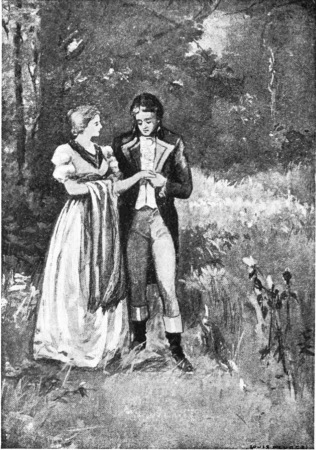

“ ‘I shall never be able to accept another in his place.’ ”

Title: Monsieur Lecoq, v. 2

Author: Emile Gaboriau

Release date: April 5, 2015 [eBook #48641]

Most recently updated: April 1, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

|

Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text. Contents (etext transcriber's note) |

VOL. II

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH OF

EMILE GABORIAU

———

PEARSON’S LIBRARY EDITION

“Monsieur Lecoq” Vol. 1 “Monsieur Lecoq” Vol. 2

“The Gilded Clique” “The Lerouge Case”

“In Peril of His Life”

“File 113”

———

Illustrated

THE PEARSON PUBLISHING CO.

NEW YORK

THE cottage where M. Lacheneur had taken refuge stood on a hill overlooking the river. It was a small and humble dwelling, though scarcely so miserable in its aspect and appointments as most of peasant abodes round about. It comprised a single storey divided into three rooms and roofed with thatch. In front was a tiny garden, where a vine straggling over the walls of the house, a few fruit-trees, and some withered vegetables just managed to exist. Small as was this garden patch, and limited as was its production, still Lacheneur’s aunt, to whom the dwelling had formerly belonged, had only succeeded in conquering the natural sterility of the soil after long years of patient perseverance. Day after day, during a lengthy period, she had regularly spread in front of the cottage three or four basketfulls of arable soil brought from a couple of miles distant; and though she had been dead for more than a twelvemonth, one could still detect a narrow pathway across the waste, worn by her patient feet in the performance of this daily task.

This was the path which M. d’Escorval, faithful to his resolution, took the following day, in the hope of obtaining from Marie-Anne’s father some explanation of his singular conduct. The baron was so engrossed in his own thoughts that he failed to realise the excessive heat as he climbed the rough hillside in the full glare of the noonday sun. When he reached the summit, however, he paused to take breath; and while wiping the perspiration from his brow, turned to look back on the valley whence he had come. It was the first time he had visited the spot, and he was surprised at the extent of the landscape offered to his view. From this point, the most elevated in the surrounding country, one can survey the course of the Oiselle for many miles; and in the distance a glimpse may be obtained of the ancient citadel of Montaignac, perched on an almost inaccessible rock. A man in the baron’s mood could, however, take but little interest in the picturesqueness of the scenery, though, when he turned his back to the valley and prepared to resume his walk, he was certainly struck by the aspect of Lacheneur’s new abode. His imagination pictured the sufferings of this unfortunate man, who, only two days before, had relinquished the splendours of the Chateau du Sairmeuse to resume the peasant life of his early youth.

“Come in!” cried a female voice when M. d’Escorval rapped at the door of the cottage. He lifted the latch, and entered a small room with white-washed walls, having no other ceiling than the thatched roof, and no other flooring than the bare ground. A table with a wooden bench on either side stood in the middle of this humble chamber, in one corner of which was an old bedstead. On a stool near the narrow casement sat Marie-Anne, working at a piece of embroidery, and clad in a peasant-girl’s usual garb.

At the sight of M. d’Escorval, she rose to her feet, and for a moment they remained standing in front of one another, she apparently calm, he visibly agitated. Lacheneur’s daughter was paler than usual, she seemed even thinner, but there was a strange, touching charm about her person; the consciousness of duty nobly fulfilled, of resignation calling for accomplishment, lending, as it were, a new radiance to her beauty.

Remembering his son, M. d’Escorval was surprised at Marie-Anne’s tranquillity. “You don’t inquire after Maurice,” he said, with a touch of reproachfulness in his voice.

“I had news of him this morning, as I have had every day,” quietly replied Marie-Anne. “I know that he is getting better, and that he was able to take some food yesterday.”

“You have not forgotten him, then?”

She trembled; a faint blush suffused her cheeks and forehead, but it was in a calm voice that she replied: “Maurice knows that it would be impossible for me to forget him, even if I wished to do so.”

“And yet you told him that you approved your father’s decision!”

“Yes, I told him so; and I shall have the courage to repeat it.”

“But you have made Maurice most wretched and unhappy, my dear child; he almost died of grief.”

She raised her head proudly, looked M. d’Escorval fully in the face and answered, “Do you think then that I haven’t suffered myself?”

M. d’Escorval was abashed for a moment; but speedily recovering himself, he took hold of Marie-Anne’s hand and, pressing it affectionately, exclaimed: “So Maurice loves you, and you love him; you are both suffering: he has nearly died of grief and still you reject him!”

“It must be so, sir.”

“You say this, my dear child—you say this, and you undoubtedly believe it. But I, who have sought to discover the necessity of this immense sacrifice, have quite failed to find any plausible reason. Explain to me why it must be so, Marie-Anne. Have you no confidence in me? Am I not an old friend? It may be that your father in his despair has adopted extreme resolutions. Let me know them and we will conquer them together. Lacheneur knows how deeply I am attached to him. I will speak to him: he will listen to me.”

“I can tell you nothing, sir.”

“What! you remain inflexible when a father entreats you to assist him, when he says to you: ‘Marie-Anne, you hold my son’s happiness, life, and reason in your hands. Can you be so cruel——’ ”

“Ah! it is you who are cruel, sir,” answered Marie-Anne with tears glittering in her eyes; “it is you who are without pity. Cannot you see what I suffer? No, I have nothing to tell you; there is nothing you can say to my father. Why try to unnerve me when I require all my courage to struggle against my despair? Maurice must forget me; he must never see me again. This is fate; and he must not fight against it. It would be folly. Beseech him to leave the country, and if he refuses, you, who are his father, must command him to do so. And you too, in heaven’s name fly from us. We shall bring misfortune upon you. Never return here; our house is accursed. The fate that overshadows us may ruin you as well.”

She spoke almost wildly, and her voice was so loud that it reached an adjoining room, the door of which suddenly opened, M. Lacheneur appearing upon the threshold. At the sight of M. d’Escorval the whilom lord of Sairmeuse could not restrain an oath; but there was more sorrow and anxiety than anger in his manner, as he said: “What, you here, baron?”

The consternation into which Marie-Anne’s words had thrown M. d’Escorval was so intense that he could only just manage to stammer a reply. “You have abandoned us entirely; I was anxious about you. Have you forgotten your old friendship? I come to you——”

“Why did you not inform me of the honour that the baron had done me, Marie-Anne?” said Lacheneur sternly.

She tried to speak, but could not; and it was the baron who replied; “Why, I have but just arrived, my dear friend.”

M. Lacheneur looked suspiciously, first at his daughter and then at the baron. His brow was overcast as he was evidently wondering what M. d’Escorval and Marie-Anne had said to each other whilst they were alone. Still, however great his disguise may have been, he seemed to master it; and it was with his old-time affability of manner that he invited M. d’Escorval to follow him into the adjoining room. “It is my reception room and study combined,” he said smilingly.

This room, although much larger than the first, was, however, quite as scantily furnished, but piled up on the floor and table were a number of books and packages, which two men were busy sorting and arranging. One of these men was Chanlouineau, whom M. d’Escorval at once recognized, though he did not remember having ever seen the other one, a young fellow of twenty or thereabouts. With the latter’s identity he was, however, soon made acquainted.

“This is my son, Jean,” said Lacheneur. “He has changed since you last saw him ten years ago.”

It was true. Fully ten years had elapsed since the baron last saw Lacheneur’s son. How time flies! He had known Jean as a boy and he now found him a man. Young Lacheneur was just in his twenty-first year, but with his haggard features and precocious beard he looked somewhat older. He was tall and well built, and his face indicated more than average intelligence. Still he did not convey a favorable impression. His restless eyes betokened a prying curiosity of mind, and his smile betrayed an unusual degree of shrewdness, amounting almost to cunning. He made a deep bow when his father introduced him; but he was evidently out of temper.

“Having no longer the means to keep Jean in Paris,” resumed M. Lacheneur, “I have made him return as you see. My ruin will, perhaps, prove a blessing to him. The air of great cities is not good for a peasant’s son. Fools that we are, we send our children to Paris that they may learn to rise above their fathers. But they do nothing of the kind. They think only of degrading themselves.”

“Father,” interrupted the young man; “father, wait at least until we are alone!”

“M. d’Escorval is not a stranger,” retorted M. Lacheneur, and then turning again to the baron, he continued; “I must have wearied you by telling you again and again; ‘I am very pleased with my son. He has a commendable ambition; he is working faithfully and is bound to succeed.’ Ah! I was a poor foolish father! The friend whom I commissioned to call on Jean and tell him to return here has enlightened me as to the truth. The model young man you see here only left the gaming-house to run to some public ball. He was in love with a wretched little ballet girl at some low theatre; and to please this creature, he also went on the stage with his face painted red and white.”

“It’s not a crime to appear on the stage,” interrupted Jean with a flushed face.

“No; but it is a crime to deceive one’s father and to affect virtues one doesn’t possess! Have I ever refused you money? No; and yet you have got into debt on all sides. You owe at least twenty thousand francs!”

Jean hung his head; he was evidently angry, but he feared his father.

“Twenty thousand francs!” repeated M. Lacheneur. “I had them a fortnight ago; now I haven’t a halfpenny. I can only hope to obtain this sum through the generosity of the Duke or the Marquis de Sairmeuse.”

The baron uttered an exclamation of surprise. He only knew of the scene at the parsonage and believed that there would be no further connection between Lacheneur and the duke’s family. Lacheneur perceived M. d’Escorval’s amazement, and it was with every token of sincerity and good faith that he resumed: “What I say astonishes you. Ah! I understand why. My anger at first led me to indulge in all sorts of absurd threats. But I am calm now, and realize my injustice. What could I expect the duke to do? To make me a present of Sairmeuse? He was a trifle brusque, I confess, but that is his way; at heart he is the best of men.”

“Have you seen him again?”

“No; but I have seen his son. I have even been with him to the chateau to select the articles which I desire to keep. Oh! he refused me nothing. Everything was placed at my disposal—everything. I selected what I wanted, furniture, clothes, linen. Everything is to be brought here; and I shall be quite a great man.”

“Why not seek another house? This——”

“This pleases me. Its situation suits me perfectly.”

In fact, after all, thought M. d’Escorval, why should not the Sairmeuse’s have regretted their odious conduct? And if they had done so might not Lacheneur, in spite of indignation, agree to accept honourable conditions?

“To say that the marquis has been kind is saying too little,” continued Lacheneur. “He has shown us the most delicate attentions. For example, having noticed how much Marie-Anne regrets the loss of her flowers, he has promised to send her plants to stock our small garden, and they will be renewed every month.”

Like all passionate men, M. Lacheneur overdid his part. This last remark was too much; it awakened a terrible suspicion in M. d’Escorval’s mind. “Good heavens!” he thought, “does this wretched man meditate some crime?” He glanced at Chanlouineau, and his anxiety increased, for on hearing Lacheneur speak of the marquis and Marie-Anne, the stalwart young farmer had turned livid.

“It is decided,” resumed Lacheneur with an air of unbounded satisfaction, “that they will give me the ten thousand francs bequeathed to me by Mademoiselle Armande. Moreover, I am to fix upon such a sum as I consider a just recompense for my services. And that is not all: they have offered me the position of manager at Sairmeuse; and I was to be allowed to occupy the game-keeper’s cottage, where I lived so long. But on reflection I refused this offer. After having enjoyed a fortune which did not belong to me during so many years, I am now anxious to amass a fortune of my own.”

“Would it be indiscreet in me to inquire what you intend to do?”

“Not the least in the world. I am going to turn pedlar.”

M. d’Escorval could not believe his ears. “Pedlar?” he repeated.

“Yes, M. le Baron. Look, there is my pack in that corner.”

“But that’s absurd,” exclaimed M. d’Escorval. “People can scarcely earn their daily bread in this way!”

“You are wrong, sir. I have considered the subject carefully; the profits are thirty per cent. And besides, there will be three of us to sell the goods, for I shall confide one pack to my son, and another to Chanlouineau.”

“What! Chanlouineau?”

“He has become my partner in the enterprise.”

“And his farm—who will take care of that?”

“He will employ day labourers.” And then, as if wishing to make M. d’Escorval understand that his visit had lasted quite long enough, Lacheneur began arranging such of the little packages as were intended for his own pack.

But the baron was not to be got rid of so easily, especially now that his suspicions had almost ripened into certainty. “I must speak with you alone,” he said in a curt tone.

M. Lacheneur turned round. “I am very busy,” he replied with evident reluctance of manner.

“I only ask for five minutes. But if you haven’t the time to spare to-day, I can return to-morrow—the day after to-morrow—or any day when I can see you in private.”

Lacheneur saw plainly that it would be impossible to escape this interview, so with a gesture of a man who resigns himself to a necessity, he bade his son and Chanlouineau withdraw.

They left the room, and as soon as the door had closed behind them, Lacheneur exclaimed: “I know very well, M. le Baron, the arguments you intend to advance; and the reason of your coming. You come to ask me again for Marie-Anne. I know that my refusal has nearly killed Maurice. Believe me, I have suffered cruelly at the thought; but my refusal is none the less irrevocable. There is no power in the world capable of changing my resolution. Don’t ask my motives; I cannot reveal them; but rest assured that they are sufficiently weighty.”

“Are we not your friends?” asked M. d’Escorval.

“You—!” exclaimed Lacheneur with affectionate cordiality—”ah! You know it well!—you are the best, the only friends I have here below. I should be the greatest wretch living if I did not retain the recollection of your kindness until my eyes close in death. Yes, you are my friends, yes, I am devoted to you—and it is for that very reason, that I answer your proposals with no, no, never!”

There was no longer any room for doubt. M. d’Escorval seized Lacheneur’s hands, and almost crushing them in his grasp, “Unfortunate man!” he exclaimed, “What do you intend to do? Of what terrible vengeance are you dreaming!”

“I swear to you——”

“Oh! do not swear. You cannot deceive a man of my age and of my experience. I divine your intentions—you hate the Sairmeuse family more mortally than ever.”

“I——”

“Yes, you; and if you pretend to forget the way they treated you, it is only that they may forget it. These people have offended you too cruelly not to fear you; you understand this, and you are doing all in your power to reassure them. You accept their advances—you kneel before them—why? Because they will be more completely in your power when you have lulled their suspicions to rest; and then you can strike them more surely—”

He paused; the door of the front room opened, and Marie-Anne appeared upon the threshold. “Father,” said she, “Here is the Marquis de Sairmeuse.”

The mention of this name at such a juncture was so ominously significant that M. d’Escorval could not restrain a gesture of surprise and fear. “He dares to come here!” he thought. “What, is he not afraid the very walls will fall and crush him?”

M. Lacheneur cast a withering glance at his daughter. He suspected her of a ruse which might force him to reveal his secret; and for a second his features were distorted by a fit of passionate rage. By an effort, however, he succeeded in regaining his composure. He sprang to the door, pushed Marie-Anne aside, and leaning out exclaimed: “Deign to excuse me, M. le Marquis, if I take the liberty of asking you to wait a moment; I am just finishing some business, and I will be with you in a few minutes.”

Neither agitation nor anger could be detected in his voice; but rather, a respectful deference and a feeling of profound gratitude. Having spoken in this fashion he closed the door again and turned to M. d’Escorval. The baron, still standing with folded arms, had witnessed this scene with the air of a man who distrusts the evidence of his own senses; and yet he understood the meaning of the incident only too well. “So this young man comes here?” he said to Lacheneur.

“Almost every day—not at this hour usually, but a trifle later.”

“And you receive him? You welcome him?”

“Certainly. How can I be insensible to the honour he confers upon me? Moreover, we have subjects of mutual interest to discuss. We are now occupied in legalising the restitution of Sairmeuse. I can also give him much useful information, and many hints regarding the management of the property.”

“And do you expect to make me, your old friend, believe that a man of your superior intelligence is deceived by the excuses the marquis makes for these frequent visits? Look me in the eye, and then tell me, if you dare, that you believe these visits are addressed to you!”

Lacheneur’s glance did not waver. “To whom else could they be addressed?” he inquired.

This obstinate serenity disappointed the baron’s expectations. He could not have received a heavier blow. “Take care Lacheneur,” he said sternly. “Think of the situation in which you place your daughter, between Chanlouineau, who wishes to make her his wife, and M. de Sairmeuse, who hopes to make her—”

“Who hopes to make her his mistress—is that what you mean? Oh, say the word. But what does that matter? I am sure of Marie-Anne.”

M. d’Escorval shuddered. “In other words,” said he, in bitter indignation, “you make your daughter’s honour and reputation your stake in the game you are playing.”

This was too much. Lacheneur could restrain his furious passion no longer. “Well, yes!” he exclaimed, with a frightful oath; “yes, you have spoken the truth. Marie-Anne must be, and will be the instrument of my plans. A man in my situation is free from the considerations by which others are guided. Fortune, friends, life, honour—I have been forced to sacrifice everything. Perish my daughter’s virtue—perish my daughter herself—what do they signify if I can but succeed?”

Never had M. d’Escorval seen Lacheneur so excited. His eyes flashed, and as he spoke, shook his clenched fist wildly in the air, as though he were threatening some miserable enemy. “So you admit it,” exclaimed M. d’Escorval; “you admit that you propose revenging yourself on the Sairmeuse family, and that Chanlouineau is to be your accomplice?”

“I admit nothing,” Lacheneur replied. “Let me reassure you.” Then raising his hand as if to take an oath, he added in a solemn voice: “Before God, who hears my word, by all that I hold sacred in this world, by the memory of the wife I loved and whom I mourn to-day, I swear to you, that I am plotting nothing against the Sairmeuse family; that I have no thought of touching a hair of their heads. I use them only because they are absolutely indispensable to me. They will aid me without injuring themselves.”

For a moment the baron remained silent. He was evidently trying to reconcile Lacheneur’s conflicting utterances. “How can one believe this assurance after your previous avowal?” he evidently enquired.

“Oh, you may refuse to believe me if you choose,” rejoined Lacheneur, who had now regained all his self-possession. “But whether you believe me or not I must decline to speak any further on the subject. I have said too much already. I know that your visit and your questions have been solely prompted by your friendship, and I cannot help feeling both proud and grateful. Still I can tell you no more. The events of the last few days demand that we should separate. Our paths in life lie far apart, and I can only say to you what I said yesterday to the Abbe-Midon. If you are my friend never come here again under any pretext whatever. Even if you hear I am dying, do not come, and should you meet me, turn aside, shun me as you would some deadly pestilence.”

Lacheneur paused, as if expecting some further observation from the baron, but the latter remained silent, reflecting that the words he had just heard were substantially a repetition of what Marie-Anne had previously told him.

“There is still a wiser course you might pursue,” resumed the ex-lord of Sairmeuse, after a brief interval. “Here in the district there is but little chance of your son’s sorrow soon subsiding. Turn which way he will—alas, I know myself, that even the very trees and flowers will remind him of a happier time. So leave this neighborhood, take him with you, and go far away.”

“Ah! how can I do that when Fouche has virtually imprisoned me here!”

“All the more reason why you should listen to my advice. You were one of the emperor’s friends, hence you are regarded with suspicion. You are surrounded by spies, and your enemies are watching for an opportunity to ruin you. They would seize on the slightest pretext to throw you into prison—a letter, a word, an act capable of misconstruction. The frontier is not far off; so I repeat, go and wait in a foreign land for happier times.”

“That I will never do,” said M. d’Escorval proudly. His words and accent showing plainly enough how futile further discussion would be.

“Ah! you are like the Abbe Midon,” sadly rejoined Lacheneur; “you won’t believe me. Who knows how much your coming here this morning may cost you? It is said that no one can escape his destiny. But if some day the executioner lays his hand on your shoulder, remember that I warned you, and don’t curse me for what may happen.”

Lacheneur paused once more, and seeing that even this sinister prophecy produced no impression on the baron, he pressed his hand as if to bid him an eternal farewell, and opened the door to admit the Marquis de Sairmeuse. Martial was, perhaps, annoyed at meeting M d’Escorval; but he nevertheless bowed with studied politeness, and began a lively conversation with M. Lacheneur, telling him that the articles he had selected at the chateau were at that moment on their way.

M. d’Escorval could do no more. It was quite impossible for him to speak with Marie-Anne, over whom Chanlouineau and Jean were both jealously mounting guard. Accordingly, he reluctantly took his leave, and oppressed by cruel forebodings, slowly descended the hill which he had climbed an hour before so full of hope.

What should he say to Maurice? He was revolving this query in his mind and had just reached the little pine grove skirting the waste, when the sound of hurried footsteps behind induced him to look back. Perceiving to his great surprise that the young Marquis de Sairmeuse was approaching and motioning him to stop, the baron paused, wondering what Martial could possibly want of him.

The latter’s features wore a most ingenuous air, as he hastily raised his hat and exclaimed: “I hope, sir, that you will excuse me for having followed you when you hear what I have to say. I do not belong to your party and our doctrines and preferences are very different. Still I have none of your enemies’ passion and malice. For this reason I tell you that if I were in your place I would take a journey abroad. The frontier is but a few miles off; a good horse, a short gallop, and you have crossed it. A word to the wise is—salvation!”

Having thus spoken and without waiting for any reply, Martial abruptly turned and retraced his steps.

“One might suppose there was a conspiracy to drive me away!” murmured M. d’Escorval in his amazement. “But I have good reason to distrust this young man’s disinterestedness.” The young marquis was already far off. Had he been less preoccupied, he would have perceived two figures in the grove—Mademoiselle Blanche de Courtornieu, followed by the inevitable Aunt Medea, had come to play the spy.

THE Marquis de Courtornieu idolised his daughter. This was alike an incontestable and an uncontested fact. When people spoke to him concerning the young lady they invariably exclaimed: “You who adore your daughter—” And in a like manner whenever the marquis spoke of her himself, he always contrived to say: “I who adore Blanche.” In point of fact, however, he would have given a good deal, even a third of his fortune, to get rid of this smiling, seemingly artless girl, who, despite her apparent simplicity, had proved more than a match for him with all his diplomatic experience. Her fancies were legion, and however capricious they chanced to be it was useless to resist them. At one time he had hoped to ward his daughter off by inviting Aunt Medea to come and live at the chateau, but the weak-minded spinster had proved a most fragile barrier, and soon Blanche had returned to the charge more audacious and capricious than ever. Sometimes the marquis revolted, but nine times out of ten he paid dearly for his attempts at rebellion. When Blanche turned her cold, steel-like eyes upon him with a certain peculiar expression, his courage evaporated. Her weapon was irony; and knowing his weak points she dealt her blows with wonderful precision.

Such being the position of affairs, it is easy to understand how devoutly M. de Courtornieu prayed and hoped that some eligible young aristocrat would ask for his daughter’s hand, and thus free him from bondage. He had announced on every side that he intended to give her a dowry of a million francs, a declaration which had brought a host of eager suitors to Courtornieu. But, unfortunately, though many of these wooers would have suited the marquis well enough, not one had been so fortunate as to please the capricious Blanche. Her father presented a candidate; she received him graciously, lavished all her charms upon him; but as soon as his back was turned, she disappointed all her father’s hopes by rejecting him. “He is too short, or too tall. His rank is not equal to ours. He is a fool—his nose is so ugly.” Such were the reasons she would give for her refusal; and from these summary decisions there was no appeal. Arguments and persuasion were alike useless. The condemned man had only to take himself off and be forgotten.

Still, as this inspection of would-be husbands amused the capricious Blanche, she encouraged her father in his efforts to find a suitor. Despite all his perseverance, however, to please her, the poor marquis was beginning to despair, when fate dropped the Duke de Sairmeuse and his son at his very door. At sight of Martial he had a presentiment that the rara avis he was seeking was found at last; and believing best to strike the iron while it was hot, he broached the subject to the duke on the morrow of their first meeting. M. de Courtornieu’s overtures were favourably received, and the matter was soon decided. Indeed, having the desire to transform Sairmeuse into a principality, the duke could not fail to be delighted with an alliance with one of the oldest and wealthiest families in the neighbourhood. “Martial, my son,” he said, “Possesses in his own right, an income of at least six hundred thousand francs.”

“I shall give my daughter a dowry of at least—yes, at least fifteen hundred thousand,” replied M. de Courtornieu.

“His majesty is favourably disposed towards me,” resumed his grace. “I can obtain any important diplomatic position for Martial.”

“In case of trouble,” was the retort, “I have many friends among the opposition.”

The treaty was thus concluded; but M. de Courtornieu took good care not to speak of it to his daughter. If he told her how much he desired the match, she would be sure to oppose it. Non-intervention accordingly seemed advisable. The correctness of his policy was soon fully demonstrated. One morning Blanche entered her father’s study and peremptorily declared, “Your capricious daughter has decided, papa, that she would like to become the Marchioness de Sairmeuse.”

It cost M. de Courtornieu quite an effort to conceal his delight; but he feared that if Blanche discovered his satisfaction the game would be lost. Accordingly, he presented several objections, which were quickly disposed of; and, at last, he ventured to opine: “Then the marriage is half decided as one of the parties consents. It only remains to ascertain if—”

“The other will consent,” retorted the vain heiress; who, it should be remarked, had for several days previously been assiduously engaged in the agreeable task of fascinating Martial and bringing him to her feet. With a skilful affectation of simplicity and frankness, she had allowed the young marquis to perceive that she enjoyed his society, and without being absolutely forward she had made him evident advances. Now, however, the time had come to beat a retreat—a manœuvre so successfully practised by coquettes, and which usually suffices to enslave even a hesitating suitor. Hitherto, Blanche had been gay, spiritual, and coquettish; now she gradually grew quiet and reserved. The giddy school girl had given place to a shrinking maiden; and it was with rare perfection that she played her part in the divine comedy of “first love.” Martial could not fail to be fascinated by the modest timidity and chaste fears of a virgin heart now awaking under his influence to a consciousness of the tender passion. Whenever he made his appearance Blanche blushed and remained silent. Directly he spoke she grew confused; and he could only occasionally catch a glimpse of her beautiful eyes behind the shelter of their long lashes. Who could have taught her this refinement of coquetry? Strange as it may seem, she had acquired her acquaintance with all the artifices of love during her convent education.

One thing she had not learnt, however, that clever as one may be, one is ofttimes duped by one’s own imagination. Great actresses so enter into the spirit of their part that they frequently end by shedding real tears. This knowledge came to Blanche one evening when a bantering remark from the Duke de Sairmeuse apprised her of the fact that Martial was in the habit of going to Lacheneur’s house every day. She had previously been annoyed at the young marquis’s admiration of Marie-Anne, but now she experienced a feeling of real jealousy; and her sufferings were so intolerable that fearing she might reveal them she hurriedly left the drawing-room and hastened to her own room.

“Can it be that he does not love me?” she murmured. She shivered at the thought; and for the first time in her life this haughty heiress distrusted her own power. She reflected that Martial’s position was so exalted that he could afford to despise rank; that he was so rich that wealth had no attractions for him; and that she herself might not be so pretty and so charming as her flatterers had led her to suppose. Still Martial’s conduct during the past week—and heaven knows with what fidelity her memory recalled each incident!—was well calculated to reassure her. He had not, it is true, formally declared himself; but it was evident that he was paying his addresses to her. His manner was that of the most respectful, but the most infatuated of lovers.

Her reflections were interrupted by the entrance of her maid, bringing a large bouquet of roses which Martial had just sent. She took the flowers, and while arranging them in a vase, bedewed them with the first sincere tears she had shed since she was a child.

She was so pale and sad, so unlike herself when she appeared the next morning at breakfast, that Aunt Medea felt alarmed. But Blanche had prepared an excuse, which she presented in such sweet tones that the old lady was as much amazed as if she had witnessed a miracle. M. de Courtornieu was no less astonished, and wondered what new freak it was that his daughter’s doleful face betokened. He was still more alarmed when immediately after breakfast, Blanche asked to speak with him. She followed him into his study, and as soon as they were alone, before he had even had time to sit down she entreated him to tell her what had passed between the Duke de Sairmeuse and himself; she wished to know if Martial had been informed of the intended alliance, and what he had replied. Her voice was meek, her eyes tearful; and her manner indicated the most intense anxiety.

The marquis was delighted. “My wilful daughter has been playing with fire,” he thought, stroking his chin caressingly; “and upon my word she has scorched herself.” Then with a smile on his face he added aloud. “Yesterday, my child, the Duke de Sairmeuse formally asked for your hand on his son’s behalf; and your consent is all that is lacking. So rest easy, my beautiful lovelorn damsel—you will be a duchess.”

She hid her face in her hands to conceal her blushes. “You know my decision, father,” she faltered in an almost inaudible voice; “we must make haste.”

He started back thinking he had not heard her words aright. “Make haste!” he repeated.

“Yes, father. I have fears.”

“What fears, in heaven’s name?”

“I will tell you when everything is settled,” she replied, at the same time making her escape from the room.

She did not doubt the reports which had reached her concerning Martial’s frequent visits to Marie-Anne, still she wished to ascertain the truth for herself. Accordingly, on leaving her father, she told Aunt Medea to dress herself, and without vouchsafing a single word of explanation, took her with her to the Reche and stationed herself in the pine grove so as to command a view of M. Lacheneur’s cottage.

It chanced to be the very day when M. d’Escorval called on Marie-Anne’s father, in hopes of obtaining some definite explanation of his conduct. Blanche saw the baron climb the slope, and shortly afterwards Martial followed the same route. She had been rightly informed; there was no room for further doubt, and her first impulse was to return home. But on reflection she resolved to wait and ascertain how long the Marquis remained with this girl she hated. M. d’Escorval’s visit was a brief one, and scarcely had he left the cottage than she saw Martial hasten out after him, and speak to him. She breathed again.

The marquis had only made a brief call, perhaps, on some matter of business, and no doubt, like M. d’Escorval, he was now going home again. Not at all, however, after a moment’s conversation with the baron, Martial returned to the cottage.

“What are we doing here?” asked Aunt Medea.

“Let me alone! Hold your tongue!” angrily replied Blanche, whose attention had just been attracted by a number of wheels, a tramp of horse’s hoofs, a loud cracking of whips, and a brisk exchange of oaths, such as waggoners in a difficulty usually resort to.

All this racket heralded the approach of the vehicles conveying M. Lacheneur’s furniture and clothes. The noise must have reached the cottage on the slope, for Martial speedily appeared on the threshold, followed by Lacheneur, Jean, Chanlouineau, and Marie-Anne. Every one was soon busy unloading the waggons, and judging from the young marquis’s gestures and manner, it seemed as if he were directing the operation. He was certainly bestirring himself immensely. Hurrying to and fro, talking to everybody, and at times not even disdaining to lend a hand.

“He, a nobleman makes himself at home in that wretched hovel!” quoth Blanche to herself. “How horrible! Ah! I see only too well that this dangerous creature can do what she likes with him.”

All this, however, was nothing compared with what was to come. A third cart drawn by a single horse, and laden with shrubs and pots of flowers soon halted in front of the cottage. At this sight Blanche was positively enraged. “Flowers!” she exclaimed, in a voice hoarse with passion. “He sends her flowers, as he does me—only he sends me a bouquet, while for her he pillages the gardens of Sairmeuse.”

“What are you saying about flowers?” inquired the impoverished relative.

Blanche curtly rejoined that she had not made the slightest allusion to flowers. She was suffocating; and yet she obstinately refused to leave the grove, and go home as Aunt Medea repeatedly suggested. No; she must see the finish, and although a couple of hours were spent in unloading the furniture, still she lingered with her eyes fixed on the cottage and its surroundings. Some time after the empty waggons had gone off, Martial re-appeared on the threshold, Marie-Anne was with him, and they remained talking in full view of the grove where Blanche and her chaperone were concealed. For a long while it seemed as if the young marquis could not promptly make up his mind to leave, and when he did so, it was with evident reluctance that he slowly walked away. Marie-Anne still standing on the door-step waved her hand after him with a friendly gesture of farewell.

The young marquis was scarcely out of sight when Blanche turned to her aunt and hurriedly exclaimed: “I must speak to that creature; come quick!” Had Marie-Anne been within speaking distance at that moment, she would certainly have learnt the cause of her former friend’s anger and hatred. But fate willed it otherwise. Three hundred yards of rough ground intervened between the two; and in crossing this space Blanche had time enough to reflect.

She soon bitterly regretted having shown herself at all. But Marie-Anne, who was still standing on the threshold of the cottage had seen her approaching, and it was consequently quite impossible to retreat. She accordingly utilized the few moments still at her disposal in recovering her self-control, and composing her features; and she had her sweetest smile on her lips when she greeted the girl who she had styled “that creature,” only a few minutes previously. Still she was embarrassed, scarcely knowing what excuse to give for her visit, hence with the view of gaining time she pretended to be quite out of breath. “Ah! It is not very easy to reach you, dear Marie-Anne,” she said at last; “you live on the top of a perfect mountain.”

Mademoiselle Lacheneur did not reply. She was greatly surprised, and did not attempt to conceal the fact.

“Aunt Medea pretended to know the road,” continued Blanche; “but she led me astray. Didn’t you aunt?”

As usual the impecunious relative assented, and her niece resumed: “But at last we are here. I couldn’t resign myself to hearing nothing about you, my dear, especially after all your misfortunes. What have you been doing? Did my recommendation procure you the work you wanted?”

Marie-Anne was deeply touched by the kindly interest which her former friend displayed in her welfare, and with perfect frankness, she confessed that all her efforts had been fruitless. It had even seemed to her that several ladies had taken pleasure in treating her unkindly.

Blanche was not listening, however. Close by stood the flowers brought from Sairmeuse; and there perfume rekindled her anger. “At all events,” she interrupted, “you have something here which will almost make you forget the gardens of Sairmeuse. Who sent you those beautiful flowers?”

Marie-Anne turned crimson. For a moment she did not speak, but at last she stammered: “They are a mark of attention from the Marquis de Sairmeuse.”

“So she confesses it!” thought Mademoiselle de Courtornieu, amazed at what she was pleased to consider an outrageous piece of impudence. But she succeeded in concealing her rage beneath a loud burst of laughter; and it was in a tone of raillery that she rejoined: “Take care, my dear friend, I am going to call you to account. You are accepting flowers from my fiance.”

“What, the Marquis de Sairmeuse!”

“Yes, he has asked for my hand; and my father has promised it to him. It is a secret as yet; but I see no danger in confiding in your friendship.”

Blanche really believed that this information would crush her rival; but though she watched her closely, she failed to detect the slightest trace of emotion in her face. “What dissimulation!” thought the heiress, and then with affected gaiety, she resumed aloud: “And the country folks will see two weddings at about the same time, since you are going to be married as well, my dear.”

“I married?”

“Yes, you—you little deceiver! Everybody knows that you are engaged to a young man in the neighbourhood, named—wait, I know—Chanlouineau.”

Thus the report which annoyed Marie-Anne so much reached her from every side. “Everybody is for once mistaken,” she replied energetically. “I shall never be that young man’s wife.”

“But why? People speak well of him personally, and he is very well off.”

“Because,” faltered Marie-Anne; “because——” Maurice d’Escorval’s name trembled on her lips; but unfortunately she did not give it utterance. She was as it were abashed by a strange expression on Blanche’s face. How often one’s destiny depends on such an apparently trivial circumstance as this!

“What an impudent worthless creature!” thought Blanche; and then in cold sneering tones that unmistakably betrayed her hatred, she said: “You are wrong, believe me, to refuse such an offer. This young fellow Chanlouineau will at all events save you from the painful necessity of toiling with your own hands, and of going from door to door in quest of work which is refused you. But no matter; I”—she laid great stress upon this word—”I will be more generous than your other old acquaintances. I have a great deal of embroidery to be done. I shall send it to you by my maid, and you two may settle the price together. It’s late now, and we must go. Good-bye, my dear. Come, Aunt Medea.”

So saying, the haughty heiress turned away, leaving Marie-Anne petrified with surprise, sorrow, and indignation. Although less experienced than Blanche, she understood well enough that this strange visit concealed some mystery—but what? She stood motionless, gazing after her departing visitors, when she felt a hand laid gently on her shoulder. She trembled, and turning quickly found herself face to face with her father.

Lacheneur was intensely pale and agitated, and a sinister light glittered in his eyes. “I was there,” said he pointing to the door, “and I heard everything.”

“Father!”

“What! would you try to defend her after she came here to crush you with her insolent good fortune—after she overwhelmed you with her ironical pity and scorn! I tell you they are all like this—these girls, whose heads have been turned by flattery, and who believe that the blood in their veins is different to ours. But patience! The day of reckoning is near at hand!”

He paused. Those whom he threatened would have trembled had they seen him at that moment, so plain it was that he harboured in his mind some terrible design of retributive vengeance.

“And you, my darling, my poor Marie-Anne,” he continued, “you did not understand the insults she heaped upon you. You are wondering why she treated you with such disdain. Ah, well! I will tell you: she imagines that the Marquis de Sairmeuse is your lover.”

Marie-Anne turned as pale as her father, and quivered from head to foot. “Can it be possible?” she exclaimed. “Great God! What shame! What humiliation!”

“Why should it astonish you?” said Lacheneur, coldly. “Haven’t you expected this result ever since the day when, to ensure the success of my plans, you consented to receive the attentions of this marquis, whom you loathe as much as I despise?”

“But Maurice! Maurice will despise me! I can bear anything, yes, everything but that.”

Lacheneur made no reply. Marie-Anne’s despair was heart-rending; he felt that he could not bear to witness it, that it would shake his resolution, and accordingly he re-entered the house.

His penetration was not at fault, in surmising that Blanche’s visit would lead to something new, for biding the time when she might fully revenge herself in a way worthy of her hatred, Mademoiselle de Courtornieu availed herself of a favourite weapon among the jealous—calumny, and two or three abominable stories which she concocted, and which she induced Aunt Medea to circulate in the neighbourhood virtually ruined Marie-Anne’s reputation.

These scandalous reports even came to Martial’s ears, but Blanche was greatly mistaken if she had imagined that they would induce him to cease his visits to Lacheneur’s cottage. He went there more frequently than ever and stayed much longer than he had been in the habit of doing before. Dissatisfied with the progress of his courtship, and fearful that he was being duped, he even watched the house. And then one evening, when the young marquis was quite sure that Lacheneur, his son, and Chanlouineau were absent, it so happened that he perceived a man leave the cottage, descend the slope and hasten across the fields. He followed in pursuit, but the fugitive escaped him. He believed, however, that he had recognized Maurice d’Escorval.

WHEN Maurice narrated to his father the various incidents which had marked his interview with Marie-Anne in the pine grove near La Reche, M. d’Escorval was prudent enough to make no allusion to the hopes of final victory which he, himself, still entertained. “My poor Maurice,” he thought, “is heart-broken, but resigned. It is better for him to remain without hope than to be exposed to the danger of another possible disappointment.”

But passion is not always blind, and Maurice divined what the baron tried to conceal—and clung to this faint hope in his father’s intervention, as tenaciously as a drowning man clings to the proverbial straw. If he refrained from speaking on the subject, it was only because he felt convinced that his parents would not tell him the truth. Still he watched all that went on in the house with that subtlety of penetration which fever so often imparts, and nothing that his father said or did escaped his vigilant eyes and ears. He heard the baron put on his boots, ask for his hat, and select a cane from among those placed in the hall stand; and a moment later he, moreover, heard the garden-gate grate upon its hinges. Plainly enough M. d’Escorval was going out. Weak as he was, Maurice succeeded in dragging himself to the window in time to ascertain the truth of his surmise. “If my father is going out,” he thought, “it can only be to visit M. Lacheneur; and if he is going to La Reche he has evidently not relinquished all hope.”

With this thought in his mind Maurice sank into an arm-chair close at hand, intending to watch for his father’s return; by doing so, he might know his fate a few moments sooner. Three long hours elapsed before the baron returned, and by his dejected manner Maurice plainly saw that all hope was lost. Of this, he was sure, as sure as the criminal who reads the fatal verdict in the judge’s solemn face. He required all his energy to regain his couch, and for a moment he felt that he should die. Soon, however, he grew ashamed of this weakness, which he judged unworthy of him, and prompted by a desire to know exactly what had happened he rang the bell, and told the servant who answered his summons that he wished to speak with his father. M. d’Escorval promptly made his appearance.

“Well!” exclaimed Maurice, as his father crossed the threshold of the room.

The baron felt that all denial would be useless. “Lacheneur is deaf to my remonstrances and entreaties,” he replied, sadly. “There is no hope, my poor boy; you must submit. I will not tell you that time will assuage the sorrow that now seems insupportable—for you wouldn’t believe me if I did. But I do say to you be a man, and prove your courage. I will say even more: fight against all thought of Marie-Anne, as a traveller on the brink of a precipice fights against the thought of vertigo.”

“Have you seen Marie-Anne, father? Have you spoken to her?”

“I found her even more inflexible than Lacheneur.”

“They reject me, and yet no doubt they receive Chanlouineau.”

“Chanlouineau is living there.”

“Good heavens! And Martial de Sairmeuse?”

“He is their familiar guest. I saw him there.”

Evidently enough each of these replies fell upon Maurice like a thunderbolt. But M. d’Escorval had armed him self with the imperturbable courage of a surgeon, who only grasps his instrument more firmly when the patient groans and writhes beneath his touch. He felt that it was necessary to extinguish the last ray of hope in his son’s heart.

“It is evident that M. Lacheneur has lost his reason!” exclaimed Maurice.

The baron shook his head despondently. “I thought so myself at first,” he murmured.

“But what does he say in justification of his conduct? He must say something.”

“Nothing: he refuses any explanation.”

“And you, father, with all your knowledge of human nature, with all your wide experience, have not been able to fathom his intentions?”

“I have my suspicions,” M. d’Escorval replied; “but only suspicions. It is possible that Lacheneur, listening to the voice of hatred, is dreaming of some terrible revenge. He may, perhaps, think of organizing some conspiracy against the emigres. Such a supposition would explain everything. Chanlouineau would be his aider and abettor; and he pretends to be reconciled to the Marquis de Sairmeuse in order to obtain information through him—”

The blood had returned to Maurice’s pale cheeks. “Such a conspiracy,” said he, “would not explain M. Lacheneur’s obstinate rejection of my suit.”

“Alas! yes, it would, my poor boy. It is through Marie-Anne that Lacheneur exerts such great influence over Chanlouineau and the marquis. If she became your wife to-day, they would desert him to-morrow. Then, too, it is precisely because he has such sincere regard for us, that he is determined to keep us out of a hazardous, even perilous enterprise. However, of course, this is merely a conjecture.”

“Still, I see that it is necessary to submit,” faltered Maurice. “I must resign myself; forget, I cannot.”

He said this because he wished to reassure his father; though, in reality, he thought exactly the reverse. “If Lacheneur is organizing a conspiracy,” he murmured to himself, “he must need assistance. Why should I not offer mine? If I aid him in his preparations, if I share his hopes and dangers, he cannot refuse me his daughter’s hand. Whatever he may wish to undertake, I can surely be of greater assistance to him than Chanlouineau.”

From that moment Maurice dwelt upon this thought; and the result was that he no longer pined and fretted, but did all he could to hasten his convalescence. This passed so rapidly that the Abbe Midon, who had taken the place of the physician from Montaignac, was positively astonished. Madame d’Escorval was delighted at her son’s wonderful improvement in health and spirits, and declared that she would never have believed he could be so soon and so easily consoled. The baron did not try to diminish his wife’s satisfaction, though he regarded this almost miraculous recovery with considerable distrust, having, indeed, a vague perception of the truth. Skilfully, however, as he questioned his son he could draw nothing from him; for Maurice had decided to keep whatever determinations he had formed a secret even from his parents. What good would it do to trouble them? and, besides, he feared remonstrance and opposition; which he was anxious to avoid although firmly resolved to carry out his plans, even if he were compelled to leave the paternal roof.

One day in the second week of September the abbe declared that Maurice might resume his ordinary life, and that, as the weather was pleasant it would be well for him to spend much of his time in the open air. In his delight, Maurice embraced the worthy priest, at the same time remarking that he had felt afraid the shooting season would pass by without his bagging a single bird. In reality he cared but little for a day on the cover; the partiality he feigned being prompted by the idea that “shooting” would furnish him with an excuse for frequent and protracted absences from home.

He had never felt happier then he did the morning when, with his gun over his shoulder, he crossed the Oiselle and started for M. Lacheneur’s cottage at La Reche. He had just reached the little pine grove, and was about to pause, when he perceived Jean Lacheneur and Chanlouineau leave the house, each laden with a pedlar’s pack. This circumstance delighted him, as he might now expect to find M. Lacheneur and Marie-Anne alone in the cottage.

He hastened up the slope and lifted the door latch without pausing to rap. Marie-Anne and her father were kneeling on the hearth in front of a blazing fire. On hearing the door open, they turned; and at the sight of Maurice, they both sprang to their feet. Lacheneur with a composed look on his face, and Marie-Anne blushing to the roots of her hair. “What brings you here?” they exclaimed in the same breath.

Under other circumstances, Maurice d’Escorval would have been dismayed by such an unengaging greeting, but now he scarcely noticed it.

“You have no business to return here against my wishes, and after what I said to you, M. d’Escorval,” exclaimed Lacheneur, rudely.

Maurice smiled, he was perfectly cool, and not a detail of the scene before him had escaped his notice. If he had felt any doubts before, they were now dispelled. On the fire he saw a large cauldron of moulten lead, while several bullet-moulds stood on the hearth, besides the andirons.

“If, sir, I venture to present myself at your house,” said young d’Escorval in a grave, impressive voice, “it is because I know everything. I have discovered your revengeful projects. You are looking for men to aid you, are you not? Very well! look me in the face, in the eyes, and tell me if I am not one of those a leader is glad to enrol among his followers?”

Lacheneur seemed terribly agitated. “I don’t know what you mean,” he faltered, forgetting his feigned anger; “I have no such projects as you suppose.”

“Would you assert this upon oath? If so, why are you casting those bullets? You are clumsy conspirators. You should lock your door; some one else might have opened it.” And adding example to precept, he turned and pushed the bolt. “This is only an imprudence,” he continued: “but to reject a willing volunteer would be a mistake for which your associates would have a right to call you to account. Pray understand that I have no desire to force myself into your confidence. Whatever your cause may be, I declare it mine; whatever you wish, I wish; I adopt your plans; your enemies are my enemies; command me and I will obey you. I only ask one favour, that of fighting, conquering, or dying by your side.”

“Oh! father refuse him!” exclaimed Marie-Anne, “refuse him! It would be a crime to accept his offer.”

“A crime! And why, if you please?” asked Maurice.

“Because our cause is not your cause; because its success is doubtful; because dangers surround us on every side.”

Maurice interrupted her with a cry of scorn. “And you think to dissuade me,” said he, “by warning one of the dangers which you a girl can yet afford to brave. You cannot think me a coward! If peril threatens you, all the more reason to accept my aid. Would you desert me if I were menaced, would you hide yourself, saying, ‘Let him perish, so that I be saved!’ Speak! would you do this?”

Marie-Anne averted her face and made no reply. She could not force herself to utter an untruth; and on the other hand she was unwilling to answer: “I would act as you are acting.” She prudently waited for her father’s decision.

“If I complied with your request, Maurice,” said M. Lacheneur, “in less than three days you would curse me, and ruin us by some outburst of anger. Loving Marie-Anne as you do, you could not behold her equivocal position unmoved. Remember, she must neither discourage Chanlouineau nor the marquis. I know as well as you do that the part is a shameful one; and that it must result in the loss of a girl’s most precious possession—her reputation; still, to ensure our success, it must be so.”

Maurice did not wince. “So be it,” he said calmly. “Marie-Anne’s fate will be that of all women who have devoted themselves to the political cause of the man they love, be he father, brother, or lover. She will be slandered and insulted, and still what does it matter! Let her continue her task. I consent to it, for I shall never doubt her, and I shall know how to hold my peace. If we succeed, she shall be my wife, if we fail—” The gesture with which young d’Escorval concluded his sentence expressed more strongly than any verbal protestations that come what might he was ready and resigned.

Lacheneur seemed deeply moved. “At least give me time for reflection,” said he.

“There is no necessity, sir, for further reflection.”

“But you are only a child, Maurice; and your father is my friend.”

“What of that?”

“Rash boy! don’t you understand that by compromising yourself you also compromise the Baron d’Escorval? You think you are only risking your own head, but you are also endangering your father’s life—”

“Oh, there has been too much parleying already!” interrupted Maurice, “there have been too many remonstrances. Answer me in a word! Only understand this: if you refuse, I shall immediately return home and blow out my brains.”

It was plain from the young man’s manner that this was no idle threat. The strange fire gleaming in his eyes, and the impressive tone of his voice, convinced both his listeners that he really intended to effect his deadly purpose; and Marie-Anne, with a heart full of cruel apprehensions, clasped her hands and turned to her father with a pleading look.

“You are one of us, then,” sternly exclaimed Lacheneur after a brief pause; “but do not forget that your threats alone induced me to consent; and whatever may happen to you or yours, remember that you would have it so.”

These gloomy words, ominous as they were, produced, however, no impression upon Maurice, who, feverish with anxiety a moment before, was now well-nigh delirious with joy.

“At present,” continued Lacheneur, “I must tell you my hopes, and acquaint you with the cause for which I am toiling—”

“What does that matter to me?” replied Maurice gaily; and springing towards Marie-Anne he seized her hand and raised it to his lips, crying, with the joyous laugh of youth: “Here is my cause—none other!”

Lacheneur turned aside. Perhaps he remembered that a sacrifice of his own obstinate pride would suffice to assure his daughter’s and her lover’s happiness.

Still if a feeling of remorse crept into his mind, he swiftly banished it, and with increased sternness of manner exclaimed: “It is necessary, however, that you should understand our agreement.”

“Let me know your conditions, sir,” said Maurice.

“First of all your visits here—after certain rumours that I have circulated—would arouse suspicion. You must only come here at night time, and then only at hours agreed upon in advance—never when you are not expected.” Lacheneur paused, and then seeing that Maurice’s attitude implied unreserved consent, he added: “You must also find some way to cross the river without employing the ferryman, who is a dangerous fellow.”

“We have an old skiff; I will persuade my father to have it repaired.”

“Very well. Will you also promise me to avoid the Marquis de Sairmeuse?”

“I will.”

“Wait a moment—we must be prepared for any emergency. Perhaps in spite of our precautions you may meet him here. M. de Sairmeuse is arrogance itself; and he hates you. You detest him, and you are very hasty. Swear to me that if he provokes you, you will ignore his insults.”

“But I should be considered a coward.”

“Probably; but will you swear?”

Maurice was hesitating when an imploring look from Marie-Anne decided him. “I swear it!” he said gravely.

“As far as Chanlouineau is concerned it would be better not to let him know of our agreement; but I will see to that point myself.” Lacheneur paused once more and reflected for a moment whether he had left anything forgotten. “All that remains, Maurice,” he soon resumed, “is to give you a last and very important piece of advice. Do you know my son?”

“Certainly; we were formerly the best of friends when we met during the holidays.”

“Very well. When you know my secret—for I shall confide it to you without reserve—beware of Jean.”

“What, sir?”

“Beware of Jean. I repeat it.” And Lacheneur’s face flushed as he added: “Ah! it is a painful avowal for a father; but I have no confidence in my own son. He knows no more of my plans than I told him on the day of his arrival. I deceive him, because I fear he might betray us. Perhaps it would be wise to send him away; but in that case, what would people say? Most assuredly they would say that I wanted to save my own blood, while I was ready to risk the lives of others. Still I may be mistaken; I may misjudge him.” He sighed, and again added: “Beware!”

It will be understood from the foregoing that it was really Maurice d’Escorval whom the Marquis de Sairmeuse perceived leaving Lacheneur’s cottage on the night he played the spy. Martial was not positively certain of the fugitive’s identity, but the very idea made his heart swell with anger. “What part am I playing here, then?” he exclaimed indignantly.

Passion had hitherto so completely blinded him that even if no pains had been taken to deceive him, he would probably have remained in blissful ignorance of the true condition of affairs. He fully believed in the sincerity of Lacheneur’s formal courtesy and politeness and of Jean’s studied respect; while Chanlouineau’s almost servile obsequiousness did not surprise him in the least. And since Marie-Anne welcomed him cordially he had concluded that his suit was favourably progressing. Having himself forgotten the incidents which marked the return of his family to Sairmeuse, he concluded that every one else had ceased to remember them. Moreover, he was of opinion that he had acted with great generosity, and that he was fully entitled to the gratitude of the Lacheneurs; for Marie-Anne’s father had received the legacy bequeathed him by Mademoiselle Armande, with an indemnity for his past services; and in addition he had selected whatever furniture he pleased among the appointments of the chateau. In goods and coin he had been presented with quite sixty thousand francs; and the hard fisted old duke, enraged at such prodigality, although it did not cost him a penny, had discontentedly growled, “He must be hard to please indeed if he is not satisfied with what we’ve done for him.”

Such being the position of affairs, and having for so long supposed that he was the only visitor to the cottage on La Reche, Martial was perfectly incensed when he discovered that such was not the case. Was he, after all, merely a shameless girl’s foolish dupe? So great was his anger, that for more than a week he did not go to Lacheneur’s house. His father concluded that his ill humour was caused by some misunderstanding with Marie-Anne; and he took advantage of this opportunity to obtain his son’s consent to a marriage with Blanche de Courtornieu. Goaded to the last extremity, tortured by doubt and fear, the young marquis eventually agreed to his father’s proposals; and, naturally enough, the duke did not allow such a good resolution to grow cold. In less than forty-eight hours the engagement was made public; the marriage contract was drawn up, and it was announced that the wedding would take place early in the spring. A grand banquet was given at Sairmeuse in honour of the betrothal—a banquet all the more brilliant since there were other victories to be celebrated, for the Duke de Sairmeuse had just received, with his brevet of lieutenant-general, a commission placing him in command of the military district of Montaignac; while the Marquis de Courtornieu had also been appointed provost-marshal of the same region.

Thus it was that Blanche triumphed, for, after this public betrothal, might she not consider that Martial was bound to her? For a fortnight, indeed, he scarcely left her side, finding in her society a charm which almost made him forget his love for Marie-Anne. But, unfortunately, the haughty heiress could not resist the temptation to make a slighting allusion to the lowliness of the marquis’s former tastes; finding, moreover, an opportunity to inform him that she furnished Marie-Anne with work to aid her in earning a living. Martial forced himself to smile; but the disparaging remarks made by his betrothed concerning Marie-Anne aroused his sympathy and indignation; and the result was that the very next day he went to Lacheneur’s house.

In the warmth of the greeting which there awaited him all his anger vanished, and all his suspicions were dispelled. He perceived that Marie-Anne’s eyes beamed with joy on seeing him again, and could not help thinking he should win her yet. All the household were really delighted at his return; as the son of the commander of the military forces at Montaignac, and the prospective son-in-law of the provost-marshal, Martial was bound to prove a most valuable instrument. “Through him, we shall have an eye and an ear in the enemy’s camp,” said Lacheneur. “The Marquis de Sairmeuse will be our spy.”

And such he soon became, for he speedily resumed his daily visits to the cottage. It was now December, and the roads were scarcely passable; but neither rain, snow, nor mud could keep Martial away. He generally made his appearance at ten o’clock in the morning, seated himself on a stool in the shadow of a tall fire-place, and then he and Marie-Anne began to talk by the hour. She always seemed greatly interested in what was going on at Montaignac, and he told her everything he knew, whether it were of a military, political, or social character.

At times they remained alone. Lacheneur, Chanlouineau, and Jean were tramping about the country with their pedlar’s packs. Business was indeed prospering so well that Lacheneur had even purchased a horse in order to extend the circuit of his rounds. But, although the usual occupants of the cottage might be away, it so happened that Martial’s conversation was generally interrupted by visitors. It was indeed really surprising to see how many peasants called at the cottage to speak with M. Lacheneur. They called at all hours and in rapid succession, sometimes alone, and at others in little batches of two or three. And to each of these peasants Marie-Anne had something to say in private. Then she would offer them refreshments; and at times one might have imagined oneself in an ordinary village wine shop. But what can daunt a lover’s courage? Martial endured the peasants and their carouses without a murmur. He laughed and jested with them, shook them by the hand, and at times he even drained a glass in their company.

He gave many other proofs of moral courage. He offered to assist M. Lacheneur in making up his accounts; and once—it happened about the middle of February—seeing Chanlouineau worrying over the composition of a letter, he actually volunteered to act as his amanuensis. “The letter is not for me, but for an uncle of mine who is about to marry his daughter,” said the stalwart young farmer.

Martial took a seat at the table, and at Chanlouineau’s dictation, but not without many erasures, indited the following epistle:

“My dear friend—We are at last agreed, and the marriage is decided on. We are now busy preparing for the wedding, which will take place on —— We invite you to give us the pleasure of your company. We count upon you, and be assured that the more friends you bring with you the better we shall be pleased.”

Had Martial seen the smile upon Chanlouineau’s lips when he requested him to leave the date for the wedding a blank, he would certainly have suspected that he had been caught in a snare. But he did not see it, and, besides, he was in love.

“Ah! marquis,” remarked his father one day, “Chupin tells me you are always at Lacheneur’s. When will you recover from your foolish fancy for that little girl?”

Martial did not reply. He felt that he was at that “little girl’s” mercy. Each glance she gave him made his heart throb wildly. He lingered by her side a willing captive; and if she had asked him to make her his wife he would certainly not have refused. But Marie-Anne had no such ambition. All her thoughts and wishes were for her father’s success.

Maurice and Marie-Anne had become M. Lacheneur’s most intrepid auxiliaries. They were looking forward to such a magnificent reward. Feverish, indeed, was the activity which Maurice displayed! All day long he hurried from hamlet to hamlet, and in the evening, as soon as dinner was over, he made his escape from the drawing-room, sprang into his boat, and hastened to La Reche.

M. d’Escorval could not fail to notice his son’s long and frequent absences. He watched him, and soon discovered that some secret understanding existed between Maurice and Lacheneur. Recollecting his previous suspicion that Lacheneur was harbouring some seditious design he became greatly alarmed for his son’s safety, and decided to go to La Reche and try once more to learn the truth. Previous repulses had diminished his confidence in his own persuasive powers, and being anxious for an auxiliary’s assistance he asked the Abbe Midon to accompany him.

It was the 4th of March, and half-past four in the evening when M. d’Escorval and the cure started from Sairmeuse bound for the cottage at La Reche. They were both anxious as to the result of the step they were taking, and scarcely exchanged a dozen words as they walked towards the banks of the Oiselle. They had crossed the river and traversed the familiar pine grove, when on reaching the outskirts of the waste they witnessed a strange sight well calculated to increase their anxiety and alarm.

Night was swiftly approaching, but yet it was still sufficiently light to distinguish objects at a short distance, and on the summit of the slope they could perceive in front of Lacheneur’s cottage a group of twenty persons who, judging by their frequent gesticulations, were engaged in animated conversation. Lacheneur himself was there, and his manner plainly indicated that he was in a state of great excitement. Suddenly he waved his hand, the others clustered round him, and he began to speak. What was he saying? The baron and the priest were still too far off to distinguish his words, but when he ceased they were startled by a loud acclamation which literally rent the air. Suddenly the former lord of Sairmeuse struck a match, and setting fire to a bundle of straw lying before him he tossed it on to the roof of the cottage, shouting as he did so, “Yes, the die is cast! and this will prove to you that I shall not draw back!”

Five minutes later the house was in flames and in the distance the baron and his companion could perceive a ruddy glare illuminating the windows of the citadel at Montaignac, while on every hillside round about glowed the light of other incendiary fires. The whole district was answering Lacheneur’s signal.

AH! ambition is a fine thing! The Duke de Sairmeuse and the Marquis de Courtornieu were considerably past middle-age; they had weathered many storms and vicissitudes; they possessed millions in hard cash, and owned the finest estates in the province. Under these circumstances it might have been supposed that their only desire was to end their days in peace and quietness. It would have been easy for them to lead a happy and useful life by seeking to promote the welfare of the district, and they might have gone down to their graves amid a chorus of benedictions and regrets.

But no. They longed to have a hand in managing the state vessel; they were not content with remaining simple passengers. The duke, appointed to the command of the military forces, and the marquis, invested with high judicial functions at Montaignac, were both obliged to leave their beautiful chateaux and install themselves in somewhat dingy quarters in the town. And yet they did not murmur at the change, for their vanity was satisfied. Louis XVIII. was on the throne; their prejudices were triumphant; and they felt supremely happy. It is true that sedition was already rife on every side, but had they not hundreds and thousands of allies at hand to assist them in suppressing it? And when thoughtful politicians spoke of “discontent,” the duke and his associates looked at them with the thorough contempt of the sceptic who does not believe in ghosts.

On the 4th of March, 1816, the duke was just sitting down to dinner at his house in Montaignac when he heard a loud noise in the hall. He rose to go and see what was the matter when the door was suddenly flung open and a man entered the room panting and breathless. This man was Chupin, once a poacher, but now enjoying the position of head gamekeeper on the Sairmeuse estates. It was evident, from his manner and appearance, that something very extraordinary had happened.

“What is the matter?” inquired the duke.

“They are coming!” cried Chupin; “they are already on the way!”

“Who are coming? who?”

Chupin made no verbal reply, but handed the duke a copy of the letter written by Martial under Chanlouineau’s dictation. “My dear friend,” so M. de Sairmeuse read. “We are at last agreed, and the marriage is decided on. We are now busy preparing for the wedding, which will take place on the fourth of March.” The date was no longer blank: but still the duke had naturally failed to understand the purport of the missive. “Well, what of it?” he asked.

Chupin tore his hair. “They are on the way,” he repeated. “The peasants—all the peasants of the district, they intend to take possession of Montaignac, dethrone Louis XVIII., bring back the emperor, or at least, the emperor’s son, and crown him as Napoleon II. Ah, the wretches! they have deceived me. I suspected this outbreak, but I did not think it was so near at hand.”

This unexpected intelligence well-nigh stupefied the duke. “How many are there?” he asked.

“Ah! how do I know, your grace? Two thousand, perhaps—perhaps ten thousand.”

“All the town’s people are with us.”

“No, your grace, no. The rebels have accomplices here. All the retired officers of the imperial army are waiting to assist them.”

“Who are the leaders of the movement?”

“Lacheneur, the Abbe Midon, Chanlouineau, the Baron d’Escorval——”

“Enough!” cried the duke.

Now that the danger was certain, his coolness returned, and his herculean form, a trifle bowed by the weight of years, rose to its full height. He gave the bell-rope a violent pull; and directly his valet entered, he bade him bring his uniform and pistols at once. The servant was about to obey, when the duke added: “Wait! Let some one take a horse, and go and tell my son to come here without a moment’s delay. Take one of the swiftest horses. The messenger ought to go to Sairmeuse and back in two hours.” On hearing these words, Chupin pulled at the duke’s coat tail to attract his attention.

“Well, what is it now?” asked M. de Sairmeuse impatiently.

The old poacher raised his finger to his lips, as if recommending silence, and as soon as the valet had left the room, he exclaimed: “It is useless to send for the marquis!”

“And why, you fool?”

“Because, because—excuse me—I——”

“Zounds! will you speak, or not?”

Chupin regretted that he had gone so far. “Because the marquis——”

“Well?”

“He is engaged in it.”

The duke overturned the dinner-table with a terrible blow of his clenched fist. “You lie, you wretch!” he thundered with terrible oaths.

His anger was so threatening, that the old poacher sprang to the door and turned the knob, ready for flight. “May I lose my head if I do not speak the truth,” he insisted. “Ah! Lacheneur’s daughter is a regular sorceress. All the gallants of the neighbourhood are in the ranks; Chanlouineau, young D’ Escorval, your son——”

M. de Sairmeuse was pouring forth a torrent of curses upon Marie-Anne when his valet re-entered the room. He suddenly checked himself, put on his uniform, and ordering Chupin to follow him, he hastened from the house. He was still hoping that Chupin had exaggerated the danger; but when he reached the Place d’Armes commanding an extensive view of the surrounding country, whatever illusions he may have retained immediately vanished. Signal lights gleamed on every side, and Montaignac seemed surrounded by a circle of flame.

“There are the signals,” murmured Chupin. “The rebels will be here before two o’clock in the morning.”

The duke made no reply, but hastened towards M. de Courtornieu’s house. He was striding onward, when on turning a corner, he espied two men talking in a doorway; they also had perceived him, and at sight of his glittering epaulettes they both took flight. The duke instinctively started in pursuit, overtook one of the men, and seizing him by the collar, sternly asked: “Who are you? What is your name?”