. The other vessels of the squadron were subjected to the same inspection. Mr. Lowington and Dr. Winstock attended the health officer in his visit to the Josephine and the Tritonia.

“You find our vessels in excellent health,” said Dr. Winstock, when the examination was completed.

“Very good; but we cannot get over the fact that you come from Genoa, where the smallpox is prevailing badly. Vessels from that port are quarantined at Marseilles for from three days to a fortnight; but I shall not be hard with you, as you have a skilful surgeon on board,” replied the health officer, touching his hat to Dr. Winstock; “but my orders from the authorities are imperative that all vessels from infected or doubtful ports shall be fumigated before any person from them is allowed to land in the city. We have had the yellow fever so severely all summer that we are very cautious.”

“Is it necessary to fumigate?” asked Dr. Winstock, with a smile.

“The authorities require it, and I am not at liberty to dispense with it,” answered the official. “But it will detain you only a few hours. You will land the ship’s company of each vessel, and they will be fumigated on shore. While they are absent our people will purify the vessels.”

“Is there any yellow fever in the city now?” asked the surgeon of the fleet.

“None at all. The frost has entirely killed it; but we have many patients who are recovering from the disease. The people who went away have all returned, and we call the city healthy[32].”

The quarantine grounds were pointed out to the principal; and the fleet was soon at anchor within a cable’s length of the shore. Study and recitation were suspended for the rest of the day. All the boats of the American Prince were manned; her fires were banked; the entire ship’s company were transferred to the shore; and the vessel was given up to the quarantine officers, who boarded her and proceeded with their work. In a couple of hours the steamer and her crew were disposed of; and then came the turn of the Josephine, for only one vessel could be treated at a time.

When all hands were mustered on board of the Tritonia, the two delinquents in the brig were let out to undergo the inspection with the others. The decision of the health officer requiring the vessels to be fumigated, and the fact that the process would require but a few hours, were passed through each of the schooners as well as the steamer, and in a short time were known to every student in the fleet. As usual they were disposed to make fun of the situation, though it was quite a sensation for the time. During the excitement Bark Lingall improved the opportunity to confer with Lon Gibbs and Ben Pardee. Lon was willing to undertake any thing that Bark suggested. Ben was rather a prudent fellow, but soon consented to take part in the enterprise. Certainly neither of these worthies would have assented if the proposition to join had been made by Bill Stout, in whom they had as little confidence as Bark had manifested. The alliance had hardly been agreed upon before the vice-principal happened to see the four marines talking together, and[33] ordered Marline to recommit two of them to the brig. The boatswain locked them into their prison, and left them to their own reflections. The excitement on deck was still unabated, and the cabins and steerage were deserted even by the stewards.

“I think our time has come,” said Bill Stout, after he had satisfied himself that no one but the occupants of the brig was in the steerage. “If we don’t strike at once we shall lose our chance, for they say we are going up to the city to-night.”

“They will have to let us out to be fumigated with the rest of the crew,” answered Bark Lingall. “We haven’t drawn lots yet, either.”

“Never mind the lot now: I will do the job myself,” replied Bill magnanimously. “I should rather like the fun of it.”

“All right, though I am willing to take my chances. I won’t back out of any thing.”

“You are true blue, Bark, when you get started; but I would rather do the thing than not.”

“Very well, I am willing; and when the scratch comes I will back you up. But I do not see how you are going to manage it, Bill,” added Bark, looking about him in the brig.

“The vice has made an easy thing of it for us. While the fellows were all on deck, I went to my berth and got a little box of matches I bought in Genoa when we were there. I have it in my pocket now. All I have to do is to take off this scuttle, and go down into the hold. As we don’t know how soon the fellows will be sent ashore, I think I had better be about it now[34].”

Bill Stout put his fingers into the ring on the trap-door, and lifted it a little way.

“Hold on, Bill,” interposed Bark. “You are altogether too fast. When Marline comes down to let us out, where shall I say you are?”

“That’s so: I didn’t think of that,” added Bill, looking rather foolish. “He will see the scuttle, and know just where I am.”

“And, when the blaze comes off, he will see just who started it,” continued Bark. “That won’t do anyhow.”

“But I don’t mean to give it up,” said Bill, scratching his head as he labored to devise a better plan.

The difficulty was discussed for some time, but there seemed to be no way of meeting it. Bill was one of the crew of the second cutter, and he was sure to be missed when the ship’s company were piped away. If Bark, who did not belong to any boat, took his oar, the boatswain, whose place was in the second cutter when all hands left the vessel, would notice the change. Bill was almost in despair, and insisted that no amount of brains could overcome the difficulty. The conspirator who was to “do the job” was certain to be missed when the ship’s company took to the boats. To be missed was to proclaim who the incendiary was when the fire was investigated.

“We may as well give it up for the present, and wait for a better time,” suggested Bark, who was as unable as his companion to solve the problem.

“No, I won’t,” replied Bill, taking a newspaper from his breast-pocket. “We may never have another chance; and I believe in striking while the iron is hot[35].”

“Don’t get us into a scrape for nothing. We can’t do any thing now,” protested Bark.

“Now’s the day, and now’s the hour!” exclaimed Bill, scowling like the villain of a melodrama.

“What are you going to do?” demanded Bark, a little startled by the sudden energy of his fellow-conspirator.

“Hold on, and you shall see,” answered Bill, as he raised the trap-door over the scuttle.

“But stop, Bill! you were not to do any thing without my consent.”

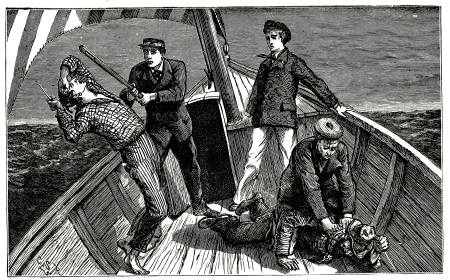

“All hands on deck! man the boats in fire order,” yelled the boatswain on deck, after he had blown the proper pipe.

Bill Stout paid no attention to the call or to the remonstrance of his companion. Raising the trap, he descended to the hold by the ladder under the scuttle. Striking a match, he set fire to the newspaper in his hand, and then cast it into the heap of hay and sawdust that lay near the foot of the ladder. Hastily throwing the box-covers and cases on the pile, he rushed up the steps into the brig, and closed the scuttle. He was intensely excited, and Bark was really terrified at what he considered the insane rashness of his associate in crime. But there was no time for further talk; for Marline appeared at this moment, and unlocked the door of the brig.

“Come, my hearties, you must go on shore for an hour to have the smallpox smoked out of you; and I wish they could smoke out some of the mischief that’s in you at the same time,” said the adult boatswain. “Come, and bear a hand lively, for all hands are in boats by this time[36].”

Bill Stout led the way; and on this occasion he needed no hurrying, for he was in haste to get away from the vessel before the blaze revealed itself. In a moment more he was on the thwart in the second cutter where he belonged. Bark’s place was in another boat, and they separated when they reached the deck. The fire-bill assigned every person on board of the vessel to a place in one of the boats, so that every professor and steward as well as every officer and seaman knew where to go without any orders. It was the arrangement for leaving the ship in case of fire; and it had worked with perfect success in the Young America when she was sunk by the collision with the Italian steamer. As the boats pulled away from the Tritonia, the quarantine people boarded her to perform the duty belonging to them.

Bill Stout endeavored to compose himself, but with little success, though the general excitement prevented his appearance from being noticed. He was not so hardened in crime that he could see the vessel on fire without being greatly disturbed by the act; and it was more than probable that, by this time, he was sorry he had done it. He did not expect the fire to break out for some little time; and it had not occurred to him that the quarantine people would extend their operation to the hold of the vessel.

The boats landed on the beach; and all hands were marched up to a kind of tent, a short distance from the water. There were fifty-five of them, and they were divided into two squads for the fumigating process.

“How is this thing to be done?” asked Scott, as he halted by the side of Raimundo, at the tent.

“I have not the least idea what it is all about,” replied the young Spaniard.

“I suppose we are to take up our quarters in this tent.”

“Not for very long; for all the rest of the squadron have been operated upon in a couple of hours.”

The health officer now beckoned them to enter the tent. It was of the shape of a one-story house. The canvas on the sides and end was tacked down to heavy planks on the ground, so as to make it as tight as possible. There was only a small door; and, when the first squad had entered, it was carefully closed, so that the interior seemed to be almost air-tight. In the centre of the tent was a large tin pan, which contained some chemical ingredient. The health officer then poured another ingredient into the pan; and the union of the two created quite a tempest, a dense smoke or vapor rising from the vessel, which immediately filled the tent.

“Whew!” whistled Scott, as he inhaled the vapor. “These Spaniards ought to have a patent for getting up a bad smell. This can’t be beat, even by the city of Chicago.”

“I am glad you think my countrymen are good for something,” laughed Raimundo.

The students coughed, sneezed, and made all the fuss that was necessary, and a good deal more. The health officer laughed at the antics of the party, and dismissed them in five minutes, cleansed from all taint of smallpox or yellow fever.

“Where’s your blaze?” asked Bark Lingall, as they withdrew from the others who had just left the tent.

“Hush up! don’t say a word about it,” whispered Bill; “it hasn’t got a-going yet[38].”

“But those quarantine folks are on board; and if there were any fire there they would have seen it before this time,” continued Bark nervously.

“Dry up! not another word! If we are seen talking together the vice will know that we are at the bottom of the matter.”

Bill Stout shook off his companion, and walked about with as much indifference as he could assume. Every minute or two he glanced at the Tritonia, expecting to see the flames, or at least the smoke, rising above her decks. But no flame or smoke appeared, not even the vapor of the disinfectants.

The second squad of the ship’s company were sent into the tent after the preparations were completed; and in the course of an hour the health officer gave the vice-principal permission to return to his vessel. The boats were manned; the professors and others took their places, and the bowmen shoved off. Bill began to wonder where his blaze was, for ample time had elapsed for the flames to envelop the schooner, if she was to burn at all. Still there was no sign of fire or smoke about the beautiful craft. She rested on the water as lightly and as trimly as ever. Bill could not understand it; but he came to the conclusion that the quarantine men had extinguished the flames. The burning of the vessel did not rest upon his conscience, it is true; but he was not satisfied, as he probably would not have been if the Tritonia had been destroyed. He felt as though he had attempted to do a big thing, and had failed. He was not quite the hero he intended to be in the estimation of his fellow-conspirators.

The four boats of the Tritonia came alongside the[39] schooner; and, when the usual order of things had been fully restored, the signal for sailing appeared on the steamer. The odor of the chemicals remained in the cabin and steerage for a time; but the circulation of the air soon removed it. It was four o’clock in the afternoon; and, in order to enable the students to see what they might of the city as the fleet went up to the port, the lessons were not resumed. The fore-topsail, jib, and mainsail were set, the anchor weighed, and the Tritonia followed the Prince in charge of a pilot who had presented himself as soon as the fumigation was completed.

“You belong in the cage,” said Marline, walking up to the two conspirators, as soon as the schooner began to gather headway.

Bill and Bark followed the boatswain to the steerage, and were locked into the brig.

“Here we are again,” said Bark, when Marline had returned to the deck. “I did not expect when we left, to come back again.”

“Neither did I; and I don’t understand it,” replied Bill, with a sheepish look. “I certainly fixed things right for something different. I lighted the newspaper, and put it under the hay, sawdust, and boxes. I was sure there would be a blaze in fifteen minutes. I can’t explain it; and I am going down to see how it was.”

“Not now: some one will see you,” added Bark.

“No; everybody is looking at the sights. Besides, as the thing has failed, I want to fix things so that no one will suspect any thing if the pile of hay and stuff should be overhauled.”

Bark made no further objection, and his companion[40] hastened down the ladder. Pulling over the pile of rubbish, he found the newspaper he had ignited. Only a small portion of it was burned, and it was evident that the flame had been smothered when the boxes and covers had been thrown on the heap. Nothing but the newspaper bore the marks of the fire; and, putting this into his pocket, he returned to the brig.

“I shall do better than that next time,” said he, when he had explained to Bark the cause of the failure.

Bill Stout was as full of plans and expedients as ever; and, before the anchor went down, he was willing to believe that “the job” could be better done at another time.

CHAPTER III.

A GRANDEE OF SPAIN.

The port, or harbor, of Barcelona is formed by an inlet of the sea. A triangular tongue of land, with a long jetty projecting from its southern point, shelters it from the violence of the sea, except on the south-east. On the widest part of the tongue of land is the suburb of Barceloneta, or Little Barcelona, inhabited by sailors and other lower orders of people.

“I can just remember the city as it was when I left it in a steamer to go to Marseilles, about ten years ago,” said Raimundo, as he and Scott stood on the lee side of the quarter-deck, looking at the objects of interest that were presented to them. “It does not seem to have changed much.”

“It don’t look any more like Spain than the rest of the world,” added the lieutenant.

“This hill on the left is Monjuich, seven hundred and fifty-five feet high. It has a big fort on the top of it, which commands the town as well as the harbor. The city is a walled town, with redoubts all the way around it. The walls take in the citadel, which you see above the head of the harbor. The city was founded by Hamilcar more than two hundred years[42] before Christ, and afterwards became a Roman colony. There is lots of history connected with the city, but I will not bore you with it.”

“Thank you for your good intentions,” laughed Scott. “But how is it that you don’t care to see the people of your native city after an absence of ten years?”

“I don’t care about having this story told all through the ship, Scott,” replied the young Spaniard, glancing at the students on deck.

“Of course I will not mention it, if you say so.”

“I have always kept it to myself, though I have no strong reason for doing so; and I would not say any thing about it now if I did not feel the need of a friend. I am sure I can rely on you, Scott.”

“When I can do any thing for you, Don, you may depend upon me; and not a word shall ever pass my lips till you request it.”

“I don’t know but you will think I am laying out the plot of a novel, like the story of Giulia Fabiano, whom O’Hara assisted to a happy conclusion,” replied Raimundo, with a smile. “I couldn’t help thinking of my own case when her history was related to me; for, so far, the situations are very much the same.”

“I have seen all I want to of the outside of Barcelona; and if you like, we will go down into the cabin where we shall be alone for the present,” suggested Scott.

“That will suit me better,” answered Raimundo, as he followed his companion.

“We shall be out of hearing of everybody here, I think,” said Scott, as he seated himself in the after-part of the cabin.

“There is not much romance in the story yet; and I[43] don’t know that there ever will be,” continued the Spaniard. “It is a family difficulty; and such things are never pleasant to me, however romantic they may be.”

“Well, Don, I don’t want you to tell the story for my sake; and don’t harrow up your feelings to gratify my curiosity,” protested Scott.

“I shall want your advice, and perhaps your assistance; and for this reason only I shall tell you all about it. Here goes. My grandfather was a Spanish merchant of the city of Barcelona; and when he was fifty years old he had made a fortune of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, which is a big pile of money in Spain. He had three sons, and a strong weakness, as our friend O’Hara would express it. I suppose you know something about the grandees of Spain, Scott?”

“Not a thing,” replied the third lieutenant candidly. “I have heard the word, and I know they are the nobles of Spain; and that’s all I know.”

“That’s about all any ordinary outsider would be expected to know about them. There is altogether too much nobility and too little money in Spain. Some of the grandees are still very rich and powerful; but physically and financially the majority of them are played out. I am sorry to say it, but laziness is a national peculiarity: I am a Spaniard, and I will not call it by any hard names. Pride and vanity go with it. There are plenty of poor men who are too proud to work, or to engage in business of any kind. Of course such men do not get on very well; and, the longer they live, the poorer they grow. This is especially the case with the played-out nobility.

“My grandfather was the son of a grandee who had[44] lost all his property. He was a Castilian, with pride and dignity enough to fit out half a dozen Americans. He would rather have starved than do any sort of business. My grandfather, though it appears that he gloried in the title of the grandee, was not quite willing to be starved on his patrimonial acres. His stomach conquered his pride. He was the elder son; and while he was a young man his father died, leaving him the empty title, with nothing to support its dignity. I have been told that he actually suffered from hunger. He had no brothers; and his sisters were all married to one-horse nobles like himself. He was alone in his ruined castle.

“Without telling any of his people where he was going, he journeyed to Barcelona, where, being a young man of good parts, he obtained a situation as a clerk. In time he became a merchant, and a very prosperous one. As soon as his circumstances would admit, he married, and had three sons. As he grew older, the Castilian pride of birth came back to him, and he began to think about the title he had dropped when he became a merchant. He desired to found a family with wealth as well as a name. He was still the Count de Escarabajosa.”

“Of what?” asked Scott.

“The Count de Escarabajosa,” repeated Raimundo.

“Well, I don’t blame him for dropping his title if he had to carry as long a name as that around with him. It was a heavy load for him, poor man!”

“The title was not of much account, according to my Uncle Manuel, who told me the story; for my grandfather was only a second or third class grandee—not[45] one of the first, who were allowed to speak to the king with their hats on. At any rate, I think my grandfather did wisely not to think much of his title till his fortune was made. His oldest son, Enrique, was my father; and that’s my name also.”

“Yours? Are you not entered in the ship’s books as Henry;” interposed Scott.

“No; but Enrique is the Spanish for Henry. When my grandfather died, he bequeathed his fortune to my father, who also inherited his title, though he gave the other two sons enough to enable them to make a start in business. If my father should die without any male heir, the fortune, consisting largely of houses, lands, and farms, in and near Barcelona, was to go to the second son, whose name was Alejandro. In like manner the fortune was to pass to the third son, if the second died without a male heir. This was Spanish law, as well as the will of my grandfather. Two years after the death of my grandfather, and when I was about six years old, my father died. I was his only child. You will see, Scott, that under the will of my grandfather I was the heir of the fortune, and the title too for that matter, though it is of no account.”

“Then, Don, you are the Count de What-ye-call-it?” said Scott, taking off his cap, and bowing low to the young grandee.

“The Count de Escarabajosa,” laughed Raimundo; “but I would not have the fellows on board know this for the world; and this is one reason why I wanted to have my story kept a secret.”

“Not a word from me. But I shall hardly dare to speak to you without taking off my cap. The Count de[46] Scaribagiosa! My eyes! what a long tail our cat has got!”

“That’s it! I can see just what would happen if you should spin this yarn to the crowd,” added the grandee, shaking his head.

“But I won’t open my mouth till you command me to do so. What would Captain Wainwright say if he only knew that he had a Spanish grandee under his orders? He might faint.”

“Don’t give him an opportunity.”

“I won’t. But spin out the yarn: I am interested.”

“My father died when I was only six; and my Uncle Alejandro was appointed my guardian by due process of law. Now, I don’t want to say a word against Don Alejandro, and I would not if the truth did not compel me to do so. My Uncle Manuel, who lives in New York, is my authority; and I give you the facts just as he gave them to me only a year before I left home to join the ship. Don Alejandro took me to his own house as soon as he was appointed my guardian. To make a long story short, he was a bad man, and he did not treat me well. I was rather a weakly child at six, and I stood between my uncle and my grandfather’s large fortune. If I died, Don Alejandro would inherit the estate. My Uncle Manuel insists that he did all he could, short of murdering me in cold blood, to help me out of the world. I remember how ill he treated me, but I was too young to understand the meaning of his conduct.

“My Uncle Manuel was not so fortunate in business as his father had been, though he saved the capital my grandfather had bequeathed to him. The agency of a[47] large mercantile house in Barcelona was offered to him if he would go to America; and he promptly decided to seek his fortune in New York. Manuel had quarrelled with Alejandro on account of the latter’s treatment of me; and a great many hard words passed between them. But Manuel was so well satisfied in regard to Alejandro’s intentions, that he dared not leave me in the keeping of his brother when he went to the New World. Though it was a matter of no small difficulty, he decided to take me with him to New York.

“I did not like my Uncle Alejandro, and I did like my Uncle Manuel. I was willing to go anywhere with the latter; and when he called to bid farewell to my guardian, on the eve of his departure, he beckoned to me as he went out of the house. I followed him, and he managed to conceal his object from the servants; for my Uncle Alejandro did not attend him to the front door. He had arranged a more elaborate plan to obtain possession of me; but when he saw me in the hall, he was willing to adopt the simpler method that was then suggested to him. His baggage was on board of the steamer for Marseilles, and he had no difficulty in conveying me to the vessel. I was kept out of sight in the state-room till the steamer was well on her way. I will not trouble you with what I remember of the journey; but in less than three weeks we were in New York, which has been my home ever since.”

“But what did your guardian say to all this?” asked Scott. “Did he discover what had become of you?”

“I don’t know what he said; but he has been at work for seven years to obtain possession of me. As I disappeared at the same time my Uncle Manuel left, no[48] doubt Alejandro suspected what had become of me. At any rate, he sent an agent to New York to bring me back to Spain; but Manuel kept me out of the way. As soon as I could speak English well enough, he sent me to a boarding-school. I ‘cut up’ so that he was obliged to take me away, and send me to another. I am sorry to say that I did no better, and was sent to half a dozen different schools in the course of three years. I was active, and full of mischief; but I grew into a strong and healthy boy from a very puny and sickly one.

“At last my uncle sent me on board of the academy ship; but he told me before I went, that if I did not learn my lessons, and behave myself like a gentleman, he would send me back to my Uncle Alejandro in Spain. He would no longer attempt to keep me out of the way of my legal guardian. Partly on account of this threat, and partly because I like the institution, I have done as well as I could.”

“And no one has done any better,” added Scott.

“No doubt my Uncle Manuel has received good accounts of me from the principal, for he has been very kind to me. He wrote to me, after I had informed him that the squadron was going to Spain, that I must not go there; but he added that I was almost man grown, and ought to be able to take care of myself. I thought so too: at any rate, I have taken the chances in coming here.”

“But you are a minor; and I suppose Don Alejandro, if he can get hold of you, will have the right to take possession of your corpus.”

“No doubt of that[49].”

“But does your guardian know that you are a student in the academy squadron?” asked Scott.

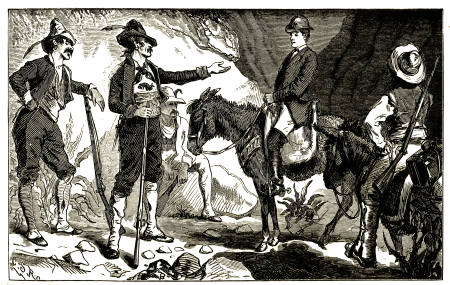

“I don’t know: it is not impossible, or even improbable. Alejandro has had agents out seeking me, and they may have ascertained where I am. For aught I know, my guardian may have made his arrangements to capture me as soon as the fleet comes to anchor. But I don’t mean to be captured; for I should have no chance in a Spanish court, backed by the principal, the American minister, and the counsel. By law I belong to my guardian; and that is the whole of it. Now, Scott, you are the best friend I have on this side of the Atlantic; and I want you to help me.”

“That I will do with all my might and main, Don,” protested Scott.

“I don’t ask you to tell any lies, or to do any thing wrong,” said Raimundo.

“What can I do for you? that’s the question.”

“I shall keep out of sight while the vessels are at this port; and I want you to be on the lookout for any Spaniards in search of a young man named Raimundo, and let me know. When you go on shore, I want you to find out all you can about my Uncle Alejandro. If I should happen to run away at any time, you will know, if no one else does, why I did so.”

“Don’t you think it would be a good thing to tell the vice-principal your story, and ask him to help you out in case of any trouble?” suggested Scott.

“No: that would not do. If Mr. Pelham should do any thing to help me keep out of the way, he would be charged with breaking or evading the Spanish laws; and that would get him into trouble. I ought not to[50] have come here; but now I must take the responsibility, and not shove it off on the vice-principal.”

“Who pays your bills, Don?”

“My Uncle Manuel, of course. He has a half interest in the house for which he went out as an agent; and I suppose he is worth more money to-day than his father ever was. He is as liberal as he is rich. He sent me a second letter of credit for a hundred pounds when we were at Leghorn; and I drew half of it in Genoa in gold, so as to be ready for any thing that might happen in Spain.”

“Do you really expect that your uncle will make a snap at you?” asked Scott, with no little anxiety in his expression.

“I have no knowledge whatever in regard to his movements. I know that he has sent agents to the United States to look me up, and that my Uncle Manuel has had sharp work to keep me out of their way. I have been bundled out of New York in the middle of the night to keep me from being kidnapped by his emissaries; for my uncle has never believed that he had any case in law, even in the States.”

“It is really quite a serious matter to you, Don.”

“Serious? You know that my countrymen have the reputation of using knives when occasion requires; and I also know that Don Alejandro has not a good character in Barcelona.”

“But suppose you went back to him: do you believe he would ill-treat you now?”

“No, I don’t. I have grown to be too big a fellow to be abused like a child. I think I could take care of myself, so far as that is concerned. But my uncle has[51] been nursing his wrath for years on account of my absence. He has sons of his own, who are living on my property; for I learn that Alejandro has done nothing to increase the small sum his father left him. He and his sons want my fortune. I might be treated with the utmost kindness and consideration, if I returned; but that would not convince me that I was not in constant peril. Spain is not England or the United States, and I have read a great deal about my native land,” said Raimundo, shaking his head. “I agree with my uncle Manuel, that I must not risk myself in the keeping of my guardian.”

“Suppose Don Alejandro should come on board as soon as we anchor, Don: what could you do? You would not be in condition to run away. Where could you go?” inquired Scott.

“I know just what I should do; but I will not put you in condition to be tempted to tell any lies,” replied Raimundo, smiling. “One thing more: I shall not be safe anywhere in Spain. My uncle does not want me for any love he bears me; and it would answer his purpose just as well if I should be drowned in crossing a river, fall off any high place, or be knifed in some lonely corner. There are still men enough in Spain who use the knife, though the country is safe under ordinary circumstances.”

“Upon my word, I shall be hardly willing to let you go out of my sight,” added Scott. “I shall have to take you under my protection.”

“I am afraid your protection will not do me much good, except in the way I have indicated.”

“Well, you may be sure I will do all I can to serve[52] and save you,” continued Scott, taking the hand of his friend, as the movements on deck indicated that the schooner was ready to anchor.

“Thank you, Scott; thank you. With your help, I shall feel that I am almost out of danger.”

Raimundo decided to remain in the cabin, as his watch was not called; but Scott went on deck, as much to look out for any suspicious Spaniards, as for the purpose of seeing what was to be seen. The American Prince had already anchored; and her two consorts immediately followed her example. The sails were hardly furled, and every thing made snug, before the signal, “All hands attend lecture,” appeared on the flag-ship.

All the vessels of the fleet were surrounded by boats from the shore, most of them to take passengers to the city. The adult forward officers were stationed at the gangways, to prevent any persons from coming on board; and the boatmen were informed that no one would go on shore that night. Scott hastened below, to tell his friend that all hands were ordered on board of the steamer to attend the lecture. Raimundo declared, that, as no one could possibly recognize him after so many years of absence, he should go on board of the Prince, with the rest of the ship’s company.

The boats were lowered; and in a short time all the students were assembled in the grand saloon, where Professor Mapps was ready to discourse upon the geography and history of Spain.

CHAPTER IV.

THE PROFESSOR’S TALK ABOUT SPAIN.

As usual, the professor had a large map posted where all could see it. It was a map of Spain and Portugal in this instance, in which the physical as well as the political features of the peninsula were exhibited. The instructor pointed at the map, and commenced his lecture.

“The ancient name of Spain was Iberia; the Latin, Hispania. The Spaniards call their country España. Notice the mark over the n in this word, which gives it the value of ny, the same as the French gn. You will find it in many Spanish words.

“With Portugal, Spain forms a peninsula whose greatest length, from east to west, is six hundred and twenty miles; and, from north to south, five hundred and forty miles. It is separated from the rest of Europe by the Pyrenees Mountains: they extend quite across the isthmus, which is two hundred and forty miles wide. It contains two hundred and fourteen thousand square miles, of which one hundred and seventy-eight thousand belong to Spain, and thirty-six thousand to Portugal. Spain is not quite four times as large as the State of New York; and Portugal is a little larger than the State of Maine.

“Spain has nearly fourteen hundred miles of seacoast, four-sevenths of which is on the Mediterranean. Spain is a mountainous country. About one-half of its area is on the great central plateau, from two to three thousand feet above the level of the sea. The mountain ranges, you observe, extend mostly east and west, which gives the rivers, of course, the same general direction. The Cantabrian and the Pyrenees are the same range, the former extending along the northern coast to the Atlantic. Between this range and the Sierra Guadarrama are the valleys of the Duero and the Ebro. This range reaches nearly from the mouth of the Tagus to the mouth of the Ebro, and takes several names in different parts of the peninsula. The mountains of Toledo are about in the centre of Spain. South of these are the Sierra Morena, with the basin of the Guadiana on the north and that of the Guadalquiver on the south. Near the southern coast is the Sierra Nevada, which contains the Cerro de Mulahacen, 11,678 feet, the highest peak in the peninsula. Sierra means a saw, which a chain of mountains may resemble; though some say it comes from the Arabic word Sehrah, meaning wild land.

“There are two hundred and thirty rivers in Spain; but only six of them need be mentioned. The Minho is in the north-west, and separates Spain and Portugal for about forty miles. It is one hundred and thirty miles long, and navigable for thirty. The Duero, called the Douro in Portugal, has a course of four hundred miles, about two-thirds of which is in Spain. It is navigable through Portugal, and a little way into Spain, though only for boats. The Tagus is the longest[55] river of the peninsula, five hundred and forty miles. It is navigable only to Abrantes in Portugal, about eighty miles; though Philip II. built several boats at Toledo, loaded them with grain, and sent them down to Lisbon. The Guadiana is in the south-west, three hundred and eighty miles long, and navigable only thirty-five. Near its source this river, like the Rhone and some others, indulges in the odd freak of disappearing, and flowing through an underground channel for twenty miles. The river loses itself gradually in an expanse of marshes, and re-appears in the form of several small lakes, which are called ‘los ojos de la Guadiana,’—the eyes of the Guadiana.

“The Guadalquiver is two hundred and eighty miles long, and, like all the rivers I have mentioned, flows into the Atlantic. It is navigable to Cordova, and large vessels go up to Seville. The Ebro is the only large river that flows into the Mediterranean. It is three hundred and forty miles long, and is navigable for boats about half this distance. Great efforts have been made to improve the navigation of some of these rivers, especially the largest of them. There are no lakes of any consequence in Spain, the largest being a mere lagoon on the seashore near Valencia.

“Spain has a population of sixteen millions, which places it as the tenth in rank among the nations of Europe. In territorial extent it is the seventh. It is said that Spain, as a Roman province, had a population of forty millions.

“Spain, including the Balearic and Canary Islands, contains forty-nine provinces, each of which has its local government, and its representation in the national[56] legislature, or Cortes. But you should know something of the old divisions, since these are often mentioned in the history of the country. There are fourteen of them, each of which was formerly a kingdom, principality, or province. Castile was the largest, including Old and New Castile, and was in the north-central part of the peninsula. This was the realm of Isabella; and, by her marriage with Ferdinand, it was united with Aragon, lying next east of it. East of Aragon, forming the north-east corner of Spain, is Catalonia, of which Barcelona is the chief city. North of Castile, on or near the Bay of Biscay, are the three Basque provinces. Bordering the Pyrenees, nearest to France, is the little kingdom of Navarre, with Aragon on the east. Forming the north-western corner of the peninsula is the kingdom of Galicia. East of it, on the Bay of Biscay, is the principality of the Asturias. South of this, and between Castile and Portugal, is the kingdom of Leon, which was attached to Castile in the eleventh century. Estremadura is between Portugal and New Castile. La Mancha, the country of Don Quixote, is south of New Castile. Valencia and Murcia are on the east, bordering on the Mediterranean. Andalusia is on both sides of the Guadalquiver, including the three modern provinces of Seville, Cordova, and Jaen. Granada is in the south, on the Mediterranean. You will hear the different parts of Spain spoken of under these names more than any other.

“The principal vegetable productions of Spain are those of the vine and olive. The export of wine is ten million dollars; and of olive-oil, four millions. Raisins, flour, cork, wool, and brandy are other important[57] exports, to say nothing of the fruits of the South, such as grapes and oranges. Silver, quicksilver, lead, and iron are the most valuable minerals. Silk is produced in Valencia, Murcia, and Granada.

“The climate of Spain, as you would suppose from its mountainous character, is very various. The north, which is in the latitude of New England, is very different from this region of our own country. On the table-lands of the centre, it is hot in summer and cold in winter. In the south, the weather is hot in summer, but very mild in winter. Even here in Barcelona, the mercury seldom goes down to the freezing point. The average winter temperature of Malaga is about fifty-five degrees Fahrenheit.

“Three thousand miles of railroad have been built, and two thousand miles more have been projected. One can go to all the principal cities in Spain now by rail from Madrid; and those on the seacoast are connected by several lines of steamers.

“The army consists of one hundred and fifty thousand men, and may be increased in time of war by calling out the reserves; for every man over twenty is liable to do military duty. The navy consists of one hundred and ten vessels, seventy-three of which are screw steamers, twenty-four paddle steamers, and thirteen sailing vessels. Seven of the screws are iron-clad frigates. They are manned by thirteen thousand sailors and marines; and this navy is therefore quite formidable.

“The government is a constitutional monarchy. The king executes the laws through his ministers, but is not held responsible for any thing. If things do not work[58] well, the ministers are to bear the blame, and his Majesty may dismiss them at pleasure. The laws are made by the Cortes, which consists of two bodies, the Senate and the Congress. Any Spaniard who is of age, and not deprived of his civil rights, may be a member of the Congreso, or lower house. Four senators are elected for each province. They must be forty years old, be in possession of their civil rights, and must have held some high office under the government in the army or navy, in the church, or in certain educational institutions.

“The present king is Amedeo I., second son of Vittorio Emanuele, king of Italy. He was elected king of Spain Nov. 16, 1870.[1]

“All but sixty thousand of the population of Spain are Roman Catholics; and of this faith is the national church, though all other forms of worship are tolerated. In 1835 and in 1836 the Cortes suppressed all conventual institutions, and confiscated their property for the benefit of the nation. In 1833 there were in Spain one hundred and seventy-five thousand ecclesiastics of all descriptions, including monks and nuns. In 1862 this number had been reduced to about forty thousand, which exhibits the effect of the legislation of the Cortes. The archbishop of Toledo is the head of the Church, primate of Spain.

“Though there are ten universities in Spain some of them very ancient and very celebrated, the population[59] of Spain have been in a state of extreme ignorance till quite a recent period. At the beginning of the present century, it was rare to find a peasant or an ordinary workman who could read. Efforts have been put forth since 1812 to promote popular education; but with no great success, till within the last forty years. In 1868 there were a million and a quarter of pupils in the public and private schools; and not more than one in ten of the population are unable to read. But the sum expended for public education in Spain is less per annum than the city of Boston devotes to this object.