Title: Montreal, 1535-1914. Vol. 1. Under the French Régime, 1535-1760

Author: William H. Atherton

Release date: December 29, 2014 [eBook #47809]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charlene Taylor, Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe,

Christian Boissonnas and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet

Archive/Canadian Libraries)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

By

WILLIAM HENRY ATHERTON, Ph. D.

Qui manet in patria et patriam

cognoscere temnit

Is mihi non civis, sed peregrinus erit

VOLUME I

ILLUSTRATED

THE S. J. CLARKE PUBLISHING COMPANY

MONTREAL VANCOUVER CHICAGO

1914

| CHAPTER I | |

| 1535-1542 | |

| HOCHELAGA | |

| THE ARRIVAL OF JACQUES CARTIER AT HOCHELAGA ON HIS SECOND VOYAGE TO CANADA—HIS ROYAL COMMISSION—THE FRUITLESS DEVICE OF DONNACONA TO FRIGHTEN CARTIER FROM VISITING HOCHELAGA—THE DIFFICULTY OF CROSSING LAKE ST. PETER—THE ARRIVAL AND RECEPTION AT HOCHELAGA—JACQUES CARTIER THE FIRST HISTORIAN OF MONTREAL—DESCRIPTION OF THE TOWN—CARTIER RECITES THE FIRST CHAPTER OF ST. JOHN'S GOSPEL OVER AGOHANNA, THE LORD OF THE COUNTRY—MOUNT ROYAL NAMED AND VISITED—CARTIER'S ACCOUNT OF THE VIEW FROM THE MOUNTAIN TOP—CARTIER'S SECOND VISIT IN 1540 TO HOCHELAGA AND TO TUTONAGUY, THE SITE OF THE FUTURE MONTREAL—THE PROBABLE VISIT OF DE ROBERVAL IN 1542. NOTES: THE SITE OF HOCHELAGA—HOCHELAGA'S CIVILIZATION—CANADA—GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF MOUNT ROYAL AND THE MONTEREGIAN HILLS. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| 1516-1627 | |

| COLONIZATION | |

| UNDER THE EARLY TRADING COMPANIES OF NEW FRANCE | |

| FRENCH COLONIZATION, A CHRISTIANIZING MOVEMENT—THE CROSS AND CROWN—ROBERVAL'S COMMISSION TO COLONIZE CANADA AND HOCHELAGA—FEUDALISM PROJECTED—CRIMINALS AND MALEFACTORS TO BE SENT AS COLONISTS—JACQUES CARTIER SAILS IN ADVANCE—CHARLESBOURG ROYAL, THE FIRST COLONY, STARTED—CARTIER SAILS FOR HOCHELAGA AND PASSES TUTONAGUY—CARTIER SAILS SECRETLY FOR FRANCE—CHARLESBOURG A FAILURE—DEATH OF CARTIER—HIS GREAT NEPHEW, NOEL, VISITS THE GREAT SAULT IN 1557—THE FIRST PRIVATE MONOPOLY TO NOEL AND OTHERS—THE FIRST ROYAL TRADE MONOPOLY TO DE LA ROCHE—THE EDICT OF NANTES—CHAUVIN, A HUGUENOT, SECURES A TRADE MONOPOLY—TADOUSSAC, THE COURT OF KING [Pg iv] PETAUD—EYMARD DE CHASTES RECEIVES A COMMISSION AND ENGAGES THE SERVICES OF A ROYAL GEOGRAPHER, SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN—CHAMPLAIN'S FIRST VISIT TO THE SAULT—DE MONTS, SUCCEEDING DE CHASTES, RETAINS CHAMPLAIN AS HIS LIEUTENANT—QUEBEC CHOSEN BY CHAMPLAIN—CHAMPLAIN BECOMES A COMPANY PROMOTER AND MANAGING DIRECTOR, THE SHAREHOLDERS BEING MOSTLY HUGUENOTS, THE PRINCE DE CONDE, GOVERNOR GENERAL—CHAMPLAIN'S BLUNDER IN ALLYING HIMSELF WITH THE ALGONQUINS AND HURONS AGAINST THE IROQUOIS, AFTERWARDS THE CAUSE OF IROQUOIS HOSTILITIES AGAINST THE FUTURE MONTREAL—THE COMING OF THE "RECOLLECTS"—CHAMPLAIN'S ATTEMPT AT A REAL COLONIZING SETTLEMENT AT QUEBEC—THE JESUITS ARRIVE—THE COMPANY OF ONE HUNDRED ASSOCIATES | 23 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| 1603-1625 | |

| THE GREAT SAULT | |

| CHAMPLAIN THE FIRST TRADER | |

| THE HISTORY OF HOCHELAGA AFTER CARTIER'S VISIT—CHAMPLAIN, THE FIRST CARTOGRAPHER OF THE ISLAND OF MONTREAL—ITS DESCRIPTION IN 1603—CHAMPLAIN EXPLORES THE NEIGHBORHOOD—PLACE ROYALE IN 1611—ST. HELEN'S ISLAND NAMED—THE FIRST TRADING TRANSACTION RECORDED—CHAMPLAIN SHOOTS THE RAPIDS, 1613—THE EXPLORATION OF THE OTTAWA VALLEY—1615 THE FIRST MASS IN CANADA AT RIVIERE DES PRAIRIES—1625 THE DROWNING OF VIEL AND AHUNTSIC AT SAULT-AU-RECOLLET—THE INTENTION OF CHAMPLAIN TO MAKE A PERMANENT SETTLEMENT ON THE ISLAND | 35 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| 1627-1641 | |

| COLONIZATION UNDER THE COMPANY OF ONE HUNDRED ASSOCIATES | |

| THE CHARTER OF THE HUNDRED ASSOCIATES THE BASIS OF THE SEIGNEURIAL SYSTEM TO BE AFTERWARDS ESTABLISHED AT MONTREAL—THE ENGLISH IN 1629 CAPTURE QUEBEC—1632, CANADA AGAIN CEDED TO THE FRENCH—1633, THE COMING OF THE JESUITS—THE RECOLLECTS DO NOT RETURN—THREE RIVERS IS ESTABLISHED—DESCRIPTION OF COLONIAL LIFE AT QUEBEC—DEATH OF CHAMPLAIN IN 1635—THE RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS TO BE IMITATED AFTERWARDS AT MONTREAL—THE "RELATIONS DES JESUITES"—THE IROQUOIS BEGIN THEIR ATTACKS—THE NEWS OF A REINFORCEMENT AND DISAPPOINTMENT THAT MONTREAL HAS BEEN CHOSEN AS ITS HEADQUARTERS | 49 |

| CHAPTER V[Pg v] | |

| 1640-1641 | |

| MONTREAL | |

| THE COMPANY OF NOTRE DAME DE MONTREAL | |

| PREVIOUS COLONIZATION REVIEWED—MONTREAL CEDED TO SIEUR DE CHAUSSEE IN 1636 AND LATER TO DE LAUSON—THE DESIGN OF THE SETTLEMENT OF MONTREAL ENTERS THE MIND OF M. DE LA DAUVERSIERE—THE FIRST ASSOCIATES OF THE COMPANY OF NOTRE DAME DE MONTREAL—THE CESSION OF THE ISLAND OF MONTREAL TO THEM IN 1640—THE RELIGIOUS NATURE OF THE NEW COLONIZING COMPANY—TRADING FACILITIES CRIPPLED—POLITICAL DEPENDENCE ON QUEBEC SAFEGUARDED—M. OLIER FOUNDS THE CONGREGATION OF ST. SULPICE IN PARIS IN VIEW OF THE MONTREAL MISSION—PREPARATIONS FOR THE FOUNDATION AND ESTABLISHMENT OF THE FULLY ORGANIZED SETTLEMENT OF "VILLA MARIE"—PAUL DE CHOMEDEY DE MAISONNEUVE CHOSEN AS LOCAL GOVERNOR—THE CALL OF JEANNE MANCE TO FOUND THE HOTEL DIEU—THE EXPEDITION STARTS—MAISONNEUVE ARRIVES AT QUEBEC—THE FIRST CLASH OF THE GOVERNORS—MONTMAGNY OFFERS THE ISLE OF ORLEANS FOR THE NEW SETTLEMENT—MAISONNEUVE IS FIRM FOR THE ISLAND OF MONTREAL—THE FIRST FORMAL POSSESSION OF MONTREAL AT PLACE ROYALE—WINTER AT ST. MICHEL AND STE. FOY—FRICTION BETWEEN THE RIVAL GOVERNORS | 57 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| 1642-1643 | |

| VILLE MARIE | |

| FOUNDED BY PAUL DE CHOMEDEY DE MAISONNEUVE | |

| THE DEPARTURE OF THE EXPEDITION FROM MONTREAL—THE ARRIVAL AT PLACE ROYALE—THE "VENI CREATOR SPIRITUS" AND MASS ON THE "COMMON"—VIMONT'S PROPHECY—ACTIVITIES OF ENCAMPMENT—THE FIRST REINFORCEMENT—THE FIRST QUASI-PAROCHIAL CHAPEL BUILT IN WOOD—ALGONQUINS VISIT THE CAMP—FLOODS AND THE PILGRIMAGE TO THE MOUNTAIN—PEACEFUL DAYS—PRIMITIVE FERVOUR AND SIMPLICITY—THE DREADED IROQUOIS AT LAST APPEAR—FIRST ATTACK—THE FIRST CEMETERY—"CASTLE DANGEROUS"—THE ARRIVAL OF THE SECOND REINFORCEMENT—Les Véritables Motifs. NOTES: THE HURONS, ALGONQUINS AND IROQUOIS | 73 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| 1644-1651 | |

| PROGRESS AND WAR | |

| THE COMPANY OF MONTREAL CONFIRMED BY LOUIS XIV—MAISONNEUVE REAPPOINTED GOVERNOR—A SYNDIC ELECTED; THE FIRST STEP IN REPRESENTATIVE [Pg vi] GOVERNMENT—THE BUILDING OF THE HOTEL-DIEU—MILITARY HISTORY—PILOT, THE WATCHDOG OF THE FORT—THE EXPLOIT OF PLACE D'ARMES—FEAR OF IROQUOIS—LABARRE'S REINFORCEMENT—AGRICULTURE BEGINS—MONTREAL'S FREE TRADE MOVEMENT—THE FIRST IROQUOIS WAR IS OVER—MAISONNEUVE GOES TO FRANCE—THE PROMOTION IN PARIS OF A BISHOPRIC FOR MONTREAL—CHARLES LE MOYNE—THE FORTIFICATIONS OF THE FORT—WAR AGAIN—THE SALARIES OF THE GOVERNOR OF QUEBEC, THREE RIVERS AND MONTREAL—THE CAMP VOLANT—FINANCIAL GLOOM IN MONTREAL—MUTUAL BENEFIT ASSOCIATION—A PICTURE OF MONTREAL—A TAX PERILOUS, SUDDEN AND FREQUENT—THE HOTEL-DIEU A FORTRESS FOR FOUR YEARS—THE ABANDONMENT OF THE SETTLEMENT THREATENED—MAISONNEUVE GOES TO FRANCE FOR SUCCOUR—THE SKELETON SOLDIERS—MONTREAL A FORLORN HOPE | 87 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| 1652-3 | |

| CRITICAL YEARS | |

| LAMBERT CLOSSE, COMMANDANT | |

| MAISONNEUVE'S SUCCESS IN PARIS—MADAME DE BULLION'S DONATIONS—"PARMENDA"—THE EXPLOIT OF LAMBERT CLOSSE—THE PHANTOM SHIP—MONTREAL REPORTED AT QUEBEC TO BE BLOTTED OUT—PROPOSALS OF PEACE FROM THE ONONDAGAS—MARCH OF MOHAWKS ON MONTREAL—CHARLES LE MOYNE AND ANONTAHA TO PARLEY FOR PEACE—A PATCHED UP PEACE—THE END OF THE SECOND IROQUOIS WAR | 105 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| 1653-4 | |

| THE SECOND FOUNDATION OF MONTREAL | |

| THE GREAT REINFORCEMENT OF 1653 | |

| MAISONNEUVE RETURNS WITH A RELIEF FORCE—THE MONTREAL CONTINGENT THE SAVIOURS OF CANADA—THE ORIGIN AND TRADES OF THE NEW COLONISTS—MARGUERITE BOURGEOYS, THE FIRST SCHOOLMISTRESS, ARRIVES—HER CALL—SHIP FEVER—ARRIVAL AT QUEBEC—THE GOVERNOR OF QUEBEC WOULD RETAIN THE RELIEF CONTINGENT—MAISONNEUVE FIRM FOR MONTREAL—THE WORK OF CONSOLIDATING THE ENLARGED COLONY AT VILLE MARIE—BUILDING ACTIVITIES—AGRICULTURAL AND INDUSTRIAL OCCUPATIONS—MARRIAGE CONTRACTS—JEANNE MANCE AND MARGUERITE BOURGEOYS, THE MOTHERS OF THE SETTLEMENT—THE KNIGHTLY MAISONNEUVE, A "Chevalier sans reproche"—THE MILITARY CONFRATERNITY—THE MOUNTAIN CROSS REPLACED—MEDICAL CONTRACTS—THE GOVERNMENT OF MONTREAL—THE ELECTION OF A SYNDIC—THE "NEW" CEMETERY—THE NEW "PARISH" CHURCH—THE MARRIAGE OF CHARLES LE MOYNE WITH CATHERINE PRIMOT—A RARE SCANDAL—THE PRIMITIVE FERVOUR STILL MAINTAINED | 111 |

| [Pg vii] CHAPTER X | |

| 1654-1657 | |

| IROQUOIS AND JESUITS | |

| THE DEPARTURE OF THE JESUITS | |

| RENEWAL OF HOSTILITIES IN THE SPRING—PEACE—WAMPUM NECKLACES AND BELTS—MONTREAL HEADQUARTERS OF PEACE PARLEYS—AUTUMN ATTACKS—"LA BARRIQUE"—MONTREAL LEFT SEVERELY ALONE—CHIEF "LA GRANDE ARMES"—M. DE LAUSON PERSECUTING MONTREAL—THE COMPLETION OF THE PARISH CHURCH—PENDING ECCLESIASTICAL CHANGES IN MONTREAL—NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL NOTICES ON THE EARLY JESUIT MISSIONARIES IN MONTREAL—PONCET—JOGUES—LE MOYNE—BUTEAUX—DRUILLETTES—ALBANEL—LE JEUNE—PARKMAN'S ESTIMATE OF THE SUCCESS OF THE JESUIT MISSIONS—DR. GRANT'S APPRECIATION OF THEIR WORK | 123 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| 1655-1658 | |

| THE COMING OF THE SULPICIANS | |

| 1657 | |

| MAISONNEUVE GOES TO FRANCE—ARRANGES FOR HOSPITALIERES AND SULPICIANS—BISHOPRIC FOR NEW FRANCE—THE NOMINATIONS OF DE QUEYLUS AND LAVAL—THE APPOINTMENT DELAYED—THE DEATH OF M. OLIER—THE ARRIVAL OF DE QUEYLUS AND MAISONNEUVE AT QUEBEC—TWO RIVAL "GRANDS VICAIRES"—DE QUEYLUS GOES TO MONTREAL AND QUICKLY RETURNS TO RULE THE CHURCH IN QUEBEC—THE INTRUSION RESENTED—THE SULPICIANS IN MONTREAL—TRIBUTE TO THEM AS CIVIC AND RELIGIOUS ADMINISTRATORS—IROQUOIS HOSTILITIES RESUMED—THE HEAD OF JEAN ST. PERE—THE CHURCH IN MONTREAL TAKES ON "PARISH" PRETENSIONS—CHURCH WARDENS AND "LA FABRIQUE"—THE FIRST SCHOOL HOUSE—THE FLIGHT TO MONTREAL FROM ONONDAGA—PRECAUTIONARY ORDINANCES BY MAISONNEUVE—FORTIFIED REDOUBTS—THE ECCLESIASTICAL DISPUTE SETTLED—DE QUEN "GRAND VICAIRE" OF QUEBEC, DE QUEYLUS OF MONTREAL—BON SECOURS CHURCH DELAYED—JEANNE MANCE AND MARGUERITE BOURGEOYS VISIT FRANCE | 137 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| 1659 | |

| THE NEW REINFORCEMENT FOR MONTREAL | |

| THE COMING OF LAVAL | |

| RETROSPECT OF MAISONNEUVE'S JUDICIAL SENTENCES—FIRST DEATH SENTENCE—INJURIOUS LANGUAGE—CALUMNY—BANISHMENT—GAMES OF CHANCE, DRUNKENNESS [Pg viii] AND BLASPHEMY, ETC., FORBIDDEN—THE GOVERNOR GENERAL AND THE LOCAL GOVERNOR OF MONTREAL—A PESSIMISTIC PICTURE OF MONTREAL IN 1659—A BISHOP FOR NEW FRANCE—LAVAL, CONSECRATED BISHOP OF PETREA IN ARABIA, ARRIVES AT QUEBEC AS VICAR APOSTOLIC—DE QUEYLUS RECALLED TO FRANCE—THE REINFORCEMENT ARRIVES WITH JEANNE MANCE AND MARGUERITE BOURGEOYS—THE STORY OF ITS JOURNEY—DIFFICULTIES AT LA FLECHE—SHIP FEVER ON THE ST. ANDRE—DIFFICULTIES AT QUEBEC—LAVAL WOULD RETAIN THE HOSPITALIERES BROUGHT BY JEANNE MANCE—THEY ARE FINALLY ALLOWED TO PROCEED TO THE HOTEL-DIEU OF MONTREAL | 151 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| 1660 | |

| HOW MONTREAL SAVED NEW FRANCE | |

| DOLLARD'S EXPLOIT AT THE LONG SAULT | |

| UNIVERSAL FEAR OF IROQUOIS IN THE COLONY—THE GARRISON OFFICERS AT MONTREAL—ADAM DOLLARD, SIEUR DES ORMEAUX—THE PERMISSION FROM THE GOVERNOR TO LEAD AN ATTACK UP COUNTRY—HIS COMPANIONS—PREPARATIONS—WILLS AND THE SACRAMENTS—THE FLOTILLA OF CANOES—THE LONG SAULT REACHED—THE DILAPIDATED IROQUOIS WAR CAMP—ANONTAHA AND MITIWEMEG—THE AMBUSH AND ATTACK—THE RETREAT TO THE STOCKADE—THE SIEGE—THIRST—THE ALGONQUINS DESERT—FIVE HUNDRED IROQUOIS ALLIES ARRIVE—THE TERRIBLE ATTACK AND RESISTANCE—A GLORIOUS DEFEAT—RADISSON'S ACCOUNT—THE INVENTORY OF DOLLARD—UNPAID BILLS—THE NAMES OF THE "COMPANIONS"—NEW FRANCE SAVED—A CONVOY OF BEAVER SKINS REACHES MONTREAL—A REINFORCEMENT OF TROOPS FROM FRANCE ASKED FOR TO WIPE OUT THE IROQUOIS | 163 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| 1661-1662 | |

| HOSTILITIES AND LOSSES | |

| MONTREAL THE THEATRE OF IROQUOIS CARNAGE—THE FIRST SULPICIAN SLAUGHTERED, M. LE MAITRE—THE SECOND, M. VIGNAL—THE FIRST VISIT OF LAVAL TO MONTREAL—THE ABBE DE QUEYLUS AGAIN APPEARS—ECCLESIASTICAL DISPUTES LEGAL, NOT PERSONAL—THE DEATH OF LAMBERT CLOSSE—THE EXPLOIT OF PICOTE DE BELESTRE—MAISONNEUVE'S ORDINANCE AGAINST SALE OF LIQUOR TO INDIANS—INDIAN ORGIES AND BLOODSHED—THE GOVERNOR GENERAL AT QUEBEC DISAPPROVES OF MAISONNEUVE'S ACTION—THE FAMOUS LIQUOR TRAFFIC DISPUTES—JEANNE MANCE LEAVES FOR FRANCE | 173 |

| [Pg ix] CHAPTER XV | |

| 1663-1664 | |

| THE SOVEREIGN COUNCIL AND THE SEIGNEURS OF THE ISLAND | |

| GREAT CHANGES, PHYSICAL AND POLITICAL | |

| MILITIA SQUADS ESTABLISHED—THE FORMATION OF THE CONFRATERNITY OF THE HOLY FAMILY—THE EARTHQUAKE AT MONTREAL—POLITICAL CHANGES—THE RESIGNATION OF THE COMPANY OF ONE HUNDRED ASSOCIATES—CANADA BECOMES A CROWN COLONY—THE TRANSFER OF THE SEIGNEURY OF THE ISLAND FROM THE COMPANY OF MONTREAL TO THE "GENTLEMEN OF THE SEMINARY"—ROYAL GOVERNMENT—THE APPOINTMENT OF THE SOVEREIGN COUNCIL—CHANGE IN THE MONTREAL JUDICIAL SYSTEM—FORMER HOME RULE PRIVILEGES RESCINDED—MONTREAL UNDER QUEBEC—PIERRE BOUCHER'S DESCRIPTION OF CANADA AND MONTREAL—SOCIAL LIFE OF THE PERIOD—MONTREAL SOLDIERY—THE ELECTION OF POLICE JUDGES—ATTEMPT TO SUPPLANT MAISONNEUVE AS LOCAL GOVERNOR—DISCORD IN THE SOVEREIGN COUNCIL | 181 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| 1665 | |

| THE RECALL OF DE MAISONNEUVE | |

| THE GOVERNOR GENERAL DE COURCELLES AND THE INTENDANT TALON ARRIVE—THE DUAL REIGN INHARMONIOUS—SIEUR DE TRACY, LIEUTENANT GENERAL OF THE KING FOR NORTH AMERICA, ARRIVES—THE CARIGNAN-SALLIERES REGIMENT—CAPTURE OF CHARLES LE MOYNE BY IROQUOIS—BUILDING OF OUTLYING FORTS—PREPARATIONS FOR WAR—THE DISMISSAL OF MAISONNEUVE—AN UNRECOGNIZED MAN—HIS MONUMENT—MAISONNEUVE IN PARIS—A TRUE CANADIAN | 191 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| 1666-1670 | |

| THE SUBDUAL OF THE IROQUOIS | |

| THE END OF THE HEROIC AGE | |

| PRIMITIVE EXPEDITIONS UNDER DE COURCELLES, SOREL AND DE TRACY—THE ROYAL TROOPS AND THE MONTREAL "BLUE COATS"—DOLLIER DE CASSON, THE SOLDIER CHAPLAIN—THE VICTORY OVER THE IROQUOIS—THE HOTEL-DIEU AT MONTREAL RECEIVES THE SICK AND WOUNDED—THE CONFIRMATION OF THE GENTLEMEN OF THE SEMINARY AS SEIGNEURS—THE LIEUTENANT GENERAL AND INTENDANT IN MONTREAL—THE "DIME"—THE CENSUS OF 1667—MORE CLERGY NEEDED—THE ABBE DE QUEYLUS RETURNS, WELCOMED BY LAVAL AND MADE VICAR GENERAL—REINFORCEMENT OF SULPICIANS— [Pg x] THEIR FIRST MISSION AT KENTE—THE RETURN OF THE RECOLLECTS—THE ARRIVAL OF PERROT AS LOCAL GOVERNOR OF MONTREAL | 195 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| 1671-1672 | |

| THE FEUDAL SYSTEM ESTABLISHED | |

| THE SEIGNEURS OF THE MONTREAL DISTRICT | |

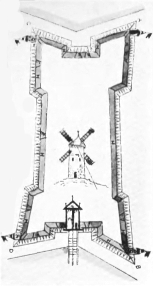

| SUBURBAN GROWTH—THE EARLIEST OUTLYING FIEFS—PRAEDIA MILITARIA—MILITARY SEIGNEURIES OF THE MONTREAL DISTRICT—THE FEUDAL SYSTEM—THE "NOBLESSE"—THE "PARISHES"—"CENS ET RENTES"—"LODS ET VENTES"—TRIBUTE TO THE FEUDALISM OF THE CLERICAL "SEIGNEURS OF MONTREAL"—MUNICIPAL OFFICERS—ORDER IN PROCESSIONS—THE CHURCH WARDENS—THE SOLDIER COLONISTS—CATTLE BREEDING, HORSES, ASSES—AGRICULTURE—NEW CONCESSIONS—LAWS REGULATING OPENING UP THE LAND—FIRST PUBLIC ROADS AND BRIDGES AT MONTREAL—NOTE: FORTS AND REDOUBTS | 203 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| 1666-1672 | |

| ECONOMICAL PROGRESS | |

| INDUSTRIES, TRADE AND LABOUR | |

| COMMERCE—MINING—SHIP BUILDING—INDUSTRIES—A "MUNICIPAL" BREWERY—THE FIRST MARKET—PRICES—LABOUR—MEDICAL MEN | 213 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| 1666-1672 | |

| COLONIZATION AND POPULATION | |

| ENCOURAGEMENT OF MARRIAGE—BACHELORS TAXED—"FILLES DU ROI"—DOWRIES—PENSIONS FOR LARGE FAMILIES—MONTREAL HEALTHY FOR WOMEN—NOTE ON IMMIGRATION | 215 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| 1667-1672 | |

| EXPEDITIONS FROM MONTREAL | |

| LA SALLE—DOLLIER DE CASSON—DE COURCELLES | |

| A FEUDAL VILLAGE AND ITS YOUNG SEIGNEUR—LA SALLE'S JESUIT TRAINING—AN EX-JESUIT—THE SEIGNEURY OF ST. SULPICE—SOLD—THE FEVER FOR EXPLORATION—LA SALLE, DOLLIER DE CASSON AND GALINEE—SOLDIER OUTRAGES [Pg xi] ON INDIANS—THE EXPEDITION TO LAKES ERIE AND ONTARIO—LA SALLE RETURNS—HIS SEIGNEURY NICKNAMED "LA CHINE"—THE SULPICIANS TAKE POSSESSION OF LAKE ERIE FOR LOUIS XIV—RETURN TO MONTREAL—DE GALINEE'S MAP—THE SUBSEQUENT EXPEDITION OF THE GOVERNOR GENERAL, DE COURCELLES | 221 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| 1667-1672 | |

| EDUCATION | |

| AT QUEBEC: JACQUES LEBER, JEANNE LEBER, CHARLES LE MOYNE (OF LONGUEUIL), LOUIS PRUDHOMME—MARGUERITE BOURGEOYS' SCHOOL AT MONTREAL—"GALLICIZING" INDIAN CHILDREN—GANNENSAGONAS—THE SULPICIANS AT GENTILLY—THE JESUITS AT MADELEINE LA PRAIRIE | 229 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| 1666-1672 | |

| GARRISON LIFE—SLACKENING MORALS | |

| SIEUR DE LA FREDIERE—LIQUOR TRAFFIC WITH THE INDIANS—SOLDIERS MURDER INDIANS—THE CARION-DE LORMEAU DUEL—THE FIRST BALL IN CANADA—LARCENIES, ETC.—A CORNER IN WHEAT—THE "VOLUNTAIRES," OR DAY LABOURERS—THE TAVERNS—A POLICE RAID—"HOTEL" LIFE—BLASPHEMY PUNISHED—THE LORDS' VINEYARDS RUINED | 233 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| 1671-1673 | |

| NOTABLE LOSSES | |

| DE QUEYLUS FINALLY LEAVES VILLE MARIE—DE COURCELLES AND TALON RECALLED—TRIBUTE TO THEIR ADMINISTRATION—MGR. DE LAVAL ABSENT FOR THREE YEARS—THREE DEATHS—MADAME DE PELTRIE—MARIE L'INCARNATION—JEANNE MANGE—HER LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT | 239 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| 1672-1675 | |

| TOWN PLANNING AND ARCHITECTURE | |

| THE FOUNDATION OF THE PARISH CHURCH AND BON SECOURS CHAPEL | |

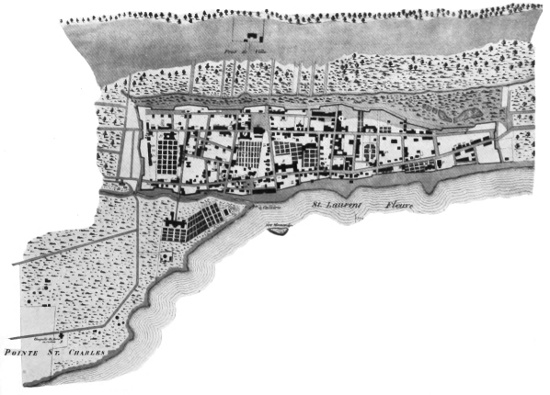

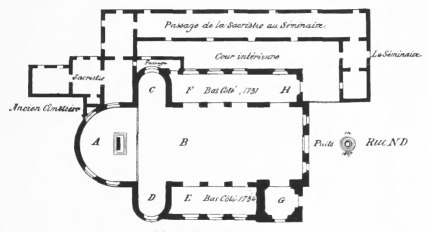

| THE FIRST STREET SURVEY—"LOW" TOWN AND "UPPER" TOWN—THE ORIGIN OF THE NAMES OF THE STREETS—COMPLAINTS AGAINST CITIZENS STILL CULTIVATING [Pg xii] THE STREETS—ORDERS TO BEGIN BUILDING—THE NEW PARISH CHURCH—THE FOUNDATION STONES AND PLAQUES—THE DEMOLITION OF THE FORT FORBIDDEN—THE CHURCH OF BON SECOURS—THE POWDER MAGAZINE IN ITS GARRET—A PICTURE OF MONTREAL | 241 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| 1672-1682 | |

| ALTERCATIONS | |

| FRONTENAC'S FIRST TERM OF GOVERNORSHIP | |

| I. THE RIVAL GOVERNORS | |

| II. CHURCH AND STATE | |

| III. THE GOVERNOR, THE INTENDANT AND THE SOVEREIGN COUNCIL | |

| I. THE TWO GOVERNORS—PERROT—ILE PERROT—REMONSTRANCES OF CITIZENS—FRONTENAC—A "VICE-ROI"—GENEROUS ATTEMPT TO GRANT REPRESENTATIVE GOVERNMENT RESTRAINED—FORT FRONTENAC (OR KINGSTON)—CORVEES—THE GOVERNOR GENERAL—EXPEDITION STARTS FOR MONTREAL—LA SALLE—THE FRONTENAC-PERROT DUEL COMMENCES—PERROT IMPRISONED—COUREURS DE BOIS—DULUTH—CHICAGO—FRONTENAC RULES MONTREAL | |

| II. THE FRONTENAC-FENELON DUEL—THE EASTER SERMON IN THE HOTEL-DIEU—LA SALLE PRESENT IN THE CHAPEL—M. FENELON RESIGNS FROM THE SULPICIANS—THE TRIAL BEFORE THE SOVEREIGN COUNCIL—THE MONTREAL PARTY PRESENT THEIR CASE IN FRANCE—FRONTENAC AND FENELON REPRIMANDED, PERROT IN PRISON—PERROT QUICKLY RELEASED AND SENT BACK AS LOCAL GOVERNOR OF MONTREAL | |

| III. THE MONTREAL COMPLAINTS HAVE A RESULT—THE REARRANGEMENT OF THE POSITIONS OF HONOUR IN THE SOVEREIGN COUNCIL—THE GOVERNOR AND THE INTENDANT, DUCHESNEAU—RIVAL FACTIONS—CENTRALIZATION AND HOME RULE THE CAUSE OF FRENCH FAILURE IN CANADA—PERROT MADE GOVERNOR OF ACADIA | 247 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| 1672-1683 | |

| TRADE AT MONTREAL UNDER FRONTENAC AND PERROT | |

| WEST INDIA COMPANY SUPPRESSED—MONTREAL HEAD OF FUR INDUSTRY—EXPEDITIONS—MARQUETTE—JOLIET—THE ANNUAL FAIRS—LAVAL RETURNS—THE "CONGREGATION" CONFIRMED—THE INDIAN MISSIONS—CATHERINE TEKAKWITHA—THE "FORT DES MESSIEURS"—EXPLORATIONS—LA SALLE, DULUTH, HENNEPIN—LOUISIANA NAMED—THE GOVERNOR GENERAL AND THE INTENDANT—FACTIONS AT MONTREAL, "A PLAGUE ON BOTH YOUR HOUSES!"—FRONTENAC AND DUCHESNEAU RECALLED | 265 |

| [Pg xiii] CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| 1683-1687 | |

| WAR AGAIN. THE IROQUOIS. NEW YORK AND HUDSON'S BAY | |

| THE GOVERNMENTS OF DE LA BARRE AND DENONVILLE | |

| GOVERNOR DE LA BARRE OPPOSES LA SALLE—THE POW-WOW IN THE NEW PARISH CHURCH—WAR PREPARATIONS AT MONTREAL—THE DISEASE-STRICKEN EXPEDITIONS RETURN—LAVAL LEAVES FOR FRANCE—THE PIONEER PAPER MONEY INVENTED TO PAY THE SOLDIERS—NOTES ON "CARDS" AND CURRENCY DURING FRENCH REGIME—GOVERNOR DENONVILLE AND MGR. DE ST. VALLIER ARRIVE—CALLIERES BECOMES GOVERNOR OF MONTREAL—A GLOOMY REPORT ON THE "YOUTH" AND DRAMSHOPS—MGR. DE ST. VALLIER'S MANDEMENT OF THE VANITY OF THE WOMEN—THE FORTIFICATIONS REPAIRED—SALE OF ARMS CONDEMNED—THE STRUGGLE FOR CANADA BY THE ENGLISH OF NEW YORK—THE STRUGGLE FOR HUDSON'S BAY—THE PARTY FROM MONTREAL UNDER THE SONS OF CHARLES LE MOYNE—THE DEATH OF LA SALLE—OTHER MONTREAL DISCOVERERS—A PSYCHOLOGICAL APPRECIATION OF LA SALLE'S CHARACTER | 273 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| 1687-1689 | |

| IROQUOIS REVENGE | |

| DENONVILLE'S TREACHERY AND THE MASSACRE OF LACHINE | |

| ST. HELEN'S ISLAND A MILITARY STATION—FORT FRONTENAC—DENONVILLE'S TREACHERY—THE FEAST—INDIANS FOR THE GALLEYS OF FRANCE—THE WAR MARCH AGAINST THE SENECAS—THE RETURN—MONTREAL AN INCLOSED FORTRESS—DE CALLIERES' PLAN FOR THE INVASION OF NEW YORK—THE STRUGGLE FOR TRADE SUPREMACY—MONTREAL BESIEGED—KONDIARONK, THE RAT, KILLS THE PEACE—DENONVILLE RECALLED—CALLIERES' PLAN FAILS—THE MASSACRE AT LACHINE—DENONVILLE'S TREACHERY REVENGED. NOTE: THE EXPLOIT AT THE RIVIERE DES PRAIRIES | 285 |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| 1689-1698 | |

| MONTREAL PROWESS AT HOME AND ABROAD | |

| FRONTENAC'S SECOND TERM OF GOVERNMENT | |

| FRONTENAC RETURNS—REVIEW AT MONTREAL—INDIANS FROM THE GALLEYS SENT WITH PEACE OVERTURES—NEW ENGLAND TO BE ATTACKED—THE MONTREAL LEADERS—THREE SUCCESSFUL EXPEDITIONS—RETALIATION MEDITATED BY THE ENGLISH—TRADE FLOWING BACK TO MONTREAL—THE GRAND COUNCIL IN THE MARKET—FRONTENAC LEADS THE WAR DANCE—JOHN SCHUYLER'S PARTY AGAINST MONTREAL RETIRES—SIR WILLIAM PHIPPS SEIZES QUEBEC— [Pg xiv] THE MONTREAL CONTINGENT—PETER SCHUYLER DEFEATED AT LA PRAIRIE—THE COLONY IN DIRE DANGER—MADELEINE DE VERCHERES, HER DEED OF ARMES—THE EXPEDITION VIA CHAMBLY—ARRIVAL OF FURS FROM MICHILLIMACKINAC—FRONTENAC, THE SAVIOUR OF THE COUNTRY—MONTREAL PROWESS EAST AND WEST—A PLEIAD OF MONTREAL NAMES—THE LE MOYNE FAMILY—NEWFOUNDLAND—HUDSON'S BAY—FORT FRONTENAC AGAIN—THE DEATH OF FRONTENAC | 293 |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| 1688-1698 | |

| SOCIAL, CIVIL AND RELIGIOUS PROGRESS | |

| THE PICKET ENCLOSURE—FORTIFICATIONS STRENGTHENED—GARRISON JEALOUSIES—PRESEANCE—THE "CONGREGATION" BURNT DOWN—A POOR LAW BOARD—TO QUEBEC ON FOOT—THE CHURCH OF THE "CONGREGATION" ON FIRE—THE ENCLOSING OF A RECLUSE—THE JESUIT RESIDENCE—THE RECOLLECTS—THE "PRIE DIEU" INCIDENT—MGR. DE ST. VALLIER'S BENEFACTIONS—THE FRERES CHARON—FIRST GENERAL HOSPITAL—TECHNICAL EDUCATION—THE SEMINARY BEING BUILT—SULPICIAN ADMINISTRATION—THE MARKET PLACE. NOTE: THE GENTLEMEN OF THE SEMINARY | 305 |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| 1698-1703 | |

| THE GREAT INDIAN PEACE SIGNED AT MONTREAL. THE FOUNDATION OF DETROIT | |

| THE GOVERNMENT OF DE CALLIERES | |

| DE CALLIERES—PREPARATIONS FOR PEACE—DEATH OF THE "RAT"—THE GREAT PEACE SIGNED AT MONTREAL—LA MOTTE-CARDILLAC—THE FOUNDATION OF DETROIT—THE DEATH OF MARGUERITE BOURGEOYS | 315 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| 1697-1713 | |

| FROM THE TREATY OF RYSWICK TO THE TREATY OF UTRECHT QUEEN ANNE'S WAR | |

| MONTREAL SAVED BY LAND AND WATER | |

| "THE FRENCH HAVE ALWAYS COMMENCED HOSTILITIES IN CANADA"—SAMUEL VECHT IN MONTREAL—MONTREAL TO BE INVADED BY WOOD CREEK—NICHOLSON'S ARMY ROUTED BY DYSENTERY—THE "BOSTONNAIS" PLAN A SECOND [Pg xv]DESCENT ON MONTREAL—JEANNE LEBER'S STANDARD—THE EXPEDITION OF SIR HOVENDER WALKER AGAINST QUEBEC—THE VOW OF THE MONTREAL LADIES—"OUR LADY OF VICTORIES" BUILT IN COMMEMORATION—PEACE OF UTRECHT—COMPARISON BETWEEN NEW ENGLAND AND NEW FRANCE. NOTE: THE CHATEAU DE RAMEZAY | 323 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| 1700-1721 | |

| HALF A CENTURY OF PEACE AND PROGRESS | |

| CIVIC SIDE LIGHTS | |

| I. | |

| THE LONG PEACE—THE TWO GOVERNORS—TAVERN LICENSES—PERMIT TO MARRY—CULTIVATION OF HEMP—FIRST ATTEMPT OF THE LACHINE CANAL BY THE SEIGNEURS—GEDEON DE CATALOGNE—CHAUSSEGROS DE LERY—"SEDITIOUS ASSEMBLIES"—CLAUDE DE RAMEZAY—WAR PRICES—LINEN AND CLOTH INDUSTRIES DEVELOPED—AN ORDINANCE AGAINST DIRTY STREETS—AGAINST PIGS IN THE HOUSES—MARKET REGULATIONS—THE USE OF THE COMMONS—SALE OF LIQUOR TO SAVAGES—THE SEIGNEURS AND THE HABITANTS—REGULATIONS CONCERNING TANNERS, SHOEMAKERS AND BUTCHERS—ENGLISH MERCHANDISE NOT TO BE TOLERATED AT MONTREAL—A MARKET FOR CANADIAN PRODUCTS DESIRED—CONCENTRATION IN THE EAST VERSUS EXPANSION IN THE WEST—CONGES—FAST DRIVING—ROAD MAKING—HORSE BREEDING RESTRAINED—PIGS TO BE MUZZLED—LIQUOR LICENSES OVERHAULED—SNOW-SHOEING TO BE CULTIVATED—DIVERSE NATIONAL ORIGINS—A MARBLE QUARRY—THE DEATH OF A RECLUSE—MURDERER BURNT IN EFFIGY—CARD MONEY—A "BOURSE" FOR THE MERCHANTS—PATENTS OF NOBILITY TO THE LEBER AND LE MOYNE FAMILIES—PARTRIDGE SHOOTING—A "CURE ALL" PATENT MEDICINE—POSTAL SERVICE—A PICTURE OF MONTREAL ABOUT 1721 BY CHARLEVOIX | 331 |

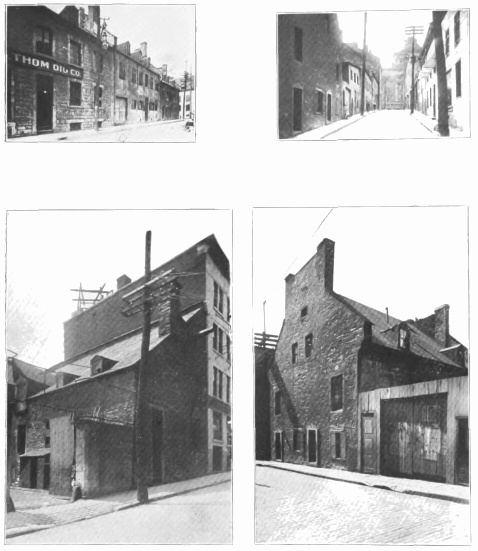

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| 1721-1748 | |

| SIDE LIGHTS OF CIVIC PROGRESS | |

| II | |

| THE FIRE OF 1721—BUILDING REGULATIONS—STONE ENCOURAGED—TOWN EMBELLISHMENT—CITY PLANNING—THE FORTIFICATIONS—PEW RENTING—CHATEAU DE VAUDREUIL—TRADE WITH NEW ENGLAND FORBIDDEN—ILLICIT LIQUOR TRAFFIC—DEATHS OF DE RAMEZAY AND DE VAUDREUIL—EVEN NATURALIZED STRANGERS FORBIDDEN TO TRADE—DESCRIPTION OF INDIAN LIFE AT MONTREAL—MONTREAL IS FOLLOWED BY QUEBEC IN THE REFORM OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES—VERENDRYE'S EXPEDITION FROM MONTREAL—[Pg xvi] RELIGIOUS ASYLUM FORBIDDEN—FIRST SAILING VESSEL OF LAKE SUPERIOR—THE "OUTRAGED CRUCIFIX"—SORCERY, MAGIC AND SACRILEGE—THE LEGEND OF THE RED CROSS—PUNISHMENT OF "BREAKING ALIVE" IN THE MARKET PLACE—CARE OF FOUNDLINGS—SULPICIANS FOUND LA PRESENTATION—SKATING IN THE STREETS; FAST DRIVING. NOTES: THE DISCOVERIES OF LA VERENDRYE—CHATEAU VAUDREUIL | 347 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| 1749-1755 | |

| SIDELIGHTS OF CIVIC PROGRESS | |

| III | |

| PETER KALM—THE FIRST SWEDES IN MONTREAL—THE FRENCH WOMEN CONTRASTED WITH THOSE OF THE AMERICAN COLONIES—DOMESTIC ECONOMY—THE MEN EXTREMELY CIVIL—MECHANICAL TRADES BACKWARD—WATCHMAKERS—THE TREATY OF AIX-LA-CHAPELLE CELEBRATED—PAPER MONEY—WAGES—PEN PICTURE OF MONTREAL IN 1749—ITS BUILDINGS AND THEIR PURPOSES—FRIDAY, MARKET DAY—THERMOMETRICAL AND CLIMATIC OBSERVATIONS—NATURAL HISTORY CULTIVATED—MONTREAL THE HEADQUARTERS OF THE INDIAN TRADE—THE GOODS FOR BARTER—THE LADIES MORE POLISHED AND VOLATILE AT QUEBEC BUT MORE MODEST AND INDUSTRIOUS AT MONTREAL—ECONOMIC FACTS—WINE AND SPRUCE BEER—PRICES AND COST OF LIVING—CONSENTS TO MARRIAGE—SOCIAL AND DOMESTIC CUSTOMS—FRANQUET'S JOURNEY FROM QUEBEC TO MONTREAL BY RIVER, FIVE DAYS—POUCHOT'S APPRECIATIONS OF CANADIANS—THE TRADE SYSTEM OF THE COUNTRY—GOVERNMENTAL MAGAZINES AND UP-COUNTRY FORTS—PRIVATE TRADE AT THE POSTS—ITINERANT PEDDLERS. NOTE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PARISH CHURCH | 359 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | |

| EDUCATION—PRIMARY, SECONDARY AND TECHNICAL | |

| A RECORD FROM 1657 TO 1760 | |

| FRENCH PRONUNCIATION—SCHOOL FOR GIRLS—THE CONGREGATION—BOARDING SCHOOLS—SCHOOLS OF DOMESTIC ECONOMY—NORMAL SCHOOLS—SCHOOLS FOR BOYS—ABBE SOUART FIRST SCHOOLMASTER—THE FIRST ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS—SCHOOL BOOKS—BOOKS ON PEDAGOGY—LATIN SCHOOLS, THE HIGH SCHOOLS OF THE PERIOD—LATIN BOOKS—ATTEMPT AT A CLASSICAL COLLEGE—FAILURE—TECHNICAL EDUCATION—JEAN FRANÇOIS CHARON—THE GENERAL HOSPITAL—ARTS AND MANUFACTURES—LES FRERES CHARON—A NORMAL SCHOOL FOR CANADA AT ROCHELLE PROJECTED—FRERE TURC GOES TO ST. DOMINGO—THE BROTHERS OF THE CHRISTIAN SCHOOLS INVITED TWICE TO COME TO CANADA—BROTHER DENIS AND PACIFICUS IN MONTREAL—THE FRERES CHARON IN EVIL DAYS—THE HOSPITAL TRANSFERRED TO MADAME D'YOUVILLE | 377 |

| [Pg xvii] CHAPTER XXXVIII | |

| 1747 | |

| THE GENERAL HOSPITAL OF MONTREAL UNDER MADAME D'YOUVILLE | |

| MADAME D'YOUVILLE—TIMOTHEE DE SILVAIN—CONFRATERNITY OF THE HOLY FAMILY—"SŒURS GRISES"—PERSEVERANCE THROUGH OPPOSITION—FIRE OF 1745—PROVISIONAL CONTROL OF HOSPITAL—ATTEMPT TO ANNEX THE GENERAL HOSPITAL TO THAT OF QUEBEC—THE "GREY NUNS" FORMERLY APPROVED AS "SISTERS OF CHARITY" | 387 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX | |

| MONTREAL, MILITARY HEADQUARTERS | |

| THE FINAL STRUGGLE FOR SUPREMACY—THE SEVEN YEARS, 1756-1763—THE CAMPAIGN OF 1756 (OSWEGO)—THE WINTER AT MONTREAL | |

| REVIEW—CELERON DE BIENVILLE—DE VAUDREUIL—MONTCALM—HIS MILITARY AND HOUSEHOLD STAFF—DE LEVIS, BOURLAMAQUE, BOUGAINVILLE—CHATEAU DE VAUDREUIL—THE MEETING OF MONTCALM AND DE VAUDREUIL—MONTCALM'S POSITION—THE THREE MILITARY ARMS—THE MILITIA, MARINE, REGULARS—THE RED ALLIES—CAPITULATION OF OSWEGO—SACKING—TE DEUM IN THE PARISH CHURCH—THE TWO PREJUGES—WINTER IN MONTREAL—GAMING AT QUEBEC—A WINTER WAR PARTY—SOCIAL GAYETIES AT MONTREAL—SCARCITY OF PROVISIONS—SHIPS AWAITED | 391 |

| CHAPTER XL | |

| THE CAMPAIGN OF 1657 | |

| THE SIEGE OF WILLIAM HENRY—WINTER GAYETY AND GAUNT FAMINE | |

| SHIPS ARRIVE—NEWS OF GREAT INTERNATIONAL WAR—RED ALLIES IN MONTREAL—STRONG LIQUOR—PREPARATIONS FOR WAR—FORT WILLIAM HENRY FALLS—ARRIVAL OF SAVAGES AND TWO HUNDRED ENGLISH PRISONERS—CANNIBALISM—THE PAPER MONEY—FEAR OF FAMINE—MONTCALM'S LETTER TO TROOPS ON RETRENCHMENT—A SELF-DENYING ORDINANCE—GAMING AMID SOCIAL MISERY—HORSE FLESH FOR THE SOLDIERS—DE LEVIS PUTS DOWN A REVOLT—THE "HUNGER STRIKE"—THE LETTERS OF MONTCALM—BIGOT AND LA GRANDE SOCIETE—"LA FRIPONNE" AT MONTREAL—MURRAY'S CRITICISM. NOTE: THE PECULATORS | 403 |

| [Pg xviii] CHAPTER XLI | |

| 1758 | |

| THE VICTORY OF CARILLON | |

| A WINTER OF GAYETY AND FOREBODING | |

| SIXTY LEAGUES ON THE ICE—SHIPS ARRIVE—FAMINE CEASES—ENGLISH MOBILIZATION—TICONDEROGA (CARILLON)—MILITARY JEALOUSIES—SAINT-SAUVEUR—RECONCILIATION OF MONTCALM AND VAUDREUIL—ENMITIES RENEWED—WINTER IN MONTREAL—HIGH COST OF LIVING—THE "ENCYCLOPEDIA"—AVARICE AND GRAFT—MADAME DE VAUDREUIL | 415 |

| CHAPTER XLII | |

| 1759 | |

| THE FALL OF QUEBEC | |

| MONTREAL THE SEAT OF GOVERNMENT | |

| THE SPRING ICE SHOVE—NEWS FROM FRANCE—MILITARY HONOURS SENT BUT POOR REINFORCEMENTS—PROJECTED FRENCH INVASION OF ENGLAND—GLOOM IN CANADA—THE MONTREAL MILITIA AT THE SIEGE OF QUEBEC—FALL OF QUEBEC, MONTREAL SEAT OF GOVERNMENT—THE WINTER ATTEMPT TO REGAIN QUEBEC—THE EXPECTED FRENCH FLEET NEVER ARRIVES—RETREAT OF FRENCH TO MONTREAL | 425 |

| CHAPTER XLIII | |

| 1760 | |

| THE FALL OF MONTREAL | |

| THE CAPITULATION | |

| THE LAST STAND AT MONTREAL—THE APPROACH OF THE BRITISH ARMIES—SURRENDER OF ARMS BY FRENCH ON THE ROUTE—PAPER MONEY VALUELESS—MURRAY'S ADVANCE FROM QUEBEC—HAVILAND'S PROGRESS FROM LAKE CHAMPLAIN—AMHERST'S DESCENT FROM OSWEGO—MONTREAL WITHIN AND WITHOUT—THE COUNCIL OF WAR IN THE CHATEAU VAUDREUIL—THE TERMS OF CAPITULATION—THE NEGOTIATIONS WITH AMHERST—HONOURS OF WAR REFUSED—DE LEVIS' CHAGRIN—THE CAPITULATION SIGNED—THE CONDITIONS—FORMAL POSSESSION OF TOWN BY THE BRITISH—THE END OF THE FRENCH REGIME | 431 |

| [Pg xix] APPENDIX I | |

| THE GOVERNMENT OF LA NOUVELLE FRANCE | |

| THE GOVERNMENT OF MONTREAL UNDER LA NOUVELLE FRANCE—ROYAL COMMISSIONS—VICEROYS—GOVERNORS—INTENDANTS—BISHOPS—FRENCH AND ENGLISH SOVEREIGNS—LOCAL GOVERNORS OF MONTREAL—THE SEIGNEURS OF THE SEMINARY | 441 |

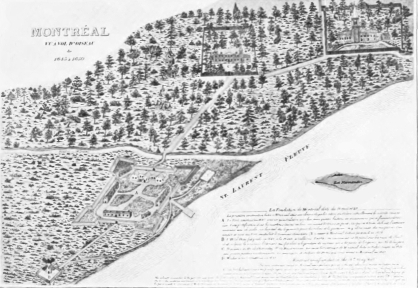

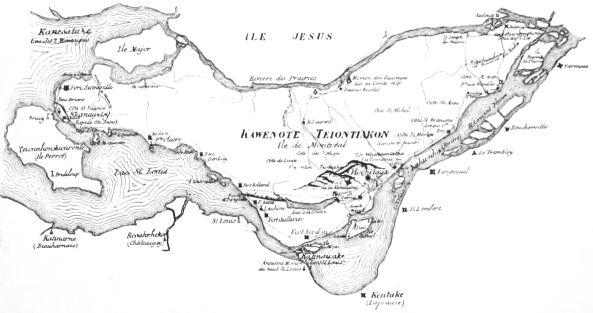

| APPENDIX II | |

| AN INVENTORY OF THE CHARTS AND PLANS OF THE ISLAND AND TOWN OF MONTREAL UP TO 1760 | 447 |

The history now being prepared seems necessary; for we are at a period of great flux and change and progress. The city is being transformed, modernized and enlarged before our very eyes. Old landmarks are daily disappearing and there is a danger of numerous memories of the past passing with them.

We are growing so wonderfully in wealth through the importance of our commerce and in the size of our population by the accretion of newcomers of many national origins and creeds, to whom for the most part the history of the romantic story of Montreal is a sealed books, that a fuller presentation of our development and growth is called for, to supplement previous sketches and to meet the conditions of the hour.

It is hardly needful, therefore, to offer any apology for the present undertaking. For if the continuity of a city's growth and development is to be preserved in the memory of the citizens of each generation, this can only be done through the medium of an historical survey, issued at certain suitable intervals, such as the one now offered, connecting the present with the past, and presenting to the new generation, out of the intricate chain of events and varying vicissitudes that have woven themselves into the texture of the city's organic life, the story of those forces which have moulded its growth and have produced those resultant characteristic features which make it the individualized city of today and none other.

Montreal being a unique city, with a personality of its own, its history, beyond that of any city of the new world, is particularly interesting and fruitful for such a retrospect. Dealing with the fortunes of several peoples, the original inhabitants of Hochelaga visited by Jacques Cartier in 1535, the French colonists from 1642 and the Anglo-Saxons and Gaels from their influx in 1760, together with the steady addition of those of other national origins of later years, the story of Montreal, passing over the greater part of four centuries, is full of romance and colour and quickly moving incidents; of compelling interest to the ordinary student, but how much more so to those who have any way leagued their fortunes with it, and assisted in its progress and in its making!

Such cannot dip into the pages of the history of this ancient and modern city without finding fresh motives for renewed enthusiasm and for deeper pride.

For Montreal is still in the making, with its future before it.

The present work is especially dedicated to those who would realize the duties of good citizenship and it is the hope of the writer that it may serve to deepen the sense of civic pride now happily being cultivated here. To foster this civic pride is the justifying reason why he has been induced by his friends to launch on a long and laborious task, sweetened though it may be by the pleasure anticipated of communion with the scenes and thoughts and deeds of a romantic past and a wonderfully progressive present.

All history is profitable. Perhaps, however, civic history has not been cultivated sufficiently. The present work is an attempt to repair this by interesting Montrealers in their citizenship so that by placing before them the deeds of the doers of the past, they may realize they are dwellers in no mean city. We would hope that something of the spirit of love for their cities, of the Romans, Athenians, or Florentines, might be reincarnated, here in Montreal. Good citizenship would then be thoroughly understood as the outcome of a passionate love of all that is upright, noble and uplifting in human conduct, applied to the life of a city by which it shall be made beautiful and lovable in the sight of God and man. For this purpose the life story of any city that has reached any eminence and has a worthy past should be known by good citizens so that they begin to love it with a personal love.

For like each nation, each city has its own individuality, its own characteristic entity, its own form of life which must be made the most of by art and thoughtful love.

This is not merely true of the physical being of a city from the city planner's point of view. There is also a specific character in the spiritual, artistic, moral and practical life of every city that has grown into virility and made an impress on the world.

Every such city is unique; it has its predominant virtues and failings. You may partially eliminate the latter and enlarge the former, but the city being human—the product of the sum total of the qualities and defects of its inhabitants—it takes on a character, a personality, a mentality all its own.

Civic history then leads us to delve down into the origins of things to find out the causes and sources of that ultimate city character which we see reflected today in such a city as Montreal.

The research is fascinating and satisfactory to the citizen who would know his surroundings, and live in them intelligently with consideration for the diverse view points of those of his fellow citizens who have different national origins and divergent mental outlooks from his own.

Yet while this city character is in a way fixed, still it is not so stable but that it will be susceptible to further development in the times that are to come with new problems and new situations to grapple with.

The peculiar pleasure of the reading of the history of Montreal will be to witness the development of its present character from the earliest date of the small pioneering, religious settlement of French colonists, living simple and uneventful days, but chequered by the constant fear of the forays of Indian marauders on to the "Castle Dangerous" of Ville Marie, through its more mature periods of city formation, then onward through the difficult days of the fusion of the French and English civilization starting in 1760, to the complex life of the great and prosperous cosmopolitan city of today, the port and commercial centre of Canada—the old and new régimes making one harmonious unity, but with its component parts easily discernible. The city's motto is aptly chosen, "Concordia Salus."

Much there will be learned in the history of Montreal of the past that will explain the present and the mentality of its people. Tout savoir, c'est tout pardonner.

A clue to the future will also be afforded beforehand. Certainly it will be seen that Montreal is great and will be greater still, because great thoughts, high ideals, strenuous purposes have been born and fostered within its walls.

The thinking student will witness the law of cause and effect, of action, and reaction, ever at work, and will read design where the undisciplined mind would only see chaos and blind forces at work.

Recognizing that the city is a living organism with a personality of its own, he will watch with ever increasing interest the life emerging from the seed and at work in all the varying stages of its growth and development. He will see the first rude beginning of the city, its struggles for existence, its organized life in its social and municipal aspects, its beginnings of art and learning, the building of its churches, the conscious struggles of its people to realize itself, the troubles of its household, the battle of virtue and vice, its relation to other cities, the story of its attacks from without, the conflicts with opposing ideas, the influx of new elements into the population, the adaptation of the organism to new habits of government and thought, to new methods of business, and the inauguration of untried and new industrial enterprises, the growth of its harbour, and its internal and external commerce, the conception of its own destiny as one of the great cities of the world—all these and more it is the purpose of a history of Montreal to unfold to the thoughtful citizen who would understand the life in which he is playing his part not as a blind factor but as an intelligent co-operator in the intricate and absorbing game of life.

But let it not be thought that while peering into the past we shall become blind to the present. In this "History of Montreal" we shall picture the busy world as we see it round us. Here are heroic and saintly deeds being done today in our midst. The foundations of new and mighty works even surpassing those of the past are being laid in the regions of religion, philanthropy, art, science, commerce, engineering, government and city planning this very hour, and their builders are unconsciously building unto fame.

Besides, therefore, portraying the past, we would wish to present a moving picture of the continued development of Montreal from the beginning, tracing it to the living present from the "mustard seed" so long ago spoken of by Père Vimont in reference to the handful of his fellow pioneers assembled at Mass on the day of the arrival on May 18, 1642, at the historic spot marked today by the monument in Place Royale, to the mighty tree of his prophecy that now has covered the whole Island of Montreal, and by the boldness, foresight and enterprise of Montreal's master builders, has stretched its conquering arms of streams and iron across the mighty continent discovered by Jacques Cartier in 1535.

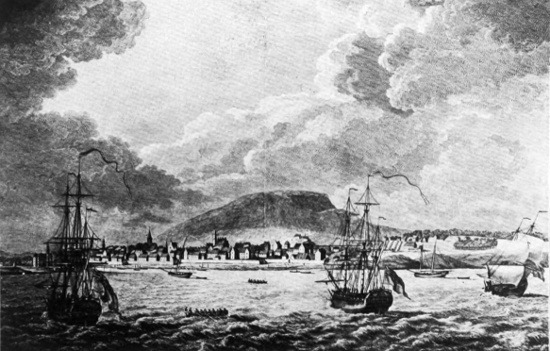

What Montreal was and is, we know. Its future we can only surmise. But it is bound to be a great one. Its position, with its mountain in the centre and its encircling waterways, with the glorious St. Lawrence at its feet, proclaims it as the ideal location for one of the greatest cities in the world. It is no cause for wonder that Jacques Cartier, visiting it in 1535, after naming the mountain "Mount Royal" in honour of his king, Francis I of France, should have commended it as favourable for a settlement in his description of his voyage to Hochelaga, and that Champlain in 1611 should have made it his trading post[Pg xxiv] and further endorsed it as a suitable place for a permanent settlement, and that Maisonneuve should have carried it into execution in 1642. They had the instinct of the city planner—that is all.

That they did not err, the history of Montreal will abundantly show.

WILLIAM HENRY ATHERTON.

"QUI MANET IN PATRIA ET PATRIAM COGNOSCERE TEMNIT IS MIHI NON CIVIS, SED PEREGRINUS ERIT"

In placing before the public the first volume of the History of Montreal, under the title of "Under the French Régime," I would first dedicate it to a group of prominent lovers of the city, truly deserving the name of good citizens, who originally encouraged me to undertake the historical researches necessary for this work in the view that an orderly narration of the city's origins and gradual development would thereby foster the right spirit of civic pride in those who do not merely dwell in this ancient and new city, but have linked their fortunes with it at least for a while.

Secondly, it is dedicated to those who endorsed the above invitation by subscribing for copies, thus making publication possible.

Thirdly, it is dedicated to all good citizens of Montreal, whether by birth or adoption, who will welcome this attempt to interest them in their citizenship.

Further, it is offered to all students of the civic life and progress of our Canadian cities through the medium of the historical method. May it encourage a healthy Canadian civic consciousness begotten of the records of the doings of the early makers of our Canadian cities.

May it encourage the careful keeping of early historical documents, especially among those new municipalities now growing up in the new Canada of today.

I wish to take this opportunity of thanking those who have especially made my way easy in this first volume by affording me access to books or documents. Among these are: Mr. W. D. Lighthall, president of the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Montreal, who was also the first to encourage this present work, Dr. A. Doughty, Mr. C. H. Gould, of the McGill University Library, Mr. Crevecœur, of the Fraser Institute, and to other representatives of public and private libraries. To Mr. E. Z. Massicotte, the careful archivist of the district of Montreal, I am especially indebted for much courteous and valuable assistance of which the following pages will give many indications. In general, the sources consulted are sufficiently indicated in the text or foot notes. They will be seen to be the best available.

I beg to thank those who have helped me to illustrate the work and particularly Mr. Edgar Gariépy, who has keenly aided me.

September, 1914.

WILLIAM HENRY ATHERTON.

1535-1542

HOCHELAGA

THE ARRIVAL OF JACQUES CARTIER AT HOCHELAGA ON HIS SECOND VOYAGE TO CANADA—HIS ROYAL COMMISSION—THE FRUITLESS DEVICE OF DONNACONA TO FRIGHTEN CARTIER FROM VISITING HOCHELAGA—THE DIFFICULTY OF CROSSING LAKE ST. PETER—THE ARRIVAL AND RECEPTION AT HOCHELAGA—JACQUES CARTIER THE FIRST HISTORIAN OF MONTREAL—DESCRIPTION OF THE TOWN—CARTIER RECITES THE FIRST CHAPTER OF ST. JOHN'S GOSPEL OVER AGOHANNA, THE LORD OF THE COUNTRY—MOUNT ROYAL NAMED AND VISITED—CARTIER'S ACCOUNT OF THE VIEW FROM THE MOUNTAIN TOP—CARTIER'S SECOND VISIT IN 1540 TO HOCHELAGA AND TO TUTONAGUY, THE SITE OF THE FUTURE MONTREAL—THE PROBABLE VISIT OF DE ROBERVAL IN 1542. NOTES: THE SITE OF HOCHELAGA—HOCHELAGA'S CIVILIZATION—CANADA—GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF MOUNT ROYAL AND THE MONTEREGIAN HILLS.

The story of Montreal, as far as authentic historical documents are concerned, begins with Saturday, October 2, 1535. On that day, the Indian natives of Hochelaga had been quickly apprised that two strange large vessels containing many palefaced wanderers, wonderfully attired and speaking an unknown tongue, had come up the river, and were now lying off its sloping margin. The people immediately prepare quickly to receive them with a hospitality of which we shall hear. The women busy themselves in preparing their presents while the men hurriedly run down the hill slope to the water's edge, to be soon also followed by the women and children. There they found a good gathering of swarthy and bronzed men of the sea, mariners from St. Malo, to the number of twenty-eight, simple men, but adored by the natives as superior beings. All hail to them! Would that of the seventy-four [1] names we have preserved to us, of those who sailed from St. Malo, we had those of them who were privileged to come up to Hochelaga, as we must yet call it.

Besides the sailors, there are, however, six whose dress and bearing mark them out as men of some distinction, as indeed they are; for one is Claude du [Pg 2] Pont Briand, cup bearer to My Lord the Dauphin; the second and third, gentlemen adventurers of some rank, Charles de la Pommeraye and Jehan Gouion; the fourth and fifth are the bronzed and rugged captains of the small fleet lying down the river at Lake St. Peter, Guillaume le Breton, captain of the Emerillon, and Marc Jalobert, captain of the Petite Hermine, brother-in-law of the sixth. This last, a firm set man of forty-five years, and of commanding appearance, is none other than Jacques Cartier, captain of the Grande Hermine, pilot and captain general of the fleet, and he has come with a royal commission [2] explore new seas and lands for his sovereign maste Francis I of France, whose flags proudly wave from the prows of either vessel now tossing in the Hochelagan waters.

Jacques Cartier claims notice, for he is at once the discoverer and the first historian of Montreal. He is a mariner, of a dignified profession, and was born in 1491, though De Costa and others say, in 1494, at the seaport of St. Malo in Brittany, the fertile cradle of many hardy daring corsairs and adventurers on the waters. Early the young son of Jamet Cartier and Geseline Jansart seems to have turned his thoughts to a seafaring life as he met the bronzed mariners arriving at the wharves of St. Malo, and telling strange stories of their perils and triumphs. On the 2d of May, 1519, being now a master pilot, he married Catherine des Granches, the daughter of the high constable of the city.

We know only imperfectly of his wanderings on the sea after this. He seems to have gone to Brazil. But he probably joined the band of those Norman ships going to Newfoundland on their fishing expeditions, and became well acquainted with the waters thereabout, and able to pilot them to some good purpose.

How Cartier became interested in discovering the passage to the Northwest we do not know; though it was the dream of so many navigators at that time to find a way to China and the east ports of India. To the man who should find it there would be undying fame, and many there were who strove for it. Probably Cartier believed that he should find the long expected route to India through one of the openings in the coast in the vicinity of Newfoundland, then thought to be but a projection of the eastern coast of Asia! At any rate, in 1533, we find him being introduced to Francis I of France by the high admiral of France, Phillipe Chabot, Sieur de Brion, to endeavour to persuade the king to allow him the means to secure the western passage for his royal master and the flag of France. The permission was granted, the vice admiral, the Sieur de Meilleraye personally undertaking to supervise the equipment of the vessels, and Cartier now is to be ranked among those others whose names have come down to us as leaders of expeditions.

We next find him armed with the Royal Commission, preparing to fit his vessels, and seeking for St. Malo men to man them in the service of the king. He had his difficulties in meeting the obstructions and jealousies that stood in his way. But on the 20th of April, 1534, he sailed with pilots, masters and seamen to the number of sixty, who were solemnly sworn by the vice admiral, Sieur de Meilleraye. It is not the purpose of this book to describe the discovery of Canada which Cartier made on this first voyage although the task is a fascinating one, since we have his own recital to follow. On July 24th, having planted on the coast of Gaspé a cross of the length of thirty feet bearing a shield adorned[Pg 3] with the fleur-de-lys and inscribed "Vive le Roi de France," he made preparations for the return home, reaching St. Malo on September 5th.

But he had not, as yet, stumbled upon the discovery of the mouth of the St. Lawrence, up which the kingdom of the Hochelagans lay, on which we are to fix our gaze. The news of his discoveries were received with enthusiasm, and on the Friday in Pentecost week, May 19, 1535, we find Jacques Cartier and his men sailing away from St. Malo, after having confessed themselves and received the benedictions of the archbishop and the godspeeds of their friends. The names of those accompanying Cartier—"pilots, masters and seamen, and others"—are preserved in the archives of St. Malo, numbering seventy-four, of whom several were of some distinction and twelve at least were related to him by blood or marriage, some led thither perhaps by the hope of trade. Two of the names are those of Dom Guillaume le Breton and Dom Antoine. It has been claimed the title Dom indicates that they were probably secular priests, and acted as chaplains, according to the general custom when the expedition was a royal mission. But this is not likely; in this case Guillaume le Breton was the captain of the Emerillon. Among those not mentioned in the list of Carrier's men were two young Indians, Taignoagny and Agaya, whom Cartier had seized at Gaspé before leaving to return to France, after his first voyages, and whose appearance in France created unusual interest. These were now to be useful as interpreters to the tribes to be visited. Cartier had however to regret some of their dealings on his behalf. Charity begins at home and so it did with these French-veneered Indians on mingling with their own.

The Royal Commission signed by Phillipe de Chabot, admiral of France, and giving greeting "to the Captain and Master Pilot Jacques Cartier of St. Malo," dated October 31, 1534, may here be quoted in part.

"We have commissioned and deputed, commission and depute you by the will and command of the King to conduct, direct, and employ three ships, equipped and provisioned each for fifteen months for the accomplishment of the voyage to the lands by you already begun and discovered beyond the Newlands; * * * the said three ships you shall take, and hire the number of pilots, masters and seamen as shall seem to you to be fitting and necessary for the accomplishment of this voyage. * * * We charge and command all the said pilots, masters and seamen, and others who shall be on the same ships, to obey and follow you for the service of the King in this as above, as they would do to ourselves, without any contradiction or refusal, and this under pains customary in such cases to those who are found disobedient and acting contrary."

The three ships that had been assigned to him were the Grande Hermine, the Petite Hermine and the Emerillon, the first being a tall ship of 126 burthen and the others of sixty and forty respectively, and they were provisioned for fifteen months. How the expedition encountered storms and tempests, delaying its progress until they reached the Strait of St. Peter, where familiar objects began to meet the eyes of the captive Indians on board; how they eagerly pointed out to Cartier the way into Canada; how they told him of the gold to be found in the land of the Saguenay; how Cartier visited the lordly Donnacona, lord of Canada; how at last on his resolve to pursue the journey to the land of Hochelaga he found himself in the great river of Canada which he named St. Lawrence; how he passed up the river by mountain and lowland, headlands and harbours, meadows, brush and forests, scattering saints' names on his way to Stadaconé [3] whence he determined to push his way to Hochelaga before winter—can be read at length in the recital of the second voyage of Jacques Cartier.

It is legitimate only for us to place before our readers that part concerning the approach to Hochelaga. Hitherto, on his journey, Cartier had received all help in his progress from the friendly natives; but effort was made to dissuade him from going up to Hochelaga. Cartier, however, always made reply that notwithstanding every difficulty he would go there if it were possible to him "because he had commandment from the king to go the farthest that he could." On the contrary the lordly savage Donnacona and the two captives, Dom Agaya and Taignoagny, used every device to turn the captain from his quest. An attempt will be made hereafter to prevent a visit to Montreal as we shall see when we speak of Maisonneuve and the settlement of Ville Marie.

Carrier's account has the following for September 18th: [4]

"HOW THE SAID DONNACONA, TAIGNOAGNY, AND OTHERS DEVISED AN ARTIFICE AND HAD THREE MEN DRESSED IN THE GUISE OF DEVILS, FEIGNING TO HAVE COME FROM CUDOUAGNY, THEIR GOD, FOR TO HINDER US FROM GOING TO THE SAID HOCHELAGA. [5]

"The next day, the 18th of the said month, thinking always to hinder us from going to Hochelaga, they devised a grand scheme which they effected thus: They had three men attired in the style of three devils, that had horns as long as one's arms, and were clothed in skins of dogs, black and white, and had their faces painted as black as coal, and they caused them to be put into one of their boats unknown to us, and then came with their band near our ships as they had been accustomed, who kept themselves in the woods without appearing for two hours, waiting till the time and the tide should come for the arrival of the said boat, at which time they all came forth, and presented themselves before our said ships without approaching them as they were wont to do; and asked them if they wanted to have the boat, whereupon the said Taignoagny replied to them, not at that time, but that presently he would enter into the said ships. And suddenly came the said boat wherein were the three men appearing to be three devils, having put horns on their heads, and he in the midst made a marvelous [Pg 5] speech in coming, and they passed along our ships with their said boat, without in any wise turning their looks toward us, and went on striking and running on shore with their said boat; and, all at once, the said Lord Donnacona and his people seized the said boat and the said three men, the which were let fall to the bottom of it like dead men, and they carried the whole together into the woods, which were distant from the said ships a stone's throw; and not a single person remained before our said ships, but all withdrew themselves. And they, having retired, began a declamation and a discourse that we heard from our ships, which lasted half an hour. After which the said Taignoagny and Dom Agaya marched from the said woods toward us, having their hands joined, and their hats under their elbows, causing great admiration. And the said Taignoagny began to speak and cry out three times, 'Jesus! Jesus! Jesus!' raising his eyes toward heaven. Then Dom Agaya began to say, 'Jesus Maria! Jacques Cartier,' looking toward heaven like the other, the captain seeing their gestures and ceremonies, began to ask what was the matter, and what it was new that had happened, who responded that there were piteous news, saying 'Nenny, est il bon,' and the said captain demanded of them afresh what it was, and they replied that their God, named Cudouagny, had spoken at Hochelaga, and that the three men aforesaid had come from him to announce to them the tidings that there was so much ice and snow that they would all die. With which words we all fell to laughing and to tell that their God Cudouagny was but a fool, and that he knew not what he said, and that they should say it to his messengers and that Jesus would guard them well from the cold if they would believe in him. And then the said Taignoagny and his companion asked the said captain if he had spoken to Jesus and he replied that his priests [6] had spoken to him and that he would make fair weather; whereupon they thanked the said captain very much, and returned into the woods to tell the news to the others, who came out of the said woods immediately, feigning to be delighted with the said words thus spoken by the said captain. And to show that they were delighted with them, as soon as they were before the ships they began with a common voice to utter three shrieks and howls, which is their token of joy, and betook themselves to dancing and singing, as they had done from custom. But for conclusion, the said Taignoagny and Dom Agaya told our said captain that the said Donnacona would not that any of them should go with him to Hochelaga if he did not leave a hostage, who should abide ashore with the said Donnacona. To which he replied to them that if they had not decided to go there with good courage they might remain and that for him he would not leave off making efforts to go there."

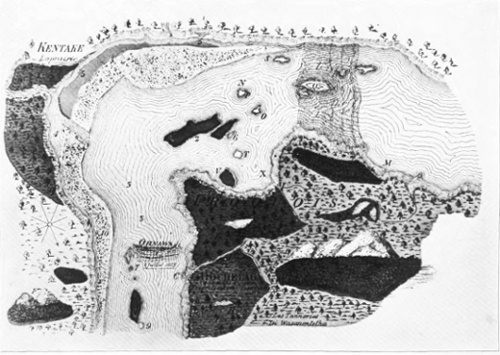

We have seen the manifest disinclination of Donnacona's party to allow the discoverers to proceed to Hochelaga. Was it because the Hochelagans were a hostile people or was it from selfish reasons to keep the presents of the generous strangers for themselves? At any rate, Cartier sets out for Hochelaga and on Tuesday, September 26th, enters Lake St. Peter with a pinnace and two boats. This lake was not named by Cartier, but subsequently it was named Lac d'Angoulesme, either in honour of his birthplace or more probably that of [Pg 6]Francis I, who was Count of Angoulême. It was left for Champlain entering upon the lake, on the feast of SS. Peter and Paul, June 29, 1603, to give it its present name. Cartier's pinnace could not cross Lake St. Peter owing to the shallowness of the water [7] which forced him to take the boats to Hochelaga, starting about six miles below St. Mary's current. The journey through Lake St. Peter and the arrival at Hochelaga must now be followed in the words of Jacques Cartier, the first historian of Montreal (Phinney Baxter, pp. 157-171).

"The said twenty-eighth day of September we came into a great lake and shoal of the said river, about five or six leagues broad and twelve long, and navigated that day up the said lake without finding shallowing or deepening, and coming to one of the ends of the said lake, not any passage or egress appeared to us; it seemed rather to be completely closed without any stream. And we found at the said end but a fathom and a half, wherefore it behooved us to lay to and heave out our anchor, and go to seek passage with our boats. And we found that there were four or five streams all flowing from the said river into this lake and coming from the said Hochelaga; but, by their flowing out so, there are bars and passages made by the course of the water, where there was then only a fathom in depth. And the said bars being passed, there are four or five fathoms, which was at the time of year of the lowest waters, as we saw by the flow of the said waters that they increased more than two fathoms by pike.

"All these streams flow by and surround five or six fair islands [8] which form the head of said lake; then they come together about fifteen leagues above all into one. That day we went to one of them, where we found five men, who were hunting wild beasts, the which came as familiarly to our boats as if they had seen us all their lives, without having fear or apprehension; and our said boats having come to land, one of these men took our captain in his arms and carried him ashore as lightly as he would have carried a child of five years, so large and strong was this man. We found they had a great pile of wild rats, [9] which live in the water, and are as large as rabbits, and wonderfully good to eat, of which they made a present to our captain, who gave them knives and paternosters for recompense. We asked them by sign if that was the way to Hochelaga; they answered us yes, and that it was still three days journey to go there.

"HOW THE CAPTAIN HAD THE BOATS FITTED OUT FOR TO GO TO THE SAID HOCHELAGA, AND LEFT THE PINNACE, OWING TO THE DIFFICULTY OF THE PASSAGE; AND HOW HE CAME TO THE SAID HOCHELAGA, AND THE RECEPTION THAT THE PEOPLE GAVE US AT OUR ARRIVAL.

"The next day our captain, seeing that it was not possible then to be able to pass the said pinnace, had the boats victualed and fitted out, and put in provisions for the longest time that he possibly could and that the said boats could [Pg 7] take in, and set out with them accompanied with a part of the gentlemen,—to wit, Claude du Pont Briand, grand cupbearer to my lord the Dauphin, Charles de la Pommeraye, Jehan Gouion, with twenty-eight mariners, including with them Marc Jalobert and Guillaume le Breton, having the charge under the said Cartier,—for to go up the said river the farthest that it might be possible for us. And we navigated with weather at will until the second day of October, when we arrived at the said Hochelaga, which is about forty-five leagues distant from the place where the said pinnace was left, during which time and on the way we found many folks of the country, the which brought fish and other victuals, dancing and showing great joy at our coming. And to attract and hold them in amity with us, the said captain gave them for recompense some knives, paternosters, and other trivial goods, with which they were much content. And we having arrived at the said Hochelaga, more than a thousand persons presented themselves before us, men, women and children alike, the which gave us a good reception as ever father did to child, showing marvelous joy; for the men in one band danced, the women on the other side and the children on the other, the which brought us store of fish and of their bread made of coarse millet, [10] which they cast into our said boats in the way that it seemed as if it tumbled from the air. Seeing this, our said captain landed with a number of his men, and as soon as he was landed they gathered all about him, and about all the others, giving them an unrestrained welcome. And the women brought their children in their arms to make them touch the said captain and others, making a rejoicing which lasted more than half an hour. And our captain, witnessing their liberality and good will, caused all the women to be seated and ranged in order, and gave them certain paternosters of tin and other trifling things, and to a part of the men knives. Then he retired on board the said boats to sup and pass the night, while these people remained on the shore of the said river nearest the said boats all night making fires and dancing, crying all the time 'Aguyaze,' which is their expression of mirth and joy.

"HOW THE CAPTAIN WITH GENTLEMEN, AND TWENTY-FIVE SEAMEN, WELL ARMED AND IN GOOD ORDER, WENT TO THE TOWN OF HOCHELAGA, AND OF THE SITUATION OF THE SAID PLACE.

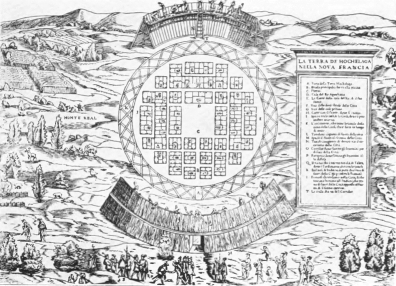

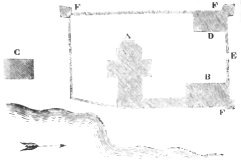

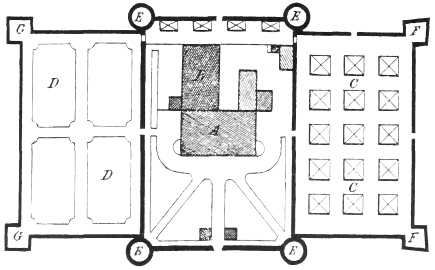

"The next day, in the early morning, the captain attired himself and had his men put in order to go to see the town and habitation of the said people, and a mountain that is adjacent to their said town, whither the gentleman and twenty mariners went with the said captain, and left the rest for the guard of the boats, and took three men of the said Town of Hochelaga to bring and conduct them to the said place. And we, being on the road, found it as well beaten as it might be possible to behold, and the fairest and best land, all full of oaks as fine as there be in a forest of France under the which all the ground was covered with acorns. And we, having marched about a league and a half, found on the way one of the chief lords of the Town of Hochelaga, accompanied by a number of persons, the which made us a sign that we should rest at the said [Pg 8] place near a fire that they had made by the said road, which we did, and then the said lord began to make a discourse and oration, as heretofore is said to be their custom of showing joy and familiarity, this lord thereby showing welcome to the said captain and his company; the which captain gave him a couple of hatchets and a couple of knives, with a cross and memorial of the crucifixion, which he made him kiss, and hung it on his neck, for which he rendered thanks to the said captain. This done, we marched farther on, and about half a league from there we began to find the land cultivated, and fair, large fields full of grain of their country, which is like Brazil millet, as big or bigger than peas, on which they live just as we do on wheat; and in the midst of these fields is located and seated the Town of Hochelaga, near to and adjoining a mountain, which is cultivated round about it and highly fertile, from the summit of which one sees a very great distance. We named the said mountain Mont Royal. The said town is quite round and inclosed with timbers in three rows in the style of a pyramid, crossed at the top, having the middle row in the style of a perpendicular line; and ranged with timbers laid along, well joined and tied in their manner, and is in height about two pikes. There is in this town but one gate and entrance, which fastens with bars, upon which and in many places of the said inclosure there are kinds of galleries and ladders to mount to them, which are furnished with rocks and stones for the guard and defense of it.

"There are within this town about fifty long houses of about fifty paces or more each, and twelve or fifteen paces wide and all made of timbers covered and garnished with great pieces of bark and strips of the said timber, as broad as tables, well tied artificially according to their manner. And within these there are many lodgings and chambers, and in the middle of these houses there is a great room on the ground where they make their fire and live in common; after that the men retire with their wives and children to their said chambers. Likewise they have granaries at the top of their houses where they put their corn of which they make their bread, which they call 'carraconny,' [11] and they make it in the manner following: They have mortars of wood as for braying flax, and beat the said corn into powder with pestles of wood; then they mix it into paste and make round cakes of it, which they put on a broad stone which is hot; then they cover it with hot stones, and so bake their bread instead of in an oven. They make likewise many stews of the said corn, and beans and peas of which they have enough, and also of big cucumbers and other fruits. They have also in their houses great vessels like tons, where they put their fish, eels and others, the which they dry in the smoke during the summer and live upon it in the winter. And of this they make a great store, as we have seen by experience. All their living is without any taste of salt, and they lie on barks of trees stretched upon the earth, with wretched coverings of skins from which they make their clothing—namely, wolves, beavers, martens, foxes, wild cats, deer, stags, and other wild beasts; but the most part of them go almost entirely naked. The most precious thing that they have in their world is 'esnogny,' [12] the which is white as snow, and [Pg 9] they take it into the same river from the cornibotz [13] in the manner which follows: When a man heserved death, or when they have taken any enemies in war, they kill them, then cut them into the buttocks, thighs, and shoulders with great gashes; afterward in the places where the said esnogny is they sink the said body to the bottom of the water, and leave it ten or twelve hours, then draw it up and find within the said gashes and incisions the said cornibots, of which they make bead money and use it as we do gold and silver, and hold it the most precious thing in the world. It has the virtue of stanching blood from the nostrils, because we have tried it.

"All the said people give themselves only to tillage and fishing for a living; for the goods of this world they make no account, because they have no knowledge of them, and as they budge not from their country, and do not go about like those of Canada [14] and of the Saguenay. Notwithstanding the said Canadians are their subjects, with eight or nine other peoples who are upon the said river.

"HOW WE ARRIVED AT THE SAID TOWN AND OF THE RECEPTION WHICH WAS MADE UP THERE, AND HOW THE CAPTAIN MADE THEM PRESENTS; AND OTHER THINGS THAT THE SAID CAPTAIN DID, AS SHALL BE SEEN IN THIS CHAPTER.

"When we had arrived near the town, a great number of the inhabitants of it presented themselves before us, who after their fashion of doing, gave us a good reception; and by our guides and conductors we were brought to the middle of the town, where there was a place between the houses the extent of a stone's throw or about in a square, who made us a sign that we should stop at the said place, which we did. And suddenly all the women and girls of the said town assembled together, a part of whom were burdened with children in their arms, and who came to us to stroke our faces, arms, and other places upon our bodies that they could touch; weeping with joy to see us; giving us the best welcome that was possible to them, and making signs to us that it might please us to touch their said children. After the which things the men made the women retire, and seated themselves on the ground about us, as if we might wish to play a mystery. And, suddenly, a number of men came again, who brought each a square mat in the fashion of a carpet, and spread them out upon the ground in the middle of the said place and made us rest upon them. After which things were thus done there was brought by nine or ten men the king and lord of the country, whom they all call in their language Agohanna, who was seated upon a great skin of a stag; and they came to set him down in the said place upon the said mats beside our captain, making us a sign that he was their lord and king. This Agohanna was about the age of fifty years and was not better appareled than the others, save that he had about his head a kind of red band for a crown, made of the quills of porcupines and this lord was wholly impotent and diseased in his limbs.

"After he had made his sign of salutation to the said captain and to his folks, making them evident signs that they should make them very welcome, he [Pg 10] showed his arms and legs to the said captain, praying that he would touch them, as though he would beg healing and health from him; and then the captain began to stroke his arms and legs with his hands; whereupon the said Agohanna took the band and crown that he had upon his head and gave it to our captain: and immediately there were brought to the said captain many sick ones, as blind, one-eyed, lame, impotent, and folks so very old that the lids of their eyes hung down even upon their cheeks, setting and laying them down nigh to our said captain for him to touch them, so that it seemed as if God had descended there in order to cure them.

"Our said captain, seeing the mystery and faith of this said people, recited the Gospel of St. John; to wit, the In principio, making the sign of the cross on the poor sick ones, praying God that he might give them knowledge of our holy faith and the passion of our Saviour, and the grace to receive Christianity and baptism. Then our said captain took a prayer book and read full loudly, word by word, the passion of our Lord, so that all the bystanders could hear it, while all these poor people kept a great silence and were marvelously good hearers, looking up to heaven and making the same ceremonies that they saw us make; after which the captain made all the men range themselves on one side, the women on another, and the children another, and gave to the chiefs hatchets, to the others knives, and to the women paternosters and other trifling articles; then he threw into the midst of the place among the little children some small rings and Agnus Dei of tin, at which they showed a marvelous joy. This done the said captain commanded the trumpets and other instruments of music to sound, with which the said people were greatly delighted; after which things we took leave of them and withdrew. Seeing this, the women put themselves before us for to stop us, and brought us of their victuals, which they had prepared for us, as fish, stews, beans and other things, thinking to make us eat and dine at the said place; and because their victuals were not to our taste and had no savor of salt, we thanked them, making them a sign that we did not need to eat.

"After we had issued from the said town many men and women came to conduct us upon the mountain aforesaid, which was by us named Mont Royal, distant from the said place some quarter of a league; and we, being upon this mountain, had sight and observance of more than thirty leagues round about it. Toward the north of which is a range of mountains which stretches east and west, and toward the south as well; between which mountains the land is the fairest that it may be possible to see, smooth, level, and tillable; and in the middle of the said lands we saw the said river, beyond the place where our boats were left, where there is a waterfall, [15] the most impetuous that it may be possible to see, and which it was impossible for us to pass. And we saw this river as far as we could discern, grand, broad and extensive, which flowed toward the southwest and passed near three fair, round mountains which we saw and estimated that they were about fifteen leagues from us. And we were told and shown by signs by our said three men of the country who had conducted us that there were three such falls of water on the said river like that where our said boats were, but we could not understand what the distance was between the one and the other.[Pg 11] Then they showed us by signs that, the said falls being passed, one could navigate more than three moons by the said river; and beyond they showed us that along the said mountains, being toward the north, there is a great stream, which descends from the west like the said river. [16] We reckoned that this is the stream which passed by the realm and province of Saguenay, and, without having made them any request or sign, they took the chain from the captain's whistle, which was of silver, and the haft of a poniard, the which was of copper, yellow like gold, which hung at the side of one of our mariners, and showed that it came from above the said river, and that there were Agojuda, which is to say evil folk, the which are armed even to the fingerhowing us the style of their armor, which is of cords and of wood laced and woven together, giving us to understand that the said Agojuda carried on continual war against one another; but by default of speech we could not learn how far it was to the said country. Our captain showed them some red copper, [17] which they call caignetdaze, pointing them toward the said place, and asking by signs if it came from there, and they began to shake their heads, saying no, and showing that it came from Saguenay, which is to the contrary of the preceding. After which things thus seen and understood, we withdrew to our boats, which was not without being conducted by a great number of the said people, of which part of them, when they saw our folk weary, loaded them upon themselves, as upon horsesd carried them. And we, having arrived at our said boats, made sail to return to our pinnace, for doubt that there might be some hindrance; which departure was not made without great regret of the said people, for as far as they could follow us down the said river they would follow us, and we accomplished so much that we arrived at our said pinnace Monday, the fourth day of October."

The reader must have been struck with the pride of the Hochelagans in conducting their visitors to the mountain as well as at the accurate and picturesque description given by Cartier of the scene that met his delighted gaze. Today the same beautiful sight may be seen by the visitor who makes his way to the "lookout" or the observatory. The landscape at his feet has been covered with a busy city and its suburbs, its manufactories, its public buildings and its homes and villas, but still it appears as if all these were peeping out of a garden. All around the green fields and pleasant meadows are there as of yore. From this height the disfigurements of the lower city are not visible. Montreal has been described as a beautiful lady handsomely gowned, but whose skirt fringes are sadly mud and dust stained.