TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

A ROAD-BOOK TO OLD CHELSEA

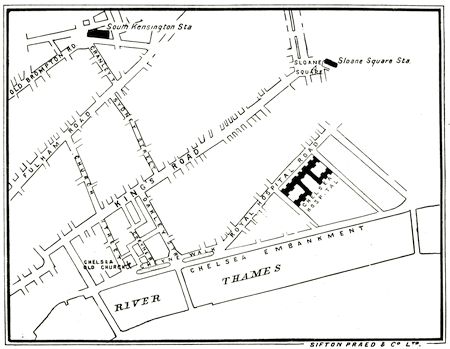

THE ROADS THAT LEAD TO CHELSEA.

Frontispiece.

A ROAD-BOOK TO

OLD CHELSEA

BY

G. B. STUART

“By what means the time is so well-abbreviated I know not,

except weeks be shorter in Chelsey, than in other places!”

KATHERYN THE QUEENE.

Extract from a letter of Queen Katharine Parr to the

Lord High Admiral Seymour, written from Chelsea, 1547

WITH SKETCH MAP AND FIVE ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

HUGH REES, LTD.

5 REGENT STREET, PALL MALL, S.W.

1914

PREFACE

OF the making of books about Chelsea, may there never be an end, so rich and unexhausted is our history, so inspiring to those who labour in its service! Every year, as fresh records become accessible, Chelsea is presented to us from some different standpoint, historical, architectural, or frankly human, and there is ever a welcome and a place for each volume as it appears.

They are books full of research and of suggestion, illustrated by portraits and maps from rare sources, and clinching hitherto unsolved problems. They quickly become our library friends and companions, because, though some of their matter may be familiar, each has, for its own individual charm, that personal outlook of its author which expresses, with wider and more resourceful knowledge than ours, the love we all bear to our home by the river.

It is because in love of our subject we and the greater writers are equal, that I dare to put forth a new Guide to Chelsea; a little foot-page, a link-boy, a caddy if you will, just to show the way to strangers, to disembarrass them of unnecessary impedimenta, to point out special places of interest which may be visited in a summer afternoon, within that charmed circle of our parish, where every inch is enchanted ground.

G. B. S.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE ROAD TO THE CHURCH | 9 |

| II. | THE OLD CHURCH: NORTH SIDE AND CHANCEL | 15 |

| III. | THE OLD CHURCH: SOUTH SIDE AND THE MORE CHAPEL | 23 |

| IV. | THE OLD CHURCH: THE NAVE AND ITS MONUMENTS | 31 |

| V. | CHURCH STREET TO QUEEN’S ELM | 39 |

| VI. | CHEYNE WALK FROM EAST TO WEST | 47 |

| VII. | SIDE STREETS AND BACK GARDENS | 57 |

| VIII. | THE ROAD TO THE ROYAL HOSPITAL | 65 |

| L’ENVOI | 73 |

A ROAD-BOOK TO OLD CHELSEA

CHAPTER I

Omnibuses for Chelsea—The Mystery House—Dr. Phéné’s garden—Cheyne House and Tudor Lane—Leigh Hunt’s home—Cheyne Row and Carlyle—The Tollsey Cottage and James II.—The Lawrences and Lombards’ Row—The Fieldings and Justice Walk.

PRESUMING, O stranger, that you will reach Chelsea by motor-bus—either from Kensington by No. 49, from Piccadilly by No. 19, or from the Strand by No. 11—I will ask you to alight at Chelsea Town Hall and turn with me down Oakley Street. As we face the river, there is always fresh air to meet us, and in summer time, above the road smell of asphalt and petrol, there floats a soft, keen savour of growing things and green bushes, hidden away behind walls; if an old door opens, we catch a glimpse of gardens and sometimes of a “mulberry-bush,” grown to forest size, which, planted by the men who fled from the terror of St. Bartholomew, still fruits and flourishes to repay Chelsea hospitality.

On the right-hand side, where we turn into Upper Cheyne Row, stands the much-talked-about “Mystery House” of the late eccentric Dr. Phéné. It has never been much of a mystery to its neighbours. Dr. Phéné built it as a storehouse for his collections—some valuable, others worthless—and plastered it with the discarded ornaments[10] of the old Horticultural Gardens. The old gentleman was vastly proud of his design, and loved to plant himself at the street corner and encourage the remarks of passers-by: that the work was chaotic, and dropping to pieces before it was finished, troubled him not at all, and Chelsea forgave him the architectural monstrosity for the sake of the garden, which his leisurely building methods preserved. The wall which encloses it is one of Dr. Phéné’s happiest “finds,” and is said to be a part of old St. Paul’s—it certainly bears the carven arms of several London boroughs, and is not incongruous to its surroundings; behind it blackbirds, thrushes, and wood-pigeons fancy themselves in the country, and birds and men alike rejoice that the complications of the Phéné property still preserve their shade and shelter untouched.

Cheyne House, which also belonged to Dr. Phéné, was less highly esteemed by him than his Renaissance effort, and has been allowed to drop into grievous ruin: it is the house “of ancient gravity and beauty” of which Mr. E. V. Lucas writes so affectionately in his Wanderer in London. It sits back, with its eyes closed, wrapped in its ancient vine, and no one will ever know its three-hundred-year-old secrets. For in the old maps it shows bravely in the centre of its park, and a little narrow walk, called Tudor Lane, led from it to the river, where possibly it had its own landing-stage; a beautiful state reception room at the back had seven windows giving on the terrace. It is sad and strange that so little is known of its inhabitants in the past.

No. 4 Upper Cheyne Row is a modern interpolation, filling up the Tudor Lane aperture; but No. 6 is another really old house, dating by its leases from 1665, and having a splendid mulberry tree, which in a document of 1702 is mentioned as “unalienable from the property.”

No. 10 (at that time No. 4) was Leigh Hunt’s home for seven years from 1833 to 1840, where, as Carlyle wrote, “the noble Hunt will receive you into his Tinkerdom, in the spirit of a King.” He was often in absolute want during this period, yet his belief in the human and the divine was never shaken by poverty, illness, or distress of mind, and the beautiful quality of his work was maintained in spite of perpetual difficulties.

The date 1708 on the side wall above Cheyne Cottage fixes the building of Cheyne Row and the west end of Upper Cheyne Row; a beautiful old house which was cleared away in 1894 to make room for the Roman Catholic Church of the Holy Redeemer was called Orange House, in political compliment, and its next-door neighbour, York House, was named after James II. These two were probably older than the others, and Lord Cheyne, who formed the Row, built his newer houses into line with those already existing. Some of the iron work of the balconies, etc., and the porticoes, are worth noting.

Carlyle’s House (now No. 24) can be visited every week-day, between the hours of 10 a.m. and sunset—admission 1s., Saturdays 6d.—and it speaks for itself. I will only add a reference to Mrs. N., the old servant who spent years in Carlyle’s service, and finished her honoured days in ours—her descriptions of “the Master” writing his Frederick the Great were about the most intimate revelations that have yet been made of the Carlyle ménage!

The Master would be so immersed in his subject—maps and books being spread all over the floor of his room “in his wrestle with Frederick”—that his lunch would remain unheeded until, stretching up a vague hand, he plunged it into the dish of hashed mutton or rice pudding, as the case might be—regardless of plate, spoon, or decorum. “It was no cook’s credit to cook for him,” was Mrs. N.’s verdict, “a cook that respected herself simply couldn’t do it,” and though she adored Mrs. Carlyle, she left her service to restore her own self-respect.

Cheyne Cottage was once the Toll Gate for entering Chelsea Parish at the south-west angle—there was another Toll Gate, I think, at the Fulham end of Church Street, but it was probably to this one on the river bank that James Duke of York, afterwards James II., came one winter night a few minutes later than the recognised closing time, eight o’clock. James was unpopular, and the old woman who kept the gate a staunch Protestant, so that to the outriders’ challenge, “Open to the Duke of York!” she[12] shrilled back defiance from her bedroom window, “Be ye Duke or devil, ye don’t enter by this gate after eight of the clock!” and so left James and his coach to lumber on to Whitehall through the bankside mud, as best he might.

When I first knew Chelsea, the old board with the toll prices and distances under the Royal arms of Charles II. was preserved at the cottage, but this has, I believe, been surrendered to the London Museum.

Lawrence Street, between Cheyne Row and the Old Church, boasts the sponsorship of the Lawrence family, goldsmiths and bankers, whose mansion adjoined the church, and whose business premises leave their name to the group of very old houses immediately west of Church Street. These houses, though actually standing in Cheyne Walk, are called Lombards’ Row in commemoration of the Lawrences’ banking business.

Fielding, the novelist, and his brother the Justice lived in the big eighteenth-century house facing Justice Walk, and Tobias Smollett lived close by, in a house now pulled down. In the big garden at the back, impecunious “Sunday men,” whose debts kept them at home on other days, were entertained every week at a “rare good Sunday dinner, all being welcome whatever the state of their coats.”

And the Chelsea China Factory existed also at the upper end of Lawrence Street for nearly forty years. Dr. Johnson used to experiment there, having an ambition to excel in a porcelain paste of his own invention, but his composition would not stand the baking process—perhaps he had too weighty a hand in the mixing!—and he gave up the work in disgust. Chelsea china commands enormous prices, as its supply was so limited.

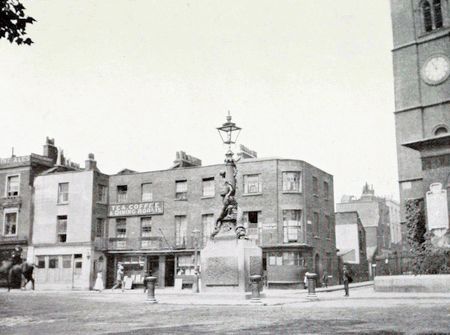

So by Justice Walk and a turn to the left down Church Street, we reach the Old Church, the heart of Old Chelsea; a still living, warmly beating heart, after eight centuries.

NOTES

CHAPTER II

The Old Church—Its origin—The new St. Luke’s—Old dedication revived—Henry VIII.’s Marriage to Jane Seymour in the Lawrence Chapel—Princess Elizabeth—The squint and lepers—The plague at Chelsea—The Hungerford memorial—The Bray tomb—Anecdotes of the Rev. R. H. Davies’ incumbency.

THE Old Church is first mentioned as the Parish Church of Chelsea in 1290, when the Pope granted “relaxation” to penitents visiting it on All Saints’ Day. It was then, as now, dedicated to All Saints, though for 300 years in between it has been known as St. Luke’s (like the modern Parish Church in Sydney Street). The late Rev. R. H. Davies, for nearly sixty years known and loved at the Old Church, has suggested that the nucleus of the building may have been the Lawrence Chapel, belonging as library and chapel to the Manor House; it is obviously the oldest part of the church, and the chancel and nave have been later added, as the growth of the parish demanded more church room. Many distinct enlargements are recorded, and that of 1670 almost doubled its size and gave it the present square tower.

At that date our riverside village was a fashionable country place. Mr. Pepys writes of taking boat up to Chelsea of a Sunday to see the pretty young ladies who flocked to the church and made very sweet singing. But presently the tide of fashion ebbed away from the Thames side, and building and population congregated further north: in 1824 St. Luke’s, Sydney Street, was consecrated as the Parish Church, and the mother by the river became the daughter of the new building.

In 1910, after the latest and most sympathetic of restorations, the dedication to All Saints was revived; I always regret that the Saxon form, All Hallows’ found in some old documents, was not chosen, to denote that a church—if not this actual building—existed here from before Norman times.

Let us begin our survey at the Lawrence Chapel, on the north side. Here, tradition says, Henry VIII. was married to Jane Seymour, in haste and secrecy to secure the bride’s position, three days after the execution of Anne Boleyn. The marriage was openly repeated with great ceremony ten days later: Jane Seymour is said to have been a damsel who loved delicate eating, and to have been wooed by Henry with many presents of game and venison from the King’s Larder, a house for the preparation of royal dainties on the riverside now demolished.

The altar, before which they were married, stood under the east window of the Lawrence Chapel, now occupied by the tomb of Sir John Lawrence; it is good to remember that of this rather questionable marriage was born Edward VI., who gave us our prayer book.

Under the little window in the north wall (filled lately with quite unnecessary modern glass), is the seat assigned by tradition to Elizabeth, when, as a somewhat neglected Princess, she lived with her step-mother, “Katheryn the Queene,” at Chelsea Place.

Some of the original oak pews remain in the Lawrence Chapel, and a panel with a mitre on it recalls the residence of the Bishops of Winchester in Chelsea; some queer little benches for two persons, very narrow and high-backed, tell of a time and a rule when lounging in church was unknown!

The north wall is dated 1350, and the fact that its roofing differs entirely from that of the chancel and other chapels, supports the suggestion that it had been the Manor library.

The Lawrence monuments are interesting. Thomas Lawrence, the banker and goldsmith of Lombards’ Row, appears with all his Elizabethan family about him. His epitaph is often quoted:

Thus Thomas Lawrence spekes to Tymes ensuing:

That Death is sure, and Tyme is past renuing!

He was the father of Mrs. Sara Colvile, whose rising figure blocks a beautifully carved window—worth seeing from the vestry side—and of Sir John Lawrence, whose epitaph begins with the trenchant lines:

When bad men dy, and turn to their last Sleepe,

What Stir, the Poets and Ingravers keepe!

The Italian triumphal arch, for which the chancel arch was cut, and the symmetry of the church for ever dislocated, is to the memory of one Richard Gervaise, 1563, son of a mercer and sheriff of London, who may have been a business partner or relative of the Lawrences; the brasses of Sir Henry and Lady Christina Waver, 1460, have been stolen from the pavement, where many other Lawrence names are recorded.

The Lawrence Chapel subsequently became the property of the Rawlings family, whose crest appears on several of the pew doors, and in 1894 the Rev. R. H. Davies succeeded in securing it for the church.

The squint, or hagioscope, shows a glimpse of the altar in the chancel, and tradition has it that lepers used to assemble at the little north door (now leading into the new vestry) or at the north windows to witness the elevation of the Host, without contaminating the congregation; for lepers, I hope we may read, sufferers from ague and marsh-fever, which was a prevailing scourge of the low lands about the river.

By the by, it is outside the north wall that the plague victims were buried in a long grave, when the plague visited Chelsea in 1626, and Lady Danvers, mother of George Herbert, nursed her stricken neighbours so bravely. The Chelsea plague-fosse has never been disturbed. A provincial plague-pit known to me was opened in the course of new road-making a few years ago, and four labourers died of a strange, malignant fever. Whether this was the result of coincidence, or of superstitious fear,[18] or of real infection, I cannot say, but we do well, I think, to leave our Chelsea plague-pit unmeddled with!

The chancel of the Old Church was built in the thirteenth century, and the nave added much later: the magnificent roof of oak arched beams, like the ribs of a ship, was discovered under the plaster in 1910. The altar, a fine Jacobean table, and the enclosing rails are of Charles I.’s time, when Archbishop Laud decreed that rails should encircle the altar; the east window put in, in 1857, to lessen the glare of light at morning service is fairly harmless, and harmonises with the shadowy church better than more brilliant glass would do. The very beautiful cross and candlesticks were given in 1910, in memory of Charles Kelly, Esq.

The aumbry, now used as a credence table, was discovered plastered over in 1855; it was originally intended for a safe, in which the church plate could be kept, and the bar and hinge settings can be traced.

To the left of the altar is the Hungerford Memorial slab. Thomas Hungerford, a knight of Wiltshire, married a Chelsea heiress, Drusilla Maidenhead, daughter of Lord Sandys. Hungerford served under four sovereigns; he was present at the “wining of Bologne,” as he calls the Siege of Boulogne in Henry VIII.’s reign, and died “at the adge of seventy yeres.” He was obviously a prophet of reformed spelling!

The Bray tomb, now crammed under the chancel wall to clear the approach to the altar, is the oldest of our monuments. Its brasses have been torn away and its carving obscured by plaster. The Brays were Lords of the Manor previous to the Lawrences, and probably the Lawrence Chapel was originally their property. This tomb commemorates four generations of Brays, the last being Sir John Bray, 1557, the order of whose funeral has been preserved at the College of Arms, and has been reproduced in modern pageantry. Lately the Bray family, residing in Surrey, have restored this ancestral tomb. Sir Reginald Bray, of this family, was the architect of Henry VII. Chapel at Westminster.

A tiny door in the wall used to lead to the old vestry.[19] Here Mr, Davies, for so many years incumbent of the Old Church, spent much of his time, which was always at the service of inquiring visitors. He had many excellent stories to tell of his adventures in the vestry. Once he was “held up” there for many hours by a bogus photographer who, pretending to take pictures of the church, plugged up the vestry door and broke open the alms boxes. The incumbent sat quietly reading and writing, secure in the knowledge that he had cleared the boxes that morning, until he was presently retrieved by his family, who supposed that he had forgotten the dinner-hour! Had the thief known where to look, the real parish funds were at the moment in the vestry itself.

Another time Mr. Davies showed a pair of visitors round the church and was about to receive a small tip for his trouble, when he hastened to explain that he was the parson, not the caretaker, and was delighted to have been available as guide. A sovereign was substituted for the intended gratuity, which he gratefully accepted for the poor of his parish. Later, after the visitors had left, one of them came hurrying back and explained that they had inadvertently run short of money for a return journey. Might they borrow back the sovereign, which should be posted to Mr. Davies in the course of a few hours? Of course the money was relinquished—and never heard of again!

Mr. Davies himself told me these anecdotes, as delightfully as he always told a story; they seem to have become part of the history of the church he so dearly loved. A third—the appearance of Sir Thomas More’s ghost—belongs to the next chapter, with other More gossip.

NOTES

CHAPTER III

The More Chapel—Holbein—Erasmus—Sir Thomas More’s arrest—Mistress More—The Duchess of Northumberland—The Gorges—The Stanley tomb—“The Bird and the Baby”—The Dacre helmet—Sir Thomas More’s ghost.

THE More Chapel was built in 1528 (date on the east pillar) to accommodate the family and retainers of Sir Thomas More, Lord Chancellor of England, living in great state at Beaufort House, but not too proud to act as “server” at the altar of his Parish Church. The two pillars evidently guarding the front seat of this family pew are worth careful inspection; the west pillar is said to have been carved by Holbein while on a visit to More’s house—a visit which lasted several years. The east pillar is less well executed and may be by another hand, but both bear the symbolic ornament, dear to the spirit of the time, introducing coats of arms, crest, punning references to family names and signs, which develop in hieroglyphics the career of the great Chancellor. More’s tomb, designed by himself during his imprisonment in the Tower, is in the south wall of the church, and here we find a curious surviving reference to his friendship with another celebrated visitor to Chelsea, Erasmus. In the Latin epitaph cut in slate, which Sir Thomas prepared for his tomb, a word has been omitted and a space left. The word is “Hereticks,” whom he declared he hated implacably, along with “thieves and murderers”; Erasmus found this too sweeping and begged him to cross out the word. He took his friend’s advice but forgot to insert a substitute word, and the space[24] remains, a witness to the tolerance of Erasmus and the sweet reasonableness of the Chancellor.

Sir Thomas’s favourite motto, “Serve God and be merrie,” is better known than his pompous Latin inscription, as it deserves to be.

Tradition makes the More Chapel the scene of Sir Thomas’s farewell message to his wife. On the morning of his arrest, she was waiting for him after Mass in the family pew; he had been acting as “server” at the altar, and had been hurried from thence straight to the river and the Tower.

A young groom, by the Chancellor’s orders, went to his wife with this message, which the varlet was bidden to repeat exactly in his master’s words:

“Bid Mistress More wait no longer for Master More, for he hath been led away by the King’s command.” A smart box on the ear from the insulted lady rewarded the servant for his literal fulfilment of his lord’s mandate. “What do you mean, sirrah, to speak of Mistress and Master More when you name the Chancellor of England and his lady?” but when the boy persisted in his orders, she began to perceive her husband’s hidden design and realise that he had fallen from his high estate, and in this fashion would break it to her. She was his second wife, and neither beautiful nor very sweet-tempered, but Sir Thomas ever treated her with the most courteous consideration, joked at her shrewishness, and complimented her whenever he could. Still we cannot help suspecting that on this occasion he was a little relieved to send the message of his downfall by the young groom instead of having to deliver it in person.

The next tomb of interest in the More Chapel is that of the Duchess of Northumberland, 1555, mother of thirteen children, of whom Robert Earl of Leicester, Guildford Dudley, husband of Lady Jane Grey, and Mary, mother of Sir Philip Sydney, were the most celebrated.

This lovely monument has been barbarously treated: the spirals were broken off in 1832 to make room for seats and increase the letting value of the chapel, and its awkward position suggests that it has been pushed out of[25] its original setting. Several of the brasses have been wrenched away. Chaucer’s tomb in Westminster Abbey is almost a replica of what it must have been when whole, and is probably by the same designer.

The Duke and Duchess of Northumberland succeeded Queen Katharine Parr as tenants of the Manor House, the Tudor palace in Cheyne Walk: the Duke and his son Guildford both died on Tower Hill, with the “nine days’ Queen,” and it is greatly to the credit of Queen Mary I. that she interested herself in the bereaved Duchess, and restored to her part of her confiscated possessions. In Elizabeth’s reign the family flourished again, and there is a minute description extant of the Duchess’s gorgeous funeral at the Old Church.

But the fact that the More Chapel continued to be the family pew pertaining to Beaufort House suggests that the Northumberland tomb was originally in a far more conspicuous position, and was presently pushed aside to make way for territorial claims. Sir Arthur and Lady Gorges were at Beaufort House in 1620. He is Spenser’s “Alcyon,” and the poet’s Daphnaida was an elegy on Lady Gorges’ death. The younger Arthur, grandson of this pair of Spenser’s friends, is

He who had all the Gorges’ soules in one.

His epitaph is worth spelling out, though it is rather a back-breaking business, and it is noteworthy that his wife, who perhaps was much older than himself, and was certainly very much married, prepared the inscriptions, but omitted to leave orders for the insertion of her own death-date, which, after considerable preamble, is left out altogether.

Under the east window lies the splendidly ornate monument of the Stanleys. Sir Robert, whose medallion portrait is supported by the figures of Justice and Fortitude, married a daughter of Sir Arthur Gorges. The children, Ferdinand and Henrietta, are dear little people in stiff Stuart dresses.

Their epitaph beginning,

The Eagle death, greedy of such sweete prey,

With nimble eyes marked where these children lay—

refers to the Stanley family legend of “The Bird and the Baby,” of which two children-ancestors were the heroes. An eagle hovers over the tomb.

The helmet hanging incongruously in mid-air has the Dacre crest, and is not in its proper place here; a helmet exhibited in church often implies that the wearer fought in the Crusades, but this probably is part of the heraldic ornament of the great Dacre memorial in the nave.

The inscription to Sir Robert Stanley is really beautiful in the stately wording and measured metre of the seventeenth century, and is worth quoting entire:

To say a Stanley lies here, that alone

Were epitaph enough; noe brass, nor stone,

No glorious Tomb, nor Monumental Hearse,

Noe gilded trophy, nor Lamp-laboured Verse

Can dignify this grave, nor sett it forth,

Like the immortal fame of his owne Worth.

So, Reader, fixe not here, but quit this Room

And fly to Abram’s bosom—there’s his tombe,

There rests his Soule, and for his other parts

They are embalmed and shrined in good men’s hearts—

A nobler Monument of Stone or Lime

Noe Art could raise, for this shall outlast Tyme!

“Lamp-laboured verse” is first-rate.

We cannot leave the More Chapel without referring to the controversy, dear to the antiquarian papers, as to whether the Chancellor’s body were ever brought from Tower Hill after the fatal July 6, 1535, to be interred in the church he loved. All tradition and probability point to this belief; though his head, exposed on London Bridge, and rescued by his devoted daughter Margaret Roper, was consigned by her to the keeping of St. Dunstan’s Church, Canterbury.

Now for another of Mr. Davies’ anecdotes of the Old Church.

Some twenty years ago, a marvellous story ran round Chelsea that Sir Thomas More’s ghost had been seen to emerge from the south wall monument and, crossing the sanctuary, disappear into the opposite wall. The figure was unquestionably that of the Chancellor, for besides being quaintly dressed, it was without a head—which clinched the matter. Lady artists, painting in the body of the church, had seen the apparition steal across the chancel, in the gloaming, and spreading the news abroad, soon brought half London to inquire into the marvel.

Unluckily Mr. Davies was on guard in his beloved church, and his explanation was crushingly disappointing. He stationed all would-be ghost seekers halfway down the middle aisle, and then produced the ghost—himself—passing from the tiny south door behind the tomb to the vestry opposite, a shawl drawn over his head and wrapped about his shoulders, giving the required appearance of headlessness.

Both south door and vestry door within the chancel are now done away with, and even newspaper reporters have heard no more of the ghost.

NOTES

CHAPTER IV

The Dacre tomb and charities—Lady Jane Cheyne, who gave her name to Cheyne Walk—The churchwarden’s official seat—The pulpit where Wesley preached—Dr. Baldwin Hamey and his servant Fletcher—Church burials and the More descendants—The chained books—Public Bible-reading in the eighteenth century—The font and organ—The Queen’s Royal Volunteers—The Ashburnham bell—Books of authority on Chelsea history.

THE most beautiful monument in the church is the great Dacre tomb. Lady Dacre was a Sackville and an heiress, and succeeded to the possession of Sir Thomas More’s Beaufort House. She married Lord Dacre of the South—a magnificent Elizabethan title—and their name is still venerated year by year in Chelsea and Westminster for the gifts and charities to which they devoted their fortune. They left no family—the poor stiff little daughter in the very uncomfortably designed cradle beside them having been their only child—and their estates in Chelsea, Kensington, and Brompton passed to Lord Burleigh, with numberless bequests attached for local objects. Emanuel Hospital, Westminster, is their foundation, and Chelsea has the right to two annual presentations conditionally on the tomb being kept clean and in repair. One is tempted to ask whether the conditions are being fulfilled, for the colouring of the wonderful canopy could surely be very much improved by a little knowledgeable wiping and polishing, and the Elizabethan pair themselves—he in late heavy armour, she in “French hood,” Mary, Queen of Scots’ introduction, and ruff—might be reverently dusted with advantage to their beautiful Renaissance detail. The tomb originally stood in the More Chapel, which Lady[32] Dacre inherited with Beaufort House, and was moved to its present position in 1667. It is unfortunately placed very much askew to the window and the water-gate which it completely blocks—and this is the more to be regretted because the south side is deficient in exits, and the restoration of the water-gate, as seen in an old print, would add to the beauty and convenience of the church.

In the north wall, and almost opposite the Dacre tomb (if anything in the Old Church can be accounted to pair with anything else!), reclines Lady Jane Cheyne, a very heroically proportioned lady, daughter of the first Duke of Newcastle, and, like her father, an ardent royalist. As quite a girl she held Welbeck House, with a slender garrison, for King Charles, and all her life she devoted her fortune to the maintenance of the royal cause and support of her father in exile. She married Lord Cheyne, of a Buckinghamshire family, and bought the Manor House and Palace which had been the scene of so much Tudor history-making, where she lived to see the Restoration of King Charles II. and to benefit Chelsea by her good deeds for fourteen years. Cheyne Walk is named after her, to commemorate her benevolence and exemplary life at the great house which had sheltered many less admirable characters; she was a special patroness of the church, where she directed the renovations of 1667, and possibly it is to her taste that we owe the unfortunate prominence of two magnificent monuments which would have gained so much by being more discreetly located. Lady Jane’s figure and surroundings are scarcely in proportion, but she is an aristocrat to her finger tips—those wonderful finger tips, which seem to have been assured to the royalists of Vandyke’s day!—and one can imagine her holding a fortress, or later, writing a manual of elegant devotions, with equal distinction.

The little three-cornered pew, to the right of Lady Jane’s tomb, is the dignified sitting intended for the churchwarden; the mitre which is still found on a panel here and there tells of the Bishop of Winchester’s residence in Chelsea during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Standing in the middle aisle, the beauty of the pulpit[33] carving must strike every lover of oak, and it is inspiring to think that a broad-minded Chelsea rector, the Hon. and Rev. W. B. Cadogan, invited John Wesley and Whitfield to occupy it. The canopy of the pulpit has been lost, but from wood once part of the “three-decker” structure, the chairs have been fashioned which stand by the altar; the font-cover of oak was found in 1910 in a neglected corner of the tower, and with it two handsome Georgian pewter alms dishes dated 1754; these have been restored to use for Sunday collections. Among the hatchments, many of which remain unidentified, that of Rector Cadogan has been recognised with its motto “Christ, the Hope of Glory”; he died in 1797.

On the pillar north of the pulpit hangs the tablet of the clever and eccentric Dr. Baldwin Hamey, who retired from medical practice in 1665 and came to live at Chelsea. He gave liberally to the church restoration fund—perhaps influenced by Lady Jane Cheyne’s enthusiasm—but as a scientist he was intolerant of dogma, and used to carry a leather-bound Virgil to church with him, which passed for a Testament, and saved him from the tedium of listening to doctrine to which he did not conform. He was buried, uncoffined and merely wrapped in a sheet, in the chancel, and his epitaph is a hopeless one, “When the breath goeth out of a Man, he returneth to his Earth,” but later, in 1880, the Royal College of Physicians restored his tablet “in grateful remembrance of their benefactor,” and in spite of the declared pessimism of his creed, his good work is not “interred with his bones,” but lives in the kindly worded remembrance of his scientific brotherhood.

On the opposite pillar (south side) a tiny figure of St. Luke, “the doctor’s saint,” stands on a bracket; it formerly decorated the canopy of the pulpit. It was contributed by John Fletcher—Dr. Hamey’s servant and assistant—to the ornamentation of the church at its restoration in 1667, when the “beloved physician” was still patron of the parish. No one has ever satisfactorily explained why, for 300 years, the old dedication to All Saints was in abeyance, and St. Luke was substituted; perhaps at the Reformation St. Luke, the man[34] of science, was considered a more suitable patron for the Church of the New Learning.

The stones and inscriptions on the floor of the church show that many Chelsea people lie beneath. Sometimes the scrutiny of names leads to considerable enlightenment of family and local history, but for Chelsea’s visitors this study has no special attraction, so we will not burden them with pavement inscriptions. From a corner between the More Chapel and the nave, nine leaden coffins were removed about forty years ago, when the heating of the church necessitated new stove-pipes. These coffins were supposed to belong to the More family, and may have enclosed the bodies of Will and Margaret Roper, of “Mistress More,” the Chancellor’s second wife, and of Bishop Fisher, but their identification was uncertain. They were removed to the Parish Church in Sydney Street and privately re-interred.

The chained books under the south window are a more cheerful reminder of Tudor times, and of Henry VIII.’s decree of a Parish Church Bible, though these are not the original sixteenth-century volumes, but a later set presented by Sir Hans Sloane. They consist of:

A “Vinegar” Bible (Baskett’s edition, dated 1717).

The Book of Common Prayer, 1723.

The Book of Homilies (2 volumes) formerly belonging to Trelawny, the great Bishop of Winchester, 1683.

Two volumes (Nos. I. and III.) of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. A very fine edition dated 1684.

Tradition connects these two volumes of Foxe with Charles II., who died in the year 1685. It is possible, though no history of the books records the fact as certain, that they were the King’s property, given or lent to his physician; we love royal tradition in Chelsea, and there is nothing against our adopting this one.

The volumes themselves are splendidly bound, printed, and illustrated, but during a careless or too confiding period, when the oak book-case was open to all comers, several illustrations and some of the brass clasps and hinges were carried off as souvenirs, and the case is now strictly locked. It, and the chains, are comparatively modern.

I knew an old Chelsea lady who told me that her grandmother was in the habit of repairing to the church every Tuesday and reading aloud from the Bible to as many hearers as cared to listen for an hour, and that the school children regularly attended the reading. While this links us curiously with a past when the Bible was still a rarity, not to be found in everybody’s hands, it makes a suggestion of supplementary education from which our own century might profitably learn a lesson.

The font dates from about 1673; the gilding on the cover is the original work. The ship’s bucket in oak standing beside it was presented by members of the choir in 1910. The organ, a very sweet-toned instrument, has been recently beautifully repaired and enlarged by the Rev. Malcolm and Mrs. Farmer.

The Colours of the Chelsea Volunteers are the only two flags remaining of a considerable number which adorned the church in 1814. The King’s Colour is said to have been worked by Queen Charlotte and her daughters, and an old print depicts her presenting it to the regiment of the “Queen’s Royal Volunteers”; the picture is chiefly remarkable for the immense amount of cumbrous clothing worn by the Volunteers, and the very scanty draperies of Queen Charlotte and her ladies. The corps was raised in 1804, when Bonaparte threatened invasion, and the Regimental Colour bears a medallion portrait of St. Luke, and the inscription, “St. Luke, Chelsea.” A board in the porch chronicles this presentation, but beyond a loyal willingness to serve, I do not know that the Chelsea Volunteers were ever called upon to show further fight. Opposite this board the Ashburnham Bell reposes, a witness to the legend of 1679, when the Hon. William Ashburnham, swamped in the mud of Chelsea Reach, regained his bearings by hearing the church clock strike nine, and made for the shore by the sound, instead of plunging further into the tideway.

In gratitude, he presented this bell to be rung at nine every night from Michaelmas to Lady Day, and left a sum of money to endow it The bell-ringing ceased in 1822, when the peal of the old church was broken up to provide[36] new bells for St. Luke’s in Sydney Street, but in memory of the Ashburnham deliverance and bequest the clock is illuminated every evening at sunset, and by oil lantern, by candle, by gas, and now by electricity, tells the story of the rescue to all who pass by.

I have, for want of space, omitted many smaller tablets and inscriptions, which, curious enough in their way, and important in the mosaic of our parish history, are yet little interesting to the passing visitor, unless he is bent on following up some special clue of family or local weight. Should such be his study, I would counsel him to refer to Mr. Reginald’s Blunt’s Historical Handbook, to Mr. Randall Davies’ splendid History of the Old Church, or to the Rev. S. P. T. Prideaux’s Short Account of Chelsea Old Church, to all of which I am infinitely beholden.

NOTES

CHAPTER V

Sir Hans Sloane—His houses and bequests—The gates of Beaufort House living in Piccadilly—The clock—The restoration of 1910—Church Lane—The Petyt House—Queen Elizabeth’s Cofferer—Church Lane and its residents—The Rectory—The King’s Theatre and the stocks—Upper Church Street and the Queen’s Elm.

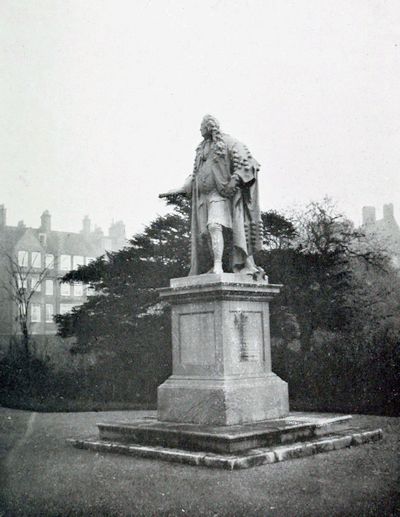

THE tomb of Sir Hans Sloane is the chief object of interest in the little strip of churchyard which remains to the Old Church. It shows the urn and serpents of Esculapius, and its epitaph is pleasant reading; we fancy we see the courtly, kindly, pompous old physician who lived at Beaufort House and must have been a familiar figure on the riverside, pacing with dignity, or being carried in his chair to the Physic Garden which he presented to the Apothecaries Company and to Chelsea. His name has been repeated in a score of ways; throughout the district his daughters and co-heiresses, in their turn, have stood sponsor to many of our streets. Their marriages link the Past and Present with names that are, literally, part of Chelsea. Sir Hans, an Ulsterman by birth, first lived in Sir Thomas More’s “Great House,” which he caused to be pulled down—it had fallen into disrepair, and was overweighted by its grounds and expensive gardens.[1] He later removed to the Manor House, once Henry VIII.’s Palace, which occupied the space now filled by the houses of Cheyne Walk stretching westward from the corner of Oakley Street to Manor Street.

Sir Hans’ collection of natural curiosities and works of art formed the nucleus of the British Museum: he had wished that his rarities could have remained and have been exhibited in the Manor House itself, and that the adjoining gardens should be opened to the public, but this was found impracticable; the estate was divided and sold after Sir Hans’ death, and Cheyne Walk’s separate houses were built. Many of these show in their basements the solid remains of Tudor masonry.

Of the thousands who daily pass Devonshire House, Piccadilly, we wonder how many persons know the history of the great iron gates which adorn the Duke’s otherwise forbidding wall? They are the gateway designed by Inigo Jones for Beaufort House when occupied by the Earl of Middlesex. Sir Hans, when he demolished the Chancellor’s beautiful home, gave the gates to the Earl of Burlington and they were set up for a time at Chiswick; the late Duke of Devonshire recovered them, and set them up once more, in front of a great town house. Pope’s funny little verse to the gates, which he met on the road to Chiswick in an ignominious cart, is well known—

“O Gate, how cam’st thou hither?”

“I was brought from Chelsea last year

Battered by Wind and Weather!”

and often quoted, but few inquire whose gate it was and where it has gone to.

If time and space allowed, there are a hundred more points of interest about the Old Church over which we might linger, but it is impossible to do more than indicate its chief features in a guide-book of our present dimensions. Suffice to mention that the tower, replacing an earlier steeple, was built in 1679; that the clock, made and presented by Sir Hans Sloane’s gardener, a Quaker and amateur mechanic, is still keeping good time after more than 150 years’ work; that the new vestry is built as a memorial to Mr. Davies’ long incumbency.

The latest restoration of the church in 1910 owes its[41] origin to the short but vigorous rule of Mr. Prideaux, who recognised the necessity and did not allow himself to be daunted by the immense difficulties of the work required. Some of our conservative Chelsea hearts dreaded it, as though the Huns and Vandals were at our church gates, but the sympathetic manner in which it was carried out reconciled even the most fearful to the unavoidable changes.

As we remember the Rev. R. H. Davies very gratefully for freeing the two chapels from the thrall of private ownership, so we thank the Rev. S. P. T. Prideaux for so bravely carrying through the immense work of the restoration and re-beautifying of 1910.

To his successor, the Rev. M. S. Farmer, we owe the completion of the organ and the careful and reverent re-arrangement of the surrounding church garden.

As we leave the church, Cheyne Walk stretches stately and placid to either side of us, and the river beyond, which used to lap the churchyard wall when Henry VIII. was rowed up in his royal barge to visit the beloved Chancellor (whose head he presently cut off), shows like silver between the bounds of its magnificent embankment; all this must have a chapter to itself, and as we are at Church Street corner, we will take the opportunity of turning due north and following it, the “Church Lane” of older days, to its end at Queen’s Elm.

Just above the church lies the Petyt House, erected in 1706 by William Petyt; it has been rebuilt, but its Queen Anne character has been kept. A grim-faced portrait of its founder hangs inside, and the house is still used for Sunday-school and parish purposes, “Church purposes” being strictly prescribed. It was originally the parish school, succeeding a parochial school built somewhere near the same site by Rector Ward, “Cofferer to Queen Elizabeth,” in 1595. “Cofferer” is a delightful title, and suggests comfortable resources in the background.

Church Street is now a squalid thoroughfare leading from Fulham and King’s Road straight to the Embankment by a short cut that is narrow, crowded, and always swarming with children. But in the seventeenth and[42] eighteenth centuries it was dignified and residential, and even now if you obliterate in your mind’s eye the ugly, cheap shop fronts you will find Queen Anne brickwork behind; generous windows, warmly tiled roofs, and panelled rooms within. Here in the good Queen’s days lived the élite of the literary world: Bishop Atterbury schemed for the Stuarts in a “house on the waterside,” probably opposite the church; Dean Swift had his lodging a little further up the lane, where he deplored “confounded coarse sheets and an awkward bed”; Addison came across the fields from Sandford Manor House to meet the wits at Don Saltero’s coffee-house; Dr. Arbuthnot and Sir John Shadwell, the Queen’s physicians, and many others, scientists and men of letters, lived in the Church Street houses which to-day are stables, laundries, offices, and small shops.

Trelawny, Bishop of Winchester, was a force in this coterie’s earlier days; later Dr. Johnson visited here. Possibly the existence of great houses and influential owners of property in and about our Village of Palaces brought the wits and writers to Chelsea: Shrewsbury House, Winchester House, Lindsey House, Essex House, and others were in the possession of noblemen who might happily count as patrons to launch a new book or a new enterprise if the authors knew how to play their cards well and politely.

A few hundred yards above the Petyt House the rectory wall begins, and one of the most delightful houses and gardens in London is seen behind it. An older rectory house existed on much the same site from the early sixteenth century, and the roll of Chelsea rectors being complete since 1289, it may well have been earlier still. But in 1694 we read that Rector John King found the rectory house so dilapidated that he removed to lodgings in Church Lane, and it was probably rebuilt shortly afterwards. Rector Blunt, and our present rector, Archdeacon Bevan, have done much to beautify and improve it, and though they have generously given part of its surrounding land for necessary parish purposes, the garden, with Queen Elizabeth’s mulberry-tree, still remains a joy and refreshment to many—an oasis of flowers, and trees, and lovely[43] age-old turf in the midst of the busiest commercial quarter of the parish.

The General Omnibus Company has its office where once the stage coaches used to rumble in from the Great North Road; and the King’s House, an unrivalled cinematograph theatre, faces the corner where, tradition says, the stocks used to stand for the wholesome punishment of miscreants and disturbers of the peace. If only the cinema could reproduce some of the scenes which were enacted on this spot two hundred years ago, how interesting would be the revival, and how Suffragettes would tremble!

Upper Church Street, across the King’s Road, was till recently a pretty countrified street, irregularly set with charming houses small and big. Here lived Felix Moscheles, the painter, Mr. De Morgan, the novelist, Mr. Bernard Partridge, the Punch cartoonist, reflecting and adding to the effulgence of the Chelsea Arts Club. But the newly planned Avenue of the Vale, with its antennæ of new streets in every direction, has cost us Church Street as we have loved it since childhood; “c’est magnifique,” this new tasteful suburb of old Chelsea, but it is not the homely purlieu that we, and Dean Swift, used to know.

Even as I write the hammers of the housebreakers are busy on the walls of “The Queen’s Elm” public-house, an ugly structure enough which no one can regret for itself, though with the passing of its existence as a house of refreshment one fears its Elizabethan legend may disappear also. Here under an elm the Queen “stood up” for shelter in a storm of rain with Lord Burleigh, who inherited the Dacre property in Chelsea and Brompton, and was probably conducting her Majesty to one or other of his newly acquired properties. Elizabeth was fond of paying surprise visits to her subjects, and on one occasion when she went to Beaufort House unexpectedly, in its owner’s absence, she was unrecognised, and refused admittance. Under the elm at the corner of Church Street and Fulham Road legend says she and her great minister talked of umbrellas, which about this time were first introduced from the East, but were not yet in general—even in royal—use.

As I passed the old public-house, the stucco frontage of which was falling in clouds of dust to the ground, I saw for the first time a beautifully pitched and red-tiled roof disclosed at the back of the building. It, too, may be gone to-morrow, but I like to think I have just caught a farewell glimpse of the roof that sheltered Queen Bess.

NOTES

CHAPTER VI

Cheyne Walk—The King’s Road and the Queen’s—George Eliot—Dr. Dominiceti’s baths—A French author’s cleverness—“The Yorkshire Grey”—Cecil Lawson’s pictures—Rossetti, Mr. and Mrs. H. R. Haweis, and their guests—The Don Saltero—“The Magpie”—Remains of Shrewsbury House and Mary Queen of Scots—The Children’s Hospital—Crosby Hall, Lindsey House, Turner’s House—The way between the Pales.

CHEYNE WALK is beautiful at all seasons and under all aspects; each time that I regard it from a fresh point, or return to it after a temporary absence, I think, “Never has it looked so lovely before!”

But for the purposes of historical interest it is well to walk it from end to end, or rather, to loiter in it, and, for choice, in early autumn, when the sunshine is as mellow as the tones of the old brick, and the trees and creepers are not too heavily green to obscure its gracious lines.

So, if you will see this riverside row of storied houses aright, turn with me down Flood Street—when you leave your motor-bus at the Town Hall—and begin at the beginning of the Walk that will lead you through the drama, tragic and comic, of at least five centuries.

Until a few years ago the two main thoroughfares from London to Chelsea were the King’s Road and the Queen’s Road. In that their juxtaposition recalled an interesting tradition, I am sorry that Queen’s Road has lately been altered to Royal Hospital Road.

For in the days of Charles II. the King had a private road for his coach through the fields to Chelsea, where dwelt Mistress Elinor Gwynn (at Sandford Manor when she received the King’s visits, but, report says, in a squalid[48] little riverside hovel, not far from Chelsea Barracks, in her previous chrysalis stage), and Queen Catharine of Braganza, who also visited at Chelsea, paying less lively duty calls, as wives must, objected to using her husband’s route lest a domestic matter, which she preferred to ignore, should be forced on her attention.

So the King came his road and the Queen hers, following parallel paths, and poor, stupid Catharine tried to keep her eyes shut to her consort’s “merry” ways. Had she tried to make her own a little less stiff, bigoted, and unintelligent, she might have been happier, for she was young and pretty enough to charm Charles at first; her determined adherence to Portuguese manners, dress, and language was as much to blame for Charles’s neglect, as his own inconstant nature.

The first two houses in Cheyne Walk are modern, but then begins the row of beautiful mansions which forms the Walk, as distinguished from the previous frontage of great buildings standing detached, in the gardens of the Manor House. These buildings were pulled down and the gardens surrendered to the builders in 1717, and housebuilding on the riverside began apace. In No. 4 George Eliot (Mrs. Cross) lived for a few weeks only, and died from the result of a chill in 1880, just as she had begun to find pleasure in her beautiful view. At No. 5 James Camden Nield lived a miser’s life, and left a fortune of half a million pounds to Queen Victoria, whose Uncle Leopold congratulates her in one of his letters “on having a little money of her own” in her early married life. At No. 6 Dr. Dominiceti had his famous medicinal baths, a wonder-working quackery of the eighteenth century of which in heated argument Dr. Johnson said to an opponent of differing views:

“Well, sir, go to Dominiceti and get fumigated, and be sure that the steam be directed to thy head, for that is the peccant part!”

Between No. 6 and Manor Street some modern houses have been interpolated. No. 11, I think, is the number which has been omitted from the sequence in numbering them, and a clever French novelist has taken advantage[49] of this peculiarity to lay the scene of his story in the nonexistent house, which he can consequently describe with all the exuberance of his fancy. I have met French visitors walking round this end of Cheyne Walk in great perplexity trying to locate their author’s plot: the fact that larger buildings took the place of humbler ones, and that the numbers beyond could not be disturbed, account for the omission.

Some thirty years ago, when the old houses were demolished, a considerable portion of an underground passage was laid bare to the right of Manor Street. It was obviously a section of that subterranean passage which connected the Chelsea Palace with Kensington. I crept down it for the space of a yard or two, and rejoiced to think that the Princess Elizabeth might have done the same, in one of those romping games with her stepfather, the Lord High Admiral Seymour, which “Katheryn the Queene” found too hoydenish for the young lady’s age and dignity. Nos. 13 and 14, formerly one house, were the well-known inn “The Yorkshire Grey,” with its own stairs at the riverside, dear to country visitors from the north of England.

No. 15, now in the possession of Lord Courtney of Penwith, was in the seventies the home of the artist family of William Lawson. Cecil Lawson’s pictures of Chelsea before the Embankment was built, were exhibited in a one-man show at Burlington House a few years back, and gave an exquisite idea of the waterside in its rural days, Queen’s House, No. 16, was once called Tudor House, and its basement is said to contain remains of the original Tudor workmanship of Henry VIII.’s Palace. Whether this is so or not, it is unquestionably on the site of some of the old Manor House buildings; the name was changed by the Rev. H. R. Haweis, who favoured the idea that many Queens—Katharine Parr, Elizabeth, Anne of Cleves, Catharine of Braganza—must have occupied the position, though not the actual mansion.

Mr. Haweis’ tenancy followed on that of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who lived here from 1863 to 1882. William Rossetti, George Meredith, Algernon Swinburne, and[50] others of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood joined at first in the ménage; then came Dante Rossetti’s short and sad married life, and later he lived secluded, spending much of his time in his garden at the back, where he tried to acclimatise strange animals, of whose wild ways exaggerated reports were spread abroad, perhaps to ensure the poet’s privacy.

Of Rossetti’s later life, I who write can speak as an eye-witness, for in 1878 we went to live next door, at No. 17, and found him a quiet, very retiring, but most polite and obliging neighbour. As our gardens at the back adjoined we often saw him pacing under his trees dressed in an old brown dressing-gown like a friar’s habit. He went nowhere and received little company. Once we had lost a pet tortoise, which came up from under the dividing wall on Mr. Rossetti’s side of the boundary: the poet lifted it gently back and dropped it over without a word, then scurried away indoors, lest we might be moved to overwhelm him with thanks. He died while at Margate for his health, and I remember we had hardly heard the news, when we saw people (certainly unauthorised) removing all sorts of parcels and pieces of furniture from the house to a cab, which was loaded outside and in, and driven rapidly away.

When his effects came to be examined much of value had disappeared, but who were the culprits was never known.

Mr. and Mrs. H. R. Haweis’ tenancy of Queen’s House was very different. They entertained half London at their big crushes, which always had a character and a “go” which made them eagerly sought after and vastly amusing. Nearly always the party was built round some lion of the literary or scientific world. Ernest Renan and Oliver Wendell Holmes happen to be two guests whom I particularly recall. Renan was big, overblown, with the rolling gait and merry, round face of Southern France: Oliver Wendell Holmes was tiny, silver-haired, fragile as a bright-eyed little field mouse. Mr. Haweis, who did not know what shyness meant, exploited his visitors with the utmost vivacity and good nature; he had the social[51] instinct in a high degree, and enjoyed his own parties so heartily that few of his guests could fail to do the same.

Nos. 17 and 18 were in 1718 the celebrated Don Saltero Museum and Coffee-house, removed from Danvers Street to this more eligible situation; the old site is now occupied by the baker’s shop, 77, Cheyne Walk. “James Salter, the coffee man,” was at one time valet to Sir Hans Sloane, and may have formed the idea of his museum from pickings, let us hope discarded, by this eminent collector. He was an Irishman who could mix punch, and draw teeth, play a little on the fiddle, and keep his patrons amused, though his wonderful curios read like simple rubbish to-day, and strongly remind us of the bogus collections which used to be a sideshow at bazaars in the country. Still, “Forget me not at Salter’s, in thy next bowl!” said the wits, and a galaxy of wonderful men must have met at “the Don’s” of an afternoon as Richard Steele describes it in the Tatler. The famous collection was sold in 1799, and the coffee-house became a public-house; in 1867 it was divided into two private residences.

The houses Nos. 19 to 26 were built about sixty years later than those we have been considering, when the last part of the Manor frontage was taken down; the difference in style is easy to trace—there is a uniformity of style, which has evidently been aimed at, and the magnificent ironwork of the earlier date is wanting.

At No. 24 there are vaults which undoubtedly date from Tudor times, and tradition says that the gnarled old wisteria embracing No. 20 is a creeper of the Manor House garden. All these houses have fine panelling, staircases and fireplaces, and handrails—some of earlier fashion than the buildings themselves, which points at their adaptation from previous mansions.

Modern houses intervene in the curve where stood Winchester House, the Bishop’s Palace: at No. 27 Mr. and Mrs. Bram Stoker lived, in the palmy days of the Lyceum Theatre under Sir Henry Irving’s management, and dispensed delightful Irish hospitality.

Across Oakley Street, we come to a lately restored house which bears the old sign of the Magpie and Stump. The “Magpie Inn,” one of the oldest houses in Chelsea, was a rendezvous for the supporters of the Stuart cause in 1715 and 1745; they could slip away by water if in danger of discovery. Next come, alas! some lamentable gaps, interspersed with a few odd walls and gables still remaining, parts of old Shrewsbury House, where Mary Queen of Scots was held in custody by the Earl of Shrewsbury. The form of the house cannot be traced, though an old print gives it as a hollow square standing back from the present roadway; it was broken up in 1813, but without doubt parts of it have been built into the present small houses.

By the by, the Earl of Shrewsbury who had charge of Queen Mary was also fourth husband of the notorious Bess of Hardwick, and Queen Elizabeth is reported to have pitied him for having such intimate acquaintance with “two she devils.”

No. 48 was once a Quakers’ Meeting House. The Hospital for Incurable Children, of which Queen Alexandra is President, nobly fills the site of some very old, tall houses, in one of which Holman Hunt painted his “Light of the World”; the old vine was preserved, and still bears small, sweet grapes in a hot season; the children’s voices sound merrily as you pass their open windows, and the saddest inmates are those who, having been sent here as incurable, are told that they are nearly healed and must shortly return to their homes.

Beyond Lombards’ Row, already noticed, where the old Archway House stood to shelter Jacobite plotters, are some new houses which are surely an anachronism in our Queen Anne Walk (the original dates hereabouts are 1710-11), but the Copper Door is a fine piece of work, and a splendid reflector of sunshine.

Across Danvers Street lies the waste land surrounding the lately erected Crosby Hall, of which I do not suffer myself to write, so keenly do I resent its importation into the hallowed precincts of Sir Thomas More’s whilom garden. Those who wish to inspect it can do so by inquiring for the custodian and the keys at More’s Gardens Mansions (entrance corner of Beaufort Street).

Crossing Beaufort Street, all the houses are gracious and of good report, and the entire proportions of Lindsey House can be made out from the pavement on the riverside, sub-divided as it now is into five or six different dwellings, and at one gabled end slightly extended.

This was the great house of Sir Theodore de Mayerne, Court Physician, 1639; of Robert, Earl of Lindsey, Lord High Chamberlain, 1671; of Count Zinzendorf, the Moravian Leader, 1750: it occupied a part of the grounds of Beaufort House, and rose to importance as that great mansion declined. The Moravian fraternity had their colony and chapel and burying-ground behind Millman Street, where members of their persuasion were buried upright, under small square headstones, with the object, tradition says, of rising more quickly at the General Resurrection than other people. Finally, after passing many picturesque houses and some squalid modern interpolations, we come to Turner’s house, with the balcony where he watched the sunrise, and with the south-west window where he died with the sunset flooding his face in 1851.

Cheyne Walk ends at World’s End Passage, “the way between the Pales,” as the map of 1717 has it, which led across the fields and marshes to Kensington.

NOTES

CHAPTER VII

Lots Road—Ashburnham House—Sandford Manor—Beaufort House and a corner of a “fayre garden”—Tudor bricks—Danvers House and the Herberts—Lord Wharton’s scheme of silk production—Henry VIII.’s Hunting Lodge in Glebe Place—The Manor House gardens and those who have walked there.

AS WE HAVE reached the western limit of Cheyne Walk and may not be there again, for the uninteresting industrial district which begins here is not likely to tempt us back, we will say a few words about some of the old names that survive, under very altered conditions, and then turn our backs on it.

Lots Road, which might easily suggest the dreary desert tramp of the migrating Patriarch, is so called because it is built on the site of four lots of pasture-land belonging to the manor, and the first of the property to be sold. In 1740 this land surrounded Chelsea Farm, the residence of the Methodist Lady Huntingdon, the friend of Whitfield and inventor of a “Persuasion” all her own. Then, in sharp contrast, it became Chelsea Gardens, later opened as Cremorne, and closed in 1875, when its pretensions to fashion had been eclipsed in rowdyism.

Further to the north-west lay Ashburnham House, whither Master William Ashburnham was steering on the memorable night when he was nearly submerged in Chelsea Reach: the name has been well preserved in the handsome church and adjacent block of mansions.

Chelsea Creek was once a much-used waterway to Kensington, and the old lock-keeper’s cottage used to be a picturesque object; there was perhaps a back way[58] to Sandford Manor House, occupied first by Nell Gwynn, later by Addison, which gallants and savants used in turn. The remains of the little old dwelling stand in the yard of the Gas Company, to the right of the railway, and accessible from King’s Road at Stanley Bridge; but they are rather a deplorable relic of two popular historic figures, and any day may see them swept away. There are some survivals which even the keenest antiquarian must feel had better be graciously obliterated if they cannot be restored to dignity. Addison’s description of his home as Sandys’ End, written in 1708, scarcely prepares us for the desolation of its present-day appearance.

Returning eastward, along Cheyne Walk, we naturally turn up Beaufort Street, and try to realise, while the tram screams at us from the middle of the road, that Sir Thomas More’s fair house and gardens lay here on either hand. The Clock-house entry to the Moravian burial-ground is perhaps the original north-west corner of these grounds; on the east they stretch to Danvers Street. Here and there are still to be found pieces of wall which show the unmistakable nuggets of Tudor brickwork; and I once saw the surprising spectacle of a correctly attired clergyman astride a twelve-foot wall at the back of the old Pheasantry, trying to detach a brick as a memento of his visit to the Chancellor’s domain. I regret that I failed to observe his descent, but I met him later ruefully amused and very dirty; and he had to confess that the sixteenth-century builders had been too clever for him, and he had torn his hands and his clothes for no result. But the Chancellor’s motto, “Serve God and be merrie,” was certainly his also; and the fact that he had not been able to detach one brick seemed to convince him of its undoubted Tudor-ness!

Those who would read of “the Greatest House in Chelsea,” and Sir Thomas More’s life there, should get Mr, Randall Davies’ recently published book and study its complete record; here we can only briefly relate how after More’s execution it was granted to the Marquis of Winchester, inherited by Lady Dacre, bequeathed by her to Lord Burleigh, and later occupied by Sir Arthur Gorges, the[59] Dukes of Buckingham, the Dukes of Beaufort, and finally was bought and pulled down by Sir Hans Sloane, who seems to have had a mania for demolishing historic great houses. Perhaps as a physician his sanitary instincts were more alert than his feelings of sentiment.

There is just one corner of Beaufort Street where a realisation of the past may really be achieved in a very delightful and unexpected manner. Turn in at the iron gateway to Argyle Mansions (at the right-hand side of the street, where the tramlines end and the King’s Road crosses), and you will find yourself in an undreamed of survival of a part of the Chancellor’s garden. You will find some old trees and a mulberry-bush, and some turf, that is Chelsea, not London, sward; you will be hard to please or to interest if you cannot picture a garden scene here: Sir Thomas with his arm about his “Meg’s” shoulder—Erasmus reading in the shade—perhaps the King’s Majesty himself, swaggering condescendingly, and as yet uncrossed in his desires and uncontradicted in his supremacy.

It is but a scrap of green, but it is genuine Chelsea history—far more so than the intrusive Crosby Hall, which hunches its shoulder to the garden a few hundred yards further on and whose connection with Sir Thomas is remote and with Chelsea is nil.

Danvers Street with its tablet, “This is Danvers Street, begun in ye year 1696 by Benjamin Stallwood,” commemorates the older Danvers House, home of the versatile Sir John Danvers, a courtier, a regicide, and then a courtier again as the whirligig of time carried him along. His wife was the pious and beautiful Lady Herbert, mother by her first marriage of Lord Herbert of Cherbury and of George Herbert, the sweet singer; the Herbert family was constant at church, and it is pleasant to think that some of the poet’s “Church Porch” thoughts may have come to him in the calm seclusion of the Old Church. Lord Wharton, who later lived at Danvers House and was the author of the famous Whig song “Lillibulero” to which Purcell wrote the music, tried to introduce the silk industry into Chelsea, for the employment of the French Huguenots who had a colony hereabouts. Two thousand mulberry[60] trees were planted along the north of King’s Road, on the Elm Park estate, and in other large gardens, but unluckily a mulberry was chosen which did not approve itself to English silkworms, and after a specimen petticoat had been presented to Queen Caroline, we hear no more of the venture.

But this doubtless accounts for the many odd-corner mulberry trees in our various back-gardens: Queen Elizabeth has been associated with several of them, and without hesitation we believe that she planted the Rectory garden tree—but for the rest, we credit Lord Wharton.

A little intricate turn, opposite the new County School buildings, into Glebe Place brings us, at the south-east corner, to Henry VIII.’s Hunting Lodge, a tiny dwelling, with beautiful fish-scale tiling, and so narrow a doorway that our ordinary conception of King Hal’s figure seems to give the lie to this tradition. But Henry was doubtless of slenderer build when he came to shoot bernagle on the riverside, and incidentally to court Mistress Jane Seymour; it is worth asking the present occupier of the little house for permission to see the ladder stairway to the floor above. Again we are amazed to think how Henry ever mounted it; the Lodge, as it is called still, must have been very convenient in old days to that Tudor Lane which divided Upper Cheyne Row and ran straight to the Thames side, where in the reeds of the Battersea shore wild geese were plentiful.

The gardens at the back of the Cheyne Walk houses east of Oakley Street are all hallowed ground, for here without a doubt stretched the lawns and glades of the royal pleasaunce, where “Katheryn the Queene” waited so anxiously for the Lord High Admiral—her fourth husband, it is true, but her first love; where she bade him play with romance, at the little gate in the fields, in the letter which he told her not to write but which she could not resist writing.

Presently, Elizabeth the hoyden was romping and flirting with her stepfather in these very precincts, and poor Queen Katharine was sadly disillusioned and crept away to Sudeley to die. Anne of Cleves may have paced here in sedate Dutch fashion, debating whether she should invite her whilom husband to tea, which she certainly did and found it quite entertainment enough. Lady Jane Grey visited here, and as Guildford Dudley lived hard by, perhaps conducted her priggish courtship under these very trees. By-and-by Sir Hans Sloane is wheeled up in his invalid chair and matures his practical plans for breaking up the estate and sending a tide of new building over Chelsea.

Afterwards, when each house had its individual garden, the company that flocked to Cheyne Walk was, in Georgian times, scarcely less distinguished, and in our own day no less interesting: some magnet quality in the very earth surely brings those who are dear and delightful to rest in Chelsea by the river?

NOTES

CHAPTER VIII

Carlyle’s and Rossetti’s monuments—Paradise Row as it used to be—Hortense de Mazarin—Whistler’s White House and the Victoria Hospital—The Physick Garden—Swan Walk and Doggett’s race for the “Coat and Badge”—The Royal Hospital—Poor, pretty Nelly’s pleasure house—The Chapel—The Hall—An American offer—A French Eagle—Walpole House and a Queen at dinner—Ranelagh and its Rotunda—The Pensioners’ Gardens.

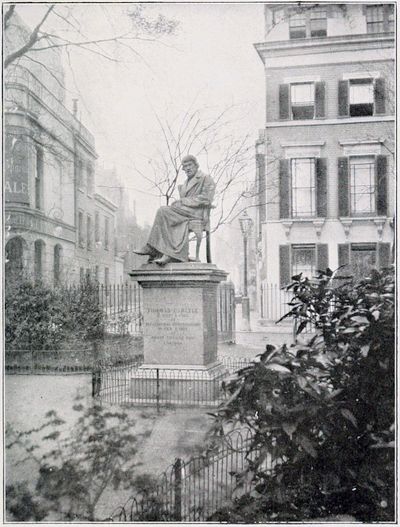

IN the Embankment Gardens, facing Cheyne Row and Queen’s House respectively, are the statue of Carlyle by Boehm and the Drinking Fountain Memorial to Rossetti, with a portrait in relief by his friend, Ford Madox Brown. Both are excellent likenesses, though Carlyle’s is a peaceful presentment, and Rossetti’s mournful and rather repellent.

Passing through the gardens, I have often been reminded of the Greek painter and the birds who pecked at his grapes, for the children often stop to finger the pile of books under Carlyle’s chair. “They’m real books, ain’t they, missus, wat the old genelman wrote?” Thus we talk of Carlyle still, a stone’s throw from his study windows. It is interesting to know that the annual number of visitors to the Carlyle House increases steadily, and the custodian assures us that the knowledge of his works—intelligent, not merely curious—increases also, though among Colonials and Americans he is better known than among ordinary English people. And for “Colonials” read Scotch, or Scotch extracted.

Leaving Cheyne Walk behind and walking eastward, we pass blocks of new flats and modern houses where once was Queen’s Road and beautiful Paradise Row—a terrace of houses that three hundred years ago was a centre of life[66] and fashion. Here lived Hortense Duchesse de Mazarin, who dared not marry Charles II. in his days of exile, but flirted with him extensively later, and accepted a pension from him of £4,000 a year, which she spent on riotous entertainments rather than on paying her just rates and debts. Charles, Duke of St. Albans, son of Nell Gwynn and the Merry Monarch, lived here, and so did Mary Astell, the Suffragette of her times, whose advanced views found little favour with the wits at the Don Saltero or the fashionables of the Court, though serious John Evelyn sees fit to commend her. Dukes and earls and “smart” bishops jostled each other in Paradise Row in the gay Stuart days, then artists, physicians, scientists, and schoolmasters succeeded to the fine old houses with their stately forecourts, and Elizabeth Fry established her “School of Discipline” for homeless and vagabond girls at the corner in 1828. Finally, in 1908 it was swept away, and re-created to meet modern requirements as Royal Hospital Road.

Tite Street turns off towards the river, and holds two buildings of note: Mr. Whistler’s White House, which looks as if it had strayed out of its way from Constantinople, and the Victoria Hospital for Children, a splendid new building, embracing, as its nucleus, Gough House, built by the Earl of Carberry in Charles II.’s time. Sir Richard Gough, who succeeded the Earl, gave it its name. The hospital is an unspeakable boon to the poor of the district; it has seventy beds, and a very extensive out-patients’ department, as well as a convalescent home at Broadstairs. Visitors can visit it daily between 2 and 4 p.m., and all parents must owe it their gratitude for its devotion to the cause of all children in illness.

The Physick Garden entrance faces Swan Walk, and a ring at the resounding bell in the wall will bring an answering gardener, who will admit the inquiring visitor; but it is generally understood that such visits are made for reasons of botanical or scientific research.

There is no fee, but visitors sign their names in the register, and, if I am not mistaken, enter the object of their special study. The garden, presented by Sir Hans Sloane to the Apothecaries Company, is mainly designed for the use and assistance of students of medicine and botany. All the plants grown in it have their medicinal value. Only one of the Lebanon cedars planted in 1683 remains.

Linnæus, Sir Joseph Banks, Mrs. Elizabeth Blackwell (the “better horse” of the luckless Alexander Blackwell, who dwelt in Swan Walk and would never have written his Herbal without “the grey mare’s” clever assistance), Philip Miller, of the Gardeners’ Dictionary, all loved the Physick Garden, and used it as Sir Hans intended.

The old houses in Swan Walk—four or five in number—are all beautiful in their stately proportions and mellow colouring.

The “Old Swan Inn,” a hostel for country junketings in Pepys’s time, stood on the waterside till the Embankment came to Chelsea. It was the goal for Doggett’s watermen’s race, still rowed on August 1 in commemoration of the Protestant Succession. This year, 1914, it will celebrate its 200th anniversary. The “Coat and Badge” (the latter the silver token of the White Horse of Hanover) were annually held by the victor, and a couple of guineas accrued to him as well from the loyal Irish Orangemen’s pockets. Wentworth House, on the Embankment, now occupies the site, and the “Old Paradise Wharf and Stairs” were just beyond.

And now, whether we walk by the Embankment or by the parallel road, we reach the grounds of the Royal Hospital—that most perfect work of Sir Christopher Wren, which, oddly enough, Chelsea people still persist in calling “Controversy College,” Archbishop Laud’s name for it when James I. tried to coax it into a sort of theological academy. If you ask your way to the Royal Hospital, you will invariably be corrected, and “the College” substituted, and why the name remains is a Chelsea mystery.

Nell Gwynn’s part in its foundation as an asylum for old soldiers may be a myth, but is as certain to live as the Hospital to stand. “What is this? King Charles’s Hospital?” and its pretty rejoinder, “And Nelly’s pleasure house,” was almost the most popular quotation of our Chelsea Pageant in June 1908.

Every 29th of May King Charles’s statue is wreathed with oak, and the pensioners get double rations of beef and plum pudding, and if you fall into conversation with one of the red-coated old soldiers in the hospital gardens, where they love to saunter and watch the nursemaids and the children and the emancipated terriers of a morning, you will find that he is well up in the legend of “poor, pretty Nelly,” and proud of his connection with an institution which is in no sense a charity.

It is impossible here to describe all that is to be seen at Chelsea Hospital, but there is no difficulty in going over it—either with a guide from the secretary’s office on application, or informally by presenting oneself at service at the Chapel on Sundays (11 a.m. and 6.30 p.m.) and glancing into the hall and the kitchens as one passes out through the beautiful colonnade, which gives upon the garden side. The old pensioners are courteous to visitors and love to show all they can. The great staircases leading to the rooms above are worth noticing, and so are the doorways, and the wonderful balance and proportion of the long lines of windows. Restrictions are few, and one is struck by the ease and freedom of the place, as compared with similar institutions in other countries.

In the chapel, the wonderful collection of flags taken in action is worth studying, with the official handbook; perhaps as interesting a study is that of the faces and expressions of the ranks of old soldiers as they sit in orderly rows. The service is not long, though when the preacher allows himself an extra five minutes’ law, I have seen a hand steal tentatively to a coat-pocket, and a before-dinner pipe stealthily prepared under shelter of the pew ledge.