Title: The Old Furniture Book, with a Sketch of Past Days and Ways

Author: N. Hudson Moore

Release date: January 8, 2015 [eBook #47917]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Brian Wilsden and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Four instances of the text "facing page—," have been removed as the 'Figure references' have been linked to their respective illustrations.

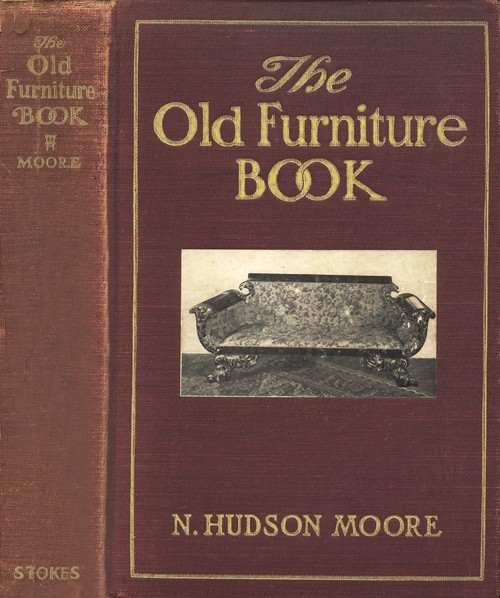

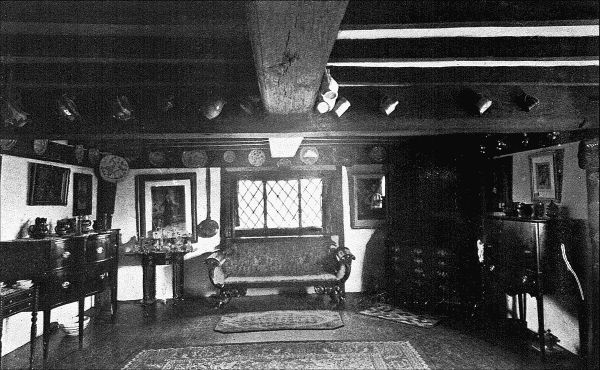

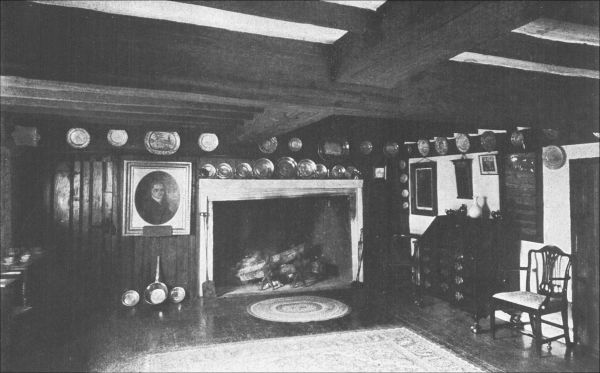

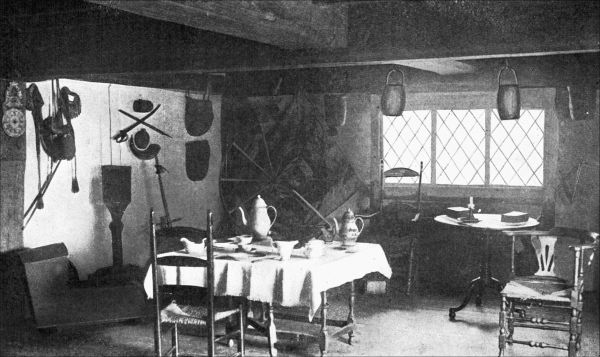

HALL IN KING HOOPER HOUSE. Danvers Mass.

THE

OLD FURNITURE BOOK

WITH A SKETCH OF

PAST DAYS AND WAYS

BY

N. HUDSON MOORE

AUTHOR OF

"THE OLD CHINA BOOK"

With one hundred and twelve illustrations

Second Edition

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1903,

By Frederick A. Stokes Company

All Rights Reserved

Published in October, 1903

"To a Lady

Who Shall Be Named Later."

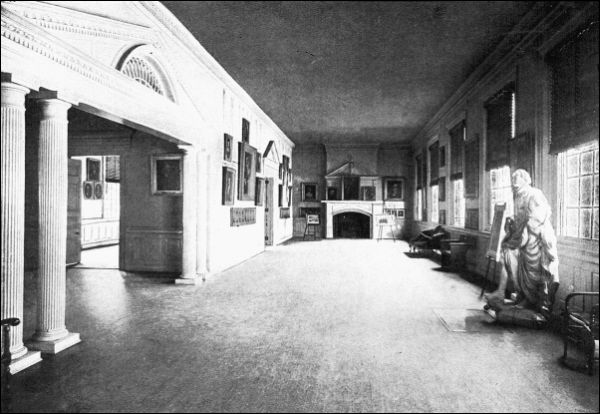

| Frontispiece—Hall in "King Hooper" House, Danvers, Mass. | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| FIGURE | |

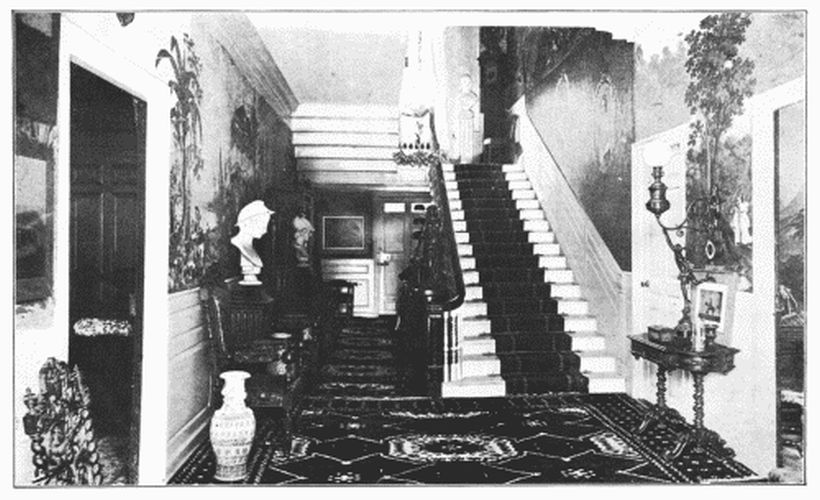

| 1. | Old Oak Bedstead |

| 2. | Olive-Wood Chest |

| 3. | Old Oak Chest |

| 4. | Chest with One Drawer |

| 5. | Oak Chest on Frame (English) |

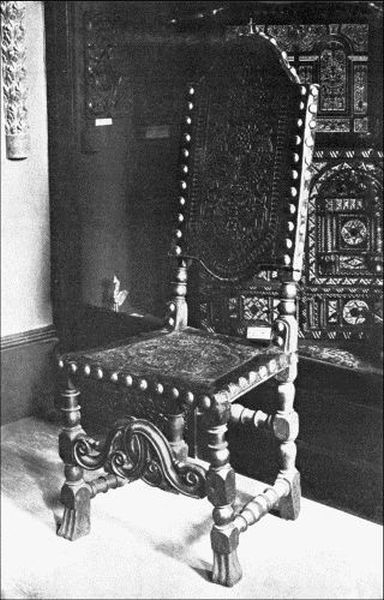

| 6. | Spanish Leather Chair |

| 7. | Turned Chair with Leather Cover |

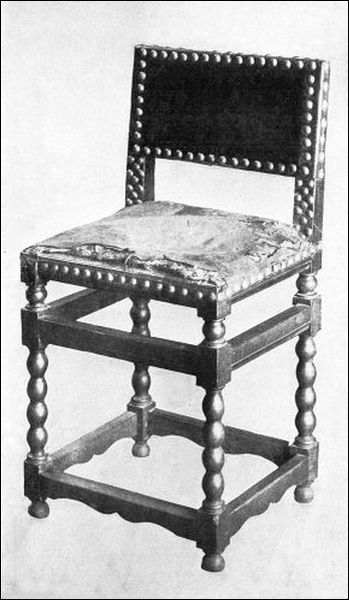

| 8. | English Chair (1680) Italian Chair (Same Period) |

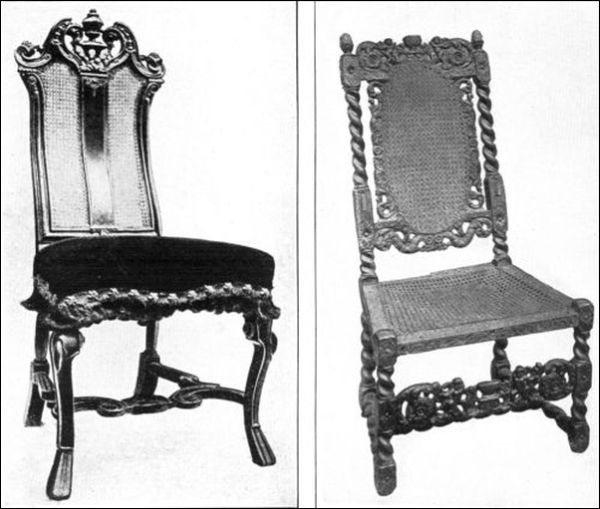

| 9. | Cane Chair, Flemish Style |

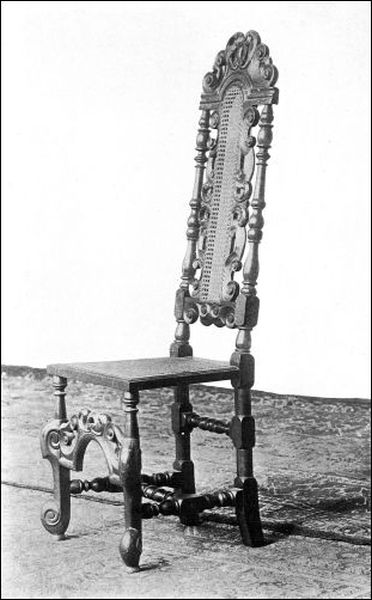

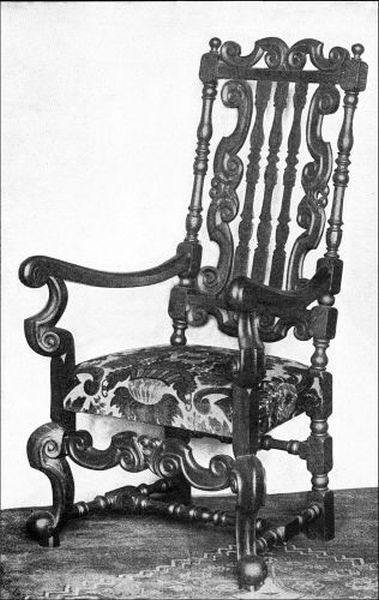

| 10. | Turned and Carved Arm-Chair |

| CHAPTER II | |

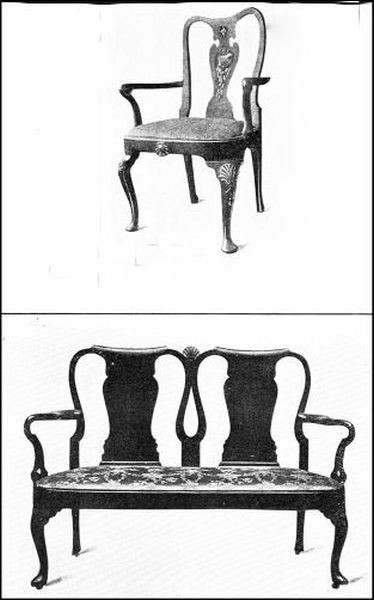

| 11. | Dutch Furniture, called "Queen Anne" |

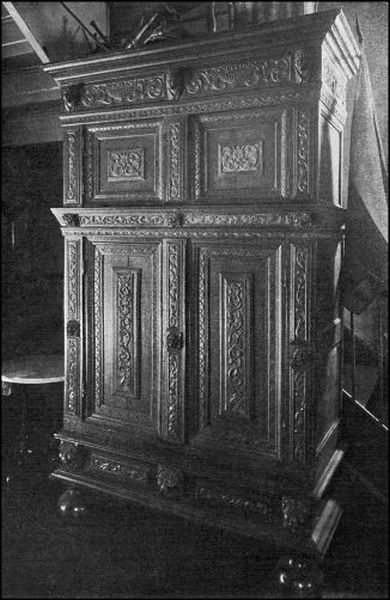

| 12. | Carved Kas |

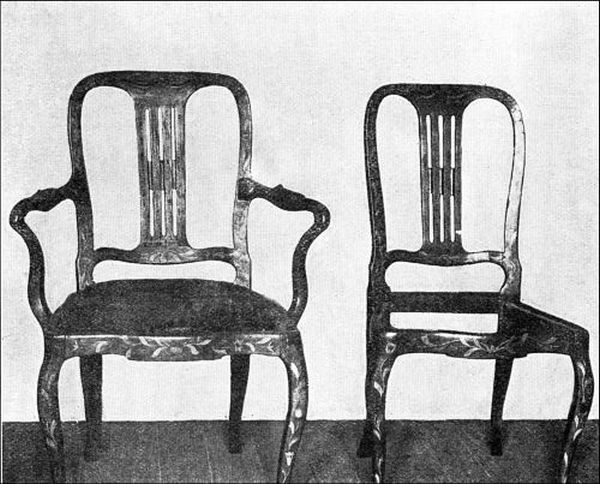

| 13. | Marquetry Chairs |

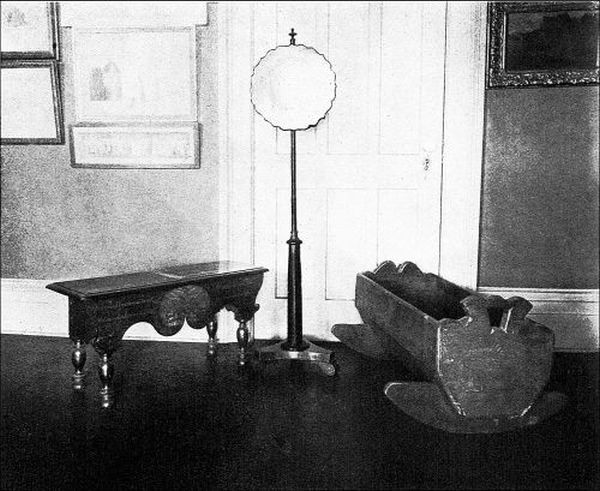

| 14. | Screen, Cradle, and Church Stool |

| 15. | Ebony Cabinet |

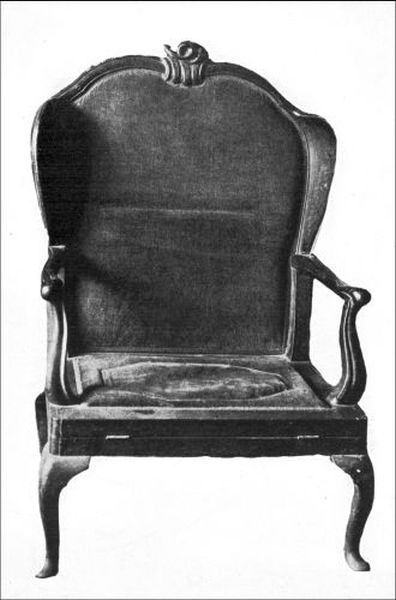

| 16. | Bed Chair |

| 17. | Marquetry Desk |

| CHAPTER III | |

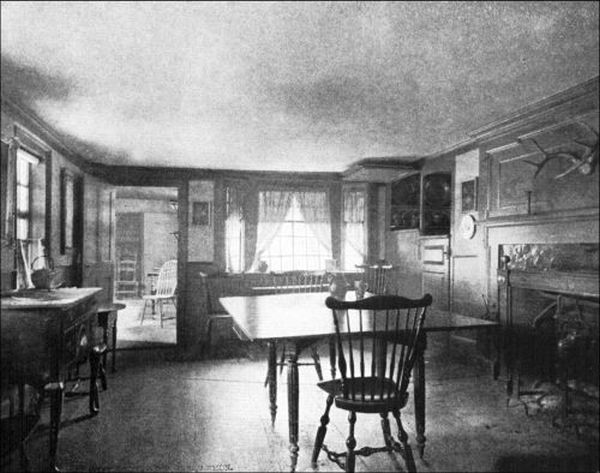

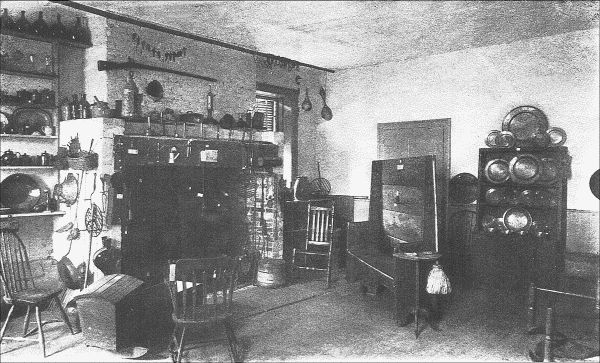

| 18. | Kitchen, Wayside Inn, Sudbury, Mass. |

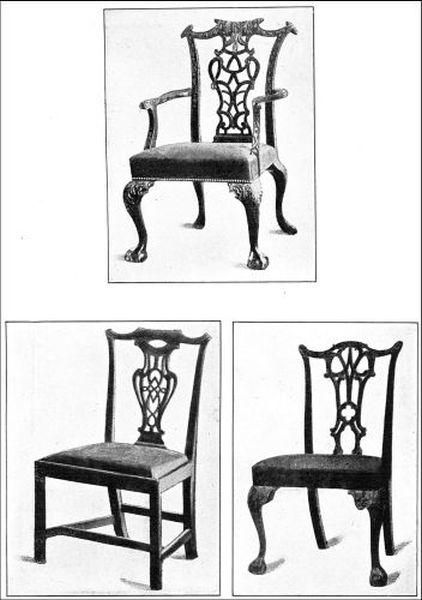

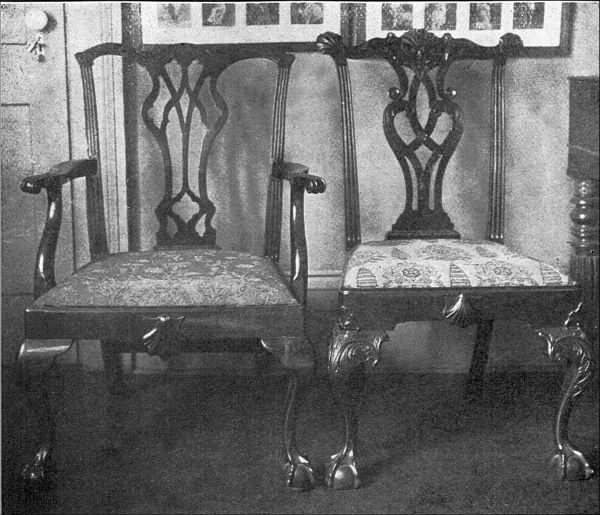

| 19. | Chippendale Chairs |

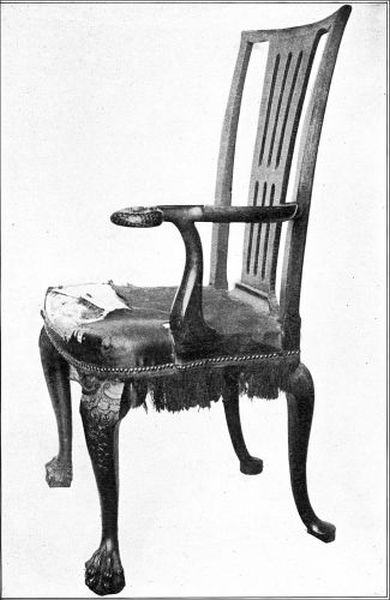

| 20. | Chippendale Chair |

| 21. | Carved Cedar Table |

| 22. | Chippendale Chairs |

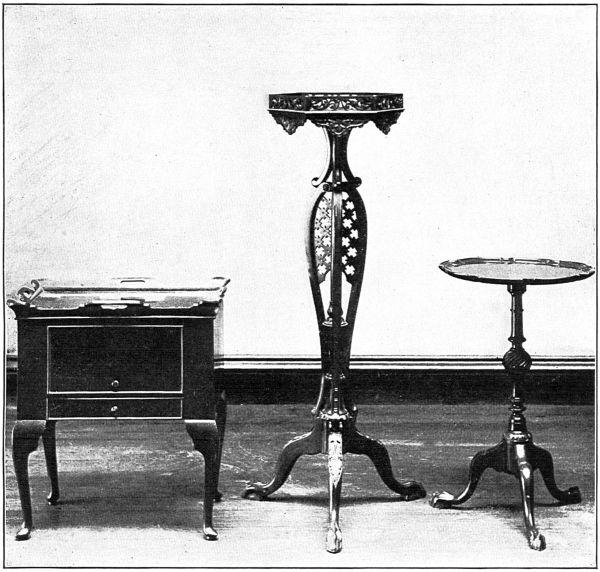

| 23. | Chippendale Candle, Tea and Music Stands |

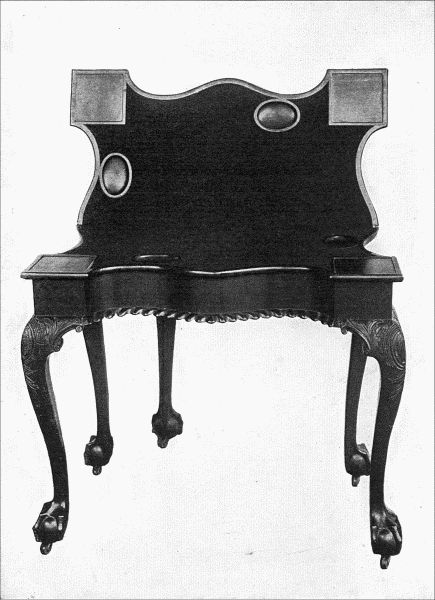

| 24. | Chippendale Card-Table |

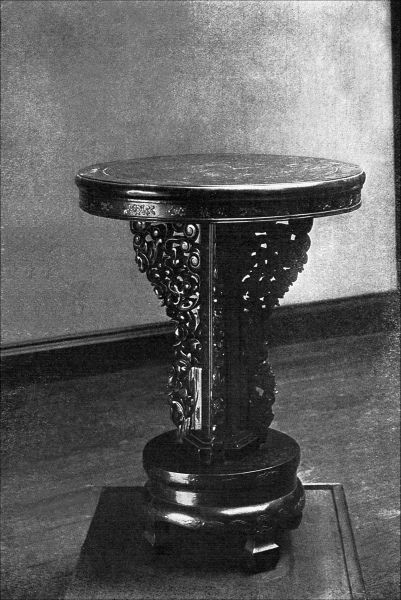

| 25. | Chippendale Marble-Topped Table |

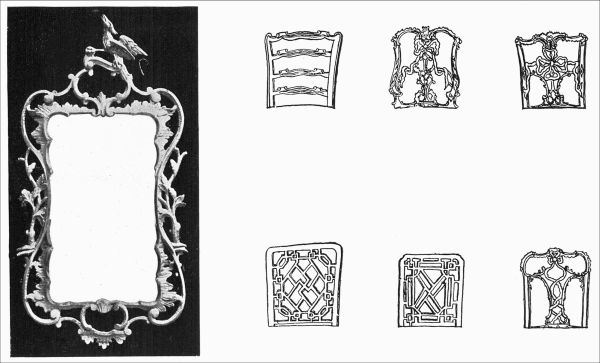

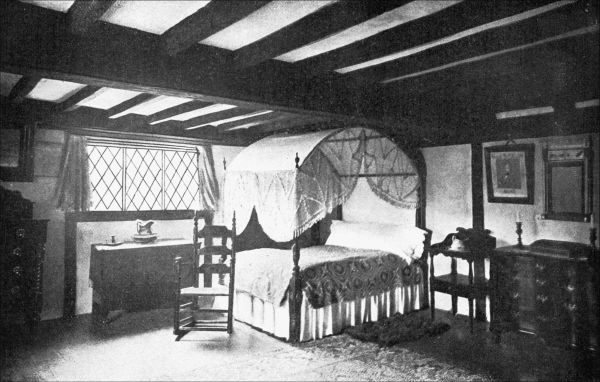

| 26. | Chippendale Chair-Backs and Mirror-Frame |

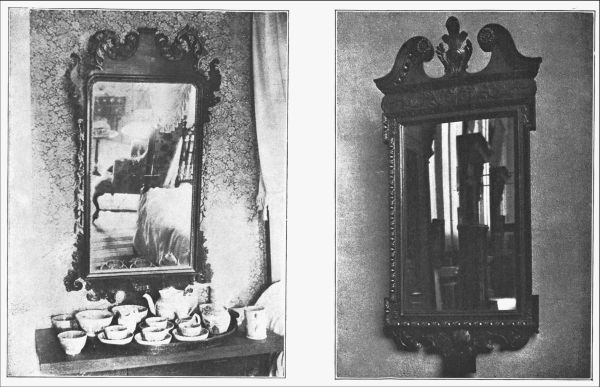

| CHAPTER IV | |

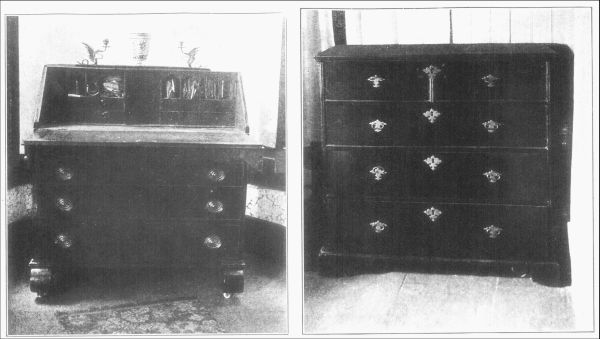

| 27. | Room in Whipple House, Ipswich, Mass. |

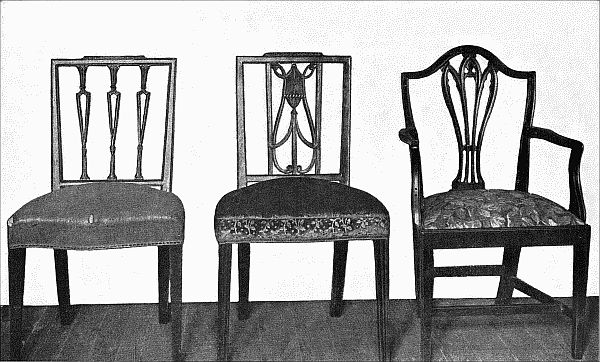

| 28. | Chippendale, Sheraton, and Hepplewhite Chairs |

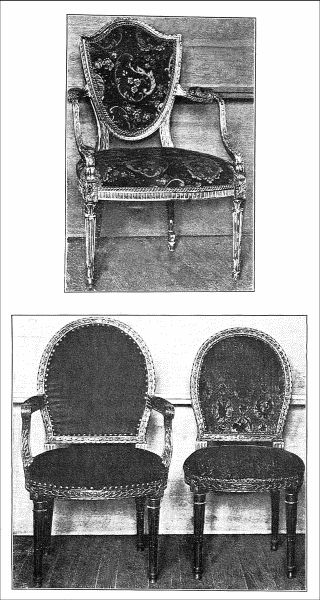

| 29. | Adam Chairs |

| 30. | Hepplewhite Chairs |

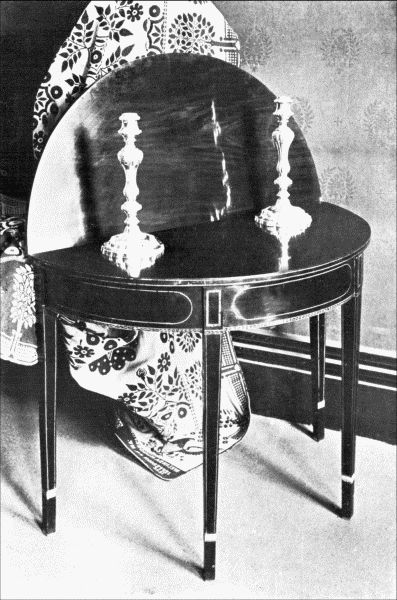

| 31. | Hepplewhite Card-Table |

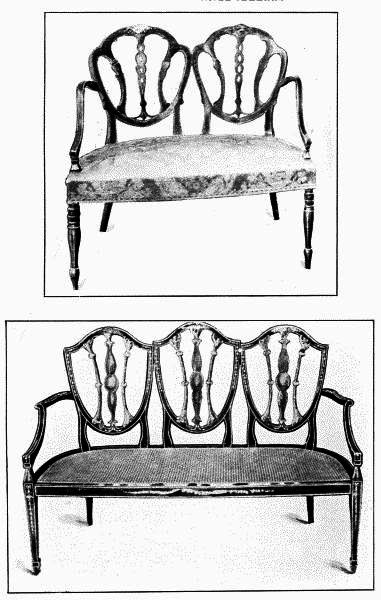

| 32. | Hepplewhite Settees |

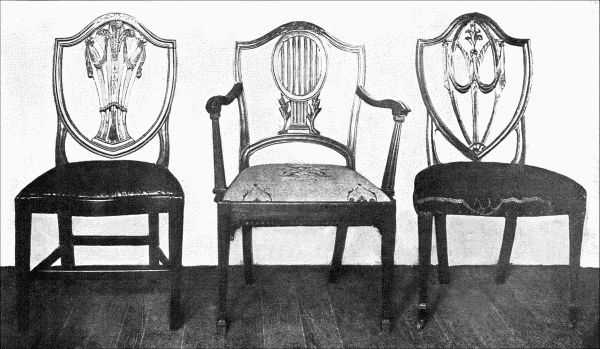

| 33. | Sheraton Chairs |

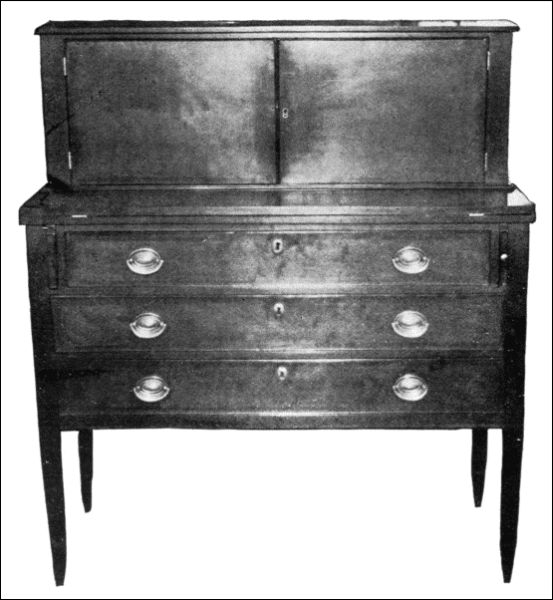

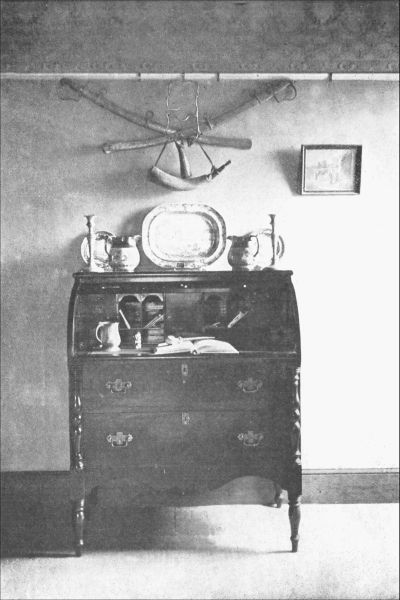

| 34. | Sheraton Desk |

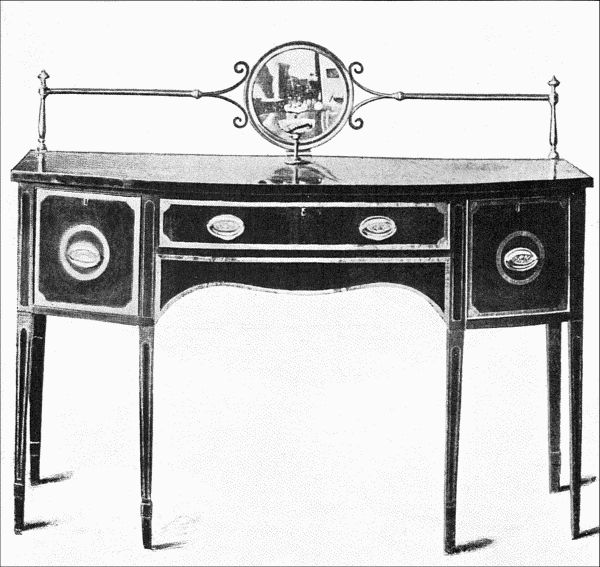

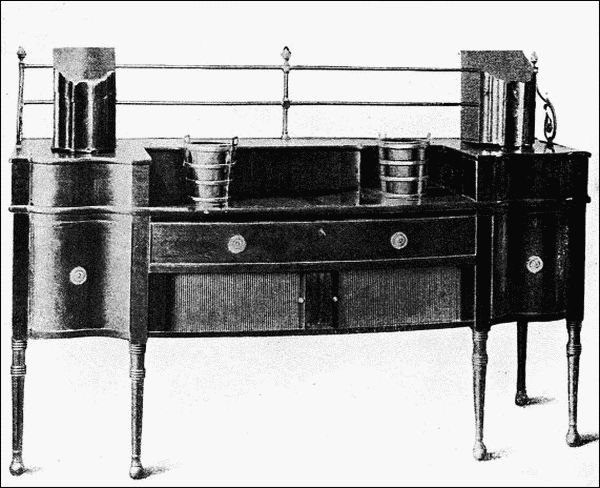

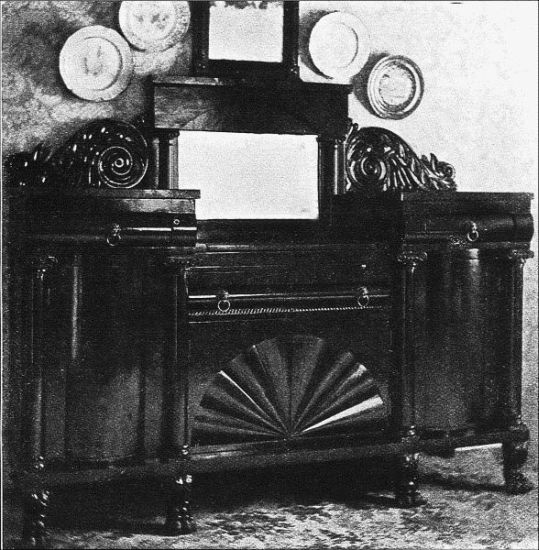

| 35. | Sideboard |

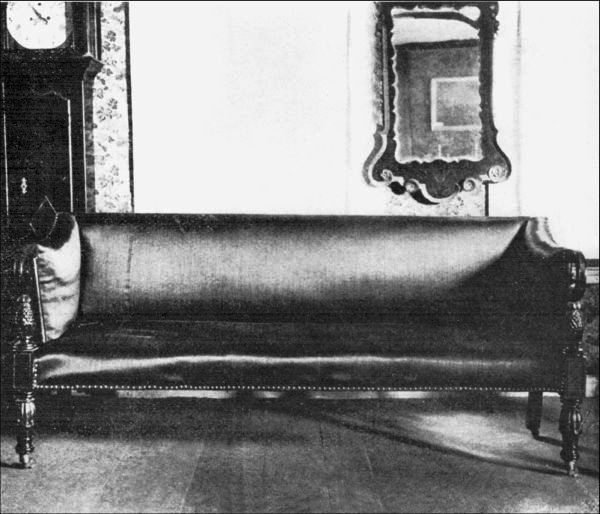

| 36. | Sofa, Sheraton Style |

| 37. | Sheraton Sideboard |

| 38. | Sheraton Sideboard |

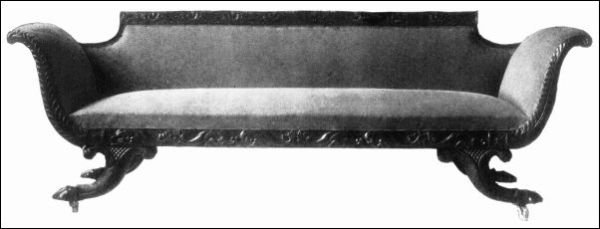

| 39. | Empire Sofa |

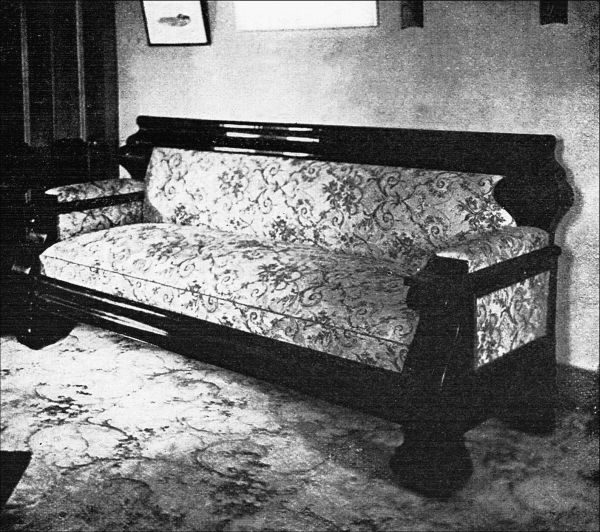

| 40. | Empire Sofa |

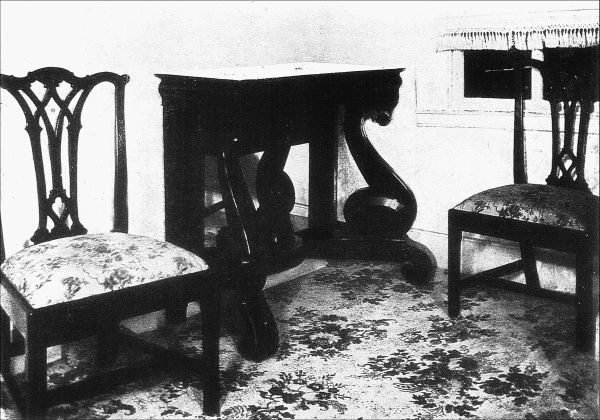

| 41. | Pier-Table |

| 42. | Empire Sideboard |

| 43. | Empire Work-Table |

| CHAPTER V | |

| 44. | Kitchen at Deerfield, Mass. |

| 45. | William Penn's Table |

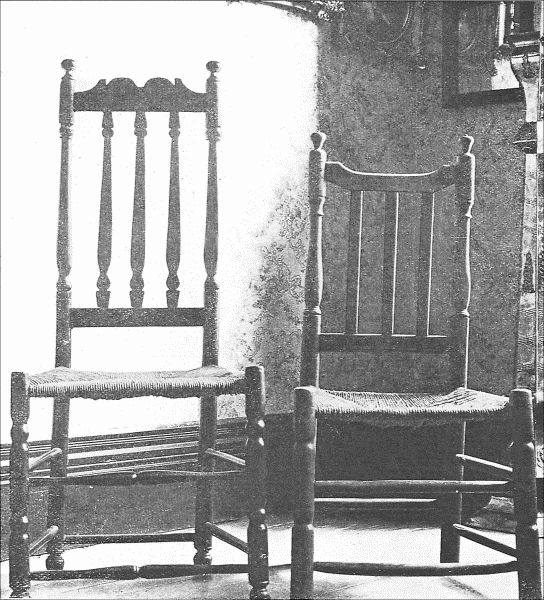

| 46. | Rush-Bottomed Chairs |

| 47. | Connecticut Chest |

| 48. | Mahogany Desk |

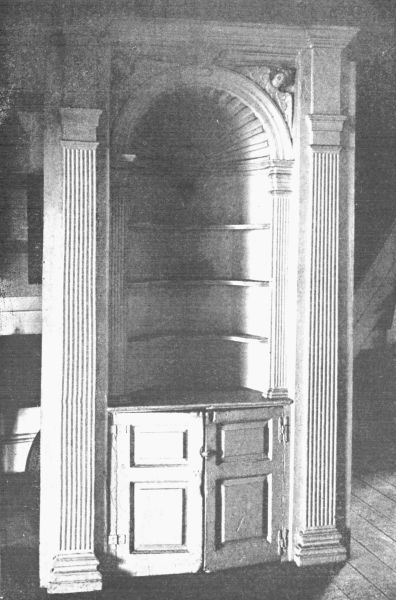

| 49. | Corner Cupboard |

| 50. | Banquet-Room, Independence Hall, Philadelphia |

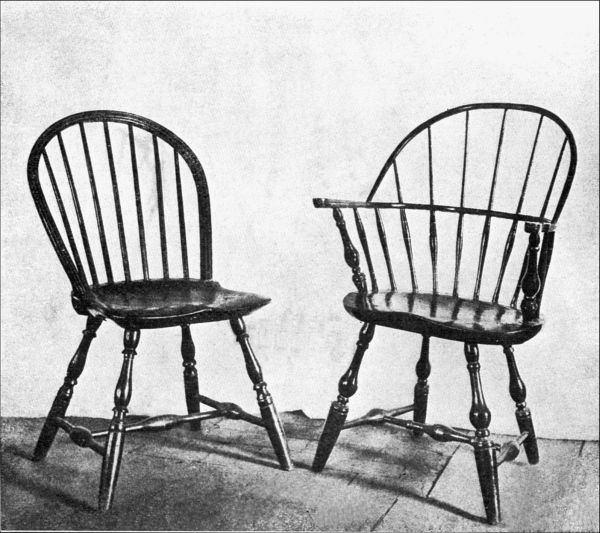

| 51. | Windsor Chairs |

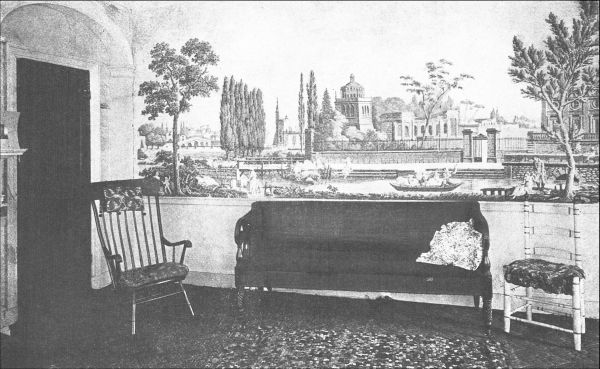

| 52. | Wall-Paper |

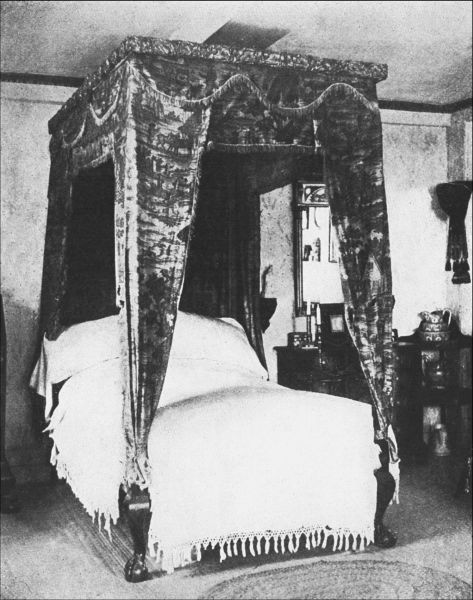

| 53. | Bed at Concord, Mass. |

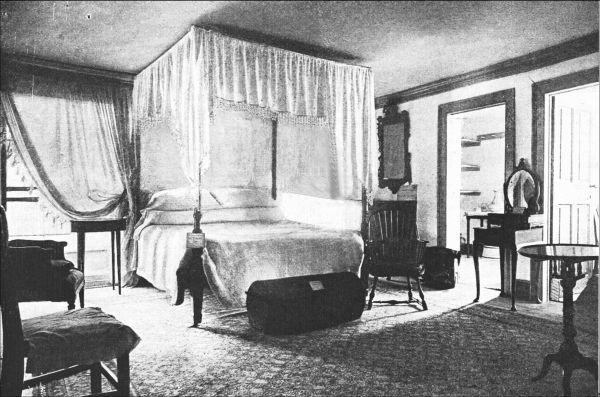

| 54. | Bed at Mount Vernon |

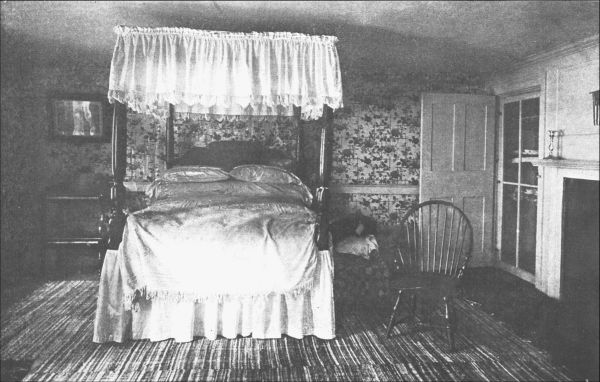

| 55. | Bed at Somerville, N. J. |

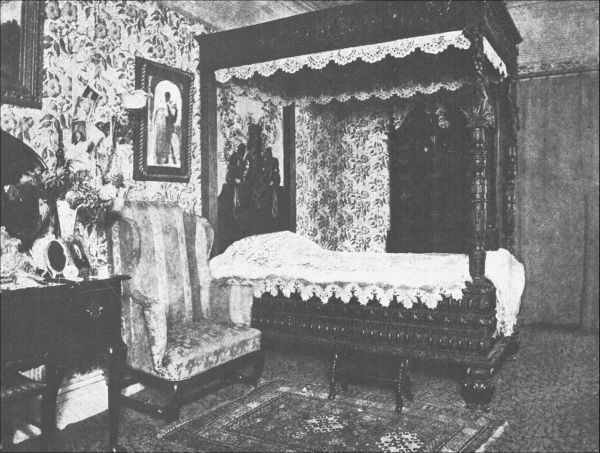

| 56. | Carved Oak Bedstead |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| 57. | Room in Whipple House, Ipswich, Mass. |

| 58. | Carved and Gilded and Mahogany Mirror-Frames |

| 59. | Mahogany Desk and Chest of Drawers |

| 60. | Combined Bookcase and Desk |

| 61. | Field Bed |

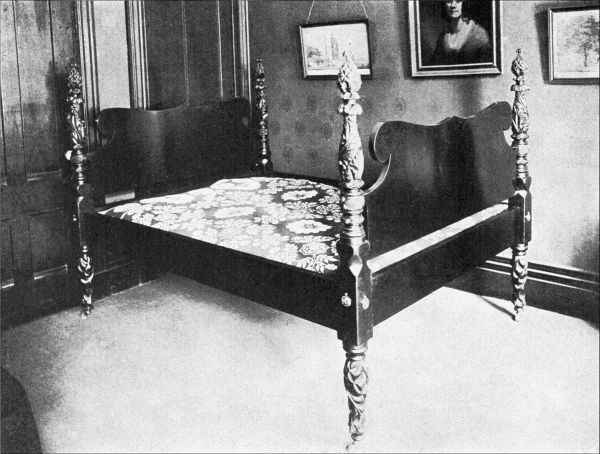

| 62. | Low Four-Post Bed |

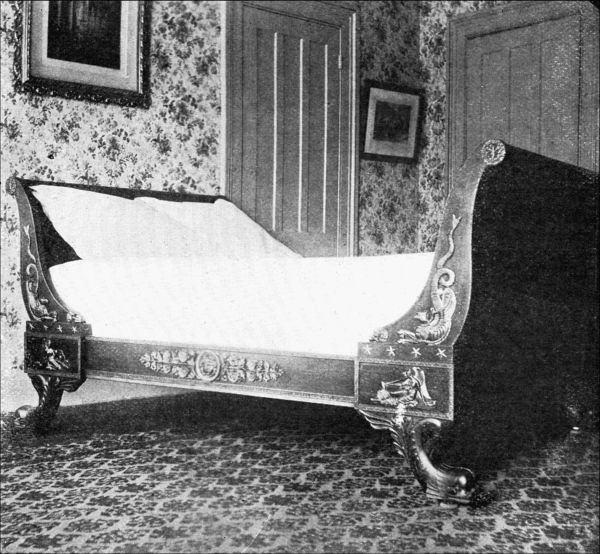

| 63. | French Bed |

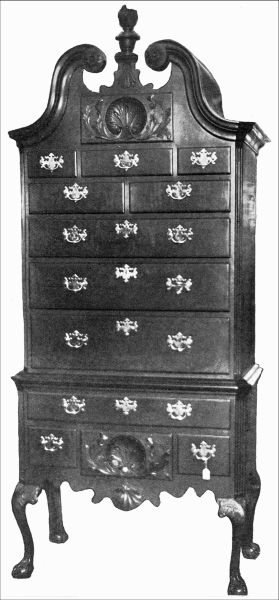

| 64. | Highboy |

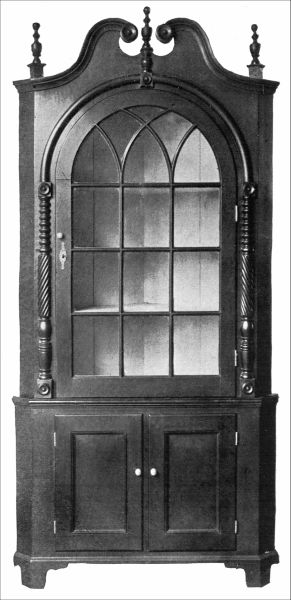

| 65. | Corner Cupboard |

| 66. | Inlaid and Lacquered Table and Chair |

| 67. | Lacquered Table |

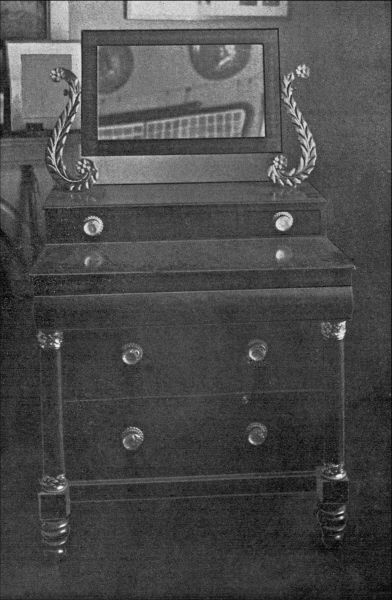

| 68. | Mahogany Bureau |

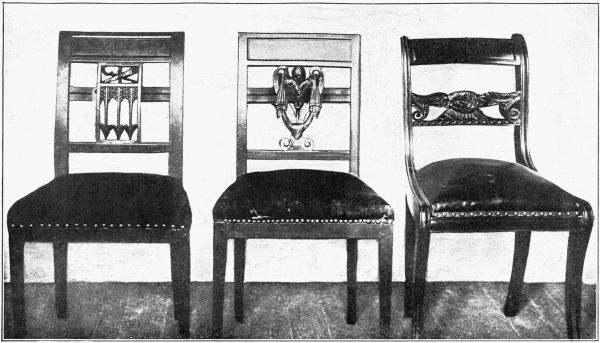

| 69. | American-Made Chairs |

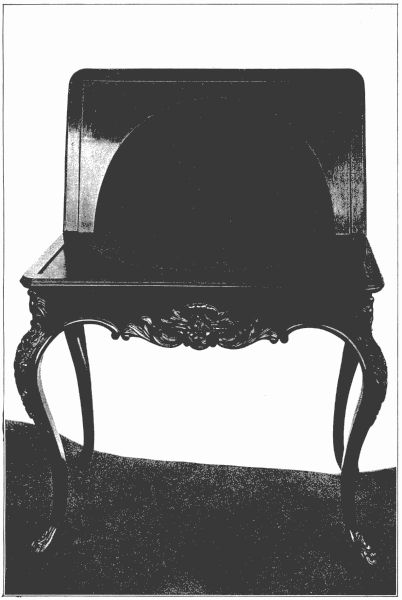

| 70. | American-Made Rosewood Card Table |

| CHAPTER VII | |

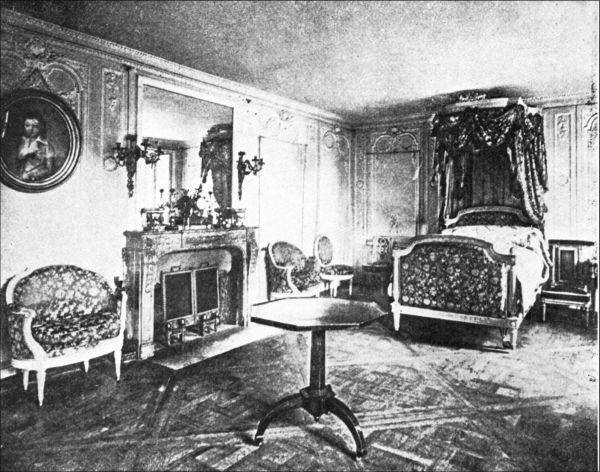

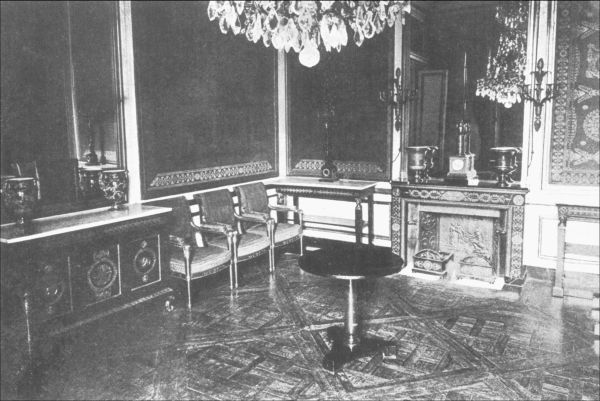

| 71. | Bedroom of Anne of Austria at Fontainebleau |

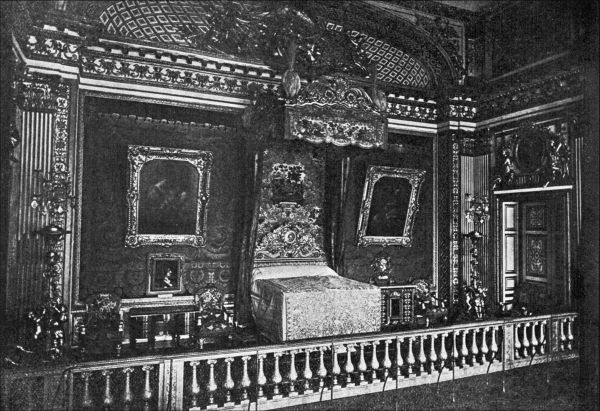

| 72. | Bed of Louis XIV at Versailles |

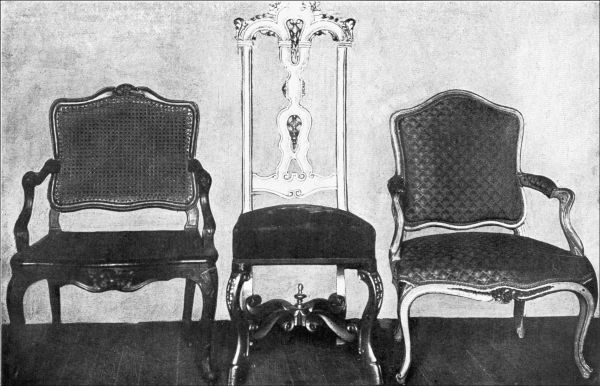

| 73. | Chairs of the Period of Louis XIV |

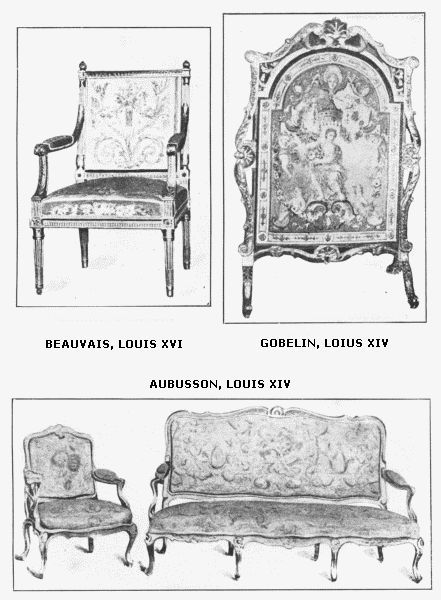

| 74. | Tapestry Furniture |

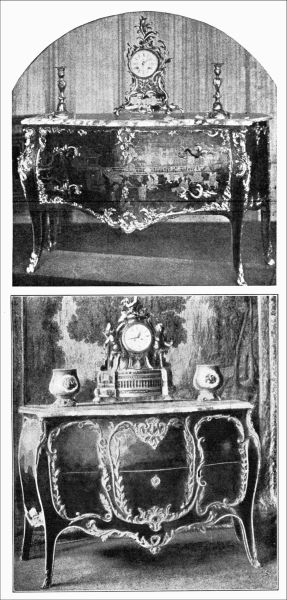

| 75. | Commodes of the Time of Louis XV |

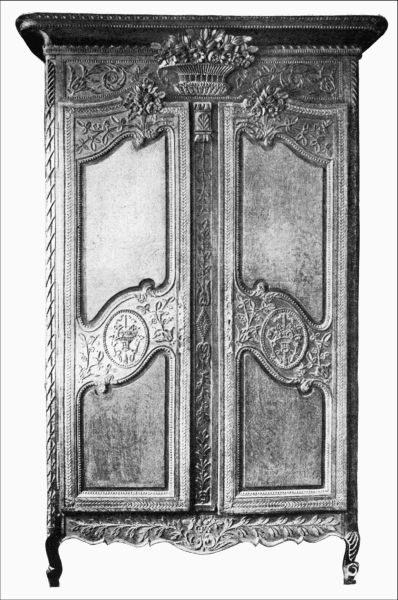

| 76 | Garderobe Period of Louis XV |

| 77. | Bedroom of Marie Antoinette at the Little Trianon |

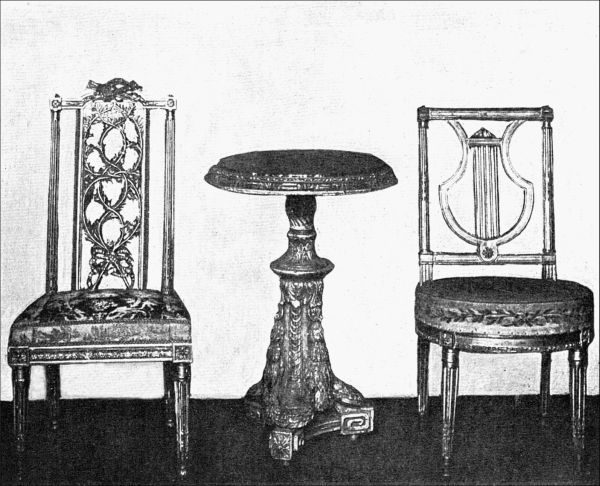

| 78. | Chairs and Table of Louis XVI Style |

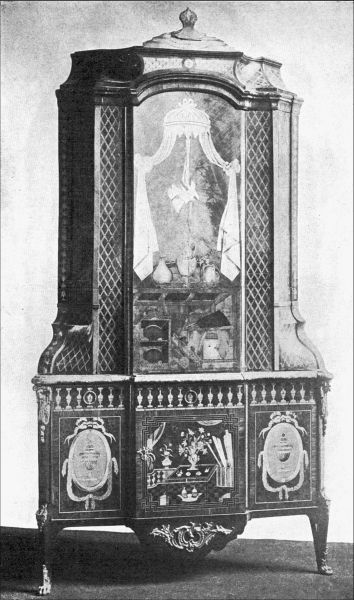

| 79. | Encoignure, Period of Louis XVI |

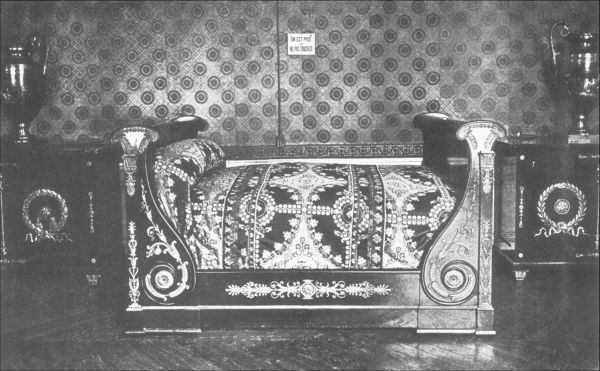

| 80. | Bed of Josephine at Fontainebleau |

| 81. | Bed of Napoleon at Grand Trianon |

| 82. | Room at Fontainebleau with Historic Table |

| 83. | Empire Reading and Writing Desk |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| 84. | Organ in St. Michael's Church, Charleston, S. C. |

| 85. | Spinet |

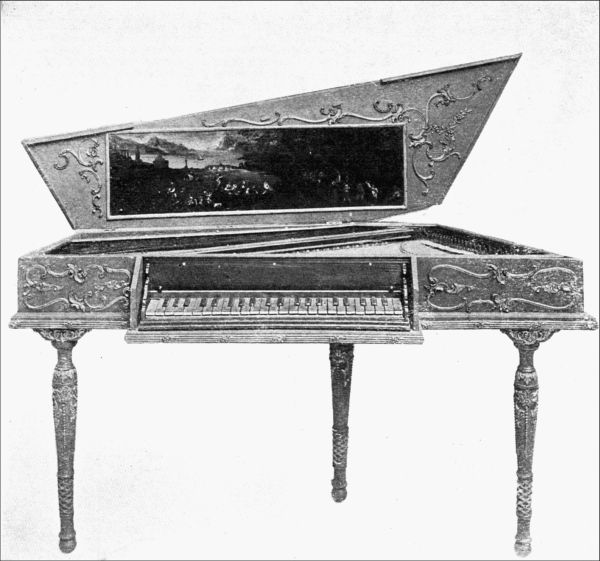

| 86. | Harpsichord |

| 87. | Cristofori Piano |

| 88. | Harp |

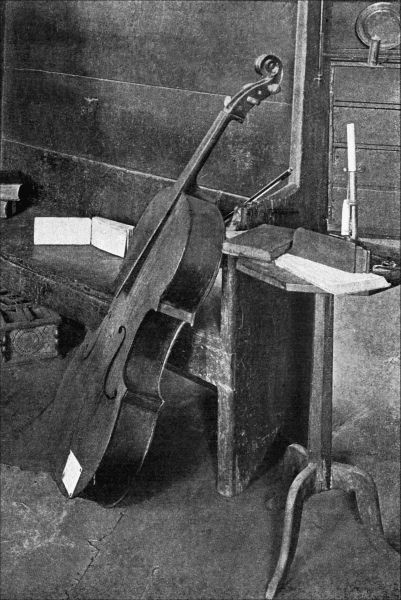

| 89. | Bass Viol |

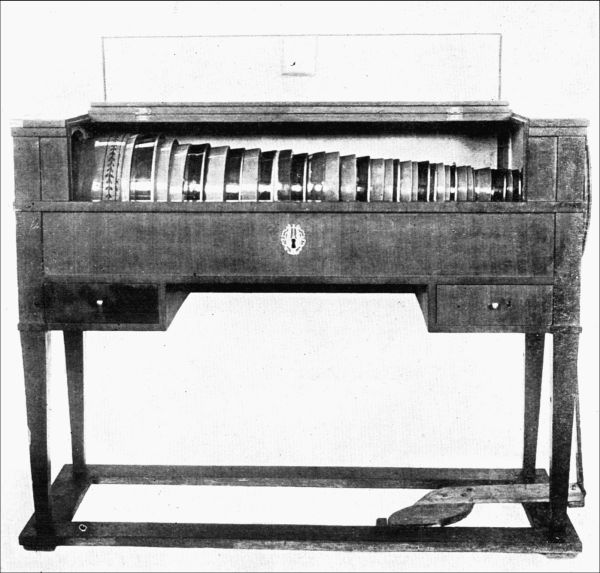

| 90. | Glass Harmonica |

| 91. | Geib Piano |

| 92. | Nuns Piano |

| 93. | Upright Piano |

| CHAPTER IX | |

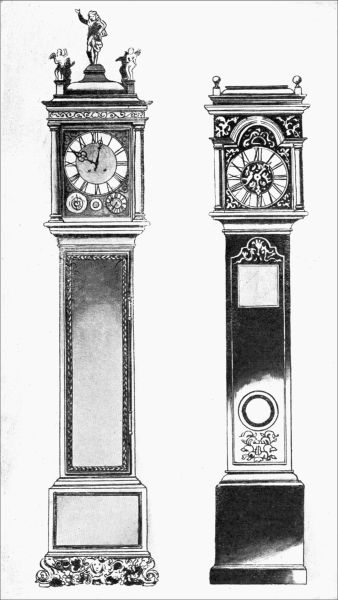

| 94. | Tall-Case Clocks, English |

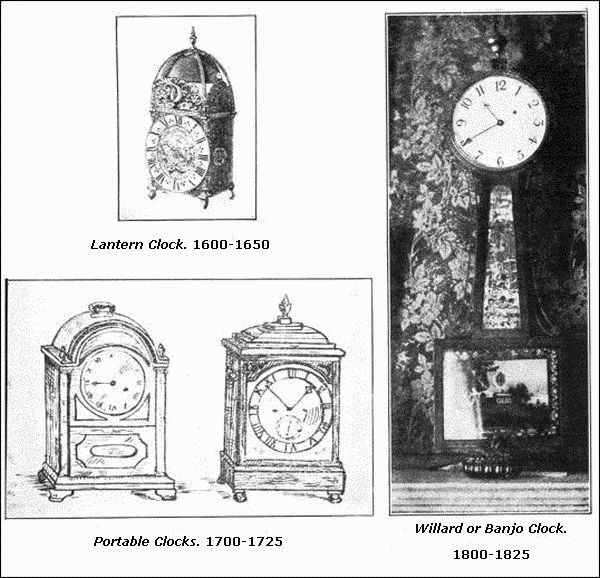

| 95. | Three Centuries of Clocks.—Lantern, Portable, and Willard or Banjo Clocks |

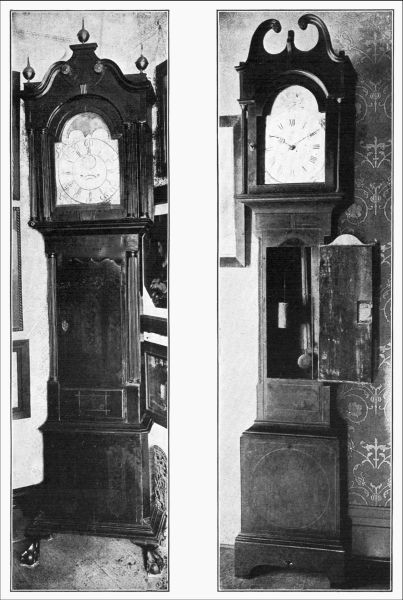

| 96. | Tall-Case Clocks, English and American |

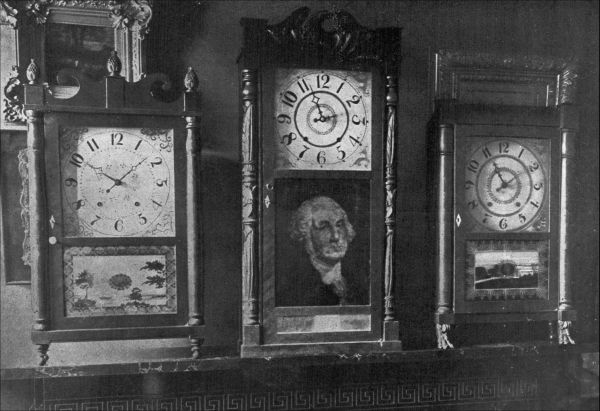

| 97. | Mantel Clocks |

| CHAPTER X | |

| 98. | Kitchen of Whipple House, Ipswich, Mass. |

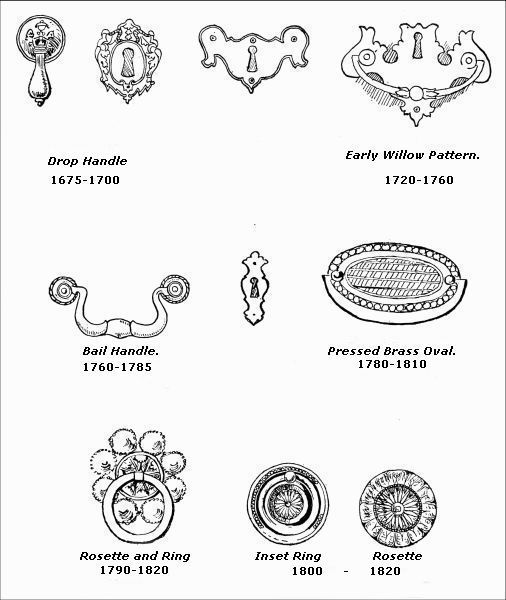

| 99. | Handles, Escutcheons, etc. |

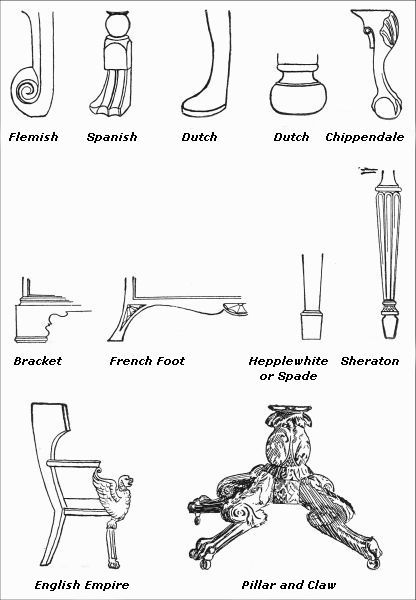

| 100. | Feet |

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Old Oak, Old Leather, Turkey Work, etc. | 1 |

| II. | Dutch Furniture | 28 |

| III. | Chippendale | 48 |

| IV. | Adam, Sheraton, Empire | 73 |

| V. | Colonial and Later Periods | 95 |

| VI. | Colonial and Later Periods—Continued | 128 |

| VII. | French Furniture | 148 |

| VIII. | Musical Instruments | 173 |

| IX. | Clocks | 197 |

| X. | Handles, Feet, Stuffs, etc. | 222 |

| Index | 237 |

With the revival of interest in all "antiques," which is so widely spread at this time, any of us who chance to own an old piece of furniture feel an added degree of affection for it if we can give it an approximate date and assign it to a maker or a country. There is much good old furniture in the United States, chiefly of Spanish, Dutch and English make, though there are constant importations of other makes, notably French, since it is recognized on all sides that Americans are becoming the collectors of the world. Our public museums are gradually filling with works of art presented by broad-minded citizens, while the private galleries are rich and increasing every day. To keep pace with these possessions, furniture from old palaces and manor-houses is being hauled forth and set up again in our New World homes. Indeed, whole interiors have been removed from ancient dwellings, and the superb carvings of other days become the ornaments of modern houses, like the gilded oak panels from the Hotel Montmorency which were built into the Deacon House in Boston, or like Mrs. Gardiner's [Pg 2] Venetian carved wood which decorates her palace in the Boston Fens.

Oak panelling, like everything else, passed through various periods and styles. In Queen Elizabeth's time the panels were carried to within about two feet of the cornice; then, after some years, there came a division into lower and upper panelling, the upper beginning at about the height of the back of a chair from the floor. Pictures became more common, and they were frequently let into the upper panelling, and then it was discarded altogether, only the lower half or dado being retained. This, too, after some years, became old-fashioned, and the board known as skirting, or base-board, was all that was left of the handsome sheathing which extended from the floor almost to the ceiling. This old oak panelling was entirely without polish or varnish of any kind, and grew with years and dust almost black in colour. Sometimes it was inlaid with other woods, and often it was made for the rooms where it was placed. Where the panels are carved, they are generally bought in that state and set in plain framework by the household joiner. If, however, the frame is carved and the panels plain, they were made to suit the taste and purse of the owner of the mansion. Oak panelling took the place of the arras, tapestry hangings, and crude woodwork of earlier times. Of course it was adopted by the rich and luxurious, for it rendered more air-tight the draughty buildings.

Figure 1. OLD OAK BEDSTEAD.

The oldest furniture was made of oak, more or less carved, whether of Spanish, Italian, Dutch, or English make. The multiplication of objects which we consider necessary as "furnishings" were pleasingly [Pg 3] absent, and chests used as receptacles for clothes or linens, for seats by day and beds by night, with a few beds also of carved oak, and tables, made up the chief articles of domestic use.

Even the very word "furniture" itself is of obscure origin and was used formerly, as now, to describe the fittings of houses, churches, and other buildings.

There are a few terms applied to furniture referring either to its decoration or process of manufacture with which it is well to become acquainted. They are given here in the order of their importance.

Veneering is the process of coating common wood with slices of rare and costly woods fastened down with glue by screw presses made to fit the surface to be covered. It was first used in the reign of William and Mary, in the last decade of the seventeenth century. Until that time furniture had been made of solid wood. Veneer of this early period, particularly burr-walnut veneer, was about one sixteenth of an inch thick, and was sometimes applied to oak. Chippendale, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton used mahogany and satin-wood both solid and for veneers. When used as veneers they were all hand-cut, as they are in all high-class furniture to-day. It was not till the late Georgian period that machinery for cutting veneer was first used, and slices were produced one thirty-second of an inch in thickness. Most of the cheaper kinds of modern furniture are veneered.

Marquetry is veneer of different woods, forming a mosaic of ornamental designs. In the early days of the art, figure subjects, architectural designs, and interiors were often represented in this manner.

Rococo, made up from two French words meaning [Pg 4] rock and shells, roequaille et coquaille, is a florid style of ornamentation which was in vogue in the latter part of the eighteenth century.

Buhl, or Boulle, is inlaid work with tortoise-shell or metals in arabesques or cartouches. It derived its name from Boule, a French wood-carver who brought it to its highest perfection.

Ormolu refers to designs in brass mounted upon the surface of the wood. This metal was given an exceedingly brilliant colour by the use of less zinc and more copper than is commonly used in the composition of brass, and was sometimes still further made bright by the use of varnish and lacquer.

Baroque. This word, which was derived from the Portuguese baroco, meant originally a large irregular pearl. At first the term was used only by jewellers, but it gradually became technically applied to describe a kind of ornament which became popular on furniture early in the nineteenth century, after the rage for the classic had passed. It consisted of a wealth of ornament lavished in an unmeaning manner merely for display; and scrolls, curves, and designs from leaves were used to cover pieces, making them lack beauty and that grace which comes from pure and simple lines.

Lacquer is coloured or opaque varnish applied to metallic objects as well as wood. The name is obtained from "resin lac," the material which is used as the base of all lacquers. In the East Indies the whole surface of wooden objects, large and small, is covered with bright-coloured lacquers. The Japanese lacquers are the finest that are made. They excel in the variety and exquisite perfection of this style of [Pg 5] work, and under their skilful manipulation it becomes one of the choicest forms of decorative art. The most highly prized lacquer is on a gold ground, some specimens of which reached Europe in the time of Louis XV.

Japanning. This style of treating wood and metal derives its name from the fact of its being an imitation of the famous lacquering of Japan, although the latter is prepared with entirely different materials and processes, and is in every way much more durable, brilliant, and beautiful than any European "Japan work." This latter process is done in clear transparent varnishes, or in black or colours, but the black japan is the most common. By japanning a very brilliant polished surface may be secured, which is more durable than ordinary painted or varnished work. It is usually applied to small articles of wood, to clock-faces, papier-maché, etc.

Joined furniture. All the parts are joined by mortise and tenon, no nails or glue being used. This method prevents the parts from warping or springing, as so much of the modern machine-made furniture does.

Figure 1 shows an ancient carved-oak bed of the time of Queen Elizabeth, with grotesque carvings on the headboard in Renaissance style, which is said to have been introduced into England by Holbein. This bed has an interesting history. It belongs to the Herricks of Beaumanor Park, and came to them from Professor Babington, of St. John's College, Cambridge, England. He inherited it from his father, whose ancestors kept the "Blue Boar" inn at Leicester, where Richard III slept the night before the battle of Bosworth [Pg 6] Field, in August, 1485. This has always been called "King Richard's Bed," and many learned antiquaries have waxed eloquent for and against this assumption. Mr. Henry Shaw, author of "Specimens of Early Furniture," published in 1836, says it is a good specimen of the modern four-poster of Elizabeth's time, the more ancient beds being without foot-posts. In fact the earlier beds were mere couches. As more luxury was demanded they grew larger, counterpanes were made of the richest materials, gorgeously embroidered with the arms and badges of their owners, and from their great cost and imperishable character descended from one generation to another. They provided employment, too, for the lady of the castle and her bower maidens, who had no end of leisure which had to be filled in some way, and which dragged along for many a long year, broken only by the chance visit of a wandering hawker or my lord's return from the wars.

Hollingbourne Manor, in Kent, is one of the old mansions still standing which was built in Queen Elizabeth's time. The manor was originally owned by Sir Thomas Culpeper, and his initials appear in many places about the house. In the great hall the fireplace has an iron back with the initials "T. C." and the date 1683 wrought in it. The present owner, Mr. Gerald Arbuthnot, has preserved the old-time atmosphere as much as possible, and in connection with home-made tapestry the "needle-room" is especially interesting. In that room the four Ladies Culpeper, daughters of that John, Lord Culpeper, who was exiled for his devotion to King Charles, spent so much of their time making tapestry that one of the [Pg 7] sisters became blind from the effects of her close application. Among the pieces of the handiwork of the four sisters preserved is a magnificent altar-cloth which they presented to the parish church. For two centuries and a half a needle left by the fingers of the worker remained sticking in the corner of the cloth, but it was stolen about two years ago by some one of a party of antiquarians visiting the Manor.

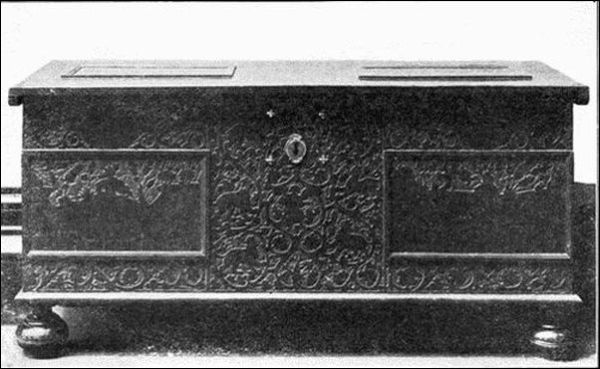

Figure 2. OLIVE-WOOD CHEST.

In Mr. Shaw's book already quoted are many items concerning these great and handsome beds, which were often the finest pieces of furniture in the castle or manor, and from the safe seclusion of which the king or great lord received the homage of his vassals.

The bed and bedstead were sometimes classed separately, but in many inventories the former word covers the bedstead and all its furnishings. The fittings of the bed were well in keeping with the fine carved woodwork, and were of softest feathers or down. Sheets of linen, and rugs or blankets of fine wool, were covered by a cloth woven of samite, damask, or heavy with gold threads.

Richard, Earl of Arundel, in 1392, left to Philippa, his second wife,—

—"a blue bed marked with my arms and the arms of my late wife, also the hangings of the hall, which were lately made in London, of blue tapestry with red roses, with the arms of my sons, the Earl Marshall, Lord Charlton, and Mons. Willm. Beauchamp; to my son Richard, a standing bed called "Clove"; also a bed of silk embroidered with the arms of Arundel and Warren quarterly; to my dear son Thomas, my blue bed of silk embroidered with greffins; to my daughter Margaret my blue bed."

Not many earls had so great a store of worldly goods.

In 1434 Joanne, Lady Bergavenny, devises—

—"a bed of gold swans, with tapettar of green tapestry, with bunches and flowers of diverse colours; and two pair of sheets of Raynes; a pair of fustian, six pairs of other sheets; six pairs of blankets; six mattrasses; six pillows; and with cushions and bancoves that longen with the bed aforesaid."

This was only one bed of six specified by this lady, several being of velvet, silk, and one of "bande kyn," a rich and splendid stuff of gold thread and silk, still farther enriched with embroidery. Before the cloth spread or counterpane the covering was of fur. It was also the fashion in these primitive times to name the beds, like that specified "Clove" in the Earl of Arundel's inventory, sometimes with the names of flowers, sometimes with those of the planets or of birds. The beds were surmounted with testers or canopies of rich silk edged with fringes, and suspended from the rafters of the room by silk cords. There were side-curtains also, and much carving on the headboard, while the foot-posts, as we have said, are wanting in the earliest beds, prior to the year 1500. Mr. Shaw goes on to say that there are very few beds still extant which date before Elizabethan times, and that the most ancient he met with was of the time of Henry VIII., and belonged to a clergyman of Blackheath who bought it out of an old manor-house. The posts and back are elaborately carved in Gothic style, but the cornice is missing.

Of Elizabethan times there are several noted beds extant, the finest of them being known as the "Great Bed of Ware" mentioned by Shakespeare in "Twelfth Night." It is seven feet high and ten feet square. There is one in the South Kensington Museum, London, more richly carved than the one we show, [Pg 9] and having in addition a carved foot-board. This bed is dated 1593.

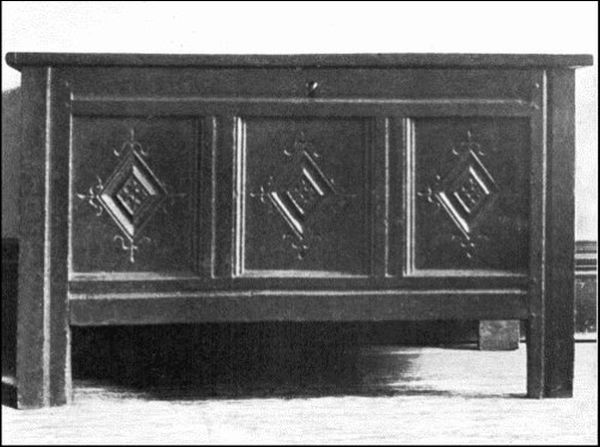

Figure 3. OLD OAK CHEST.

The curtains and hangings which have in our day become mere ornaments were during the Elizabethan period most necessary. Windows unglazed, and rude walls unplastered, or at best hung with tapestry, permitted drafts to wander through the sleeping-rooms, so that the curtains were closely drawn at night for actual protection. At best in many a castle or dwelling of the wealthy but one bed would be found, and that belonged to the lord and lady, the rest of the family taking their rest on rugs or cushions bestowed on the floor, or on chests or settees, or even on tables.

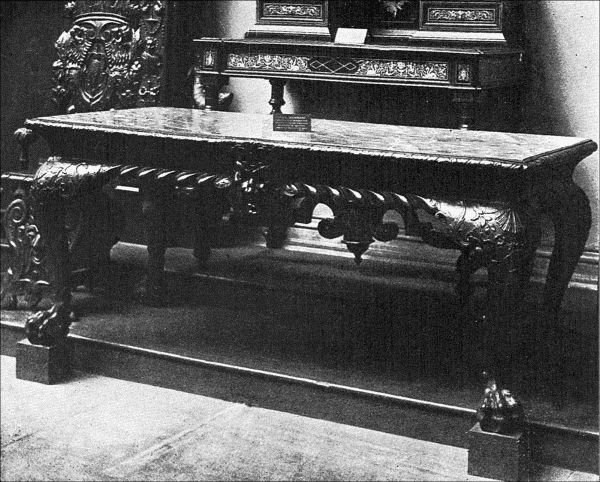

There are also found, though rarely, oak tables of this period, or perhaps a little later, heavily carved along the sides, and with ponderous turned legs and plain stout braces. These tables, perhaps the earliest approach to a sideboard, are so long that they have six legs, the top seldom being less than twelve feet in length. One we refer to was found recently in an old barn in England, where it had lain since the neighbouring manor-house had been pulled down in 1760. While its condition was good,—that is, needing no restoring,—it had become nearly black and almost fossilized from exposure. It is now used as a sideboard by the vicar of the parish who found it in its lowly estate, and on it stand pewter and plate, also antiques from the neighbourhood. Such treasures can seldom be found here, certainly not any that have lain concealed since 1760.

After the Elizabethan period the next one of importance may be called Jacobean. James I. encouraged [Pg 10] his people to use chairs instead of stools. It was not long before settles, lounges, and "scrowled chairs," the latter inlaid with coloured woods, crowded out the stools of former days, and the idea of enriching the useful became the interest of the skilled workman, and utility was no longer the measure of value. Stools, to be sure, were still used, but they had heavy cushions of brocade, or worked stuff, or velvet, and were hung around with a rich fringe and with gimp, fastened with fancy nails. The arm-chairs of this period, a fashion introduced from Venice, had the legs in a curved X shape across the front, and chairs are still extant which were used by James I. himself. These chairs, which are all somewhat similar in design, were rendered still more comfortable by a loose cushion which could be adapted to the inclination of the sitter. The bedsteads of the period were also smothered in draperies, the tester trimmed with rows upon rows of fringe, the head-boards, carved and gilded, being about the only woodwork allowed to show.

As we have said, the earliest wood used, at least in northern England, seems to have been oak. At the close of the sixteenth century there was furniture decorated with inlays of different coloured woods, marbles, agate, or lapis lazuli. Ivory carved and inlaid, carved and gilded wood, metals and tortoise-shell, were used also in making the sumptuous furniture of the Renaissance. The greatest elegance of form and detail was observed during this century, and it declined noticeably all over Europe, during the seventeenth century. The framework became heavy and bulky and the details coarse. Silver furniture made in Spain and Italy was used in the courts of the [Pg 11] French and English kings. Then came the carved and gilded furniture which received its greatest perfection in Italy, though it was made throughout Europe till late in the eighteenth century.

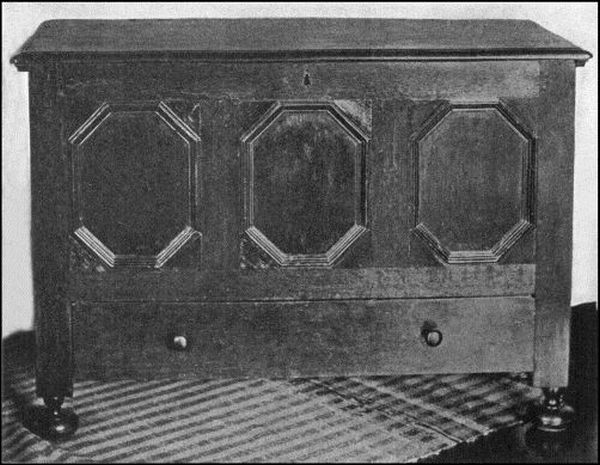

Figure 4. CHEST WITH ONE DRAWER.

Second only to the bed in importance as an item of household furnishing was the chest, a seat by day, a bed by night, and a storehouse of valuables always. It usually stood at the foot of the bed, possibly so that it could not be pilfered at night without the owner's knowledge. Some chests, heavily made, provided with locks and bound with iron, held all the worldly wealth of the owner, as well as his papers and deeds. Before the time of James I. bills of exchange were not used, and the actual coin passed in all transactions. Italy was the first country to establish banks, the money-dealers of Florence practising banking as early as the thirteenth century. Holland followed their example, and in 1609 the Bank of Amsterdam was founded, but kept in its coffers the actual coin paid in, being merely a repository for safe keeping. England had no bank until the seventeenth century, when this business was undertaken by the goldsmiths of London. The Bank of England was not founded until 1694. It can be easily seen how necessary a part of the household goods a stout chest for valuables was, especially in remote parts of the country, where access to the cities was not easy. Not alone in houses was the chest a necessary article; one or more were a part of every church's furniture, and in them were kept the vestments, church linen, the plate, and other valuables.

There is a lawsuit mentioned in the Court Records of New Amsterdam, where one of two sisters living at [Pg 12] Jericho, Long Island, about 1647, sues a neighbour for coming into their house and breaking into her chest, which was in her bedroom, and stealing from it several measures of wheat which were stored therein, as well as some coins which were in the till.

The wearing-apparel of the family also was kept in these chests, and for years before her marriage the daughter of the house was employed in filling one up with linen spun and woven through all the different processes from the flax, the size and fullness of the chest often proving quite a factor in the marriage negotiations.

The chests of the Jacobean time, enriched with mouldings, panellings, and drop ornaments, are by no means unknown in America. They are furnished with drawers, cupboards, and then drawers above, making them massive and useful pieces of furniture. They stand upon large round legs, and the handles to drawers and cupboards are drops. In Italy marriage chests were beautifully painted, often by famous masters, and sometimes gilded as well. In Holland the chests were carved or inlaid; and many of these, owing to the commercial relations between England and Holland, found their way into the former country and thence to America, in addition to those brought directly from the Low Countries. Chests were used as trunks by travelers long before Shakespeare's time, and he makes a chest play an important part in "Cymbeline." In the early days of the American colonies, when the settlers sent back to England for comforts not procurable in America, these were generally despatched in chests for safe keeping and to preserve their contents. The following letter shows a [Pg 13] lady's desire to get hold of her property which had been unduly detained. Lady Moody was a member in 1643 of the Colony of Massachusetts, but, "being taken with the error of denying baptism to infants, was dealt with by many of the elders," As she persisted in her "error" she was persuaded by friends, in order to avoid further trouble, to move to the New Netherlands. This she did, and it is noted by the Rev. Thomas Cobbett, of Lynn, that "Lady Moody is to sitt down on Long Island, from under civil and church watch, among the Dutch."

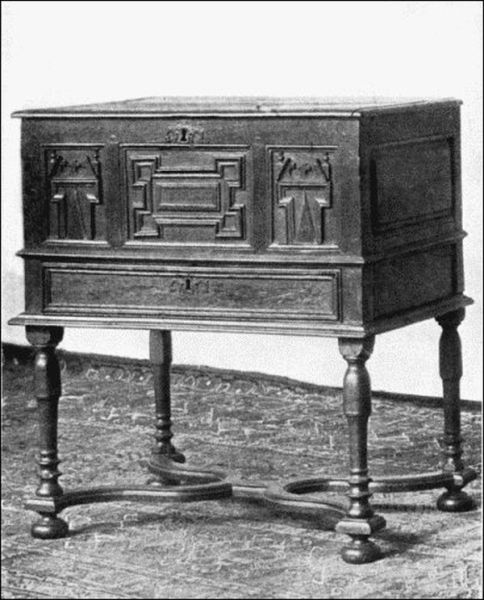

Figure 5. OAK CHEST ON FRAME. English.

Later she became a warm friend of the younger Winthrop, and many letters passed between them. The following was written in 1649:

"Wurthi Sur:

My respective love to you, remembering and acknowledging your many kindnesses and respect to me. I have written divers lines to you, but I doubt you have not received it. At present being in haste I can not unlay myselfe, but my request is yt you will be pleased by this note, if in your wisdom you see not a convenienter opertunity to send me those things yt Mr Throgmorton bought for me, and I understand are with you, for I am in great need of ye, together with Mark Lucas's chest and other things.

"So, with my respective love to you and your wife and Mrs Locke remembered, hoping you and they with your children are in helth, I rest; committing you to ye protection of ye Almighty. Pray remember my necessity in this thing.

Deborah Moody."

Chests are to be found in the well-settled as well as in out-of-the-way corners, and of Dutch, English, and American make. The Dutch, broadly speaking, are more common in the neighbourhood of New York, Albany, and other places settled by these pioneers [Pg 14] from Holland, while the English-made ones, many of them, are to be found in New England, and scattered over the Eastern States as well, since in the past year I have seen two fine ones, both found in the western part of New York State. The very earliest chests which were among the effects of our first settlers are very plain affairs, hardly more than boxes mounted on simple sawed legs. They were all furnished with locks, and generally with rude handles, and we can well conceive the motley array of household and personal "stuff" which came over in them. Elder Brewster's chest is in the Memorial Hall at Plymouth, and is just such a plain box on legs as has been described.

Though there were many oak chests undoubtedly brought over during these early years, there were also many of pine, and, being plain and cheap receptacles, more easily damaged than if of harder wood, they gave way to better and more ornate pieces as soon as the family fortunes warranted it.

In Flanders were made many fronts of chests only, quite elaborately carved, and sent to England, there to be fitted with the other parts. Among the guilds the chest-makers bore an important part, as chests, particularly of churches, were sometimes fastened with two locks, and the lock plates were often very highly and handsomely wrought. Of later years chests of every degree of elegance and beauty have found their way to America; some covered with carving of the florid style of the Renaissance, some still showing traces of the fine gilding with which they were covered. Even some of historic interest are owned here, such as the carved chest of olive-wood said to have belonged [Pg 15] to the Stuarts, and brought to this country by a member of the family who fled to Virginia after the beheading of Charles I. It remained in the possession of a family named Stuart till recently, and was bought by its present owner, Miss C. F. Marsh, of Clermont-on-the-James. This chest, though restored as to its feet, is remarkable on account of the decorations on the inside of its lid, which are unusual in that place, and from the fact that they are done in burnt work as well as carving. A portrait of James I. occupies the centre, and there are carved panels on either side depicting the "Judgment of Solomon." On the top of the lid the arms of the Stuarts are burnt in, while the front is decorated with panels of castles and warriors, and above the middle panel are the British lions supporting the royal arms. This chest is about six feet in length, twenty-four inches high, and twenty-two inches wide. The plantation on which it was found belonged to Captain John Smith in 1610. Its real value was quite unknown to those who possessed it. It was sold at auction, and was bought by a German farmer for a feed-box, on account of its strength. He carted it home, and was so satisfied with his bargain that he was quite unwilling to sell. It is made of eight-inch planks of olive-wood, cut several centuries ago in Palestine.

Nor is this the only chest of this description in the country. In Memorial Hall, Philadelphia, is one very similar to it (Figure 2), but in a perfect state of preservation, with the original ball feet and more ornate twisted wrought-iron handles. The style of decoration on the two chests is quite similar, they are both made of olive-wood, but the wrought-iron handles are much [Pg 16] handsomer on the Philadelphia chest than on the Stuart one. It has, however, no carving on the inside of the lid; the four panels of carving are enclosed with a moulding; but the lions rampant are very well done, and there are figures in cavalier costume on the panels. While, of course, elegant chests like these are most uncommon, it is the less ornate specimens which prove the most interesting, because there is more likelihood of our becoming possessed of them.

Figure 3 represents a good specimen of one of these early chests. It is of English make, entirely of oak, the boards of the bottom being as heavy and solid as lead. The top is a heavy plank of oak with a fine grain. The chest is panelled within and has one till. The lock is modern, and some nails have been driven to hold the chest together, for the back legs as well as the sides are worm-eaten. This chest is three feet nine inches long, twenty-eight inches high, and twenty inches wide, and is in good condition save for the nails. Its date is about the last quarter of the seventeenth century. It was found in New York State and belongs to Mr. W. M. Hoyt of Rochester. While oak and pine were the most common materials for these chests, olive-wood was sometimes used, as we have seen, and sometimes the panels were of cedar, and the ornaments of some of the softer woods, like pine or maple, coloured and stained to imitate ebony. American walnut came into use late in the seventeenth century, but, although used in furniture and popular as a veneer, it was not used for chests. Cypress wood was also in demand as a material for chests, the aromatic smell keeping off the pest of housekeepers, the moth. In summer time the heavy woollen tapestries and [Pg 17] woollen clothes of the family were stowed away, and the former, at least, from their cost and the labour expended upon them, had to be carefully protected.

Figure 6. SPANISH LEATHER CHAIR.

The roughest sort of a chest was called a "standard," and in it were packed the more perishable movables and furniture; and in moving from one residence to another these standards were carried by pack-horses or on rude carts. Chinese chests of teak-wood, lacquer, or cedar are very rarely met with, though you will sometimes see them in old homes in England, where some ancestor of the family followed the sea.

The inventory of the estate of Colonel Francis Epes, of Henrico County, Virginia, dated October 1, 1678, is a long and varied one. The first article recorded is "One foure foot chest of drawers seder Sprinkled new, but damnified £1-10.0." Further along are mentioned—

—"one middle size calve skin truncke with drawers. One old leather truncke with lock and key ... one old middle size chest with lock and key. One small old chest with lock and key. Two other old chests without keys and one without hinges."

Quite a number of chests and trunks for one family when it is noted that they had chests of drawers also. When the Rev. Samuel Sewall, so well-known from his voluminous diary, returned from a trip to England in 1689, he brought with him on the ship "America" a trunk for each of his three children, with their names and the dates of their births carved thereon. Presumably these trunks did not come over empty. He brought also a sea-chest, a barrel of books, a large trunk marked H. S. with nails, two smaller trunks, a deal box of linen, a small case of liquors, and a great case of bottles. He slept on a feather bed laid above [Pg 18] a straw bed on the voyage, and was comfortably covered with a bedquilt.

American oak was used, however, in many American-made chests. Some of the early chests, particularly those found in the United States, stand flat on the ground. Others have legs, sometimes formed by the continuation of the stiles, as those parts of the chests are called which hold the panels on the sides. The two boards which occupy the top and bottom of the sides and back and front are called the rails. The upper rails in some of the chests of early make have a row of carving on them which adds still further to the beauty of the chest, and in some instances the stiles are also carved. Ordinarily, however, the stiles are plain or with but a slight moulding, and the rails are quite plain. Geometric patterns in arched, diamond, or square form were early employed, each maker copying industriously the patterns used by other makers and only occasionally having the originality to design for himself. After the legs formed by the continuation of the stiles came legs made in the shape of great balls such as were used on much Dutch furniture and were copied by the English makers.

The great Dutch kas, or chest, was a very large and ornamental piece of furniture, carved, painted, or decorated in marquetry. Such pieces are unusual now, most of them having been gathered in by collectors or museums, the Dutch towns along the Hudson, as well as Albany and Schenectady, having been pretty well picked over.

The evolution of the bureau from the chest is an interesting study, and shows plainly the different periods through which the useful and homely "kist" [Pg 19] passed before it emerged into such an ornamental thing as the carved and decorated highboy. The first step in its upward career was taken when a drawer was added below the chest proper. This came as early as the last half of the seventeenth century, those chests belonging to the first half being without drawers. Sometimes this single drawer was divided, and the very earliest specimens had the runners on which the drawers moved on the sides, and not on the bottom, as came later. The sides of the drawer were hollowed out in a groove, and a stout runner was affixed to the side of the chest. Such a chest is shown in Figure 4. With the appearance of drawers came a difference in ornamentation, and mouldings in great variety were used, beading and turned drops also coming in for use. These patterns were merely the familiar mouldings used in wainscots and panellings put to the purpose of adorning the chests. The early chests without drawers ran in the neighbourhood of five feet long and twenty-four inches high. As the drawers were added, the chests naturally rose in height, and to prevent their becoming too bulky they decreased in length.

A nice example of one of these early oak chests, mounted on turned legs and with curved strainers, is shown in Figure 5. It is in a fine state of preservation and has the original brass escutcheons. It was evidently intended as a receptacle for valuables, as both drawer and chest are made to lock. It belongs to the Waring Galleries, London. Two drawers followed one, the chest portion still retaining its prominence, and in this simple way the chest of drawers grew from the box-like affair of 1600 and [Pg 20] later. By 1710 chests were looked upon as "old," and so advertised for sale, although they continued to be made until the middle of the eighteenth century. They were too useful to be abandoned by a people who were obliged to be often on the move, and who needed some stout receptacle in which to carry their household and personal goods.

There are chests which are peculiar to certain localities, notably in New England, which were doubtless made by a single cabinet-maker, his workmen and apprentices. They are almost entirely confined to these localities, and are therefore of less interest to the collector in general than such pieces as are more widely distributed. Under this head comes that style of receptacle known as the Hadley Chest, and the Connecticut chest shown in Chapter V. The Dutch chests were often of pine, painted, only the choicest ones being of walnut. One inventory records a "chest brought from Havanna,"—probably Spanish.

After matters became a little less anxious for the early settlers, personal comfort began to be thought of more, and such colonists as had brought no chairs began to send for them to England or have them made in America. Every ship from England took out fresh comforts, and the dignitaries of the colonies had substantial household gear. Tables, chairs, beds, and carpets,—these latter not for floors, but for use as table-covers,—are mentioned with great frequency in the inventories, and the settlers' house, albeit many of them boasted of but four rooms, had more than a modest degree of luxury.

Figure 7. TURNED CHAIR WITH LEATHER COVER.

The New Haven Colony—as indeed did all the Colonies—had, as her chief officers, men used to the [Pg 21] best that England afforded, and the following inventory speaks for itself. John Haynes, governor of Connecticut, in 1653 left an estate at Hartford valued at £1,400. In his hall, one of the most esteemed parts of the house at this period, were,—

| 5 leather and 4 flag-bottomed chairs | 1 tin hanging candlestick |

| 1 firelock musket | 1 carbine |

| 1 pr. cob-irons | 1 gilded looking-glass |

| 1 table and 3 joined stools | 7 cushions |

| 1 matchlock do. | 1 rapier |

| 1 iron back | 1 smoothing-iron |

—the whole valued at £8 13s. 10d. The parlor had velvet chairs and stools, also Turkey-wrought chairs, and a green cloth carpet valued at £1 10s. There were also curtains of say, curtain rods and "vallants," many napkins, as these were necessary from lack of forks, and much Holland bed and table linen. There were many chests and "lean-to" or livery cupboards.

"The men's chamber," had "a bedstead with two flock beds; one feather boulster, one flock do.; one blanket; one coverlet." His best rooms had feather beds. In the cellar were many brewing-vessels and wooden-ware, while the kitchen had a complete "garnish" of pewter, but not a single piece of crockery. Brass candlesticks, iron possnets and porringers, and the useful brass warming-pan were here also. Theophilus Eaton, also governor of Connecticut, left in 1657 an inventory of goods of even greater value.

Even earlier than this, rich furniture was imported by those who could afford it, and in 1645 a Mistress Lake, sister-in-law of Governor Winthrop the younger, sent to England for the furnishings for her daughter's [Pg 22] new house. There were many items in the list, and among them were only one—

—"bedsteede of carven oak; 2 armed cheares with fine rushe bottums; three large & three small silvern spoons, & 6 of horne."

As late as 1755 "armed cheares" were highly esteemed, and Joseph Allison, of Albany, N. Y., bequeathed two to his second son, a walking-cane to his firstborn, and to his youngest son some clothes. Chairs, stools, and cushions are mentioned in many inventories as being covered with "set work;" this was heavy woolen tapestry much after the fashion of Oriental rugs, and most durable. It is rather unusual to find no mention of leather chairs in inventories, for they were used in America late in 1600, and chairs covered with "redd lether," as well as with Spanish leather, are of frequent occurrence.

Lion Gardiner was one of the chief proprietors of Easthampton, L. I., in 1653, where he passed the last ten years of his life "rummaging old papers" and in other peaceful pursuits. The inventory of his estate is set out fully and seems scant enough.

| 2 Great Bookes | several bookes |

| 4 Great cheirs | 15 peeces of pewter |

| 13 peeces of hollow pewter | 4 porringers & 4 saucers |

| 5 pewter spoons | A stubing how |

| A broad how |

A little how |

| Horses | Cattle |

| Swine | Clothing |

| Bedding | 2 pastry boards |

| Cooking utensils | A cickell |

| A cheese press | A churn |

It was this same Lion Gardiner who, after the Pequot War, bought from the Indians the island [Pg 23] Monchonock, embracing thirty-five acres of hill and dale. The price paid was a large black dog, a gun, some powder and shot, a few Dutch blankets. This is the place which we know to-day as Gardiner's Island. The "great cheirs" mentioned in the inventory were, no doubt, either Turkey-work or leather, and seem to be the only articles of this kind of furniture possessed by him.

Figure 8. ENGLISH CHAIR. C. 1680 ITALIAN CHAIR. Same Period.

In 1638, in London, a man named Christopher took out a patent for decorating leather, which somewhat reduced its cost. Up to this time all leather was imported from Spain or Holland.

Figure 6 is a fine example of a Portuguese or Spanish leather chair, as they were variously called, and shows well the splendid and ornamental leather as well as the rich carving seen particularly on the front brace. The leather is fastened to the frame with large brass nails, and that part of the oak frame which is exposed is turned work. On many of these chairs there are three little metal ornaments on the curved top. In this example two are lost. Besides the carving on the front brace, a pattern which was often adopted and copied by English and Dutch cabinet-makers, this chair shows well that form of foot which came to be known as the "Spanish foot." It is seen on all makes of furniture, and with some variations of form, but always turns out at the base, and has the grooved work so conspicuous in Figure 6. There is no doubt that this was an exceedingly popular style of chair, for there are many examples almost exactly like this in many collections. This particular one is in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Another style of leather chair is shown in Figure 7, [Pg 24] and its solidity is a great contrast to the Spanish chair previously shown. The woodwork is turned, and the heavy underbracing shaped, while the second bracing is a feature peculiar to this chair itself. The date of this piece is probably about 1650, or a little later,—about the same date as similar turned pieces which are covered with Turkey work. The leather on the seat is so old and worn that it seems as if it had never been renewed, while the back is much fresher and looks comparatively new. The seat of this chair is so high from the floor that a footstool was a necessity, and in the old inventories the item of "low stools," or "foot-banks" appears with some frequency. This chair is of about the same period as the Spanish leather chairs. Many leather chairs are found in the United States, both North and South, and are probably of English make. Some inventories mention them as "old," as early as 1667, and many were in use in different parts of the country.

But while most of our early New England colonists were grappling with the serious business of life, almost content if they could scrape together enough to eat and to wear, and a substantial roof to cover them, in England life was taking a more ornamental aspect. Charles II., indolent and fond of luxury, came to the throne in 1660. Two years later he married Catherine of Braganza, a Portuguese princess, and both of them introduced a more elegant style of living; his French and her Spanish training leading them to require more comforts than had hitherto been known in England.

Figure 9. CANE CHAIR, FLEMISH STYLE.

Among other things which were exported from Holland was cane furniture of a superior quality. It became very much the fashion, and was in Spanish or [Pg 25] Flemish styles, both of which were copied or adapted by English cabinet-makers. Some of this furniture found its way to America, and there are pieces to be found showing all three styles, Flemish, Spanish, and English adaptation. In Figure 8 is shown an example of the English treatment of the Spanish style, at least as to foot; while the flat underbrace is English, the curved back and bandy leg are quite Dutch. The carving on the top is very beautiful, and the knees of the front legs carved, not with the usual shell, but with heads, and below these an oval with moulding. This chair is in the South Kensington Museum, London, and dates from about 1680. The wood is walnut, and the scrolls and foliage on the back stand out in high relief; the seat, originally as now, is covered with a rich brocade, with fine brass nails and a fringe.

The second chair is one of about the same period, of very beautifully carved oak, and not restored. The arms are missing, but show the places where they originally were. It has lost its feet, but the exquisite carving on the underbrace and top is still quite intact and quite Italian in style. This chair is at the Waring Galleries, London.

A very splendid example of the Flemish treatment of the same style is shown in Figure 9, the oak woodwork being carved and turned, and the foot turning out in true Flemish style. The date of the chairs shown in both Figures 8 and 9 is prior to 1700.

The wealthy people of Charles II.'s time all indulged in these chairs. Before that period stools had been in general use, and only the master, mistress, or guest of honour occupied the few chairs possessed in a household.

In New England centres like Salem, Boston, or New Haven, even before the time of Charles II., there was in some of the houses comfort as we understand it. Mr. George Lamberton, of the New Haven Colony, sailed in 1646 to England upon business in the "Great Ship." She was never heard from again, and her loss crippled the little colony almost beyond belief. Mr. Lamberton's inventory shows a variety of items. He had as many as eighty napkins; bedding and table, chimney and board cloths in proportion; feather and down beds with their accompanying hangings. These with more than a dozen cushions to make soft the stiff chairs and settles, silver plate, four chests, ten boxes and trunks, eleven chairs, five stools, and three tables, both round and square, made up comfortable furnishings for a house with probably not more than four rooms. The colonists were not only "plain people," but there were those who came, shortly after the first settlement, who brought with them the household goods and clothes to which they had been accustomed. The "Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth" tells not only of the stress of living and the struggle with Indians and forest creatures. There was time to reprehend the frivolities of women's wear, and the pastor's wife was the chief offender in the matter of over-gay apparel. She was a young widow when Mr. Johnson married her, and brought goodly estate and personal belongings to her second husband. She continued to wear the clothes she had brought with her, and the chief exceptions were taken to the cork-soled shoes she wore, and the whalebone in the bodice and sleeves of her gown. Both the pastor and his wife seem to have been more than reasonable, since [Pg 27] they were willing to reform the cut of their garments as far as they could "without spoiling of them."

Figure 10. TURNED AND CARVED ARM CHAIR

While the general habit of the Puritans was to keep their houses and apparel extremely plain, yet here and there among them bits of comfort and elegance would crop out. Among the stiff and straight-backed chairs, one with stuffing would be found, while in the more luxurious and easy-going South they were not so rare. The covering probably was "sett work or Turkey work;" but then, too, brocade ones were found, and such a chair as is shown in Figure 10 would be an ornament in any home. It is a fine example of walnut-wood, turned and carved with bannister back and stuffed seat. The covering has been restored, but is of a pattern which was of the period. The out-turned Flemish foot is more ball-like in shape than is often seen, but it has the bowed knees which are so familiar.

Yet, if the chairs were none too comfortable, there were few families in any of the settlements that did not own at least one feather bed. If not feathers, then "flock beds" were used, that is chopped rags, or feathers and flock mixed, or, as a last resort, the down from the brown soft, cat-tails which grew plentifully in every marsh was utilized instead of more costly material.

Miss Singleton, in her exhaustive book "Furniture of Our Forefathers," says that probably the first pieces of furniture that were landed on the shores of the Hudson came in the ship Fortune, and were brought by Hendrich Christiansen, of Cleep, who founded a little settlement of four houses and thirty persons in 1615. A little later came the Tiger, The Little Fox, and the Nightingale, all bringing colonists and their household furniture. The early Dutch settlers were better fitted to start an infant colony than their New England brothers. The Dutch were ever colonizers and knew just how to plan and prepare a settlement. The trouble with the Indians was not so constant as it was with the New England colonies, although on one occasion New Amsterdam was almost wiped out. On the whole, the Dutch seem to have treated the Indians more wisely, buying the lands of them and having the purchase further confirmed by grants. In New Amsterdam the settlers were comfortably fixed, comparatively speaking, long before the New England colonists were, for they had a sawmill in operation as early as 1627, the machinery for which had been sent from Holland, and which was worked by wind-power.

Figure 11. DUTCH FURNITURE, CALLED "QUEEN ANNE".

The Dutch settled at Albany and its neighbourhood and around Schenectady, as well as those at New Amsterdam, had many creature comforts. In 1643 [Pg 29] Albany was a colony of about one hundred persons living in about thirty rough board houses. By 1689 the number of inhabitants had increased to 700 and the houses to 150. During the next ten years the improvements were rapid and wonderful; gardens grew, filled with flowers and fruit; the class of houses improved; wealthy merchants came to such a rich market (of furs chiefly); and the Dutch city grew apace, and the fine beaver-skins which were so plenty bought luxuries for the pioneers. That luxury is not too strong a word to use is shown by the splendid carved kas shown in Figure 12, which now belongs to the Albany Historical Society, and is a piece of furniture which may date back as far as the last quarter of the seventeenth century. It is made of walnut, and stands over eight feet high, with cupboard and shelves. While this chest was of unusual beauty, there was a certain solidity and ponderous character observable in most of the Dutch furniture. It is characteristic of the people themselves and is noted in everything belonging to them. Their very ships had long, high-sounding names, The Angel Gabriel, The Van Rensselaer Arms, King David, Queen Esther, King Solomon, The Great Christopher, The Crowned Sea-Bears, and brought in their flat hulks fine goods from all quarters.

Figure 12. CARVED KAS.

The dress of the portly Dutch vrouw was in unison with her cleanliness and love of thrift, for her gown—whether of cloth, or her very bettermost one of silk—was cut short enough to well clear the ground, and showed her shoes with shining buckles, and her bright-coloured stockings, often clocked with her favorite flower, the tulip. The hair was drawn back from the brow, smoothed and flattened and covered with a cap [Pg 30] which, among the wealthy, was bordered with Flanders lace, and in any case was fluted, plaited, and snowy white.

The practical education which the Dutch women always obtained in their own country sharpened their judgment, and the laws which permitted her to hold real estate and carry on business in her own name, even if a married woman, gave her an added independence. It was no unusual thing for women to engage in business on their own account and to carry it on without the aid or interference of the men of the family. At home in the Low Countries, the women had sold at the market, beside the produce of the gardens and poultry yards, the products of their own industry as well,—laces, linen, cloth of wool, etc., and as early as 1656 they sought and obtained permission to hold their market in the new country as they had in the old. Curaçao provided for them many luxuries, such as "lemons, parrots, and paroquettes," besides a variety of liquors. The women grew flax in their own door-yards for the finest linen, and every house had its spinning-wheel.

Hospitality was dispensed at these homes, supper being a favorite meal, and as "early to bed and early to rise" was a national motto the guests were expected to come early and to leave early also,—nine o'clock verging on riotous dissipation. Madam Steenwych was noted for her suppers, which were more substantial than the waffles and tea which was the usual menu. In 1664, after her husband's death, she married Dominie Selyns. At this time she had in her living-room twelve Russia leather chairs, two easy-chairs with silver lace, one cupboard of fine French [Pg 31] nut-wood, one round and one square table, one cabinet, thirteen pictures, one dressing-box, cushions, and curtains. Her chairs with silver lace may have well been like the handsome pair of marquetry ones shown in Figure 13. The seat of the side chair is entirely gone, but the arm-chair yet retains a portion of its cover of wool plush, no doubt the original one, since some of the stuffing protrudes, and it is dried sea-kale instead of hair. The wood is maple with an inlay of satin-wood. These chairs belong to the Museum connected with Cooper Institute, New York, which is being carefully gathered by the Misses Hewitt.

Property had become valuable, and loss had been sustained by fire, so in August, 1658, 250 leather fire-buckets for public use were ordered from Holland, together with hooks and ladders. In addition each household was required to have a certain number of buckets of their own, which were to be kept hanging under the back stoop.

In 1686 a rich Dutch burgher in New Amsterdam owned a house of eight rooms over cellars filled, no doubt, with choice liquors and schnapps, and the rooms above set out with chairs and tables, cabinets, cupboards and a "great looking-glass." Ornaments were there, too,—alabaster images and nineteen gaily decorated porcelain dishes. Nor was the house suffered to want for thorough cleansing, as there were thirteen scrubbing and thirty-one rubbing brushes, twenty-four pounds of Spanish soap, and seven other brushes. With an increase of prosperity our Dutch housewives lost no whit of their notions of cleanliness, for here is a housecleaning described, presumably by a victim, a hundred years later.

"The husband gone, the ceremony begins. The walls are stripped of their furniture; paintings, prints, and looking-glasses lie in huddled heaps about the floors; the curtains are torn from their testers, the beds crammed into windows; chairs and tables, bedsteads and cradles crowd the yard; and the garden fence bends beneath the weight of carpets, blankets, cloth cloaks, old coats, under-petticoats, and ragged breeches. This ceremony completed, and the house thoroughly evacuated, the next operation is to smear the walls and ceilings with brushes dipped into a solution of lime called whitewash; to pour buckets of water over the floor and scratch all the partitions and wainscots with hard brushes charged with soft soap and stone-cutter's sand."

Even these thrifty pioneers did not all accrue many goods, for 1707, when Hellegonda De Kay, of New York, came to make her will, she was obliged to leave her "entire worldly estate" to one daughter. It consisted of one Indian slave. The Dutch wife had an equal interest with her husband in disposing of household goods and furniture. She was always consulted, and sometimes she even signed the will with her husband. The wives of the English settlers, whether Quaker or Puritan, did not have the rights of their Dutch sisters in the ownership of household goods. The wife's dowry passed into her husband's hands at marriage, and remained there until his death, as the inventory of the estate of Alexander Allyn of Hartford, Conn., who died in 1708, testifies.

"Estate that deceased had with his wife Elizabeth in marriage (now left to her)."

"One round table; bed with furnishings; chest of drawers; two trunks; a box; books; earthenware; glasses; pewter platters; plates; bason; porringers; cups; spoons; tinware; a fork; trenchers; four chairs; nine pounds in silver money; table-cloths; napkins; towels; a looking-glass; a chest; a silver salt; [Pg 33] porringer; wine-cup and spoon; a brass pot; an iron pot; two brass skillets and hooks."

The following extract from a will drawn in 1759 by a man eighty years old shows the Friend's point of view as to whom the household stuff belonged. He wills to his wife as long as she liveth, unless she marries again (she was seventy years old at the time),

"two good feather beds and full furniture, and all my negro bedding; and all my grain, either growing or cut, or in store at the time of my decease; and all my flax and wool, and yarn and new cloth and cattle hides, leather, and soap, and meat, and all other provisions which I have in store in my house, either meat or drink, and all my negro men and one of my negro women, such of them as she shall choose, and my negro girl named Priss; and if I should chance to dye when I have cattle a-fatting my wife shall have them for the provision of herself and family, at my wife's disposal."

No doubt the feather beds and "negro bedding," as well as the "new cloth," had been made by the patient fingers of this wife of fifty years' standing; but she must forfeit all this fruit of her labour should she marry again. The Dutch system seems preferable.

In another inventory, that of Charles Mott, also a Long Island Quaker, dated 1740, the eldest son has the house and homestead, "together with the negro boy Jack and one feather bed." The sole provision for his wife was "four pounds a year" to be paid to her by the eldest son "so long as she remains my widow." He seems to have put a premium on her filling his place, and that quickly.

Possibly our Dutch settlers were more notable house wives than their sisters in New England or the South. In the latter region the mistress did not contribute [Pg 34] with her own hands to the cleanliness of her home, but she had onerous duties in overlooking the work of sometimes over a hundred negroes, seeing to their food, clothes, and shelter. Our New England wives were still suffering from Indian depredations, and the young housewives whose doors were driven thick with nails to repel the deadly tomahawk, as Mistress David Chapin's was at Chicopee in 1705, would probably not have risked her "goods" out of doors, as did the Dutch housewives at Albany.

Figure 13. MARQUETRY CHAIRS.

The Dutch kitchen utensils seem numerous and varied. Possets, pans, jack-spits, strainers and skillets were seen in inventories as well as the more familiar pots and kettles. The prosperous Dutch at home had sent out and brought back many a rich argosy, and silks and tissues, porcelains and lacquers, carved ivory and fantastic carved wood, spices and plants had been brought to Holland and found their way to America. There were many ships unloaded at New York filled with spoils from the East, which were eagerly bought up. There was a variety of moneys current,—beaver-skins; wampum; Spanish pistoles, worth 17s. 6d.; Arabian chequins at 10s.; "pieces of eight" (as the Spanish reals were called), which, if they weighed 16 pennyweight (except those of Peru) passed for 5s.; and French crowns worth 5s. Peruvian pieces of eight and Dutch dollars were valued at 4s., and all English coin passed "as it goes in England." These were the values in 1705, but they varied somewhat, the currency being inflated by one governor, though his act created such a disturbance that he was obliged to withdraw it. The Long Island Dutch seem to have had less rich belongings than those up the Hudson and about [Pg 35] Albany. Around Jamaica and Hempstead were stout clapboard and shingle houses, but the inventories are not lavish. Daniel Denton, writing in 1670 "A Brief Description of New York," says this about his dearly loved Hempstead.

"May you should see the woods and Fields so curiously bedeckt with Roses and an innumerable multitude of delightful Flowers not only pleasing to the eye but smell. That you may behold Nature contending with Art and striving to equal if not excel many gardens in England."

But he has little to say about the way of living, except that it is "godly."

The records of New Amsterdam, which are so wonderfully complete, show what a valuable assistant to these first settlers was the powerful West India Company. By 1633 there were five stone houses containing the Company's workshops; and as the land near at hand was poor,—"scrubby" the Dutch farmers called it,—they spread out to the neighbouring New Jersey, Long Island, Gowanus, and East River shores and from 1636 to 1640 were busy with their settlements.

By 1651 New Amsterdam was prosperous enough to have a brick house so good and well built as to be worth 5,195 florins (about $2,100 of our money). In 1649 Adam Roelantsen, a general factotum of the West India Company, whose name constantly appears in the town records, (as he was unfortunately addicted to strong waters, and under these conditions was very quarrelsome and aggressive,) owned the following house. It was a clapboard structure covered with a reed roof, and eighteen by thirty feet in size. It stood gable end toward the street, and at the front [Pg 36] door was the usual "portal" with its wooden seats. Outside of the frame the chimney of squared timber was carried up, while within the fireplace had a mantelpiece and the living room had "fifty-one leaves of wainscot." There was a bedstead or state-bed built in, but of the movables no record is left. In reading these old records it is noticed that matters moved quickly; not much time was spent in grief and repining; and to illustrate we give the experience of one woman whose career does not seem to have excited any comment among her contemporaries. In 1685 William Cox married a young woman named Sarah Bradley, who had come from England with her father and brothers to settle in New Amsterdam. She was said to have been handsome and dashing, and certainly she needed spirit to carry her through her subsequent career. Four years after her marriage her husband met with the following accident, thus described by a political opponent.

"Mr. Cox, to show his fine clothes, undertook to goe to Amboy to proclaime the King, who, coming whome againe, was fairely drowned, which accident startled our commanders here very much; there is a good rich widdow left. The manner of his being drowned was comeing on board a cannow from Capt Cornelis' Point at Staten Islands, goeing into the boate, slipt down betwixt the cannow and the boate, the water not being above his chin, but very muddy, stuck fast in, and, striving to get out, bobbing his head under, receaved to much water in. They brought him ashore with life in him, but all would not fetch him againe."

The good rich "widdow" whom he left soon changed her loneliness for the pleasures of married life, this time with Mr. John Oort. He, too, made a brief stay, for by May 16, 1691, the widow Sarah Oort [Pg 37] had the necessary license under colonial law for her marriage to no less a person than Captain William Kidd. They lived comfortably in a house left by Sarah's first husband, Mr. Cox (who left her with an estate of several thousand pounds) till Captain Kidd set out on his notable voyage in the "Adventure." The goods which Mrs. Oort had at the time of her marriage to Captain Kidd were the following: fifty-four chairs, of Turkey work and double and single nailed; five tables with their carpets (covers); four curtained beds with their outfits; three chests of drawers; two dressing-boxes; a desk; four looking-glasses; two stands; a screen; a clock; andirons; fire-irons; fenders; chafing-dishes; (3) candlesticks of silver, brass, pewter, and tin; leather fire-buckets; over one hundred ounces of silver plate; and a dozen glasses. The screen, no doubt, was such a one as is shown in the same figure, No. 14, as the Dutch cradle, which was used for many years in the Pruyn family, of Albany. The third object in the picture is what is known as a church stool, and was useful in keeping the good vrouw's feet off the cold floors. This stool is painted black and is dated 1702. There is a lurid picture of the Last Judgment painted on it, and also a verse in Dutch, which reads as follows:

"The judgment of God is now at hand. There is still time; let us separate the pious from the wicked and entreat God for the joy of heaven."

All these articles are now at the rooms of the Historical Society, Albany.

William Kidd was executed in May, 1701, and, nothing daunted by her matrimonial ventures, Sarah took as her fourth husband, in 1703, Christopher [Pg 38] Rousby, a man of considerable influence in the colony. She lived until 1745, and left surviving her four children.

While the houses were rough, some with but two rooms, yet articles even of luxury were there and offered for sale. As early as 1654 a casket inlaid with ebony was sold and brought thirty beavers and nineteen guilders. Cornelis Barentsen sued Cristina Capoens in 1656 for payment for a bed he sold her, payment to be made in fourteen days. The price was six beavers (about $57.00), which Cristina seemed unable to pay, but which payment was ordered by the court. In June, 1666, the administrators of the estate of the late Jan Ryerson sold some "beasts" (horses, calves, and hogs), as well as furniture at public sale. "The payment for the beasts, also the bed, bolsters, and pillows," was to be made in "whole merchantable beavers, or otherwise in good strung seewant, beavers' price, at twenty-four guilders the beaver."

Here is the inventory of a bride who was married at New Amsterdam in 1691, and although her husband was a man of consideration and some wealth it was deemed of sufficient importance to record.

"A half-worn bed; one pillow; two cushions of ticking, with feathers; one rug; four sheets; four cushion-covers; two iron pots; three pewter dishes; one pewter basin; one iron roster; one schuryn spoon; two cowes about five years old; one case or cupboard, one table."

August 31, 1694, Jan Becker's inventory entered at Albany, New York, showed a long list. Besides abundant household goods he had—

"A silver spoon; 3 pr. gold buttons; 5 doz. & 10 silver buttons for shirts; & 2 silver scnuffies."

Figure 14. DUTCH SCREEN, CRADLE AND CHURCH STOOL.

It is not difficult to picture in the mind how these old Dutch houses looked when the living-room was made snug and warm of a winter's evening. At various places along the Hudson and on Long Island there are still standing some of these old, low-ceiled, wooden houses, with sloping roof and great chimney. The furniture was generally of oak (particularly if it had been brought from home) and carved. The most important objects in the room are the mantelpiece and the bed, the former of carved wood, its ornate character significant of the wealth of the owner, and its size seldom less than the height of the room. The bed was frequently built in the room, a sort of bunk, hung with curtains often of bright chintz, though, judging from the inventories, "purple calico" curtains were immensely popular, just as this same fabric is beloved to-day by the pretty maid-servants one sees tripping through the quaint old streets of Holland. There were stools; not many chairs; tables, one or two; each with its bright carpet or cover; racks on the wall for what delft the mistress had; and below it the treasured spoons. In the great kas, which took up a large portion of the room, was the linen, covers for tables, side-tables, shelves, etc., and all the napkins and choice belongings of the housewife. If this kas was carved oak it sometimes stood on a frame; sometimes it had ponderous locks. If it was painted or inlaid wood it might reach nearly to the floor, and then stand upon large ball feet. Some of these kas were so large and heavy that it was almost impossible to move them, and there is the record of one vrouw who upon moving from Flatbush was obliged to abandon hers, leaving it behind her and selling it for £25:

In the Van Rensselaer family is a marriage kas which goes back to the beginning of the eighteenth century. It was imported from Holland by the parents of Katherine Van Brugh, who wished their only daughter to have everything that money could buy, and during her early years it was being filled with linen and household goods woven under her father's roof. It was no light task to fill this great chest, for it stood seven feet high and proportionally wide. It is of carved oak, has many drawers and receptacles, and will hold the silver and finery of the mistress, while there are secret drawers for "duccatoons and jacobuses." The keyhole is concealed under a movable cover of carved wood, which looks like a part of the carving when dropped in place. The ponderous key is of iron and has many wards.

If the family was quite well to do and owned a good stock of clothes, there would be one or more smaller cases, or chests, in which these were stored away. Much furniture was made here by Dutch workmen, who followed the fashions of their native land. They found abundant material, and more was brought into the country,—in devious ways sometimes, but still it came.

The court records for New Amsterdam for 1644 report a bark, Croisie, of Biscay, which was brought into the harbour as a prize by the ship La Garce, being laden with sugar, tobacco, and ebony. The claim of the master of the La Garce was granted, and the goods sold.

Nearly always there was a little silver,—spoons, mugs, and a salt-cellar; and, as years passed on, much coin was beaten by some member of the family (for [Pg 41] there were many Dutch silversmiths) into tankards,—splendid heavy vessels, capable of holding a quart, with cover and thumb-piece, and showing the marks of the mallet on the bottom and inside, for all of these pieces of plate were hand-made. Waiters and massive bowls were seen in nearly every family of easy circumstances, and they scarcely ever went out of the family, as it was a matter of pride to retain them. Much of this fine old plate is treasured to-day by descendants of its former owners. It has survived better than the furniture, indestructible as that seemed.

In 1739 Lowrens Claesen, of Schenectady, had, among other property, a gold seal ring and a silver cup marked "L. V. V." Myndert Fredricksen of Albany County, New York, blacksmith, left in 1703 a great silver tankard, a church book with silver clasps and chains, and a silver tumbler marked "M. F." A blacksmith in those days meant a worker in iron, and this one must have been prosperous, for he owned his house and land, and furniture as well as silver.

But even if silver were lacking there were brass skillets and warming-pans, and pewter was the ordinary table furniture, which was scoured to a polish little short of silver. One or two pieces of brightly decorated Delft ware was the crowning glory of the housewife's treasures, and far too precious for every-day use. So holes were drilled in the edge, and a stout cord passed through, so that it could be hung upon the wall. There was, of course, a clock also, and leather chairs. Nicholas Van Rensselaer, of Albany, who died in 1679, was a wealthy and important member of the colony of Albany. His house had two beds, two looking-glasses, two chests of drawers, two tables, one [Pg 42] of oak and one of nut-wood; also a table of pine, as well as six stools of the same; a sleeping-bunk or built-in bed, over twenty pictures, a desk, and, of course, brushes and kitchen utensils. These goods were disposed of through four rooms. Not only were all the necessaries abundant, but some very elegant furniture came in with almost every ship, and even before 1700, ebony chairs, boxes and cabinets are mentioned in the inventories; but such splendid pieces as the cabinet shown in Figure 15, with carved panels in the doors, and carved twisted legs, were only occasionally to be met with. The doors conceal shelves, and above are two drawers with drop handles. There are pieces similar to this to be found in the United States in private houses as well as in museums. This cabinet belongs to the Waring Galleries, London.

Children slept in trundle beds, which during the day were pushed under the large bed, often a four-post bedstead when not the sleeping-bunk. One thing was found in every house, rich or poor, and this was some means for striking fire. Tinder and steel, with scorched linen, were an indispensable part of every household. Sometimes it was necessary to borrow coals from a neighbour, and there were stringent town laws ordering that "fire shall always be covered when carried from house to house." In the "Court Records of New Amsterdam" one of the earliest laws regulated the carrying about of hot coals, and several Dutch vrouws were hauled to court for breaking them.

Figure 15. EBONY CABINET.

The furniture in these houses was by no means all of Dutch or domestic make. They had what they were able to get, and among painted kas and inlaid chests would be Spanish chairs or stools, and English [Pg 43] walnut beds with serge hangings, folding tables and Turkey-work chairs. Before the close of the seventeenth century there came direct to New York Dutch ships from the Orient, or from the Low Countries themselves, loaded with rich goods, among which was much furniture. Styles had begun to change a little; the Dutch were absorbing ideas from the Chinese and copying and adapting forms and decorations. Beautiful lacquer work was coming in, and splendid inlaid or marquetry work; not any more in two colours, as was the earliest style, but in a variety of colours and in divers patterns, and standing upon bandy legs with ball and claw, or what is known as the Dutch foot, instead of the straight or turned leg.

The inventories show how far East Indian goods were coming in, and there is frequent mention of "East India baskets," boxes, trunks, and even cabinets. The most usual woods were black walnut, white oak and nut-wood, which was hickory. Occasionally pieces were made of olive-wood, or of pine-wood painted black. Ebony was used for inlay and for adornment for frames. Looking-glasses were mentioned in nearly every list, the earliest coming from Venice. By 1670 looking-glass was manufactured at Lambeth, England, in the Duke of Buckingham's works, and was not now so costly as to be seen only among the wealthy. The cupboards were no longer uniformly made with solid doors, but glass was introduced, so that the family wealth of silver and china could be easily seen. By 1727 mahogany is mentioned occasionally in the inventories, and it could be bought by those who were wealthy enough to afford it.

Probably the Spaniards were the earliest users of [Pg 44] mahogany, followed by the Dutch and English. Furniture made of this wood is known to have existed in New York prior to 1700, and in Philadelphia a little later. The old Spanish mahogany was a rich, dark, heavy wood, susceptible of a high polish. It darkened with age and was not stained. The new mahogany, at least that which comes from Mexico, is of a light, more yellow colour, and requires staining, as age does not darken it. It is light in weight. The mere lifting of a piece enables one to judge whether it is made from Spanish wood.

The carpets referred to in nearly every inventory were not floor-coverings, but table-covers,—small rugs, no doubt, but far too precious to be worn out by rough-shod feet walking over them. The floors were scoured white, and were strewn with sand which showed the artistic capacity of mistress or maid in the way it had patterns drawn in it by broom-handle or pointed stick. It was not until the middle of the century that carpets became at all common, and even then they are mentioned in the inventories as very choice possessions. There were "flowered carpets," "Scotch ditto," "rich and beautiful Turkey carpets," and Persian carpets also. The colonists traded with Hamburg and Holland for "duck, checquered linen, oznaburgs, cordage, and tea,"—goods appreciated by the housewife, and which she could not make.

Figure 16. BED CHAIR.

The festivities indulged in by the Dutch settlers were generally connected with the table; they played backgammon, or bowls when the weather was fine and they could go out of doors. The cards they used numbered seventy-three to the pack, and there was no queen, her place being supplied by a cavalier who [Pg 45] was attended by a hired man, and they both supported the king. Cards were not popular, however, except among the English settlers, and they followed the home fashions.